|

New York |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

Manhattan, looking southward from Top of the Rock Central Park Unisphere, Queens Brooklyn Bridge Grand Central Terminal Statue of Liberty United Nations headquarters Times Square Bronx Zoo Staten Island Ferry |

|

|

Flag Seal Wordmark |

|

| Nickname(s):

The Big Apple, The City That Never Sleeps, Gotham, and others |

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: 40°42′46″N 74°00′22″W / 40.71278°N 74.00611°WCoordinates: 40°42′46″N 74°00′22″W / 40.71278°N 74.00611°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| Region | Mid-Atlantic |

| Constituent counties (boroughs) | Bronx (The Bronx) Kings (Brooklyn) New York (Manhattan) Queens (Queens) Richmond (Staten Island) |

| Historic colonies | New Netherland Province of New York |

| Settled | 1624 |

| Consolidated | 1898 |

| Named for | James, Duke of York |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor–council |

| • Body | New York City Council |

| • Mayor | Eric Adams (D) |

| Area

[2] |

|

| • Total | 472.43 sq mi (1,223.59 km2) |

| • Land | 300.46 sq mi (778.18 km2) |

| • Water | 171.97 sq mi (445.41 km2) |

| Elevation

[3] |

33 ft (10 m) |

| Population

(2020)[4] |

|

| • Total | 8,804,190 |

| • Estimate

(July 2021)[5] |

8,467,513 |

| • Rank | 1st in the United States 1st in New York State |

| • Density | 29,302.66/sq mi (11,313.81/km2) |

| • Urban

[6] |

19,426,449 |

| • Urban density | 5,980.8/sq mi (2,309.2/km2) |

| • Metro

[7] |

20,140,470 |

| Demonym | New Yorker |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

100xx–104xx, 11004–05, 111xx–114xx, 116xx |

| Area code(s) | 212/646/332, 718/347/929, 917 |

| FIPS code | 36-51000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 975772 |

| GDP (City, 2021) | $886 billion[8] (1st) |

| GMP (Metro, 2021) | $2.0 trillion[9] (1st) |

| Largest borough by area | Queens (109 square miles or 280 square kilometres) |

| Largest borough by population | Brooklyn (2020 Census 2,736,074) |

| Largest borough by GDP (2021) | Manhattan ($651.6 billion)[8] |

| Website | nyc.gov |

New York, often called New York City[a] or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over 300.46 square miles (778.2 km2), New York City is the most densely populated major city in the United States and more than twice as populous as Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest city. New York City is located at the southern tip of New York State. It constitutes the geographical and demographic center of both the Northeast megalopolis and the New York metropolitan area, the largest metropolitan area in the U.S. by both population and urban landmass. With over 20.1 million people in its metropolitan statistical area and 23.5 million in its combined statistical area as of 2020, New York is one of the world’s most populous megacities, and over 58 million people live within 250 mi (400 km) of the city.[10] New York City is a global cultural, financial, entertainment, and media center with a significant influence on commerce, health care and life sciences,[11] research, technology, education, politics, tourism, dining, art, fashion, and sports. Home to the headquarters of the United Nations, New York is an important center for international diplomacy[12][13] and is sometimes described as the capital of the world.[14][15]

Situated on one of the world’s largest natural harbors and extending into the Atlantic Ocean, New York City comprises five boroughs, each of which is coextensive with a respective county of the state of New York. The five boroughs, which were created in 1898 when local governments were consolidated into a single municipal entity, are: Brooklyn (in Kings County), Queens (in Queens County), Manhattan (in New York County), The Bronx (in Bronx County), and Staten Island (in Richmond County).[16]

As of 2021, the New York metropolitan area is the largest metropolitan economy in the world with a gross metropolitan product of over $2.4 trillion. If the New York metropolitan area were a sovereign state, it would have the eighth-largest economy in the world. New York City is an established safe haven for global investors.[17] As of 2022, New York is home to the highest number of billionaires[18][19] and millionaires[20] of any city in the world.

The city and its metropolitan area constitute the premier gateway for legal immigration to the United States. As many as 800 languages are spoken in New York,[21] making it the most linguistically diverse city in the world. New York City is home to more than 3.2 million residents born outside the U.S., the largest foreign-born population of any city in the world as of 2016.[22]

New York City traces its origins to a trading post founded on the southern tip of Manhattan Island by Dutch colonists in approximately 1624. The settlement was named New Amsterdam (Dutch: Nieuw Amsterdam) in 1626 and was chartered as a city in 1653. The city came under British control in 1664 and was renamed New York after King Charles II of England granted the lands to his brother, the Duke of York.[23][24] The city was regained by the Dutch in July 1673 and was renamed New Orange for one year and three months; the city has been continuously named New York since November 1674. New York City was the capital of the United States from 1785 until 1790,[25] and has been the largest U.S. city since 1790. The Statue of Liberty greeted millions of immigrants as they came to the U.S. by ship in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is a symbol of the U.S. and its ideals of liberty and peace.[26] In the 21st century, New York City has emerged as a global node of creativity, entrepreneurship,[27] and as a symbol of freedom and cultural diversity.[28] The New York Times has won the most Pulitzer Prizes for journalism and remains the U.S. media’s «newspaper of record».[29] In 2019, New York City was voted the greatest city in the world in a survey of over 30,000 people from 48 cities worldwide, citing its cultural diversity.[30]

Many districts and monuments in New York City are major landmarks, including three of the world’s ten most visited tourist attractions in 2013.[31] A record 66.6 million tourists visited New York City in 2019. Times Square is the brightly illuminated hub of the Broadway Theater District,[32] one of the world’s busiest pedestrian intersections[31][33] and a major center of the world’s entertainment industry.[34] Many of the city’s landmarks, skyscrapers, and parks are known around the world, and the city’s fast pace led to the phrase New York minute. The Empire State Building is a global standard of reference to describe the height and length of other structures.[35]

Manhattan’s real estate market is among the most expensive in the world.[36][37] Providing continuous 24/7 service and contributing to the nickname The City That Never Sleeps, the New York City Subway is the largest single-operator rapid transit system in the world with 472 passenger rail stations, and Penn Station in Midtown Manhattan is the busiest transportation hub in the Western Hemisphere.[38] The city has over 120 colleges and universities, including Columbia University, an Ivy League university routinely ranked among the world’s top universities,[39] New York University, and the City University of New York system, the largest urban public university system in the nation. Anchored by Wall Street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan, New York City has been called both the world’s leading financial center[40] and the most powerful city in the world,[41] and is home to the world’s two largest stock exchanges by total market capitalization, the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq.[42][43]

The Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, part of the Stonewall National Monument, is considered the historic epicenter of LGBTQ+ culture[44] and the birthplace of the modern gay rights movement.[45][46] New York City is the headquarters of the global art market, with numerous art galleries and auction houses collectively hosting half of the world’s art auctions, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art is both the largest art museum and the most visited museum in the United States.[47] Governors Island in New York Harbor is planned to host a US$1 billion research and education center poised to make New York City the global leader in addressing the climate crisis.[48]

Etymology

In 1664, New York was named in honor of the Duke of York, who would become King James II of England.[49] James’s elder brother, King Charles II, appointed the Duke as proprietor of the former territory of New Netherland, including the city of New Amsterdam, when England seized it from Dutch control.[50]

History

Early history

In the pre-Columbian era, the area of present-day New York City was inhabited by Algonquian Native Americans, including the Lenape. Their homeland, known as Lenapehoking, included the present-day areas of Staten Island, Manhattan, the Bronx, the western portion of Long Island (including the areas that would later become the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens), and the Lower Hudson Valley.[51]

The first documented visit into New York Harbor by a European was in 1524 by Italian Giovanni da Verrazzano, an explorer from Florence in the service of the French crown.[52] He claimed the area for France and named it Nouvelle Angoulême (New Angoulême).[53] A Spanish expedition, led by the Portuguese captain Estêvão Gomes sailing for Emperor Charles V, arrived in New York Harbor in January 1525 and charted the mouth of the Hudson River, which he named Río de San Antonio (‘Saint Anthony’s River’). The Padrón Real of 1527, the first scientific map to show the East Coast of North America continuously, was informed by Gomes’ expedition and labeled the northeastern United States as Tierra de Esteban Gómez in his honor.[54]

In 1609, the English explorer Henry Hudson rediscovered New York Harbor while searching for the Northwest Passage to the Orient for the Dutch East India Company.[55] He proceeded to sail up what the Dutch would name the North River (now the Hudson River), named first by Hudson as the Mauritius after Maurice, Prince of Orange. Hudson’s first mate described the harbor as «a very good Harbour for all windes» and the river as «a mile broad» and «full of fish».[56] Hudson sailed roughly 150 miles (240 km) north,[57] past the site of the present-day New York State capital city of Albany, in the belief that it might be an oceanic tributary before the river became too shallow to continue.[56] He made a ten-day exploration of the area and claimed the region for the Dutch East India Company. In 1614, the area between Cape Cod and Delaware Bay was claimed by the Netherlands and called Nieuw-Nederland (‘New Netherland’).

