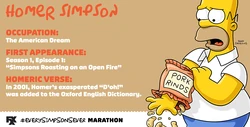

| Homer Simpson | |

|---|---|

| The Simpsons character | |

Homer eating a classic strawberry sprinkled donut |

|

| First appearance |

|

| Created by | Matt Groening |

| Designed by | Matt Groening |

| Voiced by | Dan Castellaneta |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Homer Jay Simpson |

| Occupation |

|

| Affiliation | Springfield Nuclear Power Plant |

| Family |

|

| Spouse | Marge Bouvier |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Home | 742 Evergreen Terrace, Springfield, United States |

| Nationality | American |

Homer Jay Simpson is a fictional character and the main protagonist of the American animated sitcom The Simpsons.[1] He is voiced by Dan Castellaneta and first appeared, along with the rest of his family, in The Tracey Ullman Show short «Good Night» on April 19, 1987. Homer was created and designed by cartoonist Matt Groening while he was waiting in the lobby of producer James L. Brooks’s office. Groening had been called to pitch a series of shorts based on his comic strip Life in Hell but instead decided to create a new set of characters. He named the character after his father, Homer Groening. After appearing for three seasons on The Tracey Ullman Show, the Simpson family got their own series on Fox, which debuted December 17, 1989. The show was later acquired by Disney in 2019.

As the nominal foreman of the paternally eponymous family, Homer and his wife Marge have three children: Bart, Lisa and Maggie. As the family’s provider, he works at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant as safety inspector. Homer embodies many American working class stereotypes: he is obese, immature, outspoken, aggressive, balding, lazy, ignorant, unprofessional, and fond of beer, junk food and watching television. However, he is fundamentally a good man and is staunchly protective of his family, especially when they need him the most. Despite the suburban blue-collar routine of his life, he has had a number of remarkable experiences, including going to space, climbing the tallest mountain in Springfield by himself, fighting former President George H. W. Bush, and winning a Grammy Award as a member of a barbershop quartet.

In the shorts and earlier episodes, Castellaneta voiced Homer with a loose impression of Walter Matthau; however, during the second and third seasons of the half-hour show, Homer’s voice evolved to become more robust, to allow the expression of a fuller range of emotions. He has appeared in other media relating to The Simpsons—including video games, The Simpsons Movie, The Simpsons Ride, commercials, and comic books—and inspired an entire line of merchandise. His signature catchphrase, the annoyed grunt «D’oh!», has been included in The New Oxford Dictionary of English since 1998 and the Oxford English Dictionary since 2001.

Homer is one of the most influential characters in the history of television, and is widely considered to be an American cultural icon. The British newspaper The Sunday Times described him as «The greatest comic creation of [modern] time». He was named the greatest character «of the last 20 years» in 2010 by Entertainment Weekly, was ranked the second-greatest cartoon character by TV Guide, behind Bugs Bunny, and was voted the greatest television character of all time by Channel 4 viewers. For voicing Homer, Castellaneta has won four Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Voice-Over Performance and a special-achievement Annie Award. In 2000, Homer and his family were awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Role in The Simpsons

Homer Jay Simpson is the bumbling husband of Marge, and father to Bart, Lisa and Maggie Simpson.[2] He is the son of Mona and Abraham «Grampa» Simpson. Homer held over 188 different jobs in the first 400 episodes of The Simpsons.[3] In most episodes, he works as the nuclear safety inspector at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant (in Sector 7-G), a position which he has held since «Homer’s Odyssey», the third episode of the series, despite the fact that he is totally unsuitable for it.[4] At the nuclear plant, Homer is often ignored and completely forgotten by his boss Mr. Burns, and he constantly falls asleep and neglects his duties. Matt Groening has stated that he decided to have Homer work at the power plant because of the potential for Homer to wreak severe havoc.[5] Each of his other jobs has lasted only one episode. In the first half of the series, the writers developed an explanation about how he got fired from the plant and was then rehired in every episode. In later episodes, he often began a new job on impulse, without any mention of his regular employment.[6]

The Simpsons uses a floating timeline in which the characters never physically age, and, as such, the show is generally assumed to be always set in the current year. Nevertheless, in several episodes, events in Homer’s life have been linked to specific time periods.[2] «Mother Simpson» (season seven, 1995) depicts Homer’s mother, Mona, as a radical who went into hiding in 1969 following a run-in with the law;[7] «The Way We Was» (season two, 1991) shows Homer falling in love with Marge Bouvier as a senior at Springfield High School in 1974;[8] and «I Married Marge» (season three, 1991) implies that Marge became pregnant with Bart in 1980.[9] However, the episode «That ’90s Show» (season 19, 2008) contradicted much of this backstory, portraying Homer and Marge as a twentysomething childless couple in the early 1990s.[10] The episode «Do Pizza Bots Dream of Electric Guitars» (season 32, 2021) further contradicts this backstory, putting Homer’s adolescence in the 1990s. Showrunner Matt Selman has explained that no version was the «official continuity.» and that «they all kind of happened in their imaginary world, you know, and people can choose to love whichever version they love.»[11]

Due to the floating timeline, Homer’s age has changed occasionally as the series developed; he was 34 in the early episodes,[8] 36 in season four,[12] 38 and 39 in season eight,[13] and 40 in the eighteenth season,[14] although even in those seasons his age is inconsistent.[2] In the fourth season episode «Duffless», Homer’s drivers license shows his birthdate of being May 12, 1956,[15] which would have made him 36 years old at the time of the episode. During Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein’s period as showrunners, they found that as they aged, Homer seemed to become older too, so they increased his age to 38. His height is 6′ (1.83 m).[16]

Character

Creation

Naming the characters after members of his own family, Groening named Homer after his father, who himself had been named after the ancient Greek poet of the same name.[17][18][19] Very little else of Homer’s character was based on him, and to prove that the meaning behind Homer’s name was not significant, Groening later named his own son Homer.[20][21] According to Groening, «Homer originated with my goal to both amuse my real father, and just annoy him a little bit. My father was an athletic, creative, intelligent filmmaker and writer, and the only thing he had in common with Homer was a love of donuts.»[22] Although Groening has stated in several interviews that Homer was named after his father, he also claimed in several 1990 interviews that a character called precisely Homer Simpson in the 1939 Nathanael West novel The Day of the Locust as well as in the eponymous 1975 movie, was the inspiration.[2][23][24] In 2012 he clarified, «I took that name from a minor character in the novel The Day of the Locust… Since Homer was my father’s name, and I thought Simpson was a funny name in that it had the word “simp” in it, which is short for “simpleton”—I just went with it.»[25] Homer’s middle initial «J», which stands for «Jay»,[26] is a «tribute» to animated characters such as Bullwinkle J. Moose and Rocket J. Squirrel from The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show, who got their middle initial from Jay Ward.[27]

Homer made his debut with the rest of the Simpson family on April 19, 1987, in The Tracey Ullman Show short «Good Night».[28] In 1989, the shorts were adapted into The Simpsons, a half-hour series airing on the Fox Broadcasting Company. Homer and the Simpson family remained the main characters on this new show.[29]

Design

As currently depicted in the series, Homer’s everyday clothing consists of a white shirt with short sleeves and open collar, blue pants, and gray shoes. He is overweight and bald, except for a fringe of hair around the back and sides of his head and two curling hairs on top, and his face always sports a growth of beard stubble that instantly regrows whenever he shaves.

Homer’s design has been revised several times over the course of the series. Left to right: Homer as he appeared in «Good Night» (1987), «Bathtime» (1989), and «Bart the Genius» (1990).

