Оксид кальция

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 149.

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 149.

Негашёная известь – это оксид кальция. Его получают в лабораториях и промышленным путём из природных материалов. Вещество активно используется в строительстве и промышленности.

Физические свойства

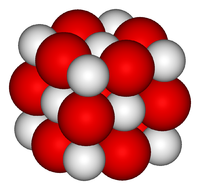

Оксид кальция – неорганическое кристаллическое вещество в виде белого или серо-белого порошка без запаха и вкуса. Твёрдое вещество кристаллизуется в кубические гранецентрированные кристаллические решётки по типу хлорида натрия (NaCl).

Общее описание вещества представлено в таблице.

|

Признак |

Значение |

|

Формула соединения оксид кальция |

CaO |

|

Температура плавления |

2627°C |

|

Температура кипения |

2850°C |

|

Растворимость |

В глицерине. В этаноле не растворяется, с водой образует гидроксид |

|

Молярная масса |

56,077 г/моль |

|

Плотность |

3,37 г/см3 |

|

Химическая связь в кристалле |

Ионная |

Оксид кальция – едкое вещество, относящееся ко второму классу опасности. Агрессивные свойства проявляет при взаимодействии с водой, образуя гашёную известь.

Получение

Оксид кальция также называют жжёной известью из-за способа получения. Получают негашёную известь путём нагревания и разложения известняка – карбоната кальция (CaCO3).

Это природное вещество, встречающееся в форме минералов – арагонита, ватерита, кальцита. Входит в состав мрамора, мела, известняка.

Реакция получения оксида кальция из известняка выглядит следующим образом:

CaCO3 → CaO + CO2.

Кроме того, негашёную известь можно получить двумя способами:

- из простых веществ, наращивая оксидный слой на металле –

2Ca + O2 → 2CaO;

- при термической обработке гидроксида или солей кальция –

Ca(OH)2 → CaO + H2O; 2Ca(NO3)2 → 2CaO + 4NO2 + O2.

Реакции протекают при высоких температурах. Температура сожжения известняка – 900-1200°C. При 200-300°C на поверхности металла начинает образовываться оксид. Для разложения солей и гидроксида необходима температура в 500-600°C.

Химические свойства

Оксид кальция является высшим оксидом и максимально проявляет окислительные свойства. Соединения взаимодействует с неорганическими веществами и свободными галогенами. Основные химические свойства оксида приведены в таблице.

|

Реакции |

Что образуется |

Молекулярное уравнение |

|

С водой |

Образуется гидроксид (гашёная известь). Реакция протекает бурно с выделением тепла |

CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2 |

|

С кислотами |

Растворяется, образуя соли |

CaO + 2HCl → CaCl2 +H2O |

|

С оксидами неметаллов (кислотными остатками) |

Образуются соли |

CaO + SO2 → CaSO3 |

|

С углеродом при нагревании |

Образуется карбид кальция |

CaO + 3С → СаС2 + CO |

|

С алюминием |

Восстанавливает кальций. Образуется оксид алюминия |

3CaO + 2Al → Са + Al2O3 |

Применение

Оксид используется в пищевой промышленности в качестве:

- улучшителя муки и хлеба;

- пищевой добавки Е529;

- регулятора кислотности;

- питательной среды для дрожжей;

- катализатора гидрогенизации (присоединения водорода) жиров.

Кроме того, негашёная известь применяется в химической и строительной промышленности для производства различных веществ:

- масел;

- стеарата кальция;

- солидола;

- огнеупорных материалов;

- гипса;

- высокоглиноземистого цемента;

- силикатного кирпича.

Что мы узнали?

Оксид кальция или негашёная известь – кристаллическое вещество, бурно реагирующее с водой и образующее гашёную известь. Широко используется в промышленности, в частности пищевой и строительной. Зарегистрирован как пищевая добавка Е529. Имеет высокие температуры плавления и кипения, растворяется только в глицерине. Образуется при сжигании карбоната кальция. Проявляет окислительные свойства, образует соли с оксидами и кислотами, взаимодействует с углеродом и алюминием.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Владимир Комаров

10/10

-

Сергей Ефремов

4/10

Оценка доклада

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 149.

А какая ваша оценка?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ionic crystal structure of calcium oxide O2- |

|

Powder sample of white calcium oxide |

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Calcium oxide |

|

| Other names

Lime |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

CAS Number |

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.763 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E529 (acidity regulators, …) |

|

Gmelin Reference |

485425 |

| KEGG |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 1910 |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

InChI

|

|

|

SMILES

|

|

| Properties | |

|

Chemical formula |

CaO |

| Molar mass | 56.0774 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to pale yellow/brown powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.34 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 2,613 °C (4,735 °F; 2,886 K)[1] |

| Boiling point | 2,850 °C (5,160 °F; 3,120 K) (100 hPa)[2] |

|

Solubility in water |

Reacts to form calcium hydroxide |

| Solubility in Methanol | Insoluble (also in diethyl ether, octanol) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.8 |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−15.0×10−6 cm3/mol |

| Structure | |

|

Crystal structure |

Cubic, cF8 |

| Thermochemistry | |

|

Std molar |

40 J·mol−1·K−1[3] |

|

Std enthalpy of |

−635 kJ·mol−1[3] |

| Pharmacology | |

|

ATCvet code |

QP53AX18 (WHO) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H302, H314, H315, H335 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P301+P312, P301+P330+P331, P302+P352, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P312, P321, P330, P332+P313, P362, P363, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3 0 2

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[4] |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 2 mg/m3[4] |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

25 mg/m3[4] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Hazard.com |

| Related compounds | |

|

Other anions |

Calcium sulfide Calcium hydroxide Calcium selenide Calcium telluride |

|

Other cations |

Beryllium oxide Magnesium oxide Strontium oxide Barium oxide Radium oxide |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). Infobox references |

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term «lime» connotes calcium-containing inorganic materials, in which carbonates, oxides and hydroxides of calcium, silicon, magnesium, aluminium, and iron predominate. By contrast, quicklime specifically applies to the single chemical compound calcium oxide. Calcium oxide that survives processing without reacting in building products such as cement is called free lime.[5]

Quicklime is relatively inexpensive. Both it and the chemical derivative calcium hydroxide (of which quicklime is the base anhydride) are important commodity chemicals.

