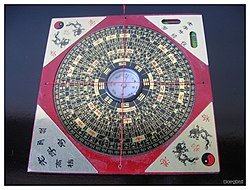

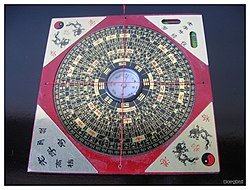

Feng shui analysis of a 癸山丁向 site, with an auspicious circle[1]

| Feng shui | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 风水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «wind-water» | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | phong thủy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | ฮวงจุ้ย (Huang chui) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 풍수 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ふうすい | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | Pungsóy, Punsóy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer | ហុងស៊ុយ (hongsaouy) |

Feng shui ( [2]), sometimes called Chinese geomancy, is an ancient Chinese traditional practice which claims to use energy forces to harmonize individuals with their surrounding environment. The term feng shui means, literally, «wind-water» (i.e. fluid). From ancient times, landscapes and bodies of water were thought to direct the flow of the universal Qi – «cosmic current» or energy – through places and structures. More broadly, feng shui includes astronomical, astrological, architectural, cosmological, geographical and topographical dimensions.[3][4]

Historically, as well as in many parts of the contemporary Chinese world, feng shui was used to orient buildings and spiritually significant structures such as tombs, as well as dwellings and other structures. One scholar writes that in contemporary Western societies, however, «feng shui tends to be reduced to interior design for health and wealth. It has become increasingly visible through ‘feng shui consultants’ and corporate architects who charge large sums of money for their analysis, advice and design.»[4]

Feng shui has been identified as both non-scientific and pseudoscientific by scientists and philosophers[5] and has been described as a paradigmatic example of pseudoscience.[6] It exhibits a number of classic pseudoscientific aspects, such as making claims about the functioning of the world which are not amenable to testing with the scientific method.[7]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The Yangshao and Hongshan cultures provide the earliest known evidence for the use of feng shui. Until the invention of the magnetic compass, feng shui relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe.[8]

In 4000 BC, the doors of dwellings in Banpo were aligned with the asterism Yingshi just after the winter solstice—this sited the homes for solar gain.[9] During the Zhou era, Yingshi was known as Ding and it was used to indicate the appropriate time to build a capital city, according to the Shijing. The late Yangshao site at Dadiwan (c. 3500–3000 BC) includes a palace-like building (F901) at its center. The building faces south and borders a large plaza. It stands on a north–south axis with another building that apparently housed communal activities. Regional communities may have used the complex. [10]

A grave at Puyang (around 4000 BC) that contains mosaics— a Chinese star map of the Dragon and Tiger asterisms and Beidou (the Big Dipper, Ladle or Bushel)— is oriented along a north–south axis.[11] The presence of both round and square shapes in the Puyang tomb, at Hongshan ceremonial centers and at the late Longshan settlement at Lutaigang,[12]

suggests that gaitian cosmography (heaven-round, earth-square) existed in Chinese society long before it appeared in the Zhoubi Suanjing.[13]

Cosmography that bears a resemblance to modern feng shui devices and formulas appears on a piece of jade unearthed at Hanshan and dated around 3000 BC. Archaeologist Li Xueqin links the design to the liuren astrolabe, zhinan zhen and luopan.[14]

Beginning with palatial structures at Erlitou,[15] all capital cities of China followed rules of feng shui for their design and layout. During the Zhou era, the Kaogong ji (Chinese: 考工記; «Manual of Crafts») codified these rules. The carpenter’s manual Lu ban jing (魯班經; «Lu ban’s manuscript») codified rules for builders. Graves and tombs also followed rules of feng shui from Puyang to Mawangdui and beyond. From the earliest records, the structures of the graves and dwellings seem to have followed the same rules.[citation needed]

Early instruments and techniques[edit]

Some of the foundations of feng shui go back more than 3,500 years[16] before the invention of the magnetic compass. It originated in Chinese astronomy.[17] Some current techniques can be traced to Neolithic China,[18] while others were added later (most notably the Han dynasty, the Tang, the Song, and the Ming).[19]

The astronomical history of feng shui is evident in the development of instruments and techniques. According to the Zhouli, the original feng shui instrument may have been a gnomon. Chinese used circumpolar stars to determine the north–south axis of settlements. This technique explains why Shang palaces at Xiaotun lie 10° east of due north. In some of the cases, as Paul Wheatley observed, they bisected the angle between the directions of the rising and setting sun to find north.[20] This technique provided the more precise alignments of the Shang walls at Yanshi and Zhengzhou. Rituals for using a feng shui instrument required a diviner to examine current sky phenomena to set the device and adjust their position in relation to the device.[21]

The oldest examples of instruments used for feng shui are liuren astrolabes, also known as shi. These consist of a lacquered, two-sided board with astronomical sightlines. The earliest examples of liuren astrolabes have been unearthed from tombs that date between 278 BC and 209 BC. Along with divination for Da Liu Ren[22] the boards were commonly used to chart the motion of Taiyi through the nine palaces.[23][24] The markings on a liuren/shi and the first magnetic compasses are virtually identical.[25]

The magnetic compass was invented for feng shui and has been in use since its invention.[26] Traditional feng shui instrumentation consists of the Luopan or the earlier south-pointing spoon (指南針 zhinan zhen)—though a conventional compass could suffice if one understood the differences. A feng shui ruler (a later invention) may also be employed.[citation needed]

Foundational concepts[edit]

Definition and classification[edit]

The goal of feng shui as practiced today is to situate the human-built environment on spots with good qi, an imagined form of «energy». The «perfect spot» is a location and an axis in time.[27][1]

Traditional feng shui is inherently a form of ancestor worship. Popular in farming communities for centuries, it was built on the idea that the ghosts of ancestors and other independent, intangible forces, both personal and impersonal, affected the material world, and that these forces needed to be placated through rites and suitable burial places, which the feng shui practitioner would assist with for a fee. The primary underlying value was material success for the living.[28]

According to Stuart Vyse, feng shui is «a very popular superstition.»[29] The PRC government has also labeled it as superstitious.[30] Feng shui is classified as a pseudoscience since it exhibits a number of classic pseudoscientific aspects such as making claims about the functioning of the world which are not amenable to testing with the scientific method.[7] It has been identified as both non-scientific and pseudoscientific by scientists and philosophers,[5] and has been described as a paradigmatic example of pseudoscience.[6]

Qi (ch’i)[edit]

A traditional turtle-back tomb of southern Fujian, surrounded by an omega-shaped ridge protecting it from the «noxious winds» from the three sides[31]

Qi (气, pronounced «chee», «cee», or «tsee») is a movable positive or negative life force which plays an essential role in feng shui. The Book of Burial says that burial takes advantage of «vital qi«. The goal of feng shui is to take advantage of vital qi by appropriate siting of graves and structures.[1]

Polarity[edit]

Polarity is expressed in feng shui as yin and yang theory. That is, it is of two parts: one creating an exertion and one receiving the exertion. The development of this theory and its corollary, five phase theory (five element theory), have also been linked with astronomical observations of sunspot.[32]

The Five Elements or Forces (wu xing) – which, according to the Chinese, are metal, earth, fire, water, and wood – are first mentioned in Chinese literature in a chapter of the classic Book of History. They play a very important part in Chinese thought: ‘elements’ meaning generally not so much the actual substances as the forces essential to human life.[33] Earth is a buffer, or an equilibrium achieved when the polarities cancel each other.[citation needed] While the goal of Chinese medicine is to balance yin and yang in the body, the goal of feng shui has been described as aligning a city, site, building, or object with yin-yang force fields.[34]

Bagua (eight trigrams)[edit]

Eight diagrams known as bagua (or pa kua) loom large in feng shui, and both predate their mentions in the Yijing (or I Ching).[35] The Lo (River) Chart (Luoshu) was developed first,[36] and is sometimes associated with Later Heaven arrangement of the bagua. This and the Yellow River Chart (Hetu, sometimes associated with the Earlier Heaven bagua) are linked to astronomical events of the sixth millennium BC, and with the Turtle Calendar from the time of Yao.[37] The Turtle Calendar of Yao (found in the Yaodian section of the Shangshu or Book of Documents) dates to 2300 BC, plus or minus 250 years.[38]

In Yaodian, the cardinal directions are determined by the marker-stars of the mega-constellations known as the Four Celestial Animals:[38]

- East: The Azure Dragon (Spring equinox)—Niao (Bird 鳥), α Scorpionis

- South: The Vermilion Bird (Summer solstice)—Huo (Fire 火), α Hydrae

- West: The White Tiger (Autumn equinox)—Mǎo (Hair 毛), η Tauri (the Pleiades)

- North: The Black Tortoise (Winter solstice)—Xū (Emptiness, Void 虛), α Aquarii, β Aquarii

The diagrams are also linked with the sifang (four directions) method of divination used during

the Shang dynasty.[39] The sifang is much older, however. It was used at Niuheliang, and figured large in Hongshan culture’s astronomy. And it is this area of China that is linked to Yellow Emperor (Huangdi) who allegedly invented the south-pointing spoon (see compass).[40]

Traditional feng shui[edit]

Traditional feng shui is an ancient system based upon the observation of heavenly time and earthly space. Literature, as well as archaeological evidence, provide some idea of the origins and nature of feng shui techniques. Aside from books, there is also a strong oral history. In many cases, masters have passed on their techniques only to selected students or relatives.[41] Modern practitioners of feng shui draw from several branches in their own practices.

