|

|

| Other names | The American flag,

|

|---|---|

| Use | National flag and ensign |

| Proportion | 10:19 |

| Adopted |

|

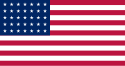

| Design | Thirteen horizontal stripes alternating red and white; in the canton, 50 white stars of alternating numbers of six and five per horizontal row on a blue field |

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the American flag or the U.S. flag, consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the canton (referred to specifically as the «union») bearing fifty small, white, five-pointed stars arranged in nine offset horizontal rows, where rows of six stars (top and bottom) alternate with rows of five stars. The 50 stars on the flag represent the 50 U.S. states, and the 13 stripes represent the thirteen British colonies that declared independence from Great Britain, and became the first states in the U.S.[1] Nicknames for the flag include the Stars and Stripes,[2][3] Old Glory,[4] and the Star-Spangled Banner.

History

The current design of the U.S. flag is its 27th; the design of the flag has been modified officially 26 times since 1777. The 48-star flag was in effect for 47 years until the 49-star version became official on July 4, 1959. The 50-star flag was ordered by then president Eisenhower on August 21, 1959, and was adopted in July 1960. It is the longest-used version of the U.S. flag and has been in use for over 62 years.[5]

First flag

The first flag resembling the modern stars and stripes was an unofficial flag sometimes called the «Grand Union Flag», or «the Continental Colors.» It consisted of 13 red-and-white stripes, with the British Jack in the upper left-hand-corner. It first appeared on December 3, 1775, when Continental Navy Lieutenant John Paul Jones flew it aboard Captain Esek Hopkin’s flagship Alfred in the Delaware River.[citation needed] It remained the national flag until June 14, 1777.[6] At the time of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the Continental Congress would not legally adopt flags with «stars, white in a blue field» for another year. The «Grand Union Flag» has historically been referred to as the first national flag of the United States. [7]

The Continental Navy raised the Colors as the ensign of the fledgling nation in the American War for Independence – likely with the expedient of transforming their previous British red ensign by adding white stripes.[7][8] The name «Grand Union» was first applied to the Continental Colors by George Henry Preble in his 1872 book known as History of the American Flag.[8]

The flag closely resembles the flag of the British East India Company during that era, and Sir Charles Fawcett argued in 1937 that the company flag inspired the design of the U.S. flag.[9] Both flags could have been easily constructed by adding white stripes to a British Red Ensign, one of the three maritime flags used throughout the British Empire at the time. However, an East India Company flag could have from nine to 13 stripes and was not allowed to be flown outside the Indian Ocean.[10] Benjamin Franklin once gave a speech endorsing the adoption of the company’s flag by the United States as their national flag. He said to George Washington, «While the field of your flag must be new in the details of its design, it need not be entirely new in its elements. There is already in use a flag, I refer to the flag of the East India Company.»[11] This was a way of symbolizing American loyalty to the Crown as well as the United States’ aspirations to be self-governing, as was the East India Company. Some colonists also felt that the company could be a powerful ally in the American War of Independence, as they shared similar aims and grievances against the British government’s tax policies. Colonists, therefore, flew the company’s flag to endorse the company.[12]

However, the theory that the Grand Union Flag was a direct descendant of the flag of the East India Company has been criticized as lacking written evidence.[13] On the other hand, the resemblance is obvious, and some of the Founding Fathers of the United States were aware of the East India Company’s activities and of their free administration of India under Company rule.[13]

Flag Resolution of 1777

On June 14, 1777, the Second Continental Congress passed the Flag Resolution which stated: «Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.»[14] Flag Day is now observed on June 14 of each year. While scholars still argue about this, tradition holds that the new flag was first hoisted in June 1777 by the Continental Army at the Middlebrook encampment.[15]

Both the stripes (barry) and the stars (mullets) have precedents in classical heraldry. Mullets were comparatively rare in early modern heraldry. However, an example of mullets representing territorial divisions predating the U.S. flag is the Valais 1618 coat of arms, where seven mullets stood for seven districts.

Another widely repeated theory is that the design was inspired by the coat of arms of George Washington’s family, which includes three red stars over two horizontal red bars on a white field.[16] Despite the similar visual elements, there is «little evidence»[17] or «no evidence whatsoever»[18] to support the claimed connection with the flag design. The Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington, published by the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon, calls it an «enduring myth» backed by «no discernible evidence.»[19] The story seems to have originated with the 1876 play Washington: A Drama in Five Acts, by the English poet Martin Farquhar Tupper, and was further popularized through repetition in the children’s magazine St. Nicholas.[17][18]

The first official U.S. flag flown during battle was on August 3, 1777, at Fort Schuyler (Fort Stanwix) during the Siege of Fort Stanwix. Massachusetts reinforcements brought news of the adoption by Congress of the official flag to Fort Schuyler. Soldiers cut up their shirts to make the white stripes; scarlet material to form the red was secured from red flannel petticoats of officers’ wives, while material for the blue union was secured from Capt. Abraham Swartwout’s blue cloth coat. A voucher is extant that Congress paid Capt. Swartwout of Dutchess County for his coat for the flag.[20]

The 1777 resolution was probably meant to define a naval ensign. In the late 18th century, the notion of a national flag did not yet exist or was only nascent. The flag resolution appears between other resolutions from the Marine Committee. On May 10, 1779, Secretary of the Board of War Richard Peters expressed concern that «it is not yet settled what is the Standard of the United States.»[21] However, the term «Standard» referred to a national standard for the Army of the United States. Each regiment was to carry the national standard in addition to its regimental standard. The national standard was not a reference to the national or naval flag.[22]

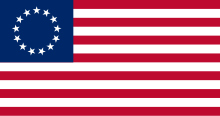

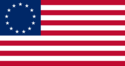

The Flag Resolution did not specify any particular arrangement, number of points, nor orientation for the stars and the arrangement or whether the flag had to have seven red stripes and six white ones or vice versa.[23] The appearance was up to the maker of the flag. Some flag makers arranged the stars into one big star, in a circle or in rows and some replaced a state’s star with its initial.[24] One arrangement features 13 five-pointed stars arranged in a circle, with the stars arranged pointing outwards from the circle (as opposed to up), the Betsy Ross flag. Experts have dated the earliest known example of this flag to be 1792 in a painting by John Trumbull.[25]

Despite the 1777 resolution, the early years of American independence featured many different flags. Most were individually crafted rather than mass-produced. While there are many examples of 13-star arrangements, some of those flags included blue stripes[26] as well as red and white. Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, in an October 3, 1778 letter to Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies, described the American flag as consisting of «13 stripes, alternately red, white, and blue, a small square in the upper angle, next to the flagstaff, is a blue field, with 13 white stars, denoting a new Constellation.»[27] John Paul Jones used a variety of 13-star flags on his U.S. Navy ships including the well-documented 1779 flags of the Serapis and the Alliance. The Serapis flag had three rows of eight-pointed stars with red, white, and blue stripes. However, the flag for the Alliance had five rows of eight-pointed stars with 13 red and white stripes, and the white stripes were on the outer edges.[28] Both flags were documented by the Dutch government in October 1779, making them two of the earliest known flags of 13 stars.[29]

Designer of the first stars and stripes

Francis Hopkinson’s flag for the United States, an interpretation, with 13 six-pointed stars arranged in five rows[30]

Francis Hopkinson’s flag for the U.S. Navy, an interpretation, with 13 six-pointed stars arranged in five rows[31]

