- Крестное знамение Богословско-литургический словарь

- Крестное знамение Святые отцы и учителя Церкви

- Крестное знамение преп. Оптинские старцы

- Крестное знамение прав. Иоанн Кронштадтский

- О крестном знамении прот. Серафим Слободской

- Крестное знамение игумен Марк (Лозинский)

- О крестном знамении и его силе прот. Николай Успенский

- Крестное знамение преп. Амвросий Оптинский (Гренков)

- Крестное знамение прот. Димитрий Владыков

- Крестное знамение преп. Варсонофий Великий и Иоанн Пророк

- О крестном знамении мученик Николай Варжанский

- «Воцерковление для начинающих» свящ. Александр Торик

- О перстосложении для крестного знамения проф. Н.И. Субботин

- Крестное знамение еп. Виссарион (Нечаев)

- Крестное знамение архим. Макарий (Веретенников)

- Перстосложение

- Доказательства о древности трехперстного сложения и святительского имянословного благословения иеросхимонах Иоанн (Малиновский)

Кре́стное зна́мение – осенение знамением Креста, внешне выражаемое в таком движении руки, что оно воспроизводит символическое очертание Креста, на котором был распят Господь Иисус Христос; при этом осеняющий выражает внутреннюю веру во Святую Троицу; во Христа как в вочеловечившегося Сына Божьего, Искупителя людей; любовь и благодарность по отношению к Богу, надежду на Его защиту от действия падших духов, надежду на спасение.

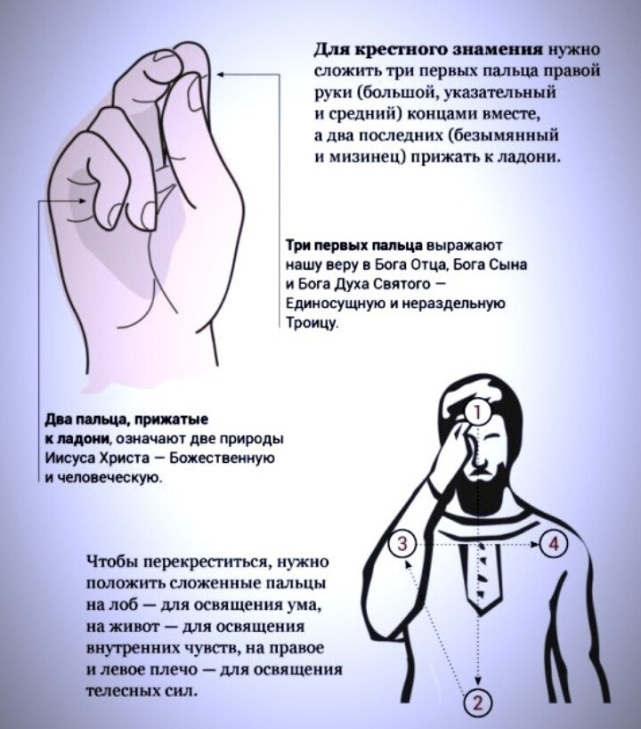

Сложенные вместе три первых пальца выражают нашу веру в Бога Отца, Бога Сына и Бога Святого Духа как единосущную и нераздельную Троицу, а два пальца, пригнутые к ладони, означают, что Сын Божий по воплощении Своем, будучи Богом, стал человеком, то есть означают Его две природы – Божескую и человеческую.

Осенять себя крестным знамением надо не торопясь: возложить его на лоб (1), на живот (2), на правое плечо (3) и затем на левое (4). Опустив правую руку можно делать поясной или земной поклон.

Осеняя себя крестным знамением, мы прикасаемся сложенными вместе тремя пальцами ко лбу – для освящения нашего ума, к животу – для освящения наших внутренних чувств (сердца), потом к правому, затем левому плечам – для освящения наших телесных сил.

О тех же, которые знаменуют себя всей пятерней, или кланяются, не окончив еще креста, или махают рукой своей по воздуху или по груди своей, святитель Иоанн Златоуст сказал: «Тому неистовому маханию бесы радуются». Напротив, крестное знамение, совершаемое правильно и неспешно, с верою и благоговением, устрашает бесов, утишает греховные страсти и привлекает Божественную благодать.

Сознавая свою греховность и недостоинство перед Богом, мы, в знак нашего смирения, сопровождаем нашу молитву поклонами. Они бывают поясными, когда наклоняемся до пояса, и земные, когда, кланяясь и становясь на колена, касаемся головою земли.

«Обычай делать крестное знамение берет начало со времен апостольских» (Полн. Правосл. богослов. энциклоп. Словарь, СПб. Изд. П.П.Сойкина, б.г., с. 1485).Во время Тертуллиана крестное знамение уже глубоко вошло в жизнь современных ему христиан. В трактате «О венце воина» (около 211 г.) он пишет, что мы ограждаем свое чело крестным знамением при всех обстоятельствах жизни: входя в дом и выходя из него, одеваясь, возжигая светильники, ложась спать, садясь за какое-либо занятие.

Крестное знамение не является лишь частью религиозного обряда. Прежде всего, это – великое оружие. Патерики, отечники и жития святых содержат много примеров, свидетельствующих о той реальной духовной силе, которой обладает образ Креста.

Уже святые апостолы силою крестного знамения совершали чудеса. Однажды апостол Иоанн Богослов нашел лежащим при дороге больного человека, сильно страдавшего горячкой, и исцелил его крестным знамением (Димитрий Ростовский, святитель. Житие святого апостола и евангелиста Иоанна Богослова. 26 сентября).

Преподобный Антоний Великий говорит о силе крестного знамения против демонов: «Посему, когда демоны приходят к вам ночью, хотят возвестить будущее или говорят: “Мы – ангелы”, не внимайте им – потому что лгут. Если будут они хвалить ваше подвижничество и ублажать вас, не слушайте их и нимало не сближайтесь с ними, лучше же себя и дом свой запечатлейте крестом и помолитесь. Тогда увидите, что они сделаются невидимыми, потому что боязливы и особенно страшатся знамения креста Господня. Ибо, крестом отъяв у них силу, посрамил их Спаситель» (Житие преподобного отца нашего Антония, описанное святым Афанасием в послании к инокам, пребывающим в чужих странах. 35).

В «Лавсаике» рассказывается о том, как авва Дорофей, сотворив крестное знамение, выпил воду, взятую из колодца, на дне которого был аспид: «Однажды авва Дорофей послал меня, Палладия, часу в девятом к своему колодцу налить кадку, из которой все брали воду. Было уже время обеда. Придя к колодцу, я увидел на дне его аспида и в испуге, не начерпав воды, побежал с криком: “Погибли мы, авва, на дне колодца я видел аспида”. Он усмехнулся скромно, потому что был ко мне весьма внимателен, и, покачав головой, сказал: “Если бы диаволу вздумалось набросать аспидов или других ядовитых гадов во все колодцы и источники, ты не стал бы вовсе пить?” Потом, придя из кельи, он сам налил кадку и, сотворив крестное знамение над ней, первый тотчас испил воды и сказал: “Где крест, там ничего не может злоба сатаны”».

Преподобный Венедикт Нурсийский (480–543) за строгую свою жизнь был избран в 510 году игуменом пещерного монастыря Виковаро. Святой Венедикт с усердием правил монастырем. Строго соблюдая устав постнического жития, он никому не позволял жить по своей воле, так что иноки стали раскаиваться, что выбрали себе такого игумена, который совершенно не подходил к их испорченным нравам. Некоторые решили его отравить. Они смешали яд с вином и дали пить игумену во время обеда. Святой сотворил над чашею крестное знамение, и сосуд силою святого креста тотчас же разбился, как бы от удара камнем. Тогда человек Божий познал, что чаша была смертоносна, ибо не могла выдержать животворящего креста» (Димитрий Ростовский, святитель. Житие преподобного отца нашего Венедикта. 14 марта).

Протоиерей Василий Шустин (1886–1968) вспоминает о старце Нектарии Оптинском: «Батюшка говорит мне: “Вытряси прежде самовар, затем налей воды, а ведь часто воду забывают налить и начинают разжигать самовар, а в результате самовар испортят и без чаю остаются. Вода стоит вот там, в углу, в медном кувшине; возьми его и налей”. Я подошел к кувшину, а тот был очень большой, ведра на два, и сам по себе массивный. Попробовал его подвинуть, нет – силы нету, тогда я хотел поднести к нему самовар и налить воды. Батюшка заметил мое намерение и опять мне повторяет: “Ты возьми кувшин и налей воду в самовар”. – “Да ведь, батюшка, он слишком тяжелый для меня, я его с места не могу сдвинуть”. Тогда батюшка подошел к кувшину, перекрестил его и говорит: “Возьми”, – и я поднял и с удивлением смотрел на батюшку: кувшин мне почувствовался совершенно легким, как бы ничего не весящим. Я налил воду в самовар и поставил кувшин обратно с выражением удивления на лице. А батюшка меня спрашивает: “Ну, что, тяжелый кувшин?” – “Нет, батюшка. Я удивляюсь: он совсем легкий”. – “Так вот и возьми урок, что всякое послушание, которое нам кажется тяжелым, при исполнении бывает очень легко, потому что это делается как послушание”. Но я был прямо поражен: как он уничтожил силу тяжести одним крестным знамением!» (См.: Шустин Василий, протоиерей. Запись об Иоанне Кронштадтском и об Оптинских старцах. М., 1991).

