Coordinates: 41°43′57″N 49°56′49″W / 41.73250°N 49.94694°W

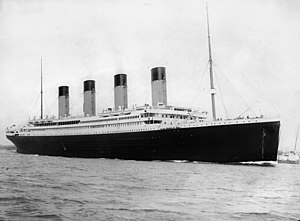

Titanic departing Southampton on 10 April 1912 |

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | RMS Titanic |

| Owner | |

| Operator | White Star Line |

| Port of registry | |

| Route | Southampton to New York City |

| Ordered | 17 September 1908 |

| Builder | Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Cost | GB£1.5 million (£150 million in 2019) |

| Yard number | 401 |

| Way number | 400 |

| Laid down | 31 March 1909 |

| Launched | 31 May 1911 |

| Completed | 2 April 1912 |

| Maiden voyage | 10 April 1912 |

| In service | 1912 |

| Out of service | 15 April 1912 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Struck an iceberg at 11:40 pm (ship’s time) 14 April 1912 on her maiden voyage and sank 2 h 40 min later on 15 April 1912; 110 years ago. |

| Status | Wreck |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 46,329 GRT, 21,831 NRT |

| Displacement | 52,310 tons |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 92 ft 6 in (28.2 m) |

| Height | 175 ft (53.3 m) (keel to top of funnels) |

| Draught | 34 ft 7 in (10.5 m) |

| Depth | 64 ft 6 in (19.7 m) |

| Decks | 9 (A–G) |

| Installed power | 24 double-ended and five single-ended boilers feeding two reciprocating steam engines for the wing propellers, and a low-pressure turbine for the centre propeller;[3] output: 46,000 HP |

| Propulsion | Two three-blade wing propellers and one centre propeller |

| Speed | Cruising: 21 kn (39 km/h; 24 mph). Max: 23 kn (43 km/h; 26 mph) |

| Capacity | Passengers: 2,453, crew: 874. Total: 3,327 (or 3,547 according to other sources) |

| Notes | Lifeboats: 20 (sufficient for 1,178 people) |

RMS Titanic was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard, more than 1,500 died, making it the deadliest sinking of a single ship up to that time.[a] It remains the deadliest peacetime sinking of an ocean liner or cruise ship.[4] The disaster drew public attention, provided foundational material for the disaster film genre, and has inspired many artistic works.

RMS Titanic was the largest ship afloat at the time she entered service and the second of three Olympic-class ocean liners operated by the White Star Line. She was built by the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast. Thomas Andrews, the chief naval architect of the shipyard, died in the disaster.[5] Titanic was under the command of Captain Edward Smith, who went down with the ship. The ocean liner carried some of the wealthiest people in the world, as well as hundreds of emigrants from Great Britain and Ireland, Scandinavia, and elsewhere throughout Europe, who were seeking a new life in the United States and Canada.

The first-class accommodation was designed to be the pinnacle of comfort and luxury, with a gymnasium, swimming pool, smoking rooms, high-class restaurants and cafes, a Turkish bath and hundreds of opulent cabins. A high-powered radiotelegraph transmitter was available for sending passenger «marconigrams» and for the ship’s operational use.[6] Titanic had advanced safety features, such as watertight compartments and remotely activated watertight doors, contributing to its reputation as «unsinkable».

Titanic was equipped with 16 lifeboat davits, each capable of lowering three lifeboats, for a total of 48 boats; she carried only 20 lifeboats, four of which were collapsible and proved hard to launch while she was sinking (Collapsible A nearly swamped and was filled with a foot of water until rescue, Collapsible B completely overturned while launching). Together, the 20 lifeboats could hold 1,178 people—about half the number of passengers on board, and one third of the number of passengers the ship could have carried at full capacity (consistent with the maritime safety regulations of the era). When the ship sank, many of the lifeboats that had been lowered were only filled up to an average of 60%.[7]

Background

Gaumont newsreel containing the only known footage of Titanic, 1912

The name Titanic derives from the Titans of Greek mythology. Built in Belfast, Ireland, in what was then the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, RMS Titanic was the second of the three Olympic-class ocean liners—the first was RMS Olympic and the third was HMHS Britannic.[8] Britannic was originally to be called Gigantic and was to be over 1,000 feet (300 m) long.[9][failed verification] They were by far the largest vessels of the British shipping company White Star Line’s fleet, which comprised 29 steamers and tenders in 1912.[10] The three ships had their genesis in a discussion in mid-1907 between the White Star Line’s chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, and the American financier J. P. Morgan, who controlled the White Star Line’s parent corporation, the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMM).

The White Star Line faced an increasing challenge from its main rivals, Cunard—which had recently launched Lusitania and Mauretania, the fastest passenger ships then in service—and the German lines Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd. Ismay preferred to compete on size rather than speed, and proposed to commission a new class of liners that would be larger than anything that had gone before, as well as being the last word in comfort and luxury.[11] The White Star Line sought an upgrade of its fleet primarily in order to respond to the introduction of the Cunard giants, but also to considerably strengthen its position on the Southampton–Cherbourg–New York service that had been inaugurated in 1907. The new ships would have sufficient speed to maintain a weekly service with only three ships instead of the original four. Thus, the Olympic and Titanic would replace RMS Teutonic of 1889, RMS Majestic of 1890 as well as RMS Adriatic of 1907. RMS Oceanic would remain on the route until the third new ship could be delivered.[citation needed] Majestic would be brought back into her old spot on White Star Line’s New York service after Titanic‘s loss.[12]

The ships were constructed by the Belfast shipbuilder Harland and Wolff, which had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867.[13] Harland and Wolff was given a great deal of latitude in designing ships for the White Star Line; the usual approach was for the latter to sketch out a general concept which the former would take away and turn into a ship design. Cost considerations were a relatively low priority; Harland and Wolff was authorised to spend what it needed on the ships, plus a five percent profit margin.[13] In the case of the Olympic-class ships, a cost of £3 million (approximately £310 million in 2019) for the first two ships was agreed plus «extras to contract» and the usual five percent fee.[14]

Harland and Wolff put their leading designers to work designing the Olympic-class vessels. The design was overseen by Lord Pirrie, a director of both Harland and Wolff and the White Star Line; naval architect Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff’s design department; Edward Wilding, Andrews’ deputy and responsible for calculating the ship’s design, stability and trim; and Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard’s chief draughtsman and general manager.[15] Carlisle’s responsibilities included the decorations, equipment and all general arrangements, including the implementation of an efficient lifeboat davit design.[b]

On 29 July 1908, Harland and Wolff presented the drawings to J. Bruce Ismay and other White Star Line executives. Ismay approved the design and signed three «letters of agreement» two days later, authorising the start of construction.[18] At this point the first ship—which was later to become Olympic—had no name, but was referred to simply as «Number 400», as it was Harland and Wolff’s four-hundredth hull. Titanic was based on a revised version of the same design and was given the number 401.[19]

Dimensions and layout

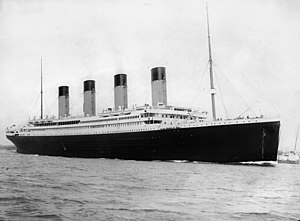

Starboard view of Titanic

Titanic was 882 feet 9 inches (269.06 m) long with a maximum breadth of 92 feet 6 inches (28.19 m).

