(Нотр-Дам) (фр. Notre Dame de Paris) — географическое и духовное «сердце» Парижа, расположен в восточной части острова Сите, на месте первой христианской церкви Парижа — базилики Святого Стефана, построенной, в свою очередь, на месте галло-римского храма Юпитера.

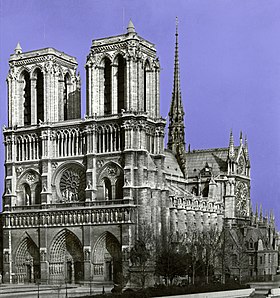

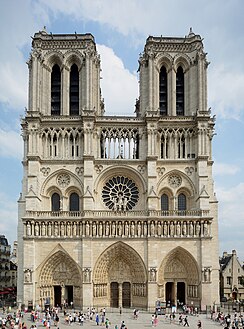

В соборе проявляется двойственность стилистических влияний: с одной стороны, присутствуют отголоски романского стиля Нормандии со свойственным ему мощным и плотным единством, а с другой, — использованы новаторские архитектурные достижения готического стиля, которые придают зданию легкость и создают впечатление простоты вертикальной конструкции.

Высота собора — 35 м, длина — 130 м, ширина — 48 м, высота колоколен — 69 м, вес колокола Эммануэль в восточной башне — 13 тонн, его языка — 500 кг.

История

Строительство началось в 1163, при Людовике VII Французском. Историки расходятся в мнениях о том, кто именно заложил первый камень в фундамент собора — епископ Морис де Сюлли или папа Александр III. Главный алтарь собора освятили в мае 1182 года, к 1196 году неф здания был почти закончен, работы продолжались только на главном фасаде.

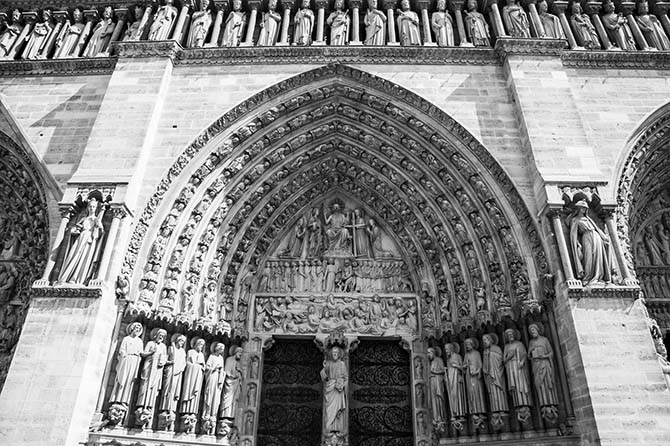

Мощный и величественный фасад разделён по вертикали на три части пилястрами, а по горизонтали — на три яруса галереями, при этом нижний ярус, в свою очередь, имеет три глубоких портала. Над ними идёт аркада (Галерея Королей) с двадцатью восемью статуями, представляющими царей древней Иудеи.

Строительство западного фронтона, с его отличительными двумя башнями, началось ок. 1200 года.

В ходе строительства собора в нём принимало участие много разных архитекторов, о чём свидетельствуют отличающиеся стилем и разные по высоте западная сторона и башни. Башни были закончены в 1245, а весь собор — в 1345 году.

Собор с его великолепным внутренним убранством в течение многих веков служил местом проведения королевских бракосочетаний, императорских коронаций и национальных похорон.

Как и в других готических храмах, здесь нет настенной живописи, и единственным источником цвета являются многочисленные витражи высоких стрельчатых окон.

Во времена Людовика XIV, в конце XVII века, собор пережил серьёзные перемены: могилы и витражи были разрушены.

В ходе Великой Французской революции, в конце XVIII века, статуи царей были низвергнуты восставшим народом, многие из сокровищ собора были разрушены или расхищены, сам же собор вообще был под угрозой сноса, и спасло его лишь превращение в «Храм Разума», а позднее он использовался как винный склад.

Собор был возвращён церкви и вновь освящён в 1802 году, при Наполеоне.

Реставрация началась в 1841 г. под руководством архитектора Виолле-ле-Дюка (1814—1879). Этот известный парижский реставратор также занимался реставрацией Амьенского собора, крепости Каркассон на юге Франции и готической церкви Сент-Шапель. Восстановление здания и скульптур, замена разбитых статуй и сооружение знаменитого шпиля длились 23 года. Виолле-ле-Дюку также принадлежит идея галереи химер на фасаде собора. Статуи химер установлены на верхней площадке у подножия башен.

В эти же годы были снесены постройки, примыкавшие к собору, в результате чего перед его фасадом образовалась нынешняя площадь.

В соборе хранится одна из великих христианских реликвий — Терновый венец Иисуса Христа. До 1063 года венец находился на горе Сион в Иерусалиме, откуда его перевезли во дворец византийских императоров в Константинополе. Балдуин II де Куртенэ, последний император Латинской империи, был вынужден заложить реликвию в Венеции, но из-за нехватки средств её на что было выкупить. В 1238 году король Франции Людовик IX приобрёл венец у византийского императора. 18 августа 1239 года король внёс его в Нотр-Дам де Пари. В 1243—1248 при королевском дворце на острове Сите была построена Сент-Шапель (Святая часовня) для хранения Тернового венца, который находился здесь до Французской революции. Позднее венец был передан в сокровищницу Нотр-Дам де Пари.

Католическая энциклопедия.

.

2011.

For the Victor Hugo novel, see The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

For other uses, see Notre Dame (disambiguation) and Notre Dame de Paris (disambiguation).

Template:Infobox church

Notre-Dame de Paris (French: [nɔtʁə dam də paʁi] (Audio file «Cathedrale de Nothre Dame.ogg » not found); meaning «Our Lady of Paris»), also known as Notre-Dame Cathedral or simply Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité in the fourth arrondissement of Paris, France.[1] The cathedral is widely considered to be one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture, and it is among the largest and most well-known church buildings in the world. The naturalism of its sculptures and stained glass are in contrast with earlier Romanesque architecture.

As the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the Archbishop of Paris, currently Cardinal André Vingt-Trois.[2] The cathedral treasury contains a reliquary, which houses some of Catholicism’s most important relics, including the purported Crown of Thorns, a fragment of the True Cross, and one of the Holy Nails.

In the 1790s, Notre-Dame suffered desecration in the radical phase of the French Revolution when much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. An extensive restoration supervised by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc began in 1845. A project of further restoration and maintenance began in 1991.

Architecture

File:Notre Dame de Paris by night.jpg The western facade illuminated at night The spire and east side of the cathedral The north rose window is a fine example of Gothic Rayonnant style.

Notre-Dame de Paris was among the first buildings in the world to use the flying buttress. The building was not originally designed to include the flying buttresses around the choir and nave but after the construction began, the thinner walls grew ever higher and stress fractures began to occur as the walls pushed outward. In response, the cathedral’s architects built supports around the outside walls, and later additions continued the pattern. The total surface area is 5,500 m² (interior surface 4,800 m²).

Many small individually crafted statues were placed around the outside to serve as column supports and water spouts. Among these are the famous gargoyles, designed for water run-off, and chimeras. The statues were originally colored as was most of the exterior. The paint has worn off. The cathedral was essentially complete by 1345. The cathedral has a narrow climb of 387 steps at the top of several spiral staircases; along the climb it is possible to view its most famous bell and its gargoyles in close quarters, as well as having a spectacular view across Paris when reaching the top.

Contemporary critical reception

John of Jandun recognized the cathedral as one of Paris’s three most important buildings [prominent structures] in his 1323 Treatise on the Praises of Paris:

| “ | That most glorious church of the most glorious Virgin Mary, mother of God, deservedly shines out, like the sun among stars. And although some speakers, by their own free judgment, because [they are] able to see only a few things easily, may say that some other is more beautiful, I believe however, respectfully, that, if they attend more diligently to the whole and the parts, they will quickly retract this opinion. Where indeed, I ask, would they find two towers of such magnificence and perfection, so high, so large, so strong, clothed round about with such a multiple variety of ornaments? Where, I ask, would they find such a multipartite arrangement of so many lateral vaults, above and below? Where, I ask, would they find such light-filled amenities as the many surrounding chapels? Furthermore, let them tell me in what church I may see such a large cross, of which one arm separates the choir from the nave. Finally, I would willingly learn where [there are] two such circles, situated opposite each other in a straight line, which on account of their appearance are given the name of the fourth vowel [O] ; among which smaller orbs and circlets, with wondrous artifice, so that some arranged circularly, others angularly, surround windows ruddy with precious colors and beautiful with the most subtle figures of the pictures. In fact I believe that this church offers the carefully discerning such cause for admiration that its inspection can scarcely sate the soul. | ” |

|

—Jean de Jandun, Tractatus de laudibus Parisius[3] |

Construction history

In 1160, because the church in Paris had become the «Parish church of the kings of Europe», Bishop Maurice de Sully deemed the previous Paris cathedral, Saint-Étienne (St Stephen’s), which had been founded in the 4th century, unworthy of its lofty role, and had it demolished shortly after he assumed the title of Bishop of Paris. As with most foundation myths, this account needs to be taken with a grain of salt; archeological excavations in the 20th century suggested that the Merovingian cathedral replaced by Sully was itself a massive structure, with a five-aisled nave and a façade some 36m across. It is possible therefore that the faults with the previous structure were exaggerated by the Bishop to help justify the rebuilding in a newer style. According to legend, Sully had a vision of a glorious new cathedral for Paris, and sketched it on the ground outside the original church.

