A ninja (忍者, Japanese pronunciation: [ɲiꜜɲdʑa]) or shinobi (忍び, [ɕinobi]) was a covert agent, mercenary, or guerrilla warfare expert in feudal Japan. The functions of a ninja included, reconnaissance, espionage, infiltration, deception, ambush, bodyguarding and their fighting skills in martial arts, including ninjutsu.[1] Their covert methods of waging irregular warfare were deemed dishonorable and beneath the honor of the samurai.[2] Though shinobi proper, as specially trained warriors, spies, and mercenaries, appeared in the 15th century during the Sengoku period,[3] antecedents may have existed as early as the 12th century.[4][5]

In the unrest of the Sengoku period, jizamurai families, that is, elite peasant-warriors, in Iga Province and the adjacent Kōka District formed ikki — «revolts» or «leagues» — as a means of self-defense. They became known for their military activities in the nearby regions and sold their services as mercenaries and spies. It is from these areas that much of the knowledge regarding the ninja is drawn. Following the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th century, the ninja faded into obscurity.[6] A number of shinobi manuals, often based on Chinese military philosophy, were written in the 17th and 18th centuries, most notably the Bansenshūkai (1676).[7]

By the time of the Meiji Restoration (1868), shinobi had become a topic of popular imagination and mystery in Japan. Ninja figured prominently in legend and folklore, where they were associated with legendary abilities such as invisibility, walking on water and control over natural elements. Much of their perception in popular culture is based on such legends and folklore, as opposed to the covert actors of the Sengoku period.

Etymology

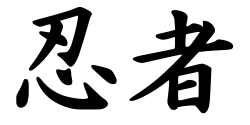

The word «ninja» in kanji script

Ninja is the on’yomi (Early Middle Chinese–influenced) reading of the two kanji «忍者». In the native kun’yomi reading, it is pronounced shinobi, a shortened form of shinobi-no-mono (忍びの者).[8]

The word shinobi appears in the written record as far back as the late 8th century in poems in the Man’yōshū.[9][10] The underlying connotation of shinobi (忍) means «to steal away; to hide» and—by extension—»to forbear», hence its association with stealth and invisibility. Mono (者) means «a person».

Historically, the word ninja was not in common use, and a variety of regional colloquialisms evolved to describe what would later be dubbed ninja. Along with shinobi, these include monomi («one who sees»), nokizaru («macaque on the roof»), rappa («ruffian»), kusa («grass») and Iga-mono («one from Iga»).[6] In historical documents, shinobi is almost always used.

Kunoichi (くノ一)is, originally, an argot which means «woman»;[11]: p168 it supposedly comes from the characters くノ一 (respectively hiragana ku, katakana no and kanji ichi), which make up the three strokes that form the kanji for «woman» (女).[11]: p168 In fiction written in the modern era kunoichi means «female ninja».[11]: p167

In the Western world, the word ninja became more prevalent than shinobi in the post–World War II culture, possibly because it was more comfortable for Western speakers.[12] In English, the plural of ninja can be either unchanged as ninja, reflecting the Japanese language’s lack of grammatical number, or the regular English plural ninjas.[13]

History

Despite many popular folktales, historical accounts of the ninja are scarce. Historian Stephen Turnbull asserts that the ninja were mostly recruited from the lower class, and therefore little literary interest was taken in them.[14] The social origin of the ninja is seen as the reason they agree to operate in secret, trading their service for money without honor and glory.[15] The scarcity of historical accounts is also demonstrated in war epics such as The Tale of Hōgen (Hōgen Monogatari) and The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari), which focus mainly on the aristocratic samurai, whose deeds were apparently more appealing to the audience.[12]

Historian Kiyoshi Watatani states that the ninja were trained to be particularly secretive about their actions and existence:

So-called ninjutsu techniques, in short are the skills of shinobi-no-jutsu and shinobijutsu, which have the aims of ensuring that one’s opponent does not know of one’s existence, and for which there was special training.[16]

However, some ninjutsu books described specifically what tactics ninja should use to fight, and the scenarios a ninja might find themselves can be deduced from those tactics. For example, in the manuscript of volume 2 of Kanrin Seiyō (間林清陽) which is the original book of Bansenshūkai (万川集海), there are 48 points of ninja’s fighting techniques, such as how to make makibishi from bamboo, how to make footwear that makes no sound, fighting techniques when surrounded by many enemies, precautions when using swords at night, how to listen to small sounds, kuji-kiri that prevents guard dogs from barking, and so on.[17][18]

Predecessors

Yamato Takeru dressed as a maidservant, preparing to kill the Kumaso leaders. Woodblock print on paper. Yoshitoshi, 1886.

The title ninja has sometimes been attributed retrospectively to the semi-legendary 4th-century prince Yamato Takeru.[19] In the Kojiki, the young Yamato Takeru disguised himself as a charming maiden and assassinated two chiefs of the Kumaso people.[20] However, these records take place at a very early stage of Japanese history, and they are unlikely to be connected to the shinobi of later accounts. The first recorded use of espionage was under the employment of Prince Shōtoku in the 6th century.[21] Such tactics were considered unsavory even in early times, when, according to the 10th-century Shōmonki, the boy spy Hasetsukabe no Koharumaru was killed for spying against the insurgent Taira no Masakado.[22] Later, the 14th-century war chronicle Taiheiki contained many references to shinobi[19] and credited the destruction of a castle by fire to an unnamed but «highly skilled shinobi«.[23]

Early history

It was not until the 15th century that spies were specially trained for their purpose.[14] It was around this time that the word shinobi appeared to define and clearly identify ninja as a secretive group of agents. Evidence for this can be seen in historical documents, which began to refer to stealthy soldiers as shinobi during the Sengoku period.[24] Later manuals regarding espionage are often grounded in Chinese military strategy, quoting works such as The Art of War by Sun Tzu.[25]

The ninja emerged as mercenaries in the 15th century, where they were recruited as spies, raiders, arsonists and even terrorists. Amongst the samurai, a sense of ritual and decorum was observed, where one was expected to fight or duel openly. Combined with the unrest of the Sengoku period, these factors created a demand for men willing to commit deeds considered disreputable for conventional warriors.[21][2] By the Sengoku period, the shinobi had several roles, including spy (kanchō), scout (teisatsu), surprise attacker (kishu), and agitator (konran).[24] The ninja families were organized into larger guilds, each with their own territories.[26] A system of rank existed. A jōnin («upper person») was the highest rank, representing the group and hiring out mercenaries. This is followed by the chūnin («middle person»), assistants to the jōnin. At the bottom was the genin («lower person»), field agents drawn from the lower class and assigned to carry out actual missions.[27]

Iga and Kōga clans

The plains of Iga, nested in secluded mountains, gave rise to villages specialized in the training of ninja.

The Iga and Kōga clans have come to describe jizamurai families living in the province of Iga (modern Mie Prefecture) and the adjacent region of Kōka (later written as Kōga), named after a village in what is now Shiga Prefecture. From these regions, villages devoted to the training of ninja first appeared.[28] The remoteness and inaccessibility of the surrounding mountains in Iga may have had a role in the ninja’s secretive development.[27] Historical documents regarding the ninja’s origins in these mountainous regions are considered generally correct.[29] The chronicle Go Kagami Furoku writes, of the two clans’ origins:

There was a retainer of the family of Kawai Aki-no-kami of Iga, of pre-eminent skill in shinobi, and consequently for generations the name of people from Iga became established. Another tradition grew in Kōga.[29]

Likewise, a supplement to the Nochi Kagami, a record of the Ashikaga shogunate, confirms the same Iga origin:

Inside the camp at Magari of the shōgun [Ashikaga] Yoshihisa there were shinobi whose names were famous throughout the land. When Yoshihisa attacked Rokkaku Takayori, the family of Kawai Aki-no-kami of Iga, who served him at Magari, earned considerable merit as shinobi in front of the great army of the shōgun. Since then successive generations of Iga men have been admired. This is the origin of the fame of the men of Iga.[30]

A distinction is to be made between the ninja from these areas, and commoners or samurai hired as spies or mercenaries. Unlike their counterparts, the Iga and Kōga clans were professionals, specifically trained for their roles.[24] These professional ninja were actively hired by daimyōs between 1485 and 1581,[24] until Oda Nobunaga invaded Iga Province and wiped out the organized clans.[31] Survivors were forced to flee, some to the mountains of Kii, but others arrived before Tokugawa Ieyasu, where they were well treated.[32] Some former Iga clan members, including Hattori Hanzō, would later serve as Tokugawa’s bodyguards.[33]

