|

Cairo القاهرة |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city |

|

|

The Nile and surrounding buildings at night Ibn Tulun Mosque Muizz Street Talaat Harb Square Baron Empain Palace Cairo Citadel Cairo Opera House |

|

|

Flag Emblem |

|

| Nickname:

City of a Thousand Minarets |

|

|

Cairo Location of Cairo within Egypt Cairo Cairo (Arab world) Cairo Cairo (Africa) |

|

| Coordinates: 30°2′40″N 31°14′9″E / 30.04444°N 31.23583°ECoordinates: 30°2′40″N 31°14′9″E / 30.04444°N 31.23583°E | |

| Country | Egypt |

| Governorate | Cairo |

| First major foundation | 641–642 AD (Fustat) |

| Last major foundation | 969 AD (Cairo) |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Khaled Abdel Aal[2] |

| Area

[a][3] |

|

| • Metro | 2,734 km2 (1,056 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 23 m (75 ft) |

| Population

(2022) |

|

| • Capital city | 10,100,166 [1] |

| • Density | 8,011/km2 (20,750/sq mi) |

| • Metro

[3] |

21,900,000 |

| • Demonym | Cairene |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EST) |

| 5 digit postal code system |

11511 to 11938[4] |

| Area code | (+20) 2 |

| Website | cairo.gov.eg |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Historic Cairo |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, v, vi |

| Designated | 1979 |

| Reference no. | 89 |

Cairo ( KY-roh; Arabic: القاهرة, romanized: al-Qāhirah, pronounced [ælqɑ(ː)ˈheɾɑ]) is the capital of Egypt and the city-state Cairo Governorate, and is the country’s largest city, home to 10 million people.[5] It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metropolitan area, with a population of 21.9 million,[3] is the 12th-largest in the world by population. Cairo is associated with ancient Egypt, as the Giza pyramid complex and the ancient cities of Memphis and Heliopolis are located in its geographical area. Located near the Nile Delta,[6][7] the city first developed as Fustat, a settlement founded after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 640 next to an existing ancient Roman fortress, Babylon. Under the Fatimid dynasty a new city, al-Qāhirah, was founded nearby in 969. It later superseded Fustat as the main urban centre during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods (12th–16th centuries).[8] Cairo has long been a centre of the region’s political and cultural life, and is titled «the city of a thousand minarets» for its preponderance of Islamic architecture. Cairo’s historic center was awarded World Heritage Site status in 1979.[9] Cairo is considered a World City with a «Beta +» classification according to GaWC.[10]

Today, Cairo has the oldest and largest cinema and music industry in the Arab world, as well as the world’s second-oldest institution of higher learning, Al-Azhar University. Many international media, businesses, and organizations have regional headquarters in the city; the Arab League has had its headquarters in Cairo for most of its existence.

With a population of over 10 million[11] spread over 453 km2 (175 sq mi), Cairo is by far the largest city in Egypt. An additional 9.5 million inhabitants live close to the city. Cairo, like many other megacities, suffers from high levels of pollution and traffic. The Cairo Metro, opened in 1987, is the oldest metro system in Africa,[12] and ranks amongst the fifteen busiest in the world,[13] with over 1 billion[14] annual passenger rides. The economy of Cairo was ranked first in the Middle East in 2005,[15] and 43rd globally on Foreign Policy‘s 2010 Global Cities Index.[16]

Etymology[edit]

Egyptians often refer to Cairo as Maṣr (IPA: [mɑsˤɾ]; مَصر), the Egyptian Arabic name for Egypt itself, emphasizing the city’s importance for the country.[17][18] Its official name al-Qāhirah (القاهرة) means ‘the Vanquisher’ or ‘the Conqueror’, supposedly due to the fact that the planet Mars, an-Najm al-Qāhir (النجم القاهر, ‘the Conquering Star’), was rising at the time when the city was founded,[19] possibly also in reference to the much awaited arrival of the Fatimid Caliph Al-Mu’izz who reached Cairo in 973 from Mahdia, the old Fatimid capital. The location of the ancient city of Heliopolis is the suburb of Ain Shams (Arabic: عين شمس, ‘Eye of the Sun’).

There are a few Coptic names of the city. Tikešrōmi (Coptic: Ϯⲕⲉϣⲣⲱⲙⲓ Late Coptic: [di.kɑʃˈɾoːmi]) is attested in the 1211 text The Martyrdom of John of Phanijoit and is either a calque meaning ‘man breaker’ (Ϯ-, ‘the’, ⲕⲁϣ-, ‘to break’, and ⲣⲱⲙⲓ, ‘man’), akin to Arabic al-Qāhirah, or a derivation from Arabic قَصْر الرُوم (qaṣr ar-rūm, «the Roman castle»), another name of Babylon Fortress in Old Cairo.[20] The form Khairon (Coptic: ⲭⲁⲓⲣⲟⲛ) is attested in the modern Coptic text Ⲡⲓⲫⲓⲣⲓ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ϯⲁⲅⲓⲁ ⲙ̀ⲙⲏⲓ Ⲃⲉⲣⲏⲛⲁ (The Tale of Saint Verina).[21][better source needed] Lioui (Ⲗⲓⲟⲩⲓ Late Coptic: [lɪˈjuːj]) or Elioui (Ⲉⲗⲓⲟⲩⲓ Late Coptic: [ælˈjuːj]) is another name which is descended from the Greek name of Heliopolis (Ήλιούπολις).[20] Some argue that Mistram (Ⲙⲓⲥⲧⲣⲁⲙ Late Coptic: [ˈmɪs.təɾɑm]) or Nistram (Ⲛⲓⲥⲧⲣⲁⲙ Late Coptic: [ˈnɪs.təɾɑm]) is another Coptic name for Cairo, although others think that it’s rather a name of an Abbasid capital Al-Askar.[22] Ⲕⲁϩⲓⲣⲏ (Kahi•ree) is a popular modern rendering of an Arabic name (others being Ⲕⲁⲓⲣⲟⲛ [Kairon] and Ⲕⲁϩⲓⲣⲁ [Kahira]) which is modern folk etymology meaning ‘land of sun’. Some argue that it was a name of an Egyptian settlement upon which Cairo was built, but it is rather doubtful as this name is not attested in any Hieroglyphic or Demotic source, although some researchers, like Paul Casanova, view it as a legitimate theory.[20] Cairo is also referred to as Ⲭⲏⲙⲓ (Late Coptic: [ˈkɪ.mi]) or Ⲅⲩⲡⲧⲟⲥ (Late Coptic: [ˈɡɪp.dos]), which means Egypt in Coptic, the same way it is referred to in Egyptian Arabic.[22]

Sometimes the city is informally referred to as Cairo by people from Alexandria (IPA: [ˈkæjɾo]; Egyptian Arabic: كايرو).[23]

History[edit]

Ancient settlements[edit]

The area around present-day Cairo had long been a focal point of Ancient Egypt due to its strategic location at the junction of the Nile Valley and the Nile Delta regions (roughly Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt), which also placed it at the crossing of major routes between North Africa and the Levant.[24][25] Memphis, the capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom and a major city up until the Ptolemaic period, was located a short distance south of present-day Cairo.[26] Heliopolis, another important city and major religious center, was located in what are now the northeastern suburbs of Cairo.[26] It was largely destroyed by the Persian invasions in 525 BC and 343 BC and partly abandoned by the late first century BC.[24]

However, the origins of modern Cairo are generally traced back to a series of settlements in the first millennium AD. Around the turn of the fourth century,[27] as Memphis was continuing to decline in importance,[28] the Romans established a large fortress along the east bank of the Nile. The fortress, called Babylon, was built by the Roman emperor Diocletian (r. 285–305) at the entrance of a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea that was created earlier by emperor Trajan (r. 98–115).[b][29] Further north of the fortress, near the present-day district of al-Azbakiya, was a port and fortified outpost known as Tendunyas (Coptic: ϯⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓⲁⲥ)[30] or Umm Dunayn.[31][32][33] While no structures older than the 7th century have been preserved in the area aside from the Roman fortifications, historical evidence suggests that a sizeable city existed. The city was important enough that its bishop, Cyrus, participated in the Second Council of Ephesus in 449.[34] However, the Byzantine-Sassanian War between 602 and 628 caused great hardship and likely caused much of the urban population to leave for the countryside, leaving the settlement partly deserted.[32] The site today remains at the nucleus of the Coptic Orthodox community, which separated from the Roman and Byzantine churches in the late 4th century. Cairo’s oldest extant churches, such as the Church of Saint Barbara and the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (from the late 7th or early 8th century), are located inside the fortress walls in what is now known as Old Cairo or Coptic Cairo.[35]

Fustat and other early Islamic settlements[edit]

Excavated ruins of Fustat (2004 photo)

