| League of Legends | |

|---|---|

Logo variant from 2019 |

|

| Developer(s) | Riot Games |

| Publisher(s) | Riot Games |

| Director(s) | Andrei van Roon[1] |

| Producer(s) | Jeff Jew |

| Platform(s) |

|

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | MOBA |

| Mode(s) | Multiplayer |

League of Legends (LoL), commonly referred to as League, is a 2009 multiplayer online battle arena video game developed and published by Riot Games. Inspired by Defense of the Ancients, a custom map for Warcraft III, Riot’s founders sought to develop a stand-alone game in the same genre. Since its release in October 2009, League has been free-to-play and is monetized through purchasable character customization. The game is available for Microsoft Windows and macOS.

In the game, two teams of five players battle in player-versus-player combat, each team occupying and defending their half of the map. Each of the ten players controls a character, known as a «champion», with unique abilities and differing styles of play. During a match, champions become more powerful by collecting experience points, earning gold, and purchasing items to defeat the opposing team. In League‘s main mode, Summoner’s Rift, a team wins by pushing through to the enemy base and destroying their «Nexus», a large structure located within.

League of Legends has received generally positive reviews; critics highlighted its accessibility, character designs, and production value. The game’s long lifespan has resulted in a critical reappraisal, with reviews trending positively; the negative and abusive in-game behavior of its players, criticized since early in the game’s lifetime, persists despite Riot’s attempts to fix the problem. In 2019, League regularly peaked at eight million concurrent players, and its popularity has led to tie-ins such as music videos, comic books, short stories, and the animated series Arcane. Its success has also spawned several spin-off video games, including a mobile version, a digital collectible card game and a turn-based role-playing game, among others. A massively multiplayer online role-playing game based on the property is in development.

Regularly cited as the world’s largest esport, the game has an international competitive scene consisting of multiple regional leagues. They culminate in the annual League of Legends World Championship. The 2019 event registered over 100 million unique viewers, peaking at a concurrent viewership of 44 million during the finals. Domestic and international events have been broadcast on livestreaming websites such as Twitch, YouTube, Bilibili, and on cable television sports channel ESPN.

Gameplay

Four champions in the bottom lane of Summoner’s Rift, surrounded by minions. The red health bars indicate that they are opposing players.

League of Legends is a multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) game in which the player controls a character («champion») with a set of unique abilities from an isometric perspective.[2][3] As of 2023, there are over 160 champions available to play.[4] Over the course of a match, champions gain levels by accruing experience points (XP) through killing enemies.[5] Items can be acquired to increase champions’ strength,[6] and are bought with gold, which players accrue passively over time and earn actively by defeating the opposing team’s minions,[2] champions, or defensive structures.[5][6] In the main game mode, Summoner’s Rift, items are purchased through a shop menu available to players only when their champion is in the team’s base.[2] Each match is discrete; levels and items do not transfer from one match to another.[7]

Summoner’s Rift

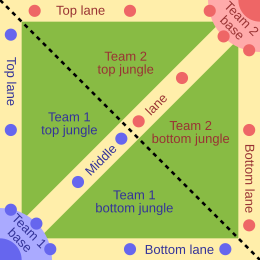

A simplified representation of Summoner’s Rift. The yellow paths are the «lanes» down which minions march; blue and red dots represent turrets. The fountains are the dark areas within each base, and are beside each Nexus. The dotted black line indicates the river.

Summoner’s Rift is the flagship game mode of League of Legends and the most prominent in professional-level play.[8][9][10] The mode has a ranked competitive ladder; a matchmaking system determines a player’s skill level and generates a starting rank from which they can climb. There are nine tiers; the least skilled are Iron, Bronze, and Silver, and the highest are Master, Grandmaster, and Challenger.[11][a]

Two teams of five players compete to destroy the opposing team’s «Nexus», which is guarded by the enemy champions and defensive structures known as «turrets».[13] Each team’s Nexus is located in their base, where players start the game and reappear after death.[13] Non-player characters known as minions are generated from each team’s Nexus and advance towards the enemy base along three lanes guarded by turrets: top, middle, and bottom.[14] Each team’s base contains three «inhibitors», one behind the third tower from the center of each lane. Destroying one of the enemy team’s inhibitors causes stronger allied minions to spawn in that lane, and allows the attacking team to damage the enemy Nexus and the two turrets guarding it.[15] The regions in between the lanes are collectively known as the «jungle», which is inhabited by «monsters» that, like minions, respawn at regular intervals. Like minions, monsters provide gold and XP when killed.[16] Another, more powerful class of monster resides within the river that separates each team’s jungle.[17] These monsters require multiple players to defeat and grant special abilities to their slayers’ team. For example, teams can gain a powerful allied unit after killing the Rift Herald, permanent strength boosts by killing dragons, and stronger, more durable minions by killing Baron Nashor.[18]

Summoner’s Rift matches can last from as little as 15 minutes to over an hour.[19] Although the game does not enforce where players may go, conventions have arisen over the game’s lifetime: typically one player goes in the top lane, one in the middle lane, one in the jungle, and two in the bottom lane.[2][5][20] Players in a lane kill minions to accumulate gold and XP (termed «farming») and try to prevent their opponent from doing the same. A fifth champion, known as a «jungler», farms the jungle monsters and, when powerful enough, assists their teammates in a lane.[21]

Other modes

Besides Summoner’s Rift, League of Legends has two other permanent game modes. ARAM («All Random, All Mid») is a five-versus-five mode like Summoner’s Rift, but on a map called Howling Abyss with only one long lane, no jungle area, and with champions randomly chosen for players.[22][23][24] Given the small size of the map, players must be vigilant in avoiding enemy abilities.[25]

Teamfight Tactics is an auto battler released in June 2019 and made a permanent game mode the following month.[26][27] As with others in its genre, players build a team and battle to be the last one standing. Players do not directly affect combat but position their units on a board for them to fight automatically against opponents each round.[28] Teamfight Tactics is available for iOS and Android and has cross-platform play with the Windows and macOS clients.[29]

Other game modes have been made available temporarily, typically aligning with in-game events.[30][31] Ultra Rapid Fire (URF) mode was available for two weeks as a 2014 April Fools Day prank. In the mode, champion abilities have no resource cost, significantly reduced cooldown timers, increased movement speed, reduced healing, and faster attacks.[32][33] A year later, in April 2015, Riot disclosed that they had not brought the mode back because its unbalanced design resulted in player «burnout». The developer also said the costs associated with maintaining and balancing URF were too high.[34] Other temporary modes include One for All and Nexus Blitz. One for All has players pick a champion for all members of their team to play.[35][36] In Nexus Blitz, players participate in a series of mini-games on a compressed map.[37]

Development

Pre-release

Riot Games’ West Los Angeles headquarters (2015)

Riot Games’ founders Brandon Beck and Marc Merill had an idea for a spiritual successor to Defense of the Ancients, known as DotA. A mod for Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos, DotA required players to buy Warcraft III and install custom software; The Washington Post‘s Brian Crecente said the mod «lacked a level of polish and was often hard to find and set up».[38] Phillip Kollar of Polygon noted that Blizzard Entertainment supported Warcraft III with an expansion pack, then shifted their focus to other projects while the game still had players. Beck and Merill sought to create a game that would be supported over a significantly longer period.[39]

