21 мая 2018Литература

История муми-троллей

Как возникло слово «муми-тролль», откуда взялись Тофсла и Вифсла, в каком порядке нужно читать книги Туве Янссон и другие важные вопросы

18+

Муми-тролли — одни из самых популярных сказочных персонажей ХХ века, благодаря которым их создательница Туве Янссон стала символом Финляндии. Уже многие десятилетия о жителях Муми-долины снимают мультфильмы, существует огромная линейка сувенирной продукции, музей муми-троллей, тематические парки в Финляндии и Японии (где скоро откроется уже второй парк). Цикл о муми-троллях — не просто увлекательное чтение для детей, но многогранные художественные тексты, занимающие филологов, психологов, философов, искусствоведов в той же мере, что и читателей всех возрастов. Как у шведоговорящей финки получилось создать попкультурный миф такого масштаба?

Кто такая Туве Янссон

1 / 2

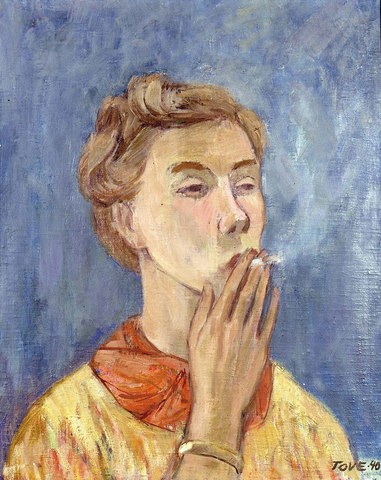

Туве Янссон. Автопортрет. 1940 год© Moomin Characters™

2 / 2

Туве Янссон в своей мастерской. 1956 годReino Loppinen / Wikimedia Commons

Туве Марика Янссон (1914–2001) — не только создательница мира муми-троллей. Ее книги «Дочь скульптора» (1968) и «Летняя книга» (1972) переведены на многие языки и считаются классикой финской литературы. Сама же Янссон считала себя прежде всего художницей: она писала картины всю жизнь, экспериментировала с самыми разными техниками и художественными направлениями (от импрессионизма до абстракционизма), участвовала во многих выставках. Особенно известны ее росписи стен в административных зданиях в разных городах Финляндии и даже алтаря церкви в городе Теува.

Туве начала рисовать в раннем детстве. Ее отец, Виктор Янссон, был известным скульптором, а мать — шведка Сигне Хаммарштен-Янссон — художницей-графиком и иллюстратором (она нарисовала сотни марок для Финляндии, обретшей в 1918 году независимость). Братья Туве Янссон тоже выбрали творческие профессии. Пер Улоф стал фотографом, а Ларс — графиком и иллюстратором: многие годы он помогал сестре рисовать комиксы о муми-троллях, а с 1960 года по 1975-й работал над новыми выпусками уже в одиночку (когда контракт закончился, Янссон устала от работы и не стала продлевать его). И все же несмотря на то, что Янссон — художница, карикатурист, иллюстратор, автор нескольких романов, сборников рассказов, пьес и сценариев, национальное, а затем и мировое признание она получила именно как автор «Муми-троллей».

Как появились муми-тролли

В 1939 году начинающая художница Туве Янссон была в ужасе от событий, происходивших в Европе и в Финляндии, и, судя по ее письмам и дневникам, понимала, что надвигается еще бо́льшая катастрофа:

«Порой меня охватывает такая нескончаемая безнадежность, когда я думаю о тех молодых, которых убивают на фронте. Разве нет у нас у всех, у финнов, русских, немцев, права жить и создавать что-то своей жизнью… Можно ли надеяться, давать новую жизнь в этом аду, который все равно будет повторяться раз за разом…» Туула Карьялайнен. Туве Янссон: работай и люби. М., 2017.

Творчество стало даваться Янссон гораздо тяжелее, и, чтобы преодолеть этот кризис, она решила написать историю о необыкновенно счастливой семье. Образ главного героя она придумала еще в детстве: после спора с братом Пером Улофом об Иммануиле Канте она нарисовала его на стене уличного туалета на острове архипелага Пеллинки (где они летом отдыхали семьей) и сообщила, что это самое уродливое существо на свете. Янссон назвала его Снорком и часто рисовала впоследствии. А вот само слово «муми-тролль» появилось в 1930-е, когда Туве училась в Стокгольме и жила у своего дяди Эйнара Хаммерштена. Тот рассказывал ей о неприятных и пугающих «му-у-умитроллях», которые живут за печкой и охраняют его еду от ночных набегов племянницы. Они издают протяжные вздохи — отсюда название. С тех пор в дневниках Янссон стала использовать слово «муми-тролль» для обозначения чего-то ужасного или пугающего. Снорк же стал своего рода подписью Янссон Например, его можно увидеть в финском политическом журнале «Гарм», где Туве начала работать еще подростком. Именно там была опубликована ее знаменитая карикатура на Гитлера в виде орущего младенца, которому на блюдечке подносят страны Европы..

В 1939 году образ Снорка лег в основу истории о маленьких троллях и потопе. Тогда же Янссон решила дать этому персонажу и его семье общее название — муми-тролли. Книга могла так и остаться незаконченной и неизданной, если бы не друзья Янссон и в первую очередь ее возлюбленный — политик и интеллектуал Атос Виртанен, за которого она хотела выйти замуж (но так и не вышла). Именно он поддержал Туве и неоднократно говорил о том, что история муми-троллей — это детская сказка, которую должен увидеть мир.

Хронология

Так как текстов о муми-троллях по-настоящему много и не все они переведены, в их хронологии довольно легко запутаться. Выходили они в следующем порядке:

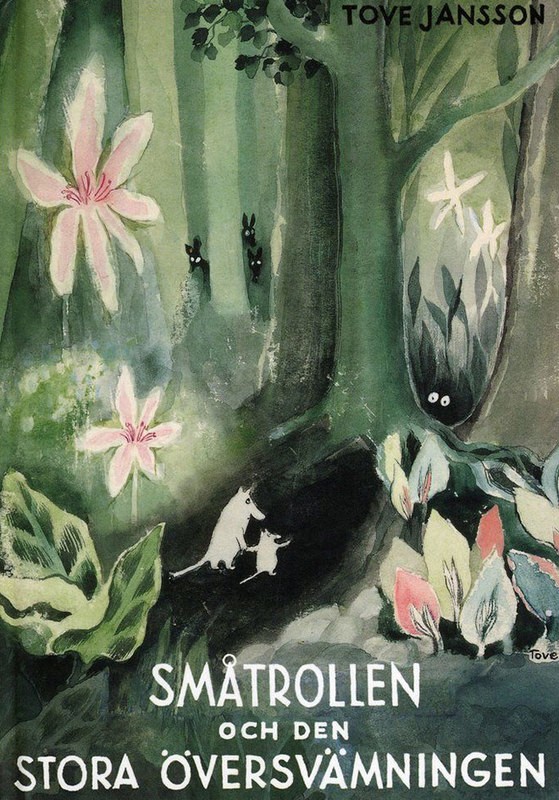

1945 — «Маленькие тролли и большое наводнение»

1946 — «Комета прилетает» В 1956 году вышла новая редакция текста под названием «Муми-тролль и комета», в 1968-м — еще одна версия.

1947–1948 — комиксы о муми-троллях на шведском в газете Ny Tid

1948 — «Шляпа волшебника»

1950 — «Мемуары папы Муми-тролля»

1952 — книжка-картинка «Что дальше? Книга о Мюмле, Муми-тролле и Малышке Мю»

1954 — «Опасное лето»

1954–1975 — комиксы о муми-троллях на английском в британском издании The Evening News Переводчиком на английский был брат Туве Ларс. С 1959 года он начинает работать над комиксами в качестве художника, а с 1960 года становится единоличным автором комиксов о муми-троллях.

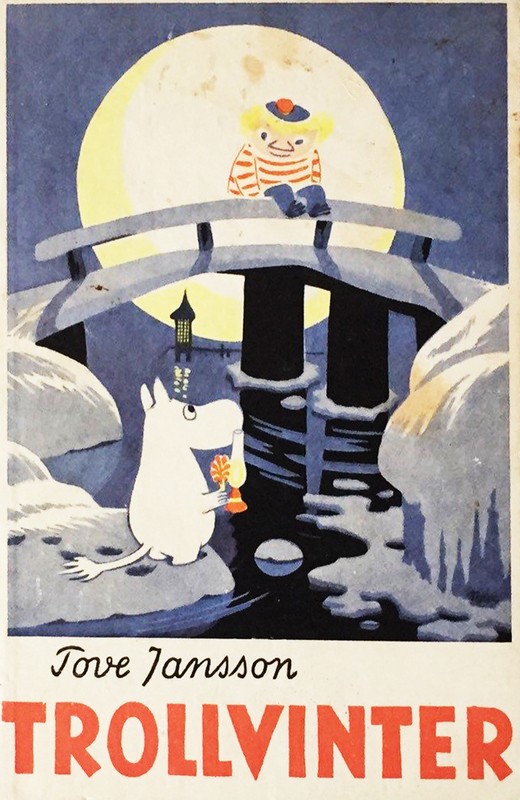

1957 — «Волшебная зима»

1960 — книжка-картинка «Кто утешит Кнютта?»

1962 — сборник рассказов «Дитя-невидимка»

1965 — «Папа и море»

1971 — «В конце ноября»

1977 — книжка-картинка «Опасное путешествие»

1980 — «Непрошеный гость» Также переводят как «Мошенники в доме муми-троллей». Это книжка-картинка с фотографиями кукольной модели Муми-дома в качестве иллюстраций. Написана в прозе, переведена на английский, но очень мало известна и не входит в канон сказок о муми-троллях.

1993 — сборник «Песни долины муми-троллей» Книга песен, написанная Туве Янссон совместно с Ларсом (оба писали тексты песен, вдохновленных сказками о муми-троллях) и Эрной Тауро (автор музыки). В книге есть тексты и аккорды.