Каково происхождение крестного знамения?

Происхождение крестного знамения точно неизвестно. Свт. Василий Великий относил его к Таинствам, которые передаются в молчании по преданию и не записаны апостолами (“О том, откуда получил начало, и какую силу имеет слог «с», и вместе о не изложенных в Писании узаконениях Церкви”).

Есть ли в Священном Писании какие-либо указания на крестное знамение?

Прообразами крестного знамения в Священном Писании послужили заповедь «о знаке на челе», данная Господом прор. Иезекиилю (Иез.9:4), и слова Откровения Иоанна Богослова о «печатях на челах» верных (Откр.7:3, 9:4, 14:1). С крестным знамением пророчество Иезекииля связывают Тертуллиан, Ориген и сщмч. Киприан Карфагенский (“Что в этом знамении крестном заключается спасение для всех, кои будут назнаменованы им на челах своих”), при этом Ориген толкует «знак на челе» как изображение последней буквы евр. алфавита «тав», которая отождествляется с греч. буквой «тау» и по форме может напоминать крест (связь между «тау» и формой креста для распятия усматривали и некоторые языческие авторы). Возможно, знак креста выступал как один из вариантов написания имени Божия, чем объясняется присутствие знаков «тав» и креста в некоторых кумранских и иудейских магических текстах.

Как в древней Церкви совершалось крестное знамение?

Чаще всего в ранних источниках упоминается совершение крестного знамения одним пальцем или всей рукой, подчеркивая этим веру в единого Бога – в противовес языческому многобожию. Однако какое при этом употреблялось перстосложение и каким было направление движения (слева направо или справа налево), не указывается. Вероятно, наиболее распространенной формой было крестное знамение одним (указательным или большим) пальцем, о чем писали свт. Епифаний Кипрский и свт. Григорий Великий (“О Мартирии, иноке Валерийской области”). Однако свт. Кирилл Иерусалимский, говоря о крестном знамении, использует множественное число – «пальцами» (“Поучения огласительные” и также Patrologija Graeca). Наиболее распространенным местом наложения крестного знамения был лоб, о чем, например пишет Тертуллиан (“О венце воина”), иногда в сочетании с др. частями тела: лбом и областью сердца (о чем сообщает Пруденций — “Аврелий Пруденций Клемент”) или лбом, ушами, глазами и устами (согласно Киприану Карфагенскому). Также упоминается наложение крестного знамения на глаза, уста и область сердца (согласно Григорию Нисскому — “Послание о жизни преподобной Макрины”), уста и грудь и на все тело (согласно Тертуллиану — “Послание к жене”). К IV веку христиане стали осенять крестом все свое тело, то есть появился «широкий крест».

Двоеперстие при совершении крестного знамения, как считают некоторые исследователи, своим появлением было обязано распространению начиная с середины V в. ереси монофизитства; хотя прямых подтверждений этой точки зрения нет, из монофизитских источников и из позднейших свидетельств православно-монофизитской полемики видно, что для монофизитов одноперстие служило аргументом в пользу монофизитства, что заставляло православных использовать двоеперстие в качестве контраргумента. Распространению двоеперстия (имевшему место не только в греческом мире, но и на Западе) должно было способствовать и закрепление его в иконографии (но не наоборот).

Знаменитый пример использования пальцев руки в богословской дискуссии — выступление свт. Мелетия Антиохийского на Антиохийском Соборе 361 г. с обличением арианства, когда он проиллюстрировал мысль о единосущии Отца, Сына и Св. Духа путем разгибания трех пальцев руки и затем сгибания двух из них (много позднее на Руси этот пример сыграл определенную роль в полемике вокруг двоеперстия, поскольку интерпретировался как свидетельство об определенном перстосложении, хотя из рассказа древних церковных историков такой вывод сделать нельзя).

После распространения двоеперстия его богословское толкование как исповедания двух природ во Христе (что символизируют соединенные вместе указательный и средний пальцы) и одновременно троичности Лиц Божества (что символизируют соединенные вместе остальные пальцы) стало в Византии классическим. Тем не менее и после распространения двоеперстия византийская святоотеческая мысль продолжала подчеркивать второстепенность способа перстосложения по отношению к самому знаку креста, — напр., прп. Феодор Студит писал, что тот, кто изобразит крест «хоть как-нибудь и [даже] одним только перстом, [тот] тотчас обращает в бегство враждебного демона» (Патрология Миня).

Когда Русь крестилась в Православие, в Византии была достаточно распространена традиция креститься двумя перстами, каковой обычай перешел и на Русь. Около XIII в. в Византии двоеперстие было вытеснено троеперстием. Первым ясным свидетельством о троеперстии у греков является т. н. Прение Панагиота с Азимитом. Впрочем, известны и более поздние свидетельства о продолжении бытования у греков двоеперстия. Тем не менее со временем троеперстие распространилось в греческом мире повсеместно (так, в Пидалионе прп. Никодима Святогорца, в комментарии на 91‑е прав. свт. Василия Великого, Д. упоминается как старая форма перстосложения), а имевшие, очевидно, место случаи сосуществования троеперстия и двоеперстия никогда не вызывали споров и полемики, как это случилось на Руси.

В силу отрыва Руси от Византии, обычай совершать крестное знамение тремя пальцами не был введен на Руси до Никона. Староверы, не зная ничего о дальнейшем развитии церковной культуры в Византии, упорно держались за двуперстие.

В каких ситуациях следует налагать на себя крестное знамение?

Многие писатели Древней Церкви говорят о необходимости совершать крестное знамение как можно чаще и в самых разных жизненных ситуациях. Согласно Тертуллиану (“О венце воина”. § III), «при всяком входе и выходе, когда мы обуваемся и одеваемся, перед купаниями и приемами пищи, зажигая ли светильники, отходя ли ко сну, садясь ли или принимаясь за какое-либо дело, мы осеняем свое чело крестным знамением». Он же первым упоминает (“Послание к жене”. Глава 5) христианский обычай крестить свою постель перед сном. А, например, солдаты-христиане, согласно Пруденцию, крестились перед боем (“Аврелий Пруденций Клемент”).

Когда впервые стали совершать крестное знамение за богослужением?

В богослужении, по крайней мере, начиная с III в., крестное знамение используется как священнослужителями при совершении Таинств, так и всеми верными в определенные моменты службы. Уже Ориген сообщает о крестном знамении перед началом молитвы и чтения Священного Писания (см. Selecta in Ezechielem). Во многих традициях встречается наложение «печати» на чело оглашаемых при подготовке к принятию крещения или в качестве послекрещального signatio на новокрещеных.

Совершалось ли в древности крестное знамение за трапезой?

Перед трапезой крестное знамение всегда имело особое значение. Как на Востоке, так и на Западе встречаются истории о чудесном спасении при угрозе отравления ядом. Блж. Иоанн Мосх говорит, что Иулиан Бострский трижды крестообразно осенил перстом чашу со словами: «Во имя Отца и Сына и Святого Духа» и, выпив тайно подмешанный яд, остался невредим» (“О Иулиане, епископе Бостры”). Прп. Венедикт Нурсийский, которого также хотели отравить, «простерши руку, сделал над сосудом знамение креста, и сосуд, долго до того времени бывший в употреблении, так расселся от этого знамения, как будто бы вместо [наложения знамения] креста святой муж бросил в него камень», сообщает св. Григорий Великий (“Диалоги”).

Нужно ли осенять себя крестным знамением во время искушений?

Святые отцы призывали налагать крестное знамение при преодолении разных страстей. Например, блж. Иероним Стридонский упоминал совершение крестного знамения при печали и скорби о покойных, а свт. Иоанн Златоуст учил: «Обидел ли кто тебя? Огради крестным знамением грудь; вспомни все, что происходило на Кресте – и все погаснет» (Беседа 87). Однако чаще всего крестное знамение упоминается, в том числе сщмч. Киприаном Карфагенским (“Книга о падщих”), в качестве невидимой печати, отгоняющей диавола. Один из разделов «Апостольского предания» сщмч. Ипполита Римского подробно раскрывает именно этот аспект крестного знамения (“О крестном знамении”). Но больше всего о борьбе с демонами с помощью крестного знамения говорится в монашеской письменности. В Житии прп. Антония Великого приводится такое наставление: «Демоны, — говорит он, — производят мечтания для устрашения боязливых. Посему запечатлейте себя крестным знамением и идите назад смело, демонам же предоставьте делать из себя посмешище» (“Поучения”). В житии свт. Григория Чудотворца, епископа Неокесарийского, рассказывается о том, как он, будучи вынужден заночевать в языческом храме, изгнал всех демонов, начертав крестное знамение в воздухе во время обычных вечерних молитв. К помощи крестного знамения против демонов прибегали даже неверующие. Так, император Юлиан Отступник, уже отрекшись от веры, однажды невольно перекрестился, когда был испуган, пишет свт. Григорий Богослов (“Слово 4”).

