Знак евро

Знак евро (€) — это символ официальной валюты Евросоюза. Он был основан на греческой букве эпсилон (ε). Также он похож на первую букву слова «Европа». Две параллельные линии символа представляют собой стабильность этой валюты.

Как набрать знак евро

| Метод | Сочетание клавиш |

|---|---|

| Скопировать значок евро | € (Ctrl + C -> Ctrl + V) |

| Значок евро на клавиатуре |

|

| Значок евро в word и в excel |

|

| Знак евро на клавиатуре windows |

|

| Знак евро на клавиатуре Mac | Alt + Shift + 2 |

Другие символы

| Знак рубля |

|

|---|---|

| Значок доллара |

|

| Любой символ | в английской раскладке: Win + R -> ввести в окно: charmap -> OK |

Краткая история евро

Решение о названии «евро» было принято в 1995 году на заседании Европейского Совета в Мадриде.

Эту валюту сначала ввели в виртуальной форме (1 января 1999 года), а в физической (в виде банкнот и монет) она появилась только 1 января 2002 года.

Создателем символа евро был графический дизайнер Артур Айзенменгер, который также создал Европейский флаг и знак CE («европейское соответствие»).

Символ евро ставится перед числом или после?

В большинстве случаев символ евро ставится перед числом (например, € 6,99), но в некоторых странах его могут помещать и после. Знак фунта тоже ставится перед числом (например, £1,999.00).

Узнайте, что такое Криптовалюта и Европа.

Знак евро

Евро ( Euro )

Евро — официальная валюта в странах т.н. «Еврозоны». Международное обозначение Евро — €. Латиницей название записывается как Euro (с прописной или строчной буквы — по-разному в разных языках); по-гречески — Ευρω ; кириллическое написание — Евро (в болгарском, македонском, русском и сербском; в Черногории употребляется вариант Еуро ).

В безналичных расчетах новая денежная единица Евросоюза была введена с 1 января 1999, заменив собой ЭКЮ; в наличных — с 1 января 2002. К 2015 году на Евро перешли 19 (из 27) стран Европейского Союза:

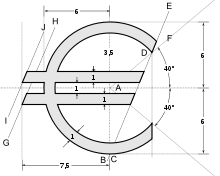

Официальная спецификация знака Евро

Варианты начертания знака Евро

В Великобритании, Швеции, Дании решили не заменять национальную валюту. Латвия и Литва планировали перейти на Евро в 2009 году, но переход был отложен (Латвия таки перешла с 2014, а Литва — с 2015). Болгария и Венгрия планировали перейти на Евро к 2010 году, но этот переход тоже отложен, Чехия и Польша — к 2011 (тоже пока не перешли), Румыния — к 2014 (тоже нет). Помимо этого, Евро официально используют страны, не являющиеся членами ЕС: Ватикан, Монако, Сан-Марино. Неофициально Евро также используется в Андорре, Черногории и автономном крае Косово.

Основная проблема с данным знаком заключается в том, что он слишком жестко описан и мало подвержен гарнитурным вариациям (см. выше рисунок с официальной спецификацией). Из-за этого Еврокомиссии пришлось переписывать правила использования знака, остановившись в конце концов на том, что это просто официальный знак, но в нем есть определенные признаки, которые должны обязательно присутствовать, когда этот знак рисуется для какого-либо шрифта. Поэтому шрифтовые вариации зачастую далеко отступают от официальной спецификации; единственное, что остается неизменным — загогулина (для которой, как правило, берется прописная литера C ), перечеркнутая двумя горизонтальными линиями.

Расположение знака по отношению к цифрам, обозначающим денежную сумму, отличается от страны к стране. Хотя официально рекомендуется помещать его перед цифрами, но, как правило, знак € располагают так же, как это было принято для национальных валют стран Еврозоны ранее, до ввода в действие Евро.

Запись в HTML €

€ Кодировка UNICODE U + 20AC

Еще раз — полная таблица со всеми знаками валют:

|

Универсальное обозначение валюты | Generic currency symbol | ¤ | |||

| Украинская валюта | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Гривна | Украина | Hryvnia | UAH | ₴ | грн |

| Основные валюты | ||||||

|

Доллар | США | Dollar | USD | $ | |

|

Евро | Европейский Союз | Euro | EUR | € | |

|

Фунт Стерлингов | Великобритания | Pound Sterling | GBP | £ | |

|

Иена | Япония | Yen | JPY | ¥ | 円 圓 |

|

Юань | Китай | Yuán | CNY | ¥ | 元 圓 |

|

Рубль | Россия | Ruble | RUB | ₽ | руб. |

| Прочие валюты | ||||||

|

Шекель | Израиль | Sheqel | ILS | ₪ | |

|

Рупия | Индия | Rupee | INR | ₨ | Rs Rp ₹ |

|

Вона | Корея | Won | KRW | ₩ | |

|

Наира | Нигерия | Naira | NGN | ₦ | |

|

Бат | Таиланд | Baht | THB | ฿ | |

|

Донг | Вьетнам | Dông | VND | ₫ | |

|

Кип | Лаос | Kip | LAK | ₭ | |

|

Риель | Камбоджа | Riel | KHR | ៛ | |

|

Тугрик | Монголия | Tögrög | MNT | ₮ | |

|

Песо | Филиппины | Peso | PHP | ₱ | |

|

Риал | Иран | Rial | IRR | ﷼ | |

|

Колон | Коста-Рика | Colon | CRC | ₡ | |

|

Гуарани | Парагвай | Guarani | PYG | ₲ | G. |

|

Афгани | Афганистан | Afghani | AFN | ؋ | |

|

Седи | Гана | Cedi | GHS | ₵ | |

|

Тенге | Казахстан | Tenge | KZT | ₸ | |

|

Турецкая лира | Турция | Turkish Lira | TRY | ₺ | TL |

|

Манат | Азербайджан | Manat | AZN | ₼ | |

|

Лари | Грузия | Lari | GEL | ₾ | ლ |

|

Злотый | Польша | Złoty | PLN | Zł | |

| Устаревшие валюты | ||||||

|

ЭКЮ | Европейское Сообщество | ECU | XEU | ₠ | |

|

Песета | Испания | Peseta | ESP | ₧ | Pts |

|

Франк | Франция | Franc | FRF | ₣ | F |

|

Лира | Италия | Lira | ITL | ₤ | |

|

Флорин Гульден |

Нидерланды | Florin Gulden |

NLG | ƒ | |

|

Драхма | Греция | Drachma | GRD | ₯ | |

|

Крузейро | Бразилия | Cruzeiro | BRZ | ₢ | Cr |

|

Аустрал | Аргентина | Austral | ARA | ₳ | |

| Производные денежные единицы | ||||||

|

Цент | 1 /100 доллара | Cent | ¢ | c | |

|

Милль | 1 /1000 доллара | Mill | ₥ | ||

|

Пфенниг | 1 /100 марки | Pfennig | ₰ | ||

| Bitcoin (куда ж без него:) Bitcoin | BTC |

Таблица условных обозначений валют

Если у вас вместо символов, обозначающих ту или иную валюту, видны прямоугольники, либо другие непонятные символы, не соответствующие их графическому представлению, показанному в левой колонке — это значит, что на вашем компьютере не устанвлены новые шрифты для поддержки данных обозначений. Ничего страшного.

Источник

Знаки валют

Универсальное обозначение валюты ( Generic currency symbol )

Этот символ используется как универсальное обозначение для любой валюты, но как правило — для обозначения редко используемых валют в случае отсутствия соответствующего специального знака. В общем, запись знака ¤ с последующей денежной суммой обозначает соответствующее количество единиц некоторой валюты (какой конкретно — должно быть понятно из контекста документа).

Запись в HTML ¤

¤ Кодировка UNICODE U + 00A4

На Minfin.com.ua можно подбирать депозиты легко в разных украинских банках. С помощью депозитного калькулятора можно рассчитать прибыльность по вкладу. На кредитном каталоге вы можете удобно подобрать кредит без отказа, микрозайм, круглосуточный кредит и другие виды онлайн кредитов.

актуальные курсы валют с разных источников: НБУ, межбанка и курсы в банках Украины.

