|

|

| Product type | Safety razors, shaving supplies, personal care products |

|---|---|

| Owner | Procter & Gamble |

| Country | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Introduced | September 28, 1901; 121 years ago[1] |

| Markets | Worldwide |

| Previous owners | The Gillette Company |

| Tagline | «The Best a Man Can Get» (1989–2019) «The Best Men Can Be» (since 2019) |

| Website | gillette.com |

Gillette is an American brand of safety razors and other personal care products including shaving supplies, owned by the multi-national corporation Procter & Gamble (P&G). Based in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, it was owned by The Gillette Company, a supplier of products under various brands until that company merged into P&G in 2005. The Gillette Company was founded by King C. Gillette in 1901 as a safety razor manufacturer.[2]

Under the leadership of Colman M. Mockler Jr. as CEO from 1975 to 1991,[3] the company was the target of multiple takeover attempts, from Ronald Perelman[4] and Coniston Partners.[3] In January 2005, Procter & Gamble announced plans to merge with the Gillette Company.[5]

The Gillette Company’s assets were incorporated into a P&G unit known internally as «Global Gillette». In July 2007, Global Gillette was dissolved and incorporated into Procter & Gamble’s other two main divisions, Procter & Gamble Beauty and Procter & Gamble Household Care. Gillette’s brands and products were divided between the two accordingly. The Gillette R&D center in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Gillette South Boston Manufacturing Center (known as «Gillette World Shaving Headquarters»), still exist as functional working locations under the Procter & Gamble-owned Gillette brand name.[6] Gillette’s subsidiaries Braun and Oral-B, among others, have also been retained by P&G.

History

Inception and early years

The key figures of the Gillette Safety Razor Company’s first years, from left to right: King Camp Gillette, William Emery Nickerson, and John Joyce

1915-16 advert for the Milady Décolleté Gillette; first safety razor marketed exclusively for women

The Gillette company and brand originate from the late 19th century when salesman and inventor King Camp Gillette came up with the idea of a safety razor that used disposable blades. Safety razors at the time were essentially short pieces of a straight razor clamped to a holder. The blade had to be stropped before each shave and after a time needed to be honed by a cutler.[7] Gillette’s invention was inspired by his mentor at Crown Cork & Seal Company, William Painter, who had invented the Crown cork. Painter encouraged Gillette to come up with something that, like the Crown cork, could be thrown away once used.[8][9]

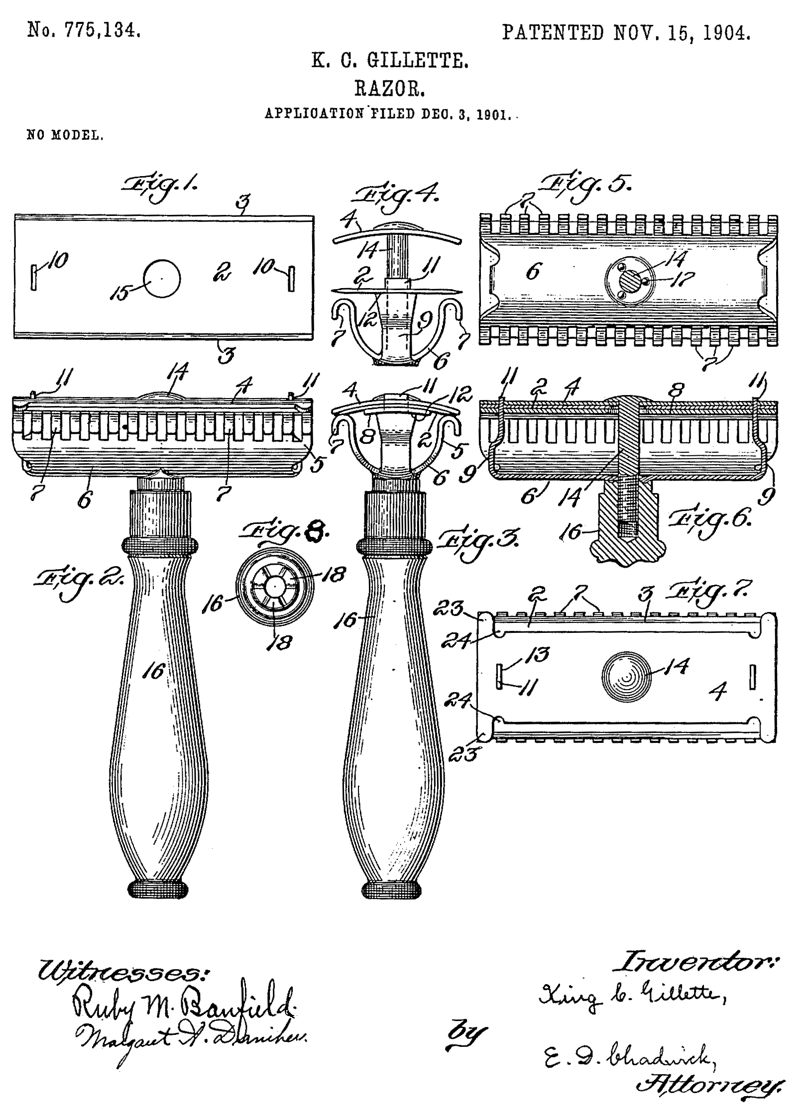

While Gillette came up with the idea in 1895, developing the concept into a working model and drawings that could be submitted to the Patent Office took six years. Gillette had trouble finding anyone capable of developing a method to manufacture blades from thin sheet steel, but finally found William Emery Nickerson, an MIT graduate with a degree in chemistry. Gillette and other members of the project founded The American Safety Razor Company on September 28, 1901. The company had issues getting funding until Gillette’s old friend John Joyce invested the necessary amount for the company to begin manufacturing.[10][8][9] Production began slowly in 1903, but the following year Nickerson succeeded in building a new blade grinding machine that had bottlenecked production. During its first year of operation, the company had sold 51 razors and 168 blades, but the second year saw sales rise to 90,884 razors and 123,648 blades. The company was renamed to the Gillette Safety Razor Company in 1904 and it quickly began to expand outside the United States. In 1905 the company opened a sales office in London and a blade manufacturing plant in Paris, and by 1906 Gillette had a blade plant in Canada, a sales operation in Mexico, and a European distribution network that sold in many nations, including Russia.[8][11]

First World War and the 1920s

Due to its premium pricing strategy, the Gillette Safety Razor Company’s razor and blade unit sales grew at a modest pace from 1908 to 1916. Disposable razor blades still were not a true mass-market product, and barbershops and self-shaving with a straight razor were still popular methods of grooming. Among the general U.S. population, a two-day stubble was not uncommon. This changed once the United States declared war on the Central Powers in 1917; military regulations required every soldier to provide their own shaving kit, and Gillette’s compact kit with disposable blades outsold competitors whose razors required stropping. Gillette marketed their razor by designing a military-only case decorated with U.S. Army and Navy insignia and in 1917 the company sold 1.1 million razors.[12]

The Khaki Set, the safety razor set produced by Gillette for the U.S. Army during the First World War[13]

In 1918, the U.S. military began issuing Gillette shaving kits to every U.S. serviceman. Gillette’s sales rose to 3.5 million razors and 32 million blades. As a consequence, millions of servicemen got accustomed to daily shaving using Gillette’s razor. After the war, Gillette utilized this in their domestic marketing and used advertising to reinforce the habit acquired during the war.[12]

