Имя Люцифер: значение, происхождение, талисманы

- 22 Февраля, 2019

- Значение

У каждого имени есть своя история, которая накапливается за годы его использования. Люди оставляют свой отпечаток на нем. Поэтому и неудивительно, что имена имеют огромное влияние на жизнь и судьбу своих носителей.

Некоторые имена с годами забываются, оставаясь на слуху лишь благодаря легендарным носителям. Другие же то возвращаются, то снова теряются среди большого разнообразия. Значение имени не всегда совпадает с тем, каким себе его представляют окружающие. Иногда предрассудки не позволяют увидеть истинную характеристику. Это коснулось и значения имени Люцифер.

Для большинства людей – это имя Сатаны, дьявола, который правит Адом. Однако стоит лишь немного глубже копнуть, и на свет появляется куда более глубокое его значение и характеристика.

Происхождение и значение имени Люцифер

В Библии лишь единожды Люцифер был назван по имени. Оно перешло в Писание из Вульгаты Иеронима, написанной на латыни. Имя Люцифер – это не символ Сатаны или дьявола. Оно не имеет ничего общего с королем Ада. Не стоит заблуждаться на этот счет.

Слово «люцифер» имеет еврейские корни. Некоторые ученые также приписывают ему греческое и даже латинское происхождение. Но в любом языке все имена Люцифера трактуются примерно одинаково.

Оно означает «утреннюю звезду», «сияющий», «светоносный». Эти значения никак не относятся к Сатане. Люцифер – это свет, который побеждает тьму. Именно так и был назван архангел самим Богом.

Имя имеет очень богатую историю, которая довольно интересна. Хоть сегодня Люцифер у многих ассоциируется именно с дьяволом, таким положение дел было не всегда. Во времена Римской империи «светозарными» называли правителей и просто обыкновенных мужчин. Сильное имя никак не соотносили с Сатаной.

Тайна имени

Люцифер имеет очень богатую историю. Так, «несущий свет» в древние времена не имел ничего общего с дьяволом. Этим именем была награждена Венера, потому что она приносила свет в те часы, когда не было солнца.

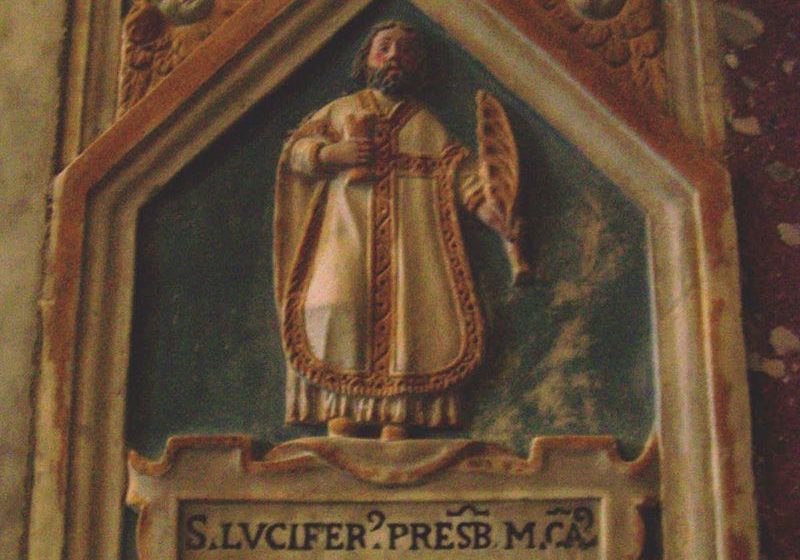

Имя падшего ангела стало синонимом Сатаны лишь в семнадцатом веке. Тогда христианская религия начала преподносить Люцифера и дьявола, как одно целое. Но ранее, в четвертом веке, имя Люцифер носил и епископ. Таким образом, сложно поверить, что дьявол может носить «светозарное» имя.

Характер имени

Влияние на жизнь и судьбу носителя определяется силой и характером имени. Казалось бы, обычный набор букв способен наделить человека различными чертами характера. Имя падшего ангела обладает большой энергией.

Оно наделяет своего носителя лидерскими качествами. С ранних лет Люцифер желает держать все под своим контролем. Он стремится занять доминирующее положение в любой ситуации. Мужчина не любит подчиняться или слушаться других людей.

Носителя имени Люцифер не останавливает даже то, что силы, брошенные на достижение лидерской позиции, могут не окупиться. Для него не важен результат. Главное – добиться силы и власти.

Люцифера не пугает даже то, что его конкуренты могут быть в разы сильнее и опытнее. Наоборот, уязвимая позиция лишь заставляет Люцифера прикладывать больше усилий. С годами могут меняться цели и масштабы желаний. Но одно останется неизменным – власть и положение. Это то, что руководит носителями имени Люцифер.

Мужчина обладает сильным характером. Его трудно сломить. Люцифер живет ради самореализации. Ему легко заводить новые знакомства. Умение преподнести себя в лучшем свете позволяет Люциферу легко добиваться своих целей.

Он прекрасно справляется с поставленными задачами. Однако у Люцифера есть и существенные недостатки в характере. Если ему предстоит заняться сразу несколькими делами, то он не сможет сконцентрироваться. Его силы будут растрачены попусту, а работа не продвинется ни на шаг. Люциферу тяжело концентрироваться сразу на нескольких задачах. Также в ступор его вводят ситуации, когда нужно принять важное решение.

Его худшая черта – склонность к колебаниям. Он может сто раз передумать, поменять решение и снова усомниться в правильности выбора. Эту черту характера Люциферу будет очень трудно преодолеть.

Значение букв имени

Каждая буква имени имеет свое толкование. Эта трактовка не имеет ничего общего с самим именем.

Буква «Л» символизирует изобретательных и творческих личностей. Но при принятии решений они опираются только на логику и здравый смысл. Бывают капризными и эгоистичными. Трудно справляются с потерями и расставанием.

Буква «Ю» означает импульсивность и чрезмерную эмоциональность. Тяжело находят партнера, но в браке верны и романтичны.

Буква «Ц» — это символ упрямства, почитания традиций и неумения усмирять темперамент. Чрезмерная амбициозность портит жизнь носителя.

Буква «И» одаривает носителя умением ценить прекрасное. Человек наделен способностью находить гармонию с самим собой.

Буква «Ф» — это символ силы и стойкости. Дружелюбие и открытость привлекают людей. Однако им трудно открываться перед знакомыми.

Буква «Е» одаривает человека общительностью. Но также она символизирует желание верить только своим суждениям. Это и становится причиной частого одиночества.

Буква «Р» влияет на характер и таланты носителя. Она дарит человеку способность к ремеслам. Носитель способен уступать в ситуациях до тех пор, пока это не будет задевать его гордость.

Число имени

Тайна кроется не только в происхождении, но и в нумерологии имени. Число Люцифера – восьмерка. Эта цифра показывает, что носители имени – это сильные и целеустремленные личности.

Они идут к своим целям, не сворачивая с пути. Им легко заводить новые знакомства. Но порой они бывают чересчур открытыми. Многим кажется, что «восьмерки» — это обладатели ледяного характера. Им не свойственно яркое проявление чувств. Однако внутри них кроется целый водоворот эмоций, который «восьмерки» пытаются контролировать.

Талисманы

Как и у любого другого имени, есть вещи, которые приносят удачу Люциферу. Талисманы, цвета, камни – все это может облегчить существование носителя. Сильное имя требует таких же «покровителей».

Цвета Люцифера – это насыщенный черный и глубокий красный. Они приносят не только удачу, но и помогают справиться с недостатками темперамента. Числа 5, 8, 12 и 35 также относятся к счастливым.

Сатурн и Марс – это планеты-покровители Люцифера. Удачные металлы – олово и железо. Астрологи отмечают, что имя идеально подходит мальчикам, которые были рождены под знаками Скорпиона или Козерога.

Люциферам отлично подходят такие камни, как опал, кварц, кальцит и коралл. Удачу принесут красные или черные розы, высаженные дома. Лучший домашний питомец – это кот. Используя эти нехитрые подсказки и окружив себя удачей, можно надеяться на лучшую судьбу.

Внешний вид Люцифера

Мужчины, носящие это имя – модники, которые очень трепетно относятся к своему внешнему виду. Они тщательно следят за новыми тенденция и стараются одеваться со вкусом, но при этом выделяться из толпы.

Люцифер обладает хорошим вкусом. Это позволяет ему умело подчеркивать при помощи одежды свои сильные стороны, но скрывать слабые.

Люцифер и отношения

Особое место в жизни Люцифера занимает личная жизнь. Мужчина очень романтичен и привязан к своей спутнице. Он наделен способностью видеть в человеке все самое лучшее. Люцифер не стесняется делать комплименты своей половинке.

Однако его чувства могут быстро угаснуть. Стоит только отношениям потерять свою исключительность, захлебнуться под тяготами быта, Люцифер сразу же перестает любить свою избранницу.

Мужчина не умеет долго жить в неприятных отношениях, поэтому сразу разрывает нежелательные связи. Но сентиментальность еще долго заставляет Люцифера вспоминать о своих спутницах.

Качества Люцифера как архангела и то, как имя влияет на своего носителя, практически никак не связано. Не стоит думать лишь о том, что оно символизирует владыку Ада. Он был так назван самим Господом. Светоносный Люцифер был любимым сыном Бога, сильным архангелом и прекрасным воином. Лишь нежелание любить людей и почитать их заставило его пойти против Отца.

