@breadcrumbs([«breadcrumbs» => $breadcrumbs])@endbreadcrumbs

«Битлз» — загадка легендарного названия

2019-01-16T10:09:00+05:00

В международный день «Битлз» попробуем разобраться, как появляются уникальные слова и каким образом они становятся легендой.

«Битлз» — загадка легендарного названия

Уроки русского

2019-01-16T05:09:00+00:00

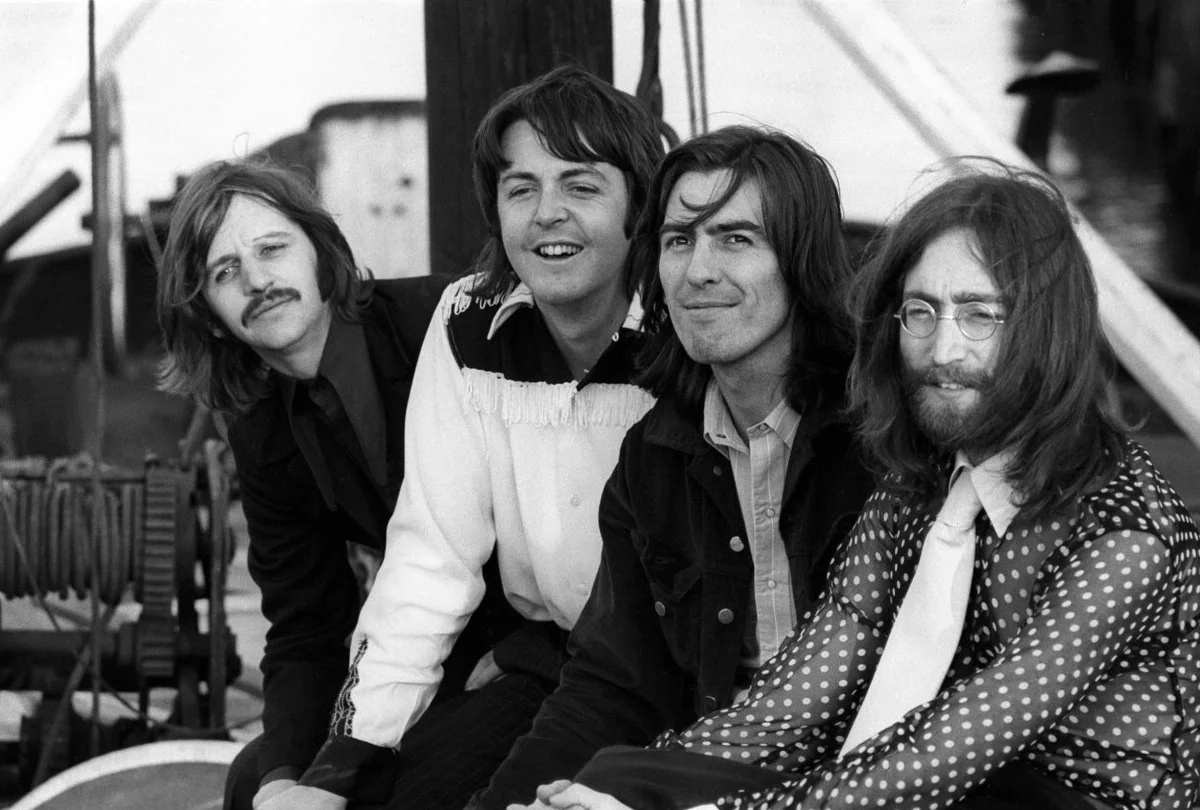

Наверняка всем знакомо название группы «Битлз» (англ. The Beatles), на музыке которой выросло несколько поколений. А слово «битлы» – было символическим для молодежи 60-70х годов прошлого века. Этими «битлами» хотели быть все: надевали брюки-клеш, подметающие тротуары вместо дворников, отращивали длинные волосы, из-за которых ребятам ставили двойки на начальной военной подготовке. И слушали любимые песни на кассетных магнитофонах.

Что же скрывает в себе название группы «The Beatles». До сих пор нет однозначного ответа, кто именно придумал это слово. Джон Леннон заявлял, что название ему привиделось во сне: пылающий человек сказал: „Пусть будут beetles“» (Багс). Да, да, сначала слово в написании звучало как «Жуки» (Beetles).

Но музыканты мечтали о двойном значении и смысле. И заменили одну букву в слове так, что сразу бросался в глаза корень «beat» -бит, а это уже ритм, удар, музыка.

Этот синтезированный вариант названия группы был переведен в Советском Союзе сначала как «Жуки-ударники». Но неопределенное слово, означающее нечто «исповедующие бит», у нашего народа все же обрело звучание «Битлы», и стало популярным, и даже родным на многие годы.

Интересно! Когда создалась группа, то сначала она носила название Сильвер Битлз-Silver B E E tles (Серебряные Жуки), а в моде в то время доминировало бит-музыка-B E A T-music!

Фанаты признаются: « Мы так любили «Битлз»! И уже неважно, что есть группы гораздо круче них, что Джон совсем сбрендил от этой экстравагантной Йоко Оно (главное-«Земляничные поляны»!), и пусть Пол позже «затупеет» на коммерческой музыке (главное-он увидел во сне шедевр-«Вчера»), а Джорджу «сорвёт крышу» от восточной музыки (главное_»Бангладеш»), и пусть Ринго окажется самым посредственным ударником в мире (главное -его большой нос и хитрая улыбка—«Я -самый лучший»). «Битлы»-это уже классика и «BEATLES» FOREVER!!!!!».

Фанатов группы «Битлз» полно и сейчас. Интересно, станут ли такими же символическими новые названия популярных исполнителей. Будем ли мы через полвека представлять вместо чеканной монеты певицу Монеточкку, или ассоциировать гречку не с крупой, а с поющей девушкой?

Другие выпуски

2023-03-03T10:33:00+05:00

2023-03-01T10:28:00+05:00

2023-02-17T16:15:00+05:00

2023-02-17T15:11:00+05:00

2023-02-17T10:06:00+05:00

2023-01-19T17:48:00+05:00

2023-01-17T17:42:00+05:00

2023-01-12T10:37:00+05:00

2022-12-31T10:32:00+05:00

2022-12-30T10:26:00+05:00

29 января 1960 г.

Бруно Цериотти (Bruno Ceriotti, историк): «В этот день группа «Рори Сторм и Ураганы» (Rory Storm And The Hurricanes) выступает в «Кембридж-Холле» (Cambridge Hall, Southport). Состав группы: Эл Колдуэлл (он же Рори Сторм), Джонни Берн (он же Джонни «Гитара»), Ти Брайен, Уолтер «Уолли» Эймонд (он же Лу Уолтерс), Ричард Старки (он же Ринго Старр)».

Из дневника Джонни «Гитары» (группа «Рори Сторм и Ураганы»): «Сауспорт. Сыграли паршиво».

(условная дата)

Питер Фрэйм: «Когда в январе 1960 г. Стю Сатклифф присоединился к группе, то первое, что он сделал, это предложил изменить ее название на «Битэлз» (The Beatals), которое в скором времени (в апреле) будет немного изменено».

прим. – считается, что название группы «Beatles» появилось в апреле 1960 г. Скорее всего, со слов Пола Маккартни (Пол: «Однажды апрельским вечером 1960 года…»). По мнению ресурса thebeatleschronology.com название «Битэлз» (The Beatals) было предложено Стю Сатклиффом в январе 1960 г. и таким было первоначальное название группы. Его упоминает Пол Маккартни в своем письме, адресованном в летний лагерь «Батлинз». Возможно, что выступая в художественном колледже по пятницам в первых месяцах 1960 года, они вообще никак не назывались официально.

Из интервью Пола Маккартни для интервью для «Flaming Pie»:

Пол: Долгие годы была неясность с тем, кто же придумал название «Битлз». Джордж и я точно помним, что дело было так. Джон и несколько приятелей из школы искусств снимали квартиру. Мы там все кучковались на старых матрасах – так здорово было. Слушали пластинки Джонни Барнетта, бесились до утра, как это у подростков заведено. И вот как-то однажды Джон, Стю, Джордж и я шли по улице, вдруг Джон и Стю говорят: «Эй, у нас есть идея, как назвать группу – «Битлз», через букву «a» (если следовать правилам грамматики, полагалось писать «The Beetles» – «жуки».) Мы с Джорджем удивились, а Джон говорит: «Ну да, мы со Стю до этого додумались».

Так эта история вспоминается мне и Джорджу. Но с годами кое-кто стал думать, что Джону самому пришла в голову идея названия группы, и в качестве доказательства ссылаются на статью «Краткое отступление по поводу сомнительного происхождения «Битлз», которую Джон написал в начале 60-х для газеты «Мерсибит». Там были такие строки: «Жили-были три маленьких мальчика, их звали Джон, Джордж и Пол… Многие спрашивают: что такое «Битлз», почему «Битлз», как возникло это название? Оно возникло из видения. Явился человек на пылающем пироге и сказал им: «Отныне вы «Битлз» с буквой «a». Конечно, не было никакого видения. Джон пошутил, в туповатой манере, типичной для того времени. Но кое-кто не понял юмора. Хотя, вроде, все так очевидно.

Джордж: «Откуда взялось название – вопрос спорный. Джон утверждает, что его выдумал он, но я помню, что накануне вечером он разговаривал со Стюартом. У группы «Крикетс», которая подыгрывала Бадди Холли, было похожее название, но на самом деле Стюарт обожал Марлона Брандо, а в фильме «Дикарь» есть сцена, в которой Ли Марвин говорит: «Джонни, мы искали тебя, «жуки» скучают по тебе, всем «жукам» недостает тебя». Возможно, она вспомнилась и Джону, и Стю одновременно, и мы оставили это название. Мы приписываем его поровну Сатклиффу и Леннону».

