Всего найдено: 4

Здравствуйте, уважаемые эксперты! Склоняется ли фамилия де Вега? Заранее благодарю за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Склоняется.

Словарь имён собственных

ЛОПЕ ДЕ ВЕГА, Лопе де Веги; полн. имя Лопе Феликс де Вега Карпьо [пэ, дэ, вэ] (исп. драматург)

Добрый день! Нигде не могу найти ответ на вопрос, склоняется ли фамилия Лопе де Вега, именно эта фамилия. Помогите, пожалуйста.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Склоняется часть де Вега.

ЛОПЕ ДЕ ВЕГА, Лопе де Веги; полн. имя Лопе Феликс де Вега Карпьо [пэ, дэ, вэ] (исп. драматург)

Как определить, в каких случаях приставка «де» перед фамилией пишется с маленькой буквы, а в каких с большой, и в каких случаях она отделяется от фамилии апострофом, в каких пишется слитно, а в каких — через пробел?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Общее правило таково: служебные слова, входящие в состав западноевропейских фамилий (ван, де, делла, ла, фон и т. п.), пишутся со строчной буквы, например: Лопе де Вега, Оноре де Бальзак, Шарль де Голль. Однако в некоторых именах Де традиционно пишется с прописной буквы, например: Шарль Де Костер, Роберт Де Ниро.

«Де» в фамилиях с прописной или со строчной? Например Роберт Де Ниро

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Общее правило таково: служебные слова, входящие в состав западноевропейских фамилий (ван, де, делла, ла, фон и т. п.), пишутся со строчной буквы, например: Лопе де Вега, Оноре де Бальзак, Шарль де Голль. Однако в некоторых именах служебные слова традиционно пишутся с прописной буквы. Правильно: Роберт Де Ниро.

In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is de Vega and the second or maternal family name is Carpio.

|

Lope de Vega KOM |

|

|---|---|

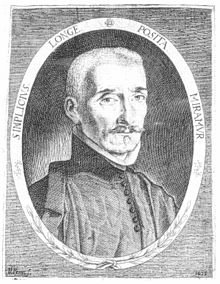

Portrait of Lope de Vega |

|

| Born | Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio 25 November 1562 Madrid, Castile |

| Died | 27 August 1635 (aged 72) Madrid, Castile |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright, novelist |

| Language | Spanish |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Notable works | Fuenteovejuna

The Dog in the Manger The Knight from Olmedo |

| Children | 15 |

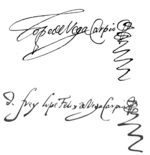

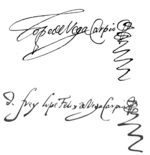

| Signature | |

|

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio ( LOH-pay dee VAY-gə, Spanish: [ˈfeliɣz ˈlope ðe ˈβeɣa i ˈkaɾpjo]; 25 November 1562 – 27 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. He was one of the key figures in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish literature is second only to that of Miguel de Cervantes,[1] while the sheer volume of his literary output is unequalled, making him one of the most prolific authors in the history of literature. He was nicknamed «The Phoenix of Wits» and «Monster of Nature» (in Spanish: Fénix de los Ingenios, Monstruo de Naturaleza) by Cervantes because of his prolific nature.

Lope de Vega renewed the Spanish theatre at a time when it was starting to become a mass cultural phenomenon. He defined its key characteristics, and along with Pedro Calderón de la Barca and Tirso de Molina, took Spanish Baroque theatre to its greatest heights. Because of the insight, depth and ease of his plays, he is regarded as one of the greatest dramatists in Western literature, his plays still being produced worldwide. He was also considered one of the best lyric poets in the Spanish language and wrote several novels. Although not well known in the English-speaking world, his plays were presented in England as early as the 1660s, when diarist Samuel Pepys recorded having attended some adaptations and translations of them, although he omits to mention the author.

Some 3,000 sonnets, three novels, four novellas, nine epic poems, and about 500 plays are attributed to him. Although he has been criticised for putting quantity ahead of quality, nevertheless at least 80 of his plays are considered masterpieces. He was a friend of the writer Francisco de Quevedo and an arch-enemy of the dramatist Juan Ruiz de Alarcón. The volume of his lifework made him envied by not only contemporary authors such as Cervantes and Luis de Góngora, but also by many others: for instance, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once wished he had been able to produce such a vast and colourful oeuvre.[2]

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Lope de Vega Carpio[3] was born in Madrid, in the Puerta de Guadalajara to a family of natives of the valley of Carriedo.[4] His father, Félix de Vega, was an embroiderer. Little is known of his mother, Francisca Fernández Flores. He later took the distinguished surname of Carpio from his paternal grandmother, Catalina del Carpio.

After a brief stay in Valladolid, his father moved to Madrid in 1561, perhaps drawn by the possibilities of the new capital city. However, Lope de Vega would later affirm that his father arrived in Madrid through a love affair from which his future mother was to rescue him. Thus the writer became the fruit of this reconciliation and owed his existence to the same jealousies he would later analyze so much in his dramatic works.

The first indications of young Lope’s genius became apparent in his earliest years. His friend and biographer Pérez de Montalbán stated that at the age of five he was already reading Spanish and Latin. While he was still unable to write, he would share his breakfast with the older boys in exchange for their help scribing his verses.[5] By his tenth birthday, he was translating Latin verse. He wrote his first play when he was 12, allegedly El verdadero amante, as he would later affirm in his dedication of the work to his son Lope, although these statements are most probably exaggerations.

His great talent bore him to the school of poet and musician Vicente Espinel in Madrid, to whom he later always referred with veneration. In his fourteenth year he continued his studies in the Colegio Imperial, a Jesuit school in Madrid, from which he absconded to take part in a military expedition in Portugal. Following that escapade, he had the good fortune of being taken into the protection of the Bishop of Ávila, who recognized the lad’s talent and saw him enrolled in the University of Alcalá. Following graduation, Lope had planned to follow in his patron’s footsteps and join the priesthood, but those plans were dashed by falling in love and realizing that celibacy was not for him. Thus he failed to attain a bachelor’s degree and made what living he could as a secretary to aristocrats or by writing plays.

In 1583 Lope enlisted in the Spanish Navy and saw action at the Battle of Ponta Delgada in the Azores, under the command of his future friend Álvaro de Bazán, 1st Marquis of Santa Cruz, to whose son he would later dedicate a play.

Following this, he returned to Madrid and began his career as a playwright in earnest. He also began a love affair with Elena Osorio (the «Filis» of his poems), who was separated from her husband, actor Cristóbal Calderón, and was the daughter of a leading theater director. When, after some five years of this torrid affair, Elena spurned Lope in favor of another suitor, his vitriolic attacks on her and her family landed him in jail for libel and, ultimately, earned him the punishment of eight years’ banishment from the court and two years’ exile from Castile.

Exile[edit]

After libelling members of his family in his writing,[6] Lope de Vega undauntedly went into exile. He took with him 16-year-old Isabel de Alderete y Urbina, known in his poems by the anagram «Belisa,» the daughter of Philip II’s court painter, Diego de Urbina. The two married under pressure from her family on 10 May 1588.

Just a few weeks later, on 29 May, Lope signed up for another tour of duty with the Spanish Navy: this was the summer of 1588, and the Armada was about to sail against England. It is likely that his military enlistment was the condition required by Isabel’s family, eager to be rid of such an ill presentable son-in-law, to forgive him for carrying her away.[7]

Lope’s luck again served him well, however, and his ship, the San Juan, was one of the vessels to make it home to Spanish harbors in the aftermath of that failed expedition. Back in Spain by December 1588, he settled in the city of Valencia. There he lived with Isabel de Urbina and continued perfecting his dramatic formula participating regularly in the tertulia known as the Academia de los nocturnos, in the company of such accomplished dramatists as the canon Francisco Agustín Tárrega, the secretary to the Duke of Gandía Gaspar de Aguilar, Guillén de Castro, Carlos Boyl, and Ricardo de Turia. With them he refined his approach to theatrical writing by violating the unity of action and weaving two plots together in a single play, a technique known as imbroglio.

In 1590, at the end of his two years’ exile from the realm, he moved to Toledo to serve Francisco de Ribera Barroso, who later became the 2nd Marquis of Malpica, and, some time later, Antonio Álvarez de Toledo, 5th Duke of Alba. In this later appointment he became gentleman of the bedchamber to the ducal court of the House of Alba, where he lived from 1592 to 1595. Here he read the work of Juan del Encina, from whom he improved the character of the donaire, perfecting still further his dramatic formula. In the fall of 1594, Isabel de Urbina died of postpartum complications. It was around this time that Lope wrote his pastoral novel La Arcadia, which included many poems and was based on the Duke’s household in Alba de Tormes.

Return to Castile[edit]

In 1595, following Isabel’s death in childbirth, he left the Duke’s service and – eight years having passed – returned to Madrid. There were other love affairs and other scandals: Antonia Trillo de Armenta, who earned him another lawsuit, and Micaela de Luján, an illiterate but beautiful actress, who inspired a rich series of sonnets, rewarded him with four children and was his lover until around 1608. In 1598, he married Juana de Guardo, the daughter of a wealthy butcher. Nevertheless, his trysts with others – including Micaela – continued.

