Как правильно пишется словосочетание «голеностопный сустав»

- Как правильно пишется слово «голеностопный»

- Как правильно пишется слово «сустав»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: ампир — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «голеностопный»

Ассоциации к слову «сустав»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «голеностопный сустав»

Предложения со словосочетанием «голеностопный сустав»

- По статистике, чаще всего встречается растяжение связок голеностопного сустава.

- Чаще всего отёк возникает на стопе, в области голеностопного сустава и в нижней половине голени.

- То есть имеет место устойчивость и уменьшается возможность травмы голеностопного сустава.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «голеностопный сустав»

- Надоедал Климу студент Попов; этот голодный человек неутомимо бегал по коридорам, аудиториям, руки его судорожно, как вывихнутые, дергались в плечевых суставах; наскакивая на коллег, он выхватывал из карманов заношенной тужурки письма, гектографированные листки папиросной бумаги и бормотал, втягивая в себя звук с:

- Он вытаскивал ее за задние лапы из-под верстака и выделывал с нею такие фокусы, что у нее зеленело в глазах и болело во всех суставах.

- Порывался я броситься на землю, чтобы облобызать честные нозе его, и не мог: словно тайная сила оковала все суставы мои и не допустила меня, недостойного, вкусить такого блаженства.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «сустав»

- коленный сустав

тазобедренный сустав

плечевой сустав - суставы пальцев

суставы рук

суставы позвоночника - в области суставов

подвижность суставов

заболевания суставов - суставы побелели

суставы хрустнули

суставы скрипели - хрустнуть суставами

разминать суставы

скрипеть суставами - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «голеностопный сустав»

-

Голе́носто́пный суста́в (лат. articulátio talocrurális) — сочленение костей голени со стопой — подвижное соединение большеберцовой, малоберцовой и таранной костей человека. Сложный по строению, блоковидный по форме, образован суставными поверхностями дистальных (расположенных дальше от туловища) эпифизов обеих берцовых костей, охватывающими «вилкой» блок таранной кости. К верхней суставной поверхности таранной кости прилежит большеберцовая кость, а по бокам — суставные поверхности наружной и внутренней лодыжек. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания ГОЛЕНОСТОПНЫЙ СУСТАВ

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

голеностопный

- голеностопный

-

голеностопный

Слитно или раздельно? Орфографический словарь-справочник. — М.: Русский язык.

.

1998.

Смотреть что такое «голеностопный» в других словарях:

-

голеностопный — голеностопный … Слитно. Раздельно. Через дефис.

-

ГОЛЕНОСТОПНЫЙ — ГОЛЕНОСТОПНЫЙ, ая, ое: голеностопный сустав сустав, соединяющий кости голени и стопы. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

-

ГОЛЕНОСТОПНЫЙ — прил. от слов голень и стопа; см., напр., Голеностопный сустав … Психомоторика: cловарь-справочник

-

голеностопный — ая, ое. голеностопный сустав … Словарь многих выражений

-

Голеностопный сустав — Правый голеностопный сустав, вид сбоку … Википедия

-

Голеностопный сустав — Голеностопный сустав, articulatio talocruralis, образован суставными поверхностями дистальных эпифизов большеберцовой и малоберцовой кoстей и суставной поверхностью блока таранной кости. На большеберцовой кости суставная поверхность представлена… … Атлас анатомии человека

-

голеностопный узел — Узел протеза нижней конечности, включающий в себя искусственную стопу и щиколотку. [ГОСТ Р 51819 2001] Тематики протезирование и ортезирование конечностей … Справочник технического переводчика

-

Голеностопный сустав — I Голеностопный сустав (articulatio talocruralis) образован дистальными эпифизами костей голени и таранной костью. Дистальные концы костей голени соединяются между собой межберцовым синдесмозом (передней и задней межберцовыми связками) и… … Медицинская энциклопедия

-

Голеностопный сустав — Рис. 1. Полиэтиленовый пакет со льдом, наложенный на голеностопный сустав при растяжении связок. Рис. 1. Полиэтиленовый пакет со льдом, наложенный на голеностопный сустав при растяжении связок. Голеностопный сустав блоковидный сустав,… … Первая медицинская помощь — популярная энциклопедия

-

Голеностопный — прил. Сочленяющий кости голени и стопы (о суставе). Толковый словарь Ефремовой. Т. Ф. Ефремова. 2000 … Современный толковый словарь русского языка Ефремовой

Quotes of the Day

Цитаты дня на английском языке

«The more refined and subtle our minds, the more vulnerable they are.»

Paul Tournier

«Everything has been figured out, except how to live.»

Jean-Paul Sartre

«The whole secret of life is to be interested in one thing profoundly and in a thousand things well.»

Horace Walpole

«Everything’s got a moral, if only you can find it.»

Lewis Carroll

Голеностопный сустав ( анат.) — сустав, соединяющий кости голени и стопы.

См. также голеностопный.

Источник (печатная версия): Словарь русского языка: В 4-х т. / РАН, Ин-т лингвистич. исследований; Под ред. А. П. Евгеньевой. — 4-е изд., стер. — М.: Рус. яз.; Полиграфресурсы, 1999;

Голе́носто́пный суста́в (лат. articulátio talocrurális) — сочленение костей голени со стопой — подвижное соединение большеберцовой, малоберцовой и таранной костей человека. Сложный по строению, блоковидный по форме, образован суставными поверхностями дистальных (расположенных дальше от туловища) эпифизов обеих берцовых костей, охватывающими «вилкой» блок таранной кости. К верхней суставной поверхности таранной кости прилежит большеберцовая кость, а по бокам — суставные поверхности наружной и внутренней лодыжек.

В суставе возможны движения:

фронтальная ось — сгибание и разгибание стопы;

сагиттальная ось — незначительное отведение и приведение.

Источник: Wipedia.org

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Ankle | |

|---|---|

Lateral view of the human ankle |

|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tarsus |

| MeSH | D000842 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.041 |

| TA2 | 165 |

| FMA | 9665 |

| Anatomical terminology

[edit on Wikidata] |

The ankle, or the talocrural region,[1] or the jumping bone (informal) is the area where the foot and the leg meet.[2] The ankle includes three joints: the ankle joint proper or talocrural joint, the subtalar joint, and the inferior tibiofibular joint.[3][4][5] The movements produced at this joint are dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot. In common usage, the term ankle refers exclusively to the ankle region. In medical terminology, «ankle» (without qualifiers) can refer broadly to the region or specifically to the talocrural joint.[1][6]

The main bones of the ankle region are the talus (in the foot), and the tibia and fibula (in the leg). The talocrural joint is a synovial hinge joint that connects the distal ends of the tibia and fibula in the lower limb with the proximal end of the talus.[7] The articulation between the tibia and the talus bears more weight than that between the smaller fibula and the talus.

Structure[edit]

Region[edit]

The ankle region is found at the junction of the leg and the foot. It extends downwards (distally) from the narrowest point of the lower leg and includes the parts of the foot closer to the body (proximal) to the heel and upper surface (dorsum) of the foot.[8]: 768

Ankle joint[edit]

The talocrural joint is the only mortise and tenon joint in the human body,[9]: 1418 the term likening the skeletal structure to the woodworking joint of the same name. The bony architecture of the ankle consists of three bones: the tibia, the fibula, and the talus. The articular surface of the tibia may be referred to as the plafond (French for «ceiling»).[10] The medial malleolus is a bony process extending distally off the medial tibia. The distal-most aspect of the fibula is called the lateral malleolus. Together, the malleoli, along with their supporting ligaments, stabilize the talus underneath the tibia.

