|

Marilyn Monroe |

|

|---|---|

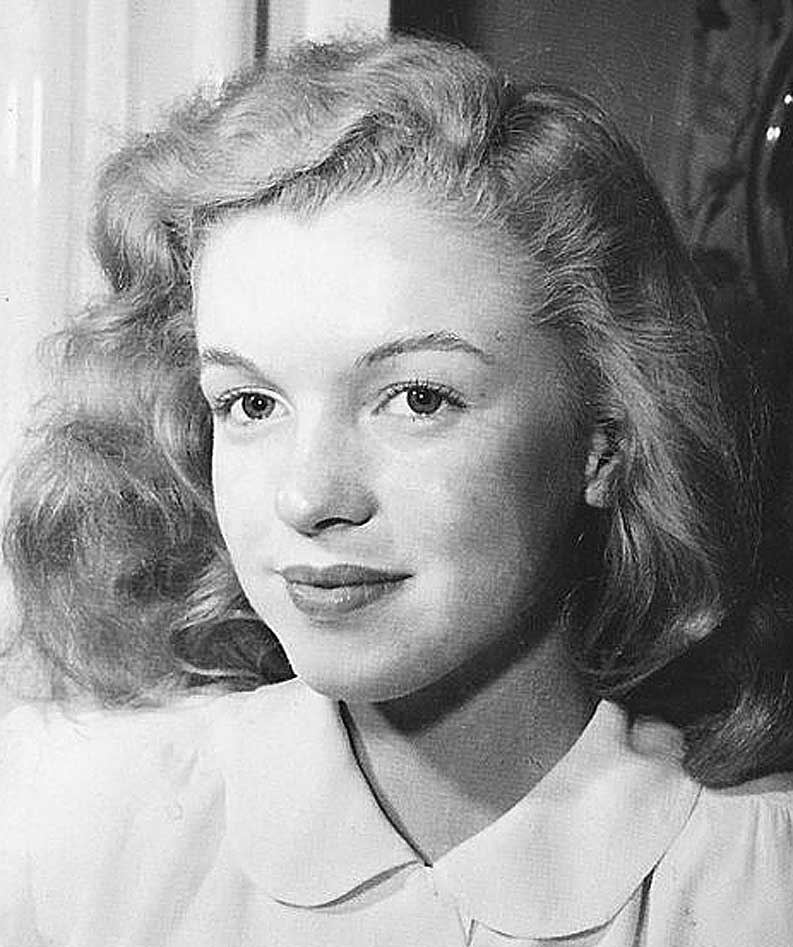

Monroe in 1953 |

|

| Born |

Norma Jeane Mortenson[a] June 1, 1926 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | August 4, 1962 (aged 36)

Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Barbiturate overdose |

| Burial place | Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Other names | Norma Jeane Baker |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1945–1962 |

| Spouses |

James Dougherty (m. 1942; div. 1946) Joe DiMaggio (m. 1954; div. 1955) Arthur Miller (m. 1956; div. 1961) |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Berniece Baker Miracle (half-sister) |

| Website | marilynmonroe.com |

| Signature | |

Marilyn Monroe (; born Norma Jeane Mortenson; June 1, 1926 – August 4, 1962) was an American actress, model, and singer. Famous for playing comic «blonde bombshell» characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and early 1960s, as well as an emblem of the era’s sexual revolution. She was a top-billed actress for a decade, and her films grossed $200 million (equivalent to $2 billion in 2021) by the time of her death in 1962.[3] Long after her death, Monroe remains a major icon of pop culture.[4] In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked her sixth on their list of the greatest female screen legends from the Golden Age of Hollywood.

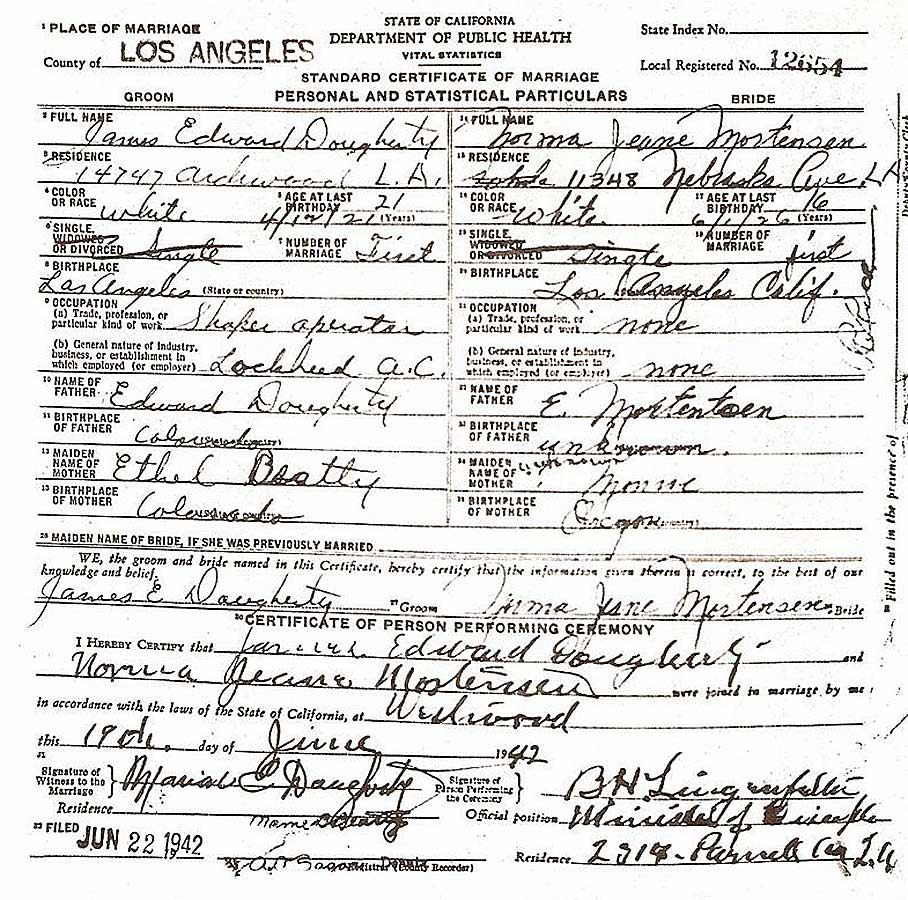

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Monroe spent most of her childhood in a total of 12 foster homes and an orphanage[5] before marrying James Dougherty at age sixteen. She was working in a factory during World War II when she met a photographer from the First Motion Picture Unit and began a successful pin-up modeling career, which led to short-lived film contracts with 20th Century Fox and Columbia Pictures. After a series of minor film roles, she signed a new contract with Fox in late 1950. Over the next two years, she became a popular actress with roles in several comedies, including As Young as You Feel and Monkey Business, and in the dramas Clash by Night and Don’t Bother to Knock. Monroe faced a scandal when it was revealed that she had posed for nude photographs prior to becoming a star, but the story did not damage her career and instead resulted in increased interest in her films.

By 1953, Monroe was one of the most marketable Hollywood stars. She had leading roles in the film noir Niagara, which overtly relied on her sex appeal, and the comedies Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire, which established her star image as a «dumb blonde». The same year, her nude images were used as the centerfold and on the cover of the first issue of Playboy. Monroe played a significant role in the creation and management of her public image throughout her career, but felt disappointed when typecast and underpaid by the studio. She was briefly suspended in early 1954 for refusing a film project but returned to star in The Seven Year Itch (1955), one of the biggest box office successes of her career.

When the studio was still reluctant to change Monroe’s contract, she founded her own film production company in 1954. She dedicated 1955 to building the company and began studying method acting under Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. Later that year, Fox awarded her a new contract, which gave her more control and a larger salary. Her subsequent roles included a critically acclaimed performance in Bus Stop (1956) and her first independent production in The Prince and the Showgirl (1957). She won a Golden Globe for Best Actress for her role in Some Like It Hot (1959), a critical and commercial success. Her last completed film was the drama The Misfits (1961).

Monroe’s troubled private life received much attention. She struggled with addiction and mood disorders. Her marriages to retired baseball star Joe DiMaggio and to playwright Arthur Miller were highly publicized, but ended in divorce. On August 4, 1962, she died at age 36 from an overdose of barbiturates at her Los Angeles home. Her death was ruled a probable suicide.

