| Caligula | ||

|---|---|---|

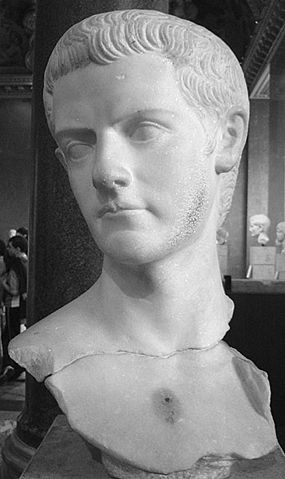

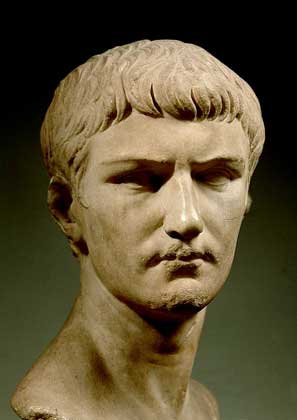

Marble bust of Caligula dating from his reign, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art |

||

| Roman emperor | ||

| Reign | 16 March 37 – 24 January 41 | |

| Predecessor | Tiberius | |

| Successor | Claudius | |

| Born | Gaius Julius Caesar 31 August AD 12 Antium, Italy |

|

| Died | 24 January AD 41 (aged 28) Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy |

|

| Burial |

Mausoleum of Augustus |

|

| Spouses |

|

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| Dynasty | Julio-Claudian | |

| Father | Germanicus | |

| Mother | Agrippina |

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August AD 12 – 24 January AD 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from AD 37 until his assassination in AD 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, Augustus’ granddaughter. Caligula was born into the first ruling family of the Roman Empire, conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Although Gaius was named after Gaius Julius Caesar, he acquired the nickname «Caligula» («little caliga«, a type of military boot) from his father’s soldiers during their campaign in Germania. When Germanicus died at Antioch in 19, Agrippina returned with her six children to Rome, where she became entangled in a bitter feud with Tiberius. The conflict eventually led to the destruction of her family, with Caligula as the sole male survivor. In 26, Tiberius withdrew from public life to the island of Capri, and in 31, Caligula joined him there. Following the former’s death in 37, Caligula succeeded him as emperor. There are few surviving sources about the reign of Caligula, though he is described as a noble and moderate emperor during the first six months of his rule. After this, the sources focus upon his cruelty, sadism, extravagance, and sexual perversion, presenting him as an insane tyrant.

While the reliability of these sources is questionable, it is known that during his brief reign, Caligula worked to increase the unconstrained personal power of the emperor, as opposed to countervailing powers within the principate. He directed much of his attention to ambitious construction projects and luxurious dwellings for himself, and he initiated the construction of two aqueducts in Rome: the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus. During his reign, the empire annexed the client kingdom of Mauretania as a province. In early 41, Caligula was assassinated as a result of a conspiracy by officers of the Praetorian Guard, senators, and courtiers. However, the conspirators’ attempt to use the opportunity to restore the Roman Republic was thwarted. On the day of the assassination of Caligula, the Praetorians declared Caligula’s uncle, Claudius, as the next emperor. Caligula’s death marked the official end of the Julii Caesares in the male line, though the Julio-Claudian dynasty continued to rule until the demise of his nephew, Nero.

Early life[edit]

Caligula was born in Antium on 31 August 12 CE, the third of six surviving children born to Germanicus, a grandson of Mark Antony, and his second cousin Agrippina the Elder,[2] who was the daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder, making her the granddaughter of Augustus.[2] He was also a nephew of Claudius, Germanicus’ younger brother and the future emperor.[3] He had two older brothers, Nero and Drusus,[2] and three younger sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla and Julia Livilla.[2][4] At the age of two or three, he accompanied his father, Germanicus, on campaigns in the north of Germania.[5] He wore a miniature soldier’s outfit, including army boots (caligae) and armour.[5] The soldiers thus nicknamed him Caligula («little [soldier’s] boot»).[6] He reportedly grew to dislike the nickname.[7]

Germanicus died at Antioch, Syria province, in AD 19, aged only 33. Suetonius claims that Germanicus was poisoned by an agent of Tiberius, who viewed Germanicus as a political rival.[8] After the death of his father, Caligula lived with his mother, Agripinna the Elder, until her relations with Tiberius deteriorated.[9] Tiberius would not allow Agrippina to remarry for fear her husband would be a rival.[10] Agrippina and Caligula’s brother, Nero, were banished in the year 29 CE on charges of treason.[11][12] The adolescent Caligula was sent to live with his great-grandmother (Tiberius’ mother), Livia;[9] After her death, he was sent to live with his grandmother Antonia Minor.[9] In the year 30 CE, his brother Drusus was imprisoned on charges of treason, and his brother Nero died in exile from either starvation or suicide.[12][13] Suetonius writes that after the banishment of his mother and brothers, Caligula and his sisters were nothing more than prisoners of Tiberius under the close watch of soldiers.[14] In the year 31, Caligula was remanded to the personal care of Tiberius on Capri, where he lived for six years.[9] To the surprise of many, Caligula was spared by Tiberius.[15] Roman historians describe Caligula as an excellent natural actor who recognized the danger he was in, and hid his resentment towards Tiberius.[9][16] An observer said of Caligula, «Never was there a better servant or a worse master!»[9][16]

Caligula claimed to have planned to kill Tiberius with a dagger to avenge his mother and brother: however, having brought the weapon into Tiberius’ bedroom he did not kill the Emperor but instead threw the dagger down on the floor. Supposedly Tiberius knew of this plot but did nothing about it.[17] Suetonius claims that Caligula was by this time already cruel and vicious: he writes that when Tiberius brought Caligula to the island of Capri, his purpose was to allow Caligula to live in order that he «prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world.»[18] In 33, Tiberius gave Caligula an honorary quaestorship, a position he held until his rise to emperor.[19] Meanwhile, both Caligula’s mother and his brother Drusus died in prison.[20][21] Caligula was briefly married to Junia Claudilla in the year 33, though she died in childbirth the following year.[17] Caligula spent time befriending the Praetorian prefect, Naevius Sutorius Macro, an important ally.[17] Macro spoke well of Caligula to Tiberius, attempting to quell any ill will or suspicion the Emperor felt towards Caligula.[22] In the year 35, Caligula was named joint heir to Tiberius’ estate along with Tiberius Gemellus.[23]

Emperor[edit]

Early reign[edit]

Caligula Depositing the Ashes of his Mother and Brother in the Tomb of his Ancestors, by Eustache Le Sueur, 1647

When Tiberius died on 16 March AD 37, his estate and the titles of the principate were left to Caligula and to Tiberius’ own grandson, Gemellus, who were to serve as joint heirs. Although Tiberius was 77 and on his deathbed, some ancient historians still conjecture that he was murdered.[17][24] Tacitus writes that Macro smothered Tiberius with a pillow to hasten Caligula’s accession, much to the joy of the Roman people,[24] while Suetonius writes that Caligula may have carried out the killing, though this is not recorded by any other ancient historian.[17] Seneca the Elder and Philo, who both wrote during Tiberius’ reign, as well as Josephus, record Tiberius as dying a natural death.[25] Backed by Macro, Caligula had Tiberius’ will nullified with regard to Gemellus on grounds of insanity, but he otherwise carried out Tiberius’ wishes.[26] Caligula was proclaimed emperor by the Senate on 18 March.[27] He accepted the powers of the principate and entered Rome on 28 March amid a crowd that hailed him as «our baby» and «our star», among other nicknames.[27][28]

Caligula is described as the first emperor who was admired by everyone in «all the world, from the rising to the setting sun.»[29] Caligula was loved by many for being the beloved son of the popular Germanicus[28] and because he was not Tiberius.[30] Suetonius said that over 160,000 animals were sacrificed during three months of public rejoicing to usher in the new reign.[31][32] Philo describes the first seven months of Caligula’s reign as completely blissful.[33] Caligula’s first acts were said to be generous in spirit, though many were political in nature.[26] To gain support, he granted bonuses to the military, including the Praetorian Guard, city troops and the army outside Italy.[26] He destroyed Tiberius’ treason papers, declared that treason trials were a thing of the past, and recalled those who had been sent into exile.[34] He helped those who had been harmed by the imperial tax system, banished certain sexual deviants, and put on lavish spectacles for the public, including gladiatorial games.[35][36] Caligula collected and brought back the bones of his mother and of his brothers and deposited their remains in the tomb of Augustus.[37]

