Я, честно говоря, думал, что эта тема уже давно изжила себя, но прочитав комментарии к некоторым видео на YouTube и понаблюдав за беседой в чате Telegram, я пришел к выводу, что здесь все еще не так однозначно. Так что я решил высказать свое мнение, потому что оно самую малость отличается от мнений по этому поводу многих других блоггеров. И сейчас я расскажу, что имею в виду.

Начнем с хрестоматийного примера, и сначала исключим два варианта, которые очевидно неправильны. «Ксиоми» неправильно, потому что это исковерканная прямая транслитерация, которая в оригинале звучит как «эксаэмай». Это — наиболее простой вариант из прямого прочтения, но так, честно говоря, никто не говорит.

Вопрос стоит в двух других вариантах: «шаоми» и «сяоми», и в споре по этому поводу было сломано немало копий. Ведь дело в том, что ранее бывший вице-президент компании Хьюго Барра настаивал на варианте «шаоми», а китайцы говорили как «сяоми», так и «шаоми».

Что же правильнее? На самом деле, разобраться в этом довольно легко. По русским правилам произношения, это слово должно читаться как «сяоми», из чего получается следующая картина. Если вы говорите по-русски, то максимально грамотный вариант — это «сяоми», но если вы предпочитаете говорить на английский манер, то можно произносить и «шаоми».

Оба варианта одинаково допустимы, просто первый — адаптированный русский, а второй — адаптирован для англоговорящих. Да, возможно мои аргументы сейчас звучат неубедительно, но для формирования полной картины стоит обратить внимание на еще один бренд, в произношении имени которого возникают разночтения.

Как правильно произносить Huawei

Как бы это не звучало, но в случае с Huawei разночтений гораздо меньше. И у нас, и в Китае, это слово произносится как «хуавей». Не слишком ловко, но и без всяких затей. А вот для американцев произносить название бренда очень сложно, а потому производитель искусственно создал для рынка США альтернативную транскрипцию: «уа-уэй».

Будет ли правильно произносить название этого бренда, как «уа-уэй»? Ну, формально — да, как и другие два варианта. Но зачем, если наше произношение практически не отличается от оригинального китайского? Это просто три разных версии слова, адаптированные под разные рынки сбыта. Зачем употреблять англофицированные слова — непонятно, но делать это в принципе можно, ничего страшного не произойдет.

То же самое происходит и с другими брендами. Возвращаясь к «шаоми» и «уа-уэй», если говорить так и быть последовательным, то в таком случае стоит тогда употреблять «сэмсан» вместо «самсунг», «майкрософт» вместо «микрософт», «ноукиа» вместо «нокия», «уанплас» вместо «ванплюс», «би-эм-дабл-ю» вместо «бэ-эм-вэ» и т.д. Все это будет правильно, но это будет английское произношение вместо русского, вот и все.

Поэтому и «шаоми», и «сяоми», это оба — допустимые варианты. Но, исходя чисто из логики, было бы разумнее использовать русифицированный термин, так как в ином случае непонятно, из какого языка заимствовать адаптацию.

Не стесняйтесь использовать нормальные адаптированные русскоязычные версии терминов, в этом нет ничего страшного. Да, они могут звучать коряво или грубовато, в сравнение с другими языками, но у тех же немцев есть такая же проблема. А они ведь ни в чем себе не отказывают, так а чем мы хуже немцев?

Источник: Argument600

|

|

Headquarters in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China |

|

|

Native name |

华为技术有限公司 |

|---|---|

|

Romanized name |

Huáwèi jìshù yǒuxiàn gōngsī |

| Type | Private |

| ISIN | HK0000HWEI11 |

| Industry |

|

| Founded | 15 September 1987; 35 years ago |

| Headquarters |

Shenzhen , China |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

Ren Zhengfei (founder & CEO) Liang Hua (chairman) Meng Wanzhou (deputy chairwoman & CFO) He Tingbo (Director) |

| Products |

|

| Brands | Huawei |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

195,000 (2021)[2] |

| Parent | Huawei Investment & Holding[3] |

| Subsidiaries | Honor (2013–2020) Caliopa Chinasoft International FutureWei Technologies HexaTier HiSilicon iSoftStone |

| Website | www.huawei.com |

| Footnotes / references [4] |

| Huawei | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Huawei» in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters |

||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华为 | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華為 | |||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Splendid Achievement» or «Chinese Achievement» | |||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 华为技术有限公司 | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 華為技術有限公司 | |||||||||||||||

|

Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. ( HWAH-way; Chinese: 华为; pinyin: Huáwèi) is a Chinese multinational technology corporation headquartered in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, that designs, develops, manufactures and sells telecommunications equipment, consumer electronics, smart devices and various rooftop solar power products.

The corporation was founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, a former officer in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).[5] Initially focused on manufacturing phone switches, Huawei has expanded its business to include building telecommunications networks, providing operational and consulting services and equipment to enterprises inside and outside of China, and manufacturing communications devices for the consumer market.[6]

Huawei has deployed its products and services in more than 170 countries and areas.[7] It overtook Ericsson in 2012 as the largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer in the world,[8] and overtook Apple in 2018 as the second-largest manufacturer of smartphones in the world, behind Samsung Electronics.[9] In 2018, Huawei reported annual revenue of US$108.5 billion.[10] In July 2020, Huawei surpassed Samsung and Apple in the number of phones shipped worldwide for the first time.[11]

Although successful internationally, Huawei has faced difficulties in some markets, arising from undue state support, links to the PLA and Ministry of State Security (MSS), and concerns that Huawei’s infrastructure equipment may enable surveillance by the Chinese government.[12][13] With the development of 5G wireless networks, there have been calls from the U.S. and its allies to not do any kind of business with Huawei or other Chinese telecommunications companies such as ZTE.[14] Huawei has argued that its products posed «no greater cybersecurity risk» than those of any other vendor, that the US has not shown evidence of espionage, and that the allegations are hypocritical as the American government itself conducts state survelliance programmes.[15] However, experts point out that the 2014 Counter-Espionage Law and 2017 National Intelligence Law of the People’s Republic of China are far-reaching legislation that compels Huawei and other companies to cooperate in gathering intelligence.[16] According to former staff «it is no secret that employees often work with intelligence officials embedded in the company»,[17][5] with 25,000 Huawei employees previously serving in the MSS or the PLA, including former chairwoman Sun Yafang.[18][19][20] Intelligence agencies have also implicated Huawei in several hacks of telecom networks,[21][22] while several rival telecom manufacturers like Nortel and Cisco Systems have traced industrial espionage back to Huawei.[23]

Despite claims that it operates as a private company, questions regarding Huawei’s ownership and control persist. Huawei is considered a national champion in China’s «techno-nationalist development strategies», and has received extensive support including financing from state-owned banks,[24] plus China has engaged in diplomatic lobbying and threatened trade reprisals against countries who considered blocking Huawei’s participation from 5G.[17][12] Huawei has assisted in the surveillance and mass detention of Uyghurs in Xinjiang internment camps, resulting in sanctions by the United States Department of State.[25][26][27][28] Huawei also tested a facial recognition AI that recognizes ethnicity-specific features to alert government authorities of members of an ethnic group.[29]

In the midst of an ongoing trade war between China and the United States, Huawei was restricted from doing commerce with U.S. companies due to alleged previous willful violations of U.S. sanctions against Iran. On 29 June 2019, U.S. President Donald Trump reached an agreement to resume trade talks with China and announced that he would ease the aforementioned sanctions on Huawei. Huawei cut 600 jobs at its Santa Clara research center in June, and in December 2019 founder Ren Zhengfei said it was moving the center to Canada because the restrictions would block them from interacting with US employees.[30][31] In 2020, Huawei agreed to sell the Honor brand to a state-owned enterprise of the Shenzhen municipal government to «ensure its survival», after the U.S. sanctions against them.[32] In November 2022, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) banned sales or import of equipment made by Huawei for national security reasons.[33]

Name[edit]

According to the company founder Ren Zhengfei, the name Huawei comes from a slogan he saw on a wall, Zhonghua youwei meaning «China has promise» (Chinese: 中华有为; pinyin: Zhōng huá yǒu wéi), when he was starting up the company and needed a name.[34] Zhonghua or Hua means China,[35] while youwei means «promising/to show promise».[36][37] Huawei has also been translated as «splendid achievement» or «China is able», which are possible readings of the name.[38]

In Chinese pinyin, the name is Huáwéi,[39] and pronounced [xwǎwéɪ] in Mandarin Chinese; in Cantonese, the name is transliterated with Jyutping as Waa4-wai4 and pronounced [wȁːwɐ̏i]. However, pronunciation of Huawei by non-Chinese varies in other countries, for example «Hoe-ah-wei» in Belgium and the Netherlands.[40]

The company had considered changing the name in English out of concern that non-Chinese people may find it hard to pronounce,[41] but decided to keep the name, and launched a name recognition campaign instead to encourage a pronunciation closer to «Wah-Way» using the words «Wow Way».[42][43]

History[edit]

Early years[edit]

During the 1980s, the Chinese government tried to modernize the country’s underdeveloped telecommunications infrastructure. A core component of the telecommunications network was telephone exchange switches, and in the late 1980s, several Chinese research groups endeavoured to acquire and develop the technology, usually through joint ventures with foreign companies.

