|

Mecca مكة

|

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

| Makkah al-Mukarramah (مكة المكرمة) | |

|

Masjid al-Haram (Great Mosque of Mecca) Mecca skyline The Kaaba Jabal al-Nour Neighborhood of Mina |

|

|

Mecca |

|

| Coordinates: 21°25′21″N 39°49′24″E / 21.42250°N 39.82333°E | |

| Country | Saudi Arabia |

| Province | Mecca Province |

| Governorate | Holy Capital Governorate |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Saleh Al-Turki |

| • Provincial Governor | Khalid bin Faisal Al Saud |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,200 km2 (500 sq mi) |

| • Land | 760 km2 (290 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 277 m (909 ft) |

| Population

(2015) |

|

| • Total | 1,578,722 |

| • Estimate

(2020) |

2,042,000 |

| • Rank | 3rd in Saudi Arabia |

| Demonym | Makki (مكي) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Area code | +966-12 |

| Website | hmm.gov.sa |

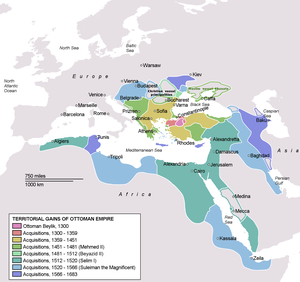

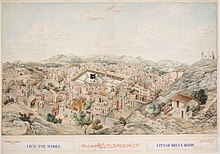

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah,[a] commonly shortened to Makkah[b]) is the holiest city in Islam and the capital of Mecca Province in Saudi Arabia.[2] It is 70 km (43 mi) inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley 277 m (909 ft) above sea level. Its last recorded population was 1,578,722 in 2015.[3] Its estimated metro population in 2020 is 2.042 million, making it the third-most populated city in Saudi Arabia after Riyadh and Jeddah. Pilgrims more than triple this number every year during the Ḥajj pilgrimage, observed in the twelfth Hijri month of Dhūl-Ḥijjah.

Mecca is generally considered «the fountainhead and cradle of Islam».[4][5] Mecca is revered in Islam as the birthplace of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The Hira cave atop the Jabal al-Nur («Mountain of Light»), just outside the city, is where Muslims believe the Quran was first revealed to Muhammad.[6] Visiting Mecca for the Ḥajj is an obligation upon all able Muslims. The Great Mosque of Mecca, known as the Masjid al-Haram, is home to the Ka’bah, believed by Muslims to have been built by Abraham and Ishmael. It is one of Islam’s holiest sites and the direction of prayer for all Muslims (qibla).[7]

Muslim rulers from in and around the region long tried to take the city and keep it in their control, and thus, much like most of the Hejaz region, the city has seen several regime changes. The city was most recently conquered in the Saudi conquest of Hejaz by Ibn Saud and his allies in 1925. Since then, Mecca has seen a tremendous expansion in size and infrastructure, with newer, modern buildings such as the Abraj Al Bait, the world’s fourth-tallest building and third-largest by floor area, towering over the Great Mosque. The Saudi government has also carried out the destruction of several historical structures and archaeological sites,[8] such as the Ajyad Fortress.[9][10][11] Non-Muslims are strictly prohibited from entering the city.[12][13]

Under the Saudi government, Mecca is governed by the Mecca Regional Municipality, a municipal council of 14 locally elected members headed by the mayor (called Amin in Arabic) appointed by the Saudi government. In 2015, the mayor of the city was Osama bin Fadhel Al-Barr;[14][15] as of January 2022, mayor of is Saleh Al-Turki.[16] The City of Mecca amanah, which constitutes Mecca and the surrounding region, is the capital of the Mecca Province, which includes the neighbouring cities of Jeddah and Ta’if, even though Jeddah is considerably larger in population compared to Mecca. The Provincial Governor of the province from 16 May 2007 was Prince Khalid bin Faisal Al Saud.[17]

Etymology[edit]

Mecca has been referred to by many names. As with many Arabic words, its etymology is obscure.[18] Widely believed to be a synonym for Makkah, it is said to be more specifically the early name for the valley located therein, while Muslim scholars generally use it to refer to the sacred area of the city that immediately surrounds and includes the Ka’bah.[19][20]

Bakkah[edit]

The Quran refers to the city as Bakkah in Surah Al Imran (3), verse 96: «Indeed the first House [of worship], established for mankind was that at Bakkah». This is presumed to have been the name of the city at the time of Abraham (Ibrahim in Islamic tradition) and it is also transliterated as Baca, Baka, Bakah, Bakka, Becca and Bekka, among others.[21][22][23]

Makkah, Makkah al-Mukarramah and Mecca[edit]

Makkah is the official transliteration used by the Saudi government and is closer to the Arabic pronunciation.[24][25] The government adopted Makkah as the official spelling in the 1980s, but it is not universally known or used worldwide.[24] The full official name is Makkah al-Mukarramah (Arabic: مكة المكرمة, lit. ‘Makkah the Honored’).[24] Makkah is used to refer to the city in the Quran in Surah Al-Fath (48), verse 24.[18][26]

The word Mecca in English has come to be used to refer to any place that draws large numbers of people, and because of this some English-speaking Muslims have come to regard the use of this spelling for the city as offensive.[24] Nonetheless, Mecca is the familiar form of the English transliteration for the Arabic name of the city.

The historic consensus in academic scholarship has long been that «Macoraba», the place mentioned in Arabia Felix by Claudius Ptolemy, is Mecca.[27] More recent study has questioned this association.[28] Many etymologies have been proposed: the traditional one is that it is derived from the Old South Arabian root M-K-R-B which means «temple».[28]

Other names[edit]

Another name used for Mecca in the Quran is at 6:92 where it is called Umm al-Qurā[29] (أُمّ ٱلْقُرَى, meaning «Mother of all Settlements»).[26] The city has been called several other names in both the Quran and ahadith. Another name used historically for Mecca is Tihāmah.[30] According to Arab and Islamic tradition, another name for Mecca, Fārān, is synonymous with the Desert of Paran mentioned in the Old Testament at Genesis 21:21.[31] Arab and Islamic tradition holds that the wilderness of Paran, broadly speaking, is the Tihamah coastal plain and the site where Ishmael settled was Mecca.[31] Yaqut al-Hamawi, the 12th-century Syrian geographer, wrote that Fārān was «an arabized Hebrew word, one of the names of Mecca mentioned in the Torah.»[32]

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

In 2010, Mecca and the surrounding area became an important site for paleontology with respect to primate evolution, with the discovery of a Saadanius fossil. Saadanius is considered to be a primate closely related to the common ancestor of the Old World monkeys and apes. The fossil habitat, near what is now the Red Sea in western Saudi Arabia, was a damp forest area between 28 million and 29 million years ago.[33] Paleontologists involved in the research hope to find further fossils in the area.[34]

Early history (up to 6th century CE)[edit]

The early history of Mecca is still largely disputed, as there are no unambiguous references to it in ancient literature prior to the rise of Islam.[35] The first unambiguous reference to Mecca in external literature occurs in 741 CE, in the Byzantine-Arab Chronicle, though here the author places the region in Mesopotamia rather than the Hejaz.[36]

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus writes about Arabia in the 1st century BCE in his work Bibliotheca historica, describing a holy shrine: «And a temple has been set up there, which is very holy and exceedingly revered by all Arabians».[37] Claims have been made this could be a reference to the Ka’bah in Mecca. However, the geographic location Diodorus describes is located in northwest Arabia, around the area of Leuke Kome, within the former Nabataean Kingdom and the Roman province of Arabia Petraea.[38][39]

Ptolemy lists the names of 50 cities in Arabia, one going by the name of Macoraba. There has been speculation since 1646 that this could be a reference to Mecca. Historically, there has been a general consensus in scholarship that Macoraba mentioned by Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE is indeed Mecca, but more recently, this has been questioned.[40][41] Bowersock favors the identity of the former, with his theory being that «Macoraba» is the word «Makkah» followed by the aggrandizing Aramaic adjective rabb (great). The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus also enumerated many cities of Western Arabia, most of which can be identified. According to Bowersock, he did mention Mecca as «Geapolis» or «Hierapolis», the latter one meaning «holy city» potentially referring to the sanctuary of the Kaaba.[42] Patricia Crone, from the Revisionist school of Islamic studies on the other hand, writes that «the plain truth is that the name Macoraba has nothing to do with that of Mecca […] if Ptolemy mentions Mecca at all, he calls it Moka, a town in Arabia Petraea».[43]

Recent research suggests that «Mecca was small» and the population of Mecca at the time of Muhammad was around 550.[44]

Procopius’ 6th century statement that the Ma’ad tribe possessed the coast of western Arabia between the Ghassanids and the Himyarites of the south supports the Arabic sources tradition that associates Quraysh as a branch of the Ma’add and Muhammad as a direct descendant of Ma’ad ibn Adnan.[45][46]

Historian Patricia Crone has cast doubt on the claim that Mecca was a major historical trading outpost.[47][48] However, other scholars such as Glen W. Bowersock disagree and assert that Mecca was a major trading outpost.[49][50] Crone later on disregarded some of her theories.[51] She argues that Meccan trade relied on skins, hides, manufactured leather goods, clarified butter, Hijazi woollens, and camels. She suggests that most of these goods were destined for the Roman army, which is known to have required colossal quantities of leather and hides for its equipment.