В каком порядке читать

История публикаций и особенно переводов «Муми-троллей» необычна. Во-первых, Туве Янссон писала на шведском языке для языкового меньшинства Финляндии, к которому принадлежала сама, ее книги стали переводить на финский довольно поздно. После относительно незаметного выхода первой книги о муми-троллях в 1945-м, спустя год выходит вторая часть муми-эпопеи «Комета прилетает», принесшая муми-троллям известность на родине, а в 1948 году — «Шляпа волшебника», книга, с которой началась всемирная слава Янссон. В 1950 году ее публикуют в Великобритании в переводе Элизабет Порч, в 1951-м она попадает в США, где тут же переводят и «Комета прилетает». Все следующие книги цикла на английском выходят через год-два после публикации. С первой же книгой, «Маленькие тролли и большое наводнение», англоговорящий читатель познакомился только в 2005 году.

1 / 4

«Комета прилетает». Первое издание. 1946 год© Söderström & Co

2 / 4

«Муми-тролль и комета». Первое издание на русском языке. 1967 год© Издательство «Детская литература»

3 / 4

«Шляпа волшебника». Первое издание. 1948 год© Schildts Förlags

4 / 4

«Шляпа волшебника». Первое издание на английском языке. 1950 год© Penguin Books

В 1950-е годы Туве Янссон переводят на несколько языков, а ее комиксы о муми-троллях выходят в английской газете The Evening News. Первый перевод «Комета прилетает» на финский появляется только в 1955 году, а в 1967 году эта книга в переводе Владимира Смирнова становится первым изданием о муми-троллях в СССР.

В итоге «Комета прилетает» стала считаться первой книгой цикла, и дело не только в истории перевода. «Маленькие тролли и большое наводнение» отличаются от остальных сказок серии: муми-тролль и его семья в этой книге — это еще не нежные и трогательные существа, которых всегда представляет себе читатель, а как раз тролли, тощие и несуразные (это связано в том числе и с тем, что Финляндия голодала всю войну). Необычно и словосочетание «маленькие тролли» (småtrollen): в 1945 году издатели были уверены, что придуманное Янссон слово «муми-тролли» (mumintrollen) будет непонятно читателям, поэтому в названии лучше использовать всем известное слово. Однако именно в этой книге герои находят долину своей мечты, в которую приплывает дом, построенный Муми-папой. Получается, что первая катастрофа в жизни муми-троллей стала своеобразным актом творения муми-вселенной:

«Они шли целый день, и где бы они ни проходили, везде было прекрасно, потому что после дождя распустились чудеснейшие цветы, а повсюду на деревьях появились цветы и фрукты. Стоило им чуточку потрясти дерево, как вокруг них на землю начинали падать фрукты. В конце концов они пришли в маленькую долину. Красивее им в тот день видеть ничего не довелось. И там, посреди зеленого луга, стоял дом, сильно напоминавший печь, очень красивый дом, выкрашенный голубой краской.

— Это же мой дом! — вне себя от радости воскликнул папа. — Он приплыл сюда и стоит теперь здесь, в этой долине!»

Остальные книги тоже не принято читать в определенном порядке: в цикле нет сквозного сюжета, каждая история целостна и воспринимается как отдельная сказка или сборник рассказов. Однако, если все-таки прочитать серию в хронологическом порядке, можно заметить довольно важный мотив: как взрослеет Муми-тролль, как меняется его взгляд на мир и как он сталкивается со все более сложными философскими проблемами.

Финская исследовательница Туве Холландер, проанализировавшая иллюстрации к циклу о муми-троллях, пишет, что хронологический порядок чтения позволяет увидеть, как классическая идиллия постепенно превращается в более серьезный и печальный мир. Кроме того, становится понятно, что серия имеет циклическую композицию: в «Маленьких троллях» появляется семья, которая в конце книги находит лучший в мире дом; в последней книге цикла («В конце ноября») семья его покидает, и осиротевшие жители Муми-долины ждут возвращения тепла и любви.

Некоторые исследователи делят девять книг о муми-троллях на приключенчески-веселую и философскую части. Если первые пять книг насыщены событиями, то шестая («Волшебная зима») открывает новую сторону муми-мира: эта книга, как и следующие, — об отношениях и самопознании. Шестую книгу Туве написала после встречи с Тууликки Пиетиля, которая стала ее возлюбленной и прожила с Янссон вплоть до ее смерти. Именно она вдохновила писательницу на новые книги и другой, более лирический взгляд на муми-троллей, хотя та была уверена, что устала от своих героев и не сможет написать ничего нового. Основными темами четырех «философских» томов цикла становятся процесс взросления Муми-тролля, обретение муми-троллями нового дома, ностальгия муми-мамы по старому дому и, наконец, переживание жителями Муми-долины потери муми-троллей и обретение себя.

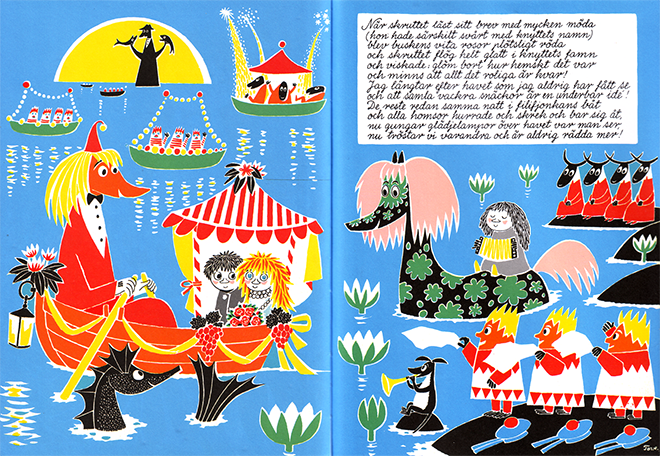

Комиксы и книжки-картинки стоят особняком: это отдельная история, создававшаяся с расчетом на другую аудиторию. Комиксы Янссон писала для взрослых, некоторые из них отчасти дублируют и дополняют сюжеты книг, при этом в них больше агрессии, политики и черного юмора. Книжки-картинки в стихах «Что дальше? Книга о Мюмле, Муми-тролле и Малышке Мю», «Кто утешит Кнютта?» и «Опасное путешествие» адресованы в основном совсем маленьким детям. И совсем отдельно стоят малоизвестные книжка с фотоиллюстрациями «Непрошеный гость» (или «Мошенники в Муми-доме») и сборник песен «Песни долины муми-троллей», не переведенные на русский язык.

Что легло в основу цикла о муми-троллях

С одной стороны, книги о муми-троллях — совершенно самостоятельное явление. Янссон выдумывает свой собственный мир, фактически творит миф о счастливом месте и счастливых существах. Каждое из них она придумала и назвала, пополнив бестиарий европейской детской литературы множеством удивительных персонажей. С другой — нельзя не заметить, что у «Муми-троллей» много источников.

Дронт Эдвард, вдохновленный образом Додо из «Алисы в Стране чудес» Льюиса Кэрролла, появляется в «Мемуарах папы Муми-тролля», а потоп из первой книги серии, «Маленькие тролли и большое наводнение», отсылает к эпизоду с морем слез Алисы. Янссон очень любила Кэрролла и даже сама проиллюстрировала «Алису» для шведского издания 1966 года. А в «Опасном путешествии» обыгрывается «Алиса в Зазеркалье»: на первой странице книжки-картинки девочка Сусанна отчитывает кота за то, что он спит, когда ей хочется приключений, а «Алиса в Зазеркалье» начинается с ее диалога с кошкой Диной и ее котятами, которых она тоже отчитывает.

1 / 4

Туве Янссон. Иллюстрация к «Алисе в Стране чудес». 1966 год© Moomin Characters™ / Tate Publishing

2 / 4

Туве Янссон. Иллюстрация к «Алисе в Стране чудес». 1966 год© Moomin Characters™ / Tate Publishing

3 / 4

Туве Янссон. Иллюстрация к «Алисе в Стране чудес». 1966 год© Moomin Characters™ / Tate Publishing

4 / 4

Туве Янссон. Иллюстрация к «Алисе в Стране чудес». 1966 год© Moomin Characters™ / Tate Publishing

Другой источник — это Библия. Отсюда и «большое наводнение», и конец света с египетской саранчой в «Муми-тролле и комете», и концепция Муми-долины как рая, и образ левиафана-Морры.

В книгах и комиксах — множество аллюзий и отсылок к книгам, картинам и фильмам. Например, в «Шляпе волшебника» Муми-тролль и фрекен Снорк играют в Тарзана, и Муми-тролль начинает говорить цитатами из фильма, на ломаном английском пародируя нескладную речь главного героя: «Tarzan hungry, Tarzan eat now».

Поэтика книг о муми-троллях

Тем не менее попадание человеческой культуры в мир муми-троллей не приближает их к читателю, а, скорее, наоборот, подчеркивает замкнутость этого мира. И это понятно: ведь Муми-долина — классическая европейская пастораль, уединенное место на лоне природы, которое делает героя мудрее и счастливее. Время в этом месте не линейно, но циклично: здесь очень важны времена года, хотя никто из персонажей не знает, какой сейчас год. Этот календарь движется по кругу: осенью делают запасы, зимой впадают в спячку, весной встречают возрождающуюся природу и возвращающегося из странствий Снусмумрика, а летом устраивают праздники.

Времена года были невероятно важны и для самой Туве Янссон: лето ассоциировалось у нее с детством и счастьем, а «В конце ноября» — книга о сиротстве, о печали и о холоде — написана после смерти матери.

1 / 3

Остров Кловхарун© Moomin Characters™

2 / 3

Туве Янссон на острове Кловхарун© Moomin Characters™

3 / 3

Туве Янссон и Тууликки Пиетиля на острове Кловхарун© Moomin Characters™

Отдельную роль в идиллической Муми-долине играют описания природы. Многим иностранным читателям она казалась фантастической, хотя на самом деле природа долины списана с натуры. Это острова недалеко от Хельсинки, где семья Янссон снимала дачу, когда Туве была еще девочкой. В 1964 году писательница купила островок Кловхарун, где они с Ларсом построили небольшой дом. В нем вместе с Тууликки Пиетиля они проводили каждое лето вплоть до конца 1990-х. Этот остров фигурирует в «Летней книге» Янссон и в «Записках с острова» (1996), написанных вместе с Пиетиля.

