А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

латви́йский, (от Ла́твия)

Рядом по алфавиту:

ла́сты , ласт и -ов, ед. ласт, -а

ла́стящийся

лат , -а (ден. ед.)

ла́та , -ы (часть оснастки паруса)

латаки́йский , (от Латаки́я)

латаки́йцы , -ев, ед. -и́ец, -и́йца, тв. -и́йцем

лата́ние , -я (от лата́ть) (сниж.)

лата́ния , -и (пальма)

ла́танный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана, прич. (сниж.)

ла́тано-перела́тано , (сниж.)

ла́таный , прил. (сниж.)

ла́таный-перела́таный

лататы́ , : зада́ть лататы́ (сниж.)

лата́ть(ся) , -а́ю, -а́ет(ся) (сниж.)

латви́йка , -и, р. мн. -и́ек

латви́йский , (от Ла́твия)

латви́йско-росси́йский

латви́йцы , -ев, ед. -и́ец, -и́йца, тв. -и́йцем

латга́лка , -и, р. мн. -лок

латга́лы , -ов, ед. -га́л, -а

латга́льский

латга́льцы , -ев, ед. -лец, -льца, тв. -льцем

ла́текс , -а

ла́тексный

латенсифика́ция , -и

лате́нский , (лате́нская культу́ра, археол.)

лате́нтность , -и

лате́нтный , кр. ф. -тен, -тна

лате́нция , -и

латера́льность , -и

латера́льный

Латышский (латвийский) язык

1. Общая информация о латышском языке.

Латышский язык является государственным языком Латвийской Республики. Он широко распрострянён в бытовой сфере, является обязательным для использования в законодательной сфере, судопроизводстве, делопроизводстве и образовании. Как показывают статистические данные, в Латвии проживает 1,4 миллиона носителей латышского языка, а еще 140 тысяч — за ее пределами.

Язык латышского народа принадлежит к семье индоевропейских языков, группе балтских языков. Древне балтские племена латгалов, селов, земгалов, куршей и ливов оказали огромное влияние на развитие данной группы языков. По своей структуре и лексическим, фонетическим и грамматическим особенностям близким к латышскому считается литовский язык. Их разделение произошло в VI–VII веках нашей эры, но даже сейчас они имеют множество общих черт.

Латышский язык распадается на 3 основных диалекта (ливский, средний, аугшземский), которые в свою очередь делятся на 512 говоров.

За основу литературного латышского языка взят средний диалект, который более, чем все остальные отображает все особенности древнего формирования латышского, его звуки и интонации.

За всю историю развития латышского языка наблюдалась конкуренция со стороны немецкого и русского языков. Самое заметное влияние русского языка на латышский наблюдается в советский период. До сих пор в стране проживает большое количество русскоговорящих граждан. Это помогает путешественнику из России в Латвии преодолеть языковой барьер, так как он сможет объясниться с местным населением на своем родном языке.

Сегодня латышский язык относят к современному европейскому языку, и является государственным языком Латвийской республики. Им пользуются латыши, представляющие все слои общества. Латышский выполняет самые важные социолингвистические функции в многоэтническом сообществе Латвии.

В Латвии 1,4 миллиона носителей латышского языка, а также около 150 000 за границей. Латышский язык можно даже считать широко распространенным языком, т.е. в мире всего около 250 языков, на которых говорят более одного миллиона человек, и среди них – латышский язык.

2. История латышского языка.

Появление первых письменных документов на латышском языке возникает в 16 – 17 в. Первой печатной книгой считается катехизис, появившийся в 1585 году. Далее была напечатана версия лютеранского катехизиса на латышском языке. Георг Манселиус внёс огромный вклад в создание первого латышского словаря в 1638 году «Lettus». Основоположниками создания латышской системы письма были немецкие монахи, они же являются создателями религиозных текстов. В основе лежала немецкая система письма, однако она не полностью отражала особенности разговорного латышского языка. Тексты этого периода были написаны готическим шрифтом.

Создание в начале XIII века на латыни «Хроники Ливонии» принадлежало католическому священнику Генриху, предположительно, латгалу по происхождению написал на латыни. В книге было дано описание событий, связанных с завоеванием эстонских и ливских земель.

В начале 20 века формируются различные идеи по реформе латышской системы письма. Однако принятой считается система, разработанная Й. Эндзелин и К. Мюленбах. На смену готическому шрифту в новом алфавите приходит латинский. Далее алфавит не претерпевал изменений до включения Латвии в Советский Союз. В последующие годы правительством Латвийской ССР были внесены поправки и буквы r и o, а также лигатура ch, были исключены из латышского письма. С того времени существует два различных варианта латышского письма. Латыши живущие за пределами Латвии продолжают пользоваться системой, существовавшей до 1940 года, в то время как в Латвии используется система с изменениями, внесенными советским правительством. Поэтому до сих пор не предпринято попыток выбрать какую-то одну систему или провести реформу латышского письма.

Большенство букв латышского алфавита взяты из латинского 22 из 33 букв (исключены Q q, W w, X x, Y y), а остальные 11 образованы при помощи диакритических значков.

XVII в. связан с появлением первых светских книг, азбук и др., написанных по-латышски (опять же, непонятно-леттен-это латгальский, латгало-латышский или латышский) священниками-немцами (в 1644 г. вышла первая из них, составленная И. Г. Регехузеном, священником из Айзкраукле), нескольких словарей, отдельных статей, посвященных вопросам правописания.

Благодаря немецким грамматистам фиксировались законы создаваемого латышского языка, описывались сравнительно верные правила морфологии, стабилизировалось правописание. В целом набрался довольно богатый лексический материал. Переводные латышско-немецкие двуязычные словари составляли основную часть. Однако все эти языковедческие работы XVII в. в основном не использовались латышами, зато имели большое значение для иноземцев в Латвии, прежде всего для священников-немцев. В настоящее время этот материал является ценным и незаменимым.

Одним из наиболее ярких и известных представителей латышской духовной литературы XVII в. был немецкий священник Георг Манцель (1593—1654). Долгое время он был священником в сельских приходах, что помогло хорошо овладеть латышским языком. Некоторое время он был профессором теологии Тартуского университета, затем стал его проректором, наконец ректором. В 1638 г. Остаток своей жизни он провёл в своём родном городе, где был придворным священником в Елгаве (Митаве).

Манцель считался одним из наиболее образованных людей Латвии в свое время. Помимо теологии он интересовался также языкознанием, естественными науками, поэзией.

Первым произведением Манцеля, опубликованном на латышском языке является «Латышский катехизис» (Lettisch Vade mecum, 1631). Он представляет собой переработанное и дополненное издание лютеранского пособия.

Главным произведением Манцеля является посвящённый немецким священникам «Долгожданный сборник латышских проповедей» (1654). Он обращяется к ним с просьбой лучше изучить немецкий язык для того, чтобы лучше понимать прихожан.

Христофор Фюрекер (примерно 1615—1685) также внёс огромный вклад в развитие духовной литературы XVII в. В университете в Тарту он занимался изучением теологии, а затем начал работать домашним учителем в поместьях Курземе. Основу его деятельности составляли переводы с немецкого языка большого количества лютеранских церковных псалмов. Он стал основоположником силлабо-тонического стихосложения с различными размерами и ритмами. Также он внёс вклад в копилку материала для латышской грамматики и для немецко-латышского словаря. Его материалы использовались в трудах других авторов.

Он был примером и идейным покровителем для других священников, которые сочиняли и переводили духовные песнопения, но с меньшим успехом. Иоганн Вишман был одним из последователей Фюрекера. В своей книге «Не немецкий Опиц» (1697) он даёт теоретические и практические советы по написанию псалмов. Мнение автора заключается в том, что он считает поэтическое искусство ремеслом, которому каждый может научиться путем непрестанных упражнений. Таким образом, благодаря этой книге появляются первые попытки в области теории латышской поэзии.

Все церковные песнопения Фюрекера и многих его последователей были собраны в конце XVII в. в единую, так называемую «Книгу песен». Она переиздавалась много раз и стала распространенной книгой, которую можно было найти в любом крестьянском доме.

Георг Эльгер — единственный известный католический автор в XVII в.(1585—1672). Им были опубликованы католические псалмы, евангельские тексты, катехизис, однако они не отражали жизнь латышского народа и содержали не очень хороший перевод. Самым крупным произведением Эльгера считается польско-латинско- латышский словарь (Вильнюс, 1683).

Все названные авторы носили немецкую фамилию. Представителем латышей в области латышской духовной литературы XVII в. был лишь один латыш (с немецкой фамилией) — Иоганн Рейтер (1632—1695). Он имел образование в области теологии, медицины и юриспруденции, много путешествовал, прожил бурную жизнь. Им были переведены на латышский язык некоторые тексты Нового Завета, опубликована молитва «Отче наш» на сорока языках. Рейтеру часто приходилось уклоняться от нападок из-за своего происхождения, а также потому, что он осмеливался защищать крестьян от произвола помещиков. Однажды он был даже арестован и удален из прихода.

Одним из лучших переводов Библии в XVII в. считался перевод Библии, выполненный пастором Эрнстом Глюком (1652—1705) и его помощниками. Сначала в Риге появился Новый Завет в 1685 г., а всё издание Библии появилось лишь в 1694 г. Перевод сделан с оригинала (древнегреческого и древнееврейского). Этот первый перевод Библии был очень важным, так как благодаря ему происходила стабилизация орфографии латышского письменного языка.

Основоположником национальной латышской грамматики и поэтики был Г. Ф. Штендер, во 2-й полов. XVIII в. В 1868 И. П. Крауклисом в Риге на русском языке опубликовано “Руководство для изучения латышского языка. Грамматика”. В 1872 г. К. Хр. Ульман опубликовал в Риге “Латышско-немецкий словарь”. Грамматические исследования И. Вельме, в Москве, “О латышском причастии” (1885) и “О троякой долготе латышских гласных (1893); П. Крумберга, “Aussprache lett. Debuwörter” (1881); К. Мюленбаха, по Л. синтаксису (“Daži jautajumi par Latw. walodu”, 1891); Лаутенбаха, Д. Пельца, внесли огромный вклад в развитие грамматики.

Хорошие диалектологические тексты представляют “Latw. tautas dzeesmas” (“Л. нар. песни”), изд. Л. лит. общ. в 1877 г., и образцы говоров в II вып. “Сборника латышских. общин.” в Митаве (1893). “Латышско-русский” и “Русско-латышский” словари изданы Вольдемаром и И. Сирогисом (СПб., 1873 и 1890).