Beck and Merill held a DotA tournament for students at the University of Southern California, with an ulterior goal of recruitment. There they met Jeff Jew, later a producer on League of Legends. Jew was very familiar with DotA and spent much of the tournament teaching others how to play. Beck and Merill invited him to an interview, and he joined Riot Games as an intern.[38] Beck and Merill recruited two figures involved with DotA: Steve Feak, one of its designers,[38] and Steve Mescon, who ran a support website to assist players.[40][41] Feak said early development was highly iterative, comparing it to designing DotA.[42]

A demonstration of League of Legends built in the Warcraft III game engine was completed in four months and then shown at the 2007 Game Developers Conference.[39] There, Beck and Merill had little success with potential investors. Publishers were confused by the game’s free-to-play business model and lack of a single-player mode. The free-to-play model was untested outside of Asian markets,[38] so publishers were primarily interested in a retail release, and the game’s capacity for a sequel.[39] In 2008, Riot reached an agreement with holding company Tencent to oversee the game’s launch in China.[39]

League of Legends was announced October 7, 2008, for Microsoft Windows.[43][44] Closed beta-testing began in April 2009.[43][45] Upon the launch of the beta, seventeen champions were available.[46] Riot initially aimed to ship the game with 20 champions but doubled the number before the game’s full release in North America on October 27, 2009.[47][48] The game’s full name was announced as League of Legends: Clash of Fates. Riot planned to use the subtitle to signal when future content was available, but decided they were silly and dropped it before launch.[39]

Post-release

League of Legends receives regular updates in the form of patches. Although previous games had utilized patches to ensure no one strategy dominated, League of Legends‘ patches made keeping pace with the developer’s changes a core part of the game. In 2014, Riot standardized their patch cadence to once approximately every two or three weeks.[49]

The development team includes hundreds of game designers and artists. In 2016, the music team had four full-time composers and a team of producers creating audio for the game and its promotional materials.[50] As of 2021, the game has over 150 champions,[51] and Riot Games periodically overhauls the visuals and gameplay of the oldest in the roster.[52] Although only available for Microsoft Windows at launch, a Mac version of the game was made available in March 2013.[53]

Revenue model

League of Legends uses a free-to-play business model. Several forms of purely cosmetic customization—for example, «skins» that change the appearance of champions—can be acquired after buying an in-game currency called Riot Points (RP).[54] Skins have five main pricing tiers, ranging from $4 to $25.[55] As virtual goods, they have high profit margins.[50] A loot box system has existed in the game since 2016; these are purchasable virtual «chests» with randomized, cosmetic items.[56] These chests can be bought outright or acquired at a slower rate for free by playing the game. The practice has been criticized as a form of gambling.[57] In 2019, Riot Games’ CEO said that he hoped loot boxes would become less prevalent in the industry.[58] Riot has also experimented with other forms of monetization. In August 2019, they announced an achievement system purchasable with Riot Points. The system was widely criticized for its high cost and low value.[59]

In 2014, Ubisoft analyst Teut Weidemann said that only around 4% of players paid for cosmetics—significantly lower than the industry standard of 15 to 25%. He argued the game was only profitable because of its large player base.[60] In 2017, the game had a revenue of US$2.1 billion;[61] in 2018, a lower figure of $1.4 billion still positioned it as one of the highest-grossing games of 2018.[62] In 2019, the number rose to $1.5 billion, and again to $1.75 billion in 2020.[62][61] According to magazine Inc., players collectively played three billion hours every month in 2016.[50]

Plot

See also: League of Legends § Spin-offs and other media

Before 2014, players existed in-universe as political leaders, or «Summoners», commanding champions to fight on the Fields of Justice—for example, Summoner’s Rift—to avert a catastrophic war.[63] Sociologist Matt Watson said the plot and setting were bereft of the political themes found in other role-playing games, and presented in reductive «good versus evil» terms.[64] In the game’s early development, Riot did not hire writers, and designers wrote character biographies only a paragraph long.[39]

In September 2014, Riot Games rebooted the game’s fictional setting, removing summoners from the game’s lore to avoid «creative stagnation».[63][65] Luke Plunkett wrote for Kotaku that, although the change would upset long-term fans, it was necessary as the game’s player base grew in size.[66] Shortly after the reboot, Riot hired Warhammer writer Graham McNeill.[67] Riot’s storytellers and artists create flavor text, adding «richness» to the game, but very little of this is seen as a part of normal gameplay. Instead, that work supplies a foundation for the franchise’s expansion into other media,[50] such as comic books and spin-off video games.[68][69] The Fields of Justice were replaced by a new fictional setting—a planet called Runeterra. The setting has elements from several genres—from Lovecraftian horror to traditional sword and sorcery fantasy.[70]

Reception

League of Legends received generally favorable reviews on its initial release, according to review aggregator website Metacritic.[71] Many publications noted the game’s high replay value.[83][84][85] Kotaku reviewer Brian Crecente admired how items altered champion play styles.[85] Quintin Smith of Eurogamer concurred, praising the amount of experimentation offered by champions.[86] Comparing it to Defense of the Ancients, Rick McCormick of GamesRadar+ said that playing League of Legends was «a vote for choice over refinement».[87]

Given the game’s origins, other reviewers frequently compared aspects of it to DotA. According to GamesRadar+ and GameSpot, League of Legends would feel familiar to those who had already played DotA.[74][88] The game’s inventive character design and lively colors distinguished the game from its competitors.[80] Smith concluded his review by noting that, although there was not «much room for negativity», Riot’s goal of refining DotA had not yet been realized.[86]

Although Crecente praised the game’s free-to-play model,[85] GameSpy‘s Ryan Scott was critical of the grind required for non-paying players to unlock key gameplay elements, calling it unacceptable in a competitive game.[89][b] Many outlets said the game was underdeveloped.[84][80] A physical version of the game was available for purchase from retailers; GameSpot‘s Kevin VanOrd said it was an inadvisable purchase because the value included $10 of store credit for an unavailable store.[84] German site GameStar noted that none of the bonuses in that version were available until the launch period had ended and refused to carry out a full review.[91] IGN‘s Steve Butts compared the launch to the poor state of CrimeCraft‘s release earlier in 2009; he indicated that features available during League of Legends‘s beta were removed for the release, even for those who purchased the retail version.[80] Matches took unnecessarily long to find for players, with long queue times,[85][80][92] and GameRevolution mentioned frustrating bugs.[93]

Some reviewers addressed toxicity in the game’s early history. Crecente wrote that the community was «insular» and «whiney» when losing.[85] Butts speculated that League of Legends inherited many of DotA‘s players, who had developed a reputation for being «notoriously hostile» to newcomers.[80]