Preparation[edit]

Calcium oxide is usually made by the thermal decomposition of materials, such as limestone or seashells, that contain calcium carbonate (CaCO3; mineral calcite) in a lime kiln. This is accomplished by heating the material to above 825 °C (1,517 °F),[6][7] a process called calcination or lime-burning, to liberate a molecule of carbon dioxide (CO2), leaving quicklime behind. This is also one of the few chemical reactions known in prehistoric times.[8]

- CaCO3(s) → CaO(s) + CO2(g)

The quicklime is not stable and, when cooled, will spontaneously react with CO2 from the air until, after enough time, it will be completely converted back to calcium carbonate unless slaked with water to set as lime plaster or lime mortar.

Annual worldwide production of quicklime is around 283 million tonnes. China is by far the world’s largest producer, with a total of around 170 million tonnes per year. The United States is the next largest, with around 20 million tonnes per year.[9]

Approximately 1.8 t of limestone is required per 1.0 t of quicklime. Quicklime has a high affinity for water and is a more efficient desiccant than silica gel. The reaction of quicklime with water is associated with an increase in volume by a factor of at least 2.5.[10]

Uses[edit]

A demonstration of slaking of quicklime as a strongly exothermic reaction. Drops of water are added to pieces of quicklime. After a while, a pronounced exothermic reaction occurs (‘slaking of lime’). The temperature can reach up to some 300 °C (572 °F).

- The major use of quicklime is in the basic oxygen steelmaking (BOS) process. Its usage varies from about 30 to 50 kilograms (65–110 lb) per ton of steel. The quicklime neutralizes the acidic oxides, SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3, to produce a basic molten slag.[10]

- Ground quicklime is used in the production of aerated concrete blocks, with densities of ca. 0.6–1.0 g/cm3 (9.8–16.4 g/cu in).[10]

- Quicklime and hydrated lime can considerably increase the load carrying capacity of clay-containing soils. They do this by reacting with finely divided silica and alumina to produce calcium silicates and aluminates, which possess cementing properties.[10]

- Small quantities of quicklime are used in other processes; e.g., the production of glass, calcium aluminate cement, and organic chemicals.[10]

- Heat: Quicklime releases thermal energy by the formation of the hydrate, calcium hydroxide, by the following equation:[11]

-

- CaO (s) + H2O (l) ⇌ Ca(OH)2 (aq) (ΔHr = −63.7 kJ/mol of CaO)

- As it hydrates, an exothermic reaction results and the solid puffs up. The hydrate can be reconverted to quicklime by removing the water by heating it to redness to reverse the hydration reaction. One litre of water combines with approximately 3.1 kilograms (6.8 lb) of quicklime to give calcium hydroxide plus 3.54 MJ of energy. This process can be used to provide a convenient portable source of heat, as for on-the-spot food warming in a self-heating can, cooking, and heating water without open flames. Several companies sell cooking kits using this heating method.[12]

- It is known as a food additive to the FAO as an acidity regulator, a flour treatment agent and as a leavener.[13] It has E number E529.

- Light: When quicklime is heated to 2,400 °C (4,350 °F), it emits an intense glow. This form of illumination is known as a limelight, and was used broadly in theatrical productions before the invention of electric lighting.[14]

- Cement: Calcium oxide is a key ingredient for the process of making cement.

- As a cheap and widely available alkali. About 50% of the total quicklime production is converted to calcium hydroxide before use. Both quick- and hydrated lime are used in the treatment of drinking water.[10]

- Petroleum industry: Water detection pastes contain a mix of calcium oxide and phenolphthalein. Should this paste come into contact with water in a fuel storage tank, the CaO reacts with the water to form calcium hydroxide. Calcium hydroxide has a high enough pH to turn the phenolphthalein a vivid purplish-pink color, thus indicating the presence of water.

- Paper: Calcium oxide is used to regenerate sodium hydroxide from sodium carbonate in the chemical recovery at Kraft pulp mills.

- Plaster: There is archeological evidence that Pre-Pottery Neolithic B humans used limestone-based plaster for flooring and other uses.[15][16][17] Such Lime-ash floor remained in use until the late nineteenth century.

- Chemical or power production: Solid sprays or slurries of calcium oxide can be used to remove sulfur dioxide from exhaust streams in a process called flue-gas desulfurization.

- Mining: Compressed lime cartridges exploit the exothermic properties of quicklime to break rock. A shot hole is drilled into the rock in the usual way and a sealed cartridge of quicklime is placed within and tamped. A quantity of water is then injected into the cartridge and the resulting release of steam, together with the greater volume of the residual hydrated solid, breaks the rock apart. The method does not work if the rock is particularly hard.[18][19][20]

- Disposal of corpses: Historically, it was mistakenly believed that quicklime was efficacious in accelerating the decomposition of corpses. The application of quicklime can, in fact, promote preservation. Quicklime can aid in eradicating the stench of decomposition, which may have led people to the erroneous conclusion.[21]

- It has been determined that the durability of ancient Roman concrete is attributed in part to the use of quicklime as an ingredient. Combined with hot mixing, the quicklime creates macrosized lime clasts with a characteristically brittle nano-particle architecture. As cracks form in the concrete they preferentially pass through the structurally weaker lime clasts, fracturing them. When water enters these cracks it creates a calcium-saturated solution which can recrystallize as calcium carbonate, quickly filling the crack. [22]

Weapon[edit]

In 80 BC, the Roman general Sertorius deployed choking clouds of caustic lime powder to defeat the Characitani of Hispania, who had taken refuge in inaccessible caves.[23] A similar dust was used in China to quell an armed peasant revolt in 178 AD, when lime chariots equipped with bellows blew limestone powder into the crowds.[24]

Quicklime is also thought to have been a component of Greek fire. Upon contact with water, quicklime would increase its temperature above 150 °C (302 °F) and ignite the fuel.[25]

David Hume, in his History of England, recounts that early in the reign of Henry III, the English Navy destroyed an invading French fleet by blinding the enemy fleet with quicklime.[26] Quicklime may have been used in medieval naval warfare – up to the use of «lime-mortars» to throw it at the enemy ships.[27]