The entire Simpson family was designed so that they would be recognizable in silhouette.[30] The family was crudely drawn because Groening had submitted basic sketches to the animators, assuming they would clean them up; instead, they just traced over his drawings.[17] By coincidence or not, Homer’s look bears a resemblance to the cartoon character Adamsson, created by Swedish cartoonist Oscar Jacobsson in 1920.[31] Homer’s physical features are generally not used in other characters; for example, in the later seasons, no characters other than Homer, Grampa Simpson, Lenny Leonard, and Krusty the Clown have a similar beard line.[32] When Groening originally designed Homer, he put his initials into the character’s hairline and ear: the hairline resembled an ‘M’, and the right ear resembled a ‘G’. Groening decided that this would be too distracting and redesigned the ear to look normal. However, he still draws the ear as a ‘G’ when he draws pictures of Homer for fans.[33] The basic shape of Homer’s head is described by director Mark Kirkland as a tube-shaped coffee can with a salad bowl on top.[34] During the shorts, the animators experimented with the way Homer would move his mouth when talking. At one point, his mouth would stretch out back «beyond his beardline»; but this was dropped when it got «out of control.»[35] In some early episodes, Homer’s hair was rounded rather than sharply pointed because animation director Wes Archer felt it should look disheveled. Homer’s hair evolved to be consistently pointed.[36] During the first three seasons, Homer’s design for some close-up shots included small lines which were meant to be eyebrows. Groening strongly disliked them and they were eventually dropped.[36]

In the season seven (1995) episode «Treehouse of Horror VI», Homer was computer animated into a three-dimensional character for the first time for the «Homer3» segment of the episode. The computer animation directors at Pacific Data Images worked hard not to «reinvent the character».[37] In the final minute of the segment, the 3D Homer ends up in a real world, live-action Los Angeles. The scene was directed by David Mirkin and was the first time a Simpsons character had been in the real world in the series.[37] Because «Lisa’s Wedding» (season six, 1995) is set fifteen years in the future, Homer’s design was altered to make him older in the episode. He is heavier; one of the hairs on top of his head was removed; and an extra line was placed under the eye. A similar design has been used in subsequent flashforwards.[38]

Voice

«I was trying to find something I was more comfortable with that had more power to it, so I had to drop the voice down. … People will say to me, ‘Boy, I’m glad they replaced the guy that was there that first season.’ That was me!»

Homer’s voice is performed by Dan Castellaneta, who voices numerous other characters, including Grampa Simpson, Krusty the Clown, Barney Gumble, Groundskeeper Willie, Mayor Quimby and Hans Moleman. Castellaneta had been part of the regular cast of The Tracey Ullman Show and had previously done some voice-over work in Chicago alongside his wife Deb Lacusta. Voices were needed for the Simpsons shorts, so the producers decided to ask Castellaneta and fellow cast member Julie Kavner to voice Homer and Marge rather than hire more actors.[39][40] In the shorts and first season of the half-hour show, Homer’s voice is different from the majority of the series. The voice began as a loose impression of Walter Matthau, but Castellaneta could not «get enough power behind that voice»,[40] or sustain his Matthau impression for the nine- to ten-hour-long recording sessions, and had to find something easier.[3] During the second and third seasons of the half-hour show, Castellaneta «dropped the voice down»[39] and developed it as more versatile and humorous, allowing Homer a fuller range of emotions.[41]

Castellaneta’s normal speaking voice does not bear any resemblance to Homer’s.[42] To perform Homer’s voice, Castellaneta lowers his chin to his chest[40] and is said to «let his I.Q. go».[43] While in this state, he has ad-libbed several of Homer’s least intelligent comments,[43] such as the line «S-M-R-T; I mean, S-M-A-R-T!» from «Homer Goes to College» (season five, 1993) which was a genuine mistake made by Castellaneta during recording.[44] Castellaneta likes to stay in character during recording sessions,[45] and he tries to visualize a scene so that he can give the proper voice to it.[46] Despite Homer’s fame, Castellaneta claims he is rarely recognized in public, «except, maybe, by a die-hard fan».[45]

«Homer’s Barbershop Quartet» (season five, 1993) is the only episode where Homer’s voice was provided by someone other than Castellaneta. The episode features Homer forming a barbershop quartet called The Be Sharps; and, at some points, his singing voice is provided by a member of The Dapper Dans.[47] The Dapper Dans had recorded the singing parts for all four members of The Be Sharps. Their singing was intermixed with the normal voice actors’ voices, often with a regular voice actor singing the melody and the Dapper Dans providing backup.[48]

Until 1998, Castellaneta was paid $30,000 per episode. During a pay dispute in 1998, Fox threatened to replace the six main voice actors with new actors, going as far as preparing for casting of new voices.[49] However, the dispute was soon resolved and he received $125,000 per episode until 2004 when the voice actors demanded that they be paid $360,000 an episode.[49] The issue was resolved a month later,[50] and Castellaneta earned $250,000 per episode.[51] After salary re-negotiations in 2008, the voice actors receive approximately $400,000 per episode.[52] Three years later, with Fox threatening to cancel the series unless production costs were cut, Castellaneta and the other cast members accepted a 30 percent pay cut, down to just over $300,000 per episode.[53]

Character development

Executive producer Al Jean notes that in The Simpsons‘ writing room, «everyone loves writing for Homer», and many of his adventures are based on experiences of the writers.[54] In the early seasons of the show, Bart was the main focus. But, around the fourth season, Homer became more of the focus. According to Matt Groening, this was because «With Homer, there’s just a wider range of jokes you can do. And there are far more drastic consequences to Homer’s stupidity. There’s only so far you can go with a juvenile delinquent. We wanted Bart to do anything up to the point of him being tried in court as a dad. But Homer is a dad, and his boneheaded-ness is funnier. […] Homer is launching himself headfirst into every single impulsive thought that occurs to him.»[22]

Homer’s behavior has changed a number of times through the run of the series. He was originally «very angry» and oppressive toward Bart, but these characteristics were toned down somewhat as his persona was further explored.[55] In early seasons, Homer appeared concerned that his family was going to make him look bad; however, in later episodes he was less anxious about how he was perceived by others.[56] In the first several years, Homer was often portrayed as dumb yet well-meaning, but during Mike Scully’s tenure as executive producer (seasons nine, 1997 to twelve, 2001), he became more of «a boorish, self-aggrandizing oaf».[57] Chris Suellentrop of Slate wrote, «under Scully’s tenure, The Simpsons became, well, a cartoon. … Episodes that once would have ended with Homer and Marge bicycling into the sunset… now end with Homer blowing a tranquilizer dart into Marge’s neck.»[58] Fans have dubbed this incarnation of the character «Jerkass Homer».[59][60][61] At voice recording sessions, Castellaneta has rejected material written in the script that portrayed Homer as being too mean. He believes that Homer is «boorish and unthinking, but he’d never be mean on purpose.»[62] When editing The Simpsons Movie, several scenes were changed to make Homer more sympathetic.[63]

The writers have depicted Homer with a declining intelligence over the years; they explain this was not done intentionally, but it was necessary to top previous jokes.[64] For example, in «When You Dish Upon a Star», (season 10, 1998) the writers included a scene where Homer admits that he cannot read. The writers debated including this plot twist because it would contradict previous scenes in which Homer does read, but eventually they decided to keep the joke because they found it humorous. The writers often debate how far to go in portraying Homer’s stupidity; one suggested rule is that «he can never forget his own name».[65]

Personality

The comic efficacy of Homer’s personality lies in his frequent bouts of bumbling stupidity, laziness and his explosive anger. He has a low intelligence level and is described by director David Silverman as «creatively brilliant in his stupidity».[66] Homer also shows immense apathy towards work, is overweight, and «is devoted to his stomach».[66] His short attention span is evidenced by his impulsive decisions to engage in various hobbies and enterprises, only to «change … his mind when things go badly».[66] Homer often spends his evenings drinking Duff Beer at Moe’s Tavern, and was shown in the episode «Duffless» (season four, 1993) as a full-blown alcoholic.[67] He is very envious of his neighbors, Ned Flanders and his family, and is easily enraged by Bart. Homer will often strangle Bart on impulse upon Bart angering him (and can also be seen saying one of his catchphrases, «Why you little—!») in a cartoonish manner. The first instance of Homer strangling Bart was in the short «Family Portrait». According to Groening, the rule was that Homer could only strangle Bart impulsively, never with premeditation,[68] because doing so «seems sadistic. If we keep it that he’s ruled by his impulses, then he can easily switch impulses. So, even though he impulsively wants to strangle Bart, he also gives up fairly easily.»[22] Another of the original ideas entertained by Groening was that Homer would «always get his comeuppance or Bart had to strangle him back», but this was dropped.[69] Homer shows no compunction about expressing his rage, and does not attempt to hide his actions from people outside the family.[66]

