| European mink | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Mustela |

| Species: |

M. lutreola |

| Binomial name | |

| Mustela lutreola

(Linnaeus, 1761) |

|

|

|

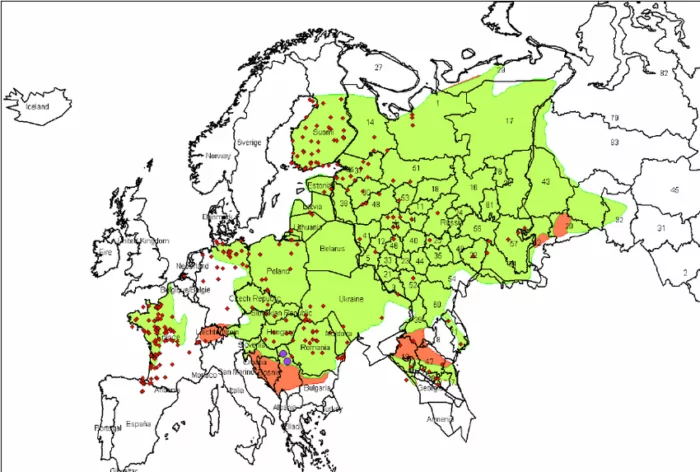

| European mink range

Extant, resident Probably Extant, resident Extinct |

The European mink (Mustela lutreola), also known as the Russian mink and Eurasian mink, is a semiaquatic species of mustelid native to Europe.

It is similar in colour to the American mink, but is slightly smaller and has a less specialized skull.[2] Despite having a similar name, build and behaviour, the European mink is not closely related to the American mink, being much closer to the European polecat and Siberian weasel (kolonok).[3][4] The European mink occurs primarily by forest streams unlikely to freeze in winter.[5] It primarily feeds on voles, frogs, fish, crustaceans and insects.[6]

The European mink is listed by the IUCN as Critically Endangered due to an ongoing reduction in numbers, having been calculated as declining more than 50% over the past three generations and expected to decline at a rate exceeding 80% over the next three generations.[1] European mink numbers began to shrink during the 19th century, with the species rapidly becoming extinct in some parts of Central Europe. During the 20th century, mink numbers declined all throughout their range, the reasons for which having been hypothesised to be due to a combination of factors, including climate change, competition with (as well as diseases spread by) the introduced American mink, habitat destruction, declines in crayfish numbers and hybridisation with the European polecat. In Central Europe and Finland, the decline preceded the introduction of the American mink, having likely been due to the destruction of river ecosystems, while in Estonia, the decline seems to coincide with the spread of the American mink.[7]

Evolution and taxonomy[edit]

Fossil finds of the European mink are very rare, thus indicating the species is either a relative newcomer to Europe, probably having originated in North America,[8] or a recent speciation caused by hybridization. It likely first arose in the Middle Pleistocene, with several fossils in Europe dated to the Late Pleistocene being found in caves and some suggesting early exploitation by humans. Genetic analyses indicate, rather than being closely related to the American mink, the European mink’s closest relative is the European polecat (perhaps due to past hybridization)[3] and the Siberian weasel,[4] being intermediate in form between true polecats and other members of the genus. The closeness between the mink and polecat is emphasized by the fact the species can hybridize.[9][10][11]

Subspecies[edit]

As of 2005,[12] seven subspecies are recognised.

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern mink M. l. lutreola (Nominate subspecies) |

Linnaeus, 1758 | The pelt is dark brownish-chestnut or dark brown with a diffuse broad belt on the back. The tail tip is black and the underfur is dark bluish-grey. The overall pelage is long, compact and silky. Adult males measure 365–380 mm (14.4–15.0 in) in body length and have a tail length of 36–42 mm (1.4–1.7 in) (38% of its body length).[13] | Northern European Russia and Finland | alba (de Sélys Longchamps, 1839)

alpinus (Ogérien, 1863) |

| French mink M. l. biedermanni |

Matschie, 1912 | France | armorica (Matschie, 1912) | |

| M. l. binominata | Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, 1951 | caucasica (Novikov, 1939) | ||

| Middle European mink M. l. cylipena |

Matschie, 1912 | A very large subspecies, it is only slightly smaller than M. l. turovi. The fur is quite dark and corresponds to the colour of M. l. novikovi. Adult males measure 420–430 mm (17–17 in) in length, while females measure 370–400 mm (15–16 in). Tail length in males is 160 mm (6.3 in), while in females it is 140–180 mm (5.5–7.1 in).[14] | The Kaliningrad Oblast, Lithuania, western Latvia, middle Europe (except the extreme west (France), Hungary, Romania, the former Yugoslavia and Poland) | albica (Matschie, 1912)

budina (Matschie, 1912) |

| Middle Russian mink M. l. novikovi |

Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, 1951 | A moderately-sized subspecies, it is slightly larger than M. l. lutreola. It is lighter-coloured than M. l. lutreola, being dark tawny or dark brown with a film of light reddish highlights. The dark belt on the back is weakly defined or absent. The pelage is overall shorter, less dense and less silky than M. l. lutreola. Adult males measure 360–420 mm (14–17 in) in body length.[15] | The middle zone of the European part of the former Soviet Union (Estonia, eastern Latvia, Belarus, eastern Ukraine, and the lower Don and lower Volga regions) | borealis (Novikov, 1939) |

| Carpathian mink Mustela l. transsylvanica

|

Éhik, 1932 | Smaller than M. l. turovi, with dark tawny fur[16] | Moldavia, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and the former Yugoslavia | ehiki (Kretzoi, 1942)

hungarica (Éhik, 1932) |

| Caucasian mink M. l. turovi |

Kuznetsov in Novikov, 1939 | A large-sized subspecies, it has quite long, but sparse and coarse pelage and less compact underfur. The fur is light tawny or light brown with clear rusty highlights. The underfur is light bluish-grey. White chest markings are much more frequent in this subspecies than in others. The ends of the limbs are often white. Adult males usually measure more than 42 cm (17 in) long.[15] | The Caucasus, the lower Don and lower Volga regions, probably eastern Ukraine |

Description[edit]

Build[edit]

Skull, as illustrated in Miller’s Catalogue of the Mammals of Western Europe (Europe exclusive of Russia) in the collection of the British Museum

The European mink is a typical representative of the genus Mustela, having a greatly elongated body with short limbs. However, compared to its close relative, the Siberian weasel, the mink is more compact and less thinly built, thus approaching ferrets and European polecats in build. The European mink has a large, broad head with short ears. The limbs are short, with relatively well-developed membranes between the digits, particularly on the hind feet. The mink’s tail is short, and does not exceed half the animal’s body length (constituting about 40% of its length).[17] The European mink’s skull is less elongated than the kolonok’s, with more widely spaced zygomatic arches and has a less massive facial region. In general characteristics, the skull is intermediate in shape between that of the Siberian weasel and the European polecat. Overall, the skull is less specialized for carnivory than that of polecats and the American mink. Males measure 373–430 mm (14.7–16.9 in) in body length, while females measure 352–400 mm (13.9–15.7 in). Tail length is 153–190 mm (6.0–7.5 in) in males and 150–180 mm (5.9–7.1 in).[18] Overall weight is 550–800 grams (1.21–1.76 lb).[9] It is a fast and agile animal, which swims and dives skilfully. It is able to run along stream beds, and stay underwater for one to two minutes.[19] When swimming, it paddles with both its front and back limbs simultaneously.[5]

Fur[edit]

European mink face — note the white markings on the upper lip, which are absent in the American species.