Substitutes[edit]

Limestone is a substitute for lime in many applications, which include agriculture, fluxing, and sulfur removal. Limestone, which contains less reactive material, is slower to react and may have other disadvantages compared with lime, depending on the application; however, limestone is considerably less expensive than lime. Calcined gypsum is an alternative material in industrial plasters and mortars. Cement, cement kiln dust, fly ash, and lime kiln dust are potential substitutes for some construction uses of lime. Magnesium hydroxide is a substitute for lime in pH control, and magnesium oxide is a substitute for dolomitic lime as a flux in steelmaking.[28]

Safety[edit]

Because of vigorous reaction of quicklime with water, quicklime causes severe irritation when inhaled or placed in contact with moist skin or eyes. Inhalation may cause coughing, sneezing, and labored breathing. It may then evolve into burns with perforation of the nasal septum, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Although quicklime is not considered a fire hazard, its reaction with water can release enough heat to ignite combustible materials.[29]

Mineral[edit]

Calcium oxide is also a separate mineral species (with the unit formula CaO), named ‘Lime’.[30][31] It has an isometric crystal system, and can form a solid solution series with monteponite. The crystal is brittle, pyrometamorphic, and is unstable in moist air, quickly turning into portlandite (Ca(OH)2).[32]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.55. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ Calciumoxid Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. GESTIS database

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A21. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0093». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ «free lime» Archived 2017-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. DictionaryOfConstruction.com.

- ^ Merck Index of Chemicals and Drugs, 9th edition monograph 1650

- ^ Kumar, Gupta Sudhir; Ramakrishnan, Anushuya; Hung, Yung-Tse (2007), Wang, Lawrence K.; Hung, Yung-Tse; Shammas, Nazih K. (eds.), «Lime Calcination», Advanced Physicochemical Treatment Technologies, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, vol. 5, pp. 611–633, doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-173-4_14, ISBN 978-1-58829-860-7, retrieved 2022-07-26

- ^ «Lime throughout history | Lhoist — Minerals and lime producer». Lhoist.com. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Miller, M. Michael (2007). «Lime». Minerals Yearbook (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. p. 43.13.

- ^ a b c d e f Tony Oates (2007), «Lime and Limestone», Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–32, doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_317, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Collie, Robert L. «Solar heating system» U.S. Patent 3,955,554 issued May 11, 1976

- ^ Gretton, Lel. «Lime power for cooking — medieval pots to 21st century cans». Old & Interesting. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ «Compound Summary for CID 14778 — Calcium Oxide». PubChem.

- ^ Gray, Theodore (September 2007). «Limelight in the Limelight». Popular Science: 84. Archived from the original on 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ University, Tel Aviv. «Neolithic man: The first lumberjack?». phys.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ Karkanas, P.; Stratouli, G. (2011). «Neolithic Lime Plastered Floors in Drakaina Cave, Kephalonia Island, Western Greece: Evidence of the Significance of the Site». The Annual of the British School at Athens. 103: 27–41. doi:10.1017/S006824540000006X. S2CID 129562287.

- ^ Connelly, Ashley Nicole (May 2012) Analysis and Interpretation of Neolithic Near Eastern Mortuary Rituals from a Community-Based Perspective. Baylor University Thesis, Texas

- ^ Walker, Thomas A (1888). The Severn Tunnel Its Construction and Difficulties. London: Richard Bentley and Son. p. 92.

- ^ «Scientific and Industrial Notes». Manchester Times. Manchester, England: 8. 13 May 1882.

- ^ US Patent 255042, 14 March 1882

- ^

- ^ «Riddle solved: Why was Roman concrete so durable?», MIT News, January 6, 2023

- ^ Plutarch, «Sertorius 17.1–7», Parallel Lives

- ^ Adrienne Mayor (2005), «Ancient Warfare and Toxicology», in Philip Wexler (ed.), Encyclopedia of Toxicology, vol. 4 (2nd ed.), Elsevier, pp. 117–121, ISBN 0-12-745354-7

- ^ Croddy, Eric (2002). Chemical and biological warfare: a comprehensive survey for the concerned citizen. Springer. p. 128. ISBN 0-387-95076-1.

- ^ David Hume (1756). History of England. Vol. I.

- ^ Sayers, W. (2006). «The Use of Quicklime in Medieval Naval Warfare». The Mariner’s Mirror. Volume 92. Issue 3. pp. 262–269.

- ^ «Lime» (PDF). Prd-wret.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com. p. 96. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ ww25.hazard.com http://ww25.hazard.com/msds/mf/baker/baker/files/c0462.htm?subid1=20230203-0103-092e-9982-d576d3e248aa. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ «List of Minerals». Ima-mineralogy.org. 21 March 2011.

- ^ Fiquet, G.; Richet, P.; Montagnac, G. (Dec 1999). «High-temperature thermal expansion of lime, periclase, corundum and spinel». Physics and Chemistry of Materials. 27 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1007/s002690050246. S2CID 93706828. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ «Lime». Mindat.org. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

External links[edit]

- Lime Statistics & Information from the United States Geological Survey

- Factors Affecting the Quality of Quicklime

- American Scientist (discussion of 14C dating of mortar)

- Chemical of the Week – Lime

- Material Safety Data Sheet

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ionic crystal structure of calcium oxide O2- |

|

Powder sample of white calcium oxide |

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Calcium oxide |

|

| Other names

Lime |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

CAS Number |

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.763 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E529 (acidity regulators, …) |

|

Gmelin Reference |

485425 |

| KEGG |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 1910 |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

InChI

|

|

|

SMILES

|

|

| Properties | |

|

Chemical formula |

CaO |

| Molar mass | 56.0774 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to pale yellow/brown powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.34 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 2,613 °C (4,735 °F; 2,886 K)[1] |

| Boiling point | 2,850 °C (5,160 °F; 3,120 K) (100 hPa)[2] |

|

Solubility in water |

Reacts to form calcium hydroxide |

| Solubility in Methanol | Insoluble (also in diethyl ether, octanol) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.8 |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

