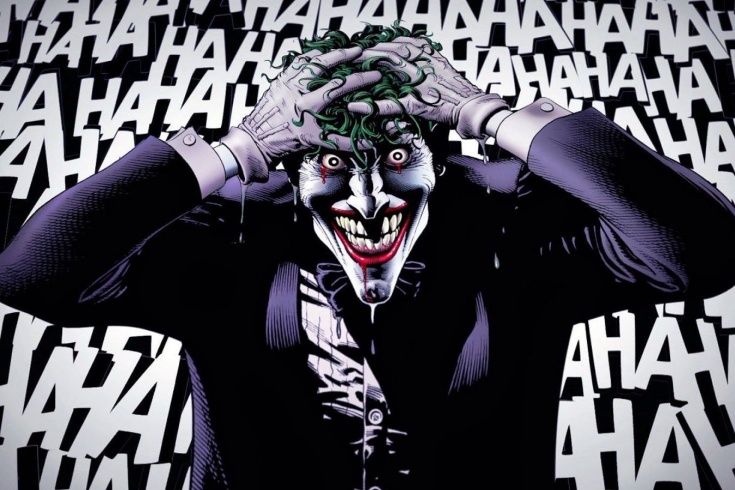

После многих лет танцев вокруг придания Джокеру какого-либо действительно окончательного происхождения, недавний комикс в продолжающейся серии небрежно упомянул это происхождение для фанатов вместе с оригинальным именем Джокера. Важность происхождения комиксов всегда была важна для их персонажей, но Джокер — это действительно особый случай.

Джокер — один из редких персонажей, который на самом деле существует не сам по себе, а скорее как фон для другого конкретного персонажа, а именно Бэтмена. С учетом того, насколько ужасающ он практически во всех аспектах, Джокер никогда не нуждался в предыстории, поскольку знание большего просто уменьшило бы это.

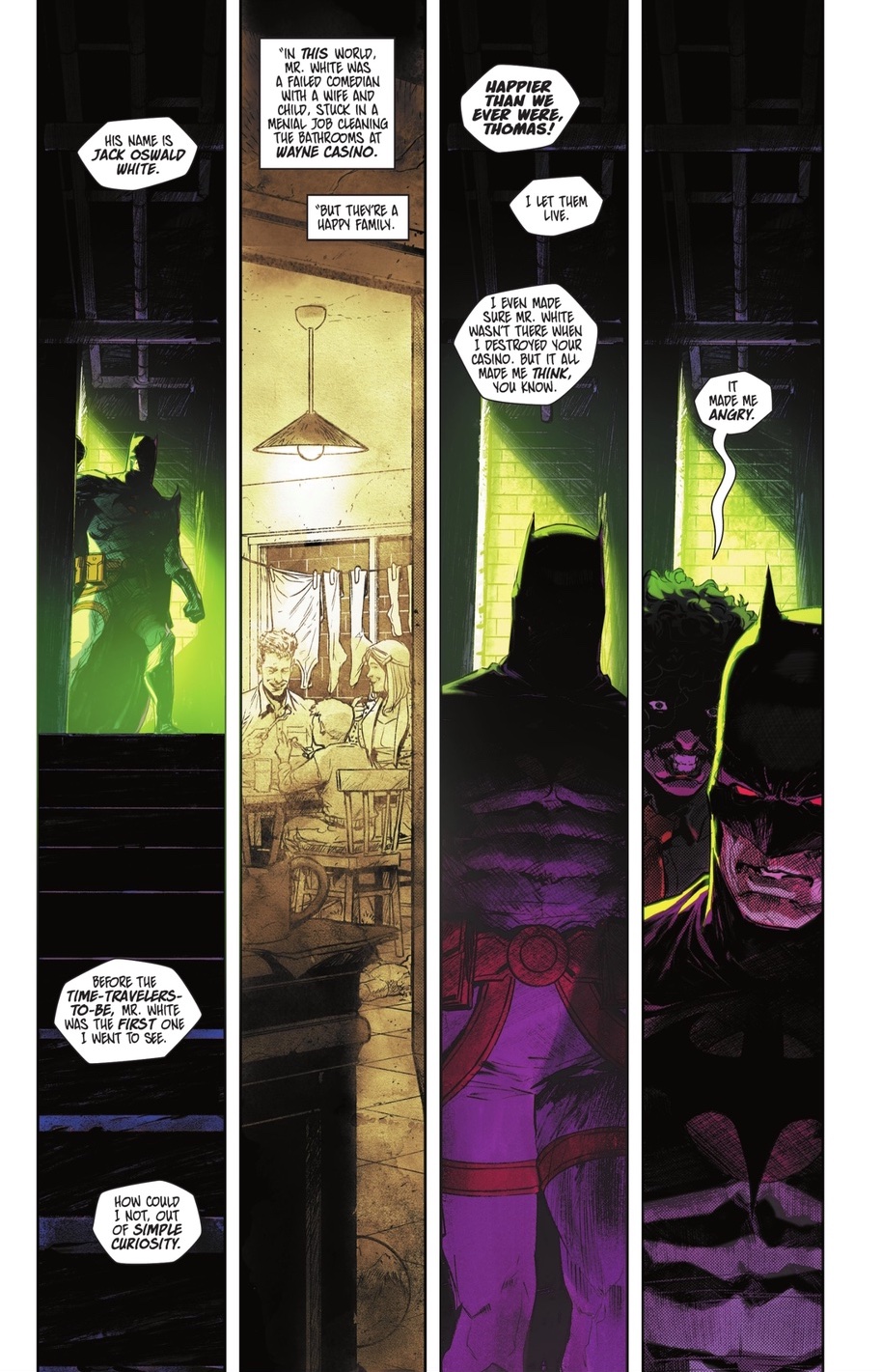

Вот почему предыстория Джокера остается расплывчатой и туманной, с множеством вариантов того, кем он является на самом деле. По словам самого Джокера в The Killing Joke, одной из самых важных историй о Джокере, когда-либо написанных, ему нравится сохранять свою предысторию как «множественный выбор». Последний выпуск Flashpoint Beyond, возможно, положил конец всему этому, поскольку было подтверждено, что имя Джокера — Джек Освальд Уайт.

Его имя происходит из нескольких мест. Джек был именем оригинальной личности Джокера в «Бэтмене» Тима Бертона, и на протяжении многих лет оно использовалось для других воплощений персонажа. Чтобы было ясно, эта конкретная история имеет дело с несколькими реальностями (или Землями), поэтому существует несколько Джокеров. Однако конкретно указано, что этот персонаж с Земли-0, изначальной реальности вселенной DC и оригиналов всех их героев.

Что же касается фактической предыстории Джека Освальда Уайта, то она довольно точно соответствует тому, что многие считают весьма вероятным его происхождением. Джек был комиком-неудачником, которому мир нанес слишком много ударов, что в конце концов свело его с ума. Это не так уж далеко от фильма «Джокер» 2019 года, и, поскольку на подходе «Джокер 2», это происхождение станет более заметным.

В конечном счете, эта информация, вероятно, не слишком сильно изменит того, кем является Джокер в большинстве историй, что, вероятно, хорошо. Джокер часто проявляет себя лучше всего, когда он прямо противостоит Бэтмену, поэтому отсутствие Джокера в Gotham Knights, вероятно, к лучшему.

«The Joker» redirects here. For other characters called Joker or other uses of «The Joker», see Joker.

| Joker | |

|---|---|

Promotional artwork for Batman: Three Jokers (2020), depicting the major incarnations of the Joker from the Golden Age (bottom) to the Silver Age (middle) to the Modern Age (top) by Jason Fabok. |

|

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| First appearance | Batman #1 (cover-dated spring 1940; published April 25, 1940)[1] |

| Created by |

|

| In-story information | |

| Team affiliations |

|

| Notable aliases | Red Hood[2] |

| Abilities |

|

The Joker is a supervillain appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson, and first appeared in the debut issue of the comic book Batman on April 25, 1940. Credit for the Joker’s creation is disputed; Kane and Robinson claimed responsibility for the Joker’s design while acknowledging Finger’s writing contribution. Although the Joker was planned to be killed off during his initial appearance, he was spared by editorial intervention, allowing the character to endure as the archenemy of the superhero Batman.

In his comic book appearances, the Joker is portrayed as a criminal mastermind. Introduced as a psychopath with a warped, sadistic sense of humor, the character became a goofy prankster in the late 1950s in response to regulation by the Comics Code Authority, before returning to his darker roots during the early 1970s. As Batman’s nemesis, the Joker has been part of the superhero’s defining stories, including the murder of Jason Todd—the second Robin and Batman’s ward—and the paralysis of one of Batman’s allies, Barbara Gordon. The Joker has had various possible origin stories during his decades of appearances. The most common story involves him falling into a tank of chemical waste that bleaches his skin white and turns his hair green and lips bright red; the resulting disfigurement drives him insane. The antithesis of Batman in personality and appearance, the Joker is considered by critics to be his perfect adversary.

