King Lear is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane and a proscribed crux of political machinations. The first known performance of any version of Shakespeare’s play was on Saint Stephen’s Day in 1606. The three extant publications from which modern editors derive their texts are the 1608 quarto (Q1) and the 1619 quarto (Q2, unofficial and based on Q1) and the 1623 First Folio. The quarto versions differ significantly from the folio version.

The play was often revised after the English Restoration for audiences who disliked its dark and depressing tone, but since the 19th century Shakespeare’s original play has been regarded as one of his supreme achievements.

Both the title role and the supporting roles have been coveted by accomplished actors, and the play has been widely adapted. In his A Defence of Poetry, Percy Bysshe Shelley called King Lear «the most perfect specimen of the dramatic art existing in the world», and the play is regularly cited as one of the greatest works of literature ever written.[1][2][3]

Characters[edit]

- Lear – King of Britain

- Earl of Gloucester

- Earl of Kent – later disguised as Caius

- Fool – Lear’s fool

- Edgar – Gloucester’s first-born son

- Edmund – Gloucester’s illegitimate son

- Goneril – Lear’s eldest daughter

- Regan – Lear’s second daughter

- Cordelia – Lear’s youngest daughter

- Duke of Albany – Goneril’s husband

- Duke of Cornwall – Regan’s husband

- Gentleman – attends Cordelia

- Oswald – Goneril’s loyal steward

- King of France – suitor and later husband to Cordelia

- Duke of Burgundy – suitor to Cordelia

- Old man – tenant of Gloucester

- Curan – courtier

Plot[edit]

Act I[edit]

King Lear of Britain, elderly and wanting to retire from the duties of the monarchy, decides to divide his realm among his three daughters, and declares he will offer the largest share to the one who loves him most. The eldest, Goneril, speaks first, declaring her love for her father in fulsome terms. Moved by her flattery, Lear proceeds to grant to Goneril her share as soon as she has finished her declaration, before Regan and Cordelia have a chance to speak. He then awards to Regan her share as soon as she has spoken. When it is finally the turn of his youngest and favourite daughter, Cordelia, at first she refuses to say anything («Nothing, my Lord») and then declares there is nothing to compare her love to, no words to express it properly; she says honestly but bluntly that she loves him according to her bond, no more and no less, and will reserve half of her love for her future husband. Infuriated, Lear disinherits Cordelia and divides her share between her elder sisters.

The Earl of Gloucester and the Earl of Kent observe that, by dividing his realm between Goneril and Regan, Lear has awarded his realm in equal shares to the peerages of the Duke of Albany (Goneril’s husband) and the Duke of Cornwall (Regan’s husband). Kent objects to Lear’s unfair treatment of Cordelia. Enraged by Kent’s protests, Lear banishes him from the country. Lear then summons the Duke of Burgundy and the King of France, who have both proposed marriage to Cordelia. Learning that Cordelia has been disinherited, the Duke of Burgundy withdraws his suit, but the King of France is impressed by her honesty and marries her nonetheless. The King of France is shocked by Lear’s decision because up until this time Lear has only praised and favoured Cordelia («… she whom even but now was your best object, / The argument of your praise, balm of your age, …»).[4] Meanwhile, Gloucester has introduced his illegitimate son Edmund to Kent.

Lear announces he will live alternately with Goneril and Regan, and their husbands. He reserves to himself a retinue of 100 knights, to be supported by his daughters. After Cordelia bids farewell to them and leaves with the King of France, Goneril and Regan speak privately, revealing that their declarations of love were false and that they view Lear as a foolish old man.

Gloucester’s son Edmund resents his illegitimate status and plots to dispose of his legitimate older half-brother, Edgar. He tricks his father with a forged letter, making him think that Edgar plans to usurp the estate. The Earl of Kent returns from exile in disguise (calling himself Caius), and Lear hires him as a servant. At Albany and Goneril’s house, Lear and Kent quarrel with Oswald, Goneril’s steward. Lear discovers that now that Goneril has power, she no longer respects him. She orders him to reduce the number of his disorderly retinue. Enraged, Lear departs for Regan’s home. The Fool reproaches Lear with his foolishness in giving everything to Regan and Goneril and predicts that Regan will treat him no better.

Act II[edit]

Edmund learns from Curan, a courtier, that there is likely to be war between Albany and Cornwall and that Regan and Cornwall are to arrive at Gloucester’s house that evening. Taking advantage of the arrival of the duke and Regan, Edmund fakes an attack by Edgar, and Gloucester is completely taken in. He disinherits Edgar and proclaims him an outlaw.

Bearing Lear’s message to Regan, Kent meets Oswald again at Gloucester’s home, quarrels with him again and is put in the stocks by Regan and her husband Cornwall. When Lear arrives, he objects to the mistreatment of his messenger, but Regan is as dismissive of her father as Goneril was. Lear is enraged but impotent. Goneril arrives and supports Regan’s argument against him. Lear yields completely to his rage. He rushes out into a storm to rant against his ungrateful daughters, accompanied by the mocking Fool. Kent later follows to protect him. Gloucester protests against Lear’s mistreatment. With Lear’s retinue of a hundred knights dissolved, the only companions he has left are his Fool and Kent. Wandering on the heath after the storm, Edgar, in the guise of a madman named Tom o’ Bedlam, meets Lear. Edgar babbles madly while Lear denounces his daughters. Kent leads them all to shelter.

Act III[edit]

Kent tells a gentleman that a French army has landed in Britain, aiming to reinstate Lear to the throne. He then sends the gentleman to give Cordelia a message while he looks for King Lear on the heath. Meanwhile, Edmund learns that Gloucester is aware of France’s impending invasion and betrays his father to Cornwall, Regan, and Goneril. Once Edmund leaves with Goneril to warn Albany about the invasion, Gloucester is arrested, and Regan and Cornwall gouge out Gloucester’s eyes. As they do this, a servant is overcome with rage and attacks Cornwall, mortally wounding him. Regan kills the servant and tells Gloucester that Edmund betrayed him. Then, as she did to her father in Act II, she sends Gloucester out to wander the heath.

Act IV[edit]

Edgar, in his madman’s disguise, meets his blinded father on the heath. Gloucester, sightless and failing to recognise Edgar’s voice, begs him to lead him to a cliff at Dover so that he may jump to his death. Goneril discovers that she finds Edmund more attractive than her honest husband Albany, whom she regards as cowardly. Albany has developed a conscience—he is disgusted by the sisters’ treatment of Lear and Gloucester—and denounces his wife. Goneril sends Edmund back to Regan. After receiving news of Cornwall’s death, she fears her newly widowed sister may steal Edmund and sends him a letter through Oswald. Now alone with Lear, Kent leads him to the French army, which is commanded by Cordelia. But Lear is half-mad and terribly embarrassed by his earlier follies. At Regan’s instigation, Albany joins his forces with hers against the French. Goneril’s suspicions about Regan’s motives are confirmed and returned, as Regan rightly guesses the meaning of her letter and declares to Oswald that she is a more appropriate match for Edmund. Edgar pretends to lead Gloucester to a cliff, then changes his voice and tells Gloucester he has miraculously survived a great fall. Lear appears, by now, completely mad. He rants that the whole world is corrupt and runs off.

Oswald appears, still looking for Edmund. On Regan’s orders, he tries to kill Gloucester but is killed by Edgar. In Oswald’s pocket, Edgar finds Goneril’s letter, in which she encourages Edmund to kill her husband and take her as his wife. Kent and Cordelia take charge of Lear, whose madness quickly passes. Regan, Goneril, Albany, and Edmund meet with their forces. Albany insists that they fight the French invaders but not harm Lear or Cordelia. The two sisters lust for Edmund, who has made promises to both. He considers the dilemma and plots the deaths of Albany, Lear, and Cordelia. Edgar gives Goneril’s letter to Albany. The armies meet in battle, the Britons defeat the French, and Lear and Cordelia are captured. Edmund sends Lear and Cordelia off with secret joint orders from him (representing Regan and her forces) and Goneril (representing the forces of her estranged husband, Albany) for the execution of Cordelia.

Act V[edit]

The victorious British leaders meet, and the recently widowed Regan now declares she will marry Edmund. But Albany exposes the intrigues of Edmund and Goneril and proclaims Edmund a traitor. Regan falls ill, having been poisoned by Goneril, and is escorted offstage, where she dies. Edmund defies Albany, who calls for a trial by combat. Edgar appears masked and in armour and challenges Edmund to a duel. No one knows who he is. Edgar wounds Edmund fatally, though Edmund does not die immediately. Albany confronts Goneril with the letter which was intended to be his death warrant; she flees in shame and rage. Edgar reveals himself and reports that Gloucester died offstage from the shock and joy of learning that Edgar is alive, after Edgar revealed himself to his father.

