This article is about the military alliance. For other uses, see NATO (disambiguation).

| Organisation du traité de l’Atlantique nord | |

Logo |

|

Flag |

|

Member states shown in dark green |

|

| Abbreviation | NATO, OTAN |

|---|---|

| Formation | 4 April 1949 (73 years ago) |

| Type | Military alliance |

| Headquarters | Brussels, Belgium |

|

Membership |

30 states

|

|

Official language |

English and French[1] |

|

Secretary General |

Jens Stoltenberg |

|

Chair of the NATO Military Committee |

Lt. Admiral Rob Bauer, Royal Netherlands Navy |

|

Supreme Allied Commander Europe |

General Christopher G. Cavoli, United States Army |

|

Supreme Allied Commander Transformation |

Général Philippe Lavigne, French Air and Space Force |

| Expenses (2021) | US$1.050 trillion[2] |

| Website | www.nato.int |

|

Anthem: «The NATO Hymn» Motto: «Animus in consulendo liber» |

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; French: Organisation du traité de l’Atlantique nord, OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two North American. Established in the aftermath of World War II, the organization implemented the North Atlantic Treaty, signed in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 1949.[3][4] NATO is a collective security system: its independent member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties. During the Cold War, NATO operated as a check on the perceived threat posed by the Soviet Union. The alliance remained in place after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and has been involved in military operations in the Balkans, the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa. The organization’s motto is animus in consulendo liber[5] (Latin for «a mind unfettered in deliberation»).

NATO’s main headquarters are located in Brussels, Belgium, while NATO’s military headquarters are near Mons, Belgium. The alliance has targeted its NATO Response Force deployments in Eastern Europe, and the combined militaries of all NATO members include around 3.5 million soldiers and personnel.[6] Their combined military spending as of 2020 constituted over 57 percent of the global nominal total.[7] Moreover, members have agreed to reach or maintain the target defence spending of at least two percent of their GDP by 2024.[8][9]

NATO formed with twelve founding members and has added new members eight times, most recently when North Macedonia joined the alliance in March 2020. Following the acceptance of their applications for membership in June 2022, Finland and Sweden are anticipated to become the 31st and 32nd members, with their Accession Protocols to the North Atlantic Treaty now in the process of being ratified by the existing members.[10] In addition, NATO currently recognizes Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, and Ukraine as aspiring members.[3] Enlargement has led to tensions with non-member Russia, one of the twenty additional countries participating in NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme. Another nineteen countries are involved in institutionalized dialogue programmes with NATO.

History

The Treaty of Dunkirk was signed by France and the United Kingdom on 4 March 1947, during the aftermath of World War II and the start of the Cold War, as a Treaty of Alliance and Mutual Assistance in the event of possible attacks by Germany or the Soviet Union. In March 1948, this alliance was expanded in the Treaty of Brussels to include the Benelux countries, forming the Brussels Treaty Organization, commonly known as the Western Union.[11] Talks for a wider military alliance, which could include North America, also began that month in the United States, where their foreign policy under the Truman Doctrine promoted international solidarity against actions they saw as communist aggression, such as the February 1948 coup d’état in Czechoslovakia. These talks resulted in the signature of the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949 by the member states of the Western Union plus the United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland.[12] Canadian diplomat Lester B. Pearson was a key author and drafter of the treaty.[13][14][15]

The North Atlantic Treaty was largely dormant until the Korean War initiated the establishment of NATO to implement it with an integrated military structure. This included the formation of Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in 1951, which adopted many of the Western Union’s military structures and plans,[16] including their agreements on standardizing equipment and agreements on stationing foreign military forces in European countries. In 1952, the post of Secretary General of NATO was established as the organization’s chief civilian. That year also saw the first major NATO maritime exercises, Exercise Mainbrace and the accession of Greece and Turkey to the organization.[17][18] Following the London and Paris Conferences, West Germany was permitted to rearm militarily, as they joined NATO in May 1955, which was, in turn, a major factor in the creation of the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact, delineating the two opposing sides of the Cold War.[19]

The building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 marked a height in Cold War tensions, when 400,000 US troops were stationed in Europe.[20] Doubts over the strength of the relationship between the European states and the United States ebbed and flowed, along with doubts over the credibility of the NATO defence against a prospective Soviet invasion – doubts that led to the development of the independent French nuclear deterrent and the withdrawal of France from NATO’s military structure in 1966.[21][22] In 1982, the newly democratic Spain joined the alliance.[23]

The Revolutions of 1989 in Europe led to a strategic re-evaluation of NATO’s purpose, nature, tasks, and focus on the continent. In October 1990, East Germany became part of the Federal Republic of Germany and the alliance, and in November 1990, the alliance signed the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) in Paris with the Soviet Union. It mandated specific military reductions across the continent, which continued after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact in February 1991 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union that December, which removed the de facto main adversaries of NATO.[24] This began a draw-down of military spending and equipment in Europe. The CFE treaty allowed signatories to remove 52,000 pieces of conventional armaments in the following sixteen years,[25] and allowed military spending by NATO’s European members to decline by 28 percent from 1990 to 2015.[26] In 1990 assurances were given by several Western leaders to Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would not expand further east, as revealed by memoranda of private conversations.[27][28][29][30] However, the final text of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, signed later that year, contained no mention of the issue of eastward expansion.

The Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 marked a turning point in NATO’s role in Europe, and this section of the wall is now displayed outside NATO Headquarters.

In the 1990s, the organization extended its activities into political and humanitarian situations that had not formerly been NATO concerns.[31] During the Breakup of Yugoslavia, the organization conducted its first military interventions in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 and later Yugoslavia in 1999.[32] These conflicts motivated a major post-Cold War military restructuring. NATO’s military structure was cut back and reorganized, with new forces such as the Headquarters Allied Command Europe Rapid Reaction Corps established.

Politically, the organization sought better relations with the newly autonomous Central and Eastern European states, and diplomatic forums for regional cooperation between NATO and its neighbours were set up during this post-Cold War period, including the Partnership for Peace and the Mediterranean Dialogue initiative in 1994, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council in 1997, and the NATO–Russia Permanent Joint Council in 1998. At the 1999 Washington summit, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic officially joined NATO, and the organization also issued new guidelines for membership with individualized «Membership Action Plans». These plans governed the addition of new alliance members: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia in 2004, Albania and Croatia in 2009, Montenegro in 2017, and North Macedonia in 2020.[33] The election of French President Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007 led to a major reform of France’s military position, culminating with the return to full membership on 4 April 2009, which also included France rejoining the NATO Military Command Structure, while maintaining an independent nuclear deterrent.[22][34][35]

Article 5 of the North Atlantic treaty, requiring member states to come to the aid of any member state subject to an armed attack, was invoked for the first and only time after the September 11 attacks,[36] after which troops were deployed to Afghanistan under the NATO-led ISAF. The organization has operated a range of additional roles since then, including sending trainers to Iraq, assisting in counter-piracy operations,[37] and in 2011 enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1973.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea led to strong condemnation by all NATO members,[38] and was one of the seven times that Article 4, which calls for consultation among NATO members, has been invoked. Prior times included during the Iraq War and Syrian Civil War.[39] At the 2014 Wales summit, the leaders of NATO’s member states formally committed for the first time to spend the equivalent of at least two percent of their gross domestic products on defence by 2024, which had previously been only an informal guideline.[40] At the 2016 Warsaw summit, NATO countries agreed on the creation of NATO Enhanced Forward Presence, which deployed four multinational battalion-sized battlegroups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland.[41] Before and during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, several NATO countries sent ground troops, warships and fighter aircraft to reinforce the alliance’s eastern flank, and multiple countries again invoked Article 4.[42][43][44] In March 2022, NATO leaders met at Brussels for an extraordinary summit which also involved Group of Seven and European Union leaders.[45] NATO member states agreed to establish four additional battlegroups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia,[41] and elements of the NATO Response Force were activated for the first time in NATO’s history.[46]