Католики латыши инфлянтских уездов стремились к созданию особого латышского наречия. В 1732 г. в Вильне выходит книга Иосифа Акиелевича, которая раскрывает особенности диалектов вост.-латвиского, зап.-латышского. и курляндского. Затем она была переиздана Т. Коссовским в 1853 г. в Риге.

3. Сравнительный анализ литовского и латышского языка.

Одной из отличительных черт латышского языка от литовского языка является фиксированное ударение на первом слоге (вероят¬но, влияние финно-угорского субстрата). Произошло сокращение долгих гласных в конечных слогах многосложных слов, монофтонгизирование дифтонгов, выпаадение кратких гласных (кроме u). Изменения коснулись и древних тавтосиллабических (относящиеся к одному слогу) сочетаний an>uo, en>ie, in>ī, un>ū; перед гласными переднего ряда согласные k>c, g>dz [ʒ]. Существует противопоставление между задне- и среднеязычными согласными k—ķ, g—ģ. В долгих слогах (т. е. в слогах, содержащих долгие гласные, дифтонги и тавтосиллабические сочетания гласных с m, n, ņ, l, ļ, r) существуют следующие древние слоговые интонации, которые сохранены до сих пор: длительная (mãte ‘мать’), прерывистая (meîta ‘дочь’), нисходящая (rùoka ‘рука’). В морфологии со временем утрачены средний род и формы двойственного числа, древний инструментальный падеж совпал в единственном числе с аккузативом, во множественном числе — с дативом. Исчезли прилагательные с основой на u. Однако определённые и неопределённые формы прилагательных сохранились. Для глагола характерны простые и сложные формы настоящего, прошедшего и будущего времени; неразличение числа в 3 м лице. Глагол имеет оригинальные долженствовательное и пересказочное наклонения. В большинстве случаев зафиксирован свободный порядок слов в предложении, в котором определяемое стоит после определения. Основная часть лексики исконно балтийская. Встречаются заимствования из германских языков, особенно средненижненемецкого (elle ‘ад’, mūris ‘каменная стена’; stunda ‘час’), из славянских, преиму-ще¬ствен¬но русского (bļoda ‘миска’; sods ‘наказание’, grēks ‘грех’), из прибалтийско-финских языков (kāzas ‘свадьба’, puika ‘мальчик’) и т. п.

4. Диалекты

В латышском языке языковедми выделяется три диалекта: среднелатышский (распространен в центральной части Латвии), который также является базой литовского языка; ливонский (распространен на территориях проживания ливов, то есть в северной части Курземе и северо-западной части Видземе) и верхнелатышский (распространен на востоке Латвии). Наиболее сильному влиянию со стороны славянских языков подвержен латгальский язык. За основу современного латышского литературного языка взят среднелатышский диалект. Распространение диалектов на территории Латвии (синий — ливонский диалект, зеленый — среднелатышский, желтый — верхнелатышский).

5. Заимствования

Латышский язык, контактируя с другими языками, развивался не только по своим собственным законам, но и впитывал, заимствовал, приспосабливая под себя лексику и грамматику этих языков. Многие заимствования взяты из Белорусского, литовского, ливского, русского, эстонского языков, так как являлись языками соседних стран и основных торговых партнеров. Так как немецкий, польский, русский, шведский были государственными языками, они становились средством культурного обмена. Религиозные службы велись католиками на латыни. Это многоязычное соседство на протяжении длительного периода влияло на развитие словарного запаса и грамматическую систему латышского языка. В период Средних веков и вплоть до начала ХХ века немецкий язык считался центром государственного управления, науки и образования. Поэтому наибольшее количество заимствований из немецкого языка (около 3000). В последние десятилетия появляется все больше заимствований из английского.

6. Перевод с латышского языка

Выполняя перевод с латышского языка, нужно учитывать ряд особенностей данного языка:

1. Обратите внимание на то, на что в тексте оригинала делается смысловой акцент. Порядок слов в латышском предложении довольной свободный, так что в первую очередь он будет зависеть от смыслового ударения.

2. При переводе на латышский язык помните о следующих особенностях:

• В единственном числе с предлогами возможно употребление родительного, дательного и винительного падежей, а во множественном числе применяется только дательный падеж.

• Творительный падеж единственного числа в подавляющем большинстве случаев совпадает с винительным падежом, а творительный падеж множественного числа — с дательным. Практически всегда он употребляется после предлога ar (с). При этом во множественном числе предлог может быть опущен.

• Звательный падеж существует только в единственном числе. В современном латышском у многих слов звательный падеж совпадает с именительным.

• Определение стоит после определяемого слова. Прилагательные имеют полную и краткую формы, краткая форма склоняется.

3. В латышском необходимо применять вспомогательный глагол (глагол-связку) «быть». Если выраженное сказуемым действие отсутствует, а в предложении содержится утверждение, глагол «быть» формально становится сказуемым.

4. Категория рода в латышском языке представлена только мужским и женским родом. Помните, что среднего рода не существует.

5. В латышском языке как нарицательные существительные, так и имена собственные мужского рода имеют окончание -s. Очевидно, что при переводе имен латышского происхождения окончание -s сохранится. Трудности могут возникнуть при переводе имен иностранного происхождения.

6. Как и в случае с любым другим языком, помните, что ваша задача заключается в передаче смысла, а не в дословном переводе текста. Важно найти в языке перевода смысловые эквиваленты, а не подбирать слова из словаря. При работе с латышским следует обратить внимание на большое по сравнению с другими языками количество архаизмов, которые используются даже в повседневной жизни.

7. В латышском много заимствований из русского и других славянских языков. Однако часть слов пришли в латышский язык много веков назад, слово могло со временем изменить свое значение. Удостоверьтесь, что понимаете его правильно. Даже если слово кажется вам знакомым, проверьте себя по словарю. «Ложные друзья переводчика» есть почти во всех языках.

8. Будьте внимательны при использовании диакритических значков. Из-за отсутствия на большинстве клавиатур диакритиков возник «неофициальный» способ письма по-латышски, где апостроф ставится вместо гачека или седили, а долготу звука показывает двойное написание буквы. Такой способ письма примелем только в неформальных случаях.

7. Интересные факты

Кофе и кава

Грамматический род слова кофе, как и многих других слов, в разных языках не совпадает. Я взял навскидку восемь языков и оказалось, что почти везде в них кофе — женского рода, а в болгарском — среднего.

укр. кава ж. чорна кава (черная)

бел. кава ж. чорная кава (черная)

сербск. кафа ж. бела кафа (с молоком)

болг. кафе ср. чисто кафе (черное)

чешск. kava ж. rozpustna kava (растворимая)

словенск. kava ж. ledena kava (холодная)

польск. kawa ж. kawa pravdziwa (натуральная)

лтш. kafija ж. mana kafija (моя)

лит. kava ж. šviežia kava (свежая)

Больше всего повезло прибалтам, потому что ни в литовском, ни в латышском языках невозможен спор о том, среднего рода кофе или мужского — среднего рода в этих языках

Хлеб по-латышски

«Хлеб».

Рига (Латвия), апрель 2005

Maize хлеб

maizite булочка

pelnīt maizi зарабатывать на хлеб

Любите Latviju

Многие конструкции в латышском языке интуитивно понятны человеку, говорящему на русском.

«Любите Латвию!»

Рига (Латвия), ноябрь 2006

Latviju — винительный падеж слова Latvija, окончание которого (а вместе с ним и произношение всего слова) полностью совпадает с правилами русского языка.

Латышский и латвийский

Название латышского языка часто искажают и говорят «латвийский язык». Поэтому интересно сравнить, как навание звучит на соседних языках. В балтийских и славянских языках выделяется три группы, в пределах которых название приближенно звучит либо латышский, либо латвийский, либо летонский:

рус. латышский язык

укр. латиська мова

чешск. lotyština

польск. język łotewski

латышск. latviešu valoda

болг. латвийски език

литовск. latvių kalba

македонск. латвиски јазик

хорв. letonski jezik

сербск. летонски језик

По-русски допустим только вариант латышский язык.

Белое бельё

Название постельного белья в языках, родственных русскому, происходит от слова белый:

рус. белье (белый)

укр. білизна (білий)

лит. baltiniai (baltas)

лтш. veļa (balts)

Латышский язык почему-то оказался исключением.

Названия соседних стран в балтийских языках

Латышские названия стран заметно отличаются по звучанию и от русских, и от литовских:

рус. латышск. литовск.

Россия Krievija Rusija

Украина Ukraina Ukraina

Белоруссия Baltkrievija Baltarusija

Литва Lietuva Lietuva

Латвия Latvija Latvija

Эстония Igaunija Estija

Польша Polija Lenkija

Интересно, что название Польши по-латышски ближе к русскому, чем к литовскому, тогда как для других стран литовские названия схожи с русскими, а латышские — наоборот сильно отличаются.

Структура названия Белоруссии одинакова во всех трех языках: белый (balts, baltas) + Россия (Krievija, Russija).

Клавиатура и тастатура

Смысл слов тастатура и клавиатура в русском языке различается. Однако, на некоторые языки клавиатура переводится именно как tastatura.

болг. клавиатура

польск. klawiatura

укр. клавіатура

чешск. klávesnice

литовск. klaviatura

лтш. klaviatūra, tastatūra

нем. Tastatur

сербск. тастатура

Большинство приведенных примеров раскладываются на две группы — с основами клавиатур- и тастатур-. Стоит обратить внимание на чешское слово, в котором есть чередование: kláves-. Интересно, что в латышском языке употребляют оба слова: klaviatūra и tastatūra. В русском языке слово тастатура имеет более узкое значение — кнопочный номеронабиратель, т.е. тот, который пришел на смену дисковому на телефонном аппарате. Тастатурой называют и специализированные мини-клавиатуры на приборах.

Vai jūs zināt, ka…

Vai jūs zināt, ka… по-латышски означает знаете ли вы, что…

vai ли

jūs вы

zināt 2 л. ед ч. от zināti знать

ka что

Фраза отличается от русской только тем, что вопросительная частица vai ли стоит в начале предложения, а не после глагола.

Евро

В большинстве стран, где официальная валюта — евро, название пишется Euro и латиницей.