The Muslim conquest of Byzantine Egypt was led by Amr ibn al-As from 639 to 642. Babylon Fortress was besieged in September 640 and fell in April 641. In 641 or early 642, after the surrender of Alexandria (the Egyptian capital at the time), he founded a new settlement next to Babylon Fortress.[36][37] The city, known as Fustat (Arabic: الفسطاط, romanized: al-Fusṭāṭ, lit. ‘the tent’), served as a garrison town and as the new administrative capital of Egypt. Historians such as Janet Abu-Lughod and André Raymond trace the genesis of present-day Cairo to the foundation of Fustat.[38][39] The choice of founding a new settlement at this inland location, instead of using the existing capital of Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, may have been due to the new conquerors’ strategic priorities. One of the first projects of the new Muslim administration was to clear and re-open Trajan’s ancient canal in order to ship grain more directly from Egypt to Medina, the capital of the caliphate in Arabia.[40][41][42][43] Ibn al-As also founded a mosque for the city at the same time, now known as the Mosque of Amr Ibn al-As, the oldest mosque in Egypt and Africa (although the current structure dates from later expansions).[25][44][45][46]

In 750, following the overthrow of the Umayyad caliphate by the Abbasids, the new rulers created their own settlement to the northeast of Fustat which became the new provincial capital. This was known as al-Askar (Arabic: العسكر, lit. ‘the camp’) as it was laid out like a military camp. A governor’s residence and a new mosque were also added, with the latter completed in 786.[47] In 861, on the orders of the Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil, a Nilometer was built on Roda Island near Fustat. Although it was repaired and given a new roof in later centuries, its basic structure is still preserved today, making it the oldest preserved Islamic-era structure in Cairo today.[48][49]

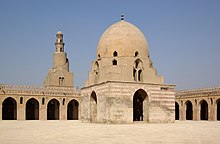

In 868 a commander of Turkic origin named Bakbak was sent to Egypt by the Abbasid caliph al-Mu’taz to restore order after a rebellion in the country. He was accompanied by his stepson, Ahmad ibn Tulun, who became effective governor of Egypt. Over time, Ibn Tulun gained an army and accumulated influence and wealth, allowing him to become the de facto independent ruler of both Egypt and Syria by 878.[50][51][52] In 870, he used his growing wealth to found a new administrative capital, al-Qata’i (Arabic: القطائـع, lit. ‘the allotments’), to the northeast of Fustat and of al-Askar.[52][53] The new city included a palace known as the Dar al-Imara, a parade ground known as al-Maydan, a bimaristan (hospital), and an aqueduct to supply water. Between 876 and 879 Ibn Tulun built a great mosque, now known as the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, at the center of the city, next to the palace.[51][53] After his death in 884, Ibn Tulun was succeeded by his son and his descendants who continued a short-lived dynasty, the Tulunids. In 905, the Abbasids sent general Muhammad Sulayman al-Katib to re-assert direct control over the country. Tulunid rule was ended and al-Qatta’i was razed to the ground, except for the mosque which remains standing today.[54][55]

Foundation and expansion of Cairo[edit]

A plan of Cairo before 1200 AD, as reconstructed by Stanley Lane-Poole (1906), showing the location of Fatimid structures, Saladin’s Citadel, and earlier sites (Fustat not shown)

In 969, the Shi’a Isma’ili Fatimid empire conquered Egypt after ruling from Ifriqiya. The Fatimid general Jawhar Al Saqili founded a new fortified city northeast of Fustat and of former al-Qata’i. It took four years to build the city, initially known as al-Manṣūriyyah,[56] which was to serve as the new capital of the caliphate. During that time, the construction of the al-Azhar Mosque was commissioned by order of the caliph, which developed into the third-oldest university in the world. Cairo would eventually become a centre of learning, with the library of Cairo containing hundreds of thousands of books.[57] When Caliph al-Mu’izz li Din Allah arrived from the old Fatimid capital of Mahdia in Tunisia in 973, he gave the city its present name, Qāhirat al-Mu’izz («The Vanquisher of al-Mu’izz»),[56] from which the name «Cairo» (al-Qāhira) originates. The caliphs lived in a vast and lavish palace complex that occupied the heart of the city. Cairo remained a relatively exclusive royal city for most of this era, but during the tenure of Badr al-Gamali as vizier (1073–1094) the restrictions were loosened for the first time and richer families from Fustat were allowed to move into the city.[58] Between 1087 and 1092 Badr al-Gamali also rebuilt the city walls in stone and constructed the city gates of Bab al-Futuh, Bab al-Nasr, and Bab Zuweila that still stand today.[59]

During the Fatimid period Fustat reached its apogee in size and prosperity, acting as a center of craftsmanship and international trade and as the area’s main port on the Nile.[60] Historical sources report that multi-story communal residences existed in the city, particularly in its center, which were typically inhabited by middle and lower-class residents. Some of these were as high as seven stories and could house some 200 to 350 people.[61] They may have been similar to Roman insulae and may have been the prototypes for the rental apartment complexes which became common in the later Mamluk and Ottoman periods.[61]

However, in 1168 the Fatimid vizier Shawar set fire to unfortified Fustat to prevent its potential capture by Amalric, the Crusader king of Jerusalem. While the fire did not destroy the city and it continued to exist afterward, it did mark the beginning of its decline. Over the following centuries it was Cairo, the former palace-city, that became the new economic center and attracted migration from Fustat.[62][63]

While the Crusaders did not capture the city in 1168, a continuing power struggle between Shawar, King Amalric, and the Zengid general Shirkuh led to the downfall of the Fatimid establishment.[64] In 1169, Shirkuh’s nephew Saladin was appointed as the new vizier of Egypt by the Fatimids and two years later he seized power from the family of the last Fatimid caliph, al-‘Āḍid.[65] As the first Sultan of Egypt, Saladin established the Ayyubid dynasty, based in Cairo, and aligned Egypt with the Sunni Abbasids, who were based in Baghdad.[66] In 1176, Saladin began construction on the Cairo Citadel, which was to serve as the seat of the Egyptian government until the mid-19th century. The construction of the Citadel definitively ended Fatimid-built Cairo’s status as an exclusive palace-city and opened it up to common Egyptians and to foreign merchants, spurring its commercial development.[67] Along with the Citadel, Saladin also began the construction of a new 20-kilometre-long wall that would protect both Cairo and Fustat on their eastern side and connect them with the new Citadel. These construction projects continued beyond Saladin’s lifetime and were completed under his Ayyubid successors.[68]

Apogee and decline under the Mamluks[edit]

In 1250, during the Seventh Crusade, the Ayyubid dynasty had a crisis with the death of al-Salih and power transitioned instead to the Mamluks, partly with the help of al-Salih’s wife, Shajar ad-Durr, who ruled for a brief period around this time.[69][70] Mamluks were soldiers who were purchased as young slaves and raised to serve in the sultan’s army. Between 1250 and 1517 the throne of the Mamluk Sultanate passed from one mamluk to another in a system of succession that was generally non-hereditary, but also frequently violent and chaotic.[71][72] The Mamluk Empire nonetheless became a major power in the region and was responsible for repelling the advance of the Mongols (most famously at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260) and for eliminating the last Crusader states in the Levant.[73]

Despite their military character, the Mamluks were also prolific builders and left a rich architectural legacy throughout Cairo.[74] Continuing a practice started by the Ayyubids, much of the land occupied by former Fatimid palaces was sold and replaced by newer buildings, becoming a prestigious site for the construction of Mamluk religious and funerary complexes.[75] Construction projects initiated by the Mamluks pushed the city outward while also bringing new infrastructure to the centre of the city.[76] Meanwhile, Cairo flourished as a centre of Islamic scholarship and a crossroads on the spice trade route among the civilisations in Afro-Eurasia.[77] Under the reign of the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad (1293–1341, with interregnums), Cairo reached its apogee in terms of population and wealth.[78] By 1340, Cairo had a population of close to half a million, making it the largest city west of China.[77]

Multi-story buildings occupied by rental apartments, known as a rab’ (plural ribā’ or urbu), became common in the Mamluk period and continued to be a feature of the city’s housing during the later Ottoman period.[79][80] These apartments were often laid out as multi-story duplexes or triplexes. They were sometimes attached to caravanserais, where the two lower floors were for commercial and storage purposes and the multiple stories above them were rented out to tenants. The oldest partially-preserved example of this type of structure is the Wikala of Amir Qawsun, built before 1341.[79][80] Residential buildings were in turn organized into close-knit neighbourhoods called a harat, which in many cases had gates that could be closed off at night or during disturbances.[80]

