Приблизительное время чтения: 13 мин.

Новый Завет начинается с Евангелия от Матфея. Значит ли это, что апостол Матфей действительно написал свою книгу первым? Или его Евангелие просто самое важное?

Скорее всего, мы никогда не узнаем точно, в какой именно последовательности были написаны четыре Евангелия. Споры об этом в библейской науке идут с XVIII века, но окончательной ясности так и нет. Тем не менее, есть много причин считать, что Евангелие от Матфея в самом деле появилось на свет раньше трех других.

Но давайте обо всем по порядку.

Откуда мы знаем, что Евангелие от Матфея написал именно Матфей?

А действительно, откуда? Ведь история литературы (и христианской в том числе) знает много псевдоэпиграфов – произведений, подписанных именами других, подчас даже вымышленных авторов. А из текста самого Евангелия совершенно не следует, что его написал апостол Матфей. О Матфее и упоминается-то вскользь: Проходя оттуда [из Капернаума. – Прим. ред.], Иисус увидел человека, сидящего у сбора пошлин, по имени Матфея, и говорит ему: следуй за Мною. И он встал и последовал за Ним (Мф 9:9). А другие евангелисты называют этого сборщика пошлин вообще другим именем – Левий Алфеев (Мк 2:14), или просто Левий (Лк 5:27-29)…

Прежде всего скажем, что понятие авторства в Евангелиях вообще довольно условное. Как писал в начале XX века известный российский богослов, историк Церкви и библеист Николай Глубоковский, «Евангелие как избавление людей от грехов и дарование им спасения было принесено Богочеловеком, принадлежит только Ему», и только Сам Христос может считаться его Автором в собственном смысле. Греческий предлог κατὰ, который мы привычно переводим как «от» (Евангелие от Матфея, от Марка и т.д.), по смыслу ближе к «по» или «согласно»: Евангелие «по Матфею», или «согласно Марку». Апостолы-евангелисты были не авторами, а скорее составителями, редакторами, может быть, даже отчасти компиляторами воспоминаний о Христе. Поэтому вопрос о том, чье имя стоит в заглавии, важен, но не критичен.

Но что касается конкретно Матфея – о его непосредственном участии в написании Евангелия имеются вполне надежные свидетельства его близких современников.

Что это за свидетельства?

Первым о Матфее как составителе Евангелия говорит иерапольский епископ Папий (70-163 гг.). Он был знаком если не с самими апостолами (на этот счет у историков Церкви разные мнения), то по крайней мере с их ближайшим окружением. С дочерьми апостола Филиппа, которые жили в Иераполе. С неким «старцем Иоанном», в котором иногда видят апостола Иоанна Богослова. Со святым Поликарпом Смирнским, который лично встречался «с Иоанном и с теми остальными, кто своими глазами видел Господа».

Папий написал труд «Толкования изречений Господних», из которого сохранились только цитаты (в «Истории Церкви» Евсевия Кесарийского). Там он сообщает, что апостол Марк рассказал о жизни и учении Христа, точно переложив на греческий язык проповеди апостола Петра, а Матфей «составил логии (греч. λόγια – изречения или, возможно, беседы. – Прим. ред.) Христа по-еврейски, которые каждый переводил, как мог».

Матфея уверенно называет составителем Евангелия и священномученик Ириней Лионский (130-202 гг.). Откуда он мог об этом узнать? Он был учеником священномученика Поликарпа Смирнского, а тот, как мы уже сказали, лично общался с апостолами. В авторстве Матфея не сомневаются ни Климент Александрийский (150 – 215 гг.), ни Тертуллиан (155/165 – 220/240 гг.), ни Татиан (120-185 гг.), предпринявший, возможно, первую в истории попытку соединить четыре Евангелия в одно. О Матфее как авторе первого Евангелия писал на границе IV и V веков и блаженный Иероним Стридонский. Его свидетельство хотя и позднее, но ценно тем, что он провел много лет в Палестине, изучая местный язык, обычаи и предания, и занимаясь переводом Священного Писания на латынь.

Только в XIX веке у западных ученых-библеистов стали возникать сомнения в том, что первое Евангелие написал сам Матфей. Брюса Мецгера, одного из самых авторитетных западных библеистов XX и начала XXI века, смущало то, как «покорно» Матфей – один из двенадцати ближайших учеников Христа! – следует в своем повествовании за Марком, который не был личным свидетелем большинства евангельских событий. Другой современный исследователь, Ричард Бокэм, сомневается, что автора первого Евангелия звали Матфеем. Имена Матфей и Левий были в то время одними из самых распространенных в Иудее, и один человек не мог называться обоими сразу, объяснял он.

Но оба эти сомнения так или иначе связаны с предположением, что Евангелие от Матфея было написано не первым, что его автор «шел по следам» апостола Марка. А это предположение далеко не доказано (есть и «за», и много «против»). Тогда как вся церковная традиция, уходящая корнями в I-II века, убедительно свидетельствует: Евангелие от Матфея написал не кто иной, как Матфей.

Но, может быть, Матфей записал не все Евангелие, а только те самые «логии» – отдельные изречения Спасителя?

Существует и такая гипотеза. Один из ее вариантов пересказывает тот же Мецгер. Матфей составил сборник высказываний Иисуса (возможно, на арамейском языке), предполагает этот ученый. Затем сборник перевели на греческий, в результате чего появился источник речений Спасителя, который современные ученые обозначают буквой Q. А известное нам Евангелие – произведение неизвестного нам христианина, который использовал и Евангелие от Марка, и Матфеев сборник, и еще какие-то источники. Имя Матфея было просто перенесено со сборника речений на полное Евангелие.

Нет, однако, никаких серьезных причин считать, что записанные Матфеем по-еврейски «логии» Христа (о них, напомним, впервые сообщил Папий Иерапольский) – это именно сборник отдельных изречений, а не цельное повествование о Христе. Николай Глубоковский отстаивал мнение, что Матфей сразу же написал связный текст, который Папий назвал «логиями», просто чтобы подчеркнуть особенности этого Евангелия по сравнению с Евангелием от Марка: у Матфея действительно гораздо больше «прямой речи» Господа. Чего стоит хотя бы Нагорная проповедь, занимающая целых три главы (с пятой по седьмую)! Некоторые ученые-библеисты даже выделяют ее в самостоятельную «книгу внутри книги».

Кто перевел еврейский текст на греческий, неизвестно (Папий, напомним, писал, что переводчики были разные). Существует даже предположение, что это сделал апостол Иоанн Богослов! Но ничто не мешает считать, что дошедший до нас греческий текст – дело рук самого же апостола Матфея, считал Глубоковский. Во всяком случае, множество современников Папия – апостол Варнава, Климент Римский, Игнатий Богоносец, неизвестный автор книги «Дидахе» («Учение двенадцати апостолов»), Афинагор Афинский, Феофил Антиохийский – цитировали Евангелие от Матфея очень близко к тому самому тексту, который известен сегодня всей Церкви. Видимо, еврейский текст был рано вытеснен из употребления и не успел широко разойтись, предполагал Глубоковский.

Существовал ли вообще этот еврейский текст, если он не сохранился до наших времен?

Предположение, что Евангелие от Матфея было написано сразу же по-гречески, родилось только в начале XVI в.: такую версию высказали знаменитый ученый-гуманист и исследователь Библии Эразм Роттердамский и католический кардинал Каетан. Развивая этот ход мысли дальше, протестантские ученые со временем предположили, что Матфей писал и не первым (известным сторонником этой гипотезы был, например, живший в XIX – начале XX века немецкий богослов Генрих-Юлий Гольцман).

Но, во-первых, о существовании еврейского оригинала свидетельствует множество церковных писателей I-V веков. Это и уже упомянутые нами Папий Иерапольский и Ириней Лионский, и Евсевий Кесарийский, писавший свою «Церковную историю» во времена императора Константина Великого (середина IV века). По его сведениям, еще в конце II века египетский христианский богослов Пантен, основатель знаменитого впоследствии Александрийского училища, обнаружил еврейский текст Евангелия от Матфея … в Индии, куда его веком раньше привез проповедовавший там апостол Варфоломей! «Это известие дорого для нас тем, что оно не может быть выведено из Папия и дает нам новое, самостоятельное и независимое свидетельство о первоначальном еврейском языке писания Матфеева», – замечает Глубоковский.

Кроме того, какой-то еврейский текст хранился, по свидетельству Иеронима Стридонского, в библиотеке Кесарии Палестинской. Блаженный Иероним писал, что лично «имел возможность списать это Евангелие у назореев, которые в сирийском городе Верии пользуются этой книгой». То ли это был подлинник, то ли созданное на его основе и популярное среди иудеохристиан «Евангелие от евреев» – теперь уже не разобрать. Впоследствии текст был утрачен.

