харакири

-

1

харакири

Sokrat personal > харакири

-

2

харакири

harakiri

имя существительное:словосочетание:

Русско-английский синонимический словарь > харакири

-

3

харакири

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > харакири

-

4

харакири

Русско-английский словарь Смирнитского > харакири

-

5

харакири

нескл.

hara-kiri* * *

* * *

Новый русско-английский словарь > харакири

-

6

харакири

hara-kiri [hæ-]; seppuku [-‘p(j)uː-]

Новый большой русско-английский словарь > харакири

-

7

харакири

Русско-английский учебный словарь > харакири

-

8

харакири

Русско-английский большой базовый словарь > харакири

-

9

своп “харакири”

- harakiri swap

Русско-английский словарь нормативно-технической терминологии > своп “харакири”

-

10

сделать себе харакири

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > сделать себе харакири

См. также в других словарях:

-

ХАРАКИРИ — (японск.). Японский обычай, ко которому приговоренные к казни, а также удрученные безысходным горем или отчаянием лишали себя жизни, вспарывая живот. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. ХАРАКИРИ… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

харакири — ХАРАКИРИ, нескл., с. Наказание, нагоняй. Сделать харакири кому распечь, изругать, побить кого л. Японское «харакири» самурайское самоубийство путем вспарывания живота … Словарь русского арго

-

харакири — нагоняй, наказание, самоубийство Словарь русских синонимов. харакири сущ., кол во синонимов: 3 • нагоняй (44) • … Словарь синонимов

-

ХАРАКИРИ — (от японского хара живот и кири резать), в Японии самоубийство вспарыванием живота. Известно со времени средневековья. Принято в среде самураев, совершалось по приговору или по собственному решению … Современная энциклопедия

-

ХАРАКИРИ — (от япон. хара живот и кири резать) в Японии самоубийство вспарыванием живота. Известно со времен средневековья. Принятая в среде самураев, эта форма самоубийства совершалась по приговору или добровольно (в тех случаях, когда была затронута честь … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ХАРАКИРИ — ХАРАКИРИ, нескл., ср. (япон.). Самоубийство путем вспарывания живота кинжалом, принятое у японских самураев. Толковый словарь Ушакова. Д.Н. Ушаков. 1935 1940 … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

ХАРАКИРИ — ХАРАКИРИ, нескл., ср. У японских самураев: самоубийство путём вспарывания живота. Сделать себе х. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

-

Харакири — или сеппуко (первое чисто японское слово, второе китайского происхождения) распарывание живота являлось в течениенескольких столетий среди японцев наиболее популярным способомсамоубийства. Возникновение Х. относят к средним векам, когда к… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

Харакири — (от япон. хара живот и кири резать) в Японии самоубийство вспарыванием живота. Известно со времен средневековья. Принятая в среде самураев, эта форма самоубийства совершалась по приговору или добровольно (в тех случаях, когда была затронута честь … Политология. Словарь.

-

харакири — харакири, сеппуку (сэппуку) япон. ритуальное самоубийство путём вспарывания живота (было принято среди самурайского сословия средневековой Японии) … Универсальный дополнительный практический толковый словарь И. Мостицкого

-

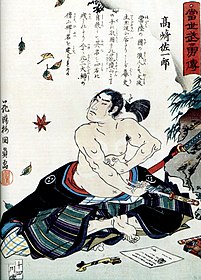

Харакири — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Харакири (значения). Куникадзу Утагава (1850 е) Харакири (яп. 腹切り … Википедия

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «харакири» на английский

nn

Его ультра-атакующий стиль футбола иногда назывался «харакири», видом самоубийства.

His ultra-attacking style of football was at times described as ‘harakiri‘; a form of suicide.

Чем знатнее клан, тем почётнее считалось совершение харакири в его поместье.

The more famous the clan, the more honorable it was considered to commit harakiri on his estate.

Внимание — миф: именно катаной самураи совершали харакири.

Attention is a myth: it was the katana samurai who made the hara-kiri.

В XV веке военное сословие ввело харакири в качестве традиции и привилегии.

In the 15th century military class established the hara-kiri as a custom and privilege.

Иногда даймё приказывал выполнить харакири в качестве гарантий мирного соглашения.

Sometimes a daimyō was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement.

А вот харакири всегда считался поступком, достойным уважения, идеальным решением всех проблем…

But the act of seppuku was always considered worthy of respect, the ideal solution to all problems…

Затем он вошел в кабинет командующего и совершил сеппуку (харакири).

Then he withdrew to the commandant’s office and committed seppuku (harakiri).

Нелегко будет заставить его совершить харакири.

It won’t be easy to make him commit harakiri.

Он мог бы попытаться спастись, совершив обряд харакири.

He could try to escape, After the rite of harakiri.

Kuratas следует установить функцию харакири (ритуальное самоубийство).

The Kuratas should install a harakiri (ritual suicide) function.

Когда Kaizaki отказался изменить курс, менеджер достал нож и совершил харакири.

When Kaizaki refused to change course, the manager took out a knife and committed hara-kiri.

Они должны стоять на своих жирных белых коленях и благодарить меня за то, что я спасла эту партию от совершения политического харакири.

They should be down on their fat, white knees, thanking me for saving this party from committing political seppuku.

Как по мне, они выглядели так, будто харакири… это уже не для них.

To me they look like a hara-kiri… is redundant.

У него нет ни малейшего намерения покончить с собой, не говоря уже о почетном харакири.

He hasn’t the slightest intention of killing himself, yet he speaks of honorable harakiri.

За многие годы ритуал харакири претерпел изменения.

The rite of harakiri has changed over time.

Это было бы равнозначно политическому харакири.

Indeed, it will be political harakiri.

Бросить все было для него своеобразным психологическим харакири.

To give it up was tantamount to psychological harakiri.

Одной из самых страшных вещей в пути самурая является сэппуку (также известное как «харакири»).

One of the most terrifying things about the way of the samurai is seppuku (also known as «hara-kiri«).

Это ритуальный кинжал, который использовался только для одной цели — совершения сэппуку или харакири.

This is a ritual dagger that was used only for one purpose — performing seppuku or hara-kiri.

Однако последовало харакири, еще 3-4 неудачных хода.

However hara-kiri followed, another 3-4 poor moves.

Результатов: 212. Точных совпадений: 212. Затраченное время: 46 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

харакири — перевод на английский

Не в силах больше терпеть позор и жить в нищете, он предпочел достойную смерть с помощью харакири. Теперь он просит разрешения воспользоваться нашим передним двором для совершения ритуала.

Rather than live on in such poverty and disgrace, he wishes to die honorably by harakiri and asks for permission to use our forecourt.

Не в силах более жить в нищете, тщетно ожидая смерти, ты решил прервать свою жизнь как надлежит самураю — с помощью харакири.

Rather than live on in endless poverty, idly waiting for death, you wish to end your life in a manner befitting a samurai, by harakiri.

Они вовсе не намерены совершать харакири. И только из-за того, что нуждаются в пище и одежде, они предстают перед нашими вратами и скрыто занимаются вымогательством.

They have no intention whatsoever of performing harakiri, and just because they’re hurting a little for food and clothing, they show up at our gate to practice their thinly disguised extortion.

У него нет ни малейшего намерения покончить с собой, не говоря уже о почетном харакири.

He hasn’t the slightest intention of killing himself, yet he speaks of honorable harakiri.