Reassessment

Fan cosplay of the League of Legends champion Nidalee

Regular updates to the game have resulted in a reappraisal by some outlets; IGN‘s second reviewer, Leah B. Jackson, explained that the website’s original review had become «obsolete».[81] Two publications increased their original scores: GameSpot from 6 to 9,[76][77] and IGN from 8 to 9.2.[80][81] The variety offered by the champion roster was described by Steven Strom of PC Gamer as «fascinating»;[82] Jackson pointed to «memorable» characters and abilities.[81] Although the items had originally been praised at release by other outlets such as Kotaku,[85] Jackson’s reassessment criticized the lack of item diversity and viability, noting that the items recommended to the player by the in-game shop were essentially required because of their strength.[81]

While reviewers were pleased with the diverse array of play styles offered by champions and their abilities,[81][77][82] Strom thought that the female characters still resembled those in «horny Clash of Clans clones» in 2018.[82] Two years before Strom’s review, a champion designer responded to criticism by players that a young, female champion was not conventionally attractive. He argued that limiting female champions to one body type was constraining, and said progress had been made in Riot’s recent releases.[94]

Comparisons persisted between the game and others in the genre. GameSpot‘s Tyler Hicks wrote that new players would pick up League of Legends quicker than DotA and that the removal of randomness-based skills made the game more competitive.[77] Jackson described League of Legends’ rate of unlock for champions as «a model of generosity», but less than DotA‘s sequel, Dota 2 (2013), produced by Valve, wherein characters are unlocked by default.[81] Strom said the game was fast-paced compared to Dota 2‘s «yawning» matches, but slower than those of Blizzard Entertainment’s «intentionally accessible» MOBA Heroes of the Storm (2015).[82]

Accolades

At the first Game Developers Choice Awards in 2010, the game won four major awards: Best Online Technology, Game Design, New Online Game, and Visual Arts.[95] At the 2011 Golden Joystick Awards, it won Best Free-to-Play Game.[96] Music produced for the game won a Shorty Award,[97] and was nominated at the Hollywood Music in Media Awards.[98]

League of Legends has received awards for its contribution to esports. It was nominated for Best Esports Game at The Game Awards in 2017 and 2018,[99][100] then won in 2019, 2020, and 2021.[101][102][103] Specific events organized by Riot for esports tournaments have been recognized by awards ceremonies. Also at The Game Awards, the Riot won Best Esports Event for the 2019, 2020 and 2021 League World Championships.[101][102][103] At the 39th Sports Emmy Awards in 2018, League of Legends won Outstanding Live Graphic Design for the 2017 world championship; as part of the pre-competition proceedings, Riot used augmented reality technology to have a computer-generated dragon fly across the stage.[104][105][106]

Player behavior

League of Legends’ player base has a longstanding reputation for «toxicity»—negative and abusive in-game behavior,[107][108][109] with a survey by the Anti-Defamation League indicating that 76% of players have experienced in-game harassment.[110] Riot Games has acknowledged the problem and responded that only a small portion of the game’s players are consistently toxic. According to Jeffrey Lin, the lead designer of social systems at Riot Games, the majority of negative behavior is committed by players «occasionally acting out».[111] Several major systems have been implemented to tackle the issue. One such measure is basic report functionality; players can report teammates or opponents who violate the game’s code of ethics. The in-game chat is also monitored by algorithms that detect several types of abuse.[111] An early system was the «Tribunal»—players who met certain requirements were able to review reports sent to Riot. If enough players determined that the messages were a violation, an automated system would punish them.[112] Lin said that eliminating toxicity was an unrealistic goal, and the focus should be on rewarding good player behavior.[113] To that effect, Riot reworked the «Honor system» in 2017, allowing players to award teammates with virtual medals following games, for one of three positive attributes. Acquiring these medals increases a player’s «Honor level», rewarding them with free loot boxes over time.[114]

In esports

League of Legends is one of the world’s largest esports, described by The New York Times as its «main attraction».[115] Online viewership and in-person attendance for the game’s esports events outperformed those of the National Basketball Association, the World Series, and the Stanley Cup in 2016.[116] For the 2019 and 2020 League of Legends World Championship finals, Riot Games reported 44 and 45 peak million concurrent viewers respectively.[117][118] Harvard Business Review said that League of Legends epitomized the birth of the esports industry.[119]

As of April 2021, Riot Games operates 12 regional leagues internationally,[120][121][122] four of which—China, Europe, Korea, and North America—have franchised systems.[123][124][125][126][127] In 2017, this system comprised 109 teams and 545 players.[128] League games are typically livestreamed on platforms such as Twitch and YouTube.[118] The company sells streaming rights to the game;[50] the North American league playoff is broadcast on cable television by sports network ESPN.[129] In China, the rights to stream international events such as the World Championships and the Mid-Season Invitational were sold to Bilibili in Fall 2020 for a three-year deal reportedly worth US$113 million,[130][131][132] while exclusive streaming rights for the domestic and other regional leagues are owned by Huya Live.[133] The game’s highest-paid professional players have commanded salaries of above $1 million—over three times the highest-paid players of Overwatch.[134] The scene has attracted investment from businesspeople otherwise unassociated with esports, such as retired basketball player Rick Fox, who founded his own team.[135] In 2020, his team’s slot in the North American league was sold to the Evil Geniuses organization for $33 million.[136]

Spin-offs and other media

Games

For the 10th anniversary of League of Legends in 2019, Riot Games announced several games at various stages of production that were directly related to the League of Legends intellectual property (IP).[137][138] A stand-alone version of Teamfight Tactics was announced for mobile operating systems iOS and Android at the event and released in March 2020. The game has cross-platform play with the Windows and macOS clients.[29] Legends of Runeterra, a free-to-play digital collectible card game, launched in April 2020 for Microsoft Windows; the game features characters from League of Legends.[139][140][141] League of Legends: Wild Rift is a version of the game for mobile operating systems Android, iOS, and unspecified consoles.[142][c] Instead of porting the game from League of Legends, Wild Rift‘s character models and environments were entirely rebuilt.[145] A single-player, turn-based role-playing game, Ruined King: A League of Legends Story, was released in 2021 for PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S, Nintendo Switch, and Windows.[69] It was the first title released under Riot Games’ publishing arm, Riot Forge, wherein non-Riot studios develop games using League of Legends characters.[146] In December 2020, Greg Street, vice-president of IP and Entertainment at Riot Games, announced that a massively multiplayer online role-playing game based on the game is in development.[147] Song of Nunu: A League of Legends Story, a third-person adventure game revolving around the champion Nunu’s search for his mother, with the help of the yeti Willump, was announced for a planned release in 2022. It is being developed by Tequila Works, the creators of Rime.[148]

Music

Riot Games’ first venture into music was in 2014 with the virtual heavy metal band Pentakill, promoting a skin line of the same name.[149][150] Pentakill is composed of seven champions, and their music was primarily made by Riot Games’ in-house music team but featured cameos by Mötley Crüe drummer Tommy Lee and Danny Lohner, a former member of industrial rock band Nine Inch Nails. Their second album, Grasp of the Undying, reached Number 1 on the iTunes metal charts in 2017.[150]

