Yōkai (妖怪, «strange apparition») are a class of supernatural entities and spirits in Japanese folklore. The word yōkai is a loanword from the Chinese term yaoguai and is composed of the kanji for «demon; fairy; sprite» and «suspicious; apparition; monster; ghost; spectre»[1][2] Yōkai are also referred to as ayakashi (あやかし), mononoke (物の怪) or mamono (魔物). Despite often being translated as such, yōkai are not literally demons in the Western sense of the word, but are instead spirits and entities. Their behavior can range from malevolent or mischievous to benevolent to humans.

Yōkai often have animal features (such as the kappa, depicted as appearing similar to a turtle, and the tengu, commonly depicted with wings), but may also appear humanoid in appearance, such as the kuchisake-onna. Some yōkai resemble inanimate objects (such as the tsukumogami), while others have no discernible shape. Yōkai are typically described as having spiritual or supernatural abilities, with shapeshifting being the most common trait associated with them. Yōkai that shapeshift are known as bakemono (化け物) or obake (お化け).

Japanese folklorists and historians explain yōkai as personifications of «supernatural or unaccountable phenomena to their informants.» In the Edo period, many artists, such as Toriyama Sekien, invented new yōkai by taking inspiration from folk tales or purely from their own imagination. Today, several such yōkai (such as the amikiri) are mistakenly thought to originate in more traditional folklore.[3]

Concept[edit]

The concept of yōkai, their causes and phenomena related to them varies greatly throughout Japanese culture and historical periods; typically, the older the time period, the higher the number of phenomena deemed to be supernatural and the result of yōkai.[4] According to Japanese ideas of animism, spirit-like entities were believed to reside in all things, including natural phenomena and objects.[5] Such spirits possessed emotions and personalities: peaceful spirits were known as nigi-mitama, who brought good fortune; violent spirits, known as ara-mitama, brought ill fortune, such as illness and natural disasters. Neither type of spirit was considered to be yōkai.

One’s ancestors and particularly respected departed elders could also be deemed to be nigi-mitama, accruing status as protective spirits who brought fortune to those who worshipped them. Animals, objects and natural features or phenomena were also venerated as nigi-mitama or propitiated as ara-mitama depending on the area.

Despite the existence of harmful spirits, rituals for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama were performed, aiming to quell maleficent spirits, prevent misfortune and alleviate the fear arising from phenomena and events that otherwise had no explanation.[6] The ritual for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama was known as the chinkon (鎮魂, lit. ‘the calming of the spirits’ or ‘reqiuem’).[7] Chinkon rituals for ara-mitama that failed to achieve deification as benevolent spirits, whether through a lack of sufficient veneration or through losing worshippers and thus their divinity, became yōkai.[8]

Over time, phenomena and events thought to be supernatural became fewer and fewer, with the depictions of yōkai in picture scrolls and paintings beginning to standardize, evolving more into caricatures than fearsome spiritual entities. Elements of the tales and legends surrounding yōkai began to be depicted in public entertainment, beginning as early as the Middle Ages in Japan.[9] During and following the Edo period, the mythology and lore of yōkai became more defined and formalized.[10]

-

-

-

-

-

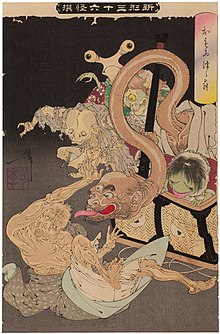

Gama Yōkai from the Saigama to Ukiyo Soushi Kenkyu Volume 2, special issue Kaii[11] Tamababaki

-

-

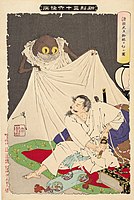

Theatre Curtain with Yokai by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1880)

Types[edit]

The folklorist Tsutomu Ema studied the literature and paintings depicting yōkai and henge (変化, lit. ‘changed things/mutants’), dividing them into categories as presented in the Nihon Yōkai Henge Shi and the Obake no Rekishi:

- Categories based on a yōkai‘s «true form»:

- Human

- Animal

- Plant

- Object

- Natural phenomenon

- Categories depending on the source of mutation:

- Mutation related to this world

- Spiritual or mentally related mutation

- Reincarnation or afterworld related mutation

- Material related mutation

- Categories based on external appearance:

- Human

- Animal

- Plant

- Artifact

- Structure or building

- Natural object or phenomenon

- Miscellaneous or appearance compounding more than one category

In other folklorist categorizations, yōkai are classified, similarly to the nymphs of Greek mythology, by their location or the phenomena associated with their manifestation. Yōkai are indexed in the book 綜合日本民俗語彙 («A Complete Dictionary of Japanese Folklore», Sogo Nihon Minzoku Goi)[12] as follows:

- Yama no ke (mountains)

- michi no ke (paths)

- ki no ke (trees)

- mizu no ke (water)

- umi no ke (the sea)

- yuki no ke (snow)

- oto no ke (sound)

- dōbutsu no ke (animals, either real or imaginary)

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

- 772 CE: in the Shoku Nihongi, there is the statement «Shinto purification is performed because yōkai appear very often in the imperial court», using the word yōkai to not refer to any one phenomenon in particular, but to strange phenomena in general.

- Middle of the Heian period (794–1185/1192): In The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, there is the statement «there are tenacious mononoke«, as well as a statement by Murasaki Shikibu that «the mononoke have become quite dreadful», which are the first appearances of the word mononoke.

- 1370: In the Taiheiki, in the fifth volume, there is the statement, «Sagami no Nyudo was not at all frightened by yōkai.»

The ancient times were a period abundant in literature and folktales mentioning and explaining yōkai. Literature such as the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki, and various Fudoki expositioned on legends from the ancient past, and mentions of oni, orochi, among other kinds of mysterious phenomena can already be seen in them.[13] In the Heian period, collections of stories about yōkai and other supernatural phenomena were published in multiple volumes, starting with publications such as the Nihon Ryōiki and the Konjaku Monogatarishū, and in these publications, mentions of phenomena such as Hyakki Yagyō can be seen.[14] The yōkai that appear in this literature were passed on to later generations.[15] However, despite the literature mentioning and explaining these yōkai, they were never given any visual depictions. In Buddhist paintings such as the Hell Scroll (Nara National Museum), which came from the later Heian period, there are visual expressions of the idea of oni, but actual visual depictions would only come later in the Middle Ages, from the Kamakura period and beyond.[16]

Yamata no Orochi was originally a local god but turned into a yōkai who was slain by Susanoo.[17] Yasaburo was originally a bandit whose vengeful spirit (onryō) turned into a poisonous snake upon death and plagued the water in a paddy, but eventually became deified as the «wisdom god of the well».[18] Kappa and inugami are sometimes treated as gods in one area and yōkai in other areas. From these examples, it can be seen that among Japanese gods, there are some beings that can go from god to yōkai and vice versa.[19]

Post-classical history[edit]

Medieval Japan was a time period where publications such as emakimono, Otogi-zōshi, and other visual depictions of yōkai started to appear. While there were religious publications such as the Jisha Engi (寺社縁起), others, such as the Otogizōshi, were intended more for entertainment, starting the trend where yōkai became more and more seen as subjects of entertainment. For examples, tales of yōkai extermination could be said to be a result of emphasizing the superior status of human society over yōkai.[9] Publications included:

- The Ooe-yama Shuten-doji Emaki (about an oni), the Zegaibou Emaki (about a tengu), the Tawara no Touta Emaki (俵藤太絵巻) (about a giant snake and a centipede), the Tsuchigumo Zoshi (土蜘蛛草紙) (about tsuchigumo), and the Dojo-ji Engi Emaki (about a giant snake). These emaki were about yōkai that come from even older times.

- The Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, in which Sugawara no Michizane was a lightning god who took on the form of an oni, and despite attacking people after doing this, he was still deified as a god in the end.[9]

- The Junirui Emaki, the Tamamono Soshi, (both about Tamamo-no-Mae), and the Fujibukuro Soushi Emaki (about a monkey). These emaki told of yōkai mutations of animals.

- The Tsukumogami Emaki, which told tales of thrown away none-too-precious objects that come to have a spirit residing in them planning evil deeds against humans, and ultimately get exorcised and sent to peace.

- The Hyakki Yagyō Emaki, depicting many different kinds of yōkai all marching together

In this way, yōkai that were mentioned only in writing were given a visual appearance in the Middle Ages. In the Otogizōshi, familiar tales such as Urashima Tarō and Issun-bōshi also appeared.

The next major change in yōkai came after the period of warring states, in the Edo period.

Modern history[edit]

Edo period[edit]

- 1677: Publication of the Shokoku Hyakumonogatari, a collection of tales of various monsters.

- 1706: Publication of the Otogi Hyakumonogatari. In volumes such as Miyazu no Ayakashi (volume 1) and Unpin no Yōkai (volume 4), collections of tales that seem to come from China were adapted into a Japanese setting.[20]

- 1712: Publication of the Wakan Sansai Zue by Terajima Ryōan, a collection of tales based on the Chinese Sancai Tuhui.