Нужно ли осенять себя крестным знамением, если вдруг оказался в неправославном храме?

Церковные писатели IV–V вв. сообщают об обязательном наложении христианами крестного знамения при вынужденном входе в языческий храм или синагогу. Например, свт. Иоанн Златоуст (“Против иудеев”) пишет: «Как войдешь ты в синагогу? Если запечатлеешь лицо свое [крестным знамением], тотчас убежит вся вражеская сила, обитающая в синагоге; а если не запечатлеешь, то уже при самом входе ты бросишь свое оружие, и тогда диавол, нашедши тебя беззащитным и безоружным, причинит тебе множество зла». Особое внимание наложению крестного знамения уделялось даже при переходе из одного помещения в другое внутри монастыря или храма во времена прп. Колумбана Люксейского (VI–VII вв.) в ирландской монашеской традиции, где за неналожение крестного знамения даже предусматривалась епитимия.

Не считается ли язычеством вера в то, что после совершения крестного знамения можно исцелиться от того или иного недуга?

Упоминания о чудесных исцелениях после совершения крестного знамения встречаются, например, в монашеской письменности. Так, подвижник Петр «положил свою руку на глаз больного, изобразил знамение спасительного креста, и болезнь сразу исчезла», сообщает блж. Феодорит Кирский (“История боголюбцев”). Другой подвижник, пишет блж. Феодорит, – прп. Лимней – исцелял с помощью крестного знамения с призыванием имени Божия змеиные укусы.

Что дать почитать человеку, не признающему силу крестного знамения?

Такому человеку можно, например, предложить книгу «Толкование Канона на Воздвижение Честнаго и Животворящаго Креста Господня», творение святого Космы, составлено Никодимом Святогорцем. Перевод с греческого под редакцией профессора И. Н. Корсунского.

В чем отличие крестного знамения у православных и католиков?

Православные для совершения крестного знамения складывают три первые пальца правой руки (большой, указательный и средний), а два других пальца пригибают к ладони; после чего последовательно касаются лба, верхней части живота, правого плеча, затем левого. Три сложенных вместе перста символизируют Пресвятую Троицу; символическое значение двух других пальцев в разное время могло быть разным. Так, первоначально у греков они вовсе ничего не означали. Позднее, на Руси, под влиянием полемики со старообрядцами (утверждавшими, что «никонияне из креста Христова Христа упразднили») эти два пальца были переосмыслены как символ двух природ, соединенных в Ипостаси Христа: Божественной и человеческой. Это толкование является сейчас самым распространённым, хотя встречаются и другие (например, в Румынской церкви эти два пальца толкуются как символ Адама и Евы, припадающих к Троице). Рука, изображая крест, касается сначала правого плеча, потом левого, что символизирует традиционное для христианства противопоставление правой стороны как места спасённых и левой как места погибающих (Мф.25:31-46). Таким образом, поднося руку сначала к правому, затем к левому плечу, христианин просит причислить его к участи спасённых и избавить от участи погибающих.

Наиболее принятый и распространенный вариант в католическом мире – совершение крестного знамения пятью пальцами, открытой ладонью, слева направо, в память о пяти ранах на теле Христа.

Когда крестное знамение следует и не следует совершать на богослужении?

В современной практике Русской Православной Церкви крестное знамение обязательно совершается при благословении священным предметом — Евангелием, Крестом или Чашей. Также принято осенять себя крестным знамением при чтении или пении «Приидите, поклонимся», Трисвятого, в начале и при окончании чтения Священного Писания, на «Аллилуия», при чтении и пении Символа веры, на отпусте. Обычай креститься во время каждого из прошений различных ектений не является уставным (в греческой и древнерусской традициях он не встречается). Крестное знамение совершается при прохождении по храму напротив Царских врат. Крестятся при поставлении свечи на подсвечник перед иконой, перед прикладыванием к иконе, перед потреблением просфор. Креститься не положено во время архиерейского или иерейского приветствия «Мир всем» или иных возгласов, сопровождаемых благословением народа рукой. Крестное знамение не совершается во время чтения или пения псалмов и стихир, запрещено креститься при подходе к Святой Чаше для Причащения. Крестное знамение в определенных случаях сочетается с поклонами, но при этом они не должны совершаться одновременно с крестным знамением.

На иконах Иисус Христос или какой-либо святой порой изображаются, складывающими пальцы в особом перстосложении. Как это понимать?

Не только Иисус Христос или святые на иконах складывают пальцы в особом перстосложении, именуемом именословным. Так делает и православный священник, благословляя людей или предметы. Считается, что пальцы, сложенные таким образом, изображают буквы ІСХС, из которых потом надо сложить ІС ХС и мысленно прибавить титло, чтобы получилось имя Иисус Христос – І͠С Х͠С (Ιησούς Χριστός) в древнегреческом написании. При благословении руку при начертании поперечной линии креста ведут сначала налево (относительно преподающего благословение), потом направо, то есть, у человека, благословляемого таким образом, сначала осеняется правое плечо, потом левое. Архиерей имеет право преподавать благословение сразу двумя руками.

Почему на иконах Христос или какой-либо святой изображены с двоеперстием?

В православной иконографии рука, сложенная в крестное знамение, является распространенным элементом. В ходе полемики 2‑й половины XVII – начала XX веков по вопросу двоеперстия как его сторонники, так и его противники нередко ссылались на те или иные раннехристианские и византийские иконографические изображения. В очень большой степени широкое использование древних христианских изображений в целях апологии двоеперстия было вызвано тем, что в позднейшей практике, сохранявшейся на Руси до реформ патриарха Никона, и при совершении крестного знамения, и при священническом (или епископском) благословении употреблялось одно и то же двоеперстие, поэтому любые изображения Господа Иисуса Христа или святых с поднятой рукой и перстосложением, сходным с двоеперстием, воспринимались как однозначное свидетельство о двоеперстии (т. е., иными словами, как изображения благословения с использованием двоеперстия; необходимо отметить, что собственно крестное знамение в иконографии встречается редко). Впрочем, наряду с двоеперстием в иконографии Господа Иисуса Христа и святых часто встречаются и иные формы перстосложения – просто раскрытая ладонь, вытянутый указательный палец и т. н. ораторский жест (когда все пальцы, кроме большого и безымянного, вытянуты, а эти два сложены вместе), восходящий, как думает немало ученых, к античной традиции; возникновение двоеперстия в иконографии нередко связывали с упомянутым ораторским жестом. Однако такой подход к двоеперстию в иконографии, когда оно отождествляется с двоеперстным перстосложением при благословении (и тем более крестном знамении), неверен. Двоеперстие в иконографии Господа Иисуса Христа (а затем и святых) связано с т. н. жестом величия, состоявшем в поднятии руки с разогнутыми и соединенными вместе указательным и средним пальцами и согнутыми остальными (т. е. внешне совпадавшем с двоеперстием), который восходит к дохристианской римской традиции, где изображался в качестве знака триумфа. Так, одно из самых ранних изображений Христа с жестом величия (ошибочно отождествляемым полемистами с двоеперстием) в сюжете «Вход Господень в Иерусалим» на саркофаге Адельфии; символика жеста состоит не в двуперстном благословении Христом жителей Иерусалима, а в том, что Он изображен входящим в Святой град как Победитель и истинный Царь. Позднее жест величия, как и другие римские атрибуты (престол, клавы и др.), становится обычным элементом изображений Господа Иисуса Христа во славе. При этом, следует иметь в виду, существует немало типов изображений Господа Иисуса Христа, на которых упомянутый жест символизирует благословение.

Цитаты о крестном знамении

«Крестное знамение надо полагать правильно, со страхом Божиим, с верою, а не махать рукой. А потом поклониться, тогда оно имеет силу».

преподобный Севастиан Карагандинский

«Вначале христиане крестились одним перстом, подчеркивая этим веру в единого Бога – в противовес языческому многобожию. После Никейского вселенского собора (325 г.), сформулировавшего догмат о единстве двух природ во Христе, христиане стали креститься двумя перстами. Когда Русь крестилась в православие, в Византии крестились еще двумя перстами, каковой обычай перешел и на Русь. Затем, в XI веке, в противовес очередной ереси, отрицавшей Троичность Божию, было положено креститься тремя перстами (символ троичности). Но, в силу отрыва Руси от Византии, этот обычай не был введен на Руси до Никона. Староверы, не зная ничего о дальнейшем развитии церковной культуры в Византии, упорно держались за двуперстие».