Pentakill was followed by K/DA, a virtual K-pop girl group composed of four champions. As with Pentakill, K/DA is promotional material for a skin line by the same name.[151] The group’s debut single, «Pop/Stars», which premiered at the 2018 League of Legends World Championship, garnered over 400 million views on YouTube and sparked widespread interest from people unfamiliar with League of Legends.[152] After a two-year hiatus, in August 2020, Riot Games released «The Baddest», the pre-release single for All Out, the five-track debut EP from K/DA which followed in November that year.[153]

In 2019, Riot created a virtual hip hop group called True Damage,[154] featuring the champions Akali, Yasuo, Qiyana, Senna, and Ekko.[155] The vocalists—Keke Palmer, Thutmose, Becky G, Duckwrth, and Soyeon—performed a live version of the group’s debut song, «Giants», during the opening ceremony of the 2019 League of Legends World Championship, alongside holographic versions of their characters.[155] The in-game cosmetics promoted by the music video featured a collaboration with fashion house Louis Vuitton.[156]

Comics

Riot announced a collaboration with Marvel Comics in 2018.[68] Riot had previously experimented with releasing comics through its website.[157][158] Shannon Liao of The Verge noted that the comic books were «a rare opportunity for Riot to showcase its years of lore that has often appeared as an afterthought».[68] The first comic was League of Legends: Ashe—Warmother, which debuted in 2018, followed by League of Legends: Lux that same year.[159] A print version of the latter was released in 2019.[160]

Animated series

In a video posted to celebrate the tenth anniversary of League of Legends, Riot announced an animated television series, Arcane,[161] the company’s first production for television.[162] Arcane was a collaborative effort between Riot Games and animation studio Fortiche Production.[162] In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, head of creative development Greg Street said the series is «not a light-hearted show. There are some serious themes that we explore there, so we wouldn’t want kids tuning in and expecting something that it’s not.»[161] The series is set in the utopian city of Piltover and its underground, oppressed sister city, Zaun.[162][163][164] The series was set to be released in 2020 but was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.[165] On November 6, 2021, Arcane premiered on Netflix following the 2021 League of Legends World Championship,[166] and was available through Tencent Video in China.[162] The series received critical acclaim upon release, with IGN’s Rafael Motomayor asking rhetorically if the series marked the end of the «video game adaptation curse».[167] It stars Hailee Steinfeld as Vi, Ella Purnell as Jinx, Kevin Alejandro as Jayce, and Katie Leung as Caitlyn.[168] Following the season one finale, Netflix announced a second season was in development.[162]

Notes

- ^ Prior to this, there were seven tiers: Bronze, Silver, Gold, Platinum, Diamond, Master, and Challenger.[12]

- ^ Scott’s review referenced a now-retired system of in-game bonuses to champions which could be slowly earned while playing or purchased outright with real money.[90]

- ^ Although some sources have stated that the game will be available for the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One,[143] others mention the Nintendo Switch.[144] Riot has made no official announcements about the consoles on which the game will be available.

References

- ^ «League of Legends’s reporting in Champion select feature set for July launch». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Blue, Rosario (July 18, 2020). «League of Legends: a beginner’s guide». TechRadar. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Watson, Max (Summer 2015). «A medley of meanings: Insights from an instance of gameplay in League of Legends» (PDF). Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology. 6.1 (2068–0317): 233. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

Similar to an RTS, players control the action from an isometric perspective, however, instead of controlling multiple units, each player only controls a single champion.

- ^ Xu, Davide (January 2023). «HOW MANY CHAMPIONS ARE IN LEAGUE OF LEGENDS». esports.net. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ a b «League of Legends translated». BBC Sport. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Watson, Max (Summer 2015). «A medley of meanings: Insights from an instance of gameplay in League of Legends» (PDF). Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology. 6.1 (2068–0317): 225. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

[…] all champion experience, gold, and items are lost after an individual match is over […]

- ^ Rand, Emily (September 17, 2019). «How the meta has evolved at the League of Legends World Championship». ESPN. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ «Esports primer: League of Legends». Reuters. March 25, 2020. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Barrabi, Thomas (December 3, 2019). «Saudi Arabia to host ‘League of Legends’s esports competition with Riot Games». Fox Business. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Kou, Yubo; Gui, Xinning (October 2020). «Emotion Regulation in eSports Gaming: A Qualitative Study of League of Legends». Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. Vol. 4. p. 158:4. doi:10.1145/3415229. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ Gao, Gege; Min, Aehong; Shih, Patrick C. (November 28, 2017). «Gendered design bias: gender differences of in-game character choice and playing style in league of legends». Proceedings of the 29th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction. OZCHI ’17. Brisbane, Australia: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 310. doi:10.1145/3152771.3152804. ISBN 978-1-4503-5379-3.

- ^ a b «League of Legends terminology explained». BBC Sport. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

Each team has 11 turrets. Every lane features two turrets in the lane, with a third at the end protecting the base and one of the three inhibitors. The last two turrets guard the Nexus and can only be attacked once an inhibitor is destroyed.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

The last two turrets guard the Nexus and can only be attacked once an inhibitor is destroyed. Remember those minions? Take down an inhibitor and that lane will begin to spawn allied Super Minions, who do extra damage and present a difficult challenge for the enemy team.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

… a jungler kills various monsters in the jungle, like the Blue Buff, the Red Buff, Raptors, Gromps, Wolves and Krugs. Like minions, these monsters grant you gold and experience.

- ^ Watson, Max (Summer 2015). «A medley of meanings: Insights from an instance of gameplay in League of Legends» (PDF). Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology. 6 (1): 233. ISSN 2068-0317. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

After a champion or neutral monster is killed, a period of time must pass before it can respawn and rejoin the game.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

Getting strong enough to destroy the enemy Nexus comes with time. Games last anywhere from 15 minutes to, at times, even hours, depending on strategy and skill.

- ^ Gilliam, Ryan (September 29, 2016). «The complete beginner’s guide to League of Legends». The Rift Herald. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 18, 2020). «League 101: A League of Legends beginner’s guide». ESPN. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

Junglers start in the jungle, with the sole goal of powering up their characters to become strong enough to invade one of the three lanes to outnumber the opponents in that lane.