Mecca is mentioned in the following early Quranic manuscripts:

- Codex Is. 1615 I, folio 47v, radiocarbon dated to 591–643 CE.

- Codex Ṣanʿāʾ DAM 01–29.1, folio 29a, radiocarbon dated between 633 and 665 CE.

- Codex Arabe 331, folio 40 v, radiocarbon dated between 652 and 765 CE.

The earliest Muslim inscriptions are from the Mecca-Ta’if area.[52]

Islamic narrative

Mecca mentioned in Quranic manuscript Codex Arabe 331 (Q48:24)

In the Islamic view, the beginnings of Mecca are attributed to the Biblical figures, Abraham, Hagar and Ishmael. The civilization of Mecca is believed to have started after Ibrāhīm (Abraham) left his son Ismāʿīl (Ishmael) and wife Hājar (Hagar) in the valley at Allah’s command.[citation needed] Some people from the Yemeni tribe of Jurhum settled with them, and Isma’il reportedly married two women, one after divorcing the first, on Ibrahim’s advice. At least one man of the Jurhum helped Ismāʿīl and his father to construct or according to Islamic narratives, reconstruct, the Ka’bah (‘Cube’),[53][19][54] which would have social, religious, political and historical implications for the site and region.[55][56]

Muslims see the mention of a pilgrimage at the Valley of Baca in the Old Testament chapter Psalm 84:3–6 as a reference to Mecca, similar to the Quran at Surah 3:96 In the Sharḥ al-Asāṭīr, a commentary on the Samaritan midrashic chronology of the Patriarchs, of unknown date but probably composed in the 10th century CE, it is claimed that Mecca was built by the sons of Nebaioth, the eldest son of Ismāʿīl or Ishmael.[57][58][59]

Thamudic inscriptions

Some Thamudic inscriptions which were discovered in the south Jordan contained names of some individuals such as ʿAbd Mekkat (عَبْد مَكَّة, «Servant of Mecca»).[60]

There were also some other inscriptions which contained personal names such as Makki (مَكِّي, «Makkahn»), but Jawwad Ali from the University of Baghdad suggested that there’s also a probability of a tribe named «Makkah».[61]

Under the Quraish[edit]

Sometime in the 5th century, the Ka’bah was a place of worship for the deities of Arabia’s pagan tribes. Mecca’s most important pagan deity was Hubal, which had been placed there by the ruling Quraish tribe.[62][63] and remained until the Conquest of Mecca by Muhammad.[citation needed] In the 5th century, the Quraish took control of Mecca, and became skilled merchants and traders. In the 6th century, they joined the lucrative spice trade, since battles elsewhere were diverting trade routes from dangerous sea routes to more secure overland routes. The Byzantine Empire had previously controlled the Red Sea, but piracy had been increasing.[citation needed] Another previous route that ran through the Persian Gulf via the Tigris and Euphrates rivers was also being threatened by exploitations from the Sassanid Empire, and was being disrupted by the Lakhmids, the Ghassanids, and the Roman–Persian Wars. Mecca’s prominence as a trading center also surpassed the cities of Petra and Palmyra.[64][65] The Sassanids however did not always pose a threat to Mecca, as in 575 CE they protected it from a Yemeni invasion, led by its Christian leader Abraha. The tribes of southern Arabia asked the Persian king Khosrau I for aid, in response to which he came south to Arabia with foot-soldiers and a fleet of ships near Mecca.[66]

By the middle of the 6th century, there were three major settlements in northern Arabia, all along the south-western coast that borders the Red Sea, in a habitable region between the sea and the Hejaz mountains to the east. Although the area around Mecca was completely barren, it was the wealthiest of the three settlements with abundant water from the renowned Zamzam Well and a position at the crossroads of major caravan routes.[67]

The harsh conditions and terrain of the Arabian peninsula meant a near-constant state of conflict between the local tribes, but once a year they would declare a truce and converge upon Mecca in an annual pilgrimage. Up to the 7th century, this journey was intended for religious reasons by the pagan Arabs to pay homage to their shrine, and to drink Zamzam. However, it was also the time each year that disputes would be arbitrated, debts would be resolved, and trading would occur at Meccan fairs. These annual events gave the tribes a sense of common identity and made Mecca an important focus for the peninsula.[68]

The Year of the Elephant (570 CE)

The «Year of the Elephant» is the name in Islamic history for the year approximately equating to 570–572 CE, when, according to Islamic sources such as Ibn Ishaq, Abraha descended upon Mecca, riding an elephant, with a large army after building a cathedral at San’aa, named al-Qullays in honor of the Negus of Axum. It gained widespread fame, even gaining attention from the Byzantine Empire.[69] Abraha attempted to divert the pilgrimage of the Arabs from the Ka’bah to al-Qullays, effectively converting them to Christianity. According to Islamic tradition, this was the year of Muhammad’s birth.[69] Abraha allegedly sent a messenger named Muhammad ibn Khuza’i to Mecca and Tihamah with a message that al-Qullays was both much better than other houses of worship and purer, having not been defiled by the housing of idols.[69] When Muhammad ibn Khuza’i got as far as the land of Kinana, the people of the lowland, knowing what he had come for, sent a man of Hudhayl called ʿUrwa bin Hayyad al-Milasi, who shot him with an arrow, killing him. His brother Qays who was with him, fled to Abraha and told him the news, which increased his rage and fury and he swore to raid the Kinana tribe and destroy the Ka’bah. Ibn Ishaq further states that one of the men of the Quraysh tribe was angered by this, and going to Sana’a, entering the church at night and defiling it; widely assumed to have done so by defecating in it.[70][71]

Abraha marched upon the Ka’bah with a large army, which included one or more war elephants, intending to demolish it. When news of the advance of his army came, the Arab tribes of Quraysh, Kinanah, Khuza’a and Hudhayl united in the defense of the Ka’bah and the city. A man from the Himyarite Kingdom was sent by Abraha to advise them that Abraha only wished to demolish the Ka’bah and if they resisted, they would be crushed. Abdul Muttalib told the Meccans to seek refuge in the hills while he and some members of the Quraysh remained within the precincts of the Kaaba. Abraha sent a dispatch inviting Abdul-Muttalib to meet with Abraha and discuss matters. When Abdul-Muttalib left the meeting he was heard saying: «The Owner of this House is its Defender, and I am sure he will save it from the attack of the adversaries and will not dishonor the servants of His House.»[72][73]

Abraha eventually attacked Mecca. However, the lead elephant, known as Mahmud,[74] is said to have stopped at the boundary around Mecca and refused to enter. It has been theorized that an epidemic such as by smallpox could have caused such a failed invasion of Mecca.[75] The reference to the story in Quran is rather short. According to the 105th Surah of the Quran, Al-Fil, the next day, a dark cloud of small birds sent by Allah appeared. The birds carried small rocks in their beaks, and bombarded the Ethiopian forces, and smashed them to a state like that of eaten straw.[76]

Economy

Camel caravans, said to have first been used by Muhammad’s great-grandfather, were a major part of Mecca’s bustling economy. Alliances were struck between the merchants in Mecca and the local nomadic tribes, who would bring goods – leather, livestock, and metals mined in the local mountains – to Mecca to be loaded on the caravans and carried to cities in Shaam and Iraq.[77] Historical accounts also provide some indication that goods from other continents may also have flowed through Mecca. Goods from Africa and the Far East passed through en route to Syria including spices, leather, medicine, cloth, and slaves; in return Mecca received money, weapons, cereals and wine, which in turn were distributed throughout Arabia.[citation needed] The Meccans signed treaties with both the Byzantines and the Bedouins, and negotiated safe passages for caravans, giving them water and pasture rights. Mecca became the center of a loose confederation of client tribes, which included those of the Banu Tamim. Other regional powers such as the Abyssinians, Ghassanids, and Lakhmids were in decline leaving Meccan trade to be the primary binding force in Arabia in the late 6th century.[68]

Muhammad and the conquest of Mecca[edit]