Еще раз — полная таблица со всеми знаками валют:

|

Универсальное обозначение валюты | Generic currency symbol | ¤ | |||

| Украинская валюта | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Гривна | Украина | Hryvnia | UAH | ₴ | грн |

| Основные валюты | ||||||

|

Доллар | США | Dollar | USD | $ | |

|

Евро | Европейский Союз | Euro | EUR | € | |

|

Фунт Стерлингов | Великобритания | Pound Sterling | GBP | £ | |

|

Иена | Япония | Yen | JPY | ¥ | 円 圓 |

|

Юань | Китай | Yuán | CNY | ¥ | 元 圓 |

|

Рубль | Россия | Ruble | RUB | ₽ | руб. |

| Прочие валюты | ||||||

|

Шекель | Израиль | Sheqel | ILS | ₪ | |

|

Рупия | Индия | Rupee | INR | ₨ | Rs Rp ₹ |

|

Вона | Корея | Won | KRW | ₩ | |

|

Наира | Нигерия | Naira | NGN | ₦ | |

|

Бат | Таиланд | Baht | THB | ฿ | |

|

Донг | Вьетнам | Dông | VND | ₫ | |

|

Кип | Лаос | Kip | LAK | ₭ | |

|

Риель | Камбоджа | Riel | KHR | ៛ | |

|

Тугрик | Монголия | Tögrög | MNT | ₮ | |

|

Песо | Филиппины | Peso | PHP | ₱ | |

|

Риал | Иран | Rial | IRR | ﷼ | |

|

Колон | Коста-Рика | Colon | CRC | ₡ | |

|

Гуарани | Парагвай | Guarani | PYG | ₲ | G. |

|

Афгани | Афганистан | Afghani | AFN | ؋ | |

|

Седи | Гана | Cedi | GHS | ₵ | |

|

Тенге | Казахстан | Tenge | KZT | ₸ | |

|

Турецкая лира | Турция | Turkish Lira | TRY | ₺ | TL |

|

Манат | Азербайджан | Manat | AZN | ₼ | |

|

Лари | Грузия | Lari | GEL | ₾ | ლ |

|

Злотый | Польша | Złoty | PLN | Zł | |

| Устаревшие валюты | ||||||

|

ЭКЮ | Европейское Сообщество | ECU | XEU | ₠ | |

|

Песета | Испания | Peseta | ESP | ₧ | Pts |

|

Франк | Франция | Franc | FRF | ₣ | F |

|

Лира | Италия | Lira | ITL | ₤ | |

|

Флорин Гульден |

Нидерланды | Florin Gulden |

NLG | ƒ | |

|

Драхма | Греция | Drachma | GRD | ₯ | |

|

Крузейро | Бразилия | Cruzeiro | BRZ | ₢ | Cr |

|

Аустрал | Аргентина | Austral | ARA | ₳ | |

| Производные денежные единицы | ||||||

|

Цент | 1 /100 доллара | Cent | ¢ | c | |

|

Милль | 1 /1000 доллара | Mill | ₥ | ||

|

Пфенниг | 1 /100 марки | Pfennig | ₰ | ||

| Bitcoin (куда ж без него:) Bitcoin | BTC |

Таблица условных обозначений валют

Если у вас вместо символов, обозначающих ту или иную валюту, видны прямоугольники, либо другие непонятные символы, не соответствующие их графическому представлению, показанному в левой колонке — это значит, что на вашем компьютере не устанвлены новые шрифты для поддержки данных обозначений. Ничего страшного.

Источник

Давайте раз и навсегда закроем вопрос о том, как правильно писать валюты.

Вот рубль по-русски можно написать такими вариантами: руб., р., ₽, RUB, RUR.

А вот варианты с долларами: доллары, $, USD.

Так какой вариант выбрать? А как писать: в начале или в конце? А пробел нужен?

Лебедев в своем «Ководстве» пишет:

Как бы соблазнительно ни выглядел доллар слева от суммы, писать его в русских текстах можно только справа. (Исключение могут составлять финансовые и биржевые тексты, но это отраслевой стандарт, который не может распространяться на остальные области.)

Артемий Лебедев

Так же он отмечает:

В русском языке единица измерения, стоящая перед значением, означает примерно столько: «долларов сто». А не писать пробел перед знаком доллара, это все равно что писать 50руб.

Артемий Лебевев

Илья Бирман с этим не согласился.

Лебедев не понимает, что $ — это знак, а не сокращение. Когда написано «$100» я это читаю «сто долларов», и мне нисколько не мешает, что знак $ стоит перед числом. И ни одному человеку в мире это не мешает. Знак доллара всегда и везде ставятся перед числом, и без пробела; <…>

Илья Бирман

Потом, однако, признал в этом свою неправоту.

Есть очень много ясности в вопросах использования. И много темных мест.

Я много времени проработал дизайнером финансовых продуктов и теперь точно знаю, как надо.

Однозначные символы: $, ¥, ₽, €, ₣, £, ₩,…

Это все типографские символы. Лигатуры. Они входят в Стандарт Юникод, но не стандартизированы в ISO по правилам их использования.

Символы валют очень популярны, вы встретите их везде: на ценниках, в банковских приложениях, в общих и тематических статьях.

Однозначные символы нативны. Часто, они изображены на самих купюрах. Люди их быстро узнают и легко считывают. А значок доллара вообще равен значку денег.

Много, однако, неясностей.

Где писать?

Непонятно где их ставить, в начале или в конце? Лебедев топит за то, что нужно писать в конце, якобы в России у нас так. А если это международный сервис? Например, интернет-магазин, локализованный на разных языках. На русском писать так, а на английском по-другому?

Пробел нужен?

В США пишут без пробела $100 (хотя тоже не всегда). У нас символ ₽ намекает на то, что это единица изменения, хотя это спорно. По системе СИ единица изменения пишется через пробел и точка в конце не ставится.

Чей доллар?

Мало кто знает, но доллар – это название валюты очень многих стран. Не только США. Есть например, австралийский доллар, канадский, либерийский, доллар Намибии и еще пару десятков стран. Все они обозначаются символом $.

А еще есть аргентинское песо, боливийский боливиано, бразильский реал, кабо-вердийский эскудо и еще много валют, которые вообще не доллары, но обозначаются значком $.

Как тут быть, если в одной системе я использую сразу несколько из этих валют? Как их различать между собой?

Боливиец живет в своей стране, заходит в магазин, видит ценники и понимает, что условно, хлеб за 10 $ – это значит хлеб за десять боливийский боливиано.

А что случается, когда он заходит на брокерскую биржу, где целая система разных международных валют?

Символ?

Вообще не у всех валют есть однозначные символы. Их очень мало. Все, что есть в заголовке этого раздела и еще пару символов, этим наверное и ограничится. Если вы знаете еще какие-нибудь символы, напишите, пожалуйста, в комментарии.

Большая часть валют вообще не использует лигатуры: арабский дирхам, бахрейнский динар, белорусский рубль, венгерский форинт.

А даже если есть, то не факт, что они будут в Юникоде. А даже если есть в Юникоде, то не факт, что они будут в гарнитуре, которую вы используете в своем проекте. Попробуйте, например в Фигме ввести символ армянского драма ֏ на разных гарнитурах.

Как вводить?

На Windows все зависит от клавиатуры, с которой вы вводите. На клавиатуре Apple с русской раскладкой символ ₽ доступен по Alt + р.

Значок доллара тоже $ доступен, но не просто. На Mac OS, например нужно переключиться на английскую раскладку и потом Shift + 4. Со значком евро еще сложнее: на английской раскладке Shif + Alt + 4.

Остальные символы не доступны на клавиатурах, поэтому их придется гуглить.

Многозначные коды: USD, RUB, BTC, ETH, …

Коды валют стандартизированы в ISO 4217 и все они трехзначные. Вроде все круто, есть международный стандарт, будем его придерживаться. Но и здесь есть непонятные места.

Проблема в том, что этот стандарт не учитывает валюты непризнанных государств, типа приднестровского рубля RUP или абхазского апсара LTU. А в целом на этой можно закрыть глаза

Так же в этом стандарте нет криптовалют. Тоже можно закрыть глаза. Но криптовалют много. На сегодняшний день их более 18-ти тысяч, а количество комбинаций их трехзначных символов латинского алфавита составляет 17576. Поэтому очень много криптовалют используют четыре знака: FLOW, USDT, MANA, NEXO.

Где писать?

Все просто. Стандарт ISO 4217 не регламентирует с какой стороны от числа нужно писать код валюты, мол, придерживайтесь тех традиций, которые установлены в вашей системе.

Пробел?

Пробел точно ставится в любом случае.

Сокращения: руб., р., дол., …

В сокращенной англоязычной культуре не приняты сокращения (хотя раньше сокращали).

В России мы чаще всего видим именно сокращения р. или руб. вместо ₽.

