From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Kaiju (Japanese: 怪獣, Hepburn: Kaijū, lit. ‘Strange Beast’) is a Japanese media genre involving giant monsters. The word kaiju can also refer to the giant monsters themselves, which are usually depicted attacking major cities and battling either the military or other monsters. The kaiju genre is a subgenre of tokusatsu entertainment.

The 1954 film Godzilla is commonly regarded as the first kaiju film. Kaiju characters are often somewhat metaphorical in nature; Godzilla, for example, serves as a metaphor for nuclear weapons, reflecting the fears of post-war Japan following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon 5 incident. Other notable examples of kaiju characters include Rodan, Mothra, Clifford the Big Red Dog, King Ghidorah and Gamera.

Etymology[edit]

The Japanese word kaijū originally referred to monsters and creatures from ancient Japanese legends;[1] it earlier appeared in the Chinese Classic of Mountains and Seas.[2][3] After sakoku had ended and Japan was opened to foreign relations in the mid-19th century, the term kaijū came to be used to express concepts from paleontology and legendary creatures from around the world. For example, in 1908 it was suggested that the extinct Ceratosaurus-like cryptid was alive in Yukon Territory,[4] and this was referred to as kaijū.[5] However, there are no traditional depictions of kaiju or kaiju-like creatures in Japanese folklore; but rather the origins of kaiju are found in film.[6]

Genre elements were present at the end of Winsor McCay’s 1921 animated short Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: The Pet,[7] in which a mysterious giant animal starts destroying the city, until it is countered by a massive airstrike. It was based on a 1905 episode of McCay’s comic strip series.[8]

The 1925 movie The Lost World featured many dinosaurs, including a brontosaurus that breaks loose in London and destroys Tower Bridge. In 1942 Fleischer Studios released The Arctic Giant, the fourth of seventeen animated short films based upon the DC Comics character Superman, in which he has to stop a giant dinosaur from attacking the city of Metropolis.

The dinosaurs of The Lost World were animated by pioneering stop motion techniques by Willis H. O’Brien, who would some years later animate the giant gorilla-like creature breaking loose in New York City, for the 1933 movie King Kong (1933). The enormous success of King Kong can be seen as the definitive breakthrough of monster movies. RKO Pictures later licensed the King Kong character to Japanese studio Toho, resulting in the co-productions King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967), both directed by Ishirō Honda.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) featured a fictional dinosaur (animated by Ray Harryhausen), which is released from its frozen, hibernating state by an atomic bomb test within the Arctic Circle. The American movie was released in Japan in 1954 under the title The Atomic Kaiju Appears, marking the first use of the genre’s name in a film title.[9] However, Gojira (transliterated as Godzilla) is commonly regarded as the first kaiju film in the west and was released in 1954. Tomoyuki Tanaka, a producer for Toho Studios in Tokyo, needed a film to release after his previous project was halted. Seeing how well the Hollywood giant monster movie genre films King Kong and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms had done in Japanese box offices, and himself a fan of these films, he set out to make a new movie based on them and created Godzilla.[10] Tanaka aimed to combine Hollywood giant monster movies with the re-emerged Japanese fears of atomic weapons that arose from the Daigo Fukuryū Maru fishing boat incident; and so he put a team together and created the concept of a giant radioactive creature emerging from the depths of the ocean, a creature that would become the monster Godzilla.[11] Godzilla initially had commercial success in Japan, inspiring other kaiju movies.[12]

Terminology[edit]

The term kaijū translates literally as «strange beast».[13] Kaiju can be antagonistic, protagonistic, or a neutral force of nature, but more specifically as preternatural creatures of divine power. Succinctly, they are not merely, «big animals.» Godzilla, for example, from its first appearance in the initial 1954 entry in the Godzilla franchise, has manifest all of these aspects. Other examples of kaiju include Rodan, Mothra, King Ghidorah, Anguirus, King Kong, Gamera, Daimajin, Gappa, Guilala and Yonggary. There are also subcategories including Mecha Kaiju (Meka-Kaijū), featuring mechanical or cybernetic characters, including Mogera, Mechani-Kong, Mechagodzilla, Gigan, which are an off-shoot of kaiju. Likewise, the collective sub-category Ultra-Kaiju (Urutora-Kaijū) is a separate strata of kaijū, which specifically originate in the long-running Ultra Series franchise, but can also be referred to simply by kaijū. As a noun, kaijū is an invariant, as both the singular and the plural expressions are identical.[citation needed]

Kaijū eiga[edit]

Kaijū eiga (怪獣映画, «kaiju film») is a film featuring one or more kaiju.

Kaijin[edit]

Kaijin (怪人 lit. «strange person») refers to distorted human beings or humanoid-like creatures. The origin of kaijin goes back to the early 20th Century Japanese literature, starting with Edogawa Rampo’s 1936 novel, The Fiend with Twenty Faces. The story introduced Edogawa’s master detective, Kogoro Akechi’s arch-nemesis, the eponymous «Fiend,» a mysterious master of disguise, whose real face was unknown; the Moriarty to Akechi’s Sherlock. Catching the public’s imagination, many such literary and movie (and later television) villains took on the mantle of kaijin. To be clear, kaijin is not an offshoot of kaiju. The first-ever kaijin that appeared on film was The Great Buddha Arrival a lost film, made in 1934.

After the Pacific War, the term was modernized when it was adopted to describe the bizarre, genetically engineered and cybernetically enhanced evil humanoid spawn conceived for the Kamen Rider Series in 1971. This created a new splinter of the term, which quickly propagated through the popularity of superhero programs produced from the 1970s, forward. These kaijin possess rational thought and the power of speech, as do human beings. A successive kaijin menagerie, in diverse iterations, appeared over numerous series, most notably the Super Sentai programs premiering in 1975 (later carried over into Super Sentai’s English iteration as Power Rangers in the 1990s).

This created yet another splinter, as the kaijin of Super Sentai have since evolved to feature unique forms and attributes (i.e. gigantism), existing somewhere between kaijin and kaiju.[citation needed]

Daikaiju[edit]

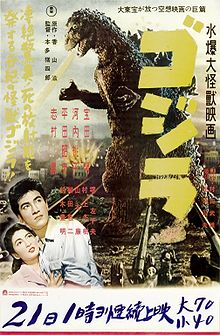

Daikaijū (大怪獣) literally translates as «giant kaiju» or «great kaiju«. This hyperbolic term was used to denote greatness of the subject kaiju; the prefix dai- emphasizing great size, power, and/or status. The first known appearance of the term daikaiju in the 20th Century was in the publicity materials for the original 1954 release of Godzilla. Specifically, in the subtitle on the original movie poster, Suibaku Daikaiju Eiga (水爆大怪獣映画), lit. «H-Bomb Giant Monster Movie» (in proper English, «The Giant H-Bomb Monster Movie»).[citation needed]

Seijin[edit]

Seijin (星人 lit. «star people»), appears within Japanese words for extraterrestrial aliens, such as Kaseijin (火星人), which means «Martian». Aliens can also be called uchūjin (宇宙人) which means «spacemen». Among the best known Seijin in the genre can be found in the Ultra Series, such as Alien Baltan from Ultraman, a race of crustacean-like aliens who have gone on to become one of the franchise’s most enduring and recurring characters other than the Ultras themselves.[citation needed]

Toho has produced a variety of kaiju films over the years (many of which feature Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra); but other Japanese studios contributed to the genre by producing films and shows of their own: Daiei Film (Kadokawa Pictures), Tsuburaya Productions, and Shochiku and Nikkatsu Studios.[citation needed]

Monster techniques[edit]

Eiji Tsuburaya, who was in charge of the special effects for Godzilla, developed a technique to animate the kaiju that became known colloquially as «suitmation».[14] Where Western monster movies often used stop motion to animate the monsters, Tsubaraya decided to attempt to create suits, called «creature suits», for a human (suit actor) to wear and act in.[15] This was combined with the use of miniature models and scaled-down city sets to create the illusion of a giant creature in a city.[16] Due to the extreme stiffness of the latex or rubber suits, filming would often be done at double speed, so that when the film was shown, the monster was smoother and slower than in the original shot.[10] Kaiju films also used a form of puppetry interwoven between suitmation scenes which served for shots that were physically impossible for the suit actor to perform. From the 1998 release of Godzilla, American-produced kaiju films strayed from suitmation to computer-generated imagery (CGI). In Japan, CGI and stop-motion have been increasingly used for certain special sequences and monsters, but suitmation has been used for an overwhelming majority of kaiju films produced in Japan of all eras.[16][17]

Selected media[edit]

Films[edit]

Manga[edit]

- Cloverfield/Kishin (Kadokawa Shoten; 2008)

- Godzilla manga (Toho, Shogakukan, Kodansha; 1954-present)

- Go Nagai Creator of Kaijus

- Garla (ガルラ, garura)(June 1976 – March 1978 Published by Tomy Company, Ltd.)

- MachineSaur (マシンザウラー, マシンサウル, Machine Sauer, Mashinzaura)(December 1979 – March 1986 Published by Tomy Company, Ltd.)

- Attack on Titan (Kodansha; 2009–2021)

- Kaiju Girl Caramelise (2018)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Kadokawa Shoten; 1994 – 2013)

- ULTRAMAN (Shogakukan; 2011–present)

- Kaiju No. 8 (Shonen Jump+; 2020–present)

Novels[edit]

- Nemesis Saga by Jeremy Robinson (St Martins Press/Breakneck Media; 2013–2016). A series of six novels featuring Nemesis, Karkinos, Typhon, Scylla, Drakon, Scryon, Giger, Lovecraft, Ashtaroth and Hyperion (Mechakaiju)

- The Kaiju Preservation Society by John Scalzi (Tor; 2022).