Ren Zhengfei, a former deputy director of the People’s Liberation Army engineering corps, founded Huawei in 1987 in Shenzhen. The company reports that it had RMB 21,000 (about $5,000 at the time) in registered capital from Ren Zhengfei and five other investors at the time of its founding where each contributed RMB 3,500.[44] These five initial investors gradually withdrew their investments in Huawei. The Wall Street Journal has suggested, however, that Huawei received approximately «$46 billion in loans and other support, coupled with $25 billion in tax cuts» since the Chinese government had a vested interest in fostering a company to compete against Apple and Samsung.[45][46][47]

Ren sought to reverse engineer and steal foreign technologies with local researchers. China borrowed liberally from Qualcomm and other industry leaders (PBX as an example) in order to enter the market. At a time when all of China’s telecommunications technology was imported from abroad, Ren hoped to build a domestic Chinese telecommunication company that could compete with, and ultimately replace, foreign competitors.[48]

During its first several years the company’s business model consisted mainly of reselling private branch exchange (PBX) switches imported from Hong Kong.[6][49] Meanwhile, it was reverse-engineering imported switches and investing heavily in research and development to manufacture its own technologies.[6] By 1990 the company had approximately 600 R&D staff and began its own independent commercialization of PBX switches targeting hotels and small enterprises.[50]

The company’s first major breakthrough came in 1993 when it launched its C&C08 program controlled telephone switch. It was by far the most powerful switch available in China at the time. By initially deploying in small cities and rural areas and placing emphasis on service and customizability, the company gained market share and made its way into the mainstream market.[51]

Huawei also won a key contract to build the first national telecommunications network for the People’s Liberation Army, a deal one employee described as «small in terms of our overall business, but large in terms of our relationships».[52] In 1994, founder Ren Zhengfei had a meeting with Party general secretary Jiang Zemin, telling him that «switching equipment technology was related to national security, and that a nation that did not have its own switching equipment was like one that lacked its own military.» Jiang reportedly agreed with this assessment.[6]

In the 1990s, Canadian telecom giant Nortel outsourced production of their entire product line to Huawei.[23] They subsequently outsourced much of their product engineering to Huawei as well.[53]

Another major turning point for the company came in 1996 when the government in Beijing adopted an explicit policy of supporting domestic telecommunications manufacturers and restricting access to foreign competitors. Huawei was promoted by both the government and the military as a national champion, and established new research and development offices.[6]

Foreign expansion[edit]

Beginning in the late 1990s, Huawei built communications networks throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.[54] It is the most important Chinese telecommunications company operating in these regions.[54]

In 1997, Huawei won a contract to provide fixed-line network products to Hong Kong company Hutchison Whampoa.[51] Later that year, Huawei launched wireless GSM-based products and eventually expanded to offer CDMA and UMTS. In 1999, the company opened a research and development (R&D) centre in Bengaluru, India to develop a wide range of telecom software.[50]

In May 2003, Huawei partnered with 3Com on a joint venture known as H3C, which was focused on enterprise networking equipment. It marked 3Com’s re-entrance into the high-end core routers and switch market, after having abandoned it in 2000 to focus on other businesses. 3Com bought out Huawei’s share of the venture in 2006 for US$882 million.[55][56]

In 2004, Huawei signed a $10 billion credit line with China Development Bank to provide low-cost financing to customers buying its telecommunications equipment to support its sales outside of China. This line of credit was tripled to $30 billion in 2009.[57]

In 2005, Huawei’s foreign contract orders exceeded its domestic sales for the first time. Huawei signed a global framework agreement with Vodafone. This agreement marked the first time a telecommunications equipment supplier from China had received Approved Supplier status from Vodafone Global Supply Chain.[58][non-primary source needed] Huawei also signed a contract[when?] with British Telecom to deploy its multi-service access network (MSAN) and the transmission equipment for its 21st Century Network (21CN).[citation needed]

In 2007, Huawei began a joint venture with U.S. security software vendor Symantec Corporation, known as Huawei Symantec, which aimed to provide end-to-end solutions for network data storage and security. Huawei bought out Symantec’s share in the venture in 2012, with The New York Times noting that Symantec had fears that the partnership «would prevent it from obtaining United States government classified information about cyber threats».[59]

In May 2008, Australian carrier Optus announced that it would establish a technology research facility with Huawei in Sydney.[60] In October 2008, Huawei reached an agreement to contribute to a new GSM-based HSPA+ network being deployed jointly by Canadian carriers Bell Mobility and Telus Mobility, joined by Nokia Siemens Networks.[61] In November 2020, Telus dropped the plan to build 5G network with Huawei.[62] Huawei delivered one of the world’s first LTE/EPC commercial networks for TeliaSonera in Oslo, Norway in 2009.[50] Norway-based telecommunications Telenor instead selected Ericsson due to security concerns with Huawei.[63]

In July 2010, Huawei was included in the Global Fortune 500 2010 list published by the U.S. magazine Fortune for the first time, on the strength of annual sales of US$21.8 billion and net profit of US$2.67 billion.[64][65]

In October 2012, it was announced that Huawei would move its UK headquarters to Green Park, Reading, Berkshire.[66]

Huawei also has expanding operations in Ireland since 2016. As well as a headquarters in Dublin, it has facilities in Cork and Westmeath.[67]

In September 2017, Huawei created a Narrowband IoT city-aware network using a «one network, one platform, N applications» construction model utilizing ‘Internet of things’ (IoT), cloud computing, big data, and other next-generation information and communications technology, it also aims to be one of the world’s five largest cloud players in the near future.[68][69]

In April 2019, Huawei established the Huawei Malaysia Global Training Centre (MGTC) at Cyberjaya, Malaysia.[70]

Recent performance[edit]

By 2018, Huawei had sold 200 million smartphones.[71] They reported that strong consumer demand for premium range smart phones helped the company reach consumer sales in excess of $52 billion in 2018.[72]

Huawei announced worldwide revenues of $105.1 billion for 2018, with a net profit of $8.7 billion.[73] Huawei’s Q1 2019 revenues were up 39% year-over-year, at US$26.76 billion.[74]

In 2019, Huawei reported revenue of US$122 billion.[75] By the second quarter of 2020, Huawei had become the world’s top smartphone seller, overtaking Samsung for the first time.[11] In 2021, Huawei was ranked the second-largest R&D investor in the world by the EU Joint Research Centre (JRC) in its EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard[76] and ranked fifth in the world in US patents according to a report by Fairview Research’s IFI Claims Patent Services.[77]

However, heavy international sanctions saw Huawei’s revenues drop by 32% in the 2021 third quarter.[78] Linghao Bao, an analyst at policy research firm Trivium China said the «communications giant went from being the second-largest smartphone maker in the world, after Samsung, to essentially dead.»[79] By the end of third quarter in 2022, Huawei revenue had dropped a further 19.7% since the beginning of the year.[80]

Corporate affairs[edit]

Huawei classifies itself as a «collective» entity and prior to 2019 did not refer to itself as a private company. Richard McGregor, author of The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers, said that this is «a definitional distinction that has been essential to the company’s receipt of state support at crucial points in its development».[81] McGregor argued that «Huawei’s status as a genuine collective is doubtful.»[81] Huawei’s position has shifted in 2019 when, Dr. Song Liuping, Huawei’s chief legal officer, commented on the US government ban, said: «Politicians in the US are using the strength of an entire nation to come after a private company.» (emphasis added).[82]

Leadership[edit]

Ren Zhengfei is the founder and CEO of Huawei and has the power to veto any decisions made by the board of directors.[83][84]