To begin the construction, the bishop had several houses demolished and had a new road built to transport materials for the rest of the cathedral. Construction began in 1163 during the reign of Louis VII, and opinion differs as to whether Sully or Pope Alexander III laid the foundation stone of the cathedral. However, both were at the ceremony. Bishop de Sully went on to devote most of his life and wealth to the cathedral’s construction. Construction of the choir took from 1163 until around 1177 and the new High Altar was consecrated in 1182 (it was normal practice for the eastern end of a new church to be completed first, so that a temporary wall could be erected at the west of the choir, allowing the chapter to use it without interruption while the rest of the building slowly took shape). After Bishop Maurice de Sully’s death in 1196, his successor, Eudes de Sully (no relation) oversaw the completion of the transepts and pressed ahead with the nave, which was nearing completion at the time of his own death in 1208. By this stage, the western facade had also been laid out, though it was not completed until around the mid-1240s.[4]

Numerous architects worked on the site over the period of construction, which is evident from the differing styles at different heights of the west front and towers.[citation needed] Between 1210 and 1220, the fourth architect oversaw the construction of the level with the rose window and the great halls beneath the towers.

The most significant change in design came in the mid 13th century, when the transepts were remodeled in the latest Rayonnant style; in the late 1240s Jean de Chelles added a gabled portal to the north transept topped off by a spectacular rose window. Shortly afterwards (from 1258) Pierre de Montreuil executed a similar scheme on the southern transept. Both these transept portals were richly embellished with sculpture; the south portal features scenes from the lives of St Stephen and of various local saints, while the north portal featured the infancy of Christ and the story of Theophilus in the tympanum, with a highly influential statue of the Virgin and Child in the trumeau.[5]

Timeline of construction

- 1160 Maurice de Sully (named Bishop of Paris) orders the original cathedral demolished.

- 1163 Cornerstone laid for Notre-Dame de Paris; construction begins.

- 1182 Apse and choir completed.

- 1196 Bishop Maurice de Sully dies.

- c.1200 Work begins on western facade.

- 1208 Bishop Eudes de Sully dies. Nave vaults nearing completion.

- 1225 Western facade completed.

- 1250 Western towers and north rose window completed.

- c.1245–1260s Transepts remodelled in the Rayonnant style by Jean de Chelles then Pierre de Montreuil

- 1250–1345 Remaining elements completed.

Crypt

File:La crypte archéologique du Parvis de Notre-Dame (Paris) (8274683584).jpg The Archaeological Crypt of Notre-Dame de Paris.

The Archaeological Crypt of the Paris Notre-Dame (La crypte archéologique du Parvis de Notre-Dame) was created in 1965 to protect a range of historical ruins, discovered during construction work and spanning from the earliest settlement in Paris to the modern day. The crypts are managed by the Musée Carnavalet and contain a large exhibit, detailed models of the architecture of different time periods, and how they can be viewed within the ruins. The main feature still visible is the under-floor heating installed during the Roman occupation.[6]

Alterations, vandalism, and restorations

In 1548, rioting Huguenots damaged features of Notre-Dame, considering them idolatrous.[7] During the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV, the cathedral underwent major alterations as part of an ongoing attempt to modernize cathedrals throughout Europe. A colossal statue of St Christopher, standing against a pillar near the western entrance and dating from 1413, was destroyed in 1786. Tombs and stained glass windows were destroyed. The north and south rose windows were spared this fate, however.

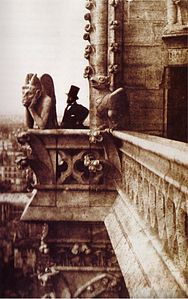

File:Henri Le Secq near a Gargoyle.jpg An 1853 photo by Charles Nègre of Henri Le Secq next to Le Stryge

In 1793, during the French Revolution, the cathedral was rededicated to the Cult of Reason, and then to the Cult of the Supreme Being. During this time, many of the treasures of the cathedral were either destroyed or plundered. The 13th century spire was torn down[8] and the statues located at the west facade were beheaded.[9] Many of the heads were found during a 1977 excavation nearby and are on display at the Musée de Cluny. For a time the Goddess of Liberty replaced the Virgin Mary on several altars.[10] The cathedral’s great bells managed to avoid being melted down. The cathedral came to be used as a warehouse for the storage of food.[7]

A controversial restoration programme was initiated in 1845, overseen by architects Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Viollet Le Duc was responsible for the restorations of several dozen castles, palaces and cathedrals across France. The restoration lasted twenty five years[7] and included a taller and more ornate reconstruction of the flèche (a type of spire),[8] as well as the addition of the chimeras on the Galerie des Chimères. Viollet le Duc always signed his work with a bat, the wing structure of which most resembles the Gothic vault (see Château de Roquetaillade).

The Second World War caused more damage. Several of the stained glass windows on the lower tier were hit by stray bullets. These were remade after the war, but now sport a modern geometrical pattern, not the old scenes of the Bible.

In 1991, a major programme of maintenance and restoration was initiated, which was intended to last ten years, but was still in progress as of 2010,[7] the cleaning and restoration of old sculptures being an exceedingly delicate matter. Circa 2014, much of the lighting was upgraded to LED lighting.[11]

Organ and organists

File:Organ of Notre-Dame de Paris.jpg The organ of Notre-Dame de Paris

Though numerous organs have been installed in the cathedral over time, the earliest models were inadequate for the building.[citation needed] The first more noted organ[citation needed] was finished in the 18th century by the noted builder François-Henri Clicquot. Some of Clicquot’s original pipework in the pedal division continues to sound from the organ today. The organ was almost completely rebuilt and expanded in the 19th century by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll.

The position of titular organist («head» or «chief» organist; French: titulaires des grands orgues) at Notre-Dame is considered one of the most prestigious organist posts in France, along with the post of titular organist of Saint Sulpice in Paris, Cavaillé-Coll’s largest instrument.

The organ has 7,952 pipes, with ca 900 classified as historical. It has 110 real stops, five 56-key manuals and a 32-key pedalboard. In December 1992, a two-year restoration of the organ was completed that fully computerized the organ under three LANs (Local Area Networks). The restoration also included a number of additions, notably two further horizontal reed stops en chamade in the Cavaille-Coll style. The Notre-Dame organ is therefore unique in France in having five fully independent reed stops en chamade.

Among the best-known organists at Notre-Dame de Paris was Louis Vierne, who held this position from 1900 to 1937. Under his tenure, the Cavaillé-Coll organ was modified in its tonal character, notably in 1902 and 1932. Léonce de Saint-Martin held the post between 1932 and 1954. Pierre Cochereau initiated further alterations (many of which were already planned by Louis Vierne), including the electrification of the action between 1959 and 1963. The original Cavaillé-Coll console, (which is now located near the organ loft), was replaced by a new console in Anglo-American style and the addition of further stops between 1965 and 1972, notably in the pedal division, the recomposition of the mixture stops, a 32′ plenum in the Neo-Baroque style on the Solo manual, and finally the adding of three horizontal reed stops «en chamade» in the Iberian style.

After Cochereau’s sudden death in 1984, four new titular organists were appointed at Notre-Dame in 1985: Jean-Pierre Leguay, Olivier Latry, Yves Devernay (who died in 1990), and Philippe Lefebvre. This was reminiscent of the 18th-century practice of the cathedral having four titular organists, each one playing for three months of the year.

Bells

File:Bourdon Marie (Notre-Dame de Paris) 1.ogg The new bell, Marie, ringing in the nave The new bells of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral on public display in the nave in February 2013 The treasure consists of important ornaments of the Fourteenth Century.

The cathedral has 10 bells. The largest, Emmanuel, original to 1681, is located in the south tower and weighs just over 13 tons and is tolled to mark the hours of the day and for various occasions and services. This bell is always rung first, at least 5 seconds before the rest. Until recently, there were four additional 19th-century bells on wheels in the north tower, which were swing chimed. These bells were meant to replace nine which were removed from the cathedral during the Revolution and were rung for various services and festivals. The bells were once rung by hand before electric motors allowed them to be rung without manual labor. When it was discovered that the size of the bells could cause the entire building to vibrate, threatening its structural integrity, they were taken out of use. The bells also had external hammers for tune playing from a small clavier.

On the night of 24 August 1944 as the Île de la Cité was taken by an advance column of French and Allied armoured troops and elements of the Resistance, it was the tolling of the Emmanuel that announced to the city that its liberation was under way.