Offstage, Goneril, her plans thwarted, commits suicide. The dying Edmund decides, though he admits it is against his own character, to try to save Lear and Cordelia, but his confession comes too late. Soon after, Albany sends men to countermand Edmund’s orders. Lear enters bearing Cordelia’s corpse in his arms, having survived by killing the executioner. Kent appears and Lear now recognises him. Albany urges Lear to resume his throne, but as with Gloucester, the trials Lear has been through have finally overwhelmed him, and he dies. Albany then asks Kent and Edgar to take charge of the throne. Kent declines, explaining that his master is calling him on a journey and he must follow. However, Edgar accepts and rises to king of Britain, as a result of King Lears death.

Sources[edit]

The first edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande, printed in 1577

Shakespeare’s play is based on various accounts of the semi-legendary Brythonic figure Leir of Britain, whose name has been linked by some scholars[who?] to the Brythonic god Lir/Llŷr, though in actuality the names are not etymologically related.[5][6][7] Shakespeare’s most important source is probably the second edition of The Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande by Raphael Holinshed, published in 1587. Holinshed himself found the story in the earlier Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth, which was written in the 12th century. Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, published 1590, also contains a character named Cordelia, who also dies from hanging, as in King Lear.[8]

Other possible sources are the anonymous play King Leir (published in 1605); The Mirror for Magistrates (1574), by John Higgins; The Malcontent (1604), by John Marston; The London Prodigal (1605); Montaigne’s Essays, which were translated into English by John Florio in 1603; An Historical Description of Iland of Britaine (1577), by William Harrison; Remaines Concerning Britaine (1606), by William Camden; Albion’s England (1589), by William Warner; and A Declaration of egregious Popish Impostures (1603), by Samuel Harsnett, which provided some of the language used by Edgar while he feigns madness.[9] King Lear is also a literary variant of a common folk tale, Love Like Salt, Aarne–Thompson type 923, in which a father rejects his youngest daughter for a statement of her love that does not please him.[10][11][12]

The source of the subplot involving Gloucester, Edgar, and Edmund is a tale in Philip Sidney’s Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia (1580–90), with a blind Paphlagonian king and his two sons, Leonatus and Plexitrus.[13]

Changes from source material[edit]

Besides the subplot involving the Earl of Gloucester and his sons, the principal innovation Shakespeare made to this story was the death of Cordelia and Lear at the end; in the account by Geoffrey of Monmouth, Cordelia restores Lear to the throne, and succeeds him as ruler after his death. During the 17th century, Shakespeare’s tragic ending was much criticised and alternative versions were written by Nahum Tate, in which the leading characters survived and Edgar and Cordelia were married (despite the fact that Cordelia was previously betrothed to the King of France). As Harold Bloom states: «Tate’s version held the stage for almost 150 years, until Edmund Kean reinstated the play’s tragic ending in 1823.»[14]

Holinshed states that the story is set when Joash was King of Judah (c. 800 BC), while Shakespeare avoids dating the setting, only suggesting that it is sometime in the pre-Christian era.

The characters of Earl «Caius» of Kent and The Fool were created wholly by Shakespeare in order to engage in character-driven conversations with Lear. Oswald the steward, the confidant of Goneril, was created as a similar expository device.

Shakespeare’s Lear and other characters makes oaths to Jupiter, Juno, and Apollo. While the presence of Roman religion in Britain is technically an anachronism, nothing was known about any religion that existed in Britain at the time of Lear’s alleged life.

Holinshed identifies the personal names of the Duke of Albany (Maglanus), the Duke of Cornwall (Henninus), and the Gallic/French leader (Aganippus). Shakespeare refers to these characters by their titles only, and also changes the nature of Albany from a villain to a hero, by reassigning Albany’s wicked deeds to Cornwall. Maglanus and Henninus are killed in the final battle, but are survived by their sons Margan and Cunedag. In Shakespeare’s version, Cornwall is killed by a servant who objects to the torture of the Earl of Gloucester, while Albany is one of the few surviving main characters. Isaac Asimov surmised that this alteration was due to the title Duke of Albany being held in 1606 by Prince Charles, the younger son of Shakespeare’s benefactor King James.[15] However, this explanation is faulty, because James’ older son, Prince Henry, held the title Duke of Cornwall at the same time.

Date and text[edit]

There is no direct evidence to indicate when King Lear was written or first performed. It is thought to have been composed sometime between 1603 and 1606. A Stationers’ Register entry notes a performance before James I on 26 December 1606. The 1603 date originates from words in Edgar’s speeches which may derive from Samuel Harsnett’s Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures (1603).[16] A significant issue in the dating of the play is the relationship of King Lear to the play titled The True Chronicle History of the Life and Death of King Leir and his Three Daughters, which was published for the first time after its entry in the Stationers’ Register of 8 May 1605. This play had a significant effect on Shakespeare, and his close study of it suggests that he was using a printed copy, which suggests a composition date of 1605–06.[17] Conversely, Frank Kermode, in the Riverside Shakespeare, considers the publication of Leir to have been a response to performances of Shakespeare’s already-written play; noting a sonnet by William Strachey that may have verbal resemblances with Lear, Kermode concludes that «1604–05 seems the best compromise».[18]

A line in the play that regards «These late eclipses in the sun and moon»[19] appears to refer to a phenomenon of two eclipses that occurred over London within a few days of each other—the lunar eclipse of 27 September 1605 and the solar eclipse of 12 October 1605. This remarkable pair of events stirred up much discussion among astrologers. Edmund’s line «A prediction I read this other day…»[20] apparently refers to the published prognostications of the astrologers, which followed after the eclipses. This suggests that those lines in Act I were written sometime after both the eclipses and the published comments.[21]

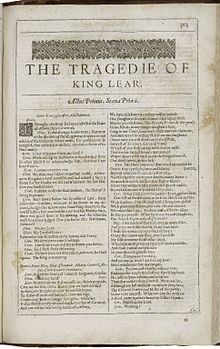

The first page of King Lear, printed in the Second Folio of 1632

The modern text of King Lear derives from three sources: two quartos, one published in 1608 (Q1) and the other in 1619 (Q2),[a] and the version in the First Folio of 1623 (F1). Q1 has «many errors and muddles».[22] Q2 was based on Q1. It introduced corrections and new errors.[22] Q2 also informed the Folio text.[23] Quarto and Folio texts differ significantly. Q1 contains 285 lines not in F1; F1 contains around 100 lines not in Q1. Also, at least a thousand individual words are changed between the two texts, each text has different styles of punctuation, and about half the verse lines in the F1 are either printed as prose or differently divided in the Q1. Early editors, beginning with Alexander Pope, conflated the two texts, creating the modern version that has been commonly used since. The conflated version originated with the assumptions that the differences in the versions do not indicate any re-writing by the author; that Shakespeare wrote only one original manuscript, which is now lost; and that the Quarto and Folio versions contain various distortions of that lost original. In 2021, Duncan Salkeld endorsed this view, suggesting that Q1 was typeset by a reader dictating to the compositor, leading to many slips caused by mishearing.[24] Other editors, such as Nuttall and Bloom, have suggested Shakespeare himself maybe was involved in reworking passages in the play to accommodate performances and other textual requirements of the play.[25]

As early as 1931, Madeleine Doran suggested that the two texts had independent histories, and that these differences between them were critically interesting. This argument, however, was not widely discussed until the late 1970s, when it was revived, principally by Michael Warren and Gary Taylor, who discuss a variety of theories including Doran’s idea that the Quarto may have been printed from Shakespeare’s foul papers, and that the Folio may have been printed from a promptbook prepared for a production.[26]

The New Cambridge Shakespeare has published separate editions of Q and F; the most recent Pelican Shakespeare edition contains both the 1608 Quarto and the 1623 Folio text as well as a conflated version; the New Arden edition edited by R. A. Foakes offers a conflated text that indicates those passages that are found only in Q or F. Both Anthony Nuttall of Oxford University and Harold Bloom of Yale University have endorsed the view of Shakespeare having revised the tragedy at least once during his lifetime.[25] As Bloom indicates: «At the close of Shakespeare’s revised King Lear, a reluctant Edgar becomes King of Britain, accepting his destiny but in the accents of despair. Nuttall speculates that Edgar, like Shakespeare himself, usurps the power of manipulating the audience by deceiving poor Gloucester.»[25]

Interpretations and analysis[edit]

Analysis and criticism of King Lear over the centuries has been extensive.

