комодский варан

- комодский варан

-

ком’одский вар’ан

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «комодский варан» в других словарях:

-

Комодский варан — Комодский, или комодосский варан Комодский варан (Varanus komodoensis) … Википедия

-

Комодский варан — Комодский варан. КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН (комодосский варан), пресмыкающееся (семейство вараны). Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина свыше 3 м (до 4,75 м), масса до 166 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН — (комодосский варан), пресмыкающееся (семейство вараны). Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина свыше 3 м (до 4,75 м), масса до 166 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Роет норы (до 5 м).… … Современная энциклопедия

-

комодский варан — сущ., кол во синонимов: 1 • варан (3) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН — пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

комодский варан — пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина до 3 м, масса до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Комодский варан — гигантский варан (Varanus komodoensis), крупнейший представитель не только варанов (См. Вараны), но и всех современных ящериц. Самые крупные экземпляры длиной свыше 3 м и весят до 150 кг (по последним данным). Обитает К. в. на островах… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН — пресмыкающееся сем. варанов. Самая крупная совр. ящерица: дл. до 3 м, масса до 150 кг. Обитает на неск. о вах Малайского арх. (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Фло рес). Выкапывает норы глуб. до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью … Естествознание. Энциклопедический словарь

-

комодский варан — (комодоский варан), самая крупная ящерица мировой фауны. См. Варановые. .(Источник: «Биология. Современная иллюстрированная энциклопедия.» Гл. ред. А. П. Горкин; М.: Росмэн, 2006.) … Биологический энциклопедический словарь

-

Комодский дракон — ? Комодский варан Научная классификация Царство: Животные Тип: Хордовые … Википедия

Смотреть что такое КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН в других словарях:

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

гигантский варан (Varanus komodoensis), крупнейший представитель не только варанов (См. Вараны), но и всех современных ящериц. Самые крупные эк… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

комодский варан

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 1

• варан (3)

Словарь синонимов ASIS.В.Н. Тришин.2013.

.

Синонимы:

варан

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

1) Орфографическая запись слова: комодский варан2) Ударение в слове: ком`одский вар`ан3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): комодский варан4) Фоне… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

пресмыкающееся сем. варанов. Самая крупная совр. ящерица: дл. до 3 м, масса до 150 кг. Обитает на неск. о-вах Малайского арх. (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и … смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

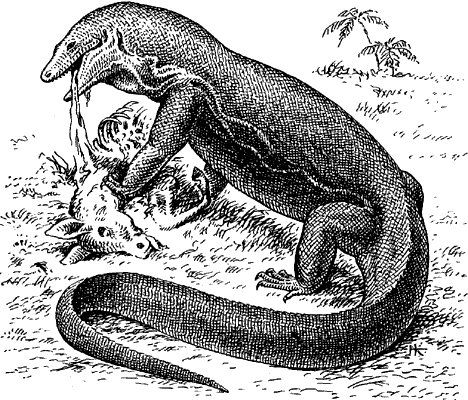

(комодосский варан), пресмыкающееся (семейство вараны). Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина свыше 3 м (до 4,75 м), масса до 166 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Роет норы (до 5 м). Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. Охраняется на острове Комодо, который получил статус национального парка.

<p class=»tab»><img style=»max-width:300px;» src=»https://words-storage.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/production/article_images/1598/55e9d2d7-1e22-43b0-8ae5-16a23571f820″ title=»КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН фото» alt=»КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН фото» class=»responsive-img img-responsive»>

</p><p class=»tab»>Комодский варан.</p>… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН, пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книге Международного совета охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП). Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка.<br><br><br>… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН — пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книге Международного совета охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП). Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка.<br>… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН , пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книге Международного совета охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП). Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка…. смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН, пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книге Международного совета охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП). Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка…. смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

— пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупнаясовременная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на несколькихостровах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес).Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными,обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книгеМеждународного совета охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП).Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка…. смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

комо́дский вара́н

(комодоский варан), самая крупная ящерица мировой фауны. См. Варановые.

.(Источник: «Биология. Современная иллюстрированная э… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН (комодосский варан), пресмыкающееся (семейство вараны). Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина свыше 3 м (до 4,75 м), масса до 166 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Роет норы (до 5 м). Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. Охраняется на острове Комодо, который получил статус национального парка. <br>… смотреть

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

(Varanus komodoensis)1) Komodo dragon

2) giant lizard of Komodo

3) Komodo dragon monitor

4) ora

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН

Начальная форма — Комодский варан, единственное число, именительный падеж, мужской род, одушевленное

Толковый словарь русского языка. Поиск по слову, типу, синониму, антониму и описанию. Словарь ударений.

комодский варан

ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

Комо́дский вара́н — пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина до 3 м, масса до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книге МСОП. Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка.

* * *

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН — КОМО́ДСКИЙ ВАРА́Н (Varanus komodoensis), ящерица семейства варанов (см. ВАРАНЫ), самая крупная из современных ящериц. Ее длина вместе с хвостом более 3 м, масса до 140 кг. Комодский варан распространен на нескольких небольших островах в Восточной Индонезии (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес) и выполняет здесь роль отсутствующих хищников. Он выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м, прекрасно плавает. Питается варан падалью, реже живыми животными — оленями, кабанами и обезьянами.

Комодский варан яйцекладущий — в конце июля самка откладывает до 30 яиц. Для человека может быть опасен. Комодский варан включен в Международную Красную книгу. На острове Комодо для его сохранения создан резерват. Комодский варан был открыт в 1912 году. Местные жители называли его «буая дарат» (сухопутный крокодил). Первые серьезные исследования, в ходе которых были развеяны легенды о семиметровых особях, начались только в 1920-е годы.

БОЛЬШОЙ ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН — пресмыкающееся семейства варанов. Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина св. 3 м, весит до 150 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Выкапывает норы глубиной до 5 м. Хорошо плавает. Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. В Красной книге Международного совета охраны природы и природных ресурсов (МСОП). Охраняется на о. Комодо, который получил статус национального парка.

ИЛЛЮСТРИРОВАННЫЙ ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

Комодский варан.

КОМОДСКИЙ ВАРАН (комодосский варан), пресмыкающееся (семейство вараны). Самая крупная современная ящерица: длина свыше 3 м (до 4,75 м), масса до 166 кг. Обитает на нескольких островах Малайского архипелага (Комодо, Ринджа, Падар и Флорес). Роет норы (до 5 м). Питается копытными, обезьянами, падалью. Иногда нападает на людей. Охраняется на острове Комодо, который получил статус национального парка.

Комодский варан.

ОРФОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

СИНОНИМЫ

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 1

ПОЛЕЗНЫЕ СЕРВИСЫ

Комодский варан

⇒ Правильное написание:

комодский варан

⇒ Гласные буквы в слове:

комодский варан

гласные выделены красным

гласными являются: о, о, и, а, а

общее количество гласных: 5 (пять)

• ударная гласная:

комо́дский вара́н

ударная гласная выделена знаком ударения « ́»

ударение падает на буквы: о, а,

• безударные гласные:

комодский варан

безударные гласные выделены пунктирным подчеркиванием « »

безударными гласными являются: о, и, а

общее количество безударных гласных: 3 (три)

⇒ Согласные буквы в слове:

комодский варан

согласные выделены зеленым

согласными являются: к, м, д, с, к, й, в, р, н

общее количество согласных: 9 (девять)

• звонкие согласные:

комодский варан

звонкие согласные выделены одинарным подчеркиванием « »

звонкими согласными являются: м, д, й, в, р, н

общее количество звонких согласных: 6 (шесть)

• глухие согласные:

комодский варан

глухие согласные выделены двойным подчеркиванием « »

глухими согласными являются: к, с, к

общее количество глухих согласных: 3 (три)

⇒ Формы слова:

комо́дский вара́н

⇒ Количество букв и слогов:

гласных букв: 5 (пять)

согласных букв: 9 (девять)

всего букв: 14 (четырнадцать)

всего слогов: 5 (пять)

.

| Komodo dragon

Temporal range: PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male at the Cincinnati Zoo | |

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

|

CITES Appendix I (CITES)[3] |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Varanidae |

| Genus: | Varanus |

| Subgenus: | Varanus |

| Species: |

V. komodoensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Varanus komodoensis

Ouwens, 1912[4] |

|

|

|

| Komodo dragon distribution |

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), also known as the Komodo monitor, is a member of the monitor lizard family Varanidae that is endemic to the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. It is the largest extant species of lizard, growing to a maximum length of 3 m (9.8 ft), and weighing up to 70 kg (150 lb).