−15.0×10−6 cm3/mol |

| Structure | |

|

Crystal structure |

Cubic, cF8 |

| Thermochemistry | |

|

Std molar |

40 J·mol−1·K−1[3] |

|

Std enthalpy of |

−635 kJ·mol−1[3] |

| Pharmacology | |

|

ATCvet code |

QP53AX18 (WHO) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H302, H314, H315, H335 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P301+P312, P301+P330+P331, P302+P352, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P312, P321, P330, P332+P313, P362, P363, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3 0 2

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[4] |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 2 mg/m3[4] |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

25 mg/m3[4] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Hazard.com |

| Related compounds | |

|

Other anions |

Calcium sulfide Calcium hydroxide Calcium selenide Calcium telluride |

|

Other cations |

Beryllium oxide Magnesium oxide Strontium oxide Barium oxide Radium oxide |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). Infobox references |

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term «lime» connotes calcium-containing inorganic materials, in which carbonates, oxides and hydroxides of calcium, silicon, magnesium, aluminium, and iron predominate. By contrast, quicklime specifically applies to the single chemical compound calcium oxide. Calcium oxide that survives processing without reacting in building products such as cement is called free lime.[5]

Quicklime is relatively inexpensive. Both it and the chemical derivative calcium hydroxide (of which quicklime is the base anhydride) are important commodity chemicals.

Preparation[edit]

Calcium oxide is usually made by the thermal decomposition of materials, such as limestone or seashells, that contain calcium carbonate (CaCO3; mineral calcite) in a lime kiln. This is accomplished by heating the material to above 825 °C (1,517 °F),[6][7] a process called calcination or lime-burning, to liberate a molecule of carbon dioxide (CO2), leaving quicklime behind. This is also one of the few chemical reactions known in prehistoric times.[8]

- CaCO3(s) → CaO(s) + CO2(g)

The quicklime is not stable and, when cooled, will spontaneously react with CO2 from the air until, after enough time, it will be completely converted back to calcium carbonate unless slaked with water to set as lime plaster or lime mortar.

Annual worldwide production of quicklime is around 283 million tonnes. China is by far the world’s largest producer, with a total of around 170 million tonnes per year. The United States is the next largest, with around 20 million tonnes per year.[9]

Approximately 1.8 t of limestone is required per 1.0 t of quicklime. Quicklime has a high affinity for water and is a more efficient desiccant than silica gel. The reaction of quicklime with water is associated with an increase in volume by a factor of at least 2.5.[10]

Uses[edit]

A demonstration of slaking of quicklime as a strongly exothermic reaction. Drops of water are added to pieces of quicklime. After a while, a pronounced exothermic reaction occurs (‘slaking of lime’). The temperature can reach up to some 300 °C (572 °F).

- The major use of quicklime is in the basic oxygen steelmaking (BOS) process. Its usage varies from about 30 to 50 kilograms (65–110 lb) per ton of steel. The quicklime neutralizes the acidic oxides, SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3, to produce a basic molten slag.[10]

- Ground quicklime is used in the production of aerated concrete blocks, with densities of ca. 0.6–1.0 g/cm3 (9.8–16.4 g/cu in).[10]

- Quicklime and hydrated lime can considerably increase the load carrying capacity of clay-containing soils. They do this by reacting with finely divided silica and alumina to produce calcium silicates and aluminates, which possess cementing properties.[10]

- Small quantities of quicklime are used in other processes; e.g., the production of glass, calcium aluminate cement, and organic chemicals.[10]

- Heat: Quicklime releases thermal energy by the formation of the hydrate, calcium hydroxide, by the following equation:[11]

-

- CaO (s) + H2O (l) ⇌ Ca(OH)2 (aq) (ΔHr = −63.7 kJ/mol of CaO)

- As it hydrates, an exothermic reaction results and the solid puffs up. The hydrate can be reconverted to quicklime by removing the water by heating it to redness to reverse the hydration reaction. One litre of water combines with approximately 3.1 kilograms (6.8 lb) of quicklime to give calcium hydroxide plus 3.54 MJ of energy. This process can be used to provide a convenient portable source of heat, as for on-the-spot food warming in a self-heating can, cooking, and heating water without open flames. Several companies sell cooking kits using this heating method.[12]

- It is known as a food additive to the FAO as an acidity regulator, a flour treatment agent and as a leavener.[13] It has E number E529.

- Light: When quicklime is heated to 2,400 °C (4,350 °F), it emits an intense glow. This form of illumination is known as a limelight, and was used broadly in theatrical productions before the invention of electric lighting.[14]

- Cement: Calcium oxide is a key ingredient for the process of making cement.

- As a cheap and widely available alkali. About 50% of the total quicklime production is converted to calcium hydroxide before use. Both quick- and hydrated lime are used in the treatment of drinking water.[10]

- Petroleum industry: Water detection pastes contain a mix of calcium oxide and phenolphthalein. Should this paste come into contact with water in a fuel storage tank, the CaO reacts with the water to form calcium hydroxide. Calcium hydroxide has a high enough pH to turn the phenolphthalein a vivid purplish-pink color, thus indicating the presence of water.

- Paper: Calcium oxide is used to regenerate sodium hydroxide from sodium carbonate in the chemical recovery at Kraft pulp mills.

- Plaster: There is archeological evidence that Pre-Pottery Neolithic B humans used limestone-based plaster for flooring and other uses.[15][16][17] Such Lime-ash floor remained in use until the late nineteenth century.

- Chemical or power production: Solid sprays or slurries of calcium oxide can be used to remove sulfur dioxide from exhaust streams in a process called flue-gas desulfurization.

