Ljubljana[a] (also known by other historical names) is the capital and largest city of Slovenia.[14][15] It is the country’s cultural, educational, economic, political and administrative center.

|

Ljubljana |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city |

|

Clockwise from top: Ljubljana Castle; Franciscan Church of the Annunciation; Kazina Palace at Congress Square; one of the Dragons on the Dragon Bridge; Visitation of Mary Church on Rožnik Hill; Ljubljana City Hall; and Ljubljanica with the Triple Bridge in distance |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

|

Ljubljana Location of Ljubljana in Slovenia Ljubljana Ljubljana (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 46°03′05″N 14°30′22″E / 46.05139°N 14.50611°ECoordinates: 46°03′05″N 14°30′22″E / 46.05139°N 14.50611°E | |

| Country | |

| Municipality | City Municipality of Ljubljana |

| First mention | 1112–1125 |

| Town privileges | 1220–1243 |

| Roman Catholic diocese | 6 December 1461 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Zoran Janković (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 163.8 km2 (63.2 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,334 km2 (901 sq mi) |

| Elevation

[2] |

295 m (968 ft) |

| Population

(2020)[3] |

|

| • Capital city | |

| • Density | 1,712/km2 (4,430/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 537,893[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal codes |

1000–1211, 1231, 1260, 1261[4] |

| Area code | 01 (+386 1 if calling from abroad) |

| Vehicle Registration | LJ |

| Website | www.ljubljana.si |

During antiquity, a Roman city called Emona stood in the area.[16] Ljubljana itself was first mentioned in the first half of the 12th century. Situated at the middle of a trade route between the northern Adriatic Sea and the Danube region, it was the historical capital of Carniola,[17] one of the Slovene-inhabited parts of the Habsburg monarchy.[14] It was under Habsburg rule from the Middle Ages until the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. After World War II, Ljubljana became the capital of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The city retained this status until Slovenia became independent in 1991 and Ljubljana became the capital of the newly formed state.[18]

NameEdit

The origin of the name Ljubljana is unclear. In the Middle Ages, both the river and the town were also known by the German name Laibach. This name was in official use as an endonym until 1918, and it remains frequent as a German exonym, both in common speech and official use. The city is called Lubiana in Italian and Labacum in Latin.[19]

The earliest attestation of the German name is from 1144 and the earliest attestation of the Slovenian form is 1146. The Greek form of the latter, Λυπλιανές (Lyplianes), is attested in a 10th-century source, the Life of Gregentios, which locates it in the country of the Avars in the 6th century. This part of the Life is based on a north Italian source written not long after the conquest of 774.[20]

For most scholars, a problem has been in how to connect the Slovene and the German names. The origin from the Slavic ljub— «to love, like» was in 2007 supported as the most probable by the linguist Tijmen Pronk, a specialist in comparative Indo-European linguistics and Slovene dialectology, from the University of Leiden.[21] He supported the thesis that the name of the river derived from that of the settlement.[22] Linguist Silvo Torkar, who specialises in Slovene personal and place names,[23] argued that the name Ljubljana derives from Ljubija, the original name of the Ljubljanica River flowing through it, itself derived from the Old Slavic male name Ljubovid, «the one of a lovely appearance». The name Laibach, he claimed, was actually a hybrid of German and Slovene and derived from the same personal name.[24]

Dragon symbolEdit

The city’s symbol is the Ljubljana Dragon. It is depicted on the top of the tower of Ljubljana Castle in the Ljubljana coat of arms and on the Ljubljanica-crossing Dragon Bridge (Zmajski most).[25] It represents power, courage, and greatness.

Several explanations describe the origin of the Ljubljana Dragon. According to a Slavic myth, the slaying of a dragon releases the waters and ensures the fertility of the earth, and it is thought that the myth is tied to the Ljubljana Marsh, the expansive marshy area that periodically threatens Ljubljana with flooding.[26] According to Greek legend, the Argonauts on their return home after having taken the Golden Fleece found a large lake surrounded by a marsh between the present-day towns of Vrhnika and Ljubljana. There Jason struck down a monster. This monster evolved into the dragon that today is present in the city coat of arms and flag.[27]

It is historically more believable that the dragon was adopted from Saint George, the patron of the Ljubljana Castle chapel built in the 15th century. In the legend of Saint George, the dragon represents the old ancestral paganism overcome by Christianity. According to another explanation, related to the second, the dragon was at first only a decoration above the city coat of arms. In the Baroque, it became part of the coat of arms, and in the 19th and especially the 20th century, it outstripped the tower and other elements in importance.

HistoryEdit

PrehistoryEdit

Around 2000 BC, the Ljubljana Marsh was settled by people living in pile dwellings. Prehistoric pile dwellings and the oldest wooden wheel in the world[28] are among the most notable archeological findings from the marshland. These lake-dwelling people survived through hunting, fishing and primitive agriculture. To get around the marshes, they used dugout canoes made by cutting out the inside of tree trunks. Their archaeological remains, nowadays in the Municipality of Ig, have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site since June 2011, in the common nomination of six Alpine states.[29][30]

Later, the area remained a transit point, for groups including the Illyrians, followed by a mixed nation of the Celts and the Illyrians called the Iapydes, and then in the 3rd century BC a Celtic tribe, the Taurisci.[31]

AntiquityEdit

Around 50 BC, the Romans built a military encampment that later became a permanent settlement called Iulia Aemona.[33][34][35] This entrenched fort was occupied by the Legio XV Apollinaris.[36] In 452, it was destroyed by the Huns under Attila’s orders,[33] and later by the Ostrogoths and the Lombards.[37] Emona housed 5,000 to 6,000 inhabitants and played an important role during battles. Its plastered brick houses, painted in different colours, were connected to a drainage system.[33]

In the 6th century, the ancestors of the Slovenes moved in. In the 9th century, they fell under Frankish domination, while experiencing frequent Magyar raids.[38] Not much is known about the area during the settlement of Slavs in the period between the downfall of Emona and the Early Middle Ages.

Middle AgesEdit

The parchment sheet Nomina defunctorum («Names of the Dead»), most probably written in the second half of 1161, mentions the nobleman Rudolf of Tarcento, a lawyer of the Patriarchate of Aquileia, who had bestowed a canon with 20 farmsteads beside the castle of Ljubljana (castrum Leibach) to the Patriarchate. According to the historian Peter Štih’s deduction, this happened between 1112 and 1125, the earliest mention of Ljubljana.[39]

The property changed hands repeatedly until the first half of the 12th century. The territory south of the Sava where Ljubljana developed, gradually became property of the Carinthian Dukes of the House of Sponheim.[39] Urban settlement started in the second half of the 12th century.[39] At around 1200, market rights were granted to Old Square (Stari trg),[40] which at the time was one of Ljubljana’s three original districts. The other two districts were an area called «Town» (Mesto), built around the predecessor of the present-day Ljubljana Cathedral at one side of the Ljubljanica River, and New Square (Novi trg) at the other side.[41] The Franciscan Bridge, a predecessor of the present-day Triple Bridge, and the Butchers’ Bridge connected the walled areas with wooden buildings.[41] Ljubljana acquired the town privileges at some time between 1220 and 1243.[42] Seven fires erupted during the Middle Ages.[43] Artisans organised themselves into guilds. The Teutonic Knights, the Conventual Franciscans, and the Franciscans settled there.[44] In 1256, when the Carinthian duke Ulrich III of Spanheim became lord of Carniola, the provincial capital was moved from Kamnik to Ljubljana.

In the late 1270s, Ljubljana was conquered by King Ottokar II of Bohemia.[45] In 1278, after Ottokar’s defeat, it became—together with the rest of Carniola—property of Rudolph of Habsburg.[37][38] It was administered by the Counts of Gorizia from 1279 until 1335,[40][46][47] when it became the capital town of Carniola.[38] Renamed Laibach, it was owned by the House of Habsburg until 1797.[37] In 1327, the Ljubljana’s «Jewish Quarter»—now only «Jewish Street» (Židovska ulica) remains—was established with a synagogue, and lasted until Emperor Maximilian I in 1515 succumbed to medieval antisemitism and expelled Jews from Ljubljana, for which he demanded a certain payment from the town.[40] In 1382, in front of St. Bartholomew’s Church in Šiška, at the time a nearby village, now part of Ljubljana, a peace treaty was signed between the Republic of Venice and Leopold III of Habsburg.[40]

Early modernEdit

In the 15th century, Ljubljana became recognised for its art, particularly painting and sculpture. The Roman Rite Catholic Diocese of Ljubljana was established in 1461 and the Church of St. Nicholas became the diocesan cathedral.[38] After the 1511 Idrija earthquake,[48][49][50][51] the city was rebuilt in the Renaissance style and a new wall was built around it.[52] Wooden buildings were forbidden after a large fire at New Square in 1524.