Ну, а во-вторых, у греческого текста известного нам Евангелия от Матфея есть характерные особенности, убедительно свидетельствующие в пользу существования еврейского прототипа.

Явным отголоском еврейского оригинала исследователи считают, например, слова Архангела Гавриила, обращенные к праведному Иосифу: наречешь имя Ему Иисус, ибо Он спасет людей Своих от грехов их (Мф 1:21). Понятными они становятся только в еврейском подлиннике, где «Иисус» значит «Бог спасает».

Описывая распятие Христа, Матфей приводит Его возглас по-еврейски: Или, Или! лама савахфани? то есть: Боже Мой, Боже Мой! для чего Ты Меня оставил? (Мф 27:46) Без этого возгласа осталась бы непонятным, почему окружавшие насмехались над Распятым, говоря: Илию зовет Он (Мф 27:47). (Тот же самый возглас содержит, правда, и Евангелие от Марка, но это объяснимо, если считать, что апостол Марк писал после Матфея и частично использовал его работу.)

Еще одна особенность Евангелия от Матфея – изобилие ссылок на ветхозаветные пророчества о Христе. Причем Матфей единственный заимствует эти пророчества не только из греческой Библии – Септуагинты (как другие евангелисты), но и из еврейского текста. Например, в формулировке еврейского оригинала, а не Септуагинты, приводится заповедь: Возлюби Господа Бога твоего всем сердцем твоим (Мф 22:37), и это не единственный случай.

Септуагинта

Название перевода книг Ветхого Завета на греческий язык, выполненного в египетской Александрии начиная с 280-х гг. до Р. Х. Ко времени земной жизни Христа этот перевод имел широкое хождение и пользовался авторитетом по всей Римской империи, говорившей преимущественно по-гречески. Даже Палестина не была исключением: ведь оригинальный текст Ветхого Завета был написан на древнееврейском, который знали далеко не все иудеи — об этом свидетельствует хотя бы факт существования должности переводчика при синагогах. Даже Иосиф Флавий, знаменитый иудейский историк I века по Р. Х., цитируя Библию, постоянно обращался к Септуагинте.

Специалисты по языкознанию находят в тексте Евангелия от Матфея и другие особенности, которые трудно объяснить, если отрицать наличие еврейского прототипа. Например, Матфей часто употребляет не очень характерную для греческого языка частицу ἰδού (в русском переводе – «се» или «вот»). Похоже, что это просто греческая «калька» многозначного еврейского слова hinnê. Или такое выражение, как «ответив, сказал» (Мф 21:21): по-гречески – как и по-русски – звучит тяжело, но зато буквально соответствует распространенному древнееврейскому обороту.

Хорошо, пусть у Евангелия от Матфея был еврейский прототип. Это ведь еще не доказывает, что оно было написано первым!

Не доказывает, но подводит близко к такому выводу.

Матфей адресовал свой труд своим соотечественникам, евреям – это видно не только из языка, но и из особенностей повествования.

В середине и конце I века до Р. Х. евреи особенно напряженно ждали Мессию из рода царя Давида – Спасителя, который, по их представлениям, должен был избавить народ иудейский от рабства римлянам (а в действительности – всех людей от рабства греху и смерти). И Матфей открывает свое Евангелия с родословия – длинного перечня предков Иисуса Христа. Целью было убедить читателя-иудея в том, что Христос и есть Тот Мессия: ведь Он тоже происходит от родоначальника еврейского народа Авраама и является потомком Давида, как и предсказывал ветхозаветный пророк Исаия.

Те или иные ветхозаветные пророчества, исполнившиеся на Иисусе Христе, приводят все четыре евангелиста, но у Матфея, как подсчитали библеисты, их на девять больше. И это особенно важные для иудеев пророчества – о том, что Иисус родится от Девы (Ис 7:14); что Он будет вынужден на время бежать из Иудеи в Египет (Ос 11:1); что проповедь Христа начнется с Галилеи (Ис 9:1-2); что люди оценят Его в тридцать сребреников, и на эти деньги будет куплена земля горшечника (Зах 11:12-13), и многие другие…

Итак, Матфей писал для христиан из евреев. Но из книги Деяний апостолов следует, что уже через недолгое время после Вознесения Господа Иисуса Христа произошло великое гонение на церковь в Иерусалиме; и все, кроме Апостолов, рассеялись по разным местам Иудеи и Самарии (Деян 8:1). А еще спустя какое-то время и сами апостолы разошлись по дальним странам и стали проповедовать Христа язычникам. Логично предположить, что Матфей написал Евангелие в те годы, когда христианская община в Иерусалиме была еще в расцвете сил.

Есть ли еще какие-то доказательства, что Евангелие от Матфея появилось раньше других?

Прежде всего это все те же самые свидетельства ранней Церкви. О том, что Матфей написал свое Евангелие раньше других апостолов, уверенно писал Ириней Лионский. Климент Александрийский знал или предполагал, что первыми появились Евангелия с родословиями – перечнями земных прародителей Господа Иисуса Христа, то есть Евангелия от Матфея и от Луки. В целом же традиционный церковный взгляд выразил еще в начале V века блаженный Августин Иппонийский: Матфей писал свое Евангелие первым, Марк и Лука опирались на него, а Иоанн дополнял то, о чем умолчали евангелисты-предшественники.

А этот взгляд подтверждается научными данными?

Установлено, во всяком случае, то, что в эпоху древней Церкви наиболее известным и авторитетным было именно Евангелие от Матфея. Церковные писатели I-III веков цитируют его гораздо чаще, чем тексты других евангелистов. Составители издания Biblia Patristica (сборник библейских изречений, расположенных по частоте цитируемости в творениях святых отцов) подсчитали, что Евангелие от Матфея авторы той эпохи цитируют 3550 раз, от Луки – 3250, от Иоанна – около 2000, а от Марка – всего 1460.

Выдержки из Матфеева Евангелия приводит уже спутник Павла Варнава (конец I века). В частности – он призывает христиан как можно внимательнее наблюдать за собой, чтобы не оказалось, что много званых, но мало избранных (Мф 22:14). Ясные параллели с Матфеем видны и в посланиях священномученика Игнатия Богоносца: к примеру, в начале Послания к Смирнянам он пишет, что Христос «крестился от Иоанна, чтобы всякая правда могла быть исполнена им», почти дословно воспроизводя слова Христа в Евангелии от Матфея (Мф 3:15).

В христианском памятнике конца I или начала II века «Учение двенадцати апостолов» («Дидахе») молитва «Отче наш» приводится в том же виде, что и у Матфея (Мф 6:9-13). Цитируются и слова Спасителя: Не давайте святыни псам, – которые есть только в первом Евангелии (Мф 7:6).

Словом, у нас более чем достаточно причин доверять выводу блаженного Августина.

Когда же было написано Евангелие от Матфея? И сохранились ли какие-нибудь ранние рукописи?

По данным Иринея Лионского (жившего, напомним, во второй половине II века), «Матфей издал у евреев на их собственном языке писание Евангелия, в то время как Петр и Павел в Риме благовествовали и основали Церковь». Апостол Павел прибыл в Рим, как считается, около 62 года – значит, и Евангелие от Матфея (по крайней мере, его еврейский прототип) появилось около этого времени.

Николай Глубоковский предлагал «отодвинуть» дату его написания на несколько лет назад. Он объяснял: в 59 г. апостол Павел приезжал в Иерусалим и из всех апостолов нашел там только Иакова с несколькими пресвитерами (священниками) (Деян 21:18-19). Значит, прочие апостолы, и Матфей в их числе, уже отправились проповедовать в другие земли – и Евангелие к этому времени, вероятнее всего, уже было написано, рассуждал он.

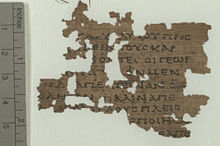

Что же касается рукописей, то одним из самых древних документов, запечатлевших фрагменты Евангелия от Матфея, считается папирус, известный археологам и библеистам под обозначением P45. Создан он был, согласно современной датировке, в первой половине III века. Изначально это были переплетенные листы папируса размером 254 на 203 мм, на которых были записаны тексты всех четырех Евангелий и Деяний апостолов. Сейчас из 220 листов осталось только 30, причем сохранились в основном фрагменты Деяний (13 листов), Евангелий от Марка (6) и от Луки (7). Тексты Матфеева и Иоаннова Евангелий представлены всего лишь двумя фрагментарными листами.