С.А. Левицкий

«Не стыдимся исповедовать Распятого; с дерзновением да будет налагаема перстами печать, т. е. крест, на челе и на всем, на вкушаемом хлебе, на чашах с питием, на входах и исходах, перед сном, когда ложимся и когда встаем, бываем в пути и покоимся. Это – великое предохранение, доставляемое бедным даром, немощным без труда, потому что от Бога – благодать сия, знамение верных, страх демонам. На кресте победил их, властно поверг их позору (Кол.2:15). Как скоро видят крест, вспоминают Распятого; страшатся Сокрушившего главы змиевы. Не пренебрегай же этой печатью, потому что дается даром; напротив того, за это более почти Благодетеля».

свт. Кирилл Иерусалимский

Making the sign of the cross (Latin: signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with the right hand, often accompanied by spoken or mental recitation of the Trinitarian formula: «In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.»[1]

The use of the sign of the cross traces back to early Christianity, with the second century Apostolic Tradition directing that it be used during the minor exorcism of baptism, during ablutions before praying at fixed prayer times, and in times of temptation.[2]

The movement is the tracing of the shape of a cross in the air or on one’s own body, echoing the traditional shape of the cross of the Christian crucifixion narrative. Where this is done with fingers joined, there are two principal forms: one—three fingers, right to left—is exclusively used by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Church of the East and the Eastern Catholic Churches in the Byzantine, Assyrian and Chaldean traditions; the other—left to right to middle, other than three fingers—sometimes used in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, Lutheranism, Anglicanism and in Oriental Orthodoxy. The sign of the cross is used in some denominations of Methodism and within some branches of Presbyterianism such as the Church of Scotland and in the PCUSA and some other Reformed Churches. The ritual is rare within other branches of Protestantism.

Many individuals use the expression «cross my heart and hope to die» as an oath, making the sign of the cross, in order to show «truthfulness and sincerity», sworn before God, in both personal and legal situations.[3]

Origins[edit]

The sign of the cross was originally made in some parts of the Christian world with the right-hand thumb across the forehead only.[4] In other parts of the early Christian world it was done with the whole hand or with two fingers.[5] Around the year 200 in Carthage (modern Tunisia, Africa), Tertullian wrote: «We Christians wear out our foreheads with the sign of the cross.»[6] Vestiges of this early variant of the practice remain: in the Roman Rite of the Mass in the Catholic Church, the celebrant makes this gesture on the Gospel book, on his lips, and on his heart at the proclamation of the Gospel;[4] on Ash Wednesday a cross is traced in ashes on the forehead; chrism is applied, among places on the body, on the forehead for the Holy Mystery of Chrismation in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[4]

Gesture[edit]

Historically, Western Catholics (the Latin Church) have made the motion from left to right, while Eastern Catholics have made the motion from right to left.[7] The Eastern Orthodox custom is also to make the motion from right to left.[8]

In the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches, the tips of the first three fingers (the thumb, index, and middle ones) are brought together, and the last two (the «ring» and little fingers) are pressed against the palm. The first three fingers express one’s faith in the Trinity, while the remaining two fingers represent the two natures of Jesus, divine and human.[9]

Motion[edit]

The sign of the cross is made by touching the hand sequentially to the forehead, lower chest or stomach, and both shoulders, accompanied by the Trinitarian formula: at the forehead In the name of the Father (or In nomine Patris in Latin); at the stomach or heart and of the Son (et Filii); across the shoulders and of the Holy Spirit/Ghost (et Spiritus Sancti); and finally: Amen.[10]

There are several interpretations, according to Church Fathers:[11] the forehead symbolizes Heaven; the solar plexus (or top of stomach), the earth; the shoulders, the place and sign of power. It also recalls both the Trinity and the Incarnation. Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) explained: «The sign of the cross is made with three fingers, because the signing is done together with the invocation of the Trinity. … This is how it is done: from above to below, and from the right to the left, because Christ descended from the heavens to the earth…»[12]

There are some variations: for example a person may first place the right hand in holy water. After moving the hand from one shoulder to the other, it may be returned to the top of the stomach. It may also be accompanied by the recitation of a prayer (e.g., the Jesus Prayer, or simply «Lord have mercy»). In some Catholic regions, like Spain, Italy and Latin America, it is customary to form a cross with the index finger and thumb and then to kiss one’s thumb at the conclusion of the gesture,[13]

Sequence[edit]

Cyril of Jerusalem (315–386)[14] wrote in his book about the Smaller Sign of the Cross.

Many have been crucified throughout the world, but by none of these are the devils scared; but when they see even the Sign of the Cross of Christ, who was crucified for us, they shudder. For those men died for their own sins, but Christ for the sins of others; for He did no sin, neither was guile found in His mouth. It is not Peter who says this, for then we might suspect that he was partial to his Teacher; but it is Esaias who says it, who was not indeed present with Him in the flesh, but in the Spirit foresaw His coming in the flesh.[15]

For others only hear, but we both see and handle. Let none be weary; take your armour against the adversaries in the cause of the Cross itself; set up the faith of the Cross as a trophy against the gainsayers. For when you are going to dispute with unbelievers concerning the Cross of Christ, first make with your hand the sign of Christ’s Cross, and the gainsayer will be silenced. Be not ashamed to confess the Cross; for Angels glory in it, saying, We know whom you seek, Jesus the Crucified. Matthew 28:5 Might you not say, O Angel, I know whom you seek, my Master? But, I, he says with boldness, I know the Crucified. For the Cross is a Crown, not a dishonour.[15]

Let us not then be ashamed to confess the Crucified. Be the Cross our seal made with boldness by our fingers on our brow, and on everything; over the bread we eat, and the cups we drink; in our comings in, and goings out; before our sleep, when we lie down and when we rise up; when we are in the way, and when we are still. Great is that preservative; it is without price, for the sake of the poor; without toil, for the sick; since also its grace is from God. It is the Sign of the faithful, and the dread of devils: for He triumphed over them in it, having made a show of them openly Colossians 2:15; for when they see the Cross they are reminded of the Crucified; they are afraid of Him, who bruised the heads of the dragon. Despise not the Seal, because of the freeness of the gift; out for this the rather honour your Benefactor.[15]

John of Damascus (650–750)[16]

Moreover we worship even the image of the precious and life-giving Cross, although made of another tree, not honouring the tree (God forbid) but the image as a symbol of Christ. For He said to His disciples, admonishing them, Then shall appear the sign of the Son of Man in Heaven Matthew 24:30, meaning the Cross. And so also the angel of the resurrection said to the woman, You seek Jesus of Nazareth which was crucified. Mark 16:6 And the Apostle said, We preach Christ crucified. 1 Corinthians 1:23 For there are many Christs and many Jesuses, but one crucified. He does not say speared but crucified. It behooves us, then, to worship the sign of Christ. For wherever the sign may be, there also will He be. But it does not behoove us to worship the material of which the image of the Cross is composed, even though it be gold or precious stones, after it is destroyed, if that should happen. Everything, therefore, that is dedicated to God we worship, conferring the adoration on Him.[17]

Herbert Thurston indicates that at one time both Eastern and Western Christians moved the hand from the right shoulder to the left. German theologian Valentin Thalhofer thought writings quoted in support of this point, such as that of Innocent III, refer to the small cross made upon the forehead or external objects, in which the hand moves naturally from right to left, and not the big cross made from shoulder to shoulder.[4] Andreas Andreopoulos, author of The Sign of the Cross, gives a more detailed description of the development and the symbolism of the placement of the fingers and the direction of the movement.[18]

Use[edit]

Catholicism[edit]

Within the Roman Catholic church, the sign of the cross is a sacramental, which the Church defines as «sacred signs which bear a resemblance to the sacraments»; that «signify effects, particularly of a spiritual nature, which are obtained through the intercession of the Church»; and that «always include a prayer, often accompanied by a specific sign, such as the laying on of hands, the sign of the cross, or the sprinkling of holy water (which recalls Baptism).»[19] Section 1670 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) states, «Sacramentals do not confer the grace of the Holy Spirit in the way that the sacraments do, but by the Church’s prayer, they prepare us to receive grace and dispose us to cooperate with it. For well-disposed members of the faithful, the liturgy of the sacraments and sacramentals sanctifies almost every event of their lives with the divine grace which flows from the Paschal mystery of the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ.»[19] Section 1671 of the CCC states: «Among sacramentals blessings (of persons, meals, objects, and places) come first. Every blessing praises God and prays for his gifts. In Christ, Christians are blessed by God the Father ‘with every spiritual blessing.’ This is why the Church imparts blessings by invoking the name of Jesus, usually while making the holy sign of the cross of Christ.»[19] Section 2157 of the CCC states: «The Christian begins his day, his prayers, and his activities with the Sign of the Cross: ‘in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.’ The baptized person dedicates the day to the glory of God and calls on the Savior’s grace which lets him act in the Spirit as a child of the Father. The sign of the cross strengthens us in temptations and difficulties.»[20]

John Vianney said a genuinely made Sign of the Cross «makes all hell tremble.»[21]

The Catholic Church’s Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite, the priest and the faithful make the Sign of the Cross at the conclusion of the Entrance Chant and the priest or deacon «makes the Sign of the Cross on the book and on his forehead, lips, and breast» when announcing the Gospel text (to which the people acclaim: «Glory to you, O Lord»).[22]

The sign of the cross is expected at two points of the Mass: the laity sign themselves during the introductory greeting of the service and at the final blessing; optionally, other times during the Mass when the laity often cross themselves are during a blessing with holy water, when concluding the penitential rite, in imitation of the priest before the Gospel reading (small signs on forehead, lips, and heart), and perhaps at other times out of private devotion.

