На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «Евросоюз» на английский

Предложения

Некоторые считают, что национализм погубит Евросоюз.

Many have predicted that economic nationalism would one day tear apart the European Union.

Безусловно, распустить Евросоюз можно и нужно.

There is no doubt that the European Union can and should be dissolved.

Темпы роста польской экономики после вхождения в Евросоюз.

This was caused by an upturn in the Polish economy following entry into EU.

Евросоюз решил наказать Болгарию за коррупцию…

EU to Criticise Romania And Bulgaria on Corruption…

Это первое голосование после вступления страны в Евросоюз.

It is the first time we are voting after Cyprus joined the European Union.

Евросоюз как модель западной цивилизации тоже исчез.

European Union as a model of Western civilization has also ceased to be.

Накануне Евросоюз одобрил отправку в Косово специальной полицейской миссии.

Earlier this week, the European Union approved the dispatch of a special police mission to Kosovo.

Изменение тенденции произошло с вхождением Польши в Евросоюз.

The big change in immigration trends came with the accession of Poland to the European Union.

Именно поэтому европейские страны создали Евросоюз.

«Евросоюз всегда был фундаментально социальным проектом.

The European Union has always been primarily a political project.

«Евросоюз не превратится в военный союз.

Евросоюз в этом случае не поможет.

Therefore, European Union will not help us out in this case.

А без сильной независимой Германии невозможен сильный Евросоюз.

Without a strong Germany, you don’t really have a strong European Union.

По экономическому объему Евросоюз сопоставим с США.

Economically, the European Union is on a par with the United States.

При этом Евросоюз обязуется помогать Украине в проведении этих реформ.

The European Union is helping Ukraine with the task of implementing these reforms.

Латвия входит в состав таких международных организаций как Евросоюз, ВТО, является участницей Шенгенского договора.

Latvia is a member of a number of international organizations, including the European Union, the WTO, and is a party to the Schengen Agreement.

Валюта: Греция входит в Евросоюз.

Currency: The Republic of Ireland is part of the European Union.

Норвежцы дважды высказались против вступления в Евросоюз.

Norway’s population has twice narrowly voted down proposals to join the EU.

Самый сложный дипломатический орешек будет Евросоюз.

С новым соглашением Евросоюз возобновил движение вперед.

With the new agreement, the Union has once again started to move.

Предложения, которые содержат Евросоюз

Результатов: 11230. Точных совпадений: 11230. Затраченное время: 108 мс

This article is about the European Union. For the various levels of integration within European countries including EU member states, see European integration.

|

European Union

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Flag |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: «In Varietate Concordia» (Latin)

«United in Diversity» |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: «Anthem of Europe» | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

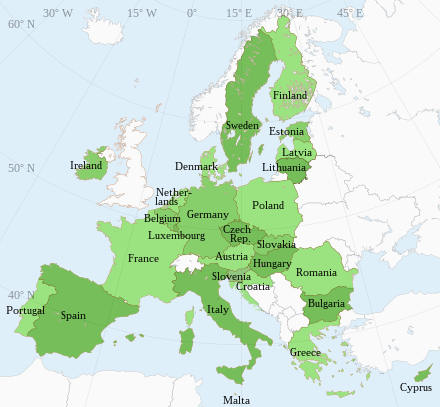

Location of the European Union (dark green) in Europe (dark grey) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Brussels (de facto)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Institutional seats |

Brussels

Frankfurt

Luxembourg City

Strasbourg

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest metropolis | Paris | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | 24 languages 3 main official languages

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official scripts |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion

(2015)[2] |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | European | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Continental union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Membership |

27 members

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Mixed intergovernmental directorial parliamentary confederation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• President of the European Council |

Charles Michel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• President of the Commission |

Ursula von der Leyen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | The European Parliament and the Council | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Upper house |

Council of the European Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Lower house |

European Parliament | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Formation[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Brussels |

17 March 1948 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Paris |

18 April 1951 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Rome |

1 January 1958 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Single European Act |

1 July 1987 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Maastricht |

1 November 1993 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Treaty of Lisbon |

1 December 2009 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total |

4,233,262 km2 (1,634,472 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Water (%) |

3.08 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 2022 estimate |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Density |

106/km2 (274.5/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Per capita |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Total |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Per capita |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gini (2020) | medium |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR)

Others

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC to UTC+2 (WET, CET, EET) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+1 to UTC+3 (WEST, CEST, EEST) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (see also Summer time in Europe)[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .eu[b] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website |

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of 27 member states that are located primarily in Europe.[7][8] The union has a total area of 4,233,255.3 km2 (1,634,469.0 sq mi) and an estimated total population of nearly 447 million. The EU has often been described as a sui generis political entity (without precedent or comparison) combining the characteristics of both a federation and a confederation.[9][10]

Containing 5.8 per cent of the world population in 2020,[c] the EU generated a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of around US$17.1 trillion in 2021,[5] constituting approximately 18 per cent of global nominal GDP.[12] Additionally, all EU states but Bulgaria have a very high Human Development Index according to the United Nations Development Programme. Its cornerstone, the Customs Union, paved the way to establishing an internal single market based on standardised legal framework and legislation that applies in all member states in those matters, and only those matters, where the states have agreed to act as one. EU policies aim to ensure the free movement of people, goods, services and capital within the internal market;[13] enact legislation in justice and home affairs; and maintain common policies on trade,[14] agriculture,[15] fisheries and regional development.[16] Passport controls have been abolished for travel within the Schengen Area.[17] The eurozone is a group composed of the 20 EU member states that have fully implemented the economic and monetary union and use the euro currency. Through the Common Foreign and Security Policy, the union has developed a role in external relations and defence. It maintains permanent diplomatic missions throughout the world and represents itself at the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the G7 and the G20. Due to its global influence, the European Union has been described by some scholars as an emerging superpower.[18][19][20]

The union was established along with its citizenship when the Maastricht Treaty came into force in 1993, and was subsequently incorporated as an international law juridical person upon entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, [21] but its beginnings may be traced to its earliest predecessors incorporated primarily by a group of founding states known as the Inner Six (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany) at the start of modern institutionalised European integration in 1948 and onwards, namely to the Western Union (WU, 1954 renamed Western European Union, WEU), the International Authority for the Ruhr (IAR), the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Economic Community (EEC, 1993 renamed European Community, EC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), established, respectively, by the 1948 Treaty of Brussels, the 1948 London Six-Power Conference, the 1951 Treaty of Paris, the 1957 Treaty of Rome and the 1957 Euratom Treaty. These increasingly amalgamated bodies later known collectively as the European Communities have grown since, along with their legal successor, the EU, both in size through accessions of further 21 states as well as in power through acquisitions of various policy areas to their remit by the virtue of the abovementioned treaties, as well as numerous other ones, such as the Modified Brussels Treaty, the Merger Treaty, the Single European Act, the Treaty of Amsterdam and the Treaty of Nice. In 2012, the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[22]

After the creation by six states, 22 other states joined the union in 1973–2013. The United Kingdom became the only member state to leave the EU in 2020;[23] ten countries are aspiring or negotiating to join it.