Her total height, measured from the base of the keel to the top of the bridge, was 104 feet (32 m).[20] She measured 46,329 GRT and 21,831 NRT[21] and with a draught of 34 feet 7 inches (10.54 m), she displaced 52,310 tons.[8]

All three of the Olympic-class ships had ten decks (excluding the top of the officers’ quarters), eight of which were for passenger use. From top to bottom, the decks were:

- The Boat Deck, on which the lifeboats were housed. It was from here during the early hours of 15 April 1912 that Titanic‘s lifeboats were lowered into the North Atlantic. The bridge and wheelhouse were at the forward end, in front of the captain’s and officers’ quarters. The bridge stood 8 feet (2.4 m) above the deck, extending out to either side so that the ship could be controlled while docking. The wheelhouse stood within the bridge. The entrance to the First Class Grand Staircase and gymnasium were located midships along with the raised roof of the First Class lounge, while at the rear of the deck were the roof of the First Class smoke room and the relatively modest Second Class entrance. The wood-covered deck was divided into four segregated promenades: for officers, First Class passengers, engineers, and Second Class passengers respectively. Lifeboats lined the side of the deck except in the First Class area, where there was a gap so that the view would not be spoiled.[22][23]

- A Deck, also called the Promenade Deck, extended along the entire 546 feet (166 m) length of the superstructure. It was reserved exclusively for First Class passengers and contained First Class cabins, the First Class lounge, smoke room, reading and writing rooms, and Palm Court.[22]

- B Deck, the Bridge Deck, was the top weight-bearing deck and the uppermost level of the hull. More First Class passenger accommodations were located here with six palatial staterooms (cabins) featuring their own private promenades. On Titanic, the À La Carte Restaurant and the Café Parisien provided luxury dining facilities to First Class passengers. Both were run by subcontracted chefs and their staff; all were lost in the disaster. The Second Class smoking room and entrance hall were both located on this deck. The raised forecastle of the ship was forward of the Bridge Deck, accommodating Number 1 hatch (the main hatch through to the cargo holds), numerous pieces of machinery and the anchor housings.[c] Aft of the Bridge Deck was the raised Poop Deck, 106 feet (32 m) long, used as a promenade by Third Class passengers. It was where many of Titanic‘s passengers and crew made their last stand as the ship sank. The forecastle and Poop Deck were separated from the Bridge Deck by well decks.[24][25]

- C Deck, the Shelter Deck, was the highest deck to run uninterrupted from stem to stern. It included both well decks; the aft one served as part of the Third Class promenade. Crew cabins were housed below the forecastle and Third Class public rooms were housed below the Poop Deck. In between were the majority of First Class cabins and the Second Class library.[24][26]

- D Deck, the Saloon Deck, was dominated by three large public rooms—the First Class Reception Room, the First Class Dining Saloon and the Second Class Dining Saloon. An open space was provided for Third Class passengers. First, Second and Third Class passengers had cabins on this deck, with berths for firemen located in the bow. It was the highest level reached by the ship’s watertight bulkheads (though only by eight of the fifteen bulkheads).[24][27]

- E Deck, the Upper Deck, was predominantly used for passenger accommodation for all three classes plus berths for cooks, seamen, stewards and trimmers. Along its length ran a long passageway nicknamed ‘Scotland Road’, in reference to a famous street in Liverpool. Scotland Road was used by Third Class passengers and crew members.[24][28]

- F Deck, the Middle Deck, was the last complete deck, and mainly accommodated Second and Third Class passengers and several departments of the crew. The Third Class dining saloon was located here, as were the swimming pool, Turkish bath and kennels.[24][28][29]

- G Deck, the Lower Deck, was the lowest complete deck that carried passengers, and had the lowest portholes, just above the waterline. The squash court was located here along with the travelling post office where letters and parcels were sorted ready for delivery when the ship docked. Food was also stored here. The deck was interrupted at several points by orlop (partial) decks over the boiler, engine and turbine rooms.[24][30]

- The Orlop Decks, and the Tank Top below that, were on the lowest level of the ship, below the waterline. The orlop decks were used as cargo spaces, while the Tank Top—the inner bottom of the ship’s hull—provided the platform on which the ship’s boilers, engines, turbines and electrical generators were housed. This area of the ship was occupied by the engine and boiler rooms, areas which passengers would have been prohibited from seeing. They were connected with higher levels of the ship by flights of stairs; twin spiral stairways near the bow provided access up to D Deck.[24][30]

Features

Power

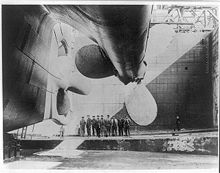

RMS Olympic‘s rudder with central and port wing propellers;[d] for scale, note the man at the bottom of the photo.[32]

Titanic was equipped with three main engines—two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion steam engines and one centrally placed low-pressure Parsons turbine—each driving a propeller. The two reciprocating engines had a combined output of 30,000 horsepower (22,000 kW). The output of the steam turbine was 16,000 horsepower (12,000 kW).[20] The White Star Line had used the same combination of engines on an earlier liner, Laurentic, where it had been a great success.[33] It provided a good combination of performance and speed; reciprocating engines by themselves were not powerful enough to propel an Olympic-class liner at the desired speeds, while turbines were sufficiently powerful but caused uncomfortable vibrations, a problem that affected the all-turbine Cunard liners Lusitania and Mauretania.[34] By combining reciprocating engines with a turbine, fuel usage could be reduced and motive power increased, while using the same amount of steam.[35]

The two reciprocating engines were each 63 feet (19 m) long and weighed 720 tons, with their bedplates contributing a further 195 tons.[34] They were powered by steam produced in 29 boilers, 24 of which were double-ended and five single-ended, which contained a total of 159 furnaces.[36] The boilers were 15 feet 9 inches (4.80 m) in diameter and 20 feet (6.1 m) long, each weighing 91.5 tons and capable of holding 48.5 tons of water.[37]

They were heated by burning coal, 6,611 tons of which could be carried in Titanic‘s bunkers, with a further 1,092 tons in Hold 3. The furnaces required over 600 tons of coal a day to be shovelled into them by hand, requiring the services of 176 firemen working around the clock.[38] 100 tons of ash a day had to be disposed of by ejecting it into the sea.[39] The work was relentless, dirty and dangerous, and although firemen were paid relatively generously,[38] there was a high suicide rate among those who worked in that capacity.[40]

Exhaust steam leaving the reciprocating engines was fed into the turbine, which was situated aft. From there it passed into a surface condenser, to increase the efficiency of the turbine and so that the steam could be condensed back into water and reused.[41] The engines were attached directly to long shafts which drove the propellers. There were three, one for each engine; the outer (or wing) propellers were the largest, each carrying three blades of manganese-bronze alloy with a total diameter of 23.5 feet (7.2 m).[37] The middle propeller was slightly smaller at 17 feet (5.2 m) in diameter,[42] and could be stopped but not reversed.

Titanic‘s electrical plant was capable of producing more power than an average city power station of the time.[43] Immediately aft of the turbine engine were four 400 kW steam-driven electric generators, used to provide electrical power to the ship, plus two 30 kW auxiliary generators for emergency use.[44] Their location in the stern of the ship meant they remained operational until the last few minutes before the ship sank.[45]

Titanic lacked a searchlight in accordance with the ban on the use of searchlights in the merchant navy.[46][47]

Technology

Compartments and funnels

The interiors of the Olympic-class ships were subdivided into 16 primary compartments divided by 15 bulkheads that extended above the waterline. Eleven vertically closing watertight doors could seal off the compartments in the event of an emergency.[48] The ship’s exposed decking was made of pine and teak, while interior ceilings were covered in painted granulated cork to combat condensation.[49] Standing above the decks were four funnels, each painted buff with black tops; only three were functional—the aftmost one was a dummy, installed for aesthetic purposes and kitchen ventilation. Two masts, each 155 ft (47 m) high, supported derricks for working cargo.

Rudder and steering engines

Titanic‘s rudder was so large—at 78 feet 8 inches (23.98 m) high and 15 feet 3 inches (4.65 m) long, weighing over 100 tons—that it required steering engines to move it. Two steam-powered steering engines were installed, though only one was used at any one time, with the other one kept in reserve. They were connected to the short tiller through stiff springs, to isolate the steering engines from any shocks in heavy seas or during fast changes of direction.[50] As a last resort, the tiller could be moved by ropes connected to two steam capstans.[51] The capstans were also used to raise and lower the ship’s five anchors (one port, one starboard, one in the centreline and two kedging anchors).[51]

Water, ventilation and heating

The ship was equipped with her own waterworks, capable of heating and pumping water to all parts of the vessel via a complex network of pipes and valves. The main water supply was taken aboard while Titanic was in port, but in an emergency, the ship could also distil fresh water from seawater, though this was not a straightforward process as the distillation plant quickly became clogged by salt deposits. A network of insulated ducts conveyed warm air, driven by electric fans, around the ship, and First Class cabins were fitted with additional electric heaters.[43]

Radio communications

Marconi Company receiving equipment for a 5 kilowatt ocean liner station (in the picture, the wireless radio room of Titanic‘s sister ship, Olympic)

The only known picture of Titanic‘s wireless radio room, taken by the Catholic priest Francis Browne. Harold Bride is seated at the desk.