In early 2012, as part of a €2 million project, the four old bells in the north tower were deemed unsatisfactory and removed. The plan originally was to melt them down and recast new bells from the material. However, a legal challenge resulted in the bells being saved in extremis at the foundry.[12] As of early 2013, they are still merely set aside until their fate is decided. A set of 8 new bells was cast by the same foundry, Cornille-Havard, in Normandy that had cast the four in 1856. At the same time, a much larger bell called Marie was cast in Asten, Netherlands by Royal Eijsbouts — it now hangs with Emmanuel in the south tower. The 9 new bells, which were delivered to the cathedral at the same time (31 January 2013),[13] are designed to replicate the quality and tone of the cathedral’s original bells.

| Name | Mass | Diameter | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emmanuel | 13271 kg | 261 cm | FTemplate:Sharp2 |

| Marie | 6023 kg | 206.5 cm | GTemplate:Sharp2 |

| Gabriel | 4162 kg | 182.8 cm | ATemplate:Sharp2 |

| Anne Geneviève | 3477 kg | 172.5 cm | B2 |

| Denis | 2502 kg | 153.6 cm | CTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Marcel | 1925 kg | 139.3 cm | DTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Étienne | 1494 kg | 126.7 cm | ETemplate:Sharp3 |

| Benoît-Joseph | 1309 kg | 120.7 cm | FTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Maurice | 1011 kg | 109.7 cm | GTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Jean-Marie | 782 kg | 99.7 cm | ATemplate:Sharp3 |

Ownership

Under a 1905 law, Notre-Dame de Paris is among seventy churches in Paris built before that year that are owned by the French State. While the building itself is owned by the state, the Catholic Church is the designated beneficiary, having the exclusive right to use it for religious purpose in perpetuity. The archdiocese is responsible for paying the employees, security, heating and cleaning, and assuring that the cathedral is open for free to visitors. The archdiocese does not receive subsidies from the French State.[15]

Significant events

- 1170: Existence of a cathedral school operating at Notre-Dame. This corporation of teachers and students will evolve in 1200 into the University of Paris in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste.

- 1185: Heraclius of Caesarea calls for the Third Crusade from the still-incomplete cathedral.

- 1239: The Crown of Thorns is placed in the cathedral by St. Louis during the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle.

- 1302: Philip the Fair opens the first States-General.

- 16 December 1431: Henry VI of England is crowned King of France.[16]

- 1450: Wolves of Paris are trapped and killed on the parvis of the cathedral.

- 7 November 1455: Isabelle Romée, the mother of Joan of Arc, petitions a papal delegation to overturn her daughter’s conviction for heresy.

- 1 January 1537: James V of Scotland is married to Madeleine of France

- 24 April 1558: Mary, Queen of Scots is married to the Dauphin Francis (later Francis II of France), son of Henry II of France.

- 18 August 1572: Henry of Navarre (later Henry IV of France) marries Margaret of Valois. The marriage takes place not in the cathedral but on the parvis of the cathedral, as Henry IV is Protestant.[17]

- 10 September 1573: The Cathedral was the site of a vow made by Henry of Valois following the interregnum of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that he would both respect traditional liberties and the recently passed religious freedom law.[18]

- 10 November 1793: the Festival of Reason.

File:Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of Napoleon edit.jpg The coronation of Napoleon I, on 2 December 1804 at Notre-Dame, as portrayed in the 1807 painting The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David

- 2 December 1804: the coronation ceremony of Napoleon I and his wife Joséphine, with Pope Pius VII officiating.

- 1831: The novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame was published by French author Victor Hugo.

- 18 April 1909: Joan of Arc is beatified.

- 16 May 1920: Joan of Arc is canonized.

- 1900: Louis Vierne is appointed organist of Notre-Dame de Paris after a heavy competition (with judges including Charles-Marie Widor) against the 500 most talented organ players of the era. On 2 June 1937 Louis Vierne dies at the cathedral organ (as was his lifelong wish) near the end of his 1750th concert.

- 11 February 1931: Antonieta Rivas Mercado shot herself at the altar with a pistol property of her lover Jose Vasconcelos. She died instantly.

- 26 August 1944: The Te Deum Mass takes place in the cathedral to celebrate the liberation of Paris. (According to some accounts the Mass was interrupted by sniper fire from both the internal and external galleries.)

- 12 November 1970: The Requiem Mass of General Charles de Gaulle is held.

- 26 June 1971: Philippe Petit surreptitiously strings a wire between the two towers of Notre-Dame and tight-rope walks across it. Petit later performed a similar act between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

- 31 May 1980: After the Magnificat of this day, Pope John Paul II celebrates Mass on the parvis of the cathedral.

- January 1996: The Requiem Mass of François Mitterrand is held.

- 10 August 2007: The Requiem Mass of Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, former Archbishop of Paris and famous Jewish convert to Catholicism, is held.

- 12 December 2012:The Notre-Dame Cathedral begins a year long celebration of the 850th anniversary of the laying of the first building block for the cathedral.[19]

- 21 May 2013: Around 1,500 visitors were evacuated from Notre-Dame Cathedral after Dominique Venner, a historian, placed a letter on the Church altar and shot himself. He died immediately.[20][21]

The cathedral is renowned for its Lent sermons founded by the famous Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire in the 1860s. In recent years, however, an increasing number have been given by leading public figures and state

employed academics.

Gallery

Emmanuel, the great bourdon bell, at the Notre-Dame de Paris

A wide angle view of Notre-Dame’s western façade

Notre-Dame’s facade showing the Portal of the Virgin, Portal of the Last Judgment, and Portal of St-Anne

A view of Notre-Dame from Montparnasse Tower

A wide angle view of Notre-Dame’s western facade

The Statue of Virgin and Child inside Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame’s high altar with the kneeling statues of Louis XIII and Louis XIV

One of Notre-Dame’s well known gargoyle statues

South rose window of Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame at the end of the 19th century

Flying buttresses of Notre-Dame

Memorial tablet to the British Empire dead of the First World War

Tympanum of the Last Judgment

Statue of Joan of Arc in Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral interior

See also

Lua error: bad argument #2 to ‘title.new’ (unrecognized namespace name ‘Portal’).

- Architecture of Paris

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the Paris region

- Maîtrise Notre-Dame de Paris

- Musée de Notre-Dame de Paris

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

- Little Dedo

- Virgin of Paris

References

- ↑ Notre Dame, meaning «Our Lady» in French, is frequently used in the names of churches including the cathedrals of Chartres, Rheims and Rouen.

- ↑ «Discoverfrance.net». Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ Erik Inglis, «Gothic Architecture and a Scholastic: Jean de Jandun’s Tractatus de laudibus Parisius (1323),» Gesta, XLII/1 (2003), 63–85.

- ↑ Caroline Bruzelius, The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 69, No. 69 (Dec. 1987), pp. 540–569.

- ↑ Paul Williamson (10 April 1995). Gothic Sculpture, 1140–1300. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-030006-338-7.

- ↑ Crypte archéologique du parvis Notre-Dame website Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Jason Chavis. «Facts on the Notre Dame Cathedral in France». USA Today. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 http://www.notredamedeparis.fr/The-spire

- ↑ «Visiting the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris: Attractions, Tips & Tours». planetware. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ James A. Herrick, The Making of the New Spirituality, InterVarsity Press, 2004 ISBN 0-8308-3279-3, p. 75-76

- ↑ Metcalfe, John. «Notre Dame Cathedral Just Got an LED Makeover.» The Atlantic Cities. The Atlantic Monthly Group, 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ «Le Figaro article from 9 November 2012 (in French)». Le Figaro. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ «Les Neuf Cloches Geantes Sont Arrivees A Notre Dame De Paris». L’Express (in French). 31 January 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Sonnerie des nouvelles cloches de Notre-Dame de Paris (notredameparis.fr)

- ↑ Communique of the Press and Communication Service of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Paris, November 2014.

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Lebigue, «L’ordo du sacre d’Henri VI à Notre-Dame de Paris (16 décembre 1431)», Notre-Dame de Paris 1163–2013, ed. Cédric Giraud, Turnhout : Brepols, 2013, p. 319-363.

- ↑ Hiatt, Charles, Notre Dame de Paris: a short history & description of the cathedral, (George Bell & Sons, 1902), 12.

- ↑ Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish–Lithuanian State, 1386–1795. Warsaw: University of Washington Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-295-98093-1. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ↑ «Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral celebrates 850 years». GIE ATOUT FRANCE. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ «Notre-Dame Cathedral evacuated after man commits suicide». Fox News Channel. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Frémont, Anne-Laure. «Un historien d’extrême droite se suicide à Notre-Dame». Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 21 May 2013.

Bibliography

<templatestyles src=»Refbegin/styles.css» />

- Bruzelius, Caroline. «The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris.» Art Bulletin (1987): 540–569 in JSTOR.

- Davis, Michael T. «Splendor and Peril: The Cathedral of Paris, 1290–1350.» The Art Bulletin (1998) 80#1 pp: 34–66.