Muhammad was born in Mecca in 570 CE, and thus Islam has been inextricably linked with it ever since. He was born into the faction of Banu Hashim in the ruling tribe of Quraysh. It was in the nearby mountain cave of Hira on Jabal al-Nour that Muhammad began receiving divine revelations from God through the archangel Jibreel in 610 CE, according to Islamic tradition. Advocating his form of Abrahamic monotheism against Meccan paganism, and after enduring persecution from the pagan tribes for 13 years, Muhammad emigrated to Medina (hijrah) in 622 CE with his companions, the Muhajirun, to Yathrib (later renamed Medina). The conflict between the Quraysh and the Muslims is accepted to have begun at this point. Overall, Meccan efforts to annihilate Islam failed and proved to be costly and unsuccessful.[citation needed] During the Battle of the Trench in 627 CE, the combined armies of Arabia were unable to defeat Muhammad’s forces (as the trench surrounding Muhammad’s forces protected them from harm and a storm was sent to breach the Quraysh tribe).[78]

In 628 CE, Muhammad and his followers wanted to enter Mecca for pilgrimage, but were blocked by the Quraysh. Subsequently, Muslims and Meccans entered into the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, whereby the Quraysh and their allies promised to cease fighting Muslims and their allies and promised that Muslims would be allowed into the city to perform the pilgrimage the following year. It was meant to be a ceasefire for 10 years; however, just two years later, the Banu Bakr, allies of the Quraish, violated the truce by slaughtering a group of the Banu Khuza’ah, allies of the Muslims. Muhammad and his companions, now 10,000 strong, marched into Mecca and conquered the city. The pagan imagery was destroyed by Muhammad’s followers and the location Islamized and rededicated to the worship of Allah alone. Mecca was declared the holiest site in Islam ordaining it as the center of Muslim pilgrimage (Hajj), one of the Islamic faith’s Five Pillars.

Muhammad then returned to Medina, after assigning ‘Akib ibn Usaid as governor of the city. His other activities in Arabia led to the unification of the Arabian Peninsula under the banner of Islam.[64][78] Muhammad passed away in 632 CE. Within the next few hundred years, the area under the banner of Islam stretched from North Africa into Asia and parts of Europe. As the Islamic realm grew, Mecca continued to attract pilgrims from all across the Muslim world and beyond, as Muslims came to perform the annual Hajj pilgrimage. Mecca also attracted a year-round population of scholars, pious Muslims who wished to live close to the Kaaba, and local inhabitants who served the pilgrims. Due to the difficulty and expense of the Hajj, pilgrims arrived by boat at Jeddah, and came overland, or joined the annual caravans from Syria or Iraq.[citation needed]

Medieval and pre-modern times[edit]

Mecca was never the capital of any of the Islamic states. Muslim rulers did contribute to its upkeep, such as during the reigns of ‘Umar (r. 634–644 CE) and ‘Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656 CE) when concerns of flooding caused the caliphs to bring in Christian engineers to build barrages in the low-lying quarters and construct dykes and embankments to protect the area around the Kaaba.[64]

Muhammad’s return to Medina shifted the focus away from Mecca and later even further away when ‘Ali, the fourth caliph, took power and chose Kufa as his capital. The Umayyad Caliphate moved the capital to Damascus in Syria and the Abbasid Caliphate to Baghdad, in modern-day Iraq, which remained the center of the Islamic Empire for nearly 500 years. Mecca re-entered Islamic political history during the Second Fitna, when it was held by Abdullah ibn az-Zubayr and the Zubayrids.[citation needed] The city was twice besieged by the Umayyads in 683 CE and 692 CE, and for some time thereafter, the city figured little in politics, remaining a city of devotion and scholarship governed by various other factions. In 930 CE, Mecca was attacked and sacked by Qarmatians, a millenarian Shi’a Isma’ili Muslim sect led by Abū-Tāhir Al-Jannābī and centered in eastern Arabia.[79] The Black Death pandemic hit Mecca in 1349 CE.[80]

Ibn Battuta’s description of Mecca[edit]

One of the most famous travelers to Mecca in the 14th century was a Moroccan scholar and traveler, Ibn Battuta. In his rihla (account), he provides a vast description of the city. Around the year 1327 CE or 729 AH, Ibn Battuta arrived at the holy city. Immediately, he says, it felt like a holy sanctuary, and thus he started the rites of the pilgrimage. He remained in Mecca for three years and left in 1330 CE. During his second year in the holy city, he says his caravan arrived «with a great quantity of alms for the support of those who were staying in Mecca and Medina». While in Mecca, prayers were made for (not to) the King of Iraq and also for Salaheddin al-Ayyubi, Sultan of Egypt and Syria at the Ka’bah. Battuta says the Ka’bah was large, but was destroyed and rebuilt smaller than the original and that it contained images of angels and prophets including Jesus (Isa in Islamic tradition), his mother Mary (Maryam in Islamic tradition), and many others. Battuta describes the Ka’bah as an important part of Mecca due to the fact that many people make the pilgrimage to it. Battuta describes the people of the city as being humble and kind, and also willing to give a part of everything they had to someone who had nothing. The inhabitants of Mecca and the village itself, he says, were very clean. There was also a sense of elegance to the village.[81]

Under the Ottomans

In 1517, the then Sharif of Mecca, Barakat bin Muhammad, acknowledged the supremacy of the Ottoman Caliph but retained a great degree of local autonomy.[82] In 1803 the city was captured by the First Saudi State,[83] which held Mecca until 1813, destroying some of the historic tombs and domes in and around the city. The Ottomans assigned the task of bringing Mecca back under Ottoman control to their powerful Khedive (viceroy) and Wali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha. Muhammad Ali Pasha successfully returned Mecca to Ottoman control in 1813. In 1818, the Saud were defeated again but survived and founded the Second Saudi State that lasted until 1891 and led on to the present country of Saudi Arabia. In 1853, Sir Richard Francis Burton undertook the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina disguised as a Muslim. Although Burton was certainly not the first non-Muslim European to make the Hajj (Ludovico di Varthema did this in 1503),[84] his pilgrimage remains one of the most famous and documented of modern times. Mecca was regularly hit by cholera outbreaks. Between 1830 and 1930, cholera broke out among pilgrims at Mecca 27 times.[85]

Modern history[edit]

Hashemite Revolt and subsequent control by the Sharifate of Mecca

In World War I, the Ottoman Empire was at war with the Allies. It had successfully repulsed an attack on Istanbul in the Gallipoli campaign and on Baghdad in the Siege of Kut. The British intelligence agent T.E. Lawrence conspired with the Ottoman governor, Hussain bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca to revolt against the Ottoman Empire and it was the first city captured by his forces in the 1916 Battle of Mecca. Sharif’s revolt proved a turning point of the war on the eastern front. Hussein declared a new state, the Kingdom of Hejaz, declaring himself the Sharif of the state and Mecca his capital. News reports in November 1916 via contact in Cairo with returning Hajj pilgrims, stated that with the Ottoman Turkish authorities gone, the Hajj of 1916 was free of the previous massive extortion and monetary demands made by the Turks who were agents of the Ottoman government.[86]

Saudi Arabian conquest and modern history

Following the 1924 Battle of Mecca, the Sharif of Mecca was overthrown by the Saud family, and Mecca was incorporated into Saudi Arabia.[87] Under Saudi rule, much of the historic city has been demolished as a result of the Saudi government fearing these sites might become sites of association in worship besides Allah (shirk). The city has been expanded to include several towns previously considered to be separate from the holy city and now is just a few kilometers outside the main sites of the Hajj, Mina, Muzdalifah and Arafat. Mecca is not served by any airport, due to concerns about the city’s safety. It is instead served by the King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah (approx. 70 km away) internationally and the Ta’if Regional Airport (approx. 120 km away) for domestic flights.[citation needed]

The city today is at the junction of the two most important highways in all of the Saudi Arabian highway system, Highway 40, which connects the city to Jeddah in the west and the capital, Riyadh and Dammam in the east and Highway 15, which connects it to Medina, Tabuk and onward to Jordan in the north and Abha and Jizan in the south. The Ottomans had planned to extend their railway network to the holy city, but were forced to abandon this plan due to their entry into the First World War. This plan was later carried out by the Saudi government, which connected the two holy cities of Medina and Mecca with the modern Haramain high-speed railway system which runs at 300 km/h (190 mph) and connects the two cities via Jeddah, King Abdulaziz International Airport and King Abdullah Economic City near Rabigh within two hours.[citation needed]

The haram area of Mecca, in which the entry of non-Muslims is forbidden, is much larger than that of Medina.