- 1716: In the specialized dictionary Sesetsu Kojien (世説故事苑), there is an entry on yōkai, which stated, «Among the commoners in my society, there are many kinds of kaiji (mysterious phenomena), often mispronounced by commoners as ‘kechi.’ Types include the cry of weasels, the howling of foxes, the bustling of mice, the rising of the chicken, the cry of the birds, the pooping of the birds on clothing, and sounds similar to voices that come from cauldrons and bottles. These types of things appear in the Shōseiroku, methods of exorcising them can be seen, so it should serve as a basis.»[21]

- 1788: Publication of the Bakemono chakutocho by Masayoshi Kitao. This was a kibyoshi diagram book of yōkai, but it was prefaced with the statement «it can be said that the so-called yōkai in our society is a representation of our feelings that arise from fear»,[22] and already in this era, while yōkai were being researched, it indicated that there were people who questioned whether yōkai really existed or not.

It was in this era that the technology of the printing press and publication was first started to be widely used, that a publishing culture developed, and was frequently a subject of kibyoshi[23] and other publications.

As a result, kashi-hon shops that handled such books spread and became widely used, making the general public’s impression of each yōkai fixed, spreading throughout all of Japan. For example, before the Edo period, there were plenty of interpretations about what the yōkai were that were classified as kappa, but because of books and publishing, the notion of kappa became anchored to what is now the modern notion of kappa. Also, including other kinds of publications, other than yōkai born from folk legend, there were also many invented yōkai that were created through puns or word plays; the Gazu Hyakki Hagyo by Sekien Toriyama is one example. When the Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai became popular in the Edo period, it is thought that one reason for the appearance of new yōkai was a demand for entertaining ghost stories about yōkai no one has ever heard of before, resulting in some that were simply made up for the purpose of telling an entertaining story. The kasa-obake and the tōfu-kozō are known examples of these.[24]

They are also frequently depicted in ukiyo-e, and there are artists that have drawn famous yōkai like Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Kawanabe Kyōsai, and Hokusai, and there are also Hyakki Yagyō books made by artists of the Kanō school.

In this period, toys and games like karuta and sugoroku, frequently used yōkai as characters. Thus, with the development of a publishing culture, yōkai depictions that were treasured in temples and shrines were able to become something more familiar to people, and it is thought that this is the reason that even though yōkai were originally things to be feared, they have then become characters that people feel close to.[25]

Meiji and Taishō periods[edit]

The Heavy Basket from the Shinkei Sanjurokkei Sen by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1892

- 1891: Publication of the Seiyuu Youkai Kidan by Shibue Tamotsu. It introduced folktales from Europe, such as the Grimm Tales.

- 1896: Publication of the Yōkaigaku Kogi by Inoue Enryō

- 1900: Performance of the kabuki play Yami no Ume Hyakumonogatari at the Kabuki-za in January. It was a performance in which appeared numerous yōkai such as the Kasa ippon ashi, skeletons, yuki-onna, osakabe-hime, among others. Onoe Kikugorō V played the role of many of these, such as the osakabe-hime.

- 1914: Publication of the Shokubutsu Kaiko by Mitsutaro Shirai. Shirai expositioned on plant yōkai from the point of view of a plant pathologist and herbalist.

With the Meiji Restoration, Western ideas and translated western publications began to make an impact, and western tales were particularly sought after. Things like binbogami, yakubyogami, and shinigami were talked about, and shinigami were even depicted in classical rakugo, and although the shinigami were misunderstood as a kind of Japanese yōkai or kami, they actually became well known among the populace through a rakugo called Shinigami by San’yūtei Enchō, which were adoptions of European tales such as the Grimm fairy tale «Godfather Death» and the Italian opera Crispino e la comare (1850). Also, in 1908, Kyōka Izumi and Tobari Chikufuu jointedly translated Gerhart Hauptmann’s play The Sunken Bell. Later works of Kyōka such as Yasha ga Ike were influenced by The Sunken Bell, and so it can be seen that folktales that come from the West became adapted into Japanese tales of yōkai.

Shōwa period[edit]

Since yōkai have been introduced in various kinds of media, they have become well known among the old, the young, men and women. The kamishibai from before the war, and the manga industry, as well as the kashi-hon shops that continued to exist until around the 1970s, as well as television contributed to the public knowledge and familiarity with yōkai. Yōkai play a role in attracting tourism revitalizing local regions, like the places depicted in the Tono Monogatari like Tōno, Iwate, Iwate Prefecture and the Tottori Prefecture, which is Shigeru Mizuki’s place of birth.

In this way, yōkai are spoken about in legends in various forms, but traditional oral storytelling by the elders and the older people is rare, and regionally unique situations and background in oral storytelling are not easily conveyed. For example, the classical yōkai represented by tsukumogami can only be felt as something realistic by living close to nature, such as with tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs), foxes and weasels. Furthermore, in the suburbs, and other regions, even when living in a primary-sector environment, there are tools that are no longer seen, such as the inkstone, the kama (a large cooking pot), or the tsurube (a bucket used for getting water from a well), and there exist yōkai that are reminiscent of old lifestyles such as the azukiarai and the dorotabo. As a result, even for those born in the first decade of the Shōwa period (1925–1935), except for some who were evacuated to the countryside, they would feel that those things that become yōkai are «not familiar» and «not very understandable». For example, in classical rakugo, even though people understand the words and what they refer to, they are not able to imagine it as something that could be realistic. Thus, the modernization of society has had a negative effect on the place of yōkai in classical Japanese culture.[opinion]

On the other hand, the yōkai introduced through mass media are not limited to only those that come from classical sources like folklore, and just as in the Edo period, new fictional yōkai continue to be invented, such as scary school stories and other urban legends like kuchisake-onna and Hanako-san, giving birth to new yōkai. From 1975 onwards, starting with the popularity of kuchisake-onna, these urban legends began to be referred to in mass media as «modern yōkai«.[26] This terminology was also used in recent publications dealing with urban legends,[27] and the researcher on yōkai, Bintarō Yamaguchi, used this especially frequently.[26]

During the 1970s, many books were published that introduced yōkai through encyclopedias, illustrated reference books, and dictionaries as a part of children’s horror books, but along with the yōkai that come from classics like folklore, Kaidan, and essays, it has been pointed out by modern research that there are some mixed in that do not come from classics, but were newly created. Some well-known examples of these are the gashadokuro and the jubokko. For example, Arifumi Sato is known to be a creator of modern yōkai, and Shigeru Mizuki, a manga artist of yōkai, in writings concerning research about yōkai, pointed out that newly-created yōkai do exist,[28][29] and Mizuki himself, through GeGeGe no Kitaro, created about 30 new yōkai.[30] There has been much criticism that this mixing of classical yōkai with newly created yōkai is making light of tradition and legends.[28][29] However, since there have already been those from the Edo period like Sekien Toriyama who created many new yōkai, there is also the opinion that it is unreasonable to criticize modern creations without doing the same for classical creations too.[28] Furthermore, there is a favorable view that says that introducing various yōkai characters through these books nurtured creativity and emotional development of young readers of the time.[29]

In popular culture[edit]

Yōkai are often referred to as Japanese spirits or East Asian ghosts, like the Hanako-san legend or the story of the «Slit-mouthed girl», both of which hail from Japanese legend. The term yōkai can also be interpreted as «something strange or unusual».

See also[edit]

- Dokkaebi – Legendary creature from Korean mythology and folklore

- Kijimunaa – Indigenous Ryukyuan belief system (legendary beings from the Ryukyu Islands)

- List of legendary creatures from Japan – Legendary creatures and entities in traditional Japanese mythology

- Yaoguai – Creature from Chinese mythology

- Yōsei – Spiritlike creature from Japanese folklore

- Yūrei – Figures in Japanese folklore similar to ghosts

References[edit]

- ^ «#kanji 妖怪». Jisho.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ «ようかい». Jisho.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ «Toriyama Sekien». Obakemono. The Obakemono Project. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ 小松和彦 2015, p. 24

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 16

- ^ 宮田登 2002, p. 14, 小松和彦 2015, pp. 201–204

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, pp. 16–18

- ^ 宮田登 2002, pp. 12–14、小松和彦 2015, pp. 205–207

- ^ a b c 小松和彦 2011, pp. 21–22

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, pp. 188–189

- ^ 近藤瑞木・佐伯 孝弘 2007

- ^ 民俗学研究所『綜合日本民俗語彙』第5巻 平凡社 1956年 403–407頁 索引では「霊怪」という部門の中に「霊怪」「妖怪」「憑物」が小部門として存在している。

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 20

- ^ 『今昔物語集』巻14の42「尊勝陀羅尼の験力によりて鬼の難を遁るる事」

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 78

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 21

- ^ 小松和彦 2015, p. 46

- ^ 小松和彦 2015, p. 213

- ^ 宮田登 2002, p. 12, 小松和彦 2015, p. 200

- ^ 太刀川清 (1987). 百物語怪談集成. 国書刊行会. pp. 365–367.