In October 37, Caligula fell seriously ill or perhaps was poisoned. He soon recovered from his illness, but many believed that the illness turned the young emperor toward the diabolical: he started to kill off or exile those who were close to him or whom he saw as a serious threat. It is possible that his illness reminded him of his mortality and of the desire of others to advance into his place.[38] He had his cousin and adopted son Tiberius Gemellus executed – an act that outraged Caligula’s and Gemellus’ mutual grandmother Antonia Minor. She is said to have committed suicide, although Suetonius hints that Caligula poisoned her. He had his father-in-law Marcus Junius Silanus and his brother-in-law Marcus Lepidus executed as well. His uncle Claudius was spared only because Caligula preferred to keep him as a laughing stock. His favourite sister, Julia Drusilla, died in 38 of a fever: his other two sisters, Livilla and Agrippina the Younger, were exiled. He hated being the grandson of Agrippa and slandered Augustus by repeating a falsehood that his mother was conceived as the result of an incestuous relationship between Augustus and his daughter Julia the Elder.[39]

Public reform and financial crisis[edit]

Quadrans celebrating the abolition of a tax in AD 38 by Caligula.[40] The obverse of the coin contains a picture of a Pileus which symbolizes the liberation of the people from the tax burden. Caption: C. CAESAR DIVI AVG. PRON[EPOS] (great-grandson of) AVG. / PON. M., TR. P. III, P. P., COS. DES. RCC. (probably Res Civium Conservatae, i.e. the interests of citizens have been preserved)

In the year 38, Caligula focused his attention on political and public reform. He published the accounts of public funds, which had not been made public during the reign of Tiberius. He aided those who lost property in fires, abolished certain taxes, and gave out prizes to the public at gymnastic events. He allowed new members into the equestrian and senatorial orders.[41] Perhaps most significantly, he restored the practice of elections.[42] Cassius Dio said that this act «though delighting the rabble, grieved the sensible, who stopped to reflect, that if the offices should fall once more into the hands of the many … many disasters would result».[43] During the same year, though, Caligula was criticized for executing people without full trials and for forcing the Praetorian prefect, Macro, to commit suicide. Macro had fallen out of favor with the emperor, probably due to an attempt to ally himself with Gemellus when it appeared that Caligula might die of fever.[44]

According to Cassius Dio, a financial crisis emerged in 39.[44] Suetonius places the beginning of this crisis in 38.[45] Caligula’s political payments for support, generosity and extravagance had exhausted the state’s treasury. Ancient historians state that Caligula began falsely accusing, fining and even killing individuals for the purpose of seizing their estates.[46] Historians describe a number of Caligula’s other desperate measures. To gain funds, Caligula asked the public to lend the state money.[47] He levied taxes on lawsuits, weddings and prostitution.[48] Caligula began auctioning the lives of the gladiators at shows.[46][49] Wills that left items to Tiberius were reinterpreted to leave the items instead to Caligula.[50] Centurions who had acquired property by plunder were forced to turn over spoils to the state.[50] The current and past highway commissioners were accused of incompetence and embezzlement and forced to repay money.[50]

According to Suetonius, in the first year of Caligula’s reign he squandered 2.7 billion sesterces that Tiberius had amassed.[45] His nephew Nero both envied and admired the fact that Gaius had run through the vast wealth Tiberius had left him in so short a time.[51] However, some historians have shown scepticism towards the large number of sesterces quoted by Suetonius and Dio. According to Wilkinson, Caligula’s use of precious metals to mint coins throughout his principate indicates that the treasury most likely never fell into bankruptcy.[52] He does point out, however, that it is difficult to ascertain whether the purported ‘squandered wealth’ was from the treasury alone due to the blurring of «the division between the private wealth of the emperor and his income as head of state.»[52] Furthermore, Alston points out that Caligula’s successor, Claudius, was able to donate 15,000 sesterces to each member of the Praetorian Guard in 41,[24] suggesting the Roman treasury was solvent.[53] A brief famine of unknown extent occurred, perhaps caused by this financial crisis, but Suetonius claims it resulted from Caligula’s seizure of public carriages;[46] according to Seneca, grain imports were disrupted because Caligula re-purposed grain boats for a pontoon bridge.[54]

Construction and senatorial feud[edit]

The Vatican Obelisk was first brought from Egypt to Rome by Caligula. It was the centerpiece of a large racetrack he built.

Despite financial difficulties, Caligula embarked on a number of construction projects during his reign. Some were for the public good, though others were for himself. Josephus describes Caligula’s improvements to the harbours at Rhegium and Sicily, allowing increased grain imports from Egypt, as his greatest contributions.[55] These improvements may have been in response to the famine.[56] Caligula completed the temple of Augustus and the theatre of Pompey and began an amphitheatre beside the Saepta.[57] He also expanded the imperial palace.[58] Later, he began the construction of aqueducts Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus, which Pliny the Elder considered to be engineering marvels.[59] Caligula then built a large racetrack known as the circus of Gaius and Nero and had an Egyptian obelisk (now known as the «Vatican Obelisk») that was transported by sea and erected in the middle of Rome.[60]

At Syracuse, he repaired the city walls and the temples of the gods.[57] He had new roads built and pushed to keep roads in good condition.[61] Caligula had planned to rebuild the palace of Polycrates at Samos, to finish the temple of Didymaean Apollo at Ephesus and to found a city high up in the Alps.[57] He also intended to dig a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece and sent a chief centurion to survey the work.[57] In 39, Caligula performed a spectacular stunt by ordering a temporary floating bridge to be built using ships as pontoons, stretching for over two miles from the resort of Baiae to the neighbouring port of Puteoli.[62][63] It was said that the bridge was to rival the Persian king Xerxes’ pontoon bridge crossing of the Hellespont.[63] Caligula, who could not swim,[64] then proceeded to ride his favourite horse Incitatus across, wearing the breastplate of Alexander the Great.[63] This act was in defiance of a prediction by Tiberius’ soothsayer Thrasyllus of Mendes that Caligula had «no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding a horse across the Bay of Baiae».[63]

Caligula had two large ships constructed for himself (which were recovered from the bottom of Lake Nemi around 1930). The ships were among the largest vessels in the ancient world. The smaller ship was designed as a temple dedicated to Diana. The larger ship was essentially an elaborate floating palace with marble floors and plumbing.[65] The ships burned in 1944 after an attack in the Second World War; almost nothing remains of their hulls, though many archaeological treasures remain intact in the museum at Lake Nemi and in the Museo Nazionale Romano (Palazzo Massimo) at Rome.[66] In 39, relations between Caligula and the Roman Senate deteriorated.[67] The subject of their disagreement is unknown. A number of factors, though, aggravated this feud. The Senate had become accustomed to ruling without an emperor between the departure of Tiberius for Capri in 26 and Caligula’s accession.[68] Additionally, Tiberius’ treason trials had eliminated a number of pro-Julian senators such as Asinius Gallus.[68] Caligula reviewed Tiberius’ records of treason trials and decided, based on their actions during these trials, that numerous senators were not trustworthy.[67] He ordered a new set of investigations and trials.[67] He replaced the consul and had several senators put to death.[69] Suetonius reports that other senators were degraded by being forced to wait on him and run beside his chariot.[69] Soon after his break with the Senate, Caligula faced a number of additional conspiracies against him.[70] A conspiracy involving his brother-in-law was foiled in late 39.[70] Soon afterwards, the Governor of Germany, Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, was executed for connections to a conspiracy.[70]

Western expansion[edit]

Map of the Roman Empire and neighboring states during the reign of Gaius Caligula (AD 37–41)

Italy and Roman provinces

Independent countries

Client states (Roman puppets)