В написании есть два исключения, одно из которых попало на банкноты (это греческое Ευρώ). С греческим названием по-другому быть и не могло, потому что алфавит там не латинский.

О втором исключении мир узнал позже: это латышское Eiro [эйро]. Хотя буквы и латинские, но Европа по-латышски — Eiropa.

Существуют и другие варианты написания, но в странах, где так пишут, евро не является основной валютой:

Евро рус., болг., макед., русск., сербск.

Євро укр.

Еўра бел.

Evro словенск.

Euras лит.

Eŭro эсп.

Т-рубашка

Слово футболка в латышском языке построено по той же схеме, что и в английском:

рус.

рубашка

футболка англ.

shirt

t-shirt лтш.

krekls

t-krekls

А вот в литовском языке футболка futbolininko marškinėliai дословно означает футбольная майка.

Балтийские и славянские названия месяцев

Латышский и литовский языки близки так же, как русский и украинский. И хотя данные языки считаются схожими, но в пределах этих пар есть отличия, например: разные принципы именования месяцев. Более того, образуются перекрестные пары: русский — латышский, украинский — литовский.

Соответствие русских и латышских названий очевидно и комментировать его нет смысла, а вот для литовских я добавил отдельный столбец с переводом.

рус. лтш. лит. лит. знач. укр.

январь janvāris sausis sausas — сухой січень

февраль februāris vasaris vasara — лето лютий

март marts kovas kovas — грач березень

апрель aprīlis balandis balandis — голубь квітень

май maijs gegužė gegutė — кукушка травень

июнь jūnijs birželis beržas — береза червень

июль jūlijs liepa liepa — липа липень

август augusts rugpjūtis rugis — рожь, pjūtis — жатва серпень

сентябрь septembris rugsėjis rugis — рожь, sėti — сеять вересень

октябрь oktobris spalis spaliai — костра жовтень

ноябрь novembris lapkritis lapkritys — листопад листопад

декабрь decembris gruodis gruodаs — замерзшая грязь грудень

Сводная таблица славянских названий месяцев — таблица для названий месяцев на семи языках. Похожие названия выделены цветом и видны сразу.

Литовские названия всех весенних и части летних месяцев происходят от названий птиц. Три литовских названия (июля, ноября и декабря) дословно совпадают с украинскими.

Слово костра — множественное число названия жесткой коры растений костерь.

Спасибо Артуру Мумму за присланную расшифровку литовских названий августа и сентября.

Vaist-

В русском языке слова аптека и лекарство имеют разные корни, а в литовском один — vaist-:

vaistas лекарство

vaistažolė лекарственная трава

vaistinė аптека

vaistininkas аптекарь

vaistininkė аптекарша

Интересно, что в латышском языке лекарство zāles и аптека aptieka имеют разные корни; а слово лекарственный ārstniecības вообще состоит из частей, образующих в итоге значение врачебный.

Балтийский глагол быть

В балтийских языках сохранилась необходимость применять вспомогательный глагол (глагол-связку) быть. Если нет действия, которое выражено сказуемым, а в предложении содержится утверждение, формальным сказуемым становится глагол быть.

Начальная форма этого глагола в латышском языке — būt, в литовском — būti. Как и во многих европейских языках, глагол спрягается по собственным правилам. Ниже показаны варианты глагола в настоящем времени (слева — латышские, справа — литовские).

I л. я, мы

II л. ты, вы

III л. ж. он, они

III л. ж. она, они

ед. ч.

es esmu

tu esi

viņš ir

viņa ir мн. ч.

mēs esam

jūs esat

viņi ir

viņas ir

ед. ч.

aš esu

tu esi

jis yra

ji yra мн. ч.

mes esame

jus esate

jie yra

jos yra

В обоих языках в третьем лице существует единая форма глагола независимо от числа и рода. Формы глагола быть в латышском языке имеют ударение на первом слоге, а в литовском (ударение выделено) в большинстве случаев на последнем (за исключением множественного числа первого и второго лица).

Буква ā в окончаниях

Черта над буквой в латышском языке — garumzīme — как и во многих языках обозначает долгий гласный звук.

В латышском языке черта часто встречается в окончании существительных, стоящих в форме местного падежа. Существительные в этом падеже отвечают на вопрос где? и примерно соответствуют русскому предложному.

«Первая новогодняя елка в Риге в 1510 году». PIRMA JAUNGADA EGLE RIGA 1510 GADA

Рига (Латвия), ноябрь 2006

На показанной надписи три слова оканчиваются буквой Ā. Первое — числительное женского рода, а два других — существительные в местном падеже (иначе он называется локативом). Rīgā переводится в Риге, gadā — в году. «Начальные» формы этих слов — соответственно Rīga и gads. Здесь, кстати, встречается еще и числительное с точкой: 1510.gadā в 1510-м году.

Grūst и vilkt

Два простых латышских слова на дверях: grūst и vilkt, означающие соответственно от себя и на себя.

Слово vilkt тянуть похоже на русское волочь.

Этимология слова grūst менее очевидна; понятно, что грусть тут ни при чем. Помочь может форма единственного числа первого лица gružu толкаю, созвучное русскому гружу. Как и в русском языке, происходит чередование согласных s — ž и з — ж.

Nākt и iet

Латышские слова iet и nākt переводятся на русский парой идти и ходить. Однако между языками есть различие. Хотя и тут, и там по два слова, принцип их использования различается.

В латышском языке употребление слов зависит не от частоты повторения действия, а от направления. Если речь идет о приближении, употребляют nākt, если об отдалении,— iet.

Я еду…

Es nāku no Rīga …из Риги

Es eju uz Rīgu …в Ригу

Интересно, что при этом время употребляется со словом iet (то есть оно отдаляется: laiks iet), а времена года — со словом nākt: gada laiki nāk.

Определительный генетив в латышском языке

В латышском языке есть понятие определительного генетива, которое обозначает конструкцию из пары существительных, первое из которых стоит в родительном падеже и является определением для второго.

Например: piena upe молочная река. Молоко в именительном падеже — piens, в родительном — piena.

В английском такие пары из двух существительных встречаются часто, но там существительные не изменяются по родам. Например: milk river.

Хотя в учебниках пишут, что подобной конструкции не существует в русском языке, я не соглашусь с этим. Подобный способ есть, но он не распространен в речи, требует прилагательного, и существительные стоят в другом порядке. Например: стол красного дерева.

Россия в Прибалтике

В каждой прибалтийской стране пользуются уникальным переводом слов России и русский:

Латышский Литовский Эстонский

Россия

русский

по-русски Krievija

krievu, krievisks

krieviski Rusija

rusas, rusė

rusų, rusiškai Venemaa

vene

vene keel

Латышское название происходит от названия древних кривичей; эстонское (как и финское venaje) — от ванов и венетов; литовцы же называют русских так же, как и сами русские.

Ударение в латышском и литовском языках

Удивительное рядом. Литовский и латышский языки — два, оставшиеся в балтийской группе (третий — несуществующий ныне прусский). Тем не менее, языки заметно отличаются, и нынешний литовский язык, например, более архаичен по сравнению с латышским. Косвенно это проявляется в правилах расстановки ударений.

В латышском языке ударение всегда падает на первый слог; в литовском языке ударение не фиксированное и в разных словах приходится на разные слоги.

Личные местоимения в латышском и литовском языках

Личные местоимения в латышском и литовском языках по сути те же, что и в русском. Те же лица, те же числа. Местоимение второго лица множественного числа вы, как и в русском, часто порываются писать с прописной буквы.

Есть только одно отличие: в третьем лице множественное число имеет две формы — для мужского и женского рода. Если речь идет про лица обоего пола, употребляется местоимение мужского рода.

es я

tu ты

viņš он

viņa она mēs мы

jūs вы

viņi они (муж.)

viņas они (жен.)

aš я

tu ты

jis он

ji она mes мы

jus вы

jie они (муж.)

jos они (жен.)

8. Фонетические особенности латышского языка

Основные отличительные черты фонетического строя современного литовского языка:

1) противопоставление гласных по долготе-краткости;

2) наличие только кратких согласных;

3) наличие дифтонгов и дифтонгичных сочетаний гласных с сонорными согласными (e.g. am, om, in, ir, el и т.д.) перед другим согласным;

4) наличие трех слоговых интонаций в ударном слоге (1 краткой и двух долгих);

5) фонематическое противопоставление твердых и мягких согласных в позиции только перед гласными заднего ряда (ср. аналогичное положение в совр. болгарском языке в славянской группе);

6) обязательная позиционная палатализация согласных перед всеми гласными переднего ряда и другими палатализованными согласными: lydėti ~ «ли:де:ти» (не «лы:дэ:ты», как это произнес бы латыш);

7) переход палатализовнных «t / d» в «č / dž» перед задними гласными: viltis (надежда) ► vilčiai(надежде, д.п.);

ограниченное количество возможных звуков в исходе большинства слов в силу того, что литовские знаменательные части речи (кроме наречий) никогда не выступают в речи в форме чистой основы без флексий.

Гласные

В литовском алфавите 12 гласных букв. Они передают такие звуки:

A a :: [a], [a:] (в некоторых словах только под ударением)

Ą ą :: [a:]

E e :: [æ], [æ:] (в некоторых словах только под ударением), [e] (в заимствованиях)

Ę ę :: [æ:]

Ė ė :: [e:]

I i :: [ɪ]

Į į :: [i:]

Y y :: [i:]

O o :: [o:], [o] (в заимствованиях)

U u :: [u]

Ų ų :: [u:]

Ū ū :: [u:]

Для обозначения долгих гласных в литовском языке используются буквы с крючком. В литовском языке им даётся название «носинес райдес», т.е. «носовые буквы». Однако название это не связыно с носовым произношением, так как в современном языке оно не сохранилось, а компенсировалось долготой. Тем не менее, буквы эти пишут не просто так: в некоторых словоформах носовой согласный может восстанавливаться. Например: kąsti [`kaːsʲtʲɪ] (кусать

Перед «e, ę, ė, i, į, y» все согласные смягчаются, особенно перед теми буквами, что обозначают долгие звуки. Т.е. слово «senas (старый)» звучит не [`sæ:nas], a [`sʲæ:nas] (почти как «сяянас»). Перед гласными заднего ряда на мягкость указывает буква «i» (как и в польском языке): siųsti [sʲu:sʲtʲɪ], akiai [a:kʲæi].

