|

Luhansk People’s Republic[b] Луганская Народная Республика |

|

|---|---|

|

Military occupation and annexation |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Государственный Гимн Луганской Народной Республики Gosudarstvennyy Gimn Luganskoy Narodnoy Respubliki «State Anthem of the Luhansk People’s Republic» |

|

![Ukraine's Luhansk Oblast in Europe, claimed and militarily contested as the Luhansk People's Republic by Russia and its separatist militant formations[4]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Location_of_Lugansk_People%27s_Republic.png/250px-Location_of_Lugansk_People%27s_Republic.png)

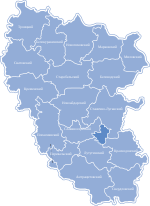

Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast in Europe, claimed and militarily contested as the Luhansk People’s Republic by Russia and its separatist militant formations[4] |

|

| Occupied country | Ukraine |

| Occupying power | Russia |

| Breakaway state[a] | Lugansk People’s Republic (2014–2022) |

| Disputed republic of Russia | Lugansk People’s Republic (2022–present) |

| Entity established | 27 April 2014[5] |

| Eastern Ukraine offensive | 24 February 2022 |

| Annexation by Russia | 30 September 2022 |

| Administrative centre | Luhansk |

| Government | |

| • Body | People’s Council |

| • Head of the LPR | Leonid Pasechnik |

| Population

(2019)[6] |

|

| • Total | 1,485,300[c] |

The Luhansk People’s Republic or Lugansk People’s Republic[d] (Russian: Луга́нская Наро́дная Респу́блика, romanized: Luganskaya Narodnaya Respublika, IPA: [lʊˈɡanskəjə nɐˈrodnəjə rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə]; abbreviated as LPR or LNR, Russian: ЛНР) is an unrecognised republic of Russia in the occupied parts of eastern Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast, with its capital in Luhansk.[7][8] The LPR was created by militarily-armed Russian-backed separatists in 2014, and it initially operated as a breakaway state until it was annexed by Russia in 2022.

Following Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity in 2014, pro-Russian unrest erupted in the eastern part of the country. Shortly thereafter, Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine, while the armed separatists seized government buildings and proclaimed the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) and Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) as independent states, which received no international recognition from United Nations member states before 2022. This sparked the War in Donbas, part of the wider Russo-Ukrainian War.

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognised the LPR and DPR as sovereign states. Three days later, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, partially under the pretext of protecting the republics. Russian forces captured more of Luhansk Oblast (almost the entirety of it),[9] which became part of the LPR. In September 2022, Russia announced the annexation of the LPR and other occupied territories, following disputed referendums which were illegal under international law. The United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling on countries not to recognise what it called the «attempted illegal annexation» and demanded that Russia «immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw».[10]

The Head of the Luhansk People’s Republic is Leonid Pasechnik, and its parliament is the People’s Council. The ideology of the LPR is said to have been shaped by right-wing Russian nationalism, neo-imperialism and Orthodox fundamentalism.[11] Organizations such as the United Nations Human Rights Office and Human Rights Watch have reported human rights abuses in the LPR, including internment, torture, extrajudicial killings, forced conscription, as well as political and media repression. Ukraine views the LPR and DPR as terrorist organisations.[12] The LPR and DPR are sometimes described as puppet states of Russia during their periods of nominal independence.[1][2][3]

Geography and demographics

The 2014 constitution of the Luhansk People’s Republic (art. 54.1) defined the territory of the republic as «determined by the borders existing on the day of establishment», without describing the borders.[13] From February 2015 up until February 2022, the LPR’s de facto borders were the Russo–Ukrainian border (south and east), the border between Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast and Donetsk Oblast (west), and the line of contact with Ukrainian troops (north) as defined in the Minsk agreements between Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE. When the Russian president announced recognition of the republics’ independence on February 22, 2022, he said «we recognized all their fundamental documents, including the constitution. And the constitution spells out the borders within the Donetsk and Luhansk regions at the time when they were part of Ukraine».[14]

Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast and the LPR-controlled area from April 2014 to February 2022 are both landlocked.

The highest point in left-bank Ukraine is Mohyla Mechetna hill (367.1 m (1,204 ft) above sea level), which is located in the vicinity of the city of Petrovske, in LPR-controlled territory.[15]

In December 2017, approximately 1.4 million lived in the LPR’s territory, with 435,000 in the city of Luhansk.[16] Leaked documents suggest that less than three million people, less than half of the pre-war population, remained in the separatist territories that Moscow controlled in eastern Ukraine in early February 2022, and 38% of those remaining were pensioners.[17]

On 18 February 2022, the LPR and DPR separatist authorities ordered a general evacuation of women and children to Russia, and the next day a full mobilization of males «able to hold a weapon in their hands».[18]

History

Luhansk and Donetsk People’s republics are located in the historical region of Donbas, which was added to Ukraine in 1922.[19] The majority of the population speaks Russian as their first language. Attempts by various Ukrainian governments to question the legitimacy of the Russian culture in Ukraine had since the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine often resulted in political conflict. In the Ukrainian national elections, a remarkably stable pattern had developed, where Donbas and the Western Ukrainian regions had voted for the opposite candidates since the presidential election in 1994. Viktor Yanukovych, a Donetsk native, had been elected as a president of Ukraine in 2010. His overthrow in the 2014 Ukrainian revolution led to protests in Eastern Ukraine, which gradually escalated into an armed conflict between the newly formed Ukrainian government and the local armed militias.[20]

Formation (2014–2015)

Occupation of government buildings

A Luhansk People’s Republic People’s Militia member in June 2014

A demonstration in Luhansk, 1 May 2014

On 5 March 2014, 12 days after the protesters in Kyiv seized the president’s office (at the time Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had already fled Ukraine[21]),[22] a crowd of people in front of the Luhansk Oblast State Administration building proclaimed Aleksandr Kharitonov as «People’s Governor» in Luhansk region. On 9 March 2014 Luganskaya Gvardiya of Kharitonov stormed the government building in Luhansk and forced the newly appointed Governor of Luhansk Oblast, Mykhailo Bolotskykh, to sign a letter of resignation.[23]

One thousand pro-Russian activists seized and occupied the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) building in the city of Luhansk on 6 April 2014, following similar occupations in Donetsk and Kharkiv.[24][25] The activists demanded that separatist leaders who had been arrested in previous weeks be released.[24] In anticipation of attempts by the government to retake the building, barricades were erected to reinforce the positions of the activists.[26][27] It was proposed by the activists that a «Lugansk Parliamentary Republic» be declared on 8 April 2014, but this did not occur.[28][29] By 12 April, the government had regained control over the SBU building with the assistance of local police forces.[30]

Several thousand protesters gathered for a ‘people’s assembly’ outside the regional state administration (RSA) building in Luhansk city on 21 April. These protesters called for the creation of a ‘people’s government’, and demanded either federalisation of Ukraine or incorporation of Luhansk into the Russian Federation.[31] They elected Valery Bolotov as ‘People’s Governor’ of Luhansk Oblast.[32] Two referendums were announced by the leadership of the activists. One was scheduled for 11 May, and was meant to determine whether the region would seek greater autonomy (and potentially independence), or retain its previous constitutional status within Ukraine. Another referendum, meant to be held on 18 May in the event that the first referendum favoured autonomy, was to determine whether the region would join the Russian Federation, or become independent.[33]

Valery Bolotov proclaims the Act of Independence of the Luhansk People’s Republic, 12 May 2014