Life and career

1926–1943: Childhood and first marriage

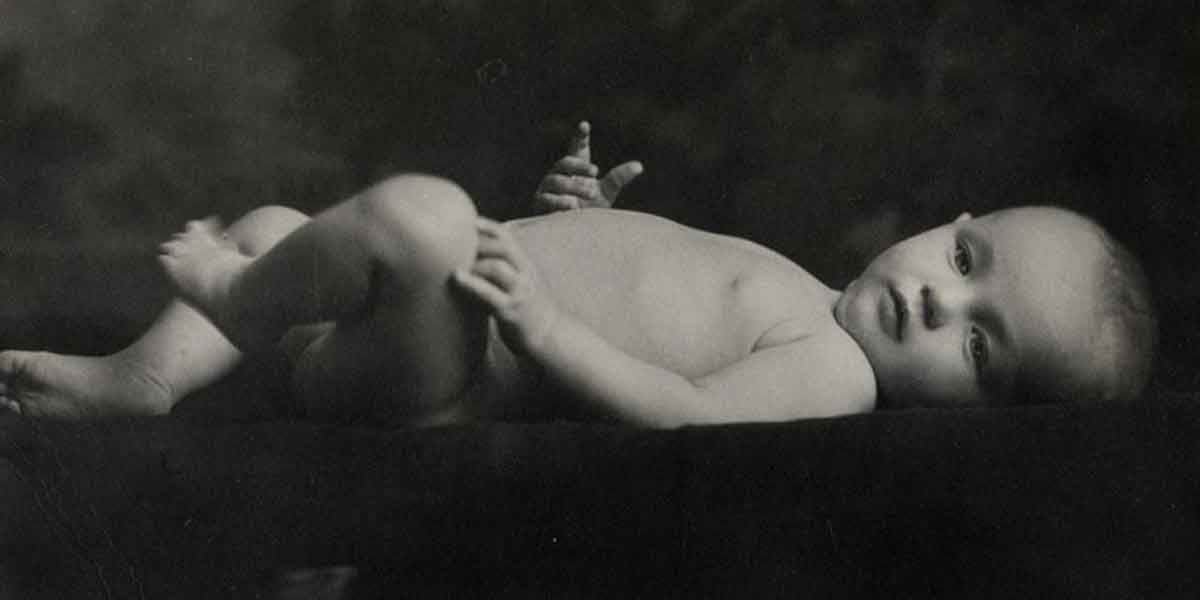

Monroe as an infant, c. 1927

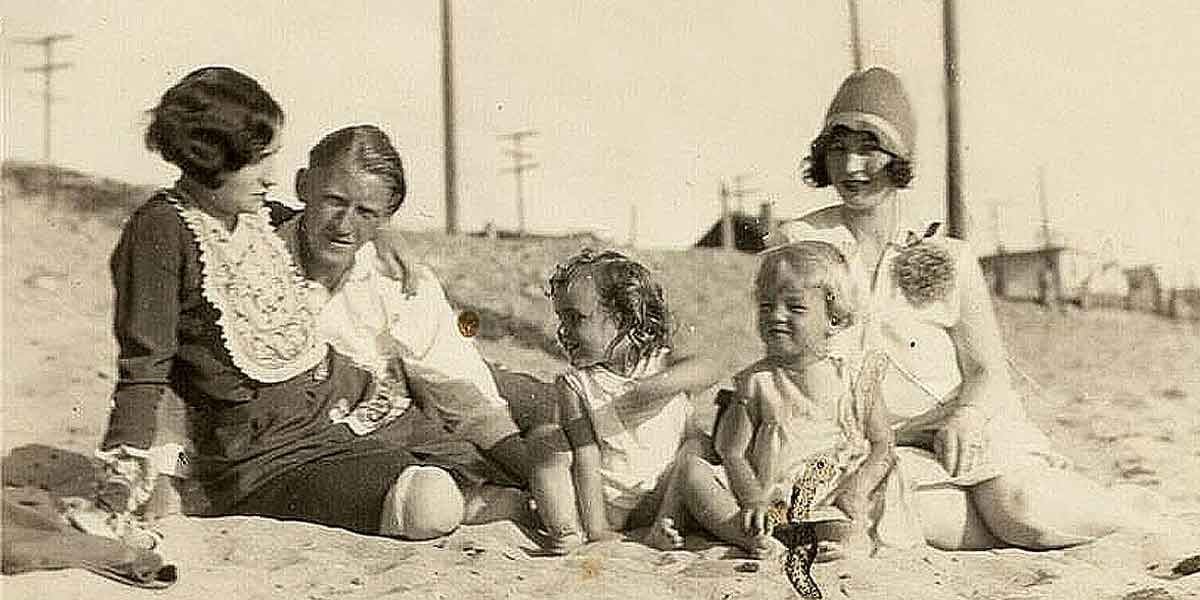

Marilyn Monroe was born Norma Jeane Mortenson on June 1, 1926, at the Los Angeles General Hospital in Los Angeles, California. Her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker (née Monroe; 1902–1984), was born in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico[7] to a poor Midwestern family who migrated to California at the turn of the century.[8] At age 15, Gladys married John Newton Baker, an abusive man nine years her senior. They had two children, Robert (1918–1933) and Berniece (1919–2014). She successfully filed for divorce and sole custody in 1923, but Baker kidnapped the children soon after and moved with them to his native Kentucky.

Monroe was not told that she had a sister until she was 12, and they met for the first time in 1944 when Monroe was 17 or 18. Following the divorce, Gladys worked as a film negative cutter at Consolidated Film Industries.[13] In 1924, she married Martin Edward Mortensen, but they separated just months later and divorced in 1928.[13][b] In 2022, DNA testing indicated that Monroe’s father was Charles Stanley Gifford (1898–1965),[18][19][20]

a co-worker of Gladys, with whom she had an affair in 1925. Monroe also had two other half-siblings from Gifford’s marriage with his first wife, a sister, Doris (1920–1933), and a brother, Charles (1922–2015).[21]

Although Gladys was mentally and financially unprepared for a child, Monroe’s early childhood was stable and happy. Gladys placed her daughter with evangelical Christian foster parents Albert and Ida Bolender in the rural town of Hawthorne. She also lived there for six months, until she was forced to move back to the city for employment. She then began visiting her daughter on weekends. In the summer of 1933, Gladys bought a small house in Hollywood with a loan from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and moved seven-year-old Monroe in with her.

They shared the house with lodgers, actors George and Maude Atkinson and their daughter, Nellie. In January 1934, Gladys had a mental breakdown and was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.[26] After several months in a rest home, she was committed to the Metropolitan State Hospital. She spent the rest of her life in and out of hospitals and was rarely in contact with Monroe. Monroe became a ward of the state, and her mother’s friend Grace Goddard took responsibility over her and her mother’s affairs.

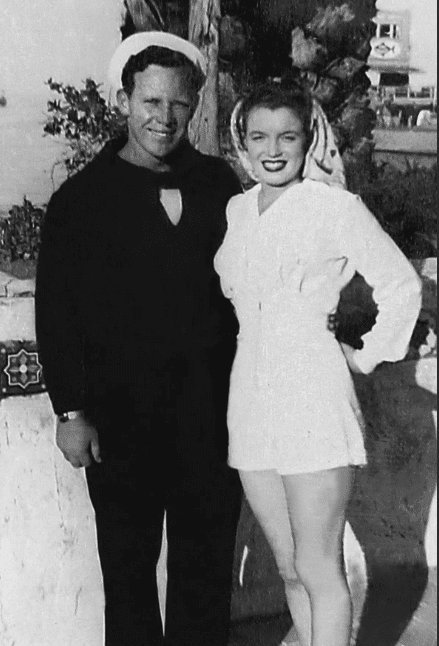

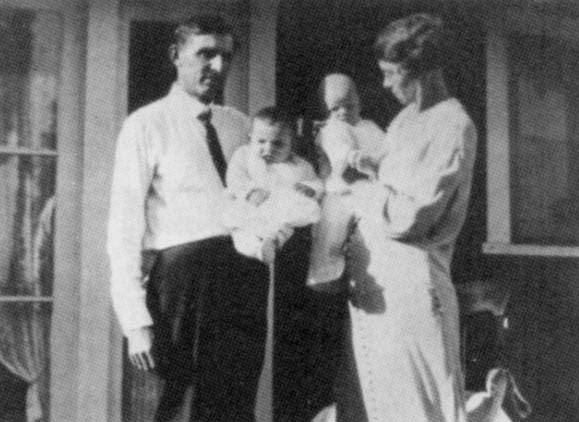

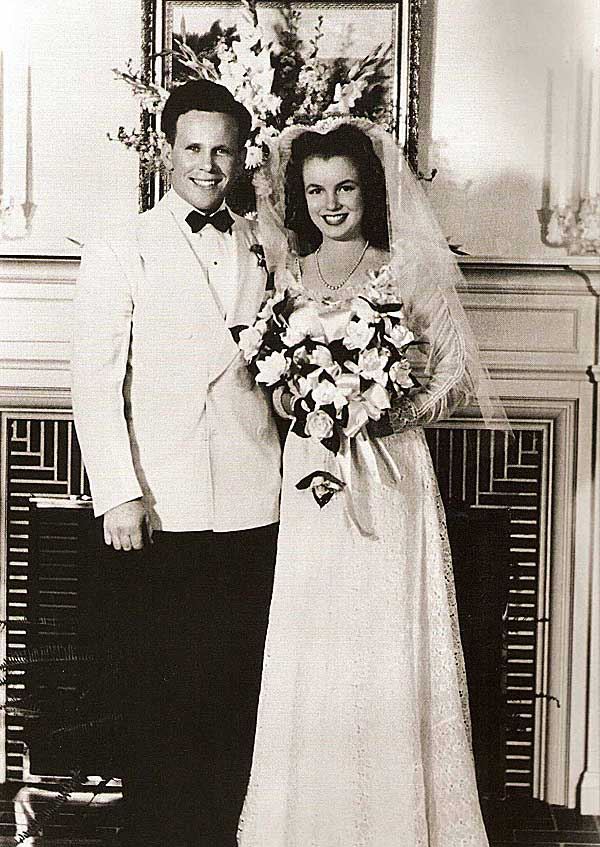

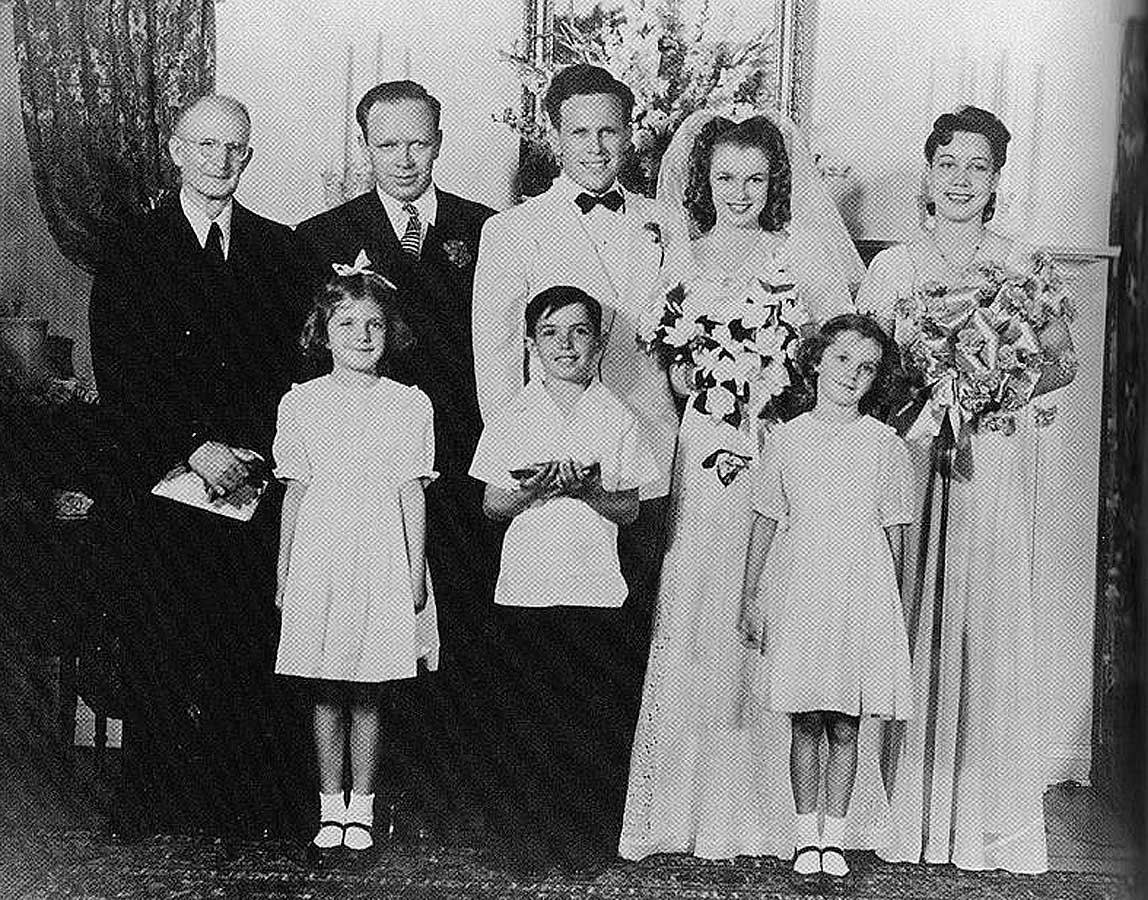

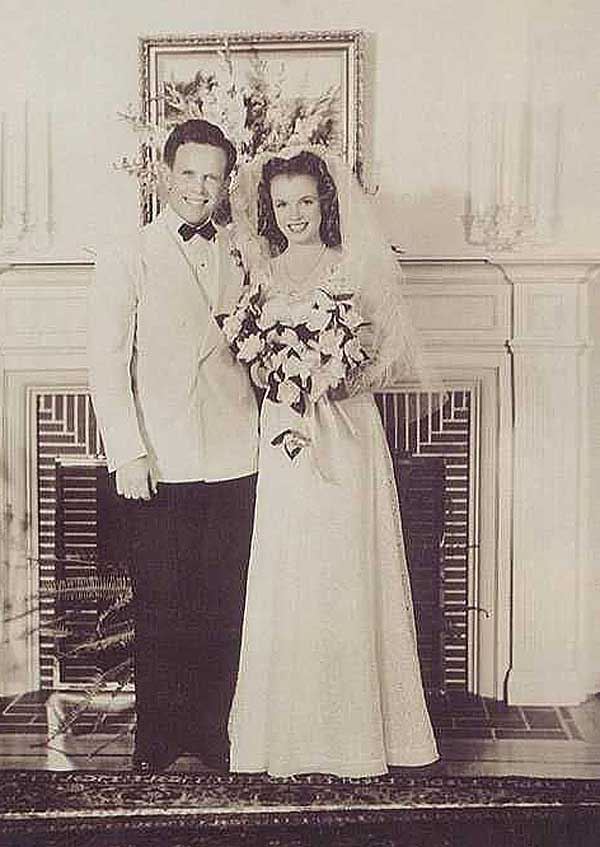

Monroe with her first husband, James Dougherty, c. 1943–44. They married when she was 16 years old.