После согласных оппозиция гласных «a, ą ~ e, ę» нейтрализуется (после твердых выступает [a(: )], а после мягких — [æ]/[æ:]). Т.е., сочетания «be» и «bia» произносятся идентично: [bʲæ]. Тем не менее, при смягчении перед «а» литовские «t / d» чередуются по общему их правилу: naktis ► nakčia.

Фонемы [o] и [e] — периферийные: они встречаются только в заимствованных словах и в стилистически окрашенной речи. Краткое [o] встречается в некоторых литовских словах, напр., в имени «Aldona [al`dona]». В современном языке такое произношение заменяется на нормальное долгое.

Из дифтонгов втречаются в исконно литовских словах такие: ai, au, ei, ie, uo, ui. Подробнее об особенностях дифтонгов и дифтонгичных сочетаниях написано ниже (в разделе «Интонация»).

Согласные

У согласных в латышском языке наблюдается общие черты с согласными русского языка. У них нет ни придыханий, ни альвеолярных или ретрофлексных артикуляций, как в некоторых германских языках. Отметим, что в исконно балтийских словах звук [x] перешел в «s»: (лит) sausas ~ (русс) сухой. Звуки «h [h]» и «ch [x]» встречаются только в заимствованиях их других языков: chemija (химия), Praha (город Прага). Тем не менее, перед гласными переднего ряда они поддаются правилам литовской палатализации.

Мягкость согласных, как отмечалось выше — важное фонематическое явление в литовском языке: manas (мой) ~ menas (искусство); rašau (я пишу) ~ rašiau (я писал); siūlau (я предлагаю) ~ siūliau (я предлагал).

Твердые согласные выступают в литовском языке в конце слова, перед твердыми согласными и перед гласными заднего ряда. Характерная для русского языка сильная веляризация твердых для литовского языка не характерна. Поэтому некоторые согласные звучат мягче, «нежнее» русских. Особенно это заметно у согласных «š, ž, l». Твердое «dž» в литовском языке выходит из употребления. Даже слова типа «džazas (джаз)» произносятся «джя:зас». Перед гласными переднего ряда согласные смягчаются по-разному в зависимости от самого гласного. Перед кратким «i [ɪ]» согласные смягчаются слабо. Перед «e [æ] / ė [e:]» смягчение сильнее. Сильнее всего согласные смягчаются перед «į / y [i:]». Иностранные заимствования типа «telefonas» произносятся с мягкими (!) согласными перед передними гласными: «телефонас (не «тэлэфонас»)». Помните также о кратком закрытом «е» и кратком «о» в таких словах. Звук «dz» в литовском языке редкий.

Интонация

В литовском языке ударных слог может быть произноситься с тремя вариантами интонаций: грависная (краткая), акутная (падающая) или циркумфлексная (растущая протяжная). На письме интонации записывают только в учебной литературе.

При употреблении городским населением в речи современного литовского языка различия между акутом и циркумфлексом утрачиваются на монофтонгах и глайде «uo» (также иногда и «ie»). По этой причине, описывая эти интонации, акцент будет делаться на дифтонги и дифтонгичные сочетания.

Краткая интонация встречается только над краткими гласными. Т.е., в словарях значек » ` » сигнализирует о кратком произношении гласного: màno (мое, моя, мои), mamà (мама).

Внимание! Двойные буквы в русских транскрипциях даны не столько для обозначения особой долготы, сколько для указания того, куда делать нажим при произношении.

Акутная интонация, в отличие от традиционного ее использования для растущих тонов, в литуанистике используется для обозначения падающего (!) тона. У дифтонгов и дифтонгичных сочетаний акутная интонация (обозначается как гравис на «u / i»!!!) произносится с более сильным ударением на первом элементе, который звучит четко и ясно: ái «аай», éi «яяй», íe «иэ», áu «аау», él «яял», ìm «им», ám «аам» и т.д.. Примеры слов: láisvas (свободный) — «лаайсвас», áidas (эхо) — «аайдас», láimė (счастье) — «лаайме», véidas (лидо) — «вяяйдас», líepa (липа) — «лиепа», táu (тебе) — «таау», kélmas (пень) — «кяялмас», vaikáms (детям) — «вэйкаамс».

Дифтонг «ui» в акутной интонации почти никогда не встречается.

Циркумфлекс в литовском языке обозначает растущую интонацию, т.е. нажим делается на конечную часть звука. Слог с циркумфлексом звучит протяжно и напряженно. У монофтонгов эта интонация в современном языке не отличается от акутной. А вот у дифтонгов разница ощущается сильно — в силу того, что ударным элементом становится конечный элемент, первые элемент сокращается и уподобляется ему. То есть: aĩ «эии», aũ (оуу), eĩ (еии), iẽ (йяя), uĩ (уии), am̃ (ам), el̃ (ел) и т.д.

Примеры для сравнения:

láisvas (свободный) — «лаайсвас» :: laĩvas (корабль) — «лэиивас»

spáusti (нажать) — «спааусьти» :: Kaũnas (город Ковно) — «коуунас»

véidas (лицо) — «вяяйдас» :: peĩlis (нож) — «пеиилис»

kélmas (пень) — «кяялмас» :: mel̃stis (молиться) — «мельсьтис»

9. Грамматические особенности латышского языка

В области морфологии сохранилось множество архаичных черт, которые преобладают над важными инновациями. Основные черты литовской морфологии:

1) сохранение семи флективных падежей (как и в большинстве славянских) в системе именного склонения (аблатив в балтийских утрачен);

2) наличие трех периферийных агглютинативных локативных падежей (иллатива, адессива и аллатива), которые образовались вторично на финно-угорком субстрате;

3) употребление инессива всегда без предлога;

4) утрата среднего рода именем существительным;

5) наличие полной парадигмы двойственного числа у имени и глагола, которая активно используется диалектально, но выпала из употребления в городах в первой половине 20го века;

6) наличие кратких (именных) и полных (местоименных) форм у имени прилагательного (как и в славянских);

7) утрата склонения у притяжательных местоимений в разговорном и нейтральном письменном стиле;

утрата личных окончаний в 3м лице всех трех чисел у всех глаголов;

9) плохо развитая категория вида (совершенного и несовершенного) в системе глагола;

10) наличие итеративного прошедшего времени (чисто литовское явление);

11) наличие особого императивного суффикса «-k-«;

12) большое количество причастных форм у глагола (больше 10);

13) наличие особых псевдо-пассивных причастий от непереходных глаголов;

14) наличие супина и особой инфинитивной формы;

15) наличие множества аналитических и причастно-пересказывательных форм у глагола;

16) единтсвенная временная форма сослагательного наклонения;

17) несочетаемость предлогов с дательным падежом;

18) конструкция «дательный самостоятельный»;

19) оформление агента в пассивной конструкции, объекта отрицательного сказуемого и объекта супина родительным падежом;

20) употребление родительного падежа в качестве подлежащего;

21) препозиция несогласованного генетивного определения;

22) широкое распространение родительного падежа вместо относительных прилагательных;

23) полное отсутствие категории одушевленности.

Существительное

У существительного в литовском языке имеются такие категории, как род (мужской и женский), число (в диалектах три) и падеж: Vadininkas (именительный), Kilmininkas (родительный), Naudininkas (дательный), Galininas (винительный), Įnagininkas (творительный), Vietininkas (местный), Šauksmininkas (звательный).

Есть 5 склонений и 11 основных парадигм в них:

1) сущ. м.р. на «-as, -is, -ys»;

2) сущ. ж.р. на «-a, -ė, (-i)»;

3) сущ. м./ж.р. на ударенное «-is»;

4) сущ. м.р. на «-us, -ius»;

5) сущ. на «-uo» (их немного и они расщиряют основу, ср. русс. «имя — имени»).

Пример склонения сущ. м.р. 1 гр. «ratas (круг, колесо)» и сущ. ж.р. 2 гр. «varna (ворона)».

N. rãtas ~ rãtai

G. rãto ~ rãtų

D. rãtui ~ rãtams

A. rãtą ~ ratùs

I. ratù ~ rãtais

L. ratè ~ rãtuose

V. rãte! ~ rãtai!

N. várna ~ várnos

G. várnos ~ várnų

D. várnai ~ várnoms

A. várną ~ várnas

I. várna ~ várnomis

L. várnoje ~ várnose

V. várna! ~ várnos!

Отметим, что литовское склонение не ограничивается запоминанием таблицы склонения. Литовские существительные и прилагательные разбиваются на 4 большие группы — классы акцентуации. В зависимости от группы ацентуации ударение при склонении меняет свое качество и перемещается с основы на окончание и обратно, напр: rãtas ► ratè ► rãte! ► rãtams ► ratùs.

Таким образом, встретив новое литовское слово, нужно выучить его в следующей форме: rãtas (1) (2), где значок «тильда» показывает исходное ударение, число (1) указывает на группу склонение, а число (2) — на группу ударения. Только в таком случае, пользуясь комбинированной таблицой склонений и ударений, можно правильно образовать все формы.

Обратите внимание на то, что омонимичные внешне формы могут различаться типом и местом ударения.

Дуалис редок: (N-A-V) dvi varni (G) dviejų varnų (D) dvíem varnom (I) dviẽm varnom (L) dviese varnose.

Прилагательное

Имя прилагательное в литовском языке согласуется с существительным в роде, числе и падеже. В предикативной функции литовские прилагательные сохранили форму среднего рода ед.ч. им.п.: man gera (мне хорошо).

Прилагательные литовского языка склоняются по именному типу с некоторыми местоименными вкраплениями. Кроме того, они образуют полностью местоименные формы с помощью личного местоимения «jis / ji (он / она)». В отличие от русского языка, где эти формы стали фактически единственной формой прилагательного, и латышского, где они употребляются согласно четко определенных правил, в литовском языке данные формы употребляеются довольно редко (в основном в топонимах и застывших названиях). Существительное, снабженное определением в местоименной (определенной) форме, выделяется из ряда себе подобных, т.е. на нем особо акцентируется внимание. Определенная формы прилагательного также употребляется при обращении. Относительные прилагательные в определенной форме почти никогда не выступают.

В литовском языке у прилагательных есть три склонения — на «-as», «-us» и «-is» (относительные): geras (хороший), skanus (вкусный), auksinis (золотой).

