Как правильно пишется словосочетание «эффект плацебо»

- Как правильно пишется слово «эффект»

- Как правильно пишется слово «плацебо»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: масс-спектрометр — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «эффект»

Ассоциации к слову «плацебо»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «эффект плацебо»

Предложения со словосочетанием «эффект плацебо»

- По некоторым сведениям, эффект плацебо может проявляться в каждом третьем случае.

- Ведь можно научить людей проделывать с собой то же самое, рассказав им, как работает эффект плацебо.

- Часть I даёт подробные знания и дополнительные сведения, необходимые для понимания эффекта плацебо и механизмов его работы в мозге и теле.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «эффект плацебо»

- Кое-где местами, в котловинах, собралась вода, столь чистая и прозрачная, что исследователь замечает ее только тогда, когда попадает в нее ногой. Тут опять есть очень глубокий колодец и боковые ходы. В этом большом зале наблюдателя невольно поражают удивительные акустические эффекты — на каждое громкое слово отвечает стоголосое эхо, а при падении камня в колодец поднимается грохот, словно пушечная пальба: кажется, будто происходят обвалы и рушатся своды.

- Справедливо, что возвышенное отрицательное выше возвышенного положительного; потому надобно согласиться, что «перевесом идеи над формою» усиливается эффект возвышенного, как может он усиливаться многими другими обстоятельствами, напр., уединенностью возвышенного явления (пирамида в открытой степи величественнее, нежели была бы среди других громадных построек; среди высоких холмов ее величие исчезло бы); но усиливающее эффект обстоятельство не есть еще источник самого эффекта, притом перевеса идеи над образом, силы над явлением очень часто не бывает в положительном возвышенном.

- Дурной эффект, что мало дам вообще.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «эффект»

- побочные эффекты

произведённый эффект

обратный эффект - эффект неожиданности

эффект разорвавшейся бомбы

эффект присутствия - для достижения максимального эффекта

для усиления эффекта

для получения эффекта - эффект получился

эффект усиливается

эффект оказался - произвести эффект

давать эффект

создавать эффект - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «эффект плацебо»

-

1. психол. улучшение самочувствия человека благодаря вере в эффективность некоторого воздействия, в действительности никак не влияющим (Викисловарь)

Все значения словосочетания ЭФФЕКТ ПЛАЦЕБО

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «эффект»

- Страсть к блеску, к эффекту была ахиллесовскою пяткою натуры Марлинского, лишила его талант развития, способности идти вперед и наложила на него характер легкости и хрупкости.

- Когда народ стремится в своей речи только эффекту, говорит готовыми фразами, невоздержанно исполненными громких слов, оставляющими вас холодными как лед, он в полном падении.

- Я — за изучение именно литературной техники, то есть грамотности, то есть умения затрачивать наименьшее количество слов для достижения наибольшего количества эффекта, наибольшей простоты, пластичности и картинности изображаемых словами вещей, лиц, пейзажей, событий — вообще явлений социального бытия.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Пилюля из крахмала, сахарные шарики и инъекции подсоленной воды — сложно поверить, что в XXI веке эти средства до сих пор используют для лечения и, более того, они нередко работают. Forbes Life разобрался, как устроен эффект плацебо и на что способно человеческое воображение

Плацебо (в переводе с латыни — «понравлюсь») — это собирательный термин для любых медицинских препаратов и манипуляций, лишенных какого бы то ни было терапевтического действия. Простыми словами, не приносящих пациенту ни пользы, ни вреда — именно поэтому на медицинском жаргоне плацебо называют «пустышкой». Говоря «плацебо», обычно представляют себе таблетку, но на самом деле его видов намного больше. Это могут быть уколы неактивных препаратов, физиотерапия выключенными приборами и даже имитация хирургических вмешательств, когда пациенту дают наркоз, накладывают швы, но не производят более никаких манипуляций. Многие альтернативные методы лечения, например гомеопатию, акупунктуру и аюрведу, доказательная медицина тоже относит к плацебо.

Только в США половина врачей-терапевтов регулярно (2-3 раза в месяц) прописывают плацебо своим пациентам: дело в том, что «пустышка» обладает важным эффектом. «Плацебо нередко выступает как магическая сила: вера пациента в действенность препарата или безграничное доверие своему лечащему врачу запускает внутренние резервы исцеления нашего организма, — объясняет Марина Казанфарова, руководитель образовательного центра Международного медицинского кластера. — Это хороший инструмент, когда большую роль в развитии заболевания играет психосоматика».

История вопроса

Еще в XVI веке Амбруаз Паре, французский хирург и один из отцов современной медицины, писал, что лечение должно «иногда исцелять, часто — облегчать состояние и всегда утешать больного». Тогда же французский философ Мишель Монтень сказал, что «есть люди, которых исцеляет один только вид лекарства». Но в медицинскую практику понятие плацебо вошло только два века спустя — впервые его употребил шотландский акушер Уильям Смелли, предположив, что роженицам было бы неплохо давать «какое-нибудь безобидное и приятное поддельное лекарство, плацебо, чтобы отвлечь от боли». Постепенно в XVIII веке «пустышки» действительно начали использоваться: доктора и фармацевты прописывали особенно впечатлительным пациентам сладкие пилюли или, наоборот, соленую воду, обещая исцеление. Нередко это работало.

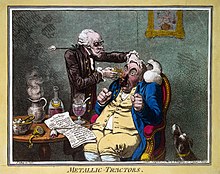

Но первым научным доказательством пользы плацебо стало экзотическое изобретение американского врача Элишы Перкинса. Он изготовил металлические палочки, которые назвал «вытягивателями Перкинса», и продавал по баснословной цене: их нужно было помещать в ноздри, чтобы якобы избавиться от болей — и это работало. Пользу «вытягивателей» решил проверить английский физиолог Джон Хайгарт. Он изготовил точно такие же палочки, но деревянные, и убедил своих пациентов в том, что их действие ничуть не хуже оригинальных. В результате у 4 из 5 больных ревматизмом после использования значительно уменьшились боли — а значит, «вытягиватели Перкинса» были просто пустышкой. Свои наблюдения Хайгарт описал в книге «Наше воображение как способ лечение телесных недугов».

Впрочем, широкого распространения в медицинской практике плацебо в XVIII и XIX веке не получило: из-за превалирующей христианской морали обманывать пациента, давая ему «пустышку», считалось неэтичным. Все изменилось в XX веке с развитием медицинской науки: ученым стало очевидно, что плацебо — незаменимый инструмент для клинических исследований. А в 40-х годах американский анестезиолог Генри Бичер, работавший на итальянском фронте во время Второй мировой войны, в условиях нехватки морфия вкалывал солдатам физраствор. Он с удивлением обнаружил, что в 40% случаев боль действительно отступает. По результатам своих наблюдений Бичер написал знаменитую книгу «Всемогущее плацебо», где впервые употребил термин «эффект плацебо».

Как работает плацебо

Точный механизм действия плацебо ученым до сих пор неизвестен, на этот счет есть несколько теорий.

Первая гласит, что основа эффекта плацебо — банальные условные рефлексы: в ответ на привычный стимул организм выдает привычный ответ. Простыми словами, если мы привыкли ассоциировать таблетки с облегчением боли, их прием будет стимулировать выброс эндогенных опиатов — наших природных обезболивающих. Даже если никакого действующего вещества в лекарстве нет. Есть исследования с помощью МРТ, доказывающие, что после приема плацебо у пациентов активизируются опиоидные рецепторы в мозгу.

Другая теория — что эффект плацебо происходит из теории ожиданий. Это психологическая концепция, суть которой в том, что основа человеческой мотивации и успеха — вера в то, что конкретные действия ведут к конкретным результатам. На практике это выглядит так: пациент ходит в клинику, выполняет рекомендации доктора, принимает лекарства и проходит различные процедуры, веря, что это облегчит его состояние. В результате запускаются механизмы саморегуляции психики, которые действительно помогают достичь желаемого результата. Это подтверждают исследования о том, что эффект плацебо значительно усиливается, если врач ему подыгрывает: подробно рассказывает пациенту, насколько лучше ему станет после приема «пустышки» плацебо, и вообще демонстрирует энтузиазм и поддержку.

Наконец, есть версия, что некоторые люди априори подвержены эффекту плацебо: это пациенты с более высокой чувствительностью к дофамину, «гормону вознаграждения».

