Всего найдено: 7

Здравствуйте!

В Интернете везде по-разному, а из примеров на вашем сайте не вполне понятно: склоняется ли название департамента Франции Кот-д‘Ор? Понятно, что со словом департамент не склоняется, а если отдельно? Из Кот-д‘Ор? или из Кот-д‘Ора? Заранее спасибо.

Евгения

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Это склоняемое слово, правильно: из Кот-д’Ора.

Доброе утро, уважаемая Грамота! Расскажите, пожалуйста, каковы функции апострофа в совр. рус. языке? (И в частности корректно ли, н-р, китайские и японские иероглифы в рус. транскрипции в косвенных падежах отделять апострофом? Н-р: Син’а.) (И еще: можно ли в слове «апостроф» делать ударение на втором слоге?)

С нетерпением жду ответ!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Апостроф (ударение в этом слове ставится на последнем слоге, вариант апостроф недопустим) в современном русском письме используется для передачи иностранных фамилий с начальными буквами Д и О; при этом воспроизводится написание языка-источника: д’Артаньян, Жанна д’Арк, О’Нил, О’Коннор; то же в географических наименованиях: Кот-д‘Ивуар.

Кроме этого, апострофом отделяются русские окончания и суффиксы от предшествующей части слова, передаваемой средствами иной графической системы (в частности, латиницей), например: c-moll’ная увертюра, пользоваться e-mail’ом. Если иноязычное слово передается кириллицей, апостроф не используется.

Следует также отметить, что после орфографической реформы 1917 – 1918 гг., упразднившей написание Ъ на конце слов, пишущие иногда избегали и употребления разделительного Ъ, хотя оно было регламентировано правилами правописания. В практике письма получило некоторое распространение употребление апострофа в функции Ъ: с’езд, об’ём, из’ятие и т. п. Однако такое употребление апострофа не соответствует современным нормам письма.

Здравствуйте. Скажите, пожалуйста, какого правильное написание названия страны Кот-д‘Ивуар (особо интересует правомерность использования апострофа) и города Шарм-эль-Шейх (появилось ли определённость или существует два равнозначных варианта). Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Кот-д’Ивуар, Шарм-эш-Шейх.

Общероссийский классификатор стран мира: Кот д’Ивуар.

Словарь имён собственных: Кот-д‘Ивуар.

Как правильно?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правилен второй вариант c дефисом.

Здравствуйте!

Склоняется ли Кот-д‘Ивуар по падежам? Можно ли сказать, например, «я была в Кот-д‘Ивуаре?

Заранее благодарю.

Ольга.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, это название склоняется, Вы написали верно.

Как правильно пишется название страны: Республика Кит Д’Ивуар?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Кот-д‘Ивуар_.

Есть такое государство — Тринидад и Тобаго.

Как называются жители этой страны?

Тринидадцы, тобажане, тринбагонианцы?

Или жители Кот Д’Ивуара?

Ивуарийцы, котдивуарийцы?

Есть ли какие-то правила при формировании таких слов?

Монегаски, манкунианцы, валлийцы, ливерпудлианцы — это корректные названия?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Жители Тринидада и Тобаго — _тринидадцы_. Жители Кот-д‘Ивуара — _ивуарийцы_ и _котдивуарцы_. _Монегаски, валлийцы_ — корректно, возможно также _монакцы_ и _уэльсцы_. О _манчестерцах_ и _манкунианцах_ см. подробно в http://spravka.gramota.ru/hardwords.html?no=109&_sf=80 [«Непростых словах»]. Аналогично: ливерпульцы — жители Ливерпуля, ливерпудлианцы — игроки футбольного клуба из этого города.

Русский язык не выработал единых и всеобъемлющих правил создания слов — названий жителей. Есть, конечно, некоторые общие закономерности, но многое определяется традицией, степенью распространенности самоназваний жителей, историческими особенностями и пр.

Кот-д’Ивуа́р (фр. Côte d’Ivoire [kot diˈvwaʁ]), официальное название — Респу́блика Кот-д’Ивуа́р (фр. République de Côte d’Ivoire [ʁepyˈblik də kot diˈvwaʁ]) — государство в Западной Африке. Граничит с Либерией, Гвинеей, Мали, Буркина-Фасо и Ганой, с юга омывается водами Гвинейского залива Атлантического океана. До 1960 года — колония Франции.

В стране насчитывается более 60 этнических групп. Столица — Ямусукро (с населением 231 тыс. жителей), главный экономический и культурный центр страны — Абиджан (около 5,2 млн чел.). Официальный язык — французский, основные местные языки — дьюла, бауле, бете. Национальный праздник — День провозглашения независимости (7 августа 1960 года).

Этимология[править | править код]

До 1986 года название государства официально переводилось на русский язык как Республика Бе́рег Слоно́вой Ко́сти. В октябре 1985 года съезд правящей Демократической партии постановил, что слово «Кот-д’Ивуар» является географическим названием и его не нужно переводить с французского[6].

Тем не менее, за пределами стран бывшего СССР название государства по-прежнему переводится (англ. Ivory Coast, нем. Elfenbeinküste, исп. Costa del Marfil, польск. Wybrzeże Kości Słoniowej и т.п.)

Природные условия[править | править код]

Преимущественно равнинная страна, покрытая влажнотропическими лесами на юге и высокотравной саванной на севере.

Природные ресурсы — нефть, газ, алмазы, марганец, железная руда, кобальт, бокситы, медь, золото, никель, тантал.

Климат[править | править код]

Климат — экваториальный на юге и субэкваториальный на севере. Средняя годовая температура — от + 26 до + 28 °C. Годовые суммы осадков — от 1100 мм на севере до 5000 мм на юге.

Страна лежит в двух климатических поясах — субэкваториальном на севере и экваториальном на юге. Среднемесячные температуры повсюду от +25 до +30 °C, но количество осадков и их режим различны. Климат в южной части страны, в зоне экваториального климата, жаркий и влажный с сильными дождями. Температура колеблется от 22 до 32 °C, а самые сильные дожди идут с апреля по июль, а также в октябре и ноябре. Здесь весь год господствует океанический воздух и не бывает ни одного месяца без осадков, сумма которых за год доходит до 2400 мм. На севере, в субэкваториальном климате, разница температур более резкая (в январе опускается до +12 °C ночью, а летом превышает +40 °C), осадков гораздо меньше (1100—1800 мм) и ярко выражен сухой зимний период. С декабря по февраль в северных областях страны дуют ветры харматан, приносящие жаркий воздух и песок из Сахары, резко сокращая видимость и затрудняя дыхание.

Внутренние реки[править | править код]

Главные реки — Сасандра, Бандама и Комоэ, однако ни одна из них не судоходна более чем на 65 км от устья из-за многочисленных порогов и резкого снижения уровня воды в сухой период.

Растительность[править | править код]

Для Кот-д’Ивуара характерен тропический климат с четырьмя климатическими сезонами в прибрежных и центральных районах и двумя сезонами в северной саванне. Флора Кот-д’Ивуара изменяется с юга страны, где произрастают густые тропические леса из вечнозелёных растений (африканская лофира, ироко, красное басамское дерево, иангон, чёрное эбеновое дерево и др.), до севера, где преобладает саванна с редколесьем и травянистыми растениями. По берегам водоёмов на юге, около 4-й параллели, расположена зона тропического леса из деревьев, растущих в воде. В этой зоне культивируют кофе, какао, бананы и ананасы. На западе этой зоны находится Национальный парк «Taи» — один из последних первичных лесов Африки, признанный ЮНЕСКО мировым достоянием.

Далее на север, в центре страны располагается влажная тропическая зона. Здесь начинается господство саванны, однако на этой широте ещё много деревьев[7]. Саванна используется для выращивания кофе, а на её северных границах располагаются плантации хлопчатника. Начиная отсюда тропический климат определяет обилие больших саванн с густыми травами и зарослями кустарников. Здесь возделывают такие культуры, как просо, сорго, рис, хлопчатник и множество огородных растений.

Многие растения флоры Кот-д’Ивуара представляют интерес как источники пищевых, технических и лекарственных продуктов.

Животный мир[править | править код]

В Кот-д’Ивуаре водятся шакалы, гиены, леопарды, слоны, шимпанзе, крокодилы, несколько видов ящериц и ядовитых змей.

Природоохранные территории[править | править код]

Страна обладает одной из самых развитых систем национальных парков в Западной Африке. Национальный парк Таи включён в список Всемирного наследия.

История[править | править код]

Доколониальный период[править | править код]

Территорию современного Кот д’Ивуара ещё в 1-м тысячелетии до нашей эры заселяли пигмеи, занимавшиеся в условиях каменного века охотой и собирательством. Затем туда стали переселяться и другие африканские народы, первыми из них были сенуфо, пришедшие в XI веке с северо-запада.

В XV—XVI веках с севера пришли племена манде (малинке, дьюла и др.), оттеснившие сенуфо. В начале XVIII века манде создали государство Конг, которое стало важным торговым центром и центром распространения ислама в Западной Африке.

Колониальный период[править | править код]

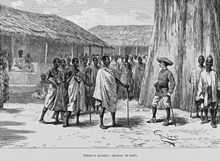

Карта 1729 г., на которой отмечен берег Слоновой кости

Впервые европейцы начали высаживаться на берегу современного Кот д’Ивуара в XV веке. Это были португальцы, голландцы, датчане. Португальцы были первыми, в 1460-х годах. Европейцы покупали у аборигенов слоновую кость, золото, рабов.

Первыми поселенцами из Европы стали французские миссионеры, высадившиеся там в 1637 году. Их первое поселение вскоре было уничтожено аборигенами. Через полвека, в 1687 году, была создана новая французская миссия, на этот раз при вооружённой охране. В начале XVIII века французы попытались основать на побережье ещё два поселения, но они просуществовали лишь несколько лет.

Французы вновь занялись освоением Берега Слоновой Кости с 1842 года. Они восстановили форт Гран-Басам (на побережье, недалеко от нынешнего Абиджана), а к 1846 году установили свой протекторат практически над всеми прибрежными племенами.

