- India — Индия

Смотрите также

фосфид индия — indium phosphide

селенид индия — indium selenide

антимонид индия — indium antimonide

бромокись индия — indium oxybromide

хлорокись индия — indium oxychloride

гидроокись индия — indium hydroxide

оксид индия и олова — indium-tin oxide

фильтр на арсениде индия — indium arsenide filter

легирование фосфида индия — doping of indium phosphide

приёмник из арсенида индия — indium-arsenide detector

сернистый индий; сульфид индия — indium sulphide

нанопроволока из нитрида индия — indium nitride nanowire

азотнокислый индий; нитрат индия — indium nitrate

сернокислый индий; сульфат индия — indium sulphate

мышьяковистый индий; арсенид индия — indium arsenide

соединения индия; индий соединения — indium compounds

полуторная окись индия; окись индия — indium oxide

оксид индия и олова; оксид индия-олова — indium tin oxide

параметрический диод из антимонида индия — indium antimonide varactor

кислый сернистый индий; сульфгидрат индия — indium hydrosulphide

солнечный элемент на основе фосфида индия — indium phosphide-based solar cell

нанопроволока из оксида олова с примесью индия — indium-doped tin oxide nanowire

двойная соль сернокислого рубидия и сернокислого индия — rubidium indium alum

сурьмянисто-индиевый приёмник; приёмник из антимонида индия — indium-antimonide detector

ещё 14 примеров свернуть

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

инди́йский, (от И́ндия; к инди́йцы)

Рядом по алфавиту:

индивидуа́ция , -и

индиви́дуум , -а

индигена́т , -а и индижена́т, -а

индиги́рский , (от Индиги́рка)

инди́го , нескл., с. (вещество) и неизм. (цвет)

инди́говый

индиго́идный

индиго́иды , -ов, ед. -о́ид, -а

индигокарми́н , -а

индигоно́с , -а

индигоно́сный

индигофе́ра , -ы

и́ндиевый

индижена́т , -а и индигена́т, -а

и́ндий , -я

инди́йский , (от И́ндия; к инди́йцы)

Инди́йский океа́н

Инди́йский субконтине́нт

Инди́йско-Индокита́йская подо́бласть , (зоогеографическая)

инди́йско-кита́йский

инди́йско-росси́йский

инди́йцы , -ев, ед. инди́ец, -и́йца, тв. -и́йцем

индика́н , -а

индикати́в , -а

индикати́вный

индика́тор , -а

индика́торный

индикатри́са , -ы

индикацио́нный

индика́ция , -и

инди́кт , -а

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — индийский

Ударение и произношение — инд`ийский

Значение слова -прил. 1) Относящийся к Индии, индийцам, связанный с ними. 2) Свойственный индийцам, характерный для них и для Индии. 3) Принадлежащий Индии, индийцам. 4) Созданный, выведенный и т.п. в Индии или индийцами.

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — СВЁКЛА?

Слово состоит из букв:

И,

Н,

Д,

И,

Й,

С,

К,

И,

Й,

Похожие слова:

вест-индийский

древнеиндийский

неиндийский

протоиндийский

Рифма к слову индийский

артиллерийский, австрийский, российский, английский, александрийский, кавалерийский, ловайский, гвардейский, полицейский, европейский, поэтический, купеческий, панический, эгоистический, кутузовский, корчевский, виртембергский, голландский, георгиевский, августовский, московский, педантический, княжеский, героический, комический, фурштадский, ольденбургский, павлоградский, козловский, ребяческий, дипломатический, персидский, киевский, раевский, пржебышевский, семеновский, дружеский, сангвинический, понятовский, политический, кавалергардский, логический, стратегический, адский, человеческий, шведский, электрический, иронический, измайловский, энергический, физический, чарторижский, господский, нелогический, трагический, католический, исторический, фантастический, платовский, петербургский, робкий, ловкий, дикий, низкий, узкий, негромкий, одинокий, бойкий, звонкий, тонкий, крепкий, глубокий, великий, гладкий, жаркий, сладкий, жалкий, легкий, скользкий, пылкий, неловкий, невысокий, резкий, высокий, жестокий, близкий, некий, далекий, редкий, яркий, неробкий, широкий, громкий, дерзкий, краснорожий, удовольствий, георгий, препятствий, рыжий, похожий, строгий, орудий, приветствий, жребий, отлогий, бедствий, свежий, действий, происшествий, условий, сергий, пологий, божий, проезжий, религий, сословий, хорунжий, самолюбий, непохожий, дивизий, кривоногий, толсторожий, муругий, последствий, приезжий

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

| Hindustani | |

|---|---|

| Hindi–Urdu | |

|

|

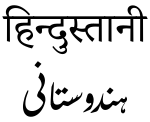

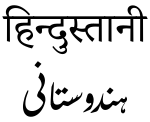

The word Hindustani in the Devanagari and Perso-Arabic (Nastaliq) scripts |

|

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ɦɪn̪d̪ʊst̪äːniː] |

| Native to | India and Pakistan |

| Region | Hindustani Belt (North India), Deccan, Pakistan |

|

Native speakers |

c. 250 million (2011 & 2017 censuses)[1] L2 speakers: ~500 million (1999–2016)[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Shauraseni Prakrit

|

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

|

|

Signed forms |

Indian Signing System (ISS)[5] |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | hi – Hindiur – Urdu |

| ISO 639-2 | hin – Hindiurd – Urdu |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:hin – Hindiurd – Urdu |

| Glottolog | hind1270 |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-qa to -qf |

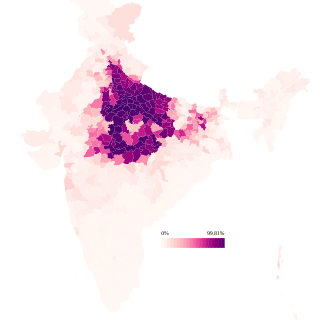

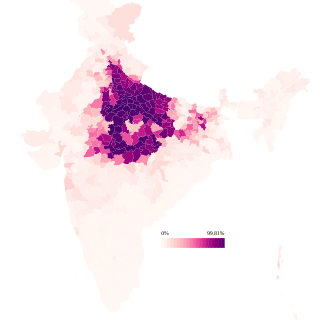

Areas (red) where Hindustani (Delhlavi or Kauravi) is the native language |

Hindustani (; Devanagari: हिन्दुस्तानी,[9][b] Hindustānī; Perso-Arabic:[c] ہندوستانی, Hindūstānī, lit. ‘of Hindustan’)[10][2][3] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in Northern and Central India and Pakistan, and used as a lingua franca in both countries.[11][12] Hindustani is a pluricentric language with two standard registers, known as Hindi and Urdu. Thus, it is also called Hindi–Urdu.[13][14][15] Colloquial registers of the language fall on a spectrum between these standards.[16][17]

The concept of a Hindustani language as a «unifying language» or «fusion language» was endorsed by Mahatma Gandhi.[18] The conversion from Hindi to Urdu (or vice versa) is generally achieved just by transliteration between the two scripts, instead of translation which is generally only required for religious and literary texts.[19]

Some scholars trace the language’s first written poetry, in the form of Old Hindi, to as early as 769 AD.[20] However this view is not generally accepted.[21][22][23] During the period of the Delhi Sultanate, which covered most of today’s India, eastern Pakistan, southern Nepal and Bangladesh[24] and which resulted in the contact of Hindu and Muslim cultures, the Sanskrit and Prakrit base of Old Hindi became enriched with loanwords from Persian, evolving into the present form of Hindustani.[25][26][27][28][29][30] The Hindustani vernacular became an expression of Indian national unity during the Indian Independence movement,[31][32] and continues to be spoken as the common language of the people of the northern Indian subcontinent,[33] which is reflected in the Hindustani vocabulary of Bollywood films and songs.[34][35]

The language’s core vocabulary is derived from Prakrit (a descendant of Sanskrit),[17][20][36][37] with substantial loanwords from Persian and Arabic (via Persian).[38][39][20][40]

As of 2020, Hindi and Urdu together constitute the 3rd-most-spoken language in the world after English and Mandarin, with 810 million native and second-language speakers, according to Ethnologue,[41] though this includes millions who self-reported their language as ‘Hindi’ on the Indian census but speak a number of other Hindi languages than Hindustani.[42] The total number of Hindi–Urdu speakers was reported to be over 300 million in 1995, making Hindustani the third- or fourth-most spoken language in the world.[43][20]

History

Early forms of present-day Hindustani developed from the Middle Indo-Aryan apabhraṃśa vernaculars of present-day North India in the 7th–13th centuries, chiefly the Dehlavi dialect of the Western Hindi category of Indo-Aryan languages that is known as Old Hindi.[44][29] Hindustani emerged as a contact language around Delhi, a result of the increasing linguistic diversity that occurred due to Muslim rule, while the use of its southern dialect, Dakhani, was promoted by Muslim rulers in the Deccan.[45][46] Amir Khusrow, who lived in the thirteenth century during the Delhi Sultanate period in North India, used these forms (which was the lingua franca of the period) in his writings and referred to it as Hindavi (Persian: ھندوی, lit. ‘of Hind or India‘).[47][30] The Delhi Sultanate, which comprised several Turkic and Afghan dynasties that ruled much of the subcontinent from Delhi,[48] was succeeded by the Mughal Empire in 1526.