1979 Grand Mosque seizure

On 20 November 1979, two hundred armed dissidents led by Juhayman al-Otaibi, seized the Grand Mosque, claiming the Saudi royal family no longer represented pure Islam and that the Masjid al-Haram and the Ka’bah, must be held by those of true faith. The rebels seized tens of thousands of pilgrims as hostages and barricaded themselves in the mosque. The siege lasted two weeks, and resulted in several hundred deaths and significant damage to the shrine, especially the Safa-Marwah gallery. A multinational force was finally able to retake the mosque from the dissidents.[88] Since then, the Grand Mosque has been expanded several times, with many other expansions being undertaken in the present day.

Destruction of Islamic heritage sites

Under Saudi rule, it has been estimated that since 1985, about 95% of Mecca’s historic buildings, most over a thousand years old, have been demolished.[9][89] It has been reported that there are now fewer than 20 structures remaining in Mecca that date back to the time of Muhammad. Some important buildings that have been destroyed include the house of Khadijah, the wife of Muhammad, the house of Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s birthplace and the Ottoman-era Ajyad Fortress.[90] The reason for much of the destruction of historic buildings has been for the construction of hotels, apartments, parking lots, and other infrastructure facilities for Hajj pilgrims.[89][91]

Incidents during pilgrimage

Mecca has been the site of several incidents and failures of crowd control because of the large numbers of people who come to make the Hajj.[92][93][94] For example, on 2 July 1990, a pilgrimage to Mecca ended in tragedy when the ventilation system failed in a crowded pedestrian tunnel and 1,426 people were either suffocated or trampled to death in a stampede.[95] On 24 September 2015, 700 pilgrims were killed in a stampede at Mina during the stoning-the-Devil ritual at Jamarat.[96]

Significance in Islam[edit]

The Hajj involves pilgrims visiting Al-Haram Mosque, but mainly camping and spending time in the plains of Mina and Arafah

Mecca holds an important place in Islam and is the holiest city in all branches of the religion. The city derives its importance from the role it plays in the Hajj and ‘Umrah.

Masjid al-Haram[edit]

The Masjid al-Haram is the site of two of the most important rites of both the Hajj and of the Umrah, the circumambulation around the Ka’bah (tawaf) and the walking between the two mounts of Safa and Marwa (sa’ee). The masjid is also the site of the Zamzam Well. According to Islamic tradition, a prayer in the masjid is equal to 100,000 prayers in any other masjid around the world.[97]

Kaaba[edit]

There is a difference of opinion between Islamic scholars upon who first built the Ka’bah, some believe it was built by the angels while others believe it was built by Adam. Regardless, it was built several times before reaching its current state. The Ka’bah is also the common direction of prayer (qibla) for all Muslims. The surface surrounding the Ka’bah on which Muslims circumambulate it is known as the Mataf.

Hajr-e-Aswad (The Black Stone)[edit]

The Black Stone is a stone, considered by scientists to be a meteorite or of similar origin and believed by Muslims to be of divine origin. It is set in the eastern corner of the Ka’bah and it is Sunnah to touch and kiss the stone. The area around the stone is generally always crowded and guarded by policemen to ensure the pilgrims’ safety. In Islamic tradition, the stone was sent down from Jannah (Paradise) and used to build the Ka’bah. It used to be a white stone (and was whiter than milk). Because of the worldly sins of man, it slowly changed color to black over the years after it was brought down to Earth.

Maqam Ibrahim[edit]

This is the stone that Ibrahim (Abraham) stood on to build the higher parts of the Ka’bah. It contains two footprints that are comparatively larger than average modern-day human feet. The stone is raised and housed in a golden hexagonal chamber beside the Ka’bah on the Mataf plate.

Safa and Marwa[edit]

Muslims believe that in the divine revelation to Muhammad, the Quran, Allah describes the mountains of Safa and Marwah as symbols of His divinity. Walking between the two mountains seven times, 4 times from Safa to Marwah and 3 times from Marwah interchangeably, is considered a mandatory pillar (rukn) of ‘Umrah.

Panorama of the al-Masjid al-Haram, also known as the Grand Mosque of Mecca, during the Hajj pilgrimage

Hajj and ‘Umrah[edit]

The Hajj pilgrimage, also called the greater pilgrimage, attracts millions of Muslims from all over the world and almost triples Mecca’s population for one week in the twelfth and final Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah. In 2019, the Hajj attracted 2,489,406 pilgrims to the holy city.[98] The ‘Umrah, or the lesser pilgrimage, can be done at anytime during the year. Every adult, healthy Muslim who has the financial and physical capacity to travel to Mecca must perform the Hajj at least once in a lifetime. Umrah, the lesser pilgrimage, is not obligatory, but is recommended in the Quran.[99] In addition to the Masjid al-Haram, pilgrims also must visit the nearby towns of Mina/Muna, Muzdalifah and Mount Arafat for various rituals that are part of the Hajj.

Jabal an-Nur[edit]

Jabal al-Nour, the mountain atop which is the Hira cave, where it is believed Muhammad received his first revelation.

This is a mountain believed by Muslims to have been the place where Muhammad spent his time away from the bustling city of Mecca in seclusion.[100][101] The mountain is located on the eastern entrance of the city and is the highest point in the city at 642 meters (2,106 feet).

Hira’a Cave[edit]

Situated atop Jabal an-Nur, this is the place where Muslims believe Muhammad received the first revelation from Allah through the archangel Gabriel (Jibril in Islamic tradition) at the age of 40.[100][101]

Geography[edit]

Mecca is located in the Hejaz region, a 200 km (124 mi) wide strip of mountains separating the Nafud desert from the Red Sea. The city is situated in a valley with the same name around 70 km (44 mi) east of the port city of Jeddah. Mecca is one of the lowest cities in elevation in the Hejaz region, located at an elevation of 277 m (909 ft) above sea level at 21º23′ north latitude and 39º51′ east longitude. Mecca is divided into 34 districts.

The city centers on the al-Haram area, which contains the Masjid al-Haram. The area around the mosque is the old city and contains the most famous district of Mecca, Ajyad. The main street that runs to al-Haram is the Ibrahim al-Khalil Street, named after Ibrahim. Traditional, historical homes built of local rock, two to three stories long are still present within the city’s central area, within view of modern hotels and shopping complexes. The total area of modern Mecca is over 1,200 km2 (460 sq mi).[102]

Elevation[edit]

Mecca is at an elevation of 277 m (909 ft) above sea level, and approximately 70 km (44 mi) inland from the Red Sea.[67] It is one of the lowest in the Hejaz region. Although some mountain peaks in Mecca reach 1,000m in height.

Topography[edit]

The city center lies in a corridor between mountains, which is often called the «Hollow of Mecca». The area contains the valley of al-Taneem, the valley of Bakkah and the valley of Abqar.[64][103] This mountainous location has defined the contemporary expansion of the city.

Sources of water[edit]

Due to Mecca’s climatic conditions water scarcity has been an issue throughout its history. In pre-modern Mecca, the city used a few chief sources of water. Among them were local wells, such as the Zamzam Well, that produced generally brackish water. Finding a sustainable water source to supply Mecca’s permanent population and the large number of annual pilgrims was an undertaking that began in the Abbasid era under the auspices of Zubayda, the wife of the caliph Harun ar-Rashid.[c] She donated funds for the deepening of Zamzam Well and funded a massive construction project likely costing 1.75 Million gold dinars. The project encompassed the construction of an underground aqueduct from the Arabic: عين حنين, romanized: ʿAyn Ḥunayn, lit. ‘Spring of Hunayn’ and smaller water sources in the area to Mecca in addition to the construction of a waterworks on Mount Arafat called Arabic: عين زبيدة, romanized: ʿAyn Zubayda, lit. ‘Spring of Zubayda’ using a separate conduit to connect it to Mecca and the Masjid al-Haram. Over time however the system deteriorated and failed to fulfil its function. Thus in 1245 CE, 1361 CE, 1400 CE, 1474 CE, and 1510 CE different rulers invested into extensive repairs of the system. In 1525 CE due to the system’s troubles persisting however the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent began a construction project to rebuild the aqueduct in its entirety, the project took until 1571 CE to be completed. Its water quality was greatly lacking during the 19th century until a restoration and cleaning project by Osman Pasha began.[104]

Another source which sporadically provided water was rainfall which was stored by the people in small reservoirs or cisterns. According to al-Kurdī, there had been 89 floods by 1965. In the last century, the most severe flood was that of 1942. Since then, dams have been built to ameliorate this problem.[103]

In the modern day water treatment plants and desalination facilities have been constructed and are being constructed to provide suitable amounts of water fit for human consumption to the city.[105][106]

Climate[edit]