Благодаря этим событиям, имя получило заряд колоссальной энергии. И даже спустя тысячелетия оно оказывает сильное влияние на судьбу своего носителя.

| Чаще всего используется | Люцифер |

| Мужское/женское | Мужское |

| Перевод (с латинского) | Светоносный, излучающий свет |

| Что означает | «Утренняя звезда» |

| Сокращение | Люци |

| Уменьшительно-ласкательные формы | Люциус, Люциферушка |

| Каким именем крестить | — |

| Церковное имя | Люцифер |

| Именины | — |

| Первое упоминание | Впервые упоминается в древнеримской мифологии в качестве персофиникации утренней звезды (планеты Венеры) |

| Национальность имени | Римское |

| Отчества, которые сочетаются с именем | Владимировна, Васильевна, Дмитриевна, Петровна, Сергеевна, Александровна, Степановна, Васильевна, Антоновна. |

| Как пишется по-английски | Liutsifer |

| Варианты ников для соцсетей | @Liutsifer@, Lyuzi |

Своими корнями наименование Люцифер уходит в древнеримскую мифологию. На латинском языке оно обозначает светоносный, сияющий, излучающий свет. Использовалось для персонификации планеты Венеры – утренней звезды, предвестника рассвета и восходящего солнца. Часто Люцифера изображали в виде красивого ангела с кувшином в руках, из которого струился свет. В древнегреческой мифологии аналогом Люцифера являлся Фосфор, в древнеславянской – Денница.

У всех вышеперечисленных древних народов наименование божества имело значение, связанное с появлением утренней зари, красотой, совершенством, радостью и Светом, способным разогнать даже самую страшную тьму.

Характеристика имени

Имя Люцифер для мальчика – символ протеста, самодостаточности, лидерства. Это сильный характер с несгибаемой волей, не признающий никаких авторитетов, правил, принципов. Отличительная черта обладателя имени – целеустремленность, настойчивость, упрямство.

С самого детства Люцифер чрезвычайно любознателен. Ему все всегда интересно. Для него важно искать новые источники вдохновения, которые бы подталкивали на «великие» дела. Интеллектуальная жажда настолько велика, что стоит только остановиться в своих поисках истины, знаний, как вся жизнь вдруг теряет всякий смысл.

Любознательность делает Люфицера весьма разносторонним человеком. У него всегда много интересов, хобби, часто меняет работу, как только перестает в ней находить новые грани и пути для саморазвития. Весьма озабочен своим имиджем, внутренним миром и внешней привлекательностью. Ему важно, что про него думают и говорят, но своей линии поведения из-за чьих-то домыслов менять не станет. Судьба юноши всегда в его собственных руках. Он уверен в себе и всегда знает, чего хочет от жизни.

Мистическое имя создает вокруг своего носителя некий ореол таинственности. Юноша, мужчина весьма привлекателен для противоположного пола, красив, обаятелен. Перед ним трудно устоять. На первый взгляд, Люцифер общителен и легок на подъем, однако свои внутренние страхи, переживания и чувства он может открыть лишь избранным.

История происхождения

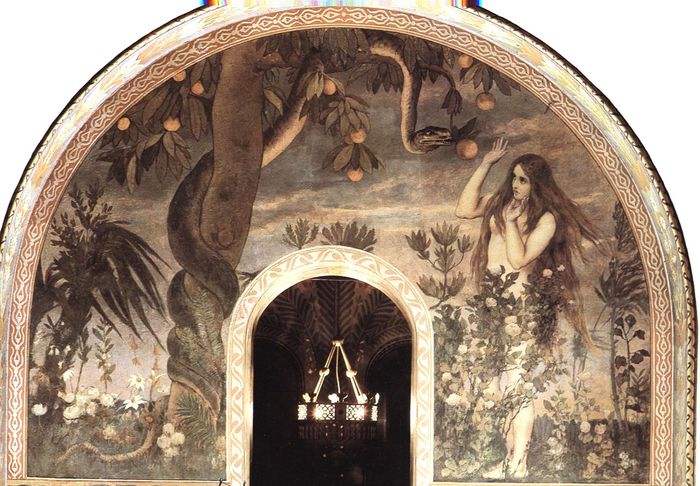

История современного значения наименования связывается с ветхозаветным героем. В библейской традиции Люцифер являлся архангелом, который, однако, воспротивился Богу. Притворившись змеем искусителем (по одной из версии), он соблазнил Адама и Еву, из-за чего те вкусили запретный плод с дерева жизни. Кроме этого, архангел неоднократно бунтовал против воли Бога, за что в конце концов был изгнан в Ад. Падший ангел в темном Царстве стал полновластным правителем и подчинил своей воле множество существ.

Женился на Лилит, первой жене Адама, и вместе они породили множество бесов, чертей и прочей нечистой силы. В христианской традиции наименование символизирует собой исчадие ада, является синонимом самого Дьявола. В связи с этим, произносится с особой осторожностью, упоминается редко, а простым верующим Церковь рекомендует его вообще не использовать. Во многих странах данным именем запрещено называть детей, что закреплено на законодательном уровне (Германия, Франция, Новая Зеландия и пр.).

Имя в истории

В Древнем Риме Люцифером называли достойных сильных мужей Республики. Это были представители военной элиты, видные государственные деятели, ученые, врачи – все те, кто работал на благо своей Родины, прославляя ее своим трудом и действиями.

В период христианизации Европы и позже имя начинает терять свою популярность. А во времена позднего Средневековья (17 в.) приобретает негативное значение. Связано это было с однобоким толкованием книги Исаии христианскими писателями. Именно в этом источнике используется имя Люцифер как осуждающий эпитет в адрес царя Вавилона.

Это послужило основой для того, чтобы начать ассоциировать имя с самим Дьяволом и прочей нечистой силой. С тех пор оно воспринимается как нечто запретное, ужасное, мистическое. Так изначально лучезарное имя, символизирующее утреннюю зарю, свет, красоту и радость, стало синонимом Сатаны.

Характеристика по астрологии и нумерологии

| Лучший знак зодиака | Скорпион, Козерог |

| Планета-покровитель.

Характеристика планеты |

Сатурн – порядок, самодисциплина, стремление к осуществлению поставленных целей, мудрость, сила, власть.

Марс – воинственность, физическая сила, непоколебимость, решительность, власть, лидерство. |

| Камень-талисман, оберег | Голубой опал, сапфир, аметист |

| Стихия | Земля – практичность, основательность, трудолюбие, жесткость, выносливость, прагматизм, терпение |

| Растительный символ | Сосна |

| Цвет | Красный, черный |

| Число имени | 8 – знак бесконечности, наделяет своих обладателей практичностью, интеллектом, холодным расчетом, честностью, предвещает стабильность, материальный успех. |

| Благоприятный день | Вторник |

| Идеальный сезон | Зима – активность, целеустремленность, общительность, оптимизм, некоторая гордыня, понимание собственной значимости (иногда чрезмерно) |

| Год | Тигр – своеволие, упрямство, активность, решительность, сила духа, лидерские качества, дерзость, страсть |

Совместимость с женскими именами

Прекрасные, гармоничные отношения ждут Люцифера в браке с:

- Татьяной

- Дарьей

- Валерией

- Таисией

- Ольгой

- Надеждой

- Натальей

- Светланой

- Эмилией.

Известные люди

Люцифер Каларийский – католический священник, итальянский епископ (Сардиния).

- Lucifer |ˈluːsɪfər| — Люцифер, сатана, утренняя звезда, падший ангел, Венера

гордый как Люцифер — as proud as Lucifer

ЛЮЦИФЕР — (лат. Lucifer, от lux, lucis свет, и ferre нести). 1) сатана. 2) поэтическая часть утренней звезды Венеры. 3) фосфор светодавец. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. ЛЮЦИФЕР 1) по священному Писанию… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

Люцифер — см. Сатана. Литературная энциклопедия. В 11 т.; М.: издательство Коммунистической академии, Советская энциклопедия, Художественная литература. Под редакцией В. М. Фриче, А. В. Луначарского. 1929 1939 … Литературная энциклопедия

люцифер — дьявол, сатана, венера Словарь русских синонимов. люцифер сущ., кол во синонимов: 5 • бес (33) • венера … Словарь синонимов

ЛЮЦИФЕР — ЛЮЦИФЕР, в христианстве падший ангел, дьявол … Современная энциклопедия

ЛЮЦИФЕР — в христианской мифологии падший ангел, дьявол … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

ЛЮЦИФЕР — см. Фосфор … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

ЛЮЦИФЕР — Луцифер (лат. Lucifer, «утренняя звезда», т. е. планета Венера; в том же значении греч. ό έωσφόρος слав. Денница), в христианской традиции одно из обозначений сатаны как горделивого и бессильного подражателя тому свету, который составляет… … Энциклопедия мифологии

Люцифер — (лат. Lucifer) или Фосфор (jwsjoroV) светоносец , названиеутренней звезды; у отцов церкви Л., сын зари (ср. книгу пророка Исаии,XIV, 12) является обозначением диавола … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

Люцифер — Л у ц и ф е р (лат. Lucifer, «утренняя звезда», т. е. планета Венера; в том же значении греч. 6 ёсостфбрех;, слав. Д е н н и ц а), в христианской традиции одно из обозначений сатаны как горделивого и бессильного подражателя тому свету, который… … Энциклопедия культурологии

Люцифер — Название алгоритма шифрования, положенного в основу DES алгоритма. [[http://www.rfcmd.ru/glossword/1.8/index.php?a=index d=23]] Тематики защита информации EN Lucifer … Справочник технического переводчика

Люцифер — ЛЮЦИФЕР, в христианстве падший ангел, дьявол. … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

Артём Кононенко

Ученик

(96),

закрыт

11 лет назад

перевести другое слово или фразу

другие переводы

имя существительное

- Lucifer

Люцифер

сатана

утренняя звезда

падший ангел

Венера

Предложите свой перевод или просто оставьте комментарий

Оцените наш проект

Рейтинг:

Имя*:

Электронная почта:

Отзыв:

Glosbe предназначен для предоставления услуг людям, а не интернет-роботам.