Билл Харри: «Я был очевидцем того, как Джон и Стюарт [Сатклифф] придумали название «Битлз». Я называл их группой из колледжа, потому что они больше не использовали название «Кворримен» и не могли придумать новое. Они сидели в доме, где Леннон и Сатклифф снимали квартиру и пытались придумать название, получались глупые названия, вроде «Лунных собак». Стюарт сказал: «Мы исполняем много песен Бадди Холли, почему бы нам не назвать свою группу по примеру группы Бадди Холли «Сверчки». Джон ответил: «Да, давайте вспомним названия насекомых». Тогда и появилось название «Жуки». А название стало постоянным с августа 1960 года».

Пол: «Название придумали Джон и Стюарт. Они учились в школе искусств, и, если нас с Джорджем родители еще загоняли спать, Стюарт и Джон могли делать то, о чем мы только мечтали, – не ложиться спать всю ночь. Тогда они и придумали это название.

Однажды апрельским вечером 1960 года, гуляя по Гамбьер-Террас возле Ливерпульского собора, Джон и Стюарт объявили: «Мы хотим назвать группу «Битлз» (The Beatles). Мы подумали: «Хм, звучит жутковато, верно? Что-то гадкое и ползучее, да?» А потом они объяснили, что в этом случае у слова появляется двойной смысл, и это было прекрасно… – «Ничего страшного, у этого слова два значения». Название одной из наших любимых групп, «Сверчки» (The Crickets), тоже имеет два значения: игра в крикет и так же называются маленькие кузнечики. Вот это здорово, считали мы, вот это по-настоящему литературное название. (Мы потом разговаривали с «Крикетс» и выяснили, что они вообще не подозревали о двойном значении своего названия)».

Полина Сатклифф: «Стюарту не нравилось название группы «Джонни и Лунные псы», которое он считал неоригинальным. Оно казалось ему эдаким эхом таких известных групп, как «Клифф Ричард и Тени», «Джонни и Пираты».

Билл Харри: «Название «Биитлз» (Beetles, жуки) придумал Стюарт, потому что это было насекомое, и он хотел связать его с группой Бадди Холли «Сверчки», поскольку группа «Кворримен» (прим. – или «Джонни и Лунные псы», или то и другое?) использовала в своем репертуаре много номеров Холли. Так они рассказали мне в то время».

Пол: «Я думаю, Бадди Холли был моим первым кумиром. Дело не в том, что мы просто его любили. Его любили многие. Бадди оказал на нас огромное влияние из-за своих аккордов. Потому что когда мы учились играть на гитаре, многие его вещи были основаны на трех аккордах, а эти аккорды мы к тому времени и разучили. Это большое дело, слышать пластинку и понимать: «Э, да я же могу это сыграть!». Это так вдохновляло. К тому же на объявленном турне по Британии Джин Винсент должен был выступать с группой «The Beat Boys». Как насчет «The Beetles» (Жуки)?.

Полина Сатклифф: «Стюарт предложил новое название для группы. У Бадди Холли была группа «Сверчки», и в ближайшие месяцы с британским турне должен был приехать Джин Винсент с группой «Бит Бойз» (Beat Boys). Почему бы им не стать «жуками» (Beetles)? Одна из банд байкеров в [фильме] «Дикий» (The Wild One) тоже так называлась. Стю был большим поклонником Марлона Брандо, популярного в то время киноактера. Он по нескольку раз смотрел фильмы с его участием, но особенно ему запал в душу один фильм – «Дикий». Показанный в Британии фильм имел шумный успех, многие хотели быть похожим на героя Брандо, одетого в кожу лидера мотобайкеров. Они ездили на своих мотоциклах в сопровождении группы «цыпочек», и были известны под названием «Жуки» (The Beetles)».

Пол: «В фильме «Дикарь», когда герой говорит: «Даже «Жуки» скучают по тебе!» – он указывает на девчонок на мотоциклах. Один друг как-то заглянул в словарь американского сленга и выяснил, что «жуки» – это подружки мотоциклистов. Вот и думайте теперь сами!».

Альберт Голдман: «Новый участник группы Стю Сатклифф предложил группе новое имя «Beetles» (Жуки) — так назывались соперники Марлона Брандо в романтическом фильме о мотоциклистах «Дикарь».

Дейв Пирсэйлс (Dave Persails): «Во втором издании автобиографии «Битлз» Хантер Дэвис сообщил, что Дерек Тейлор рассказал ему о том, что это название было придумано под впечатлением от фильма «Дикий». Банда мотоциклистов в черной коже называлась «Жуки» (Beetles). Как пишет Дэвис: «Стю Сатклифф посмотрев этот фильм, услышал это замечание, а вернувшись домой, предложил его Джону в качестве нового названия их группы. Джон согласился, но сказал, что писаться название будет как «Битлз» (Beatles), чтобы подчеркнуть, что это бит-группа». Эту историю Тэйлор повторил в своей книге».

Дерек Тейлор: «Стю Сатклифф посмотрел знаменитый тогда фильм «Дикий» (прим. – премьера фильма состоялась 30 декабря 1953 года) и сразу после фильма предложил название. В сюжете фильма присутствует моторизованная банда подростков «Жуки». В то время Стюарт подражал Марлону Брандо. Всегда было много обсуждений на счет того, кто придумал название «Битлз». Джон утверждал, что придумал он. Но если вы посмотрите фильм «Дикий», то увидите сцену с мотоциклетной бандой, где банда Джонни (в исполнении Брандо) находится в кофе-баре, и другая банда, возглавляемая Чино (Ли Мэрвин) вьезжает в город, нарываясь на драку».

Дейв Пирсэйлс (Dave Persails): «Действительно, в фильме песонаж Чино называет свою банду как «Жуки». В 1975 году Джордж Харрисон в своем радиоинтервью соглашается с этой версией происхождения названия, и более чем вероятно, что именно он был источником этой версии для Дерека Тейлора, который просто ее пересказал».

Джордж: «Джон говорил, подражая американскому акценту: «Куда мы стремимся, парни?», и мы отвечали: «На самую вершину, Джонни!». Мы говорили это смеху ради, но это на самом деле был Джонни, как я полагаю, из «Дикого». Потому что, когда Ли Мэрвин подьезжает со своей бандой байкеров, если я не ослышался, могу поклянуться, что когда Марлон Брандо обращается к Ли Мэрвину, то Ли Мэрвин обращается к нему «Слушай, Джонни, я думаю так-то и так, «Жуки» считают, что ты то-то и то…», как если бы его банда байкеров называлась «Жуки».

Дейв Пирсэйлс (Dave Persails): «Билл Харри отрицает версию с фильмом «Дикий», потому что, как он утверждает, этот фильм был запрещен в Англии до конца 1960-х, и никто из «Битлз», скорее всего, не смотрел его в то время, когда было придумано название».

Билл Харри: «История с фильмом «Дикий» не вызывает доверия. Он был запрещен вплоть до конца 1960-х годов, и они не могли его увидеть. Их комментарии были сделаны задним числом».

Дейв Пирсэйлс (Dave Persails): «Если это и так, то, наверняка, «Битлз», по крайней мере, слышали об этом фильме (в конце концов, он ведь был под запретом), и, возможно, была известна сюжетная линия фильма, включая название банды байкеров. Такая возможность, в дополнение к тому, что рассказал Джордж, делает это правдоподобным».

Билл Харри: «Также они не были знакомы с сюжетом картины до таких подробностей, как небольшие диалоги или неопределенное название. Иначе я бы услышал об этом во время своих многочисленных разговоров с ними».

Из интервью с Дасти Спрингфилд в программе «На старт, внимание, марш!» 4 октября 1963 г.

Дасти Спрингфилд: Джон, вопрос, который вам, скорее всего, задавали уже тысячу раз, но на который вы всегда… вы все приводите разные версии, отвечаете по-разному, поэтому, ты мне сейчас на него ответишь. Как возникло название «Битлз»?

Джон: Я просто его выдумал.

Дасти Спрингфилд: Ты просто его выдумал? Еще один блестящий Битл!

Джон: Нет-нет, на самом деле.

Дасти Спрингфилд: До этого вы как-то еще назывались?

Джон: Назывались, эээ, «Кворримен» (прим. – Джон называет название «Каменотесы», но не «Джонни и Лунные псы». Опять же к тому, что в это время использовалось оба названия?).

Дасти Спрингфилд: Ооо. У вас суровый характер.

Из интервью с «Битлз»:

Джон: Когда мне было двенадцать лет, то у меня было видение. Я увидел человека на пылающем пироге, и он сказал: «Вы – «Битлз» с [буквой] «а», так и вышло.

Из интервью 1964 года:

Джордж: Джону пришло название «Битлз»…

Джон: В видении, когда мне было…

Джордж: Давным-давно, видите ли, когда мы подыскивали, когда нам было нужно название, и все придумывали название, и он придумал «Битлз».

Из интервью с Бобом Костасом в ноябре 1991 г.:

Пол: Нас спросили, эээ, кто-то спросил: «Как возникла группа?». И вместо того, чтобы ответить: «Группа образовалась, когда эти парни собрались вместе в зале вултонской ратуши в 19…», Джон пробомотал что-то вроде «У нас было видение. Один человек появился перед нами на булочке, и у нас было видение.