As a result of their size, Komodo dragons are apex predators, and dominate the ecosystems in which they live. Komodo dragons hunt and ambush prey including invertebrates, birds, and mammals. It has been claimed that they have a venomous bite; there are two glands in the lower jaw that secrete several toxic proteins. The biological significance of these proteins is disputed, but the glands have been shown to secrete an anticoagulant. Komodo dragons’ group behavior in hunting is exceptional in the reptile world. The diet of Komodo dragons mainly consists of Javan rusa (Rusa timorensis), though they also eat considerable amounts of carrion. Komodo dragons also occasionally attack humans.

Mating begins between May and August, and the eggs are laid in September; as many as 20 eggs are deposited at a time in an abandoned megapode nest or in a self-dug nesting hole. The eggs are incubated for seven to eight months, hatching in April, when insects are most plentiful. Young Komodo dragons are vulnerable and dwell in trees to avoid predators, such as cannibalistic adults. They take 8 to 9 years to mature and are estimated to live up to 30 years.

Komodo dragons were first recorded by Western scientists in 1910. Their large size and fearsome reputation make them popular zoo exhibits. In the wild, their range has contracted due to human activities, and is likely to contract further from the effects of climate change; due to this, they are listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. They are protected under Indonesian law, and Komodo National Park was founded in 1980 to aid protection efforts.

Taxonomic history

Komodo dragons were first documented by Europeans in 1910, when rumors of a «land crocodile» reached Lieutenant van Steyn van Hensbroek of the Dutch colonial administration.[5] Widespread notoriety came after 1912, when Peter Ouwens, the director of the Zoological Museum of Bogor, Java, published a paper on the topic after receiving a photo and a skin from the lieutenant, as well as two other specimens from a collector.[4]

The first two live Komodo dragons to arrive in Europe were exhibited in the Reptile House at London Zoo when it opened in 1927.[6] Joan Beauchamp Procter made some of the earliest observations of these animals in captivity and she demonstrated their behaviour at a Scientific Meeting of the Zoological Society of London in 1928.[7]

The Komodo dragon was the driving factor for an expedition to Komodo Island by W. Douglas Burden in 1926. After returning with 12 preserved specimens and two live ones, this expedition provided the inspiration for the 1933 movie King Kong.[8] It was also Burden who coined the common name «Komodo dragon».[9] Three of his specimens were stuffed and are still on display in the American Museum of Natural History.[10]

The Dutch island administration, realizing the limited number of individuals in the wild, soon outlawed sport hunting and heavily limited the number of individuals taken for scientific study. Collecting expeditions ground to a halt with the occurrence of World War II, not resuming until the 1950s and 1960s, when studies examined the Komodo dragon’s feeding behavior, reproduction, and body temperature. At around this time, an expedition was planned in which a long-term study of the Komodo dragon would be undertaken. This task was given to the Auffenberg family, who stayed on Komodo Island for 11 months in 1969. During their stay, Walter Auffenberg and his assistant Putra Sastrawan captured and tagged more than 50 Komodo dragons.[11]

Research from the Auffenberg expedition proved enormously influential in raising Komodo dragons in captivity.[12] Research after that of the Auffenberg family has shed more light on the nature of the Komodo dragon, with biologists such as Claudio Ciofi continuing to study the creatures.[13]

Etymology

The Komodo dragon, as depicted on the 50 rupiah coin, issued by Indonesia

The Komodo dragon is also sometimes known as the Komodo monitor or the Komodo Island monitor in scientific literature,[14] although this name is uncommon. To the natives of Komodo Island, it is referred to as ora, buaya darat (‘land crocodile’), or biawak raksasa (‘giant monitor’).[15][5]

Evolutionary history

The evolutionary development of the Komodo dragon started with the genus Varanus, which originated in Asia about 40 million years ago and migrated to Australia, where it evolved into giant forms (the largest of all being the recently extinct Varanus priscus, or «Megalania»), helped by the absence of competing placental carnivorans. Around 15 million years ago, a collision between the continental landmasses of Australia and Southeast Asia allowed these larger varanids to move back into what is now the Indonesian archipelago, extending their range as far east as the island of Timor.

The Komodo dragon is believed to have differentiated from its Australian ancestors about 4 million years ago. However, fossil evidence from Queensland suggests the Komodo dragon actually evolved in Australia, before spreading to Indonesia.[1][16]

Dramatic lowering of sea level during the last glacial period uncovered extensive stretches of continental shelf that the Komodo dragon colonised, becoming isolated in their present island range as sea levels rose afterwards.[1][5] Fossils of extinct Pliocene species of similar size to the modern Komodo dragon, such as Varanus sivalensis, have been found in Eurasia as well, indicating that they fared well even in environments containing competition, such as mammalian carnivores, until the climate change and extinction events that marked the beginning of the Pleistocene.[1]

Genetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA shows the Komodo dragon to be the closest relative (sister taxon) of the lace monitor (V. varius), with their common ancestor diverging from a lineage that gave rise to the crocodile monitor (Varanus salvadorii) of New Guinea.[17][18][19] A 2021 study showed that during the Miocene, Komodo dragons had hybridized with the ancestors of the Australian sand monitor (V. gouldii), thus providing further evidence that the Komodo dragon had once inhabited Australia.[20][21][22] Genetic analysis indicates that the population from northern Flores is genetically distinct from other populations of the species.[2]

Description

In the wild, adult Komodo dragons usually weigh around 70 kg (150 lb), although captive specimens often weigh more.[23] According to Guinness World Records, an average adult male will weigh 79 to 91 kg (174 to 201 lb) and measure 2.59 m (8.5 ft), while an average female will weigh 68 to 73 kg (150 to 161 lb) and measure 2.29 m (7.5 ft).[24] The largest verified specimen in captive was 3.13 m (10.3 ft) long and weighed 166 kg (366 lb), including its undigested food.[5] The largest wild specimen had a length 3.04 m (10.0 ft), a snout-vent length (SVL) 1.54 m (5 ft 1 in) and a mass of 81.5 kg (180 lb) excluding stomach contents.[25][26] The heaviest reached a mass in 87.4 kg (193 lb).[25] The study noted that weights greater than 100 kg (220 lb) were possible but only after the animal had consumed a large meal.[25][26]

The Komodo dragon has a tail as long as its body, as well as about 60 frequently replaced, serrated teeth that can measure up to 2.5 cm (1 in) in length. Its saliva is frequently blood-tinged because its teeth are almost completely covered by gingival tissue that is naturally lacerated during feeding.[27] It also has a long, yellow, deeply forked tongue.[5] Komodo dragon skin is reinforced by armoured scales, which contain tiny bones called osteoderms that function as a sort of natural chain-mail.[28][29] The only areas lacking osteoderms on the head of the adult Komodo dragon are around the eyes, nostrils, mouth margins, and pineal eye, a light-sensing organ on the top of the head. Where lizards typically have one or two varying patterns or shapes of osteoderms, komodos have four: rosette, platy, dendritic, and vermiform.[30] This rugged hide makes Komodo dragon skin a poor source of leather. Additionally, these osteoderms become more extensive and variable in shape as the Komodo dragon ages, ossifying more extensively as the lizard grows. These osteoderms are absent in hatchlings and juveniles, indicating that the natural armor develops as a product of age and competition between adults for protection in intraspecific combat over food and mates.[31]

Senses

Komodo dragon using its tongue to sample the air

As with other varanids, Komodo dragons have only a single ear bone, the stapes, for transferring vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea. This arrangement means they are likely restricted to sounds in the 400 to 2,000 hertz range, compared to humans who hear between 20 and 20,000 hertz.[5][32] They were formerly thought to be deaf when a study reported no agitation in wild Komodo dragons in response to whispers, raised voices, or shouts. This was disputed when London Zoological Garden employee Joan Procter trained a captive specimen to come out to feed at the sound of her voice, even when she could not be seen.[33]