The winter fur of the European mink is very thick and dense, but not long, and quite loosely fitting. The underfur is particularly dense compared with that of more land-based members of the genus Mustela. The guard hairs are quite coarse and lustrous, with very wide contour hairs which are flat in the middle, as is typical in aquatic mammals. The length of the hairs on the back and belly differ little, a further adaptation to the European mink’s semiaquatic way of life. The summer fur is somewhat shorter, coarser and less dense than the winter fur, though the differences are much less than in purely terrestrial mustelids.[20]

In dark coloured individuals, the fur is dark brown or almost blackish-brown, while light individuals are reddish brown. Fur colour is evenly distributed over the whole body, though in a few cases, the belly is a bit lighter than the upper parts. In particularly dark individuals, a dark, broad dorsal belt is present. The limbs and tail are slightly darker than the trunk. The face has no colour pattern, though its upper and lower lips and chin are pure white. White markings may also occur on the lower surface of the neck and chest. Occasionally, colour mutations such as albinos and white spots throughout the pelage occur. The summer fur is somewhat lighter, and dirty in tone, with more reddish highlights.[20]

Differences from American mink[edit]

The European mink is similar to the American mink, but with several important differences. The tail is longer in the American species, almost reaching half its body length. The winter fur of the American mink is denser, longer and more closely fitting than that of the European mink. Unlike the European mink, which has white patches on both upper and lower lips, the American mink almost never has white marks on the upper lip.[21] The European mink’s skull is much less specialised than the American species’ in the direction of carnivory, bearing more infantile features, such as a weaker dentition and less strongly developed projections.[22] The European mink is reportedly less efficient than the American species underwater.[5]

Behaviour[edit]

Territorial and denning behaviours[edit]

The European mink does not form large territories, possibly due to the abundance of food on the banks of small water bodies. The size of each territory varies according to the availability of food; in areas with water meadows with little food, the home range is 60–100 hectares (150–250 acres), though it is more usual for territories to be 12–14 hectares (30–35 acres). Summer territories are smaller than winter territories. Along shorelines, the length of a home range varies from 250–2,000 m (270–2,190 yd), with a width of 50–60 m (55–66 yd).[23]

The European mink has both a permanent burrow and temporary shelters. The former is used all year except during floods, and is located no more than 6–10 m (6.6–10.9 yd) from the water’s edge. The construction of the burrow is not complex, often consisting of one or two passages 8–10 cm (3.1–3.9 in) in diameter and 1.40–1.50 m (1.53–1.64 yd) in length, leading to a nest chamber measuring 48 cm × 55 cm (19 in × 22 in). Nesting chambers are lined with straw, moss, mouse wool and bird feathers.[23] It is more sedentary than the American mink, and will confine itself for long periods in its burrow in very cold weather.[5]

Reproduction and development[edit]

During the mating season, the sexual organs of the female enlarge greatly and become pinkish-lilac in colour, which is in contrast with the female American mink, whose organs do not change.[5] In the Moscow Zoo, estrus was observed on 22–26 April, with copulation lasting from 15 minutes to an hour. The average litter consists of three to seven kits. At birth, kits weigh about 6.5 grams (0.23 oz), and grow rapidly, trebling their weight 10 days after birth. They are born blind; the eyes open after 30–31 days. The lactation period lasts 2.0 to 2.5 months, though the kits eat solid food after 20–25 days. They accompany the mother on hunting expeditions at the age of 56–70 days, and become independent at the age 70–84 days.[24]

Diet[edit]

The European mink has a diverse diet consisting largely of aquatic and riparian fauna. Differences between its diet and that of the American mink are small. Voles are the most important food source, closely followed by crustaceans, frogs and water insects. Fish are an important food source in floodlands, with cases being known of European minks catching fish weighing 1–1.2 kg (2.2–2.6 lb). The European mink’s daily food requirement is 140–180 grams (4.9–6.3 oz). In times of food abundance, it caches its food.[6]

Range and status[edit]

The European mink is mostly restricted to Europe. Its range was widespread in the 19th century, with a distribution extending from northern Spain in the west to the river Ob (just east of the Urals) in the east, and from the Archangelsk region in the north to the northern Caucasus in the south. Over the last 150 years, though, it has severely declined by more than 90% and been extirpated or greatly reduced over most of its former range. The current range includes an isolated population in northern Spain and western France, which is widely disjunct from the main range in Eastern Europe (Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Ukraine, central regions of European Russia, the Danube Delta in Romania and northwestern Bulgaria). It occurs from sea level to 1,120 m (1,220 yd).[1] In Estonia, the European mink population has been successfully re-established on the island of Hiiumaa, and there are plans for repeating the process on the nearby island of Saaremaa.[25]

Decline[edit]

The earliest actual records of decreases in European mink numbers occurred in Germany, having already become extinct in several areas by the middle of the 18th century. A similar pattern occurred in Switzerland, with no records of minks being published in the 20th century. Records of minks in Austria stopped by the late 18th century. By the 1930s–1950s, the European mink became extinct in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and possibly Bulgaria. In Finland, the main decline occurred in the 1920s-1950s and the species was thought to be extinct in the 1970s, though a few specimens were reported in the 1990s. In Latvia, the European mink was thought to be extinct for years, until a specimen was captured in 1992. In Lithuania, the last specimens were caught in 1978–79. The decline of the European mink in Estonia and Belarus was rapid during the 1980s, with only a few small, fragmented populations in the northeastern regions of both countries being reported in the 1990s. The decline of European mink numbers in Ukraine began in the late 1950s, with now only a few small and isolated populations being reported in the upper courses of the Ukrainian Carpathian rivers. Their numbers in Moldova began to drop very quickly in the 1930s, with the last known population having been confined to the lower course of the River Prut on the Romanian border by the late 1980s. In Romania, the European mink was very common and widely distributed, with 8000–10,000 being captured in 1960. Currently, Romanian mink populations are confined to the Danube Delta. In European Russia, the European mink was common and widespread in the early 20th century, but began to decline during the 1950s–1970s. The core of their range was in the Tver Region, though they began to decline there by the 1990s, which was worsened by a colonisation of the area by the American mink. Between 1981 and 1989, 388 European minks were introduced to two of the Kurile Islands, though by the 1990s, the population there was found to be lower than that originally released. In France and Spain, an isolated range occurs, extending from Brittany to northern Spain. Data from the 1990s indicate the European mink has disappeared from the northern half of this previous range.[7]

Possible reasons for decline[edit]

Habitat loss[edit]

Habitat-related declines of European mink numbers may have started during the Little Ice Age, which was further aggravated by human activity.[5] As the European mink is more dependent on wetland habitats than the American species, its decline in Central Europe, Estonia, Finland, Russia, Moldova and Ukraine has been linked to the drainage of small rivers. In mid-19th-century Germany, for example, European mink populations declined in a decade due to expanded land drainage. Although land improvement and river dredging certainly resulted in population decreases and fragmentation, in areas which still maintain suitable river ecosystems, such as Poland, Hungary, the former Czechoslovakia, Finland and Russia, the decline preceded the change in wetland habitats, and may have been caused by extensive agricultural development.[7]

Overhunting[edit]

The European mink was historically hunted extensively, particularly in Russia, where in some districts, the decline prompted a temporary ban on mink hunting to let the population recover. In the early 20th century, 40–60,000 European minks were caught annually in the Soviet Union, with a record of 75,000 individuals (an estimate which exceeds the modern global European mink population). In Finland, annual mink catches reached 3000 specimens in the 1920s. In Romania, 10,000 minks were caught annually around 1960. However, this reason alone cannot account for the decline in areas where hunting was less intense, such as in Germany.[7]

Decline of crayfish[edit]

The decline of European crayfish has been proposed as a factor in the drop in mink numbers, as minks are notably absent in the eastern side of the Urals, where crayfish are also absent. The decline in mink numbers has also been linked to the destruction of crayfish in Finland during the 1920s-1940s, when the crustaceans were infected with crayfish plague. The failure of the European mink to expand west to Scandinavia coincides with the gap in crayfish distribution.[7]

Competition with the American mink and disease[edit]

The American mink was introduced and released in Europe during the 1920s–1930s. The American mink is less dependent on wetland habitats than the European mink and is 20-40% larger. The impact of feral American minks on European mink populations has been explained through the competitive exclusion principle and because the American mink reproduces a month earlier than the European species, and matings between male American minks and female European minks result in the embryos being reabsorbed. Thus, female European minks impregnated by male American minks are unable to reproduce with their conspecifics. Disease spread by the American mink can also account for the decline. Though the presence of the American mink has coincided with the decline of European mink numbers in Belarus and Estonia, the decline of the European mink in some areas preceded the introduction of the American mink by many years, and there are areas in Russia where the American species is absent, though European mink populations in these regions are still declining.[7]

Diseases spread by the American mink can also account for the decline.[7] Twenty-seven helminth species are recorded to infest the European mink, consisting of 14 trematodes, two cestodes and 11 nematodes. The mink is also vulnerable to pulmonary filariasis, krenzomatiasis and skrjabingylosis.[24] In the Leningrad and Pskov Oblasts, 77.1% of European minks were found to be infected with skrjabingylosis.[5]

Hybridisation and competition with the European polecat[edit]

In the early 20th century, northern Europe underwent a warm climatic period which coincided with an expansion of the range of the European polecat. The European mink possibly was gradually absorbed by the polecat due to hybridisation. Also, competition with the polecat has greatly increased, due to landscape change favouring the polecat.[7] There is one record of a polecat attacking a mink and dragging it to its burrow.[24]

