|

Republic of the Union of Myanmar

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag State Seal |

|

| Anthem: ကမ္ဘာမကျေ Kaba Ma Kyei «Till the End of the World» |

|

|

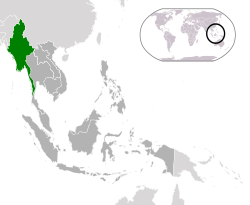

Location of Myanmar (green) in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend] |

|

| Capital | Naypyidaw[a] 19°45′N 96°6′E / 19.750°N 96.100°E |

| Largest city | Yangon[b] |

| Official language | Burmese |

| Recognised regional languages |

[citation needed] |

| Ethnic groups

(2018[1][2]) |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Burmese / Myanma[5] |

| Government | Unitary assembly-independent republic under a military junta |

|

• President |

Myint Swe (acting) |

|

• SAC Chairman and Prime Minister |

Min Aung Hlaing |

|

• SAC Vice Chairman and Deputy Prime Minister |

Soe Win[a] |

| Legislature | State Administration Council |

| Formation | |

|

• Pagan Kingdom |

23 December 849 |

|

• Toungoo dynasty |

16 October 1510 |

|

• Konbaung dynasty |

29 February 1752 |

|

• Annexation by Britain |

1 January 1886 |

|

• Independence |

4 January 1948 |

|

• 1962 coup d’état |

2 March 1962 |

|

• Renamed from «Burma» to «Myanmar» |

18 June 1989 |

|

• Restoration of presidency |

30 March 2011 |

|

• 2021 coup d’état |

1 February 2021 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

261,227 sq mi (676,570 km2) (39th) |

|

• Water (%) |

3.06 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

57,526,449[7] (25th) |

|

• Density |

196.8/sq mi (76.0/km2) (125th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2017) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 149th |

| Currency | Kyat (K) (MMK) |

| Time zone | UTC+06:30 (MMT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +95 |

| ISO 3166 code | MM |

| Internet TLD | .mm |

|

Myanmar,[b] officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar,[c] also known as Burma (the official name until 1989), is a country in Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia, and has a population of about 54 million as of 2017.[11] It is bordered by Bangladesh and India to its northwest, China to its northeast, Laos and Thailand to its east and southeast, and the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal to its south and southwest. The country’s capital city is Naypyidaw, and its largest city is Yangon (formerly Rangoon).[2]

Early civilisations in the area included the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu city-states in Upper Myanmar and the Mon kingdoms in Lower Myanmar.[12] In the 9th century, the Bamar people entered the upper Irrawaddy valley, and following the establishment of the Pagan Kingdom in the 1050s, the Burmese language, culture, and Theravada Buddhism slowly became dominant in the country. The Pagan Kingdom fell to Mongol invasions, and several warring states emerged. In the 16th century, reunified by the Taungoo dynasty, the country became the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia for a short period.[13]

The early 19th-century Konbaung dynasty ruled over an area that included modern Myanmar and briefly controlled Manipur and Assam as well. The British East India Company seized control of the administration of Myanmar after three Anglo-Burmese Wars in the 19th century, and the country became a British colony. After a brief Japanese occupation, Myanmar was reconquered by the Allies and gained independence in 1948. Following a coup d’état in 1962, it became a military dictatorship under the Burma Socialist Programme Party.

For most of its independent years, the country has been engulfed in rampant ethnic strife and its myriad ethnic groups have been involved in one of the world’s longest-running ongoing civil wars. During this time, the United Nations and several other organisations have reported consistent and systemic human rights violations in the country.[14] In 2011, the military junta was officially dissolved following a 2010 general election, and a nominally civilian government was installed. This, along with the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and political prisoners and successful elections in 2015, improved the country’s human rights record and foreign relations and led to the easing of trade and other economic sanctions,[15] although the country’s treatment of its ethnic minorities, particularly in connection with the Rohingya conflict, continued to be condemned by international organizations and many nations.[16]

Following the 2020 Myanmar general election, in which Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won a clear majority in both houses, the Burmese military (Tatmadaw) again seized power in a coup d’état.[17] The coup, which was widely condemned by the international community, led to continuous ongoing widespread protests in Myanmar and has been marked by violent political repression by the military.[18] The military also arrested Aung San Suu Kyi and charged her with crimes ranging from corruption to the violation of COVID-19 protocols, all of which have been labeled as «politically motivated» by independent observers, in order to remove her from public life.[19]

Myanmar is a member of the East Asia Summit, Non-Aligned Movement, ASEAN, and BIMSTEC, but it is not a member of the Commonwealth of Nations despite once being part of the British Empire. The country is very rich in natural resources, such as jade, gems, oil, natural gas, teak and other minerals, as well as also endowed with renewable energy, having the highest solar power potential compared to other countries of the Great Mekong Subregion. However, Myanmar has long suffered from instability, factional violence, corruption, poor infrastructure, as well as a long history of colonial exploitation with little regard to human development.[20] In 2013, its GDP (nominal) stood at US$56.7 billion and its GDP (PPP) at US$221.5 billion.[21] The income gap in Myanmar is among the widest in the world, as a large proportion of the economy is controlled by cronies of the military junta.[22] As of 2020, according to the Human Development Index, Myanmar ranks 147 out of 189 countries in terms of human development.[10] Since 2021, more than 600,000 people were displaced across Myanmar due to the surge in violence post-coup, with more than 3 million people in dire need of humanitarian assistance.[23]

Etymology

The name of the country has been a matter of dispute and disagreement, particularly in the early 21st century, focusing mainly on the political legitimacy of those using Myanmar versus Burma.[24][25] Both names derive from the earlier Burmese Mranma or Mramma, an ethnonym for the majority Burman ethnic group, of uncertain etymology.[26] The terms are also popularly thought to derive from Brahma Desha or Devanagari: ब्रह्मादेश/ब्रह्मावर्त (Sanskrit) after Brahma.[27]

In 1989, the military government officially changed the English translations of many names dating back to Burma’s colonial period or earlier, including that of the country itself: Burma became Myanmar. The renaming remains a contested issue.[28] Many political and ethnic opposition groups and countries continue to use Burma because they do not recognise the legitimacy of the ruling military government or its authority to rename the country.[29]

In April 2016, soon after taking office, speaking to foreign diplomats, Aung San Suu Kyi commented on the question of which name should be used, saying that «it is up to you, because there is nothing in the constitution of our country that says that you must use any term in particular». She continued, «I use Burma very often because I am used to using it. But it does not mean that I require other people to do that as well. And I’ll make an effort to say Myanmar from time to time so you all feel comfortable.»[30][31]

The country’s official full name is «Republic of the Union of Myanmar» (Burmese: ပြည်ထောင်စုသမ္မတ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်, Pyihtaungsu Thamada Myanma Naingngantaw, pronounced [pjìdàʊɴzṵ θàɴməda̰ mjəmà nàɪɴŋàɴdɔ̀]). Countries that do not officially recognise that name use the long form «Union of Burma» instead.[2][32] In English, the country is popularly known as either Burma or Myanmar. In Burmese, the pronunciation depends on the register used and is either Bama (pronounced [bəmà]) or Myamah (pronounced [mjəmà]).[28] The name Burma has been in use in English since the 18th century.[citation needed]

Official United States foreign policy retains Burma as the country’s name although the State Department’s website lists the country as Burma (Myanmar).[33] The CIA’s World Factbook lists the country as Burma as of February 2021.[2] The government of Canada has in the past used Burma,[34] such as in its 2007 legislation imposing sanctions[35] but as of August 2020 generally uses Myanmar.[36] The Czech Republic (itself commonly known by multiple names in English) officially uses Myanmar, although its Ministry of Foreign Affairs uses both Myanmar and Burma on its website.[37] The United Nations uses Myanmar, as does the ASEAN and as do Australia,[38] Russia, Germany,[39] China, India, Bangladesh, Norway,[40] Japan[34] and Switzerland.[41] Most English-speaking international news media refer to the country by the name Myanmar, including the BBC,[42] CNN,[43] Al Jazeera,[44] Reuters,[45] and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)/Radio Australia.[46]