What we know of Shakespeare’s wide reading and powers of assimilation seems to show that he made use of all kinds of material, absorbing contradictory viewpoints, positive and negative, religious and secular, as if to ensure that King Lear would offer no single controlling perspective, but be open to, indeed demand, multiple interpretations.

R. A. Foakes[27]

Historicist interpretations[edit]

John F. Danby, in his Shakespeare’s Doctrine of Nature – A Study of King Lear (1949), argues that Lear dramatizes, among other things, the current meanings of «Nature». The words «nature», «natural», and «unnatural» occur over forty times in the play, reflecting a debate in Shakespeare’s time about what nature really was like; this debate pervades the play and finds symbolic expression in Lear’s changing attitude to Thunder. There are two strongly contrasting views of human nature in the play: that of the Lear party (Lear, Gloucester, Albany, Kent), exemplifying the philosophy of Bacon and Hooker, and that of the Edmund party (Edmund, Cornwall, Goneril, Regan), akin to the views later formulated by Hobbes, though the latter had not yet begun his philosophy career when Lear was first performed. Along with the two views of Nature, the play contains two views of Reason, brought out in Gloucester and Edmund’s speeches on astrology (1.2). The rationality of the Edmund party is one with which a modern audience more readily identifies. But the Edmund party carries bold rationalism to such extremes that it becomes madness: a madness-in-reason, the ironic counterpart of Lear’s «reason in madness» (IV.6.190) and the Fool’s wisdom-in-folly. This betrayal of reason lies behind the play’s later emphasis on feeling.

The two Natures and the two Reasons imply two societies. Edmund is the New Man, a member of an age of competition, suspicion, glory, in contrast with the older society which has come down from the Middle Ages, with its belief in co-operation, reasonable decency, and respect for the whole as greater than the part. King Lear is thus an allegory. The older society, that of the medieval vision, with its doting king, falls into error, and is threatened by the new Machiavellianism; it is regenerated and saved by a vision of a new order, embodied in the king’s rejected daughter. Cordelia, in the allegorical scheme, is threefold: a person; an ethical principle (love); and a community. Nevertheless, Shakespeare’s understanding of the New Man is so extensive as to amount almost to sympathy. Edmund is the last great expression in Shakespeare of that side of Renaissance individualism—the energy, the emancipation, the courage—which has made a positive contribution to the heritage of the West. «He embodies something vital which a final synthesis must reaffirm. But he makes an absolute claim which Shakespeare will not support. It is right for man to feel, as Edmund does, that society exists for man, not man for society. It is not right to assert the kind of man Edmund would erect to this supremacy.»[28]

The play offers an alternative to the feudal-Machiavellian polarity, an alternative foreshadowed in France’s speech (I.1.245–256), in Lear and Gloucester’s prayers (III.4. 28–36; IV.1.61–66), and in the figure of Cordelia. Until the decent society is achieved, we are meant to take as role-model (though qualified by Shakespearean ironies) Edgar, «the machiavel of goodness»,[29] endurance, courage and «ripeness».[28]

The play also contains references to disputes between King James I and Parliament. In the 1604 elections to the House of Commons, Sir John Fortescue, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was defeated by a member of the Buckinghamshire gentry, Sir Francis Goodwin.[30] Displeased with the result, James declared the result of the Buckinghhamshire election invalid, and swore in Fortescue as the MP for Buckinghamshire while the House of Commons insisted on swearing in Goodwin, leading to a clash between King and Parliament over who had the right to decide who sat in the House of Commons.[30] The MP Thomas Wentworth, the son of another MP Peter Wentworth—often imprisoned under Elizabeth for raising the question of the succession in the Commons—was most forceful in protesting James’s attempts to reduce the powers of the House of Commons, saying the King could not just declare the results of an election invalid if he disliked who had won the seat as he was insisting that he could.[31] The character of Kent resembles Peter Wentworth in the way which is tactless and blunt in advising Lear, but his point is valid that Lear should be more careful with his friends and advisers.[31]

Just as the House of Commons had argued to James that their loyalty was to the constitution of England, not to the King personally, Kent insists his loyalty is institutional, not personal, as he is loyal to the realm of which the king is head, not to Lear himself, and he tells Lear to behave better for the good of the realm.[31] By contrast, Lear makes an argument similar to James that as king, he holds absolute power and could disregard the views of his subjects if they displease him whenever he liked.[31] In the play, the characters like the Fool, Kent and Cordelia, whose loyalties are institutional, seeing their first loyalty to the realm, are portrayed more favorably than those like Regan and Goneril, who insist they are only loyal to the king, seeing their loyalties as personal.[31] Likewise, James was notorious for his riotous, debauched lifestyle and his preference for sycophantic courtiers who were forever singing his praises out of the hope for advancement, aspects of his court that closely resemble the court of King Lear, who starts out in the play with a riotous, debauched court of sycophantic courtiers.[32] Kent criticises Oswald as a man unworthy of office who has only been promoted because of his sycophancy, telling Lear that he should be loyal to those who are willing to tell him the truth, a statement that many in England wished that James would heed.[32]

Furthermore, James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of England upon the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, thereby uniting the kingdoms of the island of Britain into one, and a major issue of his reign was the attempt to forge a common British identity.[33] James had given his sons Henry and Charles the titles of Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Albany, the same titles borne by the men married to Regan and Goneril.[34] The play begins with Lear ruling all of Britain and ends with him destroying his realm; the critic Andrew Hadfield argued that the division of Britain by Lear was an inversion of the unification of Britain by James, who believed his policies would result in a well governed and prosperous unified realm being passed on to his heir.[34] Hadfield argued that the play was meant as a warning to James as in the play a monarch loses everything by giving in to his sycophantic courtiers who only seek to use him while neglecting those who truly loved him.[34] Hadfield also argued that the world of Lear’s court is «childish» with Lear presenting himself as the father of the nation and requiring all of his subjects, not just his children, to address him in paternal terms, which infantises most of the people around him, which pointedly references James’s statement in his 1598 book The Trew Law of Free Monarchies that the king is the «father of the nation», for whom all of his subjects are his children.[35]

Psychoanalytic and psychosocial interpretations[edit]

King Lear provides a basis for «the primary enactment of psychic breakdown in English literary history».[36] The play begins with Lear’s «near-fairytale narcissism».[37]

Given the absence of legitimate mothers in King Lear, Coppélia Kahn[38] provides a psychoanalytic interpretation of the «maternal subtext» found in the play. According to Kahn, Lear’s old age forces him to regress into an infantile disposition, and he now seeks a love that is traditionally satisfied by a mothering woman, but in the absence of a real mother, his daughters become the mother figures. Lear’s contest of love between Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia serves as the binding agreement; his daughters will get their inheritance provided that they care for him, especially Cordelia, on whose «kind nursery» he will greatly depend.

Cordelia’s refusal to dedicate herself to him and love him as more than a father has been interpreted by some as a resistance to incest, but Kahn also inserts the image of a rejecting mother. The situation is now a reversal of parent-child roles, in which Lear’s madness is a childlike rage due to his deprivation of filial/maternal care. Even when Lear and Cordelia are captured together, his madness persists as Lear envisions a nursery in prison, where Cordelia’s sole existence is for him. It is only with Cordelia’s death that his fantasy of a daughter-mother ultimately diminishes, as King Lear concludes with only male characters living.

Sigmund Freud asserted that Cordelia symbolises Death. Therefore, when the play begins with Lear rejecting his daughter, it can be interpreted as him rejecting death; Lear is unwilling to face the finitude of his being. The play’s poignant ending scene, wherein Lear carries the body of his beloved Cordelia, was of great importance to Freud. In this scene, Cordelia forces the realization of his finitude, or as Freud put it, she causes him to «make friends with the necessity of dying».[39] Shakespeare had particular intentions with Cordelia’s death, and was the only writer to have Cordelia killed (in the version by Nahum Tate, she continues to live happily, and in Holinshed’s, she restores her father and succeeds him).

Alternatively, an analysis based on Adlerian theory suggests that the King’s contest among his daughters in Act I has more to do with his control over the unmarried Cordelia.[40] This theory indicates that the King’s «dethronement»[41] might have led him to seek control that he lost after he divided his land.