Mecca features a hot desert climate (Köppen: BWh), in three different plant hardiness zones: 10, 11 and 12.[107] Like most Saudi Arabian cities, Mecca retains warm to hot temperatures even in winter, which can range from 19 °C (66 °F) at night to 30 °C (86 °F) in the afternoon. Summer temperatures are extremely hot and consistently break the 40 °C (104 °F) mark in the afternoon, dropping to 30 °C (86 °F) in the evening, but humidity remains relatively low, at 30–40%. Rain usually falls in Mecca in small amounts scattered between November and January, with heavy thunderstorms also common during the winter.

| Climate data for Mecca | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.4 (99.3) |

38.3 (100.9) |

42.4 (108.3) |

44.7 (112.5) |

49.4 (120.9) |

49.6 (121.3) |

49.8 (121.6) |

49.7 (121.5) |

49.4 (120.9) |

47.0 (116.6) |

41.2 (106.2) |

38.4 (101.1) |

49.8 (121.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.5 (86.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.7 (101.7) |

42.0 (107.6) |

43.8 (110.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.8 (109.0) |

42.8 (109.0) |

40.1 (104.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.6 (76.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

31.6 (88.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.7 (96.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

29.1 (84.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28.9 (84.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 20.8 (0.82) |

3.0 (0.12) |

5.5 (0.22) |

10.3 (0.41) |

1.2 (0.05) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.4 (0.06) |

5.0 (0.20) |

5.4 (0.21) |

14.5 (0.57) |

22.6 (0.89) |

22.1 (0.87) |

111.8 (4.40) |

| Average precipitation days | 4.0 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 22.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (daily average) | 58 | 54 | 48 | 43 | 36 | 33 | 34 | 39 | 45 | 50 | 58 | 59 | 46 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 260.4 | 245.8 | 282.1 | 282.0 | 303.8 | 321.0 | 313.1 | 297.6 | 282.0 | 300.7 | 264.0 | 248.0 | 3,400.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.4 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 9.3 |

| Source 1: Jeddah Regional Climate Center[108] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sunshine hours, 1986–2000)[109] |

Economy[edit]

Pilgrims are the driving force of Mecca’s economy

The Meccan economy has been heavily dependent on pilgrimages coming for Umrah and Hajj.[110] Income generated through pilgrims not only powers the Meccan economy but has historically had far-reaching effects on the economy of the entire Arabian Peninsula. The income was generated in a number of ways. One method was taxing the pilgrims. Taxes were especially increased during the Great Depression, and many of these taxes existed to as late as 1972. Another way the Hajj generates income is through services to pilgrims. For example, the Saudi flag carrier, Saudia, generates 12% of its income from the pilgrimage. Fares paid by pilgrims to reach Mecca by land also generate income; as do the hotels and lodging companies that house them.[103] The city takes in more than $100 million, while the Saudi government spends about $50 million on services for the Hajj. There are some industries and factories in the city, but Mecca no longer plays a major role in Saudi Arabia’s economy, which is mainly based on oil exports.[111] The few industries operating in Mecca include textiles, furniture, and utensils. The majority of the economy is service-oriented.

Nevertheless, many industries have been set up in Mecca. Various types of enterprises that have existed since 1970 in the city include corrugated iron manufacturing, copper extraction, carpentry, upholstery, bakeries, farming and banking.[103] The city has grown substantially in the 20th and 21st centuries, as the convenience and affordability of jet travel has increased the number of pilgrims participating in the Hajj. Thousands of Saudis are employed year-round to oversee the Hajj and staff the hotels and shops that cater to pilgrims; these workers in turn have increased the demand for housing and services. The city is now ringed by freeways, and contains shopping malls and skyscrapers.[112]

Human resources[edit]

Formal education started to be developed in the late Ottoman period continuing slowly into Hashemite times. The first major attempt to improve the situation was made by a Jeddah merchant, Muhammad ʿAlī Zaynal Riḍā, who founded the Madrasat al-Falāḥ in Mecca in 1911–12 that cost £400,000.[103] The school system in Mecca has many public and private schools for both males and females. As of 2005, there were 532 public and private schools for males and another 681 public and private schools for female students.[113] The medium of instruction in both public and private schools is Arabic with emphasis on English as a second language, but some private schools founded by foreign entities such as International schools use the English language as the medium of instruction. Some of these are coeducational while other schools are not. For higher education, the city has only one university, Umm Al-Qura University, which was established in 1949 as a college and became a public university in 1981.

Healthcare is provided by the Saudi government free of charge to all pilgrims. There are ten main hospitals in Mecca:[114]

- Ajyad Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى أَجْيَاد)

- King Faisal Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى ٱلْمَلِك فَيْصَل بِحَي ٱلشّشه)

- King Abdulaziz Hospital (Arabic: مُسْتَشْفَى ٱلْمَلِك عَبْد ٱلْعَزِيْز بِحَي ٱلـزَّاهِر)

- Al Noor Specialist Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى ٱلنُّوْر ٱلتَّخَصُّصِي)

- Hira’a Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى حِرَاء)

- Maternity and Children’s Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى ٱلْوِلَادَة وَٱلْأَطْفَال)

- King Abdullah Medical City (مَدِيْنَة ٱلْمَلِك عَبْد ٱلله ٱلطِّبِيَّة)

- Khulais General Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى خُلَيْص ٱلْعَام)

- Al Kamel General Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى ٱلْكَامِل ٱلْعَام)

- Ibn Sina Hospital (مُسْتَشْفَى ابْن سِيْنَا بِحَدَاء / بَحْرَه)

There are also many walk-in clinics available for both residents and pilgrims. Several temporary clinics are set up during the Hajj to tend to wounded pilgrims.

Culture[edit]

Al-Haram Mosque and the Kaaba

Mecca’s culture has been affected by the large number of pilgrims that arrive annually, and thus boasts a rich cultural heritage. As a result of the vast numbers of pilgrims coming to the city each year, Mecca has become by far the most diverse city in the Muslim world.[citation needed]

Al Baik, a local fast-food chain, is very popular among pilgrims and locals alike. Until 2018, it was available only in Mecca, Medina and Jeddah, and traveling to Jeddah just to get a taste of the fried chicken was common.

Sports[edit]

In pre-modern Mecca, the most common sports were impromptu wrestling and foot races.[103] Football is now the most popular sport in Mecca and the kingdom, and the city hosts some of the oldest sport clubs in Saudi Arabia such as Al Wahda FC (established in 1945). King Abdulaziz Stadium is the largest stadium in Mecca with a capacity of 38,000.[115]

Demographics[edit]

Mecca is very densely populated. Most long-term residents live in the Old City, the area around the Great Mosque and many work to support pilgrims, known locally as the Hajj industry. ‘Iyad Madani, the Saudi Arabian Minister for Hajj, was quoted saying, «We never stop preparing for the Hajj.»[116]

Year-round, pilgrims stream into the city to perform the rites of ‘Umrah, and during the last weeks of eleventh Islamic month, Dhu al-Qi’dah, on average 2–4 million Muslims arrive in the city to take part in the rites known as Hajj.[117] Pilgrims are from varying ethnicities and backgrounds, mainly South and Southeast Asia, Europe and Africa. Many of these pilgrims have remained and become residents of the city. The Burmese are an older, more established community who number roughly 250,000.[118] Adding to this, the discovery of oil in the past 50 years has brought hundreds of thousands of working immigrants.

Non-Muslims are not permitted to enter Mecca under Saudi law,[12] and using fraudulent documents to do so may result in arrest and prosecution.[119] The prohibition extends to Ahmadis, as they are considered non-Muslims.[120] Nevertheless, many non-Muslims and Ahmadis have visited the city as these restrictions are loosely enforced. The first such recorded example of a non-Muslim entering the city is that of Ludovico di Varthema of Bologna in 1503.[121] Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, is said to have visited Mecca[122] in December 1518.[123] One of the most famous was Richard Francis Burton,[124] who traveled as a Qadiriyya Sufi from Afghanistan in 1853.

Mecca Province is the only province where expatriates outnumber Saudis.[125]

Architectural landmarks[edit]

Adorning the southern facade of the Masjid al-Haram, the Abraj al-Bait Complex, which towers over the Great Mosque, is a seven-building complex with the central clock tower having a length of 601 m (1,972 feet), making it the world’s fourth-tallest building. All seven buildings in the complex also form the third-largest building by floor area.

The Mecca Gate, known popularly as the Quran Gate, on the western entrance of the city, or from Jeddah. Located on Highway 40, it marks the boundary of the Haram area where non-Muslims are prohibited from entering. The gate was designed in 1979 by an Egyptian architect, Samir Elabd, for the architectural firm IDEA Center. The structure is that of a book, representing the Quran, sitting on a rehal, or bookrest.[126]

Communications[edit]

Press and newspapers[edit]

The first press was brought to Mecca in 1885 by Osman Nuri Pasha, an Ottoman Wāli. During the Hashemite period, it was used to print the city’s official gazette, Al Qibla. The Saudi regime expanded this press into a larger operation, introducing the new Saudi official gazette of Mecca, Umm al-Qurā.[103] Mecca also has its own paper owned by the city, Al Nadwa. However, other Saudi newspapers are also provided in Mecca such as the Saudi Gazette, Al Madinah, Okaz and Al Bilad, in addition to other international newspapers.

