«Mussolini» redirects here. For other people named Mussolini, see Mussolini family.

|

Benito Mussolini |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

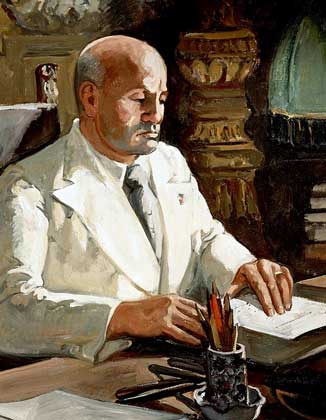

Portrait published in 1943 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 31 October 1922 – 25 July 1943 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Luigi Facta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Pietro Badoglio | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duce of the Italian Social Republic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 September 1943 – 25 April 1945 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duce of Fascism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 March 1919 – 28 April 1945 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini 29 July 1883 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 28 April 1945 (aged 61) Giulino di Mezzegra, Kingdom of Italy |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Shooting by firing squad | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | San Cassiano cemetery, Predappio, Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | PNF (1921–1943) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

Ida Dalser (m. 1914; div. 1915) Rachele Guidi (m. 1915) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic partners |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Mussolini family | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Italy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Royal Italian Army | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1915–1917 (active) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | 11th Bersaglieri Regiment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini ( MU(U)SS-ə-LEE-nee, MOOSS—, Italian: [beˈniːto aˈmilkare anˈdrɛːa mussoˈliːni];[1] 29 July 1883 – 28 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party (PNF). He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 1943, as well as «Duce» of Italian fascism from the establishment of the Italian Fasces of Combat in 1919 until his summary execution in 1945 by Italian partisans. As dictator of Italy and principal founder of fascism, Mussolini inspired and supported the international spread of fascist movements during the inter-war period.[2][3][4][5][6]

Mussolini was originally a socialist politician and a journalist at the Avanti! newspaper. In 1912, he became a member of the National Directorate of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI),[7] but he was expelled from the PSI for advocating military intervention in World War I, in opposition to the party’s stance on neutrality. In 1914, Mussolini founded a new journal, Il Popolo d’Italia, and served in the Royal Italian Army during the war until he was wounded and discharged in 1917. Mussolini denounced the PSI, his views now centering on Italian nationalism instead of socialism, and later founded the fascist movement which came to oppose egalitarianism[8] and class conflict, instead advocating «revolutionary nationalism» transcending class lines.[9] On 31 October 1922, following the March on Rome (28–30 October), Mussolini was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III, becoming the youngest individual to hold the office up to that time. After removing all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes,[10] Mussolini and his followers consolidated power through a series of laws that transformed the nation into a one-party dictatorship. Within five years, Mussolini had established dictatorial authority by both legal and illegal means and aspired to create a totalitarian state. In 1929, Mussolini signed the Lateran Treaty with the Holy See to establish Vatican City.

Mussolini’s foreign policy aimed to restore the ancient grandeur of the Roman Empire by expanding Italian colonial possessions and the fascist sphere of influence. In the 1920s, he ordered the Pacification of Libya, instructed the bombing of Corfu over an incident with Greece, established a protectorate over Albania, and incorporated the city of Fiume into the Italian state via agreements with Yugoslavia. In 1936, Ethiopia was conquered following the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and merged into Italian East Africa (AOI) with Eritrea and Somalia. In 1939, Italian forces annexed Albania. Between 1936 and 1939, Mussolini ordered the successful Italian military intervention in Spain in favor of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. Mussolini’s Italy initially tried to avoid the outbreak of a second global war, sending troops at the Brenner Pass to delay Anschluss and taking part in the Stresa Front, the Lytton Report, the Treaty of Lausanne, the Four-Power Pact and the Munich Agreement. However, Italy then alienated itself from Britain and France by aligning with Germany and Japan. Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, resulting in declarations of war by France and the UK and the start of World War II.

On 10 June 1940, Mussolini decided to enter the war on the Axis side. Despite initial success, the subsequent Axis collapse on multiple fronts and eventual Allied invasion of Sicily made Mussolini lose the support of the population and members of the Fascist Party. As a consequence, early on 25 July 1943, the Grand Council of Fascism passed a motion of no confidence in Mussolini; later that day King Victor Emmanuel III dismissed him as head of government and had him placed in custody, appointing Pietro Badoglio to succeed him as Prime Minister. After the king agreed to an armistice with the Allies, on 12 September 1943 Mussolini was rescued from captivity in the Gran Sasso raid by German paratroopers and Waffen-SS commandos led by Major Otto-Harald Mors. Adolf Hitler, after meeting with the rescued former dictator, then put Mussolini in charge of a puppet regime in northern Italy, the Italian Social Republic (Italian: Repubblica Sociale Italiana, RSI),[11] informally known as the Salò Republic, causing a civil war. In late April 1945, in the wake of near total defeat, Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci attempted to flee to Switzerland,[12] but both were captured by Italian communist partisans and summarily executed by firing squad on 28 April 1945 near Lake Como. The bodies of Mussolini and his mistress were then taken to Milan, where they were hung upside down at a service station to publicly confirm their demise.[13]

Early life

Birthplace of Benito Mussolini in Predappio; the building now hosts exhibitions on contemporary history

Mussolini’s father, Alessandro

Mussolini’s mother, Rosa

Mussolini was born on 29 July 1883 in Dovia di Predappio, a small town in the province of Forlì in Romagna. Later, during the Fascist era, Predappio was dubbed «Duce’s town» and Forlì was called «Duce’s city», with pilgrims going to Predappio and Forlì to see the birthplace of Mussolini.

Benito Mussolini’s father, Alessandro Mussolini, was a blacksmith and a socialist,[14] while his mother, Rosa (née Maltoni), was a devout Catholic schoolteacher.[15] Given his father’s political leanings, Mussolini was named Benito after liberal Mexican president Benito Juárez, while his middle names, Andrea and Amilcare, were for Italian socialists Andrea Costa and Amilcare Cipriani.[16] In return the mother obtained that he be baptised at birth.[15] Benito was the eldest of his parents’ three children. His siblings Arnaldo and Edvige followed.[17]

As a young boy, Mussolini would spend some time helping his father in his smithy.[18] Mussolini’s early political views were strongly influenced by his father, who idolized 19th-century Italian nationalist figures with humanist tendencies such as Carlo Pisacane, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Giuseppe Garibaldi.[19] His father’s political outlook combined views of anarchist figures such as Carlo Cafiero and Mikhail Bakunin, the military authoritarianism of Garibaldi, and the nationalism of Mazzini. In 1902, at the anniversary of Garibaldi’s death, Mussolini made a public speech in praise of the republican nationalist.[20]

Mussolini was sent to a boarding school in Faenza run by Salesian monks.[21] Despite being shy, he often clashed with teachers and fellow boarders due to his proud, grumpy, and violent behavior.[15] During an argument, he injured a classmate with a penknife and was severely punished.[15] After joining a new non-religious school in Forlimpopoli, Mussolini achieved good grades, was appreciated by his teachers despite his violent character, and qualified as an elementary schoolmaster in July 1901.[15][22]

Emigration to Switzerland and military service

Mussolini’s booking file following his arrest by the police on 19 June 1903, Bern, Switzerland

In 1902, Mussolini emigrated to Switzerland, partly to avoid compulsory military service.[14] He worked briefly as a stonemason in Geneva, Fribourg and Bern, but was unable to find a permanent job.