Myanmar is known by a name deriving from Burma as opposed to Myanmar in Spanish, Italian, Romanian, and Greek – Birmania being the local version of Burma in both Italian and Spanish, Birmânia in Portuguese, and Birmanie in French.[47] As in the past, French-language media today consistently use Birmanie.[48][49]

There is no established pronunciation of the English name Myanmar, and at least nine different pronunciations exist. Those with two syllables are listed as more common by major UK and US dictionaries except Collins: , , , . Dictionaries and other sources also report pronunciations with three syllables , , , , .[50]

As John Wells explains, the English spellings of both Myanmar and Burma assume a non-rhotic variety of English, in which the letter r before a consonant or finally serves merely to indicate a long vowel: [ˈmjænmɑː, ˈbɜːmə]. So the pronunciation of the last syllable of Myanmar as [mɑːr] or of Burma as [bɜːrmə] by some speakers in the UK and most speakers in North America is in fact a spelling pronunciation based on a misunderstanding of non-rhotic spelling conventions. The final r in Myanmar was not intended for pronunciation and is there to ensure that the final a is pronounced with the broad ah () in «father». If the Burmese name မြန်မာ [mjəmà] were spelled «Myanma» in English, this would be pronounced at the end by all English speakers. If it were spelled «Myanmah», the end would be pronounced by all English speakers.

History

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence shows that Homo erectus lived in the region now known as Myanmar as early as 750,000 years ago, with no more erectus finds after 75,000 years ago.[51] The first evidence of Homo sapiens is dated to about 25,000 BP with discoveries of stone tools in central Myanmar.[52] Evidence of Neolithic age domestication of plants and animals and the use of polished stone tools dating to sometime between 10,000 and 6,000 BCE has been discovered in the form of cave paintings in Padah-Lin Caves.[53]

The Bronze Age arrived c. 1500 BCE when people in the region were turning copper into bronze, growing rice and domesticating poultry and pigs; they were among the first people in the world to do so.[54] Human remains and artefacts from this era were discovered in Monywa District in the Sagaing Region.[55] The Iron Age began around 500 BCE with the emergence of iron-working settlements in an area south of present-day Mandalay.[56] Evidence also shows the presence of rice-growing settlements of large villages and small towns that traded with their surroundings as far as China between 500 BCE and 200 CE.[57] Iron Age Burmese cultures also had influences from outside sources such as India and Thailand, as seen in their funerary practices concerning child burials. This indicates some form of communication between groups in Myanmar and other places, possibly through trade.[58]

Early city-states

Around the second century BCE the first-known city-states emerged in central Myanmar. The city-states were founded as part of the southward migration by the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu people, the earliest inhabitants of Myanmar of whom records are extant, from present-day Yunnan.[59] The Pyu culture was heavily influenced by trade with India, importing Buddhism as well as other cultural, architectural and political concepts, which would have an enduring influence on later Burmese culture and political organisation.[60]

By the 9th century, several city-states had sprouted across the land: the Pyu in the central dry zone, Mon along the southern coastline and Arakanese along the western littoral. The balance was upset when the Pyu came under repeated attacks from Nanzhao between the 750s and the 830s. In the mid-to-late 9th century the Bamar people founded a small settlement at Bagan. It was one of several competing city-states until the late 10th century, when it grew in authority and grandeur.[61]

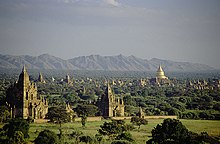

Pagan Kingdom

Pagan gradually grew to absorb its surrounding states until the 1050s–1060s when Anawrahta founded the Pagan Kingdom, the first ever unification of the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Pagan Empire and the Khmer Empire were two main powers in mainland Southeast Asia.[62] The Burmese language and culture gradually became dominant in the upper Irrawaddy valley, eclipsing the Pyu, Mon and Pali norms[clarification needed] by the late 12th century.[63] Theravada Buddhism slowly began to spread to the village level, although Tantric, Mahayana, Hinduism, and folk religion remained heavily entrenched. Pagan’s rulers and wealthy built over 10,000 Buddhist temples in the Pagan capital zone alone. Repeated Mongol invasions in the late 13th century toppled the four-century-old kingdom in 1287.[63]

Pagan’s collapse was followed by 250 years of political fragmentation that lasted well into the 16th century. Like the Burmans four centuries earlier, Shan migrants who arrived with the Mongol invasions stayed behind. Several competing Shan States came to dominate the entire northwestern to eastern arc surrounding the Irrawaddy valley. The valley too was beset with petty states until the late 14th century when two sizeable powers, Ava Kingdom and Hanthawaddy Kingdom, emerged. In the west, a politically fragmented Arakan was under competing influences of its stronger neighbours until the Kingdom of Mrauk U unified the Arakan coastline for the first time in 1437. The kingdom was a protectorate of the Bengal Sultanate at different time periods.[64]

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Ava fought wars of unification but could never quite reassemble the lost empire. Having held off Ava, the Mon-speaking Hanthawaddy entered its golden age, and Arakan went on to become a power in its own right for the next 350 years. In contrast, constant warfare left Ava greatly weakened, and it slowly disintegrated from 1481 onward. In 1527, the Confederation of Shan States conquered Ava and ruled Upper Myanmar until 1555.

Like the Pagan Empire, Ava, Hanthawaddy and the Shan states were all multi-ethnic polities. Despite the wars, cultural synchronisation continued. This period is considered a golden age for Burmese culture. Burmese literature «grew more confident, popular, and stylistically diverse», and the second generation of Burmese law codes as well as the earliest pan-Burma chronicles emerged.[65] Hanthawaddy monarchs introduced religious reforms that later spread to the rest of the country.[66] Many splendid temples of Mrauk U were built during this period.

Taungoo and Konbaung

Political unification returned in the mid-16th century, through the efforts of Taungoo, a former vassal state of Ava. Taungoo’s young, ambitious King Tabinshwehti defeated the more powerful Hanthawaddy in the Toungoo–Hanthawaddy War. His successor Bayinnaung went on to conquer a vast swath of mainland Southeast Asia including the Shan states, Lan Na, Manipur, Mong Mao, the Ayutthaya Kingdom, Lan Xang and southern Arakan. However, the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia unravelled soon after Bayinnaung’s death in 1581, completely collapsing by 1599. Ayutthaya seized Tenasserim and Lan Na, and Portuguese mercenaries established Portuguese rule at Thanlyin (Syriam).

The dynasty regrouped and defeated the Portuguese in 1613 and Siam in 1614. It restored a smaller, more manageable kingdom, encompassing Lower Myanmar, Upper Myanmar, Shan states, Lan Na and upper Tenasserim. The restored Toungoo kings created a legal and political framework whose basic features continued well into the 19th century. The crown completely replaced the hereditary chieftainships with appointed governorships in the entire Irrawaddy valley and greatly reduced the hereditary rights of Shan chiefs. Its trade and secular administrative reforms built a prosperous economy for more than 80 years. From the 1720s onward, the kingdom was beset with repeated Meithei raids into Upper Myanmar and a nagging rebellion in Lan Na. In 1740, the Mon of Lower Myanmar founded the Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom. Hanthawaddy forces sacked Ava in 1752, ending the 266-year-old Toungoo Dynasty.

After the fall of Ava, the Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War involved one resistance group under Alaungpaya defeating the Restored Hanthawaddy, and by 1759 he had reunited all of Myanmar and Manipur and driven out the French and the British, who had provided arms to Hanthawaddy. By 1770, Alaungpaya’s heirs had subdued much of Laos and fought and won the Burmese–Siamese War against Ayutthaya and the Sino-Burmese War against Qing China.[67]

With Burma preoccupied by the Chinese threat, Ayutthaya recovered its territories by 1770 and went on to capture Lan Na by 1776. Burma and Siam went to war until 1855, but all resulted in a stalemate, exchanging Tenasserim (to Burma) and Lan Na (to Ayutthaya). Faced with a powerful China and a resurgent Ayutthaya in the east, King Bodawpaya turned west, acquiring Arakan (1785), Manipur (1814) and Assam (1817). It was the second-largest empire in Burmese history but also one with a long ill-defined border with British India.[68]

The breadth of this empire was short-lived. In 1826, Burma lost Arakan, Manipur, Assam and Tenasserim to the British in the First Anglo-Burmese War. In 1852, the British easily seized Lower Burma in the Second Anglo-Burmese War. King Mindon Min tried to modernise the kingdom and in 1875 narrowly avoided annexation by ceding the Karenni States. The British, alarmed by the consolidation of French Indochina, annexed the remainder of the country in the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885.