Показать ещё примеры для «harakiri»…

Я говорю вам, что мы совершаем харакири,… каждый день, прямо здесь, в классе.

I tell you we’re committing hara-kiri every day, right here in this class-room.

Ты должен совершить харакири в воздаяние!

You must commit hara-kiri in recompense!

Как по мне, они выглядели так, будто харакири это уже не для них.

To me they look like a hara-kiri is redundant.

Господин Ако был приговорён к совершению харакири, а его вассалы, ставшие ронинами, скрывались под видом лекарей и торговцев…

Lord Akou was made to commit hara-kiri as his vassals scattered as ronin, disguised as merchants and doctors…

Показать ещё примеры для «hara-kiri»…

Мы заставим его сделать харакири.

We’ll force his hand and make him commit harakiri.

Ты вовсе и не собирался делать харакири!

You never intended to commit harakiri.

Харакири вовсе не было твоей целью.

You never intended to commit harakiri.

Теперь стало отчетливо ясно, что решение позволить отставному воину клана Фукушима, Мотоме Чиджива, в январе этого года умереть с помощью харакири, было признано верным.

Furthermore, it has become clear that when another former retainer of the Fukushima Clan, one Motome Chijiiwa, asked to commit harakiri in January of this year, we did not err in our chosen response.

На вашем месте я бы сделал харакири.

If I were you, I would commit harakiri.

Показать ещё примеры для «commit harakiri»…

За то, что преступил закон нашего союза, Такито Сейяме приказано сделать харакири.

For violating the rules of our troop, Takito Seyama has been ordered to commit hara-kiri.

Не желая страдать от бесчестья, он попросил о харакири.

Rather than suffer dishonor he asked to commit hara-kiri.

Так преданы компании, что сделают себе харакири, если не справятся

So devoted to the company that they would commit Hara-Kiri if they failed it.

Рядовой Такакура докажет свою верность нашему Императору и сделает себе харакири!

Private Takakura will prove loyalty to our Emperor and commit hara-kiri!

Сделай харакири, как полковник Такакура!

Commit hara-kiri like Colonel Takakura!

Показать ещё примеры для «commit hara-kiri»…

Отправить комментарий

Перевод «харакири» на английский

Ваш текст переведен частично.

Вы можете переводить не более 999 символов за один раз.

Войдите или зарегистрируйтесь бесплатно на PROMT.One и переводите еще больше!

<>

харакири

ср.р.

существительное

Склонение

мн.

харакири

hara-kiri

Они принудят его совершить харакири.

They’ll make him commit hara-kiri.

Контексты

Они принудят его совершить харакири.

They’ll make him commit hara-kiri.

Мы все еще не в состоянии дать разумное и достаточно обоснованное научное объяснение массовой гибели птиц и рыб, происходящей во всем мире, разве что только ограничиться одной причиной — «харакири!».

We still have not been able to reasonably ascertain an integral scientific reasoning behind the massive deaths of birds and fish happening around the world, except with the word ‘Harakiri.’

Мы заставим его сделать харакири.

We’ll force his hand and make him commit hara-kiri.

Прошлой ночью он сделал себе харакири.

He committed hara-kiri last night.

Но именно он решил умереть, совершив харакири.

But it was he who declared his wish to commit hara-kiri.

Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с русского на английский

Вам нужно переводить на английский сообщения в чатах, письма бизнес-партнерам и в службы поддержки онлайн-магазинов или домашнее задание? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет с русского на английский и еще на 20+ языков.

Точный переводчик

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом с русского на английский, а также смотрите английскую транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов слов с примерами употребления в предложениях. Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим перевод с английского на русский и с русского на английский. Переводите в браузере на персональных компьютерах, ноутбуках, на мобильных устройствах или установите мобильное приложение Переводчик PROMT.One для iOS и Android.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One бесплатно переводит онлайн с русского на азербайджанский, арабский, греческий, иврит, испанский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, татарский, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, украинский, финский, французский, эстонский и японский.

Staged seppuku with ritual attire and kaishaku

| Seppuku | |||

|---|---|---|---|

«Seppuku» in kanji |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 切腹 | ||

| Hiragana | せっぷく | ||

| Katakana | セップク | ||

|

Seppuku (切腹, ‘cutting [the] belly’), also called hara-kiri (腹切り, lit. ‘abdomen/belly cutting’, a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritualistic suicide by disembowelment. While harakiri refers to the act of disemboweling one’s self, seppuku refers to the ritual and usually would involve decapitation after the act as a sign of mercy. Harakiri refers solely to the act of disembowelment and would only be assigned as a punishment towards acts deemed too heinous for seppuku.[1] It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honour, but was also practiced by other Japanese people during the Shōwa period[2][3] (particularly officers near the end of World War II) to restore honour for themselves or for their families.[4][5][6] As a samurai practice, seppuku was used voluntarily by samurai to die with honour rather than fall into the hands of their enemies (and likely be tortured), as a form of capital punishment for samurai who had committed serious offences, or performed because they had brought shame to themselves.[1] The ceremonial disembowelment, which is usually part of a more elaborate ritual and performed in front of spectators, consists of plunging a short blade, traditionally a tantō, into the belly and drawing the blade from left to right, slicing the belly open.[7] If the cut is deep enough, it can sever the abdominal aorta, causing a rapid death by blood loss.[citation needed]

The first recorded act of seppuku was performed by Minamoto no Yorimasa during the Battle of Uji in 1180.[8] Seppuku was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands and to attenuate shame and avoid possible torture.[9][10] Samurai could also be ordered by their daimyō (feudal lords) to carry out seppuku. Later, disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to carry out seppuku rather than be executed in the normal manner.[11] The most common form of seppuku for men was composed of the cutting of the abdomen, and when the samurai was finished, he stretched out his neck for an assistant to sever his spinal cord. It was the assistant’s job to decapitate the samurai in one swing, otherwise it would bring great shame to the assistant and his family. Those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to carry out seppuku. Samurai generally could carry out the act only with permission.

Sometimes a daimyō was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement. This weakened the defeated clan so that resistance effectively ceased. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used an enemy’s suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of daimyōs. When the Hōjō Clan were defeated at Odawara in 1590, Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired daimyō Hōjō Ujimasa and the exile of his son Ujinao; with this act of suicide, the most powerful daimyō family in eastern Japan was completely defeated.

Etymology[edit]

Samurai about to perform seppuku

The term seppuku is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots setsu 切 («to cut», from Middle Chinese tset; compare Mandarin qiē and Cantonese chit) and fuku 腹 («belly», from MC pjuwk; compare Mandarin fù and Cantonese fūk).

It is also known as harakiri (腹切り, «cutting the stomach»;[12] often misspelled/mispronounced «hiri-kiri» or «hari-kari» by American English speakers).[13] Harakiri is written with the same kanji as seppuku but in reverse order with an okurigana. In Japanese, the more formal seppuku, a Chinese on’yomi reading, is typically used in writing, while harakiri, a native kun’yomi reading, is used in speech. As Ross notes,

It is commonly pointed out that hara-kiri is a vulgarism, but this is a misunderstanding. Hara-kiri is a Japanese reading or Kun-yomi of the characters; as it became customary to prefer Chinese readings in official announcements, only the term seppuku was ever used in writing. So hara-kiri is a spoken term, but only to commoners and seppuku a written term, but spoken amongst higher classes for the same act.[14]

The practice of performing seppuku at the death of one’s master, known as oibara (追腹 or 追い腹, the kun’yomi or Japanese reading) or tsuifuku (追腹, the on’yomi or Chinese reading), follows a similar ritual.