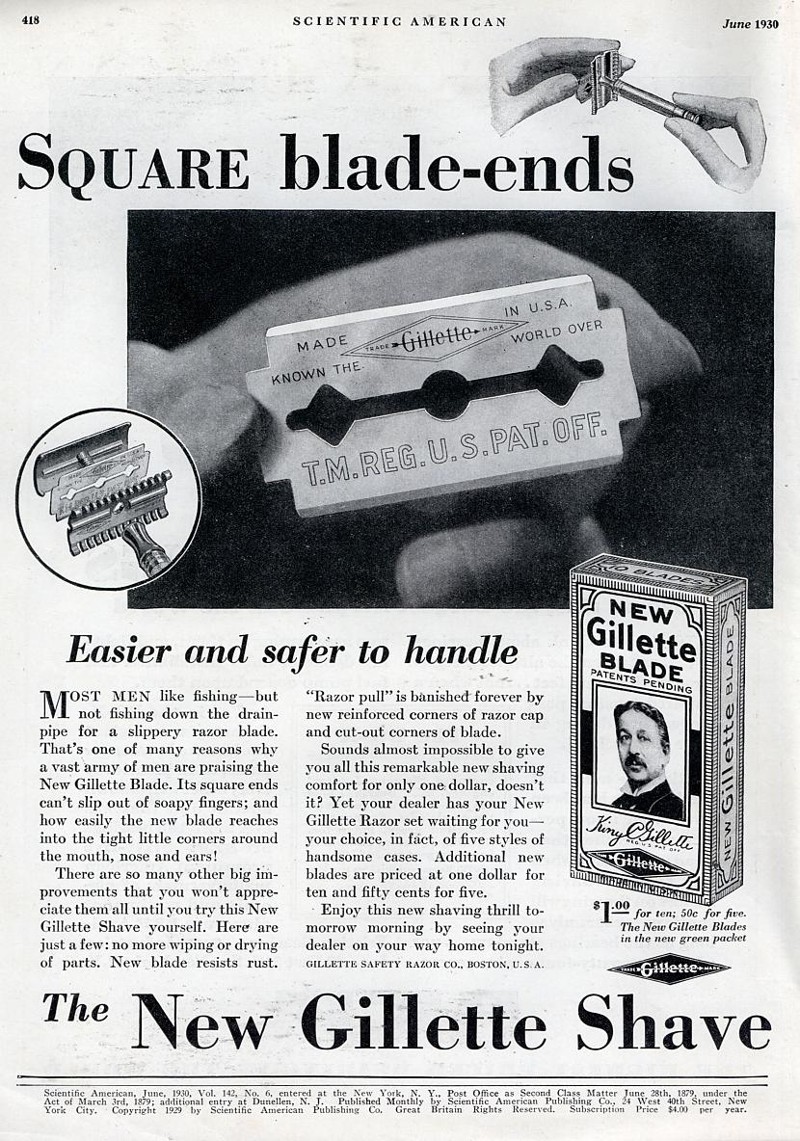

Gillette’s original razor patent was due to expire in November 1921 and to stay ahead of an upcoming competition, the company introduced the New Improved Gillette Safety Razor in spring 1921 and switched to the razor and blades pricing structure the company is known for today. While the New Improved razor was sold for $5 (equivalent to $76 in 2021) – the selling price of the previous razor – the original razor was renamed to the Old Type and sold in inexpensive packaging as «Brownies» for $1 (equivalent to $15 in 2021). While some Old Type models were still sold in various kinds of packaging for an average price of $3.50, the Brownie razors made a Gillette much more affordable for the average person and expanded the company’s blade market significantly. From 1917 to 1925, Gillette’s unit sales increased tenfold. The company also expanded its overseas operations right after the war by opening a manufacturing plant in Slough, near London, to build New Improved razors, and setting up dozens of offices and subsidiaries in Europe and other parts of the world.[14]

Gillette experienced a setback at the end of the 1920s as its competitor AutoStrop sued for patent infringement. The case was settled out of court with Gillette agreeing to buy out AutoStrop for 310,000 non-voting shares. However, before the deal went through, it was revealed in an audit that Gillette had been overstating its sales and profits by $12 million over a five-year period and giving bonuses to its executives based on these numbers. AutoStrop still agreed to the buyout but instead demanded a large amount of preferred stock with voting rights. The merger was announced on October 16, 1930, and gave AutoStrop’s owner Henry Gaisman controlling interest in Gillette.[15]

1930s and the Second World War

A 1930s Gillette One-Piece Tech razor and a pack of Blue Blades

The Great Depression weakened Gillette’s position in the market significantly. The company had fallen behind its competitors in blade manufacturing technology in the 1920s and had let quality control slip while over-stretching its production equipment in order to hurry a new Kroman razor and blade to market in 1930. In 1932, Gillette apologized for the reduction in blade quality, withdrew the Kroman blade, and introduced the Blue Blade (initially called the Blue Super Blade) as its replacement.[16] Other Gillette introductions during the Depression years were the Brushless Shaving Cream and an electric shaver that was soon discontinued due to modest sales.[17]

In 1938 Gillette introduced the Thin Blade, which was cheaper and about half the weight of the Blue Blade, even though it cost almost as much to manufacture. The Thin Blade became more popular than the Blue Blade for several years during the Second World War due to high demand of low-cost products and the shortage of carbon steel.[18] Beginning in 1939, Gillette began investing significant amounts on advertising in sports events after its advertising in the World Series increased sales more than double the company had expected.[19] It eventually sponsored a radio program, the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports, which would move to television as well as that medium expanded in the late 1940s.[20] While the Cavalcade aired many of the notable sporting events of the time (the Kentucky Derby, college football bowl games, and baseball, amongst others) it became most famous for its professional boxing broadcasts.

Though competition hit Gillette hard in the domestic market during the Great Depression, overseas operations helped keep the company afloat. In 1935 more than half of Gillette’s earnings came from foreign operations and in 1938 – the worst of the Depression years for Gillette, with a mere 18 percent market share – nearly all of the company’s $2.9 million earnings came from outside the United States. AutoStrop’s Brazilian factory allowed Gillette to start expanding into the Latin America. In England the Gillette and AutoStrop operations were combined under the Gillette name, where the company built a new blade manufacturing plant in London. In 1937, Gillette’s Berlin factory produced 40 percent of Germany’s 900 million blades and retained a 65 to 75 percent share of the German blade market.[21]

The Second World War reduced Gillette’s blade production both domestically and internationally. As a result of the war, many markets were closed off, German and Japanese forces expropriated the company’s plants and property, and Gillette’s plants in Boston and London were partially converted for weapons production. In 1942, the War Production Board ordered Gillette to dedicate its entire razor production and most blade production to the U.S. military. By the end of the war, servicemen had been issued 12.5 million razors and 1.5 billion blades. Gillette also assisted the U.S. Army in military intelligence by producing copies of German razor blades for secret agents venturing behind German lines so that their identities wouldn’t be compromised by their shaving equipment. The company also manufactured razors that concealed money and escape maps in their handles, and magnetic double-edge blades that prisoners of war could use as a compass.[22]

Recovery from the war and diversification

During the post-war years, Gillette began to quickly ramp up production by modernizing its major manufacturing plants in the United States and England, expanding the capacity of several foreign plants, and re-opening plants closed during the war. The company opened a new plant in Switzerland and began manufacturing blades in Mexico City. Sales rose to $50 million in 1946 and in 1947 Gillette sold a billion blades. By 1950, Gillette’s share of the U.S. blade market had climbed to 50 percent.[23] During the 1950s, the company updated and in some cases moved some of its older European factories: the Paris factory, for example, was moved to Annecy.[24]

A 1958 Gillette Super Speed razor and a blade dispenser

In 1947 Gillette introduced the Gillette Super Speed razor and along with it the Speed-pak blade dispenser the company had developed during the war. The dispenser allowed the blade to be slid out of the dispenser into the razor without danger of touching the sharp edge. It also had a compartment for holding used blades.[25][26]

In 1948 Gillette bought the home permanent kit manufacturer The Toni Company[27] and later expanded into other feminine products such as shampoos and hair sprays. In 1955 the company bought the ballpoint pen manufacturer Paper Mate[25][28] and in 1960 they introduced Right Guard aerosol deodorant. Gillette bought the disposable hospital supplies manufacturer Sterilon Corporation in 1962.[29]

Television advertising played a big part in Gillette’s post-war growth in the United States. The company began TV advertising in 1944 and in 1950 it spent $6 million to acquire exclusive sponsorship rights to the World Series for six years. By the mid-1950s, 85 percent of Gillette’s advertising budget was used for television advertising. The company also advertised the Toni product line by sponsoring the TV show Arthur Godfrey and His Friends and the 1958 Miss America contest and its winner.[30][31]

1950s TV commercial for Gillette’s Blue Blades

Although Gillette’s immediate priority after the war was satisfying U.S. demand and later diversifying its domestic business, the company pursued expansion in foreign markets that showed potential for growth, such as Latin America and Asia. However, the Cold War restricted Gillette’s operations in many parts of the world and closed entire markets the company would have otherwise entered in Russia, China, Eastern Europe, Near East, Cuba, and parts of Asia. More and more countries demanded local ownership for foreign enterprise in exchange for continued operation or entry into their markets. Outside the U.S. and European markets, Gillette spent time and money building manufacturing facilities and distribution networks in anticipation that the markets would eventually be opened up and nationalistic restrictions lifted. Some of Gillette’s joint ventures included a 40 percent Gillette 60 percent Malaysian mini-plant operation that began production in 1970, and an Iranian manufacturing plant with 51 percent government ownership. The Iran plant was one of Gillette’s largest and most modern factories until the Iranian Revolution of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini rose into power and American businesses were targeted as enemies of the new government, forcing Gillette to abandon the operation and withdraw from the country.[32]