- Jacobs, Jay, ed. The Horizon Book of Great Cathedrals. New York City: American Heritage Publishing, 1968

- Janson, H.W. History of Art. 3rd Edition. New York City: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1986

- Myers, Bernard S. Art and Civilization. New York City: McGraw-Hill, 1957

- Michelin Travel Publications. The Green Guide Paris. Hertfordshire, UK: Michelin Travel Publications, 2003

- Temko, Allan. Notre-Dame of Paris (Viking Press, 1955)

- Tonazzi, Pascal. Florilège de Notre-Dame de Paris (anthologie), Editions Arléa, Paris, 2007, ISBN 2-86959-795-9

- Wright, Craig. Music and ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge University Press, 2008)

External links

- «Monument historique – PA00086250». Mérimée database of Monuments Historiques (in French). France: Ministère de la Culture. 1993. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Official website of Notre-Dame de Paris Template:Fr icon (English)

- List of Facts about the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris

- Notre-Dame de Paris’s Singers

- Official site of Music at Notre-Dame de Paris

- Panoramic view

- Further information on the Organ with specifications of the Grandes Orgues and the Orgue de Choeur

- Photos: Notre-Dame de Paris — The Gothic Cathedral, Flickr

Template:Paris

|

v • d • e Tourism in Paris |

|

|---|---|

| Landmarks |

* Arc de Triomphe

|

| Museums (list) |

* Army Museum

|

| Religious buildings |

* Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

|

| Hôtels particuliers and palaces |

* Élysée Palace

|

| Bridges, streets, areas, squares and waterways |

* Avenue de l’Opéra

|

| Parks and gardens |

* Bois de Boulogne

|

| Sport venues |

* AccorHotels Arena

|

| Cemeteries |

* Montmartre Cemetery

|

| Région parisienne |

* Basilica of Saint-Denis

|

| Culture and events |

* Bastille Day military parade

|

| Other |

* Axe historique

|

For the Victor Hugo novel, see The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

For other uses, see Notre Dame (disambiguation) and Notre Dame de Paris (disambiguation).

Template:Infobox church

Notre-Dame de Paris (French: [nɔtʁə dam də paʁi] (Audio file «Cathedrale de Nothre Dame.ogg » not found); meaning «Our Lady of Paris»), also known as Notre-Dame Cathedral or simply Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité in the fourth arrondissement of Paris, France.[1] The cathedral is widely considered to be one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture, and it is among the largest and most well-known church buildings in the world. The naturalism of its sculptures and stained glass are in contrast with earlier Romanesque architecture.

As the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the Archbishop of Paris, currently Cardinal André Vingt-Trois.[2] The cathedral treasury contains a reliquary, which houses some of Catholicism’s most important relics, including the purported Crown of Thorns, a fragment of the True Cross, and one of the Holy Nails.

In the 1790s, Notre-Dame suffered desecration in the radical phase of the French Revolution when much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. An extensive restoration supervised by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc began in 1845. A project of further restoration and maintenance began in 1991.

Architecture

File:Notre Dame de Paris by night.jpg The western facade illuminated at night The spire and east side of the cathedral The north rose window is a fine example of Gothic Rayonnant style.

Notre-Dame de Paris was among the first buildings in the world to use the flying buttress. The building was not originally designed to include the flying buttresses around the choir and nave but after the construction began, the thinner walls grew ever higher and stress fractures began to occur as the walls pushed outward. In response, the cathedral’s architects built supports around the outside walls, and later additions continued the pattern. The total surface area is 5,500 m² (interior surface 4,800 m²).

Many small individually crafted statues were placed around the outside to serve as column supports and water spouts. Among these are the famous gargoyles, designed for water run-off, and chimeras. The statues were originally colored as was most of the exterior. The paint has worn off. The cathedral was essentially complete by 1345. The cathedral has a narrow climb of 387 steps at the top of several spiral staircases; along the climb it is possible to view its most famous bell and its gargoyles in close quarters, as well as having a spectacular view across Paris when reaching the top.

Contemporary critical reception

John of Jandun recognized the cathedral as one of Paris’s three most important buildings [prominent structures] in his 1323 Treatise on the Praises of Paris:

| “ | That most glorious church of the most glorious Virgin Mary, mother of God, deservedly shines out, like the sun among stars. And although some speakers, by their own free judgment, because [they are] able to see only a few things easily, may say that some other is more beautiful, I believe however, respectfully, that, if they attend more diligently to the whole and the parts, they will quickly retract this opinion. Where indeed, I ask, would they find two towers of such magnificence and perfection, so high, so large, so strong, clothed round about with such a multiple variety of ornaments? Where, I ask, would they find such a multipartite arrangement of so many lateral vaults, above and below? Where, I ask, would they find such light-filled amenities as the many surrounding chapels? Furthermore, let them tell me in what church I may see such a large cross, of which one arm separates the choir from the nave. Finally, I would willingly learn where [there are] two such circles, situated opposite each other in a straight line, which on account of their appearance are given the name of the fourth vowel [O] ; among which smaller orbs and circlets, with wondrous artifice, so that some arranged circularly, others angularly, surround windows ruddy with precious colors and beautiful with the most subtle figures of the pictures. In fact I believe that this church offers the carefully discerning such cause for admiration that its inspection can scarcely sate the soul. | ” |

|

—Jean de Jandun, Tractatus de laudibus Parisius[3] |

Construction history

In 1160, because the church in Paris had become the «Parish church of the kings of Europe», Bishop Maurice de Sully deemed the previous Paris cathedral, Saint-Étienne (St Stephen’s), which had been founded in the 4th century, unworthy of its lofty role, and had it demolished shortly after he assumed the title of Bishop of Paris. As with most foundation myths, this account needs to be taken with a grain of salt; archeological excavations in the 20th century suggested that the Merovingian cathedral replaced by Sully was itself a massive structure, with a five-aisled nave and a façade some 36m across. It is possible therefore that the faults with the previous structure were exaggerated by the Bishop to help justify the rebuilding in a newer style. According to legend, Sully had a vision of a glorious new cathedral for Paris, and sketched it on the ground outside the original church.

To begin the construction, the bishop had several houses demolished and had a new road built to transport materials for the rest of the cathedral. Construction began in 1163 during the reign of Louis VII, and opinion differs as to whether Sully or Pope Alexander III laid the foundation stone of the cathedral. However, both were at the ceremony. Bishop de Sully went on to devote most of his life and wealth to the cathedral’s construction. Construction of the choir took from 1163 until around 1177 and the new High Altar was consecrated in 1182 (it was normal practice for the eastern end of a new church to be completed first, so that a temporary wall could be erected at the west of the choir, allowing the chapter to use it without interruption while the rest of the building slowly took shape). After Bishop Maurice de Sully’s death in 1196, his successor, Eudes de Sully (no relation) oversaw the completion of the transepts and pressed ahead with the nave, which was nearing completion at the time of his own death in 1208. By this stage, the western facade had also been laid out, though it was not completed until around the mid-1240s.[4]

Numerous architects worked on the site over the period of construction, which is evident from the differing styles at different heights of the west front and towers.[citation needed] Between 1210 and 1220, the fourth architect oversaw the construction of the level with the rose window and the great halls beneath the towers.

The most significant change in design came in the mid 13th century, when the transepts were remodeled in the latest Rayonnant style; in the late 1240s Jean de Chelles added a gabled portal to the north transept topped off by a spectacular rose window. Shortly afterwards (from 1258) Pierre de Montreuil executed a similar scheme on the southern transept. Both these transept portals were richly embellished with sculpture; the south portal features scenes from the lives of St Stephen and of various local saints, while the north portal featured the infancy of Christ and the story of Theophilus in the tympanum, with a highly influential statue of the Virgin and Child in the trumeau.[5]

Timeline of construction

- 1160 Maurice de Sully (named Bishop of Paris) orders the original cathedral demolished.

- 1163 Cornerstone laid for Notre-Dame de Paris; construction begins.

- 1182 Apse and choir completed.

- 1196 Bishop Maurice de Sully dies.

- c.1200 Work begins on western facade.

- 1208 Bishop Eudes de Sully dies. Nave vaults nearing completion.

- 1225 Western facade completed.

- 1250 Western towers and north rose window completed.

- c.1245–1260s Transepts remodelled in the Rayonnant style by Jean de Chelles then Pierre de Montreuil

- 1250–1345 Remaining elements completed.

Crypt

File:La crypte archéologique du Parvis de Notre-Dame (Paris) (8274683584).jpg The Archaeological Crypt of Notre-Dame de Paris.

The Archaeological Crypt of the Paris Notre-Dame (La crypte archéologique du Parvis de Notre-Dame) was created in 1965 to protect a range of historical ruins, discovered during construction work and spanning from the earliest settlement in Paris to the modern day. The crypts are managed by the Musée Carnavalet and contain a large exhibit, detailed models of the architecture of different time periods, and how they can be viewed within the ruins. The main feature still visible is the under-floor heating installed during the Roman occupation.[6]

Alterations, vandalism, and restorations

In 1548, rioting Huguenots damaged features of Notre-Dame, considering them idolatrous.[7] During the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV, the cathedral underwent major alterations as part of an ongoing attempt to modernize cathedrals throughout Europe. A colossal statue of St Christopher, standing against a pillar near the western entrance and dating from 1413, was destroyed in 1786. Tombs and stained glass windows were destroyed. The north and south rose windows were spared this fate, however.