During this time he studied the ideas of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the sociologist Vilfredo Pareto, and the syndicalist Georges Sorel. Mussolini also later credited the Christian socialist Charles Péguy and the syndicalist Hubert Lagardelle as some of his influences.[23] Sorel’s emphasis on the need for overthrowing decadent liberal democracy and capitalism by the use of violence, direct action, the general strike and the use of neo-Machiavellian appeals to emotion, impressed Mussolini deeply.[14]

Mussolini became active in the Italian socialist movement in Switzerland, working for the paper L’Avvenire del Lavoratore, organizing meetings, giving speeches to workers, and serving as secretary of the Italian workers’ union in Lausanne.[24] Angelica Balabanov reportedly introduced him to Vladimir Lenin, who later criticized Italian socialists for having lost Mussolini from their cause.[25] In 1903, he was arrested by the Bernese police because of his advocacy of a violent general strike, spent two weeks in jail, and was deported to Italy. After he was released there, he returned to Switzerland.[26] In 1904, having been arrested again in Geneva and expelled for falsifying his papers, Mussolini returned to Lausanne, where he attended the University of Lausanne’s Department of Social Science, following the lessons of Vilfredo Pareto.[27] In 1937, when he was prime minister of Italy, the University of Lausanne awarded Mussolini an honorary doctorate on the occasion of its 400th anniversary.[28]

In December 1904, Mussolini returned to Italy to take advantage of an amnesty for desertion of the military. He had been convicted for this in absentia.[29] Since a condition for being pardoned was serving in the army, he joined the corps of the Bersaglieri in Forlì on 30 December 1904.[30] After serving for two years in the military (from January 1905 until September 1906), he returned to teaching.[31]

Political journalist, intellectual and socialist

In February 1909,[32] Mussolini again left Italy, this time to take the job as the secretary of the labor party in the Italian-speaking city of Trento, which at the time was part of Austria-Hungary (it is now within Italy). He also did office work for the local Socialist Party, and edited its newspaper L’Avvenire del Lavoratore (The Future of the Worker). Returning to Italy, he spent a brief time in Milan, and in 1910 he returned to his hometown of Forlì, where he edited the weekly Lotta di classe (The Class Struggle).

Mussolini thought of himself as an intellectual and was considered to be well-read. He read avidly; his favorites in European philosophy included Sorel, the Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, French Socialist Gustave Hervé, Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta, and German philosophers Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the founders of Marxism.[33][34] Mussolini had taught himself French and German and translated excerpts from Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Kant.

A portrait of Mussolini in the early 1900s

During this time, he published «Il Trentino veduto da un Socialista» (Italian: «Trentino as seen by a Socialist») in the radical periodical La Voce.[35] He also wrote several essays about German literature, some stories, and one novel: L’amante del Cardinale: Claudia Particella, romanzo storico (The Cardinal’s Mistress). This novel he co-wrote with Santi Corvaja, and it was published as a serial book in the Trento newspaper Il Popolo. It was released in installments from 20 January to 11 May 1910.[36] The novel was bitterly anticlerical, and years later was withdrawn from circulation after Mussolini made a truce with the Vatican.[14]

He had become one of Italy’s most prominent socialists. In September 1911, Mussolini participated in a riot, led by socialists, against the Italian war in Libya. He bitterly denounced Italy’s «imperialist war», an action that earned him a five-month jail term.[37] After his release, he helped expel Ivanoe Bonomi and Leonida Bissolati from the Socialist Party, as they were two «revisionists» who had supported the war.

He was rewarded with the editorship of the Socialist Party newspaper Avanti! Under his leadership, its circulation soon rose from 20,000 to 100,000.[38] John Gunther in 1940 called him «one of the best journalists alive»; Mussolini was a working reporter while preparing for the March on Rome, and wrote for the Hearst News Service until 1935.[25] Mussolini was so familiar with Marxist literature that in his own writings he would not only quote from well-known Marxist works but also from the relatively obscure works.[39] During this period Mussolini considered himself an «authoritarian communist»[40] and a Marxist and he described Karl Marx as «the greatest of all theorists of socialism.»[41]

In 1913, he published Giovanni Hus, il veridico (Jan Hus, true prophet), an historical and political biography about the life and mission of the Czech ecclesiastic reformer Jan Hus and his militant followers, the Hussites. During this socialist period of his life, Mussolini sometimes used the pen name «Vero Eretico» («sincere heretic»).[42]

Mussolini rejected egalitarianism, a core doctrine of socialism.[8] He was influenced by Nietzsche’s anti-Christian ideas and negation of God’s existence.[43] Mussolini felt that socialism had faltered, in view of the failures of Marxist determinism and social democratic reformism, and believed that Nietzsche’s ideas would strengthen socialism. While associated with socialism, Mussolini’s writings eventually indicated that he had abandoned Marxism and egalitarianism in favor of Nietzsche’s übermensch concept and anti-egalitarianism.[43]

When World War I began in August 1914, a large number of socialist parties worldwide followed the rising nationalist current and supported their country’s intervention in the war.[44][45] In Italy, the outbreak of the war created a surge of Italian nationalism and intervention was supported by a variety of political factions. One of the most prominent and popular Italian nationalist supporters of the war was Gabriele d’Annunzio who promoted Italian irredentism and helped sway the Italian public to support intervention in the war.[46] The Italian Liberal Party under the leadership of Paolo Boselli promoted intervention in the war on the side of the Allies and utilized the Società Dante Alighieri to promote Italian nationalism.[47][48] Italian socialists were divided on whether to support the war or oppose it.[49] Prior to Mussolini taking a position on the war, a number of revolutionary syndicalists had announced their support of intervention, including Alceste De Ambris, Filippo Corridoni, and Angelo Oliviero Olivetti.[50] The Italian Socialist Party decided to oppose the war after anti-militarist protestors had been killed, resulting in a general strike called Red Week.[51]

Mussolini initially held official support for the party’s decision and, in an August 1914 article, Mussolini wrote «Down with the War. We remain neutral.» He saw the war as an opportunity, both for his own ambitions as well as those of socialists and Italians. He was influenced by anti-Austrian Italian nationalist sentiments, believing that the war offered Italians in Austria-Hungary the chance to liberate themselves from rule of the Habsburgs. He eventually decided to declare support for the war by appealing to the need for socialists to overthrow the Hohenzollern and Habsburg monarchies in Germany and Austria-Hungary who he said had consistently repressed socialism.[52]

Members of Italy’s Arditi corps in 1918 holding daggers, a symbol of their group. The Arditi‘s black uniform and use of the fez were adopted by Mussolini in the creation of his Fascist movement.

Mussolini further justified his position by denouncing the Central Powers for being reactionary powers; for pursuing imperialist designs against Belgium and Serbia as well as historically against Denmark, France, and against Italians, since hundreds of thousands of Italians were under Habsburg rule. He argued that the fall of Hohenzollern and Habsburg monarchies and the repression of «reactionary» Turkey would create conditions beneficial for the working class. While he was supportive of the Entente powers, Mussolini responded to the conservative nature of Tsarist Russia by stating that the mobilization required for the war would undermine Russia’s reactionary authoritarianism and the war would bring Russia to social revolution. He said that for Italy the war would complete the process of Risorgimento by uniting the Italians in Austria-Hungary into Italy and by allowing the common people of Italy to be participating members of the Italian nation in what would be Italy’s first national war. Thus he claimed that the vast social changes that the war could offer meant that it should be supported as a revolutionary war.[50]

As Mussolini’s support for the intervention solidified, he came into conflict with socialists who opposed the war. He attacked the opponents of the war and claimed that those proletarians who supported pacifism were out of step with the proletarians who had joined the rising interventionist vanguard that was preparing Italy for a revolutionary war. He began to criticize the Italian Socialist Party and socialism itself for having failed to recognize the national problems that had led to the outbreak of the war.[9] He was expelled from the party for his support of intervention.