History

Origins

The European Federalist Movement, founded in Milan in 1943 by a group of activists led by Altiero Spinelli, propagated European integration.

After the First World War, but particularly with Second World War, internationalism was gaining, with the creation of the Bretton Woods System in 1944, the United Nations in 1945 and the French Union (1946–1958), the latter directing decolonization by possibly integrating its colonies into a European community.[24] In this light European integration was seen, already during the war, as an antidote to the extreme nationalism which had devastated parts of the continent.[25]

The Ventotene prison Manifesto of 1941 by Altiero Spinelli propagated European integration through the Italian Resistance and after 1943 through the European Federalist Movement. Winston Churchill called in 1943 for a post-war «Council of Europe»[26][27] and on 19 September 1946, at the University of Zürich, coincidentally[28] parallel to the Hertenstein Congress of the Union of European Federalists, for a United States of Europe.[29] Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, who successfully established during the interwar period the oldest organization for European integration, the Paneuropean Union, founded in June 1947 the European Parliamentary Union (EPU).

Towards the end of World War II, the Three Allied Powers discussed during the Tehran Conference and the ensuing 1943 Moscow Conference the plans to establish joint institutions. This led to a decision at the Yalta Conference in 1944 to include Free France as the Fourth Allied Power and to form a European Advisory Commission, later replaced by the Council of Foreign Ministers and the Allied Control Council, following the German surrender and the Potsdam Agreement in 1945.

The growing rift among the Four Powers became evident as a result of the rigged 1947 Polish legislative election which constituted an open breach of the Yalta Agreement, followed by the announcement of the Truman Doctrine on 12 March 1947. On 4 March 1947 France and the United Kingdom signed the Treaty of Dunkirk for mutual assistance in the event of future military aggression in the aftermath of World War II against any of the pair. The rationale for the treaty was the threat of a potential future military attack, specifically a Soviet one in practice, though publicised under the disguise of a German one, according to the official statements. Immediately following the February 1948 coup d’état by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, the London Six-Power Conference was held, resulting in the Soviet boycott of the Allied Control Council and its incapacitation, an event marking the beginning of the Cold War. The remainder of the year 1948 marked the beginning of the institutionalised modern European integration.

Initial years and the Paris Treaty (1948–1957)

The year 1948 marked the beginning of the institutionalised modern European integration. In March 1948 the Treaty of Brussels was signed, establishing the Western Union (WU), followed by the International Authority for the Ruhr. Furthermore, the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), the predecessor of the OECD, was also founded in 1948 to manage the Marshall Plan, triggering as a Soviet response formation of the Comecon. The ensuing Hague Congress of May 1948 was a pivotal moment in European integration, as it led to the creation of the European Movement International, the College of Europe[30] and most importantly to the foundation of the Council of Europe on 5 May 1949 (today its Europe day). The Council of Europe was one of the first institutions to bring the sovereign nations of (then only Western) Europe together, raising great hopes and fevered debates in the following two years for further European integration.[citation needed] It has since been a broad forum to further cooperation and shared issues, achieving for example the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950. Essential for the actual birth of the institutions of the EU was the Schuman Declaration on 9 May 1950 (the day after the fifth Victory in Europe Day) and the decision by six nations (France, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, West Germany and Italy) to follow Schuman and draft the Treaty of Paris. This treaty created in 1952 the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which was built on the International Authority for the Ruhr, installed by the Western Allies in 1949 to regulate the coal and steel industries of the Ruhr area in West Germany.[31] Backed by the Marshall Plan with large funds coming from the United States since 1948, the ECSC became a milestone organization, enabling European economic development and integration and being the origin of the main institutions of the EU such as the European Commission and Parliament.[32] Founding fathers of the European Union understood that coal and steel were the two industries essential for waging war, and believed that by tying their national industries together, a future war between their nations became much less likely.[33]

In parallel with Schuman, the Pleven Plan of 1951 tried but failed to tie the institutions of the developing European community under the European Political Community, which was to include the also proposed European Defence Community, an alternative to West Germany joining NATO which was established in 1949 under the Truman Doctrine. In 1954 the Modified Brussels Treaty transformed the Western Union into the Western European Union (WEU). West Germany eventually joined in 1955 both WEU and NATO, prompting the Soviet Union to form the Warsaw Pact in 1955 as an institutional framework for its military domination in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Assessing the progress of European integration the Messina Conference was held in 1955, ordering the Spaak report, which in 1956 recommended the next significant steps of European integration.

Treaty of Rome (1958–1972)

In 1957, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Rome, which created the European Economic Community (EEC) and established a customs union. They also signed another pact creating the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) for co-operation in developing nuclear power. Both treaties came into force in 1958.[33] Although the EEC and Euratom were created separately from the ECSC, they shared the same courts, and the Common Assembly. The EEC was headed by Walter Hallstein (Hallstein Commission) and Euratom was headed by Louis Armand (Armand Commission) and then Étienne Hirsch (Hirsch Commission).[34][35] The OEEC was in turn reformed in 1961 into the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and its membership was extended to non-European states, the US and Canada. During the 1960s, tensions began to show, with France seeking to limit supranational power. Nevertheless, in 1965 an agreement was reached, and on 1 July 1967 the Merger Treaty created a single set of institutions for the three communities, which were collectively referred to as the European Communities.[36][37] Jean Rey presided over the first merged commission (Rey Commission).[38]

First enlargement, and European co-operation (1973–1993)

1973–1980: Denmark, Ireland and the UK joined

1981–1985: Greece joined

1986–2002: Portugal and Spain joined

In 1973, the communities were enlarged to include Denmark (including Greenland), Ireland, and the United Kingdom.[39] Norway had negotiated to join at the same time, but Norwegian voters rejected membership in a referendum. The Ostpolitik and the ensuing détente led to establishment of a first truly pan-European body, the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), predecessor of the modern Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). In 1979, the first direct elections to the European Parliament were held.[40] Greece joined in 1981. In 1985, Greenland left the Communities, following a dispute over fishing rights. During the same year, the Schengen Agreement paved the way for the creation of open borders without passport controls between most member states and some non-member states.[41] In 1986, the European flag began to be used by the EEC[42] and the Single European Act was signed. Portugal and Spain joined in 1986.[43] In 1990, after the fall of the Eastern Bloc, the former East Germany became part of the communities as part of a reunified Germany.[44]

Treaties of Maastricht, Amsterdam and Nice (1993–2004)

The European Union was formally established when the Maastricht Treaty—whose main architects were Horst Köhler,[45] Helmut Kohl and François Mitterrand—came into force on 1 November 1993.[21][46] The treaty also gave the name European Community to the EEC, even if it was referred to as such before the treaty. With further enlargement planned to include the former communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as Cyprus and Malta, the Copenhagen criteria for candidate members to join the EU were agreed upon in June 1993. The expansion of the EU introduced a new level of complexity and discord.[47] In 1995, Austria, Finland, and Sweden joined the EU.