Francis Hopkinson of New Jersey, a naval flag designer and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, designed a flag in 1777[32] while he was the chairman of the Continental Navy Board’s Middle Department, sometime between his appointment to that position in November 1776 and the time that the flag resolution was adopted in June 1777. The Navy Board was under the Continental Marine Committee.[33] Not only did Hopkinson claim that he designed the U.S. flag, but he also claimed that he designed a flag for the U.S. Navy. Hopkinson was the only person to have made such a claim during his own life when he sent a letter and several bills to Congress for his work. These claims are documented in the Journals of the Continental Congress and George Hasting’s biography of Hopkinson. Hopkinson initially wrote a letter to Congress, via the Continental Board of Admiralty, on May 25, 1780.[34] In this letter, he asked for a «Quarter Cask of the Public Wine» as payment for designing the U.S. flag, the seal for the Admiralty Board, the seal for the Treasury Board, Continental currency, the Great Seal of the United States, and other devices. However, in three subsequent bills to Congress, Hopkinson asked to be paid in cash, but he did not list his U.S. flag design. Instead, he asked to be paid for designing the «great Naval Flag of the United States» in the first bill; the «Naval Flag of the United States» in the second bill; and «the Naval Flag of the States» in the third, along with the other items. The flag references were generic terms for the naval ensign that Hopkinson had designed: a flag of seven red stripes and six white ones. The predominance of red stripes made the naval flag more visible against the sky on a ship at sea. By contrast, Hopkinson’s flag for the United States had seven white stripes and six red ones – in reality, six red stripes laid on a white background.[35] Hopkinson’s sketches have not been found, but we can make these conclusions because Hopkinson incorporated different stripe arrangements in the Admiralty (naval) Seal that he designed in the Spring of 1780 and the Great Seal of the United States that he proposed at the same time. His Admiralty Seal had seven red stripes;[36] whereas his second U.S. Seal proposal had seven white ones.[37] Remnants of Hopkinson’s U.S. flag of seven white stripes can be found in the Great Seal of the United States and the President’s seal.[35] When Hopkinson was chairman of the Navy Board, his position was like that of today’s Secretary of the Navy.[38] The payment was not made, most likely, because other people had contributed to designing the Great Seal of the United States,[39] and because it was determined he already received a salary as a member of Congress.[40][41] This contradicts the legend of the Betsy Ross flag, which suggests that she sewed the first Stars and Stripes flag at the request of the government in the Spring of 1776.[42][43]

On 10 May 1779, a letter from the War Board to George Washington stated that there was still no design established for a national standard, on which to base regimental standards, but also referenced flag requirements given to the board by General von Steuben.[44] On 3 September, Richard Peters submitted to Washington «Drafts of a Standard» and asked for his «Ideas of the Plan of the Standard,» adding that the War Board preferred a design they viewed as «a variant for the Marine Flag.» Washington agreed that he preferred «the standard, with the Union and Emblems in the center.»[44] The drafts are lost to history but are likely to be similar to the first Jack of the United States.[44]

The origin of the stars and stripes design has been muddled by a story disseminated by the descendants of Betsy Ross. The apocryphal story credits Betsy Ross for sewing one of the first flags from a pencil sketch handed to her by George Washington. No such evidence exists either in George Washington’s diaries or the Continental Congress’s records. Indeed, nearly a century passed before Ross’s grandson, William Canby, first publicly suggested the story in 1870.[45] By her family’s own admission, Ross ran an upholstery business, and she had never made a flag as of the supposed visit in June 1776.[46] Furthermore, her grandson admitted that his own search through the Journals of Congress and other official records failed to find corroborating evidence for his grandmother’s story.[47]

George Henry Preble states in his 1882 text that no combined stars and stripes flag was in common use prior to June 1777,[48] and that no one knows who designed the 1777 flag.[49] Historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich argues that there was no «first flag» worth arguing over.[50] Researchers accept that the United States flag evolved, and did not have one design. Marla Miller writes, «The flag, like the Revolution it represents, was the work of many hands.»[51]

The family of Rebecca Young claimed that she sewed the first flag.[52] Young’s daughter was Mary Pickersgill, who made the Star-Spangled Banner Flag.[53][54] She was assisted by Grace Wisher, a 13-year-old African American girl.[55]

Later flag acts

The 48-star flag was in use from 1912 to 1959, the second longest-used U.S. flag. The current U.S. flag is the longest-used flag, having surpassed the 1912 version in 2007.

Oil painting depicting the 39 historical U.S. flags.

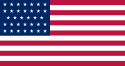

In 1795, the number of stars and stripes was increased from 13 to 15 (to reflect the entry of Vermont and Kentucky as states of the Union). For a time the flag was not changed when subsequent states were admitted, probably because it was thought that this would cause too much clutter. It was the 15-star, 15-stripe flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write «Defence of Fort M’Henry», later known as «The Star-Spangled Banner», which is now the American national anthem. The flag is currently on display in the exhibition «The Star-Spangled Banner: The Flag That Inspired the National Anthem» at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History in a two-story display chamber that protects the flag while it is on view.[56]

On April 4, 1818, a plan was passed by Congress at the suggestion of U.S. Naval Captain Samuel C. Reid[57] in which the flag was changed to have 20 stars, with a new star to be added when each new state was admitted, but the number of stripes would be reduced to 13 so as to honor the original colonies. The act specified that new flag designs should become official on the first July 4 (Independence Day) following the admission of one or more new states.[58]

In 1912, the 48-star flag was adopted. This was the first time that a flag act specified an official arrangement of the stars in the canton, namely six rows of eight stars each, where each star would point upward.[58] The U.S. Army and U.S. Navy, however, has already been using standardized designs. Throughout the 19th century, different star patterns, both rectangular and circular, had been abundant in civilian use.[citation needed]

In 1960, the current 50-star flag was adopted, incorporating the most recent change, from 49 stars to 50, when the present design was chosen, after Hawaii gained statehood in August 1959. Before that, the admission of Alaska in January 1959 had prompted the debut of a short-lived 49-star flag.[58]

49- and 50-star unions

A U.S. flag with gold fringe and a gold eagle on top of the flag pole

When Alaska and Hawaii were being considered for statehood in the 1950s, more than 1,500 designs were submitted to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Although some were 49-star versions, the vast majority were 50-star proposals. At least three of these designs were identical to the present design of the 50-star flag.[59] At the time, credit was given by the executive department to the United States Army Institute of Heraldry for the design. The 49- and 50-star flags were each flown for the first time at Fort McHenry on Independence Day, in 1959 and 1960 respectively.[60]

On July 4, 2007, the 50-star flag became the version of the flag in the longest use, surpassing the 48-star flag that was used from 1912 to 1959.[citation needed]

«Flower Flag» arrives in Asia

The U.S. flag was brought to the city of Canton (Guǎngzhōu) in China in 1784 by the merchant ship Empress of China, which carried a cargo of ginseng.[61] There it gained the designation «Flower Flag» (Chinese: 花旗; pinyin: huāqí; Cantonese Yale: fākeì).[62] According to a pseudonymous account first published in the Boston Courier and later retold by author and U.S. naval officer George H. Preble:

When the thirteen stripes and stars first appeared at Canton, much curiosity was excited among the people. News was circulated that a strange ship had arrived from the further end of the world, bearing a flag «as beautiful as a flower». Every body went to see the kwa kee chuen [花旗船; Fākeìsyùhn], or «flower flagship». This name at once established itself in the language, and America is now called the kwa kee kwoh [花旗國; Fākeìgwok], the «flower flag country»—and an American, kwa kee kwoh yin [花旗國人; Fākeìgwokyàhn]—»flower flag countryman»—a more complimentary designation than that of «red headed barbarian»—the name first bestowed upon the Dutch.[63][64]

In the above quote, the Chinese words are written phonetically based on spoken Cantonese. The names given were common usage in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[65]

Chinese now refer to the United States as Měiguó from Mandarin (simplified Chinese: 美国; traditional Chinese: 美國). Měi is short for Měilìjiān (simplified Chinese: 美利坚; traditional Chinese: 美利堅, phono-semantic matching of «American») and «guó» means «country», so this name is unrelated to the flag. However, the «flower flag» terminology persists in some places today: for example, American ginseng is called flower flag ginseng (simplified Chinese: 花旗参; traditional Chinese: 花旗參) in Chinese, and Citibank, which opened a branch in China in 1902, is known as Flower Flag Bank (花旗银行).[65]

Similarly, Vietnamese also uses the borrowed term from Chinese with Sino-Vietnamese reading for the United States, as Hoa Kỳ from 花旗 («Flower Flag»). The United States is also called nước Mỹ in Vietnamese before the name Měiguó was popular amongst Chinese.[citation needed]

Additionally, the seal of Shanghai Municipal Council in Shanghai International Settlement from 1869 included the U.S. flag as part of the top left-hand shield near the flag of the U.K., as the U.S. participated in the creation of this enclave in the Chinese city of Shanghai. It is also included in the badge of the Kulangsu Municipal Police in the International Settlement of Kulangsu, Amoy.[66]

President Richard Nixon presented a U.S. flag and moon rocks to Mao Zedong during his visit to China in 1972. They are now on display at the National Museum of China.[citation needed]