Интересно, что выявлены факторы, которые гарантированно усиливают действие плацебо:

— Большое количество таблеток за один прием

— Высокая цена лекарства

— Название известного медицинского бренда на упаковке

— Желтый или красный цвет пилюли с плацебо

— Инъекции работают лучше, чем пероральные препараты

— Мужчины более подвержены эффекту плацебо, чем женщины

— Доброжелательная обстановка в клинике и поддержка семьи

«В целом можно сказать, что плацебо больше всего действует на пациентов с подвижной психикой, а также заболевания, в развитии которых играет важную роль нервная система, — объясняет Наталья Шиндряева, д. м. н., профессор кафедры неврологии ИПО Сеченовского университета. — Это, например, повышенная тревожность, депрессивные состояния, хронический болевой синдром, дерматиты».

Плацебо для клинических исследований

«Современная медицинская наука относится к плацебо как к средству помощи людям, как бы странно это ни звучало. Если бы не было плацебо, мы не смогли бы убедиться в эффективности большинства современных препаратов», — комментирует Марина Болдинова, врач общей практики, член Европейской организации здравоохранения. Действительно, сегодня плацебо-контролируемые клинические исследования — золотой стандарт во всех развитых странах.

Их суть заключается в том, чтобы тестировать действие каждого нового медицинского препарата на двух группах пациентов: одна из них получает непосредственно лекарство, другая — «пустышку». Как правило, плацебо применяют на 1-й и 2-й фазе исследований: чтобы подтвердить безопасность и специфическое действие активного вещества. «Только при условии получения статистической разницы в результатах препарат выводится на рынок, — объясняет Марина Казанфарова из ММК. — Этот метод действительно позволяет защищать пациентов и не допускает попадания в аптеки «волшебных пилюль» без терапевтического эффекта. Благодаря плацебо в том числе только один препарат из десяти проходит испытания».

Обратная сторона медали

Споры о том, насколько этично применять плацебо, не утихают с момента его изобретения по сей день. В том числе в аспекте клинических исследований: многим кажется несправедливым, что одна группа испытуемых получает потенциально эффективное лекарство, а другая — «пустышку». Современная наука решает этот вопрос так: в плацебо-контролируемых исследованиях задействуют минимально возможное число участников и при возможности сравнивают новый препарат не с плацебо, а с уже существующим лекарством. «Неэтичность использования плацебо для исследований — это широкомасштабный миф, — объясняет Марина Болдинова. — Потому что люди, которые на это идут, подписывают множество юридических документов. Практически ни один подобный судебный процесс не разрешился в пользу пациента».

В том, что касается терапевтического использования плацебо, самое главное, по мнению врачей, — сохранять здравый смысл. «Применение плацебо допустимо, если пациент требует медикаментозного лечения, но при этом в нем не нуждается. Или для того, чтобы помочь ему снять напряжение, отпустить ситуацию, — объясняет Марина Казанфарова. — Как правило, плацебо работает на ранних стадиях легких заболеваний и только ограниченный срок. Недобросовестное использование этого метода может приводить к тому, что пациент теряет драгоценное время, которое мог бы потратить на то, чтобы принимать действенную терапию».

Интересно, что у плацебо есть и обратный эффект — его называют «ноцебо». Действие, соответственно, полностью противоположное: принимая «пустышку», человек испытывает всевозможные неприятные симптомы — от тошноты до головокружения. Как объясняет Наталья Шиндряева, в практике врача эффект плацебо и ноцебо — это показатель работы нервной системы пациента, его отношения к лечению. Негативно настроенный человек, получая «пустышку», скорее всего, будет воспринимать ее как ноцебо и чувствовать себя все хуже и хуже — и не исключено, что то же самое будет происходить и при обычной терапии.

В то же время сила человеческого воображения действительно безгранична: доказано, что, даже зная, что он принимает «пустышку», человек может ощутить положительный эффект. Ведь все дело в позитивном мышлении — именно на нем, по сути, зиждется магия плацебо.

Placebos are typically inert tablets, such as sugar pills.

A placebo ( plə-SEE-boh) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value.[1] Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like saline), sham surgery,[2] and other procedures.[3]

In general, placebos can affect how patients perceive their condition and encourage the body’s chemical processes for relieving pain[4] and a few other symptoms,[5] but have no impact on the disease itself.[6][4] Improvements that patients experience after being treated with a placebo can also be due to unrelated factors, such as regression to the mean (a statistical effect where an unusually high or low measurement is likely to be followed by a less extreme one).[4] The use of placebos in clinical medicine raises ethical concerns, especially if they are disguised as an active treatment, as this introduces dishonesty into the doctor–patient relationship and bypasses informed consent.[7] While it was once assumed that this deception was necessary for placebos to have any effect, there is some evidence that placebos may have subjective effects even when the patient is aware that the treatment is a placebo (known as open-label placebo).[8]

In drug testing and medical research, a placebo can be made to resemble an active medication or therapy so that it functions as a control; this is to prevent the recipient or others from knowing (with their consent) whether a treatment is active or inactive, as expectations about efficacy can influence results.[9][10] In a placebo-controlled clinical trial any change in the control group is known as the placebo response, and the difference between this and the result of no treatment is the placebo effect.[11] Some researchers now recommend comparing the experimental treatment with an existing treatment when possible, instead of a placebo.[12]

The idea of a placebo effect—a therapeutic outcome derived from an inert treatment—was discussed in 18th century psychology,[13] but became more prominent in the 20th century. An influential 1955 study entitled The Powerful Placebo firmly established the idea that placebo effects were clinically important,[14] and were a result of the brain’s role in physical health. A 1997 reassessment found no evidence of any placebo effect in the source data, as the study had not accounted for regression to the mean.[15][16]

Etymology[edit]

Placebo (pronounced /plaˈkebo/ or /plaˈt͡ʃebo) is Latin for [I] shall be pleasing. It was used as a name for the Vespers in the Office of the Dead, taken from its incipit, a quote from the Vulgate’s Psalm 116:9, placēbō Dominō in regiōne vīvōrum, «[I] shall please the Lord in the land of the living.»[17][18][19] From that, a singer of placebo became associated with someone who falsely claimed a connection to the deceased to get a share of the funeral meal, and hence a flatterer, and so a deceptive act to please.[20]

Definitions[edit]

The American Society of Pain Management Nursing defines a placebo as «any sham medication or procedure designed to be void of any known therapeutic value».[1]

In a clinical trial, a placebo response is the measured response of subjects to a placebo; the placebo effect is the difference between that response and no treatment.[11] The placebo response may include improvements due to natural healing, declines due to natural disease progression, the tendency for people who were temporarily feeling either better or worse than usual to return to their average situations (regression toward the mean), and errors in the clinical trial records, which can make it appear that a change has happened when nothing has changed.[21] It is also part of the recorded response to any active medical intervention.[22]

Measurable placebo effects may be either objective (e.g. lowered blood pressure) or subjective (e.g. a lowered perception of pain).[1]

Effects[edit]

Placebos can improve patient-reported outcomes such as pain and nausea.[6][23] This effect is unpredictable and hard to measure, even in the best conducted trials.[6] For example, if used to treat insomnia, placebos can cause patients to perceive that they are sleeping better, but do not improve objective measurements of sleep onset latency.[24] A 2001 Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis of the placebo effect looked at trials in 40 different medical conditions, and concluded the only one where it had been shown to have a significant effect was for pain.[14]

By contrast, placebos do not appear to affect the actual diseases, or outcomes that are not dependent on a patient’s perception.[6] One exception to the latter is Parkinson’s disease, where recent research has linked placebo interventions to improved motor functions.[5][25][26]

Measuring the extent of the placebo effect is difficult due to confounding factors.[16] For example, a patient may feel better after taking a placebo due to regression to the mean (i.e. a natural recovery or change in symptoms).[15][27][28] It is harder still to tell the difference between the placebo effect and the effects of response bias, observer bias and other flaws in trial methodology, as a trial comparing placebo treatment and no treatment will not be a blinded experiment.[6][15] In their 2010 meta-analysis of the placebo effect, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Gøtzsche argue that «even if there were no true effect of placebo, one would expect to record differences between placebo and no-treatment groups due to bias associated with lack of blinding.»[6] Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche concluded that their study «did not find that placebo interventions have important clinical effects in general».[6] In a study in 2010, patients given open-label placebo in the context of a supportive patient-practitioner relationship and a persuasive rationale had clinically meaningful symptom improvement that was significantly better than a no-treatment control group with matched patient-provider interaction.[29]

