|

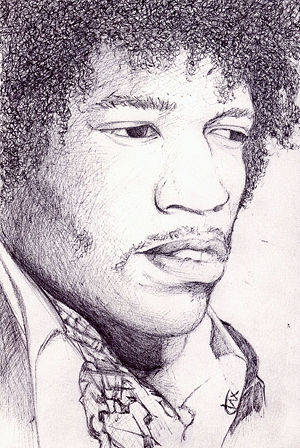

Jimi Hendrix |

|

|---|---|

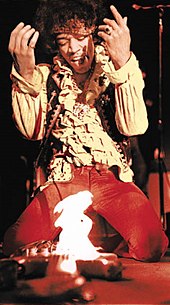

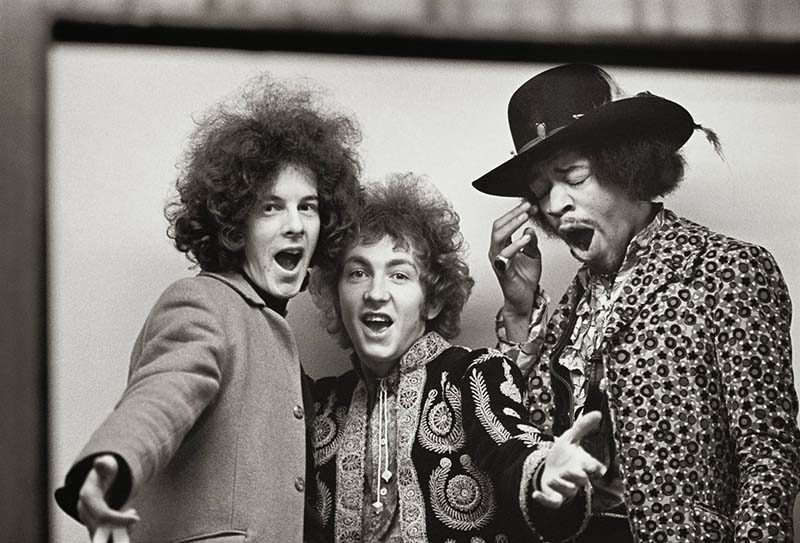

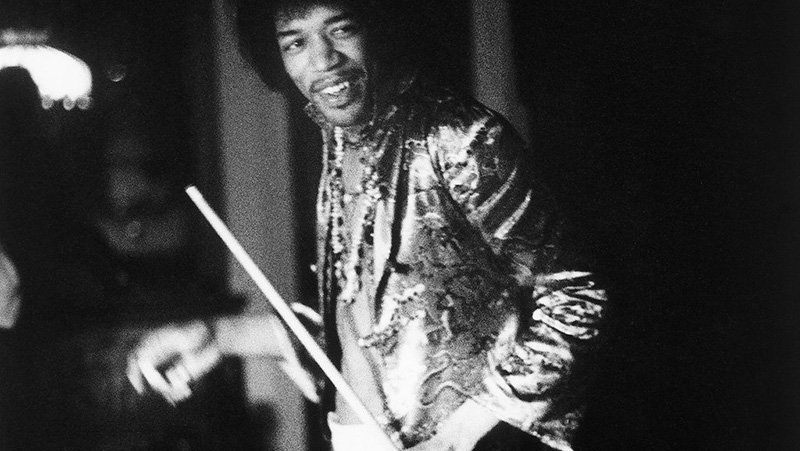

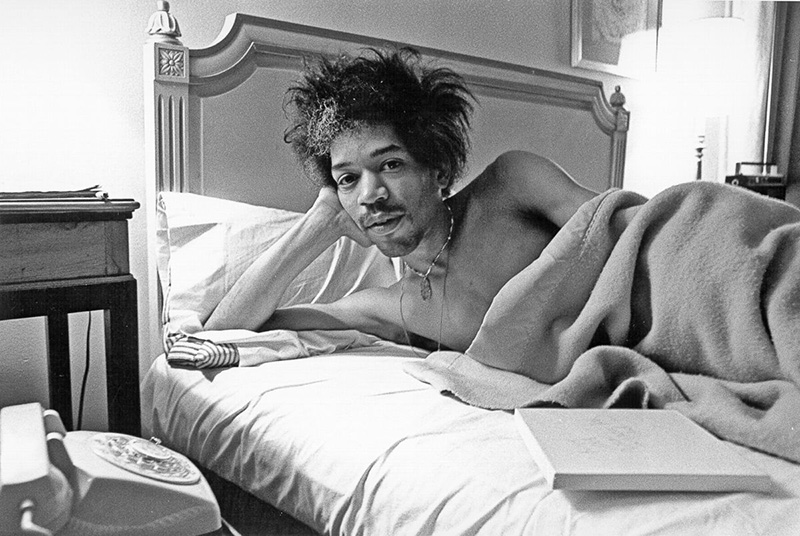

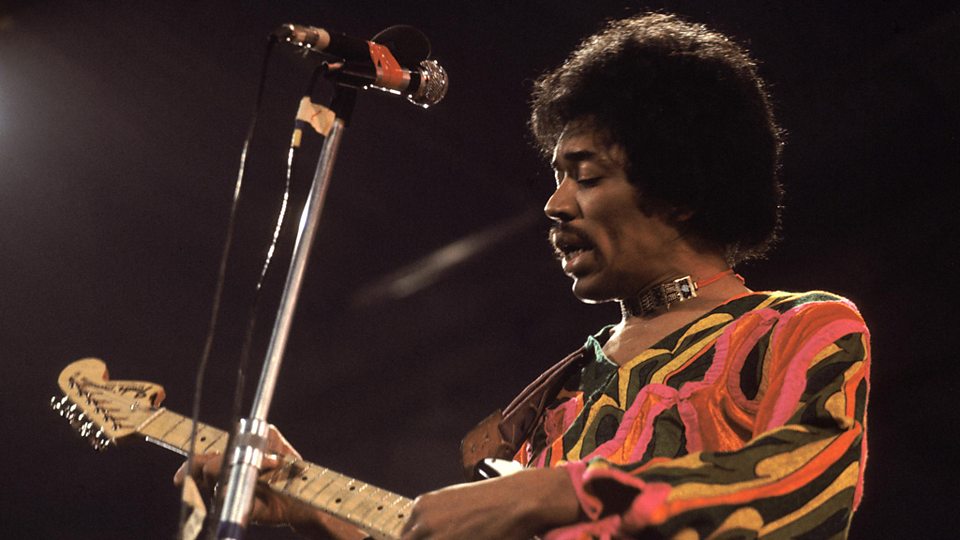

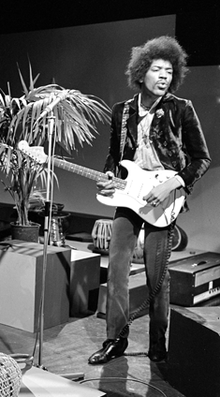

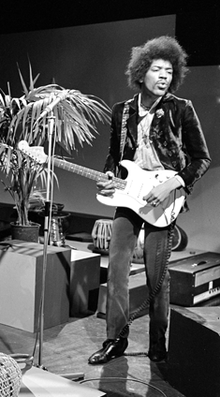

Hendrix performing on the Dutch television show Hoepla in 1967 |

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Johnny Allen Hendrix |

| Born | November 27, 1942 Seattle, Washington, US |

| Died | September 18, 1970 (aged 27) Kensington, London, England |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Years active | 1962–1970 |

| Labels |

|

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | jimihendrix.com |

James Marshall «Jimi» Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, singer and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most influential electric guitarists in the history of popular music, and one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame describes him as «arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music.»[1]

Born in Seattle, Washington, Hendrix began playing guitar at the age of 15. In 1961, he enlisted in the US Army, but was discharged the following year. Soon afterward, he moved to Clarksville then Nashville, Tennessee, and began playing gigs on the chitlin’ circuit, earning a place in the Isley Brothers’ backing band and later with Little Richard, with whom he continued to work through mid-1965. He then played with Curtis Knight and the Squires before moving to England in late 1966 after bassist Chas Chandler of the Animals became his manager. Within months, Hendrix had earned three UK top ten hits with the Jimi Hendrix Experience: «Hey Joe», «Purple Haze», and «The Wind Cries Mary». He achieved fame in the US after his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and in 1968 his third and final studio album, Electric Ladyland, reached number one in the US. The double LP was Hendrix’s most commercially successful release and his first and only number one album. The world’s highest-paid performer,[2] he headlined the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970 before his accidental death in London from barbiturate-related asphyxia on September 18, 1970.

Hendrix was inspired by American rock and roll and electric blues. He favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain, and was instrumental in popularizing the previously undesirable sounds caused by guitar amplifier feedback. He was also one of the first guitarists to make extensive use of tone-altering effects units in mainstream rock, such as fuzz distortion, Octavia, wah-wah, and Uni-Vibe. He was the first musician to use stereophonic phasing effects in recordings. Holly George-Warren of Rolling Stone commented: «Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began.»[3]

Hendrix was the recipient of several music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year and in 1968, Billboard named him the Artist of the Year and Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year. Disc and Music Echo honored him with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970, Guitar Player named him the Rock Guitarist of the Year. The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. Rolling Stone ranked the band’s three studio albums, Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland, among the 100 greatest albums of all time, and they ranked Hendrix as the greatest guitarist and the sixth-greatest artist of all time.