Mauretania seized by Caligula

Former Roman provinces Thrace and Commagena made client states by Caligula

In 40, Caligula expanded the Roman Empire into Mauretania,[2] a client kingdom of Rome ruled by Ptolemy of Mauretania. Caligula invited Ptolemy to Rome and then suddenly had him executed.[71] Mauretania was annexed by Caligula and subsequently divided into two provinces, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, separated by the river Malua.[72] Pliny claims that division was the work of Caligula, but Dio states that in 42 an uprising took place, which was subdued by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, and the division only took place after this.[73] This confusion might mean that Caligula decided to divide the province, but the division was postponed because of the rebellion.[74] The first known equestrian governor of the two provinces was Marcus Fadius Celer Flavianus, in office in 44.[74]

Details on the Mauretanian events of 39–44 are unclear. Cassius Dio wrote an entire chapter on the annexation of Mauretania by Caligula, but it is now lost.[75] Caligula’s move seemingly had a strictly personal political motive – fear and jealousy of his cousin Ptolemy – and thus the expansion may not have been prompted by pressing military or economic needs.[76] However, the rebellion of Tacfarinas had shown how exposed Africa Proconsularis was to its west and how the Mauretanian client kings were unable to provide protection to the province, and it is thus possible that Caligula’s expansion was a prudent response to potential future threats.[74]

Caligula also made a significant attempt at expanding into Britannia.[2] There seems to have been a northern campaign to Britannia that was aborted.[75] This campaign is derided by ancient historians with accounts of Gauls dressed up as Germanic tribesmen at his triumph and Roman troops ordered to collect seashells as «spoils of the sea».[77] The few primary sources disagree on what precisely occurred. Modern historians have put forward numerous theories in an attempt to explain these actions. This trip to the English Channel could have merely been a training and scouting mission.[78] The mission may have been to accept the surrender of the British chieftain Adminius.[79] «Seashells», or conchae in Latin, may be a metaphor for something else such as female genitalia (perhaps the troops visited brothels) or boats (perhaps they captured several small British boats).[80] The conquest of Britannia was later achieved during the reign of his successor, Claudius.

Claims of divinity[edit]

Caligula and Roma Cameo depicting Caligula and Roma, a personification of Rome

When several client kings came to Rome to pay their respects to him and argued about their nobility of descent, he allegedly cried out the Homeric line:[81] «Let there be one lord, one king.»[58] In 40, Caligula began implementing very controversial policies that introduced religion into his political role. Caligula began appearing in public dressed as various gods and demigods such as Hercules, Mercury, Venus and Apollo.[82] Reportedly, he began referring to himself as a god when meeting with politicians and he was referred to as «Jupiter» on occasion in public documents.[83][84] A sacred precinct was set apart for his worship at Miletus in the province of Asia and two temples were erected for worship of him in Rome.[84] The Temple of Castor and Pollux on the forum was linked directly to the imperial residence on the Palatine and dedicated to Caligula.[84][85]

He would appear there on occasion and present himself as a god to the public. Caligula had the heads removed from various statues of gods located across Rome and replaced them with his own.[86] It is said that he wished to be worshipped as Neos Helios, the «New Sun». Indeed, he was represented as a sun god on Egyptian coins.[87] Caligula’s religious policy was a departure from that of his predecessors. According to Cassius Dio, living emperors could be worshipped as divine in the east and dead emperors could be worshipped as divine in Rome.[88] Augustus had the public worship his spirit on occasion, but Dio describes this as an extreme act that emperors generally shied away from.[88] Caligula took things a step further and had those in Rome, including senators, worship him as a tangible, living god.[89]

Eastern policy[edit]

Caligula needed to quell several riots and conspiracies in the eastern territories during his reign. Aiding him in his actions was his good friend, Herod Agrippa, who became governor of the territories of Batanaea and Trachonitis after Caligula became emperor in 37.[90] The cause of tensions in the east was complicated, involving the spread of Greek culture, Roman law and the rights of Jews in the empire. Caligula did not trust the prefect of Egypt, Aulus Avilius Flaccus. Flaccus had been loyal to Tiberius, had conspired against Caligula’s mother and had connections with Egyptian separatists.[91] In 38, Caligula sent Agrippa to Alexandria unannounced to check on Flaccus.[92] According to Philo, the visit was met with jeers from the Greek population who saw Agrippa as the king of the Jews.[93] As a result, riots broke out in the city.[94] Caligula responded by removing Flaccus from his position and executing him.[95]

In 39, Agrippa accused his uncle Herod Antipas, the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, of planning a rebellion against Roman rule with the help of Parthia. Herod Antipas confessed and Caligula exiled him. Agrippa was rewarded with his territories.[96] Riots again erupted in Alexandria in 40 between Jews and Greeks.[97] Jews were accused of not honouring the emperor.[97] Disputes occurred in the city of Jamnia.[98] Jews were angered by the erection of a clay altar and destroyed it.[98] In response, Caligula ordered the erection of a statue of himself in the Jewish Temple of Jerusalem,[99] a demand in conflict with Jewish monotheism.[100] In this context, Philo wrote that Caligula «regarded the Jews with most especial suspicion, as if they were the only persons who cherished wishes opposed to his».[100]

The Governor of Syria, Publius Petronius, fearing civil war if the order were carried out, delayed implementing it for nearly a year.[101] Agrippa finally convinced Caligula to reverse the order.[97] However, Caligula issued a second order to have his statue erected in the Temple of Jerusalem. In Rome, another statue of himself, of colossal size, was made of gilt brass for the purpose. However, according to Josephus, when the ship carrying the statue was still underway, news of Caligula’s death reached Petronius. Thus, the statue was never installed.[102]

Scandals[edit]

Roman sestertius depicting Caligula, c. AD 38. The reverse shows Caligula’s three sisters, Agrippina, Drusilla and Julia Livilla, with whom Caligula was rumoured to have carried on incestuous relationships. Caption: C. CAESAR AVG. GERMANICVS PON. M. TR. POT. / AGRIPPINA DRVSILLA IVLIA S. C.

Philo of Alexandria and Seneca the Younger, contemporaries of Caligula, describe him as an insane emperor who was self-absorbed and short-tempered, killed on a whim, and indulged in too much spending and sex.[103] He is accused of sleeping with other men’s wives and bragging about it,[104] killing for mere amusement,[105] deliberately wasting money on his bridge, causing starvation,[54] and wanting a statue of himself in the Temple of Jerusalem for his worship.[99] Once, at some games at which he was presiding, he was said to have ordered his guards to throw an entire section of the audience into the arena during the intermission to be eaten by the wild beasts because there were no prisoners to be used and he was bored.[106][107]

While repeating the earlier stories, the later sources of Suetonius and Cassius Dio provide additional tales of insanity. They accuse Caligula of incest with his sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Drusilla, and Livilla, and say he prostituted them to other men.[108] Additionally, they mention affairs with various men including his brother-in-law Marcus Lepidus.[109][110] They state he sent troops on illogical military exercises,[75][111] turned the palace into a brothel,[47] and, most famously, planned or promised to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul,[112][113]

and appointed a priest to serve him.[84] The validity of these accounts is debatable. In Roman political culture, insanity and sexual perversity were often presented hand-in-hand with poor government.[114]

Assassination and aftermath[edit]

Caligula’s actions as emperor were described as being especially harsh to the Senate, to the nobility and to the equestrian order.[115] According to Josephus, these actions led to several failed conspiracies against Caligula.[116] Eventually, officers within the Praetorian Guard led by Cassius Chaerea succeeded in murdering the emperor.[117] The plot is described as having been planned by three men, but many in the Senate, army and equestrian order were said to have been informed of it and involved in it.[118] The situation had escalated when, in 40, Caligula announced to the Senate that he planned to leave Rome permanently and to move to Alexandria in Egypt, where he hoped to be worshipped as a living god. The prospect of Rome losing its emperor and thus its political power was the final straw for many. Such a move would have left both the Senate and the Praetorian Guard powerless to stop Caligula’s repression and debauchery. With this in mind Chaerea persuaded his fellow conspirators, who included Marcus Vinicius and Lucius Annius Vinicianus, to put their plot into action quickly.[citation needed]

According to Josephus, Chaerea had political motivations for the assassination.[119] Suetonius sees the motive in Caligula calling Chaerea derogatory names.[120] Caligula considered Chaerea effeminate because of a weak voice and for not being firm with tax collection.[121] Caligula would mock Chaerea with names like «Priapus» and «Venus».[122] On 24 January 41,[124] Cassius Chaerea and other guardsmen accosted Caligula as he addressed an acting troupe of young men beneath the palace, during a series of games and dramatics being held for the Divine Augustus.[125] Details recorded on the events vary somewhat from source to source, but they agree that Chaerea stabbed Caligula first, followed by a number of conspirators.[126] Suetonius records that Caligula’s death resembled that of Julius Caesar. He states that both the elder Gaius Julius Caesar (Julius Caesar) and the younger Gaius Julius Caesar (Caligula) were stabbed 30 times by conspirators led by a man named Cassius (Cassius Longinus and Cassius Chaerea respectively).[127] By the time Caligula’s loyal Germanic guard responded, the Emperor was already dead. The Germanic guard killed several assassins and conspirators, along with some innocent senators and bystanders.[128] These wounded conspirators were treated by the physician Arcyon.