Jeremy Howick has argued that combining so many varied studies to produce a single average might obscure that «some placebos for some things could be quite effective.»[30] To demonstrate this, he participated in a systematic review comparing active treatments and placebos using a similar method, which generated a conclusion that there is «no difference between treatment and placebo effects».[31][30]

Factors influencing the power of the placebo effect[edit]

A review published in JAMA Psychiatry found that, in trials of antipsychotic medications, the change in response to receiving a placebo had increased significantly between 1960 and 2013. The review’s authors identified several factors that could be responsible for this change, including inflation of baseline scores and enrollment of fewer severely ill patients.[32] Another analysis published in Pain in 2015 found that placebo responses had increased considerably in neuropathic pain clinical trials conducted in the United States from 1990 to 2013. The researchers suggested that this may be because such trials have «increased in study size and length» during this time period.[33]

Children seem to have a greater response than adults to placebos.[34]

The administration of the placebos can determine the placebo effect strength. Studies have found that taking more pills would strengthen the effect. Besides, capsules appear to be more influential than pills, and injections are even stronger than capsules.[35]

Some studies have investigated the use of placebos where the patient is fully aware that the treatment is inert, known as an open-label placebo.[36] A 2017 meta-analysis based on 5 studies found some evidence that open-label placebos may have positive effects in comparison to no treatment,[8] which may open new avenues for treatments,[36] but noted the trials were done with a small number of participants and hence should be interpreted with «caution» until further better controlled trials are conducted.[8][36] An updated 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis based on 11 studies also found a significant, albeit slightly smaller overall effect of open-label placebos, while noting that «research on OLPs is still in its infancy».[37]

If the person dispensing the placebo shows their care towards the patient, is friendly and sympathetic, or has a high expectation of a treatment’s success, then the placebo would be more effectual.[35]

Symptoms and conditions[edit]

A 2010 Cochrane Collaboration review suggests that placebo effects are apparent only in subjective, continuous measures, and in the treatment of pain and related conditions.[6]

Pain[edit]

Placebos are believed to be capable of altering a person’s perception of pain. «A person might reinterpret a sharp pain as uncomfortable tingling.»[4]

One way in which the magnitude of placebo analgesia can be measured is by conducting «open/hidden» studies, in which some patients receive an analgesic and are informed that they will be receiving it (open), while others are administered the same drug without their knowledge (hidden). Such studies have found that analgesics are considerably more effective when the patient knows they are receiving them.[38]

Depression[edit]

In 2008, a controversial meta-analysis led by psychologist Irving Kirsch, analyzing data from the FDA, concluded that 82% of the response to antidepressants was accounted for by placebos.[39] However, there are serious doubts about the used methods and the interpretation of the results, especially the use of 0.5 as the cut-off point for the effect size.[40] A complete reanalysis and recalculation based on the same FDA data discovered that the Kirsch study had «important flaws in the calculations». The authors concluded that although a large percentage of the placebo response was due to expectancy, this was not true for the active drug. Besides confirming drug effectiveness, they found that the drug effect was not related to depression severity.[41]

Another meta-analysis found that 79% of depressed patients receiving placebo remained well (for 12 weeks after an initial 6–8 weeks of successful therapy) compared to 93% of those receiving antidepressants. In the continuation phase however, patients on placebo relapsed significantly more often than patients on antidepressants.[42]

Negative effects[edit]

A phenomenon opposite to the placebo effect has also been observed. When an inactive substance or treatment is administered to a recipient who has an expectation of it having a negative impact, this intervention is known as a nocebo (Latin nocebo = «I shall harm»).[43] A nocebo effect occurs when the recipient of an inert substance reports a negative effect or a worsening of symptoms, with the outcome resulting not from the substance itself, but from negative expectations about the treatment.[44][45]

Another negative consequence is that placebos can cause side-effects associated with real treatment.[46] Failure to minimise nocebo side-effects in clinical trials and clinical practice raises a number of recently explored ethical issues.[47]

Withdrawal symptoms can also occur after placebo treatment. This was found, for example, after the discontinuation of the Women’s Health Initiative study of hormone replacement therapy for menopause. Women had been on placebo for an average of 5.7 years. Moderate or severe withdrawal symptoms were reported by 4.8% of those on placebo compared to 21.3% of those on hormone replacement.[48]

Ethics[edit]

In research trials[edit]

Knowingly giving a person a placebo when there is an effective treatment available is a bioethically complex issue. While placebo-controlled trials might provide information about the effectiveness of a treatment, it denies some patients what could be the best available (if unproven) treatment. Informed consent is usually required for a study to be considered ethical, including the disclosure that some test subjects will receive placebo treatments.

The ethics of placebo-controlled studies have been debated in the revision process of the Declaration of Helsinki.[49] Of particular concern has been the difference between trials comparing inert placebos with experimental treatments, versus comparing the best available treatment with an experimental treatment; and differences between trials in the sponsor’s developed countries versus the trial’s targeted developing countries.[50]

Some suggest that existing medical treatments should be used instead of placebos, to avoid having some patients not receive medicine during the trial.[12]

In medical practice[edit]

The practice of doctors prescribing placebos that are disguised as real medication is controversial. A chief concern is that it is deceptive and could harm the doctor–patient relationship in the long run. While some say that blanket consent, or the general consent to unspecified treatment given by patients beforehand, is ethical, others argue that patients should always obtain specific information about the name of the drug they are receiving, its side effects, and other treatment options.[51] This view is shared by some on the grounds of patient autonomy.[52] There are also concerns that legitimate doctors and pharmacists could open themselves up to charges of fraud or malpractice by using a placebo.[53] Critics also argued that using placebos can delay the proper diagnosis and treatment of serious medical conditions.[54]

Despite the abovementioned issues, 60% of surveyed physicians and head nurses reported using placebos in an Israeli study, with only 5% of respondents stating that placebo use should be strictly prohibited.[55] A British Medical Journal editorial said, «that a patient gets pain relief from a placebo does not imply that the pain is not real or organic in origin …the use of the placebo for ‘diagnosis’ of whether or not pain is real is misguided.»[56] A survey in the United States of more than 10,000 physicians came to the result that while 24% of physicians would prescribe a treatment that is a placebo simply because the patient wanted treatment, 58% would not, and for the remaining 18%, it would depend on the circumstances.[57]

Referring specifically to homeopathy, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Science and Technology Committee has stated:

In the Committee’s view, homeopathy is a placebo treatment and the Government should have a policy on prescribing placebos. The Government is reluctant to address the appropriateness and ethics of prescribing placebos to patients, which usually relies on some degree of patient deception. Prescribing of placebos is not consistent with informed patient choice—which the Government claims is very important—as it means patients do not have all the information needed to make choice meaningful. A further issue is that the placebo effect is unreliable and unpredictable.[58]

In his 2008 book Bad Science, Ben Goldacre argues that instead of deceiving patients with placebos, doctors should use the placebo effect to enhance effective medicines.[59] Edzard Ernst has argued similarly that «As a good doctor you should be able to transmit a placebo effect through the compassion you show your patients.»[60] In an opinion piece about homeopathy, Ernst argues that it is wrong to support alternative medicine on the basis that it can make patients feel better through the placebo effect.[61] His concerns are that it is deceitful and that the placebo effect is unreliable.[61] Goldacre also concludes that the placebo effect does not justify alternative medicine, arguing that unscientific medicine could lead to patients not receiving prevention advice.[59]

Placebo researcher Fabrizio Benedetti also expresses concern over the potential for placebos to be used unethically, warning that there is an increase in «quackery» and that an «alternative industry that preys on the vulnerable» is developing.[62]

Mechanisms[edit]

The mechanism for the placebo «effect» remains unknown. An open-label study in 2010 showed that it had an effect even when patients were clearly told that the placebo pill they were receiving was an inactive (i.e., «inert») substance like a sugar pill that contained no medication. These results challenge the «conventional wisdom» that placebo effects require «intentional ignorance».[29] A placebo presented as a stimulant may trigger an effect on heart rhythm and blood pressure, but when administered as a depressant, the opposite effect.[63]

Psychology[edit]

The «placebo effect» may be related to expectations, yet open-label studies prove it has effects.