The Gospel of Matthew[note 1] is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel’s Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people (the Jews) but is rejected by them and how, after his resurrection, he sends the disciples to the gentiles instead.[3] Matthew wishes to emphasize that the Jewish tradition should not be lost in a church that was increasingly becoming gentile.[4] The gospel reflects the struggles and conflicts between the evangelist’s community and the other Jews, particularly with its sharp criticism of the scribes and Pharisees[5] with the position that through their rejection of Christ, the Kingdom of God has been taken away from them and given instead to the church.[6]

The divine nature of Jesus was a major issue for the Matthaean community, the crucial element separating the early Christians from their Jewish neighbors; while Mark begins with Jesus’s baptism and temptations, Matthew goes back to Jesus’s origins, showing him as the Son of God from his birth, the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament.[7] The title Son of David identifies Jesus as the healing and miracle-working Messiah of Israel (it is used exclusively in relation to miracles), sent to Israel alone.[8] As Son of Man he will return to judge the world, an expectation which his disciples recognize but of which his enemies are unaware.[9] As Son of God, God is revealing himself through his son, and Jesus proving his sonship through his obedience and example.[10]

Most scholars believe the gospel was composed between AD 80 and 90, with a range of possibility between AD 70 to 110; a pre-70 date remains a minority view.[11][12] The work does not identify its author, and the early tradition attributing it to the apostle Matthew is rejected by modern scholars.[13][14] He was probably a male Jew, standing on the margin between traditional and non-traditional Jewish values, and familiar with technical legal aspects of scripture being debated in his time.[15] Writing in a polished Semitic «synagogue Greek», he drew on the Gospel of Mark as a source, plus a hypothetical collection of sayings known as the Q source (material shared with Luke but not with Mark) and hypothetical material unique to his own community, called the M source or «Special Matthew».[16][17]

Composition[edit]

[edit]

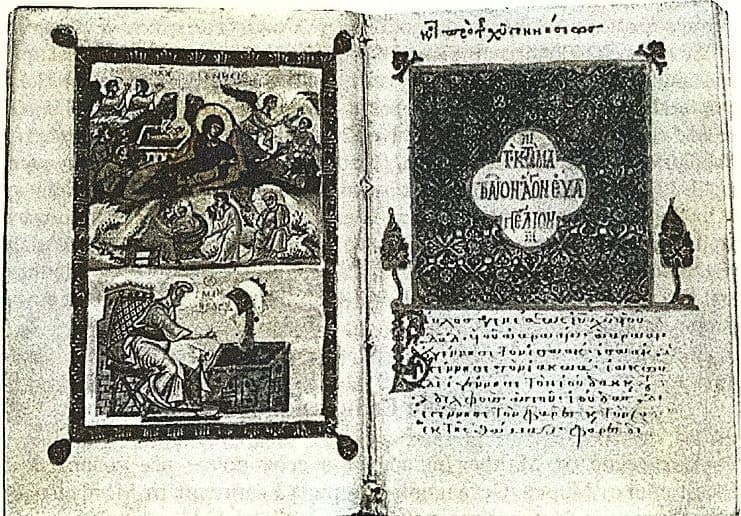

Papyrus 𝔓4, fragment of a flyleaf with the title of the Gospel of Matthew, ευαγγελιον κ̣ατ̣α μαθ᾽θαιον (euangelion kata Maththaion). Dated to late 2nd or early 3rd century, it is the earliest manuscript title for Matthew.

The traditional attribution to the apostle Matthew, first attested by Papias of Hierapolis (attestation dated c. 125 AD),[18] is rejected by modern scholars,[13][14] and the majority view today is that the author was an anonymous male Jew writing in the last quarter of the 1st century familiar with technical legal aspects of scripture, and standing on the margin between traditional and non-traditional Jewish values.[19][15][note 2] The majority also believe that Mark was the first gospel to be composed and that Matthew (who includes some 600 of Mark’s 661 verses) and Luke both drew upon it as a major source for their works.[20][21] The author of Matthew did not, however, simply copy Mark, but used it as a base, emphasizing Jesus’s place in the Jewish tradition and including details not found in Mark.[22]

There are an additional 220 (approximately) verses, shared by Matthew and Luke but not found in Mark, from a second source, a hypothetical collection of sayings to which scholars give the name «Quelle» («source» in the German language), or the Q source.[23] This view, known as the two-source hypothesis (Mark and Q), allows for a further body of tradition known as «Special Matthew», or the M source, meaning material unique to Matthew; this may represent a separate source, or it may come from the author’s church, or he may have composed these verses himself.[21] The author also had the Greek scriptures at his disposal, both as book-scrolls (Greek translations of Isaiah, the Psalms etc.) and in the form of «testimony collections» (collections of excerpts), and the oral stories of his community.[24]

Setting[edit]

The gospel of Matthew is a work of the second generation of Christians, for whom the defining event was the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Romans in AD 70 in the course of the First Jewish–Roman War (AD 66–73); from this point on, what had begun with Jesus of Nazareth as a Jewish messianic movement became an increasingly gentile phenomenon evolving in time into a separate religion.[25] The community to which Matthew belonged, like many 1st-century Christians, was still part of the larger Jewish community: hence the designation Jewish Christian to describe them.[26] The relationship of Matthew to this wider world of Judaism remains a subject of study and contention, the principal question being to what extent, if any, Matthew’s community had cut itself off from its Jewish roots.[27] Certainly there was conflict between Matthew’s group and other Jewish groups, and it is generally agreed that the root of the conflict was the Matthew community’s belief in Jesus as the Messiah and authoritative interpreter of the law, as one risen from the dead and uniquely endowed with divine authority.[28]

The author wrote for a community of Greek-speaking Jewish Christians located probably in Syria (Antioch, the largest city in Roman Syria and the third-largest in the empire, is often mentioned).[29] Unlike Mark, Matthew never bothers to explain Jewish customs, since his intended audience was a Jewish one; unlike Luke, who traces Jesus’s ancestry back to Adam, father of the human race, he traces it only to Abraham, father of the Jews; of his three presumed sources only «M», the material from his own community, refers to a «church» (ecclesia), an organised group with rules for keeping order; and the content of «M» suggests that this community was strict in keeping the Jewish law, holding that they must exceed the scribes and the Pharisees in «righteousness» (adherence to Jewish law).[30] Writing from within a Jewish-Christian community growing increasingly distant from other Jews and becoming increasingly gentile in its membership and outlook, Matthew put down in his gospel his vision «of an assembly or church in which both Jew and Gentile would flourish together».[31]

Structure and content[edit]

Structure: narrative and discourses[edit]

Matthew, alone among the gospels, alternates five blocks of narrative with five of discourse, marking each off with the phrase «When Jesus had finished»[32] (see Five Discourses of Matthew). Some scholars see in this a deliberate plan to create a parallel to the first five books of the Old Testament; others see a three-part structure based around the idea of Jesus as Messiah, a set of weekly readings spread out over the year, or no plan at all.[33] Davies and Allison, in their widely used commentary, draw attention to the use of «triads» (the gospel groups things in threes),[34] and R. T. France, in another influential commentary, notes the geographic movement from Galilee to Jerusalem and back, with the post-resurrection appearances in Galilee as the culmination of the whole story.[35]

Prologue: genealogy, Nativity and infancy (Matt. 1–2)[edit]

The Gospel of Matthew begins with the words «The Book of Genealogy [in Greek, «Genesis»] of Jesus Christ», deliberately echoing the words of Genesis 2:4 in the Old Testament in Greek.[note 3] The genealogy tells of Jesus’s descent from Abraham and King David and the miraculous events surrounding his virgin birth,[note 4] and the infancy narrative tells of the massacre of the innocents, the flight into Egypt, and eventual journey to Nazareth.

First narrative and Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 3:1–8:1)[edit]

The first narrative section begins. John the Baptist baptizes Jesus, and the Holy Spirit descends upon him. Jesus prays and meditates in the wilderness for forty days, and is tempted by Satan. His early ministry by word and deed in Galilee meets with much success, and leads to the Sermon on the Mount, the first of the discourses. The sermon presents the ethics of the kingdom of God, introduced by the Beatitudes («Blessed are…»). It concludes with a reminder that the response to the kingdom will have eternal consequences, and the crowd’s amazed response leads into the next narrative block.[36]

Second narrative and discourse (Matt. 8:2–11:1)[edit]

From the authoritative words of Jesus, the gospel turns to three sets of three miracles interwoven with two sets of two discipleship stories (the second narrative), followed by a discourse on mission and suffering.[37] Jesus commissions the Twelve Disciples and sends them to preach to the Jews, perform miracles, and prophesy the imminent coming of the Kingdom, commanding them to travel lightly, without staff or sandals.[38]

Third narrative and discourse (Matt. 11:2–13:53)[edit]

Opposition to Jesus comes to a head with accusations that his deeds are done through the power of Satan. Jesus in turn accuses his opponents of blaspheming the Holy Spirit. The discourse is a set of parables emphasizing the sovereignty of God, and concluding with a challenge to the disciples to understand the teachings as scribes of the Kingdom of Heaven.[39] (Matthew avoids using the holy word God in the expression «Kingdom of God»; instead he prefers the term «Kingdom of Heaven», reflecting the Jewish tradition of not speaking the name of God).[40]

Fourth narrative and discourse (Matt. 13:54–19:1)[edit]

The fourth narrative section reveals that the increasing opposition to Jesus will result in his crucifixion in Jerusalem, and that his disciples must therefore prepare for his absence.[41] The instructions for the post-crucifixion church emphasize responsibility and humility. This section contains the two feedings of the multitude (Matthew 14:13–21 and 15:32–39) along with the narrative in which Simon, newly renamed Peter (Πέτρος, Petros, meaning «stone»), calls Jesus «the Christ, the son of the living God», and Jesus states that on this «bedrock» (πέτρα, petra) he will build his church (Matthew 16:13–19).