The cryptoporticus (underground corridor) beneath the imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill where this event took place was discovered by archaeologists in 2008.[129] The Senate attempted to use Caligula’s death as an opportunity to restore the Republic.[130] Chaerea tried to persuade the military to support the Senate.[131] The military, though, remained loyal to the idea of imperial monarchy.[131] Uncomfortable with lingering imperial support, the assassins sought out and killed Caligula’s wife, Caesonia, and killed their young daughter, Julia Drusilla, by smashing her head against a wall.[132] They were unable to reach Caligula’s uncle, Claudius. After a soldier, Gratus, found Claudius hiding behind a palace curtain, he was spirited out of the city by a sympathetic faction of the Praetorian Guard[133] to their nearby camp.[134] Claudius became emperor after procuring the support of the Praetorian Guard. Claudius granted a general amnesty, although he executed a few junior officers involved in the conspiracy, including Chaerea.[135]

According to Suetonius, Caligula’s body was placed under turf until it was burned and entombed by his sisters. He was buried within the Mausoleum of Augustus; in 410, during the Sack of Rome, the ashes in the tomb were scattered.

Legacy[edit]

Historiography[edit]

The facts and circumstances of Caligula’s reign are mostly lost to history. Only two sources contemporary with Caligula have survived – the works of Philo and Seneca. Philo’s works, On the Embassy to Gaius and Flaccus, give some details on Caligula’s early reign, but mostly focus on events surrounding the Jewish population in Judea and Egypt with whom he sympathizes. Seneca’s various works give mostly scattered anecdotes on Caligula’s personality. Seneca was almost put to death by Caligula in AD 39 likely due to his associations with conspirators.[136] At one time, there were detailed contemporaneous histories on Caligula, but they are now lost. Additionally, the historians who wrote them are described as biased, either overly critical or praising of Caligula.[137] Nonetheless, these lost primary sources, along with the works of Seneca and Philo, were the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Caligula written by the next generations of historians. A few of the contemporaneous historians are known by name. Fabius Rusticus and Cluvius Rufus both wrote condemning histories on Caligula that are now lost. Fabius Rusticus was a friend of Seneca who was known for historical embellishment and misrepresentation.[138] Cluvius Rufus was a senator involved in the assassination of Caligula.[139]

Caligula’s sister, Agrippina the Younger, wrote an autobiography that certainly included a detailed explanation of Caligula’s reign, but it too is lost. Agrippina was banished by Caligula for her connection to Marcus Lepidus, who conspired against him.[70] The inheritance of Nero, Agrippina’s son and the future emperor, was seized by Caligula. Gaetulicus, a poet, produced a number of flattering writings about Caligula, but they are lost. The bulk of what is known of Caligula comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio. Suetonius wrote his history on Caligula 80 years after his death, while Cassius Dio wrote his history over 180 years after Caligula’s death. Cassius Dio’s work is invaluable because it alone gives a loose chronology of Caligula’s reign. A handful of other sources add a limited perspective on Caligula. Josephus gives a detailed description of Caligula’s assassination. Tacitus provides some information on Caligula’s life under Tiberius. In a now lost portion of his Annals, Tacitus gave a detailed history of Caligula. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History has a few brief references to Caligula. There are few surviving sources on Caligula and none of them paints Caligula in a favourable light. The paucity of sources has resulted in significant gaps in modern knowledge of the reign of Caligula. Little is written on the first two years of Caligula’s reign. Additionally, there are only limited details on later significant events, such as the annexation of Mauretania, Caligula’s military actions in Britannia, and his feud with the Roman Senate. According to legend, during his military actions in Britannia Caligula grew addicted to a steady diet of European sea eels, which led to their Latin name being Coluber caligulensis.[140]

Health[edit]

All surviving sources, except Pliny the Elder, characterize Caligula as insane. However, it is not known whether they are speaking figuratively or literally. Additionally, given Caligula’s unpopularity among the surviving sources, it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. Recent sources are divided in attempting to ascribe a medical reason for his behavior, citing as possibilities encephalitis, epilepsy or meningitis.[141] The question of whether Caligula was insane (especially after his illness early in his reign) remains unanswered.[141] Philo of Alexandria, Josephus and Seneca state that Caligula was insane, but describe this madness as a personality trait that came through experience.[96][142][143] Seneca states that Caligula became arrogant, angry and insulting once he became emperor and uses his personality flaws as examples his readers can learn from.[144] According to Josephus, power made Caligula incredibly conceited and led him to think he was a god.[96] Philo of Alexandria reports that Caligula became ruthless after nearly dying of an illness in the eighth month of his reign in 37.[145] Juvenal reports he was given a magic potion that drove him insane.

Suetonius said that Caligula had «falling sickness», or epilepsy, when he was young.[146][147] Modern historians have theorized that Caligula lived with a daily fear of seizures.[148] Despite swimming being a part of imperial education, Caligula could not swim.[149] Epileptics are discouraged from swimming in open waters because unexpected fits can lead to death if timely rescue is difficult.[150] Caligula reportedly talked to the full moon:[69] Epilepsy was long associated with the moon.[151]

Suetonius described Caligula as sickly-looking, skinny and pale: «he was tall, very pale, ill-shaped, his neck and legs very slender, his eyes and temples hollow, his brows broad and knit, his hair thin, and the crown of the head bald. The other parts of his body were much covered with hair … He was crazy both in body and mind, being subject, when a boy, to the falling sickness. When he arrived at the age of manhood he endured fatigue tolerably well. Occasionally he was liable to faintness, during which he remained incapable of any effort».[152][153] Based on scientific reconstructions of his official painted busts, Caligula had brown hair, brown eyes, and fair skin.[154] Some modern historians think that Caligula had hyperthyroidism.[155] This diagnosis is mainly attributed to Caligula’s irritability and his «stare» as described by Pliny the Elder.

Burial site[edit]

On 17 January 2011, police in Nemi, Italy, announced that they believed they had discovered the site of Caligula’s burial, after arresting a thief caught smuggling a statue which they believed to be of the emperor.[156] The claim has been met with scepticism by Cambridge historian Mary Beard.[157]

Cultural depictions[edit]

In film and series[edit]

- Welsh actor Emlyn Williams was cast as Caligula in the never-completed 1937 film I, Claudius.[158]

- He was played by Ralph Bates in the 1968 ITV historical drama series, The Caesars.[159]

- American actor Jay Robinson famously portrayed a sinister and scene-stealing Caligula in two epic films of the 1950s, The Robe (1953) and its sequel Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954).[160]

- He was played by John Hurt in the 1976 BBC mini-series I, Claudius.[161]

- A feature-length historical film Caligula was completed in 1979 with Malcolm McDowell in the lead role.

- He was portrayed by David Brandon in the 1982 historical exploitation film Caligula… The Untold Story.[162]

- Caligula is a character in the 2015 NBC series A.D. The Bible Continues and is played by British actor Andrew Gower. His portrayal emphasises Caligula’s «dabauched and dangerous» persona [163] as well as his sexual appetite, quick temper, and violent nature.