The following excerpts are from a police report prepared by the Inspector-General of Public Security in Milan, G. Gasti, that describe his background and his position on the First World War that resulted in his ousting from the Italian Socialist Party. The Inspector General wrote:

Professor Benito Mussolini, … 38, revolutionary socialist, has a police record; elementary school teacher qualified to teach in secondary schools; former first secretary of the Chambers in Cesena, Forlì, and Ravenna; after 1912 editor of the newspaper Avanti! to which he gave a violent suggestive and intransigent orientation. In October 1914, finding himself in opposition to the directorate of the Italian Socialist party because he advocated a kind of active neutrality on the part of Italy in the War of the Nations against the party’s tendency of absolute neutrality, he withdrew on the twentieth of that month from the directorate of Avanti! Then on the fifteenth of November [1914], thereafter, he initiated publication of the newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia, in which he supported—in sharp contrast to Avanti! and amid bitter polemics against that newspaper and its chief backers—the thesis of Italian intervention in the war against the militarism of the Central Empires. For this reason he was accused of moral and political unworthiness and the party thereupon decided to expel him … Thereafter he … undertook a very active campaign in behalf of Italian intervention, participating in demonstrations in the piazzas and writing quite violent articles in Popolo d’Italia …[38]

In his summary, the Inspector also noted:

He was the ideal editor of Avanti! for the Socialists. In that line of work he was greatly esteemed and beloved. Some of his former comrades and admirers still confess that there was no one who understood better how to interpret the spirit of the proletariat and there was no one who did not observe his apostasy with sorrow. This came about not for reasons of self-interest or money. He was a sincere and passionate advocate, first of vigilant and armed neutrality, and later of war; and he did not believe that he was compromising with his personal and political honesty by making use of every means—no matter where they came from or wherever he might obtain them—to pay for his newspaper, his program and his line of action. This was his initial line. It is difficult to say to what extent his socialist convictions (which he never either openly or privately abjure) may have been sacrificed in the course of the indispensable financial deals which were necessary for the continuation of the struggle in which he was engaged … But assuming these modifications did take place … he always wanted to give the appearance of still being a socialist, and he fooled himself into thinking that this was the case.[53]

Beginning of Fascism and service in World War I

Mussolini as an Italian soldier, 1917

After being ousted by the Italian Socialist Party for his support of Italian intervention, Mussolini made a radical transformation, ending his support for class conflict and joining in support of revolutionary nationalism transcending class lines.[9] He formed the interventionist newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia and the Fascio Rivoluzionario d’Azione Internazionalista («Revolutionary Fasces of International Action») in October 1914.[48] His nationalist support of intervention enabled him to raise funds from Ansaldo (an armaments firm) and other companies to create Il Popolo d’Italia to convince socialists and revolutionaries to support the war.[54] Further funding for Mussolini’s Fascists during the war came from French sources, beginning in May 1915. A major source of this funding from France is believed to have been from French socialists who sent support to dissident socialists who wanted Italian intervention on France’s side.[55]

On 5 December 1914, Mussolini denounced orthodox socialism for failing to recognize that the war had made national identity and loyalty more significant than class distinction.[9] He fully demonstrated his transformation in a speech that acknowledged the nation as an entity, a notion he had rejected prior to the war, saying:

The nation has not disappeared. We used to believe that the concept was totally without substance. Instead we see the nation arise as a palpitating reality before us! … Class cannot destroy the nation. Class reveals itself as a collection of interests—but the nation is a history of sentiments, traditions, language, culture, and race. Class can become an integral part of the nation, but the one cannot eclipse the other.[56]

The class struggle is a vain formula, without effect and consequence wherever one finds a people that has not integrated itself into its proper linguistic and racial confines—where the national problem has not been definitely resolved. In such circumstances the class movement finds itself impaired by an inauspicious historic climate.[57]

Mussolini continued to promote the need of a revolutionary vanguard elite to lead society. He no longer advocated a proletarian vanguard, but instead a vanguard led by dynamic and revolutionary people of any social class.[57] Though he denounced orthodox socialism and class conflict, he maintained at the time that he was a nationalist socialist and a supporter of the legacy of nationalist socialists in Italy’s history, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Carlo Pisacane. As for the Italian Socialist Party and its support of orthodox socialism, he claimed that his failure as a member of the party to revitalize and transform it to recognize the contemporary reality revealed the hopelessness of orthodox socialism as outdated and a failure.[58] This perception of the failure of orthodox socialism in the light of the outbreak of World War I was not solely held by Mussolini; other pro-interventionist Italian socialists such as Filippo Corridoni and Sergio Panunzio had also denounced classical Marxism in favor of intervention.[59]

These basic political views and principles formed the basis of Mussolini’s newly formed political movement, the Fasci d’Azione Rivoluzionaria in 1914, who called themselves Fascisti (Fascists).[60] At this time, the Fascists did not have an integrated set of policies and the movement was small, ineffective in its attempts to hold mass meetings, and was regularly harassed by government authorities and orthodox socialists.[61] Antagonism between the interventionists, including the Fascists, versus the anti-interventionist orthodox socialists resulted in violence between the Fascists and socialists. The opposition and attacks by the anti-interventionist revolutionary socialists against the Fascists and other interventionists were so violent that even democratic socialists who opposed the war such as Anna Kuliscioff said that the Italian Socialist Party had gone too far in a campaign of silencing the freedom of speech of supporters of the war. These early hostilities between the Fascists and the revolutionary socialists shaped Mussolini’s conception of the nature of Fascism in its support of political violence.[62]

Mussolini became an ally with the irredentist politician and journalist Cesare Battisti.[38] When World War I started, Mussolini, like many Italian nationalists, volunteered to fight. He was turned down because of his radical Socialism and told to wait for his reserve call up. He was called up on 31 August and reported for duty with his old unit, the Bersaglieri. After a two-week refresher course he was sent to Isonzo front where he took part in the Second Battle of the Isonzo, September 1915. His unit also took part in the Third Battle of the Isonzo, October 1915.[63]

The Inspector General continued:

He was promoted to the rank of corporal «for merit in war». The promotion was recommended because of his exemplary conduct and fighting quality, his mental calmness and lack of concern for discomfort, his zeal and regularity in carrying out his assignments, where he was always first in every task involving labor and fortitude.[38]

Mussolini’s military experience is told in his work Diario di guerra. Overall, he totaled about nine months of active, front-line trench warfare. During this time, he contracted paratyphoid fever.[64] His military exploits ended in February 1917 when he was wounded accidentally by the explosion of a mortar bomb in his trench. He was left with at least 40 shards of metal in his body and had to be evacuated from the front.[63][64] He was discharged from the hospital in August 1917 and resumed his editor-in-chief position at his new paper, Il Popolo d’Italia. He wrote there positive articles about Czechoslovak Legions in Italy.

On 25 December 1915, in Treviglio, he contracted a marriage with his compatriot Rachele Guidi, who had already borne him a daughter, Edda, at Forlì in 1910. In 1915, he had a son with Ida Dalser, a woman born in Sopramonte, a village near Trento.[22][16][65] He legally recognized this son on 11 January 1916.