In the 17th century Lope’s literary output reached its peak. From 1607 he was also employed as a secretary, but not without various additional duties, by the Duke of Sessa. Once that decade was over, however, his personal situation took a turn for the worse. His favorite son, Carlos Félix (by Juana), died and, in 1612, Juana herself died in childbirth. After the heartbreaking loss of his son and lover, Lope summoned his remaining children still alive under the same roof to devote himself to Christianity. His writing in the early 1610s also assumed heavier religious influences and, in 1614, he joined the priesthood.[8] The taking of holy orders did not, however, impede his romantic dalliances; what is more, he supplied his employer the duke with various female companions. The most notable and lasting of Lope’s relationships was with Marta de Nevares, who met him in 1616 and would remain with him until her death in 1632.

Further tragedies followed in 1635 with the loss of Lope, his son by Micaela and a worthy poet in his own right, in a shipwreck off the coast of Venezuela, and the abduction and subsequent abandonment of his beloved youngest daughter Antonia. Lope de Vega took to his bed and died of scarlet fever, in Madrid, on 27 August of that year.

Priesthood[edit]

Lope de Vega dressed in cassock. (Madrid, 1902).

The period of life that characterizes priestly ordination of Lope de Vega was one of profound existential crisis, perhaps impelled by the death of close relatives. To this inspiration respond his Sacred Rhymes and the numerous devout works he began to compose, as well as the meditative and philosophical tone that appears in his last verses. On the night of December 19, 1611, the writer was the victim of an assassination attempt from which he could barely escape.[9] Juana de Guardo suffered frequent illnesses and in 1612 Carlos Félix died of fevers. On August 13 of the following year, Juana de Guardo died while giving birth to Feliciana. So many misfortunes affected Lope emotionally, and on May 24, 1614, he finally decided to be ordained a priest.

The literary expression of this crisis and its repentances are the Sacred Rhymes, published in 1614; there it says: «If the body wants to be earth on earth / the soul wants to be heaven in heaven», unredeemed dualism that constitutes all its essence. The Sacred Rhymes constitute a book at the same time introspective in the sonnets (he uses the technique of the spiritual exercises that he learned in his studies with the Jesuits) as devotee for the poems dedicated to diverse saints or inspired in the sacred iconography, then in full deployment thanks to the recommendations emanated from the Council of Trent.

In 1627 he was admitted as a knight of the Order of Malta. This was an enormous honour for him since he had always taken an interest in orders of chivalry. In 1603 he had published the play El valor de Malta (The Valour of Malta) about the maritime battles of the Order. In his portrait by Eugenio Caxés he wears the habit of the Order of Malta.

Work[edit]

Title page of El testimonio vengado.

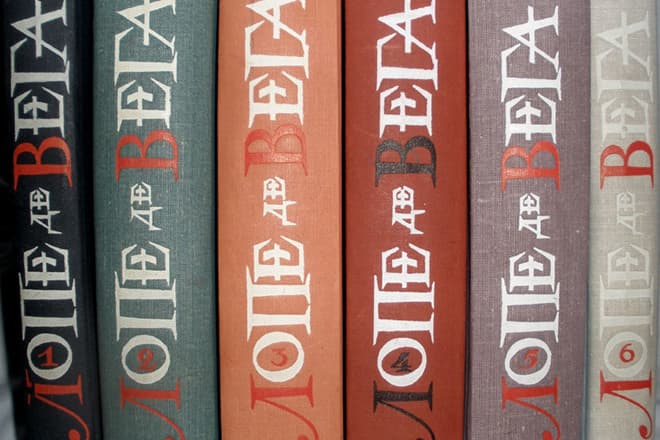

Lope’s non-dramatic works were collected and published in Spain in the eighteenth century under the title Obras Sueltas (Madrid, 21 vols., 1776–79). The more important elements of this collection include the following:

- La Arcadia (1598), a pastoral romance;

- La Dragontea (1598), an epic poem of Sir Francis Drake’s last expedition and death;

- El Isidro (1599), a poetic narrative of the life of Saint Isidore, future patron saint of Madrid, composed in octosyllabic quintillas;

- La Hermosura de Angélica (1602), an epic poem in three books, is a quasi sequel to Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso.

Lope de Vega was one of the greatest Spanish poets of his time, along with Luis de Góngora and Francisco de Quevedo. His poems of Moorish and pastoral themes were extremely popular in the 1580s and 1590s, and in these, he portrayed elements of his own love affairs (appearing as a moor called Zaide or a shepherd called Belardo). In 1602 he published two hundred sonnets in the collection La Hermosura de Angélica and in 1604 he republished them with new material in Rimas. In 1614, his religious sonnets appeared in a book entitled Rimas sacras, which was another bestseller. In 1634, in a third book with similar title, Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos, which has been considered his poetic masterpiece and the most modern book of 17th-century poetry, Lope created a heteronym, he concludes the identity of Tome de Burguillos, who has a deep and intimate romantic connection with a maid named Juana. This is a direct comparison and clash with Lope’s skeptical outlook on society.

Background[edit]

Lope was the playwright who established in Spanish drama the three-act comedia as the definitive form, ignoring the precepts of the prevailing school of his contemporaries. In Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609), which was his artistic manifesto and the justification of his style which broke the neoclassical three unities of place, time and action, he showed that he knew the established rules of poetry but refused to follow them on the grounds that the «vulgar» Spaniard cared nothing about them: «Let us then speak to him in the language of fools, since it is he who pays us» are famous lines from his manifesto.[10]

Lope boasted that he was a Spaniard pur sang (pure-blooded), maintaining that a writer’s business is to write so as to make himself understood, and took the position of a defender of the language of ordinary life.[10]

Lope’s literary influence was chiefly Latin-Italian and, while he defended the tradition of the nation and the simplicity of the old Castilian,[10] he emphasized his university education and the difference between those educated in the classics and the layman.

The majority of his works were written in haste and to order. Lope confessed that «more than a hundred of my comedies have taken only twenty-four hours to pass from the Muses to the boards of the theatre.» His biographer Pérez de Montalbán tells how in Toledo, Lope composed fifteen acts in as many days – five comedies in two weeks.[10]

In spite of some discrepancies in the figures, Lope’s own records indicate that by 1604 he had composed 230 three-act plays (comedias). The figure had risen to 483 by 1609, to 800 by 1618, to 1000 by 1620, and to 1500 by 1632. Montalbán, in his Fama Póstuma (1636) set down the total of Lope’s dramatic productions at 1800 comedias and more than 400 shorter sacramental plays. Of these, 637 plays are known by their titles, but only about 450 are extant. Many of these pieces were printed during Lope’s lifetime, mostly by the playwright himself in the shape of twelve-play volumes, but also by booksellers who surreptitiously bought manuscripts from the actors who performed them.

Themes and sources[edit]

The classification of this large mass of dramatic literature is a task of great difficulty. The terms traditionally employed – comedy, tragedy, and the like – are difficult to apply to Lope’s oeuvre and another approach to categorization has been suggested. Lope’s work essentially belongs to the drama of intrigue, the plot determining everything else. Lope used history, especially Spanish history, as his main source of subject matter. There were few national and patriotic subjects, from the reign of King Pelayo to the history of his own age, he did not put upon the stage. Nevertheless, Lope’s most celebrated plays belong to the class called capa y espada («cloak and dagger»), where the plots are chiefly love intrigues along with affairs of honor, most commonly involving the petty nobility of medieval Spain.[10]

Among the best known works of this class are El perro del hortelano (The Dog in the Manger), El castigo sin venganza (Punishment without Revenge),[11] and El maestro de danzar (The Dance Teacher).

In some of these, Lope strives to set forth some moral maxim and to illustrate its abuse with a living example. On the theme that poverty is no crime, in the play Las Flores de Don Juan, he uses the history of two brothers to illustrate the triumph of virtuous poverty over opulent vice, while indirectly attacking the institution of primogeniture, which often places in the hands of an unworthy person the honor and substance of a family when younger members would be better qualified for the trust. However, such morality pieces are rare in Lope’s repertory; generally, his aim is to amuse and stir with his focus being on the plot, not concerning himself with instruction.[10]

In El villano en su rincón, described as a romantic comedy, Francis I of France ends up spending the night in a woodcutter’s hut, after becoming lost during a hunt, resulting in a confrontation between peasant-philosopher and king. The peasant’s refusal to even look upon the king’s magnificence, grand and dramatic compared with the humble rincón, is rebuked by a gentleman of the king’s court: «a king of such might/that the Scythian and fierce Turk/tremble before his golden fleurs de lis!»[12]

Legacy[edit]

Lope encountered a poorly organized dramatic tradition; plays were sometimes composed in four acts, sometimes in three, and though they were written in verse, the structure of the versification was left to the individual writer. Because the Spanish public liked it, he adopted the style of drama which was then in vogue. He enlarged its narrow framework to a great degree, introducing a wide range of material for dramatic situations – the Bible, ancient mythology, the lives of the saints, ancient history, Spanish history, the legends of the Middle Ages, the writings of the Italian novelists, current events, and everyday Spanish life in the 17th century. Prior to Lope, playwrights sketched the conditions of persons and their characters superficially. With fuller observation and more careful description, Lope de Vega depicted real character types with language and accouterments appropriate to their position in society. The old comedy was awkward and poor in its versification. Lope introduced order into all the forms of national poetry, from the old romance couplets to the lyrical combinations borrowed from Italy. He wrote that those who should come after him had only to go on along the path which he had opened.[10]