Ancestors of the language were known as Hindui, Hindavi, Zabān-e Hind (transl. ’Language of India’), Zabān-e Hindustan (transl. ’Language of Hindustan’), Hindustan ki boli (transl. ’Language of Hindustan’), Rekhta, and Hindi.[11][49] Its regional dialects became known as Zabān-e Dakhani in southern India, Zabān-e Gujari (transl. ’Language of Gujars’) in Gujarat, and as Zabān-e Dehlavi or Urdu around Delhi. It is an Indo-Aryan language, deriving its base primarily from the Western Hindi dialect of Delhi, also known as Khariboli.[50]

Although the Mughals were of Timurid (Gurkānī) Turco-Mongol descent,[51] they were Persianised, and Persian had gradually become the state language of the Mughal empire after Babur,[52][53][54][55] a continuation since the introduction of Persian by Central Asian Turkic rulers in the Indian Subcontinent,[56] and the patronisation of it by the earlier Turko-Afghan Delhi Sultanate. The basis in general for the introduction of Persian into the subcontinent was set, from its earliest days, by various Persianised Central Asian Turkic and Afghan dynasties.[57]

Hindustani began to take shape as a Persianised vernacular during the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 AD) and Mughal Empire (1526–1858 AD) in South Asia.[58] Hindustani retained the grammar and core vocabulary of the local Delhi dialect.[58][59] However, as an emerging common dialect, Hindustani absorbed large numbers of Persian, Arabic, and Turkic loanwords, and as Mughal conquests grew it spread as a lingua franca across much of northern India; this was a result of the contact of Hindu and Muslim cultures in Hindustan that created a composite Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb.[27][25][28][60] The language was also known as Rekhta, or ‘mixed’, which implies that it was mixed with Persian.[61][62] Written in the Perso-Arabic, Devanagari,[63] and occasionally Kaithi or Gurmukhi scripts,[64] it remained the primary lingua franca of northern India for the next four centuries, although it varied significantly in vocabulary depending on the local language. Alongside Persian, it achieved the status of a literary language in Muslim courts and was also used for literary purposes in various other settings such as Sufi, Nirgun Sant, Krishna Bhakta circles, and Rajput Hindu courts. Its majors centres of development included the Mughal courts of Delhi, Lucknow, Agra and Lahore as well as the Rajput courts of Amber and Jaipur.[65]

In the 18th century, towards the end of the Mughal period, with the fragmentation of the empire and the elite system, a variant of Hindustani, one of the successors of apabhraṃśa vernaculars at Delhi, and nearby cities, came to gradually replace Persian as the lingua franca among the educated elite upper class particularly in northern India, though Persian still retained much of its pre-eminence for a short period. The term Hindustani was given to that language.[66] The Perso-Arabic script form of this language underwent a standardisation process and further Persianisation during this period (18th century) and came to be known as Urdu, a name derived from Persian: Zabān-e Urdū-e Mualla (‘language of the court’) or Zabān-e Urdū (زبان اردو, ‘language of the camp’). The etymology of the word Urdu is of Chagatai origin, Ordū (‘camp’), cognate with English horde, and known in local translation as Lashkari Zabān (لشکری زبان),[67] which is shorted to Lashkari (لشکری).[68] This is all due to its origin as the common speech of the Mughal army. As a literary language, Urdu took shape in courtly, elite settings. Along with English, it became the first official language of British India in 1850.[69][70]

Hindi as a standardised literary register of the Delhi dialect arose in the 19th century; the Braj dialect was the dominant literary language in the Devanagari script up until and through the 19th century. While the first literary works (mostly translations of earlier works) in Sanskritised Hindustani were already written in the early 19th century as part of a literary project that included both Hindu and Muslim writers (e.g. Lallu Lal, Insha Allah Khan), the call for a distinct Sanskritised standard of the Delhi dialect written in Devanagari under the name of Hindi became increasingly politicised in the course of the century and gained pace around 1880 in an effort to displace Urdu’s official position.[71]

John Fletcher Hurst in his book published in 1891 mentioned that the Hindustani or camp language of the Mughal Empire’s courts at Delhi was not regarded by philologists as a distinct language but only as a dialect of Hindi with admixture of Persian. He continued: «But it has all the magnitude and importance of separate language. It is linguistic result of Muslim rule of eleventh & twelfth centuries and is spoken (except in rural Bengal) by many Hindus in North India and by Musalman population in all parts of India.» Next to English it was the official language of British Raj, was commonly written in Arabic or Persian characters, and was spoken by approximately 100,000,000 people.[72] The process of hybridization also led to the formation of words in which the first element of the compound was from Khari Boli and the second from Persian, such as rajmahal ‘palace’ (raja ‘royal, king’ + mahal ‘house, place’) and rangmahal ‘fashion house’ (rang ‘colour, dye’ + mahal ‘house, place’).[73] As Muslim rule expanded, Hindustani speakers traveled to distant parts of India as administrators, soldiers, merchants, and artisans. As it reached new areas, Hindustani further hybridized with local languages. In the Deccan, for instance, Hindustani blended with Telugu and came to be called Dakhani. In Dakhani, aspirated consonants were replaced with their unaspirated counterparts; for instance, dekh ‘see’ became dek, ghula ‘dissolved’ became gula, kuch ‘some’ became kuc, and samajh ‘understand’ became samaj.[74]

When the British colonised the Indian subcontinent from the late 18th through to the late 19th century, they used the words ‘Hindustani’, ‘Hindi’, and ‘Urdu’ interchangeably. They developed it as the language of administration of British India,[75] further preparing it to be the official language of modern India and Pakistan. However, with independence, use of the word ‘Hindustani’ declined, being largely replaced by ‘Hindi’ and ‘Urdu’, or ‘Hindi-Urdu’ when either of those was too specific. More recently, the word ‘Hindustani’ has been used for the colloquial language of Bollywood films, which are popular in both India and Pakistan and which cannot be unambiguously identified as either Hindi or Urdu.

Registers

Although, at the spoken level, Hindi and Urdu are considered registers of a single language, Hindustani or Hindi-Urdu, as they share a common grammar and core vocabulary,[16][17][76][36][20] they differ in literary and formal vocabulary; where literary Hindi draws heavily on Sanskrit and to a lesser extent Prakrit, literary Urdu draws heavily on Persian and Arabic loanwords.[77] The grammar and base vocabulary (most pronouns, verbs, adpositions, etc.) of both Hindi and Urdu, however, are the same and derive from a Prakritic base, and both have Persian/Arabic influence.[76]

New Testament cover page in Hindustani language was published in 1842

First chapter of New Testament in Hindustani language

The standardised registers Hindi and Urdu are collectively known as Hindi-Urdu.[10] Hindustani is the lingua franca of the north and west of the Indian subcontinent, though it is understood fairly well in other regions also, especially in the urban areas.[11] This has led it to be characterised as a continuum that ranges between Hindi and Urdu.[78] A common vernacular sharing characteristics with Sanskritised Hindi, regional Hindi and Urdu, Hindustani is more commonly used as a vernacular than highly Sanskritised Hindi or highly Persianised Urdu.[33]

This can be seen in the popular culture of Bollywood or, more generally, the vernacular of North Indians and Pakistanis, which generally employs a lexicon common to both Hindi and Urdu speakers.[35] Minor subtleties in region will also affect the ‘brand’ of Hindustani, sometimes pushing the Hindustani closer to Urdu or to Hindi. One might reasonably assume that the Hindustani spoken in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh (known for its usage of Urdu) and Varanasi (a holy city for Hindus and thus using highly Sanskritised Hindi) is somewhat different.[10]

Modern Standard Hindi

Standard Hindi, one of the 22 officially recognized languages of India and the official language of the Union, is usually written in the indigenous Devanagari script of India and exhibits less Persian and Arabic influence than Urdu. It has a literature of 500 years, with prose, poetry, religion and philosophy. One could conceive of a wide spectrum of dialects and registers, with the highly Persianised Urdu at one end of the spectrum and a heavily Sanskritised variety spoken in the region around Varanasi, at the other end. In common usage in India, the term Hindi includes all these dialects except those at the Urdu spectrum. Thus, the different meanings of the word Hindi include, among others:[citation needed]

- standardized Hindi as taught in schools throughout India (except some states such as Tamil Nadu),

- formal or official Hindi advocated by Purushottam Das Tandon and as instituted by the post-independence Indian government, heavily influenced by Sanskrit,

- the vernacular dialects of Hindustani as spoken throughout India,

- the neutralized form of Hindustani used in popular television and films (which is nearly identical to colloquial Urdu), or

- the more formal neutralized form of Hindustani used in television and print news reports.