Huawei disclosed its list of board of directors for the first time in 2010.[85] Liang Hua is the current chair of the board. As of 2019, the members of the board are Liang Hua, Guo Ping, Xu Zhijun, Hu Houkun, Meng Wanzhou (CFO and deputy chairwoman), Ding Yun, Yu Chengdong, Wang Tao, Xu Wenwei, Shen-Han Chiu, Chen Lifang, Peng Zhongyang, He Tingbo, Li Yingtao, Ren Zhengfei, Yao Fuhai, Tao Jingwen, and Yan Lida.[86]

Guo Ping is the Chairman of Huawei Device, Huawei’s mobile phone division.[87] Huawei’s Chief Ethics & Compliance Officer is Zhou Daiqi[88] who is also Huawei’s Communist Party Committee Secretary.[89] Their Chief legal officer is Song Liuping.[82]

Ownership[edit]

Huawei claims it is an employee-owned company, but it remains a point of dispute.[83][90] Ren Zhengfei retains approximately 1 percent of the shares of Huawei’s holding company, Huawei Investment & Holding,[90] with the remainder of the shares held by a trade union committee (not a trade union per se, and the internal governance procedures of this committee, its members, its leaders or how they are selected all remain undisclosed to the public) that is claimed to be representative of Huawei’s employee shareholders.[83][91] The company’s trade union committee is registered with and pay dues to the Shenzhen federation of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, which is controlled by the Chinese Communist Party.[92] This is also due to a limitation in Chinese law preventing limited liability companies from having more than 50 shareholders.[93] About half of Huawei staff participate in this scheme (foreign employees are not eligible), and hold what the company calls «virtual restricted shares». These shares are non-tradable and are allocated to reward performance.[94] When employees leave Huawei, their shares revert to the company, which compensates them for their holding.[95] Although employee shareholders receive dividends,[91] their shares do not entitle them to any direct influence in management decisions, but enables them to vote for members of the 115-person Representatives’ Commission from a pre-selected list of candidates.[91] The Representatives’ Commission selects Huawei Holding’s board of directors and Board of Supervisors.[96]

Christopher Balding of Fulbright University and Donald C. Clarke of George Washington University have described Huawei’s virtual stock program as “purely a profit-sharing incentive scheme” that “has nothing to do with financing or control”.[97] They found that, after a few stages of historical morphing, employees do not own a part of Huawei through their shares. Instead, the «virtual stock is a contract right, not a property right; it gives the holder no voting power in either Huawei Tech or Huawei Holding, cannot be transferred, and is cancelled when the employee leaves the firm, subject to a redemption payment from Huawei Holding TUC at a low fixed price».[98][83] The same scholars added, «given the public nature of trade unions in China, if the ownership stake of the trade union committee is genuine, and if the trade union and its committee function as trade unions generally function in China, then Huawei may be deemed effectively state-owned.»[83]

In 2021, Huawei did not report its ultimate beneficial ownership in Europe as required by European anti-money laundering laws.[99]

Lobbying[edit]

In July 2021, Huawei hired Tony Podesta as a consultant and lobbyist, with a goal of nurturing the company’s relationship with the Biden administration.[100][101]

Partners[edit]

As of the beginning of 2010, approximately 80% of the world’s top 50 telecoms companies had worked with Huawei.[102]

In 2016, German camera company Leica has established a partnership with Huawei, and Leica cameras will be co-engineered into Huawei smartphones, including the P and Mate Series. The first smartphone to be co-engineered with a Leica camera was the Huawei P9.[103]

In August 2019, Huawei collaborated with eyewear company Gentle Monster and released smartglasses.[104] In November 2019, Huawei partners with Devialet and unveiled a new specifically designed speaker, the Sound X.[105] In October 2020, Huawei released its own mapping service, Petal Maps, which was developed in partnership with Dutch navigation device manufacturer TomTom.[106]

Products and services[edit]

Huawei is organized around three core business segments:[107]

- Carrier Network Business Group – provides wireless networks, fixed networks, global services, carrier software, core networks and network energy solutions that are deployed by communications carriers

- Enterprise Business Group – Huawei’s industry sales team

- Consumer Business Group – the core of this group is «1 + 8 + N» where «1» represents mobile phones; «8» represents tablets, PCs, VR devices, wearables, smart screens, smart audio, smart speakers, and head units; and «N» represents ubiquitous Internet of Things (IoT) devices[108]

- Cloud & AI Business Group — Huawei’s server, storage products and cloud services

Huawei announced its Enterprise business in January 2011 to provide network infrastructure, fixed and wireless communication, data center, and cloud computing for global telecommunications customers.[109]

Telecommunication networks[edit]

Huawei offers mobile and fixed softswitches, plus next-generation home location register and Internet Protocol Multimedia Subsystems (IMS). Huawei sells xDSL, passive optical network (PON) and next-generation PON (NG PON) on a single platform. The company also offers mobile infrastructure, broadband access and service provider routers and switches (SPRS). Huawei’s software products include service delivery platforms (SDPs), base station subsystems, and more.[110]

Global services[edit]

Huawei Global Services provides telecommunications operators with equipment to build and operate networks as well as consulting and engineering services to improve operational efficiencies.[111] These include network integration services such as those for mobile and fixed networks; assurance services such as network safety; and learning services, such as competency consulting.[110]

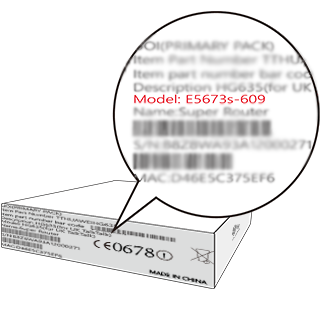

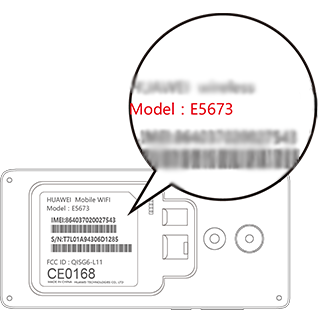

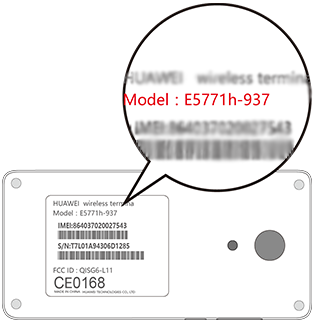

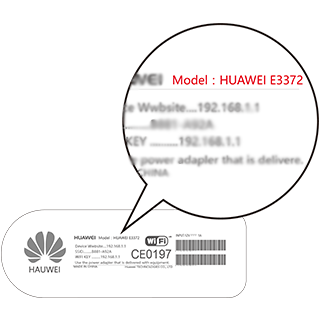

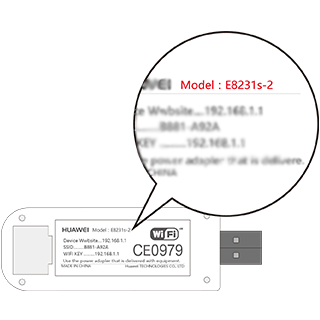

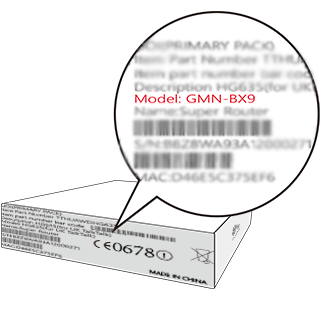

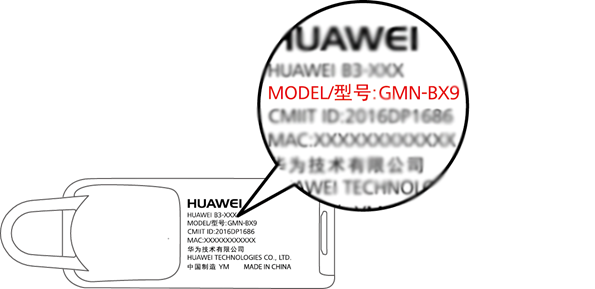

Devices[edit]

A Huawei Band 7 fitness tracker in Wilderness Green colour.

Huawei’s Devices division provides white-label products to content-service providers, including USB modems, wireless modems and wireless routers for mobile Wi-Fi,[112] embedded modules, fixed wireless terminals, wireless gateways, set-top boxes, mobile handsets and video products.[113] Huawei also produces and sells a variety of devices under its own name, such as the IDEOS smartphones, tablet PCs and Huawei Smartwatch.[114][115]

Phones[edit]

Huawei is the second-biggest smartphone maker in the world, after Samsung, as of the first quarter of 2019.

