Приветствие в японском языке можно выразить различными способами, так же как и в любом другом языке. Выбор конкретной фразы зависит от того, в какой обстановке вы находитесь, к кому обращаетесь, и в какое время суток это происходит.

«Здравствуйте» по-японски

Универсальным приветствием на все случаи жизни, в любое время суток и применимое для всех людей, независимо от финансового или социального положения, является хорошо знакомое многим конитива (коничива или, как ещё некоторые не правильно говорят конишуа) konnichiwa. Это слово является аналогом нашего «Здравствуйте» или «Приветствую Вас».

- 今日は — (kon-ni-chi-wa)

- こんにちは — (kon-ni-chi-wa)

«Алло» по-японски

Эту фразу вы наверняка неоднократно слышали в аниме. Вообще «moshi moshi» можно перевести как «привет», но используют его исключительно в качестве приветствия по телефону, то есть это аналог русского «алло». Звонящий отвечает также — «moshi moshi». Использовать эту фразу можно в любое время суток, но, повторюсь, только по телефону.

もしもし — (moshi moshi)

Охайё: «Доброе утро» по-японски

Чаще всего по утрам (до обеда) от японцев можно услышать «Охайё» — это сокращение от фразы «Ohayōgozaimasu», что переводится как «Доброе утро». На японском наиболее распространён именно сокращенный вариант, то есть «Ohayō».

- おはようございます — (Ohayōgozaimasu)

- お早うございます — (Ohayōgozaimasu)

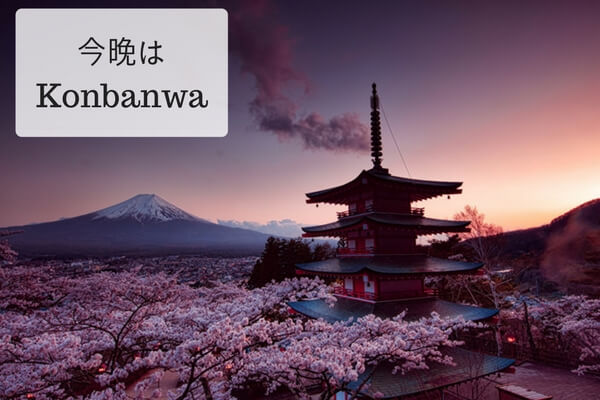

«Добрый вечер» по-японски

В вечернее время японцы говорят друг другу «Konbanwa». Это уважительное приветствие, поэтому его также можно использовать и после ужина.

- こんばんは — (Konbanwa)

- 今晩は — (Konbanwa)

«Доброй ночи» по-японски

Расставаясь с наступления темноты, в Японии принято говорить «Oyasuminasai». На русский язык это можно перевести как «спокойной ночи». Однако учтите, что это же выражение японцы используют и для приветствия в ночное время (но чаще всё же для прощание). С близкими людьми можно использовать сокращенное выражение «Oyasumi».

- おやすみ — (Oyasumi)

- おやすみなさい — (Oyasuminasai)

«Привет! Давно не виделись!» по-японски

При встречи со старым знакомым или родственником в Японии говорят «Hisashiburi». Гораздо реже используется полное выражение «Ohisashiburidesune». Примерное его значение «Привет! Давно не виделись!».

久しぶり- (Hisashiburi)

Короткое приветствие на японском

В современной Японии молодёжь часто использует в качестве приветствия фразу «Yāhō». Чаще всего им пользуются девушки. Парни же сократили его ещё больше — «Yo». Появилось это приветствие в Осаке, а позже распространилось по всей Японии.

ヤーホー — (Yaho)

«Привет, чувак» на японском языке

Японские парни одного возраста (ТОЛЬКО парни, девушки эту фразу не используют) в неформальной обстановке часто здороваются другу с другом, говоря «Ossu». Дословно это можно перевести как «эй пижон» или «привет, чувак», «здорова» и т. д.

おっす — (Ossu)

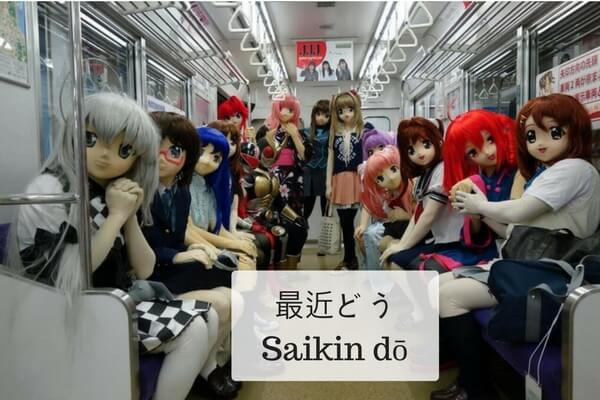

«Как дела?» по-японски

У японцев есть выражение «Привет, как дела?» или «Привет, как поживаете?» и звучит оно так: «Ogenkidesuka». Однако, близкие знакомые, друзья, коллеги или одноклассники, если хотят спросить «как ты?» или приветствуя, сказать по-японски «как дела?», то гораздо чаще используют выражение «Saikin dō».

最近どう — (Saikin dō)

Неформальные приветствия на японском языке

Ещё несколько приветствий, которые можно использовать при встрече с близкими друзьями:

- ハイー! — hai! — привет! (заимствованный вариант от английского hi)

- ハイハイー! — hai hai! — привет, привет!

- こんちゃ! — koncha! — «здарова!» (сокращенный вариант от konnichiwa)

Фраза Иероглифы Чтение иероглифов Обращение по-японски “Извините…” (при обращении с вопросом к незнакомому человеку или официальному лицу) すみません Сумимасэн… Приветствия по-японски Добрый день こんにちは Коннитива Добрый вечер こんばんは Комбанва Доброе утро おはようございます Охайо:гозаимас Здарова, привет! おう оу Приятно познакомиться 初めまして。どうぞよろしく Хадзимэмаситэ. До:дзойоросику Рад с вами познакомиться 初めまして。よろしくお願いします Хадзимэмаситэ, ёросику о-нэгаи симас Как поживаете? おげんきですか О гэнки дэска? Нормально. Здоров (неформально) げんきよ Гэнки йо Да. Все хорошо はい。げんきです Хай. Гэнки дэс. Давно не виделись お久し振りですね О хисасибури дэс нэ Прощания по-японски Спокойной ночи お休みなさい Оясуми насай Спокойной ночи (простой, разговорный вариант) おやすみ оясуми До свидания さようなら Сайо:нара пока; увидимся またね матанэ пока じゃ дзя Пока (Пожелание счастливого дня членам семьи уходящим куда-либо на время из дома) いってらっしゃい Иттэрассяй Пока, я ещё вернусь. (Говорит тот, кто уходит на время из дома, из офиса.) 行って来ます Иттэкимас Приход-уход по-японски Входите, пожалуйста どうぞお入りください До:зо охаирикудасай Добро пожаловать. Входите (обычно употребляется продавцами) いらっしゃいませ Ирассяимасэ Добро пожаловать (Менее официально) いいらっしゃい Иирассяй “Разрешите войти” (Дословно: извините, пожалуйста) ごめんください Гомэнкудасай “Извините, что беспокою” (при входе) お邪魔します Одзямасимас Садитесь, пожалуйста どうぞ。おかけください До:зо окакэкудасай “Извините за беспокойство” (входя в комнату). 失礼します Сицурэйсимас В качестве «спасибо» на приглашение сесть. “До свидания” (уходя) “Пожалуйста, сначала вы” (пропуская через дверь). お先に Осакини “Извините” (что прохожу первым). “Спасибо” (что пропустили меня первым). “До свидания” (Извините, что покидаю офис первым). После вас お先へどうぞ Осаки э до:зо. Спасибо (дословно извините) すみません Сумимасэн а вот и я (вернулся) ただいま Тадаима С возвращением お帰りなさい Окаэринасай Благодарность по-японски Спасибо どうも До:мо Большое спасибо どうもありがとう До:мо аригато: Очень большое спасибо ^_^ どうもありがとうございます До:мо аригато: годзаимас Спасибо (только по отношению к старшим по возрасту или по положению) どうもすみません До:мо сумимасэн Не стоит благодарности どういたしまして。 До:итасимаситэ Нет, вам спасибо こちらこそ Котиракосо Нет, вам спасибо (неформально) いいえ ийэ Хорошо, согласен いいよ Ий ё премного благодарен, отличная работа おつかれさま оцукарэ сама пожалуйста, прошу вас お願いします онэгаи симас спасибо ありがとう аригато “Спасибо” (перед едой). いただきます Итадакимас Спасибо” (после еды) ご馳走さま Готисо:сама не стоит благодарности どういたしまして до: итасимаситэ Просьбы по-японски Прошу おねがい онэгаи пожалуйста ください кудасаи помогите! 助けて таскэтэ Извинения по-японски Извините ごめんなさい Гомэн насай Извините, что заставил вас ждать お待たせしました О-матасэ симасита Поздравления по-японски Поздравляю おめでとうございます Омэдэто: годзаимас Поздравляю с днем рождения お誕生日おめでとうございます Отандзё:би омэдэто: годзаимас Поздравляю с Новым годом 明けましておめでとうございます Акэмаситэ омэдэто:годзаимас Прочие фразы на японском я люблю тебя 愛してるよ Айситэру ё! 好きだ СуКИ ДА 好きよ СуКИ Ё! 大好き Дайски (очень люблю) ты мне нравишься ( = я люблю тебя) 1.おまえのことが好きだ 1.омаэ но котога СуКИ да (мужской вариант) 2.あなたのことが好きです 2.аната но котога СуКИ дэс (вежливый, женский вариант) 3. имя+именной суффикc のことが好きだ(です) будьте здоровы , берегите себя, выздоравливайте скорее お大事に Одайдзини что сейчас делаешь ? 今、何してる? Има нани ситэру? такова жизнь これが人生 корэ га дзинсэи ничего не поделаешь しかたがない сиката га наи я не понимаю; я не знаю わかりません вакаримасэн до дна! かんぱい Кампай Алло もしもし Мосимоси Никогда не прощу 絶対に許さない Дзэттай ни юрусанай

Вот кстати замечательное видео с базовыми японскими фразами. Слова и выражения там озвучиваются японкой, а перевод фраз русский.

