Что означает LA? Выше приведено одно из значений LA. Вы можете скачать изображение ниже, чтобы распечатать или поделиться им с друзьями через Twitter, Facebook, Google или Pinterest. Если вы веб-мастер или блоггер, не стесняйтесь размещать изображение на вашем сайте. LA может иметь другие определения. Пожалуйста, прокрутите вниз, чтобы увидеть его определения на английском и другие пять значений на вашем языке.

Значение LA

На следующем изображении представлено одно из определений LA на английском языке.Вы можете скачать файл изображения в формате PNG для автономного использования или отправить изображение определения LA своим друзьям по электронной почте.

Другие значения LA

Как упомянуто выше, у LA есть другие значения. Пожалуйста, знайте, что пять других значений перечислены ниже.Вы можете щелкнуть ссылки слева, чтобы увидеть подробную информацию о каждом определении, включая определения на английском и вашем местном языке.

Определение в английском языке: Los Angeles

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

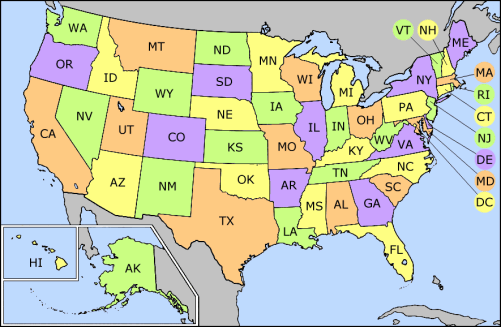

Several sets of codes and abbreviations are used to represent the political divisions of the United States for postal addresses, data processing, general abbreviations, and other purposes.

Table[edit]

This table includes abbreviations for three independent countries related to the United States through Compacts of Free Association, and other comparable postal abbreviations, including those now obsolete.

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name and status of region | ISO | ANSI | USPS | USCG | GPO | AP | Other abbreviations |

|||||||

| United States of America | Federal state | US USA 840 |

US | 00 | U.S. | U.S. | U.S.A. | |||||||

| Alabama | State | US-AL | AL | 01 | AL | AL | Ala. | Ala. | ||||||

| Alaska | State | US-AK | AK | 02 | AK | AK | Alaska | Alaska | Ak.[1] | |||||

| Arizona | State | US-AZ | AZ | 04 | AZ | AZ | Ariz. | Ariz. | ||||||

| Arkansas | State | US-AR | AR | 05 | AR | AR | Ark. | Ark. | ||||||

| California | State | US-CA | CA | 06 | CA | CF | Calif. | Calif. | Cal. | |||||

| Colorado | State | US-CO | CO | 08 | CO | CL | Colo. | Colo. | ||||||

| Connecticut | State | US-CT | CT | 09 | CT | CT | Conn. | Conn. | ||||||

| Delaware | State | US-DE | DE | 10 | DE | DL | Del. | Del. | ||||||

| District of Columbia | Federal district | US-DC | DC | 11 | DC | DC | D.C. | D.C. | Dis. Col.[2] | |||||

| Florida | State | US-FL | FL | 12 | FL | FL | Fla. | Fla. | ||||||

| Georgia | State | US-GA | GA | 13 | GA | GA | Ga. | Ga. | Geo.[1] | |||||

| Hawaii | State | US-HI | HI | 15 | HI | HA | Hawaii | Hawaii | Hi.[1] | |||||

| Idaho | State | US-ID | ID | 16 | ID | ID | Idaho | Idaho | Ida.[1] | |||||

| Illinois | State | US-IL | IL | 17 | IL | IL | Ill. | Ill. | ||||||

| Indiana | State | US-IN | IN | 18 | IN | IN | Ind. | Ind. | ||||||

| Iowa | State | US-IA | IA | 19 | IA | IA | Iowa | Iowa | Ioa.[a] | |||||

| Kansas | State | US-KS | KS | 20 | KS | KA | Kans. | Kan. | Ka. | |||||

| Kentucky | State | US-KY | KY | 21 | KY | KY | Ky. | Ky. | Ken., Kent.[b] | |||||

| Louisiana | State | US-LA | LA | 22 | LA | LA | La. | La. | ||||||

| Maine | State | US-ME | ME | 23 | ME | ME | Maine | Maine | ||||||

| Maryland | State | US-MD | MD | 24 | MD | MD | Md. | Md. | Mar., Mary. | |||||

| Massachusetts | State | US-MA | MA | 25 | MA | MS | Mass. | Mass. | ||||||

| Michigan | State | US-MI | MI | 26 | MI | MC | Mich. | Mich. | ||||||

| Minnesota | State | US-MN | MN | 27 | MN | MN | Minn. | Minn. | ||||||

| Mississippi | State | US-MS | MS | 28 | MS | MI | Miss. | Miss. | ||||||

| Missouri | State | US-MO | MO | 29 | MO | MO | Mo. | Mo. | ||||||

| Montana | State | US-MT | MT | 30 | MT | MT | Mont. | Mont. | ||||||

| Nebraska | State | US-NE | NE | 31 | NE | NB | Nebr. | Neb. | ||||||

| Nevada | State | US-NV | NV | 32 | NV | NV | Nev. | Nev. | ||||||

| New Hampshire | State | US-NH | NH | 33 | NH | NH | N.H. | N.H. | ||||||

| New Jersey | State | US-NJ | NJ | 34 | NJ | NJ | N.J. | N.J. | N. Jersey[2] | |||||

| New Mexico | State | US-NM | NM | 35 | NM | NM | N. Mex. | N.M. | New M., New Mex. | |||||

| New York | State | US-NY | NY | 36 | NY | NY | N.Y. | N.Y. | N. York[2] | |||||

| North Carolina | State | US-NC | NC | 37 | NC | NC | N.C. | N.C. | N. Car. | |||||

| North Dakota | State | US-ND | ND | 38 | ND | ND | N. Dak. | N.D. | ||||||

| Ohio | State | US-OH | OH | 39 | OH | OH | Ohio | Ohio | O.,[3] Oh.[1] | |||||

| Oklahoma | State | US-OK | OK | 40 | OK | OK | Okla. | Okla. | ||||||

| Oregon | State | US-OR | OR | 41 | OR | OR | Oreg. | Ore. | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | State | US-PA | PA | 42 | PA | PA | Pa. | Pa. | Penn.,[1] Penna.[4] | |||||

| Rhode Island | State | US-RI | RI | 44 | RI | RI | R.I. | R.I. | R.I. & P.P. | |||||

| South Carolina | State | US-SC | SC | 45 | SC | SC | S.C. | S.C. | S. Car. | |||||

| South Dakota | State | US-SD | SD | 46 | SD | SD | S. Dak. | S.D. | SoDak | |||||

| Tennessee | State | US-TN | TN | 47 | TN | TN | Tenn. | Tenn. | ||||||

| Texas | State | US-TX | TX | 48 | TX | TX | Tex. | Texas | ||||||

| Utah | State | US-UT | UT | 49 | UT | UT | Utah | Utah | Ut.[1] | |||||

| Vermont | State | US-VT | VT | 50 | VT | VT | Vt. | Vt. | Verm.[5] | |||||

| Virginia | State | US-VA | VA | 51 | VA | VA | Va. | Va. | Virg. | |||||

| Washington | State | US-WA | WA | 53 | WA | WN | Wash. | Wash. | Wn.[6] | |||||

| West Virginia | State | US-WV | WV | 54 | WV | WV | W. Va. | W.Va. | W.V., W. Virg. | |||||

| Wisconsin | State | US-WI | WI | 55 | WI | WS | Wis. | Wis. | Wisc. | |||||

| Wyoming | State | US-WY | WY | 56 | WY | WY | Wyo. | Wyo. | ||||||

| American Samoa | Insular area (Territory) | AS ASM 016 US-AS |

AS | 60 | AS | AS | A.S. | |||||||

| Guam | Insular area (Territory) | GU GUM 316 US-GU |

GU | 66 | GU | GU | Guam | |||||||

| Northern Mariana Islands | Insular area (Commonwealth) | MP MNP 580 US-MP |

MP | 69 | MP | CM | M.P. | CNMI[7] | ||||||

| Puerto Rico | Insular area (Commonwealth) | PR PRI 630 US-PR |

PR | 72 | PR | PR | P.R. | |||||||

| U.S. Virgin Islands | Insular area (Territory) | VI VIR 850 US-VI |

VI | 78 | VI | VI | V.I. | U.S.V.I. | ||||||

| U.S. Minor Outlying Islands | Insular areas | UM UMI 581 US-UM |

UM | 74 | UM | |||||||||

| Baker Island | Island | UM-81 | 81 | XB[8] | ||||||||||

| Howland Island | Island | UM-84 | 84 | XH[8] | ||||||||||

| Jarvis Island | Island | UM-86 | 86 | XQ[8] | ||||||||||

| Johnston Atoll | Atoll | UM-67 | 67 | XU[8] | ||||||||||

| Kingman Reef | Atoll | UM-89 | 89 | XM[8] | ||||||||||

| Midway Islands | Atoll | UM-71 | 71 | QM[8] | ||||||||||

| Navassa Island | Island | UM-76 | 76 | XV[8] | ||||||||||

| Palmyra Atoll[c] | Atoll[c] | UM-95 | 95 | XL[8] | ||||||||||

| Wake Island | Atoll | UM-79 | 79 | QW[8] | ||||||||||

| Marshall Islands | Freely associated state | MH MHL 584 |

MH | 68 | MH | |||||||||

| Micronesia | Freely associated state | FM FSM 583 |

FM | 64 | FM | |||||||||

| Palau | Freely associated state | PW PLW 585 |

PW | 70 | PW | |||||||||

| U.S. Armed Forces – Americas[d] | US military mail code | AA | ||||||||||||

| U.S. Armed Forces – Europe[e] | US military mail code | AE | ||||||||||||

| U.S. Armed Forces – Pacific[f] | US military mail code | AP | ||||||||||||

| Nebraska | Obsolete postal code[g] | NB | ||||||||||||

| Northern Mariana Islands | Obsolete postal code[h] | CM | ||||||||||||

| Panama Canal Zone | Obsolete postal code | PZ PCZ 594 |

CZ | |||||||||||

| Philippine Islands | Obsolete postal code | PH PHL 608[9] |

PI | |||||||||||

| Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands | Obsolete postal code | PC PCI 582 |