Пример склоения прилагательного «mažas (1) (4) (маленький)»:

Singular:

N. mãžas ~ mažàsis; mažà ~ mažóji

G. mãžo ~ mãžojo; mažõs ~ mažõsios

D. mažám ~ mažájam; mãžai ~ mãžajai

A. mãžą ~ mãžąjį; mãžą ~ mãžąją

I. mažù ~ mažúoji; mažà ~ mažą́ja

L. mažamè ~ mažãjame; mažojè ~ mažõjoje

Plural:

N. mažì ~ mažíeji; mãžos ~ mãžosios

G. mažų̃ ~ mažų̃jų; mažų̃ ~ mažų̃jų

D. mažíems ~ mažíesiems; mažóms ~ mažõsioms

A. mažùs ~ mažúosius; mažàs ~ mažą́sias

I. mažaĩs ~ mažaĩsiais; mažomìs ~ mažõsiomis

L. mažuosè ~ mažúosiuose; mažosè ~ mažõsiose

Как видите, перед местоименной флексией собтсвенная флексия прилагательного часто подвергается видоизменениям. Кроме того, есть местоименные формы, которые требуют особого места ударения (независимо от того, к какой группе акцентуации принадлежит прилагательное).

Глагол

Литовский глагол характеризуется исключительным морфологическим богатством. Исландский язык просто нервно курит в сторонке.

Литовские глаголы делятся на три спряжения по типу основы в настоящем и прошедшем времени (она же служит и формой 3го лица во всех числах). Ко второму спряжению относятся некоторые глаголы на «-ėti», к третьему — почти все на «-yti» и некоторые на «-oti».

Основы этих глаголов образуются просто:

2 спряжение: mylėti (любить) ► myli (любит / любят) ► mylėjo (он/она/они любил(-а/-и))

3 спряжение: dažyti (красить) ► dažo (красит / красят) ► dažė (он/она/они красил(-а/-и))

Все остальные глаголы относятся к первому спряжению. И их — большинство. Вот тут-то и начинается веселье с аблаутами, удлинениями и сокращениями гласных, инфиксами, смягчением и прочими ужасами. Что-либо определить по инфинитиву можно научиться, но все равно надо фактически каждый новый глагол учить по словарю.

Основы настоящего и прошедшего времени у этих глаголов имеют «-(i)a» и «-o / -ė». Примеры спряжений:

dirbti (работать) ► dirba ► dirbo

kepti (печь) ► kepa ► kepė

dėti (класть, деть) ► deda ► dėjo

žaisti (играть) ► žaidžia ► žaidė

vogti (красть) ► vagia ► vogė

smogti (бить) ► smogia ► smogė

reikšti (означать) ► reiškia ► reiškė

gerti (пить) ► geria ► gėrė

vilti (разочаровывать) ► vilia ► vylė

plauti (полоскать) ► plauna ► plovė

ginti (гнать) ► gena ► ginė

dygti (прорастать) ► dygsta ► dygo

gimti (рождаться) ► gimsta ► gimė

siųsti (посылать) ► siunčia ► siuntė

kirpti (стричь) ► kerpa ► kirpo

tapti (становиться) ► tampa ► tapo

justi (ощущать) ► junta ► juto

snigti (снежить) ► sninga ► snigo

giedoti (петь) ► gieda ► giedojo

kentėti (страдать) ► kenčia ► kentėjo

kabėti (висеть) ► kaba ► kabėjo

lyti (лить, дождить) ► lyja ► lijo

В каждой из приведенных выше парадигм далеко не один глагол.

Будущее время образуется от основы инфинитива с помощью суффикса «-s». Аналогично образуется прошедшее итеративное с суффиксом «-dav-«. Сослагательное наклонение имеет специфичные формы. Глагол спрягается по лицам и числам. Пример спряженеия в наст., прош., буд. времени и сосл. наклонении (глагол «gerti»):

aš (я) :: geriu, gėriau, gersiu, gerčiau

tu (ты) :: geri, gėrei, gersi, gertum

jis (он) / juodu (они оба) / jie (они) :: geria, gėrė, gers, gertų

(mudu (мы оба) :: geriava, gėrėva, gersiva, gertu(mė)va)

(judu (вы оба) :: geriata, gėrėta, gersita, gertu(mė)ta)

mes (мы) :: geriame, gėrėme, gersime, gertu(mė)me

jūs (вы) :: geriate, gėrėte, gersite, gertu(mė)te

Литовский глагол имеет возвратные формы на «-s(i)»: mes mylimės, jis jaučiasi, aš stengiuosi и т.д..

Имератив имеет особый суффикс «-k-«: sėsk ir ėsk (сядь и ешь)! rašykite (пишите)! Неличные формы глагола образуются от разных основ (инфинитива, настоящего, прошедшего и будущего времени). В мужском роде ед. числа имен. падежа некотрые из них имеют особую стянутую форму. Причастия-прилагательные склоняются в особой парадигме с особой расстановкой ударений.

Основные формы:

Наст.вр. акт.: dirbąs (работающий, ж.р. dirbanti) — суфф. «-nt-«

Прош.вр. акт.: dirbęs (работавший, ж.р. dirbusi) — суфф. «-us-«

Буд.вр. акт.: dirbsiąs (тот, что будет работать, ж.р. dirbsianti) — суфф. «-siant-«

Наст.вр. пасс.: dirbamas (тот, который обрабатывают) — суфф. «-m-«

Прош.вр. пасс.: dirbtas (обработанный) — суфф. «-t-«

Буд.вр. пасс.: dirbsimas (тот, который будут обрабатывать) — суфф. «-sim-«

Полупричастие: dirbdamas (как «работая», только изменяется по родам и числам!) — суфф.»-dam-«

Причатие должествования: dirbtinas (такой, над которым следует работать) — суфф. «-tin-» (инфититив + «-n-«)

Супин: dirbtų (чтобы работать)

Инфтинитив: dirbti (работать)

Инф. II: dirbte (dirbtinai) (передает качетво другого действия, т.е. «работой», «как работа»). Хорший пример: bėgte bėga (бегом бежит).

В современном языке супин употребляется редко и характерен в целом только для книжного стиля.

От форм активных причатий образуются герундии: dirbant (работая), dirbus (работав). В причастных оборотах с такими формами их субъект стоит в дательном падеже (дательный самостоятельный): jam dirbant, visi žiūri (когда он работает, все смотрят).

Пассивный залог никогда не образуется с помощью возвратного «-si»! Для него используются пассивные причастия: ji yra visų mylima (она всеми любима); knyga yra jau parašyta (книга уже написанна). Агент пассивной конструкции стоит в генитиве.

Пассивные причастия (особенно настоящего времени) образуются также и от непереходных глаголов. Они употребляются в первую очередь в форме среднего рода в разноых описательных контсрукциях: jų čia būtą («их тут бывши», т.е. «они тут были»); pas mus lietuviškai kalbama («у нас по-литовски говоримо», т.е. «у нас говорят по-литовски»); čia moterų dirbama («тут женщин работаемо», т.е. «тут работают женщины»).

Активные причастия могут употребляться как сказуемое с эвиденциальным значением: žiniose sakė, kad prezidentas turįs pasirašyti tą dokumentą (в новостях говорили, что президент должен бы подписать этот документ).

Местоимение

Местоимения литовского языка склоняются по падежам, родам и числам. Выборочные примеры склонения:

N. aš (я), tas (тот), jie (они, м.р.), kas (кто, что)

G. manęs, to, jų, ko/kieno

D. man, tam, jiems, kam

A. mane, tą, juos, ką

I. manimi, tuo, jais, kuo

L. manyje, tame, juose, kame

Предлог

Предлоги литовского языка управляют родительным, винительным или творительным падежом. Важные предлоги:

į ką — во что

su kuo — с чем

be ko — без чего

po ko — после чего

po kuo — под чем

už ką — за что

už ko — за чем

pagai ką — согласно чего

pagal ką — относительно чего

ant ko — на что, на чем

apie ką — о чем

aplink ką — вокруг чего

pro ką — мимо чего

per ką — через что

iš ko — из чего

nuo ko — от чего

link ko — по направлению к чему

prie ko — при чём, перед чем

prieš ką — перед чем

po ką — по чему

išilgai ko — вдоль чего

Латышский язык — синтетический. Он имеет развитую систему склонения и спряжения. Несмотря на высокий уровень синтетизма, латышская грамматика проще, чем грамматика родственного литовского языка — в ней более упрощённые парадигмы склонения и спряжения. Например, отмирает творительный падеж, упрощено падежное управление во множественном числе, глагол в сослагательном наклонении имеет только одну форму для всех лиц и обоих чисел на «-tu», тогда как в литовском имеется целый набор окончаний: «-čiau, -tum, -tų, -tume, -tute, -tų». В латышском языке нет среднего рода. Существительные мужского рода имеют окончание s, š, is, us, а женского — a, e, s (редко). В латышском языке есть две формы обращения: официальная и неофициальная. Например, ты (tu) при вежливом обращении превратится в Jūs (Вы). Порядок слов в предложениях — вольный, то есть зависит от того, на какое слово падает смысловое ударение. Так, например, предложение «В стакане — вода» будет выглядеть так: Glāzē ir ūdens, а «Вода в стакане» — так: Ūdens ir glāzē. В латышском языке нет артиклей (то есть «дом» будет māja, а «Он дома» — Viņš ir mājās), однако прилагательные содержат понятие определённости/неопределённости.

Имя существительное

Имеет категории рода, числа и падежа. Родов в латышском языке два — мужской и женский. Чисел также два — единственное и множественное. Падежей семь:

Nominatīvs — именительный : kas? — кто? что? (в латышском нет отдельного вопросительно-относительного местоимения для неодушевлённых предметов)

Ģenitīvs — родительный : kā? — кого? чего?

Datīvs — дательный : kam? — кому? чему?

Akuzatīvs — винительный : ko? — кого? что?

Instrumentālis — творительный : ar ko? — с кем? с чем?

Lokatīvs — местный : kur? — где? (употребляется без предлога)

Vokatīvs — звательный : используется при обращении

Особенности падежной системы:

• во множественном числе с предлогами употребляется только дательный падеж, тогда как в единственном возможны родительный, дательный, и винительный.