In 2002, euro banknotes and coins replaced national currencies in 12 of the member states. Since then, the eurozone has increased to encompass 19 countries. The euro currency became the second-largest reserve currency in the world. In 2004, the EU saw its biggest enlargement to date when Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia joined the union.[48]

Treaty of Lisbon, and Brexit (2004–present)

In 2007, Bulgaria and Romania became EU members. Later that year, Slovenia adopted the euro,[48] followed by Cyprus and Malta in 2008, Slovakia in 2009, Estonia in 2011, Latvia in 2014, and Lithuania in 2015.

On 1 December 2009, the Lisbon Treaty entered into force and reformed many aspects of the EU. In particular, it changed the legal structure of the European Union, merging the EU three pillars system into a single legal entity provisioned with a legal personality, created a permanent president of the European Council, the first of which was Herman Van Rompuy, and strengthened the position of the high representative of the union for foreign affairs and security policy.[49][50]

In 2012, the EU received the Nobel Peace Prize for having «contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy, and human rights in Europe».[51][52] In 2013, Croatia became the 28th EU member.[53]

From the beginning of the 2010s, the cohesion of the European Union has been tested by several issues, including a debt crisis in some of the Eurozone countries, increasing migration from Africa and Asia, and the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU.[54] A referendum in the UK on its membership of the European Union was held in 2016, with 51.9 per cent of participants voting to leave.[55] The UK formally notified the European Council of its decision to leave on 29 March 2017, initiating the formal withdrawal procedure for leaving the EU; following extensions to the process, the UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020, though most areas of EU law continued to apply to the UK for a transition period which lasted until 31 December 2020.[56]

Timeline

Since the end of World War II, sovereign European countries have entered into treaties and thereby co-operated and harmonised policies (or pooled sovereignty) in an increasing number of areas, in the European integration project or the construction of Europe (French: la construction européenne). The following timeline outlines the legal inception of the European Union (EU)—the principal framework for this unification. The EU inherited many of its present responsibilities from the European Communities (EC), which were founded in the 1950s in the spirit of the Schuman Declaration.

| Legend: S: signing F: entry into force T: termination E: expiry de facto supersession Rel. w/ EC/EU framework: de facto inside outside |

[Cont.] | |||||||||||||||

| (Pillar I) | ||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom) | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||

|

(Distr. of competences) |

||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | ||||||||||||||||

| Schengen Rules | European Community (EC) | |||||||||||||||

| ‘TREVI’ | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA, pillar II) | |||||||||||||||

| [Cont.] | Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC, pillar II) | |||||||||||||||

Anglo-French alliance |

[Defence arm handed to NATO] | European Political Co-operation (EPC) | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, pillar III) |

|||||||||||||

| [Tasks defined following the WEU’s 1984 reactivation handed to the EU] | ||||||||||||||||

| [Social, cultural tasks handed to CoE] | [Cont.] |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Entente Cordiale |

Dunkirk Treaty[i] |

Brussels Treaty[i] |

London and Washington treaties[i] |

Paris treaties: ECSC and EDC[ii] |

Protocol Modifying and |

Rome treaties: EEC and EAEC |

WEU-CoE agreement[i] |

Brussels (Merger) Treaty[iii] |

Davignon report |

European Council conclusions |

Single European Act (SEA) |

Schengen Treaty and Convention |

Maastricht Treaty[iv][v] |

Amsterdam Treaty |

Nice Treaty |

Lisbon Treaty[vi] |

- ^ a b c d e Although not EU treaties per se, these treaties affected the development of the EU defence arm, a main part of the CFSP. The Franco-British alliance established by the Dunkirk Treaty was de facto superseded by WU. The CFSP pillar was bolstered by some of the security structures that had been established within the remit of the 1955 Modified Brussels Treaty (MBT). The Brussels Treaty was terminated in 2011, consequently dissolving the WEU, as the mutual defence clause that the Lisbon Treaty provided for EU was considered to render the WEU superfluous. The EU thus de facto superseded the WEU.

- ^ Plans to establish a European Political Community (EPC) were shelved following the French failure to ratify the Treaty establishing the European Defence Community (EDC). The EPC would have combined the ECSC and the EDC.

- ^ The European Communities obtained common institutions and a shared legal personality (i.e. ability to e.g. sign treaties in their own right).

- ^ The treaties of Maastricht and Rome form the EU’s legal basis, and are also referred to as the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), respectively. They are amended by secondary treaties.

- ^ Between the EU’s founding in 1993 and consolidation in 2009, the union consisted of three pillars, the first of which were the European Communities. The other two pillars consisted of additional areas of cooperation that had been added to the EU’s remit.

- ^ The consolidation meant that the EU inherited the European Communities’ legal personality and that the pillar system was abolished, resulting in the EU framework as such covering all policy areas. Executive/legislative power in each area was instead determined by a distribution of competencies between EU institutions and member states. This distribution, as well as treaty provisions for policy areas in which unanimity is required and qualified majority voting is possible, reflects the depth of EU integration as well as the EU’s partly supranational and partly intergovernmental nature.

Politics

The European Union operates through a hybrid system of supranational and intergovernmental decision-making,[57][58] and according to the principles of conferral (which says that it should act only within the limits of the competences conferred on it by the treaties) and of subsidiarity (which says that it should act only where an objective cannot be sufficiently achieved by the member states acting alone). Laws made by the EU institutions are passed in a variety of forms.[59] Generally speaking, they can be classified into two groups: those which come into force without the necessity for national implementation measures (regulations) and those which specifically require national implementation measures (directives).[d]

EU policy is in general promulgated by EU directives, which are then implemented in the domestic legislation of its member states, and EU regulations, which are immediately enforceable in all member states. Lobbying at EU level by special interest groups is regulated to try to balance the aspirations of private initiatives with public interest decision-making process.[60]

Budget

EU funding programmes 2014–2020

(€1,087 billion)[61]

Sustainable Growth/Natural Resources (38.6%)

Competitiveness for Growth and Jobs (13.1%)

Global Europe (6.1%)

Economic, Territorial and Social Cohesion (34.1%)

Administration (6.4%)

Security and Citizenship (1.7%)

The European Union had an agreed budget of €120.7 billion for the year 2007 and €864.3 billion for the period 2007–2013,[62] representing 1.10 per cent and 1.05 per cent of the EU-27’s GNI forecast for the respective periods. In 1960, the budget of the European Community was 0.03 per cent of GDP.[63]

In the 2010 budget of €141.5 billion, the largest single expenditure item was «cohesion & competitiveness» with around 45 per cent of the total budget.[64] Next was «agriculture» with approximately 31 per cent of the total.[64] «Rural development, environment and fisheries» takes up around 11 per cent.[64] «Administration» accounts for around 6 per cent.[64] The «EU as a global partner» and «citizenship, freedom, security and justice» had approximately 6 per cent and 1 per cent respectively.[64]

In November 2020, two members of the union, Hungary and Poland, blocked approval to the EU’s budget at a meeting in the Committee of Permanent Representatives (Coreper), citing a proposal that linked funding with adherence to the rule of law. The budget included a COVID-19 recovery fund of €750 billion. The budget may still be approved if Hungary and Poland withdraw their vetoes after further negotiations in the council and the European Council.[65][66]

Bodies combatting fraud have also been established, including the European Anti-fraud Office and the European Public Prosecutor’s Office. The latter is a decentralized independent body of the European Union (EU), established under the Treaty of Lisbon between 22 of the 27 states of the EU following the method of enhanced cooperation.[67] The European Public Prosecutor’s Office investigate and prosecute fraud against the budget of the European Union and other crimes against the EU’s financial interests including fraud concerning EU funds of over €10,000 and cross-border VAT fraud cases involving damages above €10 million.