TT |

History[edit]

As early as October 1831, the United States Post Office recognized common abbreviations for states and territories. However, they accepted these abbreviations only because of their popularity, preferring that patrons spell names out in full to avoid confusion.[3]

The traditional abbreviations for U.S. states and territories, widely used in mailing addresses prior to the introduction of two-letter U.S. postal abbreviations, are still commonly used for other purposes (such as legal citation), and are still recognized (though discouraged) by the Postal Service.[10]

Modern two-letter abbreviated codes for the states and territories originated in October 1963, with the issuance of Publication 59: Abbreviations for Use with ZIP Code, three months after the Post Office introduced ZIP codes in July 1963. The purpose, rather than to standardize state abbreviations per se, was to make room in a line of no more than 23 characters for the city, the state, and the ZIP code.[3]

Since 1963, only one state abbreviation has changed. Originally Nebraska was «NB»; but, in November 1969, the Post Office changed it to «NE» to avoid confusion with New Brunswick in Canada.[3]

Prior to 1987, when the U.S. Secretary of Commerce approved the two-letter codes for use in government documents,[11] the United States Government Printing Office (GPO) suggested its own set of abbreviations, with some states left unabbreviated. Today, the GPO supports United States Postal Service standard.[12]

Current use of traditional abbreviations[edit]

Legal citation manuals, such as The Bluebook and The ALWD Citation Manual, typically use the «traditional abbreviations» or variants thereof.

Codes for states and territories[edit]

ISO standard 3166[edit]

ANSI standard INCITS 38:2009[edit]

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) established alphabetic and numeric codes for each state and outlying areas in ANSI standard INCITS 38:2009. ANSI standard INCITS 38:2009 replaced the Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) standards FIPS 5-2, FIPS 6-4, and FIPS 10-4. The ANSI alphabetic state code is the same as the USPS state code except for U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, which have an ANSI code «UM» but no USPS code—and U.S. Military Mail locations, which have USPS codes («AA», «AE», «AP») but no ANSI code.

Postal codes[edit]

The United States Postal Service (USPS) has established a set of uppercase abbreviations to help process mail with optical character recognition and other automated equipment.[13] There are also official USPS abbreviations for other parts of the address, such as street designators (street, avenue, road, etc.).

These two-letter codes are distinguished from traditional abbreviations such as Calif., Fla., or Tex. The Associated Press Stylebook states that in contexts other than mailing addresses, the traditional state abbreviations should be used.[14] However, the Chicago Manual of Style now recommends use of the uppercase two-letter abbreviations, with the traditional forms as an option.[15]

The postal abbreviation is the same as the ISO 3166-2 subdivision code for each of the fifty states.

These codes do not overlap with the 13 Canadian subnational postal abbreviations. The code for Nebraska changed from NB to NE in November 1969 to avoid a conflict with New Brunswick.[3] Canada likewise chose MB for Manitoba to prevent conflict with either Massachusetts (MA), Michigan (MI), Minnesota (MN), Missouri (MO), or Montana (MT).

Coast Guard vessel prefixes[edit]

The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) uses a set of two-letter prefixes for vessel numbers;[16] 39 states and the District of Columbia have the same USPS and USCG abbreviations. USCG prefixes have also been established for five outlying territories; all are the same as the USPS abbreviations except the Mariana Islands. The twelve cases where USPS and USCG abbreviations differ are listed below and marked in bold red in the table above, and do include three inland states with a small Coast Guard contingent. These twelve abbreviations were changed to avoid conflicting with the ISO 3166 two-digit country codes.

| California | Colorado | Delaware | Hawaii | Kansas | Michigan | Mississippi | Massachusetts | Nebraska | Washington | Wisconsin | Mariana Islands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USPS | CA | CO | DE | HI | KS | MI | MS | MA | NE | WA | WI | MP |

| USCG | CF | CL | DL | HA | KA | MC | MI | MS | NB | WN | WS | CM |

See also[edit]

- Australian abbreviation system

- Canadian abbreviation system

- ISO 3166-2:US

- United States Postal Service address formatting information

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Ioa.» or (more typically) «IOA» found in Iowa post office cancellations from the 1870s.

- ^ Not to be confused with Kent, England

- ^ a b The Palmyra Atoll is an unorganized incorporated territory of the United States that was previously a part of the Territory of Hawaii.

- ^ The U.S. Armed Forces – Americas include the Caribbean Sea and exclude the United States, Canada, and Greenland.

- ^ The U.S. Armed Forces – Europe include the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, Canada, Greenland, Africa, and Southwest Asia.

- ^ The U.S. Armed Forces – Pacific include the Indian Ocean, Oceania, and Asia except Southwest Asia.

- ^ Former USPS code «NB» for Nebraska is now obsolete; it was changed to NE in November 1969 to avoid confusion with New Brunswick, Canada.

- ^ Former USPS code «CM» for the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands is now obsolete; it was changed to MP in 1988 to match ISO 3166-1.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Consolidated Listing of FAA Certificated Repair Stations. U.S. Dept. of Transportation. December 9, 1970. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Navy of the United States. Washington, D.C.: [U.S.] Government Printing Office. January 1, 1863. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e USPS Postal History: State Abbreviations Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ^ Arthur, Andy. «Penna. the Abbreviation». AndyArthur.org. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Fisher, Richard S. (1857). A new and complete statistical gazetteer of the United States of America. J. H. Colton and Company. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ «search on WN». Digitum.washingtonhistory.org. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ «Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands». www.doi.gov. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Geopolitical Entities, Names, and Codes Standard». NSG Standards Registry. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ «Philippine diplomats will now use PH or PHL instead of RP». GMA News. October 28, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ «USPS Postal News, «It’s Okay to Say ‘I Don’t Know,’ So Long As You Find Out!» January 9, 2009″. About.usps.com. January 9, 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Hawes, Kristi G. (May 28, 1987). «Information Technology Laboratory». NIST. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 30th Edition [1] Accessed April 21, 2009.

- ^ United States Postal Service (June 2020). «Appendix B. Two–Letter State and Possession Abbreviations. Postal Addressing Standards». Postal Explorer. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Robbins, Sonia J. (January 4, 2004). «State Abbreviations». New York University. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009.

- ^ Harper, Russell David, ed. (2017) [1906]. «10.27 Abbreviations for US states and territories». The Chicago manual of style (17th ed.). The University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/cmos17. ISBN 9780226287058. LCCN 2017020712.

In bibliographies, tabular matter, lists, and mailing addresses, they are usually abbreviated. In all such contexts, Chicago prefers the two-letter postal codes to the conventional abbreviations.

- ^ 33 CFR 173, App. A

External links[edit]

- USPS acronyms and abbreviations

- U.S. Census Bureau

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Several sets of codes and abbreviations are used to represent the political divisions of the United States for postal addresses, data processing, general abbreviations, and other purposes.

Table[edit]

This table includes abbreviations for three independent countries related to the United States through Compacts of Free Association, and other comparable postal abbreviations, including those now obsolete.

