| Gandalf | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| First appearance | The Hobbit (1937) |

| Last appearance | Unfinished Tales (1980) |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | See Names |

| Race | Maia |

| Affiliation | Company of the Ring |

| Weapon |

|

Gandalf is a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien’s novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. He is a wizard, one of the Istari order, and the leader of the Fellowship of the Ring. Tolkien took the name «Gandalf» from the Old Norse «Catalogue of Dwarves» (Dvergatal) in the Völuspá.

As a wizard and the bearer of one of the Three Rings, Gandalf has great power, but works mostly by encouraging and persuading. He sets out as Gandalf the Grey, possessing great knowledge and travelling continually. Gandalf is focused on the mission to counter the Dark Lord Sauron by destroying the One Ring. He is associated with fire; his ring of power is Narya, the Ring of Fire. As such, he delights in fireworks to entertain the hobbits of the Shire, while in great need he uses fire as a weapon. As one of the Maiar, he is an immortal spirit from Valinor, but his physical body can be killed.

In The Hobbit, Gandalf assists the 13 dwarves and the hobbit Bilbo Baggins with their quest to retake the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the dragon, but leaves them to urge the White Council to expel Sauron from his fortress of Dol Guldur. In the course of the quest, Bilbo finds a magical ring. The expulsion succeeds, but in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf reveals that Sauron’s retreat was only a feint, as he soon reappeared in Mordor. Gandalf further explains that, after years of investigation, he is sure that Bilbo’s ring is the One Ring that Sauron needs to dominate the whole of Middle-earth. The Council of Elrond creates the Fellowship of the Ring, with Gandalf as its leader, to defeat Sauron by destroying the Ring. He takes them south through the Misty Mountains, but is killed fighting a Balrog, an evil spirit-being, in the underground realm of Moria. After he dies, he is sent back to Middle-earth to complete his mission as Gandalf the White. He reappears to three of the Fellowship and helps to counter the enemy in Rohan, then in Gondor, and finally at the Black Gate of Mordor, in each case largely by offering guidance. When victory is complete, he crowns Aragorn as King before leaving Middle-earth for ever to return to Valinor.

Tolkien once described Gandalf as an angel incarnate; later, both he and other scholars have likened Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his «Wanderer» guise. Others have described Gandalf as a guide-figure who assists the protagonists, comparable to the Cumaean Sibyl who assisted Aeneas in Virgil’s The Aeneid, or to Virgil himself in Dante’s Inferno. Scholars have likened his return in white to the transfiguration of Christ; he is further described as a prophet, representing one element of Christ’s threefold office of prophet, priest, and king, where the other two roles are taken by Frodo and Aragorn.

The Gandalf character has been featured in radio, television, stage, video game, music, and film adaptations, including Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 animated film. His best-known portrayal is by Ian McKellen in Peter Jackson’s 2001–2003 The Lord of the Rings film series, where the actor based his acclaimed performance on Tolkien himself. McKellen reprised the role in Jackson’s 2012–2014 film series The Hobbit.

Names[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Tolkien derived the name Gandalf from Gandálfr, a dwarf in the Völuspá’s Dvergatal, a list of dwarf-names.[1] In Old Norse, the name means staff-elf. This is reflected in his name Tharkûn, which is «said to mean ‘Staff-man'» in Khuzdul, one of Tolkien’s invented languages.[T 1]

In-universe names[edit]

Gandalf is given several names and epithets in Tolkien’s writings. Faramir calls him the Grey Pilgrim, and reports Gandalf as saying, «Many are my names in many countries. Mithrandir[a] among the Elves, Tharkûn to the Dwarves, Olórin I was in my youth in the West that is forgotten, in the South Incánus, in the North Gandalf; to the East I go not.»[T 2] In an early draft of The Hobbit, he is called Bladorthin, while the name Gandalf is used by the dwarf who later became Thorin Oakenshield.[2]

Each Wizard is distinguished by the colour of his cloak. For most of his manifestation as a wizard, Gandalf’s cloak is grey, hence the names Gandalf the Grey and Greyhame, from Old English hame, «cover, skin». Mithrandir is a name in Sindarin meaning «the Grey Pilgrim» or «the Grey Wanderer». Midway through The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf becomes the head of the order of Wizards, and is renamed Gandalf the White. This change in status (and clothing) introduces another name for the wizard: the White Rider. However, characters who speak Elvish still refer to him as Mithrandir. At times in The Lord of the Rings, other characters address Gandalf by insulting nicknames: Stormcrow, Láthspell («Ill-news» in Old English), and «Grey Fool».[T 1]

Characteristics[edit]

Tolkien describes Gandalf as the last of the wizards to appear in Middle-earth, one who «seemed the least, less tall than the others, and in looks more aged, grey-haired and grey-clad, and leaning on a staff».[T 1] Yet the Elf Círdan who met him on arrival nevertheless considered him «the greatest spirit and the wisest» and gave him the Elven Ring of Power called Narya, the Ring of Fire, containing a «red» stone for his aid and comfort. Tolkien explicitly links Gandalf to the element fire later in the same essay:[T 1]

Warm and eager was his spirit (and it was enhanced by the ring Narya), for he was the Enemy of Sauron, opposing the fire that devours and wastes with the fire that kindles, and succours in wanhope and distress; but his joy, and his swift wrath, were veiled in garments grey as ash, so that only those that knew him well glimpsed the flame that was within. Merry he could be, and kindly to the young and simple, yet quick at times to sharp speech and the rebuking of folly; but he was not proud, and sought neither power nor praise … Mostly he journeyed tirelessly on foot, leaning on a staff, and so he was called among Men of the North Gandalf ‘the Elf of the Wand’. For they deemed him (though in error) to be of Elven-kind, since he would at times work wonders among them, loving especially the beauty of fire; and yet such marvels he wrought mostly for mirth and delight, and desired not that any should hold him in awe or take his counsels out of fear. … Yet it is said that in the ending of the task for which he came he suffered greatly, and was slain, and being sent back from death for a brief while was clothed then in white, and became a radiant flame (yet veiled still save in great need).[T 1]

Fictional biography[edit]

Valinor[edit]

In Valinor, Gandalf was called Olórin.[T 1] He was one of the Maiar of Valinor, specifically, one of the people of the Vala Manwë; he was said to be the wisest of the Maiar. He was closely associated with two other Valar: Irmo, in whose gardens he lived, and Nienna, the patron of mercy, who gave him tutelage. When the Valar decided to send the order of the Wizards (Istari) across the Great Sea to Middle-earth to counsel and assist all those who opposed Sauron, Olórin was proposed by Manwë. Olórin initially begged to be excused, declaring he was too weak and that he feared Sauron, but Manwë replied that that was all the more reason for him to go.[T 1]

As one of the Maiar, Gandalf was not a mortal Man but an angelic being who had taken human form. As one of those spirits, Olórin was in service to the Creator (Eru Ilúvatar) and the Creator’s ‘Secret Fire’. Along with the other Maiar who entered into Middle-earth as the five Wizards, he took on the specific form of an old man as a sign of his humility. The role of the wizards was to advise and counsel but never to attempt to match Sauron’s strength with their own. It might be, too, that the kings and lords of Middle-earth would be more receptive to the advice of a humble old man than a more glorious form giving them direct commands.[T 1]

Middle-earth[edit]

The wizards arrived in Middle-earth separately, early in the Third Age; Gandalf was the last, landing in the Havens of Mithlond. He seemed the oldest and least in stature, but Círdan the Shipwright felt that he was the greatest on their first meeting in the Havens, and gave him Narya, the Ring of Fire. Saruman, the chief Wizard, learned of the gift and resented it. Gandalf hid the ring well, and it was not widely known until he left with the other ring-bearers at the end of the Third Age that he, and not Círdan, was the holder of the third of the Elven-rings.[T 1]

Gandalf’s relationship with Saruman, the head of their Order, was strained. The Wizards were commanded to aid Men, Elves, and Dwarves, but only through counsel; they were forbidden to use force to dominate them, though Saruman increasingly disregarded this.[T 1]

The White Council[edit]

Gandalf suspected early on that an evil presence, the Necromancer of Dol Guldur, was not a Nazgûl but Sauron himself. He went to Dol Guldur[T 3] to discover the truth, but the Necromancer withdrew before him, only to return with greater force,[T 3] and the White Council was formed in response.[T 3] Galadriel had hoped Gandalf would lead the council, but he refused, declining to be bound by any but the Valar who had sent him. Saruman was chosen instead, as the most knowledgeable about Sauron’s work in the Second Age.[T 4][T 1]

Gandalf returned to Dol Guldur «at great peril» and learned that the Necromancer was indeed Sauron. The following year a White Council was held, and Gandalf urged that Sauron be driven out.[T 3] Saruman, however, reassured the Council that Sauron’s evident effort to find the One Ring would fail, as the Ring would long since have been carried by the river Anduin to the Sea; and the matter was allowed to rest. But Saruman began actively seeking the Ring near the Gladden Fields where Isildur had been killed.[T 4][T 1]