Konbaung kings extended Restored Toungoo’s administrative reforms and achieved unprecedented levels of internal control and external expansion. For the first time in history, the Burmese language and culture came to predominate the entire Irrawaddy valley. The evolution and growth of Burmese literature and theatre continued, aided by an extremely high adult male literacy rate for the era (half of all males and 5% of females).[69] Nonetheless, the extent and pace of reforms were uneven and ultimately proved insufficient to stem the advance of British colonialism.

British Burma (1885–1948)

The landing of British forces in Mandalay after the last of the Anglo-Burmese Wars, which resulted in the abdication of the last Burmese monarch, King Thibaw Min

British troops firing a mortar on the Mawchi road, July 1944

In the 19th century, Burmese rulers, whose country had not previously been of particular interest to European traders, sought to maintain their traditional influence in the western areas of Assam, Manipur and Arakan. Pressing them, however, was the British East India Company, which was expanding its interests eastwards over the same territory. Over the next sixty years, diplomacy, raids, treaties and compromises, known collectively as the Anglo-Burmese Wars, continued until Britain proclaimed control over most of Burma.[70] With the fall of Mandalay, all of Burma came under British rule, being annexed on 1 January 1886.

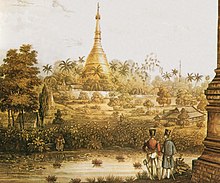

Throughout the colonial era, many Indians arrived as soldiers, civil servants, construction workers and traders and, along with the Anglo-Burmese community, dominated commercial and civil life in Burma. Rangoon became the capital of British Burma and an important port between Calcutta and Singapore. Burmese resentment was strong, and was vented in violent riots that periodically paralysed Rangoon until the 1930s.[71] Some of the discontent was caused by a disrespect for Burmese culture and traditions, such as the British refusal to remove shoes when they entered pagodas. Buddhist monks became the vanguards of the independence movement. U Wisara, an activist monk, died in prison after a 166-day hunger strike to protest against a rule that forbade him to wear his Buddhist robes while imprisoned.[72]

On 1 April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain, and Ba Maw became the first Prime Minister and Premier of Burma. Ba Maw was an outspoken advocate for Burmese self-rule, and he opposed the participation of Great Britain, and by extension Burma, in World War II. He resigned from the Legislative Assembly and was arrested for sedition. In 1940, before Japan formally entered the war, Aung San formed the Burma Independence Army in Japan.

As a major battleground, Burma was devastated during World War II by the Japanese invasion. Within months after they entered the war, Japanese troops had advanced on Rangoon, and the British administration had collapsed. A Burmese Executive Administration headed by Ba Maw was established by the Japanese in August 1942. Wingate’s British Chindits were formed into long-range penetration groups trained to operate deep behind Japanese lines.[73] A similar American unit, Merrill’s Marauders, followed the Chindits into the Burmese jungle in 1943.[74]

Beginning in late 1944, allied troops launched a series of offensives that led to the end of Japanese rule in July 1945. The battles were intense with much of Burma laid waste by the fighting. Overall, the Japanese lost some 150,000 men in Burma with 1,700 prisoners taken.[75] Although many Burmese fought initially for the Japanese as part of the Burma Independence Army, many Burmese, mostly from the ethnic minorities, served in the British Burma Army.[76] The Burma National Army and the Arakan National Army fought with the Japanese from 1942 to 1944 but switched allegiance to the Allied side in 1945. Overall, 170,000 to 250,000 Burmese civilians died during World War II.[77]

Following World War II, Aung San negotiated the Panglong Agreement with ethnic leaders that guaranteed the independence of Myanmar as a unified state. Aung Zan Wai, Pe Khin, Bo Hmu Aung, Sir Maung Gyi, Dr. Sein Mya Maung, Myoma U Than Kywe were among the negotiators of the historic Panglong Conference negotiated with Bamar leader General Aung San and other ethnic leaders in 1947. In 1947, Aung San became Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council of Myanmar, a transitional government. But in July 1947, political rivals[78] assassinated Aung San and several cabinet members.[79]

Independence (1948–1962)

On 4 January 1948, the nation became an independent republic, under the terms of the Burma Independence Act 1947. The new country was named the Union of Burma, with Sao Shwe Thaik as its first president and U Nu as its first prime minister. Unlike most other former British colonies and overseas territories, Burma did not become a member of the Commonwealth. A bicameral parliament was formed, consisting of a Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Nationalities,[80] and multi-party elections were held in 1951–1952, 1956 and 1960.

The geographical area Burma encompasses today can be traced to the Panglong Agreement, which combined Burma Proper, which consisted of Lower Burma and Upper Burma, and the Frontier Areas, which had been administered separately by the British.[81]

In 1961, U Thant, the Union of Burma’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations and former secretary to the prime minister, was elected Secretary-General of the United Nations, a position he held for ten years.[82] Among the Burmese to work at the UN when he was secretary-general was Aung San Suu Kyi (daughter of Aung San), who went on to become winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize.

When the non-Burman ethnic groups pushed for autonomy or federalism, alongside having a weak civilian government at the centre, the military leadership staged a coup d’état in 1962. Though incorporated in the 1947 Constitution, successive military governments construed the use of the term ‘federalism’ as being anti-national, anti-unity and pro-disintegration.[83]

Military rule (1962–2011)

On 2 March 1962, the military led by General Ne Win took control of Burma through a coup d’état, and the government had been under direct or indirect control by the military since then. Between 1962 and 1974, Myanmar was ruled by a revolutionary council headed by the general. Almost all aspects of society (business, media, production) were nationalised or brought under government control under the Burmese Way to Socialism,[84] which combined Soviet-style nationalisation and central planning.

A new constitution of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma was adopted in 1974. Until 1988, the country was ruled as a one-party system, with the general and other military officers resigning and ruling through the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP).[85] During this period, Myanmar became one of the world’s most impoverished countries.[86] There were sporadic protests against military rule during the Ne Win years, and these were almost always violently suppressed. On 7 July 1962, the government broke up demonstrations at Rangoon University, killing 15 students.[84] In 1974, the military violently suppressed anti-government protests at the funeral of U Thant. Student protests in 1975, 1976, and 1977 were quickly suppressed by overwhelming force.[85]

Protesters gathering in central Rangoon, 1988.

In 1988, unrest over economic mismanagement and political oppression by the government led to widespread pro-democracy demonstrations throughout the country known as the 8888 Uprising. Security forces killed thousands of demonstrators, and General Saw Maung staged a coup d’état and formed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). In 1989, SLORC declared martial law after widespread protests. The military government finalised plans for People’s Assembly elections on 31 May 1989.[87] SLORC changed the country’s official English name from the «Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma» to the «Union of Myanmar» on 18 June 1989 by enacting the adaptation of the expression law.

In May 1990, the government held free multiparty elections for the first time in almost 30 years, and the National League for Democracy (NLD), the party of Aung San Suu Kyi, won[88] earning 392 out of a total 492 seats (i.e., 80% of the seats). However, the military junta refused to cede power[89] and continued to rule the nation, first as SLORC and, from 1997, as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) until its dissolution in March 2011. General Than Shwe took over the Chairmanship – effectively the position of Myanmar’s top ruler – from General Saw Maung in 1992 and held it until 2011.[90]

On 23 June 1997, Myanmar was admitted into the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. On 27 March 2006, the military junta, which had moved the national capital from Yangon to a site near Pyinmana in November 2005, officially named the new capital Naypyidaw, meaning «city of the kings».[91]

In August 2007, an increase in the price of fuel led to the Saffron Revolution led by Buddhist monks that were dealt with harshly by the government.[92] The government cracked down on them on 26 September 2007, with reports of barricades at the Shwedagon Pagoda and monks killed. There were also rumours of disagreement within the Burmese armed forces, but none was confirmed. The military crackdown against unarmed protesters was widely condemned as part of the international reactions to the Saffron Revolution and led to an increase in economic sanctions against the Burmese Government.