Following the Battle of Okehazama in 1560, Tokugawa employed a group of eighty Kōga ninja, led by Tomo Sukesada. They were tasked to raid an outpost of the Imagawa clan. The account of this assault is given in the Mikawa Go Fudoki, where it was written that Kōga ninja infiltrated the castle, set fire to its towers, and killed the castellan along with two hundred of the garrison.[34] The Kōga ninja are said to have played a role in the later Battle of Sekigahara (1600), where several hundred Kōga assisted soldiers under Torii Mototada in the defence of Fushimi Castle.[35] After Tokugawa’s victory at Sekigahara, the Iga acted as guards for the inner compounds of Edo Castle, while the Kōga acted as a police force and assisted in guarding the outer gate.[33] In 1614, the initial «winter campaign» at the Siege of Osaka saw the ninja in use once again. Miura Yoemon, a ninja in Tokugawa’s service, recruited shinobi from the Iga region, and sent 10 ninja into Osaka Castle in an effort to foster antagonism between enemy commanders.[36] During the later «summer campaign», these hired ninja fought alongside regular troops at the Battle of Tennōji.[36]

Shimabara rebellion

Ninja historic illustration, Meiwa era, circa 1770

A final but detailed record of ninja employed in open warfare occurred during the Shimabara Rebellion (1637–1638).[37] The Kōga ninja were recruited by shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu against Christian rebels led by Amakusa Shirō, who made a final stand at Hara Castle, in Hizen Province. A diary kept by a member of the Matsudaira clan, the Amakusa Gunki, relates: «Men from Kōga in Ōmi Province who concealed their appearance would steal up to the castle every night and go inside as they pleased.»[38]

The Ukai diary, written by a descendant of Ukai Kanemon, has several entries describing the reconnaissance actions taken by the Kōga.

They [the Kōga] were ordered to reconnoitre the plan of construction of Hara Castle, and surveyed the distance from the defensive moat to the ni-no-maru (second bailey), the depth of the moat, the conditions of roads, the height of the wall, and the shape of the loopholes.[38]

— Entry: 6th day of the 1st month

Suspecting that the castle’s supplies might be running low, the siege commander Matsudaira Nobutsuna ordered a raid on the castle’s provisions. Here, the Kōga captured bags of enemy provisions, and infiltrated the castle by night, obtaining secret passwords.[39] Days later, Nobutsuna ordered an intelligence gathering mission to determine the castle’s supplies. Several Kōga ninja—some apparently descended from those involved in the 1562 assault on an Imagawa clan castle—volunteered despite being warned that chances of survival were slim.[40] A volley of shots was fired into the sky, causing the defenders to extinguish the castle lights in preparation. Under the cloak of darkness, ninja disguised as defenders infiltrated the castle, capturing a banner of the Christian cross.[40] The Ukai diary writes,

We dispersed spies who were prepared to die inside Hara castle. … those who went on the reconnaissance in force captured an enemy flag; both Arakawa Shichirobei and Mochizuki Yo’emon met extreme resistance and suffered from their serious wounds for 40 days.[40]

— Entry: 27th day of the 1st month

As the siege went on, the extreme shortage of food later reduced the defenders to eating moss and grass.[41] This desperation would mount to futile charges by the rebels, where they were eventually defeated by the shogunate army. The Kōga would later take part in conquering the castle:

More and more general raids were begun, the Kōga ninja band under the direct control of Matsudaira Nobutsuna captured the ni-no-maru and the san-no-maru (outer bailey) …[42]

— Entry: 24th day of the 2nd month

With the fall of Hara Castle, the Shimabara Rebellion came to an end, and Christianity in Japan was forced underground.[43] These written accounts are the last mention of ninja in war.[44]

Edo period

After the Shimabara Rebellion, there were almost no major wars or battles until the bakumatsu era. To earn a living, ninja had to be employed by the governments of their Han (domain), or change their profession. Many lords still hired ninja, not for battle but as bodyguards or spies. Their duties included spying on other domains, guarding the daimyō, and fire patrol.[45] A few domains like Tsu, Hirosaki and Saga continued to employ their own ninja into the bakumatsu era, although their precise numbers are unknown.[46][47]

Many former ninja were employed as security guards by the Tokugawa shogunate, though the role of espionage was transferred to newly created organizations like the Onmitsu and the Oniwaban.[48] Others used their ninjutsu knowledge to become doctors, medicine sellers, merchants, martial artists, and fireworks manufacturers.[49] Some unemployed ninja were reduced to banditry, such as Fūma Kotarō and Ishikawa Goemon.[50]

| Ninja employed in each domain, Edo period[51] | |

| Han (domain) | Number of ninja |

|---|---|

| Kishū Domain | 200+ |

| Kishiwada Domain | 50 |

| Kawagoe Domain | 50 |

| Matsue Domain | 30 |

| Hirosaki Domain | 20 |

| Fukui Domain | 12 |

| Hikone Domain | 10 |

| Okayama Domain | 10 |

| Akō Domain | 5 |

Contemporary

A copy of the legendary 40-page book called «Kanrinseiyo» made in 1748

Between 1960 and 2010 artifacts dating to the Siege of Odawara (1590) were uncovered which experts say are ninja weapons.[52] Ninja were spies and saboteurs and likely participated in the siege.[52] The Hojo clan failed to save the castle from Toyotomi Hideyoshi forces.[52] The uncovered flat throwing stones are likely predecessors of the shuriken.[52] The clay caltrops preceded makibishi caltrops.[52] Archeologist Iwata Akihiro of Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore said the flat throwing stones «were used to stop the movement of the enemy who was going to attack [a soldier] at any moment, and while the enemy freezed the soldier escaped,».[52] The clay caltrops could «stop the movement of the enemy who invaded the castle,» These weapons were hastily constructed yet effective and used by a «battle group which can move into action as ninjas».[52]

Mie University founded the world’s first research centre devoted to the ninja in 2017. A graduate master course opened in 2018. It is located in Iga (now Mie Prefecture). There are approximately 3 student enrollments per year. Students must pass an admission test about Japanese history and be able to read historical ninja documents.[53] Scientific researchers and scholars of different disciplines study ancient documents and how it can be used in the modern world.[54]

In 2020, the 45-year-old Genichi Mitsuhashi was the first student to graduate from the master course of ninja studies at Mie University. For 2 years he studied historical records and the traditions of the martial art. Similar to the original ninja, by day he was a farmer and grew vegetables while he did ninja studies and trained martial arts in the afternoon.[53]

On June 19, 2022, Kōka city in Shiga Prefecture announced that a written copy of «Kanrinseiyo», which is the original source of a famous book on the art of ninja called «Bansenshukai» (1676) from the Edo period was discovered in a warehouse of Kazuraki Shrine.[55] The handwritten reproduction was produced in 1748.[56] The book describes 48 types of ninjutsu.[55] It has information about specific methods such as attaching layers of cotton to the bottom of straw sandals to prevent noise when sneaking around, attacking to the right when surrounded by a large number of enemies, throwing charred owl and turtle powder when trying to hide, and casting spells.[55] It also clarified methods and how to manufacture and use ninjutsu tools, such as cane swords and «makibishi» (Japanese caltrop).[55]

Oniwaban

In the early 18th century, shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune founded the oniwaban («garden keepers»), an intelligence agency and secret service. Members of the oniwaban were agents involved in collecting information on daimyō and government officials.[57] The secretive nature of the oniwaban—along with the earlier tradition of using Iga and Kōga clan members as palace guards—have led some sources to define the oniwabanshū as «ninja».[58] This portrayal is also common in later novels and jidaigeki. However, there is no written link between the earlier shinobi and the later oniwaban.

Roles

The ninja were stealth soldiers and mercenaries hired mostly by daimyōs.[59] Their primary roles were those of espionage and sabotage, although assassinations were also attributed to ninja. Although they were considered the anti-samurai and were disdained by those belonging to the samurai class, they were necessary for warfare and were even employed by the samurai themselves to carry out operations that were forbidden by bushidō.[15]

A page from the Shōninki (1681), detailing a list of possible disguises

In his Buke Myōmokushō, military historian Hanawa Hokinoichi writes of the ninja:

They travelled in disguise to other territories to judge the situation of the enemy, they would inveigle their way into the midst of the enemy to discover gaps, and enter enemy castles to set them on fire, and carried out assassinations, arriving in secret.[60]

Espionage

Espionage was the chief role of the ninja. With the aid of disguises, the ninja gathered information on enemy terrain and building specifications, as well as obtaining passwords and communiques. The aforementioned supplement to the Nochi Kagami briefly describes the ninja’s role in espionage:

Concerning ninja, they were said to be from Iga and Kōga, and went freely into enemy castles in secret. They observed hidden things, and were taken as being friends.[30]

Later in history, the Kōga ninja would become regarded as agents of the Tokugawa bakufu, at a time when the bakufu used the ninja in an intelligence network to monitor regional daimyōs as well as the Imperial court.[26]

Sabotage

Arson was the primary form of sabotage practiced by the ninja, who targeted castles and camps.

The Tamon-in Nikki (16th century)—a diary written by abbot Eishun of Kōfuku-ji temple—describes an arson attack on a castle by men of the Iga clans.