Matthew 16:13–19 forms the foundation for the papacy’s claim of authority.[citation needed]

Fifth narrative and discourse (Matt. 19:2–26:1)[edit]

Jesus travels toward Jerusalem, and the opposition intensifies: he is tested by Pharisees as soon as he begins to move toward the city, and when he arrives he is soon in conflict with the Temple’s traders and religious leaders. He teaches in the Temple, debating with the chief priests and religious leaders and speaking in parables about the Kingdom of God and the failings of the chief priests and the Pharisees. The Herodian caucus also become involved in a scheme to entangle Jesus,[42] but Jesus’s careful response to their enquiry, «Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s»,[43] leaves them marveling at his words.[44]

The disciples ask about the future, and in his final discourse (the Olivet Discourse) Jesus speaks of the coming end.[45] There will be false Messiahs, earthquakes, and persecutions, the sun, moon, and stars will fail, but «this generation» will not pass away before all the prophecies are fulfilled.[38] The disciples must steel themselves for ministry to all the nations. At the end of the discourse, Matthew notes that Jesus has finished all his words, and attention turns to the crucifixion.[45]

Conclusion: Passion, Resurrection and Great Commission (Matt. 26:2–28:20)[edit]

The events of Jesus’s last week occupy a third of the content of all four gospels.[46] Jesus enters Jerusalem in triumph and drives the money changers from the Temple, holds a last supper, prays to be spared the coming agony (but concludes «if this cup may not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done»), and is betrayed. He is tried by the Jewish leaders (the Sanhedrin) and before Pontius Pilate, and Pilate washes his hands to indicate that he does not assume responsibility. Jesus is crucified as king of the Jews, mocked by all. On his death there is an earthquake, the veil of the Temple is rent, and saints rise from their tombs. Mary Magdalene and another Mary discover the empty tomb, guarded by an angel, and Jesus himself tells them to tell the disciples to meet him in Galilee.

After the resurrection the remaining disciples return to Galilee, «to the mountain that Jesus had appointed», where he comes to them and tells them that he has been given «all authority in heaven and on Earth.» He gives the Great Commission: «Therefore go and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you». Jesus will be with them «to the very end of the age».[47]

Theology[edit]

Christology[edit]

Christology is the theological doctrine of Christ, «the affirmations and definitions of Christ’s humanity and deity».[48] There are a variety of Christologies in the New Testament, albeit with a single centre—Jesus is the figure in whom God has acted for mankind’s salvation.[49]

Matthew has taken over his key Christological texts from Mark, but sometimes he has changed the stories he found in Mark, giving evidence of his own concerns.[50] The title Son of David identifies Jesus as the healing and miracle-working Messiah of Israel (it is used exclusively in relation to miracles), and the Jewish messiah is sent to Israel alone.[8] As Son of Man he will return to judge the world, a fact his disciples recognise but of which his enemies are unaware.[9] As Son of God he is named Immanuel (God with us),[51] God revealing himself through his son, and Jesus proving his sonship through his obedience and example.[10]

Relationship with the Jews[edit]

Matthew’s prime concern was that the Jewish tradition should not be lost in a church that was increasingly becoming gentile.[4] This concern lies behind the frequent citations of Jewish scripture, the evocation of Jesus as the new Moses along with other events from Jewish history, and the concern to present Jesus as fulfilling, not destroying, the Law.[52] Matthew must have been aware of the tendency to distort Paul’s teaching of the law no longer having power over the New Testament Christian into antinomianism, and addressed Christ’s fulfilling of what the Israelites expected from the «Law and the Prophets» in an eschatological sense, in that he was all that the Old Testament had predicted in the Messiah.[53]

The gospel has been interpreted as reflecting the struggles and conflicts between the evangelist’s community and the other Jews, particularly with its sharp criticism of the scribes and Pharisees.[5] It tells how Israel’s Messiah, rejected and executed in Israel, pronounces judgment on Israel and its leaders and becomes the salvation of the gentiles.[54] Prior to the crucifixion of Jesus, the Jews are referred to as Israelites—the honorific title of God’s chosen people. After it, they are called Ioudaios(Jews), a sign that—due to their rejection of the Christ—the «Kingdom of Heaven» has been taken away from them and given instead to the church.[6]

Comparison with other writings[edit]

Christological development[edit]

The divine nature of Jesus was a major issue for the community of Matthew, the crucial element marking them from their Jewish neighbors. Early understandings of this nature grew as the gospels were being written. Before the gospels, that understanding was focused on the revelation of Jesus as God in his resurrection, but the gospels reflect a broadened focus extended backwards in time.[7]

Mark[edit]

Matthew is a creative reinterpretation of Mark,[55] stressing Jesus’s teachings as much as his acts,[56] and making subtle changes in order to stress his divine nature: for example, Mark’s «young man» who appears at Jesus’s tomb becomes «a radiant angel» in Matthew.[57] The miracle stories in Mark do not demonstrate the divinity of Jesus, but rather confirm his status as an emissary of God (which was Mark’s understanding of the Messiah).[58]

Chronology[edit]

There is a broad disagreement over chronology between Matthew, Mark and Luke on one hand and John on the other: all four agree that Jesus’s public ministry began with an encounter with John the Baptist, but Matthew, Mark and Luke follow this with an account of teaching and healing in Galilee, then a trip to Jerusalem where there is an incident in the Temple, climaxing with the crucifixion on the day of the Passover holiday. John, by contrast, puts the Temple incident very early in Jesus’s ministry, has several trips to Jerusalem, and puts the crucifixion immediately before the Passover holiday, on the day when the lambs for the Passover meal were being sacrificed in Temple.[59]

Canonical positioning[edit]

The early patristic scholars regarded Matthew as the earliest of the gospels and placed it first in the canon, and the early Church mostly quoted from Matthew, secondarily from John, and only distantly from Mark.[60]

See also[edit]

- Authorship of the Bible

- Gospel of the Ebionites

- Gospel of the Hebrews

- Gospel of the Nazarenes

- Hebrew Gospel hypothesis

- The Visual Bible: Matthew

- Il vangelo secondo Matteo, a film by Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Jewish–Christian gospels

- List of omitted Bible verses

- List of Gospels

- Sermon on the Mount

- St Matthew Passion – an oratorio by J. S. Bach

- Textual variants in the Gospel of Matthew

- Shem Tob’s Hebrew Gospel of Matthew

Notes[edit]

- ^ The book is sometimes called the Gospel according to Matthew (Greek: Κατὰ Ματθαῖον/Μαθθαῖον Εὐαγγέλιον, romanized: Katà Mat(h)thaîon Euangélion), or simply Matthew.[1] It is most commonly abbreviated as «Matt.»[2]

- ^ This view is based on three arguments: (a) the setting reflects the final separation of Church and Synagogue, about 85 AD; (b) it reflects the capture of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70 AD; (c) it uses Mark, usually dated around 70 AD, as a source. (See R. T. France (2007), The Gospel of Matthew, p. 18.) France himself is not convinced by the majority—see his Commentary, pp. 18–19. Allison adds that «Ignatius of Antioch, the Didache, and Papias—all from the first part of the second century—show knowledge of Matthew, which accordingly must have been composed before 100 CE. (See e.g. Ign., Smyrn. 1; Did. 8.2.)» See Dale Allison, «Matthew» in Muddiman and Barton’s The Gospels (Oxford Bible Commentary), Oxford 2010, p. 27.

- ^ France, p. 26 note 1, and p. 28: «The first two words of Matthew’s gospel are literally «book of genesis».

- ^ France, p. 28 note 7: «All MSS and versions agree in making it explicit that Joseph was not Jesus’ father, with the one exception of sys, which reads «Joseph, to whom was betrothed Mary the virgin, begot Jesus.»

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 807. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021.

- ^ «Bible Book Abbreviations». Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Luz 2005b, pp. 233–34.

- ^ a b Davies & Allison 1997, p. 722.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 182.

- ^ a b Strecker 2000, pp. 369–70.

- ^ a b Peppard 2011, p. 133.

- ^ a b Luz 1995, pp. 86, 111.

- ^ a b Luz 1995, pp. 91, 97.

- ^ a b Luz 1995, p. 93.

- ^ Duling 2010, pp. 298–99.

- ^ France 2007, p. 19.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 174.