Ancestry and childhood

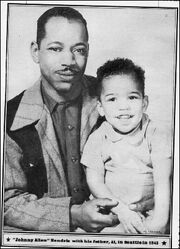

Hendrix’s paternal grandparents, Ross and Nora Hendrix, pre-1912

Hendrix had African American and Irish ancestry. His paternal grandfather, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix, was born in 1866 out of an extramarital affair between a woman named Fanny and a grain merchant from Urbana, Ohio, or Illinois, one of the wealthiest men in the area at that time.[4][nb 1] Hendrix’s paternal grandmother, Zenora «Nora» Rose Moore, was a former dancer and vaudeville performer.[6][nb 2] Hendrix and Moore relocated to Vancouver, where they had a son they named James Allen Hendrix on June 10, 1919; the family called him «Al».[13]

In 1941, after moving to Seattle, Al met Lucille Jeter (1925–1958) at a dance; they married on March 31, 1942.[14] Lucille’s father (Jimi’s maternal grandfather) was Preston Jeter (born 1875), whose mother was born in similar circumstances as Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix.[15] Lucille’s mother, née Clarice Lawson, had African American ancestors who had been enslaved people.[16] Al, who had been drafted by the US Army to serve in World War II, left to begin his basic training three days after the wedding.[17] Johnny Allen Hendrix was born on November 27, 1942, in Seattle; he was the first of Lucille’s five children. In 1946, Johnny’s parents changed his name to James Marshall Hendrix, in honor of Al and his late brother Leon Marshall.[18][nb 3]

Stationed in Alabama at the time of Hendrix’s birth, Al was denied the standard military furlough afforded servicemen for childbirth; his commanding officer placed him in the stockade to prevent him from going AWOL to see his infant son in Seattle. He spent two months locked up without trial, and while in the stockade received a telegram announcing his son’s birth.[6][nb 4] During Al’s three-year absence, Lucille struggled to raise their son.[22] When Al was away, Hendrix was mostly cared for by family members and friends, especially Lucille’s sister Delores Hall and her friend Dorothy Harding.[23] Al received an honorable discharge from the US Army on September 1, 1945. Two months later, unable to find Lucille, Al went to the Berkeley, California, home of a family friend named Mrs. Champ, who had taken care of and had attempted to adopt Hendrix; this is where Al saw his son for the first time.[24]

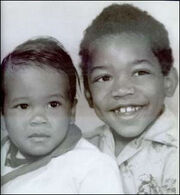

After returning from service, Al reunited with Lucille, but his inability to find steady work left the family impoverished. They both struggled with alcohol, and often fought when intoxicated. The violence sometimes drove Hendrix to withdraw and hide in a closet in their home.[25] His relationship with his brother Leon (born 1948) was close but precarious; with Leon in and out of foster care, they lived with an almost constant threat of fraternal separation.[26] In addition to Leon, Hendrix had three younger siblings: Joseph, born in 1949, Kathy in 1950, and Pamela, 1951, all of whom Al and Lucille gave up to foster care and adoption.[27] The family frequently moved, staying in cheap hotels and apartments around Seattle. On occasion, family members would take Hendrix to Vancouver, Canada to stay at his grandmother’s. A shy and sensitive boy, he was deeply affected by his life experiences.[28] In later years, he confided to a girlfriend that he had been the victim of sexual abuse by a man in uniform.[29] On December 17, 1951, when Hendrix was nine years old, his parents divorced; the court granted Al custody of him and Leon.[30]

First instruments

At Horace Mann Elementary School in Seattle during the mid-1950s, Hendrix’s habit of carrying a broom with him to emulate a guitar gained the attention of the school’s social worker. After more than a year of his clinging to a broom like a security blanket, she wrote a letter requesting school funding intended for underprivileged children, insisting that leaving him without a guitar might result in psychological damage.[31] Her efforts failed, and Al refused to buy him a guitar.[31][nb 5]

In 1957, while helping his father with a side-job, Hendrix found a ukulele amongst the garbage they were removing from an older woman’s home. She told him that he could keep the instrument, which had only one string.[33] Learning by ear, he played single notes, following along to Elvis Presley songs, particularly «Hound Dog».[34][nb 6] By the age of 33, Hendrix’s mother Lucille had developed cirrhosis of the liver, and on February 2, 1958, she died when her spleen ruptured.[36] Al refused to take James and Leon to attend their mother’s funeral; he instead gave them shots of whiskey and instructed them that was how men should deal with loss.[36][nb 7] In 1958, Hendrix completed his studies at Washington Junior High School and began attending, but did not graduate from, Garfield High School.[37][nb 8]

In mid-1958, at age 15, Hendrix acquired his first acoustic guitar, for $5[40] (equivalent to $47 in 2021). He played for hours daily, watching others and learning from more experienced guitarists, and listening to blues artists such as Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, and Robert Johnson.[41] The first tune Hendrix learned to play was the television theme «Peter Gunn».[42] Around that time, Hendrix jammed with boyhood friend Sammy Drain and his keyboard-playing brother.[43] In 1959, attending a concert by Hank Ballard & the Midnighters in Seattle, Hendrix met the group’s guitarist Billy Davis.[44] Davis showed him some guitar licks and got him a short gig with the Midnighters.[45] The two remained friends until Hendrix’s death in 1970.[46]

Soon after he acquired the acoustic guitar, Hendrix formed his first band, the Velvetones. Without an electric guitar, he could barely be heard over the sound of the group. After about three months, he realized that he needed an electric guitar.[47] In mid-1959, his father relented and bought him a white Supro Ozark.[47] Hendrix’s first gig was with an unnamed band in the Jaffe Room of Seattle’s Temple De Hirsch, but they fired him between sets for showing off.[48] He joined the Rocking Kings, which played professionally at venues such as the Birdland club. When his guitar was stolen after he left it backstage overnight, Al bought him a red Silvertone Danelectro.[49]

Military service

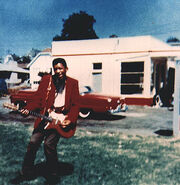

Hendrix in the US Army, 1961

Before Hendrix was 19 years old, law authorities had twice caught him riding in stolen cars. Given a choice between prison or joining the Army, he chose the latter and enlisted on May 31, 1961.[50] After completing eight weeks of basic training at Fort Ord, California, he was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.[51] He arrived on November 8, and soon afterward he wrote to his father: «There’s nothing but physical training and harassment here for two weeks, then when you go to jump school … you get hell. They work you to death, fussing and fighting.»[52] In his next letter home, Hendrix, who had left his guitar in Seattle at the home of his girlfriend Betty Jean Morgan, asked his father to send it to him as soon as possible, stating: «I really need it now.»[52] His father obliged and sent the red Silvertone Danelectro on which Hendrix had hand-painted the words «Betty Jean» to Fort Campbell.[53] His apparent obsession with the instrument contributed to his neglect of his duties, which led to taunting and physical abuse from his peers, who at least once hid the guitar from him until he had begged for its return.[54] In November 1961, fellow serviceman Billy Cox walked past an army club and heard Hendrix playing.[55] Impressed by Hendrix’s technique, which Cox described as a combination of «John Lee Hooker and Beethoven», Cox borrowed a bass guitar and the two jammed.[56] Within weeks, they began performing at base clubs on the weekends with other musicians in a loosely organized band, the Casuals.[57]

Hendrix completed his paratrooper training and, on January 11, 1962, Major General C. W. G. Rich awarded him the prestigious Screaming Eagles patch.[52] By February, his personal conduct had begun to draw criticism from his superiors. They labeled him an unqualified marksman and often caught him napping while on duty and failing to report for bed checks.[58] On May 24, Hendrix’s platoon sergeant, James C. Spears, filed a report in which he stated: «He has no interest whatsoever in the Army … It is my opinion that Private Hendrix will never come up to the standards required of a soldier. I feel that the military service will benefit if he is discharged as soon as possible.»[59] On June 29, 1962, Hendrix was granted a general discharge under honorable conditions.[60] Hendrix later spoke of his dislike of the army and that he had received a medical discharge after breaking his ankle during his 26th parachute jump.[61][nb 9] However, no Army records have been produced that indicate that he received or was discharged for any injuries.[63]

Career

Early years

In September 1962, after Cox was discharged from the Army, he and Hendrix moved about 20 miles (32 km) across the state line from Fort Campbell to Clarksville, Tennessee, and formed a band, the King Kasuals.[64] In Seattle, Hendrix saw Butch Snipes play with his teeth and now the Kasuals’ second guitarist, Alphonso «Baby Boo» Young, was performing this guitar gimmick.[65] Not to be upstaged, Hendrix also learned to play in this way. He later explained: «The idea of doing that came to me … in Tennessee. Down there you have to play with your teeth or else you get shot. There’s a trail of broken teeth all over the stage.»[66]

Although they began playing low-paying gigs at obscure venues, the band eventually moved to Nashville’s Jefferson Street, which was the traditional heart of the city’s black community and home to a thriving rhythm and blues music scene.[67] They earned a brief residency playing at a popular venue in town, the Club del Morocco, and for the next two years Hendrix made a living performing at a circuit of venues throughout the South that were affiliated with the Theater Owners’ Booking Association (TOBA), widely known as the chitlin’ circuit.[68] In addition to playing in his own band, Hendrix performed as a backing musician for various soul, R&B, and blues musicians, including Wilson Pickett, Slim Harpo, Sam Cooke, Ike & Tina Turner[69] and Jackie Wilson.[70]

In January 1964, feeling he had outgrown the circuit artistically, and frustrated by having to follow the rules of bandleaders, Hendrix decided to venture out on his own. He moved into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where he befriended Lithofayne Pridgon, known as «Faye», who became his girlfriend.[71] A Harlem native with connections throughout the area’s music scene, Pridgon provided him with shelter, support, and encouragement.[72] Hendrix also met the Allen twins, Arthur and Albert.[73][nb 10] In February 1964, Hendrix won first prize in the Apollo Theater amateur contest.[75] Hoping to secure a career opportunity, he played the Harlem club circuit and sat in with various bands. At the recommendation of a former associate of Joe Tex, Ronnie Isley granted Hendrix an audition that led to an offer to become the guitarist with the Isley Brothers’ backing band, the I.B. Specials, which he readily accepted.[76]

First recordings

In March 1964, Hendrix recorded the two-part single «Testify» with the Isley Brothers. Released in June, it failed to chart.[77] In May, he provided guitar instrumentation for the Don Covay song, «Mercy Mercy». Issued in August by Rosemart Records and distributed by Atlantic, the track reached number 35 on the Billboard chart.[78]