Вероятно, вы создали много запросов или другие факторы позволили Glosbe идентифицировать вас как робота и заблокировать доступ к данным.

Чтобы продолжить, подтвердите, что вы человек, решив CAPTCHA.

This article is about the mythological and religious figure. For other uses, see Lucifer (disambiguation).

Lucifer[a] is one of various figures in folklore associated with the planet Venus. The entity’s name was subsequently absorbed into Christianity as a name for the devil. Modern scholarship generally translates the term in the relevant Bible passage (Isaiah 14:12), where the Greek Septuagint reads ὁ ἑωσφόρος ὁ πρωὶ, as «morning star» or «shining one» rather than as a proper noun, Lucifer, as found in the Latin Vulgate.

As a name for the Devil in Christian theology, the more common meaning in English, «Lucifer» is the rendering of the Hebrew word הֵילֵל, hêlēl, (pronunciation: hay-lale)[1] in Isaiah[2] given in the King James Version of the Bible. The translators of this version took the word from the Latin Vulgate,[3] which translated הֵילֵל by the Latin word lucifer (uncapitalized),[4][5] meaning «the morning star», «the planet Venus», or, as an adjective, «light-bringing».[6]

As a name for the planet in its morning aspect, «Lucifer» (Light-Bringer) is a proper noun and is capitalized in English. In Greco-Roman civilization, it was often personified and considered a god[7] and in some versions considered a son of Aurora (the Dawn).[8] A similar name used by the Roman poet Catullus for the planet in its evening aspect is «Noctifer» (Night-Bringer).[9]

Roman folklore and etymology[edit]

Lucifer (the morning star) represented as a winged child pouring light from a jar. Engraving by G. H. Frezza, 1704

In Roman folklore, Lucifer («light-bringer» in Latin) was the name of the planet Venus, though it was often personified as a male figure bearing a torch. The Greek name for this planet was variously Phosphoros (also meaning «light-bringer») or Heosphoros (meaning «dawn-bringer»).[10] Lucifer was said to be «the fabled son of Aurora[11] and Cephalus, and father of Ceyx». He was often presented in poetry as heralding the dawn.[10]

Planet Venus in alignment with Mercury (above) and the Moon (below)

The Latin word corresponding to Greek Phosphoros is Lucifer. It is used in its astronomical sense both in prose[b][c] and poetry.[d][e] Poets sometimes personify the star, placing it in a mythological context.[f][g]

Lucifer’s mother Aurora corresponds to goddesses in other cultures. The name «Aurora» is cognate to the name of the Vedic goddess Ushas, that of the Lithuanian goddess Aušrinė, and that of the Greek goddess Eos, all three of whom are also goddesses of the dawn. All four are considered derivatives of the Proto-Indo-European stem *h₂ewsṓs[19] (later *Ausṓs), «dawn», a stem that also gave rise to Proto-Germanic *Austrō, Old Germanic *Ōstara and Old English Ēostre/Ēastre. (Whence also Modern German «Österreich» meaning «Eastern Kingdom», as well as Modern English «east».) This agreement has led scholars to reconstruct a Proto-Indo-European dawn goddess.[20]

The 2nd-century Roman mythographer Pseudo-Hyginus said of the planet:[21]

The fourth star is that of Venus, Luciferus by name. Some say it is Juno’s. In many tales it is recorded that it is called Hesperus, too. It seems to be the largest of all stars. Some have said it represents the son of Aurora and Cephalus, who surpassed many in beauty, so that he even vied with Venus, and, as Eratosthenes says, for this reason it is called the star of Venus. It is visible both at dawn and sunset, and so properly has been called both Luciferus and Hesperus.

The Latin poet Ovid, in his 1st-century epic Metamorphoses, describes Lucifer as ordering the heavens:[22]

Aurora, watchful in the reddening dawn, threw wide her crimson doors and rose-filled halls; the Stellae took flight, in marshaled order set by Lucifer who left his station last.

Ovid, speaking of Phosphorus and Hesperus (the Evening Star, the evening appearance of the planet Venus) as identical, makes him the father of Daedalion.[23] Ovid also makes him the father of Ceyx,[24][25] while the Latin grammarian Servius makes him the father of the Hesperides or of Hesperis.[26]

In the classical Roman period, Lucifer was not typically regarded as a deity and had few, if any, myths,[10] though the planet was associated with various deities and often poetically personified. Cicero stated that «You say that Sol the Sun and Luna the Moon are deities, and the Greeks identify the former with Apollo and the latter with Diana. But if Luna (the Moon) is a goddess, then Lucifer (the Morning-Star) also and the rest of the Wandering Stars (Stellae Errantes) will have to be counted gods; and if so, then the Fixed Stars (Stellae Inerrantes) as well.»[27]

Planet Venus, Sumerian folklore, and fall from heaven motif[edit]

The motif of a heavenly being striving for the highest seat of heaven only to be cast down to the underworld has its origins in the motions of the planet Venus, known as the morning star.

The Sumerian goddess Inanna (Babylonian Ishtar) is associated with the planet Venus, and Inanna’s actions in several of her myths, including Inanna and Shukaletuda and Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld appear to parallel the motion of Venus as it progresses through its synodic cycle.[28][29][30][31]

A similar theme is present in the Babylonian myth of Etana. The Jewish Encyclopedia comments:

The brilliancy of the morning star, which eclipses all other stars, but is not seen during the night, may easily have given rise to a myth such as was told of Ethana and Zu: he was led by his pride to strive for the highest seat among the star-gods on the northern mountain of the gods […] but was hurled down by the supreme ruler of the Babylonian Olympus.[32]

The fall from heaven motif also has a parallel in Canaanite mythology. In ancient Canaanite religion, the morning star is personified as the god Attar, who attempted to occupy the throne of Ba’al and, finding he was unable to do so, descended and ruled the underworld.[33][34] The original myth may have been about the lesser god Helel trying to dethrone the Canaanite high god El, who lived on a mountain to the north.[35][36] Hermann Gunkel’s reconstruction of the myth told of a mighty warrior called Hêlal, whose ambition was to ascend higher than all the other stellar divinities, but who had to descend to the depths; it thus portrayed as a battle the process by which the bright morning star fails to reach the highest point in the sky before being faded out by the rising sun.[37] However, the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible argues that no evidence has been found of any Canaanite myth or imagery of a god being forcibly thrown from heaven, as in the Book of Isaiah (see below). It argues that the closest parallels with Isaiah’s description of the king of Babylon as a fallen morning star cast down from heaven are to be found not in Canaanite myths, but in traditional ideas of the Jewish people, echoed in the Biblical account of the fall of Adam and Eve, cast out of God’s presence for wishing to be as God, and the picture in Psalm 82 of the «gods» and «sons of the Most High» destined to die and fall.[38] This Jewish tradition has echoes also in Jewish pseudepigrapha such as 2 Enoch and the Life of Adam and Eve.[32][39] The Life of Adam and Eve, in turn, shaped the idea of Iblis in the Quran.[40]

The Greek myth of Phaethon, a personification of the planet Jupiter,[41] follows a similar pattern.[37]

Christianity[edit]

In the Bible[edit]

In the Book of Isaiah, chapter 14, the king of Babylon is condemned in a prophetic vision by the prophet Isaiah and is called הֵילֵל בֶּן-שָׁחַר (Helel ben Shachar, Hebrew for «shining one, son of the morning»),[38] who is addressed as הילל בן שחר (Hêlêl ben Šāḥar),[42][43][44][45] The title «Hêlêl ben Šāḥar» refers to the planet Venus as the morning star, and that is how the Hebrew word is usually interpreted.[46][47] The Hebrew word transliterated as Hêlêl[48] or Heylel,[49] occurs only once in the Hebrew Bible.[48] The Septuagint renders הֵילֵל in Greek as Ἑωσφόρος[50][51][52][53][54] (heōsphoros),[55][56] «bringer of dawn», the Ancient Greek name for the morning star.[57] Similarly the Vulgate renders הֵילֵל in Latin as Lucifer, the name in that language for the morning star. According to the King James Bible-based Strong’s Concordance, the original Hebrew word means «shining one, light-bearer», and the English translation given in the King James text is the Latin name for the planet Venus, «Lucifer»,[49] as it was already in the Wycliffe Bible.

However, the translation of הֵילֵל as «Lucifer» has been abandoned in modern English translations of Isaiah 14:12. Present-day translations render הֵילֵל as «morning star» (New International Version, New Century Version, New American Standard Bible, Good News Translation, Holman Christian Standard Bible, Contemporary English Version, Common English Bible, Complete Jewish Bible), «daystar» (New Jerusalem Bible, The Message), «Day Star» (New Revised Standard Version, English Standard Version), «shining one» (New Life Version, New World Translation, JPS Tanakh), or «shining star» (New Living Translation).

