This article is about the Native American tribe. For the U.S. state, see Massachusetts.

|

Location of the Massachusett and related peoples of southern New England. |

| Regions with significant populations |

|---|

| Languages |

| English, formerly Massachusett language |

| Religion |

| Christianity (Puritanism), Indigenous religion, traditionally Algonquian traditional religion. |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Nipmuc, Wampanoag, Narraganasett, Mohegan, Pequot, Pocomtuc, Montaukett and other Algonquian peoples |

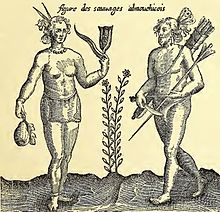

The Massachusett were a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for «At the Great Hill,» referring to the Blue Hills overlooking Boston Harbor from the south.[1]

As some of the first people to make contact with European explorers in New England, the Massachusett and fellow coastal peoples were severely decimated from an outbreak of leptospirosis circa 1619, which had mortality rates as high as 90 percent in these areas. This was followed by devastating impacts of virgin soil epidemics such as smallpox, influenza, scarlet fever and others to which the Indigenous people lacked natural immunity. Their territories, on the more fertile and flat coastlines, with access to coastal resources, were mostly taken over by English colonists, as the Massachusett were too few in number to put up any effective resistance.

Missionary John Eliot converted the majority of the Massachusett to Christianity and founded praying towns, where the converted Native Americans were expected to submit to the colonial laws and assimilate to European culture, yet they were allowed to use their language. Through intermediaries, Eliot learned the Massachusett language and even published a translation of the Bible. The language, related to other Eastern Algonquian languages of southern New England, slowly faded, ceasing to serve as the primary language of the Massachusett communities by the 1750s. The language likely went extinct by the dawn of the 19th century.

The last of Massachusett common lands were sold in the early 19th century, loosening the community and social bonds that held the Massachusett families together, and most of the Massachusett were forced to settle amongst neighboring European Americans, but mainly settled the poorer sections of towns where they were segregated with Black Americans, recent immigrants and other Native Americans. Surviving Massachusett assimilated and integrated into the surrounding communities.

Name[edit]

Endonyms[edit]

The native name is written Massachuseuck (Muhsachuweeseeak) /məhs at͡ʃəw iːs iː ak/—singular Massachusee (Muhsachuweesee).[citation needed] It translates as «at the great hill,»[2] referring to the Great Blue Hill, located in Ponkapoag.

Exonyms[edit]

English settlers adopted the term Massachusett for the name for the people, language, and ultimately as the name of their colony which became the American state of Massachusetts. John Smith first published the term Massachusett in 1616.[2] Narragansett people called the tribe Massachêuck.[2]

Territory[edit]

Neponset River in Dorchester, within historic homelands of the Massachusett

The historic territory of the Massachusett people consisted mainly of the hilly, heavily forested and comparatively fertile coastal plain along the southern side of Massachusetts Bay in what is now eastern Massachusetts. Major watersheds in Massachusett territory included the Charles River and the Neponset River.[3]

The Pennacook lived north of the Massachusett tribe, the Nipmuc to the west, Narragansett to the southwest in Rhode Island, and Pokanoket, now known as Wampanoag to the south.[3] Anthropologist John R. Swanton wrote that their territory extended as far north as what is now Salem, Massachusetts, and south to Marshfield and Brockton. He wrote later they claimed lands in the Great Cedar Swamp (near present-day Lakeville), previously controlled by Wampanoag.[4]

By the 1660s the Massachusett moved into praying towns, such as Natick and Ponkapoag (Canton).

Swanton lists the following: Massachusett settlements.

- Conohasset, Cohasset

- Cowate, praying town, Charles River falls

- Magaehnak, six miles from Sudbury

- Massachuset, Blue Hills Reservation, on the border of Milton, Canton, Randolph and Quincy

- Mishawum, Charlestown, Boston

- Mystic, Medford

- Nahapassumkeck, northern coast of Plymouth County

- Natick, Praying town

- Neponset, on Neponset River near Stoughton

- Nonantum, Newton

- Pequimmit, praying town, Stoughton

- Pocapawmet, South Shore

- Punkapog, praying town, Canton

- Saugus, near Lynn

- Seccasaw, northern part of Plymouth County

- Titicut, praying town, possibly Wampanoag, Middleborough

- Topeent, northern coast of Plymouth County

- Toant, in or near Boston

- Unquatiquisset, Milton and Lower Mills

- Wessagusset, near Weymouth

- Winnisimmet, Chelsea

- Wonasquam, near Annisquam[4]

Divisions[edit]

Massachusett people settled in villages; however, these were organized into larger bands.

Swanton writes about six major bands named for their sachems or leaders.

- Chickatawbut, later led by his son Wompatuck and subsequent heirs, additional region/band led by Obtakiest; Massachusett territory south of the Charles River and west of Ponkapoag Pond

- Nanepashemet, south of the Charles River. His territory was divided between his three sons:

-

-

- Winnepurkit, Deer Island and Boston Harbor

- Wonohaquaham, Winnisimmet and Saugus

- Montowampate, Massebequash and Lynn

-

- Manatahqua, around Nahant and Swampscott

- Cato, east of the Concord River

- Nahaton, around the area of Natick

- Cutshamekin, around Dorchester, Sudbury, and Milton.[5]

The appointment of guardians to administer the assets of the Praying Indians and represent them before the colony in 1743 ended the authority of local chiefs and the last vestiges of traditional tribal organization.[6]

Language[edit]

The index and first page of Genesis from Eliot’s translation of the Bible into the Natick speech of Massachusett in 1663, the Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God.

The Massachusett language, Massachusee unontꝏwaok (Muhsachuweesee unôtuwôâôk) /məhsatʃəwiːsiː ənãtəwaːãk/), was an important language of New England as it was also the native language of the Wampanoag, Nauset, Cowesset and Pawtucket people. Due to its similarity with other closely related languages of the region, a simplified pidgin of it was also used as a regional language of trade and intertribal communication.[7] By the 1750s, Massachusett was no longer the predominant language of the community and by 1798, only one Massachusett elder of advanced age spoke the language at Natick. Factors that led to the decline of the spoken language include the rapid rates of intermarriage with non-Indian spouses outside the speech community in the mid-18th century, the need for English for employment and participation in general society, the lack of prestige regarding the Indian language and the dissolution of Indian communities and outmigration of people leading to greater isolation of speakers. The Wampanoag on Noepe, with its more secure land base and larger population, held onto Massachusett as the communal language into the 1770s and went extinct with the death of the last Wampanoag dialect—and last speakers of any Massachusett dialect—in the 1890s.[8][9][10]

Early subsistence[edit]

The «Three Sisters» of maize, beans and squash

The Massachusett occupied fertile flatlands. Men and women cleared fields first by burning trees, then by removing stumps. Women grew food crops, but men were involved in tobacco cultivation.[11] Women used clamshell hoes.[12] Women cultivated crops such as northern flint corn, called weachimineash in Massachusett, a variety of brands, squashes, and pumpkins.[13] They planted corn in mounds, then planted beans that grew up the cornstalks, and finally the cucurbits, which protected roots and discouraged weeds.[11] This companion planting method is called the Three Sisters.[14]

Other regional plant foods included grapes, strawberries, blackberries, currants, cherries, plums, raspberries, acorns, hickory nuts, chestnuts, butternuts, and leafy greens and pseudocereals such as chenopods.[15]

Massachusett people lived in conditional sedentary villages built along rivers.[16] Families lived in domed houses, called wétu in Massachusett.[17] The base structure of curved wooden support beams was covered with woven mats in the winter or chestnut bark in the summer. Inside, possessions were stored in hemp dogbane bags and baskets of all sizes.[18] Men carved wooden bowls and spoons as dining utensils.[18]

Water transport was by both either carved dugout canoes and birchbark canoes.[19]

History[edit]

European exploration of the 16th century[edit]

The first known European encounter may have been in 1605 when French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in Boston Harbor.[20] Champlain met with Massachusett leaders on several of the Boston Harbor Islands and anchored off Shawmut to conduct trade. Champlain was accompanied by an Algonquin guide and his «Massachusett-speaking»—wife who helped translate.[citation needed] Despite mapping the region to promote French interest, colonization support was deterred by the dense population and resistance to contact by some of the Massachusett leaders[21] The region was later mapped as «New England» by John Smith who followed in many of Champlain’s footsteps, but also made landfall at Wessagusset and Conohasset where he conducted trade and met with the chiefs, and helped promote further English colonial settlement in the region.[22]

17th-century epidemics[edit]

A man covered in the scars and lesions of a severe smallpox infection

With increasing levels of contact with European fishermen and explorers, the Massachusett and neighboring tribes were increasingly affected by infectious diseases. With minimal livestock, Indigenous peoples of the Americas lacked immunity to many zoonotic diseases carried by Europeans and the animals they brought. These introduced diseases quickly became a series of virgin soil epidemics that devastated populations.