Lope de Vega also encountered other poets who were unimpressed with his discoveries and attempted to defame his writing. The Spanish poet Pedro de Torres Rámila wrote his thoughts on Lope in his Latin satire Spongia (Paris, 1617). Torres wrote personal attacks on Lope’s sacramental plays and sought to scandalize his name and reputation. This attempt backfired on Torres due to the overwhelmingly negative responses his Spongia received from the public after its release. Scholars and poets alike came to the defense of Lope de Vega and wrote many counterclaims against the Spongia directed at Torres himself, like Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca’s Exposulatio Spongiae[13]

List of works[edit]

Plays[edit]

Listed here are some of the better-known of de Vega’s plays:

- El maestro de danzar (1594) (The Dancing Master)

- Los locos de Valencia (Madness in Valencia)

- El acero de Madrid (The Steel of Madrid)

- El perro del Hortelano (The Gardener’s Dog, a variation of The Dog in the Manger fable)

- La viuda valenciana

- Peribáñez y el comendador de Ocaña

- Fuenteovejuna

- El anzuelo de Fenisa (Fenisa’s Hook)

- El cordobés valeroso Pedro Carbonero

- Mujeres y criados (Women and Servants)

- El mejor alcalde, el Rey (The Best Mayor, The King)

- El Nuevo Mundo descubierto por Cristóbal Colón (The New World Discovered by Christopher Columbus)

- El caballero de Olmedo (The Knight from Olmedo)

- La dama boba (The Stupid Lady; The Lady-Fool)

- El amor enamorado

- El castigo sin venganza (Punishment Without Revenge)

- Las bizarrías de Belisa

- El mayordomo de la duquesa de Amalfi (The Duchess of Amalfi’s Steward)

- Lo Fingido Verdadero (What you Pretend Has Become Real)

- El niño inocente de La Guardia (The Innocent Child of La Guardia)

- La fe rompida

- El Honrado Hermano (The Honourable Brother, based in the Classic story of the Horatii and Curiatii)

In January 2023, an anonymous work in the collection of the National Library of Spain, La francesa Laura (The Frenchwoman Laura), was identified with the help of artificial intelligence as another comedy by Lope de Vega. The comedy was classified as a late work of Lope de Vega and dated from 1628 to 1630, as its flattering treatment of France could be attributed to the momentary good relationship between Spain and France during the Thirty Years’ War, having England as a common enemy. Later investigations by literary historians confirmed the findings of artificial intelligence.[14]

Opera[edit]

- La selva sin amor (18 December 1627) (The Lovelorn Forest), the first Spanish opera, with music by Alessandro Piccinini.[15]

Epic poems and lyrical poetry[edit]

- La Dragontea (1598) («Drake the Pirate»)

- El Isidro (1599) («Isidro»)

- La hermosura de Angélica (1602) («The Beauty of Angelica»)

- Rimas (1602) («Rhymes»)

- Arte nuevo de hacer comedias (1609)

- Jerusalén conquistada (1609)

- Rimas sacras (1614)

- La Filomena (1621)

- La Circe (1624)

- El laurel de Apolo (1630)

- La Gatomaquia (1634)

- Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos (1634)

Prose fiction[edit]

- Arcadia (published 1598) (The Arcadia), pastoral romance in prose, interspersed with verse

- El peregrino en su patria (published 1604) (The Pilgrim in his Own Country), adaption of Byzantine novels

- Pastores de Belen : prosas y versos divinos (published 1614)

- Novelas a Marcia Leonarda

- Las fortunas de Diana (published 1621)

- La desdicha por la honra (published 1624)

- La más prudente venganza (published 1624)

- Guzmán el Bravo (published 1624)

- La Dorotea (published 1632)

In popular culture[edit]

In Harry Turtledove’s alternate history novel Ruled Britannia, in which the Spanish Armada was successful, Vega is depicted as a Spanish soldier-playwright on occupation duty in defeated England, who interacts with William Shakespeare. The novel’s viewpoint narration alternates between the two playwrights.

A 2010 Spanish-language film about de Vega, entitled Lope, is available with English subtitles as The Outlaw.[16]

Vega is played by actor Víctor Clavijo in the Spanish TV series El Ministerio del Tiempo.[17] In his first appearance he played Vega in 1588, on the eve of the Spanish Armada, while the second episode depicted Vega in 1604.

Tribute[edit]

A municipality in Northern Samar in the Philippines was named after de Vega, created in 1980 from the 22 barangays of Catarmán.

A street in the Santa Cruz district of the City of Manila, Philippines is also named after the playwright.

On November 25, 2017, Google celebrated his 455th birthday with a Google Doodle.[18]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Works of Lope de Vega». www.classicspanishbooks.com. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Cfr. Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe: in 1828 Eckermann recorded having a conversation about the extent of the author’s works, in which Goethe expressed his admiration towards Lope’s.

- ^ Certificate of baptism: «En seis de Diciembre de mil quinientos y sesenta y dos años, el Muy Reverendo Señor Licenciado Muñoz bautizó a Lope, hijo de Feliz de Vega y de Francisca su mujer. Compadre mayor, Antonio Gómez; madrina su mujer». Joaquín de Entrambasaguas, Vida de Lope de Vega, Ed. Labor, 1936, p. 20.

- ^ Rennert, Hugo Albert (1904). The Life of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), by Hugo Albert Rennert … Gowans and Gray. OCLC 457734398.

- ^ Rennert, Hugo Albert (1904). The Life of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), by Hugo Albert Rennert … Gowans and Gray. OCLC 457734398.

- ^ Rennert, Hugo Albert (1904). The Life of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), by Hugo Albert Rennert … Gowans and Gray. OCLC 457734398.

- ^ Guillermo Carrascón, «Modelos de comedia: Lope y Cervantes», Artifara 2 (2002) ‘Monographica’, nota 7.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Félix de Lope de Vega Carpio» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ El suceso consta en José del Corral, Sucedió en Madrid (Ediciones La Librería, 2000) y ABC (26 de febrero de 2016): «El intento de asesinato a Lope de Vega que nunca se resolvió.»

- ^ a b c d e f g

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Vega Carpio, Lope Felix de». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 965–967.

- ^ Lope de Vega: Three Major Plays, translated by Gwynne Edwards, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-954017-4

- ^ Forcione, Alban K. (2009). Majesty and Humanity: Kings and Their Doubles in the Political Drama of the Spanish Golden Age. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300153309.

- ^ García Aguilar, Ignacio. «Echoes and reflections of the controversy over Spongia (1617) in the approvals and dedications of Lope de Vega / Echoes and Reflections of the Spongia’s (1617) Controversy in Lope de Vega’s Approvals and Dedications.» Calliope: Journal of the Society for Renaissance and Baroque Hispanic Poetry, vol. 26 no. 1, 2021, p. 58-80. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/796140. Accessed November 1, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Sam (5 February 2023). «Artificial intelligence uncovers lost work by titan of Spain’s ‘Golden Age’«. The Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ [1]Melveena McKendrick: «Theatre in Spain, 1490–1700», p. 215. CUP Archive, 1992. ISBN 978-0-521-42901-6

- ^ C. Fanjul, Sergio (22 August 2010). «Un Lope apasionado y pendenciero». El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Pimentel, Aurelio (14 March 2017). «Lope de Vega y Cervantes vuelven a ‘El Ministerio del Tiempo’ en la tercera temporada». Radiotelevisión Española (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ «Lope de Vega’s 455th Birthday». Google. 25 November 2017.

Sources[edit]

- Calderón, Lope de Vega and (2019). Theatre Database. Retrieved from http://www.theatredatabase.com/17th_century/calderon_and_lope_de_vega.html

- Goldáraz, Luis H. (2018, November 30). Lope, el verso y la vida . Libertad Digital. Retrieved from https://www.libertaddigital.com/cultura/libros/2018-11-30/antonio-sanchez-jimenez-presenta-la-biografia-de-lope-de-vega-1276629134/

- Hayes, Francis C. (1967). Lope de Vega. Twayne’s World Author Series. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Hennigfeld, Ursula (2008). Der ruinierte Körper. Petrarkistische Sonette in transkultureller Perspektive. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.

- Ray Keck, author of Love’s Dialectic: Mimesis and Allegory in the Romances of Lope de Vega

- Samson, Alexander; Thacker, Jonathan (2018). A Companion to Lope de Vega (Paperback ed.). Tamesis. ISBN 978-1855663251.

- Lope de Vega, Félix Arturo (2019). LibriVox. Retrieved from https://librivox.org/author/229?primary_key=229&search_category=author&search_page=1&search_form=get_results

- Lope de Vega, The Works of (2011). Spanish Books. Retrieved from https://www.classicspanishbooks.com/16th-cent-baroque-lope-works.html

- Lope Felix de (Carpio) Vega. (2011). Hutchinson’s Biography Database, 1.

- Morley, S., & Allardice, L. (2003). Double takes. New Statesman, 132(4639), 46.

- Vega Carpio, Félix Lope de (2019). Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, 1.

- Vega Carpio, Lope Felix de (2000). Theatre History. Retrieved from http://www.theatrehistory.com/spanish/lope001.html

- Vega, Lope de (2012). Britannica Biographies, 1.