In a modern translation from the original Hebrew, the passage in which the phrase «Lucifer» or «morning star» occurs begins with the statement: «On the day the Lord gives you relief from your suffering and turmoil and from the harsh labour forced on you, you will take up this taunt against the king of Babylon: How the oppressor has come to an end! How his fury has ended!»[58] After describing the death of the king, the taunt continues:

How you have fallen from heaven, morning star, son of the dawn! You have been cast down to the earth, you who once laid low the nations! You said in your heart, «I will ascend to the heavens; I will raise my throne above the stars of God; I will sit enthroned on the mount of assembly, on the utmost heights of Mount Zaphon. I will ascend above the tops of the clouds; I will make myself like the Most High.» But you are brought down to the realm of the dead, to the depths of the pit. Those who see you stare at you, they ponder your fate: «Is this the man who shook the earth and made kingdoms tremble, the man who made the world a wilderness, who overthrew its cities and would not let his captives go home?»[59]

For the unnamed «king of Babylon»,[60] a wide range of identifications have been proposed.[61] They include a Babylonian ruler of the prophet Isaiah’s own time,[61] the later Nebuchadnezzar II, under whom the Babylonian captivity of the Jews began,[62] or Nabonidus,[61][63] and the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser, Sargon II and Sennacherib.[64][65] Verse 20 says that this king of Babylon will not be «joined with them [all the kings of the nations] in burial, because thou hast destroyed thy land, thou hast slain thy people; the seed of evil-doers shall not be named for ever», but rather be cast out of the grave, while «All the kings of the nations, all of them, sleep in glory, every one in his own house».[46][66] Herbert Wolf held that the «king of Babylon» was not a specific ruler but a generic representation of the whole line of rulers.[67]

Isaiah 14:12 became a source for the popular conception of the fallen angel motif.[68] Rabbinical Judaism has rejected any belief in rebel or fallen angels.[69] In the 11th century, the Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer illustrates the origin of the «fallen angel myth» by giving two accounts, one relates to the angel in the Garden of Eden who seduces Eve, and the other relates to the angels, the benei elohim who cohabit with the daughters of man (Genesis 6:1–4).[70] An association of Isaiah 14:12–18 with a personification of evil, called the devil, developed outside of mainstream Rabbinic Judaism in pseudepigrapha,[71] and later in Christian writings,[72] particularly with the apocalypses.[73]

As the devil[edit]

The metaphor of the morning star that Isaiah 14:12 applied to a king of Babylon gave rise to the general use of the Latin word for «morning star», capitalized, as the original name of the devil before his fall from grace, linking Isaiah 14:12 with Luke 10 («I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven»)[74] and interpreting the passage in Isaiah as an allegory of Satan’s fall from heaven.[75][76]

Considering pride as a major sin peaking in self-deification, Lucifer (Hêlêl) became the template for the devil.[77] As a result, Lucifer was identified with the devil in Christianity and in Christian popular literature,[3] as in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, Joost van den Vondel’s Lucifer, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost.[78] Early medieval Christianity fairly distinguished between Lucifer and Satan. While Lucifer, as the devil, is fixated in hell, Satan executes the desires of Lucifer as his vassal.[79][80]

Interpretations[edit]

Gustave Doré, illustration to Paradise Lost, book IX, 179–187: «he [Satan] held on / His midnight search, where soonest he might finde / The Serpent: him fast sleeping soon he found».

Aquila of Sinope derives the word hêlêl, the Hebrew name for the morning star, from the verb yalal (to lament). This derivation was adopted as a proper name for an angel who laments the loss of his former beauty.[81] The Christian church fathers – for example Hieronymus, in his Vulgate – translated this as Lucifer. The equation of Lucifer with the fallen angel probably occurred in 1st century Palestinian Judaism. The church fathers brought the fallen lightbringer Lucifer into connection with the Devil on the basis of a saying of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (10.18 EU): «I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning.»[82]

Some Christian writers have applied the name «Lucifer» as used in the Book of Isaiah, and the motif of a heavenly being cast down to the earth, to the devil. Sigve K. Tonstad argues that the New Testament War in Heaven theme of Revelation 12, in which the dragon «who is called the devil and Satan […] was thrown down to the earth», was derived from the passage about the Babylonian king in Isaiah 14.[83] Origen (184/185–253/254) interpreted such Old Testament passages as being about manifestations of the devil.[84][85][86] Origen was not the first to interpret the Isaiah 14 passage as referring to the devil: he was preceded by at least Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 225), who in his Adversus Marcionem (book 5, chapters 11 and 17) twice presents as spoken by the devil the words of Isaiah 14:14: «I will ascend above the tops of the clouds; I will make myself like the Most High».[87][88][89] Though Tertullian was a speaker of the language in which the word «lucifer» was created, «Lucifer» is not among the numerous names and phrases he used to describe the devil.[90] Even at the time of the Latin writer Augustine of Hippo (354–430), a contemporary of the composition of the Vulgate, «Lucifer» had not yet become a common name for the devil.[91]

Augustine of Hippo’s work Civitas Dei (5th century) became the major opinion of Western demonology including in the Catholic Church. For Augustine, the rebellion of the devil was the first and final cause of evil. By this he rejected some earlier teachings about Satan having fallen when the world was already created.[92] Further, Augustine rejects the idea that envy could have been the first sin (as some early Christians believed, evident from sources like Cave of Treasures in which Satan has fallen because he envies humans and refused to prostrate himself before Adam), since pride («loving yourself more than others and God») is required to be envious («hatred for the happiness of others»).[93] He argues that evil came first into existence by the free will of Lucifer.[94] Lucifer’s attempt to take God’s throne is not an assault on the gates of heaven, but a turn to solipsism in which the devil becomes God in his world.[95] When the King of Babel uttered his phrase in Isaiah, he was speaking through the spirit of Lucifer, the head of devils. He concluded that everyone who falls away from God are within the body of Lucifer, and is a devil.[96]

Adherents of the King James Only movement and others who hold that Isaiah 14:12 does indeed refer to the devil have decried the modern translations.[97][98][99][100][101][102] An opposing view attributes to Origen the first identification of the «Lucifer» of Isaiah 14:12 with the devil and to Tertullian and Augustine of Hippo the spread of the story of Lucifer as fallen through pride, envy of God and jealousy of humans.[103]

The 1409 Lollard manuscript titled Lanterne of Light associated Lucifer with the deadly sin of the pride.

Protestant theologian John Calvin rejected the identification of Lucifer with Satan or the devil. He said: «The exposition of this passage, which some have given, as if it referred to Satan, has arisen from ignorance: for the context plainly shows these statements must be understood in reference to the king of the Babylonians.»[104] Martin Luther also considered it a gross error to refer this verse to the devil.[105]

Counter-Reformation writers, like Albertanus of Brescia, classified the seven deadly sins each to a specific Biblical demon.[106] He, as well as Peter Binsfield, assigned Lucifer to the sin pride.[107]

Gnosticism[edit]

Since Lucifer’s sin mainly consists of self-deification, some Gnostic sects identified Lucifer with the creator deity in the Old Testament.[108] In the Bogomil and Cathar text Gospel of the Secret Supper, Lucifer is a glorified angel but fell from heaven to establish his own kingdom and became the Demiurge who created the material world and trapped souls from heaven inside matter. Jesus descended to earth to free the captured souls.[109][110] In contrast to mainstream Christianity, the cross was denounced as a symbol of Lucifer and his instrument in an attempt to kill Jesus.[111]

Latter Day Saint movement[edit]

Lucifer is regarded within the Latter Day Saint movement as the pre-mortal name of the devil. Mormon theology teaches that in a heavenly council, Lucifer rebelled against the plan of God the Father and was subsequently cast out.[112] The Doctrine and Covenants reads:

And this we saw also, and bear record, that an angel of God who was in authority in the presence of God, who rebelled against the Only Begotten Son whom the Father loved and who was in the bosom of the Father, was thrust down from the presence of God and the Son, and was called Perdition, for the heavens wept over him—he was Lucifer, a son of the morning. And we beheld, and lo, he is fallen! is fallen, even a son of the morning! And while we were yet in the Spirit, the Lord commanded us that we should write the vision; for we beheld Satan, that old serpent, even the devil, who rebelled against God, and sought to take the kingdom of our God and his Christ—Wherefore, he maketh war with the saints of God, and encompasseth them round about.

— Doctrine and Covenants 76:25–29[113]

After becoming Satan by his fall, Lucifer «goeth up and down, to and fro in the earth, seeking to destroy the souls of men».[114] Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints consider Isaiah 14:12 to be referring to both the king of the Babylonians and the devil.[115][116]

Other occurrences[edit]

Anthroposophy[edit]

Rudolf Steiner’s writings, which formed the basis for Anthroposophy, characterised Lucifer as a spiritual opposite to Ahriman, with Christ between the two forces, mediating a balanced path for humanity. Lucifer represents an intellectual, imaginative, delusional, otherworldly force which might be associated with visions, subjectivity, psychosis and fantasy. He associated Lucifer with the religious/philosophical cultures of Egypt, Rome and Greece. Steiner believed that Lucifer, as a supersensible Being, had incarnated in China about 3000 years before the birth of Christ.