This morning, the sixth day of the 11th month of Tenbun 10 [1541], the Iga-shu entered Kasagi castle in secret and set fire to a few of the priests’ quarters. They also set fire to outbuildings in various places inside the San-no-maru. They captured the ichi-no-maru (inner bailey) and the ni-no-maru (second bailey).[61]

In 1558, Rokkaku Yoshikata employed a team of ninja to set fire to Sawayama Castle. A chūnin captain led a force of 48 ninja into the castle by means of deception. In a technique dubbed bakemono-jutsu («ghost technique»), his men stole a lantern bearing the enemy’s family crest (mon), and proceeded to make replicas with the same mon. By wielding these lanterns, they were allowed to enter the castle without a fight. Once inside, the ninja set fire to the castle, and Yoshitaka’s army would later emerge victorious.[62] The mercenary nature of the shinobi is demonstrated in another arson attack soon after the burning of Sawayama Castle. In 1561, commanders acting under Kizawa Nagamasa hired three Iga ninja of genin rank to assist the conquest of a fortress in Maibara. Rokkaku Yoshitaka, the same man who had hired Iga ninja just years earlier, was the fortress holder—and target of attack. The Asai Sandaiki writes of their plans: «We employed shinobi-no-mono of Iga… They were contracted to set fire to the castle».[63] However, the mercenary shinobi were unwilling to take commands. When the fire attack did not begin as scheduled, the Iga men told the commanders, who were not from the region, that they could not possibly understand the tactics of the shinobi. They then threatened to abandon the operation if they were not allowed to act on their own strategy. The fire was eventually set, allowing Nagamasa’s army to capture the fortress in a chaotic rush.[63]

Assassination

The best-known cases of assassination attempts involve famous historical figures. Deaths of famous persons have sometimes been attributed to assassination by ninja, but the secretive natures of these scenarios have made them difficult to prove.[14] Assassins were often identified as ninja later on, but there is no evidence to prove whether some were specially trained for the task or simply a hired thug.

The warlord Oda Nobunaga’s notorious reputation led to several attempts on his life. In 1571, a Kōga ninja and sharpshooter by the name of Sugitani Zenjubō was hired to assassinate Nobunaga. Using two arquebuses, he fired two consecutive shots at Nobunaga, but was unable to inflict mortal injury through Nobunaga’s armor.[64] Sugitani managed to escape, but was caught four years later and put to death by torture.[64] In 1573, Manabe Rokurō, a vassal of daimyō Hatano Hideharu, attempted to infiltrate Azuchi Castle and assassinate the sleeping Nobunaga. However, this also ended in failure, and Manabe was forced to commit suicide, after which his body was openly displayed in public.[64] According to a document, the Iranki, when Nobunaga was inspecting Iga province—which his army had devastated—a group of three ninja shot at him with large-caliber firearms. The shots flew wide of Nobunaga, however, and instead killed seven of his surrounding companions.[65]

The ninja Hachisuka Tenzō was sent by Nobunaga to assassinate the powerful daimyō Takeda Shingen, but ultimately failed in his attempts. Hiding in the shadow of a tree, he avoided being seen under the moonlight, and later concealed himself in a hole he had prepared beforehand, thus escaping capture.[66]

An assassination attempt on Toyotomi Hideyoshi was also thwarted. A ninja named Kirigakure Saizō (possibly Kirigakure Shikaemon) thrust a spear through the floorboards to kill Hideyoshi, but was unsuccessful. He was «smoked out» of his hiding place by another ninja working for Hideyoshi, who apparently used a sort of primitive «flamethrower».[67] Unfortunately, the veracity of this account has been clouded by later fictional publications depicting Saizō as one of the legendary Sanada Ten Braves.

Uesugi Kenshin, the famous daimyō of Echigo Province, was rumored to have been killed by a ninja. The legend credits his death to an assassin who is said to have hidden in Kenshin’s lavatory, and fatally injured Kenshin by thrusting a blade or spear into his anus.[68] While historical records showed that Kenshin suffered abdominal problems, modern historians have generally attributed his death to stomach cancer, esophageal cancer, or cerebrovascular disease.[69]

Psychological warfare

In battle, the ninja were also used to cause confusion amongst the enemy.[70] A degree of psychological warfare in the capturing of enemy banners can be seen illustrated in the Ōu Eikei Gunki, composed between the 16th and 17th centuries:

Within Hataya castle there was a glorious shinobi whose skill was renowned, and one night he entered the enemy camp secretly. He took the flag from Naoe Kanetsugu’s guard … and returned and stood it on a high place on the front gate of the castle.[71]

Countermeasures

A variety of countermeasures were taken to prevent the activities of the ninja. Precautions were often taken against assassinations, such as weapons concealed in the lavatory, or under a removable floorboard.[72] Buildings were constructed with traps and trip wires attached to alarm bells.[73]

Japanese castles were designed to be difficult to navigate, with winding routes leading to the inner compound. Blind spots and holes in walls provided constant surveillance of these labyrinthine paths, as exemplified in Himeji Castle. Nijō Castle in Kyoto is constructed with long «nightingale» floors, which rested on metal hinges (uguisu-bari) specifically designed to squeak loudly when walked over.[74] Grounds covered with gravel also provided early notice of unwanted intruders, and segregated buildings allowed fires to be better contained.[75]

Training

The skills required of the ninja have come to be known in modern times as ninjutsu (忍術), but it is unlikely they were previously named under a single discipline, rather distributed among a variety of espionage and survival skills. Some view ninjutsu as evidence that ninja were not simple mercenaries because texts contained not only information on combat training, but also information about daily needs, which even included mining techniques.[76] The guidance provided for daily work also included elements that enable the ninja to understand the martial qualities of even the most menial task.[76] These factors show how the ninjutsu established among the ninja class the fundamental principle of adaptation.[76]

The first specialized training began in the mid-15th century, when certain samurai families started to focus on covert warfare, including espionage and assassination.[77] Like the samurai, ninja were born into the profession, where traditions were kept in, and passed down through the family.[26][78] According to Turnbull, the ninja was trained from childhood, as was also common in samurai families.

Outside the expected martial art disciplines, a youth studied survival and scouting techniques, as well as information regarding poisons and explosives.[79] Physical training was also important, which involved long-distance runs, climbing, stealth methods of walking[80] and swimming.[81] A certain degree of knowledge regarding common professions was also required if one was expected to take their form in disguise.[79] Some evidence of medical training can be derived from one account, where an Iga ninja provided first-aid to Ii Naomasa, who was injured by gunfire in the Battle of Sekigahara. Here the ninja reportedly gave Naomasa a «black medicine» meant to stop bleeding.[82]

With the fall of the Iga and Kōga clans, daimyōs could no longer recruit professional ninja, and were forced to train their own shinobi. The shinobi was considered a real profession, as demonstrated in the 1649 bakufu law on military service, which declared that only daimyōs with an income of over 10,000 koku were allowed to retain shinobi.[83] In the two centuries that followed, a number of ninjutsu manuals were written by descendants of Hattori Hanzō as well as members of the Fujibayashi clan, an offshoot of the Hattori. Major examples include the Ninpiden (1655), the Bansenshūkai (1675), and the Shōninki (1681).[7]

Modern schools that claim to train ninjutsu arose from the 1970s, including that of Masaaki Hatsumi (Bujinkan), Stephen K. Hayes (To-Shin Do), and Jinichi Kawakami (Banke Shinobinoden). The lineage and authenticity of these schools are a matter of controversy.

Tactics

The ninja did not always work alone. Teamwork techniques exist: For example, in order to scale a wall, a group of ninja may carry each other on their backs, or provide a human platform to assist an individual in reaching greater heights.[84] The Mikawa Go Fudoki gives an account where a coordinated team of attackers used passwords to communicate. The account also gives a case of deception, where the attackers dressed in the same clothes as the defenders, causing much confusion.[34] When a retreat was needed during the Siege of Osaka, ninja were commanded to fire upon friendly troops from behind, causing the troops to charge backwards to attack a perceived enemy. This tactic was used again later on as a method of crowd dispersal.[36]

Most ninjutsu techniques recorded in scrolls and manuals revolve around ways to avoid detection, and methods of escape.[7] These techniques were loosely grouped under corresponding natural elements. Some examples are:

- Hitsuke: The practice of distracting guards by starting a fire away from the ninja’s planned point of entry. Falls under «fire techniques» (katon-no-jutsu).[85]

- Tanuki-gakure: The practice of climbing a tree and camouflaging oneself within the foliage. Falls under «wood techniques» (mokuton-no-jutsu).[85]

- Ukigusa-gakure: The practice of throwing duckweed over water to conceal underwater movement. Falls under «water techniques» (suiton-no-jutsu).[85]

- Uzura-gakure: The practice of curling into a ball and remaining motionless to appear like a stone. Falls under «earth techniques» (doton-no-jutsu).[85]

