Конфуциа́нство (кит. трад. 儒, упр. 学, пиньинь: Rúxu, палл.: Жсюэ) — этико-философское учение, разработанное Конфуцием (553—480 до н. э.) и развитое его последователями, вошедшее в религиозный комплекс Китая, Кореи, Японии и некоторых других стран. Конфуцианство является мировоззрением, общественной этикой, политической идеологией, научной традицией, образом жизни, иногда рассматривается как философия, иногда — как религия.

Все значения слова «конфуцианство»

-

Что касается влияния конфуцианства на китайское общество, обращают на себя внимание два аспекта.

-

Некоторые считают, что это лишь традиция, бытовавшая в одной из школ конфуцианства.

-

Поэтому учёные мужи, воспитанные в традициях конфуцианства, стали связывать представление о чае как об общеупотребимом напитке с конфуцианскими принципами умеренности и скромности.

- (все предложения)

- Склонение

существительного «конфуцианство» - Разбор по составу слова «конфуцианство»

Олег Пак

Гуру

(4038)

8 лет назад

Конфуций, 孔夫子 (кит. , читается «Кун Фуцзы», латиницей Kong Fuzi, Kung-fu-tzu, чаще пишется проще — 孔子 «Кун цзы», Kong Zi), Confucius (англ. ) как пишется Конфуций

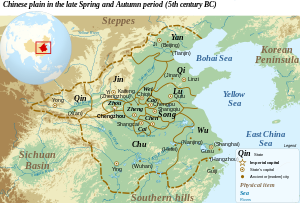

Конфуций (годы жизни — 551-479 до н. э.) появился на свет и жил во время больших политических и социальных потрясений, когда в состоянии внутреннего кризиса находился чжоуский Китай. Власть правителя (вана) ослабла уже давно. Патриархально-родовые нормы разрушались, родовая аристократия гибла в междоусобицах. Крушение древних устоев, междоусобные распри, алчность и продажность чиновников, страдания и бедствия простого народа вызывали резкую критику со стороны ревнителей старины.

Основы учения Конфуция

Учение Конфуция, в общем-то, понять совсем не сложно. Истины его довольно просты. Конфуций, высоко ставя минувшее время и выступая с критикой современности, создал на основе этого противопоставления собственный идеал цзюнь-цзы (совершенного человека). Он должен обладать высокой моралью и двумя достоинствами, важнейшими в его представлении: чувством долга и гуманностью. Гуманность (жень) подразумевала сдержанность, скромность, бескорыстие, достоинство, любовь к людям. Жень — практически недосягаемый идеал, представляющий собой совокупность различных совершенств, которыми обладали только древние. Философ считал гуманным из современников лишь себя, а также Янь Хуэя, своего любимого ученика. Учение Конфуция также подразумевает, что для цзюнь-цзы недостаточно одной гуманности. Другим важным качеством он должен был обладать — чувством долга, то есть моральными обязательствами, которые в силу своих добродетелей гуманный человек сам на себя накладывает. Как правило, чувство долга обусловлено высшими принципами и знаниями, а не расчетом. Еще одна его концепция — это «следование срединному пути» (по-китайски — «чжун юн»). Мудрец предостерегает своих учеников от увлечения крайностями. Это лишь основные постулаты учения, которое предложил Конфуций. Философия его не ограничивается ими, с ней можно ознакомиться более подробно. Тема нашей статьи — биография, а не учение этого мыслителя. Поэтому мы решили ограничиться лишь кратким изложением того, о чем говорил и писал Конфуций. Философия и жизнь его неразделимы, в чем вы вскоре убедитесь.

Появление на свет Конфуция

Великий мыслитель родился в 551 году до н. э. Конфуций, биография которого нас интересует, появился на свет в царстве Лу. Отец его, Шулян Хэ, принадлежал к знатному княжескому роду, был храбрым воином. У него родились в первом браке лишь девочки, девять дочерей, но не было наследника. Во втором браке родился столь долгожданный мальчик, но он оказался, к несчастью, калекой. Тогда, уже в преклонном возрасте (63 лет), он решается вступить в третий брак. Женой его соглашается стать девушка, принадлежащая к роду Янь, посчитавшая, что следует выполнить волю отца. Появление великого человека предвещали видения, которые после свадьбы посещали эту девушку. Рождению этого ребенка сопутствовали многие чудесные обстоятельства. На теле его, согласно традиции, имелось 49 знаков, говорящих о будущем величии. Так появился на свет Кун-фу-цзы, известный на Западе как Конфуций. Биография его была необычной с самых ранних лет.

Детство будущего мудреца

Отец его умер, когда будущему философу исполнилось всего три года. Молодая мать решила посвятить всю свою жизнь воспитанию сына. Постоянное ее руководство сильно повлияло на формирование характера Конфуция. Он отличался уже в раннем детстве талантом предсказателя и выдающимися способностями. Конфуций любил играть, подражая различным церемониям, повторяя бессознательно священные ритуалы древности. Это удивляло окружающих. В детстве Конфуций был далек от свойственных его возрасту игр. Основным его развлечением были беседы со старцами и мудрецами. В возрасте семи лет пошел в школу Конфуций. Биография его открывается новой страницей. Школьные годы дали множество знаний, пригодившихся в дальнейшем. Обязательным было усвоение шести умений: слушать музыку, выполнять ритуалы, управлять колесницей, стрелять из лука, считать и писать.

Успешная сдача экзаменов

С огромной восприимчивостью к учению родился Конфуций, биография которого представлена в этой статье. Его выдающийся ум заставлял мальчика постоянно читать и усваивать все изложенные в классических книгах того времени знания. Впоследствии из-за этого о нем говорили, что у него не было учителей, а были лишь ученики. Конфуций по окончании школы единственным среди всех учащихся сдал со стопроцентным результатом сложнейшие экзамены.

Первые должности Конфуция

Он занимал уже в 17 лет должность хранителя амбаров, государственного чиновника. Конфуций говорил, что он должен заботиться единственно о том, чтобы были верны его счета. Позже в ведение его поступил также скот царства Лу. Мудрец отмечал, что его забота теперь в том, чтобы овцы и быки были хорошо откормлены. Он говорил, что не следует беспокоиться о том, какой пост ты занимаешь. Следует лишь думать, хорошо ли служишь ты на этом месте. Точно неизвестно, в каком возрасте стал служить Конфуций (в 20 или в 26-27 лет), а также как долго длилась эта служба. Значительно большее внимание в древних трактатах уделено одной из основных черт этого мыслителя в молодости: он не только не боялся спрашивать, но и при этом добивался исчерпывающего ответа.

Женитьба и рождение сына

В 19 лет мудрец взял себе жену из семьи Ци, которая проживала в Суне, царстве его предков. Это вряд ли было бы возможно без благосклонности луских аристократов. У Конфуция через год родился сын. Чжаогун, луский правитель, послал философу крупного карпа, что являлось в то время символом пожелания всех благ семье. Сына назвали поэтому Бо Юй («бо» означает «старший из братьев», а «юй» — «рыба»). Конфуций хотел иметь еще детей, однако судьба распорядилась иначе.

Посещение столицы

За бесспорные достоинства в 25 лет Конфуций был отмечен уже всем культурным сообществом. Приглашение правителя посетить столицу Китая стало одним из самых важных моментов в его жизни. Это путешествие позволило мудрецу осознать себя в полной мере хранителем древней традиции и наставником. Он решил открыть школу, которая основана была на традиционных учениях. Человек учился здесь познавать законы этого мира, людей, а также открывать в себе новые возможности.

Ученики Конфуция

Своих учеников Конфуций хотел видеть целостными людьми, которые были бы полезны обществу и государству. Поэтому он обучал их различным областям знания. Конфуций с учениками был тверд и прост. Он писал, что не просвещает того, кто не хочет знать. Среди учеников Конфуция своими знаниями уже на начальном этапе выделялись Цзы Лу, Цзэн Дянь, Янь Лу и другие. Самым преданным оказался Цзы Лу, который проделал со своим учителем весь жизненный путь и похоронил его торжественно, с соблюдением этических норм.

Конфуций — министр правосудия

Далеко распространилась слава о нем. Такой степени достигло признание его мудрости, что ему в возрасте 52 лет предложили пост министра правосудия — наиболее ответственную в государстве должность в те времена. Значительно изменилась жизнь Конфуция. Он заведовал теперь политическими преступлениями и уголовными делами. По сути, у Конфуция были функции верховного прокурора. Благодаря этому он становился ближайшим советником царя.

Как проявил себя Конфуций на ответственном посту?

На посту мудрец был очень активен. Он проявил себя как опытный и умелый политик, ценящий и знающий ритуалы, как усмиритель вассалов, не желавших покориться правителю, а также как справедливый судья. Его правление было в целом довольно успешным. Конфуций так много сделал для своей страны, что близлежащие государства начали опасаться блестяще развивающегося благодаря усилиям одной личности царства. Наветы и клевета привели к тому, что советам Конфуция перестал внимать правитель Лу. Конфуцию пришлось покинуть родное государство. Он отправился в путешествие, наставляя нищих и правителей, пахарей и князей, стариков и молодых.