Over the next four years, Monroe’s living situation changed often. For the first 16 months, she continued living with the Atkinsons, and may have been sexually abused during this time.[c] Always a shy girl, she now also developed a stutter and became withdrawn. In the summer of 1935, she briefly stayed with Grace and her husband Erwin «Doc» Goddard and two other families. In September 1935, Grace placed her in the Los Angeles Orphans Home. The orphanage was «a model institution» and was described in positive terms by her peers, but Monroe felt abandoned.

Encouraged by the orphanage staff, who thought that Monroe would be happier living in a family, Grace became her legal guardian in 1936, but did not take her out of the orphanage until the summer of 1937. Monroe’s second stay with the Goddards lasted only a few months because Doc molested her. She then lived for brief periods with her relatives and Grace’s friends and relatives in Los Angeles and Compton.

Monroe’s childhood experiences first made her want to become an actress: «I didn’t like the world around me because it was kind of grim … When I heard that this was acting, I said that’s what I want to be … Some of my foster families used to send me to the movies to get me out of the house and there I’d sit all day and way into the night. Up in front, there with the screen so big, a little kid all alone, and I loved it.»[43]

Monroe found a more permanent home in September 1938, when she began living with Grace’s aunt Ana Lower in the west-side district of Sawtelle. She was enrolled at Emerson Junior High School and went to weekly Christian Science services with Lower. She excelled in writing and contributed to the school newspaper, but was otherwise a mediocre student. Owing to the elderly Lower’s health problems, Monroe returned to live with the Goddards in Van Nuys in about early 1941.

The same year, she began attending Van Nuys High School.[48] In 1942, the company that employed Doc Goddard relocated him to West Virginia. California child protection laws prevented the Goddards from taking Monroe out of state, and she faced having to return to the orphanage. As a solution, she married their neighbors’ 21-year-old son, factory worker James Dougherty, on June 19, 1942, just after her 16th birthday.[51]

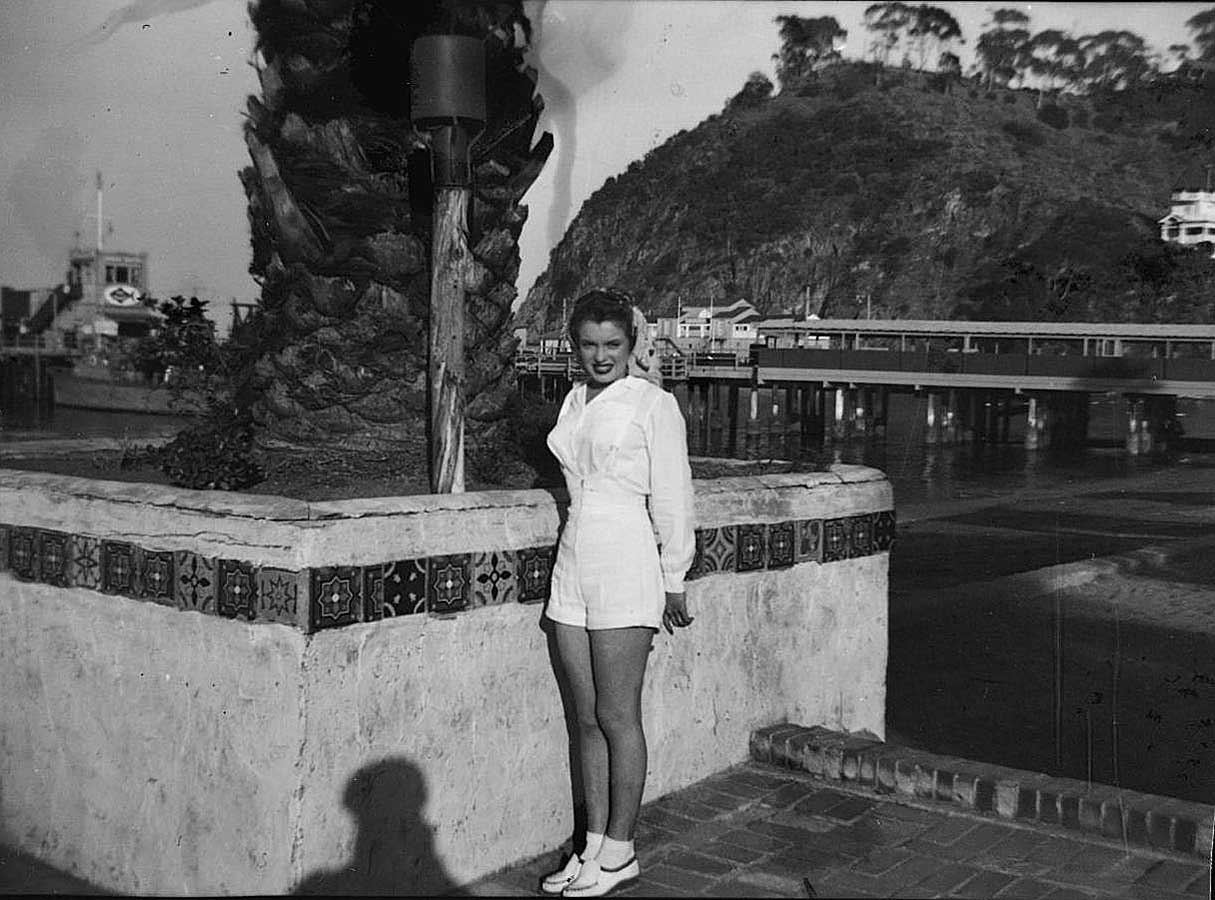

Monroe subsequently dropped out of high school and became a housewife. She found herself and Dougherty mismatched, and later said she was «dying of boredom» during the marriage.[52] In 1943, Dougherty enlisted in the Merchant Marine and was stationed on Santa Catalina Island, where Monroe moved with him.

1944–1948: Modeling and first film roles

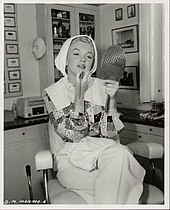

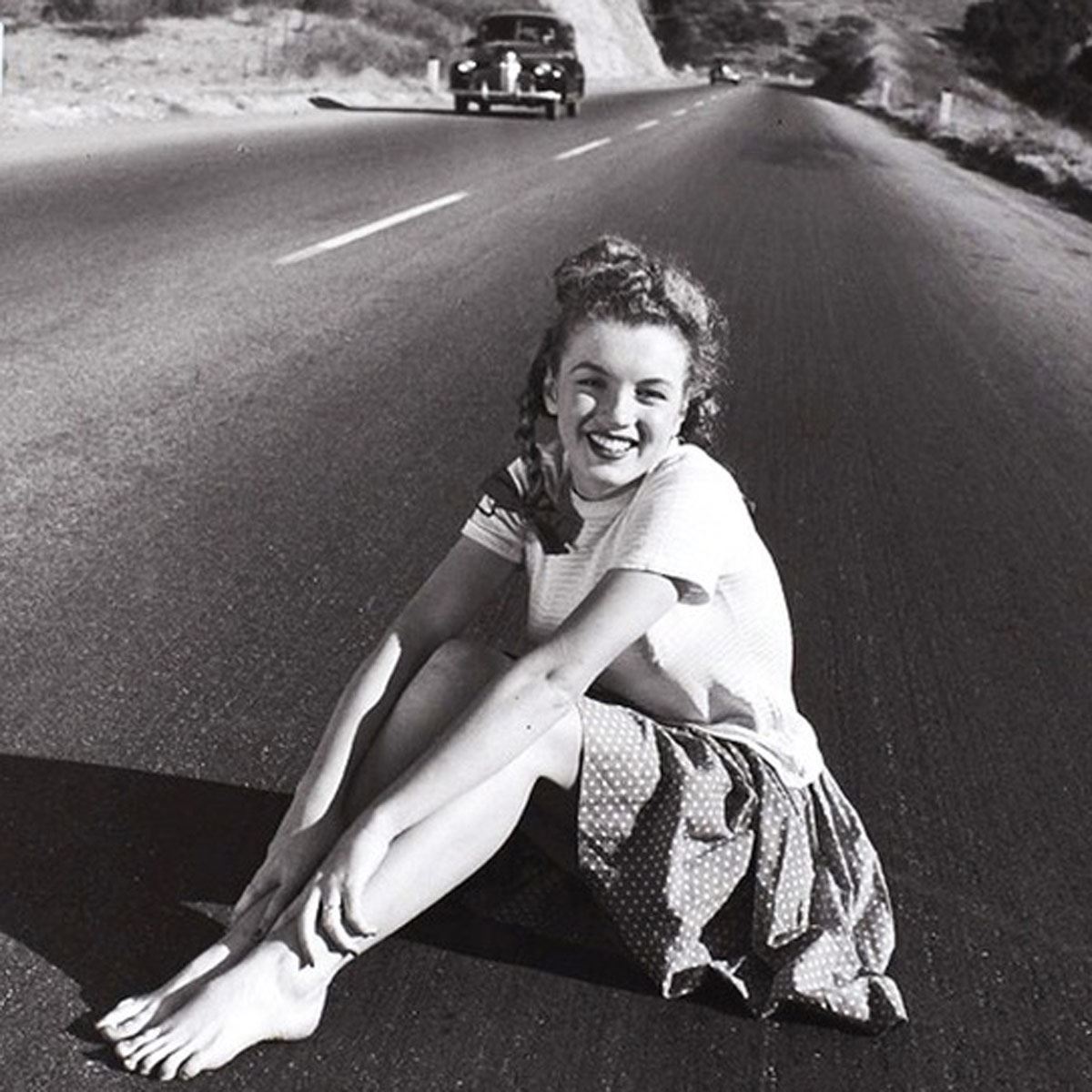

A photo of Monroe taken by David Conover in mid-1944 at the Radioplane Company

In April 1944, Dougherty was shipped out to the Pacific, where he remained for most of the next two years. Monroe moved in with her in-laws and began a job at the Radioplane Company, a munitions factory in Van Nuys. In late 1944, she met photographer David Conover, who had been sent by the U.S. Army Air Forces’ First Motion Picture Unit to the factory to shoot morale-boosting pictures of female workers.[54] Although none of her pictures were used, she quit working at the factory in January 1945 and began modeling for Conover and his friends.[55][56] Defying her deployed husband, she moved on her own and signed a contract with the Blue Book Model Agency in August 1945.

The agency deemed Monroe’s figure more suitable for pin-up than high fashion modeling, and she was featured mostly in advertisements and men’s magazines.[58] To make herself more employable, she straightened her hair and dyed it blonde. According to Emmeline Snively, the agency’s owner, Monroe quickly became one of its most ambitious and hard-working models; by early 1946, she had appeared on 33 magazine covers for publications such as Pageant, U.S. Camera, Laff, and Peek. As a model, Monroe occasionally used the pseudonym Jean Norman.