- In Spanish

- Alonso, Dámaso, En torno a Lope, Madrid, Gredos, 1972, 212 pp. ISBN 9788424904753

- Castro, Américo y Hugo A. Rennert, Vida de Lope de Vega: (1562-1635) ed. de Fernando Lázaro Carreter, Salamanca, 1968.

- De Salvo, Mimma, «Notas sobre Lope de Vega y Jerónima de Burgos: un estado de la cuestión», pub. en Homenaje a Luis Quirante. Cuadernos de Filología, anejo L, 2 vols., tomo I, 2002, págs. 141-156. Versión en línea revisada en 2008. URL. Consulta 28-09-2010.

- «Lengua y literatura, Historia de las literaturas», en Enciclopedia metódica Larousse, vol. III, Ciudad de México, Larousse, 1983, págs 99–100. ISBN 968-6042-14-8

- Huerta Calvo, Javier, Historia del Teatro Español, Madrid, Gredos, 2003.

- Menéndez Pelayo, Marcelino, Estudios sobre el teatro de Lope de Vega, Madrid, Editorial Artes Gráficas, 1949, 6 volúmenes.

- MONTESINOS, José Fernández, Estudios sobre Lope de Vega, Salamanca, Anaya, 1967.

- Pedraza Jiménez, Felipe B., El universo poético de Lope de Vega, Madrid, Laberinto, 2004.

- —, Perfil biográfico, Barcelona, Teide, 1990, págs. 3-23.

- Rozas, Juan Manuel, Estudios sobre Lope de Vega, Madrid, Cátedra, 1990.

- Pedraza Jiménez, Felipe B., Lope de Vega: pasiones, obra y fortuna del monstruo de naturaleza, EDAF, Madrid, 2009 (ISBN 9788441421424).

- Arellano, Ignacio, Historia del teatro español del siglo XVII, Cátedra, Madrid, 1995 (ISBN 9788437613680).

- Arellano, Ignacio; Mata, Carlos; Vida y obra de Lope de Vega, Bibliotheca homolegens, Madrid, 2011 (ISBN 978-84-92518-72-2).

External links[edit]

In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is de Vega and the second or maternal family name is Carpio.

|

Lope de Vega KOM |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Lope de Vega |

|

| Born | Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio 25 November 1562 Madrid, Castile |

| Died | 27 August 1635 (aged 72) Madrid, Castile |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright, novelist |

| Language | Spanish |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Notable works | Fuenteovejuna

The Dog in the Manger The Knight from Olmedo |

| Children | 15 |

| Signature | |

|

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio ( LOH-pay dee VAY-gə, Spanish: [ˈfeliɣz ˈlope ðe ˈβeɣa i ˈkaɾpjo]; 25 November 1562 – 27 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. He was one of the key figures in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish literature is second only to that of Miguel de Cervantes,[1] while the sheer volume of his literary output is unequalled, making him one of the most prolific authors in the history of literature. He was nicknamed «The Phoenix of Wits» and «Monster of Nature» (in Spanish: Fénix de los Ingenios, Monstruo de Naturaleza) by Cervantes because of his prolific nature.

Lope de Vega renewed the Spanish theatre at a time when it was starting to become a mass cultural phenomenon. He defined its key characteristics, and along with Pedro Calderón de la Barca and Tirso de Molina, took Spanish Baroque theatre to its greatest heights. Because of the insight, depth and ease of his plays, he is regarded as one of the greatest dramatists in Western literature, his plays still being produced worldwide. He was also considered one of the best lyric poets in the Spanish language and wrote several novels. Although not well known in the English-speaking world, his plays were presented in England as early as the 1660s, when diarist Samuel Pepys recorded having attended some adaptations and translations of them, although he omits to mention the author.

Some 3,000 sonnets, three novels, four novellas, nine epic poems, and about 500 plays are attributed to him. Although he has been criticised for putting quantity ahead of quality, nevertheless at least 80 of his plays are considered masterpieces. He was a friend of the writer Francisco de Quevedo and an arch-enemy of the dramatist Juan Ruiz de Alarcón. The volume of his lifework made him envied by not only contemporary authors such as Cervantes and Luis de Góngora, but also by many others: for instance, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once wished he had been able to produce such a vast and colourful oeuvre.[2]

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Lope de Vega Carpio[3] was born in Madrid, in the Puerta de Guadalajara to a family of natives of the valley of Carriedo.[4] His father, Félix de Vega, was an embroiderer. Little is known of his mother, Francisca Fernández Flores. He later took the distinguished surname of Carpio from his paternal grandmother, Catalina del Carpio.

After a brief stay in Valladolid, his father moved to Madrid in 1561, perhaps drawn by the possibilities of the new capital city. However, Lope de Vega would later affirm that his father arrived in Madrid through a love affair from which his future mother was to rescue him. Thus the writer became the fruit of this reconciliation and owed his existence to the same jealousies he would later analyze so much in his dramatic works.

The first indications of young Lope’s genius became apparent in his earliest years. His friend and biographer Pérez de Montalbán stated that at the age of five he was already reading Spanish and Latin. While he was still unable to write, he would share his breakfast with the older boys in exchange for their help scribing his verses.[5] By his tenth birthday, he was translating Latin verse. He wrote his first play when he was 12, allegedly El verdadero amante, as he would later affirm in his dedication of the work to his son Lope, although these statements are most probably exaggerations.

His great talent bore him to the school of poet and musician Vicente Espinel in Madrid, to whom he later always referred with veneration. In his fourteenth year he continued his studies in the Colegio Imperial, a Jesuit school in Madrid, from which he absconded to take part in a military expedition in Portugal. Following that escapade, he had the good fortune of being taken into the protection of the Bishop of Ávila, who recognized the lad’s talent and saw him enrolled in the University of Alcalá. Following graduation, Lope had planned to follow in his patron’s footsteps and join the priesthood, but those plans were dashed by falling in love and realizing that celibacy was not for him. Thus he failed to attain a bachelor’s degree and made what living he could as a secretary to aristocrats or by writing plays.

In 1583 Lope enlisted in the Spanish Navy and saw action at the Battle of Ponta Delgada in the Azores, under the command of his future friend Álvaro de Bazán, 1st Marquis of Santa Cruz, to whose son he would later dedicate a play.

Following this, he returned to Madrid and began his career as a playwright in earnest. He also began a love affair with Elena Osorio (the «Filis» of his poems), who was separated from her husband, actor Cristóbal Calderón, and was the daughter of a leading theater director. When, after some five years of this torrid affair, Elena spurned Lope in favor of another suitor, his vitriolic attacks on her and her family landed him in jail for libel and, ultimately, earned him the punishment of eight years’ banishment from the court and two years’ exile from Castile.

Exile[edit]

After libelling members of his family in his writing,[6] Lope de Vega undauntedly went into exile. He took with him 16-year-old Isabel de Alderete y Urbina, known in his poems by the anagram «Belisa,» the daughter of Philip II’s court painter, Diego de Urbina. The two married under pressure from her family on 10 May 1588.

Just a few weeks later, on 29 May, Lope signed up for another tour of duty with the Spanish Navy: this was the summer of 1588, and the Armada was about to sail against England. It is likely that his military enlistment was the condition required by Isabel’s family, eager to be rid of such an ill presentable son-in-law, to forgive him for carrying her away.[7]

Lope’s luck again served him well, however, and his ship, the San Juan, was one of the vessels to make it home to Spanish harbors in the aftermath of that failed expedition. Back in Spain by December 1588, he settled in the city of Valencia. There he lived with Isabel de Urbina and continued perfecting his dramatic formula participating regularly in the tertulia known as the Academia de los nocturnos, in the company of such accomplished dramatists as the canon Francisco Agustín Tárrega, the secretary to the Duke of Gandía Gaspar de Aguilar, Guillén de Castro, Carlos Boyl, and Ricardo de Turia. With them he refined his approach to theatrical writing by violating the unity of action and weaving two plots together in a single play, a technique known as imbroglio.

In 1590, at the end of his two years’ exile from the realm, he moved to Toledo to serve Francisco de Ribera Barroso, who later became the 2nd Marquis of Malpica, and, some time later, Antonio Álvarez de Toledo, 5th Duke of Alba. In this later appointment he became gentleman of the bedchamber to the ducal court of the House of Alba, where he lived from 1592 to 1595. Here he read the work of Juan del Encina, from whom he improved the character of the donaire, perfecting still further his dramatic formula. In the fall of 1594, Isabel de Urbina died of postpartum complications. It was around this time that Lope wrote his pastoral novel La Arcadia, which included many poems and was based on the Duke’s household in Alba de Tormes.

Return to Castile[edit]

In 1595, following Isabel’s death in childbirth, he left the Duke’s service and – eight years having passed – returned to Madrid. There were other love affairs and other scandals: Antonia Trillo de Armenta, who earned him another lawsuit, and Micaela de Luján, an illiterate but beautiful actress, who inspired a rich series of sonnets, rewarded him with four children and was his lover until around 1608. In 1598, he married Juana de Guardo, the daughter of a wealthy butcher. Nevertheless, his trysts with others – including Micaela – continued.