Comics[edit]

- Godzilla comics (Toho, Marvel Comics, Dark Horse Comics, IDW; 1976–present)

- Tokyo Storm Warning (Wildstorm; 2003)

- Enormous (Image Comics; 2012, 2014, 2021–present) as Future Released.

- The Kaiju Score (AfterShock; 2020–present)

- The Stone King (ComiXology Original; 2018–present)

- Dinosaurs Attack! (Topps Comics/IDW; 1988, 2013)

- The Nemesis Saga comics by Jeremy Robinson and Matt Frank (American Gothic Press/IDW Publishing; 2015–2016)

Video games[edit]

- Godzilla video games (Toho, Pipeworks, Bandai; 1983–present)

- Ultraman video games (Tsuburaya; 1984–present)

- Gamera Video games (Kadokawa of Games; 1995–present as North American released)

- Time Gal (Taito; 1985)

- Shadow of the Colossus (developed by SCE Japan Studio and Team Ico, and published by Sony Computer Entertainment, 2005)

- Shadow of the Colossus remake (developed by Bluepoint Games, and published by Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2018)

- King of the Monsters (SNK; 1991)

- Rampage (1986) (formerly owned by Midway Games and now owned by its successor Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment; 2021)

- Rampage: Total Destruction (Midway Games, 2006)

- Dawn of the Monsters (Developed by 13AM Games and published by WayForward, 2022) as a spiritual successor to SNK’s King of the Monsters

- Megaton Musashi (Developed by Level-5, 2021, 2022)

- Roarr! The Adventures of Rampage Rex – Jurassic Edition (Born Lucky Games, 2018)

- Terror of Hemasaurus (Developed by Loren Lemcke and published by Digerati Distribution, 2022, 2023)

- GigaBash (Passion Republic, 2022)

- Robot Alchemic Drive (Sandlot; 2002)

- DEMOLITION ROBOTS K.K. (, 2020, 2021) – Mechas A Former Dystopian Wars/Robot Killer.

- War of the Monsters (Sony, Incognito Entertainment; 2003)

- Peter Jackson’s King Kong (2005)

- Pacific Rim video game (Yuke’s/Reliance; 2013)

- City Shrouded in Shadow (Bandai Namco Entertainment; 2017)

- Colossal Kaiju Combat (Sunstone Games; Cancelled)

- 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim (Sega, Atlus, Vanillaware, 2019)

- Fight Crab (2020–21, – stage City rampage)

- DAIKAIJU DAIKESSEN (2019, 2021, 2022 OneSecretPseudo)

- Attack of the Giant Crab (2022)

Board games[edit]

- Godzilla Game

- Godzilla: Tokyo Clash

- Smash Up

- Monsterpocalypse

- King of Tokyo

- King of New York

- Monsters Menace America

- Smash City

- The Creature That Ate Sheboygan

- Campy Creatures

Television[edit]

- Marine Kong (Nisan Productions; April 3 – September 25, 1960)

- Ultra Series (Tsuburaya Productions; January 2, 1966–present)

- Ambassador Magma (P Productions; July 4, 1966 – September 25, 1967)

- The King Kong Show (Toei Animation; September 10, 1966 – August 31, 1969)

- Kaiju Booska (Tsuburaya Productions; November 9, 1966 – September 27, 1967)

- Captain Ultra (Toei Company; April 16 – September 24, 1967)

- Kaiju ouji (P Productions; October 2, 1967 – March 25, 1968)

- Giant Robo (Toei Company; October 11, 1967 – April 1, 1968)

- Giant Phantom Monster Agon (Nippon Television; January 2–8, 1968)

- Mighty Jack (Tsuburaya Productions; April 6 – June 29, 1968)

- Spectreman (P Productions; January 2, 1971 – March 25, 1972)

- Kamen Rider (Toei Company; April 3, 1971–present)

- Silver Kamen (Senkosha Productions; November 28, 1971 – May 21, 1972)

- Mirrorman (Tsuburaya Productions; December 5, 1971 – November 26, 1972)

- Redman (Tsuburaya Productions; April 3 – September 8, 1972)

- Thunder Mask (Nippon Television; October 3, 1972 – March 27, 1973)

- Ike! Godman (Toho Company; October 5, 1972 – April 10, 1973)

- Assault! Human!! (Toho Company; October 7 – December 30, 1972)

- Iron King (Senkosha Productions; October 8, 1972 – April 8, 1973)

- Jumborg Ace (Tsuburaya Productions; January 17 – December 29, 1973)

- Fireman (Tsuburaya Productions; January 17 – July 31, 1973)

- Demon Hunter Mitsurugi (International Television Films and Fuji TV; January 8, 1973 – March 26, 1973)

- Zone Fighter (Toho Company; April 2 – September 24, 1973)

- Super Robot Red Baron (Nippon Television; July 4, 1973 – March 27, 1974)

- Kure Kure Takora (Toho Company; October 1, 1973 – September 27, 1974)

- Ike! Greenman (Toho Company; November 12, 1973 – September 27, 1974)

- Super Sentai (Toei Company and Marvel Comics (1979-1982); April 3, 1975–present)

- Daitetsujin 17 (Toei Company; March 18, 1977 — November 11, 1977)

- Super Robot Mach Baron (Nippon Television; October 7, 1974 – March 31, 1975)

- Dinosaur War Izenborg (Tsuburaya Productions; October 17, 1977 – June 30, 1978)

- Spider-Man (Toei Company and Marvel Comics; May 17, 1978 – March 14, 1979)

- Godzilla (Hanna-Barbera; September 9, 1978 – December 8, 1979)

- Megaloman (Toho Company; May 7 – December 24, 1979)

- Metal Hero Series (Toei Company; March 5, 1982 — January 24, 1999)

- Godzilland (Toho Company; 1992 – 1996)

- Gridman the Hyper Agent (Tsuburaya Productions; April 3, 1993 – January 8, 1994)

- Power Rangers (Saban Entertainment and Toei Company; August 28, 1993–present)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Gainax; October 4, 1995 – March 27, 1996)

- Godzilla Kingdom (Toho Company; October 1, 1996 – August 15, 1997)

- Godzilla Island (Toho Company; October 6, 1997 – September 30, 1998)

- Godzilla: The Series (Sony Pictures Television; September 12, 1998 – April 22, 2000)

- Godzilla TV (Toho Company; October 1999 – March 2000)

- Betterman (Sunrise; April 1, 1999 – September 30, 1999)

- Dai-Guard (Xebec; October 5, 1998 – March 28, 2000)

- Kong: The Animated Series (BKN; September 9, 2000 – March 26, 2001)

- Tekkōki Mikazuki (Media Factory; October 23, 2000 – March 24, 2001)

- SFX Giant Legend: Line (Independent; April 25 – May 26, 2003)

- Chouseishin Series (Toho Company; October 4, 2003 – June 24, 2006)

- Bio Planet WoO (Tsuburaya Productions; April 9 – August 13, 2006)

- Daimajin Kanon (Kadokawa Pictures; April 2 – October 1, 2010)

- SciFi Japan TV (ACTV Japan; August 10, 2012–present)

- Attack on Titan (Wit Studio and MAPPA; April 7, 2013 – scheduled)

- Kong: King of the Apes (Netflix; April 15, 2016 – May 4, 2018)

- Mech-X4 (Disney XD; November 11, 2016 – August 20, 2018)

- Darling in the Franxx (Studio Trigger; January 13, 2018 – July 7, 2018)

- SSSS.Gridman (Tsuburaya Productions and Studio Trigger; October 7, 2018 – December 23, 2018)

- Godziban (Toho Company; August 9, 2019–present)

- I’m Home, Chibi Godzilla (Toho Company; July 15, 2020–present)

- Pacific Rim: The Black (Polygon Pictures; March 4, 2021–April 19, 2022)

- Godzilla Singular Point (Toho Company; April 1, 2021 – June 24, 2021)

- SSSS.Dynazenon (Tsuburaya Productions and Studio Trigger; April 2, 2021 – June 18, 2021)

- Super Giant Robot Brothers (Reel FX Creative Studios, Assemblage Entertainment; Netflix; August 4, 2022-present)

- Hourglass (Legendary Television; to be released)

- Skull Island (Legendary Television; Netflix; to be released)

- Gamera: Rebirth (Kadokawa Studio; Netflix; to be released)

Other appearances[edit]

- Steven Spielberg cited Godzilla as an inspiration for Jurassic Park (1993), specifically Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), which he saw in his youth.[18] During its production, Spielberg described Godzilla as «the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies because it made you believe it was really happening.»[19] One scene in the second movie (The Lost World: Jurassic Park), the T-Rex is rampaging through San Diego. One scene shows Japanese businessmen fleeing. One of them states that they left Japan to get away from this, hinting that Godzilla shares the same universe as the Jurassic Park movies. Godzilla also influenced the Spielberg film Jaws (1975).[20][21]

- In the Japanese language original of Cardcaptor Sakura anime series, Sakura’s brother Toya likes to tease her by regularly calling her «kaiju«, relating to her noisily coming down from her room for breakfast every morning.[22]

- The Polish cartoon TV series Bolek and Lolek makes a reference to the kaiju film industry in the mini-series «Bolek and Lolek’s Great Journey» by featuring a robot bird (similar to Rodan) and a saurian monster (in reference to Godzilla) as part of a Japanese director’s monster star repertoire.[citation needed]

- The Inspector Gadget film had Robo-Gadget attacking San Francisco a’la Kaiju monsters. In addition, similar to The Lost World, it shows a Japanese man while fleeing from Robo-Gadget declaring in his native tongue that he left Tokyo specifically to get away from this.