Because the motion of the subtalar joint provides a significant contribution to positioning the foot, some authors will describe it as the lower ankle joint, and call the talocrural joint the upper ankle joint.[11] Dorsiflexion and Plantarflexion are the movements that take place in the ankle joint. When the foot is plantar flexed, the ankle joint also allows some movements of side to side gliding, rotation, adduction, and abduction.[12]

The bony arch formed by the tibial plafond and the two malleoli is referred to as the ankle «mortise» (or talar mortise). The mortise is a rectangular socket.[1] The ankle is composed of three joints: the talocrural joint (also called talotibial joint, tibiotalar joint, talar mortise, talar joint), the subtalar joint (also called talocalcaneal), and the Inferior tibiofibular joint.[3][4][5] The joint surface of all bones in the ankle are covered with articular cartilage.

The distances between the bones in the ankle are as follows:[13]

- Talus — medial malleolus : 1.70 ± 0.13 mm

- Talus — tibial plafond: 2.04 ± 0.29 mm

- Talus — lateral malleolus: 2.13 ± 0.20 mm

Decreased distances indicate osteoarthritis.

Ligaments[edit]

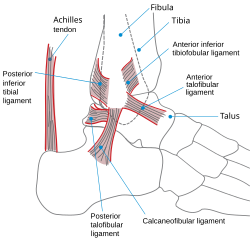

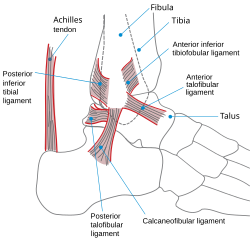

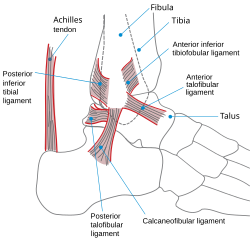

The ankle joint is bound by the strong deltoid ligament and three lateral ligaments: the anterior talofibular ligament, the posterior talofibular ligament, and the calcaneofibular ligament.

- The deltoid ligament supports the medial side of the joint, and is attached at the medial malleolus of the tibia and connect in four places to the talar shelf of the calcaneus, calcaneonavicular ligament, the navicular tuberosity, and to the medial surface of the talus.

- The anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments support the lateral side of the joint from the lateral malleolus of the fibula to the dorsal and ventral ends of the talus.

- The calcaneofibular ligament is attached at the lateral malleolus and to the lateral surface of the calcaneus.

Though it does not span the ankle joint itself, the syndesmotic ligament makes an important contribution to the stability of the ankle. This ligament spans the syndesmosis, i.e. the articulation between the medial aspect of the distal fibula and the lateral aspect of the distal tibia. An isolated injury to this ligament is often called a high ankle sprain.

The bony architecture of the ankle joint is most stable in dorsiflexion.[14] Thus, a sprained ankle is more likely to occur when the ankle is plantar-flexed, as ligamentous support is more important in this position. The classic ankle sprain involves the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which is also the most commonly injured ligament during inversion sprains. Another ligament that can be injured in a severe ankle sprain is the calcaneofibular ligament.

Retinacula, tendons and their synovial sheaths, vessels, and nerves[edit]

A number of tendons pass through the ankle region. Bands of connective tissue called retinacula (singular: retinaculum) allow the tendons to exert force across the angle between the leg and foot without lifting away from the angle, a process called bowstringing.[11]

The superior extensor retinaculum of foot extends between the anterior (forward) surfaces of the tibia and fibula near their lower (distal) ends. It contains the anterior tibial artery and vein and the tendons of the tibialis anterior muscle within its tendon sheath and the unsheathed tendons of extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus muscles. The deep peroneal nerve passes under the retinaculum while the superficial peroneal nerve is outside of it. The inferior extensor retinaculum of foot is a Y-shaped structure. Its lateral attachment is on the calcaneus, and the band travels towards the anterior tibia where it is attached and blends with the superior extensor retinaculum. Along with that course, the band divides and another segment attaches to the plantar aponeurosis. The tendons which pass through the superior extensor retinaculum are all sheathed along their paths through the inferior extensor retinaculum and the tendon of the fibularis tertius muscle is also contained within the retinaculum.

The flexor retinaculum of foot extends from the medial malleolus to the medical process of the calcaneus, and the following structures in order from medial to lateral: the tendon of the tibialis posterior muscle, the tendon of the flexor digitorum longus muscle, the posterior tibial artery and vein, the tibial nerve, and the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus muscle.

The fibular retinacula hold the tendons of the fibularis longus and fibularis brevis along the lateral aspect of the ankle region. The superior fibular retinaculum extends from the deep transverse fascia of the leg and lateral malleolus to calcaneus. The inferior fibular retinaculum is a continuous extension from the inferior extensor retinaculum to the calcaneus.[9]: 1418–9

Mechanoreceptors[edit]

Mechanoreceptors of the ankle send proprioceptive sensory input to the central nervous system (CNS).[15] Muscle spindles are thought to be the main type of mechanoreceptor responsible for proprioceptive attributes from the ankle.[16] The muscle spindle gives feedback to the CNS system on the current length of the muscle it innervates and to any change in length that occurs.

It was hypothesized that muscle spindle feedback from the ankle dorsiflexors played the most substantial role in proprioception relative to other muscular receptors that cross at the ankle joint. However, due to the multi-planar range of motion at the ankle joint there is not one group of muscles that is responsible for this.[17] This helps to explain the relationship between the ankle and balance.

In 2011, a relationship between proprioception of the ankle and balance performance was seen in the CNS. This was done by using a fMRI machine in order to see the changes in brain activity when the receptors of the ankle are stimulated.[18] This implicates the ankle directly with the ability to balance. Further research is needed in order to see to what extent does the ankle affect balance.

Function[edit]

Historically, the role of the ankle in locomotion has been discussed by Aristotle and Leonardo da Vinci. There is no question that ankle push-off is a significant force in human gait, but how much energy is used in leg swing as opposed to advancing the whole-body center of mass is not clear.[19]

Clinical significance[edit]

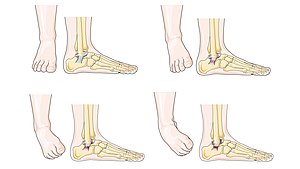

A diagram illustrating varying severity of ankle sprain

Traumatic injury[edit]

Of all major joints, the ankle is the most commonly injured. If the outside surface of the foot is twisted under the leg during weight bearing, the lateral ligament, especially the anterior talofibular portion, is subject to tearing (a sprain) as it is weaker than the medial ligament and it resists inward rotation of the talocrural joint.[8]: 825

Fractures[edit]

Fracture of both sides of the ankle with dislocation as seen on anteroposterior X-ray. (1) fibula, (2) tibia, (arrow) medial malleolus, (arrowhead) lateral malleolus

An ankle fracture is a break of one or more of the bones that make up the ankle joint.[20] Symptoms may include pain, swelling, bruising, and an inability to walk on the injured leg.[20] Complications may include an associated high ankle sprain, compartment syndrome, stiffness, malunion, and post-traumatic arthritis.[20][21]

Ankle fractures may result from excessive stress on the joint such as from rolling an ankle or from blunt trauma.[20][21] Types of ankle fractures include lateral malleolus, medial malleolus, posterior malleolus, bimalleolar, and trimalleolar fractures.[20] The Ottawa ankle rule can help determine the need for X-rays.[21] Special X-ray views called stress views help determine whether an ankle fracture is unstable.

