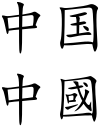

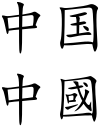

Иероглиф:

中国

Транскрипция (пиньинь):

zhōngguó

Перевод:

Китай; китайский

Написание традиционными иероглифами:

中國

Таблица соответствия иероглифов:

| Упрощенные | Традиционные |

|---|---|

| 国 | 國 |

- Произношение ►

Примеры использования 中国

如今中国的小皇帝越来越多,这将成为中国未来的一个社会问题。

rújīn zhōngguó de xiǎo huángdì yuè lái yuè duō, zhè jiāng chéngwéi zhōngguó wèilái de yīgè shèhuì wèntí.

В настоящее время в Китае все больше и больше маленьких императоров. В будущем это станет социальной проблемой.

我不知道中国的尺寸。

wǒ bù zhīdào zhōngguó de chǐcùn.

Я не знаю китайских размеров.

您能介绍几个好吃的中国菜吗?

nín néng jièshào jǐ gè hào chī de zhōngguó cài ma?

Вы могли бы порекомендовать нам какие-нибудь вкусные китайские блюда?

请问,去中国银行怎么坐车?

qǐngwèn, qù zhōngguó yínháng zěnme zuòchē?

Простите, какой автобус идет до Банка Китая?

我来中国工作。

wǒ lái zhōngguó gōngzuò.

Я приехал на работу / по делу.

谢谢,你可以入境了。欢迎来中国!

xièxiè, nǐ kěyǐ rùjìngle. huānyíng lái zhōngguó!

Спасибо. Теперь вы можете въехать в страну. Добро пожаловать в Китай!

是的,我去过中国的很多地方。

shì de, wǒ qùguò zhōngguó de hěnduō dìfāng.

Да, я объездил много мест в Китае.

| China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«China» in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōngguó | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Middle or Central State[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōnghuá | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་གོ་ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cungguek | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭگو | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai gurun |

The names of China include the many contemporary and historical appellations given in various languages for the East Asian country known as Zhōngguó (中國/中国, «middle country») in its national language, Standard Mandarin. China, the name in English for the country, was derived from Portuguese in the 16th century, and became common usage in the West in the subsequent centuries.[2] It is believed to be a borrowing from Middle Persian, and some have traced it further back to Sanskrit. It is also thought that the ultimate source of the name China is the Chinese word «Qin» (Chinese: 秦), the name of the dynasty that unified China but also existed as a state for many centuries prior. There are, however, other alternative suggestions for the origin of the word.

Chinese names for China, aside from Zhongguo, include Zhōnghuá (中華/中华, «central beauty»), Huáxià (華夏/华夏, «beautiful grandness»), Shénzhōu (神州, «divine state») and Jiǔzhōu (九州, «nine states»). Hàn (漢/汉) and Táng (唐) are common names given for the Chinese ethnicity, despite the Chinese nationality (Zhōnghuá Mínzú) not referencing any singular ethnicity. The People’s Republic of China (Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó) and Republic of China (Zhōnghuá Mínguó) are the official names for the two contemporary sovereign states currently claiming sovereignty over the traditional area of China. «Mainland China» is used to refer to areas under the jurisdiction of the PRC, usually excluding Hong Kong and Macau.

There are also names for China used around the world that are derived from the languages of ethnic groups other than the Han; examples include «Cathay» from the Khitan language and «Tabgach» from Tuoba.

Sinitic names[edit]

Zhongguo[edit]

Pre-Qing[edit]

The brocade armband with the words «Five stars rising in the east, being a propitious sign for Zhongguo (中國)», made in the Han dynasty.

The Nestorian Stele 大秦景教流行中國碑 entitled «Stele to the propagation in Zhongguo (中國) of the luminous religion of Daqin (Roman Empire)», was erected in China in 781 during Tang dynasty.

The most important Korean document, Hunminjeongeum, dated 1446, where it compares Joseon’s speech to that of Zhongguo (中國) (Middle Kingdom; China), which was during the reign of Ming dynasty at the time. Korean and other neighbouring societies have addressed the various regimes and dynasties on the Chinese mainland at differing times as the «Middle Kingdom».

Zhōngguó (中國) is the most common Chinese name for China in modern times. The earliest appearance of this two-character term is on the bronze vessel He zun (dating to 1038–c. 1000 BCE), during the early Western Zhou period. The phrase «zhong guo» came into common usage in the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), when it referred to the «Central States»; the states of the Yellow River Valley of the Zhou era, as distinguished from the tribal periphery.[3] In later periods, however, Zhongguo was not used in this sense. Dynastic names were used for the state in Imperial China and concepts of the state aside from the ruling dynasty were little understood.[2] Rather, the country was called by the name of the dynasty, such as «Han» (漢), «Tang» (唐), «Great Ming» (Da Ming 大明), «Great Qing» (Da Qing 大清), as the case might be. Until the 19th century when the international system came to require a common legal language, there was no need for a fixed or unique name.[4]

As early as the Spring and Autumn period, Zhongguo could be understood as either the domain of the capital or used to refer the Chinese civilization (zhuxia 諸夏 «the various Xia»[5][6] or zhuhua 諸華 «various Hua»[7][8]), and the political and geographical domain that contained it, but Tianxia was the more common word for this idea. This developed into the usage of the Warring States period when, other than the cultural-civilizational community, it could be the geopolitical area of Chinese civilization, equivalent to Jiuzhou. In a more limited sense it could also refer to the Central Plain or the states of Zhao, Wei, and Han, etc., geographically central amongst the Warring States.[9] Although Zhongguo could be used before the Song dynasty period to mean the transdynastic Chinese culture or civilization to which Chinese people belonged, it was in the Song dynasty when writers used Zhongguo as a term to describe the transdynastic entity with different dynastic names over time but having a set territory and defined by common ancestry, culture, and language.[10]

There were different usages of the term Zhongguo in every period. It could refer to the capital of the emperor to distinguish it from the capitals of his vassals, as in Western Zhou. It could refer to the states of the Central Plain to distinguish them from states in outer regions. The Shi Jing defines Zhongguo as the capital region, setting it in apposition to the capital city.[11][12] During the Han dynasty, three usages of Zhongguo were common. The Records of the Grand Historian uses Zhongguo to denote the capital,[13][14] and also uses the concept zhong («center, central») and zhongguo to indicate the center of civilization: «There are eight famous mountains in the world: three in Man and Yi (the barbarian wilds), five in Zhōngguó.» (天下名山八,而三在蠻夷,五在中國。)[15][16] In this sense, the term Zhongguo is synonymous with Huáxià (華夏/华夏) and Zhōnghuá (中華/中华), names of China that were first authentically attested since Warring States period[17] and Eastern Jin period,[18][19] respectively.

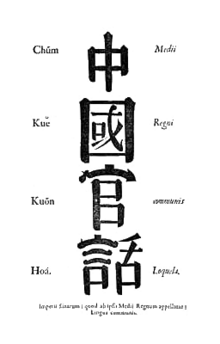

«Middle Kingdom’s Common Speech» (Medii Regni Communis Loquela, Zhongguo Guanhua, 中國官話), the frontispiece of an early Chinese grammar published by Étienne Fourmont in 1742[20]

From the Qin to Ming dynasty literati discussed Zhongguo as both a historical place or territory and as a culture. Writers of the Ming period in particular used the term as a political tool to express opposition to expansionist policies that incorporated foreigners into the empire.[21] In contrast foreign conquerors typically avoided discussions of Zhongguo and instead defined membership in their empires to include both Han and non-Han peoples.[22]

Qing[edit]

Zhongguo appeared in a formal international legal document for the first time during the Qing dynasty in the Treaty of Nerchinsk, 1689. The term was then used in communications with other states and in treaties. The Manchu rulers incorporated Inner Asian polities into their empire, and Wei Yuan, a statecraft scholar, distinguished the new territories from Zhongguo, which he defined as the 17 provinces of «China proper» plus the Manchu homelands in the Northeast. By the late 19th century the term had emerged as a common name for the whole country. The empire was sometimes referred to as Great Qing but increasingly as Zhongguo (see the discussion below).[23]

Dulimbai Gurun is the Manchu name for China, with «Dulimbai» meaning «central» or «middle,» and «Gurun» meaning «nation» or «state.»[24][25][26] The historian Zhao Gang writes that «not long after the collapse of the Ming, China [Zhongguo] became the equivalent of Great Qing (Da Qing)—another official title of the Qing state», and «Qing and China became interchangeable official titles, and the latter often appeared as a substitute for the former in official documents.»[27] The Qing dynasty referred to their realm as «Dulimbai Gurun» in Manchu. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing realm (including present day Manchuria, Xinjiang, Mongolia, Tibet and other areas) as «China» in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state, rejecting the idea that China only meant Han areas; both Han and non-Han peoples were part of «China». Officials used «China» (though not exclusively) in official documents, international treaties, and foreign affairs, and the «Chinese language» (Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i bithe) referred to Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol languages, and the term «Chinese people» (中國人; Zhōngguórén; Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) referred to all Han, Manchus, and Mongol subjects of the Qing.[28] Ming loyalist Han literati held to defining the old Ming borders as China and using «foreigner» to describe minorities under Qing rule such as the Mongols, as part of their anti-Qing ideology.[29]

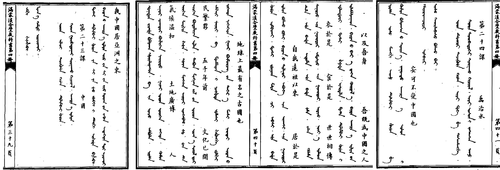

Chapter China (中國) of «The Manchurian, Mongolian and Han Chinese Trilingual Textbook» (滿蒙漢三語合璧教科書) published in Qing dynasty: «Our country China is located in East Asia… For 5000 years, culture flourished (in the land of China)… Since we are Chinese, how can we not love China.»