The Quest of Erebor[edit]

«The Quest of Erebor» in Unfinished Tales elaborates upon the story behind The Hobbit. It tells of a chance meeting between Gandalf and Thorin Oakenshield, a Dwarf-king in exile, in the Prancing Pony inn at Bree. Gandalf had for some time foreseen the coming war with Sauron, and knew that the North was especially vulnerable. If Rivendell were to be attacked, the dragon Smaug could cause great devastation. He persuaded Thorin that he could help him regain his lost territory of Erebor from Smaug, and so the quest was born.[T 5]

The Hobbit[edit]

Gandalf meets with Bilbo in the opening of The Hobbit. He arranges for a tea party, to which he invites the thirteen dwarves, and thus arranges the travelling group central to the narrative. Gandalf contributes the map and key to Erebor to assist the quest.[T 6] On this quest Gandalf acquires the sword, Glamdring, from the trolls’ treasure hoard.[T 7] Elrond informs them that the sword was made in Gondolin, a city long ago destroyed, where Elrond’s father lived as a child.[T 8]

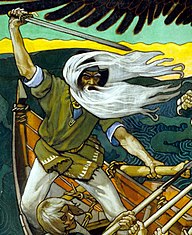

After escaping from the Misty Mountains pursued by goblins and wargs, the party is carried to safety by the Great Eagles.[T 9] Gandalf then persuades Beorn to house and provision the company for the trip through Mirkwood. Gandalf leaves the company before they enter Mirkwood, saying that he had pressing business to attend to.[T 10]

He turns up again before the walls of Erebor disguised as an old man, revealing himself when it seems the Men of Esgaroth and the Mirkwood Elves will fight Thorin and the dwarves over Smaug’s treasure. The Battle of Five Armies ensues when hosts of goblins and wargs attack all three parties.[T 11] After the battle, Gandalf accompanies Bilbo back to the Shire, revealing at Rivendell what his pressing business had been: Gandalf had once again urged the council to evict Sauron, since quite evidently Sauron did not require the One Ring to continue to attract evil to Mirkwood.[T 12] Then the Council «put[s] forth its power» and drives Sauron from Dol Guldur. Sauron had anticipated this, and had feigned a withdrawal, only to reappear in Mordor.[T 13]

The Lord of the Rings[edit]

Gandalf the Grey[edit]

Gandalf spent the years between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings travelling Middle-earth in search of information on Sauron’s resurgence and Bilbo Baggins’s mysterious ring, spurred particularly by Bilbo’s initial misleading story of how he had obtained it as a «present» from Gollum. During this period, he befriended Aragorn and became suspicious of Saruman. He spent as much time as he could in the Shire, strengthening his friendship with Bilbo and Frodo, Bilbo’s orphaned cousin and adopted heir.[T 13]

Gandalf returns to the Shire for Bilbo’s «eleventy-first» (111th) birthday party, bringing many fireworks for the occasion. After Bilbo, as a prank on his guests, puts on the ring and disappears, Gandalf strongly encourages his old friend to leave the ring to Frodo, as they had planned. Bilbo becomes hostile and accuses Gandalf of trying to steal the ring. Alarmed, Gandalf impresses on Bilbo the foolishness of this accusation. Coming to his senses, Bilbo admits that the ring has been troubling him, and leaves it behind for Frodo as he departs for Rivendell.[T 14]

Over the next 17 years, Gandalf travels extensively, searching for answers on the ring. He finds some answers in Isildur’s scroll, in the archives of Minas Tirith. He also wants to question Gollum, who had borne the ring for many years. Gandalf searches long and hard for Gollum, often assisted by Aragorn. Aragorn eventually succeeds in capturing Gollum. Gandalf questions Gollum, threatening him with fire when he proves unwilling to speak. Gandalf learns that Sauron has forced Gollum under torture in his fortress, Barad-dûr, to tell what he knows of the ring. This reinforces Gandalf’s growing suspicion that Bilbo’s ring is the One Ring.[T 13]

Returning to the Shire, Gandalf confirms his suspicion by throwing the Ring into Frodo’s hearth-fire and reading the writing that appears on the Ring’s surface. He tells Frodo the history of the Ring, and urges him to take it to Rivendell, saying that he would be in grave danger if he stayed in the Shire. Gandalf says he will attempt to return for Frodo’s 50th birthday party, to accompany him on the road; and that meanwhile Frodo should arrange to leave quietly, as the servants of Sauron will be searching for him.[T 15]

Outside the Shire, Gandalf encounters the wizard Radagast the Brown, who brings the news that the Nazgûl have ridden out of Mordor—and a request from Saruman that Gandalf come to Isengard. Gandalf leaves a letter to Frodo (urging his immediate departure) with Barliman Butterbur at the Prancing Pony, and heads towards Isengard. There Saruman reveals his true intentions, urging Gandalf to help him obtain the Ring for his own use. Gandalf refuses, and Saruman imprisons him at the top of his tower. Eventually Gandalf is rescued by Gwaihir the Eagle.[T 13]

Gwaihir sets Gandalf down in Rohan, where Gandalf appeals to King Théoden for a horse. Théoden, under the evil influence of Gríma Wormtongue, Saruman’s spy and servant, tells Gandalf to take any horse he pleases, but to leave quickly. It is then that Gandalf meets the great horse Shadowfax who will be his mount and companion. Gandalf rides hard for the Shire, but does not reach it until after Frodo has set out. Knowing that Frodo and his companions will be heading for Rivendell, Gandalf makes his own way there. He learns at Bree that the Hobbits have fallen in with Aragorn. He faces the Nazgûl at Weathertop but escapes after an all-night battle, drawing four of them northward.[T 13] Frodo, Aragorn and company face the remaining five on Weathertop a few nights later.[T 16] Gandalf reaches Rivendell just before Frodo’s arrival.[T 13]

In Rivendell, Gandalf helps Elrond drive off the Nazgûl pursuing Frodo, and plays a leading role in the Council of Elrond as the only person who knows the full history of the Ring. He reveals that Saruman has betrayed them and is in league with Sauron. When it is decided that the Ring has to be destroyed, Gandalf volunteers to accompany Frodo—now the Ring-bearer—in his quest. He persuades Elrond to let Frodo’s cousins Merry and Pippin join the Fellowship.[T 13]

The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand Glamdring gleamed, cold and white. His enemy halted again, facing him, and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings. It raised the whip, and the thongs whined and cracked. Fire came from its nostrils. But Gandalf stood firm. «You cannot pass,» he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. «I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass.»

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Taking charge of the Fellowship (comprising nine representatives of the free peoples of Middle-earth, «set against the Nine Riders»), Gandalf and Aragorn lead the Hobbits and their companions south.[T 17] After an unsuccessful attempt to cross Mount Caradhras in winter, they cross under the mountains through the Mines of Moria under the Misty Mountains, though only Gimli the Dwarf is enthusiastic about that route. In Moria, they discover that the dwarf colony established there by Balin has been annihilated by orcs. The Fellowship fights with the orcs and trolls of Moria and escapes them.[T 18]

At the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, they encounter «Durin’s Bane», a fearsome Balrog from ancient times. Gandalf faces the Balrog to enable the others to escape. After a brief exchange of blows, Gandalf breaks the bridge beneath the Balrog with his staff. As the Balrog falls, it wraps its whip around Gandalf’s legs, dragging him over the edge. Gandalf falls into the abyss, crying «Fly, you fools!».[T 19]

Gandalf and the Balrog fall into a deep lake in Moria’s underworld. Gandalf pursues the Balrog through the tunnels for eight days until they climb to the peak of Zirakzigil. Here they fight for two days and nights. The Balrog is defeated and cast down onto the mountainside. Gandalf too dies, and his body lies on the peak while his spirit travels «out of thought and time».[T 20]

Gandalf the White[edit]

Gandalf is «sent back»[b] as Gandalf the White, and returns to life on the mountain top. Gwaihir carries him to Lothlórien, where he is healed of his injuries and re-clothed in white robes by Galadriel. He travels to Fangorn Forest, where he encounters Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas (who are tracking Merry and Pippin). They mistake him for Saruman, but he stops their attacks and reveals himself.[T 20]

They travel to Rohan, where Gandalf finds that king Théoden has been further weakened by Wormtongue’s influence. He breaks Wormtongue’s hold over Théoden, and convinces the king to join in the fight against Sauron.[T 21] Gandalf sets off to gather warriors of the Westfold to assist Théoden in the coming battle with Saruman. Gandalf arrives just in time to defeat Saruman’s army in the battle of Helm’s Deep.[T 22] Gandalf and the King ride to Isengard, which has just been destroyed by Treebeard and his Ents, who are accompanied by Merry and Pippin.[T 23] Gandalf breaks Saruman’s staff and expels him from the White Council and the Order of Wizards; Gandalf takes Saruman’s place as head of both. Wormtongue makes an attempt to kill Gandalf or Saruman with the palantír of Orthanc, but misses both. Pippin retrieves the palantír, but Gandalf quickly takes it.[T 24] After the group leaves Isengard, Pippin takes the palantír from a sleeping Gandalf, looks into it, and comes face to face with Sauron himself. Gandalf gives the palantír to Aragorn and takes the chastened Pippin with him to Minas Tirith to keep the young hobbit out of further trouble.[T 25]