Disguises

The use of disguises is common and well documented. Disguises came in the form of priests, entertainers, fortune tellers, merchants, rōnin, and monks.[86] The Buke Myōmokushō states,

Shinobi-monomi were people used in secret ways, and their duties were to go into the mountains and disguise themselves as firewood gatherers to discover and acquire the news about an enemy’s territory… they were particularly expert at travelling in disguise.[30]

A komusō monk is one of many possible disguises

A mountain ascetic (yamabushi) attire facilitated travel, as they were common and could travel freely between political boundaries. The loose robes of Buddhist priests also allowed concealed weapons, such as the tantō.[87] Minstrel or sarugaku outfits could have allowed the ninja to spy in enemy buildings without rousing suspicion. Disguises as a komusō, a mendicant monk known for playing the shakuhachi, were also effective, as the large «basket» hats traditionally worn by them concealed the head completely.[88]

Equipment

Ninja used a large variety of tools and weaponry, some of which were commonly known, but others were more specialized. Most were tools used in the infiltration of castles. A wide range of specialized equipment is described and illustrated in the 17th-century Bansenshūkai,[89] including climbing equipment, extending spears,[82] rocket-propelled arrows,[90] and small collapsible boats.[91]

Outerwear

Kuro shozoku ninja costume and waraji (sandals). The image of the ninja costume being black is strong. However, in reality, ninjas wore navy blue-dyed farmers’ working clothes, which were also believed to repel vipers.

Antique Japanese gappa (travel cape) and cloth zukin (hood) with kusari (chain armour) concealed underneath

While the image of a ninja clad in black garb (shinobi shōzoku) is prevalent in popular media, there is no written evidence for such attire.[92] Instead, it was much more common for the ninja to be disguised as civilians. The popular notion of black clothing is likely rooted in artistic convention; early drawings of ninja showed them dressed in black to portray a sense of invisibility.[60] This convention was an idea borrowed from the puppet handlers of bunraku theater, who dressed in total black in an effort to simulate props moving independently of their controls.[93] Despite the lack of hard evidence, it has been put forward by some authorities that black robes, perhaps slightly tainted with red to hide bloodstains, was indeed the sensible garment of choice for infiltration.[60]

Clothing used was similar to that of the samurai, but loose garments (such as leggings) were tucked into trousers or secured with belts. The tenugui, a piece of cloth also used in martial arts, had many functions. It could be used to cover the face, form a belt, or assist in climbing.

The historicity of armor specifically made for ninja cannot be ascertained. While pieces of light armor purportedly worn by ninja exist and date to the right time, there is no hard evidence of their use in ninja operations. Depictions of famous persons later deemed ninja often show them in samurai armor. There were lightweight concealable types of armour made with kusari (chain armour) and small armor plates such as karuta that could have been worn by ninja including katabira (jackets) made with armour hidden between layers of cloth. Shin and arm guards, along with metal-reinforced hoods are also speculated to make up the ninja’s armor.[60]

Tools

A page from the Ninpiden, showing a tool for breaking locks

Tools used for infiltration and espionage are some of the most abundant artifacts related to the ninja. Ropes and grappling hooks were common, and were tied to the belt.[89] A collapsible ladder is illustrated in the Bansenshukai, featuring spikes at both ends to anchor the ladder.[94] Spiked or hooked climbing gear worn on the hands and feet also doubled as weapons.[95] Other implements include chisels, hammers, drills, picks, and so forth.

The kunai was a heavy pointed tool, possibly derived from the Japanese masonry trowel, which it closely resembles. Although it is often portrayed in popular culture as a weapon, the kunai was primarily used for gouging holes in walls.[96] Knives and small saws (hamagari) were also used to create holes in buildings, where they served as a foothold or a passage of entry.[97] A portable listening device (saoto hikigane) was used to eavesdrop on conversations and detect sounds.[98]

The mizugumo was a set of wooden shoes supposedly allowing the ninja to walk on water.[91] They were meant to work by distributing the wearer’s weight over the shoes’ wide bottom surface. The word mizugumo is derived from the native name for the Japanese water spider (Argyroneta aquatica japonica). The mizugumo was featured on the show MythBusters, where it was demonstrated unfit for walking on water. The ukidari, a similar footwear for walking on water, also existed in the form of a flat round bucket, but was probably quite unstable.[99] Inflatable skins and breathing tubes allowed the ninja to stay underwater for longer periods of time.[100]

Goshiki-mai (go, five; shiki, color; mai, rice) colored (red, blue, yellow, black, purple)[101] rice grains used, in a code system,[102][103] and to make trails that could be followed later.[104][105][106]

Despite the large array of tools available to the ninja, the Bansenshukai warns one not to be overburdened with equipment, stating «a successful ninja is one who uses but one tool for multiple tasks».[107]

Weaponry

Although shorter swords and daggers were used, the katana was probably the ninja’s weapon of choice, and was sometimes carried on the back.[88] The katana had several uses beyond normal combat. In dark places, the scabbard could be extended out of the sword, and used as a long probing device.[108] The sword could also be laid against the wall, where the ninja could use the sword guard (tsuba) to gain a higher foothold.[109] The katana could even be used as a device to stun enemies before attacking them, by putting a combination of red pepper, dirt or dust, and iron filings into the area near the top of the scabbard, so that as the sword was drawn the concoction would fly into the enemy’s eyes, stunning him until a lethal blow could be made. While straight swords were used before the invention of the katana,[110] there’s no known historical information about the straight ninjatō pre-20th century. The first photograph of a ninjatō appeared in a booklet by Heishichirō Okuse in 1956.[111][112] A replica of a ninjatō is on display at the Ninja Museum of Igaryu.

An array of darts, spikes, knives, and sharp, star-shaped discs were known collectively as shuriken. While not exclusive to the ninja,[113] they were an important part of the arsenal, where they could be thrown in any direction.[114] Bows were used for sharpshooting, and some ninjas’ bows were intentionally made smaller than the traditional yumi (longbow).[115] The chain and sickle (kusarigama) was also used by the ninja.[116] This weapon consisted of a weight on one end of a chain, and a sickle (kama) on the other. The weight was swung to injure or disable an opponent, and the sickle used to kill at close range.

Explosives introduced from China were known in Japan by the time of the Mongol Invasions in the 13th century.[117] Later, explosives such as hand-held bombs and grenades were adopted by the ninja.[100] Soft-cased bombs were designed to release smoke or poison gas, along with fragmentation explosives packed with iron or ceramic shrapnel.[84]

Along with common weapons, a large assortment of miscellaneous arms were associated with the ninja. Some examples include poison,[89] makibishi (caltrops),[118] shikomizue (cane swords),[119] land mines,[120] fukiya (blowguns), poisoned darts, acid-spurting tubes, and firearms.[100] The happō, a small eggshell filled with metsubushi (blinding powder), was also used to facilitate escape.[121]

Legendary abilities

Superhuman or supernatural powers were often associated with the ninja with a style of Japanese martial arts in ninjutsu. Some legends include flight, invisibility, shapeshifting, teleportation, the ability to «split» into multiple bodies (bunshin), the summoning of animals (kuchiyose), and control over the five classical elements. These fabulous notions have stemmed from popular imagination regarding the ninja’s mysterious status, as well as romantic ideas found in later Japanese art of the Edo period. Magical powers were rooted in the ninja’s own misinformation efforts to disseminate fanciful information. For example, Nakagawa Shoshunjin, the 17th-century founder of Nakagawa-ryū, claimed in his own writings (Okufuji Monogatari) that he had the ability to transform into birds and animals.[83]

Perceived control over the elements may be grounded in real tactics, which were categorized by association with forces of nature. For example, the practice of starting fires to cover a ninja’s trail falls under katon-no-jutsu («fire techniques»).[118] By dressing in identical clothing, a coordinated team of ninjas could instill the perception of a single assailant being in multiple locations.

Actor portraying Nikki Danjō, a villain from the kabuki play Sendai Hagi. Shown with hands in a kuji-in seal, which allows him to transform into a giant rat. Woodblock print on paper. Kunisada, 1857.

The ninja’s adaption of kites in espionage and warfare is another subject of legends. Accounts exist of ninja being lifted into the air by kites, where they flew over hostile terrain and descended into, or dropped bombs on enemy territory.[91] Kites were indeed used in Japanese warfare, but mostly for the purpose of sending messages and relaying signals.[122] Turnbull suggests that kites lifting a man into midair might have been technically feasible, but states that the use of kites to form a human «hang glider» falls squarely in the realm of fantasy.[123]

Kuji-kiri

Kuji-kiri is an esoteric practice which, when performed with an array of hand «seals» (kuji-in), was meant to allow the ninja to enact superhuman feats.