Super Blue and the Wilkinson shock

In 1960, Gillette introduced the Super Blue blade, the company’s first coated blade, and the first significantly improved razor blade since the Blue Blade of the 1930s. The new blade was coated with silicone and in Gillette’s laboratory testing produced much more comfortable and close shaves by reducing the blade’s adhesion to whiskers. Super Blue was a success and sold more than the Blue Blade and Thin Blade combined. By the end of 1961, Gillette’s double edge blade market share had risen to 90 percent and the company held a total razor blade market share of 70 percent.[33]

In 1962, roughly two years after the introduction of the Super Blue blade, Wilkinson Sword introduced the world’s first razor blade made from stainless steel. According to users, the blade stayed sharp about three times longer than the best carbon steel blades – including Gillette’s. Wilkinson’s introduction took Gillette by surprise and the company struggled to respond as its smaller rivals, Schick and the American Safety Razor Company, came out with their own stainless steel blade. However, during the development of the silicon coating for the Super Blue blade, Gillette had also discovered the method of producing coated stainless steel blades that Wilkinson Sword was using and managed to patent it before Wilkinson did. The English company was forced to pay royalty to Gillette for each blade it sold.[34]

Gillette hesitated in bringing its own stainless steel blades to market as Super Blue had been a huge success and replacing it with a longer-lasting blade would have reduced profits. The company eventually brought the Gillette Stainless blade to the market in August 1963, about a year after Wilkinson’s stainless blades. As a result of the affair, Gillette’s share of the double-edge blade market dropped from 90 percent to about 70 percent.[34]

Two years after the introduction of the Gillette Stainless blades, the company brought out the Super Stainless blades – known in Europe as Super Silver – that were made from an improved steel alloy. Gillette also introduced the Techmatic, a new type of razor that used a continuous spool of stainless blade housed in a plastic cartridge.[35][36]

The success of the coated Super Blue blades marked the start of a period when chemistry became as important as metallurgy in Gillette’s blade manufacturing. The Super Blue’s coating was a result of teamwork between the Gillette’s British and American scientists.[37] As a result of the Wilkinson ordeal, Gillette’s then-chairman Carl Gilbert increased the company’s spending on research and development facilities in the U.S., championed the building of a research facility in Rockville, Maryland, and encouraged further expansion of R&D activities in England.[38]

Trac II: The move to cartridge razors

Patent drawing of the abandoned Atra razor and a picture of a Deluxe model Trac II razor

The development of Gillette’s first twin-blade razor began in early 1964 in the company’s Reading laboratories in England when a new employee, Norman C. Welsh, experimented with tandem blades and discovered what he called the «hysteresis effect»; a blade pulling the whisker out of the hair follicle before cutting it, and enabling a second blade to cut the whisker even shorter before it retracted back into the follicle. For six years afterwards, Welsh and his colleagues worked on a means of utilizing the hysteresis effect, almost exclusively concentrating on what would later be known as the Atra twin-blade system. The Atra razor featured two blades set in a plastic cartridge with edges that faced each other. Using the razor required the user to move it in an up-and-down scrubbing motion, and whiskers were cut on both the up and down strokes. Another twin-blade system with blades set in tandem, codenamed «Rex», also existed, but it had too many technical problems and was behind Atra in development.[39]

In consumer tests, the Atra razor had outperformed existing razor systems, but Gillette’s marketing executives feared the razor would meet resistance among shavers due to the unfamiliar scrubbing motion required to use it. Even though the Atra project was so far along in mid-1970 that packaging and production machinery was nearly ready for a full market introduction, Gillette decided to start a development drive to finish Rex instead as it did not require learning a new way to shave. The project succeeded, Atra was abandoned, and Gillette announced the first twin-blade razor – now renamed to Trac II – in the fall of 1971. The Trac II captured the premium shaving market and came out in time to counter Wilkinson Sword’s Bonded Blade system that utilized single-blade cartridges.[40]

The challenge of disposables

In 1974, the French Société Bic introduced the world’s first disposable razor. The razor was first brought to the market in Greece, where it sold well, after which it was introduced to Italy and many other European countries. Gillette hurried to develop their own disposable before Bic could bring their razor to the United States. Gillette designed a single-blade razor similar to Bic’s but soon abandoned the concept in favor of a razor that was essentially a Trac II cartridge molded into a blue plastic handle. Gillette introduced this disposable as the Good News in 1976, about a year before Bic’s razor reached the United States, and managed to establish market leadership once Bic and other competitors came to market. Good News was released under various names in Europe and was equally and sometimes even more successful than Bic’s razor. Gillette quickly brought its razor to markets Bic hadn’t yet reached, such as Latin America where the razor was known as Prestobarba.[41]

In Latin America, Gillette used a so-called cannibalization strategy by selling the razor in several market segments: along with the heavily advertised Prestobarba, the razor was also sold under different names – such as Permasharp II in Mexico and Probak II in Brazil – and sold for at least 10 to 15 percent less. The less expensive variants were differentiated from the blue Prestobarba by manufacturing them from yellow plastic with handle less ergonomically comfortable, and in addition, they were not advertised or eventually has negative marketing[42] aimed at promoting the sale of the most profitable products in Gillette’s razors line. The strategy was successful and later market arrivals were unable to gain a major foothold. Once the approach proved to be a successful one, Gillette’s subsidiaries in Russia, Poland, and multiple Asian and Near Eastern markets began utilizing the same strategy.[43]

While Gillette managed to retain market leadership against Bic and other competitors, the popularity of disposable razors, their higher production cost compared to cartridges, and price competition eroded the company’s profits. Gillette had at first hoped that disposables would take no more than 10 percent of the total razor and blades market, but by 1980, disposables accounted for more than 27 percent of the world shaving market in terms of unit sales, and 22 percent of total revenue.[44][45] John W. Symons began steering Gillette into a different direction after becoming the director of Gillette’s European Sales Group in 1979. Despite Gillette’s strong sales and a large share of the European razor and blades market – 70 percent, which was higher than in the United States – cash flow was declining. In Symons’s view, the issue was Gillette’s attempt to compete with Bic in the disposables market, which was eating into the sales of its more profitable cartridge razors. Symons reduced the marketing budget of disposables in Europe and hired the advertising agency BBDO’s London branch to create an ad campaign to make Gillette’s blade and razor systems – such as Contour – more desirable in the eyes of men. The new marketing strategy, combined with cutting costs and centralizing production increased profits. In 1985, Gillette’s profits in the European market were $96 million, while two years previously they were $77 million.[46]

The logo of Gillette used from 1989 to 2008.

In 1980, Gillette introduced Atra – known in Europe as Contour – a twin-blade razor with a pivoting head. The razor became a best-seller in the United States during its first year and eventually became a market leader in Europe.[47]

Acquisitions and takeover attempts

In 1984, Gillette agreed to acquire Oral-B Laboratories from dental care company Cooper Laboratories for $188.5 million in cash.[48] Revlon Group’s Ronald Perelman offered to purchase 86.1 percent of Gillette for $3.8 billion in 1986, valuing the company at $4.1 billion.[49] Gillette also bought back Revlon’s stake in the company for $558 million.[50] Revlon made two additional unsolicited requests to purchase Gillette for $4.66 billion and $5.4 billion in June and August 1987, respectively, both of which were rejected by Gillette’s board of directors.[51][52][53]

In 1988, Coniston Partners acquired approximately 6 percent of Gillette.[54] Hoping to acquire four directors’ seats and pressure Gillette to sell, Coniston forced a proxy vote in April. The companies filed suits against one another, resulting in a settlement in August. Gillette repurchased approximately 16 million shares for $720 million and Coniston agreed not to purchase many Gillette shares, participate in proxy contests, or otherwise seek control of the company for three years.[55][56]