Персонажи

Еще одна особенность книг о муми-троллях — гармоничное сосуществование в замкнутом пространстве разных героев. Обитатели Муми-долины не похожи друг на друга: среди них есть ворчуны, тревожные натуры, нарциссичные персонажи, но в доме муми-троллей каждый из них находит приют и любовь, каждого принимают таким, какой он есть. На эту особенность книг Янссон обратили внимание психологи и педагоги, и истории о муми-троллях часто используются в сказкотерапии и в методиках нового направления дошкольной педагогики — эмоциональном воспитании.

Однако литературных критиков, среди которых были и некоторые друзья Янссон, раздражала богемность и буржуазность героев: обитатели Муми-долины не ходят на работу, курят, пьют и ругаются, рожают детей вне брака.

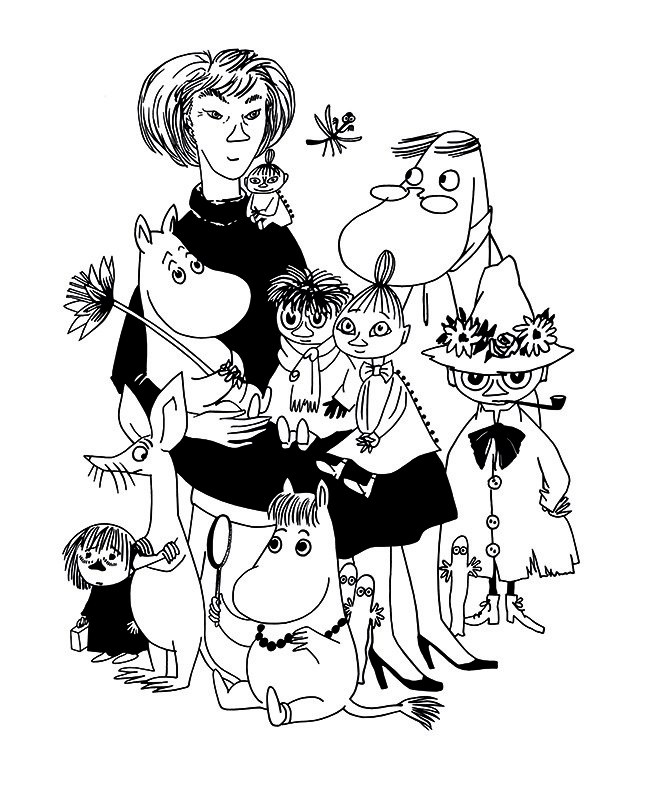

Все герои «Муми-троллей» в той или иной степени списаны с реальных людей. Себя Янссон изобразила в образах Муми-тролля, Малышки Мю и хомсы Тофта, Снусмумрик списан с вышеупомянутого Атоса Виртанена, а Тууликки Пиетиля, как нетрудно догадаться, — это Туу-тикки, которая открывает Муми-троллю мир зимы. Всеми любимая Муми-мама — это, конечно, образ матери Туве Янссон, а бесконечные вечеринки и пребывание в Муми-доме самых разных существ на правах жителей отражают семейный уклад Янссонов, богемной семьи, у которой всегда были гости и настоящие вечеринки. Тофсла и Вифсла — это сама Туве Янссон и Вивика Бандлер, актриса и режиссер, с которой у писательницы был роман. До 1971 года гомосексуальные отношения в Финляндии карались законом, и Туве с Вивикой скрывали свой роман: обсуждая по телефону планы и отношения, они прибегали к эвфемизмам и кодовым словам. Неразлучные подруги Тофсла и Вифсла тоже говорят на языке, который не совсем понятен остальным: он состоит из обычных слов, к которым приделывается суффикс «фсла».

Исследовательница Майя Лииса Харью называет книги Янссон феноменом так называемой переходной литературы — crossover literature: другими словами, это универсальный текст, обращенный к читателям разных возрастов и поколений. Янссон стала самой успешной финской писательницей, а комиксы о муми-троллях на пике популярности печатались в 120 газетах 40 стран мира, и это неудивительно. Янссон — представительница языкового меньшинства, родившаяся в семье художников в период обесценивания «буржуазных ценностей». После тридцати она поняла, что любит женщину. Мало кто мог настолько остро прочувствовать необходимость в мире, где тебя могут принять таким, какой ты есть, и где есть место каждому. В своих книгах Янссон воплотила мечту о таком безопасном пространстве и через историю Муми-тролля рассказала о себе и о собственном духовном взрослении, поместила в мир Муми-долины всех любимых людей, воссоздала утраченный мир своих детских воспоминаний, а потом рассказала о том, как научиться жить без него.

микрорубрики

Ежедневные короткие материалы, которые мы выпускали последние три года

Архив

The Moomins, comic book cover by Tove Jansson From left to right: Sniff, Snufkin, Moominpappa, Moominmamma, Moomintroll (Moomin), the Mymble’s daughter, Groke, Snork Maiden and Hattifatteners |

|

| Author | Tove Jansson |

|---|---|

| Original title | Mumintroll |

| Translator |

|

| Illustrator | Tove Jansson |

| Country | Finland |

| Language | Finland Swedish[1] |

| Genre | Children’s fantasy |

| Publisher | Drawn & Quarterly, Macmillan, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Schildts, Zangavar, Sort of Books |

| Media type | Print, digital |

| Website | Official website |

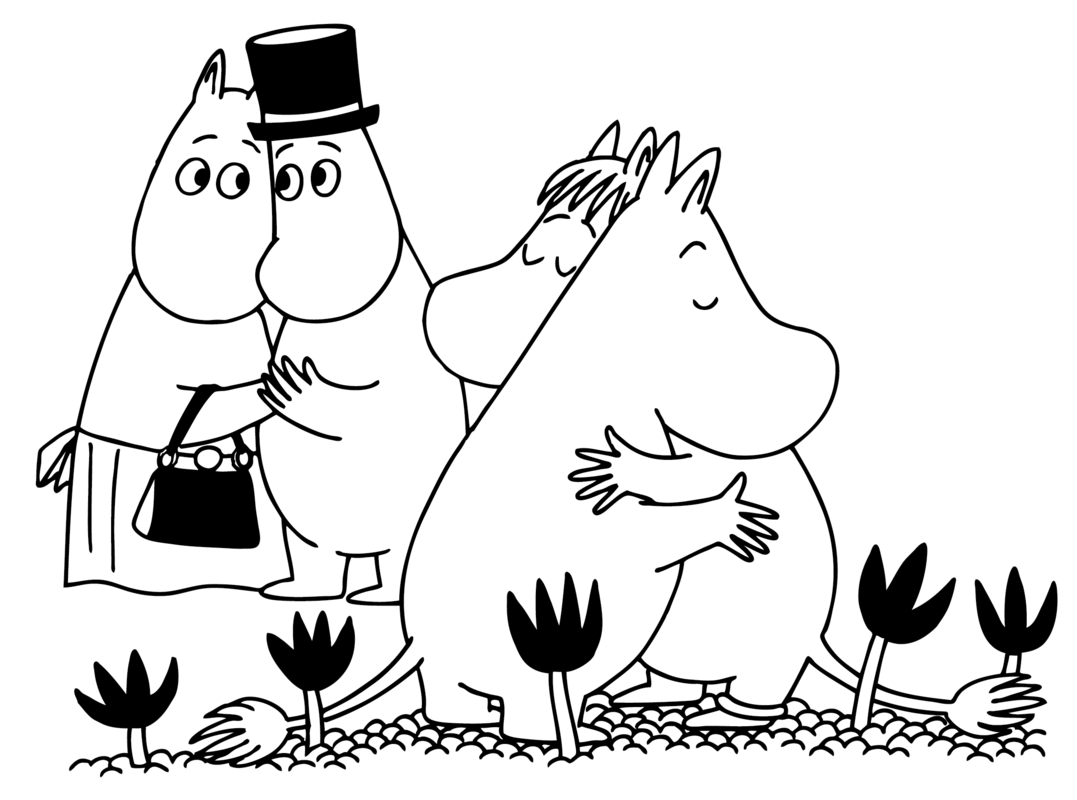

The Moomins (Swedish: Mumintroll) are the central characters in a series of novels, short stories, and a comic strip by Finnish writer and illustrator Tove Jansson, originally published in Swedish by Schildts[2] in Finland. They are a family of white, round fairy-tale characters with large snouts that make them resemble the hippopotamus. However, despite this resemblance, the Moomin family are trolls. The family live in their house in Moominvalley and have had many adventures with their various friends.

In all, nine books were released in the series, together with five picture books and a comic strip being released between 1945 and 1993.

The Moomins have since been the basis for numerous television series, films and even two theme parks: one called Moomin World in Naantali, Finland, and another Akebono Children’s Forest Park in Hannō, Saitama, Japan.

Etymology[edit]

In a letter to Paul Ariste, an Estonian linguist, Jansson wrote in 1973 that she had created an artificial word which expresses something soft. She came up with an ad hoc Swedish word mumintrollet, because, in her opinion, the consonant sound of m in particular conveys a sensation of softness. As an artist, Jansson gave the Moomins a shape that also expresses softness, as opposed to flabbiness.[3]

Synopsis and characters[edit]

Finnish Moomin toys from the 1950s

The Moomin stories concern several eccentric and oddly-shaped characters, some of whom are related to each other. The central family consists of Moominpappa, Moominmamma and Moomintroll.[4]

Other characters, such as Hemulens, Sniff, the Snork Maiden, Snufkin and Little My are accepted into or attach themselves to the family group from time to time, generally living separate lives in the surrounding Moominvalley, where the series is set, and in which the Moomin family decides to live at the end of The Moomins and the Great Flood.

Characters[edit]

- Moomintroll, also referred to as «Moomin» in some of the English translations: The main protagonist, the little boy of the family, interested in and excited about everything he sees and finds, always trying to be good, but sometimes getting into trouble while doing so; he is very brave and always finds a way to make his friends happy.

- Moominpappa: Orphaned in his younger years, he is a somewhat restless soul who left the orphanage to venture out into the world in his youth but has now settled down, determined to be a responsible father to his family.