In psychology, the two main hypotheses of the placebo effect are expectancy theory and classical conditioning.[64]

In 1985, Irving Kirsch hypothesized that placebo effects are produced by the self-fulfilling effects of response expectancies, in which the belief that one will feel different leads a person to actually feel different.[65] According to this theory, the belief that one has received an active treatment can produce the subjective changes thought to be produced by the real treatment. Similarly, the appearance of effect can result from classical conditioning, wherein a placebo and an actual stimulus are used simultaneously until the placebo is associated with the effect from the actual stimulus.[66] Both conditioning and expectations play a role in placebo effect,[64] and make different kinds of contributions. Conditioning has a longer-lasting effect,[67] and can affect earlier stages of information processing.[68] Those who think a treatment will work display a stronger placebo effect than those who do not, as evidenced by a study of acupuncture.[69]

Additionally, motivation may contribute to the placebo effect. The active goals of an individual changes their somatic experience by altering the detection and interpretation of expectation-congruent symptoms, and by changing the behavioral strategies a person pursues.[70] Motivation may link to the meaning through which people experience illness and treatment. Such meaning is derived from the culture in which they live and which informs them about the nature of illness and how it responds to treatment.

Placebo analgesia[edit]

Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia suggests links to the activation, and increased functional correlation between this activation, in the anterior cingulate, prefrontal, orbitofrontal and insular cortices, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, the brainstem’s periaqueductal gray matter,[71][72] and the spinal cord.[73][74][75]

Since 1978, it has been known that placebo analgesia depends upon the release of endogenous opioids in the brain.[76] Such analgesic placebos activation changes processing lower down in the brain by enhancing the descending inhibition through the periaqueductal gray on spinal nociceptive reflexes, while the expectations of anti-analgesic nocebos acts in the opposite way to block this.[73]

Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia has been summarized as showing that the placebo response is «mediated by «top-down» processes dependent on frontal cortical areas that generate and maintain cognitive expectancies. Dopaminergic reward pathways may underlie these expectancies».[77] «Diseases lacking major ‘top-down’ or cortically based regulation may be less prone to placebo-related improvement».[78]

Brain and body[edit]

In conditioning, a neutral stimulus saccharin is paired in a drink with an agent that produces an unconditioned response. For example, that agent might be cyclophosphamide, which causes immunosuppression. After learning this pairing, the taste of saccharin by itself is able to cause immunosuppression, as a new conditioned response via neural top-down control.[79] Such conditioning has been found to affect a diverse variety of not just basic physiological processes in the immune system but ones such as serum iron levels, oxidative DNA damage levels, and insulin secretion. Recent reviews have argued that the placebo effect is due to top-down control by the brain for immunity[80] and pain.[81] Pacheco-López and colleagues have raised the possibility of «neocortical-sympathetic-immune axis providing neuroanatomical substrates that might explain the link between placebo/conditioned and placebo/expectation responses».[80]: 441 There has also been research aiming to understand underlying neurobiological mechanisms of action in pain relief, immunosuppression, Parkinson’s disease and depression.[82]

Dopaminergic pathways have been implicated in the placebo response in pain and depression.[83]

Confounding factors[edit]

Placebo-controlled studies, as well as studies of the placebo effect itself, often fail to adequately identify confounding factors.[4][84][85] False impressions of placebo effects are caused by many factors including:[4][15][85][64][84]

- Regression to the mean (natural recovery or fluctuation of symptoms)

- Additional treatments

- Response bias from subjects, including scaling bias, answers of politeness, experimental subordination, conditioned answers;

- Reporting bias from experimenters, including misjudgment and irrelevant response variables.

- Non-inert ingredients of the placebo medication having an unintended physical effect

History[edit]

The word placebo was used in a medicinal context in the late 18th century to describe a «commonplace method or medicine» and in 1811 it was defined as «any medicine adapted more to please than to benefit the patient». Although this definition contained a derogatory implication[20] it did not necessarily imply that the remedy had no effect.[86]

It was recognized in the 18th and 19th centuries that drugs or remedies often were perceived to work best while they were still novel:[87]

We know that, in Paris, fashion imposes its dictates on medicine just as it does with everything else. Well, at one time, pyramidal elm bark[88] had a great reputation; it was taken as a powder, as an extract, as an elixir, even in baths. It was good for the nerves, the chest, the stomach — what can I say? — it was a true panacea. At the peak of the fad, one of Bouvard’s [sic] patients asked him if it might not be a good idea to take some: «Take it, Madame», he replied, «and hurry up while it [still] cures.» [dépêchez-vous pendant qu’elle guérit]

Placebos have featured in medical use until well into the twentieth century.[90] In 1955 Henry K. Beecher published an influential paper entitled The Powerful Placebo which proposed the idea that placebo effects were clinically important.[14] Subsequent re-analysis of his materials, however, found in them no evidence of any «placebo effect».[15]

Placebo-controlled studies[edit]

The placebo effect makes it more difficult to evaluate new treatments. Clinical trials control for this effect by including a group of subjects that receives a sham treatment. The subjects in such trials are blinded as to whether they receive the treatment or a placebo. If a person is given a placebo under one name, and they respond, they will respond in the same way on a later occasion to that placebo under that name but not if under another.[91]

Clinical trials are often double-blinded so that the researchers also do not know which test subjects are receiving the active or placebo treatment. The placebo effect in such clinical trials is weaker than in normal therapy since the subjects are not sure whether the treatment they are receiving is active.[92]

See also[edit]

- List of effects

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Placebo button

- Self-fulfilling prophecy[93]

- Nocebo

- Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism

Further reading[edit]

- Hall, Kathryn T (2022). Placebos. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262544252.

- Colloca, Luana (2018-04-20). Neurobiology of the placebo effect. Part I. Cambridge, MA. ISBN 9780128143261. OCLC 1032303151.

- Colloca, Luana (2018-08-23). Neurobiology of the placebo effect. Part II (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA, United States. ISBN 9780128154175. OCLC 1049800273.

- Erik, Vance (2016). Suggestible You: The Curious Science of Your Brain’s Ability to Deceive, Transform, and Heal. National Geographic. ISBN 978-1426217890.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Arnstein P, Broglio K, Wuhrman E, Kean MB (2011). «Use of placebos in pain management» (PDF). Pain Manag Nurs (Position Statement of the American Society for Pain Management Nursing). 12 (4): 225–9. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2010.10.033. PMID 22117754.

- ^ Gottlieb S (18 February 2014). «The FDA Wants You for Sham Surgery». Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Lanotte M, Lopiano L, Torre E, Bergamasco B, Colloca L, Benedetti F (November 2005). «Expectation enhances autonomic responses to stimulation of the human subthalamic limbic region». Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 19 (6): 500–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2005.06.004. PMID 16055306. S2CID 36092163.

- ^ a b c d e f «Placebo Effect». American Cancer Society. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2020-05-22. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- ^ a b Quattrone, Aldo; Barbagallo, Gaetano; Cerasa, Antonio; Stoessl, A. Jon (August 2018). «Neurobiology of placebo effect in Parkinson’s disease: What we have learned and where we are going». Movement Disorders. 33 (8): 1213–1227. doi:10.1002/mds.27438. ISSN 1531-8257. PMID 30230624. S2CID 52294141.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC (January 2010). Hróbjartsson A (ed.). «Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions» (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 106 (1): CD003974. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3. PMC 7156905. PMID 20091554.

- ^ Newman DH (2008). Hippocrates’ Shadow. Scribner. pp. 134–59. ISBN 978-1-4165-5153-9.

- ^ a b c Charlesworth JE, Petkovic G, Kelley JM, Hunter M, Onakpoya I, Roberts N, Miller FG, Howick J (May 2017). «Effects of placebos without deception compared with no treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis» (PDF). Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine (Systematic review and meta-analysis). 10 (2): 97–107. doi:10.1111/jebm.12251. PMID 28452193. S2CID 4577402.

- ^ «placebo». Dictionary.com. 9 April 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ «placebo». TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ a b Chaplin S (2006). «The placebo response: an important part of treatment». Prescriber. 17 (5): 16–22. doi:10.1002/psb.344. S2CID 72626022.