As of June 2022, NATO had deployed 40,000 troops along its 2,500-kilometre-long (1,550 mi) Eastern flank to deter Russian aggression. More than half of this number have been deployed in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland, which five countries muster a considerable combined ex-NATO force of 259,000 troops. To supplement Bulgaria’s Air Force, Spain sent Eurofighter Typhoons, the Netherlands sent eight F-35 attack aircraft, and additional French and US attack aircraft would arrive soon as well.[47]

NATO enjoys public support across its member states.[48]

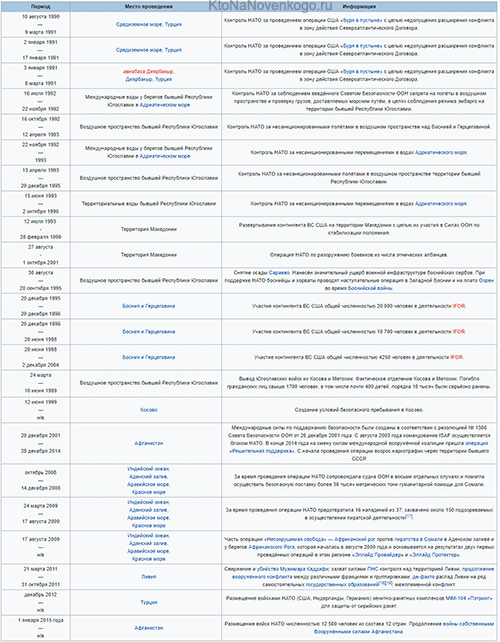

Military operations

Early operations

No military operations were conducted by NATO during the Cold War. Following the end of the Cold War, the first operations, Anchor Guard in 1990 and Ace Guard in 1991, were prompted by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Airborne early warning aircraft were sent to provide coverage of southeastern Turkey, and later a quick-reaction force was deployed to the area.[49]

Bosnia and Herzegovina intervention

The Bosnian War began in 1992, as a result of the Breakup of Yugoslavia. The deteriorating situation led to United Nations Security Council Resolution 816 on 9 October 1992, ordering a no-fly zone over central Bosnia and Herzegovina, which NATO began enforcing on 12 April 1993 with Operation Deny Flight. From June 1993 until October 1996, Operation Sharp Guard added maritime enforcement of the arms embargo and economic sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On 28 February 1994, NATO took its first wartime action by shooting down four Bosnian Serb aircraft violating the no-fly zone.[50]

On 10 and 11 April 1994, the United Nations Protection Force called in air strikes to protect the Goražde safe area, resulting in the bombing of a Bosnian Serb military command outpost near Goražde by two US F-16 jets acting under NATO direction.[51] In retaliation, Serbs took 150 U.N. personnel hostage on 14 April.[52][53] On 16 April a British Sea Harrier was shot down over Goražde by Serb forces.[54]

In August 1995, a two-week NATO bombing campaign, Operation Deliberate Force, began against the Army of the Republika Srpska, after the Srebrenica genocide.[55] Further NATO air strikes helped bring the Yugoslav Wars to an end, resulting in the Dayton Agreement in November 1995.[55] As part of this agreement, NATO deployed a UN-mandated peacekeeping force, under Operation Joint Endeavor, named IFOR. Almost 60,000 NATO troops were joined by forces from non-NATO countries in this peacekeeping mission. This transitioned into the smaller SFOR, which started with 32,000 troops initially and ran from December 1996 until December 2004, when operations were then passed onto the European Union Force Althea.[56] Following the lead of its member states, NATO began to award a service medal, the NATO Medal, for these operations.[57]

Kosovo intervention

German KFOR soldiers on patrol in southern Kosovo in 1999

In an effort to stop Slobodan Milošević’s Serbian-led crackdown on KLA separatists and Albanian civilians in Kosovo, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1199 on 23 September 1998 to demand a ceasefire. Negotiations under US Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke broke down on 23 March 1999, and he handed the matter to NATO,[58] which started a 78-day bombing campaign on 24 March 1999.[59] Operation Allied Force targeted the military capabilities of what was then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During the crisis, NATO also deployed one of its international reaction forces, the ACE Mobile Force (Land), to Albania as the Albania Force (AFOR), to deliver humanitarian aid to refugees from Kosovo.[citation needed]

The campaign was criticized over whether it had legitimacy and for the civilian casualties, including the bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. Milošević finally accepted the terms of an international peace plan on 3 June 1999, ending the Kosovo War. On 11 June, Milošević further accepted UN resolution 1244, under the mandate of which NATO then helped establish the KFOR peacekeeping force. Nearly one million refugees had fled Kosovo, and part of KFOR’s mandate was to protect the humanitarian missions, in addition to deterring violence.[60] In August–September 2001, the alliance also mounted Operation Essential Harvest, a mission disarming ethnic Albanian militias in the Republic of Macedonia.[61] As of 1 December 2013, 4,882 KFOR soldiers, representing 31 countries, continue to operate in the area.[62][non-primary source needed]

The US, the UK, and most other NATO countries opposed efforts to require the UN Security Council to approve NATO military strikes, such as the action against Serbia in 1999, while France and some others claimed that the alliance needed UN approval.[63] The US/UK side claimed that this would undermine the authority of the alliance, and they noted that Russia and China would have exercised their Security Council vetoes to block the strike on Yugoslavia, and could do the same in future conflicts where NATO intervention was required, thus nullifying the entire potency and purpose of the organization. Recognizing the post-Cold War military environment, NATO adopted the Alliance Strategic Concept during its Washington summit in April 1999 that emphasized conflict prevention and crisis management.[64][non-primary source needed]

War in Afghanistan

The September 11 attacks in the United States caused NATO to invoke its collective defence article for the first time.

The September 11 attacks in the United States caused NATO to invoke Article 5 of the NATO Charter for the first time in the organization’s history.[65] The Article states that an attack on any member shall be considered to be an attack on all. The invocation was confirmed on 4 October 2001 when NATO determined that the attacks were indeed eligible under the terms of the North Atlantic Treaty.[66][non-primary source needed] The eight official actions taken by NATO in response to the attacks included Operation Eagle Assist and Operation Active Endeavour, a naval operation in the Mediterranean Sea designed to prevent the movement of terrorists or weapons of mass destruction, and to enhance the security of shipping in general, which began on 4 October 2001.[67][non-primary source needed]

The alliance showed unity: on 16 April 2003, NATO agreed to take command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), which included troops from 42 countries. The decision came at the request of Germany and the Netherlands, the two countries leading ISAF at the time of the agreement, and all nineteen NATO ambassadors approved it unanimously. The handover of control to NATO took place on 11 August, and marked the first time in NATO’s history that it took charge of a mission outside the north Atlantic area.[68][page needed]

ISAF was initially charged with securing Kabul and surrounding areas from the Taliban, al Qaeda and factional warlords, so as to allow for the establishment of the Afghan Transitional Administration headed by Hamid Karzai. In October 2003, the UN Security Council authorized the expansion of the ISAF mission throughout Afghanistan,[69][non-primary source needed] and ISAF subsequently expanded the mission in four main stages over the whole of the country.[70][non-primary source needed]