- Mining: Compressed lime cartridges exploit the exothermic properties of quicklime to break rock. A shot hole is drilled into the rock in the usual way and a sealed cartridge of quicklime is placed within and tamped. A quantity of water is then injected into the cartridge and the resulting release of steam, together with the greater volume of the residual hydrated solid, breaks the rock apart. The method does not work if the rock is particularly hard.[18][19][20]

- Disposal of corpses: Historically, it was mistakenly believed that quicklime was efficacious in accelerating the decomposition of corpses. The application of quicklime can, in fact, promote preservation. Quicklime can aid in eradicating the stench of decomposition, which may have led people to the erroneous conclusion.[21]

- It has been determined that the durability of ancient Roman concrete is attributed in part to the use of quicklime as an ingredient. Combined with hot mixing, the quicklime creates macrosized lime clasts with a characteristically brittle nano-particle architecture. As cracks form in the concrete they preferentially pass through the structurally weaker lime clasts, fracturing them. When water enters these cracks it creates a calcium-saturated solution which can recrystallize as calcium carbonate, quickly filling the crack. [22]

Weapon[edit]

In 80 BC, the Roman general Sertorius deployed choking clouds of caustic lime powder to defeat the Characitani of Hispania, who had taken refuge in inaccessible caves.[23] A similar dust was used in China to quell an armed peasant revolt in 178 AD, when lime chariots equipped with bellows blew limestone powder into the crowds.[24]

Quicklime is also thought to have been a component of Greek fire. Upon contact with water, quicklime would increase its temperature above 150 °C (302 °F) and ignite the fuel.[25]

David Hume, in his History of England, recounts that early in the reign of Henry III, the English Navy destroyed an invading French fleet by blinding the enemy fleet with quicklime.[26] Quicklime may have been used in medieval naval warfare – up to the use of «lime-mortars» to throw it at the enemy ships.[27]

Substitutes[edit]

Limestone is a substitute for lime in many applications, which include agriculture, fluxing, and sulfur removal. Limestone, which contains less reactive material, is slower to react and may have other disadvantages compared with lime, depending on the application; however, limestone is considerably less expensive than lime. Calcined gypsum is an alternative material in industrial plasters and mortars. Cement, cement kiln dust, fly ash, and lime kiln dust are potential substitutes for some construction uses of lime. Magnesium hydroxide is a substitute for lime in pH control, and magnesium oxide is a substitute for dolomitic lime as a flux in steelmaking.[28]

Safety[edit]

Because of vigorous reaction of quicklime with water, quicklime causes severe irritation when inhaled or placed in contact with moist skin or eyes. Inhalation may cause coughing, sneezing, and labored breathing. It may then evolve into burns with perforation of the nasal septum, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Although quicklime is not considered a fire hazard, its reaction with water can release enough heat to ignite combustible materials.[29]

Mineral[edit]

Calcium oxide is also a separate mineral species (with the unit formula CaO), named ‘Lime’.[30][31] It has an isometric crystal system, and can form a solid solution series with monteponite. The crystal is brittle, pyrometamorphic, and is unstable in moist air, quickly turning into portlandite (Ca(OH)2).[32]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.55. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ Calciumoxid Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. GESTIS database

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A21. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0093». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ «free lime» Archived 2017-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. DictionaryOfConstruction.com.

- ^ Merck Index of Chemicals and Drugs, 9th edition monograph 1650

- ^ Kumar, Gupta Sudhir; Ramakrishnan, Anushuya; Hung, Yung-Tse (2007), Wang, Lawrence K.; Hung, Yung-Tse; Shammas, Nazih K. (eds.), «Lime Calcination», Advanced Physicochemical Treatment Technologies, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, vol. 5, pp. 611–633, doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-173-4_14, ISBN 978-1-58829-860-7, retrieved 2022-07-26

- ^ «Lime throughout history | Lhoist — Minerals and lime producer». Lhoist.com. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Miller, M. Michael (2007). «Lime». Minerals Yearbook (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. p. 43.13.

- ^ a b c d e f Tony Oates (2007), «Lime and Limestone», Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–32, doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_317, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Collie, Robert L. «Solar heating system» U.S. Patent 3,955,554 issued May 11, 1976

- ^ Gretton, Lel. «Lime power for cooking — medieval pots to 21st century cans». Old & Interesting. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ «Compound Summary for CID 14778 — Calcium Oxide». PubChem.

- ^ Gray, Theodore (September 2007). «Limelight in the Limelight». Popular Science: 84. Archived from the original on 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ University, Tel Aviv. «Neolithic man: The first lumberjack?». phys.org. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ Karkanas, P.; Stratouli, G. (2011). «Neolithic Lime Plastered Floors in Drakaina Cave, Kephalonia Island, Western Greece: Evidence of the Significance of the Site». The Annual of the British School at Athens. 103: 27–41. doi:10.1017/S006824540000006X. S2CID 129562287.

- ^ Connelly, Ashley Nicole (May 2012) Analysis and Interpretation of Neolithic Near Eastern Mortuary Rituals from a Community-Based Perspective. Baylor University Thesis, Texas

- ^ Walker, Thomas A (1888). The Severn Tunnel Its Construction and Difficulties. London: Richard Bentley and Son. p. 92.

- ^ «Scientific and Industrial Notes». Manchester Times. Manchester, England: 8. 13 May 1882.

- ^ US Patent 255042, 14 March 1882

- ^

- ^ «Riddle solved: Why was Roman concrete so durable?», MIT News, January 6, 2023

- ^ Plutarch, «Sertorius 17.1–7», Parallel Lives

- ^ Adrienne Mayor (2005), «Ancient Warfare and Toxicology», in Philip Wexler (ed.), Encyclopedia of Toxicology, vol. 4 (2nd ed.), Elsevier, pp. 117–121, ISBN 0-12-745354-7

- ^ Croddy, Eric (2002). Chemical and biological warfare: a comprehensive survey for the concerned citizen. Springer. p. 128. ISBN 0-387-95076-1.

- ^ David Hume (1756). History of England. Vol. I.

- ^ Sayers, W. (2006). «The Use of Quicklime in Medieval Naval Warfare». The Mariner’s Mirror. Volume 92. Issue 3. pp. 262–269.

- ^ «Lime» (PDF). Prd-wret.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com. p. 96. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ ww25.hazard.com http://ww25.hazard.com/msds/mf/baker/baker/files/c0462.htm?subid1=20230203-0103-092e-9982-d576d3e248aa. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ «List of Minerals». Ima-mineralogy.org. 21 March 2011.