Modern Standard Urdu

The phrase Zabān-e Urdu-ye Mualla in Nastaʿlīq

Main article: Urdu

Urdu is the national language and state language of Pakistan and one of the 22 officially recognised languages of India.

It is written, except in some parts of India, in the Nastaliq style of the Urdu alphabet, an extended Perso-Arabic script incorporating Indic phonemes. It is heavily influenced by Persian vocabulary and was historically also known as Rekhta.

Lashkari Zabān title in the Perso-Arabic script

As Dakhini (or Deccani) where it also draws words from local languages, it survives and enjoys a rich history in the Deccan and other parts of South India, with the prestige dialect being Hyderabadi Urdu spoken in and around the capital of the Nizams and the Deccan Sultanates.

Earliest forms of the language’s literature may be traced back to the 13th-14th century works of Amīr Khusrau Dehlavī, often called the «father of Urdu literature» while Walī Deccani is seen as the progenitor of Urdu poetry.

Bazaar Hindustani

The term bazaar Hindustani, in other words, the ‘street talk’ or literally ‘marketplace Hindustani’, has arisen to denote a colloquial register of the language that uses vocabulary common to both Hindi and Urdu while eschewing high-register and specialized Arabic or Sanskrit derived words.[79] It has emerged in various South Asian cities where Hindustani is not the main language, in order to facilitate communication across language barriers. It is characterized by loanwords from local languages.[80]

Names

Amir Khusro c. 1300 referred to this language of his writings as Dehlavi (देहलवी / دہلوی, ‘of Delhi’) or Hindavi (हिन्दवी / ہندوی). During this period, Hindustani was used by Sufis in promulgating their message across the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed] After the advent of the Mughals in the subcontinent, Hindustani acquired more Persian loanwords. Rekhta (‘mixture’), Hindi (‘Indian’), Hindustani, Hindvi, Lahori, and Dakni (amongst others) became popular names for the same language until the 18th century.[63][81] The name Urdu (from Zabān-i-Ordu, or Orda) appeared around 1780.[81] It is believed to have been coined by the poet Mashafi.[82] In local literature and speech, it was also known as the Lashkari Zabān (military language) or Lashkari.[83] Mashafi was the first person to simply modify the name Zabān-i-Ordu to Urdu.[84]

During the British Raj, the term Hindustani was used by British officials.[81] In 1796, John Borthwick Gilchrist published a «A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language».[81][85] Upon partition, India and Pakistan established national standards that they called Hindi and Urdu, respectively, and attempted to make distinct, with the result that Hindustani commonly, but mistakenly, came to be seen as a «mixture» of Hindi and Urdu.

Grierson, in his highly influential Linguistic Survey of India, proposed that the names Hindustani, Urdu, and Hindi be separated in use for different varieties of the Hindustani language, rather than as the overlapping synonyms they frequently were:

We may now define the three main varieties of Hindōstānī as follows:—Hindōstānī is primarily the language of the Upper Gangetic Doab, and is also the lingua franca of India, capable of being written in both Persian and Dēva-nāgarī characters, and without purism, avoiding alike the excessive use of either Persian or Sanskrit words when employed for literature. The name ‘Urdū’ can then be confined to that special variety of Hindōstānī in which Persian words are of frequent occurrence, and which hence can only be written in the Persian character, and, similarly, ‘Hindī’ can be confined to the form of Hindōstānī in which Sanskrit words abound, and which hence can only be written in the Dēva-nāgarī character.[2]

Literature

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2022) |

Official status

Hindustani, in its standardised registers, is one of the official languages of both India (Hindi) and Pakistan (Urdu).

Prior to 1947, Hindustani was officially recognised by the British Raj. In the post-independence period however, the term Hindustani has lost currency and is not given any official recognition by the Indian or Pakistani governments. The language is instead recognised by its standard forms, Hindi and Urdu.[86]

Hindi

Hindi is declared by Article 343(1), Part 17 of the Indian Constitution as the «official language (राजभाषा, rājabhāṣā) of the Union.» (In this context, «Union» means the Federal Government and not the entire country[citation needed]—India has 23 official languages.) At the same time, however, the definitive text of federal laws is officially the English text and proceedings in the higher appellate courts must be conducted in English.

At the state level, Hindi is one of the official languages in 10 of the 29 Indian states and three Union Territories, respectively: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal; Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and Delhi.

In the remaining states, Hindi is not an official language. In states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, studying Hindi is not compulsory in the state curriculum. However, an option to take the same as second or third language does exist. In many other states, studying Hindi is usually compulsory in the school curriculum as a third language (the first two languages being the state’s official language and English), though the intensiveness of Hindi in the curriculum varies.[87]

Urdu

Urdu is the national language (قومی زبان, qaumi zabān) of Pakistan, where it shares official language status with English. Although English is spoken by many, and Punjabi is the native language of the majority of the population, Urdu is the lingua franca. In India, Urdu is one of the languages recognised in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and is an official language of the Indian states of Bihar, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and also the Union Territories of Delhi and Jammu and Kashmir. Although the government school system in most other states emphasises Modern Standard Hindi, at universities in cities such as Lucknow, Aligarh and Hyderabad, Urdu is spoken and learnt, and Saaf or Khaalis Urdu is treated with just as much respect as Shuddha Hindi.

Geographical distribution

Besides being the lingua franca of North India and Pakistan in South Asia,[11][33] Hindustani is also spoken by many in the South Asian diaspora and their descendants around the world, including North America (e.g., in Canada, Hindustani is one of the fastest growing languages),[88] Europe, and the Middle East.

- A sizeable population in Afghanistan, especially in Kabul, can also speak and understand Hindi-Urdu due to the popularity and influence of Bollywood films and songs in the region, as well as the fact that many Afghan refugees spent time in Pakistan in the 1980s and 1990s.[89][90]

- Fiji Hindi was derived from the Hindustani linguistic group and is spoken widely by Fijians of Indian origin.

- Hindustani was also one of the languages that was spoken widely during British rule in Burma. Many older citizens of Myanmar, particularly Anglo-Indians and the Anglo-Burmese, still know it, although it has had no official status in the country since military rule began.

- Hindustani is also spoken in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, where migrant workers from various countries live and work for several years.

Phonology

Grammar

Vocabulary

Hindi-Urdu’s core vocabulary has an Indic base, being derived from Prakrit, which in turn derives from Sanskrit,[20][17][36][37] as well as a substantial amount of loanwords from Persian and Arabic (via Persian).[77][38] Hindustani contains around 5,500 words of Persian and Arabic origin.[91]

Hindustani also borrowed Persian prefixes to create new words. Persian affixes became so assimilated that they were used with original Khari Boli words as well.

Writing system

Historically, Hindustani was written in the Kaithi, Devanagari, and Urdu alphabets.[63] Kaithi and Devanagari are two of the Brahmic scripts native to India, whereas the Urdu alphabet is a derivation of the Perso-Arabic script written in Nastaʿlīq, which is the preferred calligraphic style for Urdu.

Today, Hindustani continues to be written in the Urdu alphabet in Pakistan. In India, the Hindi register is officially written in Devanagari, and Urdu in the Urdu alphabet, to the extent that these standards are partly defined by their script.

However, in popular publications in India, Urdu is also written in Devanagari, with slight variations to establish a Devanagari Urdu alphabet alongside the Devanagari Hindi alphabet.

| अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ए | ऐ | ओ | औ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ə | aː | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | eː | ɛː | oː | ɔː |

| क | क़ | ख | ख़ | ग | ग़ | घ | ङ | ||

| k | q | kʰ | x | ɡ | ɣ | ɡʱ | ŋ | ||

| च | छ | ज | ज़ | झ | झ़ | ञ | |||

| t͡ʃ | t͡ʃʰ | d͡ʒ | z | d͡ʒʱ | ʒ | ɲ[92] | |||

| ट | ठ | ड | ड़ | ढ | ढ़ | ण | |||

| ʈ | ʈʰ | ɖ | ɽ | ɖʱ | ɽʱ | ɳ | |||

| त | थ | द | ध | न | |||||

| t | tʰ | d | dʱ | n | |||||

| प | फ | फ़ | ब | भ | म | ||||

| p | pʰ | f | b | bʱ | m | ||||

| य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह | ||

| j | ɾ | l | ʋ | ʃ | ʂ | s | ɦ |

| Letter | Name of letter | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| ا | alif | a, ā, i, or u | /ə/, /aː/, /ɪ/, or /ʊ/ |