The U.S. flag took its first trip around the world in 1787–90 on board the Columbia.[62] William Driver, who coined the phrase «Old Glory», took the U.S. flag around the world in 1831–32.[62] The flag attracted the notice of the Japanese when an oversized version was carried to Yokohama by the steamer Great Republic as part of a round-the-world journey in 1871.[67]

Civil War and the flag

Prior to the Civil War, the American flag was rarely seen outside of military forts, government buildings and ships. During the American War of Independence and War of 1812 the army was not even officially sanctioned to carry the United States flag into battle. It was not until 1834 that the artillery was allowed to carry the American flag; the army would be granted to do the same in 1841. However, in 1847, in the middle of the war with Mexico, the flag was limited to camp use and not allowed to be brought into battle.[68]

This changed following the shots at Fort Sumter in 1861. The flag flying over the fort was allowed to leave with the Union troops as they surrendered. It was taken across northern cities, which spurred a wave of «Flagmania». The stars and stripes, which had no real place in the public conscious, suddenly became a part of the national identity. The flag became a symbol of the Union, and the sale of flags exploded at this time. In a reversal, the 1847 army regulations would be dropped, and the flag was allowed to be carried into battle. Some wanted to remove the stars of the states which had seceded but Abraham Lincoln was opposed, believing it would give legitimacy to the Confederate states.[69]

Historical progression of designs

In the following table depicting the 28 various designs of the United States flag, the star patterns for the flags are merely the usual patterns, often associated with the United States Navy. Canton designs, prior to the proclamation of the 48-star flag, had no official arrangement of the stars. Furthermore, the exact colors of the flag were not standardized until 1934.[70][71]

| Number of stars |

Number of stripes |

Design(s) | States represented by new stars |

Dates in use | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 13 |  |

King’s Colours instead of stars, red and white stripes represent Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia | December 3, 1775[72] – June 14, 1777 | 1+1⁄2 years |

| 13 | 13 | Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia | June 14, 1777 – May 1, 1795 | 18 years | |

| 15 | 15 |  |

Vermont, Kentucky | May 1, 1795 – July 3, 1818 | 23 years |

| 20 | 13 | Tennessee, Ohio, Louisiana, Indiana, Mississippi | July 4, 1818 – July 3, 1819 | 1 year | |

| 21 | 13 | Illinois | July 4, 1819 – July 3, 1820 | 1 year | |

| 23 | 13 | Alabama, Maine | July 4, 1820 – July 3, 1822 | 2 years | |

| 24 | 13 | Missouri | July 4, 1822 – July 3, 1836 1831 term «Old Glory» coined |

14 years | |

| 25 | 13 |

|

Arkansas | July 4, 1836 – July 3, 1837 | 1 year |

| 26 | 13 | Michigan | July 4, 1837 – July 3, 1845 | 8 years | |

| 27 | 13 | Florida | July 4, 1845 – July 3, 1846 | 1 year | |

| 28 | 13 | Texas | July 4, 1846 – July 3, 1847 | 1 year | |

| 29 | 13 | Iowa | July 4, 1847 – July 3, 1848 | 1 year | |

| 30 | 13 | Wisconsin | July 4, 1848 – July 3, 1851 | 3 years | |

| 31 | 13 | California | July 4, 1851 – July 3, 1858 | 7 years | |

| 32 | 13 | Minnesota | July 4, 1858 – July 3, 1859 | 1 year | |

| 33 | 13 | Oregon | July 4, 1859 – July 3, 1861 | 2 years | |

| 34 | 13 | Kansas | July 4, 1861 – July 3, 1863 | 2 years | |

| 35 | 13 | West Virginia | July 4, 1863 – July 3, 1865 | 2 years | |

| 36 | 13 | Nevada | July 4, 1865 – July 3, 1867 | 2 years | |

| 37 | 13 | Nebraska | July 4, 1867 – July 3, 1877 | 10 years | |

| 38 | 13 | Colorado | July 4, 1877 – July 3, 1890 | 13 years | |

| 43 | 13 | North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho | July 4, 1890 – July 3, 1891 | 1 year | |

| 44 | 13 | Wyoming | July 4, 1891 – July 3, 1896 | 5 years | |

| 45 | 13 | Utah | July 4, 1896 – July 3, 1908 | 12 years | |

| 46 | 13 | Oklahoma | July 4, 1908 – July 3, 1912 | 4 years | |

| 48 | 13 | New Mexico,[73] Arizona | July 4, 1912 – July 3, 1959 | 47 years | |

| 49 | 13 | Alaska | July 4, 1959 – July 3, 1960 | 1 year | |

| 50 | 13 | Hawaii | July 4, 1960 – present | 62 years |

Symbolism

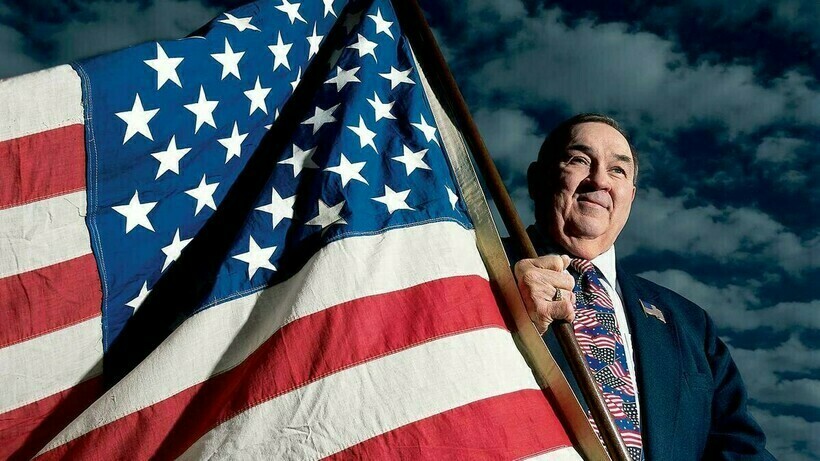

The flag of the United States is the nation’s most widely recognized symbol.[74] Within the United States, flags are frequently displayed not only on public buildings but on private residences. The flag is a common motif on decals for car windows, and on clothing ornamentation such as badges and lapel pins. Owing to the United States’s emergence as a superpower in the 20th century, the flag is among the most widely recognized symbols in the world, and is used to represent the United States.[75]

The flag has become a powerful symbol of Americanism, and is flown on many occasions, with giant outdoor flags used by retail outlets to draw customers. Reverence for the flag has at times reached religion-like fervor: in 1919 William Norman Guthrie’s book The Religion of Old Glory discussed «the cult of the flag»[76]

and formally proposed vexillolatry.[77]

Despite a number of attempts to ban the practice, desecration of the flag remains protected as free speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Scholars have noted the irony that «[t]he flag is so revered because it represents the land of the free, and that freedom includes the ability to use or abuse that flag in protest».[78] Comparing practice worldwide, Testi noted in 2010 that the United States was not unique in adoring its banner, for the flags of Scandinavian countries are also «beloved, domesticated, commercialized and sacralized objects».[79]

This nationalist attitude around the flag is a shift from earlier sentiments; the U.S. flag was largely a «military ensign or a convenient marking of American territory» that rarely appeared outside of forts, embassies, and the like until the opening of the American Civil War in April 1861, when Major Robert Anderson was forced to surrender Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor to Confederates. Anderson was celebrated in the North as a hero[80] and U.S. citizens throughout Northern states co-opted the national flag to symbolize U.S. nationalism and rejection of secessionism. Historian Adam Goodheart wrote:

For the first time American flags were mass-produced rather than individually stitched and even so, manufacturers could not keep up with demand. As the long winter of 1861 turned into spring, that old flag meant something new. The abstraction of the Union cause was transfigured into a physical thing: strips of cloth that millions of people would fight for, and many thousands die for.[81]

Color symbolism

When the flag was officially adopted in 1777, the colors of red, white and blue were not given an official meaning. However, when Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress, presented a proposed U.S. seal in 1782, he explained its center section in this way: «The colours of the pales are those used in the flag of the United States of America; White signifies purity and innocence, Red, hardiness & valor, and Blue, the colour of the Chief signifies vigilance, perseverance & justice.» These meanings have broadly been accepted as official, with some variation. In 1986, president Ronald Reagan gave his own interpretation, saying, «The colors of our flag signify the qualities of the human spirit we Americans cherish. Red for courage and readiness to sacrifice; white for pure intentions and high ideals; and blue for vigilance and justice.»[82]