Путешествие Конфуция

В то время ему исполнилось 55 лет. Конфуций был уже мыслителем, умудренным опытом, уверенным, что знания его пригодятся правителям других государств. Он сначала отправился в Вей, где пробыл 10 месяцев. Однако он был вынужден покинуть его после анонимного доноса и отправиться в Чэнь. По дороге Конфуция схватили крестьяне, принявшие его за аристократа, притеснявшего их. С достоинством держался мудрец, и вскоре вейские аристократы его вызволили, после чего он вернулся в Вей. Здесь местный правитель обращался к нему за советами. Однако через некоторое время из-за разногласий с ним Конфуций вынужден был покинуть Вей. Философ отправился в Сун, после чего — в Чэнь, где получил скромное жалование и ничего не значащий пост. Однако вскоре из-за надвигающейся войны и опасности, связанной с ней, он покинул Чэнь и отправился в Чу. Здесь он провел несколько встреч с Шэ-гуном, первым советником Чу. Эти беседы касались обеспечения процветания государства и достижения в нем стабильности. Везде, куда бы он ни шел, жители умоляли его остаться. Личность Конфуция притягивала многих. Однако мудрец всегда отвечал, что долг его распространяется на всех людей. Он считал членами одной семьи всех населяющих землю. И для всех них он должен был исполнить миссию наставника.

Жизнь Конфуция как часть его учения

Добродетель и знание для Конфуция были неразделимы. Неотъемлемой частью его учения стала сама его жизнь, которая соответствовала философским убеждениям этого мыслителя. Подобно Сократу, он со своей философией не отбывал лишь рабочее время. С другой стороны, Конфуций не уходил в свое учение и не отдалялся от жизни. Для него философия была не моделью идей, выставленных для осознания, а системой заповедей, являющихся неотделимыми от поведения философа.

Летопись «Чунь-цю»

В последние годы своей жизни Конфуций написал летопись под названием «Чунь-цю», а также отредактировал 6 Канонов, которые вошли в классику культуры Китая и сильно повлияли на национальный характер жителей этого государства. Цитаты Конфуция и сегодня знают многие, причем не только в Китае, но и во всем мире.

Последние годы жизни Конфуция

Его сын скончался в 482 году до н. э., а в 481-м — Цзы Лу, его самый любимый ученик. Смерть учителя ускорили эти беды. Конфуций умер на 73-м году жизни, в 479 году до н. э., предсказав перед этим заранее свою смерть ученикам. Несмотря на скромные биографические данные, этот мудрец остается великой фигурой в истории Китая. Китайский философ Конфуций не любил рассказывать о себе. Он лишь в нескольких строчках описал свой жизненный путь. Перескажем содержание одной известной цитаты Конфуция. В ней сказано, что в 15 лет он обратил к учению свои помыслы, в 30 — обрел прочную основу, в 40 — смог освободиться от сомнений, в 50 — познал волю Неба, еще через десять лет научился различать правду и ложь, в 70 лет начал следовать зову собственного сердца.

Могила Конфуция

Похоронили учителя у реки под названием Сышуй. Его вещи также положили в могилу. Место это вот уже более 2000 лет является местом паломничества в Китае. Имение, гробница и храм Конфуция расположены в провинции Шаньдун, в городе Цюйфу. Храм в его честь был построен в 478 году до н. э. Он разрушался и впоследствии восстанавливался в различные эпохи. Сегодня этот храм насчитывает более ста строений. На месте захоронения находится не только могила Конфуция, но и гробницы более 100 тысяч его потомков. Громадной аристократической резиденцией стал небольшой когда-то дом семьи Кун. От этой резиденции сохранилось сегодня 152 здания.

Поистине великим человеком был Конфуций. И сегодня многие люди стараются следовать его мудрости. Конфуций вдохновляет не только жителей Китая, но и людей из самых разных уголков нашей планеты.

Основной целью древнекитайского учения конфуцианства является достижение особого состояния духа – состояния «благородного мужа».

Это состояние достигается путем тренировки в себе высочайших нравственных качеств личности. Достичь состояния благородного мужа может только человек, обладающий такими навыками, как гуманность, человеколюбие и справедливость. Главное правило конфуцианства заключается в том, чтобы делать для людей то, чего желаешь самому себе.

Все эти качества основываются на трех чертах личности: мудрость, смелость, человеколюбие.

Человек, идущий по пути конфуцианства должен почтительно относиться к своим родителям в частности и своим «духовным родственникам» в более глобальном смысле, ведь Конфуций не раз говорил – страна является одной большой семьей. Это и означает любовь и доброе отношение ко всем людям.

Учение Конфуция также основано на сильном культурном воспитании, в частности на строгих правилах этикета и поведения в обществе. Благородный муж должен быть примером для других и почтительно обращаться с женщинами.

Человек в разрезе конфуцианской философии

Человек в конфуцианском мире считается частью общества, а не отдельной единицей мироздания. Жизнь отдельного члена общества должна гармонировать с жизнью всего общества в целом. Когда человек познает методы гармоничного существования в обществе, ему становятся доступны способы гармоничного сосуществования с миром и природой.

Конфуций выработал для своего учения ряд правил, основой для которых послужили древние традиционные правила китайских общин.

В своде конфуцианских правил жизни упомянуты все аспекты жизни, начиная от отдыха в свободную минуту и до ритуалов поклонения и памяти предков. При этом, каждое жизненное правило описано очень конкретно, дабы исключить даже малейшее отступление ученика от норм.

Только выполняя все правила, человек мог показать миру свое желание стать образцом. По сути, правила описывают эталон идеального, духовно и культурно развитого человека.

Основные идеи конфуцианства кратко сводятся к пяти главным чертам, которыми должен был обладать каждый человек:

— Истинное отношение – Благородный муж должен существовать в гармонии с другими людьми. Часто знатоки философии определяют истинное отношение, как высокую самодисциплину и самоконтроль.

— Истинное поведение – Идеальный член общества знает все нормы этикета и применяет их ежедневно в своей жизни. Он знаком со всеми необходимыми традициями и правилами, касающимися уважения и почитания своих предков. Истинное поведение не имеет смысла, если человек не владеет истинным отношением.

— Истинное знание – Каждый достойный человек имеет высокое образование. Он знаком с творчеством классических китайских поэтов и композиторов, помнит всю историю своей страны и разбирается в юридических нормах жизни.

Конфуций утверждал, что знания, которые не применяются в жизни – бесполезный груз. Поэтому для воспитания истинного знания необходимо развивать и предыдущие две черты характера.

— Истинное состояние духа. Человек всегда должен оставаться верным себе и своим идеалам, а также быть справедливым по отношению к другим людям. Все его поступки и действия направлены на улучшение жизни общества.

— Истинное постоянство. Развив в себе все ранее упомянутые черты, человек не имеет права отступать назад. В этом и заключается пятая особенность характера – постоянство.

Отношения в конфуцианском мире

Конфуций выделял в своей философии пять основных типов взаимоотношений между людьми, которые плотно взаимосвязаны между собой:

- Почтение между детьми и родителями;

- Доброе и благожелательное отношение между детьми: старшие мягко наставляют младших, младшие благодарно помогают старшим;

- Уважительное отношение мужа к своей жене и почитание женой своего мужа;

- Доброта в отношениях молодых людей к более зрелым членам общества и благосклонное наставничество старших над младшими;

- Уважительное отношение правителей к своим подчиненным и почитание подчиненными своего правителя.

Такой подход способствовал установлению уже упомянутого человеколюбия у каждого члена общества, независимо от занимаемого социального положения или возраста.

Издревле в Китае почитание предков считается обязанностью каждого гражданина. Это настоящий культ предков. И именно он лежит в основе каждого из перечисленных типов взаимоотношений.

Социальное равенство в конфуцианском обществе

Конфуцианские правила поведения, упомянутые ранее, включают в себя и нормы социального взаимодействия.

Данные нормы заключаются в том, что каждый должен заниматься своим делом. Не должно рыбаку управлять государством, а правителю империи – ловить рыбу.

И здесь действует уже известный нам принцип уважительного отношения между родителями и детьми. Именно в нем заложены кратко идеи конфуцианства Родители являются в данном случае наставниками, чье мнение равноценно закону. Их задача – указать молодому человеку на его место в обществе и следить, чтобы он выполнял свои функции качественно.

Скачать данный материал:

(Пока оценок нету)

Конфуцианство

– философия и религия Китая. Слово «конфуцианство» — европейского происхождения и связано с латинизированной версией имени его создателя Кун-цзы. Его представители – государственные служащие — «жу-цзя», и это означает, что конфуцианство — «учение благовоспитанных (или просвещенных) людей». Это обстоятельство позволило некоторым ученым прошлого века даже называть конфуцианство «религией учёных». Влияние конфуцианства на все китайское общество было настолько глубоким, а его воздействие на систему ценностей традиционного Китая и национальную психологию китайского народа настолько полным, что это ощущается и в сегодняшней жизни народа. На протяжении более чем двух тысячелетий (с рубежа II — I вв. до н.э. и до свержения монархии в 1911 г.) конфуцианство, объединенное с идеями школы законников, являлось официальной идеологией китайского государства.

Основатель этого философского учения Конфуций(551-479 гг. до н.э.)

жил в эпоху раздробленности Поднебесной и постоянных междоусобиц (т.е. в эпоху перемен) и в его учении в полной мере отразилась как сама эпоха, так и стремление ее элиты к преодолению порожденного переменами хаоса. Главный источник его учения — книга «Лунь юй

» («Беседы и суждения

») — высказывания и беседы с учениками, зафиксированные его последователями.

К основным идеям Конфуция и его последователей относятся:

а) идея эффективного государственного управления на нравственного самосовершенствования человека.