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name and status of region | ISO | ANSI | USPS | USCG | GPO | AP | Other abbreviations |

|||||||

| United States of America | Federal state | US USA 840 |

US | 00 | U.S. | U.S. | U.S.A. | |||||||

| Alabama | State | US-AL | AL | 01 | AL | AL | Ala. | Ala. | ||||||

| Alaska | State | US-AK | AK | 02 | AK | AK | Alaska | Alaska | Ak.[1] | |||||

| Arizona | State | US-AZ | AZ | 04 | AZ | AZ | Ariz. | Ariz. | ||||||

| Arkansas | State | US-AR | AR | 05 | AR | AR | Ark. | Ark. | ||||||

| California | State | US-CA | CA | 06 | CA | CF | Calif. | Calif. | Cal. | |||||

| Colorado | State | US-CO | CO | 08 | CO | CL | Colo. | Colo. | ||||||

| Connecticut | State | US-CT | CT | 09 | CT | CT | Conn. | Conn. | ||||||

| Delaware | State | US-DE | DE | 10 | DE | DL | Del. | Del. | ||||||

| District of Columbia | Federal district | US-DC | DC | 11 | DC | DC | D.C. | D.C. | Dis. Col.[2] | |||||

| Florida | State | US-FL | FL | 12 | FL | FL | Fla. | Fla. | ||||||

| Georgia | State | US-GA | GA | 13 | GA | GA | Ga. | Ga. | Geo.[1] | |||||

| Hawaii | State | US-HI | HI | 15 | HI | HA | Hawaii | Hawaii | Hi.[1] | |||||

| Idaho | State | US-ID | ID | 16 | ID | ID | Idaho | Idaho | Ida.[1] | |||||

| Illinois | State | US-IL | IL | 17 | IL | IL | Ill. | Ill. | ||||||

| Indiana | State | US-IN | IN | 18 | IN | IN | Ind. | Ind. | ||||||

| Iowa | State | US-IA | IA | 19 | IA | IA | Iowa | Iowa | Ioa.[a] | |||||

| Kansas | State | US-KS | KS | 20 | KS | KA | Kans. | Kan. | Ka. | |||||

| Kentucky | State | US-KY | KY | 21 | KY | KY | Ky. | Ky. | Ken., Kent.[b] | |||||

| Louisiana | State | US-LA | LA | 22 | LA | LA | La. | La. | ||||||

| Maine | State | US-ME | ME | 23 | ME | ME | Maine | Maine | ||||||

| Maryland | State | US-MD | MD | 24 | MD | MD | Md. | Md. | Mar., Mary. | |||||

| Massachusetts | State | US-MA | MA | 25 | MA | MS | Mass. | Mass. | ||||||

| Michigan | State | US-MI | MI | 26 | MI | MC | Mich. | Mich. | ||||||

| Minnesota | State | US-MN | MN | 27 | MN | MN | Minn. | Minn. | ||||||

| Mississippi | State | US-MS | MS | 28 | MS | MI | Miss. | Miss. | ||||||

| Missouri | State | US-MO | MO | 29 | MO | MO | Mo. | Mo. | ||||||

| Montana | State | US-MT | MT | 30 | MT | MT | Mont. | Mont. | ||||||

| Nebraska | State | US-NE | NE | 31 | NE | NB | Nebr. | Neb. | ||||||

| Nevada | State | US-NV | NV | 32 | NV | NV | Nev. | Nev. | ||||||

| New Hampshire | State | US-NH | NH | 33 | NH | NH | N.H. | N.H. | ||||||

| New Jersey | State | US-NJ | NJ | 34 | NJ | NJ | N.J. | N.J. | N. Jersey[2] | |||||

| New Mexico | State | US-NM | NM | 35 | NM | NM | N. Mex. | N.M. | New M., New Mex. | |||||

| New York | State | US-NY | NY | 36 | NY | NY | N.Y. | N.Y. | N. York[2] | |||||

| North Carolina | State | US-NC | NC | 37 | NC | NC | N.C. | N.C. | N. Car. | |||||

| North Dakota | State | US-ND | ND | 38 | ND | ND | N. Dak. | N.D. | ||||||

| Ohio | State | US-OH | OH | 39 | OH | OH | Ohio | Ohio | O.,[3] Oh.[1] | |||||

| Oklahoma | State | US-OK | OK | 40 | OK | OK | Okla. | Okla. | ||||||

| Oregon | State | US-OR | OR | 41 | OR | OR | Oreg. | Ore. | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | State | US-PA | PA | 42 | PA | PA | Pa. | Pa. | Penn.,[1] Penna.[4] | |||||

| Rhode Island | State | US-RI | RI | 44 | RI | RI | R.I. | R.I. | R.I. & P.P. | |||||

| South Carolina | State | US-SC | SC | 45 | SC | SC | S.C. | S.C. | S. Car. | |||||

| South Dakota | State | US-SD | SD | 46 | SD | SD | S. Dak. | S.D. | SoDak | |||||

| Tennessee | State | US-TN | TN | 47 | TN | TN | Tenn. | Tenn. | ||||||

| Texas | State | US-TX | TX | 48 | TX | TX | Tex. | Texas | ||||||

| Utah | State | US-UT | UT | 49 | UT | UT | Utah | Utah | Ut.[1] | |||||

| Vermont | State | US-VT | VT | 50 | VT | VT | Vt. | Vt. | Verm.[5] | |||||

| Virginia | State | US-VA | VA | 51 | VA | VA | Va. | Va. | Virg. | |||||

| Washington | State | US-WA | WA | 53 | WA | WN | Wash. | Wash. | Wn.[6] | |||||

| West Virginia | State | US-WV | WV | 54 | WV | WV | W. Va. | W.Va. | W.V., W. Virg. | |||||

| Wisconsin | State | US-WI | WI | 55 | WI | WS | Wis. | Wis. | Wisc. | |||||

| Wyoming | State | US-WY | WY | 56 | WY | WY | Wyo. | Wyo. | ||||||

| American Samoa | Insular area (Territory) | AS ASM 016 US-AS |

AS | 60 | AS | AS | A.S. | |||||||

| Guam | Insular area (Territory) | GU GUM 316 US-GU |

GU | 66 | GU | GU | Guam | |||||||

| Northern Mariana Islands | Insular area (Commonwealth) | MP MNP 580 US-MP |

MP | 69 | MP | CM | M.P. | CNMI[7] | ||||||

| Puerto Rico | Insular area (Commonwealth) | PR PRI 630 US-PR |

PR | 72 | PR | PR | P.R. | |||||||

| U.S. Virgin Islands | Insular area (Territory) | VI VIR 850 US-VI |

VI | 78 | VI | VI | V.I. | U.S.V.I. | ||||||

| U.S. Minor Outlying Islands | Insular areas | UM UMI 581 US-UM |

UM | 74 | UM | |||||||||

| Baker Island | Island | UM-81 | 81 | XB[8] | ||||||||||

| Howland Island | Island | UM-84 | 84 | XH[8] | ||||||||||

| Jarvis Island | Island | UM-86 | 86 | XQ[8] | ||||||||||

| Johnston Atoll | Atoll | UM-67 | 67 | XU[8] | ||||||||||

| Kingman Reef | Atoll | UM-89 | 89 | XM[8] | ||||||||||

| Midway Islands | Atoll | UM-71 | 71 | QM[8] | ||||||||||

| Navassa Island | Island | UM-76 | 76 | XV[8] | ||||||||||

| Palmyra Atoll[c] | Atoll[c] | UM-95 | 95 | XL[8] | ||||||||||

| Wake Island | Atoll | UM-79 | 79 | QW[8] | ||||||||||

| Marshall Islands | Freely associated state | MH MHL 584 |

MH | 68 | MH | |||||||||

| Micronesia | Freely associated state | FM FSM 583 |

FM | 64 | FM | |||||||||

| Palau | Freely associated state | PW PLW 585 |

PW | 70 | PW | |||||||||

| U.S. Armed Forces – Americas[d] | US military mail code | AA | ||||||||||||

| U.S. Armed Forces – Europe[e] | US military mail code | AE | ||||||||||||

| U.S. Armed Forces – Pacific[f] | US military mail code | AP | ||||||||||||

| Nebraska | Obsolete postal code[g] | NB | ||||||||||||

| Northern Mariana Islands | Obsolete postal code[h] | CM | ||||||||||||

| Panama Canal Zone | Obsolete postal code | PZ PCZ 594 |

CZ | |||||||||||

| Philippine Islands | Obsolete postal code | PH PHL 608[9] |

PI | |||||||||||

| Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands | Obsolete postal code | PC PCI 582 |

TT |

History[edit]

As early as October 1831, the United States Post Office recognized common abbreviations for states and territories. However, they accepted these abbreviations only because of their popularity, preferring that patrons spell names out in full to avoid confusion.[3]

The traditional abbreviations for U.S. states and territories, widely used in mailing addresses prior to the introduction of two-letter U.S. postal abbreviations, are still commonly used for other purposes (such as legal citation), and are still recognized (though discouraged) by the Postal Service.[10]

Modern two-letter abbreviated codes for the states and territories originated in October 1963, with the issuance of Publication 59: Abbreviations for Use with ZIP Code, three months after the Post Office introduced ZIP codes in July 1963. The purpose, rather than to standardize state abbreviations per se, was to make room in a line of no more than 23 characters for the city, the state, and the ZIP code.[3]

Since 1963, only one state abbreviation has changed. Originally Nebraska was «NB»; but, in November 1969, the Post Office changed it to «NE» to avoid confusion with New Brunswick in Canada.[3]

Prior to 1987, when the U.S. Secretary of Commerce approved the two-letter codes for use in government documents,[11] the United States Government Printing Office (GPO) suggested its own set of abbreviations, with some states left unabbreviated. Today, the GPO supports United States Postal Service standard.[12]

Current use of traditional abbreviations[edit]

Legal citation manuals, such as The Bluebook and The ALWD Citation Manual, typically use the «traditional abbreviations» or variants thereof.