| ب | be | b | /b/ |

| پ | pe | p | /p/ |

| ت | te | t | /t/ |

| ٹ | ṭe | ṭ | /ʈ/ |

| ث | se | s | /s/ |

| ج | jīm | j | /d͡ʒ/ |

| چ | che | c | /t͡ʃ/ |

| ح | baṛī he | h̤ | /h ~ ɦ/ |

| خ | khe | k͟h | /x/ |

| د | dāl | d | /d/ |

| ڈ | ḍāl | ḍ | /ɖ/ |

| ذ | zāl | z | /z/ |

| ر | re | r | /r ~ ɾ/ |

| ڑ | ṛe | ṛ | /ɽ/ |

| ز | ze | z | /z/ |

| ژ | zhe | ž | /ʒ/ |

| س | sīn | s | /s/ |

| ش | shīn | sh | /ʃ/ |

| ص | su’ād | s̤ | /s/ |

| ض | zu’ād | ż | /z/ |

| ط | to’e | t̤ | /t/ |

| ظ | zo’e | ẓ | /z/ |

| ع | ‘ain | ‘ | – |

| غ | ghain | ġ | /ɣ/ |

| ف | fe | f | /f/ |

| ق | qāf | q | /q/ |

| ک | kāf | k | /k/ |

| گ | gāf | g | /ɡ/ |

| ل | lām | l | /l/ |

| م | mīm | m | /m/ |

| ن | nūn | n | /n/ |

| ں | nūn ghunna | ṁ or m̐ | /◌̃/ |

| و | wā’o | w, v, ō, or ū | /ʋ/, /oː/, /ɔ/ or /uː/ |

| ہ | choṭī he | h | /h ~ ɦ/ |

| ھ | do chashmī he | h | /ʰ/ or /ʱ/ |

| ء | hamza | ‘ | /ʔ/ |

| ی | ye | y or ī | /j/ or /iː/ |

| ے | baṛī ye | ai or ē | /ɛː/, or /eː/ |

Because of anglicisation in South Asia and the international use of the Latin script, Hindustani is occasionally written in the Latin script. This adaptation is called Roman Urdu or Romanised Hindi, depending upon the register used. Since Urdu and Hindi are mutually intelligible when spoken, Romanised Hindi and Roman Urdu (unlike Devanagari Hindi and Urdu in the Urdu alphabet) are mostly mutually intelligible as well.

Sample text

Colloquial Hindustani

An example of colloquial Hindustani:[20]

- Devanagari: यह कितने का है?

- Urdu: یہ کتنے کا ہے؟

- Romanisation: Yah kitnē kā hai?

- English: How much is this?

The following is a sample text, Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in the two official registers of Hindustani, Hindi and Urdu. Because this is a formal legal text, differences in vocabulary are most pronounced.

Literary Hindi

अनुच्छेद १ — सभी मनुष्यों को गौरव और अधिकारों के विषय में जन्मजात स्वतन्त्रता और समानता प्राप्त हैं। उन्हें बुद्धि और अन्तरात्मा की देन प्राप्त है और परस्पर उन्हें भाईचारे के भाव से बर्ताव करना चाहिए।[93]

| Urdu transliteration |

|---|

| انُچھید ١ : سبھی منُشیوں کو گورو اور ادھکاروں کے وِشئے میں جنمجات سوَتنتْرتا پراپت ہیں۔ اُنہیں بدھی اور انتراتما کی دین پراپت ہے اور پرسپر اُنہیں بھائی چارے کے بھاؤ سے برتاؤ کرنا چاہئے۔ |

| Transliteration (ISO 15919) |

| Anucchēd 1: Sabhī manuṣyō̃ kō gaurav aur adhikārō̃ kē viṣay mē̃ janmajāt svatantratā aur samāntā prāpt haĩ. Unhē̃ buddhi aur antarātmā kī dēn prāpt hai aur paraspar unhē̃ bhāīcārē kē bhāv sē bartāv karnā cāhiē. |

| Transcription (IPA) |

| səbʰiː mənʊʂjõː koː ɡɔːɾəʋ ɔːɾ ədʰɪkɑːɾõː keː ʋɪʂəj mẽː dʒənmədʒɑːt sʋətəntɾətɑː ɔːɾ səmɑːntɑː pɾɑːpt ɦɛ̃ː ‖ ʊnʰẽː bʊdːʰɪ ɔːɾ əntəɾɑːtmɑː kiː deːn pɾɑːpt ɦɛː ɔːɾ pəɾəspəɾ ʊnʰẽː bʰɑːiːtʃɑːɾeː keː bʰɑːʋ seː bəɾtɑːʋ kəɾnɑː tʃɑːɦɪeː ‖] |

| Gloss (word-to-word) |

| Article 1—All human-beings to dignity and rights’ matter in from-birth freedom acquired is. Them to reason and conscience’s endowment acquired is and always them to brotherhood’s spirit with behaviour to do should. |

| Translation (grammatical) |

| Article 1—All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Literary Urdu

:دفعہ ١: تمام اِنسان آزاد اور حُقوق و عِزت کے اعتبار سے برابر پَیدا ہُوئے ہَیں۔ انہیں ضمِیر اور عقل ودِیعت ہوئی ہَیں۔ اِس لئے انہیں ایک دُوسرے کے ساتھ بھائی چارے کا سُلُوک کرنا چاہئے۔

| Devanagari transliteration |

|---|

| दफ़ा १ — तमाम इनसान आज़ाद और हुक़ूक़ ओ इज़्ज़त के ऐतबार से बराबर पैदा हुए हैं। उन्हें ज़मीर और अक़्ल वदीयत हुई हैं। इसलिए उन्हें एक दूसरे के साथ भाई चारे का सुलूक करना चाहीए। |

| Transliteration (ISO 15919) |

| Dafʻah 1: Tamām insān āzād aur ḥuqūq ō ʻizzat kē iʻtibār sē barābar paidā hu’ē haĩ. Unhē̃ żamīr aur ʻaql wadīʻat hu’ī haĩ. Isli’ē unhē̃ ēk dūsrē kē sāth bhā’ī cārē kā sulūk karnā cāhi’ē. |

| Transcription (IPA) |

| dəfaː eːk təmaːm ɪnsaːn aːzaːd ɔːɾ hʊquːq oː izːət keː ɛːtəbaːɾ seː bəɾaːbəɾ pɛːdaː hʊeː hɛ̃ː ʊnʱẽː zəmiːɾ ɔːɾ əql ʋədiːət hʊiː hɛ̃ː ɪs lɪeː ʊnʱẽː eːk duːsɾeː keː saːtʰ bʱaːiː tʃaːɾeː kaː sʊluːk kəɾnaː tʃaːhɪeː |

| Gloss (word-to-word) |

| Article 1: All humans free[,] and rights and dignity’s consideration from equal born are. To them conscience and intellect endowed is. Therefore, they one another’s with brotherhood’s treatment do must. |

| Translation (grammatical) |

| Article 1—All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Hindustani and Bollywood

The predominant Indian film industry Bollywood, located in Mumbai, Maharashtra uses Modern Standard Hindi, colloquial Hindustani, Bombay Hindi, Urdu,[94] Awadhi, Rajasthani, Bhojpuri, and Braj Bhasha, along with Punjabi and with the liberal use of English or Hinglish in scripts and soundtrack lyrics.

Film titles are often screened in three scripts: Latin, Devanagari and occasionally Perso-Arabic. The use of Urdu or Hindi in films depends on the film’s context: historical films set in the Delhi Sultanate or Mughal Empire are almost entirely in Urdu, whereas films based on Hindu mythology or ancient India make heavy use of Hindi with Sanskrit vocabulary.

See also

- Hindustan (Indian subcontinent)

- Languages of India

- Languages of Pakistan

- List of Hindi authors

- List of Urdu writers

- Hindi–Urdu transliteration

- Uddin and Begum Hindustani Romanisation

Notes

- ^ Not to be confused with the Bihari languages, a group of Eastern Indo-Aryan languages.

- ^ Also written as हिंदुस्तानी

- ^ This will only display in a Nastaliq font if you will have one installed, otherwise it may display in a modern Arabic font in a style more common for writing Arabic and most other non-Urdu languages such as Naskh. If this پاکستان and this پاکستان looks like this پاکستان then you are not seeing it in Nastaliq.

References

- ^ a b «Hindi» L1: 322 million (2011 Indian census), including perhaps 150 million speakers of other languages that reported their language as «Hindi» on the census. L2: 274 million (2016, source unknown). Urdu L1: 67 million (2011 & 2017 censuses), L2: 102 million (1999 Pakistan, source unknown, and 2001 Indian census): Ethnologue 21. Hindi at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

. Urdu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

.

- ^ a b c d Grierson, vol. 9–1, p. 47. We may now define the three main varieties of Hindōstānī as follows:—Hindōstānī is primarily the language of the Upper Gangetic Doab, and is also the lingua franca of India, capable of being written in both Persian and Dēva-nāgarī characters, and without purism, avoiding alike the excessive use of either Persian or Sanskrit words when employed for literature. The name ‘Urdū’ can then be confined to that special variety of Hindōstānī in which Persian words are of frequent occurrence, and which hence can only be written in the Persian character, and, similarly, ‘Hindī’ can be confined to the form of Hindōstānī in which Sanskrit words abound, and which hence can only be written in the Dēva-nāgarī character.