Александр

Искусственный Интеллект

(249559)

13 лет назад

если хираганой записывать, то かわいい

если катаканой записывать, то カワイイ

если иероглифами записывать, то 可愛い

но есть и другое слово с таким же чтением, но записывается иными иероглифами

河飯

но скорее всего оно вам не подходит

Остальные ответы

Татьяна Валерьевна

Гуру

(3801)

13 лет назад

Не могу написать, пишет, что неправильный формат

Ангел ночи

Оракул

(65502)

13 лет назад

Там точно не один иегоглиф.. . Вот составь:

Elena Fedotova

Просветленный

(25260)

13 лет назад

可愛 — милый, славный, хорошенький! Хираганой かわい! Катаканой пишуться слова иностранного происхождения! А так же иностранные имена!

Кето

Знаток

(260)

6 лет назад

але це ж не ієрогліфи… це хірагана…

Рабочая почта

Профи

(609)

4 года назад

かわいい

Автор Вероникв !!!!!!!!!!!!1111 задал вопрос в разделе Лингвистика

как пишется слово КАВАЙ на японском? и получил лучший ответ

Ответ от Александр[гуру]

если хираганой записывать, то かわいいесли катаканой записывать, то カワイイесли иероглифами записывать, то 可愛いно есть и другое слово с таким же чтением, но записывается иными иероглифами河飯но скорее всего оно вам не подходит

Ответ от Ђатьяна Валерьевна[гуру]

Не могу написать, пишет, что неправильный формат

Ответ от Ангел ночи[гуру]

Там точно не один иегоглиф.. . Вот составь:

Ответ от Elena Fedotova[гуру]

可愛 — милый, славный, хорошенький! Хираганой かわい! Катаканой пишуться слова иностранного происхождения! А так же иностранные имена!

Ответ от Кето[новичек]

але це ж не ієрогліфи… це хірагана…

Ответ от 3 ответа[гуру]

Привет! Вот подборка тем с похожими вопросами и ответами на Ваш вопрос: как пишется слово КАВАЙ на японском?

Япония как она есть. Этот фотоотчет о путешествии в Японию найден на просторах сети и предлагается вам. Потому что Япония всегда манит своей детской непосредственностью. Вот вроде и люди взрослые, и вообще – технологии, мода, а глянешь налево – кавай, глянешь направо — еще кавай.

Магазинные арбузы сразу привлекают внимание своей формой.

Кавай (kawaii) — в переводе с японского означает милый. Так вот, все, что видит путешественник вокруг, точно можно отобразить смайлом ^_^.

Это витрина магазина. Все очень нежненькое, розовенькое, очень девочковое. Не удивительно, что и мужчины в Японии кажутся какими-то неженками-мороженками. Причем это муляжи, вся продукция спрятана в морозильниках и прохладных боксах.

Вообще еда тут очень и очень красивая. Аппетитная. Как японцы умудряются не набирать вес при таком изобилии и красивом подходе — решительно непонятно.

А это блюдо йоба-соба. Где соба — лапша, а йоба — непонятно что. Автор не дает комментариев.

Сладости тоже украшены красивыми картинками. Изображениями мордочек животных украшены кексы, упаковка, посуда, салфетки, стены…

В общем, миловидное и с характерным выражением лица мордочек зверье, нежные цвета, шарики. Даже мороженое из мелких шариков — визитная карточка многих местных кафе.

А это печенье.

У местных японцев есть такой обычай. Оставляешь заявку в сети с описанием себя, своих увлечений, и местные приглашают тебя на обед. С собой дают бенто (однопорционная упакованная еда), завернутое в платочек. У этой традиции есть предыстория, а каждый предмет ритуального действия имеет свое название.

Тема вкусняшек повсюду. Много украшений и аксессуаров в стиле еды и продуктов.

Пенал-рыба

Серьги «Вишенки»

Чехол для айфона в виде яичницы с беконом

И тут мы плавно подходим к теме различных предметов для повседневного использования и декора.

Затычки для посуды с игрушками

Зверушки

Игрушки

Тема зайчиков повсюду. Котики тут тоже в чести, и их все-таки придумали сами японцы, хотя свалили все на англичан. Наконец-то нашелся человек, который развеял этот миф. По словам владельца фотографий, Kitty была выдумана компанией Sanrio. Просто здесь можно говорить, что, мол, бренд европейский.

Магазины Японии стремятся нагнать покупателей с помощью яркого, нетипичного дизайна. И судя по разнообразию подходов, стараются вовсю. Интересно, насколько востребованы там профессии архитекторов и дизайнеров. Вероятно, весьма и весьма.

А это модный магазин. Какими ни были японцы неумелыми модниками, с маркетинговым чутьем у них точно все в порядке. Эти манекены прекрасные ай-стопперы. Причем в двояком смысле, действительно «ай»-«стопперы». Оба слова в кавычках.

Наравне с кавайным милым обликом страны мы встречаемся с проявлениями утонченного вкуса к фильмам ужасов. Это инсталляция в подземном переходе. Довольно мрачно, надо отметить.

Зверушки просто повсюду… Аббревиатура WC – Water Closet — и мишка на качелях на картинке недвусмысленно намекают нам, что всем милым пандам вход в restroom открыт.

Зарядные устройства с зверями

Аксессуары для бенто — японских ланчей

Часики

Чашечки

Чехлы для айфона с зверями

Ножнички

Цветной скотч, которым замотано все, что может быть замотано, продается на каждом шагу. Преимущественно им оформляют пакеты, коробки и подарки. Японцы стремятся внести толику красоты везде, где ухитряются.

Дети могут ставить штампы. Тоже кавайные. С няшными зверушками.

Штампы

А это — традиционные японские принты на тканях и бумаге.

Из этой бумаги в отелях делают бумажных журавликов на счастье…

Много любопытных штуковин…

Бантик чтобы ноги не разъезжались в метро

Картины

Смешная подушка для сна

Футболки для папы и малыша

Сумки в форме зверей

Чувство вкуса? Нет, не слышали. Эти кошельки носят все – от мала до велика. Ладно бы там девочки, но и взрослая дама может достать из сумочки откровенно детскую безделушку.

Кошельки

Некоторые японки все еще носят традиционную одежду, хотя такое явление в индустриальных городах уже не так часто встречается.

Минти (слева) и Михо (справа). Михо носит европейские бренды, равно как в Европе любят носить одежду, пошитую на Востоке. Чего не хватает, то и нравится.

А дети одеты именно кавайно, а не эротично, они так одеваются и просто для себя, и для того, чтобы показать людям, что они работают в качестве рекламных агентов. Эта девочка раздает буклеты массажного салона.

Порой кажется, что детский сад правит миром японцев. То ли не наигрались, то ли уработались настолько, что хочется праздника везде и всегда. Даже ограждения на улицах украшены пластиковыми личиками макак.

Если ваши родственники — японцы, смело дарите им сувениры, они оценят. Здесь их много, здесь их любят. У японцев небольшие и компактные жилища, поэтому сувениры могут служить хорошим украшением.

Вот такая она, кавайная страна.

Kawaii (Japanese: かわいい or 可愛い, IPA: [kawaiꜜi]; ‘lovely’, ‘loveable’, ‘cute’, or ‘adorable’)[1] is the culture of cuteness in Japan.[2][3][4] It can refer to items, humans and non-humans that are charming, vulnerable, shy and childlike.[2] Examples include cute handwriting, certain genres of manga, anime, and characters including Hello Kitty and Pikachu from Pokémon.[5][6]

The cuteness culture, or kawaii aesthetic, has become a prominent aspect of Japanese popular culture, entertainment, clothing, food, toys, personal appearance, and mannerisms.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The word kawaii originally derives from the phrase 顔映し kao hayushi, which literally means «(one’s) face (is) aglow,» commonly used to refer to flushing or blushing of the face. The second morpheme is cognate with -bayu in mabayui (眩い, 目映い, or 目映ゆい) «dazzling, glaring, blinding, too bright; dazzlingly beautiful» (ma- is from 目 me «eye») and -hayu in omohayui (面映い or 面映ゆい) «embarrassed/embarrassing, awkward, feeling self-conscious/making one feel self-conscious» (omo- is from 面 omo, an archaic word for «face, looks, features; surface; image, semblance, vestige»). Over time, the meaning changed into the modern meaning of «cute» or «shine» , and the pronunciation changed to かわゆい kawayui and then to the modern かわいい kawaii.[8][9][10] It is commonly written in hiragana, かわいい, but the ateji, 可愛い, has also been used. The kanji in the ateji literally translates to «able to love/be loved, can/may love, lovable.»