The Joker possesses no superhuman abilities, instead using his expertise in chemical engineering to develop poisonous or lethal concoctions and thematic weaponry, including razor-tipped playing cards, deadly joy buzzers, and acid-spraying lapel flowers. The Joker sometimes works with other Gotham City supervillains, such as the Penguin and Two-Face, and groups like the Injustice Gang and Injustice League, but these relationships often collapse due to the Joker’s desire for unbridled chaos. The 1990s introduced a romantic interest for the Joker in his former psychiatrist, Harley Quinn, who became his criminal sidekick and girlfriend before finally escaping their abusive relationship. Although his primary obsession is Batman, the Joker has also fought other heroes, including Superman and Wonder Woman.

One of the most iconic characters in popular culture, the Joker has been listed among the greatest comic book villains and fictional characters ever created. The character’s popularity has seen him appear on a variety of merchandise, such as clothing and collectible items, inspire real-world structures (such as theme park attractions), and be referenced in a number of media. The Joker has been adapted in live-action, animated, and video game incarnations, including the 1960s Batman television series played by Cesar Romero and in films by Jack Nicholson in Batman (1989), Heath Ledger in The Dark Knight (2008), Jared Leto in the DC Extended Universe (2016–present), and Joaquin Phoenix in Joker (2019–present); Ledger and Phoenix each earned an Academy Award for their portrayals. Mark Hamill and others have provided the character’s voice in media ranging from animation to video games.

Creation and development

Concept

Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson are credited with creating the Joker, but their accounts of the character’s conception differ, each providing his own version of events. Finger’s, Kane’s, and Robinson’s versions acknowledge that Finger produced an image of actor Conrad Veidt in character as Gwynplaine (a man whose mouth is disfigured into a perpetual grin) in the 1928 film The Man Who Laughs as an inspiration for the Joker’s appearance, and Robinson produced a sketch of a joker playing card.[2][3]

Robinson stated that it was his 1940 card sketch that served as the character’s concept, and Finger associated that image with Veidt in the film.[2] Kane hired the 17-year-old Robinson as an assistant in 1939, after he saw Robinson in a white jacket decorated with his own illustrations.[4] Beginning as a letterer and background inker, Robinson quickly became primary artist for the newly created Batman comic book series. In a 1975 interview in The Amazing World of DC Comics, Robinson said he wanted a supreme arch-villain who could test Batman, not a typical crime lord or gangster designed to be easily disposed of. He wanted an exotic, enduring character as an ongoing source of conflict for Batman (similar to the relationship between Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty), designing a diabolically sinister, but clownish, villain.[5][6][7] Robinson was intrigued by villains; he believed that some characters are made up of contradictions, leading to the Joker’s sense of humor. He said that the name came first, followed by an image of a playing card from a deck he often had at hand: «I wanted somebody visually exciting. I wanted somebody that would make an indelible impression, would be bizarre, would be memorable like the Hunchback of Notre Dame or any other villains that had unique physical characters.»[8] He told Finger about his concept by telephone, later providing sketches of the character and images of what would become his iconic Joker playing-card design. Finger thought the concept was incomplete, providing the image of Veidt with a ghastly, permanent rictus grin.[5]

Kane countered that Robinson’s sketch was produced only after Finger had already shown the Gwynplaine image to Kane, and that it was only used as a card design belonging to the Joker in his early appearances.[3] Finger said that he was also inspired by the Steeplechase Face, an image in Steeplechase Park at Coney Island that resembled a Joker’s head, which he sketched and later shared with future editorial director Carmine Infantino.[9] In a 1994 interview with journalist Frank Lovece, Kane stated his position:

Bill Finger and I created the Joker. Bill was the writer. Jerry Robinson came to me with a playing card of the Joker. That’s the way I sum it up. [The Joker] looks like Conrad Veidt – you know, the actor in The Man Who Laughs, [the 1928 movie based on the novel] by Victor Hugo. … Bill Finger had a book with a photograph of Conrad Veidt and showed it to me and said, ‘Here’s the Joker.’ Jerry Robinson had absolutely nothing to do with it, but he’ll always say he created it till he dies. He brought in a playing card, which we used for a couple of issues for him [the Joker] to use as his playing card.[10][11]

Robinson credited himself, Finger, and Kane for the Joker’s creation. He said he created the character as Batman’s larger-than-life nemesis when extra stories were quickly needed for Batman #1, and he received credit for the story in a college course:[12]

In that first meeting when I showed them that sketch of the Joker, Bill said it reminded him of Conrad Veidt in The Man Who Laughs. That was the first mention of it … He can be credited and Bob himself, we all played a role in it. The concept was mine. Bill finished that first script from my outline of the persona and what should happen in the first story. He wrote the script of that, so he really was co-creator, and Bob and I did the visuals, so Bob was also.[13]

Finger provided his own account in 1966:

I got a call from Bob Kane…. He had a new villain. When I arrived he was holding a playing card. Apparently Jerry Robinson or Bob, I don’t recall who, looked at the card and they had an idea for a character … the Joker. Bob made a rough sketch of it. At first it didn’t look much like the Joker. It looked more like a clown. But I remembered that Grosset & Dunlap formerly issued very cheap editions of classics by Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo … The volume I had was The Man Who Laughs — his face had been permanently operated on so that he will always have this perpetual grin. And it looked absolutely weird. I cut the picture out of the book and gave it to Bob, who drew the profile and gave it a more sinister aspect. Then he worked on the face; made him look a little clown-like, which accounted for his white face, red lips, green hair. And that was the Joker![14]

Although Kane adamantly refused to share credit for many of his characters, and refuted Robinson’s claim for the rest of his life, many comic historians credit Robinson with the Joker’s creation and Finger with the character’s development.[2][3][4][9] By 2011, Finger, Kane, and Robinson had died, leaving the story unresolved.[5][9][15]

Golden Age

From the Joker’s debut in Batman #1 (April 25, 1940)

The Joker debuted in Batman #1 (April 1940) as the eponymous character’s first villain, about a year after Batman’s debut in Detective Comics #27 (May 1939). The Joker initially appeared as a remorseless serial killer and jewel thief, modeled after a joker playing card with a mirthless grin, who killed his victims with «Joker venom,» a toxin that left their faces smiling grotesquely.[16] The character was intended to be killed in his second appearance in Batman #1, after being stabbed in the heart. Finger wanted the Joker to die because of his concern that recurring villains would make Batman appear inept, but was overruled by then-editor Whitney Ellsworth; a hastily drawn panel, indicating that the Joker was still alive, was added to the comic.[2][17][18] The Joker went on to appear in nine of Batman‘s first 12 issues.[19]

The character’s regular appearances quickly defined him as the archenemy of the Dynamic Duo, Batman and Robin; he killed dozens of people, and even derailed a train.[20] By issue #13, Kane’s work on the syndicated Batman newspaper strip left him little time for the comic book; artist Dick Sprang assumed his duties, and editor Jack Schiff collaborated with Finger on stories. Around the same time, DC Comics found it easier to market its stories to children without the more mature pulp elements that had originated many superhero comics. During this period, the first changes in the Joker began to appear, portraying him as a wacky but harmless prankster; in one story, the Joker kidnaps Robin and Batman pays the ransom by check, meaning that the Joker cannot cash it without being arrested.[21] Comic book writer Mark Waid suggests that the 1942 story «The Joker Walks the Last Mile» was the beginning point for the character’s transformation into a more goofy incarnation, a period that Grant Morrison considered to have lasted the following 30 years.[22]

The 1942 cover of Detective Comics #69, known as «Double Guns» (with the Joker emerging from a genie’s lamp, aiming two guns at Batman and Robin), is considered one of the greatest superhero comic covers of the Golden Age and is the only image from that era of the character using traditional guns. Robinson said that other contemporary villains used guns, and the creative team wanted the Joker—as Batman’s adversary—to be more resourceful.[23][24]

Silver Age

The Joker was one of the few popular villains continuing to appear regularly in Batman comics from the Golden Age into the Silver Age, as the series continued during the rise in popularity of mystery and romance comics. In 1951, Finger wrote an origin story for the Joker in Detective Comics #168, which introduced the characteristic of him formerly being the criminal Red Hood, and his disfigurement the result of a fall into a chemical vat.[25]

By 1954, the Comics Code Authority had been established in response to increasing public disapproval of comic book content. The backlash was inspired by Frederic Wertham, who hypothesized that mass media (especially comic books) was responsible for the rise in juvenile delinquency, violence and homosexuality, particularly in young males. Parents forbade their children from reading comic books, and there were several mass burnings.[2] The Comics Code banned gore, innuendo and excessive violence, stripping Batman of his menace and transforming the Joker into a goofy, thieving trickster without his original homicidal tendencies.[17][26]

The character appeared less frequently after 1964, when Julius Schwartz (who disliked the Joker) became editor of the Batman comics.[2][17][27] The character risked becoming an obscure figure of the preceding era until this goofy prankster version of the character was adapted into the 1966 television series Batman, in which he was played by Cesar Romero.[2][17] The show’s popularity compelled Schwartz to keep the comics in a similar vein. As the show’s popularity waned, however, so did that of the Batman comics.[2][27] After the TV series ended in 1969, the increase in public visibility had not stopped the comic’s sales decline; editorial director Carmine Infantino resolved to turn things around, moving stories away from child-friendly adventures.[28] The Silver Age introduced several of the Joker’s defining character traits: lethal joy buzzers, acid-squirting flowers, trick guns, and goofy, elaborate crimes.[29][30]

Bronze Age

Cover of Batman #251 (September 1973) featuring «The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge», which returned the Joker to his homicidal roots. Art by Neal Adams.