The kuji («nine characters») is a concept originating from Taoism, where it was a string of nine words used in charms and incantations.[124] In China, this tradition mixed with Buddhist beliefs, assigning each of the nine words to a Buddhist deity. The kuji may have arrived in Japan via Buddhism,[125] where it flourished within Shugendō.[126] Here too, each word in the kuji was associated with Buddhist deities, animals from Taoist mythology, and later, Shinto kami.[127] The mudrā, a series of hand symbols representing different Buddhas, was applied to the kuji by Buddhists, possibly through the esoteric Mikkyō teachings.[128] The yamabushi ascetics of Shugendō adopted this practice, using the hand gestures in spiritual, healing, and exorcism rituals.[129] Later, the use of kuji passed onto certain bujutsu (martial arts) and ninjutsu schools, where it was said to have many purposes.[130] The application of kuji to produce a desired effect was called «cutting» (kiri) the kuji. Intended effects range from physical and mental concentration, to more incredible claims about rendering an opponent immobile, or even the casting of magical spells.[131] These legends were captured in popular culture, which interpreted the kuji-kiri as a precursor to magical acts.

Foreign ninja

On February 25, 2018, Yamada Yūji, the professor of Mie University and historian Nakanishi Gō announced that they had identified three people who were successful in early modern Ureshino, including the ninja Benkei Musō (弁慶夢想).[47][132] Musō is thought to be the same person as Denrinbō Raikei (伝林坊頼慶), the Chinese disciple of Marume Nagayoshi.[132] It came as a shock when the existence of a foreign samurai was verified by authorities.

Famous people

Many famous people in Japanese history have been associated or identified as ninja, but their status as ninja are difficult to prove and may be the product of later imagination. Rumors surrounding famous warriors, such as Kusunoki Masashige or Minamoto no Yoshitsune sometimes describe them as ninja, but there is little evidence for these claims.

Some well known examples include:

- Kumawakamaru (13th–14th centuries): A youth whose exiled father was ordered to death by the monk Homma Saburō. Kumakawa took his revenge by sneaking into Homma’s room while he was asleep, and assassinating him with his own sword.[134] He was son of a high counselor to Emperor Go-Daigo, not ninja. The yamabushi Daizenboh who helped Kumawakamaru’s revenge was Suppa, a kind of ninja.[135][136]

- Kumawaka (the 16th century): A suppa (ninja) who served Obu Toramasa (1504– 1565), a vassal of Takeda Shingen.[137]

- Yagyū Munetoshi (1529–1606): A renowned swordsman of the Shinkage-ryū school. Muneyoshi’s grandson, Jubei Muneyoshi, told tales of his grandfather’s status as a ninja.[59]

- Hattori Hanzō (1542–1596): A samurai serving under Tokugawa Ieyasu. His ancestry in Iga province, along with ninjutsu manuals published by his descendants have led some sources to define him as a ninja.[138] This depiction is also common in popular culture.

- Ishikawa Goemon (1558–1594): Goemon reputedly tried to drip poison from a thread into Oda Nobunaga’s mouth through a hiding spot in the ceiling,[139] but many fanciful tales exist about Goemon, and this story cannot be confirmed.

- Fūma Kotarō (d. 1603): A ninja rumored to have killed Hattori Hanzō, with whom he was supposedly rivals. The fictional weapon Fūma shuriken is named after him.

- Mochizuki Chiyome (16th century): The wife of Mochizuke Moritoki. Chiyome created a school for girls, which taught skills required of geisha, as well as espionage skills.[140]

- Momochi Sandayū (16th century): A leader of the Iga ninja clans, who supposedly perished during Oda Nobunaga’s attack on Iga province. There is some belief that he escaped death and lived as a farmer in Kii Province.[141] Momochi is also a branch of the Hattori clan.

- Fujibayashi Nagato (16th century): Considered to be one of three «greatest» Iga jōnin, the other two being Hattori Hanzō and Momochi Sandayū. Fujibayashi’s descendants wrote and edited the Bansenshukai.

- Katō Danzō (1503–1569): A famed 16th-century ninja master during the Sengoku period who was also known as «Flying Katō».

- Tateoka Doshun (16th century): An intermediate-ranking Iga ninja during the Sengoku period.

- Karasawa Genba (16th century): A samurai of the Sengoku period, in the 16th century of the common era, who served as an important retainer of the Sanada clan.

In popular culture

Jiraiya battles a giant python with the help of his summoned toad. Woodblock print on paper. Kuniyoshi, c. 1843.

The image of the ninja entered popular culture in the Edo period, when folktales and plays about ninja were conceived. Stories about the ninja are usually based on historical figures. For instance, many similar tales exist about a daimyō challenging a ninja to prove his worth, usually by stealing his pillow or weapon while he slept.[142] Novels were written about the ninja, such as Jiraiya Gōketsu Monogatari, which was also made into a kabuki play. Fictional figures such as Sarutobi Sasuke would eventually make their way into comics and television, where they have come to enjoy a culture hero status outside their original mediums.

Ninja appear in many forms of Japanese and Western popular media, including books (Kōga Ninpōchō), movies (Enter the Ninja, Revenge of the Ninja, Ninja Assassin), television (Akakage, The Master, Ninja Warrior), video games (Shinobi, Ninja Gaiden, Tenchu, Sekiro, Ghost of Tsushima), anime (Naruto, Ninja Scroll, Gatchaman), manga (Basilisk, Ninja Hattori-kun, Azumi), Western animation (Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu) and American comic books (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles). From ancient Japan to the modern world media, popular depictions range from the realistic to the fantastically exaggerated, both fundamentally and aesthetically.

Gallery

-

Tekko-kagi, hand claws

-

Ashiko, iron climbing cleats

-

Ashiko, iron climbing cleats

-

-

-

Various concealable weapons

-

See also

- Kunoichi

- Order of Assassins

- Order of Musashi Shinobi Samurai

- Sicarii

- Ninja Museum of Igaryu

References

Citations

- ^ Kawakami, pp. 21–22

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, pp. 5–6

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (19 February 2003). Ninja Ad 1460–1650. Osprey Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84176-525-9. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ Crowdy 2006, p. 50

- ^ Frederic 2002, p. 715

- ^ a b Green 2001, p. 355

- ^ a b c Green 2001, p. 358; based on different readings, Ninpiden is also known as Shinobi Hiden, and Bansenshukai can also be Mansenshukai.

- ^ Origin of word Ninja Archived 2011-05-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Takagi, Gomi & Ōno 1962, p. 191; the full poem is «Yorozu yo ni / Kokoro ha tokete / Waga seko ga / Tsumishi te mitsutsu / Shinobi kanetsumo«.

- ^ Satake et al. 2003, p. 108; the Man’yōgana used for «shinobi« is 志乃備, its meaning and characters are unrelated to the later mercenary shinobi.

- ^ a b c 吉丸雄哉(associate professor of Mie University) (April 2017). «くのいちとは何か». In 吉丸雄哉、山田雄司 編 (ed.). 忍者の誕生. 勉誠出版. ISBN 978-4-585-22151-7.

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 6

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.; American Heritage Dictionary, 4th ed.; Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1).

- ^ a b c Turnbull 2003, p. 5

- ^ a b Axelrod, Alan (2015). Mercenaries: A Guide to Private Armies and Private Military Companies. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-4833-6467-4.

- ^ Turnbull 2007, p. 144.

- ^ 甲賀で忍術書の原典発見 番犬に吠えられない呪術も「間林清陽」48カ条 (in Japanese). Sankei Shimbun. 19 June 2022. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022.

- ^ 忍者の里 甲賀市で忍術書の基となった書の写本初めて見つかる (in Japanese). NHK. 19 June 2022. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b Waterhouse 1996, pp. 34

- ^ Chamberlain 2005, pp. 249–253; Volume 2, section 80

- ^ a b Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 325

- ^ Friday 2007, pp. 58–60

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 7

- ^ a b c d Turnbull 2003, p. 9

- ^ Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 324

- ^ a b c Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 327

- ^ a b Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 121

- ^ Deal 2007, p. 165

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 23

- ^ a b c Turnbull 2003, p. 27

- ^ Green 2001, p. 357

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 9–10

- ^ a b Adams 1970, p. 43

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, pp. 44–46

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 47

- ^ a b c Turnbull 2003, p. 50

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 55

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 51

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 52

- ^ a b c Turnbull 2003, p. 53

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 54

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 54–55

- ^ Morton & Olenik 2004, p. 122

- ^ Crowdy 2006, p. 52

- ^ Yamada 2019, pp. 176–177

- ^ Yamada 2019, pp. 188–189

- ^ a b «嬉野に忍者3人いた! 江戸初期-幕末 市が委託調査氏名も特定». Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ Yamada 2019, pp. 174–175

- ^ Yamada 2019, pp. 178–179

- ^ Yamada 2019, p. 180

- ^ Yamada 2019, p. 176

- ^ a b c d e f g Owen Jarus (14 February 2022). «430-year-old ninja weapons possibly identified». Live Science. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b «Japan university awards first-ever ninja studies degree». AFP, Yahoo! News. 26 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ «Japan university to set up ninja research facilities». Telangana Today. 11 May 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d «Copy of legendary book on art of ninja found at shrine in west Japan city». Mainichi Daily News. 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022.