В глубь страны французы начали продвигаться с 1887 года. В течение двух лет французы заключили договоры с большинством племён от побережья до современной северной границы страны.

В 1892 году были установлены границы с Либерией, в 1893 году — с британской колонией Золотой Берег (современная Гана).

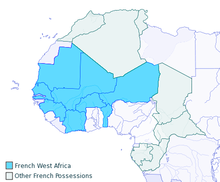

В 1893 году Берег Слоновой Кости был выделен в отдельную французскую колонию (из состава колонии Сенегал), а в 1895 году БСК был включён в состав Французской Западной Африки.

В колониальный период французы стали развивать там производство экспортных культур (кофе, какао, бананов и другие), а также добывать алмазы, золото, марганцевую руду, разрабатывали лесные богатства. Французы занялись развитием инфраструктуры, в частности строительством железных и шоссейных дорог, морских портов.

В октябре 1946 года Берегу Слоновой Кости был предоставлен статус заморской территории Франции, был создан генеральный совет территории.

В марте 1958 года была провозглашена автономная Республика Берег Слоновой Кости.

Период после обретения независимости[править | править код]

7 августа 1960 года была провозглашена независимость страны. Лидер Демократической партии Уфуэ-Буаньи стал её президентом, ДП стала правящей и единственной партией. Был провозглашён принцип неприкосновенности частной собственности. Страна продолжала оставаться аграрным и сырьевым придатком Франции, однако по африканским меркам её экономика находилась в хорошем состоянии, темпы экономического роста достигали 11 % в год. Берег Слоновой Кости в 1979 году стал мировым лидером по производству какао-бобов, однако успехи в этой области опирались на удачную конъюнктуру и сочетание наличия квалифицированных менеджеров, зарубежных инвестиций и большого количества дешёвых рабочих рук, в основном гастарбайтеров из соседних стран.

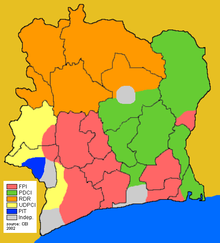

Результаты выборов 2002 года

Зоны контроля правительства и повстанцев в 2003 году

Однако в 1980-е годы цены на кофе и какао на мировых рынках упали, в 1982—1983 страну постигла жестокая засуха, начался экономический спад; к концу 1980-х годов показатель внешнего долга на душу населения превысил аналогичный показатель всех стран Африки, кроме Нигерии. Под давлением общественности Уфуэ-Буаньи пошёл на политические уступки, легализовал альтернативные правящей политические партии, инициировал избирательный процесс, и в 1990 году был избран президентом.

В 1993 году он умер и страну возглавил давно считавшийся его наследником Анри Конан Бедье. В 1995 году состоялся форум по вопросам инвестиций в экономику страны, в котором участвовали и российские компании. В конце 1990-х годов усилилась политическая нестабильность, у Бедье появился серьёзный конкурент: Алассан Уаттара. Он родился на территории Кот-д’Ивуара, a его родители были родом из Буркина Фасо, но впоследствии получили ивуарийское гражданство. Тогда как по Конституции страны на пост президента может претендовать только тот кандидат, у которого оба родителя — ивуарийцы по рождению, а не по натурализации. Таким образом, все люди, рождённые в смешанных браках, исключаются из возможной борьбы за президентский пост. Это обстоятельство усугубило уже намечавшийся раскол общества по этническому признаку. К тому времени от трети до половины населения страны составляли лица зарубежного происхождения, в основном работавшие ранее в сельском хозяйстве, пришедшем по причине ухудшившейся экономической конъюнктуры в упадок[8].

25 декабря 1999 года в стране произошёл военный переворот, организатор которого Робер Геи, бывший армейский офицер, провёл в 2000 году президентские выборы, ознаменованные подтасовками и массовыми беспорядками. Официально победителем выборов был признан лидер оппозиции Лоран Гбагбо.

19 сентября 2002 года в Абиджане против него был совершён военный мятеж, который организовал Робер Геи. В ходе мятежа Геи, а также министр внутренних дел страны Эмиль Бога Дуду были убиты. Мятеж был подавлен, но послужил началом гражданской войны между политическими группировками, представлявшими север и юг страны.

Основной повстанческой группировкой севера, возможно, пользовавшейся поддержкой правительства Буркина-Фасо, были «Патриотические силы Кот д’Ивуар» во главе с Гийомом Кигбафори Соро. Кроме того, на востоке страны действовали другие группировки.

С конца 2002 года в конфликт также вмешалась Либерия.

На стороне Гбагбо выступила Франция («операции Ликорн») (под предлогом защиты многочисленного европейского населения страны) и помогла президенту своими вооружёнными силами.

Также в Кот-д’Ивуар были направлены войска из соседних африканских стран (в том числе из Нигерии).

В 2003 году между официальными властями и повстанцами было достигнуто соглашение о прекращении столкновений, однако ситуация продолжала оставаться нестабильной: правительство контролировало только юг страны.

Прочное мирное соглашение удалось подписать только весной 2007 года.

В конце 2010 года в Кот-д’Ивуаре прошли президентские выборы, которые вылились в острый политический кризис и, как следствие, гражданскую войну. Международные организации зафиксировали многочисленные нарушения прав человека с обеих сторон, несколько сотен человек погибло. В ходе совместной операции ООН и французских войск Лоран Гбагбо был отстранён от власти, новым президентом стал Алассан Уаттара.

Политический строй[править | править код]

Кот-д’Ивуар — президентская республика. Президент страны избирается прямым голосованием сроком на 5 лет с возможностью переизбрания один раз. Он обладает всей полнотой исполнительной власти, назначает и отстраняет премьер-министра. Президент обладает законодательной инициативой наряду с двухпалатным парламентом.

Согласно Economist Intelligence Unit страна в 2018 была классифицирована по индексу демократии как гибридный режим[9].

Вооружённые силы[править | править код]

Административно-территориальное деление[править | править код]

Начиная с 2011 года, Кот-д’Ивуар административно была разделена на 12 округов и два автономных городских округа. Округа делятся на 31 регион, а регионы разделяются на 108 департаментов; департаменты подразделяются на 510 субпрефектур. В некоторых случаях, несколько деревень организованы в коммуны. Автономные округа не делятся на районы, но они содержат департаменты, супрефектуры, коммуны.

Население[править | править код]

Численность населения — 27 481 086[2] (Перепись населения 2020 года).

Годовой прирост — 2,26 % (перепись 2020);

Рождаемость — 29,1 на 1000 (фертильность — 3,67 рождений на женщину, младенческая смертность — 59,1 на 1000 рождений) (перепись 2020);

Смертность — 7,9 на 1000 (перепись 2020);

Средняя продолжительность жизни — 59 лет у мужчин, 64 года у женщин (перепись 2020);

Заражённость вирусом иммунодефицита (ВИЧ) — 2,6 % (оценка 2018 года).

Грамотность — 54 % мужчин, 41 % женщин (оценка 2018 года).

Городское население — 51,7 % (в 2020).

Этнический состав — аканы (аборон, бауле и т. д.) 28,9 %; гур (лоби) 16,1 %; северные манде 14,5 %; кру 8,5 %; южные манде (дан и т. д.) 6,9 %; другие 25,1 % (в том числе около 100 тыс. арабов и около 14 тыс. французов) (оценка 2014 года).

Языки — французский (официальный), около 60 африканских языков, из них наиболее распространённый — дьюла (как язык межплеменного общения).

Религии — мусульмане 42,9 %; католики 17,2 %; евангелисты 11,8 %; методисты 1,7 %; другие христиане 3,2 %; анимисты 3,6 %; аборигенные культы 0,5 %, атеисты 19,1 %[2]. Христиане представлены католиками, православными и протестантами (в основном пятидесятниками из Ассамблей Бога, методистами, адвентистами).

Из иностранных мигрантов — 70 % мусульман и 20 % христиан (оценка на 2008 год).

Культура[править | править код]

Традиционную культуру Кот-д’Ивуара составляют культуры её народов.

Современная ивуарийская литература представлена писателями-романистами (Жозетт Абондьо, Танелла Бони, Ахмаду Курума), детскими писателями (Вероника Таджо, авторами графических романов (Маргарита Абуэ), драматургами (Бернар Бинлин Дадье). Авторы из Кот-д’Ивуара пишут как на французском, так и на многих других языках, а в своём творчестве многие используют постколониальную теорию, обсуждая историю страны и её социальные проблемы.

В стране функционирует Национальная библиотека Кот-д’Ивуара.

Образование[править | править код]

В 1968 году около 80 % населения было неграмотно. В начальных школах обучалось: 353,7 тыс. чел (1968), 9, 5 млн (1980), к 2012 году 94,2 % детей посещали начальную школу. В 2012 году среднюю школу посещали 39 % детей. В 2020 году 60,3 процента мужчин были грамотными, но имелись огромные пробелы в образовании для женщин — лишь 38,6 % из них посещали школу. Многие дети из бедных семей от 6 до 10 лет не посещали школу. В конце 1980 года начался выпуск национальных школьных учебников, за основу которых были взяты французские школьные учебники, в которые были добавлены главы о местных обычаях и ценностях.

Большой прогресс со времени получения независимости произошёл в высшем образовании: если в 1969 году имелся один университет в Абиджане, на четырёх факультетах которого обучалось 1067 студентов, то в 1987 году в университете обучались 18 732 человека, в том числе 3200 женщин. В 2020 году насчитывалось три университета: в Абиджане, Буаке и Ямусукро. Высшим образование владеет 4 % населения. Количество студентов катастрофически уменьшилось в результате насилия и политической неопределенности в 2010 годах[10].

С 2009 года действует новая структура высшего образования, аналогичная болонской системе степеней.