History[edit]

Original definition[edit]

Kogal girl, identified by her shortened skirt. The soft bag and teddy bear that she carries are part of kawaii.

The original definition of kawaii came from Lady Murasaki’s 11th century novel The Tale of Genji, where it referred to pitiable qualities.[11] During the Shogunate period[when?] under the ideology of neo-Confucianism, women came to be included under the term kawaii as the perception of women being animalistic was replaced with the conception of women as docile.[11] However, the earlier meaning survives into the modern Standard Japanese adjectival noun かわいそう kawaisō (often written with ateji as 可哀相 or 可哀想) «piteous, pitiable, arousing compassion, poor, sad, sorry» (etymologically from 顔映様 «face / projecting, reflecting, or transmitting light, flushing, blushing / seeming, appearance»). Forms of kawaii and its derivatives kawaisō and kawairashii (with the suffix -rashii «-like, -ly») are used in modern dialects to mean «embarrassing/embarrassed, shameful/ashamed» or «good, nice, fine, excellent, superb, splendid, admirable» in addition to the standard meanings of «adorable» and «pitiable.»

Cute handwriting[edit]

In the 1970s, the popularity of the kawaii aesthetic inspired a style of writing.[12] Many teenage girls participated in this style; the handwriting was made by writing laterally, often while using mechanical pencils.[12] These pencils produced very fine lines, as opposed to traditional Japanese writing that varied in thickness and was vertical.[12] The girls would also write in big, round characters and they added little pictures to their writing, such as hearts, stars, emoticon faces, and letters of the Latin alphabet.[12]

These pictures made the writing very difficult to read.[12] As a result, this writing style caused a lot of controversy and was banned in many schools.[12] During the 1980s, however, this new «cute» writing was adopted by magazines and comics and was often put onto packaging and advertising[12] of products, especially toys for children or “cute accessories”.

From 1984 to 1986, Kazuma Yamane (山根一眞, Yamane Kazuma) studied the development of the cute handwriting (which he called Anomalous Female Teenage Handwriting) in depth.[12] This type of cute Japanese handwriting has also been called: marui ji (丸い字), meaning «round writing», koneko ji (小猫字), meaning «kitten writing», manga ji (漫画字), meaning «comic writing», and burikko ji (鰤子字), meaning «fake-child writing».[13] Although it was commonly thought that the writing style was something that teenagers had picked up from comics, Kazuma found that teenagers had come up with the style themselves, spontaneously, as an ‘underground trend’. His conclusion was based on an observation that cute handwriting predates the availability of technical means for producing rounded writing in comics.[12]

Cute merchandise[edit]

Baby-faced girl characters are rooted in Japanese society

Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, says cute fashion in Japan can be traced back to the Edo period with the popularity of netsuke.[14] Illustrator Rune Naito, who produced illustrations of «large-headed» (nitōshin) baby-faced girls and cartoon animals for Japanese girls’ magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s, is credited with pioneering what would become the culture and aesthetic of kawaii.[15]

Because of this growing trend, companies such as Sanrio came out with merchandise like Hello Kitty. Hello Kitty was an immediate success and the obsession with cute continued to progress in other areas as well. More recently, Sanrio has released kawaii characters with deeper personalities that appeal to an older audience, such as Gudetama and Aggretsuko. These characters have enjoyed strong popularity as fans are drawn to their unique quirks in addition to their cute aesthetics.[16] The 1980s also saw the rise of cute idols, such as Seiko Matsuda, who is largely credited with popularizing the trend. Women began to emulate Seiko Matsuda and her cute fashion style and mannerisms, which emphasized the helplessness and innocence of young girls.[17] The market for cute merchandise in Japan used to be driven by Japanese girls between 15 and 18 years old.[18]

Aesthetics[edit]

Soichi Masubuchi (増淵宗一, Masubuchi Sōichi), in his work Kawaii Syndrome, claims «cute» and «neat» have taken precedence over the former Japanese aesthetics of «beautiful» and «refined».[11] As a cultural phenomenon, cuteness is increasingly accepted in Japan as a part of Japanese culture and national identity. Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, believes that «cuteness» is rooted in Japan’s harmony-loving culture, and Nobuyoshi Kurita (栗田経惟, Kurita Nobuyoshi), a sociology professor at Musashi University in Tokyo, has stated that «cute» is a «magic term» that encompasses everything that is acceptable and desirable in Japan.[19]

Physical attractiveness[edit]

In Japan, being cute is acceptable for both men and women. A trend existed of men shaving their legs to mimic the neotenic look. Japanese women often try to act cute to attract men.[20] A study by Kanebo, a cosmetic company, found that Japanese women in their 20s and 30s favored the «cute look» with a «childish round face».[14] Women also employ a look of innocence in order to further play out this idea of cuteness. Having large eyes is one aspect that exemplifies innocence; therefore many Japanese women attempt to alter the size of their eyes. To create this illusion, women may wear large contact lenses, false eyelashes, dramatic eye makeup, and even have an East Asian blepharoplasty, commonly known as double eyelid surgery.[21]

Idols[edit]

Japanese idols (アイドル, aidoru) are media personalities in their teens and twenties who are considered particularly attractive or cute and who will, for a period ranging from several months to a few years, regularly appear in the mass media, e.g. as singers for pop groups, bit-part actors, TV personalities (tarento), models in photo spreads published in magazines, advertisements, etc. (But not every young celebrity is considered an idol. Young celebrities who wish to cultivate a rebellious image, such as many rock musicians, reject the «idol» label.) Speed, Morning Musume, AKB48, and Momoiro Clover Z are examples of popular idol groups in Japan during the 2000s & 2010s.[22]

Cute fashion[edit]

Lolita[edit]

Lolita fashion is a very well-known and recognizable style in Japan. Based on Victorian fashion and the Rococo period, girls mix in their own elements along with gothic style to achieve the porcelain-doll look.[23] The girls who dress in Lolita fashion try to look cute, innocent, and beautiful.[23] This look is achieved with lace, ribbons, bows, ruffles, bloomers, aprons, and ruffled petticoats. Parasols, chunky Mary Jane heels, and Bo Peep collars are also very popular.[24]

Sweet Lolita is a subset of Lolita fashion that includes even more ribbons, bows, and lace, and is often fabricated out of pastels and other light colors. Head-dresses such as giant bows or bonnets are also very common, while lighter make-up is sometimes used to achieve a more natural look. Curled hair extensions, sometimes accompanied by eyelash extensions, are also popular in helping with the baby doll look.[25] Another subset of Lolita fashion related to «sweet Lolita» is Fairy Kei.

Themes such as fruits, flowers and sweets are often used as patterns on the fabrics used for dresses. Purses often go with the themes and are shaped as hearts, strawberries, or stuffed animals. Baby, the Stars Shine Bright is one of the more popular clothing stores for this style and often carries themes. Mannerisms are also important to many Sweet Lolitas. Sweet Lolita is sometimes not only a fashion, but also a lifestyle.[25] This is evident in the 2004 film Kamikaze Girls where the main Lolita character, Momoko, drinks only tea and eats only sweets.[26]

Gothic Lolita, Kuro Lolita, Shiro Lolita, and Military Lolita are all subtypes, also, in the US Anime Convention scene Casual Lolita.

Decora[edit]

Example of Decora fashion

Decora is a style that is characterized by wearing many «decorations» on oneself. It is considered to be self-decoration. The goal of this fashion is to become as vibrant and characterized as possible. People who take part in this fashion trend wear accessories such as multicolor hair pins, bracelets, rings, necklaces, etc. By adding on multiple layers of accessories on an outfit, the fashion trend tends to have a childlike appearance. It also includes toys and multicolor clothes. Decora and Fairy Kei have some crossover.

Kimo-kawaii

Kimo-kawaii means creepy-cute or gross-cute.[27] The style started around the 1990s when some people lost interest in cute and innocent characters and fashion. It is usually achieved by wearing creepy or gross clothes or accessories.

Kawaii men

Although typically a female-dominated fashion, some men partake in the kawaii trend. Men wearing masculine kawaii accessories is very uncommon, and typically the men cross-dress as kawaii women instead by wearing wigs, false eyelashes, applying makeup, and wearing kawaii female clothing.[28] This is seen predominately in male entertainers, such as Torideta-san, a DJ who transforms himself into a kawaii woman when working at his nightclub.[28]

Japanese pop stars and actors often have longer hair, such as Takuya Kimura of SMAP. Men are also noted as often aspiring to a neotenic look. While it doesn’t quite fit the exact specifications of what cuteness means for females, men are certainly influenced by the same societal mores — to be attractive in a specific sort of way that the society finds acceptable.[29] In this way both Japanese men and women conform to the expectations of Kawaii in some way or another.