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

Position of an Eastern Orthodox person’s fingers when making the sign of the cross

In the Eastern Orthodox churches, use of the sign of the cross in worship is far more frequent than in the Western churches.[23] While there are points in liturgy at which almost all worshipers cross themselves, Orthodox faithful have significant freedom to make the sign at other times as well,[24] and many make the sign frequently throughout Divine Liturgy or other church services.[25][26] During the epiclesis (invocation of Holy Spirit as part of the consecration of the Eucharist), the priest makes the sign of the cross over the bread.[27] The early theologian Basil of Caesarea noted the use of the sign of the cross in the rite marking the admission of catechumens.[28]

Old Believers[edit]

In the Tsardom of Russia, until the reforms of Patriarch Nikon in the 17th century, it was customary to make the sign of the cross with two fingers. The enforcement of the three-finger sign (as opposed to the two-finger sign of the «Old Rite»), as well as other Nikonite reforms (which alternated certain previous Russian practices to conform with Greek customs), were among the reasons for the schism with the Old Believers whose congregations continue to use the two-finger sign of the cross (other points of dispute included iconography and iconoclasm, as well as changes in liturgical practices).[29][30][31] The Old Believers considered the two-fingered symbol to symbolize the dual nature of Christ as divine and human (the other three fingers in the palm representing the Trinity).[30]

Protestant traditions[edit]

Lutheranism[edit]

Among Lutherans the practice was widely retained. For example, Luther’s Small Catechism states that it is expected before the morning and evening prayers. Lutheranism never abandoned the practice of making the sign of the cross in principle and it was commonly retained in worship at least until the early 19th century. During the 19th and early 20th centuries it was largely in disuse until the liturgical renewal movement of the 1950s and 1960s. One exception is The Lutheran Hymnal (1941) of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), which states that «The sign of the cross may be made at the Trinitarian Invocation and at the words of the Nicene Creed ‘and the life of the world to come.‘«[32] Since then, the sign of the cross has become fairly commonplace among Lutherans at worship. The sign of the cross is now customary in the Divine Service.[33][34] Rubrics in contemporary Lutheran worship manuals, including Evangelical Lutheran Worship of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Lutheran Service Book used by LCMS and Lutheran Church–Canada, provide for making the sign of the cross at certain points in the liturgy.[35][36]

Methodism[edit]

The sign of the cross can be found in the Methodist liturgy of the United Methodist Church.[37] John Wesley, the principal leader of the early Methodists, in a 1784 revision of The Book of Common Prayer for Methodist use called The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America, instructed the presiding minister to make the sign of the cross on the forehead of children just after they have been baptized. (This book was later adopted by Methodists in the United States for their liturgy.)[37][38] Wesley did not include the sign of the cross in other rites.[37]

By the early 20th century, the use of the sign of the cross had been dropped from American Methodist worship.[37] However, its uses was subsequently restored, and the current United Methodist Church allows the pastor to «trace on the forehead of each newly baptized person the sign of the cross.»[37] This usage during baptism is reflected in the current (1992) Book of Worship of the United Methodist Church, and is widely practiced (sometimes with oil).[39] Making of the sign is also common among United Methodists on Ash Wednesday, when it is applied by the elder to the foreheads of the laity as a mark of penitence.[37][40] In some United Methodist congregations, the worship leader makes the sign of the cross toward congregants (for example, when blessing the congregation at the end of the sermon or service), and individual congregants make the sign on themselves when receiving Holy Communion.[37] The sign is also sometimes made by pastors, with oil, upon the foreheads of those seeking healing.[41] In addition to its use in baptism, some Methodist clergy make the sign at the Communion table and during the Confession of Sin and Pardon at the invocation of Jesus’ name.[42]

Whether or not a Methodist uses the sign for private prayer is a personal choice, although the UMC encourages it as a devotional practice, stating: «Many United Methodists have found this restoration powerful and meaningful. The ancient and enduring power of the sign of the cross is available for us to use as United Methodists more abundantly now than ever in our history. And more and more United Methodists are expanding its use beyond those suggested in our official ritual.»[37]

Reformed tradition and Presbyterians[edit]

In some Reformed churches, such as the Presbyterian Church (USA), the sign of the cross is used on the foreheads during baptism and the Reaffirmation of the Baptismal Covenant.[43] It is also used at times during the Benecdition, the minister will make the sign of the cross out toward the congregation while invoking the Trinity.

Anglican and Episcopalian traditions[edit]

The English Reformation reduced the use of the sign of the cross compared to its use in Catholic rites. The 1549 Book of Common Prayer reduced the use of the sign of the cross by clergy during liturgy to five occasions, although an added note («As touching, kneeling, crossing, holding up of hands, and other gestures; they may be used or left as every man’s devotion serveth, without blame») gave more leeway to the faithful to make the sign.[44] The 1552 Book of Common Prayer (revived in 1559) reduced the five set uses to a single usage, during baptism.[44] The form of the sign was touching the head, chest, then both shoulders.[45]

The use of the mandatory sign of the cross during baptism was one of several points of contention between the established Church of England and Puritans, whom objected to this sole mandatory sign of the cross,[44][45] and its connections to the church’s Catholic past.[45] Nonconformists refused to use the sign.[45] In addition to its Catholic associations, the sign of the cross was significant in English folk traditions, with the sign believed to have a protective function against evil.[45] Puritans viewed the sign of the cross as superstitious and idolatrous.[45] Use of the sign of the cross during baptism was defended by King James I at the Hampton Court Conference and by the 1604 Code of Canons, and its continued use was one of many factors in the departure of Puritans from the Church of England.[44]

The 1789 Prayer Book of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America made the sign of the cross during baptism optional, apparently in concession to varying views within the church on the sign’s use.[44] The 1892 revision of the Prayer Book, however, made the sign mandatory.[44] The Anglo-Catholic movement saw a resurgence in the use of the sign of the cross within Anglicanism, including by laity and in church architecture and decoration;[46] historically, «high church» Anglicans were more apt to make the sign of the cross than «low church» Anglicans.[47] Objections to the use of the sign of the church within Anglicanism were largely dropped in the 20th century.[44] In some Anglican traditions, the sign of the cross is made by priests when consecrating the bread and wine of the Eucharist and when giving the priestly blessing at the end of a church service, and is made by congregants when receiving Communion.[48] More recently, some Anglican bishops have adopted the Roman Catholic practice of placing a sign of the cross (+) before their signatures.[46]

Armenian Apostolic[edit]

It is common practice in the Armenian Apostolic Church to make the sign of the cross when entering or passing a church, during the start of service and at many times during Divine Liturgy. The motion is performed by joining the first three fingers, to symbolize the Holy Trinity, and putting the two other fingers in the palm, then touching one’s forehead, below the chest, left side, then right side and finishing with open hand on the chest again with bowing head.[49][50]

Assyrian Church of the East[edit]

The Assyrian Church of the East uniquely holds the sign of the cross as a sacrament in its own right. Another sacrament unique to the church is the Holy Leaven.[51]

See also[edit]

- Christian symbolism

- Crossed fingers

- Mudras

- Prayer in Christianity

- Rushma in Mandaeism

- Veneration

References[edit]

- ^ «The Prayer of the Veil». Encyclopedia Coptica. 2011. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ Hippolytus. «Apostolic Tradition» (PDF). St. John’s Episcopal Church. pp. 8, 16, 17. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Ayto, John (8 July 2010). Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780199543786.

- ^ a b c d Thurston, Herbert. «Sign of the Cross.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 20 Jan. 2015

- ^ Andreas Andreopoulos, The Sign of the Cross, Paraclete Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-55725-496-2, p. 24.

- ^ Marucchi, Orazio. «Archæology of the Cross and Crucifix.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 20 Jan. 2015

- ^ Daniel A. Helminiak, Religion and the Human Sciences: An Approach Via Spirituality (State University of New York Press (Albany, N.Y.: 1998).

- ^ Ted A. Campbell, Christian Confessions: A Historical Introduction (Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), p. 45.