- ^ a b c Ray, Aniruddha (2011). The Varied Facets of History: Essays in Honour of Aniruddha Ray. Primus Books. ISBN 978-93-80607-16-0.

There was the Hindustani Dictionary of Fallon published in 1879; and two years later (1881), John J. Platts produced his Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi and English, which implied that Hindi and Urdu were literary forms of a single language. More recently, Christopher R. King in his One Language, Two Scripts (1994) has presented the late history of the single spoken language in two forms, with the clarity and detail that the subject deserves.

- ^ Gangopadhyay, Avik (2020). Glimpses of Indian Languages. Evincepub publishing. p. 43. ISBN 9789390197828.

- ^ Norms & Guidelines Archived 13 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2009. D.Ed. Special Education (Deaf & Hard of Hearing), [www.rehabcouncil.nic.in Rehabilitation Council of India]

- ^ The Central Hindi Directorate regulates the use of Devanagari and Hindi spelling in India. Source: Central Hindi Directorate: Introduction Archived 15 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language». www.urducouncil.nic.in.

- ^ Zia, K. (1999). Standard Code Table for Urdu Archived 8 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. 4th Symposium on Multilingual Information Processing, (MLIT-4), Yangon, Myanmar. CICC, Japan. Retrieved on 28 May 2008.

- ^

- McGregor, R. S., ed. (1993), «हिंदुस्तानी», The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, p. 1071,

2. hindustani [P. hindustani] f Hindustani (a mixed Hindi dialect of the Delhi region which came to be used as a lingua franca widely throughout India and what is now Pakistan

- «हिंदुस्तानी», बृहत हिंदी कोश खंड 2 (Large Hindi Dictionary, Volume 2), केन्द्रीय हिंदी निदेशालय, भारत सरकार (Central Hindi Directorate, Government of India), p. 1458, retrieved 17 October 2021

- Das, Shyamasundar (1975), Hindi Shabda Sagar (Hindi dictionary) in 11 volumes, revised edition, Kashi (Varanasi): Nagari Pracharini Sabha, p. 5505,

हिंदुस्तानी hindustānī३ संज्ञा स्त्री॰ १. हिंदुस्तान की भाषा । २. बोलचाल या व्यवहार की वह हिंदी जिसमें न तो बहुत अरबी फारसी के शब्द हों न संस्कृत के । उ॰—साहिब लोगों ने इस देश की भाषा का एक नया नाम हिंदुस्तानी रखा । Translation: Hindustani hindustānī3 noun feminine 1. The language of Hindustan. 2. That version of Hindi employed for common speech or business in which neither many Arabic or Persian words nor Sanskrit words are present. Context: The British gave the new name Hindustani to the language of this country.

- Chaturvedi, Mahendra (1970), «हिंदुस्तानी», A Practical Hindi-English Dictionary, Delhi: National Publishing House,

hindustānī hīndusta:nī: a theoretically existent style of the Hindi language which is supposed to consist of current and simple words of any sources whatever and is neither too much biassed in favour of Perso-Arabic elements nor has any place for too much high-flown Sanskritized vocabulary

- McGregor, R. S., ed. (1993), «हिंदुस्तानी», The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, p. 1071,

- ^ a b c «About Hindi-Urdu». North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Mohammad Tahsin Siddiqi (1994), Hindustani-English code-mixing in modern literary texts, University of Wisconsin,

… Hindustani is the lingua franca of both India and Pakistan …

- ^ «Hindustani language». Encyclopedia Britannica. 1 November 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

(subscription required) lingua franca of northern India and Pakistan. Two variants of Hindustani, Urdu and Hindi, are official languages in Pakistan and India, respectively. Hindustani began to develop during the 13th century CE in and around the Indian cities of Delhi and Meerut in response to the increasing linguistic diversity that resulted from Muslim hegemony. In the 19th century its use was widely promoted by the British, who initiated an effort at standardization. Hindustani is widely recognized as India’s most common lingua franca, but its status as a vernacular renders it difficult to measure precisely its number of speakers.

- ^ Trask, R. L. (8 August 2019), «Hindi-Urdu», Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 149–150, ISBN 9781474473316,

Hindi-Urdu The most important modern Indo-Aryan language, spoken by well over 250 million people, mainly in India and Pakistan. At the spoken level Hindi and Urdu are the same language (called Hindustani before the political partition), but the two varieties are written in different alphabets and differ substantially in their abstract and technical vocabularies

- ^ Crystal, David (2001), A Dictionary of Language, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226122038,

(p. 115) Figure: A family of languages: the Indo-European family tree, reflecting geographical distribution. Proto Indo-European>Indo-Iranian>Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit)> Midland (Rajasthani, Bihari, Hindi/Urdu); (p. 149) Hindi There is little structural difference between Hindi and Urdu, and the two are often grouped together under the single label Hindi/Urdu, sometimes abbreviated to Hirdu, and formerly often called Hindustani; (p. 160) India … With such linguistic diversity, Hindi/Urdu has come to be widely used as a lingua franca.

- ^ Gandhi, M. K. (2018). An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth: A Critical Edition. Translated by Desai, Mahadev. annotation by Suhrud, Tridip. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300234077.

(p. 737) I was handicapped for want of suitable Hindi or Urdu words. This was my first occasion for delivering an argumentative speech before an audience especially composed of Mussalmans of the North. I had spoken in Urdu at the Muslim League at Calcutta, but it was only for a few minutes, and the speech was intended only to be a feeling appeal to the audience. Here, on the contrary, I was faced with a critical, if not hostile, audience, to whom I had to explain and bring home my view-point. But I had cast aside all shyness. I was not there to deliver an address in the faultless, polished Urdu of the Delhi Muslims, but to place before the gathering my views in such broken Hindi as I could command. And in this I was successful. This meeting afforded me a direct proof of the fact that Hindi-Urdu alone could become the lingua franca<Footnote M8> of India. (M8: «national language» in the Gujarati original).

- ^ a b Basu, Manisha (2017). The Rhetoric of Hindutva. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-14987-8.

Urdu, like Hindi, was a standardized register of the Hindustani language deriving from the Dehlavi dialect and emerged in the eighteenth century under the rule of the late Mughals.

- ^ a b c d Gube, Jan; Gao, Fang (2019). Education, Ethnicity and Equity in the Multilingual Asian Context. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-981-13-3125-1.

The national language of India and Pakistan ‘Standard Urdu’ is mutually intelligible with ‘Standard Hindi’ because both languages share the same Indic base and are all but indistinguishable in phonology and grammar (Lust et al. 2000).

- ^ «After experiments with Hindi as national language, how Gandhi changed his mind». Prabhu Mallikarjunan. The Feral. 3 October 2019.

- ^ Bhat, Riyaz Ahmad; Bhat, Irshad Ahmad; Jain, Naman; Sharma, Dipti Misra (2016). «A House United: Bridging the Script and Lexical Barrier between Hindi and Urdu» (PDF). Proceedings of COLING 2016, the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

Hindi and Urdu transliteration has received a lot of attention from the NLP research community of South Asia (Malik et al., 2008; Lehal and Saini, 2012; Lehal and Saini, 2014). It has been seen to break the barrier that makes the two look different.

- ^ a b c d e f g Delacy, Richard; Ahmed, Shahara (2005). Hindi, Urdu & Bengali. Lonely Planet. pp. 11–12.

Hindi and Urdu are generally considered to be one spoken language with two different literary traditions. That means that Hindi and Urdu speakers who shop in the same markets (and watch the same Bollywood films) have no problems understanding each other.

- ^ Dhanesh Jain; George Cardona, eds. (2007). The Indo-Aryan languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9. OCLC 648298147.

Such an early date for the inception of a Hindi literature, one made possible only by subsuming the large body of Apabhraṁśa literature into Hindi, has not, however, been generally accepted by scholars (p. 279).

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

The period between 1000 AD-1200/1300 AD is designated the Old NIA stage because it is at this stage that the NIA languages such as Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi, Oriya, Punjabi assumed distinct identities (p. 1, emphasis added)

- ^ Dua, Hans (2008). «Hindustani». In Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 497–500.

Hindustani as a colloquial speech developed over almost seven centuries from 1100 to 1800 (p. 497, emphasis added).

- ^ Chapman, Graham. «Religious vs. regional determinism: India, Pakistan and Bangladesh as inheritors of empire.» Shared space: Divided space. Essays on conflict and territorial organization (1990): 106-134.

- ^ a b «Women of the Indian Sub-Continent: Makings of a Culture — Rekhta Foundation». Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

The «Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb» is one such instance of the composite culture that marks various regions of the country. Prevalent in the North, particularly in the central plains, it is born of the union between the Hindu and Muslim cultures. Most of the temples were lined along the Ganges and the Khanqah (Sufi school of thought) were situated along the Yamuna river (also called Jamuna). Thus, it came to be known as the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, with the word «tehzeeb» meaning culture. More than communal harmony, its most beautiful by-product was «Hindustani» which later gave us the Hindi and Urdu languages.