The word jigai (自害) means «suicide» in Japanese. The modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[15] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[16] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese.[17] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[18]

Ritual[edit]

A tantō prepared for seppuku

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the seppuku of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a kaishakunin (idiomatically, his «second») had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the tachi (longsword), wakizashi (shortsword) or tantō (knife) into the gut and slicing the abdomen horizontally. In the absence of a kaishakunin, the samurai would then remove the blade and stab himself in the throat, or fall (from a standing position) with the blade positioned against his heart.

During the Edo period (1600–1867), carrying out seppuku came to involve an elaborate, detailed ritual. This was usually performed in front of spectators if it was a planned seppuku, as opposed to one performed on a battlefield. A samurai was bathed in cold water (to prevent excessive bleeding), dressed in a white kimono called the shiro-shōzoku (白装束) and served his favorite foods for a last meal. When he had finished, the knife and cloth were placed on another sanbo and given to the warrior. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special clothes, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. He would probably consume an important ceremonial drink of sake. He would also give his attendant a cup meant for sake.[19][20]

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to carry out seppuku after losing a battle for his master in 1582. He had just written his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner. By Tsukioka Yoshitoshi around 1890.

With his selected kaishakunin standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his tantō – which the samurai held by the blade with a cloth wrapped around so that it would not cut his hand and cause him to lose his grip – and plunge it into his abdomen, making a left-to-right cut. The kaishakunin would then perform kaishaku, a cut in which the warrior was partially decapitated. The maneuver should be done in the manners of dakikubi (lit. «embraced head»), in which way a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body, so that it can be hung in front as if embraced. Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was a skilled swordsman. The principal and the kaishakunin agreed in advance when the latter was to make his cut. Usually dakikubi would occur as soon as the dagger was plunged into the abdomen. Over time, the process became so highly ritualized that as soon as the samurai reached for his blade the kaishakunin would strike. Eventually even the blade became unnecessary and the samurai could reach for something symbolic like a fan, and this would trigger the killing stroke from his second. The fan was likely used when the samurai was too old to use the blade or in situations where it was too dangerous to give him a weapon.[21]

This elaborate ritual evolved after seppuku had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and became a para-judicial institution. The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honorably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote:

From ages past it has been considered an ill-omen by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. Further, if one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace.

In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials.

A specialized form of seppuku in feudal times was known as kanshi (諫死, «remonstration death/death of understanding»), in which a retainer would commit suicide in protest of a lord’s decision. The retainer would make one deep, horizontal cut into his abdomen, then quickly bandage the wound. After this, the person would then appear before his lord, give a speech in which he announced the protest of the lord’s action, then reveal his mortal wound. This is not to be confused with funshi (憤死, indignation death), which is any suicide made to protest or state dissatisfaction.[citation needed]

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of seppuku known as jūmonji giri (十文字切り, «cross-shaped cut»), in which there is no kaishakunin to put a quick end to the samurai’s suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut on the belly. A samurai performing jūmonji giri was expected to bear his suffering quietly until he bled to death, passing away with his hands over his face.[22]

Female ritual suicide[edit]

Female ritual suicide (incorrectly referred to in some English sources as jiigai), was practiced by the wives of samurai who have performed seppuku or brought dishonor.[23][24]

Some women belonging to samurai families committed suicide by cutting the arteries of the neck with one stroke, using a knife such as a tantō or kaiken. The main purpose was to achieve a quick and certain death in order to avoid capture. Before committing suicide, a woman would often tie her knees together so her body would be found in a “dignified” pose, despite the convulsions of death. Invading armies would often enter homes to find the lady of the house seated alone, facing away from the door. On approaching her, they would find that she had ended her life long before they reached her.[citation needed]

The wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, prepares for her suicide; note the legs tied together, a feature of female seppuku to ensure a decent posture in death

History[edit]

Stephen R. Turnbull provides extensive evidence for the practice of female ritual suicide, notably of samurai wives, in pre-modern Japan. One of the largest mass suicides was the 25 April 1185 final defeat of Taira no Tomomori.[23] The wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, is a notable example of a wife following seppuku of a samurai husband.[25] A large number of honor suicides marked the defeat of the Aizu clan in the Boshin War of 1869, leading into the Meiji era. For example, in the family of Saigō Tanomo, who survived, a total of twenty-two female honor suicides are recorded among one extended family.[26]

Religious and social context[edit]

Voluntary death by drowning was a common form of ritual or honor suicide. The religious context of thirty-three Jōdo Shinshū adherents at the funeral of Abbot Jitsunyo in 1525 was faith in Amida Buddha and belief in rebirth in his Pure land, but male seppuku did not have a specifically religious context.[27] By way of contrast, the religious beliefs of Hosokawa Gracia, the Christian wife of daimyō Hosokawa Tadaoki, prevented her from committing suicide.[28]

Terminology[edit]

The word jigai (自害) means «suicide» in Japanese. The usual modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). Related words include jiketsu (自決), jijin (自尽) and jijin (自刃).[29] In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[15] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[16] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese and Hearn seen through Japanese eyes.[17] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[18] Mostow’s context is analysis of Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly and the original Cio-Cio San story by John Luther Long. Though both Long’s story and Puccini’s opera predate Hearn’s use of the term jigai, the term has been used in relation to western Japonisme, which is the influence of Japanese culture on the western arts.[30]

As capital punishment[edit]

While the voluntary seppuku is the best known form,[1] in practice the most common form of seppuku was obligatory seppuku, used as a form of capital punishment for disgraced samurai, especially for those who committed a serious offense such as rape, robbery, corruption, unprovoked murder or treason.[31] The samurai were generally told of their offense in full and given a set time for them to commit seppuku, usually before sunset on a given day. On occasion, if the sentenced individuals were uncooperative, seppuku could be carried out by an executioner, or more often, the actual execution was carried out solely by decapitation while retaining only the trappings of seppuku; even the tantō laid out in front of the uncooperative offender could be replaced with a fan (to prevent the uncooperative offenders from using the tantō as a weapon against the observers or the executioner). This form of involuntary seppuku was considered shameful and undignified.[32] Unlike voluntary seppuku, seppuku carried out as capital punishment by executioners did not necessarily absolve, or pardon, the offender’s family of the crime. Depending on the severity of the crime, all or part of the property of the condemned could be confiscated, and the family would be punished by being stripped of rank, sold into long-term servitude, or executed.

Seppuku was considered the most honorable capital punishment apportioned to samurai. Zanshu (斬首) and sarashikubi (晒し首), decapitation followed by a display of the head, was considered harsher and was reserved for samurai who committed greater crimes. Harshest punishments, usually involving death by torturous methods like kamayude (釜茹で), death by boiling, were reserved for commoner offenders.

Forced seppuku came to be known as «conferred death» over time as it was used for punishment of criminal samurai.[32]

Recorded events[edit]

On February 15, 1868, eleven French sailors of the Dupleix entered the town of Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid, and those responsible were sentenced to death. Captain Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, «Sakai Jiken», by Mori Ōgai.