Treatment depends on the fracture type. Ankle stability largely dictates non-operative vs. operative treatment. Non-operative treatment includes splinting or casting while operative treatment includes fixing the fracture with metal implants through an open reduction internal fixation (ORIF).[20] Significant recovery generally occurs within four months while completely recovery usually takes up to one year.[20]

Ankle fractures are common, occurring in over 1.8 per 1000 adults and 1 per 1000 children per year.[21][22] They occur most commonly in young males and older females.[21]

Imaging[edit]

The initial evaluation of suspected ankle pathology is usually by projectional radiography («X-ray»).

Tibiotalar surface angle (TTS)

Varus or valgus deformity, if suspected, can be measured with the frontal tibiotalar surface angle (TTS), formed by the mid-longitudinal tibial axis (such as through a line bisecting the tibia at 8 and 13 cm above the tibial plafond) and the talar surface.[23] An angle of less than 84 degrees is regarded as talipes varus, and an angle of more than 94 degrees is regarded as talipes valgus.[24]

For ligamentous injury, there are 3 main landmarks on X-rays: The first is the tibiofibular clear space, the horizontal distance from the lateral border of the posterior tibial malleolus to the medial border of the fibula, with greater than 5 mm being abnormal. The second is tibiofibular overlap, the horizontal distance between the medial border of the fibula and the lateral border of the anterior tibial prominence, with less than 10 mm being abnormal. The final measurement is the medial clear space, the distance between the lateral aspect of the medial malleolus and the medial border of the talus at the level of the talar dome, with a measurement greater than 4 mm being abnormal. Loss of any of these normal anatomic spaces can indirectly reflect ligamentous injury or occult fracture, and can be followed by MRI or CT.[25]

Abnormalities[edit]

Clubfoot or talipes equinovarus, which occurs in one to two of every 1,000 live births, involves multiple abnormalities of the foot.[26] Equinus refers to the downard deflection of the ankle, and is named for the walking on the toes in the manner of a horse.[27] This does not occur because it is accompanied by an inward rotation of the foot (varus deformity), which untreated, results in walking on the sides of the feet. Treatment may involve manipulation and casting or surgery.[26]

Ankle joint equinus, normally in adults, relates to restricted ankle joint range of motion(ROM).[28] Calf muscle stretching exercises are normally helpful to increase the ankle joint dorsiflexion and used to manage clinical symptoms resulting from ankle equinus.[29]

Occasionally a human ankle has a ball-and-socket ankle joint and fusion of the talo-navicular joint.[30]

History[edit]

The word ankle or ancle is common, in various forms, to Germanic languages, probably connected in origin with the Latin angulus, or Greek αγκυλος, meaning bent.[31]

Other animals[edit]

Evolution[edit]

It has been suggested that dexterous control of toes has been lost in favour of a more precise voluntary control of the ankle joint.[32]

See also[edit]

- Foot

- Leg

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, A. M. R. (2013). «Lower Limb». Clinically Oriented Anatomy (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 508–669. ISBN 978-1-4511-1945-9.

- ^ WebMD (2009). «ankle». Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- ^ a b Milner, Brent K. (1999). «Musculoskeletal Imaging». In Gay, Spencer B.; Woodcock, Richard J. (eds.). Radiology Recall. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 258–383. ISBN 978-0-683-30663-7.

- ^ a b Williams, D. S. Blaise; Taunton, Jack (2007). «Foot, ankle and lower leg». In Kolt, Gregory S.; Snyder-Mackler, Lynn (eds.). Physical Therapies in Sport and Exercise. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 420–39. ISBN 978-0-443-10351-3.

- ^ a b del Castillo, Jorge (2012). «Foot and Ankle Injuries». In Adams, James G. (ed.). Emergency Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 745–55. ISBN 978-1-4557-3394-1.

- ^ Gray, Henry (1918). «Talocrural Articulation or Ankle-joint». Anatomy of the Human Body.

- ^ WebMD (2009). «ankle joint». Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- ^ a b Moore, Keith (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ a b Susan Standring (7 August 2015). Gray’s Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7020-6851-5.

- ^ David P. Barei (29 March 2012). «56. Pilon Fractures». In Robert W. Bucholz (ed.). Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults: Two Volumes Plus Integrated Content Website (Rockwood, Green, and Wilkins’ Fractures). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1928–1971. ISBN 978-1-4511-6144-1.

- ^ a b Joseph E. Muscolino (21 August 2016). Kinesiology — E-Book: The Skeletal System and Muscle Function. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 284–292. ISBN 978-0-323-39935-7.

- ^ Dr. Joseph H Volker (2018-08-08). «Ankle Joint». Earth’s Lab.

- ^ Imai, Kan; Ikoma, Kazuya; Kido, Masamitsu; Maki, Masahiro; Fujiwara, Hiroyoshi; Arai, Yuji; Oda, Ryo; Tokunaga, Daisaku; Inoue, Nozomu; Kubo, Toshikazu (2015). «Joint space width of the tibiotalar joint in the healthy foot». Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 8 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s13047-015-0086-5. ISSN 1757-1146. PMC 4490633. PMID 26146520.

- ^ Gatt, A. and Chockalingam, N., 2011. Clinical Assessment of Ankle Joint DorsiflexionA Review of Measurement Techniques. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 101(1), pp.59-69.https://doi.org/10.7547/1010059

- ^ Michelson, J. D.; Hutchins, C (1995). «Mechanoreceptors in human ankle ligaments». The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 77 (2): 219–24. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.77B2.7706334. PMID 7706334.

- ^ Lephart, S. M.; Pincivero, D. M.; Rozzi, S. L. (1998). «Proprioception of the ankle and knee». Sports Medicine. 25 (3): 149–55. doi:10.2165/00007256-199825030-00002. PMID 9554026. S2CID 13099542.

- ^ Ribot-Ciscar, E; Bergenheim, M; Albert, F; Roll, J. P. (2003). «Proprioceptive population coding of limb position in humans». Experimental Brain Research. 149 (4): 512–9. doi:10.1007/s00221-003-1384-x. PMID 12677332. S2CID 14626459.

- ^ Goble, D. J.; Coxon, J. P.; Van Impe, A.; Geurts, M.; Doumas, M.; Wenderoth, N.; Swinnen, S. P. (2011). «Brain Activity during Ankle Proprioceptive Stimulation Predicts Balance Performance in Young and Older Adults». Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (45): 16344–52. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4159-11.2011. PMC 6633212. PMID 22072686.

- ^ Zelik, Karl E.; Adamczyk, Peter G. (2016). «A unified perspective on ankle push-off in human walking». The Journal of Experimental Biology. 219 (23): 3676–3683. doi:10.1242/jeb.140376. ISSN 0022-0949. PMC 5201006. PMID 27903626.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Ankle Fractures (Broken Ankle) — OrthoInfo — AAOS». www.orthoinfo.org. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Wire J, Slane VH (9 May 2019). «Ankle Fractures». StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31194464.

- ^ Yeung DE, Jia X, Miller CA, Barker SL (April 2016). «Interventions for treating ankle fractures in children». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD010836. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010836.pub2. PMC 7111433. PMID 27033333.