In 1973, after a four-year disappearance,[2] the Joker was revived (and revised) by writer Dennis O’Neil and artist Neal Adams. Beginning with Batman #251’s «The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge», the character returns to his roots as an impulsive, homicidal maniac who matches wits with Batman.[31][32] This story began a trend in which the Joker was used, sparingly, as a central character.[33] O’Neil said his idea was «simply to take it back to where it started. I went to the DC library and read some of the early stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane and Finger were after.»[34] O’Neil’s 1973 run introduced the idea of the Joker being legally insane, to explain why the character is sent to Arkham Asylum (introduced by O’Neil in 1974 as Arkham Hospital) instead of to prison.[35] Adams modified the Joker’s appearance, changing his more average figure by extending his jaw and making him taller and leaner.[36]

DC Comics was a hotbed of experimentation during the 1970s, and in 1975 the character became the first villain to feature as the title character in a comic book series, The Joker.[37] The series followed the character’s interactions with other supervillains, and the first issue was written by O’Neil.[38] Stories balanced between emphasizing the Joker’s criminality and making him a likable protagonist whom readers could support. Although he murdered thugs and civilians, he never fought Batman; this made The Joker a series in which the character’s villainy prevailed over rival villains, instead of a struggle between good and evil.[39] Because the Comics Code Authority mandated punishment for villains, each issue ended with the Joker being apprehended, limiting the scope of each story. The series never found an audience, and The Joker was canceled after nine issues (despite a «next issue» advertisement for an appearance by the Justice League).[38][39][40] The complete series became difficult to obtain over time, often commanding high prices from collectors. In 2013, DC Comics reissued the series as a trade paperback.[41]

When Jenette Kahn became DC editor in 1976, she redeveloped the company’s struggling titles; during her tenure, the Joker would become one of DC’s most popular characters.[39] While O’Neil and Adams’ work was critically acclaimed, writer Steve Englehart and penciller Marshall Rogers’s eight-issue run in Detective Comics #471–476 (August 1977–April 1978) defined the Joker for decades to come[31] with stories emphasizing the character’s insanity. In «The Laughing Fish», the Joker disfigures fish with a rictus grin resembling his own (expecting copyright protection), and is unable to understand that copyrighting a natural resource is legally impossible.[32][35][42][43] Englehart’s and Rogers’ work on the series influenced the 1989 film Batman, and was adapted for 1992’s Batman: The Animated Series.[35][44] Rogers expanded on Adams’ character design, drawing the Joker with a fedora and trench coat.[36] Englehart outlined how he understood the character by saying that the Joker «was this very crazy, scary character. I really wanted to get back to the idea of Batman fighting insane murderers at 3 a.m. under the full moon, as the clouds scuttled by.»[17]

Modern Age

Years after the end of the 1966 television series, sales of Batman continued to fall and the title was nearly cancelled. Although the 1970s restored the Joker as Batman’s insane, lethal archenemy, it was during the 1980s that the Batman series started to turn around and the Joker came into his own as part of the «Dark Age» of comics, with mature tales of death and destruction. The shift was criticized for moving away from tamer superheroes (and villains), but comic audiences were no longer primarily children.[45][31] Several months after Crisis on Infinite Earths launched the era by killing off Silver Age icons such as the Flash and Supergirl and undoing decades of continuity,[46] Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns (1986) re-imagined Batman as an older, retired hero[47] and the Joker as a lipstick-wearing celebrity[36][48] who cannot function without his foe.[49] The late 1980s saw the Joker exert a significant impact on Batman and his supporting cast. In the 1988–89 story arc «A Death in the Family», the Joker murders Batman’s sidekick (the second Robin, Jason Todd). Todd was unpopular with fans; rather than modify his character, DC opted to let them vote for his fate and a 72-vote plurality had the Joker beat Todd to death with a crowbar. This story altered the Batman universe: instead of killing anonymous bystanders, the Joker murdered a core character; this had a lasting effect on future stories.[50][51] Written at the height of tensions between the United States and Iran, the story’s conclusion had Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini appoint the Joker his country’s ambassador to the United Nations (allowing him to temporarily escape justice).[52]

Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s 1988 graphic novel The Killing Joke expands on the Joker’s origins, describing the character as a failed comedian who adopts the identity of the Red Hood to support his pregnant wife.[25][53] Unlike The Dark Knight Returns, The Killing Joke takes place in mainstream continuity.[54] The novel is described by critics as one of the greatest Joker stories ever written, influencing later comic stories (including the forced retirement of then-Batgirl, Barbara Gordon, after she is paralyzed by the Joker) and films such as 1989’s Batman and 2008’s The Dark Knight.[55][56][57] Grant Morrison’s 1989 Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth explores the psychoses of Batman, the Joker and other rogues in the eponymous facility.[58][59]

The 1992 animated series introduced the Joker’s female sidekick: Harley Quinn, a psychiatrist who falls for—and ends up in an abusive relationship with—the Joker, becoming his supervillain accomplice. The character was popular, and was adapted into the comics as the Joker’s romantic interest in 1999.[60] In the same year, Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle’s comic book Anarky concluded with the revelation that the titular character was the Joker’s son. Breyfogle conceived the idea as a means to expand on Anarky’s characterization, but O’Neil (by then the editor for the Batman series of books) was opposed to it, and only allowed it to be written under protest, and with a promise that the revelation would eventually be revealed incorrect. However, the Anarky series was cancelled before the rebuttal could be published.[61] The Joker’s first major storyline in The New 52, DC Comics’ 2011 reboot of story continuity, was 2012’s «Death of the Family» by writer Scott Snyder and artist Greg Capullo. The story arc explores the symbiotic relationship between the Joker and Batman, and sees the villain shatter the trust between Batman and his adopted family.[19][62] Capullo’s Joker design replaced his traditional outfit with a utilitarian, messy, and disheveled appearance to convey that the character was on a mission; his face (surgically removed in 2011’s Detective Comics (vol. 2) #1) was reattached with belts, wires, and hooks, and he was outfitted with mechanics overalls.[63] The Joker’s face was restored in Snyder’s and Capullo’s «Endgame» (2014), the concluding chapter to «Death of the Family».[64][65]

The conclusion of the 2020 «Joker War» storyline by writer James Tynion IV and artist Jorge Jiménez sees the Joker leave Gotham after Batman chooses to let him die.[66] This led to a second ongoing Joker series, beginning in March 2021 with Tynion writing and Guillem March providing art.[67]

Character biography

The Joker has undergone many revisions since his 1940 debut. The most common interpretation of the character is that of a man who, while disguised as the criminal Red Hood, is pursued by Batman and falls into a vat of chemicals that bleaches his skin, colors his hair green and his lips red, and drives him insane. The reasons why the Joker was disguised as the Red Hood and his identity before his transformation have changed over time.[17]

The character was introduced in Batman #1 (1940), in which he announces that he will kill three of Gotham’s prominent citizens. Although the police protect his first announced victim, millionaire Henry Claridge, the Joker had poisoned him before making his announcement and Claridge dies with a ghastly grin on his face. Batman eventually defeats him, sending him to prison.[68] The Joker commits crimes ranging from whimsical to brutal, for reasons that, in Batman’s words, «make sense to him alone».[42] Detective Comics #168 (1951) introduced the Joker’s first origin story as the former Red Hood: a masked criminal who, during his final heist, vanished after leaping into a vat of chemicals to escape Batman. His resulting disfigurement drove him insane and led him to adopt the name «Joker», from the playing card figure he came to resemble.[25] The Joker’s Silver Age transformation into a figure of fun was established in 1952’s «The Joker’s Millions». In this story, the Joker is obsessed with maintaining his illusion of wealth and celebrity as a criminal folk hero, afraid to let Gotham’s citizens know that he is penniless and was tricked out of his fortune.[69] The 1970s redefined the character as a homicidal sociopath. «The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge» has the Joker taking violent revenge on the former gang members who betrayed him,[33] while «The Laughing Fish» portrays him chemically disfiguring fish so they will share his trademark grin, hoping to profit from a copyright, and killing bureaucrats who stand in his way.[32]