During a gathering outside the RSA building on 27 April 2014, pro-Russian activists proclaimed the «Luhansk People’s Republic».[34] The protesters issued demands, which said that the Ukrainian government should provide amnesty for all protesters, include the Russian language as an official language of Ukraine, and also hold a referendum on the status of Luhansk Oblast.[34] They then warned the Ukrainian government that if it did not meet these demands by 14:00 on 29 April, they would launch an armed insurgency in tandem with that of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR).[34][35]

As the Ukrainian government did not respond to these demands, 2,000 to 3,000 activists, some of them armed, seized the RSA building, and a local prosecutor’s office, on 29 April.[36] The buildings were both ransacked, and then occupied by the protesters.[37] Protestors waved local flags, alongside those of Russia and the neighbouring Donetsk People’s Republic.[38] The police officers that had been guarding the building offered little resistance to the takeover, and some of them defected and supported the activists.[39]

Territorial expansion

Demonstrations by pro-Russian activists began to spread across Luhansk Oblast towards the end of April. The municipal administration building in Pervomaisk was overrun on 29 April 2014, and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) flag was raised over it.[40][41] Oleksandr Turchynov, then acting president of Ukraine, admitted the next day that government forces were unable to stabilise the situation in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.[42] On the same day, activists seized control of the Alchevsk municipal administration building.[43] In Krasnyi Luch, the municipal council conceded to demands by activists to support the 11 May 2014 referendum, and followed by raising the Russian flag over the building.[40]

Insurgents occupied the municipal council building in Stakhanov on 1 May 2014. Later in the week, they stormed the local police station, business centre, and SBU building.[44][45] Activists in Rovenky occupied a police building there on 5 May, but quickly left.[46] On the same day, the police headquarters in Slovianoserbsk was seized by members of the Army of the South-East, a pro-Russian Luhansk regional militia group.[47][48] In addition, the town of Antratsyt was occupied by the Don Cossacks.[49][50]

Some said that the occupiers came from Russia;[51] the Cossacks themselves said that only a few people among them had come from Russia.[52] On 7 May, insurgents also seized the prosecutor’s office in Sievierodonetsk.[53] Luhansk People’s Republic supporters stormed government buildings in Starobilsk on 8 May, replacing the Ukrainian flag with that of the Republic.[54] Sources within the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs said that as of 10 May 2014, the day before the proposed status referendum, Ukrainian forces still retained control over 50% of Luhansk Oblast.[55]

Status referendum

A ballot paper sample for the referendum: «Do you support the declaration of state independence of the Lugansk People’s Republic? Yes or No»

The planned referendum on the status of Luhansk oblast was held on 11 May 2014.[56] The organisers of the referendum said that 96.2% of those who voted were in favour of self-rule, with 3.8% against.[57] They said that voter turnout was at 81%. There were no international observers present to validate the referendum.[57]

Declaration of independence

Following the referendum, the head of the Republic, Valery Bolotov, said that the Republic had become an «independent state».[58] The still-extant Luhansk Oblast Council did not support independence, but called for immediate federalisation of Ukraine, asserting that «an absolute majority of people voted for the right to make their own decisions about how to live».[59][60] The council also requested an immediate end to Ukrainian military activity in the region, amnesty for anti-government protestors, and official status for the Russian language in Ukraine.[60]

Valery Bolotov was wounded in an assassination attempt on 13 May.[61] Luhansk People’s Republic authorities blamed the incident on the Ukrainian government. Government forces later captured Alexei Rilke, the commander of the Army of the South-East.[62] The next day, Ukrainian border guards arrested Valery Bolotov. Just over two hours later, after unsuccessfully attempting negotiations, 150 to 200 armed separatists attacked the Dovzhansky checkpoint where he had been held. The ensuing firefight led Ukrainian government forces to free Bolotov.[63]

On 24 May 2014 the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic jointly announced their intention to form a confederative «union of People’s Republics» called New Russia.[64] Republic President Valery Bolotov said on 28 May that the Luhansk People’s Republic would begin to introduce its own legislation based on Russian law; he said Ukrainian law was unsuitable due to it being «written for oligarchs».[65] Vasily Nikitin, prime minister of the Republic, announced that elections to the State Council would take place in September.[66]

The leadership of the Luhansk People’s Republic said on 12 June 2014 that it would attempt to establish a «union state» with Russia.[67] The government added that it would seek to boost trade with Russia through legislative, agricultural and economic changes.[67]

Stakhanov, a city that had been occupied by LPR-affiliated Don Cossacks, seceded from the Luhansk People’s Republic on 14 September 2014.[68][failed verification] Don Cossacks there proclaimed the Republic of Stakhanov, and said that a «Cossack government» now ruled in Stakhanov.[68][69] However the following day this was claimed[by whom?] to be a fabrication, and an unnamed Don Cossack leader stated the 14 September meeting had, in fact, resulted in 12,000 Cossacks volunteering to join the LPR forces.[70] Elections to the LPR Supreme Council took place on 2 November 2014, as the LPR did not allow the Ukrainian parliamentary election to be held in territory under its control.[71][72]

Human rights in the early stages of the war

A ruined electronics shop in Luhansk. August 2015

In May 2014 the United Nations observed an «alarming deterioration» of human rights in insurgent-held territory in eastern Ukraine.[73] The UN detailed growing lawlessness, documenting cases of targeted killings, torture, and abduction, carried out by Luhansk People’s Republic insurgents.[74] The UN also highlighted threats, attacks, and abductions of journalists and international observers, as well as the beatings and attacks on supporters of Ukrainian unity.[74] An 18 November 2014 United Nations report on eastern Ukraine declared that the Luhansk People’s Republic was in a state of «total breakdown of law and order».[75]

The report noted «cases of serious human rights abuses by the armed groups continued to be reported, including torture, arbitrary and incommunicado detention, summary executions, forced labour, sexual violence, as well as the destruction and illegal seizure of property may amount to crimes against humanity».[75] The report also stated that the insurgents violated the rights of Ukrainian-speaking children because schools in rebel-controlled areas only teach in Russian.[75] The United Nations also accused the Ukrainian Army and Ukrainian (volunteer) territorial defence battalions of human rights abuses such as illegal detention, torture and ill-treatment, noting official denials.[75] In a 15 December 2014 press conference in Kyiv UN Assistant Secretary-General for human rights Ivan Šimonović stated that the majority of human rights violations, including executions without trial, arrests and torture, were committed in areas controlled by pro-Russian rebels.[76]

In November 2014, Amnesty International called the «People’s Court» (public trials where allegedly random locals are the jury) held in the Luhansk People’s Republic «an outrageous violation of the international humanitarian law».[77]

In January 2015, the Luhansk Communist Party criticised the current situation in the region. In their statement they expressed «deep disappointment» with how the situation developed from «authentic people’s protests a year ago» to «return of corruption and banditism».[78] In December 2015 the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine reported «Parallel ‘justice systems’ have begun operating» in territory controlled by the Luhansk People’s Republic.[79] They criticised this judiciary to be «non-transparent, subject to constant change, seriously under-resourced and, in many instances, completely non-functional».[79]

Static war period (2015–2022)

On 1 January 2015, forces loyal to the Luhansk People’s Republic ambushed and killed Alexander Bednov, head of a pro-Russian battalion called «Batman». Bednov was accused of murder, abduction and other abuses. An arrest warrant for Bednov and several other battalion members had been previously issued by the separatists’ prosecutor’s office.[80][81][82]