- ^ a b Duling 2010, pp. 301–02.

- ^ a b Duling 2010, p. 302.

- ^ Duling 2010, p. 306.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 175-176.

- ^ Keith 2016, p. 92.

- ^ Davies & Allison 1988, p. 128.

- ^ Turner 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Senior 1996, p. 22.

- ^ Harrington 1991, pp. 5–6.

- ^ McMahon 2008, p. 57.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 116.

- ^ Scholtz 2009, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Saldarini 1994, p. 4.

- ^ Senior 2001, pp. 7–8, 72.

- ^ Senior 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Nolland 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Burkett 2002, pp. 180–81.

- ^ Senior 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Davies & Allison 1988, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Davies & Allison 1988, pp. 62ff.

- ^ France 2007, pp. 2ff.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 101.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 226.

- ^ a b Harris 1985.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Browning 2004, p. 248.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 265.

- ^ Bible, Matthew 22:15–16

- ^ Bible, Matthew 22:21

- ^ Bible, Matthew 22:22

- ^ a b Turner 2008, p. 445.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 613.

- ^ Turner 2008, pp. 687–88.

- ^ Levison & Pope-Levison 2009, p. 167.

- ^ Fuller 2001, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Tuckett 2001, p. 119.

- ^ Bible, (Matthew 1:23

- ^ Senior 2001, pp. 17–18.

- ^ France 2007, pp. 179–81, 185–86.

- ^ Luz 2005b, pp. 17.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Morris 1986, p. 114.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Levine 2001, p. 373.

- ^ Edwards 2002, p. 2.

Sources[edit]

- Adamczewski, Bartosz (2010). Q or not Q? The So-Called Triple, Double, and Single Traditions in the Synoptic Gospels. Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-631-60492-2.

- Allison, D.C. (2004). Matthew: A Shorter Commentary. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08249-7.

- Aune, David E. (2001). The Gospel of Matthew in current study. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4673-0.

- —— (1987). The New Testament in its literary environment. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- Beaton, Richard C. (2005). «How Matthew Writes». In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83285-4.

- Browning, W.R.F (2004). Oxford Dictionary of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860890-5.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian’s Account of His Life and Teaching. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Clarke, Howard W. (2003). The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34235-5.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005) [1997]. «Matthew, Gospel acc. to St.». The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1064. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Davies, William David; Allison, Dale C. (1988). A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Vol. I: Introduction and Commentary on Matthew I–VII. T&T Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0-567-09481-0.

- ——; —— (1999) [1991]. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Vol. II: Commentary on Matthew VIII–XVIII. T&T Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0-567-09545-9.

- ——; —— (1997). A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Vol. III: Commentary on Matthew XIX–XXVIII. T&T Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0-567-08518-4.

- Duling, Dennis C. (2010). «The Gospel of Matthew». In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0825-6.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- Edwards, James (2002). The Gospel According to Mark. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85111-778-2.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512474-3.

- —— (2009). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-197702-2.

- —— (2012). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-220460-8.

- France, R.T (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2501-8.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5803-1.

- Farrer, Austin M. (1955). «On Dispensing With Q». In Nineham, Dennis E. (ed.). Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot. Oxford. pp. 55–88.

- Fuller, Reginald H. (2001). «Biblical Theology». In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Guide to Ideas & Issues of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514917-3.

- Goodacre, Mark (2002). The Case Against Q: Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem. Trinity Press International. ISBN 1-56338-334-9.

- Hagner, D.A. (1986). «Matthew, Gospel According to Matthew». In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Vol. 3: K–P. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-8163-2.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield.

- Keith, Chris (2016). «The Pericope Adulterae: A theory of attentive insertion». In Black, David Alan; Cerone, Jacob N. (eds.). The Pericope of the Adulteress in Contemporary Research. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-567-66580-5.

- Kupp, David D. (1996). Matthew’s Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God’s People in the First Gospel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57007-7.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2001). «Visions of kingdoms: From Pompey to the first Jewish revolt». In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Levison, J.; Pope-Levison, P. (2009). «Christology». In Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (eds.). Global Dictionary of Theology. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-7811-6.

- Luz, Ulrich (1989). Matthew 1–7. Matthew: A Commentary. Vol. 1. Translated by Linss, Wilhelm C. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8066-2402-0.

- —— (1995). The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43576-5.

- —— (2001). Matthew 8–20. Matthew: A Commentary. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-6034-5.

- —— (2005a). Matthew 21–28. Matthew: A Commentary. Vol. 3. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-3770-5.

- —— (2005b). Studies in Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3964-0.

- McMahon, Christopher (2008). «Introduction to the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles». In Ruff, Jerry (ed.). Understanding the Bible: A Guide to Reading the Scriptures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-852-8.

- Morris, Leon (1986). New Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-45571-4.

- Peppard, Michael (2011). The Son of God in the Roman World: Divine Sonship in Its Social and Political Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975370-3.

- Perkins, Pheme (1997). «The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story». In Kee, Howard Clark (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Interpretation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48593-2.

- Saldarini, Anthony (2003). Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Keener, Craig S. (1999). A commentary on the Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3821-6.

- Morris, Leon (1992). The Gospel according to Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-85111-338-8.

- Nolland, John (2005). The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2389-2.

- Saunders, Stanley P. (2009). «Matthew». In O’Day, Gail (ed.). Theological Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22711-1.

- Saldarini, Anthony (1994). Matthew’s Christian-Jewish Community. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73421-7.

- Sanford, Christopher B. (2005). Matthew: Christian Rabbi. Author House. ISBN 978-1-4208-8371-8.

- Scholtz, Donald (2009). Jesus in the Gospels and Acts: Introducing the New Testament. Saint Mary’s Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-955-6.

- Senior, Donald (2001). «Directions in Matthean Studies». In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Gospel of Matthew in Current Study: Studies in Memory of William G. Thompson, S.J. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-4673-4.

- Senior, Donald (1996). What are they saying about Matthew?. PaulistPress. ISBN 978-0-8091-3624-7.

- Stanton, Graham (1993). A gospel for a new people: studies in Matthew. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25499-5.

- Strecker, Georg (2000) [1996]. Theology of the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-0-664-22336-6.

- Tuckett, Christopher Mark (2001). Christology and the New Testament: Jesus and His Earliest Followers. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224318.

- Turner, David L. (2008). Matthew. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-2684-3.

- Van de Sandt, H.W.M. (2005). «Introduction«. Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish-Christian Milieu ?. ISBN 90-232-4077-4., in Van de Sandt, H.W.M., ed. (2005). Matthew and the Didache. Royal Van Gorcum&Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.

- Wallace, Daniel B., ed. (2011). Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament: Manuscript, Patristic, and Apocryphal Evidence. Text and canon of the New Testament. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-8906-8.

- Weren, Wim (2005). «The History and Social Setting of the Matthean Community». Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish-Christian Milieu ?. ISBN 90-232-4077-4., in Van de Sandt, H.W.M, ed. (2005). Matthew and the Didache. Royal Van Gorcum&Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.

External links[edit]

- Biblegateway.com (opens at Matt.1:1, NIV)

- A textual commentary on the Gospel of Matthew Detailed text-critical discussion of the 300 most important variants of the Greek text (PDF, 438 pages).

- Early Christian Writings Gospel of Matthew: introductions and e-texts.

Bible: Matthew public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

The Gospel of Matthew[note 1] is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel’s Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people (the Jews) but is rejected by them and how, after his resurrection, he sends the disciples to the gentiles instead.[3] Matthew wishes to emphasize that the Jewish tradition should not be lost in a church that was increasingly becoming gentile.[4] The gospel reflects the struggles and conflicts between the evangelist’s community and the other Jews, particularly with its sharp criticism of the scribes and Pharisees[5] with the position that through their rejection of Christ, the Kingdom of God has been taken away from them and given instead to the church.[6]

The divine nature of Jesus was a major issue for the Matthaean community, the crucial element separating the early Christians from their Jewish neighbors; while Mark begins with Jesus’s baptism and temptations, Matthew goes back to Jesus’s origins, showing him as the Son of God from his birth, the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament.[7] The title Son of David identifies Jesus as the healing and miracle-working Messiah of Israel (it is used exclusively in relation to miracles), sent to Israel alone.[8] As Son of Man he will return to judge the world, an expectation which his disciples recognize but of which his enemies are unaware.[9] As Son of God, God is revealing himself through his son, and Jesus proving his sonship through his obedience and example.[10]

Most scholars believe the gospel was composed between AD 80 and 90, with a range of possibility between AD 70 to 110; a pre-70 date remains a minority view.[11][12] The work does not identify its author, and the early tradition attributing it to the apostle Matthew is rejected by modern scholars.[13][14] He was probably a male Jew, standing on the margin between traditional and non-traditional Jewish values, and familiar with technical legal aspects of scripture being debated in his time.[15] Writing in a polished Semitic «synagogue Greek», he drew on the Gospel of Mark as a source, plus a hypothetical collection of sayings known as the Q source (material shared with Luke but not with Mark) and hypothetical material unique to his own community, called the M source or «Special Matthew».[16][17]

Composition[edit]

[edit]

Papyrus 𝔓4, fragment of a flyleaf with the title of the Gospel of Matthew, ευαγγελιον κ̣ατ̣α μαθ᾽θαιον (euangelion kata Maththaion). Dated to late 2nd or early 3rd century, it is the earliest manuscript title for Matthew.