Из интервью с Питером Маккейбом в августе 1971 г.:

Джон: Я раньше писал так называемые заметки «Биткомбер» (Beatcomber). Раньше я восхищался «Бичкомбером» (прим. – Beachcomber – бродяга на побережье, морская волна) в [Дейли] «Экспресс», и вот каждую неделю я писал колонку под названием «Биткомбер». И когда меня попросили написать историю о «Битлз», это когда я был в клубе Алана Уильямса «Джакаранда». Я написал с Джорджем «человека, появившегося на пылающем пироге…», потому что уже тогда спрашивали: «Откуда взялось название «Битлз»»? Билл Харри сказал: «Послушайте, они постоянно спрашивают вас об этом, так почему бы вам не рассказать им, как возникло это название?». Так что, я написал: «Был один человек, и он появился…». Я делал подобное еще в школе, все это подражание Библии: «И он появился, и сказал: «Вы – «Битлз» с [буквой] «а»… и с неба появился на пылающем пироге человек, и сказал, вы «Битлз» с «а»».

Билл Харри: «Я попросил Джона написать историю о «Битлз» для «Мерси Бит», и напечатал ее в начале 1961 года, оттуда и появилась эта история с «пылающим пирогом». Джон не имел ничего общего с названием колонки. Мне нравился «Бичкомбер» в «Дейли Экспресс», и я дал это название «Биткомбер» для его колонки. Также я придумал название «Сомнительное происхождение «Битлз» в изложении Джона Леннона» для этой статьи в первом номере».

Из интервью в «Нью-Йорк Таймс», май 1997 г., относительно названия заглавной песни альбома «Пылающий пирог»:

Пол: Любой, кто слышит слова «пылающий пирог» или «ко мне» (unto me), знает, что это шутка. Есть еще много того, что остается выдумкой из-за компромисса. Если не все согласны с историей, кто-то должен сдаться. Йоко в некотором роде настаивает на том, что у Джона полное право на это название. Она верит в то, что ему было некое видение. И это до сих пор оставляет у нас нехороший привкус во рту. Поэтому, когда я подбирал рифму к словам «плачь» (cry) и «небо» (sky), на ум пришло [слово] «пирог» (pie). «Пылающий пирог». Вот это да!

Полина Сатклифф: «Предложение Стю было принято Джоном, но так как он был основателем и лидером группы, то он должен был внести свою лепту в это дело. И хотя Джон любил и уважал Стю, для него было принципально, чтобы окончательное слово было за ним. Джон предложил заменить одну из букв. В конечном счете, мозговой штурм с Джоном привел к измененному «Битлз» (The Beatles), понимаете, как в бит-музыке».

Синтия: «Чтобы соответствовать своему меняющемуся сценическому образу, они решили также изменить и название группы. Мы устроили бурный мозговой штурм за залитым пивом столом в баре «Зал Ринсхэй» (Renshaw Hall), куда часто забегали чего-нибудь выпить».

Пол: «Размышляя над названием «Сверчки», Джон задумался, нет ли еще каких-нибудь насекомых, чтобы воспользоваться их названием и обыграть его. Стью предложил сначала «The Beetles» («Жуки»), а затем «Beatals» (от слова «beat» – ритм, удар). В то время термин «beat» обозначал не просто ритм, но определенную тенденцию в конце пятидесятых, музыкальный стиль, основанный на ритмичном, жестком рок-н-ролле. Также термин являлся реминисценцией на гремевшее тогда движение «битников», что в итоге привело к появлению таких терминов, как «биг бит» и «мерси бит». Леннон, который всегда был не прочь скаламбурить, превратил это в «Beatles» (комбинация этих слов) «просто ради шутки, чтобы это слово имело отношение к бит-музыке».

Из интервью от 10 декабря 1963 г. в Донкастере:

Пол: Его [название] придумал Джон, главным образом, просто как название, просто для группы, понимаете. Просто у нас не было никакого названия. Э, ну да, у нас было название, но у нас их было с десяток в неделю, видите ли, и нам это не нравилось, поэтому нам нужно было остановиться на одном определенном названии. И в один из вечеров Джон пришел с «Битлз», и дал что-то вроде объяснения, что оно должно писаться через «е-а», и мы сказали: «О, да, это стебно!».

Билл Харри: «Джон добавил «а». Так они рассказали мне в то время».

Из интервью 1964 года:

Интервьюер: Почему «Би» (B-e-a), вместо «Бии» (B-e-e)?

Джордж: Ну, понятное дело, видите ли…

Джон: Ну, понимаете, если вы оставляее те это с «Б», двойную «ии»… Было достаточно трудно заставить людей понять, почему это было «Би», неважно, знаете ли.

Из интервью от 10 февраля 1964 г. в нью-йоркском отеле «Плаза»:

Ринго: Джон придумал название «Битлз», и он сейчас расскажет вам об этом.

Джон: Просто оно означает «Битлз», не так ли? Понимаете? Это всего лишь название, как, например, «башмак».

Пол: «Башмак». Понимаете, мы не могли назваться «Башмаком».

Из телефонного интервью в феврале 1964 г.:

Джордж: Мы давным-давно раздумывали о названии, и просто вынесли себе мозги разными названиями, и тогда пришел Джон с этим названием «Битлз», и это было здорово, потому-что в некотором роде оно было о насекомом, а так же каламбуром, понимаете, «б-и-т» на «бит». Нам просто понравилось это название, и мы его приняли.

Из интервью с Джимом Стеком от 25 августа 1964 г.:

Джон: Ну, помнится, на днях кто-то на пресс-конференции упомянул о [группе] «Крикетс» (Сверчки). Я совсем забыл об этом. Я подыскивал название, похожее на «Сверчки», которое имеет два значение (прим. – слово «сrickets» имеет два значения, «сверчки» и игра «Крокет»), и от «сверчков» я вышел на «жуков-ударников» (Beatles). Я изменил на «Би» (B-e-a), потому что оно [слово] не имело двойного смысла – [слово] «жуки» (beetles) – «Б-двойная и-т-л-з» не имеет двойного смысла. Поэтому я изменил на «а», добавил «е» к «а», и тогда оно стало иметь двойной смысл.

Джим Стек: Какие два смысла, если конкретизировать.

Джон: Я имею в виду, что оно не означает два смысла, но оно указывает… Это «бит» (beat) и «биитлз» (beetles – жуки), и когда вы его произносите, то людям приходит на ум что-то ползучее, а когда вы его прочитываете, то это бит-музыка.

Из интервью с Редом Бирдом, радиостанция «Кей-Ти-Экс-Кью», Даллас, апрель 1990 г.:

Пол: Когда мы впервые услышали [группу] «Крикетс»… Возвращаясь к Англии, там есть игра крикет, и мы знали о жизнерадостном, вернувшемся сверчке Хоппити (прим. – мультфильм 1941 года). Так что, мы решили, что это будет блестяще, получится по-настоящему удивительное название с двойным смыслом, подобно стилю игры и жучку. Мы подумали, что это будет блестяще, мы решили, ну, что мы возьмем его. Таким образом, Джон со Стюартом пришли с этим названием, которое мы остальные ненавидели, с «Битлз», которое пишется через «а». Мы спросили: «Почему?». Они ответили: «Ну, понимаете, это «жуки», и это двойной смысл, как «Крикетс». Многое оказывало на нас влияние, разные сферы.

Синтия: «Джон любил Бадди Холли и группу «Сверчки», поэтому предложил поиграть с названиями насекомых. Именно Джону пришли в голову «Жуки» — Beetles. Он сделал из них «Beatles», обратив внимание на то, что, если поменять слоги местами, получится «les beat», а это звучит на французский манер — изысканно и остроумно. В конце концов, они остановились на названии «Серебрянные Битлз» (Silver Beatles)».

Джон: «И вот я придумал: beetles (жуки), только писать будем по-другому: «beatles» (Beatles – «гибрид» двух слов: beetle – жук и to beat – ударять), чтобы намекнуть на связь с бит-музыкой, – такая шутливая игра слов».

Полина Сатклифф: «И после мозгового штурма с Джоном родились «The Beatles» – понимаете, как в бит (beat)-музыке?»

Хантер Дэвис: «Таким образом, хотя окончательный вариант названия придумал Джон, благодяря Стю было рождено то сочетание звуков названия группы, которое стало основой имени группы».

Полина Сатклифф: «Без сомнения, если бы Стю и Джон не встретились однажды, то у группы не было бы названия «Битлз».

Ройстон Эллис (Royston Ellis, британский поэт и романист): «Когда я в июле [1960] предложил Джону, чтобы они приехали в Лондон, я спросил, как называется их группа. Когда он его произнес, я попросил, чтобы он написал название. Он пояснил, что им пришла идея от названия автомобиля «Фольсваген» (жук). Я сказал, что у них «бит» (Beat) [битниковский] образ жизни, «бит» музыка, что они поддерживают меня как поэта-битника, и я поинтересовался, почему бы им не писать свое название через «А»? Не знаю, почему считается, что это Джон принял такое написание, но это я вдохновил его остановиться на этом. В его часто цитируемой истории об этом названии упоминается «человек на пылающем пироге». Это шутливая ссылка к тому вечеру, когда я на ужин для парней (и девушек) в той квартире приготовил пирог из замороженной курицы и грибов. И я умудрился его сжечь».

Пит Шоттон: «Завершив свое обучение, я, в конце концов, для благовидной альтернативы дал уговорить себя поступить на службу в полицию. К моему ужасу, меня тут же направили на патрулирование (куда бы вы думали?!) в Гарстон, место «Кровавых ванн»! Мало того, меня еще назначили в ночную смену, при этом моим вооружением был традиционный свисток, да карманный фонарик – и этим я должен был защищаться от диких зверей тех печально известных гнусных улиц! Мне тогда не было и двадцати и, обходя свой участок, я испытывал неимоверный страх, поэтому неудивительно, что через полтора года я уволился из полиции.