- Alternate versions of several kaiju – Godzilla, Mothra, Gamera, King Ghidorah and Daimajin – appear in the Usagi Yojimbo «Sumi-e» story arc.[23]

- In the second season of Star Wars: The Clone Wars, there is a story arc composed of two episodes entitled «The Zillo Beast» and «The Zillo Beast Strikes Back», mostly influenced by Godzilla films, in which a huge reptilian beast is transported from its homeworld Malastare to the city-covered planet Coruscant, where it breaks loose and goes on a rampage.[24][25]

- In Return of the Jedi, the rancor was originally to be played by an actor in a suit similar to the way how kaiju films like Godzilla were made. However, the rancor was eventually portrayed by a puppet filmed in high speed.[26]

- In The Simpsons episode «Treehouse of Horror VI» segment «Attack of the 50-Foot Eyesores», Homer goes to Lard Lad Donuts; unable to get a «Colossal Doughnut» as advertised, he steals Lard Lad’s donut, awakening other giant advertising statues that come to life to terrorize Springfield. When Lard Lad awakes, he makes a Godzilla roar. Guillermo del Toro directed the Treehouse of Horror XXIV couch gag which made multiple references to Godzilla and other kaiju-based characters, including his own Pacific Rim characters.[citation needed]

- The South Park episode «Mecha-Streisand» features parodies of Mechagodzilla, Gamera, Ultraman, and Mothra.[27]

- Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters features the «Insanoflex», a giant robot exercise machine rampaging downtown.[28]

- In the 2009 film Crank: High Voltage, there is a sequence parodying kaiju films using the same practical effects techniques used for tokusatsu films such as miniatures and suitmation.[citation needed]

- The Japanese light novel series Gate makes use of the term kaiju as a term for giant monsters – specifically an ancient Fire Dragon – in the Special Region. Also, one of the Japanese protagonists refers to the JSDF’s tradition to fight such monsters in the films, as well as comparing said dragon with King Ghidorah at one point.[29][30]

- Godzilla and Gamera had been referenced and appear many times throughout the Dr. Slump series.[citation needed]

- In Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero, there is a dimension that is filled with giant monsters that live on one island where they co-exist with humans that live on a city island.[citation needed]

- In «Sorcerous Stabber Orphen» series kaiju are sent as a form of punishment for the breakage of everlasting laws of the world by the Goddesses of Fate.[31]

- Batholith The Summit Kaiju (Japanese: バソリス) is a mountain (kaiju) originating from «Summit Kaiju International» an American media company based in Denver, Colorado. Batholith was first introduced to Godzilla fan during G-Fest 2017, which is an annual convention devoted to the Godzilla film franchise. Batholith The Summit Kaiju has appearing in various print media, including Famous Monsters of Filmland «Ack-Ives: Godzilla Magazine, MyKaiju Godzilla Magazine MyKaiju Godzilla Magazine, Summit Kaiju online video series and other online media related to the Godzilla and Kaiju genre.

- In the «Nemesis Saga» series of novels, Kaiju, also known as Gestorumque, are genetic weapons sent by an alien race.

- Naoki Urasawa’s 2013 one-shot manga «Kaiju Kingdom» follows a «kaiju otaku» in a world where kaiju actually exist.[32]

- In the 2019 Vanillaware video game 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, protagonists battle large mechanized aliens called Kaiju.[33]

- In John Scalzi’s 2022 book The Kaiju Preservation Society, Kaiju are a species of gigantic monsters that exist in a parallel earth accessible through radiation sources.

See also[edit]

- Yokai

- Fearsome critters

Media related to Kaiju at Wikimedia Commons

References[edit]

- ^ «Les monstres japonais du 10 mai 2014 — France Inter». May 10, 2014.

- ^ «Introduction to Kaiju [in Japanese]». dic-pixiv. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ 中根, 研一 (September 2009). «A Study of Chinese monster culture – Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media [in Japanese]». The Journal of Hokkai Gakuen University. Hokkai-Gakuen University. 141 (141): 91–121. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Glanzman, Sam (July 19, 2017). Red Range: A Wild Western Adventure. Joe R. Lansdale. IDW Publishing. ISBN 978-1684062904. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ «怪世界 : 珍談奇話». NDL Digital Collections.

- ^ Foster, Michael (1998). The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. Oakland: University of California Press.

- ^ Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: The Pet (1921) – IMDb, retrieved January 10, 2021

- ^ «Survey 1 Comic Strip Essays: Katie Moody on Winsor McCay’s «Dream of the Rarebit Fiend» | Schulz Library Blog». May 30, 2013. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Mustachio, Camille (September 29, 2017). Giant Creatures in Our World: Essays on Kaiju and American Popular Culture. Jason Barr. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476668369. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Martin, Tim (May 15, 2014). «Godzilla: Why the Japanese original is no joke». Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Harvey, Ryan (December 16, 2013). «A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 1: Origins (1954–1962)». Black Gate. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press.

- ^ Yoda, Tomiko; Harootunian, Harry (2006). Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present. Duke University Press Books. p. 344. ISBN 9780822388609.

- ^ Weinstock, Jeffery (2014) The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Godziszewski, Ed (September 5, 2006). «Making of the Godzilla Suit». Classic Media 2006 DVD Special Features. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Allison, Anne (2006) Snake Person Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. Oakland: University of California Press

- ^ Failes, Ian (October 14, 2016). «The History of Godzilla Is the History of Special Effects». Inverse. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781550223484.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of «The Big G». ECW Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781550223484.

- ^ Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780753505564.

- ^ Derry, Charles (1977). Dark Dreams: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film. A. S. Barnes. p. 82. ISBN 9780498019159.

- ^ Cardcaptor Sakura, season 1 episode 1: «Sakura and the Mysterious Magic Book»; season 1 episode 15: «Sakura and Kero’s Big Fight»

- ^ Usagi Yojimbo Vol.3 #66–68: «Sumi-e, Parts 1–3»

- ^ ««The Zillo Beast» Episode Guide». Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ ««The Zillo Beast Strikes Back» Episode Guide». Archived from the original on June 28, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ «The Cinema Behind Star Wars: Godzilla». September 29, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Stone, Matt (2003). South Park: The Complete First Season: «Mecha-Streisand» (Audio commentary) (CD). Comedy Central.

- ^ «Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Gate: Jieitai Kano Chi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri, book I: «Contact», chapters II and V

- ^ Gate: Jieitai Kano Chi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri (anime series) episode 2: «Two Military Forces», episode 3: «Fire Dragon», and episode 4: «To Unknown Lands»

- ^ Mizuno, Ryou (2019). Sorcerous Stabber Orphen Anthology. Commentary (in Japanese). TO Books. p. 236. ISBN 9784864728799.

- ^ Silverman, Rebecca (October 20, 2020). «Sneeze: Naoki Urasawa Story Collection – Review». Anime News Network. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ 十三機兵防衛圏 – System. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Kaiju (Japanese: 怪獣, Hepburn: Kaijū, lit. ‘Strange Beast’) is a Japanese media genre involving giant monsters. The word kaiju can also refer to the giant monsters themselves, which are usually depicted attacking major cities and battling either the military or other monsters. The kaiju genre is a subgenre of tokusatsu entertainment.

The 1954 film Godzilla is commonly regarded as the first kaiju film. Kaiju characters are often somewhat metaphorical in nature; Godzilla, for example, serves as a metaphor for nuclear weapons, reflecting the fears of post-war Japan following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon 5 incident. Other notable examples of kaiju characters include Rodan, Mothra, Clifford the Big Red Dog, King Ghidorah and Gamera.

Etymology[edit]

The Japanese word kaijū originally referred to monsters and creatures from ancient Japanese legends;[1] it earlier appeared in the Chinese Classic of Mountains and Seas.[2][3] After sakoku had ended and Japan was opened to foreign relations in the mid-19th century, the term kaijū came to be used to express concepts from paleontology and legendary creatures from around the world. For example, in 1908 it was suggested that the extinct Ceratosaurus-like cryptid was alive in Yukon Territory,[4] and this was referred to as kaijū.[5] However, there are no traditional depictions of kaiju or kaiju-like creatures in Japanese folklore; but rather the origins of kaiju are found in film.[6]

Genre elements were present at the end of Winsor McCay’s 1921 animated short Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: The Pet,[7] in which a mysterious giant animal starts destroying the city, until it is countered by a massive airstrike. It was based on a 1905 episode of McCay’s comic strip series.[8]

The 1925 movie The Lost World featured many dinosaurs, including a brontosaurus that breaks loose in London and destroys Tower Bridge. In 1942 Fleischer Studios released The Arctic Giant, the fourth of seventeen animated short films based upon the DC Comics character Superman, in which he has to stop a giant dinosaur from attacking the city of Metropolis.