On 12 February 2015, DPR and LPR leaders Alexander Zakharchenko and Igor Plotnitsky signed the Minsk II agreement, although without any mention of their self-proclaimed titles or the republics.[83] In the Minsk agreement it is agreed to introducing amendments to the Ukrainian constitution «the key element of which is decentralisation» and the holding of elections «on temporary order of local self-governance in particular districts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, based in the line set up by the Minsk Memorandum as of 19 September 2014»; in return rebel held territory would be reintegrated into Ukraine.[83][84] Representatives of the DPR and LPR continue to forward their proposals concerning Minsk II to the Trilateral Contact Group on Ukraine.[85] Plotnitsky told journalists on 18 February 2015: «Will we be part of Ukraine? This depends on what kind of Ukraine it will be. If it remains like it is now, we will never be together.»[86]

On 20 May 2015, the leadership of the Federal State of Novorossiya announced the termination of the confederation ‘project’.[87]

On 19 April 2016, planned (organised by the LPR) local elections were postponed from 24 April to 24 July 2016.[88] On 22 July 2016, this elections was again postponed to 6 November 2016.[89] (On 2 October 2016, the DPR and LPR held «primaries» in were voters voted to nominate candidates for participation in the 6 November 2016 elections.[90] Ukraine denounced these «primaries» as illegal.[90])

The «LPR Prosecutor General’s Office» announced late September 2016, that it had thwarted a coup attempt ringleaded by former LPR appointed prime minister Gennadiy Tsypkalov (who they stated had committed suicide on 23 September while in detention).[91] Meanwhile, it had also imprisoned former LPR parliamentary speaker Aleksey Karyakin and former LPR interior minister, Igor Kornet.[92] DPR leader Zakharchenko said he had helped to thwart the coup (stating «I had to send a battalion to solve their problems»).[92]

On 4 February 2017, LPR defence minister Oleg Anashchenko was killed in a car bomb attack in Luhansk.[93] Separatists claimed «Ukrainian secret services» were suspected of being behind the attack; while Ukrainian officials suggested Anashchenko’s death may be the result of an internal power struggle among rebel leaders.[93]

Mid-March 2017 Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a decree on a temporary ban on the movement of goods to and from territory controlled by the self-proclaimed Luhansk People’s Republic and Donetsk People’s Republic; this also means that since then Ukraine does not buy coal from the Donets Black Coal Basin.[94]

On 21 November 2017, armed men in unmarked uniforms took up positions in the center of Luhansk in what appeared to be a power struggle between the head of the republic Plotnitsky and the (sacked by Plotnitsky) LPR appointed interior minister Igor Kornet.[95][96] Media reports stated that the DPR had sent armed troops to Luhansk the following night.[95][96] Three days later the website of the separatists stated that Plotnitsky had resigned «for health reasons. Multiple war wounds, the effects of blast injuries, took their toll.»[97] The website stated that security minister Leonid Pasechnik had been named acting leader «until the next elections.»[97]

Plotnitsky was stated to become the separatist’s representative to the Minsk process.[97] Plotnitsky himself did not issue a public statement on 24 November 2017.[97] Russian media reported that Plotnitsky had fled the unrecognised republic on 23 November 2017, first travelling from Luhansk to Rostov-on-Don by car and then flying to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport.[98] On 25 November the 38-member separatist republic’s People’s Council unanimously approved Plotnitsky’s resignation.[99] Pasechnik declared his adherence to the Minsk accords, claiming «The republic will be consistently executing the obligations taken under these agreements.»[100]

In June 2019 Russia started giving Russian passports to the inhabitants of the LPR and Donetsk People’s Republic under a simplified procedure allegedly on «humanitarian grounds» (such as enabling international travel for eastern Ukrainian residents whose passports have expired).[101] According to Ukrainian press by mid-2021 half a million Russian passports had been received by local residents.[102] Deputy Kremlin Chief of Staff Dmitry Kozak stated in a July 2021 interview with Politique internationale that 470 thousand local residents had received a Russian passport; he added that «as soon as the situation in Donbas is resolved….The general procedure for granting citizenship will be restored.»[103]

In early June 2020, the LPR declared Russian as the only state language on its territory, removing Ukrainian from its school curriculum.[104] Previously the separatist leaders had made Ukrainian LPR’s second state language, but in practice it was already disappearing from school curricula prior to June 2020.[105]

In January 2021 the Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic stated in a «Russian Donbas doctrine» that they aimed to seize all of the territories of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast under control by the Ukrainian government «in the near future.»[106] The document did not specifically state the intention of DPR and LPR to be annexed by Russia.[106]

Full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022–present)

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2022) |

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognised the independence of the DPR and LPR.[107] The next day, the Federation Council of Russia authorised the use of military force, and Russian forces openly advanced into both territories.[108] Russian president Vladimir Putin declared that the Minsk agreements «no longer existed», and that Ukraine, not Russia, was to blame for their collapse.[109] A military attack into Ukrainian government-controlled territory began on the morning of 24 February,[110] when Putin announced a «special military operation» to «demilitarise and denazify» Ukraine.[111][112]

On May 6, as part of the eastern Ukraine offensive, the Russian Armed Forces and Luhansk People’s Republic military started a battle to capture Sievierodonetsk, the de facto administrative capital of Ukrainian-controlled Luhansk Oblast. On 25 June 2022, Sievierodonetsk was fully occupied by Russian and separatist forces. This was followed by the capture of Lysychansk on 3 July, which brought all of Luhansk Oblast under the control of Russian and separatist forces.

This resulted in a 63 day period during which the whole of Luhansk Oblast was controlled by separatist forces. However, during the 2022 Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive starting on September 4, the village of Bilohorivka became contested between Ukrainian and Russian forces;[113] on September 10, the village was confirmed to be under Ukrainian control.[114]

Recognition and international relations

The Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) initially sought recognition as a sovereign state following its declaration of independence in April 2014. Subsequently, the LPR willingly acceded to the Russian Federation as a Russian federal subject in September–October 2022, effectively ceasing to exist as a sovereign state in any capacity and revoking its status as such in the eyes of the international community. The LPR claims direct succession to Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast.

From 2014 to 2022, Ukraine, the United Nations, and most of the international community regarded the LPR as an illegal entity occupying a portion of Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast (see: International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War). The Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR), which had a similar backstory, was regarded in the exact same way. Crimea’s status was treated slightly differently since Russia annexed that territory immediately after its declaration of independence in March 2014.

Up until February 2022, Russia did not recognise the LPR, although it maintained informal relations with the LPR. On 21 February 2022, Russia officially recognised the LPR and the DPR at the same time,[115] marking a major escalation in the 2021–2022 diplomatic crisis between Russia and Ukraine. Three days later, on 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of the entire country of Ukraine, partially under the pretext of protecting the LPR and the DPR. The war had wide-reaching repercussions for Ukraine, Russia, and the international community as a whole (see: War crimes, Humanitarian impact, Environmental impact, Economic impact, and Ukrainian cultural heritage). In September 2022, Russia made moves to consolidate the territories that it had occupied in Ukraine, including Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts. Russia officially annexed these four territories in September–October 2022.