In the 16th century, the population of Ljubljana numbered 5,000, 70% of whom spoke Slovene as their first language, with most of the rest using German.[52] The first secondary school, public library and printing house opened in Ljubljana. Ljubljana became an important educational centre.[53]

From 1529, Ljubljana had an active Slovene Protestant community. They were expelled in 1598, marking the beginning of the Counter-Reformation. Catholic Bishop Thomas Chrön ordered the public burning of eight cartloads of Protestant books.[54][55]

In 1597, the Jesuits arrived, followed in 1606 by the Capuchins, seeking to eradicate Protestantism. Only 5% of all the residents of Ljubljana at the time were Catholic, but eventually they re-Catholicized the town. The Jesuits staged the first theatre productions, fostered the development of Baroque music, and established Catholic schools. In the middle and the second half of the 17th century, foreign architects built and renovated monasteries, churches, and palaces and introduced Baroque architecture. In 1702, the Ursulines settled in the town, and the following year they opened the first public school for girls in the Slovene Lands. Some years later, the construction of the Ursuline Church of the Holy Trinity started.[56][57] In 1779, St. Christopher’s Cemetery replaced the cemetery at St. Peter’s Church as Ljubljana’s main cemetery.[58]

Late modernEdit

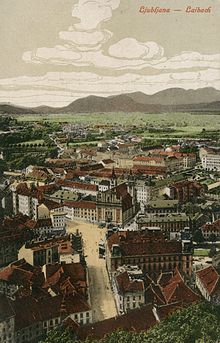

Ljubljana in the 18th century

The 1895 earthquake destroyed much of the city centre, enabling an extensive renovation program.

The oldest preserved film recordings of Ljubljana (1909), with a depiction of streets, the Ljubljana tram, and a celebration. Salvatore Spina Company, Trieste.[59]

From 1809 to 1813, during the «Napoleonic interlude», Ljubljana (as Laybach) was the capital of the Illyrian Provinces.[37][60] In 1813, the city returned to Austria and from 1815 to 1849 was the administrative centre of the Kingdom of Illyria in the Austrian Empire.[61] In 1821, it hosted the Congress of Laibach, which fixed European political borders for that period.[62][63] The first train arrived in 1849 from Vienna and in 1857 the line extended to Trieste.[60]

In 1895 Ljubljana, then a city of 31,000, suffered a serious earthquake measuring 6.1 Richter and 8–9 degrees MCS.[64][65][66][67] Some 10% of its 1,400 buildings were destroyed, although casualties were light.[64] During the subsequent reconstruction, some districts were rebuilt in the Vienna Secession style.[60] Public electric lighting arrived in 1898. The rebuilding period between 1896 and 1910 is referred to as the «revival of Ljubljana» because of architectural changes that defined the city and for reform of urban administration, health, education and tourism. The rebuilding and quick modernisation of the city were led by the mayor Ivan Hribar.[60]

In 1918, following the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the region joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[37][68][69] In 1929, Ljubljana became the capital of the Drava Banovina, a Yugoslav province.[70]

In 1941, during World War II, Fascist Italy occupied the city, and then on 3 May 1941 made Lubiana the capital of Italy’s Province of Ljubljana[71] with former Yugoslav general Leon Rupnik as mayor. After the Italian capitulation, Nazi Germany with SS-general Erwin Rösener and Friedrich Rainer took control in 1943,[68] but formally the city remained the capital of an Italian province until 9 May 1945. In Ljubljana, the Axis forces established strongholds and command centres of Quisling organisations, the Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia under Italy and the Home Guard under German control. Starting in February 1942, the city was surrounded by barbed wire, later fortified by bunkers, to prevent co-operation between the resistance movements that operated inside and outside the fence.[72][73] Since 1985, the commemorative trail has ringed the city where this iron fence once stood.[74] Postwar reprisals filled mass graves.[75][76][77][78]

After World War II, Ljubljana became the capital of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It retained this status until Slovene independence in 1991.[18]

Contemporary situationEdit

Ljubljana is the capital of independent Slovenia, which joined the European Union in 2004.[68]

GeographyEdit

Mount Saint Mary, the highest hill in Ljubljana, with the peak Grmada reaching 676 m (2,218 ft)

The city covers 163.8 km2 (63.2 sq mi). It is situated in the Ljubljana Basin in Central Slovenia, between the Alps and the Karst. Ljubljana is located some 320 km (200 mi) south of Munich, 477 km (296 mi) east of Zürich, 250 km (160 mi) east of Venice, 350 km (220 mi) southwest of Vienna, 124 km (77 mi) west of Zagreb and 400 km (250 mi) southwest of Budapest.[79] Ljubljana has grown considerably in the past 40 years, mainly by merging with nearby settlements.[80]

GeologyEdit

The city stretches out on an alluvial plain dating to the Quaternary era. The mountainous regions nearby are older, dating from the Mesozoic (Triassic) or Paleozoic.[81] Earthquakes have repeatedly devastated Ljubljana, notably in 1511 and 1895.[67]

TopographyEdit

Ljubljana has an elevation of 295 m (968 ft).[82] The city centre, located along the river, sits at 298 m (978 ft).[83] Ljubljana Castle, which sits atop Castle Hill (Grajski grič) south of the city centre, has an elevation of 366 m (1,201 ft). The highest point of the city, called Grmada, reaches 676 m (2,218 ft), 3 m (9.8 ft) more than the nearby Mount Saint Mary (Šmarna gora) peak, a popular hiking destination.[84][85] These are located in the northern part of the city.[84]

View to the south from Ljubljana Castle with the Ljubljana Marsh in the back. The building density there is substantially lower due to unsuitable ground for construction.

Bodies of waterEdit

River in the centre of Ljubljana

Bridges across the Ljubljanica River are popular tourist attractions

Koseze Pond is used for rowing, fishing, and ice skating in winter.

The main watercourses in Ljubljana are the Ljubljanica, the Sava, the Gradaščica, the Mali Graben, the Iška and the Iščica rivers. From the Trnovo District to the Moste District, around Castle Hill, the Ljubljanica partly flows through the Gruber Canal, built according to plans by Gabriel Gruber from 1772 until 1780. Next to the eastern border, the rivers Ljubljanica, Sava, and Kamnik Bistrica flow together.[86][87] The confluence is the lowest point of Ljubljana, with an elevation of 261 m (856 ft).[83]

Through its history, Ljubljana has been struck by floods. The latest was in 2010.[88] Southern and western parts of the city are more flood-endangered than northern parts.[89] The Gruber Canal has partly diminished the danger of floods in the Ljubljana Marsh, the largest marsh in Slovenia, south of the city.

The two major ponds in Ljubljana are Koseze Pond in the Šiška District and Tivoli Pond in the southern part of Tivoli City Park.[90] Koseze Pond has rare plant and animal species and is a place of meeting and recreation.[91] Tivoli Pond is a shallow pond with a small volume that was originally used for boating and ice skating, but is now used for fishing.[92]

ClimateEdit

Ljubljana’s climate is oceanic (Köppen climate classification: Cfb), bordering on a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa), with continental characteristics such as warm summers and moderately cold winters.[93][94] July and August are the warmest months with daily high temperatures generally between 25 and 30 °C (77 and 86 °F), and January is the coldest month with temperatures mostly around 0 °C (32 °F). The city experiences 90 days of frost per year, and 11 days with temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F). Precipitation is relatively evenly distributed throughout the seasons, although winter and spring tend to be somewhat drier than summer and autumn. Yearly precipitation is about 1,400 mm (55 in), making Ljubljana one of the wettest European capitals. Thunderstorms are common from May to September and can occasionally be heavy. Snow is common from December to February; on average, snow cover is recorded for 48 days a year. The city is known for its fog, appearing on average on 64 days per year, mostly in autumn and winter, and can be particularly persistent in conditions of temperature inversion.[95]

| Climate data for Ljubljana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.6 (96.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

40.2 (104.4) |

30.3 (86.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.2 (34.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.3 (−4.5) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69 (2.7) |

70 (2.8) |

88 (3.5) |

99 (3.9) |

109 (4.3) |

144 (5.7) |

115 (4.5) |

137 (5.4) |

147 (5.8) |

147 (5.8) |

129 (5.1) |

107 (4.2) |

1,362 (53.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 153 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 71 | 114 | 149 | 178 | 235 | 246 | 293 | 264 | 183 | 120 | 66 | 56 | 1,974 |

| Source 1: Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO)[96] (data for 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO)[97] OGIMET[98][99] (some extreme values for 1948–2022) |

CityscapeEdit

View of Ljubljana from Nebotičnik; Ljubljana Castle is on the left.