- Moominmamma: The calm mother, who takes care that Moominhouse is a safe place to be. She wants everyone to be happy, appreciates individuality, but settles things when someone is wronged. She always brings good food as well as whatever else may be necessary on a journey in her handbag.

- Little My: A mischievous little girl, who lives in the Moomin house and has a brave, spunky personality. She likes adventure, but loves catastrophes, and often does mean things on purpose. She finds messiness and untidiness exciting and is very down to earth when others are not.

- Sniff: A creature who lives in the Moomin house. He likes to take part in everything, but is afraid to do anything dangerous. Sniff appreciates all valuables and makes many plans to get rich, but does not succeed.

- Snork Maiden: Moomin’s friend. She is happy and energetic, but often suddenly changes her mind on things. She loves nice clothes and jewelry and is a little flirtatious. She thinks of herself as Moomin’s girlfriend.

- Snufkin: Moomin’s best friend. The lonesome philosophical traveller, who likes to play the harmonica and wanders around the world with only a few things, so as not to make his life complicated. He always comes and goes as he pleases, is carefree and has many admirers in Moominvalley. He is also shown to be quite fearless and calm in even the most dire situations, which has proven to be a great help to Moomintroll and the others when in danger.

- The younger Mymble, also referred to as «the Mymble’s daughter«: Little My’s amiable and helpful big sister, and half-sister of Snufkin. She often has romantic daydreams about the love of her life, particularly policemen.

- The Snork: Snorkmaiden’s brother. He is an introvert by nature and is always inventing things. The residents of Moominvalley often ask Snork for help solving tricky problems and building machines. Snorks are like moomintrolls, but change colour according to their mood.

- Too-Ticky: A wise woman, and good friend of the family. She has a boyish look, with a blue hat and a red-striped shirt. She dives straight into action to solve dilemmas in a practical way. Too-Ticky is the one of the people in Moominvalley, who does not hibernate, instead spending the winter in the small changing shed and storehouse over the water at the end of the Moomin’s summer landing stage.

- Stinky: A small furry creature that always plays jokes on the family in the house, where he sometimes lives. He likes pinching things, is proud of his reputation as a crook, but always gets found out. He is simple and only thinks of himself.

Biographical interpretation[edit]

Critics have interpreted various Moomin characters as being inspired by real people, especially members of the author’s family, and Tove Jansson spoke in interviews about the backgrounds of, and possible models for, her characters.[5] The first two books about the Moomins (The Moomins and the Great Flood and (Comet in Moominland) were published in 1945 and 1946 respectively, and deal with natural disasters; they were influenced by the upheavals of war and Jansson’s depression during the war years.[6] The reception of the first two Moomin books was lukewarm at first; the second book got a little more attention than its predecessor, but its sales figures were still poor.[7] Third book, Finn Family Moomintroll, which was the first Moomin book translated into English, became the first international bestseller.[8]

Tove Jansson’s life partner was the graphic artist Tuulikki Pietilä, whose personality inspired the character Too-Ticky in Moominland Midwinter.[5][9] Moomintroll and Little My have been seen as psychological self-portraits of the artist.[5][9] The Moomins, generally speaking, relate strongly to Jansson’s own family – they were bohemian, lived close to nature and were very tolerant towards diversity.[5][9][10] Moominpappa and Moominmamma are often seen as portraits of Jansson’s parents Viktor Jansson and Signe Hammarsten-Jansson.[5][9][10] Most of Jansson’s characters are on the verge of melancholy, such as the always formal Hemulen, or the strange Hattifatteners, who travel in concerted, ominous groups. Jansson uses the differences between the characters’ philosophies to provide a venue for her satirical impulses.[11]

List of books[edit]

The books in the series, in order, are:

- The Moomins and the Great Flood (Originally: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen) – 1945.

- Comet in Moominland (Originally: Kometjakten/Kometen kommer) – 1946.

- Finn Family Moomintroll, Some editions: The Happy Moomins –(Originally: Trollkarlens hatt) – 1948.

- The Exploits of Moominpappa, Some editions: Moominpappa’s Memoirs (Originally: Muminpappans bravader/Muminpappans memoarer) – 1950.

- Moominsummer Madness (Originally: Farlig midsommar) – 1954.

- Moominland Midwinter (Originally: Trollvinter) – 1957.

- Tales from Moominvalley (Originally: Det osynliga barnet) – 1962 (Short stories).

- Moominpappa at Sea (Originally: Pappan och havet) – 1965.

- Moominvalley in November (Originally: Sent i november) – 1970 (In which the Moomin family is absent).

All of the books in the main series except The Moomins and the Great Flood (Originally: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen) were translated and published in English during the 1960s and 70s. This first book would eventually be translated into English in 2005 by David McDuff and published by Schildts of Finland for the 60th anniversary of the series. A later 2012 version of the same translation, featuring Jansson’s new preface to the 1991 Scandinavian printing, was published in Britain by Sort of Books,[12] and was more widely distributed.

There are also five Moomin picture books by Tove Jansson:

- The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My (Originally: Hur gick det sen?) – 1952.

- Who Will Comfort Toffle? (Originally: Vem ska trösta knyttet?) – 1960.

- The Dangerous Journey (Originally: Den farliga resan) – 1977.

- Skurken i Muminhuset (English: Villain in the Moominhouse) – 1980

- Visor från Mumindalen (English: Songs from Moominvalley) – 1993 (No English translation published).

The first official translation of Villain in the Moominhouse by Tove Jansson historian Ant O’Neill was premiered in a reading at the ArchWay With Words literary festival on 25 September 2017.[13]

The books and comic strips have been translated from their original Swedish and English respectively into many languages. The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My is the first Moomin book to be adapted for iPad.

Comic strips[edit]

The Moomins also appeared in the form of comic strips. Their first appearance was in 1947 in the children’s section of the Ny Tid newspaper,[14] and they were introduced internationally to English readers in 1954 in the popular London newspaper The Evening News.[15][16] Tove Jansson drew and wrote all the strips until 1959. She shared the work load with her brother Lars Jansson until 1961; after that he took over the job until 1975 when the last strip was released.[17]

Drawn & Quarterly, a Canadian graphic novel publisher, released reprints of all The Evening News strips created by both Tove and Lars Jansson beginning in October 2006.[18] The first five volumes, Moomin: The Complete Tove Jansson Comic Strip have been published, whilst the sixth volume, published in May 2011, began Moomin: The Complete Lars Jansson Comic Strip. The 2015 publication Moomin: The Deluxe Anniversary Edition collected all of Tove’s work.

In the 1990s, a comic book version of Moomin was produced in Scandinavia after Dennis Livson and Lars Jansson’s animated series was shown on television. Neither Tove nor Lars Jansson had any involvement in these comic books; however, in the wake of the series, two new Moomin comic strips were launched under the artistic and content oversight of Lars and his daughter, Sophia Jansson-Zambra. Sophia now provides sole oversight for the strips.[15]

TV series and films[edit]

The story of the Moomins has been made into television series on many occasions by various groups, possibly the most well known of which is a Japanese–Dutch collaboration, that has also produced a feature-length film. However, there are also two Soviet serials, puppet animation Mumi-troll (Moomintroll) and cutout animation Shlyapa Volshebnika (Magician’s Hat) of three parts each, and the Polish–Austrian puppet animation TV series, The Moomins, which was broadcast and became popular in an edited form in the United Kingdom in the 1980s.

Two feature films re-use the footage of the Polish-Austrian series: Moomin and Midsummer Madness had its release in 2008, and in 2010 the Moomins appear in the first Nordic 3-D film production, with the title song by Björk, in Moomins and the Comet Chase. The animated film titled Moomins on the Riviera is based on Moomin comic strip story Moomin on the Riviera and was first released on 10 October 2014 in Finland[19] and made its premiere on 11 October 2014 at BFI London Film Festival in United Kingdom.[20] In an October 2014 blog article at Screendaily, Sophia Jansson states that the film’s «artistic team has made an effort to be true to the original drawings and the original text».[21]

Screenshot from the 1969–70 television animation about Moomintroll with a rifle. Jansson was known to have a very negative attitude towards the controversial content of the series.[22][23]

The Moomins, from the 1990–91 television animation. From left to right, Sniff, Moominmamma, Moominpappa, Moomintroll (Moomin) and Little My.

- Die Muminfamilie (The Moomin Family) 1959 West German marionette TV series, and its 1960 sequel Sturm im Mumintal (Storm in Moominvalley)

- Mūmin (Moomin), 1969–70 Japanese anime TV series

- Mumintrollet (Moomintroll), 1969 Swedish-language suit actor TV series produced by Sveriges Radio (Swedish national radio company)

- Shin Mūmin (New Moomin), 1972 Japanese anime TV series, remake of the 1969 series by the staff of its latter half

- Mūmin (Moomin), 1971 Japanese traditional animation film

- Mūmin (Moomin), 1972 Japanese traditional animation half-hour film[24]

- Mumindalen (Moominvalley), 1973 Swedish suit actor TV series based on Moominland Midwinter

- Mumi-troll (Moomintroll), 1978 Soviet Union stop motion serial film of Comet in Moominland

- Opowiadania Muminków (The Moomins), 1977–82 Austrian, German and Polish-produced «Fuzzy-Felt» stop motion TV series made in Poland. The series has been re-compiled a number of times in other formats:

- Moomin and Midsummer Madness, 2008 Finnish-produced compilation movie of the TV series[25]

- Moomins and the Comet Chase, 2010 Finnish-produced 3-D film compiled and converted from the 1977–82 series[26]

- Moomins and the Winter Wonderland, 2017, from the TV series.

- The Moomins, 2010 Finnish-produced high-definition video version of the 1977–82 series

- Vem ska trösta knyttet?, 1980 Swedish traditional animation half-hour film of Who Will Comfort Toffle?