When the traveller Ibn Battuta first came to Cairo in 1326, he described it as the principal district of Egypt.[81] When he passed through the area again on his return journey in 1348 the Black Death was ravaging most major cities. He cited reports of thousands of deaths per day in Cairo.[82][83] Although Cairo avoided Europe’s stagnation during the Late Middle Ages, it could not escape the Black Death, which struck the city more than fifty times between 1348 and 1517.[84] During its initial, and most deadly waves, approximately 200,000 people were killed by the plague,[85] and, by the 15th century, Cairo’s population had been reduced to between 150,000 and 300,000.[86] The population decline was accompanied by a period of political instability between 1348 and 1412. It was nonetheless in this period that the largest Mamluk-era religious monument, the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan, was built.[87] In the late 14th century the Burji Mamluks replaced the Bahri Mamluks as rulers of the Mamluk state, but the Mamluk system continued to decline.[88]

Though the plagues returned frequently throughout the 15th century, Cairo remained a major metropolis and its population recovered in part through rural migration.[88] More conscious efforts were conducted by rulers and city officials to redress the city’s infrastructure and cleanliness. Its economy and politics also became more deeply connected with the wider Mediterranean.[88] Some Mamluk sultans in this period, such as Barbsay (r. 1422–1438) and Qaytbay (r. 1468–1496), had relatively long and successful reigns.[89] After al-Nasir Muhammad, Qaytbay was one of the most prolific patrons of art and architecture of the Mamluk era. He built or restored numerous monuments in Cairo, in addition to commissioning projects beyond Egypt.[90][91] The crisis of Mamluk power and of Cairo’s economic role deepened after Qaytbay. The city’s status was diminished after Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route around the Cape of Good Hope between 1497 and 1499, thereby allowing spice traders to avoid Cairo.[77]

Ottoman rule[edit]

Cairo’s political influence diminished significantly after the Ottomans defeated Sultan al-Ghuri in the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516 and conquered Egypt in 1517. Ruling from Constantinople, Sultan Selim I relegated Egypt to a province, with Cairo as its capital.[92] For this reason, the history of Cairo during Ottoman times is often described as inconsequential, especially in comparison to other time periods.[77][93][94] However, during the 16th and 17th centuries, Cairo remained an important economic and cultural centre. Although no longer on the spice route, the city facilitated the transportation of Yemeni coffee and Indian textiles, primarily to Anatolia, North Africa, and the Balkans. Cairene merchants were instrumental in bringing goods to the barren Hejaz, especially during the annual hajj to Mecca.[93][95] It was during this same period that al-Azhar University reached the predominance among Islamic schools that it continues to hold today;[96][97] pilgrims on their way to hajj often attested to the superiority of the institution, which had become associated with Egypt’s body of Islamic scholars.[98] The first printing press of the Middle East, printing in Hebrew, was established in Cairo c. 1557 by a scion of the Soncino family of printers, Italian Jews of Ashkenazi origin who operated a press in Constantinople. The existence of the press is known solely from two fragments discovered in the Cairo Genizah.[99]

Under the Ottomans, Cairo expanded south and west from its nucleus around the Citadel.[100] The city was the second-largest in the empire, behind Constantinople, and, although migration was not the primary source of Cairo’s growth, twenty percent of its population at the end of the 18th century consisted of religious minorities and foreigners from around the Mediterranean.[101] Still, when Napoleon arrived in Cairo in 1798, the city’s population was less than 300,000, forty percent lower than it was at the height of Mamluk—and Cairene—influence in the mid-14th century.[77][101]

The French occupation was short-lived as British and Ottoman forces, including a sizeable Albanian contingent, recaptured the country in 1801. Cairo itself was besieged by a British and Ottoman force culminating with the French surrender on 22 June 1801.[102] The British vacated Egypt two years later, leaving the Ottomans, the Albanians, and the long-weakened Mamluks jostling for control of the country.[103][104] Continued civil war allowed an Albanian named Muhammad Ali Pasha to ascend to the role of commander and eventually, with the approval of the religious establishment, viceroy of Egypt in 1805.[105]

Modern era[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 2,493,514 | — |

| 1960 | 3,680,160 | +47.6% |

| 1970 | 5,584,507 | +51.7% |

| 1980 | 7,348,778 | +31.6% |

| 1990 | 9,892,143 | +34.6% |

| 2000 | 13,625,565 | +37.7% |

| 2010 | 16,899,015 | +24.0% |

| 2019 | 20,484,965 | +21.2% |

| for Cairo Agglomeration:[106] |

Aerial view 1904 from a balloon where the Egyptian Museum appears to the right side.

A panoramic view of Cairo, 1950s

Until his death in 1848, Muhammad Ali Pasha instituted a number of social and economic reforms that earned him the title of founder of modern Egypt.[107][108] However, while Muhammad Ali initiated the construction of public buildings in the city,[109] those reforms had minimal effect on Cairo’s landscape.[110] Bigger changes came to Cairo under Isma’il Pasha (r. 1863–1879), who continued the modernisation processes started by his grandfather.[111] Drawing inspiration from Paris, Isma’il envisioned a city of maidans and wide avenues; due to financial constraints, only some of them, in the area now composing Downtown Cairo, came to fruition.[112] Isma’il also sought to modernize the city, which was merging with neighbouring settlements, by establishing a public works ministry, bringing gas and lighting to the city, and opening a theatre and opera house.[113][114]

The immense debt resulting from Isma’il’s projects provided a pretext for increasing European control, which culminated with the British invasion in 1882.[77] The city’s economic centre quickly moved west toward the Nile, away from the historic Islamic Cairo section and toward the contemporary, European-style areas built by Isma’il.[115][116] Europeans accounted for five percent of Cairo’s population at the end of the 19th century, by which point they held most top governmental positions.[117]

In 1906 the Heliopolis Oasis Company headed by the Belgian industrialist Édouard Empain and his Egyptian counterpart Boghos Nubar, built a suburb called Heliopolis (city of the sun in Greek) ten kilometers from the center of Cairo.[118][119] In 1905–1907 the northern part of the Gezira island was developed by the Baehler Company into Zamalek, which would later become Cairo’s upscale «chic» neighbourhood.[120] In 1906 construction began on Garden City, a neighbourhood of urban villas with gardens and curved streets.[120]

The British occupation was intended to be temporary, but it lasted well into the 20th century. Nationalists staged large-scale demonstrations in Cairo in 1919,[77] five years after Egypt had been declared a British protectorate.[121] Nevertheless, this led to Egypt’s independence in 1922.

1924 Cairo Quran[edit]

The King Fuad I Edition of the Qur’an[122] was first published on 10 July 1924 in Cairo under the patronage of King Fuad.[123][124] The goal of the government of the newly formed Kingdom of Egypt was not to delegitimize the other variant Quranic texts («qira’at»), but to eliminate errors found in Qur’anic texts used in state schools. A committee of teachers chose to preserve a single one of the canonical qira’at «readings», namely that of the «Ḥafṣ» version,[125] an 8th-century Kufic recitation. This edition has become the standard for modern printings of the Quran[126][127] for much of the Islamic world.[128] The publication has been called a «terrific success», and the edition has been described as one «now widely seen as the official text of the Qur’an», so popular among both Sunni and Shi’a that the common belief among less well-informed Muslims is «that the Qur’an has a single, unambiguous reading». Minor amendments were made later in 1924 and in 1936 — the «Faruq edition» in honour of then ruler, King Faruq.[129]

British occupation until 1956[edit]

Everyday life in Cairo, 1950s

British troops remained in the country until 1956. During this time, urban Cairo, spurred by new bridges and transport links, continued to expand to include the upscale neighbourhoods of Garden City, Zamalek, and Heliopolis.[130] Between 1882 and 1937, the population of Cairo more than tripled—from 347,000 to 1.3 million[131]—and its area increased from 10 to 163 km2 (4 to 63 sq mi).[132]

The city was devastated during the 1952 riots known as the Cairo Fire or Black Saturday, which saw the destruction of nearly 700 shops, movie theatres, casinos and hotels in downtown Cairo.[133] The British departed Cairo following the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, but the city’s rapid growth showed no signs of abating. Seeking to accommodate the increasing population, President Gamal Abdel Nasser redeveloped Tahrir Square and the Nile Corniche, and improved the city’s network of bridges and highways.[134] Meanwhile, additional controls of the Nile fostered development within Gezira Island and along the city’s waterfront. The metropolis began to encroach on the fertile Nile Delta, prompting the government to build desert satellite towns and devise incentives for city-dwellers to move to them.[135]

After 1956[edit]

In the second half of the 20th century Cairo continue to grow enormously in both population and area. Between 1947 and 2006 the population of Greater Cairo went from 2,986,280 to 16,292,269.[136] The population explosion also drove the rise of «informal» housing (‘ashwa’iyyat), meaning housing that was built without any official planning or control.[137] The exact form of this type of housing varies considerably but usually has a much higher population density than formal housing. By 2009, over 63% of the population of Greater Cairo lived in informal neighbourhoods, even though these occupied only 17% of the total area of Greater Cairo.[138] According to economist David Sims, informal housing has the benefits of providing affordable accommodation and vibrant communities to huge numbers of Cairo’s working classes, but it also suffers from government neglect, a relative lack of services, and overcrowding.[139]