- ^ Fiquet, G.; Richet, P.; Montagnac, G. (Dec 1999). «High-temperature thermal expansion of lime, periclase, corundum and spinel». Physics and Chemistry of Materials. 27 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1007/s002690050246. S2CID 93706828. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ «Lime». Mindat.org. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

External links[edit]

- Lime Statistics & Information from the United States Geological Survey

- Factors Affecting the Quality of Quicklime

- American Scientist (discussion of 14C dating of mortar)

- Chemical of the Week – Lime

- Material Safety Data Sheet

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

| Оксид кальция | |

|

|

| Общие | |

|---|---|

| Систематическое наименование | Оксид кальция |

| Химическая формула | CaO |

| Физические свойства | |

| Состояние (ст. усл.) | твердое |

| Молярная масса | 56.077 г/моль |

| Плотность | 3.37 г/см³ |

| Термические свойства | |

| Температура плавления | 2570 °C |

| Температура кипения | 2850 °C |

| Молярная теплоёмкость (ст. усл.) | 42.05 Дж/(моль·К) |

| Энтальпия образования (ст. усл.) | -635,09 кДж/моль |

Окси́д ка́льция (окись кальция, негашёная и́звесть или «кипелка», «кираби́т») — белое кристаллическое вещество, формула CaO.

Негашёная известь и продукт её взаимодействия с водой — Ca(OH)2 (гашёная известь или «пушонка») находят обширное использование в строительном деле.

Содержание

- 1 Получение

- 2 Физические свойства

- 3 Химические свойства

- 4 Применение

- 5 Источники и литература

- 6 Ссылки

Получение

В промышленности оксид кальция получают термическим разложением известняка (карбоната кальция):

Также оксид кальция можно получить при взаимодействии простых веществ:

или при термическом разложении гидроксида кальция и кальциевых солей некоторых кислородсодержащих кислот:

Физические свойства

Оксид кальция — белое кристаллическое вещество, кристаллизующееся в кубической гранецентрированной кристаллической решетке, по типу хлорида натрия.

Химические свойства

Оксид кальция относится к основным оксидам. Растворяется в воде с выделением энергии, образуя гидроксид кальция:

-

+ 63.7кДж/моль

Как основный оксид реагирует с кислотными оксидами и кислотами, образуя соли:

Применение

Основные объёмы используются в строительстве при производстве Силикатного кирпича. Раньше известь, так же использовали в качестве известкового цемента — при смешивании с водой, оксид кальция переходит в гидроксид, который далее, поглощая из воздуха углекислый газ, сильно твердеет, превращаясь в карбонат кальция. Однако в настоящее время известковый цемент при строительстве жилых домов стараются не применять, так как полученные строения обладают способностью впитывать и накапливать сырость.

Категорически недопустимо использование известкового цемента при кладке печей — из-за термического разложения и выделения в воздух удушливого диоксида углерода.

Некоторое применение также находит в качестве доступного и недорогого огнеупорного материала — плавленный оксид кальция имеет некоторую устойчивость к воздействию воды, что позволяет его использовать в качестве огнеупора там, где применение более дорогих материалов нецелесообразно.

В небольших количествах оксид кальция также используется в лабораторной практике для осушения веществ, которые не реагируют с ним.

В пищевой промышленности зарегистрирован в качестве пищевой добавки E-529.

В промышленности для удаления диоксида серы из дымовых газов, как правило используют 15% водяной раствор. В результате реакции гашеной извести и диоксида серы получается гипс СaСO3 и СаSO4. В эксперементальных установках добивались показателя в 98% отчиски дымовых газов от диоксида серы.

Так же используется в «самогреющей» посуде. Контейнер с небольшим количеством оксида кальция помещается между двух стенок стакана, а при прокалывании капсулы с водой начинается реакция с выделением тепла.

Источники и литература

- Монастырев А. Производство цемента, извести. Москва, 2007.

- Штарк Йохан, Вихт Бернд. Цемент и известь (Пер. с нем.). Киев, 2008.

Ссылки

- http://www.allbeton.ru/library/78.html

- http://community.livejournal.com/kaduy/38246.html

|

Соединения кальция |

|---|

|

Алюминаты кальция (mCaO·nAl2O3) • Алюмогидрид кальция (Ca[AlH4]2) • Амид кальция (Ca(NH2)2) • Арсенат кальция (Ca3(AsO4)2) • Ацетат кальция ((CH3COO)2Ca) • Бисульфид кальция (Ca(HS)2) • Борат кальция (Ca3(BO3)2) • Бромид кальция (CaBr2) • Вольфрамат кальция (CaWO4) • Гексаборид кальция (CaB6) • Гексафторсиликат кальция (CaSiF6) • Гидрид кальция (CaH2) • Гидроксид кальция (Ca(OH)2) • Гидроортофосфат кальция (CaHPO4) • Гипофосфит кальция (Ca(PH2O2)) • Гипохлорит кальция (Ca(ClO)2) • Глицерофосфат кальция (C3H7CaO6P) • Глюконат кальция (C12H22CaO14) • Дигидрокарбонат кальция (Ca(HCO3)2) • 2,5-дигидроксибензолсульфонат кальция (C12H10CaO10S2) • Дигидроортофосфат кальция (Ca(H2PO4)2) • Иодат кальция (Ca(IO3)2) • Иодид кальция (CaI2) • Карбид кальция (CaC2) • Карбонат кальция (CaCO3) • Моносилицид кальция (CaSi) • Нитрат кальция (Са(NО3)2) • Нитрид кальция (Ca3N2) • Оксалат кальция (СаС2О4) • Оксид кальция (CaO) • Ортофосфат кальция (Ca3(PO4)2) • Перманганат кальция (Ca(MnO4)2) • Пероксид кальция (CaO2) • Пирофосфат кальция (Ca2P2O7) • Силикат кальция (CaSiO3) • Силицид дикальция (Ca2Si) • Силицид кальция (CaSi2) • Сульфат кальция (CaSO4) • Сульфид кальция (CaS) • Сульфит кальция (CaSO3) • Тетрагидроалюминат кальция (Ca(AlH4)2) • Титанат кальция (CaTiO3) • Триметафосфат кальция (Ca3(P3O9)2) • Флюорит (CaF2) • Формиат кальция (Ca(HCOO)2) • Фосфид кальция (Ca3P2) • Фторид кальция (CaF2) • Хлорат кальция (Ca(ClO3)2) • Хлорид кальция (CaCl2) • Хлорная известь (Ca(Cl)OCl) • Хромат кальция (CaCrO4) • Цианамид кальция (CaCN2) • Цианид кальция (Ca(CN)2) • Цитрат кальция (Ca3(C6H5O7)2) • |

Физические свойства

Оксид кальция CaO — бинарное неорганическое вещество. Белый, гигроскопичный. Тугоплавкий, термически устойчивый, летучий при очень высоких температурах. Проявляет основные свойства.