Products[edit]

The concept of kawaii has had an influence on a variety of products, including candy, such as Hi-Chew, Koala’s March and Hello Panda. Cuteness can be added to products by adding cute features, such as hearts, flowers, stars and rainbows. Cute elements can be found almost everywhere in Japan, from big business to corner markets and national government, ward, and town offices.[20][30] Many companies, large and small, use cute mascots to present their wares and services to the public. For example:

- Pikachu, a character from Pokémon, adorns the side of ten ANA passenger jets, the Pokémon Jets.

- Asahi Bank used Miffy (Nijntje), a character from a Dutch series of children’s picture books, on some of its ATM and credit cards.

- The prefectures of Japan, as well as many cities and cultural institutions, have cute mascot characters known as yuru-chara to promote tourism. Kumamon, the Kumamoto Prefecture mascot, and Hikonyan, the city of Hikone mascot, are among the most popular.[31]

- The Japan Post «Yū-Pack» mascot is a stylized mailbox;[32] they also use other cute mascot characters to promote their various services (among them the Postal Savings Bank) and have used many such on postage stamps.

- Some police forces in Japan have their own moe mascots, which sometimes adorn the front of kōban (police boxes).

- NHK, the public broadcaster, has its own cute mascots. Domokun, the unique-looking and widely recognized NHK mascot, was introduced in 1998 and quickly took on a life of its own, appearing in Internet memes and fan art around the world.

- Sanrio, the company behind Hello Kitty and other similarly cute characters, runs the Sanrio Puroland theme park in Tokyo, and painted on some EVA Air Airbus A330 jets as well. Sanrio’s line of more than 50 characters takes in more than $1 billion a year and it remains the most successful company to capitalize on the cute trend.[30]

Cute can be also used to describe a specific fashion sense[33][34] of an individual, and generally includes clothing that appears to be made for young children, apart from the size, or clothing that accentuates the cuteness of the individual wearing the clothing. Ruffles and pastel colors are commonly (but not always) featured, and accessories often include toys or bags featuring anime characters.[30]

Non-kawaii imports[edit]

Kawaii goods outlet in 100 yen shop

There have been occasions on which popular Western products failed to meet the expectations of kawaii, and thus did not do well in the Japanese market. For example, Cabbage Patch Kids dolls did not sell well in Japan, because the Japanese considered their facial features to be «ugly» and «grotesque» compared to the flatter and almost featureless faces of characters such as Hello Kitty.[11] Also, the doll Barbie, portraying an adult woman, did not become successful in Japan compared to Takara’s Licca, a doll that was modeled after an 11-year-old girl.[11]

Industry[edit]

Kawaii has gradually gone from a small subculture in Japan to an important part of Japanese modern culture as a whole. An overwhelming number of modern items feature kawaii themes, not only in Japan but also worldwide.[35] And characters associated with kawaii are astoundingly popular. «Global cuteness» is reflected in such billion-dollar sellers as Pokémon and Hello Kitty.[36] «Fueled by Internet subcultures, Hello Kitty alone has hundreds of entries on eBay, and is selling in more than 30 countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, and Taiwan.»[36]

Japan has become a powerhouse in the kawaii industry and images of Doraemon, Hello Kitty, Pikachu, Sailor Moon and Hamtaro are popular in mobile phone accessories. However, Professor Tian Shenliang says that Japan’s future is dependent on how much of an impact kawaii brings to humanity.[37]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry has also recognized the power of cute merchandise and has sent three 18-year-old women overseas in the hopes of spreading Japanese culture around the world. The women dress in uniforms and maid costumes that are commonplace in Japan.[38]

Kawaii manga and magazines have brought tremendous profit to the Japanese press industry.[citation needed] Moreover, the worldwide revenue from the computer game and its merchandising peripherals are closing in on $5 billion, according to a Nintendo press release titled «It’s a Pokémon Planet».[36]

Influence upon other cultures[edit]

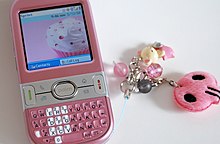

Kawaii keychain accessory attached to a pink Palm Centro smartphone

In recent years, Kawaii products have gained popularity beyond the borders of Japan in other East and Southeast Asian countries, and are additionally becoming more popular in the US among anime and manga fans as well as others influenced by Japanese culture. Cute merchandise and products are especially popular in other parts of East Asia, such as mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as Southeast Asian countries including the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.[30][39]

Sebastian Masuda, owner of 6%DOKIDOKI and a global advocate for kawaii influence, takes the quality from Harajuku to Western markets in his stores and artwork. The underlying belief of this Japanese designer is that «kawaii» actually saves the world.[40] The infusion of kawaii into other world markets and cultures is achieved by introducing kawaii via modern art; audio, visual, and written media; and the fashion trends of Japanese youth, especially in high school girls.[41]

Japanese kawaii seemingly operates as a center of global popularity due to its association with making cultural productions and consumer products «cute». This mindset pursues a global market,[42] giving rise to numerous applications and interpretations in other cultures.

The dissemination of Japanese youth fashion and «kawaii culture» is usually associated with the Western society and trends set by designers borrowed or taken from Japan.[41] With the emergence of China, South Korea and Singapore as global economic centers, the Kawaii merchandise and product popularity has shifted back to the East. In these East Asian and Southeast Asian markets, the kawaii concept takes on various forms and different types of presentation depending on the target audience.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia[edit]

Taiwanese culture, the government in particular, has embraced and elevated kawaii to a new level of social consciousness. The introduction of the A-Bian doll was seen as the development of a symbol to advance democracy and assist in constructing a collective imagination and national identity for Taiwanese people. The A-Bian dolls are kawaii likeness of sports figure, famous individuals, and now political figures that use kawaii images as a means of self-promotion and potential votes.[43] The creation of the A-Bian doll has allowed Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian staffers to create a new culture where the «kawaii» image of a politician can be used to mobilize support and gain election votes.[44]

Japanese popular «kawaii culture» has had an effect on Singaporean youth. The emergence of Japanese culture can be traced back to the mid-1980s when Japan became one of the economic powers in the world. Kawaii has developed from a few children’s television shows to an Internet sensation.[45] Japanese media is used so abundantly in Singapore that youths are more likely to imitate the fashion of their Japanese idols, learn the Japanese language, and continue purchasing Japanese oriented merchandise.[46]

The East Asian countries of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as the Southeast Asian country of Thailand either produce kawaii items for international consumption or have websites that cater for kawaii as part of the youth culture in their country. Kawaii has taken on a life of its own, spawning the formation of kawaii websites, kawaii home pages, kawaii browser themes and finally, kawaii social networking pages. While Japan is the origin and Mecca of all things kawaii, artists and businesses around the world are imitating the kawaii theme.[47]

Kawaii has truly become «greater» than itself. The interconnectedness of today’s world via the Internet has taken kawaii to new heights of exposure and acceptance, producing a kawaii «movement».[47]

The Kawaii concept has become something of a global phenomenon. The aesthetic cuteness of Japan is very appealing to people globally. The wide popularity of Japanese kawaii is often credited with it being «culturally odorless». The elimination of exoticism and national branding has helped kawaii to reach numerous target audiences and span every culture, class, and gender group.[48] The palatable characteristics of kawaii have made it a global hit, resulting in Japan’s global image shifting from being known for austere rock gardens to being known for «cute-worship».[14]

In 2014, the Collins English Dictionary in the United Kingdom entered «kawaii» into its then latest edition, defining it as a «Japanese artistic and cultural style that emphasizes the quality of cuteness, using bright colours and characters with a childlike appearance».[49]

Controversy[edit]

In his book The Power of Cute, Simon May talks about the 180 degree turn in Japan’s history, from the violence of war to kawaii starting around the 1970s, in the works of artists like Takashi Murakami, amongst others. By 1992, kawaii was seen as «the most widely used, widely loved, habitual word in modern living Japanese.»[50] Since then, there has been some controversy surrounding the term kawaii and the expectations of it in Japanese culture. Natalia Konstantinovskaia, in her article “Being Kawaii in Japan”, says that based on the increasing ratio of young Japanese girls that view themselves as kawaii, there is a possibility that “from early childhood, Japanese people are socialized into the expectation that women must be kawaii.”[51] The idea of kawaii can be tricky to balance — if a woman’s interpretation of kawaii seems to have gone too far, she is then labeled as buriko, “a woman who plays bogus innocence.”[51] In the article “Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop”, the authors make the argument that female J-pop singers are expected to be recognizable by their outfits, voice, and mannerisms as kawaii — young and cute. Any woman who becomes a J-pop icon must stay kawaii, or keep her girlishness, rather than being perceived as a woman, even if she is over 18.[52]

Superficial Charm[edit]

Japanese women who feign kawaii behaviors (e.g., high-pitched voice, squealing giggles[53]) that could be viewed as forced or inauthentic are called burikko and this is considered superficial charm.[54] The neologism developed in the 1980s, perhaps originated by comedian Kuniko Yamada (山田邦子, Yamada Kuniko).[54]

See also[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Kawaii.