- ^ Slobodskoy, Serafim Alexivich (1992). «The Sign of the Cross». The Law of God. OrthodoxPhotos.com. Translated by Price, Susan. Holy Trinity Monastery (Jordanville, New York). ISBN 978-0-88465-044-7. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2019. Original: Слободской, Серафим Алексеевич (1957). «О крестном знамении» [The Sign of the Cross]. Закон Божий [The Law of God]. Православная энциклопедия Азбука веры | православный сайт (in Russian) (published 1966). Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, John F., The Externals of the Catholic Church, P.J. Kenedy & Sons (1918)

- ^ Prayer Book, edited by the Romanian Orthodox Church, several editions (Carte de rugăciuni — Editura Institutului biblic şi de misiune al Bisericii ortodoxe române, 2005),

- ^ «Est autem signum crucis tribus digitis exprimendum, quia sub invocatione Trinitatis imprimitur, de qua dicit propheta: Quis appendit tribus digitis molem terrae? (Isa. XL.) ita quod a superiori descendat in inferius, et a dextra transeat ad sinistram, quia Christus de coelo descendit in terram, et a Judaeis transivit ad gentes. Quidam tamen signum crucis a sinistra producunt in dextram; quia de miseria transire debemus ad gloriam, sicut et Christus transivit de morte ad vitam, et de inferno ad paradisum, praesertim ut seipsos et alios uno eodemque pariter modo consignent. Constat autem quod cum super alios signum crucis imprimimus, ipsos a sinistris consignamus in dextram. Verum si diligenter attendas, etiam super alios signum crucis a dextra producimus in sinistram, quia non consignamus eos quasi vertentes dorsum, sed quasi faciem praesentantes.» (Innocentius III, De sacro altaris mysterio, II, xlv in Patrologia Latina 217, 825C—D.)

- ^ Patricia Ann Kasten, Linking Your Beads: The Rosary’s History, Mysteries, and Prayers, Our Sunday Visitor 2011, p. 34

- ^ Mark W. Elliott, Thomas C. Oden. Isaiah 40-66. Intervarsity Press (2007): p. 335

- ^ a b c Cyril of Jerusalem. Catechetical Lecture 13. [1]

- ^ Steven A. McKinion, Thomas C. Oden. Isaiah 1-39. Intervarsity Press (2004): p. 279

- ^ John of Damascus. An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Vol. 4 [2]

- ^ Andreas Andreopoulos, The Sign of the Cross, Paraclete Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-55725-496-2, pp. 11–42.

- ^ a b c Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), chap. 4, art. 1.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), section 2157.

- ^ Emmons, D. D., «Making the Sign of the Cross», Catholic Digest Archived 13 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «The Order of Mass (The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite): In Latin and in English» (PDF). International Commission on English in the Liturgy. 2010.

- ^ Daniel B. Clendenin, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective (Baker Publishing: 2003), p. 19.

- ^ Daniel B. Clendenin, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective (Baker Publishing: 2003), p. 19.

- ^ Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy: The Development of the Eucharistic Liturgy in the Byzantine Rite (1989, St. Vladimir’s Press reprint, 2003), p. 5.

- ^ Anthony Edward Siecienski, Orthodox Christianity: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press: 2019), p. 83.

- ^ Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy: The Development of the Eucharistic Liturgy in the Byzantine Rite (1989, St. Vladimir’s Press reprint, 2003), p. 157.

- ^ Daniel B. Clendenin, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective (Baker Publishing: 2003) p. 110.

- ^ Peter T. De Simone, The Old Believers in Imperial Russia: Oppression, Opportunism and Religious Identity in Tsarist Moscow (2018), pp. 13, 54, 109, 206.

- ^ a b Gary M. Hamburg, Russia’s Path Toward Enlightenment: Faith, Politics, and Reason, 1500-1801 (Yale University Press, 2016), p. 179.

- ^ Peter Hauptmann, «Old Believers» in The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Vol. 3 (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company/Brill: 2003).

- ^ The Lutheran Hymnal, 1941. Concordia Publishing House: St. Louis, page 4.

- ^ «Why Do Lutherans Make the Sign of the Cross?». Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ «Sign of the Cross». Lutheran Church — Missouri Synod. Archived from the original on 20 September 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Evangelical Lutheran Worship. Minneapolis:Augsburg Fortress, 2006

- ^ Lutheran Service Book. St. Louis: Concordia, 2006

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Why don’t we make the sign of the cross?». United Methodist Church. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ John Wesley’s Prayer Book: The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America with introduction, notes, and commentary by James F. White, 1991 OSL Publications, Akron, Ohio, page 142.

- ^ The United Methodist Book of Worship, Nashville 1992, p. 91

- ^ The United Methodist Book of Worship, Nashville 1992, p. 323.

- ^ The United Methodist Book of Worship, Nashville 1992, p. 620.

- ^ Neal, Gregory S. (2011). «Prepared and Cross-Checked». Grace Incarnate Ministries. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ J. Dudley Weaver Jr., Presbyterian Worship: A Guide for Clergy (Geneva Press: 2002), pp. 86-87.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colin Buchanan, Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism (Rowman & Littlefield, 2nd ed.: 2015), pp. 533-35.

- ^ a b c d e f Louis P. Nelson, The Beauty of Holiness: Anglicanism and Architecture in Colonial South Carolina (University of North Carolina Press: 2009), p. 152.

- ^ a b Colin Buchanan, The A to Z of Anglicanism (Scarecrow Press: 2009), pp. 126-27.

- ^ Corinne Ware, What Is Liturgy? Forward Movement Publications (1996), p. 18.

- ^ Marcus Throup, All Things Anglican: Who We Are and What We Believe (Canterbury Press, 2018).

- ^ «Making the Sign of the Cross (Khachaknkel)». Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ «In the Shadow of the Cross: The Holy Cross and Armenian History». Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Royel, Mar Awa (2013). «The Sacrament of the Holy Leaven (Malkā) in the Assyrian Church of the East». In Giraudo, Cesare (ed.). The Anaphoral Genesis of the Institution Narrative in Light of the Anaphora of Addai and Mari. Rome: Edizioni Orientalia Christiana. p. 363. ISBN 978-88-97789-34-5.

External links[edit]

Making the sign of the cross (Latin: signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with the right hand, often accompanied by spoken or mental recitation of the Trinitarian formula: «In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.»[1]

The use of the sign of the cross traces back to early Christianity, with the second century Apostolic Tradition directing that it be used during the minor exorcism of baptism, during ablutions before praying at fixed prayer times, and in times of temptation.[2]

The movement is the tracing of the shape of a cross in the air or on one’s own body, echoing the traditional shape of the cross of the Christian crucifixion narrative. Where this is done with fingers joined, there are two principal forms: one—three fingers, right to left—is exclusively used by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Church of the East and the Eastern Catholic Churches in the Byzantine, Assyrian and Chaldean traditions; the other—left to right to middle, other than three fingers—sometimes used in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, Lutheranism, Anglicanism and in Oriental Orthodoxy. The sign of the cross is used in some denominations of Methodism and within some branches of Presbyterianism such as the Church of Scotland and in the PCUSA and some other Reformed Churches. The ritual is rare within other branches of Protestantism.

Many individuals use the expression «cross my heart and hope to die» as an oath, making the sign of the cross, in order to show «truthfulness and sincerity», sworn before God, in both personal and legal situations.[3]

Origins[edit]

The sign of the cross was originally made in some parts of the Christian world with the right-hand thumb across the forehead only.[4] In other parts of the early Christian world it was done with the whole hand or with two fingers.[5] Around the year 200 in Carthage (modern Tunisia, Africa), Tertullian wrote: «We Christians wear out our foreheads with the sign of the cross.»[6] Vestiges of this early variant of the practice remain: in the Roman Rite of the Mass in the Catholic Church, the celebrant makes this gesture on the Gospel book, on his lips, and on his heart at the proclamation of the Gospel;[4] on Ash Wednesday a cross is traced in ashes on the forehead; chrism is applied, among places on the body, on the forehead for the Holy Mystery of Chrismation in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[4]

Gesture[edit]

Historically, Western Catholics (the Latin Church) have made the motion from left to right, while Eastern Catholics have made the motion from right to left.[7] The Eastern Orthodox custom is also to make the motion from right to left.[8]

In the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches, the tips of the first three fingers (the thumb, index, and middle ones) are brought together, and the last two (the «ring» and little fingers) are pressed against the palm. The first three fingers express one’s faith in the Trinity, while the remaining two fingers represent the two natures of Jesus, divine and human.[9]

Motion[edit]

The sign of the cross is made by touching the hand sequentially to the forehead, lower chest or stomach, and both shoulders, accompanied by the Trinitarian formula: at the forehead In the name of the Father (or In nomine Patris in Latin); at the stomach or heart and of the Son (et Filii); across the shoulders and of the Holy Spirit/Ghost (et Spiritus Sancti); and finally: Amen.[10]

There are several interpretations, according to Church Fathers:[11] the forehead symbolizes Heaven; the solar plexus (or top of stomach), the earth; the shoulders, the place and sign of power. It also recalls both the Trinity and the Incarnation. Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) explained: «The sign of the cross is made with three fingers, because the signing is done together with the invocation of the Trinity. … This is how it is done: from above to below, and from the right to the left, because Christ descended from the heavens to the earth…»[12]

There are some variations: for example a person may first place the right hand in holy water. After moving the hand from one shoulder to the other, it may be returned to the top of the stomach. It may also be accompanied by the recitation of a prayer (e.g., the Jesus Prayer, or simply «Lord have mercy»). In some Catholic regions, like Spain, Italy and Latin America, it is customary to form a cross with the index finger and thumb and then to kiss one’s thumb at the conclusion of the gesture,[13]

Sequence[edit]

Cyril of Jerusalem (315–386)[14] wrote in his book about the Smaller Sign of the Cross.