- ^ a b Michels KB (April 2000). «The placebo problem remains». Archives of General Psychiatry. 57 (4): 321–2. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.321. PMID 10768689.

- ^ Schwarz, K. A., & Pfister, R.: Scientific psychology in the 18th century: a historical rediscovery. In: Perspectives on Psychological Science, Nr. 11, p. 399-407.

- ^ a b c Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC (May 2001). «Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment». The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (21): 1594–602. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105243442106. PMID 11372012.

- ^ a b c d e Kienle GS, Kiene H (December 1997). «The powerful placebo effect: fact or fiction?». Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 50 (12): 1311–8. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00203-5. PMID 9449934.

- ^ a b Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC (August 2004). «Is the placebo powerless? Update of a systematic review with 52 new randomized trials comparing placebo with no treatment». Journal of Internal Medicine. 256 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01355.x. PMID 15257721. S2CID 21244034. Gøtzsche’s biographical article has further references related to this work.

- ^ «Placebo (origins of technical term)». TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

- ^ Psalms 114:9

- ^ Jacobs B (April 2000). «Biblical origins of placebo». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 93 (4): 213–4. doi:10.1177/014107680009300419. PMC 1297986. PMID 10844895.

- ^ a b Shapiro AK (1968). «Semantics of the placebo». Psychiatric Quarterly. 42 (4): 653–95. doi:10.1007/BF01564309. PMID 4891851. S2CID 2733947.

- ^ Kaptchuk, Ted J; Hemond, Christopher C; Miller, Franklin G (2020-07-20). «Placebos in chronic pain: evidence, theory, ethics, and use in clinical practice». BMJ. 370: m1668. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1668. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32690477. S2CID 220633770.

- ^ Eccles R (2002). «The powerful placebo in cough studies?». Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 15 (3): 303–8. doi:10.1006/pupt.2002.0364. PMID 12099783.

- ^ Benedetti, Fabrizio (1 February 2008). «Mechanisms of Placebo and Placebo-Related Effects Across Diseases and Treatments». Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 48 (1): 33–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094711. ISSN 0362-1642. PMID 17666008. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Yeung V, Sharpe L, Glozier N, Hackett ML, Colagiuri B (April 2018). «A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo versus no treatment for insomnia symptoms». Sleep Medicine Reviews. 38: 17–27. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2017.03.006. PMID 28554719.

- ^ Gross, Liza (February 2017). «Putting placebos to the test». PLOS Biology. 15 (2): e2001998. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001998. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5319646. PMID 28222121.

- ^ Enck, Paul; Bingel, Ulrike; Schedlowski, Manfred; Rief, Winfried (March 2013). «The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize?». Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 12 (3): 191–204. doi:10.1038/nrd3923. ISSN 1474-1776. PMID 23449306. S2CID 24556504.

- ^ McDonald CJ, Mazzuca SA, McCabe GP (1983). «How much of the placebo ‘effect’ is really statistical regression?». Statistics in Medicine. 2 (4): 417–27. doi:10.1002/sim.4780020401. PMID 6369471.

- ^ Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ (February 2005). «Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it». International Journal of Epidemiology. 34 (1): 215–20. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh299. PMID 15333621.

- ^ a b Kaptchuk, Ted J.; Friedlander, Elizabeth; Kelley, John M.; Sanchez, M. Norma; Kokkotou, Efi; Singer, Joyce P.; Kowalczykowski, Magda; Miller, Franklin G.; Kirsch, Irving; Lembo, Anthony J. (2010-12-22). «Placebos without Deception: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Irritable Bowel Syndrome». PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15591. Bibcode:2010PLoSO…515591K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015591. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3008733. PMID 21203519.

- ^ a b Hutchinson P, Moerman D (October 2018). «The Meaning Response, «Placebo» and Method». Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 15 (2): 361–378. doi:10.1353/pbm.2018.0049. PMID 30293975. S2CID 52934614.

- ^ Howick J, Friedemann C, Tsakok M, Watson R, Tsakok T, Thomas J, Perera R, Fleming S, Heneghan C (May 2013). «Are Treatments More Effective than Placebos? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis». PLOS One. 11 (1): e62599. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…862599H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062599. PMC 3655171. PMID 23690944.

- ^ Rutherford BR, Pott E, Tandler JM, Wall MM, Roose SP, Lieberman JA (December 2014). «Placebo response in antipsychotic clinical trials: a meta-analysis». JAMA Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1409–21. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1319. PMC 4256120. PMID 25321611.

- ^ Tuttle AH, Tohyama S, Ramsay T, Kimmelman J, Schweinhardt P, Bennett GJ, Mogil JS (December 2015). «Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain». Pain. 156 (12): 2616–26. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000333. PMID 26307858. S2CID 23246031.

- Lay summary in: Dahl M (October 9, 2015). «The Placebo Effect Is Getting Stronger — But Only in the U.S.» The Cut.

- ^ Rheims S, Cucherat M, Arzimanoglou A, Ryvlin P (August 2008). Klassen T (ed.). «Greater response to placebo in children than in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis in drug-resistant partial epilepsy». PLOS Medicine. 5 (8): e166. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050166. PMC 2504483. PMID 18700812.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Robin; Kosslyn, Stephen (2010). Abnormal Psychology. Worth Publishers. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4292-6356-6. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Blease, CR; Bernstein, MH; Locher, C (26 June 2019). «Open-label placebo clinical trials: is it the rationale, the interaction or the pill?». BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine (Review). 25 (5): bmjebm–2019–111209. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111209. PMC 6930978. PMID 31243047.

- ^ von Wernsdorff, Melina; Loef, Martin; Tuschen-Caffier, Brunna; Schmidt, Stefan (2021). «Effects of open-label placebos in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis». Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 3855. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3855V. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83148-6. PMC 7887232. PMID 33594150.

- ^ Price DD, Finniss DG, Benedetti F (2008). «A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: recent advances and current thought». Annual Review of Psychology. 59 (1): 565–90. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.113006.095941. PMID 17550344.

- ^ Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). «Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration». PLOS Medicine. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

- ^ Turner EH, Rosenthal R (March 2008). «Efficacy of antidepressants». BMJ. 336 (7643): 516–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39510.531597.80. PMC 2265347. PMID 18319297.

- ^ Fountoulakis KN, Möller HJ (April 2011). «Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data». The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 (3): 405–12. doi:10.1017/S1461145710000957. PMID 20800012.

- ^ Khan A, Redding N, Brown WA (August 2008). «The persistence of the placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials». Journal of Psychiatric Research. 42 (10): 791–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.10.004. PMID 18036616.

- ^ «nocebo». Mirriam-Webster Incorporated. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Häuser W, Hansen E, Enck P (June 2012). «Nocebo phenomena in medicine: their relevance in everyday clinical practice». Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 109 (26): 459–65. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0459. PMC 3401955. PMID 22833756.

- ^ «The Nocebo Effect». Priory.com. 10 February 2007. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Shapiro AK, Chassan J, Morris LA, Frick R (1974). «Placebo induced side effects». Journal of Operational Psychiatry. 6: 43–6.

- ^ Howick, Jeremy (2020). «Unethical informed consent caused by overlooking poorly measured nocebo effects». Journal of Medical Ethics. 47 (9): medethics-2019-105903. doi:10.1136/medethics-2019-105903. PMID 32063581. S2CID 211134874.

- ^ Ockene JK, Barad DH, Cochrane BB, Larson JC, Gass M, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Manson JE, Barnabei VM, Lane DS, Brzyski RG, Rosal MC, Wylie-Rosett J, Hays J (July 2005). «Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin». JAMA. 294 (2): 183–93. doi:10.1001/jama.294.2.183. PMID 16014592.

- ^ Howick J (September 2009). «Questioning the methodologic superiority of ‘placebo’ over ‘active’ controlled trials». The American Journal of Bioethics. 9 (9): 34–48. doi:10.1080/15265160903090041. PMID 19998192. S2CID 41559691.

- ^ Kottow M (December 2010). «The improper use of research placebos». Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 16 (6): 1041–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01246.x. PMID 20663001.

- ^ Asai A, Kadooka Y (May 2013). «Reexamination of the ethics of placebo use in clinical practice». Bioethics. 27 (4): 186–93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01943.x. PMID 22296589. S2CID 11300075.

- ^ Chua SJ, Pitts M (June 2015). «The ethics of prescription of placebos to patients with major depressive disorder». Chinese Medical Journal. 128 (11): 1555–7. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.157699. PMC 4733778. PMID 26021517.