Gandalf arrives in time to help to arrange the defences of Minas Tirith. His presence is resented by Denethor, the Steward of Gondor; but when his son Faramir is gravely wounded in battle, Denethor sinks into despair and madness. Together with Prince Imrahil, Gandalf leads the defenders during the siege of the city. When the forces of Mordor break the main gate, Gandalf, alone on Shadowfax, confronts the Lord of the Nazgûl. At that moment the Rohirrim arrive, compelling the Nazgûl to withdraw to fight. Gandalf is required to save Faramir from Denethor, who seeks in desperation to burn himself and his son on a funeral pyre.[T 26]

«This, then, is my counsel,» [said Gandalf.] «We have not the Ring. In wisdom or great folly it has been sent away to be destroyed, lest it destroy us. Without it we cannot by force defeat [Sauron’s] force. But we must at all costs keep his Eye from his true peril… We must call out his hidden strength, so that he shall empty his land… We must make ourselves the bait, though his jaws should close on us… We must walk open-eyed into that trap, with courage, but small hope for ourselves. For, my lords, it may well prove that we ourselves shall perish utterly in a black battle far from the living lands; so that even if Barad-dûr be thrown down, we shall not live to see a new age. But this, I deem, is our duty.»

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Aragorn and Gandalf lead the final campaign against Sauron’s forces at the Black Gate, in an effort to distract the Dark Lord’s attention from Frodo and Sam; they are at that moment scaling Mount Doom to destroy the One Ring. In a parley before the battle, Gandalf and the other leaders of the West meet the nameless lieutenant of Mordor, who shows them Frodo’s mithril shirt and other items from the Hobbits’ equipment. Gandalf rejects Mordor’s terms of surrender, and the forces of the West face the full might of Sauron’s armies, until the Ring is destroyed in Mount Doom.[T 27] Gandalf leads the Eagles to rescue Frodo and Sam from the erupting mountain.[T 28]

After the war, Gandalf crowns Aragorn as King Elessar, and helps him find a sapling of the White Tree of Gondor.[T 29] He accompanies the Hobbits back to the borders of the Shire, before leaving to visit Tom Bombadil.[T 30]

Two years later, Gandalf departs Middle-earth for ever. He boards the Ringbearers’ ship in the Grey Havens and sets sail to return across the sea to the Undying Lands; with him are his friends Frodo, Bilbo, Galadriel, and Elrond, and his horse Shadowfax.[T 31]

Concept and creation[edit]

Appearance[edit]

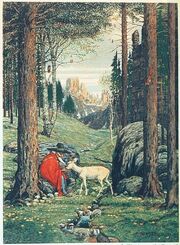

Tolkien’s biographer Humphrey Carpenter relates that Tolkien owned a postcard entitled Der Berggeist («the mountain spirit»), which he labelled «the origin of Gandalf».[3] It shows a white-bearded man in a large hat and cloak seated among boulders in a mountain forest. Carpenter said that Tolkien recalled buying the postcard during his holiday in Switzerland in 1911. Manfred Zimmerman, however, discovered that the painting was by the German artist Josef Madlener and dates from the mid-1920s. Carpenter acknowledged that Tolkien was probably mistaken about the origin of the postcard.[4]

An additional influence may have been Väinämöinen, a demigod and the central character in Finnish folklore and the national epic Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot.[5] Väinämöinen was described as an old and wise man, and he possessed a potent, magical singing voice.[6]

Throughout the early drafts, and through to the first edition of The Hobbit, Bladorthin/Gandalf is described as being a «little old man», distinct from a dwarf, but not of the full human stature that would later be described in The Lord of the Rings. Even in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf was not tall; shorter, for example, than Elrond[T 32] or the other wizards.[T 1]

Name[edit]

When writing The Hobbit in the early 1930s Tolkien gave the name Gandalf to the leader of the Dwarves, the character later called Thorin Oakenshield. The name is taken from the same source as all the other Dwarf names (save Balin) in The Hobbit: the «Catalogue of Dwarves» in the Völuspá.[7] The Old Norse name Gandalfr incorporates the words gandr meaning «wand», «staff» or (especially in compounds) «magic» and álfr «elf». The name Gandalf is found in at least one more place in Norse myth, in the semi-historical Heimskringla, which briefly describes Gandalf Alfgeirsson, a legendary Norse king from eastern Norway and rival of Halfdan the Black.[8] Gandalf is also the name of a Norse sea-king in Henrik Ibsen’s second play, The Burial Mound. The name «Gandolf» occurs as a character in William Morris’ 1896 fantasy novel The Well at the World’s End, along with the horse «Silverfax», adapted by Tolkien as Gandalf’s horse «Shadowfax». Morris’ book, inspired by Norse myth, is set in a pseudo-medieval landscape; it deeply influenced Tolkien. The wizard that became Gandalf was originally named Bladorthin.[9][10]

Tolkien came to regret his ad hoc use of Old Norse names, referring to a «rabble of eddaic-named dwarves, … invented in an idle hour» in 1937.[T 33] But the decision to use Old Norse names came to have far-reaching consequences in the composition of The Lord of the Rings; in 1942, Tolkien decided that the work was to be a purported translation from the fictional language of Westron, and in the English translation Old Norse names were taken to represent names in the language of Dale.[11] Gandalf, in this setting, is thus a representation in English (anglicised from Old Norse) of the name the Dwarves of Erebor had given to Olórin in the language they used «externally» in their daily affairs, while Tharkûn is the (untranslated) name, presumably of the same meaning, that the Dwarves gave him in their native Khuzdul language.[T 34]

Guide[edit]

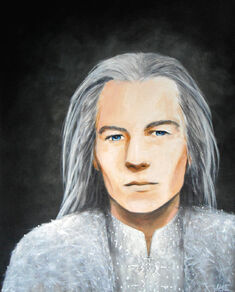

Like Odin in «Wanderer» guise—an old man with a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff:[12] Gandalf, by ‘Nidoart’, 2013

Gandalf’s role and importance was substantially increased in the conception of The Lord of the Rings, and in a letter of 1954, Tolkien refers to Gandalf as an «angel incarnate».[T 35] In the same letter Tolkien states he was given the form of an old man in order to limit his powers on Earth. Both in 1965 and 1971 Tolkien again refers to Gandalf as an angelic being.[T 36][T 37]

In a 1946 letter, Tolkien stated that he thought of Gandalf as an «Odinic wanderer».[T 38] Other commentators have similarly compared Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his «Wanderer» guise—an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff,[12][13] or likened him to Merlin of Arthurian legend or the Jungian archetype of the «wise old man».[14]

| Attribute | Gandalf | Odin |

|---|---|---|

| Accoutrements | «battered hat» cloak «thorny staff» |

Epithet: «Long-hood» blue cloak a staff |

| Beard | «the grey», «old man» | Epithet: «Greybeard» |

| Appearance | the Istari (Wizards) «in simple guise, as it were of Men already old in years but hale in body, travellers and wanderers» as Tolkien wrote «a figure of ‘the Odinic wanderer'»[T 39] |

Epithets: «Wayweary», «Wayfarer», «Wanderer» |

| Power | with his staff | Epithet: «Bearer of the [Magic] Wand» |

| Eagles | rescued repeatedly by eagles in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings |

Associated with eagles; escapes from Jotunheim back to Asgard as an eagle |

The Tolkien scholar Charles W. Nelson described Gandalf as a «guide who .. assists a major character on a journey or quest .. to unusual and distant places». He noted that in both The Fellowship of the Ring and The Hobbit, Tolkien presents Gandalf in these terms. Immediately after the Council of Elrond, Gandalf tells the Fellowship:[15]

Someone said that intelligence would be needed in the party. He was right. I think I shall come with you.[15]

Nelson notes the similarity between this and Thorin’s statement in The Hobbit:[15]

We shall soon .. start on our long journey, a journey from which some of us, or perhaps all of us (except our friend and counsellor, the ingenious wizard Gandalf) may never return.[15]