In his study of the character-portrayal of Edmund, Harold Bloom refers to him as «Shakespeare’s most original character».[42] «As Hazlitt pointed out», writes Bloom, «Edmund does not share in the hypocrisy of Goneril and Regan: his Machiavellianism is absolutely pure, and lacks an Oedipal motive. Freud’s vision of family romances simply does not apply to Edmund. Iago is free to reinvent himself every minute, yet Iago has strong passions, however negative. Edmund has no passions whatsoever; he has never loved anyone, and he never will. In that respect, he is Shakespeare’s most original character.»[42]

The tragedy of Lear’s lack of understanding of the consequences of his demands and actions is often observed to be like that of a spoiled child, but it has also been noted that his behaviour is equally likely to be seen in parents who have never adjusted to their children having grown up.[43]

Christianity[edit]

Critics are divided on the question of whether King Lear represents an affirmation of a particular Christian doctrine.[44] Those who think it does posit different arguments, which include the significance of Lear’s self-divestment.[45] For some critics, this reflects the Christian concepts of the fall of the mighty and the inevitable loss of worldly possessions. By 1569, sermons delivered at court such as those at Windsor declared how «rich men are rich dust, wise men wise dust… From him that weareth purple, and beareth the crown down to him that is clad with meanest apparel, there is nothing but garboil, and ruffle, and hoisting, and lingering wrath, and fear of death and death itself, and hunger, and many a whip of God.»[45] Some see this in Cordelia and what she symbolised—that the material body are mere husks that would eventually be discarded so that the fruit can be reached.[44]

Among those who argue that Lear is redeemed in the Christian sense through suffering are A.C. Bradley[46] and John Reibetanz, who has written: «through his sufferings, Lear has won an enlightened soul».[47] Other critics who find no evidence of redemption and emphasise the horrors of the final act include John Holloway[48][page needed] and Marvin Rosenberg.[49][page needed] William R. Elton stresses the pre-Christian setting of the play, writing that, «Lear fulfills the criteria for pagan behavior in life,» falling «into total blasphemy at the moment of his irredeemable loss».[50] This is related to the way some sources cite that at the end of the narrative, King Lear raged against heaven before eventually dying in despair with the death of Cordelia.[51]

Harold Bloom argues that King Lear transcends a morality system entirely, and thus is one of the major triumphs of the play. Bloom writes that in the play there is, » . . . no theology, no metaphysics, no ethics».[52]

Performance history[edit]

King Lear has been performed by esteemed actors since the 17th century, when men played all the roles. From the 20th century, a number of women have played male roles in the play; most commonly the Fool, who has been played (among others) by Judy Davis, Emma Thompson and Robyn Nevin. Lear himself has been played by Marianne Hoppe in 1990,[53] by Janet Wright in 1995,[54] by Kathryn Hunter in 1996–97,[55] and by Glenda Jackson in 2016 and 2019.[56]

17th century[edit]

Cover of Tate’s The History of King Lear

Shakespeare wrote the role of Lear for his company’s chief tragedian, Richard Burbage, for whom Shakespeare was writing incrementally older characters as their careers progressed.[57] It has been speculated either that the role of the Fool was written for the company’s clown Robert Armin, or that it was written for performance by one of the company’s boys, doubling the role of Cordelia.[58][59] Only one specific performance of the play during Shakespeare’s lifetime is known: before the court of King James I at Whitehall on 26 December 1606.[60][61] Its original performances would have been at The Globe, where there were no sets in the modern sense, and characters would have signified their roles visually with props and costumes: Lear’s costume, for example, would have changed in the course of the play as his status diminished: commencing in crown and regalia; then as a huntsman; raging bareheaded in the storm scene; and finally crowned with flowers in parody of his original status.[62]

All theatres were closed down by the Puritan government on 6 September 1642. Upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, two patent companies (the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company) were established, and the existing theatrical repertoire divided between them.[63] And from the restoration until the mid-19th century the performance history of King Lear is not the story of Shakespeare’s version, but instead of The History of King Lear, a popular adaptation by Nahum Tate. Its most significant deviations from Shakespeare were to omit the Fool entirely, to introduce a happy ending in which Lear and Cordelia survive, and to develop a love story between Cordelia and Edgar (two characters who never interact in Shakespeare) which ends with their marriage.[64] Like most Restoration adapters of Shakespeare, Tate admired Shakespeare’s natural genius but saw fit to augment his work with contemporary standards of art (which were largely guided by the neoclassical unities of time, place, and action).[65] Tate’s struggle to strike a balance between raw nature and refined art is apparent in his description of the tragedy: «a heap of jewels, unstrung and unpolish’t; yet so dazzling in their disorder, that I soon perceiv’d I had seiz’d a treasure.»[66][67] Other changes included giving Cordelia a confidante named Arante, bringing the play closer to contemporary notions of poetic justice, and adding titilating material such as amorous encounters between Edmund and both Regan and Goneril, a scene in which Edgar rescues Cordelia from Edmund’s attempted kidnapping and rape,[68][69] and a scene in which Cordelia wears men’s pants that would reveal the actress’s ankles.[70] The play ends with a celebration of «the King’s blest Restauration», an obvious reference to Charles II.[b]

18th century[edit]

In the early 18th century, some writers began to express objections to this (and other) Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare. For example, in The Spectator on 16 April 1711 Joseph Addison wrote «King Lear is an admirable Tragedy … as Shakespeare wrote it; but as it is reformed according to the chymerical Notion of poetical Justice in my humble Opinion it hath lost half its Beauty.» Yet on the stage, Tate’s version prevailed.[c]

David Garrick was the first actor-manager to begin to cut back on elements of Tate’s adaptation in favour of Shakespeare’s original: he retained Tate’s major changes, including the happy ending, but removed many of Tate’s lines, including Edgar’s closing speech.[72] He also reduced the prominence of the Edgar-Cordelia love story, in order to focus more on the relationship between Lear and his daughters.[73] His version had a powerful emotional impact: Lear driven to madness by his daughters was (in the words of one spectator, Arthur Murphy) «the finest tragic distress ever seen on any stage» and, in contrast, the devotion shown to Lear by Cordelia (a mix of Shakespeare’s, Tate’s and Garrick’s contributions to the part) moved the audience to tears.[d]

The first professional performances of King Lear in North America are likely to have been those of the Hallam Company (later the American Company) which arrived in Virginia in 1752 and who counted the play among their repertoire by the time of their departure for Jamaica in 1774.[74]

19th century[edit]

King Lear mourns Cordelia’s death, James Barry, 1786–1788

Charles Lamb established the Romantics’ attitude to King Lear in his 1811 essay «On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, considered with reference to their fitness for stage representation» where he says that the play «is essentially impossible to be represented on the stage», preferring to experience it in the study. In the theatre, he argues, «to see Lear acted, to see an old man tottering about the stage with a walking-stick, turned out of doors by his daughters on a rainy night, has nothing in it but what is painful and disgusting» yet «while we read it, we see not Lear but we are Lear,—we are in his mind, we are sustained by a grandeur which baffles the malice of daughters and storms.»[75][76]

King Lear was politically controversial during the period of George III’s madness, and as a result was not performed at all in the two professional theatres of London from 1811 to 1820: but was then the subject of major productions in both, within three months of his death.[77] The 19th century saw the gradual reintroduction of Shakespeare’s text to displace Tate’s version. Like Garrick before him, John Philip Kemble had introduced more of Shakespeare’s text, while still preserving the three main elements of Tate’s version: the love story, the omission of the Fool, and the happy ending. Edmund Kean played King Lear with its tragic ending in 1823, but failed and reverted to Tate’s crowd-pleaser after only three performances.[78][79] At last in 1838, William Macready at Covent Garden performed Shakespeare’s version, freed from Tate’s adaptions.[78] The restored character of the Fool was played by an actress, Priscilla Horton, as, in the words of one spectator, «a fragile, hectic, beautiful-faced, half-idiot-looking boy».[80] And Helen Faucit’s final appearance as Cordelia, dead in her father’s arms, became one of the most iconic of Victorian images.[81] John Forster, writing in the Examiner on 14 February 1838, expressed the hope that «Mr Macready’s success has banished that disgrace [Tate’s version] from the stage for ever.»[82] But even this version was not close to Shakespeare’s: the 19th-century actor-managers heavily cut Shakespeare’s scripts: ending scenes on big «curtain effects» and reducing or eliminating supporting roles to give greater prominence to the star.[83] One of Macready’s innovations—the use of Stonehenge-like structures on stage to indicate an ancient setting—proved enduring on stage into the 20th century, and can be seen in the 1983 television version starring Laurence Olivier.[84]

In 1843, the Act for Regulating the Theatres came into force, bringing an end to the monopolies of the two existing companies and, by doing so, increased the number of theatres in London.[80] At the same time, the fashion in theatre was «pictorial»: valuing visual spectacle above plot or characterisation and often required lengthy (and time-consuming) scene changes.[85] For example, Henry Irving’s 1892 King Lear offered spectacles such as Lear’s death beneath a cliff at Dover, his face lit by the red glow of a setting sun; at the expense of cutting 46% of the text, including the blinding of Gloucester.[86] But Irving’s production clearly evoked strong emotions: one spectator, Gordon Crosse, wrote of the first entrance of Lear, «a striking figure with masses of white hair. He is leaning on a huge scabbarded sword which he raises with a wild cry in answer to the shouted greeting of his guards. His gait, his looks, his gestures, all reveal the noble, imperious mind already degenerating into senile irritability under the coming shocks of grief and age.»[87]