Конфуций считал, что нравственное самосовершенствование

является предпосылкой успешной социальной жизни и деятельности на государственном поприще. Нравственность

– родовое человеческое свойство, считал Конфуций. Именно ее наличие, по мнению Конфуция, отличает человека от животных;

Социальное поведение, основанное на нравственных принципах являлось идеалом конфуцианства. Отсюда вытекало конфуцианское требование подготовки высоконравственных лидеров государства, чиновников. Через систему экзаменов (введенную во II в. до н.э. императором У-ди), требовавшую от учащегося прежде всего знания основ философии конфуцианства и легизма, во многом формировалась правящая элита — высоконравственные, благородные люди (по терминологии Кун-цзы — цзюнь — цзы). Конфуцианство предъявляло суровые требования к личности в этическом плане, настаивая на непрерывном духовном и нравственном совершенствовании: «Благородный муж стремится вверх, низкий человек движется вниз». Положительный герой конфуцианства — чиновник, государственный служащий, имеющий высокий моральный облик, ядром которого является следование Воле Неба, соблюдение принципа – жэнь

(человеколбия) , т.е. основанного на любви подчинения младшего старшему, ученика учителю, чиновника государю (ванну);

Более детально идеал и концепция нравственной личности конфуцианства обосновывалась в учении о «благородном муже

» (цзюнь-цзы

). «Благородным мужем» мог быть любой человек, независимо от происхождения, единственный критерий его «благородства» — строгое и неукоснительное следование нормам конфуцианской морали. А также этикета (ли

).

У благородного мужа имеется антипод — так называемый «низкий человек» (сяо жэнь).

Их главное отличие лаконично выражено в следующих конфуцианских положениях.

Благородный муж живет в согласии со всеми. Низкий человек ищет себе подобных.

Благородный муж беспристрастен и не терпит групповщины. Низкий человек любит сталкивать людей и сколачивать клики.

Благородный муж стойко переносит беды. Низкий человек в беде распускается.

Благородный муж с достоинством ожидает велений Небес. Низкий человек надеется на удачу.

Благородный муж помогает людям увидеть доброе в себе и не учит людей видеть в себе дурное. А низкий человек поступает наоборот.

Благородный муж в душе безмятежен. Низкий человек всегда озабочен.

То, что ищет благородный муж, находится в нем самом. То, что ищет низкий человек, находится в других.

Из конфуцианских идей жэнь, ли и цзюнь-цзы вытекала —

б) идея государства как большой семьи

. Правящие и управляемые находились в отношениях старшие — младшие: «низкие», простолюдины, должны подчиняться «благородным мужам», лучшим, старшим. Простым людям полагалось с сыновней почтительностью относиться к чиновникам. Государь, отец народа, обладал непререкаемым авторитетом и ореолом святости, воплощая собой все государство. Женщины беспрекословно должны были слушаться мужчин, дети — родителей, подчинённые — начальников. Народ воспринимался Конфуцием как могущественная, но бездуховная и инертная масса: его «можно заставить повиноваться, но нельзя заставить понимать, почему». Основная и единственная добродетель, доступная народу, — способность подчиняться, доверять и подражать правителям. «Если вы будете стремиться к добру, — обращался к ним мыслитель, — то и народ будет добрым. Мораль благородного мужа подобна ветру, мораль низкого человека подобна траве. Трава наклоняется туда, куда дует ветер»;

в) огромная роль в конфуцианстве отводится пяти базовым социальным отношениям

: (между государем и подданными, родителями и детьми, старшими и младшими братьями, мужем и женой, друзьями);

§ между государем и подданными, господином и слугой. Такие отношения считались важнейшими в обществе и доминировали над остальными. Безусловная преданность и верность господину являлась основой характера «благородного мужа» в конфуцианском понимании.

§ между родителями и детьми. Здесь подчёркивались непререкаемые права родителей, в первую очередь отца, и священная обязанность детей проявлять к ним почтительность.

§ между мужем и женой. Права мужа не ограничивались, а обязанности жены сводились к беспрекословной покорности, образцовому поведению и работе по хозяйству.

§ между старшими и младшими. Требовалось уважать не только старшего по возрасту, но и старшего по положению, чину, званию, мастерству.

§ между друзьями. Отношения между ними должны были носить характер искренней и бескорыстной взаимопомощи.

Конфуций выступает против насилия как главного средства управления государством и обществом. Конфуцианское представление об обществе основано на идее неформальных отношений, а не на мёртвой букве закона. Личный пример «благородных мужей», их стремление к добру, полагал философ, помогут государству прийти к процветанию. Рассматривая государство как живой организм, в котором иерархия напоминает связь органов в теле, Конфуций предпочитал в его управлении моральные нормы формально-правовым, а патриархально-гуманное отношение к людям — бюрократической регламентации. Конфуцианство привнесло в сознание народов не только Китая, но и всей Центральной и Восточной Азии такие нравственные нормы, которые по силе воздействия на массовое сознание были эквивалентными библейским десяти заповедям. Это, прежде всего, «пять постоянств», или пять добродетелей: человеколюбие, чувство долга, благопристойность, разумность и правдивость.

Важнейшую роль в управлении государством Конфуций отводил традиции, ритуалу

, формированию у людей определенных стереотипов поведения. В основе всех общественных и нравственных норм поведения и воспитания Конфуций стремился найти ритуал. По существу, весь текст «Лунь юя» и есть его описание. Можно сказать, что в ритуале Конфуций открыл новый тип мудрости и философии. Стержень мудрости — соблюдение ритуала, а сущность философии — его правильное объяснение и понимание;

В соответствии со значением для человека ритуала причиной, например, смуты в обществе Конфуций считал оскудение религиозных чувств и несоблюдение ритуала. Объединяющим универсальным началом всех людей и их единства с космосом он считал почтительное отношение к Небу, чувство божественного всеединства. А богом и было для него Небо как завет предков, сакральную нравственную стихию, управляющую всем миром. Царь в древнем Китае имел титул «Сын Неба» и рассматривался как посредник междуволей Неба и людьми. Проявлением божественной нравственной силы на земле и является, по Конфуцию, ритуал.

Поскольку в человеке изначально заложены корысть, алчность, жестокость, то народ рассматривался как объект воспитания со стороны справедливой власти, а важнейшей задачей государственной власти было воспитание человека.

Что такое эффективное и совершенное государство и добродетельный человек

— таковы основные темы не только философии Конфуция, но и многих других мыслителей древнего Китая.

Большую роль играл в конфуцианстве унаследованный из архаических верований, но переосмысленный им культ предков

. Конфуцианство отнюдь не предписывало своим последователям верить в реальное присутствие предков во время жертвенных актов и даже не утверждало о бессмертии их душ. Важно было вести себя так, как если бы (жу-цзай) предки действительно присутствовали, демонстрируя этим свою искренность (чэн) и развивая в себе гуманность — сыновнюю почтительность и уважение к семейным ценностям и к древности.

Следует обратить внимание на мировоззренческое и методологическое значение концепции «золотой середины

» Конфуция. «Путь золотой середины» — один из основных элементов его идеологии и важнейший принцип добродетели, ибо «золотая середина, как добродетельный принцип, является наивысшим принципом». Этот путь необходимо использовать в управлении народом для смягчения противоречий, не допуская ни «чрезмерности», ни «отставания».

Идеи Конфуция сыграли большую роль в развитии всех сторон жизни китайского общества, в том числе и в формировании его философии государственного управления. Сам он стал объектом поклонения, а в 1503 г. был причислен к лику святых. Философы, поддерживающие и развивающие учение Конфуция, получили название конфуцианцы

. После смерти Конфуция конфуцианство распалось на целый ряд школ. Наиболее значительными из которых были: идеалистическая школа Мэн-цзы

(около 372 — 289 до н. э.) и материалистическая школа Сюнь-цзы

(около 313 -238 до н. э.). Однако конфуцианство оставалось господствующей в Китае идеологией вплоть до образования Китайской Народной Республики в 1949 г. В наши дни оно в Китае переживает свое возрождение и играет серьезную мировоззренческую роль.

Конфуцианство является мировоззрением, общественной этикой, политической идеологией, научной традицией, способом жизни, иногда рассматривается как философия, иногда — как религия .

В Китае это учение известно под названием 儒 или 儒家 (то есть «школа учёных», «школа учёных книжников» или «школа образованных людей»); «конфуцианство» — это западный термин, который не имеет эквивалента в китайском языке .

Конфуцианство возникло как этико-социально-политическое учение в Период Чуньцю (722 до н. э. по 481 до н. э.) — время глубоких социальных и политических потрясений в Китае. В эпоху династии Хань конфуцианство стало официальной государственной идеологией, конфуцианские нормы и ценности стали общепризнанными .

В императорском Китае конфуцианство играло роль основной религии, принципа организации государства и общества свыше двух тысяч лет в почти неизменном виде , вплоть до начала XX века, когда учение было заменено на «три народных принципа » Китайской Республики .

Уже после провозглашения КНР, в эпоху Мао Цзэдуна , конфуцианство порицалось как учение, стоящее на пути к прогрессу. Исследователи отмечают, что несмотря на официальные гонения, конфуцианство фактически присутствовало в теоретических положениях и в практике принятия решений на протяжении как маоистской эры, так и переходного периода и времени реформ, проводимых под руководством Дэн Сяо-пина; ведущие конфуцианские философы остались в КНР и были принуждены «покаяться в своих заблуждениях» и официально признать себя марксистами, хотя фактически писали о том же, чем занимались до революции . Лишь в конце 1970-х культ Конфуция начал возрождаться и в настоящее время конфуцианство играет важную роль в духовной жизни Китая.

Центральными проблемами, которые рассматривает конфуцианство, являются вопросы об упорядочении отношений правителей и подданных, моральных качествах, которыми должен обладать правитель и подчинённый и т. д..

Формально в конфуцианстве никогда не было института церкви, но по своей значимости, степени проникновения в душу и воспитания сознания народа, воздействию на формирование стереотипа поведения, оно успешно выполняло роль религии.