Пробел и точка?

Пробел в русском языке обязательно.

Точка нужна, так как это не единица измерения, а сокращение слова «рубль».

Решение

Решение опубликую завтра утром. А пока что подпишитесь, пожалуйста на мой телеграм-канал.

| see also § euro in various languages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| ISO 4217 | ||||

| Code | EUR (numeric: 978) | |||

| Subunit | 0.01 | |||

| Unit | ||||

| Unit | euro | |||

| Plural | Varies, see language and the euro | |||

| Symbol | € | |||

| Nickname | The single currency[1] | |||

| Denominations | ||||

| Subunit | ||||

| 1⁄100 | cent (Name varies by language) |

|||

| Plural | ||||

| cent | (Varies by language) | |||

| Symbol | ||||

| cent | c | |||

| Banknotes | ||||

| Freq. used | €5, €10, €20, €50, €100[2] | |||

| Rarely used | €200, €500[2] | |||

| Coins | ||||

| Freq. used | 1c, 2c, 5c, 10c, 20c, 50c, €1, €2 | |||

| Rarely used | 1c, 2c (Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands[3]) | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| User(s) | primary: § members of Eurozone (20), also: § other users |

|||

| Issuance | ||||

| Central bank | Eurosystem | |||

| Website | www.ecb.europa.eu | |||

| Printer | see § Banknote printing | |||

| Mint | see § Coin minting | |||

| Valuation | ||||

| Inflation | 8.6% (June 2022)[4] | |||

| Source | ec.europa.eu | |||

| Method | HICP | |||

| Pegged by | see § Pegged currencies |

Euro Monetary policy

Euro Zone inflation year/year

M3 money supply increases

Marginal Lending Facility

Main Refinancing Operations

Deposit Facility Rate

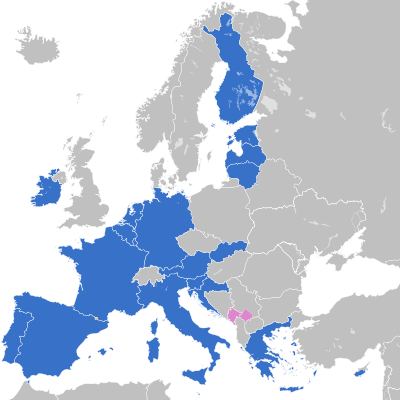

The euro (symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 20 of the 27 member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 344 million citizens as of 2023. The euro is divided into 100 cents.[5][6]

The currency is also used officially by the institutions of the European Union, by four European microstates that are not EU members,[6] the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, as well as unilaterally by Montenegro and Kosovo. Outside Europe, a number of special territories of EU members also use the euro as their currency. Additionally, over 200 million people worldwide use currencies pegged to the euro.

The euro is the second-largest reserve currency as well as the second-most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.[7][8][9][10][11] As of December 2019, with more than €1.3 trillion in circulation, the euro has one of the highest combined values of banknotes and coins in circulation in the world.[12][13]

The name euro was officially adopted on 16 December 1995 in Madrid.[14] The euro was introduced to world financial markets as an accounting currency on 1 January 1999, replacing the former European Currency Unit (ECU) at a ratio of 1:1 (US$1.1743). Physical euro coins and banknotes entered into circulation on 1 January 2002, making it the day-to-day operating currency of its original members, and by March 2002 it had completely replaced the former currencies.[15]

Between December 1999 and December 2002, the euro traded below the US dollar, but has since traded near parity with or above the US dollar, peaking at US$1.60 on 18 July 2008 and since then returning near to its original issue rate. On 13 July 2022, the two currencies hit parity for the first time in nearly two decades due in part to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[16]

Characteristics[edit]

Administration[edit]

The euro is managed and administered by the European Central Bank (ECB, Frankfurt am Main) and the Eurosystem (composed of the central banks of the eurozone countries). As an independent central bank, the ECB has sole authority to set monetary policy. The Eurosystem participates in the printing, minting and distribution of notes and coins in all member states, and the operation of the eurozone payment systems.

The 1992 Maastricht Treaty obliges most EU member states to adopt the euro upon meeting certain monetary and budgetary convergence criteria, although not all participating states have done so. Denmark has negotiated exemptions,[17] while Sweden (which joined the EU in 1995, after the Maastricht Treaty was signed) turned down the euro in a non-binding referendum in 2003, and has circumvented the obligation to adopt the euro by not meeting the monetary and budgetary requirements. All nations that have joined the EU since 1993 have pledged to adopt the euro in due course. The Maastricht Treaty was later amended by the Treaty of Nice,[18] which closed the gaps and loopholes in the Maastricht and Rome Treaties.

Eurozone members[edit]

The 20 participating members are

- Austria

- Belgium

- Croatia

- Cyprus[note 1]

- Estonia

- Finland

- France[note 2]

- Germany

- Greece

- Ireland

- Italy

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Netherlands[note 3]

- Portugal

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

EU members not using the euro[edit]

The EU member states not in the Eurozone are Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden.

Future eurozone members[edit]

The Bulgarian lev is targeted to be replaced by the euro on 1 January 2025.[19][20][21]

The Romanian leu is targeted to be replaced by the euro sometime in 2029.

EU members Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Sweden are legally obligated to adopt the euro eventually, though they have no required date for adoption, and their governments do not currently have any plans for switching. Denmark has negotiated for the right to not be required to switch.

Other users[edit]

Microstates with a monetary agreement:

- Andorra[22]

- Monaco[23]

- San Marino[24]

- Vatican City[25]

EU special territories

- French Southern and Antarctic Lands

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon[26]

Unilateral adopters

- Kosovo[27]

- Montenegro[note 4]

Pegged currencies[edit]

The currency of a number of states is pegged to the euro. These states are:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, ISO 4217 code BAM)

- Bulgaria (Bulgarian lev, BGN)

- Cape Verde (Cape Verdean escudo, CVE)

- Cameroon (Central African CFA franc, XAF)

- Central African Republic (Central African CFA franc)

- Chad (Central African CFA franc)

- Equatorial Guinea (Central African CFA franc)

- Gabon (Central African CFA franc)

- Republic of the Congo (Central African CFA franc)

- French Polynesia (CFP franc, XFP)

- New Caledonia (CFP franc)

- Wallis and Futuna (CFP franc)

- Comoros (Comorian franc, KMF)

- Denmark (Danish krone, DKK)

- North Macedonia (Macedonian denar, MKD)[28]

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta (Maltese scudo)[29]

- São Tomé and Príncipe (São Tomé and Príncipe dobra, STN)

- Benin (West African CFA franc, XOF)

- Burkina Faso (West African CFA franc)

- Côte d’Ivoire (West African CFA franc)

- Guinea-Bissau (West African CFA franc)

- Mali (West African CFA franc)

- Niger (West African CFA franc)

- Senegal (West African CFA franc)

- Togo (West African CFA franc)

Coins and banknotes[edit]

Coins[edit]

The euro is divided into 100 cents (also referred to as euro cents, especially when distinguishing them from other currencies, and referred to as such on the common side of all cent coins). In Community legislative acts the plural forms of euro and cent are spelled without the s, notwithstanding normal English usage.[30][31] Otherwise, normal English plurals are used,[32] with many local variations such as centime in France.

All circulating coins have a common side showing the denomination or value, and a map in the background. Due to the linguistic plurality in the European Union, the Latin alphabet version of euro is used (as opposed to the less common Greek or Cyrillic) and Arabic numerals (other text is used on national sides in national languages, but other text on the common side is avoided). For the denominations except the 1-, 2- and 5-cent coins, the map only showed the 15 member states which were members when the euro was introduced. Beginning in 2007 or 2008 (depending on the country), the old map was replaced by a map of Europe also showing countries outside the EU.[citation needed] The 1-, 2- and 5-cent coins, however, keep their old design, showing a geographical map of Europe with the 15 member states of 2002 raised somewhat above the rest of the map. All common sides were designed by Luc Luycx. The coins also have a national side showing an image specifically chosen by the country that issued the coin. Euro coins from any member state may be freely used in any nation that has adopted the euro.