TV[edit]

Telecommunications in the city were emphasized early under the Saudi reign. King Abdulaziz pressed them forward as he saw them as a means of convenience and better governance. While under Hussein bin Ali, there were about 20 public telephones in the entire city; in 1936, the number jumped to 450, totaling about half the telephones in the country. During that time, telephone lines were extended to Jeddah and Ta’if, but not to the capital, Riyadh. By 1985, Mecca, like other Saudi cities, possessed modern telephone, telex, radio and television communications.[103] Many television stations serving the city area include Saudi TV1, Saudi TV2, Saudi TV Sports, Al-Ekhbariya, Arab Radio and Television Network and various cable, satellite and other specialty television providers.

Radio[edit]

Limited radio communication was established within the Kingdom under the Hashemites. In 1929, wireless stations were set up in various towns in the region, creating a network that would become fully functional by 1932. Soon after World War II, the existing network was greatly expanded and improved. Since then, radio communication has been used extensively in directing the pilgrimage and addressing the pilgrims. This practice started in 1950, with the initiation of broadcasts on the Day of ‘Arafah (9 Dhu al-Hijjah), and increased until 1957, at which time Radio Makkah became the most powerful station in the Middle East at 50 kW. Later, power was increased 9-fold to 450 kW. Music was not immediately broadcast, but gradually folk music was introduced.[103]

Transportation[edit]

Air[edit]

The only airport near the city is the Mecca East airport, which is not active. Mecca is primarily served by King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah for international and regional connections and Ta’if Regional Airport for regional connections. To cater the large number of Hajj pilgrims, Jeddah Airport has Hajj Terminal, specifically for use in the Hajj season, which can accommodate 47 planes simultaneously and can receive 3,800 pilgrims per hour during the Hajj season.[127]

Roads[edit]

Entry Gate of Mecca on Highway 40

3rd Ring Road passing through Kudai Area

Mecca, similar to Medina, lies at the junction of two of the most important highways in Saudi Arabia, Highway 40, connecting it to the important port city of Jeddah in the west and the capital of Riyadh and the other major port city, Dammam, in the east. The other, Highway 15, connects Mecca to the other holy Islamic city of Medina approximately 400 km (250 mi) in the north and onward to Tabuk and Jordan. While in the south, it connects Mecca to Abha and Jizan.[128][129] Mecca is served by four ring roads, and these are very crowded compared to the three ring roads of Medina.

Mecca also has many tunnels.[130]

Rapid transit[edit]

Al Masha’er Al Muqaddassah Metro

The Al Masha’er Al Muqaddassah Metro is a metro line in Mecca opened on 13 November 2010.[131] The 18.1-kilometer (11.2-mile) elevated metro transports pilgrims to the holy sites of ‘Arafat, Muzdalifah and Mina in the city to reduce congestion on the road and is only operational during the Hajj season.[132] It consists of nine stations, three in each of the aforementioned towns.

Mecca Metro

The Mecca Metro, officially known as Makkah Mass Rail Transit, is a planned four-line metro system for the city.[133] This will be in addition to[133] the Al Masha’er Al Muqaddassah Metro which carries pilgrims.

Rail[edit]

Intercity[edit]

In 2018, a high speed intercity rail line, part of the Haramain High Speed Rail Project, named the Haramain high-speed railway line entered operation, connecting the holy cities of Mecca and Medina together via Jeddah, King Abdulaziz International Airport and King Abdullah Economic City in Rabigh.[134][135] The railway consists of 35 electric trains and is capable of transporting 60 million passengers annually. Each train can achieve speeds of up to 300 kmh (190 mph), traveling a total distance of 450 km (280 mi), reducing the travel time between the two cities to less than two hours.[136][135]

See also[edit]

- Bayt al-Mawlid, the house where Muhammad is believed to have been born

- Mecca Province

- Masjid al-Haram

- Sharifate of Mecca

Notes[edit]

- ^ Arabic: مكة المكرمة, romanized: Makkah al-Mukarramah, lit. ‘Makkah the Noble’, Hejazi pronunciation: [makːa almʊkarːama]

- ^ Arabic: مكة[1] Makkah (Hejazi pronunciation: [ˈmakːa])

- ^ Possibly following their pilgrimage in 805 CE and seeing the city’s issues with its water supply.

References[edit]

- ^ Quran 48:22

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Inc (2001). Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary. p. 724. ISBN 978-0-87779-546-9.

- ^ «Government statistics of Makkah in 2015» (PDF). 17 November 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Ogle, Vanessa (2015). The Global Transformation of Time: 1870–1950. Harvard University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780674286146.

Mecca, «the fountainhead and cradle of Islam,» would be the center of Islamic timekeeping.

- ^ Nicholson, Reynold A. (2013). Literary History Of The Arabs. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781136170164.

Mecca was the cradle of Islam, and Islam, according to Muhammad, is the religion of Abraham.

- ^ Khan, A M (2003). Historical Value Of The Qur An And The Hadith. Global Vision Publishing Ho. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-81-87746-47-8.; Al-Laithy, Ahmed (2005). What Everyone Should Know About the Qur’an. Garant. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-90-441-1774-5.

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed (2005). Mecca, The Blessed, Medina, The Radiant: The Holiest Cities of Islam. Aperture. ISBN 0-89381-752-X.

- ^ «Wahhābī (Islamic movement)». Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 9 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

Because Wahhābism prohibits the veneration of shrines, tombs, and sacred objects, many sites associated with the early history of Islam, such as the homes and graves of companions of Muhammad, were demolished under Saudi rule. Preservationists have estimated that as many as 95 percent of the historic sites around Mecca and Medina have been razed.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jerome (24 September 2011). «Mecca for the rich: Islam’s holiest site ‘turning into Vegas’«. The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017.

- ^ A Saudi tower: Mecca versus Las Vegas: Taller, holier and even more popular than (almost) anywhere else, The Economist (24 June 2010), Cairo.

- ^ Fattah, Hassan M.Islamic Pilgrims Bring Cosmopolitan Air to Unlikely City Archived 24 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times (20 January 2005).

- ^ a b Peters, Francis E. (1994). The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-691-02619-0.

- ^ Esposito, John L. (2011). What everyone needs to know about Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-19-979413-3.

Mecca, like Medina, is closed to non-Muslims

- ^ «Mayor of Makkah Receives Malaysian Consul General». Ministry of Foreign Affairs Malaysia. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Stone, Dan (3 October 2014). «The Growing Pains of the Ancient Hajj». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ «Who’s Who: Saleh Al-Turki, the new mayor of Makkah». 29 January 2022.

- ^ «Prince Khalid Al Faisal appointed as governor of Makkah region». Saudi Press Agency. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ^ a b Versteegh, Kees (2008). C.H.M. Versteegh; Kees Versteegh (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4 (Illustrated ed.). Brill. p. 513. ISBN 978-90-04-14476-7.

- ^ a b Quran 3:96

- ^ Peterson, Daniel C. (2007). Muhammad, prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-8028-0754-0.

- ^ Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). Encyclopedic dictionary of archaeology (Illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-306-46158-3.

- ^ Glassé, Cyril & Smith, Huston (2003). The new encyclopedia of Islam (Revised, illustrated ed.). Rowman Altamira. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-7591-0190-6.

- ^ Phipps, William E. (1999). Muhammad and Jesus: a comparison of the prophets and their teachings (Illustrated ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8264-1207-2.

- ^ a b c d Ham, Anthony; Brekhus Shams, Martha & Madden, Andrew (2004). Saudi Arabia (illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-667-1.

- ^ Long, David E. (2005). Culture and Customs of Saudi Arabia. Greenwood Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-313-32021-7.

- ^ a b Philip Khûri Hitti (1973). Capital cities of Arab Islam (Illustrated ed.). University of Minnesota Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8166-0663-4.

- ^ «Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), Maacah, Maacah, Macoraba». www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ a b Morris, Ian D. (2018). «Mecca and Macoraba». Al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā. 26: 3. doi:10.17613/zcdp-c225. ISSN 1068-1051.

- ^ Quran 6:92

- ^ AlSahib, AlMuheet fi Allughah, p. 303

- ^ a b Sayyid Aḥmad Khān (1870). A series of essays on the life of Muhammad: and subjects subsidiary thereto. London: Trübner & co. pp. 74–76.