The dinosaurs of The Lost World were animated by pioneering stop motion techniques by Willis H. O’Brien, who would some years later animate the giant gorilla-like creature breaking loose in New York City, for the 1933 movie King Kong (1933). The enormous success of King Kong can be seen as the definitive breakthrough of monster movies. RKO Pictures later licensed the King Kong character to Japanese studio Toho, resulting in the co-productions King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967), both directed by Ishirō Honda.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) featured a fictional dinosaur (animated by Ray Harryhausen), which is released from its frozen, hibernating state by an atomic bomb test within the Arctic Circle. The American movie was released in Japan in 1954 under the title The Atomic Kaiju Appears, marking the first use of the genre’s name in a film title.[9] However, Gojira (transliterated as Godzilla) is commonly regarded as the first kaiju film in the west and was released in 1954. Tomoyuki Tanaka, a producer for Toho Studios in Tokyo, needed a film to release after his previous project was halted. Seeing how well the Hollywood giant monster movie genre films King Kong and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms had done in Japanese box offices, and himself a fan of these films, he set out to make a new movie based on them and created Godzilla.[10] Tanaka aimed to combine Hollywood giant monster movies with the re-emerged Japanese fears of atomic weapons that arose from the Daigo Fukuryū Maru fishing boat incident; and so he put a team together and created the concept of a giant radioactive creature emerging from the depths of the ocean, a creature that would become the monster Godzilla.[11] Godzilla initially had commercial success in Japan, inspiring other kaiju movies.[12]

Terminology[edit]

The term kaijū translates literally as «strange beast».[13] Kaiju can be antagonistic, protagonistic, or a neutral force of nature, but more specifically as preternatural creatures of divine power. Succinctly, they are not merely, «big animals.» Godzilla, for example, from its first appearance in the initial 1954 entry in the Godzilla franchise, has manifest all of these aspects. Other examples of kaiju include Rodan, Mothra, King Ghidorah, Anguirus, King Kong, Gamera, Daimajin, Gappa, Guilala and Yonggary. There are also subcategories including Mecha Kaiju (Meka-Kaijū), featuring mechanical or cybernetic characters, including Mogera, Mechani-Kong, Mechagodzilla, Gigan, which are an off-shoot of kaiju. Likewise, the collective sub-category Ultra-Kaiju (Urutora-Kaijū) is a separate strata of kaijū, which specifically originate in the long-running Ultra Series franchise, but can also be referred to simply by kaijū. As a noun, kaijū is an invariant, as both the singular and the plural expressions are identical.[citation needed]

Kaijū eiga[edit]

Kaijū eiga (怪獣映画, «kaiju film») is a film featuring one or more kaiju.

Kaijin[edit]

Kaijin (怪人 lit. «strange person») refers to distorted human beings or humanoid-like creatures. The origin of kaijin goes back to the early 20th Century Japanese literature, starting with Edogawa Rampo’s 1936 novel, The Fiend with Twenty Faces. The story introduced Edogawa’s master detective, Kogoro Akechi’s arch-nemesis, the eponymous «Fiend,» a mysterious master of disguise, whose real face was unknown; the Moriarty to Akechi’s Sherlock. Catching the public’s imagination, many such literary and movie (and later television) villains took on the mantle of kaijin. To be clear, kaijin is not an offshoot of kaiju. The first-ever kaijin that appeared on film was The Great Buddha Arrival a lost film, made in 1934.

After the Pacific War, the term was modernized when it was adopted to describe the bizarre, genetically engineered and cybernetically enhanced evil humanoid spawn conceived for the Kamen Rider Series in 1971. This created a new splinter of the term, which quickly propagated through the popularity of superhero programs produced from the 1970s, forward. These kaijin possess rational thought and the power of speech, as do human beings. A successive kaijin menagerie, in diverse iterations, appeared over numerous series, most notably the Super Sentai programs premiering in 1975 (later carried over into Super Sentai’s English iteration as Power Rangers in the 1990s).

This created yet another splinter, as the kaijin of Super Sentai have since evolved to feature unique forms and attributes (i.e. gigantism), existing somewhere between kaijin and kaiju.[citation needed]

Daikaiju[edit]

Daikaijū (大怪獣) literally translates as «giant kaiju» or «great kaiju«. This hyperbolic term was used to denote greatness of the subject kaiju; the prefix dai- emphasizing great size, power, and/or status. The first known appearance of the term daikaiju in the 20th Century was in the publicity materials for the original 1954 release of Godzilla. Specifically, in the subtitle on the original movie poster, Suibaku Daikaiju Eiga (水爆大怪獣映画), lit. «H-Bomb Giant Monster Movie» (in proper English, «The Giant H-Bomb Monster Movie»).[citation needed]

Seijin[edit]

Seijin (星人 lit. «star people»), appears within Japanese words for extraterrestrial aliens, such as Kaseijin (火星人), which means «Martian». Aliens can also be called uchūjin (宇宙人) which means «spacemen». Among the best known Seijin in the genre can be found in the Ultra Series, such as Alien Baltan from Ultraman, a race of crustacean-like aliens who have gone on to become one of the franchise’s most enduring and recurring characters other than the Ultras themselves.[citation needed]

Toho has produced a variety of kaiju films over the years (many of which feature Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra); but other Japanese studios contributed to the genre by producing films and shows of their own: Daiei Film (Kadokawa Pictures), Tsuburaya Productions, and Shochiku and Nikkatsu Studios.[citation needed]

Monster techniques[edit]

Eiji Tsuburaya, who was in charge of the special effects for Godzilla, developed a technique to animate the kaiju that became known colloquially as «suitmation».[14] Where Western monster movies often used stop motion to animate the monsters, Tsubaraya decided to attempt to create suits, called «creature suits», for a human (suit actor) to wear and act in.[15] This was combined with the use of miniature models and scaled-down city sets to create the illusion of a giant creature in a city.[16] Due to the extreme stiffness of the latex or rubber suits, filming would often be done at double speed, so that when the film was shown, the monster was smoother and slower than in the original shot.[10] Kaiju films also used a form of puppetry interwoven between suitmation scenes which served for shots that were physically impossible for the suit actor to perform. From the 1998 release of Godzilla, American-produced kaiju films strayed from suitmation to computer-generated imagery (CGI). In Japan, CGI and stop-motion have been increasingly used for certain special sequences and monsters, but suitmation has been used for an overwhelming majority of kaiju films produced in Japan of all eras.[16][17]

Selected media[edit]

Films[edit]

Manga[edit]

- Cloverfield/Kishin (Kadokawa Shoten; 2008)

- Godzilla manga (Toho, Shogakukan, Kodansha; 1954-present)

- Go Nagai Creator of Kaijus

- Garla (ガルラ, garura)(June 1976 – March 1978 Published by Tomy Company, Ltd.)

- MachineSaur (マシンザウラー, マシンサウル, Machine Sauer, Mashinzaura)(December 1979 – March 1986 Published by Tomy Company, Ltd.)

- Attack on Titan (Kodansha; 2009–2021)

- Kaiju Girl Caramelise (2018)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Kadokawa Shoten; 1994 – 2013)

- ULTRAMAN (Shogakukan; 2011–present)

- Kaiju No. 8 (Shonen Jump+; 2020–present)

Novels[edit]

- Nemesis Saga by Jeremy Robinson (St Martins Press/Breakneck Media; 2013–2016). A series of six novels featuring Nemesis, Karkinos, Typhon, Scylla, Drakon, Scryon, Giger, Lovecraft, Ashtaroth and Hyperion (Mechakaiju)

- The Kaiju Preservation Society by John Scalzi (Tor; 2022).

Comics[edit]

- Godzilla comics (Toho, Marvel Comics, Dark Horse Comics, IDW; 1976–present)

- Tokyo Storm Warning (Wildstorm; 2003)

- Enormous (Image Comics; 2012, 2014, 2021–present) as Future Released.

- The Kaiju Score (AfterShock; 2020–present)

- The Stone King (ComiXology Original; 2018–present)

- Dinosaurs Attack! (Topps Comics/IDW; 1988, 2013)

- The Nemesis Saga comics by Jeremy Robinson and Matt Frank (American Gothic Press/IDW Publishing; 2015–2016)

Video games[edit]

- Godzilla video games (Toho, Pipeworks, Bandai; 1983–present)

- Ultraman video games (Tsuburaya; 1984–present)

- Gamera Video games (Kadokawa of Games; 1995–present as North American released)

- Time Gal (Taito; 1985)

- Shadow of the Colossus (developed by SCE Japan Studio and Team Ico, and published by Sony Computer Entertainment, 2005)

- Shadow of the Colossus remake (developed by Bluepoint Games, and published by Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2018)

- King of the Monsters (SNK; 1991)

- Rampage (1986) (formerly owned by Midway Games and now owned by its successor Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment; 2021)

- Rampage: Total Destruction (Midway Games, 2006)

- Dawn of the Monsters (Developed by 13AM Games and published by WayForward, 2022) as a spiritual successor to SNK’s King of the Monsters

- Megaton Musashi (Developed by Level-5, 2021, 2022)

- Roarr! The Adventures of Rampage Rex – Jurassic Edition (Born Lucky Games, 2018)

- Terror of Hemasaurus (Developed by Loren Lemcke and published by Digerati Distribution, 2022, 2023)

- GigaBash (Passion Republic, 2022)

- Robot Alchemic Drive (Sandlot; 2002)

- DEMOLITION ROBOTS K.K. (, 2020, 2021) – Mechas A Former Dystopian Wars/Robot Killer.