The coins are issued in denominations of €2, €1, 50c, 20c, 10c, 5c, 2c, and 1c. To avoid the use of the two smallest coins, some cash transactions are rounded to the nearest five cents in the Netherlands and Ireland[33][34] (by voluntary agreement) and in Finland and Italy (by law).[35] This practice is discouraged by the commission, as is the practice of certain shops of refusing to accept high-value euro notes.[36]

Commemorative coins with €2 face value have been issued with changes to the design of the national side of the coin. These include both commonly issued coins, such as the €2 commemorative coin for the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome, and nationally issued coins, such as the coin to commemorate the 2004 Summer Olympics issued by Greece. These coins are legal tender throughout the eurozone. Collector coins with various other denominations have been issued as well, but these are not intended for general circulation, and they are legal tender only in the member state that issued them.[37]

Coin minting[edit]

A number of institutions are authorised to mint euro coins:

- Bayerisches Hauptmünzamt, Munich (Mint mark: D)

- Currency Centre

- Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre

- Hamburgische Münze (J)

- Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda SA

- Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato

- Koninklijke Nederlandse Munt

- Koninklijke Munt van België/Monnaie Royale de Belgique

- Mincovňa Kremnica

- Monnaie de Paris

- Münze Österreich

- Rahapaja Oy/Myntverket i Finland Ab

- Staatliche Münze Berlin (A)

- Staatliche Münze Karlsruhe (G)

- Staatliche Münze Stuttgart (F)

- Lithuanian Mint

- Croatian Mint

Banknotes[edit]

The design for the euro banknotes has common designs on both sides. The design was created by the Austrian designer Robert Kalina.[38] Notes are issued in €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10, and €5. Each banknote has its own colour and is dedicated to an artistic period of European architecture. The front of the note features windows or gateways while the back has bridges, symbolising links between states in the union and with the future. While the designs are supposed to be devoid of any identifiable characteristics, the initial designs by Robert Kalina were of specific bridges, including the Rialto and the Pont de Neuilly, and were subsequently rendered more generic; the final designs still bear very close similarities to their specific prototypes; thus they are not truly generic. The monuments looked similar enough to different national monuments to please everyone.[39]

The Europa series, or second series, consists of six denominations and no longer includes the €500 with issuance discontinued as of 27 April 2019.[40] However, both the first and the second series of euro banknotes, including the €500, remain legal tender throughout the euro area.[40]

In December 2021, the ECB announced its plans to redesign euro banknotes by 2024. A theme advisory group, made up of one member from each euro area country, was selected to submit theme proposals to the ECB. The proposals will be voted on by the public; a design competition will also be held.[41]

Issuing modalities for banknotes[edit]

Since 1 January 2002, the national central banks (NCBs) and the ECB have issued euro banknotes on a joint basis.[42] Eurosystem NCBs are required to accept euro banknotes put into circulation by other Eurosystem members and these banknotes are not repatriated. The ECB issues 8% of the total value of banknotes issued by the Eurosystem.[42] In practice, the ECB’s banknotes are put into circulation by the NCBs, thereby incurring matching liabilities vis-à-vis the ECB. These liabilities carry interest at the main refinancing rate of the ECB. The other 92% of euro banknotes are issued by the NCBs in proportion to their respective shares of the ECB capital key,[42] calculated using national share of European Union (EU) population and national share of EU GDP, equally weighted.[43]

Banknote printing[edit]

Member states are authorised to print or to commission bank note printing. As of November 2022, these are the printers:

- Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato

- Banco de Portugal

- Bank of Greece

- Banque de France

- Bundesdruckerei

- Central Bank of Ireland

- De La Rue

- Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre

- François-Charles Oberthur

- Giesecke & Devrient

- Royal Joh. Enschedé

- National Bank of Belgium

- Oesterreichische Nationalbank

- Setec Oy

Payments clearing, electronic funds transfer[edit]

Capital within the EU may be transferred in any amount from one state to another. All intra-Union transfers in euro are treated as domestic transactions and bear the corresponding domestic transfer costs.[44] This includes all member states of the EU, even those outside the eurozone providing the transactions are carried out in euro.[45] Credit/debit card charging and ATM withdrawals within the eurozone are also treated as domestic transactions; however paper-based payment orders, like cheques, have not been standardised so these are still domestic-based. The ECB has also set up a clearing system, TARGET, for large euro transactions.[46]

History[edit]

Introduction[edit]

| Currency | Code | Rate[47] | Fixed on | Yielded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austrian schilling | ATS | 13.7603 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Belgian franc | BEF | 40.3399 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Dutch guilder | NLG | 2.20371 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Finnish markka | FIM | 5.94573 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| French franc | FRF | 6.55957 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| German mark | DEM | 1.95583 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Irish pound | IEP | 0.787564 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Italian lira | ITL | 1,936.27 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Luxembourg franc | LUF | 40.3399 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Portuguese escudo | PTE | 200.482 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Spanish peseta | ESP | 166.386 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Greek drachma | GRD | 340.75 | 19 June 2000 | 1 January 2001 |

| Slovenian tolar | SIT | 239.64 | 11 July 2006 | 1 January 2007 |

| Cypriot pound | CYP | 0.585274 | 10 July 2007 | 1 January 2008 |

| Maltese lira | MTL | 0.4293 | 10 July 2007 | 1 January 2008 |

| Slovak koruna | SKK | 30.126 | 8 July 2008 | 1 January 2009 |

| Estonian kroon | EEK | 15.6466 | 13 July 2010 | 1 January 2011 |

| Latvian lats | LVL | 0.702804 | 9 July 2013 | 1 January 2014 |

| Lithuanian litas | LTL | 3.4528 | 23 July 2014 | 1 January 2015 |

| Croatian kuna | HRK | 7.5345 | 12 July 2022 | 1 January 2023 |

The euro was established by the provisions in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. To participate in the currency, member states are meant to meet strict criteria, such as a budget deficit of less than 3% of their GDP, a debt ratio of less than 60% of GDP (both of which were ultimately widely flouted after introduction), low inflation, and interest rates close to the EU average. In the Maastricht Treaty, the United Kingdom and Denmark were granted exemptions per their request from moving to the stage of monetary union which resulted in the introduction of the euro.

The name «euro» was officially adopted in Madrid on 16 December 1995.[14] Belgian Esperantist Germain Pirlot, a former teacher of French and history, is credited with naming the new currency by sending a letter to then President of the European Commission, Jacques Santer, suggesting the name «euro» on 4 August 1995.[48]

Due to differences in national conventions for rounding and significant digits, all conversion between the national currencies had to be carried out using the process of triangulation via the euro. The definitive values of one euro in terms of the exchange rates at which the currency entered the euro are shown on the right.

The rates were determined by the Council of the European Union,[note 5] based on a recommendation from the European Commission based on the market rates on 31 December 1998. They were set so that one European Currency Unit (ECU) would equal one euro. The European Currency Unit was an accounting unit used by the EU, based on the currencies of the member states; it was not a currency in its own right. They could not be set earlier, because the ECU depended on the closing exchange rate of the non-euro currencies (principally sterling) that day.

The procedure used to fix the conversion rate between the Greek drachma and the euro was different since the euro by then was already two years old. While the conversion rates for the initial eleven currencies were determined only hours before the euro was introduced, the conversion rate for the Greek drachma was fixed several months beforehand.[note 6]

The currency was introduced in non-physical form (traveller’s cheques, electronic transfers, banking, etc.) at midnight on 1 January 1999, when the national currencies of participating countries (the eurozone) ceased to exist independently. Their exchange rates were locked at fixed rates against each other. The euro thus became the successor to the European Currency Unit (ECU). The notes and coins for the old currencies, however, continued to be used as legal tender until new euro notes and coins were introduced on 1 January 2002.

The changeover period during which the former currencies’ notes and coins were exchanged for those of the euro lasted about two months, until 28 February 2002. The official date on which the national currencies ceased to be legal tender varied from member state to member state. The earliest date was in Germany, where the mark officially ceased to be legal tender on 31 December 2001, though the exchange period lasted for two months more. Even after the old currencies ceased to be legal tender, they continued to be accepted by national central banks for periods ranging from several years to indefinitely (the latter for Austria, Germany, Ireland, Estonia and Latvia in banknotes and coins, and for Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Slovakia in banknotes only). The earliest coins to become non-convertible were the Portuguese escudos, which ceased to have monetary value after 31 December 2002, although banknotes remained exchangeable until 2022.

Currency sign[edit]

The euro sign; logotype and handwritten

A special euro currency sign (€) was designed after a public survey had narrowed the original ten proposals down to two. The European Commission then chose the design created by the Belgian artist Alain Billiet. Of the symbol, the Commission stated[30]

Inspiration for the € symbol itself came from the Greek epsilon (Є)[note 7] – a reference to the cradle of European civilisation – and the first letter of the word Europe, crossed by two parallel lines to ‘certify’ the stability of the euro.