Rise to power

Formation of the National Fascist Party

By the time he returned from service in the Allied forces of World War I, very little remained of Mussolini the socialist. Indeed, he was now convinced that socialism as a doctrine had largely been a failure. In 1917 Mussolini got his start in politics with the help of a £100 weekly wage (the equivalent of £7100 as of 2020) from the British security service MI5, to keep anti-war protestors at home and to publish pro-war propaganda. This help was authorized by Sir Samuel Hoare, who was posted in Italy at a time when Britain feared the unreliability of that ally in the war, and the possibility of the anti-war movement causing factory strikes.[66] In early 1918 Mussolini called for the emergence of a man «ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep» to revive the Italian nation.[67] Much later Mussolini said he felt by 1919 «Socialism as a doctrine was already dead; it continued to exist only as a grudge».[68] On 23 March 1919 Mussolini re-formed the Milan fascio as the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Squad), consisting of 200 members.[69]

The platform of Fasci italiani di combattimento, as published in «Il Popolo d’Italia» on 6 June 1919

The ideological basis for fascism came from a number of sources. Mussolini drew from the works of Plato, Georges Sorel, Nietzsche, and the economic ideas of Vilfredo Pareto, to develop fascism. Mussolini admired Plato’s The Republic, which he often read for inspiration.[70] The Republic expounded a number of ideas that fascism promoted, such as rule by an elite promoting the state as the ultimate end, opposition to democracy, protecting the class system and promoting class collaboration, rejection of egalitarianism, promoting the militarization of a nation by creating a class of warriors, demanding that citizens perform civic duties in the interest of the state, and utilizing state intervention in education to promote the development of warriors and future rulers of the state.[71] Plato was an idealist, focused on achieving justice and morality, while Mussolini and fascism were realist, focused on achieving political goals.[72]

The idea behind Mussolini’s foreign policy was that of spazio vitale (vital space), a concept in Italian Fascism that was analogous to Lebensraum in German National Socialism.[73] The concept of spazio vitale was first announced in 1919, when the entire Mediterranean, especially so-called Julian March, was redefined to make it appear a unified region that had belonged to Italy from the times of the ancient Roman province of Italia,[74][75] and was claimed as Italy’s exclusive sphere of influence. The right to colonize the neighboring Slovene ethnic areas and the Mediterranean, being inhabited by what were alleged to be less developed peoples, was justified on the grounds that Italy was allegedly suffering from overpopulation.[76]

Borrowing the idea first developed by Enrico Corradini before 1914 of the natural conflict between «plutocratic» nations like Britain and «proletarian» nations like Italy, Mussolini claimed that Italy’s principal problem was that «plutocratic» countries like Britain were blocking Italy from achieving the necessary spazio vitale that would let the Italian economy grow.[77] Mussolini equated a nation’s potential for economic growth with territorial size, thus in his view the problem of poverty in Italy could only be solved by winning the necessary spazio vitale.[78]

Though biological racism was less prominent in Italian Fascism than in National Socialism, right from the start the spazio vitale concept had a strong racist undercurrent. Mussolini asserted there was a «natural law» for stronger peoples to subject and dominate «inferior» peoples such as the «barbaric» Slavic peoples of Yugoslavia. He stated in a September 1920 speech:

When dealing with such a race as Slavic—inferior and barbarian—we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy … We should not be afraid of new victims … The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps … I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians …

— Benito Mussolini, speech held in Pola, 20 September 1920[79][80]

In the same way, Mussolini argued that Italy was right to follow an imperialist policy in Africa because he saw all black people as «inferior» to whites.[81] Mussolini claimed that the world was divided into a hierarchy of races (stirpe, though this was justified more on cultural than on biological grounds), and that history was nothing more than a Darwinian struggle for power and territory between various «racial masses».[81] Mussolini saw high birthrates in Africa and Asia as a threat to the «white race» and he often asked the rhetorical question «Are the blacks and yellows at the door?» to be followed up with «Yes, they are!». Mussolini believed that the United States was doomed as the American blacks had a higher birthrate than whites, making it inevitable that the blacks would take over the United States to drag it down to their level.[82] The very fact that Italy was suffering from overpopulation was seen as proving the cultural and spiritual vitality of the Italians, who were thus justified in seeking to colonize lands that Mussolini argued—on a historical basis—belonged to Italy anyway, which was the heir to the Roman Empire. In Mussolini’s thinking, demography was destiny; nations with rising populations were nations destined to conquer; and nations with falling populations were decaying powers that deserved to die. Hence, the importance of natalism to Mussolini, since only by increasing the birth rate could Italy ensure that its future as a great power that would win its spazio vitale would be assured. By Mussolini’s reckoning, the Italian population had to reach 60 million to enable Italy to fight a major war—hence his relentless demands for Italian women to have more children in order to reach that number.[81]

Mussolini and the fascists managed to be simultaneously revolutionary and traditionalist;[83][84] because this was vastly different from anything else in the political climate of the time, it is sometimes described, by some authors, as «The Third Way».[85] The Fascisti, led by one of Mussolini’s close confidants, Dino Grandi, formed armed squads of war veterans called blackshirts (or squadristi) with the goal of restoring order to the streets of Italy with a strong hand. The blackshirts clashed with communists, socialists, and anarchists at parades and demonstrations; all of these factions were also involved in clashes against each other. The Italian government rarely interfered with the blackshirts’ actions, owing in part to a looming threat and widespread fear of a communist revolution. The Fascisti grew rapidly; within two years they transformed themselves into the National Fascist Party at a congress in Rome. In 1921, Mussolini won election to the Chamber of Deputies for the first time.[16] In the meantime, from about 1911 until 1938, Mussolini had various affairs with the Jewish author and academic Margherita Sarfatti, called the «Jewish Mother of Fascism» at the time.[86]

March on Rome

In the night between 27 and 28 October 1922, about 30,000 Fascist blackshirts gathered in Rome to demand the resignation of liberal Prime Minister Luigi Facta and the appointment of a new Fascist government. On the morning of 28 October, King Victor Emmanuel III, who according to the Albertine Statute held the supreme military power, refused the government request to declare martial law, which led to Facta’s resignation. The King then handed over power to Mussolini (who stayed in his headquarters in Milan during the talks) by asking him to form a new government. The King’s controversial decision has been explained by historians as a combination of delusions and fears; Mussolini enjoyed wide support in the military and among the industrial and agrarian elites, while the King and the conservative establishment were afraid of a possible civil war and ultimately thought they could use Mussolini to restore law and order in the country, but failed to foresee the danger of a totalitarian evolution.[87]

Appointment as Prime Minister

As Prime Minister, the first years of Mussolini’s rule were characterized by a right-wing coalition government composed of Fascists, nationalists, liberals, and two Catholic clerics from the People’s Party. The Fascists made up a small minority in his original governments. Mussolini’s domestic goal was the eventual establishment of a totalitarian state with himself as supreme leader (Il Duce), a message that was articulated by the Fascist newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia, which was now edited by Mussolini’s brother, Arnaldo. To that end, Mussolini obtained from the legislature dictatorial powers for one year (legal under the Italian constitution of the time). He favored the complete restoration of state authority, with the integration of the Italian Fasces of Combat into the armed forces (the foundation in January 1923 of the Voluntary Militia for National Security) and the progressive identification of the party with the state. In political and social economy, he passed legislation that favored the wealthy industrial and agrarian classes (privatizations, liberalizations of rent laws and dismantlement of the unions).[16]

In 1923, Mussolini sent Italian forces to invade Corfu during the Corfu incident. In the end, the League of Nations proved powerless, and Greece was forced to comply with Italian demands.

Acerbo Law

In June 1923, the government passed the Acerbo Law, which transformed Italy into a single national constituency. It also granted a two-thirds majority of the seats in Parliament to the party or group of parties that received at least 25% of the votes.[88] This law applied in the elections of 6 April 1924. The national alliance, consisting of Fascists, most of the old Liberals and others, won 64% of the vote.

Squadristi violence

The assassination of the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti, who had requested that the elections be annulled because of the irregularities,[89] provoked a momentary crisis in the Mussolini government. Mussolini ordered a cover-up, but witnesses saw the car that transported Matteotti’s body parked outside Matteotti’s residence, which linked Amerigo Dumini to the murder.

Mussolini later confessed that a few resolute men could have altered public opinion and started a coup that would have swept fascism away. Dumini was imprisoned for two years. On his release, Dumini allegedly told other people that Mussolini was responsible, for which he served further prison time.

The opposition parties responded weakly or were generally unresponsive. Many of the socialists, liberals, and moderates boycotted Parliament in the Aventine Secession, hoping to force Victor Emmanuel to dismiss Mussolini.