The first non–Native American inhabitant of what would eventually become New York City was Juan Rodriguez (transliterated to the Dutch language as Jan Rodrigues), a merchant from Santo Domingo. Born in Santo Domingo of Portuguese and African descent, he arrived in Manhattan during the winter of 1613–14, trapping for pelts and trading with the local population as a representative of the Dutch. Broadway, from 159th Street to 218th Street in Upper Manhattan, is named Juan Rodriguez Way in his honor.[58][59]

Dutch rule

A permanent European presence near New York Harbor was established in 1624, making New York the 12th-oldest continuously occupied European-established settlement in the continental United States[60]—with the founding of a Dutch fur trading settlement on Governors Island. In 1625, construction was started on a citadel and Fort Amsterdam, later called Nieuw Amsterdam (New Amsterdam), on present-day Manhattan Island.[61][62] The colony of New Amsterdam was centered on what would ultimately be known as Lower Manhattan. Its area extended from the southern tip of Manhattan to modern day Wall Street, where a 12-foot wooden stockade was built in 1653 to protect against Native American and British raids.[63] In 1626, the Dutch colonial Director-General Peter Minuit, acting as charged by the Dutch West India Company, purchased the island of Manhattan from the Canarsie, a small Lenape band,[64] for «the value of 60 guilders»[65] (about $900 in 2018).[66] A disproved legend claims that Manhattan was purchased for $24 worth of glass beads.[67][68]

Following the purchase, New Amsterdam grew slowly.[24] To attract settlers, the Dutch instituted the patroon system in 1628, whereby wealthy Dutchmen (patroons, or patrons) who brought 50 colonists to New Netherland would be awarded swaths of land, along with local political autonomy and rights to participate in the lucrative fur trade. This program had little success.[69]

Since 1621, the Dutch West India Company had operated as a monopoly in New Netherland, on authority granted by the Dutch States General. In 1639–1640, in an effort to bolster economic growth, the Dutch West India Company relinquished its monopoly over the fur trade, leading to growth in the production and trade of food, timber, tobacco, and slaves (particularly with the Dutch West Indies).[24][70]

In 1647, Peter Stuyvesant began his tenure as the last Director-General of New Netherland. During his tenure, the population of New Netherland grew from 2,000 to 8,000.[71][72] Stuyvesant has been credited with improving law and order in the colony; however, he also earned a reputation as a despotic leader. He instituted regulations on liquor sales, attempted to assert control over the Dutch Reformed Church, and blocked other religious groups (including Quakers, Jews, and Lutherans) from establishing houses of worship.[73] The Dutch West India Company would eventually attempt to ease tensions between Stuyvesant and residents of New Amsterdam.[74]

English rule

In 1664, unable to summon any significant resistance, Stuyvesant surrendered New Amsterdam to English troops, led by Colonel Richard Nicolls, without bloodshed.[73][74] The terms of the surrender permitted Dutch residents to remain in the colony and allowed for religious freedom.[75] In 1667, during negotiations leading to the Treaty of Breda after the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch decided to keep the nascent plantation colony of what is now Suriname (on the northern South American coast) they had gained from the English; and in return, the English kept New Amsterdam. The fledgling settlement was promptly renamed «New York» after the Duke of York (the future King James II and VII), who would eventually be deposed in the Glorious Revolution.[76] After the founding, the duke gave part of the colony to proprietors George Carteret and John Berkeley. Fort Orange, 150 miles (240 km) north on the Hudson River, was renamed Albany after James’s Scottish title.[77] The transfer was confirmed in 1667 by the Treaty of Breda, which concluded the Second Anglo-Dutch War.[78]

On August 24, 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, Dutch captain Anthony Colve seized the colony of New York from the English at the behest of Cornelis Evertsen the Youngest and rechristened it «New Orange» after William III, the Prince of Orange.[79] The Dutch would soon return the island to England under the Treaty of Westminster of November 1674.[80][81]

Several intertribal wars among the Native Americans and some epidemics brought on by contact with the Europeans caused sizeable population losses for the Lenape between the years 1660 and 1670.[82] By 1700, the Lenape population had diminished to 200.[83] New York experienced several yellow fever epidemics in the 18th century, losing ten percent of its population to the disease in 1702 alone.[84][85]

Province of New York and slavery

In the early 18th century, New York grew in importance as a trading port while as a part of the colony of New York.[86] It also became a center of slavery, with 42% of households enslaving Africans by 1730, the highest percentage outside Charleston, South Carolina.[87] Most cases were that of domestic slavery, as a New York household then commonly enslaved few or several people. Others were hired out to work at labor. Slavery became integrally tied to New York’s economy through the labor of slaves throughout the port, and the banking and shipping industries trading with the American South. During construction in Foley Square in the 1990s, the African Burying Ground was discovered; the cemetery included 10,000 to 20,000 of graves of colonial-era Africans, some enslaved and some free.[88]

The 1735 trial and acquittal in Manhattan of John Peter Zenger, who had been accused of seditious libel after criticizing colonial governor William Cosby, helped to establish the freedom of the press in North America.[89] In 1754, Columbia University was founded under charter by King George II as King’s College in Lower Manhattan.[90]

American Revolution

The Stamp Act Congress met in New York in October 1765, as the Sons of Liberty organization emerged in the city and skirmished over the next ten years with British troops stationed there.[91] The Battle of Long Island, the largest battle of the American Revolutionary War, was fought in August 1776 within the modern-day borough of Brooklyn.[92] After the battle, in which the Americans were defeated, the British made the city their military and political base of operations in North America. The city was a haven for Loyalist refugees and escaped slaves who joined the British lines for freedom newly promised by the Crown for all fighters. As many as 10,000 escaped slaves crowded into the city during the British occupation. When the British forces evacuated at the close of the war in 1783, they transported 3,000 freedmen for resettlement in Nova Scotia.[93] They resettled other freedmen in England and the Caribbean.