Hendrix toured with the Isleys during much of 1964, but near the end of October, after growing tired of playing the same set every night, he left the band.[79][nb 11] Soon afterward, Hendrix joined Little Richard’s touring band, the Upsetters.[81] During a stop in Los Angeles in February 1965, he recorded his first and only single with Richard, «I Don’t Know What You Got (But It’s Got Me)», written by Don Covay and released by Vee-Jay Records.[82] Richard’s popularity was waning at the time, and the single peaked at number 92, where it remained for one week before dropping off the chart.[83][nb 12] Hendrix met singer Rosa Lee Brooks while staying at the Wilcox Hotel in Hollywood, and she invited him to participate in a recording session for her single, which included the Arthur Lee penned «My Diary» as the A-side, and «Utee» as the B-side.[85] Hendrix played guitar on both tracks, which also included background vocals by Lee. The single failed to chart, but Hendrix and Lee began a friendship that lasted several years; Hendrix later became an ardent supporter of Lee’s band, Love.[85]

In July 1965, Hendrix made his first television appearance on Nashville’s Channel 5 Night Train. Performing in Little Richard’s ensemble band, he backed up vocalists Buddy and Stacy on «Shotgun». The video recording of the show marks the earliest known footage of Hendrix performing.[81] Richard and Hendrix often clashed over tardiness, wardrobe, and Hendrix’s stage antics, and in late July, Richard’s brother Robert fired him.[86] On July 27, Hendrix signed his first recording contract with Juggy Murray at Sue Records and Copa Management.[87][88] He then briefly rejoined the Isley Brothers, and recorded a second single with them, «Move Over and Let Me Dance» backed with «Have You Ever Been Disappointed».[89] Later that year, he joined a New York-based R&B band, Curtis Knight and the Squires, after meeting Knight in the lobby of a hotel where both men were staying.[90] Hendrix performed with them for eight months.[91] In October 1965, he and Knight recorded the single, «How Would You Feel» backed with «Welcome Home». Despite his two-year contract with Sue,[92] Hendrix signed a three-year recording contract with entrepreneur Ed Chalpin on October 15.[93] While the relationship with Chalpin was short-lived, his contract remained in force, which later caused legal and career problems for Hendrix.[94][nb 13] During his time with Knight, Hendrix briefly toured with Joey Dee and the Starliters, and worked with King Curtis on several recordings including Ray Sharpe’s two-part single, «Help Me».[96] Hendrix earned his first composer credits for two instrumentals, «Hornets Nest» and «Knock Yourself Out», released as a Curtis Knight and the Squires single in 1966.[97][nb 14]

Feeling restricted by his experiences as an R&B sideman, Hendrix moved in 1966 to New York City’s Greenwich Village, which had a vibrant and diverse music scene.[102] There, he was offered a residency at the Cafe Wha? on MacDougal Street and formed his own band that June, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, which included future Spirit guitarist Randy California.[103][nb 15] The Blue Flames played at several clubs in New York and Hendrix began developing his guitar style and material that he would soon use with the Experience.[105][106] In September, they gave some of their last concerts at the Cafe Au Go Go in Manhattan, as the backing group for singer and guitarist then billed as John Hammond.[107][nb 16]

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

By May 1966, Hendrix was struggling to earn a living wage playing the R&B circuit, so he briefly rejoined Curtis Knight and the Squires for an engagement at one of New York City’s most popular nightspots, the Cheetah Club.[108] During a performance, Linda Keith, the girlfriend of Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards, noticed Hendrix and was «mesmerised» by his playing.[108] She invited him to join her for a drink, and the two became friends.[108]

While Hendrix was playing as Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, Keith recommended him to Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and producer Seymour Stein. They failed to see Hendrix’s musical potential, and rejected him.[109] Keith referred him to Chas Chandler, who was leaving the Animals and was interested in managing and producing artists.[110] Chandler saw Hendrix play in Cafe Wha?, a Greenwich Village, New York City nightclub.[110] Chandler liked the Billy Roberts song «Hey Joe», and was convinced he could create a hit single with the right artist.[111] Impressed with Hendrix’s version of the song, he brought him to London on September 24, 1966,[112] and signed him to a management and production contract with himself and ex-Animals manager Michael Jeffery.[113] That night, Hendrix gave an impromptu solo performance at The Scotch of St James, and began a relationship with Kathy Etchingham that lasted for two and a half years.[114][nb 17]

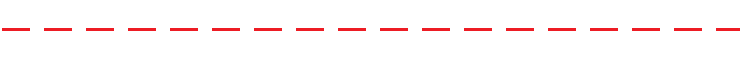

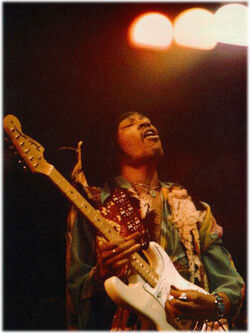

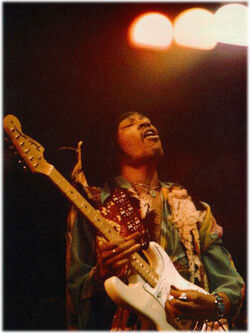

Hendrix on stage at Gröna Lund in Stockholm, Sweden in June 1967

Following Hendrix’s arrival in London, Chandler began recruiting members for a band designed to highlight his talents, the Jimi Hendrix Experience.[116] Hendrix met guitarist Noel Redding at an audition for the New Animals, where Redding’s knowledge of blues progressions impressed Hendrix, who stated that he also liked Redding’s hairstyle.[117] Chandler asked Redding if he wanted to play bass guitar in Hendrix’s band; Redding agreed.[117] Chandler began looking for a drummer and soon after contacted Mitch Mitchell through a mutual friend. Mitchell, who had recently been fired from Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, participated in a rehearsal with Redding and Hendrix where they found common ground in their shared interest in rhythm and blues. When Chandler phoned Mitchell later that day to offer him the position, he readily accepted.[118] Chandler also convinced Hendrix to change the spelling of his first name from Jimmy to the more exotic Jimi.[119]

On October 1, 1966, Chandler brought Hendrix to the London Polytechnic at Regent Street, where Cream was scheduled to perform, and where Hendrix and guitarist Eric Clapton met.[120] Clapton later said: «He asked if he could play a couple of numbers. I said, ‘Of course’, but I had a funny feeling about him.»[116] Halfway through Cream’s set, Hendrix took the stage and performed a frantic version of the Howlin’ Wolf song «Killing Floor».[116] In 1989, Clapton described the performance: «He played just about every style you could think of, and not in a flashy way. I mean he did a few of his tricks, like playing with his teeth and behind his back, but it wasn’t in an upstaging sense at all, and that was it … He walked off, and my life was never the same again».[116]

UK success

In mid-October 1966, Chandler arranged an engagement for the Experience as Johnny Hallyday’s supporting act during a brief tour of France.[119] Thus, the Jimi Hendrix Experience performed their first show on October 13, 1966, at the Novelty in Evreux.[121] Their enthusiastically received 15-minute performance at the Olympia theatre in Paris on October 18 marks the earliest known recording of the band.[119] In late October, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, managers of the Who, signed the Experience to their newly formed label, Track Records, and the group recorded their first song, «Hey Joe», on October 23.[122] «Stone Free», which was Hendrix’s first songwriting effort after arriving in England, was recorded on November 2.[123]

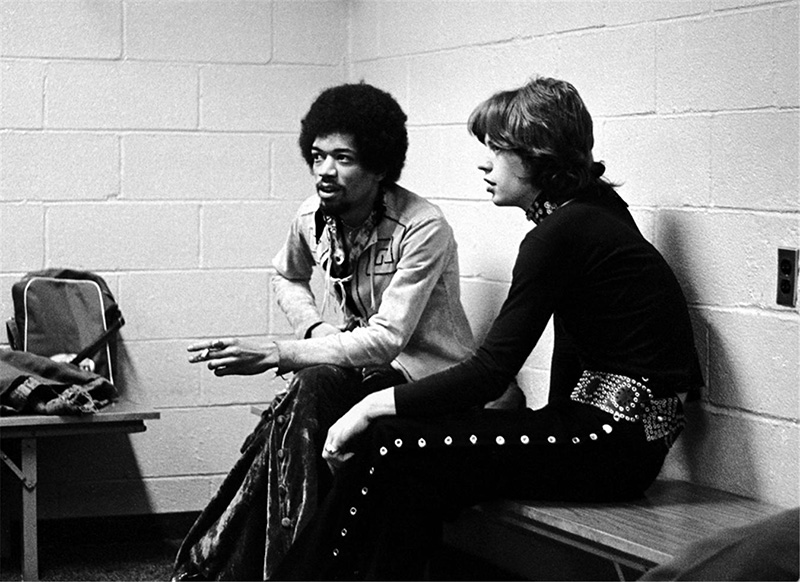

In mid-November, they performed at the Bag O’Nails nightclub in London, with Clapton, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, Brian Jones, Mick Jagger, and Kevin Ayers in attendance.[124] Ayers described the crowd’s reaction as stunned disbelief: «All the stars were there, and I heard serious comments, you know ‘shit’, ‘Jesus’, ‘damn’ and other words worse than that.»[124] The performance earned Hendrix his first interview, published in Record Mirror with the headline: «Mr. Phenomenon».[124] «Now hear this … we predict that [Hendrix] is going to whirl around the business like a tornado», wrote Bill Harry, who asked the rhetorical question: «Is that full, big, swinging sound really being created by only three people?»[125] Hendrix said: «We don’t want to be classed in any category … If it must have a tag, I’d like it to be called, ‘Free Feeling’. It’s a mixture of rock, freak-out, rave and blues».[126] Through a distribution deal with Polydor Records, the Experience’s first single, «Hey Joe», backed with «Stone Free», was released on December 16, 1966.[127] After appearances on the UK television shows Ready Steady Go! and Top of the Pops, «Hey Joe» entered the UK charts on December 29 and peaked at number six.[128] Further success came in March 1967 with the UK number three hit «Purple Haze», and in May with «The Wind Cries Mary», which remained on the UK charts for eleven weeks, peaking at number six.[129] On March 12, 1967, he performed at the Troutbeck Hotel, Ilkley, West Yorkshire, where, after about 900 people turned up (the hotel was licensed for 250) the local police stopped the gig due to safety concerns.[130]