Titanic‘s radiotelegraph equipment (then known as wireless telegraphy) was leased to the White Star Line by the Marconi International Marine Communication Company, which also supplied two of its employees, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, as operators. The service maintained a 24-hour schedule, primarily sending and receiving passenger telegrams, but also handling navigation messages including weather reports and ice warnings.[52][53][6]

The radio room was located on the Boat Deck, in the officers’ quarters. A soundproofed «Silent Room», next to the operating room, housed loud equipment, including the transmitter and a motor-generator used for producing alternating currents. The operators’ living quarters were adjacent to the working office. The ship was equipped with a ‘state of the art’ 5 kilowatt rotary spark-gap transmitter, with the wireless telegraph call sign MGY, and communication was in Morse code. This transmitter was one of the first Marconi installations to use a rotary spark-gap, which gave Titanic a distinctive musical tone that could be readily distinguished from other signals. The transmitter was one of the most powerful in the world and guaranteed to broadcast over a radius of 350 miles (563 km). An elevated T-antenna that spanned the length of the ship was used for transmitting and receiving. The normal operating frequency was 500 kHz (600 m wavelength); however, the equipment could also operate on the «short» wavelength of 1,000 kHz (300 m wavelength) that was employed by smaller vessels with shorter antennas.[54]

Passenger facilities

The passenger facilities aboard Titanic aimed to meet the highest standards of luxury. According to Titanic‘s general arrangement plans, the ship could accommodate 833 First Class Passengers, 614 in Second Class and 1,006 in Third Class, for a total passenger capacity of 2,453. In addition, her capacity for crew members exceeded 900, as most documents of her original configuration have stated that her full carrying capacity for both passengers and crew was approximately 3,547. Her interior design was a departure from that of other passenger liners, which had typically been decorated in the rather heavy style of a manor house or an English country house.[55]

Titanic was laid out in a much lighter style similar to that of contemporary high-class hotels—the Ritz Hotel was a reference point—with First Class cabins finished in the Empire style.[55] A variety of other decorative styles, ranging from the Renaissance to Louis XV, were used to decorate cabins and public rooms in First and Second Class areas of the ship. The aim was to convey an impression that the passengers were in a floating hotel rather than a ship; as one passenger recalled, on entering the ship’s interior a passenger would «at once lose the feeling that we are on board ship, and seem instead to be entering the hall of some great house on shore».[56]

Among the more novel features available to first-class passengers was a 7 ft (2.1 m) deep saltwater swimming pool, a gymnasium, a squash court, and a Turkish bath which comprised electric bath, steam room, cool room, massage room, and hot room.[56] First-class common rooms were impressive in scope and lavishly decorated. They included a Lounge in the style of the Palace of Versailles, an enormous Reception Room, a men’s Smoking Room, and a Reading and Writing Room. There was an À la Carte Restaurant in the style of the Ritz Hotel which was run as a concession by the famous Italian restaurateur Gaspare Gatti.[57] A Café Parisien decorated in the style of a French sidewalk café, complete with ivy-covered trellises and wicker furniture, was run as an annex to the restaurant. For an extra cost, first-class passengers could enjoy the finest French haute cuisine in the most luxurious of surroundings.[58] There was also a Verandah Café where tea and light refreshments were served, that offered grand views of the ocean. At 114 ft (35 m) long by 92 ft (28 m) wide, the Dining Saloon on D Deck, designed by Charles Fitzroy Doll, was the largest room afloat and could seat almost 600 passengers at a time.[59]

-

The Forward First Class Grand Staircase of Titanic‘s sister ship RMS Olympic. Titanic‘s staircase would have looked nearly identical. No known photos of Titanic‘s staircase exist.

-

The gymnasium on the Boat Deck, which was equipped with the latest exercise machines

-

The Á La Carte restaurant on B Deck (pictured here on sister ship RMS Olympic), run as a concession by Italian-born chef Gaspare Gatti

-

The 1st-Class Lounge of RMS Olympic, Titanic‘s sister ship

-

The 1st-Class Turkish Baths, located along the Starboard side of F-Deck

Third Class (commonly referred to as Steerage) accommodations aboard Titanic were not as luxurious as First or Second Class, but even so, were better than on many other ships of the time. They reflected the improved standards which the White Star Line had adopted for trans-Atlantic immigrant and lower-class travel. On most other North Atlantic passenger ships at the time, Third Class accommodations consisted of little more than open dormitories in the forward end of the vessels, in which hundreds of people were confined, often without adequate food or toilet facilities.

The White Star Line had long since broken that mould. As seen aboard Titanic, all White Star Line passenger ships divided their Third Class accommodations into two sections, always at opposite ends of the vessel from one another. The established arrangement was that single men were quartered in the forward areas, while single women, married couples and families were quartered aft. In addition, while other ships provided only open berth sleeping arrangements, White Star Line vessels provided their Third Class passengers with private, small but comfortable cabins capable of accommodating two, four, six, eight and ten passengers.[60]

Third Class accommodations also included their own dining rooms, as well as public gathering areas including adequate open deck space, which aboard Titanic comprised the Poop Deck at the stern, the forward and aft well decks, and a large open space on D Deck which could be used as a social hall. This was supplemented by the addition of a smoking room for men and a General Room on C Deck which women could use for reading and writing. Although they were not as glamorous in design as spaces seen in upper-class accommodations, they were still far above average for the period.

Leisure facilities were provided for all three classes to pass the time. As well as making use of the indoor amenities such as the library, smoking rooms, and gymnasium, it was also customary for passengers to socialise on the open deck, promenading or relaxing in hired deck chairs or wooden benches. A passenger list was published before the sailing to inform the public which members of the great and good were on board, and it was not uncommon for ambitious mothers to use the list to identify rich bachelors to whom they could introduce their marriageable daughters during the voyage.[61]

One of Titanic‘s most distinctive features was her First Class staircase, known as the Grand Staircase or Grand Stairway. Built of solid English oak with a sweeping curve, the staircase descended through seven decks of the ship, between the Boat Deck to E deck, before terminating in a simplified single flight on F Deck.[62] It was capped with a dome of wrought iron and glass that admitted natural light to the stairwell. Each landing off the staircase gave access to ornate entrance halls panelled in the William & Mary style and lit by ormolu and crystal light fixtures.[63]

At the uppermost landing was a large carved wooden panel containing a clock, with figures of «Honour and Glory Crowning Time» flanking the clock face.[62] The Grand Staircase was destroyed during the sinking and is now just a void in the ship which modern explorers have used to access the lower decks.[64] During the filming of James Cameron’s Titanic in 1997, his replica of the Grand Staircase was ripped from its foundations by the force of the inrushing water on the set. It has been suggested that during the real event, the entire Grand Staircase was ejected upwards through the dome.[65]

Mail and cargo

Although Titanic was primarily a passenger liner, she also carried a substantial amount of cargo. Her designation as a Royal Mail Ship (RMS) indicated that she carried mail under contract with the Royal Mail (and also for the United States Post Office Department). For the storage of letters, parcels and specie (bullion, coins and other valuables), 26,800 cubic feet (760 m3) of space in her holds was allocated. The Sea Post Office on G Deck was manned by five postal clerks (three Americans and two Britons), who worked 13 hours a day, seven days a week, sorting up to 60,000 items daily.[67]

The ship’s passengers brought with them a huge amount of baggage; another 19,455 cubic feet (550.9 m3) was taken up by first- and second-class baggage. In addition, there was a considerable quantity of regular cargo, ranging from furniture to foodstuffs, and a 1912 Renault Type CE Coupe de Ville motor car.[68] Despite later myths, the cargo on Titanic‘s maiden voyage was fairly mundane; there was no gold, exotic minerals or diamonds, and one of the more famous items lost in the shipwreck, a jewelled copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, was valued at only £405 (£42,700 today).[69] According to the claims for compensation filed with Commissioner Gilchrist, following the conclusion of the Senate Inquiry, the single most highly valued item of luggage or cargo was a large neoclassical oil painting entitled La Circassienne au Bain by French artist Merry-Joseph Blondel. The painting’s owner, first-class passenger Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, filed a claim for $100,000 (equivalent to $2,100,000 in 2021) in compensation for the loss of the artwork.[66]

Titanic was equipped with eight electric cranes, four electric winches and three steam winches to lift cargo and baggage in and out of the holds. It is estimated that the ship used some 415 tons of coal whilst in Southampton, simply generating steam to operate the cargo winches and provide heat and light.[70]

Lifeboats

A collapsible lifeboat with canvas sides

Like Olympic, Titanic carried a total of 20 lifeboats: 14 standard wooden Harland and Wolff lifeboats with a capacity of 65 people each and four Engelhardt «collapsible» (wooden bottom, collapsible canvas sides) lifeboats (identified as A to D) with a capacity of 47 people each. In addition, she had two emergency cutters with a capacity of 40 people each.[71][f] Olympic carried at least two collapsible boats on either side of her number one funnel.[72][73] All of the lifeboats were stowed securely on the boat deck and, except for collapsible lifeboats A and B, connected to davits by ropes. Those on the starboard side were odd-numbered 1–15 from bow to stern, while those on the port side were even-numbered 2–16 from bow to stern.[74]

Both cutters were kept swung out, hanging from the davits, ready for immediate use, while collapsible lifeboats C and D were stowed on the boat deck (connected to davits) immediately inboard of boats 1 and 2 respectively. A and B were stored on the roof of the officers’ quarters, on either side of number 1 funnel. There were no davits to lower them and their weight would make them difficult to launch by hand.[74] Each boat carried (among other things) food, water, blankets, and a spare life belt. Lifeline ropes on the boats’ sides enabled them to save additional people from the water if necessary.