- War of the Monsters (Sony, Incognito Entertainment; 2003)

- Peter Jackson’s King Kong (2005)

- Pacific Rim video game (Yuke’s/Reliance; 2013)

- City Shrouded in Shadow (Bandai Namco Entertainment; 2017)

- Colossal Kaiju Combat (Sunstone Games; Cancelled)

- 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim (Sega, Atlus, Vanillaware, 2019)

- Fight Crab (2020–21, – stage City rampage)

- DAIKAIJU DAIKESSEN (2019, 2021, 2022 OneSecretPseudo)

- Attack of the Giant Crab (2022)

Board games[edit]

- Godzilla Game

- Godzilla: Tokyo Clash

- Smash Up

- Monsterpocalypse

- King of Tokyo

- King of New York

- Monsters Menace America

- Smash City

- The Creature That Ate Sheboygan

- Campy Creatures

Television[edit]

- Marine Kong (Nisan Productions; April 3 – September 25, 1960)

- Ultra Series (Tsuburaya Productions; January 2, 1966–present)

- Ambassador Magma (P Productions; July 4, 1966 – September 25, 1967)

- The King Kong Show (Toei Animation; September 10, 1966 – August 31, 1969)

- Kaiju Booska (Tsuburaya Productions; November 9, 1966 – September 27, 1967)

- Captain Ultra (Toei Company; April 16 – September 24, 1967)

- Kaiju ouji (P Productions; October 2, 1967 – March 25, 1968)

- Giant Robo (Toei Company; October 11, 1967 – April 1, 1968)

- Giant Phantom Monster Agon (Nippon Television; January 2–8, 1968)

- Mighty Jack (Tsuburaya Productions; April 6 – June 29, 1968)

- Spectreman (P Productions; January 2, 1971 – March 25, 1972)

- Kamen Rider (Toei Company; April 3, 1971–present)

- Silver Kamen (Senkosha Productions; November 28, 1971 – May 21, 1972)

- Mirrorman (Tsuburaya Productions; December 5, 1971 – November 26, 1972)

- Redman (Tsuburaya Productions; April 3 – September 8, 1972)

- Thunder Mask (Nippon Television; October 3, 1972 – March 27, 1973)

- Ike! Godman (Toho Company; October 5, 1972 – April 10, 1973)

- Assault! Human!! (Toho Company; October 7 – December 30, 1972)

- Iron King (Senkosha Productions; October 8, 1972 – April 8, 1973)

- Jumborg Ace (Tsuburaya Productions; January 17 – December 29, 1973)

- Fireman (Tsuburaya Productions; January 17 – July 31, 1973)

- Demon Hunter Mitsurugi (International Television Films and Fuji TV; January 8, 1973 – March 26, 1973)

- Zone Fighter (Toho Company; April 2 – September 24, 1973)

- Super Robot Red Baron (Nippon Television; July 4, 1973 – March 27, 1974)

- Kure Kure Takora (Toho Company; October 1, 1973 – September 27, 1974)

- Ike! Greenman (Toho Company; November 12, 1973 – September 27, 1974)

- Super Sentai (Toei Company and Marvel Comics (1979-1982); April 3, 1975–present)

- Daitetsujin 17 (Toei Company; March 18, 1977 — November 11, 1977)

- Super Robot Mach Baron (Nippon Television; October 7, 1974 – March 31, 1975)

- Dinosaur War Izenborg (Tsuburaya Productions; October 17, 1977 – June 30, 1978)

- Spider-Man (Toei Company and Marvel Comics; May 17, 1978 – March 14, 1979)

- Godzilla (Hanna-Barbera; September 9, 1978 – December 8, 1979)

- Megaloman (Toho Company; May 7 – December 24, 1979)

- Metal Hero Series (Toei Company; March 5, 1982 — January 24, 1999)

- Godzilland (Toho Company; 1992 – 1996)

- Gridman the Hyper Agent (Tsuburaya Productions; April 3, 1993 – January 8, 1994)

- Power Rangers (Saban Entertainment and Toei Company; August 28, 1993–present)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Gainax; October 4, 1995 – March 27, 1996)

- Godzilla Kingdom (Toho Company; October 1, 1996 – August 15, 1997)

- Godzilla Island (Toho Company; October 6, 1997 – September 30, 1998)

- Godzilla: The Series (Sony Pictures Television; September 12, 1998 – April 22, 2000)

- Godzilla TV (Toho Company; October 1999 – March 2000)

- Betterman (Sunrise; April 1, 1999 – September 30, 1999)

- Dai-Guard (Xebec; October 5, 1998 – March 28, 2000)

- Kong: The Animated Series (BKN; September 9, 2000 – March 26, 2001)

- Tekkōki Mikazuki (Media Factory; October 23, 2000 – March 24, 2001)

- SFX Giant Legend: Line (Independent; April 25 – May 26, 2003)

- Chouseishin Series (Toho Company; October 4, 2003 – June 24, 2006)

- Bio Planet WoO (Tsuburaya Productions; April 9 – August 13, 2006)

- Daimajin Kanon (Kadokawa Pictures; April 2 – October 1, 2010)

- SciFi Japan TV (ACTV Japan; August 10, 2012–present)

- Attack on Titan (Wit Studio and MAPPA; April 7, 2013 – scheduled)

- Kong: King of the Apes (Netflix; April 15, 2016 – May 4, 2018)

- Mech-X4 (Disney XD; November 11, 2016 – August 20, 2018)

- Darling in the Franxx (Studio Trigger; January 13, 2018 – July 7, 2018)

- SSSS.Gridman (Tsuburaya Productions and Studio Trigger; October 7, 2018 – December 23, 2018)

- Godziban (Toho Company; August 9, 2019–present)

- I’m Home, Chibi Godzilla (Toho Company; July 15, 2020–present)

- Pacific Rim: The Black (Polygon Pictures; March 4, 2021–April 19, 2022)

- Godzilla Singular Point (Toho Company; April 1, 2021 – June 24, 2021)

- SSSS.Dynazenon (Tsuburaya Productions and Studio Trigger; April 2, 2021 – June 18, 2021)

- Super Giant Robot Brothers (Reel FX Creative Studios, Assemblage Entertainment; Netflix; August 4, 2022-present)

- Hourglass (Legendary Television; to be released)

- Skull Island (Legendary Television; Netflix; to be released)

- Gamera: Rebirth (Kadokawa Studio; Netflix; to be released)

Other appearances[edit]

- Steven Spielberg cited Godzilla as an inspiration for Jurassic Park (1993), specifically Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), which he saw in his youth.[18] During its production, Spielberg described Godzilla as «the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies because it made you believe it was really happening.»[19] One scene in the second movie (The Lost World: Jurassic Park), the T-Rex is rampaging through San Diego. One scene shows Japanese businessmen fleeing. One of them states that they left Japan to get away from this, hinting that Godzilla shares the same universe as the Jurassic Park movies. Godzilla also influenced the Spielberg film Jaws (1975).[20][21]

- In the Japanese language original of Cardcaptor Sakura anime series, Sakura’s brother Toya likes to tease her by regularly calling her «kaiju«, relating to her noisily coming down from her room for breakfast every morning.[22]

- The Polish cartoon TV series Bolek and Lolek makes a reference to the kaiju film industry in the mini-series «Bolek and Lolek’s Great Journey» by featuring a robot bird (similar to Rodan) and a saurian monster (in reference to Godzilla) as part of a Japanese director’s monster star repertoire.[citation needed]

- The Inspector Gadget film had Robo-Gadget attacking San Francisco a’la Kaiju monsters. In addition, similar to The Lost World, it shows a Japanese man while fleeing from Robo-Gadget declaring in his native tongue that he left Tokyo specifically to get away from this.

- Alternate versions of several kaiju – Godzilla, Mothra, Gamera, King Ghidorah and Daimajin – appear in the Usagi Yojimbo «Sumi-e» story arc.[23]

- In the second season of Star Wars: The Clone Wars, there is a story arc composed of two episodes entitled «The Zillo Beast» and «The Zillo Beast Strikes Back», mostly influenced by Godzilla films, in which a huge reptilian beast is transported from its homeworld Malastare to the city-covered planet Coruscant, where it breaks loose and goes on a rampage.[24][25]

- In Return of the Jedi, the rancor was originally to be played by an actor in a suit similar to the way how kaiju films like Godzilla were made. However, the rancor was eventually portrayed by a puppet filmed in high speed.[26]

- In The Simpsons episode «Treehouse of Horror VI» segment «Attack of the 50-Foot Eyesores», Homer goes to Lard Lad Donuts; unable to get a «Colossal Doughnut» as advertised, he steals Lard Lad’s donut, awakening other giant advertising statues that come to life to terrorize Springfield. When Lard Lad awakes, he makes a Godzilla roar. Guillermo del Toro directed the Treehouse of Horror XXIV couch gag which made multiple references to Godzilla and other kaiju-based characters, including his own Pacific Rim characters.[citation needed]

- The South Park episode «Mecha-Streisand» features parodies of Mechagodzilla, Gamera, Ultraman, and Mothra.[27]

- Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters features the «Insanoflex», a giant robot exercise machine rampaging downtown.[28]

- In the 2009 film Crank: High Voltage, there is a sequence parodying kaiju films using the same practical effects techniques used for tokusatsu films such as miniatures and suitmation.[citation needed]

- The Japanese light novel series Gate makes use of the term kaiju as a term for giant monsters – specifically an ancient Fire Dragon – in the Special Region. Also, one of the Japanese protagonists refers to the JSDF’s tradition to fight such monsters in the films, as well as comparing said dragon with King Ghidorah at one point.[29][30]

- Godzilla and Gamera had been referenced and appear many times throughout the Dr. Slump series.[citation needed]

- In Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero, there is a dimension that is filled with giant monsters that live on one island where they co-exist with humans that live on a city island.[citation needed]

- In «Sorcerous Stabber Orphen» series kaiju are sent as a form of punishment for the breakage of everlasting laws of the world by the Goddesses of Fate.[31]

- Batholith The Summit Kaiju (Japanese: バソリス) is a mountain (kaiju) originating from «Summit Kaiju International» an American media company based in Denver, Colorado. Batholith was first introduced to Godzilla fan during G-Fest 2017, which is an annual convention devoted to the Godzilla film franchise. Batholith The Summit Kaiju has appearing in various print media, including Famous Monsters of Filmland «Ack-Ives: Godzilla Magazine, MyKaiju Godzilla Magazine MyKaiju Godzilla Magazine, Summit Kaiju online video series and other online media related to the Godzilla and Kaiju genre.