Polecat-mink hybrids are termed khor’-tumak by furriers[9] and khonorik by fanciers.[26] Such hybridisation is very rare in the wild, and typically only occurs where European minks are declining. A polecat-mink hybrid has a poorly defined facial mask, yellow fur on the ears, grey-yellow underfur and long, dark brown guard hairs. Fairly large, the males attain the peak sizes known for European polecats (weighing 1,120–1,746 g (2.469–3.849 lb) and measuring 41–47 cm (16–19 in) in length), and females are much larger than female European minks (weighing 742 g (1.636 lb) and measuring 37 cm (15 in) in length).[10] The majority of polecat-mink hybrids have skulls bearing greater similarities to those of polecats than to minks.[11] Hybrids can swim well like minks and burrow for food like polecats. They are very difficult to tame and breed, as males are sterile, though females are fertile.[11][26] The first captive polecat-mink hybrid was created in 1978 by Soviet zoologist Dr. Dmitry Ternovsky of Novosibirsk. Originally bred for their fur (which was more valuable than that of either parent species), the breeding of these hybrids declined as European mink populations decreased.[26] Studies on the behavioural ecology of free-ranging polecat-mink hybrids in the upper reaches of the Lovat River indicate the hybrids will stray from aquatic habitats more readily than pure minks, and will tolerate both parent species entering their territories, though the hybrid’s larger size (especially the male’s) may deter intrusion. During the summer period, the diet of wild polecat-mink hybrids is more similar to that of the mink than to the polecat, as they feed predominantly on frogs. During the winter, their diets overlap more with those of polecats, and will eat a larger proportion of rodents than in the summer, though they still rely heavily on frogs and rarely scavenge ungulate carcasses as the polecat does.[10]

Predation[edit]

Predators of the European mink include the European polecat, the American mink, the golden eagle, large owls[5] and the red fox. Red fox numbers have increased greatly in areas where the wolf and Eurasian lynx have been extirpated, as well as areas where modern forestry is practised. As red foxes are known to prey on mustelids, excessive fox predation on the European mink is a possible factor, though it is improbable to have been a factor in Finland, where fox numbers were low during the early 20th century.[7]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Maran, T.; Skumatov, D.; Gomez, A.; Põdra, M.; Abramov, A.V.; Dinets, V. (2016). «Mustela lutreola«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T14018A45199861. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T14018A45199861.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1391

- ^ a b Davidson, A., Griffith, H. I., Brookes, R. C., Maran, T., MacDonald, D. W., Sidorovich, V. E., Kitchener, A. C., Irizar, I., Villate, I., Gonzales-Esteban, J., Cena, A., Moya, I. and Palazon Minano, S. 2000. Mitochondrial DNA and paleontological evidence for the origin of endangered European mink, Mustela lutreola Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Animal Conservation 3: 345–357.

- ^ a b MARMI, J., LÓPEZ-GIRÁLDEZ, J.F. & DOMINGO-ROURA, X. (2004). Phylogeny, Evolutionary History and Taxonomy of the Mustelidae based on Sequences of the Cytochrome b Gene and a Complex Repetitive Flanking Region. Zoologica Scripta, 33: 481 — 499

- ^ a b c d e f g h Youngman, Phillip M. (1990). Mustela lutreola, Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Mammalian Species, American Society of Mammalogists, No. 362, pp. 1–3, 2 figs

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1101–1102

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maran, T. and Henttonen, H. 1995. Why is the European mink, Mustela lutreola disappearing? — A review of the process and hypotheses. Annales Fennici Zoologici 32: 47–54.

- ^ Kurtén 1968, p. 98

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1086–1088

- ^ a b c Sidorovich, V. (2001) Finding on the ecology of hybrids between the European mink Mustela lutreola and polecat M.putorius at the Lovat upper reaches, NE Belarus Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Small Carnivore Conservation 24: 1-5

- ^ a b c Tumanov, Igor L. & Abramov, Alexei V. (2002) A study of the hybrids between the European Mink Mustela lutreola and the Polecat M. putorius Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Small Carnivore Conservation 27: 29-31

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). «Order Carnivora». In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1095

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1098

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1096–1097

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1099

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1080

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1083–1084

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1103

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1081–1082

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1392–1397

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1398–1399

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1102–1103

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1104–1105

- ^ Karáth, Kata (16 August 2017). «Scientists think they can save the European mink—by killing its ruthless rivals». Science. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ a b c «Khonorik: Hybrids between Mustelidae». Russian Ferret Society. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bachrach, Max (1953). «Fur: a practical treatise» (3rd ed.). New York : Prentice-Hall.

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). «Pleistocene mammals of Europe». Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- Macdonald, David (1992). The Velvet Claw: A Natural History of the Carnivores. New York: Parkwest. ISBN 0-563-20844-9.

External links[edit]

- Photos of European Mink

- European Mink: Biology and Conservation

- European mink reintroduction project, ex-situ, in-situ research with Dr. Elisabeth Peters, Mustela lutreola, Germany.

| European mink | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Mustela |

| Species: |

M. lutreola |

| Binomial name | |

| Mustela lutreola

(Linnaeus, 1761) |

|

|

|

| European mink range

Extant, resident Probably Extant, resident Extinct |

The European mink (Mustela lutreola), also known as the Russian mink and Eurasian mink, is a semiaquatic species of mustelid native to Europe.

It is similar in colour to the American mink, but is slightly smaller and has a less specialized skull.[2] Despite having a similar name, build and behaviour, the European mink is not closely related to the American mink, being much closer to the European polecat and Siberian weasel (kolonok).[3][4] The European mink occurs primarily by forest streams unlikely to freeze in winter.[5] It primarily feeds on voles, frogs, fish, crustaceans and insects.[6]

The European mink is listed by the IUCN as Critically Endangered due to an ongoing reduction in numbers, having been calculated as declining more than 50% over the past three generations and expected to decline at a rate exceeding 80% over the next three generations.[1] European mink numbers began to shrink during the 19th century, with the species rapidly becoming extinct in some parts of Central Europe. During the 20th century, mink numbers declined all throughout their range, the reasons for which having been hypothesised to be due to a combination of factors, including climate change, competition with (as well as diseases spread by) the introduced American mink, habitat destruction, declines in crayfish numbers and hybridisation with the European polecat. In Central Europe and Finland, the decline preceded the introduction of the American mink, having likely been due to the destruction of river ecosystems, while in Estonia, the decline seems to coincide with the spread of the American mink.[7]

Evolution and taxonomy[edit]

Fossil finds of the European mink are very rare, thus indicating the species is either a relative newcomer to Europe, probably having originated in North America,[8] or a recent speciation caused by hybridization. It likely first arose in the Middle Pleistocene, with several fossils in Europe dated to the Late Pleistocene being found in caves and some suggesting early exploitation by humans. Genetic analyses indicate, rather than being closely related to the American mink, the European mink’s closest relative is the European polecat (perhaps due to past hybridization)[3] and the Siberian weasel,[4] being intermediate in form between true polecats and other members of the genus. The closeness between the mink and polecat is emphasized by the fact the species can hybridize.[9][10][11]

Subspecies[edit]

As of 2005,[12] seven subspecies are recognised.

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern mink M. l. lutreola (Nominate subspecies) |

Linnaeus, 1758 | The pelt is dark brownish-chestnut or dark brown with a diffuse broad belt on the back. The tail tip is black and the underfur is dark bluish-grey. The overall pelage is long, compact and silky. Adult males measure 365–380 mm (14.4–15.0 in) in body length and have a tail length of 36–42 mm (1.4–1.7 in) (38% of its body length).[13] | Northern European Russia and Finland | alba (de Sélys Longchamps, 1839)

alpinus (Ogérien, 1863) |

| French mink M. l. biedermanni |

Matschie, 1912 | France | armorica (Matschie, 1912) | |

| M. l. binominata | Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, 1951 | caucasica (Novikov, 1939) | ||

| Middle European mink M. l. cylipena |

Matschie, 1912 | A very large subspecies, it is only slightly smaller than M. l. turovi. The fur is quite dark and corresponds to the colour of M. l. novikovi. Adult males measure 420–430 mm (17–17 in) in length, while females measure 370–400 mm (15–16 in). Tail length in males is 160 mm (6.3 in), while in females it is 140–180 mm (5.5–7.1 in).[14] | The Kaliningrad Oblast, Lithuania, western Latvia, middle Europe (except the extreme west (France), Hungary, Romania, the former Yugoslavia and Poland) | albica (Matschie, 1912)