Many have been crucified throughout the world, but by none of these are the devils scared; but when they see even the Sign of the Cross of Christ, who was crucified for us, they shudder. For those men died for their own sins, but Christ for the sins of others; for He did no sin, neither was guile found in His mouth. It is not Peter who says this, for then we might suspect that he was partial to his Teacher; but it is Esaias who says it, who was not indeed present with Him in the flesh, but in the Spirit foresaw His coming in the flesh.[15]

For others only hear, but we both see and handle. Let none be weary; take your armour against the adversaries in the cause of the Cross itself; set up the faith of the Cross as a trophy against the gainsayers. For when you are going to dispute with unbelievers concerning the Cross of Christ, first make with your hand the sign of Christ’s Cross, and the gainsayer will be silenced. Be not ashamed to confess the Cross; for Angels glory in it, saying, We know whom you seek, Jesus the Crucified. Matthew 28:5 Might you not say, O Angel, I know whom you seek, my Master? But, I, he says with boldness, I know the Crucified. For the Cross is a Crown, not a dishonour.[15]

Let us not then be ashamed to confess the Crucified. Be the Cross our seal made with boldness by our fingers on our brow, and on everything; over the bread we eat, and the cups we drink; in our comings in, and goings out; before our sleep, when we lie down and when we rise up; when we are in the way, and when we are still. Great is that preservative; it is without price, for the sake of the poor; without toil, for the sick; since also its grace is from God. It is the Sign of the faithful, and the dread of devils: for He triumphed over them in it, having made a show of them openly Colossians 2:15; for when they see the Cross they are reminded of the Crucified; they are afraid of Him, who bruised the heads of the dragon. Despise not the Seal, because of the freeness of the gift; out for this the rather honour your Benefactor.[15]

John of Damascus (650–750)[16]

Moreover we worship even the image of the precious and life-giving Cross, although made of another tree, not honouring the tree (God forbid) but the image as a symbol of Christ. For He said to His disciples, admonishing them, Then shall appear the sign of the Son of Man in Heaven Matthew 24:30, meaning the Cross. And so also the angel of the resurrection said to the woman, You seek Jesus of Nazareth which was crucified. Mark 16:6 And the Apostle said, We preach Christ crucified. 1 Corinthians 1:23 For there are many Christs and many Jesuses, but one crucified. He does not say speared but crucified. It behooves us, then, to worship the sign of Christ. For wherever the sign may be, there also will He be. But it does not behoove us to worship the material of which the image of the Cross is composed, even though it be gold or precious stones, after it is destroyed, if that should happen. Everything, therefore, that is dedicated to God we worship, conferring the adoration on Him.[17]

Herbert Thurston indicates that at one time both Eastern and Western Christians moved the hand from the right shoulder to the left. German theologian Valentin Thalhofer thought writings quoted in support of this point, such as that of Innocent III, refer to the small cross made upon the forehead or external objects, in which the hand moves naturally from right to left, and not the big cross made from shoulder to shoulder.[4] Andreas Andreopoulos, author of The Sign of the Cross, gives a more detailed description of the development and the symbolism of the placement of the fingers and the direction of the movement.[18]

Use[edit]

Catholicism[edit]

Within the Roman Catholic church, the sign of the cross is a sacramental, which the Church defines as «sacred signs which bear a resemblance to the sacraments»; that «signify effects, particularly of a spiritual nature, which are obtained through the intercession of the Church»; and that «always include a prayer, often accompanied by a specific sign, such as the laying on of hands, the sign of the cross, or the sprinkling of holy water (which recalls Baptism).»[19] Section 1670 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) states, «Sacramentals do not confer the grace of the Holy Spirit in the way that the sacraments do, but by the Church’s prayer, they prepare us to receive grace and dispose us to cooperate with it. For well-disposed members of the faithful, the liturgy of the sacraments and sacramentals sanctifies almost every event of their lives with the divine grace which flows from the Paschal mystery of the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ.»[19] Section 1671 of the CCC states: «Among sacramentals blessings (of persons, meals, objects, and places) come first. Every blessing praises God and prays for his gifts. In Christ, Christians are blessed by God the Father ‘with every spiritual blessing.’ This is why the Church imparts blessings by invoking the name of Jesus, usually while making the holy sign of the cross of Christ.»[19] Section 2157 of the CCC states: «The Christian begins his day, his prayers, and his activities with the Sign of the Cross: ‘in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.’ The baptized person dedicates the day to the glory of God and calls on the Savior’s grace which lets him act in the Spirit as a child of the Father. The sign of the cross strengthens us in temptations and difficulties.»[20]

John Vianney said a genuinely made Sign of the Cross «makes all hell tremble.»[21]

The Catholic Church’s Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite, the priest and the faithful make the Sign of the Cross at the conclusion of the Entrance Chant and the priest or deacon «makes the Sign of the Cross on the book and on his forehead, lips, and breast» when announcing the Gospel text (to which the people acclaim: «Glory to you, O Lord»).[22]

The sign of the cross is expected at two points of the Mass: the laity sign themselves during the introductory greeting of the service and at the final blessing; optionally, other times during the Mass when the laity often cross themselves are during a blessing with holy water, when concluding the penitential rite, in imitation of the priest before the Gospel reading (small signs on forehead, lips, and heart), and perhaps at other times out of private devotion.

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

Position of an Eastern Orthodox person’s fingers when making the sign of the cross

In the Eastern Orthodox churches, use of the sign of the cross in worship is far more frequent than in the Western churches.[23] While there are points in liturgy at which almost all worshipers cross themselves, Orthodox faithful have significant freedom to make the sign at other times as well,[24] and many make the sign frequently throughout Divine Liturgy or other church services.[25][26] During the epiclesis (invocation of Holy Spirit as part of the consecration of the Eucharist), the priest makes the sign of the cross over the bread.[27] The early theologian Basil of Caesarea noted the use of the sign of the cross in the rite marking the admission of catechumens.[28]

Old Believers[edit]

In the Tsardom of Russia, until the reforms of Patriarch Nikon in the 17th century, it was customary to make the sign of the cross with two fingers. The enforcement of the three-finger sign (as opposed to the two-finger sign of the «Old Rite»), as well as other Nikonite reforms (which alternated certain previous Russian practices to conform with Greek customs), were among the reasons for the schism with the Old Believers whose congregations continue to use the two-finger sign of the cross (other points of dispute included iconography and iconoclasm, as well as changes in liturgical practices).[29][30][31] The Old Believers considered the two-fingered symbol to symbolize the dual nature of Christ as divine and human (the other three fingers in the palm representing the Trinity).[30]

Protestant traditions[edit]

Lutheranism[edit]

Among Lutherans the practice was widely retained. For example, Luther’s Small Catechism states that it is expected before the morning and evening prayers. Lutheranism never abandoned the practice of making the sign of the cross in principle and it was commonly retained in worship at least until the early 19th century. During the 19th and early 20th centuries it was largely in disuse until the liturgical renewal movement of the 1950s and 1960s. One exception is The Lutheran Hymnal (1941) of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), which states that «The sign of the cross may be made at the Trinitarian Invocation and at the words of the Nicene Creed ‘and the life of the world to come.‘«[32] Since then, the sign of the cross has become fairly commonplace among Lutherans at worship. The sign of the cross is now customary in the Divine Service.[33][34] Rubrics in contemporary Lutheran worship manuals, including Evangelical Lutheran Worship of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Lutheran Service Book used by LCMS and Lutheran Church–Canada, provide for making the sign of the cross at certain points in the liturgy.[35][36]

Methodism[edit]

The sign of the cross can be found in the Methodist liturgy of the United Methodist Church.[37] John Wesley, the principal leader of the early Methodists, in a 1784 revision of The Book of Common Prayer for Methodist use called The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America, instructed the presiding minister to make the sign of the cross on the forehead of children just after they have been baptized. (This book was later adopted by Methodists in the United States for their liturgy.)[37][38] Wesley did not include the sign of the cross in other rites.[37]

By the early 20th century, the use of the sign of the cross had been dropped from American Methodist worship.[37] However, its uses was subsequently restored, and the current United Methodist Church allows the pastor to «trace on the forehead of each newly baptized person the sign of the cross.»[37] This usage during baptism is reflected in the current (1992) Book of Worship of the United Methodist Church, and is widely practiced (sometimes with oil).[39] Making of the sign is also common among United Methodists on Ash Wednesday, when it is applied by the elder to the foreheads of the laity as a mark of penitence.[37][40] In some United Methodist congregations, the worship leader makes the sign of the cross toward congregants (for example, when blessing the congregation at the end of the sermon or service), and individual congregants make the sign on themselves when receiving Holy Communion.[37] The sign is also sometimes made by pastors, with oil, upon the foreheads of those seeking healing.[41] In addition to its use in baptism, some Methodist clergy make the sign at the Communion table and during the Confession of Sin and Pardon at the invocation of Jesus’ name.[42]

Whether or not a Methodist uses the sign for private prayer is a personal choice, although the UMC encourages it as a devotional practice, stating: «Many United Methodists have found this restoration powerful and meaningful. The ancient and enduring power of the sign of the cross is available for us to use as United Methodists more abundantly now than ever in our history. And more and more United Methodists are expanding its use beyond those suggested in our official ritual.»[37]

Reformed tradition and Presbyterians[edit]

In some Reformed churches, such as the Presbyterian Church (USA), the sign of the cross is used on the foreheads during baptism and the Reaffirmation of the Baptismal Covenant.[43] It is also used at times during the Benecdition, the minister will make the sign of the cross out toward the congregation while invoking the Trinity.