The only attempt at a peaceful solution to the war took place at the Conference House on Staten Island between American delegates, including Benjamin Franklin, and British general Lord Howe on September 11, 1776. Shortly after the British occupation began, the Great Fire of New York occurred, a large conflagration on the West Side of Lower Manhattan, which destroyed about a quarter of the buildings in the city, including Trinity Church.[94]

In 1785, the assembly of the Congress of the Confederation made New York City the national capital shortly after the war. New York was the last capital of the U.S. under the Articles of Confederation and the first capital under the Constitution of the United States. New York City as the U.S. capital hosted several events of national scope in 1789—the first President of the United States, George Washington, was inaugurated; the first United States Congress and the Supreme Court of the United States each assembled for the first time; and the United States Bill of Rights was drafted, all at Federal Hall on Wall Street.[95] In 1790, New York surpassed Philadelphia as the nation’s largest city. At the end of that year, pursuant to the Residence Act, the national capital was moved to Philadelphia.[96][97]

19th century

Over the course of the nineteenth century, New York City’s population grew from 60,000 to 3.43 million.[99] Under New York State’s abolition act of 1799, children of slave mothers were to be eventually liberated but to be held in indentured servitude until their mid-to-late twenties.[100][101] Together with slaves freed by their masters after the Revolutionary War and escaped slaves, a significant free-Black population gradually developed in Manhattan. Under such influential United States founders as Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, the New York Manumission Society worked for abolition and established the African Free School to educate Black children.[102] It was not until 1827 that slavery was completely abolished in the state, and free Blacks struggled afterward with discrimination. New York interracial abolitionist activism continued; among its leaders were graduates of the African Free School. New York city’s population jumped from 123,706 in 1820 to 312,710 by 1840, 16,000 of whom were Black.[103][104]

In the 19th century, the city was transformed by both commercial and residential development relating to its status as a national and international trading center, as well as by European immigration, respectively.[105] The city adopted the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, which expanded the city street grid to encompass almost all of Manhattan. The 1825 completion of the Erie Canal through central New York connected the Atlantic port to the agricultural markets and commodities of the North American interior via the Hudson River and the Great Lakes.[106] Local politics became dominated by Tammany Hall, a political machine supported by Irish and German immigrants.[107]

Several prominent American literary figures lived in New York during the 1830s and 1840s, including William Cullen Bryant, Washington Irving, Herman Melville, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, John Keese, Nathaniel Parker Willis, and Edgar Allan Poe. Public-minded members of the contemporaneous business elite lobbied for the establishment of Central Park, which in 1857 became the first landscaped park in an American city.

The Great Irish Famine brought a large influx of Irish immigrants; more than 200,000 were living in New York by 1860, upwards of a quarter of the city’s population.[108] There was also extensive immigration from the German provinces, where revolutions had disrupted societies, and Germans comprised another 25% of New York’s population by 1860.[109]

Democratic Party candidates were consistently elected to local office, increasing the city’s ties to the South and its dominant party. In 1861, Mayor Fernando Wood called upon the aldermen to declare independence from Albany and the United States after the South seceded, but his proposal was not acted on.[102] Anger at new military conscription laws during the American Civil War (1861–1865), which spared wealthier men who could afford to pay a $300 (equivalent to $6,602 in 2021) commutation fee to hire a substitute,[110] led to the Draft Riots of 1863, whose most visible participants were ethnic Irish working class.[102]

The draft riots deteriorated into attacks on New York’s elite, followed by attacks on Black New Yorkers and their property after fierce competition for a decade between Irish immigrants and Black people for work. Rioters burned the Colored Orphan Asylum to the ground, with more than 200 children escaping harm due to efforts of the New York Police Department, which was mainly made up of Irish immigrants.[109] At least 120 people were killed.[111] Eleven Black men were lynched over five days, and the riots forced hundreds of Blacks to flee the city for Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and New Jersey. The Black population in Manhattan fell below 10,000 by 1865, which it had last been in 1820. The White working class had established dominance.[109][111] Violence by longshoremen against Black men was especially fierce in the docks area.[109] It was one of the worst incidents of civil unrest in American history.[112]

In 1898, the City of New York was formed with the consolidation of Brooklyn (until then a separate city), the County of New York (which then included parts of the Bronx), the County of Richmond, and the western portion of the County of Queens.[113] The opening of the subway in 1904, first built as separate private systems, helped bind the new city together.[114] Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the city became a world center for industry, commerce, and communication.[115]

20th century

In 1904, the steamship General Slocum caught fire in the East River, killing 1,021 people on board.[119] In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the city’s worst industrial disaster, took the lives of 146 garment workers and spurred the growth of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and major improvements in factory safety standards.[120]

New York’s non-White population was 36,620 in 1890.[121] New York City was a prime destination in the early twentieth century for African Americans during the Great Migration from the American South, and by 1916, New York City had become home to the largest urban African diaspora in North America.[122] The Harlem Renaissance of literary and cultural life flourished during the era of Prohibition.[123] The larger economic boom generated construction of skyscrapers competing in height and creating an identifiable skyline.

New York became the most populous urbanized area in the world in the early 1920s, overtaking London. The metropolitan area surpassed the 10 million mark in the early 1930s, becoming the first megacity in human history.[124] The Great Depression saw the election of reformer Fiorello La Guardia as mayor and the fall of Tammany Hall after eighty years of political dominance.[125]

Returning World War II veterans created a post-war economic boom and the development of large housing tracts in eastern Queens and Nassau County as well as similar suburban areas in New Jersey. New York emerged from the war unscathed as the leading city of the world, with Wall Street leading America’s place as the world’s dominant economic power. The United Nations headquarters was completed in 1952, solidifying New York’s global geopolitical influence, and the rise of abstract expressionism in the city precipitated New York’s displacement of Paris as the center of the art world.[126]

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent protests by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan.[127] They are widely considered to constitute the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement[116][128][129][130] and the modern fight for LGBT rights.[131][132] Wayne R. Dynes, author of the Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, wrote that drag queens were the only «transgender folks around» during the June 1969 Stonewall riots. The transgender community in New York City played a significant role in fighting for LGBT equality during the period of the Stonewall riots and thereafter.[133]

In the 1970s, job losses due to industrial restructuring caused New York City to suffer from economic problems and rising crime rates.[134] While a resurgence in the financial industry greatly improved the city’s economic health in the 1980s, New York’s crime rate continued to increase through that decade and into the beginning of the 1990s.[135] By the mid 1990s, crime rates started to drop dramatically due to revised police strategies, improving economic opportunities, gentrification, and new residents, both American transplants and new immigrants from Asia and Latin America. Important new sectors, such as Silicon Alley, emerged in the city’s economy.[136]

21st century

New York’s population reached all-time highs in the 2000 census and then again in the 2010 census.

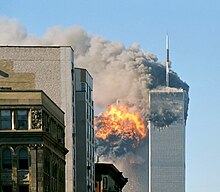

New York City suffered the bulk of the economic damage and largest loss of human life in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks.[137] Two of the four airliners hijacked that day were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center, destroying the towers and killing 2,192 civilians, 343 firefighters, and 71 law enforcement officers. The North Tower became the tallest building ever to be destroyed anywhere then or subsequently.[138]

The area was rebuilt with a new One World Trade Center, a 9/11 memorial and museum, and other new buildings and infrastructure.[139] The World Trade Center PATH station, which had opened on July 19, 1909, as the Hudson Terminal, was also destroyed in the attacks. A temporary station was built and opened on November 23, 2003. An 800,000-square-foot (74,000 m2) permanent rail station designed by Santiago Calatrava, the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, the city’s third-largest hub, was completed in 2016.[140] The new One World Trade Center is the tallest skyscraper in the Western Hemisphere[141] and the seventh-tallest building in the world by pinnacle height, with its spire reaching a symbolic 1,776 feet (541.3 m) in reference to the year of U.S. independence.[142][143][144][145]

The Occupy Wall Street protests in Zuccotti Park in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan began on September 17, 2011, receiving global attention and popularizing the Occupy movement against social and economic inequality worldwide.[146]

New York City was heavily affected by Hurricane Sandy in late October 2012. Sandy’s impacts included the flooding of the New York City Subway system, of many suburban communities, and of all road tunnels entering Manhattan except the Lincoln Tunnel. The New York Stock Exchange closed for two consecutive days. Numerous homes and businesses were destroyed by fire, including over 100 homes in Breezy Point, Queens. Large parts of the city and surrounding areas lost electricity for several days. Several thousand people in Midtown Manhattan were evacuated for six days due to a crane collapse at Extell’s One57. Bellevue Hospital Center and a few other large hospitals were closed and evacuated. Flooding at 140 West Street and another exchange disrupted voice and data communication in Lower Manhattan. At least 43 people lost their lives in New York City as a result of Sandy, and the economic losses in New York City were estimated to be roughly $19 billion. The disaster spawned long-term efforts towards infrastructural projects to counter climate change and rising seas.[147][148]

In March 2020, the first case of COVID-19 in the city was confirmed in Manhattan.[149] The city rapidly replaced Wuhan, China to become the global epicenter of the pandemic during the early phase, before the infection became widespread across the world and the rest of the nation. As of March 2021, New York City had recorded over 30,000 deaths from COVID-19-related complications. In 2022, the LGBT community in New York City became the epicenter of the monkeypox outbreak in the Western Hemisphere, prompting New York Governor Kathy Hochul and New York City Mayor Eric Adams declared corresponding public health emergencies in the state and city, respectively, in July 2022.[150]

Geography

During the Wisconsin glaciation, 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, the New York City area was situated at the edge of a large ice sheet over 2,000 feet (610 m) in depth.[151] The erosive forward movement of the ice (and its subsequent retreat) contributed to the separation of what is now Long Island and Staten Island. That action also left bedrock at a relatively shallow depth, providing a solid foundation for most of Manhattan’s skyscrapers.[152]

New York City is situated in the northeastern United States, in southeastern New York State, approximately halfway between Washington, D.C. and Boston. The location at the mouth of the Hudson River, which feeds into a naturally sheltered harbor and then into the Atlantic Ocean, has helped the city grow in significance as a trading port. Most of New York City is built on the three islands of Long Island, Manhattan, and Staten Island.