• творительный падеж в единственном числе с редкими исключениями совпадает с винительным падежом, а во множественном — с дательным. Употребляется он почти исключительно после предлога «ar — с». Тем не менее, во множественном числе предлог может опускаться: «es apmierināšu tevi ar savu dziesmu ~ es apmierināšu tevi savām dziesmām ::: я успокою тебя своей песней ~ я успокою тебя своими песнями». То есть ar dziesmu ~ (ar) dziesmām.

• звательный падеж образуется только в единственном числе и в современном языке у многих слов совпадает с именительным падежом.

В латышском языке есть 7 типов склонения. Ниже приведено несколько частотных парадигм:

Падеж «zēns(м.р., мальчик)» «brālis (м.р., брат)» «sieva (ж.р., жена)» «upe (ж.р., река)» «zivs (ж.р., рыба)» «ledus (м.р., лед)»

N. zēns brālis sieva upe zivs ledus

Ģ zēna brāļa sievas upes zivs ledus

D zēnam brālim sievai upei zivij ledum

A-I zēnu brāli sievu upi zivi ledu

L zēnā brālī sievā upē zivī ledū

V zēns! brāli! sieva! upe! zivs! ledus!

— — — — — — —

N zēni brāļi sievas upes zivis ledi

Ģ zēnu brāļu sievu upju zivju ledu

D-I zēniem brāļiem sievām upēm zivīm lediem

A zēnus brāļus sievas upes zivis ledus

L zēnos brāļos sievās upēs zivīs ledos

Имя прилагательное

Изменяется по родам, числам и падежам, то есть согласуется с существительным. Имена прилагательные в функции предиката также согласуются с подлежащим в роде и числе.

Интересной особенностью латышского прилагательного является наличие у него полных и кратких форм (ср. русск. «хороша ~ хорошая, хорош ~ хороший»). Эта особенность характерна для большинства балто-славянских языков (кроме болгарского и македонского, где рудиментарно сохраняется окончание полной формы м.р. ед.ч. на «-и», а также украинского и белорусского, где неупотребимы краткие прилагательные). В отличие от русского языка, латышские краткие прилагательные употребляются очень широко и представлены во всех падежах. Употребление полных форм:

• для особого выделения какого-то предмета из ряда себе подобных (то есть аналогично функции определительного члена): baltais zirgs ir jau vecs — (именно та) белая лошадь уже стара

• после указательных и притяжательных местоимений: tas jaunais cilvēks — тот молодой человек

• в звательном падеже: mīļais draugs! — милый друг!

• при субстантивации: klibais ar aklo iet pa ceļu — хромой со слепым идут по дороге

• в титулах: Pēteris Lielais — Пётр Великий

Примеры парадигм:

Падеж м.р. неопр. м.р. опр. ж.р. неопр. ж.р. опр.

N. salds saldais salda saldā

Ģ. salda saldā saldas saldās

D. saldam saldajam saldai saldajai

A.-I. saldu saldo saldu saldo

L. saldā saldajā saldā saldajā

— — — — —

N. saldi saldie saldas saldās

Ģ. saldu saldo saldu saldo

D.-I. saldiem saldajiem saldām saldajām

A. saldus saldos saldas saldās

L. saldos saldajos saldās saldajās

Глагол

Глаголы в латышском языке спрягаются по лицам, числам, залогам и наклонениям. У них есть множество причастных форм.

Как и в литовском языке, латышские глаголы во всех временах имеют одинаковую форму для единственного и множественного числа в третьем лице из-за утраты в этих формах флексий.

Глаголы делятся на спряжения. Основное деление — на первое (исход основы на согласный) и второе (исход основы на гласный) спряжения. Глаголы второго спряжения значительно проще, так как они не претерпевают изменений основы при спряжении. Глаголы первого спряжения пользуются палатализацией, инфиксами, аблаутом и другими средствами при образовании разных форм. Например:

just (чувствовать) — es jūtu (я чувствую) — es jutu (я чувствовал)

likt (класть) — es lieku / tu liec / viņš liek (я кладу / ты кладёшь / он кладёт) — es liku (я клал)

glābt (спасать) — es glābju (я спасаю) — es glābu (я спасал)

Примеры спряжения (глаголы nest (1 спр., «нести») и mērīt (2 спр., «мерить»)):

Лицо Наст. время Прош. время Буд. время

es mērīju mērīju mērīšu

tu mērī mērīji mērīsi

viņš/viņi mērī mērīja mērīs

mēs mērījam mērījām mērīsim

jūs mērījat mērījāt mērīsit

Лицо Наст. время Прош. время Буд. время

es nesu [næs:u] nesu [nes:u] nesīšu

tu nes [nes] nesi nesīsi

viņš/viņi nes [næs] nesa nesīs

mēs nesam nesām nesīsim

jūs nesat nesāt nesīsit

Пересказ, настоящее время (спряжение по лицам и числам отсутствует): es, tu, viņš, mēs, jūs, viņi nesot

Сослагательное наклонение (заметно падение личного спряжения по сравнению с литовским): es, tu, viņš, mēs, jūs, viņi nestu

Повелительное наклонение: nes! nesiet!

Эти основные формы глаголов (образованные от связок) в комбинации с причастиями образуют сложные глагольные формы:

перфект: esmu nesis

перфект пересказа: esot nesis

и т. д.

Примеры причастий:

ziedošs koks — цветущее дерево

noziedējis koks — отцветшее дерево

lasāma grāmata — читаемая книга

izcepta maize — испеченный хлеб

viņš iet domādams — он идет, размышляя

Предлоги и послелоги

В единственном числе латышские предлоги управляют родительным, дательным (всего несколько предлогов) или винительно-творительным падежом. Во множественном числе все предлоги и большинство послелогов (кроме ‘dēļ’, ‘pēc’ (редко)) управляют дательно-творительным падежом.

Ниже приведены основные предлоги и послелоги латышского языка.

Предлоги и послелоги с родительным падежом

aiz — за : aiz kalna (за горой)

bez — без : bez manis (без меня)

dēļ — ради, из-за : manis/mūsu dēļ (из-за меня/нас) этот послелог управляет родительным падежом в обоих числах

no — от, из : no pilsētas (из города)

pēc — по, за, через, после : pēc darba (после работы), pēc maizes (за хлебом), pēc nedēļas (через неделю), pēc plāna (по плану)

uz — на : uz galda (на столе)

pie — при, у : pie mājas (у дома)

virs — над : virs ezera (над озером)

zem — под : zem grīdas (под полом)

pirms — перед : pirms gada (год назад), pirms darba (перед работой)

Предлоги и послелоги с дательным падежом

līdz(i) — до, к. с : man līdzi (вместе со мной), līdz mežam (до леса)

pa — по : pa vienai māsai (по одной сестре)

Предлоги и послелоги с винительно-творительным падежом

ar — с : ar tēvu (с отцом)

par — о, за, чем (при сравнении) : runāt par tēvu (говорить об отце), par ko strādāt (кем работать), par ko vecāks (старше, чем кто), par ko maksāt (платить за что)

pār — через : pār ielu (через улицу)

caur — сквозь : caur logu (через окно)

gar — мимо : gar mežu (вдоль, мимо леса)

starp — между : starp mums / skolu un māju (между нами / школой и домом)

pa — по : pa ceļu (по пути), pa logu redzu … (в окно вижу …), pa dienu (днём)

ap — вокруг : ap māju (вокруг дома)

uz — в, на (о направлении) : uz darbu (на работу), uz pilsētu (в город)

Компания Е-Транс оказывает услуги по переводу и заверению любых личных документов, например, как:

Оказываем услуги по заверению переводов у нотариуса, нотариальный перевод документов с иностранных языков. Если Вам нужен нотариальный перевод с латышского (латвийского) языка на русский язык или с русского языка на латышский (латвийский) язык с нотариальным заверением паспорта, загранпаспорта, нотариальный с латышского (латвийского) языка на русский язык или с русского языка на латышский (латвийский) язык с нотариальным заверением перевод справки, справки о несудимости, нотариальный перевод с латышского (латвийского) языка на русский язык или с русского языка на латышский (латвийский) язык с нотариальным заверением диплома, приложения к нему, нотариальный перевод с латышского (латвийского) языка на русский язык или с русского языка на латышский (латвийский) язык с нотариальным заверением свидетельства о рождении, о браке, о перемене имени, о разводе, о смерти, нотариальный перевод с латышского (латвийского) языка на русский язык или с русского языка на латышский (латвийский) язык с нотариальным заверением удостоверения, мы готовы выполнить такой заказ.

Нотариальное заверение состоит из перевода, нотариального заверения с учётом госпошлины нотариуса.

Возможны срочные переводы документов с нотариальным заверением. В этом случае нужно как можно скорее принести его в любой из наших офисов.

Все переводы выполняются квалифицированными переводчиками, знания языка которых подтверждены дипломами. Переводчики зарегистрированы у нотариусов. Документы, переведённые у нас с нотариальным заверением, являются официальными и действительны во всех государственных учреждениях.

Нашими клиентами в переводах с латышского (латвийского) языка на русский язык и с русского языка на латышский (латвийский) язык уже стали организации и частные лица из Москвы, Санкт-Петербурга, Новосибирска, Екатеринбурга, Казани и других городов.

Е-Транс также может предложить Вам специальные виды переводов:

Контакты

Как заказать?