Anglican and Episcopalian traditions[edit]

The English Reformation reduced the use of the sign of the cross compared to its use in Catholic rites. The 1549 Book of Common Prayer reduced the use of the sign of the cross by clergy during liturgy to five occasions, although an added note («As touching, kneeling, crossing, holding up of hands, and other gestures; they may be used or left as every man’s devotion serveth, without blame») gave more leeway to the faithful to make the sign.[44] The 1552 Book of Common Prayer (revived in 1559) reduced the five set uses to a single usage, during baptism.[44] The form of the sign was touching the head, chest, then both shoulders.[45]

The use of the mandatory sign of the cross during baptism was one of several points of contention between the established Church of England and Puritans, whom objected to this sole mandatory sign of the cross,[44][45] and its connections to the church’s Catholic past.[45] Nonconformists refused to use the sign.[45] In addition to its Catholic associations, the sign of the cross was significant in English folk traditions, with the sign believed to have a protective function against evil.[45] Puritans viewed the sign of the cross as superstitious and idolatrous.[45] Use of the sign of the cross during baptism was defended by King James I at the Hampton Court Conference and by the 1604 Code of Canons, and its continued use was one of many factors in the departure of Puritans from the Church of England.[44]

The 1789 Prayer Book of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America made the sign of the cross during baptism optional, apparently in concession to varying views within the church on the sign’s use.[44] The 1892 revision of the Prayer Book, however, made the sign mandatory.[44] The Anglo-Catholic movement saw a resurgence in the use of the sign of the cross within Anglicanism, including by laity and in church architecture and decoration;[46] historically, «high church» Anglicans were more apt to make the sign of the cross than «low church» Anglicans.[47] Objections to the use of the sign of the church within Anglicanism were largely dropped in the 20th century.[44] In some Anglican traditions, the sign of the cross is made by priests when consecrating the bread and wine of the Eucharist and when giving the priestly blessing at the end of a church service, and is made by congregants when receiving Communion.[48] More recently, some Anglican bishops have adopted the Roman Catholic practice of placing a sign of the cross (+) before their signatures.[46]

Armenian Apostolic[edit]

It is common practice in the Armenian Apostolic Church to make the sign of the cross when entering or passing a church, during the start of service and at many times during Divine Liturgy. The motion is performed by joining the first three fingers, to symbolize the Holy Trinity, and putting the two other fingers in the palm, then touching one’s forehead, below the chest, left side, then right side and finishing with open hand on the chest again with bowing head.[49][50]

Assyrian Church of the East[edit]

The Assyrian Church of the East uniquely holds the sign of the cross as a sacrament in its own right. Another sacrament unique to the church is the Holy Leaven.[51]

See also[edit]

- Christian symbolism

- Crossed fingers

- Mudras

- Prayer in Christianity

- Rushma in Mandaeism

- Veneration

References[edit]

- ^ «The Prayer of the Veil». Encyclopedia Coptica. 2011. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ Hippolytus. «Apostolic Tradition» (PDF). St. John’s Episcopal Church. pp. 8, 16, 17. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Ayto, John (8 July 2010). Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780199543786.

- ^ a b c d Thurston, Herbert. «Sign of the Cross.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 20 Jan. 2015

- ^ Andreas Andreopoulos, The Sign of the Cross, Paraclete Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-55725-496-2, p. 24.

- ^ Marucchi, Orazio. «Archæology of the Cross and Crucifix.» The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 20 Jan. 2015

- ^ Daniel A. Helminiak, Religion and the Human Sciences: An Approach Via Spirituality (State University of New York Press (Albany, N.Y.: 1998).

- ^ Ted A. Campbell, Christian Confessions: A Historical Introduction (Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), p. 45.

- ^ Slobodskoy, Serafim Alexivich (1992). «The Sign of the Cross». The Law of God. OrthodoxPhotos.com. Translated by Price, Susan. Holy Trinity Monastery (Jordanville, New York). ISBN 978-0-88465-044-7. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2019. Original: Слободской, Серафим Алексеевич (1957). «О крестном знамении» [The Sign of the Cross]. Закон Божий [The Law of God]. Православная энциклопедия Азбука веры | православный сайт (in Russian) (published 1966). Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, John F., The Externals of the Catholic Church, P.J. Kenedy & Sons (1918)

- ^ Prayer Book, edited by the Romanian Orthodox Church, several editions (Carte de rugăciuni — Editura Institutului biblic şi de misiune al Bisericii ortodoxe române, 2005),

- ^ «Est autem signum crucis tribus digitis exprimendum, quia sub invocatione Trinitatis imprimitur, de qua dicit propheta: Quis appendit tribus digitis molem terrae? (Isa. XL.) ita quod a superiori descendat in inferius, et a dextra transeat ad sinistram, quia Christus de coelo descendit in terram, et a Judaeis transivit ad gentes. Quidam tamen signum crucis a sinistra producunt in dextram; quia de miseria transire debemus ad gloriam, sicut et Christus transivit de morte ad vitam, et de inferno ad paradisum, praesertim ut seipsos et alios uno eodemque pariter modo consignent. Constat autem quod cum super alios signum crucis imprimimus, ipsos a sinistris consignamus in dextram. Verum si diligenter attendas, etiam super alios signum crucis a dextra producimus in sinistram, quia non consignamus eos quasi vertentes dorsum, sed quasi faciem praesentantes.» (Innocentius III, De sacro altaris mysterio, II, xlv in Patrologia Latina 217, 825C—D.)

- ^ Patricia Ann Kasten, Linking Your Beads: The Rosary’s History, Mysteries, and Prayers, Our Sunday Visitor 2011, p. 34

- ^ Mark W. Elliott, Thomas C. Oden. Isaiah 40-66. Intervarsity Press (2007): p. 335

- ^ a b c Cyril of Jerusalem. Catechetical Lecture 13. [1]

- ^ Steven A. McKinion, Thomas C. Oden. Isaiah 1-39. Intervarsity Press (2004): p. 279

- ^ John of Damascus. An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Vol. 4 [2]

- ^ Andreas Andreopoulos, The Sign of the Cross, Paraclete Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-55725-496-2, pp. 11–42.

- ^ a b c Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), chap. 4, art. 1.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), section 2157.

- ^ Emmons, D. D., «Making the Sign of the Cross», Catholic Digest Archived 13 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «The Order of Mass (The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite): In Latin and in English» (PDF). International Commission on English in the Liturgy. 2010.

- ^ Daniel B. Clendenin, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective (Baker Publishing: 2003), p. 19.

- ^ Daniel B. Clendenin, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective (Baker Publishing: 2003), p. 19.

- ^ Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy: The Development of the Eucharistic Liturgy in the Byzantine Rite (1989, St. Vladimir’s Press reprint, 2003), p. 5.

- ^ Anthony Edward Siecienski, Orthodox Christianity: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press: 2019), p. 83.

- ^ Hugh Wybrew, The Orthodox Liturgy: The Development of the Eucharistic Liturgy in the Byzantine Rite (1989, St. Vladimir’s Press reprint, 2003), p. 157.

- ^ Daniel B. Clendenin, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective (Baker Publishing: 2003) p. 110.

- ^ Peter T. De Simone, The Old Believers in Imperial Russia: Oppression, Opportunism and Religious Identity in Tsarist Moscow (2018), pp. 13, 54, 109, 206.

- ^ a b Gary M. Hamburg, Russia’s Path Toward Enlightenment: Faith, Politics, and Reason, 1500-1801 (Yale University Press, 2016), p. 179.

- ^ Peter Hauptmann, «Old Believers» in The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Vol. 3 (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company/Brill: 2003).

- ^ The Lutheran Hymnal, 1941. Concordia Publishing House: St. Louis, page 4.

- ^ «Why Do Lutherans Make the Sign of the Cross?». Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ «Sign of the Cross». Lutheran Church — Missouri Synod. Archived from the original on 20 September 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Evangelical Lutheran Worship. Minneapolis:Augsburg Fortress, 2006

- ^ Lutheran Service Book. St. Louis: Concordia, 2006

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Why don’t we make the sign of the cross?». United Methodist Church. Retrieved September 19, 2022.