Their current portfolio of phones has two high-end smartphone lines, the Huawei Mate series and Huawei P series. Under the company’s current hardware release cadence, P series phones are typically directed towards mainstream consumers as the company’s flagship smartphones, refining and expanding upon technologies introduced in Mate series devices (which are typically positioned towards early adopters).[116]

Cheaper handsets fall under its Honor brand.[117] Honor was created in order to elevate Huawei-branded phones as premium offerings. In 2020, Huawei agreed to sell the Honor brand to a state-owned enterprise of the Shenzhen municipal government. Consequently, Honor was cut off from access to Huawei’s IPs, which consists of more than 100,000 active patents by the end of 2020, and additionally cannot tap into Huawei’s large R&D resources where $20 billion had been committed for 2021. However Wired magazine noted in 2021 that Honor devices still had not differentiated their software much from Huawei phones and that core apps and certain engineering features, like the Honor-engineered camera features looked «virtually identical’ across both phones.[32][117]

History of Huawei phones[edit]

In July 2003, Huawei established their handset department and by 2004, Huawei shipped their first phone, the C300. The U626 was Huawei’s first 3G phone in June 2005 and in 2006, Huawei launched the first Vodafone-branded 3G handset, the V710. The U8220 was Huawei’s first Android smartphone and was unveiled in MWC 2009. At CES 2012, Huawei introduced the Ascend range starting with the Ascend P1 S. At MWC 2012, Huawei launched the Ascend D1. In September 2012, Huawei launched their first 4G ready phone, the Ascend P1 LTE. At CES 2013, Huawei launched the Ascend D2 and the Ascend Mate. At MWC 2013, the Ascend P2 was launched as the world’s first LTE Cat4 smartphone. In June 2013, Huawei launched the Ascend P6 and in December 2013, Huawei introduced Honor as a subsidiary independent brand in China. At CES 2014, Huawei launched the Ascend Mate2 4G in 2014 and at MWC 2014, Huawei launched the MediaPad X1 tablet and Ascend G6 4G smartphone. Other launched in 2014 included the Ascend P7 in May 2014, the Ascend Mate7, the Ascend G7 and the Ascend P7 Sapphire Edition as China’s first 4G smartphone with a sapphire screen.[118]

In January 2015, Huawei discontinued the «Ascend» brand for its flagship phones, and launched the new P series with the Huawei P8.[119][120] Huawei also partnered with Google to build the Nexus 6P which was released in September 2015.[121]

In May 2018, Huawei stated that they will no longer allow unlocking the bootloader of their phones to allow installing third party system software or security updates after Huawei stops them.

[122]

The current models in the P and Mate lines, the Mate 40, Mate 40 Pro, Mate 40 5G, Mate 40 Pro 5G, P40, P40 Pro, Mate 30, Mate 30 Pro, Mate 30 5G, Mate 30 Pro 5G, P30, P30 Pro, Mate 20, Mate 20 Pro and Mate 20 X were released in 2018 and 2019.[123][124] The P30 lineup is the most recent to include Google-certified Android with Google Play.[125]

Huawei is currently the most well-known international corporation in China and a pioneer of the 5G mobile phone standard, which will be used globally in the next years.[126]

In May 2022, Huawei Mate Xs 2 goes global. Mate Xs 2 is set to arrive to European markets in June.[127]

Laptops[edit]

Huawei Matebook 2-in-1 tablet

In 2016, Huawei entered the laptop markets with the release of its Huawei MateBook series of laptops.[128] They have continued to release laptop models in this series into 2020 with their most recent models being the MateBook X Pro and Matebook 13 2020.[129]

Tablets[edit]

The HUAWEI MatePad Pro, launched in November 2019.[108] Huawei is number one in the Chinese tablet market and number two globally as of 4Q 2019.[130]

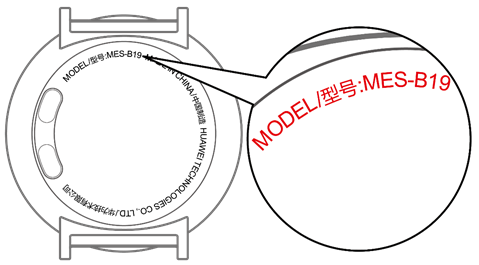

Wearables[edit]

The Huawei Watch is an Android Wear-based smartwatch developed by Huawei. It was announced at 2015 Mobile World Congress on 1 March 2015,[131] and was released at Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin on 2 September 2015.[132] It is the first smartwatch produced by Huawei.[132] Their latest watch, the Huawei Watch GT 2e, was launched in India in May, 2020.[133]

Automobile[edit]

In December 2021, the AITO M5 was unveiled as the first vehicle to be developed in cooperation with Huawei. The model was developed mainly by Seres and is essentially a restyled Seres SF5 crossover.[134] The model was sold under a new brand called AITO, which stands for “Adding Intelligence to Auto” and uses Huawei DriveONE and HarmonyOS, while the Seres SF5 used Huawei DriveONE and HiCar.[135]

-

AITO M5 front quarter view

-

AITO M5 rear quarter view

-

AITO M5 interior

Huawei has also secured collaboration with other automakers including BAIC Motor, Changan Automobile and GAC Group.[136]

Vehicles using Huawei technology include:

- Arcfox Alpha-S[137][138]

- Hozon Neta S

- Roewe Marvel X

- Changan Shenlan 03

- Changan Avatr 011

- Rising Auto R7

Software[edit]

EMUI (Emotion User Interface)[edit]

Main article: EMUI

Emotion UI (EMUI) is a ROM/OS developed by Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. and based on Google’s Android Open Source Project (AOSP). EMUI is pre-installed on most Huawei Smartphone devices and its subsidiaries the Honor series.[139]

Harmony OS[edit]

On 9 August 2019, Huawei officially unveiled Harmony OS at its inaugural developers’ conference HDC in Dongguan. Huawei described Harmony as a free, microkernel-based distributed operating system for various types of hardware, with faster inter-process communication than QNX or Google’s «Fuchsia» microkernel, and real-time resource allocation. The ARK compiler can be used to port Android APK packages to the OS. Huawei stated that developers would be able to «flexibly» deploy Harmony OS software across various device categories; the company focused primarily on IoT devices, including «smart displays», wearable devices, and in-car entertainment systems, and did not explicitly position Harmony OS as a mobile OS.[140][141]

Huawei Mobile Services (HMS)[edit]

Huawei Mobile Services (HMS) is Huawei’s solution to GMS (Google Mobile services), it was created to work over Android System, so Android applications can work over Huawei HMS Mobile phones, if those don’t use Google Mobile Services. HMS is part of Huawei ecosystem which Huawei developed complete solutions for several scenarios. One of their major application is called Huawei AppGallery, which is Huawei app store created as a competitor to Google’s Android Play Store. As of December, 2019 it was in version 4.0 and as of 16 January 2020 the company reports it has signed up 55,000 apps using its HMS Core software.[142]

Competitive position[edit]

Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. was the world’s largest telecom equipment maker in 2012[8] and China’s largest telephone-network equipment maker.[143] With 3,442 patents, Huawei became the world’s No. 1 applicant for international patents in 2014.[144][145] In 2019, Huawei had the second most patents granted by the European Patent Office.[146] In 2021, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)’s annual World Intellectual Property Indicators report ranked Huawei’s number of patent applications published under the PCT System as 1st in the world, with 5464 patent applications being published during 2020.[147] This position is consistent with their previous ranking at 1st for 4411 PCT applications in 2019.[148]

R&D centers[edit]

The company has twenty one R&D institutes in countries including China, the United States,[149] Canada,[150] the United Kingdom,[151] Pakistan, Finland, France, Belgium, Germany, Colombia, Sweden, Ireland, India,[152] Russia, Israel, and Turkey.[153][154]

Huawei is considering opening a new research and development (R&D) center in Russia (2019/2020), which would be the third in the country after the Moscow and St. Petersburg R&D centers. Huawei also announced plans (November 2018) to open an R&D center in the French city of Grenoble, which would be mainly focused on smartphone sensors and parallel computing software development. The new R&D team in Grenoble was expected to grow to 30 researchers by 2020, said the company. The company said that this new addition brought to five the number of its R&D teams in the country: two were located in Sophia Antipolis and Paris, researching image processing and design, while the other two existing teams were based at Huawei’s facilities in Boulogne-Billancourt, working on algorithms and mobile and 5G standards. The technology giant also intended to open two new research centers in Zürich and Lausanne, Switzerland. Huawei at the time employed around 350 people in Switzerland.[155][156]

