Coat of arms |

|

| Latin: Universitas Harvardiana | |

|

Former names |

Harvard College |

|---|---|

| Motto | Veritas (Latin)[1] |

|

Motto in English |

Truth |

| Type | Private research university |

| Established | 1636; 387 years ago[2] |

| Founder | Massachusetts General Court |

| Accreditation | NECHE |

|

Academic affiliations |

|

| Endowment | $50.9 billion (2022)[3][4] |

| President | Lawrence Bacow |

| Provost | Alan Garber |

|

Academic staff |

~2,400 faculty members (and >10,400 academic appointments in affiliated teaching hospitals)[5] |

| Students | 21,648 (Fall 2021)[6] |

| Undergraduates | 7,153 (Fall 2021)[6] |

| Postgraduates | 14,495 (Fall 2021)[6] |

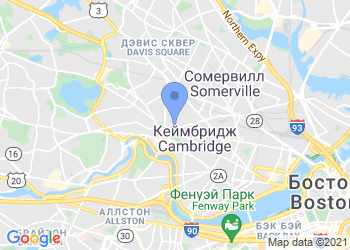

| Location |

Cambridge , Massachusetts , United States 42°22′28″N 71°07′01″W / 42.37444°N 71.11694°WCoordinates: 42°22′28″N 71°07′01″W / 42.37444°N 71.11694°W |

| Campus | Midsize city[7], 209 acres (85 ha) |

| Newspaper | The Harvard Crimson |

| Colors | Crimson, white, and black[8] |

| Nickname | Crimson |

|

Sporting affiliations |

NCAA Division I FCS – Ivy League |

| Mascot | John Harvard |

| Website | harvard.edu |

|

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and one of the most prestigious worldwide.[a]

Harvard’s founding was authorized by the Massachusetts colonial legislature, «dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust»; though never formally affiliated with any denomination, in its early years Harvard College primarily trained Congregational clergy. Its curriculum and student body were gradually secularized during the 18th century. By the 19th century, Harvard emerged as the most prominent academic and cultural institution among the Boston elite.[9][10] Following the American Civil War, under President Charles William Eliot’s long tenure (1869–1909), the college developed multiple affiliated professional schools that transformed the college into a modern research university. In 1900, Harvard co-founded the Association of American Universities.[11] James B. Conant led the university through the Great Depression and World War II, and liberalized admissions after the war.

The university is composed of ten academic faculties plus Harvard Radcliffe Institute. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences offers study in a wide range of undergraduate and graduate academic disciplines, and other faculties offer only graduate degrees, including professional degrees. Harvard has three main campuses:[12]

the 209-acre (85 ha) Cambridge campus centered on Harvard Yard; an adjoining campus immediately across Charles River in the Allston neighborhood of Boston; and the medical campus in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area.[13] Harvard’s endowment is valued at $50.9 billion, making it the wealthiest academic institution in the world.[3][4] Endowment income enables the undergraduate college to admit students regardless of financial need and provide generous financial aid with no loans.[14] Harvard Library is the world’s largest academic library system, comprising 79 individual libraries holding 20 million items.[15][16][17][18]

Throughout its existence, Harvard alumni, faculty, and researchers have included numerous heads of state, Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, members of Congress, MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Fulbright Scholars; by most metrics, Harvard ranks at the top, or near the top, of all universities globally in each of these categories.[b] Its alumni include eight U.S. presidents and 188 living billionaires, the most of any university. Fourteen Turing Award laureates have been Harvard affiliates. Students and alumni have won 10 Academy Awards, 48 Pulitzer Prizes, and 110 Olympic medals (46 gold), and they have founded many notable companies.

History

Colonial era

The Harvard Corporation seal found on Harvard diplomas. Christo et Ecclesiae («For Christ and Church») is one of Harvard’s several early mottoes.[19]

Harvard was established in 1636 in the colonial, pre-Revolutionary era by vote of the Great and General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1638, the university acquired British North America’s first known printing press.[20][21]

In 1639, it was named Harvard College after John Harvard, an English clergyman who had died soon after immigrating to Massachusetts, bequeathed it £780 and his library of some 320 volumes.[22] The charter creating Harvard Corporation was granted in 1650.

A 1643 publication defined the university’s purpose: «to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.»[23] The college trained many Puritan ministers in its early years[24]

and offered a classic curriculum that was based on the English university model—many leaders in the colony had attended the University of Cambridge—but also conformed to the tenets of Puritanism. While Harvard never affiliated with any particular denomination, many of its earliest graduates went on to become Puritan clergymen.[25]

Increase Mather served as Harvard College’s president from 1681 to 1701. In 1708, John Leverett became the first president who was not also a clergyman, marking a turning of the college away from Puritanism and toward intellectual independence.[26]

19th century

In the 19th century, Enlightenment ideas of reason and free will were widespread among Congregational ministers, putting those ministers and their congregations at odds with more traditionalist, Calvinist parties.[27]: 1–4 When Hollis Professor of Divinity David Tappan died in 1803 and President Joseph Willard died a year later, a struggle broke out over their replacements. Henry Ware was elected Hollis chair in 1805, and liberal Samuel Webber was appointed president two years later, signaling a shift from traditional ideas at Harvard to liberal, Arminian ideas.[27]: 4–5 [28]: 24

Charles William Eliot, Harvard president from 1869–1909, eliminated the favored position of Christianity from the curriculum while opening it to student self-direction. Though Eliot was an influential figure in the secularization of American higher education, he was motivated more by Transcendentalist Unitarian convictions influenced by William Ellery Channing, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and others of the time than by secularism.[29]

In 1816, Harvard launched new programs in the study of French and Spanish with George Ticknor as first professor for these language programs.

20th century

Richard Rummell’s 1906 watercolor landscape view, facing northeast.[30]

Harvard’s graduate schools began admitting women in small numbers in the late 19th century. During World War II, students at Radcliffe College (which, since its 1879 founding, had been paying Harvard professors to repeat their lectures for women) began attending Harvard classes alongside men.[31] In 1945, women were first admitted to the medical school.[32]

Since 1971, Harvard had controlled essentially all aspects of undergraduate admission, instruction, and housing for Radcliffe women; in 1999, Radcliffe was formally merged into Harvard.[33]

In the 20th century, Harvard’s reputation grew as its endowment burgeoned and prominent intellectuals and professors affiliated with the university. The university’s rapid enrollment growth also was a product of both the founding of new graduate academic programs and an expansion of the undergraduate college. Radcliffe College emerged as the female counterpart of Harvard College, becoming one of the most prominent schools for women in the United States. In 1900, Harvard became a founding member of the Association of American Universities.[11]

The student body in its first decades of the 20th century was predominantly «old-stock, high-status Protestants, especially Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians,» according to sociologist and author Jerome Karabel.[34] In 1923, a year after the percentage of Jewish students at Harvard reached 20%, President A. Lawrence Lowell supported a policy change that would have capped the admission of Jewish students to 15% of the undergraduate population. But Lowell’s idea was rejected. Lowell also refused to mandate forced desegregation in the university’s freshman dormitories, writing that, «We owe to the colored man the same opportunities for education that we do to the white man, but we do not owe to him to force him and the white into social relations that are not, or may not be, mutually congenial.»[35][36][37][38]

