|

||||

| ISO 4217 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | INR (numeric: 356) | |||

| Subunit | 0.01 | |||

| Unit | ||||

| Unit | Rupee | |||

| Symbol | ₹ | |||

| Denominations | ||||

| Subunit | ||||

| 1⁄100 | paisa | |||

| Symbol | ||||

| paisa | ||||

| Banknotes | ||||

| Freq. used | ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹200, ₹500 | |||

| Rarely used | ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, ₹2000 | |||

| Coins | ||||

| Freq. used | ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, ₹10, ₹20 | |||

| Rarely used | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Official user(s) |

|

|||

| Unofficial user(s) |

|

|||

| Issuance | ||||

| Central bank | Reserve Bank of India[5] | |||

| Website | www.rbi.org.in | |||

| Printer | Security Printing and Minting Corporation of India Limited[6] | |||

| Website | spmcil.com | |||

| Mint | India Government Mint[6] | |||

| Website | spmcil.com | |||

| Valuation | ||||

| Inflation | ||||

| Source | RBI – Annual Inflation Report | |||

| Method | Consumer price index (India)[8] | |||

| Pegged by | [1INR=1.6 Nepalese Rupee][7] |

|||

The Indian rupee (symbol: ₹; code: INR) is the official currency in the Republic of India. The rupee is subdivided into 100 paise (singular: paisa), though as of 2023, coins of denomination of 1 rupee are the lowest value in use whereas 2000 rupees is the highest. The issuance of the currency is controlled by the Reserve Bank of India. The Reserve Bank manages currency in India and derives its role in currency management on the basis of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.

Etymology[edit]

The immediate precursor of the rupee is the rūpiya—the silver coin weighing 178 grains minted in northern India, first by Sher Shah Suri during his brief rule between 1540 and 1545, and later adopted and standardized by the Mughal Empire. The weight remained unchanged well beyond the end of the Mughals until the 20th century.[9] Though Pāṇini mentions rūpya (रूप्य), it is unclear whether he was referring to coinage.[10] Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, prime minister to the first Maurya emperor Chandragupta Maurya (c. 340–290 BCE), mentions silver coins as rūpyarūpa. Other types of coins, including gold coins (suvarṇarūpa), copper coins (tāmrarūpa), and lead coins (sīsarūpa), are also mentioned.[11]

History[edit]

The history of the Indian rupee traces back to ancient India in circa 6th century BCE: ancient India was one of the earliest issuers of coins in the world,[12] along with the Chinese wen and Lydian staters.[13]

Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, prime minister to the first Maurya emperor Chandragupta Maurya (c. 340–290 BCE), mentions silver coins as rūpyarūpa, other types including gold coins (suvarṇarūpa), copper coins (tamrarūpa) and lead coins (sīsarūpa) are mentioned. Rūpa means ‘form’ or ‘shape’; for example, in the word rūpyarūpa: rūpya ‘wrought silver’ and rūpa ‘form’.[14]

The Gupta Empire produced large numbers of silver coins clearly influenced by those of the earlier Western Satraps by Chandragupta II.[15] The silver Rūpaka (Sanskrit: रूपक) coins were weighed approximately 20 ratis (2.2678g).[16]

In the intermediate times there was no fixed monetary system as reported by the Da Tang Xi Yu Ji.[17]

During his five-year rule from 1540 to 1545, Sultan Sher Shah Suri issued a coin of silver, weighing 178 grains (or 11.53 grams), which was also termed the rupiya.[18][19] During Babur’s time, the brass to silver exchange ratio was roughly 50:2.[20] The silver coin remained in use during the Mughal period, Maratha era as well as in British India.[21] Among the earliest issues of paper rupees include; the Bank of Hindustan (1770–1832), the General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1773–1775, established by Warren Hastings), and the Bengal Bank (1784–91).[citation needed]

1800s[edit]

| Indian silver rupee value (1820

–1900)[22] |

||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Exchange rate (pence per rupee) | Melt value (pence per rupee) |

| 1850 | 24.3 | 22.7 |

| 1851 | 24.1 | 22.7 |

| 1852 | 23.9 | 22.5 |

| 1853 | 24.1 | 22.8 |

| 1854 | 23.1 | 22.8 |

| 1855 | 24.2 | 22.8 |

| 1856 | 24.2 | 22.8 |

| 1857 | 24.6 | 22.9 |

| 1858 | 25.7 | 22.8 |

| 1859 | 26.0 | 23.0 |

| 1860 | 26.0 | 22.9 |

| 1861 | 23.9 | 22.6 |

| 1862 | 23.9 | 22.8 |

| 1863 | 23.9 | 22.8 |

| 1864 | 23.9 | 22.8 |

| 1865 | 23.8 | 22.7 |

| 1866 | 23.1 | 22.7 |

| 1867 | 23.2 | 22.5 |

| 1868 | 23.2 | 22.5 |

| 1869 | 23.3 | 22.5 |

| 1870 | 22.5 | 22.5 |

| 1871 | 23.1 | 22.5 |

| 1872 | 22.7 | 22.4 |

| 1873 | 22.3 | 22.0 |

| 1874 | 22.1 | 21.6 |

| 1875 | 21.6 | 21.1 |

| 1876 | 20.5 | 19.6 |

| 1877 | 20.8 | 20.4 |

| 1878 | 19.8 | 19.5 |

| 1879 | 20.0 | 19.0 |

| 1880 | 19.9 | 19.4 |

| 1881 | 19.9 | 19.2 |

| 1882 | 19.5 | 19.3 |

| 1883 | 19.5 | 18.7 |

| 1884 | 19.3 | 18.8 |

| 1885 | 18.2 | 18.0 |

| 1886 | 17.4 | 16.8 |

| 1887 | 16.9 | 16.6 |

| 1888 | 16.4 | 15.9 |

| 1889 | 16.5 | 15.8 |

| 1890 | 18.0 | 17.7 |

| 1891 | 16.7 | 16.7 |

| 1892 | 15.0 | 14.8 |

| 1893 | 14.5 | 13.2 |

| 1894 | 13.1 | 10.7 |

| 1895 | 13.6 | 11.1 |

| 1896 | 14.4 | 11.5 |

| 1897 | 15.3 | 10.2 |

| 1898 | 16.0 | 10.0 |

| 1899 | 16.0 | 10.2 |

| 1900 | 16.0 | 10.4 |

Chart showing exchange rate of Indian silver rupee coin (blue) and the actual value of its silver content (red), against British pence. (From 1850 to 1900)

Historically, the rupee was a silver coin. This had severe consequences in the nineteenth century when the strongest economies in the world were on the gold standard (that is, paper linked to gold). The discovery of large quantities of silver in the United States and several European colonies caused the panic of 1873 which resulted in a decline in the value of silver relative to gold, devaluing India’s standard currency. This event was known as «the fall of the rupee.» In Britain the Long Depression resulted in bankruptcies, escalating unemployment, a halt in public works, and a major trade slump that lasted until 1897.[23]

India was unaffected by the imperial order-in-council of 1825, which attempted to introduce British sterling coinage to the British colonies. India, at that time, was controlled by the British East India Company. The silver rupee coin continued as the currency of India through the British Raj and beyond. In 1835, British India adopted a mono-metallic silver standard based on the rupee coin; this decision was influenced by a letter written by Lord Liverpool in 1805 extolling the virtues of mono-metallism.

Following the First war of Independence in 1857, the British government took direct control of India. From 1851, gold sovereigns were produced en masse at the Royal Mint in Sydney. In an 1864 attempt to make the British gold sovereign the «imperial coin», the treasuries in Bombay and Calcutta were instructed to receive (but not to issue) gold sovereigns; therefore, these gold sovereigns never left the vaults. As the British government gave up hope of replacing the rupee in India with the pound sterling, it realised for the same reason it could not replace the silver dollar in the Straits Settlements with the Indian rupee (as the British East India Company had desired). Since the silver crisis of 1873, several nations switched over to a gold exchange standard (wherein silver or banknotes circulate locally but with a fixed gold value for export purposes), including India in the 1890s.[24]

India Council Bill[edit]

In 1870, India was connected to Britain by a submarine telegraph cable.

Around 1875, Britain started paying India for exported goods in India Council (paper) Bills (instead of silver).