Nelson gives as examples of the guide figure the Cumaean Sibyl who assisted Aeneas on his journey through the underworld in Virgil’s tale The Aeneid, and then Virgil himself in Dante’s Inferno, directing, encouraging, and physically assisting Dante as he travels through hell. In English literature, Nelson notes, Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur has the wizard Merlin teaching and directing Arthur to begin his journeys. Given these precedents, Nelson remarks, it was unsurprising that Tolkien should make use of a guide figure, endowing him, like these predecessors, with power, wisdom, experience, and practical knowledge, and «aware[ness] of [his] own limitations and [his] ranking in the order of the great».[15] Other characters who act as wise and good guides include Tom Bombadil, Elrond, Aragorn, Galadriel—who he calls perhaps the most powerful of the guide figures—and briefly also Faramir.[15]

Nelson writes that there is equally historical precedent for wicked guides, such as Edmund Spenser’s «evil palmers» in The Faerie Queene, and suggests that Gollum functions as an evil guide, contrasted with Gandalf, in Lord of the Rings. He notes that both Gollum and Gandalf are servants of The One, Eru Ilúvatar, in the struggle against the forces of darkness, and «ironically» all of them, good and bad, are necessary to the success of the quest. He comments, too, that despite Gandalf’s evident power, and the moment when he faces the Lord of the Nazgûl, he stays in the role of guide throughout, «never directly confront[ing] his enemies with his raw power.»[15]

Christ-figure[edit]

The critic Anne C. Petty, writing about «Allegory» in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, discusses Gandalf’s death and reappearance in Christian terms. She cites Michael W. Maher, S.J.: «who could not think of Gandalf’s descent into the pits of Moria and his return clothed in white as a death-resurrection motif?»[16][17] She at once notes, however, that «such a narrow [allegorical] interpretation» limits the reader’s imagination by demanding a single meaning for each character and event.[16] Other scholars and theologians have likened Gandalf’s return as a «gleaming white» figure to the transfiguration of Christ.[18][19][20]

The philosopher Peter Kreeft, like Tolkien a Roman Catholic, observes that there is no one complete, concrete, visible Christ figure in The Lord of the Rings comparable to Aslan in C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia series. However, Kreeft and Jean Chausse have identified reflections of the figure of Jesus Christ in three protagonists of The Lord of the Rings: Gandalf, Frodo and Aragorn. While Chausse found «facets of the personality of Jesus» in them, Kreeft wrote that «they exemplify the Old Testament threefold Messianic symbolism of prophet (Gandalf), priest (Frodo), and king (Aragorn).»[21][22][23]

| Christ-like attribute | Gandalf | Frodo | Aragorn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial death, resurrection |

Dies in Moria, reborn as Gandalf the White[c] |

Symbolically dies under Morgul-knife, healed by Elrond[25] |

Takes Paths of the Dead, reappears in Gondor |

| Saviour | All three help to save Middle-earth from Sauron | ||

| Threefold Messianic symbolism | Prophet | Priest | King |

Adaptations[edit]

In the BBC Radio dramatisations, Gandalf has been voiced by Norman Shelley in The Lord of the Rings (1955–1956),[26] Heron Carvic in The Hobbit (1968), Bernard Mayes in The Lord of the Rings (1979),[27] and Sir Michael Hordern in The Lord of the Rings (1981).[28]

John Huston voiced Gandalf in the animated films The Hobbit (1977) and The Return of the King (1980) produced by Rankin/Bass. William Squire voiced Gandalf in the animated film The Lord of the Rings (1978) directed by Ralph Bakshi. Ivan Krasko played Gandalf in the Soviet film adaptation The Hobbit (1985).[29] Gandalf was portrayed by Vesa Vierikko in the Finnish television miniseries Hobitit (1993).[30]

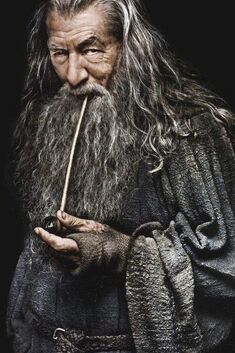

Ian McKellen portrayed Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings film series (2001–2003), directed by Peter Jackson, after Sean Connery and Patrick Stewart both turned down the role.[31][32] According to Jackson, McKellen based his performance as Gandalf on Tolkien himself:

We listened to audio recordings of Tolkien reading excerpts from Lord of the Rings. We watched some BBC interviews with him—there’s a few interviews with Tolkien—and Ian based his performance on an impersonation of Tolkien. He’s literally basing Gandalf on Tolkien. He sounds the same, he uses the speech patterns and his mannerisms are born out of the same roughness from the footage of Tolkien. So, Tolkien would recognize himself in Ian’s performance.[33]

McKellen received widespread acclaim[34] for his portrayal of Gandalf, particularly in The Fellowship of the Ring, for which he received a Screen Actors Guild Award[35] and an Academy Award nomination, both for best supporting actor.[36] Empire named Gandalf, as portrayed by McKellen, the 30th greatest film character of all time.[37] He reprised the role in The Hobbit film series (2012–2014), claiming that he enjoyed playing Gandalf the Grey more than Gandalf the White.[38][39] He voiced Gandalf for several video games based on the films, including The Two Towers,[40] The Return of the King,[41] and The Third Age.[42]

Charles Picard portrayed Gandalf in the 1999 stage production of The Two Towers at Chicago’s Lifeline Theatre.[43][44] Brent Carver portrayed Gandalf in the 2006 musical production The Lord of the Rings, which opened in Toronto.[45]

Gandalf appears in The Lego Movie, voiced by Todd Hanson.[46] Gandalf is a main character in the video game Lego Dimensions and is voiced by Tom Kane.[47]

Gandalf has his own movement in Johan de Meij’s Symphony No. 1 «The Lord of the Rings», which was written for concert band and premiered in 1988.[48] The Gandalf theme has the note sequence G-A-D-A-F, «Gandalf» as far as can be formed with the notes A to G. The result is a «striving, rising theme».[49]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Meaning «Grey Pilgrim»

- ^ In Letters, #156, Tolkien clearly implies that the «Authority» that sent Gandalf back was above the Valar (who are bound by Arda’s space and time, while Gandalf went beyond time). He clearly intends this as an example of Eru intervening to change the course of the world.

- ^ Other commentators such as Jane Chance have compared this transformed reappearance to the Transfiguration of Jesus.[24]

References[edit]

Primary[edit]

-

- This list identifies each item’s location in Tolkien’s writings.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Tolkien 1980, part 4, ch. 2, «The Istari»

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 4, ch. 5, «The Window on the West»

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1955, Appendix B

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, «Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age»

- ^ Tolkien 1980, part 3, 3, «The Quest of Erebor»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 1, «An Unexpected Party»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 2, «Roast Mutton»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 3, «A Short Rest»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, «Out of the Frying-Pan into the Fire»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 7, «Queer Lodgings»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 17, «The Clouds Burst»

- ^ Tolkien 1937, «The Last Stage»

- ^ a b c d e f g Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 2, «The Council of Elrond»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 1, «A Long-Expected Party»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 2, «The Shadow of the Past»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 11, «A Knife in the Dark»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch.3, «The Ring Goes South»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 4, «A Journey in the Dark»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 5, «The Bridge of Khazad-Dum»

- ^ a b Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 5, «The White Rider»

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 6, «The King of the Golden Hall»

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 7, «Helm’s Deep»

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 8, «The Road to Isengard»

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 10, «The Voice of Saruman»

- ^ Tolkien 1954, book 3, ch. 11, «The Palantír»

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 1, «Minas Tirith»

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 5, ch. 10, «The Black Gate Opens»

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 4, «The Field of Cormallen»

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 5, «The Steward and the King»

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 7, «Homeward Bound»

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 9, «The Grey Havens»

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 1, «Many Meetings».

- ^ Tolkien 1988, p. 452

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1967) Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #156

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #268

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #325

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #107

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #119

Secondary[edit]

- ^ Rateliff, John D. (2007). Return to Bag-End. The History of The Hobbit. Vol. 2. HarperCollins. Appendix III. ISBN 978-0-00-725066-0.

- ^ Rateliff, John D. (2007). Mr. Baggins. The History of The Hobbit. Vol. 1. HarperCollins. Chapter I(b). ISBN 978-0-00-725066-0.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. Allen & Unwin. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-0492-8037-3.

- ^ Zimmerman, Manfred (1983). «The Origin of Gandalf and Josef Madlener». Mythlore. Mythopoeic Society. 9 (4).

- ^ Snodgrass, Ellen (2009). «Kalevala (Elias Lönnrot) (1836)». Encyclopedia of the Literature of Empire. Infobase Publishing. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-1438119069.

- ^ Siikala, Anna-Leena (30 July 2007). «Väinämöinen». Kansallisbiografia. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Solopova, Elizabeth (2009). Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Fiction. New York City: North Landing Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9816607-1-4.

- ^ «Halfdan the Black Saga (Ch. 1. Halfdan Fights Gandalf and Sigtryg) in Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla: A History of the Norse Kings, transl. Samuel Laing (Norroena Society, London, 1907)». mcllibrary.org. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

The same autumn he went with an army to Vingulmark against King Gandalf. They had many battles, and sometimes one, sometimes the other gained the victory; but at last they agreed that Halfdan should have half of Vingulmark, as his father Gudrod had had it before.