- ^ Cameron, Phil (May 29, 2014). «What is ARAM and why is it brilliant? Harnessing the chaos of League of Legend’s new mode». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ LeJacq, Yannick (May 1, 2015). «League of Legends’s ‘For Fun’ Mode Just Got A Lot More Fun». Kotaku. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Talbot, Carrie (June 11, 2021). «League of Legends gets some ARAM balance tweaks next patch». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, Scott (July 1, 2017). «Mechanics and Metagame: Exploring Binary Expertise in League of Legends». Games and Culture. 12 (5): 426–444. doi:10.1177/1555412015590063. ISSN 1555-4120. S2CID 147191716. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Goslin, Austen (July 31, 2019). «Teamfight Tactics is now a permanent mode of League of Legends». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Gilroy, Joab (July 4, 2019). «An Introduction to Auto Chess, Teamfight Tactics and Dota Underlords». IGN. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Palmer, Philip (March 9, 2020). «Teamfight Tactics guide: How to play Riot’s autobattler». PC Gamer. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Harris, Olivia (March 19, 2020). «Teamfight Tactics Is Out Now For Free On Mobile With Cross-Play». GameSpot. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Carter, Chris (April 9, 2016). «League of Legends’ rotating game mode system is live». Destructoid. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Talbot, Carrie (March 31, 2021). «League of Legends patch 11.7 notes – Space Groove skins, One for All». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (April 2, 2014). «Riot Broke League Of Legends, And Fans Love It». Kotaku. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Sanchez, Miranda (April 1, 2014). «League of Legends Releases Ultra Rapid Fire Mode». IGN. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ LeJacq, Yannick (April 2, 2015). «League Of Legends Should Keep Its Ridiculous April Fool’s Joke Going». Kotaku. Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Talbot, Carrie (March 5, 2020). «League of Legends’ hilarious One for All mode is back». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Savage, Phil (May 27, 2014). «League of Legends’ new One For All: Mirror Mode gives all ten players the same champion». PC Gamer. Future plc. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Ali (August 3, 2018). «League of Legends is adding Nexus Blitz, a lightning-fast «experimental» game mode». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Crecente, Brian (October 27, 2019). «The origin story of League of Legends». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Kollar, Philip (September 13, 2016). «The past, present and future of League of Legends studio Riot Games». Polygon. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Augustine, Josh (August 17, 2010). «Riot Games’ dev counter-files «DotA» trademark». PC Gamer. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Remo, Chris (May 22, 2009). «Interview: Riot Games On The Birth Of League Of Legends». Gamasutra. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Perez, Daniel (January 16, 2009). «League of Legends Interview». 1UP. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Meer, Alec (October 7, 2008). «League Of Legends: DOTA Goes Formal». Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Park, Andrew (July 14, 2009). «League of Legends goes free-to-play». GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Crecente, Brian. «League of Legends is now 10 years old. This is the story of its birth». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

League of Legends was announced on Oct. 7, 2008 and went into closed beta in April 2009.

- ^ Kollar, Philip (December 9, 2015). «A look back at all the ways League of Legends has changed over 10 years». Polygon. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Crecente, Brian. «League of Legends is now 10 years old. This is the story of its birth». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Kolan, Nick (July 26, 2011). «Ten League of Legends Games are Started Every Second». IGN. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

The free-to-play DotA-inspired multiplayer online battle arena […] was released on October 27, 2009 […]

- ^ Goslin, Austen (November 6, 2019). «League of Legends transformed the video game industry over the last decade». Polygon. Archived from the original on September 12, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

When these patches first started around 2014 […] Now that players have grown accustomed to Riot’s cadence of a patch—more or less—every two weeks, the changes themselves are part of the mastery.

- ^ a b c d e Blakeley, Lindsay; Helm, Burt (December 2016). «Why Riot Games is Inc.’s 2016 Company of the Year». Inc. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Heath, Jerome (November 30, 2021). «All League of Legends champion release dates». Dot Esports. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (May 12, 2020). «How Riot reinvents old League of Legends champions like comic book superheroes». The Verge. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Cocke, Taylor (March 1, 2013). «League of Legends Now Available on Mac». IGN. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Kordyaka, Bastian; Hribersek, Sidney (January 8, 2019). «Crafting Identity in League of Legends – Purchases as a Tool to Achieve Desired Impressions». Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences: 1508. doi:10.24251/HICSS.2019.182. hdl:10125/59591. ISBN 978-0-9981-3312-6.

Riot’s main source of income is the sale of the in-game currency called Riot Points (RP). Players can buy virtual items using RPs, whereby the majority of them possesses no functional value (champion skins, accessories) and can be considered aesthetic items.

- ^ Friedman, Daniel (February 23, 2016). «How to get the most out of gambling on League of Legends’ Mystery Skins». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Julia (August 20, 2019). «League of Legends fans angry over Riot Games’ latest monetization effort». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Zendle, David; Cairns, Paul; Barnett, Herbie; McCall, Cade (January 1, 2020). «Paying for loot boxes is linked to problem gambling, regardless of specific features like cash-out and pay-to-win» (PDF). Computers in Human Behavior. 102: 181. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.003. ISSN 0747-5632. S2CID 198591367. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Powell, Steffan (October 18, 2019). «League of Legends: Boss says it’s ‘not for casual players’«. BBC News. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Julia (August 20, 2019). «League of Legends fans angry over Riot Games’ latest monetization effort». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Chalk, Andy (August 11, 2014). «Ubisoft analyst criticizes League of Legends monetization, warns other studios not to try it». PC Gamer. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ a b «Report: League of Legends produced $1.75 billion in revenue in 2020». Reuters. January 11, 2021. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b «Market Brief – 2018 Digital Games & Interactive Entertainment Industry Year In Review». SuperData Research. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Gilliam, Ryan (April 13, 2018). «The history of the League of Legends». The Rift Herald. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Watson, Max (Summer 2015). «A medley of meanings: Insights from an instance of gameplay in League of Legends» (PDF). Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology. 6 (1): 234. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

Moreover, LoL’s content and gameplay lack the […] strong ties to real world issues […] LoL does of course have a lore, but it recounts a fantastical alternate world which can often descend into hackneyed good and evil terms.

- ^ Gera, Emily (September 5, 2014). «Riot Games is rebooting the League of Legends lore». Polygon. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (September 4, 2014). «League Of Legends Just Destroyed Its Lore, Will Start Over». Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

[…] it’s a move Riot were always going to have to make. As League grows in popularity, so too do its chances of becoming something larger, something that can translate more easily into things like TV series and movies.

- ^ LeJacq, Yannick (June 4, 2015). «Riot Games Hires Graham McNeill For League Of Legends». Kotaku Australia. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Liao, Shannon (November 19, 2018). «League of Legends turns to Marvel comics to explore the game’s rich lore». The Verge. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Tapsell, Chris (October 31, 2020). «Single-player League of Legends «true RPG» Ruined King coming early 2021″. Eurogamer. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Marshall, Cass (December 5, 2019). «Riot’s new games are League of Legends’s best asset (and biggest threat)». Polygon. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ a b «League of Legends«. Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ «League of Legends for PC from 1UP». 1UP. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ «League of Legends – Review – PC». Eurogamer. November 27, 2009. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b McCormick, Rick (November 5, 2009). «League of Legends review». GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Hunt, Geoff. «League of Legends Review for the PC». Game Revolution. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b VanOrd, Kevin (October 17, 2013). «League of Legends – Retail Launch Review». GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hicks, Tyler (October 10, 2013). «League of Legends Review». GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ «GameSpy The Consensus League of Legend Review». GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 26, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ «League of Legends – PC – Review». GameZone. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Butts, Steve (November 5, 2009). «League of Legends Review – PC Review at IGN». IGN. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jackson, Leah B. (February 13, 2014). «League of Legends Review». IGN. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Strom, Steven (May 30, 2018). «League of Legends review». PC Gamer. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Quintin (November 27, 2009). «League of Legends». Eurogamer. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c VanOrd, Kevin (October 17, 2013). «League of Legends – Retail Launch Review». GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Crecente, Brian (November 4, 2009). «League of Legends Review: Free, Addictive, Worthy». Kotaku. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Smith, Quintin (November 27, 2009). «League of Legends». Eurogamer. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