In 1989, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway purchased $600 million worth of Gillette convertible preferred shares. Buffett filled a vacant seat on the company’s board and agreed not to sell his stake «except in a change of control or if insurance regulators force a sale of the stock in the event Gillette’s financial condition falters», reducing the chances of a takeover.[57] During late 1989 and early 1990, Gillette launched the new product Sensor with a $175 million marketing campaign in 19 countries in North America and Western Europe.[58][59]

Early to mid-1990s

In 1990, Gillette attempted to purchase Wilkinson Sword’s U.S. and non-European operations. The Department of Justice prevented the sale of Wilkinson’s U.S. assets to prevent a significant reduction in competition by eliminating one of the top four blade suppliers when Gillette already controlled approximately half of the nation’s razor market.[60][61] Gillette launched the Series line of men’s grooming products, including scented shaving gels, deodorants, and skin-care items, in 1992.[62][63] The company’s SensorExcel launched in Europe and Canada in 1993,[64] followed by the United Kingdom and United States in 1994.[65] In 1996, Gillette launched several new products for women and teenage boys, including the SensorExcel for Women, a moisturizer, a shaving gel, and a body spray.[66]

Beginning of the Razor Wars

The company launched the new shaving system Gillette Mach3 in 1998, challenging the twin-blade system which dominated the market by introducing a third blade. Gillette promoted the product, which took five years to develop and was protected by 35 patents, with a $300 million marketing campaign.[67][68] The Mach3 and replacement cartridges cost 35 percent more than the SensorExcel razor.[69] By 1999, Gillette was worth US$43 billion, and the brand value of Gillette was estimated to be worth US$16 billion. This equated to 37% of the company’s value.[70] In 2000, Gillette’s board fired CEO Michael Hawley; he was replaced by former Nabisco CEO James M. Kilts in early 2001.[71][72] In 2003, Schick-Wilkinson Sword introduced the Quattro, a four-blade shaving system, increasing the company’s market share to 17 percent. Gillette claimed the Quattro infringed on the Mach3 patents.[73] Gillette’s efforts were unsuccessful, but the company maintained approximately two-thirds of the global wet-razor market as of mid-2005.[74]

Procter & Gamble acquisition to present

In 2005, Procter & Gamble announced plans to acquire Gillette for more than $50 billion, which would position P&G as the world’s largest consumer products company.[75] The deal was approved by the Federal Trade Commission.[76][77] Gillette introduced the world’s first 5-blade razor, called the Fusion, during 2005–2006, marking the company’s first launch after the P&G acquisition.[78] By 2010, the Fusion was the world’s highest selling blade and razor brand, reaching $1 billion in annual sales faster than any prior P&G product.[79] Gillette’s Fusion ProSeries skincare line, launched in 2010, included a thermal facial scrub, a face wash, a lotion, and a moisturizer with sunscreen.[80][81] The Gillette Fusion ProGlide Styler for facial hair grooming was introduced in 2012, with André 3000, Gael García Bernal, and Adrien Brody serving as brand ambassadors.[82][83]

In 2015, the company launched a subscription service called Gillette Shave Club[note 1] and later filed a lawsuit against Dollar Shave Club for patent infringement.[86][87] The Dollar Shave Club lawsuit was criticized for revealing flaws in Gillette’s own patents[88] and as a perceived attempt to drive away an upstart competitor; the lawsuit was dropped two months later after Dollar Shave Club filed a countersuit.[89]

In 2019, the company partnered with TerraCycle to create a U.S. recycling program for blades, razors, and packaging for any brand.[90] In 2020, Gillette announced a commitment to reduce the use of virgin (unrecycled) plastics by 50 percent by 2030 and maintain zero waste to landfill status across all plants.[91]

Product history

Double-edged safety razors

Gillette razor and packaging, circa 1930s

The first safety razor using the new disposable blade went on sale in 1903.[6] Gillette maintained a limited range of models of this new type razor until 1921 when the original Gillette patent expired.[2] In anticipation of the event, Gillette introduced a redesigned razor and offered it at a variety of prices in different cases and finishes, including the long-running “aristocrat». Gillette continued to sell the original razor but instead of pricing it at $5, it was priced at $1, making a Gillette razor truly affordable to every man regardless of economic class. In 1932 the Gillette Blue Blade, so-named because it was dipped in blue lacquer, was introduced. It became one of the most recognizable blades in the world. In 1934 the «twist to open» (TTO) design was instituted, which featured butterfly-like doors that made blade changing much easier than it had been, wherein the razor head had to be detached from the handle.

Razor handles continued to advance to allow consumers to achieve a closer shave. In 1947, the new (TTO) model, the «Super Speed», was introduced. This was updated in 1955, with different versions being produced to shave more closely – the degree of closeness being marked by the color of the handle tip.

In 1955, the first adjustable razor was produced. This allowed for an adjustment of the blade to increase the closeness of the shave. The model, in various versions, remained in production until 1988.[92]

«Old type» Gillette safety razor, made between 1921 and 1928

The Super Speed razor was again redesigned in 1966 and given a black resin coated metal handle. It remained in production until 1988. A companion model the, «Knack», with a longer plastic handle, was produced from 1966 to 1975. In Europe, the Knack was sold as «Slim Twist» and «G2000» from 1978 to 1988, a later version known as «G1000» was made in England and available until 1998. A modern version of the Tech, with a plastic thin handle, is still produced and sold in several countries under the names 7 O’clock, Gillette, Nacet, Minora, Rubie, and Economica.

Discontinued products

- Techmatic was a single blade razor introduced in the mid-1960s. It featured a disposable cartridge with a razor band which was advanced by means of a lever. This exposed an unused portion of the band and was the equivalent of five blades. This product line also included the Adjustable Techmatic.

- Trac II was the world’s first two-blade razor, debuting in 1971.[93] Gillette claimed that the second blade cut the number of strokes required and reduced facial irritation. This product line also included the Trac II Plus.

- Atra (known as the Contour, Slalom, Vector in some markets) was introduced in 1977[2] and was the first razor to feature a pivoting head, which Gillette claimed made it easier for men to shave their necks. This product line also included the Atra Plus, which featured a lubricating strip, dubbed Lubra-Soft.

- Good News! was the first disposable, double-blade razor, released in 1976.[94][95] Varieties included the «Original», the «Good News! Plus», and the «Good News! Pivot Plus».

- Custom Plus was a series of disposable razors that came in many varieties: the «Fixed Disposable razor», the «Pivot Disposable razor», the «Custom Plus 3 Sensitive Disposable», and the «Custom Plus 3 Soothing Disposable». Fusion Power Phenom was released in February 2008. It had a blue and silver color scheme.[96] Other discontinued variants include the Fusion Power Gamer.

- Body was a 3 blade razor in care of the man’s body introduced in 2014. However, the Gillette Body was discontinued in 2018.

Current products

- Gillette Sensor debuted in 1990,[97] and was the first razor to have spring-loaded blades. Gillette claimed the blades receded into the cartridge head, when they make contact with skin, helping to prevent cuts and allowing for a closer shave.[98] This product line also includes the Sensor Excel,[99] the Sensor 3, and the Sensor 3 Cool.[100][101]

- Blue II is a line of disposable razors, rebranding the old brand Good News!. In Latin America, it was marketed as the Prestobarba. Another product in the line is the Blue 3, a line of three-blade disposable razors, cheaper than Sensor 3.

- Mach3 – the first three-blade razor, introduced in 1998,[102] which Gillette claims reduces irritation and requires fewer strokes. In 2016,[103] P&G upgraded the Gillette Mach3 razor: This product comes in disposable, sensitive and «turbo» variants as well.[104][105]

- Venus is a division of razors for women created in 2000. Products include Venus Divine, Venus Vibrance, Venus Embrace, Venus Breeze, Venus Spa Breeze and Venus ProSkin Moisture Rich.