Huawei also funds research partnerships with universities such as the University of British Columbia, the University of Waterloo, the University of Western Ontario, the University of Guelph, and Université Laval.[157][158]

Controversies[edit]

Huawei has faced criticism for various aspects of its operations, largely involving allegations of its products containing backdoors for Chinese government espionage—consistent with domestic laws requiring Chinese citizens and companies to cooperate with state intelligence when warranted. Huawei executives have consistently denied these allegations, having stated that the company has never received any requests by the Chinese government to introduce backdoors in its equipment, would refuse to do so, and that Chinese law did not compel them to do so.[159][160][161][162]

Early business practices[edit]

Huawei employed a complex system of agreements with local state-owned telephone companies that seemed to include illicit payments to the local telecommunications bureau employees. During the late 1990s, the company created several joint ventures with their state-owned telecommunications company customers. By 1998, Huawei had signed agreements with municipal and provincial telephone bureaus to create Shanghai Huawei, Chengdu Huawei, Shenyang Huawei, Anhui Huawei, Sichuan Huawei, and other companies. The joint ventures were actually shell companies, and were a way to funnel money to local telecommunications employees so that Huawei could get deals to sell them equipment. In the case of Sichuan Huawei, for example, local partners could get 60–70 percent of their investment returned in the form of annual ‘dividends’.[163]

Relationship with Chinese government[edit]

Huawei has claimed that it has no special relationship with the Chinese government, like other domestic private companies. However observers have noted that the Chinese government has granted Huawei much more comprehensive support than other domestic companies facing troubles abroad, such as ByteDance, since Huawei is considered a national champion in the China’s «techno-nationalist development strategies» for national security and commercial enterprises.[17][164] For instance after Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou was detained in Canada pending extradition to the United States for fraud charges, China immediately arrested Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in what was widely viewed as «hostage diplomacy».[17][165][47] China has also imposed tariffs on Australian imports in 2020, in apparent retaliation for Huawei and ZTE being excluded from Australia’s 5G network in 2018.[17]

In June 2020, when the U.K. mulled reversing an earlier decision to permit Huawei’s participation in 5G, China threatened retaliation in other sectors like power generation and high-speed rail, so then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reassured the U.K. saying “the U.S. stands with our allies and partners against the Chinese Communist Party’s coercive bullying tactics,” and «the U.S. stands ready to assist our friends in the U.K. with any needs they have, from building secure and reliable nuclear power plants to developing trusted 5G solutions that protect their citizens’ privacy».[166] On 7 October 2020, the U.K. Parliament’s Defence Committee released a report concluding that there was evidence of collusion between Huawei and Chinese state and the Chinese Communist Party, based upon ownership model and government subsidies it has received. Huawei responded by saying «this report lacks credibility as it is built on opinion rather than fact».[167]

In November 2019, the Chinese ambassador to Denmark, in meetings with high-ranking Faroese politicians, directly linked Huawei’s 5G expansion with Chinese trade, according to a sound recording obtained by Kringvarp Føroya. According to Berlingske, the ambassador threatened with dropping a planned trade deal with the Faroe Islands, if the Faroese telecom company Føroya Tele did not let Huawei build the national 5G network. Huawei said they did not knоw about the meetings.[168]

The Wall Street Journal has suggested that Huawei received approximately «$46 billion in loans and other support, coupled with $25 billion in tax cuts» since the Chinese government had a vested interest in fostering a company to compete against Apple and Samsung.[45][47] In particular, China’s state-owned banks such as the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China make loans to Huawei customers which substantially undercut competitors’ financing with lower interest and cash in advance, with China Development Bank providing a credit line totaling US$30 billion between 2004 and 2009. In 2010, the European Commission launched an investigation into China’s subsidies that distorted global markets and harmed European vendors, and Huawei offered the initial complainant US$56 million to withdraw the complaint in an attempt to shut down the investigation. Then-European Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht found that Huawei leveraged state support to underbid competitors by up to 70 percent.[24][169]

Allegations of espionage[edit]

Company founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei said “we never participate in espionage and we do not allow any of our employees to do any act like that. And we absolutely never install backdoors. Even if we were required by Chinese law, we would firmly reject that”.[170][171] Chinese Premier Li Keqiang was quoted saying «the Chinese government did not and will not ask Chinese companies to spy on other countries, such kind of action is not consistent with the Chinese law and is not how China behaves.” Huawei has cited the opinion of Zhong Lun Law Firm, whose lawyers testified to the FCC that the National Intelligence Law doesn’t apply to Huawei. The opinion of Zhong Lun lawyers, reviewed by British law firm Clifford Chance, has been distributed widely by Huawei as an “independent legal opinion”, although Clifford Chance added a disclaimer stated that “the material should not be construed as constituting a legal opinion on the application of PRC law”.[172][173] Follow up reporting from Wired cast doubt on the findings of Zhong Lun, particularly because the Chinese «government doesn’t limit itself to what the law explicitly allows» when it comes to national security.[174] «All Chinese citizens and organisations are obliged to cooperate upon request with PRC intelligence operations—and also maintain the secrecy of such operations», as explicitly stipulated in Article 7 of the 2017 PRC national intelligence-gathering activities law.[175]

Experts have pointed out that “under [President] Xi’s intensifying authoritarianism [since] Beijing promulgated a new national intelligence law» in 2017, as well as the 2014 Counter-Espionage Law, both of which are vaguely defined and far-reaching. The two laws «[compel] Chinese businesses to work with Chinese intelligence and security agencies whenever they are requested to do so”, suggesting that Huawei or other domestic major technology companies could not refuse to cooperate with Chinese intelligence.[16] One former Huawei employee said “The state wants to use Huawei, and it can use it if it wants. Everyone has to listen to the state. Every person. Every company and every individual, and you can’t talk about it. You can’t say you don’t like it. That’s just China.” The new cybersecurity law also requires domestic companies, and eventually foreign subsidiaries, to use state-certified network equipment and software so that their data and communications are fully visible to China’s Cybersecurity Bureau.[17][5][172][173] University of Nottingham’s Martin Thorley has suggested that Huawei would have no recourse to oppose the Communist Party’s request in court, since the Party controls the police, the media, the judiciary and the government.[16] Klon Kitchen has suggested that 5G dominance is essential to China in order to achieve its vision where «the prosperity of state-run capitalism is combined with the stability and security of technologically enabled authoritarianism».[176][47]

Henry Jackson Society researchers conducted an analysis of 25,000 Huawei employee CVs and found that some «worked as agents within China’s Ministry of State Security; worked on joint projects with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA); were educated at China’s leading military academy; and had been employed with a military unit linked to a cyber attack on U.S. corporations.»[18] One of the study researchers says this shows «a strong relationship between Huawei and all levels of the Chinese state, Chinese military and Chinese intelligence. This to me appears to be a systemized, structural relationship.»[177][178] Charles Parton, a British diplomat, said this “give the lie to Huawei’s claim that there is no evidence that they help the Chinese intelligence services. This gun is smoking.”[18] In addition, senior security officials in Uganda and Zambia admitted that Huawei played key roles enabling their governments to spy on political opponents.[17]

Bloomberg revealed that Australian intelligence in 2012 had detected a hack, caused by a software update from Huawei on a telecom network. The update contained malicious code that operated like a “digital wiretap” that transmitted data to China before deleting itself. Investigators nonetheless managed to reconstruct the hack, and upon tracing it to Huawei technicians have determined that this attack was perpetrated by China’s spy agency, then sharing the findings with the United States who also confirmed similar hacks. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused this of being a «slander».[21][22] Inside the African Union headquarters, whose computer systems were supplied by Huawei and paid for by the Chinese government, IT staff discovered that data transfers on its servers peaked after hours from January 2012 to January 2017, with the African Union’s internal data sent to unknown servers hosted in Shanghai.[17] In May 2019, a Huawei Mediapad M5 belonging to a Canadian IT engineer living in Taiwan was found to be sending data to servers in China despite never being authorized to do so, as the apps could not be disabled and continued to send sensitive data even after appearing to be deleted.[179] At the end of 2019, United States officials disclosed to the United Kingdom and Germany that Huawei has had the ability to covertly exploit backdoors intended for law enforcement officials since 2009, as these backdoors are found on carrier equipment like antennas and routers, and Huawei’s equipment is widely used around the world due to its low cost.[180][181]