- ^ Nosewicz, Tomasz L.; Knupp, Markus; Bolliger, Lilianna; Hintermann, Beat (2012). «The reliability and validity of radiographic measurements for determining the three-dimensional position of the talus in varus and valgus osteoarthritic ankles». Skeletal Radiology. 41 (12): 1567–1573. doi:10.1007/s00256-012-1421-6. ISSN 0364-2348. PMC 3478506. PMID 22609967.

- ^ Chapter 5 — Radiological morphology of peritalar instability in varus and valgus tilted ankles, in: T.L. Nosewicz (2018-09-25). Acute and chronic aspects of hindfoot trauma. University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Medicine (AMC-UvA). ISBN 9789463750479.

- ^ Evans, JM; Schucany, WG (October 2006). «Radiological evaluation of a high ankle sprain». Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 19 (4): 402–5. doi:10.1080/08998280.2006.11928206. PMC 1618742. PMID 17106502.

- ^ a b Gore AI, Spencer JP (2004). «The newborn foot». Am Fam Physician. 69 (4): 865–72. PMID 14989573.

- ^ Källén, Bengt (2014). «Pes Equinovarus». Epidemiology of Human Congenital Malformations. pp. 111–113. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-01472-2_22. ISBN 978-3-319-01471-5.

- ^ Gatt, Alfred; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (2011-01-01). «Clinical Assessment of Ankle Joint Dorsiflexion». Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 101 (1): 59–69. doi:10.7547/1010059. PMID 21242472.

- ^ Macklin, Katriona; Healy, Aoife; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (March 2012). «The effect of calf muscle stretching exercises on ankle joint dorsiflexion and dynamic foot pressures, force and related temporal parameters». The Foot. 22 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2011.09.001. PMID 21944945.

- ^ Ono, K.; Nakamura, M.; Kurata, Y.; Hiroshima, K. (September 1984). «Ball-and-socket ankle joint: Anatomical and kinematic analysis of the hindfoot». Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 4 (5): 564–568. doi:10.1097/01241398-198409000-00007. PMID 6490876.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Ankle» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 58.

- ^ Brouwer, B.; Ashby, P. (1992). «Corticospinal projections to lower limb motoneurons in man». Experimental Brain Research. 89 (3): 649–54. doi:10.1007/bf00229889. PMID 1644127. S2CID 24650165.

References[edit]

- Anderson, Stephen A.; Calais-Germain, Blandine (1993). Anatomy of Movement. Chicago: Eastland Press. ISBN 978-0-939616-17-6.

- McKinley, Michael P.; Martini, Frederic; Timmons, Michael J. (2000). Human Anatomy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-010011-5.

- Marieb, Elaine Nicpon (2000). Essentials of Human Anatomy and Physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4940-5.

Additional images[edit]

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ankles.

Look up ankle in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Ardizzone, Remy; Valmassy, Ronald L. (October 2005). «How To Diagnose Lateral Ankle Injuries». Podiatry Today. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Haddad, Steven L. (ed). «Foot & Ankle». Your orthopaedic connection (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons). Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Ankle | |

|---|---|

Lateral view of the human ankle |

|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tarsus |

| MeSH | D000842 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.041 |

| TA2 | 165 |

| FMA | 9665 |

| Anatomical terminology

[edit on Wikidata] |

The ankle, or the talocrural region,[1] or the jumping bone (informal) is the area where the foot and the leg meet.[2] The ankle includes three joints: the ankle joint proper or talocrural joint, the subtalar joint, and the inferior tibiofibular joint.[3][4][5] The movements produced at this joint are dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot. In common usage, the term ankle refers exclusively to the ankle region. In medical terminology, «ankle» (without qualifiers) can refer broadly to the region or specifically to the talocrural joint.[1][6]

The main bones of the ankle region are the talus (in the foot), and the tibia and fibula (in the leg). The talocrural joint is a synovial hinge joint that connects the distal ends of the tibia and fibula in the lower limb with the proximal end of the talus.[7] The articulation between the tibia and the talus bears more weight than that between the smaller fibula and the talus.

Structure[edit]

Region[edit]

The ankle region is found at the junction of the leg and the foot. It extends downwards (distally) from the narrowest point of the lower leg and includes the parts of the foot closer to the body (proximal) to the heel and upper surface (dorsum) of the foot.[8]: 768

Ankle joint[edit]

The talocrural joint is the only mortise and tenon joint in the human body,[9]: 1418 the term likening the skeletal structure to the woodworking joint of the same name. The bony architecture of the ankle consists of three bones: the tibia, the fibula, and the talus. The articular surface of the tibia may be referred to as the plafond (French for «ceiling»).[10] The medial malleolus is a bony process extending distally off the medial tibia. The distal-most aspect of the fibula is called the lateral malleolus. Together, the malleoli, along with their supporting ligaments, stabilize the talus underneath the tibia.

Because the motion of the subtalar joint provides a significant contribution to positioning the foot, some authors will describe it as the lower ankle joint, and call the talocrural joint the upper ankle joint.[11] Dorsiflexion and Plantarflexion are the movements that take place in the ankle joint. When the foot is plantar flexed, the ankle joint also allows some movements of side to side gliding, rotation, adduction, and abduction.[12]

The bony arch formed by the tibial plafond and the two malleoli is referred to as the ankle «mortise» (or talar mortise). The mortise is a rectangular socket.[1] The ankle is composed of three joints: the talocrural joint (also called talotibial joint, tibiotalar joint, talar mortise, talar joint), the subtalar joint (also called talocalcaneal), and the Inferior tibiofibular joint.[3][4][5] The joint surface of all bones in the ankle are covered with articular cartilage.

The distances between the bones in the ankle are as follows:[13]

- Talus — medial malleolus : 1.70 ± 0.13 mm

- Talus — tibial plafond: 2.04 ± 0.29 mm

- Talus — lateral malleolus: 2.13 ± 0.20 mm

Decreased distances indicate osteoarthritis.

Ligaments[edit]

The ankle joint is bound by the strong deltoid ligament and three lateral ligaments: the anterior talofibular ligament, the posterior talofibular ligament, and the calcaneofibular ligament.

- The deltoid ligament supports the medial side of the joint, and is attached at the medial malleolus of the tibia and connect in four places to the talar shelf of the calcaneus, calcaneonavicular ligament, the navicular tuberosity, and to the medial surface of the talus.

- The anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments support the lateral side of the joint from the lateral malleolus of the fibula to the dorsal and ventral ends of the talus.

- The calcaneofibular ligament is attached at the lateral malleolus and to the lateral surface of the calcaneus.

Though it does not span the ankle joint itself, the syndesmotic ligament makes an important contribution to the stability of the ankle. This ligament spans the syndesmosis, i.e. the articulation between the medial aspect of the distal fibula and the lateral aspect of the distal tibia. An isolated injury to this ligament is often called a high ankle sprain.

The bony architecture of the ankle joint is most stable in dorsiflexion.[14] Thus, a sprained ankle is more likely to occur when the ankle is plantar-flexed, as ligamentous support is more important in this position. The classic ankle sprain involves the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), which is also the most commonly injured ligament during inversion sprains. Another ligament that can be injured in a severe ankle sprain is the calcaneofibular ligament.