The traditional attribution to the apostle Matthew, first attested by Papias of Hierapolis (attestation dated c. 125 AD),[18] is rejected by modern scholars,[13][14] and the majority view today is that the author was an anonymous male Jew writing in the last quarter of the 1st century familiar with technical legal aspects of scripture, and standing on the margin between traditional and non-traditional Jewish values.[19][15][note 2] The majority also believe that Mark was the first gospel to be composed and that Matthew (who includes some 600 of Mark’s 661 verses) and Luke both drew upon it as a major source for their works.[20][21] The author of Matthew did not, however, simply copy Mark, but used it as a base, emphasizing Jesus’s place in the Jewish tradition and including details not found in Mark.[22]

There are an additional 220 (approximately) verses, shared by Matthew and Luke but not found in Mark, from a second source, a hypothetical collection of sayings to which scholars give the name «Quelle» («source» in the German language), or the Q source.[23] This view, known as the two-source hypothesis (Mark and Q), allows for a further body of tradition known as «Special Matthew», or the M source, meaning material unique to Matthew; this may represent a separate source, or it may come from the author’s church, or he may have composed these verses himself.[21] The author also had the Greek scriptures at his disposal, both as book-scrolls (Greek translations of Isaiah, the Psalms etc.) and in the form of «testimony collections» (collections of excerpts), and the oral stories of his community.[24]

Setting[edit]

The gospel of Matthew is a work of the second generation of Christians, for whom the defining event was the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Romans in AD 70 in the course of the First Jewish–Roman War (AD 66–73); from this point on, what had begun with Jesus of Nazareth as a Jewish messianic movement became an increasingly gentile phenomenon evolving in time into a separate religion.[25] The community to which Matthew belonged, like many 1st-century Christians, was still part of the larger Jewish community: hence the designation Jewish Christian to describe them.[26] The relationship of Matthew to this wider world of Judaism remains a subject of study and contention, the principal question being to what extent, if any, Matthew’s community had cut itself off from its Jewish roots.[27] Certainly there was conflict between Matthew’s group and other Jewish groups, and it is generally agreed that the root of the conflict was the Matthew community’s belief in Jesus as the Messiah and authoritative interpreter of the law, as one risen from the dead and uniquely endowed with divine authority.[28]

The author wrote for a community of Greek-speaking Jewish Christians located probably in Syria (Antioch, the largest city in Roman Syria and the third-largest in the empire, is often mentioned).[29] Unlike Mark, Matthew never bothers to explain Jewish customs, since his intended audience was a Jewish one; unlike Luke, who traces Jesus’s ancestry back to Adam, father of the human race, he traces it only to Abraham, father of the Jews; of his three presumed sources only «M», the material from his own community, refers to a «church» (ecclesia), an organised group with rules for keeping order; and the content of «M» suggests that this community was strict in keeping the Jewish law, holding that they must exceed the scribes and the Pharisees in «righteousness» (adherence to Jewish law).[30] Writing from within a Jewish-Christian community growing increasingly distant from other Jews and becoming increasingly gentile in its membership and outlook, Matthew put down in his gospel his vision «of an assembly or church in which both Jew and Gentile would flourish together».[31]

Structure and content[edit]

Structure: narrative and discourses[edit]

Matthew, alone among the gospels, alternates five blocks of narrative with five of discourse, marking each off with the phrase «When Jesus had finished»[32] (see Five Discourses of Matthew). Some scholars see in this a deliberate plan to create a parallel to the first five books of the Old Testament; others see a three-part structure based around the idea of Jesus as Messiah, a set of weekly readings spread out over the year, or no plan at all.[33] Davies and Allison, in their widely used commentary, draw attention to the use of «triads» (the gospel groups things in threes),[34] and R. T. France, in another influential commentary, notes the geographic movement from Galilee to Jerusalem and back, with the post-resurrection appearances in Galilee as the culmination of the whole story.[35]

Prologue: genealogy, Nativity and infancy (Matt. 1–2)[edit]

The Gospel of Matthew begins with the words «The Book of Genealogy [in Greek, «Genesis»] of Jesus Christ», deliberately echoing the words of Genesis 2:4 in the Old Testament in Greek.[note 3] The genealogy tells of Jesus’s descent from Abraham and King David and the miraculous events surrounding his virgin birth,[note 4] and the infancy narrative tells of the massacre of the innocents, the flight into Egypt, and eventual journey to Nazareth.

First narrative and Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 3:1–8:1)[edit]

The first narrative section begins. John the Baptist baptizes Jesus, and the Holy Spirit descends upon him. Jesus prays and meditates in the wilderness for forty days, and is tempted by Satan. His early ministry by word and deed in Galilee meets with much success, and leads to the Sermon on the Mount, the first of the discourses. The sermon presents the ethics of the kingdom of God, introduced by the Beatitudes («Blessed are…»). It concludes with a reminder that the response to the kingdom will have eternal consequences, and the crowd’s amazed response leads into the next narrative block.[36]

Second narrative and discourse (Matt. 8:2–11:1)[edit]

From the authoritative words of Jesus, the gospel turns to three sets of three miracles interwoven with two sets of two discipleship stories (the second narrative), followed by a discourse on mission and suffering.[37] Jesus commissions the Twelve Disciples and sends them to preach to the Jews, perform miracles, and prophesy the imminent coming of the Kingdom, commanding them to travel lightly, without staff or sandals.[38]

Third narrative and discourse (Matt. 11:2–13:53)[edit]

Opposition to Jesus comes to a head with accusations that his deeds are done through the power of Satan. Jesus in turn accuses his opponents of blaspheming the Holy Spirit. The discourse is a set of parables emphasizing the sovereignty of God, and concluding with a challenge to the disciples to understand the teachings as scribes of the Kingdom of Heaven.[39] (Matthew avoids using the holy word God in the expression «Kingdom of God»; instead he prefers the term «Kingdom of Heaven», reflecting the Jewish tradition of not speaking the name of God).[40]

Fourth narrative and discourse (Matt. 13:54–19:1)[edit]

The fourth narrative section reveals that the increasing opposition to Jesus will result in his crucifixion in Jerusalem, and that his disciples must therefore prepare for his absence.[41] The instructions for the post-crucifixion church emphasize responsibility and humility. This section contains the two feedings of the multitude (Matthew 14:13–21 and 15:32–39) along with the narrative in which Simon, newly renamed Peter (Πέτρος, Petros, meaning «stone»), calls Jesus «the Christ, the son of the living God», and Jesus states that on this «bedrock» (πέτρα, petra) he will build his church (Matthew 16:13–19).

Matthew 16:13–19 forms the foundation for the papacy’s claim of authority.[citation needed]

Fifth narrative and discourse (Matt. 19:2–26:1)[edit]

Jesus travels toward Jerusalem, and the opposition intensifies: he is tested by Pharisees as soon as he begins to move toward the city, and when he arrives he is soon in conflict with the Temple’s traders and religious leaders. He teaches in the Temple, debating with the chief priests and religious leaders and speaking in parables about the Kingdom of God and the failings of the chief priests and the Pharisees. The Herodian caucus also become involved in a scheme to entangle Jesus,[42] but Jesus’s careful response to their enquiry, «Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s»,[43] leaves them marveling at his words.[44]

The disciples ask about the future, and in his final discourse (the Olivet Discourse) Jesus speaks of the coming end.[45] There will be false Messiahs, earthquakes, and persecutions, the sun, moon, and stars will fail, but «this generation» will not pass away before all the prophecies are fulfilled.[38] The disciples must steel themselves for ministry to all the nations. At the end of the discourse, Matthew notes that Jesus has finished all his words, and attention turns to the crucifixion.[45]

Conclusion: Passion, Resurrection and Great Commission (Matt. 26:2–28:20)[edit]

The events of Jesus’s last week occupy a third of the content of all four gospels.[46] Jesus enters Jerusalem in triumph and drives the money changers from the Temple, holds a last supper, prays to be spared the coming agony (but concludes «if this cup may not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done»), and is betrayed. He is tried by the Jewish leaders (the Sanhedrin) and before Pontius Pilate, and Pilate washes his hands to indicate that he does not assume responsibility. Jesus is crucified as king of the Jews, mocked by all. On his death there is an earthquake, the veil of the Temple is rent, and saints rise from their tombs. Mary Magdalene and another Mary discover the empty tomb, guarded by an angel, and Jesus himself tells them to tell the disciples to meet him in Galilee.