Timeline[edit]

A 2012 White House-ordered security review found no evidence that Huawei spied for China and said instead that security vulnerabilities on its products posed a greater threat to its users. The details of the leaked review came a week after a US House Intelligence Committee report which warned against letting Huawei supply critical telecommunications infrastructure in the United States.[182]

Huawei has been at the center of espionage allegations over Chinese 5G network equipment. In 2018, the United States passed a defense funding bill that contained a passage barring the federal government from doing business with Huawei, ZTE, and several Chinese vendors of surveillance products, due to security concerns.[183][184][185] The Chinese government has threatened economic retaliation against countries that block Huawei’s market access.[186]

Similarly in November 2018, New Zealand blocked Huawei from supplying mobile equipment to national telecommunications company Spark New Zealand’s 5G network, citing a «significant network security risk» and concerns about China’s National Intelligence Law.[187][188]

In 2019, a report commissioned by the Papua New Guinea (PNG) National Cyber Security Centre, funded by the Australian government, alleged that a data center built by Huawei for the PNG government contained exploitable security flaws.[189] Huawei responded that the project «complies with appropriate industry standards and the requirements of the customer.»[189] The Government of Papua New Guinea has called the data centre a ‘failed investment’ and attempted to have the loan cancelled.[190]

Between December 2018 and January 2019, German and British intelligence agencies initially pushed back against the US’ allegations, stating that after examining Huawei’s 5G hardware and accompanying source code, they have found no evidence of malevolence and that a ban would therefore be unwarranted.[191][192] Additionally, the head of Britain’s National Cyber Security Centre (the information security arm of GCHQ) stated that the US has not managed to provide the UK with any proof of its allegations against Huawei and also their agency had concluded that any risks involving Huawei in UK’s telecom networks are «manageable».[193][192] The Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC), set up in 2010 to assuage security fears as it examined Huawei hardware and software for the UK market, was staffed largely by employees from Huawei but with regular oversight from GCHQ, which led to questions of operating independence from Huawei.[194] On 1 October 2020, an official report released by National Cyber Security Centre noted that «Huawei has failed to adequately tackle security flaws in equipment used in the UK’s telecoms networks despite previous complaints», and flagged one vulnerability of «national significance» related to broadband in 2019. The report concluded that Huawei was not confident of implementing the five-year plan of improving its software engineering processes, so there was «limited assurance that all risks to UK national security» could be mitigated in the long-term.[195] On 14 July 2020, the United Kingdom Government announced a ban on the use of company’s 5G network equipment, citing security concerns.[196] In October 2020, the British Defence Select Committee announced that it had found evidence of Huawei’s collusion with the Chinese state and that it supported accelerated purging of Huawei equipment from Britain’s telecom infrastructure by 2025, since they concluded that Huawei had «engaged in a variety of intelligence, security, and intellectual property activities» despite its repeated denials.[167][197] In November 2020, Huawei challenged the UK government’s decision, citing an Oxford Economics report that it had contributed £3.3 billion to the UK’s GDP.[198]

In January 2020, Germany’s spy chief Huawei “can’t fully be trusted”, while Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant reported on a Huawei “backdoor” in the network of a major Netherlands telecom, leading to a probe by the AIVD on the possibility that the breach had enabled spying by the Chinese government. However France’s cybersecurity chief Guillaume Poupard shrugged off German’s concerns and stated that his agency ANSSI haven’t uncovered any evidence nor seen a «smoking gun» of Huawei spying in Europe. In an interview with Bloomberg news, Poupard said “There is no situation with Huawei being caught massively spying in Europe. Elsewhere maybe it’s different, but not in Europe.»[199][200]

In March 2019, Huawei filed three defamation claims over comments suggesting ties to the Chinese government made on television by a French researcher, a broadcast journalist and a telecommunications sector expert.[199] In June 2020 ANSSI informed French telecommunications companies that they would not be allowed to renew licenses for 5G equipment made from Huawei after 2028.[201] On 28 August 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron assured the Chinese government that it did not ban Huawei products from participating in its fifth-generation mobile roll-out, but favored European providers for security reasons. The head of the France’s cybersecurity agency also stated that it has granted time-limited waivers on 5G for wireless operators that use Huawei products, a decision that likely started a «phasing out» of the company’s products.[202] Huawei has proposed new factories and research facilities to persuade countries to reconsider their bans on Huawei’s participation in their respective 5G networks, however a spokesman for France’s economy ministry confirmed that the new factory would not affect the decision to phase out use of Chinese equipment from France’s telecoms.[203][204]

In February 2020, US government officials claimed that Huawei has had the ability to covertly exploit backdoors intended for law enforcement officials in carrier equipment like antennas and routers since 2009.[205][206]

In mid July 2020, Andrew Little, the Minister in charge of New Zealand’s signals intelligence agency the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB), announced that New Zealand would not join the United Kingdom and United States in banning Huawei from the country’s 5G network.[207][208]

Following the 2020 China–India skirmishes, India announced that Huawei would be blocked from participating in the country’s 5G network for national security reasons.[209]

In May 2022, Canada’s industry minister Francois-Philippe Champagne announced that Canada will ban Huawei from the country’s 5G network, in an effort to protect the safety and security of Canadians, as well as to protect Canada’s infrastructure.[210] The Canadian federal government cited national security concerns for the move, saying that the suppliers could be forced to company with “extrajudicial directions from foreign governments” in ways that could “conflict with Canadian laws or would be detrimental to Canadian interests”. Telcos will be prevented from procuring new 4G or 5G equipment from Huawei and ZTE and must remove all ZTE- and Huawei-branded 5G equipment from their networks by June 28, 2024.[211]

Allegations of fraud and conspiracy to subvert sanctions against Iran[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2022) |

In December 2012, Reuters reported that «deep links» existed as early as 2010 between Huawei through Meng Wanzhou (who was then CFO of the firm) and an Iranian telecom importer named Skycom.[212] The US had long-standing sanctions on Iran, including against the importation of US technology goods into Iran. On 22 August 2018, the Trump administration and a New York court, including staffers of Trump’s cabinet officially issued an arrest warrant for Meng to stand trial in the United States.[213][214] On 1 December 2018, Meng was arrested in Canada at the behest of the Trump administration.[215] She faces extradition to the United States on charges of violating the sanctions regime.[216]

On 28 January 2019, the Trump administration’s cabinet and federal prosecutors formally indicted Meng and Huawei with 13 counts of bank and wire fraud (in order to mask the sale that is illegal under sanctions of U.S. technology to Iran), obstruction of justice, and misappropriating trade secrets.[217][218] The department also filed a formal extradition request for Meng with Canadian authorities that same day. Huawei responded to the charges and said that it «denies that it or its subsidiary or affiliate have committed any of the asserted violations», as well as asserted Meng was similarly innocent. The China Ministry of Industry and Information Technology believed the charges brought on by the United States were «unfair».[219]

The case for extradition of Meng to the US to face charges is ongoing as of May, 2020 with the B.C. Supreme Court judge on 27 May 2020 ruling that extradition proceedings against the Huawei executive should proceed, denying the claim of double criminality brought by Meng’s defense team.[220] On September 24, 2021, the Department of Justice announced it had suspended its charges against Meng Wanzhou after she entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with them in which she conceded she helped misrepresent the relationship between Huawei and its subsidiary Skycom to HSBC in order to transact business with Iran, but did not have to plead guilty to the fraud charges.[221] The Department of Justice will move to withdraw all the charges against Meng when the deferral period ends on December 21, 2022, on the condition that she is not charged with a crime before then.[221]

Allegations of intellectual property theft[edit]

Huawei has been accused of various instances of intellectual property theft against parties such as Nortel,[222] Cisco Systems, and T-Mobile US (where a Huawei employee had photographed a robotic arm used to stress-test smartphones and taken a fingertip from the robot).[223][224][225] The management of the company claims the US government persecutes it because Huawei’s expansion can affect American business interests.[226] In August 2018, a Texas court found that Huawei had infringed on patents held by the American firm PanOptis.[227] Huawei later settled the case.[228] In November 2018, a German court ruled against Huawei and ZTE in a patent infringement case.[229] In February 2020, the United States Department of Justice charged Huawei with racketeering and conspiring to steal trade secrets from six U.S. firms.[230][231]

