|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | metallic yellow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Au) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 79 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1337.33 K (1064.18 °C, 1947.52 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3243 K (2970 °C, 5378 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 19.3 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 17.31 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 12.55 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 342 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.418 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −3, −2, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3, +5 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.54 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 144 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 136±6 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 166 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of gold |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 2030 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 14.2 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 318 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 22.14 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −28.0×10−6 cm3/mol (at 296 K)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tensile strength | 120 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 79 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 27 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 180 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 188–216 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 188–245 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-57-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | from Latin aurum, meaning gold | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | In the Middle East (before 6000 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «Au»: from Latin aurum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of gold

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from Latin: aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal in a pure form. Chemically, gold is a transition metal and a group 11 element. It is one of the least reactive chemical elements and is solid under standard conditions. Gold often occurs in free elemental (native state), as nuggets or grains, in rocks, veins, and alluvial deposits. It occurs in a solid solution series with the native element silver (as electrum), naturally alloyed with other metals like copper and palladium, and mineral inclusions such as within pyrite. Less commonly, it occurs in minerals as gold compounds, often with tellurium (gold tellurides).

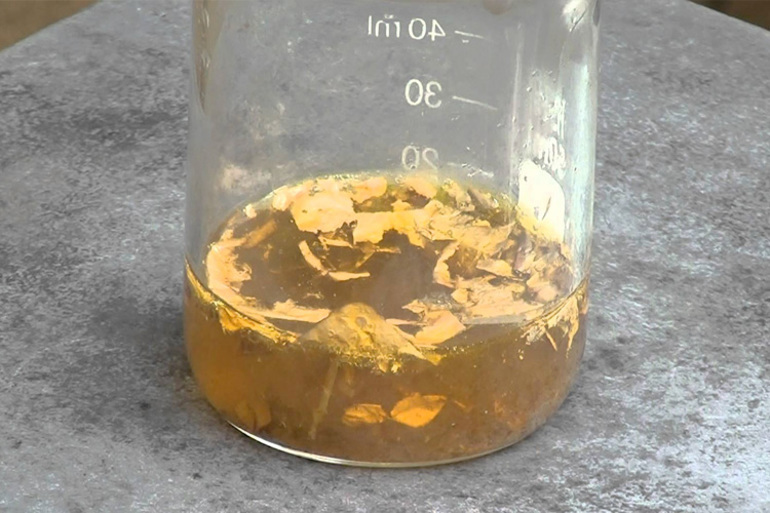

Gold is resistant to most acids, though it does dissolve in aqua regia (a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid), forming a soluble tetrachloroaurate anion. Gold is insoluble in nitric acid alone, which dissolves silver and base metals, a property long used to refine gold and confirm the presence of gold in metallic substances, giving rise to the term ‘acid test’. Gold dissolves in alkaline solutions of cyanide, which are used in mining and electroplating. Gold also dissolves in mercury, forming amalgam alloys, and as the gold acts simply as a solute, this is not a chemical reaction.

A relatively rare element,[6][7] gold is a precious metal that has been used for coinage, jewelry, and other arts throughout recorded history. In the past, a gold standard was often implemented as a monetary policy. Gold coins ceased to be minted as a circulating currency in the 1930s, and the world gold standard was abandoned for a fiat currency system after the Nixon shock measures of 1971.

In 2020, the world’s largest gold producer was China, followed by Russia and Australia.[8] A total of around 201,296 tonnes of gold exists above ground, as of 2020.[9] This is equal to a cube with each side measuring roughly 21.7 meters (71 ft). The world consumption of new gold produced is about 50% in jewelry, 40% in investments and 10% in industry.[10] Gold’s high malleability, ductility, resistance to corrosion and most other chemical reactions, and conductivity of electricity have led to its continued use in corrosion-resistant electrical connectors in all types of computerized devices (its chief industrial use). Gold is also used in infrared shielding, production of colored glass, gold leafing, and tooth restoration. Certain gold salts are still used as anti-inflammatories in medicine.

Characteristics

Gold can be drawn into a monatomic wire, and then stretched more before it breaks.[11]

A gold nugget of 5 mm (0.20 in) in size can be hammered into a gold foil of about 0.5 m2 (5.4 sq ft) in area.

Gold is the most malleable of all metals. It can be drawn into a wire of single-atom width, and then stretched considerably before it breaks.[11] Such nanowires distort via formation, reorientation and migration of dislocations and crystal twins without noticeable hardening.[12] A single gram of gold can be beaten into a sheet of 1 square metre (11 sq ft), and an avoirdupois ounce into 300 square feet (28 m2). Gold leaf can be beaten thin enough to become semi-transparent. The transmitted light appears greenish-blue, because gold strongly reflects yellow and red.[13] Such semi-transparent sheets also strongly reflect infrared light, making them useful as infrared (radiant heat) shields in visors of heat-resistant suits, and in sun-visors for spacesuits.[14] Gold is a good conductor of heat and electricity.

Gold has a density of 19.3 g/cm3, almost identical to that of tungsten at 19.25 g/cm3; as such, tungsten has been used in counterfeiting of gold bars, such as by plating a tungsten bar with gold.[15][16][17][18] By comparison, the density of lead is 11.34 g/cm3, and that of the densest element, osmium, is 22.588±0.015 g/cm3.[19]

Color

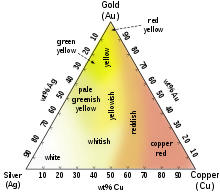

Different colors of Ag–Au–Cu alloys

Whereas most metals are gray or silvery white, gold is slightly reddish-yellow.[20] This color is determined by the frequency of plasma oscillations among the metal’s valence electrons, in the ultraviolet range for most metals but in the visible range for gold due to relativistic effects affecting the orbitals around gold atoms.[21][22] Similar effects impart a golden hue to metallic caesium.

Common colored gold alloys include the distinctive eighteen-karat rose gold created by the addition of copper. Alloys containing palladium or nickel are also important in commercial jewelry as these produce white gold alloys. Fourteen-karat gold-copper alloy is nearly identical in color to certain bronze alloys, and both may be used to produce police and other badges. Fourteen- and eighteen-karat gold alloys with silver alone appear greenish-yellow and are referred to as green gold. Blue gold can be made by alloying with iron, and purple gold can be made by alloying with aluminium. Less commonly, addition of manganese, indium, and other elements can produce more unusual colors of gold for various applications.[23]

Colloidal gold, used by electron-microscopists, is red if the particles are small; larger particles of colloidal gold are blue.[24]

Isotopes

Gold has only one stable isotope, 197

Au, which is also its only naturally occurring isotope, so gold is both a mononuclidic and monoisotopic element. Thirty-six radioisotopes have been synthesized, ranging in atomic mass from 169 to 205. The most stable of these is 195

Au with a half-life of 186.1 days. The least stable is 171

Au, which decays by proton emission with a half-life of 30 µs. Most of gold’s radioisotopes with atomic masses below 197 decay by some combination of proton emission, α decay, and β+ decay. The exceptions are 195

Au, which decays by electron capture, and 196

Au, which decays most often by electron capture (93%) with a minor β− decay path (7%).[25] All of gold’s radioisotopes with atomic masses above 197 decay by β− decay.[26]

At least 32 nuclear isomers have also been characterized, ranging in atomic mass from 170 to 200. Within that range, only 178

Au, 180

Au, 181

Au, 182

Au, and 188

Au do not have isomers. Gold’s most stable isomer is 198m2

Au with a half-life of 2.27 days. Gold’s least stable isomer is 177m2

Au with a half-life of only 7 ns. 184m1

Au has three decay paths: β+ decay, isomeric transition, and alpha decay. No other isomer or isotope of gold has three decay paths.[26]