В течение этого периода я сравнительно мало контактировал с Джоном, который, в свою очередь, был поглощен новой жизнью со Стюартом и Синтией. Наши встречи участились после того, как я стал партнером владельца кафе «Старуха» («Old Dutch»), более или менее приличного места сборищ возле Пенни-лэйн. «Старуха» была одним из немногих заведений в Ливерпуле, которые не закрывались до поздней ночи, и долго служила удобным местом встреч Джона, Пола и всех наших старых друзей.

Джон и Пол часто засиживались там ночью, после выступлений группы, а потом садились на свои автобусы на конечной остановке «Пенни-лэйн». К тому времени, когда я начал работать в «Старухе» в ночную смену, они уже избрали своей униформой черные кожаные куртки и штаны (? прим. – скорее всего, Пит со временем запамятовал, что «кожа» появилась после Гамбурга) и перекрестили себя в «Битлз».

Когда я поинтересовался происхождением этого странного названия, Джон сказал, что они со Стюартом искали что-то зоологическое, вроде «Медвежат» Фила Спектора и «Сверчков» Бадди Холли. Перепробовав и отбросив варианты, вроде «Львы», «Тигры» и т.д. они выбрали «Жуки» («Beetles»). Идея назвать свою группу такой низкой формой жизни пришлась по вкусу извращенному чувству юмора Джона.

Но, несмотря на новое название и одежду, перспективы «Битлз», и Джона – в особенности, выглядели, мягко говоря, обескураживающе. К 1960 году Мерсисайд буквально кишел сотнями рок-н-ролльных групп, и некоторые из них, например «Рори Сторм и Ураганы» или «Джерри и Задающие темп», имели гораздо больше поклонников, чем «Битлз», у которых еще и не было постоянного ударника. К тому же в Ливерпуле, занимавшем среди прочих городов достаточно скромное место, желания добиться первенства в рок-н-ролле как самоцели, не было даже у Рори и Джерри. Однако Джон уже тогда убедил себя в том, что рано или поздно вся страна, если не весь мир, станет учиться произносить слово «beetles» с буквой «а».

Лен Гарри: «Однажды они заговорили о том, что собираются переименовать название группы на «Битлз», и я подумал, какое странное название. Сразу вспоминаешь каких-то ползающих тварей. Для меня это никак не связывалось с музыкой».

Питер Фрэйм: «С января группа выступала с названием «Битэлз» (Beatals). С мая по июнь под названием «Серебряные жуки» (Silver Beetles), с июня по июль под названием «Серебряные Битлз» (Silver Beatles). С августа группа называется просто «Битлз» (Beatles)».

|

The Beatles |

|

|---|---|

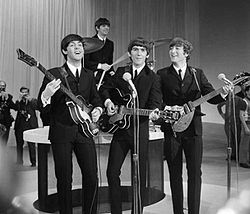

The Beatles in 1964; clockwise from top left: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and George Harrison |

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | Liverpool, England |

| Genres |

|

| Years active | 1960–1970 |

| Labels |

|

| Spinoffs | Plastic Ono Band |

| Spinoff of | The Quarrymen |

| Past members |

|

| Website | thebeatles.com |

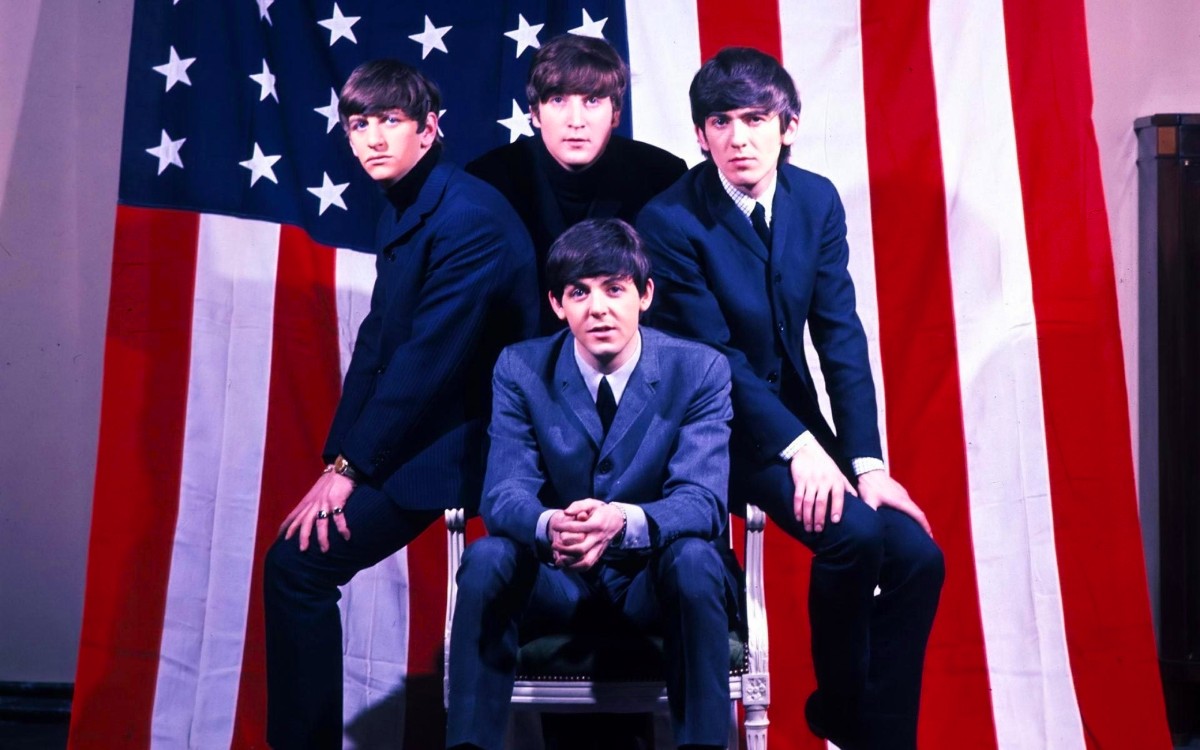

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time[1] and were integral to the development of 1960s counterculture and popular music’s recognition as an art form.[2] Rooted in skiffle, beat and 1950s rock ‘n’ roll, their sound incorporated elements of classical music and traditional pop in innovative ways; the band also explored music styles ranging from folk and Indian music to psychedelia and hard rock. As pioneers in recording, songwriting and artistic presentation, the Beatles revolutionised many aspects of the music industry and were often publicised as leaders of the era’s youth and sociocultural movements.[3]

Led by primary songwriters Lennon and McCartney, the Beatles evolved from Lennon’s previous group, the Quarrymen, and built their reputation playing clubs in Liverpool and Hamburg over three years from 1960, initially with Stuart Sutcliffe playing bass. The core trio of Lennon, McCartney and Harrison, together since 1958, went through a succession of drummers, including Pete Best, before asking Starr to join them in 1962. Manager Brian Epstein moulded them into a professional act, and producer George Martin guided and developed their recordings, greatly expanding their domestic success after signing to EMI Records and achieving their first hit, «Love Me Do», in late 1962. As their popularity grew into the intense fan frenzy dubbed «Beatlemania», the band acquired the nickname «the Fab Four», with Epstein, Martin or another member of the band’s entourage sometimes informally referred to as a «fifth Beatle».

By early 1964, the Beatles were international stars and had achieved unprecedented levels of critical and commercial success. They became a leading force in Britain’s cultural resurgence, ushering in the British Invasion of the United States pop market, and soon made their film debut with A Hard Day’s Night (1964). A growing desire to refine their studio efforts, coupled with the untenable nature of their concert tours, led to the band’s retirement from live performances in 1966. At this time, they produced records of greater sophistication, including the albums Rubber Soul (1965), Revolver (1966) and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), and enjoyed further commercial success with The Beatles (also known as «the White Album», 1968) and Abbey Road (1969). The success of these records heralded the album era, as albums became the dominant form of record consumption over singles; they also increased public interest in psychedelic drugs and Eastern spirituality, and furthered advancements in electronic music, album art and music videos. In 1968, they founded Apple Corps, a multi-armed multimedia corporation that continues to oversee projects related to the band’s legacy. After the group’s break-up in 1970, all principal former members enjoyed success as solo artists and some partial reunions have occurred. Lennon was murdered in 1980 and Harrison died of lung cancer in 2001. McCartney and Starr remain musically active.

The Beatles are the best-selling music act of all time, with estimated sales of 600 million units worldwide.[4][5] They hold the record for most number-one albums on the UK Albums Chart (15), most number-one hits on the US Billboard Hot 100 chart (20), and most singles sold in the UK (21.9 million). The band received many accolades, including seven Grammy Awards, four Brit Awards, an Academy Award (for Best Original Song Score for the 1970 documentary film Let It Be) and fifteen Ivor Novello Awards. They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, and each principal member was inducted individually between 1994 and 2015. In 2004 and 2011, the group topped Rolling Stone‘s lists of the greatest artists in history. Time magazine named them among the 20th century’s 100 most important people.