Form Branch[edit]

The Form Branch is the oldest branch of feng shui. Qing Wuzi in the Han dynasty describes it in the Book of the Tomb[42] and Guo Pu of the Jin dynasty follows up with a more complete description in The Book of Burial.[citation needed]

The Form branch was originally concerned with the location and orientation of tombs (Yin House feng shui), which was of great importance.[27] The branch then progressed to the consideration of homes and other buildings (Yang House feng shui).

The «form» in Form branch refers to the shape of the environment, such as mountains, rivers, plateaus, buildings, and general surroundings. It considers the five celestial animals (vermillion phoenix, azure dragon, white tiger, black turtle, and the yellow snake), the yin-yang concept and the traditional five elements (Wu Xing: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water).[citation needed]

The Form branch analyzes the shape of the land and flow of the wind and water to find a place with ideal qi.[43] It also considers the time of important events such as the birth of the resident and the building of the structure.

Compass Branch[edit]

The Compass branch is a collection of more recent feng shui techniques based on the Eight Directions, each of which is said to have unique qi. It uses the Luopan, a disc marked with formulas in concentric rings around a magnetic compass.[44]

The Compass Branch includes techniques such as Flying Star and Eight Mansions.[citation needed]

Western forms of feng shui[edit]

More recent forms of feng shui simplify principles that come from the traditional branches, and focus mainly on the use of the bagua.[citation needed]

Aspirations Method[edit]

The Eight Life Aspirations style of feng shui is a simple system which coordinates each of the eight cardinal directions with a specific life aspiration or station such as family, wealth, fame, etc., which come from the Bagua government of the eight aspirations. Life Aspirations is not otherwise a geomantic system.[citation needed]

List of specific feng shui branches[edit]

Ti Li (Form Branch)[edit]

Popular Xingshi Pai (形勢派) «forms» methods[edit]

- Luan Tou Pai, 巒頭派, Pinyin: luán tóu pài, (environmental analysis without using a compass)

- Xing Xiang Pai, 形象派 or 形像派, Pinyin: xíng xiàng pài, (Imaging forms)

- Xingfa Pai, 形法派, Pinyin: xíng fǎ pài

Liiqi Pai (Compass Branch)[edit]

Popular Liiqi Pai (理气派) «Compass» methods[edit]

San Yuan Method, 三元派 (Pinyin: sān yuán pài)

- Dragon Gate Eight Formation, 龍門八法 (Pinyin: lóng mén bā fǎ)

- Xuan Kong, 玄空 (time and space methods)

- Xuan Kong Fei Xing 玄空飛星 (Flying Stars methods of time and directions)

- Xuan Kong Da Gua, 玄空大卦 («Secret Decree» or 64 gua relationships)

- Xuan Kong Mi Zi, 玄空秘旨 (Mysterious Space Secret Decree)

- Xuan Kong Liu Fa, 玄空六法 (Mysterious Space Six Techniques)

- Zi Bai Jue, 紫白訣 (Purple White Scroll)

San He Method, 三合派 (environmental analysis using a compass)

- Accessing Dragon Methods

- Ba Zhai, 八宅 (Eight Mansions)

- Yang Gong Feng Shui, 楊公風水

- Water Methods, 河洛水法

- Local Embrace

Others

- Yin House Feng Shui, 陰宅風水 (Feng Shui for the deceased)

- Four Pillars of Destiny, 四柱命理 (a form of hemerology)

- Zi Wei Dou Shu, 紫微斗數 (Purple Star Astrology)

- I-Ching, 易經 (Book of Changes)

- Qi Men Dun Jia, 奇門遁甲 (Mysterious Door Escaping Techniques)

- Da Liu Ren, 大六壬 (Divination: Big Six Heavenly Yang Water Qi)

- Tai Yi Shen Shu, 太乙神數 (Divination: Tai Yi Magical Calculation Method)

- Date Selection, 擇日 (Selection of auspicious dates and times for important events)

- Chinese Palmistry, 掌相學 (Destiny reading by palm reading)

- Chinese Face Reading, 面相學 (Destiny reading by face reading)

- Major & Minor Wandering Stars (Constellations)

- Five phases, 五行 (relationship of the five phases or wuxing)

- BTB Black (Hat) Tantric Buddhist Sect (Westernised or Modern methods not based on Classical teachings)

- Symbolic Feng Shui, (New Age Feng Shui methods that advocate substitution with symbolic (spiritual, appropriate representation of five elements) objects if natural environment or object/s is/are not available or viable)

- Pierce Method of Feng Shui ( Sometimes Pronounced : Von Shway ) The practice of melding striking with soothing furniture arrangements to promote peace and prosperity

Contemporary uses of traditional feng shui[edit]

After Richard Nixon’s visit to the People’s Republic of China in 1972, feng shui practices became popular in the United States. Critics warn that claims of scientific validity have proven to be false and that the practices are pseudoscientific. Others charge that it has been reinvented and commercialized by New Age entrepreneurs,[45] or are concerned that much of the traditional theory has been lost in translation, not given proper consideration, frowned upon, or scorned.[46]

Feng shui has nonetheless found many uses. Landscape ecologists often find traditional feng shui an interesting study.[47] In many cases, the only remaining patches of Asian old forest are «feng shui woods,»[48] associated with cultural heritage, historical continuity, and the preservation of various flora and fauna species.[49] Some researchers interpret the presence of these woods as indicators that the «healthy homes,»[50] sustainability [51] and environmental components of traditional feng shui should not be easily dismissed.[49][52] Environmental scientists and landscape architects have researched traditional feng shui and its methodologies.[53][54][55] Architects study feng shui as an Asian architectural tradition.[56][57][58][59] Geographers have analyzed the techniques and methods to help locate historical sites in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada,[60] and archaeological sites in the American Southwest, concluding that Native Americans also considered astronomy and landscape features.[61]

Believers use it for healing purposes, to guide their businesses, or to create a peaceful atmosphere in their homes, although there is no empirical evidence that it is effective.[62] In particular, they use feng shui in the bedroom, where a number of techniques involving colors and arrangement are thought to promote comfort and peaceful sleep.[citation needed] Some users of feng shui may be trying to gain a sense of security or control, for example by choosing auspicious numbers for their phones or favorable house locations. Their motivation is similar to the reasons that some people consult fortune-tellers.[63][64]

In 2005, Hong Kong Disneyland acknowledged feng shui as an important part of Chinese culture by shifting the main gate by twelve degrees in their building plans. This was among actions suggested by the planner of architecture and design at Walt Disney Imagineering, Wing Chao.[65] At Singapore Polytechnic and other institutions, professionals including engineers, architects, property agents and interior designers, take courses on feng shui and divination every year, a number of whom become part-time or full-time feng shui consultants.[66]

Criticisms[edit]

Traditional feng shui[edit]

Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), one of the founding fathers of Jesuit China missions, may have been the first European to write about feng shui practices. His account in De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas[67] tells about feng shui masters (geologi, in Latin) studying prospective construction sites or grave sites «with reference to the head and the tail and the feet of the particular dragons which are supposed to dwell beneath that spot.» As a Catholic missionary, Ricci strongly criticized the «recondite science» of geomancy along with astrology as yet another superstitio absurdissima of the heathens: «What could be more absurd than their imagining that the safety of a family, honors, and their entire existence must depend upon such trifles as a door being opened from one side or another, as rain falling into a courtyard from the right or from the left, a window opened here or there, or one roof being higher than another?»[68]

Victorian-era commentators on feng shui were generally ethnocentric, and as such skeptical and derogatory of what they knew of feng shui.[69] In 1896, at a meeting of the Educational Association of China, Rev. P. W. Pitcher railed at the «rottenness of the whole scheme of Chinese architecture,» and urged fellow missionaries «to erect unabashedly Western edifices of several stories and with towering spires in order to destroy nonsense about fung-shuy.«[70]

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, feng shui was officially considered a «feudalistic superstitious practice» and a «social evil» according to the state’s ideology and was discouraged and even banned outright at times.[71] Feng shui remained popular in Hong Kong, and also in the Republic of China (Taiwan), where traditional culture was not suppressed.[72]

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) feng shui was classified as one of the so-called Four Olds that were to be wiped out. Feng shui practitioners were beaten and abused by Red Guards and their works burned. After the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the official attitude became more tolerant but restrictions on feng shui practice are still in place in today’s China. It is illegal in the PRC today to register feng shui consultation as a business and similarly advertising feng shui practice is banned. There have been frequent crackdowns on feng shui practitioners on the grounds of «promoting feudalistic superstitions» such as one in Qingdao in early 2006 when the city’s business and industrial administration office shut down an art gallery converted into a feng shui practice. Some officials who had consulted feng shui were terminated and expelled from the Communist Party.[73]

In 21st century mainland China less than one-third of the population believe in feng shui, and the proportion of believers among young urban Chinese is said to be even lower.[74] Chinese academics permitted to research feng shui are anthropologists or architects by profession, studying the history of feng shui or historical feng shui theories behind the design of heritage buildings. They include Cai Dafeng, Vice-President of Fudan University.[75] Learning in order to practice feng shui is still somewhat considered taboo. Nevertheless, it is reported that feng shui has gained adherents among Communist Party officials according to a BBC Chinese news commentary in 2006,[76] and since the beginning of Chinese economic reforms the number of feng shui practitioners is increasing.