Titanic had 16 sets of davits, each able to handle four lifeboats as Carlisle had planned. This gave Titanic the ability to carry up to 64 wooden lifeboats[75] which would have been enough for 4,000 people—considerably more than her actual capacity. However, the White Star Line decided that only 16 wooden lifeboats and four collapsibles would be carried, which could accommodate 1,178 people, only one-third of Titanic‘s total capacity. At the time, the Board of Trade’s regulations required British vessels over 10,000 tons to only carry 16 lifeboats with a capacity of 990 occupants.[71]

Therefore, the White Star Line actually provided more lifeboat accommodation than was legally required.[76][g] At the time, lifeboats were intended to ferry survivors from a sinking ship to a rescuing ship—not keep afloat the whole population or power them to shore. Had SS Californian responded to Titanic‘s distress calls, the lifeboats might have been able to ferry all passengers to safety as planned.[78]

Building and preparing the ship

Construction, launch and fitting-out

Construction in gantry, 1909–11

Launch, 1911 (unfinished superstructure)

Fitting-out, 1911–12

The sheer size of Titanic and her sister ships posed a major engineering challenge for Harland and Wolff; no shipbuilder had ever before attempted to construct vessels this size.[79] The ships were constructed on Queen’s Island, now known as the Titanic Quarter, in Belfast Harbour. Harland and Wolff had to demolish three existing slipways and build two new ones, the largest ever constructed up to that time, to accommodate both ships.[14] Their construction was facilitated by an enormous gantry built by Sir William Arrol & Co., a Scottish firm responsible for the building of the Forth Bridge and London’s Tower Bridge. The Arrol Gantry stood 228 feet (69 m) high, was 270 feet (82 m) wide and 840 feet (260 m) long, and weighed more than 6,000 tons. It accommodated a number of mobile cranes. A separate floating crane, capable of lifting 200 tons, was brought in from Germany.[80]

The construction of Olympic and Titanic took place virtually in parallel, with Olympic‘s keel laid down first on 16 December 1908 and Titanic‘s on 31 March 1909.[19] Both ships took about 26 months to build and followed much the same construction process. They were designed essentially as an enormous floating box girder, with the keel acting as a backbone and the frames of the hull forming the ribs. At the base of the ships, a double bottom 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m) deep supported 300 frames, each between 24 inches (61 cm) and 36 inches (91 cm) apart and measuring up to about 66 feet (20 m) long. They terminated at the bridge deck (B Deck) and were covered with steel plates which formed the outer skin of the ships.[81]

The 2,000 hull plates were single pieces of rolled steel plate, mostly up to 6 feet (1.8 m) wide and 30 feet (9.1 m) long and weighing between 2.5 and 3 tons.[82] Their thickness varied from 1 inch (2.5 cm) to 1.5 inches (3.8 cm).[48] The plates were laid in a clinkered (overlapping) fashion from the keel to the bilge. Above that point they were laid in the «in and out» fashion, where strake plating was applied in bands (the «in strakes») with the gaps covered by the «out strakes», overlapping on the edges. Commercial oxy-fuel and electric arc welding methods, ubiquitous in fabrication today, were still in their infancy; like most other iron and steel structures of the era, the hull was held together with over three million iron and steel rivets, which by themselves weighed over 1,200 tons. They were fitted using hydraulic machines or were hammered in by hand.[83] In the 1990s some material scientists concluded[84] that the steel plate used for the ship was subject to being especially brittle when cold, and that this brittleness exacerbated the impact damage and hastened the sinking. It is believed that, by the standards of the time, the steel plate’s quality was good, not faulty, but that it was inferior to what would be used for shipbuilding purposes in later decades, owing to advances in the metallurgy of steelmaking.[84] As for the rivets, considerable emphasis has also been placed on their quality and strength.[85][86][87][88][89]

Among the last items to be fitted on Titanic before the ship’s launch were her two side anchors and one centre anchor. The anchors themselves were a challenge to make, with the centre anchor being the largest ever forged by hand and weighing nearly 16 tons. Twenty Clydesdale draught horses were needed to haul the centre anchor by wagon from the Noah Hingley & Sons Ltd forge shop in Netherton, near Dudley, United Kingdom to the Dudley railway station two miles away. From there it was shipped by rail to Fleetwood in Lancashire before being loaded aboard a ship and sent to Belfast.[90]

The work of constructing the ships was difficult and dangerous. For the 15,000 men who worked at Harland and Wolff at the time,[91] safety precautions were rudimentary at best; a lot of the work was carried out without equipment like hard hats or hand guards on machinery. As a result, during Titanic‘s construction, 246 injuries were recorded, 28 of them «severe», such as arms severed by machines or legs crushed under falling pieces of steel. Six people died on the ship herself while she was being constructed and fitted out, and another two died in the shipyard workshops and sheds.[92] Just before the launch a worker was killed when a piece of wood fell on him.[93]

Titanic was launched at 12:15 pm on 31 May 1911 in the presence of Lord Pirrie, J. Pierpont Morgan, J. Bruce Ismay and 100,000 onlookers.[94][95] Twenty-two tons of soap and tallow were spread on the slipway to lubricate the ship’s passage into the River Lagan.[93] In keeping with the White Star Line’s traditional policy, the ship was not formally named or christened with champagne.[94] The ship was towed to a fitting-out berth where, over the course of the next year, her engines, funnels and superstructure were installed and her interior was fitted out.[96]

Although Titanic was virtually identical to the class’s lead ship Olympic, a few changes were made to distinguish both ships. The most noticeable exterior difference was that Titanic (and the third vessel in class, Britannic) had a steel screen with sliding windows installed along the forward half of the A Deck promenade. This was installed as a last minute change at the personal request of Bruce Ismay, and was intended to provide additional shelter to First Class passengers.[97] Extensive changes were made to B Deck on Titanic as the promenade space in this deck, which had proven unpopular on Olympic, was converted into additional First Class cabins, including two opulent parlour suites with their own private promenade spaces. The À la Carte restaurant was also enlarged and the Café Parisien, an entirely new feature which did not exist on Olympic, was added. These changes made Titanic slightly heavier than her sister, and thus she could claim to be the largest ship afloat. The work took longer than expected due to design changes requested by Ismay and a temporary pause in work occasioned by the need to repair Olympic, which had been in a collision in September 1911. Had Titanic been finished earlier, she might well have missed her collision with an iceberg.[93]

Sea trials

Titanic leaving Belfast for her sea trials on 2 April 1912

Titanic‘s sea trials began at 6 am on Tuesday, 2 April 1912, just two days after her fitting out was finished and eight days before she was due to leave Southampton on her maiden voyage.[98] The trials were delayed for a day due to bad weather, but by Monday morning it was clear and fair.[99] Aboard were 78 stokers, greasers and firemen, and 41 members of crew. No domestic staff appear to have been aboard. Representatives of various companies travelled on Titanic‘s sea trials: Thomas Andrews and Edward Wilding of Harland and Wolff, and Harold A. Sanderson of IMM. Bruce Ismay and Lord Pirrie were too ill to attend. Jack Phillips and Harold Bride served as radio operators and performed fine-tuning of the Marconi equipment. Francis Carruthers, a surveyor from the Board of Trade, was also present to see that everything worked and that the ship was fit to carry passengers.[100]

The sea trials consisted of a number of tests of her handling characteristics, carried out first in Belfast Lough and then in the open waters of the Irish Sea. Over the course of about 12 hours, Titanic was driven at different speeds, her turning ability was tested and a «crash stop» was performed in which the engines were reversed full ahead to full astern, bringing her to a stop in 850 yd (777 m) or 3 minutes and 15 seconds.[101] The ship covered a distance of about 80 nautical miles (92 mi; 150 km), averaging 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h) and reaching a maximum speed of just under 21 knots (24 mph; 39 km/h).[102]