The first sketch of Homer strangling Bart, drawn in 1988

Homer has complex relationships with his family. As previously noted, he and Bart are the most at odds; but the two commonly share adventures and are sometimes allies, with some episodes (particularly in later seasons) showing that the pair have a strange respect for each other’s cunning. Homer and Lisa have opposite personalities and he usually overlooks Lisa’s talents, but when made aware of his neglect, does everything he can to help her. The show also occasionally implies Homer forgets he has a third child, Maggie; while the episode «And Maggie Makes Three» suggests she is the chief reason Homer took and remains at his regular job (season six, 1995). While Homer’s thoughtless antics often upset his family, he on many occasions has also revealed himself to be a caring and loving father and husband: in «Lisa the Beauty Queen», (season four, 1992) he sold his cherished ride on the Duff blimp and used the money to enter Lisa in a beauty pageant so she could feel better about herself;[12] in «Rosebud», (season five, 1993) he gave up his chance at wealth to allow Maggie to keep a cherished teddy bear;[70] in «Radio Bart», (season three, 1992) he spearheads an attempt to dig Bart out after he had fallen down a well;[71] in «A Milhouse Divided», (season eight, 1996) he arranges a surprise second wedding with Marge to make up for their unsatisfactory first ceremony;[72] and despite a poor relationship with his father Abraham «Grampa» Simpson, whom he placed in a nursing home as soon as he could[73] while the Simpson family often do their best to avoid unnecessary contact with Grampa, Homer has shown feelings of love for his father from time to time.[74]

Homer is «a (happy) slave to his various appetites».[75] He has an apparently vacuous mind, but occasionally exhibits a surprising depth of knowledge about various subjects, such as the composition of the Supreme Court of the United States,[76] Inca mythology,[77] bankruptcy law,[78] and cell biology.[79] Homer’s brief periods of intelligence are overshadowed, however, by much longer and consistent periods of ignorance, forgetfulness, and stupidity. Homer has a low IQ of 55, which would actually make him unable to speak or perform basic tasks, and has variously been attributed to the hereditary «Simpson Gene» (which eventually causes every male member of the family to become incredibly stupid),[80] his alcohol problem, exposure to radioactive waste, repetitive cranial trauma,[81] and a crayon lodged in the frontal lobe of his brain.[82] In the 2001 episode «HOMR», Homer has the crayon removed, boosting his IQ to 105; although he bonds with Lisa, his newfound capacity for understanding and reason makes him unhappy, and he has the crayon reinserted.[82] Homer often debates with his own mind, expressed in voiceover. His mind has a tendency to offer dubious advice, which occasionally helps him make the right decision, but often fails spectacularly. His mind has even become completely frustrated and, through sound effects, walked out on Homer.[83] These exchanges were often introduced because they filled time and were easy for the animators to work on.[84] They were phased out after the producers «used every possible permutation».[84]

Producer Mike Reiss said Homer was his favorite Simpsons character to write: «Homer’s just a comedy writer’s dream. He has everything wrong with him, every comedy trope. He’s fat and bald and stupid and lazy and angry and an alcoholic. I’m pretty sure he embodies all seven deadly sins.» John Swartzwelder, who wrote 60 episodes, said he wrote Homer as if he were «a big talking dog … One moment he’s the saddest man in the world, because he’s just lost his job, or dropped his sandwich, or accidentally killed his family. Then, the next moment, he’s the happiest man in the world, because he’s just found a penny — maybe under one of his dead family members … If you write him as a dog you’ll never go wrong.»[85] Reiss felt this was insightful, saying: «Homer is just pure emotion, no long-term memory, everything is instant gratification. And, you know, has good dog qualities, too. I think, loyalty, friendliness, and just kind of continuous optimism.»[86]

Reception

Commendations

In 2000, Homer, along with the rest of the Simpson family, was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Homer’s influence on comedy and culture has been significant. In 2010, Entertainment Weekly named Homer «the greatest character of the last 20 years».[87] He was placed second on TV Guide‘s 2002 Top 50 Greatest Cartoon Characters, behind Bugs Bunny;[88] fifth on Bravo’s 100 Greatest TV Characters, one of only four cartoon characters on that list;[89] and first in a Channel 4 poll of the greatest television characters of all time.[90] In 2007, Entertainment Weekly placed Homer ninth on their list of the «50 Greatest TV icons» and first on their 2010 list of the «Top 100 Characters of the Past Twenty Years».[91][22][92] Homer was also the runaway winner in British polls that determined who viewers thought was the «greatest American»[93] and which fictional character people would like to see become the President of the United States.[94] His relationship with Marge was included in TV Guide‘s list of «The Best TV Couples of All Time».[95] In 2022, Paste writers claimed that Homer is the second best cartoon character of all time.[96]

Dan Castellaneta has won several awards for voicing Homer, including four Primetime Emmy Awards for «Outstanding Voice-Over Performance» in 1992 for «Lisa’s Pony», 1993 for «Mr. Plow»,[97] in 2004 for «Today I Am a Clown»,[98] and in 2009 for «Father Knows Worst».[99] However, in the case of «Today I Am a Clown», it was for voicing «various characters» and not solely for Homer.[98] In 2010, Castellaneta received a fifth Emmy nomination for voicing Homer and Grampa in the episode «Thursdays with Abie».[100] In 1993, Castellaneta was given a special Annie Award, «Outstanding Individual Achievement in the Field of Animation», for his work as Homer on The Simpsons.[101][102] In 2004, Castellaneta and Julie Kavner (the voice of Marge) won a Young Artist Award for «Most Popular Mom & Dad in a TV Series».[103] In 2005, Homer and Marge were nominated for a Teen Choice Award for «Choice TV Parental Units».[104] Various episodes in which Homer is strongly featured have won Emmy Awards for Outstanding Animated Program, including «Homer vs. Lisa and the 8th Commandment» in 1991, «Lisa’s Wedding» in 1995, «Homer’s Phobia» in 1997, «Trash of the Titans» in 1998, «HOMR» in 2001, «Three Gays of the Condo» in 2003 and «Eternal Moonshine of the Simpson Mind» in 2008.[97] In 2000, Homer and the rest of the Simpson family were awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame located at 7021 Hollywood Boulevard.[105] In 2017, Homer Simpson was celebrated by the National Baseball Hall of Fame, to honor the 25th anniversary of the episode «Homer at the Bat».[106]

Analysis

Homer is an «everyman» and embodies several American stereotypes of working class blue-collar men: he is crude, overweight, incompetent, dim-witted, childish, clumsy and a borderline alcoholic.[2] Matt Groening describes him as «completely ruled by his impulses».[107] Dan Castellaneta calls him «a dog trapped in a man’s body», adding, «He’s incredibly loyal – not entirely clean – but you gotta love him.»[40] In his book Planet Simpson, author Chris Turner describes Homer as «the most American of the Simpsons» and believes that while the other Simpson family members could be changed to other nationalities, Homer is «pure American».[108] In the book God in the Details: American Religion in Popular Culture, the authors comment that «Homer’s progress (or lack thereof) reveals a character who can do the right thing, if accidentally or begrudgingly.»[109] The book The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’oh! of Homer includes a chapter analyzing Homer’s character from the perspective of Aristotelian virtue ethics. Raja Halwani writes that Homer’s «love of life» is an admirable character trait, «for many people are tempted to see in Homer nothing but buffoonery and immorality. … He is not politically correct, he is more than happy to judge others, and he certainly does not seem to be obsessed with his health. These qualities might not make Homer an admirable person, but they do make him admirable in some ways, and, more importantly, makes us crave him and the Homer Simpsons of this world.»[110] In 2008, Entertainment Weekly justified designating The Simpsons as a television classic by stating, «we all hail Simpson patriarch Homer because his joy is as palpable as his stupidity is stunning».[111]