The Komodo dragon can see objects as far away as 300 m (980 ft), but because its retinas only contain cones, it is thought to have poor night vision. It can distinguish colours, but has poor visual discrimination of stationary objects.[34]

As with many other reptiles, the Komodo dragon primarily relies on its tongue to detect, taste, and smell stimuli, with the vomeronasal sense using the Jacobson’s organ, rather than using the nostrils.[35] With the help of a favorable wind and its habit of swinging its head from side to side as it walks, a Komodo dragon may be able to detect carrion from 4–9.5 km (2.5–5.9 mi) away.[34] It only has a few taste buds in the back of its throat.[35] Its scales, some of which are reinforced with bone, have sensory plaques connected to nerves to facilitate its sense of touch. The scales around the ears, lips, chin, and soles of the feet may have three or more sensory plaques.[27]

Behaviour and ecology

Male komodo dragons fighting

The Komodo dragon prefers hot and dry places and typically lives in dry, open grassland, savanna, and tropical forest at low elevations. As an ectotherm, it is most active in the day, although it exhibits some nocturnal activity. Komodo dragons are solitary, coming together only to breed and eat. They are capable of running rapidly in brief sprints up to 20 km/h (12 mph), diving up to 4.5 m (15 ft), and climbing trees proficiently when young through use of their strong claws.[23] To catch out-of-reach prey, the Komodo dragon may stand on its hind legs and use its tail as a support.[33] As it matures, its claws are used primarily as weapons, as its great size makes climbing impractical.[27]

For shelter, the Komodo dragon digs holes that can measure from 1 to 3 m (3.3 to 9.8 ft) wide with its powerful forelimbs and claws.[36] Because of its large size and habit of sleeping in these burrows, it is able to conserve body heat throughout the night and minimise its basking period the morning after.[37] The Komodo dragon hunts in the afternoon, but stays in the shade during the hottest part of the day.[9] These special resting places, usually located on ridges with cool sea breezes, are marked with droppings and are cleared of vegetation. They serve as strategic locations from which to ambush deer.[38]

Diet

Komodo dragons are apex predators.[39] They are carnivores; although they have been considered as eating mostly carrion,[40] they will frequently ambush live prey with a stealthy approach. When suitable prey arrives near a dragon’s ambush site, it will suddenly charge at the animal at high speeds and go for the underside or the throat.[27]

Komodo dragons do not deliberately allow the prey to escape with fatal injuries but try to kill prey outright using a combination of lacerating damage and blood loss. They have been recorded as killing wild pigs within seconds,[41] and observations of Komodo dragons tracking prey for long distances are likely misinterpreted cases of prey escaping an attack before succumbing to infection.

Komodo dragons eat by tearing large chunks of flesh and swallowing them whole while holding the carcass down with their forelegs. For smaller prey up to the size of a goat, their loosely articulated jaws, flexible skulls, and expandable stomachs allow them to swallow prey whole. The undigested vegetable contents of a prey animal’s stomach and intestines are typically avoided.[38] Copious amounts of red saliva the Komodo dragons produce help to lubricate the food, but swallowing is still a long process (15–20 minutes to swallow a goat). A Komodo dragon may attempt to speed up the process by ramming the carcass against a tree to force it down its throat, sometimes ramming so forcefully that the tree is knocked down.[38] A small tube under the tongue that connects to the lungs allows it to breathe while swallowing.[27]

After eating up to 80% of its body weight in one meal,[39] it drags itself to a sunny location to speed digestion, as the food could rot and poison the dragon if left undigested in its stomach for too long. Because of their slow metabolism, large dragons can survive on as few as 12 meals a year.[27] After digestion, the Komodo dragon regurgitates a mass of horns, hair, and teeth known as the gastric pellet, which is covered in malodorous mucus. After regurgitating the gastric pellet, it rubs its face in the dirt or on bushes to get rid of the mucus.[27]

Komodo excrement has a dark portion, which is stool, and a whitish portion, which is urate, the nitrogenous end-product of their digestion process

The eating habits of Komodo dragons follow a hierarchy, with the larger animals generally eating before the smaller ones. The largest male typically asserts his dominance and the smaller males show their submission by use of body language and rumbling hisses. Dragons of equal size may resort to «wrestling». Losers usually retreat, though they have been known to be killed and eaten by victors.[42][43]

The Komodo dragon’s diet is wide-ranging, and includes invertebrates, other reptiles (including smaller Komodo dragons), birds, bird eggs, small mammals, monkeys, wild boar, goats, pigs,[44] deer, horses, and water buffalo.[45] Young Komodos will eat insects, eggs, geckos, and small mammals, while adults prefer to hunt large mammals.[40] Occasionally, they attack and bite humans. Sometimes they consume human corpses, digging up bodies from shallow graves.[33] This habit of raiding graves caused the villagers of Komodo to move their graves from sandy to clay ground, and pile rocks on top of them, to deter the lizards.[38] The Komodo dragon may have evolved to feed on the extinct dwarf elephant Stegodon that once lived on Flores, according to evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond.[46]

The Komodo dragon drinks by sucking water into its mouth via buccal pumping (a process also used for respiration), lifting its head, and letting the water run down its throat.[41]

Saliva

Although previous studies proposed that Komodo dragon saliva contains a variety of highly septic bacteria that would help to bring down prey,[42][47] research in 2013 suggested that the bacteria in the mouths of Komodo dragons are ordinary and similar to those found in other carnivores. Komodo dragons have good mouth hygiene. To quote Bryan Fry: «After they are done feeding, they will spend 10 to 15 minutes lip-licking and rubbing their head in the leaves to clean their mouth … Unlike people have been led to believe, they do not have chunks of rotting flesh from their meals on their teeth, cultivating bacteria.» Nor do Komodo dragons wait for prey to die and track it at a distance, as vipers do; observations of them hunting deer, boar and in some cases buffalo reveal that they kill prey in less than half an hour.[48]

The observation of prey dying of sepsis would then be explained by the natural instinct of water buffalos, who are not native to the islands where the Komodo dragon lives, to run into water after escaping an attack. The warm, faeces-filled water would then cause the infections. The study used samples from 16 captive dragons (10 adults and six neonates) from three US zoos.[48]

Antibacterial immune factor

Researchers have isolated a powerful antibacterial peptide from the blood plasma of Komodo dragons, VK25. Based on their analysis of this peptide, they have synthesized a short peptide dubbed DRGN-1 and tested it against multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Preliminary results of these tests show that DRGN-1 is effective in killing drug-resistant bacterial strains and even some fungi. It has the added observed benefit of significantly promoting wound healing in both uninfected and mixed biofilm infected wounds.[49]

Venom

In late 2005, researchers at the University of Melbourne speculated the perentie (Varanus giganteus), other species of monitors, and agamids may be somewhat venomous. The team believes the immediate effects of bites from these lizards were caused by mild envenomation. Bites on human digits by a lace monitor (V. varius), a Komodo dragon, and a spotted tree monitor (V. scalaris) all produced similar effects: rapid swelling, localised disruption of blood clotting, and shooting pain up to the elbow, with some symptoms lasting for several hours.[50]

In 2009, the same researchers published further evidence demonstrating Komodo dragons possess a venomous bite. MRI scans of a preserved skull showed the presence of two glands in the lower jaw. The researchers extracted one of these glands from the head of a terminally ill dragon in the Singapore Zoological Gardens, and found it secreted several different toxic proteins. The known functions of these proteins include inhibition of blood clotting, lowering of blood pressure, muscle paralysis, and the induction of hypothermia, leading to shock and loss of consciousness in envenomated prey.[51][52] As a result of the discovery, the previous theory that bacteria were responsible for the deaths of Komodo victims was disputed.[53]

Other scientists have stated that this allegation of venom glands «has had the effect of underestimating the variety of complex roles played by oral secretions in the biology of reptiles, produced a very narrow view of oral secretions and resulted in misinterpretation of reptilian evolution.» According to these scientists «reptilian oral secretions contribute to many biological roles other than to quickly dispatch prey.» These researchers concluded that, «Calling all in this clade venomous implies an overall potential danger that does not exist, misleads in the assessment of medical risks, and confuses the biological assessment of squamate biochemical systems.»[54] Evolutionary biologist Schwenk says that even if the lizards have venom-like proteins in their mouths they may be using them for a different function, and he doubts venom is necessary to explain the effect of a Komodo dragon bite, arguing that shock and blood loss are the primary factors.[55][56]