In the 1860s, the British Ambassador to Japan, Algernon Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), lived within sight of Sengaku-ji where the Forty-seven Ronin are buried. In his book Tales of Old Japan, he describes a man who had come to the graves to kill himself:

I will add one anecdote to show the sanctity which is attached to the graves of the Forty-seven. In the month of September 1868, a certain man came to pray before the grave of Oishi Chikara. Having finished his prayers, he deliberately performed hara-kiri, and, the belly wound not being mortal, dispatched himself by cutting his throat. Upon his person were found papers setting forth that, being a Ronin and without means of earning a living, he had petitioned to be allowed to enter the clan of the Prince of Choshiu, which he looked upon as the noblest clan in the realm; his petition having been refused, nothing remained for him but to die, for to be a Ronin was hateful to him, and he would serve no other master than the Prince of Choshiu: what more fitting place could he find in which to put an end to his life than the graveyard of these Braves? This happened at about two hundred yards’ distance from my house, and when I saw the spot an hour or two later, the ground was all bespattered with blood, and disturbed by the death-struggles of the man.

Mitford also describes his friend’s eyewitness account of a seppuku:

Illustration titled Harakiri: Condemnation of a nobleman to suicide. drawing by L. Crépon adapted from a Japanese painting, 1867

There are many stories on record of extraordinary heroism being displayed in the harakiri. The case of a young fellow, only twenty years old, of the Choshiu clan, which was told me the other day by an eye-witness, deserves mention as a marvellous instance of determination. Not content with giving himself the one necessary cut, he slashed himself thrice horizontally and twice vertically. Then he stabbed himself in the throat until the dirk protruded on the other side, with its sharp edge to the front; setting his teeth in one supreme effort, he drove the knife forward with both hands through his throat, and fell dead.

During the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa shogun’s aide performed seppuku:

One more story and I have done. During the revolution, when the Taikun (Supreme Commander), beaten on every side, fled ignominiously to Yedo, he is said to have determined to fight no more, but to yield everything. A member of his second council went to him and said, «Sir, the only way for you now to retrieve the honor of the family of Tokugawa is to disembowel yourself; and to prove to you that I am sincere and disinterested in what I say, I am here ready to disembowel myself with you.» The Taikun flew into a great rage, saying that he would listen to no such nonsense, and left the room. His faithful retainer, to prove his honesty, retired to another part of the castle, and solemnly performed the harakiri.

[citation needed]

In his book Tales of Old Japan, Mitford describes witnessing a hara-kiri:[33]

As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the harakiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburo, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hyōgo in the month of February 1868, – an attack to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and the Hatamoto. Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveler’s fable.

The ceremony, which was ordered by the Mikado (Emperor) himself, took place at 10:30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all. After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows:

I, and I alone, unwarrantably gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kobe, and again as they tried to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and I beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.

Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible.

The kaishaku made a low bow, wiped his sword with a piece of rice paper which he had ready for the purpose, and retired from the raised floor; and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution. The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places, and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence of death upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the temple. The ceremony, to which the place and the hour gave an additional solemnity, was characterized throughout by that extreme dignity and punctiliousness which are the distinctive marks of the proceedings of Japanese gentlemen of rank; and it is important to note this fact, because it carries with it the conviction that the dead man was indeed the officer who had committed the crime, and no substitute. While profoundly impressed by the terrible scene it was impossible at the same time not to be filled with admiration of the firm and manly bearing of the sufferer, and of the nerve with which the kaishaku performed his last duty to his master.

In modern Japan[edit]

Seppuku as judicial punishment was abolished in 1873, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, but voluntary seppuku did not completely die out.[34][35] Dozens of people are known to have committed seppuku since then,[36][34][37] including General Nogi and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912, and numerous soldiers and civilians who chose to die rather than surrender at the end of World War II. The practice had been widely praised in army propaganda, which featured a soldier captured by the Chinese in the Shanghai Incident (1932) who returned to the site of his capture to perform seppuku.[38] In 1944, Hideyoshi Obata, a Lieutenant General in the Imperial Japanese Army, committed seppuku in Yigo, Guam, following the Allied victory over the Japanese in the Second Battle of Guam.[39] Obata was posthumously promoted to the rank of general. Many other high-ranking military officials of Imperial Japan would go on to commit seppuku toward the latter half of World War II in 1944 and 1945,[40] as the tide of the war turned against the Japanese, and it became clear that a Japanese victory of the war was not achievable.[41][42][43]

In 1970, author Yukio Mishima[44] and one of his followers performed public seppuku at the Japan Self-Defense Forces headquarters following an unsuccessful attempt to incite the armed forces to stage a coup d’état.[45][46] Mishima performed seppuku in the office of General Kanetoshi Mashita.[46][47] His second, a 25-year-old man named Masakatsu Morita, tried three times to ritually behead Mishima but failed, and his head was finally severed by Hiroyasu Koga, a former kendo champion.[47] Morita then attempted to perform seppuku himself[47] but when his own cuts were too shallow to be fatal, he gave the signal and was beheaded by Koga.[48][45][46]

Notable cases[edit]

List of notable seppuku cases in chronological order.

- Minamoto no Tametomo (1170)

- Minamoto no Yorimasa (1180)

- Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1189)

- Hōjō Takatoki (1333)

- Ashikaga Mochiuji (1439)

- Azai Nagamasa (1573)

- Oda Nobunaga (1582)

- Takeda Katsuyori (1582)

- Shibata Katsuie (1583)

- Hōjō Ujimasa (1590)

- Sen no Rikyū (1591)

- Toyotomi Hidetsugu (1595)

- Torii Mototada (1600)

- Tokugawa Tadanaga (1634)

- Forty-six of the Forty-seven rōnin (1703)

- Watanabe Kazan (1841)

- Tanaka Shinbei (1863)

- Takechi Hanpeita (1865)

- Yamanami Keisuke (1865)

- Byakkotai (group of samurai youths) (1868)

- Saigō Takamori (1877)

- Emilio Salgari (1911)

- Nogi Maresuke and Nogi Shizuko (1912)

- Chujiro Hayashi (1940)

- Seigō Nakano (1943)

- Yoshitsugu Saitō (1944)

- Hideyoshi Obata (1944)

- Kunio Nakagawa (1944)

- Isamu Chō and Mitsuru Ushijima (1945)

- Korechika Anami (1945)

- Takijirō Ōnishi (1945)

- Yukio Mishima (1970)

- Masakatsu Morita (1970)

- Isao Inokuma (2001)

In popular culture[edit]

The expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in Taiko by Eiji Yoshikawa, Humanity and Paper Balloons,[49] and Rashomon.[50] Seppuku is referenced and described multiple times in the 1975 James Clavell novel, Shōgun; its subsequent 1980 miniseries Shōgun brought the term and the concept to mainstream Western attention. It was staged by the young protagonist in the 1971 dark American comedy Harold and Maude.

In Puccini’s 1904 opera Madame Butterfly, wronged child-bride Cio-Cio-san commits Seppuku in the final moments of the opera, after hearing that the father of her child, although he has finally returned to Japan, much to her initial delight, has in the meantime married an American lady and has come to take the child away from her.

Throughout the novels depicting the 30th century and onward Battletech universe, members of House Kurita – who are based on feudal Japanese culture, despite the futuristic setting – frequently atone for their failures by performing seppuku.