Between February 2022 and October 2022, in addition to receiving Russian recognition, the LPR was recognised by North Korea (13 July 2022)[116] and Syria (29 June 2022).[117][118] This means that three United Nations member states recognised the LPR in total throughout its period of de facto independence. The LPR was also recognised by three other breakaway entities: the DPR, South Ossetia (19 June 2014),[119] and Abkhazia (25 February 2022).[120]

Relations with Ukraine

The LPR has been in a state of armed conflict with Ukraine ever since the former declared independence in 2014. The Ukrainian military operation against the republic is officially called an anti-terrorist operation, although it is not considered to be a terrorist entity by the Supreme Court of Ukraine itself[121] nor by either the EU, the US, or Russia.[122][123][124]

Relations with Russia

During most of its lifetime, Russia did not recognise the LPR as a state. It nevertheless recognised official documents issued by the LPR authorities, such as identity documents, diplomas, birth and marriage certificates and vehicle registration plates.[125] This recognition was introduced in February 2017[125] and enabled people living in LPR-controlled territories to travel, work or study in Russia.[125] According to the presidential decree that introduced it, the reason for the decree was «to protect human rights and freedoms» in accordance with «the widely recognised principles of international humanitarian law.»[126] Ukrainian authorities decried the decree and claimed that it was contradictory to the Minsk II agreement, and also that it «legally recognised the quasi-state terrorist groups which cover Russia’s occupation of part of Donbas.»[127]

On 21 February 2022, the Russian government recognised the Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics in dawn of 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. During the invasion, forces from the LPR fought together with Russian forces against Ukraine. On 3 July 2022, Russia claimed to have full control over Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast.[128]

Dmitry Medvedev, former Russian president and as of July 2022 vice chairman of the Russian Security Council, in July 2022 shared a map of Ukraine wherein most of Ukraine, including LPR, had been absorbed by Russia.[129]

Government and politics

A report by the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI) stated that the official ideology of the LPR is shaped by right-wing Russian nationalism, neo-imperialism and Orthodox fundamentalism.[11] Al Jazeera described it as neo-Stalinist and a «totalitarian, North Korea-like statelet».[130] The LPR and DPR are sometimes described as puppet states of Russia during their periods of nominal independence.[1][2][3]

Constitution

The People’s Council of the LPR ratified a temporary constitution on 18 May 2014.[131] Its government styles itself as a people’s republic. The form of the Luhansk People’s Republic’s parliament is called the People’s Council and has 50 deputies.[132] Aleksey Karyakin was elected as its first head on 18 May 2014.[92] Its anthem is «Glory to Luhansk People’s Republic!» (Russian: Луганской Народной Республике, Слава!), also known as «Live and Shine, LPR».[133][134]

Elections

The first parliamentary elections to the legislature of the Luhansk People’s Republic were held on 2 November 2014.[132] People of at least 30 years old who «permanently resided in Luhansk People’s Republic the last 10 years» were electable for four years and could be nominated by public organisations.[132] All residents of Luhansk Oblast were eligible to vote, even if they are residents of areas controlled by Ukrainian government forces or fled to Russia or other places in Ukraine as refugees.[71]

Ukraine urged Russia to use its influence to stop the election «to avoid a frozen conflict».[135] Russia on the other hand indicated it «will of course recognise the results of the election»; Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated that the election «will be important to legitimise the authorities there».[72] Ukraine held the 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election on 26 October 2014; these were boycotted by the Donetsk People’s Republic and hence voting for it did not take place in Ukraine’s eastern districts controlled by forces loyal to the Luhansk People’s Republic.[72][135]

On 6 July 2015 the Luhansk People’s Republic leader (LPR) Igor Plotnitsky set elections for «mayors and regional heads» for 1 November 2015 in territory under his control.[citation needed] (Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) leader Alexander Zakharchenko issued a decree on 2 July 2015 that ordered local DPR elections to be held on 18 October 2015. He said that this action was «in accordance with the Minsk agreements».[136]) On 6 October 2015 the DPR and LPR leadership postponed their planned elections to 21 February 2016.[137]

This happened 4 days after a Normandy four meeting in which it was agreed that the October 2015 Ukrainian local elections in LPR and DPR controlled territories would be held in accordance to the February 2015 Minsk II agreement.[138] At the meeting President of France François Hollande stated that in order to hold these elections (in LPR and DPR controlled territories) it was necessary «since we need three months to organize elections» to hold these elections in 2016.[138] Also during the meeting it is believed that Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to use his influence to not allow the DPR and Luhansk People’s Republic election to take place on 18 October 2015 and 1 November 2015.[138] On 4 November 2016 both DPR and LPR postponed their local elections, they had set for 6 November 2016, «until further notice».[citation needed]

Additional elections took place simultaneously in Donetsk and Luhansk republics on 11 November 2018. The official position of the U.S. and European union is that this vote is illegitimate because it was not controlled by the Ukrainian government, and that it was contrary to the 2015 Minsk agreement. Leonid Pasechnik, the head of the Luhansk People’s Republic, disagreed and said that the vote was in accordance with the Minsk Agreement. The separatist leaders said that the election was a key step toward establishing full-fledged democracy in the regions. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said that residents of eastern Ukraine should not to participate in the vote. Nevertheless, both regions reported voter turnout of more than 70 per cent as of two hours before the polls closed at 8 p.m. local time.[139][140][141]

Public opposition in the LPR is virtually non-existent.[17]

Military

Emblem of the People’s Militia

The People’s Militia of the LPR (Russian: Народная милиция ЛНР) comprise the Russian separatist forces in the LPR.[142][143][144] On 7 October 2014, by decree Igor Plotnitsky, the People’s Militia was created, with Oleg Bugrov serving as Minister of Defense and the Commander-in-Chief of the People’s Militia.[145][146] It has been reported that it is under the control 2nd Army Corps, which is subordinated to the specially created 12th Reserve Command of the Southern Military District of the Russian Armed Forces at its headquarters in the city of Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast.[147][148] By 2016 Russian officers commanded the LPR units from the battalion level up. The former commanders, some of whom retained substantial personal security forces, sometimes acted as deputy commanders.[149]

Administrative divisions

The districts of Luhansk Oblast until 2020, which are used by the LPR

In 2020, Luhansk Oblast conducted an administrative reform, reducing its 32 regions to eight districts. The LPR uses the oblast’s old administrative divisions on its controlled territory. See List of raions of Ukraine (1966-2020) § XII. Luhansk Oblast.

Human rights

Freedom House evaluates the eastern Donbas territories controlled by the LPR and DPR as «not free», scoring 4 out of 100 in its 2022 Freedom in the World index.[150] Concerns include strict control over politics by the security services, allowing no meaningful opposition, and harsh restrictions on local media. Pro-Ukrainian bloggers and journalists have been given long prison sentences, and people have been arrested for critical posts on social media. Freedom House also reported that there was a «prevailing hostility» to the Ukrainian ethnic identity and an «intensifying campaign» against the Ukrainian language and identity.

According to Freedom House, basic due process guarantees are not followed and arbitrary arrests and detentions are common. A 2020 UN report said that interviews with released prisoners «confirmed patterns of torture and ill-treatment». Abuse, including torture and sexual violence, has been widely reported to occur in separatist prisons and detention centers.[150]

A 2022 report by Al Jazeera said that «the ‘republics’ are understood to have evolved into totalitarian, North Korea-like statelets», and that reportedly thousands have been tortured and abused in «cellars» under the separatist authorities.[151]

Economy

As of May 2015, pensions started being paid in mostly Russian rubles by the Luhansk People’s Republic. 85% were in rubles, 12% in hryvnias, and 3% in dollars according to LPR Head Igor Plotnitsky.[152] Ukraine completely stopped paying pensions for the elderly and disabled in areas under DPR and LPR control on 1 December 2014.[153]

Sports and culture

The football team of the Luhansk People’s republic is ranked sixteenth in the Confederation of Independent Football Associations world ranking.[154] A football match between LPR and DPR was played on 8 August 2015 at the Metalurh Stadium in Donetsk.[155]

See also

- List of states with limited recognition

- Malaysia Airlines Flight 17

- Russian occupation of Luhansk Oblast

Notes

- ^ Russian puppet state[1][2][3]

- ^ a.k.a. «Lugansk People’s Republic»

- ^ The population of the entire Luhansk Oblast in 2019 was estimated to be 2,151,800, while 1,485,300 resided in areas under the control of the Luhansk People’s Republic. Figures are from before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- ^ It can be read as both Lugansk or Luhansk due to the fact that the Cyrillic character Г represents the sound [ɦ] in Ukrainian, roughly an equivalent to the English H, while in Russian it is usually pronounced /ɡ/.