Contemporary feng shui[edit]

One critic called the situation of feng shui in today’s world «ludicrous and confusing,» asking «Do we really believe that mirrors and flutes are going to change people’s tendencies in any lasting and meaningful way?» He called for much further study or «we will all go down the tubes because of our inability to match our exaggerated claims with lasting changes.»[45] Robert T. Carroll sums up the charges:

…feng shui has become an aspect of interior decorating in the Western world and alleged masters of feng shui now hire themselves out for hefty sums to tell people such as Donald Trump which way his doors and other things should hang. Feng shui has also become another New Age «energy» scam with arrays of metaphysical products…offered for sale to help you improve your health, maximize your potential, and guarantee fulfillment of some fortune cookie philosophy.[77]

Skeptics charge that evidence for its effectiveness is based primarily upon anecdote and users are often offered conflicting advice from different practitioners, though feng shui practitioners use these differences as evidence of variations in practice or different branches of thought. A critical analyst concluded that «Feng shui has always been based upon mere guesswork.»[46] Another objection was to the compass, a traditional tool for choosing favorable locations for property or burials.[78][79] Critics point out that the compass degrees are often inaccurate because solar winds disturb the electromagnetic field of the earth.[80] Magnetic North on the compass will be inaccurate because true magnetic north fluctuates.[81]

The American magicians Penn and Teller dedicated an episode of their Bullshit! television show to criticize the acceptance of feng shui in the Western world as science. They devised a test in which the same dwelling was visited by five different feng shui consultants: each produced a different opinion about the dwelling, showing there is no consistency in the professional practice of feng shui.[82]

Feng shui is criticized by Christians around the world.[83] Some have argued that it is «entirely inconsistent with Christianity to believe that harmony and balance result from the manipulation and channeling of nonphysical forces or energies, or that such can be done by means of the proper placement of physical objects. Such techniques, in fact, belong to the world of sorcery.»[84]

Feng shui practitioners in China have found officials that are considered superstitious and corrupt easily interested, despite official disapproval. In one instance, in 2009, county officials in Gansu, on the advice of feng shui practitioners, spent $732,000 to haul a 369-ton «spirit rock» to the county seat to ward off «bad luck.»[85] Feng shui may require social influence or money because experts, architecture or design changes, and moving from place to place is expensive. Less influential or less wealthy people lose faith in feng shui, saying that it is a game only for the wealthy.[86] Others, however, practice less expensive forms of feng shui, including hanging special (but cheap) mirrors, forks, or woks in doorways to deflect negative energy.[87]

See also[edit]

- Bagua

- Book of Burial

- Chinese fortune telling

- Chinese spiritual world concepts

- Four Symbols

- Five elements

- Geomancy

- Green Satchel Classic

- Luopan

- Tung Shing (Chinese almanac)

- Shigandang

- Ley line

- Tajul muluk

- Vastu shastra

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Bennett 1978.

- ^ «feng shui, n.». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Bruun (2003), p. 3.

- ^ a b Komjathy (2012), p. 395.

- ^ a b Fernandez-Beanato, Damian (23 August 2021). «Feng Shui and the Demarcation Project». Science & Education. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 30 (6): 1333–1351. Bibcode:2021Sc&Ed..30.1333F. doi:10.1007/s11191-021-00240-z. ISSN 0926-7220. S2CID 238736339.

- ^ a b McCain, K.; Kampourakis, K. (2019). What is Scientific Knowledge?: An Introduction to Contemporary Epistemology of Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-33660-4. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ a b Matthews 2018.

- ^ Sun Xiaochun 2000.

- ^ Pankenier 1995.

- ^ Liu 2004, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Xu et al. 2000.

- ^ Liu 2004, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Nelson et al. 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Chen Jiujin 1989.

- ^ Liu 2004, pp. 230–37.

- ^ Wang 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Feng, Shi (1990). «Zhongguo zaoqi xingxiangtu yanjiu». 自然科學史硏究 (Ziran kexueshi yanjiu) [Research on the History of Natural Science] (2).

- ^ Wang 2000, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Cheng et al. 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Wheatley 1971, p. 46.

- ^ Lewis 2006, p. 275.

- ^ Kalinowski 1996.

- ^ Yin Difei 1978.

- ^ Yan Dunjie 1978.

- ^ Kalinowski 1998.

- ^ Campbell 2001, p. 2.

- ^ a b Field 1998.

- ^ Bruun (2008), p. 49-52.

- ^ Vyse 2020b.

- ^ Vyse, Stuart (2020-01-23). Superstition: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-255131-3.

- ^ deGroot 1892, p. III, 941–42.

- ^ Allan 1991, p. 31-32.

- ^ Werner 1922, p. 84.

- ^ Swetz 2002, pp. 31, 58.

- ^ Puro 2002, p. 108–112.

- ^ Swetz 2002, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Porter 1996, p. 35-38.

- ^ a b Sun Xiaochun 1997, p. 15-18.

- ^ Wang 2000, pp. 107–128.

- ^ Nelson et al. 2006.

- ^ Cheung Ngam Fung 2007.

- ^ Sang 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Moran et al. 2002.

- ^ Cheng et al. 1998, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Johnson 1997.

- ^ a b Vierra 1997.

- ^ Whang 2006.

- ^ Chen Bixia 2008.

- ^ a b Marafa 2003.

- ^ Chen Qigao 1997.

- ^ Siu‐Yiu Lau at al. 2005.

- ^ Zhuang 1997.

- ^ Chen & Nakama 2004.

- ^ Xu Jun 2003.

- ^ Lu Hui-Chen 2002.

- ^ Park et al. 1996.

- ^ Xu Ping 1998.

- ^ Hwangbo 2002.

- ^ Lu et al. 2000.

- ^ Lai 1974.

- ^ Xu Ping 1997.

- ^ Emmons 1992, p. 48.

- ^ Zhang 2020.

- ^ Tsang 2013.

- ^ NYTimes 2005.

- ^ Asiaone 2009.

- ^ Ricci 1617, p. 103-104.

- ^ Gallagher 1953, Book I, ch. 9, pp. 84–85.

- ^ March 1968.

- ^ Cody 1996.

- ^ Chang Liang 2005.

- ^ Moore 2010.

- ^ BBC News 2001.

- ^ «司马南与巨天中在齐鲁台关于风水辩论的思考» [Thoughts on Feng Shui Debate between Sima Nan and Ju Tianzhong in Qilutai]. 2006-07-06. Archived from the original on 2008-02-15.

- ^ Fudan 2012.

- ^ Jiang Xun 2006.

- ^ Carroll/Feng Shui.

- ^ Skinner 2008.

- ^ Nguyen 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Lang 2011, p. 102.

- ^ NASA 2003.

- ^ Penn & Teller 2003.

- ^ Mah 2004.

- ^ Montenegro 2003.

- ^ NYTimes 2013.

- ^ Emmons 1992, p. 42.

- ^ Emmons 1992, p. 46.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Allan, Sarah (1991). Shape of the Turtle, The: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9449-3.

- Bruun, Ole (2003). Fengshui in China: Geomantic Divination Between State Orthodoxy and Popular Religion. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. ISBN 9780824826727.

- Bruun, Ole (2008). An Introduction to Feng Shui. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521863520.

- Campbell, Wallace H. (7 February 2001). Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour through Magnetic Fields. Elsevier. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-08-050490-2.

Written records show that a Chinese compass, Si Nan, had already been fabricated between 300 and 200 BE and used for the alignment of constructions to be magically harmonious with the natural Earth forces.

- Cheng, Jian Jun; Fernandes-Gonçalves, Adriana (1998). Chinese Feng Shui Compass: Step by Step Guide.