On 31 December 1924, MVSN consuls met with Mussolini and gave him an ultimatum: crush the opposition or they would do so without him. Fearing a revolt by his own militants, Mussolini decided to drop all pretense of democracy.[90] On 3 January 1925, Mussolini made a truculent speech before the Chamber in which he took responsibility for squadristi violence (though he did not mention the assassination of Matteotti).[91] He did not abolish the squadristi until 1927, however.[25]

Fascist Italy

Organizational innovations

German-American historian Konrad Jarausch has argued that Mussolini was responsible for an integrated suite of political innovations that made fascism a powerful force in Europe. First, he went beyond the vague promise of future national renewal, and proved the movement could actually seize power and operate a comprehensive government in a major country along fascist lines. Second, the movement claimed to represent the entire national community, not a fragment such as the working class or the aristocracy. He made a significant effort to include the previously alienated Catholic element. He defined public roles for the main sectors of the business community rather than allowing it to operate backstage. Third, he developed a cult of one-man leadership that focused media attention and national debate on his own personality. As a former journalist, Mussolini proved highly adept at exploiting all forms of mass media, including such new forms as motion pictures and radio. Fourth, he created a mass membership party, with free programs for young men, young women, and various other groups who could therefore be more readily mobilized and monitored. He shut down all alternative political formations and parties (but this step was not an innovation by any means). Like all dictators he made liberal use of the threat of extrajudicial violence, as well as actual violence by his Blackshirts, to frighten his opposition.[92]

Police state

Mussolini in his early years in power

Between 1925 and 1927, Mussolini progressively dismantled virtually all constitutional and conventional restraints on his power and built a police state. A law passed on 24 December 1925—Christmas Eve for the largely Roman Catholic country—changed Mussolini’s formal title from «President of the Council of Ministers» to «Head of the Government», although he was still called «Prime Minister» by most non-Italian news sources. He was no longer responsible to Parliament and could be removed only by the King. While the Italian constitution stated that ministers were responsible only to the sovereign, in practice it had become all but impossible to govern against the express will of Parliament. The Christmas Eve law ended this practice, and also made Mussolini the only person competent to determine the body’s agenda. This law transformed Mussolini’s government into a de facto legal dictatorship. Local autonomy was abolished, and podestàs appointed by the Italian Senate replaced elected mayors and councils.

While Italy occupied former Austro-Hungarian areas between years 1918 and 1920, five hundred «Slav» societies (for example Sokol) and slightly smaller number of libraries («reading rooms») had been forbidden, specifically so later with the Law on Associations (1925), the Law on Public Demonstrations (1926) and the Law on Public Order (1926)—the closure of the classical lyceum in Pisino, of the high school in Voloska (1918), and the five hundred Slovene and Croatian primary schools followed.[93] One thousand «Slav» teachers were forcibly exiled to Sardinia and to Southern Italy.

On 7 April 1926, Mussolini survived a first assassination attempt by Violet Gibson, an Irish woman and daughter of Lord Ashbourne, who was deported after her arrest.[94] On 31 October 1926, 15-year-old Anteo Zamboni attempted to shoot Mussolini in Bologna. Zamboni was lynched on the spot.[95][96] Mussolini also survived a failed assassination attempt in Rome by anarchist Gino Lucetti,[97] and a planned attempt by the Italian anarchist Michele Schirru,[98] which ended with Schirru’s capture and execution.[99]

All other parties were outlawed following Zamboni’s assassination attempt in 1926, though in practice Italy had been a one-party state since 1925 (with either his January speech to the Chamber or the passage of the Christmas Eve law, depending on the source). In 1928, an electoral law abolished parliamentary elections. Instead, the Grand Council of Fascism selected a single list of candidates to be approved by plebiscite. The Grand Council had been created five years earlier as a party body but was «constitutionalized» and became the highest constitutional authority in the state. On paper, the Grand Council had the power to recommend Mussolini’s removal from office, and was thus theoretically the only check on his power. However, only Mussolini could summon the Grand Council and determine its agenda. To gain control of the South, especially Sicily, he appointed Cesare Mori as a Prefect of the city of Palermo, with the charge of eradicating the Sicilian Mafia at any price. In the telegram, Mussolini wrote to Mori:

Your Excellency has carte blanche; the authority of the State must absolutely, I repeat absolutely, be re-established in Sicily. If the laws still in force hinder you, this will be no problem, as we will draw up new laws.[100]

Mori did not hesitate to lay siege to towns, using torture, and holding women and children as hostages to oblige suspects to give themselves up. These harsh methods earned him the nickname of «Iron Prefect». In 1927, Mori’s inquiries brought evidence of collusion between the Mafia and the Fascist establishment, and he was dismissed for length of service in 1929, at which time the number of murders in Palermo Province had decreased from 200 to 23. Mussolini nominated Mori as a senator, and fascist propaganda claimed that the Mafia had been defeated.[101]

In accordance with the new electoral law, the general elections took the form of a plebiscite in which voters were presented with a single PNF-dominated list. According to official figures, the list was approved by 98.43% of voters.[102]

The «Pacification of Libya»

In 1919, the Italian state had brought in a series of liberal reforms in Libya that allowed education in Arabic and Berber and allowed for the possibility that the Libyans might become Italian citizens.[103] Giuseppe Volpi, who had been appointed governor in 1921 was retained by Mussolini, and withdrew all of the measures offering equality to the Libyans.[103] A policy of confiscating land from the Libyans to hand over to Italian colonists gave new vigor to Libyan resistance led by Omar Mukhtar, and during the ensuing «Pacification of Libya», the Fascist regime waged a genocidal campaign designed to kill as many Libyans as possible.[104][103] Well over half the population of Cyrenaica were confined to 15 concentration camps by 1931 while the Royal Italian Air Force staged chemical warfare attacks against the Bedouin.[105] On 20 June 1930, Marshal Pietro Badoglio wrote to General Rodolfo Graziani:

As for overall strategy, it is necessary to create a significant and clear separation between the controlled population and the rebel formations. I do not hide the significance and seriousness of this measure, which might be the ruin of the subdued population … But now the course has been set, and we must carry it out to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica must perish.[106]

On 3 January 1933, Mussolini told the diplomat Baron Pompei Aloisi that the French in Tunisia had made an «appalling blunder» by permitting sex between the French and the Tunisians, which he predicted would lead to the French degenerating into a nation of «half-castes», and to prevent the same thing happening to the Italians gave orders to Marshal Badoglio that miscegenation be made a crime in Libya.[107]

Economic policy

Mussolini launched several public construction programs and government initiatives throughout Italy to combat economic setbacks or unemployment levels. His earliest (and one of the best known) was the Battle for Wheat, by which 5,000 new farms were established and five new agricultural towns (among them Littoria and Sabaudia) on land reclaimed by draining the Pontine Marshes. In Sardinia, a model agricultural town was founded and named Mussolinia, but has long since been renamed Arborea. This town was the first of what Mussolini hoped would have been thousands of new agricultural settlements across the country. The Battle for Wheat diverted valuable resources to wheat production away from other more economically viable crops. Landowners grew wheat on unsuitable soil using all the advances of modern science, and although the wheat harvest increased, prices rose, consumption fell and high tariffs were imposed.[108] The tariffs promoted widespread inefficiencies and the government subsidies given to farmers pushed the country further into debt.

The inauguration of Littoria in 1932

Mussolini also initiated the «Battle for Land», a policy based on land reclamation outlined in 1928. The initiative had a mixed success; while projects such as the draining of the Pontine Marsh in 1935 for agriculture were good for propaganda purposes, provided work for the unemployed and allowed for great land owners to control subsidies, other areas in the Battle for Land were not very successful. This program was inconsistent with the Battle for Wheat (small plots of land were inappropriately allocated for large-scale wheat production), and the Pontine Marsh was lost during World War II. Fewer than 10,000 peasants resettled on the redistributed land, and peasant poverty remained high. The Battle for Land initiative was abandoned in 1940.