Reproduction

Mating occurs between May and August, with the eggs laid in September.[5][57] During this period, males fight over females and territory by grappling with one another upon their hind legs, with the loser eventually being pinned to the ground. These males may vomit or defecate when preparing for the fight.[33] The winner of the fight will then flick his long tongue at the female to gain information about her receptivity.[39] Females are antagonistic and resist with their claws and teeth during the early phases of courtship. Therefore, the male must fully restrain the female during coitus to avoid being hurt. Other courtship displays include males rubbing their chins on the female, hard scratches to the back, and licking.[58] Copulation occurs when the male inserts one of his hemipenes into the female’s cloaca.[34] Komodo dragons may be monogamous and form «pair bonds», a rare behavior for lizards.[33]

Female Komodos lay their eggs from August to September and may use several types of locality; in one study, 60% laid their eggs in the nests of orange-footed scrubfowl (a moundbuilder or megapode), 20% on ground level and 20% in hilly areas.[59] The females make many camouflage nests/holes to prevent other dragons from eating the eggs.[60] Clutches contain an average of 20 eggs, which have an incubation period of 7–8 months.[33] Hatching is an exhausting effort for the neonates, which break out of their eggshells with an egg tooth that falls off before long. After cutting themselves out, the hatchlings may lie in their eggshells for hours before starting to dig out of the nest. They are born quite defenseless and are vulnerable to predation.[42] Sixteen youngsters from a single nest were on average 46.5 cm long and weighed 105.1 grams.[59]

Young Komodo dragons spend much of their first few years in trees, where they are relatively safe from predators, including cannibalistic adults, as juvenile dragons make up 10% of their diets.[33] The habit of cannibalism may be advantageous in sustaining the large size of adults, as medium-sized prey on the islands is rare.[61] When the young approach a kill, they roll around in faecal matter and rest in the intestines of eviscerated animals to deter these hungry adults.[33] Komodo dragons take approximately 8 to 9 years to mature, and may live for up to 30 years.[57]

Parthenogenesis

A Komodo dragon at London Zoo named Sungai laid a clutch of eggs in late 2005 after being separated from male company for more than two years. Scientists initially assumed she had been able to store sperm from her earlier encounter with a male, an adaptation known as superfecundation.[62] On 20 December 2006, it was reported that Flora, a captive Komodo dragon living in the Chester Zoo in England, was the second known Komodo dragon to have laid unfertilised eggs: she laid 11 eggs, and seven of them hatched, all of them male.[63] Scientists at Liverpool University in England performed genetic tests on three eggs that collapsed after being moved to an incubator, and verified Flora had never been in physical contact with a male dragon. After Flora’s eggs’ condition had been discovered, testing showed Sungai’s eggs were also produced without outside fertilization.[64] On 31 January 2008, the Sedgwick County Zoo in Wichita, Kansas, became the first zoo in the Americas to document parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons. The zoo has two adult female Komodo dragons, one of which laid about 17 eggs on 19–20 May 2007. Only two eggs were incubated and hatched due to space issues; the first hatched on 31 January 2008, while the second hatched on 1 February. Both hatchlings were males.[65][66]

Komodo dragons have the ZW chromosomal sex-determination system, as opposed to the mammalian XY system. Male progeny prove Flora’s unfertilized eggs were haploid (n) and doubled their chromosomes later to become diploid (2n) (by being fertilized by a polar body, or by chromosome duplication without cell division), rather than by her laying diploid eggs by one of the meiosis reduction-divisions in her ovaries failing. When a female Komodo dragon (with ZW sex chromosomes) reproduces in this manner, she provides her progeny with only one chromosome from each of her pairs of chromosomes, including only one of her two sex chromosomes. This single set of chromosomes is duplicated in the egg, which develops parthenogenetically. Eggs receiving a Z chromosome become ZZ (male); those receiving a W chromosome become WW and fail to develop,[67][68] meaning that only males are produced by parthenogenesis in this species.

It has been hypothesised that this reproductive adaptation allows a single female to enter an isolated ecological niche (such as an island) and by parthenogenesis produce male offspring, thereby establishing a sexually reproducing population (via reproduction with her offspring that can result in both male and female young).[67] Despite the advantages of such an adaptation, zoos are cautioned that parthenogenesis may be detrimental to genetic diversity.[69]

Encounters with humans

Humans handling a komodo dragon

Attacks on humans are rare, but Komodo dragons have been responsible for several human fatalities, in both the wild and in captivity. According to data from Komodo National Park spanning a 38-year period between 1974 and 2012, there were 24 reported attacks on humans, five of them fatal. Most of the victims were local villagers living around the national park.[70]

Conservation

The Komodo dragon is classified by the IUCN as Endangered and is listed on the IUCN Red List.[2] The species’ sensitivity to natural and man-made threats has long been recognized by conservationists, zoological societies, and the Indonesian government. Komodo National Park was founded in 1980 to protect Komodo dragon populations on islands including Komodo, Rinca, and Padar.[71] Later, the Wae Wuul and Wolo Tado Reserves were opened on Flores to aid Komodo dragon conservation.[13]

Komodo dragons generally avoid encounters with humans. Juveniles are very shy and will flee quickly into a hideout if a human comes closer than about 100 metres (330 ft). Older animals will also retreat from humans from a shorter distance away. If cornered, they may react aggressively by gaping their mouth, hissing, and swinging their tail. If they are disturbed further, they may attack and bite. Although there are anecdotes of unprovoked Komodo dragons attacking or preying on humans, most of these reports are either not reputable or have subsequently been interpreted as defensive bites. Only very few cases are truly the result of unprovoked attacks by atypical individuals who lost their fear of humans.[42]

Volcanic activity, earthquakes, loss of habitat, fire,[27][13] tourism, loss of prey due to poaching, and illegal poaching of the dragons themselves have all contributed to the vulnerable status of the Komodo dragon. A major future threat to the species is climate change via both aridification and sea level rise, which can affect the low-lying habitats and valleys that the Komodo dragon depends on, as Komodo dragons do not range into the higher-altitude regions of the islands they inhabit. Based on projections, climate change will lead to a decline in suitable habitat of 8.4%, 30.2%, or 71% by 2050 depending on the climate change scenario. Without effective conservation actions, populations on Flores are extirpated in all scenarios, while in the more extreme scenarios, only the populations on Komodo and Rinca persist in highly reduced numbers. Rapid climate change mitigation is crucial for conserving the species in the wild.[2][72] Other scientists have disputed the conclusions about the effects of climate change on Komodo dragon populations.[73]

Under Appendix I of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), commercial international trade of Komodo dragon skins or specimens is prohibited.[74][75] Despite this, there are occasional reports of illegal attempts to trade in live Komodo dragons. The most recent attempt was in March 2019, when Indonesian police in the East Java city of Surabaya reported that a criminal network had been caught trying to smuggle 41 young Komodo dragons out of Indonesia. The plan was said to include shipping the animals to several other countries in Southeast Asia through Singapore. It was hoped that the animals could be sold for up to 500 million rupiah (around US$35,000) each.[76] It was believed that the Komodo dragons had been smuggled out of East Nusa Tenggara province through the port at Ende in central Flores.[77]

In 2013, the total population of Komodo dragons in the wild was assessed as 3,222 individuals, declining to 3,092 in 2014 and 3,014 in 2015. Populations remained relatively stable on the bigger islands (Komodo and Rinca), but decreased on smaller islands, such as Nusa Kode and Gili Motang, likely due to diminishing prey availability.[78] On Padar, a former population of Komodo dragons has recently become extinct, of which the last individuals were seen in 1975.[79] It is widely assumed that the Komodo dragon died out on Padar following a major decline of populations of large ungulate prey, for which poaching was most likely responsible.[80]