On March 31, 1967, while the Experience waited to perform at the London Astoria, Hendrix and Chandler discussed ways in which they could increase the band’s media exposure. When Chandler asked journalist Keith Altham for advice, Altham suggested that they needed to do something more dramatic than the stage show of the Who, which involved the smashing of instruments. Hendrix joked: «Maybe I can smash up an elephant», to which Altham replied: «Well, it’s a pity you can’t set fire to your guitar».[131] Chandler then asked road manager Gerry Stickells to procure some lighter fluid. During the show, Hendrix gave an especially dynamic performance before setting his guitar on fire at the end of a 45-minute set. In the wake of the stunt, members of London’s press labeled Hendrix the «Black Elvis» and the «Wild Man of Borneo».[132][nb 18]

Are You Experienced

After the UK chart success of their first two singles, «Hey Joe» and «Purple Haze», the Experience began assembling material for a full-length LP.[134] In London, recording began at De Lane Lea Studios, and later moved to the prestigious Olympic Studios.[134] The album, Are You Experienced, features a diversity of musical styles, including blues tracks such as «Red House» and the R&B song «Remember».[135] It also included the experimental science fiction piece, «Third Stone from the Sun» and the post-modern soundscapes of the title track, with prominent backwards guitar and drums.[136] «I Don’t Live Today» served as a medium for Hendrix’s guitar feedback improvisation and «Fire» was driven by Mitchell’s drumming.[134]

Released in the UK on May 12, 1967, Are You Experienced spent 33 weeks on the charts, peaking at number two.[137][nb 19] It was prevented from reaching the top spot by the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.[139][nb 20] On June 4, 1967, Hendrix opened a show at the Saville Theatre in London with his rendition of Sgt. Pepper‘s title track, which was released just three days previous. Beatles manager Brian Epstein owned the Saville at the time, and both George Harrison and Paul McCartney attended the performance. McCartney described the moment: «The curtains flew back and he came walking forward playing ‘Sgt. Pepper’. It’s a pretty major compliment in anyone’s book. I put that down as one of the great honors of my career.»[140] Released in the US on August 23 by Reprise Records, Are You Experienced reached number five on the Billboard 200.[141][nb 21]

In 1989, Noe Goldwasser, the founding editor of Guitar World, described Are You Experienced as «the album that shook the world … leaving it forever changed».[143][nb 22] In 2005, Rolling Stone called the double-platinum LP Hendrix’s «epochal debut», and they ranked it the 15th greatest album of all time, noting his «exploitation of amp howl», and characterizing his guitar playing as «incendiary … historic in itself».[145]

Monterey Pop Festival

Author Michael Heatley wrote: «The iconic image by Ed Caraeff of Hendrix summoning the flames higher with his fingers will forever conjure up memories of Monterey for those who were there and the majority of us who weren’t.»[146]

Although popular in Europe at the time, the Experience’s first US single, «Hey Joe», failed to reach the Billboard Hot 100 chart upon its release on May 1, 1967.[147] Their fortunes improved when McCartney recommended them to the organizers of the Monterey Pop Festival. He insisted that the event would be incomplete without Hendrix, whom he called «an absolute ace on the guitar». McCartney agreed to join the board of organizers on the condition that the Experience perform at the festival in mid-June.[148]

On June 18, 1967,[149] introduced by Brian Jones as «the most exciting performer [he had] ever heard», Hendrix opened with a fast arrangement of Howlin’ Wolf’s song «Killing Floor», wearing what author Keith Shadwick described as «clothes as exotic as any on display elsewhere».[150] Shadwick wrote: «[Hendrix] was not only something utterly new musically, but an entirely original vision of what a black American entertainer should and could look like.»[151] The Experience went on to perform renditions of «Hey Joe», B.B. King’s «Rock Me Baby», Chip Taylor’s «Wild Thing», and Bob Dylan’s «Like a Rolling Stone», and four original compositions: «Foxy Lady», «Can You See Me», «The Wind Cries Mary», and «Purple Haze».[140] The set ended with Hendrix destroying his guitar and tossing pieces of it out to the audience.[152] Rolling Stone‘s Alex Vadukul wrote:

When Jimi Hendrix set his guitar on fire at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival he created one of rock’s most perfect moments. Standing in the front row of that concert was a 17-year-old boy named Ed Caraeff. Caraeff had never seen Hendrix before nor heard his music, but he had a camera with him and there was one shot left in his roll of film. As Hendrix lit his guitar, Caraeff took a final photo. It would become one of the most famous images in rock and roll.[153][nb 23]

Caraeff stood on a chair next to the edge of the stage and took four monochrome pictures of Hendrix burning his guitar.[156][nb 24] Caraeff was close enough to the fire that he had to use his camera to protect his face from the heat. Rolling Stone later colorized the image, matching it with other pictures taken at the festival before using the shot for a 1987 magazine cover.[156] According to author Gail Buckland, the final frame of «Hendrix kneeling in front of his burning guitar, hands raised, is one of the most famous images in rock».[156] Author and historian Matthew C. Whitaker wrote that «Hendrix’s burning of his guitar became an iconic image in rock history and brought him national attention».[157] The Los Angeles Times asserted that, upon leaving the stage, Hendrix «graduated from rumor to legend».[158] Author John McDermott wrote that «Hendrix left the Monterey audience stunned and in disbelief at what they’d just heard and seen».[159] According to Hendrix: «I decided to destroy my guitar at the end of a song as a sacrifice. You sacrifice things you love. I love my guitar.»[160] The performance was filmed by D. A. Pennebaker, and included in the concert documentary Monterey Pop, which helped Hendrix gain popularity with the US public.[161]

After the festival, the Experience was booked for five concerts at Bill Graham’s Fillmore, with Big Brother and the Holding Company and Jefferson Airplane. The Experience outperformed Jefferson Airplane during the first two nights, and replaced them at the top of the bill on the fifth.[162] Following their successful West Coast introduction, which included a free open-air concert at Golden Gate Park and a concert at the Whisky a Go Go, the Experience was booked as the opening act for the first American tour of the Monkees.[163] The Monkees requested Hendrix as a supporting act because they were fans, but their young audience disliked the Experience, who left the tour after six shows.[164] Chandler later said he engineered the tour to gain publicity for Hendrix.[165]

Axis: Bold as Love

An excerpt from the outro guitar solo. The sample demonstrates the first recording of stereo phasing.

The second Experience album, Axis: Bold as Love, opens with the track «EXP», which uses microphonic and harmonic feedback in a new, creative fashion.[166] It also showcased an experimental stereo panning effect in which sounds emanating from Hendrix’s guitar move through the stereo image, revolving around the listener.[167] The piece reflected his growing interest in science fiction and outer space.[168] He composed the album’s title track and finale around two verses and two choruses, during which he pairs emotions with personas, comparing them to colors.[169] The song’s coda features the first recording of stereo phasing.[170][nb 25] Shadwick described the composition as «possibly the most ambitious piece on Axis, the extravagant metaphors of the lyrics suggesting a growing confidence» in Hendrix’s songwriting.[172] His guitar playing throughout the song is marked by chordal arpeggios and contrapuntal motion, with tremolo-picked partial chords providing the musical foundation for the chorus, which culminates in what musicologist Andy Aledort described as «simply one of the greatest electric guitar solos ever played».[173] The track fades out on tremolo-picked 32nd note double stops.[174]

The scheduled release date for Axis was almost delayed when Hendrix lost the master tape of side one of the LP, leaving it in the back seat of a London taxi.[175] With the deadline looming, Hendrix, Chandler, and engineer Eddie Kramer remixed most of side one in a single overnight session, but they could not match the quality of the lost mix of «If 6 Was 9». Redding had a tape recording of this mix, which had to be smoothed out with an iron as it had gotten wrinkled.[176] During the verses, Hendrix doubled his singing with a guitar line which he played one octave lower than his vocals.[177] Hendrix voiced his disappointment about having re-mixed the album so quickly, and he felt that it could have been better had they been given more time.[175]

Axis featured psychedelic cover art that depicts Hendrix and the Experience as various avatars of Vishnu, incorporating a painting of them by Roger Law, from a photo-portrait by Karl Ferris.[178] The painting was then superimposed on a copy of a mass-produced religious poster.[179] Hendrix stated that the cover, which Track spent $5,000 producing, would have been more appropriate had it highlighted his American Indian heritage.[180] He said: «You got it wrong … I’m not that kind of Indian.»[180] Track released the album in the UK on December 1, 1967, where it peaked at number five, spending 16 weeks on the charts.[181] In February 1968, Axis: Bold as Love reached number three in the US.[182]

While author and journalist Richie Unterberger described Axis as the least impressive Experience album, according to author Peter Doggett, the release «heralded a new subtlety in Hendrix’s work».[183] Mitchell said: «Axis was the first time that it became apparent that Jimi was pretty good working behind the mixing board, as well as playing, and had some positive ideas of how he wanted things recorded. It could have been the start of any potential conflict between him and Chas in the studio.»[184]

Electric Ladyland

Recording for the Experience’s third and final studio album, Electric Ladyland, began as early as December 20, 1967, at Olympic Studios.[185] Several songs were attempted; however, in April 1968, the Experience, with Chandler as producer and engineers Eddie Kramer and Gary Kellgren, moved the sessions to the newly opened Record Plant Studios in New York.[186] As the sessions progressed, Chandler became increasingly frustrated with Hendrix’s perfectionism and his demands for repeated takes.[187] Hendrix also allowed numerous friends and guests to join them in the studio, which contributed to a chaotic and crowded environment in the control room and led Chandler to sever his professional relationship with Hendrix.[187] Redding later recalled: «There were tons of people in the studio; you couldn’t move. It was a party, not a session.»[188] Redding, who had formed his own band in mid-1968, Fat Mattress, found it increasingly difficult to fulfill his commitments with the Experience, so Hendrix played many of the bass parts on Electric Ladyland.[187] The album’s cover stated that it was «produced and directed by Jimi Hendrix».[187][nb 26]