If, therefore, the India Council in London should not step in to sell bills on India, the merchants and bankers would have to send silver to make good the (trade) balances. Thus a channel for the outflow of silver was stopped, in 1875, by the India Council in London.[25]

The great importance of these (Council) Bills, however, is the effect they have on the Market Price of Silver : and they have in fact been one of the most potent factors in recent years in causing the diminution in the Value of Silver as compared to Gold.[26]

The Indian and Chinese products for which silver is paid were and are, since 1873–74, very low in price, and it there fore takes less silver to purchase a larger quantity of Eastern commodities. Now, on taking the several agents into united consideration, it will certainly not seem very mysterious why silver should not only have fallen in price[25]

The great nations had recourse to two expedients for replenishing their exchequers, – first, loans, and, second, the more convenient forced loans of paper money۔[25]

Fowler Committee (1898)[edit]

The Indian Currency Committee or Fowler Committee was a government committee appointed by the British-run Government of India on 29 April 1898 to examine the currency situation in India.[27] They collected a wide range of testimony, examined as many as forty-nine witnesses, and only reported their conclusions in July 1899, after more than a year’s deliberation.[22]

The prophecy made before the Committee of 1898 by Mr. A. M. Lindsay, in proposing a scheme closely similar in principle to that which was eventually adopted, has been largely fulfilled. «This change,» he said, «will pass unnoticed, except by the intelligent few, and it is satisfactory to find that by this almost imperceptible process the Indian currency will be placed on a footing which Ricardo and other great authorities have advocated as the best of all currency systems, viz., one in which the currency media used in the internal circulation are confined to notes and cheap token coins, which are made to act precisely as if they were bits of gold by being made convertible into gold for foreign payment purposes.[28] The committee concurred in the opinion of the Indian government that the mints should remain closed to the unrestricted coinage of silver, and that a gold standard should be adopted without delay…they recommended (1) that the British sovereign be given full legal tender power in India, and (2) that the Indian mints be thrown open to its unrestricted coinage (for gold coins only).

These recommendations were acceptable to both governments, and were shortly afterwards translated into laws. The act making gold a legal tender was promulgated on 15 September 1899; and preparations were soon thereafter undertaken for the coinage of gold sovereigns in the mint at Bombay.[22]

Silver, therefore, has ceased to serve as standard; and the Indian currency system of to-day (that is 1901) may be described as that of a «limping» gold standard similar to the systems of France, Germany, Holland, and the United States.[22]

The Committee of 1898 explicitly declared themselves to be in favour of the eventual establishment of a gold currency.

This goal, if it was their goal, the Government of India have never attained.[28]

1900s[edit]

In 1913, John Maynard Keynes writes in his book Indian Currency and Finance that during financial year 1900–1901, gold coins (sovereigns) worth of £6,750,000 were given to Indian people in the hope that it will circulate as currency. But against the expectation of Government, even half of that were not returned to Government, and this experiment failed spectacularly, so Government abandoned this practice (but did not abandon the narrative of gold standard). Subsequently, much of the gold held by Government of India was shipped to Bank of England in 1901 and held there.[29]

Problems caused by the gold standard[edit]

At the onset of the First World War, the cost of gold was very low and therefore the pound sterling had high value. But during the First World War, the value of the pound fell alarmingly due to rising war expenses. At the conclusion of the war, the value of the pound was only a fraction of what it used to be prior to the commencement of the war. It remained low until 1925, when the then Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister) of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, restored it to pre-War levels. As a result, the price of gold fell rapidly. While the rest of Europe purchased large quantities of gold from the United Kingdom, there was little increase in her gold reserves. This dealt a blow to an already deteriorating British economy. The United Kingdom began to look to its possessions as India to compensate for the gold that was sold.[30]

However, the price of gold in India, on the basis of the official exchange rate of the rupee around 1S.6d., was lower than the price prevailing abroad practically throughout; the disparity in prices made the export of the metal profitable, which phenomenon continued for almost a decade. Thus, in 1931–32, there were net exports of 7.7 million ounces, valued at Rs. 579.8 million. In the following year, both the quantity and the price rose further, net exports totaling 8.4 million ounces, valued at Rs. 655.2 million. In the ten years ended March 1941, total net exports were of the order of 43 million ounces (1337.3 Tons) valued at about Rs. 3.75 billion, or an average price of Rs. 32-12-4 per tola.[31]

In the autumn of 1917 (when the silver price rose to 55 pence), there was danger of uprisings in India (against paper currency) which would handicap seriously British participation in the World War. In-convertibility (of paper currency into coin) would lead to a run on Post Office Savings Banks. It would prevent the further expansion of (paper currency) note issues and cause a rise of prices, in paper currency, that would greatly increase the cost of obtaining war supplies for export, to have reduced the silver content of this historic [rupee] coin might well have caused such popular distrust of the Government as to have precipitated an internal crisis, which would have been fatal to British success in the war.[32]

From 1931 to 1941, The United Kingdom purchased large amount of gold from India and its many other colonies just by increasing price of gold, as Britain was able to pay in printable paper currency. Similarly, on 19 June 1934, Roosevelt made Silver Purchase Act (which increased price of silver) and purchased about 44,000 tons of silver by paying paper certificates (silver certificate).[33]

In 1939, Dickson H. Leavens wrote in his book Silver Money: «In recent years the increased price of gold, measured in depreciated paper currencies, has attracted to the market (of London) large quantities (of gold) formerly hoarded or held in the form of ornaments in India and China».[32]

The Indian rupee replaced the Danish Indian rupee in 1845, the French Indian rupee in 1954 and the Portuguese Indian escudo in 1961. Following the independence of India in 1947 and the accession of the princely states to the new Union, the Indian rupee replaced all the currencies of the previously autonomous states (although the Hyderabadi rupee was not demonetised until 1959).[34] Some of the states had issued rupees equal to those issued by the British (such as the Travancore rupee). Other currencies (including the Hyderabadi rupee and the Kutch kori) had different values.

The values of the subdivisions of the rupee during British rule (and in the first decade of independence) were:

| Value (in anna) | Popular name | Value (in paise) |

|---|---|---|

| 16 anna | 1 rupee | 100 paise |

| 8 anna | 1 ardharupee / 1 athanni (dheli) | 50 paise |

| 4 anna | 1 pavala / 1 chawanni | 25 paise |

| 2 anna | 1 beda / 1 duanni | 12 paise |

| 1 anna | 1 ekanni | 6 paise |

| 1⁄2 anna | 1 paraka / 1 taka / 1 adhanni | 3 paise |

| 1⁄4 anna | 1 kani (pice) / 1 paisa (old paise) | 11⁄2 paise |

| 1⁄8 anna | 1 dhela | 3⁄4 paisa |

| 1⁄12 anna | 1 pie | 1⁄2 paisa |

|

New currency sign for the Indian rupee[edit]

In 2010, a new rupee sign (₹) was officially adopted. As its designer explained, it was derived from the combination of the Devanagari consonant «र» (ra) and the Latin capital letter «R» without its vertical bar.[35] The parallel lines at the top (with white space between them) are said to make an allusion to the flag of India,[36] and also depict an equality sign that symbolises the nation’s desire to reduce economic disparity. The first series of coins with the new rupee sign started in circulation on 8 July 2011. Before this, India used «₨» and «Re» as the symbols for multiple rupees and one rupee, respectively.

Digitization of Indian rupee[edit]

At 2022 Union budget of India, Nirmala Sitharaman from Ministry of Finance announced roll out of Digital Rupee from 2023.[37] RBI launched it on 1 November 2022 as pilot project.[38]

Coins[edit]

Pre-independence issues[edit]

Reverse: Face value, country and year of issue surrounded by wreath.

Coin made of 91.7% silver.

East India Company, 1835[edit]

The three Presidencies established by the British East India Company (Bengal, Bombay and Madras) each issued their own coinages until 1835. All three issued rupees and fractions thereof down to 1⁄8— and 1⁄16-rupee in silver. Madras also issued two-rupee coins.

Copper denominations were more varied. Bengal issued one-pie, 1⁄2-, one- and two-paise coins. Bombay issued 1-pie, 1⁄4-, 1⁄2-, 1-, 11⁄2-, 2- and 4-paise coins. In Madras there were copper coins for two and four pies and one, two and four paisa, with the first two denominated as 1⁄2 and one dub (or 1⁄96 and 1⁄48) rupee. Madras also issued the Madras fanam until 1815.

All three Presidencies issued gold mohurs and fractions of mohurs including 1⁄16, 1⁄2, 1⁄4 in Bengal, 1⁄15 (a gold rupee) and 1⁄3 (pancia) in Bombay and 1⁄4, 1⁄3 and 1⁄2 in Madras.

In 1835, a single coinage for the EIC was introduced. It consisted of copper 1⁄12, 1⁄4 and 1⁄2 anna, silver 1⁄4, 1⁄3 and 1 rupee and gold 1 and 2 mohurs. In 1841, silver 2 annas were added, followed by copper 1⁄2 pice in 1853. The coinage of the EIC continued to be issued until 1862, even after the company had been taken over by the Crown.

Regal issues, 1862–1947[edit]

In 1862, coins were introduced (known as «regal issues») which bore the portrait of Queen Victoria and the designation «India». Their denominations were 1⁄12 anna, 1⁄2 pice, 1⁄4 and 1⁄2 anna (all in copper), 2 annas, 1⁄4, 1⁄2 and one rupee (silver),[39] and five and ten rupees and one mohur (gold). The gold denominations ceased production in 1891, and no 1⁄2-anna coins were issued after 1877.

In 1906, bronze replaced copper for the lowest three denominations; in 1907, a cupro-nickel one-anna coin was introduced. In 1918–1919 cupro-nickel two-, four- and eight-annas were introduced, although the four- and eight-annas coins were only issued until 1921 and did not replace their silver equivalents. In 1918, the Bombay mint also struck gold sovereigns and 15-rupee coins identical in size to the sovereigns as an emergency measure during the First World War.