- Aegyo

- Camp (style)

- Chibi (slang)

- Culture of Japan

- Ingénue

- Kawaii metal, Kawaii bass (Music genre)

- Moe

- Yuru-chara

References[edit]

- ^ The Japanese Self in Cultural Logic Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Takei Sugiyama Libre, c. 2004 University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2840-2, p. 86.

- ^ a b Kerr, Hui-Ying (23 November 2016). «What is kawaii – and why did the world fall for the ‘cult of cute’?» Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, The Conversation.

- ^ «kawaii Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine», Oxford Dictionaries Online.

- ^ Kim, T. Beautiful is an Adjective. Accessed May 7, 2011, from http://www.guidetojapanese.org/adjectives.html Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Okazaki, Manami and Johnson, Geoff (2013). Kawaii!: Japan’s Culture of Cute. Prestel, p. 8.

- ^ Marcus, Aaron, 1943 (2017-10-30). Cuteness engineering : designing adorable products and services. ISBN 9783319619613. OCLC 1008977081.

- ^ Diana Lee, «Inside Look at Japanese Cute Culture Archived 2005-10-25 at the Wayback Machine» (September 1, 2005).

- ^ かわいい. 語源由来辞典 (Dictionary of Etymology) (in Japanese). 5 September 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛い. デジタル大辞泉 (Digital Daijisen) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛いとは. 大辞林第3版(Daijirin 3rd Ed.) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Shiokawa. «Cute But Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics». Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad and Sexy. Ed. John A. Lent. Bowling Green, Kentucky: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999. 93–125. ISBN 0-87972-779-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kinsella, Sharon. 1995. «Cuties in Japan» [1] Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine accessed August 1, 2009.

- ^ Skov, L. (1995). Women, media, and consumption in Japan. Hawai’i Press, USA.

- ^ a b c TheAge.Com: «Japan smitten by love of cute» http://www.theage.com.au/news/people/cool-or-infantile/2006/06/18/1150569208424.html Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ogawa, Takashi (25 December 2019). «Aichi exhibition showcases Rune Naito, pioneer of ‘kawaii’ culture». Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 14 January 2020.[dead link]

- ^ «The New Breed of Kawaii – Characters Who Get Us». UmamiBrain. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ See «(Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness — Japan Forum». Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2009-02-12. URL accessed February 11, 2009.

- ^ Time Asia: Young Japan: She’s a material girl http://www.time.com/time/asia/asia/magazine/1999/990503/style1.html Archived 2001-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quotes and paraphrases from: Yuri Kageyama (June 14, 2006). «Cuteness a hot-selling commodity in Japan». Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Bloomberg Businessweek, «In Japan, Cute Conquers All» Archived 2017-04-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ RiRi, Madame. «Some Japanese customs that may confuse foreigners». Japan Today. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ «Momoiro Clover Z dazzles audiences with shiny messages of hope». The Asahi Shimbun. 2012-08-29. Archived from the original on 2013-10-24.

- ^ a b Fort, Emeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Holson, Laura M. (13 March 2005). «Gothic Lolitas: Demure vs. Dominatrix». The New York Times.

- ^ a b Fort, Emmeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Mitani, Koki (29 May 2004). «Kamikaze Girls». IMDB. Archived from the original on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ^ Michel, Patrick St (2014-04-14). «The Rise of Japan’s Creepy-Cute Craze». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ a b Suzuki, Kirin. «Makeup Changes Men». Tokyo Kawaii, Etc. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Bennette, Colette (18 November 2011). «It’s all Kawaii: Cuteness in Japanese Culture». CNN. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d «Cute Inc». WIRED. December 1999. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ «Top Ten Japanese Character Mascots». Finding Fukuoka. 2012-01-13. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- ^ Japan Post site showing mailbox mascot Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ Time Asia: «Arts: Kwest For Kawaii». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.time.com/time/asia/arts/magazine/0,9754,131022,00.html Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The New Yorker «FACT: SHOPPING REBELLION: What the kids want». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?020318fa_FACT Archived 2002-03-20 at archive.today.

- ^ (Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness Archived 2013-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Roach, Mary. «Cute Inc.» Wired Dec. 1999. 01 May 2005 https://www.wired.com/wired/archive/7.12/cute_pr.html Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 卡哇伊熱潮 扭轉日本文化 Archived 2013-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «日本的»卡哇伊文化»_中国台湾网». Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ «Cute Power!». Newsweek. 7 November 1999. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ (Kataoka, 2010)

- ^ a b Tadao, T. «Dissemination of Japanese Young Fashion and Culture to the World-Enjoyable Japanese Cute (Kawaii) Fashions Spreading to the World and its Meaning». Sen-I Gakkaishi. 66 (7): 223–226.

- ^ Brown, J. (2011). «Re-framing ‘Kawaii’: Interrogating Global Anxieties Surrounding the Aesthetic of ‘Cute’ in Japanese Art and Consumer Products». International Journal of the Image. 1 (2): 1–10. doi:10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v01i02/44194.

- ^ [1]A-Bian Family. http://www.akibo.com.tw/home/gallery/mark/03.htm Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chuang, Y. C. (2011, September). «Kawaii in Taiwan politics». International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, 7(3). 1–16. Retrieved from here Archived 2019-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2]All things Kawaii. http://www.allthingskawaii.net/links/ Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hao, X., Teh, L.L. (2004). «The impact of japanese popular culture on the Singaporean youth». Keio Communication Review, 24. 17–32. Retrieved from: http://www.mediacom.keio.ac.jp/publication/pdf2004/review26/3.pdf Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Rutledge, B. (2010, October). I love kawaii. Ibuki Magazine. 1–2. Retrieved from: http://ibukimagazine.com/lifestyle-/other-trends/212-i-love-kawaii Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shearin, M. (2011, October). Triumph of kawaii. William & Mary ideation. Retrieved from: http://www.wm.edu/research/ideation/ideation-stories-for-borrowing/2011/triumph-of-kawaii5221.php Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Kawaii culture in the UK: Japan’s trend for cute». BBC News. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ May, Simon (2019). The Power of Cute. Princeton University Press. pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b Konstantinovskaia, Natalia (21 July 2017). «Being Kawaii in Japan». UCLA Study for the Center of Women.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Keith, Sarah; Hughes, Diane (December 2016). «Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop: Hughes and Keith». Journal of Popular Music Studies. 28 (4): 474–487. doi:10.1111/jpms.12195.

- ^ Merry White (29 September 1994). The material child: coming of age in Japan and America. University of California Press. pp. 129. ISBN 978-0-520-08940-2. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b «You are doing urikko!: Censoring/scrutinizing artificers of cute femininity in Japanese,» Laura Miller in Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People, edited by Janet Shibamoto Smith and Shigeko Okamoto, Oxford University Press, 2004. In Japanese.

Further reading[edit]

- Harris, Daniel (2001). Cute, quaint, hungry, and romantic: the aesthetics of consumerism. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo. ISBN 9780306810473.

- Brehm, Margrit, ed. (2002). The Japanese experience: inevitable. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany New York, New York: Hatje Cantz; Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 9783775712545.

- Cross, Gary (2004). The cute and the cool: wondrous innocence and modern American children’s culture. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195156669.

- Carpi, Giancarlo (2012). Gabriels and the Italian cute nymphet. Milan: Mazzotta. ISBN 9788820219932.

- Nittono, Hiroshi; Fukushima, Michiko; Yano, Akihiro; Moriya, Hiroki (September 2012). «The power of kawaii: viewing cute images promotes a careful behavior and narrows attentional focus». PLOS One. 7 (9): e46362. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…746362N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046362. PMC 3458879. PMID 23050022.

- Asano-Cavanagh, Yuko (October 2014). «Linguistic manifestation of gender reinforcement through the use of the Japanese term kawaii». Gender and Language. 8 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1558/genl.v8i3.341.

- Ohkura, Michiko (2019). Kawaii Engineering. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 9789811379642.

Kawaii (Japanese: かわいい or 可愛い, IPA: [kawaiꜜi]; ‘lovely’, ‘loveable’, ‘cute’, or ‘adorable’)[1] is the culture of cuteness in Japan.[2][3][4] It can refer to items, humans and non-humans that are charming, vulnerable, shy and childlike.[2] Examples include cute handwriting, certain genres of manga, anime, and characters including Hello Kitty and Pikachu from Pokémon.[5][6]

The cuteness culture, or kawaii aesthetic, has become a prominent aspect of Japanese popular culture, entertainment, clothing, food, toys, personal appearance, and mannerisms.[7]

Etymology[edit]

The word kawaii originally derives from the phrase 顔映し kao hayushi, which literally means «(one’s) face (is) aglow,» commonly used to refer to flushing or blushing of the face. The second morpheme is cognate with -bayu in mabayui (眩い, 目映い, or 目映ゆい) «dazzling, glaring, blinding, too bright; dazzlingly beautiful» (ma- is from 目 me «eye») and -hayu in omohayui (面映い or 面映ゆい) «embarrassed/embarrassing, awkward, feeling self-conscious/making one feel self-conscious» (omo- is from 面 omo, an archaic word for «face, looks, features; surface; image, semblance, vestige»). Over time, the meaning changed into the modern meaning of «cute» or «shine» , and the pronunciation changed to かわゆい kawayui and then to the modern かわいい kawaii.[8][9][10] It is commonly written in hiragana, かわいい, but the ateji, 可愛い, has also been used. The kanji in the ateji literally translates to «able to love/be loved, can/may love, lovable.»