- ^ Matthews, David John; Shackle, C.; Husain, Shahanara (1985). Urdu literature. Urdu Markaz; Third World Foundation for Social and Economic Studies. ISBN 978-0-907962-30-4.

But with the establishment of Muslim rule in Delhi, it was the Old Hindi of this area which came to form the major partner with Persian. This variety of Hindi is called Khari Boli, ‘the upright speech’.

- ^ a b Dhulipala, Venkat (2000). The Politics of Secularism: Medieval Indian Historiography and the Sufis. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 27.

Persian became the court language, and many Persian words crept into popular usage. The composite culture of northern India, known as the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb was a product of the interaction between Hindu society and Islam.

- ^ a b Indian Journal of Social Work, Volume 4. Tata Institute of Social Sciences. 1943. p. 264.

… more words of Sanskrit origin but 75% of the vocabulary is common. It is also admitted that while this language is known as Hindustani, … Muslims call it Urdu and the Hindus call it Hindi. … Urdu is a national language evolved through years of Hindu and Muslim cultural contact and, as stated by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, is essentially an Indian language and has no place outside.

- ^ a b Mody, Sujata Sudhakar (2008). Literature, Language, and Nation Formation: The Story of a Modern Hindi Journal 1900-1920. University of California, Berkeley. p. 7.

…Hindustani, Rekhta, and Urdu as later names of the old Hindi (a.k.a. Hindavi).

- ^ a b Kesavan, B. S. (1997). History Of Printing And Publishing In India. National Book Trust, India. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-237-2120-0.

It might be useful to recall here that Old Hindi or Hindavi, which was a naturally Persian- mixed language in the largest measure, has played this role before, as we have seen, for five or six centuries.

- ^ Hans Henrich Hock (1991). Principles of Historical Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 475. ISBN 978-3-11-012962-5.

During the time of British rule, Hindi (in its religiously neutral, ‘Hindustani’ variety) increasingly came to be the symbol of national unity over against the English of the foreign oppressor. And Hindustani was learned widely throughout India, even in Bengal and the Dravidian south. … Independence had been accompanied by the division of former British India into two countries, Pakistan and India. The former had been established as a Muslim state and had made Urdu, the Muslim variety of Hindi–Urdu or Hindustani, its national language.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 430 (Appendix I). ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

Hindustani — term referring to common colloquial base of HINDI and URDU and to its function as lingua franca over much of India, much in vogue during Independence movement as expression of national unity; after Partition in 1947 and subsequent linguistic polarization it fell into disfavor; census of 1951 registered an enormous decline (86-98 per cent) in no. of persons declaring it their mother tongue (the majority of HINDI speakers and many URDU speakers had done so in previous censuses); trend continued in subsequent censuses: only 11,053 returned it in 1971…mostly from S India; [see Khubchandani 1983: 90-1].

- ^ a b c Ashmore, Harry S. (1961). Encyclopaedia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 11. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 579.

The everyday speech of well over 50,000,000 persons of all communities in the north of India and in West Pakistan is the expression of a common language, Hindustani.

- ^ Tunstall, Jeremy (2008). The media were American: U.S. mass media in decline. Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-518146-3.

The Hindi film industry used the most popular street level version of Hindi, namely Hindustani, which included a lot of Urdu and Persian words.

- ^ a b Hiro, Dilip (2015). The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan. PublicAffairs. p. 398. ISBN 978-1-56858-503-1.

Spoken Hindi is akin to spoken Urdu, and that language is often called Hindustani. Bollywood’s screenplays are written in Hindustani.

- ^ a b c Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). The Culture of India. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2.

Urdu is closely related to Hindi, a language that originated and developed in the Indian subcontinent. They share the same Indic base and are so similar in phonology and grammar that they appear to be one language.

- ^ a b Chatterji, Suniti Kumar; Siṃha, Udaẏa Nārāẏana; Padikkal, Shivarama (1997). Suniti Kumar Chatterji: a centenary tribute. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0353-2.

High Hindi written in Devanagari, having identical grammar with Urdu, employing the native Hindi or Hindustani (Prakrit) elements to the fullest, but for words of high culture, going to Sanskrit. Hindustani proper that represents the basic Khari Boli with vocabulary holding a balance between Urdu and High Hindi.

- ^ a b Draper, Allison Stark (2003). India: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3838-4.

People in Delhi spoke Khari Boli, a language the British called Hindustani. It used an Indo-Aryan grammatical structure and numerous Persian «loan-words.»

- ^ Ahmad, Aijaz (2002). Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia. Verso. p. 113. ISBN 9781859843581.

On this there are far more reliable statistics than those on population. Farhang-e-Asafiya is by general agreement the most reliable Urdu dictionary. It twas compiled in the late nineteenth century by an Indian scholar little exposed to British or Orientalist scholarship. The lexicographer in question, Syed Ahmed Dehlavi, had no desire to sunder Urdu’s relationship with Farsi, as is evident even from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55,000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are derived from these sources. What distinguishes Urdu from a great many other Indian languauges … is that is draws almost a quarter of its vocabulary from language communities to the west of India, such as Farsi, Turkish, and Tajik. Most of the little it takes from Arabic has not come directly but through Farsi.

- ^ Dalmia, Vasudha (31 July 2017). Hindu Pasts: Women, Religion, Histories. SUNY Press. p. 310. ISBN 9781438468075.

On the issue of vocabulary, Ahmad goes on to cite Syed Ahmad Dehlavi as he set about to compile the Farhang-e-Asafiya, an Urdu dictionary, in the late nineteenth century. Syed Ahmad ‘had no desire to sunder Urdu’s relationship with Farsi, as is evident from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55.000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are from these sources’ (2000: 112-13). As Ahmad points out, Syed Ahmad, as a member of Delhi’s aristocratic elite, had a clear bias towards Persian and Arabic. His estimate of the percentage of Prakitic words in Urdu should therefore be considered more conservative than not. The actual proportion of Prakitic words in everyday language would clearly be much higher.

- ^ Not considering whether speakers may be bilingual in Hindi and Urdu. «What are the top 200 most spoken languages?». 3 October 2018.

- ^ «Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker’s strength — 2011» (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- ^ Gambhir, Vijay (1995). The Teaching and Acquisition of South Asian Languages. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3328-5.

The position of Hindi–Urdu among the languages of the world is anomalous. The number of its proficient speakers, over three hundred million, places it in third of fourth place after Mandarin, English, and perhaps Spanish.

- ^ First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. Brill Academic Publishers. 1993. p. 1024. ISBN 9789004097964.

Whilst the Muhammadan rulers of India spoke Persian, which enjoyed the prestige of being their court language, the common language of the country continued to be Hindi, derived through Prakrit from Sanskrit. On this dialect of the common people was grafted the Persian language, which brought a new language, Urdu, into existence. Sir George Grierson, in the Linguistic Survey of India, assigns no distinct place to Urdu, but treats it as an offshoot of Western Hindi.

- ^ Kathleen Kuiper, ed. (2011). The Culture of India. Rosen Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 9781615301492.

Hindustani began to develop during the 13th century AD in and around the Indian cities of Dehli and Meerut in response to the increasing linguistic diversity that resulted from Muslim hegemony.

- ^ Prakāśaṃ, Vennelakaṇṭi (2008). Encyclopaedia of the Linguistic Sciences: Issues and Theories. Allied Publishers. p. 186. ISBN 9788184242799.

In Deccan the dialect developed and flourished independently. It is here that it received, among others, the name Dakkhni. The kings of many independent kingdoms such as Bahmani, Ādil Shahi and Qutb Shahi that came into being in Deccan patronized the dialect. It was elevated as the official language.

- ^ Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (2008), Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7,

Apabhramsha seemed to be in a state of transition from Middle Indo-Aryan to the New Indo-Aryan stage. Some elements of Hindustani appear … the distinct form of the lingua franca Hindustani appears in the writings of Amir Khusro (1253–1325), who called it Hindwi[.]

- ^ Gat, Azar; Yakobson, Alexander (2013). Nations: The Long History and Deep Roots of Political Ethnicity and Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-107-00785-7.

- ^ Lydia Mihelič Pulsipher; Alex Pulsipher; Holly M. Hapke (2005), World Regional Geography: Global Patterns, Local Lives, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-7167-1904-5,

… By the time of British colonialism, Hindustani was the lingua franca of all of northern India and what is today Pakistan …

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 2010. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

Hindustani is a Central Indo-Aryan language based on Khari Boli (Khaṛi Boli). Its origin, development, and function reflect the dynamics of the sociolinguistic contact situation from which it emerged as a colloquial speech. It is inextricably linked with the emergence and standardisation of Urdu and Hindi.

- ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (10 September 2002), Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.), The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor, Modern Library Classics, ISBN 978-0-375-76137-9,

Note: Gurkānī is the Persianized form of the Mongolian word «kürügän» («son-in-law»), the title given to the dynasty’s founder after his marriage into Genghis Khan’s family.