Governance

Member states retain in principle all powers not conferred by them on the European Union, though the exact delimitation has on many occasions become a subject of scholarly or legal disputes. Inspired by the famous Commerce Clause and the huge impact that its interpretation and mode of application by the Supreme Court of the United States had on shaping the American federal government, the Court of Justice of the European Union has sometimes managed to expand through its case law the powers of the EU, including those related to areas other than only the ones explicitly conferred on it in the founding treaties.

In certain fields the EU has been awarded exclusive competence and mandate. These are areas in which member states have entirely renounced their own capacity to enact legislation. In other areas the EU and its member states share the competence to legislate. While both can legislate, the member states can only legislate to the extent to which the EU has not. In other policy areas the EU can only co-ordinate, support and supplement member state action but cannot enact legislation with the aim of harmonising national laws.[68] That a particular policy area falls into a certain category of competence is not necessarily indicative of what legislative procedure is used for enacting legislation within that policy area. Different legislative procedures are used within the same category of competence, and even with the same policy area. The distribution of competences in various policy areas between member states and the union is divided in the following three categories:

|

Exclusive competence |

Shared competence |

Supporting competence |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

The European Union has seven principal decision-making bodies, its institutions: the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council of the European Union, the European Commission, the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Central Bank and the European Court of Auditors. Competence in scrutinising and amending legislation is shared between the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament, while executive tasks are performed by the European Commission and in a limited capacity by the European Council (not to be confused with the aforementioned Council of the European Union). The monetary policy of the eurozone is determined by the European Central Bank. The interpretation and the application of EU law and the treaties are ensured by the Court of Justice of the European Union. The EU budget is scrutinised by the European Court of Auditors. There are also a number of ancillary bodies which advise the EU or operate in a specific area.

Branches of power

Executive branch

The European Union executive branch is organized as a directorial system, where the executive power is jointly exercised by several people. The executive branch consists of the European Council and European Commission.

The European Council sets the broad political direction to the EU. It convenes at least four times a year and comprises the president of the European Council (presently Charles Michel), the president of the European Commission and one representative per member state (either its head of state or head of government). The high representative of the union for foreign affairs and security policy (presently Josep Borrell) also takes part in its meetings. Described by some as the union’s «supreme political leadership»,[70] it is actively involved in the negotiation of treaty changes and defines the EU’s policy agenda and strategies. Its leadership role involves solving disputes between member states and the institutions, and to resolving any political crises or disagreements over controversial issues and policies. It acts as a «collective head of state» and ratifies important documents (for example, international agreements and treaties).[71] Tasks for the president of the European Council are ensuring the external representation of the EU,[72] driving consensus and resolving divergences among member states, both during meetings of the European Council and over the periods between them. The European Council should not be mistaken for the Council of Europe, an international organisation independent of the EU and based in Strasbourg.

The European Commission acts both as the EU’s executive arm, responsible for the day-to-day running of the EU, and also the legislative initiator, with the sole power to propose laws for debate.[73][74][75] The commission is ‘guardian of the Treaties’ and is responsible for their efficient operation and policing.[76] It has 27 European commissioners for different areas of policy, one from each member state, though commissioners are bound to represent the interests of the EU as a whole rather than their home state. The leader of the 27 is the president of the European Commission (presently Ursula von der Leyen for 2019–2024), proposed by the European Council, following and taking into account the result of the European elections, and is then elected by the European Parliament.[77] The President retains, as the leader responsible for the entire cabinet, the final say in accepting or rejecting a candidate submitted for a given portfolio by a member state, and oversees the commission’s permanent civil service. After the President, the most prominent commissioner is the high representative of the union for foreign affairs and security policy, who is ex-officio a vice-president of the European Commission and is also chosen by the European Council.[78] The other 26 commissioners are subsequently appointed by the Council of the European Union in agreement with the nominated president. The 27 commissioners as a single body are subject to approval (or otherwise) by vote of the European Parliament. All commissioners are first nominated by the government of the respective member state.[79]

Legislative branch

The Council of the European Union (also called the Council[80] and the «Council of Ministers», its former title)[81] forms one half of the EU’s legislature. It consists of a representative from each member state’s government and meets in different compositions depending on the policy area being addressed. Notwithstanding its different configurations, it is considered to be one single body. In addition to the legislative functions, members of the council also have executive responsibilities, such as the development of a Common Foreign and Security Policy and the coordination of broad economic policies within the Union.[82] The Presidency of the council rotates between member states, with each holding it for six months. Beginning on 1 July 2022, the position is held by the Czech Republic.[83]

The European Parliament is one of three legislative institutions of the EU, which together with the Council of the European Union is tasked with amending and approving the European Commission’s proposals. 705 members of the European Parliament (MEPs) are directly elected by EU citizens every five years on the basis of proportional representation. MEPs are elected on a national basis and they sit according to political groups rather than their nationality. Each country has a set number of seats and is divided into sub-national constituencies where this does not affect the proportional nature of the voting system.[84] In the ordinary legislative procedure, the European Commission proposes legislation, which requires the joint approval of the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union to pass. This process applies to nearly all areas, including the EU budget. The parliament is the final body to approve or reject the proposed membership of the commission, and can attempt motions of censure on the commission by appeal to the Court of Justice. The president of the European Parliament carries out the role of speaker in Parliament and represents it externally. The president and vice-presidents are elected by MEPs every two and a half years.[85]

Judicial branch

The judicial branch of the European Union is formally called the Court of Justice of the European Union and consists of two courts: the Court of Justice and the General Court.[86] The Court of Justice is the supreme court of the European Union in matters of European Union law. As a part of the Court of Justice of the European Union, it is tasked with interpreting EU law and ensuring its uniform application across all EU member states under Article 263 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The Court was established in 1952, and is based in Luxembourg. It is composed of one judge per member state – currently 27 – although it normally hears cases in panels of three, five or fifteen judges. The Court has been led by president Koen Lenaerts since 2015. The ECJ is the highest court of the European Union in matters of Union law, but not national law. It is not possible to appeal against the decisions of national courts in the ECJ, but rather national courts refer questions of EU law to the ECJ. However, it is ultimately for the national court to apply the resulting interpretation to the facts of any given case. Although, only courts of final appeal are bound to refer a question of EU law when one is addressed. The treaties give the ECJ the power for consistent application of EU law across the EU as a whole. The court also acts as an administrative and constitutional court between the other EU institutions and the Member States and can annul or invalidate unlawful acts of EU institutions, bodies, offices and agencies.

The General Court is a constituent court of the European Union. It hears actions taken against the institutions of the European Union by individuals and member states, although certain matters are reserved for the Court of Justice. Decisions of the General Court can be appealed to the Court of Justice, but only on a point of law. Prior to the coming into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, it was known as the Court of First Instance.