The deadly epidemic of 1616–1619 may have been caused by leptospirosis, a lethal blood infection, likely spread invasive black rats. This epidemic killed between 33 and 90 percent of the Native American population of New England.[23]

The Massachusetts smallpox epidemic of 1633 further decimated Native populations, as did subsequent smallpox outbreaks, occurring almost every decade.[24]

Devastation by disease and European encroachment upset political balances among New England tribes.[25]

Relations with the Plymouth Colony (1620–1626)[edit]

English settlers established their first permanent foothold in New England with the founding of the Plymouth Colony by Pilgrims in 1620 near the site of the former Wampanoag village of Patuxet,[26] just a short distance south of the historic boundary with the Massachusett. In 1621, the Pilgrims, led by Myles Standish, met Obbatinewat (Wampanoag), a local sachem loyal to Massasoit. The colonists signed a peace treaty with Obbatinewat, who in turn, introduced the Pilgrims to the Squaw Sachem of Mistick (Massachusett, c. 1590–1650), another leader.[27]

The Wampanoag chief Massasoit (c. 1581–1661) decided to ally with the Pilgrims.[26] The Pilgrims also met with Chickatawbut (Massachusett, d. 1633), the most powerful Massachusett leader of the time. Unlike Massasoit, who favored increasing ties with the new English settlers to help assist against increasing power struggles with the Pequot and the Narragansett, Chickatawbut and other Massachusett leaders were wary of the Pilgrims and their intentions.[citation needed]

Chickatawbut’s fears were confirmed when the Plymouth Colony expanded to Wessagusset, in Massachusett territory, with the arrival of a new ship of colonists. The new settlers were ill-prepared, even more so than the first Pilgrims, and quickly resorted to trading supplies with the Massachusett. As their situation worsened, the Pilgrims began raiding Massachusett villages for food and supplies. To prevent an attack, Standish ordered a preemptive strike in 1624, which led to the deaths of Pecksuot, Wituwamat, and other Massachusett warriors who were lured under the pretense of peace and negotiation to meet with the colonists.[28] Standish further angered the Massachusett when he led his men deep into their territory to suppress the nascent colony of Merrymount, which had been established by Thomas Morton and which had friendly relations with neighboring Indian tribes. These activities caused the Massachusett to halt trade with the Pilgrims for many years.[28]

Relations with the Massachusett Bay Colony (1629-1676)[edit]

The Massachusett were unable to isolate themselves from the English settlers. Despite cutting off relations with the Pilgrim settlers, dissenting English settlers, mostly Puritans who wished to reform the Church of England to conform with their view of the Protestant Reformation as opposed to separate from it, began arriving, with the first settling in Wonnisquam in 1623 and later expanding to Naumkeag in Pawtucket territory. In 1628, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was legally established, with a claim over the lands north of the Plymouth Colony. The boundary between the two colonies mirrored the traditional boundary between the Massachusett and Wampanoag, although many Massachusett, such as those at Titicut and Mattakeesett, were under the claim of the Plymouth Colony.

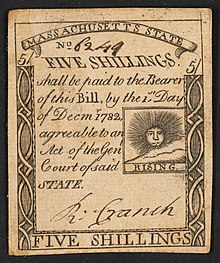

The Massachusett sachems gave many land deeds to the Pilgrims since they served to rebuff attacks from other tribes. In most cases, it was because the land had already been opened to English colonial settlement, often because the Indians living there had already died off from disease. The sachems began selling land at a price, often with stipulations allowing the Indians to collect, gather, fish or forage, but these arrangements were seldom honored by the Pilgrims. The colonists also did not understand the Indian concept of leasing land from the sachem, and instead thought of their arrangements as permanent land sales. As a result of the rapid loss of land, the Massachusett and other local tribes sent their leaders to Boston for the 1644 Acts of Submission, bringing the Indians under the control of the colonial government and subject to both its laws and conversion attempts from Christian missionaries. By the time of the submission, the Massachusett, a coastal people, had lost access to the sea and their shellfish collection sites.[29]

Demographic changes[edit]

The Native peoples of New England faced increasing pressures with the increasing levels of colonists in New England. In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony greatly expanded with the arrival of the Winthrop Fleet of 11 ships and almost one thousand colonists beginning the «Great Migration.» By the end of 1640, the colonial population, more than doubled to almost twenty thousand due to the continued arrival of ships bearing Puritan settlers fleeing the increasing levels of religious persecution during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and natural increase, as settlers often arrived as family units and raised large numbers of children.

The Pilgrims feared the Native presence, as they were a numerical majority when all the different groups of New England were taken together and were dependent on them for survival and trade and the colonists were unable to expand. The Native populations continued to fall, with diseases such as scarlet fever, typhus, measles, mumps, influenza, tuberculosis, whooping cough taking large tolls. However, a smallpox epidemic in 1633 and 1634 also took a very heavy toll, afflicting not only peoples of the coast still recovering from the losses of 1617-1619 but far inland. The Massachusett population dwindled to fewer than two thousand individuals.[30] Other epidemics occurred in 1648 and 1666, although not as devastating, outbreaks of disease continued to inflict heavy tolls well into the 19th century. With so many areas depopulated, the Pilgrims believed that God had cleared New England for their colonization efforts. By the 1630s, the Indians of New England were already a minority in their own lands.[31]

The Massachusett put up little armed resistance to colonial settlement, but other Native peoples of New England who did were subjugated during and after Pequot War in 1638. The colonists aided local Indian tribes in subduing the Pequot, resulting in massacres of Pequot non-combatants, such as in the Mystic Massacre, and the selling of many of the Indians into slavery in Bermuda. The war resulted in the complete destruction of the Pequot as a tribal entity, opening up further land in New England to colonial settlement.[32]

Adoption of Christianity[edit]

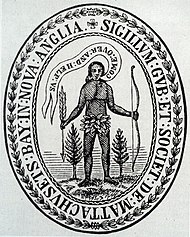

Original seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony depicting a Massachusett Indian proclaiming «Come over and help us»—a plea for conversion—inspired from Acts 16:19. Many contemporary Massachusett support initiatives to replace the Great Seal of Massachusetts which preserves most elements of the colonial original and has long been held offensive to many of the Native groups of the region.[33]

As stated in the royal charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony of 1628, «according to the Courſe of other Corporations in this our Realme of England … whereby our ſaid People, Inhabitants thee … maie wynn and incite the Natives of Country, to the Knowledg and Obedience of the onlie true God and Savior of Mankinde, and the Chriſtian Fayth, which … is the principall Ende of this Plantation.»[34] The colonists were more occupied with their survival and propagation of a Puritan refuge. Although not the first to attempt to Christianize the Natives, it was not until the missionary John Eliot, «Apostle to the Indians», arrived in the colony and attained considerable success before colonial authorities truly began to invest in the project. Eliot began to learn the language, employing the help of two Indian indentured servants fluent in English, including Cockenoe, a Montaukett originally from Long Island that also spoke Massachusett, and John Sassamon from a Neponset family. Once confident in his abilities, Eliot tried to preach to the Neponset tribe led by Cutshamekin in 1646 but was rebuffed. Later, after resuming more language studies, Eliot preached to the Nonantum tribe led by Waban and had better success, bringing Waban and most of the tribe into Christianity.[35]

The reaction to Christianity was mixed, with many Native leaders continuing to be wary of the Pilgrims and urging their people to remain traditionalists whereas many wholeheartedly embraced it. Those that did embrace the new religion often did so because the traditional medicines and rituals conducted by healers known as powwow (pawâwak) /pawaːwak/ failed to protect them from settler encroachment of their lands or the novel pathogens to which they lacked resistance. These Indians hoped that the new God of the settlers would protect them the way that it had protected the settlers and often bought into the belief that they were punished for their wickedness. Other Indians likely joined because they thought they had to. The colonial government had forced the tribal leaders of Indians as far west as Quabaug (Brookfield, Massachusetts) to sign the 1644 Acts of Submission which forced upon the Indians acceptance of the authority of the colonial government and its protection as well opening their people to missionary activity, with many Indian leaders likely still fearful of the settlers due memories of the Pequot War and the fate of the Pequot. Others converted in hopes of removing the stigma of heathenism to improve relations with the settlers, but due to synchretism and cryto-traditional practices conducted in secret by some, the Puritans continued to mistreat the Indians and cast suspicions on the sincerity of the new believers who came to be referred to as «Praying Indians» or peantamwe Indiansog (puyôhtamwee Indiansak) /pəjãhtamwiː əntʃansak/.[36]

Praying towns (1651–1675)[edit]

The Eliot Church in South Natick. The church was built in 1828 where the Indian Church once stood.