The «formal» city was also expanded. The most notable example was the creation of Madinat Nasr, a huge government-sponsored expansion of the city to the east which officially began in 1959 but was primarily developed in the mid-1970s.[140] Starting in 1977 the Egyptian government established the New Urban Communities Authority to initiate and direct the development of new planned cities on the outskirts of Cairo, generally established on desert land.[141][142][143] These new satellite cities were intended to provide housing, investment, and employment opportunities for the region’s growing population as well as to pre-empt the further growth of informal neighbourhoods.[141] As of 2014, about 10% of the population of Greater Cairo lived in the new cities.[141]

Concurrently, Cairo established itself as a political and economic hub for North Africa and the Arab world, with many multinational businesses and organisations, including the Arab League, operating out of the city. In 1979 the historic districts of Cairo were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[9]

In 1992, Cairo was hit by an earthquake causing 545 deaths, injuring 6,512 and leaving around 50,000 people homeless.[144]

2011 Egyptian revolution[edit]

A protester holding an Egyptian flag during the protests that started on 25 January 2011.

Cairo’s Tahrir Square was the focal point of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution against former president Hosni Mubarak.[145] Over 2 million protesters were at Cairo’s Tahrir square. More than 50,000 protesters first occupied the square on 25 January, during which the area’s wireless services were reported to be impaired.[146] In the following days Tahrir Square continued to be the primary destination for protests in Cairo[147] as it took place following a popular uprising that began on Tuesday, 25 January 2011 and continued until June 2013. The uprising was mainly a campaign of non-violent civil resistance, which featured a series of demonstrations, marches, acts of civil disobedience, and labour strikes. Millions of protesters from a variety of socio-economic and religious backgrounds demanded the overthrow of the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Despite being predominantly peaceful in nature, the revolution was not without violent clashes between security forces and protesters, with at least 846 people killed and 6,000 injured. The uprising took place in Cairo, Alexandria, and in other cities in Egypt, following the Tunisian revolution that resulted in the overthrow of the long-time Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.[148] On 11 February, following weeks of determined popular protest and pressure, Hosni Mubarak resigned from office.

Post-revolutionary Cairo[edit]

Under the rule of President el-Sisi, in March 2015 plans were announced for another yet-unnamed planned city to be built further east of the existing satellite city of New Cairo, intended to serve as the new capital of Egypt.[149]

Geography[edit]

The river Nile flows through Cairo, here contrasting ancient customs of daily life with the modern city of today.

Cairo is located in northern Egypt, known as Lower Egypt, 165 km (100 mi) south of the Mediterranean Sea and 120 km (75 mi) west of the Gulf of Suez and Suez Canal.[150] The city lies along the Nile River, immediately south of the point where the river leaves its desert-bound valley and branches into the low-lying Nile Delta region. Although the Cairo metropolis extends away from the Nile in all directions, the city of Cairo resides only on the east bank of the river and two islands within it on a total area of 453 km2 (175 sq mi).[151][152] Geologically, Cairo lies on alluvium and sand dunes which date from the quaternary period.[153][154]

Until the mid-19th century, when the river was tamed by dams, levees, and other controls, the Nile in the vicinity of Cairo was highly susceptible to changes in course and surface level. Over the years, the Nile gradually shifted westward, providing the site between the eastern edge of the river and the Mokattam highlands on which the city now stands. The land on which Cairo was established in 969 (present-day Islamic Cairo) was located underwater just over three hundred years earlier, when Fustat was first built.[155]

Low periods of the Nile during the 11th century continued to add to the landscape of Cairo; a new island, known as Geziret al-Fil, first appeared in 1174, but eventually became connected to the mainland. Today, the site of Geziret al-Fil is occupied by the Shubra district. The low periods created another island at the turn of the 14th century that now composes Zamalek and Gezira. Land reclamation efforts by the Mamluks and Ottomans further contributed to expansion on the east bank of the river.[156]

Because of the Nile’s movement, the newer parts of the city—Garden City, Downtown Cairo, and Zamalek—are located closest to the riverbank.[157] The areas, which are home to most of Cairo’s embassies, are surrounded on the north, east, and south by the older parts of the city. Old Cairo, located south of the centre, holds the remnants of Fustat and the heart of Egypt’s Coptic Christian community, Coptic Cairo. The Boulaq district, which lies in the northern part of the city, was born out of a major 16th-century port and is now a major industrial centre. The Citadel is located east of the city centre around Islamic Cairo, which dates back to the Fatimid era and the foundation of Cairo. While western Cairo is dominated by wide boulevards, open spaces, and modern architecture of European influence, the eastern half, having grown haphazardly over the centuries, is dominated by small lanes, crowded tenements, and Islamic architecture.

Northern and extreme eastern parts of Cairo, which include satellite towns, are among the most recent additions to the city, as they developed in the late-20th and early-21st centuries to accommodate the city’s rapid growth. The western bank of the Nile is commonly included within the urban area of Cairo, but it composes the city of Giza and the Giza Governorate. Giza city has also undergone significant expansion over recent years, and today has a population of 2.7 million.[152] The Cairo Governorate was just north of the Helwan Governorate from 2008 when some Cairo’s southern districts, including Maadi and New Cairo, were split off and annexed into the new governorate,[158] to 2011 when the Helwan Governorate was reincorporated into the Cairo Governorate.

According to the World Health Organization, the level of air pollution in Cairo is nearly 12 times higher than the recommended safety level.[159]

Climate[edit]

Cairo weather observations by French savants

In Cairo, and along the Nile River Valley, the climate is a hot desert climate (BWh according to the Köppen climate classification system[160]). Wind storms can be frequent, bringing Saharan dust into the city, from March to May and the air often becomes uncomfortably dry. High temperatures in winter range from 14 to 22 °C (57 to 72 °F), while night-time lows drop to below 11 °C (52 °F), often to 5 °C (41 °F). In summer, the highs rarely surpass 40 °C (104 °F), and lows drop to about 20 °C (68 °F). Rainfall is sparse and only happens in the colder months, but sudden showers can cause severe flooding. The summer months have high humidity due to its coastal location. Snowfall is extremely rare; a small amount of graupel, widely believed to be snow, fell on Cairo’s easternmost suburbs on 13 December 2013, the first time Cairo’s area received this kind of precipitation in many decades.[161] Dew points in the hottest months range from 13.9 °C (57 °F) in June to 18.3 °C (65 °F) in August.[162]

| Climate data for Cairo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.9 (100.2) |

43.2 (109.8) |

47.8 (118.0) |

46.4 (115.5) |

42.6 (108.7) |

43.4 (110.1) |

43.7 (110.7) |

41.0 (105.8) |

37.4 (99.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

47.8 (118.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

32.6 (90.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.3 (68.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19 (66) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 5.0 (0.20) |

3.8 (0.15) |

3.8 (0.15) |

1.1 (0.04) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (0.03) |

3.8 (0.15) |

5.9 (0.23) |

24.7 (0.97) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 mm) | 3.5 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 14.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 59 | 54 | 53 | 47 | 46 | 49 | 58 | 61 | 60 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 213 | 234 | 269 | 291 | 324 | 357 | 363 | 351 | 311 | 292 | 248 | 198 | 3,451 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 66 | 75 | 73 | 75 | 77 | 85 | 84 | 86 | 84 | 82 | 78 | 62 | 77 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7.8 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (UN) (1971–2000),[163] and NOAA for mean, record high and low and humidity[162] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute for sunshine (1931–1960)[164] and Weather2Travel (ultraviolet)[165] |

Metropolitan area and districts[edit]

Cairo city administrative boundary and districts in English

The city of Cairo forms part of Greater Cairo, the largest metropolitan area in Africa.[166] While it has no administrative body, the Ministry of Planning considers it as an economic region consisting of Cairo Governorate, Giza Governorate, and Qalyubia Governorate.[167] As a contiguous metropolitan area, various studies have considered Greater Cairo be composed of the administrative cities that are Cairo, Giza and Shubra al-Kheima, in addition to the satellite cities/new towns surrounding them.[168]

Cairo is a city-state where the governor is also the head of the city. Cairo City itself differs from other Egyptian cities in that it has an extra administrative division between the city and district levels, and that is areas, which are headed by deputy governors. Cairo consists of 4 areas (manatiq, singl. mantiqa) divided into 38 districts (ahya’, singl. hayy) and 46 qisms (police wards, 1-2 per district):[169]