Additional branches

The European Central Bank (ECB) is one of the institutions of the monetary branch of the European Union, prime component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks. It is one of the world’s most important central banks. The ECB Governing Council makes monetary policy for the Eurozone and the European Union, administers the foreign exchange reserves of EU member states, engages in foreign exchange operations, and defines the intermediate monetary objectives and key interest rate of the EU. The ECB Executive Board enforces the policies and decisions of the Governing Council, and may direct the national central banks when doing so. The ECB has the exclusive right to authorise the issuance of euro banknotes. Member states can issue euro coins, but the volume must be approved by the ECB beforehand. The bank also operates the TARGET2 payments system. The European System of Central Banks (ESCB) consists of the ECB and the national central banks (NCBs) of all 27 member states of the European Union. The ESCB is not the monetary authority of the eurozone, because not all EU member states have joined the euro. The ESCB’s objective is price stability throughout the European Union. Secondarily, the ESCB’s goal is to improve monetary and financial cooperation between the Eurosystem and member states outside the eurozone.

The European Court of Auditors (ECA) is the auditory branch of the European Union. It was established in 1975 in Luxembourg in order to improve EU financial management. It has 27 members (1 from each EU member-state) supported by approximately 800 civil servants. The European Personnel Selection Office (EPSO) is the civil service branch of the European Union, and is responsible for selecting staff to work for the institutions and agencies of the European Union including the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council of the European Union, the European Commission, the European Court of Justice, the Court of Auditors, the European External Action Service, the Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Ombudsman. Each institution is then able to recruit staff from among the pool of candidates selected by EPSO. On average, EPSO receives around 60,000-70,000 applications a year with around 1,500-2,000 candidates recruited by the European Union institutions. The European Ombudsman is the ombudsman branch of the European Union that holds the institutions, bodies and agencies of the EU to account, and promotes good administration. The Ombudsman helps people, businesses and organisations facing problems with the EU administration by investigating complaints, as well as by proactively looking into broader systemic issues. The current Ombudsman is Emily O’Reilly. The European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) is the prosecutory branch of the European Union with juridical personality, established under the Treaty of Lisbon between 22 of the 27 states of the EU following the method of enhanced cooperation. It is based in Kirchberg, Luxembourg City alongside the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Auditors.

Law

Organigram of the political system of the Union

Constitutionally, the EU bears some resemblance to both a confederation and a federation,[87][88] but has not formally defined itself as either. (It does not have a formal constitution: its status is defined by the Treaty of European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union). It is more integrated than a traditional confederation of states because the general level of government widely employs qualified majority voting in some decision-making among the member states, rather than relying exclusively on unanimity.[89][90] It is less integrated than a federal state because it is not a state in its own right: sovereignty continues to flow ‘from the bottom up’, from the several peoples of the separate member states, rather than from a single undifferentiated whole. This is reflected in the fact that the member states remain the ‘masters of the Treaties’, retaining control over the allocation of competences to the union through constitutional change (thus retaining so-called Kompetenz-kompetenz); in that they retain control of the use of armed force; they retain control of taxation; and in that they retain a right of unilateral withdrawal under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. In addition, the principle of subsidiarity requires that only those matters that need to be determined collectively are so determined.

Under the principle of supremacy, national courts are required to enforce the treaties that their member states have ratified, even if doing so requires them to ignore conflicting national law, and (within limits) even constitutional provisions.[e] The direct effect and supremacy doctrines were not explicitly set out in the European Treaties but were developed by the Court of Justice itself over the 1960s, apparently under the influence of its then most influential judge, Frenchman Robert Lecourt.[91] The question whether the secondary law enacted by the EU has a comparable status in relation to national legistaltion, has been a matter of debate among legal scholars.

Primary law

The European Union is based on a series of treaties. These first established the European Community and the EU, and then made amendments to those founding treaties.[92] These are power-giving treaties which set broad policy goals and establish institutions with the necessary legal powers to implement those goals. These legal powers include the ability to enact legislation[f] which can directly affect all member states and their inhabitants.[g] The EU has legal personality, with the right to sign agreements and international treaties.[93]

Secondary law

The main legal acts of the European Union come in three forms: regulations, directives, and decisions. Regulations become law in all member states the moment they come into force, without the requirement for any implementing measures,[h] and automatically override conflicting domestic provisions.[f] Directives require member states to achieve a certain result while leaving them discretion as to how to achieve the result. The details of how they are to be implemented are left to member states.[i] When the time limit for implementing directives passes, they may, under certain conditions, have direct effect in national law against member states. Decisions offer an alternative to the two above modes of legislation. They are legal acts which only apply to specified individuals, companies or a particular member state. They are most often used in competition law, or on rulings on State Aid, but are also frequently used for procedural or administrative matters within the institutions. Regulations, directives, and decisions are of equal legal value and apply without any formal hierarchy.[94]

Foreign relations

Foreign policy co-operation between member states dates from the establishment of the community in 1957, when member states negotiated as a bloc in international trade negotiations under the EU’s common commercial policy.[95] Steps for more wide-ranging co-ordination in foreign relations began in 1970 with the establishment of European Political Cooperation which created an informal consultation process between member states with the aim of forming common foreign policies. In 1987 the European Political Cooperation was introduced on a formal basis by the Single European Act. EPC was renamed as the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) by the Maastricht Treaty.[96]

The aims of the CFSP are to promote both the EU’s own interests and those of the international community as a whole, including the furtherance of international co-operation, respect for human rights, democracy, and the rule of law.[97] The CFSP requires unanimity among the member states on the appropriate policy to follow on any particular issue. The unanimity and difficult issues treated under the CFSP sometimes lead to disagreements, such as those which occurred over the war in Iraq.[98]

The coordinator and representative of the CFSP within the EU is the high representative of the union for foreign affairs and security policy who speaks on behalf of the EU in foreign policy and defence matters, and has the task of articulating the positions expressed by the member states on these fields of policy into a common alignment. The high representative heads up the European External Action Service (EEAS), a unique EU department[99] that has been officially implemented and operational since 1 December 2010 on the occasion of the first anniversary of the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon.[100] The EEAS will serve as a foreign ministry and diplomatic corps for the European Union.[101]

Besides the emerging international policy of the European Union, the international influence of the EU is also felt through enlargement. The perceived benefits of becoming a member of the EU act as an incentive for both political and economic reform in states wishing to fulfil the EU’s accession criteria, and are considered an important factor contributing to the reform of European formerly Communist countries.[102]: 762 This influence on the internal affairs of other countries is generally referred to as «soft power», as opposed to military «hard power».[103]

Humanitarian aid

The European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection department, or «ECHO», provides humanitarian aid from the EU to developing countries. In 2012, its budget amounted to €874 million, 51 per cent of the budget went to Africa and 20 per cent to Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and Pacific, and 20 per cent to the Middle East and Mediterranean.[104]