The European Commission also specified a euro logo with exact proportions and foreground and background colour tones.[49] Placement of the currency sign relative to the numeric amount varies from state to state, but for texts in English the symbol (or the ISO-standard «EUR») should precede the amount.[50]

Eurozone crisis[edit]

Budget deficit of the eurozone compared to the United States and the United Kingdom.

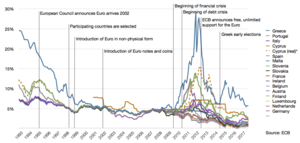

Following the U.S. financial crisis in 2008, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed in 2009 among investors concerning some European states, with the situation becoming particularly tense in early 2010.[51][52] Greece was most acutely affected, but fellow Eurozone members Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain were also significantly affected.[53][54] All these countries used EU funds except Italy, which is a major donor to the EFSF.[55] To be included in the eurozone, countries had to fulfil certain convergence criteria, but the meaningfulness of such criteria was diminished by the fact it was not enforced with the same level of strictness among countries.[56]

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2011, «[I]f the [euro area] is treated as a single entity, its [economic and fiscal] position looks no worse and in some respects, rather better than that of the US or the UK» and the budget deficit for the euro area as a whole is much lower and the euro area’s government debt/GDP ratio of 86% in 2010 was about the same level as that of the United States. «Moreover», they write, «private-sector indebtedness across the euro area as a whole is markedly lower than in the highly leveraged Anglo-Saxon economies». The authors conclude that the crisis «is as much political as economic» and the result of the fact that the euro area lacks the support of «institutional paraphernalia (and mutual bonds of solidarity) of a state».[57]

The crisis continued with S&P downgrading the credit rating of nine euro-area countries, including France, then downgrading the entire European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) fund.[58]

A historical parallel – to 1931 when Germany was burdened with debt, unemployment and austerity while France and the United States were relatively strong creditors – gained attention in summer 2012[59] even as Germany received a debt-rating warning of its own.[60][61] In the enduring of this scenario the euro serves as a mean of quantitative primitive accumulation.

Direct and indirect usage[edit]

Agreed direct usage with minting rights[edit]

The euro is the sole currency of 20 EU member states: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. These countries constitute the «eurozone», some 347 million people in total as of 2023.[62] According to bilateral agreements with the EU, the euro has also been designated as the sole and official currency in a further four European microstates awarded minting rights (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City). With all but one (Denmark) EU members obliged to join when economic conditions permit, together with future members of the EU, the enlargement of the eurozone is set to continue.

Agreed direct usage without minting rights[edit]

The euro is also the sole currency in three overseas territories of France that are not themselves part of the EU, namely Saint Barthélemy, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, as well as in the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

Unilateral direct usage[edit]

The euro has been adopted unilaterally as the sole currency of Montenegro and Kosovo. It has also been used as a foreign trading currency in Cuba since 1998,[63] Syria since 2006,[64] and Venezuela since 2018.[65] In 2009, Zimbabwe abandoned its local currency and introduced major global convertible currencies instead, including the euro and the United States dollar. The direct usage of the euro outside of the official framework of the EU affects nearly 3 million people.[66]

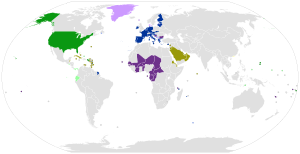

Currencies pegged to the euro[edit]

Worldwide use of the euro and the US dollar:

External adopters of the euro

Currencies pegged to the euro

Currencies pegged to the euro within narrow band

United States

External adopters of the US dollar

Currencies pegged to the US dollar

Currencies pegged to the US dollar within narrow band

Note: The Belarusian rouble is pegged to the euro, Russian rouble and US dollar in a currency basket.

Outside the eurozone, two EU member states have currencies that are pegged to the euro, which is a precondition to joining the eurozone. The Danish krone and Bulgarian lev are pegged due to their participation in the ERM II.

Additionally, a total of 21 countries and territories that do not belong to the EU have currencies that are directly pegged to the euro including 14 countries in mainland Africa (CFA franc), two African island countries (Comorian franc and Cape Verdean escudo), three French Pacific territories (CFP franc) and two Balkan countries, Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark) and North Macedonia (Macedonian denar).[28] On 1 January 2010, the dobra of São Tomé and Príncipe was officially linked with the euro.[67] Additionally, the Moroccan dirham is tied to a basket of currencies, including the euro and the US dollar, with the euro given the highest weighting.

These countries generally had previously implemented a currency peg to one of the major European currencies (e.g. the French franc, deutschmark or Portuguese escudo), and when these currencies were replaced by the euro their currencies became pegged to the euro. Pegging a country’s currency to a major currency is regarded as a safety measure, especially for currencies of areas with weak economies, as the euro is seen as a stable currency, prevents runaway inflation, and encourages foreign investment due to its stability.

In total, as of 2013, 182 million people in Africa use a currency pegged to the euro, 27 million people outside the eurozone in Europe, and another 545,000 people on Pacific islands.[62]

Since 2005, stamps issued by the Sovereign Military Order of Malta have been denominated in euro, although the Order’s official currency remains the Maltese scudo.[68] The Maltese scudo itself is pegged to the euro and is only recognised as legal tender within the Order.

Use as reserve currency[edit]

Since its introduction, the euro has been the second most widely held international reserve currency after the U.S. dollar. The share of the euro as a reserve currency increased from 18% in 1999 to 27% in 2008. Over this period, the share held in U.S. dollar fell from 71% to 64% and that held in RMB fell from 6.4% to 3.3%. The euro inherited and built on the status of the deutschmark as the second most important reserve currency. The euro remains underweight as a reserve currency in advanced economies while overweight in emerging and developing economies: according to the International Monetary Fund[69] the total of euro held as a reserve in the world at the end of 2008 was equal to $1.1 trillion or €850 billion, with a share of 22% of all currency reserves in advanced economies, but a total of 31% of all currency reserves in emerging and developing economies.

The possibility of the euro becoming the first international reserve currency has been debated among economists.[70] Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan gave his opinion in September 2007 that it was «absolutely conceivable that the euro will replace the US dollar as reserve currency, or will be traded as an equally important reserve currency».[71] In contrast to Greenspan’s 2007 assessment, the euro’s increase in the share of the worldwide currency reserve basket has slowed considerably since 2007 and since the beginning of the worldwide credit crunch related recession and European sovereign-debt crisis.[69]

Economics[edit]

Optimal currency area[edit]

In economics, an optimum currency area, or region (OCA or OCR), is a geographical region in which it would maximise economic efficiency to have the entire region share a single currency. There are two models, both proposed by Robert Mundell: the stationary expectations model and the international risk sharing model. Mundell himself advocates the international risk sharing model and thus concludes in favour of the euro.[72] However, even before the creation of the single currency, there were concerns over diverging economies. Before the late-2000s recession it was considered unlikely that a state would leave the euro or the whole zone would collapse.[73] However the Greek government-debt crisis led to former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw claiming the eurozone could not last in its current form.[74] Part of the problem seems to be the rules that were created when the euro was set up. John Lanchester, writing for The New Yorker, explains it:

The guiding principle of the currency, which opened for business in 1999, were supposed to be a set of rules to limit a country’s annual deficit to three per cent of gross domestic product, and the total accumulated debt to sixty per cent of G.D.P. It was a nice idea, but by 2004 the two biggest economies in the euro zone, Germany and France, had broken the rules for three years in a row.[75]

Transaction costs and risks[edit]

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code |

Symbol or abbreviation |

Proportion of daily volume, April 2019 |

Proportion of daily volume, April 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