File:Henri Le Secq near a Gargoyle.jpg An 1853 photo by Charles Nègre of Henri Le Secq next to Le Stryge

In 1793, during the French Revolution, the cathedral was rededicated to the Cult of Reason, and then to the Cult of the Supreme Being. During this time, many of the treasures of the cathedral were either destroyed or plundered. The 13th century spire was torn down[8] and the statues located at the west facade were beheaded.[9] Many of the heads were found during a 1977 excavation nearby and are on display at the Musée de Cluny. For a time the Goddess of Liberty replaced the Virgin Mary on several altars.[10] The cathedral’s great bells managed to avoid being melted down. The cathedral came to be used as a warehouse for the storage of food.[7]

A controversial restoration programme was initiated in 1845, overseen by architects Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Viollet Le Duc was responsible for the restorations of several dozen castles, palaces and cathedrals across France. The restoration lasted twenty five years[7] and included a taller and more ornate reconstruction of the flèche (a type of spire),[8] as well as the addition of the chimeras on the Galerie des Chimères. Viollet le Duc always signed his work with a bat, the wing structure of which most resembles the Gothic vault (see Château de Roquetaillade).

The Second World War caused more damage. Several of the stained glass windows on the lower tier were hit by stray bullets. These were remade after the war, but now sport a modern geometrical pattern, not the old scenes of the Bible.

In 1991, a major programme of maintenance and restoration was initiated, which was intended to last ten years, but was still in progress as of 2010,[7] the cleaning and restoration of old sculptures being an exceedingly delicate matter. Circa 2014, much of the lighting was upgraded to LED lighting.[11]

Organ and organists

File:Organ of Notre-Dame de Paris.jpg The organ of Notre-Dame de Paris

Though numerous organs have been installed in the cathedral over time, the earliest models were inadequate for the building.[citation needed] The first more noted organ[citation needed] was finished in the 18th century by the noted builder François-Henri Clicquot. Some of Clicquot’s original pipework in the pedal division continues to sound from the organ today. The organ was almost completely rebuilt and expanded in the 19th century by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll.

The position of titular organist («head» or «chief» organist; French: titulaires des grands orgues) at Notre-Dame is considered one of the most prestigious organist posts in France, along with the post of titular organist of Saint Sulpice in Paris, Cavaillé-Coll’s largest instrument.

The organ has 7,952 pipes, with ca 900 classified as historical. It has 110 real stops, five 56-key manuals and a 32-key pedalboard. In December 1992, a two-year restoration of the organ was completed that fully computerized the organ under three LANs (Local Area Networks). The restoration also included a number of additions, notably two further horizontal reed stops en chamade in the Cavaille-Coll style. The Notre-Dame organ is therefore unique in France in having five fully independent reed stops en chamade.

Among the best-known organists at Notre-Dame de Paris was Louis Vierne, who held this position from 1900 to 1937. Under his tenure, the Cavaillé-Coll organ was modified in its tonal character, notably in 1902 and 1932. Léonce de Saint-Martin held the post between 1932 and 1954. Pierre Cochereau initiated further alterations (many of which were already planned by Louis Vierne), including the electrification of the action between 1959 and 1963. The original Cavaillé-Coll console, (which is now located near the organ loft), was replaced by a new console in Anglo-American style and the addition of further stops between 1965 and 1972, notably in the pedal division, the recomposition of the mixture stops, a 32′ plenum in the Neo-Baroque style on the Solo manual, and finally the adding of three horizontal reed stops «en chamade» in the Iberian style.

After Cochereau’s sudden death in 1984, four new titular organists were appointed at Notre-Dame in 1985: Jean-Pierre Leguay, Olivier Latry, Yves Devernay (who died in 1990), and Philippe Lefebvre. This was reminiscent of the 18th-century practice of the cathedral having four titular organists, each one playing for three months of the year.

Bells

File:Bourdon Marie (Notre-Dame de Paris) 1.ogg The new bell, Marie, ringing in the nave The new bells of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral on public display in the nave in February 2013 The treasure consists of important ornaments of the Fourteenth Century.

The cathedral has 10 bells. The largest, Emmanuel, original to 1681, is located in the south tower and weighs just over 13 tons and is tolled to mark the hours of the day and for various occasions and services. This bell is always rung first, at least 5 seconds before the rest. Until recently, there were four additional 19th-century bells on wheels in the north tower, which were swing chimed. These bells were meant to replace nine which were removed from the cathedral during the Revolution and were rung for various services and festivals. The bells were once rung by hand before electric motors allowed them to be rung without manual labor. When it was discovered that the size of the bells could cause the entire building to vibrate, threatening its structural integrity, they were taken out of use. The bells also had external hammers for tune playing from a small clavier.

On the night of 24 August 1944 as the Île de la Cité was taken by an advance column of French and Allied armoured troops and elements of the Resistance, it was the tolling of the Emmanuel that announced to the city that its liberation was under way.

In early 2012, as part of a €2 million project, the four old bells in the north tower were deemed unsatisfactory and removed. The plan originally was to melt them down and recast new bells from the material. However, a legal challenge resulted in the bells being saved in extremis at the foundry.[12] As of early 2013, they are still merely set aside until their fate is decided. A set of 8 new bells was cast by the same foundry, Cornille-Havard, in Normandy that had cast the four in 1856. At the same time, a much larger bell called Marie was cast in Asten, Netherlands by Royal Eijsbouts — it now hangs with Emmanuel in the south tower. The 9 new bells, which were delivered to the cathedral at the same time (31 January 2013),[13] are designed to replicate the quality and tone of the cathedral’s original bells.

| Name | Mass | Diameter | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emmanuel | 13271 kg | 261 cm | FTemplate:Sharp2 |

| Marie | 6023 kg | 206.5 cm | GTemplate:Sharp2 |

| Gabriel | 4162 kg | 182.8 cm | ATemplate:Sharp2 |

| Anne Geneviève | 3477 kg | 172.5 cm | B2 |

| Denis | 2502 kg | 153.6 cm | CTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Marcel | 1925 kg | 139.3 cm | DTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Étienne | 1494 kg | 126.7 cm | ETemplate:Sharp3 |

| Benoît-Joseph | 1309 kg | 120.7 cm | FTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Maurice | 1011 kg | 109.7 cm | GTemplate:Sharp3 |

| Jean-Marie | 782 kg | 99.7 cm | ATemplate:Sharp3 |

Ownership

Under a 1905 law, Notre-Dame de Paris is among seventy churches in Paris built before that year that are owned by the French State. While the building itself is owned by the state, the Catholic Church is the designated beneficiary, having the exclusive right to use it for religious purpose in perpetuity. The archdiocese is responsible for paying the employees, security, heating and cleaning, and assuring that the cathedral is open for free to visitors. The archdiocese does not receive subsidies from the French State.[15]

Significant events

- 1170: Existence of a cathedral school operating at Notre-Dame. This corporation of teachers and students will evolve in 1200 into the University of Paris in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste.

- 1185: Heraclius of Caesarea calls for the Third Crusade from the still-incomplete cathedral.

- 1239: The Crown of Thorns is placed in the cathedral by St. Louis during the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle.

- 1302: Philip the Fair opens the first States-General.

- 16 December 1431: Henry VI of England is crowned King of France.[16]

- 1450: Wolves of Paris are trapped and killed on the parvis of the cathedral.

- 7 November 1455: Isabelle Romée, the mother of Joan of Arc, petitions a papal delegation to overturn her daughter’s conviction for heresy.

- 1 January 1537: James V of Scotland is married to Madeleine of France

- 24 April 1558: Mary, Queen of Scots is married to the Dauphin Francis (later Francis II of France), son of Henry II of France.

- 18 August 1572: Henry of Navarre (later Henry IV of France) marries Margaret of Valois. The marriage takes place not in the cathedral but on the parvis of the cathedral, as Henry IV is Protestant.[17]

- 10 September 1573: The Cathedral was the site of a vow made by Henry of Valois following the interregnum of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that he would both respect traditional liberties and the recently passed religious freedom law.[18]

- 10 November 1793: the Festival of Reason.

File:Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of Napoleon edit.jpg The coronation of Napoleon I, on 2 December 1804 at Notre-Dame, as portrayed in the 1807 painting The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David

- 2 December 1804: the coronation ceremony of Napoleon I and his wife Joséphine, with Pope Pius VII officiating.

- 1831: The novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame was published by French author Victor Hugo.

- 18 April 1909: Joan of Arc is beatified.

- 16 May 1920: Joan of Arc is canonized.