budina (Matschie, 1912) |

| Middle Russian mink M. l. novikovi |

Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, 1951 | A moderately-sized subspecies, it is slightly larger than M. l. lutreola. It is lighter-coloured than M. l. lutreola, being dark tawny or dark brown with a film of light reddish highlights. The dark belt on the back is weakly defined or absent. The pelage is overall shorter, less dense and less silky than M. l. lutreola. Adult males measure 360–420 mm (14–17 in) in body length.[15] | The middle zone of the European part of the former Soviet Union (Estonia, eastern Latvia, Belarus, eastern Ukraine, and the lower Don and lower Volga regions) | borealis (Novikov, 1939) |

| Carpathian mink Mustela l. transsylvanica

|

Éhik, 1932 | Smaller than M. l. turovi, with dark tawny fur[16] | Moldavia, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and the former Yugoslavia | ehiki (Kretzoi, 1942)

hungarica (Éhik, 1932) |

| Caucasian mink M. l. turovi |

Kuznetsov in Novikov, 1939 | A large-sized subspecies, it has quite long, but sparse and coarse pelage and less compact underfur. The fur is light tawny or light brown with clear rusty highlights. The underfur is light bluish-grey. White chest markings are much more frequent in this subspecies than in others. The ends of the limbs are often white. Adult males usually measure more than 42 cm (17 in) long.[15] | The Caucasus, the lower Don and lower Volga regions, probably eastern Ukraine |

Description[edit]

Build[edit]

Skull, as illustrated in Miller’s Catalogue of the Mammals of Western Europe (Europe exclusive of Russia) in the collection of the British Museum

The European mink is a typical representative of the genus Mustela, having a greatly elongated body with short limbs. However, compared to its close relative, the Siberian weasel, the mink is more compact and less thinly built, thus approaching ferrets and European polecats in build. The European mink has a large, broad head with short ears. The limbs are short, with relatively well-developed membranes between the digits, particularly on the hind feet. The mink’s tail is short, and does not exceed half the animal’s body length (constituting about 40% of its length).[17] The European mink’s skull is less elongated than the kolonok’s, with more widely spaced zygomatic arches and has a less massive facial region. In general characteristics, the skull is intermediate in shape between that of the Siberian weasel and the European polecat. Overall, the skull is less specialized for carnivory than that of polecats and the American mink. Males measure 373–430 mm (14.7–16.9 in) in body length, while females measure 352–400 mm (13.9–15.7 in). Tail length is 153–190 mm (6.0–7.5 in) in males and 150–180 mm (5.9–7.1 in).[18] Overall weight is 550–800 grams (1.21–1.76 lb).[9] It is a fast and agile animal, which swims and dives skilfully. It is able to run along stream beds, and stay underwater for one to two minutes.[19] When swimming, it paddles with both its front and back limbs simultaneously.[5]

Fur[edit]

European mink face — note the white markings on the upper lip, which are absent in the American species.

The winter fur of the European mink is very thick and dense, but not long, and quite loosely fitting. The underfur is particularly dense compared with that of more land-based members of the genus Mustela. The guard hairs are quite coarse and lustrous, with very wide contour hairs which are flat in the middle, as is typical in aquatic mammals. The length of the hairs on the back and belly differ little, a further adaptation to the European mink’s semiaquatic way of life. The summer fur is somewhat shorter, coarser and less dense than the winter fur, though the differences are much less than in purely terrestrial mustelids.[20]

In dark coloured individuals, the fur is dark brown or almost blackish-brown, while light individuals are reddish brown. Fur colour is evenly distributed over the whole body, though in a few cases, the belly is a bit lighter than the upper parts. In particularly dark individuals, a dark, broad dorsal belt is present. The limbs and tail are slightly darker than the trunk. The face has no colour pattern, though its upper and lower lips and chin are pure white. White markings may also occur on the lower surface of the neck and chest. Occasionally, colour mutations such as albinos and white spots throughout the pelage occur. The summer fur is somewhat lighter, and dirty in tone, with more reddish highlights.[20]

Differences from American mink[edit]

The European mink is similar to the American mink, but with several important differences. The tail is longer in the American species, almost reaching half its body length. The winter fur of the American mink is denser, longer and more closely fitting than that of the European mink. Unlike the European mink, which has white patches on both upper and lower lips, the American mink almost never has white marks on the upper lip.[21] The European mink’s skull is much less specialised than the American species’ in the direction of carnivory, bearing more infantile features, such as a weaker dentition and less strongly developed projections.[22] The European mink is reportedly less efficient than the American species underwater.[5]

Behaviour[edit]

Territorial and denning behaviours[edit]

The European mink does not form large territories, possibly due to the abundance of food on the banks of small water bodies. The size of each territory varies according to the availability of food; in areas with water meadows with little food, the home range is 60–100 hectares (150–250 acres), though it is more usual for territories to be 12–14 hectares (30–35 acres). Summer territories are smaller than winter territories. Along shorelines, the length of a home range varies from 250–2,000 m (270–2,190 yd), with a width of 50–60 m (55–66 yd).[23]

The European mink has both a permanent burrow and temporary shelters. The former is used all year except during floods, and is located no more than 6–10 m (6.6–10.9 yd) from the water’s edge. The construction of the burrow is not complex, often consisting of one or two passages 8–10 cm (3.1–3.9 in) in diameter and 1.40–1.50 m (1.53–1.64 yd) in length, leading to a nest chamber measuring 48 cm × 55 cm (19 in × 22 in). Nesting chambers are lined with straw, moss, mouse wool and bird feathers.[23] It is more sedentary than the American mink, and will confine itself for long periods in its burrow in very cold weather.[5]

Reproduction and development[edit]

During the mating season, the sexual organs of the female enlarge greatly and become pinkish-lilac in colour, which is in contrast with the female American mink, whose organs do not change.[5] In the Moscow Zoo, estrus was observed on 22–26 April, with copulation lasting from 15 minutes to an hour. The average litter consists of three to seven kits. At birth, kits weigh about 6.5 grams (0.23 oz), and grow rapidly, trebling their weight 10 days after birth. They are born blind; the eyes open after 30–31 days. The lactation period lasts 2.0 to 2.5 months, though the kits eat solid food after 20–25 days. They accompany the mother on hunting expeditions at the age of 56–70 days, and become independent at the age 70–84 days.[24]

Diet[edit]

The European mink has a diverse diet consisting largely of aquatic and riparian fauna. Differences between its diet and that of the American mink are small. Voles are the most important food source, closely followed by crustaceans, frogs and water insects. Fish are an important food source in floodlands, with cases being known of European minks catching fish weighing 1–1.2 kg (2.2–2.6 lb). The European mink’s daily food requirement is 140–180 grams (4.9–6.3 oz). In times of food abundance, it caches its food.[6]

Range and status[edit]

The European mink is mostly restricted to Europe. Its range was widespread in the 19th century, with a distribution extending from northern Spain in the west to the river Ob (just east of the Urals) in the east, and from the Archangelsk region in the north to the northern Caucasus in the south. Over the last 150 years, though, it has severely declined by more than 90% and been extirpated or greatly reduced over most of its former range. The current range includes an isolated population in northern Spain and western France, which is widely disjunct from the main range in Eastern Europe (Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Ukraine, central regions of European Russia, the Danube Delta in Romania and northwestern Bulgaria). It occurs from sea level to 1,120 m (1,220 yd).[1] In Estonia, the European mink population has been successfully re-established on the island of Hiiumaa, and there are plans for repeating the process on the nearby island of Saaremaa.[25]

Decline[edit]

The earliest actual records of decreases in European mink numbers occurred in Germany, having already become extinct in several areas by the middle of the 18th century. A similar pattern occurred in Switzerland, with no records of minks being published in the 20th century. Records of minks in Austria stopped by the late 18th century. By the 1930s–1950s, the European mink became extinct in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and possibly Bulgaria. In Finland, the main decline occurred in the 1920s-1950s and the species was thought to be extinct in the 1970s, though a few specimens were reported in the 1990s. In Latvia, the European mink was thought to be extinct for years, until a specimen was captured in 1992. In Lithuania, the last specimens were caught in 1978–79. The decline of the European mink in Estonia and Belarus was rapid during the 1980s, with only a few small, fragmented populations in the northeastern regions of both countries being reported in the 1990s. The decline of European mink numbers in Ukraine began in the late 1950s, with now only a few small and isolated populations being reported in the upper courses of the Ukrainian Carpathian rivers. Their numbers in Moldova began to drop very quickly in the 1930s, with the last known population having been confined to the lower course of the River Prut on the Romanian border by the late 1980s. In Romania, the European mink was very common and widely distributed, with 8000–10,000 being captured in 1960. Currently, Romanian mink populations are confined to the Danube Delta. In European Russia, the European mink was common and widespread in the early 20th century, but began to decline during the 1950s–1970s. The core of their range was in the Tver Region, though they began to decline there by the 1990s, which was worsened by a colonisation of the area by the American mink. Between 1981 and 1989, 388 European minks were introduced to two of the Kurile Islands, though by the 1990s, the population there was found to be lower than that originally released. In France and Spain, an isolated range occurs, extending from Brittany to northern Spain. Data from the 1990s indicate the European mink has disappeared from the northern half of this previous range.[7]