The Hudson River flows through the Hudson Valley into New York Bay. Between New York City and Troy, New York, the river is an estuary.[153] The Hudson River separates the city from the U.S. state of New Jersey. The East River—a tidal strait—flows from Long Island Sound and separates the Bronx and Manhattan from Long Island. The Harlem River, another tidal strait between the East and Hudson rivers, separates most of Manhattan from the Bronx. The Bronx River, which flows through the Bronx and Westchester County, is the only entirely freshwater river in the city.[154]

The city’s land has been altered substantially by human intervention, with considerable land reclamation along the waterfronts since Dutch colonial times; reclamation is most prominent in Lower Manhattan, with developments such as Battery Park City in the 1970s and 1980s.[155] Some of the natural relief in topography has been evened out, especially in Manhattan.[156]

The city’s total area is 468.484 square miles (1,213.37 km2); 302.643 sq mi (783.84 km2) of the city is land and 165.841 sq mi (429.53 km2) of this is water.[157][158] The highest point in the city is Todt Hill on Staten Island, which, at 409.8 feet (124.9 m) above sea level, is the highest point on the eastern seaboard south of Maine.[159] The summit of the ridge is mostly covered in woodlands as part of the Staten Island Greenbelt.[160]

Boroughs

|

New York City’s five boroughs

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Population | Land area | Density of population | GDP † | |||

| Borough | County | Census (2020) |

square miles |

square km |

people/ sq. mile |

people/ sq. km |

billions (2012 US$) 2 |

|

The Bronx |

Bronx |

1,472,654 | 42.2 | 109.3 | 34,920 | 13,482 | $ 38.725 |

|

Brooklyn |

Kings |

2,736,074 | 69.4 | 179.7 | 39,438 | 15,227 | $ 92.230 |

|

Manhattan |

New York |

1,694,263 | 22.7 | 58.8 | 74,781 | 28,872 | $ 651.619 |

|

Queens |

Queens |

2,405,464 | 108.7 | 281.5 | 22,125 | 8,542 | $ 88.578 |

|

Staten Island |

Richmond |

495,747 | 57.5 | 148.9 | 8,618 | 3,327 | $ 14.806 |

|

City of New York |

8,804,190 | 302.6 | 783.8 | 29,095 | 11,234 | $ 885.958 | |

|

State of New York |

20,215,751 | 47,126.4 | 122,056.8 | 429 | 166 | $ 1,514.779 | |

| † GDP = Gross Domestic Product Sources:[161][162][163][164] and see individual borough articles. |

New York City is sometimes referred to collectively as the Five Boroughs.[165] Each borough is coextensive with a respective county of New York State, making New York City one of the U.S. municipalities in multiple counties. There are hundreds of distinct neighborhoods throughout the boroughs, many with a definable history and character.

If the boroughs were each independent cities, four of the boroughs (Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx) would be among the ten most populous cities in the United States (Staten Island would be ranked 37th as of 2020); these same boroughs are coterminous with the four most densely populated counties in the United States: New York (Manhattan), Kings (Brooklyn), Bronx, and Queens.

Manhattan

Manhattan (New York County) is the geographically smallest and most densely populated borough. It is home to Central Park and most of the city’s skyscrapers, and is sometimes locally known as The City.[166] Manhattan’s population density of 72,033 people per square mile (27,812/km2) in 2015 makes it the highest of any county in the United States and higher than the density of any individual American city.[167]

Manhattan is the cultural, administrative, and financial center of New York City and contains the headquarters of many major multinational corporations, the United Nations headquarters, Wall Street, and a number of important universities. The borough of Manhattan is often described as the financial and cultural center of the world.[168][169]

Most of the borough is situated on Manhattan Island, at the mouth of the Hudson River and the East River, and its southern tip, at the confluence of the two rivers, represents the birthplace of New York City itself. Several small islands also compose part of the borough of Manhattan, including Randalls and Wards Islands, and Roosevelt Island in the East River, and Governors Island and Liberty Island to the south in New York Harbor.

Manhattan Island is loosely divided into the Lower, Midtown, and Uptown regions. Uptown Manhattan is divided by Central Park into the Upper East Side and the Upper West Side, and above the park is Harlem, bordering the Bronx (Bronx County).

Harlem was predominantly occupied by Jewish and Italian Americans in the 19th century until the Great Migration. It was the center of the Harlem Renaissance.

The borough of Manhattan also includes a small neighborhood on the mainland, called Marble Hill, which is contiguous with the Bronx. New York City’s remaining four boroughs are collectively referred to as the Outer Boroughs.

Brooklyn

Brooklyn (Kings County), on the western tip of Long Island, is the city’s most populous borough. Brooklyn is known for its cultural, social, and ethnic diversity, an independent art scene, distinct neighborhoods, and a distinctive architectural heritage. Downtown Brooklyn is the largest central core neighborhood in the Outer Boroughs. The borough has a long beachfront shoreline including Coney Island, established in the 1870s as one of the earliest amusement grounds in the U.S.[170] Marine Park and Prospect Park are the two largest parks in Brooklyn.[171] Since 2010, Brooklyn has evolved into a thriving hub of entrepreneurship and high technology startup firms,[172][173] and of postmodern art and design.[173][174]

Queens

Queens (Queens County), on Long Island north and east of Brooklyn, is geographically the largest borough, the most ethnically diverse county in the United States,[175] and the most ethnically diverse urban area in the world.[176][177] Historically a collection of small towns and villages founded by the Dutch, the borough has since developed both commercial and residential prominence. Downtown Flushing has become one of the busiest central core neighborhoods in the outer boroughs. Queens is the site of the Citi Field baseball stadium, home of the New York Mets, and hosts the annual U.S. Open tennis tournament at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park. Additionally, two of the three busiest airports serving the New York metropolitan area, John F. Kennedy International Airport and LaGuardia Airport, are in Queens. The third is Newark Liberty International Airport in Newark, New Jersey.

The Bronx

The Bronx (Bronx County) is both New York City’s northernmost borough, and the only one that is mostly on the mainland. It is the location of Yankee Stadium, the baseball park of the New York Yankees, and home to the largest cooperatively-owned housing complex in the United States, Co-op City.[178] It is also home to the Bronx Zoo, the world’s largest metropolitan zoo,[179] which spans 265 acres (1.07 km2) and houses more than 6,000 animals.[180] The Bronx is also the birthplace of hip hop music and its associated culture.[181] Pelham Bay Park is the largest park in New York City, at 2,772 acres (1,122 ha).[182]

Staten Island

Staten Island (Richmond County) is the most suburban in character of the five boroughs. Staten Island is connected to Brooklyn by the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, and to Manhattan by way of the free Staten Island Ferry, a daily commuter ferry that provides unobstructed views of the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and Lower Manhattan. In central Staten Island, the Staten Island Greenbelt spans approximately 2,500 acres (10 km2), including 28 miles (45 km) of walking trails and one of the last undisturbed forests in the city.[183] Designated in 1984 to protect the island’s natural lands, the Greenbelt comprises seven city parks.