U.S. dollar |

USD |

US$ |

88.3% | 88.5% |

|

2 |

Euro |

EUR |

€ |

32.3% | 30.5% |

|

3 |

Japanese yen |

JPY |

¥ / 円 |

16.8% | 16.7% |

|

4 |

Sterling |

GBP |

£ |

12.8% | 12.9% |

|

5 |

Renminbi |

CNY |

¥ / 元 |

4.3% | 7.0% |

|

6 |

Australian dollar |

AUD |

A$ |

6.8% | 6.4% |

|

7 |

Canadian dollar |

CAD |

C$ |

5.0% | 6.2% |

|

8 |

Swiss franc |

CHF |

CHF |

5.0% | 5.2% |

|

9 |

Hong Kong dollar |

HKD |

HK$ |

3.5% | 2.6% |

|

10 |

Singapore dollar |

SGD |

S$ |

1.8% | 2.4% |

|

11 |

Swedish krona |

SEK |

kr |

2.0% | 2.2% |

|

12 |

South Korean won |

KRW |

₩ / 원 |

2.0% | 1.9% |

|

13 |

Norwegian krone |

NOK |

kr |

1.8% | 1.7% |

|

14 |

New Zealand dollar |

NZD |

NZ$ |

2.1% | 1.7% |

|

15 |

Indian rupee |

INR |

₹ |

1.7% | 1.6% |

|

16 |

Mexican peso |

MXN |

$ |

1.7% | 1.5% |

|

17 |

New Taiwan dollar |

TWD |

NT$ |

0.9% | 1.1% |

|

18 |

South African rand |

ZAR |

R |

1.1% | 1.0% |

|

19 |

Brazilian real |

BRL |

R$ |

1.1% | 0.9% |

|

20 |

Danish krone |

DKK |

kr |

0.6% | 0.7% |

|

21 |

Polish złoty |

PLN |

zł |

0.6% | 0.7% |

|

22 |

Thai baht |

THB |

฿ |

0.5% | 0.4% |

|

23 |

Israeli new shekel |

ILS |

₪ |

0.3% | 0.4% |

|

24 |

Indonesian rupiah |

IDR |

Rp |

0.4% | 0.4% |

|

25 |

Czech koruna |

CZK |

Kč |

0.4% | 0.4% |

|

26 |

UAE dirham |

AED |

د.إ |

0.2% | 0.4% |

|

27 |

Turkish lira |

TRY |

₺ |

1.1% | 0.4% |

|

28 |

Hungarian forint |

HUF |

Ft |

0.4% | 0.3% |

|

29 |

Chilean peso |

CLP |

CLP$ |

0.3% | 0.3% |

|

30 |

Saudi riyal |

SAR |

﷼ |

0.2% | 0.2% |

|

31 |

Philippine peso |

PHP |

₱ |

0.3% | 0.2% |

|

32 |

Malaysian ringgit |

MYR |

RM |

0.1% | 0.2% |

|

33 |

Colombian peso |

COP |

COL$ |

0.2% | 0.2% |

|

34 |

Russian ruble |

RUB |

₽ |

1.1% | 0.2% |

|

35 |

Romanian leu |

RON |

L |

0.1% | 0.1% |

|

… |

Other | 2.2% | 2.5% | ||

| Total[note 8] | 200.0% | 200.0% |

The most obvious benefit of adopting a single currency is to remove the cost of exchanging currency, theoretically allowing businesses and individuals to consummate previously unprofitable trades. For consumers, banks in the eurozone must charge the same for intra-member cross-border transactions as purely domestic transactions for electronic payments (e.g., credit cards, debit cards and cash machine withdrawals).

Financial markets on the continent are expected to be far more liquid and flexible than they were in the past. The reduction in cross-border transaction costs will allow larger banking firms to provide a wider array of banking services that can compete across and beyond the eurozone. However, although transaction costs were reduced, some studies have shown that risk aversion has increased during the last 40 years in the Eurozone.[77]

Price parity[edit]

Another effect of the common European currency is that differences in prices—in particular in price levels—should decrease because of the law of one price. Differences in prices can trigger arbitrage, i.e., speculative trade in a commodity across borders purely to exploit the price differential. Therefore, prices on commonly traded goods are likely to converge, causing inflation in some regions and deflation in others during the transition. Some evidence of this has been observed in specific eurozone markets.[78]

Macroeconomic stability[edit]

Before the introduction of the euro, some countries had successfully contained inflation, which was then seen as a major economic problem, by establishing largely independent central banks. One such bank was the Bundesbank in Germany; the European Central Bank was modelled on the Bundesbank.[79]

The euro has come under criticism due to its regulation, lack of flexibility and rigidity towards sharing member states on issues such as nominal interest rates.[80]

Many national and corporate bonds denominated in euro are significantly more liquid and have lower interest rates than was historically the case when denominated in national currencies. While increased liquidity may lower the nominal interest rate on the bond, denominating the bond in a currency with low levels of inflation arguably plays a much larger role. A credible commitment to low levels of inflation and a stable debt reduces the risk that the value of the debt will be eroded by higher levels of inflation or default in the future, allowing debt to be issued at a lower nominal interest rate.

Unfortunately, there is also a cost in structurally keeping inflation lower than in the United States, UK, and China. The result is that seen from those countries, the euro has become expensive, making European products increasingly expensive for its largest importers; hence export from the eurozone becomes more difficult.

In general, those in Europe who own large amounts of euro are served by high stability and low inflation.

A monetary union means states in that union lose the main mechanism of recovery of their international competitiveness by weakening (depreciating) their currency. When wages become too high compared to productivity in the exports sector, then these exports become more expensive and they are crowded out from the market within a country and abroad. This drives the fall of employment and output in the exports sector and fall of trade and current account balances. Fall of output and employment in the tradable goods sector may be offset by the growth of non-exports sectors, especially in construction and services. Increased purchases abroad and negative current account balances can be financed without a problem as long as credit is cheap.[81] The need to finance trade deficit weakens currency, making exports automatically more attractive in a country and abroad. A state in a monetary union cannot use weakening of currency to recover its international competitiveness. To achieve this a state has to reduce prices, including wages (deflation). This could result in high unemployment and lower incomes as it was during the European sovereign-debt crisis.[82]

Trade[edit]

The euro increased price transparency and stimulated cross-border trade.[83] A 2009 consensus from the studies of the introduction of the euro concluded that it has increased trade within the eurozone by 5% to 10%,[84] although one study suggested an increase of only 3%[85] while another estimated 9 to 14%.[86] However, a meta-analysis of all available studies suggests that the prevalence of positive estimates is caused by publication bias and that the underlying effect may be negligible.[87] Although a more recent meta-analysis shows that publication bias decreases over time and that there are positive trade effects from the introduction of the euro, as long as results from before 2010 are taken into account. This may be because of the inclusion of the Financial crisis of 2007–2008 and ongoing integration within the EU.[88] Furthermore, older studies accounting for time trend reflecting general cohesion policies in Europe that started before, and continue after implementing the common currency find no effect on trade.[89][90] These results suggest that other policies aimed at European integration might be the source of observed increase in trade. According to Barry Eichengreen, studies disagree on the magnitude of the effect of the euro on trade, but they agree that it did have an effect.[83]

Investment[edit]

Physical investment seems to have increased by 5% in the eurozone due to the introduction.[91] Regarding foreign direct investment, a study found that the intra-eurozone FDI stocks have increased by about 20% during the first four years of the EMU.[92] Concerning the effect on corporate investment, there is evidence that the introduction of the euro has resulted in an increase in investment rates and that it has made it easier for firms to access financing in Europe. The euro has most specifically stimulated investment in companies that come from countries that previously had weak currencies. A study found that the introduction of the euro accounts for 22% of the investment rate after 1998 in countries that previously had a weak currency.[93]

Inflation[edit]

The introduction of the euro has led to extensive discussion about its possible effect on inflation. In the short term, there was a widespread impression in the population of the eurozone that the introduction of the euro had led to an increase in prices, but this impression was not confirmed by general indices of inflation and other studies.[94][95] A study of this paradox found that this was due to an asymmetric effect of the introduction of the euro on prices: while it had no effect on most goods, it had an effect on cheap goods which have seen their price round up after the introduction of the euro. The study found that consumers based their beliefs on inflation of those cheap goods which are frequently purchased.[96] It has also been suggested that the jump in small prices may be because prior to the introduction, retailers made fewer upward adjustments and waited for the introduction of the euro to do so.[97]

Exchange rate risk[edit]

One of the advantages of the adoption of a common currency is the reduction of the risk associated with changes in currency exchange rates.[83] It has been found that the introduction of the euro created «significant reductions in market risk exposures for nonfinancial firms both in and outside Europe».[98] These reductions in market risk «were concentrated in firms domiciled in the eurozone and in non-euro firms with a high fraction of foreign sales or assets in Europe».

Financial integration[edit]

The introduction of the euro increased European financial integration, which helped stimulate growth of a European securities market (bond markets are characterized by economies of scale dynamics).[83] According to a study on this question, it has «significantly reshaped the European financial system, especially with respect to the securities markets […] However, the real and policy barriers to integration in the retail and corporate banking sectors remain significant, even if the wholesale end of banking has been largely integrated.»[99] Specifically, the euro has significantly decreased the cost of trade in bonds, equity, and banking assets within the eurozone.[100] On a global level, there is evidence that the introduction of the euro has led to an integration in terms of investment in bond portfolios, with eurozone countries lending and borrowing more between each other than with other countries.[101] Financial integration made it cheaper for European companies to borrow.[83] Banks, firms and households could also invest more easily outside of their own country, thus creating greater international risk-sharing.[83]

Effect on interest rates[edit]

Secondary market yields of government bonds with maturities of close to 10 years

As of January 2014, and since the introduction of the euro, interest rates of most member countries (particularly those with a weak currency) have decreased. Some of these countries had the most serious sovereign financing problems.