- ^ «世説故事苑 3巻». 1716. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ 江戸化物草紙. アダム・カバット校注・編. 小学館. February 1999. p. 29. ISBN 978-4-09-362111-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ 草双紙 といわれる 絵本 で、ジャンルごとにより表紙が色分けされていた。黄表紙は大人向けのもので、その他に赤や青がある。

- ^ 多田克己 (2008). «『妖怪画本・狂歌百物語』妖怪総覧». In 京極夏彦 ・多田克己編 (ed.). 妖怪画本 狂歌百物語. 国書刊行会. pp. 272–273頁. ISBN 978-4-3360-5055-7.

- ^ 湯本豪一 (2008). «遊びのなかの妖怪». In 講談社コミッククリエイト編 (ed.). DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. KODANSHA Official File Magazine. Vol. 10. 講談社. pp. 30–31頁. ISBN 978-4-06-370040-4.

- ^ a b 山口敏太郎 (2007). 本当にいる日本の「現代妖怪」図鑑. 笠倉出版社. pp. 9頁. ISBN 978-4-7730-0365-9.

- ^ «都市伝説と妖怪». DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. Vol. 10. pp. 2頁.

- ^ a b c と学会 (2007). トンデモ本の世界U. 楽工社. pp. 226–231. ISBN 978-4-903063-14-0.

- ^ a b c 妖怪王(山口敏太郎)グループ (2003). 昭和の子供 懐しの妖怪図鑑. コスモブックス. アートブック本の森. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-4-7747-0635-1.

- ^ 水木しげる (1974). 妖怪なんでも入門. 小学館入門百科シリーズ. 小学館. p. 17. ISBN 978-4-092-20032-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Ballaster, R. (2005). Fables of the East, Oxford University Press.

- Fujimoto, Nicole. «Yôkai und das Spiel mit Fiktion in der edozeitlichen Bildheftliteratur» (in German) (Archive). Nachrichten der Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens (NOAG), University of Hamburg. Volume 78, issues 183–184 (2008). pp. 93–104.

- Hearn, L. (2005). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, Tuttle Publishing.

- Komatsu, K. (2017). An Introduction to Yōkai Culture: Monsters, Ghosts, and Outsiders in Japanese History, Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, ISBN 978-4-86658-049-4.

- Meyer, M. (2012). The Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, ISBN 978-0-9852-1840-9.

- Phillip, N. (2000). Annotated Myths & Legends, Covent Garden Books.

- Tyler, R. (2002). Japanese Tales (Pantheon Fairy Tale & Folklore Library), Random House, ISBN 978-0-3757-1451-1.

- Yoda, H. and Alt, M. (2012). Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-4-8053-1219-3.

- Yoda, H. and Alt, M. (2016). Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien, Dover Publishing, ISBN 978-0-4868-0035-6.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yōkai.

- Yōkai and Kaidan (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- The Ōishi Hyōroku Monogatari Picture Scroll

- Database of images of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai (Monstrous Beings)

- Collection: Supernatural in Japanese Art, from University of Michigan Museum of Art

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «ёкай» на английский

Как и многие екай, нурикабе был обманщиком.

Like many yokai, though, the nurikabe was a trickster.

Следуя по стопам исторических авторов екай энциклопедий, автор оставляет ряд его рассказов без подтверждений, вероятно, придумав их самостоятельно.

Following in the footsteps of the historical authors of yokai encyclopedias, the author leaves a number of his stories unreferenced and likely invented them himself.

Более 80 екай Сейкена были выдуманы, часто высмеивая недобросовестных монахов и кварталы красных фонарей древней Японии.

More than 80 of Seiken’s yokai were invented, often to satire unscrupulous monks and ancient Japan’s red-light districts.

Современные историки полагают, что автор исторической энциклопедии екай, в которой впервые появился тендзе-наме, скорее всего, просто придумал его без каких-либо указаний на существовавшую до этого веру в его существовании.

Modern historians now think that the author of the historic yokai encyclopedia in which the tenjo-name first appeared most likely simply invented it without any prior belief in its existence.

Автор популярной екай манги «Китаро с кладбища» (GeGeGe no Kitaro) сказал в одном из своих екай энциклопедий, что он столкнулся с нурикабе во время его военной службы в джунглях Папуа-Новой Гвинеи.

The author of the popular yokai manga GeGeGe no Kitaro has said in one of his yokai encyclopedias that he encountered a nurikabe during his military service in the jungles of Papua New Guinea.

Несмотря на суеверия, связь с тараканами не ускользнула от составителей каталогов екай, и монстра часто изображали вместе символами таракана.

Despite the superstition, the connection to cockroaches was not lost on yokai catalogers, and the monster was often depicted alongside cockroach symbolism.

Нэко Мусумэ — девушка екай, которая превращается в пугающего кошачьего монстра с клыками и кошачьими глазами, когда она сердится или голодна.

A normally-quiet yōkai girl, who transforms into a frightening cat monster with fangs and feline eyes when she is angry or hungry for fish.

Нурикабе был екай — японским монстром, похожим на стену, который появлялся на пути странников.

The nurikabe was a yokai-a Japanese monster-shaped like a wall that appeared in the paths of travelers.

Результатов: 8. Точных совпадений: 8. Затраченное время: 24 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Произношение ёкай

Ваш броузер не поддерживает аудио

ёкай – 4 результата перевода

— О чём ты? Я же ёкай.

Ёкаи бессмертны.

На самом деле, нет ничего бессмертного.

I’m an apparition.

Apparitions are immortal.

When I get serious, there’s no one who’s immortal.

— Делай, как я говорю, или тебе не жить.

Я же ёкай.

Ёкаи бессмертны.

If you don’t listen, you won’t appear in this world again. What are you talking about?

I’m an apparition.

Apparitions are immortal.

— О чём ты? Я же ёкай.

Ёкаи бессмертны.

На самом деле, нет ничего бессмертного.

I’m an apparition.

Apparitions are immortal.

When I get serious, there’s no one who’s immortal.

— Делай, как я говорю, или тебе не жить.

Я же ёкай.

Ёкаи бессмертны.

If you don’t listen, you won’t appear in this world again. What are you talking about?

I’m an apparition.

Apparitions are immortal.

Показать еще

Хотите знать еще больше переводов ёкай?

Мы используем только переведенные профессиональными переводчиками фразы ёкай для формирования нашей постоянно обновляющейся базы. Это позволяет максимально точно переводить не просто слова, но и целые фразы, учитывая контекст и особенности их использования.

Перевести новое выражение

- С английского на:

- Русский

- С русского на:

- Все языки

- Алтайский

- Английский

- Белорусский

- Иврит

- Марийский

- Немецкий

- Таджикский

- Татарский

- Украинский

- Французский

- Чувашский

- Эвенкийский

ёкай

-

1

кай

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > кай

-

2

Кай

Русско-английский географический словарь > Кай

-

3

ёкай

Русско-английский словарь Wiktionary > ёкай

-

4

Кай-Бесар

Русско-английский географический словарь > Кай-Бесар

-

5

Кай-Кечил

Русско-английский географический словарь > Кай-Кечил

-

6

Колледж Гонвилль и Кай

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Колледж Гонвилль и Кай

-

7

Рэйю-кай

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Рэйю-кай

-

8

Чан Кай-ши

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Чан Кай-ши

-

9

аляскинский кли кай

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > аляскинский кли кай

-

10

Арафурское море

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Арафурское море

-

11

П-38

ПО СТАРОЙ ПАМЯТИ

PrepP

Invar

advfixed

WO

(to do

sth.

) because of pleasant or sentimental memories of times past (

usu.

related to an old friendship, an old love, or old traditions)

(occas., to do

sth.

) as a result of a routine one followed in the past

for old times’ (timers, memories’) sake

(in limited contexts) by (from) force of habit

force of habit (makess.o.

do

sth.

)

out of old habit.Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > П-38

-

12

С-330

ЧЕСТНОЕ СЛОВО

NP

sing only

usu sentadv

(parenth)

fixedWO

(used to emphasize the truth of a statement) I am really telling the truth

word of honor

(up)on my honor (word)

honest to goodness (to God)

honest

I swear (it)

(in limited contexts) take my word for it

really.Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > С-330

-

13

Ч-67

НИ К ЧЕМУ

coll

Invar1. (кому) (

subj-compl

with copula (

subj

: any noun, most often

concr

)) a thing (or, less often, a person or group) is not needed by

s.o.

, cannot be used by

s.o.

(and, therefore,

s.o.

does not want to deal with it or him)

X Y-y ни к чему — X is of no (isn’t of any) use to Y

X isn’t (of) much use to Y

Y has no use for X

Y has no need of (for) X

(in limited contexts) X won’t help

thing X won’t do any good.2. (

subj-compl

with copula (

subj

:

infin

, deverbal noun, or это)) some action is unnecessary, useless, futile: делать X ни к чему — therefe no point (sense) in doing X

(there’s) no need to do X

itfs pointless to do X

there’s little use doing X

(in limited contexts) doing X isn’t doing (won’t do) (person Y) any good.3.

adv

without reason or cause

for no (good) reason

for no apparent reason

to no purpose.Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > Ч-67

-

14

будь добр

[formula phrase; these forms only; fixed

WO

]

=====

1. (used to express a polite request) be obliging and do what I am asking you to do:

— (please < would you>) be so kind as to…;

— would you be kind enough to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind)…;

— might I trouble you to (for a)…;

— do me a favor and…

♦ [Серебряков:] Друзья мои, пришлите мне чай в кабинет, будьте добры! (Чехов 3). [S.:] My friends, be so kind as to have my tea brought to the study (3a).