Codes for states and territories[edit]

ISO standard 3166[edit]

ANSI standard INCITS 38:2009[edit]

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) established alphabetic and numeric codes for each state and outlying areas in ANSI standard INCITS 38:2009. ANSI standard INCITS 38:2009 replaced the Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) standards FIPS 5-2, FIPS 6-4, and FIPS 10-4. The ANSI alphabetic state code is the same as the USPS state code except for U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, which have an ANSI code «UM» but no USPS code—and U.S. Military Mail locations, which have USPS codes («AA», «AE», «AP») but no ANSI code.

Postal codes[edit]

The United States Postal Service (USPS) has established a set of uppercase abbreviations to help process mail with optical character recognition and other automated equipment.[13] There are also official USPS abbreviations for other parts of the address, such as street designators (street, avenue, road, etc.).

These two-letter codes are distinguished from traditional abbreviations such as Calif., Fla., or Tex. The Associated Press Stylebook states that in contexts other than mailing addresses, the traditional state abbreviations should be used.[14] However, the Chicago Manual of Style now recommends use of the uppercase two-letter abbreviations, with the traditional forms as an option.[15]

The postal abbreviation is the same as the ISO 3166-2 subdivision code for each of the fifty states.

These codes do not overlap with the 13 Canadian subnational postal abbreviations. The code for Nebraska changed from NB to NE in November 1969 to avoid a conflict with New Brunswick.[3] Canada likewise chose MB for Manitoba to prevent conflict with either Massachusetts (MA), Michigan (MI), Minnesota (MN), Missouri (MO), or Montana (MT).

Coast Guard vessel prefixes[edit]

The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) uses a set of two-letter prefixes for vessel numbers;[16] 39 states and the District of Columbia have the same USPS and USCG abbreviations. USCG prefixes have also been established for five outlying territories; all are the same as the USPS abbreviations except the Mariana Islands. The twelve cases where USPS and USCG abbreviations differ are listed below and marked in bold red in the table above, and do include three inland states with a small Coast Guard contingent. These twelve abbreviations were changed to avoid conflicting with the ISO 3166 two-digit country codes.

| California | Colorado | Delaware | Hawaii | Kansas | Michigan | Mississippi | Massachusetts | Nebraska | Washington | Wisconsin | Mariana Islands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USPS | CA | CO | DE | HI | KS | MI | MS | MA | NE | WA | WI | MP |

| USCG | CF | CL | DL | HA | KA | MC | MI | MS | NB | WN | WS | CM |

See also[edit]

- Australian abbreviation system

- Canadian abbreviation system

- ISO 3166-2:US

- United States Postal Service address formatting information

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Ioa.» or (more typically) «IOA» found in Iowa post office cancellations from the 1870s.

- ^ Not to be confused with Kent, England

- ^ a b The Palmyra Atoll is an unorganized incorporated territory of the United States that was previously a part of the Territory of Hawaii.

- ^ The U.S. Armed Forces – Americas include the Caribbean Sea and exclude the United States, Canada, and Greenland.

- ^ The U.S. Armed Forces – Europe include the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, Canada, Greenland, Africa, and Southwest Asia.

- ^ The U.S. Armed Forces – Pacific include the Indian Ocean, Oceania, and Asia except Southwest Asia.

- ^ Former USPS code «NB» for Nebraska is now obsolete; it was changed to NE in November 1969 to avoid confusion with New Brunswick, Canada.

- ^ Former USPS code «CM» for the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands is now obsolete; it was changed to MP in 1988 to match ISO 3166-1.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Consolidated Listing of FAA Certificated Repair Stations. U.S. Dept. of Transportation. December 9, 1970. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Navy of the United States. Washington, D.C.: [U.S.] Government Printing Office. January 1, 1863. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e USPS Postal History: State Abbreviations Accessed November 7, 2011.

- ^ Arthur, Andy. «Penna. the Abbreviation». AndyArthur.org. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Fisher, Richard S. (1857). A new and complete statistical gazetteer of the United States of America. J. H. Colton and Company. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ «search on WN». Digitum.washingtonhistory.org. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ «Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands». www.doi.gov. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Geopolitical Entities, Names, and Codes Standard». NSG Standards Registry. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ «Philippine diplomats will now use PH or PHL instead of RP». GMA News. October 28, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ «USPS Postal News, «It’s Okay to Say ‘I Don’t Know,’ So Long As You Find Out!» January 9, 2009″. About.usps.com. January 9, 2009. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Hawes, Kristi G. (May 28, 1987). «Information Technology Laboratory». NIST. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 30th Edition [1] Accessed April 21, 2009.

- ^ United States Postal Service (June 2020). «Appendix B. Two–Letter State and Possession Abbreviations. Postal Addressing Standards». Postal Explorer. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Robbins, Sonia J. (January 4, 2004). «State Abbreviations». New York University. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009.

- ^ Harper, Russell David, ed. (2017) [1906]. «10.27 Abbreviations for US states and territories». The Chicago manual of style (17th ed.). The University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/cmos17. ISBN 9780226287058. LCCN 2017020712.

In bibliographies, tabular matter, lists, and mailing addresses, they are usually abbreviated. In all such contexts, Chicago prefers the two-letter postal codes to the conventional abbreviations.

- ^ 33 CFR 173, App. A

External links[edit]

- USPS acronyms and abbreviations

- U.S. Census Bureau

|

Los Angeles |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

| City of Los Angeles | |

|

The skyline of Downtown Los Angeles Hollywood Sign Griffith Observatory Echo Park Los Angeles City Hall Theme Building Venice Beach |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nickname(s):

L.A., City of Angels,[1] The Entertainment Capital of the World,[1] La-la-land, Tinseltown[1] |

|

|

OpenStreetMap |

|

|

Los Angeles Location within California Los Angeles Location within the United States Los Angeles Location within North America |

|

| Coordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′W / 34.050°N 118.250°WCoordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′W / 34.050°N 118.250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Region | Southern California |

| CSA | Los Angeles-Long Beach |

| MSA | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim |

| Pueblo | September 4, 1781[2] |

| City status | May 23, 1835[3] |

| Incorporated | April 4, 1850[4] |

| Named for | Our Lady, Queen of the Angels |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor–council[5] |

| • Body | Los Angeles City Council |

| • Mayor | Karen Bass (D) |

| • City Attorney | Hydee Feldstein Soto (D) |

| • City Controller | Kenneth Mejia (D) |

| Area

[6] |

|

| • Total | 501.55 sq mi (1,299.01 km2) |

| • Land | 469.49 sq mi (1,215.97 km2) |

| • Water | 32.06 sq mi (83.04 km2) |

| Elevation | 305 ft (93 m) |

| Highest elevation | 5,075 ft (1,576 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population

(2020)[7] |

|

| • Total | 3,898,747 |

| • Estimate

(2021)[7] |

3,849,297 |

| • Rank | 2nd in the United States 1st in California |

| • Density | 8,304.22/sq mi (3,206.29/km2) |

| • Urban

[8] |

12,237,376 (US: 2nd) |

| • Urban density | 7,476.3/sq mi (2,886.6/km2) |

| • Metro

[9] |

13,200,998 (US: 2nd) |

| Demonym(s) | Angeleno, Angelino, Angeleño[10][11] |

| Time zone | UTC–08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

List

|

| Area codes | 213/323, 310/424, 747/818 |

| FIPS code | 06-44000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1662328, 2410877 |

| Website | lacity.gov |

Los Angeles ( lawss AN-jəl-əs;[a] Spanish: Los Ángeles [los ˈaŋxeles], lit. ‘The Angels’), often referred to by its initials L.A.,[14] is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Southern California. Los Angeles is the largest city in the state of California, the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, and one of the world’s most populous megacities. With a population of roughly 3.9 million residents within the city limits as of 2020,[7] Los Angeles is known for its Mediterranean climate, ethnic and cultural diversity, being the home of the Hollywood film industry, and its sprawling metropolitan area. The majority of the city proper lies in a basin in Southern California adjacent to the Pacific Ocean in the west and extending partly through the Santa Monica Mountains and north into the San Fernando Valley, with the city bordering the San Gabriel Valley to its east. It covers about 469 square miles (1,210 km2),[6] and is the county seat of Los Angeles County, which is the most populous county in the United States with an estimated 9.86 million residents as of 2022.[15]

The area that became Los Angeles was originally inhabited by the indigenous Tongva people and later claimed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo for Spain in 1542. The city was founded on September 4, 1781, under Spanish governor Felipe de Neve, on the village of Yaanga.[16] It became a part of Mexico in 1821 following the Mexican War of Independence. In 1848, at the end of the Mexican–American War, Los Angeles and the rest of California were purchased as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and thus became part of the United States. Los Angeles was incorporated as a municipality on April 4, 1850, five months before California achieved statehood. The discovery of oil in the 1890s brought rapid growth to the city.[17] The city was further expanded with the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, which delivers water from Eastern California.