- ^ Firestone, Reuven (1990). Title Journeys in holy lands: the evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael legends in Islamic exegesis. SUNY Press. pp. 65, 205. ISBN 978-0-7914-0331-0.

- ^ Sample, Ian (14 July 2010). «Ape ancestors brought to life by fossil skull of ‘Saadanius’ primate». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016.

- ^ Laursen, Lucas (2010). «Fossil skull fingered as ape–monkey ancestor». Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2010.354.

- ^ Holland, Tom; In the Shadow of the Sword; Little, Brown; 2012; p. 303: ‘Otherwise, in all the vast corpus of ancient literature, there is not a single reference to Mecca – not one’

- ^ Holland, Tom; In the Shadow of the Sword; Little, Brown; 2012; p. 471

- ^ Translated by C.H. Oldfather, Diodorus Of Sicily, Volume II, William Heinemann Ltd., London & Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1935, p. 217.

- ^ Jan Retsö, The Arabs in Antiquity (2003), 295–300

- ^ Photius, Diodorus and Strabo (English): Stanley M. Burnstein (tr.), Agatharchides of Cnidus: On the Eritraean Sea (1989), 132–173, esp. 152–3 (§92).)

- ^ Crone, Patricia (1987). Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Princeton University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-1-59333-102-3.

- ^ Morris, Ian D. (2018). «Mecca and Macoraba» (PDF). Al-ʿUṣūr Al-Wusṭā. 26: 1–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Bowersock, G. W. (2017). The crucible of Islam. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 9780674057760.

- ^ Crane, P. Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, 1987, p.136

- ^ M. Robinson (2022). «The Population Size of Muḥammad’s Mecca and the Creation of the Quraysh». Der Islam. 1 (99): 10–37. doi:10.1515/islam-2022-0002. S2CID 247974816.

- ^ Shahid, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, volume 1, part 1. Dumbarton Oaks. p. 163. ISBN 978-0884022848.

- ^ Procopius. History. pp. I.xix.14.

- ^ Crone, Patricia; Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam; 1987; p.7

- ^ Holland, Tom (2012). In the Shadow of the Sword; Little, Brown; p. 303

- ^ Abdullah Alwi Haji Hassan (1994). Sales and Contracts in Early Islamic Commercial Law. pp. 3 ff. ISBN 978-9694081366.

- ^ Bowersock, Glen. W. (2017). Bowersock, G. W. (2017). The crucible of Islam. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press. pp. 50 ff.

- ^ Crone, Patricia (2007). «Quraysh and the Roman Army: Making Sense of the Meccan Leather Trade». Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 70 (1): 63–88. doi:10.1017/S0041977X0700002X. JSTOR 40378894. S2CID 154910558.

- ^ Hoyland, Robert (1997). Seeing Islam as others saw it. Darwin Press. p. 565. ISBN 0-87850-125-8.

- ^ Quran 2:127

- ^ Quran 22:25-37

- ^ Glassé, Cyril (1991). «Kaaba». The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-0606-3126-0.

- ^ Lings, Martin (1983). Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources. Islamic Texts Society. ISBN 978-0-946621-33-0.

- ^ Crown, Alan David (2001) Samaritan Scribes and Manuscripts. Mohr Siebeck. p. 27

- ^ Crone, Patricia and Cook, M.A. (1977) Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press. p. 22.

- ^ Lazarus-Yafeh, Hava (1992). Intertwined Worlds: Medieval Islam and Bible Criticism. Princeton University Press. pp.61–62

- ^ G. Lankester Harding & Enno Littman, Some Thamudic Inscriptions from the Hashimite Kingdom of the Jordan (Leiden, Netherlands – 1952), p. 19, Inscription No. 112A

- ^ Jawwad Ali, The Detailed History of Arabs before Islam (1993), Vol. 4, p. 11

- ^ Hawting, G.R. (1980). «The Disappearance and Rediscovery of Zamzam and the ‘Well of the Ka’ba’«. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 43 (1): 44–54 (44). doi:10.1017/S0041977X00110523. JSTOR 616125. S2CID 162654756.

- ^ Islamic World, p. 20

- ^ a b c d «Makka – The pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods», Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ Lapidus, p. 14

- ^ Bauer, S. Wise (2010). The history of the medieval world: from the conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-393-05975-5.

- ^ a b Islamic World, p. 13

- ^ a b Lapidus, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b c Hajjah Adil, Amina (2002), Prophet Muhammad, ISCA, ISBN 1-930409-11-7

- ^ «Abraha.» Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Dictionary of African Christian Biographies. 2007. (last accessed 11 April 2007)

- ^ Müller, Walter W. (1987) «Outline of the History of Ancient Southern Arabia» Archived 10 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, in Werner Daum (ed.), Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilisation in Arabia Felix.

- ^ «The Year of the Elephant». Al-Islam.org. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ «Significance Behind Prophet Mohammad’s Birth in the Year of the Elephant». aliftaa.jo. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ ʿAbdu r-Rahmān ibn Nāsir as-Saʿdī. «Tafsir of Surah al Fil – The Elephant (Surah 105)». Translated by Abū Rumaysah. Islamic Network. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

This elephant was called Mahmud and it was sent to Abrahah from Najashi, the king of Abyssinia, particularly for this expedition.

- ^ Marr JS, Hubbard E, Cathey JT (2015). «The Year of the Elephant». WikiJournal of Medicine. 2 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2015.003.

In turn citing: Willan R. (1821). «Miscellaneous works: comprising An inquiry into the antiquity of the small-pox, measles, and scarlet fever, now first published; Reports on the diseases in London, a new ed.; and detached papers on medical subjects, collected from various periodical publi». Cadell. p. 488. - ^ Quran 105:1-5

- ^ Islamic World, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Lapidus, p. 32

- ^ «Mecca». Infoplease.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «The Islamic World to 1600: The Mongol Invasions (The Black Death)». Ucalgary.ca. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Battuta, Ibn (2009). The Travels of Ibn Battuta. Cosimo.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Mecca» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 952.

- ^ «The Saud Family and Wahhabi Islam Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine». Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ Leigh Rayment. «Ludovico di Varthema». Discoverers Web. Discoverers Web. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012.

- ^ Cholera (pathology) Archived 27 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Daily Telegraph Saturday 25 November 1916, reprinted in Daily Telegraph Friday 25 November 2016 issue (p. 36)

- ^ «Mecca» at Encarta. (Archived) 1 November 2009.

- ^ «The Siege of Mecca». Doubleday(US). 28 August 2007. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ a b ‘The destruction of Mecca: Saudi hardliners are wiping out their own heritage’ Archived 19 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 6 August 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2011

- ^ ‘Shame of the House of Saud: Shadows over Mecca’, The Independent, 19 April 2006 | archived from the original on 10 March 2009

- ^ Bsheer, Rosie (20 December 2020). «How Saudi Arabia obliterated its rich cultural history». Middle East Eye. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «What is the Hajj? («Hajj disasters»)». BBC. 27 December 2006. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ^ «History of deaths on the Hajj». BBC. 17 December 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ^ Ruthven, Malise (2006). Islam in the World. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-86207-906-9.

- ^ Express & Star Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Express & Star. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ «Over 700 Dead, 800 Injured in Stampede Near Mecca During Haj». NDTV. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Adil, Salahi. (2019). Sahih Muslim (Volume 2) With the Full Commentary by Imam Nawawi. Al-Nawawi, Imam., Muslim, Imam Abul-Husain. La Vergne: Kube Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86037-767-2. OCLC 1152068721.

- ^ «الحصر الفعلي للحجاج». General Authority for Statistics (in Arabic). 17 December 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ «What is Umrah?». islamonline.com. 5 December 2007. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- ^ a b «In the Shade of the Message and Prophethood». Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b http://www.witness-pioneer.org Archived 11 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ «Mecca Municipality». Holymakkah.gov.sa. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Makka – The Modern City», Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ Peters, F. E. (1994). Mecca : a Literary History of the Muslim Holy Land. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-1-4008-8736-1. OCLC 978697983.

- ^ «FCC Aqualia wins contract to operate two wastewater treatment plants in Mecca, Saudi Arabia». www.water-technology.net. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ «Sun, Sand And Water: Solar-Powered Desalination Plant Will Help Supply Saudi Arabia With Fresh Water | GE News». www.ge.com. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Millison, Andrew (August 2019), «Climate Analogue Examples», Permaculture Design: Tools for Climate Resilience, Oregon State University, retrieved 24 March 2020

- ^ «Climate Data for Saudi Arabia». Jeddah Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ «Klimatafel von Mekka (al-Makkah) / Saudi-Arabien» (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ «How important is the Umrah pilgrimage for the Saudi economy?». TRT World. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Mecca. World Book Encyclopedia. 2003 edition. Volume M. p. 353

- ^ Howden, Daniel (19 April 2006). «Shame of the House of Saud: Shadows over Mecca». London: The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- ^ Statistical information department of the ministry of education:Statistical summary for education in Saudi Arabia (AR) Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «المستشفيات – قائمة المستشفيات» Archived 9 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. moh.gov.sa.