During the Electric Ladyland recording sessions, Hendrix began experimenting with other combinations of musicians, including Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady and Traffic’s Steve Winwood, who played bass and organ, respectively, on the 15-minute slow-blues jam, «Voodoo Chile».[187] During the album’s production, Hendrix appeared at an impromptu jam with B.B. King, Al Kooper, and Elvin Bishop.[190][nb 27] Electric Ladyland was released on October 25, and by mid-November it had reached number one in the US, spending two weeks at the top spot.[192] The double LP was Hendrix’s most commercially successful release and his only number one album.[193] It peaked at number six in the UK, spending 12 weeks on the chart.[129] Electric Ladyland included Hendrix’s cover of a Bob Dylan song, «All Along the Watchtower», which became Hendrix’s highest-selling single and his only US top 40 hit, peaking at number 20; the single reached number five in the UK.[194] «Burning of the Midnight Lamp», his first recorded song to feature a wah-wah pedal, was added to the album.[195] It was originally released as his fourth single in the UK in August 1967[196] and reached number 18 on the charts.[197]

In 1989, Noe Goldwasser, the founding editor of Guitar World, described Electric Ladyland as «Hendrix’s masterpiece».[198] According to author Michael Heatley, «most critics agree» that the album is «the fullest realization of Jimi’s far-reaching ambitions.»[187] In 2004, author Peter Doggett wrote: «For pure experimental genius, melodic flair, conceptual vision and instrumental brilliance, Electric Ladyland remains a prime contender for the status of rock’s greatest album.»[199] Doggett described the LP as «a display of musical virtuosity never surpassed by any rock musician.»[199]

Break-up of the Experience

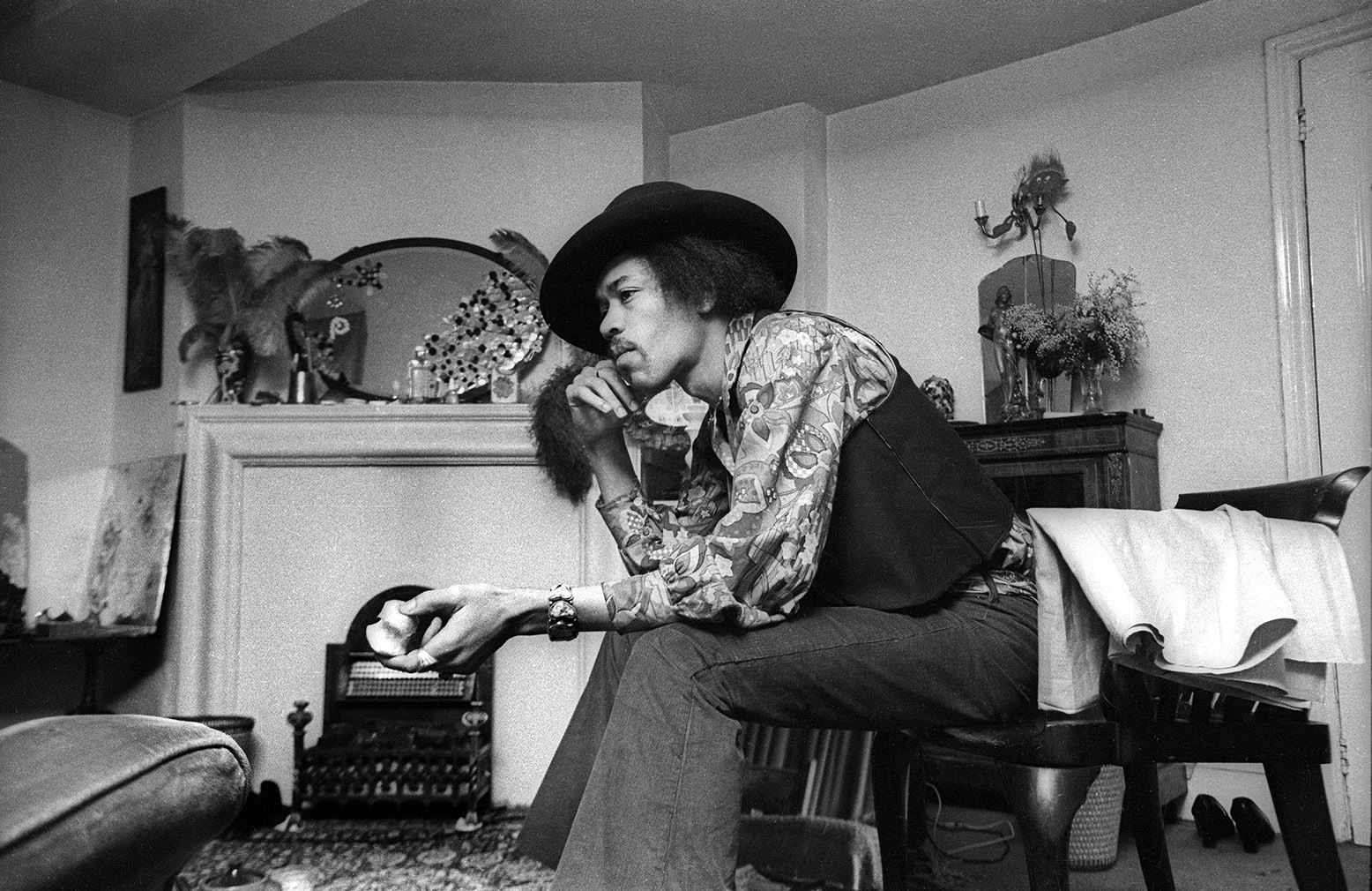

The white building (left) is 23 Brook Street where Hendrix lived. The upper floors of 23 and 25 are currently open as a museum.

In January 1969, after an absence of more than six months, Hendrix briefly moved back into his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham’s apartment in Brook Street, London, next door to the home of the composer Handel.[200][nb 28] After a performance of «Voodoo Child», on BBC’s Happening for Lulu show in January 1969, the band stopped midway through an attempt at their first hit «Hey Joe» and then launched into an instrumental version of «Sunshine of Your Love», as a tribute to the recently disbanded band Cream, until producers brought the song to a premature end.[202] Because the unplanned performance precluded Lulu’s usual closing number, Hendrix was told he would never work at the BBC again.[203] During this time, the Experience toured Scandinavia, Germany, and gave their final two performances in France.[204] On February 18 and 24, they played sold-out concerts at London’s Royal Albert Hall, which were the last European appearances of this lineup.[205][nb 29]

By February 1969, Redding had grown weary of Hendrix’s unpredictable work ethic and his creative control over the Experience’s music.[206] During the previous month’s European tour, interpersonal relations within the group had deteriorated, particularly between Hendrix and Redding.[207] In his diary, Redding documented the building frustration during early 1969 recording sessions: «On the first day, as I nearly expected, there was nothing doing … On the second it was no show at all. I went to the pub for three hours, came back, and it was still ages before Jimi ambled in. Then we argued … On the last day, I just watched it happen for a while, and then went back to my flat.»[207] The last Experience sessions that included Redding—a re-recording of «Stone Free» for use as a possible single release—took place on April 14 at Olmstead and the Record Plant in New York.[208] Hendrix then flew bassist Billy Cox to New York; they started recording and rehearsing together on April 21.[209]

The last performance of the original Experience lineup took place on June 29, 1969, at Barry Fey’s Denver Pop Festival, a three-day event held at Denver’s Mile High Stadium that was marked by police using tear gas to control the audience.[210] The band narrowly escaped from the venue in the back of a rental truck, which was partly crushed by fans who had climbed on top of the vehicle.[211] Before the show, a journalist angered Redding by asking why he was there; the reporter then informed him that two weeks earlier Hendrix announced that he had been replaced with Billy Cox.[212] The next day, Redding quit the Experience and returned to London.[210] He announced that he had left the band and intended to pursue a solo career, blaming Hendrix’s plans to expand the group without allowing for his input as a primary reason for leaving.[213] Redding later said: «Mitch and I hung out a lot together, but we’re English. If we’d go out, Jimi would stay in his room. But any bad feelings came from us being three guys who were traveling too hard, getting too tired, and taking too many drugs … I liked Hendrix. I don’t like Mitchell.»[214]

Soon after Redding’s departure, Hendrix began lodging at the eight-bedroom Ashokan House, in the hamlet of Boiceville near Woodstock in upstate New York, where he had spent some time vacationing in mid-1969.[215] Manager Michael Jeffery arranged the accommodations in the hope that the respite might encourage Hendrix to write material for a new album. During this time, Mitchell was unavailable for commitments made by Jeffery, which included Hendrix’s first appearance on US TV—on The Dick Cavett Show—where he was backed by the studio orchestra, and an appearance on The Tonight Show where he appeared with Cox and session drummer Ed Shaughnessy.[212]

Woodstock

Hendrix flashed a peace sign at the start of his performance of «The Star-Spangled Banner» at Woodstock, August 18, 1969.[216]

By 1969, Hendrix was the world’s highest-paid rock musician.[2] In August, he headlined the Woodstock Music and Art Fair that included many of the most popular bands of the time.[217] For the concert, he added rhythm guitarist Larry Lee and conga players Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez. The band rehearsed for less than two weeks before the performance, and according to Mitchell, they never connected musically.[218] Before arriving at the engagement, Hendrix heard reports that the size of the audience had grown enormously, which concerned him as he did not enjoy performing for large crowds.[219] He was an important draw for the event, and although he accepted substantially less money for the appearance than his usual fee, he was the festival’s highest-paid performer.[220][nb 30]

Hendrix decided to move his midnight Sunday slot to Monday morning, closing the show. The band took the stage around 8:00 a.m,[222] by which time Hendrix had been awake for more than three days.[223] The audience, which peaked at an estimated 400,000 people, was reduced to 30,000.[219] The festival MC, Chip Monck, introduced the group as «the Jimi Hendrix Experience», but Hendrix clarified: «We decided to change the whole thing around and call it ‘Gypsy Sun and Rainbows’. For short, it’s nothin’ but a ‘Band of Gypsys’.»[224]

An excerpt from the beginning of «The Star-Spangled Banner», at Woodstock, August 18, 1969. The sample demonstrates Hendrix’s use of feedback.