In the 17th century Lope’s literary output reached its peak. From 1607 he was also employed as a secretary, but not without various additional duties, by the Duke of Sessa. Once that decade was over, however, his personal situation took a turn for the worse. His favorite son, Carlos Félix (by Juana), died and, in 1612, Juana herself died in childbirth. After the heartbreaking loss of his son and lover, Lope summoned his remaining children still alive under the same roof to devote himself to Christianity. His writing in the early 1610s also assumed heavier religious influences and, in 1614, he joined the priesthood.[8] The taking of holy orders did not, however, impede his romantic dalliances; what is more, he supplied his employer the duke with various female companions. The most notable and lasting of Lope’s relationships was with Marta de Nevares, who met him in 1616 and would remain with him until her death in 1632.

Further tragedies followed in 1635 with the loss of Lope, his son by Micaela and a worthy poet in his own right, in a shipwreck off the coast of Venezuela, and the abduction and subsequent abandonment of his beloved youngest daughter Antonia. Lope de Vega took to his bed and died of scarlet fever, in Madrid, on 27 August of that year.

Priesthood[edit]

Lope de Vega dressed in cassock. (Madrid, 1902).

The period of life that characterizes priestly ordination of Lope de Vega was one of profound existential crisis, perhaps impelled by the death of close relatives. To this inspiration respond his Sacred Rhymes and the numerous devout works he began to compose, as well as the meditative and philosophical tone that appears in his last verses. On the night of December 19, 1611, the writer was the victim of an assassination attempt from which he could barely escape.[9] Juana de Guardo suffered frequent illnesses and in 1612 Carlos Félix died of fevers. On August 13 of the following year, Juana de Guardo died while giving birth to Feliciana. So many misfortunes affected Lope emotionally, and on May 24, 1614, he finally decided to be ordained a priest.

The literary expression of this crisis and its repentances are the Sacred Rhymes, published in 1614; there it says: «If the body wants to be earth on earth / the soul wants to be heaven in heaven», unredeemed dualism that constitutes all its essence. The Sacred Rhymes constitute a book at the same time introspective in the sonnets (he uses the technique of the spiritual exercises that he learned in his studies with the Jesuits) as devotee for the poems dedicated to diverse saints or inspired in the sacred iconography, then in full deployment thanks to the recommendations emanated from the Council of Trent.

In 1627 he was admitted as a knight of the Order of Malta. This was an enormous honour for him since he had always taken an interest in orders of chivalry. In 1603 he had published the play El valor de Malta (The Valour of Malta) about the maritime battles of the Order. In his portrait by Eugenio Caxés he wears the habit of the Order of Malta.

Work[edit]

Title page of El testimonio vengado.

Lope’s non-dramatic works were collected and published in Spain in the eighteenth century under the title Obras Sueltas (Madrid, 21 vols., 1776–79). The more important elements of this collection include the following:

- La Arcadia (1598), a pastoral romance;

- La Dragontea (1598), an epic poem of Sir Francis Drake’s last expedition and death;

- El Isidro (1599), a poetic narrative of the life of Saint Isidore, future patron saint of Madrid, composed in octosyllabic quintillas;

- La Hermosura de Angélica (1602), an epic poem in three books, is a quasi sequel to Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso.

Lope de Vega was one of the greatest Spanish poets of his time, along with Luis de Góngora and Francisco de Quevedo. His poems of Moorish and pastoral themes were extremely popular in the 1580s and 1590s, and in these, he portrayed elements of his own love affairs (appearing as a moor called Zaide or a shepherd called Belardo). In 1602 he published two hundred sonnets in the collection La Hermosura de Angélica and in 1604 he republished them with new material in Rimas. In 1614, his religious sonnets appeared in a book entitled Rimas sacras, which was another bestseller. In 1634, in a third book with similar title, Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos, which has been considered his poetic masterpiece and the most modern book of 17th-century poetry, Lope created a heteronym, he concludes the identity of Tome de Burguillos, who has a deep and intimate romantic connection with a maid named Juana. This is a direct comparison and clash with Lope’s skeptical outlook on society.

Background[edit]

Lope was the playwright who established in Spanish drama the three-act comedia as the definitive form, ignoring the precepts of the prevailing school of his contemporaries. In Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609), which was his artistic manifesto and the justification of his style which broke the neoclassical three unities of place, time and action, he showed that he knew the established rules of poetry but refused to follow them on the grounds that the «vulgar» Spaniard cared nothing about them: «Let us then speak to him in the language of fools, since it is he who pays us» are famous lines from his manifesto.[10]

Lope boasted that he was a Spaniard pur sang (pure-blooded), maintaining that a writer’s business is to write so as to make himself understood, and took the position of a defender of the language of ordinary life.[10]

Lope’s literary influence was chiefly Latin-Italian and, while he defended the tradition of the nation and the simplicity of the old Castilian,[10] he emphasized his university education and the difference between those educated in the classics and the layman.

The majority of his works were written in haste and to order. Lope confessed that «more than a hundred of my comedies have taken only twenty-four hours to pass from the Muses to the boards of the theatre.» His biographer Pérez de Montalbán tells how in Toledo, Lope composed fifteen acts in as many days – five comedies in two weeks.[10]

In spite of some discrepancies in the figures, Lope’s own records indicate that by 1604 he had composed 230 three-act plays (comedias). The figure had risen to 483 by 1609, to 800 by 1618, to 1000 by 1620, and to 1500 by 1632. Montalbán, in his Fama Póstuma (1636) set down the total of Lope’s dramatic productions at 1800 comedias and more than 400 shorter sacramental plays. Of these, 637 plays are known by their titles, but only about 450 are extant. Many of these pieces were printed during Lope’s lifetime, mostly by the playwright himself in the shape of twelve-play volumes, but also by booksellers who surreptitiously bought manuscripts from the actors who performed them.

Themes and sources[edit]

The classification of this large mass of dramatic literature is a task of great difficulty. The terms traditionally employed – comedy, tragedy, and the like – are difficult to apply to Lope’s oeuvre and another approach to categorization has been suggested. Lope’s work essentially belongs to the drama of intrigue, the plot determining everything else. Lope used history, especially Spanish history, as his main source of subject matter. There were few national and patriotic subjects, from the reign of King Pelayo to the history of his own age, he did not put upon the stage. Nevertheless, Lope’s most celebrated plays belong to the class called capa y espada («cloak and dagger»), where the plots are chiefly love intrigues along with affairs of honor, most commonly involving the petty nobility of medieval Spain.[10]

Among the best known works of this class are El perro del hortelano (The Dog in the Manger), El castigo sin venganza (Punishment without Revenge),[11] and El maestro de danzar (The Dance Teacher).

In some of these, Lope strives to set forth some moral maxim and to illustrate its abuse with a living example. On the theme that poverty is no crime, in the play Las Flores de Don Juan, he uses the history of two brothers to illustrate the triumph of virtuous poverty over opulent vice, while indirectly attacking the institution of primogeniture, which often places in the hands of an unworthy person the honor and substance of a family when younger members would be better qualified for the trust. However, such morality pieces are rare in Lope’s repertory; generally, his aim is to amuse and stir with his focus being on the plot, not concerning himself with instruction.[10]

In El villano en su rincón, described as a romantic comedy, Francis I of France ends up spending the night in a woodcutter’s hut, after becoming lost during a hunt, resulting in a confrontation between peasant-philosopher and king. The peasant’s refusal to even look upon the king’s magnificence, grand and dramatic compared with the humble rincón, is rebuked by a gentleman of the king’s court: «a king of such might/that the Scythian and fierce Turk/tremble before his golden fleurs de lis!»[12]

Legacy[edit]

Lope encountered a poorly organized dramatic tradition; plays were sometimes composed in four acts, sometimes in three, and though they were written in verse, the structure of the versification was left to the individual writer. Because the Spanish public liked it, he adopted the style of drama which was then in vogue. He enlarged its narrow framework to a great degree, introducing a wide range of material for dramatic situations – the Bible, ancient mythology, the lives of the saints, ancient history, Spanish history, the legends of the Middle Ages, the writings of the Italian novelists, current events, and everyday Spanish life in the 17th century. Prior to Lope, playwrights sketched the conditions of persons and their characters superficially. With fuller observation and more careful description, Lope de Vega depicted real character types with language and accouterments appropriate to their position in society. The old comedy was awkward and poor in its versification. Lope introduced order into all the forms of national poetry, from the old romance couplets to the lyrical combinations borrowed from Italy. He wrote that those who should come after him had only to go on along the path which he had opened.[10]

Lope de Vega also encountered other poets who were unimpressed with his discoveries and attempted to defame his writing. The Spanish poet Pedro de Torres Rámila wrote his thoughts on Lope in his Latin satire Spongia (Paris, 1617). Torres wrote personal attacks on Lope’s sacramental plays and sought to scandalize his name and reputation. This attempt backfired on Torres due to the overwhelmingly negative responses his Spongia received from the public after its release. Scholars and poets alike came to the defense of Lope de Vega and wrote many counterclaims against the Spongia directed at Torres himself, like Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca’s Exposulatio Spongiae[13]

List of works[edit]

Plays[edit]

Listed here are some of the better-known of de Vega’s plays:

- El maestro de danzar (1594) (The Dancing Master)

- Los locos de Valencia (Madness in Valencia)

- El acero de Madrid (The Steel of Madrid)

- El perro del Hortelano (The Gardener’s Dog, a variation of The Dog in the Manger fable)

- La viuda valenciana

- Peribáñez y el comendador de Ocaña

- Fuenteovejuna

- El anzuelo de Fenisa (Fenisa’s Hook)