- ^ Casey Baseel (27 June 2022). «First copy of centuries-old ninja training manual discovered, doesn’t understand dogs». Soranews 24. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022.

- ^ Tatsuya 1991, p. 443

- ^ Kawaguchi 2008, p. 215

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 29

- ^ a b c d Turnbull 2003, p. 17; Turnbull uses the name Buke Meimokushō, an alternate reading for the same title. The Buke Myōmokushō cited here is a much more common reading.

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 28

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 43

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, pp. 43–44

- ^ a b c Turnbull 2003, p. 31

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 31–32

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 30

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 32

- ^ Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu 2006, p. 36

- ^ Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu 2004, pp. 51–53; Turnbull 2003, p. 32

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 42

- ^ Turnbull 2007, p. 149

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 26

- ^ Draeger & Smith 1981, pp. 128–129

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 29–30

- ^ Fiévé & Waley 2003, p. 116

- ^ a b c Zoughari, Kacem (2010). Ninja: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan (The Secret History of Ninjutsu). North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing. pp. 47. ISBN 978-0-8048-3927-3.

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 12

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Ninja AD 1460–1650. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-78200-256-7.

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, pp. 14–15

- ^ Green 2001, pp. 359–360

- ^ Deal 2007, p. 156

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 48

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 13

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 22

- ^ a b c d Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 125

- ^ Crowdy 2006, p. 51

- ^ Deal 2007, p. 161

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 18

- ^ a b c Turnbull 2003, p. 19

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 60

- ^ a b c Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 128

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 16

- ^ Howell 1999, p. 211

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 20

- ^ Mol 2003, p. 121

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 61

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 20–21

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 21

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 62

- ^ a b c Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 329

- ^ Runnebaum, Achim (22 February 2016). «7 Things you didn’t know about Ninja». Japan Daily. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

Based on the combination of colors they dropped, or the number of grains, the Ninja could make over 100 different codes.

- ^ «10 Stealthy Ninja Tools You Haven’t Heard Of». All About Japan. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ «Communication of ninja». Ninja Encyclopedia. Japan: Ninja Lurking in History. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Yoda, Hiroko; Alt, Matt (18 December 2013). Ninja Attack!: True Tales of Assassins, Samurai, and Outlaws. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0882-0.

Goshiki-mai: These dyed rice grains were used to create discreet trails that could be followed either by the original dropper or by sharp-eyed comrades

- ^ Bull, Brett; Kuroi, Hiromitsu (2008). More Secrets of the Ninja: Their Training, Tools and Techniques. Tokyo: DH Publishing Inc. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-932897-51-7.

DH Publishing is Tokyo’s #1 publisher of Japanese pop culture books for the English speaking world.

- ^ «Bujinkan Budo Taijutsu Weapons». Online Martial Arts. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Green 2001, p. 359

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 52

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 49

- ^ Reed 1880, pp. 269–270

- ^ Okuse, Heishichirō (1956). Ninjutsu. Osaka, Kinki Nippon Tetsudō.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2018). Ninja: Unmasking the Myth. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1473850422.

- ^ Mol 2003, p. 119

- ^ Ratti & Westbrook 1991, pp. 328–329

- ^ Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 328

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 55

- ^ Bunch & Hellemans 2004, p. 161

- ^ a b Mol 2003, p. 176

- ^ Mol 2003, p. 195

- ^ Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 127

- ^ Mol 2003, p. 124

- ^ Buckley 2002, p. 257

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 22–23

- ^ Waterhouse 1996, pp. 2–3

- ^ Waterhouse 1996, pp. 8–11

- ^ Waterhouse 1996, p. 13

- ^ Waterhouse 1996, pp. 24–27

- ^ Waterhouse 1996, pp. 24–25

- ^ Teeuwen & Rambelli 2002, p. 327

- ^ Waterhouse 1996, pp. 31–33

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 29; Waterhouse 1996, p. 31

- ^ a b

«嬉野忍者調査結果 弁慶夢想 (べんけいむそう) 【武術家・山伏 / 江戸時代初期】». Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2018. - ^ McCullough 2004, p. 49

- ^ McCullough 2004, p. 48

- ^ 大膳神社 Sado Tourist Bureau

- ^ 透波 Kotobank

- ^ 熊若 忍者名鑑

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 34

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 160

- ^ Green 2001, p. 671

- ^ Adams 1970, p. 42

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 14

Sources

- Adams, Andrew (1970), Ninja: The Invisible Assassins, Black Belt Communications, ISBN 978-0-89750-030-2

- Buckley, Sandra (2002), Encyclopedia of contemporary Japanese culture, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-14344-8

- Bunch, Bryan H.; Hellemans, Alexander (2004), The history of science and technology: a browser’s guide to the great discoveries, inventions, and the people who made them, from the dawn of time to today, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-618-22123-3

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall (2005), The Kojiki: records of ancient matters, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3675-3

- Crowdy, Terry (2006), The enemy within: a history of espionage, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-933-2

- Deal, William E. (2007), Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533126-4

- Draeger, Donn F.; Smith, Robert W. (1981), Comprehensive Asian fighting arts, Kodansha, ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6

- Fiévé, Nicolas; Waley, Paul (2003), Japanese capitals in historical perspective: place, power and memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1409-4

- Friday, Karl F. (2007), The first samurai: the life and legend of the warrior rebel, Taira Masakado, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-76082-5

- Howell, Anthony (1999), The analysis of performance art: a guide to its theory and practice, Routledge, ISBN 978-90-5755-085-0

- Green, Thomas A. (2001), Martial arts of the world: an encyclopedia, Volume 2: Ninjutsu, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2

- Kawaguchi, Sunao (2008), Super Ninja Retsuden, PHP Research Institute, ISBN 978-4-569-67073-7

- Kawakami, Jin’ichi (2016), Ninja no okite, Kadokawa, ISBN 978-4-04-082106-1

- McCullough, Helen Craig (2004), The Taiheiki: A Chronicle of Medieval Japan, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3538-1

- Mol, Serge (2003), Classical weaponry of Japan: special weapons and tactics of the martial arts, Kodansha, ISBN 978-4-7700-2941-6

- Morton, William Scott; Olenik, J. Kenneth (2004), Japan: its history and culture, fourth edition, McGraw-Hill Professional, ISBN 978-0-07-141280-3

- Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu (2006), Unsolved Mysteries of Japanese History, PHP Research Institute, ISBN 978-4-569-65652-6

- Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu (2004), Zuketsu Rekishi no Igai na Ketsumatsu, PHP Research Institute, ISBN 978-4-569-64061-7

- Perkins, Dorothy (1991), Encyclopedia of Japan: Japanese History and Culture, from Abacus to Zori, Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-8160-1934-2

- Ratti, Oscar; Westbrook, Adele (1991), Secrets of the samurai: a survey of the martial arts of feudal Japan, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7

- Reed, Edward James (1880), Japan: its history, traditions, and religions: With the narrative of a visit in 1879, Volume 2, John Murray, OCLC 1309476

- Satake, Akihiro; Yasumada, Hideo; Kudō, Rikio; Ōtani, Masao; Yamazaki, Yoshiyuki (2003), Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei: Man’yōshū Volume 4, Iwanami Shoten, ISBN 4-00-240004-2

- Takagi, Ichinosuke; Gomi, Tomohide; Ōno, Susumu (1962), Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei: Man’yōshū Volume 4, Iwanami Shoten, ISBN 4-00-060007-9

- Tatsuya, Tsuji (1991), The Cambridge history of Japan Volume 4: Early Modern Japan: Chapter 9, translated by Harold Bolitho, edited by John Whitney Hall, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22355-3

- Teeuwen, Mark; Rambelli, Fabio (2002), Buddhas and kami in Japan: honji suijaku as a combinatory paradigm, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 978-0-415-29747-9

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Ninja AD 1460–1650, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-525-9

- Turnbull, Stephen (2007), Warriors of Medieval Japan, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84603-220-2

- Waterhouse, David (1996), Religion in Japan: arrows to heaven and earth, article 1: Notes on the kuji, edited by Peter F. Kornicki and James McMullen, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55028-4

- Yamada, Yūji (2019), Sengoku Shinobi no Sahō, edited by Yōko Ymda, Chiyoda,Tokyo: G.B., ISBN 978-4-906993-76-5

- Frederic, Louis (2002), Japan Encyclopedia, Belknap Harvard, ISBN 0-674-01753-6

Further reading

- Fujibayashi, Masatake; Nakajima, Atsumi. (1996). Shōninki: Ninjutsu densho. Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha. OCLC 222455224.

- Fujita, Seiko. (2004). Saigo no Ninja Dorondoron. Tokyo: Shinpūsha. ISBN 978-4-7974-9488-4.

- Fukai, Masaumi. (1992). Edojō oniwaban : Tokugawa Shōgun no mimi to me. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha. ISBN 978-4-12-101073-5.