Architecture

New York has architecturally noteworthy buildings in a wide range of styles and from distinct time periods, from the Dutch Colonial Pieter Claesen Wyckoff House in Brooklyn, the oldest section of which dates to 1656, to the modern One World Trade Center, the skyscraper at Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan and the most expensive office tower in the world by construction cost.[185]

Manhattan’s skyline, with its many skyscrapers, is universally recognized, and the city has been home to several of the tallest buildings in the world. As of 2019, New York City had 6,455 high-rise buildings, the third most in the world after Hong Kong and Seoul.[186] Of these, as of 2011, 550 completed structures were at least 330 feet (100 m) high, with more than fifty completed skyscrapers taller than 656 feet (200 m). These include the Woolworth Building, an early example of Gothic Revival architecture in skyscraper design, built with massively scaled Gothic detailing; completed in 1913, for 17 years it was the world’s tallest building.[187]

The 1916 Zoning Resolution required setbacks in new buildings and restricted towers to a percentage of the lot size, to allow sunlight to reach the streets below.[188] The Art Deco style of the Chrysler Building (1930) and Empire State Building (1931), with their tapered tops and steel spires, reflected the zoning requirements. The buildings have distinctive ornamentation, such as the eagles at the corners of the 61st floor on the Chrysler Building, and are considered some of the finest examples of the Art Deco style.[189] A highly influential example of the International Style in the United States is the Seagram Building (1957), distinctive for its façade using visible bronze-toned I-beams to evoke the building’s structure. The Condé Nast Building (2000) is a prominent example of green design in American skyscrapers[190] and has received an award from the American Institute of Architects and AIA New York State for its design.

The character of New York’s large residential districts is often defined by the elegant brownstone rowhouses and townhouses and shabby tenements that were built during a period of rapid expansion from 1870 to 1930.[191] In contrast, New York City also has neighborhoods that are less densely populated and feature free-standing dwellings. In neighborhoods such as Riverdale (in the Bronx), Ditmas Park (in Brooklyn), and Douglaston (in Queens), large single-family homes are common in various architectural styles such as Tudor Revival and Victorian.[192][193][194]

Stone and brick became the city’s building materials of choice after the construction of wood-frame houses was limited in the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1835.[195] A distinctive feature of many of the city’s buildings is the roof-mounted wooden water tower. In the 1800s, the city required their installation on buildings higher than six stories to prevent the need for excessively high water pressures at lower elevations, which could break municipal water pipes.[196] Garden apartments became popular during the 1920s in outlying areas, such as Jackson Heights.[197]

According to the United States Geological Survey, an updated analysis of seismic hazard in July 2014 revealed a «slightly lower hazard for tall buildings» in New York City than previously assessed. Scientists estimated this lessened risk based upon a lower likelihood than previously thought of slow shaking near the city, which would be more likely to cause damage to taller structures from an earthquake in the vicinity of the city.[198] Manhattan contained over 500 million square feet of office space as of 2022; the COVID-19 pandemic and hybrid work model have prompted consideration of commercial-to-residential conversion within Midtown Manhattan.[199]

Climate

| New York City | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Under the Köppen climate classification, using the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm, New York City features a humid subtropical climate (Cfa), and is thus the northernmost major city on the North American continent with this categorization. The suburbs to the immediate north and west lie in the transitional zone between humid subtropical and humid continental climates (Dfa).[200][201] By the Trewartha classification, the city is defined as having an oceanic climate (Do).[202][203] Annually, the city averages 234 days with at least some sunshine.[204] The city lies in the USDA 7b plant hardiness zone.[205]

Winters are chilly and damp, and prevailing wind patterns that blow sea breezes offshore temper the moderating effects of the Atlantic Ocean; yet the Atlantic and the partial shielding from colder air by the Appalachian Mountains keep the city warmer in the winter than inland North American cities at similar or lesser latitudes such as Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis. The daily mean temperature in January, the area’s coldest month, is 33.3 °F (0.7 °C).[206] Temperatures usually drop to 10 °F (−12 °C) several times per winter,[207] yet can also reach 60 °F (16 °C) for several days even in the coldest winter month. Spring and autumn are unpredictable and can range from cool to warm, although they are usually mild with low humidity. Summers are typically hot and humid, with a daily mean temperature of 77.5 °F (25.3 °C) in July.[206]

Nighttime temperatures are often enhanced due to the urban heat island effect. Daytime temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on average of 17 days each summer and in some years exceed 100 °F (38 °C), although this is a rare achievement, last occurring on July 18, 2012.[208] Similarly, readings of 0 °F (−18 °C) are also extremely rare, last occurring on February 14, 2016.[209] Extreme temperatures have ranged from −15 °F (−26 °C), recorded on February 9, 1934, up to 106 °F (41 °C) on July 9, 1936;[206] the coldest recorded wind chill was −37 °F (−38 °C) on the same day as the all-time record low.[210] The record cold daily maximum was 2 °F (−17 °C) on December 30, 1917, while, conversely, the record warm daily minimum was 87 °F (31 °C), on July 2, 1903.[208] The average water temperature of the nearby Atlantic Ocean ranges from 39.7 °F (4.3 °C) in February to 74.1 °F (23.4 °C) in August.[211]

The city receives 49.5 inches (1,260 mm) of precipitation annually, which is relatively evenly spread throughout the year. Average winter snowfall between 1991 and 2020 has been 29.8 inches (76 cm); this varies considerably between years. Hurricanes and tropical storms are rare in the New York area.[212] Hurricane Sandy brought a destructive storm surge to New York City on the evening of October 29, 2012, flooding numerous streets, tunnels, and subway lines in Lower Manhattan and other areas of the city and cutting off electricity in many parts of the city and its suburbs.[213] The storm and its profound impacts have prompted the discussion of constructing seawalls and other coastal barriers around the shorelines of the city and the metropolitan area to minimize the risk of destructive consequences from another such event in the future.[147][148]

The coldest month on record is January 1857, with a mean temperature of 19.6 °F (−6.9 °C) whereas the warmest months on record are July 1825 and July 1999, both with a mean temperature of 81.4 °F (27.4 °C).[214] The warmest years on record are 2012 and 2020, both with mean temperatures of 57.1 °F (13.9 °C). The coldest year is 1836, with a mean temperature of 47.3 °F (8.5 °C).[214][215] The driest month on record is June 1949, with 0.02 inches (0.51 mm) of rainfall. The wettest month was August 2011, with 18.95 inches (481 mm) of rainfall. The driest year on record is 1965, with 26.09 inches (663 mm) of rainfall. The wettest year was 1983, with 80.56 inches (2,046 mm) of rainfall.[216] The snowiest month on record is February 2010, with 36.9 inches (94 cm) of snowfall. The snowiest season (Jul–Jun) on record is 1995–1996, with 75.6 inches (192 cm) of snowfall. The least snowy season was 1972–1973, with 2.3 inches (5.8 cm) of snowfall.[217] The earliest seasonal trace of snowfall occurred on October 10, in both 1979 and 1925. The latest seasonal trace of snowfall occurred on May 9, in both 2020 and 1977.[218]

Climate data for New York (Belvedere Castle, Central Park), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1869–present[c] |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.4 (15.8) |

60.7 (15.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

82.9 (28.3) |

88.5 (31.4) |

92.1 (33.4) |

95.7 (35.4) |

93.4 (34.1) |

89.0 (31.7) |

79.7 (26.5) |

70.7 (21.5) |

62.9 (17.2) |

97.0 (36.1) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 39.5 (4.2) |

42.2 (5.7) |

49.9 (9.9) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

79.7 (26.5) |

84.9 (29.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

76.2 (24.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

44.3 (6.8) |

62.6 (17.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.7 (0.9) |

35.9 (2.2) |

42.8 (6.0) |

53.7 (12.1) |

63.2 (17.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

77.5 (25.3) |

76.1 (24.5) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.9 (14.4) |

48.0 (8.9) |

39.1 (3.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

35.8 (2.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

55.0 (12.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

70.1 (21.2) |

68.9 (20.5) |

62.3 (16.8) |

51.4 (10.8) |

42.0 (5.6) |

33.8 (1.0) |

48.9 (9.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.8 (−12.3) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