The Northern Area is divided into 8 Districts:[170]

- Shubra

- Al-Zawiya al-Hamra

- Hadayek al-Qubba

- Rod al-Farg

- Al-Sharabia

- Al-Sahel

- Al-Zeitoun

- Al-Amiriyya

Map of Northern Area, Cairo (En)

The Eastern Area divided into 9 Districts and three new cities:[171]

- Misr al-Gadidah and Al-Nozha (Heliopolis)

- Nasr City East and Nasr City West

- Al-Salam 1 (Awwal) and al-Salam 2 (Than)

- Ain Shams

- Al-Matariya

- Al-Marg

- Shorouk (Under jurisdiction of NUCA)

- Badr (Under jurisdiction of NUCA)

- Al-Qahira al-Gadida (New Cairo, three qisms, under jurisdiction of NUCA)

The Western Area divided into 9 Districts:[172]

- Manshiyat Nasser

- Al-Wayli (Incl. qism al-Daher)

- Wasat al-Qahira (Central Cairo, incl. Al-Darb al-Ahmar, al-Gamaliyya qisms)

- Bulaq

- Gharb al-Qahira (West Cairo, incl. Zamalek qism, Qasr al-Nil qism incl. Garden City and part of Down Town)

- Abdeen

- Al-Azbakiya

- Al-Muski

- Bab al-Sha’aria

The Southern Area divided into 12 Districts:[173]

- Masr El-Qadima (Old Cairo, inlc. Al-Manial)

- Al-Khalifa

- Al-Moqattam

- Al-Basatin

- Dar al-Salam

- Al-Sayeda Zeinab

- Al-Tebin

- Helwan

- Al-Ma’sara

- Al-Maadi

- Tora

- 15th of May (Under jurisdiction of NUCA)

Satellite cities[edit]

Since 1977 a number of new towns have been planned and built by the New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) in the Eastern Desert around Cairo, ostensibly to accommodate additional population growth and development of the city and stem the development of self-built informal areas, especially over agricultural land. As of 2022 four new towns have been built and have residential populations: 15th of May City, Badr City, Shorouk City, and New Cairo. In addition, two more are under construction: the New Administrative Capital.[174][175][176] And Capital Gardens, where land was allocated in 2021, and which will house most of the civil servants employed in the new capital.[177]

Planned new capital[edit]

In March 2015, plans were announced for a new city to be built east of Cairo, in an undeveloped area of the Cairo Governorate,[178] which would serve as the New Administrative Capital of Egypt.

Demographics[edit]

According to the 2017 census, Cairo had a population of 9,539,673 people, distributed across 46 qisms (police wards):[179]

| Qism | Code 2017 | Total Population | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibbîn, al- | 010100 | 72040 | 36349 | 35691 |

| Ḥulwân | 010200 | 521239 | 265347 | 255892 |

| Ma`ṣara, al- | 010300 | 270032 | 137501 | 132531 |

| 15 May (Mâyû) | 010400 | 93574 | 49437 | 44137 |

| Ṭura | 010500 | 230438 | 168152 | 62286 |

| Ma`âdî, al- | 010600 | 88575 | 43972 | 44603 |

| Basâtîn, al- | 010700 | 495443 | 260756 | 234687 |

| Dâr al-Salâm | 010800 | 525638 | 273603 | 252035 |

| Miṣr al-qadîma | 010900 | 250313 | 129582 | 120731 |

| Sayyida Zaynab, al- | 011000 | 136278 | 68571 | 67707 |

| Khalîfa, al- | 011100 | 105235 | 54150 | 51085 |

| Mukaṭṭam | 011200 | 224138 | 116011 | 108127 |

| Minsha’at Nâṣir | 011300 | 258372 | 133864 | 124508 |

| Darb al-Aḥmar, al- | 011400 | 58489 | 30307 | 28182 |

| Mûskî, al- | 011500 | 16662 | 8216 | 8446 |

| `Abdîn | 011600 | 40321 | 19352 | 20969 |

| Qaṣr al-Nîl | 011700 | 10563 | 4951 | 5612 |

| Zamâlik, al- | 011800 | 14946 | 7396 | 7550 |

| Bûlâq | 011900 | 48147 | 24105 | 24042 |

| Azbâkiyya, al- | 012000 | 19763 | 9766 | 9997 |

| Bâb al-Sha`riyya | 012100 | 46673 | 24261 | 22412 |

| Jamâliyya, al- | 012200 | 36368 | 18487 | 17881 |

| Ẓâhir, al- | 012300 | 71870 | 35956 | 35914 |

| Wâylî, al- | 012400 | 79292 | 39407 | 39885 |

| Ḥadâ’iq al-Qubba | 012500 | 316072 | 161269 | 154803 |

| Sharâbiyya, al- | 012600 | 187201 | 94942 | 92259 |

| Shubrâ | 012700 | 76695 | 38347 | 38348 |

| Rawd al-Faraj | 012800 | 145632 | 72859 | 72773 |

| Sâḥil, al- | 012900 | 316421 | 162063 | 154358 |

| Zâwiya al-Ḥamrâ’, al- | 013000 | 318170 | 162304 | 155866 |

| Amîriyya, al- | 013100 | 152554 | 77355 | 75199 |

| Zaytûn, al- | 013200 | 174176 | 87235 | 86941 |

| Maṭariyya, al- | 013300 | 602485 | 312407 | 290078 |

| `Ayn Shams (Ain Shams) | 013400 | 614391 | 315394 | 298997 |

| Marj, al- | 013500 | 798646 | 412476 | 386170 |

| Salâm 1, al- | 013600 | 480721 | 249639 | 231082 |

| Salâm 2, al- | 013700 | 153772 | 80492 | 73280 |

| Nuzha, al- | 013800 | 231241 | 117910 | 113331 |

| Miṣr al-jadîda | 013900 | 134116 | 68327 | 65789 |

| Madînat Naṣr 1 | 014000 | 634818 | 332117 | 302701 |

| Madînat Naṣr 2 | 014100 | 72182 | 38374 | 33808 |

| Qâhira al-Jadîda 1, al- | 014200 | 135834 | 70765 | 65069 |

| Qâhira al-jadîda 2, al- | 014300 | 90668 | 46102 | 44566 |

| Qâhira al-jadîda 3, al- | 014400 | 70885 | 37340 | 33545 |

| Shurûq, al- | 014500 | 87285 | 45960 | 41325 |

| Madînat Badr | 014600 | 31299 | 17449 | 13850 |

Infrastructure[edit]

Health[edit]

Cairo, as well as neighbouring Giza, has been established as Egypt’s main centre for medical treatment, and despite some exceptions, has the most advanced level of medical care in the country. Cairo’s hospitals include the JCI-accredited As-Salaam International Hospital—Corniche El Nile, Maadi (Egypt’s largest private hospital with 350 beds), Ain Shams University Hospital, Dar Al Fouad, Nile Badrawi Hospital, 57357 Hospital, as well as Qasr El Eyni Hospital.

Education[edit]

Greater Cairo has long been the hub of education and educational services for Egypt and the region.

Today, Greater Cairo is the centre for many government offices governing the Egyptian educational system, has the largest number of educational schools, and higher education institutes among other cities and governorates of Egypt.

Some of the International Schools found in Cairo:

Universities in Greater Cairo:

| University | Date of Foundation |

|---|---|

| Al Azhar University | 970–972 |

| Cairo University | 1908 |

| American University in Cairo | 1919 |

| Ain Shams University | 1950 |

| Arab Academy for Science & Technology and Maritime Transport | 1972 |

| Helwan University | 1975 |

| Sadat Academy for Management Sciences | 1981 |

| Higher Technological Institute | 1989 |

| Modern Academy In Maadi | 1993 |

| Malvern College Egypt | 2006 |

| Misr International University | 1996 |

| Misr University for Science and Technology | 1996 |

| Modern Sciences and Arts University | 1996 |

| Université Française d’Égypte | 2002 |

| German University in Cairo | 2003 |

| Arab Open University | 2003 |

| Canadian International College | 2004 |

| British University in Egypt | 2005 |

| Ahram Canadian University | 2005 |

| Nile University | 2006 |

| Future University in Egypt | 2006 |

| Egyptian Russian University | 2006 |

| Heliopolis University for Sustainable Development | 2009 |

| New Giza University | 2016 |

Transport[edit]

Cairo Metro, LRT, and monorail expansion plans

Cairo has an extensive road network, rail system, subway system and maritime services. Road transport is facilitated by personal vehicles, taxi cabs, privately owned public buses and Cairo microbuses. Cairo, specifically Ramses Station, is the centre of almost the entire Egyptian transportation network.[180]

The subway system, officially called «Metro (مترو)», is a fast and efficient way of getting around Cairo. Metro network covers Helwan and other suburbs. It can get very crowded during rush hour. Two train cars (the fourth and fifth ones) are reserved for women only, although women may ride in any car they want.