The importance of pictorialism to Irving, and to other theatre professionals of the Victorian era, is exemplified by the fact that Irving had used Ford Madox Brown’s painting Cordelia’s Portion as the inspiration for the look of his production, and that the artist himself was brought in to provide sketches for the settings of other scenes.[88] A reaction against pictorialism came with the rise of the reconstructive movement, believers in a simple style of staging more similar to that which would have pertained in renaissance theatres, whose chief early exponent was the actor-manager William Poel. Poel was influenced by a performance of King Lear directed by Jocza Savits at the Hoftheater in Munich in 1890, set on an apron stage with a three-tier Globe—like reconstruction theatre as its backdrop. Poel would use this same configuration for his own Shakespearean performances in 1893.[89]

20th century[edit]

By mid-century, the actor–manager tradition had declined, to be replaced by a structure in which the major theatre companies employed professional directors as auteurs. The last of the great actor–managers, Donald Wolfit, played Lear in 1944 on a Stonehenge-like set and was praised by James Agate as «the greatest piece of Shakespearean acting since I have been privileged to write for the Sunday Times«.[e][91] Wolfit supposedly drank eight bottles of Guinness in the course of each performance.[f]

The character of Lear in the 19th century was often that of a frail old man from the opening scene, but Lears of the 20th century often began the play as strong men displaying regal authority, including John Gielgud, Donald Wolfit and Donald Sinden.[93] Cordelia, also, evolved in the 20th century: earlier Cordelias had often been praised for being sweet, innocent and modest, but 20th-century Cordelias were often portrayed as war leaders. For example, Peggy Ashcroft, at the RST in 1950, played the role in a breastplate and carrying a sword.[94] Similarly, the Fool evolved through the course of the century, with portrayals often deriving from the music hall or circus tradition.[95]

At Stratford-upon-Avon in 1962 Peter Brook (who would later film the play with the same actor, Paul Scofield, in the role of Lear) set the action simply, against a huge, empty white stage. The effect of the scene when Lear and Gloucester meet, two tiny figures in rags in the midst of this emptiness, was said (by the scholar Roger Warren) to catch «both the human pathos … and the universal scale … of the scene».[96] Some of the lines from the radio broadcast were used by The Beatles to add into the recorded mix of the song «I Am the Walrus». John Lennon happened upon the play on the BBC Third Programme while fiddling with the radio while working on the song. The voices of actors Mark Dignam, Philip Guard, and John Bryning from the play are all heard in the song.[97][98]

Like other Shakespearean tragedies, King Lear has proved amenable to conversion into other theatrical traditions. In 1989, David McRuvie and Iyyamkode Sreedharan adapted the play then translated it to Malayalam, for performance in Kerala in the Kathakali tradition—which itself developed around 1600, contemporary with Shakespeare’s writing. The show later went on tour, and in 2000 played at Shakespeare’s Globe, completing, according to Anthony Dawson, «a kind of symbolic circle».[99] Perhaps even more radical was Ong Keng Sen’s 1997 adaptation of King Lear, which featured six actors each performing in a separate Asian acting tradition and in their own separate languages. A pivotal moment occurred when the Jingju performer playing Older Daughter (a conflation of Goneril and Regan) stabbed the Noh-performed Lear whose «falling pine» deadfall, straight face-forward into the stage, astonished the audience, in what Yong Li Lan describes as a «triumph through the moving power of noh performance at the very moment of his character’s defeat».[100][101]

In 1974, Buzz Goodbody directed Lear, a deliberately abbreviated title for Shakespeare’s text, as the inaugural production of the RSC’s studio theatre The Other Place. The performance was conceived as a chamber piece, the small intimate space and proximity to the audience enabled detailed psychological acting, which was performed with simple sets and in modern dress.[102] Peter Holland has speculated that this company/directoral decision—namely choosing to present Shakespeare in a small venue for artistic reasons when a larger venue was available—may at the time have been unprecedented.[102]

Brook’s earlier vision of the play proved influential, and directors have gone further in presenting Lear as (in the words of R. A. Foakes) «a pathetic senior citizen trapped in a violent and hostile environment». When John Wood took the role in 1990, he played the later scenes in clothes that looked like cast-offs, inviting deliberate parallels with the uncared-for in modern Western societies.[103] Indeed, modern productions of Shakespeare’s plays often reflect the world in which they are performed as much as the world for which they were written: and the Moscow theatre scene in 1994 provided an example, when two very different productions of the play (those by Sergei Zhonovach and Alexei Borodin), very different from one another in their style and outlook, were both reflections on the break-up of the Soviet Union.[104]

21st century[edit]

In 2002 and 2010, the Hudson Shakespeare Company of New Jersey staged separate productions as part of their respective Shakespeare in the Parks seasons. The 2002 version was directed by Michael Collins and transposed the action to a West Indies, nautical setting. Actors were featured in outfits indicative of looks of various Caribbean islands. The 2010 production directed by Jon Ciccarelli was fashioned after the atmosphere of the film The Dark Knight with a palette of reds and blacks and set the action in an urban setting. Lear (Tom Cox) appeared as a head of multi-national conglomerate who divided up his fortune among his socialite daughter Goneril (Brenda Scott), his officious middle daughter Regan (Noelle Fair) and university daughter Cordelia (Emily Best).[105]

In 2012, renowned Canadian director Peter Hinton directed an all-First Nations production of King Lear at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, Ontario, with the setting changed to an Algonquin nation in the 17th century.[106] The cast included August Schellenberg as Lear, Billy Merasty as Gloucester, Tantoo Cardinal as Regan, Kevin Loring as Edmund, Jani Lauzon in a dual role as Cordelia and the Fool, and Craig Lauzon as Kent.[106] This setting would later be reproduced as part of the Manga Shakespeare graphic novel series published by Self-Made Hero, adapted by Richard Appignanesi and featuring the illustrations of Ilya.

In 2015, Toronto’s Theatre Passe Muraille staged a production set in Upper Canada against the backdrop of the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837. This production starred David Fox as Lear.[107]

In the summer of 2015–2016, The Sydney Theatre Company staged King Lear, directed by Neil Armfield with Geoffrey Rush in the lead role and Robyn Nevin as the Fool. About the madness at the heart of the play, Rush said that for him «it’s about finding the dramatic impact in the moments of his mania. What seems to work best is finding a vulnerability or a point of empathy, where an audience can look at Lear and think how shocking it must be to be that old and to be banished from your family into the open air in a storm. That’s a level of impoverishment you would never want to see in any other human being, ever.»[108]

In 2016, Talawa Theatre Company and Royal Exchange Manchester co-produced a production of King Lear with Don Warrington in the title role.[109] The production, featuring a largely black cast, was described in The Guardian as being «as close to definitive as can be».[110] The Daily Telegraph wrote that «Don Warrington’s King Lear is a heartbreaking tour de force».[111] King Lear was staged by Royal Shakespeare Company, with Antony Sher in the lead role. The performance was directed by Gregory Doran and was described as having «strength and depth».[112]

In 2017, the Guthrie Theatre produced a production of King Lear with Stephen Yoakam in the title role. Armin Shimerman appeared as the fool, portraying it with «an unusual grimness, but it works»,[113] in a production that was hailed as «a devastating piece of theater, and a production that does it justice».[113]

Lear was played on Broadway by Christopher Plummer in 2004 and Glenda Jackson in 2019, with Jackson reprising her portrayal from a 2016 production at The Old Vic in London.