References

- ^ a b c Johnson, Jamie; Parekh, Marcus; White, Josh; Vasilyeva, Nataliya (4 August 2022). «Officer who ‘boasted’ of killing civilians becomes Russia’s first female commander to die». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Bershidsky, Leonid (13 November 2018). «Eastern Ukraine: Why Putin Encouraged Sham Elections in Donbass». Bloomberg News. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b c «Russian Analytical Digest No 214: The Armed Conflict in Eastern Ukraine». css.ethz.ch. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ «Путин: Россия признала ДНР и ЛНР в границах Донецкой и Луганской областей». BBC Russia. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ «Separatists Declare ‘People’s Republic’ In Ukraine’s Luhansk». RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ «Luhansk oblast». Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Ledur, Júlia (21 November 2022). «What Russia has gained and lost so far in Ukraine, visualized». The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ «Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 30». Institute for the Study of War. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ «Russia-Ukraine war latest: two killed in attack on Zaporizhzhia as Russia launches mass strikes across Ukraine». the Guardian. 17 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ «Ukraine: UN General Assembly demands Russia reverse course on ‘attempted illegal annexation’«. 12 October 2022.

- ^ a b Likhachev, Vyacheslav (July 2016). «The Far Right in the Conflict between Russia and Ukraine» (PDF). Russie.NEI.Visions in English. pp. 25–26. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

The ideas of Russian imperial (and, to some extent, ethnic) nationalism and Orthodox fundamentalism shaped the official ideology of the DNR and LNR. … It can therefore be argued that the official ideology of the DNR and LNR, which developed under the influence of Russian far-right activists, is largely right-wing, conservative and xenophobic in character.

- ^ «Ukraine’s prosecutor general classifies self-declared Donetsk and Lugansk republics as terrorist organizations». Kyiv Post. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ «Временный Основной Закон (Конституция) Луганской Народной Республики». Луганский Информационный Центр. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ «Russia Backs Ukraine Separatists’ Full Territorial Claims». The Moscow Times. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ «На даху Донбасу» [On the roof of Donbass]. Club-tourist. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ «Four Years of the Luhansk People’s Republic». Geopolitical Futures. 2 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b Roth, Andrew (18 February 2022). «What is the background to the separatist attack in east Ukraine?». The Guardian. Archived 21 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Separatist leaders in eastern Ukraine declare full military mobilisation». Reuters. 19 February 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Andrés, César García (2018). «Historical Evolution of Ukraine and its Post Communist Challenges» (PDF). Revista de Stiinte Politice (RST). 58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Petro, Nicolai N., Understanding the Other Ukraine: Identity and Allegiance in Russophone Ukraine (1 March 2015). Richard Sakwa and Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska, eds., Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, Bristol, United Kingdom: E-International Relations Edited Collections, 2015, pp. 19–35. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2574762

- ^ Ukraine Leader Was Defeated Even Before He Was Ousted Archived 24 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (3 January 2015)

- ^ «Protesters seize Ukraine president’s office, take control of Kiev». Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Nikulenko, T. The SBU Colonel Zhyvotov: with torture they were forcing the father of former chief of Luhansk SBU to convince his son to come to Donetsk, and when he refused, they killed him (Полковник СБУ Животов: Отца экс-главы Луганской СБУ пытками принуждали вызвать сына в Донецк, а когда он отказался – убили) Archived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Gordon.ua. 2 November 2016

- ^ a b «Ukraine’s eastern hot spots – GlobalPost». GlobalPost. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Over a dozen towns held by pro-Russian rebels in east Ukraine & Updates at Daily News & Analysis». dna. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Возле СБУ в Луганске готовятся к штурму и продолжают укреплять баррикады (фото)» [Near the SBU in Luhansk are preparing for the assault and continue to strengthen the barricades (photo)]. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «The Ukraine crisis: Boys from the blackstuff – The Economist». The Economist. 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Здание луганской СБУ удерживают полторы тысячи вооруженных сепаратистов – журналист : Новости УНИАН» [Lugansk SBU building is being held by 1,500 armed separatists — journalist : News UNIAN]. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ «There’s Violence on the Streets of Ukraine—and in Parliament A news roundup for April 8». The New Republic. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ^ Alan Yuhas (16 April 2014). «Crisis in east Ukraine: a city-by-city guide to the spreading conflict». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Luhansk». Interfax-Ukraine. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «В Луганске выбрали «народного губернатора» – Донбасс – Вести» [«People’s governor» elected in Luhansk — Donbass — Vesti]. Вести. 21 April 2014. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «У Луганську сепаратисти вирішили провести два референдуми — Українська правда» [In Luhansk, the separatists decided to hold two referendums — Ukrainian Pravda]. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ a b c «TASS: World – Federalization supporters in Luhansk proclaim people’s republic». TASS. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine – based on information received up until 28 April 2014, 19:00 (Kyiv time) – OSCE». Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Ukraine crisis: Pro-Russia activists take Luhansk offices». BBC News Europe. 29 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ «Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine – based on information received up until 29 April 2014, 19:00 (Kyiv time) – OSCE». Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Luhansk». Interfax-Ukraine. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «В Луганске сепаратисты взяли штурмом ОГА, правоохранители перешли на сторону митингующих : Новости УНИАН» [In Lugansk, separatists stormed the Regional State Administration, law enforcement officers went over to the side of the protesters : UNIAN news]. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 29 April 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ a b «Красный Луч и Первомайск «слились». Кто дальше? — Новости Луганска и Луганской области — Луганский Радар» [Krasny Luch and Pervomaisk «merged». Who’s next? — News of Lugansk and Luhansk region — Lugansk Radar]. Lugradar.net. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Автор: Ищук (29 April 2014). «Сепаратисты захватили горсовет Первомайска в Луганской области, — СМИ : Новости. Новости дня на сайте Подробности» [Separatists seized the city council of Pervomaisk in the Luhansk region, — media : News. News of the day on the site Details]. Podrobnosti.ua. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «Ukraine unrest: Kiev ‘helpless’ to quell parts of east». BBC News. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

I would like to say frankly that at the moment the security structures are unable to swiftly take the situation in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions back under control … More than that, some of these units either aid or co-operate with terrorist groups