- Gillette Fusion is a five-bladed razor released in 2006. The Fusion has five blades on the front and a single sixth blade on the rear for precision trimming.[106][107] Its marketing campaign was fronted by the sports stars Roger Federer, Thierry Henry, and Tiger Woods.[108][109] Razors in this product line include Fusion Power, Fusion ProGlide Shield, Fusion ProGlide, Fusion ProGlide Power,[110] and Fusion ProGlide with FlexBall Technology.[96][111] The ProGlide FlexBall has a handle that allows the razor cartridge to pivot.[112]

- Gillette All-Purpose Styler, released in 2012, is a waterproof beard trimmer that can cut four different lengths.[113]

- Treo is the first razor designed for caregivers to shave seniors and people with disabilities, was introduced in 2017.[114] The product was named one of the best inventions of 2018 by Time,[115] and later exhibited at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in 2020.[116][117]

- SkinGuard is a razor designed for people with sensitive skin, introduced during 2018–2019.[118]

- In 2019, the company launched the first heated razor, mimicking a hot towel shave.[119] The prototype was showcased at CES and later named one of the best inventions of 2019 by Time.[120] The heated razor received mixed reviews, with reviewers, including professional barbers, describing the design as flawed and the $200 price tag as overpriced.[121][122]

- King C. Gillette Beard Care Line came out in May 2020 named for the company’s founder and offers beard care products including a Complete Men’s Beard Kit, a double-sided safety razor, shave gel, beard and face wash, balm and oil.[123]

- Planet KIND Skincare Line launched in February 2021 as a new sustainable shaving and skincare brand, featuring a razor, shave cream, moisturizer and face wash. The razor is constructed from 60 percent recycled plastic and refills are designed with five blades that can each be used for up to a month. Planet KIND partnered with recycling company TerraCycle to design a program through which you can recycle the razor and blades.[124]

-

Gillette Blue II razor, circa 2007

-

Gillette Mach3 razor, circa 2015

-

Gillette Fusion ProGlide Power

Criticism and controversy

The desire to release ever more expensive products, each claiming to be the «best ever», has led Gillette to make disputed claims for its products. In 2005, an injunction was brought by rival Wilkinson Sword which was granted by the Connecticut District Court which determined that Gillette’s claims were both «unsubstantiated and inaccurate» and that the product demonstrations in Gillette’s advertising were «greatly exaggerated» and «literally false». While advertising in the United States had to be rewritten, the court’s ruling does not apply in other countries.[125]

Procter & Gamble (P&G) shaving products have been under investigation by the UK Office of Fair Trading as part of an inquiry into alleged collusion between manufacturers and retailers in setting prices.

Gillette was fined by Autorité de la concurrence in France in 2016 for price fixing on personal hygiene products.[126]

In January 2019, Gillette began a new marketing campaign, «The Best Men Can Be», to mark the 30th anniversary of the «Best a Man Can Get» slogan. The campaign was introduced with a long-form commercial entitled «We Believe», and aims to promote positive values among men – condemning acts of bullying, sexism, sexual assault, and toxic masculinity. While the campaign received praise for its acknowledgement of current social movements and for promoting positive values of masculinity, it also faced a negative response – including from right-wing critics[127] – being called left-wing propaganda, accusatory towards its customers, and misandrist and there were calls for boycotts of Gillette.[128][129][130][131][132]

In June 2019, P&G wrote-down Gillette business by $8 billion, a move which company executives attributed to currency exchange, new competitors in the market, and increased popularity of growing beards. Share prices increased following the write-down.[133]

Marketing

1922 advertisement for various New Improved and Old Type razor models

Gillette first introduced its long-time slogan, «The Best a Man Can Get», during a commercial first aired during Super Bowl XXIII in 1989.[131]

The company has sponsored Major League Baseball (MLB),[134] the 2010 Gillette Fusion ProGlide 500, and the Olympic Games,[135][136] and has naming rights to Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, home venue for the National Football League’s New England Patriots.[137][138] Athletes such as Roger Federer,[139] Tiger Woods,[140] Shoaib Malik,[141] Derek Jeter,[142] Thierry Henry,[143] Kenan Sofuoğlu,[144] Park Ji-sung,[145] Rahul Dravid,[146] Raheem Sterling,[147] Karl-Anthony Towns,[148] and Michael Clarke have been sponsored by the company,[149] as well as video gaming personality Dr Disrespect.[150]

In November 2009, Gillette became the subject of a proposed boycott in Ireland due to its endorsement by French soccer player Thierry Henry; his undetected handball foul during a FIFA World Cup qualifying match contributed to a game-winning goal by France, eliminating Ireland from contention.[151] The following month, expanding upon the controversy, media outlets observed a «curse» associated with top athletes who endorse Gillette, also citing Tiger Woods (who became the subject of an infidelity scandal in late-2009), and Roger Federer losing in an upset to Nikolay Davydenko during the 2009 ATP World Tour Finals.[152]

Since its opening in 2002, Gillette has held naming rights to Gillette Stadium in nearby Foxborough, home of the New England Patriots of the National Football League. The original agreement lasted through 2017; in 2010, P&G negotiated a 15-year extension, lasting through 2031.[153]

Since the 1990s, the company has used a marketing list to send a free sample of a Gillette razor in promotional packages to men in celebration of their 18th birthday. The campaign has occasionally resulted in the samples accidentally being sent to recipients outside of the demographic, such as a 50-year-old woman (exacerbated by the package containing the slogan «Welcome to Manhood»).[154][155]

In 2019, Gillette and Twitch partnered to form the esports group Gillette Gaming Alliance, as well as the Bits for Blades campaign which gave Twitch Bits (the site’s digital currency) to those who purchased Gillette products online. The 2019 team had eleven streamers, each representing a different country,[156] and the 2020 team had five streamers including DrLupo.[157][158] During 2020–2021, Gillette enlisted NFL players Saquon Barkley, Ashtyn Davis, Jalen Hurts, Cole Kmet, and Tua Tagovailoa as brand ambassadors.[159][160]

In science

In laser research and development, Gillette razor blades are used as a non-standard measurement as a rough estimate of a particular laser beam’s penetrative ability; a «four-Gillette laser», for example, can burn through four blades.[161]

In music

Science isn’t the only unusual setting far removed from hygiene in which a Gillette razor blade has been used. It was used as a tool to achieve a certain sound by the English rock band The Kinks. Kinks member Dave Davies became «really bored with this guitar sound – or lack of an interesting sound» so he purchased «a little green amplifier …an Elpico» from a radio spares shop in Muswell Hill,[162] and «twiddled around with it», including «taking the wires going to the speaker and putting a jack plug on there and plugging it straight into my AC30» (a larger amplifier), but did not get the sound he wanted until he got frustrated and «got a single-sided Gillette razorblade and cut round the cone [from the center to the edge] … so it was all shredded but still on there, still intact. I played and I thought it was amazing.»[163] The sound was replicated in the studio by having the Elpico plugged into the Vox AC30. It was this sound, courtesy of a Gillette razor blade that became a mainstay on many of The Kinks early recordings, including «You Really Got Me» and «All Day and All of the Night».[164]

Operations in Canada

In late 1988, Gillette announced plans to eliminate manufacturing operations in Montreal and Toronto. The Canadian unit’s executive offices remained in Montreal, with administrative, distribution, marketing, and sales operations continuing in both cities. Approximately 600 employees in Canada were laid off as part of the global restructure,[165] which followed a $720 million share repurchase and sought to «rationalize worldwide production».[166] As of 2005, Gillette was not producing products in Canada and employed approximately 200 people in Edmonton, Mississauga, and Montreal.[167]

Notes

- ^ Rebranded as Gillette On Demand in 2017.[84][85]

References

- ^ Srinivasan, R. (2014). Case Studies in Marketing: The Indian Context. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-8120349964. Archived from the original on 2021-09-02. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- ^ a b c «Gillette in His Early Days the Inventor of the Razor and the Company He Build Survived Many Close Shaves with Financial Ruin. But His Fame Never Translated into a Personal Fortune». money.cnn.com. April 1, 2003. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ a b Fowler, Glenn (1991-01-26). «Colman M. Mockler Jr. Dies at 61, Gillette’s Top Executive Since 70’s». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-09-04. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ «Gillette chairman dies of heart attack». UPI. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ «Procter & Gamble Acquires Gillette». www.cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ a b «Gillette history». gillette.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 5.

- ^ a b c McKibben 1998, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Gillette 1918.

- ^ «Gillette Blade». National History of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ McDonough, John; Egolf, Karen (June 18, 2015). The Advertising Age Encyclopedia of Advertising. Routledge. ISBN 9781135949068. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b McKibben 1998, pp. 18–20.

- ^ «Gillette U.S. Service Razor Set». National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 20–21.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 29–30.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 29–33.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 34.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 35.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Cross, Mary (2002). A Century of American Icons: 100 Products and Slogans from the 20th-Century Consumer Culture. Greenwood Press. pp. 101–02. ISBN 978-0313314810. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 34–35.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 39–40.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 40–45.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 61.