Adaptations[edit]

Film and video[edit]

The first film adaptation of King Lear was a five-minute German version made around 1905, which has not survived.[114] The oldest extant version is a ten-minute studio-based version from 1909 by Vitagraph, which, according to Luke McKernan, made the «ill-advised» decision to attempt to cram in as much of the plot as possible.[115] Two silent versions, both titled Re Lear, were made in Italy in 1910. Of these, the version by director Gerolamo Lo Savio was filmed on location, and it dropped the Edgar sub-plot and used frequent intertitling to make the plot easier to follow than its Vitagraph predecessor.[g] A contemporary setting was used for Louis Feuillade’s 1911 French adaptation Le Roi Lear Au Village, and in 1914 in America, Ernest Warde expanded the story to an hour, including spectacles such as a final battle scene.[117]

The Joseph Mankiewicz (1949) House of Strangers is often considered a Lear adaptation, but the parallels are more striking in Broken Lance (1954) in which a cattle baron played by Spencer Tracy tyrannizes his three sons, and only the youngest, Joe, played by Robert Wagner, remains loyal.[118]

The TV anthology series Omnibus (1952–1961) staged a 73-minute version of King Lear on 18 October 1953. It was adapted by Peter Brook and starred Orson Welles in his American television debut.[119]

Two screen versions of King Lear date from the early 1970s: Grigori Kozintsev’s Korol Lir,[h] and Peter Brook’s film of King Lear, which stars Paul Scofield.[122] Brook’s film starkly divided the critics: Pauline Kael said «I didn’t just dislike this production, I hated it!» and suggested the alternative title Night of the Living Dead.[i] Yet Robert Hatch in The Nation thought it as «excellent a filming of the play as one can expect» and Vincent Canby in The New York Times called it «an exalting Lear, full of exquisite terror».[j] The film drew on the ideas of Jan Kott, in particular his observation that King Lear was the precursor of absurdist theatre, and that it has parallels with Beckett’s Endgame.[124] Critics who dislike the film particularly draw attention to its bleak nature from its opening: complaining that the world of the play does not deteriorate with Lear’s suffering, but commences dark, colourless and wintry, leaving, according to Douglas Brode, «Lear, the land, and us with nowhere to go».[125] Cruelty pervades the film, which does not distinguish between the violence of ostensibly good and evil characters, presenting both savagely.[126] Paul Scofield, as Lear, eschews sentimentality: This demanding old man with a coterie of unruly knights provokes audience sympathy for the daughters in the early scenes, and his presentation explicitly rejects the tradition of playing Lear as «poor old white-haired patriarch».[127]

Korol Lir has been praised by critic Alexander Anikst for the «serious, deeply thoughtful» even «philosophical approach» of director Grigori Kozintsev and writer Boris Pasternak. Making a thinly veiled criticism of Brook in the process, Anikst praised the fact that there were «no attempts at sensationalism, no efforts to ‘modernise’ Shakespeare by introducing Freudian themes, Existentialist ideas, eroticism, or sexual perversion. [Kozintsev] … has simply made a film of Shakespeare’s tragedy.»[k] Dmitri Shostakovich provided an epic score, its motifs including an (increasingly ironic) trumpet fanfare for Lear, and a five-bar «Call to Death» marking each character’s demise.[129] Kozintzev described his vision of the film as an ensemble piece: with Lear, played by a dynamic Jüri Järvet, as first among equals in a cast of fully developed characters.[130] The film highlights Lear’s role as king by including his people throughout the film on a scale no stage production could emulate, charting the central character’s decline from their god to their helpless equal; his final descent into madness marked by his realisation that he has neglected the «poor naked wretches».[131][132] As the film progresses, ruthless characters—Goneril, Regan, Edmund—increasingly appear isolated in shots, in contrast to the director’s focus, throughout the film, on masses of human beings.[133]

Jonathan Miller twice directed Michael Hordern in the title role for English television, the first for the BBC’s Play of the Month in 1975 and the second for the BBC Television Shakespeare in 1982. Hordern received mixed reviews, and was considered a bold choice due to his history of taking much lighter roles.[134] Also for English television, Laurence Olivier took the role in a 1983 TV production for Granada Television. It was his last screen appearance in a Shakespearean role.[135]

In 1985, a major screen adaptation of the play appeared: Ran, directed by Akira Kurosawa. At the time the most expensive Japanese film ever made, it tells the story of Hidetora, a fictional 16th-century Japanese warlord, whose attempt to divide his kingdom among his three sons leads to an estrangement with the youngest, and ultimately most loyal, of them, and eventually to civil war.[136] In contrast to the cold drab greys of Brook and Kozintsev, Kurosawa’s film is full of vibrant colour: external scenes in yellows, blues and greens, interiors in browns and ambers, and Emi Wada’s Oscar-winning colour-coded costumes for each family member’s soldiers.[137][136] Hidetora has a back-story: a violent and ruthless rise to power, and the film portrays contrasting victims: the virtuous characters Sue and Tsurumaru who are able to forgive, and the vengeful Kaede (Mieko Harada), Hidetora’s daughter-in-law and the film’s Lady Macbeth-like villain.[138][139]

Screenshot from trailer for House of Strangers (1949).

«The film has two antecedents—biblical references to Joseph and his brothers and King Lear«.[140]

A scene in which a character is threatened with blinding in the manner of Gloucester forms the climax of the 1973 parody horror Theatre of Blood.[141] Comic use is made of Sir’s inability to physically carry any actress cast as Cordelia opposite his Lear in the 1983 film of the stage play The Dresser.[142] John Boorman’s 1990 Where the Heart Is features a father who disinherits his three spoiled children.[143] Francis Ford Coppola deliberately incorporated elements of Lear in his 1990 sequel The Godfather Part III, including Michael Corleone’s attempt to retire from crime throwing his domain into anarchy, and most obviously the death of his daughter in his arms. Parallels have also been drawn between Andy García’s character Vincent and both Edgar and Edmund, and between Talia Shire’s character Connie and Kaede in Ran.[144]

In 1997, Jocelyn Moorhouse directed A Thousand Acres, based on Jane Smiley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, set in 1990s Iowa.[145] The film is described, by scholar Tony Howard, as the first adaptation to confront the play’s disturbing sexual dimensions.[144] The story is told from the viewpoint of the elder two daughters, Ginny played by Jessica Lange and Rose played by Michelle Pfeiffer, who were sexually abused by their father as teenagers. Their younger sister Caroline, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh had escaped this fate and is ultimately the only one to remain loyal.[146][147]

In 1998, the BBC produced a televised version,[148] directed by Richard Eyre, of his award-winning 1997 Royal National Theatre production, starring Ian Holm as Lear. In March 2001, in a review originally posted to culturevulture.net, critic Bob Wake observed that the production was «of particular note for preserving Ian Holm’s celebrated stage performance in the title role. Stellar interpreters of Lear haven’t always been so fortunate.»[149] Wake added that other performances had been poorly documented because they suffered from technological problems (Orson Welles), eccentric televised productions (Paul Scofield), or were filmed when the actor playing Lear was unwell (Laurence Olivier).[150]

The play was adapted to the world of gangsters in Don Boyd’s 2001 My Kingdom, a version which differs from all others in commencing with the Lear character, Sandeman, played by Richard Harris, in a loving relationship with his wife. But her violent death marks the start of an increasingly bleak and violent chain of events (influenced by co-writer Nick Davies’ documentary book Dark Heart) which in spite of the director’s denial that the film had «serious parallels» to Shakespeare’s play, actually mirror aspects of its plot closely.[151][152]

Unlike Shakespeare’s Lear, but like Hidetora and Sandeman, the central character of Uli Edel’s 2002 American TV adaptation King of Texas, John Lear played by Patrick Stewart, has a back-story centred on his violent rise to power as the richest landowner (metaphorically a «king») in General Sam Houston’s independent Texas in the early 1840s. Daniel Rosenthal comments that the film was able, by reason of having been commissioned by the cable channel TNT, to include a bleaker and more violent ending than would have been possible on the national networks.[153] 2003’s Channel 4-commissioned two-parter Second Generation set the story in the world of Asian manufacturing and music in England.[154]

The Canadian comedy-drama TV series Slings & Arrows (2003–2006), which follows a fictional Shakespearean theatre festival inspired by the real-life Stratford Festival in Ontario, devotes its third season to a troubled production of King Lear. The fictional actor starring as Lear (played by William Hutt, who in real life played Lear onstage at Stratford three times to great acclaim[155]) is given the role despite concerns over his advanced age and ill health, plus a secret addiction to heroin discovered by the theatre’s director. Eventually the actor’s mental state deteriorates until he seems to believe he is Lear himself, wandering into a storm and later reciting his lines uncontrollably. William Hutt himself was in failing health when he filmed the TV role and died less than a year after the third season premiered.[156]

In 2008, a version of King Lear produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company premiered with Ian McKellen in the role of King Lear.[157]

In the 2012 romantic comedy If I Were You, there is a reference to the play when the lead characters are cast in a female version of King Lear set in modern times, with Marcia Gay Harden cast in the Lear role and Lenore Watling as «the fool». Lear is an executive in a corporate empire instead of a literal one, being phased out of her position. The off-beat play (and its cast) is a major plot element of the movie.[citation needed] The American musical drama television series Empire is partially inspired from King Lear.[158][159][160]

Carl Bessai wrote and directed a modern adaptation of King Lear titled The Lears. Released in 2017, the film starred Bruce Dern, Anthony Michael Hall and Sean Astin.[161]

On 28 May 2018, BBC Two broadcast King Lear starring Anthony Hopkins in the title role and Emma Thompson as Goneril. Directed by Richard Eyre, the play featured a 21st-century setting. Hopkins, at the age of 80, was deemed ideal for the role and «at home with Lear’s skin» by critic Sam Wollaston.[162]

Radio and audio[edit]

The first recording of the Argo Shakespeare for Argo Records was King Lear in 1957, directed and produced by George Rylands with William Devlin in the title role, Jill Balcon as Goneril and Prunella Scales as Cordelia.[163]

The Shakespeare Recording Society recorded a full-length unabridged audio productions on LP in 1965 (SRS-M-232) directed by Howard Sackler, with Paul Scofield as Lear, Cyril Cusack as Gloucester. Robert Stephens as Edmund, Rachel Roberts, Pamela Brown and John Stride.