The city’s architecture is a mix of styles. Large buildings have appeared around the city’s edges, while Ljubljana’s historic centre remains intact. Some of the oldest architecture dates to the Roman period, while Ljubljana’s downtown got its outline in the Middle Ages.[100] After the 1511 earthquake, it was rebuilt in the Baroque style following Italian, particularly Venetian, models.

After the earthquake in 1895, it was again rebuilt, this time in the Vienna Secession style, which is juxtaposed against the earlier Baroque style buildings that remain. Large sectors built in the inter-war period often include a personal touch by the architects Jože Plečnik[101] and Ivan Vurnik.[102] In the second half of the 20th century, parts of Ljubljana were redesigned by Edvard Ravnikar.[103]

CentralEdit

The central square in Ljubljana is Prešeren Square (Prešernov trg) home to the Franciscan Church of the Annunciation (Frančiškanska cerkev). Built between 1646 and 1660 (the bell towers followed), it replaced an older Gothic church. It offers an early-Baroque basilica with one nave and two rows of lateral chapels. The Baroque main altar was executed by sculptor Italian Francesco Robba. Much of the original frescos were ruined by ceiling cracks caused by the Ljubljana earthquake in 1895. The new frescos were painted by the Slovene impressionist painter Matej Sternen.

Ljubljana Castle (Ljubljanski grad) is a medieval castle with Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance architectural elements, located on the summit of Castle Hill, which dominates the city centre.[104] The area surrounding the castle has been continuously inhabited since 1200 BC.[105] The castle was built in the 12th century and was a residence of the Margraves, later the Dukes of Carniola.[106] Its Viewing Tower dates to 1848; it was manned by a guard whose duty it was to fire cannons announcing fire or important visitors or events, a function the castle still holds.[105] Cultural events and weddings also take place there.[107] In 2006, a funicular linked the city centre to the castle.[108]

Town Hall (Mestna hiša, Magistrat), located at Town Square, is the seat of city government. The original, Gothic building was completed in 1484.[109] Between 1717 and 1719,[101] the building underwent a Baroque renovation with a Venetian inspiration by architect Gregor Maček Sr.[110] Near Town Hall, at Town Square, stands a replica of the Baroque Robba Fountain. The original was moved into the National Gallery in 2006. The fountain is decorated with an obelisk; at the foot are three figures in white marble symbolising the three chief rivers of Carniola. It is work of Francesco Robba, who designed other Baroque statues there.[111]

Ljubljana Cathedral (ljubljanska stolnica), or St. Nicholas’s Cathedral (stolnica sv. Nikolaja), serves the Archdiocese of Ljubljana. Easily identifiable due to its green dome and twin towers, it is located at Cyril and Methodius Square (Ciril-Metodov trg, named for Saints Cyril and Methodius).[112] The Diocese was set up in 1461.[112] Between 1701 and 1706, Jesuit architect Andrea Pozzo designed the Baroque church with two side chapels shaped in the form of a Latin cross.[112] The dome was built in the centre in 1841.[112] The interior is decorated with Baroque frescos painted by Giulio Quaglio between 1703–1706 and 1721–1723.[112]

Nebotičnik (pronounced [nɛbɔtiːtʃniːk], «Skyscraper») is a thirteen-story building that rises to a height of 70.35 m (231 ft). It combines elements of Neoclassical and Art-Deco architecture. Predominantly a place of business, Nebotičnik is home to shops on the ground floor and first story, and offices are located on floors two to five. The sixth to ninth floors are private residences. The top three floors host a café, bar and observation deck.[113] It was designed by Slovenian architect Vladimir Šubic. The building opened on 21 February 1933.[114] It was once the tallest residential building in Europe.[114]

-

Prešeren Square in downtown Ljubljana

-

Ljubljanica River, downtown Ljubljana

Public green spacesEdit

Tivoli City Park (Mestni park Tivoli) is the largest park.[115][116] It was designed in 1813 by French engineer Jean Blanchard and now covers approximately 5 km2 (1.9 sq mi).[115] The park was laid out during the French imperial administration of Ljubljana in 1813 and named after the Parisian Jardins de Tivoli.[115] Between 1921 and 1939, it was renovated by Slovene architect Jože Plečnik, who unveiled his statue of Napoleon in 1929 in Republic Square and designed a broad central promenade, called the Jakopič Promenade (Jakopičevo sprehajališče) after the leading Slovene impressionist painter Rihard Jakopič.[115][116] Within the park, there are trees, flower gardens, several statues, and fountains.[115][116] Several notable buildings stand in the park, among them Tivoli Castle, the National Museum of Contemporary History and the Tivoli Sports Hall.[115]

Tivoli–Rožnik Hill–Šiška Hill Landscape Park is located in the western part of the city.[117]

The Ljubljana Botanical Garden (Ljubljanski botanični vrt) covers 2.40 ha (5.9 acres) next to the junction of the Gruber Canal and the Ljubljanica, south of the Old Town. It is the central Slovenian botanical garden and the oldest cultural, scientific, and educational organisation in the country. It started operating under the leadership of Franc Hladnik in 1810. Of over 4,500 plant species and subspecies, roughly a third is endemic to Slovenia, whereas the rest originate from other European places and other continents. The institution is a member of the international network Botanic Gardens Conservation International and cooperates with more than 270 botanical gardens all across the world.[118]

In 2014, Ljubljana won the European Green Capital Award for 2016 for their environmental achievements.[119]

Bridges, streets and squaresEdit

Ljubljana’s best-known bridges, listed from northern to southern ones, include the Dragon Bridge (Zmajski most), the Butchers’ Bridge (Mesarski most), the Triple Bridge (Tromostovje), the Fish Footbridge (Slovene: Ribja brv), the Cobblers’ Bridge (Slovene: Šuštarski most), the Hradecky Bridge (Slovene: Hradeckega most), and the Trnovo Bridge (Trnovski most). The last mentioned crosses the Gradaščica, whereas all other bridges cross the Ljubljanica River.

The Dragon BridgeEdit

The 1901 Dragon Bridge, decorated with dragon statues[120] on pedestals at four corners of the bridge[121][122] has become a symbol of the city[123] and is regarded as one of the most beautiful examples of a bridge made in Vienna Secession style.[25][124][123][125] It has a span of 33.34 m (109 ft 5 in)[25] and its arch was at the time the third largest in Europe.[121] It is protected as a technical monument.[126]

The Butchers’ BridgeEdit

Decorated with mythological bronze sculptures, created by Jakov Brdar, from Ancient Greek mythology and Biblical stories,[127] the Butchers’ Bridge connects the Ljubljana Open Market area and the restaurants-filled Petkovšek Embankment (Petkovškovo nabrežje). It is also known as the love padlocks-decorated bridge in Ljubljana.

The Triple BridgeEdit

The Triple Bridge is decorated with stone balusters and stone lamps on all of the three bridges and leads to the terraces looking on the river and poplar trees. It occupies a central point on the east–west axis, connecting the Tivoli City Park with Rožnik Hill, on one side, and the Ljubljana Castle on the other,[128] and the north–south axis through the city, represented by the river. It was enlarged in order to prevent the historically single bridge from being a bottleneck by adding two side pedestrian bridges to the middle one.