Основная терминология

Китайское обозначение конфуцианства не содержит отсылки к личности его основателя: это кит. упр. 儒

, пиньинь : rú

или кит. упр. 儒家

, пиньинь : rújiā

, то есть «Школа образованных людей». Таким образом, традиция никогда не возводила данной идеологической системы к теоретическому наследию одного-единственного мыслителя. Конфуцианство фактически представляет собой совокупность учений и доктрин, которые изначально стали развитием древних мифологем и идеологем. Древнее конфуцианство стало воплощением и завершением всего духовного опыта предшествующей национальной цивилизации. В этом смысле используется термин кит. упр. 儒教

, пиньинь : rújiào

.

Историческая эволюция

Шаблон:Конфуцианство

История конфуцианства неотделима от истории Китая. На протяжении тысячелетий это учение было системообразующим для китайской системы управления государством и обществом и в своей поздней модификации, известной под названием «неоконфуцианства », окончательно сформировало то, что принято именовать традиционной культурой Китая. До соприкосновения с западными державами и западной цивилизацией Китай был страной, где господствовала конфуцианская идеология.

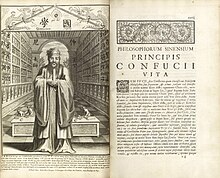

Тем не менее выделение конфуцианства в качестве самостоятельной идеологической системы и соответствующей школы связывается с деятельностью конкретного человека, который за пределами Китая известен под именем Конфуций . Это имя возникло в конце XVI века в трудах европейских миссионеров, которые таким образом на латинском языке (лат. Confucius

) передали сочетание Кун Фу-цзы (кит. упр. 孔夫子

, пиньинь : Kǒngfūzǐ

), хотя чаще используется имя 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ) с тем же значением «Учитель [из рода/по фамилии] Кун». Подлинное его имя Цю 丘 (Qiū), дословно «Холм», второе имя — Чжун-ни (仲尼Zhòngní), то есть «Второй из глины». В древних источниках это имя приводится как указание на место его рождения: в пещере в недрах глиняного священного холма, куда его родители совершали паломничество. Произошло это в 551 г. до н. э. близ современного города Цюйфу (кит. упр. 曲阜

, пиньинь : Qūfù

) в провинции Шаньдун .

После смерти Конфуция его многочисленные ученики и последователи образовали множество направлений, в III в. до н. э. их было, вероятно, около десяти. Его духовными наследниками считаются два мыслителя: Мэн-цзы (孟子) и Сюнь-цзы 荀子, авторы трактатов «Мэн-цзы» и «Сюнь-цзы». Конфуцианству, превратившемуся в авторитетную политическую и идейную силу, пришлось выдержать жестокую конкурентную борьбу с другими авторитетными политико-философскими школами Древнего Китая: моизмом (кит. упр. 墨家

, пиньинь : mòjiā

) и легизмом (кит. упр. 法家

, пиньинь : fǎjiā

). Учение последней стало официальной идеологией первой китайской империи Цинь (221-209 гг. до н. э.). Император-объединитель Цинь Шихуанди (правил в 246-210 гг. до н. э.) в 213 г. до н. э. развернул жестокие репрессии против конфуцианцев. Значительная часть учёных-конфуцианцев была отстранена от политической и интеллектуальной деятельности, а 460 оппозиционеров были закопаны живьём, были уничтожены тексты конфуцианских книг. Те, что дошли до наших дней, были восстановлены по устной передаче уже во II в. до н. э. Этот период в развитии конфуцианства именуется ранним конфуцианством

.

Выдержав жестокую конкурентную борьбу, конфуцианство при новой династии — Хань (206 г. до н. э. — 220 г. н. э.) во II-I вв. до н. э. стало официальной идеологией империи. В этот период произошли качественные изменения в развитии конфуцианства: учение разделилось на ортодоксальное (古文經學 «Школа канона древних знаков») и неортодоксальное (今文經學 «Школа канона современных знаков»). Представители первого утверждали незыблемость авторитета Конфуция и его учеников, абсолютную значимость их идей и непреложность заветов, отрицали любые попытки ревизии наследия Учителя. Представители второго направления, возглавляемые «Конфуцием эпохи Хань» — Дун Чжуншу (179-104 гг. до н. э.), настаивали на творческом подходе к древним учениям. Дун Чжуншу удалось, используя учения конкурирующих интеллектуальных школ, создать целостную доктрину, охватывающую все проявления природы и общества, и обосновать с её помощью теорию общественно-государственного устройства, которая была заложена Конфуцием и Мэн-цзы. Учение Дун Чжуншу в западном китаеведении именуется классическим конфуцианством

. Учение Конфуция в его интерпретации превратилось во всеобъемлющую мировоззренческую систему, поэтому стало официальной идеологией централизованного государства.

В период Хань конфуцианство определило всю современную политико-культурную ситуацию в Китае. В 125 г. до н. э. была учреждена Государственная академия (太學 или 國學), объединившая функции центрального гуманитарного теоретического центра и учебного заведения. Так появилась знаменитая система экзаменов кэцзюй , по результатам которой присваивалась тогда степень «придворного эрудита» (博士 bóshì). Однако теория государства тогда гораздо больше опиралась на даосские и легистские идеи.

Окончательно конфуцианство стало официальной идеологией империи гораздо позднее, при императоре Мин-ди (明帝 Míngdì, правил в 58 — 78 гг.). Это повлекло за собой складывание конфуцианского канона: унификацию древних текстов, составление списка канонических книг, которые использовались в системе экзаменов, и создание культа Конфуция с оформлением соответствующих церемоний. Первый храм Конфуция был воздвигнут в VI в., а наиболее почитаемый был сооружён в 1017 г. на месте рождения Учителя. Он включает в себя копию семейного дома Кунов, знаменитый холм и культовый ансамбль. Канонический образ Конфуция — густобородого старца, — сложился ещё позднее.

В период укрепления имперской государственности, при династии Тан (唐, 618-907 гг.) в Китае происходили существенные изменения в области культуры, всё бóльшее влияние в государстве приобретала новая — буддийская религия (佛教 fójiào), ставшая важным фактором в политической и экономической жизни. Это потребовало и существенной модификации конфуцианского учения. Инициатором процесса стал выдающийся политический деятель и учёный Хань Юй (韓愈 Hán Yù, 768-824 гг.). Деятельность Хань Юя и его учеников привела к очередному обновлению и преобразованию конфуцианства, которое в европейской литературе получило название неоконфуцианства. Историк китайской мысли Моу Цзунсань (англ.)

русск.

полагал, что разница между конфуцианством и неоконфуцианством такая же, как и между иудаизмом и христианством .

В XIX в. китайской цивилизации пришлось пережить значительный по масштабам духовный кризис, последствия которого не преодолены по сей день. Связано это было с колониальной и культурной экспансией западных держав. Результатом её стал распад имперского общества, и мучительный поиск китайским народом нового места в мире. Конфуцианцам, не желавшим поступаться традиционными ценностями, пришлось изыскивать пути синтеза традиционной китайской мысли с достижениями европейской философии и культуры. В результате, по мнению китайского исследователя Ван Бансюна (王邦雄), после войн и революций, на рубеже XIX-XX вв. сложились следующие направления в развитии китайской мысли:

- Консервативное, опирающееся на конфуцианскую традицию, и ориентирующееся на Японию. Представители: Кан Ювэй , Лян Цичао , Янь Фу (嚴復, 1854-1921), Лю Шипэй (刘师培, 1884-1919).

- Либерально-западническое, отрицающее конфуцианские ценности, ориентирующееся на США. Представители — Ху Ши (胡適, 1891-1962) и У Чжихуй (吴志辉, 1865-1953).

- Радикально-марксистское, русификаторское, также отрицающее конфуцианские ценности. Представители — Чэнь Дусю (陳獨秀, 1879-1942) и Ли Дачжао (李大钊, 1889-1927).

- Социально-политический идеализм, или суньятсенизм (三民主義 или孫文主義). Представители: Сунь Ятсен (孫中山, 1866-1925), Чан Кайши (蔣介石, 1886-1975), Чэнь Лифу (陳立夫, 1899-2001).

- Социально-культурологический идеализм, или современное неоконфуцианство (当代新儒教 dāngdài xīn rújiào).

В числе представителей первого поколения современного неоконфуцианства включаются следующие мыслители: Чжан Цзюньмай (张君劢, англ. Carsun Chang, 1886-1969), Сюн Шили (熊十力, 1885-1968) и упоминавшийся выше Лян Шумин. Двое последних мыслителей после 1949 г. остались в КНР, и на долгие годы исчезли для западных коллег. В философском отношении они пытались осмыслить и модернизировать духовное наследие Китая при помощи индийского буддизма, заложив в Китае основы сравнительной культурологии. Второе поколение современных неоконфуцианцев выросло на Тайване и в Гонконге после Второй мировой войны, все они — ученики Сюн Ши-ли. Представители: Тан Цзюньи (唐君毅, 1909-1978), Моу Цзунсань (牟宗三, 1909-1995), Сюй Фугуань (徐複觀, 1903-1982). Особенностью метода данных мыслителей было то, что они пытались наладить диалог традиционной китайской и современной западной культуры и философии. Результатом их деятельности, стал опубликованный в 1958 г. «Манифест китайской культуры людям мира» (《为中国文化敬告世界人士宣言》, англ. «A Manifesto for a Re-Appraisal of Sinology and Reconstruction of Chinese Culture»).

Последнее по времени конфуцианское течение формируется в 1970-е годы в США, в рамках совместной работы американских китаеведов и приехавших из Китая исследователей, учившихся на Западе. Данное направление, призывающее к обновлению конфуцианства с использованием западной мысли, называется «постконфуцианство» (англ. Post-Confucianism, 後儒家hòu rújiā). Ярчайшим его представителем является Ду Вэймин (杜維明, р. 1940), работающий одновременно в Китае, США и на Тайване. Его влияние на интеллектуальные круги США столь значительно, что американский исследователь Роберт Невилл (р. 1939) даже ввёл в употребление полушутливый термин «Бостонское конфуцианство» (Boston Confucianism). Это указывает на то, что в Китае в ХХ в. произошёл самый мощный за всю его историю духовный сдвиг, вызванный культурным шоком от слишком резкого соприкосновения с принципиально чуждыми моделями культуры и образа жизни, и попытки его осмысления, даже ориентированные на китайское культурное наследие, выходят за рамки собственно конфуцианства.