The Killing Joke author Alan Moore in 2008. The novel has been described as the greatest Joker story ever told.[55][56][57]

Batman: The Killing Joke (1988) built on the Joker’s 1951 origin story, portraying him as a failed comedian who participates in a robbery as the Red Hood to support his pregnant wife. Batman arrives to stop the robbery, provoking the terrified comedian into jumping into a vat of chemicals, which dyes his skin chalk-white, his hair green, and his lips bright red. His disfigurement, combined with the trauma of his wife’s earlier accidental death, drives him insane, and results in the birth of the Joker.[25] However, the Joker says that this story may not be true; he admits that he does not remember exactly what drove him insane, and says that he prefers his past to be «multiple choice».[70] In this graphic novel, the Joker shoots and paralyzes Barbara Gordon, the former Batgirl, and tortures her father, Commissioner James Gordon, to prove that it only takes «one bad day» to drive a normal man insane.[54] After Batman rescues Gordon and subdues the Joker, he offers to rehabilitate his old foe and end their rivalry. Although the Joker refuses, he shows his appreciation by sharing a joke with Batman.[71] Following the character’s maiming of Barbara, she became a more important character in the DC Universe: the Oracle, a data gatherer and superhero informant, who has her revenge in Birds of Prey by shattering the Joker’s teeth and destroying his smile.[54]

In the 1988 story «A Death in the Family», the Joker beats Jason Todd, the second Robin, with a crowbar and leaves him to die in an explosion. Todd’s death haunts Batman, and for the first time he seriously considers killing the Joker.[50] The Joker temporarily escapes justice when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini appoints him the Iranian ambassador to the United Nations, giving him diplomatic immunity; however, when he tries to poison the U.N. membership, he is defeated by Batman and Superman.[31]

In the 1999 «No Man’s Land» storyline, the Joker murders Commissioner Gordon’s second wife, Sarah, as she shields a group of infants.[72] He taunts Gordon, who shoots him in the kneecap. The Joker, lamenting that he may never walk again, collapses with laughter when he realizes that the commissioner has avenged Barbara’s paralysis.[73]

The 2000s began with the crossover story «Emperor Joker», in which the Joker steals Mister Mxyzptlk’s reality-altering power and remakes the universe in his image (torturing and killing Batman daily, before resurrecting him). When the supervillain then tries to destroy the universe, his reluctance to eliminate Batman makes him lose control, and Superman defeats him.[74] Broken by his experience, Batman’s experiences of death are transferred to Superman by the Spectre so he can heal mentally.[75] In Joker: Last Laugh (2001), the doctors at Arkham Asylum convince the character that he is dying in an attempt to rehabilitate him. Instead, the Joker (flanked by an army of «Jokerized» supervillains) launches a final crime spree. Believing that Robin (Tim Drake) has been killed in the chaos, Dick Grayson beats the Joker to death (although Batman revives his foe to keep Grayson from becoming a murderer), and the villain succeeds in making a member of the Bat-family break their rule against killing.[31][68]

In «Under the Hood» (2005), a resurrected Todd tries to force Batman to avenge his death by killing the Joker. Batman refuses, arguing that if he allowed himself to kill the Joker, he would not be able to stop himself from killing other criminals.[76] The Joker kills Alexander Luthor, Jr. in Infinite Crisis (2005) for excluding him from the Secret Society of Super Villains, which considers him too unpredictable for membership.[77][78] In Morrison’s «Batman and Son» (2006), a deranged police officer who impersonates Batman shoots the Joker in the face, scarring and disabling him. The supervillain returns in «The Clown at Midnight» (2007) as an enigmatic force who awakens and tries to kill Harley Quinn to prove to Batman that he has become more than human.[79][31] In the 2008 story arc «Batman R.I.P.» the Joker is recruited by the Black Glove to destroy Batman, but betrays the group, killing its members one by one.[68] After Batman’s apparent death in Final Crisis (2008), Grayson investigates a series of murders (which leads him to a disguised Joker).[80] The Joker is arrested, and then-Robin Damian Wayne beats him with a crowbar, paralleling Todd’s murder. When the Joker escapes, he attacks the Black Glove, burying its leader Simon Hurt alive after the supervillain considers him a failure as an opponent; the Joker is then defeated by the recently returned Batman.[81][82][83]

In DC’s The New 52, a 2011 relaunch of its titles following Flashpoint, the Joker has his own face cut off.[84] He disappears for a year, returning to launch an attack on Batman’s extended family in «Death of the Family» so he and Batman can be the best hero and villain they can be.[85] At the end of the storyline, the Joker falls off a cliff into a dark abyss.[85][86] The Joker returns in the 2014 storyline «Endgame» in which he brainwashes the Justice League into attacking Batman, believing he has betrayed their relationship.[87][88] The story implies that the Joker is immortal—having existed for centuries in Gotham as a cause of tragedy after exposure to a substance the Joker terms «dionesium»—and is able to regenerate from mortal injuries. «Endgame» restores the Joker’s face, and also reveals that he knows Batman’s secret identity.[64] The story ends with the apparent deaths of Batman and the Joker at each other’s hands, though it is revealed that they were both resurrected in a life-restoring Lazarus Pit, without their memories.[65][89]

During the «Darkseid War» (2015–2016) storyline, Batman uses Metron’s Mobius Chair to find out the Joker’s real name; the chair’s answer leaves Batman in disbelief. In the DC Universe: Rebirth (2016) one-shot, Batman informs Hal Jordan that the chair told him there were three individual Jokers, not just one.[90] This revelation was the basis for the miniseries Batman: Three Jokers (2020), written by Geoff Johns with art by Jason Fabok. Three Jokers reveals that the three Jokers, who work in tandem, include «The Criminal», a methodical mastermind based on the Golden Age Joker; «The Clown», a goofy prankster based on the Silver Age Joker; and «The Comedian», a psychopathic killer based on the Modern Age Joker.[91] The Comedian orchestrates the deaths of the other two Jokers and reveals himself as the original. The miniseries ends with the revelation that Batman knows the Joker’s true identity.[92]

Origins

«They’ve given many origins of the Joker, how he came to be. That doesn’t seem to matter—just how he is now. I never intended to give a reason for his appearance. We discussed that and Bill [Finger] and I never wanted to change it at that time. I thought—and he agreed—that it takes away some of the essential mystery.»

– Jerry Robinson, the Joker’s creator[93]

Although a number of backstories have been given, a definitive one has never been established for the Joker. An unreliable narrator, the character is uncertain of who he was before and how he became the Joker: «Sometimes I remember it one way, sometimes another …if I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!»[6][70] A story about the Joker’s origin appeared in Detective Comics #168 (February 1951), more than decade after the character’s debut. Here, the character is a laboratory worker who becomes the Red Hood (a masked criminal) to steal $1 million and retire. He falls into a vat of chemical waste when his heist is thwarted by Batman, emerging with bleached white skin, red lips, green hair and a permanent grin.[94][95]

This story was the basis for the most often-cited origin tale, Moore’s one-shot The Killing Joke.[56] The man who will become the Joker quits his job as a lab assistant in order to fulfill his dream of being a stand-up comedian, only to fail miserably. Desperate to support his pregnant wife, he agrees to help two criminals commit a robbery as the Red Hood. The heist goes awry; the comedian leaps into a chemical vat to escape Batman, surfacing disfigured. This, combined with the earlier accidental death of his wife and unborn child, drives the comedian insane, turning him into the Joker.[25][31] This version has been cited in many stories, including Batman: The Man Who Laughs (in which Batman deduces that the Red Hood survived his fall and became the Joker), Batman #450 (in which the Joker dons the Red Hood to aid his recovery after the events in «A Death in the Family», but finds the experience too traumatic), Batman: Shadow of the Bat #38 (in which Joker’s failed stand-up performance is shown), «Death of the Family»,[95] and Batman: Three Jokers (which asserts that it is the canon origin story).[96] Other stories have expanded on this origin; «Pushback» suggests that the Joker’s wife was murdered by a corrupt policeman working for the mobsters,[97] and «Payback» gives the Joker’s first name as «Jack».[95] The ending of Batman: Three Jokers establishes that the Joker’s wife did not actually die—rather, she fled to Alaska with the help of Gotham police and Batman because she feared her husband would be an abusive father; the police then told the Joker a story about her dying to protect her. The miniseries also reveals that Batman knows the Joker’s identity, and has kept it secret in order to protect the criminal’s wife and son.[96]