Possible reasons for decline[edit]

Habitat loss[edit]

Habitat-related declines of European mink numbers may have started during the Little Ice Age, which was further aggravated by human activity.[5] As the European mink is more dependent on wetland habitats than the American species, its decline in Central Europe, Estonia, Finland, Russia, Moldova and Ukraine has been linked to the drainage of small rivers. In mid-19th-century Germany, for example, European mink populations declined in a decade due to expanded land drainage. Although land improvement and river dredging certainly resulted in population decreases and fragmentation, in areas which still maintain suitable river ecosystems, such as Poland, Hungary, the former Czechoslovakia, Finland and Russia, the decline preceded the change in wetland habitats, and may have been caused by extensive agricultural development.[7]

Overhunting[edit]

The European mink was historically hunted extensively, particularly in Russia, where in some districts, the decline prompted a temporary ban on mink hunting to let the population recover. In the early 20th century, 40–60,000 European minks were caught annually in the Soviet Union, with a record of 75,000 individuals (an estimate which exceeds the modern global European mink population). In Finland, annual mink catches reached 3000 specimens in the 1920s. In Romania, 10,000 minks were caught annually around 1960. However, this reason alone cannot account for the decline in areas where hunting was less intense, such as in Germany.[7]

Decline of crayfish[edit]

The decline of European crayfish has been proposed as a factor in the drop in mink numbers, as minks are notably absent in the eastern side of the Urals, where crayfish are also absent. The decline in mink numbers has also been linked to the destruction of crayfish in Finland during the 1920s-1940s, when the crustaceans were infected with crayfish plague. The failure of the European mink to expand west to Scandinavia coincides with the gap in crayfish distribution.[7]

Competition with the American mink and disease[edit]

The American mink was introduced and released in Europe during the 1920s–1930s. The American mink is less dependent on wetland habitats than the European mink and is 20-40% larger. The impact of feral American minks on European mink populations has been explained through the competitive exclusion principle and because the American mink reproduces a month earlier than the European species, and matings between male American minks and female European minks result in the embryos being reabsorbed. Thus, female European minks impregnated by male American minks are unable to reproduce with their conspecifics. Disease spread by the American mink can also account for the decline. Though the presence of the American mink has coincided with the decline of European mink numbers in Belarus and Estonia, the decline of the European mink in some areas preceded the introduction of the American mink by many years, and there are areas in Russia where the American species is absent, though European mink populations in these regions are still declining.[7]

Diseases spread by the American mink can also account for the decline.[7] Twenty-seven helminth species are recorded to infest the European mink, consisting of 14 trematodes, two cestodes and 11 nematodes. The mink is also vulnerable to pulmonary filariasis, krenzomatiasis and skrjabingylosis.[24] In the Leningrad and Pskov Oblasts, 77.1% of European minks were found to be infected with skrjabingylosis.[5]

Hybridisation and competition with the European polecat[edit]

In the early 20th century, northern Europe underwent a warm climatic period which coincided with an expansion of the range of the European polecat. The European mink possibly was gradually absorbed by the polecat due to hybridisation. Also, competition with the polecat has greatly increased, due to landscape change favouring the polecat.[7] There is one record of a polecat attacking a mink and dragging it to its burrow.[24]

Polecat-mink hybrids are termed khor’-tumak by furriers[9] and khonorik by fanciers.[26] Such hybridisation is very rare in the wild, and typically only occurs where European minks are declining. A polecat-mink hybrid has a poorly defined facial mask, yellow fur on the ears, grey-yellow underfur and long, dark brown guard hairs. Fairly large, the males attain the peak sizes known for European polecats (weighing 1,120–1,746 g (2.469–3.849 lb) and measuring 41–47 cm (16–19 in) in length), and females are much larger than female European minks (weighing 742 g (1.636 lb) and measuring 37 cm (15 in) in length).[10] The majority of polecat-mink hybrids have skulls bearing greater similarities to those of polecats than to minks.[11] Hybrids can swim well like minks and burrow for food like polecats. They are very difficult to tame and breed, as males are sterile, though females are fertile.[11][26] The first captive polecat-mink hybrid was created in 1978 by Soviet zoologist Dr. Dmitry Ternovsky of Novosibirsk. Originally bred for their fur (which was more valuable than that of either parent species), the breeding of these hybrids declined as European mink populations decreased.[26] Studies on the behavioural ecology of free-ranging polecat-mink hybrids in the upper reaches of the Lovat River indicate the hybrids will stray from aquatic habitats more readily than pure minks, and will tolerate both parent species entering their territories, though the hybrid’s larger size (especially the male’s) may deter intrusion. During the summer period, the diet of wild polecat-mink hybrids is more similar to that of the mink than to the polecat, as they feed predominantly on frogs. During the winter, their diets overlap more with those of polecats, and will eat a larger proportion of rodents than in the summer, though they still rely heavily on frogs and rarely scavenge ungulate carcasses as the polecat does.[10]

Predation[edit]

Predators of the European mink include the European polecat, the American mink, the golden eagle, large owls[5] and the red fox. Red fox numbers have increased greatly in areas where the wolf and Eurasian lynx have been extirpated, as well as areas where modern forestry is practised. As red foxes are known to prey on mustelids, excessive fox predation on the European mink is a possible factor, though it is improbable to have been a factor in Finland, where fox numbers were low during the early 20th century.[7]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Maran, T.; Skumatov, D.; Gomez, A.; Põdra, M.; Abramov, A.V.; Dinets, V. (2016). «Mustela lutreola«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T14018A45199861. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T14018A45199861.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1391

- ^ a b Davidson, A., Griffith, H. I., Brookes, R. C., Maran, T., MacDonald, D. W., Sidorovich, V. E., Kitchener, A. C., Irizar, I., Villate, I., Gonzales-Esteban, J., Cena, A., Moya, I. and Palazon Minano, S. 2000. Mitochondrial DNA and paleontological evidence for the origin of endangered European mink, Mustela lutreola Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Animal Conservation 3: 345–357.

- ^ a b MARMI, J., LÓPEZ-GIRÁLDEZ, J.F. & DOMINGO-ROURA, X. (2004). Phylogeny, Evolutionary History and Taxonomy of the Mustelidae based on Sequences of the Cytochrome b Gene and a Complex Repetitive Flanking Region. Zoologica Scripta, 33: 481 — 499

- ^ a b c d e f g h Youngman, Phillip M. (1990). Mustela lutreola, Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Mammalian Species, American Society of Mammalogists, No. 362, pp. 1–3, 2 figs

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1101–1102

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maran, T. and Henttonen, H. 1995. Why is the European mink, Mustela lutreola disappearing? — A review of the process and hypotheses. Annales Fennici Zoologici 32: 47–54.

- ^ Kurtén 1968, p. 98

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1086–1088

- ^ a b c Sidorovich, V. (2001) Finding on the ecology of hybrids between the European mink Mustela lutreola and polecat M.putorius at the Lovat upper reaches, NE Belarus Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Small Carnivore Conservation 24: 1-5

- ^ a b c Tumanov, Igor L. & Abramov, Alexei V. (2002) A study of the hybrids between the European Mink Mustela lutreola and the Polecat M. putorius Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Small Carnivore Conservation 27: 29-31

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). «Order Carnivora». In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1095

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1098

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1096–1097

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1099

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1080

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1083–1084

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, p. 1103

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1081–1082

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1392–1397

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1398–1399

- ^ a b Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1102–1103

- ^ a b c Heptner & Sludskii 2002, pp. 1104–1105

- ^ Karáth, Kata (16 August 2017). «Scientists think they can save the European mink—by killing its ruthless rivals». Science. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ a b c «Khonorik: Hybrids between Mustelidae». Russian Ferret Society. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bachrach, Max (1953). «Fur: a practical treatise» (3rd ed.). New York : Prentice-Hall.

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). «Pleistocene mammals of Europe». Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (2002). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores (Mustelidae and Procyonidae). Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- Macdonald, David (1992). The Velvet Claw: A Natural History of the Carnivores. New York: Parkwest. ISBN 0-563-20844-9.