- ^ «League of Legends Review». GamesRadar+. January 23, 2013. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ VanOrd, Kevin (October 17, 2013). «League of Legends – Retail Launch Review». GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Scott, Ryan (November 30, 2009). «GameSpy: The Consensus: League of Legends Review». GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 26, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Gilliam, Ryan (June 19, 2017). «The new rune system fixes one of League’s biggest problems». The Rift Herald. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Graf, Michael (November 5, 2009). «League of Legends – Angespielt: Kein Test, obwohl es schon im Laden liegt» [League of Legends – Played: No review, even though it’s available in the store]. GameStar (in German). Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Squires, Jim (March 23, 2010). «League of Legends Review». Gamezebo. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ «League of Legends Review». GameRevolution. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Hernandez, Patricia (May 3, 2016). «League of Legends Champ Designer Gives Some Real Talk On Sexy Characters». Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ «Riot’s League of Legends Leads Game Developers Choice Online Award Winners». Gamasutra. October 8, 2010. Archived from the original on June 2, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ Liebl, Matt (January 5, 2021). «League of Legends Wins 2011 Golden Joystick Award for Best Free-to-Play Game». GameZone. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ «K/DA – POP/STARS – The Shorty Awards». Shorty Awards. April 29, 2019. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ «2019 Music in Visual Media Nominations». Hollywood Music in Media Awards. November 5, 2019. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Makuch, Eddie (December 8, 2017). «The Game Awards 2017 Winners Headlined By Zelda: Breath Of The Wild’s Game Of The Year». GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Grant, Christopher (December 6, 2018). «The Game Awards 2018: Here are all the winners». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Makuch, Eddie (December 13, 2019). «The Game Awards 2019 Winners: Sekiro Takes Game Of The Year». GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Stedman, Alex (December 10, 2020). «The Game Awards 2020: Complete Winners List». Variety. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Bankhurst, Adam (December 10, 2021). «The Game Awards 2021 Winners: The Full List». IGN. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Lee, Julia (May 9, 2018). «Riot Games wins a Sports Emmy for Outstanding Live Graphic Design». The Rift Herald. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (November 11, 2019). «Designing League of Legends’ stunning holographic Worlds opening ceremony». The Verge. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Goslin, Austen (October 24, 2020). «How Riot created the virtual universe of the 2020 League of Legends World Championships». Polygon. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Kou, Yubo (January 2013). «Regulating Anti-Social Behavior on the Internet: The Example of League of Legends» (PDF). IConference 2013 Proceedings: 612–622. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ «How League Of Legends Enables Toxicity». Kotaku. March 25, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (March 20, 2018). «League of Legends’s senior designer outlines how they battle rampant toxicity». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ «Free to Play? Hate, Harassment and Positive Social Experience in Online Games 2020». Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Webster, Andrew (March 6, 2015). «How League of Legends could make the internet a better place». The Verge. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Skiffington, Dillion (September 19, 2014). «League of Legends’s Neverending War On Toxic Behavior». Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (March 20, 2018). «League of Legends’s senior designer outlines how they battle rampant toxicity». Polygon. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Julia (June 13, 2017). «New Honor System: How it works and what you can get». The Rift Herald. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Segal, David (October 10, 2014). «Behind League of Legends, E-Sports’s Main Attraction». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Hardenstein, Taylor Stanton (Spring 2017). ««Skins» in the Game: Counter-Strike, Esports, and the Shady World of Online Gambling». UNLV Gaming Law Journal. 7: 119. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

A year later, the same championship was held in the 40,000-seat World Cup Stadium in Seoul, South Korea while another 27 million people watched online-more than the TV viewership for the final round of the Masters, the NBA Finals, the World Series, and the Stanley Cup Finals, for that same year.

- ^ Webb, Kevin (December 18, 2019). «More than 100 million people watched the ‘League of Legends’s World Championship, cementing its place as the most popular esport». Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Huang, Zheping (April 7, 2021). «Tencent Bets Billions on Gamers With More Fans Than NBA Stars». Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Di Fiore, Alessandro (June 3, 2014). «Disrupting the Gaming Industry with the Same Old Playbook». Harvard Business Review. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Heath, Jerome (April 12, 2021). «All of the teams qualified for the 2021 League of Legends Mid-Season Invitational». Dot Esports. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (July 21, 2020). «League of Legends esports is getting a big rebrand in an attempt to become more global». The Verge. Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Lim, Jang-won (April 20, 2021). «MSI preview: 11 teams heading to Iceland; VCS unable to attend once again». Korea Herald. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Ashton, Graham (April 30, 2017). «Franchising Comes to Chinese League of Legends, Ending Relegation in LPL». Esports Observer. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (March 27, 2018). «EU LCS changes to include salary increase, franchising and rev share». ESPN. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Samples, Rachel (April 5, 2020). «LCK to adopt franchise model in 2021». Dot Esports. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Wolf, Jacob (September 3, 2020). «LCK determines 10 preferred partners for 2021». ESPN. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (November 20, 2020). «Ten Franchise Teams for ‘League of Legends’s North American eSports League Unveiled». Variety. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Hester, Blake (December 21, 2017). «More Than 360 Million People Watched This Year’s ‘League of Legends’s Mid-Season Invitational». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (April 8, 2020). «ESPN becomes the official broadcast home for League of Legends’s Spring Split Playoffs». The Verge. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Esguerra, Tyler (August 3, 2020). «Riot signs 3-year deal granting Bilibili exclusive broadcasting rights in China for international events». Dot Esports. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ «Bilibili inks three-year contract to broadcast League of Legends in China». Reuters staff. December 6, 2019. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Chen, Hongyu (August 14, 2020). «Bilibili Shares 2020 LoL Worlds Chinese Media Rights With Penguin Esports, DouYu, and Huya». Esports Observer. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Chen, Hongyu (October 29, 2019). «Huya to Stream Korean League of Legends Matches in Three-Year Exclusive Deal». The Esports Observer. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Capps, Robert (February 19, 2020). «How to Make Billions in E-Sports». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

According to Miller, the top players make closer to $300,000, which is still relatively cheap; League of Legends player salaries can reach seven figures.

- ^ Soshnick, Scott (December 18, 2015). «Former NBA Player Rick Fox Buys eSports Team Gravity». Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Yim, Miles (November 18, 2019). «People are investing millions into League of Legends franchises. Will the bet pay off?». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Julia (October 15, 2019). «League of Legends 10th Anniversary stream announcements». Polygon. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Beckhelling, Imogen (October 16, 2019). «Here’s everything Riot announced for League of Legends’s 10 year anniversary». Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Cox, Matt (May 6, 2020). «Legends Of Runeterra review». Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Yin-Poole, Wesley (April 4, 2020). «League of Legends card game Legends of Runeterra launches end of April». Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Goslin, Austen (January 12, 2020). «Legends of Runeterra will go into open beta at the end of January». Polygon. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (October 15, 2019). «League of Legends is coming to mobile and console». The Verge. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Fischer, Tyler (October 16, 2019). «League of Legends Coming to Consoles and Phones». ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Halliday, Fergus (October 26, 2020). «Every champion confirmed for League of Legends: Wild Rift». PC World. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Beckhelling, Imogen (October 16, 2019). «Here’s everything Riot announced for League of Legends’s 10 year anniversary». Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

League of Legends: Wild Rift is a redesigned 5v5 MOBA coming to Android, iOS and console. It features a lot of the same game play as LOL on PC, but has built completely rebuilt from the ground up to make a more polished experience for players on other platforms.