- Shlyapa Volshebnika (Magician’s Hat), 1980–83 Soviet Union cutout animation serial film of Finn Family Moomintroll, different staff and aeshetic to the 1978 serial

- Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka (Moomin), 1990–91 Dutch, Finnish and Japanese-produced traditional anime TV series made in Japan

- Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka: Bōken Nikki (Delightful Moomin Family: Adventure Diary), 1991–92 Dutch and Japanese-produced traditional anime TV series made in Japan, a continuation of the 1990–91 series

- Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka: Mūmindani no Suisei (Comet in Moominland), 1992 Dutch and Japanese-produced traditional anime feature film made in Japan, a prequel to the 1990–91 series

- Hur gick det sen? (What Happened Next?), 1993 Swedish short animation film of The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My

- Փոքրիկ տրոլների կյանքից (From the Life Of the Little Trolls), 2008 Armenian short animation film based on The Last Dragon In the World (Historien om den sista draken i världen)[27]

- Moomins on the Riviera, 2014 French hand-drawn animated feature film, with a plot line taken from the comic strip.

- Moominvalley, 2019 Finnish and British-produced TV series, directed by Oscar-winner Steve Box. A crowdfunded campaign was made on April 19, 2017 to make a new «TV-series Moominvalley». Archived from the original on 2017-03-29. by Finnish company «Gutsy Animations». It successfully passed the campaign threshold.

Moomin music[edit]

The Moomin novels describe the musical activities of the Moomins, particularly those of Snufkin, his harmonica with «trills» and «twiddles». All Moomin characters sing songs, often about their thoughts and themselves. The songs often serve as core statements of the characters’ personalities.

Original songs[edit]

The Moomin Voices CD release from 2003, arranged by Mika Pohjola, in Swedish containing Tove Jansson’s original Moomin songs. A Finnish version was released in 2005.

This music was heard outside Moominvalley after they went live on theater stage in Stockholm. Director Vivica Bandler told Jansson in 1959: «Listen, here the people want songs».[28] The earlier version of the play was cast in Helsinki with no music.

Helsinki based pianist and composer Erna Tauro was commissioned to write the songs to lyrics by Jansson. The first collection consisted of six Moomin Songs (Sex muminvisor): Moomintroll’s Song (Mumintrollets visa), Little My’s Song (Lilla Mys visa), Mrs. Fillyjonk’s Song (Fru Filifjonks sång), Theater Rat Emma’s Words of Wisdom (Teaterråttan Emmas visdomsord), Misabel’s Lament (Misans klagolåt) and Final Song (Slutsång).

More songs were published in the 1960s and 1970s, when Jansson and Lars Jansson produced a series of Moomin dramas for Swedish Television. The simple, yet effective melodies by Tauro were well received by the theater and TV audiences. The first songs were either sung unaccompanied or accompanied by a pianist. While the most famous Moomin songs in Scandinavia are undoubtedly «Moomintroll’s Song» and «Little My’s Song», they appear in no context in the novels.

The original songs by Jansson and Tauro remained scattered after their initial release. The first recording of the complete collection was made in 2003 by composer and arranger Mika Pohjola on the Moomin Voices CD (Muminröster in Swedish), as a tribute to the late Tove Jansson. Tauro had died in June 1993 and some of Jansson’s last lyrics were composed by Pohjola in cooperation with Jansson’s heirs. Pohjola was also the arranger of all songs for a vocal ensemble and chamber orchestra. All voices were sung by Åland native vocalist, Johanna Grüssner. The same recording has been released in a Finnish version in 2005, Muumilauluja. The Finnish lyrics were translated by Kirsi Kunnas and Vexi Salmi.[29]

The Swedish and Finnish recordings of Moomin Voices, and their respective musical scores, have been used as course material at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.[29]

The Moomin Voices Live Band (aka. Muumilauluja-bändi) is dedicated to exclusively performing the original lyrics and unaltered stories by Tove Jansson. This band is led by Pohjola on piano, with vocalists Mirja Mäkelä and Eeppi Ursin.[30]

Other musical adaptations[edit]

Independent musical interpretations of the Moomins have been made for the nineties anime, by Pierre Kartner, with translated versions being made including in Poland and the Nordic countries. Their lyrics, however, often contain simple slogans and the music is written in a children’s pop music style and contrast sharply with the original Moomin novels and Jansson’s pictorial and descriptive, yet rhyming lyricism, as well as Erna Tauro’s Scandinavian-style songs (visor), which are occasionally influenced by Kurt Weill.

A Moomin opera was written in 1974 by the Finnish composer Ilkka Kuusisto; Jansson designed the costumes.[31]

Musicscapes from Moominvalley is a four-part work based on the Moomin compositions of composer and producer Heikki Mäenpää. It was created on the basis of the original Moomin works for the Tampere Art Museum.[32]

Twenty new Moomin songs were produced in Finland by Timo Poijärvi and Ari Vainio in 2006. This Finnish album contains no original lyrics by Jansson. However, it is based on the novel, Comet in Moominland, and adheres to the original stories. The songs are performed by Samuli Edelmann, Sani, Tommi Läntinen, Susanna Haavisto and Jore Marjaranta and other established Finnish vocalists in the pop/entertainment genre. The same twenty compositions are also available as standalone multimedia CD postcards.

The Icelandic singer Björk has composed and performed the title song (Comet Song) for the film Moomins and the Comet Chase (2010). The lyrics were written by the Icelandic writer Sjón.

In 2010, Russian composer Lex Plotnikoff (founder of symphonic metal band Mechanical Poet) released a new-age music album Hattifatteners: Stories from the Clay Shore,[33][34][35] accompanied by photos of moomin characters models by photographer/sculptor Tisha Razumovsky. Due to copyright issues, the album was later re-released as Mistland Prattlers, with references to Moomins removed.

Theatre[edit]

Several stage productions have been made from Jansson’s Moomin series, including a number that Jansson herself was involved in.

The earliest production was a 1949 theatrical version of Comet in Moominland performed at Åbo Svenska Teater.[31]

In the early 1950s, Jansson collaborated on Moomin-themed children’s plays with Vivica Bandler. By 1958, Jansson began to become directly involved in theater as Lilla Teater produced Troll i kulisserna (Troll in the wings), a Moomin play with lyrics by Jansson and music composed by Erna Tauro. The production was a success, and later performances were held in Sweden and Norway,[9] including recently at the Malmö Opera and Music Theatre in 2011.[36]

Mischief and Mystery in Moominvalley, a production created by Get Lost and Found which included puppetry and a giant pop-up book set, toured the UK from 2018, with runs at London’s Southbank Centre, Kew Gardens and the Manchester Literature Festival.[37] This production was written by Emma Edwards and Sophie Ellen Powell with puppets and set designed and made by Annie Brooks.

Video games[edit]

In 2000, Moomin’s Tale, developed and published by Sunsoft, was released for Game Boy Color. The game is based on the 1990 TV series, and there are six different stories in the game, all of which are played by the Moomintroll.[38][39][40]

Two video games were released for Nintendo DS, one exclusive to Japan.[41]

On November 3, 2021, the upcoming Moomin video game called Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley was announced. The game would be played on Snufkin and is a music-themed adventure game. The game will be developed by Norwegian-based indie game company Hyper Games. The game will be released for PC and console in 2023.[42][43][44][40]

Theme parks and displays[edit]

Moomin World[edit]

Moomin World (Muumimaailma in Finnish, Muminvärlden in Swedish) is the Moomin Theme Park especially for children. Moomin World is located on the island of Kailo beside the old town of Naantali, near the city of Turku in Western Finland.

The blueberry-coloured Moomin House is the main attraction; tourists are allowed to freely visit all five stories. It is also possible to see the Hemulen’s yellow house, Moominmama’s kitchen, the Fire Station, Snufkin’s Camp, Moominpappa’s boat, etc. Visitors may also meet Moomin characters there. Moomin World opens for the Summer season.

Moomin Ice Cave[edit]

On December 26, 2020, the underground Moomin Ice Cave theme park was opened 30 meters underneath the Spa Hotel Vesileppis in Leppävirta (56 kilometres (35 mi) south of Kuopio). The Moomin Ice Cave includes Moomin-themed ice sculptures, downhill skiing and other activities for families with children.[45][46]

Tampere Art Museum[edit]

The Moominvalley of the Tampere Art Museum is a museum devoted to the original works of Tove Jansson. It contains around 2,000 works. The museum is based on the Moomin books and has many original Moomin illustrations by Tove Jansson. The gem of the collection is a blue five-storey model of the Moominhouse, which had Tove Jansson as one of its builders. As a birthday present, the 20-year-old museum received a soundscape work based on the works of Tove Jansson, called Musicscapes from Moominvalley.

Interactive playroom[edit]

An interactive playroom about the Moomins was located at Scandinavia House, New York City, from November 11, 2006, till March 31, 2007.[47][48]

Akebono Children’s Forest Park[edit]

Akebono Children’s Forest Park (あけぼの子どもの森公園, Akebono Kodomo no Mori Kōen), also called «Moomin Valley», is a Moomin themed park for children in Hannō, Saitama in Japan that opened in July, 1997.[49][50] Tove Jansson had already in the 1970s given her personal permission to the city of Hannō to build a small Moomin-themed playground there.[51]

First announced in 2013, a new Moomin theme park was opened in March 2019 at Lake Miyazawa, Hannō. There are two zones: the free Metsä Village area, comprising lakefront restaurants and shops set among natural activities, and the Moomin-themed zone offering attractions like Moominhouse and an art museum.[52]

The theme park has become very popular, with more than one million visitors during the first three months in 2019.[53]

Moomin shops[edit]

As of January 2019, there are 20 Moomin Shops around the world, offering an extensive range of Moomin-themed goods. Finland, home of the Moomins, has three stores. There are two stores in the UK, one in the US, six in Japan. China and Hong Kong each have one store. There are three in South Korea and three in Thailand.[54]

Moomin Cafes[edit]

As of January 2018, there are 15 themed Moomin Cafes around the world – Finland, Japan, Hong Kong, Thailand, South Korea and Taiwan[55] – allowing diners to immerse themselves in the Moomin world. Diners can enjoy Moomin-inspired meals sitting at tables with larger-than-life plush versions of Moomin characters.[56]

Success in popular culture[edit]

Finnair MD-11 decorated with Moomin characters serving the Japanese route

The Moomin Boom (muumibuumi in Finnish) started in the 1990s, when Dennis Livson and Lars Jansson produced a 104-part animation series in Japan named Tales from Moominvalley, which was followed by a full-length movie Comet in Moominland. Moomin books had always been steady bestsellers in Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, but the animation started a new Moomin madness both in Finland and abroad, especially in Japan, where they are the official mascots of the Daiei chain of shopping centers. A large merchandising industry was built around the Moomin characters, covering everything from coffee cups and T-shirts to plastic models. Even the former Finnish President Tarja Halonen has been known to wear a Moomin watch.[57] New Moomin comic books and comic strips were published. Moomins were used to advertise Finland abroad: the Helsinki–Vantaa International Airport was decorated with Moomin images and Finnair decorated its aircraft on routes to Japan with Moomin designs. The peak of the Moomin Boom was the opening of the Moomin World theme park in Naantali, Finland, which has become one of Finland’s international tourist destinations.