Synthesis

The possible production of gold from a more common element, such as lead, has long been a subject of human inquiry, and the ancient and medieval discipline of alchemy often focused on it; however, the transmutation of the chemical elements did not become possible until the understanding of nuclear physics in the 20th century. The first synthesis of gold was conducted by Japanese physicist Hantaro Nagaoka, who synthesized gold from mercury in 1924 by neutron bombardment.[27] An American team, working without knowledge of Nagaoka’s prior study, conducted the same experiment in 1941, achieving the same result and showing that the isotopes of gold produced by it were all radioactive.[28] In 1980, Glenn Seaborg transmuted several thousand atoms of bismuth into gold at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory.[29][30] Gold can be manufactured in a nuclear reactor, but doing so is highly impractical and would cost far more than the value of the gold that is produced.[31]

Chemistry

Gold(III) chloride solution in water

Although gold is the most noble of the noble metals,[32][33] it still forms many diverse compounds. The oxidation state of gold in its compounds ranges from −1 to +5, but Au(I) and Au(III) dominate its chemistry. Au(I), referred to as the aurous ion, is the most common oxidation state with soft ligands such as thioethers, thiolates, and organophosphines. Au(I) compounds are typically linear. A good example is Au(CN)−2, which is the soluble form of gold encountered in mining. The binary gold halides, such as AuCl, form zigzag polymeric chains, again featuring linear coordination at Au. Most drugs based on gold are Au(I) derivatives.[34]

Au(III) (referred to as auric) is a common oxidation state, and is illustrated by gold(III) chloride, Au2Cl6. The gold atom centers in Au(III) complexes, like other d8 compounds, are typically square planar, with chemical bonds that have both covalent and ionic character. Gold(I,III) chloride is also known, an example of a mixed-valence complex.

Gold does not react with oxygen at any temperature[35] and, up to 100 °C, is resistant to attack from ozone.[36]

Some free halogens react with gold.[37] Gold is strongly attacked by fluorine at dull-red heat[38] to form gold(III) fluoride AuF3. Powdered gold reacts with chlorine at 180 °C to form gold(III) chloride AuCl3.[39] Gold reacts with bromine at 140 °C to form gold(III) bromide AuBr3, but reacts only very slowly with iodine to form gold(I) iodide AuI.

Gold does not react with sulfur directly,[40] but gold(III) sulfide can be made by passing hydrogen sulfide through a dilute solution of gold(III) chloride or chlorauric acid.

Gold readily dissolves in mercury at room temperature to form an amalgam, and forms alloys with many other metals at higher temperatures. These alloys can be produced to modify the hardness and other metallurgical properties, to control melting point or to create exotic colors.[23]

Gold is unaffected by most acids. It does not react with hydrofluoric, hydrochloric, hydrobromic, hydriodic, sulfuric, or nitric acid. It does react with selenic acid, and is dissolved by aqua regia, a 1:3 mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid. Nitric acid oxidizes the metal to +3 ions, but only in minute amounts, typically undetectable in the pure acid because of the chemical equilibrium of the reaction. However, the ions are removed from the equilibrium by hydrochloric acid, forming AuCl−4 ions, or chloroauric acid, thereby enabling further oxidation.

Gold is similarly unaffected by most bases. It does not react with aqueous, solid, or molten sodium or potassium hydroxide. It does however, react with sodium or potassium cyanide under alkaline conditions when oxygen is present to form soluble complexes.[40]

Common oxidation states of gold include +1 (gold(I) or aurous compounds) and +3 (gold(III) or auric compounds). Gold ions in solution are readily reduced and precipitated as metal by adding any other metal as the reducing agent. The added metal is oxidized and dissolves, allowing the gold to be displaced from solution and be recovered as a solid precipitate.

Rare oxidation states

Less common oxidation states of gold include −1, +2, and +5.

The −1 oxidation state occurs in aurides, compounds containing the Au− anion. Caesium auride (CsAu), for example, crystallizes in the caesium chloride motif;[41] rubidium, potassium, and tetramethylammonium aurides are also known.[42] Gold has the highest electron affinity of any metal, at 222.8 kJ/mol, making Au− a stable species,[43] analogous to the halides.

Gold also has a –1 oxidation state in covalent complexes with the group 4 transition metals, such as in titanium tetraauride and the analogous zirconium and hafnium compounds. These chemicals are expected to form gold-bridged dimers in a manner similar to titanium(IV) hydride.[44]

Gold(II) compounds are usually diamagnetic with Au–Au bonds such as [Au(CH2)2P(C6H5)2]2Cl2. The evaporation of a solution of Au(OH)3 in concentrated H2SO4 produces red crystals of gold(II) sulfate, Au2(SO4)2. Originally thought to be a mixed-valence compound, it has been shown to contain Au4+2 cations, analogous to the better-known mercury(I) ion, Hg2+2.[45][46] A gold(II) complex, the tetraxenonogold(II) cation, which contains xenon as a ligand, occurs in [AuXe4](Sb2F11)2.[47]

Gold pentafluoride, along with its derivative anion, AuF−6, and its difluorine complex, gold heptafluoride, is the sole example of gold(V), the highest verified oxidation state.[48]

Some gold compounds exhibit aurophilic bonding, which describes the tendency of gold ions to interact at distances that are too long to be a conventional Au–Au bond but shorter than van der Waals bonding. The interaction is estimated to be comparable in strength to that of a hydrogen bond.

Well-defined cluster compounds are numerous.[42] In some cases, gold has a fractional oxidation state. A representative example is the octahedral species {Au(P(C6H5)3)}2+6.

Origin

Gold production in the universe

Schematic of a NE (left) to SW (right) cross-section through the 2.020-billion-year-old Vredefort impact structure in South Africa and how it distorted the contemporary geological structures. The present erosion level is shown. Johannesburg is located where the Witwatersrand Basin (the yellow layer) is exposed at the «present surface» line, just inside the crater rim, on the left. Not to scale.

Gold is thought to have been produced in supernova nucleosynthesis, and from the collision of neutron stars,[49] and to have been present in the dust from which the Solar System formed.[50]

Traditionally, gold in the universe is thought to have formed by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) in supernova nucleosynthesis,[51] but more recently it has been suggested that gold and other elements heavier than iron may also be produced in quantity by the r-process in the collision of neutron stars.[52] In both cases, satellite spectrometers at first only indirectly detected the resulting gold.[53] However, in August 2017, the spectroscopic signatures of heavy elements, including gold, were observed by electromagnetic observatories in the GW170817 neutron star merger event, after gravitational wave detectors confirmed the event as a neutron star merger.[54] Current astrophysical models suggest that this single neutron star merger event generated between 3 and 13 Earth masses of gold. This amount, along with estimations of the rate of occurrence of these neutron star merger events, suggests that such mergers may produce enough gold to account for most of the abundance of this element in the universe.[55]

Asteroid origin theories

Because the Earth was molten when it was formed, almost all of the gold present in the early Earth probably sank into the planetary core. Therefore, most of the gold that is in the Earth’s crust and mantle has in one model thought to have been delivered to Earth later, by asteroid impacts during the Late Heavy Bombardment, about 4 billion years ago.[56][57]

Gold which is reachable by humans has, in one case, been associated with a particular asteroid impact. The asteroid that formed Vredefort impact structure 2.020 billion years ago is often credited with seeding the Witwatersrand basin in South Africa with the richest gold deposits on earth.[58][59][60][61] However, this scenario is now questioned. The gold-bearing Witwatersrand rocks were laid down between 700 and 950 million years before the Vredefort impact.[62][63] These gold-bearing rocks had furthermore been covered by a thick layer of Ventersdorp lavas and the Transvaal Supergroup of rocks before the meteor struck, and thus the gold did not actually arrive in the asteroid/meteorite. What the Vredefort impact achieved, however, was to distort the Witwatersrand basin in such a way that the gold-bearing rocks were brought to the present erosion surface in Johannesburg, on the Witwatersrand, just inside the rim of the original 300 km (190 mi) diameter crater caused by the meteor strike. The discovery of the deposit in 1886 launched the Witwatersrand Gold Rush. Some 22% of all the gold that is ascertained to exist today on Earth has been extracted from these Witwatersrand rocks.[63]