♦ В прихожей заверещал звонок… Скрипач поднял голову и попросил: «Откройте дверь, будьте любезны» (Семёнов 1)….The doorbell tinkled in the hall. The violinist lifted his head and said: «Do me a favour and open the door, will you?» (1a).

2. (used to express a demand that may go against the will of the person addressed) do what I am telling you (even if you do not want to):

— make sure that (you do(don’tdo) sth.);

— be sure (to do (not to do) sth.);

— be sure and (do sth.);

— make it a point (not) to…;

— see that you (do < don’t do> sth.);

— [with ironic intonation] please (would you) be so kind as to (not)…;

— would you be kind enough (not) to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind) (not)…

♦ «Потрудись отправиться в Орлеан, — сказал Поклен-отец… — и держи экзамен на юридическом факультете. Получи ученую степень. Будь так добр, не провались, ибо денег на тебя ухлопано порядочно» (Булгаков 5). «You will now be kind enough to take a trip to Organs,» said Poquelin the elder… wand take an examination in jurisprudence. You must get a degree. And see that you don’t fail, for I spent plenty of money on you» (5a).

♦ [Кай:] A слёзы нам ни к чему. Без них, будьте любезны (Арбузов 2). [К.:] Tears won’t help. No tears, if you please (2a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > будь добр

-

15

будь любезен

[formula phrase; these forms only; fixed

WO

]

=====

1. (used to express a polite request) be obliging and do what I am asking you to do:

— (please < would you>) be so kind as to…;

— would you be kind enough to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind)…;

— might I trouble you to (for a)…;

— do me a favor and…

♦ [Серебряков:] Друзья мои, пришлите мне чай в кабинет, будьте добры! (Чехов 3). [S.:] My friends, be so kind as to have my tea brought to the study (3a).

♦ В прихожей заверещал звонок… Скрипач поднял голову и попросил: «Откройте дверь, будьте любезны» (Семёнов 1)….The doorbell tinkled in the hall. The violinist lifted his head and said: «Do me a favour and open the door, will you?» (1a).

2. (used to express a demand that may go against the will of the person addressed) do what I am telling you (even if you do not want to):

— make sure that (you do(don’tdo) sth.);

— be sure (to do (not to do) sth.);

— be sure and (do sth.);

— make it a point (not) to…;

— see that you (do < don’t do> sth.);

— [with ironic intonation] please (would you) be so kind as to (not)…;

— would you be kind enough (not) to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind) (not)…

♦ «Потрудись отправиться в Орлеан, — сказал Поклен-отец… — и держи экзамен на юридическом факультете. Получи ученую степень. Будь так добр, не провались, ибо денег на тебя ухлопано порядочно» (Булгаков 5). «You will now be kind enough to take a trip to Organs,» said Poquelin the elder… wand take an examination in jurisprudence. You must get a degree. And see that you don’t fail, for I spent plenty of money on you» (5a).

♦ [Кай:] A слёзы нам ни к чему. Без них, будьте любезны (Арбузов 2). [К.:] Tears won’t help. No tears, if you please (2a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > будь любезен

-

16

будьте добры

[formula phrase; these forms only; fixed

WO

]

=====

1. (used to express a polite request) be obliging and do what I am asking you to do:

— (please < would you>) be so kind as to…;

— would you be kind enough to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind)…;

— might I trouble you to (for a)…;

— do me a favor and…

♦ [Серебряков:] Друзья мои, пришлите мне чай в кабинет, будьте добры! (Чехов 3). [S.:] My friends, be so kind as to have my tea brought to the study (3a).

♦ В прихожей заверещал звонок… Скрипач поднял голову и попросил: «Откройте дверь, будьте любезны» (Семёнов 1)….The doorbell tinkled in the hall. The violinist lifted his head and said: «Do me a favour and open the door, will you?» (1a).

2. (used to express a demand that may go against the will of the person addressed) do what I am telling you (even if you do not want to):

— make sure that (you do(don’tdo) sth.);

— be sure (to do (not to do) sth.);

— be sure and (do sth.);

— make it a point (not) to…;

— see that you (do < don’t do> sth.);

— [with ironic intonation] please (would you) be so kind as to (not)…;

— would you be kind enough (not) to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind) (not)…

♦ «Потрудись отправиться в Орлеан, — сказал Поклен-отец… — и держи экзамен на юридическом факультете. Получи ученую степень. Будь так добр, не провались, ибо денег на тебя ухлопано порядочно» (Булгаков 5). «You will now be kind enough to take a trip to Organs,» said Poquelin the elder… wand take an examination in jurisprudence. You must get a degree. And see that you don’t fail, for I spent plenty of money on you» (5a).

♦ [Кай:] A слёзы нам ни к чему. Без них, будьте любезны (Арбузов 2). [К.:] Tears won’t help. No tears, if you please (2a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > будьте добры

-

17

будьте любезны

[formula phrase; these forms only; fixed

WO

]

=====

1. (used to express a polite request) be obliging and do what I am asking you to do:

— (please < would you>) be so kind as to…;

— would you be kind enough to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind)…;

— might I trouble you to (for a)…;

— do me a favor and…

♦ [Серебряков:] Друзья мои, пришлите мне чай в кабинет, будьте добры! (Чехов 3). [S.:] My friends, be so kind as to have my tea brought to the study (3a).

♦ В прихожей заверещал звонок… Скрипач поднял голову и попросил: «Откройте дверь, будьте любезны» (Семёнов 1)….The doorbell tinkled in the hall. The violinist lifted his head and said: «Do me a favour and open the door, will you?» (1a).

2. (used to express a demand that may go against the will of the person addressed) do what I am telling you (even if you do not want to):

— make sure that (you do(don’tdo) sth.);

— be sure (to do (not to do) sth.);

— be sure and (do sth.);

— make it a point (not) to…;

— see that you (do < don’t do> sth.);

— [with ironic intonation] please (would you) be so kind as to (not)…;

— would you be kind enough (not) to…;

— would you please (kindly, mind) (not)…

♦ «Потрудись отправиться в Орлеан, — сказал Поклен-отец… — и держи экзамен на юридическом факультете. Получи ученую степень. Будь так добр, не провались, ибо денег на тебя ухлопано порядочно» (Булгаков 5). «You will now be kind enough to take a trip to Organs,» said Poquelin the elder… wand take an examination in jurisprudence. You must get a degree. And see that you don’t fail, for I spent plenty of money on you» (5a).

♦ [Кай:] A слёзы нам ни к чему. Без них, будьте любезны (Арбузов 2). [К.:] Tears won’t help. No tears, if you please (2a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > будьте любезны

-

18

по старой памяти

[

PrepP

;

Invar

;

adv

; fixed

WO

]

=====

⇒ (to do

sth.

) because of pleasant or sentimental memories of times past (

usu.

related to an old friendship, an old love, or old traditions); (

occas.

, to do

sth.

) as a result of a routine one followed in the past:

— for old times’ (timers, memories’) sake;

— force of habit (makes s.o. do sth.);

— out of old habit.

♦ [Кай:] Появилась в половине одиннадцатого… Вся в снегу. «Приюти, говорит, по старой памяти — девочка у меня в пути захворала…» (Арбузов 2). [К:] She turned up at ten-thirty… She was covered with snow. «Take me in-for old times’ sake,» she said. «My little girl fell ill on the journey (2a).

♦ «Ваше благородие, дозвольте вас прокатить по старой памяти?» (Шолохов 2). «Your Honour, allow me to drive you, for old time’s sake?» (2a).

♦ [Аннушка:]…Вы меня любили прежде, — хоть по старой памяти скажите, отчего я вам опротивела (Островский 8). [A.:] You loved me once. For old memories’ sake tell me why you despise me now! (8a).

♦ По старой памяти потянуло меня на Старую площадь (Зиновьев 2). Force of habit pulled me back to the Old Square (2a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > по старой памяти

-

19

честное слово

[

NP

;

sing

only;

usu. sent adv

(

parenth

); fixed

WO

]

=====

⇒ (used to emphasize the truth of a statement) I am really telling the truth:

— really.

♦ [Кай:] Растерялся я… Честное слово. Совершенно растерялся (Арбузов 2). [К..] I lost my head. Word of honour. I completely lost my head (2a).

♦ «Если бы не дети, честное слово, Едигей, не стала бы я жить сейчас» (Айтматов 2). «If it wasn’t for the children, on my honour, Yedigei, I wouldn’t go on living» (2a)

♦ «Аксакал, я тебя так люблю! Честное слово, аксакал, как отца родного» (Айтматов 1). «Aksakal, I love you Honest, I do, like my own father» (1a).