- ^ Malani A (2008). «Regulation with Placebo Effects». Chicago Unbound. 58 (3): 411–72. PMID 19353835. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ Altunç U, Pittler MH, Ernst E (January 2007). «Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials». Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 82 (1): 69–75. doi:10.4065/82.1.69. PMID 17285788.

- ^ Nitzan, Uriel; Lichtenberg, Pesach (2004-10-23). «Questionnaire survey on use of placebo». BMJ: British Medical Journal. 329 (7472): 944–946. doi:10.1136/bmj.38236.646678.55. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 524103. PMID 15377572.

- ^ Spiegel D (October 2004). «Placebos in practice». BMJ. 329 (7472): 927–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7472.927. PMC 524090. PMID 15499085.

- ^ Doctors Struggle With Tougher-Than-Ever Dilemmas: Other Ethical Issues Author: Leslie Kane. 11/11/2010

- ^ UK Parliamentary Committee Science; Technology Committee. «Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy». Archived from the original on 2012-02-24.

- ^ a b Goldacre, Ben (2008). «5: The Placebo Effect». Bad Science. Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-724019-7.

- ^ Rimmer, Abi (January 2018). «Empathy and ethics: five minutes with Edzard Ernst». The BMJ. 360 (1): k309. doi:10.1136/bmj.k309. PMID 29371199. S2CID 3511158.

- ^ a b «No to homeopathy placebo». The Guardian. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Benedetti, Fabrizio (3 March 2022). «The science of placebos is fuelling quackery». Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-030222-3. S2CID 247265071. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Kirsch I (1997). «Specifying non-specifics: Psychological mechanism of the placebo effect». In Harrington A (ed.). The Placebo Effect: An Interdisciplinary Exploration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 166–86. ISBN 978-0-674-66986-4.

- ^ a b c Stewart-Williams S, Podd J (March 2004). «The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate». Psychological Bulletin. 130 (2): 324–40. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.324. PMID 14979775.

- ^ Kirsch I (1985). «Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior». American Psychologist. 40 (11): 1189–1202. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1189.

- ^ Voudouris NJ, Peck CL, Coleman G (July 1989). «Conditioned response models of placebo phenomena: further support». Pain. 38 (1): 109–16. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(89)90080-8. PMID 2780058. S2CID 40356035.

- ^ Klinger R, Soost S, Flor H, Worm M (March 2007). «Classical conditioning and expectancy in placebo hypoalgesia: a randomized controlled study in patients with atopic dermatitis and persons with healthy skin». Pain. 128 (1–2): 31–9. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.025. PMID 17030095. S2CID 27747260.

- ^ Colloca L, Tinazzi M, Recchia S, Le Pera D, Fiaschi A, Benedetti F, Valeriani M (October 2008). «Learning potentiates neurophysiological and behavioral placebo analgesic responses». Pain. 139 (2): 306–14. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.021. PMID 18538928. S2CID 27342664.

- ^ Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, Brinkhaus B, Willich SN, Melchart D (April 2007). «The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain». Pain. 128 (3): 264–71. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. PMID 17257756. S2CID 25561695.

- ^ Geers AL, Weiland PE, Kosbab K, Landry SJ, Helfer SG (August 2005). «Goal activation, expectations, and the placebo effect». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 89 (2): 143–59. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.143. PMID 16162050.

- ^ Oken BS (November 2008). «Placebo effects: clinical aspects and neurobiology». Brain. 131 (Pt 11): 2812–23. doi:10.1093/brain/awn116. PMC 2725026. PMID 18567924.

- ^ Lidstone SC, Stoessl AJ (2007). «Understanding the placebo effect: contributions from neuroimaging». Molecular Imaging and Biology. 9 (4): 176–85. doi:10.1007/s11307-007-0086-3. PMID 17334853. S2CID 28735246.

- ^ a b Goffaux P, Redmond WJ, Rainville P, Marchand S (July 2007). «Descending analgesia—when the spine echoes what the brain expects». Pain. 130 (1–2): 137–43. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.11.011. PMID 17215080. S2CID 20841668.

- ^ Qiu YH, Wu XY, Xu H, Sackett D (October 2009). «Neuroimaging study of placebo analgesia in humans». Neuroscience Bulletin. 25 (5): 277–82. doi:10.1007/s12264-009-0907-2. PMC 5552608. PMID 19784082.

- ^ Zubieta JK, Stohler CS (March 2009). «Neurobiological mechanisms of placebo responses». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1156 (1): 198–210. Bibcode:2009NYASA1156..198Z. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04424.x. PMC 3073412. PMID 19338509.

- ^ Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL (September 1978). «The mechanism of placebo analgesia». Lancet. 2 (8091): 654–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92762-9. PMID 80579. S2CID 45403755.

- ^ Faria V, Fredrikson M, Furmark T (July 2008). «Imaging the placebo response: a neurofunctional review». European Neuropsychopharmacology. 18 (7): 473–85. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.03.002. PMID 18495442. S2CID 40020867.

- ^ Diederich NJ, Goetz CG (August 2008). «The placebo treatments in neurosciences: New insights from clinical and neuroimaging studies». Neurology. 71 (9): 677–84. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000324635.49971.3d. PMID 18725593. S2CID 29547923.

- ^ Ader R, Cohen N (1975). «Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression». Psychosomatic Medicine. 37 (4): 333–40. doi:10.1097/00006842-197507000-00007. PMID 1162023.

- ^ a b Pacheco-López G, Engler H, Niemi MB, Schedlowski M (September 2006). «Expectations and associations that heal: Immunomodulatory placebo effects and its neurobiology». Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 20 (5): 430–46. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2006.05.003. PMID 16887325. S2CID 11897104.

- ^ Colloca L, Benedetti F (July 2005). «Placebos and painkillers: is mind as real as matter?». Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 6 (7): 545–52. doi:10.1038/nrn1705. PMID 15995725. S2CID 9353193.

- ^ Benedetti F, Mayberg HS, Wager TD, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK (November 2005). «Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect». The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (45): 10390–402. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3458-05.2005. PMC 6725834. PMID 16280578.

- ^ Murray D, Stoessl AJ (December 2013). «Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of the placebo effect in neurological and psychiatric conditions». Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 140 (3): 306–18. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.009. PMID 23880289.

- ^ a b Golomb BA, Erickson LC, Koperski S, Sack D, Enkin M, Howick J (October 2010). «What’s in placebos: who knows? Analysis of randomized, controlled trials». Annals of Internal Medicine. 153 (8): 532–5. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00010. PMID 20956710. S2CID 30068755.

- ^ a b Hróbjartsson A, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG (November 2011). «Placebo effect studies are susceptible to response bias and to other types of biases». Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 64 (11): 1223–9. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.008. PMC 3146959. PMID 21524568.

- ^ Kaptchuk TJ (June 1998). «Powerful placebo: the dark side of the randomised controlled trial». The Lancet. 351 (9117): 1722–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10111-8. PMID 9734904. S2CID 34023318.

- ^ Arthur K. Shapiro, Elaine Shapiro, The Powerful Placebo: From Ancient Priest to Modern Physician, 2006, ISBN 1421401347, chapter «The Placebo Effect in Medical History»

- ^ the inner bark of Ulmus campestris: Simon Morelot, Cours élémentaire d’histoire naturelle pharmaceutique…, 1800, p. 349 «the elm, pompously named pyramidal…it had an ephemeral reputation»; Georges Dujardin-Beaumetz, Formulaire pratique de thérapeutique et de pharmacologie, 1893, p. 260

- ^ Gaston de Lévis, Souvenirs et portraits, 1780-1789, 1813, p. 240

- ^ de Craen AJ, Kaptchuk TJ, Tijssen JG, Kleijnen J (October 1999). «Placebos and placebo effects in medicine: historical overview». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 92 (10): 511–5. doi:10.1177/014107689909201005. PMC 1297390. PMID 10692902.

- ^ Whalley B, Hyland ME, Kirsch I (May 2008). «Consistency of the placebo effect». Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 64 (5): 537–41. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.007. PMID 18440407.

- ^ Vase L, Riley JL, Price DD (October 2002). «A comparison of placebo effects in clinical analgesic trials versus studies of placebo analgesia». Pain. 99 (3): 443–52. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00205-1. PMID 12406519. S2CID 21391210.