- ^ Anderson, Douglas A., ed. (1988). «Inside Information». The Annotated Hobbit. Allen & Unwin. p. 287.

- ^ Rateliff, John D. (2007). «Introduction». The History of the Hobbit, Part 1: Mr. Baggins. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. ix. ISBN 978-0618968473.

- ^ Shippey, Tom. «Tolkien and Iceland: The Philology of Envy». Nordals.hi.is. Archived from the original on 30 August 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

We know that Tolkien had great difficulty in getting his story going. In my opinion, he did not break through until, on February 9, 1942, he settled the issue of languages

- ^ a b Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1997). An investigation of the Teutonic god Óðinn; and a study of his relationship to J. R.R. Tolkien’s character, Gandalf (Thesis). University of New England.

- ^ a b Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien’s Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. pp. 95–101. ISBN 0-8020-3806-9.

- ^ Lobdell, Jared (1975). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-87548-303-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nelson, Charles W. (2002). «From Gollum to Gandalf: The Guide Figures in J. R. R. Tolkien’s «Lord of the Rings»«. Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 13 (1): 47–61. JSTOR 43308562.

- ^ a b Petty, Anne C. (2013) [2007]. «Allegory». In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Maher, Michael W. (2003). Chance, Jane (ed.). ‘A land without stain’: medieval images of Mary and their use in the characterization of Galadriel. Tolkien the Medievalist. Routledge. p. 225.

- ^ Chance, Jane (1980) [1979]. Tolkien’s Art. Papermac. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-333-29034-7.

- ^ Rutledge, Fleming (2004). The Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien’s Divine Design in The Lord of the Rings. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 157–159. ISBN 978-0-80282-497-4.

- ^ Stucky, Mark (2006). «Middle Earth’s Messianic Mythology Remixed: Gandalf’s Death and Resurrection in Novel and Film» (PDF). Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 13 (Summer): 3. doi:10.3138/jrpc.13.1.003.

- ^ a b Kreeft, Peter J. (November 2005). «The Presence of Christ in The Lord of the Rings». Ignatius Insight.

- ^ Kerry, Paul E. (2010). Kerry, Paul E. (ed.). The Ring and the Cross: Christianity and the Lord of the Rings. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-61147-065-9.

- ^ Schultz, Forrest W. (1 December 2002). «Christian Typologies in The Lord of the Rings». Chalcedon. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Nitzsche, Jane Chance (1980) [1979]. Tolkien’s Art. Papermac. p. 42. ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

- ^ Also by other commentators, such as Mathews, Richard (2016). Fantasy: The Liberation of Imagination. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-136-78554-2.

- ^ Oliver, Sarah (2012). «Gandalf». An A-Z of JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit. John Blake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7821-9090-5.

- ^ «Mind’s Eye The Lord of the Rings (1979)». SF Worlds. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ «The Lord of the Rings BBC Adaptation (1981)». SF Worlds. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ «‘The Hobbit’: Russian Soviet Version Is Cheap / Delightful». Huffington Post. New York City. 21 December 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Kajava, Jukka (29 March 1993). «Tolkienin taruista on tehty tv-sarja: Hobitien ilme syntyi jo Ryhmäteatterin Suomenlinnan tulkinnassa» [Tolkien’s tales have been turned into a TV series: The Hobbits have been brought to live in the Ryhmäteatteri theatre]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). (subscription required)

- ^ Saney, Daniel (1 August 2005). «‘Idiots’ force Connery to quit acting». Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines UK. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ «New York Con Reports, Pictures and Video». TrekMovie. 9 March 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ Ryan, Mike (6 December 2012). «Peter Jackson, ‘The Hobbit’ Director, On Returning To Middle-Earth & The Polarizing 48 FPS Format». The Huffington Post. New York City: Huffington Post Media Group. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Moore, Sam (23 March 2017). «Sir Ian McKellen to reprise role of Gandalf in new one-man show». NME. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ «Acting Awards, Honours, and Appointments». Ian McKellen. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ «The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners». oscars.org. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ «The 100 Greatest Movie Characters: 30. Gandalf». Empire. London, England: Bauer Media Group. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ Sibley, Brian (2006). «Ring-Master». Peter Jackson: A Film-maker’s Journey. HarperCollins. pp. 445–519. ISBN 0-00-717558-2.

- ^ «Ian McKellen as Gandalf in The Hobbit». Ian McKellen. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ «Gandalf». Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ «Gandalf». Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ «Gandalf». Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ «TheOneRing.net™ | Events | World Events | The Two Towers at Chicago’s Lifeline Theatre». archives.theonering.net. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Wren, Celia (October 2001). «The Mordor the Merrier». American Theatre. 18: 13–15.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (25 July 2005). «Precious News! Tony Award Winner Will Play Gandalf in Lord of the Rings Musical; Cast Announced». Playbill. Playbill. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ «Gandalf». Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

Todd Hansen is the voice of Gandalf in The LEGO Movie.

- ^ Lang, Derrick (9 April 2015). «Awesome! ‘Lego Dimensions’ combining bricks and franchises». The Denver Post. Denver, Colorado: Digital First Media. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ «Der Herr der Ringe, Johan de Meij — Sinfonie Nr.1». Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Bratman, David (2010). «Liquid Tolkien: Music, Tolkien, Middle-earth, and More Music». In Eden, Bradford Lee (ed.). Middle-earth Minstrel: Essays on Music in Tolkien. McFarland. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-0-7864-5660-4.

Sources[edit]

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Return of the Shadow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-49863-7.

| Gandalf | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| First appearance | The Hobbit (1937) |

| Last appearance | Unfinished Tales (1980) |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | See Names |

| Race | Maia |

| Affiliation | Company of the Ring |

| Weapon |

|

Gandalf is a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien’s novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. He is a wizard, one of the Istari order, and the leader of the Fellowship of the Ring. Tolkien took the name «Gandalf» from the Old Norse «Catalogue of Dwarves» (Dvergatal) in the Völuspá.

As a wizard and the bearer of one of the Three Rings, Gandalf has great power, but works mostly by encouraging and persuading. He sets out as Gandalf the Grey, possessing great knowledge and travelling continually. Gandalf is focused on the mission to counter the Dark Lord Sauron by destroying the One Ring. He is associated with fire; his ring of power is Narya, the Ring of Fire. As such, he delights in fireworks to entertain the hobbits of the Shire, while in great need he uses fire as a weapon. As one of the Maiar, he is an immortal spirit from Valinor, but his physical body can be killed.

In The Hobbit, Gandalf assists the 13 dwarves and the hobbit Bilbo Baggins with their quest to retake the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the dragon, but leaves them to urge the White Council to expel Sauron from his fortress of Dol Guldur. In the course of the quest, Bilbo finds a magical ring. The expulsion succeeds, but in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf reveals that Sauron’s retreat was only a feint, as he soon reappeared in Mordor. Gandalf further explains that, after years of investigation, he is sure that Bilbo’s ring is the One Ring that Sauron needs to dominate the whole of Middle-earth. The Council of Elrond creates the Fellowship of the Ring, with Gandalf as its leader, to defeat Sauron by destroying the Ring. He takes them south through the Misty Mountains, but is killed fighting a Balrog, an evil spirit-being, in the underground realm of Moria. After he dies, he is sent back to Middle-earth to complete his mission as Gandalf the White. He reappears to three of the Fellowship and helps to counter the enemy in Rohan, then in Gondor, and finally at the Black Gate of Mordor, in each case largely by offering guidance. When victory is complete, he crowns Aragorn as King before leaving Middle-earth for ever to return to Valinor.

Tolkien once described Gandalf as an angel incarnate; later, both he and other scholars have likened Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his «Wanderer» guise. Others have described Gandalf as a guide-figure who assists the protagonists, comparable to the Cumaean Sibyl who assisted Aeneas in Virgil’s The Aeneid, or to Virgil himself in Dante’s Inferno. Scholars have likened his return in white to the transfiguration of Christ; he is further described as a prophet, representing one element of Christ’s threefold office of prophet, priest, and king, where the other two roles are taken by Frodo and Aragorn.

The Gandalf character has been featured in radio, television, stage, video game, music, and film adaptations, including Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 animated film. His best-known portrayal is by Ian McKellen in Peter Jackson’s 2001–2003 The Lord of the Rings film series, where the actor based his acclaimed performance on Tolkien himself. McKellen reprised the role in Jackson’s 2012–2014 film series The Hobbit.