- Университет Феликса-Уфуэ-Буаньи

- Высший технологический институт Кот-д’Ивуара

- Католический университет Западной Африки

Внешняя политика[править | править код]

Экономика[править | править код]

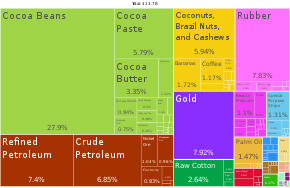

Преимущества. Хорошо развитое сельское хозяйство; важный производитель какао (первое место в мире) и кофе (четырнадцатое место в мире). Относительно хорошая инфраструктура. Растущая нефтяная и газовая промышленность, значительные иностранные инвестиции. Выгодное перераспределение долгов.

Слабые стороны. Нестабильность. Отсутствие инвестиций в образование. Сильная зависимость от какао и кофе (около четверти ВВП страны поступает от экспорта какао-бобов и кофе[11]), тяжёлый нелегальный детский труд на плантациях.

В среднем, экономика страны на протяжении последних лет демонстрирует устойчивый экономический рост в 2,5 — 3 % в год (за вычетом инфляции), а ВВП на душу населения в Кот-д`Ивуаре в 2009 году равнялся 1,7 тыс. долларов, что довольно высоко по меркам Чёрной Африки (15-е место в регионе). Ниже уровня бедности — 42 % населения (в 2006 году).

В сельском хозяйстве занято порядка 70 % активного населения страны; продукция этого сектора экономики даёт более 60 % экспортных поступлений в бюджет. Кот-д`Ивуар является крупнейшим в Африке экспортёром пальмового масла и натурального каучука. Помимо кофе и какао к основным экспортным культурам относятся бананы, хлопок, сахарный тростник, табак. Развито также выращивание кокосовой пальмы, арахиса.

В настоящее время Кот-д’Ивуар является одним из основных экспортёров ананасов в Россию.

В лесах ведутся заготовки ценных пород древесины (в том числе чёрного (эбенового) дерева), сбор сока гевеи (для производства каучука). Для сельскохозяйственных нужд разводятся овцы, козы; ведётся промысловый вылов рыбы.

Нефть и газ добываются в основном на континентальном шельфе. Кроме того, разрабатываются месторождения никелевой, марганцевой и железной руд, а также бокситов, алмазов и золота.

Иностранный капитал[править | править код]

Большое значение в экономике страны имеет французский капитал. Среди крупнейших французских корпораций в Кот-д`Ивуаре представлены Total (добыча и переработка нефти), Électricité de France (энергетика), Michelin (производство шин), Lafarge (производство стройматериалов), «Трансдев» / «Сетао» и «Буиг» (строительство), France Télécom (телекоммуникации), Castel Group[en] (производство пива и напитков), BNP Paribas, «Креди Агриколь» / «Креди Лионне» и Société Générale (финансовые услуги).

В стране присутствуют также американские компании ExxonMobil (добыча нефти), Citibank и JPMorgan Chase (финансовые услуги); британские компании Royal Dutch Shell (добыча нефти), Unilever (производство продуктов питания и бытовой химии) и Barclays (финансовые услуги); швейцарские компании Nestlé (производство кофе) и Holcim[en] (производство стройматериалов); индийские компании Tata Steel (металлургия) и Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (добыча нефти).

Внешняя торговля[править | править код]

По данным на 2017 год[12]:

Экспорт — 10,3 млрд $ — какао-бобы (37 %) и прочие какао продукты, резина и каучук (11 %), сырая нефть и нефтепродукты, золото, кофе, бананы, фрукты и орехи.

Основные покупатели — Нидерланды 15 %, США 12 %, Франция 9 %, Германия 7,1 %, Бельгия и Люксембург 7,1 %.

Импорт — 8,37 млрд $ — сырая нефть (7,9 %) и нефтепродукты; промышленные товары (машины и оборудование — 16,8 %, химические товары, включая лекарства — 11,2 % металлы — 7,2 %); продовольствие (в основном рис — 4,1 %, рыба — 3,4 % и пшеница — 1,6 %, а также напитки, табачные изделия и продукция животноводства).

Основные поставщики — Китай 20 %, Франция 16 %, Нигерия 8,1 %, Индия 6,3 %.

Входит в международную организацию стран АКТ.

СМИ[править | править код]

Государственная телерадиокомпания RTI (Radiodiffusion télévision ivoirienne — «Ивуарское радиовещание и телевидение»), создана 26 октября 1962 года, одновременно была запущена радиостанция Radio Côte d’Ivoire, 7 августа RTI запустила одноимённый телеканал, 9 декабря 1983 года телеканал Canal 2, телеканал RTI был переименован в La Première, 11 ноября 1991 года RTI запустила радиостанцию Fréquence 2. Контроль над соблюдением законов о СМИ осуществляет Высшее управление аудиовизуальной коммуникации (Haute Autorité de la communication audiovisuelle), назначается Советом Министров (до 2011 года — Национальный совет аудиовизуальной коммуникации (Conseil national de la communication audiovisuelle)).

Примечания[править | править код]

Ссылки[править | править код]

Подробности

Категория: Страны Западной Африки

Опубликовано 18.03.2015 12:15

Просмотров: 2073

До 1986 г. на русском языке название государства звучало именно так: Республика Бе́рег Слоно́вой Ко́сти.

Слон – самое ценное животное страны, источник слоновой кости. В честь этого страна и была названа. Кот-д»Ивуар – бывшая колония Франции.

Кот-д»Ивуар – страна огромного этнического разнообразия, в ней насчитывается более 60 этнических групп.

Она граничит с Либерией, Гвинеей, Мали, Буркина-Фасо и Ганой, а с юга омывается водами Гвинейского залива Атлантического океана.

Государственная символика

Флаг

– представляет собой прямоугольное полотнище с соотношением сторон 2:3 с вертикально расположенными полосами оранжевого, белого и зелёного цветов.

Оранжевая полоса символизирует саванну и плодородие земли на севере страны, белая – мир и единство, зелёная – надежду и леса юга страны.

Аналогичные цвета и такую же их трактовку имеет флаг Нигера, на котором оранжевая, белая и зелёная полосы расположены горизонтально. Флаг принят 4 декабря 1959 г.

Герб

– в центре эмблемы – голова слона. Это самое распространённое животное в Кот-д»Ивуаре, источник слоновой кости, в честь и по имени чего названа страна и народ. Восходящее солнце – традиционный символ нового начала. На ленте внизу на французском языке написано название государства. Герб принят в 2001 г.

Государственное устройство

Форма правления

– президентская республика.

Глава государства

– президент, избирается прямым голосованием сроком на 5 лет с возможностью переизбрания один раз. Он назначает и отстраняет премьер-министра.

Действующий президент с 2011 г. Алассан Уаттара

Глава правительства

– премьер-министр.

Столица

– Ямусукро.

Крупнейший город

– Абиджан.

Официальный язык

– французский. Существует около 60 африканских языков, из них наиболее распространён дьюла

(язык межплеменного общения).

Территория

– 322 460 км².

Административное деление

– 19 областей, которые делятся на 81 департамент и 2 района.

Население

– 22 400 835 чел. Средняя продолжительность жизни: 55 лет у мужчин, 57 лет у женщин. Городское население около 50%.

Религия

– мусульмане 39 %, христиане 33 % (представлены католиками, пятидесятниками из Ассамблей Бога, методистами, адвентистами), аборигенные культы 11 %, атеисты 17 %.

Валюта

– франк КФА.

Экономика

– хорошо развито сельское хозяйство; важный производитель какао (первое место в мире) и кофе (третье место в мире).

Относительно хорошая инфраструктура. Растущая нефтяная и газовая промышленность, значительные иностранные инвестиции. Страна является крупнейшим в Африке экспортёром пальмового масла и натурального каучука. К основным экспортным культурам, кроме какао и кофе, относятся бананы, хлопок, сахарный тростник, табак. Также развиты выращивание кокосовой пальмы, арахиса.

Заготовка древесины

В лесах ведутся заготовки ценных пород древесины (в том числе чёрного (эбенового) дерева), сбор сока гевеи (для производства каучука). Для сельскохозяйственных нужд разводятся овцы, козы; ведется промысловый вылов рыбы.

Нефть и газ добываются в основном на континентальном шельфе. Также разрабатываются месторождения никелевой, марганцевой и железной руд, бокситов, алмазов и золота. Экспорт

: какао, кофе, лес, нефть, хлопок, бананы, ананасы, пальмовое масло, рыба. Импорт

: нефтепродукты, промышленные товары, продовольствие.

Образование

– грамотность: 60% мужчин, 38% женщин. Обязательно начальное 6-летнее образование с 6 лет. Среднее 7-летнее образование с 12-ти лет, проходит в два цикла. Создана сеть учебных учреждений, дающих профессионально-техническое образование. В систему высшей школы входят 3 университета и 8 колледжей.

Спорт

– самый популярный вид – футбол.

Футбольная команда страны на Чемпионате мира 2010 г.

Вооружённые силы

– национальная армия сформирована в 1961 г. Вооруженные силы состоят из сухопутных войск, военно-воздушных сил, военно-морского флота, полувоенной президентской гвардии и 10-тысячного контингента резервистов. Подразделения жандармерии и милиции. чел. В декабре 2001 г. введена обязательная воинская служба.

Природа

Тропический лес

Это преимущественно равнинная страна, прибрежная зона покрыта густыми тропическими лесами. На севере и в центре страны – обширная саванна. Климат экваториальный на юге и субэкваториальный на севере.

Главные реки: Сасандра, Бандама и Комоэ. Ни одна из них не судоходна более чем на 65 км от устья из-за многочисленных порогов и резкого снижения уровня воды в сухой период.

Много национальных парков, в этом отношении страна занимает одно из первых мест в Западной Африке.

Африканский леопард

Животный мир: шакалы, гиены, леопарды, слоны, шимпанзе, крокодилы, антилопы, бегемоты, буйволы, гепарды, кабаны, львы, обезьяны, пантеры и др. Несколько видов ящериц и ядовитых змей. Много рыбы.

Культура

Традиционное народное жилище

Популярна деревянная скульптура, в том числе ритуальные маски. Кроме традиционных статуэток, изображающих предков, животных и духов-покровителей, мастера бауле изготовляют небольшие фигурки-игрушки для детей.