In the season eight episode «Homer’s Enemy» the writers decided to examine «what it would be like to actually work alongside Homer Simpson».[112] The episode explores the possibilities of a realistic character with a strong work ethic named Frank Grimes placed alongside Homer in a work environment. In the episode, Homer is portrayed as an everyman and the embodiment of the American spirit; however, in some scenes his negative characteristics and silliness are prominently highlighted.[113][114] By the end of the episode, Grimes, a hard working and persevering «real American hero», has become the villain; the viewer is intended to be pleased that Homer has emerged victorious.[113]

In Gilligan Unbound, author Paul Arthur Cantor states that he believes Homer’s devotion to his family has added to the popularity of the character. He writes, «Homer is the distillation of pure fatherhood. … This is why, for all his stupidity, bigotry and self-centered quality, we cannot hate Homer. He continually fails at being a good father, but he never gives up trying, and in some basic and important sense that makes him a good father.»[115] The Sunday Times remarked «Homer is good because, above all, he is capable of great love. When the chips are down, he always does the right thing by his children—he is never unfaithful in spite of several opportunities.»[62]

Cultural influence

Homer Simpson is one of the most popular and influential television characters by a variety of standards. USA Today cited the character as being one of the «top 25 most influential people of the past 25 years» in 2007, adding that Homer «epitomized the irony and irreverence at the core of American humor».[116] Robert Thompson, director of Syracuse University’s Center for the Study of Popular Television, believes that «three centuries from now, English professors are going to be regarding Homer Simpson as one of the greatest creations in human storytelling.»[117] Animation historian Jerry Beck described Homer as one of the best animated characters, saying, «you know someone like it, or you identify with (it). That’s really the key to a classic character.»[88] Homer has been described by The Sunday Times as «the greatest comic creation of [modern] time». The article remarked, «every age needs its great, consoling failure, its lovable, pretension-free mediocrity. And we have ours in Homer Simpson.»[62]

Despite Homer’s partial embodiment of American culture, his influence has spread to other parts of the world. In 2003, Matt Groening revealed that his father, after whom Homer was named, was Canadian, and said that this made Homer himself a Canadian.[118] The character was later made an honorary citizen of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, because Homer Groening was believed to be from there, although sources say the senior Groening was actually born in the province of Saskatchewan.[119] In 2007, an image of Homer was painted next to the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset, England as part of a promotion for The Simpsons Movie. This caused outrage among local neopagans who performed «rain magic» to try to get it washed away.[120] In 2008, a defaced Spanish euro coin was found in Avilés, Spain with the face of Homer replacing the effigy of King Juan Carlos I.[121]

On April 9, 2009, the United States Postal Service unveiled a series of five 44-cent stamps featuring Homer and the four other members of the Simpson family. They are the first characters from a television series to receive this recognition while the show is still in production.[122] The stamps, designed by Matt Groening, were made available for purchase on May 7, 2009.[123][124]

Homer has appeared, voiced by Castellaneta, in several other television shows, including the sixth season of American Idol where he opened the show;[125] The Tonight Show with Jay Leno where he performed a special animated opening monologue for the July 24, 2007, edition;[126] and the 2008 fundraising television special Stand Up to Cancer where he was shown having a colonoscopy.[127]

On February 28, 1999, Homer Simpson was made an honorary member of the Junior Common Room of Worcester College, Oxford. Homer was granted the membership by the college’s undergraduate body in the belief that ″he would benefit greatly from an Oxford education″.[128]

Homer has also been cited in the scientific literature, in relation to low intelligence or cognitive abilities. A 2010 study from Emory University showed that the RGS14 gene appeared to be impairing the development of cognitive abilities in mice (or, rather, that mice with a disabled RGS14 gene improved their cognitive abilities), prompting the authors to dub it the «Homer Simpson gene».[129]

D’oh!

Homer’s main and most famous catchphrase, the annoyed grunt «D’oh!», is typically uttered when he injures himself, realizes that he has done something stupid, or when something bad has happened or is about to happen to him. During the voice recording session for a Tracey Ullman Show short, Homer was required to utter what was written in the script as an «annoyed grunt».[130] Dan Castellaneta rendered it as a drawn out «d’ooooooh». This was inspired by Jimmy Finlayson, the mustachioed Scottish actor who appeared in 33 Laurel and Hardy films.[130] Finlayson had used the term as a minced oath to stand in for the word «Damn!» Matt Groening felt that it would better suit the timing of animation if it were spoken faster. Castellaneta then shortened it to a quickly uttered «D’oh!»[131] The first intentional use of D’oh! occurred in the Ullman short «The Krusty the Clown Show»[131] (1989), and its first usage in the series was in the series premiere, «Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire».[132]

«D’oh!» was first added to The New Oxford Dictionary of English in 1998.[130] It is defined as an interjection «used to comment on an action perceived as foolish or stupid».[133] In 2001, «D’oh!» was added to the Oxford English Dictionary, without the apostrophe («Doh!»).[134] The definition of the word is «expressing frustration at the realization that things have turned out badly or not as planned, or that one has just said or done something foolish».[135] In 2006, «D’oh!» was placed in sixth position on TV Land’s list of the 100 greatest television catchphrases.[136][137] «D’oh!» is also included in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.[138] The book includes several other quotations from Homer, including «Kids, you tried your best and you failed miserably. The lesson is never try», from «Burns’ Heir» (season five, 1994) as well as «Kids are the best, Apu. You can teach them to hate the things you hate. And they practically raise themselves, what with the Internet and all», from «Eight Misbehavin’« (season 11, 1999). Both quotes entered the dictionary in August 2007.[139]

Merchandising

Homer’s inclusion in many Simpsons publications, toys, and other merchandise is evidence of his enduring popularity. The Homer Book, about Homer’s personality and attributes, was released in 2004 and is commercially available.[140][141] It has been described as «an entertaining little book for occasional reading»[142] and was listed as one of «the most interesting books of 2004» by The Chattanoogan.[143] Other merchandise includes dolls, posters, figurines, bobblehead dolls, mugs, alarm clocks, jigsaw puzzles, Chia Pets, and clothing such as slippers, T-shirts, baseball caps, and boxer shorts.[144] Homer has appeared in commercials for Coke, 1-800-COLLECT, Burger King, Butterfinger, C.C. Lemon, Church’s Chicken, Domino’s Pizza, Intel, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Ramada Inn, Subway and T.G.I. Friday’s. In 2004, Homer starred in a MasterCard Priceless commercial that aired during Super Bowl XXXVIII.[145] In 2001, Kelloggs launched a brand of cereal called «Homer’s Cinnamon Donut Cereal», which was available for a limited time.[141][146] In June 2009, Dutch automotive navigation systems manufacturer TomTom announced that Homer would be added to its downloadable GPS voice lineup. Homer’s voice, recorded by Dan Castellaneta, features several in-character comments such as «Take the third right. We might find an ice cream truck! Mmm… ice cream.»[147]

Homer has appeared in other media relating to The Simpsons. He has appeared in every one of The Simpsons video games, including the most recent, The Simpsons Game.[148] Homer appears as a playable character in the toys-to-life video game Lego Dimensions, released via a «Level Pack» packaged with Homer’s Car and «Taunt-o-Vision» accessories in September 2015; the pack also adds an additional level based on the episode «The Mysterious Voyage of Homer».[149] Alongside the television series, Homer regularly appeared in issues of Simpsons Comics, which were published from November 29, 1993, until October 17, 2018.[150][151] Homer also plays a role in The Simpsons Ride, launched in 2008 at Universal Studios Florida and Hollywood.[152]

References

Citations

- ^ Ferguson, Murray (November 23, 2021). «Why Homer Replaced Bart As The Simpsons’ Main Character (& When)». ScreenRant. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Turner 2004, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Carroll, Larry (July 26, 2007). «‘Simpsons’ Trivia, From Swearing Lisa To ‘Burns-Sexual’ Smithers». MTV. Archived from the original on December 20, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Angus, Kat; Weis, David (July 26, 2007). «Homer Simpson’s Top Ten Jobs». Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Canada: Canwest News Service. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ Groening, Matt (writer) (2001). «Commentary for «Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire»«. The Simpsons: The Complete First Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Al Jean (writer) (2008). The Simpsons: The Complete Eleventh Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Appel, Rich; Silverman, David (November 19, 1995). «Mother Simpson». The Simpsons. Season 7. Episode 8. Fox.