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis caused extensive damage in the densely populated rice-farming delta of the Irrawaddy Division.[93] It was the worst natural disaster in Burmese history with reports of an estimated 200,000 people dead or missing, damages totalled to 10 billion US dollars, and as many as 1 million were left homeless.[94] In the critical days following this disaster, Myanmar’s isolationist government was accused of hindering United Nations recovery efforts.[95] Humanitarian aid was requested, but concerns about foreign military or intelligence presence in the country delayed the entry of United States military planes delivering medicine, food, and other supplies.[96]

In early August 2009, a conflict broke out in Shan State in northern Myanmar. For several weeks, junta troops fought against ethnic minorities including the Han Chinese,[97] Wa, and Kachin.[98][99] During 8–12 August, the first days of the conflict, as many as 10,000 Burmese civilians fled to Yunnan in neighbouring China.[98][99][100]

Civil wars

Civil wars have been a constant feature of Myanmar’s socio-political landscape since the attainment of independence in 1948. These wars are predominantly struggles for ethnic and sub-national autonomy, with the areas surrounding the ethnically Bamar central districts of the country serving as the primary geographical setting of conflict. Foreign journalists and visitors require a special travel permit to visit the areas in which Myanmar’s civil wars continue.[101]

In October 2012, the ongoing conflicts in Myanmar included the Kachin conflict,[102] between the Pro-Christian Kachin Independence Army and the government;[103] a civil war between the Rohingya Muslims and the government and non-government groups in Rakhine State;[104] and a conflict between the Shan,[105] Lahu, and Karen[106][107] minority groups, and the government in the eastern half of the country. In addition, al-Qaeda signalled an intention to become involved in Myanmar. In a video released on 3 September 2014, mainly addressed to India, the militant group’s leader Ayman al-Zawahiri said al-Qaeda had not forgotten the Muslims of Myanmar and that the group was doing «what they can to rescue you».[108] In response, the military raised its level of alertness, while the Burmese Muslim Association issued a statement saying Muslims would not tolerate any threat to their motherland.[109]

Armed conflict between ethnic Chinese rebels and the Myanmar Armed Forces resulted in the Kokang offensive in February 2015. The conflict had forced 40,000 to 50,000 civilians to flee their homes and seek shelter on the Chinese side of the border.[110] During the incident, the government of China was accused of giving military assistance to the ethnic Chinese rebels.[111] Clashes between Burmese troops and local insurgent groups have continued, fuelling tensions between China and Myanmar.[112]

Period of liberalisation, 2011–2021

The military-backed Government had promulgated a «Roadmap to Discipline-flourishing Democracy» in 1993, but the process appeared to stall several times, until 2008 when the Government published a new draft national constitution, and organised a (flawed) national referendum which adopted it. The new constitution provided for election of a national assembly with powers to appoint a president, while practically ensuring army control at all levels.[113]

A general election in 2010 — the first for twenty years — was boycotted by the NLD. The military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party declared victory, stating that it had been favoured by 80 per cent of the votes; fraud, however, was alleged.[114][115] A nominally civilian government was then formed, with retired general Thein Sein as president.[116]

A series of liberalising political and economic actions – or reforms – then took place. By the end of 2011 these included the release of pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest, the establishment of the National Human Rights Commission, the granting of general amnesties for more than 200 political prisoners, new labour laws that permitted labour unions and strikes, a relaxation of press censorship, and the regulation of currency practices.[117] In response, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Myanmar in December 2011 – the first visit by a US Secretary of State in more than fifty years[118] – meeting both President Thein Sein and opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[119]

Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD party participated in the 2012 by-elections, facilitated by the government’s abolition of the laws that previously barred it.[120] In the April 2012 by-elections, the NLD won 43 of the 45 available seats. The 2012 by-elections were also the first time that international representatives were allowed to monitor the voting process in Myanmar.[121]

Myanmar’s improved international reputation was indicated by ASEAN’s approval of Myanmar’s bid for the position of ASEAN chair in 2014.[122]

2015 general elections

General elections were held on 8 November 2015. These were the first openly contested elections held in Myanmar since the 1990 general election (which was annulled[123]). The results gave the NLD an absolute majority of seats in both chambers of the national parliament, enough to ensure that its candidate would become president, while NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi is constitutionally barred from the presidency.[123][124]

The new parliament convened on 1 February 2016,[125] and on 15 March 2016, Htin Kyaw was elected as the first non-military president since the military coup of 1962.[126] On 6 April 2016, Aung San Suu Kyi assumed the newly created role of state counsellor, a role akin to a prime minister.[127]

Analysis of liberalisation period

Throughout this decade of apparent liberalisation, opinions differed whether a transition to liberal democracy was underway. To some it appeared merely that the Burmese military was allowing certain civil liberties while clandestinely institutionalising itself further into Burmese politics and economy.[128]

2020 elections and 2021 military coup d’état

Election and aftermath

In Myanmar’s 2020 parliamentary election,

the ostensibly ruling National League for Democracy (NLD), the party of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, competed with various other smaller parties – particularly the military-affiliated Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). Other parties and individuals allied with specific ethnic minorities also ran for office.[129]

Suu Kyi’s NLD won the 2020 Myanmar general election on 8 November in a landslide, again winning supermajorities in both houses[129][130]—winning 396 out of 476 elected seats in parliament.[131]

The USDP, regarded as a proxy for the military, suffered a «humiliating» defeat[132][133] – even worse than in 2015[133] – capturing only 33 of the 476 elected seats.[131][132]

As the election results began emerging, the USDP rejected them, urging a new election with the military as observers.[129][133]

More than 90 other smaller parties contested the vote, including more than 15 who complained of irregularities. However, election observers declared there were no major irregularities in the voting.[132]

The military – arguing that it had found over 8 million irregularities in voter lists, in over 300 townships – called on Myanmar’s Union Election Commission (UEC) and government to review the results, but the commission dismissed the claims for lack of any evidence.[131][134]

The election commission declared that any irregularities were too few and too minor to affect the outcome of the election.[132] However, despite the election commission validating the NLD’s overwhelming victory,[134] the USDP and Myanmar’s military persistently alleged fraud[135][136] and the military threatened to «take action».[132][137][138][139][140]

In January, 2021, just before the new parliament was to be sworn in, The NLD announced that Suu Kyi would retain her State Counsellor role in the upcoming government.

[141]

Coup

In the early morning of 1 February 2021, the day parliament was set to convene, the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military, detained State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other members of the ruling party.[132]

[142][143] The military handed power to military chief Min Aung Hlaing and declared a state of emergency for one year[144][142] and began closing the borders, restricting travel and electronic communications nationwide.[143]

The military announced it would replace the existing election commission with a new one, and a military media outlet indicated new elections would be held in about one year – though the military avoided making an official commitment to that.[143]

State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint were placed under house arrest, and the military began filing various charges against them. The military expelled NLD party Members of Parliament from the capital city, Naypyidaw.[143] By 15 March 2021 the military leadership continued to extend martial law into more parts of Yangon, while security forces killed 38 people in a single day of violence.[145]

Reaction

Protesters against the military coup in Myanmar

By the second day of the coup, thousands of protesters were marching in the streets of the nation’s largest city, and commercial capital, Yangon, and other protests erupted nationwide, largely halting commerce and transportation. Despite the military’s arrests and killings of protesters, the first weeks of the coup found growing public participation, including groups of civil servants, teachers, students, workers, monks and religious leaders – even normally disaffected ethnic minorities.[146][147][143]

The coup was immediately condemned by the United Nations Secretary General, and leaders of democratic nations – including the United States President Joe Biden, western European political leaders, Southeast Asian democracies, and others around the world, who demanded or urged release of the captive leaders, and an immediate return to democratic rule in Myanmar. The U.S. threatened sanctions on the military and its leaders, including a «freeze» of US$1 billion of their assets in the U.S.[146][143]

India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Russia, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines and China refrained from criticizing the military coup.[148][149][150][151] The representatives of Russia and China had conferred with the Tatmadaw leader Gen. Hlaing just days before the coup.[152][153][154] Their possible complicity angered civilian protesters in Myanmar.[155][156] However, both of those nations refrained from blocking a United Nations Security Council resolution calling for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and the other detained leaders[146][143] – a position shared by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.[143]

International development and aid partners – business, non-governmental, and governmental – hinted at suspension of partnerships with Myanmar. Banks were closed and social media communications platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, removed Tatmadaw postings. Protesters appeared at Myanmar embassies in foreign countries.[146][143]

Geography

Myanmar map of Köppen climate classification.