Mantle return theories

Notwithstanding the impact above, much of the rest of the gold on Earth is thought to have been incorporated into the planet since its very beginning, as planetesimals formed the planet’s mantle, early in Earth’s creation. In 2017, an international group of scientists, established that gold «came to the Earth’s surface from the deepest regions of our planet»,[64] the mantle, evidenced by their findings at Deseado Massif in the Argentinian Patagonia.[65][clarification needed]

Occurrence

On Earth, gold is found in ores in rock formed from the Precambrian time onward.[66] It most often occurs as a native metal, typically in a metal solid solution with silver (i.e. as a gold/silver alloy). Such alloys usually have a silver content of 8–10%. Electrum is elemental gold with more than 20% silver, and is commonly known as white gold. Electrum’s color runs from golden-silvery to silvery, dependent upon the silver content. The more silver, the lower the specific gravity.

Native gold occurs as very small to microscopic particles embedded in rock, often together with quartz or sulfide minerals such as «fool’s gold», which is a pyrite.[67] These are called lode deposits. The metal in a native state is also found in the form of free flakes, grains or larger nuggets[66] that have been eroded from rocks and end up in alluvial deposits called placer deposits. Such free gold is always richer at the exposed surface of gold-bearing veins, owing to the oxidation of accompanying minerals followed by weathering; and by washing of the dust into streams and rivers, where it collects and can be welded by water action to form nuggets.

Gold sometimes occurs combined with tellurium as the minerals calaverite, krennerite, nagyagite, petzite and sylvanite (see telluride minerals), and as the rare bismuthide maldonite (Au2Bi) and antimonide aurostibite (AuSb2). Gold also occurs in rare alloys with copper, lead, and mercury: the minerals auricupride (Cu3Au), novodneprite (AuPb3) and weishanite ((Au,Ag)3Hg2).

Recent research suggests that microbes can sometimes play an important role in forming gold deposits, transporting and precipitating gold to form grains and nuggets that collect in alluvial deposits.[68]

Another recent study has claimed water in faults vaporizes during an earthquake, depositing gold. When an earthquake strikes, it moves along a fault. Water often lubricates faults, filling in fractures and jogs. About 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) below the surface, under very high temperatures and pressures, the water carries high concentrations of carbon dioxide, silica, and gold. During an earthquake, the fault jog suddenly opens wider. The water inside the void instantly vaporizes, flashing to steam and forcing silica, which forms the mineral quartz, and gold out of the fluids and onto nearby surfaces.[69]

Seawater

The world’s oceans contain gold. Measured concentrations of gold in the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific are 50–150 femtomol/L or 10–30 parts per quadrillion (about 10–30 g/km3). In general, gold concentrations for south Atlantic and central Pacific samples are the same (~50 femtomol/L) but less certain. Mediterranean deep waters contain slightly higher concentrations of gold (100–150 femtomol/L) attributed to wind-blown dust and/or rivers. At 10 parts per quadrillion the Earth’s oceans would hold 15,000 tonnes of gold.[70] These figures are three orders of magnitude less than reported in the literature prior to 1988, indicating contamination problems with the earlier data.

A number of people have claimed to be able to economically recover gold from sea water, but they were either mistaken or acted in an intentional deception. Prescott Jernegan ran a gold-from-seawater swindle in the United States in the 1890s, as did an English fraudster in the early 1900s.[71] Fritz Haber did research on the extraction of gold from sea water in an effort to help pay Germany’s reparations following World War I.[72] Based on the published values of 2 to 64 ppb of gold in seawater a commercially successful extraction seemed possible. After analysis of 4,000 water samples yielding an average of 0.004 ppb it became clear that extraction would not be possible and he ended the project.[73]

History

Oldest golden artifacts in the world (4600 BC — 4200 BC) from Varna necropolis, Bulgaria — grave offerings on exposition in Varna Museum.

The Muisca raft, between circa 600-1600 AD. The figure refers to the ceremony of the legend of El Dorado. The zipa used to cover his body in gold dust, and from his raft, he offered treasures to the Guatavita goddess in the middle of the sacred lake. This old Muisca tradition became the origin of the legend of El Dorado.

This Muisca raft figure is on display in the Gold Museum, Bogotá, Colombia.

The earliest recorded metal employed by humans appears to be gold, which can be found free or «native». Small amounts of natural gold have been found in Spanish caves used during the late Paleolithic period, c. 40,000 BC.[75]

The oldest gold artifacts in the world are from Bulgaria and are dating back to the 5th millennium BC (4,600 BC to 4,200 BC), such as those found in the Varna Necropolis near Lake Varna and the Black Sea coast, thought to be the earliest «well-dated» finding of gold artifacts in history.[76][66][77][78] Several prehistoric Bulgarian finds are considered no less old – the golden treasures of Hotnitsa, Durankulak, artifacts from the Kurgan settlement of Yunatsite near Pazardzhik, the golden treasure Sakar, as well as beads and gold jewelry found in the Kurgan settlement of Provadia – Solnitsata (“salt pit”). However, Varna gold is most often called the oldest since this treasure is the largest and most diverse.[79]

Gold artifacts probably made their first appearance in Ancient Egypt at the very beginning of the pre-dynastic period, at the end of the fifth millennium BC and the start of the fourth, and smelting was developed during the course of the 4th millennium; gold artifacts appear in the archeology of Lower Mesopotamia during the early 4th millennium.[80] As of 1990, gold artifacts found at the Wadi Qana cave cemetery of the 4th millennium BC in West Bank were the earliest from the Levant.[81] Gold artifacts such as the golden hats and the Nebra disk appeared in Central Europe from the 2nd millennium BC Bronze Age.

The oldest known map of a gold mine was drawn in the 19th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt (1320–1200 BC), whereas the first written reference to gold was recorded in the 12th Dynasty around 1900 BC.[82] Egyptian hieroglyphs from as early as 2600 BC describe gold, which King Tushratta of the Mitanni claimed was «more plentiful than dirt» in Egypt.[83] Egypt and especially Nubia had the resources to make them major gold-producing areas for much of history. One of the earliest known maps, known as the Turin Papyrus Map, shows the plan of a gold mine in Nubia together with indications of the local geology. The primitive working methods are described by both Strabo and Diodorus Siculus, and included fire-setting. Large mines were also present across the Red Sea in what is now Saudi Arabia.

Gold is mentioned in the Amarna letters numbered 19[84] and 26[85] from around the 14th century BC.[86][87]

Gold is mentioned frequently in the Old Testament, starting with Genesis 2:11 (at Havilah), the story of the golden calf, and many parts of the temple including the Menorah and the golden altar. In the New Testament, it is included with the gifts of the magi in the first chapters of Matthew. The Book of Revelation 21:21 describes the city of New Jerusalem as having streets «made of pure gold, clear as crystal». Exploitation of gold in the south-east corner of the Black Sea is said to date from the time of Midas, and this gold was important in the establishment of what is probably the world’s earliest coinage in Lydia around 610 BC.[88] The legend of the golden fleece dating from eighth century BCE may refer to the use of fleeces to trap gold dust from placer deposits in the ancient world. From the 6th or 5th century BC, the Chu (state) circulated the Ying Yuan, one kind of square gold coin.