- ^ B.F. Manz, «Tīmūr Lang», in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, «Timurid Dynasty», Online Academic Edition, 2007. (Quotation: «Turkic dynasty descended from the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), renowned for its brilliant revival of artistic and intellectual life in Iran and Central Asia. … Trading and artistic communities were brought into the capital city of Herat, where a library was founded, and the capital became the centre of a renewed and artistically brilliant Persian culture.»)

- ^ «Timurids». The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). New York City: Columbia University. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica article: Consolidation & expansion of the Indo-Timurids, Online Edition, 2007.

- ^ Bennett, Clinton; Ramsey, Charles M. (2012). South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny. A&C Black. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4411-5127-8.

- ^ Laet, Sigfried J. de Laet (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 734. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7.

- ^ a b Taj, Afroz (1997). «About Hindi-Urdu». The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Strnad, Jaroslav (2013). Morphology and Syntax of Old Hindī: Edition and Analysis of One Hundred Kabīr vānī Poems from Rājasthān. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25489-3.

Quite different group of nouns occurring with the ending -a in the dir. plural consists of words of Arabic or Persian origin borrowed by the Old Hindi with their Persian plural endings.

- ^ Farooqi, M. (2012). Urdu Literary Culture: Vernacular Modernity in the Writing of Muhammad Hasan Askari. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02692-7.

Historically speaking, Urdu grew out of interaction between Hindus and Muslims.

- ^ Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ^ Alyssa Ayres (23 July 2009). Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-0-521-51931-1.

- ^ a b c Pollock, Sheldon (2003). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. p. 912. ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4.

- ^ «Rekhta: Poetry in Mixed Language, The Emergence of Khari Boli Literature in North India» (PDF). Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ «Rekhta: Poetry in Mixed Language, The Emergence of Khari Boli Literature in North India» (PDF). Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^

Nijhawan, S. 2016. «Hindi, Urdu or Hindustani? Revisiting ‘National Language’ Debates through Radio Broadcasting in Late Colonial India.» South Asia Research 36(1):80–97. doi:10.1177/0262728015615486. - ^ Khalid, Kanwal. «LAHORE DURING THE GHANAVID PERIOD.»

- ^ Aijazuddin Ahmad (2009). Geography of the South Asian Subcontinent: A Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1.

- ^ Coatsworth, John (2015). Global Connections: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. United States: Cambridge Univ Pr. p. 159. ISBN 9780521761062.

- ^ Tariq Rahman (2011). «Urdu as the Language of Education in British India» (PDF). Pakistan Journal of History and Culture. NIHCR. 32 (2): 1–42.

- ^ King, Christopher R. (1994). One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Hurst, John Fletcher (1992). Indika, The country and People of India and Ceylon. Concept Publishing Company. p. 344. GGKEY:P8ZHWWKEKAJ.

- ^ «Hindustani language | Origins & Vocabulary | Britannica». archive.ph. 1 April 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ «Hindustani language | Origins & Vocabulary | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (2003). Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-78737-6.

- ^ a b Peter-Dass, Rakesh (2019). Hindi Christian Literature in Contemporary India. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-070224-8.

Two forms of the same language, Nagarai Hindi and Persianized Hindi (Urdu) had identical grammar, shared common words and roots, and employed different scripts.

- ^ a b Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

The primary sources of non-IA loans into MSH are Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Turkic and English. Conversational registers of Hindi/Urdu (not to mentioned formal registers of Urdu) employ large numbers of Persian and Arabic loanwords, although in Sanskritized registers many of these words are replaced by tatsama forms from Sanskrit. The Persian and Arabic lexical elements in Hindi result from the effects of centuries of Islamic administrative rule over much of north India in the centuries before the establishment of British rule in India. Although it is conventional to differentiate among Persian and Arabic loan elements into Hindi/Urdu, in practice it is often difficult to separate these strands from one another. The Arabic (and also Turkic) lexemes borrowed into Hindi frequently were mediated through Persian, as a result of which a throrough intertwining of Persian and Arabic elements took place, as manifest by such phenomena as hybrid compounds and compound words. Moreover, although the dominant trajectory of lexical borrowing was from Arabic into Persian, and thence into Hindi/Urdu, examples can be found of words that in origin are actually Persian loanwords into both Arabic and Hindi/Urdu.

- ^ Rahman, Tariq (2011). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 99. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014.

- ^ King, Robert D. (10 January 2001). «The poisonous potency of script: Hindi and Urdu». International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2001 (150). doi:10.1515/ijsl.2001.035. ISSN 0165-2516.

- ^ Smith, Ian (2008). «Pidgins, Creoles, and Bazaar Hindi». In Kachru, Braj B; Kachru, Yamuna; Sridhar, S.N (eds.). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 254. ISBN 1139465503

- ^ a b c d Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003), «A Long History of Urdu Literarature, Part 1», in Pollock (ed.), Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia, p. 806, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4

- ^ Garcia, Maria Isabel Maldonado. 2011. «The Urdu language reforms.» Studies 26(97).

- ^ Alyssa Ayres (23 July 2009). Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780521519311.

- ^ P.V.Kate (1987). Marathwada Under the Nizams. p. 136. ISBN 9788170990178.

- ^ A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language, Chronicle Press, 1796, retrieved 8 January 2007

- ^ Schmidt, Ruth L (2003). Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). Urdu. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 318–319. ISBN 9780700711307.

- ^ Government of India: National Policy on Education Archived 20 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Census data shows Canada increasingly bilingual, linguistically diverse».

- ^ Hakala, Walter N. (2012). «Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan’s Cultures» (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and ’90s, at least three million Afghans—mostly Pashtun—fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi- and Urdu-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and being educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). «Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection». Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- ^ Kuczkiewicz-Fraś, Agnieszka (2008). Perso-Arabic Loanwords in Hindustani. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. p. x. ISBN 978-83-7188-161-9.

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2006), Hindi, John Benjamins Publishing, p. 17, ISBN 90-272-3812-X

- ^ «UDHR — Hindi» (PDF). UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner.

- ^ «Decoding the Bollywood poster». National Science and Media Museum. 28 February 2013.

Bibliography

- Asher, R. E. 1994. «Hindi.» Pp. 1547–49 in The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, edited by R. E. Asher. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-035943-4.

- Bailey, Thomas G. 1950. Teach yourself Hindustani. London: English Universities Press.

- Chatterji, Suniti K. 1960. Indo-Aryan and Hindi (rev. 2nd ed.). Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Dua, Hans R. 1992. «Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language.» In Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations, edited by M. G. Clyne. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994a. «Hindustani.» Pp. 1554 in The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, edited by R. E. Asher. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- —— 1994b. «Urdu.» Pp. 4863–64 in The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, edited by R. E. Asher. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Rai, Amrit. 1984. A house divided: The origin and development of Hindi-Hindustani. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561643-X

Further reading

- Henry Blochmann (1877). English and Urdu dictionary, romanized (8 ed.). Calcutta: Printed at the Baptist mission press for the Calcutta school-book society. p. 215. Retrieved 6 July 2011.the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1908). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language (3 ed.). London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., ltd. p. 264. Retrieved 6 July 2011.the University of Michigan

- Duncan Forbes (1857). A dictionary, Hindustani and English, accompanied by a reversed dictionary, English and Hindustani. archive.org (2nd ed.). London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company. p. 1144. OCLC 1043011501. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- John Thompson Platts (1874). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. Vol. 6423 of Harvard College Library preservation microfilm program. London: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 6 July 2011.Oxford University

- —— (1892). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. London: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 6 July 2011.the New York Public Library

- —— (1884). A dictionary of Urdū, classical Hindī, and English (reprint ed.). London: H. Milford. p. 1259. Retrieved 6 July 2011.Oxford University

- Shakespear, John. A Dictionary, Hindustani and English. 3rd ed., much enl. London: Printed for the author by J.L. Cox and Son: Sold by Parbury, Allen, & Co., 1834.

- Taylor, Joseph. A dictionary, Hindoostanee and English. Available at Hathi Trust. (A dictionary, Hindoostanee and English / abridged from the quarto edition of Major Joseph Taylor; as edited by the late W. Hunter; by William Carmichael Smyth.)

External links

- Bolti Dictionary (Hindustani)

- Hamari Boli (Hindustani)

- Khan Academy (Hindi-Urdu): academic lessons taught in Hindi-Urdu

- Hindustani as an anxiety between Hindi–Urdu Commitment

- Hindi? Urdu? Hindustani? Hindi-Urdu?