After the resurrection the remaining disciples return to Galilee, «to the mountain that Jesus had appointed», where he comes to them and tells them that he has been given «all authority in heaven and on Earth.» He gives the Great Commission: «Therefore go and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you». Jesus will be with them «to the very end of the age».[47]

Theology[edit]

Christology[edit]

Christology is the theological doctrine of Christ, «the affirmations and definitions of Christ’s humanity and deity».[48] There are a variety of Christologies in the New Testament, albeit with a single centre—Jesus is the figure in whom God has acted for mankind’s salvation.[49]

Matthew has taken over his key Christological texts from Mark, but sometimes he has changed the stories he found in Mark, giving evidence of his own concerns.[50] The title Son of David identifies Jesus as the healing and miracle-working Messiah of Israel (it is used exclusively in relation to miracles), and the Jewish messiah is sent to Israel alone.[8] As Son of Man he will return to judge the world, a fact his disciples recognise but of which his enemies are unaware.[9] As Son of God he is named Immanuel (God with us),[51] God revealing himself through his son, and Jesus proving his sonship through his obedience and example.[10]

Relationship with the Jews[edit]

Matthew’s prime concern was that the Jewish tradition should not be lost in a church that was increasingly becoming gentile.[4] This concern lies behind the frequent citations of Jewish scripture, the evocation of Jesus as the new Moses along with other events from Jewish history, and the concern to present Jesus as fulfilling, not destroying, the Law.[52] Matthew must have been aware of the tendency to distort Paul’s teaching of the law no longer having power over the New Testament Christian into antinomianism, and addressed Christ’s fulfilling of what the Israelites expected from the «Law and the Prophets» in an eschatological sense, in that he was all that the Old Testament had predicted in the Messiah.[53]

The gospel has been interpreted as reflecting the struggles and conflicts between the evangelist’s community and the other Jews, particularly with its sharp criticism of the scribes and Pharisees.[5] It tells how Israel’s Messiah, rejected and executed in Israel, pronounces judgment on Israel and its leaders and becomes the salvation of the gentiles.[54] Prior to the crucifixion of Jesus, the Jews are referred to as Israelites—the honorific title of God’s chosen people. After it, they are called Ioudaios(Jews), a sign that—due to their rejection of the Christ—the «Kingdom of Heaven» has been taken away from them and given instead to the church.[6]

Comparison with other writings[edit]

Christological development[edit]

The divine nature of Jesus was a major issue for the community of Matthew, the crucial element marking them from their Jewish neighbors. Early understandings of this nature grew as the gospels were being written. Before the gospels, that understanding was focused on the revelation of Jesus as God in his resurrection, but the gospels reflect a broadened focus extended backwards in time.[7]

Mark[edit]

Matthew is a creative reinterpretation of Mark,[55] stressing Jesus’s teachings as much as his acts,[56] and making subtle changes in order to stress his divine nature: for example, Mark’s «young man» who appears at Jesus’s tomb becomes «a radiant angel» in Matthew.[57] The miracle stories in Mark do not demonstrate the divinity of Jesus, but rather confirm his status as an emissary of God (which was Mark’s understanding of the Messiah).[58]

Chronology[edit]

There is a broad disagreement over chronology between Matthew, Mark and Luke on one hand and John on the other: all four agree that Jesus’s public ministry began with an encounter with John the Baptist, but Matthew, Mark and Luke follow this with an account of teaching and healing in Galilee, then a trip to Jerusalem where there is an incident in the Temple, climaxing with the crucifixion on the day of the Passover holiday. John, by contrast, puts the Temple incident very early in Jesus’s ministry, has several trips to Jerusalem, and puts the crucifixion immediately before the Passover holiday, on the day when the lambs for the Passover meal were being sacrificed in Temple.[59]

Canonical positioning[edit]

The early patristic scholars regarded Matthew as the earliest of the gospels and placed it first in the canon, and the early Church mostly quoted from Matthew, secondarily from John, and only distantly from Mark.[60]

See also[edit]

- Authorship of the Bible

- Gospel of the Ebionites

- Gospel of the Hebrews

- Gospel of the Nazarenes

- Hebrew Gospel hypothesis

- The Visual Bible: Matthew

- Il vangelo secondo Matteo, a film by Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Jewish–Christian gospels

- List of omitted Bible verses

- List of Gospels

- Sermon on the Mount

- St Matthew Passion – an oratorio by J. S. Bach

- Textual variants in the Gospel of Matthew

- Shem Tob’s Hebrew Gospel of Matthew

Notes[edit]

- ^ The book is sometimes called the Gospel according to Matthew (Greek: Κατὰ Ματθαῖον/Μαθθαῖον Εὐαγγέλιον, romanized: Katà Mat(h)thaîon Euangélion), or simply Matthew.[1] It is most commonly abbreviated as «Matt.»[2]

- ^ This view is based on three arguments: (a) the setting reflects the final separation of Church and Synagogue, about 85 AD; (b) it reflects the capture of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70 AD; (c) it uses Mark, usually dated around 70 AD, as a source. (See R. T. France (2007), The Gospel of Matthew, p. 18.) France himself is not convinced by the majority—see his Commentary, pp. 18–19. Allison adds that «Ignatius of Antioch, the Didache, and Papias—all from the first part of the second century—show knowledge of Matthew, which accordingly must have been composed before 100 CE. (See e.g. Ign., Smyrn. 1; Did. 8.2.)» See Dale Allison, «Matthew» in Muddiman and Barton’s The Gospels (Oxford Bible Commentary), Oxford 2010, p. 27.

- ^ France, p. 26 note 1, and p. 28: «The first two words of Matthew’s gospel are literally «book of genesis».

- ^ France, p. 28 note 7: «All MSS and versions agree in making it explicit that Joseph was not Jesus’ father, with the one exception of sys, which reads «Joseph, to whom was betrothed Mary the virgin, begot Jesus.»

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 807. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021.

- ^ «Bible Book Abbreviations». Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Luz 2005b, pp. 233–34.

- ^ a b Davies & Allison 1997, p. 722.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 182.

- ^ a b Strecker 2000, pp. 369–70.

- ^ a b Peppard 2011, p. 133.

- ^ a b Luz 1995, pp. 86, 111.

- ^ a b Luz 1995, pp. 91, 97.

- ^ a b Luz 1995, p. 93.

- ^ Duling 2010, pp. 298–99.

- ^ France 2007, p. 19.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 174.

- ^ a b Duling 2010, pp. 301–02.

- ^ a b Duling 2010, p. 302.

- ^ Duling 2010, p. 306.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 175-176.

- ^ Keith 2016, p. 92.

- ^ Davies & Allison 1988, p. 128.

- ^ Turner 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Senior 1996, p. 22.

- ^ Harrington 1991, pp. 5–6.

- ^ McMahon 2008, p. 57.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 116.

- ^ Scholtz 2009, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Saldarini 1994, p. 4.

- ^ Senior 2001, pp. 7–8, 72.

- ^ Senior 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Nolland 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Burkett 2002, pp. 180–81.

- ^ Senior 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Davies & Allison 1988, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Davies & Allison 1988, pp. 62ff.

- ^ France 2007, pp. 2ff.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 101.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 226.

- ^ a b Harris 1985.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Browning 2004, p. 248.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 265.

- ^ Bible, Matthew 22:15–16

- ^ Bible, Matthew 22:21

- ^ Bible, Matthew 22:22

- ^ a b Turner 2008, p. 445.

- ^ Turner 2008, p. 613.

- ^ Turner 2008, pp. 687–88.

- ^ Levison & Pope-Levison 2009, p. 167.

- ^ Fuller 2001, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Tuckett 2001, p. 119.

- ^ Bible, (Matthew 1:23

- ^ Senior 2001, pp. 17–18.

- ^ France 2007, pp. 179–81, 185–86.

- ^ Luz 2005b, pp. 17.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Morris 1986, p. 114.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Levine 2001, p. 373.

- ^ Edwards 2002, p. 2.

Sources[edit]

- Adamczewski, Bartosz (2010). Q or not Q? The So-Called Triple, Double, and Single Traditions in the Synoptic Gospels. Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-631-60492-2.

- Allison, D.C. (2004). Matthew: A Shorter Commentary. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08249-7.

- Aune, David E. (2001). The Gospel of Matthew in current study. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4673-0.

- —— (1987). The New Testament in its literary environment. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

- Beaton, Richard C. (2005). «How Matthew Writes». In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83285-4.

- Browning, W.R.F (2004). Oxford Dictionary of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860890-5.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian’s Account of His Life and Teaching. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Clarke, Howard W. (2003). The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34235-5.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005) [1997]. «Matthew, Gospel acc. to St.». The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1064. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Davies, William David; Allison, Dale C. (1988). A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Vol. I: Introduction and Commentary on Matthew I–VII. T&T Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0-567-09481-0.