- de Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1892). The Religious System of China. E.J. Brill., various years, vol I-II-III-IV-V-VI

- Guo Pu. «The Zangshu, or Book of Burial«. Professor Field’s Fengshui Gate. Translated by Field, Stephen L. Archived from the original on 2020-05-21..

- Lang, Kenneth R. (2011). The Cambridge Guide to the Solar System (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49417-5.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (June 2006). The Construction of Space in Early China. Suny Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6608-7.

- Liu, Li (2004). The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81184-2.

- Lu, Hui-Chen (2002). A Comparative analysis between western-based environmental design and feng-shui for housing sites. OCLC 49999768.

- Magli, Giulio (2020). Sacred Landscapes of Imperial China: Astronomy, Feng Shui, and the Mandate of Heaven. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-49324-0.

- Michael R. Matthews (2019). Feng Shui: Teaching About Science and Pseudoscience. Cham: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18822-1. ISBN 978-3-030-18822-1. Wikidata Q116742539.

- Moran, Elizabeth; Joseph Yu; Val Biktashev (2002). The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Feng Shui. Pearson Education. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Nguyen, Phil N. (2008). Feng Shui for the Curious and Serious. Vol. 1. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4691-1882-6.

- Paton, Michael John (2013). Five Classics of Fengshui: Chinese Spiritual Geography in Historical and Environmental Perspective. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24986-8.. Includes translations of Archetypal burial classic of Qing Wu; The inner chapter of the Book of burial rooted in antiquity ; The yellow emperor’s classic of house siting; Twenty four difficult problems; The secretly passed down water dragon classic.

- Porter, Deborah Lynn (January 1996). From Deluge to Discourse: Myth, History, and the Generation of Chinese Fiction. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3033-0.

- Puro, Jon (2002). «Feng Shui». In Shermer, Michael (ed.). The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-653-8.

- Ricci, Matteo; Nicolas Trigault (1953). China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci, 1583-1610. Translated by Louis Joseph Gallagher. Random House., length=616 pages ## 71

- Matteo Ricci (1617). Nicolas Trigault (ed.). De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas. Gualterus.

- Sang, Larry (2004). Feng Shui Facts and Myths. Translated by Sylvia Lam. American Feng Shui Institute (www.amfengshui.com). p. 75. ISBN 978-0-9644583-4-5., length=150 pages

- Skinner, Stephen (2008). Guide to the Feng Shui Compass: A Compendium of Classical Feng Shui. Golden Hoard. ISBN 978-0-9547639-9-2.

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997). The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. BRILL. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3.

- Sun, Xiaochun (2000). «Crossing the Boundaries Between Heaven and Man: Astronomy in Ancient China». Astronomy Across Cultures. Science Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Science. Vol. 1. pp. 423–454. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4179-6_15. ISBN 978-94-010-5820-9.

- Swetz, Frank J. (2002). The Legacy of the Luoshu: the 4,000 year search for the meaning of the magic square of order three. ISBN 978-0-8126-9448-2.

- Tsang, A. Katat (2013). «Problem Translation». Learning to Change Lives: The Strategies and Skills Learning and Development Approach. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1401-7. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2ttqpq.

- Vyse, Stuart (2020-01-23). Superstition: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-255131-3.

- Wang, Aihe (2000). Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02749-6.

- Werner, E. T. C. (1922). Myths and Legends of China. London Bombay Sydney: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd. Dover reprint ISBN 0-486-28092-6

- Wheatley, Paul (1971). The Pivot of the Four Quarters: A Preliminary Enquiry Into the Origins and Character of the Ancient Chinese City. Aldine Publishing Company. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-85224-174-5.

- Xu, Zhenoao; W. Pankenier; Yaotiao Jiang (2000). East-Asian Archaeoastronomy: Historical Records of Astronomical Observations of China, Japan and Korea. Earth Space Institute Book Series. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-5699-302-3., length=440, Review= https://physicstoday.scitation.org/doi/full/10.1063/1.1445553

- Zhang, Li (2020). «Cultivating Happiness». Anxious China: Inner Revolution and Politics of Psychotherapy (1 ed.). University of California Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv125js0p. ISBN 978-0-520-34418-1. JSTOR j.ctv125js0p. S2CID 242967723.

Theses[edit]

- Chen, Bixia (14 March 2008). A Comparative Study on the Feng Shui Village Landscape and Feng Shui Trees in East Asia (Thesis). hdl:10232/4817.

- Xu, Jun (30 September 2003). A Framework for Site Analysis with Emphasis on Feng Shui and Contemporary Environmental Design Principles (Thesis). hdl:10919/29291.

Articles and chapters[edit]

- Bourguignon, Erika (2005). «Geomancy». In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 3437–3438.

- Bennett, Steven J. (1978). «Patterns of the Sky and Earth: A Chinese Science of Applied Cosmology». Chinese Science. 3: 1–26. JSTOR 43896378.

- Chen, B. X.; Nakama, Y. (2004). «A summary of research history on Chinese Feng-shui and application of feng shui principles to environmental issues» (PDF). Kyusyu J. For. Res. 57: 297–301.

- Chen, Qigao; Feng, Ya; Wang, Gonglu (May 1997). «Healthy Buildings Have Existed in China Since Ancient Times». Indoor and Built Environment. 6 (3): 179–187. doi:10.1177/1420326X9700600309. S2CID 109578261.

- Cody, Jeffrey W. (1996). «Striking a Harmonious Chord: Foreign Missionaries and Chinese-style Buildings, 1911–1949». Architronic. 5 (3): 1–30. OCLC 888791587.

- Emmons, Charles F. (June 1992). «Hong Kong’s Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting». The Journal of Popular Culture. 26 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1992.00039.x.

- Henderson, John B. (1994). «Chinese Cosmographical Thought: The High Intellectual Tradition» (PDF). In Woodward, J.B.; Harley, David (eds.). The History of Cartography: Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies. Vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 203–27.

- Hwangbo, Alfred B. (2002). «An Alternative Tradition in Architecture: Conceptions in Feng Shui and ITS Continuous Tradition». Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. 19 (2): 110–130. JSTOR 43030604.

- Johnson, Mark (Spring 1997). «Reality Testing in Feng Shui». Qi Journal. 7 (1).

- Kalinowski, Marc (1996). «The Use of the Twenty-eight Xiu as a Day-Count in Early China». Chinese Science (13): 55–81. JSTOR 43290380.

- Kalinowski, Marc; Brooks, Phyllis (1998). «The Xingde Texts from Mawangdui». Early China. 23: 125–202. doi:10.1017/S0362502800000973. S2CID 163626838.

- Komjathy, Louis (2012). «Feng Shui (Geomancy)». In Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Vol. 1. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Reference. pp. 395–396.

- Lai, Chuen-Yan David (December 1974). «A Feng Shui model as a Location Index». Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 64 (4): 506–513. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1974.tb00999.x.

- Lu, Su-Ju; Jones, Peter Blundell (January 2000). «House design by surname in Feng Shui». The Journal of Architecture. 5 (4): 355–367. doi:10.1080/13602360050214386. S2CID 145206158.

- Lau, Stephen Siu-Yiu; Garcia, Renato; Ou, Ying‐Qing; Kwok, Man‐Mo; Zhang, Ying; Jie Shen, Shao; Namba, Hitomi (December 2005). «Sustainable design in its simplest form: Lessons from the living villages of Fujian rammed earth houses». Structural Survey. 23 (5): 371–385. doi:10.1108/02630800510635119.

- Mah, Yeow B. (2004). «Living in harmony with one’s environment: a Christian response to ‘Feng Shui’«. Asia Journal of Theology. 18 (2): 340–361.

- Marafa, Lawal (December 2003). «Integrating natural and cultural heritage: the advantage of feng shui landscape resources». International Journal of Heritage Studies. 9 (4): 307–323. doi:10.1080/1352725022000155054. S2CID 145221348.

- March, Andrew L. (1968). «An Appreciation of Chinese Geomancy». The Journal of Asian Studies. 27 (2): 253–267. doi:10.2307/2051750. JSTOR 2051750. S2CID 144873575.

- Matthews, Michael R. (2018). «Feng Shui: Educational Responsibilities and Opportunities». In Matthews, Michael R. (ed.). History, Philosophy and Science Teaching: New Perspectives. Science: Philosophy, History and Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-319-62616-1.

- Montenegro, Marcia (2003). «Feng Shui: New Dimensions in Design». Christian Research Journal. 26 (1).

- Nelson, Sarah M.; Matson, Rachel A.; Roberts, Rachel M.; Rock, Chris; Stencel, Robert E. (2006). «Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang». Journal of East Asian Material Culture. S2CID 6794721.