In the early 1940s, several changes were implemented. The 1⁄12 anna and 1⁄2 pice ceased production, the 1⁄4 anna was changed to a bronze, holed coin, cupro-nickel and nickel-brass 1⁄2-anna coins were introduced, nickel-brass was used to produce some one- and two-annas coins, and the silver composition was reduced from 91.7 to 50 percent. The last of the regal issues were cupro-nickel 1⁄4-, 1⁄2— and one-rupee pieces minted in 1946 and 1947, bearing the image of George VI, King and Emperor on the obverse and an Indian lion on the reverse.

Post-independence issues[edit]

Independent pre-decimal issues, 1950–1957[edit]

India’s first coins after independence were issued in 1950 in denominations of 1 pice, 1⁄2, one and two annas, 1⁄4, 1⁄2 and one-rupee. The sizes and composition were the same as the final regal issues, except for the one-pice (which was bronze, but not holed).

Independent decimal issues, 1957–present[edit]

In 1964, India introduced aluminium coins for denominations up to 20p.

The first decimal-coin issues in India consisted of 1, 2, 5, 10, 25 and 50 naye paise, and 1 rupee. The 1 naya paisa was bronze; the 2, 5, and 10 naye paise were cupro-nickel, and the 25 naye paise (nicknamed chawanni; 25 naye paise equals 4 annas), 50 naye paise (also called athanni; 50 naye paise equalled 8 old annas) and 1-rupee were nickel. In 1964, the words naya/naye were removed from all coins. Between 1957 and 1967, aluminium one-, two-, three-, five- and ten-paise coins were introduced. In 1968 nickel-brass 20-paise coins were introduced, and replaced by aluminium coins in 1982. Between 1972 and 1975, cupro-nickel replaced nickel in the 25- and 50-paise and the 1-rupee coins; in 1982, cupro-nickel two-rupee coins were introduced. In 1988 stainless steel 10-, 25- and 50-paise coins were introduced, followed by 1- and 5-rupee coins in 1992. Five-rupee coins, made from brass, are being minted by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

In 1997 the 20 paise coin was discontinued, followed by the 10 paise coin in 1998, and the 25 paise in 2002.

Between 2005 and 2008 new, lighter fifty-paise, one-, two-, and five-rupee coins were introduced, made from ferritic stainless steel. The move was prompted by the melting-down of older coins, whose face value was less than their scrap value. The demonetisation of the 25-paise coin and all paise coins below it took place, and a new series of coins (50 paise – nicknamed athanni – one, two, five, and ten rupees with the new rupee sign) were put into circulation in 2011. In 2016 the 50 paise coin was last minted, but small commodities of prices are in 50 paise. Coins commonly in circulation are one, two, five, ten, and twenty rupees.[40][41] Although it is still legal tender, the 50-paise (athanni) coin is rarely seen in circulation.[42]

| Value | Technical parameters | Description | Year of | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | Mass | Composition | Shape | Obverse | Reverse | First minting | Last minting | |

| 50 paise | 19 mm | 3.79 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, the word «PAISE» in English and Hindi, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | 2016 |

| 50 paise | 22 mm | 3.79 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, hand in a fist | 2008 | |

| ₹1 | 25 mm | 4.85 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India, value | Value, two stalks of wheat | 1992 | 2004 |

| ₹1 | 25 mm | 4.95 g | Ferritic

stainless steel |

Circular | Unity from diversity,

cross dividing 4 dots |

Value, Emblem of India, Year

of minting |

2004 | 2007 |

| ₹1 | 25 mm | 4.85 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, hand showing thumb (an expression in the Bharata Natyam Dance) | 2007 | 2011 |

| ₹1 | 22 mm | 3.79 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, new rupee sign, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | 2018 |

| ₹2 | 26 mm | 6 g | Cupro-Nickel | Eleven-sided | Emblem of India, Value | National integration | 1982 | 2004 |

| ₹2 | 26.75 mm | 5.8 g | Ferritic

stainless steel |

Circular | Unity from diversity,

cross dividing 4 dots |

Value, Emblem of India, Year

of minting |

2005 | 2007 |

| ₹2 | 27 mm | 5.62 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India, year of minting | Value, hand showing two fingers (Hasta Mudra – hand gesture from the dance Bharata Natyam) | 2007 | 2011 |

| ₹2 | 25 mm | 4.85 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, new rupee sign, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | 2018 |

| ₹2 | 23 mm | 4.07 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, rupee sign, year of issue, grains depicting the agricultural dominance of the country | 2019 | |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 9 g | Cupro-Nickel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value | 1992 | 2006 |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 6 g | Ferritic stainless steel | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, wavy lines | 2007 | 2009 |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 6 g | Brass | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, wavy lines | 2009 | 2011 |

| ₹5 | 23 mm | 6 g | Nickel-Brass | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, new rupee sign, floral motif and year of minting | 2011 | 2018 |

| ₹5 | 25 mm | 6.74 g | Nickel-Brass | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, rupee sign, year of issue, grains depicting the agricultural dominance of the country | 2019 | |

| ₹10 | 27 mm | 7.62 g | Bimetallic | Circular | Emblem of India and

year of minting |

Value with outward radiating pattern of 15 spokes | 2006 | 2010 |

| ₹10 | 27 mm | 7.62 g | Bimetallic | Circular | Emblem of India and year of minting | Value with outward radiating pattern of 10 spokes, new rupee sign | 2011 | 2018 |

| ₹10 | 27 mm | 7.74 g | Bimetallic | Circular | Emblem of India | Value, rupee sign, year of issue, grains depicting the agricultural dominance of the country | 2019 | |

| ₹20 | 27 mm | 8.54 g | Bimetallic | Dodecagonal | Emblem of India | Value, rupee sign, year of issue, grains depicting the agricultural dominance of the country | 2020 |

The coins are minted at the four locations of the India Government Mint. The ₹1, ₹2, and ₹5 coins have been minted since independence. The Government of India is set to introduce a new ₹20 coin with a dodecagonal shape, and like the ₹10 coin, also bi-metallic, along with new designs for the new versions of the ₹1, ₹2, ₹5 and ₹10 coins, which was announced on 6 March 2019.[44]

Minting[edit]

The Government of India has the only right to mint the coins and one rupee note. The responsibility for coinage comes under the Coinage Act, 1906 which is amended from time to time. The designing and minting of coins in various denominations is also the responsibility of the Government of India. Coins are minted at the four India Government Mints at Mumbai, Kolkata, Hyderabad, and Noida.[45] The coins are issued for circulation only through the Reserve Bank in terms of the RBI Act.[46]

Commemorative coins[edit]

After independence, the Government of India Mint, minted numismatics coins imprinted with Indian statesmen, historical and religious figures. In the years 2010 and 2011, for the first time ever, ₹75, ₹150 and ₹1000 coins were minted in India to commemorate the Platinum Jubilee of the Reserve Bank of India, the 150th birth anniversary of the birth of Rabindranath Tagore and 1000 years of the Brihadeeswarar Temple, respectively. In 2012, a ₹60 coin was also issued to commemorate 60 years of the Government of India Mint, Kolkata. ₹100 coin was also released commemorating the 100th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s return to India.[47] Commemorative coins of ₹125 were released on 4 September 2015 and 6 December 2015 to honour the 125th anniversary of the births of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and B. R. Ambedkar, respectively.[48][49]

Banknotes[edit]

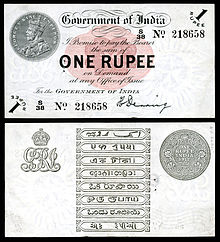

Pre-independence issues[edit]

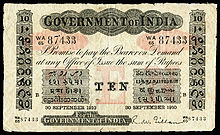

In 1861, the Government of India introduced its first paper money: ₹10 note in 1864, ₹5 note in 1872, ₹10,000 note in 1899, ₹100 note in 1900, ₹50 note in 1905, ₹500 note in 1907 and ₹1,000 note in 1909. In 1917, ₹1 and ₹21⁄2 notes were introduced. The Reserve Bank of India began banknote production in 1938, issuing ₹2, ₹5, ₹10, ₹50, ₹100, ₹1,000 and ₹10,000 notes while the government continued issuing ₹1 note but demonetized the ₹500 and ₹2 1⁄2 notes.

Post-independence issues[edit]

After independence, new designs were introduced to replace the portrait of George VI. The government continued issuing the Re1 note, while the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued other denominations (including the ₹5,000 and ₹10,000 notes introduced in 1949). All pre-independence banknotes were officially demonetised with effect from 28 April 1957.[50][51]

During the 1970s, ₹20 and ₹50 notes were introduced; denominations higher than ₹100 were demonetised in 1978. In 1987, the ₹500 note was introduced, followed by the ₹1,000 note in 2000 while ₹1 and ₹2 notes were discontinued in 1995.