King Lear was broadcast live on the BBC Third Programme on 29 September 1967, starring John Gielgud, Barbara Jefford, Barbara Bolton and Virginia McKenna as Lear and his daughters.[164] At Abbey Road Studios, John Lennon used a microphone held to a radio to overdub fragments of the play (Act IV, Scene 6)[165] onto the song «I Am the Walrus», which The Beatles were recording that evening. The voices recorded were those of Mark Dignam (Gloucester), Philip Guard (Edgar) and John Bryning (Oswald).[97][98]

On 10 April 1994, Kenneth Branagh’s Renaissance Theatre Company performed a radio adaptation directed by Glyn Dearman starring Gielgud as Lear, with Keith Michell as Kent, Richard Briers as Gloucester, Dame Judi Dench as Goneril, Emma Thompson as Cordelia, Eileen Atkins as Regan, Kenneth Branagh as Edmund, John Shrapnel as Albany, Robert Stephens as Cornwall, Denis Quilley as Burgundy, Sir Derek Jacobi as France, Iain Glen as Edgar and Michael Williams as The Fool.[166]

Naxos AudioBooks released an audio production in 2002 with Paul Scofield as Lear, Alec McCowen as Gloucester, Kenneth Branagh as The Fool, and a full cast.[167] It was nominated for an Audie Award for Audio Drama in 2003.

In October 2017, Big Finish Productions released an audio adaptation full cast drama. Adapted by Nicholas Pegg. The full cast starred David Warner as the titular King Lear, Lisa Bowerman as Regan, Louise Jameson as Goneril, Trevor Cooper as Oswald / Lear’s Gentleman / Third Messenger, Raymond Coulthard (Edmund / Cornwall’s Servant / Second Messenger / Second Gentleman), Barnaby Edwards (The King of France / Old Man / Herald), Ray Fearon (The Duke of Cornwall), Mike Grady (The Fool), Gwilym Lee (Edgar / the Duke of Burgundy), Tony Millan (The Earl of Gloucester / First Messenger), Nicholas Pegg (The Duke of Albany / Gloucester’s Servant / Curan) and Paul Shelley (The Earl of Kent)[168]

Opera[edit]

German composer Aribert Reimann’s opera Lear premiered on 9 July 1978.

Japanese composer’s Toshio Hosokawa’s opera Vision of Lear premiered on 19 April 1998 at the Munich Biennale.

Finnish composer Aulis Sallinen’s opera Kuningas Lear premiered on 15 September 2000.[169]

Novels[edit]

Jane Smiley’s 1991 novel A Thousand Acres, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, is based on King Lear, but set in a farm in Iowa in 1979 and told from the perspective of the oldest daughter.[170]

The 2009 novel Fool by Christopher Moore is a comedic retelling of King Lear from the perspective of the court jester.[171]

Edward St Aubyn’s 2017 novel Dunbar is a modern retelling of King Lear, commissioned as part of the Hogarth Shakespeare series.[172]

On 27 March 2018, Tessa Gratton published a high fantasy adaptation of King Lear titled The Queens of Innis Lear with Tor Books.[173]

Preti Taneja’s 2018 novel We That Are Young is based on King Lear and set in India.[174]

The 2021 novel Learwife by J. R. Thorpe imagines the story of Lear’s wife and the mother of his children, who is not present in the play.[175]

See also[edit]

- Illegitimacy in fiction

- Nothing comes from nothing

- Shakespearean fool

- Fool (novel)

- Water and Salt

- Cap-o’-Rushes

- The Goose-Girl at the Well

- The Dirty Shepherdess

- The Yiddish King Lear

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The 1619 quarto is part of William Jaggard’s so-called False Folio.

- ^ Jean I. Marsden cites Tate’s Lear line 5.6.119.[69]

- ^ Quoted by Jean I. Marsden.[71]

- ^ Jean I. Marsden cites Gray’s Inn Journal 12 January 1754.[73]

- ^ Quoted by Stanley Wells.[90]

- ^ According to Ronald Harwood, quoted by Stanley Wells.[92]

- ^ This version appears on the British Film Institute video compilation Silent Shakespeare (1999).[116]

- ^ The original title of this film in Cyrillic script is Король Лир and the sources anglicise it with different spellings. Daniel Rosenthal gives it as Korol Lir,[120] while Douglas Brode gives it as Karol Lear.[121]

- ^ Pauline Kael’s New Yorker review is quoted by Douglas Brode.[123]

- ^ Both quoted by Douglas Brode.[122]

- ^ Quoted by Douglas Brode.[128]

References[edit]

All references to King Lear, unless otherwise specified, are taken from the Folger Shakespeare Library’s Folger Digital Editions texts edited by Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Under their referencing system, 1.1.246–248 means act 1, scene 1, lines 246 through 248.

- ^ «A Defence of Poetry by Percy Bysshe Shelley». 17 December 2022.

- ^ Burt 2008, p. 1.

- ^ «Top 100 Works in World Literature by Norwegian Book Clubs, with the Norwegian Nobel Institute — the Greatest Books».

- ^ King Lear, 1.1.246–248.

- ^ Jackson 1953, p. 459.

- ^ Ekwall 1928, p. xlii.

- ^ Stevenson 1918.

- ^ Foakes 1997, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Hadfield 2007, p. 208.

- ^ «In other literary forms of the Middle Ages there occasionally appear oral tales. Geoffrey of Monmouth, in telling the story of King Lear, includes the incident of Love Like Salt (Type 923) …». Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 181. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Mitakidou & Manna 2002, p. 100.

- ^ Ashliman 2013.

- ^ McNeir 1968.

- ^ Bloom 2008, p. 53.

- ^ Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare, Volume II, section «King Lear».

- ^ Kermode 1974, p. 1249.

- ^ Foakes 1997, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Kermode 1974, p. 1250.

- ^ King Lear, 1.2.103

- ^ King Lear, 1.2.139

- ^ Shaheen 1999, p. 606.

- ^ a b Foakes Ard3, p. 111

- ^ Foakes Ard3, p. 113

- ^ Salkeld, Duncan (16 March 2021). «Q/F: The Texts of King Lear». The Library. 22 (1): 3–32. doi:10.1093/library/22.1.3.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2008, p. xii.

- ^ Taylor & Warren 1983, p. 429.

- ^ Foakes 1997, p. 107.

- ^ a b Danby 1949, p. 50.

- ^ Danby 1949, p. 151.

- ^ a b Hadfield 2004, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e Hadfield 2004, p. 105.

- ^ a b Hadfield 2004, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Hadfield 2004, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c Hadfield 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Hadfield 2004, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Brown 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Brown 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Kahn 1986.

- ^ Freud 1997, p. 120.

- ^ McLaughlin 1978, p. 39.

- ^ Croake 1983, p. 247.

- ^ a b Bloom 2008, p. 317.

- ^ Kamaralli 2015.

- ^ a b Peat 1982, p. 43.

- ^ a b Kronenfeld 1998, p. 181.

- ^ Bradley 1905, p. 285.

- ^ Reibetanz 1977, p. 108.

- ^ Holloway 1961.

- ^ Rosenberg 1992.

- ^ Elton 1988, p. 260.

- ^ Pierce 2008, p. xx.

- ^ Iannone, Carol (1997). «Harold Bloom and ‘King Lear’: Tragic Misreading». The Hudson Review. 50 (1): 83–94. doi:10.2307/3852392. JSTOR 3852392.

- ^ Croall 2015, p. 70.

- ^ Nestruck 2016.

- ^ Gay 2002, p. 171.

- ^ Cavendish 2016.

- ^ Taylor 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Thomson 2002, p. 143.

- ^ Taylor 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Hunter 1972, p. 45.