Роспись домов

Развиты художественные народные промыслы: плетение корзин и циновок из веревок, соломы и тростника, гончарство, роспись внешних сторон домов, изготовление ювелирных украшений из бронзы, золота и меди, ткачество.

Развито производство батика – своеобразные картины на тканях с изображением животных или растительного орнамента.

Профессиональное изобразительное искусство стало развиваться после получения независимости. Известный художник Каджо Ждеймс Хура.

Художник Бен Хайне

родился в 1983 г. в Абиджане (Республика Кот д»Ивуар), а сейчас живет и работает в Брюсселе. Он не только талантливый иллюстратор, но еще и полиглот: свободно владеет английским, французским и голландским языками, а также немного говорит по-польски, испански и русски. Выставки его работ проходят во многих странах мира.

Недавно он представил серию огромных 3D-рисунков, выполненных карандашом. Изюминка их в том, что сам мастер проникает «внутрь» виртуальной реальности, по крайней мере, глядя на картины, создается именно такое впечатление.

Современная литература

основана на традициях устного народного творчества и развивается в основном на французском языке. Наиболее крупным из литераторов считается поэт, прозаик и драматург Бернар Дадье.

Музыкально-танцевальное искусство является важной частью культуры народов Кот-д»Ивуара. Из музыкальных инструментов распространены балафоны, барабаны тамтамы, гитары, кора (ксилофон), погремушки, рожки, арфы и лютни, трещотки, трубы и флейты.

В 1938 в г. Абиджане создан Туземный театр.

Первый фильм «На дюнах одиночества» снят режиссёром Т. Басори в 1963 г.

Туризм

Условия для развития индустрии туризма хорошие: благоприятный климат, разнообразие богатого растительного и животного мира, песчаные пляжи побережья Гвинейского залива и самобытная культура местных народов. Достопримечательности в Абиджане: Национальный музей (традиционное искусство и ремёсла, в том числе богатая коллекция масок), картинная галерея Шарди.

Объекты всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО в Кот-д»Ивуар

Мон-Нимба

Природоохранная зона в горах Нимба на территориях Гвинеи и Кот-д»Ивуара.

В резервате представлены три основных типа растительности: горные луга, леса и саванна. На вершине горы растут луга. Ниже по склону встречаются миртовые. Леса в основном расположены в долинах и у подножия горы. На территории резервата обитают и эндемики. Здесь водится живородящая жаба, а также западный подвид шимпанзе.

Национальный парк Тай

Расположен на западе страны, на границе с Либерией. Создан для защиты одного из последних массивов влажного экваториального леса в Западной Африке.

Находится на высоте от 80 до 396 м, высшая точка – гора Ньенокуэ. Парк расположен на плато, пересечённом несколькими глубокими долинами. Весь водосток из парка происходит в бассейн реки Кавальи. На юго-западе парка имеются болота.

Парк является последним большим остатком Верхне-Гвинейской сельвы, когда-то занимавших территории современных Ганы, Того, Кот-д»Ивуара, Сьерра-Леоне, Либерии, Гвинеи и Гвинеи-Бисау. Около 90 % тропических лесов Кот-д»Ивуара были уничтожены в последние 50 лет. На территории парка произрастают 1300 видов высших растений, из которых около 50 эндемичных.

Из млекопитающих встречаются 11 видов обезьян, в том числе шимпанзе и несколько видов мартышек, карликовый бегемот, бонго, африканский буйвол, несколько видов дукеров.

Поголовье слонов составляет около 750 особей.

Национальный парк Комоэ

Основан в 1977 г. Парк изначально был включён в список всемирного наследия из-за разнообразия растений по берегам реки Комоэ, включая нетронутые участки влажных тропических лесов.

Поймы вдоль реки Комоэ создают сезонные луга, которые являются пастбищами для популяции бегемотов. Три существующих вида африканских крокодилов (нильский, африканский узкорылый и тупорылый) живут в различных районах парка, а перелётные птицы используют его сезонные водно-болотные угодья. На территории парка обитают редкие виды животных: златошлемный калао, гиеновидная собака, тупорылый крокодил.

Златошлемный калао

Гиеновидная собака

Исторический город Гран-Басам

Французская колониальная столица с 1893 по 1896 гг., когда администрация была перенесена в Бинжервиль после вспышки жёлтой лихорадки. Гран-Басам оставался главным портом колонии до 1930-х годов, а затем эта функция отошла Абиджану.

Другие достопримечательности страны

Абиджан

Крупнейший город Кот-д»Ивуар и второй по населению франкоязычный город в мире после Парижа. Его население составляет 3 802 000 чел. Расположен на 4 полуостровах на берегу лагуны Эбрие. Основан в 1896 г.

Ямусукро

Президентский дворец

Административная столица Кот-д»Ивуара. В Ямусукро находится самая большая в мире церковь – базилика Нотр-Дам-де-ла-Пэ, в архитектуре которой переосмыслены мотивы собора св. Петра в Риме.

В здании высотой 158 м помещается 7000 для сидящих прихожан и ещё 11 тыс. для стоящих. Для строительства базилики завозили мрамор из Италии и цветное стекло из Франции.

История

На территории современного Кот д»Ивуара в I в. до н. э. жили пигмеи

(группа низкорослых негроидных народов). Это было время каменного века, пигмеи занимались охотой и собирательством. Постепенно сюда стали переселяться и другие африканские народы, первыми из них были сенуфо.

В XV-XVI вв. с севера пришли племена манде, оттеснившие сенуфо. В начале XVIII в. манде создали государство Конг, которое стало важным торговым и исламским центром в Западной Африке.

Колониальный период

Первые европейцы начали высаживаться на берегу современного Кот д»Ивуара в XV в. Прежде всего это были португальцы, а также голландцы, датчане. Европейцы покупали у аборигенов слоновую кость, золото, рабов.

Но первыми поселенцами стали французские миссионеры, высадившиеся там в 1637 г. Их первое поселение было уничтожено аборигенами. В 1687 г. была создана новая французская миссия.

С 1842 г. началась новая волна интереса французов к Берегу Слоновой Кости. Они восстановили форт Гран-Басам и свой протекторат практически над всеми прибрежными племенами.

С 1887 г. в течение двух лет французы заключили договоры с большинством племён от побережья до современной северной границы страны. В 1892 г. были установлены границы с Либерией, в 1893 г. – с британской колонией Золотой Берег (современная Гана).

В 1895 г. Берег Слоновой Кости был включён в состав Французской Западной Африки. Французы стали развивать там производство экспортных культур (кофе, какао, бананов и др.), добывать алмазы, золото, марганцевую руду, разрабатывали лесные богатства. Развивали и инфраструктуру: строили железные и шоссейные дороги, морские порты.

В 1946 г. Берегу Слоновой Кости был предоставлен статус заморской территории Франции. В марте 1958 г. была провозглашена автономная Республика Берег Слоновой Кости.

Независимость

Независимость страны была провозглашена 7 августа 1960 г. Лидер Демократической партии Уфуэ-Буаньи

стал её президентом.

Был провозглашён принцип неприкосновенности частной собственности, но страна продолжала оставаться аграрным и сырьевым придатком Франции, хотя и с неплохой экономикой: в 1979 г. Берег Слоновой Кости стал мировым лидером по производству какао-бобов.

Но в 1980-е гг. цены на кофе и какао на мировых рынках упали, к тому же в 1982-1983 гг. в стране была жестокая засуха. Начался экономический спад. В 1993 г. умер Уфуэ-Буаньи, и страну возглавил Анри Конан Бедье.

В конце 1990-х гг. усилилась политическая нестабильность. 25 декабря 1999 г. в стране произошёл военный переворот, организатором которого был Роберт Геи, бывший армейский офицер. Он провёл в 2000 г. президентские выборы, но не выиграл их, победителем выборов был признан лидер оппозиции Лоран Гбагбо

.

19 сентября 2002 г. в Абиджане против него был совершён военный мятеж, организованный Робертом Геи. В ходе мятежа Геи был убит. Мятеж был подавлен, но послужил началом гражданской войны между политическими группировками, представлявшими север и юг страны.

С конца 2002 г. в конфликт вмешалась Либерия. На стороне Гбагбо выступила Франция и помогла президенту своими вооруженными силами.

В 2003 г. между официальными властями и повстанцами было достигнуто соглашение о прекращении столкновений, но ситуация продолжала оставаться нестабильной.

Прочное мирное соглашение было подписано только весной 2007 г.

В конце 2010 г. в Кот-д»Ивуаре прошли президентские выборы, которые вылились в острый политический кризис, а затем в гражданскую войну. В ходе совместной операции ООН и французских войск Лоран Гбагбо был отстранён от власти, а новым президентом стал Алассан Уаттара.

Берег Слоновой кости, когда-то считавшийся образцом африканского благополучия, сегодня переживает не лучшие времена. Государственная коррупция и внешние долги, в которых страна оказалась после падения мировых цен на какао, привели к политической нестабильности и многочисленным межэтническим столкновениям, продолжающимся в стране по сей день.

Тем не менее, если Вас действительно интересуют африканская история, музыка, искусство и природа, Кот-д»Ивуар — это именно та страна, куда Вам стоит отправиться — доброжелательные люди, живописные горы Мэна, Национальный парк Комоэ, пляжи и рыбацкие деревушки Сассандры заставляют тех, кто однажды побывал здесь, возвращаться на Берег Слоновой кости снова и снова…

Республика Кот-д»Ивуар

Площадь: 322,5 тыс. км2.

Численность населения: 15 млн. человек (1998).

Государственный язык: французский.

Столица: Ямусукро (120 тыс. жителей, 1998).

Государственный праздник: День независимости (7 августа, с 1960г.).

Денежная единица: африканский франк.

Член ООН 1960 г., ОАЕ и др.

Государство расположено на западе африканского континента. Граничит на севере с Мали и Буркина-Фасо, на востоке — с Ганой, на западе — с Либерией и Гвинеей. На юге омывается водами Атлантического океана.