The Fish FootbridgeEdit

The Fish Footbridge offers a view of the neighbouring Triple Bridge to the north and the Cobbler’s Bridge to the South. It is a transparent glass-made bridge, illuminated at night by in-built LEDs.[129] From 1991 to 2014 the bridge was a wooden one and decorated with flowers, while since its reconstruction in 2014, it is made of glass. It was planned already in 1895 by Max Fabiani to build a bridge on the location, in 1913 Alfred Keller planned a staircase, later Jože Plečnik incorporated both into his own plans which, however, were not realised.[130]

The Cobbler’s BridgeEdit

The 1930 ‘Cobblers’ Bridge’ (Šuštarski, from German Schuster – Shoemaker) is another Plečnik’s creation, connecting two major areas of medieval Ljubljana. It is decorated by two kinds of pillars, the Corinthian pillars which delineate the shape of the bridge itself and the Ionic pillars as lamp-bearers.[131]

The Trnovo BridgeEdit

The Trnovo Bridge is the most prominent object of Plečnik’s renovation of the banks of the Gradaščica. It is located in the front of the Trnovo Church to the south of the city centre. It connects the neighbourhoods of Krakovo and Trnovo, the oldest Ljubljana suburbs, known for their market gardens and cultural events.[132] It was built between 1929 and 1932. It is distinguished by its width and two rows of birches that it bears, because it was meant to serve as a public space in front of the church. Each corner of the bridge is capped with a small pyramid, a signature motif of Plečnik’s, whereas the mid-span features a pair of Art-Deco male sculptures. There is also a statue of Saint John the Baptist on the bridge, the patron of the Trnovo Church. It was designed by Nikolaj Pirnat.

The Hradecky BridgeEdit

Hradecky Bridge [hinged bridge]

The Hradecky Bridge is one of the first hinged bridges in the world,[133] the first[134] and the only preserved cast iron bridge in Slovenia,[135] and one of its most highly valued technical achievements.[136][137] It has been situated on an extension of Hren Street (Hrenova ulica), between the Krakovo Embankment (Krakovski nasip) and the Gruden Embankment (Grudnovo nabrežje), connecting the Trnovo District and the Prule neighbourhood in the Center District.[138] The Hradecky Bridge was manufactured according to the plans of the senior engineer Johann Hermann from Vienna in the Auersperg iron foundry in Dvor near Žužemberk,[137] and installed in Ljubljana in 1867, at the location of today’s Cobblers’ Bridge.[139]

Streets and squaresEdit

Stritar Street with the Robba Fountain

Having already existed in the 18th century, Ljubljana’s central square, Prešeren Square’s modern appearance has developed since the end of the 19th century. After the 1895 earthquake, Max Fabiani designed the square as the hub of four streets and four banks, and in the 1980s Edvard Ravnikar proposed the circular design and the granite block pavement.[140][141] A statue of the Slovene national poet France Prešeren with a muse stands in the middle of the square. The Prešeren Monument was created by Ivan Zajec in 1905, whereas the pedestal was designed by Max Fabiani. The square and surroundings have been closed to traffic since 1 September 2007.[142] Only a tourist train leaves Prešeren Square every day, transporting tourists to Ljubljana Castle.[142]

Republic Square, originally named Revolution Square, is the largest square in Ljubljana.[143] It was designed in the second half of the 20th century by Edvard Ravnikar.[143] On 26 June 1991, the independence of Slovenia was declared here.[143] The National Assembly Building stands at its northern side, and Cankar Hall, the largest Slovenian cultural and congress centre, at the southern side.[143] At its eastern side stands the two-storey building of Maximarket, also the work of Ravnikar. It houses one of the oldest department stores in Ljubljana and a cafe, which is a popular meeting place and a place for political talks and negotiations.[144]

Congress Square (Kongresni trg) is one of the important centres of the city. It was built in 1821 for ceremonial purposes such as Congress of Ljubljana after which it was named. Since then it has been a centre for political ceremonies, demonstrations, and protests, such as the ceremony for the creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, ceremony of the liberation of Belgrade, and protests against Yugoslav authority in 1988. The square also houses several important buildings, such as the University of Ljubljana Palace, Philharmonic Hall, Ursuline Church of the Holy Trinity, and the Slovene Society Building. Star Park (Park Zvezda) is located in the centre of the square. In 2010 and 2011, the square was renovated and is now mostly closed to road traffic on ground area, however, there are five floors for commercial purposes and a parking lot located underground.[145]

Čop Street (Čopova ulica) is a major thoroughfare in the centre of Ljubljana. The street is named after Matija Čop, an early 19th-century literary figure and close friend of the Slovene Romantic poet France Prešeren. It leads from the Main Post Office (Glavna pošta) at Slovene Street (Slovenska cesta) downward to Prešeren Square and is lined with bars and stores, including the oldest McDonald’s restaurant in Slovenia. It is a pedestrian zone and regarded as the capital’s central promenade.

CultureEdit

AccentEdit

The Ljubljana accent and/or dialect (Slovene: ljubljanščina [luːblɑːŋʃnɑː] ( listen)) is considered a border dialect, since Ljubljana is situated where the Upper dialect and Lower Carniolan dialect group meet. Historically,[146] the Ljubljana dialect in the past displayed features more similar with the Lower Carniolan dialect group, but it gradually grew closer to the Upper dialect group, as a direct consequence of mass migration from Upper Carniola into Ljubljana in the 19th and 20th century. Ljubljana as a city grew mostly to the north, and gradually incorporated many villages that were historically part of Upper Carniola and so its dialect shifted away and closer to the Upper dialects. The Ljubljana dialect has also been used as a literary means in novels, such as in the novel Nekdo drug by Branko Gradišnik,[147] or in poems, such as Pika Nogavička (Slovene for Pippi Longstocking) by Andrej Rozman — Roza.[148]

The central position of Ljubljana and its dialect had crucial impact[146] on the development of the Slovenian language. It was the speech of 16th century Ljubljana that Primož Trubar a Slovenian Protestant Reformer took as a foundation of what later became standard Slovenian language, with a small addition of his native speech, the Lower Carniolan dialect.[146][149] While in Ljubljana, he lived in a house, on today’s Ribji trg, in the oldest part of the city. Living in Ljubljana had a profound impact on his work; he considered Ljubljana the capital of all Slovenes, not only because of its central position in the heart of the Slovene lands, but also because it always had an essentially Slovene character. Most of its inhabitants spoke Slovene as their mother tongue, unlike other cites in today’s Slovenia. It is estimated that in Trubar’s time around 70% of Ljubljana’s 4000 inhabitants attended mass in Slovene.[146] Trubar considered Ljubljana’s speech most suitable, since it sounded much more noble, than his own simple dialect of his hometown Rašica.[150] Trubar’s choice was later adopted also by other Protestant writers in the 16th century, and ultimately led to a formation of a more standard language.

In literary fictionEdit

Ljubljana appears in the 2005 The Historian, written by Elisabeth Kostova, and is called by its Roman name (Emona).[151]

Ljubljana is also the setting of Paulo Coelho’s 1998 novel Veronika Decides to Die.

During 2010, Ljubljana was designated as the World Book Capital by UNESCO.[152]

FestivalsEdit

Each year, over 10,000 cultural events take place in the city, including ten international theatre, music, and art festivals.[62] The Ljubljana Festival is one of the two oldest festivals in former Yugoslavia (the Dubrovnik Summer Festival was established in 1950, and the Ljubljana Festival one in 1953). Guests have included Dubravka Tomšič, Marjana Lipovšek, Tomaž Pandur, Katia Ricciarelli, Grace Bumbry, Yehudi Menuhin, Mstislav Rostropovich, José Carreras, Slid Hampton, Zubin Mehta, Vadim Repin, Valerij Gergijev, Sir Andrew Davis, Danjulo Išizaka, Midori, Jurij Bašmet, Ennio Morricone, and Manhattan Transfer. Orchestras have included the New York Philharmonic, Israel Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestras of the Bolshoi Theatre from Moscow, La Scala from Milan, and Mariinsky Theatre from Saint Petersburg. In recent years there have been 80 kinds of events and some 80,000 visitors from Slovenia and abroad.[citation needed] Other cultural venues include Križanke, Cankar Hall and the Exhibition and Convention Centre. During Book Week, starting each year on World Book Day, events and book sales take place at Congress Square. A flea market is held every Sunday in the old city.[153] On the evening of International Workers’ Day, a celebration with a bonfire takes place on Rožnik Hill.

Museums and art galleriesEdit

Interior of the Slovenian Railway Museum

Main building of the Slovenian National Gallery

Ljubljana has numerous art galleries and museums. The first purpose-built art gallery in Ljubljana was the Jakopič Pavilion, which was in the first half of the 20th century the central exhibition venue of Slovene artists. In the early 1960s, it was succeeded by Ljubljana City Art Gallery, which has presented a number of modern Slovene and foreign artists. In 2010, there were 14 museums and 56 art galleries in Ljubljana.[154] There is for example an architecture museum, a railway museum, a school museum, a sports museum, a museum of modern art, a museum of contemporary art, a brewery museum, the Slovenian Museum of Natural History and the Slovene Ethnographic Museum.[153] The National Gallery (Narodna galerija), founded in 1918,[68] and the Museum of Modern Art (Moderna galerija) exhibit the most influential Slovenian artists. In 2006, the museums received 264,470 visitors, the galleries 403,890 and the theatres 396,440.[154] The Metelkova Museum of Contemporary Art (Muzej sodobne umetnosti Metelkova), opened in 2011,[155] hosts simultaneous exhibitions, a research library, archives, and a bookshop.