♦ [Зоя:]…Вы вошли ко мне как статуя… Я, мол, светская дама, а вы — портниха… [Алла:] Зоя Денисовна, это вам показалось, честное слово (Булгаков 7). [Z.:]. You came in to me like a statue….As if to say, I’m a society lady, but you’re a dressmaker.» [A.:] Zoya Denisovna, it just seemed that way to you, I swear it! (7a).

♦ «Вы можете в Москве в два дня сделать дело, честное слово!» (Федин 1). «You can do your business in Moscow in two days, take my word for it!» (1a).

♦ [Нина:] Давайте, давайте, оправдывайте его [Васеньку], защищайте. Если хотите, чтобы он совсем рехнулся… [Васенька:] Я с ума хочу сходить, понятно тебе? Сходить с ума и ни о чем не думать! И оставь меня в покое! (Уходит в другую комнату.) [Бусыгин (Нине):] Зачем же ты так? [Сарафанов:] Напрасно, Нина, честное слово. Ты подливаешь масло в огонь (Вампилов 4). [Nina ] Go ahead, go ahead and agree with him [Vasenka], defend him If you want him to go completely crazy (Vasenka ] I want to go nuts, understand? Go nuts and not think about anything’ So leave me alone’ (He goes into the other room) [Busygin (to Nina).] Why do you do that? [Sarafanov ] It’s pointless, Nina, really You’re pouring oil on the fire (4b).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > честное слово

-

20

ни к чему

=====

1. (кому) [

subj-compl

with copula (

subj

: any noun, most often

concr

)]

⇒ a thing (or, less often, a person or group) is not needed by

s.o.

, cannot be used by

s.o.

(and, therefore,

s.o.

does not want to deal with it or him):

— Y has no need of < for> X;

— thing X won’t do any good.

♦ Она [медсестра] совсем была девочка, но роста высокого, тёмненькая и с японским разрезом глаз. На голове у ней так сложно было настроено, что ни шапочка, ни даже косынка никак не могли бы этого покрыть… Все это было Олегу совсем ни к чему, но он с интересом рассматривал ее белую корону… (Солженицын 10). She [the nurse] was no more than a girl, but quite tall, with a dark complexion and a Japanese slant to her eyes. Her hair was piled on top of her head in such a complicated way that no cap or scarf would ever have been able to cover it…. None of this was much use to Oleg, but still he studied her white tiara with interest… (10a).

♦ «Ведь ему безразлично, покойнику, — шёпотом сипел Коровьев, — ему теперь, сами согласитесь, Никанор Иванович, квартира эта ни к чему?» (Булгаков 9). «After all, it is all the same to him — to the dead man,» Koroviev hissed in a loud whisper. «You will agree yourself, Nikanor Ivanovich, that he has no use for the apartment now?» (9a).

♦ «Вот вы пренебрежительно отозвались о космосе, а ведь спутник, ракеты — это великий шаг, это восхищает, и согласитесь, что ни одно членистоногое не способно к таким свершениям»… — «Я мог бы возразить, что космос членистоногим ни к чему» (Стругацкие 3). «You scoffed at the cosmos, yet the sputniks and rockets are a great step forward-they’re amazing, and you must agree that not a single arthropod is capable of doing it.»…»I could argue by saying that arthropods have no need for the cosmos» (3a).

♦ [Кай:] А слезы нам ни к чему. Без них, будьте любезны (Арбузов 2). [К.:] Tears won’t help. No tears, if you please (2a).

2. [

subj-compl

with copula (

subj

:

infin

, deverbal noun, or это)]

⇒ some action is unnecessary, useless, futile:

— [in limited contexts] doing X isn’t doing < won’t do> (person Y) any good.

♦ Продолжать этот разговор было ни к чему (Распутин 2). There was no point in continuing the conversation (2a).

♦…[Настёна] опустила восла… Она и без того отплыла достаточно, дальше грести ни к чему (Распутин 2)….[Nastyona] dropped the oars….She was far enough away as it was, there was no need to row any further (2a).

♦ «Володя, чтобы не было недоразумений. Я разделяю линию партии. Будем держать свои взгляды при себе. Ни к чему бесполезные споры» (Рыбаков 2). «Volodya, just so there won’t be any misunderstandings, I want you to know that I accept the Party line. Let’s keep our views to ourselves. No need to have pointless arguments» (2a).

♦ Все это описывать ни к чему. Просто надо проклясть негодяев, чьей волей творилось подобное! (Ивинская 1). It is pointless to try and describe such things. All one can do is curse the evil men by whose orders they were perpetrated (1a).

♦ «Слушайте, Виктор, — сказал Голем. — Я позволил вам болтать на эту тему только для того, чтобы вы испугались и не лезли в чужую кашу. Вам это совершенно ни к чему. Вы и так уже на заметке…» (Стругацкие 1). «Listen, Victor,» said Golem. «I’ve allowed you to shoot your mouth off on this topic only to get you scared, to stop you from sticking your nose into other people’s business. This isn’t doing you any good. They’ve got an eye on you as it is» (1a).

⇒ without reason or cause:

— to no purpose.

♦ И ни к чему, некстати — у меня вырвалось (если бы я удержался): «А скажите: вам когда-нибудь случалось пробовать никотин или алкоголь?» (Замятин 1). And inappropriately, to no purpose, the words broke out (if I had only restrained myself!): «Tell me, have you ever tasted nicotine or alcohol?» (1a).

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > ни к чему

См. также в других словарях:

-

Кай — многозначный термин, употребляемый как самостоятельно, так и в сочетаниях: Содержание 1 Топонимы 2 Персоналии 2.1 Персонажи 3 … Википедия

-

КАЙ — (Kai, Kei), группа островов в северо западной части Арафурского моря (см. АРАФУРСКОЕ МОРЕ), к югу от Новой Гвинеи (см. НОВАЯ ГВИНЕЯ), в составе Малых Зондских (см. МАЛЫЕ ЗОНДСКИЕ ОСТРОВА) островов Малайского архипелага (см. МАЛАЙСКИЙ АРХИПЕЛАГ),… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Кай-Ёль — Характеристика Длина 10 км Бассейн Белое море Бассейн рек Северная Двина Водоток Устье Большая Певк · Местоположение … Википедия

-

Кай — я, муж. Стар. редк.Отч.: Каевич, Каевна.Происхождение: (Римск. личное имя Cajus (Gajus)) Словарь личных имён. КАЙ Крепкий. Название кыпчакского племени. Антрополексема. Татарские, тюркские, мусульманские мужские имена. Словарь терминов … Словарь личных имен

-

КАЙ — муж., ряз. слово, обет, зарок, договор. Положили они меж собою кай. На каю стать, договариваться. Каить что, пск. говорить? см. кае, каже, говорить, и каять. Толковый словарь Даля. В.И. Даль. 1863 1866 … Толковый словарь Даля

-

КАЙ — Обезьяна из рода сапажу; капуцин. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910 … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

кай — сущ., кол во синонимов: 8 • договор (49) • зарок (7) • капуцин (13) • … Словарь синонимов

-

кай — * caille f. Перепелка. Вот артишоки на шампанском. Индейки крылья au soleil, les cailles truffées à la moelle, Вот трюфли в соусе прованском, les lentilles au crème fouettés. 1837. Филимонов Обед. // Ф. 189. Eh bien des consommés aux diables,… … Исторический словарь галлицизмов русского языка

-

КАЙ — героический эпос у тюркских народов Южной Сибири, исполняемый сказителями кайчи. Характерны речитатив и горловое пение под аккомпанемент КОМЫСА … Этнографический словарь

-

Кай — Абориген Японии. Высота в холке в среднем 57 см, окрас черно пестрый или тигровый, шерсть короткая, прямая. Уши стоячие, хвост кольцом. Применяется для охоты в горных районах. Диковатая по характеру, нелюдимая. Ссылки: ◄ Другие охотничьи собаки … Полная энциклопедия пород собак

-

Кайё Л. — КАЙЁ (Cayeux) Люсьен (1864–1944), франц. геолог. Тр. по литологии и региональной геологии … Биографический словарь

Yōkai (妖怪, «strange apparition») are a class of supernatural entities and spirits in Japanese folklore. The word yōkai is a loanword from the Chinese term yaoguai and is composed of the kanji for «demon; fairy; sprite» and «suspicious; apparition; monster; ghost; spectre»[1][2] Yōkai are also referred to as ayakashi (あやかし), mononoke (物の怪) or mamono (魔物). Despite often being translated as such, yōkai are not literally demons in the Western sense of the word, but are instead spirits and entities. Their behavior can range from malevolent or mischievous to benevolent to humans.

Yōkai often have animal features (such as the kappa, depicted as appearing similar to a turtle, and the tengu, commonly depicted with wings), but may also appear humanoid in appearance, such as the kuchisake-onna. Some yōkai resemble inanimate objects (such as the tsukumogami), while others have no discernible shape. Yōkai are typically described as having spiritual or supernatural abilities, with shapeshifting being the most common trait associated with them. Yōkai that shapeshift are known as bakemono (化け物) or obake (お化け).