On 31 July 2006, the ISAF additionally took over military operations in the south of Afghanistan from a US-led anti-terrorism coalition.[71] Due to the intensity of the fighting in the south, in 2011 France allowed a squadron of Mirage 2000 fighter/attack aircraft to be moved into the area, to Kandahar, in order to reinforce the alliance’s efforts.[72] During its 2012 Chicago Summit, NATO endorsed a plan to end the Afghanistan war and to remove the NATO-led ISAF Forces by the end of December 2014.[73] ISAF was disestablished in December 2014 and replaced by the follow-on training Resolute Support Mission.[74]

On 14 April 2021, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said the alliance had agreed to start withdrawing its troops from Afghanistan by May 1.[75] Soon after the withdrawal of NATO troops started, the Taliban launched an offensive against the Afghan government, quickly advancing in front of collapsing Afghan Armed Forces.[76] By 15 August 2021, Taliban militants controlled the vast majority of Afghanistan and had encircled the capital city of Kabul.[77] Some politicians in NATO member states have described the chaotic withdrawal of Western troops from Afghanistan and the collapse of the Afghan government as the greatest debacle that NATO has suffered since its founding.[78][79]

Iraq training mission

Italian Major General Giovanni Armentani, Deputy Commanding General for the NATO Training Mission, meets with a U.S. Advise and Assist Brigade.

In August 2004, during the Iraq War, NATO formed the NATO Training Mission – Iraq, a training mission to assist the Iraqi security forces in conjunction with the US-led MNF-I.[80] The NATO Training Mission-Iraq (NTM-I) was established at the request of the Iraqi Interim Government under the provisions of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1546. The aim of NTM-I was to assist in the development of Iraqi security forces training structures and institutions so that Iraq can build an effective and sustainable capability that addresses the needs of the country. NTM-I was not a combat mission but is a distinct mission, under the political control of the North Atlantic Council. Its operational emphasis was on training and mentoring. The activities of the mission were coordinated with Iraqi authorities and the US-led Deputy Commanding General Advising and Training, who was also dual-hatted as the Commander of NTM-I. The mission officially concluded on 17 December 2011.[81]

Turkey invoked the first Article 4 meetings in 2003 at the start of the Iraq War. Turkey also invoked this article twice in 2012 during the Syrian Civil War, after the downing of an unarmed Turkish F-4 reconnaissance jet, and after a mortar was fired at Turkey from Syria,[82] and again in 2015 after threats by Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant to its territorial integrity.[83]

Gulf of Aden anti-piracy

Beginning on 17 August 2009, NATO deployed warships in an operation to protect maritime traffic in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean from Somali pirates, and help strengthen the navies and coast guards of regional states. The operation was approved by the North Atlantic Council and involved warships primarily from the United States though vessels from many other countries were also included. Operation Ocean Shield focused on protecting the ships of Operation Allied Provider which were distributing aid as part of the World Food Programme mission in Somalia. Russia, China and South Korea sent warships to participate in the activities as well.[84][non-primary source needed][85][non-primary source needed] The operation sought to dissuade and interrupt pirate attacks, protect vessels, and to increase the general level of security in the region.[86][non-primary source needed]

Libya intervention

During the Libyan Civil War, violence between protesters and the Libyan government under Colonel Muammar Gaddafi escalated, and on 17 March 2011 led to the passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which called for a ceasefire, and authorized military action to protect civilians. A coalition that included several NATO members began enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya shortly afterwards, beginning with Opération Harmattan by the French Air Force on 19 March.

On 20 March 2011, NATO states agreed on enforcing an arms embargo against Libya with Operation Unified Protector using ships from NATO Standing Maritime Group 1 and Standing Mine Countermeasures Group 1,[87] and additional ships and submarines from NATO members.[88] They would «monitor, report and, if needed, interdict vessels suspected of carrying illegal arms or mercenaries».[87]

On 24 March, NATO agreed to take control of the no-fly zone from the initial coalition, while command of targeting ground units remained with the coalition’s forces.[89][90] NATO began officially enforcing the UN resolution on 27 March 2011 with assistance from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.[91] By June, reports of divisions within the alliance surfaced as only eight of the 28 member states were participating in combat operations,[92] resulting in a confrontation between US Defense Secretary Robert Gates and countries such as Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, Turkey, and Germany with Gates calling on the latter to contribute more and the latter believing the organization has overstepped its mandate in the conflict.[93][94][95] In his final policy speech in Brussels on 10 June, Gates further criticized allied countries in suggesting their actions could cause the demise of NATO.[96] The German foreign ministry pointed to «a considerable [German] contribution to NATO and NATO-led operations» and to the fact that this engagement was highly valued by President Obama.[97]

While the mission was extended into September, Norway that day (10 June) announced it would begin scaling down contributions and complete withdrawal by 1 August.[98] Earlier that week it was reported Danish air fighters were running out of bombs.[99][100] The following week, the head of the Royal Navy said the country’s operations in the conflict were not sustainable.[101] By the end of the mission in October 2011, after the death of Colonel Gaddafi, NATO planes had flown about 9,500 strike sorties against pro-Gaddafi targets.[102][103] A report from the organization Human Rights Watch in May 2012 identified at least 72 civilians killed in the campaign.[104]

Following a coup d’état attempt in October 2013, Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan requested technical advice and trainers from NATO to assist with ongoing security issues.[105]

Syrian Civil War

Use of Article 5 has been threatened multiple times and four out of seven official Article 4 consultations have been called due to spillover in Turkey from the Syrian Civil War. In April 2012, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan considered invoking Article 5 of the NATO treaty to protect Turkish national security in a dispute over the Syrian Civil War.[106][107] The alliance responded quickly, and a spokesperson said the alliance was «monitoring the situation very closely and will continue to do so» and «takes it very seriously protecting its members.»[108]

After the shooting down of a Turkish military jet by Syria in June 2012 and Syrian forces shelling Turkish cities in October of 2012[109] resulting in two Article 4 consultations, NATO approved Operation Active Fence. In the past decade the conflict has only escalated. In response to the 2015 Suruç bombing, which Turkey attributed to ISIS, and other security issues along its southern border,[110][111][112][113] Turkey called for an emergency meeting. The latest consultation happened in February 2020, as part of increasing tensions due to the Northwestern Syria offensive, which involved[114] Syrian and suspected Russian airstrikes on Turkish troops, and risked direct confrontration between Russia and a NATO member.[115] Each escalation and attack has been meet with an extension of the initial Operation Active Fence mission.