- In the «Nemesis Saga» series of novels, Kaiju, also known as Gestorumque, are genetic weapons sent by an alien race.

- Naoki Urasawa’s 2013 one-shot manga «Kaiju Kingdom» follows a «kaiju otaku» in a world where kaiju actually exist.[32]

- In the 2019 Vanillaware video game 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, protagonists battle large mechanized aliens called Kaiju.[33]

- In John Scalzi’s 2022 book The Kaiju Preservation Society, Kaiju are a species of gigantic monsters that exist in a parallel earth accessible through radiation sources.

See also[edit]

- Yokai

- Fearsome critters

Media related to Kaiju at Wikimedia Commons

References[edit]

- ^ «Les monstres japonais du 10 mai 2014 — France Inter». May 10, 2014.

- ^ «Introduction to Kaiju [in Japanese]». dic-pixiv. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ 中根, 研一 (September 2009). «A Study of Chinese monster culture – Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media [in Japanese]». The Journal of Hokkai Gakuen University. Hokkai-Gakuen University. 141 (141): 91–121. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Glanzman, Sam (July 19, 2017). Red Range: A Wild Western Adventure. Joe R. Lansdale. IDW Publishing. ISBN 978-1684062904. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ «怪世界 : 珍談奇話». NDL Digital Collections.

- ^ Foster, Michael (1998). The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. Oakland: University of California Press.

- ^ Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: The Pet (1921) – IMDb, retrieved January 10, 2021

- ^ «Survey 1 Comic Strip Essays: Katie Moody on Winsor McCay’s «Dream of the Rarebit Fiend» | Schulz Library Blog». May 30, 2013. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Mustachio, Camille (September 29, 2017). Giant Creatures in Our World: Essays on Kaiju and American Popular Culture. Jason Barr. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476668369. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Martin, Tim (May 15, 2014). «Godzilla: Why the Japanese original is no joke». Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Harvey, Ryan (December 16, 2013). «A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 1: Origins (1954–1962)». Black Gate. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press.

- ^ Yoda, Tomiko; Harootunian, Harry (2006). Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present. Duke University Press Books. p. 344. ISBN 9780822388609.

- ^ Weinstock, Jeffery (2014) The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Godziszewski, Ed (September 5, 2006). «Making of the Godzilla Suit». Classic Media 2006 DVD Special Features. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Allison, Anne (2006) Snake Person Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. Oakland: University of California Press

- ^ Failes, Ian (October 14, 2016). «The History of Godzilla Is the History of Special Effects». Inverse. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781550223484.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of «The Big G». ECW Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781550223484.

- ^ Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780753505564.

- ^ Derry, Charles (1977). Dark Dreams: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film. A. S. Barnes. p. 82. ISBN 9780498019159.

- ^ Cardcaptor Sakura, season 1 episode 1: «Sakura and the Mysterious Magic Book»; season 1 episode 15: «Sakura and Kero’s Big Fight»

- ^ Usagi Yojimbo Vol.3 #66–68: «Sumi-e, Parts 1–3»

- ^ ««The Zillo Beast» Episode Guide». Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ ««The Zillo Beast Strikes Back» Episode Guide». Archived from the original on June 28, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ «The Cinema Behind Star Wars: Godzilla». September 29, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Stone, Matt (2003). South Park: The Complete First Season: «Mecha-Streisand» (Audio commentary) (CD). Comedy Central.

- ^ «Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Gate: Jieitai Kano Chi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri, book I: «Contact», chapters II and V

- ^ Gate: Jieitai Kano Chi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri (anime series) episode 2: «Two Military Forces», episode 3: «Fire Dragon», and episode 4: «To Unknown Lands»

- ^ Mizuno, Ryou (2019). Sorcerous Stabber Orphen Anthology. Commentary (in Japanese). TO Books. p. 236. ISBN 9784864728799.

- ^ Silverman, Rebecca (October 20, 2020). «Sneeze: Naoki Urasawa Story Collection – Review». Anime News Network. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ 十三機兵防衛圏 – System. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

Kaiju (Japanese: 怪獣, Hepburn: Kaijū, lit. ‘Strange Beast’) is a Japanese media genre involving giant monsters. The word kaiju can also refer to the giant monsters themselves, which are usually depicted attacking major cities and battling either the military or other monsters. The kaiju genre is a subgenre of tokusatsu entertainment.

The 1954 film Godzilla is commonly regarded as the first kaiju film. Kaiju characters are often somewhat metaphorical in nature; Godzilla, for example, serves as a metaphor for nuclear weapons, reflecting the fears of post-war Japan following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon 5 incident. Other notable examples of kaiju characters include Rodan, Mothra, Clifford the Big Red Dog, King Ghidorah and Gamera.

EtymologyEdit

The Japanese word kaijū originally referred to monsters and creatures from ancient Japanese legends;[1] it earlier appeared in the Chinese Classic of Mountains and Seas.[2][3] After sakoku had ended and Japan was opened to foreign relations in the mid-19th century, the term kaijū came to be used to express concepts from paleontology and legendary creatures from around the world. For example, in 1908 it was suggested that the extinct Ceratosaurus-like cryptid was alive in Yukon Territory,[4] and this was referred to as kaijū.[5] However, there are no traditional depictions of kaiju or kaiju-like creatures in Japanese folklore; but rather the origins of kaiju are found in film.[6]

Genre elements were present at the end of Winsor McCay’s 1921 animated short Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: The Pet,[7] in which a mysterious giant animal starts destroying the city, until it is countered by a massive airstrike. It was based on a 1905 episode of McCay’s comic strip series.[8]

The 1925 movie The Lost World featured many dinosaurs, including a brontosaurus that breaks loose in London and destroys Tower Bridge. In 1942 Fleischer Studios released The Arctic Giant, the fourth of seventeen animated short films based upon the DC Comics character Superman, in which he has to stop a giant dinosaur from attacking the city of Metropolis.

The dinosaurs of The Lost World were animated by pioneering stop motion techniques by Willis H. O’Brien, who would some years later animate the giant gorilla-like creature breaking loose in New York City, for the 1933 movie King Kong (1933). The enormous success of King Kong can be seen as the definitive breakthrough of monster movies. RKO Pictures later licensed the King Kong character to Japanese studio Toho, resulting in the co-productions King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967), both directed by Ishirō Honda.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) featured a fictional dinosaur (animated by Ray Harryhausen), which is released from its frozen, hibernating state by an atomic bomb test within the Arctic Circle. The American movie was released in Japan in 1954 under the title The Atomic Kaiju Appears, marking the first use of the genre’s name in a film title.[9] However, Gojira (transliterated as Godzilla) is commonly regarded as the first kaiju film in the west and was released in 1954. Tomoyuki Tanaka, a producer for Toho Studios in Tokyo, needed a film to release after his previous project was halted. Seeing how well the Hollywood giant monster movie genre films King Kong and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms had done in Japanese box offices, and himself a fan of these films, he set out to make a new movie based on them and created Godzilla.[10] Tanaka aimed to combine Hollywood giant monster movies with the re-emerged Japanese fears of atomic weapons that arose from the Daigo Fukuryū Maru fishing boat incident; and so he put a team together and created the concept of a giant radioactive creature emerging from the depths of the ocean, a creature that would become the monster Godzilla.[11] Godzilla initially had commercial success in Japan, inspiring other kaiju movies.[12]

TerminologyEdit

The term kaijū translates literally as «strange beast».[13] Kaiju can be antagonistic, protagonistic, or a neutral force of nature, but more specifically as preternatural creatures of divine power. Succinctly, they are not merely, «big animals.» Godzilla, for example, from its first appearance in the initial 1954 entry in the Godzilla franchise, has manifest all of these aspects. Other examples of kaiju include Rodan, Mothra, King Ghidorah, Anguirus, King Kong, Gamera, Daimajin, Gappa, Guilala and Yonggary. There are also subcategories including Mecha Kaiju (Meka-Kaijū), featuring mechanical or cybernetic characters, including Mogera, Mechani-Kong, Mechagodzilla, Gigan, which are an off-shoot of kaiju. Likewise, the collective sub-category Ultra-Kaiju (Urutora-Kaijū) is a separate strata of kaijū, which specifically originate in the long-running Ultra Series franchise, but can also be referred to simply by kaijū. As a noun, kaijū is an invariant, as both the singular and the plural expressions are identical.[citation needed]

Kaijū eigaEdit

Kaijū eiga (怪獣映画, «kaiju film») is a film featuring one or more kaiju.