When the Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land was absorbed into Dulimbai Gurun in a Manchu language memorial.[30][31][32] The Qing expounded on their ideology that they were bringing together the «outer» non-Han Chinese like the Inner Mongols, Eastern Mongols, Oirat Mongols, and Tibetans together with the «inner» Han Chinese, into «one family» united in the Qing state, showing that the diverse subjects of the Qing were all part of one family, the Qing used the phrase «Zhōngwài yījiā» (中外一家; ‘China and other [countries] as one family’) or «Nèiwài yījiā» (內外一家; ‘Interior and exterior as one family’), to convey this idea of «unification» of the different peoples.[33] A Manchu language version of a treaty with the Russian Empire concerning criminal jurisdiction over bandits called people from the Qing as «people of the Central Kingdom (Dulimbai Gurun)».[34][35][36][37] In the Manchu official Tulisen’s Manchu language account of his meeting with the Torghut Mongol leader Ayuki Khan, it was mentioned that while the Torghuts were unlike the Russians, the «people of the Central Kingdom» (dulimba-i gurun/中國; Zhōngguó) were like the Torghut Mongols, and the «people of the Central Kingdom» referred to the Manchus.[38]

Mark Elliott noted that it was under the Qing that «China» transformed into a definition of referring to lands where the «state claimed sovereignty» rather than only the Central Plains area and its people by the end of the 18th century.[39]

Elena Barabantseva also noted that the Manchu referred to all subjects of the Qing empire regardless of ethnicity as «Chinese» (中國之人; Zhōngguó zhī rén; ‘China’s person’), and used the term (中國; Zhōngguó) as a synonym for the entire Qing empire while using «Hàn rén» (漢人) to refer only to the core area of the empire, with the entire empire viewed as multiethnic.[40]

Joseph W. Esherick noted that while the Qing Emperors governed frontier non-Han areas in a different, separate system under the Lifanyuan and kept them separate from Han areas and administration, it was the Manchu Qing Emperors who expanded the definition of Zhongguo (中國) and made it «flexible» by using that term to refer to the entire Empire and using that term to other countries in diplomatic correspondence, while some Han Chinese subjects criticized their usage of the term and the Han literati Wei Yuan used Zhongguo only to refer to the seventeen provinces of China and three provinces of the east (Manchuria), excluding other frontier areas.[41] Due to Qing using treaties clarifying the international borders of the Qing state, it was able to inculcate in the Chinese people a sense that China included areas such as Mongolia and Tibet due to education reforms in geography which made it clear where the borders of the Qing state were even if they didn’t understand how the Chinese identity included Tibetans and Mongolians or understand what the connotations of being Chinese were.[42] The Treaty of Nanking (1842) English version refers to «His Majesty the Emperor of China» while the Chinese refers both to «The Great Qing Emperor» (Da Qing Huangdi) and to Zhongguo as well. The Treaty of Tientsin (1858) has similar language.[4]

In the late 19th century the reformer Liang Qichao argued in a famous passage that «our greatest shame is that our country has no name. The names that people ordinarily think of, such as Xia, Han, or Tang, are all the titles of bygone dynasties.» He argued that the other countries of the world «all boast of their own state names, such as England and France, the only exception being the Central States.»[43] The Japanese term «Shina» was proposed as a basically neutral Western-influenced equivalent for «China». Liang and Chinese revolutionaries, such as Sun Yat-sen, who both lived extensive periods in Japan, used Shina extensively, and it was used in literature as well as by ordinary Chinese. But with the overthrow of the Qing in 1911, most Chinese dropped Shina as foreign and demanded that even Japanese replace it with Zhonghua minguo or simply Zhongguo.[44] Liang went on to argue that the concept of tianxia had to be abandoned in favor of guojia, that is, «nation,» for which he accepted the term Zhongguo.[45] After the founding of the Chinese Republic in 1912, Zhongguo was also adopted as the abbreviation of Zhonghua minguo.[46]

Qing official Zhang Deyi objected to the western European name «China» and said that China referred to itself as Zhonghua in response to a European who asked why Chinese used the term guizi to refer to all Europeans.[47]

In the 20th century after the May Fourth Movement, educated students began to spread the concept of Zhōnghuá (中華/中华), which represented the people, including 56 minority ethnic groups and the Han Chinese, with a single culture identifying themselves as «Chinese». The Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China both used the title «Zhōnghuá» in their official names. Thus, Zhōngguó became the common name for both governments, and «Zhōngguó rén» for their citizens, though Taiwanese people may reject being called as such. Overseas Chinese are referred to as huáqiáo (華僑/华侨), «Chinese overseas», or huáyì (華裔/华裔), «Chinese descendants» (i.e., Chinese children born overseas).

Middle Kingdom[edit]

The English translation of Zhongguo as the «Middle Kingdom» entered European languages through the Portuguese in the 16th century and became popular in the mid-19th century. By the mid-20th century the term was thoroughly entrenched in the English language to reflect the Western view of China as the inwards-looking Middle Kingdom, or more accurately the Central Kingdom. Endymion Wilkinson points out that the Chinese were not unique in thinking of their country as central, although China was the only culture to use the concept for their name.[48] The term Zhongguo was also not commonly used as a name for China until quite recently, nor did it mean the «Middle Kingdom» to the Chinese, or even have the same meaning throughout the course of history (see above).[49]

«Zhōngguó» in different languages[edit]

- Burmese: Alaï-praï-daï[citation needed]

- Catalan: País del Mig (The Middle’s Country/State)

- Czech: Říše středu («The Empire of the Center»)

- Dutch: Middenrijk («Middle Empire» or «Middle Realm»)

- English: Middle Kingdom, Central Kingdom

- Finnish: Keskustan valtakunta («The State of the Center»)

- French: Empire du milieu («Middle Empire») or Royaume du milieu («Middle Kingdom»)

- German: Reich der Mitte («Middle Empire»)

- Greek: Mési aftokratoría (Μέση αυτοκρατορία, «Middle Empire») or Kentrikí aftokratoría (Κεντρική αυτοκρατορία, «Central Empire»)

- Hmong: Suav Teb (𖬐𖬲𖬤𖬵 𖬈𖬰𖬧𖬵), Roob Kuj (𖬌𖬡 𖬆𖬶), Tuam Tshoj (𖬐𖬧𖬵 𖬒𖬲𖬪𖬰)

- Hungarian: Középső birodalom («Middle Empire»)

- Indonesian: Tiongkok (from Tiong-kok, the Hokkien name for China)[50]

- Italian: Impero di Mezzo («Middle Empire»)

- Japanese: Chūgoku (中国; ちゅうごく)

- Kazakh: Juñgo (جۇڭگو)

- Korean: Jungguk (중국; 中國)

- Li: Dongxgok

- Lojban: jugygu’e or .djunguos.

- Manchu: ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (Dulimbai gurun) or ᠵᡠᠩᡬᠣ (Jungg’o) were the official names for «China» in Manchu language

- Mongolian: ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ (Dumdadu ulus), the official name for «China» used in Inner Mongolia

- Polish: Państwo Środka («The State of the Center»)

- Portuguese: Estado Central («Central State»)

- Russian: Срединное Царство (Sredínnoye Tsárstvo; «Middle Kingdom»)

- Slovak: Ríša stredu («The Empire of the Center»)

- Spanish: País del Centro (The Middle’s Country/State)

- Swedish: Mittens rike (The Middle’s Kingdom/Empire/Realm/State)

- Tibetan: Krung-go (ཀྲུང་གོ་), a PRC-era loanword from Mandarin; the normal Tibetan term for China (proper) is rgya nak (རྒྱ་ནག), lit. the «black country.»