Nortel’s chief security officer Brian Shields discovered then-Nortel CEO Mike S. Zafirovski’s computer and company profile were compromised by hackers working for the Chinese government, likely on behalf of Huawei. This suspected industrial espionage allowed Huawei to quickly advance its product development.[232][23][53]

In 2019, Huawei’s chief legal officer stated «In the past 30 years, no court has ever concluded that Huawei engaged in malicious IP theft…no company can become a global leader by stealing from others.»[233]

Involvement in North Korea[edit]

Documents leaked in 2019 revealed that Huawei «secretly helped the North Korean government build and maintain the country’s commercial wireless network,» possibly in violation of international sanctions.[234]

Involvement in Xinjiang internment camps[edit]

Huawei has assisted in the surveillance and mass detention of Uyghurs in Xinjiang internment camps, resulting in sanctions by the United States Department of State.[25][26][27][28] Huawei also tested a facial recognition AI that recognizes ethnicity-specific features to alert government authorities of members of an ethnic group.[29] In January 2021, it was reported that Huawei previously filed a patent with the China National Intellectual Property Administration for a technology to identify Uyghur pedestrians.[235]

In 2019, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a think tank often described as hawkish in Australian media,[236] accused Huawei of assisting in the mass detention of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang internment camps.[26][27][237] Huawei technology used by the Xinjiang internal security forces for data analysis,[238] and companies supplying Huawei operating in the Xinjiang region are accused of using forced labour.[239] However, Huawei denied these reports.[240]

U.S. business restrictions[edit]

In August 2018, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (NDAA 2019) was signed into law, containing a provision that banned Huawei and ZTE equipment from being used by the U.S. federal government, citing security concerns.[241] Huawei filed a lawsuit over the act in March 2019,[242] alleging it to be unconstitutional because it specifically targeted Huawei without granting it a chance to provide a rebuttal or due process.[243]

Additionally, on 15 May 2019, the Department of Commerce added Huawei and 70 foreign subsidiaries and «affiliates» to its Entity List under the Export Administration Regulations, citing the company having been indicted for «knowingly and willfully causing the export, re-export, sale and supply, directly and indirectly, of goods, technology and services (banking and other financial services) from the United States to Iran and the government of Iran without obtaining a license from the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)».[244] This restricts U.S. companies from doing business with Huawei without a government license.[245][246][247] Various U.S.-based companies immediately froze their business with Huawei to comply with the regulation.[248]

The May 2019 ban on Huawei was partial: it did not affect most non-American produced chips, and the Trump administration granted a series of extensions on the ban in any case,[249] with another 90-day reprieve issued in May 2020.[250] In May 2020, the U.S. extended the ban to cover semiconductors customized for Huawei and made with U.S. technology.[251] In August 2020, the U.S. again extended the ban to a blanket ban on all semiconductor sales to Huawei.[251] The blanket ban took effect in September 2020.[252]

These actions have negatively affected Huawei production, sales and financial projections.[253][254][255] However, on 29 June 2019 at the G20 summit, the US President made statements implicating plans to ease the restrictions on U.S. companies doing business with Huawei.[256][257][258] Despite this statement, on 15 May 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce extended its export restrictions to bar Huawei from producing semiconductors derived from technology or software of U.S. origin, even if the manufacturing is performed overseas.[259][260][261] In June 2020, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) designated Huawei a national security threat, thereby barring it from any U.S. subsidies.[14] In July 2020, the Federal Acquisition Regulation Council published a Federal Register notice prohibiting all federal government contractors from selling Huawei hardware to the federal government and preventing federal contractors from using Huawei hardware.[262]

In November 2020, Donald Trump issued an executive order prohibiting any American company or individual from owning shares in companies that the United States Department of Defense has listed as having links to the People’s Liberation Army, which included Huawei.[263][264][265] In January 2021, the Trump administration revoked licenses from US companies such as Intel from supplying products and technologies to Huawei.[266] In June 2021, the FCC voted unanimously to prohibit approvals of Huawei gear in U.S. telecommunication networks on national security grounds.[267]

In June 2021, the administration of Joe Biden began to persuade the United Arab Emirates to remove the Huawei Technologies Co. equipment from its telecommunications network, while ensuring to further distance itself from China. It came as an added threat to the $23 billion arms deal of F-35 fighter jets and Reaper drones between the US and the UAE. The Emirates got a deadline of four years from Washington to replace the Chinese network.[268] A report in September 2021 analyzed how the UAE was struggling between maintaining its relations with both the United States and China. While Washington had a hawkish stance towards Beijing, the increasing Emirati relations with China have strained those with America. In that light, the Western nation has raised concerns for the UAE to beware of the security threat that the Chinese technologies like Huawei 5G telecommunications network possessed. However, the Gulf nations like the Emirates and Saudi Arabia defended their decision of picking Chinese technology over the American, saying that it is much cheaper and had no political conditions.[269]

On 18 November 2020, an opposition motion calling on the government for a decision on the participation of Huawei in Canada’s 5G network and a plan on combating what it called «Chinese aggression» passed 179 to 146. The non-binding motion was supported by the NDP and Bloc Québécois.[270] In May 2022, Canada’s government banned Huawei and ZTE equipment from the country’s 5G network, with companies having until 28 June 2024 to remove 5G equipment from these Chinese vendors.[271] Christopher Parsons of the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab stated that continued use of Huawei and ZTE equipment «would have given the Chinese government leverage over Canada».[272]

On November 25, 2022, the FCC issued a ban on Huawei for national security reasons, citing the national security risk posed by the technology owned by China.[273]

Huawei’s response and stockpiling[edit]

Before the 15 September 2020 deadline, Huawei was in «survival mode» and stockpiled «5G mobile processors, Wifi, radio frequency and display driver chips and other components» from key chip suppliers and manufacturers, including Samsung, SK Hynix, TSMC, MediaTek, Realtek, Novatek, and RichWave.[252] Even in 2019, Huawei spent $23.45 billion on the stockpiling of chips and other supplies in 2019, up 73% from 2018.[252]

On its most crucial business, namely, its telecoms business (including 5G) and server business, Huawei has stockpiled 1.5 to 2 years’ worth of chips and components.[274] It began massively stockpiling from 2018, when Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of Huawei’s founder, was arrested in Canada upon U.S. request.[274] Key Huawei suppliers included Xilinx, Intel, AMD, Samsung, SK Hynix, Micron and Kioxia.[274] On the other hand, analysts predicted that Huawei could ship 195 million units of smartphones from its existing stockpile in 2021, but shipments may drop to 50 million in 2021 if rules are not relaxed.[252]

In late 2020, it was reported that Huawei plans to build a semiconductor manufacturing facility in Shanghai that does not involve U.S. technology.[275] The plan may help Huawei obtain necessary chips after its existing stockpile becomes depleted, which helps it chart a sustainable path for its telecoms business.[275] Huawei plans to collaborate with the government-run Shanghai IC R&D Center, which is partially owned by the state-owned enterprise Huahong Group.[275] Huawei may be purchasing equipment from Chinese firms such as AMEC and Naura, as well as using foreign tools which it can still find on the market.[275]

Replacement operating systems (Deepin & Harmony OS)[edit]

During the sanctions, Huawei had been working on its own in-house operating system codenamed «HongMeng OS»: in an interview with Die Welt, executive Richard Yu stated that an in-house OS could be used as a «plan B» if it were prevented from using Android or Windows as the result of U.S. action.[276][277][278] Huawei filed trademarks for the names «Ark», «Ark OS», and «Harmony» in Europe, which were speculated to be connected to this OS.[279][280] On 9 August 2019, Huawei officially unveiled Harmony OS at its inaugural HDC developers’ conference in Dongguan with the ARK compiler which can be used to port Android APK packages to the OS.[140][141]

In September 2019, Huawei began offering the Linux distribution Deepin as a pre-loaded operating system on selected Matebook models in China.[281]

Bans[edit]

Some or all Huawei products are banned in Australia, Canada, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States.[282]

See also[edit]

- AppGallery

- Huawei 4G eLTE

- Lists of Chinese companies

- HarmonyOS

- EulerOS

- Petal Maps

- Petal Search

References[edit]

- ^ «China’s Huawei Says 2021 Sales Down, Profit Up». usnews.com. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ «Huawei Annual Report 2021». Huawei. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ Zhong, Raymond (25 April 2019). «Who Owns Huawei? The Company Tried to Explain. It Got Complicated». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd. 2020 Annual Report (PDF) (Report). Huawei Investment & Holding Co. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b c «Who is the man behind Huawei and why is the U.S. intelligence community so afraid of his company?». Los Angeles Times. 10 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Ahrens, Nathaniel (February 2013). «China’s Competitiveness Myth, Reality, and Lessons for the United States and Japan. Case Study: Huawei» (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Vance, Ashlee; Einhorn, Bruce (15 September 2011). «At Huawei, Matt Bross Tries to Ease U.S. Security Fears». Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ a b «Who’s afraid of Huawei?». The Economist. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

Huawei has just overtaken Sweden’s Ericsson to become the world’s largest telecoms-equipment-maker.