- The third season of the Roman Empire series (released on Netflix in 2019) is named Caligula: The Mad Emperor with South African actor Ido Drent in the leading role.[164]

- In the award winning BBC show Horrible Histories he is portrayed by Simon Farnaby.

In literature and theatre[edit]

- Caligula, by French author Albert Camus, is a play in which Caligula returns after deserting the palace for three days and three nights following the death of his beloved sister, Drusilla. The young emperor then uses his unfettered power to «bring the impossible into the realm of the likely».[165]

- In the novel I, Claudius by English writer Robert Graves, Caligula is presented as a murderous sociopath from his childhood who became clinically insane early in his reign. In the novel, at the age of only ten, Caligula drove his father Germanicus to a state of despair and eventually death by secretly terrorizing him. Graves’ Caligula commits incest with all three of his sisters and is implied to have murdered Drusilla.[166] The novel was adapted for television in the 1976 BBC mini-series of the same name.

- Caligula appears as one of the antagonists in the popular young adult fiction novel series The Trials of Apollo. He is revealed as having become a minor god and has survived into modern times, along with two other Roman emperors, Commodus and Nero.

In opera[edit]

- A young Caligula appears as one of the characters in Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber’s opera Arminio.

- Caligula is the main character in Detlev Glanert’s opera Caligula, based on the Albert Camus play.

- Different composers from the Baroque era appear to have composed operatic works about Caligula, but most of these have been lost.

See also[edit]

- List of Roman emperors

References[edit]

- ^ Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 489. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Suetonius. «Life of Caligula». The Lives of Twelve Caesars – via uchicago.edu.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.6.

- ^ Wood, Susan (1995). «Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula». American Journal of Archaeology. 99 (3): 457–482. doi:10.2307/506945. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 506945. S2CID 191386576.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 9.

- ^ «Caligula» is formed from the Latin word caliga, meaning soldier’s boot, and the diminutive infix -ul.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of a Wise Person XVIII 2–5. See Malloch, ‘Gaius and the nobiles’, Athenaeum (2009).

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 10.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals IV.52.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals V.3.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 54.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals V.10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 64.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 62.

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals VI.20.

- ^ a b c d e Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 12.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 11

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.23.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals VI.25.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals VI.23.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius VI.35.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 76.

- ^ a b c Tacitus, Annals XII.53.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius IV.25; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIII.6.9.

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.1.

- ^ a b Henzen, Wilhelm, ed. (1874). Acta Fratrum Arvalium. p. 63.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 13.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 75.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 14.

- ^ Philo mentions widespread sacrifice, but no estimation on the degree, Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.12.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.13.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 15.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 16.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 18.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.3.

- ^ Dunstan, William E., Ancient Rome, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010, ISBN 0-7425-6834-2, p. 285.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 23

- ^ Woods, David (2010). «Caligula’s Quadrans». The Numismatic Chronicle. 170: 99–103. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 42678887.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.9–10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 16.2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.9.7.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.10.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37.

- ^ a b c Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 38.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 41.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 40.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.14.

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.15.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Nero 30

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Sam (2003). Caligula. London: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-0203003725. OCLC 57298122.

- ^ Alston, Richard (2002). Aspects of Roman history, AD 14–117. London: Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-0203011874. OCLC 648154931.

- ^ a b Seneca the Younger, On the Shortness of Life XVIII.5.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.5.

- ^ «7.4: The Julio-Claudian Emperors». Chemistry LibreTexts. 8 August 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 22.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21, Life of Claudius 20; Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXXVI.122.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History XVI.76.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.15; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37.

- ^ Wardle, David (2007). «Caligula’s Bridge of Boats – AD 39 or 40?». Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 56 (1): 118–120. doi:10.25162/historia-2007-0009. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 25598379. S2CID 164017284.

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 19.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 54.

- ^ Kroos, Kenneth A. (1 July 2011). «Central Heating for Caligula’s Pleasure Ship». The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology. 81 (2): 291–299. doi:10.1179/175812111X13033852943471. ISSN 1758-1206. S2CID 110624972.

- ^ Carlson, Deborah N. (May 2002). «Caligula’s Floating Palaces». Archaeology. 55 (3): 26–31. JSTOR 41779576.

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.16; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 30.

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals IV.41.

- ^ a b c Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 26.

- ^ a b c d Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.22.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 35.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History V.2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LX.8

- ^ a b c Barrett 2002, p. 118

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.25.

- ^ Sigman, Marlene C. (1977). «The Romans and the Indigenous Tribes of Mauritania Tingitana». Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 26 (4): 415–439. JSTOR 4435574.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 45–47.

- ^ P. Bicknell, «The Emperor Gaius’ Military Activities in AD 40», Historia 17 (1968), 496–505.

- ^ R.W. Davies, «The Abortive Invasion of Britain by Gaius», Historia 15 (1966), 124–128; S.J.V.Malloch, ‘Gaius on the Channel Coast’, Classical Quarterly 51 (2001) 551–556; See Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 44.

- ^ D. Wardle, Suetonius’ Life of Caligula: a Commentary (Brussels, 1994), 313; David Woods «Caligula’s Seashells», Greece and Rome (2000), 80–87.

- ^ Iliad, Book 2, line 204.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XI–XV.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.26.

- ^ a b c d Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.28.

- ^ Sanford, J.: «»Did Caligula have a God complex?», Stanford Report, 10 September 2003.

- ^ Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasure of Royal Scandals, p. 209. Penguin Books, New York. ISBN 0-7394-2025-9.

- ^ Allen Ward, Cedric Yeo, and Fritz Heichelheim, A History of the Roman People: Third Edition, 1999, Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History LI.20.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.26–28.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.6.10; Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.25.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus III.8, IV.21.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.26–28.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus VVI.43

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus VII.45.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus XXI.185.

- ^ a b c Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.7.2.

- ^ a b c Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.8.1.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXX.201.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXX.203.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XVI.115.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXXI.213.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.8.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Anger xviii.1, On Anger III.xviii.1; On the Shortness of Life xviii.5; Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXIX.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.1.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Anger III.xviii.1.

- ^ «Daily life in the Roman City». Aldrete, Gregory.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.10

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.11, LIX.22; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 24.

- ^ «Suetonius • Life of Caligula». penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ «Cassius Dio – Book 59». penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 46–47.

- ^ Woods, David (2014). «Caligula, Incitatus, and the Consulship». The Classical Quarterly. 64 (2): 772–777. doi:10.1017/S0009838814000470. ISSN 0009-8388. S2CID 170216093.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 55; Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.14.

- ^ Younger, John G. (2005). Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. xvi. ISBN 978-0-415-24252-3.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.1.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56; Tacitus, Annals 16.17; Josephus, Antiquities of Jews XIX.1.2.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.3.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.10, XIX.1.14.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.6.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.5.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56.

- ^ Wardle, David (1991). «When did Gaius Caligula die?» Acta Classica 34 (1991): 158–165.

- ^ Suetonius 58: «On the ninth day before the Kalends of February… Ruled three years, ten months and eight days»; Cassius Dio LIX.30.: «Thus Gaius, after doing in three years, nine months, and twenty-eight days all that has been related, learned by actual experience that he was not a god.» (this seems to give 23 January, but Dio is probably using exclusive reckoning, which does give 24).[123]

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 58.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 58; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.14.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 57, 58.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.15; Suetonius, Life of Caligula 58.

- ^ Owen, Richard (17 October 2008). «Archaeologists unearth place where Emperor Caligula met his end». The Times. The Times, London. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.

- ^ a b Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.4.4.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 59.

- ^ Suetonius. The Lives.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.1.

- ^ Suetonius The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Claudius 11; Josephus Antiquities of the Jews XIX 268–269; Cassius Dio, Roman History LX 3, 4.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.19.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals I.1.

- ^ Tacitus, Life of Gnaeus Julius Agricola X, Annals XIII.20.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.13.

- ^ Aemilius Macer, Theriaca 1.29.

- ^ a b Sidwell, Barbara (18 March 2010). «Gaius Caligula’s Mental Illness». Classical World. 103 (2): 183–206. doi:10.1353/clw.0.0165. ISSN 1558-9234. PMID 20213971.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XIII.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Person XVIII.1; Seneca the Younger, On Anger I.xx.8.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Person XVII–XVIII; Seneca the Younger, On Anger I.xx.8.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II–IV.