- Toki Pona: ma Sonko

- Uighur: جۇڭگو, romanized: Junggo

- Vietnamese: Trung Quốc (中國)

- Yi: ꍏꇩ(Zho guop)

- Zhuang: Cunghgoz (older orthography: Cuŋƅgoƨ)

«Zhōnghuá» in different languages[edit]

- Indonesian: Tionghoa (from Tiong-hôa, the Hokkien counterpart)

- Japanese: Chūka (中華; ちゅうか)

- Korean: Junghwa (중화; 中華)

- Kazakh: Juñxwa (جۇڭحوا)

- Li: Dongxhwax

- Manchu: ᠵᡠᠩᡥᡡᠸᠠ (Junghūwa)

- Tibetan: ཀྲུང་ཧྭ (krung hwa)

- Uighur: جۇڭخۇا, romanized: Jungxua

- Vietnamese: Trung hoa (中華)

- Yi: ꍏꉸ (Zho huop)

- Zhuang: Cunghvaz (Old orthography: Cuŋƅvaƨ)

Huaxia[edit]

The name Huaxia (華夏/华夏; pinyin: huáxià) is generally used as a sobriquet in Chinese text. Under traditional interpretations, it is the combination of two words which originally referred to the elegance of the traditional attire of the Han Chinese and the Confucian concept of rites.

- Hua which means «flowery beauty» (i.e. having beauty of dress and personal adornment 有服章之美,謂之華).

- Xia which means greatness or grandeur (i.e. having greatness of social customs/courtesy/polite manners and rites/ceremony 有禮儀之大,故稱夏).[51]

In the original sense, Huaxia refers to a confederation of tribes—living along the Yellow River—who were the ancestors of what later became the Han ethnic group in China.[citation needed] During the Warring States (475–221 BCE), the self-awareness of the Huaxia identity developed and took hold in ancient China.

Zhonghua minzu[edit]

Zhonghua minzu is a term meaning «Chinese nation» in the sense of a multi-ethnic national identity. Though originally rejected by the PRC, it has been used officially since the 1980s for nationalist politics.

Tianchao and Tianxia[edit]

Tianchao (天朝; pinyin: Tiāncháo), translated as «heavenly dynasty» or «Celestial Empire;»[52] and Tianxia (天下; pinyin: Tiānxià) translated as «under heaven,» are both phrases that have been used to refer to China. These terms were usually used in the context of civil wars or periods of division, with the term Tianchao evoking the idea of the realm’s ruling dynasty was appointed by heaven;[52] or that whoever ends up reunifying China is said to have ruled Tianxia, or everything under heaven. This fits with the traditional Chinese theory of rulership in which the emperor was nominally the political leader of the entire world and not merely the leader of a nation-state within the world. Historically the term was connected to the later Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE), especially the Spring and Autumn period (eighth to fourth century BCE) and the Warring States period (from there to 221 BCE, when China was reunified by the Qin state). The phrase Tianchao continues to see use on Chinese internet discussion boards, in reference to China.[52]

The phrase Tianchao was first translated into English and French in the early 19th century, appearing in foreign publicans and diplomatic correspondences,[53] with the translated phrase «Celestial Empire» occasionally used to refer to China. During this period, the term celestial was used by some to refer to the subjects of the Qing dynasty in a non-prejudicial manner,[53] derived from the term «Celestial Empire». However, the term celestial was also used in a pejorative manner during the 19th century, in reference to Chinese immigrants in Australasia and North America.[53] The translated phrase has largely fallen into disuse in the 20th century.

Translations for Tianxia include:

- Russian: Поднебесная (Podnebésnaya; lit. «under the heaven»)

Jiangshan and Heshan[edit]

Jiangshan (江山; pinyin: Jiāngshān) and Heshan (河山; pinyin: Héshān) literally mean «rivers and mountains». This term is quite similar in usage to Tianxia, and simply refers to the entire world, and here the most prominent features of which being rivers and mountains. The use of this term is also common as part of the phrase Jiangshan sheji (江山社稷; pinyin: Jiāngshān shèjì; lit. «rivers and mountains, soil and grain»), suggesting the need to implement good governance.

Jiuzhou[edit]

The name Jiuzhou (九州; pinyin: jiǔ zhōu) means «nine provinces». Widely used in pre-modern Chinese text, the word originated during the middle of Warring States period of China (c. 400–221 BCE). During that time, the Yellow River region was divided into nine geographical regions; thus this name was coined. Some people also attribute this word to the mythical hero and king Yu the Great, who, in the legend, divided China into nine provinces during his reign. (Consult Zhou for more information.)

Shenzhou[edit]

This name means Divine Realm[54] or Divine Land (神州; pinyin: Shénzhōu; lit. ‘divine/godly provinces’) and comes from the same period as Jiuzhou meaning «nine provinces». It was thought that the world was divided into nine major states, one of which is Shenzhou, which is in turn divided into nine smaller states, one of which is Jiuzhou mentioned above.

Sihai[edit]

This name, Four Seas (四海; pinyin: sìhǎi), is sometimes used to refer to the world, or simply China, which is perceived as the civilized world. It came from the ancient notion that the world is flat and surrounded by sea.

Han[edit]

| Han | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hàn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Hán | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 한 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | かん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The name Han (漢/汉; pinyin: Hàn) derives from the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220), who presided over China’s first «golden age». The Han dynasty collapsed in 220 and was followed by a long period of disorder, including Three Kingdoms, Sixteen Kingdoms, and Southern and Northern dynasties periods. During these periods, various non-Han ethnic groups established various dynasties in northern China. It was during this period that people began to use the term «Han» to refer to the natives of North China, who (unlike the minorities) were the descendants of the subjects of the Han dynasty.

During the Yuan dynasty, subjects of the empire was divided into four classes: Mongols, Semu or «Colour-eyeds», Hans, and «Southerns». Northern Chinese were called Han, which was considered to be the highest class of Chinese. This class «Han» includes all ethnic groups in northern China including Khitan and Jurchen who have in most part sinicized during the last two hundreds years. The name «Han» became popularly accepted.

During the Qing dynasty, the Manchu rulers also used the name Han to distinguish the natives of the Central Plains from the Manchus. After the fall of the Qing government, the Han became the name of a nationality within China. Today the term «Han Persons», often rendered in English as Han Chinese, is used by the People’s Republic of China to refer to the most populous of the 56 officially recognized ethnic groups of China. The «Han Chinese» are simply referred to as «Chinese» by some.

Tang[edit]

| Tang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Táng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Đường | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 당 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | とう (On), から (Kun) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The name Tang (唐; pinyin: Táng) comes from the Tang dynasty (618–690, 705–907) that presided over China’s second golden age. It was during the Tang dynasty that South China was finally and fully Sinicized; Tang would become synonymous with China in Southern China and it is usually Southern Chinese who refer to themselves as «People of Tang» (唐人, pinyin: Tángrén).[55] For example, the sinicization and rapid development of Guangdong during the Tang period would lead the Cantonese to refer to themselves as Tong-yan (唐人) in Cantonese, while China is called Tong-saan (唐山; pinyin: Tángshān; lit. ‘Tang Mountain’).[56] Chinatowns worldwide, often dominated by Southern Chinese, also became referred to Tang people’s Street (唐人街, Cantonese: Tong-yan-gaai; pinyin: Tángrénjiē). The Cantonese term Tongsan (Tang mountain) is recorded in Old Malay as one of the local terms for China, along with the Sanskrit-derived Cina. It is still used in Malaysia today, usually in a derogatory sense.

Among Taiwanese, Tang mountain (Min-Nan: Tn̂g-soaⁿ) has been used, for example, in the saying, «has Tangshan father, no Tangshan mother» (有唐山公,無唐山媽; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ū Tn̂g-soaⁿ kong, bô Tn̂g-soaⁿ má).[57][58] This refers how the Han people crossing the Taiwan Strait in the 17th and 18th centuries were mostly men, and that many of their offspring would be through intermarriage with Taiwanese aborigine women.

In Ryukyuan, karate was originally called tii (手, hand) or karatii (唐手, Tang hand) because 唐ぬ國 too-nu-kuku or kara-nu-kuku (唐ぬ國) was a common Ryukyuan name for China; it was changed to karate (空手, open hand) to appeal to Japanese people after the First Sino-Japanese War.