- ^ a b Jean, Al; Reiss, Mike; Simon, Sam; Silverman, David (January 31, 1991). «The Way We Was». The Simpsons. Season 2. Episode 12. Event occurs at[time needed]. Fox.

- ^ Martin, Jeff; Lynch, Jeffrey (December 26, 1991). «I Married Marge». The Simpsons. Season 03. Episode 12. Fox.

- ^ Selman, Matt (writer); Kirkland, Mark (director) (January 27, 2008). «That ’90s Show». The Simpsons. Season 19. Episode 11. Fox.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (July 28, 2021). «The Simpsons: Matt Selman On Continuity And His Support For a Simpsons Hit & Run Remake». IGN. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Martin, Jeff; Kirkland, Mark (October 15, 1992). «Lisa the Beauty Queen». The Simpsons. Season 4. Episode 4. Fox.

- ^ Collier, Jonathan; Kirkland, Mark (November 10, 1996). «The Homer They Fall». The Simpsons. Season 8. Episode 3. Fox.

- ^ Warburton, Matt; Sheetz, Chuck (February 18, 2007). «Springfield Up». The Simpsons. Season 18. Episode 13. Fox.

- ^ «Image: Homer Simpson driving licence». i.redd.it.

- ^ Oakley, Bill (writer) (2005). «Commentary for «Grampa vs. Sexual Inadequacy»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b BBC (2000). ‘The Simpsons’: America’s First Family (six-minute edit for the season 1 DVD) (DVD). UK: 20th Century Fox. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Sadownick, Doug (February 26, 1991). «Matt Groening». No. 571. Advocate.

- ^ De La Roca, Claudia (May 2012). «Matt Groening Reveals the Location of the Real Springfield». Smithsonian. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ Rose, Joseph (August 3, 2007). «The real people behind Homer Simpson and family». The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon: Oregonian Media Group. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (February 25, 1993). «Matt Groening; The Fun of Being Bart’s Real Dad». The New York Times. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Snierson, Dan (June 9, 2010). «‘The Simpsons’: Matt Groening and Dan Castellaneta on EW’s Greatest Character, Homer Simpson». Entertainment Weekly. New York City: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ Rense, Rip (April 13, 1990). «Laughing With The Simpsons – The animated TV series shows us what’s so funny about trying to be normal». St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri: Entertainment News Service.

- ^ Andrews, Paul (October 16, 1990). «Groening’s Bart Simpson an animated alter ego». South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Deerfield Beach, Florida: Tronc. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ De La Roca, Claudia (May 2012). «Matt Groening Reveals the Location of the Real Springfield». Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Cary, Donick; Kirkland, Mark; Nastuk, Matthew (writers) (November 15, 1998). «D’oh-in’ in the Wind». The Simpsons. Season 10. Episode 06. Fox.

- ^ Groening, Matt (writer) (2007). «Commentary for «D’oh-in in the Wind». The Simpsons: The Complete Tenth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Kuipers, Dean (April 15, 2004). «3rd Degree: Harry Shearer». Los Angeles, California: City Beat. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Groening, Matt. (2005). Commentary for «Fear of Flying», in The Simpsons: The Complete Sixth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Fink, Moritz (2019). The Simpsons: A Cultural History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-5381-1616-6.

- ^ Groening, Matt; Reiss, Mike; Kirkland, Mark (animators) (2002). «Commentary for «Principal Charming»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Second Season (DVD). Los Angeles, CA: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening, Matt (2001). Simpsons Comics Royale. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-00-711854-0.

- ^ Archer, Wes; Groening, Matt; Kirkland, Mark (animators) (2005). «A Bit From the Animators: illustrated commentary for «Summer of 4 Ft. 2»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Seventh Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Silverman, David; Archer, Wes (directors) (2004). «Illustrated commentary for «Treehouse of Horror IV»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b Groening, Matt; Isaacs, David; Levine, Ken; Reiss, Mike; Kirkland, Mark (writers) (2002). «Commentary for «Dancin’ Homer». The Simpsons: The Complete Second Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b Oakley, Bill; Weinstein, Josh; Johnson, Tim; Silverman, David; Mirkin, David; Cohen, David X. «Homer in the Third Dimpension» (2005), in The Simpsons: The Complete Seventh Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Mirkin, David (director) (2005). «Commentary for «Lisa’s Wedding». The Simpsons: The Complete Sixth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b c Elber, Lynn (August 18, 2007). «D’oh!: The Voice of Homer Is Deceivingly Deadpan». Fox News Channel. News Corp. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Luaine (February 27, 2003). «D’oh, you’re the voice». The Age. Melbourne, Australia: Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Brownfield, Paul (July 6, 1999). «He’s Homer, but This Odyssey Is His Own». Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Harden, Mark (February 9, 2000). «‘Simpsons’ voice Dan Castellaneta has some surprises for Aspen fest». The Denver Post. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Mirkin, David. (2004). Commentary for «Bart’s Inner Child», in The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Castellaneta, Dan (actor) (2004). «Commentary for «Bart’s Inner Child»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b Morrow, Terry (June 23, 2007). «Voice of Homer Simpson leads his own, simple life». The Albuquerque Tribune. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Scripps Howard News Service. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Castellaneta, Dan (actor) (2005). «Commentary for «Homer the Great». The Simpsons: The Complete Sixth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening 1997, p. 120.

- ^ Martin, Jeff (writer) (2004). «Commentary for «Homer’s Barbershop Quartet»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b Glaister, Dan (April 3, 2004). «Simpsons actors demand bigger share». The Age. Melbourne, Australia: Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ «‘Simpsons’ Cast Goes Back To Work». CBS News. May 1, 2004. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Sheridan, Peter (May 6, 2004). «Meet the Simpsons». Daily Express. Sydney, Australia: Northern & Shell Media.

- ^ «Simpsons cast sign new pay deal». BBC News. London, England. June 3, 2008. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Block, Alex Ben (October 7, 2011). «‘The Simpsons’ Renewed for Two More Seasons». The Hollywood Reporter. Los Angeles, California: Eldridge Industries. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (February 13, 2003). «The Simpsons Rakes in the D’oh!». CNN. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ^ Groening, Matt (writer) (2004). «Commentary for «Marge on the Lam». The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Reiss, Mike (writer). «Commentary for «There’s No Disgrace Like Home». The Simpsons: The Complete First Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Bonné, Jon (October 2, 2000). «‘The Simpsons’ has lost its cool». Today.com. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Suellentrop, Chris (February 12, 2003). «The Simpsons: Who turned America’s Best TV Show into a Cartoon?». Slate. Los Angeles, California: The Slate Group. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ Ritchey, Alicia (March 28, 2006). «Matt Groening, did you brain your damage?». The Lantern. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ Bonné, Jon (November 7, 2003). «The Simpsons, back from the pit». Today.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Selley, Chris; Ursi, Marco; Weinman, Jaime J. (July 26, 2007). «The life and times of Homer J.(Vol. IV)». Maclean’s. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Rogers Media. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c McIntosh, Lindsay (July 8, 2007). «There’s nobody like him … except you, me, everyone». The Sunday Times. London, England: Times Media Group. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Brooks, James L. (Director); Groening, Matt; Jean, Al; Scully, Mike; Silverman, David (Writers); Castellaneta, Dan; Smith, Yeardley (Actors) (2007). Commentary for The Simpsons Movie (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Oakley, Bill; Weinstein, Josh; Vitti, Jon; Meyer, George (Writers) (2006). «Commentary for «The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Seventh Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Scully, Mike; Hauge, Ron; Selman, Matt; Appel, Rich; Michels, Pete (Writers) (2007). «Commentary for «When You Dish Upon a Star»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Tenth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ a b c d Groening, Matt; Scully, Mike; Jean, Al; Brooks, James L.; Silverman, David (writers) (2007). The Simpsons Movie: A Look Behind the Scenes (DVD). The Sun.