Относительная молекулярная масса Mr = 56,08; относительная плотность для тв. и ж. состояния d = 3,35; tпл ≈ 2614º C; tкип = 2850º C.

Способ получения

1. Оксид кальция получается при разложении карбоната кальция при температуре 900 — 1200º C. В результате разложения образуется оксид кальция и углекислый газ:

CaCO3 = CaO + CO2

2. В результате взаимодействия гидрида кальция и кислорода при температуре 300 — 400º С образуется оксид кальция и вода:

CaH2 + O2 = CaO + H2O

3. Оксид кальция можно получить сжиганием кальция в в кислороде при температуре выше 300º С:

2Ca + O2 = 2CaO

Химические свойства

1. Оксид кальция реагирует с простыми веществами:

Оксид кальция реагирует с углеродом (коксом) при температуре 1900 — 1950º С и образует угарный газ и карбид кальция:

CaO + 3C = CaC2 + CO

2. Оксид кальция взаимодействует со сложными веществами:

2.1. Оксид кальция взаимодействует с кислотами:

2.1.1. Оксид кальция с разбавленной соляной кислотой образует хлорид кальция и воду:

CaO + 2HCl = CaCl2 + H2O

2.1.2. Оксид кальция вступает во взаимодействие с разбавленной плавиковой кислотой с образованием фторида кальция и воды:

CaO + 2HF = CaF2↓ + H2O

2.1.3. Оксид кальция вступает в реакцию с разбавленной фосфорной кислотой, образуя фосфат кальция и воду:

3CaO + 2H3PO4 = Ca3(PO4)2↓ + 3H2O

2.2. Оксид кальция реагирует с оксидами:

2.2.1. Оксид кальция при комнатной температуре реагирует с углекислым газом с образованием карбоната кальция:

CaO + CO2 = CaCO3

2.2.2. Взаимодействуя с оксидом кремния при 1100 — 1200º С оксид кальция образует силикат кальция:

CaO + SiO2 = CaSiO3

2.3. Оксид кальция взаимодействует с водой при комнатной температуре, образуя гидроксид кальция:

CaO + H2O = Ca(OH)2

Справочник содержит названия веществ и описания химических формул (в т.ч. структурные формулы и скелетные формулы).

Введите часть названия или формулу для поиска:

Общее число найденных записей: 1.

Показано записей: 1.

Оксид кальция

Брутто-формула:

CaO

CAS# 1305-78-8

Названия

Русский:

- Оксид кальция(IUPAC) [Wiki]

- кальция оксид

- окись кальция, негашёная и́звесть

Варианты формулы:

Реакции, в которых участвует Оксид кальция

-

{M}O + H2{A} -> {M}{A} + H2O

, где M =

Cu Ca Mg Ba Sr Hg Mn Cr Ni Fe Zn Pb Co; A =

SO4 -

{M}O + 2H{X} -> {M}{X}2 + H2O

, где M =

Cu Ca Mg Sr Ba Hg Mn Cr Ni Fe Cd Zn Pb; X =

Cl F Br I -

{M}O + H2O -> {M}(OH)2

, где M =

Ca Sr Ba -

{M}O + SO3 -> {M}SO4

, где M =

Ca Ba Sr -

SiO2 + CaO -> CaSiO3

Оксид кальция, характеристика, свойства и получение, химические реакции.

Оксид кальция – неорганическое вещество, имеет химическую формулу CaO.

Краткая характеристика оксида кальция

Физические свойства оксида кальция Иные свойства оксида кальция

Получение оксида кальция

Химические свойства оксида кальция

Химические реакции оксида кальция

Применение и использование оксида кальция

Краткая характеристика оксида кальция:

Оксид кальция – неорганическое вещество, порошок от белого до бледно-жёлтого цвета либо бесцветные кристаллы. Не имет запаха.

Так как валентность кальция равна двум, то оксид кальция содержит один атом кислорода и один атом кальция.

Химическая формула оксида кальция CaO.

Оксид кальция широко известен как негашёная известь.

Оксид кальция в воде не растворяется, а вступает в реакцию с ней. Практически не растворяется в этаноле. Не растворяется в диэтиловом эфире.

Оксид кальция относится к высокотоксическим веществам. Класс опасности 2. Это едкое вещество, особенно опасен при смешивании с водой.

Препарат в виде пыли и капель взвеси раздражает слизистые оболочки органов дыхания, попадая на кожу, вызывает тяжелые ожоги, особенно сильно действует на слизистую оболочку глаз.

Предельно допустимая концентрация в воздухе рабочей зоны производственных помещений – 3 мг/м3.

При работе с препаратом следует применять индивидуальные средства защиты (респираторы, защитные очки, резиновые перчатки), а также соблюдать меры личной гигиены. Не допускать попадания препарата на слизистые оболочки и на кожу.

Помещения, в которых проводятся работы с препаратом, должны быть оборудованы общей приточно-вытяжной вентиляцией, а места наибольшего пыления – укрытиями с местной вытяжной вентиляцией. Испытания препарата в лабораториях следует проводить в вытяжном шкафу.

При проведении анализа окиси кальция с использованием горючего газа следует соблюдать меры противопожарной безопасности.

См. ГОСТ 8677-76 Реактивы. Кальция оксид. Технические условия (с Изменением N 1).

Физические свойства оксида кальция:

| Наименование параметра: | Значение: |

| Химическая формула | CaO |

| Синонимы и названия иностранном языке | calcium oxide (англ.) известь негашеная (рус.) кальция окись (рус.) |

| Тип вещества | неорганическое |

| Внешний вид | порошок от белого до бледно-жёлтого цвета либо бесцветные кристаллы, без запаха |

| Цвет | бесцветный, от белого до бледно-жёлтого |

| Вкус | —* |

| Запах | не имеет |

| Агрегатное состояние (при 20 °C и атмосферном давлении 1 атм.) | твердое вещество |

| Плотность (состояние вещества – твердое вещество, при 20 °C), кг/м3 | 3370 |

| Плотность (состояние вещества – твердое вещество, при 20 °C), г/см3 | 3,37 |

| Температура кипения, °C | 2850 |

| Температура плавления, °C | 2570 |

| Температура возгонки (сублимации), °C | не имеет |

| Температура разложения, °C | не имеет |

| Молярная масса, г/моль | 56,0774 |

* Примечание:

— нет данных.