Los Angeles has a diverse economy with a broad range of industries. It has the busiest container port in the Americas.[18][19] In 2018, the Los Angeles metropolitan area had a gross metropolitan product of over $1.0 trillion,[20] making it the city with the third-largest GDP in the world, after New York City and Tokyo. Los Angeles hosted the 1932 and 1984 Summer Olympics and will host the 2028 Summer Olympics. More recently, statewide droughts in California have strained both the city’s and Los Angeles County’s water security.[21][22]

Pronunciation of the name

The local English pronunciation of the name of the city has varied over time. A 1953 article in the journal of the American Name Society asserts that the pronunciation lawss AN-jəl-əs was established following the 1850 incorporation of the city and that since the 1880s the pronunciation lohss ANG-gəl-əs emerged out of a trend in California to give places Spanish, or Spanish-sounding, names and pronunciations.[23] In 1908, librarian Charles Fletcher Lummis, who argued for the name’s pronunciation with a hard g (),[24][25] reported that there were at least 12 pronunciation variants.[26] In the early 1900s, the Los Angeles Times advocated for pronouncing it Loce AHNG-hayl-ais (), approximating Spanish [los ˈaŋxeles], by printing the respelling under its masthead for several years.[27] This did not find favor.[28]

Since the 1930s, has been most common.[29] In 1934, the United States Board on Geographic Names decreed that this pronunciation be used.[27] This was also endorsed in 1952 by a «jury» appointed by Mayor Fletcher Bowron to devise an official pronunciation.[23][27]

History

Pre-colonial history

The Los Angeles coastal area was settled by the Tongva (Gabrieleño) and Chumash tribes. Los Angeles was founded on the village of iyáanga’ or Yaanga (written «Yang-na» by the Spanish), meaning «poison oak place».[30][31][16]

Maritime explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo claimed the area of southern California for the Spanish Empire in 1542 while on an official military exploring expedition moving northward along the Pacific coast from earlier colonizing bases of New Spain in Central and South America.[32] Gaspar de Portolà and Franciscan missionary Juan Crespí reached the present site of Los Angeles on August 2, 1769.[33]

Spanish rule

In 1771, Franciscan friar Junípero Serra directed the building of the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, the first mission in the area.[34] On September 4, 1781, a group of forty-four settlers known as «Los Pobladores» founded the pueblo (town) they called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, ‘The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels’.[35] The original name of the settlement is disputed; the Guinness Book of World Records rendered it as «El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula»;[36] other sources have shortened or alternate versions of the longer name.[37] The present-day city has the largest Roman Catholic archdiocese in the United States. Two-thirds of the Mexican or (New Spain) settlers were mestizo or mulatto, a mixture of African, indigenous and European ancestry.[38] The settlement remained a small ranch town for decades, but by 1820, the population had increased to about 650 residents.[39] Today, the pueblo is commemorated in the historic district of Los Angeles Pueblo Plaza and Olvera Street, the oldest part of Los Angeles.[40]

Mexican rule

New Spain achieved its independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821, and the pueblo now existed within the new Mexican Republic. During Mexican rule, Governor Pío Pico made Los Angeles, Alta California’s regional capital.[41] By this time, the new republic introduced more secularization acts within the Los Angeles region.[42] In 1846, during the wider Mexican-American war, marines from the United States occupied the pueblo. This resulted in the siege of Los Angeles where 150 Mexican militias fought the occupiers which eventually surrendered.[43]

1847 to present

Hill Street looking north from 6th Street. Viewable are Central Park (today’s Pershing Square) on the lower left, Hotel Portsmouth on the lower right, and Hill Street tunnel at the end of the street, circa 1913

Mexican rule ended during the Mexican–American War: Americans took control from the Californios after a series of battles, culminating with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847.[44]

Railroads arrived with the completion of the transcontinental Southern Pacific line from New Orleans to Los Angeles in 1876 and the Santa Fe Railroad in 1885.[45] Petroleum was discovered in the city and surrounding area in 1892, and by 1923, the discoveries had helped California become the country’s largest oil producer, accounting for about one-quarter of the world’s petroleum output.[46]

By 1900, the population had grown to more than 102,000,[47] putting pressure on the city’s water supply.[48] The completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, under the supervision of William Mulholland, ensured the continued growth of the city.[49] Because of clauses in the city’s charter that prevented the City of Los Angeles from selling or providing water from the aqueduct to any area outside its borders, many adjacent cities and communities felt compelled to join Los Angeles.[50][51][52]

Los Angeles created the first municipal zoning ordinance in the United States. On September 14, 1908, the Los Angeles City Council promulgated residential and industrial land use zones. The new ordinance established three residential zones of a single type, where industrial uses were prohibited. The proscriptions included barns, lumber yards, and any industrial land use employing machine-powered equipment. These laws were enforced against industrial properties after the fact. These prohibitions were in addition to existing activities that were already regulated as nuisances. These included explosives warehousing, gas works, oil drilling, slaughterhouses, and tanneries. Los Angeles City Council also designated seven industrial zones within the city. However, between 1908 and 1915, the Los Angeles City Council created various exceptions to the broad proscriptions that applied to these three residential zones, and as a consequence, some industrial uses emerged within them. There are two differences between the 1908 Residence District Ordinance and later zoning laws in the United States. First, the 1908 laws did not establish a comprehensive zoning map as the 1916 New York City Zoning Ordinance did. Second, the residential zones did not distinguish types of housing; they treated apartments, hotels, and detached-single-family housing equally.[53]

In 1910, Hollywood merged into Los Angeles, with 10 movie companies already operating in the city at the time. By 1921, more than 80 percent of the world’s film industry was concentrated in L.A.[54] The money generated by the industry kept the city insulated from much of the economic loss suffered by the rest of the country during the Great Depression.[55]

By 1930, the population surpassed one million.[56] In 1932, the city hosted the Summer Olympics.

During World War II Los Angeles was a major center of wartime manufacturing, such as shipbuilding and aircraft. Calship built hundreds of Liberty Ships and Victory Ships on Terminal Island, and the Los Angeles area was the headquarters of six of the country’s major aircraft manufacturers (Douglas Aircraft Company, Hughes Aircraft, Lockheed, North American Aviation, Northrop Corporation, and Vultee). During the war, more aircraft were produced in one year than in all the pre-war years since the Wright brothers flew the first airplane in 1903, combined. Manufacturing in Los Angeles skyrocketed, and as William S. Knudsen, of the National Defense Advisory Commission put it, «We won because we smothered the enemy in an avalanche of production, the like of which he had never seen, nor dreamed possible.»[57]

After the end of World War II Los Angeles grew more rapidly than ever, sprawling into the San Fernando Valley.[58] The expansion of the Interstate Highway System during the 1950s and 1960s helped propel suburban growth and signaled the demise of the city’s electrified rail system, once the world’s largest.

As a consequence of World War II, suburban growth, and population density, many amusement parks were built and operated in this area.[59] An example is Beverly Park, which was located at the corner of Beverly Boulevard and La Cienega before being closed and substituted by the Beverly Center.[60]

Racial tensions led to the Watts riots in 1965, resulting in 34 deaths and over 1,000 injuries.[61]

In 1969, California became the birthplace of the Internet, as the first ARPANET transmission was sent from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park.[62]

In 1973, Tom Bradley was elected as the city’s first African American mayor, serving for five terms until retiring in 1993. Other events in the city during the 1970s included the Symbionese Liberation Army’s South Central standoff in 1974 and the Hillside Stranglers murder cases in 1977–1978.[63]

In early 1984, the city surpassed Chicago in population, thus becoming the second largest city in the United States.

In 1984, the city hosted the Summer Olympic Games for the second time. Despite being boycotted by 14 Communist countries, the 1984 Olympics became more financially successful than any previous,[64] and the second Olympics to turn a profit; the other, according to an analysis of contemporary newspaper reports, was the 1932 Summer Olympics, also held in Los Angeles.[65]

Racial tensions erupted on April 29, 1992, with the acquittal by a Simi Valley jury of four Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers captured on videotape beating Rodney King, culminating in large-scale riots.[66][67]

In 1994, the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake shook the city, causing $12.5 billion in damage and 72 deaths.[68] The century ended with the Rampart scandal, one of the most extensive documented cases of police misconduct in American history.[69]

In 2002, Mayor James Hahn led the campaign against secession, resulting in voters defeating efforts by the San Fernando Valley and Hollywood to secede from the city.[70]

In 2022, Karen Bass became the city’s first female mayor, making Los Angeles the largest US city to have ever had a woman as mayor. [71]

Los Angeles will host the 2028 Summer Olympics and Paralympic Games, making Los Angeles the third city to host the Olympics three times.[72][73]

Geography

Topography

Aerial satellite image of Los Angeles in March 2019

The city of Los Angeles covers a total area of 502.7 square miles (1,302 km2), comprising 468.7 square miles (1,214 km2) of land and 34.0 square miles (88 km2) of water.[74] The city extends for 44 miles (71 km) north-south and for 29 miles (47 km) east-west. The perimeter of the city is 342 miles (550 km).