×òî òàêîå «Ëàòâèÿ»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

Ëàòâèÿ ËÀÒÂÈß (Ëàòâèéñêàÿ ðåñïóáëèêà), ãîñóäàðñòâî â Âîñòî÷íîé Åâðîïå, â Ïðèáàëòèêå, îìûâàåòñÿ Áàëòèéñêèì ìîðåì è Ðèæñêèì çàëèâîì. Ïëîùàäü 64,5 òûñ. êì2. Íàñåëåíèå 2596 òûñ. ÷åëîâåê, ãîðîäñêîå 71%; ëàòûøè (52%), ðóññêèå (34%), áåëîðóñû (4,5%), óêðàèíöû, ïîëÿêè è äðóãèå. Îôèöèàëüíûé ÿçûê — ëàòûøñêèé. Âåðóþùèå — ïðîòåñòàíòû, ïðàâîñëàâíûå, êàòîëèêè. Ãëàâà ãîñóäàðñòâà — ïðåçèäåíò. Çàêîíîäàòåëüíûé îðãàí — ñåéì. Ñòîëèöà — Ðèãà. 26 ðàéîíîâ, 56 ãîðîäîâ, 37 ïîñåëêîâ ãîðîäñêîãî òèïà. Äåíåæíàÿ åäèíèöà — ëàò. Áîëüøàÿ ÷àñòü òåððèòîðèè — ìîðåííàÿ ðàâíèíà; â öåíòðàëüíîé ÷àñòè — Âèäçåìñêàÿ âîçâûøåííîñòü (âûñîòà äî 311 ì, ãîðà Ãàéçèíüêàëíñ), íà çàïàäå è âîñòîêå — õîëìèñòûå âîçâûøåííîñòè (Êóðçåìñêàÿ è Ëàòãàëüñêàÿ). Êëèìàò ïåðåõîäíûé îò ìîðñêîãî ê êîíòèíåíòàëüíîìó. Ñðåäíèå òåìïåðàòóðû ÿíâàðÿ îò — 2 äî — 7øC, èþëÿ 16 — 18øC; îñàäêîâ 500 — 800 ìì â ãîä. Ãëàâíàÿ ðåêà — Äàóãàâà (Çàïàäíàÿ Äâèíà); ìíîãî îçåð; 1/3 òåððèòîðèè ïîêðûòà ëåñîì. Íàöèîíàëüíûé ïàðê Ãàóÿ. Çàïîâåäíèêè: Ãðèíè, Ìîðèöñàëà, Ñëèòåðå è äð.  10 — 13 ââ. íà òåððèòîðèè Ëàòâèè âîçíèêëè ïåðâûå êíÿæåñòâà (Êîêíåñå, Åðñèêà, Òàëàâà).  13 — 16 ââ. ïîä âëàñòüþ íåìåöêèõ çàâîåâàòåëåé.  1562 ÷àñòü òåððèòîðèè Ëàòâèè ðàçäåëåíà ìåæäó Ïîëüøåé è Øâåöèåé.  1721 è 1795 ïðèñîåäèíåíà ê Ðîññèè (Êóðëÿíäñêàÿ, ÷àñòè Ëèôëÿíäñêîé è Âèòåáñêîé ãóáåðíèè). 17.12.1918 â Ëàòâèè ïðîâîçãëàøåíà ñîâåòñêàÿ âëàñòü. Ñ íà÷àëà 1920 íåçàâèñèìàÿ Ëàòâèéñêàÿ ðåñïóáëèêà.  àâãóñòå 1920 ïîäïèñàí ñîâåòñêî-ëàòâèéñêèé ìèðíûé äîãîâîð.  ìàå 1934 ñîâåðøåí ãîñóäàðñòâåííûé ïåðåâîðîò, óñòàíîâëåíà äèêòàòóðà: çàïðåùåíû ïîëèòè÷åñêèå ïàðòèè, ïðîôñîþçû, ðàáî÷èå îðãàíèçàöèè, ðàñïóùåí ñåéì.  èþëå 1940 íà òåððèòîðèþ Ëàòâèè ââåäåíû ñîâåòñêèå âîéñêà; 21.7.1940 îáðàçîâàíà Ëàòâèéñêàÿ ÑÑÐ, 5.8.1940 ïðèñîåäèíåíà ê ÑÑÑÐ.  1941 — 45 îêêóïèðîâàíà íåìåöêî-ôàøèñòñêèìè âîéñêàìè.  ìàå 1990 Âåðõîâíûé Ñîâåò ðåñïóáëèêè ïðèíÿë Äåêëàðàöèþ î åå íåçàâèñèìîñòè. Ëàòâèÿ — èíäóñòðèàëüíî-àãðàðíàÿ ñòðàíà. Âàëîâîé íàöèîíàëüíûé ïðîäóêò íà äóøó íàñåëåíèÿ 3410 äîëëàðîâ â ãîä. Âåäóùèå îòðàñëè ïðîìûøëåííîñòè — ìàøèíîñòðîåíèå è ìåòàëëîîáðàáîòêà (ýëåêòðîòåõíè÷åñêàÿ, ýíåðãåòè÷åñêàÿ, ðàäèîýëåêòðîííàÿ ïðîìûøëåííîñòü, ïðîèçâîäñòâî ñðåäñòâ ñâÿçè è ïðèáîðîñòðîåíèå, òðàíñïîðòíîå è ñåëüñêîõîçÿéñòâåííîå ìàøèíîñòðîåíèå), õèìè÷åñêàÿ è íåôòåõèìè÷åñêàÿ, ëåãêàÿ (òåêñòèëüíàÿ, òðèêîòàæíàÿ è äðóãèå), ïèùåâàÿ (ìÿñî-ìîëî÷íàÿ, ðûáíàÿ è äðóãèå), öåëëþëîçíî-áóìàæíàÿ; ïðîèçâîäñòâî ôàðìàöåâòè÷åñêîé, ïàðôþìåðíî-êîñìåòè÷åñêîé ïðîäóêöèè. Ðàçâèòû õóäîæåñòâåííûå ïðîìûñëû (îáðàáîòêà êîæè, ÿíòàðÿ, ðåçüáà ïî äåðåâó, âûøèâêà). Ãëàâíàÿ îòðàñëü ñåëüñêîãî õîçÿéñòâà — æèâîòíîâîäñòâî (ìîëî÷íî-ìÿñíîå ñêîòîâîäñòâî è áåêîííîå ñâèíîâîäñòâî). Ïîñåâû çåðíîâûõ è êîðìîâûõ êóëüòóð. Êàðòîôåëåâîäñòâî, îâîùåâîäñòâî. Ï÷åëîâîäñòâî, çâåðîâîäñòâî. Ýêñïîðò: ïðîäóêöèÿ ìàøèíîñòðîåíèÿ, ëåãêîé è ïèùåâîé ïðîìûøëåííîñòè. Ìîðñêîé ïîðòû: Ðèãà, Âåíòñïèëñ, Ëèåïàÿ. Ñóäîõîäñòâî ïî ðåêàì Ëèåëóïå è Äàóãàâà. Êóðîðòû: Þðìàëà, Ëèåïàÿ, Êåìåðè, Áàëäîíå è äðóãèå.

Ëàòâèÿ —

Ëàòâèéñêàÿ Ðåñïóáëèêà, ãîñóäàðñòâî â Âîñòî÷íîé Åâðîïå. Ðàñïîëîæåíà â âîñòî÷íîé Ïðèáàëòèêå. Ãðàíè÷èò… Ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ Êîëüåðà

Ëàòâèÿ — Íàñåëåíèå 2,366 ìëí ÷åë. Âîåííûé áþäæåò 198 ìëí äîëë. (2003). Ðåãóëÿðíûå ÂÑ 4,88 òûñ. ÷åë. Ðåçåðâ 13… Âîîðóæåííûå ñèëû çàðóáåæíûõ ñòðàí

латвия

-

1

Латвия

Русско-латышский словарь > Латвия

См. также в других словарях:

-

Латвия — Республика Латвия, гос во в Вост. Европе, омывается Балтийским морем. Название Латвия образовано от самоназвания жителей страны латвиеши (latviesi), русск. латыши. Географические названия мира: Топонимический словарь. М: АСТ. Поспелов Е.М. 2001 … Географическая энциклопедия

-

ЛАТВИЯ — (Латвийская республика), государство в Восточной Европе, в Прибалтике, омывается Балтийским морем и Рижским заливом. Площадь 64,5 тыс. км2. Население 2596 тыс. человек, городское 71%; латыши (52%), русские (34%), белорусы (4,5%), украинцы, поляки … Современная энциклопедия

-

Латвия — – марка автомобиля, Латвия. EdwART. Словарь автомобильного жаргона, 2009 … Автомобильный словарь

-

латвия — сущ., кол во синонимов: 1 • страна (281) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Латвия — (Latvia), небольшое гос во на вост. побережье Балтийского моря. Была частью балтийских пров. Тевтонского ордена, где большинство крупных поместий принадлежало нем. родам, т.н. балтийским баронам. Передана России при разделе Польши в кон. 18 в. С… … Всемирная история

-

ЛАТВИЯ — ЛАТВИЯ. Площадь 65.791 км2. Количество населения (на 1/1 1929 г.) 1.895.016 чел.; из них мужчин 884.696 и женщин 1.010.320. Плотность населения 28,8 чел. на 1 км9 . До империалистской войны население Л. исчислялось в 2.552.000 жит., по переписи… … Большая медицинская энциклопедия

-

ЛАТВИЯ — До 1991 года входила в состав СССР. Расположена на Восточном побережье Балтийского моря. Территория 64,5 тыс.кв.км, население 2681 тыс.человек (1990). Это индустриальная республика с развитым сельским хозяйством. Основные отрасли промышленности … Мировое овцеводство

-

Латвия — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Латвия (значения). Латвийская Республика Latvijas Republika … Википедия

-

ЛАТВИЯ — Латвийская Республика, государство в Восточной Европе. Расположена в восточной Прибалтике. Граничит на севере с Эстонией, на юге с Литвой, на востоке с Россией и Белоруссией. На западе омывается Балтийским морем. Латвия впервые получила… … Энциклопедия Кольера

-

Латвия — (Latvija), Латвийская Республика (Latvijas Republika), государство в Восточной Европе, в Прибалтике, омывается Балтийским морем и Рижским заливом. 64,5 тыс. км2. Население 2530 тыс. человек (1995), городское 69,1%; латыши (1388 тыс. человек; 1989 … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Латвия — Государственное устройство Правовая система Общая характеристика Гражданское и смежные с ним отрасли права Уголовное право и процесс Судебная система. Органы контроля Литература Государство на северо западе Восточной Европы, на побережье… … Правовые системы стран мира. Энциклопедический справочник

Вы собираетесь поехать в Латвию?

Выучите самые необходимые слова на латышском.

Здесь вы найдёте перевод более 50 важных слов и выражений с латышского на русский язык.

Это поможет вам лучше подготовиться к поездке в Латвию.

Учите вместе с нами:

- Как сказать «Привет!» по-латышски?

- Как сказать «Пока!» на латышском?

- Как будет «пожалуйста» по-латышски?

- Как будет «Спасибо!» на латышском?

- Как переводится «да» и «нет» на латышский?

- Учите числительные. Вам несомненно поможет умение считать от 1 до 10 на латышском.

- Как сказать «Меня зовут. » по-латышски?

Все слова и выражения начитаны носителями языка из Латвии.

Так вы сразу учите правильное произношение.

Используйте наш список основных выражений на латышском как маленький словарь для путешественника. Распечатайте его и положите в чемодан.