Dalu and Neidi[edit]

Dàlù (大陸/大陆; pinyin: dàlù), literally «big continent» or «mainland» in this context, is used as a short form of Zhōnggúo Dàlù (中國大陸/中国大陆, Mainland China), excluding (depending on the context) Hong Kong and Macau, and/or Taiwan. This term is used in official context in both the mainland and Taiwan, when referring to the mainland as opposed to Taiwan. In certain contexts, it is equivalent to the term Neidi (内地; pinyin: nèidì, literally «the inner land»). While Neidi generally refers to the interior as opposed to a particular coastal or border location, or the coastal or border regions generally, it is used in Hong Kong specifically to mean mainland China excluding Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. Increasingly, it is also being used in an official context within mainland China, for example in reference to the separate judicial and customs jurisdictions of mainland China on the one hand and Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan on the other.

The term Neidi is also often used in Xinjiang and Tibet to distinguish the eastern provinces of China from the minority-populated, autonomous regions of the west.

Official names[edit]

People’s Republic of China[edit]

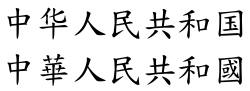

| People’s Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

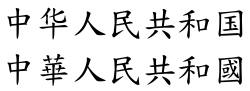

«People’s Republic of China» in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华人民共和国 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華人民共和國 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Cộng hoà Nhân dân Trung Hoa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 共和人民中華 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | สาธารณรัฐประชาชนจีน | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghvaz Yinzminz Gunghozgoz | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠪᠦᠭᠦᠳᠡ ᠨᠠᠶᠢᠷᠠᠮᠳᠠᠬᠤ ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭخۇا خەلق جۇمھۇرىيىتى | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai niyalmairgen gunghe’ gurun |

The name New China has been frequently applied to China by the Chinese Communist Party as a positive political and social term contrasting pre-1949 China (the establishment of the PRC) and the new name of the socialist state, Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó (in the older postal romanization, Chunghwa Jenmin Konghokuo) or the «People’s Republic of China» in English, was adapted from the CCP’s short-lived Chinese Soviet Republic in 1931. This term is also sometimes used by writers outside mainland China. The PRC was known to many in the West during the Cold War as «Communist China» or «Red China» to distinguish it from the Republic of China which is commonly called «Taiwan», «Nationalist China» or «Free China». In some contexts, particularly in economics, trade, and sports, «China» is often used to refer to mainland China to the exclusion of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

The official name of the People’s Republic of China in various official languages and scripts:

- Simplified Chinese: 中华人民共和国 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó) – Official language and script, used in mainland China, Singapore and Malaysia

- Traditional Chinese: 中華人民共和國 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó; Jyutping: Zung1waa4 Jan4man4 Gung6wo4gwok3) – Official script in Hong Kong and Macau, and commonly used in Taiwan (ROC)

- English: People’s Republic of China – Official in Hong Kong

- Kazakh: As used within the Republic of Kazakhstan, Қытай Халық Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Qıtay Xalıq Respwblïkası (in Latin script), قىتاي حالىق رەسپۋبلىيكاسى (in Arabic script); as used within the People’s Republic of China, جۇڭحۋا حالىق رەسپۋبليكاسى (in Arabic script), Жұңxуа Халық Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Juñxwa Xalıq Respwblïkası (in Latin script). The Cyrillic script is the predominant script in the Republic of Kazakhstan, while the Arabic script is normally used for the Kazakh language in the People’s Republic of China.

- Korean: 중화 인민 공화국 (中華人民共和國; Junghwa Inmin Gonghwaguk) – Used in Yanbian Prefecture (Jilin) and Changbai County (Liaoning)

- Manchurian: ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (Dulimbai niyalmairgen gunghe’ gurun) or ᠵᡠᠩᡥᡡᠸᠠ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝᡬᠣ (Junghūwa niyalmairgen gungheg’o)

- Mongolian: ᠪᠦᠭᠦᠳᠡ ᠨᠠᠶᠢᠷᠠᠮᠳᠠᠬᠤ ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ (Bügüde nayiramdaqu dumdadu arad ulus) – Official in Inner Mongolia; Бүгд Найрамдах Хятад Ард Улс (Bügd Nairamdakh Khyatad Ard Uls) – used in Mongolia

- Portuguese: República Popular da China – Official in Macau

- Tibetan: ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ, Wylie: krung hwa mi dmangs spyi mthun rgyal khab, ZYPY: Zhunghua Mimang Jitun Gyalkab – Official in PRC’s Tibet

- Tibetan: རྒྱ་ནག་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ, Wylie: rgya nag mi dmangs spyi mthun rgyal khab – Official in Tibet Government-in-Exile

- Uighur: جۇڭخۇا خەلق جۇمھۇرىيىت (Jungxua Xelq Jumhuriyiti) – Official in Xinjiang

- Yi: ꍏꉸꏓꂱꇭꉼꇩ (Zho huop rep mip gop hop guop) – Official in Liangshan (Sichuan) and several Yi-designated autonomous counties

- Zaiwa: Zhunghua Mingbyu Muhum Mingdan – Official in Dehong (Yunnan)

- Zhuang: Cunghvaz Yinzminz Gunghozgoz (Old orthography: Cuŋƅvaƨ Yinƨminƨ Guŋƅoƨ) – Official in Guangxi

- Polish: Chińska Republika Ludowa — Official in Poland

The official name of the People’s Republic of China in major neighboring countries official languages and scripts:

- Japanese: 中華人民共和国 (ちゅうかじんみんきょうわこく, Chūka Jinmin Kyōwakoku) – Used in Japan

- Russian: Китайская Народная Республика (Kitayskaya Narodnaya Respublika) – Used in Russia and Central Asia

- Hindi: चीनी जनवादी गणराज्य (Cheenee janavaadee ganaraajy) – Used in India

- Urdu: عوامی جمہوریہ چین (Awami Jamhoriya Cheen) – Used in Pakistan

- Burmese: တရုတ်ပြည်သူ့သမ္မတနိုင်ငံ (Tarotepyishusammataninengan) – Used in Myanmar

- Vietnamese: Cộng hòa Nhân dân Trung Hoa (共和人民中華) – Used in Vietnam

- Thai: สาธารณรัฐประชาชนจีน (S̄āṭhārṇrạṭ̄h Prachāchn Cīn) – Used in Thailand

- Khmer: សាធារណរដ្ឋប្រជាមានិតចិន – Used in Cambodia

- Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດປະຊາຊົນຈີນ (Sathalanalad Pasasonchin) – Used in Laos

- Nepali: जन गणतान्त्रिक चीन (Jana Gaṇatāntrika Cīna) – Used in Nepal

Republic of China[edit]

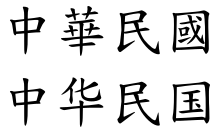

| Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

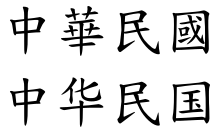

«Republic of China» in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chunghwa Minkuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Central State People’s Country | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese Taipei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華臺北 or 中華台北 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华台北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺澎金馬 個別關稅領域 or 台澎金馬 個別關稅領域 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台澎金马 个别关税领域 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣 or 台灣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Terraced Bay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese: (Ilha) Formosa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 福爾摩沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 福尔摩沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | beautiful island | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republic of Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣民國 or 台灣民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Taiwan Minkuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་དམངས་གཙོའི། ་རྒྱལ་ཁབ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Trung Hoa Dân Quốc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghvaz Minzgoz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 중화민국 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Дундад иргэн улс | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠢᠷᠭᠡᠨ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 中華民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ちゅうかみんこく | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭخۇا مىنگو | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai irgen’ Gurun |

In 1912, China adopted its official name, Chunghwa Minkuo (rendered in pinyin Zhōnghuá Mínguó) or in English as the «Republic of China», which also has sometimes been referred to as «Republican China» or the «Republican Era» (民國時代), in contrast to the empire it replaced, or as «Nationalist China«, after the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang). 中華 (Chunghwa) is a term that pertains to «China» while 民國 (Minkuo), literally «People’s State» or «Peopledom», stands for «republic».[59][60] The name had stemmed from the party manifesto of Tongmenghui in 1905, which says the four goals of the Chinese revolution was «to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive Chunghwa, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people.(Chinese: 驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權; pinyin: Qūchú dálǔ, huīfù Zhōnghuá, chuànglì mínguó, píngjūn dì quán).» The convener of Tongmenghui and Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen proposed the name Chunghwa Minkuo as the assumed name of the new country when the revolution succeeded.

With the separation from mainland China in 1949 as a result of the Chinese Civil War, the territory of the Republic of China has largely been confined to the island of Taiwan and some other small islands. Thus, the country is often simply referred to as simply «Taiwan«, although this may not be perceived as politically neutral. (See Taiwan Independence.) Amid the hostile rhetoric of the Cold War, the government and its supporters sometimes referred to itself as «Free China» or «Liberal China», in contrast to People’s Republic of China (which was historically called the «Bandit-occupied Area» (匪區) by the ROC). In addition, the ROC, due to pressure from the PRC, was forced to use the name «Chinese Taipei» (中華台北) whenever it participates in international forums or most sporting events such as the Olympic Games.