Design

Specifications

The basic design of the current flag is specified by 4 U.S.C. § 1 (1947): “The flag of the United States shall be thirteen horizontal stripes, alternate red and white; and the union of the flag shall be forty-eight stars, white in a blue field.” 4 U.S.C. § 2 outlines the addition of new stars to represent new states, with no distinction made for the shape, size, or arrangement of the stars. Executive Order 10834 (1959) specifies a 50-star design for use after Hawaii was added as a state, and Federal Specification DDD-F-416F (2005) provides additional details about the production of physical flags for use by federal agencies.[83]

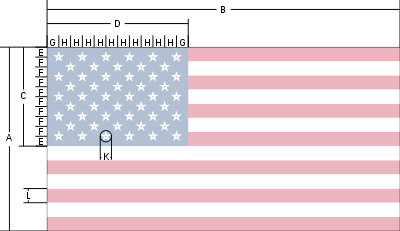

- Hoist (height) of the flag: A = 1.0

- Fly (width) of the flag: B = 1.9[84]

- Hoist (height) of the canton («union»): C = 0.5385 (A × 7/13, spanning seven stripes)

- Fly (width) of the canton: D = 0.76 (B × 2/5, two-fifths of the flag width)

- E = F = 0.0538 (C/10, one-tenth of the height of the canton)

- G = H = 0.0633 (D/12, one twelfth of the width of the canton)

- Diameter of star: K = 0.0616 (approximately L × 4/5, four-fifths of the stripe width)

- Width of stripe: L = 0.0769 (A/13, one thirteenth of the flag height)

Strictly speaking, the executive order establishing these specifications governs only flags made for or by the federal government.[85] In practice, most U.S. national flags available for sale to the public follow the federal star arrangement, but have a different width-to-height ratio; common sizes are 2 × 3 ft. or 4 × 6 ft. (flag ratio 1.5), 2.5 × 4 ft. or 5 × 8 ft. (1.6), or 3 × 5 ft. or 6 × 10 ft. (1.667). Even flags flown over the U.S. Capitol for sale to the public through Representatives or Senators are provided in these sizes.[86] Flags that are made to the prescribed 1.9 ratio are often referred to as «G-spec» (for «government specification») flags.

Colors

Federal Specification DDD-F-416F specifies the exact red, white, and blue colors to be used for physical flags procured by federal agencies with reference to the Standard Color Reference of America, 10th edition, a set of dyed silk fabric samples produced by The Color Association of the United States. The colors are «White», No. 70001; «Old Glory Red», No. 70180; and «Old Glory Blue», No. 70075.

CIE coordinates for the colors of the 9th edition of the Standard Color Reference were carefully measured and cross-checked by color scientists from the National Bureau of Standards in 1946, with the resulting coordinates adopted as a formal specification.[87] These colors form the standard for cloth, and there is no perfect way to convert them to RGB for display on screen or CMYK for printing. The «relative» coordinates in the following table were found by scaling the luminous reflectance relative to the flag’s white.

| Name | Absolute | Relative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIELAB D65 | Munsell | sRGB | GRACoL 2006 | ||||||||||||

| L* | a* | b* | H | V/C | R | G | B | 8-bit hex | C | M | Y | K | |||

| White | 88.7 | −0.2 | 5.4 | 2.5Y | 8.8/0.7 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | #FFFFFF

|

.000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| Old Glory Red | 33.9 | 51.2 | 24.7 | 5.5R | 3.3/11.1 | .698 | .132 | .203 | #B22234

|

.196 | 1.000 | .757 | .118 | ||

| Old Glory Blue | 23.2 | 13.1 | −26.4 | 8.2PB | 2.3/6.1 | .234 | .233 | .430 | #3C3B6E

|

.886 | .851 | .243 | .122 |

As with the design, the official colors are only officially required for flags produced for the U.S. federal government, and other colors are often used for mass-market flags, printed reproductions, and other products intended to evoke flag colors. The practice of using more saturated colors than the official cloth is not new. As Taylor, Knoche, and Granville wrote in 1950: «The color of the official wool bunting [of the blue field] is a very dark blue, but printed reproductions of the flag, as well as merchandise supposed to match the flag, present the color as a deep blue much brighter than the official wool.»[89]

Sometimes, Pantone Matching System (PMS) alternatives to the dyed fabric colors are recommended by US government agencies for use in websites or printed documents. One set was given on the website of the U.S. embassy in London as early as 1996; the website of the U.S. embassy in Stockholm claimed in 2001 that those had been suggested by Pantone, and that the U.S. Government Printing Office preferred a different set. A third red was suggested by a California Military Department document in 2002.[90] In 2001, the Texas legislature specified that the colors of the Texas flag should be «(1) the same colors used in the United States flag; and (2) defined as numbers 193 (red) and 281 (dark blue) of the Pantone Matching System.»[91] The current internal style guide of the State Department Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs specifies PMS 282C blue and PMS 193C red, and gives RGB and CMYK conversions generated by Adobe InDesign.[92]

| Pantone Identifier | RGB | CMYK | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | G | B | 8-bit hex | C | M | Y | K | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | #FFFFFF

|

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| PMS 193C | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.26 | #B31942

|

0.00 | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.13 | |

| PMS 282C | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.38 | #0A3161

|

1.00 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

Decoration

Traditionally, the flag may be decorated with golden fringe surrounding the perimeter of the flag as long as it does not deface the flag proper. Ceremonial displays of the flag, such as those in parades or on indoor posts, often use fringe to enhance the flag’s appearance. Traditionally, the Army and Air Force use a fringed flag for parades, color guard and indoor display, while the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard use a fringeless flag for all occasions.[citation needed]

The first recorded use of fringe on a flag dates from 1835, and the Army used it officially in 1895. No specific law governs the legality of fringe. Still, a 1925 opinion of the attorney general addresses the use of fringe (and the number of stars) «… is at the discretion of the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy …» as quoted from a footnote in previous volumes of Title 4 of the United States Code law books. This opinion is a source for claims that a flag with fringe is a military ensign rather than a civilian. However, according to the Army Institute of Heraldry, which has official custody of the flag designs and makes any change ordered, there are no implications of symbolism in using fringe.[93]

Individuals associated with the sovereign citizen movement and tax protester conspiracy arguments have claimed, based on the military usage, that the presence of a fringed flag in a civilian courtroom changes the nature or jurisdiction of the court.[94][95] Federal and state courts have rejected this contention.[95][96][97]

Display and use

The flag is customarily flown year-round at most public buildings, and it is not unusual to find private houses flying full-size (3 by 5 feet (0.91 by 1.52 m)) flags. Some private use is year-round, but becomes widespread on civic holidays like Memorial Day, Veterans Day, Presidents’ Day, Flag Day, and on Independence Day. On Memorial Day, it is common to place small flags by war memorials and next to the graves of U.S. war veterans. Also, on Memorial Day, it is common to fly the flag at half staff until noon to remember those who lost their lives fighting in U.S. wars.

Flag etiquette

The proper stationary vertical display. The union (blue box of stars) should always be in the upper-left corner.

A proper and respectful manner of disposing of a damaged flag is a ceremonial burning (as seen here at Misawa Air Base)

The United States Flag Code outlines certain guidelines for the flag’s use, display, and disposal. For example, the flag should never be dipped to any person or thing, unless it is the ensign responding to a salute from a ship of a foreign nation. This tradition may come from the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, where countries were asked to dip their flag to King Edward VII: the American flag bearer did not. Team captain Martin Sheridan is famously quoted as saying, «this flag dips to no earthly king», though the true provenance of this quotation is unclear.[98][99]

The flag should never be allowed to touch the ground and should be illuminated if flown at night. The flag should be repaired or replaced if the edges become tattered through wear. When a flag is so tattered that it can no longer serve as a symbol of the United States, it should be destroyed in a dignified manner, preferably by burning. The American Legion and other organizations regularly conduct flag retirement ceremonies, often on Flag Day, June 14. (The Boy Scouts of America recommends that modern nylon or polyester flags be recycled instead of burned due to hazardous gases produced when such materials are burned.)[100]

The Flag Code prohibits using the flag «for any advertising purpose» and also states that the flag «should not be embroidered, printed, or otherwise impressed on such articles as cushions, handkerchiefs, napkins, boxes, or anything intended to be discarded after temporary use».[101] Both of these codes are generally ignored, almost always without comment.