In 1930, in «The Doctrine of Fascism» he wrote, «The so-called crisis can only be settled by State action and within the orbit of the State.»[109] He tried to combat economic recession by introducing a «Gold for the Fatherland» initiative, encouraging the public to voluntarily donate gold jewelry to government officials in exchange for steel wristbands bearing the words «Gold for the Fatherland». Even Rachele Mussolini donated her wedding ring. The collected gold was melted down and turned into gold bars, which were then distributed to the national banks.

Government control of business was part of Mussolini’s policy planning. By 1935, he claimed that three-quarters of Italian businesses were under state control. Later that year, Mussolini issued several edicts to further control the economy, e.g. forcing banks, businesses, and private citizens to surrender all foreign-issued stock and bond holdings to the Bank of Italy. In 1936, he imposed price controls.[110] He also attempted to turn Italy into a self-sufficient autarky, instituting high barriers on trade with most countries except Germany.

In 1943, Mussolini proposed the theory of economic socialization.

Railways

Mussolini was keen to take the credit for major public works in Italy, particularly the railway system.[111] His reported overhauling of the railway network led to the popular saying, «Say what you like about Mussolini, he made the trains run on time.»[111] Kenneth Roberts, journalist and novelist, wrote in 1924:

The difference between the Italian railway service in 1919, 1920 and 1921 and that which obtained during the first year of the Mussolini regime was almost beyond belief. The cars were clean, the employees were snappy and courteous, and trains arrived at and left the stations on time — not fifteen minutes late, and not five minutes late; but on the minute.[112]

In fact, the improvement in Italy’s dire post-war railway system had begun before Mussolini took power.[111][113] The improvement was also more apparent than real. Bergen Evans wrote in 1954:

The author was employed as a courier by the Franco-Belgique Tours Company in the summer of 1930, the height of Mussolini’s heyday, when a fascist guard rode on every train, and is willing to make an affidavit to the effect that most Italian trains on which he travelled were not on schedule—or near it. There must be thousands who can support this attestation. It’s a trifle, but it’s worth nailing down.[114]

George Seldes wrote in 1936 that although the express trains carrying tourists generally—though not always—ran on schedule, the same was not true for the smaller lines, where delays were frequent,[111] while Ruth Ben-Ghiat has said that «they improved the lines that had a political meaning to them».[114]

Propaganda and cult of personality

Mussolini’s foremost priority was the subjugation of the minds of the Italian people through the use of propaganda. The regime promoted a lavish cult of personality centered on the figure of Mussolini. He pretended to incarnate the new fascist Übermensch, promoting an aesthetic of exasperated Machismo that attributed to him quasi-divine capacities.[115] At various times after 1922, Mussolini personally took over the ministries of the interior, foreign affairs, colonies, corporations, defense, and public works. Sometimes he held as many as seven departments simultaneously, as well as the premiership. He was also head of the all-powerful Fascist Party and the armed local fascist militia, the MVSN or «Blackshirts», who terrorized incipient resistance in the cities and provinces. He would later form the OVRA, an institutionalized secret police that carried official state support. In this way he succeeded in keeping power in his own hands and preventing the emergence of any rival.

Mussolini also portrayed himself as a valiant sportsman and a skilled musician. All teachers in schools and universities had to swear an oath to defend the fascist regime. Newspaper editors were all personally chosen by Mussolini, and only those in possession of a certificate of approval from the Fascist Party could practice journalism. These certificates were issued in secret; Mussolini thus skillfully created the illusion of a «free press». The trade unions were also deprived of any independence and were integrated into what was called the «corporative» system. The aim, inspired by medieval guilds and never completely achieved, was to place all Italians in various professional organizations or corporations, all under clandestine governmental control.

From 1925, Mussolini styled himself Il Duce (the leader)

Large sums of money were spent on highly visible public works and on international prestige projects. These included as the Blue Riband ocean liner SS Rex; setting aeronautical records with the world’s fastest seaplane, the Macchi M.C.72; and the transatlantic flying boat cruise of Italo Balbo, which was greeted with much fanfare in the United States when it landed in Chicago in 1933.

The principles of the doctrine of Fascism were laid down in an article by eminent philosopher Giovanni Gentile and Mussolini himself that appeared in 1932 in the Enciclopedia Italiana. Mussolini always portrayed himself as an intellectual, and some historians agree.[116] Gunther called him «easily the best educated and most sophisticated of the dictators», and the only national leader of 1940 who was an intellectual.[25] German historian Ernst Nolte said that «His command of contemporary philosophy and political literature was at least as great as that of any other contemporary European political leader.»[117]

Culture

Benito Mussolini and Fascist Blackshirt youth in 1935

Nationalists in the years after World War I thought of themselves as combating the liberal and domineering institutions created by cabinets—such as those of Giovanni Giolitti, including traditional schooling. Futurism, a revolutionary cultural movement which would serve as a catalyst for Fascism, argued for «a school for physical courage and patriotism», as expressed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1919. Marinetti expressed his disdain for «the by now prehistoric and troglodyte Ancient Greek and Latin courses», arguing for their replacement with exercise modelled on those of the Arditi soldiers («[learning] to advance on hands and knees in front of razing machine gun fire; to wait open-eyed for a crossbeam to move sideways over their heads etc.»). It was in those years that the first Fascist youth wings were formed: Avanguardia Giovanile Fascista (Fascist Youth Vanguards) in 1919, and Gruppi Universitari Fascisti (Fascist University Groups) in 1922.

After the March on Rome that brought Mussolini to power, the Fascists started considering ways to politicize Italian society, with an accent on education. Mussolini assigned former ardito and deputy-secretary for Education Renato Ricci the task of «reorganizing the youth from a moral and physical point of view.» Ricci sought inspiration with Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of Scouting, meeting with him in England, as well as with Bauhaus artists in Germany. The Opera Nazionale Balilla was created through Mussolini’s decree of 3 April 1926, and was led by Ricci for the following eleven years. It included children between the ages of 8 and 18, grouped as the Balilla and the Avanguardisti.

According to Mussolini: «Fascist education is moral, physical, social, and military: it aims to create a complete and harmoniously developed human, a fascist one according to our views». Mussolini structured this process taking in view the emotional side of childhood: «Childhood and adolescence alike … cannot be fed solely by concerts, theories, and abstract teaching. The truth we aim to teach them should appeal foremost to their fantasy, to their hearts, and only then to their minds».

The «educational value set through action and example» was to replace the established approaches. Fascism opposed its version of idealism to prevalent rationalism, and used the Opera Nazionale Balilla to circumvent educational tradition by imposing the collective and hierarchy, as well as Mussolini’s own personality cult.

Another important constituent of the Fascist cultural policy was Roman Catholicism. In 1929, a concordat with the Vatican was signed, ending decades of struggle between the Italian state and the Papacy that dated back to the 1870 takeover of the Papal States by the House of Savoy during the unification of Italy. The Lateran treaties, by which the Italian state was at last recognized by the Roman Catholic Church, and the independence of Vatican City was recognized by the Italian state, were so much appreciated by the ecclesiastic hierarchy that Pope Pius XI acclaimed Mussolini as «the Man of Providence».[118]

The 1929 treaty included a legal provision whereby the Italian government would protect the honor and dignity of the Pope by prosecuting offenders.[119] Mussolini had had his children baptized in 1923 and himself re-baptized by a Roman Catholic priest in 1927.[120] After 1929, Mussolini, with his anti-Communist doctrines, convinced many Catholics to actively support him.