Names[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Tolkien derived the name Gandalf from Gandálfr, a dwarf in the Völuspá’s Dvergatal, a list of dwarf-names.[1] In Old Norse, the name means staff-elf. This is reflected in his name Tharkûn, which is «said to mean ‘Staff-man'» in Khuzdul, one of Tolkien’s invented languages.[T 1]

In-universe names[edit]

Gandalf is given several names and epithets in Tolkien’s writings. Faramir calls him the Grey Pilgrim, and reports Gandalf as saying, «Many are my names in many countries. Mithrandir[a] among the Elves, Tharkûn to the Dwarves, Olórin I was in my youth in the West that is forgotten, in the South Incánus, in the North Gandalf; to the East I go not.»[T 2] In an early draft of The Hobbit, he is called Bladorthin, while the name Gandalf is used by the dwarf who later became Thorin Oakenshield.[2]

Each Wizard is distinguished by the colour of his cloak. For most of his manifestation as a wizard, Gandalf’s cloak is grey, hence the names Gandalf the Grey and Greyhame, from Old English hame, «cover, skin». Mithrandir is a name in Sindarin meaning «the Grey Pilgrim» or «the Grey Wanderer». Midway through The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf becomes the head of the order of Wizards, and is renamed Gandalf the White. This change in status (and clothing) introduces another name for the wizard: the White Rider. However, characters who speak Elvish still refer to him as Mithrandir. At times in The Lord of the Rings, other characters address Gandalf by insulting nicknames: Stormcrow, Láthspell («Ill-news» in Old English), and «Grey Fool».[T 1]

Characteristics[edit]

Tolkien describes Gandalf as the last of the wizards to appear in Middle-earth, one who «seemed the least, less tall than the others, and in looks more aged, grey-haired and grey-clad, and leaning on a staff».[T 1] Yet the Elf Círdan who met him on arrival nevertheless considered him «the greatest spirit and the wisest» and gave him the Elven Ring of Power called Narya, the Ring of Fire, containing a «red» stone for his aid and comfort. Tolkien explicitly links Gandalf to the element fire later in the same essay:[T 1]

Warm and eager was his spirit (and it was enhanced by the ring Narya), for he was the Enemy of Sauron, opposing the fire that devours and wastes with the fire that kindles, and succours in wanhope and distress; but his joy, and his swift wrath, were veiled in garments grey as ash, so that only those that knew him well glimpsed the flame that was within. Merry he could be, and kindly to the young and simple, yet quick at times to sharp speech and the rebuking of folly; but he was not proud, and sought neither power nor praise … Mostly he journeyed tirelessly on foot, leaning on a staff, and so he was called among Men of the North Gandalf ‘the Elf of the Wand’. For they deemed him (though in error) to be of Elven-kind, since he would at times work wonders among them, loving especially the beauty of fire; and yet such marvels he wrought mostly for mirth and delight, and desired not that any should hold him in awe or take his counsels out of fear. … Yet it is said that in the ending of the task for which he came he suffered greatly, and was slain, and being sent back from death for a brief while was clothed then in white, and became a radiant flame (yet veiled still save in great need).[T 1]

Fictional biography[edit]

Valinor[edit]

In Valinor, Gandalf was called Olórin.[T 1] He was one of the Maiar of Valinor, specifically, one of the people of the Vala Manwë; he was said to be the wisest of the Maiar. He was closely associated with two other Valar: Irmo, in whose gardens he lived, and Nienna, the patron of mercy, who gave him tutelage. When the Valar decided to send the order of the Wizards (Istari) across the Great Sea to Middle-earth to counsel and assist all those who opposed Sauron, Olórin was proposed by Manwë. Olórin initially begged to be excused, declaring he was too weak and that he feared Sauron, but Manwë replied that that was all the more reason for him to go.[T 1]

As one of the Maiar, Gandalf was not a mortal Man but an angelic being who had taken human form. As one of those spirits, Olórin was in service to the Creator (Eru Ilúvatar) and the Creator’s ‘Secret Fire’. Along with the other Maiar who entered into Middle-earth as the five Wizards, he took on the specific form of an old man as a sign of his humility. The role of the wizards was to advise and counsel but never to attempt to match Sauron’s strength with their own. It might be, too, that the kings and lords of Middle-earth would be more receptive to the advice of a humble old man than a more glorious form giving them direct commands.[T 1]

Middle-earth[edit]

The wizards arrived in Middle-earth separately, early in the Third Age; Gandalf was the last, landing in the Havens of Mithlond. He seemed the oldest and least in stature, but Círdan the Shipwright felt that he was the greatest on their first meeting in the Havens, and gave him Narya, the Ring of Fire. Saruman, the chief Wizard, learned of the gift and resented it. Gandalf hid the ring well, and it was not widely known until he left with the other ring-bearers at the end of the Third Age that he, and not Círdan, was the holder of the third of the Elven-rings.[T 1]

Gandalf’s relationship with Saruman, the head of their Order, was strained. The Wizards were commanded to aid Men, Elves, and Dwarves, but only through counsel; they were forbidden to use force to dominate them, though Saruman increasingly disregarded this.[T 1]

The White Council[edit]

Gandalf suspected early on that an evil presence, the Necromancer of Dol Guldur, was not a Nazgûl but Sauron himself. He went to Dol Guldur[T 3] to discover the truth, but the Necromancer withdrew before him, only to return with greater force,[T 3] and the White Council was formed in response.[T 3] Galadriel had hoped Gandalf would lead the council, but he refused, declining to be bound by any but the Valar who had sent him. Saruman was chosen instead, as the most knowledgeable about Sauron’s work in the Second Age.[T 4][T 1]

Gandalf returned to Dol Guldur «at great peril» and learned that the Necromancer was indeed Sauron. The following year a White Council was held, and Gandalf urged that Sauron be driven out.[T 3] Saruman, however, reassured the Council that Sauron’s evident effort to find the One Ring would fail, as the Ring would long since have been carried by the river Anduin to the Sea; and the matter was allowed to rest. But Saruman began actively seeking the Ring near the Gladden Fields where Isildur had been killed.[T 4][T 1]

The Quest of Erebor[edit]

«The Quest of Erebor» in Unfinished Tales elaborates upon the story behind The Hobbit. It tells of a chance meeting between Gandalf and Thorin Oakenshield, a Dwarf-king in exile, in the Prancing Pony inn at Bree. Gandalf had for some time foreseen the coming war with Sauron, and knew that the North was especially vulnerable. If Rivendell were to be attacked, the dragon Smaug could cause great devastation. He persuaded Thorin that he could help him regain his lost territory of Erebor from Smaug, and so the quest was born.[T 5]

The Hobbit[edit]

Gandalf meets with Bilbo in the opening of The Hobbit. He arranges for a tea party, to which he invites the thirteen dwarves, and thus arranges the travelling group central to the narrative. Gandalf contributes the map and key to Erebor to assist the quest.[T 6] On this quest Gandalf acquires the sword, Glamdring, from the trolls’ treasure hoard.[T 7] Elrond informs them that the sword was made in Gondolin, a city long ago destroyed, where Elrond’s father lived as a child.[T 8]

After escaping from the Misty Mountains pursued by goblins and wargs, the party is carried to safety by the Great Eagles.[T 9] Gandalf then persuades Beorn to house and provision the company for the trip through Mirkwood. Gandalf leaves the company before they enter Mirkwood, saying that he had pressing business to attend to.[T 10]

He turns up again before the walls of Erebor disguised as an old man, revealing himself when it seems the Men of Esgaroth and the Mirkwood Elves will fight Thorin and the dwarves over Smaug’s treasure. The Battle of Five Armies ensues when hosts of goblins and wargs attack all three parties.[T 11] After the battle, Gandalf accompanies Bilbo back to the Shire, revealing at Rivendell what his pressing business had been: Gandalf had once again urged the council to evict Sauron, since quite evidently Sauron did not require the One Ring to continue to attract evil to Mirkwood.[T 12] Then the Council «put[s] forth its power» and drives Sauron from Dol Guldur. Sauron had anticipated this, and had feigned a withdrawal, only to reappear in Mordor.[T 13]

The Lord of the Rings[edit]

Gandalf the Grey[edit]

Gandalf spent the years between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings travelling Middle-earth in search of information on Sauron’s resurgence and Bilbo Baggins’s mysterious ring, spurred particularly by Bilbo’s initial misleading story of how he had obtained it as a «present» from Gollum. During this period, he befriended Aragorn and became suspicious of Saruman. He spent as much time as he could in the Shire, strengthening his friendship with Bilbo and Frodo, Bilbo’s orphaned cousin and adopted heir.[T 13]

Gandalf returns to the Shire for Bilbo’s «eleventy-first» (111th) birthday party, bringing many fireworks for the occasion. After Bilbo, as a prank on his guests, puts on the ring and disappears, Gandalf strongly encourages his old friend to leave the ring to Frodo, as they had planned. Bilbo becomes hostile and accuses Gandalf of trying to steal the ring. Alarmed, Gandalf impresses on Bilbo the foolishness of this accusation. Coming to his senses, Bilbo admits that the ring has been troubling him, and leaves it behind for Frodo as he departs for Rivendell.[T 14]