Taiwanese politician Mei Feng had criticised the official English name of the state «Republic of China» fails to translate the Chinese character «Min» (Chinese: 民 English: people) according to Sun Yat-sen’s original interpretations, while the name should instead be translated as «the People’s Republic of China,» which confuses with the current official name of China under communist control.[61] To avoid confusion, the Chen Shui-ban led DPP administration began to put an aside of «Taiwan» next to the nation’s official name since 2005.[62]

The official name of the Republic of China in various official languages and scripts:

- English: Republic of China – Official in Hong Kong, commonly used by the United States until 1979, Chinese Taipei – official designation in several international organizations (International Olympic Committee, FIFA, Miss Universe, World Health Organization), Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu – World Trade Organization, Governing authorities on Taiwan – Official name used by the United States from 1979

- Traditional Chinese: 中華民國 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó; Jyutping: Zung1waa4 Man4gwok3), 中華臺北 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Táiběi), 臺澎金馬個別關稅領域 (pinyin: Tái-Péng-Jīn-Mǎ Gèbié Guānshuì Lǐngyù), 臺灣 (pinyin: Táiwān) – Official script in Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan and the islands controlled by the ROC

- Simplified Chinese: 中华民国 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó), 中華台北 (pinyin: Zhōnghuá Táiběi), 台澎金马个别关税领域 (pinyin: Tái-Péng-Jīn-Mǎ Gèbié Guānshuì Lǐngyù), 台湾 (pinyin: Táiwān) – Official language and script, used in Mainland China, Singapore and Malaysia

- Kazakh: As used within Republic of Kazakhstan, Қытай Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Qıtay Respwblïkası (in Latin script), قىتاي رەسپۋبلىيكاسى (in Arabic script); as used within the People’s Republic of China, Жұңxуа Республикасы (in Cyrillic script), Juñxwa Respwblïkası (in Latin script), جۇڭحۋا رەسپۋبليكاسى (in Arabic script). The Cyrillic script is the predominant script in the Republic of Kazakhstan, while the Arabic script is normally used for the Kazakh language in the People’s Republic of China.

- Korean: 중화민국 (中華民國; Junghwa Minguk) – Official in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture

- Manchurian: ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ

ᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ (Dulimbai irgen’ gurun) - Mongolian: ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ

ᠢᠷᠭᠡᠨ

ᠤᠯᠤᠰ Дундад иргэн улс (Dumdadu irgen ulus) – Official for its history name before 1949 in Inner Mongolia and Mongolia; Бүгд Найрамдах Хятад Улс (Bügd Nairamdakh Khyatad Uls) – used in Mongolia for Roc in Taiwan - Portuguese: República da China – Official in Macau, Formosa – former name

- Tibetan: ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་དམངས་གཙོའི་རྒྱལ་ཁབ།, Wylie: krung hwa dmangs gtso’i rgyal khab, ZYPY: Zhunghua Mang Zoi Gyalkab, Tibetan: ཐའེ་ཝན།, Wylie: tha’e wan – Official in PRC’s Tibet

- Tibetan: རྒྱ་ནག་དམངས་གཙོའི་རྒྱལ་ཁབ, Wylie: rgya nag dmangs gtso’i rgyal khab – Official in Tibet Government-in-Exile

- Uighur: جۇڭخۇا مىنگو, romanized: Jungxua Mingo – Official in Xinjiang

- Yi: ꍏꉸꂱꇩ (Zho huop mip guop) – Official in Liangshan (Sichuan) and several Yi-designated autonomous counties

- Zaiwa: Zhunghua Mindan – Official in Dehong (Yunnan)

- Zhuang: Cunghvaz Mingoz (Old orthography: Cuŋƅvaƨ Minƨƅoƨ) – Official in Guangxi

The official name of the Republic of China in major neighboring countries official languages and scripts:

- Japanese: 中華民国 (ちゅうかみんこく; Chūka Minkoku) – Used in Japan

- Korean: 중화민국 (中華民國; Junghwa Minguk) – Used in Korea

- Russian: Китайская Республика (Kitayskaya Respublika) – Used in Russia and Central Asia

- Hindi: चीनी गणराज्य (Cīna Gaṇrājya) – Used in India

- Urdu: جمہوریہ چین (Jumhūriyā Cīn) – Used in Pakistan

- Burmese: တရုတ်သမ္မတနိုင်ငံ (Tarotesammataninengan) – Used in Myanmar

- Vietnamese: Trung Hoa Dân Quốc (中華民國), Cộng hòa Trung Hoa (共和中華), Đài Loan (臺灣), Đài Bắc Trung Hoa (臺北中華) – Used in Vietnam

- Thai: สาธารณรัฐจีน (S̄āṭhārṇrạṭ̄h Cīn) – Used in Thailand (during 1912–1949)

- Khmer: សាធារណរដ្ឋចិន – Used in Cambodia

- Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດຈີນ (Sathalanalad Chin) – Used in Laos

- Nepali: गणतन्त्र चीन (Gaṇatāntrika Cīna) – Used in Nepal

Names in non-Chinese records[edit]

Names used in the parts of Asia, especially East and Southeast Asia, are usually derived directly from words in one of the languages of China. Those languages belonging to a former dependency (tributary) or Chinese-influenced country have an especially similar pronunciation to that of Chinese. Those used in Indo-European languages, however, have indirect names that came via other routes and may bear little resemblance to what is used in China.

Chin, China[edit]

Further information: Chinas

English, most Indo-European languages, and many others use various forms of the name China and the prefix «Sino-» or «Sin-» from the Latin Sina.[63][64] Europeans had knowledge of a country known in Greek as Thina or Sina from the early period;[65] the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea from perhaps the first century AD recorded a country known as Thin (θίν).[66] The English name for «China» itself is derived from Middle Persian (Chīnī چین). This modern word «China» was first used by Europeans starting with Portuguese explorers of the 16th century – it was first recorded in 1516 in the journal of the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa.[67][68] The journal was translated and published in England in 1555.[69]

The traditional etymology, proposed in the 17th century by Martin Martini and supported by later scholars such as Paul Pelliot and Berthold Laufer, is that the word «China» and its related terms are ultimately derived from the polity known as Qin that unified China to form the Qin Dynasty (秦, Old Chinese: *dzin) in the 3rd century BC, but existed as a state on the furthest west of China since the 9th century BC.[65][70][71] This is still the most commonly held theory, although the etymology is still a matter of debate according to the Oxford English Dictionary,[72] and many other suggestions have been mooted.[73][74]

The existence of the word Cīna in ancient Indian texts was noted by the Sanskrit scholar Hermann Jacobi who pointed out its use in the Book 2 of Arthashastra with reference to silk and woven cloth produced by the country of Cīna, although textual analysis suggests that Book 2 may not have been written long before 150 AD.[75] The word is also found in other Sanskrit texts such as the Mahābhārata and the Laws of Manu.[76] The Indologist Patrick Olivelle argued that the word Cīnā may not have been known in India before the first century BC, nevertheless he agreed that it probably referred to Qin but thought that the word itself was derived from a Central Asian language.[77] Some Chinese and Indian scholars argued for the state of Jing (荆, another name for Chu) as the likely origin of the name.[74] Another suggestion, made by Geoff Wade, is that the Cīnāh in Sanskrit texts refers to an ancient kingdom centered in present-day Guizhou, called Yelang, in the south Tibeto-Burman highlands.[76] The inhabitants referred to themselves as Zina according to Wade.[78]

The term China can also be used to refer to:

- a modern state, indicating the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or the Republic of China (ROC), where recognized;

- «Mainland China» (中國大陸/中国大陆, Zhōngguó Dàlù in Mandarin), which is the territory of the PRC minus the two special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau;

- «China proper», a term used to refer to the historical heartlands of China without peripheral areas like Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang

In economic contexts, «Greater China» (大中華地區/大中华地区, dà Zhōnghuá dìqū) is intended to be a neutral and non-political way to refer to Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Sinologists usually use «Chinese» in a more restricted sense, akin to the classical usage of Zhongguo, to the Han ethnic group, which makes up the bulk of the population in China and of the overseas Chinese.