- Pankenier, David W. (1995). «The Cosmo-political Background of Heaven’s Mandate». Early China. 20: 121–176. doi:10.1017/S0362502800004466. S2CID 157710102.

- Park, C-P.; Furukawa, N.; Yamada, M. (1996). «A Study on the Spatial Composition of Folk Houses and Village in Taiwan for the Geomancy (Feng-Shui)». Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea. 12: 129–140.

- Smith, Richard J. (2019). «The Transnational Travels of Geomancy in Premodern East Asia, C. 1600–C. 1901 Pt I». Transnational Asia. Rice University. 2 (1): 1–112. doi:10.25613/uxwv-zpzd.

- ——— (2019a). «The Transnational Travels of Geomancy in Premodern East Asia, C. 1600 — C. 1900: Part Ii». Transnational Asia. Rice University. 2 (1). doi:10.25613/i5m7-5d0i.

- Whang, Bo-Chul; Lee, Myung-Woo (13 November 2006). «Landscape ecology planning principles in Korean Feng-Shui, Bi-bo woodlands and ponds». Landscape and Ecological Engineering. 2 (2): 147–162. doi:10.1007/s11355-006-0014-8. S2CID 31234343.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2018). «Fengshui». Chinese History: A New Manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 463. ISBN 9780998888309.

- Xu, Ping (1998). «‘Feng-Shui’ Models Structured Traditional Beijing Courtyard Houses». Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. 15 (4): 271–282. JSTOR 43030469.

- Xu, Ping (21 September 1997). «Feng-shui as Clue: Identifying Prehistoric Landscape Setting Patterns in the American Southwest». Landscape Journal. 16 (2): 174–190. doi:10.3368/lj.16.2.174. S2CID 109321682.

- Zhuang, Xue Ying; Gorlett, Richard T. (1997). «Forest and forest succession in Hong Kong, China». Journal of Tropical Ecology. 13 (6): 857–866. doi:10.1017/S0266467400011032. hdl:10722/42380. JSTOR 2560242. S2CID 83846505.

Blogs and online[edit]

- Carroll, Robert T. «Feng Shui». The Skeptic’s Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- Vierra, Monty (March 1997). «Harried by «Hellions» in Taiwan». Skeptical Inquirer.

- Vyse, Stuart (May 2020). «Superstition and Real Estate». Skeptical Inquirer.

Web[edit]

- Brandmaier, Werner. «Feng Shui». Institute of Feng Shui. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2021-07-09. practitioner, turned to dowsing.

- Cheung Ngam Fung, Jacky (2007). «History of Feng Shui». Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. not really archived. Moreover the sentence to be proven is rather void

- Field, Stephen L. (1998). «Qimancy: Chinese Divination by Qi». Archived from the original on 2017-02-23.

- Penn; Teller (2003-03-07). «Feng Shui/Bottled Water». IMDb. Bullshit!. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - «Chang Liang (pseudonym), 14 January 2005, What Does Superstitious Belief of ‘Feng Shui’ Among School Students Reveal?«. Zjc.zjol.com.cn. 2005-01-31. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- «Earth’s Inconstant Magnetic Field». NASA Science. 2003-12-29. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- «蔡达峰 – Cao Dafeng». Fudan.edu.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- «Feng Shui course gains popularity». Asiaone.com. 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

Miscellaneous[edit]

Traditional China[edit]

- 陳久金 (Chen Jiujin); 張敬國 (Zhang Jingguo) (1989). «含山出土玉片圖形試考 (Hanshan chutu yupian taxing shikao)» [A preliminary analysis of the iconography in the jade fragments from the excavation site in Hanshan]. 文物 (Wenwu) [Cultural Relics, Beijing]. 4: 14–17.

- 殷涤非 (Yin Difei) (May 1978). «西汉汝阴侯墓出土的占盘和天文仪器 (Xi-Han Ruyinhou mu chutu de zhanpan he tianwen yiqi)» [The divination boards and astronomical instrument from the tomb of the Marquis of Ruyin of the Western Han]. 考古 (Kaogu) [Archaeology, Beijing]. 12: 338–343.

- 嚴敦傑 (Yan Dunjie) (May 1978). «關於西漢初期的式盤和占盤(Guanyu Xi-Han chuqi de shipan he zhanpan)» [On the cosmic boards and divination boards from the early Western Han period]. 考古 (Kaogu) [Archaeology, Beijing]. 12: 334–337.

- «武则天挖坟焚尸真相:迷信风水镇压反臣» [The truth about Wu Zetian digging graves and burning corpses]. 星岛环球网, 文史 [Sing Tao Global Network, Culture and History]. Archived from the original on 2009-12-23. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- «丧心病狂中国历史上六宗罕见的辱尸事» [Six rare humiliation incidents in Chinese history]. Archived from the original on 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- 倪方六(Ni Fangliu ) (October 2009). 中国人盗墓史(挖出正史隐藏的盗墓狂人) [The history of Chinese tomb robbers]. 上海锦绣文章出版社 (Shanghai Jinxiu Articles Publishing House). ISBN 978-7-5452-0319-6.. The «Ming Sizong robbed Li Zicheng’s ancestral grave» section can be read at 凤凰网读书频道. ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- «蒋介石挖毛泽东祖坟的玄机» [The mystery of Chiang Kai-shek digging Mao Zedong’s ancestor’s grave]. 中华命理风水论坛 [Chinese Numerology and Fengshui Forum]. 2010-06-13. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20.

Post-1949 China[edit]

- 2001 «風水迷信»困擾中國當局» [Feng Shui Superstitions Troubles Chinese Authorities]. BBC News. 9 March 2001. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- 2006 Jiang Xun (11 April 2006). «透視:從»巫毒娃娃»到風水迷信» [Focus on China: From Voodoo Dolls to Feng Shui Superstitions] (in Chinese). BBC Chinese service. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- 2010 Moore, Malcolm (2010-12-16). «Hong Kong government spends millions on feng shui». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11.

- 2013 Levin, Dan (10 May 2013). «China Officials Seek Career Shortcut With Feng Shui». The New York Times.

U.S.A[edit]

- 2005 Holson, Laura M. (25 April 2005). «The Feng Shui Kingdom». The New York Times..

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Feng Shui.

Look up feng shui in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Feng shui analysis of a 癸山丁向 site, with an auspicious circle[1]

| Feng shui | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 风水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «wind-water» | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | phong thủy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | ฮวงจุ้ย (Huang chui) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 풍수 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 風水 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ふうすい | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | Pungsóy, Punsóy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer | ហុងស៊ុយ (hongsaouy) |

Feng shui ( [2]), sometimes called Chinese geomancy, is an ancient Chinese traditional practice which claims to use energy forces to harmonize individuals with their surrounding environment. The term feng shui means, literally, «wind-water» (i.e. fluid). From ancient times, landscapes and bodies of water were thought to direct the flow of the universal Qi – «cosmic current» or energy – through places and structures. More broadly, feng shui includes astronomical, astrological, architectural, cosmological, geographical and topographical dimensions.[3][4]

Historically, as well as in many parts of the contemporary Chinese world, feng shui was used to orient buildings and spiritually significant structures such as tombs, as well as dwellings and other structures. One scholar writes that in contemporary Western societies, however, «feng shui tends to be reduced to interior design for health and wealth. It has become increasingly visible through ‘feng shui consultants’ and corporate architects who charge large sums of money for their analysis, advice and design.»[4]

Feng shui has been identified as both non-scientific and pseudoscientific by scientists and philosophers[5] and has been described as a paradigmatic example of pseudoscience.[6] It exhibits a number of classic pseudoscientific aspects, such as making claims about the functioning of the world which are not amenable to testing with the scientific method.[7]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The Yangshao and Hongshan cultures provide the earliest known evidence for the use of feng shui. Until the invention of the magnetic compass, feng shui relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe.[8]

In 4000 BC, the doors of dwellings in Banpo were aligned with the asterism Yingshi just after the winter solstice—this sited the homes for solar gain.[9] During the Zhou era, Yingshi was known as Ding and it was used to indicate the appropriate time to build a capital city, according to the Shijing. The late Yangshao site at Dadiwan (c. 3500–3000 BC) includes a palace-like building (F901) at its center. The building faces south and borders a large plaza. It stands on a north–south axis with another building that apparently housed communal activities. Regional communities may have used the complex. [10]

A grave at Puyang (around 4000 BC) that contains mosaics— a Chinese star map of the Dragon and Tiger asterisms and Beidou (the Big Dipper, Ladle or Bushel)— is oriented along a north–south axis.[11] The presence of both round and square shapes in the Puyang tomb, at Hongshan ceremonial centers and at the late Longshan settlement at Lutaigang,[12]

suggests that gaitian cosmography (heaven-round, earth-square) existed in Chinese society long before it appeared in the Zhoubi Suanjing.[13]