President James B. Conant led the university from 1933 to 1953; Conant reinvigorated creative scholarship in an effort to guarantee Harvard’s preeminence among the nation and world’s emerging research institutions. Conant viewed higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy. As such, he devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. An influential 268-page report issued by Harvard faculty in 1945 under Conant’s leadership, General Education in a Free Society, remains one the most important works in curriculum studies.[39]

Between 1945 and 1960, admissions standardized to open the university to a more diverse group of students; for example, after World War II, special exams were developed so veterans could be considered for admission.[40] No longer drawing mostly from select New England prep schools, the undergraduate college became accessible to striving middle class students from public schools; many more Jews and Catholics were admitted, but still few Blacks, Hispanics, or Asians versus the representation of these demoraphics in the general population.[41] Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Harvard incrementally became vastly more diverse.[42]

21st century

Drew Gilpin Faust, who was dean of Harvard Radcliffe Institute, became Harvard’s first female president on July 1, 2007.[43] In 2018, Faust retired and joined the board of Goldman Sachs.

On July 1, 2018, Lawrence Bacow was appointed Harvard’s 29th president.[44] Bacow intends to retire in 2023, and on December 15, 2022, it was announced that Claudine Gay will succeed him.

Campuses

Cambridge

Harvard’s 209-acre (85 ha) main campus is centered on Harvard Yard («the Yard») in Cambridge, about 3 miles (5 km) west-northwest of downtown Boston, and extends into the surrounding Harvard Square neighborhood. The Yard contains administrative offices such as University Hall and Massachusetts Hall; libraries such as Widener, Pusey, Houghton, and Lamont; and Memorial Church.

The Yard and adjacent areas include the main academic buildings of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, including the college, such as Sever Hall and Harvard Hall.

Freshman dormitories are in, or adjacent to, the Yard. Upperclassmen live in the twelve residential houses – nine south of the Yard near the Charles River, the others half a mile northwest of the Yard at the Radcliffe Quadrangle (which formerly housed Radcliffe College students). Each house is a community of undergraduates, faculty deans, and resident tutors, with its own dining hall, library, and recreational facilities.[45]

Also in Cambridge are the Law, Divinity (theology), Engineering and Applied Science, Design (architecture), Education, Kennedy (public policy), and Extension schools, as well as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in Radcliffe Yard.[46]

Harvard also has commercial real estate holdings in Cambridge.[47][48]

Allston

Harvard Business School, Harvard Innovation Labs, and many athletics facilities, including Harvard Stadium, are located on a 358-acre (145 ha) campus in Allston,[49]

a Boston neighborhood just across the Charles River from the Cambridge campus. The John W. Weeks Bridge, a pedestrian bridge over the Charles River, connects the two campuses.

The university is actively expanding into Allston, where it now owns more land than in Cambridge.[50]

Plans include new construction and renovation for the Business School, a hotel and conference center, graduate student housing, Harvard Stadium, and other athletics facilities.[51]

In 2021, the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences will expand into a new, 500,000+ square foot Science and Engineering Complex (SEC) in Allston.[52]

The SEC will be adjacent to the Enterprise Research Campus, the Business School, and the Harvard Innovation Labs to encourage technology- and life science-focused startups as well as collaborations with mature companies.[53]

Longwood

The schools of Medicine, Dental Medicine, and Public Health are located on a 21-acre (8.5 ha) campus in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area in Boston, about 3.3 miles (5.3 km) south of the Cambridge campus.[13]

Several Harvard-affiliated hospitals and research institutes are also in Longwood, including Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Joslin Diabetes Center, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. Additional affiliates, most notably Massachusetts General Hospital, are located throughout the Greater Boston area.

Other

Harvard owns the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, D.C., the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts, the Concord Field Station in Estabrook Woods in Concord, Massachusetts,[54]

the Villa I Tatti research center in Florence, Italy,[55]

the Harvard Shanghai Center in Shanghai, China,[56]

and the Arnold Arboretum in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston.

Organization and administration

Governance

| School | Founded |

| Harvard College | 1636 |

| Medicine | 1782 |

| Divinity | 1816 |

| Law | 1817 |

| Dental Medicine | 1867 |

| Arts and Sciences | 1872 |

| Business | 1908 |

| Extension | 1910 |

| Design | 1914 |

| Education | 1920 |

| Public Health | 1922 |

| Government | 1936 |

| Engineering and Applied Sciences | 2007 |

Harvard is governed by a combination of its Board of Overseers and the President and Fellows of Harvard College (also known as the Harvard Corporation), which in turn appoints the President of Harvard University.[57]

There are 16,000 staff and faculty,[58]

including 2,400 professors, lecturers, and instructors.[59]

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences is the largest Harvard faculty and has primary responsibility for instruction in Harvard College, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and the Division of Continuing Education, which includes Harvard Summer School and Harvard Extension School. There are nine other graduate and professional faculties as well as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Joint programs with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology include the Harvard–MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology, the Broad Institute, The Observatory of Economic Complexity, and edX.

Endowment

Harvard has the largest university endowment in the world, valued at about $50.9 billion as of 2022.[3][4]

During the recession of 2007–2009, it suffered significant losses that forced large budget cuts, in particular temporarily halting construction on the Allston Science Complex.[60]

The endowment has since recovered.[61][62][63][64]

About $2 billion of investment income is annually distributed to fund operations.[65]

Harvard’s ability to fund its degree and financial aid programs depends on the performance of its endowment; a poor performance in fiscal year 2016 forced a 4.4% cut in the number of graduate students funded by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.[66]

Endowment income is critical, as only 22% of revenue is from students’ tuition, fees, room, and board.[67]

Divestment

Since the 1970s, several student-led campaigns have advocated divesting Harvard’s endowment from controversial holdings, including investments in apartheid South Africa, Sudan during the Darfur genocide, and the tobacco, fossil fuel, and private prison industries.[68][69]

In the late 1980s, during the divestment from South Africa movement, student activists erected a symbolic «shantytown» on Harvard Yard and blockaded a speech by South African Vice Consul Duke Kent-Brown.[70][71]

The university eventually reduced its South African holdings by $230 million (out of $400 million) in response to the pressure.[70][72]

Academics

Teaching and learning

Harvard is a large, highly residential research university[74]

offering 50 undergraduate majors,[75]

134 graduate degrees,[76]

and 32 professional degrees.[77]

During the 2018–2019 academic year, Harvard granted 1,665 baccalaureate degrees, 1,013 graduate degrees, and 5,695 professional degrees.[77]

The four-year, full-time undergraduate program has a liberal arts and sciences focus.[74][75]

To graduate in the usual four years, undergraduates normally take four courses per semester.[78]

In most majors, an honors degree requires advanced coursework and a senior thesis.[79]

Though some introductory courses have large enrollments, the median class size is 12 students.[80]

Research

Harvard is a founding member of the Association of American Universities[81] and a preeminent research university with «very high» research activity (R1) and comprehensive doctoral programs across the arts, sciences, engineering, and medicine according to the Carnegie Classification.[74]