External links[edit]

- Photos of European Mink

- European Mink: Biology and Conservation

- European mink reintroduction project, ex-situ, in-situ research with Dr. Elisabeth Peters, Mustela lutreola, Germany.

Европейская норка — считается весьма ценной, в связи с наличием у неё теплого и достаточно красивого меха, который характеризуется разнообразием цветов и оттенков. Существует, как дикая норка, так и домашняя норка, причем некоторые любители уникальных животных содержат у себя норок в качестве домашних питомцев, но никак не для получения ценного меха.

Содержание

- 1 Европейская норка: описание

- 1.1 Внешний вид

- 1.2 Характер и образ жизни

- 1.3 Сколько живет норка

- 1.4 Половой диморфизм

- 1.5 Где обитает

- 1.6 Чем питается

- 1.7 Размножение и потомство

- 1.8 Естественные враги норок

- 2 Популяция и статус вида

- 3 В заключение

Европейская норка: описание

Норка представляет хищное млекопитающее семейства «Куньи» и рода «Ласки» и «Хорьки». Обитая в естественной среде, это животное предпочитает вести полуводный образ жизни. Как и у выдры, которая является родственницей норки, у норки между пальцами располагаются плавательные перепонки.

Внешний вид

Взрослые особи вырастают в длину до полуметра, при этом их вес составляет не больше 1 килограмма. Тело у этого млекопитающего удлиненной формы, достаточно гибкое, при этом хвост короткий, а конечности небольшие. Средняя длина тела находится в пределах 40 сантиметров, а вес – 650 граммов. Длина хвоста составляет порядка 2-х десятков сантиметров. Шерстяной покров обладает водоотталкивающими свойствами, поэтому норка может без проблем находиться в воде длительное время. Шерсть короткая, но очень густая. Кроме этого, у норки есть еще подшерсток, который также обладает водоотталкивающими характеристиками. Как правило, времена года не оказывают никакого влияния на густоту шерстяного покрова, что делает его качественным в любое время года.

Голова у норки сравнительно небольшая, при этом область морды уплощена и заужена по направлению вниз. Уши сравнительно маленькие, округлой формы, что делает их мало заметными на фоне густого и плотного меха. Глаза, хотя и небольшие, но достаточно выразительные, с живым и подвижным взглядом. Из-за особенностей образа жизни, между пальцами лап животного имеются перепонки, которые больше развиты на задних конечностях.

Интересно знать! Домашняя норка отличается тем, что у нее окрас меха более разнообразный, по сравнению с ее дикими сородичами. Селекционеры, чтобы охарактеризовать всевозможные оттенки окраса шерстяного покрова, пользуются терминологией, аналогичной определению окрасов драгоценных камней и металлов. Поэтому совсем неудивительно, что домашние норки характеризуются сапфировым, топазным, жемчужным, серебристым, стальным и т.д. типами окрасов.

Окрас шерсти диких норок более привычный и более естественный, поэтому встречаются особи, окрас шерстяного покрова которых выполнен в одном из оттенков рыжеватого, коричневатого ил буроватого цветов. Кроме этого, встречаются особи темно-коричневого или почти черного цветов, при этом вкрапления белого цвета присуще, как для домашних норок, так и диких ее сородичей. Белые отметины могут присутствовать в области груди, на морде и на животе млекопитающих.

Характер и образ жизни

Европейская норка характеризуется подвижным и живым характером поведения. Как правило, этот хищник предпочитает вести одиночный образ жизни, занимая конкретную территорию, площадью в пару десятков гектаров. Основная активность хищника приходится на темное время суток, хотя можно увидеть, что норка охотится и днем. Несмотря на тот факт, что это полуводное животное, большую часть жизни норка проводит на суше, где она находит для себя пропитание.

В летний период, когда объектов пропитания вполне достаточно норка в поисках пропитания преодолевает не больше 1 километра, а вот в зимний период, когда с пропитанием проблемы, норка может преодолевать и большие расстояния. Двигаясь в поисках пищи, для этого животного практически не существует преград, тем более, что норка прекрасно плавает и ныряет.

Находясь в толще воды, она перемещается за счет одновременных движений передними и задними конечностями, поэтому создается впечатление, что это животное не приспособлено к водной стихии, так как движения выглядят неровными, в виде неравномерных толчков. Даже течение реки, если оно не особенно стремительное, не может сбить с пути этого хищника.

Интересный факт! Норка не просто умеет плавать и нырять. Она может ходить по дну водоема, цепляясь когтями за его поверхность.

На суше норка чувствует себя не настолько уверенно. Она способна взобраться на дерево только в случае серьезной опасности. Может самостоятельно вырыть для себя нору, но при случае может занять чью-то пустующую. Формирует для себя укрытия в трещинах или углублениях грунта, в дуплах деревьев, которые располагаются не слишком высоко от поверхности земли, а также в густой прибрежной растительности.

Норка, по сравнению с другими представителями данного семейства, предпочитает все время пользоваться одним жилищем. Нора у этого хищника неглубокая и состоит из места для отдыха, из места для уборной, а также из двух входов/выходов. Один из входов обязательно ведет к воде, а второй выход может находиться среди густых зарослей растительности. Главная камера, предназначенная для жилья, выстилается различными сухими компонентами, в том числе и птичьими перьями.

Сколько живет норка

Особи, обитающие в естественных условиях, живут не больше одного десятка лет, а вот особи, содержащиеся в условиях неволи, могут прожить в 2 раза дольше.

Половой диморфизм

Отличить самку от самца можно, если сравнить их размеры, так как самцы характеризуются большими размерами тела. Что касается других внешних различий, то они не существенные, поэтому можно смело говорить о том, что половой диморфизм выражен достаточно слабо.

Где обитает

Еще не так давно подобные хищники обитали на обширных территориях, начиная от Финляндии и заканчивая Уралом, при этом южные границы ареала обитания заканчивались на Кавказе, а северные границы – на Пиренеях. Западные границы были связаны с территорией Франции и Испании. К сожалению, этим зверькам не повезло и, из-за ценного и красивого меха человек активно охотился на этих животных. Особенно активным было истребление в последние 150 лет, из-за чего общая численность норок существенно снизилась, а их ареал обитания заметно сузился.

В наше время этих млекопитающих еще можно встретить на территории Испании и Франции, в Румынии, в Украине, а также на территории России. На территории нашей страны норки даже в наше время не находятся в полной безопасности. Кроме этого, европейская норка не выдерживает конкуренции с американской норкой, которая вытесняет европейскую норку из ее естественной среды обитания.

Европейская норка предпочитает селиться вблизи различных водоемов, особенно тех, которые не имеют крутых берегов, но при этом берега имеют обильные заросли различной растительности. Для ее жизнедеятельности больше подходят небольшие речки или просто ручьи, поэтому в пределах широких и крупных рек этот хищник практически не встречается. Обитает норка также в условиях степных зон, но с обязательным наличием различных водоемов. Этого небольшого хищника можно встретить у подножий гор, в пределах быстрых горных рек, береговая зона которых имеет заросли различной растительности.

Чем питается

Норка – это хищное млекопитающее, поэтому животная пища составляет основу ее рациона питания. В водоемах она ловит рыбу и других водных обитателей, а также их икру. Находясь на суше, рацион питания расширяется за счет различных грызунов, а также небольших пернатых, если повезет поймать. Кроме этого, в меню могут присутствовать всевозможные насекомые. Животные, поселившиеся рядом с человеческим жилищем, при недостатке кормовой базы, охотятся на домашнюю птицу, а если с кормами совсем туго, то подбирают пищевые отходы человека.

Важно знать! С наступлением зимних холодов, эти животные занимаются обустройством кормовых складов, для чего животные используют свои норы или специальные камеры для хранения запасов. Как правило, норки всегда запасают на зиму достаточно объектов пропитания, так что к зимним холодам этот хищник готов всегда.

Норка характеризуется тем, что она всегда отдает предпочтение свежему мясу, поэтому может голодать некоторое время, но к протухшему мясу может притронуться только в крайнем случае.

Размножение и потомство

У этих животных брачный период начинается зимой, в феврале месяце и продолжается до апреля месяца. Этот период характеризуется тем, что самцы часто дерутся, о чем свидетельствуют громкие звуки, в виде визга, издаваемые соперниками. Когда снег еще лежит на поверхности земли, места токовищ можно определить по натоптанным вдоль берегов тропам. После завершения этого периода, как самцы, так и самки занимают свои территории и, их может ожидать следующая встреча только на следующий период размножения.