Trams in Greater Cairo and Cairo trolleybus were used as modes of transportation, but were closed in the 1970s everywhere except Heliopolis and Helwan. These were shut down in 2014, after the Egyptian Revolution.[181]

An extensive road network connects Cairo with other Egyptian cities and villages. There is a new Ring Road that surrounds the outskirts of the city, with exits that reach outer Cairo districts. There are flyovers and bridges, such as the 6th October Bridge that, when the traffic is not heavy, allow fast[180] means of transportation from one side of the city to the other.

Cairo traffic is known to be overwhelming and overcrowded.[182] Traffic moves at a relatively fluid pace. Drivers tend to be aggressive, but are more courteous at junctions, taking turns going, with police aiding in traffic control of some congested areas.[180]

In 2017, plans to construct two monorail systems were announced, one linking 6th of October to suburban Giza, a distance of 35 km (22 mi), and the other linking Nasr City to New Cairo, a distance of 52 km (32 mi).[183][184]

Other forms of transport[edit]

Façade of Terminal 3 at Cairo International Airport

Departures area of Cairo International Airport’s Terminal 1

- Cairo International Airport

- Ramses Railway Station

- Cairo Transportation Authority CTA

- Cairo Taxi/Yellow Cab

- Cairo Metro

- Cairo Nile Ferry

- Careem

- Uber

- DiDi[185]

Sports[edit]

Football is the most popular sport in Egypt,[186] and Cairo has a number of sporting teams that compete in national and regional leagues, most notably Al Ahly and Zamalek SC, who are the CAF first and second African clubs of the 20th century. The annual match between Al Ahly and El Zamalek is one of the most watched sports events in Egypt as well as the African-Arab region. The teams form the major rivalry of Egyptian football, and are the first and the second champions in Africa and the Arab world. They play their home games at Cairo International Stadium or Naser Stadium, which is the second largest stadium in Egypt, as well as the largest in Cairo and one of the largest stadiums in the world.

The Cairo International Stadium was built in 1960 and its multi-purpose sports complex that houses the main football stadium, an indoor stadium, several satellite fields that held several regional, continental and global games, including the African Games, U17 Football World Championship and was one of the stadiums scheduled that hosted the 2006 Africa Cup of Nations which was played in January 2006. Egypt later won the competition and went on to win the next edition in Ghana (2008) making the Egyptian and Ghanaian national teams the only teams to win the African Nations Cup Back to back which resulted in Egypt winning the title for a record number of six times in the history of African Continental Competition. This was followed by a third consecutive win in Angola 2010, making Egypt the only country with a record 3-consecutive and 7-total Continental Football Competition winner. This achievement had also placed the Egyptian football team as the #9 best team in the world’s FIFA rankings. As of 2021, Egypt’s national team is ranked at #46 in the world by FIFA.[187]

Cairo failed at the applicant stage when bidding for the 2008 Summer Olympics, which was hosted in Beijing, China.[188] However, Cairo did host the 2007 Pan Arab Games.[189]

There are several other sports teams in the city that participate in several sports including Gezira Sporting Club, el Shams Club, el Seid Club, Heliopolis Sporting Club and several smaller clubs, but the biggest clubs in Egypt (not in area but in sports) are Al Ahly and Zamalek. They have the two biggest football teams in Egypt. There are new sports clubs in the area of New Cairo (one hour far from Cairo’s down town), these are Al Zohour sporting club, Wadi Degla sporting club and Platinum Club.[190]

Most of the sports federations of the country are also located in the city suburbs, including the Egyptian Football Association.[191] The headquarters of the Confederation of African Football (CAF) was previously located in Cairo, before relocating to its new headquarters in 6 October City, a small city away from Cairo’s crowded districts.

In October 2008, the Egyptian Rugby Federation was officially formed and granted membership into the International Rugby Board.[192]

Egypt is internationally known for the excellence of its squash players who excel in both professional and junior divisions.[193] Egypt has seven players in the top ten of the PSA men’s world rankings, and three in the women’s top ten. Mohamed El Shorbagy held the world number one position for more than a year before being overtaken by compatriot Karim Abdel Gawad, who is number two behind Gregory Gaultier of France. Ramy Ashour and Amr Shabana are regarded as two of the most talented squash players in history. Shabana won the World Open title four times and Ashour twice, although his recent form has been hampered by injury. Egypt’s Nour El Sherbini has won the Women’s World Championship twice and has been women’s world number one for 16 consecutive months. On 30 April 2016, she became the youngest woman to win the Women’s World Championship which was held in Malaysia. In April 2017 she retained her title by winning the Women’s World Championship which was held in the Egyptian resort of El Gouna.

Cairo is the official end point of Cross Egypt Challenge where its route ends yearly in the most sacred place in Egypt, under the Great Pyramids of Giza with a huge trophy-giving ceremony.[194]

Culture[edit]

Cairo Opera House, at the National Cultural Center, Zamalek district.

Khedivial Opera House, 1869.

Cultural tourism in Egypt[edit]

Cairo Opera House[edit]

President Mubarak inaugurated the new Cairo Opera House of the Egyptian National Cultural Centres on 10 October 1988, 17 years after the Royal Opera House had been destroyed by fire. The National Cultural Centre was built with the help of JICA, the Japan International Co-operation Agency and stands as a prominent feature for the Japanese-Egyptian co-operation and the friendship between the two nations.

Khedivial Opera House[edit]

The Khedivial Opera House, or Royal Opera House, was the original opera house in Cairo. It was dedicated on 1 November 1869 and burned down on 28 October 1971. After the original opera house was destroyed, Cairo was without an opera house for nearly two decades until the opening of the new Cairo Opera House in 1988.

Cairo International Film Festival[edit]

Cairo held its first international film festival 16 August 1976, when the first Cairo International Film Festival was launched by the Egyptian Association of Film Writers and Critics, headed by Kamal El-Mallakh. The Association ran the festival for seven years until 1983.

This achievement lead to the President of the Festival again contacting the FIAPF with the request that a competition should be included at the 1991 Festival. The request was granted.

In 1998, the Festival took place under the presidency of one of Egypt’s leading actors, Hussein Fahmy, who was appointed by the Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosni, after the death of Saad El-Din Wahba. Four years later, the journalist and writer Cherif El-Shoubashy became president.

Cairo Geniza[edit]

Solomon Schechter studying documents from the Cairo Geniza, c. 1895.

The Cairo Geniza is an accumulation of almost 200,000 Jewish manuscripts that were found in the genizah of the Ben Ezra synagogue (built 882) of Fustat, Egypt (now Old Cairo), the Basatin cemetery east of Old Cairo, and a number of old documents that were bought in Cairo in the later 19th century. These documents were written from about 870 to 1880 AD and have been archived in various American and European libraries. The Taylor-Schechter collection in the University of Cambridge runs to 140,000 manuscripts; a further 40,000 manuscripts are housed at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

Food[edit]

The majority of Cairenes make food for themselves and make use of local produce markets.[195] The restaurant scene includes Arab cuisine and Middle Eastern cuisine, including local staples such as koshary. The city’s most exclusive restaurants are typically concentrated in Zamalek and around the luxury hotels lining the shore of the Nile near the Garden City district. Influence from modern western society is also evident, with American chains such as McDonald’s, Arby’s, Pizza Hut, Subway, and Kentucky Fried Chicken being easy to find in central areas.[195]

Places of worship[edit]

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Muslim mosques.[196] There are also Christian churches and temples: Coptic Orthodox Church, Coptic Catholic Church (Catholic Church), Evangelical Church of Egypt (Synod of the Nile) (World Communion of Reformed Churches).