- Hindi/Urdu-English-Kalasha-Khowar-Nuristani-Pashtu Comparative Word List

- GRN Report for Hindustani

- Hindustani Poetry

- Hindustani online resources

- National Language Authority (Urdu), Pakistan (muqtadera qaumi zaban)

| Hindustani | |

|---|---|

| Hindi–Urdu | |

|

|

The word Hindustani in the Devanagari and Perso-Arabic (Nastaliq) scripts |

|

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ɦɪn̪d̪ʊst̪äːniː] |

| Native to | India and Pakistan |

| Region | Hindustani Belt (North India), Deccan, Pakistan |

|

Native speakers |

c. 250 million (2011 & 2017 censuses)[1] L2 speakers: ~500 million (1999–2016)[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Shauraseni Prakrit

|

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

|

|

Signed forms |

Indian Signing System (ISS)[5] |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | hi – Hindiur – Urdu |

| ISO 639-2 | hin – Hindiurd – Urdu |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:hin – Hindiurd – Urdu |

| Glottolog | hind1270 |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-qa to -qf |

Areas (red) where Hindustani (Delhlavi or Kauravi) is the native language |

Hindustani (; Devanagari: हिन्दुस्तानी,[9][b] Hindustānī; Perso-Arabic:[c] ہندوستانی, Hindūstānī, lit. ‘of Hindustan’)[10][2][3] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in Northern and Central India and Pakistan, and used as a lingua franca in both countries.[11][12] Hindustani is a pluricentric language with two standard registers, known as Hindi and Urdu. Thus, it is also called Hindi–Urdu.[13][14][15] Colloquial registers of the language fall on a spectrum between these standards.[16][17]

The concept of a Hindustani language as a «unifying language» or «fusion language» was endorsed by Mahatma Gandhi.[18] The conversion from Hindi to Urdu (or vice versa) is generally achieved just by transliteration between the two scripts, instead of translation which is generally only required for religious and literary texts.[19]

Some scholars trace the language’s first written poetry, in the form of Old Hindi, to as early as 769 AD.[20] However this view is not generally accepted.[21][22][23] During the period of the Delhi Sultanate, which covered most of today’s India, eastern Pakistan, southern Nepal and Bangladesh[24] and which resulted in the contact of Hindu and Muslim cultures, the Sanskrit and Prakrit base of Old Hindi became enriched with loanwords from Persian, evolving into the present form of Hindustani.[25][26][27][28][29][30] The Hindustani vernacular became an expression of Indian national unity during the Indian Independence movement,[31][32] and continues to be spoken as the common language of the people of the northern Indian subcontinent,[33] which is reflected in the Hindustani vocabulary of Bollywood films and songs.[34][35]

The language’s core vocabulary is derived from Prakrit (a descendant of Sanskrit),[17][20][36][37] with substantial loanwords from Persian and Arabic (via Persian).[38][39][20][40]

As of 2020, Hindi and Urdu together constitute the 3rd-most-spoken language in the world after English and Mandarin, with 810 million native and second-language speakers, according to Ethnologue,[41] though this includes millions who self-reported their language as ‘Hindi’ on the Indian census but speak a number of other Hindi languages than Hindustani.[42] The total number of Hindi–Urdu speakers was reported to be over 300 million in 1995, making Hindustani the third- or fourth-most spoken language in the world.[43][20]

History

Early forms of present-day Hindustani developed from the Middle Indo-Aryan apabhraṃśa vernaculars of present-day North India in the 7th–13th centuries, chiefly the Dehlavi dialect of the Western Hindi category of Indo-Aryan languages that is known as Old Hindi.[44][29] Hindustani emerged as a contact language around Delhi, a result of the increasing linguistic diversity that occurred due to Muslim rule, while the use of its southern dialect, Dakhani, was promoted by Muslim rulers in the Deccan.[45][46] Amir Khusrow, who lived in the thirteenth century during the Delhi Sultanate period in North India, used these forms (which was the lingua franca of the period) in his writings and referred to it as Hindavi (Persian: ھندوی, lit. ‘of Hind or India‘).[47][30] The Delhi Sultanate, which comprised several Turkic and Afghan dynasties that ruled much of the subcontinent from Delhi,[48] was succeeded by the Mughal Empire in 1526.

Ancestors of the language were known as Hindui, Hindavi, Zabān-e Hind (transl. ’Language of India’), Zabān-e Hindustan (transl. ’Language of Hindustan’), Hindustan ki boli (transl. ’Language of Hindustan’), Rekhta, and Hindi.[11][49] Its regional dialects became known as Zabān-e Dakhani in southern India, Zabān-e Gujari (transl. ’Language of Gujars’) in Gujarat, and as Zabān-e Dehlavi or Urdu around Delhi. It is an Indo-Aryan language, deriving its base primarily from the Western Hindi dialect of Delhi, also known as Khariboli.[50]

Although the Mughals were of Timurid (Gurkānī) Turco-Mongol descent,[51] they were Persianised, and Persian had gradually become the state language of the Mughal empire after Babur,[52][53][54][55] a continuation since the introduction of Persian by Central Asian Turkic rulers in the Indian Subcontinent,[56] and the patronisation of it by the earlier Turko-Afghan Delhi Sultanate. The basis in general for the introduction of Persian into the subcontinent was set, from its earliest days, by various Persianised Central Asian Turkic and Afghan dynasties.[57]

Hindustani began to take shape as a Persianised vernacular during the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 AD) and Mughal Empire (1526–1858 AD) in South Asia.[58] Hindustani retained the grammar and core vocabulary of the local Delhi dialect.[58][59] However, as an emerging common dialect, Hindustani absorbed large numbers of Persian, Arabic, and Turkic loanwords, and as Mughal conquests grew it spread as a lingua franca across much of northern India; this was a result of the contact of Hindu and Muslim cultures in Hindustan that created a composite Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb.[27][25][28][60] The language was also known as Rekhta, or ‘mixed’, which implies that it was mixed with Persian.[61][62] Written in the Perso-Arabic, Devanagari,[63] and occasionally Kaithi or Gurmukhi scripts,[64] it remained the primary lingua franca of northern India for the next four centuries, although it varied significantly in vocabulary depending on the local language. Alongside Persian, it achieved the status of a literary language in Muslim courts and was also used for literary purposes in various other settings such as Sufi, Nirgun Sant, Krishna Bhakta circles, and Rajput Hindu courts. Its majors centres of development included the Mughal courts of Delhi, Lucknow, Agra and Lahore as well as the Rajput courts of Amber and Jaipur.[65]

In the 18th century, towards the end of the Mughal period, with the fragmentation of the empire and the elite system, a variant of Hindustani, one of the successors of apabhraṃśa vernaculars at Delhi, and nearby cities, came to gradually replace Persian as the lingua franca among the educated elite upper class particularly in northern India, though Persian still retained much of its pre-eminence for a short period. The term Hindustani was given to that language.[66] The Perso-Arabic script form of this language underwent a standardisation process and further Persianisation during this period (18th century) and came to be known as Urdu, a name derived from Persian: Zabān-e Urdū-e Mualla (‘language of the court’) or Zabān-e Urdū (زبان اردو, ‘language of the camp’). The etymology of the word Urdu is of Chagatai origin, Ordū (‘camp’), cognate with English horde, and known in local translation as Lashkari Zabān (لشکری زبان),[67] which is shorted to Lashkari (لشکری).[68] This is all due to its origin as the common speech of the Mughal army. As a literary language, Urdu took shape in courtly, elite settings. Along with English, it became the first official language of British India in 1850.[69][70]

Hindi as a standardised literary register of the Delhi dialect arose in the 19th century; the Braj dialect was the dominant literary language in the Devanagari script up until and through the 19th century. While the first literary works (mostly translations of earlier works) in Sanskritised Hindustani were already written in the early 19th century as part of a literary project that included both Hindu and Muslim writers (e.g. Lallu Lal, Insha Allah Khan), the call for a distinct Sanskritised standard of the Delhi dialect written in Devanagari under the name of Hindi became increasingly politicised in the course of the century and gained pace around 1880 in an effort to displace Urdu’s official position.[71]

John Fletcher Hurst in his book published in 1891 mentioned that the Hindustani or camp language of the Mughal Empire’s courts at Delhi was not regarded by philologists as a distinct language but only as a dialect of Hindi with admixture of Persian. He continued: «But it has all the magnitude and importance of separate language. It is linguistic result of Muslim rule of eleventh & twelfth centuries and is spoken (except in rural Bengal) by many Hindus in North India and by Musalman population in all parts of India.» Next to English it was the official language of British Raj, was commonly written in Arabic or Persian characters, and was spoken by approximately 100,000,000 people.[72] The process of hybridization also led to the formation of words in which the first element of the compound was from Khari Boli and the second from Persian, such as rajmahal ‘palace’ (raja ‘royal, king’ + mahal ‘house, place’) and rangmahal ‘fashion house’ (rang ‘colour, dye’ + mahal ‘house, place’).[73] As Muslim rule expanded, Hindustani speakers traveled to distant parts of India as administrators, soldiers, merchants, and artisans. As it reached new areas, Hindustani further hybridized with local languages. In the Deccan, for instance, Hindustani blended with Telugu and came to be called Dakhani. In Dakhani, aspirated consonants were replaced with their unaspirated counterparts; for instance, dekh ‘see’ became dek, ghula ‘dissolved’ became gula, kuch ‘some’ became kuc, and samajh ‘understand’ became samaj.[74]