- ^ Taylor 2002, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Gurr & Ichikawa 2000, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Marsden 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Taylor 2003, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Bradley 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Armstrong 2003, p. 312.

- ^ Jackson 1986, p. 190.

- ^ Potter 2001, p. 186.

- ^ a b Marsden 2002, p. 28.

- ^ Bradley 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Marsden 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Tatspaugh 2003, p. 528.

- ^ a b Marsden 2002, p. 33.

- ^ Morrison 2002, p. 232.

- ^ Moody 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Hunter 1972, p. 50.

- ^ Potter 2001, p. 189.

- ^ a b Potter 2001, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Wells 1997, p. 62.

- ^ a b Potter 2001, p. 191.

- ^ Gay 2002, p. 161.

- ^ Wells 1997, p. 73.

- ^ Hunter 1972, p. 51.

- ^ Foakes 1997, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Schoch 2002, pp. 58–75.

- ^ Potter 2001, p. 193.

- ^ Jackson 1986, p. 206.

- ^ Schoch 2002, p. 63.

- ^ O’Connor 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Wells 1997, p. 224.

- ^ Foakes 1997, p. 89.

- ^ Wells 1997, p. 229.

- ^ Foakes 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Foakes 1997, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Foakes 1997, p. 52.

- ^ Warren 1986, p. 266.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, pp. 134–136.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 1988, p. 128.

- ^ Dawson 2002, p. 178.

- ^ Lan 2005, p. 532.

- ^ Gillies et al. 2002, p. 265.

- ^ a b Holland 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Foakes 1997, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Holland 2001, p. 213.

- ^ Beckerman 2010.

- ^ a b Nestruck 2012.

- ^ Ouzounian 2015.

- ^ Blake 2015.

- ^ Hutchison 2015.

- ^ Hickling 2016.

- ^ Allfree 2016.

- ^ Billington 2016.

- ^ a b Ringham 2017.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 205.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, p. 83.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, p. 84.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 205–206.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Crosby 1953.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 210.

- ^ a b Brode 2001, p. 206.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 206, 209.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 206–210.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 81.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 79–80.

- ^ King Lear, 3.4.32.

- ^ Guntner 2007, pp. 134–135.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, pp. 85–87.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Rosenthal 2007, p. 84.

- ^ Guntner 2007, p. 136.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Jackson 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Griggs 2009, p. 122.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, p. 85.

- ^ McKernan & Terris 1994, p. 87.

- ^ Howard 2007, p. 308.

- ^ a b Howard 2007, p. 299.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 217.

- ^ «King Lear (1998)». BFI. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Wake, Bob (1 January 1998). «King Lear». CultureVulture. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ «Royal National Theatre». Selected Reviews 1999–2006. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Lehmann 2006, pp. 72–89.

- ^ Rosenthal 2007, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Shaughnessy 2006, p. 99.

- ^ Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia. Hutt, William. Athabasca University. Retrieved on: May 14, 2008.

- ^ McKinney, Mark (November 5, 2010). «Mark McKinney: Comedic ‘Slings And Arrows'». Fresh Air (Interview). Interviewed by Terry Gross. Philadelphia: National Public Radio. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ «King Lear [DVD] [2008]». Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Logan, Michael (31 December 2014). «Lee Daniels Builds a Soapy New Hip-Hop Empire for Fox». TV Guide. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Stack, Tim (7 January 2015). «‘Empire’: Inside Fox’s ambitious, groundbreaking musical soap». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Stacey (6 May 2014). «Lee Daniels on Fox’s ‘Empire’: ‘I Wanted to Make a Black ‘Dynasty’ ‘ (Q&A)». The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ McNary 2016.

- ^ Wollaston 2018.

- ^ Quinn 2017.

- ^ Radio Times 1967.

- ^ King Lear 4.6/245–246 and King Lear 4.6/275–284, Folger Shakespeare Library

- ^ Radio Times 1994.

- ^ «King Lear». June 2016.

- ^ Hughes Media Internet Limited. «16. King Lear – Big Finish Classics». Big Finish. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Martin (1999). «Aulis Sallinen, strong and simple». Finnish Music Quarterly. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ «King Lear in Zebulon County». archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Dirda, Michael (8 February 2009). «Michael Dirda on ‘Fool’ By Christopher Moore». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Gilbert, Sophie (10 October 2017). «King Lear Is a Media Mogul in ‘Dunbar’«. The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ «Novels». tessagratton.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ «Los Angeles Review of Books». Los Angeles Review of Books. 27 December 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Lashbrook, Angela (7 December 2021). «You Know About King Lear. A New Novel Tells His Banished Queen’s Tale». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

Bibliography[edit]

Editions of King Lear[edit]

- Foakes, R. A., ed. (1997). King Lear. The Arden Shakespeare, third series. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-903436-59-2.

- Hadfield, Andrew, ed. (2007). King Lear. The Barnes & Noble Shakespeare. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-4114-0079-5.

- Hunter, G. K., ed. (1972). King Lear. The New Penguin Shakespeare. Penguin Books.

- Kermode, Frank (1974). «Introduction to King Lear«. In Evans, G. Blakemore (ed.). The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-04402-5.

- Pierce, Joseph, ed. (2008). King Lear. Ignatius Critical Editions. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-1-58617-137-7.

Secondary sources[edit]

- Allfree, Claire (7 April 2016). «Don Warrington’s King Lear is a heartbreaking tour de force». The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Armstrong, Alan (2003). «Unfamiliar Shakespeare». In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 308–319. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Ashliman, D. L., ed. (9 February 2013). «Love Like Salt: Folktales of Types 923 and 510». Folklore and Mythology Electronic Texts. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Beckerman, Jim (21 June 2010). «Hudson Shakespeare Company takes King Lear outdoors». The Record. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Billington, Michael (2 September 2016). «King Lear review – Sher shores up his place in Shakespeare royalty». The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Blake, Elissa (19 November 2015). «Three girls – lucky me! says Geoffrey Rush as he plays in King Lear«. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2008). King Lear. Bloom’s Shakespeare Through the Ages. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-9574-4.

- Burt, Daniel S. (2008). The Drama 100 – A Ranking of the Greatest Plays of All Time (PDF). Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6073-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2022.

- Bradley, A. C. (1905) [first published 1904]. Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth (20th impression, 2nd ed.). London: Macmillan.

- Bradley, Lynne (2010). Adapting King Lear for the Stage. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4094-0597-9.

- Brode, Douglas (2001). Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today. Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-18176-8.

- Brown, Dennis (2001). «King Lear: The Lost Leader; Group Disintegration, Transformation and Suspended Reconsolidation». Critical Survey. Berghahn Books. 13 (3): 19–39. doi:10.3167/001115701782483408. eISSN 1752-2293. ISSN 0011-1570. JSTOR 41557126.

- Burnett, Mark Thornton; Wray, Ramona, eds. (2006). Screening Shakespeare in the Twenty-First Century. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2351-8.

- Greenhalgh, Susan; Shaughnessy, Robert. «Our Shakespeares: British Television and the Strains of Multiculturalism». In Burnett & Wray (2006), pp. 90–112.

- Lehmann, Courtney. «The Postnostalgic Renaissance: The ‘Place’ of Liverpool in Don Boyd’s My Kingdom«. In Burnett & Wray (2006), pp. 72–89.

- Cavendish, Dominic (5 November 2016). «King Lear, Old Vic, review: ‘Glenda Jackson’s performance will be talked about for years’«. The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Croake, James W. (1983). «Alderian Family Counseling Education». Individual Psychology. 39.

- Croall, Jonathan (2015). Performing King Lear: Gielgud to Russell Beale. Bloomsbury Publishing. doi:10.5040/9781474223898. ISBN 978-1-4742-2385-0.

- Crosby, John (22 October 1953). «Orson Welles as King Lear on TV is Impressive». New York Herald Tribune. Retrieved 18 November 2018 – via wellesnet.com.

- Danby, John F. (1949). Shakespeare’s Doctrine of Nature: A Study of King Lear. London: Faber and Faber. OL 17770097M.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1928). English River-names. Oxford: Clarendon Press. hdl:2027/uc1.b4598439. LCCN 29010319. OCLC 2793798. OL 6727840M.

- Elton, William R. (1988). King Lear and the Gods. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-0178-1.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Freud, Sigmund (1997). Writings on Art and Literature. Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2973-4.

- de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley, eds. (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521650941. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Holland, Peter (2001). «Shakespeare in the Twentieth-Century Theatre». In de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–215. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521650941. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Jackson, Russell (2001). «Shakespeare and the Cinema». In de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–234. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521650941.014. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9 – via Cambridge Core.