Monroe posing as a pin-up model for a postcard photograph c. 1940s

Through Snively, Monroe signed a contract with an acting agency in June 1946.[61] After an unsuccessful interview at Paramount Pictures, she was given a screen-test by Ben Lyon, a 20th Century-Fox executive. Head executive Darryl F. Zanuck was unenthusiastic about it, but he gave her a standard six-month contract to avoid her being signed by rival studio RKO Pictures.[d] Monroe’s contract began in August 1946, and she and Lyon selected the stage name «Marilyn Monroe».[64] The first name was picked by Lyon, who was reminded of Broadway star Marilyn Miller; the surname was Monroe’s mother’s maiden name.[65] In September 1946, she divorced Dougherty, who opposed her career.[66]

Monroe spent her first six months at Fox learning acting, singing, and dancing, and observing the film-making process. Her contract was renewed in February 1947, and she was given her first film roles, bit parts in Dangerous Years (1947) and Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (1948).[68][e] The studio also enrolled her in the Actors’ Laboratory Theatre, an acting school teaching the techniques of the Group Theatre; she later stated that it was «my first taste of what real acting in a real drama could be, and I was hooked».[70] Despite her enthusiasm, her teachers thought her too shy and insecure to have a future in acting, and Fox did not renew her contract in August 1947. She returned to modeling while also doing occasional odd jobs at film studios, such as working as a dancing «pacer» behind the scenes to keep the leads on point at musical sets.

Monroe in a 1948 publicity photo

Monroe was determined to make it as an actress, and continued studying at the Actors’ Lab. She had a small role in the play Glamour Preferred at the Bliss-Hayden Theater, but it ended after a couple of performances. To network, she frequented producers’ offices, befriended gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky, and entertained influential male guests at studio functions, a practice she had begun at Fox. She also became a friend and occasional sex partner of Fox executive Joseph M. Schenck, who persuaded his friend Harry Cohn, the head executive of Columbia Pictures, to sign her in March 1948.[74]

At Columbia, Monroe’s look was modeled after Rita Hayworth and her hair was bleached platinum blonde. She began working with the studio’s head drama coach, Natasha Lytess, who would remain her mentor until 1955.[76] Her only film at the studio was the low-budget musical Ladies of the Chorus (1948), in which she had her first starring role as a chorus girl courted by a wealthy man.[69] She also screen-tested for the lead role in Born Yesterday (1950), but her contract was not renewed in September 1948. Ladies of the Chorus was released the following month and was not a success.[78]

1949–1952: Breakthrough years

Monroe in The Asphalt Jungle (1950), one of her earliest performances to gain attention from film critics.

When her contract at Columbia ended, Monroe returned again to modeling. She shot a commercial for Pabst beer and posed for artistic nude photographs by Tom Kelley for John Baumgarth[79] calendars, using the name ‘Mona Monroe’.[80] Monroe had previously posed topless or clad in a bikini for other artists including Earl Moran, and felt comfortable with nudity.[f] Shortly after leaving Columbia, she also met and became the protégée and mistress of Johnny Hyde, the vice president of the William Morris Agency.

Through Hyde, Monroe landed small roles in several films,[g] including two critically acclaimed works: Joseph Mankiewicz’s drama All About Eve (1950) and John Huston’s film noir The Asphalt Jungle (1950).[83] Despite her screen time being only a few minutes in the latter, she gained a mention in Photoplay and according to biographer Donald Spoto «moved effectively from movie model to serious actress».[84] In December 1950, Hyde negotiated a seven-year contract for Monroe with 20th Century-Fox.[85] According to its terms, Fox could opt to not renew the contract after each year.[86] Hyde died of a heart attack only days later, which left Monroe devastated. In 1951, Monroe had supporting roles in three moderately successful Fox comedies: As Young as You Feel, Love Nest, and Let’s Make It Legal.[88] According to Spoto all three films featured her «essentially [as] a sexy ornament», but she received some praise from critics: Bosley Crowther of The New York Times described her as «superb» in As Young As You Feel and Ezra Goodman of the Los Angeles Daily News called her «one of the brightest up-and-coming [actresses]» for Love Nest.[89]

Her popularity with audiences was also growing: she received several thousand fan letters a week, and was declared «Miss Cheesecake of 1951» by the army newspaper Stars and Stripes, reflecting the preferences of soldiers in the Korean War.[90] In February 1952, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association named Monroe the «best young box office personality».[91] In her private life, Monroe had a short relationship with director Elia Kazan and also briefly dated several other men, including director Nicholas Ray and actors Yul Brynner and Peter Lawford.[92] In early 1952, she began a highly publicized romance with retired New York Yankees baseball star Joe DiMaggio, one of the most famous sports personalities of the era.

Monroe with Keith Andes in Clash by Night (1952). The film allowed Monroe to display more of her acting range in a dramatic role.

Monroe found herself at the center of a scandal in March 1952, when she revealed publicly that she had posed for a nude calendar in 1949.[94] The studio had learned about the photos and that she was publicly rumored to be the model some weeks prior, and together with Monroe decided that to prevent damaging her career it was best to admit to them while stressing that she had been broke at the time. The strategy gained her public sympathy and increased interest in her films, for which she was now receiving top billing. In the wake of the scandal, Monroe was featured on the cover of Life magazine as the «Talk of Hollywood», and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper declared her the «cheesecake queen» turned «box office smash».[96] Three of Monroe’s films —Clash by Night, Don’t Bother to Knock and We’re Not Married!— were released soon after to capitalize on the public interest.

Despite her newfound popularity as a sex symbol, Monroe also wished to showcase more of her acting range. She had begun taking acting classes with Michael Chekhov and mime Lotte Goslar soon after beginning the Fox contract, and Clash by Night and Don’t Bother to Knock showed her in different roles. In the former, a drama starring Barbara Stanwyck and directed by Fritz Lang, she played a fish cannery worker; to prepare, she spent time in a fish cannery in Monterey.[100] She received positive reviews for her performance: The Hollywood Reporter stated that «she deserves starring status with her excellent interpretation», and Variety wrote that she «has an ease of delivery which makes her a cinch for popularity».[101][102] The latter was a thriller in which Monroe starred as a mentally disturbed babysitter and which Zanuck used to test her abilities in a heavier dramatic role.[103] It received mixed reviews from critics, with Crowther deeming her too inexperienced for the difficult role,[104] and Variety blaming the script for the film’s problems.[106]

Monroe’s three other films in 1952 continued with her typecasting in comedic roles that highlighted her sex appeal. In We’re Not Married!, her role as a beauty pageant contestant was created solely to «present Marilyn in two bathing suits», according to its writer Nunnally Johnson.[107] In Howard Hawks’s Monkey Business, in which she acted opposite Cary Grant, she played a secretary who is a «dumb, childish blonde, innocently unaware of the havoc her sexiness causes around her».[108] In O. Henry’s Full House, with Charles Laughton she appeared in a passing vignette as a nineteenth-century street walker.[109] Monroe added to her reputation as a new sex symbol with publicity stunts that year: she wore a revealing dress when acting as Grand Marshal at the Miss America Pageant parade, and told gossip columnist Earl Wilson that she usually wore no underwear.[110] By the end of the year, gossip columnist Florabel Muir named Monroe the «it girl» of 1952.[111][112]

During this period, Monroe gained a reputation for being difficult to work with, which would worsen as her career progressed. She was often late or did not show up at all, did not remember her lines, and would demand several re-takes before she was satisfied with her performance.[113] Her dependence on her acting coaches—Natasha Lytess and then Paula Strasberg—also irritated directors.[114] Monroe’s problems have been attributed to a combination of perfectionism, low self-esteem, and stage fright. She disliked her lack of control on film sets and never experienced similar problems during photo shoots, in which she had more say over her performance and could be more spontaneous instead of following a script.[116] To alleviate her anxiety and chronic insomnia, she began to use barbiturates, amphetamines, and alcohol, which also exacerbated her problems, although she did not become severely addicted until 1956. According to Sarah Churchwell, some of Monroe’s behavior, especially later in her career, was also in response to the condescension and sexism of her male co-stars and directors.[118] Biographer Lois Banner said that she was bullied by many of her directors.

1953: Rising star

Monroe in Niagara (1953), which dwelt on her sex appeal

Monroe starred in three movies that were released in 1953 and emerged as a major sex symbol and one of Hollywood’s most bankable performers.[120][121] The first was the Technicolor film noir Niagara, in which she played a femme fatale scheming to murder her husband, played by Joseph Cotten.[122] By then, Monroe and her make-up artist Allan «Whitey» Snyder had developed her «trademark» make-up look: dark arched brows, pale skin, «glistening» red lips and a beauty mark.[123] According to Sarah Churchwell, Niagara was one of the most overtly sexual films of Monroe’s career.[108] In some scenes, Monroe’s body was covered only by a sheet or a towel, considered shocking by contemporary audiences. Niagara‘s most famous scene is a 30-second long shot behind Monroe where she is seen walking with her hips swaying, which was used heavily in the film’s marketing.

When Niagara was released in January 1953, women’s clubs protested it as immoral, but it proved popular with audiences. While Variety deemed it «clichéd» and «morbid», The New York Times commented that «the falls and Miss Monroe are something to see», as although Monroe may not be «the perfect actress at this point … she can be seductive—even when she walks».[126][127]

Monroe continued to attract attention by wearing revealing outfits, most famously at the Photoplay Awards in January 1953, where she won the «Fastest Rising Star» award. A pleated «sunburst» waist-tight, deep decolleté gold lamé dress designed by William Travilla for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but barely seen at all in the film, was to become a sensation.[129] Prompted by such imagery, veteran star Joan Crawford publicly called the behavior «unbecoming an actress and a lady».

While Niagara made Monroe a sex symbol and established her «look», her second film of 1953, the satirical musical comedy Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, cemented her screen persona as a «dumb blonde». Based on Anita Loos’ novel and its Broadway version, the film focuses on two «gold-digging» showgirls played by Monroe and Jane Russell. Monroe’s role was originally intended for Betty Grable, who had been 20th Century-Fox’s most popular «blonde bombshell» in the 1940s; Monroe was fast eclipsing her as a star who could appeal to both male and female audiences. As part of the film’s publicity campaign, she and Russell pressed their hand and footprints in wet concrete outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in June. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was released shortly after and became one of the biggest box office successes of the year.[133] Crowther of The New York Times and William Brogdon of Variety both commented favorably on Monroe, especially noting her performance of «Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend»; according to the latter, she demonstrated the «ability to sex a song as well as point up the eye values of a scene by her presence».[134][135]

In September, Monroe made her television debut in the Jack Benny Show, playing Jack’s fantasy woman in the episode «Honolulu Trip».[136] She co-starred with Betty Grable and Lauren Bacall in her third movie of the year, How to Marry a Millionaire, released in November. It featured Monroe as a naïve model who teams up with her friends to find rich husbands, repeating the successful formula of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. It was the second film ever released in CinemaScope, a widescreen format that Fox hoped would draw audiences back to theaters as television was beginning to cause losses to film studios.[137] Despite mixed reviews, the film was Monroe’s biggest box office success at that point in her career.[138]

Monroe was listed in the annual Top Ten Money Making Stars Poll in both 1953 and 1954,[121] and according to Fox historian Aubrey Solomon became the studio’s «greatest asset» alongside CinemaScope.[139] Monroe’s position as a leading sex symbol was confirmed in December 1953, when Hugh Hefner featured her on the cover and as centerfold in the first issue of Playboy; Monroe did not consent to the publication.[140] The cover image was a photograph taken of her at the Miss America Pageant parade in 1952, and the centerfold featured one of her 1949 nude photographs.[140]