Membership

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Former American President Barack Obama with former Turkish President Abdullah Gul and other leaders at the NATO Summit in Lisbon in November 2010

NATO has thirty members, mainly in Europe and North America. Some of these countries also have territory on multiple continents, which can be covered only as far south as the Tropic of Cancer in the Atlantic Ocean, which defines NATO’s «area of responsibility» under Article 6 of the North Atlantic Treaty. During the original treaty negotiations, the United States insisted that colonies such as the Belgian Congo be excluded from the treaty.[116][117] French Algeria was, however, covered until its independence on 3 July 1962.[118] Twelve of these thirty are original members who joined in 1949, while the other eighteen joined in one of eight enlargement rounds.[citation needed]

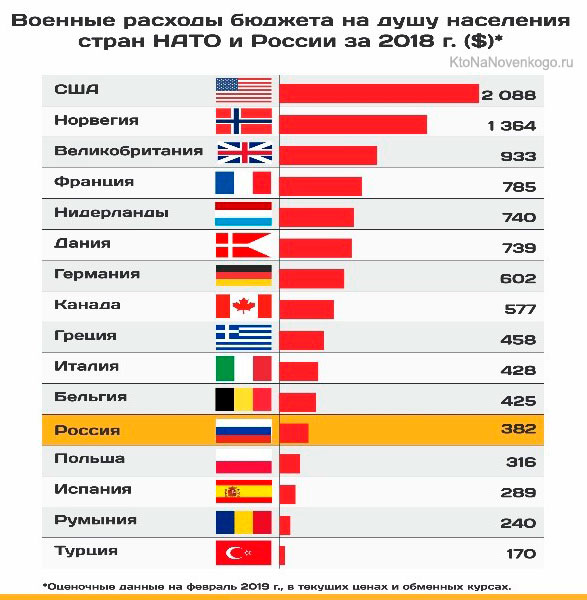

Few members spend more than two percent of their gross domestic product on defence,[119] with the United States accounting for three quarters of NATO defence spending.[120]

Special arrangements

The three Nordic countries which joined NATO as founding members, Denmark, Iceland, and Norway, chose to limit their participation in three areas: there would be no permanent peacetime bases, no nuclear warheads and no Allied military activity (unless invited) permitted on their territory. However, Denmark allowed the U.S. Air Force to maintain an existing base, Thule Air Base, in Greenland.[121]

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s, France pursued a military strategy of independence from NATO under a policy dubbed «Gaullo-Mitterrandism».[122] Nicolas Sarkozy negotiated the return of France to the integrated military command and the Defence Planning Committee in 2009, the latter being disbanded the following year. France remains the only NATO member outside the Nuclear Planning Group and unlike the United States and the United Kingdom, will not commit its nuclear-armed submarines to the alliance.[22][34]

Enlargement

Accession to the alliance is governed with individual Membership Action Plans, and requires approval by each current member. NATO currently has three candidate countries that are in the process of joining the alliance: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Finland, and Sweden. North Macedonia is the most recent state to sign an accession protocol to become a NATO member state, which it did in February 2019 and became a member state on 27 March 2020.[123][124] Its accession had been blocked by Greece for many years due to the Macedonia naming dispute, which was resolved in 2018 by the Prespa agreement.[125] In order to support each other in the process, new and potential members in the region formed the Adriatic Charter in 2003.[126] Georgia was also named as an aspiring member, and was promised «future membership» during the 2008 summit in Bucharest,[127] though in 2014, US President Barack Obama said the country was not «currently on a path» to membership.[128]

Ukraine’s relationship with NATO and Europe has been politically controversial, and improvement of these relations was one of the goals of the «Euromaidan» protests that saw the ousting of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. Ukraine is one of eight countries in Eastern Europe with an Individual Partnership Action Plan. IPAPs began in 2002, and are open to countries that have the political will and ability to deepen their relationship with NATO.[129] On 21 February 2019, the Constitution of Ukraine was amended, the norms on the strategic course of Ukraine for membership in the European Union and NATO are enshrined in the preamble of the Basic Law, three articles and transitional provisions.[130] At the June 2021 Brussels Summit, NATO leaders reiterated the decision taken at the 2008 Bucharest Summit that Ukraine would become a member of the Alliance with the Membership Action Plan (MAP) as an integral part of the process and Ukraine’s right to determine its own future and foreign policy course without outside interference.[131] On 30 November 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that an expansion of NATO’s presence in Ukraine, especially the deployment of any long-range missiles capable of striking Russian cities or missile defence systems similar to those in Romania and Poland, would be a «red line» issue for Russia.[132][133][134] Putin asked U.S. President Joe Biden for legal guarantees that NATO would not expand eastward or put «weapons systems that threaten us in close vicinity to Russian territory.»[135] NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg replied that «It’s only Ukraine and 30 NATO allies that decide when Ukraine is ready to join NATO. Russia has no veto, Russia has no say, and Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence to try to control their neighbors.»[136][137]

Russia continued to politically oppose further expansion, seeing it as inconsistent with informal understandings between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and European and US negotiators that allowed for a peaceful German reunification.[138] NATO’s expansion efforts are often seen by Moscow leaders as a continuation of a Cold War attempt to surround and isolate Russia,[139] though they have also been criticized in the West.[140] A June 2016 Levada Center poll found that 68 percent of Russians think that deploying NATO troops in the Baltic states and Poland – former Eastern bloc countries bordering Russia – is a threat to Russia.[141] In contrast, 65 percent of Poles surveyed in a 2017 Pew Research Center report identified Russia as a «major threat», with an average of 31 percent saying so across all NATO countries,[142] and 67 percent of Poles surveyed in 2018 favour US forces being based in Poland.[143] Of non-CIS Eastern European countries surveyed by Gallup in 2016, all but Serbia and Montenegro were more likely than not to view NATO as a protective alliance rather than a threat.[144] A 2006 study in the journal Security Studies argued that NATO enlargement contributed to democratic consolidation in Central and Eastern Europe.[145] China also opposes further expansion.[146]

Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, public opinion in Finland and in Sweden swung sharply in favor of joining NATO, with more citizens supporting NATO membership than those who were opposed to it for the first time. A poll on 30 March 2022 revealed that about 61% of Finns were in favor of NATO membership, as opposed to 16% against and 23% uncertain. A poll on 1 April revealed that about 51% of Swedes were in favor of NATO membership, as opposed to 27% against.[147][148] In mid-April, the governments of Finland and Sweden began exploring NATO membership, with their governments commissioning security reports on this subject.[149][150] The addition of the two Nordic countries would significantly expand NATO’s capabilities in the Arctic, Nordic, and Baltic regions.[151]

On 15 May 2022, the Finnish government announced that it would apply for NATO membership, subject to approval by the country’s parliament,[152] which voted 188–8 in favor of the move on 17 May.[153] Swedish Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson announced her country would apply for NATO membership on 17 May,[154] and both Finland and Sweden formally submitted applications for NATO membership on 18 May.[155] Turkey voiced opposition to Finland and Sweden joining NATO, accusing the two countries of providing support to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the People’s Defense Units (YPG), two Kurdish groups which Turkey has designated as terrorist organizations. On 28 June, at a NATO summit in Madrid, Turkey agreed to support the membership bids of Finland and Sweden.[156][157] On 5 July, the 30 NATO ambassadors signed off on the accession protocols for Sweden and Finland and formally approved the decisions of the NATO summit on 28 June.[158] This must be ratified by the various governments; all countries except Hungary and Turkey had ratified it in 2022.[159][160][161]

In addition to Finland and Sweden, the remaining European Economic Area or Schengen Area countries not part of NATO are Ireland, Austria and Switzerland (in addition to a few other European island countries and microstates).