History

1956–1963: Formation

The Quarrymen and name changes

In November 1956, sixteen-year-old John Lennon formed a skiffle group with several friends from Quarry Bank High School in Liverpool. They briefly called themselves the Blackjacks, before changing their name to the Quarrymen after discovering that another local group were already using the name.[6] Fifteen-year-old Paul McCartney met Lennon on 6 July 1957, and joined as a rhythm guitarist shortly after.[7] In February 1958, McCartney invited his friend George Harrison, then fifteen, to watch the band. Harrison auditioned for Lennon, impressing him with his playing, but Lennon initially thought Harrison was too young. After a month’s persistence, during a second meeting (arranged by McCartney), Harrison performed the lead guitar part of the instrumental song «Raunchy» on the upper deck of a Liverpool bus,[8] and they enlisted him as lead guitarist.[9][10]

By January 1959, Lennon’s Quarry Bank friends had left the group, and he began his studies at the Liverpool College of Art.[11] The three guitarists, billing themselves as Johnny and the Moondogs,[12] were playing rock and roll whenever they could find a drummer.[13] Lennon’s art school friend Stuart Sutcliffe, who had just sold one of his paintings and was persuaded to purchase a bass guitar with the proceeds, joined in January 1960. He suggested changing the band’s name to Beatals, as a tribute to Buddy Holly and the Crickets.[14][15] They used this name until May, when they became the Silver Beetles, before undertaking a brief tour of Scotland as the backing group for pop singer and fellow Liverpudlian Johnny Gentle. By early July, they had refashioned themselves as the Silver Beatles, and by the middle of August simply the Beatles.[16]

Early residencies and UK popularity

Allan Williams, the Beatles’ unofficial manager, arranged a residency for them in Hamburg. They auditioned and hired drummer Pete Best in mid-August 1960. The band, now a five-piece, departed Liverpool for Hamburg four days later, contracted to club owner Bruno Koschmider for what would be a 3+1⁄2-month residency.[17] Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn writes: «They pulled into Hamburg at dusk on 17 August, the time when the red-light area comes to life … flashing neon lights screamed out the various entertainment on offer, while scantily clad women sat unabashed in shop windows waiting for business opportunities.»[18]

Koschmider had converted a couple of strip clubs in the district into music venues, and he initially placed the Beatles at the Indra Club. After closing Indra due to noise complaints, he moved them to the Kaiserkeller in October.[19] When he learned they had been performing at the rival Top Ten Club in breach of their contract, he gave them one month’s termination notice,[20] and reported the underage Harrison, who had obtained permission to stay in Hamburg by lying to the German authorities about his age.[21] The authorities arranged for Harrison’s deportation in late November.[22] One week later, Koschmider had McCartney and Best arrested for arson after they set fire to a condom in a concrete corridor; the authorities deported them.[23] Lennon returned to Liverpool in early December, while Sutcliffe remained in Hamburg until late February with his German fiancée Astrid Kirchherr,[24] who took the first semi-professional photos of the Beatles.[25]

During the next two years, the Beatles were resident for periods in Hamburg, where they used Preludin both recreationally and to maintain their energy through all-night performances.[26] In 1961, during their second Hamburg engagement, Kirchherr cut Sutcliffe’s hair in the «exi» (existentialist) style, later adopted by the other Beatles.[27][28] Later on, Sutcliffe decided to leave the band early that year and resume his art studies in Germany. McCartney took over bass.[29] Producer Bert Kaempfert contracted what was now a four-piece group until June 1962, and he used them as Tony Sheridan’s backing band on a series of recordings for Polydor Records.[15][30] As part of the sessions, the Beatles were signed to Polydor for one year.[31] Credited to «Tony Sheridan & the Beat Brothers», the single «My Bonnie», recorded in June 1961 and released four months later, reached number 32 on the Musikmarkt chart.[32]

After the Beatles completed their second Hamburg residency, they enjoyed increasing popularity in Liverpool with the growing Merseybeat movement. However, they were growing tired of the monotony of numerous appearances at the same clubs night after night.[33] In November 1961, during one of the group’s frequent performances at the Cavern Club, they encountered Brian Epstein, a local record-store owner and music columnist.[34] He later recalled: «I immediately liked what I heard. They were fresh, and they were honest, and they had what I thought was a sort of presence … [a] star quality.»[35]

First EMI recordings

Epstein courted the band over the next couple of months, and they appointed him as their manager in January 1962.[36] Throughout early and mid-1962, Epstein sought to free the Beatles from their contractual obligations to Bert Kaempfert Productions. He eventually negotiated a one-month early release in exchange for one last recording session in Hamburg.[37] On their return to Germany in April, a distraught Kirchherr met them at the airport with news of Sutcliffe’s death the previous day from a brain haemorrhage.[38] Epstein began negotiations with record labels for a recording contract. To secure a UK record contract, Epstein negotiated an early end to the band’s contract with Polydor, in exchange for more recordings backing Tony Sheridan.[39] After a New Year’s Day audition, Decca Records rejected the band, saying, «Guitar groups are on the way out, Mr. Epstein.»[40] However, three months later, producer George Martin signed the Beatles to EMI’s Parlophone label.[38]

Main entrance at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios, pictured 2007)

Martin’s first recording session with the Beatles took place at EMI Recording Studios (later Abbey Road Studios) in London on 6 June 1962.[41] He immediately complained to Epstein about Best’s drumming and suggested they use a session drummer in his place.[42] Already contemplating Best’s dismissal,[43] the Beatles replaced him in mid-August with Ringo Starr, who left Rory Storm and the Hurricanes to join them.[41] A 4 September session at EMI yielded a recording of «Love Me Do» featuring Starr on drums, but a dissatisfied Martin hired drummer Andy White for the band’s third session a week later, which produced recordings of «Love Me Do», «Please Please Me» and «P.S. I Love You».[41]

Martin initially selected the Starr version of «Love Me Do» for the band’s first single, though subsequent re-pressings featured the White version, with Starr on tambourine.[41] Released in early October, «Love Me Do» peaked at number seventeen on the Record Retailer chart.[44] Their television debut came later that month with a live performance on the regional news programme People and Places.[45] After Martin suggested rerecording «Please Please Me» at a faster tempo,[46] a studio session in late November yielded that recording,[47] of which Martin accurately predicted, «You’ve just made your first No. 1.»[48]

In December 1962, the Beatles concluded their fifth and final Hamburg residency.[49] By 1963, they had agreed that all four band members would contribute vocals to their albums – including Starr, despite his restricted vocal range, to validate his standing in the group.[50] Lennon and McCartney had established a songwriting partnership, and as the band’s success grew, their dominant collaboration limited Harrison’s opportunities as a lead vocalist.[51] Epstein, to maximise the Beatles’ commercial potential, encouraged them to adopt a professional approach to performing.[52] Lennon recalled him saying, «Look, if you really want to get in these bigger places, you’re going to have to change – stop eating on stage, stop swearing, stop smoking ….»[40][nb 1]

1963–1966: Beatlemania and touring years

Please Please Me and With the Beatles

On 11 February 1963, the Beatles recorded ten songs during a single studio session for their debut LP, Please Please Me. It was supplemented by the four tracks already released on their first two singles. Martin considered recording the LP live at The Cavern Club, but after deciding that the building’s acoustics were inadequate, he elected to simulate a «live» album with minimal production in «a single marathon session at Abbey Road».[54] After the moderate success of «Love Me Do», the single «Please Please Me» was released in January 1963, two months ahead of the album. It reached number one on every UK chart except Record Retailer, where it peaked at number two.[55]

Recalling how the Beatles «rushed to deliver a debut album, bashing out Please Please Me in a day», AllMusic critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote: «Decades after its release, the album still sounds fresh, precisely because of its intense origins.»[56] Lennon said little thought went into composition at the time; he and McCartney were «just writing songs à la Everly Brothers, à la Buddy Holly, pop songs with no more thought of them than that – to create a sound. And the words were almost irrelevant.»[57]

Sample of «She Loves You». The song’s repeated use of «yeah» exclamations became a signature phrase for the group at the time.[58][59]

Released in March 1963, Please Please Me was the first of eleven consecutive Beatles albums released in the United Kingdom to reach number one.[60] The band’s third single, «From Me to You», came out in April and began an almost unbroken string of seventeen British number-one singles, including all but one of the eighteen they released over the next six years.[61] Issued in August, their fourth single, «She Loves You», achieved the fastest sales of any record in the UK up to that time, selling three-quarters of a million copies in under four weeks.[62] It became their first single to sell a million copies, and remained the biggest-selling record in the UK until 1978.[63][nb 2]

The success brought increased media exposure, to which the Beatles responded with an irreverent and comical attitude that defied the expectations of pop musicians at the time, inspiring even more interest.[64] The band toured the UK three times in the first half of the year: a four-week tour that began in February, the Beatles’ first nationwide, preceded three-week tours in March and May–June.[65] As their popularity spread, a frenzied adulation of the group took hold. On 13 October, the Beatles starred on Sunday Night at the London Palladium, the UK’s top variety show.[66] Their performance was televised live and watched by 15 million viewers. One national paper’s headlines in the following days coined the term «Beatlemania» to describe the riotous enthusiasm by screaming fans who greeted the band – and it stuck.[66][67] Although not billed as tour leaders, the Beatles overshadowed American acts Tommy Roe and Chris Montez during the February engagements and assumed top billing «by audience demand», something no British act had previously accomplished while touring with artists from the US.[68] A similar situation arose during their May–June tour with Roy Orbison.[69]

In late October, the Beatles began a five-day tour of Sweden, their first time abroad since the final Hamburg engagement of December 1962.[71] On their return to the UK on 31 October, several hundred screaming fans greeted them in heavy rain at Heathrow Airport. Around 50 to 100 journalists and photographers, as well as representatives from the BBC, also joined the airport reception, the first of more than 100 such events.[72] The next day, the band began its fourth tour of Britain within nine months, this one scheduled for six weeks.[73] In mid-November, as Beatlemania intensified, police resorted to using high-pressure water hoses to control the crowd before a concert in Plymouth.[74]

Please Please Me maintained the top position on the Record Retailer chart for 30 weeks, only to be displaced by its follow-up, With the Beatles,[75] which EMI released on 22 November to record advance orders of 270,000 copies. The LP topped a half-million albums sold in one week.[76] Recorded between July and October, With the Beatles made better use of studio production techniques than its predecessor.[77] It held the top spot for 21 weeks with a chart life of 40 weeks.[78] Erlewine described the LP as «a sequel of the highest order – one that betters the original».[79]