On returning to Belfast at about 7 pm, the surveyor signed an «Agreement and Account of Voyages and Crew», valid for 12 months, which declared the ship seaworthy. An hour later, Titanic departed Belfast to head to Southampton, a voyage of about 570 nautical miles (660 mi; 1,060 km). After a journey lasting about 28 hours, she arrived about midnight on 4 April and was towed to the port’s Berth 44, ready for the arrival of her passengers and the remainder of her crew.[103]

Maiden voyage

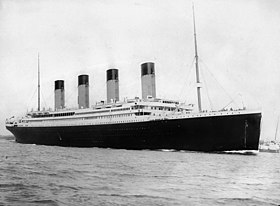

Titanic at Southampton docks, prior to departure

Titanic in Cork harbour, 11 April 1912

Both Olympic and Titanic registered Liverpool as their home port. The offices of the White Star Line, as well as Cunard, were in Liverpool, and up until the introduction of the Olympic, most British ocean liners for both Cunard and White Star, such as Lusitania and Mauretania, sailed from Liverpool followed by a port of call in Queenstown, Ireland. Since the company’s founding in 1845, a vast majority of their operations had taken place from Liverpool. However, in 1907 White Star Line established another service from Southampton on England’s south coast, which became known as White Star’s «Express Service». Southampton had many advantages over Liverpool, the first being its proximity to London.[104]

In addition, Southampton, being on the south coast, allowed ships to easily cross the English Channel and make a port of call on the northern coast of France, usually at Cherbourg. This allowed British ships to pick up clientele from continental Europe before recrossing the channel and picking up passengers at Queenstown. The Southampton-Cherbourg-New York run would become so popular that most British ocean liners began using the port after World War I. Out of respect for Liverpool, ships continued to be registered there until the early 1960s. Queen Elizabeth 2 was one of the first ships registered in Southampton when introduced into service by Cunard in 1969.[104]

Titanic‘s maiden voyage was intended to be the first of many trans-Atlantic crossings between Southampton and New York via Cherbourg and Queenstown on westbound runs, returning via Plymouth in England while eastbound. Indeed, her entire schedule of voyages through to December 1912 still exists.[105] When the route was established, four ships were assigned to the service. In addition to Teutonic and Majestic, RMS Oceanic and the brand new RMS Adriatic sailed the route. When the Olympic entered service in June 1911, she replaced Teutonic, which after completing her last run on the service in late April was transferred to the Dominion Line’s Canadian service. The following August, Adriatic was transferred to White Star Line’s main Liverpool-New York service, and in November, Majestic was withdrawn from service impending the arrival of Titanic in the coming months, and was mothballed as a reserve ship.[106][107]

White Star Line’s initial plans for Olympic and Titanic on the Southampton run followed the same routine as their predecessors had done before them. Each would sail once every three weeks from Southampton and New York, usually leaving at noon each Wednesday from Southampton and each Saturday from New York, thus enabling the White Star Line to offer weekly sailings in each direction. Special trains were scheduled from London and Paris to convey passengers to Southampton and Cherbourg respectively.[107] The deep-water dock at Southampton, then known as the «White Star Dock«, had been specially constructed to accommodate the new Olympic-class liners, and had opened in 1911.[108]

Crew

Titanic had around 885 crew members on board for her maiden voyage.[109] Like other vessels of her time, she did not have a permanent crew, and the vast majority of crew members were casual workers who only came aboard the ship a few hours before she sailed from Southampton.[110] The process of signing up recruits had begun on 23 March and some had been sent to Belfast, where they served as a skeleton crew during Titanic‘s sea trials and passage to England at the start of April.[111]

Captain Edward John Smith, the most senior of the White Star Line’s captains, was transferred from Olympic to take command of Titanic.[112] Henry Tingle Wilde also came across from Olympic to take the post of chief mate. Titanic‘s previously designated chief mate and first officer, William McMaster Murdoch and Charles Lightoller, were bumped down to the ranks of first and second officer respectively. The original second officer, David Blair, was dropped altogether.[113][h] The third officer was Herbert Pitman MBE, the only deck officer who was not a member of the Royal Naval Reserve. Pitman was the second-to-last surviving officer.

Titanic‘s crew were divided into three principal departments: Deck, with 66 crew; Engine, with 325; and Victualling, with 494.[114] The vast majority of the crew were thus not seamen but were either engineers, firemen, or stokers, responsible for looking after the engines, or stewards and galley staff, responsible for the passengers.[115] Of these, over 97% were male; just 23 of the crew were female, mainly stewardesses.[116] The rest represented a great variety of professions—bakers, chefs, butchers, fishmongers, dishwashers, stewards, gymnasium instructors, laundrymen, waiters, bed-makers, cleaners, and even a printer,[116] who produced a daily newspaper for passengers called the Atlantic Daily Bulletin with the latest news received by the ship’s wireless operators.[52][i]

Most of the crew signed on in Southampton on 6 April;[19] in all, 699 of the crew came from there, and 40% were natives of the town.[116] A few specialist staff were self-employed or were subcontractors. These included the five postal clerks, who worked for the Royal Mail and the United States Post Office Department, the staff of the First Class A La Carte Restaurant and the Café Parisien, the radio operators (who were employed by Marconi) and the eight musicians, who were employed by an agency and travelled as second-class passengers.[118] Crew pay varied greatly, from Captain Smith’s £105 a month (equivalent to £11,100 today) to the £3 10s (£370 today) that stewardesses earned. The lower-paid victualling staff could, however, supplement their wages substantially through tips from passengers.[117]

Passengers

Titanic‘s passengers numbered approximately 1,317 people: 324 in First Class, 284 in Second Class, and 709 in Third Class. Of these, 869 (66%) were male and 447 (34%) female. There were 107 children aboard, the largest number of whom were in Third Class.[119] The ship was considerably under-capacity on her maiden voyage, as she could accommodate 2,453 passengers—833 First Class, 614 Second Class, and 1,006 Third Class.[120]

Usually, a high-prestige vessel like Titanic could expect to be fully booked on its maiden voyage. However, a national coal strike in the UK had caused considerable disruption to shipping schedules in the spring of 1912, causing many crossings to be cancelled. Many would-be passengers chose to postpone their travel plans until the strike was over. The strike had finished a few days before Titanic sailed; however, that was too late to have much of an effect. Titanic was able to sail on the scheduled date only because coal was transferred from other vessels which were tied up at Southampton, such as SS City of New York and RMS Oceanic, as well as coal that Olympic had brought back from a previous voyage to New York, which had been stored at the White Star Dock.[97]

Some of the most prominent people of the day booked a passage aboard Titanic, travelling in First Class. Among them (with those who perished marked with a dagger†) were the American millionaire John Jacob Astor IV† and his wife Madeleine Force Astor (with John Jacob Astor VI in utero), industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim†, painter and sculptor Francis Davis Millet†, Macy’s owner Isidor Straus† and his wife Ida†, Denver millionairess Margaret «Molly» Brown,[j] Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife, couturière Lucy (Lady Duff-Gordon), Lieut. Col. Arthur Peuchen, writer and historian Archibald Gracie, cricketer and businessman John B. Thayer† with his wife Marian and son Jack, George Dunton Widener† with his wife Eleanor and son Harry†, Noël Leslie, Countess of Rothes, Mr.† and Mrs. Charles M. Hays, Mr. and Mrs. Henry S. Harper, Mr.† and Mrs. Walter D. Douglas, Mr.† and Mrs. George D. Wick, Mr.† and Mrs. Henry B. Harris, Mr.† and Mrs. Arthur L. Ryerson, Mr.† and Mrs.† Hudson J. C. Allison, Mr. and Mrs. Dickinson Bishop, noted architect Edward Austin Kent†, brewery heir Harry Molson†, tennis players Karl Behr and Dick Williams, author and socialite Helen Churchill Candee, future lawyer and suffragette Elsie Bowerman and her mother Edith, journalist and social reformer William Thomas Stead†, journalist and fashion buyer Edith Rosenbaum, Philadelphia and New York socialite Edith Corse Evans†, wealthy divorcée Charlotte Drake Cardeza, French sculptor Paul Chevré [fr], author Jacques Futrelle† with his wife May, silent film actress Dorothy Gibson with her mother Pauline, President of the Swiss Bankverein Col. Alfons Simonius-Blumer, James A. Hughes’s daughter Eloise, banker Robert Williams Daniel, the chairman of the Holland America Line Johan Reuchlin [de], Arthur Wellington Ross’s son John H. Ross, Washington Roebling’s nephew Washington A. Roebling II, Andrew Saks’s daughter Leila Saks Meyer with her husband Edgar Joseph Meyer† (son of Marc Eugene Meyer), William A. Clark’s nephew Walter M. Clark with his wife Virginia, great-great-grandson of soap manufacturer Andrew Pears Thomas C. Pears with wife, John S. Pillsbury’s honeymooning grandson John P. Snyder and wife Nelle, Dorothy Parker’s New York manufacturer uncle Martin Rothschild with his wife, Elizabeth, among others.[121]