NATO defense expenditure budget

The increase in the number of NATO members over the years hasn’t been sustained by an increase in the defense expenditures.[162] Being concerned about the decreasing defense budgets and aiming to improve financial equity commitments and boost the effectiveness of financial expenditure, NATO members met at the 2014 Wales Summit to establish the Defense Investment Pledge.[163][164] Members considered it necessary to contribute at least 2% of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to defense and 20% of their defense budget to major equipment which includes allocations to defense research and development by 2024.[165]

The implementation of the Defense Investment Pledge is hindered by the lack of legal binding obligation by the members, European Union fiscal laws, member states’ domestic public expenditure priorities, and political willingness.[163][162] In 2021, eight member states achieved the goal of 2% GDP contribution to defense spending.[166]

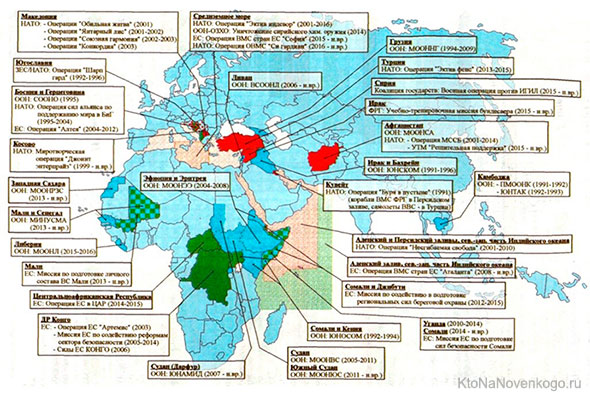

Partnerships with third countries

Partnership for Peace conducts multinational military exercises like Cooperative Archer, which took place in Tbilisi in July 2007 with 500 servicemen from four NATO members, eight PfP members, and Jordan, a Mediterranean Dialogue participant.[167]

The Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme was established in 1994 and is based on individual bilateral relations between each partner country and NATO: each country may choose the extent of its participation.[168] Members include all current and former members of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[169] The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) was first established on 29 May 1997, and is a forum for regular coordination, consultation and dialogue between all fifty participants.[170] The PfP programme is considered the operational wing of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership.[168] Other third countries also have been contacted for participation in some activities of the PfP framework such as Afghanistan.[171]

The European Union (EU) signed a comprehensive package of arrangements with NATO under the Berlin Plus agreement on 16 December 2002. With this agreement, the EU was given the possibility of using NATO assets in case it wanted to act independently in an international crisis, on the condition that NATO itself did not want to act – the so-called «right of first refusal».[172] For example, Article 42(7) of the 1982 Treaty of Lisbon specifies that «If a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power». The treaty applies globally to specified territories whereas NATO is restricted under its Article 6 to operations north of the Tropic of Cancer. It provides a «double framework» for the EU countries that are also linked with the PfP programme.[citation needed]

Additionally, NATO cooperates and discusses its activities with numerous other non-NATO members. The Mediterranean Dialogue was established in 1994 to coordinate in a similar way with Israel and countries in North Africa. The Istanbul Cooperation Initiative was announced in 2004 as a dialogue forum for the Middle East along the same lines as the Mediterranean Dialogue. The four participants are also linked through the Gulf Cooperation Council.[173] In June 2018, Qatar expressed its wish to join NATO.[174] However, NATO declined membership, stating that only additional European countries could join according to Article 10 of NATO’s founding treaty.[175] Qatar and NATO have previously signed a security agreement together in January 2018.[176]

Political dialogue with Japan began in 1990, and since then, the Alliance has gradually increased its contact with countries that do not form part of any of these cooperation initiatives.[177] In 1998, NATO established a set of general guidelines that do not allow for a formal institutionalization of relations, but reflect the Allies’ desire to increase cooperation. Following extensive debate, the term «Contact Countries» was agreed by the Allies in 2000. By 2012, the Alliance had broadened this group, which meets to discuss issues such as counter-piracy and technology exchange, under the names «partners across the globe» or «global partners».[178][179] Australia and New Zealand, both contact countries, are also members of the AUSCANNZUKUS strategic alliance, and similar regional or bilateral agreements between contact countries and NATO members also aid cooperation. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated that NATO needs to «address the rise of China,» by closely cooperating with Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea.[180] Colombia is NATO’s latest partner and Colombia has access to the full range of cooperative activities NATO offers to partners; Colombia became the first and only Latin American country to cooperate with NATO.[181]

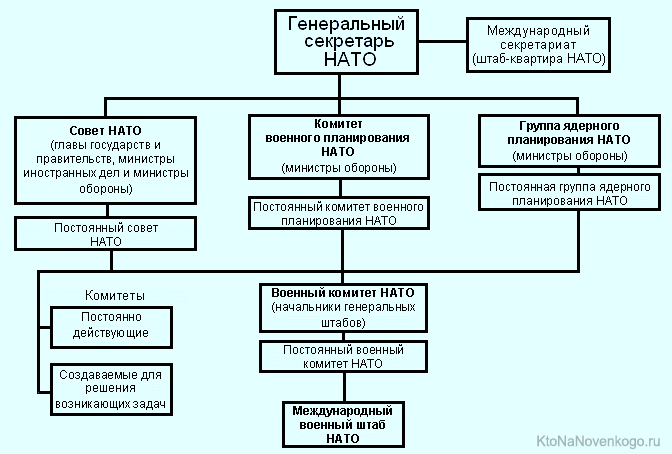

Structure

The North Atlantic Council convening in 2010 with a defence/foreign minister configuration

All agencies and organizations of NATO are integrated into either the civilian administrative or military executive roles. For the most part they perform roles and functions that directly or indirectly support the security role of the alliance as a whole.

The civilian structure includes:

- The North Atlantic Council (NAC) is the body which has effective governance authority and powers of decision in NATO, consisting of member states’ permanent representatives or representatives at higher level (ministers of foreign affairs or defence, or heads of state or government). The NAC convenes at least once a week and takes major decisions regarding NATO’s policies. The meetings of the North Atlantic Council are chaired by the secretary general and, when decisions have to be made, action is agreed upon by consensus.[182] There is no voting or decision by majority. Each state represented at the Council table or on any of its subordinate committees retains complete sovereignty and responsibility for its own decisions.[citation needed]

- NATO Headquarters, located on Boulevard Léopold III/Leopold III-laan, B-1110 Brussels, which is in the City of Brussels municipality.[183] The staff at the Headquarters is composed of national delegations of member countries and includes civilian and military liaison offices and officers or diplomatic missions and diplomats of partner countries, as well as the International Staff and International Military Staff filled from serving members of the armed forces of member states.[184] Non-governmental groups have also grown up in support of NATO, broadly under the banner of the Atlantic Council/Atlantic Treaty Association movement.[185][186]

The military structure includes:

- The Military Committee (MC) is the body of NATO that is composed of member states’ Chiefs of Defence (CHOD) and advises the North Atlantic Council (NAC) on military policy and strategy. The national CHODs are regularly represented in the MC by their permanent Military Representatives (MilRep), who often are two- or three-star flag officers. Like the council, from time to time the Military Committee also meets at a higher level, namely at the level of Chiefs of Defence, the most senior military officer in each country’s armed forces. The MC is led by its chairman, who directs NATO’s military operations.[citation needed] Until 2008 the Military Committee excluded France, due to that country’s 1966 decision to remove itself from the NATO Military Command Structure, which it rejoined in 1995. Until France rejoined NATO, it was not represented on the Defence Planning Committee, and this led to conflicts between it and NATO members.[187] Such was the case in the lead up to Operation Iraqi Freedom.[188] The operational work of the committee is supported by the International Military Staff

- Allied Command Operations (ACO) is the NATO command responsible for NATO operations worldwide.[189]

- The Rapid Deployable Corps include Eurocorps, I. German/Dutch Corps, Multinational Corps Northeast, and NATO Rapid Deployable Italian Corps among others, as well as naval High Readiness Forces (HRFs), which all report to Allied Command Operations.[190]

- Allied Command Transformation (ACT), responsible for transformation and training of NATO forces.[191]

The organizations and agencies of NATO include:

- Headquarters for the NATO Support Agency will be in Capellen Luxembourg (site of the current NATO Maintenance and Supply Agency – NAMSA).

- The NATO Communications and Information Agency Headquarters will be in Brussels, as will the very small staff which will design the new NATO Procurement Agency.