History[edit]

Original definition[edit]

Kogal girl, identified by her shortened skirt. The soft bag and teddy bear that she carries are part of kawaii.

The original definition of kawaii came from Lady Murasaki’s 11th century novel The Tale of Genji, where it referred to pitiable qualities.[11] During the Shogunate period[when?] under the ideology of neo-Confucianism, women came to be included under the term kawaii as the perception of women being animalistic was replaced with the conception of women as docile.[11] However, the earlier meaning survives into the modern Standard Japanese adjectival noun かわいそう kawaisō (often written with ateji as 可哀相 or 可哀想) «piteous, pitiable, arousing compassion, poor, sad, sorry» (etymologically from 顔映様 «face / projecting, reflecting, or transmitting light, flushing, blushing / seeming, appearance»). Forms of kawaii and its derivatives kawaisō and kawairashii (with the suffix -rashii «-like, -ly») are used in modern dialects to mean «embarrassing/embarrassed, shameful/ashamed» or «good, nice, fine, excellent, superb, splendid, admirable» in addition to the standard meanings of «adorable» and «pitiable.»

Cute handwriting[edit]

In the 1970s, the popularity of the kawaii aesthetic inspired a style of writing.[12] Many teenage girls participated in this style; the handwriting was made by writing laterally, often while using mechanical pencils.[12] These pencils produced very fine lines, as opposed to traditional Japanese writing that varied in thickness and was vertical.[12] The girls would also write in big, round characters and they added little pictures to their writing, such as hearts, stars, emoticon faces, and letters of the Latin alphabet.[12]

These pictures made the writing very difficult to read.[12] As a result, this writing style caused a lot of controversy and was banned in many schools.[12] During the 1980s, however, this new «cute» writing was adopted by magazines and comics and was often put onto packaging and advertising[12] of products, especially toys for children or “cute accessories”.

From 1984 to 1986, Kazuma Yamane (山根一眞, Yamane Kazuma) studied the development of the cute handwriting (which he called Anomalous Female Teenage Handwriting) in depth.[12] This type of cute Japanese handwriting has also been called: marui ji (丸い字), meaning «round writing», koneko ji (小猫字), meaning «kitten writing», manga ji (漫画字), meaning «comic writing», and burikko ji (鰤子字), meaning «fake-child writing».[13] Although it was commonly thought that the writing style was something that teenagers had picked up from comics, Kazuma found that teenagers had come up with the style themselves, spontaneously, as an ‘underground trend’. His conclusion was based on an observation that cute handwriting predates the availability of technical means for producing rounded writing in comics.[12]

Cute merchandise[edit]

Baby-faced girl characters are rooted in Japanese society

Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, says cute fashion in Japan can be traced back to the Edo period with the popularity of netsuke.[14] Illustrator Rune Naito, who produced illustrations of «large-headed» (nitōshin) baby-faced girls and cartoon animals for Japanese girls’ magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s, is credited with pioneering what would become the culture and aesthetic of kawaii.[15]

Because of this growing trend, companies such as Sanrio came out with merchandise like Hello Kitty. Hello Kitty was an immediate success and the obsession with cute continued to progress in other areas as well. More recently, Sanrio has released kawaii characters with deeper personalities that appeal to an older audience, such as Gudetama and Aggretsuko. These characters have enjoyed strong popularity as fans are drawn to their unique quirks in addition to their cute aesthetics.[16] The 1980s also saw the rise of cute idols, such as Seiko Matsuda, who is largely credited with popularizing the trend. Women began to emulate Seiko Matsuda and her cute fashion style and mannerisms, which emphasized the helplessness and innocence of young girls.[17] The market for cute merchandise in Japan used to be driven by Japanese girls between 15 and 18 years old.[18]

Aesthetics[edit]

Soichi Masubuchi (増淵宗一, Masubuchi Sōichi), in his work Kawaii Syndrome, claims «cute» and «neat» have taken precedence over the former Japanese aesthetics of «beautiful» and «refined».[11] As a cultural phenomenon, cuteness is increasingly accepted in Japan as a part of Japanese culture and national identity. Tomoyuki Sugiyama (杉山奉文, Sugiyama Tomoyuki), author of Cool Japan, believes that «cuteness» is rooted in Japan’s harmony-loving culture, and Nobuyoshi Kurita (栗田経惟, Kurita Nobuyoshi), a sociology professor at Musashi University in Tokyo, has stated that «cute» is a «magic term» that encompasses everything that is acceptable and desirable in Japan.[19]

Physical attractiveness[edit]

In Japan, being cute is acceptable for both men and women. A trend existed of men shaving their legs to mimic the neotenic look. Japanese women often try to act cute to attract men.[20] A study by Kanebo, a cosmetic company, found that Japanese women in their 20s and 30s favored the «cute look» with a «childish round face».[14] Women also employ a look of innocence in order to further play out this idea of cuteness. Having large eyes is one aspect that exemplifies innocence; therefore many Japanese women attempt to alter the size of their eyes. To create this illusion, women may wear large contact lenses, false eyelashes, dramatic eye makeup, and even have an East Asian blepharoplasty, commonly known as double eyelid surgery.[21]

Idols[edit]

Japanese idols (アイドル, aidoru) are media personalities in their teens and twenties who are considered particularly attractive or cute and who will, for a period ranging from several months to a few years, regularly appear in the mass media, e.g. as singers for pop groups, bit-part actors, TV personalities (tarento), models in photo spreads published in magazines, advertisements, etc. (But not every young celebrity is considered an idol. Young celebrities who wish to cultivate a rebellious image, such as many rock musicians, reject the «idol» label.) Speed, Morning Musume, AKB48, and Momoiro Clover Z are examples of popular idol groups in Japan during the 2000s & 2010s.[22]

Cute fashion[edit]

Lolita[edit]

Lolita fashion is a very well-known and recognizable style in Japan. Based on Victorian fashion and the Rococo period, girls mix in their own elements along with gothic style to achieve the porcelain-doll look.[23] The girls who dress in Lolita fashion try to look cute, innocent, and beautiful.[23] This look is achieved with lace, ribbons, bows, ruffles, bloomers, aprons, and ruffled petticoats. Parasols, chunky Mary Jane heels, and Bo Peep collars are also very popular.[24]

Sweet Lolita is a subset of Lolita fashion that includes even more ribbons, bows, and lace, and is often fabricated out of pastels and other light colors. Head-dresses such as giant bows or bonnets are also very common, while lighter make-up is sometimes used to achieve a more natural look. Curled hair extensions, sometimes accompanied by eyelash extensions, are also popular in helping with the baby doll look.[25] Another subset of Lolita fashion related to «sweet Lolita» is Fairy Kei.

Themes such as fruits, flowers and sweets are often used as patterns on the fabrics used for dresses. Purses often go with the themes and are shaped as hearts, strawberries, or stuffed animals. Baby, the Stars Shine Bright is one of the more popular clothing stores for this style and often carries themes. Mannerisms are also important to many Sweet Lolitas. Sweet Lolita is sometimes not only a fashion, but also a lifestyle.[25] This is evident in the 2004 film Kamikaze Girls where the main Lolita character, Momoko, drinks only tea and eats only sweets.[26]

Gothic Lolita, Kuro Lolita, Shiro Lolita, and Military Lolita are all subtypes, also, in the US Anime Convention scene Casual Lolita.

Decora[edit]

Example of Decora fashion

Decora is a style that is characterized by wearing many «decorations» on oneself. It is considered to be self-decoration. The goal of this fashion is to become as vibrant and characterized as possible. People who take part in this fashion trend wear accessories such as multicolor hair pins, bracelets, rings, necklaces, etc. By adding on multiple layers of accessories on an outfit, the fashion trend tends to have a childlike appearance. It also includes toys and multicolor clothes. Decora and Fairy Kei have some crossover.

Kimo-kawaii

Kimo-kawaii means creepy-cute or gross-cute.[27] The style started around the 1990s when some people lost interest in cute and innocent characters and fashion. It is usually achieved by wearing creepy or gross clothes or accessories.

Kawaii men

Although typically a female-dominated fashion, some men partake in the kawaii trend. Men wearing masculine kawaii accessories is very uncommon, and typically the men cross-dress as kawaii women instead by wearing wigs, false eyelashes, applying makeup, and wearing kawaii female clothing.[28] This is seen predominately in male entertainers, such as Torideta-san, a DJ who transforms himself into a kawaii woman when working at his nightclub.[28]

Japanese pop stars and actors often have longer hair, such as Takuya Kimura of SMAP. Men are also noted as often aspiring to a neotenic look. While it doesn’t quite fit the exact specifications of what cuteness means for females, men are certainly influenced by the same societal mores — to be attractive in a specific sort of way that the society finds acceptable.[29] In this way both Japanese men and women conform to the expectations of Kawaii in some way or another.