- ^ Jade Walker (30 April 2014). «Ukraine Unrest: Separatists Seize Buildings In Horlivka». Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ В Стаханове вооруженные люди ограбили «Бизнес-центр» [In Stakhanov, armed people robbed the «Business Center»] (in Russian). V-variant.lg.ua. 7 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Dabagian, Stepan (7 May 2014). ‘Никаких националистических идей у нас нет. Мы просто за единую Украину и не хотим в Россию’ [We have no nationalistic ideas. We are simply for a united Ukraine and do not want to become part of Russia] (in Russian). Fakty.ua. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ «Жительница города Ровеньки: «Люди не понимают, что такое «Луганская республика», но референдума хотят» (Люди рассказывают, что не доверяют новой власти, ждут, когда их освободят от «нехороших людей», и хотят остаться в составе Украины)» [A resident of the city of Rovenky: «People do not understand what the «Luhansk Republic» is, but they want a referendum» (People say they do not trust the new government, they are waiting to be freed from «bad people» and want to remain part of Ukraine)]. Gigamir.net. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «Славяносербская милиция перешла на сторону сепаратистов — Новости Луганска и Луганской области — Луганский Радар» [Slavic Serb militia went over to the side of the separatists — News of Lugansk and Lugansk region — Luhansk Radar]. Lugradar.net. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «МВД Украины заявило о захвате милиции Славяносербска — Газета.Ru | Новости» [The Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine announced the capture of the militia of Slavyanoserbsk — Gazeta.Ru & # 124; News]. Gazeta.ru. 17 June 2013. Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «Город Антрацит взяли под контроль донские казаки — источник» [The city of Anthracite was taken under control by the Don Cossacks — source]. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Донские казаки взяли под контроль город Антрацит на Луганщине ›» [Don Cossacks took control of the city of Anthracite in the Luhansk region ›]. Mr7.ru. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «Putin’s Tourists Enter Ukraine – Dmitry Tymchuk». The Huffington Post. 6 May 2014. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ Shaun Walker (6 May 2014). «Ukraine border guards keep guns trained in both directions». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Северодонецк: сепаратисты захватили здание прокуратуры » ИИИ «Поток» | Главные новости дня» [Severodonetsk: separatists seized the building of the prosecutor’s office]. Potok.ua. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «КИУ: Вчера в Старобельске штурмовали райгосадминистрацию» [KIU: Yesterday the district state administration was stormed in Starobelsk]. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Украинские силовики взяли под контроль большую часть Луганской области — источник — Обозреватель». Obozrevatel.com. 10 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «Явка на референдуме в Луганской области превысила 75% :: Политика». Top.rbc.ru. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ a b «Ukraine crisis: Will the Donetsk referendum matter?». BBC News. 12 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Separatists Declare Independence Of Luhansk Region». The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Luhansk Regional Council demands Ukraine’s immediate federalization». KyivPost. 12 May 2014. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ a b «Luhansk». Interfax-Ukraine. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Luhansk separatists say their chief wounded in assassination attempt». Kyiv Post. 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ «Avakov Announces Capture of the ‘Commander of the Army of the South-East’«. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Luhansk separatist leader Bolotov free in Ukraine after suspicious ‘shootout’«. KyivPost. 17 May 2014. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ «Луганская и Донецкая республики объединились в Новороссию». Novorossia. 24 May 2014. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ «Lugansk People’s Republic wants to rewrite its laws according to Russian model». The Voice of Russia. 28 May 2014. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ «Ukraine’s Lugansk plans to hold parliamentary elections in Sept». GlobalPost. 28 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b Тезисы К Программе Первоочередных Действий Правительства Народной Республики [Theses for Priority Actions Programme for the Government of the People’s Republic]. lugansk-online.info (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b «Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine based on information received as of 18:00 (Kyiv time), 16 September 2014» (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ «Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine based on information received as of 18:00 (Kyiv time), 15 September 2014» (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 16 September 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ «Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine based on information received as of 18:00 (Kyiv time), 18 September 2014» (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ a b LPR Head: Election to Remove Doubts Surrounding Legitimacy of Luhansk Authorities, 27 September 2014 Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, RIA Novosti (27 September 2014)

- ^ a b c Ukraine crisis: Russia to recognise rebel vote in Donetsk and Luhansk Archived 1 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (28 October 2014)

- ^ «Ukraine crisis: UN sounds alarm on human rights in east». BBC News. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ a b Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 15 May 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d Almost 1,000 dead since east Ukraine truce – UN Archived 3 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (21 November 2014)

Ukraine death toll rises to more than 4,300 despite ceasefire – U.N. Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters (21 November 2014) - ^ Majority of human rights violations in Ukraine committed by militants – UN Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (15 December 2014)

- ^ Amnesty International alarmed by extrajudicial killings in self-proclaimed Luhansk republic Archived 17 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (14 November 2014)

Rebels in Ukraine ‘post video of people’s court sentencing man to death’ Archived 19 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph (31 October 2014)

Ukraine conflict: Summary justice in rebel east Archived 1 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (3 November 2014) - ^ «Комсомол Луганска — в борьбе за Единую Украину!» [Luhansk Komsomol for united Ukraine] (in Russian). Ленинский Коммунистический Союз Молодежи Украины. 21 January 2015. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ a b Non-transparent ‘justice systems’ set up in rebel-controlled Donbas areas mostly non-functional – OSCE SMM Archived 26 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (25 December 2015)

- ^ «Abuse, torture revealed at separatists’ prison in Luhansk». Kyiv Post. 3 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ East Ukraine summit looks unlikely to happen as violence spikes in region Archived 30 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian (11 January 2015)

- ^ Ukraine Rebel ‘Batman’ Battalion Commander Killed Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (4 January 2015)

- ^ a b «Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements» (Press release) (in Russian). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 12 February 2015. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ «Minsk agreement on Ukraine crisis: text in full». The Daily Telegraph. 12 February 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Donetsk, Luhansk republics say election proposals forwarded to Contact Group on Ukraine Archived 16 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Russian News Agency «TASS» (12 May 2015)

Analysis: Donetsk and Luhansk propose amendments to Ukraine’s Constitution Archived 29 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Ukrainian Weekly (22 May 2015)

«LNR» and «DNR» agree to a special status within Ukraine Donbas Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrayinska Pravda (9 June 2015) - ^ Militia leader not sure if unrecognized Luhansk republic will remain part of «new Ukraine» Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. TASS. 18 February 2015.

- ^ «Russian-backed ‘Novorossiya’ breakaway movement collapses». Ukraine Today. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

Проект «Новороссия» закрыт [Project «New Russia» is closed]. Gazeta.ru. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015. - ^ «Местные выборы в ЛНР перенесены на 24 июля». 19 April 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Zakharchenko postponed elections «DNR» in November Archived 7 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ukrayinska Pravda (23 July 2016)

(in Ukrainian) Militants «LPR» also decided to move their «elections» Archived 8 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ukrayinska Pravda (24 July 2016) - ^ a b Defying Minsk process, Russian-backed separatists hold illegal elections Archived 3 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Kyiv Post (2 October 2016)

Donbass militia leader announces autumn primaries in Donetsk Archived 5 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, TASS news agency (23 May 2016) - ^ LPR reports one of its former ‘officials’ Tsypkalov commits suicide Archived 25 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (24 September 2016)

- ^ a b c Ukrainian rebel leaders divided by bitter purge Archived 7 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post (3 October 2016)

- ^ a b Ukraine conflict: Rebel commander killed in bomb blast Archived 4 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (4 February 2017)

- ^ Ukrainian energy industry: thorny road of reform Archived 10 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, UNIAN (10 January 2018)

- ^ a b «Kremlin ‘Following’ Situation In Ukraine’s Russia-Backed Separatist-Controlled Luhansk». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 22 November 2017. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ a b «Luhansk coup attempt continues as rival militia occupies separatist region». The Independent. 22 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ukraine rebel region’s security minister says he is new leader Archived 2 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters (24 November 2017)

Separatist Leader In Ukraine’s Luhansk Resigns Amid Power Struggle Archived 9 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe (24 November 2017) - ^ «Захар Прилепин встретил главу ЛНР в самолете в Москву». Meduza.io. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Народный совет ЛНР единогласно проголосовал за отставку Плотницкого (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Lugansk People’s Republic head resigns Archived 7 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, TASS news agency (24 November 2017)

- ^ Russia starts giving passports to Ukrainians from Donetsk, Luhansk Archived 15 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Welle (14 June 2019)

- ^ (in Ukrainian) The leader of fighters Pushilin gathered in «United Russia» Archived 15 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrayinska Pravda (15 July 2021)