Entertainment and performing artsEdit

The Slovenian National Theatre

Cankar Hall is the largest Slovenian cultural and congress center with multiple halls and a large foyer in which art film festivals, artistic performances, book fairs, and other cultural events are held.

CinemaEdit

The cinema in Ljubljana appeared for the first time at the turn of the 20th century, and quickly gained popularity among the residents. After World War II, the Cinema Company Ljubljana, later named Ljubljana Cinematographers, was established and managed a number of already functioning movie theatres in Ljubljana, including the only Yugoslav children’s theatre. Cinema festivals took place in the 1960s, and a cinematheque opened its doors in 1963. With the advent of television, video, and recently the Internet, most cinema theatres in Ljubljana closed, and the cinema mainly moved to Kolosej, a multiplex in the BTC City. It features twelve screens, including an IMAX 3D screen. The remaining theatres are Kino Komuna, Kinodvor, where art movies are accompanied by events, and the Slovenian Cinematheque. The Slovenian Cinematheque hosts the international Ljubljana LGBT Film Festival which showcases LGBT-themed films. Founded in 1984, it is the oldest film festival of its sort in Europe.[156]

Classical music, opera and balletEdit

The Slovenian Philharmonics is the central music institution in Ljubljana and Slovenia. It holds classical music concerts of domestic and foreign performers as well as educates youth. It was established in 1701 as part of Academia operosorum Labacensis and is among the oldest such institutions in Europe. The Slovene National Opera and Ballet Theatre also resides in Ljubljana, presenting a wide variety of domestic and foreign, modern and classic, opera, ballet and concert works. It serves as the national opera and ballet house. Music festivals are held in Ljubljana, chiefly in European classical music and jazz, for instance the Ljubljana Summer Festival (Ljubljanski poletni festival), and Trnfest.

TheatreEdit

In addition to the main houses, with the SNT Drama Ljubljana as the most important among them, a number of small producers are active in Ljubljana, involved primarily in physical theatre (e.g. Betontanc), street theatre (e.g. Ana Monró Theatre), theatresports championship Impro League, and improvisational theatre (e.g. IGLU Theatre). A popular form is puppetry, mainly performed in the Ljubljana Puppet Theatre. Theatre has a rich tradition in Ljubljana, starting with the 1867 first ever Slovene-language drama performance.

Modern danceEdit

The modern dance was presented in Ljubljana for the first time at the end of the 19th century and developed rapidly since the end of the 1920s. Since the 1930s when in Ljubljana was founded a Mary Wigman dance school, the first one for modern dance in Slovenia, the field has been intimately linked to the development in Europe and the United States. Ljubljana Dance Theatre is today the only venue in Ljubljana dedicated to contemporary dance. Despite this, there’s a vivid happening in the field.

Folk danceEdit

Several folk dance groups are active in Ljubljana.

JazzEdit

In July 2015, over four days, the 56th Ljubljana Jazz Festival took place. A member of the European Jazz Network, the festival presented 19 concerts featuring artists from 19 countries, including a celebration of the 75th birthday of James «Blood» Ulmer.[157]

Popular urban culture and alternative sceneEdit

In the 1980s with the emergence of subcultures in Ljubljana, an alternative culture begun to develop in Ljubljana organised around two student organisations.[158] This caused an influx of young people to the city centre, caused political and social changes, and led to the establishment of alternative art centres.[159]

- Metelkova and Rog

A Ljubljana equivalent of Copenhagen’s Freetown Christiania, a self-proclaimed autonomous Metelkova neighbourhood, was set up in a former Austro-Hungarian barracks that were built in 1882.[160][161]

In 1993, the seven buildings and 12,500 square metres (135,000 sq ft) of space were turned into art galleries, artist studios, and seven nightclubs, including two LGBTQ+ venues, playing host to music from hardcore to jazz to dub to techno. Celica Hostel is adjacent to Metelkova[162] with rooms artistically decorated by Metelkova artists. A new part of the Museum of Modern Art is the nearby Museum of Contemporary Art.[163] Another alternative culture centre is located in the former Rog factory. Both Metelkova and the Rog factory complex are near the city centre.

- Šiška Cultural Quarter

Šiška Cultural Quarter hosts art groups and cultural organisations dedicated to contemporary and avant-garde arts. Kino Šiška Centre for Urban Culture is there, a venue offering concerts of indie, punk, and rock bands as well as exhibitions take place. Museum of Transitory Art (MoTA) is a museum without a permanent collection or a fixed space. Its programs are realised in temporary physical and virtual spaces dedicated to advancing the research, production and presentation of transitory, experimental, and live art forms. Yearly MoTA organises Sonica Festival. Ljudmila (since 1994), which strives to connect research practices, technologies, science, and art.

SportsEdit

ClubsEdit

A tension between German and Slovene residents dominated the development of sport of Ljubljana in the 19th century. The first sport club in Ljubljana was the South Sokol Gymnastic Club (Gimnastično društvo Južni Sokol), established in 1863 and succeeded in 1868 by the Ljubljana Sokol (Ljubljanski Sokol). It was the parent club of all Slovene Sokol clubs as well as an encouragement for the establishment of the Croatian Sokol club in Zagreb. Members were also active in culture and politics, striving for greater integration of the Slovenes from different Crown lands of Austria-Hungary and for their cultural, political, and economic independence.

In 1885, German residents established the first sports club in the territory of nowadays Slovenia, Der Laibacher Byciklistischer Club (Ljubljana Cycling Club). In 1887, Slovene cyclists established the Slovene Cyclists Club (Slovenski biciklistični klub). In 1893 followed the first Slovene Alpine club, named Slovene Alpine Club (Slovensko planinsko društvo), later succeeded by the Alpine Association of Slovenia (Planinska zveza Slovenije). Several of its branches operate in Ljubljana, the largest of them being the Ljubljana Matica Alpine Club (Planinsko društvo Ljubljana-Matica). In 1900, the sports club Laibacher Sportverein (English: Ljubljana Sports Club) was established by the city’s German residents and functioned until 1909. In 1906, Slovenes organised themselves in its Slovene counterpart, the Ljubljana Sports Club (Ljubljanski športni klub). Its members were primarily interested in rowing, but also swimming and football. In 1911, the first Slovenian football club, Ilirija, started operating in the city. Winter sports already started to develop in the area of the nowadays Ljubljana before World War II.[164] In 1929, the first ice hockey club in Slovenia (then Yugoslavia), SK Ilirija, was established.

Nowadays, the city’s football teams which play in the Slovenian PrvaLiga are NK Olimpija Ljubljana and NK Bravo. ND Ilirija 1911 currently competes in Slovenian Second League. Ljubljana’s ice hockey clubs are HK Slavija and HK Olimpija. They both compete in the Slovenian Hockey League. The basketball teams are KD Slovan, KD Ilirija and KK Cedevita Olimpija. The latter, which has a green dragon as its mascot, hosts its matches at the 12,480-seat Arena Stožice. Ježica is women’s basketball that competes in Slovenian League. Handball is popular in female section. RK Krim is one of the best women handball teams in Europe. They won the EHF Champions League twice, in 2001 and 2003.[165] RD Slovan is male handball club from Ljubljana that currently competes in Slovenian First League. AMTK Ljubljana is the most successful speedway club in Slovenia. The Ljubljana Sports Club has been succeeded by the Livada Canoe and Kayak Club.[166]

Mass sport activitiesEdit

Each year since 1957, on 8–10 May, the recreational Walk Along the Wire has taken place to mark the liberation of Ljubljana on 9 May 1945.[167] At the same occasion, a triples competition is run on the trail, and a few days later, a student run from Prešeren Square to Ljubljana Castle is held. The last Sunday in October, the Ljubljana Marathon and a few minor competition runs take place on the city streets. The event attracts several thousand runners each year.[168]

Sport venuesEdit

The Stožice Stadium, opened since August 2010 and located in Stožice Sports Park in the Bežigrad District, is the biggest football stadium in the country and the home of the NK Olimpija Ljubljana. It is one of the two main venues of the Slovenia national football team. The park also has an indoor arena, used for indoor sports such as basketball, handball and volleyball and is the home venue of KK Olimpija, RK Krim and ACH Volley Bled among others. Beside football, the stadium is designed to host cultural events as well. Another stadium in the Bežigrad district, Bežigrad Stadium, is closed since 2008 and is deteriorating. It was built according to the plans of Jože Plečnik and was the home of the NK Olimpija Ljubljana, dissolved in 2004. Joc Pečečnik, a Slovenian multimillionaire, plans to renovate it.[169]

Šiška Sports Park is located in Spodnja Šiška, part of the Šiška District. It has a football stadium with five courts, an athletic hall, outdoor athletic areas, tennis courts, a Boules court, and a sand volleyball court. The majority of competitions are in athletics. Another sports park in Spodnja Šiška is Ilirija Sports Park, known primarily for its stadium with a speedway track. At the northern end of Tivoli Park stands the Ilirija Swimming Pool Complex, which was built as part of a swimming and athletics venue following plans by Bloudek in the 1930s and has been nearly abandoned since then, but there are plans to renovate it.