Таким образом, за более чем 2500-летнее существование конфуцианство сильно менялось, оставаясь при этом внутренне цельным комплексом, использующим одинаковый базовый набор ценностей.

Состав конфуцианского канона

Конфуцианская традиция представлена обширным рядом первоисточников, которые позволяют реконструировать собственно учение, а также выявить способы функционирования традиции в различных формах жизни китайской цивилизации.

Конфуцианский канон складывался постепенно и распадается на два набора текстов: «Пятикнижие » и «Четверокнижие ». Второй набор окончательно стал каноническим уже в рамках неоконфуцианства в XII веке. Иногда эти тексты рассматриваются в комплексе (《四書五經》Sìshū Wŭjīng). С конца XII века стало публиковаться и «Тринадцатикнижие » (《十三經》shísānjīng).

Термин «Пять канонов» («Пятиканоние») появился в правление ханьского императора У-ди (漢武帝, 140 — 87 гг. до н. э.). К тому времени большинство аутентичных текстов было утрачено, а реконструированные по устной передаче тексты были записаны «уставным письмом» (隸書lìshū), введённым Цинь Шихуанди. Особое значение для школы Дун Чжун-шу, полагающей эти тексты каноническими, приобрёл комментарий 左氏傳 (zuǒ shì zhuán) к летописи春秋 (Chūnqiū). Считалось, что её текст содержит множество аллегорий, а комментарий акцентирует «великий смысл» (大義dàyì) и помогает выявить «сокровенные речи» (微言 wēiyán) с точки зрения конфуцианской морально-политической доктрины. Школа Дун Чжун-шу также широко пользовалась апокрифами (緯書wěishū) для гадания по текстам канонов. В I в. до н. э. ситуация резко изменилась, ибо конкурирующая школа канона древних знаков (古文經學gǔwén jīngxué) заявила, что аутентичными являются тексты, написанные древними знаками, которые якобы обнаружены при реставрации дома Конфуция замурованными в стене (壁經bìjīng, «Каноны из стены»). На канонизации этих текстов настаивал Кун Ань-го (孔安國), потомок Конфуция, но получил отказ. В 8 г. на престол империи взошёл узурпатор Ван Ман (王莽, 8 — 23 гг.), провозгласивший Новую династию (дословно: 新). В целях легитимации собственной власти он стал присуждать звание эрудита (博士) знатокам «канонов древних знаков». Эта школа оперировала понятием六經 (liùjīng), то есть «Шестиканоние», в состав которых входили тексты «Пяти канонов» плюс утраченный ещё в древности «Канон музыки» (《樂經》yuè jīng). Тексты, записанные старыми и новыми знаками, резко отличались друг от друга не только в текстологическом отношении (различная разбивка на главы, состав, содержание), но и с точки зрения идеологии. Школа канонов древних знаков числила своим основателем не Конфуция, а основателя династии Чжоу — Чжоу-гуна (周公). Считалось, что Конфуций был историком и учителем, который добросовестно передавал древнюю традицию, не добавляя от себя ничего. Вновь соперничество школ старых и новых знаков вспыхнет в XVIII в. на совершенно иной идеологической основе.

Основные понятия конфуцианства и его проблематика

Базовые понятия

Если же обратиться к собственно конфуцианскому канону, то выяснится, что основных категорий мы можем выделить 22 (в качестве вариантов перевода указываются лишь самые распространённые в отечественной литературе значения и толкования)

- 仁 (rén) — человеколюбие, гуманность, достойный, гуманный человек, ядро плода, сердцевина.

- 義 (yì) — долг/справедливость, должная справедливость, чувство долга, смысл, значение, суть, дружеские отношения.

- 禮 (lǐ) — церемония, поклонение, этикет, приличия, культурность как основа конфуцианского мировоззрения, подношение, подарок.

- 道 (dào) — Дао-путь, Путь, истина, способ, метод, правило, обычай, мораль, нравственность.

- 德 (dé) — Дэ, благая сила, мана (по Е. А. Торчинову), моральная справедливость, гуманность, честность, сила души, достоинство, милость, благодеяние.

- 智 (zhì) — мудрость, ум, знание, стратагема, умудрённость, понимание.

- 信 (xìn) — искренность, вера, доверие, верный, подлинный, действительный.

- 材 (cái) — способности, талант, талантливый человек, природа человека, материал, заготовка, древесина, характер, натура, гроб.

- 孝 (xiào) — принцип сяо , почитание родителей, усердное служение родителям, усердное исполнение воли предков, усердное исполнение сыновнего (дочернего) долга, траур, траурная одежда.

- 悌 (tì) — уважение к старшим братьям, почтительное отношение к старшим, уважение, любовь младшего брата к старшему.

- 勇 (yǒng) — храбрость, отвага, мужество, солдат, воин, ополченец.

- 忠 (zhōng) — верность, преданность, искренность, чистосердечие, быть внимательным, быть осмотрительным, служить верой и правдой.

- 順 (shùn) — послушный, покорный, благонамеренный, следовать по…, повиноваться, ладиться, по душе, по нраву, благополучный, в ряд, подходящий, приятный, упорядочивать, имитировать, копировать, приносить жертву (кому-либо).

- 和 (hé) — Хэ, гармония, мир, согласие, мирный, спокойный, безмятежный, соответствующий, подходящий, умеренный, гармонировать с окружающим, вторить, подпевать, умиротворять, итог, сумма. По Л. С. Переломову: «единство через разномыслие».

- 五常 (wǔcháng) — Пять постоянств (仁, 義, 禮, 智, 信). В качестве синонима может использоваться: 五倫 (wǔlún) — нормы человеческих взаимоотношений (между государем и министром, отцом и сыном, старшим и младшим братьями, мужем и женой, между друзьями). Также может использоваться вместо 五行 (wǔxíng) — Пять добродетелей, Пять стихий (в космогонии: земля, дерево, металл, огонь, вода).

- 三綱 (sāngāng) — Три устоя (абсолютная власть государя над подданным, отца над сыном, мужа над женой). Дун Чжун-шу, как мы увидим далее, ввёл понятие三綱五常 (sāngāngwŭcháng) — «Три устоя и пять незыблемых правил» (подчинение подданного государю, подчинение сына отцу и жены — мужу, гуманность, справедливость, вежливость, разумность и верность).

- 君子 (jūnzǐ) — Цзюнь-цзы, благородный муж, совершенный человек, человек высших моральных качеств, мудрый и абсолютно добродетельный человек, не делающий ошибок. В древности: «сыновья правителей», в эпоху Мин — почтительное обозначение восьми деятелей школы Дунлинь (東林黨)2.

- 小人 (xiǎorén) — Сяо-жэнь, низкий человек, подлый люд, маленький человек, антипод цзюнь-цзы, простой народ, малодушный, неблагородный человек. Позднее стало использоваться в качестве уничижительного синонима местоимения «я» при обращении к старшим (властям или родителям).

- 中庸 (zhōngyōng) — золотая середина, «Срединное и неизменное» (как заглавие соответствующего канона), посредственный, средний, заурядный.

- 大同 (dàtóng) — Да тун, Великое Единение, согласованность, полная гармония, полное тождество, общество времён Яо (堯) и Шуня (舜).

- 小康 (xiăokāng) — Сяо кан, небольшой (средний) достаток, состояние общества, в котором изначальное Дао утрачено, среднезажиточное общество.

- 正名 (zhèngmíng) — «Исправление имён», приводить названия в соответствие с сущностью вещей и явлений.

Проблематика

В оригинальном названии конфуцианского учения отсутствует указание на имя его создателя, что соответствует исходной установке Конфуция — «передавать, а не создавать самому». Этико-философское учение Конфуция было качественно новаторским, но он идентифицировал его с мудростью древних «святых совершенномудрых», выраженных в историко-дидактических и художественных сочинениях (Шу-цзин и Ши-цзин). Конфуций выдвинул идеал государственного устройства, в котором при наличии сакрального правителя, реальная власть принадлежит «учёным» (жу), которые совмещают в себе свойства философов, литераторов и чиновников. Государство отождествлялось с обществом, социальные связи — с межличностными, основа которых усматривалась в семейной структуре. Семья выводилась из отношений между отцом и сыном. С точки зрения Конфуция, функция отца была аналогична функции Неба. Поэтому сыновняя почтительность была возведена в ранг основы добродетели-дэ.

Оценки конфуцианства как учения

Является ли конфуцианство религией? Этот вопрос был также поставлен первыми европейскими китаеведами XVI в., являвшимися монахами Ордена иезуитов, специально созданного для борьбы с ересями и обращения в христианство всех народов земного шара. Ради успешного обращения, миссионеры пытались интерпретировать господствующую идеологию, то есть неоконфуцианство, как религию, причём в христианских категориях, которые единственно были им знакомы. Проиллюстрируем это на конкретном примере.

Первым великим миссионером-синологом XVI-XVII вв. был Маттео Риччи (кит. 利瑪竇Lì Mǎdòu, 1552-1610). Если говорить современным языком, Риччи является создателем религиозно-культурологической теории, ставшей основой миссионерской деятельности в Китае, — теистического истолкования наследия древнекитайской (доконфуцианской) традиции до её полного примирения с католицизмом. Главной методологической основой данной теории стала попытка создания совместимой с христианством интерпретации предконфуцианской и раннеконфуцианской традиции.