The effect of declining interest rates, combined with excess liquidity continually provided by the ECB, made it easier for banks within the countries in which interest rates fell the most, and their linked sovereigns, to borrow significant amounts (above the 3% of GDP budget deficit imposed on the eurozone initially) and significantly inflate their public and private debt levels.[102] Following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, governments in these countries found it necessary to bail out or nationalise their privately held banks to prevent systemic failure of the banking system when underlying hard or financial asset values were found to be grossly inflated and sometimes so nearly worthless there was no liquid market for them.[103] This further increased the already high levels of public debt to a level the markets began to consider unsustainable, via increasing government bond interest rates, producing the ongoing European sovereign-debt crisis.

Price convergence[edit]

The evidence on the convergence of prices in the eurozone with the introduction of the euro is mixed. Several studies failed to find any evidence of convergence following the introduction of the euro after a phase of convergence in the early 1990s.[104][105] Other studies have found evidence of price convergence,[106][107] in particular for cars.[108] A possible reason for the divergence between the different studies is that the processes of convergence may not have been linear, slowing down substantially between 2000 and 2003, and resurfacing after 2003 as suggested by a recent study (2009).[109]

Tourism[edit]

A study suggests that the introduction of the euro has had a positive effect on the amount of tourist travel within the EMU, with an increase of 6.5%.[110]

Exchange rates[edit]

Flexible exchange rates[edit]

The ECB targets interest rates rather than exchange rates and in general, does not intervene on the foreign exchange rate markets. This is because of the implications of the Mundell–Fleming model, which implies a central bank cannot (without capital controls) maintain interest rate and exchange rate targets simultaneously, because increasing the money supply results in a depreciation of the currency. In the years following the Single European Act, the EU has liberalised its capital markets and, as the ECB has inflation targeting as its monetary policy, the exchange-rate regime of the euro is floating.

Against other major currencies[edit]

The euro is the second-most widely held reserve currency after the U.S. dollar. After its introduction on 4 January 1999 its exchange rate against the other major currencies fell reaching its lowest exchange rates in 2000 (3 May vs sterling, 25 October vs the U.S. dollar, 26 October vs Japanese yen). Afterwards it regained and its exchange rate reached its historical highest point in 2008 (15 July vs US dollar, 23 July vs Japanese yen, 29 December vs sterling). With the advent of the global financial crisis the euro initially fell, to regain later. Despite pressure due to the European sovereign-debt crisis the euro remained stable.[111] In November 2011 the euro’s exchange rate index – measured against currencies of the bloc’s major trading partners – was trading almost two percent higher on the year, approximately at the same level as it was before the crisis kicked off in 2007.[112] In mid July, 2022, the euro equalled the US dollar for a short period of time.[16]

Euro exchange rate against US dollar (USD), sterling (GBP) and Japanese yen (JPY), starting from 1999.

- Current and historical exchange rates against 32 other currencies (European Central Bank): link

| Current EUR exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK TRY PLN |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK TRY PLN |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK TRY PLN |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK TRY PLN |

Political considerations[edit]

Besides the economic motivations to the introduction of the euro, its creation was also partly justified as a way to foster a closer sense of joint identity between European citizens. Statements about this goal were for instance made by Wim Duisenberg, European Central Bank Governor, in 1998,[113] Laurent Fabius, French Finance Minister, in 2000,[114] and Romano Prodi, President of the European Commission, in 2002.[115] However, 15 years after the introduction of the euro, a study found no evidence that it has had a positive influence on a shared sense of European identity (and no evidence that it had a negative effect either).[116]

Euro in various languages[edit]

The formal titles of the currency are euro for the major unit and cent for the minor (one-hundredth) unit and for official use in most eurozone languages; according to the ECB, all languages should use the same spelling for the nominative singular.[117] This may contradict normal rules for word formation in some languages, e.g., those in which there is no eu diphthong.

Bulgaria has negotiated an exception; euro in the Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet is spelled eвро (evro) and not eуро (euro) in all official documents.[118] In the Greek script the term ευρώ (evró) is used; the Greek «cent» coins are denominated in λεπτό/ά (leptó/á). Official practice for English-language EU legislation is to use the words euro and cent as both singular and plural,[119] although the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Translation states that the plural forms euros and cents should be used in English.[120]

The word ‘euro’ is pronounced differently according to pronunciation rules in the individual languages applied; in German [ˈɔɪ̯ʁo], in English [ˈjuəɹəu], in French [øˈʁo], etc.[121]

In summary:

| Language(s) | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| In most EU languages | euro | Various; Czech: [ˈɛu̯ro], Danish: [‘öwro], Dutch: [ˈøːroː], Estonian: [ˈeu̯ro], Finnish: [ ˈeu̯ro], French: [ø.ʁo], Irish: [eurɔ], Italian: [ˈɛw.ro], Polish: [ˈɛw.rɔ], Portuguese: [ew.ɾɔ] or [ˈew.ɾu], Romanian: [eur̪o], Croatian: [euro], Slovak: [ˈɛu̯rɔ], Spanish: [ˈeuɾo], Swedish: [ɛ͡ɵrʊ] or [juːrʊ] |

| Bulgarian | евро evro | [ˈɛvro] |

| Danish | euro | [‘öwro] |

| German | Euro | [ˈɔʏ̯ro] |

| Greek | ευρώ | [eˈvɾo] |

| Hungarian | euró | [ˈɛuroː] or [ˈɛu̯roː] |

| Latvian | eiro | [ɛìɾo] |

| Lithuanian | euras | [ɛuːraːs] |

| Maltese | ewro | [ˈɛw.rɔ] |

| Serbian,[a] Slovene | evro | Serbian: [eʋro], Slovene: [ɛʋrɔ] |

For local phonetics, cent, use of plural and amount formatting (€6,00 or 6.00 €), see Language and the euro.

See also[edit]

- Captain Euro, The Raspberry Ice Cream War

- Currency union

- Digital euro

- European debt crisis

- List of currencies in Europe

- List of currencies replaced by the euro

Notes[edit]

- ^ Northern Cyprus uses Turkish lira

- ^ Including outermost regions of French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, Réunion, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- ^ Only the European part of the country is part of the European Union and uses the euro. The Caribbean Netherlands introduced the United States dollar in 2011. Curaçao, Sint Maarten and Aruba have their own currencies, which are pegged to the dollar.

- ^ See Montenegro and the euro

- ^ by means of Council Regulation 2866/98 (EC) of 31 December 1998.

- ^ by Council Regulation 1478/2000 (EC) of 19 June 2000

- ^ In the quotation, the epsilon is actually represented with the Cyrillic capital letter Ukrainian ye (Є, U+0404) instead of the technically more appropriate Greek lunate epsilon symbol (ϵ, U+03F5).

- ^ The total sum is 200% because each currency trade always involves a currency pair; one currency is sold (e.g. US$) and another bought (€). Therefore each trade is counted twice, once under the sold currency ($) and once under the bought currency (€). The percentages above are the percent of trades involving that currency regardless of whether it is bought or sold, e.g. the US dollar is bought or sold in 88% of all trades, whereas the euro is bought or sold 32% of the time.

- ^ Used in Serbia, which is not an EU member state but an EU candidate. In Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, euro is used.

References[edit]

- ^ Official documents and legislation refer to the euro as «the single currency».«Council Regulation (EC) No 1103/97 of 17 June 1997 on certain provisions relating to the introduction of the euro». Official Journal L 162, 19 June 1997 P. 0001 – 0003. European Communities. 19 June 1997. Retrieved 1 April 2009. This term is sometimes adopted by the media (Google hits for the phrase)

- ^ a b «ECB Statistical Data Warehouse, Reports>ECB/Eurosystem policy>Banknotes and coins statistics>1.Euro banknotes>1.1 Quantities». European Central Bank.

- ^ Walsh, Alistair (29 May 2017). «Italy to stop producing 1- and 2-cent coins». Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ «Euro-Zone Inflation Hits Record, Boosting Case for Big Hikes».