Myanmar has a total area of 678,500 square kilometres (262,000 sq mi). It lies between latitudes 9° and 29°N, and longitudes 92° and 102°E. Myanmar is bordered in the northwest by the Chittagong Division of Bangladesh and the Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh states of India. Its north and northeast border is with the Tibet Autonomous Region and Yunnan for a Sino-Myanmar border total of 2,185 km (1,358 mi). It is bounded by Laos and Thailand to the southeast. Myanmar has 1,930 km (1,200 mi) of contiguous coastline along the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea to the southwest and the south, which forms one quarter of its total perimeter.[2]

In the north, the Hengduan Mountains form the border with China. Hkakabo Razi, located in Kachin State, at an elevation of 5,881 metres (19,295 ft), is the highest point in Myanmar.[157] Many mountain ranges, such as the Rakhine Yoma, the Bago Yoma, the Shan Hills and the Tenasserim Hills exist within Myanmar, all of which run north-to-south from the Himalayas.[158] The mountain chains divide Myanmar’s three river systems, which are the Irrawaddy, Salween (Thanlwin), and the Sittaung rivers.[159] The Irrawaddy River, Myanmar’s longest river at nearly 2,170 kilometres (1,348 mi), flows into the Gulf of Martaban. Fertile plains exist in the valleys between the mountain chains.[158] The majority of Myanmar’s population lives in the Irrawaddy valley, which is situated between the Rakhine Yoma and the Shan Plateau.

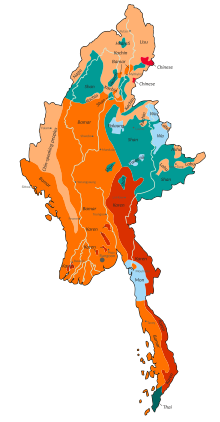

Administrative divisions

Myanmar is divided into seven states (ပြည်နယ်) and seven regions (တိုင်းဒေသကြီး), formerly called divisions.[160] Regions are predominantly Bamar (that is, mainly inhabited by Myanmar’s dominant ethnic group). States, in essence, are regions that are home to particular ethnic minorities. The administrative divisions are further subdivided into districts, which are further subdivided into townships, wards, and villages.

Below are the number of districts, townships, cities/towns, wards, village groups and villages in each division and state of Myanmar as of 31 December 2001:[161]

| No. | State/Region | Districts | Town ships |

Cities/ Towns |

Wards | Village groups |

Villages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kachin State | 4 | 18 | 20 | 116 | 606 | 2630 |

| 2 | Kayah State | 2 | 7 | 7 | 29 | 79 | 624 |

| 3 | Kayin State | 3 | 7 | 10 | 46 | 376 | 2092 |

| 4 | Chin State | 2 | 9 | 9 | 29 | 475 | 1355 |

| 5 | Sagaing Region | 8 | 37 | 37 | 171 | 1769 | 6095 |

| 6 | Tanintharyi Region | 3 | 10 | 10 | 63 | 265 | 1255 |

| 7 | Bago Region | 4 | 28 | 33 | 246 | 1424 | 6498 |

| 8 | Magway Region | 5 | 25 | 26 | 160 | 1543 | 4774 |

| 9 | Mandalay Region | 7 | 31 | 29 | 259 | 1611 | 5472 |

| 10 | Mon State | 2 | 10 | 11 | 69 | 381 | 1199 |

| 11 | Rakhine State | 4 | 17 | 17 | 120 | 1041 | 3871 |

| 12 | Yangon Region | 4 | 45 | 20 | 685 | 634 | 2119 |

| 13 | Shan State | 11 | 54 | 54 | 336 | 1626 | 15513 |

| 14 | Ayeyarwady Region | 6 | 26 | 29 | 219 | 1912 | 11651 |

| Total | 63 | 324 | 312 | 2548 | 13742 | 65148 |

Climate

Much of the country lies between the Tropic of Cancer and the Equator. It lies in the monsoon region of Asia, with its coastal regions receiving over 5,000 mm (196.9 in) of rain annually. Annual rainfall in the delta region is approximately 2,500 mm (98.4 in), while average annual rainfall in the dry zone in central Myanmar is less than 1,000 mm (39.4 in). The northern regions of Myanmar are the coolest, with average temperatures of 21 °C (70 °F). Coastal and delta regions have an average maximum temperature of 32 °C (89.6 °F).[159]

Previously and currently analysed data, as well as future projections on changes caused by climate change predict serious consequences to development for all economic, productive, social, and environmental sectors in Myanmar.[162] In order to combat the hardships ahead and do its part to help combat climate change Myanmar has displayed interest in expanding its use of renewable energy and lowering its level of carbon emissions. Groups involved in helping Myanmar with the transition and move forward include the UN Environment Programme, Myanmar Climate Change Alliance, and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation which directed in producing the final draft of the Myanmar national climate change policy that was presented to various sectors of the Myanmar government for review.[163]

In April 2015, it was announced that the World Bank and Myanmar would enter a full partnership framework aimed to better access to electricity and other basic services for about six million people and expected to benefit three million pregnant woman and children through improved health services.[164] Acquired funding and proper planning has allowed Myanmar to better prepare for the impacts of climate change by enacting programs which teach its people new farming methods, rebuild its infrastructure with materials resilient to natural disasters, and transition various sectors towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[165]

Biodiversity

Myanmar is a biodiverse country with more than 16,000 plant, 314 mammal, 1131 bird, 293 reptile, and 139 amphibian species, and 64 terrestrial ecosystems including tropical and subtropical vegetation, seasonally inundated wetlands, shoreline and tidal systems, and alpine ecosystems. Myanmar houses some of the largest intact natural ecosystems in Southeast Asia, but the remaining ecosystems are under threat from land use intensification and over-exploitation. According to the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems categories and criteria more than a third of Myanmar’s land area has been converted to anthropogenic ecosystems over the last 2–3 centuries, and nearly half of its ecosystems are threatened. Despite large gaps in information for some ecosystems, there is a large potential to develop a comprehensive protected area network that protects its terrestrial biodiversity.[166]

Myanmar continues to perform badly in the global Environmental Performance Index (EPI) with an overall ranking of 153 out of 180 countries in 2016; among the worst in the South Asian region, only ahead of Bangladesh and Afghanistan. The EPI was established in 2001 by the World Economic Forum as a global gauge to measure how well individual countries perform in implementing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The environmental areas where Myanmar performs worst (i.e. highest ranking) are air quality (174), health impacts of environmental issues (143) and biodiversity and habitat (142). Myanmar performs best (i.e. lowest ranking) in environmental impacts of fisheries (21) but with declining fish stocks. Despite several issues, Myanmar also ranks 64 and scores very good (i.e. a high percentage of 93.73%) in environmental effects of the agricultural industry because of an excellent management of the nitrogen cycle.[167][168] Myanmar is one of the most highly vulnerable countries to climate change; this poses a number of social, political, economic and foreign policy challenges to the country.[169] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.18/10, ranking it 49th globally out of 172 countries.[170]

Myanmar’s slow economic growth has contributed to the preservation of much of its environment and ecosystems. Forests, including dense tropical growth and valuable teak in lower Myanmar, cover over 49% of the country, including areas of acacia, bamboo, ironwood and Magnolia champaca. Coconut and betel palm and rubber have been introduced. In the highlands of the north, oak, pine and various rhododendrons cover much of the land.[171]

Heavy logging since the new 1995 forestry law went into effect has seriously reduced forest area and wildlife habitat.[172] The lands along the coast support all varieties of tropical fruits and once had large areas of mangroves although much of the protective mangroves have disappeared. In much of central Myanmar (the dry zone), vegetation is sparse and stunted.