Риччи, как и его преемники, исходили из того, что в древности китайцы исповедовали единобожие, но при упадке этого представления не создали стройной политеистической системы, подобно народам Ближнего Востока и античной Европы. Потому конфуцианство он оценивал как «секту учёных», которую естественно избирают китайцы, занимающиеся философией. Согласно Риччи, конфуцианцы не поклоняются идолам, веруют в одно божество, сохраняющее и управляющее всеми вещами на земле. Однако все конфуцианские доктрины половинчаты, ибо не содержат учения о Творце и, соответственно, творении мироздания. Конфуцианская идея воздаяния относился лишь к потомкам и не содержит понятий о бессмертии души, рае и аде. Вместе с тем, М. Риччи отрицал религиозный смысл конфуцианских культов. Учение же «секты книжников» направлено на достижение общественного мира, порядка в государстве, благосостояния семьи и воспитание добродетельного человека. Все эти ценности соответствуют «свету совести и христианской истине».

Совершенно иным было отношение М. Риччи к неоконфуцианству. Основным источником для исследования этого феномена является катехизис Тяньчжу ши и (《天主实录》, «Подлинный смысл Небесного Господа», 1603 г.). Несмотря на симпатию к первоначальному конфуцианству (чьи доктрины о бытии-наличии (有yǒu) и искренности «могут содержать зерно истины»), неоконфуцианство стало объектом его яростной критики. Особое внимание Риччи уделил опровержению космологических представлений о Великом Пределе (Тай цзи 太極). Естественно, он заподозрил, что порождающий мироздание Великий предел является языческой концепцией, преграждающей образованному конфуцианцу путь к Богу Живому и Истинному. Характерно, что в своей критике неоконфуцианства он был вынужден обильно прибегать к европейской философской терминологии, едва ли понятной даже самым образованным китайцам того времени… Главной миссионерской задачей Риччи было доказать, что Великий предел не мог предшествовать Богу и порождать Его. Он равным образом отвергал идею объединения человека и мироздания посредством понятия ци (氣, пневмы-субстрата, aura vitalis миссионерских переводов).

Чрезвычайно важной была полемика с конфуцианскими представлениями о человеческой природе. М. Риччи не стал оспаривать фундаментальной предпосылки конфуцианской традиции, соглашаясь с тем, что изначальная природа человека добра, — данный тезис не вступал в противоречие с доктриной о первородном грехе.

Как видим, изучение традиционных китайских философских учений было необходимо миссионеру для практических надобностей, но при этом Риччи должен был рассуждать с позиций своих оппонентов. М. Риччи, в первую очередь, необходимо было объяснить образованным китайцам, почему они ничего не слышали о Боге, и сделать это можно было только с конфуцианской позиции «возвращения к древности» (復古фу гу). Он пытался доказывать, что подлинная конфуцианская традиция была религией Бога (上帝Шан ди), а неоконфуцианство потеряло с ней всякую связь. Лишённая монотеистического (и даже теистического, как это окажется позднее) содержания неоконфуцианская традиция трактовалась Риччи только как искажение подлинного конфуцианства. (Примечательно, что подобной точки зрения придерживались и китайские мыслители-современники Риччи Гу Янь-у и Ван Чуань-шань, однако направление критики было принципиально различным). Неоконфуцианство для Риччи было неприемлемо ещё и потому, что считало мироздание единым, не отделяя, таким образом, Творца от тварей, помещая обоих в разряд тварного бытия — происходящего от безличного Тай цзи.

Перечисленные моменты определили на века отношение европейских синологов к проблемам философского неоконфуцианства в Китае. Не менее примечательно и то, что современные китайские мыслители, обратившись к исследованию данной проблемы, начали рассуждения примерно на том же теоретическом уровне, что и европейские мыслители XVIII в. В частности, Жэнь Цзи-юй (任继愈, р. 1916) утверждал, что именно неоконфуцианство и стало конфуцианской религией, однако она отличается от европейской: для Европы характерно разграничение религии, философии и науки, а в Китае они были интегрированы при господстве религии.

Те же миссионеры, и европейские Просветители, оперирующие их фактическим и теоретическим материалом поставили проблему прямо противоположным образом: конфуцианство является атеизмом. Уже Пьер Пуавр (1719-1786) утверждал, что конфуцианство показывает оптимальную модель управления атеистическим обществом. Многие последующие исследователи, например, Н. И. Зоммер (чья работа целиком приводится в приложении), также указывали, что с точки зрения европейской науки и философии учения конфуцианцев являются чисто атеистическими или, по крайней мере, пантеистическими. Такой же точки зрения придерживался современный китайский исследователь Ян Сян-куй (杨向奎, 1910-2000).

Резко выступал против трактовки конфуцианства как религии Фэн Ю-лань. Он подчёркивал, что иероглиф教 (jiāo) — «учение» в древнем обозначении конфуцианства не должен пониматься в том же значении, в каком он входит в современное слово 宗教 (zōngjiào) — «религия». Фэн Ю-лань, получивший образование и долго работавший в США, утверждал, что для религии специфично не просто признание существования духовного мира, а признание его существования в конкретных формах, что конфуцианству чуждо. Конфуцианцы не приписывали Конфуцию никаких сверхъестественных свойств, он не творил чудес, не проповедовал веры в царство не от мира сего, или рай, не призывал почитать какое-либо божество и не имел боговдохновенных книг. Носителем религиозных идей в Китае был буддизм.

Крайнюю точку зрения на конфуцианство как на атеизм продемонстрировал очень оригинальный китайский мыслитель Чжу Цянь-чжи (朱謙之, 1899-1972). Однако его позиция такова, что А. И. Кобзев называл её «экстравагантной». С 1930-х годов этот мыслитель разрабатывал теорию стимулирующего воздействия китайской цивилизации на Западную Европу. Он пришёл к следующим выводам: а) европейский Ренессанс порождён «четырьмя великими изобретениями» — бумагой, печатным делом, компасом и порохом, появившимися на Западе через посредничество монголов и арабов; б) связь европейской и китайской цивилизаций осуществлялась в три этапа: 1) «материальный контакт»; 2) «контакт в сфере искусства»; 3) «непосредственный контакт».

«Непосредственный контакт» был связан с деятельностью миссионеров-иезуитов в Китае и исследованием неоконфуцианства. Для эпохи Просвещения Конфуций был одним из идеологических ориентиров, а конфуцианство — источником прогресса философии. Именно иезуиты привезли в Европу представление об атеизме конфуцианства.

Влияние китайской философии на Германию проявилось в создании новой реальности — просветительском монархическом либерализме. Влияние китайской философии на Францию привело к созданию искусственного идеала — идеологии революции, направленной на разрушение. Непосредственно китайская философия сформировала взгляды Ф. М. Вольтера, П. А. Гольбаха, Ш. Л. Монтескьё, Д. Дидро и др. Диалектика Г. Гегеля — китайского происхождения. Диалектика «Феноменологии духа» находит соответствие с конфуцианским каноном.

Вопрос о религиозном наполнении конфуцианского учения, таким образом, остаётся открытым, хотя большинство китаеведов отвечают на него, скорее, отрицательно.

Ряд религиоведов относят конфуцианство к религии, высшим божеством в которой считалось строгое и ориентированное на добродетель Небо, а в качестве великого пророка выступал не вероучитель, возглашающий истину данного ему божественного откровения, подобно Будде или Иисусу, а мудрец Конфуций, предлагающий моральное усовершенствование в рамках строго фиксированных, освященных авторитетом древности этических норм; главным же объектом конфуцианского культа были духи предков . В виде церемониальных норм конфуцианство проникало в качестве эквивалента религиозного ритуала в жизнь каждого китайца .

Конфуций заимствовал первобытные верования: культ умерших предков, культ Земли и почитание древними китайцами своего верховного божества и легендарного первопредка Шан-ди. Впоследствии он стал ассоциироваться с Небом как высшей божественной силой, определяющей судьбу всего живого на Земле. Генетическая связь с этим источником мудрости и силы была закодирована и в самом названии страны — «Поднебесная», и в титуле ее правителя — «Сын Неба», сохранившемся до XX в.

— КОНФУЦИАНСТВО, этико политическое учение в Китае. Основы конфуцианства были заложены в 6 в. до нашей эры Конфуцием. Конфуцианство объявляло власть правителя (государя) священной, дарованной небом, а разделение людей на высших и низших (… … Современная энциклопедия

Этико политическое учение в Китае. Основы конфуцианства были заложены в 6 в. до н. э. Конфуцием. Выражая интересы наследственной аристократии, конфуцианство объявляло власть правителя (государя) священной, дарованной небом, а разделение людей на… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

Конфуцианство

— КОНФУЦИАНСТВО, этико политическое учение в Китае. Основы конфуцианства были заложены в 6 в. до нашей эры Конфуцием. Конфуцианство объявляло власть правителя (государя) священной, дарованной небом, а разделение людей на высших и низших (… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

КОНФУЦИАНСТВО, конфуцианства, мн. нет, ср. (книжн.). Система нравственно философских взглядов и традиций, основанная на учении китайского мыслителя Конфуция (5 6 вв. до н.э.). Толковый словарь Ушакова. Д.Н. Ушаков. 1935 1940 … Толковый словарь Ушакова

— (жу цзя школа великих книжников) так же, как и даосизм, зародилось в Китае в VI V веке до н.э. Входит в Сань цзяо одну из трех главных религий Китая. Философская система конфуцианства была создана Кун цзы (Конфуцием). Предшественни

Китайская цивилизация подарила миру бумагу, компас, порох, оригинальное культурное наполнение. раньше других понял важность учения среди чиновничьего аппарата, раньше других стран осознал важность передачи научных знаний и уже в раннее средневековье стоял на пороге капитализма. Современные исследователи склонны объяснять такие успехи тем, что китайская духовная жизнь не имела строгой религиозной линии на протяжении своей истории. Пока церковные догмы диктовали западному миру законы божие, Китай развивал своеобразное социально-культурное мировоззрение. Главным философским учением, заменившим политическую идеологию и религиозное сопровождение, стало конфуцианство.