In captivity

Komodo dragons have long been sought-after zoo attractions, where their size and reputation make them popular exhibits. They are, however, rare in zoos because they are susceptible to infection and parasitic disease if captured from the wild, and do not readily reproduce in captivity.[15] The first Komodo dragons were displayed at London Zoo in 1927. A Komodo dragon was exhibited in 1934 in the United States at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., but it lived for only two years. More attempts to exhibit Komodo dragons were made, but the lifespan of the animals proved very short, averaging five years in the National Zoological Park. Studies were done by Walter Auffenberg, which were documented in his book The Behavioral Ecology of the Komodo Monitor, eventually allowed for more successful management and breeding of the dragons in captivity.[12] As of May 2009, there were 35 North American, 13 European, one Singaporean, two African, and two Australian institutions which housed captive Komodo dragons.[81]

A variety of behaviors have been observed from captive specimens. Most individuals become relatively tame within a short time,[82][83] and are capable of recognising individual humans and discriminating between familiar and unfamiliar keepers.[84] Komodo dragons have also been observed to engage in play with a variety of objects, including shovels, cans, plastic rings, and shoes. This behavior does not seem to be «food-motivated predatory behavior».[39][5][85]

Even seemingly docile dragons may become unpredictably aggressive, especially when the animal’s territory is invaded by someone unfamiliar. In June 2001, a Komodo dragon seriously injured Phil Bronstein, the then-husband of actress Sharon Stone, when he entered its enclosure at the Los Angeles Zoo after being invited in by its keeper. Bronstein was bitten on his bare foot, as the keeper had told him to take off his white shoes and socks, which the keeper stated could potentially excite the Komodo dragon as they were the same colour as the white rats the zoo fed the dragon.[86][87] Although he survived, Bronstein needed to have several tendons in his foot reattached surgically.[88]

See also

- List of largest extant lizards

- Asian water monitor

- Komodo Indonesian Fauna Museum and Reptile Park

- Papua monitor (Varanus salvadorii), a monitor lizard often asserted to be the longest extant lizard

- Toxicofera, a hypothetical clade encompassing all venomous reptiles, including the Komodo dragon

- Varanus priscus (formerly known as Megalania prisca), a huge extinct varanid lizard of Pleistocene Australia

References

- ^ a b c d Hocknull SA, Piper PJ, van den Bergh GD, Due RA, Morwood MJ, Kurniawan I (2009). «Dragon’s Paradise Lost: Palaeobiogeography, Evolution and Extinction of the Largest-Ever Terrestrial Lizards (Varanidae)». PLOS ONE. 4 (9): e7241. Bibcode:2009PLoSO…4.7241H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007241. PMC 2748693. PMID 19789642.

- ^ a b c d Jessop, Tim; Ariefiandy, Achmad; Azmi, Muhammad; Ciofi, Claudio; Imansyah, Jeri; Purwandana, Deni (5 August 2021). «Varanus komodoensis«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22884A123633058. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T22884A123633058.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ «Appendices». CITES. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b Ouwens, P. A. (1912). «On a large Varanus species from the island of Komodo». Bulletin de l’Institut Botanique de Buitenzorg. 2. 6: 1–3. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ciofi, Claudio (March 1999). «The Komodo Dragon». Scientific American. 280 (3): 84–91. Bibcode:1999SciAm.280c..84C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0399-84.

- ^ Chalmers Mitchell, Peter (15 June 1927). «Reptiles at the Zoo: Opening of new house today». The London Times. London, UK. p. 17.

- ^ Procter, J. B. (1928). «On a living Komodo dragon Varanus komodoensis Ouwens, exhibited at the Scientific Meeting, October 23rd, 1928″. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 98 (4): 1017–19. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1928.tb07181.x.

- ^ Rony, Fatimah Tobing (1996). The third eye: Race, cinema, and ethnographic spectacle. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8223-1840-8.

- ^ a b «Komodo National Park Frequently Asked Questions». Komodo Foundation. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ «American Museum of Natural History: Komodo Dragons». American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ^ Cheater, Mark (August–September 2003). «Chasing the Magic Dragon». National Wildlife Magazine. 41 (5). Archived from the original on 20 February 2009.

- ^ a b Walsh, Trooper; Murphy, James Jerome; Ciofi, Claudio; De LA Panouse, Colomba (2002). Komodo Dragons: Biology and Conservation. Zoo and Aquarium Biology and Conservation Series. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-58834-073-3.

- ^ a b c «Trapping Komodo Dragons for Conservation». National Geographic. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- ^ «Varanus komodoensis». Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- ^ a b «Ora (Komodo Island Monitor or Komodo Dragon)». American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ «Australia was ‘hothouse’ for killer lizards». Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ Vidal, N.; Marin, J.; Sassi, J.; Battistuzzi, F.U.; Donnellan, S.; Fitch, A.J.; et al. (2012). «Molecular evidence for an Asian origin of monitor lizards followed by Tertiary dispersals to Africa and Australasia». Biology Letters. 8 (5): 853–855. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0460. PMC 3441001. PMID 22809723.

- ^ Fitch AJ, Goodman AE, Donnellan SC (2006). «A molecular phylogeny of the Australian monitor lizards (Squamata: Varanidae) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences». Australian Journal of Zoology. 54 (4): 253–269. doi:10.1071/ZO05038.

- ^ Ast, Jennifer C. (2001). «Mitochondrial DNA evidence and evolution in Varanoidea (Squamata)» (PDF). Cladistics. 17 (3): 211–226. doi:10.1006/clad.2001.0169. hdl:2027.42/72302. PMID 34911248.; Ast, J.C. «erratum». Cladistics. 18 (1): 125. doi:10.1006/clad.2002.0198.

- ^ Pavón-Vázquez, Carlos J.; Brennan, Ian G.; Keogh, J. Scott (2021). «A Comprehensive Approach to Detect Hybridization Sheds Light on the Evolution of Earth’s Largest Lizards». Systematic Biology. 70 (5): 877–890. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syaa102. PMID 33512509.

- ^ «Study reveals surprising history of world’s largest lizard». phys.org. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ «Komodo dragons not only inhabited ancient Australia, but also mated with our sand monitors». Australian Geographic. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b Burnie, David; Don E. Wilson (2001). Animal. New York: DK Publishing. pp. 417, 420. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ^ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ a b c Jessop, T.; Madsen, T.; Ciofi, C.; Jeriimansyah, M.; Purwandana, D.; Rudiharto, H.; Arifiandy, A.; Phillips, J. (2007). «Island differences in population size structure and catch per unit effort and their conservation implications for Komodo dragons». Biological Conservation. 135 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.10.025.

- ^ a b «The Largest Monitor Lizards by Paleonerd01 on DeviantArt». Deviantart.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tara Darling (Illustrator) (1997). Komodo Dragon: On Location (Darling, Kathy. on Location.). Lothrop, Lee and Shepard Books. ISBN 978-0-688-13777-9.

- ^

Komodo Dragons Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine . London Zoo - ^

Komodo Dragon, Varanus komodoensis 1998. Physical Characteristics Archived 17 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine . San Diego Zoo Global Zoo (1998). - ^ Hern, Daisy; ez (29 September 2019). «Here’s Why Komodo Dragons are the Toughest Lizards on Earth». Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ «Elaborate Komodo dragon armor defends against other dragons».

- ^ «Komodo Conundrum». BBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h David Badger; photography by John Netherton (2002). Lizards: A Natural History of Some Uncommon Creatures, Extraordinary Chameleons, Iguanas, Geckos, and More. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 32, 52, 78, 81, 84, 140–145, 151. ISBN 978-0-89658-520-1.

- ^ a b c «Komodo Dragon Fact Sheet». National Zoological Park. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ a b «Komodo Dragon». Singapore Zoological Gardens. Archived from the original on 14 February 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ Cogger, Harold G.; Zweifel, Richard G., eds. (1998). Encyclopedia of Reptiles & Amphibians. Illustrations by David Kirshner. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 132, 157–58. ISBN 978-0-12-178560-4.

- ^ Eric R. Pianka; Laurie J. Vitt; with a foreword by Harry W. Greene (2003). Lizards: Windows to the Evolution of Diversity. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-23401-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Ballance, Alison; Morris, Rod (2003). South Sea Islands: A natural history. Hove: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55297-609-8.

- ^ a b c d Halliday, Tim; Adler, Kraig, eds. (2002). Firefly Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. Hove: Firefly Books. pp. 112–13, 144, 147, 168–69. ISBN 978-1-55297-613-5.

- ^ a b Mattison, Chris (1992) [1989]. Lizards of the World. New York: Facts on File. pp. 16, 57, 99, 175. ISBN 978-0-8160-5716-0.