1954–1955: Conflicts with 20th Century-Fox and marriage to Joe DiMaggio

Monroe had become one of 20th Century-Fox’s biggest stars, but her contract had not changed since 1950, so that she was paid far less than other stars of her stature and could not choose her projects.[141] Her attempts to appear in films that would not focus on her as a pin-up had been thwarted by the studio head executive, Darryll F. Zanuck, who had a strong personal dislike of her and did not think she would earn the studio as much revenue in other types of roles.[142] Under pressure from the studio’s owner, Spyros Skouras, Zanuck had also decided that Fox should focus exclusively on entertainment to maximize profits and canceled the production of any «serious films». In January 1954, he suspended Monroe when she refused to begin shooting yet another musical comedy, The Girl in Pink Tights.[144]

This was front-page news, and Monroe immediately took action to counter negative publicity. On January 14, she and Joe DiMaggio were married at the San Francisco City Hall.[145] They then traveled by car[146] to San Luis Obispo,[147] then honeymooned[148] outside Idyllwild, California,[149][150][151] in the mountain lodge of Monroe’s lawyer Lloyd Wright.[152][153] On January 29, 1954, fifteen days later,[154] they flew to Japan,[155] combining a «honeymoon» with his commitment to his former San Francisco Seals coach Lefty O’Doul,[156] to help train[157] Japanese baseball teams.[158][159] From Tokyo, she traveled with Jean O’Doul,[158] Lefty’s wife, to Korea,[160][161] where she participated in a USO show,[162] singing songs from her films for over 60,000 U.S. Marines over a four-day period.[163][164][165] After returning to the U.S., she was awarded Photoplay‘s «Most Popular Female Star» prize.[166] Monroe settled with Fox in March, with the promise of a new contract, a bonus of $100,000, and a starring role in the film adaptation of the Broadway success The Seven Year Itch.[167]

In April 1954, Otto Preminger’s western River of No Return, the last film that Monroe had filmed prior to the suspension, was released. She called it a «Z-grade cowboy movie in which the acting finished second to the scenery and the CinemaScope process», but it was popular with audiences.[168] The first film she made after the suspension was the musical There’s No Business Like Show Business, which she strongly disliked but the studio required her to do for dropping The Girl in Pink Tights.[167] It was unsuccessful upon its release in late 1954, with Monroe’s performance considered vulgar by many critics.

In September 1954, Monroe began filming Billy Wilder’s comedy The Seven Year Itch, starring opposite Tom Ewell as a woman who becomes the object of her married neighbor’s sexual fantasies. Although the film was shot in Hollywood, the studio decided to generate advance publicity by staging the filming of a scene in which Monroe is standing on a subway grate with the air blowing up the skirt of her white dress on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan.[170] The shoot lasted for several hours and attracted nearly 2,000 spectators.[170] The «subway grate scene» became one of Monroe’s most famous, and The Seven Year Itch became one of the biggest commercial successes of the year after its release in June 1955.[171]

The publicity stunt placed Monroe on international front pages, and it also marked the end of her marriage to DiMaggio, who was infuriated by it. The union had been troubled from the start by his jealousy and controlling attitude; he was also physically abusive. After returning from NYC to Hollywood in October 1954, Monroe filed for divorce, after only nine months of marriage.

After filming for The Seven Year Itch wrapped up in November 1954, Monroe left Hollywood for the East Coast, where she and photographer Milton Greene founded their own production company, Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP)—an action that has later been called «instrumental» in the collapse of the studio system.[175][h] Monroe stated that she was «tired of the same old sex roles» and asserted that she was no longer under contract to Fox, as it had not fulfilled its duties, such as paying her the promised bonus.[177] This began a year-long legal battle between her and Fox in January 1955.[178] The press largely ridiculed Monroe, and she was parodied in the Broadway play Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1955), in which her lookalike Jayne Mansfield played a dumb actress who starts her own production company.[179]

After founding MMP, Monroe moved to Manhattan and spent 1955 studying acting. She took classes with Constance Collier and attended workshops on method acting at the Actors Studio, run by Lee Strasberg.[180] She grew close to Strasberg and his wife Paula, receiving private lessons at their home due to her shyness, and soon became a family member.[181] She replaced her old acting coach, Natasha Lytess, with Paula; the Strasbergs remained an important influence for the rest of her career.[182] Monroe also started undergoing psychoanalysis, as Strasberg believed that an actor must confront their emotional traumas and use them in their performances.[183][i]

Monroe continued her relationship with DiMaggio despite the ongoing divorce process; she also dated actor Marlon Brando and playwright Arthur Miller.[185] She had first been introduced to Miller by Elia Kazan in the early 1950s.[185] The affair between Monroe and Miller became increasingly serious after October 1955, when her divorce was finalized and he separated from his wife.[186] The studio urged her to end it, as Miller was being investigated by the FBI for allegations of communism and had been subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee, but Monroe refused.[187] The relationship led to the FBI opening a file on her.[186]

By the end of the year, Monroe and Fox signed a new seven-year contract, as MMP would not be able to finance films alone, and the studio was eager to have Monroe working for them again.[178] Fox would pay her $400,000 to make four films, and granted her the right to choose her own projects, directors and cinematographers.[188] She would also be free to make one film with MMP per each completed film for Fox.[188]

1956–1959: Critical acclaim and marriage to Arthur Miller

Monroe began 1956 by announcing her win over 20th Century-Fox. She legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe.[190] The press wrote favorably about her decision to fight the studio; Time called her a «shrewd businesswoman»[191] and Look predicted that the win would be «an example of the individual against the herd for years to come». In contrast, Monroe’s relationship with Miller prompted some negative comments, such as Walter Winchell’s statement that «America’s best-known blonde moving picture star is now the darling of the left-wing intelligentsia.»[192]

In March, Monroe began filming the drama Bus Stop, her first film under the new contract.[193] She played Chérie, a saloon singer whose dreams of stardom are complicated by a naïve cowboy who falls in love with her. For the role, she learned an Ozark accent, chose costumes and makeup that lacked the glamor of her earlier films, and provided deliberately mediocre singing and dancing.[194] Broadway director Joshua Logan agreed to direct, despite initially doubting Monroe’s acting abilities and knowing of her difficult reputation.[195]

The filming took place in Idaho and Arizona, with Monroe «technically in charge» as the head of MMP, occasionally making decisions on cinematography and with Logan adapting to her chronic lateness and perfectionism.[196] The experience changed Logan’s opinion of Monroe, and he later compared her to Charlie Chaplin in her ability to blend comedy and tragedy.

Monroe’s dramatic performance in Bus Stop (1956) marked a departure from her earlier comedies.

On June 29, 1956, Monroe and Miller were married at the Westchester County Court in White Plains, New York; two days later they had a Jewish ceremony at the home of Kay Brown, Miller’s literary agent, in Waccabuc, New York.[198][199] With the marriage, Monroe converted to Judaism, which led Egypt to ban all of her films.[200][j] Due to Monroe’s status as a sex symbol and Miller’s image as an intellectual, the media saw the union as a mismatch, as evidenced by Variety‘s headline, «Egghead Weds Hourglass».[202]

Bus Stop was released in August 1956 and became a critical and commercial success.[203] The Saturday Review of Literature wrote that Monroe’s performance «effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamour personality» and Crowther proclaimed: «Hold on to your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress.»[204] She also received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress for her performance.[91]

In August, Monroe also began filming MMP’s first independent production, The Prince and the Showgirl, at Pinewood Studios in England.[205] Based on a 1953 stage play by Terence Rattigan, it was to be directed and co-produced by, and to co-star, Laurence Olivier.[191] The production was complicated by conflicts between him and Monroe.[206] Olivier, who had also directed and starred in the stage play, angered her with the patronizing statement «All you have to do is be sexy», and with his demand she replicate Vivien Leigh’s stage interpretation of the character. He also disliked the constant presence of Paula Strasberg, Monroe’s acting coach, on set.[208] In retaliation, Monroe became uncooperative and began to deliberately arrive late, later saying, «if you don’t respect your artists, they can’t work well.»[206]

Monroe also experienced other problems during the production. Her dependence on pharmaceuticals escalated and, according to Spoto, she had a miscarriage. She and Greene also argued over how MMP should be run. Despite the difficulties, filming was completed on schedule by the end of 1956. The Prince and the Showgirl was released to mixed reviews in June 1957 and proved unpopular with American audiences.[211] It was better received in Europe, where she was awarded the Italian David di Donatello and the French Crystal Star awards and nominated for a BAFTA.

After returning from England, Monroe took an 18-month hiatus to concentrate on family life. She and Miller split their time between NYC, Connecticut and Long Island.[213] She had an ectopic pregnancy in mid-1957, and a miscarriage a year later;[214] these problems were most likely linked to her endometriosis.[215][k] Monroe was also briefly hospitalized due to a barbiturate overdose. As she and Greene could not settle their disagreements over MMP, Monroe bought his share of the company.[219]

Monroe returned to Hollywood in July 1958 to act opposite Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in Billy Wilder’s comedy on gender roles, Some Like It Hot. She considered the role of Sugar Kane another «dumb blonde», but accepted it due to Miller’s encouragement and the offer of 10% of the film’s profits on top of her standard pay. The film’s difficult production has since become «legendary».[222] Monroe demanded dozens of retakes, and did not remember her lines or act as directed—Curtis famously said that kissing her was «like kissing Hitler» due to the number of retakes.[223]

Monroe privately likened the production to a sinking ship and commented on her co-stars and director saying «[but] why should I worry, I have no phallic symbol to lose.»[224] Many of the problems stemmed from her and Wilder—who also had a reputation for being difficult—disagreeing on how she should play the role. She angered him by asking to alter many of her scenes, which in turn made her stage fright worse, and it is suggested that she deliberately ruined several scenes to act them her way.

In the end, Wilder was happy with Monroe’s performance, saying: «Anyone can remember lines, but it takes a real artist to come on the set and not know her lines and yet give the performance she did!»[226] Some Like It Hot was a critical and commercial success when it was released in March 1959. Monroe’s performance earned her a Golden Globe for Best Actress, and prompted Variety to call her «a comedienne with that combination of sex appeal and timing that just can’t be beat».[228] It has been voted one of the best films ever made in polls by the BBC,[229] the American Film Institute,[230] and Sight & Sound.[231]

1960–1962: Career decline and personal difficulties

After Some Like It Hot, Monroe took another hiatus until late 1959, when she starred in the musical comedy Let’s Make Love.[232] She chose George Cukor to direct and Miller rewrote some of the script, which she considered weak. She accepted the part solely because she was behind on her contract with Fox.[233] The film’s production was delayed by her frequent absences from the set.[232] During the shoot, Monroe had an extramarital affair with her co-star Yves Montand, which was widely reported by the press and used in the film’s publicity campaign.[234]

Let’s Make Love was unsuccessful upon its release in September 1960.[235] Crowther described Monroe as appearing «rather untidy» and «lacking … the old Monroe dynamism»,[236] and Hedda Hopper called the film «the most vulgar picture she’s ever done».[237] Truman Capote lobbied for Monroe to play Holly Golightly in a film adaptation of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, but the role went to Audrey Hepburn as its producers feared that Monroe would complicate the production.