Retinacula, tendons and their synovial sheaths, vessels, and nerves[edit]

A number of tendons pass through the ankle region. Bands of connective tissue called retinacula (singular: retinaculum) allow the tendons to exert force across the angle between the leg and foot without lifting away from the angle, a process called bowstringing.[11]

The superior extensor retinaculum of foot extends between the anterior (forward) surfaces of the tibia and fibula near their lower (distal) ends. It contains the anterior tibial artery and vein and the tendons of the tibialis anterior muscle within its tendon sheath and the unsheathed tendons of extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus muscles. The deep peroneal nerve passes under the retinaculum while the superficial peroneal nerve is outside of it. The inferior extensor retinaculum of foot is a Y-shaped structure. Its lateral attachment is on the calcaneus, and the band travels towards the anterior tibia where it is attached and blends with the superior extensor retinaculum. Along with that course, the band divides and another segment attaches to the plantar aponeurosis. The tendons which pass through the superior extensor retinaculum are all sheathed along their paths through the inferior extensor retinaculum and the tendon of the fibularis tertius muscle is also contained within the retinaculum.

The flexor retinaculum of foot extends from the medial malleolus to the medical process of the calcaneus, and the following structures in order from medial to lateral: the tendon of the tibialis posterior muscle, the tendon of the flexor digitorum longus muscle, the posterior tibial artery and vein, the tibial nerve, and the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus muscle.

The fibular retinacula hold the tendons of the fibularis longus and fibularis brevis along the lateral aspect of the ankle region. The superior fibular retinaculum extends from the deep transverse fascia of the leg and lateral malleolus to calcaneus. The inferior fibular retinaculum is a continuous extension from the inferior extensor retinaculum to the calcaneus.[9]: 1418–9

Mechanoreceptors[edit]

Mechanoreceptors of the ankle send proprioceptive sensory input to the central nervous system (CNS).[15] Muscle spindles are thought to be the main type of mechanoreceptor responsible for proprioceptive attributes from the ankle.[16] The muscle spindle gives feedback to the CNS system on the current length of the muscle it innervates and to any change in length that occurs.

It was hypothesized that muscle spindle feedback from the ankle dorsiflexors played the most substantial role in proprioception relative to other muscular receptors that cross at the ankle joint. However, due to the multi-planar range of motion at the ankle joint there is not one group of muscles that is responsible for this.[17] This helps to explain the relationship between the ankle and balance.

In 2011, a relationship between proprioception of the ankle and balance performance was seen in the CNS. This was done by using a fMRI machine in order to see the changes in brain activity when the receptors of the ankle are stimulated.[18] This implicates the ankle directly with the ability to balance. Further research is needed in order to see to what extent does the ankle affect balance.

Function[edit]

Historically, the role of the ankle in locomotion has been discussed by Aristotle and Leonardo da Vinci. There is no question that ankle push-off is a significant force in human gait, but how much energy is used in leg swing as opposed to advancing the whole-body center of mass is not clear.[19]

Clinical significance[edit]

A diagram illustrating varying severity of ankle sprain

Traumatic injury[edit]

Of all major joints, the ankle is the most commonly injured. If the outside surface of the foot is twisted under the leg during weight bearing, the lateral ligament, especially the anterior talofibular portion, is subject to tearing (a sprain) as it is weaker than the medial ligament and it resists inward rotation of the talocrural joint.[8]: 825

Fractures[edit]

Fracture of both sides of the ankle with dislocation as seen on anteroposterior X-ray. (1) fibula, (2) tibia, (arrow) medial malleolus, (arrowhead) lateral malleolus

An ankle fracture is a break of one or more of the bones that make up the ankle joint.[20] Symptoms may include pain, swelling, bruising, and an inability to walk on the injured leg.[20] Complications may include an associated high ankle sprain, compartment syndrome, stiffness, malunion, and post-traumatic arthritis.[20][21]

Ankle fractures may result from excessive stress on the joint such as from rolling an ankle or from blunt trauma.[20][21] Types of ankle fractures include lateral malleolus, medial malleolus, posterior malleolus, bimalleolar, and trimalleolar fractures.[20] The Ottawa ankle rule can help determine the need for X-rays.[21] Special X-ray views called stress views help determine whether an ankle fracture is unstable.

Treatment depends on the fracture type. Ankle stability largely dictates non-operative vs. operative treatment. Non-operative treatment includes splinting or casting while operative treatment includes fixing the fracture with metal implants through an open reduction internal fixation (ORIF).[20] Significant recovery generally occurs within four months while completely recovery usually takes up to one year.[20]

Ankle fractures are common, occurring in over 1.8 per 1000 adults and 1 per 1000 children per year.[21][22] They occur most commonly in young males and older females.[21]

Imaging[edit]

The initial evaluation of suspected ankle pathology is usually by projectional radiography («X-ray»).

Tibiotalar surface angle (TTS)

Varus or valgus deformity, if suspected, can be measured with the frontal tibiotalar surface angle (TTS), formed by the mid-longitudinal tibial axis (such as through a line bisecting the tibia at 8 and 13 cm above the tibial plafond) and the talar surface.[23] An angle of less than 84 degrees is regarded as talipes varus, and an angle of more than 94 degrees is regarded as talipes valgus.[24]

For ligamentous injury, there are 3 main landmarks on X-rays: The first is the tibiofibular clear space, the horizontal distance from the lateral border of the posterior tibial malleolus to the medial border of the fibula, with greater than 5 mm being abnormal. The second is tibiofibular overlap, the horizontal distance between the medial border of the fibula and the lateral border of the anterior tibial prominence, with less than 10 mm being abnormal. The final measurement is the medial clear space, the distance between the lateral aspect of the medial malleolus and the medial border of the talus at the level of the talar dome, with a measurement greater than 4 mm being abnormal. Loss of any of these normal anatomic spaces can indirectly reflect ligamentous injury or occult fracture, and can be followed by MRI or CT.[25]

Abnormalities[edit]

Clubfoot or talipes equinovarus, which occurs in one to two of every 1,000 live births, involves multiple abnormalities of the foot.[26] Equinus refers to the downard deflection of the ankle, and is named for the walking on the toes in the manner of a horse.[27] This does not occur because it is accompanied by an inward rotation of the foot (varus deformity), which untreated, results in walking on the sides of the feet. Treatment may involve manipulation and casting or surgery.[26]

Ankle joint equinus, normally in adults, relates to restricted ankle joint range of motion(ROM).[28] Calf muscle stretching exercises are normally helpful to increase the ankle joint dorsiflexion and used to manage clinical symptoms resulting from ankle equinus.[29]

Occasionally a human ankle has a ball-and-socket ankle joint and fusion of the talo-navicular joint.[30]

History[edit]

The word ankle or ancle is common, in various forms, to Germanic languages, probably connected in origin with the Latin angulus, or Greek αγκυλος, meaning bent.[31]

Other animals[edit]

Evolution[edit]

It has been suggested that dexterous control of toes has been lost in favour of a more precise voluntary control of the ankle joint.[32]

See also[edit]

- Foot

- Leg

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, A. M. R. (2013). «Lower Limb». Clinically Oriented Anatomy (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 508–669. ISBN 978-1-4511-1945-9.

- ^ WebMD (2009). «ankle». Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- ^ a b Milner, Brent K. (1999). «Musculoskeletal Imaging». In Gay, Spencer B.; Woodcock, Richard J. (eds.). Radiology Recall. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 258–383. ISBN 978-0-683-30663-7.