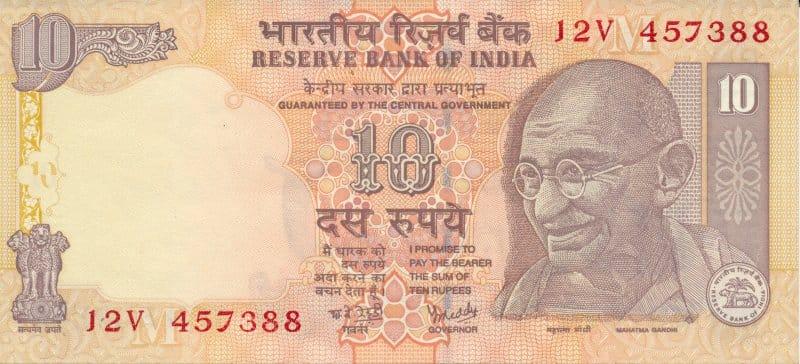

10 Rupees banknote from the 1990s

The design of banknotes is approved by the central government, on the recommendation of the central board of the Reserve Bank of India.[5] Currency notes are printed at the Currency Note Press in Nashik, the Bank Note Press in Dewas, the Bharatiya Reserve Bank Note Mudran (P) Ltd at Salboni and Mysore and at the Watermark Paper Manufacturing Mill in Narmadapuram. The Mahatma Gandhi Series of banknotes are issued by the Reserve Bank of India as legal tender. The series is so named because the obverse of each note features a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi. Since its introduction in 1996, this series has replaced all issued banknotes of the Lion Capital Series. The RBI introduced the series in 1996 with ₹10 and ₹500 banknotes. The printing of ₹5 notes (which had stopped earlier) resumed in 2009.

As of January 2012, the new ‘₹‘ sign has been incorporated into banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi Series in denominations of ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹500 and ₹1,000.[52][53][54][55] In January 2014 RBI announced that it would be withdrawing from circulation all currency notes printed prior to 2005 by 31 March 2014. The deadline was later extended to 1 January 2015. The dead line was further extended to 30 June 2016.[56]

On 8 November 2016, the RBI announced the issuance of new ₹500 and ₹2,000 banknotes in a new series after demonetisation of the older ₹500 and ₹1000 notes. The new ₹2,000 banknote has a magenta base colour, with a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi as well as the Ashoka Pillar Emblem on the front. The denomination also has a motif of the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) on the back, depicting the country’s first venture into interplanetary space. The new ₹500 banknote has a stone grey base colour with an image of the Red Fort along with the Indian flag printed on the back. Both the banknotes also have the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan logo printed on the back. The banknote denominations of ₹200, ₹100 and ₹50 have also been introduced in the new Mahatma Gandhi New Series intended to replace all banknotes of the previous Mahatma Gandhi Series.[57] On 13 June 2017, RBI introduced new ₹50 notes, but the old ones continue being legal tender. The design is similar to the current notes in the Mahatma Gandhi (New) Series, except they will come with an inset ‘A’.

On 8 November 2016, the Government of India announced the demonetisation of ₹500 and ₹1,000 banknotes[58][59] with effect from midnight of the same day, making these notes invalid.[60] A newly redesigned series of ₹500 banknote, in addition to a new denomination of ₹2,000 banknote is in circulation since 10 November 2016.[61][62]

From 2017 to 2019, the remaining banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi New Series were released in denominations of ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100 and ₹200.[63][64] The ₹1,000 note has been suspended.[57]

Current circulating banknotes[edit]

As of 26 April 2019, current circulating banknotes are in denominations of₹5, ₹10, ₹20, ₹50 and ₹100 from the Mahatma Gandhi Series and in denominations of ₹10, ₹20,[65] ₹50, ₹100, ₹200, ₹500 and ₹2,000 from the Mahatma Gandhi New Series.

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main colour | Description | Date of issue | Circulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | Watermark | |||||

|

|

₹1 | 97 mm × 63 mm | Pink | New ₹1 coin | Sagar Samrat oil rig | National Emblem of India | 2020 | Limited |

|

|

₹5 | 117 mm × 63 mm | Green | Mahatma Gandhi | Tractor | Mahatma Gandhi and electrotype denomination | 2002 / 2009 | Limited |

|

|

₹10 | 123 mm × 63 mm | Brown | Konark Sun Temple | 2017 | Wide | ||

|

|

₹20 | 129 mm × 63 mm | Yellow | Ellora Caves | 2019 | Wide | ||

|

|

₹50 | 135 mm × 66 mm | Cyan | Hampi with Chariot | 2017 | Wide | ||

|

|

₹100 | 142 mm × 66 mm | Lavender | Rani ki vav | 2018 | Wide | ||

|

|

₹200 | 146 mm × 66 mm | Orange | Sanchi Stupa | 2017 | Wide | ||

|

|

₹500 | 150 mm × 66 mm | Stone grey | Red Fort | 2017 | Wide | ||

|

|

₹2000 | 166 mm × 66 mm | Magenta | Mangalyaan | 2016 | Wide | ||

| For table standards, see the banknote specification table. |

Micro printing[edit]

The new Indian banknote series feature a few micro printed texts on various locations. The first one lies on the inner surface of the left temple of Gandhi’s spectacles that reads «भारत» (Bhārata) which means India. The next one (which are printed only on 10 and 50 denominations) is placed on the outer surface of the right temple of Gandhi’s spectacles near his ear and reads «RBI» (Reserve Bank of India) and the face value in numerals «10» or «50». The last one is written on both sides of Gandhi’s collar and reads «भारत» and «INDIA» respectively. Currency notes have 17 languages on the panel which appear on the reverse of the notes.

Micro printed texts on Gandhi’s spectacles

Micro printed texts on Gandhi’s collar

Convertibility[edit]

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code |

Symbol or abbreviation |

Proportion of daily volume, April 2019 |

Proportion of daily volume, April 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

United States dollar |

USD |

$ |

88.3% | 88.5% |

|

2 |

Euro |

EUR |

€ |

32.3% | 30.5% |

|

3 |

Japanese yen |

JPY |

¥ / 円 |

16.8% | 16.7% |

|

4 |

Sterling |

GBP |

£ |

12.8% | 12.9% |

|

5 |

Renminbi |

CNY |

¥ / 元 |

4.3% | 7.0% |

|

6 |

Australian dollar |

AUD |

A$ |

6.8% | 6.4% |

|

7 |

Canadian dollar |

CAD |

C$ |

5.0% | 6.2% |

|

8 |

Swiss franc |

CHF |

CHF |

5.0% | 5.2% |

|

9 |

Hong Kong dollar |

HKD |

HK$ |

3.5% | 2.6% |

|

10 |

Singapore dollar |

SGD |

S$ |

1.8% | 2.4% |

|

11 |

Swedish krona |

SEK |

kr |

2.0% | 2.2% |

|

12 |

South Korean won |

KRW |

₩ / 원 |

2.0% | 1.9% |

|

13 |

Norwegian krone |

NOK |

kr |

1.8% | 1.7% |

|

14 |

New Zealand dollar |

NZD |

NZ$ |

2.1% | 1.7% |

|

15 |

Indian rupee |

INR |

₹ |

1.7% | 1.6% |

|

16 |

Mexican peso |

MXN |

$ |

1.7% | 1.5% |

|

17 |

New Taiwan dollar |

TWD |

NT$ |

0.9% | 1.1% |

|

18 |

South African rand |

ZAR |

R |

1.1% | 1.0% |

|

19 |

Brazilian real |

BRL |

R$ |

1.1% | 0.9% |

|

20 |

Danish krone |

DKK |

kr |

0.6% | 0.7% |

|

21 |

Polish złoty |

PLN |

zł |

0.6% | 0.7% |

|

22 |

Thai baht |

THB |

฿ |

0.5% | 0.4% |

|

23 |

Israeli new shekel |

ILS |

₪ |

0.3% | 0.4% |

|

24 |

Indonesian rupiah |

IDR |

Rp |

0.4% | 0.4% |

|

25 |

Czech koruna |

CZK |

Kč |

0.4% | 0.4% |

|

26 |

UAE dirham |

AED |

د.إ |

0.2% | 0.4% |

|

27 |

Turkish lira |

TRY |

₺ |

1.1% | 0.4% |

|

28 |

Hungarian forint |

HUF |

Ft |

0.4% | 0.3% |

|

29 |

Chilean peso |

CLP |

CLP$ |

0.3% | 0.3% |

|

30 |

Saudi riyal |

SAR |

﷼ |

0.2% | 0.2% |

|

31 |

Philippine peso |

PHP |

₱ |

0.3% | 0.2% |

|

32 |

Malaysian ringgit |

MYR |

RM |

0.1% | 0.2% |

|

33 |

Colombian peso |

COP |

COL$ |

0.2% | 0.2% |

|

34 |

Russian ruble |

RUB |

₽ |

1.1% | 0.2% |

|

35 |

Romanian leu |

RON |

L |

0.1% | 0.1% |

|

… |

Other | 2.2% | 2.5% | ||

| Total[note 2] | 200.0% | 200.0% |

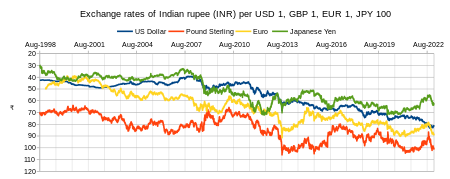

Officially, the Indian rupee has a market-determined exchange rate. However, the Reserve Bank of India trades actively in the USD/INR currency market to impact effective exchange rates. Thus, the currency regime in place for the Indian rupee with respect to the US dollar is a de facto controlled exchange rate. This is sometimes called a «managed float». On 9 May 2022, Indian Rupee traded at ₹77.41 against the US dollar, hitting an all-time low.[67] Other rates (such as the EUR/INR and INR/JPY) have the volatility typical of floating exchange rates, and often create persistent arbitrage opportunities against the RBI.[68] Unlike China, successive administrations (through RBI, the central bank) have not followed a policy of pegging the INR to a specific foreign currency at a particular exchange rate. RBI intervention in currency markets is solely to ensure low volatility in exchange rates, and not to influence the rate (or direction) of the Indian rupee in relation to other currencies.[69]

Also affecting convertibility is a series of customs regulations restricting the import and export of rupees. Legally, only up to ₹25000 can be imported or exported in cash at a time, and the possession of ₹200 and higher notes in Nepal is prohibited.[70][71] The conversion of currencies for and from rupees is also regulated.