In the 2003, film The Last Samurai, the act of seppuku is depicted twice. The defeated Imperial officer General Hasegawa commits seppuku, while his enemy Katsumoto (Ken Watanabe) acts as kaishakunin and decapitates him. Later, the mortally wounded samurai leader Katsumoto performs seppuku with former US Army Captain Nathan Algren’s help. This is also depicted en masse in the film 47 Ronin starring Keanu Reeves when the 47 ronin are punished for disobeying the shogun’s orders by avenging their master.[51] In the 2011 film My Way,[52] an Imperial Japanese colonel is ordered to commit seppuku by his superiors after ordering a retreat from an oil field overrun by Russian and Mongolian troops in the 1939 Battle of Khalkin Gol.

In Season 15 Episode 12 of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, titled «Jersey Breakdown», a Japanophile New Jersey judge with a large samurai sword collection commits harakiri when he realizes that the police are onto him for raping a 12-year-old Japanese girl in a Jersey nightclub.[53] Seppuku is depicted in season 1, episode 5, of the Amazon Prime Video TV series The Man in the High Castle (2015). In this dystopian alternate history, the Japanese Imperial Force controls the West coast of the United States after a Nazi victory against the Allies in World War Two. During the episode, the Japanese crown prince makes an official visit to San Francisco but is shot during a public address. The captain of the Imperial Guard commits seppuku because of his failure of ensuring the prince’s security. The head of the Kenpeitai, Chief Inspector Takeshi Kido, states he will do the same if the assassin is not apprehended.[54]

In the 2014 dark fantasy action role-playing video game Dark Souls II, the boss Sir Alonne performs the act of seppuku if the player defeats him within three minutes or if the player takes no damage, to retain his honor as a samurai by not falling into his enemies’ hands. in the 2015 re-release Scholar of the First Sin, it is obtainable only if the player takes no damage whatsoever.

In the 2015 tactical role-playing video game Fire Emblem Fates, Hoshidan high prince Ryoma takes his own life through the act of seppuku, which he believes will let him retain his honor as a samurai by not falling into the hands of his enemies.

In the 2016 film, Hacksaw Ridge, it is briefly shown that the leaders of the Japanese forces associated with the Battle of Okinawa committed seppuku after it became clear that they lost.

In the 2017 revival and final season of the animated series Samurai Jack, the eponymous protagonist, distressed over his many failures to accomplish his quest as told in prior seasons, is then informed by a haunting samurai spirit that he has acted dishonorably by allowing many people to suffer and die from his failures, and must perform seppuku to atone for them.[55]

In the 2022 dark fantasy action role-playing video game Elden Ring,[56] the player can receive the ability seppuku, which has the player stab themselves through the stomach and then pull it out, coating their weapon in blood to increase their damage.[57][58][59]

See also[edit]

- Harakiri – film by Masaki Kobayashi

- Japanese funeral

- Junshi – following the lord in death

- Kamikaze, Japanese suicide bombers

- Puputan, Indonesian ritual suicide

- Shame society

- Suicide in Japan

References[edit]

- ^ a b c RAVINA, MARK J. (2010). «The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigō Takamori: Samurai, «Seppuku», and the Politics of Legend». The Journal of Asian Studies. 69 (3): 691–721. doi:10.1017/S0021911810001518. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 40929189. S2CID 155001706.

- ^ Kosaka, Masataka (1990). «The Showa Era (1926-1989)». Daedalus. 119 (3): 27–47. ISSN 0011-5266. JSTOR 20025315.

- ^ «CRIME AND CRIMINAL POLICY IN JAPAN FROM 1926 TO 1988: ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF THE SHOWA ERA | Office of Justice Programs». www.ojp.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (June 22, 2015). «The Gory Way Japanese Generals Ended Their Battle on Okinawa». Time. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Frank, Downfall pp 319–320

- ^ Fuller, Hirohito’s Samurai

- ^ «The Deadly Ritual of Seppuku». Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephan R. (1977). The Samurai: A Military History. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. p. 47. ISBN 0-304-35948-3.

- ^ Andrews, Evan. «What is Seppuku?». HISTORY. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «Seppuku | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «The responsibility of the Emperor — Joi Ito’s Web». joi.ito.com. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «The Free Dictionary». Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Bryan Garner (2009). Garner’s Modern American Usage. United States: Oxford University Press. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-19-538275-4.

- ^ Ross, Christopher. Mishima’s Sword, p.68.

- ^ a b Hosey, Timothy (December 1980). Black Belt: Samurai Women. p. 47.

- ^ a b Hearn, Lafcadio (2005) [First published 1923]. Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation. p. 318.

- ^ a b Tsukishima, Kenzo (1984). ラフカディオ・ハーンの日本観: その正しい理解への試み [Lafcadio Hearn’s Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation]. p. 48.

- ^ a b Mostow, Joshua S. (2006). Wisenthal, J. L. (ed.). A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, and Contexts of Madame Butterfly, Chapter: Iron Butterfly Cio-Cio-San and Japanese Imperialism. p. 190.

- ^ Gately, Iain (2009). Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol. New York: Gotham Books. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-59240-464-3.

- ^ Samurai Fighting Arts: The Spirit and the Practice, p. 48, at Google Books

- ^ Fusé, Toyomasa (1979). «Suicide and culture in Japan: A study of seppuku as an institutionalized form of suicide». Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 15 (2): 57–63. doi:10.1007/BF00578069. S2CID 25585787.

- ^ «The Fine Art of Seppuku». 19 July 2002. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ a b Turnbull, Stephen R. (1996). The Samurai: A Military History. p. 72.

- ^ Maiese, Aniello; Gitto, Lorenzo; dell’Aquila, Massimiliano; Bolino, Giorgio (March 2014). «A peculiar case of suicide enacted through the ancient Japanese ritual of Jigai». The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 35 (1): 8–10. doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000070. PMID 24457577.

- ^ Beard, Mary Ritter (1953). The Force of Women in Japanese History. Washington, Public Affairs Press. p. 100.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2008). The Samurai Swordsman: Master of War. p. 156.

- ^ Blum, Mark L. (2008). «Death and the Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism». In Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; Walter, Mariko Namba (eds.). Collective Suicide at the Funeral of Jitsunyo. p. 164.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Samurai Women 1184–1877.

- ^ «じがい 1 0 【自害». goo 辞書.

- ^ Rij, Jan Van (2001). Madame Butterfly: Japonisme, Puccini, and the Search for the Real Cho-Cho-San. p. 71.

- ^ Pierre, Joseph M (2015-03-22). «Culturally sanctioned suicide: Euthanasia, seppuku, and terrorist martyrdom». World Journal of Psychiatry. 5 (1): 4–14. doi:10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.4. ISSN 2220-3206. PMC 4369548. PMID 25815251.

- ^ a b Fus, Toyomasa (1980). «Suicide and culture in Japan: A study of seppuku as an institutionalized form of suicide». Social Psychiatry. 15 (2): 57–63. doi:10.1007/BF00578069. S2CID 25585787. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ Tales of Old Japan by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford

- ^ a b Wudunn, Sheryl (1999-03-24). «Manager Commits Hara-Kiri to Fight Corporate Restructuring». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ Reitman, Valerie (1999-03-24). «Japanese Worker Kills Himself Near Company President’s Office». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «Corporate warrior commits hara-kiri». the Guardian. 1999-03-24. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «Former Bridgestone Manager Stabs Himself in Front of Firm’s President». WSJ. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ Hoyt, Edwin P. (2001). Japan’s War: The Great Pacific Conflict. Cooper Square Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0815411185.

- ^ Igarashi, Yoshikuni (2016). Homecomings: The Belated Return of Japan’s Lost Soldiers. Columbia University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0231177702.