However, the Joker’s unreliable memory has allowed writers to develop other origins for the character.[95] «Case Study», a Paul Dini-Alex Ross story, describes the Joker as a sadistic gangster who creates the Red Hood identity because he misses the thrill of committing robberies. He has his fateful first meeting with Batman, which results in his disfigurement. It is suggested that the Joker is sane, and researches his crimes to look like the work of a sick mind in order to avoid the death penalty. In Batman Confidential #7–12, the character, Jack, is a career criminal who is bored with his work. He encounters (and becomes obsessed with) Batman during a heist, embarking on a crime spree to attract the Caped Crusader’s attention. After Jack injures Batman’s girlfriend, Batman scars Jack’s face with a permanent grin and betrays him to a group of mobsters, who torture him in a chemical plant. Jack escapes, but falls into an empty vat as gunfire punctures chemical tanks above him. The flood of chemicals (used in anti-psychotic medication) alters his appearance and completes his transformation.[98] In The Brave and the Bold #31, the superhero Atom enters the Joker’s mind and sees the criminal’s former self — a violent sociopath who tortures animals, murders his own parents, and kills for fun while committing robberies.[99] Snyder’s «Zero Year» (2013) suggests that the pre-disfigured Joker was a criminal mastermind leading a gang of Red Hoods.[87][100]

The Joker has claimed a number of origins, including being the child of an abusive father who broke his nose, and the long-lived jester of an Egyptian pharaoh. As Batman says: «Like any other comedian, he uses whatever material will work.»[101]

Alternative versions

A number of alternate universes in DC Comics publications allow writers to introduce variations on the Joker, in which the character’s origins, behavior, and morality differ from the mainstream setting.[102] The Dark Knight Returns depicts the final battle between an aged Batman and Joker; others portray the aftermath of the Joker’s death at the hands of a number of characters, including Superman.[74][103] Still others describe distant futures in which the Joker is a computer virus or a hero trying to defeat the era’s tyrannical Batman.[104] In some stories, the Joker is someone else entirely; Flashpoint portrays Batman’s mother Martha Wayne becoming the Joker after being driven mad by her son’s murder,[105] and in Superman: Speeding Bullets, Lex Luthor becomes the Joker in a world where Superman is Batman.[106]

Characterization

Renowned as Batman’s greatest enemy,[107][108][109][110] the Joker is known by a number of nicknames, including the Clown Prince of Crime, the Harlequin of Hate, the Ace of Knaves, and the Jester of Genocide.[109][111] During the evolution of the DC Universe, interpretations and versions of the Joker have taken two main forms. The original, dominant image is that of a psychopath[112] with genius-level intelligence and a warped, sadistic sense of humor.[113][114] The other version, popular in comic books from the late 1940s to the 1960s and in the 1960s television series, is an eccentric, harmless prankster and thief.[115] Like other long-lived characters, the Joker’s character and cultural interpretations have changed with time; however, unlike other characters who may need to reconcile or ignore previous versions to make sense, more than any other comic book character, the Joker thrives on his mutable and irreconcilable identities.[116] The Joker is typically seen in a purple suit with a long-tailed, padded-shoulder jacket, a string tie, gloves, striped pants and spats on pointed-toe shoes (sometimes with a wide-brimmed hat). This appearance is such a fundamental aspect of the character that when the 2004 animated series The Batman placed the Joker in a straitjacket, it quickly redesigned him in his familiar suit.[115]

The Joker is obsessed with Batman, the pair representing a yin-yang of opposing dark and light force; although it is the Joker who represents humor and color and Batman who dwells in the dark.[117] No crime – including murder, theft, and terrorism – is beyond the Joker, and his exploits are theatrical performances that are funny to him alone. Spectacle is more important than success for the Joker, and if it is not spectacular it is boring.[118] Although the Joker claims indifference to everything, he secretly craves Batman’s attention and validation.[119][32] The character was described as having killed over 2,000 people in The Joker: Devil’s Advocate (1996). Despite this body count, he is always found not guilty by reason of insanity and sent to Arkham Asylum, avoiding the death penalty.[120][121] Many of the Joker’s acts attempt to force Batman to kill; to the Joker, the greatest victory would be to make Batman become like him. The Joker displays no instinct for self-preservation, and is willing to die to prove his point that anyone could become like him after «one bad day».[122] The Joker is the «personification of the irrational,» and represents «everything Batman [opposes].»[123]

Personality

Joker co-creator Jerry Robinson in 2008; he conceived the Joker as an exotic, enduring archvillain who could repeatedly challenge Batman

The Joker’s main characteristic is his apparent insanity, although he is not described as having any particular psychological disorder. Like a psychopath, he lacks empathy, a conscience, and concern over right and wrong. In Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, the Joker is described as capable of processing outside sensory information only by adapting to it. This enables him to create a new personality every day (depending on what would benefit him) and explains why, at different times, he is a mischievous clown or a psychopathic killer.[124] In «The Clown at Midnight» (Batman #663 (April 2007)), the Joker enters a meditative state where he evaluates his previous selves to consciously create a new personality, effectively modifying himself for his needs.[125]

The Killing Joke (in which the Joker is the unreliable narrator) explains the roots of his insanity as «one bad day»: losing his wife and unborn child and being disfigured by chemicals, paralleling Batman’s origin in the loss of his parents. He tries (and fails) to prove that anyone can become like him after one bad day by torturing Commissioner Gordon, physically and psychologically.[29][54] Batman offers to rehabilitate his foe; the Joker apologetically declines, believing it too late for him to be saved.[71] Other interpretations show that the Joker is fully aware of how his actions affect others and that his insanity as merely an act.[117] Comics scholar Peter Coogan describes the Joker as trying to reshape reality to fit himself by imposing his face on his victims (and fish) in an attempt to make the world comprehensible by creating a twisted parody of himself. Englehart’s «The Laughing Fish» demonstrates the character’s illogical nature: trying to copyright fish that bear his face, and not understanding why threatening the copyright clerk cannot produce the desired result.[35][126]

The Joker is alternatively depicted as sexual and asexual.[127] In The Dark Knight Returns and Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, the Joker is seductive toward Batman; it is uncertain if their relationship has homoerotic undertones or if the Joker is simply trying to manipulate his nemesis. Frank Miller interpreted the character as fixated on death and uninterested in sexual relationships, while Robinson believed that the Joker is capable of a romantic relationship.[127] His relationship with Harley Quinn is abusively paradoxical; although the Joker keeps her at his side, he heedlessly harms her (for example, throwing her out a window without seeing if she survives). Harley loves him, but the Joker does not reciprocate her feelings, chiding her for distracting him from other plans.[128]

Snyder’s «Death of the Family» describes the Joker as in love with Batman, although not in a traditionally romantic way. The Joker believes that Batman has not killed him because he makes Batman better and he loves the villain for that.[62][129] Batman comic book writer Peter Tomasi concurred, stating that the Joker’s main goal is to make Batman the best that he can be.[130] The Joker and Batman represent opposites: the extroverted Joker wears colorful clothing and embraces chaos, while the introverted, monochromatic Batman represents order and discipline. The Joker is often depicted as defining his existence through his conflict with Batman. In 1994’s «Going Sane», the villain tries to lead a normal life after Batman’s (apparent) death, only to become his old self again when Batman reappears; in «Emperor Joker», an apparently omnipotent Joker cannot destroy Batman without undoing himself. Since the Joker is simply «the Joker», he believes that Batman is «Batman» (with or without the costume) and has no interest in what is behind Batman’s mask, ignoring opportunities to learn Batman’s secret identity.[74][131] Given the opportunity to kill Batman, the villain demurs; he believes that without their game, winning is pointless.[119] The character has no desire for typical criminal goals like money or power; his criminality is designed only to continue his game with Batman.[84]

The Joker is portrayed as having no fear; when fellow supervillain Scarecrow doses him with fear toxin in Knightfall (1993), the Joker merely laughs and says «Boo!»[132] The villain has been temporarily rendered sane by several means, including telepathic manipulation by the Martian Manhunter[71] and being resurrected in a Lazarus Pit (an experience typically inducing temporary insanity in the subject). At these moments, the Joker is depicted as expressing remorse for his crimes;[133][134] however, during a medically induced period of partial sanity in Batman: Cacophony, he tells Batman, «I don’t hate you ’cause I’m crazy. I’m crazy ’cause I hate you,» and confirms that he will only stop killing when Batman is dead.[135][136]

Skills and equipment

The Joker’s lapel often holds an acid-spraying flower

The Joker has no inherent superhuman abilities.[137] He commits crimes with a variety of weaponized thematic props such as a deck of razor-tipped playing cards, rolling marbles, jack-in-the-boxes with unpleasant surprises and exploding cigars capable of leveling a building. The flower in his lapel sprays acid, and his hand often holds a lethal joy buzzer conducting a million volts of electricity, although both items were introduced in 1952 as harmless joke items.[30][138] However, his chemical genius provides his most-notable weapon: Joker venom, a liquid or gaseous toxin that sends its targets into fits of uncontrollable laughter; higher doses can lead to paralysis, coma or death, leaving its victim with a ghoulish, pained rictus grin. The Joker has used venom since his debut; only he knows the formula, and is shown to be gifted enough to manufacture the toxin from ordinary household chemicals. Another version of the venom (used in Joker: Last Laugh) makes its victims resemble the Joker, susceptible to his orders.[32][68][139][140] The villain is immune to venom and most poisons; in Batman #663 (April 2007), Morrison writes that being «an avid consumer of his own chemical experiments, the Joker’s immunity to poison concoctions that might kill another man in an instant has been developed over years of dedicated abuse.»[141][115]