With the medical school consistently ranking first among medical schools for research,[82] biomedical research is an area of particular strength for the university. More than 11,000 faculty and over 1,600 graduate students conduct research at the medical school as well as its 15 affiliated hospitals and research institutes.[83] The medical school and its affiliates attracted $1.65 billion in competitive research grants from the National Institutes of Health in 2019, more than twice as much as any other university.[84]

Libraries and museums

The Harvard Library system is centered in Widener Library in Harvard Yard and comprises nearly 80 individual libraries holding about 20.4 million items.[15][16][18]

According to the American Library Association, this makes it the largest academic library in the world.[16][5]

Houghton Library, the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, and the Harvard University Archives consist principally of rare and unique materials. America’s oldest collection of maps, gazetteers, and atlases both old and new is stored in Pusey Library and open to the public. The largest collection of East-Asian language material outside of East Asia is held in the Harvard-Yenching Library

The Harvard Art Museums comprise three museums. The Arthur M. Sackler Museum covers Asian, Mediterranean, and Islamic art, the Busch–Reisinger Museum (formerly the Germanic Museum) covers central and northern European art, and the Fogg Museum covers Western art from the Middle Ages to the present emphasizing Italian early Renaissance, British pre-Raphaelite, and 19th-century French art. The Harvard Museum of Natural History includes the Harvard Mineralogical Museum, the Harvard University Herbaria featuring the Blaschka Glass Flowers exhibit, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Other museums include the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, designed by Le Corbusier and housing the film archive, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, specializing in the cultural history and civilizations of the Western Hemisphere, and the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East featuring artifacts from excavations in the Middle East.

Reputation and rankings

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[85] | 1 |

| Forbes[86] | 15 |

| THE / WSJ[87] | 1 |

| U.S. News & World Report[88] | 3 |

| Washington Monthly[89] | 6 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[90] | 1 |

| QS[91] | 5 |

| THE[92] | 2 |

| U.S. News & World Report[93] | 1 |

| National Graduate Rankings[94] | |

|---|---|

| Program | Ranking |

| Biological Sciences | 4 |

| Business | 6 |

| Chemistry | 2 |

| Clinical Psychology | 10 |

| Computer Science | 16 |

| Earth Sciences | 8 |

| Economics | 1 |

| Education | 1 |

| Engineering | 22 |

| English | 8 |

| History | 4 |

| Law | 3 |

| Mathematics | 2 |

| Medicine: Primary Care | 10 |

| Medicine: Research | 1 |

| Physics | 3 |

| Political Science | 1 |

| Psychology | 3 |

| Public Affairs | 3 |

| Public Health | 2 |

| Sociology | 1 |

| Global Subject Rankings[95] | |

|---|---|

| Program | Ranking |

| Agricultural Sciences | 22 |

| Arts & Humanities | 2 |

| Biology & Biochemistry | 1 |

| Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems | 1 |

| Chemistry | 15 |

| Clinical Medicine | 1 |

| Computer Science | 47 |

| Economics & Business | 1 |

| Electrical & Electronic Engineering | 136 |

| Engineering | 27 |

| Environment/Ecology | 5 |

| Geosciences | 7 |

| Immunology | 1 |

| Materials Science | 7 |

| Mathematics | 12 |

| Microbiology | 1 |

| Molecular Biology & Genetics | 1 |

| Neuroscience & Behavior | 1 |

| Oncology | 1 |

| Pharmacology & Toxicology | 1 |

| Physics | 4 |

| Plant & Animal Science | 13 |

| Psychiatry/Psychology | 1 |

| Social Sciences & Public Health | 1 |

| Space Science | 2 |

| Surgery | 1 |

Among overall rankings, the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) has ranked Harvard as the world’s top university every year since it was released.[96]

When QS and Times Higher Education collaborated to publish the Times Higher Education–QS World University Rankings from 2004 to 2009, Harvard held the top spot every year and continued to hold first place on THE World Reputation Rankings ever since it was released in 2011.[97]

In 2019, it was ranked first worldwide by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[98] It was ranked in the first tier of American research universities, along with Columbia, MIT, and Stanford, in the 2019 report from the Center for Measuring University Performance.[99] Harvard University is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[100]

Among rankings of specific indicators, Harvard topped both the University Ranking by Academic Performance (2019–2020) and Mines ParisTech: Professional Ranking of World Universities (2011), which measured universities’ numbers of alumni holding CEO positions in Fortune Global 500 companies.[101]

According to annual polls done by The Princeton Review, Harvard is consistently among the top two most commonly named dream colleges in the United States, both for students and parents.[102][103][104]

Additionally, having made significant investments in its engineering school in recent years, Harvard was ranked third worldwide for Engineering and Technology in 2019 by Times Higher Education.[105]

In international relations, Foreign Policy magazine ranks Harvard best in the world at the undergraduate level and second in the world at the graduate level, behind the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.[106]

| School | Founded | Enrollment | U.S. News & World Report |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvard University | 1636 | 31,345[107] | 3[108] |

| Medicine | 1782 | 660 | 1[109] |

| Divinity | 1816 | 377 | N/A |

| Law | 1817 | 1,990 | 4[110] |

| Dental Medicine | 1867 | 280 | N/A |

| Arts and Sciences | 1872 | 4,824 | N/A |

| Business | 1908 | 2,011 | 5[111] |

| Extension | 1910 | 3,428 | N/A |

| Design | 1914 | 878 | N/A |

| Education | 1920 | 876 | 2[112] |

| Public Health | 1922 | 1,412 | 3[111] |

| Government | 1936 | 1,100 | 6[113] |

| Engineering | 2007 | 1,750 | 21[114] |

Student life

| Race and ethnicity[115] | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| White | 36% | |

| Asian | 21% | |

| Hispanic | 12% | |

| Foreign national | 11% | |

| Black | 11% | |

| Other[c] | 9% | |

| Economic diversity | ||

| Low-income[d] | 18% | |

| Affluent[e] | 82% |

Student life and activities are generally organized within each school.

Student government

The Undergraduate Council represents College students. The Graduate Council represents students at all twelve graduate and professional schools, most of which also have their own student government.[116]

Athletics

Both the undergraduate College and the graduate schools have intramural sports programs.

Harvard College competes in the NCAA Division I Ivy League conference. The school fields 42 intercollegiate sports teams, more than any other college in the country.[117] Every two years, the Harvard and Yale track and field teams come together to compete against a combined Oxford and Cambridge team in the oldest continuous international amateur competition in the world.[118] As with other Ivy League universities, Harvard does not offer athletic scholarships.[119] The school color is crimson.

Harvard’s athletic rivalry with Yale is intense in every sport in which they meet, coming to a climax each fall in the annual football meeting, which dates back to 1875.[120]

Harvard University Gazette

The Harvard Gazette, also called the Harvard University Gazette, is the official press organ of Harvard University. Formerly a print publication, it is now a web site. It publicizes research, faculty, teaching and events at the university. Initiated in 1906, it was originally a weekly calendar of news and events. In 1968 it became a weekly newspaper.