The Moomin Boom has been criticized for commercializing the Moomins. Friends of Tove Jansson and many old Moomin enthusiasts have stressed that the newer animations banalize the original and philosophical Moomin world to harmless family entertainment. An antithesis for the Disneyland-like Moomin World theme park is the Moomin Museum of Tampere, which exhibits the original illustrations and hand-made Moomin models by Tove Jansson.

The Jansson family has kept the rights of Moomins and controlled the Moomin Boom. The artistic control is now in the hands of Lars Jansson’s daughter, Sophia Jansson-Zambra. Wanting to keep the control over Moomins, the family has turned down offers from the Walt Disney Company.[6][58][59]

As of 2017, the Moomin brand is estimated to have a yearly retail value of 700 million EUR per year.[60]

References[edit]

- ^ Meek, Margaret (2001). Children’s Literature and National Identity. Stoke on Trent, UK: Trentham Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-85856-204-9.

- ^ «Mumin | Schildts Förlags Ab». Schildts.asiakkaat.sigmatic.fi. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ Ariste, Paul. 1975l «Uusi sõeliseid.» In Sõnasõel 3, p. 11. Tartu: Tartu Riiklik Ülikool.

- ^ Brown, Ulla (November 2004). «A Quest for What Lies Hidden» (PDF). Outwrite. 7: 8–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ a b c d e Ahola, Suvi (2008). «Jansson, Tove (1914–2001)». Biografiakeskus. Fletcher, Roderick (trans.). Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ a b Bosworth, Mark (2014-03-13). «Tove Jansson: Love, war and the Moomins». BBC News. Archived from the original on 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ Tolvanen, Juhani (2000). Muumisisarukset Tove ja Lars Jansson: Muumipeikko-sarjakuvan tarina (in Finnish). WSOY. p. 29.

- ^ «Introduction to Moomin stories: Finn Family Moomintroll, 1948». Moomin.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Liukkonen, Petri. «Tove (Marika) Jansson». Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008.

- ^ a b Rahunen, Suvi (Spring 2007). «Om Översättning Av Kulturbunda Element Från Svenska Till Finska Och Franska I Två Muminböcker Av Tove Jansson» (PDF). University of Jyväskylä. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ Philip Nel. «Moomin: The Complete Tove Jansson Comic Strip. Vol. 1 by Tove Jansson». English.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ «Tove Jansson | Sort of books». Sortof.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ «ArchWay With Words». ArchWayWithWords.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Marten, Peter. & Panzar, Katja (ed.). Starting a Great Adventure. Blue Wings Magazine. Nov. 2007.

- ^ a b «När Mumin Erövrade Världen» (in Swedish). Ny Tid. 1 December 2000. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ «D+Q to publish ‘Moomin: the complete Tove Jasson comic strip’«. Drawn & Quarterly. 19 January 2006. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Räihä, Soile (Autumn 2005). «Tove Jansson, The Moomin Business and Finnish Children». University of Tampere. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Moomin: The Complete Tove Comic Strip [Drawn & Quarterly, Montreal]. ISBN 1-894937-80-5 (Vol. 1)

- ^ «Glamour on koitua Muumien kohtaloksi Rivieralla». Nordiskfilm.fi. 29 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.(in Finnish)

- ^ «The 58th BFI London Film Festival in partnership with American Express® announces full 2014 programme». 4 September 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Mitchell, Wendy (10 October 2014). «A new adventure for the Moomins». Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ Tove Jansson kauhistui väkivaltaisista muumeista – ”Se tv-sarja oli Tovelle shokki” – Kotiliesi (in Finnish)

- ^ Tiesitkö? 1970-luvun taitteessa Japanissa tehtiin kummallista Muumit-sarjaa, joissa ryypättiin ja tapettiin vihollinen keihäällä – Yle (in Finnish)

- ^ «Mûmin (1972) — IMDb». Uk.imdb.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-24. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ «Original moomin enter». Archived from the original on October 1, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ «Moomins and the Comet Chase». Archived from the original on February 23, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ «ReAnimania 2011 Catalog by Hagop Kazanjian». Issuu.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ Songbook «Visor från Mumindalen» foreword by Boel Westin. Bonniers, Stockholm, Sweden.

- ^ a b «Moomin Voices». Moomin Voices. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ «The Official Website of Composer Pianist Producer MIKA POHJOLA». Archived from the original on January 11, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- ^ a b «Biografiakeskus, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura». Kansallisbiografia.fi. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ Moominvalley 20 years by Tampere art museum publication, ISSN 0782-3746

- ^ Hattifatteners: Stories From The Clay Shore — Look At Me

- ^ Lex Plotnikoff «Hattifatteners. Stories from the Clay Shore» | moomi-troll.ru

- ^ «Hattifatteners». Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ «Troll i kulisserna | Malmö Opera». Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ «Mischief and Mystery in Moominvalley». manchesterliteraturefestival.co.uk. 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Moomin’s Tale — Steam Games

- ^ Moomin’s Tale — IGN

- ^ a b Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley is a new puzzler starring the Moomins — GamesRadar+

- ^ «Moomins Games». Giant Bomb. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ^ Snufkin — Melody of Moominvalley (Official Site)

- ^ Hyper Games — Hypergames.no

- ^ Moomin musical adventure Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley looks lovely in first trailer — Eurogamer

- ^ «Moomin Ice Cave». Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ^ «The new ice sculptures and fun activities of the Moomin Ice Cave charms both adventurous and winter enthusiasts». Moomin.com. 2020-12-26. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- ^ «Family Fare: Meet The Moomins, Creatures in Residence». The New York Times. 24 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ «Scandinavia House – The Nordic Center in America». Scandinavia House. Archived from the original on December 10, 2006. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ «Akebono-children park facility guidance». Hannō city. 2016-03-11. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ Elle (2013-01-12). ««Moomin Valley», Akebono Children’s Forest in Hanno City». Saitama with Kids. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ Sirén, Vesa (5 June 2019). «Ihana Mörkö!». Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). pp. B 1–3.

- ^ «Japan’s Moomin Theme Park Opening Pushed Back to 2019». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Andersen, Ivar (24 December 2019). «Mammorna flockas till Mumindalen – i Japan». Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish). Helsingfors. pp. 24–25.

- ^ «Places — Moomin : Moomin». Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ «Places – Moomin». moomin.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ «Moomin, Japan’s ‘anti-loneliness’ cafe, goes viral». cnn.com. 15 May 2014. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Cord, David J. (2012). Mohamed 2.0. Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms. p. 155. ISBN 978-951-52-2898-7.

- ^ Samson, Anna (2021-09-22). «How the Moomins became an anti-fascist symbol». Huck. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ «The Moomins are from Finland». FinnStyle. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ «Moomin with the times: Moomin Characters talks the future of this classic brand». licensing.biz. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

External links[edit]

- Official English website

- Unofficial Moomin Character Guide

The Moomins, comic book cover by Tove Jansson From left to right: Sniff, Snufkin, Moominpappa, Moominmamma, Moomintroll (Moomin), the Mymble’s daughter, Groke, Snork Maiden and Hattifatteners |

|

| Author | Tove Jansson |

|---|---|

| Original title | Mumintroll |

| Translator |

|

| Illustrator | Tove Jansson |

| Country | Finland |

| Language | Finland Swedish[1] |

| Genre | Children’s fantasy |

| Publisher | Drawn & Quarterly, Macmillan, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Schildts, Zangavar, Sort of Books |

| Media type | Print, digital |

| Website | Official website |

The Moomins (Swedish: Mumintroll) are the central characters in a series of novels, short stories, and a comic strip by Finnish writer and illustrator Tove Jansson, originally published in Swedish by Schildts[2] in Finland. They are a family of white, round fairy-tale characters with large snouts that make them resemble the hippopotamus. However, despite this resemblance, the Moomin family are trolls. The family live in their house in Moominvalley and have had many adventures with their various friends.

In all, nine books were released in the series, together with five picture books and a comic strip being released between 1945 and 1993.

The Moomins have since been the basis for numerous television series, films and even two theme parks: one called Moomin World in Naantali, Finland, and another Akebono Children’s Forest Park in Hannō, Saitama, Japan.

Etymology[edit]

In a letter to Paul Ariste, an Estonian linguist, Jansson wrote in 1973 that she had created an artificial word which expresses something soft. She came up with an ad hoc Swedish word mumintrollet, because, in her opinion, the consonant sound of m in particular conveys a sensation of softness. As an artist, Jansson gave the Moomins a shape that also expresses softness, as opposed to flabbiness.[3]

Synopsis and characters[edit]

Finnish Moomin toys from the 1950s

The Moomin stories concern several eccentric and oddly-shaped characters, some of whom are related to each other. The central family consists of Moominpappa, Moominmamma and Moomintroll.[4]

Other characters, such as Hemulens, Sniff, the Snork Maiden, Snufkin and Little My are accepted into or attach themselves to the family group from time to time, generally living separate lives in the surrounding Moominvalley, where the series is set, and in which the Moomin family decides to live at the end of The Moomins and the Great Flood.

Characters[edit]

- Moomintroll, also referred to as «Moomin» in some of the English translations: The main protagonist, the little boy of the family, interested in and excited about everything he sees and finds, always trying to be good, but sometimes getting into trouble while doing so; he is very brave and always finds a way to make his friends happy.