Luciferianism[edit]

Luciferianism is a belief structure that venerates the fundamental traits that are attributed to Lucifer. The custom, inspired by the teachings of Gnosticism, usually reveres Lucifer not as the devil, but as a savior, a guardian or instructing spirit[117] or even the true god as opposed to Jehovah.[118]

In Anton LaVey’s The Satanic Bible, Lucifer is one of the four crown princes of hell, particularly that of the East, the ‘lord of the air’, and is called the bringer of light, the morning star, intellectualism, and enlightenment.[119]

Freemasonry[edit]

Léo Taxil (1854–1907) claimed that Freemasonry is associated with worshipping Lucifer. In what is known as the Taxil hoax, he alleged that leading Freemason Albert Pike had addressed «The 23 Supreme Confederated Councils of the world» (an invention of Taxil), instructing them that Lucifer was God, and was in opposition to the evil god Adonai. Taxil promoted a book by Diana Vaughan (actually written by himself, as he later confessed publicly)[120] that purported to reveal a highly secret ruling body called the Palladium, which controlled the organization and had a satanic agenda. As described by Freemasonry Disclosed in 1897:

With frightening cynicism, the miserable person we shall not name here [Taxil] declared before an assembly especially convened for him that for twelve years he had prepared and carried out to the end the most sacrilegious of hoaxes. We have always been careful to publish special articles concerning Palladism and Diana Vaughan. We are now giving in this issue a complete list of these articles, which can now be considered as not having existed.[121]

Supporters of Freemasonry assert that, when Albert Pike and other Masonic scholars spoke about the «Luciferian path,» or the «energies of Lucifer,» they were referring to the Morning Star, the light bearer, the search for light; the very antithesis of dark. Pike says in Morals and Dogma, «Lucifer, the Son of the Morning! Is it he who bears the Light, and with its splendors intolerable blinds feeble, sensual, or selfish Souls? Doubt it not!»[122] Much has been made of this quote.[123]

Taxil’s work and Pike’s address continue to be quoted by anti-masonic groups.[124]

In Devil-Worship in France, Arthur Edward Waite compared Taxil’s work to today’s tabloid journalism, replete with logical and factual inconsistencies.

Charles Godfrey Leland[edit]

In a collection of folklore and magical practices supposedly collected in Italy by Charles Godfrey Leland and published in his Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, the figure of Lucifer is featured prominently as both the brother and consort of the goddess Diana, and father of Aradia, at the center of an alleged Italian witch-cult.[125] In Leland’s mythology, Diana pursued her brother Lucifer across the sky as a cat pursues a mouse. According to Leland, after dividing herself into light and darkness:

[…] Diana saw that the light was so beautiful, the light which was her other half, her brother Lucifer, she yearned for it with exceeding great desire. Wishing to receive the light again into her darkness, to swallow it up in rapture, in delight, she trembled with desire. This desire was the Dawn. But Lucifer, the light, fled from her, and would not yield to her wishes; he was the light which flies into the most distant parts of heaven, the mouse which flies before the cat.[126]

Here, the motions of Diana and Lucifer once again mirror the celestial motions of the moon and Venus, respectively.[127] Though Leland’s Lucifer is based on the classical personification of the planet Venus, he also incorporates elements from Christian tradition, as in the following passage:

Diana greatly loved her brother Lucifer, the god of the Sun and of the Moon, the god of Light (Splendor), who was so proud of his beauty, and who for his pride was driven from Paradise.[126]

In the several modern Wiccan traditions based in part on Leland’s work, the figure of Lucifer is usually either omitted or replaced as Diana’s consort with either the Etruscan god Tagni, or Dianus (Janus, following the work of folklorist James Frazer in The Golden Bough).[125]

Gallery[edit]

-

Lucifer, by Alessandro Vellutello (1534), for Dante’s Inferno, canto 34

-

Mayor Hall and Lucifer, by an unknown artist (1870)

-

Gustave Doré’s illustration for Milton’s Paradise Lost, III, 739–742: Satan on his way to bring about the fall of man[128]

-

Gustave Doré’s illustration for Milton’s Paradise Lost, V, 1006–1015: Satan yielding before Gabriel[129]

Modern popular culture[edit]

See also[edit]

- Angra Mainyu

- Aphrodite

- Astarte

- Asura

- Aurvandil, aka Earendel

- Azazel

- Devil in popular culture

- Doctor Faustus, tragic play by Christopher Marlowe

- Erlik

- Guardian of the Threshold

- Inferno, first of the three canticas of Dante’s Divine Comedy

- Luceafărul, a literary magazine

- Luceafărul, a poem by the poet Mihai Eminescu

- Lucifer and Prometheus

- The Lucifer Effect

- Luciform body

- Lucis Trust

- Phosphorus, the morning star, aka Eosphorus and Heosphorus

- Shahar

Notes[edit]

- ^ Lucifer is the Latin name for the planet Venus in its morning appearances. It corresponds to the Greek names Φωσφόρος, «light-bringer», and Ἑωσφόρος, «dawn-bringer».

- ^ Cicero wrote: Stella Veneris, quae Φωσφόρος Graece, Latine dicitur Lucifer, cum antegreditur solem, cum subsequitur autem Hesperos. («The star of Venus, called Φωσφόρος in Greek and Lucifer in Latin when it precedes, Hesperos when it follows the sun».[12]

- ^ Pliny the Elder: Sidus appellatum Veneris […] ante matutinum exoriens Luciferi nomen accipit […] contra ab occasu refulgens nuncupatur Vesper («The star called Venus […] when it rises in the morning is given the name Lucifer […] but when it shines at sunset it is called Vesper».)[13]

- ^ Virgil wrote:

Luciferi primo cum sidere frigida rura

carpamus, dum mane novum, dum gramina canent(«Let us hasten, when first the Morning Star appears, to the cool pastures, while the day is new, while the grass is dewy»)[14]

- ^ Marcus Annaeus Lucanus:

Lucifer a Casia prospexit rupe diemque

misit in Aegypton primo quoque sole calentem(«The morning-star looked forth from Mount Casius and sent the daylight over Egypt, where even sunrise is hot»)[15]

- ^ Ovid wrote:

[…] vigil nitido patefecit ab ortu

purpureas Aurora fores et plena rosarum

atria: diffugiunt stellae, quarum agmina cogit

Lucifer et caeli statione novissimus exit(«Aurora, awake in the glowing east, opens wide her bright doors, and her rose-filled courts. The stars, whose ranks are shepherded by Lucifer the morning star, vanish, and he, last of all, leaves his station in the sky»)[16]

- ^ Statius:

Et iam Mygdoniis elata cubilibus alto

impulerat caelo gelidas Aurora tenebras,

rorantes excussa comas multumque sequenti

sole rubens; illi roseus per nubila seras

aduertit flammas alienumque aethera tardo

Lucifer exit equo, donec pater igneus orbem

impleat atque ipsi radios uetet esse sorori(«And now Aurora rising from her Mygdonian couch had driven the cold darkness on from high in the heavens, shaking out her dewy hair, her face blushing red at the pursuing sun – from him roseate Lucifer averts his fires lingering in the clouds and with reluctant horse leaves the heavens no longer his, until the blazing father make full his orb and forbid even his sister her beams»)[17][18]

References[edit]

- ^ Old Testament Hebrew Lexical Dictionary.

- ^ Isaiah 14:12

- ^ a b Kohler, Kaufmann (2006). Heaven and Hell in Comparative Religion with Special Reference to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-7661-6608-2.

Lucifer, is taken from the Latin version, the Vulgate

Originally published New York: The MacMillan Co., 1923. - ^ «Latin Vulgate Bible: Isaiah 14». DRBO.org. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ «Vulgate: Isaiah Chapter 14» (in Latin). Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles. «A Latin Dictionary». Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-57607-094-9.

dixon-kennedy lucifer.

- ^ Smith, William (1878). «Lucifer». A Smaller Classical Dictionary of Biography, Mythology, and Geography. New York City: Harper. p. 235.

- ^ Catullus 62.8.

- ^ a b c «Lucifer» in Encyclopaedia Britannica].

- ^ Auffarth, Christoph; Stuckenbruck, Loren T., eds. (2004). The Fall of the Angels. Leiden: BRILL. p. 62. ISBN 978-90-04-12668-8.

- ^ De Natura Deorum 2, 20, 53

- ^ Natural History 2, 36.

- ^ [1]Georgics3:324–325.

- ^ Lucan, Pharsalia, 10:434–435; English translation by J. D. Duff (Loeb Classical Library).

- ^ Metamorphoses 2.114–115; A. S. Kline’s Version

- ^ [2]Statius, Thebaid2, 134–150

- ^ P. Papinius Statius (2007). Thebaid and Achilleid (PDF). Vol. II. Translated by A. L. Ritchie; J. B. Hall. Collaboration with M. J. Edwards. ISBN 978-1-84718-354-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23.

- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 492.

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2.

- ^ Astronomica 2. 4 (trans. Grant).

- ^ Metamorphoses 2. 112 ff (trans. Melville).

- ^ Metamorphoses, 11:295.

- ^ Metamorphoses, 11:271.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, 1.7.4.

- ^ «EOSPHORUS & HESPERUS (Eosphoros & Hesperos) – Greek Gods of the Morning & Evening Stars».

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3. 19.