In Roman metallurgy, new methods for extracting gold on a large scale were developed by introducing hydraulic mining methods, especially in Hispania from 25 BC onwards and in Dacia from 106 AD onwards. One of their largest mines was at Las Medulas in León, where seven long aqueducts enabled them to sluice most of a large alluvial deposit. The mines at Roşia Montană in Transylvania were also very large, and until very recently, still mined by opencast methods. They also exploited smaller deposits in Britain, such as placer and hard-rock deposits at Dolaucothi. The various methods they used are well described by Pliny the Elder in his encyclopedia Naturalis Historia written towards the end of the first century AD.

During Mansa Musa’s (ruler of the Mali Empire from 1312 to 1337) hajj to Mecca in 1324, he passed through Cairo in July 1324, and was reportedly accompanied by a camel train that included thousands of people and nearly a hundred camels where he gave away so much gold that it depressed the price in Egypt for over a decade, causing high inflation.[89] A contemporary Arab historian remarked:

Gold was at a high price in Egypt until they came in that year. The mithqal did not go below 25 dirhams and was generally above, but from that time its value fell and it cheapened in price and has remained cheap till now. The mithqal does not exceed 22 dirhams or less. This has been the state of affairs for about twelve years until this day by reason of the large amount of gold which they brought into Egypt and spent there […].

Gold coin of Eucratides I (171–145 BC), one of the Hellenistic rulers of ancient Ai-Khanoum. This is the largest known gold coin minted in antiquity (169.2 g (5.97 oz); 58 mm (2.3 in)).[91]

The European exploration of the Americas was fueled in no small part by reports of the gold ornaments displayed in great profusion by Native American peoples, especially in Mesoamerica, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. The Aztecs regarded gold as the product of the gods, calling it literally «god excrement» (teocuitlatl in Nahuatl), and after Moctezuma II was killed, most of this gold was shipped to Spain.[92] However, for the indigenous peoples of North America gold was considered useless and they saw much greater value in other minerals which were directly related to their utility, such as obsidian, flint, and slate.[93] El Dorado is applied to a legendary story in which precious stones were found in fabulous abundance along with gold coins. The concept of El Dorado underwent several transformations, and eventually accounts of the previous myth were also combined with those of a legendary lost city. El Dorado, was the term used by the Spanish Empire to describe a mythical tribal chief (zipa) of the Muisca native people in Colombia, who, as an initiation rite, covered himself with gold dust and submerged in Lake Guatavita. The legends surrounding El Dorado changed over time, as it went from being a man, to a city, to a kingdom, and then finally to an empire.

Beginning in the early modern period, European exploration and colonization of West Africa was driven in large part by reports of gold deposits in the region, which was eventually referred to by Europeans as the «Gold Coast».[94] From the late 15th to early 19th centuries, European trade in the region was primarily focused in gold, along with ivory and slaves.[95] The gold trade in West Africa was dominated by the Ashanti Empire, who initially traded with the Portuguese before branching out and trading with British, French, Spanish and Danish merchants.[96] British desires to secure control of West African gold deposits played a role in the Anglo-Ashanti wars of the late 19th century, which saw the Ashanti Empire annexed by Britain.[97]

Gold played a role in western culture, as a cause for desire and of corruption, as told in children’s fables such as Rumpelstiltskin—where Rumpelstiltskin turns hay into gold for the peasant’s daughter in return for her child when she becomes a princess—and the stealing of the hen that lays golden eggs in Jack and the Beanstalk.

The top prize at the Olympic Games and many other sports competitions is the gold medal.

75% of the presently accounted for gold has been extracted since 1910, two-thirds since 1950.

One main goal of the alchemists was to produce gold from other substances, such as lead — presumably by the interaction with a mythical substance called the philosopher’s stone. Trying to produce gold led the alchemists to systematically find out what can be done with substances, and this laid the foundation for today’s chemistry, which can produce gold (albeit uneconomically) by using nuclear transmutation.[98] Their symbol for gold was the circle with a point at its center (☉), which was also the astrological symbol and the ancient Chinese character for the Sun.

The Dome of the Rock is covered with an ultra-thin golden glassier. The Sikh Golden temple, the Harmandir Sahib, is a building covered with gold. Similarly the Wat Phra Kaew emerald Buddhist temple (wat) in Thailand has ornamental gold-leafed statues and roofs. Some European king and queen’s crowns were made of gold, and gold was used for the bridal crown since antiquity. An ancient Talmudic text circa 100 AD describes Rachel, wife of Rabbi Akiva, receiving a «Jerusalem of Gold» (diadem). A Greek burial crown made of gold was found in a grave circa 370 BC.

-

Ancient Egyptian statuette of Amun; 945–715 BC; gold; 175 mm × 47 mm (6.9 in × 1.9 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Ancient Egyptian signet ring; 664–525 BC; gold; diameter: 30 mm × 34 mm (1.2 in × 1.3 in); British Museum (London)

-

Etruscan funerary wreath; 4th–3rd century BC; length: 333 mm (13.1 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Quimbaya lime container; 5th–9th century; gold; height: 230 mm (9.1 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

-

Pre-Columbian pendant with two bat-head warriors who carry spears; 11th–16th century; gold; overall: 76.2 mm (3.00 in); from the Chiriqui Province (Panama); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

English Neoclassical box; 1741; overall: 44 mm × 116 mm × 92 mm (1.7 in × 4.6 in × 3.6 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Rococo glass bottle mounted in gold; circa 1775; overall: 70 mm × 29 mm (2.8 in × 1.1 in); Cleveland Museum of Art

Etymology

An early mention of gold in the Beowulf

«Gold» is cognate with similar words in many Germanic languages, deriving via Proto-Germanic *gulþą from Proto-Indo-European *ǵʰelh₃- («to shine, to gleam; to be yellow or green»).[99][100]

The symbol Au is from the Latin: aurum, the Latin word for «gold».[101] The Proto-Indo-European ancestor of aurum was *h₂é-h₂us-o-, meaning «glow». This word is derived from the same root (Proto-Indo-European *h₂u̯es- «to dawn») as *h₂éu̯sōs, the ancestor of the Latin word Aurora, «dawn».[102] This etymological relationship is presumably behind the frequent claim in scientific publications that aurum meant «shining dawn».[103]

Culture

In popular culture gold is a high standard of excellence, often used in awards.[43] Great achievements are frequently rewarded with gold, in the form of gold medals, gold trophies and other decorations. Winners of athletic events and other graded competitions are usually awarded a gold medal. Many awards such as the Nobel Prize are made from gold as well. Other award statues and prizes are depicted in gold or are gold plated (such as the Academy Awards, the Golden Globe Awards, the Emmy Awards, the Palme d’Or, and the British Academy Film Awards).[104]

Aristotle in his ethics used gold symbolism when referring to what is now known as the golden mean. Similarly, gold is associated with perfect or divine principles, such as in the case of the golden ratio and the golden rule. Gold is further associated with the wisdom of aging and fruition. The fiftieth wedding anniversary is golden. A person’s most valued or most successful latter years are sometimes considered «golden years». The height of a civilization is referred to as a golden age.[105]

Religion

In some forms of Christianity and Judaism, gold has been associated both with the sacred and evil. In the Book of Exodus, the Golden Calf is a symbol of idolatry, while in the Book of Genesis, Abraham was said to be rich in gold and silver, and Moses was instructed to cover the Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant with pure gold. In Byzantine iconography the halos of Christ, Virgin Mary and the saints are often golden.[106]

In Islam,[107] gold (along with silk)[108][109] is often cited as being forbidden for men to wear.[110] Abu Bakr al-Jazaeri, quoting a hadith, said that «[t]he wearing of silk and gold are forbidden on the males of my nation, and they are lawful to their women».[111] This, however, has not been enforced consistently throughout history, e.g. in the Ottoman Empire.[112] Further, small gold accents on clothing, such as in embroidery, may be permitted.[113]

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Theia was seen as the goddess of gold, silver and other gems.[114]

According to Christopher Columbus, those who had something of gold were in possession of something of great value on Earth and a substance to even help souls to paradise.[115]

Wedding rings are typically made of gold. It is long lasting and unaffected by the passage of time and may aid in the ring symbolism of eternal vows before God and the perfection the marriage signifies. In Orthodox Christian wedding ceremonies, the wedded couple is adorned with a golden crown (though some opt for wreaths, instead) during the ceremony, an amalgamation of symbolic rites.