Section 8, entitled «Respect For Flag», states in part: «The flag should never be used as wearing apparel, bedding, or drapery», and «No part of the flag should ever be used as a costume or athletic uniform». Section 3 of the Flag Code[102] defines «the flag» as anything «by which the average person seeing the same without deliberation may believe the same to represent the flag of the United States of America». An additional provision that is frequently violated at sporting events is part (c) «The flag should never be carried flat or horizontally, but always aloft and free.»[103]

Although the Flag Code is U.S. federal law, there is no penalty for a private citizen or group failing to comply with the Flag Code, and it is not widely enforced—indeed, punitive enforcement would conflict with the First Amendment right to freedom of speech.[104] Passage of the proposed Flag Desecration Amendment would overrule the legal precedent that has been established.

Display on vehicles

Truck with backward flag sticker

When the flag is affixed to the right side of a vehicle of any kind (e.g., cars, boats, planes, any physical object that moves), it should be oriented so that the canton is towards the front of the vehicle, as if the flag were streaming backward from its hoist as the vehicle moves forward. Therefore, U.S. flag decals on the right sides of vehicles may appear to be reversed, with the union to the observer’s right instead of left as more commonly seen.[citation needed]

The flag has been displayed on every U.S. spacecraft designed for crewed flight starting from John Glenn’s Friendship-7 flight in 1962, including Mercury, Gemini, Apollo Command/Service Module, Apollo Lunar Module, and the Space Shuttle.[105] The flag also appeared on the S-IC first stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle used for Apollo. Nevertheless, Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo were launched and landed vertically and could not horizontal atmospheric flight as the Space Shuttle did on its landing approach, so the streaming convention was not followed. These flags were oriented with the stripes running horizontally, perpendicular to the direction of flight.

Display on uniforms

On some U.S. military uniforms, flag patches are worn on the right shoulder, following the vehicle convention with the union toward the front. This rule dates back to the Army’s early history when mounted cavalry and infantry units would designate a standard-bearer who carried the Colors into battle. As he charged, his forward motion caused the flag to stream back. Since the Stars and Stripes are mounted with the canton closest to the pole, that section stayed to the right, while the stripes flew to the left.[106] Several U.S. military uniforms, such as flight suits worn by members of the United States Air Force and Navy, have the flag patch on the left shoulder.[107][108]

Other organizations that wear flag patches on their uniforms can have the flag facing in either direction. The congressional charter of the Boy Scouts of America stipulates that Boy Scout uniforms should not imitate U.S. military uniforms; consequently, the flags are displayed on the right shoulder with the stripes facing front, the reverse of the military style.[109] Law enforcement officers often wear a small flag patch, either on a shoulder or above a shirt pocket.

Every U.S. astronaut since the crew of Gemini 4 has worn the flag on the left shoulder of his or her space suit, except for the crew of Apollo 1, whose flags were worn on the right shoulder. In this case, the canton was on the left.

-

A subdued-color flag patch, similar to the style worn on the United States Army’s ACU uniform. The patch is customarily worn reversed on the right upper sleeve.

-

Flag of the United States on American astronaut Neil Armstrong’s space suit

-

Patch with the union to the front, as seen on a Navy uniform.

Postage stamps

Flags depicted on U.S. postage stamp issues

The flag did not appear on U.S. postal stamp issues until the Battle of White Plains Issue was released in 1926, depicting the flag with a circle of 13 stars. The 48-star flag first appeared on the General Casimir Pulaski issue of 1931, though in a small monochrome depiction. The first U.S. postage stamp to feature the flag as the sole subject was issued July 4, 1957, Scott catalog number 1094.[110] Since then, the flag has frequently appeared on U.S. stamps.

Display in museums

In 1907 Eben Appleton, New York stockbroker and grandson of Lieutenant Colonel George Armistead (the commander of Fort McHenry during the 1814 bombardment), loaned the Star-Spangled Banner Flag to the Smithsonian Institution. In 1912 he converted the loan into a gift. Appleton donated the flag with the wish that it would always be on view to the public. In 1994, the National Museum of American History determined that the Star-Spangled Banner Flag required further conservation treatment to remain on public display. In 1998 teams of museum conservators, curators, and other specialists helped move the flag from its home in the Museum’s Flag Hall into a new conservation laboratory. Following the reopening of the National Museum of American History on November 21, 2008, the flag is now on display in a special exhibition, «The Star-Spangled Banner: The Flag That Inspired the National Anthem,» where it rests at a 10-degree angle in dim light for conservation purposes.[56]

Places of continuous display

U.S. flags are displayed continuously at certain locations by presidential proclamation, acts of Congress, and custom.

- Replicas of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag (15 stars, 15 stripes) are flown at two sites in Baltimore, Maryland: Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine[111] and Flag House Square.[112]

- Marine Corps War Memorial (Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima), Arlington, Virginia.[113]

- The Battle Green in Lexington, Massachusetts, site of the first shots fired in the Revolution[114]

- The White House, Washington, D.C.[115]

- Fifty U.S. flags are displayed continuously at the Washington Monument, Washington, D.C.[116]

- At continuously open U.S. Customs and Border Protection Ports of Entry.[117]

- A Civil War era flag (for the year 1863) flies above Pennsylvania Hall (Old Dorm) at Gettysburg College.[118] This building, occupied by both sides at various points of the Battle of Gettysburg, served as a lookout and battlefield hospital.

- Grounds of the National Memorial Arch in Valley Forge NHP, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania[119]

- By custom, at the Maryland home, birthplace, and grave of Francis Scott Key; at the Worcester, Massachusetts war memorial; at the plaza in Taos, New Mexico (since 1861); at the United States Capitol (since 1918); and at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, South Dakota.

- Newark Liberty International Airport’s Terminal A, Gate 17 and Boston Logan Airport’s Terminal B, Gate 32, and Terminal C, Gate 19 in memoriam of the events of September 11, 2001.[citation needed]

- Slover Mountain (Colton Liberty Flag), in Colton, California. July 4, 1917, to circa 1952 & 1997 to 2012.[120][121][122][123]

- At the ceremonial South Pole as one of the 12 flags representing the signatory countries of the original Antarctic Treaty.

- On the Moon: six crewed missions successfully landed at various locations and each had a flag raised at the site. Exhaust gases when the Ascent Stage launched to return the astronauts to their Command Module Columbia for return to Earth blew over the flag the Apollo 11 mission had placed.[124]

Particular days for display

The flag should especially be displayed at full staff on the following days:[125]

- January: 1 (New Year’s Day), third Monday of the month (Martin Luther King Jr. Day), and 20 (Inauguration Day, once every four years, which, by tradition, is postponed to the 21st if the 20th falls on a Sunday)

- February: 12 (Lincoln’s birthday) and the third Monday (legally known as Washington’s Birthday but more often called Presidents’ Day)

- March–April: Easter Sunday (date varies)

- May: Second Sunday (Mothers Day), third Saturday (Armed Forces Day), and last Monday (Memorial Day; half-staff until noon)

- June: 14 (Flag Day), third Sunday (Father’s Day)

- July: 4 (Independence Day)

- September: First Monday (Labor Day), 17 (Constitution Day), and last Sunday (Gold Star Mother’s Day)[126]

- October: Second Monday (Columbus Day) and 27 (Navy Day)

- November: 11 (Veterans Day) and fourth Thursday (Thanksgiving Day)

- December: 25 (Christmas Day)

- and such other days as may be proclaimed by the President of the United States; the birthdays of states (date of admission); and on state holidays.[127]

Display at half-staff

The flag is displayed at half-staff (half-mast in naval usage) as a sign of respect or mourning. Nationwide, this action is proclaimed by the president; statewide or territory-wide, the proclamation is made by the governor. In addition, there is no prohibition against municipal governments, private businesses, or citizens flying the flag at half-staff as a local sign of respect and mourning. However, many flag enthusiasts feel this type of practice has somewhat diminished the meaning of the original intent of lowering the flag to honor those who held high positions in federal or state offices. President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued the first proclamation on March 1, 1954, standardizing the dates and periods for flying the flag at half-staff from all federal buildings, grounds, and naval vessels; other congressional resolutions and presidential proclamations ensued. However, they are only guidelines to all other entities: typically followed at state and local government facilities and encouraged of private businesses and citizens.[citation needed]

To properly fly the flag at half-staff, one should first briefly hoist it top of the staff, then lower it to the half-staff position, halfway between the top and bottom of the staff. Similarly, when the flag is to be lowered from half-staff, it should be first briefly hoisted to the top of the staff.[128]

Federal statutes provide that the flag should be flown at half-staff on the following dates:

- May 15: Peace Officers Memorial Day (unless it is the third Saturday in May, Armed Forces Day, then full-staff)[129]

- Last Monday in May: Memorial Day (until noon)

- September 11: Patriot Day[130]

- First Sunday in October: Start of Fire Prevention Week, in honor of the National Fallen Firefighters Memorial Service.[131][132]

- December 7: National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day[133]

- For 30 days: Death of a president or former president

- For 10 days: Death of a vice president, Supreme Court chief justice/retired chief justice, or speaker of the House of Representatives.