Eliot urged Waban and the other newly converted Massachusett to settle along a bend of the Quinobequin River but were immediately sued as squatters by the residents of Dorchester. By the time Eliot began to establish the Indian mission, the Massachusett had lost access to the shellfishing beds along the coast and were soon to lose most of their remaining hunting and foraging lands due to the opening of all unfenced, «unimproved» lands. Eliot petitioned the General Court to set aside grants of lands for the Indians «in perpetuity.» Natick was established in 1651, with Ponkapoag following shortly thereafter in 1654. An additional 13 settlements were created, mostly in Nipmuc areas. These communities, settled by Praying Indians, came to be known as «Praying towns» or in Massachusett, Peantamwe Otanash (Puyôhtamwee 8tânash) /pəjãhtamwiː uːtaːnaʃ/. Ponkapoag, also spelled Punkapog, had 60 residents including Massachusett people in 1674.[37]

The establishment of the Praying towns accomplished several goals. It helped facilitate the goals of Christianization and acculturation as it allowed for easier distribution of the Massachusett-language translations of Eliot’s Bible and other works. The inhabitants were forced to observe the eight tenements of the «Leaf of Rules» distributed in the Bibles which forbid Indian cultural norms such as consenting pre-marital sex, cracking lice between teeth, avoidance of agriculture by men and re-enforced adoption of Puritan-style modesty and hairstyles.[38] For the colonial government, it brought the Indians fully under the control of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with the Praying towns occupying a status similar to autonomous English colonial settlements. The traditional power structures remained somewhat intact, as Native peoples recognized both the traditional power systems, but the chiefs and the tribal élite maintained it by adopting the roles of administrators, clerks, translators, teachers, constables, jurors and tax collectors. The confinement benefitted both the desires of Eliot and the colony, and Eliot was often accompanied by Daniel Gookin, the Superintendent to the Indians appointed to ensure cordial relations with the Indians and their adherence to the colonial laws, during his tours of the Praying towns. Similar settlements were established in the Plymouth Colony, such as the Massachusett Praying towns of Titicut and Mattakeeset.[39]

Historical marker standing on the northern boundary of what was once the Praying town of Ponkapoag, now contained in the town of Canton, Massachusetts.

The Massachusett benefited from clear titles of common land where they could plant, hunt and forage, and this likely attracted even more converts since the Praying towns established safe zones away from the constant encroachment, requests for sales of land and harassment. The Massachusett also were able to revive their prestige, which they long held prior to English colonial settlement. Many of the Praying towns were established by Native missionaries drawn from Natick’s old powerful families, affording them much respect in their adopted communities. The Massachusett began to replace the language of the Nipmuc and greatly leveled dialectal differences across the Massachusett-speaking area, due to the spread of Indian missionaries, but also because Massachusett became the language of literacy, prayer and administration, likely facilitated by its historic use as a regional second language and backed by its use in the translation of the Bible. The Massachusett leaders were also closer to the colonial authorities and thus often chosen to spread official messages, restoring the old power dynamic vis-à-vis other tribes.[39]

Life in the Praying towns became a mix of European and Indian customs. The Indians were forced to adopt Puritan habits of modesty, hairstyle, dress, and other cultural norms. They were encouraged to learn European methods of woodworking, carpentry, animal husbandry, and agriculture and Eliot arranged for many Indians to apprentice under settlers to learn these skills. Natick had an independent congregation with a Christian-style church, but the services were conducted in Massachusett with Indian preachers and the parishioners were called by Native drumming. The Praying Indians maintained many aspects of Indigenous culture, such their customary cuisine and foraging and hunting, but melded them with the European culture and Christian religion they were forced to adopt.[39] The mix of religious, cultural, and political control over the Indians was in many ways a precursor to the Indian Reservations that later developed.[40]

Humiliation of the Indians[edit]

The truce that had existed between the English colonists of the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies and the local Native peoples was tested. The submission of the local chiefs to the respective colonial governments and adoption of Christianity allowed the Indians to seek redress in the colonial legal system and removed one of the prejudices against them. The Praying Indians of Natick were brought to court several times by colonists living in settlement of Dedham who claimed some of the surrounding land, but with Eliot’s assistance, most of these attempts failed. Most of the time, however, the Indians failed, as some of the Indian interpreters and chiefs ceded lands to curry favor from the settlers to maintain special privileges, such as the Nipmuc John Wampas, who betrayed the Nipmuc and Massachusett people by selling land to the settlers to which he had no claim, but these sales were upheld in later court challenges. The Pawtucket sachem Wenepoykin, son of Nanepashemet and Squaw Sachem of Mistick, through kinship and family ties laid claim to much of Massachusett territory, and tried several times to petition the courts for lands lost in the turbulence of the 1633 epidemic that took both of his brothers to no avail, with most cases simply dismissed.[41]

King Philip’s War (1675-1676)[edit]

The outbreak of King Philip’s War from 1675 until 1676 was disastrous for both the Indians and colonists of New England. By the early 1670s, Waban and Cutshamekin had begun to address Daniel Gookin and warn of the increasing discontent of the interior Indians such as the Nipmuc people. However, the rebellion was started by the Wampanoag sachem (sôtyum) Metacomet, son of Massasoit who had welcomed and befriended Edward Winslow and the Pilgrims. Metacomet maintained the peace of his father but turned after the never-ending requests for land, but especially the execution of his brother Wamsutta for selling land to Roger Williams, seen by the Wampanoag as a very harsh measure for something outside the Plymouth Colony’s jurisdiction. In defiance, Metacomet murdered his interpreter to the colonial government, the Massachusett John Sassamon, before fleeing and seeking the support of the disgruntled tribes, culminating in the raid of Swansea in June 1675. Metacomet was able to bring the Narragansett, Nipmuc, Pocomtuc, Podunk, Tunxi peoples into his forces, organizing attacks on numerous outposts such as Sudbury, Lancaster, Turner’s Falls and other colonial settlements, leading many settlers to flee their lands for fortified towns. The settlers quickly responded by organizing units to attack the Indians loyal to Metacomet, leading to further conflict.[42]

The Massachusett, all of whom had become Praying Indians confined to praying towns, remained neutral during the war but suffered heavy casualties. The Praying Indians were attacked in their fields and harassed by neighboring colonists who had become overwhelmed with panic, hysteria, and anti-Indian sentiment. The Praying towns were also targets of Metacomet’s forces, raided for supplies, and persuaded or forced to join the fighting. To appease the settlers, the Praying Indians accepted confinement to the Praying towns, curfews, increased supervision, and voluntarily surrendered their weapons.

Most of the Praying Indians exiled to Deer Island in Boston Harbor died from exposure to the elements, starvation, and disease.

As the war progressed, the settlers decided to recruit some of the Praying Indians as scouts, guides and to fill the ranks of the colonial militia, with a regiment of Praying Indians, including many Massachusett, recruited by Daniel Gookin sent to face Metacomet’s warriors at Swansea, but it is known that other Massachusett aided the colonial militias in Lancaster, Brookfield and Mount Hope battles of the war. Metacomet was ultimately killed.