- ^ Stern, David M.; Reardon, Jim (February 18, 1993). «Duffless». The Simpsons. Season 4. Episode 16. Fox.

- ^ Groening, Matt (writer) (2002). «Commentary for «Simpson and Delilah»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Second Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Groening, Matt (writer) (2001). «Commentary for «Bart the Genius». The Simpsons: The Complete First Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Swartzwelder, John; Archer, Wes (October 21, 1993). «Rosebud». The Simpsons. Season 05. Episode 04. Fox.

- ^ Vitti, Jon (writer); Baeza, Carlos (director) (January 9, 1991). «Radio Bart». The Simpsons. Season 3. Episode 13. Fox.

- ^ Tompkins, Steve (writer); Moore, Steven Dean (director) (December 1, 1996). «A Milhouse Divided». The Simpsons. Season 8. Episode 6. Fox.

- ^ Martin, Jeff (writer); Kirkland, Mark (director) (December 3, 1992). «Lisa’s First Word». The Simpsons. Season 4. Episode 10. Fox.

- ^ Kogen, Jay (writer); Wolodarsky, Wallace (writer); Silverman, David (director) (March 28, 1991). «Old Money». The Simpsons. Season 2. Episode 17. Fox.

- ^ Turner 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Swanson, Neely (February 28, 2012). «David Mirkin, A Writer I Love». No Meaner Place. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Frink, John (writer); Persi, Raymond S. (director) (October 5, 2008). «Lost Verizon». The Simpsons. Season 20. Episode 2. Fox.

- ^ Chun, Daniel (writer); Kruse, Nancy (director) (March 11, 2007). «Rome-old and Juli-eh». The Simpsons. Season 18. Episode 15. Fox.

- ^ Gillis, Stephanie (writer); Kirkland, Mark (director) (December 7, 2008). «The Burns and the Bees». The Simpsons. Season 20. Episode 8. Fox.

- ^ Goldreyer, Ned (writer); Dietter, Susie (director) (March 8, 2008). «Lisa the Simpson». The Simpsons. Season 9. Episode 17. Fox.

- ^ Vitti, Jon (writer); Baeza, Carlos (director) (April 1, 1994). «So It’s Come to This: A Simpsons Clip Show». The Simpsons. Season 04. Episode 18. Fox.

- ^ a b Jean, Al (writer); Anderson, Mike B. (director) (January 7, 2001). «HOMR». The Simpsons. Season 12. Episode 9. Fox.

- ^ Vitti, Jon (writer); Lynch, Jeffrey (director) (February 4, 1993). «Brother from the Same Planet». The Simpsons. Season 4. Episode 14. Fox.

- ^ a b Reiss, Mike; Jean, Al (writers); Reardon, Jim (director) (2004). «Commentary for «Duffless»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Fourth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Sacks, Mike (May 2, 2021). «John Swartzwelder, sage of The Simpsons«. The New Yorker. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Gordon, Doug (August 8, 2018). «Longtime Showrunner, Writer Goes Behind the Scenes of The Simpsons«. Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Vary, Adam B. (June 1, 2010). «The 100 Greatest Characters of the Last 20 Years: Here’s our full list!». Entertainment Weekly. New York City: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ a b «Bugs Bunny tops greatest cartoon characters list». CNN. July 30, 2002. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ «The 100 Greatest TV Characters». Bravo. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ «100 Greatest TV Characters». Channel 4. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ^ «The 50 Greatest TV Icons». Entertainment Weekly. New York City: Meredith Corporation. November 13, 2007. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Vary, Adam B (June 1, 2010). «The 100 Greatest Characters of the Last 20 Years: Here’s our full list!». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ «Homer eyes ‘best American’ prize». BBC News. June 13, 2003. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ «Presidential poll win for Homer». BBC News. October 25, 2004. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ^ «Couples Pictures, The Simpsons Photos – Photo Gallery: The Best TV Couples of All Time». TV Guide. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ «The 50 Best Cartoon Characters of All Time». May 10, 2010.

- ^ a b «Primetime Emmy Awards Advanced Search». Emmys.org. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ a b Schneider, Michael (August 10, 2004). «Emmy speaks for Homer». Variety. Los Angeles, California: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ «61st Primetime Emmy Awards Quick Search». Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. September 12, 2009. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ «2010 Primetime Emmy Awards Nominations» (PDF). Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ Sandler, Adam (November 8, 1993). «‘Aladdin’ tops Annies». Variety. Los Angeles, California: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ «Legacy: 21st Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (1993)». Annie Awards. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ «25th Annual Winners and Nominees». Youngartistawards.org. Archived from the original on August 2, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ «Teen Choice Awards: 2005». IMDb. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ «Hollywood Icons». Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ «The Simpsons‘ producer Al Jean reflects on «Homer at the Bat»«. baseballhall.org. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ «Person of the Week: Matt Groening». ABC News. July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ Turner 2004, p. 80.

- ^ Mazur, Eric Michael; McCarthy, Kate (2001). God in the Details: American Religion in Popular Culture. London, England: Routledge. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-415-92564-8.

- ^ Halwani, pp. 22–23

- ^ Armstrong, Jennifer; Pastorek, Whitney; Snierson, Dan; Stack, Tim; Wheat, Alynda (June 18, 2007). «100 New TV Classics». Entertainment Weekly. Los Angeles, California: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- ^ Snierson, Dan (January 14, 2000). «Springfield of Dreams». Entertainment Weekly. New York City: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Turner 2004, pp. 99–106.

- ^ Josh Weinstein (writer) (2006). «Commentary for «Homer’s Enemy»«. The Simpsons: The Complete Eighth Season (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Cantor, Paul Arthur (2001). Gilligan Unbound: Pop Culture in the Age of Globalization. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-0-7425-0779-1.

- ^ Page, Susan (September 3, 2007). «Most influential people». USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett Company. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- ^ Baker, Bob (February 16, 2003). «The real first family». Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ «Don’t have a cow! Homer Simpson is Canadian, creator says». Yahoo!. July 18, 2003. Archived from the original (News article) on October 5, 2002. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ «Homer Simpson to become an honourary [sic] Winnipegger». Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. May 30, 2003. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ^ «Wish for rain to wash away Homer». BBC News. July 16, 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ «Spanish Sweetshop Owner Finds Homer Simpson Euro». Fox News Channel. August 10, 2008. Archived from the original on September 2, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ Szalai, George (April 1, 2009). «Postal Service launching ‘Simpsons’ stamps». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ «The Simpsons stamps launched in US». Newslite. May 8, 2009. Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ «The Simpsons Get ‘Stamping Ovation’ To Tune of 1 Billion Stamps». United States Postal Service. May 7, 2009. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- ^ Deanie79 (May 16, 2006). «Top 3 Results». Americanidol.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ «Homer Simpson to be on ‘The Tonight Show with Jay Leno’«. Tucson Citizen. July 20, 2007. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Serjeant, Jill (September 6, 2008). «Christina Applegate in telethon for cancer research». Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ «The Constitution of the JCR of Worcester College, Oxford» (PDF). p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ «Gene limits learning and memory in mice». Archived from the original on September 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c Reiss & Klickstein 2018, p. 108.

- ^ a b «What’s the story with … Homer’s D’oh!». The Herald. July 21, 2007. Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Simon, Jeremy (February 11, 1994). «Wisdom from The Simpsons‘ ‘D’ohh’ boy». The Daily Northwestern. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ^ Shewchuk, Blair (July 17, 2001). «D’oh! A Dictionary update». CBC News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ «It’s in the dictionary, D’oh!». BBC News, Entertainment. BBC. June 14, 2001. Archived from the original on December 3, 2002. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ «‘D’oh!’ The Right Thing?». Newsweek. June 15, 2001. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ «Dyn-O-Mite! TV Land lists catchphrases». USA Today. November 28, 2006. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ «The 100 greatest TV quotes and catchphrases». TV Land. 2008. Archived from the original on March 13, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ «Homer’s Odyssey». Us Weekly. May 21, 2000. Archived from the original on September 4, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- ^ Shorto, Russell (August 24, 2007). «Simpsons quotes enter new Oxford dictionary». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- ^ Groening, Matt (2005). The Homer Book. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-111661-2.