- From death until the day of interment: Supreme Court associate justice, member of the Cabinet, former vice president, president pro tempore of the Senate, or the majority and minority leaders of the Senate and House of Representatives. Also, for federal facilities within a state or territory, for the governor.

- On the day after the death: Senators, members of Congress, territorial delegates, or the resident commissioner of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

Desecration

U.S. flag being burned in protest on the eve of the 2008 election

The flag of the United States is sometimes burned as a cultural or political statement, in protest of the policies of the U.S. government, or for other reasons, both within the U.S. and abroad. The United States Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989), and reaffirmed in U.S. v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990), has ruled that due to the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, it is unconstitutional for a government (whether federal, state, or municipal) to prohibit the desecration of a flag, due to its status as «symbolic speech.» However, content-neutral restrictions may still be imposed to regulate the time, place, and manner of such expression. If the flag that was burned was someone else’s property (as it was in the Johnson case, since Johnson had stolen the flag from a Texas bank’s flagpole), the offender could be charged with petty larceny (a flag usually sells at retail for less than US$20), or with destruction of private property, or possibly both. Desecration of a flag representing a minority group may also be charged as a hate crime in some jurisdictions.[134]

Folding for storage

Though not part of the official Flag Code, according to military custom, flags should be folded into a triangular shape when not in use. To properly fold the flag:

- Begin by holding it waist-high with another person so that its surface is parallel to the ground.

- Fold the lower half of the stripe section lengthwise over the field of stars, holding the bottom and top edges securely.

- Fold the flag again lengthwise with the blue field on the outside.

- Make a rectangular fold then a triangular fold by bringing the striped corner of the folded edge to meet the open top edge of the flag, starting the fold from the left side over to the right.

- Turn the outer end point inward, parallel to the open edge, to form a second triangle.

- The triangular folding is continued until the entire length of the flag is folded in this manner (usually thirteen triangular folds, as shown at right). On the final fold, any remnant that does not neatly fold into a triangle (or in the case of exactly even folds, the last triangle) is tucked into the previous fold.

- When the flag is completely folded, only a triangular blue field of stars should be visible.

There is also no specific meaning for each fold of the flag. However, there are scripts read by non-government organizations and also by the Air Force that are used during the flag folding ceremony. These scripts range from historical timelines of the flag to religious themes.[135][136]

Use in funerals

A flag prepared for presentation to the next of kin

Traditionally, the flag of the United States plays a role in military funerals,[137] and occasionally in funerals of other civil servants (such as law enforcement officers, fire fighters, and U.S. presidents). A burial flag is draped over the deceased’s casket as a pall during services. Just prior to the casket being lowered into the ground, the flag is ceremonially folded and presented to the deceased’s next of kin as a token of respect.[138]

Surviving historical flags

Revolutionary War

- Forster Flag (1775) – Historians believe the Manchester Company of the First Essex County Militia Regiment carried this flag during the battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. The militia unit was activated but was not involved in the day’s fighting. This flag is historic because it is the oldest surviving flag depicting the 13 colonies. This flag may have been a British ensign flag that had its Union Jack removed and replaced with 13 white stripes before or after the battles of Lexington and Concord. The slight variation in the canton area suggests something else might have been sewn into place before.[139] The flag gets its name from Samuel Forster, a First Lieutenant in the Manchester Company. He took possession of the flag, and his descendants passed it down until donating it to the American Flag Heritage Foundation in 1975, two hundred years later.[140] In April 2014, the foundation sold the flag at auction.[141][142]

- Westmoreland Flag (1775?) – Flag used by the 1st Battalion of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. In 1774 the town of Hanna, the county seat of Westmoreland County, began preparations for a conflict with the mother country as tensions between the two sides began to heat up. The town decided in May 1775, following the battles of Lexington and Concord, to create two battalions. The town sheriff, John Proctor, would have command over the 1st, and the unit would see action at Trenton and Princeton. Due to the flag’s remarkable condition, it is speculated that it never flew in many battles, if at all. The flag is said to have been made in the fall of 1775 from a standard British red ensign. This flag is one of two surviving revolutionary flags that feature a coiled rattlesnake, along with the flag of the United Company of the Train of Artillery. After the war in 1810, Alexander Craig, a captain in the 2nd battalion, was given the flag. It would stay with the Craig family until donated to the Pennsylvania State Library in 1914.[143][144]

- Brandywine Flag (1777) – This flag is stated in most research as being the flag of the 7th Pennsylvania Regiment. However, the Independence National Historical Park, which currently owns the flag, states it is the flag of the Chester County Militia.[145] The flags gets its name for being used at the Battle of Brandywine which took place on September 11, 1777, less than three months after the passage of the first flag act making it one of the earliest stars and stripes.[146][147]

- Dansey Flag (1777) – Flag used by a Delaware militia early in the war. Before the Battle of Brandywine, a soldier with the British 33rd Regiment of foote named William Dansey captured the militia’s flag during a skirmish in Newark, Delaware. Dansey would take the flag back to England as a war trophy. It would remain in his family until 1927, after being auctioned off to the Delaware Historical Society. This flag would have been one of the earliest to use 13 stripes to represent the united colonies. Another interesting note about this flag is that it was most likely a Division color instead of being used by one militia regiment.[148][149]

- First Pennsylvania Rifles Flag (1776?) – Battle colors for the First Pennsylvania Regiment This regiment, also known as the First Pennsylvania Rifles, was formed in 1775 following an act passed by the Continental Congress calling for ten companies of marksmen. The regiment would participate in many significant battles during the Revolution, such as the siege of Boston, Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, and Monmouth. They would be dissolved in November 1783 following the treaty of Paris. The earliest mention of this flag was mentioned in a 1776 letter by one of its soldiers. The flag would be with the unit until the end of the war.[150]

- Third New York Regiment Flag (1779) – The Third New York was formed in 1775 on five-month enlistments that expired later that year. In 1776 however, the regiment would be re-established twice, once in January and the other in December. During the war, the Third New York saw action in Canada, White Plains, and New York, during which it participated in the defense of Fort Stanwix. In 1780 the soldiers of the third were transferred over to the 1st New York Regiment. While not the most famous of regiments in turns of battles fought, it does leave behind a legacy that can be seen in the flag of New York. In 1778 New York adopted a coat of arms for the state. The following year, the regiment’s colonel Peter Gansevoort gifted the unit a blue regimental flag bearing the newly adopted arms. This flag would serve as the basis of the current flag of New York.[151][152]

War of 1812

- Star Spangled Banner Flag (1814) – Flag that flew over Fort McHenry during a British bombardment in the War of 1812. This flag is depicted by Francis Scott Key in the song «Star-Spangled Banner» which would later become the national anthem of the United States.[153] Details : 30 x 34 ft. (Currently) 15 horizontal stripes alternating red and white stripes 14 stars (one missing) Stars arranged in a staggered 3-3-3-3-3 pattern

Antebellum Period

- Old Glory Flag – This flag was the first American Flag to be given the name «Old Glory». The flag was made in 1824 and was a gift to William Driver, a sea captain, by his mother. He named the flag ‘Old Glory’ and took it with him during his time at sea. In 1861 the flag’s original stars were replaced with 34 new ones, and an anchor was added to the corner of the canton. During the Civil war, Driver hid his flag until Nashville became under union hands, to which he flew the flag above the Tennessee capitol building.[154]