- ——; —— (1999) [1991]. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Vol. II: Commentary on Matthew VIII–XVIII. T&T Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0-567-09545-9.

- ——; —— (1997). A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. Vol. III: Commentary on Matthew XIX–XXVIII. T&T Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0-567-08518-4.

- Duling, Dennis C. (2010). «The Gospel of Matthew». In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0825-6.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- Edwards, James (2002). The Gospel According to Mark. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85111-778-2.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512474-3.

- —— (2009). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-197702-2.

- —— (2012). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-220460-8.

- France, R.T (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2501-8.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5803-1.

- Farrer, Austin M. (1955). «On Dispensing With Q». In Nineham, Dennis E. (ed.). Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot. Oxford. pp. 55–88.

- Fuller, Reginald H. (2001). «Biblical Theology». In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Guide to Ideas & Issues of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514917-3.

- Goodacre, Mark (2002). The Case Against Q: Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem. Trinity Press International. ISBN 1-56338-334-9.

- Hagner, D.A. (1986). «Matthew, Gospel According to Matthew». In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Vol. 3: K–P. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-8163-2.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield.

- Keith, Chris (2016). «The Pericope Adulterae: A theory of attentive insertion». In Black, David Alan; Cerone, Jacob N. (eds.). The Pericope of the Adulteress in Contemporary Research. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-567-66580-5.

- Kupp, David D. (1996). Matthew’s Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God’s People in the First Gospel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57007-7.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2001). «Visions of kingdoms: From Pompey to the first Jewish revolt». In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

- Levison, J.; Pope-Levison, P. (2009). «Christology». In Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (eds.). Global Dictionary of Theology. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-7811-6.

- Luz, Ulrich (1989). Matthew 1–7. Matthew: A Commentary. Vol. 1. Translated by Linss, Wilhelm C. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8066-2402-0.

- —— (1995). The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43576-5.

- —— (2001). Matthew 8–20. Matthew: A Commentary. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-6034-5.

- —— (2005a). Matthew 21–28. Matthew: A Commentary. Vol. 3. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-3770-5.

- —— (2005b). Studies in Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3964-0.

- McMahon, Christopher (2008). «Introduction to the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles». In Ruff, Jerry (ed.). Understanding the Bible: A Guide to Reading the Scriptures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-852-8.

- Morris, Leon (1986). New Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-45571-4.

- Peppard, Michael (2011). The Son of God in the Roman World: Divine Sonship in Its Social and Political Context. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975370-3.

- Perkins, Pheme (1997). «The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story». In Kee, Howard Clark (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Interpretation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48593-2.

- Saldarini, Anthony (2003). Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Keener, Craig S. (1999). A commentary on the Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3821-6.

- Morris, Leon (1992). The Gospel according to Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-85111-338-8.

- Nolland, John (2005). The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2389-2.

- Saunders, Stanley P. (2009). «Matthew». In O’Day, Gail (ed.). Theological Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22711-1.

- Saldarini, Anthony (1994). Matthew’s Christian-Jewish Community. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73421-7.

- Sanford, Christopher B. (2005). Matthew: Christian Rabbi. Author House. ISBN 978-1-4208-8371-8.

- Scholtz, Donald (2009). Jesus in the Gospels and Acts: Introducing the New Testament. Saint Mary’s Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-955-6.

- Senior, Donald (2001). «Directions in Matthean Studies». In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Gospel of Matthew in Current Study: Studies in Memory of William G. Thompson, S.J. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-4673-4.

- Senior, Donald (1996). What are they saying about Matthew?. PaulistPress. ISBN 978-0-8091-3624-7.

- Stanton, Graham (1993). A gospel for a new people: studies in Matthew. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25499-5.

- Strecker, Georg (2000) [1996]. Theology of the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-0-664-22336-6.

- Tuckett, Christopher Mark (2001). Christology and the New Testament: Jesus and His Earliest Followers. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664224318.

- Turner, David L. (2008). Matthew. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-2684-3.

- Van de Sandt, H.W.M. (2005). «Introduction«. Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish-Christian Milieu ?. ISBN 90-232-4077-4., in Van de Sandt, H.W.M., ed. (2005). Matthew and the Didache. Royal Van Gorcum&Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.

- Wallace, Daniel B., ed. (2011). Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament: Manuscript, Patristic, and Apocryphal Evidence. Text and canon of the New Testament. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-8906-8.

- Weren, Wim (2005). «The History and Social Setting of the Matthean Community». Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish-Christian Milieu ?. ISBN 90-232-4077-4., in Van de Sandt, H.W.M, ed. (2005). Matthew and the Didache. Royal Van Gorcum&Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.

External links[edit]

- Biblegateway.com (opens at Matt.1:1, NIV)

- A textual commentary on the Gospel of Matthew Detailed text-critical discussion of the 300 most important variants of the Greek text (PDF, 438 pages).

- Early Christian Writings Gospel of Matthew: introductions and e-texts.

Bible: Matthew public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

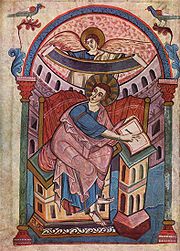

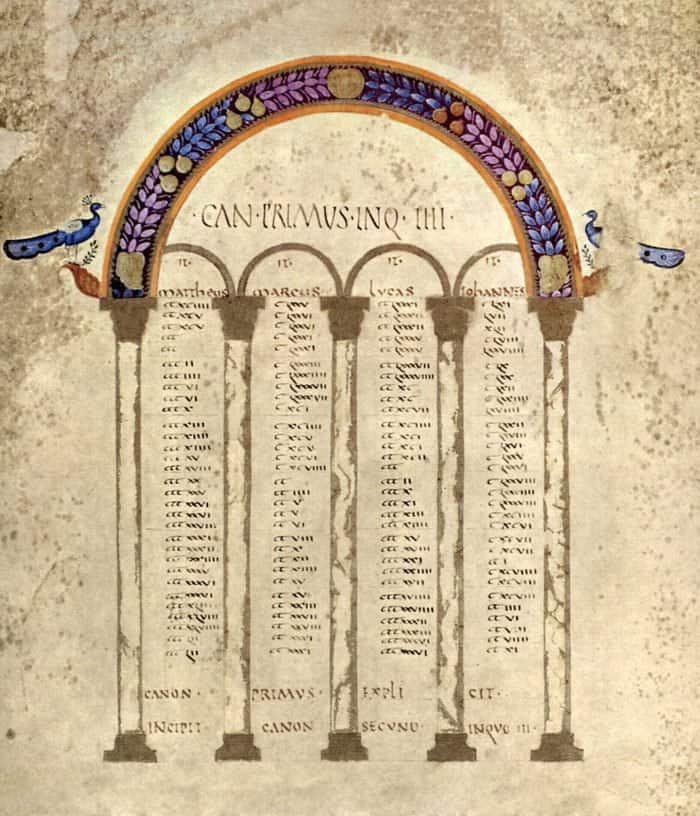

Матфей за созданием евангелия. Иллюстрация из рукописного евангелия школы Ады конца VIII — начала IX века. Библиотека Трира.

Евангелие от Матфея (греч. Ευαγγέλιον κατά Μαθθαίον или Ματθαίον) — первая книга Нового Завета и первое из четырех канонических евангелий. За ним традиционно следуют евангелия от Марка, от Луки и от Иоанна.

Содержание

- 1 Содержание и композиция

- 2 Авторство

- 2.1 Церковное предание

- 2.2 Современные исследователи

- 3 Язык

- 4 Время создания

- 5 Богословские особенности

- 6 Евангелие от Матфея в истории и культуре

- 7 Примечания

- 8 Ссылки

Содержание и композиция

Основная тема Евангелия — жизнь и проповедь Иисуса Христа, Сына Божия. Особенности Евангелия вытекают из предназначенности книги для еврейской аудитории — в Евангелии часты ссылки на мессианские пророчества Ветхого Завета, имеющие целью показать исполнение этих пророчеств в Иисусе Христе.

Начинается Евангелие с родословия Иисуса Христа, идущего по восходящей линии от Авраама до Иосифа Обручника, названного мужа Девы Марии. Это родословие, аналогичное родословие в Евангелии от Луки, и их отличия друг от друга были предметом многочисленных исследований историков и библеистов.

Главы с пятой по седьмую дают наиболее полное изложение Нагорной проповеди Иисуса, излагающей квинтессенцию христианского учения, в том числе заповеди блаженства (5:2-11) и молитву Отче наш (6:9-13).

Речи и деяния Спасителя евангелист излагает в трёх разделах, соответствующих трём сторонам служения Мессии: как Пророка и Законодателя (гл. 5 — 7), Царя над миром видимым и невидимым (гл. 8 — 25) и Первосвященника, приносящего себя в жертву за грехи всех людей (гл. 26 — 27).