Los Angeles is both flat and hilly. The highest point in the city proper is Mount Lukens at 5,074 ft (1,547 m),[75][76] located at the northeastern end of the San Fernando Valley. The eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains stretches from Downtown to the Pacific Ocean and separates the Los Angeles Basin from the San Fernando Valley. Other hilly parts of Los Angeles include the Mt. Washington area north of Downtown, eastern parts such as Boyle Heights, the Crenshaw district around the Baldwin Hills, and the San Pedro district.

Surrounding the city are much higher mountains. Immediately to the north lie the San Gabriel Mountains, which is a popular recreation area for Angelenos. Its high point is Mount San Antonio, locally known as Mount Baldy, which reaches 10,064 feet (3,068 m). Further afield, the highest point in southern California is San Gorgonio Mountain, 81 miles (130 km) east of downtown Los Angeles,[77] with a height of 11,503 feet (3,506 m).

The Los Angeles River, which is largely seasonal, is the primary drainage channel. It was straightened and lined in 51 miles (82 km) of concrete by the Army Corps of Engineers to act as a flood control channel.[78] The river begins in the Canoga Park district of the city, flows east from the San Fernando Valley along the north edge of the Santa Monica Mountains, and turns south through the city center, flowing to its mouth in the Port of Long Beach at the Pacific Ocean. The smaller Ballona Creek flows into the Santa Monica Bay at Playa del Rey.

Vegetation

The city’s oldest palm tree, dating to the late 19th century, with the LA Coliseum in the background

Los Angeles is rich in native plant species partly because of its diversity of habitats, including beaches, wetlands, and mountains. The most prevalent plant communities are coastal sage scrub, chaparral shrubland, and riparian woodland.[79] Native plants include: the California poppy, matilija poppy, toyon, Ceanothus, Chamise, Coast Live Oak, sycamore, willow and Giant Wildrye. Many of these native species, such as the Los Angeles sunflower, have become so rare as to be considered endangered. Although it is not native to the area, the official tree of Los Angeles is the Coral Tree (Erythrina caffra)[80] and the official flower of Los Angeles is the Bird of Paradise (Strelitzia reginae).[81] Mexican Fan Palms, Canary Island Palms, Queen Palms, Date Palms, and California Fan Palms are common in the Los Angeles area, although only the last is native to California, though still not native to the City of Los Angeles.

Geology

Los Angeles is subject to earthquakes because of its location on the Pacific Ring of Fire. The geologic instability has produced numerous faults, which cause approximately 10,000 earthquakes annually in Southern California, though most of them are too small to be felt.[82] The strike-slip San Andreas Fault system, which sits at the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, passes through the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The segment of the fault passing through Southern California experiences a major earthquake roughly every 110 to 140 years, and seismologists have warned about the next «big one», as the last major earthquake was the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake.[83] The Los Angeles basin and metropolitan area are also at risk from blind thrust earthquakes.[84] Major earthquakes that have hit the Los Angeles area include the 1933 Long Beach, 1971 San Fernando, 1987 Whittier Narrows, and the 1994 Northridge events. All but a few are of low intensity and are not felt. The USGS has released the UCERF California earthquake forecast, which models earthquake occurrence in California. Parts of the city are also vulnerable to tsunamis; harbor areas were damaged by waves from Aleutian Islands earthquake in 1946, Valdivia earthquake in 1960, Alaska earthquake in 1964, Chile earthquake in 2010 and Japan earthquake in 2011.[85]

Cityscape

The city is divided into many different districts and neighborhoods,[86][87] some of which were incorporated cities that have merged with Los Angeles.[88] These neighborhoods were developed piecemeal, and are well-defined enough that the city has signage which marks nearly all of them.[89]

Overview

The city’s street patterns generally follow a grid plan, with uniform block lengths and occasional roads that cut across blocks. However, this is complicated by rugged terrain, which has necessitated having different grids for each of the valleys that Los Angeles covers. Major streets are designed to move large volumes of traffic through many parts of the city, many of which are extremely long; Sepulveda Boulevard is 43 miles (69 km) long, while Foothill Boulevard is over 60 miles (97 km) long, reaching as far east as San Bernardino. Drivers in Los Angeles suffer from one of the worst rush hour periods in the world, according to an annual traffic index by navigation system maker, TomTom. LA drivers spend an additional 92 hours in traffic each year. During the peak rush hour, there is 80% congestion, according to the index.[90]

Los Angeles is often characterized by the presence of low-rise buildings, in contrast to New York City. Outside of a few centers such as Downtown, Warner Center, Century City, Koreatown, Miracle Mile, Hollywood, and Westwood, skyscrapers and high-rise buildings are not common in Los Angeles. The few skyscrapers built outside of those areas often stand out above the rest of the surrounding landscape. Most construction is done in separate units, rather than wall-to-wall. That being said Downtown Los Angeles itself has many buildings over 30 stories, with fourteen over 50 stories, and two over 70 stories, the tallest of which is the Wilshire Grand Center. Also Los Angeles is increasingly becoming a city of apartments rather than single-family dwellings, especially in the dense inner city and Westside neighborhoods.[citation needed]

Climate

| Los Angeles (Downtown) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Los Angeles has a two-season Mediterranean climate of dry summer and very mild winter (Köppen Csb on the coast and most of downtown, Csa near the metropolitan region to the west), but it receives less annual precipitation than most other Mediterranean climates, so it is near the boundary of a semi-arid climate (BSh), though narrowly missing it.[92] Daytime temperatures are generally temperate all year round. In winter, they average around 68 °F (20 °C) giving it a tropical feel although it is a few degrees too cool to be a true tropical climate on average due to cool night temperatures.[93][94] Los Angeles has plenty of sunshine throughout the year, with an average of only 35 days with measurable precipitation annually.[95]

Temperatures in the coastal basin exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on a dozen or so days in the year, from one day a month in April, May, June and November to three days a month in July, August, October and to five days in September.[95] Temperatures in the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys are considerably warmer. Temperatures are subject to substantial daily swings; in inland areas the difference between the average daily low and the average daily high is over 30 °F (17 °C).[96] The average annual temperature of the sea is 63 °F (17 °C), from 58 °F (14 °C) in January to 68 °F (20 °C) in August.[97] Hours of sunshine total more than 3,000 per year, from an average of 7 hours of sunshine per day in December to an average of 12 in July.[98]

The Los Angeles area is also subject to phenomena typical of a microclimate, causing extreme variations in temperature in close physical proximity to each other. For example, the average July maximum temperature at the Santa Monica Pier is 70 °F (21 °C) whereas it is 95 °F (35 °C) in Canoga Park, 15 miles (24 km) away.[99] The city, like much of the Southern Californian coast, is subject to a late spring/early summer weather phenomenon called «June Gloom». This involves overcast or foggy skies in the morning that yield to sun by early afternoon.[100]

More recently, statewide droughts in California have further strained the city’s water security.[101] Downtown Los Angeles averages 14.67 in (373 mm) of precipitation annually, mainly occurring between November and March,[102][96] generally in the form of moderate rain showers, but sometimes as heavy rainfall during winter storms. Rainfall is usually higher in the hills and coastal slopes of the mountains because of orographic uplift. Summer days are usually rainless. Rarely, an incursion of moist air from the south or east can bring brief thunderstorms in late summer, especially to the mountains. The coast gets slightly less rainfall, while the inland and mountain areas get considerably more. Years of average rainfall are rare. The usual pattern is a year-to-year variability, with a short string of dry years of 5–10 in (130–250 mm) rainfall, followed by one or two wet years with more than 20 in (510 mm).[96] Wet years are usually associated with warm water El Niño conditions in the Pacific, dry years with cooler water La Niña episodes. A series of rainy days can bring floods to the lowlands and mudslides to the hills, especially after wildfires have denuded the slopes.

Both freezing temperatures and snowfall are extremely rare in the city basin and along the coast, with the last occurrence of a 32 °F (0 °C) reading at the downtown station being January 29, 1979;[96] freezing temperatures occur nearly every year in valley locations while the mountains within city limits typically receive snowfall every winter. The greatest snowfall recorded in downtown Los Angeles was 2.0 inches (5 cm) on January 15, 1932.[96][103] While the most recent snowfall occurred in February 2019, the first snowfall since 1962,[104][105] with snow falling in areas adjacent to Los Angeles as recently as January 2021.[106] At the official downtown station, the highest recorded temperature is 113 °F (45 °C) on September 27, 2010,[96][107] while the lowest is 28 °F (−2 °C),[96] on January 4, 1949.[96] Within the City of Los Angeles, the highest temperature ever officially recorded is 121 °F (49 °C), on September 6, 2020, at the weather station at Pierce College in the San Fernando Valley neighborhood of Woodland Hills.[108] During autumn and winter, Santa Ana winds sometimes bring much warmer and drier conditions to Los Angeles, and raise wildfire risk.