- ^ Benedetti, Fabrizio (2008-10-16). Placebo Effects. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199559121.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-955912-1.

External links[edit]

- Program in Placebo Studies & Therapeutic Encounter (PiPS) (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School)

Look up placebo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Placebos are typically inert tablets, such as sugar pills.

A placebo ( plə-SEE-boh) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value.[1] Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like saline), sham surgery,[2] and other procedures.[3]

In general, placebos can affect how patients perceive their condition and encourage the body’s chemical processes for relieving pain[4] and a few other symptoms,[5] but have no impact on the disease itself.[6][4] Improvements that patients experience after being treated with a placebo can also be due to unrelated factors, such as regression to the mean (a statistical effect where an unusually high or low measurement is likely to be followed by a less extreme one).[4] The use of placebos in clinical medicine raises ethical concerns, especially if they are disguised as an active treatment, as this introduces dishonesty into the doctor–patient relationship and bypasses informed consent.[7] While it was once assumed that this deception was necessary for placebos to have any effect, there is some evidence that placebos may have subjective effects even when the patient is aware that the treatment is a placebo (known as open-label placebo).[8]

In drug testing and medical research, a placebo can be made to resemble an active medication or therapy so that it functions as a control; this is to prevent the recipient or others from knowing (with their consent) whether a treatment is active or inactive, as expectations about efficacy can influence results.[9][10] In a placebo-controlled clinical trial any change in the control group is known as the placebo response, and the difference between this and the result of no treatment is the placebo effect.[11] Some researchers now recommend comparing the experimental treatment with an existing treatment when possible, instead of a placebo.[12]

The idea of a placebo effect—a therapeutic outcome derived from an inert treatment—was discussed in 18th century psychology,[13] but became more prominent in the 20th century. An influential 1955 study entitled The Powerful Placebo firmly established the idea that placebo effects were clinically important,[14] and were a result of the brain’s role in physical health. A 1997 reassessment found no evidence of any placebo effect in the source data, as the study had not accounted for regression to the mean.[15][16]

Etymology[edit]

Placebo (pronounced /plaˈkebo/ or /plaˈt͡ʃebo) is Latin for [I] shall be pleasing. It was used as a name for the Vespers in the Office of the Dead, taken from its incipit, a quote from the Vulgate’s Psalm 116:9, placēbō Dominō in regiōne vīvōrum, «[I] shall please the Lord in the land of the living.»[17][18][19] From that, a singer of placebo became associated with someone who falsely claimed a connection to the deceased to get a share of the funeral meal, and hence a flatterer, and so a deceptive act to please.[20]

Definitions[edit]

The American Society of Pain Management Nursing defines a placebo as «any sham medication or procedure designed to be void of any known therapeutic value».[1]

In a clinical trial, a placebo response is the measured response of subjects to a placebo; the placebo effect is the difference between that response and no treatment.[11] The placebo response may include improvements due to natural healing, declines due to natural disease progression, the tendency for people who were temporarily feeling either better or worse than usual to return to their average situations (regression toward the mean), and errors in the clinical trial records, which can make it appear that a change has happened when nothing has changed.[21] It is also part of the recorded response to any active medical intervention.[22]

Measurable placebo effects may be either objective (e.g. lowered blood pressure) or subjective (e.g. a lowered perception of pain).[1]

Effects[edit]

Placebos can improve patient-reported outcomes such as pain and nausea.[6][23] This effect is unpredictable and hard to measure, even in the best conducted trials.[6] For example, if used to treat insomnia, placebos can cause patients to perceive that they are sleeping better, but do not improve objective measurements of sleep onset latency.[24] A 2001 Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis of the placebo effect looked at trials in 40 different medical conditions, and concluded the only one where it had been shown to have a significant effect was for pain.[14]

By contrast, placebos do not appear to affect the actual diseases, or outcomes that are not dependent on a patient’s perception.[6] One exception to the latter is Parkinson’s disease, where recent research has linked placebo interventions to improved motor functions.[5][25][26]

Measuring the extent of the placebo effect is difficult due to confounding factors.[16] For example, a patient may feel better after taking a placebo due to regression to the mean (i.e. a natural recovery or change in symptoms).[15][27][28] It is harder still to tell the difference between the placebo effect and the effects of response bias, observer bias and other flaws in trial methodology, as a trial comparing placebo treatment and no treatment will not be a blinded experiment.[6][15] In their 2010 meta-analysis of the placebo effect, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Gøtzsche argue that «even if there were no true effect of placebo, one would expect to record differences between placebo and no-treatment groups due to bias associated with lack of blinding.»[6] Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche concluded that their study «did not find that placebo interventions have important clinical effects in general».[6] In a study in 2010, patients given open-label placebo in the context of a supportive patient-practitioner relationship and a persuasive rationale had clinically meaningful symptom improvement that was significantly better than a no-treatment control group with matched patient-provider interaction.[29]

Jeremy Howick has argued that combining so many varied studies to produce a single average might obscure that «some placebos for some things could be quite effective.»[30] To demonstrate this, he participated in a systematic review comparing active treatments and placebos using a similar method, which generated a conclusion that there is «no difference between treatment and placebo effects».[31][30]

Factors influencing the power of the placebo effect[edit]

A review published in JAMA Psychiatry found that, in trials of antipsychotic medications, the change in response to receiving a placebo had increased significantly between 1960 and 2013. The review’s authors identified several factors that could be responsible for this change, including inflation of baseline scores and enrollment of fewer severely ill patients.[32] Another analysis published in Pain in 2015 found that placebo responses had increased considerably in neuropathic pain clinical trials conducted in the United States from 1990 to 2013. The researchers suggested that this may be because such trials have «increased in study size and length» during this time period.[33]

Children seem to have a greater response than adults to placebos.[34]

The administration of the placebos can determine the placebo effect strength. Studies have found that taking more pills would strengthen the effect. Besides, capsules appear to be more influential than pills, and injections are even stronger than capsules.[35]

Some studies have investigated the use of placebos where the patient is fully aware that the treatment is inert, known as an open-label placebo.[36] A 2017 meta-analysis based on 5 studies found some evidence that open-label placebos may have positive effects in comparison to no treatment,[8] which may open new avenues for treatments,[36] but noted the trials were done with a small number of participants and hence should be interpreted with «caution» until further better controlled trials are conducted.[8][36] An updated 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis based on 11 studies also found a significant, albeit slightly smaller overall effect of open-label placebos, while noting that «research on OLPs is still in its infancy».[37]

If the person dispensing the placebo shows their care towards the patient, is friendly and sympathetic, or has a high expectation of a treatment’s success, then the placebo would be more effectual.[35]

Symptoms and conditions[edit]

A 2010 Cochrane Collaboration review suggests that placebo effects are apparent only in subjective, continuous measures, and in the treatment of pain and related conditions.[6]

Pain[edit]

Placebos are believed to be capable of altering a person’s perception of pain. «A person might reinterpret a sharp pain as uncomfortable tingling.»[4]

One way in which the magnitude of placebo analgesia can be measured is by conducting «open/hidden» studies, in which some patients receive an analgesic and are informed that they will be receiving it (open), while others are administered the same drug without their knowledge (hidden). Such studies have found that analgesics are considerably more effective when the patient knows they are receiving them.[38]

Depression[edit]

In 2008, a controversial meta-analysis led by psychologist Irving Kirsch, analyzing data from the FDA, concluded that 82% of the response to antidepressants was accounted for by placebos.[39] However, there are serious doubts about the used methods and the interpretation of the results, especially the use of 0.5 as the cut-off point for the effect size.[40] A complete reanalysis and recalculation based on the same FDA data discovered that the Kirsch study had «important flaws in the calculations». The authors concluded that although a large percentage of the placebo response was due to expectancy, this was not true for the active drug. Besides confirming drug effectiveness, they found that the drug effect was not related to depression severity.[41]

Another meta-analysis found that 79% of depressed patients receiving placebo remained well (for 12 weeks after an initial 6–8 weeks of successful therapy) compared to 93% of those receiving antidepressants. In the continuation phase however, patients on placebo relapsed significantly more often than patients on antidepressants.[42]

Negative effects[edit]

A phenomenon opposite to the placebo effect has also been observed. When an inactive substance or treatment is administered to a recipient who has an expectation of it having a negative impact, this intervention is known as a nocebo (Latin nocebo = «I shall harm»).[43] A nocebo effect occurs when the recipient of an inert substance reports a negative effect or a worsening of symptoms, with the outcome resulting not from the substance itself, but from negative expectations about the treatment.[44][45]

Another negative consequence is that placebos can cause side-effects associated with real treatment.[46] Failure to minimise nocebo side-effects in clinical trials and clinical practice raises a number of recently explored ethical issues.[47]

Withdrawal symptoms can also occur after placebo treatment. This was found, for example, after the discontinuation of the Women’s Health Initiative study of hormone replacement therapy for menopause. Women had been on placebo for an average of 5.7 years. Moderate or severe withdrawal symptoms were reported by 4.8% of those on placebo compared to 21.3% of those on hormone replacement.[48]

Ethics[edit]

In research trials[edit]

Knowingly giving a person a placebo when there is an effective treatment available is a bioethically complex issue. While placebo-controlled trials might provide information about the effectiveness of a treatment, it denies some patients what could be the best available (if unproven) treatment. Informed consent is usually required for a study to be considered ethical, including the disclosure that some test subjects will receive placebo treatments.