Guardianship of the Indians[edit]

Instead of being absorbed into the general affairs of the now predominantly European region, the colony appointed a commissioner to oversee the Natick in 1743, but commissioners were later appointed for all the extant tribes in the colony. Originally, the commissioner was charged to manage the timber resources, as most of the forests of New England had been felled to make way for farm and pasture, making the timber on Indian lands a valuable commodity. Very quickly, the guardian of Natick came to control the exchange of land, once the domain of the sachems, and any funds set up by the sale of Indian products, but mainly land. As the guardians assumed more power and were rarely supervised, many instances of questionable land sales by the guardians and embezzlement of funds have been recorded. The appointment of the guardians reduced the Indians to colonial wards, as they were no longer able to directly address the courts, vote in town elections and removed the power of the Indian chiefs.[6][43]

Loss of land continued. As forest lands were lost, the Indians could no longer resort to seasonal movements on their land or eke out a living, forcing many into poverty. Land was their only commodity and was often sold by the guardians to pay for treatments for the sick, care of orphans, and debts incurred by Indians, but Indians were also the victims of unfair credit schemes that often forced the land out of their hands.[44] Without land to farm or forage, Indians were forced to seek employment and settle in the de facto segregated sections of cities.

19th century[edit]

A bog near Ponkapoag pond. Now Canton, Massachusetts, this was part of the Ponkapoag praying town

Most of the remaining lands set aside «in perpetuity» for the Native peoples had been alienated, leaving a messy patchwork of a few remaining common lands, individual allotments, leased lands, and numerous colonial proprietors in between Indian households.

The end of tribal land did not remove the restrictions of the guardians even if it was the original purpose to have stewards of the land on the Native peoples’ «behalf.» As wards of the colonial and later state government, the Indians were restricted from voting in local elections or seeking redress through the courts on their own. Some of the Indians were supported by annuities established from the funds generated by land sales or initiated by the guardians for their support. The guardians, however, no longer had to maintain the rigorous lists of people associated with the land, which long had been used to segregate the Indians from the non-Indians especially as rates of intermarriage had increased.[45]

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts ordered reports on the condition of the Indians, including the Briggs Report (1849), also known as the Bird Report.[46] These did not mention the Massachusett or the Praying Town of Natick, where Massachusett people had joined in the 17th century.

John Milton Earle launched a far more detailed report in 1859 and published in 1861.[47]

Earle writes, «Of all the tribes which held reservations, and were placed under guardianship by the States, the Natick Tribe is nearest extinct. … [O]nly two families remain, and one of these is descended equally from the Naticks and the Hassanamiscoes. Their whole number is twelve. …»[48] He continues, «This tribe has no common lands,» and recommends their remain funds be divided equally among the two surviving families.[49] Earle observes that a few Natick descendants merged into the Nipmuc people and also writes, «There are some others, who claim to be of the Natick Tribe, but the claim appears to have no foundation other than that one of their ancestors formerly resided in Natick, but it is believed that he never was supposed to belong to the tribe.»[50]

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

In the 105 years between the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869 and the creation of the Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs by legislative act in 1974, records on the Massachusett people are very few. In 1928, anthropologist Frank G. Speck published Territorial subdivisions and boundaries of the Wampanoag, Massachusett, and Nauset Indians which included 17th-century Massachusett history. At Ponkapoag, Speck met Mrs. Chapelle (died 1919) who identified as a Massachusett Indian and whose husband was Mi’kmaq. Speck estimated that in 1921 a dozen Massachusett and Narragansett descendants of the Ponkapoag praying town lived in what is now Canton.[51]

Several organizations claim descent from historical Massachusett peoples; however, these are unrecognized, meaning they are neither federally recognized tribes[52] nor state-recognized tribes.[53]

See also[edit]

- Southern New England Algonquian cuisine

- History of Massachusetts

- Native American tribes in Massachusetts

Notes[edit]

- ^ Massachusetts Historical Commission (1982). «Historic and Archaeological Resources of the Boston Area» (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Bert Salwen, «Indians of Southern New England and Long Island,» p. 172

- ^ a b Bert Salwen, «Indians of Southern New England and Long Island,» p. 161.

- ^ a b John R. Swanton, The Indian Tribes of North America, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Swanton, ‘The Indian Tribes of North America, p. 19.

- ^ a b Order Accepting the Report in Regard to the Timber and Land of Natick Indians and Appointing a Committee Thereon, Province of Massachusetts. Session Laws § 257.

- ^ Goddard, Ives. 1996. «Introduction.» Ives Goddard, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 17. Languages, pp. 1–16.

- ^ Goddard, I., & Bragdon, K. (1988). (185 ed., p. 20).

- ^ Speck, F. G. (1928). «Territorial Subdivisions and Boundaries of the Wampanoag, Massachusett, and Nauset Indians.» Frank Hodge (ed). Lancaster, PA: Lancaster Press. p. 46. (PDF)

- ^ Mandell, D. R. ‘The Saga of Sarah Muckamugg: Indian and African Intermarriage in Colonial New England.’ Sex, Love, Race: Crossing Boundaries in North American History. ed. Martha Elizabeth Hodes. New York, NY: New York Univ Pr. pp. 72–83.

- ^ a b Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, p. 108.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, p. 105.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650, p. 107.

- ^ Elizabeth S. Chilton (2002). Hart, John P.; Rieth, Christina B. (eds.). Northeast Subsistence–Settlement Change: AD 700–1300 (PDF). Albany: The University of the State of New York. p. 293. ISBN 1-55557-213-8.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 66, 72, 104, 112.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 66, 78.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 135.

- ^ a b Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 105.

- ^ Bragdon, pp. 105–06.

- ^ «Samuel de Camplain’s Expeditions: Port Saint Louis». Archaeology Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Jameson, J. F. (1907). Original Narratives of Early American History: Voyages of Samuel de Champlain 1604–1618. W. L. Grant (ed.) (pp. 49-71.) New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ^ Lawson, R. M. (2015). The Sea Mark: Captain John Smith’s Voyage to New England. (pp. 120–123). Lebanon, NH: University of New England Press.

- ^ Marr, John S.; Cathey, John T. (February 2010). «New Hypothesis for Cause of Epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619». Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (2): 281–286. doi:10.3201/eid1602.090276. PMC 2957993. PMID 20113559.

- ^ «1633-34 — Smallpox Epidemic, New England Natives, Plymouth Colonists, MA –>1000». usdeadlyevents.com. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Willison, Megan K. (2016). Gender in 17th Century Southern New England. Mansfield, CT: University of Connecticut. p. 73.

- ^ a b T.J. Brasser, «Early Indian-European Contacts,» p. 82

- ^ Moore, Nina (1888). Pilgrims and Puritans: The Story of the Planting of Plymouth and Boston. Boston: Ginn & Company. p. 172.

- ^ a b Tremblay, R. (1972). ‘Weymouth Indian History.’ Weymouth, MA: 350th Anniversary Committee Town of Weymouth. Archived 2018-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ‘^ Cogley, R. W. (1999). John Eliot’s Mission to the Indians before King Philip’s War. (pp. 23-51). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Bragdon, K. J. (2005). pp. 130-133.

- ^ Kohn, G. C. (2010). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence. (pp. 255-256). New York, NY: Infobase Publishing.

- ^ Vaughan, A. T. (1995). «Pequots and Puritans: The Causes of the War of 1637,» in Roots of American Racism: Essays on the Colonial Experience. pp. 190-198. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Lisinski, C. (2021, 11 Jan). Lawmakers vote to change Mass. state seal, motto long offensive to Native Americans. WCVB. Last visited 9 May 2021.

- ^ American History from the Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond. Charter of Massachusetts Bay 1629. University of Groningen.

- ^ Cogley, R. W. (1999). pp. .105-107.

- ^ Cogley, R. W. (1999). pp. 37-43.

- ^ Speck, Frank G. (1928). Territorial subdivisions and boundaries of the Wampanoag, Massachusett, and Nauset Indians (PDF). New York: Museum of the American Indian.

- ^ Copy of Eliot’s «Leaf of Rules» in English in Prindle, T. (1994) «Praying towns.» Nipmuc Association of Connecticut. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Cogley, R. W. (1999). pp. 111–113.

- ^ Cogley, R. W. (1999). p. 234.

- ^ Russel, F. (2018). An Early History of Malden. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

- ^ Drake, J. D. (1999). pp. 87–105.

- ^ Mandell, D. R. (2000). Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts. (p. 151). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ Mandell, D. R. (2000). Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts. (pp. 170–171). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ Earle, J. M. (1861). pp. (supplementary list) XLI-XLVII, LXI-LXII.