Climate data for Los Angeles (USC, Downtown), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1877–present |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 95 (35) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

112 (44) |

109 (43) |

106 (41) |

113 (45) |

108 (42) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 83.0 (28.3) |

82.8 (28.2) |

85.8 (29.9) |

90.1 (32.3) |

88.9 (31.6) |

89.1 (31.7) |

93.5 (34.2) |

95.2 (35.1) |

99.4 (37.4) |

95.7 (35.4) |

88.9 (31.6) |

81.0 (27.2) |

101.5 (38.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 68.0 (20.0) |

68.0 (20.0) |

69.9 (21.1) |

72.4 (22.4) |

73.7 (23.2) |

77.2 (25.1) |

82.0 (27.8) |

84.0 (28.9) |

83.0 (28.3) |

78.6 (25.9) |

72.9 (22.7) |

67.4 (19.7) |

74.8 (23.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 58.4 (14.7) |

59.0 (15.0) |

61.1 (16.2) |

63.6 (17.6) |

65.9 (18.8) |

69.3 (20.7) |

73.3 (22.9) |

74.7 (23.7) |

73.6 (23.1) |

69.3 (20.7) |

63.0 (17.2) |

57.8 (14.3) |

65.8 (18.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 48.9 (9.4) |

50.0 (10.0) |

52.4 (11.3) |

54.8 (12.7) |

58.1 (14.5) |

61.4 (16.3) |

64.7 (18.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

64.2 (17.9) |

59.9 (15.5) |

53.1 (11.7) |

48.2 (9.0) |

56.8 (13.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) |

42.9 (6.1) |

45.4 (7.4) |

48.9 (9.4) |

53.5 (11.9) |

57.4 (14.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

61.7 (16.5) |

59.1 (15.1) |

53.7 (12.1) |

45.4 (7.4) |

40.5 (4.7) |

39.2 (4.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 28 (−2) |

28 (−2) |

31 (−1) |

36 (2) |

40 (4) |

46 (8) |

49 (9) |

49 (9) |

44 (7) |

40 (4) |

34 (1) |

30 (−1) |

28 (−2) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.29 (84) |

3.64 (92) |

2.23 (57) |

0.69 (18) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.09 (2.3) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.58 (15) |

0.78 (20) |

2.48 (63) |

14.25 (362) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 34.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 225.3 | 222.5 | 267.0 | 303.5 | 276.2 | 275.8 | 364.1 | 349.5 | 278.5 | 255.1 | 217.3 | 219.4 | 3,254.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 71 | 72 | 72 | 78 | 64 | 64 | 83 | 84 | 75 | 73 | 70 | 71 | 73 |

| Source: NOAA (sun 1961–1977)[109][91][110][111] |

Climate data for Los Angeles (LAX), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1944–present |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

110 (43) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

94 (34) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 81.2 (27.3) |

80.1 (26.7) |

80.6 (27.0) |

83.1 (28.4) |

80.6 (27.0) |

79.8 (26.6) |

83.7 (28.7) |

86.0 (30.0) |

90.7 (32.6) |

90.9 (32.7) |

87.2 (30.7) |

78.8 (26.0) |

95.5 (35.3) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 66.3 (19.1) |

65.6 (18.7) |

66.1 (18.9) |

68.1 (20.1) |

69.5 (20.8) |

72.0 (22.2) |

75.1 (23.9) |

76.7 (24.8) |

76.5 (24.7) |

74.4 (23.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

66.1 (18.9) |

70.6 (21.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 57.9 (14.4) |

57.9 (14.4) |

59.1 (15.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

63.6 (17.6) |

66.4 (19.1) |

69.6 (20.9) |

70.7 (21.5) |

70.1 (21.2) |

67.1 (19.5) |

62.3 (16.8) |

57.6 (14.2) |

63.6 (17.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 49.4 (9.7) |

50.1 (10.1) |

52.2 (11.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

57.6 (14.2) |

60.9 (16.1) |

64.0 (17.8) |

64.8 (18.2) |

63.7 (17.6) |

59.8 (15.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

49.1 (9.5) |

56.6 (13.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 41.8 (5.4) |

42.9 (6.1) |

45.3 (7.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

52.7 (11.5) |

56.7 (13.7) |

60.2 (15.7) |

61.0 (16.1) |

58.7 (14.8) |

53.2 (11.8) |

46.1 (7.8) |

41.1 (5.1) |

39.4 (4.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

34 (1) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

45 (7) |

48 (9) |

52 (11) |

51 (11) |

47 (8) |

43 (6) |

38 (3) |

32 (0) |

27 (−3) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.86 (73) |

2.99 (76) |

1.73 (44) |

0.60 (15) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.11 (2.8) |

0.49 (12) |

0.82 (21) |

2.23 (57) |

12.23 (311) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 34.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 63.4 | 67.9 | 70.5 | 71.0 | 74.0 | 75.9 | 76.6 | 76.6 | 74.2 | 70.5 | 65.5 | 62.9 | 70.8 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) |

44.4 (6.9) |

46.6 (8.1) |

49.1 (9.5) |

52.7 (11.5) |

56.5 (13.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

61.2 (16.2) |

59.2 (15.1) |

54.1 (12.3) |

46.8 (8.2) |

41.4 (5.2) |

51.1 (10.6) |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961–1990)[109][112][113][114] |

Environmental issues

Viewable smog in Los Angeles in December 2005

| External audio |

|---|

A Gabrielino settlement in the area was called iyáangẚ (written Yang-na by the Spanish), which has been translated as «poison oak place».[30][31] Yang-na has also been translated as «the valley of smoke».[115][116] Owing to geography, heavy reliance on automobiles, and the Los Angeles/Long Beach port complex, Los Angeles suffers from air pollution in the form of smog. The Los Angeles Basin and the San Fernando Valley are susceptible to atmospheric inversion, which holds in the exhausts from road vehicles, airplanes, locomotives, shipping, manufacturing, and other sources.[117] The percentage of small particle pollution (the kind that penetrates into the lungs) coming from vehicles in the city can get as high as 55 percent.[citation needed]

The smog season lasts from approximately May to October.[118] While other large cities rely on rain to clear smog, Los Angeles gets only 15 inches (380 mm) of rain each year: pollution accumulates over many consecutive days. Issues of air quality in Los Angeles and other major cities led to the passage of early national environmental legislation, including the Clean Air Act. When the act was passed, California was unable to create a State Implementation Plan that would enable it to meet the new air quality standards, largely because of the level of pollution in Los Angeles generated by older vehicles.[119] More recently, the state of California has led the nation in working to limit pollution by mandating low-emission vehicles. Smog is expected to continue to drop in the coming years because of aggressive steps to reduce it, which include electric and hybrid cars, improvements in mass transit, and other measures.

The number of Stage 1 smog alerts in Los Angeles has declined from over 100 per year in the 1970s to almost zero in the new millennium.[120] Despite improvement, the 2006 and 2007 annual reports of the American Lung Association ranked the city as the most polluted in the country with short-term particle pollution and year-round particle pollution.[121] In 2008, the city was ranked the second most polluted and again had the highest year-round particulate pollution.[122] The city met its goal of providing 20 percent of the city’s power from renewable sources in 2010.[123] The American Lung Association’s 2013 survey ranks the metro area as having the nation’s worst smog, and fourth in both short-term and year-round pollution amounts.[124]

Los Angeles is also home to the nation’s largest urban oil field. There are more than 700 active oil wells within 1,500 feet (460 m) of homes, churches, schools and hospitals in the city, a situation about which the EPA has voiced serious concerns.[125]

The city has an urban population of bobcats (Lynx rufus).[126] Mange is a common problem in this population.[126] Although Serieys et al. 2014 find selection of immune genetics at several loci they do not demonstrate that this produces a real difference which helps the bobcats to survive future mange outbreaks.[126]

Demographics

| City compared to State & U.S. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 Estimate[127] | L.A. | CA | U.S. |

| Total population | 3,979,576 | 39,512,223 | 328,239,523 |

| Population change, 2010 to 2019 | +4.9% | +6.1% | +6.3% |

| Population density (people/sqmi) | 8,514.4 | 253.9 | 92.6 |

| Median household income (2018) | $58,385 | $71,228 | $60,293 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 33.7% | 33.3% | 31.5% |

| Foreign born | 37.3% | 26.9% | 13.5% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 28.5% | 36.8% | 60.4% |

| Black | 8.9% | 6.5% | 13.4% |

| Hispanic (any race) | 48.6% | 39.3% | 18.3% |

| Asian | 11.6% | 15.3% | 5.9% |

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,610 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,385 | 172.4% | |

| 1870 | 5,728 | 30.6% | |

| 1880 | 11,183 | 95.2% | |

| 1890 | 50,395 | 350.6% | |

| 1900 | 102,479 | 103.4% | |

| 1910 | 319,198 | 211.5% | |

| 1920 | 576,673 | 80.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,238,048 | 114.7% | |

| 1940 | 1,504,277 | 21.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,970,358 | 31.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,479,015 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 2,811,801 | 13.4% | |

| 1980 | 2,968,528 | 5.6% | |

| 1990 | 3,485,398 | 17.4% | |

| 2000 | 3,694,820 | 6.0% | |

| 2010 | 3,792,621 | 2.6% | |

| 2020 | 3,898,747 | 2.8% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 3,819,538 | [128] | −2.0% |

| United States Census Bureau[129] 2010–2020, 2021[7] |

The 2010 U.S. census[130] reported Los Angeles had a population of 3,792,621.[131] The population density was 8,092.3 people per square mile (2,913.0/km2). The age distribution was 874,525 people (23.1%) under 18, 434,478 people (11.5%) from 18 to 24, 1,209,367 people (31.9%) from 25 to 44, 877,555 people (23.1%) from 45 to 64, and 396,696 people (10.5%) who were 65 or older.[131] The median age was 34.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.6 males.[131]