Каждый народ, населяющий Кот-д»Ивуар, славится своим музыкальным и танцевальным искусством, устным фольклором, традиционными ремеслами. У народа сенуфо, например, развиты резьба по дереву и изготовление масок, которые охотно покупают иностранцы. У бауле, якуба, малинке распространено гончарное ремесло, домашнее ткачество, плетение изделий из соломы. Очень красочны и оригинальны танцы, связанные с какими-либо событиями или профессиональными занятиями (свадебные, по случаю сбора урожая, танцы охотников, рыбаков и др.).

В Кот-д»Ивуаре фактически две столицы: официальная — Ямусукро с 1983 г. (возникла на месте небольшой деревушки, где родился первый президент страны Феликс Уфуэ-Буаньи) и Абиджан — крупнейший административный, экономический и культурный центр страны (с пригородами насчитывает 2,2 млн. жителей). В нем сосредоточены государственные, административные учреждения, офисы местных и иностранных компаний, банки, много промышленных предприятий. В предместье — крупный морской порт. От Абиджана идет железная дорога, его пересекают все основные автодороги. В Абиджане много учебных заведений. В национальном университете обучается около 20 тыс. студентов (не только местных, но и из других африканских стран). В национальном музее — богатая коллекция масок, народных музыкальных инструментов, красочных панно на ткани (батики) и других изделий художественных ремесел. Крупные города: Буаке (около 500 тыс. жителей), Далоа (210 тыс.), Ман (185 тыс.), Корхого (180тыс.), Ганьоа (160тыс.).

Основная часть территории — слегка всхолмленная равнина. Западные и северо-западные области пересекают горные массивы. Самая высокая вершина — Нимба (1752 м). Страна находится в приэкваториальном поясе. Обширные леса славятся ценными породами красного дерева, но в результате вырубки площадь их сократилась и не превышает 3 млн. га. В центральной и северной областях леса сменяются лесосаваннами и саваннами. Сохранились многие виды хищников (львы, гепарды, гиены, шакалы) и других животных (антилопы, буйволы, обезьяны, кабаны), которые чувствуют себя привольно в национальных парках. Встречаются и стада слонов, хотя их численность резко сократилась. Обитает множество видов птиц, пресмыкающихся (ящерицы, черепахи), в том числе змей (гадюки, аспиды). В водоемах водятся крокодилы.

Туры в Кот д Ивуар

Koт-д»Ивуар самая замечательная страна Западной Африки. Здесь есть все для отдыха… солнце, пальмы, океан, рыбалка, плавно ведущие свой привычный образ жизни люди. Национальные парки поражают своим размахом, люди — гостеприимством, а кухня — разнообразием экзотических блюд.

Ямусукро

Ямусукро — столица Кот-д»Ивуара с 1983 г. Главная достопримечательность города, гордость всех жителей страны — церковь Нотр-Дам-де-ла-Пэ. Построенна в 60-ых годах XX века как символ мира и благополучия. В настоящий момент это самая высокая церковь христианского мира, созданная по образцу базилики Святого Петра в Ватикане. Уникален парковый ансамбль собора и 36 его огромных витражей, украшающих его главный зал. Особое восхищение вызывают несколько, как будто живых, вырезанных из дерева фигур созданных мастерами страны. Со смотровой площадки храма, подняться на которую Вам обязательно предложит гид, открывается захватывающая панорама всего города.

Абиджан

«Париж Западной Африки», так называют Абиджан — культурная и экономическая столица, самый крупный город страны с населением почти в 3 миллиона жителей. Абиджан расположен на четырех полуостровах лагуны, соединенной с океаном каналом Вриди построенным французами в 50х. Центральная, коммерческая часть города и район Кокоди интересны своей архитектурой. Комплекс отеля Ивори, одной из самых знаменитых гостиниц Африки, привлекает туристов со всего света. Комплекс располагает всем, что можно представить: плавательным бассейном, катком с искусственным льдом, боулингом, кинотеатром, казино и художественной галереей. Рядом с Ивори находится, построенный итальянцами и освященный римским Папой в 1985 г. Кафедральный собор Сен-Пол, не уступающий в изяществе многим храмам мира. Северо-западная окраина города — Парк-дю-Банко, представляет собой тропический лес, плавно сливающийся с городскими постройками, что гарантирует приятные прогулки (это самое прохладное место на южном побережье страны) и парк очень популярен у любителей джоггинга. Обязательно посетите традиционный большой рынок ремесленных товаров, где можно купить шкуру питона, причудливые статуэтки черного дерева, сумочки из кожи крокодила и барабаны, издающие самые зажигательные звуки мира.

Национальный парк Комоэ

В 570 км на северо-восток от Абиджана расположен самый большой в Западной Африке национальный парк Комоэ. Здесь, рядом с одноименной рекой, проходит одна из наиболее популярных «звериных троп», где можно увидеть в естественной среде, как большие стада животных в период засухи выходят в поисках воды к реке. Это великолепная возможность понаблюдать за повадками самых разнообразных представителей местной фауны. Здесь и желтоспинный дукер и бонго, и тысячи видов обезьян, включая бабуинов, так называемых зеленых обезьян и многих других. Прямо перед туристами разгуливают львы и пантеры, леопарды и антилопы, ситатунги, слоны и буйволы. вверх

Национальный парк Таи

Второй по величине парк после Комоэ — Таи, находится на юго-западе страны недалеко от района Сассандра. В Таи представлена природа не только Берега Слоновой кости (47 видов животных из 55 всей стране), но и рядом расположенных Ганы, Либерии и Сьерра-Леоне. А именно, сотни видов обезьян, леопарды и слоны, карликовые гиппопотамы и дукеры. Эндемичные виды растений, которых здесь около 11300 наименований, поражают воображение. На севере парка — пальмы разных видов, в южной его части — «черное дерево» или «эбони» и мангровые заросли.

Традиционная деревня

Достопримечательности центрального района — колоритные деревушки Бианкума, Гоусуссо, Сипиту и Данане. Город Корого — столица народа сенуфо. С XIII-го столетия, «сердце» этого города — шумный рынок. Сенуфо широко известны своей деревянной резьбой, они квалифицированные кузнецы и гончары. Большинство резчиков по дереву живет и работает в маленьком районе, так и именуемом — Квартира скульпторов. Сенуфо разделены тайными общинами. «Поро» — культ для мальчиков и «Сакрабунди» — культ для девочек, в которых они готовятся к взрослой жизни. Общины сохраняют фольклор народа, преподают племенные обычаи и прививают самообладание через строгие испытания. Детское образование разделено на три семилетних периода, заканчивающихся церемонией инициации. Каждая община имеет «священный лес», где проводится обучение (непосвященным никогда не разрешают наблюдать испытания). Некоторые ритуальные церемонии происходят непосредственно в деревнях и разрешены для посещения туристами. Они включают Ла-дансе-дес-Хоммес-Пантерес («танец людей-леопардов»), исполняемый мальчиками возвращающимися с сессии обучения в лесу и многое другое.

Традиционная деревянная маска

Обычно традиционная деревянная маска является очень точным изображением человеческого лица, слегка утрированным для более полной передачи особенностей характера. Главные мастера масок — народы бауле и якуба, которые используют маски в различных церемониях. Лицевые маски бауле чрезвычайно реалистичны и передают характерные особенности внешности или прически того человека, который послужил прообразом. А вот маски сенуфо напротив стилизованы. Наиболее распространенный тип сенуфо — «огонь» — маска-шлем, которая является компиляцией облика антилопы, бородавочника и гиены — наиболее уважаемых животных местного анимистического культа.

Фестивали и праздники

Кот-д»Ивуар славится своими фестивалями. Фестиваль Масок проходит в деревнях Мэна в феврале, красочный мартовский карнавал в Буаке и апрельский Фет дю Дипри в Гомоне, во время которого можно понаблюдать за тем, как жители деревни как бы изгоняют из своих домов злых духов. На конец года приходится два важнейших события религиозного календаря мусульман: священный месяц Рамадан и завершающий его фестиваль Эйд-аль-Фитр. В эти дни на улицах города можно понаблюдать красочные демонстрации, песнопения и танцы. Население наряжается в самые дорогие одежды, женщины угощают прохожих национальным кокосовым печеньем, а мужчины стучат в зажигательные барабаны.

Вода — источник жизни и самое дорогое сокровище на всем африканском континенте. Дань воде всегда повод для мероприятия национального масштаба. 29 ноября, в деревушке Нигуи Саф начинается Фестиваль воды, на котором запросто можно поговорить с министрами, принять участие в соревнованиях на пирогах и прокатится на двухэтажных лодках по лагуне. Здесь можно отведать самую настоящую африканскую еду, выпить кокосового молока и полакомится неповторимым какао.

7 декабря вся страна отмечает важнейший официальный праздник Кот-д»Ивуар — Национальный день. Это празднование поразит Вас своим великолепием и роскошным африканским гостеприимством.

Рыбалка

Главное энтузиазм, даже если Вы понятия не имеете что такое удочка, смело соглашайтесь на эту экскурсию. Восторг от самостоятельно пойманного трофея — гарантирован. Или просто взгляните, как изумрудная вода океана соединяется с темной речной.Профессионалам подробнее …

Мангровый лес

Пройти по настоящему мангровому лесу, даже несколько метров очень сложная задача. К счастью есть река и лодка, берите гида и вперед…

На устойчивой моторной лодке можно прокатиться по реке Дагбе, соединяющей район Сассандры и Сан-Педро. В реке водятся гиппопотамы, ламантины, крокодилы, а огромное количество вечно кричащих обезьян будет сопровождать вас в течение всей прогулки.

Водопады

Район города Ман, в центральной части страны, является территорией пышных зеленых холмов и известен далеко за пределами страны своим водопадом Ла-Каскад. Водопад находиться в бамбуковом лесу в 5 км к западу от города.

Водопад Нава заслуживает отдельного внимания. Это зрелище поистине завораживает. Плеск воды, гигантская белая пена притянет Ваши взгляды надолго.