- ^ Benediktson, D. Thomas (1989). «Caligula’s Madness: Madness or Interictal Temporal Lobe Epilepsy?». The Classical World. 82 (5): 370–375. doi:10.2307/4350416. ISSN 0009-8418. JSTOR 4350416.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 50.

- ^ Benediktson, D. Thomas (1991). «Caligula’s Phobias and Philias: Fear of Seizure?». The Classical Journal. 87 (2): 159–163. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 3297970.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Augustus 64, Life of Caligula 54.

- ^ J.H. Pearn, «Epilepsy and Drowning in Childhood,» British Medical Journal (1977) pp. 1510–1511.

- ^ O. Temkin, The Falling Sickness (2nd ed., Baltimore 1971) 3–4, 7, 13, 16, 26, 86, 92–96, 179.

- ^ Suetonius: The Lives of the Twelve Caesars; An English Translation, Augmented with the Biographies of Contemporary Statesmen, Orators, Poets, and Other Associates. Suetonius. Publishing Editor. J. Eugene Reed. Alexander Thomson. Philadelphia. Gebbie & Co. 1889.

- ^ Tibballs, Geoff (2017). Royalty’s Strangest Tales. Pavilion Books. ISBN 9781911042945.

- ^ «The True Colours Of Greek and Roman Statues By Archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann». 24 January 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ R.S. Katz, «The Illness of Caligula» CW 65(1972), 223–225; refuted by M.G. Morgan, «Caligula’s Illness Again», CW 66(1973), 327–329.

- ^ Kington, Tom (17 January 2011). «Caligula’s tomb found after police arrest man trying to smuggle statue». The Guardian. London.

- ^ Beard, Mary (18 January 2011). «This isn’t Caligula’s tomb». A don’s life. London. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Yablonsky, Linda (26 February 2006). «‘Caligula’ Gives a Toga Party (but No One’s Really Invited)». The New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ The Caesars at IMDb

- ^ Robinson, Jay. The Comeback. Word Books, 1979. ISBN 978-0-912376-45-5

- ^ I, Claudius at IMDb

- ^ Palmerini, Luca M.; Mistretta, Gaetano (1996). «Spaghetti Nightmares». Fantasma Books. p. 111.ISBN 0963498274.

- ^ Watch A.D. The Bible Continues Episodes at NBC.com, retrieved 9 May 2020

- ^ Nolan, Emma (26 March 2019). «Roman Empire Caligula The Mad Emperor Netflix release date, cast, trailer, plot». Express.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Sheaffer-Jones, Caroline (1 January 2012). «A Deconstructive Reading of Albert Camus’ Caligula: Justice and the Game of Calculations». Australian Journal of French Studies. 49 (1): 31–42. doi:10.3828/AJFS.2012.3. ISSN 0004-9468.

- ^ Graves, Robert I, Claudius (1934)

Bibliography[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 59

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, (trans. W.Whiston), Books XVIII–XIX

- Philo of Alexandria, (trans. C.D.Yonge, London, H. G. Bohn, 1854–1890):

- On the Embassy to Gaius

- Flaccus

- Seneca the Younger

- On Firmness

- On Anger

- To Marcia, On Consolation

- On Tranquility of Mind

- On the Shortness of Life

- To Polybius, On Consolation

- To Helvia, On Consolation

- On Benefits

- On the Terrors of Death (Epistle IV)

- On Taking One’s Own Life (Epistle LXXVII)

- On the Value of Advice (Epistle XCIV)

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula

- Tacitus, Annals, Book 6

Secondary material[edit]

- Balsdon, V. D. (1934). The Emperor Gaius. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Barrett, Anthony A. (1989). Caligula: the corruption of power. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5487-1.

- Grant, Michael (1979). The Twelve Caesars. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044072-0.

- Hurley, Donna W. (1993). An Historical and Historiographical Commentary on Suetonius’ Life of C. Caligula. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- Sandison, A. T. (1958). «The Madness of the Emperor Caligula». Medical History. 2 (3): 202–209. doi:10.1017/s0025727300023759. PMC 1034394. PMID 13577116.

- Wilcox, Amanda (2008). «Nature’s Monster: Caligula as exemplum in Seneca’s Dialogues». In Sluiter, Ineke; Rosen, Ralph M. (eds.). Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne: Supplements. History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity. Vol. 307. Leiden: Brill.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caligula.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Caligula.

- The portrait of Caligula in the Digital Sculpture Project

- Caligula Attempts to Conquer Britain in AD 40

- Biography from De Imperatoribus Romanis

- Franz Lidz, «Caligula’s Garden of Delights, Unearthed and Restored», New York Times, Jan. 12, 2021

|

Caligula Julio-Claudian dynasty Born: 31 August AD 12 Died: 24 January AD 41 |

||

| Roman emperors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Tiberius |

Roman emperor 37–41 |

Succeeded by

Claudius |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by

Gn. Acerronius Proculus |

Roman consul July–August 37 With: Claudius |

Succeeded by

A. Caecina Paetus |

| Preceded by

Ser. Asinius Celer |

Roman consul January 39 With: L. Apronius Caesianus |

Succeeded by

Q. Sanquinius Maximus |

| Preceded by

A. Didius Gallus |

Roman consul January 40 sine collega |

Succeeded by

G. Laecanius Bassus |

| Preceded by

G. Laecanius Bassus |

Roman consul January 41 With: Gn. Sentius Saturninus |

Succeeded by

Q. Pomponius Secundus |

| Caligula | ||

|---|---|---|

Marble bust of Caligula dating from his reign, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art |

||

| Roman emperor | ||

| Reign | 16 March 37 – 24 January 41 | |

| Predecessor | Tiberius | |

| Successor | Claudius | |

| Born | Gaius Julius Caesar 31 August AD 12 Antium, Italy |

|

| Died | 24 January AD 41 (aged 28) Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy |

|

| Burial |

Mausoleum of Augustus |

|

| Spouses |

|

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| Dynasty | Julio-Claudian | |

| Father | Germanicus | |

| Mother | Agrippina |

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August AD 12 – 24 January AD 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from AD 37 until his assassination in AD 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, Augustus’ granddaughter. Caligula was born into the first ruling family of the Roman Empire, conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Although Gaius was named after Gaius Julius Caesar, he acquired the nickname «Caligula» («little caliga«, a type of military boot) from his father’s soldiers during their campaign in Germania. When Germanicus died at Antioch in 19, Agrippina returned with her six children to Rome, where she became entangled in a bitter feud with Tiberius. The conflict eventually led to the destruction of her family, with Caligula as the sole male survivor. In 26, Tiberius withdrew from public life to the island of Capri, and in 31, Caligula joined him there. Following the former’s death in 37, Caligula succeeded him as emperor. There are few surviving sources about the reign of Caligula, though he is described as a noble and moderate emperor during the first six months of his rule. After this, the sources focus upon his cruelty, sadism, extravagance, and sexual perversion, presenting him as an insane tyrant.

While the reliability of these sources is questionable, it is known that during his brief reign, Caligula worked to increase the unconstrained personal power of the emperor, as opposed to countervailing powers within the principate. He directed much of his attention to ambitious construction projects and luxurious dwellings for himself, and he initiated the construction of two aqueducts in Rome: the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus. During his reign, the empire annexed the client kingdom of Mauretania as a province. In early 41, Caligula was assassinated as a result of a conspiracy by officers of the Praetorian Guard, senators, and courtiers. However, the conspirators’ attempt to use the opportunity to restore the Roman Republic was thwarted. On the day of the assassination of Caligula, the Praetorians declared Caligula’s uncle, Claudius, as the next emperor. Caligula’s death marked the official end of the Julii Caesares in the male line, though the Julio-Claudian dynasty continued to rule until the demise of his nephew, Nero.