- ^ a b Auffenberg, Walter (1981). The Behavioral Ecology of the Komodo Monitor. Gainesville, Florida: University Presses of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-0621-5.

- ^ a b c d Auffenberg, Walter (1981). The Behavioral Ecology of the Komodo Monitor. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-8130-0621-5.

- ^ Mader, Douglas R. (1996). Reptile Medicine and Surgery. WB Saunders Co. p. 16. ISBN 0721652085.

- ^ Lawwell, Leanne. «ADW: Varanus komodoensis: INFORMATION». Animaldiversity.org. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Vidal, John (12 June 2008). «The terrifying truth about Komodo dragons». guardian.co.uk. London, UK. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ Diamond, Jared M. (1987). «Did Komodo dragons evolve to eat pygmy elephants?». Nature. 326 (6116): 832. Bibcode:1987Natur.326..832D. doi:10.1038/326832a0. S2CID 37203256.

- ^ Montgomery, JM; Gillespie, D; Sastrawan, P; Fredeking, TM; Stewart, GL (2002). «Aerobic salivary bacteria in wild and captive Komodo dragons» (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 38 (3): 545–51. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-38.3.545. PMID 12238371. S2CID 9670009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2007.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Ellie J. C.; Tyrrell, Kerin L.; Citron, Diane M.; Cox, Cathleen R.; Recchio, Ian M.; Okimoto, Ben; Bryja, Judith; Fry, Bryan G. (June 2013). «Anaerobic and aerobic bacteriology of the saliva and gingiva from 16 captive Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis): new implications for the «bacteria as venom» model». Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 44 (2): 262–272. doi:10.1638/2012-0022R.1. ISSN 1042-7260. PMID 23805543. S2CID 9932073.

- ^ Chung, Ezra M. C.; Dean, Scott N.; Propst, Crystal N.; Bishop, Barney M.; van Hoek, Monique L. (11 April 2017). «Komodo dragon-inspired synthetic peptide DRGN-1 promotes wound-healing of a mixed-biofilm infected wound». NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes. 3 (1): 9. doi:10.1038/s41522-017-0017-2. ISSN 2055-5008. PMC 5445593. PMID 28649410.

- ^ Fry, BG; Vidal, N; Norman, JA; Vonk, FJ; Scheib, H; Ramjan, SF; Kuruppu, S; Fung, K; et al. (2006). «Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes» (PDF). Nature. 439 (7076): 584–588. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..584F. doi:10.1038/nature04328. PMID 16292255. S2CID 4386245. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ Scientists discover deadly secret of Komodo’s bite, AFP, 19 May 2009

- ^ Fry BG, Wroe S, Teeuwisse W, et al. (2009). «A central role for venom in predation by Varanus komodoensis (Komodo Dragon) and the extinct giant Varanus (Megalania) priscus«. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (22): 8969–74. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.8969F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810883106. PMC 2690028. PMID 19451641.

- ^ Staff. «Komodo dragons kill with venom, not bacteria, study says». CNN. 20 May 2009. Retrieved on 25 May 2009.

- ^ Weinstein, Scott A.; Smith, Tamara L.; Kardong, Kenneth V. (14 July 2009). «Reptile Venom Glands Form, Function, and Future». In Stephen P. Mackessy (ed.). Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles. Taylor & Francis. pp. 76–84. ISBN 978-1-4200-0866-1. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (May 2009). «Venom Might Boost Dragons Bite». San Diego Tribune. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (18 May 2009). «Chemicals in Dragon’s Glands Stir Venom Debate». The New York Times. p. D2. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b Ciofi, Claudio (2004). Varanus komodoensis. Varanoid Lizards of the World. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 197–204. ISBN 978-0-253-34366-6.

- ^ «Komodo Dragon, Varanus komodoensis«. San Diego Zoo. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ^ a b Markus Makur (2015). «‘Wotong’ bird nests help Komodos survive: Study». The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Jessop, Tim S.; Sumner, Joanna; Rudiharto, Heru; Purwandana, Deni; Imansyah, M.Jeri; Phillips, John A. (2004). «Distribution, use and selection of nest type by Komodo dragons» (PDF). Biological Conservation. 117 (5): 463. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2003.08.005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2011.

- ^ Attenborough, David (2008). Life in Cold Blood. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13718-6.

- ^ Morales, Alex (20 December 2006). «Komodo Dragons, World’s Largest Lizards, Have Virgin Births». Bloomberg Television. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ Notice by her cage in Chester Zoo in England

- ^ Henderson, Mark (21 December 2006). «Wise men testify to Dragon’s virgin birth». The Times. London. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ «Recent News – Sedgwick County Zoo». Sedgwick County Zoo. Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ «Komodo dragons hatch with no male involved». NBC News. 8 February 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ a b «Virgin births for giant lizards». BBC News. 20 December 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ «Strange but True: Komodo Dragons Show that «Virgin Births» Are Possible: Scientific American». Scientific American. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ Watts PC, Buley KR, Sanderson S, Boardman W, Ciofi C, Gibson R (December 2006). «Parthenogenesis in Komodo Dragons». Nature. 444 (7122): 1021–22. Bibcode:2006Natur.444.1021W. doi:10.1038/4441021a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17183308. S2CID 4311088.

- ^ Fariz Fardianto (22 April 2014). «5 Kasus keganasan komodo liar menyerang manusia». Merdeka.com (in Indonesian).

- ^ «The official website of Komodo National Park, Indonesia». Komodo National Park. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ^ Jones, Alice R.; Jessop, Tim S.; Ariefiandy, Achmad; Brook, Barry W.; Brown, Stuart C.; Ciofi, Claudio; Benu, Yunias Jackson; Purwandana, Deni; Sitorus, Tamen; Wigley, Tom M. L.; Fordham, Damien A. (October 2020). «Identifying island safe havens to prevent the extinction of the World’s largest lizard from global warming». Ecology and Evolution. 10 (19): 10492–10507. doi:10.1002/ece3.6705. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 7548163. PMID 33072275.

- ^ Supriatna, Jatna. «Why we must reassess the komodo dragon’s «Endangered» status». The Conversation. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ «Zipcodezoo: Varanus komodoensis (Komodo Dragon, Komodo Island Monitor, Komodo Monitor)». BayScience Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ «Appendices I, II and III». CITES. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ ‘Police foil attempt to export Komodo dragons for Rp 500 million apiece’, The Jakarta Post, 28 March 2019.

- ^ Markus Makur, ‘Lax security at Florest ports allows Komodo dragon smuggling’, The Jakarta Post, 9 April 2019.

- ^ Markus Makur (5 March 2016). «Komodo population continues to decline at national park».

- ^ Lilley, R. P. H. (1995). «A feasibility study on the in-situ captive breeding of Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) on Padar Island, Komodo National Park». MSC. Thesis: University of Kent, Canterbury, UK.

- ^ Jessop, T.S.; Forsyth, D.M.; Purwandana, D.; Imansyah, M.J.; Opat, D.S.; McDonald-Madden, E. (2005). Monitoring the ungulate prey of komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) using faecal counts (Report). Zoological Society of San Diego, USA, and the Komodo National Park Authority, Labuan Bajo, Flores, Indonesia. p. 26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.172.2230.

- ^ «ISIS Abstracts». ISIS. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ Procter, J.B. (October 1928). «On a living Komodo Dragon Varanus komodoensis Ouwens, exhibited at the Scientific Meeting». Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 98 (4): 1017–19. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1928.tb07181.x.

- ^ Lederer, G. (1931). «Erkennen wechselwarme Tiere ihren Pfleger?». Wochenschrift für Aquarien- und Terrarienkunde. 28: 636–38.

- ^ Murphy, James B.; Walsh, Trooper (2006). «Dragons and Humans». Herpetological Review. 37 (3): 269–75.

- ^ «Such jokers, those Komodo dragons». Science News. 162 (1): 78. August 2002. doi:10.1002/scin.5591620516.

- ^ Cagle, Jess (23 June 2001). «Transcript: Sharon Stone vs. the Komodo Dragon». Time. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ^ Robinson, Phillip T. (2004). Life at the Zoo: Behind the Scenes with the Animal Doctors. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-231-13248-0.