Серфинг и местный колорит

В районе порта Сассандра, что недалеко от Абиджана (250 км), расположены прекрасные пляжи. Но особенно привлекательным делает этот район то, что здесь расположены многочисленные этнические рыбацкие деревни народа фанти, с активным портом и живописной рекой. Очень рекомендуется попробовать местное «банги» — пальмовое вино, которое изготовляют только здесь.

Город Сассандра был ранее важным торговым портом, но когда в близлежащем городе Сан-Педро был построен современный терминал, его роль снизилась и сейчас весь этот район — прекрасная туристическая зона. Расположенный в 3 км к востоку Пляж-де-Бивак — одно из лучших мест для серфинга. Большие волны регистрируют и в смежном Поли-Пляж, а также в районе пляже»»й Гран-Белеби около либерийской границы. Волны на побережье Гвинейского залива очень большие и сильные, поэтому этот район считается идеальным местом для любителей серфинга.

Прогулка на пироге

Наш любимый район Сассандры богат разнообразными развлечениями для туристов. Здесь можно покататься на пироге богат разнообразными развлечениями для туристов. Здесь можно покататься на пироге, которую местные рыбаки используют для ловли рыбы. Нам поначалу, казалось, что лодка шаткая, впоследствии стала почти кораблем, когда видишь, как ловко профессиональный рыбак управляет пирогой, чувствуешь уверенность.

Порт Сан-Педро

Порт Сан-Педро расположен в 350 км западнее Абиджана недалеко от Сассандры в удобной бухте, защищенной от Гвинейского залива естественным молом. Порт введен в эксплуатацию еще в 1971 году. Через порт этого города ежедневно проходит поток леса, кофе, какао, каучука, пальмового масла и хлопка.

Содержание статьи

КОТ-Д»ИВУАР.

Республика Кот-д»Ивуар. Государство в Западной Африке. Столица

– г.Ямусукро (ок. 120 тыс. чел. – 2003). Территория – 322,46 тыс. кв. км. Административно-территориальное деление – 18 областей. Население

– 21 млн. 058 тыс. 798 чел. (оценка 2010). Официальный язык

– французский . Религия

– традиционные африканские верования, ислам и христианство. Денежная единица – франк КФА. Национальный праздник – 7 августа – День независимости (1960). Кот-д»Ивуар – член ООН с 1960, Организации африканского единства (ОАЕ) с 1963 и Африканского союза (АС) с 2002, Движения неприсоединения, Экономического сообщества государств Западной Африки (ЭКОВАС) с 1975, Экономического и валютного союза государств Западной Африки (ЮЕМОА) с 1962 и Общей Афро-маврикийской организации (ОКАМ) с 1965.

Государственный флаг

. Прямоугольное полотнище, на котором расположены три вертикальные одинакового размера полосы оранжевого, белого и зеленого цвета (белая полоса находится в центре).

Географическое положение и границы.

Континентальное государство в южной части Западной Африки. Граничит на западе с Гвинеей и Либерией , на севере – с Буркина-Фасо и Мали , на востоке – с Ганой , южное побережье страны омывается водами Гвинейского залива. Длина береговой линии – 550 км.

Природа.

Большую часть территории занимают холмистые равнины, переходящие на севере в плато высотой более 400 м над уровнем моря. На северо-западе расположены крупные горные массивы Дан и Тура с глубокими ущельями. Самая высокая точка – гора Нимба (1752 м). Полезные ископаемые – алмазы, бокситы, железо, золото, марганец, нефть, никель, природный газ и титан. Климат северных и центральных районов – субэкваториальный сухой, а южных – экваториальный влажный. Зоны этих климатов отличаются в основном количеством осадков. Среднегодовая температура воздуха составляет +26° (по Цельсию). Среднегодовое количество осадков – 1300–2300 мм в год на побережье, 2100–2300 мм в горах и 1100–1800 мм на севере. Густая речная сеть: реки Бандама, Додо, Кавалли, Комоэ, Неро, Сасандра и др., которые несудоходны из-за наличия порогов (кроме р.Кавалли). Самая крупная река – Бандама (950 км). Озера – Варапа, Дадье, Далаба, Лабион, Лупонго и др. Кот-д»Ивуар входит в число 12-ти африканских стран, удовлетворяющих потребности населения в чистой питьевой воде.

Южные районы покрыты вечнозелеными экваториальными лесами (африканская лофира, ироко, красное басамское дерево, ниангон, эбеновое дерево и др.), на севере расположены лесосаванны с галерейными лесами по берегам рек и высокотравные саванны. Из-за вырубки лесов (с целью расширения пахотных земель и экспорта древесины) их площадь сократилась с 15 млн. га в нач. 20 в. до 1 млн га в 1990. Фауна – антилопы, бегемоты, буйволы, гепарды, гиены, кабаны, леопарды, львы, обезьяны, пантеры, слоны, шакалы и др. Много птиц, змей и насекомых. Широко распространена муха цеце. В прибрежных водах много креветок и рыбы (сардина, скумбрия, тунец, угорь и др).

Население.

Среднегодовой прирост населения – 2,105%. Уровень рождаемости – 39,64 на 1000 чел., смертности – 18,48 на 1000 чел. Детская смертность – 66,43 на 1000 новорожденных. 40,6% населения – дети в возрасте до 14 лет. Жители, достигшие 65-летного возраста, составляют 2,9%. Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни – 56,19 года (55,27 у мужчин и 57,13 года у женщин). (Все показатели даны по состоянию на 2010).

Граждан Кот-д»Ивуара называют ивуарийцами. Страну населяют более 60 африканских народов и этнических групп: бауле, аньи, бакве, бамбара, бете, гере, дан (или якуба), куланго, малинке, моси, лоби, сенуфо, тура, фульбе и др. Неафриканское население в 1998 составляло 2,8% (130 тыс. чел. Ливанцев и сирийцев, а также 14 тыс. французов). Из местных языков наиболее распространены языки аньи и бауле. Ок. 25% населения – иммигранты, приехавшие на заработки из Бенина, Буркина-Фасо, Ганы, Гвинеи, Мавритании, Мали, Либерии, Нигера, Нигерии, Того и Сенегала. В кон. 1990-х правительство начало ужесточение иммиграционной политики. В результате военного переворота и начавшейся гражданской войны большая часть иммигрантов стали беженцами и внутренне перемещенными лицами. Согласно оценкам ООН в соседние африканские государства бежали 600 тыс. жителей Кот-д»Ивуара (контингент ивуарийских беженцев в Либерии в 2003 насчитывал 25 тыс. чел.). Ок. 50% населения живут в городах: Абиджан (3,1 млн. чел. – 2001), Агбовиль, Буаке, Корхого, Бундиали, Ман и др. В апреле 1983 столица перенесена в г.Ямусукро, тем не менее, г.Абиджан продолжает оставаться политическим, деловым и культурным центром страны.

Государственное устройство.

Республика. Первая конституция независимой страны принята в 1960. Действует конституция, одобренная референдумом от 23 июля 2000. Главой государства является президент, который избирается на основе всеобщего и прямого избирательного права при тайном голосовании. Он может занимать свою должность не более двух пятилетних сроков. Законодательная власть принадлежит президенту и одноместному парламенту (Национальному собранию). Депутаты парламента избираются всеобщим прямым и тайным голосованием на пять лет.

Судебная система.

Все административные, гражданские, торговые и уголовные дела рассматриваются в судах первой инстанции. В 1973 создан военный трибунал. Высшим органом судебной власти является верховный суд.

Оборона.

Национальная армия сформирована в 1961. В августе 2002 вооруженные силы Кот-д»Ивуара состояли из сухопутных войск (6,5 тыс. чел.), военно-воздушных сил (700 чел.), военно-морского флота (900 чел.), полувоенной президентской гвардии (1350 чел) и 10-тысячного контингента резервистов. Подразделения жандармерии насчитывали 7,6 тыс. чел, милиции – 1,5 тыс. чел. В декабре 2001 введена обязательная воинская служба. В 1996 при содействии Франции в стране открыт центр военной подготовки. В июле 2004 в буферной зоне между правительственными войсками и силами повстанцев находились 4 тыс. военнослужащих французской армии (по решению ООН они останутся там до выборов 2005). Франция поставляет Кот-д»Ивуару технику и оказывает помощь в военной подготовке подразделений его армии.

Внешняя политика.

Важное место занимают двусторонние связи с Францией (дипломатические отношения установлены в 1961). Она – главный торговый партнер Кот-д»Ивуара, ей принадлежит первостепенная роль в урегулировании политического кризиса 1999–2003. Кот-д»Ивуар стал первой африканских страной, установившей дипломатические отношения с ЮАР (1992), одним из первых в Африке установил их с Израилем. Межгосударственные отношения с Ганой, Мали, Нигерией, Нигером и др. странами осложнены из-за проблемы беженцев.

Дипломатические отношения с СССР установлены в январе 1967. В мае 1969 они были разорваны по инициативе правительства Кот-д»Ивуара без официального объяснения причин. Восстановлены дипломатические отношения 20 февраля 1986. В 1991 Российская Федерация признана правопреемницей СССР. Готовятся новые соглашения в области совершенствования договорно-правовой базы двусторонних отношений РФ и Кот-д»Ивуара.

Экономика.

В ее основе заложена частная форма собственности. Большинство смешанных предприятий находятся под контролем иностранного капитала (в основном французского). Кот-д»Ивуар – один из крупнейших на мировом рынке производителей и экспортеров кофе сорта «робуста» и какао-бобов. Начиная с 1960-х, стал самым крупным среди африканских государств производителем пальмового масла, по его экспорту находился на пятом месте в мире (300 тыс. т ежегодно). На экономике страны серьезно отразились последствия военного переворота: темпы роста ВВП в 2000 составили минус 0,3%, в 2003 – минус 1,9%. Инфляция в 2003 – 4,1%.

Сельское хозяйство.