Over the next 17 years, Gandalf travels extensively, searching for answers on the ring. He finds some answers in Isildur’s scroll, in the archives of Minas Tirith. He also wants to question Gollum, who had borne the ring for many years. Gandalf searches long and hard for Gollum, often assisted by Aragorn. Aragorn eventually succeeds in capturing Gollum. Gandalf questions Gollum, threatening him with fire when he proves unwilling to speak. Gandalf learns that Sauron has forced Gollum under torture in his fortress, Barad-dûr, to tell what he knows of the ring. This reinforces Gandalf’s growing suspicion that Bilbo’s ring is the One Ring.[T 13]

Returning to the Shire, Gandalf confirms his suspicion by throwing the Ring into Frodo’s hearth-fire and reading the writing that appears on the Ring’s surface. He tells Frodo the history of the Ring, and urges him to take it to Rivendell, saying that he would be in grave danger if he stayed in the Shire. Gandalf says he will attempt to return for Frodo’s 50th birthday party, to accompany him on the road; and that meanwhile Frodo should arrange to leave quietly, as the servants of Sauron will be searching for him.[T 15]

Outside the Shire, Gandalf encounters the wizard Radagast the Brown, who brings the news that the Nazgûl have ridden out of Mordor—and a request from Saruman that Gandalf come to Isengard. Gandalf leaves a letter to Frodo (urging his immediate departure) with Barliman Butterbur at the Prancing Pony, and heads towards Isengard. There Saruman reveals his true intentions, urging Gandalf to help him obtain the Ring for his own use. Gandalf refuses, and Saruman imprisons him at the top of his tower. Eventually Gandalf is rescued by Gwaihir the Eagle.[T 13]

Gwaihir sets Gandalf down in Rohan, where Gandalf appeals to King Théoden for a horse. Théoden, under the evil influence of Gríma Wormtongue, Saruman’s spy and servant, tells Gandalf to take any horse he pleases, but to leave quickly. It is then that Gandalf meets the great horse Shadowfax who will be his mount and companion. Gandalf rides hard for the Shire, but does not reach it until after Frodo has set out. Knowing that Frodo and his companions will be heading for Rivendell, Gandalf makes his own way there. He learns at Bree that the Hobbits have fallen in with Aragorn. He faces the Nazgûl at Weathertop but escapes after an all-night battle, drawing four of them northward.[T 13] Frodo, Aragorn and company face the remaining five on Weathertop a few nights later.[T 16] Gandalf reaches Rivendell just before Frodo’s arrival.[T 13]

In Rivendell, Gandalf helps Elrond drive off the Nazgûl pursuing Frodo, and plays a leading role in the Council of Elrond as the only person who knows the full history of the Ring. He reveals that Saruman has betrayed them and is in league with Sauron. When it is decided that the Ring has to be destroyed, Gandalf volunteers to accompany Frodo—now the Ring-bearer—in his quest. He persuades Elrond to let Frodo’s cousins Merry and Pippin join the Fellowship.[T 13]

The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand Glamdring gleamed, cold and white. His enemy halted again, facing him, and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings. It raised the whip, and the thongs whined and cracked. Fire came from its nostrils. But Gandalf stood firm. «You cannot pass,» he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. «I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass.»

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Taking charge of the Fellowship (comprising nine representatives of the free peoples of Middle-earth, «set against the Nine Riders»), Gandalf and Aragorn lead the Hobbits and their companions south.[T 17] After an unsuccessful attempt to cross Mount Caradhras in winter, they cross under the mountains through the Mines of Moria under the Misty Mountains, though only Gimli the Dwarf is enthusiastic about that route. In Moria, they discover that the dwarf colony established there by Balin has been annihilated by orcs. The Fellowship fights with the orcs and trolls of Moria and escapes them.[T 18]

At the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, they encounter «Durin’s Bane», a fearsome Balrog from ancient times. Gandalf faces the Balrog to enable the others to escape. After a brief exchange of blows, Gandalf breaks the bridge beneath the Balrog with his staff. As the Balrog falls, it wraps its whip around Gandalf’s legs, dragging him over the edge. Gandalf falls into the abyss, crying «Fly, you fools!».[T 19]

Gandalf and the Balrog fall into a deep lake in Moria’s underworld. Gandalf pursues the Balrog through the tunnels for eight days until they climb to the peak of Zirakzigil. Here they fight for two days and nights. The Balrog is defeated and cast down onto the mountainside. Gandalf too dies, and his body lies on the peak while his spirit travels «out of thought and time».[T 20]

Gandalf the White[edit]

Gandalf is «sent back»[b] as Gandalf the White, and returns to life on the mountain top. Gwaihir carries him to Lothlórien, where he is healed of his injuries and re-clothed in white robes by Galadriel. He travels to Fangorn Forest, where he encounters Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas (who are tracking Merry and Pippin). They mistake him for Saruman, but he stops their attacks and reveals himself.[T 20]

They travel to Rohan, where Gandalf finds that king Théoden has been further weakened by Wormtongue’s influence. He breaks Wormtongue’s hold over Théoden, and convinces the king to join in the fight against Sauron.[T 21] Gandalf sets off to gather warriors of the Westfold to assist Théoden in the coming battle with Saruman. Gandalf arrives just in time to defeat Saruman’s army in the battle of Helm’s Deep.[T 22] Gandalf and the King ride to Isengard, which has just been destroyed by Treebeard and his Ents, who are accompanied by Merry and Pippin.[T 23] Gandalf breaks Saruman’s staff and expels him from the White Council and the Order of Wizards; Gandalf takes Saruman’s place as head of both. Wormtongue makes an attempt to kill Gandalf or Saruman with the palantír of Orthanc, but misses both. Pippin retrieves the palantír, but Gandalf quickly takes it.[T 24] After the group leaves Isengard, Pippin takes the palantír from a sleeping Gandalf, looks into it, and comes face to face with Sauron himself. Gandalf gives the palantír to Aragorn and takes the chastened Pippin with him to Minas Tirith to keep the young hobbit out of further trouble.[T 25]

Gandalf arrives in time to help to arrange the defences of Minas Tirith. His presence is resented by Denethor, the Steward of Gondor; but when his son Faramir is gravely wounded in battle, Denethor sinks into despair and madness. Together with Prince Imrahil, Gandalf leads the defenders during the siege of the city. When the forces of Mordor break the main gate, Gandalf, alone on Shadowfax, confronts the Lord of the Nazgûl. At that moment the Rohirrim arrive, compelling the Nazgûl to withdraw to fight. Gandalf is required to save Faramir from Denethor, who seeks in desperation to burn himself and his son on a funeral pyre.[T 26]

«This, then, is my counsel,» [said Gandalf.] «We have not the Ring. In wisdom or great folly it has been sent away to be destroyed, lest it destroy us. Without it we cannot by force defeat [Sauron’s] force. But we must at all costs keep his Eye from his true peril… We must call out his hidden strength, so that he shall empty his land… We must make ourselves the bait, though his jaws should close on us… We must walk open-eyed into that trap, with courage, but small hope for ourselves. For, my lords, it may well prove that we ourselves shall perish utterly in a black battle far from the living lands; so that even if Barad-dûr be thrown down, we shall not live to see a new age. But this, I deem, is our duty.»

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Aragorn and Gandalf lead the final campaign against Sauron’s forces at the Black Gate, in an effort to distract the Dark Lord’s attention from Frodo and Sam; they are at that moment scaling Mount Doom to destroy the One Ring. In a parley before the battle, Gandalf and the other leaders of the West meet the nameless lieutenant of Mordor, who shows them Frodo’s mithril shirt and other items from the Hobbits’ equipment. Gandalf rejects Mordor’s terms of surrender, and the forces of the West face the full might of Sauron’s armies, until the Ring is destroyed in Mount Doom.[T 27] Gandalf leads the Eagles to rescue Frodo and Sam from the erupting mountain.[T 28]

After the war, Gandalf crowns Aragorn as King Elessar, and helps him find a sapling of the White Tree of Gondor.[T 29] He accompanies the Hobbits back to the borders of the Shire, before leaving to visit Tom Bombadil.[T 30]

Two years later, Gandalf departs Middle-earth for ever. He boards the Ringbearers’ ship in the Grey Havens and sets sail to return across the sea to the Undying Lands; with him are his friends Frodo, Bilbo, Galadriel, and Elrond, and his horse Shadowfax.[T 31]

Concept and creation[edit]

Appearance[edit]

Tolkien’s biographer Humphrey Carpenter relates that Tolkien owned a postcard entitled Der Berggeist («the mountain spirit»), which he labelled «the origin of Gandalf».[3] It shows a white-bearded man in a large hat and cloak seated among boulders in a mountain forest. Carpenter said that Tolkien recalled buying the postcard during his holiday in Switzerland in 1911. Manfred Zimmerman, however, discovered that the painting was by the German artist Josef Madlener and dates from the mid-1920s. Carpenter acknowledged that Tolkien was probably mistaken about the origin of the postcard.[4]