Typical jungle animals, particularly tigers, occur sparsely in Myanmar. In upper Myanmar, there are rhinoceros, wild water buffalo, clouded leopard, wild boars, deer, antelope, and elephants, which are also tamed or bred in captivity for use as work animals, particularly in the lumber industry. Smaller mammals are also numerous, ranging from gibbons and monkeys to flying foxes. The abundance of birds is notable with over 800 species, including parrots, myna, peafowl, red junglefowl, weaverbirds, crows, herons, and barn owl. Among reptile species there are crocodiles, geckos, cobras, Burmese pythons, and turtles. Hundreds of species of freshwater fish are wide-ranging, plentiful and are very important food sources.[173]

Government and politics

Myanmar operates de jure as a unitary assembly-independent republic under its 2008 constitution. But in February 2021, the civilian government led by Aung San Suu Kyi, was deposed by the Tatmadaw. In February 2021, Myanmar military declared a one-year state emergency and First Vice President Myint Swe became the Acting President of Myanmar and handed the power to the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Min Aung Hlaing and he assumed the role Chairman of the State Administration Council, then Prime Minister. The President of Myanmar acts as the de jure head of state and the Chairman of the State Administration Council acts as the de facto head of government.[174]

The constitution of Myanmar, its third since independence, was drafted by its military rulers and published in September 2008. The country is governed as a parliamentary system with a bicameral legislature (with an executive president accountable to the legislature), with 25% of the legislators appointed by the military and the rest elected in general elections.

The legislature, called the Assembly of the Union, is bicameral and made up of two houses: the 224-seat upper House of Nationalities and the 440-seat lower House of Representatives. The upper house consists 168 members who are directly elected and 56 who are appointed by the Burmese Armed Forces. The lower house consists of 330 members who are directly elected and 110 who are appointed by the armed forces.

Political culture

The major political parties are the National League for Democracy and the Union Solidarity and Development Party.

Myanmar’s army-drafted constitution was approved in a referendum in May 2008. The results, 92.4% of the 22 million voters with an official turnout of 99%, are considered suspect by many international observers and by the National League of Democracy with reports of widespread fraud, ballot stuffing, and voter intimidation.[175]

The elections of 2010 resulted in a victory for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party. Various foreign observers questioned the fairness of the elections.[176][177][178] One criticism of the election was that only government-sanctioned political parties were allowed to contest in it and the popular National League for Democracy was declared illegal.[179] However, immediately following the elections, the government ended the house arrest of the democracy advocate and leader of the National League for Democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi,[180] and her ability to move freely around the country is considered an important test of the military’s movement toward more openness.[179] After unexpected reforms in 2011, NLD senior leaders have decided to register as a political party and to field candidates in future by-elections.[181]

Myanmar’s political history is underlined by its struggle to establish democratic structures amidst conflicting factions. This political transition from a closely held military rule to a free democratic system is widely believed to be determining the future of Myanmar. The resounding victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy in the 2015 general election raised hope for a successful culmination of this transition.[182][183]

Myanmar rates as a corrupt nation on the Corruption Perceptions Index with a rank of 130th out of 180 countries worldwide, with 1st being least corrupt, as of 2019.[184]

Foreign relations

Though the country’s foreign relations, particularly with Western nations, have historically been strained, the situation has markedly improved since the reforms following the 2010 elections. After years of diplomatic isolation and economic and military sanctions,[185] the United States relaxed curbs on foreign aid to Myanmar in November 2011[119] and announced the resumption of diplomatic relations on 13 January 2012[186] The European Union has placed sanctions on Myanmar, including an arms embargo, cessation of trade preferences, and suspension of all aid with the exception of humanitarian aid.[187]

Sanctions imposed by the United States and European countries against the former military government, coupled with boycotts and other direct pressure on corporations by supporters of the democracy movement, have resulted in the withdrawal from the country of most U.S. and many European companies.[188] On 13 April 2012, British Prime Minister David Cameron called for the economic sanctions on Myanmar to be suspended in the wake of the pro-democracy party gaining 43 seats out of a possible 45 in the 2012 by-elections with the party leader, Aung San Suu Kyi becoming a member of the Burmese parliament.[189]

Despite Western isolation, Asian corporations have generally remained willing to continue investing in the country and to initiate new investments, particularly in natural resource extraction. The country has close relations with neighbouring India and China with several Indian and Chinese companies operating in the country. Under India’s Look East policy, fields of co-operation between India and Myanmar include remote sensing,[190] oil and gas exploration,[191] information technology,[192] hydropower[193] and construction of ports and buildings.[194]

In 2008, India suspended military aid to Myanmar over the issue of human rights abuses by the ruling junta, although it has preserved extensive commercial ties, which provide the regime with much-needed revenue.[195] The thaw in relations began on 28 November 2011, when Belarusian Prime Minister Mikhail Myasnikovich and his wife Ludmila arrived in the capital, Naypyidaw, the same day as the country received a visit by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who also met with pro-democracy opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[196] International relations progress indicators continued in September 2012 when Aung San Suu Kyi visited the United States[197] followed by Myanmar’s reformist president visit to the United Nations.[198]

In May 2013, Thein Sein became the first Myanmar president to visit the White House in 47 years; the last Burmese leader to visit the White House was Ne Win in September 1966. President Barack Obama praised the former general for political and economic reforms and the cessation of tensions between Myanmar and the United States. Political activists objected to the visit because of concerns over human rights abuses in Myanmar, but Obama assured Thein Sein that Myanmar will receive U.S. support. The two leaders discussed the release of more political prisoners, the institutionalisation of political reform and the rule of law, and ending ethnic conflict in Myanmar—the two governments agreed to sign a bilateral trade and investment framework agreement on 21 May 2013.[199]

In June 2013, Myanmar held its first ever summit, the World Economic Forum on East Asia 2013. A regional spinoff of the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, the summit was held on 5–7 June and attended by 1,200 participants, including 10 heads of state, 12 ministers and 40 senior directors from around the world.[200]

Military

Myanmar has received extensive military aid from China in the past.[201]

Myanmar has been a member of ASEAN since 1997. Though it gave up its turn to hold the ASEAN chair and host the ASEAN Summit in 2006, it chaired the forum and hosted the summit in 2014.[202] In November 2008, Myanmar’s political situation with neighbouring Bangladesh became tense as they began searching for natural gas in a disputed block of the Bay of Bengal.[203] Controversy surrounding the Rohingya population also remains an issue between Bangladesh and Myanmar.[204]

Myanmar’s armed forces are known as the Tatmadaw, which numbers 488,000. The Tatmadaw comprises the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force. The country ranked twelfth in the world for its number of active troops in service.[32] The military is very influential in Myanmar, with all top cabinet and ministry posts usually held by military officials. Official figures for military spending are not available. Estimates vary widely because of uncertain exchange rates, but Myanmar’s military forces’ expenses are high.[205] Myanmar imports most of its weapons from Russia, Ukraine, China and India.

Myanmar is building a research nuclear reactor near Pyin Oo Lwin with help from Russia. It is one of the signatories of the nuclear non-proliferation pact since 1992 and a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) since 1957. The military junta had informed the IAEA in September 2000 of its intention to construct the reactor.[206][207] In 2010 as part of the Wikileaks leaked cables, Myanmar was suspected of using North Korean construction teams to build a fortified surface-to-air missile facility.[208] As of 2019, the United States Bureau of Arms Control assessed that Myanmar is not in violation of its obligations under the Non-Proliferation Treaty but that the Myanmar government had a history of non-transparency on its nuclear programs and aims.[209]

Until 2005, the United Nations General Assembly annually adopted a detailed resolution about the situation in Myanmar by consensus.[210][211][212][213] But in 2006 a divided United Nations General Assembly voted through a resolution that strongly called upon the government of Myanmar to end its systematic violations of human rights.[214] In January 2007, Russia and China vetoed a draft resolution before the United Nations Security Council[215] calling on the government of Myanmar to respect human rights and begin a democratic transition. South Africa also voted against the resolution.[216]

Human rights and internal conflicts

Map of conflict zones in Myanmar. States and regions affected by fighting during and after 1995 are highlighted in yellow.