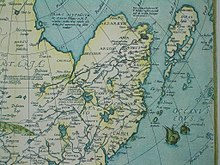

Barbuda’s 1584 map, also published by Ortelius, already applies the name China to the entire country. However, for another century many European maps continued to show Cathay as well, usually somewhere north of the Great Wall

List of derived terms[edit]

- Afrikaans: Sjina, spelling now obsolete and spelled as China (pronunciation is the same) (pronounced [ˈʃina])

- Albanian: Kinë (pronounced [kinə])

- Amharic: Chayna (from English)

- Armenian: Չինաստան (pronounced [t͡ʃʰinɑsˈtɑn])

- Assamese: চীন (pronounced [sin])

- Azeri: Çin (IPA: [tʃin])

- Basque: Txina (IPA: [tʃina])

- Bengali: চীন (pronounced [ˈtʃiːn])

- Burma: တရုတ် (pronounced [θˈjəʊt])

- Catalan: Xina ([ˈ(t)ʃi.nə])

- Chinese: 支那 Zhīnà (obsolete and considered offensive due to historical Japanese usage; originated from early Chinese translations of Buddhist texts in Sanskrit)

- Chinese: 震旦 Zhèndàn transcription of the Sanskrit/Pali «Cīnasthāna» in the Buddhist texts.

- Czech: Čína (pronounced [ˈtʃiːna])

- Danish: Kina (pronounced [ˈkʰiːnɑ])

- Dutch: China ([ʃiːnɑ])

- English: China

- Esperanto: Ĉinujo or Ĉinio, or Ĥinujo (archaic)

- Estonian: Hiina (pronounced [hiːnɑ])

- Filipino: Tsina ([tʃina])

- Finnish: Kiina (pronounced [ˈkiːnɑ])

- French: Chine ([ʃin])

- Galician: China (pronounced [ˈtʃinɐ])

- Georgian: ჩინეთი (pronounced [tʃinɛtʰi])

- German: China ([ˈçiːna] and [ʃiːnɑ], in the southern part of the German-speaking area also [ˈkiːna])

- Greek: Κίνα (Kína) ([ˈcina])

- Gujarati: Cīn ચીન (IPA [ˈtʃin])

- Hindustani: Cīn चीन or چين (IPA [ˈtʃiːn])

- Hungarian: Kína ([ˈkiːnɒ])

- Icelandic: Kína ([cʰiːna])

- Indonesian: Cina ([tʃina])

- Interlingua: China

- Irish: An tSín ([ənˠ ˈtʲiːnʲ])

- Italian: Cina ([ˈtʃiːna])

- Japanese: Shina (支那) – considered offensive in China, now largely obsolete in Japan and avoided out of deference to China (the name Chūgoku [tɕɯɡokɯ] is used instead); See Shina (word) and kotobagari.

- Javanese: ꦕꦶꦤ Cina (low speech level); ꦕꦶꦤ꧀ꦠꦼꦤ꧀ Cinten (high speech level)

- Kapampangan: Sina

- Khmer: ចិន ( [cən])

- Korean: Jina (지나; [t͡ɕinɐ])[citation needed]

- Latvian: Ķīna ([ˈciːna])

- Lithuanian: Kinija ([kʲɪnʲijaː])

- Macedonian: Кина (Kina) ([kinə])

- Malay: Cina ([tʃina])

- Malayalam: Cheenan/Cheenathi

- Maltese: Ċina ([ˈtʃiːna])

- Marathi: Cīn चीन (IPA [ˈtʃiːn])

- Nepali: Cīn चीन (IPA [ˈtsin])

- Norwegian: Kina ([ˈçìːnɑ])

- Pahlavi: Čīnī

- Persian: Chīn چين ([tʃin])

- Polish: Chiny ([ˈçinɨ])

- Portuguese: China ([ˈʃinɐ])

- Romanian: China ([ˈkina])

- Serbo-Croatian: Kina or Кина ([ˈkina])

- Sinhala: Chinaya චීනය

- Slovak: Čína ([ˈtʂiːna])

- Spanish: China ([ˈtʃina])

- Somali: Shiinaha

- Swedish: Kina ([ˈɕîːna])

- Tamil: Cīnam (சீனம்)

- Thai: จีน (RTGS: Chin [t͡ɕiːn])

- Tibetan: Rgya Nag (རྒྱ་ནག་)

- Turkish: Çin ([tʃin])

- Vietnamese: Chấn Đán 震旦 ([t͡ɕən ɗǎn] or Chi Na 支那 ([ci na])(in Buddhist texts).

- Welsh: Tsieina ([ˈtʃəina])

Seres, Ser, Serica[edit]

Sēres (Σῆρες) was the Ancient Greek and Roman name for the northwestern part of China and its inhabitants. It meant «of silk,» or «land where silk comes from.» The name is thought to derive from the Chinese word for silk, sī (絲/丝; Middle Chinese sɨ, Old Chinese *slɯ, per Zhengzhang). It is itself at the origin of the Latin for silk, «sērica«. See the main article Serica for more details.

- Ancient Greek: Σῆρες Seres, Σηρικός Serikos

- Latin: Serica

- Old Irish: Seiria, as seen in Dúan in chóicat cest[79]

This may be a back formation from sērikos (σηρικός), «made of silk», from sēr (σήρ), «silkworm», in which case Sēres is «the land where silk comes from.»

Sinae, Sin [edit]

A mid-15th century map based on Ptolemy’s manuscript Geography. Serica and Sina are marked as separate countries (top right and right respectively).

Sīnae was an ancient Greek and Roman name for some people who dwelt south of the Seres (Serica) in the eastern extremity of the habitable world. References to the Sinae include mention of a city that the Romans called Sēra Mētropolis, which may be modern Chang’an. The Latin prefixes Sino- and Sin- as well as words such as Sinica, which are traditionally used to refer to China or the Chinese, came from Sīnae.[80] It is generally thought that Chīna, Sīna and Thīna are variants that ultimately derived from Qin, which was the westernmost state in China that eventually formed the Qin Dynasty.[66] There are however other opinions on its etymology (See section on China above). Henry Yule thought that this term may have come to Europe through the Arabs, who made the China of the farther east into Sin, and perhaps sometimes into Thin.[81] Hence the Thin of the author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, who appears to be the first extant writer to employ the name in this form; hence also the Sinæ and Thinae of Ptolemy.[65][66]

Some denied that Ptolemy’s Sinae really represented the Chinese as Ptolemy called the country Sērice and the capital Sēra, but regarded them as distinct from Sīnae.[66][82] Marcian of Heraclea (a condenser of Ptolemy) tells us that the «nations of the Sinae lie at the extremity of the habitable world, and adjoin the eastern Terra incognita». The 6th century Cosmas Indicopleustes refers to a «country of silk» called Tzinista, which is understood as referring to China, beyond which «there is neither navigation nor any land to inhabit».[83] It seems probable that the same region is meant by both. According to Henry Yule, Ptolemy’s misrendering of the Indian Sea as a closed basin meant that Ptolemy must also have misplaced the Chinese coast, leading to the misconception of Serica and Sina as separate countries.[81]

In the Hebrew Bible, there is a mention of a faraway country Sinim in the Book of Isaiah 49:12 which some had assumed to be a reference to China.[66][84] In Genesis 10:17, a tribes called the Sinites were said to be the descendants of Canaan, the son of Ham, but they are usually considered to be a different people, probably from the northern part of Lebanon.[85][86]

- Arabic: Ṣīn صين

- French/English (prefix of adjectives): Sino- (i.e. Sino-American), Sinitic (the Chinese language family).

- Hebrew: Sin סין

- Irish: An tSín

- Latin: Sīnae

- Scottish Gaelic: Sìona

Cathay[edit]

This group of names derives from Khitan, an ethnic group that originated in Manchuria and conquered parts of Northern China early tenth century forming the Liao dynasty, and later in the twelfth century dominated Central Asia as the Kara Khitan Khanate. Due to long period of domination of Northern China and then Central Asia by these nomadic conquerors, the name Khitan become associated with China to the people in and around the northwestern region. Muslim historians referred to the Kara Khitan state as Khitay or Khitai; they may have adopted this form of «Khitan» via the Uyghurs of Kocho in whose language the final -n or -ń became -y.[87] The name was then introduced to medieval and early modern Europe through Islamic and Russian sources.[88] In English and in several other European languages, the name «Cathay» was used in the translations of the adventures of Marco Polo, which used this word for northern China. Words related to Khitay are still used in many Turkic and Slavic languages to refer to China. However, its use by Turkic speakers within China, such as the Uyghurs, is considered pejorative by the Chinese authority who tried to ban it.[88]

- Belarusian: Кітай (Kitay, [kʲiˈtaj])

- Bulgarian: Китай (Kitay, IPA: [kiˈtaj])

- Buryat: Хитад (Khitad)

- Classical Mongolian: Kitad[89]

- English: Cathay

- French: Cathay

- Kazakh: Қытай (Qıtay; [qətɑj])

- Kazan Tatar: Кытай (Qıtay)