An additional influence may have been Väinämöinen, a demigod and the central character in Finnish folklore and the national epic Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot.[5] Väinämöinen was described as an old and wise man, and he possessed a potent, magical singing voice.[6]

Throughout the early drafts, and through to the first edition of The Hobbit, Bladorthin/Gandalf is described as being a «little old man», distinct from a dwarf, but not of the full human stature that would later be described in The Lord of the Rings. Even in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf was not tall; shorter, for example, than Elrond[T 32] or the other wizards.[T 1]

Name[edit]

When writing The Hobbit in the early 1930s Tolkien gave the name Gandalf to the leader of the Dwarves, the character later called Thorin Oakenshield. The name is taken from the same source as all the other Dwarf names (save Balin) in The Hobbit: the «Catalogue of Dwarves» in the Völuspá.[7] The Old Norse name Gandalfr incorporates the words gandr meaning «wand», «staff» or (especially in compounds) «magic» and álfr «elf». The name Gandalf is found in at least one more place in Norse myth, in the semi-historical Heimskringla, which briefly describes Gandalf Alfgeirsson, a legendary Norse king from eastern Norway and rival of Halfdan the Black.[8] Gandalf is also the name of a Norse sea-king in Henrik Ibsen’s second play, The Burial Mound. The name «Gandolf» occurs as a character in William Morris’ 1896 fantasy novel The Well at the World’s End, along with the horse «Silverfax», adapted by Tolkien as Gandalf’s horse «Shadowfax». Morris’ book, inspired by Norse myth, is set in a pseudo-medieval landscape; it deeply influenced Tolkien. The wizard that became Gandalf was originally named Bladorthin.[9][10]

Tolkien came to regret his ad hoc use of Old Norse names, referring to a «rabble of eddaic-named dwarves, … invented in an idle hour» in 1937.[T 33] But the decision to use Old Norse names came to have far-reaching consequences in the composition of The Lord of the Rings; in 1942, Tolkien decided that the work was to be a purported translation from the fictional language of Westron, and in the English translation Old Norse names were taken to represent names in the language of Dale.[11] Gandalf, in this setting, is thus a representation in English (anglicised from Old Norse) of the name the Dwarves of Erebor had given to Olórin in the language they used «externally» in their daily affairs, while Tharkûn is the (untranslated) name, presumably of the same meaning, that the Dwarves gave him in their native Khuzdul language.[T 34]

Guide[edit]

Like Odin in «Wanderer» guise—an old man with a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff:[12] Gandalf, by ‘Nidoart’, 2013

Gandalf’s role and importance was substantially increased in the conception of The Lord of the Rings, and in a letter of 1954, Tolkien refers to Gandalf as an «angel incarnate».[T 35] In the same letter Tolkien states he was given the form of an old man in order to limit his powers on Earth. Both in 1965 and 1971 Tolkien again refers to Gandalf as an angelic being.[T 36][T 37]

In a 1946 letter, Tolkien stated that he thought of Gandalf as an «Odinic wanderer».[T 38] Other commentators have similarly compared Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his «Wanderer» guise—an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff,[12][13] or likened him to Merlin of Arthurian legend or the Jungian archetype of the «wise old man».[14]

| Attribute | Gandalf | Odin |

|---|---|---|

| Accoutrements | «battered hat» cloak «thorny staff» |

Epithet: «Long-hood» blue cloak a staff |

| Beard | «the grey», «old man» | Epithet: «Greybeard» |

| Appearance | the Istari (Wizards) «in simple guise, as it were of Men already old in years but hale in body, travellers and wanderers» as Tolkien wrote «a figure of ‘the Odinic wanderer'»[T 39] |

Epithets: «Wayweary», «Wayfarer», «Wanderer» |

| Power | with his staff | Epithet: «Bearer of the [Magic] Wand» |

| Eagles | rescued repeatedly by eagles in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings |

Associated with eagles; escapes from Jotunheim back to Asgard as an eagle |

The Tolkien scholar Charles W. Nelson described Gandalf as a «guide who .. assists a major character on a journey or quest .. to unusual and distant places». He noted that in both The Fellowship of the Ring and The Hobbit, Tolkien presents Gandalf in these terms. Immediately after the Council of Elrond, Gandalf tells the Fellowship:[15]

Someone said that intelligence would be needed in the party. He was right. I think I shall come with you.[15]

Nelson notes the similarity between this and Thorin’s statement in The Hobbit:[15]

We shall soon .. start on our long journey, a journey from which some of us, or perhaps all of us (except our friend and counsellor, the ingenious wizard Gandalf) may never return.[15]

Nelson gives as examples of the guide figure the Cumaean Sibyl who assisted Aeneas on his journey through the underworld in Virgil’s tale The Aeneid, and then Virgil himself in Dante’s Inferno, directing, encouraging, and physically assisting Dante as he travels through hell. In English literature, Nelson notes, Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur has the wizard Merlin teaching and directing Arthur to begin his journeys. Given these precedents, Nelson remarks, it was unsurprising that Tolkien should make use of a guide figure, endowing him, like these predecessors, with power, wisdom, experience, and practical knowledge, and «aware[ness] of [his] own limitations and [his] ranking in the order of the great».[15] Other characters who act as wise and good guides include Tom Bombadil, Elrond, Aragorn, Galadriel—who he calls perhaps the most powerful of the guide figures—and briefly also Faramir.[15]

Nelson writes that there is equally historical precedent for wicked guides, such as Edmund Spenser’s «evil palmers» in The Faerie Queene, and suggests that Gollum functions as an evil guide, contrasted with Gandalf, in Lord of the Rings. He notes that both Gollum and Gandalf are servants of The One, Eru Ilúvatar, in the struggle against the forces of darkness, and «ironically» all of them, good and bad, are necessary to the success of the quest. He comments, too, that despite Gandalf’s evident power, and the moment when he faces the Lord of the Nazgûl, he stays in the role of guide throughout, «never directly confront[ing] his enemies with his raw power.»[15]

Christ-figure[edit]

The critic Anne C. Petty, writing about «Allegory» in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, discusses Gandalf’s death and reappearance in Christian terms. She cites Michael W. Maher, S.J.: «who could not think of Gandalf’s descent into the pits of Moria and his return clothed in white as a death-resurrection motif?»[16][17] She at once notes, however, that «such a narrow [allegorical] interpretation» limits the reader’s imagination by demanding a single meaning for each character and event.[16] Other scholars and theologians have likened Gandalf’s return as a «gleaming white» figure to the transfiguration of Christ.[18][19][20]

The philosopher Peter Kreeft, like Tolkien a Roman Catholic, observes that there is no one complete, concrete, visible Christ figure in The Lord of the Rings comparable to Aslan in C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia series. However, Kreeft and Jean Chausse have identified reflections of the figure of Jesus Christ in three protagonists of The Lord of the Rings: Gandalf, Frodo and Aragorn. While Chausse found «facets of the personality of Jesus» in them, Kreeft wrote that «they exemplify the Old Testament threefold Messianic symbolism of prophet (Gandalf), priest (Frodo), and king (Aragorn).»[21][22][23]

| Christ-like attribute | Gandalf | Frodo | Aragorn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial death, resurrection |

Dies in Moria, reborn as Gandalf the White[c] |

Symbolically dies under Morgul-knife, healed by Elrond[25] |

Takes Paths of the Dead, reappears in Gondor |

| Saviour | All three help to save Middle-earth from Sauron | ||

| Threefold Messianic symbolism | Prophet | Priest | King |

Adaptations[edit]

In the BBC Radio dramatisations, Gandalf has been voiced by Norman Shelley in The Lord of the Rings (1955–1956),[26] Heron Carvic in The Hobbit (1968), Bernard Mayes in The Lord of the Rings (1979),[27] and Sir Michael Hordern in The Lord of the Rings (1981).[28]

John Huston voiced Gandalf in the animated films The Hobbit (1977) and The Return of the King (1980) produced by Rankin/Bass. William Squire voiced Gandalf in the animated film The Lord of the Rings (1978) directed by Ralph Bakshi. Ivan Krasko played Gandalf in the Soviet film adaptation The Hobbit (1985).[29] Gandalf was portrayed by Vesa Vierikko in the Finnish television miniseries Hobitit (1993).[30]

Ian McKellen portrayed Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings film series (2001–2003), directed by Peter Jackson, after Sean Connery and Patrick Stewart both turned down the role.[31][32] According to Jackson, McKellen based his performance as Gandalf on Tolkien himself:

We listened to audio recordings of Tolkien reading excerpts from Lord of the Rings. We watched some BBC interviews with him—there’s a few interviews with Tolkien—and Ian based his performance on an impersonation of Tolkien. He’s literally basing Gandalf on Tolkien. He sounds the same, he uses the speech patterns and his mannerisms are born out of the same roughness from the footage of Tolkien. So, Tolkien would recognize himself in Ian’s performance.[33]