- ^ «Summary under the Criteria and Evidence for the Proposed Finding: The Nipmuc Nation» (PDF). US Department of the Interior. Office of Federal Acknowledgment. 25 September 2001. p. 69. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Earle, John M. (1861). Report to the Governor and Council, Concerning the Indians of the Commonwealth, Under the Act of April 6, 1859. (pp. 7–8). Boston, MA: W. White Printers.

- ^ Earle, p. 71.

- ^ Earle, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Earle, pp. 773.

- ^ Speck, Territorial subdivisions (1928), 138–41.

- ^ «Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs». Indian Affairs Bureau. Federal Register. January 29, 2021. pp. 7554–58. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ «State Recognized Tribes». National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

References[edit]

- Bragdon, Kathleen J. (1999). Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-806131269.

- Brasser, T.J. (1978). «Early Indian-European Contacts». In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast, Vol. 15. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 78–88. ISBN 978-0-1600-4575-2.

- Conkey, Laura E.; Boissevain, Ethel; Goddard, Ives (1978). «Indians of Southern New England and Long Island: Early Period». In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast, Vol. 15. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 160–176. ISBN 978-0-1600-4575-2.

- Salwen, Bert (1978). «Indians of Southern New England and Long Island: Late Period». In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast, Vol. 15. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 177–189. ISBN 978-0-1600-4575-2.

- Speck, Frank G. (1928). Territorial subdivisions and boundaries of the Wampanoag, Massachusett, and Nauset Indians (PDF). New York: Museum of the American Indian. p. 103.

- Swanton, John R. (2003). The Indian Tribes of North America. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-806317304.

- Willison, Megan K. (2016). Gender in 17th Century Southern New England. Mansfield, CT: University of Connecticut. p. 73.

External links[edit]

Encyclopedia of North American Indians: Massachusett]

- «Massachuset», The Menotomy Journal

This article is about the Native American tribe. For the U.S. state, see Massachusetts.

|

Location of the Massachusett and related peoples of southern New England. |

| Regions with significant populations |

|---|

| Languages |

| English, formerly Massachusett language |

| Religion |

| Christianity (Puritanism), Indigenous religion, traditionally Algonquian traditional religion. |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Nipmuc, Wampanoag, Narraganasett, Mohegan, Pequot, Pocomtuc, Montaukett and other Algonquian peoples |

The Massachusett were a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for «At the Great Hill,» referring to the Blue Hills overlooking Boston Harbor from the south.[1]

As some of the first people to make contact with European explorers in New England, the Massachusett and fellow coastal peoples were severely decimated from an outbreak of leptospirosis circa 1619, which had mortality rates as high as 90 percent in these areas. This was followed by devastating impacts of virgin soil epidemics such as smallpox, influenza, scarlet fever and others to which the Indigenous people lacked natural immunity. Their territories, on the more fertile and flat coastlines, with access to coastal resources, were mostly taken over by English colonists, as the Massachusett were too few in number to put up any effective resistance.

Missionary John Eliot converted the majority of the Massachusett to Christianity and founded praying towns, where the converted Native Americans were expected to submit to the colonial laws and assimilate to European culture, yet they were allowed to use their language. Through intermediaries, Eliot learned the Massachusett language and even published a translation of the Bible. The language, related to other Eastern Algonquian languages of southern New England, slowly faded, ceasing to serve as the primary language of the Massachusett communities by the 1750s. The language likely went extinct by the dawn of the 19th century.

The last of Massachusett common lands were sold in the early 19th century, loosening the community and social bonds that held the Massachusett families together, and most of the Massachusett were forced to settle amongst neighboring European Americans, but mainly settled the poorer sections of towns where they were segregated with Black Americans, recent immigrants and other Native Americans. Surviving Massachusett assimilated and integrated into the surrounding communities.

Name[edit]

Endonyms[edit]

The native name is written Massachuseuck (Muhsachuweeseeak) /məhs at͡ʃəw iːs iː ak/—singular Massachusee (Muhsachuweesee).[citation needed] It translates as «at the great hill,»[2] referring to the Great Blue Hill, located in Ponkapoag.

Exonyms[edit]

English settlers adopted the term Massachusett for the name for the people, language, and ultimately as the name of their colony which became the American state of Massachusetts. John Smith first published the term Massachusett in 1616.[2] Narragansett people called the tribe Massachêuck.[2]

Territory[edit]

Neponset River in Dorchester, within historic homelands of the Massachusett

The historic territory of the Massachusett people consisted mainly of the hilly, heavily forested and comparatively fertile coastal plain along the southern side of Massachusetts Bay in what is now eastern Massachusetts. Major watersheds in Massachusett territory included the Charles River and the Neponset River.[3]

The Pennacook lived north of the Massachusett tribe, the Nipmuc to the west, Narragansett to the southwest in Rhode Island, and Pokanoket, now known as Wampanoag to the south.[3] Anthropologist John R. Swanton wrote that their territory extended as far north as what is now Salem, Massachusetts, and south to Marshfield and Brockton. He wrote later they claimed lands in the Great Cedar Swamp (near present-day Lakeville), previously controlled by Wampanoag.[4]

By the 1660s the Massachusett moved into praying towns, such as Natick and Ponkapoag (Canton).

Swanton lists the following: Massachusett settlements.

- Conohasset, Cohasset

- Cowate, praying town, Charles River falls

- Magaehnak, six miles from Sudbury

- Massachuset, Blue Hills Reservation, on the border of Milton, Canton, Randolph and Quincy

- Mishawum, Charlestown, Boston

- Mystic, Medford

- Nahapassumkeck, northern coast of Plymouth County

- Natick, Praying town

- Neponset, on Neponset River near Stoughton

- Nonantum, Newton

- Pequimmit, praying town, Stoughton

- Pocapawmet, South Shore

- Punkapog, praying town, Canton

- Saugus, near Lynn

- Seccasaw, northern part of Plymouth County

- Titicut, praying town, possibly Wampanoag, Middleborough

- Topeent, northern coast of Plymouth County

- Toant, in or near Boston

- Unquatiquisset, Milton and Lower Mills

- Wessagusset, near Weymouth

- Winnisimmet, Chelsea

- Wonasquam, near Annisquam[4]

Divisions[edit]

Massachusett people settled in villages; however, these were organized into larger bands.

Swanton writes about six major bands named for their sachems or leaders.

- Chickatawbut, later led by his son Wompatuck and subsequent heirs, additional region/band led by Obtakiest; Massachusett territory south of the Charles River and west of Ponkapoag Pond

- Nanepashemet, south of the Charles River. His territory was divided between his three sons:

-

-

- Winnepurkit, Deer Island and Boston Harbor

- Wonohaquaham, Winnisimmet and Saugus

- Montowampate, Massebequash and Lynn

-

- Manatahqua, around Nahant and Swampscott

- Cato, east of the Concord River

- Nahaton, around the area of Natick

- Cutshamekin, around Dorchester, Sudbury, and Milton.[5]

The appointment of guardians to administer the assets of the Praying Indians and represent them before the colony in 1743 ended the authority of local chiefs and the last vestiges of traditional tribal organization.[6]

Language[edit]

The index and first page of Genesis from Eliot’s translation of the Bible into the Natick speech of Massachusett in 1663, the Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God.