- Moominpappa: Orphaned in his younger years, he is a somewhat restless soul who left the orphanage to venture out into the world in his youth but has now settled down, determined to be a responsible father to his family.

- Moominmamma: The calm mother, who takes care that Moominhouse is a safe place to be. She wants everyone to be happy, appreciates individuality, but settles things when someone is wronged. She always brings good food as well as whatever else may be necessary on a journey in her handbag.

- Little My: A mischievous little girl, who lives in the Moomin house and has a brave, spunky personality. She likes adventure, but loves catastrophes, and often does mean things on purpose. She finds messiness and untidiness exciting and is very down to earth when others are not.

- Sniff: A creature who lives in the Moomin house. He likes to take part in everything, but is afraid to do anything dangerous. Sniff appreciates all valuables and makes many plans to get rich, but does not succeed.

- Snork Maiden: Moomin’s friend. She is happy and energetic, but often suddenly changes her mind on things. She loves nice clothes and jewelry and is a little flirtatious. She thinks of herself as Moomin’s girlfriend.

- Snufkin: Moomin’s best friend. The lonesome philosophical traveller, who likes to play the harmonica and wanders around the world with only a few things, so as not to make his life complicated. He always comes and goes as he pleases, is carefree and has many admirers in Moominvalley. He is also shown to be quite fearless and calm in even the most dire situations, which has proven to be a great help to Moomintroll and the others when in danger.

- The younger Mymble, also referred to as «the Mymble’s daughter«: Little My’s amiable and helpful big sister, and half-sister of Snufkin. She often has romantic daydreams about the love of her life, particularly policemen.

- The Snork: Snorkmaiden’s brother. He is an introvert by nature and is always inventing things. The residents of Moominvalley often ask Snork for help solving tricky problems and building machines. Snorks are like moomintrolls, but change colour according to their mood.

- Too-Ticky: A wise woman, and good friend of the family. She has a boyish look, with a blue hat and a red-striped shirt. She dives straight into action to solve dilemmas in a practical way. Too-Ticky is the one of the people in Moominvalley, who does not hibernate, instead spending the winter in the small changing shed and storehouse over the water at the end of the Moomin’s summer landing stage.

- Stinky: A small furry creature that always plays jokes on the family in the house, where he sometimes lives. He likes pinching things, is proud of his reputation as a crook, but always gets found out. He is simple and only thinks of himself.

Biographical interpretation[edit]

Critics have interpreted various Moomin characters as being inspired by real people, especially members of the author’s family, and Tove Jansson spoke in interviews about the backgrounds of, and possible models for, her characters.[5] The first two books about the Moomins (The Moomins and the Great Flood and (Comet in Moominland) were published in 1945 and 1946 respectively, and deal with natural disasters; they were influenced by the upheavals of war and Jansson’s depression during the war years.[6] The reception of the first two Moomin books was lukewarm at first; the second book got a little more attention than its predecessor, but its sales figures were still poor.[7] Third book, Finn Family Moomintroll, which was the first Moomin book translated into English, became the first international bestseller.[8]

Tove Jansson’s life partner was the graphic artist Tuulikki Pietilä, whose personality inspired the character Too-Ticky in Moominland Midwinter.[5][9] Moomintroll and Little My have been seen as psychological self-portraits of the artist.[5][9] The Moomins, generally speaking, relate strongly to Jansson’s own family – they were bohemian, lived close to nature and were very tolerant towards diversity.[5][9][10] Moominpappa and Moominmamma are often seen as portraits of Jansson’s parents Viktor Jansson and Signe Hammarsten-Jansson.[5][9][10] Most of Jansson’s characters are on the verge of melancholy, such as the always formal Hemulen, or the strange Hattifatteners, who travel in concerted, ominous groups. Jansson uses the differences between the characters’ philosophies to provide a venue for her satirical impulses.[11]

List of books[edit]

The books in the series, in order, are:

- The Moomins and the Great Flood (Originally: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen) – 1945.

- Comet in Moominland (Originally: Kometjakten/Kometen kommer) – 1946.

- Finn Family Moomintroll, Some editions: The Happy Moomins –(Originally: Trollkarlens hatt) – 1948.

- The Exploits of Moominpappa, Some editions: Moominpappa’s Memoirs (Originally: Muminpappans bravader/Muminpappans memoarer) – 1950.

- Moominsummer Madness (Originally: Farlig midsommar) – 1954.

- Moominland Midwinter (Originally: Trollvinter) – 1957.

- Tales from Moominvalley (Originally: Det osynliga barnet) – 1962 (Short stories).

- Moominpappa at Sea (Originally: Pappan och havet) – 1965.

- Moominvalley in November (Originally: Sent i november) – 1970 (In which the Moomin family is absent).

All of the books in the main series except The Moomins and the Great Flood (Originally: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen) were translated and published in English during the 1960s and 70s. This first book would eventually be translated into English in 2005 by David McDuff and published by Schildts of Finland for the 60th anniversary of the series. A later 2012 version of the same translation, featuring Jansson’s new preface to the 1991 Scandinavian printing, was published in Britain by Sort of Books,[12] and was more widely distributed.

There are also five Moomin picture books by Tove Jansson:

- The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My (Originally: Hur gick det sen?) – 1952.

- Who Will Comfort Toffle? (Originally: Vem ska trösta knyttet?) – 1960.

- The Dangerous Journey (Originally: Den farliga resan) – 1977.

- Skurken i Muminhuset (English: Villain in the Moominhouse) – 1980

- Visor från Mumindalen (English: Songs from Moominvalley) – 1993 (No English translation published).

The first official translation of Villain in the Moominhouse by Tove Jansson historian Ant O’Neill was premiered in a reading at the ArchWay With Words literary festival on 25 September 2017.[13]

The books and comic strips have been translated from their original Swedish and English respectively into many languages. The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My is the first Moomin book to be adapted for iPad.

Comic strips[edit]

The Moomins also appeared in the form of comic strips. Their first appearance was in 1947 in the children’s section of the Ny Tid newspaper,[14] and they were introduced internationally to English readers in 1954 in the popular London newspaper The Evening News.[15][16] Tove Jansson drew and wrote all the strips until 1959. She shared the work load with her brother Lars Jansson until 1961; after that he took over the job until 1975 when the last strip was released.[17]

Drawn & Quarterly, a Canadian graphic novel publisher, released reprints of all The Evening News strips created by both Tove and Lars Jansson beginning in October 2006.[18] The first five volumes, Moomin: The Complete Tove Jansson Comic Strip have been published, whilst the sixth volume, published in May 2011, began Moomin: The Complete Lars Jansson Comic Strip. The 2015 publication Moomin: The Deluxe Anniversary Edition collected all of Tove’s work.

In the 1990s, a comic book version of Moomin was produced in Scandinavia after Dennis Livson and Lars Jansson’s animated series was shown on television. Neither Tove nor Lars Jansson had any involvement in these comic books; however, in the wake of the series, two new Moomin comic strips were launched under the artistic and content oversight of Lars and his daughter, Sophia Jansson-Zambra. Sophia now provides sole oversight for the strips.[15]

TV series and films[edit]

The story of the Moomins has been made into television series on many occasions by various groups, possibly the most well known of which is a Japanese–Dutch collaboration, that has also produced a feature-length film. However, there are also two Soviet serials, puppet animation Mumi-troll (Moomintroll) and cutout animation Shlyapa Volshebnika (Magician’s Hat) of three parts each, and the Polish–Austrian puppet animation TV series, The Moomins, which was broadcast and became popular in an edited form in the United Kingdom in the 1980s.

Two feature films re-use the footage of the Polish-Austrian series: Moomin and Midsummer Madness had its release in 2008, and in 2010 the Moomins appear in the first Nordic 3-D film production, with the title song by Björk, in Moomins and the Comet Chase. The animated film titled Moomins on the Riviera is based on Moomin comic strip story Moomin on the Riviera and was first released on 10 October 2014 in Finland[19] and made its premiere on 11 October 2014 at BFI London Film Festival in United Kingdom.[20] In an October 2014 blog article at Screendaily, Sophia Jansson states that the film’s «artistic team has made an effort to be true to the original drawings and the original text».[21]

Screenshot from the 1969–70 television animation about Moomintroll with a rifle. Jansson was known to have a very negative attitude towards the controversial content of the series.[22][23]

The Moomins, from the 1990–91 television animation. From left to right, Sniff, Moominmamma, Moominpappa, Moomintroll (Moomin) and Little My.

- Die Muminfamilie (The Moomin Family) 1959 West German marionette TV series, and its 1960 sequel Sturm im Mumintal (Storm in Moominvalley)

- Mūmin (Moomin), 1969–70 Japanese anime TV series

- Mumintrollet (Moomintroll), 1969 Swedish-language suit actor TV series produced by Sveriges Radio (Swedish national radio company)

- Shin Mūmin (New Moomin), 1972 Japanese anime TV series, remake of the 1969 series by the staff of its latter half

- Mūmin (Moomin), 1971 Japanese traditional animation film

- Mūmin (Moomin), 1972 Japanese traditional animation half-hour film[24]

- Mumindalen (Moominvalley), 1973 Swedish suit actor TV series based on Moominland Midwinter

- Mumi-troll (Moomintroll), 1978 Soviet Union stop motion serial film of Comet in Moominland

- Opowiadania Muminków (The Moomins), 1977–82 Austrian, German and Polish-produced «Fuzzy-Felt» stop motion TV series made in Poland. The series has been re-compiled a number of times in other formats:

- Moomin and Midsummer Madness, 2008 Finnish-produced compilation movie of the TV series[25]

- Moomins and the Comet Chase, 2010 Finnish-produced 3-D film compiled and converted from the 1977–82 series[26]

- Moomins and the Winter Wonderland, 2017, from the TV series.

- The Moomins, 2010 Finnish-produced high-definition video version of the 1977–82 series

- Vem ska trösta knyttet?, 1980 Swedish traditional animation half-hour film of Who Will Comfort Toffle?