Hendrix’s performance included a rendition of the US national anthem, «The Star-Spangled Banner», with copious feedback, distortion, and sustain to imitate the sounds made by rockets and bombs.[225] Contemporary political pundits described his interpretation as a statement against the Vietnam War. Three weeks later Hendrix said: «We’re all Americans … it was like ‘Go America!’… We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see.»[226] Immortalized in the 1970 documentary film, Woodstock, Hendrix’s version became part of the sixties zeitgeist.[227] Pop critic Al Aronowitz of the New York Post wrote: «It was the most electrifying moment of Woodstock, and it was probably the single greatest moment of the sixties.»[226] Images of the performance showing Hendrix wearing a blue-beaded white leather jacket with fringe, a red head-scarf, and blue jeans are regarded as iconic pictures that capture a defining moment of the era.[228][nb 31] He played «Hey Joe» during the encore, concluding the 31⁄2-day festival. Upon leaving the stage, he collapsed from exhaustion.[227][nb 32] In 2011, the editors of Guitar World named his performance of «The Star-Spangled Banner» the greatest performance of all time.[231]

Band of Gypsys

A legal dispute arose in 1966 regarding a record contract that Hendrix had entered into the previous year with producer Ed Chalpin.[232] After two years of litigation, the parties agreed to a resolution that granted Chalpin the distribution rights to an album of original Hendrix material. Hendrix decided that they would record the LP, Band of Gypsys, during two live appearances.[233] In preparation for the shows he formed an all-black power trio with Cox and drummer Buddy Miles, formerly with Wilson Pickett, the Electric Flag, and the Buddy Miles Express.[234] Critic John Rockwell described Hendrix and Miles as jazz-rock fusionists, and their collaboration as pioneering.[235] Others identified a funk and soul influence in their music.[236] Concert promoter Bill Graham called the shows «the most brilliant, emotional display of virtuoso electric guitar» that he had ever heard.[237] Biographers have speculated that Hendrix formed the band in an effort to appease members of the Black Power movement and others in the black communities who called for him to use his fame to speak up for civil rights.[238]

An excerpt from the first guitar solo that demonstrates Hendrix’s innovative use of high gain and overdrive to achieve an aggressive, sustained tone.

Hendrix had been recording with Cox since April and jamming with Miles since September, and the trio wrote and rehearsed material which they performed at a series of four shows over two nights on December 31 and January 1, at the Fillmore East. They used recordings of these concerts to assemble the LP, which was produced by Hendrix.[239] The album includes the track «Machine Gun», which musicologist Andy Aledort described as the pinnacle of Hendrix’s career, and «the premiere example of [his] unparalleled genius as a rock guitarist … In this performance, Jimi transcended the medium of rock music, and set an entirely new standard for the potential of electric guitar.»[240] During the song’s extended instrumental breaks, Hendrix created sounds with his guitar that sonically represented warfare, including rockets, bombs, and diving planes.[241]

The Band of Gypsys album was the only official live Hendrix LP made commercially available during his lifetime; several tracks from the Woodstock and Monterey shows were released later that year.[242] The album was released in April 1970 by Capitol Records; it reached the top ten in both the US and the UK.[237] That same month a single was issued with «Stepping Stone» as the A-side and «Izabella» as the B-side, but Hendrix was dissatisfied with the quality of the mastering and he demanded that it be withdrawn and re-mixed, preventing the songs from charting and resulting in Hendrix’s least successful single; it was also his last.[243]

On January 28, 1970, a third and final Band of Gypsys appearance took place; they performed during a music festival at Madison Square Garden benefiting the anti-Vietnam War Moratorium Committee titled the «Winter Festival for Peace».[244] American blues guitarist Johnny Winter was backstage before the concert; he recalled: «[Hendrix] came in with his head down, sat on the couch alone, and put his head in his hands … He didn’t move until it was time for the show.»[245] Minutes after taking the stage he snapped a vulgar response at a woman who had shouted a request for «Foxy Lady». He then began playing «Earth Blues» before telling the audience: «That’s what happens when earth fucks with space».[245] Moments later, he briefly sat down on the drum riser before leaving the stage.[246] Both Miles and Redding later stated that Jeffery had given Hendrix LSD before the performance.[247] Miles believed that Jeffery gave Hendrix the drugs in an effort to sabotage the current band and bring about the return of the original Experience lineup.[246] Jeffery fired Miles after the show and Cox quit, ending the Band of Gypsys.[248]

Cry of Love Tour

Soon after the abruptly ended Band of Gypsys performance and their subsequent dissolution, Jeffery made arrangements to reunite the original Experience lineup.[249] Although Hendrix, Mitchell, and Redding were interviewed by Rolling Stone in February 1970 as a united group, Hendrix never intended to work with Redding.[250] When Redding returned to New York in anticipation of rehearsals with a re-formed Experience, he was told that he had been replaced with Cox.[251] During an interview with Rolling Stone‘s Keith Altham, Hendrix defended the decision: «It’s nothing personal against Noel, but we finished what we were doing with the Experience and Billy’s style of playing suits the new group better.»[249] Although an official name was never adopted for the lineup of Hendrix, Mitchell, and Cox, promoters often billed them as the Jimi Hendrix Experience or just Jimi Hendrix.[252]

During the first half of 1970, Hendrix sporadically worked on material for what would have been his next LP.[243] Many of the tracks were posthumously released in 1971 as The Cry of Love.[253] He had started writing songs for the album in 1968, but in April 1970 he told Keith Altham that the project had been abandoned.[243] Soon afterward, he and his band took a break from recording and began the Cry of Love tour at the L.A. Forum, performing for 20,000 people.[254] Set-lists during the tour included numerous Experience tracks as well as a selection of newer material.[254] Several shows were recorded, and they produced some of Hendrix’s most memorable live performances. At one of them, the second Atlanta International Pop Festival, on July 4, he played to the largest American audience of his career.[255] According to authors Scott Schinder and Andy Schwartz, as many as 500,000 people attended the concert.[255] On July 17, they appeared at the New York Pop Festival; Hendrix had again consumed too many drugs before the show, and the set was considered a disaster.[256] The American leg of the tour, which included 32 performances, ended in Honolulu, Hawaii, on August 1, 1970.[257] This would be Hendrix’s final concert appearance in the US.[258]

Electric Lady Studios

In 1968, Hendrix and Jeffery jointly invested in the purchase of the Generation Club in Greenwich Village.[201] They had initially planned to reopen the establishment, but when an audit of Hendrix’s expenses revealed that he had incurred exorbitant fees by block-booking recording studios for lengthy sessions at peak rates they decided to convert the building [259] into a studio of his own. Hendrix could then work as much as he wanted while also reducing his recording expenditures, which had reached a reported $300,000 annually.[260] Architect and acoustician John Storyk designed Electric Lady Studios for Hendrix, who requested that they avoid right angles where possible. With round windows, an ambient lighting machine, and a psychedelic mural, Storyk wanted the studio to have a relaxing environment that would encourage Hendrix’s creativity.[260] The project took twice as long as planned and cost twice as much as Hendrix and Jeffery had budgeted, with their total investment estimated at $1 million.[261][nb 33]

Hendrix first used Electric Lady on June 15, 1970, when he jammed with Steve Winwood and Chris Wood of Traffic; the next day, he recorded his first track there, «Night Bird Flying».[262] The studio officially opened for business on August 25, and a grand opening party was held the following day.[262] Immediately afterwards, Hendrix left for England; he never returned to the States.[263] He boarded an Air India flight for London with Cox, joining Mitchell for a performance as the headlining act of the Isle of Wight Festival.[264]

European tour

When the European leg of the Cry of Love tour began, Hendrix was longing for his new studio and creative outlet, and was not eager to fulfill the commitment. On September 2, 1970, he abandoned a performance in Aarhus after three songs, stating: «I’ve been dead a long time».[265] Four days later, he gave his final concert appearance, at the Isle of Fehmarn Festival in Germany.[266] He was met with booing and jeering from fans in response to his cancellation of a show slated for the end of the previous night’s bill due to torrential rain and risk of electrocution.[267][nb 34] Immediately following the festival, Hendrix, Mitchell, and Cox traveled to London.[269]

Three days after the performance, Cox, who was suffering from severe paranoia after either taking LSD or being given it unknowingly, quit the tour and went to stay with his parents in Pennsylvania.[270] Within days of Hendrix’s arrival in England, he had spoken with Chas Chandler, Alan Douglas, and others about leaving his manager, Michael Jeffery.[271] On September 16, Hendrix performed in public for the last time during an informal jam at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in Soho with Eric Burdon and his latest band, War.[272] They began by playing a few of their recent hits, and after a brief intermission Hendrix joined them during «Mother Earth» and «Tobacco Road». His performance was uncharacteristically subdued; he quietly played backing guitar, and refrained from the histrionics that people had come to expect from him.[273] He died less than 48 hours later.[274]

Drugs and alcohol

Hendrix entered a small club in Clarksville, Tennessee, in July 1962, drawn in by live music. He stopped for a drink and ended up spending most of the $400 ($3,924 in 2022 terms) that he had saved during his time in the Army. «I went in this jazz joint and had a drink,» he explained. «I liked it and I stayed. People tell me I get foolish, good-natured sometimes. Anyway, I guess I felt real benevolent that day. I must have been handing out bills to anyone that asked me. I came out of that place with sixteen dollars left.»[275] Alcohol eventually became «the scourge of his existence, driving him to fits of pique, even rare bursts of atypical, physical violence».[276]

Like most acid-heads, Jimi had visions and he wanted to create music to express what he saw. He would try to explain this to people, but it didn’t make sense because it was not linked to reality in any way.