When the Gazette was a print publication, it was considered a good way of keeping up with Harvard news: «If weekly reading suits you best, the most comprehensive and authoritative medium is the Harvard University Gazette«.

In 2010, the Gazette «shifted from a print-first to a digital-first and mobile-first» publication, and reduced its publication calendar to biweekly, while keeping the same number of reporters, including some who had previously worked for the Boston Globe, Miami Herald, and the Associated Press.

Notable people

Alumni

Over more than three and a half centuries, Harvard alumni have contributed creatively and significantly to society, the arts and sciences, business, and national and international affairs. Harvard’s alumni include eight U.S. presidents, 188 living billionaires, 79 Nobel laureates, 7 Fields Medal winners, 9 Turing Award laureates, 369 Rhodes Scholars, 252 Marshall Scholars, and 13 Mitchell Scholars.[121][122][123][124] Harvard students and alumni have won 10 Academy Awards, 48 Pulitzer Prizes, and 108 Olympic medals (including 46 gold medals), and they have founded many notable companies worldwide.[125][126]

- Notable Harvard alumni include:

-

2nd President of the United States John Adams (AB, 1755; AM, 1758)[127]

-

26th President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Theodore Roosevelt (AB, 1880)[131]

-

Author, political activist, and lecturer Helen Keller (AB, 1904, Radcliffe College)

-

Poet and Nobel laureate in literature T. S. Eliot (AB, 1909; AM, 1910)

-

Economist and Nobel laureate in economics Paul Samuelson (AM, 1936; PhD, 1941)

-

7th President of Ireland and United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson (LLM, 1968)

-

45th Vice President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Al Gore (AB, 1969)

-

11th Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto (AB, 1973, Radcliffe College)

-

14th Chair of the Federal Reserve and Nobel laureate in economics Ben Bernanke (AB, 1975; AM, 1975)

-

17th Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts (AB, 1976; JD, 1979)

-

Founder of Microsoft and philanthropist Bill Gates (College, 1977;[a 1] LLD hc, 2007)

-

8th Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon (MPA, 1984)

-

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Elena Kagan (JD, 1986)

-

44th President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Barack Obama (JD, 1991)[137][138]

- ^ a b Nominal Harvard College class year: did not graduate

Faculty

- Notable present and past Harvard faculty include:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Literature and popular culture

The perception of Harvard as a center of either elite achievement, or elitist privilege, has made it a frequent literary and cinematic backdrop. «In the grammar of film, Harvard has come to mean both tradition, and a certain amount of stuffiness,» film critic Paul Sherman has said.[139]

Literature

- The Sound and the Fury (1929) and Absalom, Absalom! (1936) by William Faulkner both depict Harvard student life.[non-primary source needed]

- Of Time and the River (1935) by Thomas Wolfe is a fictionalized autobiography that includes his alter ego’s time at Harvard.[non-primary source needed]

- The Late George Apley (1937) by John P. Marquand parodies Harvard men at the opening of the 20th century;[non-primary source needed] it won the Pulitzer Prize.

- The Second Happiest Day (1953) by John P. Marquand Jr. portrays the Harvard of the World War II generation.[140][141][142][143][144]

Film

Harvard permits filming on its property only rarely, so most scenes set at Harvard (especially indoor shots, but excepting aerial footage and shots of public areas such as Harvard Square) are in fact shot elsewhere.[145][146]

- Love Story (1970) concerns a romance between a wealthy Harvard hockey player (Ryan O’Neal) and a brilliant Radcliffe student of modest means (Ali MacGraw): it is screened annually for incoming freshmen.[147][148][149]

- The Paper Chase (1973)[150]

- A Small Circle of Friends (1980)[145]

- Prozac Nation (2001) is a psychological drama about a 19-year-old Harvard student with atypical depression.

See also

- 2012 Harvard cheating scandal

- Academic regalia of Harvard University

- Gore Hall

- Harvard College social clubs

- Harvard University Police Department

- Harvard University Press

- Harvard/MIT Cooperative Society

- I, Too, Am Harvard

- List of Harvard University named chairs

- List of Nobel laureates affiliated with Harvard University

- List of oldest universities in continuous operation

- Outline of Harvard University

- Secret Court of 1920

Notes

- ^ Harvard’s influence, wealth and rankings have made it among the most prestigious universities in the world.

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America’s University. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–481. ISBN 0-19-514457-0.

Harvard’s professional schools… won world prestige of a sort rarely seen among social institutions. […] Harvard’s age, wealth, quality, and prestige may well shield it from any conceivable vicissitudes.

- Spaulding, Christina (1989). «Sexual Shakedown». In Trumpbour, John (ed.). How Harvard Rules: Reason in the Service of Empire. South End Press. pp. 326–336. ISBN 0-89608-284-9.

… [Harvard’s] tremendous institutional power and prestige […] Within the nation’s (arguably) most prestigious institution of higher learning …

- David Altaner (March 9, 2011). «Harvard, MIT Ranked Most Prestigious Universities, Study Reports». Bloomberg. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Collier’s Encyclopedia. Macmillan Educational Co. 1986.

Harvard University, one of the world’s most prestigious institutions of higher learning, was founded in Massachusetts in 1636.

- Newport, Frank (August 26, 2003). «Harvard Number One University in Eyes of Public Stanford and Yale in second place». Gallup. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- Leonhardt, David (September 17, 2006). «Ending Early Admissions: Guess Who Wins?». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

The most prestigious college in the world, of course, is Harvard, and the gap between it and every other university is often underestimated.

- Hoerr, John (1997). We Can’t Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard. Temple University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781566395359.

- Wong, Alia (September 11, 2018). «At Private Colleges, Students Pay for Prestige». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

Americans tend to think of colleges as falling somewhere on a vast hierarchy based largely on their status and brand recognition. At the top are the Harvards and the Stanfords, with their celebrated faculty, groundbreaking research, and perfectly manicured quads.

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America’s University. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–481. ISBN 0-19-514457-0.

- ^ Universities all adopt different metrics to claim Nobel or other academic award affiliates, some generous while others conservative. The official Harvard count (around 40) only includes academicians affiliated at the time of winning the prize. Yet, the figure can be up to some 160 Nobel laureates, the most worldwide, if visitors and professors of various ranks are all included (the most generous criterium), as what some other universities do.