The ethics of placebo-controlled studies have been debated in the revision process of the Declaration of Helsinki.[49] Of particular concern has been the difference between trials comparing inert placebos with experimental treatments, versus comparing the best available treatment with an experimental treatment; and differences between trials in the sponsor’s developed countries versus the trial’s targeted developing countries.[50]

Some suggest that existing medical treatments should be used instead of placebos, to avoid having some patients not receive medicine during the trial.[12]

In medical practice[edit]

The practice of doctors prescribing placebos that are disguised as real medication is controversial. A chief concern is that it is deceptive and could harm the doctor–patient relationship in the long run. While some say that blanket consent, or the general consent to unspecified treatment given by patients beforehand, is ethical, others argue that patients should always obtain specific information about the name of the drug they are receiving, its side effects, and other treatment options.[51] This view is shared by some on the grounds of patient autonomy.[52] There are also concerns that legitimate doctors and pharmacists could open themselves up to charges of fraud or malpractice by using a placebo.[53] Critics also argued that using placebos can delay the proper diagnosis and treatment of serious medical conditions.[54]

Despite the abovementioned issues, 60% of surveyed physicians and head nurses reported using placebos in an Israeli study, with only 5% of respondents stating that placebo use should be strictly prohibited.[55] A British Medical Journal editorial said, «that a patient gets pain relief from a placebo does not imply that the pain is not real or organic in origin …the use of the placebo for ‘diagnosis’ of whether or not pain is real is misguided.»[56] A survey in the United States of more than 10,000 physicians came to the result that while 24% of physicians would prescribe a treatment that is a placebo simply because the patient wanted treatment, 58% would not, and for the remaining 18%, it would depend on the circumstances.[57]

Referring specifically to homeopathy, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Science and Technology Committee has stated:

In the Committee’s view, homeopathy is a placebo treatment and the Government should have a policy on prescribing placebos. The Government is reluctant to address the appropriateness and ethics of prescribing placebos to patients, which usually relies on some degree of patient deception. Prescribing of placebos is not consistent with informed patient choice—which the Government claims is very important—as it means patients do not have all the information needed to make choice meaningful. A further issue is that the placebo effect is unreliable and unpredictable.[58]

In his 2008 book Bad Science, Ben Goldacre argues that instead of deceiving patients with placebos, doctors should use the placebo effect to enhance effective medicines.[59] Edzard Ernst has argued similarly that «As a good doctor you should be able to transmit a placebo effect through the compassion you show your patients.»[60] In an opinion piece about homeopathy, Ernst argues that it is wrong to support alternative medicine on the basis that it can make patients feel better through the placebo effect.[61] His concerns are that it is deceitful and that the placebo effect is unreliable.[61] Goldacre also concludes that the placebo effect does not justify alternative medicine, arguing that unscientific medicine could lead to patients not receiving prevention advice.[59]

Placebo researcher Fabrizio Benedetti also expresses concern over the potential for placebos to be used unethically, warning that there is an increase in «quackery» and that an «alternative industry that preys on the vulnerable» is developing.[62]

Mechanisms[edit]

The mechanism for the placebo «effect» remains unknown. An open-label study in 2010 showed that it had an effect even when patients were clearly told that the placebo pill they were receiving was an inactive (i.e., «inert») substance like a sugar pill that contained no medication. These results challenge the «conventional wisdom» that placebo effects require «intentional ignorance».[29] A placebo presented as a stimulant may trigger an effect on heart rhythm and blood pressure, but when administered as a depressant, the opposite effect.[63]

Psychology[edit]

The «placebo effect» may be related to expectations, yet open-label studies prove it has effects.

In psychology, the two main hypotheses of the placebo effect are expectancy theory and classical conditioning.[64]

In 1985, Irving Kirsch hypothesized that placebo effects are produced by the self-fulfilling effects of response expectancies, in which the belief that one will feel different leads a person to actually feel different.[65] According to this theory, the belief that one has received an active treatment can produce the subjective changes thought to be produced by the real treatment. Similarly, the appearance of effect can result from classical conditioning, wherein a placebo and an actual stimulus are used simultaneously until the placebo is associated with the effect from the actual stimulus.[66] Both conditioning and expectations play a role in placebo effect,[64] and make different kinds of contributions. Conditioning has a longer-lasting effect,[67] and can affect earlier stages of information processing.[68] Those who think a treatment will work display a stronger placebo effect than those who do not, as evidenced by a study of acupuncture.[69]

Additionally, motivation may contribute to the placebo effect. The active goals of an individual changes their somatic experience by altering the detection and interpretation of expectation-congruent symptoms, and by changing the behavioral strategies a person pursues.[70] Motivation may link to the meaning through which people experience illness and treatment. Such meaning is derived from the culture in which they live and which informs them about the nature of illness and how it responds to treatment.

Placebo analgesia[edit]

Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia suggests links to the activation, and increased functional correlation between this activation, in the anterior cingulate, prefrontal, orbitofrontal and insular cortices, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, the brainstem’s periaqueductal gray matter,[71][72] and the spinal cord.[73][74][75]

Since 1978, it has been known that placebo analgesia depends upon the release of endogenous opioids in the brain.[76] Such analgesic placebos activation changes processing lower down in the brain by enhancing the descending inhibition through the periaqueductal gray on spinal nociceptive reflexes, while the expectations of anti-analgesic nocebos acts in the opposite way to block this.[73]

Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia has been summarized as showing that the placebo response is «mediated by «top-down» processes dependent on frontal cortical areas that generate and maintain cognitive expectancies. Dopaminergic reward pathways may underlie these expectancies».[77] «Diseases lacking major ‘top-down’ or cortically based regulation may be less prone to placebo-related improvement».[78]

Brain and body[edit]

In conditioning, a neutral stimulus saccharin is paired in a drink with an agent that produces an unconditioned response. For example, that agent might be cyclophosphamide, which causes immunosuppression. After learning this pairing, the taste of saccharin by itself is able to cause immunosuppression, as a new conditioned response via neural top-down control.[79] Such conditioning has been found to affect a diverse variety of not just basic physiological processes in the immune system but ones such as serum iron levels, oxidative DNA damage levels, and insulin secretion. Recent reviews have argued that the placebo effect is due to top-down control by the brain for immunity[80] and pain.[81] Pacheco-López and colleagues have raised the possibility of «neocortical-sympathetic-immune axis providing neuroanatomical substrates that might explain the link between placebo/conditioned and placebo/expectation responses».[80]: 441 There has also been research aiming to understand underlying neurobiological mechanisms of action in pain relief, immunosuppression, Parkinson’s disease and depression.[82]

Dopaminergic pathways have been implicated in the placebo response in pain and depression.[83]

Confounding factors[edit]

Placebo-controlled studies, as well as studies of the placebo effect itself, often fail to adequately identify confounding factors.[4][84][85] False impressions of placebo effects are caused by many factors including:[4][15][85][64][84]

- Regression to the mean (natural recovery or fluctuation of symptoms)

- Additional treatments

- Response bias from subjects, including scaling bias, answers of politeness, experimental subordination, conditioned answers;

- Reporting bias from experimenters, including misjudgment and irrelevant response variables.