- ^ Porter, Patrick (2010). «Paper Bullets: American Psywar in the Pacific, 1944–1945». War in History. 17 (4): 479–511. doi:10.1177/0968344510376465. ISSN 0968-3445. JSTOR 26070823. S2CID 145484317.

- ^ «Timeline: Last Days of Imperial Japan». Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «Researching Japanese War Crimes — Introductory Essats» (PDF).

- ^ «Japan’s Surrender and Aftermath». public1.nhhcaws.local. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ Williams, John (2020-05-21). «An Absurdist Noir Novel Shows Yukio Mishima’s Lighter Side». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ a b Muramatsu, Takeshi (1971-04-16). «Death as Precept». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ a b c Lebra, Joyce (1970-11-28). «Eyewitness: Mishima». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ a b c «Opinion | Enigmatic Japanese Writer Remembered». The New York Times. 1993-03-13. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ Sheppard, Gordon (2003). Ha!: a self-murder mystery. McGill-Queen’s University Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-7735-2345-6.

excerpt from Stokes, Henry Scott (2000). The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1074-3. - ^ Phillips, Alastair; Stringer, Julian (2007). Japanese Cinema: Texts And Contexts. p. 57.

- ^ Kamir, Orit (2005). Framed: Women in Law and Film. p. 64.

- ^ 47 Ronin

- ^ «다시보기 : SBS 스페셜». wizard2.sbs.co.kr (in Korean). Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ ««Law & Order: Special Victims Unit» Jersey Breakdown (TV Episode 2014)». IMDb. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Metacrone, ~ (2019-11-12). «The Man in the High Castle Season 1 Episode 5: The New Normal Recap». Metawitches. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ «XCVII». Samurai Jack. 2017-04-22. Adult Swim.

- ^ Park, Gene (April 13, 2022). «The success of ‘Elden Ring’ had nothing to do with the pandemic». The Washington Post.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «How to find the Seppuku Ash of War in Elden Ring». MSN. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ «Wo Man Die Elden Ring Asche Des Krieges Seppuku Findet». www.ggrecon.com (in German). Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- ^ Stewart, Jared (2022-05-04). «Elden Ring: How to Get the Seppuku Ash Of War». Game Rant. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

Further reading[edit]

- Rankin, Andrew (2011). Seppuku: A History of Samurai Suicide. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4770031426.

- Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1979). Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai. William Scott Wilson (trans.). Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 1-84483-594-4.

- Seward, Jack (1968). Hara-Kiri: Japanese Ritual Suicide. Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 0-8048-0231-9.

- Ross, Christoper (2006). Mishima’s Sword: Travels in Search of a Samurai Legend. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81513-3.

- Seppuku Archived 2008-09-15 at the Wayback Machine – A Practical Guide (tongue-in-cheek)

- Brinckmann, Hans (2006-07-02). «Japanese Society and Culture in Perspective: 6. Suicide, the Dark Shadow». Archived from the original on January 10, 2007.

- Freeman-Mitford, Algernon Bertram (1871). «An Account of the Hara-Kiri». Tales of Old Japan. Archived from the original on 2012-12-06.

- «The Fine Art of Seppuku».

- Zuihoden – The mausoleum of Date Masamune – When he died, twenty of his followers killed themselves to serve him in the next life. They lay in state at Zuihoden

- Seppuku and «cruel punishments» at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate

- Tokugawa Shogunate edict banning Junshi (Following one’s lord in death) From the Buke Sho Hatto (1663) –

- «That the custom of following a master in death is wrong and unprofitable is a caution which has been at times given of old; but, owing to the fact that it has not actually been prohibited, the number of those who cut their belly to follow their lord on his decease has become very great. For the future, to those retainers who may be animated by such an idea, their respective lords should intimate, constantly and in very strong terms, their disapproval of the custom. If, notwithstanding this warning, any instance of the practice should occur, it will be deemed that the deceased lord was to blame for unreadiness. Henceforward, moreover, his son and successor will be held to be blameworthy for incompetence, as not having prevented the suicides.»

- Fuse, Toyomasa (1980). «Suicide and Culture in Japan: a study of seppuku as an institutionalized form of suicide». Social Psychiatry. 15 (2): 57–63. doi:10.1007/BF00578069. S2CID 25585787.

External links[edit]

Media related to Seppuku at Wikimedia Commons

- «Hara-kiri» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Staged seppuku with ritual attire and kaishaku

| Seppuku | |||

|---|---|---|---|

«Seppuku» in kanji |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 切腹 | ||

| Hiragana | せっぷく | ||

| Katakana | セップク | ||

|

Seppuku (切腹, ‘cutting [the] belly’), also called hara-kiri (腹切り, lit. ‘abdomen/belly cutting’, a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritualistic suicide by disembowelment. While harakiri refers to the act of disemboweling one’s self, seppuku refers to the ritual and usually would involve decapitation after the act as a sign of mercy. Harakiri refers solely to the act of disembowelment and would only be assigned as a punishment towards acts deemed too heinous for seppuku.[1] It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honour, but was also practiced by other Japanese people during the Shōwa period[2][3] (particularly officers near the end of World War II) to restore honour for themselves or for their families.[4][5][6] As a samurai practice, seppuku was used voluntarily by samurai to die with honour rather than fall into the hands of their enemies (and likely be tortured), as a form of capital punishment for samurai who had committed serious offences, or performed because they had brought shame to themselves.[1] The ceremonial disembowelment, which is usually part of a more elaborate ritual and performed in front of spectators, consists of plunging a short blade, traditionally a tantō, into the belly and drawing the blade from left to right, slicing the belly open.[7] If the cut is deep enough, it can sever the abdominal aorta, causing a rapid death by blood loss.[citation needed]

The first recorded act of seppuku was performed by Minamoto no Yorimasa during the Battle of Uji in 1180.[8] Seppuku was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands and to attenuate shame and avoid possible torture.[9][10] Samurai could also be ordered by their daimyō (feudal lords) to carry out seppuku. Later, disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to carry out seppuku rather than be executed in the normal manner.[11] The most common form of seppuku for men was composed of the cutting of the abdomen, and when the samurai was finished, he stretched out his neck for an assistant to sever his spinal cord. It was the assistant’s job to decapitate the samurai in one swing, otherwise it would bring great shame to the assistant and his family. Those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to carry out seppuku. Samurai generally could carry out the act only with permission.

Sometimes a daimyō was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement. This weakened the defeated clan so that resistance effectively ceased. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used an enemy’s suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of daimyōs. When the Hōjō Clan were defeated at Odawara in 1590, Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired daimyō Hōjō Ujimasa and the exile of his son Ujinao; with this act of suicide, the most powerful daimyō family in eastern Japan was completely defeated.

Etymology[edit]

Samurai about to perform seppuku

The term seppuku is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots setsu 切 («to cut», from Middle Chinese tset; compare Mandarin qiē and Cantonese chit) and fuku 腹 («belly», from MC pjuwk; compare Mandarin fù and Cantonese fūk).