(in Ukrainian) «United Russia» went on the offensive in the Donbas Archived 15 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Ukrainian Week (15 July 2021) - ^ (in Ukrainian) At Putin assure: We distribute passports of the Russian Federation in Donbas not for annexation of ORDLO Archived 20 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrayinska Pravda (20 July 2021)

- ^ «Ukrainian language removed from schools in Russian proxy Luhansk ‘republic’«. Human Rights in Ukraine. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ ««Через дискримінацію російської»: в окупованому «виші» остаточно скасували українську» [“Due to Russian discrimination”: in the occupied “higher education” the Ukrainian was finally abolished]. Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Radio Free Europe. 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b (in Ukrainian) Militants presented the «doctrine»: provides capture of all Donbas Archived 28 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrayinska Pravda (28 January 2021)

- ^ Hernandez, Joe (22 February 2022). «Why Luhansk and Donetsk are key to understanding the latest escalation in Ukraine». NPR. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Hodge, Nathan (22 February 2022). «Russia’s Federation Council gives consent to Putin on use of armed forces abroad, Russian agencies report». CNN International. Moscow. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ «Ukraine conflict: Biden sanctions Russia over ‘beginning of invasion’«. BBC News. 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Nikolskaya, Polina; Osborn, Andrew (24 February 2022). «Russia’s Putin authorises ‘special military operation’ against Ukraine». Reuters. Moscow. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Grunau, Andrea; von Hein, Matthias; Theise, Eugen; Weber, Joscha (25 February 2022). «Fact check: Do Vladimir Putin’s justifications for going to war against Ukraine add up?». Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (3 March 2022). «Historians on What Putin Gets Wrong About ‘Denazification’ in Ukraine». Time. ISSN 0040-781X. OCLC 1311479. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Stepanenko, Kateryna (10 September 2022). «RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE CAMPAIGN ASSESSMENT, SEPTEMBER 10». understandingwar.org. Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ @GirkinGirkin (19 September 2022). «Білогорівка, Луганська обл» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ «Путин подписал указы о признании ЛНР и ДНР». TASS (in Russian). 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ «Ukraine cuts N Korea ties over recognition of separatist regions». Al Jazeera. 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ «Syria recognizes independence, sovereignty of Donetsk, Luhansk -state news agency». Reuters. 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ McFall, Caitlin (16 June 2022). «Syria to become first to recognize Donetsk, Luhansk ‘republics’ in Ukraine in support of Russia’s war». Fox News. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ South Ossetia Recognizes ‘Luhansk People’s Republic’ Archived 11 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Radio free Europe (19 June 2014)

- ^ «Abkhazia recognises Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk». OC Media. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ «Supreme Court of Ukraine». Єдиний державний реєстр судових рішень (ЄДРСР). Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- ^ «EU terrorist list». www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ «EU terrorist list – Consilium». www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ «Международные террористические организации | Интернет-портал Национального антитеррористического комитета». 2 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Putin orders Russia to recognize documents issued in rebel-held east Ukraine Archived 19 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters (18 February 2017)

- ^ Putin Signs Decree Temporarily Recognizing Passports Issued By Separatists In Ukraine Archived 18 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe (18 February 2017)

- ^ Russia accepts passports issued by east Ukraine rebels Archived 21 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (19 February 2017)

- ^ «Russia claims ‘full control’ over Ukraine’s Luhansk region», Anadolu Agency, 3 July 2022

- ^ «Medvedev dreams of the collapse of Ukraine and showed a “map”», The Odessa Journal, 28 July 2022

- ^ Mirovalev, Mansur. «Donetsk and Luhansk: What you should know about the ‘republics’«. Aljazeera. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ «Konstitutsiya Luganskoy Narodnoy Respubliki». People’s Council, Luhansk People’s Republic. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ a b c «Date of elections in Donetsk, Luhansk People’s republics the same – Nov. 2» Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Russian News Agency «TASS» (11 October 2014)

- ^ «В ЛНР утвердили официальный гимн республики (аудио)». 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ «Закон «О Государственном гимне Луганской Народной Республики»» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b Ukraine urges Russia to stop separatist elections Archived 17 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, USA TODAY (21 October 2014)

- ^ Local elections in DPR to take place on October 18 – Zakharchenko Archived 3 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (2 July 2015)

DPR, «LPR attempts to hold separate elections in Donbas on Oct 18 to have destructive consequences – Poroshenko» Archived 3 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Interfax-Ukraine (2 July 2015) - ^ Pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine postpone disputed elections Archived 1 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters (6 October 2015)

«Ukraine rebels to delay elections». The Washington Post. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. - ^ a b c Ukraine crisis: Pro-Russian rebels ‘delay disputed elections’ Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (6 October 2015)

Hollande: Elections In Eastern Ukraine Likely To Be Delayed Archived 5 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (2 October 2015)

Ukraine Is Being Told to Live With Putin Archived 6 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg News (5 October 2015) - ^ hermesauto (11 November 2018). «Ukraine rebels hold elections in defiance of West». The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ «Ukraine Rebel Regions Vote in Ballot That West Calls Bogus». Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Khalil, Rania. «LPR Election Commission Delivers Accreditations To Int’l Observers Ahead Of Sunday’s Vote». Pakistan Point. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ «Луганский Информационный Центр – Глава ЛНР поздравил военнослужащих с третьей годовщиной создания Народной милиции (ФОТО)». lug-info.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ «В Луганске отметили трехлетие создания Народной Милиции».

- ^ ««Мы не всегда афишируем нашу силу, но мы точно знаем, что наша армия нас защитит!» – Игорь Плотницкий». Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Олег Бугров, бывший министр ЛНР, в марте 2015, задержан Следственной службой ФСБ. По версии силовиков, он участвовал в поставке «Роснефтьбункеру» Archived 22 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine (порт Усть-Луга) некондиционных труб, бывших в употреблении.

- ^ «ХХІ век» № 111 от 10 October 2014

- ^ «Ukraine at OSCE: Russian corps in Donbas larger than some European armies». www.ukrinform.net. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ «Структура гибридной армии «Новороссии» (ИНФОГРАФИКА) – новости АТО». www.depo.ua (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ «Russia and the Separatists in Eastern Ukraine» (PDF). International Crisis Group. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ a b «Eastern Donbas: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report». Freedom House. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Mirovalev, Mansur. «Donetsk and Luhansk: What you should know about the ‘republics’«. www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Surkova, Yulia; Krasnolutska, Daryna (4 May 2015). «Forget Tanks. Russia’s Ruble Is Conquering Eastern Ukraine». Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Ian Bateson (12 November 2014). «Donbas civil society leaders accuse Ukraine of ‘declaring war’ on own people». Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ «Luhansk People’s Republic». CONIFA. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ «Ukraine’s First Separatist Football Derby». Sports. 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

External links

- Official website of the Council of Ministers of LPR (in Russian)[dead link]

- Lugansk Media Centre

|

Luhansk People’s Republic[b] Луганская Народная Республика |

|

|---|---|

|

Military occupation and annexation |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Государственный Гимн Луганской Народной Республики Gosudarstvennyy Gimn Luganskoy Narodnoy Respubliki «State Anthem of the Luhansk People’s Republic» |

|

![Ukraine's Luhansk Oblast in Europe, claimed and militarily contested as the Luhansk People's Republic by Russia and its separatist militant formations[4]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Location_of_Lugansk_People%27s_Republic.png/250px-Location_of_Lugansk_People%27s_Republic.png)

Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast in Europe, claimed and militarily contested as the Luhansk People’s Republic by Russia and its separatist militant formations[4] |

|

| Occupied country | Ukraine |

| Occupying power | Russia |

| Breakaway state[a] | Lugansk People’s Republic (2014–2022) |

| Disputed republic of Russia | Lugansk People’s Republic (2022–present) |

| Entity established | 27 April 2014[5] |

| Eastern Ukraine offensive | 24 February 2022 |

| Annexation by Russia | 30 September 2022 |

| Administrative centre | Luhansk |

| Government | |

| • Body | People’s Council |

| • Head of the LPR | Leonid Pasechnik |

| Population

(2019)[6] |

|

| • Total | 1,485,300[c] |

The Luhansk People’s Republic or Lugansk People’s Republic[d] (Russian: Луга́нская Наро́дная Респу́блика, romanized: Luganskaya Narodnaya Respublika, IPA: [lʊˈɡanskəjə nɐˈrodnəjə rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə]; abbreviated as LPR or LNR, Russian: ЛНР) is an unrecognised republic of Russia in the occupied parts of eastern Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast, with its capital in Luhansk.[7][8] The LPR was created by militarily-armed Russian-backed separatists in 2014, and it initially operated as a breakaway state until it was annexed by Russia in 2022.

Following Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity in 2014, pro-Russian unrest erupted in the eastern part of the country. Shortly thereafter, Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine, while the armed separatists seized government buildings and proclaimed the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) and Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) as independent states, which received no international recognition from United Nations member states before 2022. This sparked the War in Donbas, part of the wider Russo-Ukrainian War.

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognised the LPR and DPR as sovereign states. Three days later, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, partially under the pretext of protecting the republics. Russian forces captured more of Luhansk Oblast (almost the entirety of it),[9] which became part of the LPR. In September 2022, Russia announced the annexation of the LPR and other occupied territories, following disputed referendums which were illegal under international law. The United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling on countries not to recognise what it called the «attempted illegal annexation» and demanded that Russia «immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw».[10]

The Head of the Luhansk People’s Republic is Leonid Pasechnik, and its parliament is the People’s Council. The ideology of the LPR is said to have been shaped by right-wing Russian nationalism, neo-imperialism and Orthodox fundamentalism.[11] Organizations such as the United Nations Human Rights Office and Human Rights Watch have reported human rights abuses in the LPR, including internment, torture, extrajudicial killings, forced conscription, as well as political and media repression. Ukraine views the LPR and DPR as terrorist organisations.[12] The LPR and DPR are sometimes described as puppet states of Russia during their periods of nominal independence.[1][2][3]

Geography and demographics

The 2014 constitution of the Luhansk People’s Republic (art. 54.1) defined the territory of the republic as «determined by the borders existing on the day of establishment», without describing the borders.[13] From February 2015 up until February 2022, the LPR’s de facto borders were the Russo–Ukrainian border (south and east), the border between Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast and Donetsk Oblast (west), and the line of contact with Ukrainian troops (north) as defined in the Minsk agreements between Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE. When the Russian president announced recognition of the republics’ independence on February 22, 2022, he said «we recognized all their fundamental documents, including the constitution. And the constitution spells out the borders within the Donetsk and Luhansk regions at the time when they were part of Ukraine».[14]

Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast and the LPR-controlled area from April 2014 to February 2022 are both landlocked.

The highest point in left-bank Ukraine is Mohyla Mechetna hill (367.1 m (1,204 ft) above sea level), which is located in the vicinity of the city of Petrovske, in LPR-controlled territory.[15]

In December 2017, approximately 1.4 million lived in the LPR’s territory, with 435,000 in the city of Luhansk.[16] Leaked documents suggest that less than three million people, less than half of the pre-war population, remained in the separatist territories that Moscow controlled in eastern Ukraine in early February 2022, and 38% of those remaining were pensioners.[17]

On 18 February 2022, the LPR and DPR separatist authorities ordered a general evacuation of women and children to Russia, and the next day a full mobilization of males «able to hold a weapon in their hands».[18]

History

Luhansk and Donetsk People’s republics are located in the historical region of Donbas, which was added to Ukraine in 1922.[19] The majority of the population speaks Russian as their first language. Attempts by various Ukrainian governments to question the legitimacy of the Russian culture in Ukraine had since the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine often resulted in political conflict. In the Ukrainian national elections, a remarkably stable pattern had developed, where Donbas and the Western Ukrainian regions had voted for the opposite candidates since the presidential election in 1994. Viktor Yanukovych, a Donetsk native, had been elected as a president of Ukraine in 2010. His overthrow in the 2014 Ukrainian revolution led to protests in Eastern Ukraine, which gradually escalated into an armed conflict between the newly formed Ukrainian government and the local armed militias.[20]

Formation (2014–2015)

Occupation of government buildings

A Luhansk People’s Republic People’s Militia member in June 2014

A demonstration in Luhansk, 1 May 2014

On 5 March 2014, 12 days after the protesters in Kyiv seized the president’s office (at the time Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had already fled Ukraine[21]),[22] a crowd of people in front of the Luhansk Oblast State Administration building proclaimed Aleksandr Kharitonov as «People’s Governor» in Luhansk region. On 9 March 2014 Luganskaya Gvardiya of Kharitonov stormed the government building in Luhansk and forced the newly appointed Governor of Luhansk Oblast, Mykhailo Bolotskykh, to sign a letter of resignation.[23]

One thousand pro-Russian activists seized and occupied the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) building in the city of Luhansk on 6 April 2014, following similar occupations in Donetsk and Kharkiv.[24][25] The activists demanded that separatist leaders who had been arrested in previous weeks be released.[24] In anticipation of attempts by the government to retake the building, barricades were erected to reinforce the positions of the activists.[26][27] It was proposed by the activists that a «Lugansk Parliamentary Republic» be declared on 8 April 2014, but this did not occur.[28][29] By 12 April, the government had regained control over the SBU building with the assistance of local police forces.[30]

Several thousand protesters gathered for a ‘people’s assembly’ outside the regional state administration (RSA) building in Luhansk city on 21 April. These protesters called for the creation of a ‘people’s government’, and demanded either federalisation of Ukraine or incorporation of Luhansk into the Russian Federation.[31] They elected Valery Bolotov as ‘People’s Governor’ of Luhansk Oblast.[32] Two referendums were announced by the leadership of the activists. One was scheduled for 11 May, and was meant to determine whether the region would seek greater autonomy (and potentially independence), or retain its previous constitutional status within Ukraine. Another referendum, meant to be held on 18 May in the event that the first referendum favoured autonomy, was to determine whether the region would join the Russian Federation, or become independent.[33]

Valery Bolotov proclaims the Act of Independence of the Luhansk People’s Republic, 12 May 2014

During a gathering outside the RSA building on 27 April 2014, pro-Russian activists proclaimed the «Luhansk People’s Republic».[34] The protesters issued demands, which said that the Ukrainian government should provide amnesty for all protesters, include the Russian language as an official language of Ukraine, and also hold a referendum on the status of Luhansk Oblast.[34] They then warned the Ukrainian government that if it did not meet these demands by 14:00 on 29 April, they would launch an armed insurgency in tandem with that of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR).[34][35]

As the Ukrainian government did not respond to these demands, 2,000 to 3,000 activists, some of them armed, seized the RSA building, and a local prosecutor’s office, on 29 April.[36] The buildings were both ransacked, and then occupied by the protesters.[37] Protestors waved local flags, alongside those of Russia and the neighbouring Donetsk People’s Republic.[38] The police officers that had been guarding the building offered little resistance to the takeover, and some of them defected and supported the activists.[39]

Territorial expansion