- 1900: Louis Vierne is appointed organist of Notre-Dame de Paris after a heavy competition (with judges including Charles-Marie Widor) against the 500 most talented organ players of the era. On 2 June 1937 Louis Vierne dies at the cathedral organ (as was his lifelong wish) near the end of his 1750th concert.

- 11 February 1931: Antonieta Rivas Mercado shot herself at the altar with a pistol property of her lover Jose Vasconcelos. She died instantly.

- 26 August 1944: The Te Deum Mass takes place in the cathedral to celebrate the liberation of Paris. (According to some accounts the Mass was interrupted by sniper fire from both the internal and external galleries.)

- 12 November 1970: The Requiem Mass of General Charles de Gaulle is held.

- 26 June 1971: Philippe Petit surreptitiously strings a wire between the two towers of Notre-Dame and tight-rope walks across it. Petit later performed a similar act between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

- 31 May 1980: After the Magnificat of this day, Pope John Paul II celebrates Mass on the parvis of the cathedral.

- January 1996: The Requiem Mass of François Mitterrand is held.

- 10 August 2007: The Requiem Mass of Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, former Archbishop of Paris and famous Jewish convert to Catholicism, is held.

- 12 December 2012:The Notre-Dame Cathedral begins a year long celebration of the 850th anniversary of the laying of the first building block for the cathedral.[19]

- 21 May 2013: Around 1,500 visitors were evacuated from Notre-Dame Cathedral after Dominique Venner, a historian, placed a letter on the Church altar and shot himself. He died immediately.[20][21]

The cathedral is renowned for its Lent sermons founded by the famous Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire in the 1860s. In recent years, however, an increasing number have been given by leading public figures and state

employed academics.

Gallery

Emmanuel, the great bourdon bell, at the Notre-Dame de Paris

A wide angle view of Notre-Dame’s western façade

Notre-Dame’s facade showing the Portal of the Virgin, Portal of the Last Judgment, and Portal of St-Anne

A view of Notre-Dame from Montparnasse Tower

A wide angle view of Notre-Dame’s western facade

The Statue of Virgin and Child inside Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame’s high altar with the kneeling statues of Louis XIII and Louis XIV

One of Notre-Dame’s well known gargoyle statues

South rose window of Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame at the end of the 19th century

Flying buttresses of Notre-Dame

Memorial tablet to the British Empire dead of the First World War

Tympanum of the Last Judgment

Statue of Joan of Arc in Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral interior

See also

Lua error: bad argument #2 to ‘title.new’ (unrecognized namespace name ‘Portal’).

- Architecture of Paris

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the Paris region

- Maîtrise Notre-Dame de Paris

- Musée de Notre-Dame de Paris

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

- Little Dedo

- Virgin of Paris

References

- ↑ Notre Dame, meaning «Our Lady» in French, is frequently used in the names of churches including the cathedrals of Chartres, Rheims and Rouen.

- ↑ «Discoverfrance.net». Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ Erik Inglis, «Gothic Architecture and a Scholastic: Jean de Jandun’s Tractatus de laudibus Parisius (1323),» Gesta, XLII/1 (2003), 63–85.

- ↑ Caroline Bruzelius, The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 69, No. 69 (Dec. 1987), pp. 540–569.

- ↑ Paul Williamson (10 April 1995). Gothic Sculpture, 1140–1300. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-030006-338-7.

- ↑ Crypte archéologique du parvis Notre-Dame website Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Jason Chavis. «Facts on the Notre Dame Cathedral in France». USA Today. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 http://www.notredamedeparis.fr/The-spire

- ↑ «Visiting the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris: Attractions, Tips & Tours». planetware. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ James A. Herrick, The Making of the New Spirituality, InterVarsity Press, 2004 ISBN 0-8308-3279-3, p. 75-76

- ↑ Metcalfe, John. «Notre Dame Cathedral Just Got an LED Makeover.» The Atlantic Cities. The Atlantic Monthly Group, 11 March 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ «Le Figaro article from 9 November 2012 (in French)». Le Figaro. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ «Les Neuf Cloches Geantes Sont Arrivees A Notre Dame De Paris». L’Express (in French). 31 January 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Sonnerie des nouvelles cloches de Notre-Dame de Paris (notredameparis.fr)

- ↑ Communique of the Press and Communication Service of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Paris, November 2014.

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Lebigue, «L’ordo du sacre d’Henri VI à Notre-Dame de Paris (16 décembre 1431)», Notre-Dame de Paris 1163–2013, ed. Cédric Giraud, Turnhout : Brepols, 2013, p. 319-363.

- ↑ Hiatt, Charles, Notre Dame de Paris: a short history & description of the cathedral, (George Bell & Sons, 1902), 12.

- ↑ Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish–Lithuanian State, 1386–1795. Warsaw: University of Washington Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-295-98093-1. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ↑ «Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral celebrates 850 years». GIE ATOUT FRANCE. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ «Notre-Dame Cathedral evacuated after man commits suicide». Fox News Channel. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Frémont, Anne-Laure. «Un historien d’extrême droite se suicide à Notre-Dame». Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 21 May 2013.

Bibliography

<templatestyles src=»Refbegin/styles.css» />

- Bruzelius, Caroline. «The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris.» Art Bulletin (1987): 540–569 in JSTOR.

- Davis, Michael T. «Splendor and Peril: The Cathedral of Paris, 1290–1350.» The Art Bulletin (1998) 80#1 pp: 34–66.

- Jacobs, Jay, ed. The Horizon Book of Great Cathedrals. New York City: American Heritage Publishing, 1968

- Janson, H.W. History of Art. 3rd Edition. New York City: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1986

- Myers, Bernard S. Art and Civilization. New York City: McGraw-Hill, 1957

- Michelin Travel Publications. The Green Guide Paris. Hertfordshire, UK: Michelin Travel Publications, 2003

- Temko, Allan. Notre-Dame of Paris (Viking Press, 1955)

- Tonazzi, Pascal. Florilège de Notre-Dame de Paris (anthologie), Editions Arléa, Paris, 2007, ISBN 2-86959-795-9

- Wright, Craig. Music and ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge University Press, 2008)

External links

- «Monument historique – PA00086250». Mérimée database of Monuments Historiques (in French). France: Ministère de la Culture. 1993. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Official website of Notre-Dame de Paris Template:Fr icon (English)

- List of Facts about the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris

- Notre-Dame de Paris’s Singers

- Official site of Music at Notre-Dame de Paris

- Panoramic view

- Further information on the Organ with specifications of the Grandes Orgues and the Orgue de Choeur

- Photos: Notre-Dame de Paris — The Gothic Cathedral, Flickr

Template:Paris

|

v • d • e Tourism in Paris |

|

|---|---|

| Landmarks |

* Arc de Triomphe

|

| Museums (list) |

* Army Museum

|

| Religious buildings |

* Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

|

| Hôtels particuliers and palaces |

* Élysée Palace

|

| Bridges, streets, areas, squares and waterways |

* Avenue de l’Opéra

|

| Parks and gardens |

* Bois de Boulogne

|

| Sport venues |

* AccorHotels Arena

|

| Cemeteries |

* Montmartre Cemetery

|

| Région parisienne |

* Basilica of Saint-Denis

|

| Culture and events |

* Bastille Day military parade

|

| Other |

* Axe historique

|

Собор Парижской Богоматери, или Нотр Дам де Пари, – пожалуй, самый узнаваемый образец готической архитектуры. Его облик знаком практически каждому, как его название, ведь собор увековечен во множестве произведений искусства. Наряду с Эйфелевой башней, Монмартром, базиликой Сакре Кер, собор Нотр Дам является одной из главных достопримечательностей Парижа, пропустить которую не позволяет себе практически ни один турист. Ежегодно собор посещает примерно 13,5 миллионов (!) человек. Нотр Дам притягивает путешественников не только своей уникальной архитектурой – собор окутан мистическим ореолом, полон тайн, легенд и удивительных историй.

Содержание:

Нотр Дам через века: история знаменитого собора

«Каменная симфония»: архитектура Нотр Дам

На что обратить внимание в соборе Парижской Богоматери

Интересные факты о соборе Нотр Дам де Пари

Вокруг собора Нотр Дам: что интересного поблизости

Практическая информация

Как добраться

Режим работы и стоимость

Лайфхаки и советы туристам

Аудиогид по собору Нотр Дам де Пари

Нотр Дам на карте Парижа

Нотр Дам на видео

Нотр Дам через века: история знаменитого собора

На месте дошедшего до наших дней собора Нотр-Дам с античных времен возводили святилища. Еще во времена римлян здесь стоял храм Юпитера. Затем здесь появилась первая христианская базилика Парижа, возведенная на фундаменте римского храма. А в 1163 году было начато строительство того величественного собора Нотр-Дам, который мы знаем.

На протяжении веков Нотр-Дам играл важнейшую роль в жизни Парижа и всей Франции. Здесь короновали и венчали французских королей. Здесь отпевали выдающихся сынов Франции.