The character’s arsenal is inspired by his nemesis’ weaponry, such as batarangs. In «The Joker’s Utility Belt» (1952), he mimicked Batman’s utility belt with non-lethal items, such as Mexican jumping beans and sneezing powder.[138] In 1942’s «The Joker Follows Suit», the villain built his versions of the Batplane and Batmobile, the Jokergyro and Jokermobile (the latter with a large Joker face on its hood), and created a Joker-signal with which criminals could summon him for their heists.[142] The Jokermobile lasted for several decades, evolving with the Batmobile. His technical genius is not limited by practicality, allowing him to hijack Gotham’s television airwaves to issue threats, transform buildings into death traps, launch a gas attack on the city and rain poisoned glass shards on its citizens from an airship.[143][144]

The Joker is portrayed as skilled in melee combat, from his initial appearances when he defeats Batman in a sword fight (nearly killing him), and others when he overwhelms Batman but declines to kill him.[145] He is talented with firearms, although even his guns are theatrical; his long-barreled revolver often releases a flag reading «Bang», and a second trigger-pull launches the flag to skewer its target.[138][146] Although formidable in combat, the Joker’s chief asset is his mind.[104]

Relationships

The Joker’s unpredictable, homicidal nature makes him one of the most feared supervillains in the DC Universe; the Trickster says in the 1995 miniseries Underworld Unleashed, «When super-villains want to scare each other, they tell Joker stories.»[148] Gotham’s villains also feel threatened by the character; depending on the circumstances, he is as likely to fight with his rivals for control of the city as he is to join them for an entertaining outcome.[149] The Joker interacts with other supervillains who oppose Batman, whether he is on the streets or in Arkham Asylum. He has collaborated with criminals like the Penguin, the Riddler, and Two-Face, although these partnerships rarely end well due to the Joker’s desire for unbridled chaos, and he uses his stature to lead others (such as Killer Croc and the Scarecrow).[150] The Joker’s greatest rival is the smartest man in the world, Lex Luthor. Although they have a friendly partnership in 1950’s World’s Finest Comics #88, later unions emphasized their mutual hostility and clashing egos.[151]

Despite his tendency to kill subordinates on a whim, the Joker has no difficulty attracting henchmen with a seemingly infinite cash supply and intimidation; they are too afraid of their employer to refuse his demands that they wear red clown noses or laugh at his macabre jokes.[143] Even with his unpredictability and lack of superhuman powers, the 2007 limited series Salvation Run sees hundreds of villains fall under his spell because they are more afraid of him than the alternative: Luthor.[152] Batman #186 (1966) introduced the Joker’s first sidekick: the one-shot character Gaggy Gagsworthy, who is short and dressed like a clown; the character was later resurrected as an enemy of his replacement, Harley Quinn.[153][154] Introduced in the 1992 animated series, Quinn is the Joker’s former Arkham psychiatrist who develops an obsessive infatuation with him and dons a red-and-black harlequin costume to join him as his sidekick and on-off girlfriend. They have a classic abusive relationship; even though the Joker constantly insults, hurts, and even tries to kill Harley, she always returns to him, convinced that he loves her.[154][155] The Joker is sometimes shown to keep spotted hyenas as pets; this trait was introduced in the 1977 animated series The New Adventures of Batman.[143] A 1976 issue of Batman Family introduced Duela Dent as the Joker’s daughter, though her parentage claim was later proven to be false.[39]

Although his chief obsession is Batman, the character has occasionally ventured outside Gotham City to fight Batman’s superhero allies. In «To Laugh and Die in Metropolis» (1987) the character kidnaps Lois Lane, distracting Superman with a nuclear weapon. The story is notable for the Joker taking on a (relative) god and the ease with which Superman defeats him—it took only 17 pages. Asked why he came to Metropolis, the Joker replies simply: «Oh Superman, why not?»[156] In 1995, the Joker fought his third major DC hero: Wonder Woman, who drew on the Greek god of trickery to temper the Joker’s humor and shatter his confidence.[157] The character has joined supervillain groups like the Injustice Gang and the Injustice League to take on superhero groups like the Justice League.[158][159]

Literary analysis

Since the Bronze Age of Comics, the Joker has been interpreted as an archetypal trickster, displaying talents for cunning intelligence, social engineering, pranks, theatricality, and idiomatic humor. Like the trickster, the Joker alternates between malicious violence and clever, harmless whimsy.[161] He is amoral and not driven by ethical considerations, but by a shameless and insatiable nature, and although his actions are condemned as evil, he is necessary for cultural robustness.[162] The trickster employs amoral and immoral acts to destabilize the status quo and reveal cultural, political, and ethical hypocrisies that society attempts to ignore.[163] However, the Joker differs in that his actions typically only benefit himself.[164] The Joker possesses abnormal body imagery, reflecting an inversion of order. The trickster is simultaneously subhuman and superhuman, a being that indicates a lack of unity in body and mind.[165] In Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, the Joker serves as Batman’s trickster guide through the hero’s own psyche, testing him in various ways before ultimately offering to cede his rule of the Asylum to Batman.[166]

Rather than the typical anarchist interpretation, others have analysed the character as a Marxist (opposite to Batman’s capitalist), arguing that anarchism requires the rejection of all authority in favor of uncontrolled freedom.[167] The Joker rejects most authority, but retains his own, using his actions to coerce and consolidate power in himself and convert the masses to his own way of thinking, while eliminating any that oppose him.[168] In The Killing Joke, the Joker is an abused member of the underclass who is driven insane by failings of the social system.[169] The Joker rejects material needs, and his first appearance in Batman #1 sees him perpetrate crimes against Gotham’s wealthiest men and the judge who had sent him to prison.[170] Batman is wealthy, yet the Joker is able to triumph through his own innovations.[171]

Ryan Litsey described the Joker as an example of a «Nietzschean Superman,» arguing that a fundamental aspect of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Superman, the «will to power,» is exemplified in all of the Joker’s actions, providing a master morality to Batman’s slave morality.[172] The character’s indomitable «will to power» means he is never discouraged by being caught or defeated and he is not restrained by guilt or remorse.[173] Joker represents the master, who creates rules and defines them, who judges others without needing approval, and for whom something is good because it benefits him.[174] He creates his own morality and is bound only by his own rules without aspiring to something higher than himself, unlike Batman, the slave, who makes a distinction between good and evil, and is bound to rules outside of himself (such as his avoidance of killing) in his quest for justice.[175] The Joker has no defined origin story that requires him to question how he came to be, as like the Superman he does not regret or assess the past and only moves forward.[176]

The Joker’s controlling and abusive relationship with Harley Quinn has been analyzed as a means of the Joker reinforcing his own belief in his power in a world where he may be killed or neutralized by another villain or Batman.[177] Joker mirrors his identity through Harley in her appearance, and even though he may ignore or act indifferent towards her, he continues to try to subject her to his control.[177] When Harley successfully defeats Batman in Mad Love (1994), the Joker, emasculated by his own failure, severely injures her out of fear of what the other villains will think of him; however, while Harley recovers, the Joker sends her flowers, which she accepts, reasserting his control over her.[178]

Harley’s co-creator, Paul Dini, describes their relationship as Harley being someone who makes the Joker feel better about himself, and who can do the work that he does not want to do himself.[179] In the 1999 one-shot comic Batman: Harley Quinn, the Joker decides to kill Harley, after admitting that he does care for her, that their relationship is romantic, and that these feelings prevent him from fulfilling his purpose.[180] Removing the traditional male-female relationship, such as in the Batman: Thrillkiller storyline where the Joker (Bianca Steeplechase) is a female and involved in a lesbian relationship with Harley, their relationship lacks any aspects of violence or subjugation.[181]

Cultural impact and legacy

The Joker is considered one of the most recognizable and iconic fictional characters in popular culture,[182][183][184] one of the best comic villains, and one of the greatest villains of all time.[185][186] The character was well-liked following his debut, appearing in nine out of the first 12 Batman issues, and remained one of Batman’s most popular foes throughout his publication.[187] The character is considered one of the four top comic book characters, alongside Batman, Superman, and Spider-Man.[184] Indeed, when DC Comics released the original series of Greatest Stories Ever Told (1987–1988) featuring collections of stories about heroes like Batman and Superman, the Joker was the only villain included alongside them.[188] The character has been the focus of ethical discussion on the desirability of Batman (who adheres to an unbreakable code forbidding killing) saving lives by murdering the Joker (a relentless dealer of death). These debates weigh the positive (stopping the Joker permanently) against its effect on Batman’s character and the possibility that he might begin killing all criminals.[122][189][190]