- Matthew Perry Expedition Flag (1853) – On July 14, 1853, this flag was raised over Uraga, Japan during the Perry Expedition, in doing so it became the first American Flag to officially fly in mainland Japan. In 1855 it was presented to the US Naval Academy. In 1913 it received a linen backing during preservation treatments by Amelia Fowler, who would also work on restoring the Star-Spangled Banner. Nearly a century after its historic voyage to Japan, in 1945, the flag once again returned and was present at the formal surrender of Japan on board the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945. Owing to its condition, it had to be presented on its reverse side. As of 2021, the U.S. Naval Academy possesses the flag.[155]

Civil War

- Fort Sumter Flag (1861) – During the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, the flagpole was hit by artillery fire. The flag was raised again from a makeshift pole and was taken down after the Union garrison surrendered. The terms of surrender allowed the U.S. artillery to fire a salute for the flag. The flag was taken by the departing commander of the fort and was displayed to the public on a tour of the northern states. From this point, private citizens’ display of the United States flag became much more common. Four years after the flag was lowered at Fort Sumter, it flew over the fort again on April 14, 1865, following the Confederate surrender. Later that day, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.[156]

- Abraham Lincoln Assassination Flag (1865) – Flag that was placed under the head of President Abraham Lincoln following his fatal shooting while he was still in the presidential box.[157]

Reconstruction

- Little Big Horn Guidon – Guidon used by the 7th U.S. Cavalry during the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876. The battle is infamous, for all U.S. cavalry troops engaged in battle were killed, including Lt. Col George A. Custer. Sgt. Ferdinand Culbertson discovered this flag under the body of one of the slain soldiers. In 2010, this flag was sold for $2.2 million.[158]

World War II

- Iwo Jima Flag (1945) – American flag that was raised above Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima in WW2. The photo of this flag being raised by U.S. Marines was captured in the 1945 Pulitzer Prize-winning photo Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.[159]

Cold War

- Freedom 7 Flag (1961) – This American Flag flew on the Freedom-7 mission to space, becoming the first American flag to leave the Earth’s atmosphere. The flag was a last-minute addition after a local student council president asked a reporter if this flag could be taken on board. The reporter took it to the head of the NASA space task group, to which he agreed. In 1995, the flag was again taken to space to commemorate the 100th American crewed space mission.[160]

Modern day

- 9/11 Flag (2001) – Flag is believed to have been from a yacht called the «Star of America» owned by Shirley Dreifus and her late husband Spiros E. Kopelakis. The Yacht and its flag were docked in the Hudson River on the morning of 9/11. The flag was later found by three members of the New York Fire Department, George Johnson, Billy Eisengrein, and Dan McWilliams, who raised it over the rubble on a tilted flag pole (thought to be from the grounds of the Marriot hotel). This was captured in a photograph taken by Thomas Franklin, who worked for the New Jersey-based newspaper The Record. The photograph soon made its way to the Associated Press, and from there, it became shown worldwide on many newspapers’ front pages. The photo has been compared to Joe Rosenthal’s WW2 «Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima». Lori Ginker and Ricky Flores captured other photos of the same event from different angles. Shortly after the famous photograph was taken, the flag disappeared. Another flag, thought to be the real one, was toured around the country, but it was later found that the size of this flag was not the same as the one in the photograph. The one in the photo was 3×5, while the one the city possessed was larger. The flag would remain missing for nearly 15 years until a man named Brian turned an American flag into a fire station along with its halyard. Investigators determined that his flag was genuine after comparing dust samples and event photographs.[161] Today the 9/11 Memorial Museum possesses the flag.[162]

The U.S. flag has inspired many other flags for regions, political movements, and cultural groups, resulting in a stars and stripes flag family. The other national flags belonging to this family are: Chile, Cuba, Greece, Liberia, Malaysia, Puerto Rico, Togo, and Uruguay.[163]

- The flag of Bikini Atoll is symbolic of the islanders’ belief that a great debt is still owed to the people of Bikini because in 1954 the United States government detonated a thermonuclear bomb on the island as part of the Castle Bravo test.[164]

- The Republic of the United States of Brazil briefly used a flag inspired by the U.S. flag between 15 and 19 November 1889, proposed by the lawyer Ruy Barbosa. The flag had 13 green and yellow stripes, as well as a blue square with 21 white stars for the canton. The flag was vetoed by the then provisional president Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca citing concerns that it looked too similar to the American flag.[165]

- The flag of Liberia bears a close resemblance, showing the origin of the country in free people of color from North America and primarily the United States.[166] The Liberian flag has 11 similar red and white stripes, which stand for the 11 signers of the Liberian Declaration of Independence, as well as a blue square with only a single large white star for the canton. The flag is the only current flag in the world modeled after and resembling the American flag, as Liberia is the only nation in the world that was founded, colonized, established, and controlled by settlers who were free people of color and formerly enslaved people from the United States and the Caribbean aided and supported by the American Colonization Society beginning in 1822.[167]

- Despite Malaysia having no historical connections with the U.S., the flag of Malaysia greatly resembles the U.S. flag. Some theories posit that the flag of the British East India Company influenced both the Malaysian and U.S. flag.[9]

- The flag of El Salvador from 1865 to 1912. A different flag was in use, based on the flag of the United States, with a field of alternating blue and white stripes and a red canton containing white stars.[168]

- The flag of Brittany was inspired in part by the American flag.[169]

- The flag of the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, an unrecognized state that existed from 1917 to 1922, during the Russian Civil War, was divided into seven horizontal stripes that altered between green and white. In the right top corner was placed a blue canton with seven five-pointed yellow stars. Six of those were placed in two horizontal rows, each containing three stars. Next to them, on the right, was placed another star, in the middle of the height of two rows. The stars were slightly sued to the left. The seven stars and seven stripes represented the seven regions of the country.[170]

Possible future design of the flag

An artist’s rendering of one possible design for a 51-star flag, composed of 6 alternating rows of 9 and 8 stars

An artist’s rendering of a possible design for a 52-star flag, comprising 8 alternating rows of 7 and 6 stars, such as might accommodate the admission of two additional states into the Union

If a new U.S. state were to be admitted, it would require a new design of the flag to accommodate an additional star for a 51st state.[171] 51-star flags have been designed and used as a symbol by supporters of statehood in various jurisdictions.

Potential statehood candidates include U.S. territories, the national capital (Washington, D.C.), or a state created from the partition of an existing state. Residents of the District of Columbia (D.C.) and Puerto Rico have each voted for statehood in referendums (most recently in the 2016 statehood referendum in the District of Columbia[172] and the 2020 Puerto Rican status referendum[173]). Neither proposal has been approved by Congress.

In 2019, District of Columbia mayor Muriel Bowser had dozens of 51-star flags installed on Pennsylvania Avenue, the street linking the U.S. Capitol building with the White House, in anticipation of a hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives regarding potential District of Columbia statehood.[174] On June 26, 2020, the House voted to establish D.C. as the 51st state; however, the bill was not expected to pass in the Senate, and the administration of President Donald Trump indicated he would veto the bill if passed by both chambers.[175][176] It died in the Republican-controlled Senate at the end of the 116th Congress.[177]

On January 4, 2021, Delegate Norton reintroduced H.R. 51 early in the 117th Congress with a record 202 co-sponsors.[178][179] Senator Carper likewise introduced a similar bill, S. 51, into the United States Senate.[180][181] However, Democratic fellow senator Joe Manchin came out against both bills, effectively dooming their passage.[182]

According to the U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry, the United States flag never becomes obsolete. Any approved American flag may continue to be used and displayed until no longer serviceable.[183]

See also

- Ensign of the United States

- Flags of the Confederate States

- Flags of the United States

- Flags of the United States Armed Forces

- Flags of the U.S. states

- US Flag Desecration Amendment

- Fort Sumter Flag

- Nationalism in the United States

Article sections

- Colors, standards and guidons: United States

- Flag desecration: United States

Associated people

- Robert Anderson (1805–1871), lowered the Fort Sumter Flag, which became a national symbol, and he a hero

- Francis Bellamy (1855–1931), creator of the Pledge of Allegiance

- Thomas E. Franklin (1966–present), photographer of Ground Zero Spirit, better known as Raising the Flag at Ground Zero

- Christopher Gadsden (1724–1805), after whom the Gadsden flag is named

- Jasper Johns (born 1930), painter of Flag (1954–55), inspired by a dream of the flag

- Katha Pollitt (1949–present), author of a controversial essay on post-9/11 America and her refusal to fly a U.S. flag

- George Preble (1816–1885), author of History of the American Flag (1872) and photographer of the Fort McHenry flag

- Joe Rosenthal (1911–2006), photographer of Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima

References

- ^ Warner, John (1998). «Senate Concurrent Resolution 61» (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ «History of the American Flag». www.infoplease.com. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ During the Revolutionary War era, the «Rebellious Stripes» were considered as the most important element of United States flag designs, and were always mentioned before the stars. The «Stripes and Stars» would remain a popular phrase into the 19th century.