- Kyrgyz: Кытай (Kıtaj; [qɯˈtɑj])

- Medieval Latin: Cataya, Kitai

- Mongolian: Хятад (Khyatad) (the name for China used in the State of Mongolia)

- Polish: Kitaj ([ˈkʲi.taj]; now archaic)

- Portuguese: Catai ([kɐˈtaj])

- Russian: Китай (Kitay, IPA: [kʲɪˈtaj])

- Serbo-Croatian: Kitaj or Китај (now archaic; from Russian)

- Slovene: Kitajska ([kiːˈtajska])

- Spanish: Catay

- Tajik: Хитой («Khitoy»)

- Turkmen: Hytaý («Хытай»)

- Ukrainian: Китай (Kytai)

- Uighur: خىتاي, romanized: Xitay

- Uzbek: Xitoy (Хитой)

There is no evidence that either in the 13th or 14th century, Cathayans, i.e. Chinese, travelled officially to Europe, but it is possible that some did, in unofficial capacities, at least in the 13th century. During the campaigns of Hulagu (the grandson of Genghis Khan) in Persia (1256–65), and the reigns of his successors, Chinese engineers were employed on the banks of the Tigris, and Chinese astrologers and physicians could be consulted. Many diplomatic communications passed between the Hulaguid Ilkhans and Christian princes. The former, as the great khan’s liegemen, still received from him their seals of state; and two of their letters which survive in the archives of France exhibit the vermilion impressions of those seals in Chinese characters—perhaps affording the earliest specimen of those characters to reach western Europe.

Tabgach[edit]

The word Tabgach came from the metatheses of Tuoba (*t’akbat), a dominant tribe of the Xianbei and the surname of the Northern Wei emperors in the 5th century before sinicisation. It referred to Northern China, which was dominated by part-Xianbei, part-Han people.

- Byzantine Greek: Taugats

- Orhon Kok-Turk: Tabgach (variations Tamgach)

Nikan[edit]

Nikan (Manchu: ᠨᡳᡴᠠᠨ, means «Han/China») was a Manchu ethnonym of unknown origin that referred specifically to the ethnic group known in English as the Han Chinese; the stem of this word was also conjugated as a verb, nikara(-mbi), and used to mean «to speak the Chinese language.» Since Nikan was essentially an ethnonym and referred to a group of people (i.e., a nation) rather than to a political body (i.e., a state), the correct translation of «China (proper)» into the Manchu language is Nikan gurun, literally the «Nikan state» or «country of the Nikans» (i.e., country of the Hans).[citation needed]

This exonym for the Han Chinese is also used in the Daur language, in which it appears as Niaken ([njakən] or [ɲakən]).[90] As in the case of the Manchu language, the Daur word Niaken is essentially an ethnonym, and the proper way to refer to the country of the Han Chinese (i.e., «China» in a cultural sense) is Niaken gurun, while niakendaaci- is a verb meaning «to talk in Chinese.»

Kara[edit]

Japanese: Kara (から; variously written in kanji as 唐 or 漢). An identical name was used by the ancient and medieval Japanese to refer to the country that is now known as Korea, and many Japanese historians and linguists believe that the word «Kara» referring to China and/or Korea may have derived from a metonymic extension of the appellation of the ancient city-states of Gaya.

The Japanese word karate (空手, lit. «empty hand») is derived from the Okinawan word karatii (唐手, lit. «Chinese/Asian/foreign hand/trick/means/method/style») and refers to Okinawan martial arts; the character for kara was changed to remove the connotation of the style originating in China.

Morokoshi[edit]

Japanese: Morokoshi (もろこし; variously written in kanji as 唐 or 唐土). This obsolete Japanese name for China is believed to have derived from a kun reading of the Chinese compound 諸越 Zhūyuè or 百越

Bǎiyuè as «all the Yue» or «the hundred (i.e., myriad, various, or numerous) Yue,» which was an ancient Chinese name for the societies of the regions that are now southern China.

The Japanese common noun tōmorokoshi (トウモロコシ, 玉蜀黍), which refers to maize, appears to contain an element cognate with the proper noun formerly used in reference to China. Although tōmorokoshi is traditionally written with Chinese characters that literally mean «jade Shu millet,» the etymology of the Japanese word appears to go back to «Tang morokoshi,» in which «morokoshi» was the obsolete Japanese name for China as well as the Japanese word for sorghum, which seems to have been introduced into Japan from China.

Mangi[edit]

1837 map of Mongol Empire, showing Mangi in southern China

From Chinese Manzi (southern barbarians). The division of North China and South China under the Jin dynasty and Song dynasty weakened the idea of a unified China, and it was common for non-Han peoples to refer to the politically disparate North and South by different names for some time. While Northern China was called Cathay, Southern China was referred to as Mangi. Manzi often appears in documents of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty as a disparaging term for Southern China. The Mongols also called Southern Chinese Nangkiyas or Nangkiyad, and considered them ethnically distinct from North Chinese. The word Manzi reached the Western world as Mangi (as used by Marco Polo), which is a name commonly found on medieval maps. Note however that the Chinese themselves considered Manzi to be derogatory and never used it as a self-appellation.[91][92] Some early scholars believed Mangi to be a corruption of the Persian Machin (ماچين) and Arabic Māṣīn (ماصين), which may be a mistake as these two forms are derived from the Sanskrit Maha Chin meaning Great China.[93]

- Chinese: Manzi (蠻子)

- Latin: Mangi

See also[edit]

- Little China (ideology)

- Chinese romanization

- List of country name etymologies

- Names of the Qing dynasty

- Names of India

- Names of Japan

- Names of Korea

- Names of Vietnam

- Île-de-France, similar French concept

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Bilik, Naran (2015), «Reconstructing China beyond Homogeneity», Patriotism in East Asia, Political Theories in East Asian Context, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 105

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2015, p. 191.

- ^ Esherick (2006), p. 232–233

- ^ a b Zarrow, Peter Gue (2012). After Empire: The Conceptual Transformation of the Chinese State, 1885-1924. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804778688., p. 93-94.

- ^ Zuozhuan «Duke Min — 1st year — zhuan» quote: «諸夏親暱不可棄也» translation: «The various Xia are close intimates and can not be abandoned»

- ^ Du Yu, Chunqiu Zuozhuan — Collected Explanations, «Vol. 4» p. 136 of 186. quote: «諸夏中國也»

- ^ Zuozhuan «Duke Xiang — 4th year — zhuan» quote: «諸華必叛» translation: «The various Hua would surely revolt»

- ^ Du Yu, Chunqiu Zuozhuan — Collected Explanations, «Vol. 15». p. 102 of 162 quote: «諸華中國»

- ^ Ban Wang. Chinese Visions of World Order: Tian, Culture and World Politics. pp. 270–272.

- ^ Tackett, Nicolas (2017). Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4, 161–2, 174, 194, 208, 280. ISBN 9781107196773.

- ^ Classic of Poetry, «Major Hymns — Min Lu» quote: «惠此中國、以綏四方。…… 惠此京師、以綏四國 。

» Legge’s translation: «Let us cherish this centre of the kingdom, to secure the repose of the four quarters of it. […] Let us cherish this capital, to secure the repose of the States in the four quarters.» - ^ Zhu Xi (publisher, 1100s), Collected Commentaries on the Classic of Poetry (詩經集傳) «Juan A (卷阿)» p. 68 of 198 quote: «中國,京師也。四方,諸夏也。京師,諸夏之根本也。» translation: «The centre of the kingdom means the capital. The four quarters mean the various Xia. The capital is the root of the various Xia.»

- ^ Shiji, «Annals of the Five Emperors» quote: «舜曰:「天也」,夫而後之中國踐天子位焉,是為帝舜。» translation: «Shun said, ‘It is from Heaven.’ Afterwards he went to the capital, sat on the Imperial throne, and was styled Emperor Shun.»

- ^ Pei Yin, Records of the Grand Historian — Collected Explanation Vol. 1 «劉熈曰……帝王所都為中故曰中國» translation: «Liu Xi said: […] Wherever emperors and kings established their capitals is taken as the center; hence the appellation the central region«

- ^ Shiji, «Annals of Emperor Xiaowu»

- ^ Shiji «Treatise about the Feng Shan sacrifices»

- ^ Zuo zhuan, «Duke Xiang, year 26, zhuan» text: «楚失華夏.» translation: «Chu lost (the political allegiance of / the political influence over) the flourishing and grand (states).»