Источник

Palīgā! 1. sērija. фильм для изучающих латышский

Как перевести на латышский язык адрес, написанный на русском? Вообще переводится? (вн)

Так и писать — ул.Труда №5, кв. 105

Pasta sūtījumu adresēšana

Uz starptautiskajiem pasta sūtījumiem adresi raksta izsniegšanas vietas valsts vai arī citā šajā valstī zināmā valodā, vai franču valodā, valsts nosaukumu uzrādot latīņu burtiem.Uz Amerikas Savienotajām Valstīm visa adrese jāraksta drukātiem burtiem.

http://www.pasts.lv/lv/privatpersonas/pasta_sutijumi/adreseshana.html

Ответы

ovod (74) 7 (86376) 8 18 75 8 лет

Название улицы ни в коем случае нельзя переводить, ее же в таком виде ни один почтальон не найдет.

Если адрес пишется латинскими буквами (а в Латвии так и надо), то улицу Труда надо писать Truda.

Имя собственное не переводится. Пора уже знать.

http://translate.meta.ua/ru/?noredir

В ДАЛЬНЕЙШЕМ НЕ ПОЛЕНИТЕСЬ В ИНЕТЕ ПОИСКАТЬ ПЕРЕВОДЧИК.

Гришандр (25) 6 (18157) 2 6 28 8 лет

Похожие вопросы

Полное имя получателя (в формате «Фамилия Имя Отчество») или название организации (краткое или полное)

Название улицы, номер дома, номер квартиры

Название населенного пункта

Название района, области, края или республики

Название страны

Номер а/я, если есть (в формате «а/я 15»)

Почтовый индекс

KS- канзас

66547 это зип код

Apt- апартаменты номер 23

а вообще как адрес есть так его и пиши, ничего не выкидывай

В салоне.

В Риге:

Латышский язык? Сейчас объясню!

Vadim Tattoo — хороший салон;

Адрес: Kr.Barona 60;

Москва:

1. Салон Шарм.

Адрес: Пересечение Первомайской и 3 Парковой улиц.

2. На Пушкинской (метро) есть магазин Бриг, там работает парень, очень хорошо прокалывает. Ссылка на их услуги:

http://www.mlove.ru/forum/topic5891.html

tolko na angliiskom,na koreiskom ne primut na nawei po4te.

esli est risk sto na toi storone ne znajut angliiskogo pe4aew etiketku s koreiskim adresom i prikleeviaew toze.

Источник

Латвия ввела новые ограничения для проживающих там россиян

Россиянам, которые проживают в Латвии, не будут продлевать виды на жительство. Кроме того, рабочие визы тоже выдаваться не будут. Решение об этом принял парламент страны.

«Уже выданные россиянам виды на жительство будут теперь действовать только до 1 сентября 2023 года. Для их продления нужно будет подтвердить владение латышским языком», — говорится на официальном сайте Латвийского телевидения.

Таким образом, возможность продления вида на жительство для граждан РФ на основании сделанных инвестиций или приобретения недвижимости в Латвии прекращена. Ограничения коснулись и граждан Белоруссии. Исключения — это воссоединение семьи, международная защита или гуманитарные соображения.

Россия начала спецоперацию по демилитаризации и денацификации Украины в конце февраля этого года. В ответ на это Евросоюз ввел санкции, в числе которых — приостановка действия соглашения об упрощении выдачи виз между Россией и ЕС. При этом Еврокомиссия обсуждает с ЕС получение гуманитарных виз для россиян из-за объявленной в РФ мобилизации, уточняет MK.RU. При этом Латвия не будет выдавать визы россиянам, которые уклоняются от мобилизации, передает «Федеральное агентство новостей».

Россиянам, которые проживают в Латвии, не будут продлевать виды на жительство. Кроме того, рабочие визы тоже выдаваться не будут. Решение об этом принял парламент страны. «Уже выданные россиянам виды на жительство будут теперь действовать только до 1 сентября 2023 года.

Для их продления нужно будет подтвердить владение латышским языком», — говорится на официальном сайте Латвийского телевидения. Таким образом, возможность продления вида на жительство для граждан РФ на основании сделанных инвестиций или приобретения недвижимости в Латвии прекращена. Ограничения коснулись и граждан Белоруссии.

Исключения — это воссоединение семьи, международная защита или гуманитарные соображения. Россия начала спецоперацию по демилитаризации и денацификации Украины в конце февраля этого года. В ответ на это Евросоюз ввел санкции, в числе которых — приостановка действия соглашения об упрощении выдачи виз между Россией и ЕС. При этом Еврокомиссия обсуждает с ЕС получение гуманитарных виз для россиян из-за объявленной в РФ мобилизации, уточняет MK.RU. При этом Латвия не будет выдавать визы россиянам, которые уклоняются от мобилизации, передает «Федеральное агентство новостей».

Источник

«Lettonia» redirects here. For the Latvian student corporation, see Lettonia (corporation).

Coordinates: 57°N 25°E / 57°N 25°E

|

Republic of Latvia

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Dievs, svētī Latviju! (Latvian) («God Bless Latvia!») |

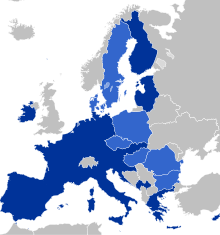

|

![Location of Latvia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/EU-Latvia.svg/250px-EU-Latvia.svg.png)

Location of Latvia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Riga 56°57′N 24°6′E / 56.950°N 24.100°E |

| Official languages | Latviana |

| Recognized languages | Livonian Latgalian |

| Ethnic groups

(2022[1]) |

|

| Religion

(2018)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Latvian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

|

• President |

Egils Levits |

|

• Prime Minister |

Krišjānis Kariņš |

|

• Speaker of the Saeima |

Edvards Smiltēns |

| Legislature | Saeima |

| Independence

from Germany and the Soviet Union |

|

|

• Declared[3] |

18 November 1918 |

|

• Recognised |

26 January 1921 |

|

• Constitution adopted |

7 November 1922 |

|

• Restored after Soviet occupation[4] |

21 August 1991 |

|

• Joined the EU |

1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi) (122nd) |

|

• Water (%) |

2.09 (2015)[5] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

1,842,226[6] (153rd) |

|

• Density |

29.6/km2 (76.7/sq mi) (147th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2021) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 39th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +371 |

| ISO 3166 code | LV |

| Internet TLD | .lvc |

|

Latvia ( or ; Latvian: Latvija [ˈlatvija]; Latgalian: Latveja; Livonian: Lețmō), officially the Republic of Latvia[14] (Latvian: Latvijas Republika, Latgalian: Latvejas Republika, Livonian: Lețmō Vabāmō), is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the Baltic states; and is bordered by Estonia to the north, Lithuania to the south, Russia to the east, Belarus to the southeast, and shares a maritime border with Sweden to the west. Latvia covers an area of 64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi), with a population of 1.9 million. The country has a temperate seasonal climate.[15] Its capital and largest city is Riga. Latvians belong to the ethno-linguistic group of the Balts and speak Latvian, one of the only two[a] surviving Baltic languages. Russians are the most prominent minority in the country, at almost a quarter of the population.

After centuries of Teutonic, Swedish, Polish-Lithuanian and Russian rule, which was mainly executed by the local Baltic German aristocracy, the independent Republic of Latvia was established on 18 November 1918 when it broke away from the German Empire and declared independence in the aftermath of World War I.[3] However, by the 1930s the country became increasingly autocratic after the coup in 1934 establishing an authoritarian regime under Kārlis Ulmanis.[16] The country’s de facto independence was interrupted at the outset of World War II, beginning with Latvia’s forcible incorporation into the Soviet Union, followed by the invasion and occupation by Nazi Germany in 1941, and the re-occupation by the Soviets in 1944 to form the Latvian SSR for the next 45 years. As a result of extensive immigration during the Soviet occupation, ethnic Russians became the most prominent minority in the country, now constituting nearly a quarter of the population. The peaceful Singing Revolution started in 1987, and ended with the restoration of de facto independence on 21 August 1991.[17] Since then, Latvia has been a democratic unitary parliamentary republic.

Latvia is a developed country, with a high-income advanced economy; ranking very high 39th in the Human Development Index. It performs favorably in measurements of civil liberties, press freedom, internet freedom, democratic governance, living standards, and peacefulness. Latvia is a member of the European Union, Eurozone, NATO, the Council of Europe, the United Nations, the Council of the Baltic Sea States, the International Monetary Fund, the Nordic-Baltic Eight, the Nordic Investment Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and the World Trade Organization.

Etymology

The name Latvija is derived from the name of the ancient Latgalians, one of four Indo-European Baltic tribes (along with Curonians, Selonians and Semigallians), which formed the ethnic core of modern Latvians together with the Finnic Livonians.[18] Henry of Latvia coined the latinisations of the country’s name, «Lettigallia» and «Lethia», both derived from the Latgalians. The terms inspired the variations on the country’s name in Romance languages from «Letonia» and in several Germanic languages from «Lettland».[19]

History

Around 3000 BC, the proto-Baltic ancestors of the Latvian people settled on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea.[20] The Balts established trade routes to Rome and Byzantium, trading local amber for precious metals.[21] By 900 AD, four distinct Baltic tribes inhabited Latvia: Curonians, Latgalians, Selonians, Semigallians (in Latvian: kurši, latgaļi, sēļi and zemgaļi), as well as the Finnic tribe of Livonians (lībieši) speaking a Finnic language.[citation needed]

In the 12th century in the territory of Latvia, there were lands with their rulers: Vanema, Ventava, Bandava, Piemare, Duvzare, Sēlija, Koknese, Jersika, Tālava and Adzele.[22]

Medieval period

Although the local people had contact with the outside world for centuries, they became more fully integrated into the European socio-political system in the 12th century.[23] The first missionaries, sent by the Pope, sailed up the Daugava River in the late 12th century, seeking converts.[24] The local people, however, did not convert to Christianity as readily as the Church had hoped.[24]

German crusaders were sent, or more likely decided to go on their own accord as they were known to do. Saint Meinhard of Segeberg arrived in Ikšķile, in 1184, traveling with merchants to Livonia, on a Catholic mission to convert the population from their original pagan beliefs. Pope Celestine III had called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe in 1193. When peaceful means of conversion failed to produce results, Meinhard plotted to convert Livonians by force of arms.[25]