- ^ a b Williams, D. S. Blaise; Taunton, Jack (2007). «Foot, ankle and lower leg». In Kolt, Gregory S.; Snyder-Mackler, Lynn (eds.). Physical Therapies in Sport and Exercise. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 420–39. ISBN 978-0-443-10351-3.

- ^ a b del Castillo, Jorge (2012). «Foot and Ankle Injuries». In Adams, James G. (ed.). Emergency Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 745–55. ISBN 978-1-4557-3394-1.

- ^ Gray, Henry (1918). «Talocrural Articulation or Ankle-joint». Anatomy of the Human Body.

- ^ WebMD (2009). «ankle joint». Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-544-18897-6.

- ^ a b Moore, Keith (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ a b Susan Standring (7 August 2015). Gray’s Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7020-6851-5.

- ^ David P. Barei (29 March 2012). «56. Pilon Fractures». In Robert W. Bucholz (ed.). Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults: Two Volumes Plus Integrated Content Website (Rockwood, Green, and Wilkins’ Fractures). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1928–1971. ISBN 978-1-4511-6144-1.

- ^ a b Joseph E. Muscolino (21 August 2016). Kinesiology — E-Book: The Skeletal System and Muscle Function. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 284–292. ISBN 978-0-323-39935-7.

- ^ Dr. Joseph H Volker (2018-08-08). «Ankle Joint». Earth’s Lab.

- ^ Imai, Kan; Ikoma, Kazuya; Kido, Masamitsu; Maki, Masahiro; Fujiwara, Hiroyoshi; Arai, Yuji; Oda, Ryo; Tokunaga, Daisaku; Inoue, Nozomu; Kubo, Toshikazu (2015). «Joint space width of the tibiotalar joint in the healthy foot». Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 8 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s13047-015-0086-5. ISSN 1757-1146. PMC 4490633. PMID 26146520.

- ^ Gatt, A. and Chockalingam, N., 2011. Clinical Assessment of Ankle Joint DorsiflexionA Review of Measurement Techniques. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 101(1), pp.59-69.https://doi.org/10.7547/1010059

- ^ Michelson, J. D.; Hutchins, C (1995). «Mechanoreceptors in human ankle ligaments». The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 77 (2): 219–24. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.77B2.7706334. PMID 7706334.

- ^ Lephart, S. M.; Pincivero, D. M.; Rozzi, S. L. (1998). «Proprioception of the ankle and knee». Sports Medicine. 25 (3): 149–55. doi:10.2165/00007256-199825030-00002. PMID 9554026. S2CID 13099542.

- ^ Ribot-Ciscar, E; Bergenheim, M; Albert, F; Roll, J. P. (2003). «Proprioceptive population coding of limb position in humans». Experimental Brain Research. 149 (4): 512–9. doi:10.1007/s00221-003-1384-x. PMID 12677332. S2CID 14626459.

- ^ Goble, D. J.; Coxon, J. P.; Van Impe, A.; Geurts, M.; Doumas, M.; Wenderoth, N.; Swinnen, S. P. (2011). «Brain Activity during Ankle Proprioceptive Stimulation Predicts Balance Performance in Young and Older Adults». Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (45): 16344–52. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4159-11.2011. PMC 6633212. PMID 22072686.

- ^ Zelik, Karl E.; Adamczyk, Peter G. (2016). «A unified perspective on ankle push-off in human walking». The Journal of Experimental Biology. 219 (23): 3676–3683. doi:10.1242/jeb.140376. ISSN 0022-0949. PMC 5201006. PMID 27903626.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Ankle Fractures (Broken Ankle) — OrthoInfo — AAOS». www.orthoinfo.org. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Wire J, Slane VH (9 May 2019). «Ankle Fractures». StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31194464.

- ^ Yeung DE, Jia X, Miller CA, Barker SL (April 2016). «Interventions for treating ankle fractures in children». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD010836. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010836.pub2. PMC 7111433. PMID 27033333.

- ^ Nosewicz, Tomasz L.; Knupp, Markus; Bolliger, Lilianna; Hintermann, Beat (2012). «The reliability and validity of radiographic measurements for determining the three-dimensional position of the talus in varus and valgus osteoarthritic ankles». Skeletal Radiology. 41 (12): 1567–1573. doi:10.1007/s00256-012-1421-6. ISSN 0364-2348. PMC 3478506. PMID 22609967.

- ^ Chapter 5 — Radiological morphology of peritalar instability in varus and valgus tilted ankles, in: T.L. Nosewicz (2018-09-25). Acute and chronic aspects of hindfoot trauma. University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Medicine (AMC-UvA). ISBN 9789463750479.

- ^ Evans, JM; Schucany, WG (October 2006). «Radiological evaluation of a high ankle sprain». Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 19 (4): 402–5. doi:10.1080/08998280.2006.11928206. PMC 1618742. PMID 17106502.

- ^ a b Gore AI, Spencer JP (2004). «The newborn foot». Am Fam Physician. 69 (4): 865–72. PMID 14989573.

- ^ Källén, Bengt (2014). «Pes Equinovarus». Epidemiology of Human Congenital Malformations. pp. 111–113. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-01472-2_22. ISBN 978-3-319-01471-5.

- ^ Gatt, Alfred; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (2011-01-01). «Clinical Assessment of Ankle Joint Dorsiflexion». Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 101 (1): 59–69. doi:10.7547/1010059. PMID 21242472.

- ^ Macklin, Katriona; Healy, Aoife; Chockalingam, Nachiappan (March 2012). «The effect of calf muscle stretching exercises on ankle joint dorsiflexion and dynamic foot pressures, force and related temporal parameters». The Foot. 22 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2011.09.001. PMID 21944945.

- ^ Ono, K.; Nakamura, M.; Kurata, Y.; Hiroshima, K. (September 1984). «Ball-and-socket ankle joint: Anatomical and kinematic analysis of the hindfoot». Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 4 (5): 564–568. doi:10.1097/01241398-198409000-00007. PMID 6490876.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Ankle» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 58.

- ^ Brouwer, B.; Ashby, P. (1992). «Corticospinal projections to lower limb motoneurons in man». Experimental Brain Research. 89 (3): 649–54. doi:10.1007/bf00229889. PMID 1644127. S2CID 24650165.

References[edit]

- Anderson, Stephen A.; Calais-Germain, Blandine (1993). Anatomy of Movement. Chicago: Eastland Press. ISBN 978-0-939616-17-6.

- McKinley, Michael P.; Martini, Frederic; Timmons, Michael J. (2000). Human Anatomy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-010011-5.

- Marieb, Elaine Nicpon (2000). Essentials of Human Anatomy and Physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4940-5.

Additional images[edit]

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ankles.

Look up ankle in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Ardizzone, Remy; Valmassy, Ronald L. (October 2005). «How To Diagnose Lateral Ankle Injuries». Podiatry Today. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Haddad, Steven L. (ed). «Foot & Ankle». Your orthopaedic connection (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons). Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

Область, где ступня и нога пересекаются

| Голеностопный сустав | |

|---|---|

Боковой вид голеностопного сустава человека Боковой вид голеностопного сустава человека |

|

| Подробности | |

| Идентификаторы | |

| Latin | tarsus |

| MeSH | D000842 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.041 |

| TA2 | 165 |

| FMA | 9665 |

| Анатомическая терминология [правка в Викиданных ] |

голеностопный сустав или голеностопная область — это область, где стопа и нога встретить. Голеностопный сустав включает три сустава : собственно голеностопный сустав или голеностопный сустав, подтаранный сустав и нижний тибиофибулярный сустав.. Движения, производимые в этом суставе: тыльное сгибание и подошвенное сгибание стопы. Обычно термин «лодыжка» относится исключительно к области лодыжки. В медицинской терминологии «голеностопный сустав» (без определителей) может в широком смысле относиться к области или конкретно к голеностопному суставу.