Japanese folklorists and historians explain yōkai as personifications of «supernatural or unaccountable phenomena to their informants.» In the Edo period, many artists, such as Toriyama Sekien, invented new yōkai by taking inspiration from folk tales or purely from their own imagination. Today, several such yōkai (such as the amikiri) are mistakenly thought to originate in more traditional folklore.[3]

Concept[edit]

The concept of yōkai, their causes and phenomena related to them varies greatly throughout Japanese culture and historical periods; typically, the older the time period, the higher the number of phenomena deemed to be supernatural and the result of yōkai.[4] According to Japanese ideas of animism, spirit-like entities were believed to reside in all things, including natural phenomena and objects.[5] Such spirits possessed emotions and personalities: peaceful spirits were known as nigi-mitama, who brought good fortune; violent spirits, known as ara-mitama, brought ill fortune, such as illness and natural disasters. Neither type of spirit was considered to be yōkai.

One’s ancestors and particularly respected departed elders could also be deemed to be nigi-mitama, accruing status as protective spirits who brought fortune to those who worshipped them. Animals, objects and natural features or phenomena were also venerated as nigi-mitama or propitiated as ara-mitama depending on the area.

Despite the existence of harmful spirits, rituals for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama were performed, aiming to quell maleficent spirits, prevent misfortune and alleviate the fear arising from phenomena and events that otherwise had no explanation.[6] The ritual for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama was known as the chinkon (鎮魂, lit. ‘the calming of the spirits’ or ‘reqiuem’).[7] Chinkon rituals for ara-mitama that failed to achieve deification as benevolent spirits, whether through a lack of sufficient veneration or through losing worshippers and thus their divinity, became yōkai.[8]

Over time, phenomena and events thought to be supernatural became fewer and fewer, with the depictions of yōkai in picture scrolls and paintings beginning to standardize, evolving more into caricatures than fearsome spiritual entities. Elements of the tales and legends surrounding yōkai began to be depicted in public entertainment, beginning as early as the Middle Ages in Japan.[9] During and following the Edo period, the mythology and lore of yōkai became more defined and formalized.[10]

-

-

-

-

-

Gama Yōkai from the Saigama to Ukiyo Soushi Kenkyu Volume 2, special issue Kaii[11] Tamababaki

-

-

Theatre Curtain with Yokai by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1880)

Types[edit]

The folklorist Tsutomu Ema studied the literature and paintings depicting yōkai and henge (変化, lit. ‘changed things/mutants’), dividing them into categories as presented in the Nihon Yōkai Henge Shi and the Obake no Rekishi:

- Categories based on a yōkai‘s «true form»:

- Human

- Animal

- Plant

- Object

- Natural phenomenon

- Categories depending on the source of mutation:

- Mutation related to this world

- Spiritual or mentally related mutation

- Reincarnation or afterworld related mutation

- Material related mutation

- Categories based on external appearance:

- Human

- Animal

- Plant

- Artifact

- Structure or building

- Natural object or phenomenon

- Miscellaneous or appearance compounding more than one category

In other folklorist categorizations, yōkai are classified, similarly to the nymphs of Greek mythology, by their location or the phenomena associated with their manifestation. Yōkai are indexed in the book 綜合日本民俗語彙 («A Complete Dictionary of Japanese Folklore», Sogo Nihon Minzoku Goi)[12] as follows:

- Yama no ke (mountains)

- michi no ke (paths)

- ki no ke (trees)

- mizu no ke (water)

- umi no ke (the sea)

- yuki no ke (snow)

- oto no ke (sound)

- dōbutsu no ke (animals, either real or imaginary)

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

- 772 CE: in the Shoku Nihongi, there is the statement «Shinto purification is performed because yōkai appear very often in the imperial court», using the word yōkai to not refer to any one phenomenon in particular, but to strange phenomena in general.

- Middle of the Heian period (794–1185/1192): In The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, there is the statement «there are tenacious mononoke«, as well as a statement by Murasaki Shikibu that «the mononoke have become quite dreadful», which are the first appearances of the word mononoke.

- 1370: In the Taiheiki, in the fifth volume, there is the statement, «Sagami no Nyudo was not at all frightened by yōkai.»

The ancient times were a period abundant in literature and folktales mentioning and explaining yōkai. Literature such as the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki, and various Fudoki expositioned on legends from the ancient past, and mentions of oni, orochi, among other kinds of mysterious phenomena can already be seen in them.[13] In the Heian period, collections of stories about yōkai and other supernatural phenomena were published in multiple volumes, starting with publications such as the Nihon Ryōiki and the Konjaku Monogatarishū, and in these publications, mentions of phenomena such as Hyakki Yagyō can be seen.[14] The yōkai that appear in this literature were passed on to later generations.[15] However, despite the literature mentioning and explaining these yōkai, they were never given any visual depictions. In Buddhist paintings such as the Hell Scroll (Nara National Museum), which came from the later Heian period, there are visual expressions of the idea of oni, but actual visual depictions would only come later in the Middle Ages, from the Kamakura period and beyond.[16]

Yamata no Orochi was originally a local god but turned into a yōkai who was slain by Susanoo.[17] Yasaburo was originally a bandit whose vengeful spirit (onryō) turned into a poisonous snake upon death and plagued the water in a paddy, but eventually became deified as the «wisdom god of the well».[18] Kappa and inugami are sometimes treated as gods in one area and yōkai in other areas. From these examples, it can be seen that among Japanese gods, there are some beings that can go from god to yōkai and vice versa.[19]

Post-classical history[edit]

Medieval Japan was a time period where publications such as emakimono, Otogi-zōshi, and other visual depictions of yōkai started to appear. While there were religious publications such as the Jisha Engi (寺社縁起), others, such as the Otogizōshi, were intended more for entertainment, starting the trend where yōkai became more and more seen as subjects of entertainment. For examples, tales of yōkai extermination could be said to be a result of emphasizing the superior status of human society over yōkai.[9] Publications included:

- The Ooe-yama Shuten-doji Emaki (about an oni), the Zegaibou Emaki (about a tengu), the Tawara no Touta Emaki (俵藤太絵巻) (about a giant snake and a centipede), the Tsuchigumo Zoshi (土蜘蛛草紙) (about tsuchigumo), and the Dojo-ji Engi Emaki (about a giant snake). These emaki were about yōkai that come from even older times.

- The Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, in which Sugawara no Michizane was a lightning god who took on the form of an oni, and despite attacking people after doing this, he was still deified as a god in the end.[9]

- The Junirui Emaki, the Tamamono Soshi, (both about Tamamo-no-Mae), and the Fujibukuro Soushi Emaki (about a monkey). These emaki told of yōkai mutations of animals.

- The Tsukumogami Emaki, which told tales of thrown away none-too-precious objects that come to have a spirit residing in them planning evil deeds against humans, and ultimately get exorcised and sent to peace.

- The Hyakki Yagyō Emaki, depicting many different kinds of yōkai all marching together

In this way, yōkai that were mentioned only in writing were given a visual appearance in the Middle Ages. In the Otogizōshi, familiar tales such as Urashima Tarō and Issun-bōshi also appeared.

The next major change in yōkai came after the period of warring states, in the Edo period.

Modern history[edit]

Edo period[edit]

- 1677: Publication of the Shokoku Hyakumonogatari, a collection of tales of various monsters.

- 1706: Publication of the Otogi Hyakumonogatari. In volumes such as Miyazu no Ayakashi (volume 1) and Unpin no Yōkai (volume 4), collections of tales that seem to come from China were adapted into a Japanese setting.[20]

- 1712: Publication of the Wakan Sansai Zue by Terajima Ryōan, a collection of tales based on the Chinese Sancai Tuhui.

- 1716: In the specialized dictionary Sesetsu Kojien (世説故事苑), there is an entry on yōkai, which stated, «Among the commoners in my society, there are many kinds of kaiji (mysterious phenomena), often mispronounced by commoners as ‘kechi.’ Types include the cry of weasels, the howling of foxes, the bustling of mice, the rising of the chicken, the cry of the birds, the pooping of the birds on clothing, and sounds similar to voices that come from cauldrons and bottles. These types of things appear in the Shōseiroku, methods of exorcising them can be seen, so it should serve as a basis.»[21]

- 1788: Publication of the Bakemono chakutocho by Masayoshi Kitao. This was a kibyoshi diagram book of yōkai, but it was prefaced with the statement «it can be said that the so-called yōkai in our society is a representation of our feelings that arise from fear»,[22] and already in this era, while yōkai were being researched, it indicated that there were people who questioned whether yōkai really existed or not.

It was in this era that the technology of the printing press and publication was first started to be widely used, that a publishing culture developed, and was frequently a subject of kibyoshi[23] and other publications.

As a result, kashi-hon shops that handled such books spread and became widely used, making the general public’s impression of each yōkai fixed, spreading throughout all of Japan. For example, before the Edo period, there were plenty of interpretations about what the yōkai were that were classified as kappa, but because of books and publishing, the notion of kappa became anchored to what is now the modern notion of kappa. Also, including other kinds of publications, other than yōkai born from folk legend, there were also many invented yōkai that were created through puns or word plays; the Gazu Hyakki Hagyo by Sekien Toriyama is one example. When the Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai became popular in the Edo period, it is thought that one reason for the appearance of new yōkai was a demand for entertaining ghost stories about yōkai no one has ever heard of before, resulting in some that were simply made up for the purpose of telling an entertaining story. The kasa-obake and the tōfu-kozō are known examples of these.[24]

They are also frequently depicted in ukiyo-e, and there are artists that have drawn famous yōkai like Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Yoshitoshi, Kawanabe Kyōsai, and Hokusai, and there are also Hyakki Yagyō books made by artists of the Kanō school.