- ^ Asian Football Stadiums Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Stadium King Abdul Aziz

- ^ «A new National Geographic Special on PBS ‘Inside Mecca’«. Anisamehdi.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Makkah al-Mukarramah and Medina». Encyclopædia Britannica: Fifteenth edition. Vol. 23. 2007. pp. 698–699.

- ^ «After the hajj: Mecca residents grow hostile to changes in the holy city». The Guardian. 14 September 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ «Saudi embassy warns against entry of non-Muslims in Mecca». ABS-CBN News. 14 March 2006. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Robert W. Hefner; Patricia Horvatich (1997). Islam in an Era of Nation-States: Politics and Religious Renewal in Muslim Southeast Asia. University of Hawai’i Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8248-1957-6. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ «The Lure Of Mecca». Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Inderjit Singh Jhajj. Guru Nanak At Mecca.

- ^ Dr Harjinder Singh Dilgeer says that Mecca was not banned to non-Muslim till nineteenth century; Sikh History in 10 volumes, Sikh University Press, (2010–2012), vol. 1, pp. 181–182

- ^ «Sir Richard Francis Burton: A Pilgrimage to Mecca, 1853». Fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Demographics Survey 2016» (PDF). Demographics Survey 2016. General Authority for Statistics. 2016.

- ^ IDEA Center Projects, Elabdar Architecture, archived from the original on 8 February 2015 – Makkah Gate

- ^ «Saudi terminal can receive 3,800 pilgrims per hour». Al Arabiya. 28 August 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- ^ «Roads» Archived 4 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. saudinf.com.

- ^ «The Roads and Ports Sectors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia» Archived 8 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. saudia-online.com. 5 November 2001

- ^ «Makkah building eight tunnels to ease congestion». Construction Weekly. 30 May 2013.

- ^ «Hajj pilgrims take the metro to Mecca». Railway Gazette International. 15 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010.

- ^ «Mecca metro contracts signed». Railway Gazette International. 24 June 2009. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ a b «Jeddah and Makkah metro plans approved». Railway Gazette International. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ «High speed stations for a high speed railway». Railway Gazette International. 23 April 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010.

- ^ a b «Saudi Arabia’s Haramain High-Speed Railway opens to public». Arab News. 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^

«Al Rajhi wins Makkah – Madinah civils contract». Railway Gazette International. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010.

Bibliography[edit]

- What life was like in the lands of the prophet: Islamic world, AD 570–1405. Time-Life Books. 1999. ISBN 978-0-7835-5465-5.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (1988). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22552-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Bianca, Stefano (2000), «Case Study 1: The Holy Cities of Islam – The Impact of Mass Transportation and Rapid Urban Change», Urban Form in the Arab World, Zurich: ETH Zurich, ISBN 978-3-7281-1972-8, 0500282056

- Bosworth, C. Edmund, ed. (2007). «Mecca». Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Dumper, Michael R. T.; Stanley, Bruce E., eds. (2008), «Makkah», Cities of the Middle East and North Africa, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO

- Rosenthal, Franz; Ibn Khaldun (1967). The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09797-8.

- Watt, W. Montgomery. «Makka – The pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods.» Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 6 June 2008

- Winder, R.B. «Makka – The Modern City.» Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2008. Brill Online. 2008

- «Quraysh». Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia (online). 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

Online[edit]

- Mecca Saudi Arabia, in Encyclopædia Britannica Online, by John Bagot Glubb, Assʿad Sulaiman Abdo, Swati Chopra, Darshana Das, Michael Levy, Gloria Lotha, Michael Ray, Surabhi Sinha, Noah Tesch, Amy Tikkanen, Grace Young and Adam Zeidan

External links[edit]

- Holy Makkah Municipality

- Saudi Information Resource – Holy Makkah

- Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al Madinah and Makkahh, by Richard Burton

|

Mecca مكة

|

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

| Makkah al-Mukarramah (مكة المكرمة) | |

|

Masjid al-Haram (Great Mosque of Mecca) Mecca skyline The Kaaba Jabal al-Nour Neighborhood of Mina |

|

|

Mecca |

|

| Coordinates: 21°25′21″N 39°49′24″E / 21.42250°N 39.82333°E | |

| Country | Saudi Arabia |

| Province | Mecca Province |

| Governorate | Holy Capital Governorate |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Saleh Al-Turki |

| • Provincial Governor | Khalid bin Faisal Al Saud |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,200 km2 (500 sq mi) |

| • Land | 760 km2 (290 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 277 m (909 ft) |

| Population

(2015) |

|

| • Total | 1,578,722 |

| • Estimate

(2020) |

2,042,000 |

| • Rank | 3rd in Saudi Arabia |

| Demonym | Makki (مكي) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Area code | +966-12 |

| Website | hmm.gov.sa |

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah,[a] commonly shortened to Makkah[b]) is the holiest city in Islam and the capital of Mecca Province in Saudi Arabia.[2] It is 70 km (43 mi) inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley 277 m (909 ft) above sea level. Its last recorded population was 1,578,722 in 2015.[3] Its estimated metro population in 2020 is 2.042 million, making it the third-most populated city in Saudi Arabia after Riyadh and Jeddah. Pilgrims more than triple this number every year during the Ḥajj pilgrimage, observed in the twelfth Hijri month of Dhūl-Ḥijjah.

Mecca is generally considered «the fountainhead and cradle of Islam».[4][5] Mecca is revered in Islam as the birthplace of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The Hira cave atop the Jabal al-Nur («Mountain of Light»), just outside the city, is where Muslims believe the Quran was first revealed to Muhammad.[6] Visiting Mecca for the Ḥajj is an obligation upon all able Muslims. The Great Mosque of Mecca, known as the Masjid al-Haram, is home to the Ka’bah, believed by Muslims to have been built by Abraham and Ishmael. It is one of Islam’s holiest sites and the direction of prayer for all Muslims (qibla).[7]

Muslim rulers from in and around the region long tried to take the city and keep it in their control, and thus, much like most of the Hejaz region, the city has seen several regime changes. The city was most recently conquered in the Saudi conquest of Hejaz by Ibn Saud and his allies in 1925. Since then, Mecca has seen a tremendous expansion in size and infrastructure, with newer, modern buildings such as the Abraj Al Bait, the world’s fourth-tallest building and third-largest by floor area, towering over the Great Mosque. The Saudi government has also carried out the destruction of several historical structures and archaeological sites,[8] such as the Ajyad Fortress.[9][10][11] Non-Muslims are strictly prohibited from entering the city.[12][13]

Under the Saudi government, Mecca is governed by the Mecca Regional Municipality, a municipal council of 14 locally elected members headed by the mayor (called Amin in Arabic) appointed by the Saudi government. In 2015, the mayor of the city was Osama bin Fadhel Al-Barr;[14][15] as of January 2022, mayor of is Saleh Al-Turki.[16] The City of Mecca amanah, which constitutes Mecca and the surrounding region, is the capital of the Mecca Province, which includes the neighbouring cities of Jeddah and Ta’if, even though Jeddah is considerably larger in population compared to Mecca. The Provincial Governor of the province from 16 May 2007 was Prince Khalid bin Faisal Al Saud.[17]

Etymology[edit]

Mecca has been referred to by many names. As with many Arabic words, its etymology is obscure.[18] Widely believed to be a synonym for Makkah, it is said to be more specifically the early name for the valley located therein, while Muslim scholars generally use it to refer to the sacred area of the city that immediately surrounds and includes the Ka’bah.[19][20]

Bakkah[edit]

The Quran refers to the city as Bakkah in Surah Al Imran (3), verse 96: «Indeed the first House [of worship], established for mankind was that at Bakkah». This is presumed to have been the name of the city at the time of Abraham (Ibrahim in Islamic tradition) and it is also transliterated as Baca, Baka, Bakah, Bakka, Becca and Bekka, among others.[21][22][23]

Makkah, Makkah al-Mukarramah and Mecca[edit]

Makkah is the official transliteration used by the Saudi government and is closer to the Arabic pronunciation.[24][25] The government adopted Makkah as the official spelling in the 1980s, but it is not universally known or used worldwide.[24] The full official name is Makkah al-Mukarramah (Arabic: مكة المكرمة, lit. ‘Makkah the Honored’).[24] Makkah is used to refer to the city in the Quran in Surah Al-Fath (48), verse 24.[18][26]