Products[edit]

The concept of kawaii has had an influence on a variety of products, including candy, such as Hi-Chew, Koala’s March and Hello Panda. Cuteness can be added to products by adding cute features, such as hearts, flowers, stars and rainbows. Cute elements can be found almost everywhere in Japan, from big business to corner markets and national government, ward, and town offices.[20][30] Many companies, large and small, use cute mascots to present their wares and services to the public. For example:

- Pikachu, a character from Pokémon, adorns the side of ten ANA passenger jets, the Pokémon Jets.

- Asahi Bank used Miffy (Nijntje), a character from a Dutch series of children’s picture books, on some of its ATM and credit cards.

- The prefectures of Japan, as well as many cities and cultural institutions, have cute mascot characters known as yuru-chara to promote tourism. Kumamon, the Kumamoto Prefecture mascot, and Hikonyan, the city of Hikone mascot, are among the most popular.[31]

- The Japan Post «Yū-Pack» mascot is a stylized mailbox;[32] they also use other cute mascot characters to promote their various services (among them the Postal Savings Bank) and have used many such on postage stamps.

- Some police forces in Japan have their own moe mascots, which sometimes adorn the front of kōban (police boxes).

- NHK, the public broadcaster, has its own cute mascots. Domokun, the unique-looking and widely recognized NHK mascot, was introduced in 1998 and quickly took on a life of its own, appearing in Internet memes and fan art around the world.

- Sanrio, the company behind Hello Kitty and other similarly cute characters, runs the Sanrio Puroland theme park in Tokyo, and painted on some EVA Air Airbus A330 jets as well. Sanrio’s line of more than 50 characters takes in more than $1 billion a year and it remains the most successful company to capitalize on the cute trend.[30]

Cute can be also used to describe a specific fashion sense[33][34] of an individual, and generally includes clothing that appears to be made for young children, apart from the size, or clothing that accentuates the cuteness of the individual wearing the clothing. Ruffles and pastel colors are commonly (but not always) featured, and accessories often include toys or bags featuring anime characters.[30]

Non-kawaii imports[edit]

Kawaii goods outlet in 100 yen shop

There have been occasions on which popular Western products failed to meet the expectations of kawaii, and thus did not do well in the Japanese market. For example, Cabbage Patch Kids dolls did not sell well in Japan, because the Japanese considered their facial features to be «ugly» and «grotesque» compared to the flatter and almost featureless faces of characters such as Hello Kitty.[11] Also, the doll Barbie, portraying an adult woman, did not become successful in Japan compared to Takara’s Licca, a doll that was modeled after an 11-year-old girl.[11]

Industry[edit]

Kawaii has gradually gone from a small subculture in Japan to an important part of Japanese modern culture as a whole. An overwhelming number of modern items feature kawaii themes, not only in Japan but also worldwide.[35] And characters associated with kawaii are astoundingly popular. «Global cuteness» is reflected in such billion-dollar sellers as Pokémon and Hello Kitty.[36] «Fueled by Internet subcultures, Hello Kitty alone has hundreds of entries on eBay, and is selling in more than 30 countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, and Taiwan.»[36]

Japan has become a powerhouse in the kawaii industry and images of Doraemon, Hello Kitty, Pikachu, Sailor Moon and Hamtaro are popular in mobile phone accessories. However, Professor Tian Shenliang says that Japan’s future is dependent on how much of an impact kawaii brings to humanity.[37]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry has also recognized the power of cute merchandise and has sent three 18-year-old women overseas in the hopes of spreading Japanese culture around the world. The women dress in uniforms and maid costumes that are commonplace in Japan.[38]

Kawaii manga and magazines have brought tremendous profit to the Japanese press industry.[citation needed] Moreover, the worldwide revenue from the computer game and its merchandising peripherals are closing in on $5 billion, according to a Nintendo press release titled «It’s a Pokémon Planet».[36]

Influence upon other cultures[edit]

Kawaii keychain accessory attached to a pink Palm Centro smartphone

In recent years, Kawaii products have gained popularity beyond the borders of Japan in other East and Southeast Asian countries, and are additionally becoming more popular in the US among anime and manga fans as well as others influenced by Japanese culture. Cute merchandise and products are especially popular in other parts of East Asia, such as mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as Southeast Asian countries including the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.[30][39]

Sebastian Masuda, owner of 6%DOKIDOKI and a global advocate for kawaii influence, takes the quality from Harajuku to Western markets in his stores and artwork. The underlying belief of this Japanese designer is that «kawaii» actually saves the world.[40] The infusion of kawaii into other world markets and cultures is achieved by introducing kawaii via modern art; audio, visual, and written media; and the fashion trends of Japanese youth, especially in high school girls.[41]

Japanese kawaii seemingly operates as a center of global popularity due to its association with making cultural productions and consumer products «cute». This mindset pursues a global market,[42] giving rise to numerous applications and interpretations in other cultures.

The dissemination of Japanese youth fashion and «kawaii culture» is usually associated with the Western society and trends set by designers borrowed or taken from Japan.[41] With the emergence of China, South Korea and Singapore as global economic centers, the Kawaii merchandise and product popularity has shifted back to the East. In these East Asian and Southeast Asian markets, the kawaii concept takes on various forms and different types of presentation depending on the target audience.

In East Asia and Southeast Asia[edit]

Taiwanese culture, the government in particular, has embraced and elevated kawaii to a new level of social consciousness. The introduction of the A-Bian doll was seen as the development of a symbol to advance democracy and assist in constructing a collective imagination and national identity for Taiwanese people. The A-Bian dolls are kawaii likeness of sports figure, famous individuals, and now political figures that use kawaii images as a means of self-promotion and potential votes.[43] The creation of the A-Bian doll has allowed Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian staffers to create a new culture where the «kawaii» image of a politician can be used to mobilize support and gain election votes.[44]

Japanese popular «kawaii culture» has had an effect on Singaporean youth. The emergence of Japanese culture can be traced back to the mid-1980s when Japan became one of the economic powers in the world. Kawaii has developed from a few children’s television shows to an Internet sensation.[45] Japanese media is used so abundantly in Singapore that youths are more likely to imitate the fashion of their Japanese idols, learn the Japanese language, and continue purchasing Japanese oriented merchandise.[46]

The East Asian countries of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea, as well as the Southeast Asian country of Thailand either produce kawaii items for international consumption or have websites that cater for kawaii as part of the youth culture in their country. Kawaii has taken on a life of its own, spawning the formation of kawaii websites, kawaii home pages, kawaii browser themes and finally, kawaii social networking pages. While Japan is the origin and Mecca of all things kawaii, artists and businesses around the world are imitating the kawaii theme.[47]

Kawaii has truly become «greater» than itself. The interconnectedness of today’s world via the Internet has taken kawaii to new heights of exposure and acceptance, producing a kawaii «movement».[47]

The Kawaii concept has become something of a global phenomenon. The aesthetic cuteness of Japan is very appealing to people globally. The wide popularity of Japanese kawaii is often credited with it being «culturally odorless». The elimination of exoticism and national branding has helped kawaii to reach numerous target audiences and span every culture, class, and gender group.[48] The palatable characteristics of kawaii have made it a global hit, resulting in Japan’s global image shifting from being known for austere rock gardens to being known for «cute-worship».[14]

In 2014, the Collins English Dictionary in the United Kingdom entered «kawaii» into its then latest edition, defining it as a «Japanese artistic and cultural style that emphasizes the quality of cuteness, using bright colours and characters with a childlike appearance».[49]

Controversy[edit]

In his book The Power of Cute, Simon May talks about the 180 degree turn in Japan’s history, from the violence of war to kawaii starting around the 1970s, in the works of artists like Takashi Murakami, amongst others. By 1992, kawaii was seen as «the most widely used, widely loved, habitual word in modern living Japanese.»[50] Since then, there has been some controversy surrounding the term kawaii and the expectations of it in Japanese culture. Natalia Konstantinovskaia, in her article “Being Kawaii in Japan”, says that based on the increasing ratio of young Japanese girls that view themselves as kawaii, there is a possibility that “from early childhood, Japanese people are socialized into the expectation that women must be kawaii.”[51] The idea of kawaii can be tricky to balance — if a woman’s interpretation of kawaii seems to have gone too far, she is then labeled as buriko, “a woman who plays bogus innocence.”[51] In the article “Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop”, the authors make the argument that female J-pop singers are expected to be recognizable by their outfits, voice, and mannerisms as kawaii — young and cute. Any woman who becomes a J-pop icon must stay kawaii, or keep her girlishness, rather than being perceived as a woman, even if she is over 18.[52]

Superficial Charm[edit]

Japanese women who feign kawaii behaviors (e.g., high-pitched voice, squealing giggles[53]) that could be viewed as forced or inauthentic are called burikko and this is considered superficial charm.[54] The neologism developed in the 1980s, perhaps originated by comedian Kuniko Yamada (山田邦子, Yamada Kuniko).[54]

See also[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Kawaii.