- El cordobés valeroso Pedro Carbonero

- Mujeres y criados (Women and Servants)

- El mejor alcalde, el Rey (The Best Mayor, The King)

- El Nuevo Mundo descubierto por Cristóbal Colón (The New World Discovered by Christopher Columbus)

- El caballero de Olmedo (The Knight from Olmedo)

- La dama boba (The Stupid Lady; The Lady-Fool)

- El amor enamorado

- El castigo sin venganza (Punishment Without Revenge)

- Las bizarrías de Belisa

- El mayordomo de la duquesa de Amalfi (The Duchess of Amalfi’s Steward)

- Lo Fingido Verdadero (What you Pretend Has Become Real)

- El niño inocente de La Guardia (The Innocent Child of La Guardia)

- La fe rompida

- El Honrado Hermano (The Honourable Brother, based in the Classic story of the Horatii and Curiatii)

In January 2023, an anonymous work in the collection of the National Library of Spain, La francesa Laura (The Frenchwoman Laura), was identified with the help of artificial intelligence as another comedy by Lope de Vega. The comedy was classified as a late work of Lope de Vega and dated from 1628 to 1630, as its flattering treatment of France could be attributed to the momentary good relationship between Spain and France during the Thirty Years’ War, having England as a common enemy. Later investigations by literary historians confirmed the findings of artificial intelligence.[14]

Opera[edit]

- La selva sin amor (18 December 1627) (The Lovelorn Forest), the first Spanish opera, with music by Alessandro Piccinini.[15]

Epic poems and lyrical poetry[edit]

- La Dragontea (1598) («Drake the Pirate»)

- El Isidro (1599) («Isidro»)

- La hermosura de Angélica (1602) («The Beauty of Angelica»)

- Rimas (1602) («Rhymes»)

- Arte nuevo de hacer comedias (1609)

- Jerusalén conquistada (1609)

- Rimas sacras (1614)

- La Filomena (1621)

- La Circe (1624)

- El laurel de Apolo (1630)

- La Gatomaquia (1634)

- Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos (1634)

Prose fiction[edit]

- Arcadia (published 1598) (The Arcadia), pastoral romance in prose, interspersed with verse

- El peregrino en su patria (published 1604) (The Pilgrim in his Own Country), adaption of Byzantine novels

- Pastores de Belen : prosas y versos divinos (published 1614)

- Novelas a Marcia Leonarda

- Las fortunas de Diana (published 1621)

- La desdicha por la honra (published 1624)

- La más prudente venganza (published 1624)

- Guzmán el Bravo (published 1624)

- La Dorotea (published 1632)

In popular culture[edit]

In Harry Turtledove’s alternate history novel Ruled Britannia, in which the Spanish Armada was successful, Vega is depicted as a Spanish soldier-playwright on occupation duty in defeated England, who interacts with William Shakespeare. The novel’s viewpoint narration alternates between the two playwrights.

A 2010 Spanish-language film about de Vega, entitled Lope, is available with English subtitles as The Outlaw.[16]

Vega is played by actor Víctor Clavijo in the Spanish TV series El Ministerio del Tiempo.[17] In his first appearance he played Vega in 1588, on the eve of the Spanish Armada, while the second episode depicted Vega in 1604.

Tribute[edit]

A municipality in Northern Samar in the Philippines was named after de Vega, created in 1980 from the 22 barangays of Catarmán.

A street in the Santa Cruz district of the City of Manila, Philippines is also named after the playwright.

On November 25, 2017, Google celebrated his 455th birthday with a Google Doodle.[18]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Works of Lope de Vega». www.classicspanishbooks.com. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Cfr. Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe: in 1828 Eckermann recorded having a conversation about the extent of the author’s works, in which Goethe expressed his admiration towards Lope’s.

- ^ Certificate of baptism: «En seis de Diciembre de mil quinientos y sesenta y dos años, el Muy Reverendo Señor Licenciado Muñoz bautizó a Lope, hijo de Feliz de Vega y de Francisca su mujer. Compadre mayor, Antonio Gómez; madrina su mujer». Joaquín de Entrambasaguas, Vida de Lope de Vega, Ed. Labor, 1936, p. 20.

- ^ Rennert, Hugo Albert (1904). The Life of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), by Hugo Albert Rennert … Gowans and Gray. OCLC 457734398.

- ^ Rennert, Hugo Albert (1904). The Life of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), by Hugo Albert Rennert … Gowans and Gray. OCLC 457734398.

- ^ Rennert, Hugo Albert (1904). The Life of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), by Hugo Albert Rennert … Gowans and Gray. OCLC 457734398.

- ^ Guillermo Carrascón, «Modelos de comedia: Lope y Cervantes», Artifara 2 (2002) ‘Monographica’, nota 7.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Félix de Lope de Vega Carpio» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ El suceso consta en José del Corral, Sucedió en Madrid (Ediciones La Librería, 2000) y ABC (26 de febrero de 2016): «El intento de asesinato a Lope de Vega que nunca se resolvió.»

- ^ a b c d e f g

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Vega Carpio, Lope Felix de». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 965–967.

- ^ Lope de Vega: Three Major Plays, translated by Gwynne Edwards, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-954017-4

- ^ Forcione, Alban K. (2009). Majesty and Humanity: Kings and Their Doubles in the Political Drama of the Spanish Golden Age. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300153309.

- ^ García Aguilar, Ignacio. «Echoes and reflections of the controversy over Spongia (1617) in the approvals and dedications of Lope de Vega / Echoes and Reflections of the Spongia’s (1617) Controversy in Lope de Vega’s Approvals and Dedications.» Calliope: Journal of the Society for Renaissance and Baroque Hispanic Poetry, vol. 26 no. 1, 2021, p. 58-80. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/796140. Accessed November 1, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Sam (5 February 2023). «Artificial intelligence uncovers lost work by titan of Spain’s ‘Golden Age’«. The Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ [1]Melveena McKendrick: «Theatre in Spain, 1490–1700», p. 215. CUP Archive, 1992. ISBN 978-0-521-42901-6

- ^ C. Fanjul, Sergio (22 August 2010). «Un Lope apasionado y pendenciero». El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Pimentel, Aurelio (14 March 2017). «Lope de Vega y Cervantes vuelven a ‘El Ministerio del Tiempo’ en la tercera temporada». Radiotelevisión Española (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ «Lope de Vega’s 455th Birthday». Google. 25 November 2017.

Sources[edit]

- Calderón, Lope de Vega and (2019). Theatre Database. Retrieved from http://www.theatredatabase.com/17th_century/calderon_and_lope_de_vega.html

- Goldáraz, Luis H. (2018, November 30). Lope, el verso y la vida . Libertad Digital. Retrieved from https://www.libertaddigital.com/cultura/libros/2018-11-30/antonio-sanchez-jimenez-presenta-la-biografia-de-lope-de-vega-1276629134/

- Hayes, Francis C. (1967). Lope de Vega. Twayne’s World Author Series. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Hennigfeld, Ursula (2008). Der ruinierte Körper. Petrarkistische Sonette in transkultureller Perspektive. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.

- Ray Keck, author of Love’s Dialectic: Mimesis and Allegory in the Romances of Lope de Vega

- Samson, Alexander; Thacker, Jonathan (2018). A Companion to Lope de Vega (Paperback ed.). Tamesis. ISBN 978-1855663251.

- Lope de Vega, Félix Arturo (2019). LibriVox. Retrieved from https://librivox.org/author/229?primary_key=229&search_category=author&search_page=1&search_form=get_results

- Lope de Vega, The Works of (2011). Spanish Books. Retrieved from https://www.classicspanishbooks.com/16th-cent-baroque-lope-works.html

- Lope Felix de (Carpio) Vega. (2011). Hutchinson’s Biography Database, 1.

- Morley, S., & Allardice, L. (2003). Double takes. New Statesman, 132(4639), 46.

- Vega Carpio, Félix Lope de (2019). Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, 1.

- Vega Carpio, Lope Felix de (2000). Theatre History. Retrieved from http://www.theatrehistory.com/spanish/lope001.html

- Vega, Lope de (2012). Britannica Biographies, 1.

- In Spanish

- Alonso, Dámaso, En torno a Lope, Madrid, Gredos, 1972, 212 pp. ISBN 9788424904753

- Castro, Américo y Hugo A. Rennert, Vida de Lope de Vega: (1562-1635) ed. de Fernando Lázaro Carreter, Salamanca, 1968.

- De Salvo, Mimma, «Notas sobre Lope de Vega y Jerónima de Burgos: un estado de la cuestión», pub. en Homenaje a Luis Quirante. Cuadernos de Filología, anejo L, 2 vols., tomo I, 2002, págs. 141-156. Versión en línea revisada en 2008. URL. Consulta 28-09-2010.

- «Lengua y literatura, Historia de las literaturas», en Enciclopedia metódica Larousse, vol. III, Ciudad de México, Larousse, 1983, págs 99–100. ISBN 968-6042-14-8

- Huerta Calvo, Javier, Historia del Teatro Español, Madrid, Gredos, 2003.

- Menéndez Pelayo, Marcelino, Estudios sobre el teatro de Lope de Vega, Madrid, Editorial Artes Gráficas, 1949, 6 volúmenes.

- MONTESINOS, José Fernández, Estudios sobre Lope de Vega, Salamanca, Anaya, 1967.