Early life[edit]

Caligula was born in Antium on 31 August 12 CE, the third of six surviving children born to Germanicus, a grandson of Mark Antony, and his second cousin Agrippina the Elder,[2] who was the daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder, making her the granddaughter of Augustus.[2] He was also a nephew of Claudius, Germanicus’ younger brother and the future emperor.[3] He had two older brothers, Nero and Drusus,[2] and three younger sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla and Julia Livilla.[2][4] At the age of two or three, he accompanied his father, Germanicus, on campaigns in the north of Germania.[5] He wore a miniature soldier’s outfit, including army boots (caligae) and armour.[5] The soldiers thus nicknamed him Caligula («little [soldier’s] boot»).[6] He reportedly grew to dislike the nickname.[7]

Germanicus died at Antioch, Syria province, in AD 19, aged only 33. Suetonius claims that Germanicus was poisoned by an agent of Tiberius, who viewed Germanicus as a political rival.[8] After the death of his father, Caligula lived with his mother, Agripinna the Elder, until her relations with Tiberius deteriorated.[9] Tiberius would not allow Agrippina to remarry for fear her husband would be a rival.[10] Agrippina and Caligula’s brother, Nero, were banished in the year 29 CE on charges of treason.[11][12] The adolescent Caligula was sent to live with his great-grandmother (Tiberius’ mother), Livia;[9] After her death, he was sent to live with his grandmother Antonia Minor.[9] In the year 30 CE, his brother Drusus was imprisoned on charges of treason, and his brother Nero died in exile from either starvation or suicide.[12][13] Suetonius writes that after the banishment of his mother and brothers, Caligula and his sisters were nothing more than prisoners of Tiberius under the close watch of soldiers.[14] In the year 31, Caligula was remanded to the personal care of Tiberius on Capri, where he lived for six years.[9] To the surprise of many, Caligula was spared by Tiberius.[15] Roman historians describe Caligula as an excellent natural actor who recognized the danger he was in, and hid his resentment towards Tiberius.[9][16] An observer said of Caligula, «Never was there a better servant or a worse master!»[9][16]

Caligula claimed to have planned to kill Tiberius with a dagger to avenge his mother and brother: however, having brought the weapon into Tiberius’ bedroom he did not kill the Emperor but instead threw the dagger down on the floor. Supposedly Tiberius knew of this plot but did nothing about it.[17] Suetonius claims that Caligula was by this time already cruel and vicious: he writes that when Tiberius brought Caligula to the island of Capri, his purpose was to allow Caligula to live in order that he «prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world.»[18] In 33, Tiberius gave Caligula an honorary quaestorship, a position he held until his rise to emperor.[19] Meanwhile, both Caligula’s mother and his brother Drusus died in prison.[20][21] Caligula was briefly married to Junia Claudilla in the year 33, though she died in childbirth the following year.[17] Caligula spent time befriending the Praetorian prefect, Naevius Sutorius Macro, an important ally.[17] Macro spoke well of Caligula to Tiberius, attempting to quell any ill will or suspicion the Emperor felt towards Caligula.[22] In the year 35, Caligula was named joint heir to Tiberius’ estate along with Tiberius Gemellus.[23]

Emperor[edit]

Early reign[edit]

Caligula Depositing the Ashes of his Mother and Brother in the Tomb of his Ancestors, by Eustache Le Sueur, 1647

When Tiberius died on 16 March AD 37, his estate and the titles of the principate were left to Caligula and to Tiberius’ own grandson, Gemellus, who were to serve as joint heirs. Although Tiberius was 77 and on his deathbed, some ancient historians still conjecture that he was murdered.[17][24] Tacitus writes that Macro smothered Tiberius with a pillow to hasten Caligula’s accession, much to the joy of the Roman people,[24] while Suetonius writes that Caligula may have carried out the killing, though this is not recorded by any other ancient historian.[17] Seneca the Elder and Philo, who both wrote during Tiberius’ reign, as well as Josephus, record Tiberius as dying a natural death.[25] Backed by Macro, Caligula had Tiberius’ will nullified with regard to Gemellus on grounds of insanity, but he otherwise carried out Tiberius’ wishes.[26] Caligula was proclaimed emperor by the Senate on 18 March.[27] He accepted the powers of the principate and entered Rome on 28 March amid a crowd that hailed him as «our baby» and «our star», among other nicknames.[27][28]

Caligula is described as the first emperor who was admired by everyone in «all the world, from the rising to the setting sun.»[29] Caligula was loved by many for being the beloved son of the popular Germanicus[28] and because he was not Tiberius.[30] Suetonius said that over 160,000 animals were sacrificed during three months of public rejoicing to usher in the new reign.[31][32] Philo describes the first seven months of Caligula’s reign as completely blissful.[33] Caligula’s first acts were said to be generous in spirit, though many were political in nature.[26] To gain support, he granted bonuses to the military, including the Praetorian Guard, city troops and the army outside Italy.[26] He destroyed Tiberius’ treason papers, declared that treason trials were a thing of the past, and recalled those who had been sent into exile.[34] He helped those who had been harmed by the imperial tax system, banished certain sexual deviants, and put on lavish spectacles for the public, including gladiatorial games.[35][36] Caligula collected and brought back the bones of his mother and of his brothers and deposited their remains in the tomb of Augustus.[37]

In October 37, Caligula fell seriously ill or perhaps was poisoned. He soon recovered from his illness, but many believed that the illness turned the young emperor toward the diabolical: he started to kill off or exile those who were close to him or whom he saw as a serious threat. It is possible that his illness reminded him of his mortality and of the desire of others to advance into his place.[38] He had his cousin and adopted son Tiberius Gemellus executed – an act that outraged Caligula’s and Gemellus’ mutual grandmother Antonia Minor. She is said to have committed suicide, although Suetonius hints that Caligula poisoned her. He had his father-in-law Marcus Junius Silanus and his brother-in-law Marcus Lepidus executed as well. His uncle Claudius was spared only because Caligula preferred to keep him as a laughing stock. His favourite sister, Julia Drusilla, died in 38 of a fever: his other two sisters, Livilla and Agrippina the Younger, were exiled. He hated being the grandson of Agrippa and slandered Augustus by repeating a falsehood that his mother was conceived as the result of an incestuous relationship between Augustus and his daughter Julia the Elder.[39]

Public reform and financial crisis[edit]

Quadrans celebrating the abolition of a tax in AD 38 by Caligula.[40] The obverse of the coin contains a picture of a Pileus which symbolizes the liberation of the people from the tax burden. Caption: C. CAESAR DIVI AVG. PRON[EPOS] (great-grandson of) AVG. / PON. M., TR. P. III, P. P., COS. DES. RCC. (probably Res Civium Conservatae, i.e. the interests of citizens have been preserved)

In the year 38, Caligula focused his attention on political and public reform. He published the accounts of public funds, which had not been made public during the reign of Tiberius. He aided those who lost property in fires, abolished certain taxes, and gave out prizes to the public at gymnastic events. He allowed new members into the equestrian and senatorial orders.[41] Perhaps most significantly, he restored the practice of elections.[42] Cassius Dio said that this act «though delighting the rabble, grieved the sensible, who stopped to reflect, that if the offices should fall once more into the hands of the many … many disasters would result».[43] During the same year, though, Caligula was criticized for executing people without full trials and for forcing the Praetorian prefect, Macro, to commit suicide. Macro had fallen out of favor with the emperor, probably due to an attempt to ally himself with Gemellus when it appeared that Caligula might die of fever.[44]

According to Cassius Dio, a financial crisis emerged in 39.[44] Suetonius places the beginning of this crisis in 38.[45] Caligula’s political payments for support, generosity and extravagance had exhausted the state’s treasury. Ancient historians state that Caligula began falsely accusing, fining and even killing individuals for the purpose of seizing their estates.[46] Historians describe a number of Caligula’s other desperate measures. To gain funds, Caligula asked the public to lend the state money.[47] He levied taxes on lawsuits, weddings and prostitution.[48] Caligula began auctioning the lives of the gladiators at shows.[46][49] Wills that left items to Tiberius were reinterpreted to leave the items instead to Caligula.[50] Centurions who had acquired property by plunder were forced to turn over spoils to the state.[50] The current and past highway commissioners were accused of incompetence and embezzlement and forced to repay money.[50]

According to Suetonius, in the first year of Caligula’s reign he squandered 2.7 billion sesterces that Tiberius had amassed.[45] His nephew Nero both envied and admired the fact that Gaius had run through the vast wealth Tiberius had left him in so short a time.[51] However, some historians have shown scepticism towards the large number of sesterces quoted by Suetonius and Dio. According to Wilkinson, Caligula’s use of precious metals to mint coins throughout his principate indicates that the treasury most likely never fell into bankruptcy.[52] He does point out, however, that it is difficult to ascertain whether the purported ‘squandered wealth’ was from the treasury alone due to the blurring of «the division between the private wealth of the emperor and his income as head of state.»[52] Furthermore, Alston points out that Caligula’s successor, Claudius, was able to donate 15,000 sesterces to each member of the Praetorian Guard in 41,[24] suggesting the Roman treasury was solvent.[53] A brief famine of unknown extent occurred, perhaps caused by this financial crisis, but Suetonius claims it resulted from Caligula’s seizure of public carriages;[46] according to Seneca, grain imports were disrupted because Caligula re-purposed grain boats for a pontoon bridge.[54]

Construction and senatorial feud[edit]

The Vatican Obelisk was first brought from Egypt to Rome by Caligula. It was the centerpiece of a large racetrack he built.