KaijinEdit

Kaijin (怪人 lit. «strange person») refers to distorted human beings or humanoid-like creatures. The origin of kaijin goes back to the early 20th Century Japanese literature, starting with Edogawa Rampo’s 1936 novel, The Fiend with Twenty Faces. The story introduced Edogawa’s master detective, Kogoro Akechi’s arch-nemesis, the eponymous «Fiend,» a mysterious master of disguise, whose real face was unknown; the Moriarty to Akechi’s Sherlock. Catching the public’s imagination, many such literary and movie (and later television) villains took on the mantle of kaijin. To be clear, kaijin is not an offshoot of kaiju. The first-ever kaijin that appeared on film was The Great Buddha Arrival a lost film, made in 1934.

After the Pacific War, the term was modernized when it was adopted to describe the bizarre, genetically engineered and cybernetically enhanced evil humanoid spawn conceived for the Kamen Rider Series in 1971. This created a new splinter of the term, which quickly propagated through the popularity of superhero programs produced from the 1970s, forward. These kaijin possess rational thought and the power of speech, as do human beings. A successive kaijin menagerie, in diverse iterations, appeared over numerous series, most notably the Super Sentai programs premiering in 1975 (later carried over into Super Sentai’s English iteration as Power Rangers in the 1990s).

This created yet another splinter, as the kaijin of Super Sentai have since evolved to feature unique forms and attributes (i.e. gigantism), existing somewhere between kaijin and kaiju.[citation needed]

DaikaijuEdit

Daikaijū (大怪獣) literally translates as «giant kaiju» or «great kaiju«. This hyperbolic term was used to denote greatness of the subject kaiju; the prefix dai- emphasizing great size, power, and/or status. The first known appearance of the term daikaiju in the 20th Century was in the publicity materials for the original 1954 release of Godzilla. Specifically, in the subtitle on the original movie poster, Suibaku Daikaiju Eiga (水爆大怪獣映画), lit. «H-Bomb Giant Monster Movie» (in proper English, «The Giant H-Bomb Monster Movie»).[citation needed]

SeijinEdit

Seijin (星人 lit. «star people»), appears within Japanese words for extraterrestrial aliens, such as Kaseijin (火星人), which means «Martian». Aliens can also be called uchūjin (宇宙人) which means «spacemen». Among the best known Seijin in the genre can be found in the Ultra Series, such as Alien Baltan from Ultraman, a race of crustacean-like aliens who have gone on to become one of the franchise’s most enduring and recurring characters other than the Ultras themselves.[citation needed]

Toho has produced a variety of kaiju films over the years (many of which feature Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra); but other Japanese studios contributed to the genre by producing films and shows of their own: Daiei Film (Kadokawa Pictures), Tsuburaya Productions, and Shochiku and Nikkatsu Studios.[citation needed]

Monster techniquesEdit

Eiji Tsuburaya, who was in charge of the special effects for Godzilla, developed a technique to animate the kaiju that became known colloquially as «suitmation».[14] Where Western monster movies often used stop motion to animate the monsters, Tsubaraya decided to attempt to create suits, called «creature suits», for a human (suit actor) to wear and act in.[15] This was combined with the use of miniature models and scaled-down city sets to create the illusion of a giant creature in a city.[16] Due to the extreme stiffness of the latex or rubber suits, filming would often be done at double speed, so that when the film was shown, the monster was smoother and slower than in the original shot.[10] Kaiju films also used a form of puppetry interwoven between suitmation scenes which served for shots that were physically impossible for the suit actor to perform. From the 1998 release of Godzilla, American-produced kaiju films strayed from suitmation to computer-generated imagery (CGI). In Japan, CGI and stop-motion have been increasingly used for certain special sequences and monsters, but suitmation has been used for an overwhelming majority of kaiju films produced in Japan of all eras.[16][17]

Selected mediaEdit

FilmsEdit

MangaEdit

- Cloverfield/Kishin (Kadokawa Shoten; 2008)

- Godzilla manga (Toho, Shogakukan, Kodansha; 1954-present)

- Go Nagai Creator of Kaijus

- Garla (ガルラ, garura)(June 1976 – March 1978 Published by Tomy Company, Ltd.)

- MachineSaur (マシンザウラー, マシンサウル, Machine Sauer, Mashinzaura)(December 1979 – March 1986 Published by Tomy Company, Ltd.)

- Attack on Titan (Kodansha; 2009–2021)

- Kaiju Girl Caramelise (2018)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Kadokawa Shoten; 1994 – 2013)

- ULTRAMAN (Shogakukan; 2011–present)

- Kaiju No. 8 (Shonen Jump+; 2020–present)

NovelsEdit

- Nemesis Saga by Jeremy Robinson (St Martins Press/Breakneck Media; 2013–2016). A series of six novels featuring Nemesis, Karkinos, Typhon, Scylla, Drakon, Scryon, Giger, Lovecraft, Ashtaroth and Hyperion (Mechakaiju)

- The Kaiju Preservation Society by John Scalzi (Tor; 2022).

ComicsEdit

- Godzilla comics (Toho, Marvel Comics, Dark Horse Comics, IDW; 1976–present)

- Tokyo Storm Warning (Wildstorm; 2003)

- Enormous (Image Comics; 2012, 2014, 2021–present) as Future Released.

- The Kaiju Score (AfterShock; 2020–present)

- The Stone King (ComiXology Original; 2018–present)

- Dinosaurs Attack! (Topps Comics/IDW; 1988, 2013)

- The Nemesis Saga comics by Jeremy Robinson and Matt Frank (American Gothic Press/IDW Publishing; 2015–2016)

Video gamesEdit

- Godzilla video games (Toho, Pipeworks, Bandai; 1983–present)

- Ultraman video games (Tsuburaya; 1984–present)

- Gamera Video games (Kadokawa of Games; 1995–present as North American released)

- Time Gal (Taito; 1985)

- Shadow of the Colossus (developed by SCE Japan Studio and Team Ico, and published by Sony Computer Entertainment, 2005)

- Shadow of the Colossus remake (developed by Bluepoint Games, and published by Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2018)

- King of the Monsters (SNK; 1991)

- Rampage (1986) (formerly owned by Midway Games and now owned by its successor Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment; 2021)

- Rampage: Total Destruction (Midway Games, 2006)

- Dawn of the Monsters (Developed by 13AM Games and published by WayForward, 2022) as a spiritual successor to SNK’s King of the Monsters

- Megaton Musashi (Developed by Level-5, 2021, 2022)

- Roarr! The Adventures of Rampage Rex – Jurassic Edition (Born Lucky Games, 2018)

- Terror of Hemasaurus (Developed by Loren Lemcke and published by Digerati Distribution, 2022, 2023)

- GigaBash (Passion Republic, 2022)

- Robot Alchemic Drive (Sandlot; 2002)

- DEMOLITION ROBOTS K.K. (, 2020, 2021) – Mechas A Former Dystopian Wars/Robot Killer.

- War of the Monsters (Sony, Incognito Entertainment; 2003)

- Peter Jackson’s King Kong (2005)

- Pacific Rim video game (Yuke’s/Reliance; 2013)

- City Shrouded in Shadow (Bandai Namco Entertainment; 2017)

- Colossal Kaiju Combat (Sunstone Games; Cancelled)

- 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim (Sega, Atlus, Vanillaware, 2019)

- Fight Crab (2020–21, – stage City rampage)

- DAIKAIJU DAIKESSEN (2019, 2021, 2022 OneSecretPseudo)

- Attack of the Giant Crab (2022)

Board gamesEdit

- Godzilla Game

- Godzilla: Tokyo Clash

- Smash Up

- Monsterpocalypse

- King of Tokyo

- King of New York

- Monsters Menace America

- Smash City

- The Creature That Ate Sheboygan

- Campy Creatures

TelevisionEdit

- Marine Kong (Nisan Productions; April 3 – September 25, 1960)

- Ultra Series (Tsuburaya Productions; January 2, 1966–present)

- Ambassador Magma (P Productions; July 4, 1966 – September 25, 1967)

- The King Kong Show (Toei Animation; September 10, 1966 – August 31, 1969)

- Kaiju Booska (Tsuburaya Productions; November 9, 1966 – September 27, 1967)

- Captain Ultra (Toei Company; April 16 – September 24, 1967)

- Kaiju ouji (P Productions; October 2, 1967 – March 25, 1968)

- Giant Robo (Toei Company; October 11, 1967 – April 1, 1968)

- Giant Phantom Monster Agon (Nippon Television; January 2–8, 1968)

- Mighty Jack (Tsuburaya Productions; April 6 – June 29, 1968)

- Spectreman (P Productions; January 2, 1971 – March 25, 1972)

- Kamen Rider (Toei Company; April 3, 1971–present)

- Silver Kamen (Senkosha Productions; November 28, 1971 – May 21, 1972)

- Mirrorman (Tsuburaya Productions; December 5, 1971 – November 26, 1972)

- Redman (Tsuburaya Productions; April 3 – September 8, 1972)

- Thunder Mask (Nippon Television; October 3, 1972 – March 27, 1973)

- Ike! Godman (Toho Company; October 5, 1972 – April 10, 1973)

- Assault! Human!! (Toho Company; October 7 – December 30, 1972)

- Iron King (Senkosha Productions; October 8, 1972 – April 8, 1973)

- Jumborg Ace (Tsuburaya Productions; January 17 – December 29, 1973)

- Fireman (Tsuburaya Productions; January 17 – July 31, 1973)