Получение оксида кальция:

Оксид кальция получается в результате следующих химических реакций:

- 1. путем термического разложения известняка:

Сa2СО3 → CaО + СО2 (t = 900-1200 oC).

Это промышленный способ получения оксида кальция. Технологически данный процесс в промышленности реализуют в специальных шахтных печах.

- 2. путем сжигания кальция на воздухе:

2Сa + О2 → 2CaО (t = 300 oC).

- 3. путем термического разложения гидроксида кальция:

Сa(OH)2 → СaO + H2О (t = 520-580 oC).

- 4. путем термического разложения нитрата кальция:

2Сa(NO3)2 → 2СaO + 4NO2 + O2 (t = 450-500 oC).

Химические свойства оксида кальция. Химические реакции оксида кальция:

Оксид кальция относится к основным оксидам.

Химические свойства оксида кальция аналогичны свойствам основных оксидов других металлов. Поэтому для него характерны следующие химические реакции:

1. реакция оксида кальция с хлором:

2CaO + 2Cl2 → 2CaCl2 + O2 (t = 700 oC).

В результате реакции образуется хлорид кальция и кислород.

2. реакция оксида кальция с кремнием:

2CaO + 5Si → 2CaSi2 + SiO2 (t = 1300 oC).

В результате реакции образуется силицид кальция и оксид кремния.

3. реакция оксида кальция с углеродом:

CaО + 3С → CaС2 + СО (t = 1900-1950 oC);

2CaO + 5C → 2CaC2 + CO2 (t = 700 oC).

В результате реакции образуется карбид кальция и оксид углерода.

4. реакция оксида кальция с алюминием:

4CaО + 2Al → 2Ca + Ca(AlO2)2 (t = 1200 oC);

2Al + 6CaO → 3CaO•Al2O3 + 3Ca (to);

2Al + 6CaO → Ca3Al2O6 + 3Ca (to).

В результате реакции образуется кальций и соответственно алюминат кальция, оксид алюминия-кальция и алюмината трикальция.

5. реакция оксида кальция с водой:

CaО + Н2О → Ca(ОН)2.

Оксид кальция реагирует с водой, образуя гидроксид кальция. Процесс имеет название «гашение извести». Химическая реакция происходит с выделением энергии (тепла).

6. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом углерода (углекислым газом):

CaО + СО2 → CaСО3.

Оксид кальция реагирует с углекислым газом (являющийся кислотным оксидом), образуя соль – карбонат кальция.

7. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом серы:

CaО + SО2 → CaSО3;

CaО + SО3 → CaSО4.

Оксид серы также является кислотным оксидом. В результате реакции образуется соответственно соль – в первом случае – сульфит кальция, во втором случае – сульфат кальция.

8. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом кремния:

CaО + SiО2 → CaSiО3 (t = 1100-1200 oC).

Оксид кремния также является кислотным оксидом. В результате реакции образуется соль – силикат кальция.

9. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом фосфора:

CaO + P2O5 → Ca(PO3)2;

3CaO + P2O5 → Ca3(PO4)2 (to);

2CaO + P2O5 → Ca2P2O7.

Оксид фосфора также является кислотным оксидом. В результате реакции образуется соль соответственно: метафосфат кальция, фосфат кальция и дифосфата кальция.

Аналогично проходят реакции оксида кальция и с другими кислотными оксидами.

10. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом алюминия:

CaО + Al2O3 → Ca(AlО2)2 (t = 1200-1300 °C).

Оксид алюминия является амфотерным оксидом. Это значит, что как амфотерный оксид оксид алюминия проявляет свойства как кислотных, так и основных соединений. В результате реакции образуется соль – алюминат кальция.

11. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом марганца:

CaО + MnO2 → CaMnO3 (t°);

Mn2O3 + CaO → CaMn2O4 (t = 900 °C).

Оксид алюминия является амфотерным оксидом. Это значит, что как амфотерный оксид оксид алюминия проявляет свойства как кислотных, так и основных соединений. В результате реакции образуется соответственно: соль – манганит кальция либо оксид марганца-кальция.

Аналогично проходят реакции оксида кальция и с другими амфотерными оксидами.

12. реакция оксида кальция с оксидом свинца:

СaО + 2PbO2 → Сa2PbО4 (tо).

В результате реакции образуется соль – плюмбит кальция. Реакция протекает при сплавлении реакционной смеси.

Аналогично проходят реакции оксида кальция и с другими оксидами.

13. реакция оксида кальция с тетраоксидом диазота:

СaО + 2N2О4 → N2O3 + Сa(NO3)2 (t = 250 °C).

Реакция идет в жидком тетраоксиде диазота. В результате реакции образуются оксид азота (III) и соль – нитрат кальция.

14. реакция оксида кальция с плавиковой кислотой:

СaO + 2HF → СaF2 + H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – фторид кальция и вода.

15. реакция оксида кальция с азотной кислотой:

СaO + 2HNO3 → 2Сa(NO3)2 + H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – нитрат кальция и вода.

Аналогично проходят реакции оксида кальция и с другими кислотами.

16. реакция оксида кальция с бромистым водородом (бромоводородом):

СaO + 2HBr → СaBr2 + H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – бромид кальция и вода.

17. реакция оксида кальция с йодоводородом:

СaO + 2HI → СaI2 + H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – йодид кальция и вода.

Применение и использование оксида кальция:

Оксид кальция используется в производстве строительных материалов, в качестве пищевой добавки E-529.

Примечание: © Фото //www.pexels.com, //pixabay.com

оксид кальция реагирует кислота 1 2 3 4 5 вода

уравнение реакций соединения масса взаимодействие оксида кальция

реакции с оксидом кальция

Коэффициент востребованности

8 958

+ 63.7кДж/моль

+ 63.7кДж/моль