Самка вынашивает свое потомство на протяжении 40 дней или чуть дольше, после чего на свет появляется от 2-х до 7 детенышей, хотя в среднем появляется на свет около 5 малышей. Появившееся на свет потомство слепое и абсолютно беспомощное. На протяжении 10 недель мать кормит свое потомство молоком. Через пару месяцев после появления на свет молодь начинает выходить из норы, отправляясь с матерью на поиски пропитания. Еще через месяц молодые норки стают полностью самостоятельными животными.

Важно помнить! Несмотря на тот факт, что семейство «куньи» не имеют никакого отношения к семейству «псовые», детенышей норки принято называть щенками.

Несмотря на то, что уже к 3-м месяцам жизни молодь становится взрослой, семейство живет вместе до наступления осени. Только потом молодые норки отправляются на поиски своих территорий. Особи становятся половозрелыми в возрасте 10 месяцев.

Естественные враги норок

Естественные враги норок представлены в основном двумя видами животных – выдрой и американской норкой, которая является родственницей. Американскую норку в свое время завезли на территорию России, после чего она стала притеснять, а порой и уничтожать свою европейскую родственницу, так как она имеет меньшие размеры.

Кроме хищных животных, для европейской норки особую опасность представляют различные болезни, при этом разносчиками опасных, паразитарных болезней являются американские норки.

Популяция и статус вида

Европейская норка в наше время оказалась на грани полного исчезновения, поэтому занесена в Красную книгу. По мнению специалистов, уменьшение численности вида связано:

- С потерей природных мест обитания, связанной с жизнедеятельностью человека.

- С промыслом, а также с действиями браконьеров.

- С уменьшением разнообразия кормовой базы.

- С наличием конкурента в виде американской норки.

- С процессом гибридизации с хорьком, поскольку самцы подобных гибридов являются бесплодными.

- С увеличением численности некоторых естественных врагов, таких, как лиса.

Действие подобных факторов привело к тому, что дикая норка оказалась на грани вымирания. В ряде стран, на территории которых еще встречаются эти хищники, принимаются меры, предназначенные для сохранения и приумножения численности подобных животных. Благодаря наличию природоохранных мер, осуществляется контроль численности норок, воссоздание природных условий обитания, а также создание резервных популяций с программами по консервации генома. Для этого дикие особи содержатся и разводятся в условиях неволи на случай, если эти животные исчезнут, обитая в условиях дикой природы.

На протяжении столетий человек занимался потребительством по отношению к этим животным, истребляя их из-за теплого, красивого меха. К сожалению, это касается не только норки, но и многих других животных, которых человек истреблял и истребляет, не задумываясь о последствиях.

К сожалению, человек начинает понимать, но становится слишком поздно. В результате, от обширного природного ареала обитания остались лишь незначительные островки, на которых еще можно встретить подобных млекопитающих. Поскольку в ряде стран принимается ряд зоозащитных мер по сохранению и приумножению численности этих животных, имеется надежда на то, что норки могут выжить, а затем расселиться по свои местам обитания. Конечно, шанс есть, но он совсем небольшой, поскольку в последнее время человек все активнее обживает новые территории, не оставляя никаких шансов для многих животных и других представителей живой природы.

В заключение

Имеется надежда на то, что человек все же одумается и начнет вкладывать средства в живую природу. К сожалению, колоссальные средства уходят совсем на другое, так как человек никак не может ужиться (мирно) друг с другом на нашей Планете. Создается впечатление, что он готов уничтожить все ради того, чтобы иметь безграничную власть над себе подобными. Об этом свидетельствуют постоянные конфликты с применением оружия, которого на нашей Планете в избытке, не говоря уже о ядерном оружии, которое может уничтожить все живое на земле за считанные минуты. Человек не понимает, что, оставшись на земле в единственном виде, его постигнет та же участь, что и других представителей живой природы.

Европейская норка – это уникальное животное, которое выполняет весьма важную роль в обеспечении баланса экосистемы нашей Планеты. Она помогает человеку в борьбе с различными грызунами, регулируя их численность на определенном уровне. Это же актуально и по отношению к другим живым обитателям, постоянство численности которых играет очень важную роль для человека, а также для живой природы в целом.

ЕВРОПЕЙСКАЯ НОРКА: Выступает в одиночном пикете против экспроприации её шубы | Факты про норок

Европейская норка

- Европейская норка

-

Европейская норка — Mustela lutreola

см. также 3.4.3. Род Хорьки— Mustela

Европейская норка [94] — Mustela lutreola

(около трети длины тела).

Мех короткий, густой. Окраска одноцветная, от рыжевато-бурой до темно-коричневой, снизу чуть светлее, а на ногах и хвосте — темнее. На губах и подбородке белое пятно (иногда заходит на горло). След, как у американской норки [93]. В прошлом была обычна по берегам водоемов (чаще лесных) по всей европейской части России южнее тундры, в Зауралье и Предкавказье. Образ жизни, как у американской норки, но в выводке не 5-7, а 2-3 детеныша. Сейчас исчезла или стала крайне редка повсюду, кроме юга Приладожья, Валдая и некоторых других районов. Численность повсюду сокращается, так что этот зверек может полностью вымереть за несколько десятилетий.

Чтобы спасти европейскую норку от исчезновения, ее завезли на Южные Курилы (где она не прижилась) и на остров Валаам. По общепринятой гипотезе, вымирание этого вида связано с вытеснением более крупным видом, американской норкой. Однако, по мнению некоторых исследователей, снижение численности европейской норки началось еще до завоза американской и, возможно, связано с перепромыслом или какими-то другими, неизвестными причинами. Местами по-прежнему добывают вместе с американской норкой. Занесена в Красную книгу России.

Таблица 14

Таблица 14 93 — американская норка; 94 — европейская норка; 95 — черный хорь; 96 — степной хорь: 47 — перевязка.

Энциклопедия природы России. — М.: ABF.

.

1998.

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Европейская норка» в других словарях:

-

Европейская норка — ? Европейская норка … Википедия

-

европейская норка — europinė audinė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Mustela lutreola angl. european mink; marshotter; Old World mink vok. europäischer Nerz; kleiner Fischotter; Krebsotter; Nerz; nordeuropäischer Nerz;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

-

Кавказская европейская норка — ? Кавказская европейская норка Научная классификация Царство: Животные Тип: Хордовые Подтип: Позвоночные … Википедия

-

Норка европейская — ? Европейская норка Научная классификация Царство: Животные Тип: Хордовые … Википедия

-

норка — europinė audinė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Mustela lutreola angl. european mink; marshotter; Old World mink vok. europäischer Nerz; kleiner Fischotter; Krebsotter; Nerz; nordeuropäischer Nerz;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

-

НОРКА — (мех) шкурка хищного земноводного зверька норки. В Европейской части СССР распространена норка обыкновенная (европейская). На севере Европейской части, на Дальнем Востоке, в Якутии, Сибири, на Урале, в Башкирии акклиматизирована американская… … Краткая энциклопедия домашнего хозяйства

-

Норка — хищный зверек с ценным мехом; название меха этого зверька. Существует два вида Н.: европейская и американская. Оба вида обитают и на территории России. Американская Н. была завезена в нашу страну в 1928 г. из Северной Америки для разведения в… … Энциклопедия моды и одежды

-

Американская норка — Mustela vison см. также 3.4.3. Род Хорьки Mustela Американская норка [93] Mustela vison (около половины длины тела). Окраска темно коричневая, белое пятно на подбородке заходит только на нижнюю губу. Изредка бывают белые пятна на груди, горле и… … Животные России. Справочник

-

обыкновенная норка — europinė audinė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Mustela lutreola angl. european mink; marshotter; Old World mink vok. europäischer Nerz; kleiner Fischotter; Krebsotter; Nerz; nordeuropäischer Nerz;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

-

русская норка — europinė audinė statusas T sritis zoologija | vardynas taksono rangas rūšis atitikmenys: lot. Mustela lutreola angl. european mink; marshotter; Old World mink vok. europäischer Nerz; kleiner Fischotter; Krebsotter; Nerz; nordeuropäischer Nerz;… … Žinduolių pavadinimų žodynas

Европейская норка (лат. Mustela lutreola) – хищный зверёк семейства куньих. Относится к отряду млекопитающих. Во многих исторических местах обитания она уже давно считается вымершим животным и указана в Красной книге как вид, находящийся под угрозой исчезновения. Точную численность популяции определить трудно, но, по оценкам, в дикой природе насчитывается менее 30 000 особей.