- «50 (US) Universities with the Most Nobel Prize Winners». www.bestmastersprograms.org. February 25, 2021. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Rachel Sugar (May 29, 2015). «Where MacArthur ‘Geniuses’ Went to College». businessinsider.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- «Top Producers». us.fulbrightonline.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- «Statistics». www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- «US Rhodes Scholars Over Time». www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- «Harvard, Stanford, Yale Graduate Most Members of Congress». Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- «The complete list of Fields Medal winners». areppim AG. 2014. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (1968). The Founding of Harvard College. Harvard University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-674-31450-4. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ An appropriation of £400 toward a «school or college» was voted on October 28, 1636 (OS), at a meeting which convened on September 8 and was adjourned to October 28. Some sources consider October 28, 1636 (OS) (November 7, 1636, NS) to be the date of founding. Harvard’s 1936 tercentenary celebration treated September 18 as the founding date, though 1836 bicentennial was celebrated on September 8, 1836. Sources: meeting dates, Quincy, Josiah (1860). History of Harvard University. 117 Washington Street, Boston: Crosby, Nichols, Lee and Co. ISBN 9780405100161.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link), p. 586 Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, «At a Court holden September 8th, 1636 and continued by adjournment to the 28th of the 8th month (October, 1636)… the Court agreed to give £400 towards a School or College, whereof £200 to be paid next year….» Tercentenary dates: «Cambridge Birthday». Time. September 28, 1936. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2006.: «Harvard claims birth on the day the Massachusetts Great and General Court convened to authorize its founding. This was Sept. 8, 1637 under the Julian calendar. Allowing for the ten-day advance of the Gregorian calendar, Tercentenary officials arrived at Sept. 18 as the date for the third and last big Day of the celebration;» «on Oct. 28, 1636 … £400 for that ‘school or college’ [was voted by] the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.» Bicentennial date: Marvin Hightower (September 2, 2003). «Harvard Gazette: This Month in Harvard History». Harvard University. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006., «Sept. 8, 1836 – Some 1,100 to 1,300 alumni flock to Harvard’s Bicentennial, at which a professional choir premieres «Fair Harvard.» … guest speaker Josiah Quincy Jr., Class of 1821, makes a motion, unanimously adopted, ‘that this assembly of the Alumni be adjourned to meet at this place on September 8, 1936.'» Tercentary opening of Quincy’s sealed package: The New York Times, September 9, 1936, p. 24, «Package Sealed in 1836 Opened at Harvard. It Held Letters Written at Bicentenary»: «September 8th, 1936: As the first formal function in the celebration of Harvard’s tercentenary, the Harvard Alumni Association witnessed the opening by President Conant of the ‘mysterious’ package sealed by President Josiah Quincy at the Harvard bicentennial in 1836.» - ^ a b c Larry Edelman (October 13, 2022). «Harvard, the richest university, is a little less rich after tough year in the markets». Boston Globe.

- ^ a b c Financial Report Fiscal Year 2022 (PDF) (Report). Harvard University. October 2022. p. 7.

- ^ a b «Harvard University Graphic Identity Standards Manual» (PDF). July 14, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c «Common Data Set 2021–2022» (PDF). Office of Institutional Research. Harvard University. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ «IPEDS – Harvard University».

- ^ «Color Scheme» (PDF). Harvard Athletics Brand Identity Guide. July 27, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Story, Ronald (1975). «Harvard and the Boston Brahmins: A Study in Institutional and Class Development, 1800–1865». Journal of Social History. 8 (3): 94–121. doi:10.1353/jsh/8.3.94. S2CID 147208647.

- ^ Farrell, Betty G. (1993). Elite Families: Class and Power in Nineteenth-Century Boston. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1593-7.

- ^ a b «Member Institutions and years of Admission». aau.edu. Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ «Faculties and Allied Institutions» (PDF). harvard.edu. Office of the Provost, Harvard University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ a b «Faculties and Allied Institutions» (PDF). Office of the Provost, Harvard University. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Kurt, Daniel (October 25, 2021). «What Harvard Actually Costs». Investopedia. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ a b «Harvard Library Annual Report FY 2013». Harvard University Library. 2013. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c «The Nation’s Largest Libraries: A Listing By Volumes Held». American Library Association. May 2009. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ^ «Speaking Volumes». Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. February 26, 1998. Archived from the original on September 9, 1999.

- ^ a b Harvard Media Relations. «Quick Facts». Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (1968). The Founding of Harvard College. Harvard University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-674-31450-4. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon (March 8, 2012). «The instrument behind New England’s first literary flowering». harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ «Rowley and Ezekiel Rogers, The First North American Printing Press» (PDF). hull.ac.uk. Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Harvard, John. «John Harvard Facts, Information». encyclopedia.com. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

He bequeathed £780 (half his estate) and his library of 320 volumes to the new established college at Cambridge, Mass., which was named in his honor.

- ^ Wright, Louis B. (2002). The Cultural Life of the American Colonies (1st ed.). Dover Publications (published May 3, 2002). p. 116. ISBN 978-0-486-42223-7.

- ^ Grigg, John A.; Mancall, Peter C. (2008). British Colonial America: People and Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-59884-025-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Harvard Office of News and Public Affairs (July 26, 2007). «Harvard guide intro». Harvard University. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ John Leverett – History – Office of the President Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Dorrien, Gary J. (January 1, 2001). The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion, 1805-1900. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22354-0. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Field, Peter S. (2003). Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-8843-2. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Shoemaker, Stephen P. (2006–2007). «The Theological Roots of Charles W. Eliot’s Educational Reforms». Journal of Unitarian Universalist History. 31: 30–45.

- ^ «An Iconic College View: Harvard University, circa 1900. Richard Rummell (1848-1924)». An Iconic College View. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Schwager, Sally (2004). «Taking up the Challenge: The Origins of Radcliffe». In Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (ed.). Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 1-4039-6098-4.

- ^ First class of women admitted to Harvard Medical School, 1945 (Report). Countway Repository, Harvard University Library. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ Radcliffe Enters Historic Merger With Harvard (Report). Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Jerome Karabel (2006). The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-618-77355-8. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ «Compelled to coexist: A history of the desegregation of Harvard’s freshman housing», Harvard Crimson, November 4, 2021

- ^ Steinberg, Stephen (September 1, 1971). «How Jewish Quotas Began». Commentary. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (March 4, 1986). «Yale’s Limit on Jewish Enrollment Lasted Until Early 1960’s Book Says». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ «Lowell Tells Jews Limits at Colleges Might Help Them». The New York Times. June 17, 1922. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Kridel, Craig, ed. (2010). «General Education in a Free Society (Harvard Redbook)». Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies. Vol. 1. SAGE. pp. 400–402. ISBN 978-1-4129-5883-7.

- ^ «The Class of 1950 | News | The Harvard Crimson». www.thecrimson.com. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ Malka A. Older. (1996). Preparatory schools and the admissions process Archived September 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The Harvard Crimson, January 24, 1996

- ^ Powell, Alvin (October 1, 2018). «An update on Harvard’s diversity, inclusion efforts». The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ «Harvard Board Names First Woman President». NBC News. Associated Press. February 11, 2007. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ «Harvard University names Lawrence Bacow its 29th president». Fox News. Associated Press. February 11, 2018. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ «The Houses». Harvard College Dean of Students Office. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ «Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University». Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ «Institutional Ownership Map – Cambridge Massachusetts» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Tartakoff, Joseph M. (January 7, 2005). «Harvard Purchases Doubletree Hotel Building – News – The Harvard Crimson». www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Logan, Tim (April 13, 2016). «Harvard continues its march into Allston, with science complex». BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ «Allston Planning and Development / Office of the Executive Vice President». harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Bayliss, Svea Herbst (January 21, 2007). «Harvard unveils big campus expansion». Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ O’Rourke, Brigid (April 10, 2020). «SEAS moves opening of Science and Engineering Complex to spring semester ’21». The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ «Our Campus». harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ «Concord Field Station». mcz.harvard.edu. Harvard University. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ «Villa I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies». Itatti.it. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ «Shanghai Center». Harvard.edu. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; Shenton, Robert (2009). Harvard A to Z. Harvard University Press. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-674-02089-4. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Burlington Free Press, June 24, 2009, page 11B, «»Harvard to cut 275 jobs» Associated Press

- ^ Office of Institutional Research (2009). Harvard University Fact Book 2009–2010 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. («Faculty»)

- ^ Vidya B. Viswanathan and Peter F. Zhu (March 5, 2009). «Residents Protest Vacancies in Allston». Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Healy, Beth (January 28, 2010). «Harvard endowment leads others down». The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Hechinger, John (December 4, 2008). «Harvard Hit by Loss as Crisis Spreads to Colleges». The Wall Street Journal. p. A1.