Titanic‘s owner J. P. Morgan was scheduled to travel on the maiden voyage but cancelled at the last minute.[122] Also aboard the ship were the White Star Line’s managing director J. Bruce Ismay and Titanic‘s designer Thomas Andrews†, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.[123]

The exact number of people aboard is not known, as not all of those who had booked tickets made it to the ship; about 50 people cancelled for various reasons,[124] and not all of those who boarded stayed aboard for the entire journey.[125] Fares varied depending on class and season. Third Class fares from London, Southampton, or Queenstown cost £7 5s (equivalent to £800 today) while the cheapest First Class fares cost £23 (£2,400 today).[107] The most expensive First Class suites were to have cost up to £870 in high season (£92,000 today).[120]

Collecting passengers

Titanic‘s maiden voyage began on Wednesday, 10 April 1912. Following the embarkation of the crew, the passengers began arriving at 9:30 am, when the London and South Western Railway’s boat train from London Waterloo station reached Southampton Terminus railway station on the quayside, alongside Titanic‘s berth.[126] The large number of Third Class passengers meant they were the first to board, with First and Second Class passengers following up to an hour before departure. Stewards showed them to their cabins, and First Class passengers were personally greeted by Captain Smith.[127] Third Class passengers were inspected for ailments and physical impairments that might lead to their being refused entry to the United States – a prospect the White Star Line wished to avoid, as it would have to carry anyone who failed the examination back across the Atlantic.[124] In all, 920 passengers boarded Titanic at Southampton – 179 First Class, 247 Second Class, and 494 Third Class. Additional passengers were to be picked up at Cherbourg and Queenstown.[97]

The maiden voyage began at noon, as scheduled. An accident was narrowly averted only a few minutes later, as Titanic passed the moored liners SS City of New York of the American Line and Oceanic of the White Star Line, the latter of which would have been her running mate on the service from Southampton. Her huge displacement caused both of the smaller ships to be lifted by a bulge of water and then dropped into a trough. New York‘s mooring cables could not take the sudden strain and snapped, swinging her around stern-first towards Titanic. A nearby tugboat, Vulcan, came to the rescue by taking New York under tow, and Captain Smith ordered Titanic‘s engines to be put «full astern».[128] The two ships avoided a collision by a distance of about 4 feet (1.2 m). The incident delayed Titanic‘s departure for about an hour, while the drifting New York was brought under control.[129][130]

After making it safely through the complex tides and channels of Southampton Water and the Solent, Titanic disembarked the Southampton pilot at the Nab Lightship and headed out into the English Channel.[131] She headed for the French port of Cherbourg, a journey of 77 nautical miles (89 mi; 143 km).[132] The weather was windy, very fine but cold and overcast.[133] Because Cherbourg lacked docking facilities for a ship the size of Titanic, tenders had to be used to transfer passengers from shore to ship. The White Star Line operated two at Cherbourg, SS Traffic and SS Nomadic. Both had been designed specifically as tenders for the Olympic-class liners and were launched shortly after Titanic.[134] (Nomadic is today the only White Star Line ship still afloat.) Four hours after Titanic left Southampton, she arrived at Cherbourg and was met by the tenders. There, 274 additional passengers were taken aboard – 142 First Class, 30 Second Class, and 102 Third Class. Twenty-four passengers left aboard the tenders to be conveyed to shore, having booked only a cross-Channel passage. The process was completed within only 90 minutes and at 8 pm Titanic weighed anchor and left for Queenstown[135] with the weather continuing cold and windy.[133]

At 11:30 am on Thursday 11 April, Titanic arrived at Cork Harbour on the south coast of Ireland. It was a partly cloudy but relatively warm day, with a brisk wind.[133] Again, the dock facilities were not suitable for a ship of Titanic‘s size, and tenders were used to bring passengers aboard. In all, 123 passengers boarded Titanic at Queenstown – three First Class, seven Second Class and 113 Third Class. In addition to the 24 cross-Channel passengers who had disembarked at Cherbourg, another seven passengers had booked an overnight passage from Southampton to Queenstown. Among the seven was Francis Browne, a Jesuit trainee who was a keen photographer and took many photographs aboard Titanic, including one of the last known photographs of the ship. The very last one was taken by another cross-channel passenger Kate Odell.[136] A decidedly unofficial departure was that of a crew member, stoker John Coffey, a Queenstown native who sneaked off the ship by hiding under mail bags being transported to shore.[137] Titanic weighed anchor for the last time at 1:30 pm and departed on her westward journey across the Atlantic.[137]

Atlantic crossing

The route of Titanic‘s maiden voyage, with the coordinates of her sinking

Titanic was planned to arrive at New York Pier 59[138] on the morning of 17 April.[139] After leaving Queenstown, Titanic followed the Irish coast as far as Fastnet Rock,[140] a distance of some 55 nautical miles (63 mi; 102 km). From there she travelled 1,620 nautical miles (1,860 mi; 3,000 km) along a Great Circle route across the North Atlantic to reach a spot in the ocean known as «the corner» south-east of Newfoundland, where westbound steamers carried out a change of course. Titanic sailed only a few hours past the corner on a rhumb line leg of 1,023 nautical miles (1,177 mi; 1,895 km) to Nantucket Shoals Light when she made her fatal contact with an iceberg.[141] The final leg of the journey would have been 193 nautical miles (222 mi; 357 km) to Ambrose Light and finally to New York Harbor.[142]

From 11 April to local apparent noon the next day, Titanic covered 484 nautical miles (557 mi; 896 km); the following day, 519 nautical miles (597 mi; 961 km); and by noon on the final day of her voyage, 546 nautical miles (628 mi; 1,011 km). From then until the time of her sinking, she travelled another 258 nautical miles (297 mi; 478 km), averaging about 21 knots (24 mph; 39 km/h).[143]

The weather cleared as she left Ireland under cloudy skies with a headwind. Temperatures remained fairly mild on Saturday 13 April, but the following day Titanic crossed a cold weather front with strong winds and waves of up to 8 feet (2.4 m). These died down as the day progressed until, by the evening of Sunday 14 April, it became clear, calm and very cold.[144]

The first three days of the voyage from Queenstown had passed without apparent incident. A fire had begun in one of Titanic‘s coal bunkers approximately 10 days prior to the ship’s departure, and continued to burn for several days into its voyage,[145] but passengers were unaware of this situation. Fires occurred frequently on board steamships at the time, due to spontaneous combustion of the coal.[146] The fires had to be extinguished with fire hoses by moving the coal on top to another bunker and by removing the burning coal and feeding it into the furnace.[147] The fire was finally extinguished on 14 April.[148][149] There has been some speculation and discussion as to whether this fire and attempts to extinguish it may have made the ship more vulnerable to its fate.[150][151]

Titanic received a series of warnings from other ships of drifting ice in the area of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, but Captain Edward Smith ignored them.[152] One of the ships to warn Titanic was the Atlantic Line’s Mesaba.[153] Nevertheless, the ship continued to steam at full speed, which was standard practice at the time.[154] Although the ship was not trying to set a speed record,[155] timekeeping was a priority, and under prevailing maritime practices, ships were often operated at close to full speed; ice warnings were seen as advisories, and reliance was placed upon lookouts and the watch on the bridge.[154] It was generally believed that ice posed little danger to large vessels. Close calls with ice were not uncommon, and even head-on collisions had not been disastrous. In 1907, SS Kronprinz Wilhelm, a German liner, had rammed an iceberg but still had been able to complete her voyage, and Captain Smith himself had declared in 1907 that he «could not imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.»[156][k]

Sinking

The sinking, based on Jack Thayer’s description. Sketched by L.P. Skidmore on board Carpathia.

The iceberg thought to have been hit by Titanic, photographed on the morning of 15 April 1912. Note the dark spot just along the berg’s waterline, which was described by onlookers as a smear of red paint.