On 24 August 2020, Israeli archaeologists discovered a trove of early Islamic gold coins near the central city of Yavne. Analysis of the extremely rare collection of 425 gold coins indicated that they were from the late 9th century. Dating to around 1,100 years back, the gold coins were from the Abbasid Caliphate.[116]

Production

Time trend of gold production

According to the United States Geological Survey in 2016, about 5,726,000,000 troy ounces (178,100 t) of gold has been accounted for, of which 85% remains in active use.[117]

Mining and prospecting

Since the 1880s, South Africa has been the source of a large proportion of the world’s gold supply, and about 22% of the gold presently accounted is from South Africa. Production in 1970 accounted for 79% of the world supply, about 1,480 tonnes. In 2007 China (with 276 tonnes) overtook South Africa as the world’s largest gold producer, the first time since 1905 that South Africa had not been the largest.[118]

In 2020, China was the world’s leading gold-mining country, followed in order by Russia, Australia, the United States, Canada, and Ghana.[8]

Relative sizes of an 860 kg (1,900 lb) block of gold ore and the 30 g (0.96 ozt) of gold that can be extracted from it, Toi gold mine, Japan.

In South America, the controversial project Pascua Lama aims at exploitation of rich fields in the high mountains of Atacama Desert, at the border between Chile and Argentina.

It has been estimated that up to one-quarter of the yearly global gold production originates from artisanal or small scale mining.[119][120][121]

The city of Johannesburg located in South Africa was founded as a result of the Witwatersrand Gold Rush which resulted in the discovery of some of the largest natural gold deposits in recorded history. The gold fields are confined to the northern and north-western edges of the Witwatersrand basin, which is a 5–7 km (3.1–4.3 mi) thick layer of archean rocks located, in most places, deep under the Free State, Gauteng and surrounding provinces.[122] These Witwatersrand rocks are exposed at the surface on the Witwatersrand, in and around Johannesburg, but also in isolated patches to the south-east and south-west of Johannesburg, as well as in an arc around the Vredefort Dome which lies close to the center of the Witwatersrand basin.[62][122] From these surface exposures the basin dips extensively, requiring some of the mining to occur at depths of nearly 4,000 m (13,000 ft), making them, especially the Savuka and TauTona mines to the south-west of Johannesburg, the deepest mines on earth. The gold is found only in six areas where archean rivers from the north and north-west formed extensive pebbly Braided river deltas before draining into the «Witwatersrand sea» where the rest of the Witwatersrand sediments were deposited.[122]

The Second Boer War of 1899–1901 between the British Empire and the Afrikaner Boers was at least partly over the rights of miners and possession of the gold wealth in South Africa.

During the 19th century, gold rushes occurred whenever large gold deposits were discovered. The first documented discovery of gold in the United States was at the Reed Gold Mine near Georgeville, North Carolina in 1803.[123] The first major gold strike in the United States occurred in a small north Georgia town called Dahlonega.[124] Further gold rushes occurred in California, Colorado, the Black Hills, Otago in New Zealand, a number of locations across Australia, Witwatersrand in South Africa, and the Klondike in Canada.

Grasberg mine located in Papua, Indonesia is the largest gold mine in the world.[125]

Extraction and refining

Gold extraction is most economical in large, easily mined deposits. Ore grades as little as 0.5 parts per million (ppm) can be economical. Typical ore grades in open-pit mines are 1–5 ppm; ore grades in underground or hard rock mines are usually at least 3 ppm. Because ore grades of 30 ppm are usually needed before gold is visible to the naked eye, in most gold mines the gold is invisible.

The average gold mining and extraction costs were about $317 per troy ounce in 2007, but these can vary widely depending on mining type and ore quality; global mine production amounted to 2,471.1 tonnes.[126]

After initial production, gold is often subsequently refined industrially by the Wohlwill process which is based on electrolysis or by the Miller process, that is chlorination in the melt. The Wohlwill process results in higher purity, but is more complex and is only applied in small-scale installations.[127][128] Other methods of assaying and purifying smaller amounts of gold include parting and inquartation as well as cupellation, or refining methods based on the dissolution of gold in aqua regia.[129]

As of 2020, the amount of carbon dioxide CO2 produced in mining a kilogram of gold is 16 tonnes, while recycling a kilogram of gold produces 53 kilograms of CO2 equivalent. Approximately 30 percent of the global gold supply is recycled and not mined as of 2020.[130]

Corporations are starting to adopt gold recycling including jewelry companies such as Generation Collection and computer companies including Dell.[131]

Consumption

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (May 2022) |

| Country | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 442.37 | 745.70 | 986.3 | 864 | 974 | |

| 376.96 | 428.00 | 921.5 | 817.5 | 1120.1 | |

| 150.28 | 128.61 | 199.5 | 161 | 190 | |

| 75.16 | 74.07 | 143 | 118 | 175.2 | |

| 77.75 | 72.95 | 69.1 | 58.5 | 72.2 | |

| 60.12 | 67.50 | 76.7 | 81.9 | 73.3 | |

| 67.60 | 63.37 | 60.9 | 58.1 | 77.1 | |

| 56.68 | 53.43 | 36 | 47.8 | 57.3 | |

| 41.00 | 32.75 | 55 | 52.3 | 68 | |

| 31.75 | 27.35 | 22.6 | 21.1 | 23.4 | |

| Other Persian Gulf Countries | 24.10 | 21.97 | 22 | 19.9 | 24.6 |

| 21.85 | 18.50 | −30.1 | 7.6 | 21.3 | |

| 18.83 | 15.87 | 15.5 | 12.1 | 17.5 | |

| 15.08 | 14.36 | 100.8 | 77 | 92.2 | |

| 7.33 | 6.28 | 107.4 | 80.9 | 140.1 | |

| Total | 1466.86 | 1770.71 | 2786.12 | 2477.7 | 3126.1 |

| Other Countries | 251.6 | 254.0 | 390.4 | 393.5 | 450.7 |

| World Total | 1718.46 | 2024.71 | 3176.52 | 2871.2 | 3576.8 |

The consumption of gold produced in the world is about 50% in jewelry, 40% in investments, and 10% in industry.[10][135]

According to the World Gold Council, China was the world’s largest single consumer of gold in 2013, overtaking India.[136]

Pollution

Gold production is associated with contribution to hazardous pollution.[137][138]

Low-grade gold ore may contain less than one ppm gold metal; such ore is ground and mixed with sodium cyanide to dissolve the gold. Cyanide is a highly poisonous chemical, which can kill living creatures when exposed in minute quantities. Many cyanide spills[139] from gold mines have occurred in both developed and developing countries which killed aquatic life in long stretches of affected rivers. Environmentalists consider these events major environmental disasters.[140][141] Up to thirty tons of used ore can dumped as waste for producing one troy ounce of gold.[142] Gold ore dumps are the source of many heavy elements such as cadmium, lead, zinc, copper, arsenic, selenium and mercury. When sulfide-bearing minerals in these ore dumps are exposed to air and water, the sulfide transforms into sulfuric acid which in turn dissolves these heavy metals facilitating their passage into surface water and ground water. This process is called acid mine drainage. These gold ore dumps are long-term, highly hazardous wastes second only to nuclear waste dumps.[142]

It was once common to use mercury to recover gold from ore, but today the use of mercury is largely limited to small-scale individual miners.[143] Minute quantities of mercury compounds can reach water bodies, causing heavy metal contamination. Mercury can then enter into the human food chain in the form of methylmercury. Mercury poisoning in humans causes incurable brain function damage and severe retardation.[144]

Gold extraction is also a highly energy-intensive industry, extracting ore from deep mines and grinding the large quantity of ore for further chemical extraction requires nearly 25 kWh of electricity per gram of gold produced.[145]

Monetary use

Gold has been widely used throughout the world as money,[146] for efficient indirect exchange (versus barter), and to store wealth in hoards. For exchange purposes, mints produce standardized gold bullion coins, bars and other units of fixed weight and purity.