- A new NATO Science and Technology Organization will be created before July 2012, consisting of Chief Scientist, a Programme Office for Collaborative S&T, and the NATO Undersea Research Centre (NURC).[citation needed]

- The NATO Standardization Agency became the NATO Standardization Office (NSO) in July 2014.[192]

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly (NATO PA) is a body that sets broad strategic goals for NATO, which meets at two session per year. NATO PA interacts directly with the parliamentary structures of the national governments of the member states which appoint Permanent Members, or ambassadors to NATO. The NATO Parliamentary Assembly is made up of legislators from the member countries of the North Atlantic Alliance as well as thirteen associate members. It is however officially a structure different from NATO, and has as aim to join deputies of NATO countries in order to discuss security policies on the NATO Council.[citation needed]

NATO is an alliance of 30 sovereign states and their individual sovereignty is unaffected by participation in the alliance. NATO has no parliaments, no laws, no enforcement, and no power to punish individual citizens. As a consequence of this lack of sovereignty the power and authority of a NATO commander are limited. NATO commanders cannot punish offences such as failure to obey a lawful order; dereliction of duty; or disrespect to a senior officer.[193] NATO commanders expect obeisance but sometimes need to subordinate their desires or plans to the operators who are themselves subject to sovereign codes of conduct like the UCMJ. A case in point was the clash between General Sir Mike Jackson and General Wesley Clark over KFOR actions at Pristina Airport.[194]

NATO commanders can issue orders to their subordinate commanders in the form of operational plans (OPLANs), operational orders (OPORDERs), tactical direction, or fragmental orders (FRAGOs) and others. The joint rules of engagement must be followed, and the Law of Armed Conflict must be obeyed at all times. Operational resources «remain under national command but have been transferred temporarily to NATO. Although these national units, through the formal process of transfer of authority, have been placed under the operational command and control of a NATO commander, they never lose their national character.» Senior national representatives, like CDS, «are designated as so-called red-cardholders». Caveats are restrictions listed «nation by nation… that NATO Commanders… must take into account.»[193]

See also

- Atlanticism

- Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union

- History of the Common Security and Defence Policy

- Ranks and insignia of NATO

- Major non-NATO ally

- List of military equipment of NATO

Similar organizations

- AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, United States)

- ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty)

- Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)

- Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA)

- Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance

- Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition (IMCTC)

- Middle East Treaty Organization (METO)

- Northeast Asia Treaty Organization (NEATO)

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)

- South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone

- Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO)

References

- ^ «English and French shall be the official languages for the entire North Atlantic Treaty Organization». Final Communiqué following the meeting of the North Atlantic Council on 17 September 1949 Archived 6 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine. «… the English and French texts [of the Treaty] are equally authentic …» The North Atlantic Treaty, Article 14 Archived 14 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2021)» (PDF). Nato.int.

- ^ a b «What is NATO?». NATO – Homepage. n.d. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Cook, Lorne (25 May 2017). «NATO, the world’s biggest military alliance, explained». Military Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ «Animus in consulendo liber». NATO. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Batchelor, Tom (9 March 2022). «Where are Nato troops stationed and how many are deployed across Europe?». The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ «The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database». SIPRI. IMF World Economic Outlook. 2021. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ The Wales Declaration on the Transatlantic Bond Archived 10 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, NATO, 5 September 2014.

- ^ Erlanger, Steven (26 March 2014). «Europe Begins to Rethink Cuts to Military Spending». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

Last year, only a handful of NATO countries met the target, according to NATO figures, including the United States, at 4.1 percent, and Britain, at 2.4 percent.

- ^ Kevin Liptak, Niamh Kennedy and Sharon Braithwaite: NATO formally invites Finland and Sweden to join alliance. CNN Politics, June 29, 2022.

- ^ «The origins of WEU: Western Union». University of Luxembourg. December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ «A short history of NATO». NATO. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ «Canada and NATO — 1949».

- ^ Findley, Paul (2011). Speaking Out: A Congressman’s Lifelong Fight Against Bigotry, Famine, and War — Paul Findley — Google Books. ISBN 9781569768914. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ The McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Biography: An International Reference Work — Google Books. McGraw-Hill. 1973. ISBN 9780070796331. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Ismay, Hastings (4 September 2001). «NATO the first five years 1949–1954». NATO. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Baldwin, Hanson (28 September 1952). «Navies Meet the Test in Operation Mainbrace». New York Times: E7. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ «NATO: The Man with the Oilcan». Time. 24 March 1952. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (14 May 2014). «Soviet Union establishes Warsaw Pact, May 14, 1955». Politico. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Olmsted, Dan (September 2020). «Should the United States Keep Troops in Germany?». National WW2 Museum. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ van der Eyden 2003, pp. 104–106.

- ^ a b c Cody, Edward (12 March 2009). «After 43 Years, France to Rejoin NATO as Full Member». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ «Spain and NATO». countrystudies.us. Source: U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Harding, Luke (14 July 2007). «Kremlin tears up arms pact with Nato». The Observer. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Kimball, Daryl (August 2017). «The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty and the Adapted CFE Treaty at a Glance». Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Techau, Jan (2 September 2015). «The Politics of 2 Percent: NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe». Carnegie Europe. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Eichler, Jan (2021). NATO’s Expansion After the Cold War: Geopolitics and Impacts for International Security. Springer Nature. pp. 34, 35. ISBN 9783030666415.

- ^ «Declassified documents show security assurances against NATO expansion to Soviet leaders from Baker, Bush, Genscher, Kohl, Gates, Mitterrand, Thatcher, Hurd, Major, and Woerner». National Security Archive. 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Wiegrefe, Klaus (18 February 2022). «Neuer Aktenfund von 1991 stützt russischen Vorwurf». Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Baker, Peter (9 January 2022). «In Ukraine Conflict, Putin Relies on a Promise That Ultimately Wasn’t». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ «NATO Announces Special 70th Anniversary Summit In London In December». Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Jing Ke (2008). «Did the US Media Reflect the Reality of the Kosovo War in an Objective Manner? A Case Study of The Washington Post and The Washington Times» (PDF). University of Rhode Island. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2019.

- ^ NATO. «Relations with the Republic of North Macedonia (Archived)». NATO. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ a b Stratton, Allegra (17 June 2008). «Sarkozy military plan unveiled». The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ «Defence Planning Committee (DPC) (Archived)». NATO. 11 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ «Invocation of Article 5 confirmed». North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 3 October 2001. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ «Counter-piracy operations». North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ «Statement by the North Atlantic Council following meeting under article 4 of the Washington Treaty». NATO Newsroom. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ «The consultation process and Article 4». NATO. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Techau, Jan (2 September 2015). «The Politics of 2 Percent: NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe». Carnegie Europe. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

A month before [the alliance’s summit in Riga in 2006], Victoria Nuland, then the U.S. ambassador to NATO, called the 2 percent metric the «unofficial floor» on defence spending in NATO. But never had all governments of NATO’s 28 nations officially embraced it at the highest possible political level – a summit declaration.

- ^ a b «NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance». NATO. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ McLeary, Paul; Toosi, Nahal (11 February 2022). «U.S. sending 3,000 more troops to Poland amid fresh Ukraine invasion warnings». Politico. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ «Spain sends warships to Black Sea, considers sending warplanes». Reuters. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ «Spain will send four fighter jets and 130 troops to Bulgaria». Reuters. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ «NATO, G7, EU leaders display unity, avoid confrontation with Russia». Deutsche Welle. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Gonzalez, Oriana (26 February 2022). «NATO Response Force deploys for first time». Axios. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ «NATO BOOSTS FORCES IN EAST TO DETER RUSSIAN MENACE». BIRN. Balkan Insight. Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. 14 June 2022.