In this period, toys and games like karuta and sugoroku, frequently used yōkai as characters. Thus, with the development of a publishing culture, yōkai depictions that were treasured in temples and shrines were able to become something more familiar to people, and it is thought that this is the reason that even though yōkai were originally things to be feared, they have then become characters that people feel close to.[25]

Meiji and Taishō periods[edit]

The Heavy Basket from the Shinkei Sanjurokkei Sen by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1892

- 1891: Publication of the Seiyuu Youkai Kidan by Shibue Tamotsu. It introduced folktales from Europe, such as the Grimm Tales.

- 1896: Publication of the Yōkaigaku Kogi by Inoue Enryō

- 1900: Performance of the kabuki play Yami no Ume Hyakumonogatari at the Kabuki-za in January. It was a performance in which appeared numerous yōkai such as the Kasa ippon ashi, skeletons, yuki-onna, osakabe-hime, among others. Onoe Kikugorō V played the role of many of these, such as the osakabe-hime.

- 1914: Publication of the Shokubutsu Kaiko by Mitsutaro Shirai. Shirai expositioned on plant yōkai from the point of view of a plant pathologist and herbalist.

With the Meiji Restoration, Western ideas and translated western publications began to make an impact, and western tales were particularly sought after. Things like binbogami, yakubyogami, and shinigami were talked about, and shinigami were even depicted in classical rakugo, and although the shinigami were misunderstood as a kind of Japanese yōkai or kami, they actually became well known among the populace through a rakugo called Shinigami by San’yūtei Enchō, which were adoptions of European tales such as the Grimm fairy tale «Godfather Death» and the Italian opera Crispino e la comare (1850). Also, in 1908, Kyōka Izumi and Tobari Chikufuu jointedly translated Gerhart Hauptmann’s play The Sunken Bell. Later works of Kyōka such as Yasha ga Ike were influenced by The Sunken Bell, and so it can be seen that folktales that come from the West became adapted into Japanese tales of yōkai.

Shōwa period[edit]

Since yōkai have been introduced in various kinds of media, they have become well known among the old, the young, men and women. The kamishibai from before the war, and the manga industry, as well as the kashi-hon shops that continued to exist until around the 1970s, as well as television contributed to the public knowledge and familiarity with yōkai. Yōkai play a role in attracting tourism revitalizing local regions, like the places depicted in the Tono Monogatari like Tōno, Iwate, Iwate Prefecture and the Tottori Prefecture, which is Shigeru Mizuki’s place of birth.

In this way, yōkai are spoken about in legends in various forms, but traditional oral storytelling by the elders and the older people is rare, and regionally unique situations and background in oral storytelling are not easily conveyed. For example, the classical yōkai represented by tsukumogami can only be felt as something realistic by living close to nature, such as with tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs), foxes and weasels. Furthermore, in the suburbs, and other regions, even when living in a primary-sector environment, there are tools that are no longer seen, such as the inkstone, the kama (a large cooking pot), or the tsurube (a bucket used for getting water from a well), and there exist yōkai that are reminiscent of old lifestyles such as the azukiarai and the dorotabo. As a result, even for those born in the first decade of the Shōwa period (1925–1935), except for some who were evacuated to the countryside, they would feel that those things that become yōkai are «not familiar» and «not very understandable». For example, in classical rakugo, even though people understand the words and what they refer to, they are not able to imagine it as something that could be realistic. Thus, the modernization of society has had a negative effect on the place of yōkai in classical Japanese culture.[opinion]

On the other hand, the yōkai introduced through mass media are not limited to only those that come from classical sources like folklore, and just as in the Edo period, new fictional yōkai continue to be invented, such as scary school stories and other urban legends like kuchisake-onna and Hanako-san, giving birth to new yōkai. From 1975 onwards, starting with the popularity of kuchisake-onna, these urban legends began to be referred to in mass media as «modern yōkai«.[26] This terminology was also used in recent publications dealing with urban legends,[27] and the researcher on yōkai, Bintarō Yamaguchi, used this especially frequently.[26]

During the 1970s, many books were published that introduced yōkai through encyclopedias, illustrated reference books, and dictionaries as a part of children’s horror books, but along with the yōkai that come from classics like folklore, Kaidan, and essays, it has been pointed out by modern research that there are some mixed in that do not come from classics, but were newly created. Some well-known examples of these are the gashadokuro and the jubokko. For example, Arifumi Sato is known to be a creator of modern yōkai, and Shigeru Mizuki, a manga artist of yōkai, in writings concerning research about yōkai, pointed out that newly-created yōkai do exist,[28][29] and Mizuki himself, through GeGeGe no Kitaro, created about 30 new yōkai.[30] There has been much criticism that this mixing of classical yōkai with newly created yōkai is making light of tradition and legends.[28][29] However, since there have already been those from the Edo period like Sekien Toriyama who created many new yōkai, there is also the opinion that it is unreasonable to criticize modern creations without doing the same for classical creations too.[28] Furthermore, there is a favorable view that says that introducing various yōkai characters through these books nurtured creativity and emotional development of young readers of the time.[29]

In popular culture[edit]

Yōkai are often referred to as Japanese spirits or East Asian ghosts, like the Hanako-san legend or the story of the «Slit-mouthed girl», both of which hail from Japanese legend. The term yōkai can also be interpreted as «something strange or unusual».

See also[edit]

- Dokkaebi – Legendary creature from Korean mythology and folklore

- Kijimunaa – Indigenous Ryukyuan belief system (legendary beings from the Ryukyu Islands)

- List of legendary creatures from Japan – Legendary creatures and entities in traditional Japanese mythology

- Yaoguai – Creature from Chinese mythology

- Yōsei – Spiritlike creature from Japanese folklore

- Yūrei – Figures in Japanese folklore similar to ghosts

References[edit]

- ^ «#kanji 妖怪». Jisho.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ «ようかい». Jisho.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ «Toriyama Sekien». Obakemono. The Obakemono Project. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ 小松和彦 2015, p. 24

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 16

- ^ 宮田登 2002, p. 14, 小松和彦 2015, pp. 201–204

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, pp. 16–18

- ^ 宮田登 2002, pp. 12–14、小松和彦 2015, pp. 205–207

- ^ a b c 小松和彦 2011, pp. 21–22

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, pp. 188–189

- ^ 近藤瑞木・佐伯 孝弘 2007

- ^ 民俗学研究所『綜合日本民俗語彙』第5巻 平凡社 1956年 403–407頁 索引では「霊怪」という部門の中に「霊怪」「妖怪」「憑物」が小部門として存在している。

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 20

- ^ 『今昔物語集』巻14の42「尊勝陀羅尼の験力によりて鬼の難を遁るる事」

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 78

- ^ 小松和彦 2011, p. 21

- ^ 小松和彦 2015, p. 46

- ^ 小松和彦 2015, p. 213

- ^ 宮田登 2002, p. 12, 小松和彦 2015, p. 200

- ^ 太刀川清 (1987). 百物語怪談集成. 国書刊行会. pp. 365–367.

- ^ «世説故事苑 3巻». 1716. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ 江戸化物草紙. アダム・カバット校注・編. 小学館. February 1999. p. 29. ISBN 978-4-09-362111-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ 草双紙 といわれる 絵本 で、ジャンルごとにより表紙が色分けされていた。黄表紙は大人向けのもので、その他に赤や青がある。

- ^ 多田克己 (2008). «『妖怪画本・狂歌百物語』妖怪総覧». In 京極夏彦 ・多田克己編 (ed.). 妖怪画本 狂歌百物語. 国書刊行会. pp. 272–273頁. ISBN 978-4-3360-5055-7.

- ^ 湯本豪一 (2008). «遊びのなかの妖怪». In 講談社コミッククリエイト編 (ed.). DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. KODANSHA Official File Magazine. Vol. 10. 講談社. pp. 30–31頁. ISBN 978-4-06-370040-4.

- ^ a b 山口敏太郎 (2007). 本当にいる日本の「現代妖怪」図鑑. 笠倉出版社. pp. 9頁. ISBN 978-4-7730-0365-9.

- ^ «都市伝説と妖怪». DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. Vol. 10. pp. 2頁.

- ^ a b c と学会 (2007). トンデモ本の世界U. 楽工社. pp. 226–231. ISBN 978-4-903063-14-0.

- ^ a b c 妖怪王(山口敏太郎)グループ (2003). 昭和の子供 懐しの妖怪図鑑. コスモブックス. アートブック本の森. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-4-7747-0635-1.

- ^ 水木しげる (1974). 妖怪なんでも入門. 小学館入門百科シリーズ. 小学館. p. 17. ISBN 978-4-092-20032-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Ballaster, R. (2005). Fables of the East, Oxford University Press.