Термин «конфуцианство» имеет европейское происхождение. Миссионеры Старого Света в конце XVI века назвали господствующую социально-политическую систему Китая по имени ее основателя — Кун Фу-цзы (учитель из рода Кун). В китайской традиции философское направление, основанное Конфуцием, носит имя «школа образованных людей», что куда лучше объясняет ее сущность.

В древнем Китае чиновники на местах назначались, поэтому государственные мужи, потерявшие место, часто становились бродячими учителями, вынужденными зарабатывать преподаванием древних писаний. Образованные люди оседали на благоприятных территориях, где и образовывались впоследствии известные школы и первые протоуниверситеты. В период Чуньцю особенно много бродячих преподавателей было в царстве Лу, которое и стало родиной Конфуция (551–479 до н. э.) и его учения.

Период раздробленности в истории Китая стал расцветом философских течений разнообразных направлений. Идеи «100 школ» развивались, не особо конкурируя между собой, пока Поднебесная империя не направила исторический корабль по курсу укрепления феодализации.

Конфуцианские ценности

Философия Конфуция зарождалась во времена неспокойные, все социальные ожидания жителей Поднебесных земель были направлены в мирную сторону. В основу конфуцианской философии заложены культы первобытного периода — культ предков и почитание первопредка всего китайского народа легендарного Шанди. Доисторический полумифический правитель, дарованный Небом, ассоциировался с высшей полубожественной силой. Отсюда берет начало традиция называть Китай «Поднебесным», а правителя — «Сыном Неба». Вспомним хотя бы знаменитый “ ” в Пекине – один из символов столицы КНР.

Первоначально учение исходило из того, что желание жить и развиваться — это принцип, лежащий в основе человеческой сущности. Главной добродетелью, согласно Конфуцию, является — гуманность (жэнь). Этот жизненный закон должен определять взаимоотношения в семье и обществе, проявляться в уважении к старшим и младшим. Для постижения жэнь человек должен самосовершенствоваться всю жизнь, силой ума избавляя себя от низменных проявлений характера.

Смысл человеческого бытия в достижении высшей степени социальной справедливости, которую можно достичь, развивая в себе положительные качества, следуя по пути саморазвития (дао). О воплощение дао в конкретном человеке можно судить по его добродетелям. Человек, дошедший до вершин дао, становится идеалом нравственности — «благородным мужем». Ему доступна гармония с собой и природой, миром и космосом.

Конфуций считал, что для каждой семьи в отдельности и единого государства в целом правила едины — «государство — это большая семья, а семья — это малое государство». Мыслитель считал, что государство создано для защиты каждого человека, поэтому от престижа монархической власти зависит народное счастье. Следование древним традициям помогает внести гармонию в социальный уклад, даже при материальных и природных трудностях. «Человек может расширить дао, но не дао человека».

Вера в загробную жизнь больше была данью сыновнего почтения к старшим родственникам, нежели религиозным культом. Конфуций верил, что строгое соблюдение ритуалов и обычаев, помогает обществу быть более стойким к социальным потрясениям, помогает понять исторический опыт и сохранить мудрость предков. Отсюда и учение об исправлении имен, гласящее что «государь должен быть государем, подданный — подданным, отец — отцом, сын — сыном». Поведение человека определяет его должность и семейное положение.

Великий мыслитель Конфуций, опираясь на полумифическую древность и нестабильную современность, создал для своей страны философскую систему, которая направила народную волю по пути развития и процветания. Его мировоззрение нашло отклик в лице современников и в душах последующих поколений. Конфуцианство не являлось строгим сводом правил, а оказалось гибким, способным пережить тысячелетия, впитывая в себя новые знания, и трансформироваться на благо всех жителей Поднебесной.

После смерти мудрейшего учителя из рода Кун, его учение продолжили развивать ученики и последователи. Уже в III веке до н. э. существовало около 10 различных конфуцианских направлений.

Исторический путь конфуцианства

Традиции «школы образованных людей» были заложены в век расцвета древнекитайской философии в эпоху раздробленности. Объединение государства под императорской рукой требовало жесткой территориальной и культурной централизации. Первый правитель единого Китая Великий Цинь Шихуанди (создатель ) для укрепления своей власти возводил не только на границе, но и в умах своих подданных. В качестве главной идеологии приоритет был отдан легизму. А носители конфуцианской философии, согласно легенде, жестоко преследовались.

Но уже следующая династия Хань сделала ставку на конфуцианство. Многочисленные последователи древней мудрости смогли восстановить утраченные тексты по устным источникам. Разные трактовки речей Конфуция создали ряд смежный учений на базе древних традиций. Со второго столетия конфуцианство становится официальной идеологией Поднебесной Империи, с этого времени быть китайцем значить быть конфуцианцем по рождению и воспитанию. Каждый чиновник обязан сдавать экзамен на знание традиционных конфуцианских ценностей. Подобная экзаменация проводилась более тысячи лет, на протяжении которых сложился целый ритуал, просуществовавший до XX века. Лучшие кандидаты подтверждали свои знания в легендарном , сдавая главный экзамен в присутствии императора.

Учение о стремлении человека к добродетелям не создавало препятствий для параллельного развития различных религиозных и философских систем. Начиная с IV века в китайское общество начинает проникать . Взаимодействие с новыми реалиями, культурная ассимиляция индийской религии, добавление мировоззренческой системы даосских школ, привело к рождению нового философского направления — неоконфуцианства.

С середины VI века начала складываться тенденция на усиление культа Конфуция и обожествление власти императора. Был издан указ о возведении храма в честь древнего мыслителя в каждом городе, что создало ряд интереснейших . На этом этапе начинает усиливаться религиозный подтекст в трактатах, основанных на творчестве — Конфуция.

Современная версия постнеоконфуцианства является коллективным творчеством множества авторов.

Родился Конфуций в 551 г. до нашей эры в царстве Лу. Отец Конфуция Шулян Хэ был храбрым воином из знатного княжеского рода. В первом браке у него родились только девочки, девять дочерей, а наследника не было. Во втором браке столь долгожданный мальчик родился, но, к несчастью, был калекой. Тогда, в возрасте 63 лет, он решается на третий брак, и его женой соглашается стать молодая девушка из рода Янь, которая считает, что нужно выполнить волю отца. Видения, которые посещают ее после свадьбы, предвещают появление великого человека. Рождению ребенка сопутствует множество чудесных обстоятельств. Согласно традиции, на его теле имелось 49 знаков будущего величия.

Так родился Кун-фу-цзы, или Учитель из рода Кун, известный на Западе под именем Конфуция.

Отец Конфуция умер, когда мальчику было 3 года, и молодая мать посвятила всю жизнь воспитанию мальчика. Ее постоянное руководство, чистота личной жизни сыграли большую роль в формировании характера ребенка. Уже в раннем детстве Конфуций отличался выдающимися способностями и талантом предсказателя. Он любил играть, подражая церемониям, бессознательно повторяя древние священные ритуалы. И это не могло не удивлять окружающих. Маленький Конфуций был далек от игр, свойственных его возрасту; главным его развлечением стали беседы с мудрецами и старцами. В 7 лет его отдали в школу, где обязательным было освоение 6 умений: умение выполнять ритуалы, умение слушать музыку, умение стрелять из лука, умение управлять колесницей, умение писать, умение считать.

Конфуций родился с беспредельной восприимчивостью к учению, пробужденный ум заставлял его читать и, самое главное, усваивать все знания, изложенные в классических книгах той эпохи, поэтому впоследствии о нем говорили: «Он не имел учителей, но лишь учеников». При окончании школы Конфуций один из всех учащихся сдал сложнейшие экзамены со стопроцентным результатом. В 17 лет он уже занимал должность государственного чиновника, хранителя амбаров. «Мои счета должны быть верны — вот единственно о чем я должен заботиться», — говорил Конфуций. Позже в его ведение поступил и скот царства Лу. «Быки и овцы должны быть хорошо откормлены — вот моя забота», — таковы были слова мудреца.

«Не беспокойся о том, что не занимаешь высокого поста. Беспокойся о том, хорошо ли служишь на том месте, где находишься».

В двадцать пять лет за свои бесспорные достоинства Конфуций был отмечен всем культурным обществом. Одним из кульминационных моментов в его жизни стало приглашение благородного правителя посетить столицу Поднебесной. Это путешествие позволило Конфуцию в полной мере осознать себя наследником и хранителем древней традиции (таковым считали его и многие современники). Он решил создать школу, основанную на традиционных учениях, где человек учился бы познавать Законы окружающего мира, людей и открывать собственные возможности. Конфуций хотел видеть своих учеников «целостными людьми», полезными государству и обществу, поэтому учил их различным областям знания, основывающимся на разных канонах. Со своими учениками Конфуций был прост и тверд: «Почему тот, кто не задает себе вопросы «почему?», заслуживает того, чтобы я задавал себе вопрос: «Почему я его должен учить?»

«Кто не жаждет знать, того не просвещаю. Кто не горит, тому не открываю. А тот, кто по одному углу не может выявить соотношения трех углов, — я для того не повторяю».