- ^ «NATO Seen Favorably Across Member States». pewresearch.org. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ «NATO’s Operations 1949–Present» (PDF). NATO. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Zenko 2010, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Zenko 2010, p. 134.

- ^ NATO Handbook: Evolution of the Conflict, NATO, archived from the original on 7 November 2001

- ^ UN Document A/54/549, Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to General Assembly resolution 53/35: The fall of Srebrenica, un.org, Archived 12 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 April 2015.

- ^ Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. liiv.

- ^ a b Zenko 2010, pp. 137–138

- ^ Clausson 2006, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Tice, Jim (22 February 2009). «Thousands more now eligible for NATO Medal». Army Times. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ «Nato to strike Yugoslavia». BBC News. 24 March 1999. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ Thorpe, Nick (24 March 2004). «UN Kosovo mission walks a tightrope». BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ «Kosovo Report Card». International Crisis Group. 28 August 2000. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Helm, Toby (27 September 2001). «Macedonia mission a success, says Nato». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ «Kosovo Force (KFOR) Key Facts and Figures» (PDF). NATO. 1 December 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ «NATO reaffirms power to take action without UN approval». CNN. 24 April 1999. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ «Allied Command Atlantic». NATO Handbook. NATO. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Münch, Philipp (2021). «Creating common sense: Getting NATO to Afghanistan». Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 19 (2): 138–166. doi:10.1057/s42738-021-00067-0.

- ^ «NATO Update: Invocation of Article 5 confirmed». Nato.int. 2 October 2001. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ «NATO’s Operations 1949–Present» (PDF). NATO. 22 January 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ David P. Auerswald, and Stephen M. Saideman, eds. NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone (Princeton U.P., 2014)[page needed]

- ^ «UNSC Resolution 1510, October 13, 2003» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ «ISAF Chronology». Nato.int. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Morales, Alex (5 October 2006). «NATO Takes Control of East Afghanistan From U.S.-Led Coalition». Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ «La France et l’OTAN». Le Monde (in French). France. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ «NATO sets «irreversible» but risky course to end Afghan war». Reuters. Reuters. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Rasmussen, Sune Engel (28 December 2014). «Nato ends combat operations in Afghanistan». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ «NATO to Cut Forces in Afghanistan, Match US Withdrawal». VOA News. 14 April 2021. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ «Afghanistan stunned by scale and speed of security forces’ collapse». The Guardian. 13 July 2021. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ «Taliban surge in Afghanistan: EU and NATO in state of shock». Deutsche Welle. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ «Afghanistan takeover sparks concern from NATO allies». Deutsche Welle. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ «Migration fears complicate Europe’s response to Afghanistan crisis». Politico. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ «Official Website». Jfcnaples.nato.int. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ El Gamal, Rania (17 December 2011). «NATO closes up training mission in Iraq». Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (3 October 2012). «NATO demands halt to Syria aggression against Turkey». Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Ford, Dana (26 July 2015). «Turkey calls for rare NATO talks after attacks along Syrian border». Cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ «Operation Ocean Shield». NATO. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ «2009 Operation Ocean Shield News Articles». NATO. October 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ «Operation Ocean Shield purpose». 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ a b «Statement by the NATO Secretary General on Libya arms embargo». NATO. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ «Press briefing by NATO Spokesperson Oana Lungescu, Brigadier General Pierre St-Amand, Canadian Air Force and General Massimo Panizzi, spokesperson of the Chairman of the Military Committee». NATO. 23 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ «NATO reaches deal to take over Libya operation; allied planes hit ground forces». Washington Post. 25 March 2011. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ «NATO to police Libya no-fly zone». English.aljazeera.net. 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ O’Sullivan, Arieh (31 March 2011). «UAE and Qatar pack an Arab punch in Libya operation». Jerusalem Post. se. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ «NATO strikes Tripoli, Gaddafi army close on Misrata» Archived 12 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Khaled al-Ramahi. Malaysia Star. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ Coughlin, Con (9 June 2011). «Political Gridlock at NATO» Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ «Gates Calls on NATO Allies to Do More in Libya» Archived 14 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Jim Garamone. US Department of Defense. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ Cloud, David S. (9 June 2011). «Gates calls for more NATO allies to join Libya air campaign» Archived 14 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 June 2011

- ^ Burns, Robert (10 June 2011). «Gates blasts NATO, questions future of alliance» Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Times. Retrieved 29 January 2013

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael (10 June 2011). «Gates rebukes European allies in farewell speech» Archived 25 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Amland, Bjoern H. (10 June 2011). «Norway to quit Libya operation by August» Archived 11 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press.

- ^ «Danish planes running out of bombs» Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Times of Malta. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011

- ^ «Danish Planes in Libya Running Out of Bombs: Report», Defense News. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011

- ^ «Navy chief: Britain cannot keep up its role in Libya air war due to cuts» Archived 13 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, James Kirkup. The Telegraph. 13 June 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2013

- ^ «NATO: Ongoing resistance by pro-Gadhafi forces in Libya is ‘surprising’«. The Washington Post. UPI. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ «NATO strategy in Libya may not work elsewhere». USA Today. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (16 May 2012). «How Many Innocent Civilians Did NATO Kill in Libya?». Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ Croft, Adrian. «NATO to advise Libya on strengthening security forces». Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ todayszaman.com: «PM: Turkey may invoke NATO’s Article 5 over Syrian border fire» Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 11 April 2012

- ^ todayszaman.com: «Observers say NATO’s fifth charter comes into play if clashes with Syria get worse» Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 11 April 2012

- ^ todayszaman.com: «NATO says monitoring tension in Turkey-Syria border» Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 12 April 2012

- ^ «The consultation process and Article 4». NATO.int. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: «Turkey calls for emergency Nato meeting to discuss Isil and PKK», 26 July 2015

- ^ Ford, Dana (27 July 2015). «Turkey calls for rare NATO talks after attacks along Syrian border». CNN. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ nytimes.com: «Turkey and U.S. Plan to Create Syria ‘Safe Zone’ Free of ISIS», 27 July 2015

- ^ «Statement by the North Atlantic Council following meeting under Article 4 of the Washington Treaty». 28 July 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ «Russia denies involvement in airstrikes on Turkish troops in Idlib». Daily Sabah. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ «Greece ‘vetoes NATO statement’ on support for Turkey amid Syria escalation». 29 February 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

The Russian military later explained that the Syrian army targeted Hayat Tahrir al-Sham terrorists operating in the province, adding that Syrian government forces were not informed about the Turkish presence in the area.

- ^ Collins 2011, pp. 122–123.

- ^ «The area of responsibility». NATO Declassified. NATO. 23 February 2013. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ «Washington Treaty». NATO. 11 April 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ Adrian Croft (19 September 2013). «Some EU states may no longer afford air forces-general». Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Craig Whitlock (29 January 2012). «NATO allies grapple with shrinking defense budgets». Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ «Denmark and NATO — 1949».

- ^ «Why the concept of Gaullo-Mitterrandism is still relevant». IRIS. 29 April 2019. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ «Macedonia signs Nato accession agreement». BBC. 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ «North Macedonia joins NATO as 30th Ally». NATO. 27 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Joy, Oliver (16 January 2014). «Macedonian PM: Greece is avoiding talks over name dispute». CNN. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Ramadanovic, Jusuf; Nedjeljko Rudovic (12 September 2008). «Montenegro, BiH join Adriatic Charter». Southeast European Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ George J, Teigen JM (2008). «NATO Enlargement and Institution Building: Military Personnel Policy Challenges in the Post-Soviet Context». European Security. 17 (2): 346. doi:10.1080/09662830802642512. S2CID 153420615.