In a reversal of then standard practice, EMI released the album ahead of the impending single «I Want to Hold Your Hand», with the song excluded to maximise the single’s sales.[80] The album caught the attention of music critic William Mann of The Times, who suggested that Lennon and McCartney were «the outstanding English composers of 1963».[77] The newspaper published a series of articles in which Mann offered detailed analyses of the music, lending it respectability.[81] With the Beatles became the second album in UK chart history to sell a million copies, a figure previously reached only by the 1958 South Pacific soundtrack.[82] When writing the sleeve notes for the album, the band’s press officer, Tony Barrow, used the superlative the «fabulous foursome», which the media widely adopted as «the Fab Four».[83]

First visit to the United States and the British Invasion

EMI’s American subsidiary, Capitol Records, hindered the Beatles’ releases in the United States for more than a year by initially declining to issue their music, including their first three singles. Concurrent negotiations with the independent US label Vee-Jay led to the release of some, but not all, of the songs in 1963.[84] Vee-Jay finished preparation for the album Introducing… The Beatles, comprising most of the songs of Parlophone’s Please Please Me, but a management shake-up led to the album not being released.[nb 3] After it emerged that the label did not report royalties on their sales, the licence that Vee-Jay had signed with EMI was voided.[86] A new licence was granted to the Swan label for the single «She Loves You». The record received some airplay in the Tidewater area of Virginia from Gene Loving of radio station WGH and was featured on the «Rate-a-Record» segment of American Bandstand, but it failed to catch on nationally.[87]

Epstein brought a demo copy of «I Want to Hold Your Hand» to Capitol’s Brown Meggs, who signed the band and arranged for a $40,000 US marketing campaign. American chart success began after disc jockey Carroll James of AM radio station WWDC, in Washington, DC, obtained a copy of the British single «I Want to Hold Your Hand» in mid-December 1963 and began playing it on-air.[88] Taped copies of the song soon circulated among other radio stations throughout the US. This caused an increase in demand, leading Capitol to bring forward the release of «I Want to Hold Your Hand» by three weeks.[89] Issued on 26 December, with the band’s previously scheduled debut there just weeks away, «I Want to Hold Your Hand» sold a million copies, becoming a number-one hit in the US by mid-January.[90] In its wake Vee-Jay released Introducing… The Beatles[91] along with Capitol’s debut album, Meet the Beatles!, while Swan reactivated production of «She Loves You».[92]

On 7 February 1964, the Beatles departed from Heathrow with an estimated 4,000 fans waving and screaming as the aircraft took off.[93] Upon landing at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, an uproarious crowd estimated at 3,000 greeted them.[94] They gave their first live US television performance two days later on The Ed Sullivan Show, watched by approximately 73 million viewers in over 23 million households,[95] or 34 per cent of the American population. Biographer Jonathan Gould writes that, according to the Nielsen rating service, it was «the largest audience that had ever been recorded for an American television program«.[96] The next morning, the Beatles awoke to a largely negative critical consensus in the US,[97] but a day later at their first US concert, Beatlemania erupted at the Washington Coliseum.[98] Back in New York the following day, the Beatles met with another strong reception during two shows at Carnegie Hall.[95] The band flew to Florida, where they appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show a second time, again before 70 million viewers, before returning to the UK on 22 February.[99]

The Beatles’ first visit to the US took place when the nation was still mourning the assassination of President John F. Kennedy the previous November.[100] Commentators often suggest that for many, particularly the young, the Beatles’ performances reignited the sense of excitement and possibility that momentarily faded in the wake of the assassination, and helped pave the way for the revolutionary social changes to come later in the decade.[101] Their hairstyle, unusually long for the era and mocked by many adults,[15] became an emblem of rebellion to the burgeoning youth culture.[102]

The group’s popularity generated unprecedented interest in British music, and many other UK acts subsequently made their American debuts, successfully touring over the next three years in what was termed the British Invasion.[103] The Beatles’ success in the US opened the door for a successive string of British beat groups and pop acts such as the Dave Clark Five, the Animals, Petula Clark, the Kinks, and the Rolling Stones to achieve success in America.[104] During the week of 4 April 1964, the Beatles held twelve positions on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, including the top five.[105][nb 4]

A Hard Day’s Night

Capitol Records’ lack of interest throughout 1963 did not go unnoticed, and a competitor, United Artists Records, encouraged its film division to offer the Beatles a three-motion-picture deal, primarily for the commercial potential of the soundtracks in the US.[107] Directed by Richard Lester, A Hard Day’s Night involved the band for six weeks in March–April 1964 as they played themselves in a musical comedy.[108] The film premiered in London and New York in July and August, respectively, and was an international success, with some critics drawing a comparison with the Marx Brothers.[109]

United Artists released a full soundtrack album for the North American market, combining Beatles songs and Martin’s orchestral score; elsewhere, the group’s third studio LP, A Hard Day’s Night, contained songs from the film on side one and other new recordings on side two.[110] According to Erlewine, the album saw them «truly coming into their own as a band. All of the disparate influences on their first two albums coalesced into a bright, joyous, original sound, filled with ringing guitars and irresistible melodies.»[111] That «ringing guitar» sound was primarily the product of Harrison’s 12-string electric Rickenbacker, a prototype given to him by the manufacturer, which made its debut on the record.[112][nb 5]

1964 world tour, meeting Bob Dylan, and stand on civil rights

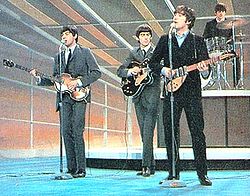

McCartney, Harrison and Lennon performing on Dutch TV in 1964

Touring internationally in June and July, the Beatles staged 37 shows over 27 days in Denmark, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand.[113][nb 6] In August and September, they returned to the US, with a 30-concert tour of 23 cities.[115] Generating intense interest once again, the month-long tour attracted between 10,000 and 20,000 fans to each 30-minute performance in cities from San Francisco to New York.[115]

In August, journalist Al Aronowitz arranged for the Beatles to meet Bob Dylan.[116] Visiting the band in their New York hotel suite, Dylan introduced them to cannabis.[117] Gould points out the musical and cultural significance of this meeting, before which the musicians’ respective fanbases were «perceived as inhabiting two separate subcultural worlds»: Dylan’s audience of «college kids with artistic or intellectual leanings, a dawning political and social idealism, and a mildly bohemian style» contrasted with their fans, «veritable ‘teenyboppers’ – kids in high school or grade school whose lives were totally wrapped up in the commercialised popular culture of television, radio, pop records, fan magazines, and teen fashion. To many of Dylan’s followers in the folk music scene, the Beatles were seen as idolaters, not idealists.»[118]

Within six months of the meeting, according to Gould, «Lennon would be making records on which he openly imitated Dylan’s nasal drone, brittle strum, and introspective vocal persona»; and six months after that, Dylan began performing with a backing band and electric instrumentation, and «dressed in the height of Mod fashion».[119] As a result, Gould continues, the traditional division between folk and rock enthusiasts «nearly evaporated», as the Beatles’ fans began to mature in their outlook and Dylan’s audience embraced the new, youth-driven pop culture.[119]

During the 1964 US tour, the group were confronted with racial segregation in the country at the time.[120][121] When informed that the venue for their 11 September concert, the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida, was segregated, the Beatles said they would refuse to perform unless the audience was integrated.[122][120][121] Lennon stated: «We never play to segregated audiences and we aren’t going to start now … I’d sooner lose our appearance money.»[120] City officials relented and agreed to allow an integrated show.[120] The group also cancelled their reservations at the whites-only Hotel George Washington in Jacksonville.[121] For their subsequent US tours in 1965 and 1966, the Beatles included clauses in contracts stipulating that shows be integrated.[121][123]

Beatles for Sale, Help! and Rubber Soul

According to Gould, the Beatles’ fourth studio LP, Beatles for Sale, evidenced a growing conflict between the commercial pressures of their global success and their creative ambitions.[124] They had intended the album, recorded between August and October 1964,[125] to continue the format established by A Hard Day’s Night which, unlike their first two LPs, contained only original songs.[124] They had nearly exhausted their backlog of songs on the previous album, however, and given the challenges constant international touring posed to their songwriting efforts, Lennon admitted, «Material’s becoming a hell of a problem».[126] As a result, six covers from their extensive repertoire were chosen to complete the album. Released in early December, its eight original compositions stood out, demonstrating the growing maturity of the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership.[124]

In early 1965, following a dinner with Lennon, Harrison and their wives, Harrison’s dentist, John Riley, secretly added LSD to their coffee.[127] Lennon described the experience: «It was just terrifying, but it was fantastic. I was pretty stunned for a month or two.»[128] He and Harrison subsequently became regular users of the drug, joined by Starr on at least one occasion. Harrison’s use of psychedelic drugs encouraged his path to meditation and Hinduism. He commented: «For me, it was like a flash. The first time I had acid, it just opened up something in my head that was inside of me, and I realised a lot of things. I didn’t learn them because I already knew them, but that happened to be the key that opened the door to reveal them. From the moment I had that, I wanted to have it all the time – these thoughts about the yogis and the Himalayas, and Ravi’s music.»[129][130] McCartney was initially reluctant to try it, but eventually did so in late 1966.[131] He became the first Beatle to discuss LSD publicly, declaring in a magazine interview that «it opened my eyes» and «made me a better, more honest, more tolerant member of society».[132]

The US trailer for Help! with (from the rear) Harrison, McCartney, Lennon and (largely obscured) Starr

Controversy erupted in June 1965 when Queen Elizabeth II appointed all four Beatles Members of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) after Prime Minister Harold Wilson nominated them for the award.[133] In protest – the honour was at that time primarily bestowed upon military veterans and civic leaders – some conservative MBE recipients returned their insignia.[134]