There is consensus that the former military regime in Myanmar (1962–2010) was one of the world’s most repressive and abusive regimes.[217][218] In November 2012, Samantha Power, Barack Obama’s Special Assistant to the President on Human Rights, wrote on the White House blog in advance of the president’s visit that «Serious human rights abuses against civilians in several regions continue, including against women and children.»[105] Members of the United Nations and major international human rights organisations have issued repeated and consistent reports of widespread and systematic human rights violations in Myanmar. The United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly[219] called on the Burmese military junta to respect human rights and in November 2009 the General Assembly adopted a resolution «strongly condemning the ongoing systematic violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms» and calling on the Burmese military regime «to take urgent measures to put an end to violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.»[220]

International human rights organisations including Human Rights Watch,[221] Amnesty International[222] and the American Association for the Advancement of Science[223] have repeatedly documented and condemned widespread human rights violations in Myanmar. The Freedom in the World 2011 report by Freedom House notes, «The military junta has … suppressed nearly all basic rights; and committed human rights abuses with impunity.» In July 2013, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners indicated that there were approximately 100 political prisoners being held in Burmese prisons.[224][225][226][227] Evidence gathered by a British researcher was published in 2005 regarding the extermination or «Burmisation» of certain ethnic minorities, such as the Karen, Karenni and Shan.[228]

Based on the evidence gathered by Amnesty photographs and video of the ongoing armed conflict between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA), attacks escalated on civilians in Rakhine State. Ming Yu Hah, Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for Campaigns said, the UN Security Council must urgently refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court.[230] The military is notorious for rampant use of sexual violence.[14]

Child soldiers

Child soldiers were reported in 2012 to have played a major part in the Burmese Army.[231] The Independent reported in June 2012 that «Children are being sold as conscripts into the Burmese military for as little as $40 and a bag of rice or a can of petrol.»[232] The UN’s Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, Radhika Coomaraswamy, who stepped down from her position a week later, met representatives of the government of Myanmar in July 2012 and stated that she hoped the government’s signing of an action plan would «signal a transformation.»[233] In September 2012, the Myanmar Armed Forces released 42 child soldiers, and the International Labour Organization met with representatives of the government as well as the Kachin Independence Army to secure the release of more child soldiers.[234] According to Samantha Power, a U.S. delegation raised the issue of child soldiers with the government in October 2012. However, she did not comment on the government’s progress towards reform in this area.[105]

Slavery and human trafficking

Forced labour, human trafficking, and child labour are common in Myanmar.[235][236] In 2007 the international movement to defend women’s human rights issues in Myanmar was said to be gaining speed.[237] Human trafficking happens mostly to women who are unemployed and have low incomes. They are mainly targeted or deceived by brokers into making them believe that better opportunities and wages exist for them abroad.[238] In 2017, the government reported investigating 185 trafficking cases. The government of Burma makes little effort to eliminate human trafficking. Burmese armed forces compel troops to acquire labour and supplies from local communities. The U.S. State Department reported that both the government and Tatmadaw were complicit in sex and labour trafficking.[239] Women and girls from all ethnic groups and foreigners have been victims of sex trafficking in Myanmar.[231] They are forced into prostitution, marriages, and or pregnancies.[240][241]

Genocide allegations and crimes against Rohingya people

The Rohingya people have consistently faced human rights abuses by the Burmese regime that has refused to acknowledge them as Burmese citizens (despite some of them having lived in Burma for over three generations)—the Rohingya have been denied Burmese citizenship since the enactment of a 1982 citizenship law.[244] The law created three categories of citizenship: citizenship, associate citizenship, and naturalised citizenship. Citizenship is given to those who belong to one of the national races such as Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Karen, Chin, Burman, Mon, Rakhine, Shan, Kaman, or Zerbadee. Associate citizenship is given to those who cannot prove their ancestors settled in Myanmar before 1823 but can prove they have one grandparent, or pre-1823 ancestor, who was a citizen of another country, as well as people who applied for citizenship in 1948 and qualified then by those laws. Naturalised citizenship is only given to those who have at least one parent with one of these types of Burmese citizenship or can provide «conclusive evidence» that their parents entered and resided in Burma prior to independence in 1948.[245] The Burmese regime has attempted to forcibly expel Rohingya and bring in non-Rohingyas to replace them[246]—this policy has resulted in the expulsion of approximately half of the 800,000[247] Rohingya from Burma, while the Rohingya people have been described as «among the world’s least wanted»[248] and «one of the world’s most persecuted minorities.»[246][249][250] But the origin of the «most persecuted minority» statement is unclear.[251]

Rohingya are not allowed to travel without official permission, are banned from owning land, and are required to sign a commitment to have no more than two children.[244] As of July 2012, the Myanmar government does not include the Rohingya minority group—classified as stateless Bengali Muslims from Bangladesh since 1982—on the government’s list of more than 130 ethnic races and, therefore, the government states that they have no claim to Myanmar citizenship.[252]

In 2007 German professor Bassam Tibi suggested that the Rohingya conflict may be driven by an Islamist political agenda to impose religious laws,[253] while non-religious causes have also been raised, such as a lingering resentment over the violence that occurred during the Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II—during this time period the British allied themselves with the Rohingya[254] and fought against the puppet government of Burma (composed mostly of Bamar Japanese) that helped to establish the Tatmadaw military organisation that remains in power except for a 5-year lapse in 2016–2021.

Since the democratic transition began in 2011, there has been continuous violence as 280 people have been killed and 140,000 forced to flee from their homes in the Rakhine state in 2014.[255] A UN envoy reported in March 2013 that unrest had re-emerged between Myanmar’s Buddhist and Muslim communities, with violence spreading to towns that are located closer to Yangon.[256]

Government reforms

According to the Crisis Group,[257] since Myanmar transitioned to a new government in August 2011, the country’s human rights record has been improving. Previously giving Myanmar its lowest rating of 7, the 2012 Freedom in the World report also notes improvement, giving Myanmar a 6 for improvements in civil liberties and political rights, the release of political prisoners, and a loosening of restrictions.[258] In 2013, Myanmar improved yet again, receiving a score of 5 in civil liberties and 6 in political freedoms.[259]

The government has assembled a National Human Rights Commission that consists of 15 members from various backgrounds.[260] Several activists in exile, including Thee Lay Thee Anyeint members, have returned to Myanmar after President Thein Sein’s invitation to expatriates to return home to work for national development.[261] In an address to the United Nations Security Council on 22 September 2011, Myanmar’s Foreign Minister Wunna Maung Lwin confirmed the government’s intention to release prisoners in the near future.[262]

The government has also relaxed reporting laws, but these remain highly restrictive.[263] In September 2011, several banned websites, including YouTube, Democratic Voice of Burma and Voice of America, were unblocked.[264] A 2011 report by the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations found that, while contact with the Myanmar government was constrained by donor restrictions, international humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) see opportunities for effective advocacy with government officials, especially at the local level. At the same time, international NGOs are mindful of the ethical quandary of how to work with the government without bolstering or appeasing it.[265]

A Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh

Following Thein Sein’s first ever visit to the UK and a meeting with Prime Minister David Cameron, the Myanmar president declared that all of his nation’s political prisoners will be released by the end of 2013, in addition to a statement of support for the well-being of the Rohingya Muslim community. In a speech at Chatham House, he revealed that «We [Myanmar government] are reviewing all cases. I guarantee to you that by the end of this year, there will be no prisoners of conscience in Myanmar.», in addition to expressing a desire to strengthen links between the UK and Myanmar’s military forces.[266]

Homosexual acts are illegal in Myanmar and can be punishable by life imprisonment.[267][268]