RBI also exercises a system of capital controls in addition to (through active trading) in currency markets. On the current account, there are no currency-conversion restrictions hindering buying or selling foreign exchange (although trade barriers exist). On the capital account, foreign institutional investors have convertibility to bring money into and out of the country and buy securities (subject to quantitative restrictions). Local firms are able to take capital out of the country to expand globally. However, local households are restricted in their ability to diversify globally. Because of the expansion of the current and capital accounts, India is increasingly moving towards full de facto convertibility.

There is some confusion regarding the interchange of the currency with gold, but the system that India follows is that money cannot be exchanged for gold under any circumstances due to gold’s lack of liquidity;[citation needed] therefore, money cannot be changed into gold by the RBI. India follows the same principle as Great Britain and the US.

Reserve Bank of India clarifies its position regarding the promissory clause printed on each banknote:

«As per Section 26 of Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, the Bank is liable to pay the value of banknote. This is payable on demand by RBI, being the issuer. The Bank’s obligation to pay the value of banknote does not arise out of a contract but out of statutory provisions. The promissory clause printed on the banknotes i.e., «I promise to pay the bearer an amount of X» is a statement which means that the banknote is a legal tender for X amount. The obligation on the part of the Bank is to exchange a banknote for coins of an equivalent amount.»[72]

Chronology[edit]

- 1991 – India began to lift restrictions on its currency. A number of reforms removed restrictions on current account transactions (including trade, interest payments and remittances and some capital asset-based transactions). Liberalised Exchange Rate Management System (LERMS) (a dual-exchange-rate system) introduced partial convertibility of the rupee in March 1992.[73]

- 1997 – A panel (set up to explore capital account convertibility) recommended that India move towards full convertibility by 2000, but the timetable was abandoned in the wake of the 1997–1998 East Asian financial crisis.

- 2006 – Prime Minister Manmohan Singh asked the Finance Minister and the Reserve Bank of India to prepare a road map for moving towards capital account convertibility.[74]

- 2016 – the Government of India announced the demonetisation of all ₹500/- and ₹1,000/- banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi Series.[75] The government claimed that the action would curtail the shadow economy and crack down on the use of illicit «black money» and counterfeit cash to fund illegal activity and terrorism.[76][77]

Exchange rates[edit]

Historic exchange rates[edit]

Pre-Independence[edit]

Graph of exchange rates of Indian rupee (INR) per USD 1, GBP 1, EUR 1, JPY 100 averaged over the month, from September 1998 to May 2013. Data source: Reserve Bank of India reference rate

For almost a century following the Great Recoinage of 1816, and adoption of the Gold Standard, until the outbreak of World War I, the silver backed Indian rupee lost value against a basket of Gold pegged currencies, and was periodically devalued to reflect the then current gold to silver reserve ratios, see above. In 1850 the official conversion rate between a pound sterling and the rupee was £0 / 2s / 0d (or £1:₹10), while between 1899 and 1914 the official conversion rate was set low at £0 / 1s / 4d (or £1:₹15), for comparison during this period the US dollar was pegged at £1:$4.79. However, this was just half of market exchange rates during 1893–1917.

The gold/silver ratio expanded during 1870–1910. Unlike India, Britain was on the gold standard. To meet the Home Charges (i.e., expenditure in the United Kingdom) the colonial government had to remit a larger number of rupees and this necessitated increased taxation, unrest and nationalism.

Between the wars the rate improved to 1s 6d (or £1:₹13.33), and remained pegged at this rate for the duration of the Breton Woods agreement, to its devaluation and pegging to the US dollar, at $1:₹7.50, in 1966.[78][79]

Post-Independence[edit]

Post Independence India followed Par value system of exchange until 1971. The country switched to pegged system in 1971 and graduated to basket peg againstfive major currencies from 1975. After the 1991 Economic liberalisation in India the currency exchange rates became market controlled.[80]

The first major impact on exchange rate after Independence was the devaluation of sterling against the US dollar in 1949, this impacted currencies that maintained a peg to the sterling, such as the Indian rupee.[81] The next major episode was in 1966 when Indian rupee was devaluated by 57% against United States dollar. Correspondingly the rates against Pound sterling too suffered depreciation.[82] In 1971 August, when the Bretton Woods system India initially announced that it will maintain a fixed rate of US$1 = Rs. 7.50 and leave Pound sterling floating.[83] However, by the end of 1971, following Smithsonian Agreement and subsequent devaluation of United States dollar, India pegged Indian rupee with Pound sterling once again with a rate of £1 = Rs. 18.9677.[84] In the above period India had a non — commercial exchange rate with Soviet Union. The Ruble — Rupee rates were announced by Soviet Union since Ruble wasn’t a freely traded currency and the commercial trade between both nations use to take place in rupee trade account following the India–Soviet Trade Treaty 1953.

In September 1975, exchange rate of Indian rupee started to be determined on the basis of basket peg. The details of currencies which forms the basket and its weightage were kept confidentially by Reserve Bank of India and the exchange rate of rupee on the basis of market fluctuation of these currencies were periodically announced by RBI.[85][86]

The next major change that occurred to Indian Rupee was devaluation by about 18% in July 1991 following the Balance of payment crisis.[87] Thereafter, in March 1992, Liberalized Exchange Rate Management System was introduced.

| Currency | ISO code | 1947 | 1966 | 1995 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian dollar | AUD | – | 5.33 | – | 27.69 | 26.07 | 33.28 | 34.02 | 34.60 | 36.81 | 38.22 | 42.00 | 56.36 | 54.91 | 48.21 | 49.96 | 49.91 | 50.64 | 50.01 | 56.30 | |||

| Bahraini dinar | BHD | – | 13.35 | 91.75 | 91.24 | 117.78 | 120.39 | 120.40 | 109.59 | 115.65 | 128.60 | 121.60 | 155.95 | 164.55 | 170.6 | 178.3 | – | 169.77 | |||||

| Bangladeshi taka | BDT | – | – | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.85 | – | 0.76 | |||||

| Canadian dollar | CAD | – | 5.90 | 23.63 | 26.00 | 30.28 | 34.91 | 41.09 | 42.92 | 44.59 | 52.17 | 44.39 | 56.88 | 49.53 | 47.94 | 52.32 | 50.21 | 51.38 | |||||

| Renminbi | CNY | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5.80 | – | – | – | 9.93 | 10.19 | 10.15 | – | 9.81 | |||||

| Emirate dirham | AED | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17.47 | 18.26 | 17.73 | 17.80 | |||||

| Euroa | EUR | – | – | 42.41 | 44.40 | 41.52 | 56.38 | 64.12 | 68.03 | 60.59 | 65.69 | – | – | 70.21 | 72.60 | 75.84 | 73.53 | 79.52 | |||||

| Israeli shekelb | ILS | 13.33 | 21.97 | 11.45 | 10.76 | 10.83 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17.08 | 16.57 | 17.47 | – | 18.36 | |||||

| Japanese yenc | JPY | 6.6 | 2.08 | 32.66 | 32.96 | 41.79 | 41.87 | 38.93 | 35.00 | 42.27 | 51.73 | 52.23 | 60.07 | 57.79 | 53.01 | 62.36 | – | 56 | |||||

| Kuwaiti dinar | KWD | – | 17.80 | 115.5 | 114.5 | 144.9 | 153.3 | 155.5 | 144.6 | 161.7 | 167.7 | 159.2 | 206.5 | 214.3 | 213.1 | 222.4 | 211.43 | ||||||

| Malaysian ringgit | MYR | 1.55 | 2.07 | 12.97 | 14.11 | 11.84 | 11.91 | 12.36 | 11.98 | 13.02 | 13.72 | 14.22 | 18.59 | 18.65 | 16.47 | 16.37 | – | 15.72 | |||||

| Maldivian rufiyaa | MVR | 1.00 | 1.33 | 2.93 | 2.91 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4.58 | 4.76 | 5.01 | 5.23 | – | 4.13 | |||||

| Pakistani rupee | PKR | 1.00 | 1.33 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.64 | – | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.45 | |||

| Pound sterling | GBP | 13.33 | 17.76 | 51.14 | 55.38 | 68.11 | 83.06 | 80.63 | 76.38 | 71.33 | 83.63 | 70.63 | 91.08 | 100.51 | 98.11 | 92.00 | 83.87 | 90.37 | |||||

| Russian rubled | RUB | 6.60 | 15.00 | 7.56 | 6.69 | 1.57 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.05 | 0.99 | – | 1.10 | |||||

| Saudi riyal | SAR | – | 1.41 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17.11 | 17.88 | – | 17.02 | |||||

| Singapore dollar / Brunei dollare | SGD / BND | 1.55 | 2.07 | 23.13 | 25.16 | 26.07 | 26.83 | 30.93 | 33.60 | 34.51 | 41.27 | 33.58 | 46.84 | 45.86 | 46.67 | 48.86 | – | 47.70 | |||||

| Sri Lankan rupee | LKR | – | 1.33 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.58 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.46 | – | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.39 | |||

| Swiss franc | CHF | – | 1.46 | 27.48 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 43.95 | 66.95 | 66.71 | 66.70 | 68.40 | – | 65.48 | |||||

| US dollar | USD | 3.30 | 7.50 | 32.45 | 35.44 | 44.20 | 45.34 | 43.95 | 39.50 | 48.76 | 45.33 | 45.00 | 68.80 | 66.07 | 66.73 | 67.19 | 65.11 | 72.10 | |||||

| a Before 1 January 1999, the European Currency Unit (ECU) b Before 1980, the Israeli pound (ILP) c 100 Japanese yen d Before 1993, the Soviet ruble (SUR), in 1995 and 1996 – per 1000 rubles e Before 1967, the Malaya and British Borneo dollar |