Cosmography that bears a resemblance to modern feng shui devices and formulas appears on a piece of jade unearthed at Hanshan and dated around 3000 BC. Archaeologist Li Xueqin links the design to the liuren astrolabe, zhinan zhen and luopan.[14]

Beginning with palatial structures at Erlitou,[15] all capital cities of China followed rules of feng shui for their design and layout. During the Zhou era, the Kaogong ji (Chinese: 考工記; «Manual of Crafts») codified these rules. The carpenter’s manual Lu ban jing (魯班經; «Lu ban’s manuscript») codified rules for builders. Graves and tombs also followed rules of feng shui from Puyang to Mawangdui and beyond. From the earliest records, the structures of the graves and dwellings seem to have followed the same rules.[citation needed]

Early instruments and techniques[edit]

Some of the foundations of feng shui go back more than 3,500 years[16] before the invention of the magnetic compass. It originated in Chinese astronomy.[17] Some current techniques can be traced to Neolithic China,[18] while others were added later (most notably the Han dynasty, the Tang, the Song, and the Ming).[19]

The astronomical history of feng shui is evident in the development of instruments and techniques. According to the Zhouli, the original feng shui instrument may have been a gnomon. Chinese used circumpolar stars to determine the north–south axis of settlements. This technique explains why Shang palaces at Xiaotun lie 10° east of due north. In some of the cases, as Paul Wheatley observed, they bisected the angle between the directions of the rising and setting sun to find north.[20] This technique provided the more precise alignments of the Shang walls at Yanshi and Zhengzhou. Rituals for using a feng shui instrument required a diviner to examine current sky phenomena to set the device and adjust their position in relation to the device.[21]

The oldest examples of instruments used for feng shui are liuren astrolabes, also known as shi. These consist of a lacquered, two-sided board with astronomical sightlines. The earliest examples of liuren astrolabes have been unearthed from tombs that date between 278 BC and 209 BC. Along with divination for Da Liu Ren[22] the boards were commonly used to chart the motion of Taiyi through the nine palaces.[23][24] The markings on a liuren/shi and the first magnetic compasses are virtually identical.[25]

The magnetic compass was invented for feng shui and has been in use since its invention.[26] Traditional feng shui instrumentation consists of the Luopan or the earlier south-pointing spoon (指南針 zhinan zhen)—though a conventional compass could suffice if one understood the differences. A feng shui ruler (a later invention) may also be employed.[citation needed]

Foundational concepts[edit]

Definition and classification[edit]

The goal of feng shui as practiced today is to situate the human-built environment on spots with good qi, an imagined form of «energy». The «perfect spot» is a location and an axis in time.[27][1]

Traditional feng shui is inherently a form of ancestor worship. Popular in farming communities for centuries, it was built on the idea that the ghosts of ancestors and other independent, intangible forces, both personal and impersonal, affected the material world, and that these forces needed to be placated through rites and suitable burial places, which the feng shui practitioner would assist with for a fee. The primary underlying value was material success for the living.[28]

According to Stuart Vyse, feng shui is «a very popular superstition.»[29] The PRC government has also labeled it as superstitious.[30] Feng shui is classified as a pseudoscience since it exhibits a number of classic pseudoscientific aspects such as making claims about the functioning of the world which are not amenable to testing with the scientific method.[7] It has been identified as both non-scientific and pseudoscientific by scientists and philosophers,[5] and has been described as a paradigmatic example of pseudoscience.[6]

Qi (ch’i)[edit]

A traditional turtle-back tomb of southern Fujian, surrounded by an omega-shaped ridge protecting it from the «noxious winds» from the three sides[31]

Qi (气, pronounced «chee», «cee», or «tsee») is a movable positive or negative life force which plays an essential role in feng shui. The Book of Burial says that burial takes advantage of «vital qi«. The goal of feng shui is to take advantage of vital qi by appropriate siting of graves and structures.[1]

Polarity[edit]

Polarity is expressed in feng shui as yin and yang theory. That is, it is of two parts: one creating an exertion and one receiving the exertion. The development of this theory and its corollary, five phase theory (five element theory), have also been linked with astronomical observations of sunspot.[32]

The Five Elements or Forces (wu xing) – which, according to the Chinese, are metal, earth, fire, water, and wood – are first mentioned in Chinese literature in a chapter of the classic Book of History. They play a very important part in Chinese thought: ‘elements’ meaning generally not so much the actual substances as the forces essential to human life.[33] Earth is a buffer, or an equilibrium achieved when the polarities cancel each other.[citation needed] While the goal of Chinese medicine is to balance yin and yang in the body, the goal of feng shui has been described as aligning a city, site, building, or object with yin-yang force fields.[34]

Bagua (eight trigrams)[edit]

Eight diagrams known as bagua (or pa kua) loom large in feng shui, and both predate their mentions in the Yijing (or I Ching).[35] The Lo (River) Chart (Luoshu) was developed first,[36] and is sometimes associated with Later Heaven arrangement of the bagua. This and the Yellow River Chart (Hetu, sometimes associated with the Earlier Heaven bagua) are linked to astronomical events of the sixth millennium BC, and with the Turtle Calendar from the time of Yao.[37] The Turtle Calendar of Yao (found in the Yaodian section of the Shangshu or Book of Documents) dates to 2300 BC, plus or minus 250 years.[38]

In Yaodian, the cardinal directions are determined by the marker-stars of the mega-constellations known as the Four Celestial Animals:[38]

- East: The Azure Dragon (Spring equinox)—Niao (Bird 鳥), α Scorpionis

- South: The Vermilion Bird (Summer solstice)—Huo (Fire 火), α Hydrae

- West: The White Tiger (Autumn equinox)—Mǎo (Hair 毛), η Tauri (the Pleiades)

- North: The Black Tortoise (Winter solstice)—Xū (Emptiness, Void 虛), α Aquarii, β Aquarii

The diagrams are also linked with the sifang (four directions) method of divination used during

the Shang dynasty.[39] The sifang is much older, however. It was used at Niuheliang, and figured large in Hongshan culture’s astronomy. And it is this area of China that is linked to Yellow Emperor (Huangdi) who allegedly invented the south-pointing spoon (see compass).[40]

Traditional feng shui[edit]

Traditional feng shui is an ancient system based upon the observation of heavenly time and earthly space. Literature, as well as archaeological evidence, provide some idea of the origins and nature of feng shui techniques. Aside from books, there is also a strong oral history. In many cases, masters have passed on their techniques only to selected students or relatives.[41] Modern practitioners of feng shui draw from several branches in their own practices.

Form Branch[edit]

The Form Branch is the oldest branch of feng shui. Qing Wuzi in the Han dynasty describes it in the Book of the Tomb[42] and Guo Pu of the Jin dynasty follows up with a more complete description in The Book of Burial.[citation needed]

The Form branch was originally concerned with the location and orientation of tombs (Yin House feng shui), which was of great importance.[27] The branch then progressed to the consideration of homes and other buildings (Yang House feng shui).

The «form» in Form branch refers to the shape of the environment, such as mountains, rivers, plateaus, buildings, and general surroundings. It considers the five celestial animals (vermillion phoenix, azure dragon, white tiger, black turtle, and the yellow snake), the yin-yang concept and the traditional five elements (Wu Xing: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water).[citation needed]

The Form branch analyzes the shape of the land and flow of the wind and water to find a place with ideal qi.[43] It also considers the time of important events such as the birth of the resident and the building of the structure.

Compass Branch[edit]

The Compass branch is a collection of more recent feng shui techniques based on the Eight Directions, each of which is said to have unique qi. It uses the Luopan, a disc marked with formulas in concentric rings around a magnetic compass.[44]

The Compass Branch includes techniques such as Flying Star and Eight Mansions.[citation needed]

Western forms of feng shui[edit]

More recent forms of feng shui simplify principles that come from the traditional branches, and focus mainly on the use of the bagua.[citation needed]

Aspirations Method[edit]

The Eight Life Aspirations style of feng shui is a simple system which coordinates each of the eight cardinal directions with a specific life aspiration or station such as family, wealth, fame, etc., which come from the Bagua government of the eight aspirations. Life Aspirations is not otherwise a geomantic system.[citation needed]

List of specific feng shui branches[edit]

Ti Li (Form Branch)[edit]

Popular Xingshi Pai (形勢派) «forms» methods[edit]

- Luan Tou Pai, 巒頭派, Pinyin: luán tóu pài, (environmental analysis without using a compass)

- Xing Xiang Pai, 形象派 or 形像派, Pinyin: xíng xiàng pài, (Imaging forms)

- Xingfa Pai, 形法派, Pinyin: xíng fǎ pài

Liiqi Pai (Compass Branch)[edit]

Popular Liiqi Pai (理气派) «Compass» methods[edit]

San Yuan Method, 三元派 (Pinyin: sān yuán pài)