- ^ Clayton, Natalie (October 31, 2020). «League of Legends’s RPG spin-off Ruined King arrives next year». Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Prescott, Shaun (December 18, 2020). «Riot is working on a League of Legends MMO». PC Gamer. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Tack, Daniel (November 16, 2021). «Tequila Works Announces Song Of Nunu: A League of Legends Story». Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Alistair (March 6, 2020). «League of Legends’s Metal Band is Getting Back Together». Kotaku UK. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Lawson, Dom (August 6, 2017). «Pentakill: how a metal band that doesn’t exist made it to No 1». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Julia (November 5, 2018). «K/DA, Riot Games’ pop girl group, explained». Polygon. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Carpenter, Nicole (October 28, 2020). «League of Legends K-pop group K/DA debuts new music video». Polygon. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (August 27, 2020). «League of Legends’s virtual K-pop group K/DA is back with a new song». The Verge. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Chan, Tim (November 16, 2019). «The True Story of True Damage: The Virtual Hip-Hop Group That’s Taking Over the Internet IRL». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Lee, Julia (November 11, 2019). «True Damage, League of Legends’s hip-hop group, explained». Polygon. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (November 11, 2019). «Designing League of Legends’s stunning holographic Worlds opening ceremony». The Verge. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Julia (August 18, 2017). «Darius’ story revealed in Blood of Noxus comic». The Rift Herald. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Liao, Shannon (November 19, 2018). «League of Legends turns to Marvel comics to explore the game’s rich lore». The Verge. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

So far, Riot has limited its comic book ambitions to panels published on its site, which are timed to certain champion updates or cosmetic skin releases. Notably, a comic featuring Miss Fortune, a deadly pirate bounty hunter and captain of her own ship who seeks revenge on the men who betrayed her, was released last September.

- ^ «Marvel and Riot Games Give Lux from ‘League of Legends’ Her Own Series in May». Marvel Entertainment. April 24, 2021. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ «‘League of Legends: Lux’ Will Come to Print for the First Time This Fall». Marvel Entertainment. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Shanley, Patrick (October 15, 2019). «Riot Games Developing Animated Series Based on ‘League of Legends’«. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Rosario, Alexandra Del (November 21, 2021). «‘Arcane’ Renewed For Season 2 By Netflix». Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ Marshall, Cass (October 15, 2019). «League of Legends is getting its own animated series called Arcane». Polygon. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Capel, Chris J. (October 16, 2019). «League of Legends Arcane animated series will show the origins of Jinx and Vi». PCGamesN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Summers, Nick (June 11, 2020). «‘League of Legends’s TV show ‘Arcane’ has been pushed back to 2021″. Engadget. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Goslin, Austen (May 3, 2021). «League of Legends animated series is heading to Netflix». Polygon. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Motamayor, Rafael (November 20, 2021). «Arcane Season 1 Review». IGN. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Cremona, Patrick (November 3, 2021). «Arcane: release date, cast and trailer for the League of Legends Netflix series». Radio Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

External links

| League of Legends | |

|---|---|

Logo variant from 2019 |

|

| Developer(s) | Riot Games |

| Publisher(s) | Riot Games |

| Director(s) | Andrei van Roon[1] |

| Producer(s) | Jeff Jew |

| Platform(s) |

|

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | MOBA |

| Mode(s) | Multiplayer |

League of Legends (LoL), commonly referred to as League, is a 2009 multiplayer online battle arena video game developed and published by Riot Games. Inspired by Defense of the Ancients, a custom map for Warcraft III, Riot’s founders sought to develop a stand-alone game in the same genre. Since its release in October 2009, League has been free-to-play and is monetized through purchasable character customization. The game is available for Microsoft Windows and macOS.

In the game, two teams of five players battle in player-versus-player combat, each team occupying and defending their half of the map. Each of the ten players controls a character, known as a «champion», with unique abilities and differing styles of play. During a match, champions become more powerful by collecting experience points, earning gold, and purchasing items to defeat the opposing team. In League‘s main mode, Summoner’s Rift, a team wins by pushing through to the enemy base and destroying their «Nexus», a large structure located within.

League of Legends has received generally positive reviews; critics highlighted its accessibility, character designs, and production value. The game’s long lifespan has resulted in a critical reappraisal, with reviews trending positively; the negative and abusive in-game behavior of its players, criticized since early in the game’s lifetime, persists despite Riot’s attempts to fix the problem. In 2019, League regularly peaked at eight million concurrent players, and its popularity has led to tie-ins such as music videos, comic books, short stories, and the animated series Arcane. Its success has also spawned several spin-off video games, including a mobile version, a digital collectible card game and a turn-based role-playing game, among others. A massively multiplayer online role-playing game based on the property is in development.

Regularly cited as the world’s largest esport, the game has an international competitive scene consisting of multiple regional leagues. They culminate in the annual League of Legends World Championship. The 2019 event registered over 100 million unique viewers, peaking at a concurrent viewership of 44 million during the finals. Domestic and international events have been broadcast on livestreaming websites such as Twitch, YouTube, Bilibili, and on cable television sports channel ESPN.

Gameplay

Four champions in the bottom lane of Summoner’s Rift, surrounded by minions. The red health bars indicate that they are opposing players.

League of Legends is a multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) game in which the player controls a character («champion») with a set of unique abilities from an isometric perspective.[2][3] As of 2023, there are over 160 champions available to play.[4] Over the course of a match, champions gain levels by accruing experience points (XP) through killing enemies.[5] Items can be acquired to increase champions’ strength,[6] and are bought with gold, which players accrue passively over time and earn actively by defeating the opposing team’s minions,[2] champions, or defensive structures.[5][6] In the main game mode, Summoner’s Rift, items are purchased through a shop menu available to players only when their champion is in the team’s base.[2] Each match is discrete; levels and items do not transfer from one match to another.[7]

Summoner’s Rift

A simplified representation of Summoner’s Rift. The yellow paths are the «lanes» down which minions march; blue and red dots represent turrets. The fountains are the dark areas within each base, and are beside each Nexus. The dotted black line indicates the river.