- ^ Munk, Nina (August 2009). «Nina Munk on Hard Times at Harvard». Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Andrew M. Rosenfield (March 4, 2009). «Understanding Endowments, Part I». Forbes. Archived from the original on March 19, 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ «A Singular Mission». Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ «Admissions Cuts Concern Some Graduate Students». Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ «Financial Report» (PDF). harvard.edu. October 24, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Welton, Alli (November 20, 2012). «Harvard Students Vote 72 Percent Support for Fossil Fuel Divestment». The Nation. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Chaidez, Alexandra A. (October 22, 2019). «Harvard Prison Divestment Campaign Delivers Report to Mass. Hall». The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b George, Michael C.; Kaufman, David W. (May 23, 2012). «Students Protest Investment in Apartheid South Africa». The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Cadambi, Anjali (September 19, 2010). «Harvard University community campaigns for divestment from apartheid South Africa, 1977–1989». Global Nonviolent Action Database. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ Robert Anthony Waters Jr. (March 20, 2009). Historical Dictionary of United States-Africa Relations. Scarecrow Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8108-6291-3. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Harvard College. «A Brief History of Harvard College». Harvard College. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c «Carnegie Classifications – Harvard University». iu.edu. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ a b «Liberal Arts & Sciences». harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ «Degree Programs» (PDF). Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Handbook. pp. 28–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ a b «Degrees Awarded». harvard.edu. Office of Institutional Research, Harvard University. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ «The Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science Degrees». college.harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ «Academic Information: The Concentration Requirement». Handbook for Students. Harvard College. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- ^ «How large are classes?». harvard.edu. Harvard College. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ «Member Institutions and Years of Admission». Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ «2023 Best Medical Schools: Research». usnews.com. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Research at Harvard Medical School». hms.harvard.edu. Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ «Which schools get the most research money?». U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ «ShanghaiRanking’s Academic Ranking of World Universities». Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ «Forbes America’s Top Colleges List 2022». Forbes. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ «Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2022». The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ «2022-2023 Best National Universities». U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ «2022 National University Rankings». Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ «ShanghaiRanking’s Academic Ranking of World Universities». Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ «QS World University Rankings 2023: Top global universities». Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ «World University Rankings 2023». Times Higher Education. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ «2022-23 Best Global Universities Rankings». U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ «Harvard University’s Graduate School Rankings». U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ «Harvard University – U.S. News Global University Rankings». U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ «Academic Ranking of World Universities——Harvard University Ranking Profile». Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Archived from the original on September 8, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ «World Reputation Rankings 2016». Times Higher Education. 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ «SCImago Institutions Rankings – Higher Education – All Regions and Countries – 2019 – Overall Rank». www.scimagoir.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Lombardi, John V.; Abbey, Craig W.; Craig, Diane D. (2020). «The Top American Research Universities: 2019 Annual Report» (PDF). mup.umass.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Massachusetts Institutions – NECHE, New England Commission of Higher Education, archived from the original on August 17, 2021, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ «World Ranking». University Ranking by Academic Performance. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ «College Hopes & Worries Press Release». PR Newswire. 2016. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ «Princeton Review’s 2012 «College Hopes & Worries Survey» Reports on 10,650 Students’ & Parents’ Top 10 «Dream Colleges» and Application Perspectives». PR Newswire. 2012. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ «2019 College Hopes & Worries Press Release». 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ contact, Press (February 11, 2019). «Harvard is #3 in World University Engineering Rankings». Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ «The Best International Relations Schools in the World». Foreign Policy.

- ^ «Harvard University Campus Information, Costs and Details». www.collegeraptor.com. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ «US News National University Rankings».

- ^ «2022 Best Graduate Schools». U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ «US News Law School Rankings».

- ^ a b «2022 Best Graduate Schools». U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ «US News Best Education Programs».

- ^ «2022 Best Graduate Schools». U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ «2022 Best Graduate Schools». U.S. News & World Report. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ «College Scorecard: Harvard University». United States Department of Education. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ a) Law School Student Government [1] Archived June 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

b) School of Education Student Council [2] Archived July 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

c) Kennedy School Student Government [3] Archived June 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

d) Design School Student Forum [4] Archived June 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

e) Student Council of Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Dental Medicine [5] Archived June 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine - ^ «Harvard : Women’s Rugby Becomes 42nd Varsity Sport at Harvard University». Gocrimson.com. August 9, 2012. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ «Yale and Harvard Defeat Oxford/Cambridge Team». Yale University Athletics. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ «The Harvard Guide: Financial Aid at Harvard». Harvard University. September 2, 2006. Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Bracken, Chris (November 17, 2017). «A game unlike any other». yaledailynews.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Siliezar, Juan (November 23, 2020). «2020 Rhodes, Mitchell Scholars named». harvard.edu. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Communications, FAS (November 24, 2019). «Five Harvard students named Rhodes Scholars». The Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Kathleen Elkins (May 18, 2018). «More billionaires went to Harvard than to Stanford, MIT and Yale combined». CNBC. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ «Statistics». www.marshallscholarship.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ «Pulitzer Prize Winners». Harvard University. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ «Companies – Entrepreneurship – Harvard Business School». entrepreneurship.hbs.edu. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Barzilay, Karen N. «The Education of John Adams». Massachusetts Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ «John Quincy Adams». The White House. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Hogan, Margaret A. (October 4, 2016). «John Quincy Adams: Life Before the Presidency». Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ «HLS’s first alumnus elected as President—Rutherford B. Hayes». Harvard Law Today. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ «Theodore Roosevelt — Biographical». Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (October 4, 2016). «Franklin D. Roosevelt: Life Before the Presidency». Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Selverstone, Marc J. (October 4, 2016). «John F. Kennedy: Life Before the Presidency». Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ «Ellen Johnson Sirleaf — Biographical». www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ L. Gregg II, Gary (October 4, 2016). «George W. Bush: Life Before the Presidency». Miller Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ «Press release: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020». nobelprize.org. Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ «Barack Obama: Life Before the Presidency». Miller Center. October 4, 2016. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ «Barack H. Obama — Biographical». Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Sarah (September 24, 2010). «‘Social Network’ taps other campuses for Harvard role». Boston.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

‘In the grammar of film, Harvard has come to mean both tradition, and a certain amount of stuffiness…. Someone from Missouri who has never lived in Boston … can get this idea that it’s all trust fund babies and ivy-covered walls.’

- ^ King, Michael (2002). Wrestling with the Angel. p. 371.