- ^ a b McKibben 1998, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Waits 2014, p. 466.

- ^ McKibben 1998, The legend of the «Which twin has the Toni?» advert between pages 52 and 53.

- ^ «A Permanent Contribution When Gillette bought a hot startup in an effort to diversify, it got something even better: the entrepreneur behind the product». money.cnn.com. April 1, 2003. Archived from the original on July 2, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 54–55.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 49–52.

- ^ «Gillette Co. | AdAge Encyclopedia of Advertising – Advertising Age». May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-05-20.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 61–66.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b McKibben 1998, pp. 56–58.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Waits 2014, p. 468.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 53.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 59.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 67–68.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 67–69.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Vitor Belfort e Lutadores UFC: Vai Amarelar — Advertising where the Probak II product from Gillette’s low-cost disposable razors line is treated with negative marketing in order to promote the Prestobarba brand, a product sold at a higher price by Gillette.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 336–37.

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Gillette and the men’s wet-shaving market Archived 2020-08-09 at the Wayback Machine, p. 2

- ^ McKibben 1998, pp. 114–17.

- ^ McKibben 1998, p. 96.

- ^ «Gillette Will Buy Cooper’s Oral-B». The New York Times. April 5, 1984. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Cole, Robert J. (November 15, 1986). «Gillette Soars $10 as Wall Street Expects Fight with Revlon». The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Belkin, Lisa (November 25, 1986). «Gillette Deals Ends Revlon Bid». The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Ziegler, Baart (June 19, 1987). «Gillette Rejects Revlon Bid». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Jahn, George (August 24, 1987). «Gillette Rejects Third Takeover Bid By Revlon». Associated Press. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Cowan, Alison Leigh (August 18, 1987). «Revlon Asks to Bid For Gillette». The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Cole, Robert J. (February 12, 1988). «Battle Begins For Control Of Gillette». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Dana (August 2, 1988). «Gillette and Coniston Reach Settlement Over Proxy Fight». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Cowan, Alison Leigh (August 2, 1988). «Gillette and Coniston Drop Suits». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Cowan, Alison Leigh (July 21, 1989). «Gillette Sells 11% Stake To Buffett». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (October 4, 1989). «Gillette Challenge to the Disposables». The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (February 25, 1990). «A Radical New Style for Stodgy Old Gillette». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Rowley, James (January 10, 1990). «Justice Plans Antitrust Lawsuit to Halt Gillette-Wilkinson Deal». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen (March 27, 1990). «Gillette In Accord on Antitrust Suit». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ «Company News; Gillette Displays New Line Of Male Skin-Care Products». The New York Times. Associated Press. September 23, 1992. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette Bets Cool Cash on Upscale Toiletry Launch». Chicago Tribune. September 21, 1992. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021 – via Bloomberg Business News.

- ^ Vainblat, Galina (July 6, 1993). «Gillette aims new razor at carving market share Analysts question need for product». The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ «New Shaving System: Gillette Co. has launched…» Los Angeles Times. October 14, 1994. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Shoebridge, Neil (October 7, 1996). «Gillette takes a gamble on women and teenage boys». Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Canedy, Dana (April 15, 1998). «Gillette Unveils Its Mach3 Razor as Stock Backs Off». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette spends $750 million to make Mach3 Huge covert operation for new production line of three-blade razor». The Baltimore Sun. August 17, 1998. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette sets Mach3 launch». CNN Money. April 14, 1998. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Jane Pavitt (2000). Brand New. ISBN 069107061X[page needed]

- ^ Herper, Matthew (October 20, 2000). «Focus On The Forbes 500s: Gillette Fires CEO». Forbes. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette taps Nabisco CEO». CNN Money. January 22, 2001. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Teather, David (August 14, 2003). «It’s Mach3 versus Quattro as Gillette crosses swords with Schick». The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ «It’s a cut-throat market». Marketing Week. June 23, 2005. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ «P&G Agrees to Buy Gillette In a $54 Billion Stock Deal». The Wall Street Journal. January 30, 2005. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ «P&G Cleared For Gillette Buy». Forbes. September 30, 2005. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ «FTC Consent Order Remedies Likely Anticompetitive Effects of Procter & Gambles Acquisition of Gillette». Federal Trade Commission. September 30, 2005. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette unveils 5-bladed razor». CNN Money. CNN. September 14, 2005. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Wohl, Jessica (May 13, 2010). «Art of Shaving says new Gillette blade sales solid». Reuters. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Evans, Matthew W. (March 9, 2010). «Gillette Launching Men’s Fusion ProSeries». Women’s Wear Daily. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Rosie (February 12, 2010). «P&G launches Gillette Fusion ProGlide Series». Marketing Week. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Peter (February 14, 2021). «The New Shaver to Consider Using Today». Esquire. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette taps Benjamin, Brody and Bernal for ProGlide Styler ads». Los Angeles Times. January 23, 2012. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Green, Dennis (May 9, 2017). «Gillette just made an unprecedented change to be more like its competitors». Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Lauren (May 9, 2017). «Gillette one ups Dollar Shave Club with on-demand razor ordering service where you text to order». CNBC. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette files patent lawsuit against Dollar Shave Club». The Denver Post. December 17, 2015. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Harwell, Drew (December 18, 2015). «Gillette’s lawsuit could tilt the battle for America’s beards». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 19, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Spiegel, David (18 December 2015). «The nick in Gillette suit against upstart Dollar Shave Club». CNBC. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Milosavljević, Marija. «How Gillette’s Ad Helped Dollar Shave Club». W3 Labs. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Peters, Adele (March 15, 2019). «You can now send Gillette your old razors to have them recycled». Fast Company. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Deonna (October 27, 2020). «Gillette plans to shave use of virgin (unrecycled) plastics by 50% by 2030». GreenBiz. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ «Vintage Gillette Adjustable Double Edge Razors». GilletteAdjustable.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Tiffany, Kaitlyn. «The absurd quest to make the «best» razor». Vox. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ Cutler, Rodney (September 11, 2007). «The Grooming Awards Hall of Fame: Gillette Good News». Esquire. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Tobias, Andrew (July 12, 1976). «Gillette’s New Ploy: Throwing Away the Razors to Sell the Blades». New York. New York Media, LLC. 9 (28): 55. ISSN 0028-7369. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b «Gillette Unveils Newest Members of Its Gillette Young Guns Lineup» (Press release). Gillette. February 11, 2008. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ «Manufacturing can thrive but struggles for respect». Reuters. 2011-12-14. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ «Gillette Ups the Razor Ante. Again». Boston.com. April 29, 2014. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Shoebridge, Neil (October 23, 1995). «Gillette’s better-blade plan has profits rising smoothly». Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Selwood, Daniel (February 20, 2018). «Gillette counters falling sales with packaging overhaul». The Grocer. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ Utroske, Deanna (March 27, 2018). «P&G launches 5 new Gillette razors to keep pace with men’s grooming preferences». Cosmetics Design. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ Tiffany, Kaitlyn (2018-12-11). «The absurd quest to make the «best» razor». Vox. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ Brunsman, Barrett. «P&G upgrades Gillette razor for first time in nearly a decade». Cincinnati Business Courier. Archived from the original on 2016-07-26. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ Day, Eliza (9 May 2020). «10 Best Razors for Men Who Like a Close Shave». The Trend Spotter. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Koeppel, Dan; Redman, Justin (December 21, 2020). «The Best Men’s Razors (for Any Face)». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Null, Christopher (October 23, 2007). «Gillette Fusion Power Phantom». Wired. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette Fusion Power Phantom». Thrillist. February 16, 2007. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette Ups the Razor Ante. Again». Boston.com. April 29, 2014. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Gilbert, Sarah. «Did Gillette’s Fusion ad doom Tiger Woods?». AOL. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Byron, Ellen (February 12, 2010). «P&G Razor Launches in Recession’s Shadow». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Eisen, Sara (2014-05-01). «Gillette hopes for a swivel in sales from new razor». CNBC. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ «Gillette’s New Razor Is Everything That’s Wrong With American Innovation». Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Foster, Megan (June 3, 2020). «The best 22 grooming gifts for dad». NBC News. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Brunsman, Barrett J. (October 17, 2017). «P&G rolls out first-of-its-kind razor». Cincinnati Business Courier. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Cooney, Samantha. «Best Inventions: A Razor Built for Assisted Shaving: Gillette Treo». Time. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (January 13, 2020). «How tech is catering to the elderly and caregivers». VentureBeat. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Brunsman, Barrett J. (August 9, 2019). «P&G begins selling first razor for people who can’t shave themselves». Cincinnati Business Courier. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Brunsman, Barrett J. (December 18, 2018). «I Tried It: P&G’s new razor the best from Gillette yet». Cincinnati Business Courier. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

Procter & Gamble Co.’s new Gillette SkinGuard razor for men with sensitive skin has begun hitting store shelves and will continue rolling out in the U.S. and Europe into early 2019, backed by a heavy investment in advertising.