It is also known as harakiri (腹切り, «cutting the stomach»;[12] often misspelled/mispronounced «hiri-kiri» or «hari-kari» by American English speakers).[13] Harakiri is written with the same kanji as seppuku but in reverse order with an okurigana. In Japanese, the more formal seppuku, a Chinese on’yomi reading, is typically used in writing, while harakiri, a native kun’yomi reading, is used in speech. As Ross notes,

It is commonly pointed out that hara-kiri is a vulgarism, but this is a misunderstanding. Hara-kiri is a Japanese reading or Kun-yomi of the characters; as it became customary to prefer Chinese readings in official announcements, only the term seppuku was ever used in writing. So hara-kiri is a spoken term, but only to commoners and seppuku a written term, but spoken amongst higher classes for the same act.[14]

The practice of performing seppuku at the death of one’s master, known as oibara (追腹 or 追い腹, the kun’yomi or Japanese reading) or tsuifuku (追腹, the on’yomi or Chinese reading), follows a similar ritual.

The word jigai (自害) means «suicide» in Japanese. The modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[15] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[16] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese.[17] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[18]

Ritual[edit]

A tantō prepared for seppuku

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the seppuku of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a kaishakunin (idiomatically, his «second») had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the tachi (longsword), wakizashi (shortsword) or tantō (knife) into the gut and slicing the abdomen horizontally. In the absence of a kaishakunin, the samurai would then remove the blade and stab himself in the throat, or fall (from a standing position) with the blade positioned against his heart.

During the Edo period (1600–1867), carrying out seppuku came to involve an elaborate, detailed ritual. This was usually performed in front of spectators if it was a planned seppuku, as opposed to one performed on a battlefield. A samurai was bathed in cold water (to prevent excessive bleeding), dressed in a white kimono called the shiro-shōzoku (白装束) and served his favorite foods for a last meal. When he had finished, the knife and cloth were placed on another sanbo and given to the warrior. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special clothes, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. He would probably consume an important ceremonial drink of sake. He would also give his attendant a cup meant for sake.[19][20]

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to carry out seppuku after losing a battle for his master in 1582. He had just written his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner. By Tsukioka Yoshitoshi around 1890.

With his selected kaishakunin standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his tantō – which the samurai held by the blade with a cloth wrapped around so that it would not cut his hand and cause him to lose his grip – and plunge it into his abdomen, making a left-to-right cut. The kaishakunin would then perform kaishaku, a cut in which the warrior was partially decapitated. The maneuver should be done in the manners of dakikubi (lit. «embraced head»), in which way a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body, so that it can be hung in front as if embraced. Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was a skilled swordsman. The principal and the kaishakunin agreed in advance when the latter was to make his cut. Usually dakikubi would occur as soon as the dagger was plunged into the abdomen. Over time, the process became so highly ritualized that as soon as the samurai reached for his blade the kaishakunin would strike. Eventually even the blade became unnecessary and the samurai could reach for something symbolic like a fan, and this would trigger the killing stroke from his second. The fan was likely used when the samurai was too old to use the blade or in situations where it was too dangerous to give him a weapon.[21]

This elaborate ritual evolved after seppuku had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and became a para-judicial institution. The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honorably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote:

From ages past it has been considered an ill-omen by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. Further, if one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace.

In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials.

A specialized form of seppuku in feudal times was known as kanshi (諫死, «remonstration death/death of understanding»), in which a retainer would commit suicide in protest of a lord’s decision. The retainer would make one deep, horizontal cut into his abdomen, then quickly bandage the wound. After this, the person would then appear before his lord, give a speech in which he announced the protest of the lord’s action, then reveal his mortal wound. This is not to be confused with funshi (憤死, indignation death), which is any suicide made to protest or state dissatisfaction.[citation needed]

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of seppuku known as jūmonji giri (十文字切り, «cross-shaped cut»), in which there is no kaishakunin to put a quick end to the samurai’s suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut on the belly. A samurai performing jūmonji giri was expected to bear his suffering quietly until he bled to death, passing away with his hands over his face.[22]

Female ritual suicide[edit]

Female ritual suicide (incorrectly referred to in some English sources as jiigai), was practiced by the wives of samurai who have performed seppuku or brought dishonor.[23][24]

Some women belonging to samurai families committed suicide by cutting the arteries of the neck with one stroke, using a knife such as a tantō or kaiken. The main purpose was to achieve a quick and certain death in order to avoid capture. Before committing suicide, a woman would often tie her knees together so her body would be found in a “dignified” pose, despite the convulsions of death. Invading armies would often enter homes to find the lady of the house seated alone, facing away from the door. On approaching her, they would find that she had ended her life long before they reached her.[citation needed]

The wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, prepares for her suicide; note the legs tied together, a feature of female seppuku to ensure a decent posture in death

History[edit]

Stephen R. Turnbull provides extensive evidence for the practice of female ritual suicide, notably of samurai wives, in pre-modern Japan. One of the largest mass suicides was the 25 April 1185 final defeat of Taira no Tomomori.[23] The wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, is a notable example of a wife following seppuku of a samurai husband.[25] A large number of honor suicides marked the defeat of the Aizu clan in the Boshin War of 1869, leading into the Meiji era. For example, in the family of Saigō Tanomo, who survived, a total of twenty-two female honor suicides are recorded among one extended family.[26]

Religious and social context[edit]

Voluntary death by drowning was a common form of ritual or honor suicide. The religious context of thirty-three Jōdo Shinshū adherents at the funeral of Abbot Jitsunyo in 1525 was faith in Amida Buddha and belief in rebirth in his Pure land, but male seppuku did not have a specifically religious context.[27] By way of contrast, the religious beliefs of Hosokawa Gracia, the Christian wife of daimyō Hosokawa Tadaoki, prevented her from committing suicide.[28]

Terminology[edit]

The word jigai (自害) means «suicide» in Japanese. The usual modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). Related words include jiketsu (自決), jijin (自尽) and jijin (自刃).[29] In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[15] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[16] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese and Hearn seen through Japanese eyes.[17] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[18] Mostow’s context is analysis of Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly and the original Cio-Cio San story by John Luther Long. Though both Long’s story and Puccini’s opera predate Hearn’s use of the term jigai, the term has been used in relation to western Japonisme, which is the influence of Japanese culture on the western arts.[30]

As capital punishment[edit]

While the voluntary seppuku is the best known form,[1] in practice the most common form of seppuku was obligatory seppuku, used as a form of capital punishment for disgraced samurai, especially for those who committed a serious offense such as rape, robbery, corruption, unprovoked murder or treason.[31] The samurai were generally told of their offense in full and given a set time for them to commit seppuku, usually before sunset on a given day. On occasion, if the sentenced individuals were uncooperative, seppuku could be carried out by an executioner, or more often, the actual execution was carried out solely by decapitation while retaining only the trappings of seppuku; even the tantō laid out in front of the uncooperative offender could be replaced with a fan (to prevent the uncooperative offenders from using the tantō as a weapon against the observers or the executioner). This form of involuntary seppuku was considered shameful and undignified.[32] Unlike voluntary seppuku, seppuku carried out as capital punishment by executioners did not necessarily absolve, or pardon, the offender’s family of the crime. Depending on the severity of the crime, all or part of the property of the condemned could be confiscated, and the family would be punished by being stripped of rank, sold into long-term servitude, or executed.

Seppuku was considered the most honorable capital punishment apportioned to samurai. Zanshu (斬首) and sarashikubi (晒し首), decapitation followed by a display of the head, was considered harsher and was reserved for samurai who committed greater crimes. Harshest punishments, usually involving death by torturous methods like kamayude (釜茹で), death by boiling, were reserved for commoner offenders.