- ^ Huan Wen (347 CE). «Memorial Recommending Qiao Yuanyan» (薦譙元彥表), quoted in Sun Sheng’s Annals of Jin (晉陽秋) (now-lost), quoted in Pei Songzhi’s annotations to Chen Shou, Records of the Three Kingdoms, «Biography of Qiao Xiu» quote: «於時皇極遘道消之會,群黎蹈顛沛之艱,中華有顧瞻之哀,幽谷無遷喬之望。»

- ^ Farmer, J. Michael (2017) «Sanguo Zhi Fascicle 42: The Biography of Qiao Zhou», Early Medieval China, 23, 22-41, p. 39. quote: «At this time, the imperial court has encountered a time of decline in the Way, the peasants have been trampled down by oppressive hardships, Zhonghua has the anguish of looking backward [toward the former capital at Luoyang], and the dark valley has no hope of moving upward.» DOI: 10.1080/15299104.2017.1379725

- ^ Fourmont, Etienne. «Linguae Sinarum Mandarinicae hieroglyphicae grammatica duplex, latinè, & cum characteribus Sinensium. Item Sinicorum Regiae Bibliothecae librorum catalogus… (A Chinese grammar published in 1742 in Paris)». Archived from the original on 2012-03-06.

- ^ Jiang 2011, p. 103.

- ^ Peter K Bol, «Geography and Culture: Middle-Period Discourse on the Zhong Guo: The Central Country,» (2009), 1, 26.

- ^ Esherick (2006), pp. 232–233

- ^ Hauer 2007, p. 117.

- ^ Dvořák 1895, p. 80.

- ^ Wu 1995, p. 102.

- ^ Zhao (2006), p. 7.

- ^ Zhao (2006), p. 4, 7–10, 12–14.

- ^ Mosca 2011, p. 94.

- ^ Dunnell 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Dunnell 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Elliott 2001, p. 503.

- ^ Dunnell 2004, pp. 76-77.

- ^ Cassel 2011, p. 205.

- ^ Cassel 2012, p. 205.

- ^ Cassel 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Cassel 2012, p. 44.

- ^ Perdue 2009, p. 218.

- ^ Elliot 2000, p. 638.

- ^ Barabantseva 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Esherick (2006), p. 232

- ^ Esherick (2006), p. 251

- ^ Liang quoted in Esherick (2006), p. 235, from Liang Qichao, «Zhongguo shi xulun» Yinbinshi heji 6:3 and in Lydia He Liu, The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Douglas R. Reynolds. China, 1898–1912: The Xinzheng Revolution and Japan. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1993 ISBN 0674116607), pp. 215–16 n. 20.

- ^ Henrietta Harrison. China (London: Arnold; New York: Oxford University Press; Inventing the Nation Series, 2001. ISBN 0-340-74133-3), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Rev. and enl., 2000 ISBN 0-674-00247-4 ), 132.

- ^ Lydia He. LIU; Lydia He Liu (30 June 2009). The Clash of Empires: the invention of China in modern world making. Harvard University Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-674-04029-8.

- ^ Wilkinson, p. 132.

- ^ Wilkinson 2012, p. 191.

- ^ Between 1967 and 2014, «Cina»/»China» is used. It was officially reverted to «Tiongkok» in 2014 by order of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono due to anti-discriminatory reasons, but usage is unforced.

- ^ 孔穎達《春秋左傳正義》:「中國有禮儀之大,故稱夏;有服章之美,謂之華。」

- ^ a b c Wang, Zhang (2014). Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-2311-4891-7.

- ^ a b c «‘Celestial’ origins come from long ago in Chinese history». Mail Tribune. Rosebud Media LLC. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Hughes, April D. (2021). Worldly Saviors and Imperial Authority in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. p. 103.

Attesting Illumination states that two saviors will manifest in the Divine Realm (shenzhou 神州; i.e. China) 799 years after Śākyamuni Buddha’s nirvāṇa.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (13 September 2013). China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 9781136791413.

- ^ H. Mark Lai (4 May 2004). Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions. AltaMira Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780759104587.

- ^ Tai, Pao-tsun (2007). The Concise History of Taiwan (Chinese-English bilingual ed.). Nantou City: Taiwan Historica. p. 52. ISBN 9789860109504.

- ^ «Entry #60161 (有唐山公,無唐山媽。)». 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan]. (in Chinese and Hokkien). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011.

- ^ 《中華民國教育部重編國語辭典修訂本》:「以其位居四方之中,文化美盛,故稱其地為『中華』。」

- ^ Wilkinson. Chinese History: A Manual. p. 32.

- ^ 梅峯.«中華民國應譯為「PRC」». 开放网.2014-07-12

- ^ BBC 中文網 (2005-08-29). «論壇:台總統府網頁加注»台灣»» (in Traditional Chinese). BBC 中文網. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

台總統府公共事務室陳文宗上周六(7月30日)表示,外界人士易把中華民國(Republic of China),誤認為對岸的中國,造成困擾和不便。公共事務室指出,為了明確區別,決定自周六起於中文繁體、簡體的總統府網站中,在「中華民國」之後,以括弧加注「臺灣」。

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed (AHD4). Boston and New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 2000, entries china, Qin, Sino-.

- ^ Axel Schuessler (2006). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawai’i Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0824829759.

- ^ a b c Yule (2005), p. 2–3 «There are reasons however for believing the word China was bestowed at a much earlier date, for it occurs in the Laws of Manu, which assert the Chinas to be degenerate Kshatriyas, and the Mahabharat, compositions many centuries older that imperial dynasty of Ts’in … And this name may have yet possibly been connected with the Ts’in, or some monarchy of the like title; for that Dynasty had reigned locally in Shen si from the ninth century before our era…»

- ^ a b c d e Samuel Wells Williams (2006). The Middle Kingdom: A Survey of the Geography, Government, Literature, Social Life, Arts and History of the Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 978-0710311672.

- ^ «China». Oxford English Dictionary (1989). ISBN 0-19-957315-8.

- ^ Barbosa, Duarte; Dames, Mansel Longworth (1989). ««The Very Great Kingdom of China»«. The Book of Duarte Barbosa. ISBN 81-206-0451-2. In the Portuguese original, the chapter is titled «O Grande Reino da China».

- ^ Eden, Richard (1555). Decades of the New World: «The great China whose kyng is thought the greatest prince in the world.»

Myers, Henry Allen (1984). Western Views of China and the Far East, Volume 1. Asian Research Service. p. 34. - ^ Wade (2009), pp. 8–11

- ^ Berthold Laufer (1912). «The Name China». T’oung Pao. 13 (1): 719–726. doi:10.1163/156853212X00377.

- ^ «China». Oxford English Dictionary.ISBN 0-19-957315-8

- ^ Yule (2005), p. 3–7

- ^ a b Wade (2009), pp. 12–13

- ^ Bodde, Derk (26 December 1986). Denis Twitchett; Michael Loewe (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 BC — AD 220. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9780521243278.

- ^ a b Wade (2009), p. 20

- ^ Liu, Lydia He, The clash of empires, p. 77. ISBN 9780674019959. «Scholars have dated the earliest mentions of Cīna to the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata and to other Sanskrit sources such as the Hindu Laws of Manu.»

- ^ Wade (2009) «This thesis also helps explain the existence of Cīna in the Indic Laws of Manu and the Mahabharata, likely dating well before Qin Shihuangdi.»

- ^ «Seiria». eDIL — Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language. 2013.

- ^ «Sino-«. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Yule (2005), p. xxxvii

- ^ Yule (2005), p. xl

- ^ Stefan Faller (2011). «The World According to Cosmas Indicopleustes – Concepts and Illustrations of an Alexandrian Merchant and Monk». Transcultural Studies. 1 (2011): 193–232. doi:10.11588/ts.2011.1.6127.

- ^ William Smith; John Mee Fuller, eds. (1893). Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible. p. 1328.

- ^ John Kitto, ed. (1845). A cyclopædia of biblical literature. p. 773.

- ^ William Smith; John Mee Fuller, eds. (1893). Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible. p. 1323.

- ^ Sinor, D. (1998), «Chapter 11 – The Kitan and the Kara Kitay», in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, vol. 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- ^ a b James A. Millward and Peter C. Perdue (2004). S.F.Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 43. ISBN 9781317451372.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Yang, Shao-yun (2014). «Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500-1200». In Fiaschetti, Francesca; Schneider, Julia (eds.). Political Strategies of Identity Building in Non-Han Empires in China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 23.

- ^ Samuel E. Martin, Dagur Mongolian Grammar, Texts, and Lexicon, Indiana University Publications Uralic and Altaic Series, Vol. 4, 1961

- ^ Yule (2005), p. 177

- ^ Tan Koon San (15 August 2014). Dynastic China: An Elementary History. The Other Press. p. 247. ISBN 9789839541885.

- ^ Yule (2005), p. 165

Sources[edit]

- Cassel, Par Kristoffer (2011). Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199792122. Retrieved 10 March 2014.