Humanitarian aid is financed directly by the budget (70 per cent) as part of the financial instruments for external action and also by the European Development Fund (30 per cent).[105] The EU’s external action financing is divided into ‘geographic’ instruments and ‘thematic’ instruments.[105] The ‘geographic’ instruments provide aid through the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI, €16.9 billion, 2007–2013), which must spend 95 per cent of its budget on official development assistance (ODA), and from the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), which contains some relevant programmes.[105] The European Development Fund (EDF, €22.7 billion for the period 2008–2013 and €30.5 billion for the period 2014–2020) is made up of voluntary contributions by member states, but there is pressure to merge the EDF into the budget-financed instruments to encourage increased contributions to match the 0.7 per cent target and allow the European Parliament greater oversight.[105][106]

In 2016, the average among EU countries was 0.4 per cent and five had met or exceeded the 0.7 per cent target: Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Sweden and the United Kingdom.[107] If considered collectively, EU member states are the largest contributor of foreign aid in the world.[108][109]

International cooperation and development partnerships

The European Union uses foreign relations instruments like the European Neighbourhood Policy which seeks to tie those countries to the east and south of the European territory of the EU to the union. These countries, primarily developing countries, include some who seek to one day become either a member state of the European Union, or more closely integrated with the European Union. The EU offers financial assistance to countries within the European Neighbourhood, so long as they meet the strict conditions of government reform, economic reform and other issues surrounding positive transformation. This process is normally underpinned by an Action Plan, as agreed by both Brussels and the target country.

There is also the worldwide European Union Global Strategy. International recognition of sustainable development as a key element is growing steadily. Its role was recognised in three major UN summits on sustainable development: the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg, South Africa; and the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) in Rio de Janeiro. Other key global agreements are the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015). The SDGs recognise that all countries must stimulate action in the following key areas – people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership – in order to tackle the global challenges that are crucial for the survival of humanity.

EU development action is based on the European Consensus on Development, which was endorsed on 20 December 2005 by EU Member States, the council, the European Parliament and the commission.[110] It is applied from the principles of Capability approach and Rights-based approach to development. Funding is provided by the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance and the Global Europe programmes.

Partnership and cooperation agreements are bilateral agreements with non-member nations.[111]

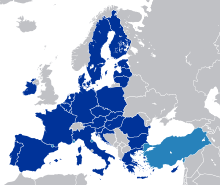

Defence

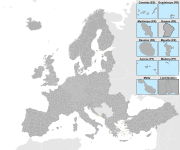

Map showing European membership of the EU and NATO

EU member only

NATO member only

EU and NATO member

The predecessors of the European Union were not devised as a military alliance because NATO was largely seen as appropriate and sufficient for defence purposes.[112] 21 EU members are members of NATO[113] while the remaining member states follow policies of neutrality.[114] The Western European Union, a military alliance with a mutual defence clause, was disbanded in 2010 as its role had been transferred to the EU.[115] Following the Kosovo War in 1999, the European Council agreed that «the Union must have the capacity for autonomous action, backed by credible military forces, the means to decide to use them, and the readiness to do so, in order to respond to international crises without prejudice to actions by NATO». To that end, a number of efforts were made to increase the EU’s military capability, notably the Helsinki Headline Goal process. After much discussion, the most concrete result was the EU Battlegroups initiative, each of which is planned to be able to deploy quickly about 1500 personnel.[116]

Since the withdrawal of the United Kingdom, France is the only member officially recognised as a nuclear weapon state and the sole holder of a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. France and Italy are also the only EU countries that have power projection capabilities outside of Europe.[117] Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium participate in NATO nuclear sharing.[118] Most EU member states opposed the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty.[119]

EU forces have been deployed on peacekeeping missions from middle and northern Africa to the western Balkans and western Asia.[120] EU military operations are supported by a number of bodies, including the European Defence Agency, European Union Satellite Centre and the European Union Military Staff.[121] The European Union Military Staff is the highest military institution of the European Union, established within the framework of the European Council, and follows on from the decisions of the Helsinki European Council (10–11 December 1999), which called for the establishment of permanent political-military institutions. The European Union Military Staff is under the authority of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Political and Security Committee. It directs all military activities in the EU context, including planning and conducting military missions and operations in the framework of the Common Security and Defence Policy and the development of military capabilities, and provides the Political and Security Committee with military advice and recommendations on military issues. In an EU consisting of 27 members, substantial security and defence co-operation is increasingly relying on collaboration among all member states.[122]

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) is an agency of the EU aiming to detect and stop illegal immigration, human trafficking and terrorist infiltration, having since 2015 a stronger role and mandate along with national authorities for border management.[123] The EU also operates the European Travel Information and Authorisation System, the Entry/Exit System, the Schengen Information System, the Visa Information System and the Common European Asylum System which provide common databases for police and immigration authorities. The impetus for the development of this co-operation was the advent of open borders in the Schengen Area and the associated cross-border crime.[17]

Member states

Map showing the member states of the European Union (clickable)

Through successive enlargements, the European Union has grown from the six founding states (Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) to 27 members. Countries accede to the union by becoming a party to the founding treaties, thereby subjecting themselves to the privileges and obligations of EU membership. This entails a partial delegation of sovereignty to the institutions in return for representation within those institutions, a practice often referred to as «pooling of sovereignty».[124][125] In some policies, there are several member states that ally with strategic partners within the union. Examples of such alliances include the Baltic Assembly, the Benelux Union, the Bucharest Nine, the Craiova Group, the EU Med Group, the Lublin Triangle, the New Hanseatic League, the Three Seas Initiative, the Visegrád Group, and the Weimar Triangle.

Several overseas territories and dependencies of various member states are also formally part of the EU.[126]

To become a member, a country must meet the Copenhagen criteria, defined at the 1993 meeting of the European Council in Copenhagen. These require a stable democracy that respects human rights and the rule of law; a functioning market economy; and the acceptance of the obligations of membership, including EU law. Evaluation of a country’s fulfilment of the criteria is the responsibility of the European Council.[127]

The four countries forming the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) are not EU members, but have partly committed to the EU’s economy and regulations: Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, which are a part of the single market through the European Economic Area, and Switzerland, which has similar ties through bilateral treaties.[128][129] The relationships of the European microstates, Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City include the use of the euro and other areas of co-operation.[130]

Subdivisions

Subdivisions of member-states are based on the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), a geocode standard for statistical purposes. The standard, adopted in 2003, is developed and regulated by the European Union, and thus only covers the member states of the EU in detail. The Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics is instrumental in the European Union’s Structural Funds and Cohesion Fund delivery mechanisms and for locating the area where goods and services subject to European public procurement legislation are to be delivered.

Maps of Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) subdivisions (prior to 2018, including non-EU member states)

-

NUTS 1

-

NUTS 2

-

NUTS 3

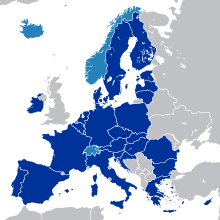

Schengen Area

Map of the Schengen Area

Schengen Area

Countries de facto participating

Members of the EU committed by treaty to join the Schengen Area in the future

The Schengen Area is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and justice policy of the EU, it mostly functions as a single jurisdiction under a common visa policy for international travel purposes. The area is named after the 1985 Schengen Agreement and the 1990 Schengen Convention, both signed in Schengen, Luxembourg. Of the 27 EU member states, 23 participate in the Schengen Area. Of the four EU members that are not part of the Schengen Area, three—Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Romania—are legally obligated to join the area in the future; Ireland maintains an opt-out, and instead operates its own visa policy. The four European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member states, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, are not members of the EU, but have signed agreements in association with the Schengen Agreement. Also, three European microstates—Monaco, San Marino, and the Vatican City—maintain open borders for passenger traffic with their neighbours, and are therefore considered de facto members of the Schengen Area due to the practical impossibility of travelling to or from them without transiting through at least one Schengen member country.