Foreign policy

In foreign policy, Mussolini was pragmatic and opportunistic. At the center of his vision lay the dream to forge a new Roman Empire in Africa and the Balkans, vindicating the so-called «mutilated victory» of 1918 imposed by the «plutodemocracies» (Britain and France) that betrayed the Treaty of London and usurped the supposed «natural right» of Italy to achieve supremacy in the Mediterranean basin.[121][122] However, in the 1920s, given Germany’s weakness, post-war reconstruction problems and the question of reparations, the situation of Europe was too unfavorable to advocate an openly revisionist approach to the Treaty of Versailles. In the 1920s, Italy’s foreign policy was based on the traditional idea of Italy maintaining «equidistant» stance from all the major powers in order to exercise «determinant weight», which by whatever power Italy chose to align with would decisively change the balance of power in Europe, and the price of such an alignment would be support for Italian ambitions in Europe and Africa.[123] In the meantime, since for Mussolini demography was destiny, he carried out relentless natalist policies designed to increase the birthrate; for example, in 1924 making advocating or giving information about contraception a criminal offense, and in 1926 ordering every Italian woman to double the number of children that they were willing to bear.[124] For Mussolini, Italy’s current population of 40 million was insufficient to fight a major war, and he needed to increase the population to at least 60 million Italians before he would be ready for war.[125]

In his early years in power, Mussolini operated as a pragmatic statesman, trying to achieve some advantages, but never at the risk of war with Britain and France. An exception was the bombardment and occupation of Corfu in 1923, following an incident in which Italian military personnel charged by the League of Nations to settle a boundary dispute between Greece and Albania were assassinated by bandits; the nationality of the bandits remains unclear. At the time of the Corfu incident, Mussolini was prepared to go to war with Britain, and only desperate pleading by the Italian Navy leadership, who argued that the Italian Navy was no match for the British Royal Navy, persuaded Mussolini to accept a diplomatic solution.[126] In a secret speech to the Italian military leadership in January 1925, Mussolini argued that Italy needed to win spazio vitale, and as such his ultimate goal was to join «the two shores of the Mediterranean and of the Indian Ocean into a single Italian territory».[126] Reflecting his obsession with demography, Mussolini went on to say that Italy did not at the present possess sufficient manpower to win a war against Britain or France, and that the time for war would come sometime in the mid-1930s, when Mussolini calculated the high Italian birth rate would finally give Italy the necessary numbers to win.[126] Subsequently, Mussolini took part in the Locarno Treaties of 1925, that guaranteed the western borders of Germany as drawn in 1919. In 1929, Mussolini ordered his Army General Staff to begin planning for aggression against France and Yugoslavia.[126] In July 1932, Mussolini sent a message to German Defense Minister General Kurt von Schleicher, suggesting an anti-French Italo-German alliance, an offer Schleicher responded to favorably, albeit with the condition that Germany needed to rearm first.[126] In late 1932–early 1933, Mussolini planned to launch a surprise attack against both France and Yugoslavia that was to begin in August 1933.[126] Mussolini’s planned war of 1933 was only stopped when he learned that the French Deuxième Bureau had broken the Italian military codes, and that the French, being forewarned of all the Italian plans, were well prepared for the Italian attack.[126]

After Adolf Hitler came into power, threatening Italian interests in Austria and the Danube basin, Mussolini proposed the Four Power Pact with Britain, France and Germany in 1933. When the Austrian ‘austro-fascist’ Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss with dictatorial power was assassinated on 25 July 1934 by National-Socialist supporters, Mussolini even threatened Germany with war in the event of a German invasion of Austria. Mussolini for a period of time continued strictly opposing any German attempt to obtain Anschluss and promoted the ephemeral Stresa Front against Germany in 1935.

Despite Mussolini’s imprisonment for opposing the Italo-Turkish War in Africa as «nationalist delirium tremens» and «a miserable war of conquest»,[25] after the Abyssinia Crisis of 1935–1936, in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War Italy invaded Ethiopia following border incidents occasioned by Italian inclusions over the vaguely drawn border between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland. Historians are still divided about the reasons for the attack on Ethiopia in 1935. Some Italian historians such as Franco Catalano and Giorgio Rochat argue that the invasion was an act of social imperialism, contending that the Great Depression had badly damaged Mussolini’s prestige, and that he needed a foreign war to distract public opinion.[127] Other historians such as Pietro Pastorelli have argued that the invasion was launched as part of an expansionist program to make Italy the main power in the Red Sea area and the Middle East.[127] A middle way interpretation was offered by the American historian MacGregor Knox, who argued that the war was started for both foreign and domestic reasons, being both a part of Mussolini’s long-range expansionist plans and intended to give Mussolini a foreign policy triumph that would allow him to push the Fascist system in a more radical direction at home.[127] Italy’s forces were far superior to the Abyssinian forces, especially in air power, and they were soon victorious. Emperor Haile Selassie was forced to flee the country, with Italy entering the capital city, Addis Ababa to proclaim an empire by May 1936, making Ethiopia part of Italian East Africa.[128]

Mussolini’s personal standard

Confident of having been given free hand by French Premier Pierre Laval, and certain that the British and French would be forgiving because of his opposition to Hitler’s revisionism within the Stresa front, Mussolini received with disdain the League of Nations’ economic sanctions imposed on Italy by initiative of London and Paris.[129] In Mussolini’s view, the move was a typically hypocritical action carried out by decaying imperial powers that intended to prevent the natural expansion of younger and poorer nations like Italy.[130] In fact, although France and Britain had already colonized parts of Africa, the Scramble for Africa had finished by the beginning of the twentieth century. The international mood was now against colonialist expansion and Italy’s actions were condemned. Furthermore, Italy was criticized for its use of mustard gas and phosgene against its enemies and also for its zero tolerance approach to enemy guerrillas, authorized by Mussolini.[128] Between 1936 and 1941 during operations to «pacify» Ethiopia, the Italians killed hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian civilians, and are estimated to have killed about 7% of Ethiopia’s total population.[131] Mussolini ordered Marshal Rodolfo Graziani «to initiate and systematically conduct a policy of terror and extermination against the rebels and the population in complicity with them. Without a policy of ten eyes to one, we cannot heal this wound in good time».[132] Mussolini personally ordered Graziani to execute the entire male population over the age of 18 in one town and in one district ordered that «the prisoners, their accomplices and the uncertain will have to be executed» as part of the «gradual liquidation» of the population.[132] Believing the Eastern Orthodox Church was inspiring Ethiopians to resist, Mussolini ordered that Orthodox priests and monks were to be targeted in revenge for guerrilla attacks.[132] Mussolini brought in Degree Law 880, which made miscegenation a crime punishable with five years in prison as Mussolini made it absolutely clear that he did not want his soldiers and officials serving in Ethiopia to ever have sex with Ethiopian women under any circumstances as he believed that multiracial relationships made his men less likely to kill Ethiopians.[132] Mussolini favored a policy of brutality partly because he believed the Ethiopians were not a nation because black people were too stupid to have a sense of nationality and therefore the guerrillas were just «bandits».[133] The other reason was because Mussolini was planning on bringing millions of Italian colonists into Ethiopia and he needed to kill off much of the Ethiopian population to make room for the Italian colonists just as he had done in Libya.[133]

The sanctions against Italy were used by Mussolini as a pretext for an alliance with Germany. In January 1936, Mussolini told the German Ambassador Ulrich von Hassell that: «If Austria were in practice to become a German satellite, he would have no objection».[134] By recognizing Austria was within the German sphere of influence, Mussolini had removed the principal problem in Italo-German relations.[134]

On 25 October 1936, an alliance was declared between Italy and Germany, which came to be known as the Rome-Berlin Axis.