The first known coins containing gold were struck in Lydia, Asia Minor, around 600 BC.[88] The talent coin of gold in use during the periods of Grecian history both before and during the time of the life of Homer weighed between 8.42 and 8.75 grams.[147] From an earlier preference in using silver, European economies re-established the minting of gold as coinage during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[148]

Bills (that mature into gold coin) and gold certificates (convertible into gold coin at the issuing bank) added to the circulating stock of gold standard money in most 19th century industrial economies.

In preparation for World War I the warring nations moved to fractional gold standards, inflating their currencies to finance the war effort.

Post-war, the victorious countries, most notably Britain, gradually restored gold-convertibility, but international flows of gold via bills of exchange remained embargoed; international shipments were made exclusively for bilateral trades or to pay war reparations.

After World War II gold was replaced by a system of nominally convertible currencies related by fixed exchange rates following the Bretton Woods system. Gold standards and the direct convertibility of currencies to gold have been abandoned by world governments, led in 1971 by the United States’ refusal to redeem its dollars in gold. Fiat currency now fills most monetary roles. Switzerland was the last country to tie its currency to gold; this was ended by a referendum in 1999.[149]

Central banks continue to keep a portion of their liquid reserves as gold in some form, and metals exchanges such as the London Bullion Market Association still clear transactions denominated in gold, including future delivery contracts. Today, gold mining output is declining.[150] With the sharp growth of economies in the 20th century, and increasing foreign exchange, the world’s gold reserves and their trading market have become a small fraction of all markets and fixed exchange rates of currencies to gold have been replaced by floating prices for gold and gold future contract. Though the gold stock grows by only 1% or 2% per year, very little metal is irretrievably consumed. Inventory above ground would satisfy many decades of industrial and even artisan uses at current prices.

The gold proportion (fineness) of alloys is measured by karat (k). Pure gold (commercially termed fine gold) is designated as 24 karat, abbreviated 24k. English gold coins intended for circulation from 1526 into the 1930s were typically a standard 22k alloy called crown gold,[151] for hardness (American gold coins for circulation after 1837 contain an alloy of 0.900 fine gold, or 21.6 kt).[152]

Although the prices of some platinum group metals can be much higher, gold has long been considered the most desirable of precious metals, and its value has been used as the standard for many currencies. Gold has been used as a symbol for purity, value, royalty, and particularly roles that combine these properties. Gold as a sign of wealth and prestige was ridiculed by Thomas More in his treatise Utopia. On that imaginary island, gold is so abundant that it is used to make chains for slaves, tableware, and lavatory seats. When ambassadors from other countries arrive, dressed in ostentatious gold jewels and badges, the Utopians mistake them for menial servants, paying homage instead to the most modestly dressed of their party.

The ISO 4217 currency code of gold is XAU.[153] Many holders of gold store it in form of bullion coins or bars as a hedge against inflation or other economic disruptions, though its efficacy as such has been questioned; historically, it has not proven itself reliable as a hedging instrument.[154] Modern bullion coins for investment or collector purposes do not require good mechanical wear properties; they are typically fine gold at 24k, although the American Gold Eagle and the British gold sovereign continue to be minted in 22k (0.92) metal in historical tradition, and the South African Krugerrand, first released in 1967, is also 22k (0.92).[155]

The special issue Canadian Gold Maple Leaf coin contains the highest purity gold of any bullion coin, at 99.999% or 0.99999, while the popular issue Canadian Gold Maple Leaf coin has a purity of 99.99%. In 2006, the United States Mint began producing the American Buffalo gold bullion coin with a purity of 99.99%. The Australian Gold Kangaroos were first coined in 1986 as the Australian Gold Nugget but changed the reverse design in 1989. Other modern coins include the Austrian Vienna Philharmonic bullion coin and the Chinese Gold Panda.[156]

Price

Gold price history in 1960–2020.

As of September 2017, gold is valued at around $42 per gram ($1,300 per troy ounce).

Like other precious metals, gold is measured by troy weight and by grams. The proportion of gold in the alloy is measured by karat (k), with 24 karat (24k) being pure gold (100%), and lower karat numbers proportionally less (18k = 75%). The purity of a gold bar or coin can also be expressed as a decimal figure ranging from 0 to 1, known as the millesimal fineness, such as 0.995 being nearly pure.

The price of gold is determined through trading in the gold and derivatives markets, but a procedure known as the Gold Fixing in London, originating in September 1919, provides a daily benchmark price to the industry. The afternoon fixing was introduced in 1968 to provide a price when US markets are open.[157]

History

Historically gold coinage was widely used as currency; when paper money was introduced, it typically was a receipt redeemable for gold coin or bullion. In a monetary system known as the gold standard, a certain weight of gold was given the name of a unit of currency. For a long period, the United States government set the value of the US dollar so that one troy ounce was equal to $20.67 ($0.665 per gram), but in 1934 the dollar was devalued to $35.00 per troy ounce ($0.889/g). By 1961, it was becoming hard to maintain this price, and a pool of US and European banks agreed to manipulate the market to prevent further currency devaluation against increased gold demand.[158]

On 17 March 1968, economic circumstances[clarification needed] caused the collapse of the gold pool, and a two-tiered pricing scheme was established whereby gold was still used to settle international accounts at the old $35.00 per troy ounce ($1.13/g) but the price of gold on the private market was allowed to fluctuate; this two-tiered pricing system was abandoned in 1975 when the price of gold was left to find its free-market level.[citation needed] Central banks still hold historical gold reserves as a store of value although the level has generally been declining.[citation needed] The largest gold depository in the world is that of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank in New York, which holds about 3%[159] of the gold known to exist and accounted for today, as does the similarly laden U.S. Bullion Depository at Fort Knox.

In 2005 the World Gold Council estimated total global gold supply to be 3,859 tonnes and demand to be 3,754 tonnes, giving a surplus of 105 tonnes.[160]

After 15 August 1971 Nixon shock, the price began to greatly increase,[161] and between 1968 and 2000 the price of gold ranged widely, from a high of $850 per troy ounce ($27.33/g) on 21 January 1980, to a low of $252.90 per troy ounce ($8.13/g) on 21 June 1999 (London Gold Fixing).[162] Prices increased rapidly from 2001, but the 1980 high was not exceeded until 3 January 2008, when a new maximum of $865.35 per troy ounce was set.[163] Another record price was set on 17 March 2008, at $1023.50 per troy ounce ($32.91/g).[163]

In late 2009, gold markets experienced renewed momentum upwards due to increased demand and a weakening US dollar.[citation needed] On 2 December 2009, gold reached a new high closing at $1,217.23.[164] Gold further rallied hitting new highs in May 2010 after the European Union debt crisis prompted further purchase of gold as a safe asset.[165][166] On 1 March 2011, gold hit a new all-time high of $1432.57, based on investor concerns regarding ongoing unrest in North Africa as well as in the Middle East.[167]

From April 2001 to August 2011, spot gold prices more than quintupled in value against the US dollar, hitting a new all-time high of $1,913.50 on 23 August 2011,[168] prompting speculation that the long secular bear market had ended and a bull market had returned.[169] However, the price then began a slow decline towards $1200 per troy ounce in late 2014 and 2015.