- ^ Meyersohn, Nathaniel (May 2, 2019). «Gillette is selling a $200 luxury razor that heats up to 122 degrees». CNN Business. CNN. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Lang, Cady. «Best Inventions: A Closer Shave: Heated Razor by GilletteLabs». Time. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Koeppel, Dan (5 July 2019). «We Tried the Gillette Heated Razor. It’s Not So Hot». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Bray, Hiawatha (12 May 2019). «In need of a spark, Gillette brings the heat». The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Kumar, Naveen (May 5, 2021). «18 beard grooming products that experts love». CNN. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Malin, Zoe (April 5, 2021). «New & Notable: Latest products from Nike, Old Navy and more». NBC News. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ «Truth in advertising» Archived 2020-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Gizmag; accessed August 22, 2014.

- ^ «Huge price-fixing fine is upheld». The Connexion. 28 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017.

- ^ «Gillette’s Ad Is More Conservative Than Critics Think». National Review. 2019-01-17. Archived from the original on 2020-12-23. Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ «Gillette faces talks of boycott over ad campaign railing against toxic masculinity». ABC News. 2019-01-16. Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ Green, Dennis (2019-01-14). «Gillette chastises men in a new commercial highlighting the #MeToo movement – and some are furious». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ «Gillette released an ad asking men to ‘act the right way.’ Then came the backlash». Boston.com. 2019-01-14. Archived from the original on 2020-12-25. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ a b «Gillette Asks How We Define Masculinity in the #MeToo Era as ‘The Best a Man Can Get’ Turns 30». Adweek. Archived from the original on 2020-12-24. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ «Gillette’s new take on ‘Best a Man Can Get’ in commercial that invokes #MeToo». Advertising Age. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-12-24. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ «Procter & Gamble writes down Gillette business but remains confident in its future». CNBC. 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Lefton, Terry (April 12, 2018). «Gillette exits role as MLB’s oldest sponsor». New York Business Journal: April 12, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Bearne, Suzanne (May 14, 2012). «Gillette kicks off Olympics coaching campaign». Marketing Week. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Brayson, Johnny. «This Olympics Commercial Has A Powerful Message». Bustle. August 4, 2016. Archived from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ «CMGI Field is now Gillette Stadium». CNN Money. CNN. August 5, 2002. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ «Gillette naming rights extended». ESPN. September 22, 2010. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Murray, Tom; Rogers, Taylor Nicole (June 7, 2020). «Roger Federer is the world’s highest-paid athlete for the first time ever. Here’s how he earned $106 million last year». Business Insider. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

In 2007, he was signed by Gillette, starring in a number of ads for the company.

- ^ «Gillette will not renew Tiger Woods». Reuters. December 23, 2010. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Thangaraj, Stanley; Burdsey, Daniel; Dudrah, Rajinder (2015). Sport and South Asian Diasporas: Playing through Time and Space. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1317684299. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

For instance, in an ad for Gillette razors, both Dravid and Malik seem reserved and dignified. This popular campaign, in which Gillette filmed identical segments of celebrity athletes strutting in black outfits, shaving, and giving each other knowing glances, presents both Dravid and Malik as antic-free and suave.

- ^ Reidy, Chris (July 11, 2011). «Gillette pays tribute to Derek Jeter». Boston.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

New York Yankee star Jeter has long been a pitch-man for Gillette, the Boston-based razor-blade brand.

- ^ Parsons, Russell (November 20, 2009). «Gillette stands by Henry despite handball». Marketing Week. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Güncelleme, Son (19 March 2008). «Dünya Şampiyonu Türk Sporcu, Gıllette Fusıon’un Reklam Filminde Yer Aldı». Haberler.com (in Turkish). March 19, 2008. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Castles, Duncan (May 22, 2011). «Park Ji-sung’s philosophy is simple – there is no ‘I’ in football». The National. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Sen, Debarati S. (June 19, 2014). «Rahul Dravid recounts his first shave with his father at a Gillette event in Mumbai». The Times of India. Archived from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Delahunty, Stephen (February 11, 2020). «Watch: Raheem Sterling helps Gillette launch ‘Made of What Matters’ campaign». PRWeek. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Amay, Joane (July 1, 2019). «NBA All-Star Karl-Anthony Towns Gives Us an Inside Look Into His Style Game». Ebony. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

KAT, a Gillette celebrity brand ambassador, is also known for his off-court style prowess.

- ^ «Gillette won’t renew contract with Woods». The Sydney Morning Herald. December 24, 2010. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

The brand, owned by Procter & Gamble Co, used Woods, Roger Federer, Lionel Messi, Australian cricket vice-captain Michael Clarke and dozens of other athletes as part of its three-year «Gillette Champions» marketing campaign.

- ^ Jarvey, Natalie (January 10, 2019). «CAA Signs Twitch Streamer DrDisrespect (Exclusive)». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Ronay, Barney (2009-11-19). «Hands-on Thierry Henry becomes public enemy numéro un». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-08-11. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ «‘Kennett Curse’ has nothing on these». Courier Mail. 2013-09-18. Archived from the original on 2020-12-26. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ «Naming-rights deal extended through 2031». Boston.com. 2010-09-22. Archived from the original on 2020-11-29. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Maheshwari, Sapna (2017-07-16). «Welcome to Manhood, Gillette Told the 50-Year-Old Woman». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ «Retail’s new niche: Aging baby boomers». The Gazette. Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Brunsman, Barrett J. (March 28, 2019). «P&G drafts video game team to boost brand with esports fans». Cincinnati Business Courier. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Takahashi, Dean (February 11, 2020). «Gillette and Twitch round up esports influencers in gaming alliance». VentureBeat. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Stam, Aleda (October 30, 2020). «How brands are getting into the Twitch game». PRWeek. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

When Gillette renewed its Gillette Gaming Alliance this year, the brand continued its Bits for Blades program, where Twitch users who buy Gillette products can enter a unique promo code at checkout and receive Twitch Bits in return.

- ^ «NFL Playbook: Tracking How Brands Are Marketing Around an Uncertain Season». Ad Age. January 4, 2021. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Lefton, Terry (January 25, 2021). «Super Bowl LV in Tampa: Hospitality reality». Tampa Bay Business Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

Gillette is hoping to do something on social media with its quintet of NFL endorsers: New York Giants running back Saquon Barkley, New York Jet safety Ashtyn Davis, Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Jalen Hurts, Chicago Bears tight end Cole Kmet and Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa.

- ^ Rachel Zurer (December 27, 2011). «Three Smart Things About Lasers». Wired. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ «Dave’s Guitars and the Green Amp». davedavies.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-25.

- ^ Hunter, Dave (January 1999). «The Kinks Guitar Sound». Voxes, Vees And Razorblades. The Guitar Magazine. Archived from the original on 2015-07-12 – via davedavies.com.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. «The Kinks». Biography. All Music. Archived from the original on 2012-06-02. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ^ «Gillette Plans to Phase Out Canada Plants». Chicago Tribune. November 24, 1988. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ Burns, John F. (November 24, 1988). «Canada Girds for Action on Trade Bill». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ McKenna, Barrie; Galt, Virginia (January 29, 2005). «P&G cuts mega-deal with Gillette». The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

Bibliography

- McKibben, Gordon (1998). Cutting Edge: Gillette’s Journey to Global Leadership. Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 0875847250.

- Waits, Robert K. (2014). A Safety Razor Compendium: The Book. ISBN 978-1312293533.

- Gillette, King Camp (February 1918). «Origin of the Gillette Razor». The Gillette Blade. Boston: Gillette Safety Razor Company.