At 11:40 pm (ship’s time) on 14 April, lookout Frederick Fleet spotted an iceberg immediately ahead of Titanic and alerted the bridge.[159] First Officer William Murdoch ordered the ship to be steered around the obstacle and the engines to be reversed,[160] but it was too late; the starboard side of Titanic struck the iceberg, creating a series of holes below the waterline.[l] The hull was not punctured by the iceberg, but rather dented such that the hull’s seams buckled and separated, allowing water to rush in. Five of the ship’s watertight compartments were breached. It soon became clear that the ship was doomed, as she could not survive more than four compartments being flooded. Titanic began sinking bow-first, with water spilling from compartment to compartment as her angle in the water became steeper.[162]

Those aboard Titanic were ill-prepared for such an emergency. In accordance with accepted practices of the time, as ships were seen as largely unsinkable and lifeboats were intended to transfer passengers to nearby rescue vessels,[163][m] Titanic only had enough lifeboats to carry about half of those on board; if the ship had carried her full complement of about 3,339 passengers and crew, only about a third could have been accommodated in the lifeboats.[165] The crew had not been trained adequately in carrying out an evacuation. The officers did not know how many they could safely put aboard the lifeboats and launched many of them barely half-full.[166] Third-class passengers were largely left to fend for themselves, causing many of them to become trapped below decks as the ship filled with water.[167] The «women and children first» protocol was generally followed when loading the lifeboats,[167] and most of the male passengers and crew were left aboard. In 2022, Claes-Gõran Wetterholm, an author and expert on Titanic, argued it was «not true» that women and children survived thanks to the gallantry of men; of the last survivors escaping on the final lifeboats leaving the starboard side of the ship, he said, the majority were men.[168] However, women and children survived at rates of about 75 percent and 50 percent, respectively, while only 20 percent of men survived.[169]

Between 2:10 and 2:15 am, a little over two and a half hours after Titanic struck the iceberg, her rate of sinking suddenly increased as the boat deck dipped underwater, and the sea poured in through open hatches and grates.[170] As her unsupported stern rose out of the water, exposing the propellers, the ship broke in two main pieces between the second and third funnels, due to the immense forces on the keel. With the bow underwater, and air trapped in the stern, the stern remained afloat and buoyant for a few minutes longer, rising to a nearly vertical angle with hundreds of people still clinging to it,[171] before foundering at 2:20 am.[172] It was long generally believed the ship sank in one piece; but the discovery of the wreck many years later revealed that the ship had broken fully in two. All remaining passengers and crew were immersed in lethally cold water with a temperature of −2 °C (28 °F). Sudden immersion into freezing water typically causes death within minutes, either from cardiac arrest, uncontrollable breathing of water, or cold incapacitation (not, as commonly believed, from hypothermia),[n] and almost all of those in the water died of cardiac arrest or other bodily reactions to freezing water, within 15–30 minutes.[175] Only five of them were helped into the lifeboats, though the lifeboats had room for almost 500 more people.[176]

Distress signals were sent by wireless, rockets, and lamp, but none of the ships that responded were near enough to reach Titanic before she sank.[177] A radio operator on board SS Birma, for instance, estimated that it would be 6 am before the liner could arrive at the scene. Meanwhile, SS Californian, which was the last to have been in contact before the collision, saw Titanic‘s flares but failed to assist.[178] Around 4 am, RMS Carpathia arrived on the scene in response to Titanic‘s earlier distress calls.[179]

706 people survived the disaster and were conveyed by Carpathia to New York, Titanic‘s original destination, and 1,517 people died.[109] Carpathia‘s captain described the place as an ice field that had included 20 large bergs measuring up to 200 feet (61 m) high and numerous smaller bergs, as well as ice floes and debris from Titanic; passengers described being in the middle of a vast white plain of ice, studded with icebergs.[180] This area is now known as Iceberg Alley.[181]

Aftermath of sinking

Immediate aftermath

The New York Times had gone to press 15 April with knowledge of the collision but not the sinking.[182]

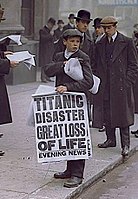

London newsboy Ned Parfett with news of the disaster, as reported on Tuesday, 16 April

Titanic had been scheduled for a 20 April departure, seen in a New York Times ad apparently unable to be pulled, overnight, before this 15 April printing.[183]

RMS Carpathia took three days to reach New York after leaving the scene of the disaster. Her journey was slowed by pack ice, fog, thunderstorms and rough seas.[184] She was, however, able to pass news to the outside world by wireless about what had happened. The initial reports were confusing, leading the American press to report erroneously on 15 April that Titanic was being towed to port by SS Virginian.[185]

Later that day, confirmation came through that Titanic had been lost and that most of her passengers and crew had died.[186] The news attracted crowds of people to the White Star Line’s offices in London, New York, Montreal,[187] Southampton,[188] Liverpool and Belfast.[189] It hit hardest in Southampton, whose people suffered the greatest losses from the sinking;[190] four out of every five crew members came from this town.[191][o]

Carpathia docked at 9:30 pm on 18 April at New York’s Pier 54 and was greeted by some 40,000 people waiting at the quayside in heavy rain.[194] Immediate relief in the form of clothing and transportation to shelters was provided by the Women’s Relief Committee, the Travelers Aid Society of New York, and the Council of Jewish Women, among other organisations.[195] Many of Titanic‘s surviving passengers did not linger in New York but headed onwards immediately to relatives’ homes. Some of the wealthier survivors chartered private trains to take them home, and the Pennsylvania Railroad laid on a special train free of charge to take survivors to Philadelphia. Titanic‘s 214 surviving crew members were taken to the Red Star Line’s steamer SS Lapland, where they were accommodated in passenger cabins.[196]

Carpathia was hurriedly restocked with food and provisions before resuming her journey to Fiume, Austria-Hungary. Her crew were given a bonus of a month’s wages by Cunard as a reward for their actions, and some of Titanic‘s passengers joined to give them an additional bonus of nearly £900 (£95,000 today), divided among the crew members.[197]

The ship’s arrival in New York led to a frenzy of press interest, with newspapers competing to be the first to report the survivors’ stories. Some reporters bribed their way aboard the pilot boat New York, which guided Carpathia into harbour, and one even managed to get onto Carpathia before she docked.[198] Crowds gathered outside newspaper offices to see the latest reports being posted in the windows or on billboards.[199] It took another four days for a complete list of casualties to be compiled and released, adding to the agony of relatives waiting for news of those who had been aboard Titanic.[p]

Insurance, aid for survivors and lawsuits

Cartoon demanding better safety from shipping companies, 1912

In January 1912, the hulls and equipment of Titanic and Olympic had been insured through Lloyd’s of London and London Marine Insurance. The total coverage was £1,000,000 (£102,000,000 today) per ship. The policy was to be «free from all average» under £150,000, meaning that the insurers would only pay for damage in excess of that sum. The premium, negotiated by brokers Willis Faber & Company (now Willis Group), was 15 s (75 p) per £100, or £7,500 (£790,000 today) for the term of one year. Lloyd’s paid the White Star Line the full sum owed to them within 30 days.[201]

Many charities were set up to help the survivors and their families, many of whom lost their sole wage earner, or, in the case of many Third Class survivors, everything they owned. In New York City, for example, a joint committee of the American Red Cross and Charity Organization Society formed to disburse financial aid to survivors and dependents of those who died.[202] On 29 April, opera stars Enrico Caruso and Mary Garden and members of the Metropolitan Opera raised $12,000 ($300,000 in 2014)[203] in benefits for victims of the disaster by giving special concerts in which versions of «Autumn» and «Nearer My God To Thee» were part of the programme.[204] In Britain, relief funds were organised for the families of Titanic‘s lost crew members, raising nearly £450,000 (£47,000,000 today). One such fund was still in operation as late as the 1960s.[205]

In the United States and Britain, more than 60 survivors combined to sue the White Star Line for damages connected to loss of life and baggage.[206] The claims totalled $16,804,112 (appr. $419 million in 2018 USD), which was far in excess of what White Star argued it was responsible for as a limited liability company under American law.[207] Because the bulk of the litigants were in the United States, White Star petitioned the United States Supreme Court in 1914, which ruled in its favour that it qualified as an LLC and found that the causes of the ship’s sinking were largely unforeseeable, rather than due to negligence.[208] This sharply limited the scope of damages survivors and family members were entitled to, prompting them to reduce their claims to some $2.5 million. White Star only settled for $664,000 (appr. $16.56 million in 2018), about 27% of the original total sought by survivors. The settlement was agreed to by 44 of the claimants in December 1915, with $500,000 set aside for the American claimants, $50,000 for the British, and $114,000 to go towards interest and legal expenses.[206][207]