- ^ Pence, Angelica (11 June 2001). «Editor stable after attack by Komodo dragon / Surgeons reattach foot tendons of Chronicle’s Bronstein in L.A.» San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

Further reading

- Attenborough, David (1957). Zoo Quest for a Dragon. London: Lutterworth Press.

- Auffenberg, Walter (1981). The Behavioral Ecology of the Komodo Monitor. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-0621-5.

- Burden, W. Douglas (1927). Dragon Lizards of Komodo: An Expedition to the Lost World of the Dutch East Indies. New York, London: G.P. Putnum’s Sons.

- Eberhard, Jo; King, Dennis; Green, Brian; Knight, Frank; Keith Newgrain (1999). Monitors: The Biology of Varanid Lizards. Malabar, Fla: Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57524-112-8.

- Lutz, Richard L; Lutz, Judy Marie (1997). Komodo: The Living Dragon. Salem, Or: DiMI Press. ISBN 978-0-931625-27-5.

External links

| Komodo dragon

Temporal range: PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male at the Cincinnati Zoo | |

|

Conservation status |

|

|

|

|

|

CITES Appendix I (CITES)[3] |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Varanidae |

| Genus: | Varanus |

| Subgenus: | Varanus |

| Species: |

V. komodoensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Varanus komodoensis

Ouwens, 1912[4] |

|

|

|

| Komodo dragon distribution |

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), also known as the Komodo monitor, is a member of the monitor lizard family Varanidae that is endemic to the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. It is the largest extant species of lizard, growing to a maximum length of 3 m (9.8 ft), and weighing up to 70 kg (150 lb).

As a result of their size, Komodo dragons are apex predators, and dominate the ecosystems in which they live. Komodo dragons hunt and ambush prey including invertebrates, birds, and mammals. It has been claimed that they have a venomous bite; there are two glands in the lower jaw that secrete several toxic proteins. The biological significance of these proteins is disputed, but the glands have been shown to secrete an anticoagulant. Komodo dragons’ group behavior in hunting is exceptional in the reptile world. The diet of Komodo dragons mainly consists of Javan rusa (Rusa timorensis), though they also eat considerable amounts of carrion. Komodo dragons also occasionally attack humans.

Mating begins between May and August, and the eggs are laid in September; as many as 20 eggs are deposited at a time in an abandoned megapode nest or in a self-dug nesting hole. The eggs are incubated for seven to eight months, hatching in April, when insects are most plentiful. Young Komodo dragons are vulnerable and dwell in trees to avoid predators, such as cannibalistic adults. They take 8 to 9 years to mature and are estimated to live up to 30 years.

Komodo dragons were first recorded by Western scientists in 1910. Their large size and fearsome reputation make them popular zoo exhibits. In the wild, their range has contracted due to human activities, and is likely to contract further from the effects of climate change; due to this, they are listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. They are protected under Indonesian law, and Komodo National Park was founded in 1980 to aid protection efforts.

Taxonomic history

Komodo dragons were first documented by Europeans in 1910, when rumors of a «land crocodile» reached Lieutenant van Steyn van Hensbroek of the Dutch colonial administration.[5] Widespread notoriety came after 1912, when Peter Ouwens, the director of the Zoological Museum of Bogor, Java, published a paper on the topic after receiving a photo and a skin from the lieutenant, as well as two other specimens from a collector.[4]

The first two live Komodo dragons to arrive in Europe were exhibited in the Reptile House at London Zoo when it opened in 1927.[6] Joan Beauchamp Procter made some of the earliest observations of these animals in captivity and she demonstrated their behaviour at a Scientific Meeting of the Zoological Society of London in 1928.[7]

The Komodo dragon was the driving factor for an expedition to Komodo Island by W. Douglas Burden in 1926. After returning with 12 preserved specimens and two live ones, this expedition provided the inspiration for the 1933 movie King Kong.[8] It was also Burden who coined the common name «Komodo dragon».[9] Three of his specimens were stuffed and are still on display in the American Museum of Natural History.[10]

The Dutch island administration, realizing the limited number of individuals in the wild, soon outlawed sport hunting and heavily limited the number of individuals taken for scientific study. Collecting expeditions ground to a halt with the occurrence of World War II, not resuming until the 1950s and 1960s, when studies examined the Komodo dragon’s feeding behavior, reproduction, and body temperature. At around this time, an expedition was planned in which a long-term study of the Komodo dragon would be undertaken. This task was given to the Auffenberg family, who stayed on Komodo Island for 11 months in 1969. During their stay, Walter Auffenberg and his assistant Putra Sastrawan captured and tagged more than 50 Komodo dragons.[11]

Research from the Auffenberg expedition proved enormously influential in raising Komodo dragons in captivity.[12] Research after that of the Auffenberg family has shed more light on the nature of the Komodo dragon, with biologists such as Claudio Ciofi continuing to study the creatures.[13]

Etymology

The Komodo dragon, as depicted on the 50 rupiah coin, issued by Indonesia

The Komodo dragon is also sometimes known as the Komodo monitor or the Komodo Island monitor in scientific literature,[14] although this name is uncommon. To the natives of Komodo Island, it is referred to as ora, buaya darat (‘land crocodile’), or biawak raksasa (‘giant monitor’).[15][5]

Evolutionary history

The evolutionary development of the Komodo dragon started with the genus Varanus, which originated in Asia about 40 million years ago and migrated to Australia, where it evolved into giant forms (the largest of all being the recently extinct Varanus priscus, or «Megalania»), helped by the absence of competing placental carnivorans. Around 15 million years ago, a collision between the continental landmasses of Australia and Southeast Asia allowed these larger varanids to move back into what is now the Indonesian archipelago, extending their range as far east as the island of Timor.

The Komodo dragon is believed to have differentiated from its Australian ancestors about 4 million years ago. However, fossil evidence from Queensland suggests the Komodo dragon actually evolved in Australia, before spreading to Indonesia.[1][16]

Dramatic lowering of sea level during the last glacial period uncovered extensive stretches of continental shelf that the Komodo dragon colonised, becoming isolated in their present island range as sea levels rose afterwards.[1][5] Fossils of extinct Pliocene species of similar size to the modern Komodo dragon, such as Varanus sivalensis, have been found in Eurasia as well, indicating that they fared well even in environments containing competition, such as mammalian carnivores, until the climate change and extinction events that marked the beginning of the Pleistocene.[1]

Genetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA shows the Komodo dragon to be the closest relative (sister taxon) of the lace monitor (V. varius), with their common ancestor diverging from a lineage that gave rise to the crocodile monitor (Varanus salvadorii) of New Guinea.[17][18][19] A 2021 study showed that during the Miocene, Komodo dragons had hybridized with the ancestors of the Australian sand monitor (V. gouldii), thus providing further evidence that the Komodo dragon had once inhabited Australia.[20][21][22] Genetic analysis indicates that the population from northern Flores is genetically distinct from other populations of the species.[2]

Description

In the wild, adult Komodo dragons usually weigh around 70 kg (150 lb), although captive specimens often weigh more.[23] According to Guinness World Records, an average adult male will weigh 79 to 91 kg (174 to 201 lb) and measure 2.59 m (8.5 ft), while an average female will weigh 68 to 73 kg (150 to 161 lb) and measure 2.29 m (7.5 ft).[24] The largest verified specimen in captive was 3.13 m (10.3 ft) long and weighed 166 kg (366 lb), including its undigested food.[5] The largest wild specimen had a length 3.04 m (10.0 ft), a snout-vent length (SVL) 1.54 m (5 ft 1 in) and a mass of 81.5 kg (180 lb) excluding stomach contents.[25][26] The heaviest reached a mass in 87.4 kg (193 lb).[25] The study noted that weights greater than 100 kg (220 lb) were possible but only after the animal had consumed a large meal.[25][26]