- Fujimoto, Nicole. «Yôkai und das Spiel mit Fiktion in der edozeitlichen Bildheftliteratur» (in German) (Archive). Nachrichten der Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens (NOAG), University of Hamburg. Volume 78, issues 183–184 (2008). pp. 93–104.

- Hearn, L. (2005). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, Tuttle Publishing.

- Komatsu, K. (2017). An Introduction to Yōkai Culture: Monsters, Ghosts, and Outsiders in Japanese History, Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, ISBN 978-4-86658-049-4.

- Meyer, M. (2012). The Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, ISBN 978-0-9852-1840-9.

- Phillip, N. (2000). Annotated Myths & Legends, Covent Garden Books.

- Tyler, R. (2002). Japanese Tales (Pantheon Fairy Tale & Folklore Library), Random House, ISBN 978-0-3757-1451-1.

- Yoda, H. and Alt, M. (2012). Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-4-8053-1219-3.

- Yoda, H. and Alt, M. (2016). Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien, Dover Publishing, ISBN 978-0-4868-0035-6.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yōkai.

- Yōkai and Kaidan (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- The Ōishi Hyōroku Monogatari Picture Scroll

- Database of images of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai (Monstrous Beings)

- Collection: Supernatural in Japanese Art, from University of Michigan Museum of Art

Yōkai (妖怪, «strange apparition») are a class of supernatural entities and spirits in Japanese folklore. The word yōkai is a loanword from the Chinese term yaoguai and is composed of the kanji for «demon; fairy; sprite» and «suspicious; apparition; monster; ghost; spectre»[1][2] Yōkai are also referred to as ayakashi (あやかし), mononoke (物の怪) or mamono (魔物). Despite often being translated as such, yōkai are not literally demons in the Western sense of the word, but are instead spirits and entities. Their behavior can range from malevolent or mischievous to benevolent to humans.

Yōkai often have animal features (such as the kappa, depicted as appearing similar to a turtle, and the tengu, commonly depicted with wings), but may also appear humanoid in appearance, such as the kuchisake-onna. Some yōkai resemble inanimate objects (such as the tsukumogami), while others have no discernible shape. Yōkai are typically described as having spiritual or supernatural abilities, with shapeshifting being the most common trait associated with them. Yōkai that shapeshift are known as bakemono (化け物) or obake (お化け).

Japanese folklorists and historians explain yōkai as personifications of «supernatural or unaccountable phenomena to their informants.» In the Edo period, many artists, such as Toriyama Sekien, invented new yōkai by taking inspiration from folk tales or purely from their own imagination. Today, several such yōkai (such as the amikiri) are mistakenly thought to originate in more traditional folklore.[3]

Concept[edit]

The concept of yōkai, their causes and phenomena related to them varies greatly throughout Japanese culture and historical periods; typically, the older the time period, the higher the number of phenomena deemed to be supernatural and the result of yōkai.[4] According to Japanese ideas of animism, spirit-like entities were believed to reside in all things, including natural phenomena and objects.[5] Such spirits possessed emotions and personalities: peaceful spirits were known as nigi-mitama, who brought good fortune; violent spirits, known as ara-mitama, brought ill fortune, such as illness and natural disasters. Neither type of spirit was considered to be yōkai.

One’s ancestors and particularly respected departed elders could also be deemed to be nigi-mitama, accruing status as protective spirits who brought fortune to those who worshipped them. Animals, objects and natural features or phenomena were also venerated as nigi-mitama or propitiated as ara-mitama depending on the area.

Despite the existence of harmful spirits, rituals for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama were performed, aiming to quell maleficent spirits, prevent misfortune and alleviate the fear arising from phenomena and events that otherwise had no explanation.[6] The ritual for converting ara-mitama into nigi-mitama was known as the chinkon (鎮魂, lit. ‘the calming of the spirits’ or ‘reqiuem’).[7] Chinkon rituals for ara-mitama that failed to achieve deification as benevolent spirits, whether through a lack of sufficient veneration or through losing worshippers and thus their divinity, became yōkai.[8]

Over time, phenomena and events thought to be supernatural became fewer and fewer, with the depictions of yōkai in picture scrolls and paintings beginning to standardize, evolving more into caricatures than fearsome spiritual entities. Elements of the tales and legends surrounding yōkai began to be depicted in public entertainment, beginning as early as the Middle Ages in Japan.[9] During and following the Edo period, the mythology and lore of yōkai became more defined and formalized.[10]

-

-

-

-

-

Gama Yōkai from the Saigama to Ukiyo Soushi Kenkyu Volume 2, special issue Kaii[11] Tamababaki

-

-

Theatre Curtain with Yokai by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1880)

Types[edit]

The folklorist Tsutomu Ema studied the literature and paintings depicting yōkai and henge (変化, lit. ‘changed things/mutants’), dividing them into categories as presented in the Nihon Yōkai Henge Shi and the Obake no Rekishi:

- Categories based on a yōkai‘s «true form»:

- Human

- Animal

- Plant

- Object

- Natural phenomenon

- Categories depending on the source of mutation:

- Mutation related to this world

- Spiritual or mentally related mutation

- Reincarnation or afterworld related mutation

- Material related mutation

- Categories based on external appearance:

- Human

- Animal

- Plant

- Artifact

- Structure or building

- Natural object or phenomenon

- Miscellaneous or appearance compounding more than one category

In other folklorist categorizations, yōkai are classified, similarly to the nymphs of Greek mythology, by their location or the phenomena associated with their manifestation. Yōkai are indexed in the book 綜合日本民俗語彙 («A Complete Dictionary of Japanese Folklore», Sogo Nihon Minzoku Goi)[12] as follows:

- Yama no ke (mountains)

- michi no ke (paths)

- ki no ke (trees)

- mizu no ke (water)

- umi no ke (the sea)

- yuki no ke (snow)

- oto no ke (sound)

- dōbutsu no ke (animals, either real or imaginary)

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

- 772 CE: in the Shoku Nihongi, there is the statement «Shinto purification is performed because yōkai appear very often in the imperial court», using the word yōkai to not refer to any one phenomenon in particular, but to strange phenomena in general.

- Middle of the Heian period (794–1185/1192): In The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, there is the statement «there are tenacious mononoke«, as well as a statement by Murasaki Shikibu that «the mononoke have become quite dreadful», which are the first appearances of the word mononoke.

- 1370: In the Taiheiki, in the fifth volume, there is the statement, «Sagami no Nyudo was not at all frightened by yōkai.»

The ancient times were a period abundant in literature and folktales mentioning and explaining yōkai. Literature such as the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki, and various Fudoki expositioned on legends from the ancient past, and mentions of oni, orochi, among other kinds of mysterious phenomena can already be seen in them.[13] In the Heian period, collections of stories about yōkai and other supernatural phenomena were published in multiple volumes, starting with publications such as the Nihon Ryōiki and the Konjaku Monogatarishū, and in these publications, mentions of phenomena such as Hyakki Yagyō can be seen.[14] The yōkai that appear in this literature were passed on to later generations.[15] However, despite the literature mentioning and explaining these yōkai, they were never given any visual depictions. In Buddhist paintings such as the Hell Scroll (Nara National Museum), which came from the later Heian period, there are visual expressions of the idea of oni, but actual visual depictions would only come later in the Middle Ages, from the Kamakura period and beyond.[16]

Yamata no Orochi was originally a local god but turned into a yōkai who was slain by Susanoo.[17] Yasaburo was originally a bandit whose vengeful spirit (onryō) turned into a poisonous snake upon death and plagued the water in a paddy, but eventually became deified as the «wisdom god of the well».[18] Kappa and inugami are sometimes treated as gods in one area and yōkai in other areas. From these examples, it can be seen that among Japanese gods, there are some beings that can go from god to yōkai and vice versa.[19]

Post-classical history[edit]

Medieval Japan was a time period where publications such as emakimono, Otogi-zōshi, and other visual depictions of yōkai started to appear. While there were religious publications such as the Jisha Engi (寺社縁起), others, such as the Otogizōshi, were intended more for entertainment, starting the trend where yōkai became more and more seen as subjects of entertainment. For examples, tales of yōkai extermination could be said to be a result of emphasizing the superior status of human society over yōkai.[9] Publications included:

- The Ooe-yama Shuten-doji Emaki (about an oni), the Zegaibou Emaki (about a tengu), the Tawara no Touta Emaki (俵藤太絵巻) (about a giant snake and a centipede), the Tsuchigumo Zoshi (土蜘蛛草紙) (about tsuchigumo), and the Dojo-ji Engi Emaki (about a giant snake). These emaki were about yōkai that come from even older times.

- The Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, in which Sugawara no Michizane was a lightning god who took on the form of an oni, and despite attacking people after doing this, he was still deified as a god in the end.[9]

- The Junirui Emaki, the Tamamono Soshi, (both about Tamamo-no-Mae), and the Fujibukuro Soushi Emaki (about a monkey). These emaki told of yōkai mutations of animals.

- The Tsukumogami Emaki, which told tales of thrown away none-too-precious objects that come to have a spirit residing in them planning evil deeds against humans, and ultimately get exorcised and sent to peace.