- ^ Cathcourt, Will (27 March 2014). «Obama Tells Georgia to Forget About NATO After Encouraging It to Join». The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ «NATO Topics: Individual Partnership Action Plans». Nato.int. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ «The law amending the Constitution on the course of accession to the EU and NATO has entered into force | European integration portal». eu-ua.org (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ «Brussels Summit Communiqué issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels 14 June 2021». NATO. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ «Russia will act if Nato countries cross Ukraine ‘red lines’, Putin says». The Guardian. 30 November 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «NATO Pushes Back Against Russian President Putin’s ‘Red Lines’ Over Ukraine». The Drive. 1 December 2021. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «Putin warns Russia will act if NATO crosses its red lines in Ukraine». Reuters. 30 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «Putin Demands NATO Guarantees Not to Expand Eastward». U.S. News & World Report. 1 December 2021. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «NATO chief: «Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence»«. Axios. 1 December 2021. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ «Is Russia preparing to invade Ukraine? And other questions». BBC News. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Klussmann, Uwe; Schepp, Matthias; Wiegrefe, Klaus (26 November 2009). «NATO’s Eastward Expansion: Did the West Break Its Promise to Moscow?». Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ «Medvedev warns on Nato expansion». BBC News. 25 March 2008. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Art 1998, pp. 383–384

- ^ Levada-Center and Chicago Council on Global Affairs about Russian-American relations Archived 19 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Levada-Center. 4 November 2016.

- ^ «Pew survey: Russia disliked around world; most in Poland, Turkey see Kremlin as major threat». Kyiv Post. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ «NATO summit: Poland pins its hopes on the USA». Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Smith, Michael (10 February 2017). «Most NATO Members in Eastern Europe See It as Protection». Gallup. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Epstein, Rachel (2006). «Nato Enlargement and the Spread of Democracy: Evidence and Expectations». Security Studies. 14: 63. doi:10.1080/09636410591002509. S2CID 143878355.

- ^ «China joins Russia in opposing Nato expansion». BBC News. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Jennifer Hansler; Natasha Bertrand (8 April 2022). «Finland and Sweden could soon join NATO, prompted by Russian war in Ukraine». Cable News Network. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ «Finland is hurtling towards NATO membership». The Economist. 8 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ Gerard O’Dwyer (14 April 2022). «Finland and Sweden pursue unlinked NATO membership». DefenseNews. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ «Sweden’s PM wants to apply to join Nato at end of June: report». The Local. 13 April 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ «Going Nordic: What NATO Membership Would Mean for Finland and Sweden». RealClear Defense. 18 April 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Lehto, Essi (15 May 2022). «Finnish president confirms country will apply to join NATO». Reuters. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ «Finland’s Parliament approves NATO membership application». Deutsche Welle. 17 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Don Jacobson (16 May 2022). «Sweden approves historic NATO membership application». UPI.

- ^ Henley, Jon (18 May 2022). «Sweden and Finland formally apply to join Nato». The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ «Turkey clears way for Finland, Sweden to join NATO — Stoltenberg». Reuters. 28 June 2022. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022.

- ^ «NATO: Finland and Sweden poised to join NATO after Turkey drops objection». Sky News. 28 June 2022. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022.

- ^ Emmot, Robin; Siebold, Sabine (5 July 2022). «Finland, Sweden sign to join NATO but need ratification». Reuters. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ «When will Sweden and Finland join NATO? Tracking the ratification process across the Alliance». 8 August 2022.

- ^ «Návrh na vyslovenie súhlasu Národnej rady Slovenskej republiky s Protokolom k Severoatlantickej zmluve o pristúpení Fínskej republiky (tlač 1086) — tretie čítanie. Hlasovanie o návrhu uznesenia». K NR SR. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ «Návrh na vyslovenie súhlasu Národnej rady Slovenskej republiky s Protokolom k Severoatlantickej zmluve o pristúpení Švédskeho kráľovstva (tlač 1087) — tretie čítanie. Hlasovanie o návrhu uznesenia». K NR SR. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b Techau, Jan. «The Politics of 2 Percent: NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe». Carnegie Europe. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b Alozious, Juuko (19 May 2022). «NATO’s Two Percent Guideline: A Demand for Military Expenditure Perspective». Defence and Peace Economics. 33 (4): 475–488. doi:10.1080/10242694.2021.1940649. ISSN 1024-2694. S2CID 237888569.

- ^ NATO. «Wales Summit Declaration issued by NATO Heads of State and Government (2014)». NATO. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ NATO. «Wales Summit Declaration issued by NATO Heads of State and Government (2014)». NATO. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ NATO. «Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2021)». NATO. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ «Cooperative Archer military exercise begins in Georgia». RIA Novosti. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b «Partnership for Peace». Nato.int. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ «Nato and Belarus – partnership, past tensions and future possibilities». Foreign Policy and Security Research Center. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ «NATO Topics: The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council». Nato.int. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ «Declaration by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan». Nato.int. Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Boxhoorn, Bram (21 September 2005). «Broad Support for NATO in the Netherlands». ATA Education. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ «NATO Partner countries». Nato.int. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ «Qatar eyes full NATO membership: Defense minister». The Peninsula. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ «Nato rejects Qatar membership ambition». Dhaka Tribune. 6 June 2018. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ «Qatar signs security agreement with NATO». NATO. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ «NATO Topics:NATO’s relations with Contact Countries». www.nato.int. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013.

- ^ «NATO PARTNERSHIPS: DOD Needs to Assess U.S. Assistance in Response to Changes to the Partnership for Peace Program» (PDF). United States Government Accountability Office. September 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ «Partners». NATO. 2 April 2012. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ «NATO needs to address China’s rise, says Stoltenberg». Reuters. 7 August 2019. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ «Relations with Colombia». nato.int. 19 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ «Topic: Consensus decision-making at NATO». NATO. 5 July 2016. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ «NATO homepage». Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- ^ «NATO Headquarters». NATO. 10 August 2010. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Small, Melvin (1 June 1998). «The Atlantic Council—The Early Years» (PDF). NATO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ «Atlantic Treaty Association and Youth Atlantic Treaty Association». NATO. 7 April 2016. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ «France to rejoin NATO command». CNN. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (18 February 2003). «Reaching accord, EU warns Saddam of his ‘last chance’«. International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ «About us». Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ «The Rapid Deployable Corps». NATO. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ «Who We Are». Allied Command Transformation. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ «NATO Standardization Office (NSO)». NATO. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ a b Randall, Thomas E. (July 2014). «Legal Authority of NATO Commanders» (PDF). NATO Legal Gazette (34): 39–45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Jackson, General Sir Mike (4 September 2007). «Gen Sir Mike Jackson: My clash with Nato chief». Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

Works cited

- Art, Robert J. (1998). «Creating a Disaster: NATO’s Open Door Policy». Political Science Quarterly. 113 (3): 383–403. doi:10.2307/2658073. JSTOR 2658073.

- Bethlehem, Daniel L.; Weller, Marc (1997). The ‘Yugoslav’ Crisis in International Law. Cambridge International Documents Series. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46304-1. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Clausson, M.I. (2006). NATO: Status, Relations, and Decision-Making. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60021-098-3. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Collins, Brian J. (2011). NATO: A Guide to the Issues. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35491-5. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- van der Eyden, Ton (2003). Public management of society: rediscovering French institutional engineering in the European context. Vol. 1. IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-58603-291-3. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Zenko, Micah (2010). Between Threats and War: U.S. Discrete Military Operations in the Post-Cold War World. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7191-7. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

Further reading