The last film Monroe completed was John Huston’s The Misfits, which Miller had written to provide her with a dramatic role.[239] She played a recently divorced woman who becomes friends with three aging cowboys, played by Clark Gable, Eli Wallach and Montgomery Clift. The filming in the Nevada desert between July and November 1960 was again difficult.[240] Monroe’s and Miller’s marriage was effectively over, and he began a new relationship with set photographer Inge Morath.[239]

Monroe disliked that he had based her role partly on her life, and thought it inferior to the male roles. She also struggled with Miller’s habit of rewriting scenes the night before filming. Her health was also failing: she was in pain from gallstones, and her drug addiction was so severe that her makeup usually had to be applied while she was still asleep under the influence of barbiturates. In August, filming was halted for her to spend a week in a hospital detox. Despite her problems, Huston said that when Monroe was acting, she «was not pretending to an emotion. It was the real thing. She would go deep down within herself and find it and bring it up into consciousness.»[243]

Monroe and Miller separated after filming wrapped, and she obtained a Mexican divorce in January 1961.[244] The Misfits was released the following month, failing at the box office. Its reviews were mixed, with Variety complaining of frequently «choppy» character development,[246] and Bosley Crowther calling Monroe «completely blank and unfathomable» and writing that «unfortunately for the film’s structure, everything turns upon her».[247] It has received more favorable reviews in the 21st century. Geoff Andrew of the British Film Institute has called it a classic,[248] Huston scholar Tony Tracy called Monroe’s performance the «most mature interpretation of her career»,[249] and Geoffrey McNab of The Independent praised her «extraordinary» portrayal of the character’s «power of empathy».[250]

Monroe was next to star in a television adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s Rain for NBC, but the project fell through as the network did not want to hire her choice of director, Lee Strasberg.[251] Instead of working, she spent the first six months of 1961 preoccupied by health problems. She underwent a cholecystectomy and surgery for her endometriosis, and spent four weeks hospitalized for depression.[252][l] She was helped by DiMaggio, with whom she rekindled a friendship, and dated his friend Frank Sinatra for several months.[254] Monroe also moved permanently back to California in 1961, purchasing a house at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive in Brentwood, Los Angeles, in early 1962.[255]

Monroe on the set of Something’s Got to Give. She was absent for most of the production due to illness and was fired by Fox in June 1962, two months before her death.

Monroe returned to the public eye in the spring of 1962. She received a «World Film Favorite» Golden Globe Award and began to shoot a film for Fox, Something’s Got to Give, a remake of My Favorite Wife (1940).[256] It was to be co-produced by MMP, directed by George Cukor and to co-star Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse.[257] Days before filming began, Monroe caught sinusitis. Despite medical advice to postpone the production, Fox began it as planned in late April.

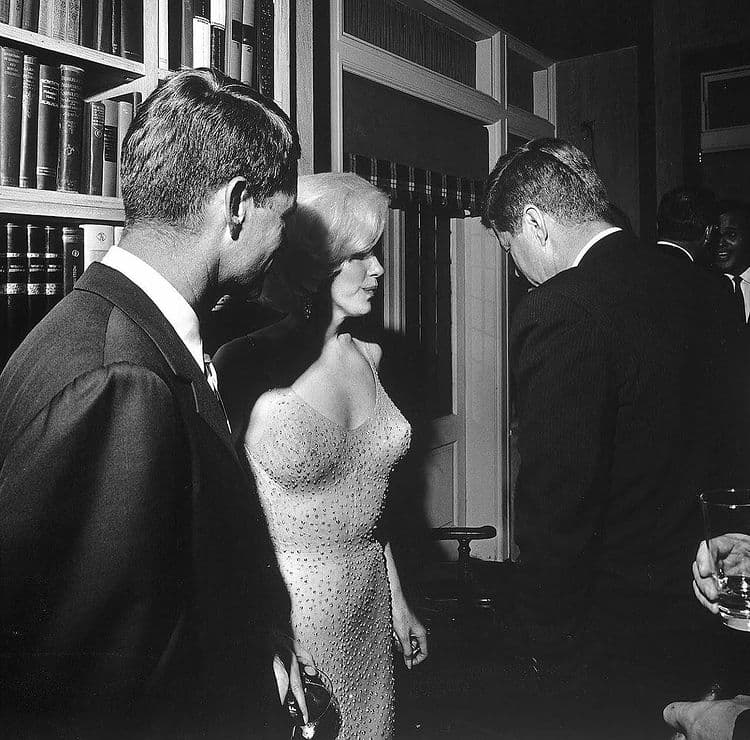

Monroe was too sick to work for most of the next six weeks, but despite confirmations by multiple doctors, the studio pressured her by alleging publicly that she was faking it. On May 19, she took a break to sing «Happy Birthday, Mr. President» on stage at President John F. Kennedy’s early birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden in New York.[259] She drew attention with her costume: a beige, skintight dress covered in rhinestones, which made her appear nude.[259][m] Monroe’s trip to New York caused even more irritation for Fox executives, who had wanted her to cancel it.

Monroe next filmed a scene for Something’s Got to Give in which she swam naked in a swimming pool.[262] To generate advance publicity, the press was invited to take photographs; these were later published in Life. This was the first time that a major star had posed nude at the height of their career.[263] When she was again on sick leave for several days, Fox decided that it could not afford to have another film running behind schedule when it was already struggling with the rising costs of Cleopatra (1963).[264] On June 7, Fox fired Monroe and sued her for $750,000 in damages.[265] She was replaced by Lee Remick, but after Martin refused to make the film with anyone other than Monroe, Fox sued him as well and shut down the production.[266] The studio blamed Monroe for the film’s demise and began spreading negative publicity about her, even alleging that she was mentally disturbed.[265]

Fox soon regretted its decision and reopened negotiations with Monroe later in June; a settlement about a new contract, including recommencing Something’s Got to Give and a starring role in the black comedy What a Way to Go! (1964), was reached later that summer. She was also planning on starring in a biopic of Jean Harlow. To repair her public image, Monroe engaged in several publicity ventures, including interviews for Life and Cosmopolitan and her first photo shoot for Vogue.[269] For Vogue, she and photographer Bert Stern collaborated for two series of photographs, one a standard fashion editorial and another of her posing nude, which were published posthumously with the title The Last Sitting.

Death and funeral

During her final months, Monroe lived at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. Her housekeeper Eunice Murray was staying overnight at the home on the evening of August 4, 1962. Murray woke at 3:00 a.m. on August 5 and sensed that something was wrong. She saw light from under Monroe’s bedroom door but was unable to get a response and found the door locked. Murray then called Monroe’s psychiatrist, Ralph Greenson, who arrived at the house shortly after and broke into the bedroom through a window to find Monroe dead in her bed. Monroe’s physician, Hyman Engelberg, arrived at around 3:50 a.m. and pronounced her dead. At 4:25 a.m., the Los Angeles Police Department was notified.

Monroe died between 8:30 p.m. and 10:30 p.m. on August 4,; the toxicology report showed that the cause of death was acute barbiturate poisoning. She had 8 mg% (milligrams per 100 milliliters of solution) chloral hydrate and 4.5 mg% of pentobarbital (Nembutal) in her blood, and 13 mg% of pentobarbital in her liver. Empty medicine bottles were found next to her bed. The possibility that Monroe had accidentally overdosed was ruled out because the dosages found in her body were several times the lethal limit.[276]

The Los Angeles County Coroners Office was assisted in their investigation by the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Team, who had expert knowledge on suicide. Monroe’s doctors stated that she had been «prone to severe fears and frequent depressions» with «abrupt and unpredictable mood changes», and had overdosed several times in the past, possibly intentionally.[276] Due to these facts and the lack of any indication of foul play, deputy coroner Thomas Noguchi classified her death as a probable suicide.

Monroe’s sudden death was front-page news in the United States and Europe. According to Lois Banner, «it’s said that the suicide rate in Los Angeles doubled the month after she died; the circulation rate of most newspapers expanded that month», and the Chicago Tribune reported that they had received hundreds of phone calls from members of the public requesting information about her death.[280] French artist Jean Cocteau commented that her death «should serve as a terrible lesson to all those whose chief occupation consists of spying on and tormenting film stars», her former co-star Laurence Olivier deemed her «the complete victim of ballyhoo and sensation», and Bus Stop director Joshua Logan said that she was «one of the most unappreciated people in the world».[281]

Her funeral, held at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery on August 8, was private and attended by only her closest associates. The service was arranged by Joe DiMaggio, Monroe’s half-sister Berniece Baker Miracle, and Monroe’s business manager Inez Melson. Hundreds of spectators crowded the streets around the cemetery. Monroe was later entombed at Crypt No. 24 at the Corridor of Memories.[283]

In the following decades, several conspiracy theories, including murder and accidental overdose, have been introduced to contradict suicide as the cause of Monroe’s death.[284] The speculation that Monroe had been murdered first gained mainstream attention with the publication of Norman Mailer’s Marilyn: A Biography in 1973, and in the following years became widespread enough for the Los Angeles County District Attorney John Van de Kamp to conduct a «threshold investigation» in 1982 to see whether a criminal investigation should be opened.[285] No evidence of foul play was found.[286]

Screen persona and reception

The 1940s had been the heyday for actresses who were perceived as tough and smart—such as Katharine Hepburn and Barbara Stanwyck—who had appealed to women-dominated audiences during the war years. 20th Century-Fox wanted Monroe to be a star of the new decade who would draw men to movie theaters, and saw her as a replacement for the aging Betty Grable, their most popular «blonde bombshell» of the 1940s. According to film scholar Richard Dyer, Monroe’s star image was crafted mostly for the male gaze.[288]

Actress Jean Harlow in 1934; Monroe took inspiration from her to develop her star image.

From the beginning, Monroe played a significant part in the creation of her public image, and towards the end of her career exerted almost full control over it.[290] She devised many of her publicity strategies, cultivated friendships with gossip columnists such as Sidney Skolsky and Louella Parsons, and controlled the use of her images. In addition to Grable, she was often compared to another well-known blonde, 1930s film star Jean Harlow. The comparison was prompted partly by Monroe, who named Harlow as her childhood idol, wanted to play her in a biopic, and even employed Harlow’s hair stylist to color her hair.

Monroe’s screen persona focused on her blonde hair and the stereotypes that were associated with it, especially dumbness, naïveté, sexual availability and artificiality.[294] She often used a breathy, childish voice in her films, and in interviews gave the impression that everything she said was «utterly innocent and uncalculated», parodying herself with double entendres that came to be known as «Monroeisms». For example, when she was asked what she had on in the 1949 nude photo shoot, she replied, «I had the radio on».

As seen in this publicity photo for The Seven Year Itch (1955), Monroe wore figure-hugging outfits that enhanced her sexual attractiveness

In her films, Monroe usually played «the girl», who is defined solely by her gender.[288] Her roles were almost always chorus girls, secretaries, or models: occupations where «the woman is on show, there for the pleasure of men.»[288] Monroe began her career as a pin-up model, and was noted for her hourglass figure.[297] She was often positioned in film scenes so that her curvy silhouette was on display, and frequently posed like a pin-up in publicity photos.[297] Her distinctive, hip-swinging walk also drew attention to her body and earned her the nickname «the girl with the horizontal walk».[108]

Monroe often wore white to emphasize her blondness and drew attention by wearing revealing outfits that showed off her figure. Her publicity stunts often revolved around her clothing either being shockingly revealing or even malfunctioning,[299] such as when a shoulder strap of her dress snapped during a press conference.[299] In press stories, Monroe was portrayed as the embodiment of the American Dream, a girl who had risen from a miserable childhood to Hollywood stardom. Stories of her time spent in foster families and an orphanage were exaggerated and even partly fabricated. Film scholar Thomas Harris wrote that her working-class roots and lack of family made her appear more sexually available, «the ideal playmate», in contrast to her contemporary, Grace Kelly, who was also marketed as an attractive blonde, but due to her upper-class background was seen as a sophisticated actress, unattainable for the majority of male viewers.[302]

Although Monroe’s screen persona as a dim-witted but sexually attractive blonde was a carefully crafted act, audiences and film critics believed it to be her real personality. This became a hindrance when she wanted to pursue other kinds of roles, or to be respected as a businesswoman. The academic Sarah Churchwell studied narratives about Monroe and wrote:

The biggest myth is that she was dumb. The second is that she was fragile. The third is that she couldn’t act. She was far from dumb, although she was not formally educated, and she was very sensitive about that. But she was very smart indeed—and very tough. She had to be both to beat the Hollywood studio system in the 1950s. […] The dumb blonde was a role—she was an actress, for heaven’s sake! Such a good actress that no one now believes she was anything but what she portrayed on screen.[304]

Biographer Lois Banner writes that Monroe often subtly parodied her sex symbol status in her films and public appearances, and that «the ‘Marilyn Monroe’ character she created was a brilliant archetype, who stands between Mae West and Madonna in the tradition of twentieth-century gender tricksters.»[306] Monroe herself stated that she was influenced by West, learning «a few tricks from her—that impression of laughing at, or mocking, her own sexuality». She studied comedy in classes by mime and dancer Lotte Goslar, famous for her comic stage performances, and Goslar also instructed her on film sets. In Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, one of the films in which she played an archetypal dumb blonde, Monroe had the sentence «I can be smart when it’s important, but most men don’t like it» added to her character’s lines.