In August 2020, the gold price picked up to US$2060 per ounce after a complexive growth of 59% from August 2018 to October 2020, a period during which it outplaced the Nasdaq total return of 54%.[170]

Gold futures are traded on the COMEX exchange.[171] These contacts are priced in USD per troy ounce (1 troy ounce = 31.1034768 grams).[172] Below are the CQG contract specifications outlining the futures contracts:

| Gold (GCA) | |

|---|---|

| Exchange: | COMEX |

| Sector: | Metal |

| Tick Size: | 0.1 |

| Tick Value: | 10 USD |

| BPV: | 100 |

| Denomination: | USD |

| Decimal Place: | 1 |

Medicinal uses

Medicinal applications of gold and its complexes have a long history dating back thousands of years.[173] Several gold complexes have been applied to treat rheumatoid arthritis, the most frequently used being aurothiomalate, aurothioglucose, and auranofin. Both gold(I) and gold(III) compounds have been investigated as possible anti-cancer drugs. For gold(III) complexes, reduction to gold(0/I) under physiological conditions has to be considered. Stable complexes can be generated using different types of bi-, tri-, and tetradentate ligand systems, and their efficacy has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo.[174]

Other applications

Jewelry

Because of the softness of pure (24k) gold, it is usually alloyed with base metals for use in jewelry, altering its hardness and ductility, melting point, color and other properties. Alloys with lower karat rating, typically 22k, 18k, 14k or 10k, contain higher percentages of copper or other base metals or silver or palladium in the alloy.[23] Nickel is toxic, and its release from nickel white gold is controlled by legislation in Europe.[23] Palladium-gold alloys are more expensive than those using nickel.[175] High-karat white gold alloys are more resistant to corrosion than are either pure silver or sterling silver. The Japanese craft of Mokume-gane exploits the color contrasts between laminated colored gold alloys to produce decorative wood-grain effects.

By 2014, the gold jewelry industry was escalating despite a dip in gold prices. Demand in the first quarter of 2014 pushed turnover to $23.7 billion according to a World Gold Council report.

Gold solder is used for joining the components of gold jewelry by high-temperature hard soldering or brazing. If the work is to be of hallmarking quality, the gold solder alloy must match the fineness (purity) of the work, and alloy formulas are manufactured to color-match yellow and white gold. Gold solder is usually made in at least three melting-point ranges referred to as Easy, Medium and Hard. By using the hard, high-melting point solder first, followed by solders with progressively lower melting points, goldsmiths can assemble complex items with several separate soldered joints. Gold can also be made into thread and used in embroidery.

Electronics

Only 10% of the world consumption of new gold produced goes to industry,[10] but by far the most important industrial use for new gold is in fabrication of corrosion-free electrical connectors in computers and other electrical devices. For example, according to the World Gold Council, a typical cell phone may contain 50 mg of gold, worth about 2 dollars 82 cents. But since nearly one billion cell phones are produced each year, a gold value of US$2.82 in each phone adds to US$2.82 billion in gold from just this application.[176] (Prices updated to November 2022)

Though gold is attacked by free chlorine, its good conductivity and general resistance to oxidation and corrosion in other environments (including resistance to non-chlorinated acids) has led to its widespread industrial use in the electronic era as a thin-layer coating on electrical connectors, thereby ensuring good connection. For example, gold is used in the connectors of the more expensive electronics cables, such as audio, video and USB cables. The benefit of using gold over other connector metals such as tin in these applications has been debated; gold connectors are often criticized by audio-visual experts as unnecessary for most consumers and seen as simply a marketing ploy. However, the use of gold in other applications in electronic sliding contacts in highly humid or corrosive atmospheres, and in use for contacts with a very high failure cost (certain computers, communications equipment, spacecraft, jet aircraft engines) remains very common.[177]

Besides sliding electrical contacts, gold is also used in electrical contacts because of its resistance to corrosion, electrical conductivity, ductility and lack of toxicity.[178] Switch contacts are generally subjected to more intense corrosion stress than are sliding contacts. Fine gold wires are used to connect semiconductor devices to their packages through a process known as wire bonding.

The concentration of free electrons in gold metal is 5.91×1022 cm−3.[179] Gold is highly conductive to electricity, and has been used for electrical wiring in some high-energy applications (only silver and copper are more conductive per volume, but gold has the advantage of corrosion resistance). For example, gold electrical wires were used during some of the Manhattan Project’s atomic experiments, but large high-current silver wires were used in the calutron isotope separator magnets in the project.

It is estimated that 16% of the world’s presently-accounted-for gold and 22% of the world’s silver is contained in electronic technology in Japan.[180]

Medicine

Metallic and gold compounds have long been used for medicinal purposes. Gold, usually as the metal, is perhaps the most anciently administered medicine (apparently by shamanic practitioners)[181] and known to Dioscorides.[182][183] In medieval times, gold was often seen as beneficial for the health, in the belief that something so rare and beautiful could not be anything but healthy. Even some modern esotericists and forms of alternative medicine assign metallic gold a healing power.

In the 19th century gold had a reputation as an anxiolytic, a therapy for nervous disorders. Depression, epilepsy, migraine, and glandular problems such as amenorrhea and impotence were treated, and most notably alcoholism (Keeley, 1897).[184]

The apparent paradox of the actual toxicology of the substance suggests the possibility of serious gaps in the understanding of the action of gold in physiology.[185] Only salts and radioisotopes of gold are of pharmacological value, since elemental (metallic) gold is inert to all chemicals it encounters inside the body (e.g., ingested gold cannot be attacked by stomach acid). Some gold salts do have anti-inflammatory properties and at present two are still used as pharmaceuticals in the treatment of arthritis and other similar conditions in the US (sodium aurothiomalate and auranofin). These drugs have been explored as a means to help to reduce the pain and swelling of rheumatoid arthritis, and also (historically) against tuberculosis and some parasites.[186]

Gold alloys are used in restorative dentistry, especially in tooth restorations, such as crowns and permanent bridges. The gold alloys’ slight malleability facilitates the creation of a superior molar mating surface with other teeth and produces results that are generally more satisfactory than those produced by the creation of porcelain crowns. The use of gold crowns in more prominent teeth such as incisors is favored in some cultures and discouraged in others.

Colloidal gold preparations (suspensions of gold nanoparticles) in water are intensely red-colored, and can be made with tightly controlled particle sizes up to a few tens of nanometers across by reduction of gold chloride with citrate or ascorbate ions. Colloidal gold is used in research applications in medicine, biology and materials science. The technique of immunogold labeling exploits the ability of the gold particles to adsorb protein molecules onto their surfaces. Colloidal gold particles coated with specific antibodies can be used as probes for the presence and position of antigens on the surfaces of cells.[187] In ultrathin sections of tissues viewed by electron microscopy, the immunogold labels appear as extremely dense round spots at the position of the antigen.[188]

Gold, or alloys of gold and palladium, are applied as conductive coating to biological specimens and other non-conducting materials such as plastics and glass to be viewed in a scanning electron microscope. The coating, which is usually applied by sputtering with an argon plasma, has a triple role in this application. Gold’s very high electrical conductivity drains electrical charge to earth, and its very high density provides stopping power for electrons in the electron beam, helping to limit the depth to which the electron beam penetrates the specimen. This improves definition of the position and topography of the specimen surface and increases the spatial resolution of the image. Gold also produces a high output of secondary electrons when irradiated by an electron beam, and these low-energy electrons are the most commonly used signal source used in the scanning electron microscope.[189]