- Pedraza Jiménez, Felipe B., El universo poético de Lope de Vega, Madrid, Laberinto, 2004.

- —, Perfil biográfico, Barcelona, Teide, 1990, págs. 3-23.

- Rozas, Juan Manuel, Estudios sobre Lope de Vega, Madrid, Cátedra, 1990.

- Pedraza Jiménez, Felipe B., Lope de Vega: pasiones, obra y fortuna del monstruo de naturaleza, EDAF, Madrid, 2009 (ISBN 9788441421424).

- Arellano, Ignacio, Historia del teatro español del siglo XVII, Cátedra, Madrid, 1995 (ISBN 9788437613680).

- Arellano, Ignacio; Mata, Carlos; Vida y obra de Lope de Vega, Bibliotheca homolegens, Madrid, 2011 (ISBN 978-84-92518-72-2).

External links[edit]

Биография

Жизнь писателя, поэта и драматурга, написавшего две тысячи пьес, Лопе де Вега была полна любовных приключений и отчасти напоминала его произведения, в которых комедия переплеталась с трагедией. В историю выдающийся представитель золотого века Испании вошел как основатель испанского национального театра.

Детство и юность

Феликс Лопе де Вега и Карпио (полное имя писателя) родился 25 ноября 1562 года, в крупнейшем городе Испании – Мадриде. Его отец и мать, крестьяне по происхождению, перебрались в Мадрид, в котором глава семейства освоил золотошвейное ремесло. Скопив необходимую сумму денег, он купил патент на дворянское звание и сделал все возможное, чтобы сын получил лучшее образование.

С ранних лет Лопе отличался феноменальной восприимчивостью к наукам: ему легко давалось изучение языков и литературных творений писателей прошлого. Так, прозаик в возрасте 10 лет перевел поэму Клавдия Клавдиана «Похищение Прозерпины», а в 13 сочинил свою первую комедию «Истинный любовник». Сначала Феликс обучался в иезуитском колледже, а затем — в университете в Алькала и Королевской академии.

За сатиру на семью отвергнувшей его возлюбленной Феликс был осужден на 10 лет изгнания из Мадрида. Несмотря на это, Лопе вернулся в столицу, чтобы похитить новую даму сердца и тайно жениться на ней. В 1588 году он принял участие в походе Непобедимой армады, после поражения которой поселился в Валенсии, где и создал ряд драматических произведений для поддержания семьи.

Лопе де Вега состоял секретарем у герцога Альбы (1590 год), маркиза Малвпика (1596 год) и герцога Лемосского (1598 год). К этому же периоду относится расцвет его драматического творчества. В 1609-ом драматург получил звание добровольного слуги инквизиции, а в 1614-ом принял сан священника.

Литература и театр

По признанию Лопе, он написал 1500 комедий, а его первый биограф довел это число до 1800. Стоит отметить, что на сегодняшний момент ученым известны названия только 800 пьес драматурга, поэтому многие считают, что число созданных писателем произведений завышено.

Недраматические произведения Френсиса, при первой публикации составившие 21 том, складываются из «Доротеи» (длинное прозаическое повествование в форме диалога), трех романов, нескольких новелл, пяти крупных и четырех малых эпических поэм, рассказа о христианских мучениках в Японии, двух религиозных произведений, а также огромного массива лирической поэзии и сочинений.

В творчестве Лопе традиционно выделяются две стилевые тенденции – усложненная, искусственная, старательно возводимая к гуманистической традиции Возрождения и более свободная, живая, естественная, своей непосредственностью близкая народному творчеству. Первая представлена эпическими поэмами, романами и стихотворениями, а вторая – пьесами, автобиографическими стихами, балладами и песнями.

В целом, различие определялось аудиторией: ученый стиль – для просвещенных знатоков, народный – для широкой публики. В теории Лопе признавал законность классических правил, составлявших для него понятие искусства. Так, в поэзии писатель обращался, прежде всего, к воображению и чувствам, а не к разуму.

Созидательная энергия Лопе дала ему силы, вопреки рассудочности века, утвердить новый тип пьесы, в которой трагедия переплетается с комедией, а граница между этими стилями размыта. Внешне она характеризуется делением на три акта и широким спектром стихотворных размеров в рамках одной пьесы. Внутренне этот тип драмы характеризуется преобладанием действия над характером.

Сюжеты пьес Лопе отражают ценности, общественные нормы и условности эпохи, в которой он жил. В одних его драмах главенствует исторический сюжет, а в других – вымышленный. В книгах создателя произведения «Овечий источник» любовь, в соответствии с традициями литературы XVI века, поначалу идеализировалась в романтическом и рыцарственном духе, а затем она предстала перед читателями в виде источника социального конфликта, рожденного противостоянием природы и цивилизации.

Также у де Веги есть развлекательные комедии, типичные для этого жанра, такие, как «Изобретательная влюбленная», в которой интрига построена на хитроумии, с каким молодая женщина обходит светские условности, чтобы завоевать избранника.

Более оригинальную комедию представляет собой «Собака на сене», в которой графиня обнаруживает, что влюбилась в собственного секретаря. Легкий финал не заглушает заложенной в пьесе социальной критики, касающейся классовых различий, которые теряют свою силу перед магией любви. Еще одна излюбленна тема Лопе – тема чести, которая является основополагающей в его широко известных пьесах «Овечий источник», «Лучший мэр – король» и «Перибаньес».

Лопе не только придал испанской драме мощное социальное звучание, но также расширил ее диапазон, выведя религиозную тематику на подмостки публичного театра, который до него был преимущественно светским. Религиозные пьесы поэта в большинстве своем либо носили библейский характер и иллюстрировали эпизоды Ветхого Завета, либо представляли собой «комедии о жизни святых».

Личная жизнь

В 1583 начинающий драматург вступил в любовную связь с актрисой Еленой Осорио (история их любви нашла отражение в вершинном творении прозаика — диалогическом романе «Доротея»).

Интрижка с замужней дамой длилась пять лет, но в итоге ветреная артистка нашла себе нового, более богатого поклонника. Покинутый Лопе отомстил бывшей возлюбленной весьма оригинально: он написал пару злобных эпиграмм в адрес актрисы, которые незамедлительно собственноручно распространил среди труппы.

В ответ Елена подала на Феликса в суд за клевету, и в 1588 году писателя изгнали из столицы Испании. Через три месяца после оглашения приговора драматург женился на дочери придворного герольда Изабель де Урбине, а затем отправился в поход на борту корабля, входящего в состав Непобедимой армады.

После поражения Непобедимой армады поэт поступил на службу к герцогу Альбе и вместе с женой поселился в Валенсии. Скромная должность секретаря позволяла ему и обеспечивать семью, и работать над пьесами. Именно в этот период из — под его пера вышла комедия «Учитель танцев».

В 1595 году Лопе возвращается в Мадрид, оставив в Валенсии три дорогих ему могилы — жены и двух маленьких дочек. В столице Испании он устраивается на новую должность и знакомится с новой музой, актрисой Микаэлой де Лухан (в стихах и прозе он называл ее Камила Лусинда). Эту связь не мог прервать даже новый брак писателя с дочерью богатого торговца мясом Хуаной де Гуардо.

Лопе нашел в себе силы прервать эту связь в период серьезного духовного кризиса (в 1609 году он стал доверенным лицом инквизиции, а в 1614 — священником). Душевное состояние писателя было усугублено последовавшими друг за другом смертями — любимого сына Карлоса Феликса, жены, а затем и любовницы Микаэлы. Свидетельство пережитой Лопе духовной драмы — сборник «Священные стихи», увидевший свет в 1614-ом.

Уже будучи пожилым человеком, писатель встретил свою последнюю любовь — двадцатилетнюю Марту де Неварес, которую воспевал в стихах и в прозе под разными именами (Амарилис, Марсия, Леонарда) и которой посвятил комедию «Валенсианская вдова», а также новеллы «Приключения Дианы», «Мученик чести», «Благоразумная месть» и «Гусман Смелый».

Последние годы жизни Лопе — череда личных катастроф: в 1632-ом умерла Марта, за два года до смерти ослепшая и потерявшая рассудок, в том же году похищают его дочь, а в морском походе погибает и сын. Стоит отметить, что, несмотря на трудности, творческая деятельность Лопе не прерывалась ни на один день.

Смерть

Лопе де Вега творил вплоть до своей смерти. Последнюю комедию автор написал за год до кончины, а последнюю поэму — за четыре дня. Пару последних лет прозаик старался искупить свои грехи и поэтому вел аскетичную жизнь, проводя большую часть времени в молитвах.

Поэт умер 27 августа 1635 года. На похороны драматурга-монаха пришли как коллеги по творческому цеху, так и поклонники его таланта.

В 2010 году режиссер Андруча Уэддингтон снял фильм «Лопе де Вега: Распутник и соблазнитель», в основе сюжета которого лежит история жизни Феликса. Кроме того, в разное время были экранизированы пьесы «Учитель танцев» (1952 год), «Собака на сене» (1977 год), «Дурочка» (2006 год).