- Hokinoichi, Hanawa. (1923–1933). Buke Myōmokushō. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. OCLC 42921561.

- Ishikawa, Masatomo. (1982). Shinobi no sato no kiroku. Tokyo: Suiyōsha. ISBN 978-4-88066-110-0.

- Mol, Serge (2016). Takeda Shinobi Hiden: Unveiling Takeda Shingen’s Secret Ninja Legacy. Eibusha. pp. 1–192. ISBN 978-90-813361-3-0.

- Mol, Serge (2008). Invisible armor: An Introduction to the Esoteric Dimension of Japan’s Classical Warrior Arts. Eibusha. pp. 1–160. ISBN 978-90-813361-0-9.

- Nawa, Yumio. (1972). Hisshō no heihō ninjutsu no kenkyū: gendai o ikinuku michi. Tokyo: Nichibō Shuppansha. OCLC 122985441.

- Nawa. Yumio. (1967). Shinobi no buki. Tokyo: Jinbutsu Ōraisha. OCLC 22358689.

- Okuse, Heishichirō. (1967). Ninjutsu: sono rekishi to ninja. Tokyo: Jinbutsu Ōraisha. OCLC 22727254.

- Okuse, Heishichirō. (1964). Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei. Tokyo: Jinbutsu Ōraisha. OCLC 51008989.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2017). Ninja: Unmasking the Myth. Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, UK: Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-5042-2.

- Watatani, Kiyoshi. (1972). Bugei ryūha hyakusen. Tokyo: Akita Shoten. OCLC 66598671.

- Yamaguchi, Masayuki. (1968). Ninja no seikatsu. Tokyo: Yūzankaku. OCLC 20045825.

External links

Media related to Ninja at Wikimedia Commons

A ninja (忍者, Japanese pronunciation: [ɲiꜜɲdʑa]) or shinobi (忍び, [ɕinobi]) was a covert agent, mercenary, or guerrilla warfare expert in feudal Japan. The functions of a ninja included, reconnaissance, espionage, infiltration, deception, ambush, bodyguarding and their fighting skills in martial arts, including ninjutsu.[1] Their covert methods of waging irregular warfare were deemed dishonorable and beneath the honor of the samurai.[2] Though shinobi proper, as specially trained warriors, spies, and mercenaries, appeared in the 15th century during the Sengoku period,[3] antecedents may have existed as early as the 12th century.[4][5]

In the unrest of the Sengoku period, jizamurai families, that is, elite peasant-warriors, in Iga Province and the adjacent Kōka District formed ikki — «revolts» or «leagues» — as a means of self-defense. They became known for their military activities in the nearby regions and sold their services as mercenaries and spies. It is from these areas that much of the knowledge regarding the ninja is drawn. Following the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th century, the ninja faded into obscurity.[6] A number of shinobi manuals, often based on Chinese military philosophy, were written in the 17th and 18th centuries, most notably the Bansenshūkai (1676).[7]

By the time of the Meiji Restoration (1868), shinobi had become a topic of popular imagination and mystery in Japan. Ninja figured prominently in legend and folklore, where they were associated with legendary abilities such as invisibility, walking on water and control over natural elements. Much of their perception in popular culture is based on such legends and folklore, as opposed to the covert actors of the Sengoku period.

Etymology

The word «ninja» in kanji script

Ninja is the on’yomi (Early Middle Chinese–influenced) reading of the two kanji «忍者». In the native kun’yomi reading, it is pronounced shinobi, a shortened form of shinobi-no-mono (忍びの者).[8]

The word shinobi appears in the written record as far back as the late 8th century in poems in the Man’yōshū.[9][10] The underlying connotation of shinobi (忍) means «to steal away; to hide» and—by extension—»to forbear», hence its association with stealth and invisibility. Mono (者) means «a person».

Historically, the word ninja was not in common use, and a variety of regional colloquialisms evolved to describe what would later be dubbed ninja. Along with shinobi, these include monomi («one who sees»), nokizaru («macaque on the roof»), rappa («ruffian»), kusa («grass») and Iga-mono («one from Iga»).[6] In historical documents, shinobi is almost always used.

Kunoichi (くノ一)is, originally, an argot which means «woman»;[11]: p168 it supposedly comes from the characters くノ一 (respectively hiragana ku, katakana no and kanji ichi), which make up the three strokes that form the kanji for «woman» (女).[11]: p168 In fiction written in the modern era kunoichi means «female ninja».[11]: p167

In the Western world, the word ninja became more prevalent than shinobi in the post–World War II culture, possibly because it was more comfortable for Western speakers.[12] In English, the plural of ninja can be either unchanged as ninja, reflecting the Japanese language’s lack of grammatical number, or the regular English plural ninjas.[13]

History

Despite many popular folktales, historical accounts of the ninja are scarce. Historian Stephen Turnbull asserts that the ninja were mostly recruited from the lower class, and therefore little literary interest was taken in them.[14] The social origin of the ninja is seen as the reason they agree to operate in secret, trading their service for money without honor and glory.[15] The scarcity of historical accounts is also demonstrated in war epics such as The Tale of Hōgen (Hōgen Monogatari) and The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari), which focus mainly on the aristocratic samurai, whose deeds were apparently more appealing to the audience.[12]

Historian Kiyoshi Watatani states that the ninja were trained to be particularly secretive about their actions and existence:

So-called ninjutsu techniques, in short are the skills of shinobi-no-jutsu and shinobijutsu, which have the aims of ensuring that one’s opponent does not know of one’s existence, and for which there was special training.[16]

However, some ninjutsu books described specifically what tactics ninja should use to fight, and the scenarios a ninja might find themselves can be deduced from those tactics. For example, in the manuscript of volume 2 of Kanrin Seiyō (間林清陽) which is the original book of Bansenshūkai (万川集海), there are 48 points of ninja’s fighting techniques, such as how to make makibishi from bamboo, how to make footwear that makes no sound, fighting techniques when surrounded by many enemies, precautions when using swords at night, how to listen to small sounds, kuji-kiri that prevents guard dogs from barking, and so on.[17][18]

Predecessors

Yamato Takeru dressed as a maidservant, preparing to kill the Kumaso leaders. Woodblock print on paper. Yoshitoshi, 1886.

The title ninja has sometimes been attributed retrospectively to the semi-legendary 4th-century prince Yamato Takeru.[19] In the Kojiki, the young Yamato Takeru disguised himself as a charming maiden and assassinated two chiefs of the Kumaso people.[20] However, these records take place at a very early stage of Japanese history, and they are unlikely to be connected to the shinobi of later accounts. The first recorded use of espionage was under the employment of Prince Shōtoku in the 6th century.[21] Such tactics were considered unsavory even in early times, when, according to the 10th-century Shōmonki, the boy spy Hasetsukabe no Koharumaru was killed for spying against the insurgent Taira no Masakado.[22] Later, the 14th-century war chronicle Taiheiki contained many references to shinobi[19] and credited the destruction of a castle by fire to an unnamed but «highly skilled shinobi«.[23]

Early history

It was not until the 15th century that spies were specially trained for their purpose.[14] It was around this time that the word shinobi appeared to define and clearly identify ninja as a secretive group of agents. Evidence for this can be seen in historical documents, which began to refer to stealthy soldiers as shinobi during the Sengoku period.[24] Later manuals regarding espionage are often grounded in Chinese military strategy, quoting works such as The Art of War by Sun Tzu.[25]

The ninja emerged as mercenaries in the 15th century, where they were recruited as spies, raiders, arsonists and even terrorists. Amongst the samurai, a sense of ritual and decorum was observed, where one was expected to fight or duel openly. Combined with the unrest of the Sengoku period, these factors created a demand for men willing to commit deeds considered disreputable for conventional warriors.[21][2] By the Sengoku period, the shinobi had several roles, including spy (kanchō), scout (teisatsu), surprise attacker (kishu), and agitator (konran).[24] The ninja families were organized into larger guilds, each with their own territories.[26] A system of rank existed. A jōnin («upper person») was the highest rank, representing the group and hiring out mercenaries. This is followed by the chūnin («middle person»), assistants to the jōnin. At the bottom was the genin («lower person»), field agents drawn from the lower class and assigned to carry out actual missions.[27]

Iga and Kōga clans

The plains of Iga, nested in secluded mountains, gave rise to villages specialized in the training of ninja.