- ^ «The euro». European Commission website. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ a b «What is the euro area?». European Commission website. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ «IMF Data – Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserve – At a Glance». International Monetary Fund. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ «Foreign exchange turnover in April 2013: preliminary global results» (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ «Triennial Central Bank Survey 2007» (PDF). BIS. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Aristovnik, Aleksander; Čeč, Tanja (30 March 2010). «Compositional Analysis of Foreign Currency Reserves in the 1999–2007 Period. The Euro vs. The Dollar As Leading Reserve Currency» (PDF). Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper No. 14350. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Boesler, Matthew (11 November 2013). «There Are Only Two Real Threats to the US Dollar’s Status As The International Reserve Currency». Business Insider. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ «1.2 Euro banknotes, values». European Central Bank Statistical Data Warehouse. 14 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ «2.2 Euro coins, values». European Central Bank Statistical Data Warehouse. 14 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ a b «Madrid European Council (12/95): Conclusions». European Parliament. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ «Initial changeover (2002)». European Central Bank. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ a b «Euro Falls Near Parity With Dollar, a Threshold Watched Closely by Investors». The New York Times. 12 July 2022. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ «The Euro». European Commission. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ^ Nice, Treaty of. «Treaty of Nice». About Parliament. Not Available. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ «Bulgaria gives up its goal to join eurozone in 2024». EURACTIV Bulgaria. 17 February 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ «Why Bulgaria Abandoned Its Goal to Join Euro in 2024». The Washington Post. 17 February 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ «Bulgaria Will Not Make It Into Eurozone In January 2024 As Planned». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 18 February 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ «Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Principality of Andorra». Official Journal of the European Union. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ «By monetary agreement between France (acting for the EC) and Monaco». Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ «By monetary agreement between Italy (acting for the EC) and San Marino». Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ «By monetary agreement between Italy (acting for the EC) and Vatican City». Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ «By agreement of the EU Council». Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ «By UNMIK administration direction 1999/2». Unmikonline.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ a b Cardoso, Paulo. «Interview – Governor of the National Bank of Macedonia – Dimitar Bogov». The American Times United States Emerging Economies Report (USEER Report). Hazlehurst Media SA. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ «Numismatica | Ordine di Malta Italia». www.ordinedimaltaitalia.org. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b «How to use the euro name and symbol». European Commission. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ European Commission. «Spelling of the words «euro» and «cent» in official Community languages as used in Community Legislative acts» (PDF). Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ^ European Commission Directorate-General for Translation. «English Style Guide: A handbook for authors and translators in the European Commission» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2008.; European Union. «Interinstitutional style guide, 7.3.3. Rules for expressing monetary units». Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ «Ireland to round to nearest 5 cents starting October 28». 27 October 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ «Rounding». Central Bank of Ireland.

- ^ European Commission (January 2007). «Euro cash: five and familiar». Europa. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (22 March 2010) «Commission frowns on shop signs that say: ‘€500 notes not accepted'», EU Observer

- ^ European Commission (15 February 2003). «Commission communication: The introduction of euro banknotes and coins one year after COM(2002) 747». Europa (web portal). Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ «Robert Kalina, designer of the euro banknotes, at work at the Oesterreichische Nationalbank in Vienna». European Central Bank. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Schmid, John (3 August 2001). «Etching the Notes of a New European Identity». International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ a b «Banknotes». European Central Bank. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ ECB (6 December 2021). «ECB to redesign euro banknotes by 2024». Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Scheller, Hanspeter K. (2006). The European Central Bank: History, Role and Functions (PDF) (2nd ed.). p. 103. ISBN 978-92-899-0027-0.

Since 1 January 2002, the NCBs and the ECB have issued euro banknotes on a joint basis.

- ^

«Capital Subscription». European Central Bank. Retrieved 18 December 2011.The NCBs’ shares in this capital are calculated using a key which reflects the respective country’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU – in equal weightings. The ECB adjusts the shares every five years and whenever a new country joins the EU. The adjustment is done on the basis of data provided by the European Commission.

- ^ «Regulation (EC) No 2560/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 2001 on cross-border payments in euro». EUR-lex – European Communities, Publications office, Official Journal L 344, 28 December 2001 P. 0013 – 0016. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ «Cross border payments in the EU, Euro Information, The Official Treasury Euro Resource». United Kingdom Treasury. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ European Central Bank. «TARGET». Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ «Use of the euro». European Central Bank. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ «Germain Pirlot ‘uitvinder’ van de euro» (in Dutch). De Zeewacht. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ «The €uro: Our Currency». European Commission. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ «Position of the ISO code or euro sign in amounts». Interinstitutional style guide. Bruxelles, Belgium: Europa Publications Office. 5 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ George Matlock (16 February 2010). «Peripheral euro zone government bond spreads widen». Reuters. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «Acropolis now». The Economist. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ European Debt Crisis Fast Facts, CNN Library (last updated 22 January 2017).

- ^ Ricardo Reis, Looking for a Success in the Euro Crisis Adjustment Programs: The Case of Portugal, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Brookings Institution (Fall 2015), p. 433.

- ^ «Efsf, come funziona il fondo salvastati europeo». 4 November 2011.

- ^ «The politics of the Maastricht convergence criteria». Voxeu.org. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ «State of the Union: Can the euro zone survive its debt crisis?» (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 1 March 2011. p. 4. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ «S&P downgrades euro zone’s EFSF bailout fund». Reuters. 16 January 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Delamaide, Darrell (24 July 2012). «Euro crisis brings world to brink of depression». MarketWatch. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Lindner, Fabian, «Germany would do well to heed the Moody’s warning shot», The Guardian, 24 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Buergin, Rainer, «Germany, Juncker Push Back After Moody’s Rating Outlook Cuts Archived 28 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine», washpost.bloomberg, 24 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ a b Population Reference Bureau. «2013 World Population Data Sheet» (PDF). Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ «Cuba to adopt euro in foreign trade». BBC News. 8 November 1998. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ «US row leads Syria to snub dollar». BBC News. 14 February 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ Rosati, Andrew; Zerpa, Fabiola (17 October 2018). «Dollars Are Out, Euros Are in as U.S. Sanctions Sting Venezuela». Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ «Zimbabwe: A Critical Review of Sterp». 17 April 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ «1 euro equivale a 24.500 dobras» [1 euro is equivalent to 24,500 dobras] (in Portuguese). Téla Nón. 4 January 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ «Retrieved 3 October 2017».

- ^ a b «Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) – Updated COFER tables include first quarter 2009 data. June 30, 2009» (PDF). Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ «Will the Euro Eventually Surpass the Dollar As Leading International Reserve Currency?» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ «Euro could replace dollar as top currency – Greenspan». Reuters. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ Mundell, Robert (1970) [published 1973]. «A Plan for a European Currency». In Johnson, H. G.; Swoboda, A. K. (eds.). The Economics of Common Currencies – Proceedings of Conference on Optimum Currency Areas. 1970. Madrid. London: Allen and Unwin. pp. 143–172. ISBN 9780043320495.

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry (14 September 2007). «The Breakup of the Euro Area by Barry Eichengreen». NBER Working Paper (w13393). SSRN 1014341.

- ^ «Greek debt crisis: Straw says eurozone ‘will collapse’«. BBC News. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ John Lanchester, «Euro Science,» The New Yorker, 10 October 2011.

- ^ «Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2022» (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. 27 October 2022. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Benchimol, J., 2014. Risk aversion in the Eurozone, Research in Economics, vol. 68, issue 1, pp. 40–56.

- ^ Goldberg, Pinelopi K.; Verboven, Frank (2005). «Market Integration and Convergence to the Law of One Price: Evidence from the European Car Market». Journal of International Economics. 65 (1): 49–73. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.494.1517. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2003.12.002. S2CID 26850030.

- ^ de Haan, Jakob (2000). The History of the Bundesbank: Lessons for the European Central Bank. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21723-1.

- ^ Silvia, Steven J (2004). «Is the Euro Working? The Euro and European Labour Markets». Journal of Public Policy. 24 (2): 147–168. doi:10.1017/s0143814x0400008x. JSTOR 4007858. S2CID 152633940.

- ^ Ernest Pytlarczyk, Stefan Kawalec (June 2012). «Controlled Dismantlement of the Euro Area in Order to Preserve the European Union and Single European Market». CASE Center for Social and Economic Research. p. 11. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Martin Feldstein (January–February 2012). «The Failure of the Euro». Foreign Affairs. Chapter: Trading Places.

- ^ a b c d e f Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 212–213. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- ^ «The euro’s trade effects» (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ «The Euro Effect on Trade is not as Large as Commonly Thought» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2009.