The Komodo dragon has a tail as long as its body, as well as about 60 frequently replaced, serrated teeth that can measure up to 2.5 cm (1 in) in length. Its saliva is frequently blood-tinged because its teeth are almost completely covered by gingival tissue that is naturally lacerated during feeding.[27] It also has a long, yellow, deeply forked tongue.[5] Komodo dragon skin is reinforced by armoured scales, which contain tiny bones called osteoderms that function as a sort of natural chain-mail.[28][29] The only areas lacking osteoderms on the head of the adult Komodo dragon are around the eyes, nostrils, mouth margins, and pineal eye, a light-sensing organ on the top of the head. Where lizards typically have one or two varying patterns or shapes of osteoderms, komodos have four: rosette, platy, dendritic, and vermiform.[30] This rugged hide makes Komodo dragon skin a poor source of leather. Additionally, these osteoderms become more extensive and variable in shape as the Komodo dragon ages, ossifying more extensively as the lizard grows. These osteoderms are absent in hatchlings and juveniles, indicating that the natural armor develops as a product of age and competition between adults for protection in intraspecific combat over food and mates.[31]

Senses

Komodo dragon using its tongue to sample the air

As with other varanids, Komodo dragons have only a single ear bone, the stapes, for transferring vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea. This arrangement means they are likely restricted to sounds in the 400 to 2,000 hertz range, compared to humans who hear between 20 and 20,000 hertz.[5][32] They were formerly thought to be deaf when a study reported no agitation in wild Komodo dragons in response to whispers, raised voices, or shouts. This was disputed when London Zoological Garden employee Joan Procter trained a captive specimen to come out to feed at the sound of her voice, even when she could not be seen.[33]

The Komodo dragon can see objects as far away as 300 m (980 ft), but because its retinas only contain cones, it is thought to have poor night vision. It can distinguish colours, but has poor visual discrimination of stationary objects.[34]

As with many other reptiles, the Komodo dragon primarily relies on its tongue to detect, taste, and smell stimuli, with the vomeronasal sense using the Jacobson’s organ, rather than using the nostrils.[35] With the help of a favorable wind and its habit of swinging its head from side to side as it walks, a Komodo dragon may be able to detect carrion from 4–9.5 km (2.5–5.9 mi) away.[34] It only has a few taste buds in the back of its throat.[35] Its scales, some of which are reinforced with bone, have sensory plaques connected to nerves to facilitate its sense of touch. The scales around the ears, lips, chin, and soles of the feet may have three or more sensory plaques.[27]

Behaviour and ecology

Male komodo dragons fighting

The Komodo dragon prefers hot and dry places and typically lives in dry, open grassland, savanna, and tropical forest at low elevations. As an ectotherm, it is most active in the day, although it exhibits some nocturnal activity. Komodo dragons are solitary, coming together only to breed and eat. They are capable of running rapidly in brief sprints up to 20 km/h (12 mph), diving up to 4.5 m (15 ft), and climbing trees proficiently when young through use of their strong claws.[23] To catch out-of-reach prey, the Komodo dragon may stand on its hind legs and use its tail as a support.[33] As it matures, its claws are used primarily as weapons, as its great size makes climbing impractical.[27]

For shelter, the Komodo dragon digs holes that can measure from 1 to 3 m (3.3 to 9.8 ft) wide with its powerful forelimbs and claws.[36] Because of its large size and habit of sleeping in these burrows, it is able to conserve body heat throughout the night and minimise its basking period the morning after.[37] The Komodo dragon hunts in the afternoon, but stays in the shade during the hottest part of the day.[9] These special resting places, usually located on ridges with cool sea breezes, are marked with droppings and are cleared of vegetation. They serve as strategic locations from which to ambush deer.[38]

Diet

Komodo dragons are apex predators.[39] They are carnivores; although they have been considered as eating mostly carrion,[40] they will frequently ambush live prey with a stealthy approach. When suitable prey arrives near a dragon’s ambush site, it will suddenly charge at the animal at high speeds and go for the underside or the throat.[27]

Komodo dragons do not deliberately allow the prey to escape with fatal injuries but try to kill prey outright using a combination of lacerating damage and blood loss. They have been recorded as killing wild pigs within seconds,[41] and observations of Komodo dragons tracking prey for long distances are likely misinterpreted cases of prey escaping an attack before succumbing to infection.

Komodo dragons eat by tearing large chunks of flesh and swallowing them whole while holding the carcass down with their forelegs. For smaller prey up to the size of a goat, their loosely articulated jaws, flexible skulls, and expandable stomachs allow them to swallow prey whole. The undigested vegetable contents of a prey animal’s stomach and intestines are typically avoided.[38] Copious amounts of red saliva the Komodo dragons produce help to lubricate the food, but swallowing is still a long process (15–20 minutes to swallow a goat). A Komodo dragon may attempt to speed up the process by ramming the carcass against a tree to force it down its throat, sometimes ramming so forcefully that the tree is knocked down.[38] A small tube under the tongue that connects to the lungs allows it to breathe while swallowing.[27]

After eating up to 80% of its body weight in one meal,[39] it drags itself to a sunny location to speed digestion, as the food could rot and poison the dragon if left undigested in its stomach for too long. Because of their slow metabolism, large dragons can survive on as few as 12 meals a year.[27] After digestion, the Komodo dragon regurgitates a mass of horns, hair, and teeth known as the gastric pellet, which is covered in malodorous mucus. After regurgitating the gastric pellet, it rubs its face in the dirt or on bushes to get rid of the mucus.[27]

Komodo excrement has a dark portion, which is stool, and a whitish portion, which is urate, the nitrogenous end-product of their digestion process

The eating habits of Komodo dragons follow a hierarchy, with the larger animals generally eating before the smaller ones. The largest male typically asserts his dominance and the smaller males show their submission by use of body language and rumbling hisses. Dragons of equal size may resort to «wrestling». Losers usually retreat, though they have been known to be killed and eaten by victors.[42][43]

The Komodo dragon’s diet is wide-ranging, and includes invertebrates, other reptiles (including smaller Komodo dragons), birds, bird eggs, small mammals, monkeys, wild boar, goats, pigs,[44] deer, horses, and water buffalo.[45] Young Komodos will eat insects, eggs, geckos, and small mammals, while adults prefer to hunt large mammals.[40] Occasionally, they attack and bite humans. Sometimes they consume human corpses, digging up bodies from shallow graves.[33] This habit of raiding graves caused the villagers of Komodo to move their graves from sandy to clay ground, and pile rocks on top of them, to deter the lizards.[38] The Komodo dragon may have evolved to feed on the extinct dwarf elephant Stegodon that once lived on Flores, according to evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond.[46]

The Komodo dragon drinks by sucking water into its mouth via buccal pumping (a process also used for respiration), lifting its head, and letting the water run down its throat.[41]

Saliva

Although previous studies proposed that Komodo dragon saliva contains a variety of highly septic bacteria that would help to bring down prey,[42][47] research in 2013 suggested that the bacteria in the mouths of Komodo dragons are ordinary and similar to those found in other carnivores. Komodo dragons have good mouth hygiene. To quote Bryan Fry: «After they are done feeding, they will spend 10 to 15 minutes lip-licking and rubbing their head in the leaves to clean their mouth … Unlike people have been led to believe, they do not have chunks of rotting flesh from their meals on their teeth, cultivating bacteria.» Nor do Komodo dragons wait for prey to die and track it at a distance, as vipers do; observations of them hunting deer, boar and in some cases buffalo reveal that they kill prey in less than half an hour.[48]

The observation of prey dying of sepsis would then be explained by the natural instinct of water buffalos, who are not native to the islands where the Komodo dragon lives, to run into water after escaping an attack. The warm, faeces-filled water would then cause the infections. The study used samples from 16 captive dragons (10 adults and six neonates) from three US zoos.[48]

Antibacterial immune factor

Researchers have isolated a powerful antibacterial peptide from the blood plasma of Komodo dragons, VK25. Based on their analysis of this peptide, they have synthesized a short peptide dubbed DRGN-1 and tested it against multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Preliminary results of these tests show that DRGN-1 is effective in killing drug-resistant bacterial strains and even some fungi. It has the added observed benefit of significantly promoting wound healing in both uninfected and mixed biofilm infected wounds.[49]

Venom

In late 2005, researchers at the University of Melbourne speculated the perentie (Varanus giganteus), other species of monitors, and agamids may be somewhat venomous. The team believes the immediate effects of bites from these lizards were caused by mild envenomation. Bites on human digits by a lace monitor (V. varius), a Komodo dragon, and a spotted tree monitor (V. scalaris) all produced similar effects: rapid swelling, localised disruption of blood clotting, and shooting pain up to the elbow, with some symptoms lasting for several hours.[50]