- Dragon Gate Eight Formation, 龍門八法 (Pinyin: lóng mén bā fǎ)

- Xuan Kong, 玄空 (time and space methods)

- Xuan Kong Fei Xing 玄空飛星 (Flying Stars methods of time and directions)

- Xuan Kong Da Gua, 玄空大卦 («Secret Decree» or 64 gua relationships)

- Xuan Kong Mi Zi, 玄空秘旨 (Mysterious Space Secret Decree)

- Xuan Kong Liu Fa, 玄空六法 (Mysterious Space Six Techniques)

- Zi Bai Jue, 紫白訣 (Purple White Scroll)

San He Method, 三合派 (environmental analysis using a compass)

- Accessing Dragon Methods

- Ba Zhai, 八宅 (Eight Mansions)

- Yang Gong Feng Shui, 楊公風水

- Water Methods, 河洛水法

- Local Embrace

Others

- Yin House Feng Shui, 陰宅風水 (Feng Shui for the deceased)

- Four Pillars of Destiny, 四柱命理 (a form of hemerology)

- Zi Wei Dou Shu, 紫微斗數 (Purple Star Astrology)

- I-Ching, 易經 (Book of Changes)

- Qi Men Dun Jia, 奇門遁甲 (Mysterious Door Escaping Techniques)

- Da Liu Ren, 大六壬 (Divination: Big Six Heavenly Yang Water Qi)

- Tai Yi Shen Shu, 太乙神數 (Divination: Tai Yi Magical Calculation Method)

- Date Selection, 擇日 (Selection of auspicious dates and times for important events)

- Chinese Palmistry, 掌相學 (Destiny reading by palm reading)

- Chinese Face Reading, 面相學 (Destiny reading by face reading)

- Major & Minor Wandering Stars (Constellations)

- Five phases, 五行 (relationship of the five phases or wuxing)

- BTB Black (Hat) Tantric Buddhist Sect (Westernised or Modern methods not based on Classical teachings)

- Symbolic Feng Shui, (New Age Feng Shui methods that advocate substitution with symbolic (spiritual, appropriate representation of five elements) objects if natural environment or object/s is/are not available or viable)

- Pierce Method of Feng Shui ( Sometimes Pronounced : Von Shway ) The practice of melding striking with soothing furniture arrangements to promote peace and prosperity

Contemporary uses of traditional feng shui[edit]

After Richard Nixon’s visit to the People’s Republic of China in 1972, feng shui practices became popular in the United States. Critics warn that claims of scientific validity have proven to be false and that the practices are pseudoscientific. Others charge that it has been reinvented and commercialized by New Age entrepreneurs,[45] or are concerned that much of the traditional theory has been lost in translation, not given proper consideration, frowned upon, or scorned.[46]

Feng shui has nonetheless found many uses. Landscape ecologists often find traditional feng shui an interesting study.[47] In many cases, the only remaining patches of Asian old forest are «feng shui woods,»[48] associated with cultural heritage, historical continuity, and the preservation of various flora and fauna species.[49] Some researchers interpret the presence of these woods as indicators that the «healthy homes,»[50] sustainability [51] and environmental components of traditional feng shui should not be easily dismissed.[49][52] Environmental scientists and landscape architects have researched traditional feng shui and its methodologies.[53][54][55] Architects study feng shui as an Asian architectural tradition.[56][57][58][59] Geographers have analyzed the techniques and methods to help locate historical sites in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada,[60] and archaeological sites in the American Southwest, concluding that Native Americans also considered astronomy and landscape features.[61]

Believers use it for healing purposes, to guide their businesses, or to create a peaceful atmosphere in their homes, although there is no empirical evidence that it is effective.[62] In particular, they use feng shui in the bedroom, where a number of techniques involving colors and arrangement are thought to promote comfort and peaceful sleep.[citation needed] Some users of feng shui may be trying to gain a sense of security or control, for example by choosing auspicious numbers for their phones or favorable house locations. Their motivation is similar to the reasons that some people consult fortune-tellers.[63][64]

In 2005, Hong Kong Disneyland acknowledged feng shui as an important part of Chinese culture by shifting the main gate by twelve degrees in their building plans. This was among actions suggested by the planner of architecture and design at Walt Disney Imagineering, Wing Chao.[65] At Singapore Polytechnic and other institutions, professionals including engineers, architects, property agents and interior designers, take courses on feng shui and divination every year, a number of whom become part-time or full-time feng shui consultants.[66]

Criticisms[edit]

Traditional feng shui[edit]

Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), one of the founding fathers of Jesuit China missions, may have been the first European to write about feng shui practices. His account in De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas[67] tells about feng shui masters (geologi, in Latin) studying prospective construction sites or grave sites «with reference to the head and the tail and the feet of the particular dragons which are supposed to dwell beneath that spot.» As a Catholic missionary, Ricci strongly criticized the «recondite science» of geomancy along with astrology as yet another superstitio absurdissima of the heathens: «What could be more absurd than their imagining that the safety of a family, honors, and their entire existence must depend upon such trifles as a door being opened from one side or another, as rain falling into a courtyard from the right or from the left, a window opened here or there, or one roof being higher than another?»[68]

Victorian-era commentators on feng shui were generally ethnocentric, and as such skeptical and derogatory of what they knew of feng shui.[69] In 1896, at a meeting of the Educational Association of China, Rev. P. W. Pitcher railed at the «rottenness of the whole scheme of Chinese architecture,» and urged fellow missionaries «to erect unabashedly Western edifices of several stories and with towering spires in order to destroy nonsense about fung-shuy.«[70]

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, feng shui was officially considered a «feudalistic superstitious practice» and a «social evil» according to the state’s ideology and was discouraged and even banned outright at times.[71] Feng shui remained popular in Hong Kong, and also in the Republic of China (Taiwan), where traditional culture was not suppressed.[72]

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) feng shui was classified as one of the so-called Four Olds that were to be wiped out. Feng shui practitioners were beaten and abused by Red Guards and their works burned. After the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the official attitude became more tolerant but restrictions on feng shui practice are still in place in today’s China. It is illegal in the PRC today to register feng shui consultation as a business and similarly advertising feng shui practice is banned. There have been frequent crackdowns on feng shui practitioners on the grounds of «promoting feudalistic superstitions» such as one in Qingdao in early 2006 when the city’s business and industrial administration office shut down an art gallery converted into a feng shui practice. Some officials who had consulted feng shui were terminated and expelled from the Communist Party.[73]

In 21st century mainland China less than one-third of the population believe in feng shui, and the proportion of believers among young urban Chinese is said to be even lower.[74] Chinese academics permitted to research feng shui are anthropologists or architects by profession, studying the history of feng shui or historical feng shui theories behind the design of heritage buildings. They include Cai Dafeng, Vice-President of Fudan University.[75] Learning in order to practice feng shui is still somewhat considered taboo. Nevertheless, it is reported that feng shui has gained adherents among Communist Party officials according to a BBC Chinese news commentary in 2006,[76] and since the beginning of Chinese economic reforms the number of feng shui practitioners is increasing.

Contemporary feng shui[edit]

One critic called the situation of feng shui in today’s world «ludicrous and confusing,» asking «Do we really believe that mirrors and flutes are going to change people’s tendencies in any lasting and meaningful way?» He called for much further study or «we will all go down the tubes because of our inability to match our exaggerated claims with lasting changes.»[45] Robert T. Carroll sums up the charges:

…feng shui has become an aspect of interior decorating in the Western world and alleged masters of feng shui now hire themselves out for hefty sums to tell people such as Donald Trump which way his doors and other things should hang. Feng shui has also become another New Age «energy» scam with arrays of metaphysical products…offered for sale to help you improve your health, maximize your potential, and guarantee fulfillment of some fortune cookie philosophy.[77]

Skeptics charge that evidence for its effectiveness is based primarily upon anecdote and users are often offered conflicting advice from different practitioners, though feng shui practitioners use these differences as evidence of variations in practice or different branches of thought. A critical analyst concluded that «Feng shui has always been based upon mere guesswork.»[46] Another objection was to the compass, a traditional tool for choosing favorable locations for property or burials.[78][79] Critics point out that the compass degrees are often inaccurate because solar winds disturb the electromagnetic field of the earth.[80] Magnetic North on the compass will be inaccurate because true magnetic north fluctuates.[81]

The American magicians Penn and Teller dedicated an episode of their Bullshit! television show to criticize the acceptance of feng shui in the Western world as science. They devised a test in which the same dwelling was visited by five different feng shui consultants: each produced a different opinion about the dwelling, showing there is no consistency in the professional practice of feng shui.[82]

Feng shui is criticized by Christians around the world.[83] Some have argued that it is «entirely inconsistent with Christianity to believe that harmony and balance result from the manipulation and channeling of nonphysical forces or energies, or that such can be done by means of the proper placement of physical objects. Such techniques, in fact, belong to the world of sorcery.»[84]

Feng shui practitioners in China have found officials that are considered superstitious and corrupt easily interested, despite official disapproval. In one instance, in 2009, county officials in Gansu, on the advice of feng shui practitioners, spent $732,000 to haul a 369-ton «spirit rock» to the county seat to ward off «bad luck.»[85] Feng shui may require social influence or money because experts, architecture or design changes, and moving from place to place is expensive. Less influential or less wealthy people lose faith in feng shui, saying that it is a game only for the wealthy.[86] Others, however, practice less expensive forms of feng shui, including hanging special (but cheap) mirrors, forks, or woks in doorways to deflect negative energy.[87]

See also[edit]

- Bagua

- Book of Burial

- Chinese fortune telling

- Chinese spiritual world concepts

- Four Symbols

- Five elements

- Geomancy

- Green Satchel Classic

- Luopan

- Tung Shing (Chinese almanac)

- Shigandang

- Ley line

- Tajul muluk

- Vastu shastra

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Bennett 1978.