Но во время Великой французской революции эта богатая история стала почти приговором собору: здание чудом уцелело! Якобинцы жаждали снести «твердыню мракобесия», но за свою главную святыню вступились сами парижане, собрав за него огромный выкуп. Здание сохранили, но изрядно над ним «поиздевались»: в частности, Нотр-Дам лишился своего знаменитого шпиля, размещенного на крыше, почти все его колокола переплавили на пушки, разрушили множество скульптур. Особенно пострадали скульптуры иудейских царей, размещенные над тремя порталами фасада: статуи обезглавили. А сам собор объявили Храмом Разума.

С 1802 года в Нотр-Даме снова стали проходить богослужения, а тремя годами позже именно здесь было совершена коронация Наполеона Бонапарта и Жозефины. Впрочем, несмотря на значимость собора, Нотр-Дам пребывал в крайне ветхом состоянии и отчаянно нуждался в реставрации. Кто знает, сохранилось бы это здание до наших дней, если бы не… Виктор Гюго и его знаменитый роман «Собор Парижской Богоматери»!

После публикации книги в 1830 году парижане вспомнили о своем архитектурном и историческом сокровище и наконец, задумались о его сохранении и реставрации. К тому времени возраст здания составлял уже почти 7 веков! В XIX веке под умелым руководством архитектора Дюка была проведена первая серьезная реставрация собора. Тогда же Нотр-Дам обрел и знаменитую галерею химер, которая сегодня так впечатляет гостей Парижа.

А в 2013 году Париж отмечал 850-летие Нотр-Дама. В качестве подарка собор получил новые колокола и отреставрированный орган.

В Нотр-Дам-де-Пари хранятся две христианские реликвии: один из фрагментов Тернового венца, который по преданию был водружен на голову Иисуса Христа, а также один из гвоздей, которыми римские легионеры прибивали Христа к кресту.

«Каменная симфония»: архитектура собора Нотр Дам

Величественное и монументальное здание собора является подлинным шедевром ранней готики. Особое впечатление производят его стрельчатые крестовые своды, прекрасные витражи и окна-розы, украшенные скульптурами входные порталы. В этом сооружении восхищает и архитектурная гармония, и дыхание истории, которое ощущается во всем его облике. Не зря Виктор Гюго называл собор Парижской Богоматери «каменной симфонией».

Нотр-Дам де Пари снаружи

Наибольшее внимание привлекает главный, западный фасад собора – он является одним из самых узнаваемых архитектурных образов. Визуально фасад разделен на три части, как по вертикали, так и по горизонтали. В нижней части находятся три портала (монументальных входа), каждый из которых имеет свое название: портал Страшного суда (центральный), портал Богоматери (левый) и портал Святой Анны (правый). Названия соответствуют сюжетам, которые изображены в удивительно красивых скульптурных композициях на сводах порталов.

В центре портала Страшного суда – фигура Христа. Под ним – встающие из могил мертвецы, разбуженные зовом ангельских труб. По левую руку Христа – грешники, отправляющиеся в ад. По правую – праведники, идущие в Рай.

Над порталами расположена так называемая «галерея царей«, представленная 28 статуями иудейских правителей. Она пострадала сильнее всего во время революции, и в процессе большой реставрации в XIX веке все разрушенные статуи были заменены на новые.

Любопытно, что уже 1977 году, во время строительных работ под одним из парижских домов, были найдены оригинальные скульптуры, утраченные в годы революции. Впоследствии выяснилось, что будущий владелец дома в разгар революционных волнений выкупил несколько статуй, заявив, что они нужны ему для фундамента. В действительности этот человек сохранил изваяния под своим домом – видимо, «до лучших времен». Сегодня эти статуи хранятся в музее Клуни.

Со стороны западного фасада можно и рассмотреть две колокольные башни, взмывающие ввысь. Кстати, хотя на первый взгляд они кажутся симметричными, присмотревшись можно заметить легкую, едва уловимую асимметрию: левая башня несколько массивнее правой.

Если будет возможность, обойдите собор по периметру, чтобы увидеть и боковые фасады, их впечатляющие входные порталы с виртуозно выполненными рельефами, а также рассмотреть восточную апсиду храма (алтарный выступ) с удивительно красивыми резными сводчатыми арками.

Внутреннее пространство

Первое, что бросается в глаза внутри собора – необычное освещение. Свет проникает внутрь здания через многочисленные разноцветные витражи, создавая причудливую игру света на сводах центрального нефа. При этом больше всего света попадает на алтарь. Такая продуманная система освещения создает особую мистическую атмосферу.

Вместо массивных стен внутри собора Нотр-Дам – сводчатые арки и колонны. Такая организация пространства стала настоящим открытием готического стиля и позволила украсить собор множество цветных витражей.

Центральный неф Нотр-Дама кажется огромным. Масштабность собора связана с его изначальным предназначением – ведь по задумке создателей, он должен был вмещать в себя все население Парижа! И Нотр-Дам действительно прекрасно справлялся с этой задачей в то время, когда количество жителей французской столицы не превышало 10 тысяч человек. И все это население проживало на острове Сите, где находится собор.

Узнать много интересного об истории острова Сите, где и зародился Париж, можно в нашей аудиоэкскурсии «Колыбель Парижа«, доступной в приложении Travelry.

На что обратить внимание в соборе Нотр Дам

С западной стороны собора находится гордость Нотр-Дам – большой старинный орган, созданный еще в XV веке! А за ним виднеется и одно из трех витражных окон в форме розы, которые являются настоящими готическими шедеврами и украшают собор с XII столетия.

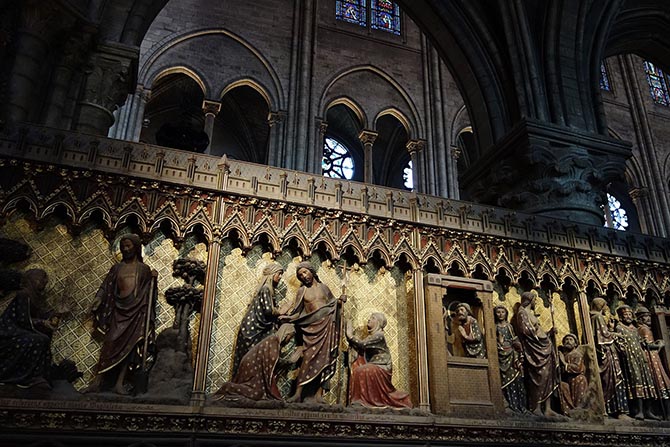

Перед алтарем находится отгороженное пространство, предназначавшееся для священников и церковных певчих и называемое хОрами. Отдельного внимания заслуживает ограда хоров – она искусно украшена цветными скульптурными композициями с изображением евангельских сюжетов, созданными еще в XIII-XIV веках! Их цветовое оформление было восстановлено при реставрации в XIX веке.

Ваше внимание привлекут и многочисленные интересные скульптуры, украшающие собор Нотр Дам. В частности, барочная скульптура «Пьета» за главным алтарем.

В нашей аудиоэкскурсии по острову Сите мы пройдемся по собору Нотр-Дам, обращая внимание на самое интересное и узнавая об истории и оформлении здания.

Сокровищница

Со стороны реки к Нотр-Даму примыкает небольшая пристройка, которая заслуживает особого внимания. Ведь именно в ней находится храмовая сокровищница, где хранятся важнейшие христианские реликвии (в том числе легендарный Терновый венец, попавший в Париж, по преданию, еще в 1239 году!), а также ценные предметы церковного обихода, представляющие собой изящные произведения искусства. Коллекция очень богата и разнообразна.

Интересные факты о соборе Нотр Дам

- В 1572 году в соборе Нотр Дам состоялась очень необычная церемония венчания. Генрих Наваррский (будущий король Генрих IV) вступал в брак с Маргаритой де Валуа. Невеста была католичкой, и ничто не мешало ей быть в храме, а вот Генрих в то время был гугенотом, а потому был вынужден провести собственное венчание… на паперти, перед входом в храм.

- Именно в соборе Нотр Дам де Пари начался легендарный судебный процесс над Жанной Д’Арк, который проходил уже после ее казни и полностью оправдал французскую героиню.

- Знаменитые горгульи, которые украшают собор, имеют не только декоративное, но и вполне практическое значение: они являются частью водостоков, защищающих строение от воздействия дождевой воды. Собственно, само их название произошло от французского gargouille — «водосточная труба, желоб». Оформленные в виде гротескных персонажей, горгульи и химеры также символизируют человеческие грехи и злых духов, которые изгнаны их храма.

- Если будете рассматривать высокий шпиль, который взмывает ввысь над собором Нотр Дам, можете заметить фигуры двенадцати апостолов, расположенных у основания шпиля. Любопытная деталь: все апостолы смотрят вокруг, и лишь апостол Фома повернулся к шпилю. Еще со Средних веков он считался покровителем строителей и архитекторов, и в его образе архитектор Дюк, проводивший реставрацию в XIX веке и восстановивший шпиль, изобразил самого себя! Именно поэтому апостол Фома так внимательно рассматривает сооружение.