Candidate countries

There are eight countries that are recognised as candidates for membership: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine.[132][133][134] Norway, Switzerland and Iceland have submitted membership applications in the past, but subsequently frozen or withdrawn them.[135] Additionally, Georgia and Kosovo are officially recognised as potential candidates,[132][136] and have submitted membership applications.[137]

Former members

Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty provides the basis for a member to leave the EU. Two territories have left the union: Greenland (an autonomous province of Denmark) withdrew in 1985;[138] the United Kingdom formally invoked Article 50 of the Consolidated Treaty on European Union in 2017, and became the only sovereign state to leave when it withdrew from the EU in 2020.

Geography

Topographic map of Europe (EU highlighted)

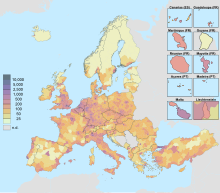

The EU’s member states cover an area of 4,233,262 square kilometres (1,634,472 sq mi).[l] The EU’s highest peak is Mont Blanc in the Graian Alps, 4,810.45 metres (15,782 ft) above sea level.[139] The lowest points in the EU are Lammefjorden, Denmark, and Zuidplaspolder, Netherlands, at 7 m (23 ft) below sea level.[140] The landscape, climate, and economy of the EU are influenced by its coastline, which is 65,993 kilometres (41,006 mi) long.

Including the overseas territories of France which are located outside the continent of Europe, but which are members of the union, the EU experiences most types of climate from Arctic (north-east Europe) to tropical (French Guiana), rendering meteorological averages for the EU as a whole meaningless. The majority of the population lives in areas with a temperate maritime climate (North-Western Europe and Central Europe), a Mediterranean climate (Southern Europe), or a warm summer continental or hemiboreal climate (Central Europe and Southeastern Europe).[141]

Climate

The climate of the European Union is of a temperate, continental nature, with a maritime climate prevailing on the western coasts and a mediterranean climate in the south. The climate is strongly conditioned by the Gulf Stream, which warms the western region to levels unattainable at similar latitudes on other continents. Western Europe is oceanic, while eastern Europe is continental and dry. Four seasons occur in western Europe, while southern Europe experiences a wet season and a dry season. Southern Europe is hot and dry during the summer months. The heaviest precipitation occurs downwind of water bodies due to the prevailing westerlies, with higher amounts also seen in the Alps. Tornadoes occur within Europe, but tend to be weak. The Netherlands experiences a disproportionately high number of tornadic events.

Environment

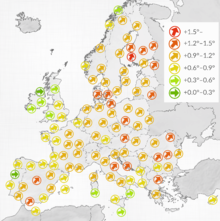

Increase of average yearly temperature in selected cities in Europe (1900–2017)[142]

In 1957, when the European Economic Community was founded, it had no environmental policy.[143] Over the past 50 years, an increasingly dense network of legislation has been created, extending to all areas of environmental protection, including air pollution, water quality, waste management, nature conservation, and the control of chemicals, industrial hazards, and biotechnology.[143] According to the Institute for European Environmental Policy, environmental law comprises over 500 Directives, Regulations and Decisions, making environmental policy a core area of European politics.[144]

European policy-makers originally increased the EU’s capacity to act on environmental issues by defining it as a trade problem.[143] Trade barriers and competitive distortions in the Common Market could emerge due to the different environmental standards in each member state.[145] In subsequent years, the environment became a formal policy area, with its own policy actors, principles and procedures. The legal basis for EU environmental policy was established with the introduction of the Single European Act in 1987.[144]

Initially, EU environmental policy focused on Europe. More recently, the EU has demonstrated leadership in global environmental governance, e.g. the role of the EU in securing the ratification and coming into force of the Kyoto Protocol despite opposition from the United States. This international dimension is reflected in the EU’s Sixth Environmental Action Programme,[146] which recognises that its objectives can only be achieved if key international agreements are actively supported and properly implemented both at EU level and worldwide. The Lisbon Treaty further strengthened the leadership ambitions.[143] EU law has played a significant role in improving habitat and species protection in Europe, as well as contributing to improvements in air and water quality and waste management.[144]

Mitigating climate change is one of the top priorities of EU environmental policy. In 2007, member states agreed that, in the future, 20 per cent of the energy used across the EU must be renewable, and carbon dioxide emissions have to be lower in 2020 by at least 20 per cent compared to 1990 levels.[147] In 2017, the EU emitted 9.1 per cent of global greenhouse-gas emissions.[148] The European Union claims that already in 2018, its GHG emissions were 23% lower than in 1990.[149]

The EU has adopted an emissions trading system to incorporate carbon emissions into the economy.[150] The European Green Capital is an annual award given to cities that focuses on the environment, energy efficiency, and quality of life in urban areas to create smart city. In the 2019 elections to the European Parliament, the green parties increased their power, possibly because of the rise of post materialist values.[151] Proposals to reach a zero carbon economy in the European Union by 2050 were suggested in 2018 – 2019. Almost all member states supported that goal at an EU summit in June 2019. The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, and Poland disagreed.[152] In June 2021 the European Union passed a European Climate Law with targets of 55% GHG emissions reduction by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050.[153] In 2021 the European Union and the United States pledged to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030. The pledge is considered as a big achievement for climate change mitigation.[154]

Economy

GDP (PPP) per capita in 2019 (including non-EU countries)

EU member states own the estimated third largest after the United States (US$146 trillion) and China (US$85 trillion) net wealth in the world, equal to around one sixth (US$78 trillion) of the US$464 trillion global wealth.[155] Of the top 500 largest corporations in the world measured by revenue in 2010, 161 had their headquarters in the EU.[156] In 2016, unemployment in the EU stood at 8.9 per cent[157] while inflation was at 2.2 per cent, and the account balance at −0.9 per cent of GDP. The average annual net earnings in the European Union was around €25,000[158] in 2021. There is a significant variation in nominal GDP per capita within individual EU states. The difference between the richest and poorest regions (281 NUTS-2 regions of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) ranged, in 2017, from 31 per cent (Severozapaden, Bulgaria) of the EU28 average (€30,000) to 253 per cent (Luxembourg), or from €4,600 to €92,600.[159]

Economic and monetary union

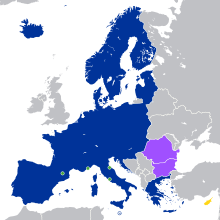

Economic and Monetary Union

Members of the Eurozone

ERM II member

ERM II member with opt-out (Denmark)

Other EU members

The creation of a European single currency became an official objective of the European Economic Community in 1969. In 1992, having negotiated the structure and procedures of a currency union, the member states signed the Maastricht Treaty and were legally bound to fulfil the agreed-on rules including the convergence criteria if they wanted to join the monetary union. The states wanting to participate had first to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. To prevent the joining states from getting into financial trouble or crisis after entering the monetary union, they were obliged in the Maastricht treaty to fulfil important financial obligations and procedures, especially to show budgetary discipline and a high degree of sustainable economic convergence, as well as to avoid excessive government deficits and limit the government debt to a sustainable level, as agreed in the European Fiscal Pact.