A number of sport venues are located in Tivoli Park. An outdoor swimming pool in Tivoli, constructed by Bloudek in 1929, was the first Olympic-size swimming pool in Yugoslavia. The Tivoli Recreational Centre in Tivoli is Ljubljana’s largest recreational centre and has three swimming pools, saunas, a Boules court, a health club, and other facilities.[170] There are two skating rinks, a basketball court, a winter ice rink, and ten tennis courts in its outdoor area.[171] The Tivoli Hall consists of two halls. The smaller one accepts 4,050 spectators and is used for basketball matches. The larger one can accommodate 6,000 spectators and is primarily used for hockey, but also for basketball matches. The halls are also used for concerts and other cultural events. The Slovenian Olympic Committee has its office in the building.[172]

The Tacen Whitewater Course, located on a course on the Sava, 8 km (5 mi) northwest of the city centre, hosts a major international canoe/kayak slalom competition almost every year, examples being the ICF Canoe Slalom World Championships in 1955, 1991, and 2010.[173]

Since the 1940s,[164] a ski slope has been in use in Gunclje,[174] in the northwestern part of the city.[175] It is 600 m (2,000 ft) long and has two ski lifts, its maximum incline is 60° and the difference in height from the top to the bottom is 155 m (509 ft).[174] Five ski jumping hills stand near the ski slope.[164] Several Slovenian Olympic and World Cup medalists trained and competed there.[164][176] In addition, the Arena Triglav complex of six jumping hills is located in the Šiška District.[177][178] A ski jumping hill, built in 1954 to plans by Stanko Bloudek, was located in Šiška near Vodnik Street (Vodnikova cesta) until 1976. International competitions for the Kongsberg Cup were held there, attended by thousands of spectators.[179] The ice rinks in Ljubljana include Koseze Pond and Tivoli Hall. In addition, in the 19th century and the early 20th century, Tivoli Pond and a marshy meadow in Trnovo, named Kern, were used for ice skating.[180]

EconomyEdit

BTC City is the largest shopping mall, sports, entertainment, and business area in Ljubljana.

Industry is the most important employer, notably in the pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals and food processing.[62] Other fields include banking, finance, transport, construction, skilled trades and services and tourism. The public sector provides jobs in education, culture, health care and local administration.[62]

The Ljubljana Stock Exchange (Ljubljanska borza), purchased in 2008 by the Vienna Stock Exchange,[181] deals with large Slovenian companies. Some of these have their headquarters in the capital: for example, the retail chain Mercator, the oil company Petrol d.d. and the telecommunications concern Telekom Slovenije.[182] Over 15,000 enterprises operate in the city, most of them in the tertiary sector.[183]

Numerous companies and over 450 shops are located in the BTC City, the largest business, shopping, recreational, entertainment and cultural centre in Slovenia. It is visited each year by 21 million people.[184][185] It occupies an area of 475,000 m2 (5,110,000 sq ft) in the Moste District in the eastern part of Ljubljana.[186][187][188]

About 74% of Ljubljana households use district heating from the Ljubljana Power Station.[189]

GovernmentEdit

The city of Ljubljana is governed by the City Municipality of Ljubljana (Slovene: Mestna občina Ljubljana; MOL), which is led by the city council. The president of the city council is called the mayor. Members of the city council and the mayor are elected in the local election, held every four years. Among other roles, the city council drafts the municipal budget, and is assisted by various boards active in the fields of health, sports, finances, education, environmental protection and tourism.[190] The municipality is subdivided into 17 districts represented by district councils. They work with the municipality council to make known residents’ suggestions and prepare activities in their territories.[191][192]

Between 2002 and 2006, Danica Simšič was mayor of the municipality.[193] Since the municipal elections of 22 October 2006 until his confirmation as a deputy in the National Assembly of Slovenian in December 2011, Zoran Janković, previously the managing director of the Mercator retail chain, was the mayor of Ljubljana. In 2006, he won 62.99% of the popular vote.[194] On 10 October 2010, Janković was re-elected for another four-year term with 64.79% of the vote. From 2006 until October 2010, the majority on the city council (the Zoran Janković List) held 23 of 45 seats.[194] On 10 October 2010, Janković’s list won 25 out of 45 seats in the city council. From December 2011 onwards, when Janković’s list won the early parliamentary election, the deputy mayor Aleš Čerin was decided by him to lead the municipality. Čerin did not hold the post of mayor.[195] After Janković had failed to be elected as the Prime Minister in the National Assembly, he participated at the mayoral by-election on 25 March 2012 and was elected for the third time with 61% of the vote. He retook the leadership of the city council on 11 April 2012.[196]

Public order in Ljubljana is enforced by the Ljubljana Police Directorate (Policijska uprava Ljubljana).[197] There are five areal police stations and four sectoral police stations in Ljubljana.[198] Public order and municipal traffic regulations are also supervised by the city traffic wardens (Mestno redarstvo).[199] Ljubljana has a quiet and secure reputation.[198][200]

DemographicsEdit

In 1869, Ljubljana had about 22,600 inhabitants,[201] a figure that grew to almost 60,000 by 1931.[68]

At the 2002 census, 39% of Ljubljana inhabitants were Catholic; 30% had no religion, an unknown religion or did not reply; 19% atheist; 6% Eastern Orthodox; 5% Muslim; and the remaining 0.7% Protestant or another religion.[202]

Approximately 91% of the population speaks Slovene as their primary native language. The second most-spoken language is Bosnian, with Serbo-Croatian being the third most-spoken language.[203]

| 1600 | 1700 | 1754 | 1800 | 1846 | 1869 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1921 | 1931 | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2002 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6,000 | 7,500 | 9,400 | 10,000 | 18,000 | 22,593 | 26,284 | 30,505 | 36,547 | 41,727 | 53,294 | 59,768 | 98,599 | 113,340 | 135,366 | 173,853 | 224,817 | 258,873 | 267,008 | 280,088 | 282,994 | 288,307 | 292,988 | 295,504 |

EducationEdit

Primary educationEdit

In Ljubljana today there are over 50 public elementary schools with over 20,000 pupils.[154][208] This also includes an international elementary school for foreign pupils. There are two private elementary schools: a Waldorf elementary school and a Catholic elementary school. In addition, there are several elementary music schools.

Historically the first school in Ljubljana belonged to Teutonic Knights and was established in the 13th century. It originally accepted only boys; girls were accepted from the beginning of the 16th century. Parochial schools are attested in the 13th century, at St. Peter’s Church and at Saint Nicholas’s Church, the later Ljubljana Cathedral. Since 1291, there were also trade-oriented private schools in Ljubljana. In the beginning of the 17th century, there were six schools in Ljubljana and later three. A girls’ school was established by Poor Clares, followed in 1703 by the Ursulines. Their school was for about 170 years the only public girls’ school in Carniola. These schools were mainly private or established by the city.[209]

In 1775, the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa proclaimed elementary education obligatory and Ljubljana got its normal school, intended as a learning place for teachers. In 1805, the first state music school was established in Ljubljana. In the time of Illyrian Provinces, «école primaire«, a unified four-year elementary school program with a greater emphasis on Slovene, was introduced. The first public schools, unrelated to religious education, appeared in 1868.

Secondary educationEdit

The first complete Realschule (technical grammar school) was established in Ljubljana in 1871.