- На крыше его ризницы собора Нотр Дам (это небольшая пристройка с южной стороны) размещены пчелиные ульи!

Еще много любопытных фактов о соборе Нотр Дам и других достопримечательностях острова Сите Вы узнаете из нашей аудиоэкскурсии «Колыбель Парижа».

Вокруг собора Нотр Дам: что интересного поблизости

- На площади перед Нотр-Дамом расположен «нулевой километр» – небольшая бронзовая звезда, вмонтированная в площадь. Именно от этой точки идет отсчет протяженности всех автомагистралей страны.

- Также на площади перед собором находится археологическая крипта (Крипта Нотр-Да де Пари), представляющая собой музей археологических артефактов, найденных в окрестностях Нотр-Дама во время раскопок. Экспонаты охватывают широчайший отрезок истории – почти 20 веков, начиная с античности и заканчивая XIX веком.

- В южной части площади перед собором Нотр Дам восседает верхом на коне король Карл Великий, правивший франками в VIII и начале IX века. Памятник ему появился здесь во второй половине XIX века.

- Восточная апсида Собора Парижской Богоматери выходит в уютный тенистый сад на берегу Сены, называемый сквером Иоанна XXIII. Именно отсюда можно рассмотреть прекрасные ажурные готические арки апсиды собора и его шпиль.

- Чуть дальше, на самой восточной оконечности острова Сите, притаился еще один крошечный сквер — Иль де Франс. В нем находится Мемориал мученикам депортации, в память 200 000 французов, отправленных фашистами в концлагеря. А возле мемориала разбит красивый и ухоженный розовый сад.

- Недалеко от собора, на живописной набережной О-Флер, стоит дом, в котором когда-то жили прославленные влюбленные Пьер Абеляр и Элоиза (дом №9).

Как видите, не только в самом соборе Нотр Дам, но и вокруг него можно провести много насыщенных и познавательных часов, рассматривая окружающие его сооружения, изучая памятники старины и отдыхая в близлежащих скверах. Ну а если пройти чуть дальше, то перед Вами откроются и другие исторические и архитектурные сокровища острова Сите: часовня Сен-Шапель, Дворец Правосудия, замок Консьержери и другие интересные достопримечательности. Они входят в маршрут нашей аудиоэкскурсии «Колыбель Парижа», в которой Вас ждет много увлекательных историй и интересных рассказов.

Нотр Дам: практическая информация

Как добраться

Из отдаленных районов Парижа добраться до Собора Парижской Богоматери удобнее всего на метро – неподалеку от собора расположены станции Cite и Saint-Michel — Notre-Dame.

А из близлежащих районов (например, 1, 2, 5, 6 округов) вполне удобно дойти пешком. Остров Сите, на котором расположен собор Нотр Дам де Пари, соединяется как с правым, так и с левым берегами Сены старинными мостами.

Собор закрыт на реконструкцию после пожара, случившегося в апреле 2019 года и серьезно повредившего сооружение.

Читайте также:

Париж недорого: как сэкономить и что посетить бесплатно

Нотр Дам: лайфхаки и советы туристам

-

Как избежать очереди

Раньше «головной болью» туристов была огромная очередь в собор Нотр-Дам. Теперь это уже не такая большая проблема, т.к. с недавнего времени можно выбрать точное время посещения с помощью специальных аппаратов, установленных рядом с собором, или с помощью мобильного приложения Jefile (в русском варианте – «ВнеОчереди»). Скачайте его на мобильное устройство, укажите в приложении количество человек, желающих посетить собор, и выберите время посещения. Таким образом, Вы заранее «займете» очередь и сможете подойти к собору в нужное время!

-

Как послушать орган

Богослужения в Нотр-Даме проводят каждый день. Начинаются они в 11:30 и примечательны тем, что во время литургии можно послушать знаменитый орган собора – один из самых мощных и больших в мире.

-

Когда увидеть Терновый Венец

Увидеть главную святыню собора Нотр Дам – Терновый Венец Спасителя — можно в первую пятницу каждого месяца и в каждую пятницу католического Великого поста, в 15.00. А в Страстную пятницу (по католическому календарю) Терновый Венец выносят почти на целый день: с 10 до 17.00.

Что еще стоит знать туристам

- В соборе Нотр Дам нет запрета на фотографирование, но нельзя использовать вспышку.

- В соборе регулярно проводятся бесплатные экскурсии на разных языках. Если вы хотите попасть на русскоязычную экскурсию, дату и время ее проведения стоит уточнить заранее.

- Стоит помнить о том, что собор является действующим, а потому нежелательно находиться в нем в вызывающих нарядах и вести себя слишком шумно, если идет богослужение.

- В собор не пускают с объемным багажом.

Аудиогид по собору Нотр Дам де Пари

Туристы могут воспользоваться официальным аудиогидом, в который также включен русский язык. За использование официального аудиогида придется заплатить € 5.

Напомним также, что подробный, обстоятельный и увлекательный рассказ о соборе Нотр Дам де Пари входит в нашу аудиоэкскурсию по острову Сите, в которой мы предлагаем совершить путешествие по разным эпохам истории Парижа, с самого момента зарождения города, и узнать много любопытных фактов и о соборе, и об острове, на котором он стоит.

Собор Нотр Дам на карте Парижа

Нотр Дам де Пари на видео

Отели недалеко от собора Нотр Дам

Читайте также:

Париж самостоятельно: советы и секреты

Лучшие музеи Парижа

Монмартр в Париже: интересные места и маршрут прогулки

Неизвестный Париж: в стороне от туристических троп

Неделя в Париже: маршруты на каждый день

| Notre-Dame de Paris | |

|---|---|

South façade and the nave of Notre-Dame in 2017, two years before the fire |

|

|

|

| 48°51′11″N 2°20′59″E / 48.8530°N 2.3498°ECoordinates: 48°51′11″N 2°20′59″E / 48.8530°N 2.3498°E | |

| Location | Parvis Notre-Dame – Place Jean-Paul-II, Paris |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Website | www.notredamedeparis.fr |

| History | |

| Status | Closed/Under renovation after the 2019 fire |

| Architecture | |

| Style | French Gothic |

| Years built | 1163–1345 |

| Groundbreaking | 1163 |

| Completed | 1345 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 128 m (420 ft) |

| Width | 48 m (157 ft) |

| Nave height | 35 metres (115 ft)[1] |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Tower height | 69 m (226 ft) |

| Number of spires | 0 (There was one before the fire of April 2019) |

| Spire height | 91.44 m (300.0 ft) (formerly)[2] |

| Bells | 10 |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Paris |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Laurent Ulrich |

| Rector | Olivier Ribadeau Dumas |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Sylvain Dieudonné[3] |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Criteria | i, ii, iii |

| Designated | 1991 |

| Part of | Paris, Banks of the Seine |

| Reference no. | 600 |

|

Monument historique |

|

| Official name | Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris |

| Type | Cathédrale |

| Designated | 1862[4] |

| Reference no. | PA00086250 |

Notre-Dame de Paris (French: [nɔtʁ(ə) dam də paʁi] (listen); meaning «Our Lady of Paris«), referred to simply as Notre-Dame,[a] is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is considered one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture. Several of its attributes set it apart from the earlier Romanesque style, particularly its pioneering use of the rib vault and flying buttress, its enormous and colourful rose windows, and the naturalism and abundance of its sculptural decoration.[5] Notre Dame also stands out for its musical components, notably its three pipe organs (one of which is historic) and its immense church bells.[6]

Construction of the cathedral began in 1163 under Bishop Maurice de Sully and was largely completed by 1260, though it was modified frequently in the centuries that followed. In the 1790s, during the French Revolution, Notre-Dame suffered extensive desecration; much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. In the 19th century, the coronation of Napoleon I and the funerals of many of the French Republic’s presidents took place at the cathedral.

The 1831 publication of Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris (known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) inspired popular interest in the cathedral, which led to a major restoration project between 1844 and 1864, supervised by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. On August 26, 1944, the Liberation of Paris from German occupation was celebrated in Notre-Dame with the singing of the Magnificat. Beginning in 1963, the cathedral’s façade was cleaned of centuries of soot and grime. Another cleaning and restoration project was carried out between 1991 and 2000.[7]

The cathedral is one of the most widely recognized symbols of the city of Paris and the French nation. In 1805, it was awarded the honorary status of a minor basilica. As the cathedral of the archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the archbishop of Paris (Laurent Ulrich).

In the early 21st century, approximately 12 million people visited Notre-Dame annually, making it the most visited monument in Paris.[8] The cathedral has long been renowned for its Lent sermons, a tradition founded in the 1830s by the Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire. In recent years, these sermons have increasingly often been given by leading public figures or government-employed academics.

Over time, the cathedral has gradually been stripped of many of its original decorations and artworks. However, the cathedral still contains several noteworthy examples of Gothic, Baroque, and 19th-century sculptures, a number of 17th- and early 18th-century altarpieces, and some of the most important relics in Christendom – including the Crown of Thorns, a sliver of the true cross and a nail from the true cross.