- ^ Marvin Alan Sweeney (1996). Isaiah 1–39. Eerdmans. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8028-4100-1. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Cooley, Jeffrey L. (2008). «Inana and Šukaletuda: A Sumerian Astral Myth». KASKAL. 5: 161–172. ISSN 1971-8608.

- ^ Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 0-7141-1705-6.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6.

- ^ a b «Lucifer». Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the gods and goddesses of Canaan. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-8264-6830-7.

- ^ Boyd, Gregory A. (1997). God at War: The Bible & Spiritual Conflict. InterVarsity Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0-8308-1885-3.

- ^ Pope, Marvin H. (1955). Marvin H. Pope, El in the Ugaritic Texts. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Gary V. Smith (30 August 2007). Isaiah 1–30. B&H Publishing Group. pp. 314–315. ISBN 978-0-8054-0115-8. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ a b Gunkel, Hermann (2006) [1895]. «Isa 14:12–14». Creation And Chaos in the Primeval Era And the Eschaton. A Religio-historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12. Translated by Whitney, K. William Jr. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-0-8028-2804-0.

… it is even more definitely certain that we are dealing with a native myth!]

- ^ a b Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (2003). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 511. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Schwartz, Howard (2004). Tree of souls: The mythology of Judaism. New York City: OUP. p. 108. ISBN 0-19-508679-1.

- ^ Houtman, Iberdina; Kadari, Tamar; Poorthuis, Marcel; Tohar, Vered (2016). Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 66. ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6.

- ^ Cicero. De Natura Deorum. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ «Isaiah 14 Biblos Interlinear Bible». Interlinearbible.org. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ «Isaiah 14 Hebrew OT: Westminster Leningrad Codex». Wlc.hebrewtanakh.com. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ «Astronomy – Helel, Son of the Morning». Jewish Encyclopedia (1906 ed.). Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Wilken, Robert (2007). Isaiah: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators. Grand Rapids MI: Wm Eerdmans Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8028-2581-0.

- ^ a b «Isaiah Chapter 14». mechon-mamre.org. The Mamre Institute. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Gunkel expressly states that «the name Helel ben Shahar clearly states that it is a question of a nature myth. Morning Star, son of Dawn has a curious fate. He rushes gleaming up towards heaven, but never reaches the heights; the sunlight fades him away.» (Schöpfung und Chaos, p. 133)

- ^ a b «Hebrew Concordance: hê·lêl – 1 Occurrence – Bible Suite». Bible Hub. Leesburg, Florida: Biblos.com. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ a b Strong’s Concordance, H1966

- ^ «LXX Isaiah 14» (in Greek). Septuagint.org. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ «Greek OT (Septuagint/LXX): Isaiah 14» (in Greek). Bibledatabase.net. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ «LXX Isaiah 14» (in Greek). Biblos.com. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ «Septuagint Isaiah 14» (in Greek). Sacred Texts. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ «Greek Septuagint (LXX) Isaiah – Chapter 14» (in Greek). Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Neil Forsyth (1989). The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth. Princeton University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-691-01474-6. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Nwaocha Ogechukwu Friday (30 May 2012). The Devil: What Does He Look Like?. American Book Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-58982-662-5. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Bernard A.; with word definitions by J. Lust; Eynikel, E.; Hauspie, K. (2009). Analytical lexicon to the Septuagint (Expanded ed.). Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-56563-516-6.

- ^ Isaiah 14:3–4

- ^ Isaiah 14:12–17

- ^ Carol J. Dempsey (2010). Isaiah: God’s Poet of Light. Chalice Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8272-1630-3. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Manley, Johanna, ed. (1995). Isaiah through the Ages. Menlo Park, Calif.: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-0-9622536-3-8. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Breslauer, S. Daniel, ed. (1997). The seductiveness of Jewish myth : challenge or response?. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 280. ISBN 0-7914-3602-0.

- ^ Roy F. Melugin; Marvin Alan Sweeney (1996). New Visions of Isaiah. Sheffield: Continuum International. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-85075-584-5. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Laney, J. Carl (1997). Answers to Tough Questions from Every Book of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8254-3094-7. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Doorly, William J. (1992). Isaiah of Jerusalem. New York: Paulist Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8091-3337-6. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Isaiah 14:18

- ^ Wolf, Herbert M. (1985). Interpreting Isaiah: The Suffering and Glory of the Messiah. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Academie Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-310-39061-9.

- ^ Herzog, Schaff- (1909). Samuel MacAuley Jackson; Charles Colebrook Sherman; George William Gilmore (eds.). The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Thought: Chamier-Draendorf (Volume 3 ed.). USA: Funk & Wagnalls Co. p. 400. ISBN 1-4286-3183-6.

Heylel (Isa. xiv. 12), the «day star, fallen from heaven,» is interesting as an early instance of what, especially in pseudepigraphic literature, became a dominant conception, that of fallen angels.

- ^ Bamberger, Bernard J. (2006). Fallen Angels: Soldiers of Satan’s Realm (1. paperback ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Jewish Publ. Soc. of America. pp. 148, 149. ISBN 0-8276-0797-0.

- ^ Adelman, Rachel (2009). pp. 61–62.

- ^ ‘The Jewish Encyclopedia’, Volume VIII, p. 204, Funk & Wagnalls, London, 1912.

- ^ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Eerdmans. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8028-3634-2. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Berlin, Adele, ed. (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-19-973004-9.

The notion of Satan as the opponent of God and the chief evil figure in a panoply of demons seems to emerge in the Pseudepigrapha … Satan’s expanded role describes him as … cast out of heaven as a fallen angel (a misinterpretation of Is 14.12).»

- ^ Luke 10:18

- ^ The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories. Merriam-Webster. 1991. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-87779-603-9. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

name Lucifer was born -magazine.

- ^ Harold Bloom (2005). Satan. Infobase Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7910-8386-4. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Litwa, M. David (2016). Desiring Divinity: Self-deification in Early Jewish and Christian Mythmaking. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-046717-3. p. 46

- ^ Adelman, Rachel (2009). The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe De-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha. Leiden: BRILL. p. 67. ISBN 978-90-04-17049-0.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell: Biographie des Teufels: das radikal Böse und die Macht des Guten in der Welt. Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2000, retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Dendle, Peter (2001). Satan Unbound: The Devil in Old English Narrative Literature. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8369-2.p. 10

- ^ Bonnetain, Yvonne S (2015). Loki: Beweger der Geschichten [Loki: Movers of the stories] (in German). Roter Drache; ISBN 978-3-939459-68-2 / OCLC 935942344. pg. 263

- ^ Theißen, Gerd (2009). Erleben und Verhalten der ersten Christen: Eine Psychologie des Urchristentums [Experience and Behavior of the First Christians: A Psychology of Early Christianity] (in German). Gütersloher Verlagshaus; ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6. pg. 251

- ^ Sigve K Tonstad (20 January 2007). Saving God’s Reputation. London, New York City: Continuum. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-567-04494-5. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph Francis (2002). The Problem of Evil in the Western Tradition. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8146-5104-9.

- ^ Auffarth, Christoph; Stuckenbruck, Loren T., eds. (2004). p. 62.

- ^ Fekkes, Jan (1994). Isaiah and Prophetic Traditions in the Book of Revelation. London, New York City: Continuum. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-85075-456-5.

- ^ Isaiah 14:14

- ^ Migne, Patrologia latina, vol. 2, cols. 500 and 514

- ^ «Tertullian : Ernest Evans, Adversus Marcionem. Book 5 (English)». www.tertullian.org. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell (1987). Satan: The Early Christian Tradition. Cornell University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8014-9413-0. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Link, Luther (1995). The Devil: A Mask without a Face. Clerkenwell, London: Reaktion Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-948462-67-2.

- ^ Schreckenberg, Heinz; Schubert, Kurt (1992). Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity. Augsburg Fortress, Publishers; ISBN 978-0-8006-2519-1. pg. 253

- ^ Burns, J. Patout (1988). «Augustine on the Origin and Progress of Evil». The Journal of Religious Ethics. 16 (1): 9–27. JSTOR 40015076.

- ^ Babcock, William S. (1988). «Augustine on Sin and Moral Agency». The Journal of Religious Ethics. 16 (1): 28–55. JSTOR 40015077.

- ^ Aiello, Thomas (28 September 2010). «The Man Plague: Disco, the Lucifer Myth, and the Theology of ‘It’s Raining Men’: The Man Plague». The Journal of Popular Culture. 43 (5): 926–941. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5931.2010.00780.x. PMID 21140934.

- ^ Hollerich, M. J.; Christman, A. R. (2007). Isaiah: Interpreted by Early Christian Medieval Commentators. Cambridge: Eerdmans. pp. 175–176

- ^ Larry Alavezos (29 September 2010). A Primer on Salvation and Bible Prophecy. TEACH Services. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-57258-640-6. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ David W. Daniels (2003). Answers to Your Bible Version Questions. Chick Publications. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7589-0507-9. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ William Dembski (2009). The End of Christianity. B&H Publishing Group. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8054-2743-1. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Cain, Andrew (2011). The fathers of the church. Jerome. Commentary on Galatians. Washington, D.C.: CUA Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8132-0121-4.

- ^ Hoffmann, Tobias, ed. (2012). A Companion to Angels in Medieval Philosophy. Leiden: BRILL. p. 262. ISBN 978-90-04-18346-9.

- ^ Nicolas de Dijon (1730). Prediche Quaresimali: Divise In Due Tomi (in Italian). Vol. 2. Storti. p. 230.