Economy[edit]

The NBE towers as viewed from the Nile

Informal economy in Cairo

Cairo’s economy has traditionally been based on governmental institutions and services, with the modern productive sector expanding in the 20th century to include developments in textiles and food processing — specifically the production of sugar cane. As of 2005, Egypt has the largest non-oil based GDP in the Arab world. [197]

Cairo accounts for 11% of Egypt’s population and 22% of its economy (PPP). The majority of the nation’s commerce is generated there, or passes through the city. The great majority of publishing houses and media outlets and nearly all film studios are there, as are half of the nation’s hospital beds and universities. This has fuelled rapid construction in the city, with one building in five being less than 15 years old.[197]

This growth until recently surged well ahead of city services. Homes, roads, electricity, telephone and sewer services were all in short supply. Analysts trying to grasp the magnitude of the change coined terms like «hyper-urbanization».[197]

Automobile manufacturers from Cairo[edit]

- Arab American Vehicles Company[198]

- Egyptian Light Transport Manufacturing Company (Egyptian NSU pedant)

- Ghabbour Group[199] (Fuso, Hyundai and Volvo)

- MCV Corporate Group[200] (a part of the Daimler AG)

- Mod Car[201]

- Seoudi Group[202] (Modern Motors: Nissan, BMW (formerly); El-Mashreq: Alfa Romeo and Fiat)

- Speranza[203][204] (former Daewoo Motors Egypt; Chery, Daewoo)

- General Motors Egypt

Cityscape and landmarks[edit]

Tahrir Square[edit]

Tahrir Square was founded during the mid 19th century with the establishment of modern downtown Cairo. It was first named Ismailia Square, after the 19th-century ruler Khedive Ismail, who commissioned the new downtown district’s ‘Paris on the Nile’ design. After the Egyptian Revolution of 1919 the square became widely known as Tahrir (Liberation) Square, though it was not officially renamed as such until after the 1952 Revolution which eliminated the monarchy. Several notable buildings surround the square including, the American University in Cairo’s downtown campus, the Mogamma governmental administrative Building, the headquarters of the Arab League, the Nile Ritz Carlton Hotel, and the Egyptian Museum. Being at the heart of Cairo, the square witnessed several major protests over the years. However, the most notable event in the square was being the focal point of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution against former president Hosni Mubarak.[205] In 2020 the government completed the erection of a new monument in the center of the square featuring an ancient obelisk from the reign of Ramses II, originally unearthed at Tanis (San al-Hagar) in 2019, and four ram-headed sphinx statues moved from Karnak.[206][207][208]

Egyptian Museum[edit]

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, known commonly as the Egyptian Museum, is home to the most extensive collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities in the world. It has 136,000 items on display, with many more hundreds of thousands in its basement storerooms. Among the collections on display are the finds from the tomb of Tutankhamun.[209]

Grand Egyptian Museum[edit]

Much of the collection of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, including the Tutankhamun collection, are slated to be moved to the new Grand Egyptian Museum, under construction in Giza and was due to open by the end of 2020.[210][211]

Cairo Tower[edit]

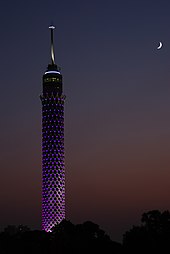

The Cairo Tower is a free-standing tower with a revolving restaurant at the top. It provides a bird’s eye view of Cairo to the restaurant patrons. It stands in the Zamalek district on Gezira Island in the Nile River, in the city centre. At 187 m (614 ft), it is 44 m (144 ft) higher than the Great Pyramid of Giza, which stands some 15 km (9 mi) to the southwest.[212]

Old Cairo[edit]

This area of Cairo is so-named as it contains the remains of the ancient Roman fortress of Babylon and also overlaps the original site of Fustat, the first Arab settlement in Egypt (7th century AD) and the predecessor of later Cairo. The area includes the Coptic Cairo, which holds a high concentration of old Christian churches such as the Hanging Church, the Greek Orthodox Church of St. George, and other Christian or Coptic buildings, most of which are located over the site of the ancient Roman fortress. It is also the location of the Coptic Museum, which showcases the history of Coptic art from Greco-Roman to Islamic times, and of the Ben Ezra Synagogue, the oldest and best-known synagogue in Cairo, where the important collection of Geniza documents were discovered in the 19th century.[213] To the north of this Coptic enclave is the Amr ibn al-‘As Mosque, the first mosque in Egypt and the most important religious centre of what was formerly Fustat, founded in 642 AD right after the Arab conquest but rebuilt many times since.[214]

Islamic Cairo[edit]

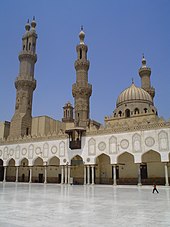

Al-Azhar Mosque, view of Fatimid-era courtyard and Mamluk minarets

Cairo holds one of the greatest concentrations of historical monuments of Islamic architecture in the world.[215] The areas around the old walled city and around the Citadel are characterized by hundreds of mosques, tombs, madrasas, mansions, caravanserais, and fortifications dating from the Islamic era and are often referred to as «Islamic Cairo», especially in English travel literature.[216] It is also the location of several important religious shrines such as the al-Hussein Mosque (whose shrine is believed to hold the head of Husayn ibn Ali), the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi’i (founder of the Shafi’i madhhab, one of the primary schools of thought in Sunni Islamic jurisprudence), the Tomb of Sayyida Ruqayya, the Mosque of Sayyida Nafisa, and others.[217]

The first mosque in Egypt was the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in what was formerly Fustat, the first Arab-Muslim settlement in the area. However, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun is the oldest mosque that still retains its original form and is a rare example of Abbasid architecture from the classical period of Islamic civilization. It was built in 876–879 AD in a style inspired by the Abbasid capital of Samarra in Iraq.[218] It is one of the largest mosques in Cairo and is often cited as one of the most beautiful.[219][220] Another Abbasid construction, the Nilometer on Roda Island, is the oldest original structure in Cairo, built in 862 AD. It was designed to measure the level of the Nile, which was important for agricultural and administrative purposes.[221]

The settlement that was formally named Cairo (Arabic: al-Qahira) was founded to the northeast of Fustat in 959 AD by the victorious Fatimid army. The Fatimids built it as a separate palatial city which contained their palaces and institutions of government. It was enclosed by a circuit of walls, which were rebuilt in stone in the late 11th century AD by the vizir Badr al-Gamali,[222] parts of which survive today at Bab Zuwayla in the south and Bab al-Futuh and Bab al-Nasr in the north. Among the extant monuments from the Fatimid era are the large Mosque of al-Hakim, the Aqmar Mosque, Juyushi Mosque, Lulua Mosque, and the Mosque of Al-Salih Tala’i.[223][217]

One of the most important and lasting institutions founded in the Fatimid period was the Mosque of al-Azhar, founded in 970 AD, which competes with the Qarawiyyin in Fes for the title of oldest university in the world.[224] Today, al-Azhar University is the foremost Center of Islamic learning in the world and one of Egypt’s largest universities with campuses across the country.[224] The mosque itself retains significant Fatimid elements but has been added to and expanded in subsequent centuries, notably by the Mamluk sultans Qaytbay and al-Ghuri and by Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda in the 18th century.[225]

The most prominent architectural heritage of medieval Cairo, however, dates from the Mamluk period, from 1250 to 1517 AD. The Mamluk sultans and elites were eager patrons of religious and scholarly life, commonly building religious or funerary complexes whose functions could include a mosque, madrasa, khanqah (for Sufis), a sabil (water dispensary), and a mausoleum for themselves and their families.[74] Among the best-known examples of Mamluk monuments in Cairo are the huge Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan, the Mosque of Amir al-Maridani, the Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad (whose twin minarets were built above the gate of Bab Zuwayla), the Sultan Al-Ghuri complex, the funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay in the Northern Cemetery, and the trio of monuments in the Bayn al-Qasrayn area comprising the complex of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun, the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, and the Madrasa of Sultan Barquq. Some mosques include spolia (often columns or capitals) from earlier buildings built by the Romans, Byzantines, or Copts.[215]

The Mamluks, and the later Ottomans, also built wikalas or caravanserais to house merchants and goods due to the important role of trade and commerce in Cairo’s economy.[226] Still intact today is the Wikala al-Ghuri, which today hosts regular performances by the Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe.[227] The Khan al-Khalili is a commercial hub which also integrated caravanserais (also known as khans).[228]

Citadel of Cairo[edit]

The Citadel is a fortified enclosure begun by Salah al-Din in 1176 AD on an outcrop of the Muqattam Hills as part of a large defensive system to protect both Cairo to the north and Fustat to the southwest.[226] It was the centre of Egyptian government and residence of its rulers until 1874, when Khedive Isma’il moved to ‘Abdin Palace.[229] It is still occupied by the military today, but is now open as a tourist attraction comprising, notably, the National Military Museum, the 14th century Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad, and the 19th century Mosque of Muhammad Ali which commands a dominant position on Cairo’s skyline.[230]

Khan el-Khalili[edit]

Khan el-Khalili is an ancient bazaar, or marketplace adjacent to the Al-Hussein Mosque. It dates back to 1385, when Amir Jarkas el-Khalili built a large caravanserai, or khan. (A caravanserai is a hotel for traders, and usually the focal point for any surrounding area.) This original caravanserai building was demolished by Sultan al-Ghuri, who rebuilt it as a new commercial complex in the early 16th century, forming the basis for the network of souqs existing today.[231] Many medieval elements remain today, including the ornate Mamluk-style gateways.[232] Today, the Khan el-Khalili is a major tourist attraction and popular stop for tour groups.[233]

Society[edit]