- Shlyapa Volshebnika (Magician’s Hat), 1980–83 Soviet Union cutout animation serial film of Finn Family Moomintroll, different staff and aeshetic to the 1978 serial

- Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka (Moomin), 1990–91 Dutch, Finnish and Japanese-produced traditional anime TV series made in Japan

- Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka: Bōken Nikki (Delightful Moomin Family: Adventure Diary), 1991–92 Dutch and Japanese-produced traditional anime TV series made in Japan, a continuation of the 1990–91 series

- Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka: Mūmindani no Suisei (Comet in Moominland), 1992 Dutch and Japanese-produced traditional anime feature film made in Japan, a prequel to the 1990–91 series

- Hur gick det sen? (What Happened Next?), 1993 Swedish short animation film of The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My

- Փոքրիկ տրոլների կյանքից (From the Life Of the Little Trolls), 2008 Armenian short animation film based on The Last Dragon In the World (Historien om den sista draken i världen)[27]

- Moomins on the Riviera, 2014 French hand-drawn animated feature film, with a plot line taken from the comic strip.

- Moominvalley, 2019 Finnish and British-produced TV series, directed by Oscar-winner Steve Box. A crowdfunded campaign was made on April 19, 2017 to make a new «TV-series Moominvalley». Archived from the original on 2017-03-29. by Finnish company «Gutsy Animations». It successfully passed the campaign threshold.

Moomin music[edit]

The Moomin novels describe the musical activities of the Moomins, particularly those of Snufkin, his harmonica with «trills» and «twiddles». All Moomin characters sing songs, often about their thoughts and themselves. The songs often serve as core statements of the characters’ personalities.

Original songs[edit]

The Moomin Voices CD release from 2003, arranged by Mika Pohjola, in Swedish containing Tove Jansson’s original Moomin songs. A Finnish version was released in 2005.

This music was heard outside Moominvalley after they went live on theater stage in Stockholm. Director Vivica Bandler told Jansson in 1959: «Listen, here the people want songs».[28] The earlier version of the play was cast in Helsinki with no music.

Helsinki based pianist and composer Erna Tauro was commissioned to write the songs to lyrics by Jansson. The first collection consisted of six Moomin Songs (Sex muminvisor): Moomintroll’s Song (Mumintrollets visa), Little My’s Song (Lilla Mys visa), Mrs. Fillyjonk’s Song (Fru Filifjonks sång), Theater Rat Emma’s Words of Wisdom (Teaterråttan Emmas visdomsord), Misabel’s Lament (Misans klagolåt) and Final Song (Slutsång).

More songs were published in the 1960s and 1970s, when Jansson and Lars Jansson produced a series of Moomin dramas for Swedish Television. The simple, yet effective melodies by Tauro were well received by the theater and TV audiences. The first songs were either sung unaccompanied or accompanied by a pianist. While the most famous Moomin songs in Scandinavia are undoubtedly «Moomintroll’s Song» and «Little My’s Song», they appear in no context in the novels.

The original songs by Jansson and Tauro remained scattered after their initial release. The first recording of the complete collection was made in 2003 by composer and arranger Mika Pohjola on the Moomin Voices CD (Muminröster in Swedish), as a tribute to the late Tove Jansson. Tauro had died in June 1993 and some of Jansson’s last lyrics were composed by Pohjola in cooperation with Jansson’s heirs. Pohjola was also the arranger of all songs for a vocal ensemble and chamber orchestra. All voices were sung by Åland native vocalist, Johanna Grüssner. The same recording has been released in a Finnish version in 2005, Muumilauluja. The Finnish lyrics were translated by Kirsi Kunnas and Vexi Salmi.[29]

The Swedish and Finnish recordings of Moomin Voices, and their respective musical scores, have been used as course material at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts.[29]

The Moomin Voices Live Band (aka. Muumilauluja-bändi) is dedicated to exclusively performing the original lyrics and unaltered stories by Tove Jansson. This band is led by Pohjola on piano, with vocalists Mirja Mäkelä and Eeppi Ursin.[30]

Other musical adaptations[edit]

Independent musical interpretations of the Moomins have been made for the nineties anime, by Pierre Kartner, with translated versions being made including in Poland and the Nordic countries. Their lyrics, however, often contain simple slogans and the music is written in a children’s pop music style and contrast sharply with the original Moomin novels and Jansson’s pictorial and descriptive, yet rhyming lyricism, as well as Erna Tauro’s Scandinavian-style songs (visor), which are occasionally influenced by Kurt Weill.

A Moomin opera was written in 1974 by the Finnish composer Ilkka Kuusisto; Jansson designed the costumes.[31]

Musicscapes from Moominvalley is a four-part work based on the Moomin compositions of composer and producer Heikki Mäenpää. It was created on the basis of the original Moomin works for the Tampere Art Museum.[32]

Twenty new Moomin songs were produced in Finland by Timo Poijärvi and Ari Vainio in 2006. This Finnish album contains no original lyrics by Jansson. However, it is based on the novel, Comet in Moominland, and adheres to the original stories. The songs are performed by Samuli Edelmann, Sani, Tommi Läntinen, Susanna Haavisto and Jore Marjaranta and other established Finnish vocalists in the pop/entertainment genre. The same twenty compositions are also available as standalone multimedia CD postcards.

The Icelandic singer Björk has composed and performed the title song (Comet Song) for the film Moomins and the Comet Chase (2010). The lyrics were written by the Icelandic writer Sjón.

In 2010, Russian composer Lex Plotnikoff (founder of symphonic metal band Mechanical Poet) released a new-age music album Hattifatteners: Stories from the Clay Shore,[33][34][35] accompanied by photos of moomin characters models by photographer/sculptor Tisha Razumovsky. Due to copyright issues, the album was later re-released as Mistland Prattlers, with references to Moomins removed.

Theatre[edit]

Several stage productions have been made from Jansson’s Moomin series, including a number that Jansson herself was involved in.

The earliest production was a 1949 theatrical version of Comet in Moominland performed at Åbo Svenska Teater.[31]

In the early 1950s, Jansson collaborated on Moomin-themed children’s plays with Vivica Bandler. By 1958, Jansson began to become directly involved in theater as Lilla Teater produced Troll i kulisserna (Troll in the wings), a Moomin play with lyrics by Jansson and music composed by Erna Tauro. The production was a success, and later performances were held in Sweden and Norway,[9] including recently at the Malmö Opera and Music Theatre in 2011.[36]

Mischief and Mystery in Moominvalley, a production created by Get Lost and Found which included puppetry and a giant pop-up book set, toured the UK from 2018, with runs at London’s Southbank Centre, Kew Gardens and the Manchester Literature Festival.[37] This production was written by Emma Edwards and Sophie Ellen Powell with puppets and set designed and made by Annie Brooks.

Video games[edit]

In 2000, Moomin’s Tale, developed and published by Sunsoft, was released for Game Boy Color. The game is based on the 1990 TV series, and there are six different stories in the game, all of which are played by the Moomintroll.[38][39][40]

Two video games were released for Nintendo DS, one exclusive to Japan.[41]

On November 3, 2021, the upcoming Moomin video game called Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley was announced. The game would be played on Snufkin and is a music-themed adventure game. The game will be developed by Norwegian-based indie game company Hyper Games. The game will be released for PC and console in 2023.[42][43][44][40]

Theme parks and displays[edit]

Moomin World[edit]

Moomin World (Muumimaailma in Finnish, Muminvärlden in Swedish) is the Moomin Theme Park especially for children. Moomin World is located on the island of Kailo beside the old town of Naantali, near the city of Turku in Western Finland.

The blueberry-coloured Moomin House is the main attraction; tourists are allowed to freely visit all five stories. It is also possible to see the Hemulen’s yellow house, Moominmama’s kitchen, the Fire Station, Snufkin’s Camp, Moominpappa’s boat, etc. Visitors may also meet Moomin characters there. Moomin World opens for the Summer season.

Moomin Ice Cave[edit]

On December 26, 2020, the underground Moomin Ice Cave theme park was opened 30 meters underneath the Spa Hotel Vesileppis in Leppävirta (56 kilometres (35 mi) south of Kuopio). The Moomin Ice Cave includes Moomin-themed ice sculptures, downhill skiing and other activities for families with children.[45][46]

Tampere Art Museum[edit]

The Moominvalley of the Tampere Art Museum is a museum devoted to the original works of Tove Jansson. It contains around 2,000 works. The museum is based on the Moomin books and has many original Moomin illustrations by Tove Jansson. The gem of the collection is a blue five-storey model of the Moominhouse, which had Tove Jansson as one of its builders. As a birthday present, the 20-year-old museum received a soundscape work based on the works of Tove Jansson, called Musicscapes from Moominvalley.

Interactive playroom[edit]

An interactive playroom about the Moomins was located at Scandinavia House, New York City, from November 11, 2006, till March 31, 2007.[47][48]

Akebono Children’s Forest Park[edit]

Akebono Children’s Forest Park (あけぼの子どもの森公園, Akebono Kodomo no Mori Kōen), also called «Moomin Valley», is a Moomin themed park for children in Hannō, Saitama in Japan that opened in July, 1997.[49][50] Tove Jansson had already in the 1970s given her personal permission to the city of Hannō to build a small Moomin-themed playground there.[51]

First announced in 2013, a new Moomin theme park was opened in March 2019 at Lake Miyazawa, Hannō. There are two zones: the free Metsä Village area, comprising lakefront restaurants and shops set among natural activities, and the Moomin-themed zone offering attractions like Moominhouse and an art museum.[52]

The theme park has become very popular, with more than one million visitors during the first three months in 2019.[53]

Moomin shops[edit]

As of January 2019, there are 20 Moomin Shops around the world, offering an extensive range of Moomin-themed goods. Finland, home of the Moomins, has three stores. There are two stores in the UK, one in the US, six in Japan. China and Hong Kong each have one store. There are three in South Korea and three in Thailand.[54]

Moomin Cafes[edit]

As of January 2018, there are 15 themed Moomin Cafes around the world – Finland, Japan, Hong Kong, Thailand, South Korea and Taiwan[55] – allowing diners to immerse themselves in the Moomin world. Diners can enjoy Moomin-inspired meals sitting at tables with larger-than-life plush versions of Moomin characters.[56]

Success in popular culture[edit]

Finnair MD-11 decorated with Moomin characters serving the Japanese route