Despite financial difficulties, Caligula embarked on a number of construction projects during his reign. Some were for the public good, though others were for himself. Josephus describes Caligula’s improvements to the harbours at Rhegium and Sicily, allowing increased grain imports from Egypt, as his greatest contributions.[55] These improvements may have been in response to the famine.[56] Caligula completed the temple of Augustus and the theatre of Pompey and began an amphitheatre beside the Saepta.[57] He also expanded the imperial palace.[58] Later, he began the construction of aqueducts Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus, which Pliny the Elder considered to be engineering marvels.[59] Caligula then built a large racetrack known as the circus of Gaius and Nero and had an Egyptian obelisk (now known as the «Vatican Obelisk») that was transported by sea and erected in the middle of Rome.[60]

At Syracuse, he repaired the city walls and the temples of the gods.[57] He had new roads built and pushed to keep roads in good condition.[61] Caligula had planned to rebuild the palace of Polycrates at Samos, to finish the temple of Didymaean Apollo at Ephesus and to found a city high up in the Alps.[57] He also intended to dig a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece and sent a chief centurion to survey the work.[57] In 39, Caligula performed a spectacular stunt by ordering a temporary floating bridge to be built using ships as pontoons, stretching for over two miles from the resort of Baiae to the neighbouring port of Puteoli.[62][63] It was said that the bridge was to rival the Persian king Xerxes’ pontoon bridge crossing of the Hellespont.[63] Caligula, who could not swim,[64] then proceeded to ride his favourite horse Incitatus across, wearing the breastplate of Alexander the Great.[63] This act was in defiance of a prediction by Tiberius’ soothsayer Thrasyllus of Mendes that Caligula had «no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding a horse across the Bay of Baiae».[63]

Caligula had two large ships constructed for himself (which were recovered from the bottom of Lake Nemi around 1930). The ships were among the largest vessels in the ancient world. The smaller ship was designed as a temple dedicated to Diana. The larger ship was essentially an elaborate floating palace with marble floors and plumbing.[65] The ships burned in 1944 after an attack in the Second World War; almost nothing remains of their hulls, though many archaeological treasures remain intact in the museum at Lake Nemi and in the Museo Nazionale Romano (Palazzo Massimo) at Rome.[66] In 39, relations between Caligula and the Roman Senate deteriorated.[67] The subject of their disagreement is unknown. A number of factors, though, aggravated this feud. The Senate had become accustomed to ruling without an emperor between the departure of Tiberius for Capri in 26 and Caligula’s accession.[68] Additionally, Tiberius’ treason trials had eliminated a number of pro-Julian senators such as Asinius Gallus.[68] Caligula reviewed Tiberius’ records of treason trials and decided, based on their actions during these trials, that numerous senators were not trustworthy.[67] He ordered a new set of investigations and trials.[67] He replaced the consul and had several senators put to death.[69] Suetonius reports that other senators were degraded by being forced to wait on him and run beside his chariot.[69] Soon after his break with the Senate, Caligula faced a number of additional conspiracies against him.[70] A conspiracy involving his brother-in-law was foiled in late 39.[70] Soon afterwards, the Governor of Germany, Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, was executed for connections to a conspiracy.[70]

Western expansion[edit]

Map of the Roman Empire and neighboring states during the reign of Gaius Caligula (AD 37–41)

Italy and Roman provinces

Independent countries

Client states (Roman puppets)

Mauretania seized by Caligula

Former Roman provinces Thrace and Commagena made client states by Caligula

In 40, Caligula expanded the Roman Empire into Mauretania,[2] a client kingdom of Rome ruled by Ptolemy of Mauretania. Caligula invited Ptolemy to Rome and then suddenly had him executed.[71] Mauretania was annexed by Caligula and subsequently divided into two provinces, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, separated by the river Malua.[72] Pliny claims that division was the work of Caligula, but Dio states that in 42 an uprising took place, which was subdued by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, and the division only took place after this.[73] This confusion might mean that Caligula decided to divide the province, but the division was postponed because of the rebellion.[74] The first known equestrian governor of the two provinces was Marcus Fadius Celer Flavianus, in office in 44.[74]

Details on the Mauretanian events of 39–44 are unclear. Cassius Dio wrote an entire chapter on the annexation of Mauretania by Caligula, but it is now lost.[75] Caligula’s move seemingly had a strictly personal political motive – fear and jealousy of his cousin Ptolemy – and thus the expansion may not have been prompted by pressing military or economic needs.[76] However, the rebellion of Tacfarinas had shown how exposed Africa Proconsularis was to its west and how the Mauretanian client kings were unable to provide protection to the province, and it is thus possible that Caligula’s expansion was a prudent response to potential future threats.[74]

Caligula also made a significant attempt at expanding into Britannia.[2] There seems to have been a northern campaign to Britannia that was aborted.[75] This campaign is derided by ancient historians with accounts of Gauls dressed up as Germanic tribesmen at his triumph and Roman troops ordered to collect seashells as «spoils of the sea».[77] The few primary sources disagree on what precisely occurred. Modern historians have put forward numerous theories in an attempt to explain these actions. This trip to the English Channel could have merely been a training and scouting mission.[78] The mission may have been to accept the surrender of the British chieftain Adminius.[79] «Seashells», or conchae in Latin, may be a metaphor for something else such as female genitalia (perhaps the troops visited brothels) or boats (perhaps they captured several small British boats).[80] The conquest of Britannia was later achieved during the reign of his successor, Claudius.

Claims of divinity[edit]

Caligula and Roma Cameo depicting Caligula and Roma, a personification of Rome

When several client kings came to Rome to pay their respects to him and argued about their nobility of descent, he allegedly cried out the Homeric line:[81] «Let there be one lord, one king.»[58] In 40, Caligula began implementing very controversial policies that introduced religion into his political role. Caligula began appearing in public dressed as various gods and demigods such as Hercules, Mercury, Venus and Apollo.[82] Reportedly, he began referring to himself as a god when meeting with politicians and he was referred to as «Jupiter» on occasion in public documents.[83][84] A sacred precinct was set apart for his worship at Miletus in the province of Asia and two temples were erected for worship of him in Rome.[84] The Temple of Castor and Pollux on the forum was linked directly to the imperial residence on the Palatine and dedicated to Caligula.[84][85]

He would appear there on occasion and present himself as a god to the public. Caligula had the heads removed from various statues of gods located across Rome and replaced them with his own.[86] It is said that he wished to be worshipped as Neos Helios, the «New Sun». Indeed, he was represented as a sun god on Egyptian coins.[87] Caligula’s religious policy was a departure from that of his predecessors. According to Cassius Dio, living emperors could be worshipped as divine in the east and dead emperors could be worshipped as divine in Rome.[88] Augustus had the public worship his spirit on occasion, but Dio describes this as an extreme act that emperors generally shied away from.[88] Caligula took things a step further and had those in Rome, including senators, worship him as a tangible, living god.[89]

Eastern policy[edit]