Причины исчезновения несколько. Первым фактором стал ценный мех норки, на который всегда есть спрос. Вторым – заселение американской норки, которая вытеснила европейскую из естественной среды обитания. Третий фактор – уничтожение водоёмов и мест, пригодных для жизни. И последнее – эпидемии. Европейские норки подвержены вирусам так же, как и собаки. Особенно это касается мест, где популяция отличается большой численностью. Пандемии – одна из причин сокращения поголовья этих уникальных млекопитающих.

Описание

Европейская норма довольно мелкое животное. Самцы иногда вырастают до 40 см при весе в 750 г, а самки и того меньше – весом около пол килограмма и длинной чуть больше 25 см. Тело вытянутое, конечности короткие. Хвост не пушистый длиной 10-15 см.

Мордочка узкая, слегка сплюснутая, с маленькими круглыми ушками, почти спрятанными в густой шерсти и шустрыми глазками. Пальцы норки сочленены перепонкой, особенно хорошо это заметно на задних конечностях.

Мех густой, плотный, не длинный, с хорошей подпушкой, которая остаётся сухой даже после длительных водных процедур. Окрас однотонный, от светло – до тёмно-коричневого, редко чёрного цвета. На подбородке и груди – белое пятнышко.

География и среда обитания

Ранее европейские норки обитали на всей территории Европы, от Финляндии до Испании. Однако теперь их можно найти только на небольших ареалах в Испании, Франции, Румынии, Украине и России. Большая часть этого вида обитает в России. Здесь их численность составляет 20 000 особей – две трети от общемирового количества.

Этот вид имеет очень специфические требования к местообитаниям, что является одной из причин уменьшения численности популяции. Они – полуводные существа, живущие как в воде, так и на суше, поэтому им приходится селиться вблизи водоёмов. Характерно, что селятся зверьки исключительно возле пресноводных озёр, рек, ручейков и болот. Случаи появления Европейской норки вдоль морского побережья не зафиксированы.

Кроме того, Mustela lutreola нуждаются в густой растительности, расположенной вдоль береговой линии. Они организовывают свои жилища, выкапывая логова или заселяя полые брёвна, по-хозяйски утепляя их травой и листьями, тем самым создавая уют себе и потомству.

Повадки

Норки – ночные хищники, наиболее комфортно ощущающие себя в сумерках. Но иногда охотятся и ночью. Охота происходит интересным способом – свою добычу зверушка выслеживает с берега, где проводит основную часть времени.

Норки – отличные пловцы, пальцы с перепонками помогают им пользоваться лапами, как ластами. При необходимости хорошо ныряют, в случае опасности проплывают под водой до 20 метров. После короткого вдоха, могут продолжить заплыв.

Питание

Норки – плотоядные животные, а это значит, что они едят мясо. Мыши, кролики, рыба, раки, змеи, лягушки и водоплавающая птица являются частью их диеты. Известно, что европейская норка питается некоторой растительностью. Остатки шкурок часто хранятся в их логове.

Питается любыми мелкими обитателями водоемов и окрестностей. Базовой пищей являются: крысы, мыши, рыба, земноводные, лягушки, раки, жуки и личинки.

Около поселений иногда охотятся на цыплят, утят и другую мелкую домашнюю живность. В период голода могут питаться отходами.

Предпочтение отдают свежей добыче: в неволе при нехватке качественного мяса голодают по несколько дней, до того как переходят на подпорченное мясо.

До начала похолодания стараются делать запасы в своём убежище из пресноводных, рыбы, грызунов, иногда птиц. В неглубоких водоёмах складируют обездвиженных и сложенных лягушек.

Размножение

Европейские норки – одиночки. В группы они не сбиваются, живут отдельно друг от друга. Исключение составляет период спаривания, когда активные самцы начинают устраивать погони и драки за готовыми к спариванию самками. Происходит это в начале весны, а уже к концу апреля – начала мая, после 40 дневной беременности, на свет появляется многочисленное потомство. Обычно в одном приплоде от двух до семи детёнышей. На молоке мать их держит до четырёх месяцев, потом они полностью переходят на мясное питание. Мать покидают примерно через полгода, а через 10-12 месяцев, достигают половой зрелости.

Европейская норка (лат. Mustela lutreola) – хищный зверёк семейства куньих. Относится к отряду млекопитающих. Во многих исторических местах обитания она уже давно считается вымершим животным и указана в Красной книге Республики Татарстан как вид, находящийся под угрозой исчезновения.

Этот вид имеет очень специфические требования к местообитаниям, что является одной из причин уменьшения численности популяции. Они – полуводные существа, живущие как в воде, так и на суше, поэтому им приходится селиться вблизи водоёмов. На территории Республики Татарстан в начале XX в. была обычным видом во всех пойменных угодьях. Сокращение ареала и численности в Республики Татарстан отмечены с конца 20-х гг. прошлого века. Территориально зафиксированы в Высокогорском районе и в Бугульминском районе. В угодьях, заселенных европейской норкой, необходимо не допускать охоту на околоводных млекопитающих, уничтожение береговой растительности, сплав леса, сброс отходов агропромышленного комплекса.

Европейская норма довольно мелкое животное. Самцы иногда вырастают до 40 см при весе в 750 г, а самки и того меньше – весом около пол килограмма и длинной чуть больше 25 см. Тело вытянутое, конечности короткие. Хвост не пушистый длиной 10-15 см.

Европейская норка характеризуется подвижным и живым характером поведения. Как правило, этот хищник предпочитает вести одиночный образ жизни, занимая конкретную территорию, площадью в пару десятков гектаров. Несмотря на тот факт, что это полуводное животное, большую часть жизни норка проводит на суше, где она находит для себя пропитание.

Норка – это хищное млекопитающее, поэтому животная пища составляет основу ее рациона питания. В водоемах она ловит рыбу и других водных обитателей, а также их икру. Находясь на суше, рацион питания расширяется за счет различных грызунов, а также небольших пернатых, если повезет поймать.

Европейская норка – это уникальное животное, которое выполняет весьма важную роль в обеспечении баланса экосистемы нашей Планеты. Она помогает человеку в борьбе с различными грызунами, регулируя их численность на определенном уровне. Это же актуально и по отношению к другим живым обитателям, постоянство численности которых играет очень важную роль для человека, а также для живой природы в целом.

Интересные факты:

1. Норки – отличные пловцы, пальцы с перепонками помогают им пользоваться лапами, как ластами.

2. Норка, по сравнению с другими представителями данного семейства, предпочитает все время пользоваться одним жилищем.

3. Норки – отличные пловцы, пальцы с перепонками помогают им пользоваться лапами, как ластами. При необходимости хорошо ныряют, в случае опасности проплывают под водой до 20 метров.

4. Пушистые зверьки не только защищаются резким запахом, но и помечают так свою территорию. Но у них есть также и второй способ завоевания земель – горловые железы. Норки трутся шеей о деревья и камни, помечая их.

5. В зимнее время года норки ведут подснежную охоту: они прорывают под настом многочисленные ходы, выискивая себе добычу. Таким способом зверёк в день обходит территорию в 1.5-2 километра.

Норка европейская является хищным млекопитающим, представителем семейства куньи. Для нее характерна плавательная перепонка между пальцами ног. Распространено животное на востоке Европы, вдоль берегов рек, где находит для себя корм – рыбу, лягушек, раков. Норки долгое время служили объектом промысла с целью добычи их меха, очень популярного на пушном рынке. Сейчас численность популяции уменьшается еще и в связи с вытеснением норкой американской.

-

1

Описание европейской норки -

2

Особенности питания европейской норки -

3

Распространение европейской норки -

4

Распространенные подвиды европейской норки -

5

Самец и самка европейской норки: основные отличия -

6

Поведение европейской норки -

7

Размножение европейской норки -

8

Естественные враги европейской норки -

9

Интересные факты о европейской норке:

Описание европейской норки

— Реклама —

Шерсть короткая, густая, плотная, подпушь очень густая, не намокает даже если долго находится под водой. Летний и зимний мех по структуре практически одинаков. Мех окрашен одноцветно от рыжевато-бурого до темно-коричневого цвета, более светлый снизу тела и более темный в области конечностей и хвоста. Попадаются практически черные и буро-рыжие особи. На подбородке, а иногда и на груди, расположено белое пятно. Линька происходит осенью и весной.

Особенности питания европейской норки

Распространение европейской норки

Сейчас европейская норка обитает на нескольких ограниченных участках: на севере Испании и западе Франции, в дельтах Дуная в Румынии, на Украине и в России.

— Реклама —