According to Dyer, Monroe became «virtually a household name for sex» in the 1950s and «her image has to be situated in the flux of ideas about morality and sexuality that characterised the Fifties in America», such as Freudian ideas about sex, the Kinsey report (1953), and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963).[310] By appearing vulnerable and unaware of her sex appeal, Monroe was the first sex symbol to present sex as natural and without danger, in contrast to the 1940s femme fatales.[311] Spoto likewise describes her as the embodiment of «the postwar ideal of the American girl, soft, transparently needy, worshipful of men, naïve, offering sex without demands», which is echoed in Molly Haskell’s statement that «she was the Fifties fiction, the lie that a woman had no sexual needs, that she is there to cater to, or enhance, a man’s needs.»[312] Monroe’s contemporary Norman Mailer wrote that «Marilyn suggested sex might be difficult and dangerous with others, but ice cream with her», while Groucho Marx characterized her as «Mae West, Theda Bara, and Bo Peep all rolled into one».[313] According to Haskell, due to her sex symbol status, Monroe was less popular with women than with men, as they «couldn’t identify with her and didn’t support her», although this would change after her death.[314]

Dyer has also argued that Monroe’s blonde hair became her defining feature because it made her «racially unambiguous» and exclusively white just as the civil rights movement was beginning, and that she should be seen as emblematic of racism in twentieth-century popular culture.[315] Banner agreed that it may not be a coincidence that Monroe launched a trend of platinum blonde actresses during the civil rights movement, but has also criticized Dyer, pointing out that in her highly publicized private life, Monroe associated with people who were seen as «white ethnics», such as Joe DiMaggio (Italian-American) and Arthur Miller (Jewish). According to Banner, she sometimes challenged prevailing racial norms in her publicity photographs; for example, in an image featured in Look in 1951, she was shown in revealing clothes while practicing with African-American singing coach Phil Moore.

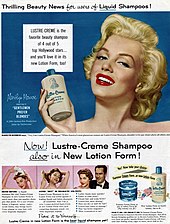

Monroe in a Lustre-Creme shampoo advertisement of 1953

Monroe was perceived as a specifically American star, «a national institution as well known as hot dogs, apple pie, or baseball» according to Photoplay. Banner calls her the symbol of populuxe, a star whose joyful and glamorous public image «helped the nation cope with its paranoia in the 1950s about the Cold War, the atom bomb, and the totalitarian communist Soviet Union». Historian Fiona Handyside writes that the French female audiences associated whiteness/blondness with American modernity and cleanliness, and so Monroe came to symbolize a modern, «liberated» woman whose life takes place in the public sphere.[320] Film historian Laura Mulvey has written of her as an endorsement for American consumer culture:

If America was to export the democracy of glamour into post-war, impoverished Europe, the movies could be its shop window … Marilyn Monroe, with her all American attributes and streamlined sexuality, came to epitomise in a single image this complex interface of the economic, the political, and the erotic. By the mid 1950s, she stood for a brand of classless glamour, available to anyone using American cosmetics, nylons and peroxide.[321]

Twentieth Century-Fox further profited from Monroe’s popularity by cultivating several lookalike actresses, such as Jayne Mansfield and Sheree North.[322] Other studios also attempted to create their own Monroes: Universal Pictures with Mamie Van Doren,[323] Columbia Pictures with Kim Novak,[324] and The Rank Organisation with Diana Dors.[325]

Filmography

- Seven Sirens (1946)

- Dangerous Years (1947)

- Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (1948)

- Ladies of the Chorus (1948)

- Love Happy (1949)

- A Ticket to Tomahawk (1950)

- The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

- All About Eve (1950)

- The Fireball (1950)

- Right Cross (1951)

- Home Town Story (1951)

- As Young as You Feel (1951)

- Love Nest (1951)

- Let’s Make It Legal (1951)

- Clash by Night (1952)

- We’re Not Married! (1952)

- Don’t Bother to Knock (1952)

- Monkey Business (1952)

- O. Henry’s Full House (1952)

- Niagara (1953)

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

- How to Marry a Millionaire (1953)

- River of No Return (1954)

- There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954)

- The Seven Year Itch (1955)

- Bus Stop (1956)

- The Prince and the Showgirl (1957)

- Some Like It Hot (1959)

- Let’s Make Love (1960)

- The Misfits (1961)

- Something’s Got to Give (1962–unfinished)

Legacy

Monroe in a publicity photo for Photoplay magazine in 1953

According to The Guide to United States Popular Culture, «as an icon of American popular culture, Monroe’s few rivals in popularity include Elvis Presley and Mickey Mouse… no other star has ever inspired such a wide range of emotions—from lust to pity, from envy to remorse.»[326] Art historian Gail Levin stated that Monroe may have been «the most photographed person of the 20th century»,[116] and The American Film Institute has named her the sixth greatest female screen legend in American film history. The Smithsonian Institution has included her on their list of «100 Most Significant Americans of All Time»,[327] and both Variety and VH1 have placed her in the top ten in their rankings of the greatest popular culture icons of the twentieth century.[328][329]

Hundreds of books have been written about Monroe. She has been the subject of numerous films, plays, operas, and songs, and has influenced artists and entertainers such as Andy Warhol and Madonna.[330][331] She also remains a valuable brand:[332] her image and name have been licensed for hundreds of products, and she has been featured in advertising for brands such as Max Factor, Chanel, Mercedes-Benz, and Absolut Vodka.[333][334]

Monroe’s enduring popularity is tied to her conflicted public image.[335] On the one hand, she remains a sex symbol, beauty icon and one of the most famous stars of classical Hollywood cinema.[336][337][338] On the other, she is also remembered for her troubled private life, unstable childhood, struggle for professional respect, as well as her death and the conspiracy theories that surrounded it.[339] She has been written about by scholars and journalists who are interested in gender and feminism;[340] these writers include Gloria Steinem, Jacqueline Rose,[341] Molly Haskell,[342] Sarah Churchwell,[334] and Lois Banner.[343] Some, such as Steinem, have viewed her as a victim of the studio system.[340][344] Others, such as Haskell,[345] Rose,[341] and Churchwell,[334] have instead stressed Monroe’s proactive role in her career and her participation in the creation of her public persona.

Owing to the contrast between her stardom and troubled private life, Monroe is closely linked to broader discussions about modern phenomena such as mass media, fame, and consumer culture.[346] According to academic Susanne Hamscha, Monroe has continued relevance to ongoing discussions about modern society, and she is «never completely situated in one time or place» but has become «a surface on which narratives of American culture can be (re-)constructed», and «functions as a cultural type that can be reproduced, transformed, translated into new contexts, and enacted by other people».[346] Similarly, Banner has called Monroe the «eternal shapeshifter» who is re-created by «each generation, even each individual… to their own specifications».[347]

Monroe remains a cultural icon, but critics are divided on her legacy as an actress. David Thomson called her body of work «insubstantial»[348] and Pauline Kael wrote that she could not act, but rather «used her lack of an actress’s skills to amuse the public. She had the wit or crassness or desperation to turn cheesecake into acting—and vice versa; she did what others had the ‘good taste’ not to do».[349] In contrast, Peter Bradshaw wrote that Monroe was a talented comedian who «understood how comedy achieved its effects»,[350] and Roger Ebert wrote that «Monroe’s eccentricities and neuroses on sets became notorious, but studios put up with her long after any other actress would have been blackballed because what they got back on the screen was magical».[351] Similarly, Jonathan Rosenbaum stated that «she subtly subverted the sexist content of her material» and that «the difficulty some people have discerning Monroe’s intelligence as an actress seems rooted in the ideology of a repressive era, when super feminine women weren’t supposed to be smart».[352]

See also

- Marilyn Monroe performances and awards

- Marilyn Monroe in popular culture

Notes

- ^ Monroe had her screen name made into her legal name in early 1956.[1][2]

- ^ Gladys named Mortensen as Monroe’s father in the birth certificate (although the name was misspelled),[14] but it is unlikely that he was the father as their separation had taken place well before she became pregnant. Biographers Fred Guiles and Lois Banner stated that her father was likely Charles Stanley Gifford, Gladys’s superior at RKO Studios, with whom she had an affair in 1925,[16] whereas Donald Spoto thought that another co-worker was probably the father.

- ^ Monroe spoke about being sexually abused by a lodger when she was eight years old to her biographers Ben Hecht in 1953–1954 and Maurice Zolotow in 1960, and in interviews for Paris Match and Cosmopolitan. Although she refused to name the abuser, Banner believes he was George Atkinson, as he was a lodger and fostered Monroe when she was eight; Banner also states that Monroe’s description of the abuser fits other descriptions of Atkinson. Banner has argued that the abuse may have been a major causative factor in Monroe’s mental health problems, and has also written that as the subject was taboo in mid-century United States, Monroe was unusual in daring to speak about it publicly. Spoto does not mention the incident but states that Monroe was sexually abused by Grace’s husband in 1937 and by a cousin while living with a relative in 1938.[34] Barbara Leaming repeats Monroe’s account of the abuse, but earlier biographers Fred Guiles, Anthony Summers and Carl Rollyson have doubted the incident owing to lack of evidence beyond Monroe’s statements.[35]

- ^ RKO’s owner Howard Hughes had expressed an interest in Monroe after seeing her on a magazine cover.

- ^ It has sometimes been claimed that Monroe appeared as an extra in other Fox films during this period, including Green Grass of Wyoming, The Shocking Miss Pilgrim, and You Were Meant For Me, but there is no evidence to support this.[69]

- ^ Baumgarth was initially not happy with the photos, but published one of them in 1950; Monroe was not publicly identified as the model until 1952. Although she then contained the resulting scandal by claiming she had reluctantly posed nude due to an urgent need for cash, biographers Spoto and Banner have stated that she was not pressured (although according to Banner, she was initially hesitant due to her aspirations of movie stardom) and regarded the shoot as simply another work assignment.

- ^ In addition to All About Eve and The Asphalt Jungle, Monroe’s 1950 films were Love Happy, A Ticket to Tomahawk, Right Cross and The Fireball. Monroe also had a role in Home Town Story, released in 1951.