Current exchange rates[edit]

| Current INR exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD AED JPY USD |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD AED JPY USD |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD AED JPY USD |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD AED JPY USD |

Worldwide rupee usage[edit]

As the Straits Settlements were originally an outpost of the British East India Company, the Indian rupee was made the sole official currency of the Straits Settlements in 1837, as it was administered as part of British India. This attempt was resisted by the locals. However, Spanish dollars continued to circulate and 1845 saw the introduction of coinage for the Straits Settlements using a system of 100 cents = 1 dollar, with the dollar equal to the Spanish dollar or Mexican peso. In 1867, administration of the Straits Settlements was separated from India and the Straits dollar was made the standard currency, and attempts to reintroduce the rupee were finally abandoned.[90]

After the Partition of India, the Pakistani rupee came into existence, initially using Indian coins and Indian currency notes simply overstamped with «Pakistan». Previously the Indian rupee was an official currency of other countries, including Aden, Oman, Dubai, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the Trucial States, Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, the Seychelles and Mauritius.

The Indian government introduced the Gulf rupee as a replacement for the Indian rupee for circulation outside the country with the Reserve Bank of India (Amendment) Act of 1 May 1959.[91] The creation of a separate currency was an attempt to reduce the strain on India’s foreign reserves from gold smuggling. After India devalued the rupee on 6 June 1966, those countries still using it – Oman, Qatar, and the Trucial States (which became the United Arab Emirates in 1971) – replaced the Gulf rupee with their own currencies. Kuwait and Bahrain had already done so in 1961 with Kuwaiti dinar and in 1965 with Bahraini dinar, respectively.[92]

The Bhutanese ngultrum is pegged at par with the Indian rupee; both currencies are accepted in Bhutan. The Nepalese rupee is pegged at ₹0.625; the Indian rupee is accepted in Bhutan and Nepal, except ₹500 and ₹1000 banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi Series and the ₹200, ₹500 and ₹2,000 banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi New Series, which are not legal tender in Bhutan and Nepal and are banned by their respective governments, though accepted by many retailers.[93] On 29 January 2014, Zimbabwe added the Indian rupee as a legal tender to be used.[94][95]

See also[edit]

- Coinage of India

- Rupee

- History of the rupee

- Paisa

- Indian paisa

- History of the taka

- Coins of British India

- Great Depression in India

- Coins of the Indian rupee

- Indian anna

- Indian pie

- Zero rupee note

- Fake Indian currency note

- The Standard Reference Guide to Indian Paper Money

- Reserve Bank of India

- Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934

- RBI Monetary Museum

Notes[edit]

- ^ Alongside Zimbabwean dollar (suspended indefinitely from 12 April 2009), the Pound sterling, Euro, United States dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, Indian rupee, Chinese yuan, and Japanese yen have been adopted as official currencies for all government transactions.

- ^ The total sum is 200% because each currency trade always involves a currency pair; one currency is sold (e.g. US$) and another bought (€). Therefore each trade is counted twice, once under the sold currency ($) and once under the bought currency (€). The percentages above are the percent of trades involving that currency regardless of whether it is bought or sold, e.g. the US dollar is bought or sold in 88% of all trades, whereas the euro is bought or sold 32% of the time.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Frequently Asked Questions». Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ «Nepal writes to RBI to declare banned new Indian currency notes legal». The Economic Times. Times Internet. 6 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ «Indian Rupee to be legal tender in Zimbabwe». Deccan Herald. 29 January 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Hungwe, Brian (29 January 2014). «Zimbabwe’s multi-currency confusion». BBC. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ a b «FAQ – Your Guide to Money Matters». Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ a b Ministry of Finance – Department of Economic Affairs (30 April 2010). Sixth Report, Committee on Public Undertakings – Security Printing and Minting Corporation of India Limited (PDF). Lok Sabha Secretariat. p. 8. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ «Nepal to keep currency pegged to Indian rupee». Business Line. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ «Reserve Bank of India — Annual Report». rbi.org.in. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ «Mogul Coinage». RBI Monetary Museum. Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 5 October 2002.

Sher Shah issued a coin of silver which was termed the Rupiya. This weighed 178 grains and was the precursor of the modern rupee. It remained largely unchanged till the early 20th Century

- ^ Goyal, Shankar (1999), «The Origin and Antiquity of Coinage in India», Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 80 (1/4): 144, JSTOR 41694581,

Panini makes the statement (V.2.120) that a ‘form’ (rüpa) when ‘stamped’ (ahata) or when praise-worthy (prašamsa) takes the ending ya (i.e. rupya). … Whether Panini was familiar with coins or not, his Astadhyayi does not specifically state.

- ^ R Shamasastry (1915), Arthashastra Of Chanakya, pp. 115, 119, 125, retrieved 15 April 2021

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh (January 2002). The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious …, Volume 6. Cosmo Publications. p. 1599. ISBN 81-7755-257-0.

- ^ Schaps, David M. (2006), «The Invention of Coinage in Lydia, in India, and in China» (PDF), XIV International Economic History Congress, Helsinki: International Economic History Association

- ^ «A short history of ancient Indian coinage». worldcoincatalog.com. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ Allan & Stern (2008)

- ^ «Rupaka, Rūpaka: 23 definitions». Wisdom Library. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Da Tang Xiyu Ji. Great Tang Dynasty Records of the Western World. Trübner’s Oriental Series. Vol. 1–2. Translated by Samuel Beal (First ed.). London: Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner & Co. 1906 [1884].

- ^ «Etymology of rupee». Online Etymology Dictionary. 20 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ «Mughal Coinage». RBI Monetary Museum. Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008.

- ^ Dughlat, Mirza Muhammad Haidar. «CXII». In Elias, N. (ed.). The Tarikh-I-Rashidi. Translated by Ross, E. Denison. Ebook Version 1.0 Edited and Presented By Mohammed Murad Butt. Karakoram Books – via Internet Archive.

- ^ «Pre-Colonial India & Princely States: Coinage». RBI Monetary Museum. Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d Andrew, A. Piatt (August 1901). «Indian Currency Problems of the Last Decade». The Quarterly Journal of Economics. pp. 483–514. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ W. B. Sutch, The Long Depression, 1865–1895. (1957)

- ^ «Chapter II» . Indian Currency and Finance – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b c Moore, J S (23 October 2016). «The Silver Question». The North American Review. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ MacLeod, Henry Dunning (1883). «The Theory and Practice of Banking». Retrieved 18 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chishti, M. Anees (2001), Committees and commissions in pre-independence India 1836–1947, Volume 3, Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-803-7,

… The Indian Currency Committee was appointed by the Royal Warrant of 29 April 1898 … by the closing of the Indian Mints to what is known as the free coinage of Silver …

- ^ a b John Maynard Keynes (1913). «Chapter I» . Indian Currency and Finance – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Chapter IV» . Indian Currency and Finance – via Wikisource.

- ^ Balachandran, G. (1996). John Bullion’s Empire: Britain’s Gold Problem and India Between the Wars. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-0428-6., p. 6

- ^ S. L. N. Simha, ed. (2005) [1970]. «2. Currency, Exchange and Banking Prior to 1935» (PDF). History of the Reserve Bank of India. The Reserve Bank of India. pp. 40–81.

- ^ a b Leavens, Dickson H (1939). «Silver Money» (PDF). Cowles Foundation.

- ^ Four Years of the Silver Program. 14 December 1937. CQ Press.

- ^ Razack, Rezwan; Jhunjhunwalla, Kishore (2012). The Revised Standard Reference Guide to Indian Paper Money. Coins & Currencies. ISBN 978-81-89752-15-6.

- ^ Kumar, D. Udaya. «Currency Symbol for Indian Rupee» (PDF). IDC School of Design. Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ «Indian Rupee Joins Elite Currency Club». Theworldreporter.com. 17 July 2010.