- ^ «feng shui, n.». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Bruun (2003), p. 3.

- ^ a b Komjathy (2012), p. 395.

- ^ a b Fernandez-Beanato, Damian (23 August 2021). «Feng Shui and the Demarcation Project». Science & Education. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 30 (6): 1333–1351. Bibcode:2021Sc&Ed..30.1333F. doi:10.1007/s11191-021-00240-z. ISSN 0926-7220. S2CID 238736339.

- ^ a b McCain, K.; Kampourakis, K. (2019). What is Scientific Knowledge?: An Introduction to Contemporary Epistemology of Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-33660-4. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ a b Matthews 2018.

- ^ Sun Xiaochun 2000.

- ^ Pankenier 1995.

- ^ Liu 2004, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Xu et al. 2000.

- ^ Liu 2004, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Nelson et al. 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Chen Jiujin 1989.

- ^ Liu 2004, pp. 230–37.

- ^ Wang 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Feng, Shi (1990). «Zhongguo zaoqi xingxiangtu yanjiu». 自然科學史硏究 (Ziran kexueshi yanjiu) [Research on the History of Natural Science] (2).

- ^ Wang 2000, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Cheng et al. 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Wheatley 1971, p. 46.

- ^ Lewis 2006, p. 275.

- ^ Kalinowski 1996.

- ^ Yin Difei 1978.

- ^ Yan Dunjie 1978.

- ^ Kalinowski 1998.

- ^ Campbell 2001, p. 2.

- ^ a b Field 1998.

- ^ Bruun (2008), p. 49-52.

- ^ Vyse 2020b.

- ^ Vyse, Stuart (2020-01-23). Superstition: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-255131-3.

- ^ deGroot 1892, p. III, 941–42.

- ^ Allan 1991, p. 31-32.

- ^ Werner 1922, p. 84.

- ^ Swetz 2002, pp. 31, 58.

- ^ Puro 2002, p. 108–112.

- ^ Swetz 2002, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Porter 1996, p. 35-38.

- ^ a b Sun Xiaochun 1997, p. 15-18.

- ^ Wang 2000, pp. 107–128.

- ^ Nelson et al. 2006.

- ^ Cheung Ngam Fung 2007.

- ^ Sang 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Moran et al. 2002.

- ^ Cheng et al. 1998, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Johnson 1997.

- ^ a b Vierra 1997.

- ^ Whang 2006.

- ^ Chen Bixia 2008.

- ^ a b Marafa 2003.

- ^ Chen Qigao 1997.

- ^ Siu‐Yiu Lau at al. 2005.

- ^ Zhuang 1997.

- ^ Chen & Nakama 2004.

- ^ Xu Jun 2003.

- ^ Lu Hui-Chen 2002.

- ^ Park et al. 1996.

- ^ Xu Ping 1998.

- ^ Hwangbo 2002.

- ^ Lu et al. 2000.

- ^ Lai 1974.

- ^ Xu Ping 1997.

- ^ Emmons 1992, p. 48.

- ^ Zhang 2020.

- ^ Tsang 2013.

- ^ NYTimes 2005.

- ^ Asiaone 2009.

- ^ Ricci 1617, p. 103-104.

- ^ Gallagher 1953, Book I, ch. 9, pp. 84–85.

- ^ March 1968.

- ^ Cody 1996.

- ^ Chang Liang 2005.

- ^ Moore 2010.

- ^ BBC News 2001.

- ^ «司马南与巨天中在齐鲁台关于风水辩论的思考» [Thoughts on Feng Shui Debate between Sima Nan and Ju Tianzhong in Qilutai]. 2006-07-06. Archived from the original on 2008-02-15.

- ^ Fudan 2012.

- ^ Jiang Xun 2006.

- ^ Carroll/Feng Shui.

- ^ Skinner 2008.

- ^ Nguyen 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Lang 2011, p. 102.

- ^ NASA 2003.

- ^ Penn & Teller 2003.

- ^ Mah 2004.

- ^ Montenegro 2003.

- ^ NYTimes 2013.

- ^ Emmons 1992, p. 42.

- ^ Emmons 1992, p. 46.

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Allan, Sarah (1991). Shape of the Turtle, The: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9449-3.

- Bruun, Ole (2003). Fengshui in China: Geomantic Divination Between State Orthodoxy and Popular Religion. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. ISBN 9780824826727.

- Bruun, Ole (2008). An Introduction to Feng Shui. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521863520.

- Campbell, Wallace H. (7 February 2001). Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour through Magnetic Fields. Elsevier. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-08-050490-2.

Written records show that a Chinese compass, Si Nan, had already been fabricated between 300 and 200 BE and used for the alignment of constructions to be magically harmonious with the natural Earth forces.

- Cheng, Jian Jun; Fernandes-Gonçalves, Adriana (1998). Chinese Feng Shui Compass: Step by Step Guide.

- de Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1892). The Religious System of China. E.J. Brill., various years, vol I-II-III-IV-V-VI

- Guo Pu. «The Zangshu, or Book of Burial«. Professor Field’s Fengshui Gate. Translated by Field, Stephen L. Archived from the original on 2020-05-21..

- Lang, Kenneth R. (2011). The Cambridge Guide to the Solar System (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49417-5.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (June 2006). The Construction of Space in Early China. Suny Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6608-7.

- Liu, Li (2004). The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81184-2.

- Lu, Hui-Chen (2002). A Comparative analysis between western-based environmental design and feng-shui for housing sites. OCLC 49999768.

- Magli, Giulio (2020). Sacred Landscapes of Imperial China: Astronomy, Feng Shui, and the Mandate of Heaven. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-49324-0.

- Michael R. Matthews (2019). Feng Shui: Teaching About Science and Pseudoscience. Cham: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18822-1. ISBN 978-3-030-18822-1. Wikidata Q116742539.

- Moran, Elizabeth; Joseph Yu; Val Biktashev (2002). The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Feng Shui. Pearson Education. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Nguyen, Phil N. (2008). Feng Shui for the Curious and Serious. Vol. 1. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4691-1882-6.

- Paton, Michael John (2013). Five Classics of Fengshui: Chinese Spiritual Geography in Historical and Environmental Perspective. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24986-8.. Includes translations of Archetypal burial classic of Qing Wu; The inner chapter of the Book of burial rooted in antiquity ; The yellow emperor’s classic of house siting; Twenty four difficult problems; The secretly passed down water dragon classic.

- Porter, Deborah Lynn (January 1996). From Deluge to Discourse: Myth, History, and the Generation of Chinese Fiction. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3033-0.

- Puro, Jon (2002). «Feng Shui». In Shermer, Michael (ed.). The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-653-8.

- Ricci, Matteo; Nicolas Trigault (1953). China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci, 1583-1610. Translated by Louis Joseph Gallagher. Random House., length=616 pages ## 71

- Matteo Ricci (1617). Nicolas Trigault (ed.). De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas. Gualterus.

- Sang, Larry (2004). Feng Shui Facts and Myths. Translated by Sylvia Lam. American Feng Shui Institute (www.amfengshui.com). p. 75. ISBN 978-0-9644583-4-5., length=150 pages

- Skinner, Stephen (2008). Guide to the Feng Shui Compass: A Compendium of Classical Feng Shui. Golden Hoard. ISBN 978-0-9547639-9-2.

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997). The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. BRILL. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3.

- Sun, Xiaochun (2000). «Crossing the Boundaries Between Heaven and Man: Astronomy in Ancient China». Astronomy Across Cultures. Science Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Science. Vol. 1. pp. 423–454. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4179-6_15. ISBN 978-94-010-5820-9.

- Swetz, Frank J. (2002). The Legacy of the Luoshu: the 4,000 year search for the meaning of the magic square of order three. ISBN 978-0-8126-9448-2.