The Iga and Kōga clans have come to describe jizamurai families living in the province of Iga (modern Mie Prefecture) and the adjacent region of Kōka (later written as Kōga), named after a village in what is now Shiga Prefecture. From these regions, villages devoted to the training of ninja first appeared.[28] The remoteness and inaccessibility of the surrounding mountains in Iga may have had a role in the ninja’s secretive development.[27] Historical documents regarding the ninja’s origins in these mountainous regions are considered generally correct.[29] The chronicle Go Kagami Furoku writes, of the two clans’ origins:

There was a retainer of the family of Kawai Aki-no-kami of Iga, of pre-eminent skill in shinobi, and consequently for generations the name of people from Iga became established. Another tradition grew in Kōga.[29]

Likewise, a supplement to the Nochi Kagami, a record of the Ashikaga shogunate, confirms the same Iga origin:

Inside the camp at Magari of the shōgun [Ashikaga] Yoshihisa there were shinobi whose names were famous throughout the land. When Yoshihisa attacked Rokkaku Takayori, the family of Kawai Aki-no-kami of Iga, who served him at Magari, earned considerable merit as shinobi in front of the great army of the shōgun. Since then successive generations of Iga men have been admired. This is the origin of the fame of the men of Iga.[30]

A distinction is to be made between the ninja from these areas, and commoners or samurai hired as spies or mercenaries. Unlike their counterparts, the Iga and Kōga clans were professionals, specifically trained for their roles.[24] These professional ninja were actively hired by daimyōs between 1485 and 1581,[24] until Oda Nobunaga invaded Iga Province and wiped out the organized clans.[31] Survivors were forced to flee, some to the mountains of Kii, but others arrived before Tokugawa Ieyasu, where they were well treated.[32] Some former Iga clan members, including Hattori Hanzō, would later serve as Tokugawa’s bodyguards.[33]

Following the Battle of Okehazama in 1560, Tokugawa employed a group of eighty Kōga ninja, led by Tomo Sukesada. They were tasked to raid an outpost of the Imagawa clan. The account of this assault is given in the Mikawa Go Fudoki, where it was written that Kōga ninja infiltrated the castle, set fire to its towers, and killed the castellan along with two hundred of the garrison.[34] The Kōga ninja are said to have played a role in the later Battle of Sekigahara (1600), where several hundred Kōga assisted soldiers under Torii Mototada in the defence of Fushimi Castle.[35] After Tokugawa’s victory at Sekigahara, the Iga acted as guards for the inner compounds of Edo Castle, while the Kōga acted as a police force and assisted in guarding the outer gate.[33] In 1614, the initial «winter campaign» at the Siege of Osaka saw the ninja in use once again. Miura Yoemon, a ninja in Tokugawa’s service, recruited shinobi from the Iga region, and sent 10 ninja into Osaka Castle in an effort to foster antagonism between enemy commanders.[36] During the later «summer campaign», these hired ninja fought alongside regular troops at the Battle of Tennōji.[36]

Shimabara rebellion

Ninja historic illustration, Meiwa era, circa 1770

A final but detailed record of ninja employed in open warfare occurred during the Shimabara Rebellion (1637–1638).[37] The Kōga ninja were recruited by shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu against Christian rebels led by Amakusa Shirō, who made a final stand at Hara Castle, in Hizen Province. A diary kept by a member of the Matsudaira clan, the Amakusa Gunki, relates: «Men from Kōga in Ōmi Province who concealed their appearance would steal up to the castle every night and go inside as they pleased.»[38]

The Ukai diary, written by a descendant of Ukai Kanemon, has several entries describing the reconnaissance actions taken by the Kōga.

They [the Kōga] were ordered to reconnoitre the plan of construction of Hara Castle, and surveyed the distance from the defensive moat to the ni-no-maru (second bailey), the depth of the moat, the conditions of roads, the height of the wall, and the shape of the loopholes.[38]

— Entry: 6th day of the 1st month

Suspecting that the castle’s supplies might be running low, the siege commander Matsudaira Nobutsuna ordered a raid on the castle’s provisions. Here, the Kōga captured bags of enemy provisions, and infiltrated the castle by night, obtaining secret passwords.[39] Days later, Nobutsuna ordered an intelligence gathering mission to determine the castle’s supplies. Several Kōga ninja—some apparently descended from those involved in the 1562 assault on an Imagawa clan castle—volunteered despite being warned that chances of survival were slim.[40] A volley of shots was fired into the sky, causing the defenders to extinguish the castle lights in preparation. Under the cloak of darkness, ninja disguised as defenders infiltrated the castle, capturing a banner of the Christian cross.[40] The Ukai diary writes,

We dispersed spies who were prepared to die inside Hara castle. … those who went on the reconnaissance in force captured an enemy flag; both Arakawa Shichirobei and Mochizuki Yo’emon met extreme resistance and suffered from their serious wounds for 40 days.[40]

— Entry: 27th day of the 1st month

As the siege went on, the extreme shortage of food later reduced the defenders to eating moss and grass.[41] This desperation would mount to futile charges by the rebels, where they were eventually defeated by the shogunate army. The Kōga would later take part in conquering the castle:

More and more general raids were begun, the Kōga ninja band under the direct control of Matsudaira Nobutsuna captured the ni-no-maru and the san-no-maru (outer bailey) …[42]

— Entry: 24th day of the 2nd month

With the fall of Hara Castle, the Shimabara Rebellion came to an end, and Christianity in Japan was forced underground.[43] These written accounts are the last mention of ninja in war.[44]

Edo period

After the Shimabara Rebellion, there were almost no major wars or battles until the bakumatsu era. To earn a living, ninja had to be employed by the governments of their Han (domain), or change their profession. Many lords still hired ninja, not for battle but as bodyguards or spies. Their duties included spying on other domains, guarding the daimyō, and fire patrol.[45] A few domains like Tsu, Hirosaki and Saga continued to employ their own ninja into the bakumatsu era, although their precise numbers are unknown.[46][47]

Many former ninja were employed as security guards by the Tokugawa shogunate, though the role of espionage was transferred to newly created organizations like the Onmitsu and the Oniwaban.[48] Others used their ninjutsu knowledge to become doctors, medicine sellers, merchants, martial artists, and fireworks manufacturers.[49] Some unemployed ninja were reduced to banditry, such as Fūma Kotarō and Ishikawa Goemon.[50]

| Ninja employed in each domain, Edo period[51] | |

| Han (domain) | Number of ninja |

|---|---|

| Kishū Domain | 200+ |

| Kishiwada Domain | 50 |

| Kawagoe Domain | 50 |

| Matsue Domain | 30 |

| Hirosaki Domain | 20 |

| Fukui Domain | 12 |

| Hikone Domain | 10 |

| Okayama Domain | 10 |

| Akō Domain | 5 |

Contemporary

A copy of the legendary 40-page book called «Kanrinseiyo» made in 1748

Between 1960 and 2010 artifacts dating to the Siege of Odawara (1590) were uncovered which experts say are ninja weapons.[52] Ninja were spies and saboteurs and likely participated in the siege.[52] The Hojo clan failed to save the castle from Toyotomi Hideyoshi forces.[52] The uncovered flat throwing stones are likely predecessors of the shuriken.[52] The clay caltrops preceded makibishi caltrops.[52] Archeologist Iwata Akihiro of Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore said the flat throwing stones «were used to stop the movement of the enemy who was going to attack [a soldier] at any moment, and while the enemy freezed the soldier escaped,».[52] The clay caltrops could «stop the movement of the enemy who invaded the castle,» These weapons were hastily constructed yet effective and used by a «battle group which can move into action as ninjas».[52]

Mie University founded the world’s first research centre devoted to the ninja in 2017. A graduate master course opened in 2018. It is located in Iga (now Mie Prefecture). There are approximately 3 student enrollments per year. Students must pass an admission test about Japanese history and be able to read historical ninja documents.[53] Scientific researchers and scholars of different disciplines study ancient documents and how it can be used in the modern world.[54]

In 2020, the 45-year-old Genichi Mitsuhashi was the first student to graduate from the master course of ninja studies at Mie University. For 2 years he studied historical records and the traditions of the martial art. Similar to the original ninja, by day he was a farmer and grew vegetables while he did ninja studies and trained martial arts in the afternoon.[53]

On June 19, 2022, Kōka city in Shiga Prefecture announced that a written copy of «Kanrinseiyo», which is the original source of a famous book on the art of ninja called «Bansenshukai» (1676) from the Edo period was discovered in a warehouse of Kazuraki Shrine.[55] The handwritten reproduction was produced in 1748.[56] The book describes 48 types of ninjutsu.[55] It has information about specific methods such as attaching layers of cotton to the bottom of straw sandals to prevent noise when sneaking around, attacking to the right when surrounded by a large number of enemies, throwing charred owl and turtle powder when trying to hide, and casting spells.[55] It also clarified methods and how to manufacture and use ninjutsu tools, such as cane swords and «makibishi» (Japanese caltrop).[55]

Oniwaban

In the early 18th century, shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune founded the oniwaban («garden keepers»), an intelligence agency and secret service. Members of the oniwaban were agents involved in collecting information on daimyō and government officials.[57] The secretive nature of the oniwaban—along with the earlier tradition of using Iga and Kōga clan members as palace guards—have led some sources to define the oniwabanshū as «ninja».[58] This portrayal is also common in later novels and jidaigeki. However, there is no written link between the earlier shinobi and the later oniwaban.

Roles