- ^ Gibbs, Samuel (1 August 2018). «Huawei beats Apple to become second-largest smartphone maker». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ «Huawei expects ‘eventful’ 2018 to deliver $108.5bn in revenue». Reuters. 3 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b Sherisse Pham (30 July 2020). «Samsung slump makes Huawei the world’s biggest smartphone brand for the first time, report says». CNN. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ a b Yap, Chuin-Wei (25 December 2019). «State Support Helped Fuel Huawei’s Global Rise». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany (24 June 2020). «Defense Department produces list of Chinese military-linked companies». Axios. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ a b McCabe, David (30 June 2020). «F.C.C. Designates Huawei and ZTE as National Security Threats». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ McCaskill, Steve (28 February 2019). «Huawei: US has no evidence for security claims». TechRadar. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b c «Huawei says it would never hand data to China’s government. Experts say it wouldn’t have a choice». CNBC. 5 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brandao, Doowan Lee, Shannon (30 April 2021). «Huawei Is Bad for Business». Foreign Policy.

- ^ a b c Mendick, Robert (6 July 2019). «‘Smoking gun’: Huawei staff employment records link them to Chinese military agencies». National Post.

- ^ Gertz, Bill (11 October 2011). «Chinese telecom firm tied to spy ministry; CIA: Beijing funded Huawei». The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ «Huawei Annual Report Details Directors, Supervisory Board for First Time» (PDF). Open Source Center. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ a b «Chinese Spies Accused of Using Huawei in Secret Australia Telecom Hack — BNN Bloomberg». 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b https://www.news.com.au/technology/online/security/key-details-of-huawei-security-breach-in-australia-revealed/news-story/ad329132e7b1d552ba1fb77fcc3f8714[bare URL]

- ^ a b c Kehoe, John (26 May 2014). «How Chinese hacking felled telecommunication giant Nortel». afr.com. Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ a b «There is a Solution to the Huawei Challenge».

- ^ a b «Documents link Huawei to China’s surveillance programs». The Washington Post. 14 December 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Wheeler, Caroline (22 December 2019). «Chinese tech giant Huawei ‘helps to persecute Uighurs’«. The Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b c VanderKlippe, Nathan (29 November 2019). «Huawei providing surveillance tech to China’s Xinjiang authorities, report finds». The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b Kelly, Laura; Mills Rodrigo, Chris (15 July 2020). «US announces sanctions on Huawei, citing human rights abuses». The Hill. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b Harwell, Drew; Dou, Eva (8 December 2020). «Huawei tested AI software that could recognize Uighur minorities and alert police, report says». The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ «Huawei moving US research center to Canada». Associated Press. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ McLeod, James (9 December 2019). «‘Who’s going to make the first move?’: Canada not alone in the Huawei dilemma». Financial Post. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b Lawler, Richard (17 November 2020). «Huawei sells Honor phone brand to ‘ensure’ its survival». Engadget. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Bartz, Diane; Alper, Alexandra (25 November 2022). «U.S. bans Huawei, ZTE equipment sales citing national security risk». Reuters. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ «任正非:华为名源自中华有为 我们要教外国人怎么念_科技频道_凤凰网». tech.ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ «中华». MDBG.

- ^ «有为». MDBG.

- ^ «有为 yǒuwéi». LINE Dict. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Vaswani, Karishma (6 March 2019). «Huawei: The story of a controversial company». BBC. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ «华为». MDBG.

- ^ Segers, Rien (29 January 2016). Multinational Management: A Casebook on Asia’s Global Market Leaders. Springer. p. 87. ISBN 9783319230122.

- ^ Thomson, Ainsley (4 September 2013). «Huawei Mulled Changing Its Name as Foreigners Found it Too Hard». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ «Wow Way or Huawei? A readable Chinese brand is the first key in unlocking America’s market». South China Morning Post. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Miller, Matthew (10 January 2018). «Huawei launches unlocked Mate 10 Pro in US, backed by Wonder Woman». ZD Net. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ «Huawei, a self-made world-class company or agent of China’s global strategy?». Ash Center. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ a b «Huawei reportedly got by with a lot of help from the Chinese government». 26 December 2019.

- ^ «Huawei denies receiving billions in financial aid from Chinese government».

- ^ a b c d «Huawei’s Decline Shows Why China Will Struggle to Dominate». Bloomberg.com. 19 September 2021.

- ^ Peilei Fan, «Catching Up through Developing Innovation Capacity: Evidence from China’s Telecom Equipment Industry,» Technovation 26 (2006): 359–368

- ^ «The Startup: Who is Huawei». BBC Future. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ a b c «Milestones». Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016.

- ^ a b Christine Chang; Amy Cheng; Susan Kim; Johanna Kuhn Osius; Jesus Reyes; Daniel Turgel (2009). «Huawei Technologies: A Chinese Trail Blazer In Africa». Business Today. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Gilley, Bruce (28 December 2000). «Huawei’s Fixed Line to Beijing». Far Eastern Economic Review: 94–98.

- ^ a b Smith, Jim. «Did Outsourcing and Corporate Espionage Kill Nortel?». assemblymag.com. Assembly Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ a b Murphy, Dawn C. (2022). China’s rise in the Global South : the Middle East, Africa, and Beijing’s alternative world order. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-5036-3060-4. OCLC 1249712936.

- ^ Hochmuth, Phil (29 November 2006). «3Com buys out Huawei joint venture for $882 million». Network World. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ «3Com exits enterprise network stage». ITworld. 26 March 2001. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Mcmorrow, Ryan (30 May 2019). «Huawei a key beneficiary of China subsidies that US wants ended». Phys.org. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ «Huawei Becomes an Approved Supplier for Vodafone’s Global Supply Chain». Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. 20 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Perlroth, Nicole; Markoff, John (26 March 2012). «Symantec Dissolves Alliance with Huawei of China». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Marcus Browne (20 May 2008). «Optus opens up mobile research shop with Huawei». ZDNet Australia. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ «Bell teams up with rival Telus on 3G». The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ «Telus to build out 5G network without China’s Huawei». The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Klesty, Victoria; Solsvik, Terje (13 December 2019). «Norway’s Telenor picks Ericsson for 5G, abandoning Huawei». Reuters. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ «397. Huawei Technologies». Fortune. 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ «Huawei Financial Results». Huawei. 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ «Reading move for Chinese communication giant / Reading Chronicle / News / Roundup». Readingchronicle.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Quann, Jack. «Huawei announces 100 jobs as it opens new Dublin office». Newstalk. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Bridgwater, Adrian. «Huawei CEO Ambitions: We Will Be One Of Five Major ‘World Clouds’«. Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ «Huawei Creates the ‘Nervous System’ of Smart Cities and Launches IoT City Demo Based on NB-IoT with Weifang». AsiaOne. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ «YB Dr Ong Kian Ming Deputy Minister of International Trade and Industry visits Huawei Malaysia Global Training Centre». Huawei. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ «Huawei Hits 200 Million Smartphone Sales in 2018». AnandTech. 25 December 2018. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ «China’s Huawei eyes smartphone supremacy this year after record 2018 sales». Reuters. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ «Financial Highlights – About Huawei». huawei. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Cherrayil, Naushad K.; phones, Mike Moore 2019-04-23T09:50:43Z Mobile (23 April 2019). «Huawei revenue soars despite US allegations and restrictions». TechRadar. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ «Huawei Thumbs its Nose at the US Government With Record High Revenues | Tom’s Hardware». tomshardware.com. 31 December 2019.

- ^ European Commission. Joint Research Centre (2021). The 2021 EU industrial R&D investment scoreboard. Luxembourg. doi:10.2760/472514. ISBN 978-92-76-44399-5. ISSN 2599-5731.

- ^ «Huawei Ranks No. 5 in U.S. Patents in Sign of Chinese Growth». 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.