In July, the Beatles’ second film, Help!, was released, again directed by Lester. Described as «mainly a relentless spoof of Bond»,[135] it inspired a mixed response among both reviewers and the band. McCartney said: «Help! was great but it wasn’t our film – we were sort of guest stars. It was fun, but basically, as an idea for a film, it was a bit wrong.»[136] The soundtrack was dominated by Lennon, who wrote and sang lead on most of its songs, including the two singles: «Help!» and «Ticket to Ride».[137]

The Help! album, the group’s fifth studio LP, mirrored A Hard Day’s Night by featuring soundtrack songs on side one and additional songs from the same sessions on side two.[138] The LP contained all original material save for two covers, «Act Naturally» and «Dizzy Miss Lizzy»; they were the last covers the band would include on an album, except for Let It Be‘s brief rendition of the traditional Liverpool folk song «Maggie Mae».[139] The band expanded their use of vocal overdubs on Help! and incorporated classical instruments into some arrangements, including a string quartet on the pop ballad «Yesterday».[140] Composed by and sung by McCartney – none of the other Beatles perform on the recording[141] – «Yesterday» has inspired the most cover versions of any song ever written.[142] With Help!, the Beatles became the first rock group to be nominated for a Grammy Award for Album of the Year.[143]

The Beatles at a press conference in Minnesota in August 1965, shortly after playing at Shea Stadium in New York

The group’s third US tour opened with a performance before a world-record crowd of 55,600 at New York’s Shea Stadium on 15 August – «perhaps the most famous of all Beatles’ concerts», in Lewisohn’s description.[144] A further nine successful concerts followed in other American cities. At a show in Atlanta, the Beatles gave one of the first live performances ever to make use of a foldback system of on-stage monitor speakers.[145] Towards the end of the tour, they met with Elvis Presley, a foundational musical influence on the band, who invited them to his home in Beverly Hills.[146][147]

September 1965 saw the launch of an American Saturday-morning cartoon series, The Beatles, that echoed A Hard Day’s Night‘s slapstick antics over its two-year original run.[148] The series was a historical milestone as the first weekly television series to feature animated versions of real, living people.[149]

In mid-October, the Beatles entered the recording studio; for the first time when making an album, they had an extended period without other major commitments.[150] Until this time, according to George Martin, «we had been making albums rather like a collection of singles. Now we were really beginning to think about albums as a bit of art on their own.»[151] Released in December, Rubber Soul was hailed by critics as a major step forward in the maturity and complexity of the band’s music.[152] Their thematic reach was beginning to expand as they embraced deeper aspects of romance and philosophy, a development that NEMS executive Peter Brown attributed to the band members’ «now habitual use of marijuana».[153] Lennon referred to Rubber Soul as «the pot album»[154] and Starr said: «Grass was really influential in a lot of our changes, especially with the writers. And because they were writing different material, we were playing differently.»[154] After Help!‘s foray into classical music with flutes and strings, Harrison’s introduction of a sitar on «Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)» marked a further progression outside the traditional boundaries of popular music. As the lyrics grew more artful, fans began to study them for deeper meaning.[155]

Sample of «Norwegian Wood» from Rubber Soul (1965). Harrison’s use of a sitar on this song is representative of the Beatles’ incorporation of unconventional instrumentation into rock music.[152]

While some of Rubber Soul‘s songs were the product of Lennon and McCartney’s collaborative songwriting,[156] the album also included distinct compositions from each,[157] though they continued to share official credit. «In My Life», of which each later claimed lead authorship, is considered a highlight of the entire Lennon–McCartney catalogue.[158] Harrison called Rubber Soul his «favourite album»,[154] and Starr referred to it as «the departure record».[159] McCartney has said, «We’d had our cute period, and now it was time to expand.»[160] However, recording engineer Norman Smith later stated that the studio sessions revealed signs of growing conflict within the group – «the clash between John and Paul was becoming obvious», he wrote, and «as far as Paul was concerned, George could do no right».[161] In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked Rubber Soul fifth among «The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time»,[162] and AllMusic’s Richie Unterberger describes it as «one of the classic folk-rock records».[163]

Controversies, Revolver and final tour

Capitol Records, from December 1963 when it began issuing Beatles recordings for the US market, exercised complete control over format,[84] compiling distinct US albums from the band’s recordings and issuing songs of their choosing as singles.[164][nb 7] In June 1966, the Capitol LP Yesterday and Today caused an uproar with its cover, which portrayed the grinning Beatles dressed in butcher’s overalls, accompanied by raw meat and mutilated plastic baby dolls. According to Beatles biographer Bill Harry, it has been incorrectly suggested that this was meant as a satirical response to the way Capitol had «butchered» the US versions of the band’s albums.[166] Thousands of copies of the LP had a new cover pasted over the original; an unpeeled «first-state» copy fetched $10,500 at a December 2005 auction.[167] In England, meanwhile, Harrison met sitar maestro Ravi Shankar, who agreed to train him on the instrument.[168]

During a tour of the Philippines the month after the Yesterday and Today furore, the Beatles unintentionally snubbed the nation’s first lady, Imelda Marcos, who had expected them to attend a breakfast reception at the Presidential Palace.[169] When presented with the invitation, Epstein politely declined on the band members’ behalf, as it had never been his policy to accept such official invitations.[170] They soon found that the Marcos regime was unaccustomed to taking no for an answer. The resulting riots endangered the group and they escaped the country with difficulty.[171] Immediately afterwards, the band members visited India for the first time.[172]

We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity.

– John Lennon, 1966[173]

Almost as soon as they returned home, the Beatles faced a fierce backlash from US religious and social conservatives (as well as the Ku Klux Klan) over a comment Lennon had made in a March interview with British reporter Maureen Cleave.[174] «Christianity will go», Lennon had said. «It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I will be proved right … Jesus was alright but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.»[175] His comments went virtually unnoticed in England, but when US teenage fan magazine Datebook printed them five months later, it sparked a controversy with Christians in America’s conservative Bible Belt region.[174] The Vatican issued a protest, and bans on Beatles’ records were imposed by Spanish and Dutch stations and South Africa’s national broadcasting service.[176] Epstein accused Datebook of having taken Lennon’s words out of context. At a press conference, Lennon pointed out, «If I’d said television was more popular than Jesus, I might have got away with it.»[177] He claimed that he was referring to how other people viewed their success, but at the prompting of reporters, he concluded: «If you want me to apologise, if that will make you happy, then okay, I’m sorry.»[177]

Sample of «Eleanor Rigby» from Revolver (1966). The album involves innovative compositional approaches, arrangements and recording techniques. This song, primarily written by McCartney, prominently features classical strings in a novel fusion of musical styles.

Released in August 1966, a week before the Beatles’ final tour, Revolver marked another artistic step forward for the group.[178] The album featured sophisticated songwriting, studio experimentation, and a greatly expanded repertoire of musical styles, ranging from innovative classical string arrangements to psychedelia.[178] Abandoning the customary group photograph, its Aubrey Beardsley-inspired cover – designed by Klaus Voormann, a friend of the band since their Hamburg days – was a monochrome collage and line drawing caricature of the group.[178] The album was preceded by the single «Paperback Writer», backed by «Rain».[179] Short promotional films were made for both songs; described by cultural historian Saul Austerlitz as «among the first true music videos»,[180] they aired on The Ed Sullivan Show and Top of the Pops in June.[181]

Among the experimental songs on Revolver was «Tomorrow Never Knows», the lyrics for which Lennon drew from Timothy Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Its creation involved eight tape decks distributed about the EMI building, each staffed by an engineer or band member, who randomly varied the movement of a tape loop while Martin created a composite recording by sampling the incoming data.[182] McCartney’s «Eleanor Rigby» made prominent use of a string octet; Gould describes it as «a true hybrid, conforming to no recognisable style or genre of song».[183] Harrison’s emergence as a songwriter was reflected in three of his compositions appearing on the record.[184] Among these, «Taxman», which opened the album, marked the first example of the Beatles making a political statement through their music.[185] In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked Revolver at #11 on their list of «The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time».[186]

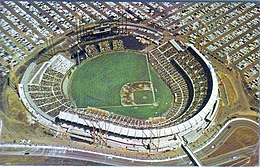

San Francisco’s Candlestick Park (pictured in the early 1960s) was the venue for the Beatles’ final concert before a paying audience.