The Massachusett language, Massachusee unontꝏwaok (Muhsachuweesee unôtuwôâôk) /məhsatʃəwiːsiː ənãtəwaːãk/), was an important language of New England as it was also the native language of the Wampanoag, Nauset, Cowesset and Pawtucket people. Due to its similarity with other closely related languages of the region, a simplified pidgin of it was also used as a regional language of trade and intertribal communication.[7] By the 1750s, Massachusett was no longer the predominant language of the community and by 1798, only one Massachusett elder of advanced age spoke the language at Natick. Factors that led to the decline of the spoken language include the rapid rates of intermarriage with non-Indian spouses outside the speech community in the mid-18th century, the need for English for employment and participation in general society, the lack of prestige regarding the Indian language and the dissolution of Indian communities and outmigration of people leading to greater isolation of speakers. The Wampanoag on Noepe, with its more secure land base and larger population, held onto Massachusett as the communal language into the 1770s and went extinct with the death of the last Wampanoag dialect—and last speakers of any Massachusett dialect—in the 1890s.[8][9][10]

Early subsistence[edit]

The «Three Sisters» of maize, beans and squash

The Massachusett occupied fertile flatlands. Men and women cleared fields first by burning trees, then by removing stumps. Women grew food crops, but men were involved in tobacco cultivation.[11] Women used clamshell hoes.[12] Women cultivated crops such as northern flint corn, called weachimineash in Massachusett, a variety of brands, squashes, and pumpkins.[13] They planted corn in mounds, then planted beans that grew up the cornstalks, and finally the cucurbits, which protected roots and discouraged weeds.[11] This companion planting method is called the Three Sisters.[14]

Other regional plant foods included grapes, strawberries, blackberries, currants, cherries, plums, raspberries, acorns, hickory nuts, chestnuts, butternuts, and leafy greens and pseudocereals such as chenopods.[15]

Massachusett people lived in conditional sedentary villages built along rivers.[16] Families lived in domed houses, called wétu in Massachusett.[17] The base structure of curved wooden support beams was covered with woven mats in the winter or chestnut bark in the summer. Inside, possessions were stored in hemp dogbane bags and baskets of all sizes.[18] Men carved wooden bowls and spoons as dining utensils.[18]

Water transport was by both either carved dugout canoes and birchbark canoes.[19]

History[edit]

European exploration of the 16th century[edit]

The first known European encounter may have been in 1605 when French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in Boston Harbor.[20] Champlain met with Massachusett leaders on several of the Boston Harbor Islands and anchored off Shawmut to conduct trade. Champlain was accompanied by an Algonquin guide and his «Massachusett-speaking»—wife who helped translate.[citation needed] Despite mapping the region to promote French interest, colonization support was deterred by the dense population and resistance to contact by some of the Massachusett leaders[21] The region was later mapped as «New England» by John Smith who followed in many of Champlain’s footsteps, but also made landfall at Wessagusset and Conohasset where he conducted trade and met with the chiefs, and helped promote further English colonial settlement in the region.[22]

17th-century epidemics[edit]

A man covered in the scars and lesions of a severe smallpox infection

With increasing levels of contact with European fishermen and explorers, the Massachusett and neighboring tribes were increasingly affected by infectious diseases. With minimal livestock, Indigenous peoples of the Americas lacked immunity to many zoonotic diseases carried by Europeans and the animals they brought. These introduced diseases quickly became a series of virgin soil epidemics that devastated populations.

The deadly epidemic of 1616–1619 may have been caused by leptospirosis, a lethal blood infection, likely spread invasive black rats. This epidemic killed between 33 and 90 percent of the Native American population of New England.[23]

The Massachusetts smallpox epidemic of 1633 further decimated Native populations, as did subsequent smallpox outbreaks, occurring almost every decade.[24]

Devastation by disease and European encroachment upset political balances among New England tribes.[25]

Relations with the Plymouth Colony (1620–1626)[edit]

English settlers established their first permanent foothold in New England with the founding of the Plymouth Colony by Pilgrims in 1620 near the site of the former Wampanoag village of Patuxet,[26] just a short distance south of the historic boundary with the Massachusett. In 1621, the Pilgrims, led by Myles Standish, met Obbatinewat (Wampanoag), a local sachem loyal to Massasoit. The colonists signed a peace treaty with Obbatinewat, who in turn, introduced the Pilgrims to the Squaw Sachem of Mistick (Massachusett, c. 1590–1650), another leader.[27]

The Wampanoag chief Massasoit (c. 1581–1661) decided to ally with the Pilgrims.[26] The Pilgrims also met with Chickatawbut (Massachusett, d. 1633), the most powerful Massachusett leader of the time. Unlike Massasoit, who favored increasing ties with the new English settlers to help assist against increasing power struggles with the Pequot and the Narragansett, Chickatawbut and other Massachusett leaders were wary of the Pilgrims and their intentions.[citation needed]

Chickatawbut’s fears were confirmed when the Plymouth Colony expanded to Wessagusset, in Massachusett territory, with the arrival of a new ship of colonists. The new settlers were ill-prepared, even more so than the first Pilgrims, and quickly resorted to trading supplies with the Massachusett. As their situation worsened, the Pilgrims began raiding Massachusett villages for food and supplies. To prevent an attack, Standish ordered a preemptive strike in 1624, which led to the deaths of Pecksuot, Wituwamat, and other Massachusett warriors who were lured under the pretense of peace and negotiation to meet with the colonists.[28] Standish further angered the Massachusett when he led his men deep into their territory to suppress the nascent colony of Merrymount, which had been established by Thomas Morton and which had friendly relations with neighboring Indian tribes. These activities caused the Massachusett to halt trade with the Pilgrims for many years.[28]

Relations with the Massachusett Bay Colony (1629-1676)[edit]

The Massachusett were unable to isolate themselves from the English settlers. Despite cutting off relations with the Pilgrim settlers, dissenting English settlers, mostly Puritans who wished to reform the Church of England to conform with their view of the Protestant Reformation as opposed to separate from it, began arriving, with the first settling in Wonnisquam in 1623 and later expanding to Naumkeag in Pawtucket territory. In 1628, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was legally established, with a claim over the lands north of the Plymouth Colony. The boundary between the two colonies mirrored the traditional boundary between the Massachusett and Wampanoag, although many Massachusett, such as those at Titicut and Mattakeesett, were under the claim of the Plymouth Colony.

The Massachusett sachems gave many land deeds to the Pilgrims since they served to rebuff attacks from other tribes. In most cases, it was because the land had already been opened to English colonial settlement, often because the Indians living there had already died off from disease. The sachems began selling land at a price, often with stipulations allowing the Indians to collect, gather, fish or forage, but these arrangements were seldom honored by the Pilgrims. The colonists also did not understand the Indian concept of leasing land from the sachem, and instead thought of their arrangements as permanent land sales. As a result of the rapid loss of land, the Massachusett and other local tribes sent their leaders to Boston for the 1644 Acts of Submission, bringing the Indians under the control of the colonial government and subject to both its laws and conversion attempts from Christian missionaries. By the time of the submission, the Massachusett, a coastal people, had lost access to the sea and their shellfish collection sites.[29]

Demographic changes[edit]

The Native peoples of New England faced increasing pressures with the increasing levels of colonists in New England. In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony greatly expanded with the arrival of the Winthrop Fleet of 11 ships and almost one thousand colonists beginning the «Great Migration.» By the end of 1640, the colonial population, more than doubled to almost twenty thousand due to the continued arrival of ships bearing Puritan settlers fleeing the increasing levels of religious persecution during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and natural increase, as settlers often arrived as family units and raised large numbers of children.

The Pilgrims feared the Native presence, as they were a numerical majority when all the different groups of New England were taken together and were dependent on them for survival and trade and the colonists were unable to expand. The Native populations continued to fall, with diseases such as scarlet fever, typhus, measles, mumps, influenza, tuberculosis, whooping cough taking large tolls. However, a smallpox epidemic in 1633 and 1634 also took a very heavy toll, afflicting not only peoples of the coast still recovering from the losses of 1617-1619 but far inland. The Massachusett population dwindled to fewer than two thousand individuals.[30] Other epidemics occurred in 1648 and 1666, although not as devastating, outbreaks of disease continued to inflict heavy tolls well into the 19th century. With so many areas depopulated, the Pilgrims believed that God had cleared New England for their colonization efforts. By the 1630s, the Indians of New England were already a minority in their own lands.[31]

The Massachusett put up little armed resistance to colonial settlement, but other Native peoples of New England who did were subjugated during and after Pequot War in 1638. The colonists aided local Indian tribes in subduing the Pequot, resulting in massacres of Pequot non-combatants, such as in the Mystic Massacre, and the selling of many of the Indians into slavery in Bermuda. The war resulted in the complete destruction of the Pequot as a tribal entity, opening up further land in New England to colonial settlement.[32]

Adoption of Christianity[edit]

Original seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony depicting a Massachusett Indian proclaiming «Come over and help us»—a plea for conversion—inspired from Acts 16:19. Many contemporary Massachusett support initiatives to replace the Great Seal of Massachusetts which preserves most elements of the colonial original and has long been held offensive to many of the Native groups of the region.[33]