…praised as an iconic chronicle of his generation and his WASP-ish class.

- ^ Halberstam, Michael J. (February 18, 1953). «White Shoe and Weak Will». Harvard Crimson.

The book is written slickly, but without distinction…. The book will be quick, enjoyable reading for all Harvard men.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (December 23, 2009). «Second Reading». The Washington Post.

’…a balanced and impressive novel…’ [is] a judgment with which I [agree].

- ^ Du Bois, William (February 1, 1953). «Out of a Jitter-and-Fritter World». The New York Times. p. BR5.

exhibits Mr. Phillips’ talent at its finest

- ^ «John Phillips, The Second Happiest Day». Southwest Review. Vol. 38. p. 267.

So when the critics say the author of «The Second Happiest Day» is a new Fitzgerald, we think they may be right.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Nathaniel L. (September 21, 1999). «University, Hollywood Relationship Not Always a ‘Love Story’«. Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on September 10, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Sarah Thomas (September 24, 2010). «‘Social Network’ taps other campuses for Harvard role». boston.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ «Never Having To Say You’re Sorry for 25 Years…» Harvard Crimson. June 3, 1996. Archived from the original on July 17, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (August 20, 2010). «The Disease: Fatal. The Treatment: Mockery». The New York Times.

- ^ Gewertz, Ken (February 8, 1996). «A Many-Splendored ‘Love Story’. Movie filmed at Harvard 25 years ago helped to define a generation». Harvard University Gazette.

- ^ Walsh, Colleen (October 2, 2012). «The Paper Chase at 40». Harvard Gazette.

Bibliography

- Abelmann, Walter H., ed. The Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology: The First 25 Years, 1970–1995 (2004). 346 pp.

- Beecher, Henry K. and Altschule, Mark D. Medicine at Harvard: The First 300 Years (1977). 569 pp.

- Bentinck-Smith, William, ed. The Harvard Book: Selections from Three Centuries (2d ed.1982). 499 pp.

- Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; and Shenton, Robert. Harvard A to Z (2004). 396 pp. excerpt and text search

- Bethell, John T. Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-674-37733-8

- Bunting, Bainbridge. Harvard: An Architectural History (1985). 350 pp.

- Carpenter, Kenneth E. The First 350 Years of the Harvard University Library: Description of an Exhibition (1986). 216 pp.

- Cuno, James et al. Harvard’s Art Museums: 100 Years of Collecting (1996). 364 pp.

- Elliott, Clark A. and Rossiter, Margaret W., eds. Science at Harvard University: Historical Perspectives (1992). 380 pp.

- Hall, Max. Harvard University Press: A History (1986). 257 pp.

- Hay, Ida. Science in the Pleasure Ground: A History of the Arnold Arboretum (1995). 349 pp.

- Hoerr, John, We Can’t Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard; Temple University Press, 1997, ISBN 1-56639-535-6

- Howells, Dorothy Elia. A Century to Celebrate: Radcliffe College, 1879–1979 (1978). 152 pp.

- Keller, Morton, and Phyllis Keller. Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America’s University (2001), major history covers 1933 to 2002 online edition

- Lewis, Harry R. Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education (2006) ISBN 1-58648-393-5

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. Three Centuries of Harvard, 1636–1936 (1986) 512pp; excerpt and text search

- Powell, Arthur G. The Uncertain Profession: Harvard and the Search for Educational Authority (1980). 341 pp.

- Reid, Robert. Year One: An Intimate Look inside Harvard Business School (1994). 331 pp.

- Rosovsky, Henry. The University: An Owner’s Manual (1991). 312 pp.

- Rosovsky, Nitza. The Jewish Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe (1986). 108 pp.

- Seligman, Joel. The High Citadel: The Influence of Harvard Law School (1978). 262 pp.

- Sollors, Werner; Titcomb, Caldwell; and Underwood, Thomas A., eds. Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-American Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe (1993). 548 pp.

- Trumpbour, John, ed., How Harvard Rules. Reason in the Service of Empire, Boston: South End Press, 1989, ISBN 0-89608-283-0

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, ed., Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. 337 pp.

- Winsor, Mary P. Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum (1991). 324 pp.

- Wright, Conrad Edick. Revolutionary Generation: Harvard Men and the Consequences of Independence (2005). 298 pp.

External links

- Official website

- Harvard University at College Navigator, a tool from the National Center for Education Statistics

Coat of arms |

|

| Latin: Universitas Harvardiana | |

|

Former names |

Harvard College |

|---|---|

| Motto | Veritas (Latin)[1] |

|

Motto in English |

Truth |

| Type | Private research university |

| Established | 1636; 387 years ago[2] |

| Founder | Massachusetts General Court |

| Accreditation | NECHE |

|

Academic affiliations |

|

| Endowment | $50.9 billion (2022)[3][4] |

| President | Lawrence Bacow |

| Provost | Alan Garber |

|

Academic staff |

~2,400 faculty members (and >10,400 academic appointments in affiliated teaching hospitals)[5] |

| Students | 21,648 (Fall 2021)[6] |

| Undergraduates | 7,153 (Fall 2021)[6] |

| Postgraduates | 14,495 (Fall 2021)[6] |

| Location |

Cambridge , Massachusetts , United States 42°22′28″N 71°07′01″W / 42.37444°N 71.11694°WCoordinates: 42°22′28″N 71°07′01″W / 42.37444°N 71.11694°W |

| Campus | Midsize city[7], 209 acres (85 ha) |

| Newspaper | The Harvard Crimson |

| Colors | Crimson, white, and black[8] |

| Nickname | Crimson |

|

Sporting affiliations |

NCAA Division I FCS – Ivy League |

| Mascot | John Harvard |

| Website | harvard.edu |

|

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and one of the most prestigious worldwide.[a]

Harvard’s founding was authorized by the Massachusetts colonial legislature, «dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust»; though never formally affiliated with any denomination, in its early years Harvard College primarily trained Congregational clergy. Its curriculum and student body were gradually secularized during the 18th century. By the 19th century, Harvard emerged as the most prominent academic and cultural institution among the Boston elite.[9][10] Following the American Civil War, under President Charles William Eliot’s long tenure (1869–1909), the college developed multiple affiliated professional schools that transformed the college into a modern research university. In 1900, Harvard co-founded the Association of American Universities.[11] James B. Conant led the university through the Great Depression and World War II, and liberalized admissions after the war.

The university is composed of ten academic faculties plus Harvard Radcliffe Institute. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences offers study in a wide range of undergraduate and graduate academic disciplines, and other faculties offer only graduate degrees, including professional degrees. Harvard has three main campuses:[12]

the 209-acre (85 ha) Cambridge campus centered on Harvard Yard; an adjoining campus immediately across Charles River in the Allston neighborhood of Boston; and the medical campus in Boston’s Longwood Medical Area.[13] Harvard’s endowment is valued at $50.9 billion, making it the wealthiest academic institution in the world.[3][4] Endowment income enables the undergraduate college to admit students regardless of financial need and provide generous financial aid with no loans.[14] Harvard Library is the world’s largest academic library system, comprising 79 individual libraries holding 20 million items.[15][16][17][18]

Throughout its existence, Harvard alumni, faculty, and researchers have included numerous heads of state, Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, members of Congress, MacArthur Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Fulbright Scholars; by most metrics, Harvard ranks at the top, or near the top, of all universities globally in each of these categories.[b] Its alumni include eight U.S. presidents and 188 living billionaires, the most of any university. Fourteen Turing Award laureates have been Harvard affiliates. Students and alumni have won 10 Academy Awards, 48 Pulitzer Prizes, and 110 Olympic medals (46 gold), and they have founded many notable companies.