43.9 (6.6) |

52.7 (11.5) |

61.8 (16.6) |

60.3 (15.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

38.4 (3.6) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

7.7 (−13.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

−15 (−26) |

3 (−16) |

12 (−11) |

32 (0) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

5 (−15) |

−13 (−25) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.64 (92) |

3.19 (81) |

4.29 (109) |

4.09 (104) |

3.96 (101) |

4.54 (115) |

4.60 (117) |

4.56 (116) |

4.31 (109) |

4.38 (111) |

3.58 (91) |

4.38 (111) |

49.52 (1,258) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.8 (22) |

10.1 (26) |

5.0 (13) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.5 (1.3) |

4.9 (12) |

29.8 (76) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 125.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 11.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61.5 | 60.2 | 58.5 | 55.3 | 62.7 | 65.2 | 64.2 | 66.0 | 67.8 | 65.6 | 64.6 | 64.1 | 63.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.0 (−7.8) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

34.0 (1.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

57.4 (14.1) |

61.9 (16.6) |

62.1 (16.7) |

55.6 (13.1) |

44.1 (6.7) |

34.0 (1.1) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

40.3 (4.6) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 162.7 | 163.1 | 212.5 | 225.6 | 256.6 | 257.3 | 268.2 | 268.2 | 219.3 | 211.2 | 151.0 | 139.0 | 2,534.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 54 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 59 | 63 | 59 | 61 | 51 | 48 | 57 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990; dew point 1965–1984)[208][220][204][221] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[222]

See Climate of New York City for additional climate information from the outer boroughs. |

| Sea temperature data for New York | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 41.7 (5.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

40.2 (4.5) |

45.1 (7.3) |

52.5 (11.4) |

64.5 (18.1) |

72.1 (22.3) |

74.1 (23.4) |

70.1 (21.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

54.3 (12.4) |

47.2 (8.4) |

55.4 (13.0) |

| Source: Weather Atlas[222] |

See or edit raw graph data.

Parks

The city of New York has a complex park system, with various lands operated by the National Park Service, the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. In its 2018 ParkScore ranking, the Trust for Public Land reported that the park system in New York City was the ninth-best park system among the fifty most populous U.S. cities.[223] ParkScore ranks urban park systems by a formula that analyzes median park size, park acres as percent of city area, the percent of city residents within a half-mile of a park, spending of park services per resident, and the number of playgrounds per 10,000 residents. In 2021, the New York City Council banned the use of synthetic pesticides by city agencies and instead required organic lawn management. The effort was started by teacher Paula Rogovin’s kindergarten class at P.S. 290.[224]

National parks

Gateway National Recreation Area contains over 26,000 acres (110 km2), most of it in New York City.[225] In Brooklyn and Queens, the park contains over 9,000 acres (36 km2) of salt marsh, wetlands, islands, and water, including most of Jamaica Bay and the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. Also in Queens, the park includes a significant portion of the western Rockaway Peninsula, most notably Jacob Riis Park and Fort Tilden. In Staten Island, it includes Fort Wadsworth, with historic pre-Civil War era Battery Weed and Fort Tompkins, and Great Kills Park, with beaches, trails, and a marina.

The Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island Immigration Museum are managed by the National Park Service and are in both New York and New Jersey. They are joined in the harbor by Governors Island National Monument. Historic sites under federal management on Manhattan Island include Stonewall National Monument; Castle Clinton National Monument; Federal Hall National Memorial; Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site; General Grant National Memorial (Grant’s Tomb); African Burial Ground National Monument; and Hamilton Grange National Memorial. Hundreds of properties are listed on the National Register of Historic Places or as a National Historic Landmark.

State parks

There are seven state parks within the confines of New York City. Some of them include:

- The Clay Pit Ponds State Park Preserve is a natural area that includes extensive riding trails.

- Riverbank State Park is a 28-acre (11 ha) facility that rises 69 feet (21 m) over the Hudson River.[226]

- Marsha P. Johnson State Park is a state park in Brooklyn and Manhattan that borders the East River that was renamed in honor of Marsha P. Johnson.[227]

City parks

New York City has over 28,000 acres (110 km2) of municipal parkland and 14 miles (23 km) of public beaches.[228] The largest municipal park in the city is Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, with 2,772 acres (1,122 ha).[182][229]

- Central Park, an 843-acre (3.41 km2)[182] park in middle-upper Manhattan, is the most visited urban park in the United States and one of the most filmed locations in the world, with 40 million visitors in 2013.[230] The park has a wide range of attractions; there are several lakes and ponds, two ice-skating rinks, the Central Park Zoo, the Central Park Conservatory Garden, and the 106-acre (0.43 km2) Jackie Onassis Reservoir.[231] Indoor attractions include Belvedere Castle with its nature center, the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theater, and the historic Carousel. On October 23, 2012, hedge fund manager John A. Paulson announced a $100 million gift to the Central Park Conservancy, the largest ever monetary donation to New York City’s park system.[232]

- Washington Square Park is a prominent landmark in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan. The Washington Square Arch at the northern gateway to the park is an iconic symbol of both New York University and Greenwich Village.

- Prospect Park in Brooklyn has a 90-acre (36 ha) meadow, a lake, and extensive woodlands. Within the park is the historic Battle Pass, prominent in the Battle of Long Island.[233]

- Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, with its 897 acres (363 ha) making it the city’s fourth largest park,[234] was the setting for the 1939 World’s Fair and the 1964 World’s Fair[235] and is host to the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center and the annual U.S. Open Tennis Championships tournament.[236]

- Over a fifth of the Bronx’s area, 7,000 acres (28 km2), is dedicated to open space and parks, including Pelham Bay Park, Van Cortlandt Park, the Bronx Zoo, and the New York Botanical Gardens.[237]

- In Staten Island, the Conference House Park contains the historic Conference House, site of the only attempt of a peaceful resolution to the American Revolution which was conducted in September 1775, attended by Benjamin Franklin representing the Americans and Lord Howe representing the British Crown.[238] The historic Burial Ridge, the largest Native American burial ground within New York City, is within the park.[239]

Military installations

Brooklyn is home to Fort Hamilton, the U.S. military’s only active duty installation within New York City,[240] aside from Coast Guard operations. The facility was established in 1825 on the site of a small battery used during the American Revolution, and it is one of America’s longest serving military forts.[241] Today, Fort Hamilton serves as the headquarters of the North Atlantic Division of the United States Army Corps of Engineers and for the New York City Recruiting Battalion. It also houses the 1179th Transportation Brigade, the 722nd Aeromedical Staging Squadron, and a military entrance processing station. Other formerly active military reservations still used for National Guard and military training or reserve operations in the city include Fort Wadsworth in Staten Island and Fort Totten in Queens.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1698 | 4,937 | — |

| 1712 | 5,840 | +18.3% |

| 1723 | 7,248 | +24.1% |

| 1737 | 10,664 | +47.1% |

| 1746 | 11,717 | +9.9% |

| 1756 | 13,046 | +11.3% |

| 1771 | 21,863 | +67.6% |

| 1790 | 49,401 | +126.0% |

| 1800 | 79,216 | +60.4% |

| 1810 | 119,734 | +51.1% |

| 1820 | 152,056 | +27.0% |

| 1830 | 242,278 | +59.3% |

| 1840 | 391,114 | +61.4% |

| 1850 | 696,115 | +78.0% |

| 1860 | 1,174,779 | +68.8% |

| 1870 | 1,478,103 | +25.8% |

| 1880 | 1,911,698 | +29.3% |

| 1890 | 2,507,414 | +31.2% |

| 1900 | 3,437,202 | +37.1% |

| 1910 | 4,766,883 | +38.7% |

| 1920 | 5,620,048 | +17.9% |

| 1930 | 6,930,446 | +23.3% |

| 1940 | 7,454,995 | +7.6% |

| 1950 | 7,891,957 | +5.9% |

| 1960 | 7,781,984 | −1.4% |

| 1970 | 7,894,862 | +1.5% |

| 1980 | 7,071,639 | −10.4% |

| 1990 | 7,322,564 | +3.5% |

| 2000 | 8,008,278 | +9.4% |

| 2010 | 8,175,133 | +2.1% |

| 2020 | 8,804,190 | +7.7% |

| Note: Census figures (1790–2010) cover the present area of all five boroughs, before and after the 1898 consolidation. For New York City itself before annexing part of the Bronx in 1874, see Manhattan#Demographics.[242] Source: U.S. Decennial Census;[243] 1698–1771[244] 1790–1890[242][245] 1900–1990[246] 2000–2010[247][248][249] 2010–2020[250] |

| Historical demographics | 2020[251] | 2010[252] | 1990[253] | 1970[253] | 1940[253] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 30.9% | 33.3% | 43.4% | 64.0% | 92.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 28.3% | 28.6% | 23.7% | 15.2% | 1.6% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 20.2% | 22.8% | 28.8% | 21.1% | 6.1% |

| Asian and Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 15.6% | 12.6% | 7.0% | 1.2% | 0.2% |

| Native American (non-Hispanic) | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.1% | N/A |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | 3.4% | 1.8% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