— Kathy Etchingham[277]

Roby and Schreiber assert that Hendrix first used LSD when he met Linda Keith in late 1966. Shapiro and Glebbeek, however, assert that Hendrix used it in June 1967 at the earliest while attending the Monterey Pop Festival.[278] According to Hendrix biographer Charles Cross, the subject of drugs came up one evening in 1966 at Keith’s New York apartment. One of Keith’s friends offered Hendrix «acid», a street name for LSD, but Hendrix asked for LSD instead, showing what Cross describes as «his naivete and his complete inexperience with psychedelics».[279] Before that, Hendrix had only sporadically used drugs, including cannabis, hashish, amphetamines, and occasionally cocaine.[279] After 1967, he regularly used cannabis, hashish, LSD, and amphetamines, particularly while touring.[280] According to Cross, «few stars were as closely associated with the drug culture as Jimi».[281]

Drug abuse and violence

When Hendrix drank to excess or mixed drugs with alcohol, often he became angry and violent.[282] His friend Herbie Worthington said Hendrix «simply turned into a bastard» when he drank.[283] According to friend Sharon Lawrence, liquor «set off a bottled-up anger, a destructive fury he almost never displayed otherwise».[284]

In January 1968, the Experience travelled to Sweden to start a one-week tour of Europe. During the early morning hours of the first day, Hendrix got into a drunken brawl in the Hotel Opalen in Gothenburg, smashing a plate-glass window and injuring his right hand, for which he received medical treatment.[283] The incident culminated in his arrest and release, pending a court appearance that resulted in a large fine.[285]

In 1969, Hendrix rented a house in Benedict Canyon, California, that was burglarized. Later, while under the influence of drugs and alcohol, he accused his friend Paul Caruso of the theft, threw punches and stones at him, and chased him away from his house.[286] A few days later Hendrix hit his girlfriend, Carmen Borrero, above her eye with a vodka bottle during a drunken, jealous rage, and gave her a cut that required stitches.[283]

Canadian drug charges and trial

Hendrix was passing through customs at Toronto International Airport on May 3, 1969, when authorities found a small amount of heroin and hashish in his luggage, and charged him with drug possession.[287] He was released on $10,000 bail, and was required to return on May 5 for an arraignment hearing.[288] The incident proved stressful for Hendrix, and it weighed heavily on his mind during the seven months leading up to his December 1969 trial.[287] For the Crown to prove possession, they had to show that Hendrix knew that the drugs were there.[289] During the jury trial, he testified that a fan had given him a vial of what he thought was legal medication which he put in his bag.[290] He was acquitted of the charges.[291] Mitchell and Redding later revealed that everyone had been warned about a planned drug bust the day before flying to Toronto; both men also stated that they believed that the drugs had been planted in Hendrix’s bag without his knowledge.[292]

Death, post-mortem, and burial

The Samarkand Hotel, where Hendrix spent his final hours

Details concerning Hendrix’s last day and death are disputed.[293] He spent much of September 17, 1970, in London with Monika Dannemann, the only witness to his final hours.[294] Dannemann said that she prepared a meal for them at her apartment in the Samarkand Hotel around 11 p.m., when they shared a bottle of wine.[295] She drove him to the residence of an acquaintance at approximately 1:45 a.m., where he remained for about an hour before she picked him up and drove them back to her flat at 3 a.m.[296] She said that they talked until around 7 a.m., when they went to sleep. Dannemann awoke around 11 a.m. and found Hendrix breathing but unconscious and unresponsive. She called for an ambulance at 11:18 a.m., and it arrived nine minutes later.[297] Ambulancemen transported Hendrix to St Mary Abbots Hospital where Dr. John Bannister pronounced him dead at 12:45 p.m. on September 18.[298][299][300]

Coroner Gavin Thurston ordered a post-mortem examination which was performed on September 21 by Professor Robert Donald Teare, a forensic pathologist.[301] Thurston completed the inquest on September 28 and concluded that Hendrix aspirated his own vomit and died of asphyxia while intoxicated with barbiturates.[302] Citing «insufficient evidence of the circumstances», he declared an open verdict.[303] Dannemann later revealed that Hendrix had taken nine of her prescribed Vesparax sleeping tablets, 18 times the recommended dosage.[304]

Desmond Henley embalmed Hendrix’s body[305] which was flown to Seattle on September 29.[306] Hendrix’s family and friends held a service at Dunlap Baptist Church in Seattle’s Rainier Valley on Thursday, October 1; his body was interred at Greenwood Cemetery in nearby Renton,[307] the location of his mother’s grave.[308] Family and friends traveled in 24 limousines, and more than 200 people attended the funeral, including Mitch Mitchell, Noel Redding, Miles Davis, John Hammond, and Johnny Winter.[309][310]

Hendrix is often cited as one example of an allegedly disproportionate number of musicians dying at age 27, including Brian Jones, Alan Wilson, Jim Morrison, and Janis Joplin in the same era, a phenomenon referred to as the 27 Club.[311]

By 1967, as Hendrix was gaining in popularity, many of his pre-Experience recordings were marketed to an unsuspecting public as Jimi Hendrix albums, sometimes with misleading later images of Hendrix.[312] The recordings, which came under the control of producer Ed Chalpin of PPX, with whom Hendrix had signed a recording contract in 1965, were often re-mixed between their repeated reissues, and licensed to record companies such as Decca and Capitol.[313][314] Hendrix publicly denounced the releases, describing them as «malicious» and «greatly inferior», stating: «At PPX, we spent on average about one hour recording a song. Today I spend at least twelve hours on each song.»[315] These unauthorized releases have long constituted a substantial part of his recording catalogue, amounting to hundreds of albums.[316]

Some of Hendrix’s unfinished fourth studio album was released as the 1971 title The Cry of Love.[253] Although the album reached number three in the US and number two in the UK, producers Mitchell and Kramer later complained that they were unable to make use of all the available songs because some tracks were used for 1971’s Rainbow Bridge; still others were issued on 1972’s War Heroes.[317] Material from The Cry of Love was re-released in 1997 as First Rays of the New Rising Sun, along with the other tracks that Mitchell and Kramer had wanted to include.[318][nb 35] Four years after Hendrix’s death, producer Alan Douglas acquired the rights to produce unreleased music by Hendrix; he attracted criticism for using studio musicians to replace or add tracks.[320]

In 1993, MCA Records delayed a multimillion-dollar sale of Hendrix’s publishing copyrights because Al Hendrix was unhappy about the arrangement.[321] He acknowledged that he had sold distribution rights to a foreign corporation in 1974, but stated that it did not include copyrights and argued that he had retained veto power of the sale of the catalogue.[321] Under a settlement reached in July 1995, Al Hendrix regained control of his son’s song and image rights.[322] He subsequently licensed the recordings to MCA through the family-run company Experience Hendrix LLC, formed in 1995.[323] In August 2009, Experience Hendrix announced that it had entered a new licensing agreement with Sony Music Entertainment’s Legacy Recordings division, to take effect in 2010.[324] Legacy and Experience Hendrix launched the 2010 Jimi Hendrix Catalog Project starting with the release of Valleys of Neptune in March of that year.[325] In the months before his death, Hendrix recorded demos for a concept album tentatively titled Black Gold, now in the possession of Experience Hendrix LLC, but it has not been released.[326][nb 36]

Equipment

Guitars

Hendrix played a variety of guitars, but was most associated with the Fender Stratocaster.[328] He acquired his first in 1966, when a girlfriend loaned him enough money to purchase a used Stratocaster built around 1964.[329] He used it often during performances and recordings.[330] In 1967, he described the Stratocaster as «the best all-around guitar for the stuff we’re doing»; he praised its «bright treble and deep bass».[331]

Hendrix mainly played right-handed guitars that were turned upside down and restrung for left-hand playing.[332] Because of the slant of the Stratocaster’s bridge pickup, his lowest string had a brighter sound, while his highest string had a darker sound, the opposite of the intended design.[333] Hendrix also used Fender Jazzmasters, Duosonics, two different Gibson Flying Vs, a Gibson Les Paul, three Gibson SGs, a Gretsch Corvette, and a Fender Jaguar.[334] He used a white Gibson SG Custom for his performances on The Dick Cavett Show in September 1969, and a black Gibson Flying V during the Isle of Wight festival in 1970.[335][nb 37]

Amplifiers

During 1965 and 1966, while Hendrix was playing back-up for soul and R&B acts in the US, he used an 85-watt Fender Twin Reverb amplifier.[337] When Chandler brought Hendrix to England in October 1966, he supplied him with 30-watt Burns amps, which Hendrix thought were too small for his needs.[338][nb 38] After an early London gig when he was unable to use his Fender Twin, he asked about the Marshall amps he had noticed other groups using.[338] Years earlier, Mitch Mitchell had taken drum lessons from Marshall founder Jim Marshall, and he introduced Hendrix to Marshall.[339] At their initial meeting, Hendrix bought four speaker cabinets and three 100-watt Super Lead amplifiers; he grew accustomed to using all three in unison.[338] The equipment arrived on October 11, 1966, and the Experience used it during their first tour.[338]

Marshall amps were important to the development of Hendrix’s overdriven sound and his use of feedback, creating what author Paul Trynka described as a «definitive vocabulary for rock guitar».[340] Hendrix usually turned all the control knobs to the maximum level, which became known as the Hendrix setting.[341] During the four years prior to his death, he purchased between 50 and 100 Marshall amplifiers.[342] Jim Marshall said Hendrix was «the greatest ambassador» his company ever had.[343]

Effects

A 1968 King Vox-Wah wah-wah pedal similar to the one owned by Hendrix[344]

One of Hendrix’s signature effects was the wah-wah pedal, which he first heard used with an electric guitar in Cream’s «Tales of Brave Ulysses», released in May 1967.[345] That July, while performing at the Scene club in New York City, Hendrix met Frank Zappa, whose band the Mothers of Invention were performing at the adjacent Garrick Theater. Hendrix was fascinated by Zappa’s application of the pedal, and he experimented with one later that evening.[346][nb 39] He used a wah pedal during the opening to «Voodoo Child (Slight Return)», creating one of the best-known wah-wah riffs of the classic rock era.[348] He also uses the effect on «Up from the Skies», «Little Miss Lover», and «Still Raining, Still Dreaming».[347]

Hendrix used a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face and a Vox wah pedal during recording sessions and performances, but also experimented with other guitar effects.[349] He enjoyed a fruitful long-term collaboration with electronics enthusiast Roger Mayer, whom he once called «the secret» of his sound.[350] Mayer introduced him to the Octavia, an octave-doubling effect pedal, in December 1966, and he first recorded with it during the guitar solo to «Purple Haze».[351]

Hendrix also used the Uni-Vibe, designed to simulate the modulation effects of a rotating Leslie speaker. He uses the effect during his performance at Woodstock and on the Band of Gypsys track «Machine Gun», which prominently features the Uni-vibe along with an Octavia and a Fuzz Face.[352] For performances, he plugged his guitar into the wah-wah, which was connected to the Fuzz Face, then the Uni-Vibe, and finally a Marshall amplifier.[353]

Influences

As an adolescent in the 1950s, Hendrix became interested in rock and roll artists such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry.[354] In 1968, he told Guitar Player magazine that electric blues artists Muddy Waters, Elmore James, and B. B. King inspired him during the beginning of his career; he also cited Eddie Cochran as an early influence.[355] Of Muddy Waters, the first electric guitarist of which Hendrix became aware, he said: «I heard one of his records when I was a little boy and it scared me to death because I heard all of these sounds.»[356] In 1970, he told Rolling Stone that he was a fan of western swing artist Bob Wills and while he lived in Nashville, the television show the Grand Ole Opry.[357]

I don’t happen to know much about jazz. I know that most of those cats are playing nothing but blues, though—I know that much.