- ^ a b «D’Oh! Eat Homer for breakfast». CNN. September 10, 2001. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ^ Hunter, Simon (November 15, 2004). «The perfect present for a ‘Doh’ nut». The News Letter.

- ^ Evans, Bambi (February 9, 2005). «Bambi Evans: The Most Interesting Books Of 2004». The Chattanoogan. Archived from the original on February 10, 2005. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ «Homer Simpson stuff». The Simpsons Shop. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ Sampey, Kathleen (January 30, 2004). «Homer Simpson Is ‘Priceless’ for MasterCard». Adweek. Archived from the original on December 14, 2004. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ^ Fonseca, Nicholas (November 15, 2001). «Cereal Numbers». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- ^ «Homer Simpson joins the TomTom GPS voice lineup». Daily News. June 17, 2009. Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Walk, Gary Eng (November 5, 2007). «Work of Bart». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ «Game review: Lego Dimensions Doctor Who Level Pack is about time». November 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ Radford, Bill (November 19, 2000). «Groening launches Futurama comics». The Gazette.

- ^ Shutt, Craig. «Sundays with the Simpsons». MSNBC. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ MacDonald, Brady (April 9, 2008). «Simpsons ride features 29 characters, original voices». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

Sources

- Groening, Matt (1997). Richmond, Ray; Coffman, Antonia (eds.). The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family (1st ed.). New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-06-095252-5. LCCN 98141857. OCLC 37796735. OL 433519M.

- Halwani, Raja (1999). «Homer and Aristotle». In Irwin, William; Conrad, Mark T.; Skoble, Aeon (eds.). The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’oh! of Homer. Chicago, Illinois: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9433-8.

- Reiss, Mike; Klickstein, Mathew (2018). Springfield confidential: jokes, secrets, and outright lies from a lifetime writing for the Simpsons. New York City: Dey Street Books. ISBN 978-0062748034.

- Turner, Chris (2004). Planet Simpson: How a Cartoon Masterpiece Documented an Era and Defined a Generation. Foreword by Douglas Coupland. (1st ed.). Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0-679-31318-2. OCLC 55682258.

Further reading

- Alberti, John, ed. (2003). Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2849-1.

- Brown, Alan; Logan, Chris (2006). The Psychology of The Simpsons. BenBella Books. ISBN 978-1-932100-70-9.

- Fink, Moritz (2019). The Simpsons: A Cultural History. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-1616-6.

- Groening, Matt (2005). The Homer Book. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-111661-2.

- Groening, Matt (1991). The Simpsons Uncensored Family Album. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-096582-2.

- Pinsky, Mark I (2004). The Gospel According to The Simpsons: The Spiritual Life of the World’s Most Animated Family. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22419-6.

External links

Look up d’oh in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Media related to Homer Simpson at Wikimedia Commons

- Homer Simpson on IMDb

| Homer Simpson | |

|---|---|

| The Simpsons character | |

Homer eating a classic strawberry sprinkled donut |

|

| First appearance |

|

| Created by | Matt Groening |

| Designed by | Matt Groening |

| Voiced by | Dan Castellaneta |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Homer Jay Simpson |

| Occupation |

|

| Affiliation | Springfield Nuclear Power Plant |

| Family |

|

| Spouse | Marge Bouvier |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Home | 742 Evergreen Terrace, Springfield, United States |

| Nationality | American |

Homer Jay Simpson is a fictional character and the main protagonist of the American animated sitcom The Simpsons.[1] He is voiced by Dan Castellaneta and first appeared, along with the rest of his family, in The Tracey Ullman Show short «Good Night» on April 19, 1987. Homer was created and designed by cartoonist Matt Groening while he was waiting in the lobby of producer James L. Brooks’s office. Groening had been called to pitch a series of shorts based on his comic strip Life in Hell but instead decided to create a new set of characters. He named the character after his father, Homer Groening. After appearing for three seasons on The Tracey Ullman Show, the Simpson family got their own series on Fox, which debuted December 17, 1989. The show was later acquired by Disney in 2019.

As the nominal foreman of the paternally eponymous family, Homer and his wife Marge have three children: Bart, Lisa and Maggie. As the family’s provider, he works at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant as safety inspector. Homer embodies many American working class stereotypes: he is obese, immature, outspoken, aggressive, balding, lazy, ignorant, unprofessional, and fond of beer, junk food and watching television. However, he is fundamentally a good man and is staunchly protective of his family, especially when they need him the most. Despite the suburban blue-collar routine of his life, he has had a number of remarkable experiences, including going to space, climbing the tallest mountain in Springfield by himself, fighting former President George H. W. Bush, and winning a Grammy Award as a member of a barbershop quartet.

In the shorts and earlier episodes, Castellaneta voiced Homer with a loose impression of Walter Matthau; however, during the second and third seasons of the half-hour show, Homer’s voice evolved to become more robust, to allow the expression of a fuller range of emotions. He has appeared in other media relating to The Simpsons—including video games, The Simpsons Movie, The Simpsons Ride, commercials, and comic books—and inspired an entire line of merchandise. His signature catchphrase, the annoyed grunt «D’oh!», has been included in The New Oxford Dictionary of English since 1998 and the Oxford English Dictionary since 2001.

Homer is one of the most influential characters in the history of television, and is widely considered to be an American cultural icon. The British newspaper The Sunday Times described him as «The greatest comic creation of [modern] time». He was named the greatest character «of the last 20 years» in 2010 by Entertainment Weekly, was ranked the second-greatest cartoon character by TV Guide, behind Bugs Bunny, and was voted the greatest television character of all time by Channel 4 viewers. For voicing Homer, Castellaneta has won four Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Voice-Over Performance and a special-achievement Annie Award. In 2000, Homer and his family were awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Role in The Simpsons

Homer Jay Simpson is the bumbling husband of Marge, and father to Bart, Lisa and Maggie Simpson.[2] He is the son of Mona and Abraham «Grampa» Simpson. Homer held over 188 different jobs in the first 400 episodes of The Simpsons.[3] In most episodes, he works as the nuclear safety inspector at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant (in Sector 7-G), a position which he has held since «Homer’s Odyssey», the third episode of the series, despite the fact that he is totally unsuitable for it.[4] At the nuclear plant, Homer is often ignored and completely forgotten by his boss Mr. Burns, and he constantly falls asleep and neglects his duties. Matt Groening has stated that he decided to have Homer work at the power plant because of the potential for Homer to wreak severe havoc.[5] Each of his other jobs has lasted only one episode. In the first half of the series, the writers developed an explanation about how he got fired from the plant and was then rehired in every episode. In later episodes, he often began a new job on impulse, without any mention of his regular employment.[6]

The Simpsons uses a floating timeline in which the characters never physically age, and, as such, the show is generally assumed to be always set in the current year. Nevertheless, in several episodes, events in Homer’s life have been linked to specific time periods.[2] «Mother Simpson» (season seven, 1995) depicts Homer’s mother, Mona, as a radical who went into hiding in 1969 following a run-in with the law;[7] «The Way We Was» (season two, 1991) shows Homer falling in love with Marge Bouvier as a senior at Springfield High School in 1974;[8] and «I Married Marge» (season three, 1991) implies that Marge became pregnant with Bart in 1980.[9] However, the episode «That ’90s Show» (season 19, 2008) contradicted much of this backstory, portraying Homer and Marge as a twentysomething childless couple in the early 1990s.[10] The episode «Do Pizza Bots Dream of Electric Guitars» (season 32, 2021) further contradicts this backstory, putting Homer’s adolescence in the 1990s. Showrunner Matt Selman has explained that no version was the «official continuity.» and that «they all kind of happened in their imaginary world, you know, and people can choose to love whichever version they love.»[11]