- ^ Bose, Shritama (2 February 2022). «Budget 2022: Digital rupee from FY23». Financial Express. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ «India cenbank to start pilot of digital rupee on Nov 1». Reuters. 31 October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ J. Franklin Campbell (13 October 2004). «VICTORIA | The Coins of British India One Rupee: Mint Mark Varieties (1874–1901)». jfcampbell.us. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b «Issue of new series of Coins». RBI. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ «This numismatist lays hands on coins with Rupee symbol». The Times of India. 29 August 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ «Coins of 25 paise and below will not be Legal Tender from June 30, 2011 : RBI appeals to Public to Exchange them up to June 29, 2011». RBI. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ «Reserve Bank of India – Coins». Rbi.org.in. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ «PM releases new series of visually impaired friendly coins». Prime Minister’s Office. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ About Us – Dept. of Commerce. Reserve Bank of India.

- ^ Reserve Bank of India – Coins. Rbi.org.in. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Gaikwad, Rahi (9 January 2015). «India, South Africa discuss UNSC reforms». The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ «Teachers’ day: PM Narendra Modi releases Rs 125 coin in honour of Dr S Radhakrishnan». The Financial Express. 4 September 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ «PM Narendra Modi releases Rs 10, Rs 125 commemorative coins honouring Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar». The Financial Express. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ «Currency Notes without Asoka Pillar Emblem to Cease to be Legal Tender» (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive.

- ^ «Legal Tender of Currency and Bank Notes» (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive.

- ^ «Issue of ‘ 10/- Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol (‘)». RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ «Issue of ‘ 500 Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol». RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ «Issue of ‘ 1000 Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol». RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ «Issue of ‘100 Banknotes with incorporation of Rupee symbol». RBI. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ «Withdrawal of Currencies Issued Prior to 2005». Press Information Bureau. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b «RBI to issue ₹1,000, ₹100, ₹50 with new features, design in coming months». Business Line. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Mukherjee, Amrita (14 November 2016). «How I feel super rich with Rs 100 and Rs 10 in my purse». Asia Times. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ «India’s demonetization takes its toll on major sectors». Asia Times. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Killawala, Alpana (8 November 2016). «Withdrawal of Legal Tender Status for ₹ 500 and ₹ 1000 Notes: RBI Notice» (Press release). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Killawala, Alpana (8 November 2016). «Issue of ₹500 Banknotes (Press Release)» (PDF) (Press release). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Killawala, Alpana (8 November 2016). «Issue of ₹2000 Banknotes (Press Release)» (PDF) (Press release). Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ «RBI Introduces ₹ 200 denomination banknote». Reserve Bank of India. 24 August 2017.

- ^ «RBI to Issue New Design ₹ 100 Denomination Banknote». Reserve Bank of India. 19 July 2018.

- ^ «Reserve Bank of India – Press Releases». rbi.org.in. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ «Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2022» (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. 27 October 2022. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ «Indian Rupee falls to all-time low against US dollar». Business Today. 9 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ «Convertibility: Patnaik, 2004» (PDF). Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

- ^ Chandra, Shobhana (26 September 2007). «‘Neither the government nor the central bank takes a view on the rupee (exchange rate movements), as long as the movement is orderly’, says Indian Minister of Finance». Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ «RBI Master Circular on Import of Goods and Services». Rbi.org.in. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ «RBI Master Circular on Export of Goods and Services». Rbi.org.in. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Reserve bank of India Frequently Asked Questions Archived 12 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine rbi.org.in Retrieved 27 August 2013

- ^ Rituparna Kar and Nityananda Sarkar: Mean and volatility dynamics of Indian rupee/US dollar exchange rate series: an empirical investigation in Asia-Pacific Finan Markets (2006) 13:41–69, p. 48. doi:10.1007/s10690-007-9034-0 .

- ^ «The ‘Fuller Capital Account Convertibility Report’» (PDF). 31 July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ «Withdrawal of Legal Tender Status for ₹ 500 and ₹ 1000 Notes: RBI Notice (Revised)». Reserve Bank of India. 8 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ «Here is what PM Modi said about the new Rs 500, Rs 2000 notes and black money». India Today. 8 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ «Notes out of circulation». The Times of India. 8 November 2016.

- ^ Chandra, Saurabh (21 August 2013). «The fallacy of ‘dollar = rupee’ in 1947». Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ «Historical exchange rates from 1953 with graph and charts». Fxtop.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ «Reserve Bank of India — Publications». m.rbi.org.in. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ «Pound devalued 30 per cent». The Guardian. Guardian Century 1940-1949. 19 September 1949. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Gupta, Sujay (7 June 2016). «Forgotten legacy of 6/6/66 — Times of India». The Times of India. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Verghese, S. K. (1973). «International Monetary Crises and the Indian Rupee». Economic and Political Weekly. 8 (30): 1342–1348. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4362898.

- ^ Wadhva, Charan D.; Paul, Samuel (1973). «The Dollar Devaluation and India’s Balance of Payments». Economic and Political Weekly. 8 (10): 517–522. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4362402.

- ^ Tikku, M. K. (7 April 2015). «High-powered Indian team of financial experts to visit Moscow to sort out rouble-rupee exchange rate differences». India Today. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Verghese, S. K. (1979). «Exchange Rate of Indian Rupee since Its Basket Link». Economic and Political Weekly. 14 (28): 1160–1165. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4367782.

- ^ «Reserve Bank of India». rbi.org.in. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ «FXHistory: historical currency exchange rates» (database). OANDA Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 April 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ^ «The fallacy of ‘dollar = rupee’ in 1947». DNA. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ «Straits Settlements (1867–1946)». Dcstamps.com. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Kamalakaran, Ajay (14 September 2021). «Gulf rupee: When the Reserve Bank of India played central banker in West Asia». Scroll.in. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Ranjan, Rajiv; Prakash, Anand (April 2010). «Internationalisation of currency: the case of the Indian rupee and Chinese renminbi» (PDF). RBI Staff Studies. Department of Economic Analysis and Policy, Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ «Don’t take 1,000 and 500 Indian rupee notes to Nepal». RBI Staff Studies. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ «Indian Rupee to be legal tender in Zimbabwe». Deccan Herald. The Printers Mysore. 29 January 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Hungwe, Brian (6 February 2014). «Zimbabwe’s multi-currency confusion». BBC News.

Sources[edit]

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

External links[edit]

- A gallery of all Indian currency issues

- «Gallery of Indian Rupee Notes introduced till date». Reserve Bank of India. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- The banknotes of India (in English and German)

|

||||

| ISO 4217 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | INR (numeric: 356) | |||

| Subunit | 0.01 | |||

| Unit | ||||

| Unit | Rupee | |||

| Symbol | ₹ | |||

| Denominations | ||||

| Subunit | ||||

| 1⁄100 | paisa | |||

| Symbol | ||||

| paisa | ||||

| Banknotes | ||||

| Freq. used | ₹10, ₹20, ₹50, ₹100, ₹200, ₹500 | |||

| Rarely used | ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, ₹2000 | |||

| Coins | ||||

| Freq. used | ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, ₹10, ₹20 | |||

| Rarely used | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Official user(s) |

|

|||

| Unofficial user(s) |

|

|||

| Issuance | ||||

| Central bank | Reserve Bank of India[5] | |||

| Website | www.rbi.org.in | |||

| Printer | Security Printing and Minting Corporation of India Limited[6] | |||

| Website | spmcil.com | |||

| Mint | India Government Mint[6] | |||

| Website | spmcil.com | |||

| Valuation | ||||

| Inflation | ||||

| Source | RBI – Annual Inflation Report | |||

| Method | Consumer price index (India)[8] | |||

| Pegged by | [1INR=1.6 Nepalese Rupee][7] |

|||

The Indian rupee (symbol: ₹; code: INR) is the official currency in the Republic of India. The rupee is subdivided into 100 paise (singular: paisa), though as of 2023, coins of denomination of 1 rupee are the lowest value in use whereas 2000 rupees is the highest. The issuance of the currency is controlled by the Reserve Bank of India. The Reserve Bank manages currency in India and derives its role in currency management on the basis of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.