- Demon Hunter Mitsurugi (International Television Films and Fuji TV; January 8, 1973 – March 26, 1973)

- Zone Fighter (Toho Company; April 2 – September 24, 1973)

- Super Robot Red Baron (Nippon Television; July 4, 1973 – March 27, 1974)

- Kure Kure Takora (Toho Company; October 1, 1973 – September 27, 1974)

- Ike! Greenman (Toho Company; November 12, 1973 – September 27, 1974)

- Super Sentai (Toei Company and Marvel Comics (1979-1982); April 3, 1975–present)

- Daitetsujin 17 (Toei Company; March 18, 1977 — November 11, 1977)

- Super Robot Mach Baron (Nippon Television; October 7, 1974 – March 31, 1975)

- Dinosaur War Izenborg (Tsuburaya Productions; October 17, 1977 – June 30, 1978)

- Spider-Man (Toei Company and Marvel Comics; May 17, 1978 – March 14, 1979)

- Godzilla (Hanna-Barbera; September 9, 1978 – December 8, 1979)

- Megaloman (Toho Company; May 7 – December 24, 1979)

- Metal Hero Series (Toei Company; March 5, 1982 — January 24, 1999)

- Godzilland (Toho Company; 1992 – 1996)

- Gridman the Hyper Agent (Tsuburaya Productions; April 3, 1993 – January 8, 1994)

- Power Rangers (Saban Entertainment and Toei Company; August 28, 1993–present)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Gainax; October 4, 1995 – March 27, 1996)

- Godzilla Kingdom (Toho Company; October 1, 1996 – August 15, 1997)

- Godzilla Island (Toho Company; October 6, 1997 – September 30, 1998)

- Godzilla: The Series (Sony Pictures Television; September 12, 1998 – April 22, 2000)

- Godzilla TV (Toho Company; October 1999 – March 2000)

- Betterman (Sunrise; April 1, 1999 – September 30, 1999)

- Dai-Guard (Xebec; October 5, 1998 – March 28, 2000)

- Kong: The Animated Series (BKN; September 9, 2000 – March 26, 2001)

- Tekkōki Mikazuki (Media Factory; October 23, 2000 – March 24, 2001)

- SFX Giant Legend: Line (Independent; April 25 – May 26, 2003)

- Chouseishin Series (Toho Company; October 4, 2003 – June 24, 2006)

- Bio Planet WoO (Tsuburaya Productions; April 9 – August 13, 2006)

- Daimajin Kanon (Kadokawa Pictures; April 2 – October 1, 2010)

- SciFi Japan TV (ACTV Japan; August 10, 2012–present)

- Attack on Titan (Wit Studio and MAPPA; April 7, 2013 – scheduled)

- Kong: King of the Apes (Netflix; April 15, 2016 – May 4, 2018)

- Mech-X4 (Disney XD; November 11, 2016 – August 20, 2018)

- Darling in the Franxx (Studio Trigger; January 13, 2018 – July 7, 2018)

- SSSS.Gridman (Tsuburaya Productions and Studio Trigger; October 7, 2018 – December 23, 2018)

- Godziban (Toho Company; August 9, 2019–present)

- I’m Home, Chibi Godzilla (Toho Company; July 15, 2020–present)

- Pacific Rim: The Black (Polygon Pictures; March 4, 2021–April 19, 2022)

- Godzilla Singular Point (Toho Company; April 1, 2021 – June 24, 2021)

- SSSS.Dynazenon (Tsuburaya Productions and Studio Trigger; April 2, 2021 – June 18, 2021)

- Super Giant Robot Brothers (Reel FX Creative Studios, Assemblage Entertainment; Netflix; August 4, 2022-present)

- Hourglass (Legendary Television; to be released)

- Skull Island (Legendary Television; Netflix; to be released)

- Gamera: Rebirth (Kadokawa Studio; Netflix; to be released)

Other appearancesEdit

- Steven Spielberg cited Godzilla as an inspiration for Jurassic Park (1993), specifically Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), which he saw in his youth.[18] During its production, Spielberg described Godzilla as «the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies because it made you believe it was really happening.»[19] One scene in the second movie (The Lost World: Jurassic Park), the T-Rex is rampaging through San Diego. One scene shows Japanese businessmen fleeing. One of them states that they left Japan to get away from this, hinting that Godzilla shares the same universe as the Jurassic Park movies. Godzilla also influenced the Spielberg film Jaws (1975).[20][21]

- In the Japanese language original of Cardcaptor Sakura anime series, Sakura’s brother Toya likes to tease her by regularly calling her «kaiju«, relating to her noisily coming down from her room for breakfast every morning.[22]

- The Polish cartoon TV series Bolek and Lolek makes a reference to the kaiju film industry in the mini-series «Bolek and Lolek’s Great Journey» by featuring a robot bird (similar to Rodan) and a saurian monster (in reference to Godzilla) as part of a Japanese director’s monster star repertoire.[citation needed]

- The Inspector Gadget film had Robo-Gadget attacking San Francisco a’la Kaiju monsters. In addition, similar to The Lost World, it shows a Japanese man while fleeing from Robo-Gadget declaring in his native tongue that he left Tokyo specifically to get away from this.

- Alternate versions of several kaiju – Godzilla, Mothra, Gamera, King Ghidorah and Daimajin – appear in the Usagi Yojimbo «Sumi-e» story arc.[23]

- In the second season of Star Wars: The Clone Wars, there is a story arc composed of two episodes entitled «The Zillo Beast» and «The Zillo Beast Strikes Back», mostly influenced by Godzilla films, in which a huge reptilian beast is transported from its homeworld Malastare to the city-covered planet Coruscant, where it breaks loose and goes on a rampage.[24][25]

- In Return of the Jedi, the rancor was originally to be played by an actor in a suit similar to the way how kaiju films like Godzilla were made. However, the rancor was eventually portrayed by a puppet filmed in high speed.[26]

- In The Simpsons episode «Treehouse of Horror VI» segment «Attack of the 50-Foot Eyesores», Homer goes to Lard Lad Donuts; unable to get a «Colossal Doughnut» as advertised, he steals Lard Lad’s donut, awakening other giant advertising statues that come to life to terrorize Springfield. When Lard Lad awakes, he makes a Godzilla roar. Guillermo del Toro directed the Treehouse of Horror XXIV couch gag which made multiple references to Godzilla and other kaiju-based characters, including his own Pacific Rim characters.[citation needed]

- The South Park episode «Mecha-Streisand» features parodies of Mechagodzilla, Gamera, Ultraman, and Mothra.[27]

- Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters features the «Insanoflex», a giant robot exercise machine rampaging downtown.[28]

- In the 2009 film Crank: High Voltage, there is a sequence parodying kaiju films using the same practical effects techniques used for tokusatsu films such as miniatures and suitmation.[citation needed]

- The Japanese light novel series Gate makes use of the term kaiju as a term for giant monsters – specifically an ancient Fire Dragon – in the Special Region. Also, one of the Japanese protagonists refers to the JSDF’s tradition to fight such monsters in the films, as well as comparing said dragon with King Ghidorah at one point.[29][30]

- Godzilla and Gamera had been referenced and appear many times throughout the Dr. Slump series.[citation needed]

- In Penn Zero: Part-Time Hero, there is a dimension that is filled with giant monsters that live on one island where they co-exist with humans that live on a city island.[citation needed]

- In «Sorcerous Stabber Orphen» series kaiju are sent as a form of punishment for the breakage of everlasting laws of the world by the Goddesses of Fate.[31]

- Batholith The Summit Kaiju (Japanese: バソリス) is a mountain (kaiju) originating from «Summit Kaiju International» an American media company based in Denver, Colorado. Batholith was first introduced to Godzilla fan during G-Fest 2017, which is an annual convention devoted to the Godzilla film franchise. Batholith The Summit Kaiju has appearing in various print media, including Famous Monsters of Filmland «Ack-Ives: Godzilla Magazine, MyKaiju Godzilla Magazine MyKaiju Godzilla Magazine, Summit Kaiju online video series and other online media related to the Godzilla and Kaiju genre.

- In the «Nemesis Saga» series of novels, Kaiju, also known as Gestorumque, are genetic weapons sent by an alien race.

- Naoki Urasawa’s 2013 one-shot manga «Kaiju Kingdom» follows a «kaiju otaku» in a world where kaiju actually exist.[32]

- In the 2019 Vanillaware video game 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, protagonists battle large mechanized aliens called Kaiju.[33]

- In John Scalzi’s 2022 book The Kaiju Preservation Society, Kaiju are a species of gigantic monsters that exist in a parallel earth accessible through radiation sources.

See alsoEdit

- Yokai

- Fearsome critters

- Media related to Kaiju at Wikimedia Commons

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «Les monstres japonais du 10 mai 2014 — France Inter». May 10, 2014.

- ^ «Introduction to Kaiju [in Japanese]». dic-pixiv. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ 中根, 研一 (September 2009). «A Study of Chinese monster culture – Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media [in Japanese]». The Journal of Hokkai Gakuen University. Hokkai-Gakuen University. 141 (141): 91–121. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Glanzman, Sam (July 19, 2017). Red Range: A Wild Western Adventure. Joe R. Lansdale. IDW Publishing. ISBN 978-1684062904. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ «怪世界 : 珍談奇話». NDL Digital Collections.

- ^ Foster, Michael (1998). The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. Oakland: University of California Press.

- ^ Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: The Pet (1921) – IMDb, retrieved January 10, 2021