The isotope gold-198 (half-life 2.7 days) is used in nuclear medicine, in some cancer treatments and for treating other diseases.[190][191]

Cuisine

- Gold can be used in food and has the E number 175.[192] In 2016, the European Food Safety Authority published an opinion on the re-evaluation of gold as a food additive. Concerns included the possible presence of minute amounts of gold nanoparticles in the food additive, and that gold nanoparticles have been shown to be genotoxic in mammalian cells in vitro.[193]

- Gold leaf, flake or dust is used on and in some gourmet foods, notably sweets and drinks as decorative ingredient.[194] Gold flake was used by the nobility in medieval Europe as a decoration in food and drinks,[195]

- Danziger Goldwasser (German: Gold water of Danzig) or Goldwasser (English: Goldwater) is a traditional German herbal liqueur[196] produced in what is today Gdańsk, Poland, and Schwabach, Germany, and contains flakes of gold leaf. There are also some expensive (c. $1000) cocktails which contain flakes of gold leaf. However, since metallic gold is inert to all body chemistry, it has no taste, it provides no nutrition, and it leaves the body unaltered.[197]

- Vark is a foil composed of a pure metal that is sometimes gold,[198] and is used for garnishing sweets in South Asian cuisine.

Miscellanea

- Gold produces a deep, intense red color when used as a coloring agent in cranberry glass.

- In photography, gold toners are used to shift the color of silver bromide black-and-white prints towards brown or blue tones, or to increase their stability. Used on sepia-toned prints, gold toners produce red tones. Kodak published formulas for several types of gold toners, which use gold as the chloride.[199]

- Gold is a good reflector of electromagnetic radiation such as infrared and visible light, as well as radio waves. It is used for the protective coatings on many artificial satellites, in infrared protective faceplates in thermal-protection suits and astronauts’ helmets, and in electronic warfare planes such as the EA-6B Prowler.

- Gold is used as the reflective layer on some high-end CDs.

- Automobiles may use gold for heat shielding. McLaren uses gold foil in the engine compartment of its F1 model.[200]

- Gold can be manufactured so thin that it appears semi-transparent. It is used in some aircraft cockpit windows for de-icing or anti-icing by passing electricity through it. The heat produced by the resistance of the gold is enough to prevent ice from forming.[201]

- Gold is attacked by and dissolves in alkaline solutions of potassium or sodium cyanide, to form the salt gold cyanide—a technique that has been used in extracting metallic gold from ores in the cyanide process. Gold cyanide is the electrolyte used in commercial electroplating of gold onto base metals and electroforming.

- Gold chloride (chloroauric acid) solutions are used to make colloidal gold by reduction with citrate or ascorbate ions. Gold chloride and gold oxide are used to make cranberry or red-colored glass, which, like colloidal gold suspensions, contains evenly sized spherical gold nanoparticles.[202]

- Gold, when dispersed in nanoparticles, can act as a heterogeneous catalyst of chemical reactions.

Toxicity

Pure metallic (elemental) gold is non-toxic and non-irritating when ingested[203] and is sometimes used as a food decoration in the form of gold leaf.[204] Metallic gold is also a component of the alcoholic drinks Goldschläger, Gold Strike, and Goldwasser. Metallic gold is approved as a food additive in the EU (E175 in the Codex Alimentarius). Although the gold ion is toxic, the acceptance of metallic gold as a food additive is due to its relative chemical inertness, and resistance to being corroded or transformed into soluble salts (gold compounds) by any known chemical process which would be encountered in the human body.

Soluble compounds (gold salts) such as gold chloride are toxic to the liver and kidneys. Common cyanide salts of gold such as potassium gold cyanide, used in gold electroplating, are toxic by virtue of both their cyanide and gold content. There are rare cases of lethal gold poisoning from potassium gold cyanide.[205][206] Gold toxicity can be ameliorated with chelation therapy with an agent such as dimercaprol.

Gold metal was voted Allergen of the Year in 2001 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society; gold contact allergies affect mostly women.[207] Despite this, gold is a relatively non-potent contact allergen, in comparison with metals like nickel.[208]

A sample of the fungus Aspergillus niger was found growing from gold mining solution; and was found to contain cyano metal complexes, such as gold, silver, copper, iron and zinc. The fungus also plays a role in the solubilization of heavy metal sulfides.[209]

See also

Iron pyrite or «fool’s gold»

- Bulk leach extractable gold, for sampling ores

- Chrysiasis (dermatological condition)

- Digital gold currency, form of electronic currency

- GFMS business consultancy

- Goldbacks, a popular form of local currency-gold embedded in polymer ‘notes’

- Gold fingerprinting, use impurities to identify an alloy

- Gold standard in banking

- List of countries by gold production

- Tumbaga, alloy of gold and copper

- Iron pyrite, fool’s gold

- Nordic gold, non-gold copper alloy

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Gold». CIAAW. 2017.

- ^ Mézaille, Nicolas; Avarvari, Narcis; Maigrot, Nicole; Ricard, Louis; Mathey, François; Le Floch, Pascal; Cataldo, Laurent; Berclaz, Théo; Geoffroy, Michel (1999). «Gold(I) and Gold(0) Complexes of Phosphinine‐Based Macrocycles». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 38 (21): 3194–3197. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991102)38:21<3194::AID-ANIE3194>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 10556900.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). «Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds». CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kelly, P. F. (2015). Properties of Materials. CRC Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-4822-0624-1.

- ^ Duckenfield, Mark (2016). The Monetary History of Gold: A Documentary History, 1660–1999. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 9781315476124.

Its scarcity makes it a useful store of value; however, its relative rarity reduced its utility as a currency, especially for transactions in small denominations.

- ^ Pearce, Susan M. (1993). Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study. Smithsonian Books. p. 53. ISBN 9781588345172.

Its scarcity makes it a useful store of value; however, its relative rarity reduced its utility as a currency, especially for transactions in small denominations. … Rarity is, nevertheless, in itself a source of value, and so is the degree of difficulty which surrounds the winning of the raw material, especially if it is exotic and has to be brought some distance. Gold is, geologically, a relatively rare material on earth and occurs only in specific places which are remote from most other places.

- ^ a b «Gold Production & Mining Data by Country».

- ^ «Above-ground stocks». gold.org. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Soos, Andy (6 January 2011). «Gold Mining Boom Increasing Mercury Pollution Risk». Advanced Media Solutions, Inc. Oilprice.com. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ a b Kizuka, Tokushi (1 April 2008). «Atomic configuration and mechanical and electrical properties of stable gold wires of single-atom width» (PDF). Physical Review B. 77 (15): 155401. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..77o5401K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.155401. hdl:2241/99261. ISSN 1098-0121. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2021.

- ^ Che Lah, Nurul Akmal; Trigueros, Sonia (2019). «Synthesis and modelling of the mechanical properties of Ag, Au and Cu nanowires». Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 20 (1): 225–261. Bibcode:2019STAdM..20..225L. doi:10.1080/14686996.2019.1585145. PMC 6442207. PMID 30956731.

- ^ «Gold: causes of color». Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Mallan, Lloyd (1971). Suiting up for space: the evolution of the space suit. John Day Co. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-381-98150-1.

- ^ Gray, Theo (14 March 2008). «How to Make Convincing Fake-Gold Bars». Popular Science. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ Willie, Jim (18 November 2009) «Zinc Dimes, Tungsten Gold & Lost Respect Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine». Kitco

- ^ «Largest Private Refinery Discovers Gold-Plated Tungsten Bar | Coin Update». news.coinupdate.com.

- ^ «Austrians Seize False Gold Tied to London Bullion Theft». The New York Times. 22 December 1983. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Arblaster, J. W. (1995). «Osmium, the Densest Metal Known» (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 39 (4): 164. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.