As preparations were made for a tour of the US, the Beatles knew that their music would hardly be heard. Having originally used Vox AC30 amplifiers, they later acquired more powerful 100-watt amplifiers, specially designed for them by Vox, as they moved into larger venues in 1964; however, these were still inadequate. Struggling to compete with the volume of sound generated by screaming fans, the band had grown increasingly bored with the routine of performing live.[187] Recognising that their shows were no longer about the music, they decided to make the August tour their last.[188]

The band performed none of their new songs on the tour.[189] In Chris Ingham’s description, they were very much «studio creations … and there was no way a four-piece rock ‘n’ roll group could do them justice, particularly through the desensitising wall of the fans’ screams. ‘Live Beatles’ and ‘Studio Beatles’ had become entirely different beasts.»[190] The band’s concert at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on 29 August was their last commercial concert.[191] It marked the end of four years dominated by almost non-stop touring that included over 1,400 concert appearances internationally.[192]

1966–1970: Studio years

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Freed from the burden of touring, the Beatles embraced an increasingly experimental approach as they recorded Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, beginning in late November 1966.[194] According to engineer Geoff Emerick, the album’s recording took over 700 hours.[195] He recalled the band’s insistence «that everything on Sgt. Pepper had to be different. We had microphones right down in the bells of brass instruments and headphones turned into microphones attached to violins. We used giant primitive oscillators to vary the speed of instruments and vocals and we had tapes chopped to pieces and stuck together upside down and the wrong way around.»[196] Parts of «A Day in the Life» featured a 40-piece orchestra.[196] The sessions initially yielded the non-album double A-side single «Strawberry Fields Forever»/»Penny Lane» in February 1967;[197] the Sgt. Pepper LP followed with a rush-release in May.[198] The musical complexity of the records, created using relatively primitive four-track recording technology, astounded contemporary artists.[193] Among music critics, acclaim for the album was virtually universal.[199] Gould writes:

The overwhelming consensus is that the Beatles had created a popular masterpiece: a rich, sustained, and overflowing work of collaborative genius whose bold ambition and startling originality dramatically enlarged the possibilities and raised the expectations of what the experience of listening to popular music on record could be. On the basis of this perception, Sgt. Pepper became the catalyst for an explosion of mass enthusiasm for album-formatted rock that would revolutionise both the aesthetics and the economics of the record business in ways that far outstripped the earlier pop explosions triggered by the Elvis phenomenon of 1956 and the Beatlemania phenomenon of 1963.[200]

In the wake of Sgt. Pepper, the underground and mainstream press widely publicised the Beatles as leaders of youth culture, as well as «lifestyle revolutionaries».[3] The album was the first major pop/rock LP to include its complete lyrics, which appeared on the back cover.[201][202] Those lyrics were the subject of critical analysis; for instance, in late 1967 the album was the subject of a scholarly inquiry by American literary critic and professor of English Richard Poirier, who observed that his students were «listening to the group’s music with a degree of engagement that he, as a teacher of literature, could only envy».[203][nb 8] The elaborate cover also attracted considerable interest and study.[204] A collage designed by pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, it depicted the group as the fictional band referred to in the album’s title track[205] standing in front of a crowd of famous people.[206] The heavy moustaches worn by the group reflected the growing influence of hippie style,[207] while cultural historian Jonathan Harris describes their «brightly coloured parodies of military uniforms» as a knowingly «anti-authoritarian and anti-establishment» display.[208]

Sgt. Pepper topped the UK charts for 23 consecutive weeks, with a further four weeks at number one in the period through to February 1968.[209] With 2.5 million copies sold within three months of its release,[210] Sgt. Pepper‘s initial commercial success exceeded that of all previous Beatles albums.[211] It sustained its immense popularity into the 21st century while breaking numerous sales records.[212] In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked Sgt. Pepper at number one on its list of the greatest albums of all time.[162]

Magical Mystery Tour and Yellow Submarine

The Beatles in 1967; clockwise from left: Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr

Two Beatles film projects were conceived within weeks of completing Sgt. Pepper: Magical Mystery Tour, a one-hour television film, and Yellow Submarine, an animated feature-length film produced by United Artists.[213] The group began recording music for the former in late April 1967, but the project then lay dormant as they focused on recording songs for the latter.[214] On 25 June, the Beatles performed their forthcoming single «All You Need Is Love» to an estimated 350 million viewers on Our World, the first live global television link.[215] Released a week later, during the Summer of Love, the song was adopted as a flower power anthem.[216] The Beatles’ use of psychedelic drugs was at its height during that summer.[217] In July and August, the group pursued interests related to similar utopian-based ideology, including a week-long investigation into the possibility of starting an island-based commune off the coast of Greece.[218]

On 24 August, the group were introduced to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in London. The next day, they travelled to Bangor for his Transcendental Meditation retreat. On 27 August, their manager’s assistant, Peter Brown, phoned to inform them that Epstein had died.[219] The coroner ruled the death an accidental carbitol overdose, although it was widely rumoured to be a suicide.[220][nb 9] His death left the group disoriented and fearful about the future.[222] Lennon recalled: «We collapsed. I knew that we were in trouble then. I didn’t really have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music, and I was scared. I thought, ‘We’ve fuckin’ had it now.‘«[223] Harrison’s then-wife Pattie Boyd remembered that «Paul and George were in complete shock. I don’t think it could have been worse if they had heard that their own fathers had dropped dead.»[224] During a band meeting in September, McCartney recommended that the band proceed with Magical Mystery Tour.[214]

The Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack was released in the UK as a six-track double extended play (EP) in early December 1967.[84][225] It was the first example of a double EP in the UK.[226][227] The record carried on the psychedelic vein of Sgt. Pepper,[228] however, in line with the band’s wishes, the packaging reinforced the idea that the release was a film soundtrack rather than a follow-up to Sgt. Pepper.[225] In the US, the soundtrack appeared as an identically titled LP that also included five tracks from the band’s recent singles.[106] In its first three weeks, the album set a record for the highest initial sales of any Capitol LP, and it is the only Capitol compilation later to be adopted in the band’s official canon of studio albums.[229]

Magical Mystery Tour first aired on Boxing Day to an audience of approximately 15 million.[230] Largely directed by McCartney, the film was the band’s first critical failure in the UK.[231] It was dismissed as «blatant rubbish» by the Daily Express; the Daily Mail called it «a colossal conceit»; and The Guardian labelled the film «a kind of fantasy morality play about the grossness and warmth and stupidity of the audience».[232] Gould describes it as «a great deal of raw footage showing a group of people getting on, getting off, and riding on a bus».[232] Although the viewership figures were respectable, its slating in the press led US television networks to lose interest in broadcasting the film.[233]

The group were less involved with Yellow Submarine, which featured the band appearing as themselves for only a short live-action segment.[234] Premiering in July 1968, the film featured cartoon versions of the band members and a soundtrack with eleven of their songs, including four unreleased studio recordings that made their debut in the film.[235] Critics praised the film for its music, humour and innovative visual style.[236] A soundtrack LP was issued seven months later; it contained those four new songs, the title track (already issued on Revolver), «All You Need Is Love» (already issued as a single and on the US Magical Mystery Tour LP) and seven instrumental pieces composed by Martin.[237]

India retreat, Apple Corps and the White Album

In February 1968, the Beatles travelled to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s ashram in Rishikesh, India, to take part in a three-month meditation «Guide Course». Their time in India marked one of the band’s most prolific periods, yielding numerous songs, including a majority of those on their next album.[238] However, Starr left after only ten days, unable to stomach the food, and McCartney eventually grew bored and departed a month later.[239] For Lennon and Harrison, creativity turned to question when an electronics technician known as Magic Alex suggested that the Maharishi was attempting to manipulate them.[240] When he alleged that the Maharishi had made sexual advances to women attendees, a persuaded Lennon left abruptly just two months into the course, bringing an unconvinced Harrison and the remainder of the group’s entourage with him.[239] In anger, Lennon wrote a scathing song titled «Maharishi», renamed «Sexy Sadie» to avoid potential legal issues. McCartney said, «We made a mistake. We thought there was more to him than there was.»[240]

In May, Lennon and McCartney travelled to New York for the public unveiling of the Beatles’ new business venture, Apple Corps.[241] It was initially formed several months earlier as part of a plan to create a tax-effective business structure, but the band then desired to extend the corporation to other pursuits, including record distribution, peace activism, and education.[242] McCartney described Apple as «rather like a Western communism».[243] The enterprise drained the group financially with a series of unsuccessful projects[244] handled largely by members of the Beatles’ entourage, who were given their jobs regardless of talent and experience.[245] Among its numerous subsidiaries were Apple Electronics, established to foster technological innovations with Magic Alex at the head, and Apple Retailing, which opened the short-lived Apple Boutique in London.[246] Harrison later said, «Basically, it was chaos … John and Paul got carried away with the idea and blew millions, and Ringo and I just had to go along with it.»[243]

The Beatles, known as «the White Album» for its minimalist cover, conceived by pop artist Richard Hamilton «in direct contrast to Sgt. Pepper«, while also suggesting a «clean slate»[247]

From late May to mid-October 1968, the group recorded what became The Beatles, a double LP commonly known as «the White Album» for its virtually featureless cover.[248] During this time, relations between the members grew openly divisive.[249] Starr quit for two weeks, leaving his bandmates to record «Back in the U.S.S.R.» and «Dear Prudence» as a trio, with McCartney filling in on drums.[250] Lennon had lost interest in collaborating with McCartney,[251] whose contribution «Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da» he scorned as «granny music shit».[252] Tensions were further aggravated by Lennon’s romantic preoccupation with avant-garde artist Yoko Ono, whom he insisted on bringing to the sessions despite the group’s well-established understanding that girlfriends were not allowed in the studio.[253] McCartney has recalled that the album «wasn’t a pleasant one to make».[254] He and Lennon identified the sessions as the start of the band’s break-up.[255][256]

With the record, the band executed a wider range of musical styles[257] and broke with their recent tradition of incorporating several musical styles in one song by keeping each piece of music consistently faithful to a select genre.[258] During the sessions, the group upgraded to an eight-track tape console, which made it easier for them to layer tracks piecemeal, while the members often recorded independently of each other, affording the album a reputation as a collection of solo recordings rather than a unified group effort.[259] Describing the double album, Lennon later said: «Every track is an individual track; there isn’t any Beatle music on it. [It’s] John and the band, Paul and the band, George and the band.»[260] The sessions also produced the Beatles’ longest song yet, «Hey Jude», released in August as a non-album single with «Revolution».[261]

Issued in November, the White Album was the band’s first Apple Records album release, although EMI continued to own their recordings.[262] The record attracted more than 2 million advance orders, selling nearly 4 million copies in the US in little over a month, and its tracks dominated the playlists of American radio stations.[263] Its lyric content was the focus of much analysis by the counterculture.[264] Despite its popularity, reviewers were largely confused by the album’s content, and it failed to inspire the level of critical writing that Sgt. Pepper had.[263] General critical opinion eventually turned in favour of the White Album, and in 2003, Rolling Stone ranked it as the tenth greatest album of all time.[162]

Abbey Road, Let It Be and separation