History

Colonial era

The Harvard Corporation seal found on Harvard diplomas. Christo et Ecclesiae («For Christ and Church») is one of Harvard’s several early mottoes.[19]

Harvard was established in 1636 in the colonial, pre-Revolutionary era by vote of the Great and General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1638, the university acquired British North America’s first known printing press.[20][21]

In 1639, it was named Harvard College after John Harvard, an English clergyman who had died soon after immigrating to Massachusetts, bequeathed it £780 and his library of some 320 volumes.[22] The charter creating Harvard Corporation was granted in 1650.

A 1643 publication defined the university’s purpose: «to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.»[23] The college trained many Puritan ministers in its early years[24]

and offered a classic curriculum that was based on the English university model—many leaders in the colony had attended the University of Cambridge—but also conformed to the tenets of Puritanism. While Harvard never affiliated with any particular denomination, many of its earliest graduates went on to become Puritan clergymen.[25]

Increase Mather served as Harvard College’s president from 1681 to 1701. In 1708, John Leverett became the first president who was not also a clergyman, marking a turning of the college away from Puritanism and toward intellectual independence.[26]

19th century

In the 19th century, Enlightenment ideas of reason and free will were widespread among Congregational ministers, putting those ministers and their congregations at odds with more traditionalist, Calvinist parties.[27]: 1–4 When Hollis Professor of Divinity David Tappan died in 1803 and President Joseph Willard died a year later, a struggle broke out over their replacements. Henry Ware was elected Hollis chair in 1805, and liberal Samuel Webber was appointed president two years later, signaling a shift from traditional ideas at Harvard to liberal, Arminian ideas.[27]: 4–5 [28]: 24

Charles William Eliot, Harvard president from 1869–1909, eliminated the favored position of Christianity from the curriculum while opening it to student self-direction. Though Eliot was an influential figure in the secularization of American higher education, he was motivated more by Transcendentalist Unitarian convictions influenced by William Ellery Channing, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and others of the time than by secularism.[29]

In 1816, Harvard launched new programs in the study of French and Spanish with George Ticknor as first professor for these language programs.

20th century

Richard Rummell’s 1906 watercolor landscape view, facing northeast.[30]

Harvard’s graduate schools began admitting women in small numbers in the late 19th century. During World War II, students at Radcliffe College (which, since its 1879 founding, had been paying Harvard professors to repeat their lectures for women) began attending Harvard classes alongside men.[31] In 1945, women were first admitted to the medical school.[32]

Since 1971, Harvard had controlled essentially all aspects of undergraduate admission, instruction, and housing for Radcliffe women; in 1999, Radcliffe was formally merged into Harvard.[33]

In the 20th century, Harvard’s reputation grew as its endowment burgeoned and prominent intellectuals and professors affiliated with the university. The university’s rapid enrollment growth also was a product of both the founding of new graduate academic programs and an expansion of the undergraduate college. Radcliffe College emerged as the female counterpart of Harvard College, becoming one of the most prominent schools for women in the United States. In 1900, Harvard became a founding member of the Association of American Universities.[11]

The student body in its first decades of the 20th century was predominantly «old-stock, high-status Protestants, especially Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians,» according to sociologist and author Jerome Karabel.[34] In 1923, a year after the percentage of Jewish students at Harvard reached 20%, President A. Lawrence Lowell supported a policy change that would have capped the admission of Jewish students to 15% of the undergraduate population. But Lowell’s idea was rejected. Lowell also refused to mandate forced desegregation in the university’s freshman dormitories, writing that, «We owe to the colored man the same opportunities for education that we do to the white man, but we do not owe to him to force him and the white into social relations that are not, or may not be, mutually congenial.»[35][36][37][38]

President James B. Conant led the university from 1933 to 1953; Conant reinvigorated creative scholarship in an effort to guarantee Harvard’s preeminence among the nation and world’s emerging research institutions. Conant viewed higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy. As such, he devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. An influential 268-page report issued by Harvard faculty in 1945 under Conant’s leadership, General Education in a Free Society, remains one the most important works in curriculum studies.[39]

Between 1945 and 1960, admissions standardized to open the university to a more diverse group of students; for example, after World War II, special exams were developed so veterans could be considered for admission.[40] No longer drawing mostly from select New England prep schools, the undergraduate college became accessible to striving middle class students from public schools; many more Jews and Catholics were admitted, but still few Blacks, Hispanics, or Asians versus the representation of these demoraphics in the general population.[41] Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Harvard incrementally became vastly more diverse.[42]

21st century

Drew Gilpin Faust, who was dean of Harvard Radcliffe Institute, became Harvard’s first female president on July 1, 2007.[43] In 2018, Faust retired and joined the board of Goldman Sachs.

On July 1, 2018, Lawrence Bacow was appointed Harvard’s 29th president.[44] Bacow intends to retire in 2023, and on December 15, 2022, it was announced that Claudine Gay will succeed him.

Campuses

Cambridge

Harvard’s 209-acre (85 ha) main campus is centered on Harvard Yard («the Yard») in Cambridge, about 3 miles (5 km) west-northwest of downtown Boston, and extends into the surrounding Harvard Square neighborhood. The Yard contains administrative offices such as University Hall and Massachusetts Hall; libraries such as Widener, Pusey, Houghton, and Lamont; and Memorial Church.

The Yard and adjacent areas include the main academic buildings of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, including the college, such as Sever Hall and Harvard Hall.

Freshman dormitories are in, or adjacent to, the Yard. Upperclassmen live in the twelve residential houses – nine south of the Yard near the Charles River, the others half a mile northwest of the Yard at the Radcliffe Quadrangle (which formerly housed Radcliffe College students). Each house is a community of undergraduates, faculty deans, and resident tutors, with its own dining hall, library, and recreational facilities.[45]

Also in Cambridge are the Law, Divinity (theology), Engineering and Applied Science, Design (architecture), Education, Kennedy (public policy), and Extension schools, as well as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in Radcliffe Yard.[46]

Harvard also has commercial real estate holdings in Cambridge.[47][48]

Allston

Harvard Business School, Harvard Innovation Labs, and many athletics facilities, including Harvard Stadium, are located on a 358-acre (145 ha) campus in Allston,[49]

a Boston neighborhood just across the Charles River from the Cambridge campus. The John W. Weeks Bridge, a pedestrian bridge over the Charles River, connects the two campuses.

The university is actively expanding into Allston, where it now owns more land than in Cambridge.[50]

Plans include new construction and renovation for the Business School, a hotel and conference center, graduate student housing, Harvard Stadium, and other athletics facilities.[51]