In Ljubljana there are ten public and three private grammar schools. The public schools divide into general gymnasiums and classical gymnasiums, the latter offering Latin and Greek as foreign languages. Some general schools offer internationally oriented European departments, and some offer sport departments, allowing students to more easily adjust their sport and school obligations. All state schools are free, but the number of students they can accept is limited. The private secondary schools include a Catholic grammar school and a Waldorf grammar school. There are also professional grammar schools in Ljubljana, offering economical, technical, or artistic subjects (visual arts, music). All grammar schools last four years and conclude with the matura exam.

Historically, upon a proposal by Primož Trubar, the Carniolan Estates’ School (1563–1598) was established in 1563 in the period of Slovene Reformation. Its teaching languages were mainly Latin and Greek, but also German and Slovene, and it was open for both sexes and all social strata. In 1597, Jesuits established the Jesuit College (1597–1773), intended to transmit general education. In 1773, secondary education came under the control of the state. A number of reforms were implemented in the 19th century; there was more emphasis on general knowledge and religious education was removed from state secondary schools. In 1910, there were 29 secondary schools in Ljubljana, among them classical and real gymnasiums and Realschules (technical secondary schools).

Tertiary educationEdit

In 2011, the University had 23 faculties and three academies, located around Ljubljana. They offer Slovene-language courses in medicine, applied sciences, arts, law, administration, natural sciences, and other subjects.[210] The university has more than 63,000 students and some 4,000 teaching faculty.[208] Students make up one-seventh of Ljubljana’s population, giving the city a youthful character.[208][211]

Historically, higher schools offering the study of general medicine, surgery, architecture, law and theology, started to operate in Ljubljana under the French annexation of Slovene territory, in 1810–1811. The Austro-Hungarian Empire never allowed Slovenes to establish their own university in Ljubljana, and the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia’s most important university, was founded in 1919, after Slovenes joined the first Yugoslavia.[68][208] When it was founded, the university comprised five faculties: law, philosophy, technology, theology and medicine. From the beginning, the seat of the university has been at Congress Square in a building that served as the State Mansion of Carniola from 1902 to 1918.

LibrariesEdit

- National and University Library of Slovenia

The National and University Library of Slovenia is the Slovene national and university library. In 2011, it held about 1,307,000 books, 8,700 manuscripts, and numerous other textual, visual and multimedia resources, altogether 2,657,000 volumes.[212]

- Central Technological Library

The second largest university library in Ljubljana is the Central Technological Library, the national library and information hub for natural sciences and technology.

- Municipal Library and other libraries

The Municipal City Library of Ljubljana, established in 2008, is the central regional library and the largest Slovenian general public library. In 2011, it held 1,657,000 volumes, among these 1,432,000 books and a multitude of other resources in 36 branches.[213] Altogether, there are 5 general public libraries and over 140 specialised libraries in Ljubljana.[154]

Besides the two largest university libraries there are libraries at individual faculties, departments and institutes of the University of Ljubljana. The largest among them are the Central Humanist Library in the field of humanities, the Central Social Sciences Library, the Central Economic Library in the field of economics, the Central Medical Library in the field of medical sciences, and the Libraries of the Biotechnical Faculty in the field of biology and biotechnology.[214]

- History

The first libraries in Ljubljana were located in monasteries. The first public library was the Carniolan Estates’ Library, established in 1569 by Primož Trubar. In the 17th century, the Jesuit Library collected numerous works, particularly about mathematics. In 1707, the Seminary Library was established; it is the first and oldest public scientific library in Slovenia. Around 1774, after the dissolution of Jesuits, the Lyceum Library was formed from the remains of the Jesuit Library as well as several monastery libraries.

ScienceEdit

The first society of the leading scientists and public workers in Carniola was the Dismas Fraternity (Latin: Societas Unitorum), formed in Ljubljana in 1688.[215] In 1693, the Academia Operosorum Labacensium was founded and lasted with an interruption until the end of the 18th century. The next academy in Ljubljana, the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, was not established until 1938.

TransportEdit

Railway near the central workshop in Moste

Air transportEdit

Ljubljana Jože Pučnik Airport (ICAO code LJLJ; IATA code LJU), located 26 km (16 mi) northwest of the city, has flights to numerous European destinations. Among the companies that fly from there are Air France, Air Serbia, Brussels Airlines, easyJet, Finnair, Lufthansa, Swiss, Wizz Air, Transavia and Turkish Airlines. The destinations are mainly European.[216] This airport has superseded the original Ljubljana airport, in operation from 1933 until 1963.[217][218] It was located in the Municipality of Polje (nowadays the Moste District), on a plain between Ljubljanica and Sava next to the railroad in Moste.[218] There was a military airport in Šiška from 1918 until 1929.[219]

Rail transportEdit

In the Ljubljana Rail Hub, the Pan-European railway corridors V (the fastest link between the North Adriatic, and Central and Eastern Europe)[220] and X (linking Central Europe with the Balkans)[221] and the main European lines (E 65, E 69, E 70) intersect.[222] All international transit trains in Slovenia drive through the Ljubljana hub, and all international passenger trains stop there.[223] The area of Ljubljana has six passenger stations and nine stops.[224] For passengers, the Slovenian Railways company offers the possibility to buy a daily or monthly city pass that can be used to travel between them.[225] The Ljubljana railway station is the central station of the hub. The Ljubljana Moste Railway Station is the largest Slovenian railway dispatch. The Ljubljana Zalog Railway Station is the central Slovenian rail yard.[223] There are a number of industrial rails in Ljubljana.[226] At the end of 2006,[227] the Ljubljana Castle funicular started to operate. The rail goes from Krek Square (Krekov trg) near the Ljubljana Central Market to Ljubljana Castle. It is especially popular among tourists. The full trip lasts 60 seconds.

RoadsEdit

Ljubljana is located where Slovenia’s two main freeways intersect,[228] connecting the freeway route from east to west, in line with Pan-European Corridor V, and the freeway in the north–south direction, in line with Pan-European Corridor X.[229] The city is linked to the southwest by A1-E70 to the Italian cities of Trieste and Venice and the Croatian port of Rijeka.[230] To the north, A1-E57 leads to Maribor, Graz and Vienna. To the east, A2-E70 links it with the Croatian capital Zagreb, from where one can go to Hungary or important cities of the former Yugoslavia, such as Belgrade.[230] To the northwest, A2-E61 goes to the Austrian towns of Klagenfurt and Salzburg, making it an important entry point for northern European tourists.[230] A toll sticker system has been in use on the Ljubljana Ring Road since 1 July 2008.[231][232] The centre of the city is more difficult to access especially in the peak hours due to long arteries with traffic lights and a large number of daily commuters.[233] The core city centre has been closed for motor traffic since September 2007 (except for residents with permissions), creating a pedestrian zone around Prešeren Square.[234]

Public transportEdit

The historical Ljubljana tram system was completed in 1901 and was replaced by buses in 1928,[235] which were in turn abolished and replaced by trams in 1931[235] with its final length of 18.5 km (11.5 mi) in 1940.[236] In 1959, it was abolished in favor of automobiles;[237] the tracks were dismantled and tram cars were transferred to Osijek and Subotica.[238] Reintroduction of an actual tram system to Ljubljana has been proposed repeatedly in the 2000s.[239][240]

There are numerous taxi companies in the city.

Older type of city bus on the streets of Ljubljana

The Ljubljana Bus Station, the Ljubljana central bus hub, is located next to the Ljubljana railway station. The city bus network, run by the Ljubljana Passenger Transport (LPP) company, is Ljubljana’s most widely used means of public transport. The fleet is relatively modern. The number of dedicated bus lanes is limited, which can cause problems in peak hours when traffic becomes congested.[241] Bus rides may be paid with the Urbana payment card (also used for the funicular) or with a mobile phone. Sometimes the buses are called trole (referring to trolley poles), harking back to the 1951–1971 days when Ljubljana had trolleybus (trolejbus) service.[242] There were five trolleybus lines in Ljubljana, until 1958 alongside the tram.[237]

Another means of public road transport in the city centre is the Cavalier (Kavalir), an electric shuttle bus vehicle operated by LPP since May 2009. There are three such vehicles in Ljubljana. The ride is free and there are no stations because it can be stopped anywhere. It can carry up to five passengers; most of them are elderly people and tourists.[243] The Cavalier drives in the car-free zone in the Ljubljana downtown. The first line links Čop Street, Wolf Street and the Hribar Embankment, whereas the second links Town Square, Upper Square, and Old Square.[244] There is also a trackless train (tractor with wagons decorated to look like a train) for tourists in Ljubljana, linking Cyril and Methodius Square in the city centre with Ljubljana Castle.[245]

BicyclesEdit

BicikeLJ, a Ljubljana-based self-service bicycle network, is free of charge for the first hour.