Слава о нем распространилась далеко за пределы соседних царств. Признание его мудрости достигло такой степени, что он занял пост Министра правосудия — в те времена самую ответственную должность в государстве. Он сделал так много для своей страны, что соседние государства стали опасаться царства, блестяще развивавшегося усилиями одной личности. Клевета и наветы привели к тому, что правитель Лу перестал внимать советам Конфуция. Конфуций покинул родное государство и отправился в путешествие по стране, наставляя правителей и нищих, князей и пахарей, молодых и стариков. Везде, где он проходил, его умоляли остаться, однако он неизменно отвечал: «Мой долг распространяется на всех людей без различия, ибо я считаю всех, кто населяет землю, членами одной семьи, в которой я должен исполнять священную миссию Наставника».

Для Конфуция знание и добродетель были едины и неразделимы, и поэтому жизнь в соответствии со своими философскими убеждениями являлась неотъемлемой частью самого учения. «Подобно Сократу, он не отбывал «рабочее время» со своей философией. Не был он и «червем», зарывшимся в свое учение и сидящим на стуле вдали от жизни. Философия была для него не моделью идей, выставляемых для человеческого осознания, но системой заповедей, неотъемлемых от поведения философа». В случае Конфуция можно смело ставить знак равенства между его философией и его человеческой судьбой.

Умер мудрец в 479 году до нашей эры; свою смерть он предсказал ученикам заранее.

Несмотря на внешне скромные биографические данные, Конфуций остается величайшей фигурой в духовной истории Китая. Один из его современников говорил: «Поднебесная давно пребывает в хаосе. Но ныне Небо возжелало сделать Учителя пробуждающим колоколом»

Конфуций не любил говорить о себе и весь свой жизненный путь описал в нескольких строчках:

«В 15 лет я обратил свои помыслы к учению.

В 30 лет — я обрёл прочную основу.

В 40 лет — я сумел освободиться от сомнений.

В 50 лет — я познал волю Неба.

В 60 лет — я научился отличать правду от лжи.

В 70 лет — я стал следовать зову моего сердца и не нарушал Ритуала».

В этом высказывании весь Конфуций — человек и идеал традиции, известной как конфуцианство. Его путь от учёбы через познание «воли Неба» к свободному следованию желаниям сердца и соблюдению правил поведения, которые он считал священными, «небесными», стал нравственным ориентиром всей культуры Китая.

— один из величайших мыслителей древнего мира, мудрец, великий китайский философ, основатель философской системы, названной «конфуцианство». Учение Великого учителя оказало огромное влияние на духовную и политическую жизнь Китая и Восточной Азии. Настоящее имя Конфуция — Кун Цю, в литературе его часто именуют Кун Фу-Цзы, что значило учитель Кун или Цзы-Учитель. Родился Конфуций зимой 551 г. до н.э., судя по родословной, являлся потомком знатного, но давно обедневшего рода. Он был сыном чиновника и его 17-летней наложницы. В возрасте трех лет Конфуций лишился отца и семья жила в очень стесненных условиях. С детства Конфуций познал бедность, нужду и тяжелый труд. Стремление стать культурным человеком сподвигло его заниматься самосовершенствованием и самообразованием. Позже, когда Конфуция хвалили за прекрасные знания многих искусств и ремесел, он говорил, что этому поспособствовала бедность, которая заставила приобретать все эти знания, чтобы заработать на жизнь. В 19 лет Конфуций женился, у него было трое детей — сын и две дочки. В молодости он работал смотрителем госземель и складов, однако понял, что его призвание состоит в обучении других.

В 22 года он открыл частную школу, куда принимал всех желающих независимо от их материального положения и происхождения, однако не удерживал в школе тех,

В сопровождении 12 учеников, неотступно следовавших за своим наставником, Конфуций путешествовал по царствам Древнего Китая, где стремился на практике применить свои принципы правильного и мудрого государственного

Благодаря мудрому правлению Конфуция герцогство Лу начало заметно процветать, что вызвало огромную зависть у соседних князей. Им удалось рассорить герцога и мудреца, в результате чего на 56-м году жизни Конфуций покидает отечество и долгих 14 лет странствует в сопровождении учеников по Китаю. Он жил при дворах и в народе, ему льстили, заискивали, иногда оказывали почести, но не предлагали государственных должностей. В 484 году благодаря одному влиятельному ученику, занимавшему важный пост в Лу, Конфуций смог вернуться в родную провинцию. Последние годы Конфуций занимался преподаванием и книгами — составил летопись Лу «Чуньцю» за период 722-481 год до н.э., редактировал «Шу цзин»,»Ши Цзинь». Из литературного наследия Древнего Китая больше всего восхвалял «И цзин» — «Книгу перемен».

Знаменитый мыслитель эпохи династии Чжоу Кун-цзы (что значит «учитель Кун») известен в Европе под именем Конфуций.

Конфуций родился в знатной, но обедневшей семье в 551 году до н. э., когда государство уже сотрясали смуты и внутренние распри. Он долгое время служил мелким чиновником у правителей разных княжеств, путешествуя по всей стране. Значительных чинов Конфуций так и не достиг, но зато многое узнал о жизни своего народа и составил собственное представление о принципах справедливости в государстве. Золотым веком общественного порядка и гармонии он считал первые годы правления династии Чжоу, а время в которое жил сам Конфуций считал царством нарастающего хаоса. По его мнению, все беды происходили из-за того, что князья забыли все те великие принципы, которым руководствовались прежние правители. Поэтому он разработалособую систему морально-этических догм и норм поведения человека, основывающихся на почитании предков, повиновении родителям, уважении к старшим, человеколюбии.

Конфуций учил,что мудрый правитель должен подавать пример справедливого обращения с подданными, а те, в свою очередь, обязаны почитать правителя и повиноваться ему. Такими же, по его мнению, должны быть отношения и в каждой семье. Конфуций верил, что судьба каждого человека определяется небом, и поэтому он должен занимать в обществе подобающее положение: правитель должен быть правителем, чиновник — чиновником, а простолюдин — простолюдином, отец — отцом, сын — сыном. По его мнению, если порядок нарушается, тогда общество утрачивает свою гармонию. Чтобы сохранить ее, правитель правитель должен умело управлять при помощи чиновников и законов. Удел «ничтожного человека» — повиноваться, а назначение «благородного мужа» — повелевать.

Проповеди Конфуция пользовались большой популярностью среди аристократов, и особенно среди чиновников. На рубеже старой и новой эры сам Конфуций был обожествлен, а его учение оставалось в Китае официальным вплоть до падения монархии в 1911 году.

Во многих городах Китая в честь Конфуция были возведены храмы, где претенденты на получение ученых степеней и должностей чиновников совершали обязательные поклонения и жертвоприношения. В конце XIX века в стране насчитывалось 1 560 таких храмов, куда доставлялись животные и шелк для жертвоприношений (в год около 62 600 свиней, кроликов, овец, оленей и 27 тысяч кусков шелка) и затем раздавались молячимся.

Так возникло религиозное направление — конфуцианство, суть которого — почитание предков. В своем семейном родовом храме китайцы размещают таблички — чжу, — перед которыми совершают обряды и приносятся жертвоприношения.

Конфуций был образованным, но в то же время обычным человеком. Желание людей поклоняться чему-либо или кому-либо привело к возникновению новой религии, которая до сих пор оказывает значительное влияние на миллионы людей.

Поднебесной .

Биография

Конфуций был сыном 63-летнего военного Шулян Хэ (叔梁纥, Shūliáng Hé) и семнадцатилетней наложницы по имени Янь Чжэнцзай (颜征在 Yán Zhēngzài). Отец будущего философа скончался, когда сыну его исполнилось всего полтора года. Отношения между матерью Конфуция Янь Чжэнцзай и двумя старшими женами были напряженными, причиной чего был гнев старшей жены, которая так и не смогла родить сына, что очень важно для китайцев того периода. Вторая жена, родившая Шулян Хэ слабого, болезненного мальчика (которого назвали Бо Ни), тоже недолюбливала молодую наложницу. Поэтому мать Конфуция вместе с сыном покинула дом, в котором он родился, и вернулась на родину, в г. Цюйфу , но к родителям не вернулась и стала жить самостоятельно .

С раннего детства Конфуций много работал, поскольку маленькая семья жила в бедности. Однако его мать, Янь Чжэнцзай, вознося молитвы предкам (это было необходимой частью культа предков , повсеместного в Китае), рассказывала сыну о великих деяниях его отца и его предков. Так у Конфуция крепло осознание того, что ему необходимо занять достойное его рода место, поэтому он начал заниматься самообразованием, в первую очередь — изучать необходимые каждому аристократу Китая того времени искусства . Усердное обучение принесло свои плоды и Конфуция назначили сначала распорядителем амбаров (чиновником, ответственным за прием и выдачу зерна) в клане Цзи царства Лу (Восточный Китай, современная провинция Шаньдун) , а потом чиновником, отвечающим за скот. Будущему философу тогда исполнилось — по оценкам разных исследователей — от 20 до 25 лет, он уже был женат (с 19 лет) и имел сына (по имени Ли, известного также под прозвищем Бо Юй) .

Это было время заката империи Чжоу , когда власть императора стала номинальной, разрушалось патриархальное общество и на место родовой знати пришли правители отдельных царств, окружённые незнатными чиновниками. Крушение древних устоев семейно-кланового быта, междоусобные распри, продажность и алчность чиновников, бедствия и страдания простого народа — всё это вызывало резкую критику ревнителей старины.

Осознав невозможность повлиять на политику государства, Конфуций подал в отставку и отправился в сопровождении учеников в путешествие по Китаю, во время которого он пытался донести свои идеи правителям различных областей. В возрасте около 60 лет Конфуций вернулся домой и провёл последние годы жизни, обучая новых учеников, а также систематизируя литературное наследие прошлого Ши-цзин

(Книга Песен), И цзин

(Книга Перемен) и др.