In 2016, Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi was accused of failing to protect Myanmar’s Muslim minority.[269] Since August 2017 Doctors Without Borders have treated 113 Rohingya refugee females for sexual assault with all but one describing military assailants.[270]

Economy

A proportional representation of Myanmar exports, 2019

Myanmar’s economy is one of the fastest growing economies in the world with a nominal GDP of US$76.09 billion in 2019 and an estimated purchasing power adjusted GDP of US$327.629 billion in 2017 according to the World Bank.[271][improper synthesis?] Foreigners are able to legally lease but not own property.[272] In December 2014, Myanmar set up its first stock exchange, the Yangon Stock Exchange.[273]

The informal economy’s share in Myanmar is one of the biggest in the world and is closely linked to corruption, smuggling and illegal trade activities.[274][275] In addition, decades of civil war and unrest have contributed to Myanmar’s current levels of poverty and lack of economic progress. Myanmar lacks adequate infrastructure. Goods travel primarily across the Thai border (where most illegal drugs are exported) and along the Irrawaddy River.[276]

Both China and India have attempted to strengthen ties with the government for economic benefit in the early 2010s. Many Western nations, including the United States and Canada, and the European Union, historically imposed investment and trade sanctions on Myanmar. The United States and European Union eased most of their sanctions in 2012.[277] From May 2012 to February 2013, the United States began to lift its economic sanctions on Myanmar «in response to the historic reforms that have been taking place in that country.»[278] Foreign investment comes primarily from China, Singapore, the Philippines, South Korea, India, and Thailand.[279] The military has stakes in some major industrial corporations of the country (from oil production and consumer goods to transportation and tourism).[280][281]

Economic history

The trains are relatively slow in Myanmar. The railway trip from Bagan to Mandalay takes about 7.5 hours (179 km or 111 mi).

Under the British administration, the people of Burma were at the bottom of the social hierarchy, with Europeans at the top, Indians, Chinese, and Christianized minorities in the middle, and Buddhist Burmese at the bottom.[282] Forcefully integrated into the world economy, Burma’s economy grew by involving itself with extractive industries and cash crop agriculture. However, much of the wealth was concentrated in the hands of Europeans. The country became the world’s largest exporter of rice, mainly to European markets, while other colonies like India suffered mass starvation.[283] Being a follower of free market principles, the British opened up the country to large-scale immigration with Rangoon exceeding New York City as the greatest immigration port in the world in the 1920s. Historian Thant Myint-U states, «This was out of a total population of only 13 million; it was equivalent to the United Kingdom today taking 2 million people a year.» By then, in most of Burma’s largest cities, Rangoon, Akyab, Bassein and Moulmein, the Indian immigrants formed a majority of the population. The Burmese under British rule felt helpless, and reacted with a «racism that combined feelings of superiority and fear».[282]

Crude oil production, an indigenous industry of Yenangyaung, was taken over by the British and put under Burmah Oil monopoly. British Burma began exporting crude oil in 1853.[284] European firms produced 75% of the world’s teak.[29] The wealth was, however, mainly concentrated in the hands of Europeans. In the 1930s, agricultural production fell dramatically as international rice prices declined and did not recover for several decades.[285] During the Japanese invasion of Burma in World War II, the British followed a scorched earth policy. They destroyed major government buildings, oil wells and mines that developed for tungsten (Mawchi), tin, lead and silver to keep them from the Japanese. Myanmar was bombed extensively by the Allies.[citation needed]

After independence, the country was in ruins with its major infrastructure completely destroyed. With the loss of India, Burma lost relevance and obtained independence from the British. After a parliamentary government was formed in 1948, Prime Minister U Nu embarked upon a policy of nationalisation and the state was declared the owner of all of the land in Burma. The government tried to implement an eight-year plan partly financed by injecting money into the economy, but this caused inflation to rise.[286] The 1962 coup d’état was followed by an economic scheme called the Burmese Way to Socialism, a plan to nationalise all industries, with the exception of agriculture. While the economy continued to grow at a slower rate, the country eschewed a Western-oriented development model, and by the 1980s, was left behind capitalist powerhouses like Singapore which were integrated with Western economies.[287][86] Myanmar asked for admittance to a least developed country status in 1987 to receive debt relief.[288]

Agriculture

Rice is Myanmar’s largest agricultural product.

The major agricultural product is rice, which covers about 60% of the country’s total cultivated land area. Rice accounts for 97% of total food grain production by weight. Through collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute 52 modern rice varieties were released in the country between 1966 and 1997, helping increase national rice production to 14 million tons in 1987 and to 19 million tons in 1996. By 1988, modern varieties were planted on half of the country’s ricelands, including 98 per cent of the irrigated areas.[289] In 2008 rice production was estimated at 50 million tons.[290]

Myanmar produces precious stones such as rubies, sapphires, pearls, and jade. Rubies are the biggest earner; 90% of the world’s rubies come from the country, whose red stones are prized for their purity and hue. Thailand buys the majority of the country’s gems. Myanmar’s «Valley of Rubies», the mountainous Mogok area, 200 km (120 mi) north of Mandalay, is noted for its rare pigeon’s blood rubies and blue sapphires.[291]

Many U.S. and European jewellery companies, including Bulgari, Tiffany and Cartier, refuse to import these stones based on reports of deplorable working conditions in the mines. Human Rights Watch has encouraged a complete ban on the purchase of Burmese gems based on these reports and because nearly all profits go to the ruling junta, as the majority of mining activity in the country is government-run.[292] The government of Myanmar controls the gem trade by direct ownership or by joint ventures with private owners of mines.[293]

Rare-earth elements are also a significant export, as Myanmar supplies around 10% of the world’s rare earths.[294] Conflict in Kachin State has threatened the operations of its mines as of February 2021.[295][296]

Other industries include agricultural goods, textiles, wood products, construction materials, gems, metals, oil and natural gas. Myanmar Engineering Society has identified at least 39 locations capable of geothermal power production and some of these hydrothermal reservoirs lie quite close to Yangon which is a significant underutilised resource for electrical production.[297]

Tourism

The government receives a significant percentage of the income of private-sector tourism services.[298] The most popular available tourist destinations in Myanmar include big cities such as Yangon and Mandalay; religious sites in Mon State, Pindaya, Bago and Hpa-An; nature trails in Inle Lake, Kengtung, Putao, Pyin Oo Lwin; ancient cities such as Bagan and Mrauk-U; as well as beaches in Nabule,[299] Ngapali, Ngwe-Saung, Mergui.[300] Nevertheless, much of the country is off-limits to tourists, and interactions between foreigners and the people of Myanmar, particularly in the border regions, are subject to police scrutiny. They are not to discuss politics with foreigners, under penalty of imprisonment and, in 2001, the Myanmar Tourism Promotion Board issued an order for local officials to protect tourists and limit «unnecessary contact» between foreigners and ordinary Burmese people.[301]

The most common way for travellers to enter the country is by air.[302] According to the website Lonely Planet, getting into Myanmar is problematic: «No bus or train service connects Myanmar with another country, nor can you travel by car or motorcycle across the border – you must walk across.» They further state that «It is not possible for foreigners to go to/from Myanmar by sea or river.»[302] There are a few border crossings that allow the passage of private vehicles, such as the border between Ruili (China) to Mu-se, the border between Htee Kee (Myanmar) and Phu Nam Ron (Thailand)—the most direct border between Dawei and Kanchanaburi, and the border between Myawaddy and Mae Sot, Thailand. At least one tourist company has successfully run commercial overland routes through these borders since 2013.[303]

Flights are available from most countries, though direct flights are limited to mainly Thai and other ASEAN airlines. According to Eleven magazine, «In the past, there were only 15 international airlines and increasing numbers of airlines have begun launching direct flights from Japan, Qatar, Taiwan, South Korea, Germany and Singapore.»[304] Expansions were expected in September 2013 but are mainly Thai and other Asian-based airlines.[304]

Demographics

A block of apartments in downtown Yangon, facing Bogyoke Market. Much of Yangon’s urban population resides in densely populated flats.

| Population[305][306] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Million |

| 1950 | 17.1 |

| 2000 | 46.1 |

| 2021 | 53.8 |