On 11 July 1936, an Austro-German treaty was signed under which Austria declared itself to be a «German state» whose foreign policy would always be aligned with Berlin, and allowed for pro-Nazis to enter the Austrian cabinet.[134] Mussolini had applied strong pressure on the Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg to sign the treaty in order to improve his relations with Hitler.[134] After the sanctions against Italy ended in July 1936, the French tried hard to revive the Stresa Front, displaying what Sullivan called «an almost humiliating determination to retain Italy as an ally».[135] In January 1937, Britain signed a «Gentleman’s Agreement» with Mussolini intended to limit Italian intervention in Spain, and was seen by the British Foreign Office as the first step towards creating an Anglo-Italian alliance.[136] In April 1938, Britain and Italy signed the Easter Accords under which Britain promised to recognise Ethiopia as Italian in exchange for Italy pulling out of the Spanish Civil War. The Foreign Office understood that it was the Spanish Civil War that was pulling Rome and Berlin closer together, and believed if Mussolini could be persuaded to disengage from Spain, then he would return to the Allied camp. To get Mussolini out of Spain, the British were prepared to pay such prices such as recognising King Victor Emmanuel III as Emperor of Ethiopia. The American historian Barry Sullivan wrote that both the British and the French very much wanted a rapprochement with Italy to undo the damage caused by the League of Nations sanctions, and that «Mussolini chose to ally with Hitler, rather than being forced…»[135]

Reflecting the new pro-German foreign policy on 25 October 1936, Mussolini agreed to form a Rome-Berlin Axis, sanctioned by a cooperation agreement with Nazi Germany and signed in Berlin. Furthermore, the conquest of Ethiopia cost the lives of 12,000 Italians and another 4,000 to 5,000 Libyans, Eritreans, and Somalis fighting in Italian service.[137] Mussolini believed that conquering Ethiopia would cost 4 to 6 billion lire, but the true costs of the invasion proved to be 33.5 billion lire.[137] The economic costs of the conquest proved to be a staggering blow to the Italian budget, and seriously delayed Italian efforts at military modernization as the money that Mussolini had earmarked for military modernization was instead spent in conquering Ethiopia, something that helped to drive Mussolini towards Germany.[138] To help cover the huge debts run up during the Ethiopian war, Mussolini devalued the lire by 40% in October 1936.[137] Furthermore, the costs of occupying Ethiopia was to cost the Italian treasury another 21.1 billion lire between 1936 and 1940.[137] Additionally, Italy was to lose 4,000 men killed fighting in the Spanish Civil War while Italian intervention in Spain cost Italy another 12 to 14 billion lire.[137] In the years 1938 and 1939, the Italian government took in 39.9 billion lire in taxes while the entire Italian gross national product was 153 billion lire, which meant the Ethiopian and Spanish wars imposed economically crippling costs on Italy.[137] Only 28% of the entire military Italian budgets between 1934 and 1939 was spent on military modernization with the rest all being consumed by Mussolini’s wars, which led to a rapid decline in Italian military power.[139] Between 1935 and 1939, Mussolini’s wars cost Italy the equivalent of US$860 billion in 2022 values, a sum that was even proportionally a larger burden given that Italy was such a poor country.[137] The 1930s were a time of rapid advances in military technology, and Sullivan wrote that Mussolini picked exactly the wrong time to fight his wars in Ethiopia and Spain.[137] At the same time that the Italian military was falling behind the other great powers, a full scale arms race had broken out, with Germany, Britain and France spending increasingly large sums of money on their militaries as the 1930s advanced, a situation that Mussolini privately admitted seriously limited Italy’s ability to fight a major war on its own, and thus required a great power ally to compensate for increasing Italian military backwardness.[140]

From 1936 through 1939, Mussolini provided huge amounts of military support to the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. This active intervention on the side of Franco further distanced Italy from France and Britain. As a result, Mussolini’s relationship with Adolf Hitler became closer, and he chose to accept the German annexation of Austria in 1938, followed by the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1939. In May 1938, during Hitler’s visit to Italy, Mussolini told the Führer that Italy and France were deadly enemies fighting on «opposite sides of the barricade» concerning the Spanish Civil War, and the Stresa Front was «dead and buried».[141] At the Munich Conference in September 1938, Mussolini continued to pose as a moderate working for European peace, while helping Nazi Germany annex the Sudetenland. The 1936 Axis agreement with Germany was strengthened by signing the Pact of Steel on 22 May 1939, that bound together Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in a full military alliance.

Members of TIGR, a Slovene partisan group, plotted to kill Mussolini in Kobarid in 1938, but their attempt was unsuccessful.

World War II

Gathering storm

By the late 1930s, Mussolini’s obsession with demography led him to conclude that Britain and France were finished as powers, and that it was Germany and Italy who were destined to rule Europe if for no other reason than their demographic strength.[142] Mussolini stated his belief that declining birth rates in France were «absolutely horrifying» and that the British Empire was doomed because one-quarter of the British population was over 50.[142] As such, Mussolini believed that an alliance with Germany was preferable to an alignment with Britain and France as it was better to be allied with the strong instead of the weak.[143] Mussolini saw international relations as a Social Darwinian struggle between «virile» nations with high birth rates that were destined to destroy «effete» nations with low birth rates. Mussolini believed that France was a «weak and old» nation as the French weekly death rate exceeded the birthrate by 2,000, and he had no interest in an alliance with France.[144]

Such was the extent of Mussolini’s belief that it was Italy’s destino to rule the Mediterranean because of Italy’s high birth rate that he neglected much of the serious planning and preparations necessary for a war with the Western powers.[145] The only arguments that held Mussolini back from full alignment with Berlin were his awareness of Italy’s economic and military unpreparedness, meaning he required further time to rearm, and his desire to use the Easter Accords of April 1938 as a way of splitting Britain from France.[146] A military alliance with Germany as opposed to the already existing looser political alliance with the Reich under the Anti-Comintern Pact (which had no military commitments) would end any chance of Britain implementing the Easter Accords.[147] The Easter Accords in turn were intended by Mussolini to allow Italy to take on France alone by sufficiently improving Anglo-Italian relations that London would presumably remain neutral in the event of a Franco-Italian war (Mussolini had imperial designs on Tunisia, and had some support in that country[148]).[147] In turn, the Easter Accords were intended by Britain to win Italy away from Germany.

Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and foreign minister, summed up the dictator’s foreign policy objectives regarding France in an entry of his diary dated 8 November 1938: Djibouti would have to be ruled in common with France; «Tunisia, with a more or less similar regime; Corsica, Italian and never Frenchified and therefore under our direct control, the border at the river Var.»[149] As for Savoy, which was not «historically or geographically Italian», Mussolini claimed that he was not interested in it. On 30 November 1938, Mussolini invited the French ambassador André François-Poncet to attend the opening of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, during which the assembled deputies, at his cue, began to demonstrate loudly against France, shouting that Italy should annex «Tunis, Nice, Corsica, Savoy!», which was followed by the deputies marching into the street carrying signs demanding that France turn over Tunisia, Savoy, and Corsica to Italy.[150] The French premier, Édouard Daladier, promptly rejected the Italian demands for territorial concessions, and for much of the winter of 1938–39, France and Italy were on the verge of war.[151]

In January 1939, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, visited Rome, during which visit Mussolini learned that though Britain very much wanted better relations with Italy, and was prepared to make concessions, it would not sever all ties with France for the sake of an improved Anglo-Italian relationship.[152] With that, Mussolini grew more interested in the German offer of a military alliance, which had first been made in May 1938.[152] In February 1939, Mussolini gave a speech before the Fascist Grand Council, during which he proclaimed his belief that a state’s power is «proportional to its maritime position» and that Italy was a «prisoner in the Mediterranean and the more populous and powerful Italy becomes, the more it will suffer from its imprisonment. The bars of this prison are Corsica, Tunisia, Malta, Cyprus: the sentinels of this prison are Gibraltar and Suez».[153]