New York City is the most populous city in the United States,[254] with 8,804,190 residents[250] incorporating more immigration into the city than outmigration since the 2010 United States census.[255][256] More than twice as many people live in New York City as compared to Los Angeles, the second-most populous U.S. city;[254] and New York has more than three times the population of Chicago, the third-most populous U.S. city. New York City gained more residents between 2010 and 2020 (629,000) than any other U.S. city, and a greater amount than the total sum of the gains over the same decade of the next four largest U.S. cities, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Phoenix, Arizona combined.[257][258] New York City’s population is about 44% of New York State’s population,[259] and about 39% of the population of the New York metropolitan area.[260] The majority of New York City residents in 2020 (5,141,538, or 58.4%) were living on Long Island, in Brooklyn, or in Queens.[261]

Population density

In 2020, the city had an estimated population density of 29,302.37 inhabitants per square mile (11,313.71/km2), rendering it the nation’s most densely populated of all larger municipalities (those with more than 100,000 residents), with several small cities (of fewer than 100,000) in adjacent Hudson County, New Jersey having greater density, as per the 2010 census.[262] Geographically co-extensive with New York County, the borough of Manhattan’s 2017 population density of 72,918 inhabitants per square mile (28,154/km2) makes it the highest of any county in the United States and higher than the density of any individual American city.[263][264][265] The next three densest counties in the United States, placing second through fourth, are also New York boroughs: Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens respectively.[266]

Race and ethnicity

Further information: Category:Ethnic groups in New York City, African Americans in New York City, Bangladeshis in New York City, Caribbeans in New York City, Chinese in New York City, Dominican Americans in New York City, Filipinos in New York City, Fuzhounese in New York City, Indians in New York City, Irish in New York City, Italians in New York City, Japanese in New York City, Koreans in New York City, Pakistanis in New York City, Puerto Ricans in New York City, Russians in New York City, and Ukrainians in New York City

The city’s population in 2020 was 30.9% White (non-Hispanic), 28.7% Hispanic or Latino, 20.2% Black or African American (non-Hispanic), 15.6% Asian, and 0.2% Native American (non-Hispanic).[268] A total of 3.4% of the non-Hispanic population identified with more than one race. Throughout its history, New York has been a major port of entry for immigrants into the United States. More than 12 million European immigrants were received at Ellis Island between 1892 and 1924.[269] The term «melting pot» was first coined to describe densely populated immigrant neighborhoods on the Lower East Side. By 1900, Germans constituted the largest immigrant group, followed by the Irish, Jews, and Italians.[270] In 1940, Whites represented 92% of the city’s population.[253]

Approximately 37% of the city’s population is foreign born, and more than half of all children are born to mothers who are immigrants as of 2013.[271][272] In New York, no single country or region of origin dominates.[271] The ten largest sources of foreign-born individuals in the city as of 2011 were the Dominican Republic, China, Mexico, Guyana, Jamaica, Ecuador, Haiti, India, Russia, and Trinidad and Tobago,[273] while the Bangladeshi-born immigrant population has become one of the fastest growing in the city, counting over 74,000 by 2011.[22][274]

Asian Americans in New York City, according to the 2010 census, number more than one million, greater than the combined totals of San Francisco and Los Angeles.[275] New York contains the highest total Asian population of any U.S. city proper.[276] The New York City borough of Queens is home to the state’s largest Asian American population and the largest Andean (Colombian, Ecuadorian, Peruvian, and Bolivian) populations in the United States, and is also the most ethnically and linguistically diverse urban area in the world.[277][177]

The Chinese population constitutes the fastest-growing nationality in New York State. Multiple satellites of the original Manhattan’s Chinatown—home to the highest concentration of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere,[278] as well as in Brooklyn, and around Flushing, Queens, are thriving as traditionally urban enclaves—while also expanding rapidly eastward into suburban Nassau County[279] on Long Island,[280] as the New York metropolitan region and New York State have become the top destinations for new Chinese immigrants, respectively, and large-scale Chinese immigration continues into New York City and surrounding areas,[281][282][283][284][285][286] with the largest metropolitan Chinese diaspora outside Asia,[22][287] including an estimated 812,410 individuals in 2015.[288]

In 2012, 6.3% of New York City was of Chinese ethnicity, with nearly three-fourths living in either Queens or Brooklyn, geographically on Long Island.[289] A community numbering 20,000 Korean-Chinese (Chaoxianzu or Joseonjok) is centered in Flushing, Queens, while New York City is also home to the largest Tibetan population outside China, India, and Nepal, also centered in Queens.[290] Koreans made up 1.2% of the city’s population, and Japanese 0.3%. Filipinos were the largest Southeast Asian ethnic group at 0.8%, followed by Vietnamese, who made up 0.2% of New York City’s population in 2010. Indians are the largest South Asian group, comprising 2.4% of the city’s population, with Bangladeshis and Pakistanis at 0.7% and 0.5%, respectively.[291] Queens is the preferred borough of settlement for Asian Indians, Koreans, Filipinos and Malaysians,[292][281] and other Southeast Asians;[293] while Brooklyn is receiving large numbers of both West Indian and Asian Indian immigrants.

New York City has the largest European and non-Hispanic white population of any American city. At 2.7 million in 2012, New York’s non-Hispanic White population is larger than the non-Hispanic White populations of Los Angeles (1.1 million), Chicago (865,000), and Houston (550,000) combined.[294] The non-Hispanic White population was 6.6 million in 1940.[295] The non-Hispanic White population has begun to increase since 2010.[296]

The European diaspora residing in the city is very diverse. According to 2012 census estimates, there were roughly 560,000 Italian Americans, 385,000 Irish Americans, 253,000 German Americans, 223,000 Russian Americans, 201,000 Polish Americans, and 137,000 English Americans. Additionally, Greek and French Americans numbered 65,000 each, with those of Hungarian descent estimated at 60,000 people. Ukrainian and Scottish Americans numbered 55,000 and 35,000, respectively. People identifying ancestry from Spain numbered 30,838 total in 2010.[297]

People of Norwegian and Swedish descent both stood at about 20,000 each, while people of Czech, Lithuanian, Portuguese, Scotch-Irish, and Welsh descent all numbered between 12,000 and 14,000.[298] Arab Americans number over 160,000 in New York City,[299] with the highest concentration in Brooklyn. Central Asians, primarily Uzbek Americans, are a rapidly growing segment of the city’s non-Hispanic White population, enumerating over 30,000, and including more than half of all Central Asian immigrants to the United States,[300] most settling in Queens or Brooklyn. Albanian Americans are most highly concentrated in the Bronx,[301] while Astoria, Queens is the epicenter of American Greek culture as well as the Cypriot community.