- ^ Corson, Ron (2008). «Who is Lucifer…or Satan misidentified». newprotestants.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Calvin, John (2007). Commentary on Isaiah. Vol. I:404. Translated by John King. Charleston, S.C.: Forgotten Books.

- ^ Ridderbos, Jan (1985). The Bible Student’s Commentary: Isaiah. Translated by John Vriend. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Regency. p. 142.

- ^ Patrick Gilli (ed.). La pathologie du pouvoir: vices, crimes et délits des gouvernants: antiquité, moyen âge, époque moderne (2016). Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions, vol. 198. Brill. pg. 494

- ^ Levack, B. (2013). The Devil Within: Possession and Exorcism in the Christian West. Yale University Press. pg. 278

- ^ Litwa, M. David (2016). Desiring Divinity: Self-deification in Early Jewish and Christian Mythmaking. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-046717-3. p. 46

- ^ Michael C. Thomsett (2011). Heresy in the Roman Catholic Church: A History. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-48539-0 p. 71

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer (2009). The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition. Shambhala. ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0. p. 745–755, 831

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer (2009). The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition. Shambhala. ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0. p. 745–755, 751

- ^ «Devils». Encyclopedia of Mormonism. Archived from the original on 2018-09-22. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ^ «D&C 76:25–29».

- ^ «D&C 10:27».

- ^ «Lucifer». churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ «Isaiah 14:12, footnote c».

- ^ Michelle Belanger (2007). Vampires in Their Own Words: An Anthology of Vampire Voices. Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-7387-1220-8.

- ^ Spence, L. (1993). An Encyclopedia of Occultism. Carol Publishing.

- ^ LaVey, Anton Szandor (1969). «The Book of Lucifer: The Enlightenment». The Satanic Bible. New York: Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-01539-9.

- ^ «Leo Taxil’s confession». Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon. 2 April 2001. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Freemasonry Disclosed April 1897

- ^ (Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma, p. 321).

- ^ (Masonic information: Lucifer).

- ^ «Leo Taxil: The tale of the Pope and the Pornographer». Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- ^ a b Magliocco, Sabina. (2009). Aradia in Sardinia: The Archaeology of a Folk Character. Pp. 40-60 in Ten Years of Triumph of the Moon. Hidden Publishing.

- ^ a b Charles G. Leland, Aradia: The Gospel of Witches, Theophania Publishing, US, 2010.

- ^ Magliocco, Sabina. (2006). Italian American Stregheria and Wicca: Ethnic Ambivalence in American Neopaganism. Pp. 55-86 in Michael Strmiska, ed., Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio.

- ^ «Paradise Lost: Illustrations by Gustave Doré». 2011-07-08. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ «Paradise Lost: Illustrations by Gustave Doré». 2010-09-23. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

Further reading[edit]

- Charlesworth, James H., ed. (2010). The Old Testament pseudepigrapha. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson. ISBN 978-1-59856-491-4.

- TBD; Elwell, Walter A.; Comfort, Philip W. (2001). Walter A. Elwell; Philip Wesley Comfort (eds.). Tyndale Bible Dictionary, Dayspring, Daystar. Wheaton, Ill.: Tyndale House Publishers. p. 363. ISBN 0-8423-7089-7.

- Campbell, Joseph (1972). Myths To Live By (Repr. 2nd ed.). [London]: Souvenir Press. ISBN 0-285-64731-8.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Lucifer.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lucifer.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2010). Lucifer (classical mythology). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Lucifer (devil)» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article is about the mythological and religious figure. For other uses, see Lucifer (disambiguation).

Lucifer[a] is one of various figures in folklore associated with the planet Venus. The entity’s name was subsequently absorbed into Christianity as a name for the devil. Modern scholarship generally translates the term in the relevant Bible passage (Isaiah 14:12), where the Greek Septuagint reads ὁ ἑωσφόρος ὁ πρωὶ, as «morning star» or «shining one» rather than as a proper noun, Lucifer, as found in the Latin Vulgate.

As a name for the Devil in Christian theology, the more common meaning in English, «Lucifer» is the rendering of the Hebrew word הֵילֵל, hêlēl, (pronunciation: hay-lale)[1] in Isaiah[2] given in the King James Version of the Bible. The translators of this version took the word from the Latin Vulgate,[3] which translated הֵילֵל by the Latin word lucifer (uncapitalized),[4][5] meaning «the morning star», «the planet Venus», or, as an adjective, «light-bringing».[6]

As a name for the planet in its morning aspect, «Lucifer» (Light-Bringer) is a proper noun and is capitalized in English. In Greco-Roman civilization, it was often personified and considered a god[7] and in some versions considered a son of Aurora (the Dawn).[8] A similar name used by the Roman poet Catullus for the planet in its evening aspect is «Noctifer» (Night-Bringer).[9]

Roman folklore and etymology[edit]

Lucifer (the morning star) represented as a winged child pouring light from a jar. Engraving by G. H. Frezza, 1704

In Roman folklore, Lucifer («light-bringer» in Latin) was the name of the planet Venus, though it was often personified as a male figure bearing a torch. The Greek name for this planet was variously Phosphoros (also meaning «light-bringer») or Heosphoros (meaning «dawn-bringer»).[10] Lucifer was said to be «the fabled son of Aurora[11] and Cephalus, and father of Ceyx». He was often presented in poetry as heralding the dawn.[10]

Planet Venus in alignment with Mercury (above) and the Moon (below)

The Latin word corresponding to Greek Phosphoros is Lucifer. It is used in its astronomical sense both in prose[b][c] and poetry.[d][e] Poets sometimes personify the star, placing it in a mythological context.[f][g]

Lucifer’s mother Aurora corresponds to goddesses in other cultures. The name «Aurora» is cognate to the name of the Vedic goddess Ushas, that of the Lithuanian goddess Aušrinė, and that of the Greek goddess Eos, all three of whom are also goddesses of the dawn. All four are considered derivatives of the Proto-Indo-European stem *h₂ewsṓs[19] (later *Ausṓs), «dawn», a stem that also gave rise to Proto-Germanic *Austrō, Old Germanic *Ōstara and Old English Ēostre/Ēastre. (Whence also Modern German «Österreich» meaning «Eastern Kingdom», as well as Modern English «east».) This agreement has led scholars to reconstruct a Proto-Indo-European dawn goddess.[20]

The 2nd-century Roman mythographer Pseudo-Hyginus said of the planet:[21]

The fourth star is that of Venus, Luciferus by name. Some say it is Juno’s. In many tales it is recorded that it is called Hesperus, too. It seems to be the largest of all stars. Some have said it represents the son of Aurora and Cephalus, who surpassed many in beauty, so that he even vied with Venus, and, as Eratosthenes says, for this reason it is called the star of Venus. It is visible both at dawn and sunset, and so properly has been called both Luciferus and Hesperus.

The Latin poet Ovid, in his 1st-century epic Metamorphoses, describes Lucifer as ordering the heavens:[22]

Aurora, watchful in the reddening dawn, threw wide her crimson doors and rose-filled halls; the Stellae took flight, in marshaled order set by Lucifer who left his station last.

Ovid, speaking of Phosphorus and Hesperus (the Evening Star, the evening appearance of the planet Venus) as identical, makes him the father of Daedalion.[23] Ovid also makes him the father of Ceyx,[24][25] while the Latin grammarian Servius makes him the father of the Hesperides or of Hesperis.[26]

In the classical Roman period, Lucifer was not typically regarded as a deity and had few, if any, myths,[10] though the planet was associated with various deities and often poetically personified. Cicero stated that «You say that Sol the Sun and Luna the Moon are deities, and the Greeks identify the former with Apollo and the latter with Diana. But if Luna (the Moon) is a goddess, then Lucifer (the Morning-Star) also and the rest of the Wandering Stars (Stellae Errantes) will have to be counted gods; and if so, then the Fixed Stars (Stellae Inerrantes) as well.»[27]

Planet Venus, Sumerian folklore, and fall from heaven motif[edit]

The motif of a heavenly being striving for the highest seat of heaven only to be cast down to the underworld has its origins in the motions of the planet Venus, known as the morning star.