In the present day, Cairo is heavily urbanized and most Cairenes live in apartment buildings. Because of the influx of people into the city, lone standing houses are rare, and apartment buildings accommodate for the limited space and abundance of people. Single detached houses are usually owned by the wealthy.[234] Formal education is also seen as important, with twelve years of standard formal education. Cairenes can take a standardized test similar to the SAT to be accepted to an institution of higher learning, but most children do not finish school and opt to pick up a trade to enter the work force.[234] Egypt still struggles with poverty, with almost half the population living on $2 or less a day.[235]

Women’s rights[edit]

The civil rights movement for women in Cairo — and by extent, Egypt — has been a struggle for years. Women are reported to face constant discrimination, sexual harassment, and abuse throughout Cairo. A 2013 UN study found that over 99% of Egyptian women reported experiencing sexual harassment at some point in their lives.[236] The problem has persisted in spite of new national laws since 2014 defining and criminalizing sexual harassment.[237] The situation is so severe that in 2017, Cairo was named by one poll as the most dangerous megacity for women in the world.[238] In 2020, the social media account «Assault Police» began to name and shame perpetrators of violence against women, in an effort to dissuade potential offenders.[239] The account was founded by student Nadeen Ashraf, who is credited for instigating an iteration of the #MeToo movement in Egypt.[240]

Pollution[edit]

The air pollution in Cairo is a matter of serious concern. Greater Cairo’s volatile aromatic hydrocarbon levels are higher than many other similar cities.[241] Air quality measurements in Cairo have also been recording dangerous levels of lead, carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, and suspended particulate matter concentrations due to decades of unregulated vehicle emissions, urban industrial operations, and chaff and trash burning. There are over 4,500,000 cars on the streets of Cairo, 60% of which are over 10 years old, and therefore lack modern emission cutting features. Cairo has a very poor dispersion factor because of its lack of rain and its layout of tall buildings and narrow streets, which create a bowl effect.[242]

In recent years, a black cloud (as Egyptians refer to it) of smog has appeared over Cairo every autumn due to temperature inversion. Smog causes serious respiratory diseases and eye irritations for the city’s citizens. Tourists who are not familiar with such high levels of pollution must take extra care.[243]

Cairo also has many unregistered lead and copper smelters which heavily pollute the city. The results of this has been a permanent haze over the city with particulate matter in the air reaching over three times normal levels. It is estimated that 10,000 to 25,000 people a year in Cairo die due to air pollution-related diseases. Lead has been shown to cause harm to the central nervous system and neurotoxicity particularly in children.[244] In 1995, the first environmental acts were introduced and the situation has seen some improvement with 36 air monitoring stations and emissions tests on cars. Twenty thousand buses have also been commissioned to the city to improve congestion levels, which are very high.[245]

The city also suffers from a high level of land pollution. Cairo produces 10,000 tons of waste material each day, 4,000 tons of which is not collected or managed. This is a huge health hazard, and the Egyptian Government is looking for ways to combat this. The Cairo Cleaning and Beautification Agency was founded to collect and recycle the waste; they work with the Zabbaleen community that has been collecting and recycling Cairo’s waste since the turn of the 20th century and live in an area known locally as Manshiyat naser.[246] Both are working together to pick up as much waste as possible within the city limits, though it remains a pressing problem.

Water pollution is also a serious problem in the city as the sewer system tends to fail and overflow. On occasion, sewage has escaped onto the streets to create a health hazard. This problem is hoped to be solved by a new sewer system funded by the European Union, which could cope with the demand of the city.[citation needed] The dangerously high levels of mercury in the city’s water system has global health officials concerned over related health risks.[citation needed]

International relations[edit]

The Headquarters of the Arab League is located in Tahrir Square, near the downtown business district of Cairo.

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Cairo is twinned with:[247]

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Amman, Jordan

Baghdad, Iraq

Beijing, China

Damascus, Syria

East Jerusalem, Palestine

Istanbul, Turkey

Kairouan, Tunisia

Khartoum, Sudan

Muscat, Oman

Palermo Province, Italy

Rabat, Morocco

Sanaa, Yemen

Seoul, South Korea

Stuttgart, Germany

Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Tbilisi, Georgia

Tokyo, Japan

Tripoli, Libya

Notable people[edit]

- Rabab Al-Kadhimi (1918 — 1998), dentist and poet

- Gamal Aziz, also known as Gamal Mohammed Abdelaziz, former president and chief operating officer of Wynn Resorts, and former CEO of MGM Resorts International, indicted as part of the 2019 college admissions bribery scandal

- Yasser Arafat (4/ 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004) Born Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini was the 3rd Chairman of The PLO and first president of the Palestinian Authority

- Abu Sa’id al-Afif, 15th-century Samaritan

- Boutros Ghali (1922–2016), former Secretary-General of the United Nations

- Avi Cohen (1956–2010), Israeli international footballer

- Dalida (1933–1987), Italian-Egyptian singer who lived most of her life in France, received 55 golden records and was the first singer to receive a diamond disc

- Farouk El-Baz (born 1938), an Egyptian American space scientist who worked with NASA to assist in the planning of scientific exploration of the Moon, including the selection of landing sites for the Apollo missions and the training of astronauts in lunar observations and photography.

- Ahmed Mourad Bey Zulfikar (1888–1945), Egyptian chief of police.

- Mohamed ElBaradei (born 1942), former Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, 2005 Nobel Peace Prize laureate

- Nourane Foster (born 1987), Cameroonian entrepreneur, politician, and member of the National Assembly.

- Mauro Hamza, fencing coach

- Taco Hemingway (born 1990), Polish hip-hop artist

- Dorothy Hodgkin (1910–1994), British chemist, credited with the development of protein crystallography, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964

- Yakub Kadri Karaosmanoğlu (1889–1974), Turkish novelist

- Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006), novelist, Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988

- Roland Moreno (1945–2012), French inventor, engineer, humorist and author who invented the smart card

- Gamal Abdel Nasser (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second President of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970.

- Gaafar Nimeiry (1930–2009), President of Sudan

- Ahmed Sabri (1889–1955), painter

- Naguib Sawiris (born 1954), Egyptian businessman, 62nd richest person on Earth in 2007 list of billionaires, reaching US$10.0 billion with his company Orascom Telecom Holding

- Dina Zulfikar (born 1962), Egyptian film distributor and animal welfare activist

- Mohamed Sobhi (born 1948), Egyptian film, television and stage actor, director

- Blessed Maria Caterina Troiani (1813–1887), a charitable activist

- Magdi Yacoub (born 1935), Egyptian-British cardiothoracic surgeon

- Hesham Youssef, Egyptian diplomat

- Ahmed Zulfikar (15 August 1952 – 1 May 2010) was an Egyptian mechanical engineer and entrepreneur

- Ezz El-Dine Zulficar, (October 28, 1919 – July 1, 1963) was an Egyptian film director, screenwriter, actor and producer. known for his distinctive style, which blends romance and action. Zulficar was one of the most influential filmmakers in the Egyptian Cinema’s golden age

- Mona Zulficar (born 1950) Egyptian lawyer and human rights activist and was included in the Forbes 2021 list of the «100 most powerful businesswomen in the Arab region»

See also[edit]

- Charles Ayrout

- Cultural tourism in Egypt

- List of buildings in Cairo

- List of cities and towns in Egypt

- Outline of Cairo

- Outline of Egypt

- Architecture of Egypt

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Cairo Metropolitan is enlarged to cover all the area within the Governorate limits. Government statistics consider that the whole governorate is urban and the whole governorate is treated like as the metropolitan-city of Cairo. Governorate Cairo is considered a city-proper and functions as a municipality. The city of Alexandria is on the same principle as the city of Cairo, being a governorate-city. Because of this, it is difficult to divide Cairo into urban, rural, subdivisions, or to eliminate certain parts of the metropolitan administrative territory on various theme (unofficial statistics and data).

- ^ The historical chronicler John of Nikiou attributed the construction of the fortress to Trajan, but more recent excavations date the fortress to the time of Diocletian. A succession of canals connecting the Nile Valley with the Red Sea were also previously dug around this region in different periods prior to Trajan. Trajan’s canal fell out of use some time between the reign of Diocletian and the 7th century.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Population Estimates By Sex & Governorate 1/1/2022* (Theme: Census — pg.4)». Capmas.gov.eg. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ «Official Portal of Cairo Governorate». Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b c «Major Agglomerations of the World — Population Statistics and Maps». www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ «Cairo Postal Code». cz. 25 November 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ «About Cairo». Cairo Governorate. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Santa Maria Tours (4 September 2009). «Cairo – «Al-Qahira» – is Egypt’s capital and the largest city in the Middle East and Africa». PRLog. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ «World’s Densest Cities». Forbes. 21 December 2006. Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Raymond 1993, p. 83-85.

- ^ a b «Historic Cairo». UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ «The World According to GaWC 2016». Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Loughborough University. 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2017.