Forced seppuku came to be known as «conferred death» over time as it was used for punishment of criminal samurai.[32]

Recorded events[edit]

On February 15, 1868, eleven French sailors of the Dupleix entered the town of Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid, and those responsible were sentenced to death. Captain Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, «Sakai Jiken», by Mori Ōgai.

In the 1860s, the British Ambassador to Japan, Algernon Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), lived within sight of Sengaku-ji where the Forty-seven Ronin are buried. In his book Tales of Old Japan, he describes a man who had come to the graves to kill himself:

I will add one anecdote to show the sanctity which is attached to the graves of the Forty-seven. In the month of September 1868, a certain man came to pray before the grave of Oishi Chikara. Having finished his prayers, he deliberately performed hara-kiri, and, the belly wound not being mortal, dispatched himself by cutting his throat. Upon his person were found papers setting forth that, being a Ronin and without means of earning a living, he had petitioned to be allowed to enter the clan of the Prince of Choshiu, which he looked upon as the noblest clan in the realm; his petition having been refused, nothing remained for him but to die, for to be a Ronin was hateful to him, and he would serve no other master than the Prince of Choshiu: what more fitting place could he find in which to put an end to his life than the graveyard of these Braves? This happened at about two hundred yards’ distance from my house, and when I saw the spot an hour or two later, the ground was all bespattered with blood, and disturbed by the death-struggles of the man.

Mitford also describes his friend’s eyewitness account of a seppuku:

Illustration titled Harakiri: Condemnation of a nobleman to suicide. drawing by L. Crépon adapted from a Japanese painting, 1867

There are many stories on record of extraordinary heroism being displayed in the harakiri. The case of a young fellow, only twenty years old, of the Choshiu clan, which was told me the other day by an eye-witness, deserves mention as a marvellous instance of determination. Not content with giving himself the one necessary cut, he slashed himself thrice horizontally and twice vertically. Then he stabbed himself in the throat until the dirk protruded on the other side, with its sharp edge to the front; setting his teeth in one supreme effort, he drove the knife forward with both hands through his throat, and fell dead.

During the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa shogun’s aide performed seppuku:

One more story and I have done. During the revolution, when the Taikun (Supreme Commander), beaten on every side, fled ignominiously to Yedo, he is said to have determined to fight no more, but to yield everything. A member of his second council went to him and said, «Sir, the only way for you now to retrieve the honor of the family of Tokugawa is to disembowel yourself; and to prove to you that I am sincere and disinterested in what I say, I am here ready to disembowel myself with you.» The Taikun flew into a great rage, saying that he would listen to no such nonsense, and left the room. His faithful retainer, to prove his honesty, retired to another part of the castle, and solemnly performed the harakiri.

[citation needed]

In his book Tales of Old Japan, Mitford describes witnessing a hara-kiri:[33]

As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the harakiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburo, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hyōgo in the month of February 1868, – an attack to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and the Hatamoto. Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveler’s fable.

The ceremony, which was ordered by the Mikado (Emperor) himself, took place at 10:30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all. After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows:

I, and I alone, unwarrantably gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kobe, and again as they tried to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and I beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.

Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible.

The kaishaku made a low bow, wiped his sword with a piece of rice paper which he had ready for the purpose, and retired from the raised floor; and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution. The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places, and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence of death upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the temple. The ceremony, to which the place and the hour gave an additional solemnity, was characterized throughout by that extreme dignity and punctiliousness which are the distinctive marks of the proceedings of Japanese gentlemen of rank; and it is important to note this fact, because it carries with it the conviction that the dead man was indeed the officer who had committed the crime, and no substitute. While profoundly impressed by the terrible scene it was impossible at the same time not to be filled with admiration of the firm and manly bearing of the sufferer, and of the nerve with which the kaishaku performed his last duty to his master.

In modern Japan[edit]

Seppuku as judicial punishment was abolished in 1873, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, but voluntary seppuku did not completely die out.[34][35] Dozens of people are known to have committed seppuku since then,[36][34][37] including General Nogi and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912, and numerous soldiers and civilians who chose to die rather than surrender at the end of World War II. The practice had been widely praised in army propaganda, which featured a soldier captured by the Chinese in the Shanghai Incident (1932) who returned to the site of his capture to perform seppuku.[38] In 1944, Hideyoshi Obata, a Lieutenant General in the Imperial Japanese Army, committed seppuku in Yigo, Guam, following the Allied victory over the Japanese in the Second Battle of Guam.[39] Obata was posthumously promoted to the rank of general. Many other high-ranking military officials of Imperial Japan would go on to commit seppuku toward the latter half of World War II in 1944 and 1945,[40] as the tide of the war turned against the Japanese, and it became clear that a Japanese victory of the war was not achievable.[41][42][43]

In 1970, author Yukio Mishima[44] and one of his followers performed public seppuku at the Japan Self-Defense Forces headquarters following an unsuccessful attempt to incite the armed forces to stage a coup d’état.[45][46] Mishima performed seppuku in the office of General Kanetoshi Mashita.[46][47] His second, a 25-year-old man named Masakatsu Morita, tried three times to ritually behead Mishima but failed, and his head was finally severed by Hiroyasu Koga, a former kendo champion.[47] Morita then attempted to perform seppuku himself[47] but when his own cuts were too shallow to be fatal, he gave the signal and was beheaded by Koga.[48][45][46]

Notable cases[edit]

List of notable seppuku cases in chronological order.

- Minamoto no Tametomo (1170)

- Minamoto no Yorimasa (1180)

- Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1189)

- Hōjō Takatoki (1333)

- Ashikaga Mochiuji (1439)

- Azai Nagamasa (1573)

- Oda Nobunaga (1582)

- Takeda Katsuyori (1582)

- Shibata Katsuie (1583)

- Hōjō Ujimasa (1590)

- Sen no Rikyū (1591)

- Toyotomi Hidetsugu (1595)

- Torii Mototada (1600)

- Tokugawa Tadanaga (1634)

- Forty-six of the Forty-seven rōnin (1703)

- Watanabe Kazan (1841)

- Tanaka Shinbei (1863)

- Takechi Hanpeita (1865)

- Yamanami Keisuke (1865)

- Byakkotai (group of samurai youths) (1868)

- Saigō Takamori (1877)

- Emilio Salgari (1911)

- Nogi Maresuke and Nogi Shizuko (1912)

- Chujiro Hayashi (1940)

- Seigō Nakano (1943)

- Yoshitsugu Saitō (1944)

- Hideyoshi Obata (1944)

- Kunio Nakagawa (1944)

- Isamu Chō and Mitsuru Ushijima (1945)

- Korechika Anami (1945)

- Takijirō Ōnishi (1945)

- Yukio Mishima (1970)

- Masakatsu Morita (1970)

- Isao Inokuma (2001)

In popular culture[edit]

The expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in Taiko by Eiji Yoshikawa, Humanity and Paper Balloons,[49] and Rashomon.[50] Seppuku is referenced and described multiple times in the 1975 James Clavell novel, Shōgun; its subsequent 1980 miniseries Shōgun brought the term and the concept to mainstream Western attention. It was staged by the young protagonist in the 1971 dark American comedy Harold and Maude.

In Puccini’s 1904 opera Madame Butterfly, wronged child-bride Cio-Cio-san commits Seppuku in the final moments of the opera, after hearing that the father of her child, although he has finally returned to Japan, much to her initial delight, has in the meantime married an American lady and has come to take the child away from her.