— Hendrix on jazz music[358]

Cox stated that during their time serving in the US military, he and Hendrix primarily listened to southern blues artists such as Jimmy Reed and Albert King. According to Cox, «King was a very, very powerful influence».[355] Howlin’ Wolf also inspired Hendrix, who performed Wolf’s «Killing Floor» as the opening song of his US debut at the Monterey Pop Festival.[359] The influence of soul artist Curtis Mayfield can be heard in Hendrix’s guitar playing, and the influence of Bob Dylan can be heard in Hendrix’s songwriting; he was known to play Dylan’s records repeatedly, particularly Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde.[360]

Legacy

He changed everything. What don’t we owe Jimi Hendrix? For his monumental rebooting of guitar culture «standards of tone», technique, gear, signal processing, rhythm playing, soloing, stage presence, chord voicings, charisma, fashion, and composition? … He is guitar hero number one.

— Guitar Player magazine, May 2012[361]

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame biography for the Experience states: «Jimi Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music. Hendrix expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive, technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll.»[1] Musicologist Andy Aledort described Hendrix as «one of the most creative» and «influential musicians that has ever lived».[362] Music journalist Chuck Philips wrote: «In a field almost exclusively populated by white musicians, Hendrix has served as a role model for a cadre of young black rockers. His achievement was to reclaim title to a musical form pioneered by black innovators like Little Richard and Chuck Berry in the 1950s.»[363]

Hendrix favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain.[126] He was instrumental in developing the previously undesirable technique of guitar amplifier feedback, and helped to popularize use of the wah-wah pedal in mainstream rock.[364] He rejected the standard barre chord fretting technique used by most guitarists in favor of fretting the low 6th string root notes with his thumb.[365] He applied this technique during the beginning bars of «Little Wing», which allowed him to sustain the root note of chords while also playing melody. This method has been described as piano style, with the thumb playing what a pianist’s left hand would play and the other fingers playing melody as a right hand.[366] Having spent several years fronting a trio, he developed an ability to play rhythm chords and lead lines together, giving the audio impression that more than one guitarist was performing.[367][nb 40] He was the first artist to incorporate stereophonic phasing effects in rock music recordings.[370] Holly George-Warren of Rolling Stone wrote: «Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began.»[3][nb 41]

While creating his unique musical voice and guitar style, Hendrix synthesized diverse genres, including blues, R&B, soul, British rock, American folk music, 1950s rock and roll, and jazz.[372] Musicologist David Moskowitz emphasized the importance of blues music in Hendrix’s playing style, and according to authors Steven Roby and Brad Schreiber, «[He] explored the outer reaches of psychedelic rock».[373] His influence is evident in a variety of popular music formats, and he has contributed significantly to the development of hard rock, heavy metal, funk, post-punk, grunge,[374] and hip hop music.[375] His lasting influence on modern guitar players is difficult to overstate; his techniques and delivery have been abundantly imitated by others.[376] Despite his hectic touring schedule and notorious perfectionism, he was a prolific recording artist who left behind numerous unreleased recordings.[377] More than 40 years after his death, Hendrix remains as popular as ever, with annual album sales exceeding that of any year during his lifetime.[378]

As with his contemporary Sly Stone, Hendrix embraced the experimentalism of white musicians in progressive rock in the late 1960s and inspired a wave of progressive soul musicians that emerged by the next decade.[379] He has directly influenced numerous funk and funk rock artists, including Prince, George Clinton, John Frusciante of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic, and Ernie Isley of the Isley Brothers.[380] Hendrix influenced post-punk guitarists such as John McGeoch of Siouxsie and the Banshees and Robert Smith of the Cure.[381] Grunge guitarists such as Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains,[382] and Mike McCready and Stone Gossard of Pearl Jam have cited Hendrix as an influence.[374] Hendrix’s influence also extends to many hip hop artists, including De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Digital Underground, Beastie Boys, and Run–D.M.C.[383] Miles Davis was deeply impressed by Hendrix, and he compared Hendrix’s improvisational abilities with those of saxophonist John Coltrane.[384][nb 42] Desert blues artists from the Sahara desert region including Mdou Moctar and Tinariwen have also acknowledged Hendrix’s influence.[386][387]

Rock and roll fans still debate whether Hendrix actually said that Chicago co-founder Terry Kath was a better guitar player than him,[388] but Kath named Hendrix as a major influence: «But then there was Hendrix, man. Jimi was really the last cat to freak me. Jimi was playing all the stuff I had in my head. I couldn’t believe it, when I first heard him. Man, no one can ever do what he did with a guitar. No one can ever take his place.»[389]

Hendrix also influenced Black Sabbath,[390] industrial artist Marilyn Manson,[391] blues musician Stevie Ray Vaughan,

Randy Hansen,[392]

Uli Jon Roth,[393] pop singer Halsey,[394] Kiss’s Ace Frehley,[395] Metallica‘s Kirk Hammett, Aerosmith’s Brad Whitford,[396] Judas Priest’s Richie Faulkner,[397] instrumental rock guitarist Joe Satriani, King’s X singer/bassist Doug Pinnick,[398] Adrian Belew,[399] and heavy metal virtuoso Yngwie Malmsteen, who said: «[Hendrix] created modern electric playing, without question … He was the first. He started it all. The rest is history.»[400] «For many», Hendrix was «the preeminent black rocker», according to Jon Caramanica.[401] Members of the Soulquarians, an experimental black music collective active during the late 1990s and early 2000s, were influenced by the creative freedom in Hendrix’s music and extensively used Electric Lady Studios to work on their own music.[402]

Recognition and awards

Hendrix received several prestigious rock music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year.[403] In 1968, Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year.[403] Also in 1968, the City of Seattle gave him the keys to the city.[404] Disc & Music Echo newspaper honored him with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970 Guitar Player magazine named him the Rock Guitarist of the Year.[405]

Rolling Stone ranked his three non-posthumous studio albums, Are You Experienced (1967), Axis: Bold as Love (1967), and Electric Ladyland (1968) among the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[406] They ranked Hendrix number one on their list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time, and number six on their list of the 100 greatest artists of all time.[407] Guitar World’s readers voted six of Hendrix’s solos among the top 100 Greatest Guitar Solos of All Time: «Purple Haze» (70), «The Star-Spangled Banner» (52; from Live at Woodstock), «Machine Gun» (32; from Band of Gypsys), «Little Wing» (18), «Voodoo Child (Slight Return)» (11), and «All Along the Watchtower» (5).[408] Rolling Stone placed seven of his recordings in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time: «Purple Haze» (17), «All Along the Watchtower» (47) «Voodoo Child (Slight Return)» (102), «Foxy Lady» (153), «Hey Joe» (201), «Little Wing» (366), and «The Wind Cries Mary» (379).[409] They also included three of Hendrix’s songs in their list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time: «Purple Haze» (2), «Voodoo Child» (12), and «Machine Gun» (49).[410]

A star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was dedicated to Hendrix on November 14, 1991, at 6627 Hollywood Boulevard.[411] The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005.[1][412] In 1998, Hendrix was inducted into the Native American Music Hall of Fame during its first year.[413][nb 43] In 1999, readers of Rolling Stone and Guitar World ranked Hendrix among the most important musicians of the 20th century.[415] In 2005, his debut album, Are You Experienced, was one of 50 recordings added that year to the US National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress, «[to] be preserved for all time … [as] part of the nation’s audio legacy».[416] In Seattle, November 27, 1992, which would have been Hendrix’s 50th birthday, was made Jimi Hendrix Day, largely due to the efforts of his boyhood friend, guitarist Sammy Drain.[417][418]

The blue plaque identifying Hendrix’s former residence at 23 Brook Street, London, was the first issued by English Heritage to commemorate a pop star. Next door is the former residence of George Frideric Handel, 25 Brook Street,[419] which opened to the public as the Handel House Museum in 2001. From 2016 the museum made use of the upper floors of 23 for displays about Hendrix and was rebranded as Handel & Hendrix in London.

A memorial statue of Hendrix playing a Stratocaster stands near the corner of Broadway and Pine Streets in Seattle. In May 2006, the city renamed a park near its Central District Jimi Hendrix Park, in his honor.[420] In 2012, an official historic marker was erected on the site of the July 1970 Second Atlanta International Pop Festival near Byron, Georgia. The marker text reads, in part: «Over thirty musical acts performed, including rock icon Jimi Hendrix playing to the largest American audience of his career.»[421]

Hendrix’s music has received a number of Hall of Fame Grammy awards, starting with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992, followed by two Grammys in 1999 for his albums Are You Experienced and Electric Ladyland; Axis: Bold as Love received a Grammy in 2006.[422][423] In 2000, he received a Hall of Fame Grammy award for his original composition, «Purple Haze», and in 2001, for his recording of Dylan’s «All Along the Watchtower». Hendrix’s rendition of «The Star-Spangled Banner» was honored with a Grammy in 2009.[422]

The United States Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp honoring Hendrix in 2014.[424] On August 21, 2016, Hendrix was inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame in Dearborn, Michigan.[425] The James Marshall «Jimi» Hendrix United States Post Office in Renton Highlands near Seattle, about a mile from Hendrix’s grave and memorial, was renamed for Hendrix in 2019.[426]