As stated in the royal charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony of 1628, «according to the Courſe of other Corporations in this our Realme of England … whereby our ſaid People, Inhabitants thee … maie wynn and incite the Natives of Country, to the Knowledg and Obedience of the onlie true God and Savior of Mankinde, and the Chriſtian Fayth, which … is the principall Ende of this Plantation.»[34] The colonists were more occupied with their survival and propagation of a Puritan refuge. Although not the first to attempt to Christianize the Natives, it was not until the missionary John Eliot, «Apostle to the Indians», arrived in the colony and attained considerable success before colonial authorities truly began to invest in the project. Eliot began to learn the language, employing the help of two Indian indentured servants fluent in English, including Cockenoe, a Montaukett originally from Long Island that also spoke Massachusett, and John Sassamon from a Neponset family. Once confident in his abilities, Eliot tried to preach to the Neponset tribe led by Cutshamekin in 1646 but was rebuffed. Later, after resuming more language studies, Eliot preached to the Nonantum tribe led by Waban and had better success, bringing Waban and most of the tribe into Christianity.[35]

The reaction to Christianity was mixed, with many Native leaders continuing to be wary of the Pilgrims and urging their people to remain traditionalists whereas many wholeheartedly embraced it. Those that did embrace the new religion often did so because the traditional medicines and rituals conducted by healers known as powwow (pawâwak) /pawaːwak/ failed to protect them from settler encroachment of their lands or the novel pathogens to which they lacked resistance. These Indians hoped that the new God of the settlers would protect them the way that it had protected the settlers and often bought into the belief that they were punished for their wickedness. Other Indians likely joined because they thought they had to. The colonial government had forced the tribal leaders of Indians as far west as Quabaug (Brookfield, Massachusetts) to sign the 1644 Acts of Submission which forced upon the Indians acceptance of the authority of the colonial government and its protection as well opening their people to missionary activity, with many Indian leaders likely still fearful of the settlers due memories of the Pequot War and the fate of the Pequot. Others converted in hopes of removing the stigma of heathenism to improve relations with the settlers, but due to synchretism and cryto-traditional practices conducted in secret by some, the Puritans continued to mistreat the Indians and cast suspicions on the sincerity of the new believers who came to be referred to as «Praying Indians» or peantamwe Indiansog (puyôhtamwee Indiansak) /pəjãhtamwiː əntʃansak/.[36]

Praying towns (1651–1675)[edit]

The Eliot Church in South Natick. The church was built in 1828 where the Indian Church once stood.

Eliot urged Waban and the other newly converted Massachusett to settle along a bend of the Quinobequin River but were immediately sued as squatters by the residents of Dorchester. By the time Eliot began to establish the Indian mission, the Massachusett had lost access to the shellfishing beds along the coast and were soon to lose most of their remaining hunting and foraging lands due to the opening of all unfenced, «unimproved» lands. Eliot petitioned the General Court to set aside grants of lands for the Indians «in perpetuity.» Natick was established in 1651, with Ponkapoag following shortly thereafter in 1654. An additional 13 settlements were created, mostly in Nipmuc areas. These communities, settled by Praying Indians, came to be known as «Praying towns» or in Massachusett, Peantamwe Otanash (Puyôhtamwee 8tânash) /pəjãhtamwiː uːtaːnaʃ/. Ponkapoag, also spelled Punkapog, had 60 residents including Massachusett people in 1674.[37]

The establishment of the Praying towns accomplished several goals. It helped facilitate the goals of Christianization and acculturation as it allowed for easier distribution of the Massachusett-language translations of Eliot’s Bible and other works. The inhabitants were forced to observe the eight tenements of the «Leaf of Rules» distributed in the Bibles which forbid Indian cultural norms such as consenting pre-marital sex, cracking lice between teeth, avoidance of agriculture by men and re-enforced adoption of Puritan-style modesty and hairstyles.[38] For the colonial government, it brought the Indians fully under the control of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with the Praying towns occupying a status similar to autonomous English colonial settlements. The traditional power structures remained somewhat intact, as Native peoples recognized both the traditional power systems, but the chiefs and the tribal élite maintained it by adopting the roles of administrators, clerks, translators, teachers, constables, jurors and tax collectors. The confinement benefitted both the desires of Eliot and the colony, and Eliot was often accompanied by Daniel Gookin, the Superintendent to the Indians appointed to ensure cordial relations with the Indians and their adherence to the colonial laws, during his tours of the Praying towns. Similar settlements were established in the Plymouth Colony, such as the Massachusett Praying towns of Titicut and Mattakeeset.[39]

Historical marker standing on the northern boundary of what was once the Praying town of Ponkapoag, now contained in the town of Canton, Massachusetts.

The Massachusett benefited from clear titles of common land where they could plant, hunt and forage, and this likely attracted even more converts since the Praying towns established safe zones away from the constant encroachment, requests for sales of land and harassment. The Massachusett also were able to revive their prestige, which they long held prior to English colonial settlement. Many of the Praying towns were established by Native missionaries drawn from Natick’s old powerful families, affording them much respect in their adopted communities. The Massachusett began to replace the language of the Nipmuc and greatly leveled dialectal differences across the Massachusett-speaking area, due to the spread of Indian missionaries, but also because Massachusett became the language of literacy, prayer and administration, likely facilitated by its historic use as a regional second language and backed by its use in the translation of the Bible. The Massachusett leaders were also closer to the colonial authorities and thus often chosen to spread official messages, restoring the old power dynamic vis-à-vis other tribes.[39]

Life in the Praying towns became a mix of European and Indian customs. The Indians were forced to adopt Puritan habits of modesty, hairstyle, dress, and other cultural norms. They were encouraged to learn European methods of woodworking, carpentry, animal husbandry, and agriculture and Eliot arranged for many Indians to apprentice under settlers to learn these skills. Natick had an independent congregation with a Christian-style church, but the services were conducted in Massachusett with Indian preachers and the parishioners were called by Native drumming. The Praying Indians maintained many aspects of Indigenous culture, such their customary cuisine and foraging and hunting, but melded them with the European culture and Christian religion they were forced to adopt.[39] The mix of religious, cultural, and political control over the Indians was in many ways a precursor to the Indian Reservations that later developed.[40]

Humiliation of the Indians[edit]

The truce that had existed between the English colonists of the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies and the local Native peoples was tested. The submission of the local chiefs to the respective colonial governments and adoption of Christianity allowed the Indians to seek redress in the colonial legal system and removed one of the prejudices against them. The Praying Indians of Natick were brought to court several times by colonists living in settlement of Dedham who claimed some of the surrounding land, but with Eliot’s assistance, most of these attempts failed. Most of the time, however, the Indians failed, as some of the Indian interpreters and chiefs ceded lands to curry favor from the settlers to maintain special privileges, such as the Nipmuc John Wampas, who betrayed the Nipmuc and Massachusett people by selling land to the settlers to which he had no claim, but these sales were upheld in later court challenges. The Pawtucket sachem Wenepoykin, son of Nanepashemet and Squaw Sachem of Mistick, through kinship and family ties laid claim to much of Massachusett territory, and tried several times to petition the courts for lands lost in the turbulence of the 1633 epidemic that took both of his brothers to no avail, with most cases simply dismissed.[41]

King Philip’s War (1675-1676)[edit]

The outbreak of King Philip’s War from 1675 until 1676 was disastrous for both the Indians and colonists of New England. By the early 1670s, Waban and Cutshamekin had begun to address Daniel Gookin and warn of the increasing discontent of the interior Indians such as the Nipmuc people. However, the rebellion was started by the Wampanoag sachem (sôtyum) Metacomet, son of Massasoit who had welcomed and befriended Edward Winslow and the Pilgrims. Metacomet maintained the peace of his father but turned after the never-ending requests for land, but especially the execution of his brother Wamsutta for selling land to Roger Williams, seen by the Wampanoag as a very harsh measure for something outside the Plymouth Colony’s jurisdiction. In defiance, Metacomet murdered his interpreter to the colonial government, the Massachusett John Sassamon, before fleeing and seeking the support of the disgruntled tribes, culminating in the raid of Swansea in June 1675. Metacomet was able to bring the Narragansett, Nipmuc, Pocomtuc, Podunk, Tunxi peoples into his forces, organizing attacks on numerous outposts such as Sudbury, Lancaster, Turner’s Falls and other colonial settlements, leading many settlers to flee their lands for fortified towns. The settlers quickly responded by organizing units to attack the Indians loyal to Metacomet, leading to further conflict.[42]

The Massachusett, all of whom had become Praying Indians confined to praying towns, remained neutral during the war but suffered heavy casualties. The Praying Indians were attacked in their fields and harassed by neighboring colonists who had become overwhelmed with panic, hysteria, and anti-Indian sentiment. The Praying towns were also targets of Metacomet’s forces, raided for supplies, and persuaded or forced to join the fighting. To appease the settlers, the Praying Indians accepted confinement to the Praying towns, curfews, increased supervision, and voluntarily surrendered their weapons.