Summoner’s Rift is the flagship game mode of League of Legends and the most prominent in professional-level play.[8][9][10] The mode has a ranked competitive ladder; a matchmaking system determines a player’s skill level and generates a starting rank from which they can climb. There are nine tiers; the least skilled are Iron, Bronze, and Silver, and the highest are Master, Grandmaster, and Challenger.[11][a]

Two teams of five players compete to destroy the opposing team’s «Nexus», which is guarded by the enemy champions and defensive structures known as «turrets».[13] Each team’s Nexus is located in their base, where players start the game and reappear after death.[13] Non-player characters known as minions are generated from each team’s Nexus and advance towards the enemy base along three lanes guarded by turrets: top, middle, and bottom.[14] Each team’s base contains three «inhibitors», one behind the third tower from the center of each lane. Destroying one of the enemy team’s inhibitors causes stronger allied minions to spawn in that lane, and allows the attacking team to damage the enemy Nexus and the two turrets guarding it.[15] The regions in between the lanes are collectively known as the «jungle», which is inhabited by «monsters» that, like minions, respawn at regular intervals. Like minions, monsters provide gold and XP when killed.[16] Another, more powerful class of monster resides within the river that separates each team’s jungle.[17] These monsters require multiple players to defeat and grant special abilities to their slayers’ team. For example, teams can gain a powerful allied unit after killing the Rift Herald, permanent strength boosts by killing dragons, and stronger, more durable minions by killing Baron Nashor.[18]

Summoner’s Rift matches can last from as little as 15 minutes to over an hour.[19] Although the game does not enforce where players may go, conventions have arisen over the game’s lifetime: typically one player goes in the top lane, one in the middle lane, one in the jungle, and two in the bottom lane.[2][5][20] Players in a lane kill minions to accumulate gold and XP (termed «farming») and try to prevent their opponent from doing the same. A fifth champion, known as a «jungler», farms the jungle monsters and, when powerful enough, assists their teammates in a lane.[21]

Other modes

Besides Summoner’s Rift, League of Legends has two other permanent game modes. ARAM («All Random, All Mid») is a five-versus-five mode like Summoner’s Rift, but on a map called Howling Abyss with only one long lane, no jungle area, and with champions randomly chosen for players.[22][23][24] Given the small size of the map, players must be vigilant in avoiding enemy abilities.[25]

Teamfight Tactics is an auto battler released in June 2019 and made a permanent game mode the following month.[26][27] As with others in its genre, players build a team and battle to be the last one standing. Players do not directly affect combat but position their units on a board for them to fight automatically against opponents each round.[28] Teamfight Tactics is available for iOS and Android and has cross-platform play with the Windows and macOS clients.[29]

Other game modes have been made available temporarily, typically aligning with in-game events.[30][31] Ultra Rapid Fire (URF) mode was available for two weeks as a 2014 April Fools Day prank. In the mode, champion abilities have no resource cost, significantly reduced cooldown timers, increased movement speed, reduced healing, and faster attacks.[32][33] A year later, in April 2015, Riot disclosed that they had not brought the mode back because its unbalanced design resulted in player «burnout». The developer also said the costs associated with maintaining and balancing URF were too high.[34] Other temporary modes include One for All and Nexus Blitz. One for All has players pick a champion for all members of their team to play.[35][36] In Nexus Blitz, players participate in a series of mini-games on a compressed map.[37]

Development

Pre-release

Riot Games’ West Los Angeles headquarters (2015)

Riot Games’ founders Brandon Beck and Marc Merill had an idea for a spiritual successor to Defense of the Ancients, known as DotA. A mod for Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos, DotA required players to buy Warcraft III and install custom software; The Washington Post‘s Brian Crecente said the mod «lacked a level of polish and was often hard to find and set up».[38] Phillip Kollar of Polygon noted that Blizzard Entertainment supported Warcraft III with an expansion pack, then shifted their focus to other projects while the game still had players. Beck and Merill sought to create a game that would be supported over a significantly longer period.[39]

Beck and Merill held a DotA tournament for students at the University of Southern California, with an ulterior goal of recruitment. There they met Jeff Jew, later a producer on League of Legends. Jew was very familiar with DotA and spent much of the tournament teaching others how to play. Beck and Merill invited him to an interview, and he joined Riot Games as an intern.[38] Beck and Merill recruited two figures involved with DotA: Steve Feak, one of its designers,[38] and Steve Mescon, who ran a support website to assist players.[40][41] Feak said early development was highly iterative, comparing it to designing DotA.[42]

A demonstration of League of Legends built in the Warcraft III game engine was completed in four months and then shown at the 2007 Game Developers Conference.[39] There, Beck and Merill had little success with potential investors. Publishers were confused by the game’s free-to-play business model and lack of a single-player mode. The free-to-play model was untested outside of Asian markets,[38] so publishers were primarily interested in a retail release, and the game’s capacity for a sequel.[39] In 2008, Riot reached an agreement with holding company Tencent to oversee the game’s launch in China.[39]

League of Legends was announced October 7, 2008, for Microsoft Windows.[43][44] Closed beta-testing began in April 2009.[43][45] Upon the launch of the beta, seventeen champions were available.[46] Riot initially aimed to ship the game with 20 champions but doubled the number before the game’s full release in North America on October 27, 2009.[47][48] The game’s full name was announced as League of Legends: Clash of Fates. Riot planned to use the subtitle to signal when future content was available, but decided they were silly and dropped it before launch.[39]

Post-release

League of Legends receives regular updates in the form of patches. Although previous games had utilized patches to ensure no one strategy dominated, League of Legends‘ patches made keeping pace with the developer’s changes a core part of the game. In 2014, Riot standardized their patch cadence to once approximately every two or three weeks.[49]

The development team includes hundreds of game designers and artists. In 2016, the music team had four full-time composers and a team of producers creating audio for the game and its promotional materials.[50] As of 2021, the game has over 150 champions,[51] and Riot Games periodically overhauls the visuals and gameplay of the oldest in the roster.[52] Although only available for Microsoft Windows at launch, a Mac version of the game was made available in March 2013.[53]

Revenue model

League of Legends uses a free-to-play business model. Several forms of purely cosmetic customization—for example, «skins» that change the appearance of champions—can be acquired after buying an in-game currency called Riot Points (RP).[54] Skins have five main pricing tiers, ranging from $4 to $25.[55] As virtual goods, they have high profit margins.[50] A loot box system has existed in the game since 2016; these are purchasable virtual «chests» with randomized, cosmetic items.[56] These chests can be bought outright or acquired at a slower rate for free by playing the game. The practice has been criticized as a form of gambling.[57] In 2019, Riot Games’ CEO said that he hoped loot boxes would become less prevalent in the industry.[58] Riot has also experimented with other forms of monetization. In August 2019, they announced an achievement system purchasable with Riot Points. The system was widely criticized for its high cost and low value.[59]

In 2014, Ubisoft analyst Teut Weidemann said that only around 4% of players paid for cosmetics—significantly lower than the industry standard of 15 to 25%. He argued the game was only profitable because of its large player base.[60] In 2017, the game had a revenue of US$2.1 billion;[61] in 2018, a lower figure of $1.4 billion still positioned it as one of the highest-grossing games of 2018.[62] In 2019, the number rose to $1.5 billion, and again to $1.75 billion in 2020.[62][61] According to magazine Inc., players collectively played three billion hours every month in 2016.[50]

Plot

See also: League of Legends § Spin-offs and other media

Before 2014, players existed in-universe as political leaders, or «Summoners», commanding champions to fight on the Fields of Justice—for example, Summoner’s Rift—to avert a catastrophic war.[63] Sociologist Matt Watson said the plot and setting were bereft of the political themes found in other role-playing games, and presented in reductive «good versus evil» terms.[64] In the game’s early development, Riot did not hire writers, and designers wrote character biographies only a paragraph long.[39]