Due to the floating timeline, Homer’s age has changed occasionally as the series developed; he was 34 in the early episodes,[8] 36 in season four,[12] 38 and 39 in season eight,[13] and 40 in the eighteenth season,[14] although even in those seasons his age is inconsistent.[2] In the fourth season episode «Duffless», Homer’s drivers license shows his birthdate of being May 12, 1956,[15] which would have made him 36 years old at the time of the episode. During Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein’s period as showrunners, they found that as they aged, Homer seemed to become older too, so they increased his age to 38. His height is 6′ (1.83 m).[16]

Character

Creation

Naming the characters after members of his own family, Groening named Homer after his father, who himself had been named after the ancient Greek poet of the same name.[17][18][19] Very little else of Homer’s character was based on him, and to prove that the meaning behind Homer’s name was not significant, Groening later named his own son Homer.[20][21] According to Groening, «Homer originated with my goal to both amuse my real father, and just annoy him a little bit. My father was an athletic, creative, intelligent filmmaker and writer, and the only thing he had in common with Homer was a love of donuts.»[22] Although Groening has stated in several interviews that Homer was named after his father, he also claimed in several 1990 interviews that a character called precisely Homer Simpson in the 1939 Nathanael West novel The Day of the Locust as well as in the eponymous 1975 movie, was the inspiration.[2][23][24] In 2012 he clarified, «I took that name from a minor character in the novel The Day of the Locust… Since Homer was my father’s name, and I thought Simpson was a funny name in that it had the word “simp” in it, which is short for “simpleton”—I just went with it.»[25] Homer’s middle initial «J», which stands for «Jay»,[26] is a «tribute» to animated characters such as Bullwinkle J. Moose and Rocket J. Squirrel from The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show, who got their middle initial from Jay Ward.[27]

Homer made his debut with the rest of the Simpson family on April 19, 1987, in The Tracey Ullman Show short «Good Night».[28] In 1989, the shorts were adapted into The Simpsons, a half-hour series airing on the Fox Broadcasting Company. Homer and the Simpson family remained the main characters on this new show.[29]

Design

As currently depicted in the series, Homer’s everyday clothing consists of a white shirt with short sleeves and open collar, blue pants, and gray shoes. He is overweight and bald, except for a fringe of hair around the back and sides of his head and two curling hairs on top, and his face always sports a growth of beard stubble that instantly regrows whenever he shaves.

Homer’s design has been revised several times over the course of the series. Left to right: Homer as he appeared in «Good Night» (1987), «Bathtime» (1989), and «Bart the Genius» (1990).

The entire Simpson family was designed so that they would be recognizable in silhouette.[30] The family was crudely drawn because Groening had submitted basic sketches to the animators, assuming they would clean them up; instead, they just traced over his drawings.[17] By coincidence or not, Homer’s look bears a resemblance to the cartoon character Adamsson, created by Swedish cartoonist Oscar Jacobsson in 1920.[31] Homer’s physical features are generally not used in other characters; for example, in the later seasons, no characters other than Homer, Grampa Simpson, Lenny Leonard, and Krusty the Clown have a similar beard line.[32] When Groening originally designed Homer, he put his initials into the character’s hairline and ear: the hairline resembled an ‘M’, and the right ear resembled a ‘G’. Groening decided that this would be too distracting and redesigned the ear to look normal. However, he still draws the ear as a ‘G’ when he draws pictures of Homer for fans.[33] The basic shape of Homer’s head is described by director Mark Kirkland as a tube-shaped coffee can with a salad bowl on top.[34] During the shorts, the animators experimented with the way Homer would move his mouth when talking. At one point, his mouth would stretch out back «beyond his beardline»; but this was dropped when it got «out of control.»[35] In some early episodes, Homer’s hair was rounded rather than sharply pointed because animation director Wes Archer felt it should look disheveled. Homer’s hair evolved to be consistently pointed.[36] During the first three seasons, Homer’s design for some close-up shots included small lines which were meant to be eyebrows. Groening strongly disliked them and they were eventually dropped.[36]

In the season seven (1995) episode «Treehouse of Horror VI», Homer was computer animated into a three-dimensional character for the first time for the «Homer3» segment of the episode. The computer animation directors at Pacific Data Images worked hard not to «reinvent the character».[37] In the final minute of the segment, the 3D Homer ends up in a real world, live-action Los Angeles. The scene was directed by David Mirkin and was the first time a Simpsons character had been in the real world in the series.[37] Because «Lisa’s Wedding» (season six, 1995) is set fifteen years in the future, Homer’s design was altered to make him older in the episode. He is heavier; one of the hairs on top of his head was removed; and an extra line was placed under the eye. A similar design has been used in subsequent flashforwards.[38]

Voice

«I was trying to find something I was more comfortable with that had more power to it, so I had to drop the voice down. … People will say to me, ‘Boy, I’m glad they replaced the guy that was there that first season.’ That was me!»

Homer’s voice is performed by Dan Castellaneta, who voices numerous other characters, including Grampa Simpson, Krusty the Clown, Barney Gumble, Groundskeeper Willie, Mayor Quimby and Hans Moleman. Castellaneta had been part of the regular cast of The Tracey Ullman Show and had previously done some voice-over work in Chicago alongside his wife Deb Lacusta. Voices were needed for the Simpsons shorts, so the producers decided to ask Castellaneta and fellow cast member Julie Kavner to voice Homer and Marge rather than hire more actors.[39][40] In the shorts and first season of the half-hour show, Homer’s voice is different from the majority of the series. The voice began as a loose impression of Walter Matthau, but Castellaneta could not «get enough power behind that voice»,[40] or sustain his Matthau impression for the nine- to ten-hour-long recording sessions, and had to find something easier.[3] During the second and third seasons of the half-hour show, Castellaneta «dropped the voice down»[39] and developed it as more versatile and humorous, allowing Homer a fuller range of emotions.[41]

Castellaneta’s normal speaking voice does not bear any resemblance to Homer’s.[42] To perform Homer’s voice, Castellaneta lowers his chin to his chest[40] and is said to «let his I.Q. go».[43] While in this state, he has ad-libbed several of Homer’s least intelligent comments,[43] such as the line «S-M-R-T; I mean, S-M-A-R-T!» from «Homer Goes to College» (season five, 1993) which was a genuine mistake made by Castellaneta during recording.[44] Castellaneta likes to stay in character during recording sessions,[45] and he tries to visualize a scene so that he can give the proper voice to it.[46] Despite Homer’s fame, Castellaneta claims he is rarely recognized in public, «except, maybe, by a die-hard fan».[45]

«Homer’s Barbershop Quartet» (season five, 1993) is the only episode where Homer’s voice was provided by someone other than Castellaneta. The episode features Homer forming a barbershop quartet called The Be Sharps; and, at some points, his singing voice is provided by a member of The Dapper Dans.[47] The Dapper Dans had recorded the singing parts for all four members of The Be Sharps. Their singing was intermixed with the normal voice actors’ voices, often with a regular voice actor singing the melody and the Dapper Dans providing backup.[48]

Until 1998, Castellaneta was paid $30,000 per episode. During a pay dispute in 1998, Fox threatened to replace the six main voice actors with new actors, going as far as preparing for casting of new voices.[49] However, the dispute was soon resolved and he received $125,000 per episode until 2004 when the voice actors demanded that they be paid $360,000 an episode.[49] The issue was resolved a month later,[50] and Castellaneta earned $250,000 per episode.[51] After salary re-negotiations in 2008, the voice actors receive approximately $400,000 per episode.[52] Three years later, with Fox threatening to cancel the series unless production costs were cut, Castellaneta and the other cast members accepted a 30 percent pay cut, down to just over $300,000 per episode.[53]

Character development

Executive producer Al Jean notes that in The Simpsons‘ writing room, «everyone loves writing for Homer», and many of his adventures are based on experiences of the writers.[54] In the early seasons of the show, Bart was the main focus. But, around the fourth season, Homer became more of the focus. According to Matt Groening, this was because «With Homer, there’s just a wider range of jokes you can do. And there are far more drastic consequences to Homer’s stupidity. There’s only so far you can go with a juvenile delinquent. We wanted Bart to do anything up to the point of him being tried in court as a dad. But Homer is a dad, and his boneheaded-ness is funnier. […] Homer is launching himself headfirst into every single impulsive thought that occurs to him.»[22]