Most of the Praying Indians exiled to Deer Island in Boston Harbor died from exposure to the elements, starvation, and disease.

As the war progressed, the settlers decided to recruit some of the Praying Indians as scouts, guides and to fill the ranks of the colonial militia, with a regiment of Praying Indians, including many Massachusett, recruited by Daniel Gookin sent to face Metacomet’s warriors at Swansea, but it is known that other Massachusett aided the colonial militias in Lancaster, Brookfield and Mount Hope battles of the war. Metacomet was ultimately killed.

Guardianship of the Indians[edit]

Instead of being absorbed into the general affairs of the now predominantly European region, the colony appointed a commissioner to oversee the Natick in 1743, but commissioners were later appointed for all the extant tribes in the colony. Originally, the commissioner was charged to manage the timber resources, as most of the forests of New England had been felled to make way for farm and pasture, making the timber on Indian lands a valuable commodity. Very quickly, the guardian of Natick came to control the exchange of land, once the domain of the sachems, and any funds set up by the sale of Indian products, but mainly land. As the guardians assumed more power and were rarely supervised, many instances of questionable land sales by the guardians and embezzlement of funds have been recorded. The appointment of the guardians reduced the Indians to colonial wards, as they were no longer able to directly address the courts, vote in town elections and removed the power of the Indian chiefs.[6][43]

Loss of land continued. As forest lands were lost, the Indians could no longer resort to seasonal movements on their land or eke out a living, forcing many into poverty. Land was their only commodity and was often sold by the guardians to pay for treatments for the sick, care of orphans, and debts incurred by Indians, but Indians were also the victims of unfair credit schemes that often forced the land out of their hands.[44] Without land to farm or forage, Indians were forced to seek employment and settle in the de facto segregated sections of cities.

19th century[edit]

A bog near Ponkapoag pond. Now Canton, Massachusetts, this was part of the Ponkapoag praying town

Most of the remaining lands set aside «in perpetuity» for the Native peoples had been alienated, leaving a messy patchwork of a few remaining common lands, individual allotments, leased lands, and numerous colonial proprietors in between Indian households.

The end of tribal land did not remove the restrictions of the guardians even if it was the original purpose to have stewards of the land on the Native peoples’ «behalf.» As wards of the colonial and later state government, the Indians were restricted from voting in local elections or seeking redress through the courts on their own. Some of the Indians were supported by annuities established from the funds generated by land sales or initiated by the guardians for their support. The guardians, however, no longer had to maintain the rigorous lists of people associated with the land, which long had been used to segregate the Indians from the non-Indians especially as rates of intermarriage had increased.[45]

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts ordered reports on the condition of the Indians, including the Briggs Report (1849), also known as the Bird Report.[46] These did not mention the Massachusett or the Praying Town of Natick, where Massachusett people had joined in the 17th century.

John Milton Earle launched a far more detailed report in 1859 and published in 1861.[47]

Earle writes, «Of all the tribes which held reservations, and were placed under guardianship by the States, the Natick Tribe is nearest extinct. … [O]nly two families remain, and one of these is descended equally from the Naticks and the Hassanamiscoes. Their whole number is twelve. …»[48] He continues, «This tribe has no common lands,» and recommends their remain funds be divided equally among the two surviving families.[49] Earle observes that a few Natick descendants merged into the Nipmuc people and also writes, «There are some others, who claim to be of the Natick Tribe, but the claim appears to have no foundation other than that one of their ancestors formerly resided in Natick, but it is believed that he never was supposed to belong to the tribe.»[50]

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

In the 105 years between the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869 and the creation of the Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs by legislative act in 1974, records on the Massachusett people are very few. In 1928, anthropologist Frank G. Speck published Territorial subdivisions and boundaries of the Wampanoag, Massachusett, and Nauset Indians which included 17th-century Massachusett history. At Ponkapoag, Speck met Mrs. Chapelle (died 1919) who identified as a Massachusett Indian and whose husband was Mi’kmaq. Speck estimated that in 1921 a dozen Massachusett and Narragansett descendants of the Ponkapoag praying town lived in what is now Canton.[51]

Several organizations claim descent from historical Massachusett peoples; however, these are unrecognized, meaning they are neither federally recognized tribes[52] nor state-recognized tribes.[53]

See also[edit]

- Southern New England Algonquian cuisine

- History of Massachusetts

- Native American tribes in Massachusetts

Notes[edit]

- ^ Massachusetts Historical Commission (1982). «Historic and Archaeological Resources of the Boston Area» (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Bert Salwen, «Indians of Southern New England and Long Island,» p. 172

- ^ a b Bert Salwen, «Indians of Southern New England and Long Island,» p. 161.

- ^ a b John R. Swanton, The Indian Tribes of North America, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Swanton, ‘The Indian Tribes of North America, p. 19.

- ^ a b Order Accepting the Report in Regard to the Timber and Land of Natick Indians and Appointing a Committee Thereon, Province of Massachusetts. Session Laws § 257.

- ^ Goddard, Ives. 1996. «Introduction.» Ives Goddard, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 17. Languages, pp. 1–16.

- ^ Goddard, I., & Bragdon, K. (1988). (185 ed., p. 20).

- ^ Speck, F. G. (1928). «Territorial Subdivisions and Boundaries of the Wampanoag, Massachusett, and Nauset Indians.» Frank Hodge (ed). Lancaster, PA: Lancaster Press. p. 46. (PDF)

- ^ Mandell, D. R. ‘The Saga of Sarah Muckamugg: Indian and African Intermarriage in Colonial New England.’ Sex, Love, Race: Crossing Boundaries in North American History. ed. Martha Elizabeth Hodes. New York, NY: New York Univ Pr. pp. 72–83.

- ^ a b Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, p. 108.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, p. 105.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, 1500–1650, p. 107.

- ^ Elizabeth S. Chilton (2002). Hart, John P.; Rieth, Christina B. (eds.). Northeast Subsistence–Settlement Change: AD 700–1300 (PDF). Albany: The University of the State of New York. p. 293. ISBN 1-55557-213-8.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 66, 72, 104, 112.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 66, 78.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 135.

- ^ a b Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 105.

- ^ Bragdon, pp. 105–06.

- ^ «Samuel de Camplain’s Expeditions: Port Saint Louis». Archaeology Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Jameson, J. F. (1907). Original Narratives of Early American History: Voyages of Samuel de Champlain 1604–1618. W. L. Grant (ed.) (pp. 49-71.) New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ^ Lawson, R. M. (2015). The Sea Mark: Captain John Smith’s Voyage to New England. (pp. 120–123). Lebanon, NH: University of New England Press.

- ^ Marr, John S.; Cathey, John T. (February 2010). «New Hypothesis for Cause of Epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619». Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (2): 281–286. doi:10.3201/eid1602.090276. PMC 2957993. PMID 20113559.

- ^ «1633-34 — Smallpox Epidemic, New England Natives, Plymouth Colonists, MA –>1000». usdeadlyevents.com. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Willison, Megan K. (2016). Gender in 17th Century Southern New England. Mansfield, CT: University of Connecticut. p. 73.

- ^ a b T.J. Brasser, «Early Indian-European Contacts,» p. 82

- ^ Moore, Nina (1888). Pilgrims and Puritans: The Story of the Planting of Plymouth and Boston. Boston: Ginn & Company. p. 172.

- ^ a b Tremblay, R. (1972). ‘Weymouth Indian History.’ Weymouth, MA: 350th Anniversary Committee Town of Weymouth. Archived 2018-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ‘^ Cogley, R. W. (1999). John Eliot’s Mission to the Indians before King Philip’s War. (pp. 23-51). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Bragdon, K. J. (2005). pp. 130-133.