There were 1,413,995 housing units—up from 1,298,350 during 2005–2009[131]—at an average density of 2,812.8 households per square mile (1,086.0/km2), of which 503,863 (38.2%) were owner-occupied, and 814,305 (61.8%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.1%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.1%. 1,535,444 people (40.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 2,172,576 people (57.3%) lived in rental housing units.[131]

According to the 2010 United States Census, Los Angeles had a median household income of $49,497, with 22.0% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[131]

Race and ethnicity

| Racial and ethnic composition | 1940[132] | 1970[132] | 1990[132] | 2010[133] | 2020[133] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 7.1% | 17.1% | 39.9% | 48.5% | 46.9% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 86.3% | 61.1% | 37.3% | 28.7% | 28.9% |

| Asian (non-Hispanic) | 2.2% | 3.6% | 9.8% | 11.1% | 11.7% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 4.2% | 17.9% | 14.0% | 9.2% | 8.3% |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | N/A | N/A | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.0% | 3.3% |

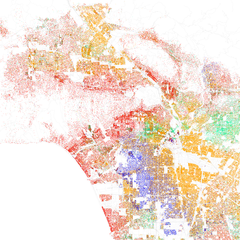

Map of racial and ethnic distribution in Los Angeles as of the 2010 U.S. Census. Each dot is 25 people: ⬤ White

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Other

According to the 2010 census, the racial makeup of Los Angeles included: 1,888,158 Whites (49.8%), 365,118 African Americans (9.6%), 28,215 Native Americans (0.7%), 426,959 Asians (11.3%), 5,577 Pacific Islanders (0.1%), 902,959 from other races (23.8%), and 175,635 (4.6%) from two or more races.[131] Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 1,838,822 persons (48.5%). Los Angeles is home to people from more than 140 countries speaking 224 different identified languages.[134] Ethnic enclaves like Chinatown, Historic Filipinotown, Koreatown, Little Armenia, Little Ethiopia, Tehrangeles, Little Tokyo, Little Bangladesh, and Thai Town provide examples of the polyglot character of Los Angeles.

Non-Hispanic Whites were 28.7% of the population in 2010,[131] compared to 86.3% in 1940.[132] The majority of the Non-Hispanic White population is living in areas along the Pacific coast as well as in neighborhoods near and on the Santa Monica Mountains from the Pacific Palisades to Los Feliz.

Mexican ancestry make up the largest ethnic group of Hispanics at 31.9% of the city’s population, followed by those of Salvadoran (6.0%) and Guatemalan (3.6%) heritage. The Hispanic population has a long established Mexican-American and Central American community and is spread well-nigh throughout the entire city of Los Angeles and its metropolitan area. It is most heavily concentrated in regions around Downtown as East Los Angeles, Northeast Los Angeles and Westlake. Furthermore, a vast majority of residents in neighborhoods in eastern South Los Angeles towards Downey are of Hispanic origin.[citation needed]

The largest Asian ethnic groups are Filipinos (3.2%) and Koreans (2.9%), which have their own established ethnic enclaves—Koreatown in the Wilshire Center and Historic Filipinotown.[135] Chinese people, which make up 1.8% of Los Angeles’s population, reside mostly outside of Los Angeles city limits and rather in the San Gabriel Valley of eastern Los Angeles County, but make a sizable presence in the city, notably in Chinatown.[136] Chinatown and Thaitown are also home to many Thais and Cambodians, which make up 0.3% and 0.1% of Los Angeles’s population, respectively. The Japanese comprise 0.9% of LA’s population and have an established Little Tokyo in the city’s downtown, and another significant community of Japanese Americans is in the Sawtelle district of West Los Angeles. Vietnamese make up 0.5% of Los Angeles’s population. Indians make up 0.9% of the city’s population. The city is also home to Armenians, Assyrians, and Iranians, many of whom live in enclaves like Little Armenia and Tehrangeles.[citation needed]

African Americans have been the predominant ethnic group in South Los Angeles, which has emerged as the largest African American community in the western United States since the 1960s. The neighborhoods of South Los Angeles with highest concentration of African Americans include Crenshaw, Baldwin Hills, Leimert Park, Hyde Park, Gramercy Park, Manchester Square and Watts.[137] Apart from South Los Angeles, neighborhoods in the Central region of Los Angeles, as Mid-City and Mid-Wilshire have a moderate concentration of African Americans as well.[citation needed]

Los Angeles has the second largest Mexican, Armenian, Salvadoran, Filipino and Guatemalan population by city in the world, the third largest Canadian population in the world, and has the largest Japanese, Iranian/Persian, Cambodian and Romani (Gypsy) population in the country.[138]

There is an Italian community in Los Angeles. Italians are concentrated in San Pedro.[139]

Religion

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, Christianity is the most prevalently practiced religion in Los Angeles (65%).[140][141] The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles is the largest archdiocese in the country.[143] Cardinal Roger Mahony, as the archbishop, oversaw construction of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, which opened in September 2002 in Downtown Los Angeles.[144]

In 2011, the once common, but ultimately lapsed, custom of conducting a procession and Mass in honor of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, in commemoration of the founding of the City of Los Angeles in 1781, was revived by the Queen of Angels Foundation and its founder Mark Albert, with the support of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles as well as several civic leaders.[145] The recently revived custom is a continuation of the original processions and Masses that commenced on the first anniversary of the founding of Los Angeles in 1782 and continued for nearly a century thereafter.

With 621,000 Jews in the metropolitan area, the region has the second-largest population of Jews in the United States, after New York City.[146] Many of Los Angeles’s Jews now live on the Westside and in the San Fernando Valley, though Boyle Heights once had a large Jewish population prior to World War II due to restrictive housing covenants. Major Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods include Hancock Park, Pico-Robertson, and Valley Village, while Jewish Israelis are well represented in the Encino and Tarzana neighborhoods, and Persian Jews in Beverly Hills. Many varieties of Judaism are represented in the greater Los Angeles area, including Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, and Reconstructionist. The Breed Street Shul in East Los Angeles, built in 1923, was the largest synagogue west of Chicago in its early decades; it is no longer in daily use as a synagogue and is being converted to a museum and community center.[147][148] The Kabbalah Centre also has a presence in the city.[149]

The International Church of the Foursquare Gospel was founded in Los Angeles by Aimee Semple McPherson in 1923 and remains headquartered there to this day. For many years, the church convened at Angelus Temple, which, at its construction, was one of the largest churches in the country.[150]

Los Angeles has had a rich and influential Protestant tradition. The first Protestant service in Los Angeles was a Methodist meeting held in a private home in 1850 and the oldest Protestant church still operating, First Congregational Church, was founded in 1867.[151] In the early 1900s the Bible Institute Of Los Angeles published the founding documents of the Christian Fundamentalist movement and the Azusa Street Revival launched Pentecostalism.[151] The Metropolitan Community Church also had its origins in the Los Angeles area.[152] Important churches in the city include First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood, Bel Air Presbyterian Church, First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles, West Angeles Church of God in Christ, Second Baptist Church, Crenshaw Christian Center, McCarty Memorial Christian Church, and First Congregational Church.

The Los Angeles California Temple, the second-largest temple operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is on Santa Monica Boulevard in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. Dedicated in 1956, it was the first temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints built in California and it was the largest in the world when completed.[153]

The Hollywood region of Los Angeles also has several significant headquarters, churches, and the Celebrity Center of Scientology.[154][155]

Because of Los Angeles’s large multi-ethnic population, a wide variety of faiths are practiced, including Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Sikhism, Baháʼí, various Eastern Orthodox Churches, Sufism, Shintoism, Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religion and countless others. Immigrants from Asia for example, have formed a number of significant Buddhist congregations making the city home to the greatest variety of Buddhists in the world. The first Buddhist joss house was founded in the city in 1875.[151] Atheism and other secular beliefs are also common, as the city is the largest in the Western U.S. Unchurched Belt.

Homelessness

As of January 2020, there are 41,290 homeless people in the City of Los Angeles, comprising roughly 62% of the homeless population of LA County.[156] This is an increase of 14.2% over the previous year (with a 12.7% increase in the overall homeless population of LA County).[157][158] The epicenter of homelessness in Los Angeles is the Skid Row neighborhood, which contains 8,000 homeless people, one of the largest stable populations of homeless people in the United States.[159][160] The increased homeless population in Los Angeles has been attributed to lack of housing affordability[161] and to substance abuse.[162] Almost 60 percent of the 82,955 people who became newly homeless in 2019 said their homelessness was because of economic hardship.[157] In Los Angeles, black people are roughly four times more likely to experience homelessness.[157][163]

Crime

LAPD on May Day 2006 in front of the new Caltrans District 7 Headquarters