Etymology[edit]

The immediate precursor of the rupee is the rūpiya—the silver coin weighing 178 grains minted in northern India, first by Sher Shah Suri during his brief rule between 1540 and 1545, and later adopted and standardized by the Mughal Empire. The weight remained unchanged well beyond the end of the Mughals until the 20th century.[9] Though Pāṇini mentions rūpya (रूप्य), it is unclear whether he was referring to coinage.[10] Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, prime minister to the first Maurya emperor Chandragupta Maurya (c. 340–290 BCE), mentions silver coins as rūpyarūpa. Other types of coins, including gold coins (suvarṇarūpa), copper coins (tāmrarūpa), and lead coins (sīsarūpa), are also mentioned.[11]

History[edit]

The history of the Indian rupee traces back to ancient India in circa 6th century BCE: ancient India was one of the earliest issuers of coins in the world,[12] along with the Chinese wen and Lydian staters.[13]

Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, prime minister to the first Maurya emperor Chandragupta Maurya (c. 340–290 BCE), mentions silver coins as rūpyarūpa, other types including gold coins (suvarṇarūpa), copper coins (tamrarūpa) and lead coins (sīsarūpa) are mentioned. Rūpa means ‘form’ or ‘shape’; for example, in the word rūpyarūpa: rūpya ‘wrought silver’ and rūpa ‘form’.[14]

The Gupta Empire produced large numbers of silver coins clearly influenced by those of the earlier Western Satraps by Chandragupta II.[15] The silver Rūpaka (Sanskrit: रूपक) coins were weighed approximately 20 ratis (2.2678g).[16]

In the intermediate times there was no fixed monetary system as reported by the Da Tang Xi Yu Ji.[17]

During his five-year rule from 1540 to 1545, Sultan Sher Shah Suri issued a coin of silver, weighing 178 grains (or 11.53 grams), which was also termed the rupiya.[18][19] During Babur’s time, the brass to silver exchange ratio was roughly 50:2.[20] The silver coin remained in use during the Mughal period, Maratha era as well as in British India.[21] Among the earliest issues of paper rupees include; the Bank of Hindustan (1770–1832), the General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1773–1775, established by Warren Hastings), and the Bengal Bank (1784–91).[citation needed]

1800s[edit]

| Indian silver rupee value (1820

–1900)[22] |

||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Exchange rate (pence per rupee) | Melt value (pence per rupee) |

| 1850 | 24.3 | 22.7 |

| 1851 | 24.1 | 22.7 |

| 1852 | 23.9 | 22.5 |

| 1853 | 24.1 | 22.8 |

| 1854 | 23.1 | 22.8 |

| 1855 | 24.2 | 22.8 |

| 1856 | 24.2 | 22.8 |

| 1857 | 24.6 | 22.9 |

| 1858 | 25.7 | 22.8 |

| 1859 | 26.0 | 23.0 |

| 1860 | 26.0 | 22.9 |

| 1861 | 23.9 | 22.6 |

| 1862 | 23.9 | 22.8 |

| 1863 | 23.9 | 22.8 |

| 1864 | 23.9 | 22.8 |

| 1865 | 23.8 | 22.7 |

| 1866 | 23.1 | 22.7 |

| 1867 | 23.2 | 22.5 |

| 1868 | 23.2 | 22.5 |

| 1869 | 23.3 | 22.5 |

| 1870 | 22.5 | 22.5 |

| 1871 | 23.1 | 22.5 |

| 1872 | 22.7 | 22.4 |

| 1873 | 22.3 | 22.0 |

| 1874 | 22.1 | 21.6 |

| 1875 | 21.6 | 21.1 |

| 1876 | 20.5 | 19.6 |

| 1877 | 20.8 | 20.4 |

| 1878 | 19.8 | 19.5 |

| 1879 | 20.0 | 19.0 |

| 1880 | 19.9 | 19.4 |

| 1881 | 19.9 | 19.2 |

| 1882 | 19.5 | 19.3 |

| 1883 | 19.5 | 18.7 |

| 1884 | 19.3 | 18.8 |

| 1885 | 18.2 | 18.0 |

| 1886 | 17.4 | 16.8 |

| 1887 | 16.9 | 16.6 |

| 1888 | 16.4 | 15.9 |

| 1889 | 16.5 | 15.8 |

| 1890 | 18.0 | 17.7 |

| 1891 | 16.7 | 16.7 |

| 1892 | 15.0 | 14.8 |

| 1893 | 14.5 | 13.2 |

| 1894 | 13.1 | 10.7 |

| 1895 | 13.6 | 11.1 |

| 1896 | 14.4 | 11.5 |

| 1897 | 15.3 | 10.2 |

| 1898 | 16.0 | 10.0 |

| 1899 | 16.0 | 10.2 |

| 1900 | 16.0 | 10.4 |

Chart showing exchange rate of Indian silver rupee coin (blue) and the actual value of its silver content (red), against British pence. (From 1850 to 1900)

Historically, the rupee was a silver coin. This had severe consequences in the nineteenth century when the strongest economies in the world were on the gold standard (that is, paper linked to gold). The discovery of large quantities of silver in the United States and several European colonies caused the panic of 1873 which resulted in a decline in the value of silver relative to gold, devaluing India’s standard currency. This event was known as «the fall of the rupee.» In Britain the Long Depression resulted in bankruptcies, escalating unemployment, a halt in public works, and a major trade slump that lasted until 1897.[23]

India was unaffected by the imperial order-in-council of 1825, which attempted to introduce British sterling coinage to the British colonies. India, at that time, was controlled by the British East India Company. The silver rupee coin continued as the currency of India through the British Raj and beyond. In 1835, British India adopted a mono-metallic silver standard based on the rupee coin; this decision was influenced by a letter written by Lord Liverpool in 1805 extolling the virtues of mono-metallism.

Following the First war of Independence in 1857, the British government took direct control of India. From 1851, gold sovereigns were produced en masse at the Royal Mint in Sydney. In an 1864 attempt to make the British gold sovereign the «imperial coin», the treasuries in Bombay and Calcutta were instructed to receive (but not to issue) gold sovereigns; therefore, these gold sovereigns never left the vaults. As the British government gave up hope of replacing the rupee in India with the pound sterling, it realised for the same reason it could not replace the silver dollar in the Straits Settlements with the Indian rupee (as the British East India Company had desired). Since the silver crisis of 1873, several nations switched over to a gold exchange standard (wherein silver or banknotes circulate locally but with a fixed gold value for export purposes), including India in the 1890s.[24]

India Council Bill[edit]

In 1870, India was connected to Britain by a submarine telegraph cable.

Around 1875, Britain started paying India for exported goods in India Council (paper) Bills (instead of silver).

If, therefore, the India Council in London should not step in to sell bills on India, the merchants and bankers would have to send silver to make good the (trade) balances. Thus a channel for the outflow of silver was stopped, in 1875, by the India Council in London.[25]

The great importance of these (Council) Bills, however, is the effect they have on the Market Price of Silver : and they have in fact been one of the most potent factors in recent years in causing the diminution in the Value of Silver as compared to Gold.[26]

The Indian and Chinese products for which silver is paid were and are, since 1873–74, very low in price, and it there fore takes less silver to purchase a larger quantity of Eastern commodities. Now, on taking the several agents into united consideration, it will certainly not seem very mysterious why silver should not only have fallen in price[25]

The great nations had recourse to two expedients for replenishing their exchequers, – first, loans, and, second, the more convenient forced loans of paper money۔[25]

Fowler Committee (1898)[edit]

The Indian Currency Committee or Fowler Committee was a government committee appointed by the British-run Government of India on 29 April 1898 to examine the currency situation in India.[27] They collected a wide range of testimony, examined as many as forty-nine witnesses, and only reported their conclusions in July 1899, after more than a year’s deliberation.[22]

The prophecy made before the Committee of 1898 by Mr. A. M. Lindsay, in proposing a scheme closely similar in principle to that which was eventually adopted, has been largely fulfilled. «This change,» he said, «will pass unnoticed, except by the intelligent few, and it is satisfactory to find that by this almost imperceptible process the Indian currency will be placed on a footing which Ricardo and other great authorities have advocated as the best of all currency systems, viz., one in which the currency media used in the internal circulation are confined to notes and cheap token coins, which are made to act precisely as if they were bits of gold by being made convertible into gold for foreign payment purposes.[28] The committee concurred in the opinion of the Indian government that the mints should remain closed to the unrestricted coinage of silver, and that a gold standard should be adopted without delay…they recommended (1) that the British sovereign be given full legal tender power in India, and (2) that the Indian mints be thrown open to its unrestricted coinage (for gold coins only).

These recommendations were acceptable to both governments, and were shortly afterwards translated into laws. The act making gold a legal tender was promulgated on 15 September 1899; and preparations were soon thereafter undertaken for the coinage of gold sovereigns in the mint at Bombay.[22]

Silver, therefore, has ceased to serve as standard; and the Indian currency system of to-day (that is 1901) may be described as that of a «limping» gold standard similar to the systems of France, Germany, Holland, and the United States.[22]

The Committee of 1898 explicitly declared themselves to be in favour of the eventual establishment of a gold currency.

This goal, if it was their goal, the Government of India have never attained.[28]

1900s[edit]

In 1913, John Maynard Keynes writes in his book Indian Currency and Finance that during financial year 1900–1901, gold coins (sovereigns) worth of £6,750,000 were given to Indian people in the hope that it will circulate as currency. But against the expectation of Government, even half of that were not returned to Government, and this experiment failed spectacularly, so Government abandoned this practice (but did not abandon the narrative of gold standard). Subsequently, much of the gold held by Government of India was shipped to Bank of England in 1901 and held there.[29]

Problems caused by the gold standard[edit]

At the onset of the First World War, the cost of gold was very low and therefore the pound sterling had high value. But during the First World War, the value of the pound fell alarmingly due to rising war expenses. At the conclusion of the war, the value of the pound was only a fraction of what it used to be prior to the commencement of the war. It remained low until 1925, when the then Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister) of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, restored it to pre-War levels. As a result, the price of gold fell rapidly. While the rest of Europe purchased large quantities of gold from the United Kingdom, there was little increase in her gold reserves. This dealt a blow to an already deteriorating British economy. The United Kingdom began to look to its possessions as India to compensate for the gold that was sold.[30]