Пьесы

- 1594 – «Учитель танцев»

- 1596 – «Командоры Кордовы»

- 1598 – «Аркадия»

- 1613 – «Дурочка»

- 1612 – «Вифлеемские пастухи»

- 1613 – «Овечий источник»

- 1614 – «Периваньес и командор Оканьи»

- 1618 – «Собака на сене»

- 1619 – «Валенсианская вдова»

- 1621 – «Приключения Дианы»

- 1623 – «Звезда Севильи»

- 1624 – «Девушка с кувшином»

- 1631 – «Наказание – не мщение»

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с фамилией Вега.

Феликс Ло́пе де Ве́га Ка́рпьо[5] (исп. Félix Lope de Vega Carpio; 25 ноября 1562[1][2][…], Мадрид[2][1][…] — 27 августа 1635[2][1][…], Мадрид[3]) — испанский драматург, поэт и прозаик, выдающийся представитель золотого века Испании. Автор около двух тысяч пьес, из которых 426 дошли до наших дней, и около трёх тысяч сонетов.

Биография

Родился в семье ремесленника-золотошвея. С ранних лет обнаружились творческие способности (в 10-летнем возрасте перевёл в стихах «Похищение Прозерпины» Клавдиана). Учился в университете в Алькале. Сразу получили известность его романсы: в них, как и в других жанрах Лопе видел воплощение своего эстетического идеала, согласно которому Природа всегда должна стоять выше Искусства.

Однако университет окончить ему не удалось. За сатиру на семью отвергнувшей его возлюбленной он был осуждён на 10 лет изгнания из Мадрида. Несмотря на это Лопе возвращается в столицу, чтобы похитить новую даму сердца и тайно жениться на ней. Эта история отразилась в вершинном творении Лопе де Вега — диалогическом романе «Доротея» (1634), при создании которой драматург вдохновлялся комедией в прозе «Эуфрозина» Жорже Феррейры де Вашконселуша.

В 1588 году принял участие в походе «Непобедимой армады», после поражения которой поселился в Валенсии, где и создал ряд драматических произведений для поддержания семьи.

Был секретарём герцога Альбы (1590), маркиза Малвпика (1596) и герцога Лемосского (1598). К этому периоду относится расцвет его драматического творчества. Лопе де Вега принимает активное участие в организации пышных театрализованных праздников. Придворный стиль жизни, намёки на любовные связи, чувства самого Лопе де Вега и известных ему людей, переживания писателя, связанные со смертью его первой жены Исабель де Урбина (1594), легли в основу сюжета его пасторального романа «Аркадия» (1598).

В 1598 году он женился на дочери богатого торговца Хуане де Гуардо. Но главное место в жизни Лопе де Вега на протяжении 1599—1608 годов занимала актриса Микаэла де Лухан (в стихах и прозе Лопе — Камила Лусинда). В период серьёзного духовного кризиса Лопе де Вега разорвал эту связь.

В 1609 году он становится добровольным слугой инквизиции и получает звание familiar del Santo oficio de la Inquisición. Душевное состояние писателя было усугублено последовавшими друг за другом смертями любимого сына Карлоса Феликса (1612), жены (1613), а затем и Микаэлы. Свидетельство пережитой духовной драмы — сборник «Священные стихи», опубликованный в 1614 году.

В своей эклоге «Filis» де Вега восхваляет чистоту латыни, португальское сердце и испанское перо писательницы Бернарды Феррейры де Ласерды[6].

В 1616 году Лопе де Вега встретил свою последнюю любовь — двадцатилетнюю Марту де Неварес, которую воспел в стихах и в прозе под разными именами (Амарилис, Марсия Леонарда) и которой посвятил одну из лучших своих комедий — «Валенсианскую вдову» (1604, перераб. в 1616—1618?), а также новеллы: «Приключения Дианы» (1621), «Мученик чести», «Благоразумная месть», «Гусман Смелый». Последние годы жизни Лопе де Вега представляют собой целую череду личных катастроф: в 1632 году умерла Марта, за два года до смерти ослепшая и потерявшая рассудок, в том же году в морском походе погиб сын Лопе де Вега, а его дочь была похищена любовником. Но творческая деятельность Лопе де Вега не прерывалась ни на один день.

Творчество

Лопе де Вега создал более 2000 пьес, до наших дней сохранилось 427[7][8]. Дерзкий в жизни, Лопе де Вега поднял руку и на традиции испанской драматургии — отказался от принятого тогда принципа единства места, времени и действия, сохранив лишь последнее, и смело объединял в своих пьесах элементы комического и трагического, создав классический тип испанской драмы.

31 января 2023 года агентство Reuters сообщило, что хранившаяся в архиве Национальной библиотеки Испании анонимная пьеса «Французская Лаура» (исп. «La francesa Laura») принадлежит авторству Лопе де Вега и написана им за несколько лет до своей смерти в 1635 году[9].

Пьесы Лопе де Вега затрагивают различные темы: социально-политические драмы из отечественной и иностранной истории (например, пьеса о Лжедмитрии «Великий герцог Московский»), исторические хроники («Доблестный кордовец Педро Карбонеро»), любовные истории («Собака на сене», «Девушка с кувшином», «Учитель танцев»).

В драмах Лопе де Вега велик исторический пласт. Среди них «Последний готский король», «Граф Фернан Гонсалес», «Зубцы стен Торо», «Юность Бернарда дель Карпио», «Незаконный сын Мударра» и др., — пьесы, в основе которых народные романсы и «Песнь о моём Сиде». Трактовка исторических событий у Лопе близка или совпадает с той, которую столетиями давали романсеро. Театр Лопе де Вега на более высоком уровне разыгрывал знакомые любому жителю Пиренеев сюжеты.

Пьесы Феликса Лопе де Вега построены таким образом, что случай, вмешивающийся в поток явлений, опрокидывает спокойный ход действия, доводя напряжение драматических переживаний до степени трагизма, чтобы затем ввести это взволнованное море страстей и своеволия в русло законности и строгой католической морали. Любовная интрига, развитие и разрешение которой составляют стержень его драматической фабулы, именно в силу того, что она в состоянии раскрыть всё могущество человеческих инстинктов и своеволия, служит у Лопе де Вега, с одной стороны, для показа всей полноты и многообразия человеческого поведения в семье и обществе, с другой — даёт возможность наглядно продемонстрировать значимость политических и религиозных идей, господствовавших в современном писателю обществе.

Лопе де Вега в своих многочисленных комедиях (комедия «плаща и шпаги» «Учитель танцев», «Собака на сене» и др.) обнаруживает талант комического писателя. Его комедии, которых «и сейчас нельзя читать и видеть без смеха» (Луначарский), насыщены яркой, часто несколько плакатной весёлостью. Особая роль в них отводится слугам, история которых образует параллельную интригу пьес. Остроумные, лукавые, сыплющие меткими пословицами и поговорками, слуги большей частью являются сосредоточением комической стихии произведения, в чём Лопе де Вега предвосхищает Мольера и автора «Севильского цирюльника» — Бомарше.

Пьесы

- Валенсианская вдова / La viuda valenciana

- Глупая для других, умная для себя / La boba para los otros y discreta para sí

- Девушка с кувшином / La moza de cántaro

- Дурочка / La dama boba

- Звезда Севильи / La estrella de Sevilla

- Изобретательная влюблённая / La discreta enamorada

- Крестьянка из Хетафе / La villana de Getafe

- Лучший мэр — король / El mejor alcalde, el rey

- Овечий источник / Fuenteovejuna (Фуэнте Овехуна) — по пьесе создан балет «Лауренсия»

- Периваньес и командор Оканьи / Peribáñez y el comendador de Ocaña

- Собака на сене / El perro del hortelano

- Уехавший остался дома

- Учитель танцев / El maestro de danzar

Кинематограф

- Экранизаци

- 1952 — «Учитель танцев»

- 1977 — «Собака на сене»

- 1996 — «Собака на сене»

- 2006 — «Дурочка»

- Биография драматурга

- 2010 — «Лопе де Вега: Распутник и соблазнитель»

- 2-я серия 1-го сезона испанского фантастического сериала «Министерство времени» посвящена Лопе де Вега

Наследие

В 1932 году муниципалитетом Мадрида учреждена ежегодная театральная «Премия Лопе де Вега».

См. также

- Дом-музей Лопе де Веги

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 group of authors Vega Carpio, Lope Felix de (англ.) // Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information / H. Chisholm — 11 — New York, Cambridge, England: University Press, 1911. — Vol. 27.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 М. В. Лопе де Вега // Энциклопедический словарь — СПб.: Брокгауз — Ефрон, 1896. — Т. XVIII. — С. 4—6.

- ↑ 1 2 Плавскин З. И., Плавскин З. И. Вега Карпьо // Краткая литературная энциклопедия — М.: Советская энциклопедия, 1962. — Т. 1.

- ↑ LIBRIS — 2016.

- ↑ Вега Карпьо / И. В. Устинова // Большая российская энциклопедия : [в 35 т.] / гл. ред. Ю. С. Осипов. — М. : Большая российская энциклопедия, 2004—2017.

- ↑ Серда, Бернарда Феррейра // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- ↑ 426-я была найдена в 2014 году, 427-я в 2023-м

- ↑ Нашли неизданную пьесу Лопе де Веги. Национальная библиотека Республики Беларусь (24 января 2014). — 426-я известная пьеса. Дата обращения: 2023-2-4.

- ↑ A.I. uncovers unknown play by Spanish great in library archive (англ.). Reuters (202-02-31). Дата обращения: 2023-2-4.

Литература