In 2006, the Joker was number one on Wizard magazine’s «100 Greatest Villains of All Time.»[191] In 2008 Wizard‘s list of «200 Greatest Comic Book Characters of All Time» placed the Joker fifth,[192] and the character was eighth on Empire‘s list of «50 Greatest Comic Book Characters» (the highest-ranked villain on both lists).[193] In 2009, the Joker was second on IGN‘s list of «Top 100 Comic Book Villains,»[194] and in 2011, Wired named him «Comics’ Greatest Supervillain.»[195] Complex, CollegeHumor, and WhatCulture named the Joker the greatest comic book villain of all time[183][137][196] while IGN listed him the top DC Comics villain in 2013,[197] and Newsarama as the greatest Batman villain.[107]

The Joker’s popularity (and his role as Batman’s enemy) has involved the character in most Batman-related media, from television to video games.[2][6] These adaptations of the character have been received positively[19] on film,[198][199] television,[200] and in video games.[201] As in the comics, the character’s personality and appearance shift; he is campy, ferocious or unstable, depending on the author and the intended audience.[19]

The character inspired theme-park roller coasters (The Joker’s Jinx,[202][203] The Joker in Mexico and California,[204][205] and The Joker Chaos Coaster),[206] and featured in story-based rides such as Justice League: Battle for Metropolis.[206] The Joker is one of the few comic book supervillains to be represented on children’s merchandise and toys, appearing on items including action figures, trading cards, board games, money boxes, pajamas, socks, and shoes.[184][207] The Jokermobile was a popular toy; a Corgi die-cast metal replica was successful during the 1950s, and in the 1970s a Joker-styled, flower power-era Volkswagen microbus was manufactured by Mego.[143] In 2015, The Joker: A Serious Study of the Clown Prince of Crime became the first academic book to be published about a supervillain.[184]

Since 2012–2013, the Joker has inspired a large number of internet memes, often focused on the character’s portrayal in films (see below). According to Steven T. Wright of The Outline, the character «came to symbolize the archetype of the ‘edgelord,’ a vapid, self-styled provocateur who prides himself in his ability to ‘trigger’ those who hold progressive viewpoints.»[208] The phrase «We live in a society» is commonly associated with the Joker in memes; it garnered particular notoriety after a trailer for the film Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021) featured Joker saying the line.[209][210]

In other media

The Joker has appeared in a variety of media, including television series, animated and live-action films. WorldCat (a catalog of libraries in 170 countries) records over 250 productions featuring the Joker as a subject, including films, books, and video games,[207] and Batman films which feature the character are typically the most successful.[130] The character’s earliest on-screen adaptation was in the 1966 television series Batman and its film adaptation Batman, in which he was played as a cackling prankster by Cesar Romero (reflecting his contemporary comic counterpart).[182][211][212] The Joker then appeared in the animated television series The Adventures of Batman (1968, voiced by Larry Storch),[213] The New Adventures of Batman (1977, voiced by Lennie Weinrib)[214] and The Super Powers Team: Galactic Guardians (1985, voiced by Frank Welker).[215][216]

A darker version of the Joker named Jack Napier (played by Jack Nicholson) made his film debut in 1989’s Batman, which earned over $400 million at the worldwide box office. The role was a defining performance in Nicholson’s career and was considered to overshadow Batman’s, with film critic Roger Ebert saying that the audience must sometimes remind themselves not to root for the Joker.[217][218] Batman‘s success led to the 1992 television series, Batman: The Animated Series. Voiced by Mark Hamill, the Joker retained the darker tone of the comics in stories acceptable for young children.[219][220] Hamill’s Joker is considered a defining portrayal, and he voiced the character in spin-off films (1993’s Batman: Mask of the Phantasm and 2000’s Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker), video games (2001’s Batman: Vengeance), related series (1996’s Superman: The Animated Series, 2000’s Static Shock and 2001’s Justice League), action figures, toys and amusement-park voiceovers.[221][222][223][224] A redesigned Joker, voiced by Kevin Michael Richardson, appeared in 2004’s The Batman; Richardson was the first African-American to play the character.[225][226]

After Christopher Nolan’s successful 2005 Batman film reboot, Batman Begins, which ended with a teaser for the Joker’s involvement in a sequel, the character appeared in 2008’s The Dark Knight, played by Heath Ledger as an avatar of anarchy and chaos.[227][228] While Batman Begins earned a worldwide total of $370 million;[229] The Dark Knight earned over $1 billion and was the highest-grossing film of the year, setting several contemporary box-office records (including highest-grossing midnight opening, opening day and opening weekend).[230][231] Ledger won a posthumous Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance, the first acting Oscar ever won for a superhero film.[232][233] The Joker has featured in a number of animated projects, such as 2009’s Batman: The Brave and the Bold (voiced by Jeff Bennett)[234] and 2011’s Young Justice (voiced by Brent Spiner).[235] In comic book adaptations, the character has been voiced by John DiMaggio in 2010’s Batman: Under the Red Hood and 2020’s Batman: Death in the Family, and by Michael Emerson in 2012’s two-parter The Dark Knight Returns.[236][237]

The television series Gotham (2014–2019) explores the mythology of the Joker through twin brothers Jerome and Jeremiah Valeska, played by Cameron Monaghan.[238] Jared Leto portrays the Joker in the DC Extended Universe, beginning with Suicide Squad (2016);[239] Leto reprised the role in Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021).[240] Zach Galifianakis voiced the character in The Lego Batman Movie (2017).[241] The 2019 film Joker focuses on the origins of the Joker (named Arthur Fleck) as portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix. Although the film was controversial for its violence and portrayal of mental illness, Phoenix’s performance received widespread acclaim.[242][243][244][245] Like The Dark Knight before it, Joker grossed over $1 billion at the box office, breaking contemporary financial records, and earned numerous awards including an Academy Award for Best Actor for Phoenix.[246][245][247] Barry Keoghan makes a cameo appearance as the Joker in Matt Reeves’ film The Batman (2022), where he is credited as «Unseen Arkham Prisoner».[248]

The Joker has also been featured in video games. Hamill returned to voice the character in 2009’s critically acclaimed Batman: Arkham Asylum, its equally praised 2011 sequel Batman: Arkham City and the multiplayer DC Universe Online.[249] Hamill was replaced by Troy Baker for the 2013 prequel, Batman: Arkham Origins, and the Arkham series’ animated spin-off Batman: Assault on Arkham,[221][250][251][252] while Hamill returned for the 2015 series finale, Batman: Arkham Knight.[253] Richard Epcar has voiced the Joker in a series of fighting games including, Mortal Kombat vs. DC Universe (2008),[254] Injustice: Gods Among Us (2013),[255] its sequel Injustice 2 (2017),[256] and Mortal Kombat 11 (2019).[257] The character also appeared in Lego Batman: The Videogame (2008), Lego Batman 2: DC Super Heroes (2012) and its animated adaptation, and Lego Batman 3: Beyond Gotham (2014) (the latter three voiced by Christopher Corey Smith),[258][259][260] as well as Lego DC Super-Villains (2018), with the role reprised by Hamill. Anthony Ingruber voices the Joker in Batman: The Telltale Series (2016)[261] and its sequel Batman: The Enemy Within (2017).[262]

References

Citations

- ^ Zalben, Alex (March 28, 2014). «When Is Batman’s Birthday, Actually?». New York City: MTV News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Eason, Brian K. (July 11, 2008). «Dark Knight Flashback: The Joker, Part I». Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c O’Neal, Sean (December 8, 2011). «R.I.P. Jerry Robinson, creator of the Joker». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b «Jerry Robinson». The Daily Telegraph. London. December 12, 2011. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c «R.I.P. Jerry Robinson …» Ain’t It Cool News. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Patrick, Seb (December 13, 2013). «The Joker: The Nature of Batman’s Greatest Foe». Den of Geek. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- ^ Tollin 1975, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (August 12, 2011). «R.I.P. Jerry Robinson, Creator of Batman’s Nemesis, the Joker». io9. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c Seifert, Mark (August 12, 2013). ««He Made Batman, No One Else. Kane Had Nothing To Do With It. Bill Did It All» – Carmine Infantino on Bill Finger». Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ «The man who was The Joker». Den of Geek. July 15, 2008. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Lovece, Frank (May 17, 1994). «Web Exclusives – Bob Kane interview». FrankLovece.com (official site of Entertainment Weekly writer). Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ «Meet the Joker’s Maker, Jerry Robinson» (interview)». The Ongoing Adventures of Rocket Llama. July 21, 2009. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ «The Joker’s Maker Tackles The Man Who Laughs» (interview)». The Ongoing Adventures of Rocket Llama. August 5, 2009. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Finger in a panel discussion at New York Academy Convention, August 14, 1966, transcribed in Hanerfeld, Mark (February 14, 1967). «Con-Tinued». Batmania. 1 (14): 8–9. Retrieved August 1, 2017. Page 8 archived and Page 9 archived from the originals on August 17, 2017.