Кот-д»Ивуар – страна с развитым товарным земледелием. Доля сельскохозяйственной продукции в ВВП – 29% (2001). Площадь обрабатываемых земель составляет 9,28%, орошаемых – 730 кв. км. (1998). Выращивают ананасы, бананы, батат, какао-бобы, кокосовые орехи, кофе, кукурузу, маниоку (кассаву), просо, рис, сахарный тростник, сорго, таро, хлопок и ямс. Животноводство (разведение коров, коз, овец, свиней) и птицеводство из-за распространения мухи цеце развито только в северных районах. Ежегодно вылавливается 65–70 тыс. т рыбы. Кот-д»Ивуар – один их крупных поставщиков леса и лесоматериалов их ценных тропических пород.

Промышленность.

Доля промышленной продукции в ВВП составляет 22% (2001). Горнодобывающая промышленность развита слабо. Добыча алмазов в 1998 составила 15 тыс. карат, золота – 3,4 т. На долю обрабатывающей промышленности приходится ок. 13% ВВП (предприятия по переработке сельскохозяйственной продукции (в том числе производству пальмового масла и каучука), дерево- и металлообрабатывающие заводы, обувные и текстильные фабрики, а также предприятия химической промышленности). В кон. 1990-х Кот-д»Ивуар находился на четвертом месте в мире по развитию промышленности по переработке какао-бобов (225 тыс. т ежегодно). Хорошо налажено местное производство потребительских товаров.

Энергетика.

В 2001 г. 61,9% электроэнергии вырабатывалось на ТЭС, 38,1% – на ГЭС (Аяме, на р.Белая Бандама, в Таабо). Кот-д»Ивуар экспортирует электроэнергию в соседние страны (1,3 млрд. кВт – 2001). Ведется добыча нефти (1027 тыс. т – 1997).

Транспорт.

Общая протяженность железных дорог – 660 км, автодорог – 68 тыс. км (6 тыс. км имеют твердое покрытие, большая часть автодорог проложена на юге) – 2002. Главные морские порты – Абиджан и Сан-Педро. В 2003 насчитывалось 37 аэропортов и взлетно-посадочных площадок (с твердым покрытием – 7). Международные аэропорты находятся в городах Абиджан, Буаке и Ямусукро.

Внешняя торговля.

Кот-д»Ивуар – одно из немногих государств Африки, во внешнеторговом балансе которого лидирует экспорт. В 2003 объем экспорта составил 5,29 млрд. долл. США, а импорта – 2,78 млн. долл. США. Основные экспортные товары: кофе, какао-бобы, нефть, строительный лес и лесоматериалы, хлопок, бананы, пальмовое масло, рыба. Основные партнеры по экспорту: Франция (13,7%), Нидерланды (12,2%), США (7,2%), Германия (5,3%), Мали (4,4%), Бельгия (4,2%), Испания (4,1%) – 2002. Основные товары импорта – нефтепродукты, оборудование, продукты питания. Основные партнеры по импорту: Франция (22,4%), Нигерия (16,3%), Китай (7,8%), а также Италия (4,1%) – 2002.

Финансы и кредит.

Денежная единица – франк КФА, состоящий из 100 сантимов. В декабре 2003 курс национальной валюты составлял: 1долл. США = 581,2 франка КФА.

Административное устройство.

Страна разделена на 18 областей, которые состоят из 57 департаментов.

Политические организации.

Сложилась многопартийная система: в 2000 насчитывалось 90 политических партий и объединений. Наиболее влиятельные из них: Ивуарийский народный фронт

, ИНФ (Front populaire ivoirien, FPI). Правящая партия. Основана в 1983 во Франции, легализована в 1990. Председатель – Н»Гессан Аффи (Affi N»Gessan), генеральный секретарь – Урето Сильвэн Миака (Sylvain Miaka Oureto); Демократическая партия Кот-д»Ивуара

, ДПКИ (Parti démocratigue de la Côte d»Ivoire, PDCI). Партия основана в 1946 как местная секция Демократического объединения Африки (ДОА). Лидер – Бедье Анри Конан (Henri Konan Bedié); Ивуарийская партия трудящихся

, ИПТ (Parti ivoirien des travailleurs, PIT). Партия социал-демократов, стала легальной в 1990. Генеральный секретарь – Водье Франсис (Srancis Wodié); Объединение

республиканцев

, ОР (Rassemblement des républicais). Партия основана в 1994 в результате раскола ДПКИ. Влиятельна в северных мусульманских районах. Лидер – Уаттара Алассан Драман (Alassane Dramme Ouattara), генеральный секретарь – Диабате Генриетта Дагба (Henriette Dagba Diabaté); Союз за демократию и мир Кот-д»Ивуара

,

СДМКИ (Union pour la democratie et pour la paix de la Côte d»Ivoire, UDPCI). Основана в 2001 в результате раскола ДПКИ. Лидер – Акото Яо Поль (Paul Akoto Yao).

Профсоюзные объединения.

Всеобщий союз трудящихся Кот-д»Ивуара (Union générale des travailleurs de Côte d»Ivoire, UGTCI). Создан в 1962, насчитывает 100 тыс. членов. Генеральный секретарь – Ниамкей Адико (Adiko Niamkey).

Религии.

55% коренного населения придерживаются традиционных верований и культов (анимализм, фетишизм, культ предков и сил природы и др.), 25% – мусульмане (преимущественно сунниты), христианство исповедуют 20% населения (католики – 85%, протестанты – 15%) – 1999. (Количество мусульман гораздо больше, так как они составляют большинство среди нелегальных иностранных рабочих. Мусульмане живут в основном в северных районах страны). Действуют несколько афрохристианских церквей. Распространение христианства началось в кон. 19 в.

Образование.

Обязательно начальное образование (6 лет), которое дети получают с шестилетнего возраста. Среднее образование (7 лет) начинается в возрасте 12-ти лет и проходит в два цикла. В 1970-х в начальных и частично средних школах был широко распространен метод телевизионного обучения. Создана сеть учебных учреждений, дающих профессионально-техническое образование. В систему высшей школы входят три университета и восемь колледжей. В 2000 на двенадцати факультетах и отделениях национального университета в г.Абиджане (основан в 1964) обучались 45 тыс. студентов и работали 990 преподавателей. Обучение ведется на французском языке. Образование в государственных учебных заведениях является бесплатным. В 2004 грамотными были 42,48 % населения (40,27% мужчин и 44,76% женщин).

Здравоохранение.

Распространены тропические болезни – билхарциоз, желтая лихорадка, малярия, «сонная болезнь», шистоматоз и др. В долинах рек распространено тяжелое заболевание под названием «речная слепота». Отмечается один из самых высоких в странах Западной Африки уровень заболевания лепрой (проказой). Остро стоит проблема СПИДа. В 1988 от него умерли 250 чел., в 2001 – 75 тыс. чел., насчитывалось 770 тыс. ВИЧ-инфицированных. В серед. 1990-х национальное радиовещание начало транслировать специальную информационно-просветительскую программу «Говорящий барабан», посвященную проблемам СПИДа. В кон. 1980-х США открыли в г.Абиджане исследовательский центр по изучению и контролю за этим заболеванием.

Пресса, радиовещание, телевидение и Интернет.

Издаются на французском языке: ежедневные газеты «Ивуар-суар» (Ivoir-soir – «Ивуар-вечер») и «Вуа» (La Voie – «Путь», печатный орган ИНФ), еженедельные газеты «Белье» (Le Bélier – «Овен»), «Демократ» (Le Démocrate – «Демократ», печатный орган ДПКИ), «Нувель оризон» (Le Nouvel horizon – «Новый горизонт», печатный орган ИНФ) и «Жен демократ» (Le Jeune démocrate – «Молодой демократ»), еженедельник «Абиджан сет жур» (Abidjan 7 jours – «Абиджан за неделю»), ежемесячная газета «Алиф» (Alif – «Алиф»), освещающая проблемы ислама, ежемесячный журнал «Эбюрнеа» (Eburnéa) и др. Правительственное информационное агентство – «Агентство печати Кот-д»Ивуара», АИП (Agence ivoirienne de presse, AIP). Создано в 1961. Правительственная служба «Ивуарийское радиовещание и телевидение» основана в 1963. АИП и служба находятся в г.Абиджане. 9 тыс. Интернет-пользователей (2002).

Туризм.

Страна располагает целым комплексом необходимых условий для развития индустрии туризма: благоприятный климат, разнообразие богатого растительного и животного мира, прекрасные песчаные пляжи побережья Гвинейского залива и самобытная культура местных народов. Активное развитие туристической индустрии началось с реализации в 1970 специальной программы, рассчитанной до 1980 (22% капиталовложений составили иностранные инвестиции). Были выделены восемь туристических зон, на территории которых к концу 1980-х построено более 170-ти гостиниц разного класса. В 1990-х в Абиджане построены фешенебельные ультрасовременные отели «Гольф» и «Ивуар», оборудованные площадками для игры в гольф и ледовыми дорожками. До 1997 доходы от туристического бизнеса ежегодно составляли ок. 140 млн. долл. США. В 1998 страну посетили 301 тыс. иностранных туристов. В 1997 на рынке успешно работали 15 туристических агентств, многие из которых занимались также организацией делового туризма.

Достопримечательности в Абиджане: Национальный музей (представлено традиционное искусство и ремесла, в том числе богатая коллекция масок), картинная галерея Шарди. Другие достопримечательности – национальный парк Комоэ, известный музей Гбон Кулибали в г.Корхого (изделия гончарного, кузнечного и деревянного ремесел), живописные горные пейзажи в местности Ман, собор Богородицы Мира (очень напоминает собор святого Петра в Риме) в г.Ямусукро, водопад Монт Тонкуи. Национальный парк Таи (на юго-западе) с большим количеством эндемичных растений включен ООН в категорию мировых достояний. Национальная кухня – «атьеке» (блюдо, приготовленное из маниоки, под рыбным или мясным соусом), «кеджена» (жареная курица с рисом и овощами), «фуфу» (шарики из теста, приготовленного из ямса, маниоки или бананов, которые подают к рыбе или мясу с добавлением соусов).

Архитектура.