There is a considerable amount of bicycle traffic in Ljubljana, especially in the warmer months of the year. It is also possible to rent a bike. Since May 2011, the BicikeLJ, a self-service bicycle rental system offers the residents and visitors of Ljubljana 600 bicycles and more than 600 parking spots at 60 stations in the wider city centre area. The daily number of rentals is around 2,500.[246][247] There was an option to rent a bike even before the establishment of BicikeLJ.[248]

There are still some conditions for cyclists in Ljubljana that have been criticised, including cycle lanes in poor condition and constructed in a way that motorised traffic is privileged. There are also many one-way streets which therefore cannot be used as alternate routes so it is difficult to legally travel by bicycle through the city centre.[249][250] Through years, some prohibitions have been partially abolished by marking cycle lanes on the pavement.[251][252] Nevertheless, the situation has been steadily improving; in 2015, Ljubljana placed 13th in a ranking of the world’s most bicycle-friendly cities.[253] In 2016, Ljubljana was 8th on the Copenhagenize list.[254]

Water transportEdit

The river transport on the Ljubljanica and the Sava was the main means of cargo transport to and from the city until the mid-19th century, when railroads were built. Today, the Ljubljanica is used by a number of tourist boats, with wharves under the Butchers’ Bridge, at Fish Square, at Court Square, at Breg, at the Poljane Embankment, and elsewhere.

HealthcareEdit

Ljubljana has a rich history of discoveries in medicine and innovations in medical technology. The majority of secondary and tertiary care in Slovenia takes place in Ljubljana. The Ljubljana University Medical Centre is the largest hospital centre in Slovenia. The Faculty of Medicine (University of Ljubljana) and the Ljubljana Institute of Oncology are other two central medical institutions in Slovenia. The Ljubljana Community Health Centre is the largest health centre in Slovenia. It has seven units at 11 locations. Since 1986, Ljubljana is part of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network.[255]

International relationsEdit

Twin towns and sister citiesEdit

Ljubljana is twinned with:[256]

|

|

|

See alsoEdit

- List of people from Ljubljana

NotesEdit

- ^ Pronunciation: lewb-LYAH-nə, LUUB-lee-AH-nə,[7][8][9] LEW-blee-AH-nə, lee-OO—;[8][9][10][11][12] Slovene: [ljuˈbljàːna] ( listen),[13] locally also [luˈblàːna].

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «Osebna izkaznica – RRA LUR». rralur.si. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ «Nadmorska višina naselij, kjer so sedeži občin» [Height above sea level of seats of municipalities] (in Slovenian and English). Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. 2002. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- ^ «Ljubljana, Ljubljana». Place Names. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Zip Codes in Slovenia from 1000 to 1434 (in Slovene) Archived 14 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine Acquired on 28 April 2015.

- ^ Known as: Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918–1929)

- ^ Known as: Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1963); Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1963–1992)

- ^ «Ljubljana». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022.

- ^ a b «Ljubljana». Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ a b «Ljubljana». Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ «Ljubljana». The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ «Slovenski pravopis 2001 — Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU in Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti — izid poizvedbe». bos.zrc-sazu.si. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ a b Vuk Dirnberk, Vojka; Tomaž Valantič. «Statistični portret Slovenije v EU 2010» [Statistical Portrait of Slovenia in the EU 2010] (PDF). Statistični Portret Slovenije V Eu …=Statistical Portrait of Slovenia in the Eu (in Slovenian and English). Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. ISSN 1854-5734. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Zavodnik Lamovšek, Alma. Drobne, Samo. Žaucer, Tadej (2008). «Small and Medium-Size Towns as the Basis of Polycentric Urban Development» (PDF). Geodetski Vestnik. Vol. 52, no. 2. Association of Surveyors of Slovenia. p. 303. ISSN 0351-0271. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ «Emona, Legacy of a Roman City – Culture of Slovenia». www.culture.si. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ Mehle Mihovec, Barbka (19 March 2008). «Kje so naše meje?» [Where are our borders?]. Gorenjski glas (in Slovenian). Gorenjski glas. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ a b «Volitve» [Elections]. Statistični letopis 2011 [Statistical Yearbook 2011]. Statistical Yearbook 2011. Vol. 15. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. 2011. p. 108. ISSN 1318-5403. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Libri Antichi Libri Rari. «Città di stampa dei LIBRI ANTICHI dei LIBRI VECCHI dei LIBRI RARI». Osservatoriolibri.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Albrecht Berger, ed. (2006), Life and Works of Saint Gregentios, Archbishop of Taphar: Introduction, Critical Edition and Translation, De Gruyter, pp. 14–17 and 190.

- ^ «Dr T.C. (Tijmen) Pronk». Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, University of Leiden. 2009. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Pronk, Tijmen (2007). «The Etymology of Ljubljana – Laibach». Folia Onomastica Croatica. 16: 185–191. ISSN 1330-0695.

- ^ «Dr. Silvo Torkar» (in Slovenian). Fran Ramovš Institute of the Slovenian Language. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Pronk, Tijmen. «O neprepoznanih ali napačno prepoznanih slovanskih antroponimih v slovenskih zemljepisnih imenih: Čadrg, Litija, Trebija, Ljubija, Ljubljana, Biljana» [On the unrecognized or incorrectly recognized Slavic anthroponyms in Slovenian toponyms: Čadrg, Litija, Trebija, Ljubija, Ljubljana, Biljana] (PDF). The Etymology of Ljubljana – Laibach (in Slovenian): 257–273. ISSN 1330-0695. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2011.

- ^ a b c C Abdunur (2001). ARCH’01: Troisième conferénce internationale sur les ponts en arc. Presses des Ponts. p. 124. ISBN 978-2-85978-347-1.

- ^ Exhibition catalogue Emona: myth and reality Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine; Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana 2010

- ^ «The dragon – city emblem». Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ novisplet.com. «Najstarejše kolo z osjo na svetu – 5150 let». ljubljanskobarje.si. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ «Prehistoric Pile Dwellings Listed as UNESCO World Heritage». Slovenia News. Government Communication Office. 28 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ Maša Štiftar de Arzu, ed. (14 October 2011). «Pile-dwellings in the Ljubljansko Barje on UNESCO List» (PDF). Embassy Newsletter. Embassy of Slovenia in Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ «First settlers». Archived from the original on 18 March 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ Bernarda Županek (2010) «Emona, Legacy of a Roman City» Archived 17 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana, Ljubljana.

- ^ a b c «The Times of Roman Emona». Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ «Roman Emona». Culture.si. Ministry of culture of the republic of Slovenia. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ «Emona, Legacy of a Roman City». Culture.si. Ministry of culture of the republic of Slovenia. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ (in French) Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. de Gruyter, 1988. ISBN 3-11-011893-9. Google Books, p.343 Archived 3 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Daniel Mallinus, La Yougoslavie, Éd. Artis-Historia, Brussels, 1988, D/1988/0832/27, p. 37-39.

- ^ a b c d «Ljubljana in the Middle Ages». Archived from the original on 18 March 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Peter Štih (2010). Castrum Leibach: the first recorded mention of Ljubljana and the city’s early history: facsimile with commentary and a history introduction (PDF). City Municipality of Ljubljana. ISBN 978-961-6449-36-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2015. COBISS 252833024

- ^ a b c d Darinka Kladnik (October 2006). «Ljubljana Town Hall» (PDF). Ljubljana Tourist Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b «Srednjeveška Ljubljana – Luwigana» [Ljubljana of the Middle Ages – Luwigana]. Arhitekturni vodnik [Architectural Guide]. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ Nered, Andrej (2009). «Kranjski deželni stanovi do leta 1518: Mesta» [Carniolan Provincial Estates Until 1518: Towns]. Dežela – knez – stanovi: oblikovanje kranjskih deželnih stanov in zborov do leta 1518 [The Land – the Prince – the Estates: the Formation of Carniolan Provincial Estates and Assemblies Until 1518] (in Slovenian). Založba ZRC. p. 170. ISBN 9789612541309. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Kušar, Domen (2003). «Vpliv požarov na razvoj in podobo srednjeveških mest» [The Influence of Fires on the Development and Image of Towns in the Middle Ages]. Urbani izziv [Urban Challenge] (in Slovenian). 14 (2). Archived from the original on 21 September 2018.