Capital Markets Union and financial institutions

Free movement of capital is intended to permit movement of investments such as property purchases and buying of shares between countries.[160] Until the drive towards economic and monetary union the development of the capital provisions had been slow. Post-Maastricht there has been a rapidly developing corpus of ECJ judgements regarding this initially neglected freedom. The free movement of capital is unique insofar as it is granted equally to non-member states.

The European System of Financial Supervision is an institutional architecture of the EU’s framework of financial supervision composed by three authorities: the European Banking Authority, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority and the European Securities and Markets Authority. To complement this framework, there is also a European Systemic Risk Board under the responsibility of the central bank. The aim of this financial control system is to ensure the economic stability of the EU.[161]

Eurozone and banking union

In 1999, the currency union started to materialise through introducing a common accounting (virtual) currency in eleven of the member states. In 2002, it was turned into a fully-fledged conventible currency, when euro notes and coins were issued, while the phaseout of national currencies in the eurozone (consisting by then of 12 member states) was initiated. The eurozone (constituted by the EU member states which have adopted the euro) has since grown to 20 countries.[162][163]

The 20 EU member states known collectively as the eurozone have fully implemented the currency union by superseding their national currencies with the euro. The currency union represents 345 million EU citizens.[164] The euro is the second largest reserve currency as well as the second most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.[165][166][167]

The euro, and the monetary policies of those who have adopted it in agreement with the EU, are under the control of the ECB.[168] The ECB is the central bank for the eurozone, and thus controls monetary policy in that area with an agenda to maintain price stability. It is at the centre of the Eurosystem, which comprehends all the Eurozone national central banks.[169] The ECB is also the central institution of the Banking Union established within the eurozone and manages its Single Supervisory Mechanism. These is also a Single Resolution Mechanism in case of a bank default.

Trade

As a political entity, the European Union is represented in the World Trade Organization (WTO). Two of the original core objectives of the European Economic Community were the development of a common market, subsequently becoming a single market, and a customs union between its member states.

Single market

The single market involves the free circulation of goods, capital, people, and services within the EU,[164] The free movement of services and of establishment allows self-employed persons to move between member states to provide services on a temporary or permanent basis. While services account for 60 per cent to 70 per cent of GDP, legislation in the area is not as developed as in other areas. This lacuna has been addressed by the Services in the Internal Market Directive 2006 which aims to liberalise the cross border provision of services.[170] According to the treaty the provision of services is a residual freedom that only applies if no other freedom is being exercised.

Customs union

The customs union involves the application of a common external tariff on all goods entering the market. Once goods have been admitted into the market they cannot be subjected to customs duties, discriminatory taxes or import quotas, as they travel internally. The non-EU member states of Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland participate in the single market but not in the customs union.[128] Half the trade in the EU is covered by legislation harmonised by the EU.[171]

The European Union Association Agreement does something similar for a much larger range of countries, partly as a so-called soft approach (‘a carrot instead of a stick’) to influence the politics in those countries.

The European Union represents all its members at the World Trade Organization (WTO), and acts on behalf of member states in any disputes. When the EU negotiates trade related agreement outside the WTO framework, the subsequent agreement must be approved by each individual EU member state government.[172]

External trade

The European Union has concluded free trade agreements (FTAs)[173] and other agreements with a trade component with many countries worldwide and is negotiating with many others.[174] The European Union’s services trade surplus rose from $16 billion in 2000 to more than $250 billion in 2018.[175] In 2020, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, China became the EU’s largest trading partner, displacing the United States.[176] The European Union is the largest exporter in the world[177] and in 2008 was the largest importer of goods and services.[178][179] Internal trade between the member states is aided by the removal of barriers to trade such as tariffs and border controls. In the eurozone, trade is helped by not having any currency differences to deal with amongst most members.[172]

Competition and consumer protection

The EU operates a competition policy intended to ensure undistorted competition within the single market.[m] In 2001 the commission for the first time prevented a merger between two companies based in the United States (General Electric and Honeywell) which had already been approved by their national authority.[180] Another high-profile case, against Microsoft, resulted in the commission fining Microsoft over €777 million following nine years of legal action.[181]

Energy

| Consumed energy (2012) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy source | Origin | Percents | ||

| Oil | Imported | 33% | ||

| Domestic | 6% | |||

| Gas | Imported | 14% | ||

| Domestic | 9% | |||

| Nuclear[n] | Imported | 0% | ||

| Domestic | 13% | |||

| Coal/Lignite | Imported | 0% | ||

| Domestic | 10% | |||

| Renewable | Imported | 0% | ||

| Domestic | 7% | |||

| Other | Imported | 7% | ||

| Domestic | 1% |

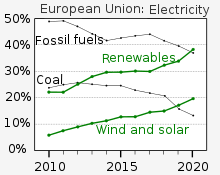

In 2020, renewables overtook fossil fuels as the European Union’s main source of electricity for the first time.[182]

In 2006, the EU-27 had a gross inland energy consumption of 1,825 million tonnes of oil equivalent (toe).[183] Around 46 per cent of the energy consumed was produced within the member states while 54 per cent was imported.[183] In these statistics, nuclear energy is treated as primary energy produced in the EU, regardless of the source of the uranium, of which less than 3 per cent is produced in the EU.[184]

The EU has had legislative power in the area of energy policy for most of its existence; this has its roots in the original European Coal and Steel Community. The introduction of a mandatory and comprehensive European energy policy was approved at the meeting of the European Council in October 2005, and the first draft policy was published in January 2007.[185]

The EU has five key points in its energy policy: increase competition in the internal market, encourage investment and boost interconnections between electricity grids; diversify energy resources with better systems to respond to a crisis; establish a new treaty framework for energy co-operation with Russia while improving relations with energy-rich states in Central Asia[186] and North Africa; use existing energy supplies more efficiently while increasing renewable energy commercialisation; and finally increase funding for new energy technologies.[185]

In 2007, EU countries as a whole imported 82 per cent of their oil, 57 per cent of their natural gas[187] and 97.48 per cent of their uranium[184] demands. The three largest suppliers of natural gas to the European Union are Russia, Norway and Algeria, that amounted for about three quarters of the imports in 2019.[188] There is a strong dependence on Russian energy that the EU has been attempting to reduce.[189] However, in May 2022, it was reported that the European Union is preparing another sanction against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. It is expected to target Russian oil, Russian and Belarusian banks, as well as individuals and companies. According to an article by Reuters, two diplomats stated that the European Union may impose a ban on imports of Russian oil by the end of 2022.[190] In May 2022, the EU Commission published the ‘RePowerEU’ initiative, a €300 billion plan outlining the path towards the end of EU dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2030 and the acceleration on the clean energy transition.[191]

Transport