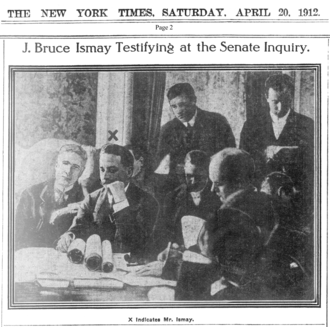

Investigations into the disaster

Senate Inquiry: Within five days of the sinking, The New York Times published several columns relating to Ismay’s conduct—concerning which «there has been so much comment».[209] Columns included the statement of attorney Karl H. Behr indicating Ismay had helped supervise loading of passengers in lifeboats, and of William E. Carter stating that he and Ismay boarded a lifeboat only after there were no more women.[209]

Even before the survivors arrived in New York, investigations were being planned to discover what had happened, and what could be done to prevent a recurrence. Inquiries were held in both the United States and the United Kingdom, the former more robustly critical of traditions and practices, and scathing of the failures involved, and the latter broadly more technical and expert-orientated.[210]

The US Senate’s inquiry into the disaster was initiated on 19 April, a day after Carpathia arrived in New York.[211] The chairman, Senator William Alden Smith, wanted to gather accounts from passengers and crew while the events were still fresh in their minds. Smith also needed to subpoena all surviving British passengers and crew while they were still on American soil, which prevented them from returning to the UK before the American inquiry was completed on 25 May.[212] The British press condemned Smith as an opportunist, insensitively forcing an inquiry as a means of gaining political prestige and seizing «his moment to stand on the world stage». Smith, however, already had a reputation as a campaigner for safety on US railroads, and wanted to investigate any possible malpractices by railroad tycoon J. P. Morgan, Titanic‘s ultimate owner.[213]

The British Board of Trade’s inquiry into the disaster was headed by Lord Mersey, and took place between 2 May and 3 July. Being run by the Board of Trade, who had previously approved the ship, it was seen by some[like whom?] as having little interest in its own or White Star’s conduct being found negligent.[214]

Each inquiry took testimony from both passengers and crew of Titanic, crew members of Leyland Line’s Californian, Captain Arthur Rostron of Carpathia and other experts.[215] The British inquiry also took far greater expert testimony, making it the longest and most detailed court of inquiry in British history up to that time.[216] The two inquiries reached broadly similar conclusions: the regulations on the number of lifeboats that ships had to carry were out of date and inadequate,[217] Captain Smith had failed to take proper heed of ice warnings,[218] the lifeboats had not been properly filled or crewed, and the collision was the direct result of steaming into a dangerous area at too high a speed.[217]

Neither inquiry’s findings listed negligence by IMM or the White Star Line as a factor. The American inquiry concluded that since those involved had followed standard practice, the disaster was an act of God.[219] The British inquiry concluded that Smith had followed long-standing practice that had not previously been shown to be unsafe,[220] noting that British ships alone had carried 3.5 million passengers over the previous decade with the loss of just 10 lives,[221] and concluded that Smith had done «only that which other skilled men would have done in the same position». Lord Mersey did, however, find fault with the «extremely high speed (twenty-two knots) which was maintained» following numerous ice warnings,[222] noting that «what was a mistake in the case of the Titanic would without doubt be negligence in any similar case in the future».[220]

The recommendations included strong suggestions for major changes in maritime regulations to implement new safety measures, such as ensuring that more lifeboats were provided, that lifeboat drills were properly carried out and that wireless equipment on passenger ships was manned around the clock.[223] An International Ice Patrol was set up to monitor the presence of icebergs in the North Atlantic, and maritime safety regulations were harmonised internationally through the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea; both measures are still in force today.[224]

On 18 June 1912, Guglielmo Marconi gave evidence to the Court of Inquiry regarding the telegraphy. Its final report recommended that all liners carry the system and that sufficient operators maintain a constant service.[225]

Role of the SS Californian

SS Californian, which had tried to warn Titanic of the danger from pack-ice

One of the most controversial issues examined by the inquiries was the role played by SS Californian, which had been only a few miles from Titanic but had not picked up her distress calls or responded to her signal rockets. Californian had warned Titanic by radio of the pack ice (that was the reason Californian had stopped for the night) but was rebuked by Titanic‘s senior wireless operator, Jack Phillips.[226]

Testimony before the British inquiry revealed that at 10:10 pm, Californian observed the lights of a ship to the south; it was later agreed between Captain Stanley Lord and Third Officer C.V. Groves (who had relieved Lord of duty at 11:10 pm) that this was a passenger liner.[226] At 11:50 pm, the officer had watched that ship’s lights flash out, as if she had shut down or turned sharply, and that the port light was now visible.[226] Morse light signals to the ship, upon Lord’s order, were made between 11:30 pm and 1:00 am, but were not acknowledged.[227] If Titanic was as far from the Californian as Lord claimed, then he knew, or should have known, that Morse signals would not be visible. A reasonable and prudent course of action would have been to awaken the wireless operator and to instruct him to attempt to contact Titanic by that method. Had Lord done so, it is possible he could have reached Titanic in time to save additional lives.[78]

Captain Lord had gone to the chartroom at 11:00 pm to spend the night;[228] however, Second Officer Herbert Stone, now on duty, notified Lord at 1:10 am that the ship had fired five rockets. Lord wanted to know if they were company signals, that is, coloured flares used for identification. Stone said that he did not know and that the rockets were all white.[clarification needed] Captain Lord instructed the crew to continue to signal the other vessel with the Morse lamp, and went back to sleep. Three more rockets were observed at 1:50 am and Stone noted that the ship looked strange in the water, as if she were listing. At 2:15 am, Lord was notified that the ship could no longer be seen. Lord asked again if the lights had had any colours in them, and he was informed that they were all white.[229]

Californian eventually responded. At around 5:30 am, Chief Officer George Stewart awakened wireless operator Cyril Furmstone Evans, informed him that rockets had been seen during the night, and asked that he try to communicate with any ship. He got news of Titanic‘s loss, Captain Lord was notified, and the ship set out to render assistance. She arrived well after Carpathia had already picked up all the survivors.[230]

The inquiries found that the ship seen by Californian was in fact Titanic and that it would have been possible for Californian to come to her rescue; therefore, Captain Lord had acted improperly in failing to do so.[231][q]

Survivors and victims

The number of casualties of the sinking is unclear, due to a number of factors. These include confusion over the passenger list, which included some names of people who cancelled their trip at the last minute, and the fact that several passengers travelled under aliases for various reasons and were therefore double-counted on the casualty lists.[233] The death toll has been put at between 1,490 and 1,635 people.[234] The tables below use figures from the British Board of Trade report on the disaster.[109] While the use of the Marconi wireless system did not achieve the result of bringing a rescue ship to Titanic before it sank, the use of wireless did bring Carpathia in time to rescue some of the survivors who otherwise would have perished due to exposure.[6]

The water temperature was well below normal in the area where Titanic sank. It also contributed to the rapid death of many passengers during the sinking. Water temperature readings taken around the time of the accident were reported to be −2 °C (28 °F). Typical water temperatures were normally around 7 °C (45 °F) during mid-April.[235] The coldness of the water was a critical factor, often causing death within minutes for many of those in the water.

Fewer than a third of those aboard Titanic survived the disaster. Some survivors died shortly afterwards; injuries and the effects of exposure caused the deaths of several of those brought aboard Carpathia.[236] The figures show stark differences in the survival rates of the different classes aboard Titanic. Although only 3% of first-class women were lost, 54% of those in third-class died. Similarly, five of six first-class and all second-class children survived, but 52 of the 79 in third-class perished. The differences by gender were even bigger: nearly all female crew members, first- and second-class passengers were saved. Men from the First Class died at a higher rate than women from the Third Class.[237] In total, 50% of the children survived, 20% of the men and 75% of the women.

The last living survivor, Millvina Dean from England, who, at only nine weeks old, was the youngest passenger on board, died aged 97 on 31 May 2009.[238] Two special survivors were the stewardess Violet Jessop and the stoker Arthur John Priest,[239] who survived the sinkings of both Titanic and HMHS Britannic and were aboard RMS Olympic when she was rammed in 1911.[240][241][242]

Retrieval and burial of the dead