The New York City metropolitan statistical area, has the largest foreign-born population of any metropolitan region in the world. The New York region continues to be by far the leading metropolitan gateway for legal immigrants admitted into the United States, substantially exceeding the combined totals of Los Angeles and Miami.[281] It is home to the largest Jewish and Israeli communities outside Israel, with the Jewish population in the region numbering over 1.5 million in 2012 and including many diverse Jewish sects, predominantly from around the Middle East and Eastern Europe, and including a rapidly growing Orthodox Jewish population, also the largest outside Israel.[290]

The metropolitan area is also home to 20% of the nation’s Indian Americans and at least 20 Little India enclaves, and 15% of all Korean Americans and four Koreatowns;[248] the largest Asian Indian population in the Western Hemisphere; the largest Russian American,[282] Italian American, and African American populations; the largest Dominican American, Puerto Rican American, and South American[282] and second-largest overall Hispanic population in the United States, numbering 4.8 million;[297] and includes multiple established Chinatowns within New York City alone.[302]

Ecuador, Colombia, Guyana, Peru, Brazil, and Venezuela are the top source countries from South America for immigrants to the New York City region; the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean; Nigeria, Egypt, Ghana, Tanzania, Kenya, and South Africa from Africa; and El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala in Central America.[303] Amidst a resurgence of Puerto Rican migration to New York City, this population had increased to approximately 1.3 million in the metropolitan area as of 2013. In 2022, New York City began receiving thousands of Latino immigrants bused from the state of Texas, mostly originating from Venezuela, Ecuador, Columbia, and Honduras.[304]

Since 2010, Little Australia has emerged and is growing rapidly, representing the Australasian presence in Nolita, Manhattan.[305][306][307][308] In 2011, there were an estimated 20,000 Australian residents of New York City, nearly quadruple the 5,537 in 2005.[309][310] Qantas Airways of Australia and Air New Zealand have been planning for long-haul flights from New York to Sydney and Auckland, which would both rank among the longest non-stop flights in the world.[311] A Little Sri Lanka has developed in the Tompkinsville neighborhood of Staten Island.[312] Le Petit Sénégal, or Little Senegal, is based in Harlem. Richmond Hill, Queens is often thought of as «Little Guyana» for its large Guyanese community,[313] as well as Punjab Avenue (ਪੰਜਾਬ ਐਵੇਨਿਊ), or Little Punjab, for its high concentration of Punjabi people. Little Poland is expanding rapidly in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

Religion

Christianity

Largely as a result of Western European missionary work and colonialism, Christianity is the largest religion (59% adherent) in New York City,[314] which is home to the highest number of churches of any city in the world.[14] Roman Catholicism is the largest Christian denomination (33%), followed by Protestantism (23%), and other Christian denominations (3%). The Roman Catholic population are primarily served by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York and Diocese of Brooklyn. Eastern Catholics are divided into numerous jurisdictions throughout the city. Evangelical Protestantism is the largest branch of Protestantism in the city (9%), followed by Mainline Protestantism (8%), while the converse is usually true for other cities and metropolitan areas.[315] In Evangelicalism, Baptists are the largest group; in Mainline Protestantism, Reformed Protestants compose the largest subset. The majority of historically African American churches are affiliated with the National Baptist Convention (USA) and Progressive National Baptist Convention. The Church of God in Christ is one of the largest predominantly Black Pentecostal denominations in the area. Approximately 1% of the population is Mormon. The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America and other Orthodox Christians (mainstream and independent) were the largest Eastern Christian groups. The American Orthodox Catholic Church (initially led by Aftimios Ofiesh) was founded in New York City in 1927.

Judaism

Judaism, the second-largest religion practiced in New York City, with approximately 1.6 million adherents as of 2022, represents the largest Jewish community of any city in the world, greater than the combined totals of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem.[318][319] Nearly half of the city’s Jews live in Brooklyn.[317][316] The ethno-religious population makes up 18.4% of the city and its religious demographic makes up 8%.[320] The first recorded Jewish settler was Jacob Barsimson, who arrived in August 1654 on a passport from the Dutch West India Company.[321] Following the assassination of Alexander II of Russia, for which many blamed «the Jews», the 36 years beginning in 1881 experienced the largest wave of Jewish immigration to the United States.[322] In 2012, the largest Jewish denominations were Orthodox, Haredi, and Conservative Judaism.[323] Reform Jewish communities are prevalent through the area. 770 Eastern Parkway is the headquarters of the international Chabad Lubavitch movement, and is considered an icon, while Congregation Emanu-El of New York in Manhattan is the largest Reform synagogue in the world.

Islam

Islam ranks as the third largest religion in New York City, following Christianity and Judaism, with estimates ranging between 600,000 and 1,000,000 observers of Islam, including 10% of the city’s public school children.[324] Given both the size and scale of the city, as well as its relative proxinity and accessibility by air transportation to the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia, 22.3% of American Muslims live in New York City, with 1.5 million Muslims in the greater New York metropolitan area, representing the largest metropolitan Muslim population in the Western Hemisphere[325]—and the most ethnically diverse Muslim population of any city in the world.[326] Powers Street Mosque in Brooklyn is one of the oldest continuously operating mosques in the U.S., and represents the first Islamic organization in both the city and the state of New York.[327][328]

Hinduism and other religious affiliations

Following these three largest religious groups in New York City are Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Zoroastrianism, and a variety of other religions. As of 2023, 24% of Greater New Yorkers identified with no organized religious affiliation, including 4% Atheist.[329]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

New York City has been described as the gay capital of the world, and is home to one of the world’s largest LGBTQ populations and the most prominent.[44] The New York metropolitan area is home to about 570,000 self-identifying gay and bisexual people, the largest in the United States.[332][333] Same-sex sexual activity between consenting adults has been legal in New York since the New York v. Onofre case in 1980 which invalidated the state’s sodomy law.[334] Same-sex marriages in New York were legalized on June 24, 2011, and were authorized to take place on July 23, 2011.[335] Brian Silverman, the author of Frommer’s New York City from $90 a Day, wrote the city has «one of the world’s largest, loudest, and most powerful LGBT communities», and «Gay and lesbian culture is as much a part of New York’s basic identity as yellow cabs, high-rise buildings, and Broadway theatre».[336] LGBT travel guide Queer in the World states, «The fabulosity of Gay New York is unrivaled on Earth, and queer culture seeps into every corner of its five boroughs».[337] LGBT advocate and entertainer Madonna stated metaphorically, «Anyways, not only is New York City the best place in the world because of the queer people here. Let me tell you something, if you can make it here, then you must be queer.»[338]

The annual New York City Pride March (or gay pride parade) proceeds southward down Fifth Avenue and ends at Greenwich Village in Lower Manhattan; the parade is the largest pride parade in the world, attracting tens of thousands of participants and millions of sidewalk spectators each June.[339][30] The annual Queens Pride Parade is held in Jackson Heights and is accompanied by the ensuing Multicultural Parade.[340]

Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019 was the largest international Pride celebration in history, produced by Heritage of Pride and enhanced through a partnership with the I ❤ NY program’s LGBT division, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, with 150,000 participants and five million spectators attending in Manhattan alone. New York City is also home to the largest transgender population in the world, estimated at more than 50,000 in 2018, concentrated in Manhattan and Queens; however, until the June 1969 Stonewall riots, this community had felt marginalized and neglected by the gay community.[340][133] Brooklyn Liberation March, the largest transgender-rights demonstration in LGBTQ history, took place on June 14, 2020, stretching from Grand Army Plaza to Fort Greene, Brooklyn, focused on supporting Black transgender lives, drawing an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 participants.[342][343]

Wealth and income disparity

New York City, like other large cities, has a high degree of income disparity, as indicated by its Gini coefficient of 0.55 as of 2017.[344] In the first quarter of 2014, the average weekly wage in New York County (Manhattan) was $2,749, representing the highest total among large counties in the United States.[345] In 2022, New York City was home to the highest number of billionaires of any city in the world, including former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, with a total of 107.[18] New York also had the highest density of millionaires per capita among major U.S. cities in 2014, at 4.6% of residents.[346] New York City is one of the relatively few American cities levying an income tax (about 3%) on its residents.[347][348][349] As of 2018, there were 78,676 homeless people in New York City.[350]

Economy