The Sumerian goddess Inanna (Babylonian Ishtar) is associated with the planet Venus, and Inanna’s actions in several of her myths, including Inanna and Shukaletuda and Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld appear to parallel the motion of Venus as it progresses through its synodic cycle.[28][29][30][31]

A similar theme is present in the Babylonian myth of Etana. The Jewish Encyclopedia comments:

The brilliancy of the morning star, which eclipses all other stars, but is not seen during the night, may easily have given rise to a myth such as was told of Ethana and Zu: he was led by his pride to strive for the highest seat among the star-gods on the northern mountain of the gods […] but was hurled down by the supreme ruler of the Babylonian Olympus.[32]

The fall from heaven motif also has a parallel in Canaanite mythology. In ancient Canaanite religion, the morning star is personified as the god Attar, who attempted to occupy the throne of Ba’al and, finding he was unable to do so, descended and ruled the underworld.[33][34] The original myth may have been about the lesser god Helel trying to dethrone the Canaanite high god El, who lived on a mountain to the north.[35][36] Hermann Gunkel’s reconstruction of the myth told of a mighty warrior called Hêlal, whose ambition was to ascend higher than all the other stellar divinities, but who had to descend to the depths; it thus portrayed as a battle the process by which the bright morning star fails to reach the highest point in the sky before being faded out by the rising sun.[37] However, the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible argues that no evidence has been found of any Canaanite myth or imagery of a god being forcibly thrown from heaven, as in the Book of Isaiah (see below). It argues that the closest parallels with Isaiah’s description of the king of Babylon as a fallen morning star cast down from heaven are to be found not in Canaanite myths, but in traditional ideas of the Jewish people, echoed in the Biblical account of the fall of Adam and Eve, cast out of God’s presence for wishing to be as God, and the picture in Psalm 82 of the «gods» and «sons of the Most High» destined to die and fall.[38] This Jewish tradition has echoes also in Jewish pseudepigrapha such as 2 Enoch and the Life of Adam and Eve.[32][39] The Life of Adam and Eve, in turn, shaped the idea of Iblis in the Quran.[40]

The Greek myth of Phaethon, a personification of the planet Jupiter,[41] follows a similar pattern.[37]

Christianity[edit]

In the Bible[edit]

In the Book of Isaiah, chapter 14, the king of Babylon is condemned in a prophetic vision by the prophet Isaiah and is called הֵילֵל בֶּן-שָׁחַר (Helel ben Shachar, Hebrew for «shining one, son of the morning»),[38] who is addressed as הילל בן שחר (Hêlêl ben Šāḥar),[42][43][44][45] The title «Hêlêl ben Šāḥar» refers to the planet Venus as the morning star, and that is how the Hebrew word is usually interpreted.[46][47] The Hebrew word transliterated as Hêlêl[48] or Heylel,[49] occurs only once in the Hebrew Bible.[48] The Septuagint renders הֵילֵל in Greek as Ἑωσφόρος[50][51][52][53][54] (heōsphoros),[55][56] «bringer of dawn», the Ancient Greek name for the morning star.[57] Similarly the Vulgate renders הֵילֵל in Latin as Lucifer, the name in that language for the morning star. According to the King James Bible-based Strong’s Concordance, the original Hebrew word means «shining one, light-bearer», and the English translation given in the King James text is the Latin name for the planet Venus, «Lucifer»,[49] as it was already in the Wycliffe Bible.

However, the translation of הֵילֵל as «Lucifer» has been abandoned in modern English translations of Isaiah 14:12. Present-day translations render הֵילֵל as «morning star» (New International Version, New Century Version, New American Standard Bible, Good News Translation, Holman Christian Standard Bible, Contemporary English Version, Common English Bible, Complete Jewish Bible), «daystar» (New Jerusalem Bible, The Message), «Day Star» (New Revised Standard Version, English Standard Version), «shining one» (New Life Version, New World Translation, JPS Tanakh), or «shining star» (New Living Translation).

In a modern translation from the original Hebrew, the passage in which the phrase «Lucifer» or «morning star» occurs begins with the statement: «On the day the Lord gives you relief from your suffering and turmoil and from the harsh labour forced on you, you will take up this taunt against the king of Babylon: How the oppressor has come to an end! How his fury has ended!»[58] After describing the death of the king, the taunt continues:

How you have fallen from heaven, morning star, son of the dawn! You have been cast down to the earth, you who once laid low the nations! You said in your heart, «I will ascend to the heavens; I will raise my throne above the stars of God; I will sit enthroned on the mount of assembly, on the utmost heights of Mount Zaphon. I will ascend above the tops of the clouds; I will make myself like the Most High.» But you are brought down to the realm of the dead, to the depths of the pit. Those who see you stare at you, they ponder your fate: «Is this the man who shook the earth and made kingdoms tremble, the man who made the world a wilderness, who overthrew its cities and would not let his captives go home?»[59]

For the unnamed «king of Babylon»,[60] a wide range of identifications have been proposed.[61] They include a Babylonian ruler of the prophet Isaiah’s own time,[61] the later Nebuchadnezzar II, under whom the Babylonian captivity of the Jews began,[62] or Nabonidus,[61][63] and the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser, Sargon II and Sennacherib.[64][65] Verse 20 says that this king of Babylon will not be «joined with them [all the kings of the nations] in burial, because thou hast destroyed thy land, thou hast slain thy people; the seed of evil-doers shall not be named for ever», but rather be cast out of the grave, while «All the kings of the nations, all of them, sleep in glory, every one in his own house».[46][66] Herbert Wolf held that the «king of Babylon» was not a specific ruler but a generic representation of the whole line of rulers.[67]

Isaiah 14:12 became a source for the popular conception of the fallen angel motif.[68] Rabbinical Judaism has rejected any belief in rebel or fallen angels.[69] In the 11th century, the Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer illustrates the origin of the «fallen angel myth» by giving two accounts, one relates to the angel in the Garden of Eden who seduces Eve, and the other relates to the angels, the benei elohim who cohabit with the daughters of man (Genesis 6:1–4).[70] An association of Isaiah 14:12–18 with a personification of evil, called the devil, developed outside of mainstream Rabbinic Judaism in pseudepigrapha,[71] and later in Christian writings,[72] particularly with the apocalypses.[73]

As the devil[edit]

The metaphor of the morning star that Isaiah 14:12 applied to a king of Babylon gave rise to the general use of the Latin word for «morning star», capitalized, as the original name of the devil before his fall from grace, linking Isaiah 14:12 with Luke 10 («I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven»)[74] and interpreting the passage in Isaiah as an allegory of Satan’s fall from heaven.[75][76]

Considering pride as a major sin peaking in self-deification, Lucifer (Hêlêl) became the template for the devil.[77] As a result, Lucifer was identified with the devil in Christianity and in Christian popular literature,[3] as in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, Joost van den Vondel’s Lucifer, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost.[78] Early medieval Christianity fairly distinguished between Lucifer and Satan. While Lucifer, as the devil, is fixated in hell, Satan executes the desires of Lucifer as his vassal.[79][80]

Interpretations[edit]

Gustave Doré, illustration to Paradise Lost, book IX, 179–187: «he [Satan] held on / His midnight search, where soonest he might finde / The Serpent: him fast sleeping soon he found».

Aquila of Sinope derives the word hêlêl, the Hebrew name for the morning star, from the verb yalal (to lament). This derivation was adopted as a proper name for an angel who laments the loss of his former beauty.[81] The Christian church fathers – for example Hieronymus, in his Vulgate – translated this as Lucifer. The equation of Lucifer with the fallen angel probably occurred in 1st century Palestinian Judaism. The church fathers brought the fallen lightbringer Lucifer into connection with the Devil on the basis of a saying of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (10.18 EU): «I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning.»[82]

Some Christian writers have applied the name «Lucifer» as used in the Book of Isaiah, and the motif of a heavenly being cast down to the earth, to the devil. Sigve K. Tonstad argues that the New Testament War in Heaven theme of Revelation 12, in which the dragon «who is called the devil and Satan […] was thrown down to the earth», was derived from the passage about the Babylonian king in Isaiah 14.[83] Origen (184/185–253/254) interpreted such Old Testament passages as being about manifestations of the devil.[84][85][86] Origen was not the first to interpret the Isaiah 14 passage as referring to the devil: he was preceded by at least Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 225), who in his Adversus Marcionem (book 5, chapters 11 and 17) twice presents as spoken by the devil the words of Isaiah 14:14: «I will ascend above the tops of the clouds; I will make myself like the Most High».[87][88][89] Though Tertullian was a speaker of the language in which the word «lucifer» was created, «Lucifer» is not among the numerous names and phrases he used to describe the devil.[90] Even at the time of the Latin writer Augustine of Hippo (354–430), a contemporary of the composition of the Vulgate, «Lucifer» had not yet become a common name for the devil.[91]

Augustine of Hippo’s work Civitas Dei (5th century) became the major opinion of Western demonology including in the Catholic Church. For Augustine, the rebellion of the devil was the first and final cause of evil. By this he rejected some earlier teachings about Satan having fallen when the world was already created.[92] Further, Augustine rejects the idea that envy could have been the first sin (as some early Christians believed, evident from sources like Cave of Treasures in which Satan has fallen because he envies humans and refused to prostrate himself before Adam), since pride («loving yourself more than others and God») is required to be envious («hatred for the happiness of others»).[93] He argues that evil came first into existence by the free will of Lucifer.[94] Lucifer’s attempt to take God’s throne is not an assault on the gates of heaven, but a turn to solipsism in which the devil becomes God in his world.[95] When the King of Babel uttered his phrase in Isaiah, he was speaking through the spirit of Lucifer, the head of devils. He concluded that everyone who falls away from God are within the body of Lucifer, and is a devil.[96]

Adherents of the King James Only movement and others who hold that Isaiah 14:12 does indeed refer to the devil have decried the modern translations.[97][98][99][100][101][102] An opposing view attributes to Origen the first identification of the «Lucifer» of Isaiah 14:12 with the devil and to Tertullian and Augustine of Hippo the spread of the story of Lucifer as fallen through pride, envy of God and jealousy of humans.[103]

The 1409 Lollard manuscript titled Lanterne of Light associated Lucifer with the deadly sin of the pride.

Protestant theologian John Calvin rejected the identification of Lucifer with Satan or the devil. He said: «The exposition of this passage, which some have given, as if it referred to Satan, has arisen from ignorance: for the context plainly shows these statements must be understood in reference to the king of the Babylonians.»[104] Martin Luther also considered it a gross error to refer this verse to the devil.[105]