- ^ Monroe and Greene had first met and had a brief affair in 1949, and met again in 1953, when he photographed her for Look. She told him about her grievances with the studio, and Greene suggested that they start their own production company.[176]

- ^ Monroe underwent psychoanalysis regularly from 1955 until her death. Her analysts were psychiatrists Margaret Hohenberg (1955–57), Anna Freud (1957), Marianne Kris (1957–61), and Ralph Greenson (1960–62).[184]

- ^ Monroe identified with the Jewish people as a «dispossessed group» and wanted to convert to make herself part of Miller’s family. She was instructed by Rabbi Robert Goldberg and converted on July 1, 1956.[200] Monroe’s interest in Judaism as a religion was limited: she called herself a «Jewish atheist» and did not practice the faith after divorcing Miller aside from retaining some religious items.[200] Egypt also lifted her ban after the divorce was finalized in 1961.[200]

- ^ Endometriosis also caused her to experience severe menstrual pain throughout her life, necessitating a clause in her contract allowing her to be absent from work during her period; her endometriosis also required several surgeries.[215] It has sometimes been alleged that Monroe underwent several abortions, and that unsafe abortions made by persons without proper medical training would have contributed to her inability to maintain a pregnancy. The abortion rumors began from statements made by Amy Greene, the wife of Milton Greene, but have not been confirmed by any concrete evidence.[217] Furthermore, Monroe’s autopsy report did not note any evidence of abortions.[217]

- ^ Monroe first admitted herself to the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic in New York, at the suggestion of her psychiatrist Marianne Kris.[253] Kris later stated that her choice of hospital was a mistake: Monroe was placed on a ward meant for severely mentally ill people with psychosis, where she was locked in a padded cell and not allowed to move to a more suitable ward or leave the hospital.[253] Monroe was finally able to leave the hospital after three days with the help of Joe DiMaggio, and moved to the Columbia University Medical Center, spending a further 23 days there.[253]

- ^ Monroe and Kennedy had mutual friends and were familiar with each other. Although they sometimes had casual sexual encounters, there is no evidence that their relationship was serious.[260]

- ^ The actors and actresses posing with her include the following, from left to right: Ofelia Montesco, Xavier Loyá, Monroe, unknown person in the back, Patricia Morán, Bertha Moss, Nadia Haro Oliva, and José Baviera.

References

- ^ «How Did Marilyn Monroe Get Her Name? This Photo Reveals the Story». Time.

- ^ «Monroe divorce papers for auction». April 21, 2005 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Hertel, Howard; Heff, Don (August 6, 1962). «Marilyn Monroe Dies; Pills Blamed». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Chapman 2001, pp. 542–543; Hall 2006, p. 468.

- ^ «Marilyn Monroe | Biography, Death, Movies, & Facts | Britannica».

- ^ «Inside Marilyn Monroe’s Family Tree». November 17, 2020.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 9–10; Rollyson 2014, pp. 26–29.

- ^ a b Churchwell 2004, p. 150, citing Spoto and Summers; Banner 2012, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 150, citing Spoto, Summers and Guiles.

- ^ Miller, Korin; Spanfeller, Jamie (September 29, 2022). «Did Marilyn Monroe Ever Meet Her Biological Father? All About Charles Stanley Gifford». Women’s Health. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Keslassy, Elsa (April 4, 2022). «Marilyn Monroe’s Biological Father Revealed in Documentary ‘Marilyn, Her Final Secret’«. Variety. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Article in Daily Mirror by Graeme Culliford August 5, 2022

- ^ San Jacinto Valley Cemetery records, San Jacinto, California plot R-3-W-H

- ^ Anagnoson, Alex (October 2, 2022). «The Truth About Marilyn Monroe’s Siblings». Nicki Swift. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 55; Churchwell 2004, pp. 166–173.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 166–173.

- ^ Meryman, Richard (September 14, 2007). «Great interviews of the 20th century: «When you’re famous you run into human nature in a raw kind of way»«. The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 70–75.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 70–78.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 90–91; Churchwell 2004, p. 176.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 90–93; Churchwell 2004, pp. 176–177.

- ^ «Yank USA 1945». Wartime Press. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 95–107.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 114.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Churchwell 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 122–126.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 204–216, citing Summers, Spoto and Guiles for Schenck; Banner 2012, pp. 141–144; Spoto 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Summers 1985, p. 43.

- ^ Ortner, Jon. «Sex Goddesses & Pin-Up Queens». issue magazine. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 159–162.

- ^ Riese & Hitchens 1988, p. 228; Spoto 2001, p. 182.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 182.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 179–187; Churchwell 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 192.

- ^ a b Kahana, Yoram (January 30, 2014). «Marilyn: The Globes’ Golden Girl». Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA). Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 180–181; Banner 2012, pp. 163–167, 181–182 for Kazan and others.

- ^ Summers 1985, p. 58; Spoto 2001, pp. 210–213.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (May 4, 1952). «They Call Her The Blowtorch Blonde». Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 194–195; Churchwell 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 194–195.

- ^ «Clash By Night». American Film Institute. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (July 19, 1952). «Don’t Bother to Knock». The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ «Review: Don’t Bother to Knock». Variety. December 31, 1951. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 200.

- ^ a b c Churchwell 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Muir, Florabel (October 19, 1952). «Marilyn Monroe Tells: How to Deal With Wolves». Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Marilyn Monroe as told to Florabel Muir (January 1953). «Wolves I Have Known». Motion Picture. p. 41. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 238.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 139, 195, 233–234, 241, 244, 372.

- ^ a b «Filmmaker interview – Gail Levin». Public Broadcasting Service. July 19, 2006. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 257–264.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 221; Churchwell 2004, pp. 61–65; Lev 2013, p. 168.

- ^ a b «The 2006 Motion Picture Almanac, Top Ten Money Making Stars». Quigley Publishing Company. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 233.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 25, 62.

- ^ «Niagara Falls Vies With Marilyn Monroe». The New York Times. January 22, 1953. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ «Review: ‘Niagara’«. Variety. December 31, 1952. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ GlamAmor:History of Fashion in Film, May 24, 2014

- ^ Solomon 1988, p. 89; Churchwell 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Brogdon, William (July 1, 1953). «Gentlemen Prefer Blondes». Variety. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (July 16, 1953). «Gentlemen Prefer Blondes». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 250.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 238; Churchwell 2004, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Solomon 1988, p. 89; Churchwell 2004, p. 65; Lev 2013, p. 209.

- ^ Solomon 1988, p. 89.

- ^ a b Churchwell 2004, p. 217.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 68, 208–209.

- ^ Summers 1985, p. 92; Spoto 2001, p. 254–259.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 260.

- ^ Hoppe, Art (January 15, 1954). «Joe Di Maggio Marries Marilyn Monroe at San Francisco City Hall». San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

Di Maggio said he didn’t know where they would spend their honeymoon but they would ‘probably just get in the car and go’ tonight.

- ^ Middlecamp, David (March 25, 2016). «Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe’s Central Coast honeymoon». San Luis Obispo Tribune. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Mungo, Ray (January 15, 1993). Palm Springs Babylon: Sizzling Stories From The Desert Playground Of The Stars. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-06438-9.

In January , 1954 , Marilyn and Joe DiMaggio spent their honeymoon in the area, mostly tucked away playing billiards in a cabin up in the Idyllwild Hills .

- ^ «Past Tense: January 30, 2014». Idyllwild Town Crier. January 30, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ «Before Our Time: Idyllwild’s SMASH!». Idyllwild Town Crier. June 6, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ «ERNIE MAXWELL: Idyllwild ‘old-timer’ remembers much of mountain town’s history». The Desert Sun. Palm Springs, California. September 1, 1984. Retrieved June 12, 2022 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ «Marilyn Monroe extensive archive of her agent Charles K. Feldman’s files of (150+) typed and handwritten letters, memos, clippings and telegrams from the Famous Artists Corporation». Heritage Auctions. December 11, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

Marilyn Monroe is giving press statements in New York that she was not returning to 20th-Fox, where she is under contract, and also that she was dismissing her attorney, Lloyd Wright, and her agency, Famous Artists…

- ^ O’Hagan, Andrew (January 22, 2013). The Atlantic Ocean: Reports from Britain and America. HMH. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-547-72789-9.

- ^ «When Marilyn Monroe Interrupted Her Honeymoon to Go to Korea». HistoryNet. December 3, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Melinda. «Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio Honeymoon in Japan». MarilynMonroe.ca. Ontario, Canada. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ «Marilyn Monroe, (Left Center), and Jean O’Doul, the wife «Lefty» O’Doul, (Right Center), are shown posing with pretty Japanese Geisha Girls after a «Sukiyaki» Dinner in Kobe. The dinner was given by the Central League, one of Japan’s professional baseball organizations. Husbands DiMaggio and O’Doul were among the diners. Miss Monroe and DiMaggio are flying home today». Getty Images. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ «The streak continues for ‘Lefty’ O’Doul». Santa Rosa Press Democrat. September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Doyle, Jack. ««Marilyn & Joe, et al.» A 70-Year Saga». The Pop History Dig. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 262–263.

- ^ «Marilyn Monroe (left) stands with (l to r) Marine Col. William K. Jones and Jean O’Doul while visiting American troops in Korea». Getty Images. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Warner, Gary A. (November 12, 2012). «Lefty O’Doul’s is the best baseball bar in San Francisco». Orlando Sentinel. Orange County Register. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

The name on the card is «Norma Jean DiMaggio» — the legal name of DiMaggio’s then-wife, Marilyn Monroe, who needed the card to make overseas visits to build the morale of American troops in Korea.

- ^ Parr, Patrick (August 23, 2018). «Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan». Japan Today. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ O’Doul, Jean (December 12, 2013). «A Marilyn Monroe Group of Never-Before-Seen Black and White Snapshots from Korea, 1954». Heritage Auctions. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Jennifer Jean (February 14, 2014). Marilyn Monroe & Joe DiMaggio — Love In Japan, Korea & Beyond. J.J. Avenue Productions. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-9914291-6-5.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 241.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 267.

- ^ a b Spoto 2001, p. 271.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Spoto 2001, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 331.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 295–298; Churchwell 2004, p. 246.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 158–159, 252–254.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 302–303.

- ^ a b Spoto 2001, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 338.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 302.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 327.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 350.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 310–313.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 312–313, 375, 384–385, 421, 459 on years and names.

- ^ a b Spoto 2001; Churchwell 2004, p. 253, for Miller; Banner 2012, p. 285, for Brando.

- ^ a b Spoto 2001, p. 337; Meyers 2010, p. 98.

- ^ Summers 1985, p. 157; Spoto 2001, pp. 318–320; Churchwell 2004, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Spoto 2001, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Article by Chris Bodenner in The Atlantic February 24, 2006

- ^ a b Spoto 2001, p. 341.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 343–345.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 345.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 352–357.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 352–354.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 354–358, for location and time; Banner 2012, p. 297, 310.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Schreck, Tom (November 2014). «Marilyn Monroe’s Westchester Wedding; Plus, More County Questions And Answers». Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Meyers 2010, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, pp. 253–257; Meyers 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 358–359; Churchwell 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 358.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 372.

- ^ a b Churchwell 2004, pp. 258–261.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 370–379.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 392–393, 406–407.

- ^ a b Churchwell 2004, pp. 274–277.

- ^ a b Churchwell 2004, pp. 271–274.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 389–391.

- ^ Churchwell 2004, p. 626.

- ^ Spoto 2001, pp. 399–407; Churchwell 2004, p. 262.

- ^ Banner 2012, p. 327 on «sinking ship» and «phallic symbol»; Rose 2014, p. 100 for full quote.

- ^ Spoto 2001, p. 406.

- ^ «Review: ‘Some Like It Hot’«. Variety. February 24, 1959. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ «The 100 greatest comedies of all time». BBC. August 22, 2017. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ «Some Like It Hot». American Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Christie, Ian (September 2012). «The top 50 Greatest Films of All Time». British Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.