Разнообразны архитектурные формы традиционного жилища: на юге – прямоугольные или квадратные деревянные дома с двускатной крышей из листьев пальмы, в центральных областях распространены глинобитные дома прямоугольной формы (иногда углы закругленные) под плоской кровлей, разделенные на несколько помещений, на востоке – прямоугольной формы с плоскими крышами, а в остальных районах дома круглые или овальные в плане, соломенная крыша имеет коническую форму. Внешняя сторона глинобитных домов часто покрывается рисунками геометрических фигур, птиц, реальных и мистических животных, которые выполняются красками желтого, красного и черного цвета. Приметой современных городов стали фешенебельные гостиницы и супермаркеты из железобетонных конструкций и стекла.

Изобразительное искусство и ремесла.

Важное место в традиционной ивуарийской культуре занимает деревянная скульптура, прежде всего маски. Особенно разнообразны ритуальные маски у народа сенуфо. У народов дан и гере встречаются маски с подвижной челюстью. Деревянную скульптуру народа бауле искусствоведы считают лучшим образцом африканской круглой скульптуры некультового характера. Кроме традиционных статуэток, изображающих предков, животных и разнообразных духов-покровителей, мастера бауле изготовляют небольшие фигурки-игрушки для детей. Интересны глиняные погребальные статуэтки народа аньи. Хорошо развиты художественные народные промыслы: плетение корзин и циновок из веревок, соломы и тростника, гончарство (изготовление домашней утвари и предметов декора интерьера), роспись внешних сторон домов, изготовление ювелирных украшений из бронзы, золота и меди, а также ткачество. Развито производство батика – своеобразные картины на тканях с изображением животных или растительного орнамента. Батики народа сенуфо представлены во многих музеях мира. Профессиональное изобразительное искусство стало развиваться после получения независимости. За пределами страны хорошо известно имя художника Каджо Ждеймса Хуры. В 1983 Национальная ассоциация художников организовала первую профессиональную выставку мастеров живописи Кот-д»Ивуара, в которой приняли участие более 40 художников.

Литература.

Современная литература основана на традициях устного народного творчества и развивается в основном на французском языке. Ее становление связано с национальной драматургией. Наиболее крупным из литераторов считается поэт, прозаик и драматург Бернар Дадье. Писатели – М.Асамуа, Э.Декрэн, С.Дембеле, Б.З.Зауру, М.Коне, А.Лоба, Ш.З.Нокан и др. В 2000 вышел последний роман («Аллах не обязан») известного писателя Амаду Курумы (умер во Франции в декабре 2003). Его первый роман «Солнце независимости» (1970) включен в учебные программы многих африканских, американских и европейских университетов. Наиболее известные поэты – Ф.Амуа, Г.Анала, Д.Бамба, Ж-М.Боньини, Ж.Додо и Б.З.Зауру.

Музыка и театр.

Музыкально-танцевальное искусство имеет давние традиции и является важной частью культуры народов Кот-д»Ивуара. Из музыкальных инструментов распространены балафоны, барабаны тамтамы, гитары, кора (ксилофон), погремушки, рожки, своеобразные арфы и лютни, трещотки, трубы и флейты. Хоровое пение сопровождается самобытными танцами. Интересны ритуальные танцы народа бауле, танец гe-гблин

(«люди на ходулях») у народа дан, а также кинион-пли

(танец сбора урожая). В 1970–1980-х созданы Национальная балетная труппа фольклорного танца и группа «Гюла». На Всеафриканском фестивале музыки, проходившем в 2000 в г.Сан-Сити (ЮАР), одну из премий получил известный ивуарийский музыкант Ванамх.

Развитие театрального искусства началось с создания в 1930-х любительских школьных коллективов. В 1938 в г.Абиджане создан так называемый Туземный театр. После получения независимости при Национальном институте искусств создана профессиональная театральная школа, в которой преподавали актеры из Франции. Ставились пьесы французских и ивуарийских авторов. Пользовалась популярностью пьеса «Туньянтиги» («Глаголющий истину») местного писателя А.Курумы. В 1980-х особо популярной была театральная труппа «Котеба».

Кинематография.

Развивается с 1960-х. Первый фильм – На дюнах одиночества

– снят режиссером Т.Басори в 1963. В 1974 создана Ассоциация профессиональных кинематографистов. В 1993 ивуарийский режиссер Адама Руамба снял фильм Во имя Христа

. В 2001 вышел фильм Аданггаман

известного ивуарийского режиссера Роже Гноана М»Бала (о проблемах рабства) и лента Молокососы из Бронкса

(о жизни в г.Абиджане) французского режиссера Элиара Делатура, живущего в Кот-д»Ивуаре.

История.

Доколониальный период.

Современная территория Кот-д»Ивуара была заселена пигмеями еще в нач. каменного века. С 1-го тысячелетия н.э. с запада началось проникновение других народов несколькими миграционными потоками. Первыми переселенцами были сенуфо, которые постепенно стали приобщаться к земледелию. Процесс заселения, продолжавшийся несколько столетий почти до начала колониального завоевания, в значительной мере был связан с работорговлей в прибрежных районах Золотого Берега (современная Гана), от которой спасались бегством местные жители.

Колониальный период.

Европейцы (португальцы, англичане, датчане и голландцы) высаживались на побережье нынешнего Кот-д»Ивуара в кон. 15 в. Начало колонизации положили в 1637 французские миссионеры. Хозяйственное освоение началось в 1840-х: французские колонисты добывали золото, заготавливали и вывозили тропическую древесину, разбивали плантации завезенного из Либерии кофе. 10 марта 1893 Берег Слоновой Кости был официально объявлен колонией Франции, а с 1895 включен во Французскую Западную Африку (ФЗА). Местное население оказывало активное сопротивление колонизаторам (восстания аньи в 1894–1895, гуро в 1912–1913 и др.). Оно усилилось в годы первой мировой войны в связи с насильственной вербовкой во французскую армию. В межвоенный период колония стала крупным производителем кофе, какао-бобов и тропической древесины. В 1934 ее административным центром стал Абиджан. Первая партия африканского населения – Демократическая партия Берега Слоновой Кости (ДП БСК) – создана в 1945 на основе союзов местных фермеров. Она стала территориальной секцией ДОА (Демократического объединения Африки) – общей политической организации ФЗА, во главе которой стоял африканский плантатор Феликс Уфуэ-Буаньи. Под влиянием национально-освободительного движения Франция в 1957 предоставила БСК право на создание территориального законодательного собрания (парламента). В 1957 БСК получил статус автономной республики. После выборов в законодательное собрание (апрель 1959) сформировано правительство во главе с Ф.Уфуэ-Буаньи.

Период независимого развития.

Независимость провозглашена 7 августа

1960. Президентом Республики Берег Слоновой Кости (БСК) стал Ф.Уфуэ-Буаньи. Провозглашена политика экономического либерализма, в основе которого была неприкосновенность частной собственности. ДП БСК стала единственной и правящей партией. В 1960–1980-х отличительной чертой развития страны стали высокие темпы роста экономики (в основном за счет экспорта кофе и какао-бобов): в 1960–1970 прирост ВВП составил 11%, в 1970–1980 – 6–7%. Доход на душу населения в 1975 – 500 долл. США (в 1960 – 150 долл. США). В 1980-х в связи с падением мировых цен на кофе и какао-бобы начался экономический спад. Бессменным президентом оставался Ф.Уфуэ-Буаньи. В октябре 1985 страна получила название «Республика Кот-д»Ивуар», ДП БСК переименована в ДПКИ –

«Демократическая партия Кот-д»Ивуара». Под давлением общественного движения за демократические свободы в мае 1990 введена многопартийность. На президентских выборах 1990 победил Ф.Уфуэ-Буаньи. Главным направлением экономической политики в 1990-е стало расширение приватизации (в 1994–1998 приватизированы более 50-ти компаний). После смерти Ф.Уфуэ-Буаньи (1993) президентом стал его преемник Анри Конан Бедье (избран в 1995). До 1994 экономика находилась в состоянии упадка из-за обвала мировых цен на кофе и какао-бобы, повышения цен на нефть, жестокой засухи 1982–1983, непродуманного расходования правительством внешних займов, а также случаев их прямого расхищения. Правительство начало проводить политику поощрения привлечения иностранных инвестиций в экономику. В октябре 1995 в стране состоялся форум «Инвестировать в Кот-д»Ивуар», в котором среди 350-ти иностранных фирм участвовали и российские компании. В 1996 проведен «Горный форум». Прирост ВВП в 1998 составил ок. 6% (1994 – 2,1%), уровень инфляции в 1996–1997 – 3% (1994 – 32%).

Характерной чертой развития страны в 1960–1999 была политическая стабильность. В серед. 1990-х действовало более 50-ти политических партий. Внесение поправки в конституцию (статья 35-я – наделение правом быть избранным в государственные органы власти только лиц, имеющих ивуарийское гражданство по рождению, вследствие брака или натурализации) не допустило выдвижение на пост президента кандидатуры Алласана Уаттары (буркинийца по происхождению). Он выдвигался партией «Объединение республиканцев» (ОР) и составлял серьезную конкуренцию А.Конану Бедье, единственному кандидату на предстоящих президентских выборах 2000. Многотысячные демонстрации, организованные оппозицией в сентябре 1998 в знак протеста против дискриминационной статьи конституции, сопровождались столкновениями с полицией. Политическая напряженность усилилась в октябре 1999 – в столице и других города прошли массовые демонстрации в поддержку А.Д.Уаттары, начались аресты активистов оппозиции. Их поддержали солдаты, недовольные задержкой выплаты им жалованья. Власти недооценили серьезность ситуации. Выступление военных возглавил отставной генерал Робер Гей. Мятежники взяли под контроль все ключевые службы столицы. Было объявлено о приостановлении действия конституции, смещении действующего президента, роспуске правительства и парламента. Власть перешла к Национальному комитету общественного спасения (НКОС) во главе с Р.Геем. Обстановка в стране вскоре была нормализована. В январе 2000 сформировано переходное правительство, в котором генерал Р.Гей занял пост президента республики и министра обороны.

Кот-д»Ивуар в 21 веке