- ^ Gustines, George Gene (October 4, 2010). «The Joker in the Deck: Birth of a Supervillain». The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Cohen, Alex (July 16, 2008). «The Joker: Torn Between Goof And Evil». NPR. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Gallagher, Simon (September 1, 2013). «10 Terrible Mistakes That Almost Ruined Batman For Everyone». WhatCulture. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Boucher, Geoff (August 1, 2012). «The Joker returns to ‘Batman’ pages, building on 72-year history». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Fleisher, Michael L. (1976). The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes, Volume 1: Batman. New York City: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 234–250. ISBN 0-02-538700-6. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Manning 2011, pp. 24, 27.

Not coincidentally, DC found it easier to market their comics to kids without the salacious overtones of the pulp magazines from which many superhero comics had sprung.

- ^ Weiner & Peaslee 2015, p. 36.

- ^ «Pictures of the day: 9 November 2010». The Daily Telegraph. London. November 9, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ «Rare Superman, Batman covers heading for auction». The Jerusalem Post. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Post Group. Associated Press. November 9, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e «The Origins Of! The Joker». Cracked. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 171.

- ^ a b Macek III, J.C. (February 26, 2013). «Spotlight on The Dark Knight: ‘The Smile on the Bat’«. PopMatters. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 173.

Because the surge in public visibility hadn’t helped stop Batman’s comic book slide, editorial director Carmine Infantino vowed to turn things around … and moved even further away from schoolboy-friendly adventures.

- ^ a b Parker, John (November 7, 2011). «The Evolution of the Joker: Still Crazy After All These Years». Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Cronin, Brian (March 15, 2014). «When We First Met – Joker’s Deadly Bag of Tricks». Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eason, Brian K. (July 16, 2008). «Dark Knight Flashback: The Joker, Part II». Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Phillips, Daniel (January 18, 2008). «Rogue’s Gallery: The Joker». IGN. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

[T]he Joker decides to brand every fish product in Gotham with his trademark grin, going so far as to blackmail and murder copyright officials until he’s compensated for his hideous innovation.

- ^ a b Patrick, Seb (July 15, 2008). «10 Essential Joker Stories». Den of Geek. London, England: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Pearson, Roberta E.; Uricchio, William (1991). «Notes from the Batcave: An Interview with Dennis O’Neil.». The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-85170-276-6.

- ^ a b c d «Joker Panel Interview: Steve Englehart on The Laughing Fish». The Ongoing Adventures of Rocket Llama. August 9, 2009. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c Phillips, Daniel (December 8, 2008). «Why So Serious?: The Many Looks of Joker (Page 2)». IGN. Los Angeles, California: j2 Global. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 176.

- ^ a b Sims, Chris (September 12, 2013). «Bizarro Back Issues: The Joker’s Solo Series (1975)». Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Manning 2011, p. 177.

- ^ Duncan Smith 2013, p. 380.

- ^ Weiner & Peaslee 2015, p. XVI.

- ^ a b Sanderson, Peter (May 13, 2005). «Comics in Context #84: Dark Definitive». IGN. Los Angeles, California: j2 Global. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Greenberger and Manning, p. 163: «In this fondly remembered tale that was later adapted into an episode of the 1990s cartoon Batman: The Animated Series, the Joker poisoned the harbors of Gotham so that the fish would all bear his signature grin, a look the Joker then tried to trademark in order to collect royalties.»

- ^ «Batman Artist Rogers is Dead». Sci Fi. March 28, 2007. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

Even though their Batman run was only six issues, the three laid the foundation for later Batman comics. Their stories include the classic ‘Laughing Fish’ (in which the Joker’s face appeared on fish); they were adapted for Batman: The Animated Series in the 1990s. Earlier drafts of the 1989 Batman film with Michael Keaton as the Dark Knight were based heavily on their work

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 183

DC birthed the Dark Age with the twelve-part Crisis on Infinite Earths. Not only did the series kill off Silver Age icons the Flash and Supergirl, it cleared out decades of continuity bramble…

- ^ Strike, Joe (July 15, 2008). «Frank Miller’s ‘Dark Knight’ brought Batman back to life». Daily News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Esposito, Joey (July 9, 2012). «Scott Snyder Talks About the Joker’s Brutal Return». IGN. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Hilary (June 9, 2005). «Batman: A Death in the Family Review». IGN. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Patrick, Seb (November 24, 2008). «Batman: A Death In The Family». Den of Geek. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Greenberger and Manning, p. 38: «Offering keen insight into both the minds of the Joker and Batman, this special is considered by most Batman fans to be the definitive Joker story of all time.»

- ^ a b c d Manning 2011, p. 188.

- ^ a b Patrick, Seb (April 28, 2008). «Batman: The Killing Joke Deluxe Edition review». Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Goldstein, Hilary (May 24, 2005). «Batman: The Killing Joke Review». IGN. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Cronin, Brian (August 1, 2015). «75 Greatest Joker Stories: #5-1». Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Serafino, Jason (August 22, 2011). «The 25 Best DC Comics of All Time». Complex. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ Serafino, Jason (July 17, 2012). «The 25 Best DC Comics of All Time». Complex. Archived from the original on January 7, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (May 24, 2005). «Batman: Harley Quinn Review». IGN. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ^ Best, Daniel (January 6, 2007). «Batman: Alan Grant & Norm Breyfogle Speak Out». 20th Century Danny Boy. Australian Web Archive. Archived from the original on October 21, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Renaud, Jeffrey (February 14, 2013). «Scott Snyder Plays Joker In ‘Death of the Family’«. Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ Clark, Noelene (October 10, 2012). «‘Batman: Death of the Family’: Snyder, Capullo’s Joker is no joke». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Rogers, Vaneta (January 28, 2015). «Post-Convergence Batman Will Have New Status Quo ‘No One Has Done in 75 Years of Batman’«. Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Kelly, Stuart (April 30, 2015). «Has DC killed Batman and the Joker?». The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ Polo, Susana (October 6, 2020). «The Joker War is over, but it changed Gotham City». Polygon. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Holub, Christian (December 15, 2020). «The Joker is getting his own monthly comic from DC». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kroner, Brian (December 21, 2012). «Geek’s 20 Greatest Joker Moments Ever, Part II». Geek Exchange. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 27.

- ^ a b Moore, Alan (w), Bolland, Brian (a). The Killing Joke: 38–40 (March 1988), DC Comics, 1401209270

- ^ a b c Hughes, Joseph (August 19, 2013). «So What Really Happened at the End Of ‘The Killing Joke’? [Opinion]». Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ Bricken, Rob (September 11, 2009). «The Joker’s 10 Craziest Kills». Topless Robot. Village Voice Media. Archived from the original on October 10, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Rucka, Greg, Grayson, Devin (w), Scott, Damion, Eaglesham, Dale (p), Parsons, Sean, Buscema, Sal, Hunter, Rob (i), Rambo, Pamela (col). «No Man’s Land – Endgame: Part 3 – Sleep in Heavenly Peace» Detective Comics 741 (February 2000), Burbank, California: DC Comics

- ^ a b c Kroner, Brian (December 21, 2012). «Geek’s 20 Greatest Joker Moments Ever, Part III». Geek Exchange. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ^ Loeb, Jeph, DeMatteis, J.M., Schultz, Mark, Kelly, Joe (w), McGuiness, Ed, Miller, Mike, Mahnke, Doug, Kano (p), Smith, Cam, Marzan, Jose, Nguyen, Tom, McCrea, John, Alquiza, Marlo, Durrurthy, Armando, various others (i). Superman: Emperor Joker vSuperman #160–161, Adventures of Superman #582–583, Action Comics 769–770, Superman: The Man of Steel 104–105, and Emperor Joker.,: 224 (January 2007), DC Comics, 9781401211936

- ^ Mahnke, Doug, Winick, Judd, Lee, Paul (w). Batman: Under The Hood 635–641: 176 (November 2005), DC Comics, 9781401207564

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Jimenez, Phil, Pérez, George, Reis, Ivan, Bennet, Joe (p), Lanning, Andy, Pérez, George, Reis, Ivan Ordway, Jerry, Parsons, Sean, Thibert, Art (i). «Infinite Crisis #7» Infinite Crisis #7 7: 31/6–7 (June 2006), DC Comics

- ^ Buxton, Marc (December 4, 2014). «Almost Got Him: 10 Times the Joker Almost Nailed Batman». Den of Geek. London, England: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 195.

- ^ Morrison, Grant (w). Batman and Robin 12 (May 2010), DC Comics

- ^ Sims, Chris (July 8, 2010). «Roundtable Review: ‘Batman And Robin’ #13». Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Uzumeri, David (November 3, 2010). «Black Mass: Batman And Robin #16 [Annotations]». Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.