- Aegyo

- Camp (style)

- Chibi (slang)

- Culture of Japan

- Ingénue

- Kawaii metal, Kawaii bass (Music genre)

- Moe

- Yuru-chara

References[edit]

- ^ The Japanese Self in Cultural Logic Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Takei Sugiyama Libre, c. 2004 University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2840-2, p. 86.

- ^ a b Kerr, Hui-Ying (23 November 2016). «What is kawaii – and why did the world fall for the ‘cult of cute’?» Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, The Conversation.

- ^ «kawaii Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine», Oxford Dictionaries Online.

- ^ Kim, T. Beautiful is an Adjective. Accessed May 7, 2011, from http://www.guidetojapanese.org/adjectives.html Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Okazaki, Manami and Johnson, Geoff (2013). Kawaii!: Japan’s Culture of Cute. Prestel, p. 8.

- ^ Marcus, Aaron, 1943 (2017-10-30). Cuteness engineering : designing adorable products and services. ISBN 9783319619613. OCLC 1008977081.

- ^ Diana Lee, «Inside Look at Japanese Cute Culture Archived 2005-10-25 at the Wayback Machine» (September 1, 2005).

- ^ かわいい. 語源由来辞典 (Dictionary of Etymology) (in Japanese). 5 September 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛い. デジタル大辞泉 (Digital Daijisen) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ 可愛いとは. 大辞林第3版(Daijirin 3rd Ed.) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Shiokawa. «Cute But Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics». Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad and Sexy. Ed. John A. Lent. Bowling Green, Kentucky: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999. 93–125. ISBN 0-87972-779-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kinsella, Sharon. 1995. «Cuties in Japan» [1] Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine accessed August 1, 2009.

- ^ Skov, L. (1995). Women, media, and consumption in Japan. Hawai’i Press, USA.

- ^ a b c TheAge.Com: «Japan smitten by love of cute» http://www.theage.com.au/news/people/cool-or-infantile/2006/06/18/1150569208424.html Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ogawa, Takashi (25 December 2019). «Aichi exhibition showcases Rune Naito, pioneer of ‘kawaii’ culture». Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 14 January 2020.[dead link]

- ^ «The New Breed of Kawaii – Characters Who Get Us». UmamiBrain. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ See «(Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness — Japan Forum». Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2009-02-12. URL accessed February 11, 2009.

- ^ Time Asia: Young Japan: She’s a material girl http://www.time.com/time/asia/asia/magazine/1999/990503/style1.html Archived 2001-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quotes and paraphrases from: Yuri Kageyama (June 14, 2006). «Cuteness a hot-selling commodity in Japan». Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Bloomberg Businessweek, «In Japan, Cute Conquers All» Archived 2017-04-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ RiRi, Madame. «Some Japanese customs that may confuse foreigners». Japan Today. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ «Momoiro Clover Z dazzles audiences with shiny messages of hope». The Asahi Shimbun. 2012-08-29. Archived from the original on 2013-10-24.

- ^ a b Fort, Emeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Holson, Laura M. (13 March 2005). «Gothic Lolitas: Demure vs. Dominatrix». The New York Times.

- ^ a b Fort, Emmeline (2010). A Guide to Japanese Street Fashion. 6 Degrees.

- ^ Mitani, Koki (29 May 2004). «Kamikaze Girls». IMDB. Archived from the original on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ^ Michel, Patrick St (2014-04-14). «The Rise of Japan’s Creepy-Cute Craze». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ a b Suzuki, Kirin. «Makeup Changes Men». Tokyo Kawaii, Etc. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Bennette, Colette (18 November 2011). «It’s all Kawaii: Cuteness in Japanese Culture». CNN. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d «Cute Inc». WIRED. December 1999. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ «Top Ten Japanese Character Mascots». Finding Fukuoka. 2012-01-13. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- ^ Japan Post site showing mailbox mascot Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ Time Asia: «Arts: Kwest For Kawaii». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.time.com/time/asia/arts/magazine/0,9754,131022,00.html Archived 2006-02-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The New Yorker «FACT: SHOPPING REBELLION: What the kids want». Retrieved on 2006-04-19 from http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?020318fa_FACT Archived 2002-03-20 at archive.today.

- ^ (Research Paper) Kawaii: Culture of Cuteness Archived 2013-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Roach, Mary. «Cute Inc.» Wired Dec. 1999. 01 May 2005 https://www.wired.com/wired/archive/7.12/cute_pr.html Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 卡哇伊熱潮 扭轉日本文化 Archived 2013-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «日本的»卡哇伊文化»_中国台湾网». Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ «Cute Power!». Newsweek. 7 November 1999. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ (Kataoka, 2010)

- ^ a b Tadao, T. «Dissemination of Japanese Young Fashion and Culture to the World-Enjoyable Japanese Cute (Kawaii) Fashions Spreading to the World and its Meaning». Sen-I Gakkaishi. 66 (7): 223–226.

- ^ Brown, J. (2011). «Re-framing ‘Kawaii’: Interrogating Global Anxieties Surrounding the Aesthetic of ‘Cute’ in Japanese Art and Consumer Products». International Journal of the Image. 1 (2): 1–10. doi:10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v01i02/44194.

- ^ [1]A-Bian Family. http://www.akibo.com.tw/home/gallery/mark/03.htm Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chuang, Y. C. (2011, September). «Kawaii in Taiwan politics». International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, 7(3). 1–16. Retrieved from here Archived 2019-05-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2]All things Kawaii. http://www.allthingskawaii.net/links/ Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hao, X., Teh, L.L. (2004). «The impact of japanese popular culture on the Singaporean youth». Keio Communication Review, 24. 17–32. Retrieved from: http://www.mediacom.keio.ac.jp/publication/pdf2004/review26/3.pdf Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Rutledge, B. (2010, October). I love kawaii. Ibuki Magazine. 1–2. Retrieved from: http://ibukimagazine.com/lifestyle-/other-trends/212-i-love-kawaii Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shearin, M. (2011, October). Triumph of kawaii. William & Mary ideation. Retrieved from: http://www.wm.edu/research/ideation/ideation-stories-for-borrowing/2011/triumph-of-kawaii5221.php Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Kawaii culture in the UK: Japan’s trend for cute». BBC News. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ May, Simon (2019). The Power of Cute. Princeton University Press. pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b Konstantinovskaia, Natalia (21 July 2017). «Being Kawaii in Japan». UCLA Study for the Center of Women.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Keith, Sarah; Hughes, Diane (December 2016). «Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ voices in J-pop: Hughes and Keith». Journal of Popular Music Studies. 28 (4): 474–487. doi:10.1111/jpms.12195.

- ^ Merry White (29 September 1994). The material child: coming of age in Japan and America. University of California Press. pp. 129. ISBN 978-0-520-08940-2. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b «You are doing urikko!: Censoring/scrutinizing artificers of cute femininity in Japanese,» Laura Miller in Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People, edited by Janet Shibamoto Smith and Shigeko Okamoto, Oxford University Press, 2004. In Japanese.

Further reading[edit]

- Harris, Daniel (2001). Cute, quaint, hungry, and romantic: the aesthetics of consumerism. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo. ISBN 9780306810473.

- Brehm, Margrit, ed. (2002). The Japanese experience: inevitable. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany New York, New York: Hatje Cantz; Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 9783775712545.

- Cross, Gary (2004). The cute and the cool: wondrous innocence and modern American children’s culture. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195156669.

- Carpi, Giancarlo (2012). Gabriels and the Italian cute nymphet. Milan: Mazzotta. ISBN 9788820219932.

- Nittono, Hiroshi; Fukushima, Michiko; Yano, Akihiro; Moriya, Hiroki (September 2012). «The power of kawaii: viewing cute images promotes a careful behavior and narrows attentional focus». PLOS One. 7 (9): e46362. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…746362N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046362. PMC 3458879. PMID 23050022.

- Asano-Cavanagh, Yuko (October 2014). «Linguistic manifestation of gender reinforcement through the use of the Japanese term kawaii». Gender and Language. 8 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1558/genl.v8i3.341.

- Ohkura, Michiko (2019). Kawaii Engineering. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 9789811379642.

かわいい (kawaii)

Надо отметить, что не так давно это слово могли использовать только по отношению к животным или детям, а женщины стеснялись употреблять это слово в разговоре со старшими или с людьми более высокого социального статуса. Возможно, это связано с тем, что раньше японское общество было нацелено на экономический рост, и японское общество ожидало от мужчин и женщин зрелого поведения. Сейчас, как мы знаем, японская экономика занимает второе место в мире, и старые поведенческие стереотипы разрушаются. На сегодняшний день в обществе существует совсем другой идеал – оставаться молодым как можно дольше.

P.S. Есть очень интересное и емкое слово — кимокаваий – сокращение фразы «кимоти варуи кэдо, каваий», означающей «странный (дурацкий), но славный». «Кимоти варуи» — это полная противоположность слова «каваий», но если что-то странное и непонятное вызывает симпатию, эти слова могут быть сгруппированы с прилагательным «каваий».

Хотите выучить 400 японских слов за 21 день? Вам сюда!

Каваий[1] (яп. 可愛い?) — японское слово, означающее «милый», «прелестный», «хорошенький»[1], «славный», «любезный». Это субъективное определение может описывать любой объект, который индивидуум сочтёт прелестным.