Основными костями области голеностопного сустава являются таранная кость (в стопе), а также большеберцовой кости и малоберцовой кости (в ноге). Голеностопный сустав — это синовиальный шарнирный сустав, который соединяет дистальные концы большеберцовой и малоберцовой костей нижней конечности с проксимальным концом таранной кости. Сочленение между большеберцовой костью и таранной костью имеет больший вес, чем сочленение между малоберцовой костью и таранной костью.

Содержание

- 1 Структура

- 1.1 Область

- 1.2 Голеностопный сустав

- 1.3 Связки

- 1.4 Сетчатка, сухожилия и их синовиальные оболочки, сосуды и нервы

- 1.5 Механорецепторы

- 2 Функция

- 3 Клиническая значимость

- 3.1 Травматическое повреждение

- 3.1.1 Переломы

- 3.2 Визуализация

- 3.3 Отклонения

- 3.1 Травматическое повреждение

- 4 История болезни

- 5 Другие животные

- 5.1 Развитие

- 6 См. Также

- 7 Сноски

- 8 Ссылки

- 9 Дополнительные изображения

- 10 Внешние ссылки

Структура

Область

Как область, лодыжка находится в стык ноги и ноги. Он простирается вниз (дистально ) от самой узкой точки голени и включает части стопы, расположенные ближе к телу (проксимальные), до пятки и верхней поверхности (dorsum ) стопы.

Голеностопный сустав

Голеностопный сустав — единственный паз и шип в человеческом теле, термин, приравнивающий структуру скелета к обработке дерева стык с одноименным названием. Костная структура голеностопного сустава состоит из трех костей: большеберцовой кости, малоберцовой кости и таранной кости. Суставная поверхность большеберцовой кости может называться плафоном (французское для «потолка»). медиальная лодыжка — это костный отросток, отходящий дистально от медиальной большеберцовой кости. Самая дистальная часть малоберцовой кости называется боковой лодыжкой. Вместе лодыжки и поддерживающие их связки стабилизируют таранную кость под большеберцовой костью.

Поскольку движение подтаранного сустава вносит значительный вклад в позиционирование стопы, некоторые авторы называют его нижним голеностопным суставом, а голеностопный сустав — верхним голеностопным суставом. Тыльное сгибание и подошвенное сгибание — это движения, которые происходят в голеностопном суставе. Когда стопа согнута на подошве, голеностопный сустав также допускает некоторые движения из стороны в сторону, скольжение, вращение, приведение и отведение.

Костная дуга, образованная тибиальным плафоном и двумя лодыжками, называется щиколотка «врезная » (или таранная врезка). Врезка представляет собой розетку прямоугольной формы. Голеностопный сустав состоит из трех суставов: голеностопного сустава (также называемого голеностопным суставом, тибио-тибиальным суставом, таранной пазухой, таранным суставом), подтаранного сустава (также называемого таранно-пяточным суставом) и нижнего тибиофибулярного сустава.. Суставная поверхность всех костей голеностопного сустава покрыта суставным хрящом.

. Расстояния между костями в голеностопном суставе следующие:

- Таранная кость — медиальная лодыжка: 1,70 ± 0,13 мм

- Талус — большеберцовый плафон: 2,04 ± 0,29 мм

- Талус — латеральная лодыжка: 2,13 ± 0,20 мм

Уменьшение расстояния указывает на остеоартрит.

Связки

Голеностопный сустав связан прочная дельтовидная связка и три боковые связки: передняя таранно-малоберцовая связка, задняя таранно-малоберцовая связка и пяточно-малоберцовая связка.

- дельтовидная связка поддерживает медиальную сторону сустава, прикрепляется к медиальной лодыжке большеберцовой кости и соединяется в четырех местах с таранной полкой пяточной кости, пяточно-ладьевидная связка, бугристость ладьевидной кости и медиальная поверхность таранной кости.

- Передняя и задняя таранно-малоберцовые связки поддерживают латеральную сторону сустава f От боковой лодыжки малоберцовой кости до дорсального и вентрального концов таранной кости.

- Пяточно-малоберцовая связка прикрепляется к боковой лодыжке и к боковой поверхности пяточной кости.

Хотя синдесмотическая связка не охватывает самого голеностопного сустава, она вносит важный вклад в стабильность голеностопного сустава. Эта связка охватывает синдесмоз, то есть сочленение между медиальной стороной дистального отдела малоберцовой кости и латеральной стороной дистального отдела большеберцовой кости. Изолированное повреждение этой связки часто называют высоким растяжением голеностопного сустава.

Костная структура голеностопного сустава наиболее стабильна при тыльном сгибании. Таким образом, растяжение голеностопного сустава более вероятно, когда голеностопный сустав согнут на подошве, поскольку связочная опора более важна в этом положении. Классическое растяжение связок голеностопного сустава связано с передней таранно-малоберцовой связкой (ATFL), которая также является наиболее часто травмируемой связкой при инверсионных растяжениях. Еще одна связка, которая может быть повреждена при тяжелом растяжении связок голеностопного сустава, — это пяточно-малоберцовая связка.

сетчатка, сухожилия и их синовиальные оболочки, сосуды и нервы

Несколько сухожилий проходят через область голеностопного сустава. Полосы соединительной ткани, называемые ретинакулами (в единственном числе: retinaculum), позволяют сухожилиям прикладывать силу через угол между ногой и стопой, не отрываясь от угла, этот процесс называется натяжением тетивы. удерживатель верхнего разгибателя стопы проходит между передними (передними) поверхностями большеберцовой кости и малоберцовой кости около их нижних (дистальных) концов. Он содержит переднюю большеберцовую артерию и вены, а также сухожилия передней большеберцовой мышцы внутри сухожильного влагалища и сухожилия без оболочки длинного разгибателя большого пальца стопы и длинный разгибатель пальцев мышцы. глубокий малоберцовый нерв проходит под удерживателем, а поверхностный малоберцовый нерв находится за его пределами. удерживатель нижних разгибателей стопы представляет собой Y-образную структуру. Его латеральное прикрепление находится на пяточной кости, а полоса перемещается к передней большеберцовой кости, где она прикрепляется и сливается с удерживателем верхнего разгибателя. При этом полоса разделяется, и другой сегмент прикрепляется к подошвенному апоневрозу. Все сухожилия, которые проходят через удерживатель верхнего разгибателя, покрываются футляром на своем пути через удерживатель нижнего разгибателя, а сухожилие третичной мышцы большого пальца также содержится в сетчатке.

удерживатель сгибателей стопы простирается от медиальной лодыжки до медицинского отростка пяточной кости и следующие структуры в порядке от медиального к латеральному: сухожилие задней большеберцовой мышцы мышца, сухожилие мышцы длинного сгибателя пальцев, задняя большеберцовая артерия и вена, большеберцовый нерв, и сухожилие мышцы сгибателя большого пальца стопы.