Credit for the term «Stars and Stripes» has been given to the Marquis de Lafayette. See Mastai (1973), p. 29. - ^ «USFlag.org: A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America – «OLD GLORY!»«. www.usflag.org. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ Streufert, Duane. «A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America – The 50 Star Flag». USFlag.org. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Joint Committee on Printing, United States Congress (1989). Our Flag. H. Doc. 100-247. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 3.

- ^ a b Leepson, Marc (2004). Flag: An American Biography.

- ^ a b Ansoff, Peter (2006). «The Flag on Prospect Hill» (PDF). Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 13: 91–98. doi:10.5840/raven2006134. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2015.

- ^ a b The Striped Flag of the East India Company, and its Connexion with the American «Stars and Stripes» at Flags of the World

- ^ East India Company (United Kingdom) at Flags of the World

- ^ Johnson, Robert (2006). Saint Croix 1770–1776: The First Salute to the Stars and Stripes. AuthorHouse. p. 71. ISBN 978-1425970086.

- ^ Horton, Tom (2014). «Exposing the Origins of Old Glory’s stripes». History’s Lost Moments: The Stories Your Teacher Never Told You. Vol. 5. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1490744698.

- ^ a b «Saltires and Stars & Stripes». The Economic Times. September 22, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ «A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875». memory.loc.gov.

- ^ Guenter (1990).

- ^ «Washington Window». Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Vile, John R. (2018). The American Flag: An Encyclopedia of the Stars and Stripes in U.S. History, Culture, and Law. ABC-CLIO. p. 342. ISBN 978-1-4408-5789-8.

- ^ a b Leepson, Marc (2007). «Chapter Ten: The Hundredth Anniversary». Flag: An American Biography. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4299-0647-0.

- ^ Capps, Alan. «Coat of Arms». The Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Connell, R.W.; Mack, W.P. (2004). Naval Ceremonies, Customs, and Traditions. Naval Institute Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-55750-330-5. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Mastai, 60.

- ^ Furlong, Rear Admiral William Rea; McCandless, Commodore Byron (1981). So Proudly We Hail. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 115–116.

- ^ Williams, Earl P. Jr. (October 2012). «Did Francis Hopkinson Design Two Flags?» (PDF). NAVA News (216): 7–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Lane, Megan (November 14, 2011). «Five hidden messages in the American flag». BBC News. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Cooper, Grace Rogers (1973). Thirteen-Star Flags. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Cooper, Grace Rogers (1973). Thirteen-Star Flags. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 9 (in paper), pp. 21/80 (in pdf). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.639.8200.

In 1792, Trumbull painted thirteen stars in a circle in his General George Washington at Trenton in the Yale University Art Gallery. In his unfinished rendition of the Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, dates not established, the circle of stars is suggested and one star shows six points while the thirteen stripes are red, white, and blue. How accurately the artist depicted the star design that he saw is not known. At times, he may have offered a poetic version of the flag he was interpreting which was later copied by the flag maker. The flag sheets and the artists do not agree.

- ^ Cooper, Grace Rogers (1973). Thirteen-Star Flags. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 3.

- ^ Furlong, p. 130.

- ^ Moeller, Henry W (1992). Unfurling the History of the Stars and Stripes. Mattituck, NY: Amereon House. pp. 25–26, color plates 5A, 5B.

- ^ Williams, Earl W. Jr. (October 2012). «Did Francis Hopkinson Design Two Flags?». NAVA News (216): 7.

- ^ Williams (2012), p. 7.

- ^ Hess, Debra (2008). The American Flag. Benchmark Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7614-3389-7.

- ^ Hastings, George E. (1926). The Life and Works of Francis Hopkinson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 218.

- ^ Hastings, p. 240.

- ^ a b Williams, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Moeller, Henry W., Ph.D. (January 2002). «Two Early American Ensigns on the Pennsylvania State Arms». NAVA News (173): 4.

- ^ Patterson, Richard Sharpe; Dougall, Richardson (1978) [1976 i.e. 1978]. The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States. Department and Foreign Service series; 161 Department of State publication; 8900. Washington: Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State: for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. p. 37. LCCN 78602518. OCLC 4268298.

- ^ Zall, Paul M. (1976). Comical Spirit of Seventy-Six: The Humor of Francis Hopkinson. San Marino, California: Huntington Library. p. 10.

- ^ Williams, Earl P. Jr. (Spring 1988). «The ‘Fancy Work’ of Francis Hopkinson: Did He Design the Stars and Stripes?». Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives. 20 (1): 47–48.

- ^ «Journals of the Continental Congress – Friday, October 27, 1780». Library of Congress. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ Furlong, William Rea; McCandless, Byron (1981). So Proudly We Hail : The History of the United States Flag. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 98–101. ISBN 978-0-87474-448-4.

- ^ Federal Citizen Information Center: The History of the Stars and Stripes Archived September 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ Embassy of the United States of America [1]. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ a b c Furlong, William Rea; McCandless, Byron (1981). So Proudly We Hail: The History of the United States Flag. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-87474-448-4.

- ^ Crews, Ed. «The Truth About Betsy Ross». Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ^ Canby, George; Balderston, Lloyd (1917). The Evolution of the American flag. Philadelphia: Ferris and Leach. pp. 48, 103.

- ^ Canby, William J. «The History of the Flag of the United States: A Paper read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (March 1870)». Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ Preble 1882, p. 244.

- ^ Preble 1882, p. 256.

- ^ Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (October 2007). «How Betsy Ross Became Famous». Common-Place. Vol. 8, no. 1. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Marla R. (2010). Betsy Ross and the Making of America. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8050-8297-5.

- ^ Schaun, George and Virginia. «Historical Portrait of Mrs. Mary Young Pickersgill». The Greenberry Series on Maryland. Annapolis, MD: Greenberry Publications. 5: 356.

- ^ Furlong, William Rea; McCandless, Byron (1981). So Proudly We Hail : The History of the United States Flag. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-87474-448-4.

- ^ «The Star-Spangled Banner: Making the Flag». National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ^ Yuen, Helen and Asantewa Boakyewa (May 30, 2014). «The African American girl who helped make the Star-Spangled Banner». O Say Can You See?. Smithsonian. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ a b «The Star-Spangled Banner Online Exhibition». National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ United States Government (1861). Our Flag (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. S. Doc 105-013.

- ^ a b c United States Embassy Stockholm (October 5, 2005). «United States Flag History». United States Embassy. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ These designs are in the Eisenhower Presidential Archives in Abilene, Kansas. Only a small fraction of them have ever been published.

- ^ Rasmussen, Frederick. «A half-century ago, new 50-star American flag debuted in Baltimore». The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ Preble, George Henry (1880). History of the Flag of the United States of America (second revised ed.). Boston: A. Williams and Co. p. 298.

- ^ a b c March, Eva (1917). The Little Book of the Flag. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 92.

- ^ «Curiosa Sinica». Boston Courier. June 15, 1843.

- ^ «Chinese Etymologies». Kendall’s Expositor. Vol. 3, no. 14. Washington, D.C.: William Greer. June 27, 1843. p. 222 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b See Chinese English Dictionary Archived April 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

Olsen, Kay Melchisedech, Chinese Immigrants: 1850–1900 (2001), p. 7.

«Philadelphia’s Chinatown: An Overview Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine», The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Leonard, Dr. George, «The Beginnings of Chinese Literature in America: the Angel Island Poems».[dead link] - ^ International Settlement of Kulangsu (Gulangyu, China) at Flags of the World

- ^ «American Flag Raised Over Buddhist Temple in Japan on July 4, 1872» Archived February 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The American Flag : Two Centuries of Concord and Conflict. VZ Publications. 2006. p. 68.

- ^ Leepson, Marc (2005). Flag : An American Biography. Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 94–109.

- ^ (For alternate versions of the flag of the United States, see the Stars of the U.S. Flag page Archived February 22, 2005, at the Wayback Machine at the Flags of the World website.)

- ^ «Facts about the United States Flag». Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved April 22, 2022.