Further reading

- «King C. Gillette, The Man and His Wonderful Shaving Device» by Russell Adams (1978), published by Little Brown & Co. of Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

- Rodriguez, Ginger G.; Salamie, David E.; Shepherd, Kenneth R. (2005) [previous versions of the article in the volume 3 and 20]. Grant, Tina (ed.). «The Gillette Company». International Directory of Company Histories. Farmington Hills, Michigan: St.James Press (Thomson Gale). 68: 171–76. ISBN 1558625437.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gillette.

- Official website

- Vintage Gillette Adjustable Double Edge Razors: A Reference website

|

|

| Product type | Safety razors, shaving supplies, personal care products |

|---|---|

| Owner | Procter & Gamble |

| Country | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Introduced | September 28, 1901; 121 years ago[1] |

| Markets | Worldwide |

| Previous owners | The Gillette Company |

| Tagline | «The Best a Man Can Get» (1989–2019) «The Best Men Can Be» (since 2019) |

| Website | gillette.com |

Gillette is an American brand of safety razors and other personal care products including shaving supplies, owned by the multi-national corporation Procter & Gamble (P&G). Based in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, it was owned by The Gillette Company, a supplier of products under various brands until that company merged into P&G in 2005. The Gillette Company was founded by King C. Gillette in 1901 as a safety razor manufacturer.[2]

Under the leadership of Colman M. Mockler Jr. as CEO from 1975 to 1991,[3] the company was the target of multiple takeover attempts, from Ronald Perelman[4] and Coniston Partners.[3] In January 2005, Procter & Gamble announced plans to merge with the Gillette Company.[5]

The Gillette Company’s assets were incorporated into a P&G unit known internally as «Global Gillette». In July 2007, Global Gillette was dissolved and incorporated into Procter & Gamble’s other two main divisions, Procter & Gamble Beauty and Procter & Gamble Household Care. Gillette’s brands and products were divided between the two accordingly. The Gillette R&D center in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Gillette South Boston Manufacturing Center (known as «Gillette World Shaving Headquarters»), still exist as functional working locations under the Procter & Gamble-owned Gillette brand name.[6] Gillette’s subsidiaries Braun and Oral-B, among others, have also been retained by P&G.

History

Inception and early years

The key figures of the Gillette Safety Razor Company’s first years, from left to right: King Camp Gillette, William Emery Nickerson, and John Joyce

1915-16 advert for the Milady Décolleté Gillette; first safety razor marketed exclusively for women

The Gillette company and brand originate from the late 19th century when salesman and inventor King Camp Gillette came up with the idea of a safety razor that used disposable blades. Safety razors at the time were essentially short pieces of a straight razor clamped to a holder. The blade had to be stropped before each shave and after a time needed to be honed by a cutler.[7] Gillette’s invention was inspired by his mentor at Crown Cork & Seal Company, William Painter, who had invented the Crown cork. Painter encouraged Gillette to come up with something that, like the Crown cork, could be thrown away once used.[8][9]

While Gillette came up with the idea in 1895, developing the concept into a working model and drawings that could be submitted to the Patent Office took six years. Gillette had trouble finding anyone capable of developing a method to manufacture blades from thin sheet steel, but finally found William Emery Nickerson, an MIT graduate with a degree in chemistry. Gillette and other members of the project founded The American Safety Razor Company on September 28, 1901. The company had issues getting funding until Gillette’s old friend John Joyce invested the necessary amount for the company to begin manufacturing.[10][8][9] Production began slowly in 1903, but the following year Nickerson succeeded in building a new blade grinding machine that had bottlenecked production. During its first year of operation, the company had sold 51 razors and 168 blades, but the second year saw sales rise to 90,884 razors and 123,648 blades. The company was renamed to the Gillette Safety Razor Company in 1904 and it quickly began to expand outside the United States. In 1905 the company opened a sales office in London and a blade manufacturing plant in Paris, and by 1906 Gillette had a blade plant in Canada, a sales operation in Mexico, and a European distribution network that sold in many nations, including Russia.[8][11]

First World War and the 1920s

Due to its premium pricing strategy, the Gillette Safety Razor Company’s razor and blade unit sales grew at a modest pace from 1908 to 1916. Disposable razor blades still were not a true mass-market product, and barbershops and self-shaving with a straight razor were still popular methods of grooming. Among the general U.S. population, a two-day stubble was not uncommon. This changed once the United States declared war on the Central Powers in 1917; military regulations required every soldier to provide their own shaving kit, and Gillette’s compact kit with disposable blades outsold competitors whose razors required stropping. Gillette marketed their razor by designing a military-only case decorated with U.S. Army and Navy insignia and in 1917 the company sold 1.1 million razors.[12]

The Khaki Set, the safety razor set produced by Gillette for the U.S. Army during the First World War[13]

In 1918, the U.S. military began issuing Gillette shaving kits to every U.S. serviceman. Gillette’s sales rose to 3.5 million razors and 32 million blades. As a consequence, millions of servicemen got accustomed to daily shaving using Gillette’s razor. After the war, Gillette utilized this in their domestic marketing and used advertising to reinforce the habit acquired during the war.[12]

Gillette’s original razor patent was due to expire in November 1921 and to stay ahead of an upcoming competition, the company introduced the New Improved Gillette Safety Razor in spring 1921 and switched to the razor and blades pricing structure the company is known for today. While the New Improved razor was sold for $5 (equivalent to $76 in 2021) – the selling price of the previous razor – the original razor was renamed to the Old Type and sold in inexpensive packaging as «Brownies» for $1 (equivalent to $15 in 2021). While some Old Type models were still sold in various kinds of packaging for an average price of $3.50, the Brownie razors made a Gillette much more affordable for the average person and expanded the company’s blade market significantly. From 1917 to 1925, Gillette’s unit sales increased tenfold. The company also expanded its overseas operations right after the war by opening a manufacturing plant in Slough, near London, to build New Improved razors, and setting up dozens of offices and subsidiaries in Europe and other parts of the world.[14]

Gillette experienced a setback at the end of the 1920s as its competitor AutoStrop sued for patent infringement. The case was settled out of court with Gillette agreeing to buy out AutoStrop for 310,000 non-voting shares. However, before the deal went through, it was revealed in an audit that Gillette had been overstating its sales and profits by $12 million over a five-year period and giving bonuses to its executives based on these numbers. AutoStrop still agreed to the buyout but instead demanded a large amount of preferred stock with voting rights. The merger was announced on October 16, 1930, and gave AutoStrop’s owner Henry Gaisman controlling interest in Gillette.[15]

1930s and the Second World War

A 1930s Gillette One-Piece Tech razor and a pack of Blue Blades

The Great Depression weakened Gillette’s position in the market significantly. The company had fallen behind its competitors in blade manufacturing technology in the 1920s and had let quality control slip while over-stretching its production equipment in order to hurry a new Kroman razor and blade to market in 1930. In 1932, Gillette apologized for the reduction in blade quality, withdrew the Kroman blade, and introduced the Blue Blade (initially called the Blue Super Blade) as its replacement.[16] Other Gillette introductions during the Depression years were the Brushless Shaving Cream and an electric shaver that was soon discontinued due to modest sales.[17]

In 1938 Gillette introduced the Thin Blade, which was cheaper and about half the weight of the Blue Blade, even though it cost almost as much to manufacture. The Thin Blade became more popular than the Blue Blade for several years during the Second World War due to high demand of low-cost products and the shortage of carbon steel.[18] Beginning in 1939, Gillette began investing significant amounts on advertising in sports events after its advertising in the World Series increased sales more than double the company had expected.[19] It eventually sponsored a radio program, the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports, which would move to television as well as that medium expanded in the late 1940s.[20] While the Cavalcade aired many of the notable sporting events of the time (the Kentucky Derby, college football bowl games, and baseball, amongst others) it became most famous for its professional boxing broadcasts.

Though competition hit Gillette hard in the domestic market during the Great Depression, overseas operations helped keep the company afloat. In 1935 more than half of Gillette’s earnings came from foreign operations and in 1938 – the worst of the Depression years for Gillette, with a mere 18 percent market share – nearly all of the company’s $2.9 million earnings came from outside the United States. AutoStrop’s Brazilian factory allowed Gillette to start expanding into the Latin America. In England the Gillette and AutoStrop operations were combined under the Gillette name, where the company built a new blade manufacturing plant in London. In 1937, Gillette’s Berlin factory produced 40 percent of Germany’s 900 million blades and retained a 65 to 75 percent share of the German blade market.[21]