сетчатка малоберцовой кости удерживают сухожилия длинной малоберцовой мышцы и малоберцовой мышцы вдоль латеральной стороны область щиколотки. Верхний ретинакулум малоберцовой кости простирается от глубокой поперечной фасции голени и боковой лодыжки до пяточной кости. Нижний удерживатель малоберцовой кости представляет собой непрерывное продолжение от удерживателя нижних разгибателей к пяточной кости.

Механорецепторы

Механорецепторы голеностопного сустава посылают проприоцептивные сенсорные сигналы в центральную нервную систему (ЦНС). Мышечные веретена считаются основным типом механорецепторов, отвечающих за проприоцептивные свойства голеностопного сустава. Мышечное веретено сообщает системе ЦНС о текущей длине мышцы, которую оно иннервирует, и о любом изменении длины, которое происходит.

Была высказана гипотеза, что обратная связь мышечного веретена от тыльных сгибателей голеностопного сустава играет наиболее существенную роль в проприоцепции по сравнению с другими мышечными рецепторами, пересекающими голеностопный сустав. Однако из-за многоплоскостного диапазона движений в голеностопном суставе за это не отвечает ни одна группа мышц. Это помогает объяснить взаимосвязь между лодыжкой и балансом.

В 2011 году связь между проприоцепцией голеностопного сустава и балансом была обнаружена в ЦНС. Это было сделано с помощью аппарата фМРТ, чтобы увидеть изменения активности мозга при стимуляции рецепторов голеностопного сустава. Это напрямую влияет на лодыжку со способностью балансировать. Необходимы дальнейшие исследования, чтобы увидеть, в какой степени лодыжка влияет на равновесие.

Функция

Исторически роль голеностопного сустава в движении обсуждалась Аристотелем и Леонардо да Винчи. Нет никаких сомнений в том, что отталкивание голеностопного сустава является значительной силой в походке человека, но сколько энергии используется при замахе ногой по сравнению с движением центра масс всего тела , определяется неясно.

Клиническое значение

Травматическое повреждение

Из всех основных суставов наиболее часто травмируется голеностопный сустав. Если внешняя поверхность стопы перекручена под ногой во время нагрузки, боковая связка, особенно передняя таранно-малоберцовая часть, подвержена разрывам (растяжение ), поскольку она слабее медиальной связки и сопротивляется вращению внутрь голеностопного сустава.

Переломы

Симптомы перелома голеностопного сустава могут быть аналогичны таковым при растяжении связок голеностопного сустава (боль ), хотя обычно они часто более серьезны по сравнению. Чрезвычайно редко происходит вывих голеностопного сустава только при наличии повреждения связки.

Таранная кость чаще всего ломается двумя способами. Первый — это гипердорсифлексия, при которой шейка таранной кости прижимается к большеберцовой кости и вызывает переломы. Второй — прыжок с высоты — тело сломано, поскольку таранная кость передает силу от стопы к костям нижних конечностей.

При переломе голеностопного сустава таранная кость может стать нестабильной и подвывихнуть или вывихнуть. Люди могут жаловаться на экхимоз (синяк) или на неправильное положение, ненормальное движение или отсутствие движения. Диагноз обычно ставится на основании рентгеновского снимка. В зависимости от типа перелома лечение проводится либо хирургическим путем, либо наложением гипса.

Визуализация

Первоначальная оценка подозреваемой патологии голеностопного сустава обычно проводится с помощью проекционной рентгенографии («рентген»).

Варусная или вальгусная деформация, если подозревается, может быть измерена с помощью фронтального тибиоталарного угла поверхности (TTS), образованного средне-продольной осью большеберцовой кости (например, через линию, пересекающую большеберцовую кость пополам) на 8 и 13 см выше тибиального плафона) и таранной поверхности. Угол менее 84 градусов рассматривается как варусная косолапость, а угол более 94 градусов — как вальгусная косолапость.

Для травмы связок на рентгеновских снимках можно выделить 3 основных ориентира: первый — светлое пространство большеберцовой кости, горизонтальное расстояние от латеральной границы задней большеберцовой лодыжки до медиальной границы малоберцовой кости, при этом отклонение более 5 мм от нормы. Второй — это тибиофибулярное перекрытие, горизонтальное расстояние между медиальной границей малоберцовой кости и латеральной границей переднего выступа большеберцовой кости с отклонением менее 10 мм. Окончательным измерением является медиальное чистое пространство, расстояние между латеральной стороной медиальной лодыжки и медиальной границей таранной кости на уровне купола таранной кости, при этом значение более 4 мм является ненормальным. Утрата любого из этих нормальных анатомических пространств может косвенно отражать повреждение связок или скрытый перелом, и может сопровождаться МРТ или КТ.

Аномалии

Косолапость или эквиноварусная косолапость, которая возникает в 1-2 раза на каждые 1000 живорождений приходится несколько аномалий стопы. Эквинус относится к отклонению лодыжки вниз и назван в честь ходьбы на пальцах ног в манере лошади. Этого не происходит, потому что он сопровождается вращением стопы внутрь (варусная деформация ), которая без лечения приводит к ходьбе по бокам стопы. Лечение может включать манипуляции, наложение гипса или хирургическое вмешательство.

Иногда на голеностопном суставе человека обнаруживается шарнирно-гнездовой голеностопный сустав и сращение таранно-ладьевидной кости.

История

Слово лодыжка или лодыжка распространено в различных формах в германских языках, вероятно, связано по происхождению с латинским angulus или греческим αγκυλος, что означает согнутый.

Другие животные

Эволюция

Было высказано предположение, что ловкий контроль пальцев ног был утрачен в пользу более точного произвольного контроля над голеностопным суставом.

См. Также

- Нога

- Нога

Сноски

Материалы, относящиеся к лодыжкам на Викискладе

Ссылки

- Андерсон, Стивен А. ; Кале-Жермен, Бландин (1993). Анатомия движения. Чикаго: Eastland Press. ISBN 978-0-939616-17-6.

- McKinley, Michael P.; Мартини, Фредерик; Тиммонс, Майкл Дж. (2000). Анатомия человека. Энглвуд Клиффс, Нью-Джерси: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-010011-5.

- Мариеб, Элейн Никпон (2000). Основы анатомии и физиологии человека. Сан-Франциско: Бенджамин Каммингс. ISBN 978-0-8053-4940-5.

Дополнительные изображения

Тыльная сторона стопы. Голеностопный сустав. Глубокое рассечение

тыльной стороны стопы. Голеностопный сустав. Глубокое рассечение

Голеностопный сустав. Глубокое рассечение. Вид спереди.

Тыльная сторона стопы. Голеностопный сустав. Глубокое вскрытие

Внешние ссылки

| На Викискладе есть материалы, связанные с лодыжками. |

| Найдите ankle в Викисловаре, бесплатном словаре. |

- Ардиццоне, Реми; Валмаси, Рональд Л. (октябрь 2005 г.). «Как диагностировать боковые травмы лодыжки». Подиатрия сегодня. Архивировано из оригинала 4 января 2010 г. Получено 21 сентября 2017 г.

- Хаддад, Стивен Л. (ред.). «Стопа и лодыжка». Ваше ортопедическое соединение (Американская академия хирургов-ортопедов). Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2010 г. Получено 21 сентября 2017 г. CS1 maint: дополнительный текст: список авторов (ссылка )